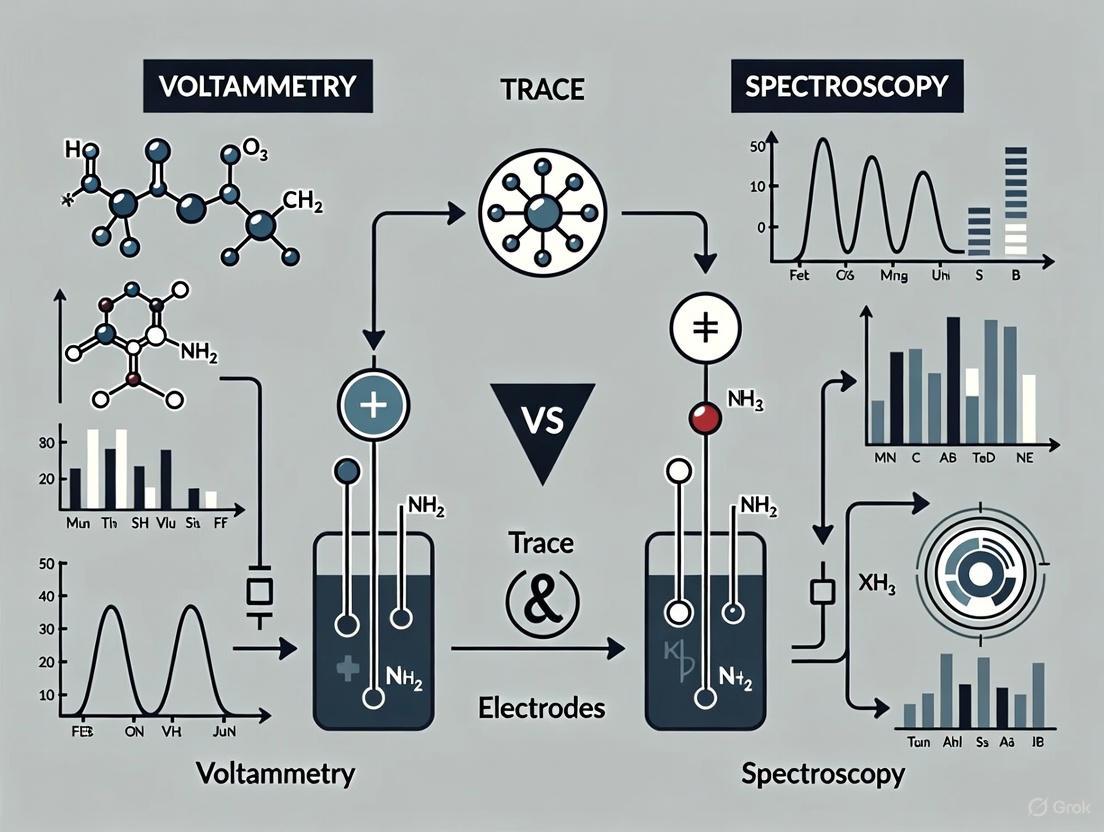

Voltammetry vs. Spectroscopy for Trace Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

This article provides a comparative analysis of voltammetry and spectroscopy for trace analysis, catering to researchers and scientists in pharmaceutical and environmental fields.

Voltammetry vs. Spectroscopy for Trace Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Development Professionals

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of voltammetry and spectroscopy for trace analysis, catering to researchers and scientists in pharmaceutical and environmental fields. It explores the foundational principles of both techniques, with a focus on voltammetry's unique capability for metal speciation analysis and its application in detecting trace metals and bioactive compounds. The scope includes methodological applications across different sample matrices, advanced troubleshooting protocols, and a direct validation of performance metrics against established spectroscopic methods. The article synthesizes key takeaways to guide method selection and discusses future trends, including the integration of nanotechnology and AI, to address evolving challenges in biomedical research and quality control.

Core Principles and Analytical Scope: Understanding Voltammetry's Edge in Speciation

In the critical field of trace metal analysis, the choice of analytical technique profoundly influences the quality and applicability of research outcomes. The central thesis of this guide is that while spectroscopic methods are powerful for determining total metal concentrations, voltammetric techniques provide a distinct and often superior advantage for speciation analysis, which is essential for understanding metal bioavailability, toxicity, and environmental cycling. This article provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these two methodological families, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the evidence needed to select the optimal tool for their specific trace analysis challenges.

Fundamental Principles: A Tale of Two Techniques

Understanding the core operational principles of voltammetry and spectroscopy is key to appreciating their comparative strengths and applications.

The Voltammetric Approach

Voltammetry is an electrochemical technique where a varying potential is applied to an electrode in an electrolyte solution, and the resulting current is measured. The redox reactions of the analyte at the electrode surface generate a current proportional to its concentration [1]. A typical setup uses a three-electrode system: a working electrode, a reference electrode, and a counter electrode [1]. Stripping voltammetry, a particularly sensitive branch, involves a two-stage process: first, a preconcentration step where metal ions are accumulated onto the electrode surface, and second, a stripping step where they are released back into solution, producing a measurable current signal [2] [3]. This pre-concentration is the key to its exceptional sensitivity.

The Spectroscopic Approach

Spectroscopic techniques, such as Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), operate on different principles. They typically involve atomizing the sample in a high-energy source (e.g., a plasma or flame) and measuring the interaction of light with the atoms or ions. This interaction can be the absorption of specific wavelengths (AAS) or the detection of mass-to-charge ratios (ICP-MS). While these methods are excellent for determining the total concentration of metals, they generally cannot distinguish between different chemical species of the same metal without coupling to separation techniques like chromatography [2].

Fundamental Workflows of Voltammetry and Spectroscopy

Performance Comparison: Data-Driven Decision Making

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and application-specific strengths of voltammetric and spectroscopic techniques, based on experimental data from the literature.

Table 1: Overall Analytical Performance Comparison

| Parameter | Voltammetric Techniques | Spectroscopic Techniques (e.g., ICP-MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | ppt to ppb range (e.g., Cd: 0.045 μg/L, Pb: 0.045 μg/L) [4] | ppt to ppb range (often superior for total metal analysis) |

| Analysis Speed | Minutes per sample (Rapid techniques like FSCV can operate at sub-second resolution) [5] | Seconds to minutes per sample (for multi-element analysis) |

| Speciation Capability | Direct speciation (Labile/inert fractions, redox species) [2] | Requires coupling with separation techniques (e.g., HPLC-ICP-MS) |

| Portability & On-Site Use | High (Miniaturizable electrodes, portable potentiostats) [4] [5] | Low (Typically requires laboratory infrastructure) |

| Cost & Operational Complexity | Lower cost, simpler operation [3] [5] | High capital and maintenance cost, complex operation |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; direct analysis often possible [2] | Often extensive; may require acid digestion |

Table 2: Application-Based Technique Selection

| Research Goal | Recommended Technique | Supporting Experimental Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Speciation in Natural Waters | Voltammetry (ASV, CLE-AdCSV) | Direct discrimination of labile metal fractions and complexation strength (log K = 12-14 for strong ligands, <10 for weak ligands) [2] |

| Total Trace Metal Content | Spectroscopy (ICP-MS) | High sensitivity for total concentration of multiple elements simultaneously [3] |

| On-Site/In-Situ Monitoring | Voltammetry | Successful field deployment for Pb and Cd in plants; fulfills "6 S's" criteria (Sensitivity, Selectivity, Size, Stability, Safe materials, Speed) [4] [5] |

| Rare Earth Element (REE) Analysis | Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) | Determination of Ce, Eu, and other lanthanides via their complexes with ligands like alizarin S [3] |

Experimental Protocols: A Look Under the Hood

To illustrate the practical application of these techniques, below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the performance comparison.

Voltammetric Protocol for Trace Metal Speciation

Method: Competitive Ligand Exchange-Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CLE-AdCSV) for Iron Speciation in Seawater [2].

- 1. Sample Collection & Preservation: Collect water samples using trace-metal-clean protocols. Filter through a 0.2 μm membrane to separate dissolved metals. Preserve at pH 1.8-2.0 if not analyzed immediately.

- 2. Ligand Addition: Add a well-defined competitive ligand (e.g., salicylaldoxime) to a known volume of the filtered sample. The ligand competes with natural organic ligands for binding to the target metal ions.

- 3. Adsorptive Accumulation: Apply a constant potential to the working electrode (e.g., a hanging mercury drop electrode) for a set time (e.g., 30-60 seconds). During this step, the metal-ligand complex adsorbs onto the electrode surface.

- 4. Potential Scan: Initiate a cathodic potential scan. The adsorbed metal complex is reduced, generating a peak current.

- 5. Titration & Data Modeling: Repeat steps 2-4 after standard additions of the target metal ion. The resulting titration data is fitted to a complexation model to determine the concentration of natural ligands and their conditional stability constants (log K).

Voltammetric Protocol for On-Site Analysis

Method: Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (DP-ASV) for Lead and Cadmium in Officinal Plants [4].

- 1. On-Site Sample Preparation: Grind the plant leaf sample and leach it with dilute acid (e.g., 0.1 M HNO₃) directly in the field.

- 2. Electrode Modification: Use a portable potentiostat with a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). Form an in-situ mercury film (iMF) on the GCE by adding a mercury salt to the measurement solution.

- 3. Optimized Deposition: Apply a deposition potential of -1.20 V for 195 seconds to reduce and accumulate Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ onto the iMF-GCE.

- 4. Stripping Scan: Apply a differential pulse waveform to strip the metals from the electrode. The oxidation of each metal produces a distinct current peak at a characteristic potential.

- 5. Quantification: Use the standard addition method with the portable instrument to quantify concentrations, achieving detection limits of 0.045 μg/L for Pb and 0.63 μg/L for Cd [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials and reagents required for voltammetric trace metal analysis, drawing from the experimental protocols discussed.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetric Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common working electrode substrate; provides a stable, renewable surface for analysis. | Determination of Pb and Cd in plant materials [4]. |

| Bismuth Film Electrode | A "green" alternative to mercury electrodes; forms alloys with target metals for stripping analysis. | Portable and disposable sensors for environmental monitoring [5]. |

| Competitive Ligands | Binds to target metals, forming electroactive complexes for highly sensitive adsorptive measurements. | Speciation of Fe, Cu, and Co in natural waters (e.g., using salicylaldoxime, tropolone) [2]. |

| Alizarin S | A complexing agent that forms adsorptive complexes with specific rare earth elements. | Determination of Cerium (Ce) and other lanthanides in environmental samples [3]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes electromigration of analytes; defines the electrochemical window. | Acetate buffer for Pb/Cd analysis; KCl or KNO₃ for general purpose [4]. |

The battle between voltammetric and spectroscopic techniques is not about declaring an overall winner, but about strategic alignment with research objectives. The experimental data and protocols presented herein lead to a clear conclusion:

Voltammetry is the unequivocal choice for research requiring metal speciation, on-site or in-situ measurements, and for projects with limited budgets without compromising on sensitivity. Its ability to directly probe labile fractions and complexation kinetics provides insights into biogeochemical processes that spectroscopy alone cannot offer.

Spectroscopy, particularly ICP-MS, remains the gold standard for the rapid, ultra-sensitive determination of total multi-element concentrations in a sample, especially within a centralized laboratory setting.

Therefore, the research question itself defines the battlefield. For studies of metal bioavailability, toxicity, and dynamic environmental processes, voltammetry provides the fundamental toolkit to define and win that battle.

In both environmental and pharmacological research, the total concentration of a metal is a poor indicator of its potential biological effect or toxicity. The bioavailability of a metal—its ability to be taken up and interact with living organisms—is predominantly governed by its specific chemical form, or species, rather than its total quantity [2]. For instance, more than 99% of copper in natural waters can be complexed by organic ligands, dramatically reducing its bioavailability and toxicity to phytoplankton and other organisms [2]. This principle is foundational to ecotoxicological models like the Free Ion Activity Model (FIAM) and the Biotic Ligand Model (BLM), which posit that the free hydrated metal ion is often the primary bioavailable species [6] [7].

The ability to distinguish between these different metal species is known as speciation analysis. While spectroscopic techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) excel at quantifying total metal concentrations with high sensitivity, they are generally incapable of discriminating between different chemical forms without coupling to separation techniques, which can alter the original speciation [2] [3]. In contrast, voltammetric methods are inherently capable of direct metal speciation analysis with minimal sample preparation, making them uniquely suited for assessing metal bioavailability [2] [7]. This article provides a objective comparison of these two analytical approaches, underscoring why voltammetry offers a distinct advantage in speciation studies critical for environmental monitoring and drug development.

Fundamental Principles: How Voltammetry Accesses Speciation Information

Core Voltammetric Techniques for Speciation

Voltammetry is a branch of electroanalytical chemistry that measures current as a function of an applied potential. For trace metal analysis, stripping voltammetry is the most sensitive family of techniques, characterized by a two-stage process: a preconcentration (deposition) step followed by a measurement (stripping) step [2] [3]. The key techniques for speciation analysis include:

- Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV): The metal is electrochemically reduced and preconcentrated as an amalgam at the electrode surface (e.g., a mercury or bismuth film electrode). Subsequently, it is re-oxidized (stripped), producing a current peak used for quantification. The ASV-labile fraction is considered highly relevant for toxicity and bioavailability [2] [7].

- Competitive Ligand Exchange-Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CLE-AdCSV): This powerful equilibrium-based method determines complexation parameters. An added ligand competes with natural ligands for the target metal, forming an electroactive complex that adsorbs on the electrode surface. This allows for the indirect determination of the free metal ion concentration and the characterization of natural organic ligands [2] [6].

- Absence of Gradients and Nernstian Equilibrium Stripping (AGNES): This technique provides direct access to the free metal ion concentration by applying a specific potential program that establishes equilibrium between the metal in the electrode and the free metal ion in solution, effectively isolating this critical species [6] [7].

The Speciation Advantage: Labile vs. Inert Fractions

The principal strength of voltammetry lies in its operational nature. The electrochemical response is dependent on the kinetics and thermodynamics of metal complex dissociation. During the deposition step, only metal species that can dissociate rapidly enough to contribute to the diffusion flux to the electrode are measured. This fraction is termed "labile" and includes free metal ions and weak, rapidly dissociating complexes [2]. In contrast, strongly bound or "inert" complexes do not dissociate on the experimental timescale and are not detected [2]. This lability is directly related to bioavailability, as the same kinetic principles govern metal uptake by biological membranes [2] [7]. Consequently, voltammetry provides a functionally relevant measurement that spectroscopic totals cannot.

Direct Comparison: Voltammetry vs. Spectroscopy for Metal Analysis

The following table summarizes the core differences between voltammetric and spectroscopic techniques for trace metal analysis, particularly in the context of speciation and bioavailability.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis: Voltammetry vs. Spectroscopy for Trace Metal Analysis

| Feature | Voltammetric Techniques | Spectroscopic Techniques (ICP-MS, AAS, ICP-OES) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Output | Free ion concentration, labile fraction, complexation parameters | Total elemental concentration |

| Speciation Capability | Direct, often with minimal sample preparation | Requires coupling to separation techniques (e.g., HPLC-ICP-MS) |

| Information on Bioavailability | High (measures kinetically labile fractions correlated with uptake) | Indirect (requires inference from total concentration) |

| Sensitivity | Excellent (trace to ultra-trace levels) | Excellent to superior (especially ICP-MS) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal; suitable for direct, on-site analysis | Often extensive (digestion, acidification) |

| Portability & Cost | High portability; relatively low cost and operational expenses | Laboratory-bound; high capital and operational costs |

| Multi-Element Capacity | Limited, typically a few elements simultaneously | Excellent, true multi-element capability |

| Key Applicable Models | FIAM, BLM (provides direct input parameters) | FIAM, BLM (requires assumption or independent measurement of free ion) |

Experimental Protocols & Data: Illustrating the Voltammetric Advantage

Protocol: Determining Bioavailable Copper via CLE-AdCSV

The following workflow is standard for assessing copper speciation in natural waters, such as seawater or freshwater, to evaluate its potential bioavailability and toxicity [2].

Title: CLE-AdCSV Workflow for Copper Speciation

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Collection and Pretreatment: Collect water samples with minimal perturbation to avoid altering speciation. Filter through a 0.2 or 0.45 μm membrane to obtain the "dissolved" fraction [6].

- Ligand Addition and Equilibration: Spike the sample with a well-characterized competitive ligand (e.g., salicylaldoxime) at a known concentration. The system is allowed to equilibrate (typically for several hours) so that the added ligand competes with natural ligands for binding to copper [2].

- Voltammetric Measurement: The pH is adjusted to an optimal value. An adsorptive accumulation potential is applied to the working electrode (e.g., a hanging mercury drop electrode), causing the Cu-Ladd complex to adsorb to the surface. A cathodic potential sweep is then applied, reducing the metal in the adsorbed complex and generating a stripping current peak [2] [7].

- Titration and Data Analysis: The measurement is repeated after multiple standard additions of copper to the sample. The resulting titration data is modeled using established methods (e.g., Van den Berg/Ružić linearization) to determine the concentration of natural ligands and their conditional stability constants (K). From these parameters, the free Cu²⁺ concentration ([Cu²⁺]) is calculated [2].

Protocol: Direct Free Ion Measurement with AGNES

AGNES is specifically designed to quantify the free metal ion concentration, a key parameter in the FIAM and BLM models [7].

Detailed Procedure:

- Deposition to Equilibrium: A potential (E1) is applied to the working electrode (a mercury-based electrode) that is sufficiently negative to reduce the target metal ion (e.g., Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺) and preconcentrate it as an amalgam. The key is that this step is prolonged until Nernstian equilibrium is established between the metal in the amalgam and the free metal ion in solution, with an absence of concentration gradients in the diffusion layer [7].

- Equilibrium Stripping: The preconcentrated metal is stripped back into the solution, typically using a differential pulse voltammetry scan. The measured stripping signal is directly proportional to the free metal ion concentration in the sample [7].

Comparative Experimental Data

The following table compiles illustrative data from voltammetric studies, demonstrating its capability to speciate metals at environmentally and biologically relevant concentrations.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Voltammetric Speciation Studies in Aqueous Media

| Metal | Technique | Matrix | Measured Fraction / Parameter | Reported Value | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper (Cu) | CLE-AdCSV | Seawater [2] | Free Cu²⁺ Concentration | Often < 0.01 nM (non-toxic levels) | >99% of dissolved Cu is organically complexed, mitigating toxicity. |

| Iron (Fe) | CLE-AdCSV | Ocean Water (Surface) [2] | Organically Complexed Fe | >99% of total dissolved Fe | Explains "iron limitation" in HNLC* regions despite total Fe. |

| Lead (Pb) | SWASV [8] | Drinking Water | ASV-labile Pb | LOD below WHO/EPA limits | The labile fraction is monitored for direct compliance with health standards. |

| Zinc (Zn), Cadmium (Cd) | AGNES [7] | Freshwater/Synthetic | Free Ion Concentration [Zn²⁺], [Cd²⁺] | Direct quantification possible | Validates models like FIAM and BLM with direct input parameters. |

| Multiple (Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn) | SWASV with Bi-film GCE [9] | Water | ASV-labile Metals | LOD: 0.65-1.07 ppb | Demonstrates portability and multi-metal capability for labile fractions. |

HNLC: High Nutrient-Low Chlorophyll; *LOD: Limit of Detection*

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful voltammetric speciation requires a set of specific reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetric Speciation

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Surface where electrochemical reaction occurs. Defines sensitivity and applicability. | Hg-drop (HMDE) for CLE-AdCSV; Bismuth-film (BiFE) for ASV; Solid Au/CNT-modified electrodes [10] [9]. |

| Competitive Ligand | A known ligand added to compete with natural ligands for the target metal. | Salicylaldoxime (for Fe, Cu); DMG (for Ni); Cupferron (for Ga, V) [2] [10]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic strength and controls electrical migration; can be a buffer. | Acetate buffer (pH ~4.5); Ammonia buffer; HEPES for biological samples [8]. |

| Standard Metal Solutions | High-purity solutions for standard addition calibration. | Used in titration to determine complexation capacity and free ion concentration [2] [7]. |

| Complexing Agent for AdSV | Forms an adsorbable complex with metals that are not easily reduced. | Alizarin S (for Eu); DTPA or Morin (for other REEs) [3]. |

The choice between voltammetry and spectroscopy is not a matter of which technique is universally "better," but which is more appropriate for the scientific question at hand. For research demanding a simple, accurate, and total elemental concentration, particularly for multiple elements, ICP-MS remains the gold standard. However, when the objective is to understand the environmental impact, bioavailability, or toxicity of trace metals, voltammetry provides irreplaceable speciation data.

Its unique ability to discriminate between labile and inert metal fractions directly, without altering the sample's equilibrium, offers a functional perspective that aligns with biological uptake processes. Coupled with its portability, low cost, and capability for on-site and in-situ measurements, voltammetry establishes itself as an indispensable tool for any researcher or professional seeking to move beyond total concentrations and truly decipher the bioavailable world of trace metals.

The accurate detection of trace-level analytes is a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, with profound implications for environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and clinical diagnostics. The selection of an appropriate analytical method hinges on a fundamental understanding of its sensitivity and detection limit—the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the absence of that analyte. Detection limit defines this minimum detectable quantity with acceptable certainty, while sensitivity refers to the ability of a method to discriminate between small differences in analyte concentration. Within this landscape, voltammetry and spectroscopy represent two powerful, yet fundamentally different, approaches for quantitative trace analysis. Voltammetric techniques measure current resulting from the reduction or oxidation of electroactive species at an electrode interface, whereas spectroscopic methods typically quantify the absorption of light by analyte molecules.

The core thesis of this guide posits that while spectroscopic methods offer robust, general-purpose analysis for a wide range of compounds, advanced voltammetric techniques, particularly those employing specialized electrode configurations and signal-enhancement strategies, can achieve unparalleled sensitivity for specific electroactive analytes, often surpassing optical methods in detection power for trace metal and organic compound analysis. This article provides a systematic comparison of the sensitivity and detection limits of these techniques, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to guide researchers in selecting the optimal method for their specific trace analysis challenges.

Voltammetric Techniques: Principles and Performance Data

Fundamentals of Voltammetry for Trace Detection

Voltammetry encompasses a family of electroanalytical techniques that measure current as a function of applied potential. The exceptional sensitivity of certain voltammetric methods for trace analysis stems from their ability to incorporate a pre-concentration step, where the analyte is accumulated onto or into the working electrode before the actual measurement. This principle is most effectively employed in stripping voltammetry, which operates in two distinct stages: first, an electroactive species is deposited onto the electrode surface at a constant potential; second, the concentrated species is "stripped" back into solution using a potential sweep, generating a highly sensitive current response [11]. The signal is directly proportional to the analyte's concentration, while the applied potential at which stripping occurs provides qualitative identification.

The design and material of the working electrode are critical for optimizing voltammetric sensitivity. Common electrodes include the glassy carbon electrode (GCE), mercury-based electrodes (e.g., HMDE, Hg(Ag)FE) renowned for their high hydrogen overvoltage and renewable surface, and advanced modified electrodes where the surface is coated with a chemical film or nanomaterial to enhance selectivity and signal amplification [12] [11]. The recent development of ultramicroelectrode arrays (UMEAs) has further pushed the boundaries of sensitivity. These arrays consist of thousands of microscopic electrodes operating in parallel, which significantly amplify the faradaic current while minimizing detrimental effects like capacitive charging currents and solution resistance, enabling detection in low-electrolyte environments and achieving very low detection limits [13] [14].

Quantitative Detection Limits in Voltammetry

The following table summarizes the typical detection limits achievable with various voltammetric techniques for a selection of analytes, underscoring the method's capability for ultra-trace determination.

Table 1: Detection Limits of Voltammetric Techniques for Various Analytes

| Analyte | Voltammetric Technique | Working Electrode | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BDE-47 (Flame Retardant) | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Sludge Biochar-modified GCE | 5 ng L⁻¹ (≈ 1 x 10⁻¹¹ M) | 0.005 - 0.6 μg L⁻¹ | [12] |

| Ga(III) (Gallium) | Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) | PbFE/MWCNT/SGCE | 9.5 x 10⁻¹⁰ M | 3.0 x 10⁻⁹ – 4.0 x 10⁻⁷ M | [11] |

| Ga(III) (Gallium) | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | HMDE | 5.7 x 10⁻¹¹ M | Not Specified | [11] |

| Ga(III) (Gallium) | Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) | Hg(Ag)FE | 3.6 x 10⁻¹⁰ M | 1.25 x 10⁻⁹ – 9.0 x 10⁻⁸ M | [11] |

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Cd, Pb) | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Ultramicroelectrode Arrays (UMEAs) | ppt to ppb range | Not Specified | [14] |

The data reveals that stripping voltammetry consistently achieves detection limits in the nanomolar to picomolar range (10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹¹ M), making it one of the most sensitive analytical techniques available. The use of modified electrodes, such as the sludge biochar-modified GCE, demonstrates how material science can be leveraged to create highly adsorptive and conductive surfaces, further pushing detection limits for persistent organic pollutants like BDE-47 into the ng/L range [12].

Experimental Protocol: Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry for Gallium

The following detailed methodology, adapted from procedures for determining trace gallium, exemplifies the careful optimization required for a highly sensitive voltammetric analysis [11].

- Electrode and Apparatus Preparation: Utilize a three-electrode system. The working electrode is a mercury-based film electrode (Hg(Ag)FE). A Pt wire serves as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) electrode is the reference. All potentials are reported versus this reference. Polish the electrode surface (if solid) to a mirror finish with alumina slurry (0.05 μm) before each experiment.

- Reagent and Solution Preparation: Prepare a 0.1 M acetate buffer supporting electrolyte at pH 4.8. The complexing agent is a 0.01 M catechol solution. Prepare a 1000 mg L⁻¹ Ga(III) stock standard solution from high-purity gallium salt. Dilute this stock daily to prepare working standards. Use ultra-pure water (18.2 MΩ·cm) for all solutions.

- Pre-concentration/Accumulation Step: Transfer 10 mL of the supporting electrolyte and the Ga(III) standard/sample into the voltammetric cell. Deoxygenate the solution by purging with high-purity nitrogen gas for 600 seconds. While stirring the solution, deposit the analyte onto the electrode at a potential of -0.5 V for 60 seconds. During this step, Ga(III) forms a complex with catechol that adsorbs onto the electrode surface.

- Stripping and Measurement: After the accumulation period, stop the stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for 10 seconds. Initiate the potential sweep from -0.5 V to -1.2 V using a square-wave waveform. The reduction current of the adsorbed gallium-catechol complex is measured, producing a peak-shaped voltammogram.

- Calibration and Quantification: Record the stripping voltammograms for a series of standard Ga(III) solutions. Plot the peak current height as a function of the Ga(III) concentration to construct a calibration curve. The concentration of Ga(III) in an unknown sample is determined by interpolating its peak current onto this calibration curve.

Spectroscopic Techniques: Principles and Performance Data

Fundamentals of Spectroscopy for Trace Detection

Spectroscopic techniques for trace analysis are primarily based on the Beer-Lambert Law, which states that the absorbance of light by a solution is directly proportional to the concentration of the absorbing species and the path length of the light through the solution. In a typical UV-Vis spectrophotometer, light from a deuterium or tungsten lamp is passed through a monochromator to select a specific wavelength, which then travels through the sample cell (cuvette), and the transmitted intensity is measured by a photodetector [15]. The resulting absorbance spectrum provides both quantitative (concentration) and qualitative (identity via λ_max) information about the analyte.

For elemental analysis, Inductively Coupled Plasma techniques coupled with optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) or mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) represent the gold standard. These methods involve atomizing and ionizing the sample in a high-temperature plasma. ICP-OES measures the characteristic light emitted by excited atoms, while ICP-MS separates and counts the ions based on their mass-to-charge ratio, offering exceptional sensitivity [16]. The versatility of spectroscopic methods allows them to detect a wide range of analytes, from nutrients and metal ions in water to organic pharmaceuticals.

Quantitative Detection Limits in Spectroscopy

The table below compares the detection capabilities of common spectroscopic methods, illustrating their broad applicability and the superior sensitivity of mass spectrometry-based approaches.

Table 2: Detection Limits of Spectroscopic Techniques for Various Applications

| Technique | Detectable Elements/Analytes | Typical Sensitivity/DL Range | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICP-MS | Li to U (Most elements) | ppm to ppt (μg/L to ng/L) | Ultra-trace metal analysis, environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics [16] |

| ICP-OES | Li to U (Most elements) | ppm (μg/L) | Major and trace element analysis in water, soils, and materials [16] [11] |

| Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS) | Mainly metallic elements (up to 70) | ppm (μg/L) | Trace metal analysis in biological and environmental samples [16] [11] |

| UV-Vis Spectrophotometry | Chromophoric compounds (Nitrate, Fe, Cu, organics) | Generally low ppm (mg/L) | Water quality parameters (nitrate, phosphate), pharmaceutical analysis [17] [15] |

| CHNOS Analyzer | C, H, N, O, S | 0.05–0.1 wt% (Not for traces) | Bulk organic composition analysis [16] |

While UV-Vis spectrophotometry is a workhorse for routine analysis due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness, its detection limits are typically in the milligram-per-liter (ppm) range, making it less sensitive than advanced voltammetric methods for trace analysis [17]. In contrast, ICP-MS stands out as the most sensitive spectroscopic technique, capable of detecting elements at concentrations as low as parts-per-trillion (ppt or ng/L), rivaling and often exceeding the sensitivity of stripping voltammetry for metal ions [16].

Critical Comparison and Application Scenarios

Side-by-Side Technique Comparison

The choice between voltammetry and spectroscopy is multifaceted, depending on the required detection limit, analytical scope, and operational constraints.

Table 3: Direct Comparison of Voltammetry and Spectroscopy for Trace Analysis

| Characteristic | Voltammetry (e.g., Stripping Methods) | Spectroscopy (e.g., ICP-MS, UV-Vis) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limit | ppb to ppt (for electroactive species) [12] [11] [14] | ppt (ICP-MS) to ppm (UV-Vis) [16] [17] |

| Analyte Scope | Electroactive species (metals, specific organics). Limited to what can be oxidized/reduced. | Very broad (most elements via ICP; chromophores via UV-Vis). |

| Selectivity | High (from applied potential and electrode modification). | Moderate to High (from wavelength or mass). |

| Sample Volume | Small (mL or less) [11] | Varies (mL for UV-Vis; low mL for ICP). |

| Cost & Operational Complexity | Low to Moderate (relatively inexpensive equipment). | High for ICP-MS (expensive instrumentation and operation). |

| Portability | High (suitable for field-deployable sensors) [14] | Low (generally laboratory-bound instruments). |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate (can have longer analysis times due to pre-concentration). | High (rapid analysis, especially for ICP-MS). |

| Multi-element Capability | Limited (typically sequential) | Excellent (simultaneous multi-element detection). |

The experimental workflow for each technique highlights their different approaches to achieving sensitivity, from electrochemical pre-concentration to plasma-based atomization.

Selection Guide for Analytical Scenarios

The following decision logic can help researchers navigate the technique selection process based on their specific analytical problem.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of sensitive analytical methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components for voltammetric and spectroscopic analyses.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Trace Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., Acetate Buffer, KCl) | Carries current, minimizes resistance (iR drop), and controls pH in the electrochemical cell. | Essential for all voltammetric experiments to ensure well-defined mass transport and a stable potential field [12] [11]. |

| Complexing Agents (e.g., Catechol, Cupferron) | Forms an adsorbable complex with the target metal ion, enabling its pre-concentration in AdSV. | Crucial for enhancing the sensitivity and selectivity of stripping voltammetry for metals like Ga(III) [11]. |

| Electrode Modifiers (e.g., Sludge Biochar, MWCNTs) | Increases effective surface area, provides adsorption sites, and enhances electron transfer kinetics. | Used to fabricate modified electrodes for lower detection limits and improved analyte selectivity [12] [11]. |

| High-Purity Standards | Used for instrument calibration to ensure quantitative accuracy. | Critical for all quantitative analytical techniques, including voltammetry and spectroscopy. |

| Deoxygenation Agent (High-Purity N₂ or Ar) | Removes dissolved oxygen from solutions to prevent interfering redox reactions. | A mandatory step in most voltammetric analyses of reducible species to avoid overlapping oxygen reduction waves [12]. |

| Digestion Acids (e.g., HNO₃, HCl) | Dissolves and decomposes solid samples into a liquid form for analysis. | Essential for sample preparation in elemental analysis via ICP-MS/OES or AAS [16]. |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that both voltammetry and spectroscopy offer powerful pathways for trace analysis, yet they possess distinct performance profiles. Stripping voltammetry emerges as a uniquely sensitive technique for electroactive analytes, achieving detection limits in the ppt range, often with lower cost and higher portability than its spectroscopic counterparts. Its strength lies in targeted, ultra-trace analysis of specific metals or organic pollutants, especially in scenarios requiring field deployment. In contrast, spectroscopic methods, particularly ICP-MS, provide unrivalled breadth of analyte coverage and multi-element capability down to similar ultra-trace levels, establishing it as the benchmark for comprehensive elemental analysis in centralized laboratories.

The choice between these techniques is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the analytical problem at hand. Researchers must weigh factors such as the required detection limit, the nature and number of target analytes, available budget, and the need for portability. The ongoing development of novel electrode materials and the miniaturization of spectroscopic instruments will continue to push the boundaries of sensitivity and accessibility, further empowering scientists in drug development, environmental monitoring, and beyond to solve increasingly complex analytical challenges.

The Role of Electrode Materials and Supporting Electrolytes in Voltammetry

Voltammetry is a powerful electrochemical technique widely employed for the quantitative determination and speciation analysis of trace elements and organic molecules. Its application spans environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and energy storage research. The performance of voltammetric methods is critically dependent on two fundamental components: the electrode material, which serves as the platform for electron transfer reactions, and the supporting electrolyte, which governs ionic conductivity and interfacial processes. Within the broader context of analytical research, voltammetry offers distinct advantages over spectroscopic techniques for trace analysis, including minimal sample preparation, capability for direct speciation analysis, and portability for in-situ measurements. This guide provides a comparative analysis of electrode and electrolyte selection, supported by experimental data and protocols, to optimize voltammetric systems for trace-level determination.

Comparative Analysis of Electrode Materials

The choice of electrode material significantly influences voltammetric parameters such as sensitivity, selectivity, potential window, and reproducibility. Different materials interact uniquely with analytes, leading to variations in electron transfer kinetics and surface reactivity.

Performance Metrics of Common Electrode Materials

Table 1: Comparative performance of electrode materials in voltammetric analysis

| Electrode Material | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations | Electrochemical Stability Window | Sensitivity Enhancement Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon (GCE) | General purpose, dissolved organic molecules, metal ions [18] | Wide potential window, good mechanical stability, low background current | Surface fouling in complex matrices, requires periodic polishing | Moderate to wide (solvent-dependent) | Chemical modification with nanomaterials, polymers [18] |

| Sludge Biochar-Modified GCE | Trace organic pollutants (e.g., BDE-47) in water [12] | High surface area, abundant functional groups, cost-effective from waste | Batch-to-batch variability, complex characterization | Similar to base GCE | Pyrolysis optimization (600°C for pore development) [12] |

| Transition Metal Oxides/Sulfides | Energy storage (supercapacitors), electrocatalysis [19] | High pseudocapacitance, reversible redox activity, tunable morphology | Limited electronic conductivity, synthesis complexity | Varies with composition | Nanostructuring, hybrid composites with carbon materials [19] |

| Bare Metal Electrodes | Fundamental studies, electroplating [18] | Excellent conductivity, well-defined surfaces | Narrow potential window, surface oxidation issues | Narrow in aqueous solutions | Not applicable for bare operation |

Impact of Electrode Material on Voltammetric Response

The fundamental role of electrode materials is exemplified in comparative studies. Research has demonstrated that bare electrodes may produce no detectable redox curves due to poor conductivity or fouling issues, while glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) produce well-defined redox peaks owing to their favorable electron transfer properties and chemical stability [18]. The performance of GCEs can be substantially enhanced through surface modification with various materials. For instance, modifying GCEs with sludge biochar creates an interface with increased surface area and additional adsorption sites, significantly improving sensitivity for detecting persistent organic pollutants like 2,2',4,4'-tetrabromodiphenyl ether (BDE-47) at trace concentrations (detection limit of 5 ng L⁻¹) [12].

The modification protocol involves precise thermal treatment, where pyrolysis at 600°C in an oxygen-free environment optimizes the biochar's pore structure and functional groups, thereby enhancing analyte enrichment and electron transfer kinetics [12]. This approach demonstrates the principle of tailoring electrode surfaces to specific analytical challenges.

Comparative Analysis of Supporting Electrolytes

Supporting electrolytes facilitate charge transport while influencing electrochemical processes through ionic strength effects, ion-pair formation, and specific interactions with analytes.

Performance Characteristics of Supporting Electrolytes

Table 2: Properties and performance of supporting electrolytes in different solvents

| Supporting Electrolyte | Solvent Compatibility | Conductivity Performance | Key Influencing Parameters | Typical Applications | Stability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tetraalkylammonium Salts (e.g., Bu₄NBF₄, Et₄NBF₄) | Aprotic polar solvents (DMF, DLG, ACN) [20] | Λ° order: MeEt₃N⁺ > Et₄N⁺ > Bu₄N⁺; Lower in high viscosity solvents [20] | Viscosity, ion association constants, Walden product | Organic electro-synthesis, non-aqueous electrochemistry [20] | Electrochemical stability, minimal interference with analytes |

| Inorganic Salts (e.g., Na₂SO₄, KCl) | Aqueous solutions [21] | High in aqueous media, concentration-dependent | pH, buffering capacity, ionic strength | Environmental analysis, metal speciation [2] [21] | pH changes at electrodes may require buffering [21] |

| Acid/Base Electrolytes (e.g., H₂SO₄, phosphate buffers) | Aqueous solutions [22] | High conductivity, pH control | pH, buffer capacity, current density | Controlled potential studies, pH-dependent reactions [22] | Buffering prevents extreme pH shifts at electrodes [22] |

| Ionic Liquids & Deep Eutectic Solvents | Various, including non-aqueous [23] | Moderate to high, enhances solubility | Viscosity, ion size, operating temperature | Redox flow batteries, specialty applications [23] | High thermal stability, tunable properties |

Electrolyte Effects on Fundamental Parameters

The conductivity behavior of supporting electrolytes follows predictable trends based on ionic properties. In the bio-renewable solvent dihydrolevoglucosenone (DLG), molar conductivities (Λ°) of tetraalkylammonium salts decrease with increasing cation size: MeEt₃NBF₄ (9.20 S cm² mol⁻¹) > Et₄NBF₄ (8.88 S cm² mol⁻¹) > Bu₄NBF₄ (7.36 S cm² mol⁻¹) [20]. This trend reflects stronger ion-solvent interactions with smaller cations. The Walden product (Λ°η), which accounts for solvent viscosity effects, follows the same order, confirming the advantage of smaller cations for conductivity in viscous media [20].

The buffering capacity of supporting electrolytes significantly influences local pH conditions at electrode surfaces. Recent investigations demonstrate that electrolytes with buffering characteristics substantially slow the propagation of pH fronts from electrodes compared to unbuffered systems [22] [21]. This effect is crucial in applications where reaction kinetics and product distributions are pH-dependent, such as in aqueous CO₂ electrolysis or metal speciation studies [2] [21].

Experimental Protocols for System Optimization

Electrode Modification and Characterization Protocol

Sludge Biochar-Modified GCE for Trace BDE-47 Detection [12]:

- Biochar Preparation: Pyrolyze municipal sludge at 600°C in an oxygen-free tubular furnace for 2 hours to develop optimal pore structure.

- Electrode Modification: Prepare a homogeneous suspension of sludge biochar in ethanol (1 mg mL⁻¹). Deposit 5 μL of this suspension onto a polished GCE surface and allow to dry under ambient conditions.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Employ a standard three-electrode system with the modified GCE as working electrode, Pt wire counter electrode, and Ag/AgCl reference electrode in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

- Optimization: Determine optimal parameters: scan rate (20-100 mV s⁻¹), accumulation time (30-120 s), and pH (6-8) using cyclic voltammetry or differential pulse voltammetry.

- Calibration: Construct calibration curve from 0.005 μg L⁻¹ to 0.6 μg L⁻¹ BDE-47, achieving detection limit of 5 ng L⁻¹.

Electrolyte Selection and Evaluation Protocol

Characterization of Supporting Electrolytes in Green Solvents [20]:

- Solvent Purification: Purify the solvent (e.g., DLG) through appropriate methods to remove impurities and water.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare electrolyte solutions at varying concentrations (0.01-0.1 M) in the target solvent.

- Conductivity Measurements: Measure specific conductance using a conductivity meter with temperature control (20-40°C).

- Viscosity Determination: Obtain kinematic viscosity using an Ubbelohde viscometer at controlled temperatures.

- Data Analysis: Calculate molar conductivity and fit using the Lee and Wheaton equation in the Pethybridge and Taba form (LWPT model) to determine limiting molar conductance (Λ°) and association constants (Kₐ).

- Electrochemical Window: Determine the electrochemical potential window by cyclic voltammetry in a three-electrode cell.

Voltammetry Versus Spectroscopy for Trace Analysis

The selection between voltammetric and spectroscopic techniques involves strategic considerations based on analytical requirements:

Table 3: Comparison of voltammetry and spectroscopy for trace analysis

| Parameter | Voltammetry | Spectroscopy (ICP-MS, HPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Speciation Capability | Direct speciation (labile/inert fractions, redox states) without separation [2] | Requires hyphenated techniques (e.g., LC-ICP-MS) for speciation |

| Detection Limits | Sub-nanomolar for many metals and organics (e.g., 5 ng L⁻¹ for BDE-47) [12] | Similar or better for total concentrations (ppt-ppb) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal, often direct analysis [2] | Often extensive preparation (digestion, derivatization) |

| Portability | Excellent for field deployment [12] | Generally laboratory-based |

| Analysis Time | Rapid (minutes) [12] | Variable (minutes to hours) |

| Cost | Lower instrumentation costs [12] | High capital and maintenance costs |

| Matrix Effects | Susceptible to fouling, but addressable with modifiers [12] [18] | Complex matrices may require extensive cleanup |

Voltammetry excels in speciation analysis, distinguishing between different metal forms (free ions, labile complexes, inert complexes) without physical separation techniques [2]. For example, anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) can determine the ASV-labile fraction of metals, which is most relevant to bioavailability and toxicity assessments in environmental samples [2]. This capability for direct speciation represents a significant advantage over spectroscopic methods that typically provide only total element concentrations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key reagents and materials for voltammetric analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrodes | Working electrode platform with wide potential window | General voltammetry, modifier substrate [12] [18] |

| Tetrabutylammonium Hexafluorophosphate (Bu₄NPF₆) | Supporting electrolyte for non-aqueous systems | Organic electrosynthesis, wide potential window studies [20] |

| Sludge Biochar | Electrode modifier for enhanced sensitivity | Trace pollutant detection, waste-derived material [12] |

| Phosphate Buffers | pH control and buffering capacity in aqueous systems | pH-dependent studies, biological molecules [12] |

| Transition Metal Oxides (e.g., MnO₂, RuO₂) | Pseudocapacitive materials, electrocatalysts | Energy storage studies, sensor development [19] |

| Ionic Liquids | Advanced electrolytes with tunable properties | Non-aqueous systems, thermal stability requirements [23] |

| pH Indicators (e.g., thymol blue) | Visualization and quantification of pH gradients | Monitoring local pH changes in electrochemical cells [21] |

Conceptual Framework and Workflows

Diagram 1: Decision framework for analytical method selection between voltammetry and spectroscopy, highlighting optimization pathways for electrode and electrolyte components in voltammetry.

Diagram 2: Interrelationship between electrode materials and supporting electrolytes in determining key voltammetric performance parameters, highlighting the multifaceted nature of system optimization.

The synergistic relationship between electrode materials and supporting electrolytes forms the foundation of effective voltammetric analysis. Electrode selection dictates electron transfer kinetics and surface interactions, while supporting electrolytes control mass transport and interfacial conditions. The comparative data presented demonstrates that modified electrodes like sludge biochar-GCE significantly enhance sensitivity for trace organic analysis, while proper electrolyte selection based on conductivity parameters and buffering capacity ensures reproducible results. Within trace analysis research, voltammetry provides distinct advantages for speciation studies and field applications where minimal sample preparation and direct chemical form discrimination are prioritized over total concentration measurements provided by spectroscopic techniques. The optimization protocols and comparative data presented serve as a guide for researchers designing voltammetric methods tailored to specific analytical challenges in pharmaceutical, environmental, and materials development applications.

Trace analysis, the measurement of components at low concentrations such as parts-per-billion or parts-per-trillion, is fundamental to environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and material sciences [24] [25]. The accuracy of such analyses is critically dependent on the selection of appropriate instrumental techniques, with voltammetry and spectroscopy representing two principal approaches. This guide provides a objective comparison of these methodologies, focusing on their operational parameters, performance characteristics, and practical implementation for researchers and drug development professionals. The requirement for high-quality data in these fields demands a thorough understanding of each technique's capabilities, from sensitivity and selectivity to cost-effectiveness and ease of use [25]. This overview synthesizes experimental data and procedural details to inform strategic instrument selection within a structured analytical framework.

Technical Comparison: Voltammetry versus Spectroscopy

The choice between voltammetric and spectroscopic techniques involves trade-offs between sensitivity, selectivity, operational complexity, and cost. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of each approach for trace metal analysis, drawing from applications in environmental and pharmaceutical contexts [2] [3] [25].

Table 1: Comparative overview of voltammetry and spectroscopy for trace analysis.

| Feature | Voltammetry | Spectroscopy (ICP-MS cited as example) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Analytical Figures of Merit | ||

| Typical Detection Limits | Part-per-trillion (ppt) to part-per-billion (ppb) level [3] | Part-per-trillion (ppt) and sub-ppt level [3] |

| Selectivity | Achieved via applied potential and chemical speciation (e.g., ASV-labile fraction) [2] | High elemental selectivity and multi-element capability [2] |

| Analyte Scope | Metals (Cu, Pb, Cd, Zn, REEs); speciation of redox states, labile/inert fractions [2] [3] | Wide range of metals; total element concentration only [2] |

| Operational & Practical Considerations | ||

| Sample Throughput | Moderate; can be high with automated systems [26] | High |

| Sample Volume | Can be very small (mL scale) | Typically requires larger volumes (though micro-systems exist) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal for direct analysis; may require pH adjustment or ligand addition [2] | Often extensive; typically requires acid digestion [2] |

| Cost of Instrumentation | Relatively low cost [3] | High capital and operational cost [3] |

| Key Strengths | Speciation analysis, low operational cost, potential for in-situ analysis [2] | Ultra-low detection limits, wide dynamic range, high throughput [3] |

| Key Limitations | Limited to electroactive species; matrix effects can be significant | Provides total content only, not speciation; complex and costly maintenance [2] [3] |

Voltammetric techniques, particularly stripping methods like Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) and Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV), are highly sensitive due to a built-in preconcentration step [2] [3]. Their defining advantage is the ability to perform speciation analysis, discriminating between different chemical forms of an element (e.g., free ions, organic complexes, redox states) that dictate bioavailability and toxicity [2]. This is crucial in fields like environmental science and pharmacology where chemical form is as important as total concentration.

Spectroscopic techniques, such as Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), offer superior multi-element capabilities and extremely low detection limits [3]. However, they generally require sample digestion and provide information only on total element content, losing all speciation data [2]. The operational costs and instrumental complexity of techniques like ICP-MS are also significantly higher than those of most voltammetric systems [3].

Experimental Protocols for Trace Analysis

Voltammetric Protocol for Trace Metal Speciation

The following protocol outlines a generalized procedure for determining trace metal concentrations and their speciation in natural water samples using Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (AdCSV), based on methodologies for metals like iron and copper [2].

- 1. Sample Collection and Pre-treatment: Collect water samples using trace-metal clean protocols. Filter through a 0.45 μm or 0.2 μm membrane to separate dissolved from particulate fractions [2]. Adjust the sample pH to an optimal value for complex formation using ultra-pure buffers (e.g., ammonium acetate, borate) [2] [25].

- 2. Complexation and Ligand Exchange: Add a specific complexing agent (ligand) to the sample. Common ligands include dimethylglyoxime for nickel and cobalt, or catechol for iron [2] [3]. In Competing Ligand Exchange (CLE) methods, a known concentration of a competing ligand is added to determine the metal's complexation strength with natural organic ligands in the sample [2].

- 3. Preconcentration (Adsorption) Step: Transfer the sample to an electrochemical cell. At the working electrode (e.g., a hanging mercury drop electrode), apply a constant potential that causes the neutral metal-ligand complex to adsorb onto the electrode surface for a defined time (e.g., 30-120 seconds) with stirring. This step accumulates the analyte, enhancing sensitivity [2] [3].

- 4. Voltammetric Scan (Stripping): After a brief equilibration period without stirring, initiate a cathodic potential sweep. This scan reduces the adsorbed metal complex, generating a measurable current peak. The peak current is proportional to the metal concentration in the sample, and the peak potential is characteristic of the metal and ligand used [2].

- 5. Data Analysis and Quantification: Quantify the analyte using the standard addition method to compensate for matrix effects. Add known increments of a standard metal solution to the sample and repeat the measurement. Plot the peak current versus the standard concentration; the absolute value of the x-intercept gives the original sample concentration [2].

Spectroscopic Protocol for Total Trace Metal Analysis

This protocol describes a standard procedure for determining total metal content using ICP-MS, a benchmark spectroscopic technique for ultra-trace analysis [3] [25].

- 1. Sample Digestion: For solid samples (e.g., soil, tissue, pharmaceuticals), perform acid digestion. Weigh a representative, homogenized sample into a digestion vessel. Add a mixture of high-purity acids (e.g., nitric acid, hydrochloric acid) and heat using a hot block, microwave, or open-vessel system until the sample is fully dissolved and a clear digestate is obtained [25].

- 2. Dilution and Internal Standardization: Dilute the cooled digestate to a known volume with high-resistivity (18.2 MΩ·cm) water. Add a known amount of an internal standard (e.g., Indium, Rhodium, or Bismuth) to all samples, calibration standards, and blanks. The internal standard corrects for instrumental drift and matrix suppression/enhancement effects during analysis [25].

- 3. Instrument Calibration: Prepare a series of multi-element calibration standards in the same acid matrix as the samples. A blank and at least three standard solutions of increasing concentration are typically used to establish a calibration curve [25].

- 4. Sample Analysis and Data Acquisition: Introduce the samples and standards into the ICP-MS via a peristaltic pump and nebulizer. The sample is converted into an aerosol, injected into the argon plasma (~6000-10000 K), where it is desolvated, vaporized, atomized, and ionized. The resulting ions are separated by a mass spectrometer and detected. The signal intensity for each isotope is measured [3].

- 5. Data Processing and QC: The instrument software calculates analyte concentrations based on the calibration curve and the internal standard response. A rigorous program of quality control samples, including continuing calibration verification standards and blanks, must be interspersed throughout the analytical run to ensure data validity [25].

Workflow and Logical Relationships

The decision-making process for selecting an analytical technique and the subsequent workflow for trace analysis can be visualized through the following logical pathways.

Technique Selection Logic

This diagram outlines the key decision nodes for choosing between voltammetry and spectroscopy based on analytical goals and practical constraints.

Diagram 1: A decision pathway for selecting between voltammetry and spectroscopy based on analytical requirements.

Generalized Trace Analysis Workflow

This workflow illustrates the common and technique-specific steps involved in a rigorous trace analysis, from sampling to data reporting.

Diagram 2: A comparative workflow for voltammetric and spectroscopic trace analysis, highlighting shared and distinct procedural steps.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting the voltammetric and spectroscopic experiments described in this guide.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for voltammetric and spectroscopic trace analysis.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Complexing Agents (for AdSV) | Forms electroactive complexes with target metals for adsorptive accumulation. | Dimethylglyoxime (for Ni, Co), Catechol (for Fe), 8-Hydroxyquinoline (for various REEs). Choice dictates selectivity and sensitivity [2] [3]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducts current and controls ionic strength/pH, defining the electrochemical window. | High-purity salts (e.g., acetate, borate, ammonia buffers). Must be free of electroactive impurities [2]. |

| Working Electrodes | Surface where the electrochemical reaction occurs. | Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) for adsorptive techniques; Mercury Film and Bismuth/Carbon electrodes for ASV [2] [3]. |

| Ultra-Pure Acids & Reagents | Sample digestion and cleaning for both techniques. | Trace metal grade nitric and hydrochloric acids. Essential for maintaining low blanks in both voltammetry and ICP-MS [25]. |

| Internal Standards (for ICP-MS) | Corrects for instrument drift and matrix effects. | Elements not present in samples (e.g., Indium (In), Rhodium (Rh), Bismuth (Bi)), added to all samples and standards [25]. |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Validates analytical accuracy and method performance. | Samples with certified concentrations of target analytes in a matching matrix (e.g., river water, soil). Critical for quality assurance [25]. |

| Solid-Phase Extraction (SPE) Cartridges | Selective isolation and pre-concentration of analytes from complex matrices. | Used in sample prep for both techniques to remove interferents and concentrate analytes, improving sensitivity and selectivity [25]. |

Techniques in Action: Voltammetric and Spectroscopic Applications in Real-World Analysis

The accurate determination of trace metal concentrations is a cornerstone of environmental monitoring, industrial quality control, and biomedical research. For decades, analytical techniques have been broadly divided into two camps: electrochemical methods, such as voltammetry, and spectroscopic methods, including Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). Within this landscape, stripping voltammetry stands out for its exceptional sensitivity and unique capabilities in metal speciation analysis [27].

Stripping voltammetry techniques are electrochemical methods renowned for their extremely low detection limits, capable of measuring metal concentrations in the 10^{-9} to 10^{-12} M range [27]. This sensitivity often surpasses many conventional spectroscopic techniques for certain applications, while offering the additional benefits of portability, lower operational costs, and the ability to perform in-situ measurements [27] [11]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the three primary stripping voltammetry techniques—Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV), Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV), and Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CSV)—contrasting their performance with spectroscopic methods and detailing the experimental protocols that underpin their application in trace metal analysis.

Stripping voltammetry operates in two fundamental stages: a preconcentration step where metal species are accumulated onto the working electrode, and a stripping step where they are removed, generating a measurable current proportional to their concentration [27] [28]. The specific mechanisms of these steps differentiate ASV, AdSV, and CSV.

Core Principles and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the foundational workflow and key differentiators of each stripping voltammetry technique.

Comparative Performance Data

The table below summarizes key performance metrics and application data for the three stripping voltammetry techniques, providing a direct comparison of their capabilities.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Stripping Voltammetry Techniques for Trace Metal Analysis

| Feature | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) | Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CSV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mechanism | Electrolytic reduction to metal, then anodic oxidation [27] [28] | Adsorption of metal-ligand complex, then cathodic reduction [27] | Formation of insoluble salt, then cathodic reduction [28] |

| Target Analytes | Cu, Cd, Pb, Zn, In, Tl [27] | Over 20 trace metals including Ga, Ni, Co, Fe, U [27] [11] | Anions & metals forming insoluble salts (e.g., halides, S²⁻) [28] |

| Typical Detection Limit | (10^{-9}) - (10^{-10}) M [27] [28] | (10^{-10}) - (10^{-12}) M [27] | Comparable to AdSV [28] |

| Example: Ga(III) Analysis | LoD: (5.7 \times 10^{-11}) M [11] | LoD: (3.6 \times 10^{-10}) - (9.5 \times 10^{-10}) M [11] | Not commonly used for Ga |

| Key Advantage | Direct analysis of electroplatable metals; well-established | Extreme sensitivity for non-electroplatable metals; wide applicability | Specificity for anions and certain metal complexes |

Experimental Protocols: From Theory to Practice

Detailed Methodologies

A robust experimental protocol is critical for obtaining reliable and reproducible data in stripping voltammetry. The following section outlines standard procedures for each technique.

Protocol for Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV)

- Sample Preparation: The water sample is placed in an electrochemical cell. A supporting electrolyte, such as 0.02 M NaClO₄ and 0.005 M CH₃COOH at pH 3.2, is added to ensure sufficient conductivity and control the ionic strength [11]. For complex matrices, sample acidification and UV digestion may be required to break down organic metal complexes.

- Deaeration: An inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) is purged through the solution for 5-10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere electrochemically.

- Preconcentration/Deposition: The working electrode (e.g., HMDE or MFE) is held at a constant, negative potential. During this time, target metal ions (e.g., Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺) are reduced and deposited as metals onto the electrode surface. The deposition time can vary from 30 to 300 seconds, depending on the required sensitivity [27] [11].

- Equilibration: After deposition, the stirring is stopped, and the solution is allowed to become quiescent for a brief period (e.g., 15-30 seconds).

- Stripping: The potential is scanned linearly or pulsed in a positive (anodic) direction. The deposited metals are re-oxidized back into solution, generating a characteristic current peak for each metal at its specific oxidation potential.

- Data Analysis: The concentration of each metal is quantified by comparing the peak current (or peak area) to a calibration curve constructed from standard additions [27].

Protocol for Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV)

- Sample and Reagent Preparation: The sample is placed in the cell with a suitable buffer, such as 0.1 M acetate buffer at pH 4.8-5.6, to control the pH for complex formation [11].

- Complex Formation: A specific complexing agent (AL), such as cupferron or catechol, is added to the solution. This ligand forms a stable, adsorptive complex with the target metal ion (e.g., Ga(III)) [27] [11].

- Deaeration: The solution is purged with an inert gas to remove oxygen.

- Preconcentration/Adsorption: The working electrode is held at a constant potential where the metal-ligand complex is adsorbed onto the electrode surface. This is a physical accumulation, not an electrochemical reduction. Accumulation times are typically 60 seconds [11].

- Equilibration: Stirring is stopped for a short equilibration period.

- Stripping: The potential is scanned linearly or pulsed in a negative (cathodic) direction. The adsorbed complex is reduced, producing a measurable current peak.

- Data Analysis: The peak height/area is proportional to the concentration of the metal in the sample, as determined by standard addition methods [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful application of stripping voltammetry relies on a carefully selected set of materials and reagents. The following table details the key components of the voltammetric toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Stripping Voltammetry

| Item | Function/Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Surface where preconcentration and stripping occur; defines technique sensitivity and selectivity [27]. | Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE), Mercury Film Electrode (MFE), Screen-Printed Electrodes, Bismuth/Gold Electrodes [27] [11]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for the electrochemical cell [27]. | Ag/AgCl (with KCl electrolyte), Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE). |

| Counter/Auxiliary Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit in the three-electrode system [27]. | Platinum wire, glassy carbon rod. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and defines the ionic strength/pH of the solution; minimizes migration current [27]. | Acetate buffer (pH ~4-5), Ammonia buffer (pH ~9), NaClO₄, KCl, acetic acid [11]. |

| Complexing Agent (for AdSV) | Forms an adsorptive complex with the target metal, enabling its preconcentration [27] [11]. | Cupferron, Catechol, Dimethylglyoxime, 8-Hydroxyquinoline. |

| Standard Solutions | Used for the method of standard additions to quantify analyte concentration. | Certified single- or multi-element stock solutions (e.g., 1000 ppm). |

Stripping Voltammetry vs. Spectroscopy: An Objective Comparison

When selecting an analytical technique for trace metal analysis, researchers must weigh the relative merits of stripping voltammetry against the more widely used spectroscopic methods. The following diagram outlines the key decision factors in selecting a technique.

The choice between stripping voltammetry and spectroscopic techniques like ICP-MS or GFAAS is application-dependent. Voltammetry excels in scenarios requiring ultra-trace detection in clean or moderately complex matrices, metal speciation studies to determine toxicity and bioavailability, and projects with budget constraints or a need for on-site analysis [27] [11]. Its ability to provide information on metal oxidation states and labile fractions is a unique advantage over most bulk spectroscopic techniques [27].

Conversely, spectroscopic methods are generally superior for high-throughput analysis of samples with very complex matrices (e.g., biological tissues, soils), simultaneous multi-element analysis covering a large portion of the periodic table, and when determining total metal content without the need for speciation is sufficient [11]. However, this often comes with higher costs for instrumentation, maintenance, and operation, and typically requires a laboratory setting [11].

Stripping voltammetry, encompassing ASV, AdSV, and CSV, represents a powerful suite of techniques for trace metal analysis. Its unparalleled sensitivity, portability for field deployment, and unique capability for metal speciation make it an indispensable tool in the analytical chemist's arsenal. While spectroscopic methods like ICP-MS offer broader multi-element coverage and higher throughput for routine analysis, stripping voltammetry provides a cost-effective, sensitive, and information-rich alternative, particularly for targeted analyses and studies where understanding metal form and bioavailability is as critical as knowing its total concentration. The continued development of portable and automated voltammetric systems ensures its growing relevance in environmental monitoring, industrial process control, and biomedical research [27].

Electroanalysis has emerged as a critical tool in the pharmaceutical industry, offering versatile and sensitive methods for drug analysis [29]. Voltammetry, a technique that measures current under an applied voltage, is particularly valued for its high sensitivity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to analyze complex pharmaceutical compositions with minimal sample preparation [29] [30]. Unlike traditional chromatographic methods like HPLC, which often require extensive sample preparation and expensive solvents, voltammetric methods operate with minimal sample volumes and offer rapid analysis, making them especially suitable for routine quality control and therapeutic drug monitoring [29] [31].

The fundamental principle of voltammetry relies on the redox behavior of analytes at an electrode surface. When a voltage is applied, electroactive species undergo oxidation or reduction, generating a current signal proportional to their concentration [29]. Different voltammetric techniques, including cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), and square wave voltammetry (SWV), provide complementary information about electrochemical properties and quantification capabilities [29]. Recent advancements have significantly enhanced voltammetric applications through the integration of nanostructured electrodes, artificial intelligence for data interpretation, and the development of portable sensors for real-time monitoring [29].

Experimental Protocols for Thymoquinone Quantification

Square Wave Voltammetry with Carbon Paste Electrode

A recent innovative study developed a sensitive and cost-effective method for thymoquinone (TQ) determination using square-wave voltammetry with an environmentally friendly carbon paste electrode [31]. This protocol is particularly notable as it introduces, for the first time, an oxidation-based voltammetric strategy for TQ detection, broadening the analytical framework beyond conventional reduction-based approaches [31].

Apparatus and Reagents: The measurements were performed using a µAutolab Type III potentiostat/galvanostat controlled by GPES software. The three-electrode system consisted of a carbon paste electrode as the working electrode, a silver/silver chloride reference electrode, and a platinum wire auxiliary electrode. The carbon paste was prepared from graphite powder and paraffin oil in a ratio of 1.0 g graphite to 0.3 mL oil. Supporting electrolytes included hydrochloric acid and Britton-Robinson buffers across pH ranges from 0.3 to 6.0 [31].

Procedure: The stock solution of thymoquinone was prepared by dissolving an appropriate amount in distilled water, though complete dissolution required approximately two days. Working solutions with lower concentrations were prepared by appropriate dilution of the stock solution. The voltammetric measurements were carried out in a 15 mL cell volume after optimizing parameters including electrode material, electrolyte composition, and scan settings. The method addressed the complex voltammetric response through in-depth evaluation of both classical and modern analytical techniques, including cumulative voltammetry [31].

Calibration and Validation: Three calibration curve construction methods were tested based on current height, peak area, and the cumulative voltammetry concept. The broadest linear range was established using peak current height, with a limit of detection of 8.9 nmol·L⁻¹ and limit of quantification of 29.8 nmol·L⁻¹. The method was validated through analysis of real samples, including Nigella sativa seed oil and dietary supplements, with results showing strong correlation with HPLC reference methods [31].

Electrochemical Biosensor with GCE/rGO/CuO

An alternative methodology combined innovative extraction with advanced sensor technology for TQ quantification [32].

Extraction Protocol: Electrospun nanofibers with polyvinyl chloride/ethylene vinyl acetate latex/electrochemically (reduced graphene oxide/polypyrrole)/Silybum marianum inflorescence extract were prepared as a sorbent for TQ extraction from black seed. Factors affecting TQ adsorption/desorption were optimized using design-expert 12.0 and one-at-a-time methods. The electrospinning process was conducted with specific parameters: voltage of 14 KV, flow rate of 0.9 mL/h, and distance of 10 cm [32].

Sensor Development and Measurement: A nonenzymatic electrochemical biosensor was constructed using copper (II) oxide nanoparticles/reduced graphene oxide/glassy carbon electrode. The biosensor was applied to human blood serum samples with the standard addition method using spiked TQ. The method achieved a linear range of 50–1000 μM with a detection limit of 4.85 μM [32].

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize experimental data from recent studies applying voltammetry to pharmaceutical analysis, highlighting key performance metrics for various bioactive compounds.

Table 1: Voltammetric Methods for Thymoquinone Quantification

| Method | Electrode | Linear Range | LOD | LOQ | Sample Matrix | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWV | Carbon Paste | Not specified | 8.9 nmol·L⁻¹ | 29.8 nmol·L⁻¹ | Nigella sativa oil, supplements | [31] |

| Electrochemical Biosensor | GCE/rGO/CuO | 50–1000 μM | 4.85 μM | Not specified | Human blood serum | [32] |

| DPV | Low-cost Potentiostat with MIP | 1–200 μM | 0.2 μM | Not specified | Black cumin | [33] |

Table 2: Voltammetric Methods for Other Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Compound | Method | Electrode | Linear Range | LOD | Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bumadizone | SWV | 10% nRGO-modified CPE | 0.9×10²-15×10² ng mL⁻¹ | Not specified | Pharmaceutical forms, biological fluids | [34] |

| Resorcinol | SWV | ZnFe₂O₄/NPs/IL/CPE | 3.0 μM to 500 μM | 1.46 μM | Pharmaceutical creams | [30] |

| Sulfamethoxazole | DPV | Not specified | 6.59 to 96.27 μM | 1.98 μM | Water, pharmaceutical formulations | [35] |