Voltammetry: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of voltammetry, an essential electrochemical technique in analytical chemistry.

Voltammetry: Principles, Methods, and Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of voltammetry, an essential electrochemical technique in analytical chemistry. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of voltammetry, including the three-electrode system and the interpretation of voltammograms. It delves into key methodological variations such as Cyclic Voltammetry and Differential Pulse Voltammetry, highlighting their specific applications in pharmaceutical analysis, quality control, and environmental monitoring of drug residues. The article also addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, optimization strategies for enhanced sensitivity, and a comparative analysis of voltammetry against other analytical techniques, providing a vital resource for its implementation in biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding Voltammetry: Core Principles and Electrochemical Fundamentals

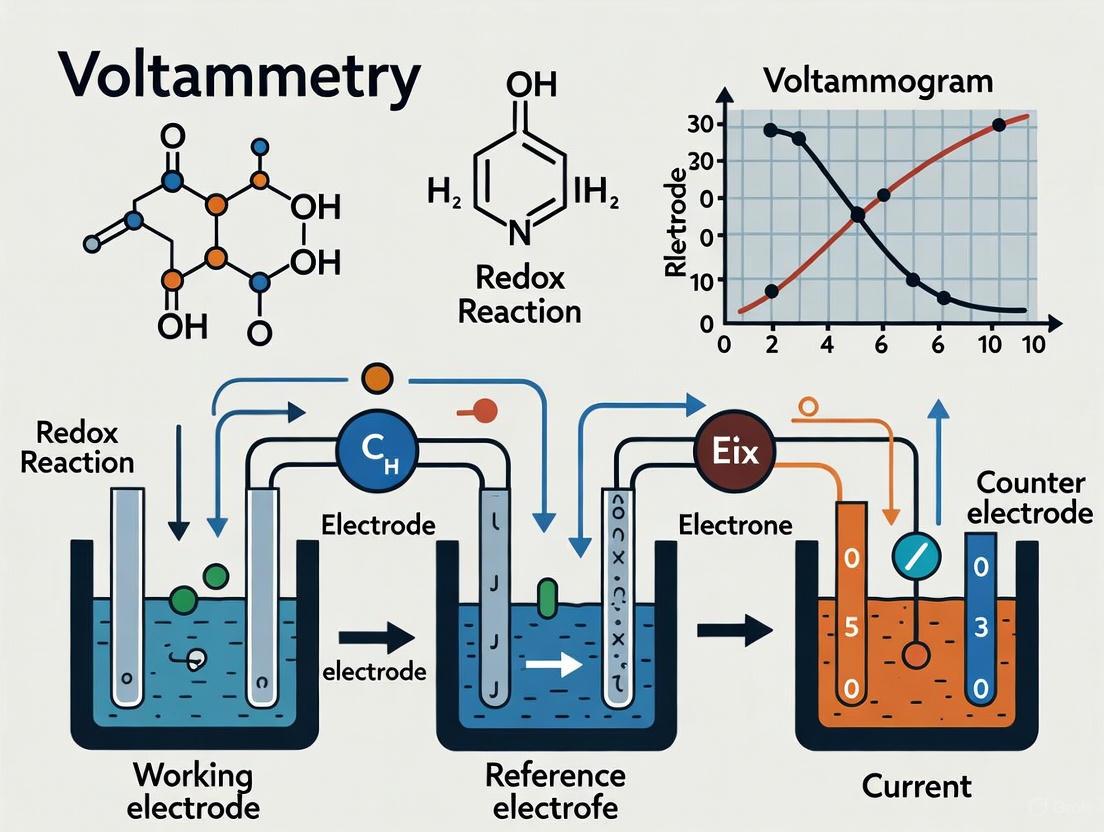

Voltammetry comprises a set of powerful electrochemical techniques used for both quantitative analysis and the study of reaction mechanisms. These methods are defined by their core operational principle: measuring current as a function of an applied potential in an electrochemical cell [1] [2]. The resulting current-potential plot, known as a voltammogram, provides a wealth of information about the analyte, including its identity, concentration, and the kinetics of its redox reactions [1]. The relationship between current, potential, and analyte concentration forms the theoretical foundation that makes voltammetry an indispensable tool in modern analytical chemistry, particularly in fields like drug development where it offers distinct advantages of high sensitivity, rapid analysis times, and cost-effective instrumentation [1] [3].

The significance of voltammetry stems from its ability to exploit Faraday's laws of electrolysis, which establish a direct relationship between the electrical charge passed through an electrode and the amount of substance produced or consumed at the electrode-solution interface [1] [2]. This fundamental relationship enables researchers to precisely quantify analytes at trace levels while simultaneously gaining insights into their redox behavior. When properly executed, voltammetric techniques can detect analytes at remarkably low concentrations, with careful method validation allowing for reliable determination of limits of detection (LOD) appropriate for forensic and pharmaceutical applications [3].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

The Electrochemical Cell and Three-Electrode System

While a simple electrochemical cell requires only two electrodes, modern voltammetry almost universally employs a three-electrode system to ensure precise potential control and accurate current measurement [2] [4]. This configuration addresses a critical limitation of two-electrode systems: the difficulty in maintaining a constant potential while measuring resistance and compensating for redox events at the working electrode [4].

Diagram: Three-Electrode System Configuration. The potentiostat applies potential between working (WE) and reference (RE) electrodes while measuring current between WE and counter (CE) electrodes [2] [4].

The three-electrode configuration consists of:

- Working Electrode (WE): The electrode where the redox reaction of interest occurs. Its potential is precisely controlled relative to the reference electrode. Common materials include mercury, gold, platinum, and various carbon forms (glassy carbon, graphite) [2].

- Reference Electrode (RE): Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured and controlled. No significant current passes through this electrode to prevent potential drift. Common examples include saturated calomel (SCE) and silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrodes [1] [4].

- Counter Electrode (CE): Completes the electrical circuit by carrying the current needed to balance the current flowing at the working electrode. Typically has a much larger surface area than the working electrode to prevent current limitation [1] [4].

This separation of function ensures that the current observed at the working electrode is completely balanced by the current passing at the counter electrode, while the reference electrode maintains a stable potential without significant current passage [4].

Faradaic and Capacitive Currents

The total current measured in voltammetric experiments consists of two distinct components with different origins and characteristics:

Faradaic Current: This current results from the reduction or oxidation of electroactive species at the electrode surface, following Faraday's law of electrolysis [2]. The faradaic current is the analytical signal of interest, as it directly correlates with analyte concentration through the relationship:

q = nFm

where q is the electric charge passed, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol), and m is the number of moles of substance reacted [2].

Capacitive Current: Also known as charging current, this non-faradaic current arises from the charging and discharging of the electrical double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface, which behaves similarly to a capacitor [2]. This current represents a significant source of background signal that can obscure faradaic responses, particularly at low analyte concentrations.

The sensitivity of any voltammetric technique is ultimately determined by the ratio of faradaic to capacitive currents [2]. A key goal in developing voltammetric methods is therefore to maximize this ratio through electronic instrumentation, electrode design, and chemical modification of the electrode-solution interface.

Mass Transport to the Electrode Surface

For a species to undergo electron transfer and generate faradaic current, it must first reach the electrode surface through one of three mass transport mechanisms:

- Diffusion: Movement due to a concentration gradient established when electroactive species are consumed or generated at the electrode surface [2]. This is the primary mass transport mechanism in unstirred solutions during most voltammetric experiments.

- Migration: Movement of charged species in an electric field, which can be minimized by adding excess supporting electrolyte to the solution [2].

- Convection: Bulk movement of solution due to stirring, flow, or electrode rotation, which can enhance mass transport in certain experimental configurations [2].

The diffusion-limited current (i_d) is described by a combination of Faraday's law and Fick's first law of diffusion [4]:

i_d = nFAD_0(∂C_0/∂x)_0

where A is the electrode area, D_0 is the diffusion coefficient of the analyte, and (∂C_0/∂x)_0 is the concentration gradient at the electrode surface.

Major Voltammetric Techniques

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Cyclic Voltammetry is one of the most widely used voltammetric techniques for studying redox mechanisms and thermodynamics [4]. In CV, the potential of the working electrode is scanned linearly in time between two set values (initial potential and vertex potential) before being reversed back to the initial potential, creating a triangular waveform [4]. The resulting voltammogram typically shows characteristic "duck-shaped" curves with peak currents for both the forward and reverse scans [4].

The peak current (i_p) in a reversible system is described by the Randles-Sevcik equation [4]:

i_p = (2.69×10^5)n^(3/2)AD^(1/2)Cv^(1/2) (at 298 K)

where C is the concentration (mol/cm³), v is the potential scan rate (V/s), and the other parameters are as previously defined. This equation demonstrates the direct dependence of the measured current on analyte concentration, forming the basis for quantitative analysis.

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)

Square Wave Voltammetry is a pulsed technique that offers significant advantages in sensitivity and background suppression compared to traditional CV [5]. In SWV, the potential waveform consists of a series of symmetric square-wave pulses superimposed on a staircase ramp [5]. Current is sampled twice during each square-wave cycle: once at the end of the forward pulse and once at the end of the reverse pulse [5]. The differential current (forward minus reverse) is plotted against the base potential, resulting in a peak-shaped voltammogram where the peak height is proportional to analyte concentration [5].

The strength of SWV lies in its effective minimization of capacitive currents through the current sampling protocol, resulting in significantly improved signal-to-noise ratios compared to continuous scanning techniques [5]. For a reversible one-electron reduction, the peak current can be described by [5]:

i_p = nFAD_0^(1/2)C_0(πtp)^(-1/2)ψ

where tp is the experimental timescale, and ψ is a dimensionless peak current parameter.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Voltammetric Techniques

| Technique | Excitation Waveform | Key Features | Primary Applications | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Linear potential sweep with reversal | "Duck-shaped" voltammogram; studies reversibility | Mechanism studies, thermodynamics, qualitative analysis | Moderate (μM range) |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Square pulses on staircase baseline | Background suppression, sensitive differential current | Trace analysis, quantitative measurements, kinetics | Low (nM range) [3] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Small amplitude pulses on linear ramp | Minimized charging current, peak-shaped output | Trace analysis of organic compounds, pharmaceuticals | Low (nM range) [1] |

Comparative Performance of Voltammetric Techniques

Different voltammetric techniques offer varying capabilities for electron transfer rate measurement and quantitative analysis. Recent research has systematically compared these approaches for studying immobilized redox systems:

Table 2: Applicable Ranges of Electron Transfer Rate Constants (k_HET) for Immobilized Redox Proteins

| Technique | Applicable k_HET Range (sâ»Â¹) | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | 0.5 - 70 | Direct visualization of reversibility, established theory | Limited upper range for immobilized systems |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | 5 - 120 | Broad dynamic range, high sensitivity | Complex interpretation for non-reversible systems |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | 0.5 - 5 | Complementary frequency-domain information | Limited to small potential perturbations |

This comparative analysis demonstrates that SWV covers a broader range of electron transfer rates compared to CV and EIS, making it particularly valuable for studying systems with faster kinetics [6].

Experimental Considerations and Protocols

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful voltammetric analysis requires careful selection of reagents and materials to ensure reproducible and meaningful results:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Purpose | Typical Composition/Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes migration current, provides conductivity | Inert salts (KCl, NaClO₄, TBAPF₆) at 0.1-1.0 M concentration |

| Solvent System | Dissolves analyte and electrolyte, wide potential window | Aqueous buffers, acetonitrile, DMF, dichloromethane |

| Internal Standard | Potential calibration, method validation | Ferrocene/Ferrocenium (Fc/Fcâº) in non-aqueous systems |

| Working Electrodes | Platform for redox reactions, defines active surface | Glassy carbon, gold, platinum, mercury film electrodes |

| Reference Electrodes | Provides stable potential reference | Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) |

| Purifying Agents | Removes oxygen and impurities from solutions | Nitrogen/argon sparging, chemical scrubbers |

| Standard Solutions | Calibration, method validation | Certified reference materials of target analytes |

| Lapatinib | Lapatinib|EGFR/HER2 Inhibitor|For Research Use | Lapatinib is a potent, selective dual inhibitor of EGFR and HER2 tyrosine kinases for cancer research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Metronidazole-D3 | Metronidazole-D3, CAS:83413-09-6, MF:C6H9N3O3, MW:174.17 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

General Experimental Protocol for Square Wave Voltammetry

The following protocol provides a standardized approach for conducting Square Wave Voltammetry experiments, based on established methodologies [5]:

Instrument Setup: Configure the potentiostat with a three-electrode system in an electrochemical cell. Ensure proper connections of working, reference, and counter electrodes.

Solution Preparation: Prepare the analyte solution in appropriate solvent with supporting electrolyte at concentration 0.1-0.5 M. Degas with inert gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

Parameter Optimization:

- Square Wave Amplitude: Typically 25-50 mV

- Step Potential: Usually 1-10 mV

- Frequency: 5-25 Hz (higher frequencies increase sensitivity but may distort kinetics)

- Potential Window: Set initial and final potentials to bracket the expected redox event

Induction Period: Apply initial potential conditions for 10-30 seconds to equilibrate the system before data collection [5].

Data Acquisition: Execute the SWV experiment, collecting both forward and reverse currents. Most modern instruments will automatically calculate the differential current.

Relaxation Period: Allow the system to equilibrate under final conditions before returning to idle state [5].

Data Analysis: Plot differential current versus applied potential. Measure peak height for quantitative analysis or peak potential for qualitative characterization.

Determining Limits of Detection in Voltammetry

Accurate determination of the Limit of Detection (LOD) is crucial for validating voltammetric methods, particularly in regulated fields like pharmaceutical development [3]. Several approaches can be employed:

Visual Evaluation: The lowest concentration providing an observable oxidation or reduction peak is reported as LOD. This subjective approach requires presentation of appropriate data for justification [3].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): A more objective method where LOD is defined as the concentration yielding a signal 3-3.3 times the noise level [3]:

LOD = 3 × noise (in current units)

where noise is measured as the highest-lowest point in baseline near analyte response.

Statistical Method from Blank Measurement: Following established guidelines [3]:

LOD = X̄_B + 3.3 × σ_B

where X̄_B is the mean blank signal and σ_B is the standard deviation of the blank signal.

Recent comparative studies have highlighted that LOD values can vary significantly depending on the calculation method employed, emphasizing the need for consistent application of a single validated approach, particularly when comparing methods across different studies [3].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Voltammetric techniques continue to evolve, with recent advancements pushing the boundaries of sensitivity and spatial resolution. The development of opto-iontronic microscopy represents a cutting-edge innovation that combines optical microscopy with nanohole electrodes to monitor electrochemical processes at the nanoscale, enabling detection within volumes as small as an attoliter (100 nm)³ [7]. This approach uses total internal reflection illumination, electric-double-layer modulation, cyclic voltammetry, and lock-in detection to probe ion dynamics in nanoconfined environments [7].

Such advancements highlight the ongoing potential of voltammetry to address increasingly challenging analytical problems, from single-molecule electrochemistry to real-time monitoring of reaction intermediates. The fundamental relationship between current, potential, and analyte concentration continues to provide the theoretical foundation for these technological innovations, ensuring voltammetry's continued relevance in both basic research and applied analytical science.

For researchers in drug development and related fields, voltammetry offers a versatile toolkit for quantitative analysis, mechanism elucidation, and method validation. When properly implemented with attention to the core principles outlined in this guide, voltammetric methods can provide reliable, sensitive, and reproducible data to support the development and characterization of new chemical entities and pharmaceutical compounds.

In electrochemical research, particularly in voltammetry, the three-electrode system represents a fundamental experimental configuration that enables precise measurement and control of electrochemical reactions. Voltammetry, the study of current as a function of applied potential, relies on this system to obtain accurate analytical data in the form of voltammograms [8]. Unlike the simpler two-electrode setups used in everyday batteries, the three-electrode system separates the functions of potential measurement and current control, thereby overcoming significant limitations that previously hampered precise electrochemical investigations [9] [10]. This sophisticated approach allows researchers to study electrochemical half-cell reactivity with unprecedented accuracy, making it indispensable for applications ranging from fundamental reaction mechanism studies to drug development and battery material characterization [11] [1].

The evolution from two-electrode to three-electrode configurations in the 1920s marked a critical advancement in electrochemical science [9]. In a two-electrode system, the substantial current passing through the cell causes solution voltage drop (IR drop) and polarization of the counter electrode, making the working electrode potential challenging to determine accurately [10]. The introduction of a reference electrode created the now-standard "three-electrode, two-circuit" system that effectively eliminates this ambiguity by providing a stable potential reference point unaffected by current flow [9] [10]. This technical whitpaper explores the core components, working principles, and experimental implementation of the three-electrode system within the context of voltammetry research, providing drug development professionals and scientists with essential knowledge for leveraging this powerful configuration in their investigative work.

Core Components and Their Functions

The three-electrode system consists of three distinct electrodes, each serving a specific function in the electrochemical cell. Understanding the role and requirements of each component is essential for proper experimental setup and reliable data acquisition.

Working Electrode (WE)

The Working Electrode serves as the stage where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs [9] [12]. This electrode must exhibit specific characteristics to ensure reproducible and meaningful results. The working electrode should be chemically inert relative to the electrolyte, possess a reproducible surface state, and present a controlled geometric area to the solution [9]. During voltammetric experiments, the potential at the working electrode is precisely controlled and varied while the resulting current is measured, providing the fundamental data for analysis [11] [8].

Common working electrode materials include glassy carbon, platinum, gold, and conductive oxides such as FTO and ITO [9]. For specific applications like battery research, composite battery electrodes prepared as test coupons may serve as working electrodes [9]. In corrosion testing, the working electrode is typically a sample of the corroding metal, while for physical electrochemistry experiments, inert materials like platinum or gold are preferred [12]. Proper preparation of the working electrode surface is critical, often requiring standardized cleaning and pretreatment protocols to ensure experimental reproducibility [9].

Reference Electrode (RE)

The Reference Electrode provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured and controlled [9] [12]. This component is crucial for precise potential control because it ideally draws negligible current, allowing its potential to remain constant regardless of current flow in the rest of the circuit [9]. An ideal reference electrode exhibits good reversibility, follows the Nernst equation, has high exchange current density for quick potential restoration, and demonstrates excellent stability and reproducibility [13].

The choice of reference electrode depends on the experimental conditions, particularly the electrolyte composition. Common reference electrodes include the saturated calomel electrode (SCE), silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl), and the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) for aqueous systems [13] [10]. For non-aqueous systems, such as those used in lithium-ion battery research, non-aqueous reference electrodes like Ag/Ag+ (acetonitrile) are employed [13]. In some field applications, a pseudo-reference electrode (a piece of the working electrode material) may be used [12]. To minimize potential drift and measurement errors, the reference electrode is often connected to the test solution via a salt bridge or Luggin capillary, which reduces uncompensated solution resistance [13].

Counter Electrode (CE)

The Counter Electrode, also known as the Auxiliary Electrode, completes the current path in the electrochemical cell and supplies the current needed to balance the electron flow at the working electrode [9] [12]. This electrode must be highly conductive, chemically stable in the electrolyte, and typically possesses a larger surface area than the working electrode to avoid becoming polarized itself [9] [13]. The counter electrode's primary function is to ensure that current measurements accurately reflect processes occurring at the working electrode without introducing additional experimental variables.

Common counter electrode materials include platinum, graphite, and other inert conductors [13] [10]. In laboratory cells, platinum wire or mesh is frequently used, while graphite rods may be preferred in certain applications to avoid contamination—for instance, in prolonged tests where platinum dissolution and deposition onto the working electrode could artificially affect activity measurements [10]. The counter electrode often operates at extreme potentials where solvent or supporting electrolyte oxidation or reduction occurs, but this does not interfere with measurements because the critical potential control is maintained between the working and reference electrodes [8].

Table 1: Electrode Types and Their Characteristics in Three-Electrode Systems

| Electrode Type | Primary Function | Common Materials | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode (WE) | Site of electrochemical reaction of interest; potential controlled and current measured | Glassy carbon, platinum, gold, conductive oxides (FTO/ITO) [9] | Chemically inert, reproducible surface, controlled geometric area [9] |

| Reference Electrode (RE) | Provides stable potential reference for WE potential measurement/control | Ag/AgCl, SCE, Hg/HgO [13] [10] | Minimal current draw, stable potential, follows Nernst equation [9] [13] |

| Counter Electrode (CE) | Completes current circuit; balances current at WE | Platinum, graphite [9] [13] | High conductivity, large surface area, chemically stable [9] [13] |

Working Principle and Instrumentation

The three-electrode system operates on the principle of separating potential measurement from current control, enabled by sophisticated instrumentation known as a potentiostat. This arrangement creates what is often described as a "three-electrode, two-circuit" system that forms the foundation for modern electrochemical experiments [9] [10].

The "Two-Circuit" Concept

In the three-electrode configuration, two distinct electrical circuits operate simultaneously yet independently. The potential circuit consists of a high-impedance voltmeter connected between the working and reference electrodes, dedicated to measuring and controlling the working electrode potential without drawing significant current [9] [10]. The current circuit includes an ammeter between the working and counter electrodes, responsible for supplying and measuring the current required for the electrochemical reaction [9] [10]. This separation is crucial because it allows precise control of the working electrode potential while preventing current flow from affecting the stability of the reference electrode potential [9].

The potentiostat serves as the central control unit that implements this two-circuit concept. As illustrated in the schematic below, the potentiostat's electrometer circuit measures the voltage difference between the reference and working electrodes with high input impedance and minimal input current, preserving the reference electrode's stable potential [12]. The control amplifier compares this measured cell voltage with the desired voltage from the signal source (typically a computer-controlled digital-to-analog converter) and drives current into the cell through the counter electrode to maintain the set potential [12]. Simultaneously, a current-to-voltage converter measures the cell current by forcing it to flow through a measurement resistor, with the voltage drop providing a precise current measurement [12].

Diagram 1: The "Two-Circuit" Concept of a Three-Electrode System

The Role of the Potentiostat

The potentiostat is the electronic instrument that makes three-electrode measurements possible by serving as both a precise voltage source and a sensitive current meter [12]. Its fundamental operation involves maintaining a user-defined potential between the working and reference electrodes while measuring the resulting current flowing between the working and counter electrodes [12]. Modern potentiostats incorporate multiple measurement ranges to accommodate currents varying by several orders of magnitude, from picoamperes to amperes, using autoranging algorithms to select appropriate measurement resistors [12].

Key components of a potentiostat include the electrometer for high-impedance voltage measurement, the control amplifier for maintaining the set potential, the signal source for generating potential waveforms, and the current-to-voltage converter for current measurement [12]. The instrument's performance characteristics—including voltage and current measurement accuracy, low-noise design, bandwidth, and input capacitance—significantly impact data quality, particularly in sensitive techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) [9] [12]. For voltammetric methods such as cyclic voltammetry (CV) and linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), the potentiostat must accurately generate potential sweeps while precisely measuring the resulting faradaic currents that carry information about analyte concentration and reaction kinetics [11] [8].

Experimental Implementation and Methodologies

Successful implementation of the three-electrode system requires careful attention to experimental design, electrode preparation, and selection of appropriate measurement techniques. This section outlines key methodologies and practical considerations for researchers.

Electrode Preparation and Cell Assembly

Proper electrode preparation is essential for obtaining reproducible electrochemical data. The working electrode typically requires meticulous surface pretreatment, which may include polishing with alumina or diamond slurry to a mirror finish, followed by sonication in solvents to remove adsorbed particles [10]. For modified electrodes, catalyst inks are prepared by dispersing the catalyst material in a solvent with binders like Nafion, then drop-casting onto the electrode surface [10]. The reference electrode must be verified to have a stable potential, often checked against standard solutions, and properly maintained according to manufacturer specifications to prevent contamination [13]. The counter electrode should be cleaned and may require periodic regeneration or replacement if degradation occurs.

Cell assembly follows specific geometric considerations to minimize measurement errors. The reference electrode should be positioned close to the working electrode using a Luggin capillary to reduce uncompensated solution resistance (IR drop), but not so close as to shield the working electrode surface [9] [13]. The counter electrode should have sufficient surface area and be positioned symmetrically relative to the working electrode to ensure uniform current distribution [9]. All electrodes must be firmly fixed in place, and the cell must be sealed to prevent contamination or evaporation of the electrolyte during experiments.

Common Voltammetric Techniques

The three-electrode system enables various voltammetric techniques that provide insights into electrochemical processes. Two of the most prominent methods are cyclic voltammetry and linear sweep voltammetry:

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a powerful technique where the potential at the working electrode is scanned linearly with time in a forward direction, then reversed back to the starting potential while measuring the current [11] [4]. This method provides information about the thermodynamics of redox processes, reaction kinetics, and coupled chemical reactions [4]. The resulting voltammogram typically shows characteristic peaks corresponding to oxidation and reduction events, with the peak separation indicating the reversibility of the electrochemical reaction [11]. For reversible systems, the peak separation is approximately 57/n mV, where n is the number of electrons transferred [11].

Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) involves scanning the potential in a single direction from a starting potential to an end potential while monitoring the current [11]. This technique is particularly useful for determining onset potentials of electrochemical reactions, studying diffusion-controlled processes, and evaluating electrocatalytic activity [11]. In LSV, the voltage sweep starts in a region where few reactions occur, continues through the kinetically controlled region, and into the diffusion-limited region where current reaches a maximum before decreasing as the diffusion layer expands [11].

Table 2: Key Voltammetric Techniques Enabled by Three-Electrode Systems

| Technique | Potential Waveform | Key Applications | Data Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Linear forward and reverse sweep between two potentials [11] | Study of redox mechanisms, reaction kinetics, reversibility [11] [4] | Current vs. potential plot with oxidation/reduction peaks [4] |

| Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) | Linear sweep in one direction [11] | Determination of onset potentials, diffusion studies [11] | Current vs. potential plot with characteristic waves [11] |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Small AC potential perturbation over range of frequencies [9] | Interface characterization, resistance analysis, kinetic studies [9] | Complex impedance plotted in Nyquist or Bode format [9] |

| Potentiostatic/Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration (PITT/GITT) | Potential or current steps with relaxation periods [9] [13] | Diffusion coefficient measurements, battery material characterization [9] [13] | Current or potential transients during steps [13] |

Experimental Workflow

A generalized workflow for three-electrode experiments encompasses several critical stages, from initial setup to data analysis, as illustrated below:

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Three-Electrode Voltammetry

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of three-electrode systems requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the electrochemical application. The table below details essential components for assembling and utilizing these systems in research settings.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Three-Electrode Systems

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrodes | Glassy carbon electrode, Platinum electrode, Gold electrode, Metal oxide electrodes (FTO/ITO) [9] [10] | Provide controlled surface for electrochemical reactions; choice depends on potential window and reactivity requirements |

| Reference Electrodes | Ag/AgCl (aqueous), Saturated calomel electrode (SCE), Hg/HgO (alkaline), Ag/Ag+ (non-aqueous) [13] [10] | Maintain stable, known reference potential for accurate potential control and measurement |

| Counter Electrodes | Platinum wire/mesh, Graphite rod, Glassy carbon rod [9] [13] [10] | Complete current circuit with sufficient conductivity and stability to not limit reactions |

| Electrolyte Salts | KCl, NaClO₄, TBAPF₆, LiPF₆ [13] [8] | Provide ionic conductivity while being electrochemically inert in potential window of interest |

| Solvents | Water, Acetonitrile, Dimethylformamide (DMF), Propylene carbonate [13] [8] | Dissolve electrolyte and analyte; choice depends on analyte solubility and required potential window |

| Redox Probes | Ferrocene, Potassium ferricyanide, Ruthenium hexamine [4] [8] | Validate system performance and reference potential calibration |

| Surface Treatment | Alumina polishing slurry, Diamond paste, Detergents [10] | Create reproducible electrode surface finish for consistent results |

| Binders/Modifiers | Nafion solution, Conductive carbon black [10] | Immobilize catalysts on electrode surfaces or modify electrode properties |

Critical Practical Considerations

Implementing three-electrode systems effectively requires attention to several practical aspects that significantly impact data quality and interpretation.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

Several factors require optimization for reliable three-electrode measurements. Reference electrode placement is critical—positioning too far from the working electrode increases uncompensated solution resistance, while positioning too close can cause shielding effects [9] [13]. The counter electrode surface area should significantly exceed that of the working electrode to prevent current limitations [9]. IR compensation techniques should be applied to correct for potential drops across solution resistance, either manually (typically 80-95% of measured solution resistance) or using automatic compensation features in modern potentiostats [10].

Common issues encountered in three-electrode systems include unstable reference potentials (often due to contamination or clogged frits), noisy current measurements (frequently caused by improper shielding or ground loops), and distorted voltammetric shapes (potentially indicating improper cell geometry or insufficient electrolyte conductivity) [12]. Regular validation using standard redox couples like ferrocene/ferrocenium (for non-aqueous systems) or potassium ferricyanide (for aqueous systems) helps identify systematic errors [4] [8].

Advanced Applications in Research

The three-electrode system finds diverse applications across scientific disciplines. In battery research, it enables precise characterization of individual electrode materials within complete cells, allowing researchers to study formation of solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) layers, measure diffusion coefficients via GITT and PITT, and analyze impedance characteristics of electrode materials [9] [13]. For electrocatalyst development, three-electrode configurations facilitate evaluation of new materials for reactions like hydrogen evolution (HER), oxygen evolution (OER), and oxygen reduction (ORR) by providing accurate overpotential measurements free from counter electrode effects [10].

In pharmaceutical and biosensing applications, three-electrode systems support drug quantification, metabolite detection, and mechanistic studies of biological redox processes [1]. The ability to precisely control potential makes these systems ideal for studying redox-active drug molecules and developing sensitive detection schemes based on pulsed voltammetric techniques like differential pulse voltammetry and square wave voltammetry, which offer enhanced sensitivity for trace analysis [1]. The fundamental principles of the three-electrode system thus underpin advancements across energy storage, materials science, and biomedical research.

The three-electrode system represents an essential configuration in modern electrochemical research, providing the foundation for precise potential control and accurate current measurement in voltammetric experiments. By separating the functions of potential referencing and current balancing into distinct electrodes, this system enables researchers to study electrochemical processes with unprecedented accuracy, free from the limitations that plagued earlier two-electrode setups. The continued refinement of three-electrode methodologies—coupled with advancements in potentiostat technology, electrode materials, and experimental protocols—ensures that this fundamental approach will remain indispensable for unraveling complex electrochemical mechanisms across diverse fields including energy storage, materials science, and pharmaceutical development.

For researchers engaged in drug development and related disciplines, mastery of three-electrode systems provides powerful capabilities for characterizing redox-active compounds, understanding reaction mechanisms, and developing sensitive analytical methods. The principles and practices outlined in this technical guide offer both foundational knowledge and practical insights for implementing these systems effectively, ultimately supporting the advancement of electrochemical science and its applications to pressing challenges in health and technology.

Voltammetry is a category of electroanalytical methods used in analytical chemistry and various industrial processes where information about an analyte is obtained by measuring the current as the potential is varied [8]. The analytical data for a voltammetric experiment is presented in the form of a voltammogram, a plot that displays the current produced by the analyte versus the potential of the working electrode [8]. This current-potential curve serves as a fingerprint of the electrochemical activity of the system under study, providing critical insights into redox behavior, reaction kinetics, and mass transport properties.

The interpretation of these curves is fundamental across numerous scientific disciplines, including battery research [14], electrocatalysis [15], pharmaceutical analysis [16] [17], and environmental monitoring. For researchers in drug development, voltammetry offers a rapid, cost-effective, and precise means for quantifying active pharmaceutical ingredients and their metabolites in complex matrices such as biological fluids [16] [17]. This guide provides a comprehensive framework for interpreting voltammograms, enabling researchers to extract maximum information from these powerful electrochemical signatures.

Fundamental Principles and Plotting Conventions

The Electrochemical Cell and the Three-Electrode System

Most voltammetry experiments employ a three-electrode system to investigate half-cell reactivity [4] [8]. Each electrode has a distinct role:

- Working Electrode: This is the electrode where the redox reaction of interest occurs. Its potential is varied in a controlled manner relative to the reference electrode. Common materials include glassy carbon, platinum, gold, and mercury [18] [8].

- Reference Electrode: This electrode maintains a constant, known potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel electrode - SCE) against which the potential of the working electrode is measured and controlled [15] [18]. It is designed to pass minimal current [4] [8].

- Counter Electrode (Auxiliary Electrode): This electrode completes the electrical circuit, facilitating the flow of current needed to balance the charge transfer occurring at the working electrode [18] [8]. It is typically made from an inert material like platinum or graphite [15] [18].

This configuration separates the role of potential measurement (reference electrode) from current carrying (counter electrode), enabling precise control of the working electrode potential even when current is flowing [4] [8].

Figure 1: Three-Electrode System Setup.

Voltammogram Plotting Conventions

Before interpreting a voltammogram, it is crucial to identify the plotting convention used, as there is no universal standard [19]. The two most common conventions are:

- IUPAC Convention: This is the modern standard. It plots anodic (oxidizing) currents upward on the vertical axis and more positive (anodic) potentials toward the right on the horizontal axis [19].

- Polarographic (Classic) Convention: This older tradition plots cathodic (reducing) currents upward and negative (cathodic) potentials toward the right [19].

The IUPAC convention is more intuitive for those outside specialized electroanalytical research because positive values are plotted to the right and upward [19]. For the remainder of this guide, the IUPAC convention will be used.

Interpreting a Cyclic Voltammogram

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a cornerstone technique where the electrode potential is swept linearly between two limits and then swept back, completing one or more cycles [14] [4]. The resulting "duck-shaped" voltammogram provides a wealth of qualitative and quantitative information [14] [4].

Characteristic Features and Processes

The interpretation of a cyclic voltammogram hinges on recognizing its characteristic features, which correspond to specific electrochemical processes. The diagram below maps the key components of a typical CV for a reversible redox couple.

Figure 2: Cyclic Voltammogram Interpretation.

The forward scan (from A to D) typically drives an oxidation reaction, while the reverse scan (from D to F) drives the corresponding reduction [4]. The process at the working electrode is governed by the Nernst equation (E = Eâ° - (RT/zF) ln(Q)) which relates the applied potential to the concentration ratio of the reduced and oxidized species [4] [8]. The current response is a combination of faradaic current (from electron transfer) and capacitive current (from charging the electrical double-layer) [18].

Criteria for Reversibility, Quasi-Reversibility, and Irreversibility

The reversibility of an electrochemical reaction is diagnostically important and is assessed by examining the peak separation and shape [18].

Table 1: Diagnostic Criteria for Electrochemical Reversibility in Cyclic Voltammetry.

| Parameter | Reversible System | Quasi-Reversible System | Irreversible System | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Separation (ΔEp) | ΔEp = Epa - Epc ≈ 59/n mV at 25°C [18] | > 59/n mV | Large separation; reverse peak often absent | ||

| Peak Current Ratio ( | ipa/ipc | ) | ≈ 1 [4] | ≈ 1 (but peaks broader) | ≠1 |

| Peak Potential vs. Scan Rate | Independent of scan rate | Shifts with scan rate | Shifts with scan rate | ||

| Peak Current vs. Scan Rate | ip ∠v1/2 [4] | ip ∠v1/2 (deviation at high rates) | ip ∠v1/2 |

For example, a study on Ni/Al-carbonate hydrotalcite catalysts reported anodic and cathodic peaks at 0.62 V and 0.42 V, respectively, corresponding to a quasi-reversible redox behavior of Ni(II)/Ni(III) centers [15].

Quantitative Analysis: The Randles-Sevcik Equation

For a reversible, diffusion-controlled system, the peak current (ip) is quantitatively described by the Randles-Sevcik equation [4] [18]. This relationship allows researchers to determine the concentration of an analyte or its diffusion coefficient.

At 298 K (25°C), the equation is [4]: ip = (2.69 × 105) * n3/2 * A * D1/2 * C * v1/2

Table 2: Parameters of the Randles-Sevcik Equation.

| Symbol | Parameter | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|

| ip | Peak Current | Amperes (A) |

| n | Number of electrons transferred in the redox event | dimensionless |

| A | Electrode surface area | cm² |

| D | Diffusion coefficient of the analyte | cm²/s |

| C | Bulk concentration of the analyte | mol/cm³ |

| v | Scan rate | V/s |

The direct proportionality between the peak current (ip) and the square root of the scan rate (v1/2) is a key indicator of a diffusion-controlled process [4] [18]. A plot of ip vs. v1/2 should yield a straight line, and its slope can be used to determine n or D if the other parameters are known. If the current is instead proportional to the scan rate itself (ip ∠v), it suggests a surface-confined, adsorption-controlled process [15].

Experimental Protocols and the Researcher's Toolkit

A Standard Cyclic Voltammetry Methodology

The following protocol, inspired by studies on modified electrodes and pharmaceutical compounds, outlines a typical CV experiment [15] [16].

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the working electrode (e.g., a 3 mm diameter glassy carbon electrode) with an alumina slurry (e.g., 0.3 μm) on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with purified water and then sonicate in water and/or ethanol for a few minutes to remove adsorbed polishing material. Air dry [15].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the analyte of interest and a supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.04 M Britton-Robinson buffer, KCl, etc.) at a concentration much higher than the analyte (typically 0.1 M) to minimize solution resistance and ensure diffusion-controlled mass transport [16] [8]. For drug analysis, this may involve dissolving a pure standard in a solvent like methanol and diluting with the buffer [16].

- Cell Assembly: Transfer the solution to the electrochemical cell. Insert the three electrodes: working, reference, and counter. Degas the solution by purging with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for 5-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere by undergoing reduction [15].

- Instrumental Parameters: Set the following parameters on the potentiostat:

- Initial and Vertex Potentials: Define the potential window to encompass the expected redox events while avoiding solvent/electrolyte decomposition [14].

- Scan Rate: A common starting point is 0.1 V/s (100 mV/s), but a range should be tested (e.g., 0.01 - 1 V/s) for kinetic analysis [14] [15].

- Number of Cycles: Often 3-5 cycles are run to observe stability and achieve a reproducible response [14].

- Data Acquisition: Initiate the potential scan. The potentiostat will apply the potential waveform and record the resulting current, generating the voltammogram.

- Data Analysis: Identify peak currents and potentials. Perform a scan rate study and analyze the data using the Randles-Sevcik equation and reversibility criteria.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Voltammetric Experiments.

| Reagent/Material | Function and Importance |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃, Bu₄NPF₆) | Minimizes solution resistance, eliminates migratory mass transport, and ensures the reaction is diffusion-controlled. The choice depends on the solvent (aqueous/non-aqueous) [4] [8]. |

| Buffer Solutions (e.g., Britton-Robinson, Phosphate) | Controls the pH of the solution, which is critical for proton-coupled electron transfer reactions and studying drug molecules [16]. |

| Electrode Polishing Supplies (Alumina, Diamond slurry) | Ensures a clean, reproducible electrode surface, which is vital for obtaining consistent and accurate current measurements [15]. |

| Internal Standard (e.g., Ferrocene) | Used in non-aqueous electrochemistry as a reference to report and correct potentials, as recommended by IUPAC [4] [8]. |

| Redox Mediators / Modified Electrodes (e.g., Ni-LDH, nRGO) | Enhance sensitivity and selectivity. They can catalyze reactions or pre-concentrate analytes at the electrode surface [15] [16]. |

| Solvents (Water, Acetonitrile, DMF) | The medium for the electrochemical reaction. Must be pure, electrochemically inert in the chosen potential window, and able to dissolve the analyte and electrolyte [16]. |

| Roflumilast-d3 | Roflumilast-d3, CAS:1189992-00-4, MF:C17H14Cl2F2N2O3, MW:406.2 g/mol |

| Sulfadimethoxine-13C6 | Sulfadimethoxine-13C6, CAS:1334378-48-1, MF:C12H14N4O4S, MW:316.29 g/mol |

Advanced Interpretation and Practical Applications

The Impact of Scan Rate

Scan rate is a critical experimental parameter that acts as a "temporal lens" on the electrochemical process [14]. Its effect on the voltammogram provides deep insight into the reaction mechanism.

- Kinetic vs. Diffusion Control: As shown in Figure 5 of the search results, faster scan rates produce higher peak currents [14]. The relationship between peak current and scan rate (ip ∠v1/2 for diffusion control; ip ∠v for adsorption control) helps distinguish the nature of the electrochemical process [4] [15].

- Observing Intermediates: At faster scan rates, the timescale of the experiment becomes shorter than the lifetime of a chemical reaction that may follow the electron transfer (a CE or EC mechanism). This can allow for the detection of unstable intermediates that would not be visible at slower scan rates.

- Hysteresis and Catalysis: In electrocatalysis studies, the difference between the forward and reverse scans (hysteresis) can indicate catalytic behavior. For instance, in the study of Ni-LDH for methanol oxidation, hysteresis observed at 0.60 V highlighted efficient charge transport and catalytic activity [15].

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Bioanalytical Research

Voltammetry is indispensable in drug development due to its sensitivity, selectivity, and ability to handle complex matrices without extensive sample preparation [16] [17].

- Drug Quantification and Degradant Analysis: Voltammetric methods can be developed to quantify active pharmaceutical ingredients in the presence of their degradation products. For example, a novel method was established for the anti-inflammatory drug bumadizone (BUM) that successfully determined the drug in the presence of its alkaline-induced degradant without preliminary separation, achieving excellent recovery from spiked serum and urine samples [16].

- Alkaloid and Metabolite Determination: A recent review covering 2005-2025 critically analyzed voltammetric methodologies for 26 alkaloids and their metabolites, linking their electrochemical behavior to chemical structure. This provides a valuable resource for pharmaceutical analysis, food safety, and forensic monitoring [17].

- Sensor Development: The use of modified electrodes, such as nano-reduced graphene oxide (nRGO), significantly enhances analytical performance. One study found that a 10% nRGO-modified carbon paste electrode offered high selectivity and low detection limits for BUM, demonstrating the power of material science in advancing voltammetric drug analysis [16].

The voltammogram is a rich source of electrochemical information. A systematic approach to its interpretation—involving the identification of characteristic features, assessment of reversibility, application of quantitative models like the Randles-Sevcik equation, and thoughtful variation of experimental parameters like scan rate—enables researchers to decode complex electrode processes. For professionals in drug development and related fields, mastering this interpretation is key to leveraging voltammetry's full potential for sensitive, selective, and reliable analysis of pharmaceuticals and biologics, thereby accelerating discovery and ensuring quality.

Voltammetry, a cornerstone of electrochemical analysis, provides profound insights into reaction mechanisms and analyte concentrations by measuring current as a function of applied potential. The interpretation of voltammetric data relies fundamentally on three interconnected theoretical pillars: the Nernst equation, which describes electrochemical equilibrium; Butler-Volmer kinetics, which governs electron transfer rates; and Fick's laws of diffusion, which quantify mass transport. Together, these models form a comprehensive framework for understanding and deconvoluting the complex current-potential-time relationships observed in techniques such as cyclic voltammetry and linear sweep voltammetry. This guide examines each component in detail and demonstrates their integrated application in voltammetric analysis for research and drug development applications.

Theoretical Foundations

The Nernst Equation: Predicting Equilibrium Potentials

The Nernst Equation describes the thermodynamic relationship between the electrochemical potential of a half-cell and the activities (or concentrations) of the participating redox species under equilibrium conditions [20] [21]. For a general reduction reaction:

[ \text{O} + z\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{R} ]

The Nernst Equation is expressed as:

[ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}} ]

Where E is the equilibrium potential, Eâ° is the standard electrode potential, R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹), T is the absolute temperature, z is the number of electrons transferred, F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·molâ»Â¹), and aRed and aOx are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [22] [20].

For practical applications with dilute solutions where activities approximate concentrations, the equation is commonly written using the formal potential Eâ°':

[ E = E^{0'} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{[\text{Red}]}{[\text{Ox}]} ]

At room temperature (25°C), substituting the constants and converting to base-10 logarithm yields the simplified form:

[ E = E^{0'} - \frac{0.0591\, \text{V}}{z} \log_{10} \frac{[\text{Red}]}{[\text{Ox}]} ]

This simplified version is particularly useful for quick calculations [22]. The Nernst equation fundamentally predicts how the equilibrium position shifts with applied potential—as the voltage is swept to more reductive values, the equilibrium shifts to favor conversion of reactant at the electrode surface, driving current flow [23].

Table 1: Key Parameters in the Nernst Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Potential | E | Volt (V) | Potential at the working electrode |

| Standard Potential | Eâ° | Volt (V) | Potential under standard conditions |

| Formal Potential | Eâ°' | Volt (V) | Potential under specific experimental conditions |

| Gas Constant | R | J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹ | Universal gas constant |

| Temperature | T | Kelvin (K) | Absolute temperature |

| Electrons Transferred | z | Dimensionless | Number of electrons in redox reaction |

| Faraday Constant | F | C·molâ»Â¹ | Charge per mole of electrons |

Butler-Volmer Kinetics: Describing Electron Transfer Rates

While the Nernst equation addresses electrochemical equilibrium, the Butler-Volmer model describes the kinetics of electron transfer when the system is perturbed from equilibrium by an overpotential, η = E - E_eq [24] [25]. This model quantifies how the current density depends on the overpotential and the intrinsic properties of the electron transfer reaction.

For the reaction O + z e⻠⇌ R, the Butler-Volmer equation is given by:

[ j = j0 \left{ \exp\left(-\frac{\alphac z F \eta}{RT}\right) - \exp\left(\frac{\alpha_a z F \eta}{RT}\right) \right} ]

Where j is the current density, j₀ is the exchange current density, αa and αc are the anodic and cathodic charge transfer coefficients (typically αa + αc = 1), and η is the overpotential [24] [25] [8].

The model rests on several key assumptions: a simple one-step electron transfer mechanism, a homogeneous electrode surface, the absence of significant mass transport limitations, and a constant symmetry factor [25]. Under high overpotential conditions (|η| > ~0.1 V), the Butler-Volmer equation simplifies to the Tafel equation, where the current depends exponentially on the overpotential [24] [8].

Table 2: Key Parameters in the Butler-Volmer Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Density | j | A·mâ»Â² | Current per unit electrode area |

| Exchange Current Density | jâ‚€ | A·mâ»Â² | Current at equilibrium, reflects inherent reaction rate |

| Overpotential | η | Volt (V) | Deviation from equilibrium potential |

| Anodic Transfer Coefficient | α₠| Dimensionless | Measure of anodic activation barrier symmetry |

| Cathodic Transfer Coefficient | αc | Dimensionless | Measure of cathodic activation barrier symmetry |

Fick's Laws of Diffusion: Quantifying Mass Transport

In quiescent (unstirred) voltammetric experiments, the supply of electroactive species to the electrode surface is governed by diffusion, as described by Fick's laws [26] [27] [8]. These laws quantify how concentration gradients drive mass transport.

Fick's First Law states that the diffusive flux is proportional to the negative concentration gradient:

[ J = -D \frac{\partial C}{\partial x} ]

Where J is the diffusion flux (mol·mâ»Â²Â·sâ»Â¹), D is the diffusion coefficient (m²·sâ»Â¹), and ∂C/∂x is the concentration gradient (mol·mâ»â´) [26] [27]. The negative sign indicates flux occurs from high to low concentration.

Fick's Second Law describes how concentration changes with time due to diffusion:

[ \frac{\partial C}{\partial t} = D \frac{\partial^2 C}{\partial x^2} ]

This partial differential equation is identical in form to the heat equation and provides the foundation for modeling time-dependent diffusion processes [26]. In voltammetry, the current is proportional to the flux of electroactive species at the electrode surface (Jx=0), linking Fick's laws directly to the faradaic current response [8].

Table 3: Key Parameters in Fick's Laws of Diffusion

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Flux | J | mol·mâ»Â²Â·sâ»Â¹ | Amount of substance flowing per unit area per time |

| Diffusion Coefficient | D | m²·sâ»Â¹ | Measure of mobility in solution |

| Concentration | C | mol·mâ»Â³ | Amount of substance per unit volume |

| Distance from Electrode | x | meter (m) | Spatial coordinate normal to electrode surface |

Integrated Framework for Voltammetry

Interrelationship of Theoretical Models in Voltammetry

In voltammetric techniques, the three models operate in concert to determine the observed current response. The Nernst equation establishes the equilibrium conditions and predicts how the surface concentrations of redox species relate to the applied potential [23]. When the potential is swept away from equilibrium, the Butler-Volmer kinetics determine the rate of electron transfer based on the overpotential and the surface concentrations [24] [8]. Simultaneously, Fick's laws govern the diffusion of fresh reactant to the electrode surface and the removal of product, creating the characteristic current peaks observed in voltammograms [23] [8].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationship between these core models in shaping a voltammetric experiment:

The interplay between these processes determines whether a system exhibits "reversible" (fast kinetics, Nernstian), "quasi-reversible," or "irreversible" (slow kinetics) behavior in voltammetry [23]. In reversible systems, electron transfer is rapid relative to the voltage scan rate, and the surface concentrations follow the Nernst equation, with the response dominated by mass transport. In irreversible systems, slow electron transfer kinetics control the response, leading to broader peaks that shift with scan rate [23].

Application to Voltammetric Techniques

Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) applies a linear potential ramp from an initial to a final value [23] [8]. The current response initially rises as the potential shifts the equilibrium to favor the redox reaction, increasing the flux of reactant to the electrode. A peak current occurs when the diffusion layer has grown sufficiently that the flux of reactant to the electrode can no longer satisfy the surface concentration demanded by the Nernst equation for that potential [23]. The current then decays following Cottrell-like behavior (current ∠timeâ»Â¹/²) [23].

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) extends LSV by reversing the potential scan at a defined switching potential [23] [8]. The resulting voltammogram contains both forward and reverse scans, providing information about the redox reaction and the stability of the generated products. For a reversible, single-electron transfer with stable species, key characteristics include [23]:

- Peak separation (ΔEp) = 59/z mV

- Peak current ratio (Ipa/Ipc) = 1

- Peak current proportional to the square root of scan rate (Ip ∠v¹/²)

The scan rate (v) critically affects the voltammetric response by controlling the relative timescales of diffusion and electron transfer. Faster scans allow less time for diffusion, resulting in higher flux, larger peak currents, and a thinner diffusion layer [23]. The following diagram visualizes how the theoretical models interact during a cyclic voltammetry experiment:

Experimental Protocols

Standard Three-Electrode Configuration

Voltammetric measurements require a carefully controlled electrochemical cell. The standard three-electrode system consists of [8]:

- Working Electrode (WE): The electrode where the reaction of interest occurs. Common materials include glassy carbon, platinum, gold, and for historical context, mercury (e.g., HMDE, DME) [28] [8]. The surface must be clean and well-defined.

- Reference Electrode (RE): Provides a stable, known reference potential against which the working electrode potential is measured and controlled (e.g., Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel). It should not pass significant current [8].

- Counter Electrode (Auxiliary Electrode): Completes the electrical circuit, passing all current required to balance the reaction at the working electrode (e.g., platinum wire) [8].

A supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl) is added at a high concentration to minimize solution resistance and eliminate electrostatic migration of the analyte [28] [8]. The solution is typically purged with an inert gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚, Ar) before analysis to remove dissolved oxygen, which can be electrochemically reduced and interfere with measurements [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Voltammetric Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes solution resistance; ensures diffusion-controlled conditions | Potassium chloride (KCl), Tetraalkylammonium salts, Phosphate buffer |

| Solvent | Dissolves analyte and electrolyte; defines electrochemical window | Water, Acetonitrile, Dimethylformamide (DMF) |

| Redox Probe (for calibration) | Validates electrode performance and instrument response | Potassium ferricyanide, Ferrocene (for non-aqueous) |

| Working Electrode Material | Surface for electron transfer; defines reactivity and potential window | Glassy Carbon, Platinum, Gold, Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) |

| Purging Gas | Removes dissolved oxygen to prevent interference | Nitrogen (Nâ‚‚), Argon (Ar) |

The Nernst equation, Butler-Volmer kinetics, and Fick's laws of diffusion provide an indispensable, interconnected framework for interpreting voltammetric data. The Nernst equation establishes the thermodynamic foundation, Butler-Volmer kinetics describes the electron transfer rates, and Fick's laws quantify the mass transport by diffusion. Their combined application allows researchers to deconvolute complex voltammograms, extract critical parameters such as formal potentials, rate constants, and diffusion coefficients, and elucidate underlying reaction mechanisms. For drug development professionals and researchers, mastery of these core models is essential for leveraging voltammetry in applications ranging from antioxidant capacity assessment and metal complex characterization to the study of biological electron transfer processes.

The Role of the Supporting Electrolyte and Solvent Electrochemical Window

In the field of electroanalytical chemistry, voltammetry stands as a powerful technique for investigating electron transfer processes, with applications spanning from trace metal detection to neurotransmitter monitoring [29] [30]. The methodology involves measuring current as a function of applied potential to obtain quantitative and qualitative information about electroactive species [8]. While the fundamental instrumentation—typically a three-electrode system consisting of working, reference, and auxiliary electrodes—is well-established [8], the experimental outcomes are profoundly influenced by two critical components: the supporting electrolyte and the solvent's electrochemical window [31] [32]. These elements collectively establish the thermodynamic and kinetic boundaries within which electrochemical reactions can be reliably studied. This technical guide examines the fundamental roles, selection criteria, and practical considerations for these components within the context of voltammetric analysis, providing researchers with a framework for optimizing electrochemical experiments.

Fundamental Principles of Voltammetry

Voltammetry encompasses a category of electroanalytical methods where information about an analyte is obtained by measuring current as the potential is varied [8]. The resulting output, a voltammogram, plots current against applied potential and provides insights into analyte concentration, redox potentials, and reaction kinetics [8]. The technique relies on a three-electrode system to precisely control the working electrode potential while measuring the faradaic current resulting from the oxidation or reduction of analytes [8].

The governing mathematical models include the Nernst equation for thermodynamic predictions, the Butler-Volmer equation for describing the current-potential relationship in heterogeneous electron transfer, and Fick's laws of diffusion for modeling mass transport [8]. Various voltammetric techniques have been developed, including linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), and square-wave voltammetry (SWV), each offering distinct advantages for specific analytical challenges [29] [30].

The Supporting Electrolyte: Functions and Selection Criteria

Primary Functions in Voltammetric Analysis

The supporting electrolyte, often referred to as background or inert electrolyte, is an essential component added to the electrochemical cell to ensure interpretable results [33]. Its fundamental purposes include:

- Conductivity Enhancement: Most liquid media used in electrochemistry (e.g., water, organic solvents) are poor conductors, making it difficult to pass electrical current between electrodes. The supporting electrolyte provides ionic conductivity to the solution, facilitating current flow [31] [30].

- Migration Current Elimination: Application of a potential difference creates an electric field that causes charged species to move toward oppositely charged electrodes (migration). The supporting electrolyte, added in excess (typically 10-50 times the concentration of the analyte), carries the majority of this migration current, ensuring that the transport of electroactive species occurs primarily through diffusion [30]. This simplifies data interpretation, as the current becomes directly proportional to analyte concentration via the Cottrell equation [29].

- IR Drop Minimization: Solution resistance leads to an ohmic potential drop (IR drop) that can distort voltammetric measurements. By increasing conductivity, the supporting electrolyte minimizes this effect, ensuring accurate potential control at the working electrode [33] [34].

- Controlling Experimental Conditions: Supporting electrolytes help maintain constant ionic strength and, when using buffers, constant pH, both critical for obtaining reproducible results [30] [33].

Essential Properties and Common Selection

To properly fulfill its functions, an ideal supporting electrolyte should be [33]:

- Completely dissociated in the solvent (a strong electrolyte)

- Sufficiently soluble to achieve the required ionic strength

- Chemically inert toward other solutes (no precipitation, complexation, or redox reactions)

- Electroinactive within the potential range being studied

- Non-adsorbing on electrode surfaces, or at least not inhibiting the reaction of interest

Table 1: Commonly Used Supporting Electrolytes and Their Applications

| Electrolyte | Common Solvents | Key Properties and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium Perchlorate (NaClO₄) | Water, acetone, acetonitrile, DMF, DMSO | High solubility (2096 g/L at 25°C); kinetically inert redox behavior; suitable for complexation studies [30] [33]. |

| Tetraalkylammonium Salts (e.g., Buâ‚„Nâº) | Acetone, acetonitrile, DMF, DMSO | Wide potential windows in organic solvents; minimal specific adsorption on many electrodes [30]. |

| Alkali Metal Salts (e.g., NaCl, KCl) | Water, acetone, acetonitrile | Cost-effective; chloride ions can break down protective layers on anode surfaces in electrocoagulation processes [31] [30]. |

| Strong Acids (e.g., Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) | Water | Provides high proton concentration; acts as both supporting electrolyte and pH buffer [31] [30]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Water | Maintains constant pH; essential for reactions involving H⺠or OH⻠participation [30]. |

Impact on Analytical Performance

The choice of supporting electrolyte can significantly influence voltammetric results. In electrocoagulation processes, chloride ions (Clâ») can break down protective layers on anode surfaces, increasing dissolution rates, while sulfate (SO₄²â») and bicarbonate (HCO₃â») ions may form or strengthen such layers, potentially hindering electrode processes [31]. Furthermore, specific ions can compete with target analytes for surface sites on metal hydroxides, potentially interfering with adsorption or co-precipitation processes [31]. For instance, high concentrations of SO₄²⻠and HCO₃⻠can hinder arsenate adsorption in electrocoagulation systems [31].

The Electrochemical Window: Definition and Determining Factors

Fundamental Concept

The electrochemical window (EW) refers to the potential range within which the solvent-electrolyte system remains electrochemically inert [32]. It is defined as the voltage difference between the anodic limit (where oxidation occurs) and the cathodic limit (where reduction occurs), typically determined using techniques like linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) or cyclic voltammetry (CV) [32]. Outside this window, the electrolyte or solvent undergoes irreversible redox reactions, generating background currents that obscure analytical signals.

Factors Influencing the Electrochemical Window

Several factors determine the practical electrochemical window in voltammetric experiments:

- Solvent Properties: The inherent stability of the solvent molecules against oxidation and reduction establishes the fundamental boundaries. Aqueous solutions typically offer a limited window of approximately 1.2-2 V due to water electrolysis, while organic solvents like acetonitrile or propylene carbonate can provide windows exceeding 3 V [32].

- Electrolyte Composition: Both the cation and anion of the supporting electrolyte have decomposition potentials that can become the limiting factors. For ionic liquids, the [TFSI]â» anion demonstrates wider EWs compared to [BFâ‚„]â»-based systems [32].

- Electrode Material: The working electrode material significantly influences the observed EW. Research has shown that for 1-n-butyl-3-methylimidazolium tetrafluoroborate, the reductive window followed the sequence Au ≈ GC > Pt, while the oxidation window magnitude followed Au > GC ≈ Pt [32].

- Water and Impurity Content: Trace water can dramatically narrow the EW, particularly in non-aqueous systems, by participating in electrolysis reactions. One study noted a 2 V narrowing of the EW for imidazolium-based ionic liquids in the presence of water [32].

- Cut-off Current Density: The EW is conventionally determined at an arbitrary current density cutoff, typically between 0.1 and 1.0 mA/cm², which can affect the reported values [32].

Table 2: Factors Affecting the Electrochemical Window and Experimental Control Strategies

| Factor | Impact on Electrochemical Window | Experimental Control Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Solvent Type | Determines fundamental anodic and cathodic stability limits | Select solvent with appropriate dielectric constant and donor/acceptor properties for the target potential range. |

| Electrolyte Ions | Cation and anion have specific decomposition potentials | Choose electroinactive ions with redox potentials beyond the region of interest (e.g., perchlorate salts) [33]. |

| Working Electrode | Catalyzes specific decomposition reactions; affects overpotentials | Select electrode material (Au, GC, Pt) based on required anodic and cathodic limits [32]. |

| Water Content | Enables water electrolysis, narrowing usable window | Implement rigorous drying procedures for non-aqueous studies; use hydrophobic ionic liquids [32]. |

| Temperature | Affects reaction kinetics and decomposition rates | Maintain constant temperature; report experimental conditions for reproducibility [32]. |

Methodologies for Determining Electrochemical Windows and Optimizing Supporting Electrolytes

Experimental Protocol for Electrochemical Window Determination

The following methodology provides a standardized approach for determining the electrochemical window of a solvent-electrolyte system:

- Cell Preparation: Use a three-electrode system with a polished working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, platinum, or gold), a non-reactive counter electrode (e.g., platinum wire), and an appropriate reference electrode (e.g., Ag/Ag⺠for non-aqueous systems) [32].

- Solution Preparation: Dry the solvent thoroughly and store over molecular sieves. Use high-purity supporting electrolyte at a concentration sufficient to provide adequate conductivity (typically 0.1-1.0 M) [33] [35].

- Deaeration: Sparge the solution with an inert gas (nitrogen or argon) for 15-20 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can contribute to redox processes within the potential window [35].

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- Data Analysis:

- Identify the anodic limit (EAL) and cathodic limit (ECL) at a predetermined current density cutoff (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mA/cm²) [32].

- Calculate the electrochemical window as EW = EAL - ECL.

- Report all experimental conditions including electrode material, reference electrode, scan rate, and temperature.

Supporting Electrolyte Optimization Procedure

To select and optimize a supporting electrolyte for a specific voltammetric application:

- Preliminary Selection: Based on the solvent and target potential range, identify candidate electrolytes that are soluble, conductive, and likely electroinactive in the region of interest (refer to Table 1) [30] [33].

- Background Current Assessment:

- Record voltammograms (preferably CV or DPV) of the candidate electrolyte solutions without analyte.

- Compare background currents and flatness of the current-potential relationship in the target region.

- Select electrolytes with minimal background currents in the potential range of interest.

- Analyte Response Evaluation:

- Add the target analyte to each candidate electrolyte solution.

- Record voltammograms and evaluate key parameters: peak sharpness, signal-to-noise ratio, stability on repeated cycling, and reproducibility.

- Interference Testing:

- Test for complexation effects by comparing formal potentials across different electrolytes.

- Evaluate adsorption tendencies by examining peak current ratios in CV.

- Concentration Optimization:

- Perform a concentration series of the selected supporting electrolyte (typically 0.05-1.0 M) while monitoring analyte response.

- Choose the minimum concentration that provides satisfactory conductivity and elimination of migration effects.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Voltammetric Studies

| Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolytes | Sodium perchlorate (NaClO₄), Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF₆), Potassium nitrate (KNO₃), Lithium perchlorate (LiClO₄) | Provide ionic conductivity; suppress migration effects; maintain constant ionic strength [30] [33] [35]. |

| Solvent Systems | Deionized water, Acetonitrile, Dimethylformamide (DMF), Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) | Dissolve analyte and electrolyte; determine fundamental electrochemical window; must be purified and dried for non-aqueous work [30] [32]. |

| Working Electrodes | Glassy carbon (GC), Platinum (Pt), Gold (Au), Hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE) | Serve as electron transfer surface; choice affects electrochemical window and catalytic properties [8] [32]. |

| Reference Electrodes | Saturated calomel electrode (SCE), Ag/AgCl, Ag/Ag⺠(non-aqueous), Ferrocene/Ferrocenium (internal) | Provide stable, known reference potential for accurate potential control [8] [35]. |

| Purification Materials | Molecular sieves, Nitrogen/Argon gas, Alumina powder for polishing | Remove contaminants and oxygen; maintain electrode reproducibility [32] [35]. |

| Sulfadimethoxine-d4 | Sulfadimethoxine-d4, MF:C12H14N4O4S, MW:314.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Topiramate-13C6-1 | Topiramate-13C6-1, CAS:1217455-55-4, MF:C12H21NO8S, MW:345.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |