Voltammetry for Trace Metal Analysis: Advanced Electrochemical Techniques for Environmental and Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of voltammetric techniques for the determination of trace metals in environmental samples, with significant implications for biomedical and clinical research.

Voltammetry for Trace Metal Analysis: Advanced Electrochemical Techniques for Environmental and Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of voltammetric techniques for the determination of trace metals in environmental samples, with significant implications for biomedical and clinical research. It covers the foundational principles of electroanalytical methods, explores specific methodologies like anodic stripping voltammetry and square wave voltammetry with their applications in analyzing water, soil, and plant tissues. The content addresses common troubleshooting scenarios and optimization strategies for reliable analysis, while also presenting validation protocols and comparative assessments with spectroscopic techniques. With a focus on recent advances in sensor technology and green analytical chemistry, this resource serves researchers and scientists seeking robust, sensitive, and cost-effective solutions for trace metal analysis in complex matrices.

Fundamentals of Voltammetry: Principles and Advantages for Trace Metal Analysis

Core Principles of Electrochemical Stripping Analysis

Electrochemical stripping analysis is a powerful analytical technique renowned for its exceptional sensitivity in detecting trace and ultratrace concentrations of metal ions in environmental samples [1]. As a two-step electromalytical method, it combines an initial preconcentration phase with a subsequent measurement (stripping) phase, enabling the determination of metal concentrations at levels as low as parts per billion (ppb) or even parts per trillion (ppt) [2]. This capability makes it indispensable for monitoring toxic heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, mercury, and arsenic in water, soil, and food matrices, addressing critical environmental and public health concerns [1] [3]. The technique has evolved significantly with advancements in electrode materials, particularly nanomaterials, and instrumentation, expanding its applications for real-time, on-site, and in situ measurements [4].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Fundamental Mechanism

The exceptional sensitivity of stripping voltammetry stems from its two-stage operational principle that separates preconcentration from measurement [2].

- Preconcentration Step: The target analyte is accumulated onto or into the working electrode surface from the bulk solution. This step significantly enhances the concentration of the analyte at the electrode interface compared to its bulk concentration, providing the foundation for high sensitivity.

- Stripping Step: The accumulated analyte is subsequently stripped back into the solution through the application of a controlled potential waveform. The current generated during this re-dissolution process is measured and serves as the analytical signal, which is proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the original solution.

This dual-phase approach differentiates stripping analysis from other voltammetric techniques and is responsible for its remarkably low detection limits, which can extend to the picomolar range [2].

Key Stripping Voltammetry Techniques

The specific method of preconcentration and measurement defines the primary variants of stripping voltammetry, each suited to particular classes of analytes.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Stripping Voltammetry Techniques

| Technique | Preconcentration Mechanism | Stripping Step | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Electrolytic reduction of metal ions to form an amalgam or film on the electrode [3]. | Anodic potential scan re-oxidizes metals, generating a measurable current [3]. | Determination of heavy metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu) [1]. |

| Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) | Adsorption of a metal complex with a surface-active complexing agent onto the electrode surface [5] [3]. | Reduction or oxidation of the adsorbed complex [3]. | Analysis of metals that are difficult to deposit electrolytically (e.g., Ni, Co, U, rare earth elements) [5]. |

| Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CSV) | Anodic formation of an insoluble film with the electrode material (e.g., mercury salt) [3]. | Cathodic potential scan reduces the film, generating a measurable current [3]. | Determination of anions and organic compounds that form insoluble salts with mercury. |

The Critical Role of Electrode Materials

The working electrode is at the heart of the sensing process, and its physicochemical properties—such as conductivity, surface area, and binding affinity—are crucial for determining the sensor's sensitivity, selectivity, and reproducibility [1]. Recent research focuses extensively on modifying and functionalizing electrodes with nanostructured materials to enhance their performance [1].

Key Electrode Materials and Modifiers:

- Carbon Nanomaterials: Single-walled and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs, MWCNTs), graphene, and carbon black improve conductivity and provide a high surface area [1] [6].

- Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), bismuth, silver, and cobalt oxide (Co₃O₄) nanoparticles enhance catalytic activity, sensitivity, and selectivity for specific metals [1] [2] [7].

- Bismuth Films: A popular "green" alternative to mercury, bismuth films offer well-defined stripping signals and low background current, and can be plated onto carbon substrates [4] [7].

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): These porous materials provide high surface areas and specific binding sites, improving preconcentration efficiency [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Simultaneous Determination of Arsenic and Mercury using a Modified Electrode

This protocol outlines the simultaneous detection of As³⁺ and Hg²⁺ using a Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) modified with cobalt oxide and gold nanoparticles (Co₃O₄/AuNPs) via Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) [2].

1. Sensor Fabrication:

- Polishing: Polish a bare GCE sequentially with alumina slurries (1.0 μm and 0.3 μm) to a mirror finish. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- Modification: Deposit a suspension of Co₃O₄ nanoparticles onto the clean GCE surface and allow to dry.

- Electrodeposition of AuNPs: Immerse the Co₃O₄/GCE in a solution of HAuCl₄ (e.g., 0.5 mM in 0.1 M K₂SO₄). Apply a constant potential of -0.8 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 60 seconds to electrodeposit AuNPs, forming the final Co₃O₄/AuNPs/GCE sensor.

2. Measurement Procedure (ASV):

- Supporting Electrolyte: Use 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 5.0) as the electrolyte.

- Accumulation/Preconcentration: Immerse the sensor in the stirred sample solution. Apply an accumulation potential of -1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 120 seconds to reduce and deposit As and Hg onto the electrode surface.

- Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow the solution to equilibrate for 10 seconds.

- Stripping Scan: Record the stripping voltammogram by applying a positive-going differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) scan from -0.5 V to +0.4 V. The oxidation peaks for As³⁺ and Hg²⁺ will appear at distinct potentials (e.g., ≈ -0.1 V for As and ≈ +0.25 V for Hg).

3. Calibration and Analysis:

- Generate calibration curves by plotting the peak current (Ip) against concentration for standard solutions of As³⁺ and Hg²⁺.

- The sensor exhibits a wide linear dynamic range (e.g., 10–900 ppb for As³⁺ and 10–650 ppb for Hg²⁺) with recoveries of 96%–116% in real water samples [2].

Protocol: Determination of Nickel and Cobalt using Adsorptive Striammetry (AdSV)

This method is suitable for determining metals like Ni and Co, which form stable complexes with specific ligands [7].

1. Electrode Preparation:

- Use a scTRACE Gold electrode modified with an ex-situ plated bismuth film [7].

- Supporting Electrolyte and Complexation: Prepare a solution containing an ammonia buffer (pH ~9.2) and the complexing agent dimethylglyoxime (DMG). The DMG complexes with Ni(II) and Co(II) in the sample to form surface-active complexes.

2. Measurement Procedure (AdSV):

- Accumulation/Adsorption: Immerse the electrode in the stirred solution. Apply an accumulation potential (e.g., -0.7 V) for a set time (e.g., 60 seconds). This causes the Ni-DMG and Co-DMG complexes to adsorb onto the electrode surface.

- Stripping Scan: Record the voltammogram using a cathodic (negative-going) DPV scan. The reduction of the metal in the adsorbed complex (e.g., Ni²⁺ to Ni⁰ in the complex) produces a peak current. The peak heights are proportional to the concentration of Ni and Co in the solution.

- This method can achieve detection limits as low as 0.2 µg/L for Ni using a laboratory instrument [7].

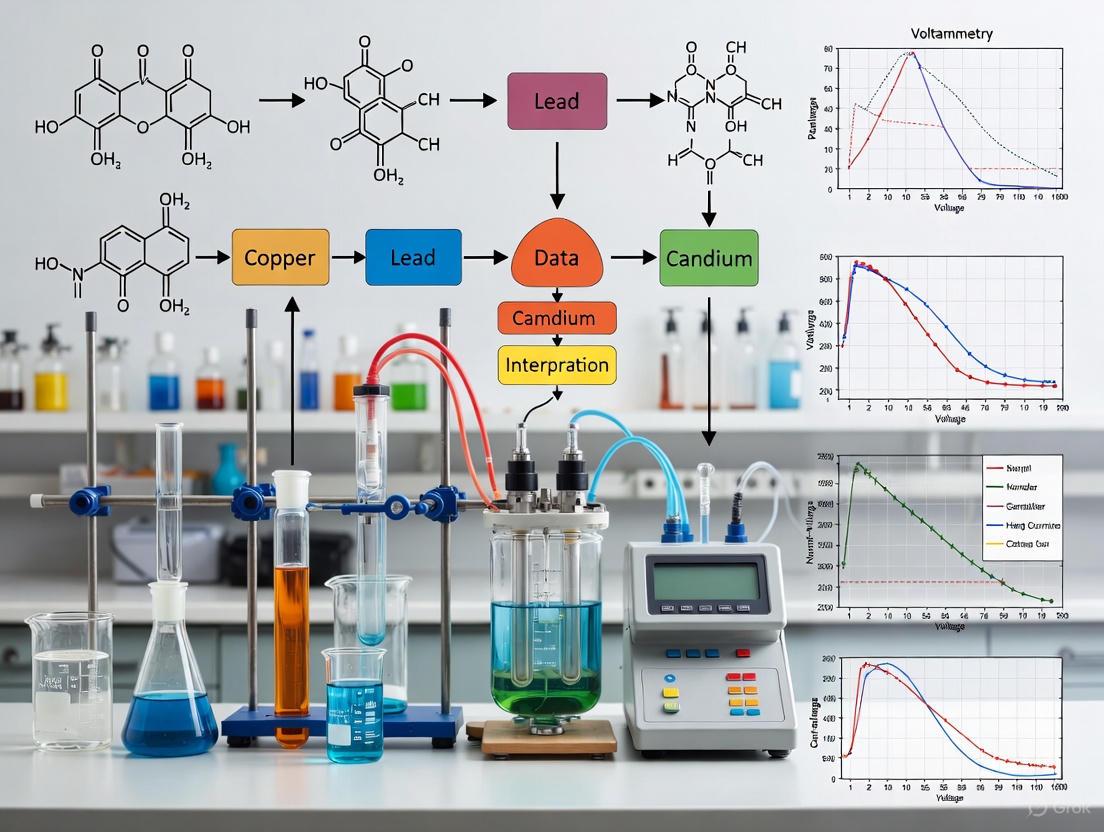

Workflow Diagram

The following diagram illustrates the general experimental workflow for anodic and adsorptive stripping voltammetry, from sample preparation to data analysis.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and instruments essential for conducting electrochemical stripping analysis.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Stripping Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrodes | Serves as the platform for analyte preconcentration and stripping. Choice depends on target metal and required potential window. | ScTRACE Gold: For As, Cu; can be modified with Bi/Ag films [8] [7]. Bismuth Film Electrodes: "Green" alternative to mercury for Cd, Pb, Zn [4]. Glassy Carbon (GCE): Often modified with nanomaterials (e.g., AuNPs, Co₃O₄, CNTs) [2]. |

| Complexing Agents | Forms adsorbable complexes with target metal ions for AdSV, enabling determination of metals not amenable to ASV. | DMG (Dimethylglyoxime): For determination of Ni and Co [7]. Cupferron: Used for AdSV of Ga(III) and other metals [6]. Catechol/DTPA: Used for complexation in AdSV of various ions [6]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic conductivity, controls pH, and can influence the electrochemical reaction and complex formation. | Acetate buffer (pH ~5), ammonia buffer (pH ~9), nitric acid, perchloric acid. Choice is optimized for specific analysis [2] [6]. |

| Standard Solutions | Used for calibration and method validation. | High-purity single- and multi-element standards at various concentrations (e.g., 1000 mg/L). |

| Nanomaterial Modifiers | Enhance electrode sensitivity, selectivity, and stability by increasing surface area and providing catalytic sites. | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): Excellent for As and Hg detection [2]. Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): Improve conductivity and surface area [1] [6]. Metal Oxide Nanoparticles (e.g., Co₃O₄): Often used in composites [2]. |

| Portable Instrumentation | Enables on-site, real-time analysis, which is critical for environmental monitoring. | 946 Portable VA Analyzer (Metrohm): Allows for mobile use and immediate results at the sample source [8] [7]. |

Advanced Concepts and Future Directions

The field of electrochemical stripping analysis is rapidly advancing, driven by the demand for more sophisticated monitoring capabilities.

Criteria for Ideal Field Deployable Sensors: The "6 S's"

For a sensor to be effective for real-time, on-site, in situ measurements, it should ideally conform to six critical benchmarks, known as the "6 S's" [4]:

- Sensitivity: Ability to detect trace concentrations (<1 ppm) of target analytes.

- Selectivity: Ability to distinguish the target metal from other similarly charged ions and matrix interferents.

- Size: Miniaturization of electrodes and instrumentation for portability and access to hard-to-reach environments.

- Stability: Robust performance over time and resistance to fouling in complex matrices.

- Safe Materials: Use of environmentally friendly electrode materials to replace toxic mercury.

- Speed: Capability for high-time-resolution measurements to capture dynamic chemical processes.

Emerging Frontiers

- Real-Time and In-Situ Monitoring: The development of portable, submersible voltammetric probes, such as the Voltammetric In-Situ Profiling (VIP) system, allows for direct measurements in dynamic environments like lakes and oceans without sample collection, which can alter metal speciation [4].

- Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV): An emerging technique that offers sub-second temporal resolution for monitoring metal concentration changes in real time, fulfilling the "speed" criterion [4].

- Novel Nanocomposites: Continued research into hybrid materials, such as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and bi-metallic nanocomposites, aims to further improve sensor architecture, functionalization, and anti-fouling properties [1].

Electrochemical stripping analysis remains a cornerstone technique for trace metal analysis, offering unparalleled sensitivity, portability, and cost-effectiveness. Its core principles, rooted in the two-step process of preconcentration and stripping, provide a robust framework for detecting environmentally significant metals at regulatory levels. Ongoing innovations in electrode materials, the adoption of mercury-free sensors, and the push towards fully integrated, in-situ monitoring devices ensure that stripping voltammetry will continue to be a vital tool for researchers and environmental scientists addressing the global challenge of heavy metal contamination.

The accurate determination of trace metals in environmental samples is a cornerstone of environmental monitoring, regulatory compliance, and toxicological research. While classical spectroscopic and spectrometric techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma-Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), and X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) have long been established, voltammetric methods have emerged as powerful alternatives and complementary techniques. The selection of an appropriate analytical method significantly influences the data quality, the scope of speciation information, and the practical feasibility of environmental monitoring programs. This application note provides a detailed comparison of these key analytical techniques, focusing on their operational principles, performance metrics, and applicability within environmental research. The content is structured to serve researchers and scientists by providing clear experimental protocols and data-driven insights for informed method selection.

Fundamental Principles

Voltammetry: This electrochemical technique involves applying a potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current. In stripping voltammetry, a preconcentration step, where metal ions are deposited onto the working electrode, is followed by a stripping step that quantifies the metals. It is particularly noted for its ability to perform metal speciation analysis, distinguishing between different chemical forms of a metal, such as free ions, labile complexes, and inert species [9] [10]. Common modalities include Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) and Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (AdCSV).

ICP-MS: This technique uses high-temperature argon plasma to atomize and ionize a sample. The resulting ions are then separated and quantified based on their mass-to-charge ratio. ICP-MS is renowned for its exceptionally low detection limits and capability for multi-element analysis [11] [12].

AAS: AAS quantifies elements by measuring the absorption of light at element-specific wavelengths by free atoms in the gaseous state. Graphite Furnace AAS (GFAAS) offers lower detection limits than flame AAS and is a reference method in many environmental standards [13].

XRF: XRF is a non-destructive technique that irradiates a sample with X-rays, causing the emission of secondary (fluorescent) X-rays. The energies of these emitted X-rays are characteristic of the elements present, allowing for qualitative and quantitative analysis. Portable XRF (FP XRF) is widely used for in-situ screening [14] [12] [15].

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize key performance characteristics and operational parameters for the four techniques, based on data from environmental analysis studies.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Performance Characteristics

| Parameter | Voltammetry | ICP-MS | AAS (GFAA) | XRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | ppt to ppb range [13] | ppt to ppb range [11] | ppb range [13] | ppm range [15] |

| Multi-element Capability | Good for several metals simultaneously [16] | Excellent | Limited (typically sequential) | Excellent |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate to High | Very High | Low to Moderate | Very High (field) |

| Tolerance to Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) | Moderate | Low (typically <0.2%) [11] | Moderate | High (solid samples) [11] |

| Sample Consumption | Low | Low | Very Low | Virtually none |

Table 2: Comparison of Practical and Operational Factors

| Factor | Voltammetry | ICP-MS | AAS (GFAA) | XRF |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capital Cost | Low [13] [17] | Very High | Medium | Low (portable) to High (lab) |

| Operational Complexity | Moderate | High | Moderate | Low (field units) |

| Speciation Capability | Yes (directly) [9] [10] | With coupling (e.g., HPLC-ICP-MS) | No | Limited (valence state) |

| Portability / On-site Use | Yes (with portable systems) [16] [10] | No | No | Yes (inherently) [14] [12] |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (often just acidification) [17] | Extensive (digestion often required) | Extensive (digestion often required) | Minimal to none |

A critical study comparing voltammetry and ICP-MS for the analysis of heavy metals (Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn, As, Ni) in PM10 airborne particulate matter demonstrated that the differences between the two methods remained within the level of uncertainty required by European Directives. The voltammetric method achieved recoveries between 92% and 103% for a Certified Reference Material (NIST 1648) and its method detection limits satisfied the European Standard EN 14902 [13].

Technique Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a decision-making workflow for selecting an appropriate analytical technique based on key research questions and sample properties.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Determination of Heavy Metals in PM10 Airborne Particulate Matter by Voltammetry

This protocol is adapted from a study comparing voltammetry and ICP-MS, which demonstrated compliance with European Standard EN 14902 [13].

3.1.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Quartz Fiber Filters (e.g., Whatman QMA) | Sample collection medium for PM10 particulate matter. |

| High-Purity Nitric Acid (HNO₃) & Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | For microwave-assisted acid digestion of filters. |

| Acetate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) | Serves as the supporting electrolyte for ASV determination of Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn. |

| Dimethylglyoxime (DMG) | Complexing agent for the adsorptive stripping voltammetric determination of Ni. |

| Standard Solutions of Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn, As, Ni | For instrument calibration and quantification. |

| Nitrogen Gas (N₂) | High-purity grade for deaerating solutions to remove dissolved oxygen. |

3.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sample Collection: Collect PM10 airborne particulate matter on quartz fiber filters using a low-volume sampler operating at 2.3 m³ h⁻¹ for a 24-hour period, according to EN 12341 [13].

- Microwave Digestion:

- Transfer a section of the exposed filter to a microwave digestion vessel.

- Add a mixture of concentrated HNO₃ and HCl (exact ratios as per EN 14902 or optimized in-house).

- Carry out digestion using a controlled microwave heating program (e.g., Millestone ETHOS TC).

- After cooling, dilute the digestate with high-purity water and filter if necessary.

- Voltammetric Analysis:

- Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) for Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn:

- Transfer an aliquot of the digestate to the voltammetric cell.

- Add acetate buffer to achieve a 0.1 M concentration and adjust pH to ~4.5.

- Purge the solution with N₂ for 5-10 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Pre-concentration step: Apply a negative deposition potential (e.g., -1.2 V) while stirring for a defined time (e.g., 60-300 s) to reduce and deposit metal ions onto the working electrode.

- Stripping step: Scan the potential in a positive direction using a differential pulse or square wave waveform. Record the stripping voltammogram.

- Identify metals by their characteristic peak potentials and quantify by comparing peak heights/areas to a calibration curve.

- Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry for Ni:

- Use a separate aliquot of the digestate.

- Add DMG as a complexing agent and an ammonia buffer.

- Accumulate the Ni-DMG complex on the electrode by adsorptive accumulation at a suitable potential.

- Scan the potential in a negative direction to reduce the adsorbed complex, generating the analytical signal.

- Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) for Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn:

- Quality Control:

- Analyze procedural blanks (clean filters taken through the entire process).

- Analyze Certified Reference Materials (e.g., NIST 1648 Urban Dust) to validate recovery and accuracy.

- Perform replicate analyses to assess precision.

Protocol: Cross-Validation of Soil Metal Concentrations using FP XRF and ICP-MS

This protocol is based on studies highlighting the need to correct field XRF readings for accurate results [14] [12].

3.2.1 Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Soil Analysis

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Field Portable XRF (FP XRF) Analyzer | e.g., Thermo Fisher or Bruker models, calibrated for soil analysis. |

| ICP-MS Instrument | For reference analysis. |

| Polypropylene Sample Cups | With XRF film windows for holding soil samples. |

| High-Purity HNO₃, HCl, HF | For microwave-assisted acid digestion of soil samples. |

| NIST Soil Certified Reference Materials (e.g., 2709, 2710) | For quality control and XRF calibration verification. |

| 250 μm Sieve | For standardizing particle size of soil samples. |

3.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Soil Sampling and Preparation:

- Field Portable XRF Analysis:

- Fill a polypropylene sample cup with the prepared soil.

- Analyze the sample using the FP XRF analyzer in "soil mode" for a minimum of 80 source seconds to ensure good counting statistics.

- Record the concentrations for target metals (e.g., As, Pb).

- Laboratory ICP-MS Analysis:

- Digest a subsample (e.g., 0.5 g) of the same sieved soil using a mixture of HNO₃, HCl, and HF in a microwave digestion system, following EPA Method 3051 or equivalent.

- Dilute the cooled digestate and analyze by ICP-MS following EPA Method 6020.

- Data Comparison and Correction:

- Compare the results from FP XRF and ICP-MS using statistical methods (e.g., paired t-tests, linear regression, Bland-Altman plots).

- If a consistent bias is observed, develop a site- or instrument-specific correction factor. A study in a Superfund community found that a ratio correction factor method provided the best agreement between FP XRF and ICP-MS for arsenic and lead [12].

- Apply this correction factor to future FP XRF field screening data for more accurate predictions of ICP-MS equivalent concentrations.

Critical Discussion and Applications

The Unique Role of Voltammetry in Metal Speciation

A defining advantage of voltammetry over the other techniques is its direct capability for metal speciation analysis in aqueous samples. Techniques like ICP-MS and AAS typically measure total metal concentration after vigorous digestion. In contrast, voltammetry can distinguish between chemically different forms of a metal, such as free hydrated ions, labile metal complexes, and inert complexes, without extensive pretreatment [9] [10]. This is crucial because the bioavailability, toxicity, and geochemical cycling of a metal are strongly dependent on its chemical form. For instance, more than 99% of copper in surface seawater can be organically complexed, drastically reducing its bioavailability [9]. Voltammetric methods, particularly Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) and Competing Ligand Exchange-Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CLE-AdCSV), are widely used to study such speciation, providing insights that are critical for accurate environmental risk assessment [9] [10].

Addressing Challenges and Artifacts in Traditional Techniques

Even established techniques like ICP-MS have potential pitfalls that researchers must recognize. For example, a 2024 study on the analysis of Sr and Ba in coal and ash highlights that incomplete digestion due to the formation of refractory fluoride compounds (e.g., AlF₃, K₂SiF₆) during microwave-assisted digestion with HF can lead to significant underestimation of concentrations by ICP-MS [18]. This finding underscores the importance of method validation and the utility of a technique like XRF as a non-destructive cross-checking method to evaluate the accuracy of wet-chemical digestion-based methods [18].

Similarly, field-portable XRF, while rapid and convenient, is sensitive to sample conditions. Studies consistently show that soil moisture exceeding 10% can cause under-reporting of metal concentrations during in-situ analysis [14]. For the most accurate results, XRF analysis should be performed on homogenized, air-dried, and sieved samples in a laboratory setting [14] [12].

The choice between voltammetry, ICP-MS, AAS, and XRF is not a matter of identifying a single "best" technique, but rather of selecting the most fit-for-purpose tool for a specific analytical challenge. ICP-MS remains the benchmark for ultra-trace multi-element total concentration analysis. AAS is a robust and established technique for routine analysis of a limited number of elements. XRF is unparalleled for non-destructive, high-throughput screening of solid samples, especially in the field.

Voltammetry carves out its essential niche by offering a unique combination of low detection limits, speciation capability, portability, and lower operational costs. Its ability to provide information on metal lability and complexation directly in aqueous samples makes it invaluable for advanced environmental chemistry studies. The protocols and data presented herein provide a framework for researchers to make informed decisions, develop robust analytical methods, and leverage the synergistic use of these techniques to advance research in trace metal analysis of environmental samples.

Voltammetry, particularly stripping voltammetry, has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for trace metal analysis in environmental samples, offering distinct advantages over traditional spectroscopic methods. This technique's exceptional sensitivity allows for the detection of metal ions at ultratrace concentrations (parts-per-trillion levels), meeting rigorous environmental monitoring standards [9] [2]. The fundamental portability of modern voltammetric systems enables real-time, on-site analysis—a transformative capability for field environmental science that eliminates the need for sample transportation and preservation [19] [1]. Furthermore, the remarkable cost-effectiveness of these methods, achieved through minimal reagent consumption and simplified instrumentation, makes sophisticated metal analysis accessible without sacrificing performance [17] [20].

These advantages collectively address critical limitations of standard laboratory-based techniques like inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) and atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), which despite their sensitivity, remain largely confined to laboratory settings due to their high operational costs, complex infrastructure requirements, and lack of portability [1] [21]. The integration of voltammetry into environmental monitoring protocols represents a paradigm shift toward decentralized, rapid, and economically sustainable metal analysis.

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of voltammetric methods for trace metal detection is demonstrated through their exceptional sensitivity, wide linear dynamic ranges, and low detection limits across various environmental matrices. The following tables summarize key analytical figures of merit from recent research.

Table 1: Analytical performance of voltammetric methods for single metal detection

| Target Analyte | Electrode Material | Technique | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Sample Matrix | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd) | in-situ Hg film GCE | DP-ASV | N/R | 0.63 μg L⁻¹ | Officinal plants | [19] |

| Lead (Pb) | in-situ Hg film GCE | DP-ASV | N/R | 0.045 μg L⁻¹ | Officinal plants | [19] |

| Arsenic (As³⁺) | Co₃O₄/AuNPs GCE | SWASV | 10-900 ppb | N/R | River/Drinking water | [2] |

| Mercury (Hg²⁺) | Co₃O₄/AuNPs GCE | SWASV | 10-650 ppb | N/R | River/Drinking water | [2] |

| Gallium (Ga(III)) | PbFE/MWCNT/SGCE | AdSV | 3.0×10⁻⁹–4.0×10⁻⁷ M | 9.5×10⁻¹⁰ M | Tap/River water | [6] |

| Cobalt (Co(II)) | Hg(Ag)FE with o-NF | CV | 0.040–0.160 μM | 0.010 μM | Reservoir water | [21] |

Table 2: Performance comparison of voltammetry versus traditional techniques

| Analytical Aspect | Voltammetric Methods | Traditional Methods (AAS/ICP-MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limits | ppt to ppb range | ppb to ppt range |

| Equipment Cost | Low to moderate | High |

| Portability | Excellent (field-deployable) | Limited (laboratory-bound) |

| Analysis Speed | Rapid (minutes) | Moderate to slow |

| Sample Volume | Small (μL to mL) | Larger typically required |

| Operator Skill Required | Moderate | High |

| Power Requirements | Low | High |

| Consumable Costs | Low | High |

The data in Table 1 demonstrates the exceptional sensitivity achievable with voltammetric methods, with detection limits for lead reaching 0.045 μg L⁻¹, significantly below the World Health Organization's maximum contamination level for drinking water [19] [17]. The modification of electrode surfaces with nanomaterials (e.g., Co₃O₄/AuNPs, MWCNT) significantly enhances electrochemical performance by increasing surface area, improving electron transfer kinetics, and providing specific binding sites for target analytes [1] [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (DP-ASV) for Lead and Cadmium in Plant Samples

This protocol describes the optimized method for simultaneous determination of Pb and Cd in officinal plant leaves using DP-ASV with an in-situ mercury film glassy carbon electrode (iMF-GCE) [19].

Reagents and Materials

- Glassy carbon working electrode (3 mm diameter)

- Platinum wire counter electrode

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Mercury standard solution (for in-situ film formation)

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) as supporting electrolyte

- Nitric acid (concentrated, for sample digestion)

- Certified reference materials (for method validation)

- Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity)

Equipment

- Portable potentiostat with differential pulse capability

- Ultrasonic bath for sample preparation

- Portable centrifuge for sample clarification

- pH meter with combination electrode

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sample Preparation

- Accurately weigh 0.5 g of dried, homogenized plant material into digestion vessels

- Add 5 mL concentrated HNO₃ and digest at 95°C for 2 hours

- Cool, dilute to 25 mL with ultrapure water, and centrifuge at 4000 rpm for 10 minutes

- Filter supernatant through 0.45 μm membrane filter

Electrode Preparation

- Polish glassy carbon electrode with 0.05 μm alumina slurry on microcloth

- Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water

- Activate electrode surface by cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ (-0.2 to +1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 10 cycles)

In-situ Mercury Film Formation

- Transfer 10 mL of sample extract to electrochemical cell

- Add acetate buffer to final concentration of 0.1 M

- Add Hg(II) standard to final concentration of 20 mg L⁻¹

- Apply deposition potential of -1.20 V for 30 s with stirring

Analysis by DP-ASV

- Optimize parameters: deposition potential -1.20 V, deposition time 195 s, equilibration time 10 s

- Record voltammogram from -1.0 V to -0.2 V using pulse amplitude 50 mV, pulse width 50 ms

- Measure peak currents at -0.65 V (Cd) and -0.45 V (Pb)

Quantification

- Use standard addition method with at least three spikes

- Plot calibration curves for each metal

- Calculate concentrations in original sample considering dilution factors

The experimental workflow for this protocol is summarized in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1: Workflow for DP-ASV analysis of Pb and Cd in plants

Protocol 2: Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) for Simultaneous Arsenic and Mercury Detection

This protocol details the simultaneous determination of As³⁺ and Hg²⁺ in water samples using a Co₃O₄ and Au nanoparticles modified glassy carbon electrode [2].

Reagents and Materials

- Co₃O₄ nanoparticles (synthesized by hydrothermal method)

- Gold nanoparticle solution (20 nm diameter)

- Glassy carbon electrode (3 mm diameter)

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.0) as supporting electrolyte

- Standard solutions of As(III) and Hg(II) (1000 mg L⁻¹)

- Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity)

Equipment

- Portable potentiostat with square wave capability

- Magnetic stirrer with temperature control

- Ultrasonic probe for electrode modification

Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrode Modification

- Polish GCE sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina slurry

- Prepare Co₃O₄ suspension (1 mg mL⁻¹ in water) and sonicate for 30 minutes

- Drop-cast 5 μL of Co₃O₄ suspension onto GCE surface and dry under IR lamp

- Electrochemically deposit AuNPs by cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ containing 1 mM HAuCl₄

Optimized Parameters

- Supporting electrolyte: 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 5.0)

- Deposition potential: -0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Deposition time: 120 s

- Square wave parameters: frequency 25 Hz, amplitude 25 mV, step potential 4 mV

Analysis Procedure

- Transfer 10 mL of filtered water sample to electrochemical cell

- Add supporting electrolyte to final concentration of 0.1 M

- Decorate solution with nitrogen for 300 s to remove oxygen

- Apply deposition potential with stirring

- Record square wave stripping voltammogram from -0.6 V to +0.4 V

- Identify As³⁺ peak at approximately -0.1 V and Hg²⁺ peak at +0.25 V

Validation

- Spike recovery tests in real water samples (river, drinking water)

- Compare with certified reference materials

- Statistical validation using Student's t-test

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of voltammetric methods for trace metal analysis requires specific reagent solutions optimized for target analytes and sample matrices. The following table details critical reagents and their functions.

Table 3: Essential research reagents for voltammetric trace metal analysis

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Purpose | Application Examples | Optimization Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acetate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5-5.6) | Supporting electrolyte; controls pH and ionic strength | Pb, Cd, Ga, Co detection [19] [6] [21] | Optimal pH depends on target metal; affects complex formation |

| Mercury(II) Nitrate | Forms in-situ mercury film on electrodes | ASV for Pb, Cd, Zn [19] | 20 mg L⁻¹ typical concentration; enables metal amalgamation |

| Dimethylglyoxime (DMG) | Complexing agent for cobalt | AdSV for Co(II) [21] | Forms stable complexes; enhances selectivity and sensitivity |

| Cupferron | Complexing agent for gallium | AdSV for Ga(III) [6] | Enables adsorptive accumulation on electrode surface |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Electrode modifier; enhances conductivity and catalysis | As(III) detection [2] | Provides active sites for arsenic oxidation |

| Cobalt Oxide Nanoparticles | Electrode modifier; increases surface area | As(III) and Hg(II) detection [2] | Synergistic effect with AuNPs for simultaneous detection |

| Nitric Acid (concentrated) | Sample digestion medium | Plant, soil samples [19] [17] | Complete digestion requires heating; high purity essential |

The strategic selection and optimization of these reagents directly impact method sensitivity, selectivity, and overall performance. Complexing agents like dimethylglyoxime and cupferron enable the determination of metals that are difficult to analyze by direct reduction, expanding the application range of voltammetric methods [6] [21].

Technological Integration and Workflow

Modern voltammetric systems incorporate advanced materials and smart technologies that enhance their practical implementation in environmental analysis. The integration of these components creates a sophisticated ecosystem for trace metal monitoring, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Integrated voltammetric system for environmental metal analysis

The synergy between advanced sensor platforms and detection principles enables the exceptional performance of modern voltammetric systems. Nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes, including carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and various nanoparticles, significantly increase electrode surface area and provide catalytic activity that lowers detection limits and improves selectivity [1] [2]. The strategic selection of detection principles—Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) for readily reduced metals, Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) for metals requiring complexation, and Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CSV) for anion analysis—ensures optimal performance across diverse analytical scenarios [9] [6].

Recent innovations have further enhanced field applicability through smartphone integration, where mobile devices control instrumentation, process data, and display results in real-time [22]. This technological convergence delivers comprehensive analytical outputs including not only quantitative metal concentration data but also crucial speciation information that directly relates to metal bioavailability and toxicity [9].

Understanding Detection Limits and Selectivity Mechanisms

Voltammetry has emerged as a powerful analytical technique for the determination of trace heavy metals in environmental samples, offering a compelling alternative to traditional spectroscopic methods due to its high sensitivity, portability, and cost-effectiveness [23] [17] [24]. The core principle involves applying a potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current, which is proportional to the concentration of electroactive species [25]. For trace metal analysis, the technique's performance is critically dependent on two fundamental parameters: the detection limit, which defines the lowest measurable concentration, and selectivity, which ensures accurate measurement in complex sample matrices containing potential interferents [23] [26]. Recent advancements in electrode materials and voltammetric techniques have significantly enhanced both these aspects, enabling reliable detection of metal ions at environmentally relevant concentrations, often in the parts per billion (ppb) range or lower [23] [27] [28]. This document outlines the core mechanisms governing these parameters and provides detailed protocols for their optimization, serving as a vital resource for researchers developing and applying voltammetric sensors for environmental monitoring.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) of Lead and Cadmium Using a Bismuth-Modified Sensor

This protocol details the determination of trace Pb(II) and Cd(II) in water samples using an eco-friendly, bismuth nanoparticle-modified electrode and Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV), a highly sensitive technique for trace metal analysis [28].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- Screen-printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCE) or Injection-moulded Carbon Electrodes: Serve as the conductive substrate [27] [28].

- Bismuth Rod: Source for generating bismuth nanoparticles via spark discharge [28].

- Acetate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5): Serves as the supporting electrolyte to maintain a consistent ionic strength and pH [28].

- Standard Solutions of Pb(II) and Cd(II) (1000 mg L⁻¹): Used for preparing calibration standards and spiking samples [28].

- Potassium Ferrocyanide (K₄[Fe(CN)₆]): Added to the sample solution to enhance the stripping signal [28].

- Nitric Acid (HNO₃, 30%) and Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂, 30%): Used for sample digestion when analyzing complex matrices like honey [28].

- Portable Potentiostat: For performing the electrochemical measurements [28].

- High-Voltage Power Supply: For the spark discharge process to modify the electrode with bismuth [28].

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Modification (Bismuth Deposition):

- Connect a bismuth rod to the cathode and a bare carbon working electrode to the anode of a high-voltage power supply.

- Initiate the sparking process by bringing the bismuth rod into contact with the electrode surface and sweeping it uniformly across the entire active area. This deposits bismuth nanoparticles onto the carbon surface, forming the Bi/WE [28].

- Sample Preparation:

- For water samples (e.g., tap water): Mix 9.5 mL of the sample with 0.5 mL of 2 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5). Add 10 µL of a 10 mM K₄[Fe(CN)₆] solution to achieve a final concentration of 10 µM [28].

- For complex matrices (e.g., honey): Accurately weigh 1.0 g of honey and digest it on a hotplate with 5 mL of 30% HCl and 1 mL of 30% H₂O₂ for 20 minutes until nearly dry. Dissolve the residue in 10 mL of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) containing 10 µM K₄[Fe(CN)₆] [28].

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- Transfer the prepared sample solution into the electrochemical cell.

- Immerse the three-electrode system (Bi-working electrode, Ag/AgCl-reference electrode, carbon-counter electrode) into the solution.

- Initiate the ASV sequence on the potentiostat:

- Deposition/Pre-concentration Step: Apply a constant negative deposition potential (e.g., -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for a set time (e.g., 240 s) under stirring. This reduces the target metal ions (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) to their metallic state (Pb⁰, Cd⁰) and alloys them with the bismuth film.

- Equilibration Step: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for a short period (e.g., 10 s).

- Stripping Step: Apply a positive-going potential sweep (e.g., from -1.2 V to -0.2 V) using a square wave or differential pulse waveform. This oxidizes (strips) the accumulated metals back into the solution, generating characteristic current peaks for each metal.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify the stripping peaks for Cd and Pb based on their characteristic potentials.

- Quantify the metal concentrations using the method of standard additions, which involves spiking the sample with known concentrations of the target analytes and measuring the increase in peak current [28].

- Electrode Modification (Bismuth Deposition):

Protocol for Simultaneous Detection of Multiple Metals Using a Co₃O₄ Nanocube-Modified Electrode

This protocol describes the simultaneous determination of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Hg(II) using a Co₃O₄ nanocube (Co₃O₄-NC) modified screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) and the Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) technique, highlighting the role of advanced nanomaterials in achieving high selectivity [27].

Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

- Screen-printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE): A disposable and portable electrode platform [27].

- Co₃O₄ Nanocubes (Co₃O₄-NC): Synthesized via a facile hydrothermal method using cobalt nitrate and KOH; these provide a high surface area and specific crystal planes that enhance metal adsorption and electron transfer [27].

- Acetate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5): The optimized supporting electrolyte for this analysis [27].

- Standard Solutions of Pb(II), Cu(II), and Hg(II).

- Potentiostat with DPV capability.

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Modification:

- Prepare a dispersion of the synthesized Co₃O₄-NCs in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol/water).

- Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the dispersion onto the working electrode area of the SPCE.

- Allow the modified electrode (Co₃O₄-NC/SPCE) to dry at room temperature.

- Sample Preparation:

- Dilute water samples (tap or pond water) with the 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) in a defined ratio.

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- Place the modified Co₃O₄-NC/SPCE in the sample solution.

- Utilize DPV for the simultaneous detection. The DPV parameters (pulse amplitude, pulse width, step potential) should be optimized, for example, using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to achieve the highest sensitivity and resolution between the closely spaced peaks of the three metals [27] [29].

- The DPV scan is performed without a separate deposition step in this specific application, as the Co₃O₄-NC itself provides sufficient preconcentration via adsorption [27].

- Data Analysis:

- The Co₃O₄-NC/SPCE generates three distinct, well-separated voltammetric peaks for the oxidation of Pb, Cu, and Hg.

- Measure the peak currents and correlate them to concentration using a pre-established calibration curve. The sensor has demonstrated high selectivity in the presence of other potential interfering ions and nitro compounds [27].

- Electrode Modification:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs essential materials and their functions for developing and applying voltammetric sensors for trace metal analysis.

| Reagent/Material | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Bismuth (Bi) Nanoparticles | A non-toxic, "green" alternative to mercury. Forms alloys with target metals during ASV, enhancing stripping signal and sensitivity for metals like Cd, Pb, and Zn [28]. |

| Graphene & Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Provides a high surface-area conductive base. Prevents aggregation of metal oxides, facilitates electron transfer, and can be functionalized to improve adsorption of metal ions [23] [24]. |

| Metal Oxide Nanomaterials (e.g., Co₃O₄) | Act as electrocatalysts. Their specific crystal planes (e.g., Co₃O₄ (111)) enhance adsorption and selectivity towards heavy metal ions, enabling simultaneous detection [27] [24]. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH ~4.5) | A common supporting electrolyte. Maintains optimal pH for the analysis of many heavy metals, ensuring consistent electrochemical behavior and proton activity [26] [28] [17]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPE) | Disposable, mass-producible, and portable electrode platforms. Ideal for field-deployable sensors and minimize cross-contamination between samples [27] [28]. |

Performance Data and Comparison

The tables below summarize the analytical performance of various voltammetric approaches and electrode materials for the detection of heavy metals, as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Comparison of Detection Limits and Linear Ranges for Key Heavy Metals

| Target Metal | Electrode Material | Voltammetric Technique | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Application Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb(II) | Co₃O₄ Nanocubes/SPCE [27] | DPV | Not Specified | 4.1 ± 0.2 nM | Tap & Pond Water |

| Pb(II) | Bi-NP/Plastic Electrode [28] | ASV | Not Specified | 0.6 μg L⁻¹ (~2.9 nM) | Water & Honey |

| Cd(II) | Bi-NP/Plastic Electrode [28] | ASV | Not Specified | 0.7 μg L⁻¹ (~6.2 nM) | Water & Honey |

| Hg(II) | Co₃O₄ Nanocubes/SPCE [27] | DPV | Not Specified | 0.1 ± 0.005 nM | Tap & Pond Water |

| Cu(II) | Co₃O₄ Nanocubes/SPCE [27] | DPV | Not Specified | 0.9 ± 0.04 nM | Tap & Pond Water |

| Sn(II) | HMDE with Tropolone [26] | AdSV | Up to 4.0 × 10⁻⁹ M | 5.0 × 10⁻¹² M | Sea Water |

Table 2: Voltammetric Techniques and Their Selectivity Mechanisms

| Technique | Acronym | Core Principle | Primary Selectivity Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry | ASV | Electrolytic pre-concentration followed by anodic dissolution [26] | Distinct stripping potentials of metals; use of Bi-film to avoid intermetallic compounds [28]. |

| Square Wave Voltammetry | SWV | Application of a square waveform to discriminate against capacitive current [17] | High resolution of closely spaced peaks; often coupled with ASV (SWASV) [17] [24]. |

| Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry | AdSV | Pre-concentration via adsorption of a metal-ligand complex [26] | Selective complexation of specific metal ions with ligands like tropolone or catechol [26]. |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry | DPV | Measurement of current difference before and after a potential pulse [24] | Resolution of overlapping peaks via the pulse profile; effective on nanomaterial-modified electrodes [27] [24]. |

Visualization of Workflows and Mechanisms

ASV Experimental Workflow

This diagram illustrates the step-by-step workflow for trace metal analysis using Anodic Stripping Voltammetry, from sample preparation to quantitative result.

Selectivity Mechanisms in Voltammetry

This diagram outlines the primary strategies employed to achieve selectivity in voltammetric analysis of heavy metals, which is crucial for accurate analysis in complex environmental samples.

The Role of Modern Microprocessor-Controlled Instrumentation

Modern microprocessor-controlled instrumentation has fundamentally transformed the practice of voltammetric trace metal analysis in environmental samples. These advanced systems enable a transition from labor-intensive laboratory procedures to highly automated, precise, and sensitive in-situ measurements. The integration of sophisticated digital electronics, automated control systems, and robust data processing capabilities has made it possible to deploy voltammetric analyzers directly in field and aquatic environments for real-time monitoring of toxic metals such as Pb, Cd, Hg, and As at trace levels [30] [31]. This application note details the operational principles, experimental protocols, and key applications of these microprocessor-based systems within environmental research and monitoring contexts.

Core Capabilities and Technical Specifications

Modern microprocessor-controlled voltammetric instruments offer significant advantages over traditional analytical techniques like Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), particularly for in-situ applications and metal speciation studies [30] [1]. These systems integrate multiple key functions:

- Precise Potential Control and Current Measurement: Microprocessors generate highly stable potential waveforms and measure nanoscale currents with exceptional signal-to-noise ratios, even in compact, field-deployable instruments [30].

- Automated Multi-Technique Operation: A single instrument can seamlessly execute various voltammetric techniques (e.g., ASV, DPV, SWV) through software control, allowing method optimization for different target metals and matrices without hardware changes [1].

- Advanced Data Processing and Signal Enhancement: Onboard algorithms perform real-time signal averaging, background subtraction, and peak deconvolution, enabling reliable detection in complex environmental matrices like seawater and soil extracts [31].

- System Control and Automation: Microprocessors manage ancillary functions such as sample introduction, reagent addition, electrode conditioning, and anti-fouling measures, ensuring analytical consistency and long-term deployment capability [30] [31].

Table 1: Key Voltammetric Techniques Enabled by Microprocessor Control

| Technique | Acronym | Principle | Key Advantages for Trace Metal Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry | ASV | Pre-concentration of metals onto electrode followed by oxidative stripping | Extremely low detection limits (ppb to ppt range) [1] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry | DPV | Measurement of current difference before and after potential pulses | High sensitivity and resolution of overlapping peaks [1] [32] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry | SWV | Application of a square wave superimposed on a staircase potential | Fast scan times and effective rejection of capacitive current [1] [32] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: In-Situ Profiling of Bioavailable Trace Metals in Water

This protocol utilizes a microprocessor-controlled submersible voltammetric analyzer, such as a Voltammetric In-Situ Profiling (VIP) System or TracMetal sensor [31].

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for In-Situ Voltammetric Analysis

| Item | Function | Specification/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Submersible Voltammetric Analyzer | Core measurement unit | Integrated microprocessor, multi-channel potentiostat, and data logger. Must be pressure-rated for deployment depth [31]. |

| Gel-Integrated Microelectrode (GIME) | Working electrode | Typically Hg or Au-based micro-electrode array. The gel membrane (e.g., agarose) prevents fouling by excluding particulates and colloids while allowing free metal ions to diffuse to the electrode surface [30] [31]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides stable potential | Ag/AgCl (with KCl electrolyte) is standard for aquatic measurements. |

| Counter (Auxiliary) Electrode | Completes the circuit | Platinum wire or similar inert material. |

| Internal Standard Solution | For calibration | Standard addition method using solutions of target metals (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) at known concentrations. |

| pH/Ionic Strength Buffer | Conditions the sample | For ex-situ measurements, a buffer like acetate (pH ~4.5) is often used. In-situ systems may measure without perturbation [30]. |

2. Workflow

3. Procedure Steps

- System Calibration & Deployment: Calibrate the electrode response in the laboratory using standard additions of target metals. Program the microprocessor with the measurement sequence (potential windows, timings). Deploy the instrument at the target site [31].

- Automated Measurement Cycle:

- Pre-concentration: The microprocessor applies a constant negative potential to the working electrode, reducing target metal ions and forming an amalgam. The duration is programmed based on expected metal concentrations.

- Equilibrium: A brief rest period with stirring stopped ensures a quiescent solution for the stripping step.

- Stripping: The microprocessor applies a positive-going potential sweep (e.g., in SWV or DPV mode). The metals are re-oxidized, generating a characteristic current peak for each metal. The peak current is proportional to concentration [30] [1].

- Data Handling: The onboard microprocessor records the voltammogram, identifies peaks based on pre-set potential windows, and calculates concentrations using the calibration data. Results are stored internally or transmitted to a surface platform [31].

- Anti-Fouling Management: The microprocessor can run automated cleaning cycles by applying a high anodic or cathodic potential to clean the electrode surface between measurements, countering biofouling or organic adsorption [30].

Protocol: Determination of Trace Metals in Soil/Sediment Porewater

This protocol involves ex-situ analysis using a portable, microprocessor-controlled potentiostat.

1. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- Portable Potentiostat: Compact, battery-operated instrument with microprocessor control.

- Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs): Disposable, pre-fabricated electrodes, often modified with Bismuth (Bi) or Antimony (Sb) as environmentally friendly alternatives to mercury [1] [31].

- Extraction Solution: Dilute nitric acid (e.g., 0.5 M HNO₃) or chelating agents for extracting bioavailable metal fractions from soil.

- Supporting Electrolyte: Acetate buffer (pH 4.5) is commonly used.

- Standard Solutions: For the standard addition method.

2. Workflow

3. Procedure Steps

- Sample Preparation: Collect and homogenize soil/sediment core samples. Extract porewater by centrifugation or filtration under an inert atmosphere to prevent oxidation [1].

- Digestion (if required): For samples containing strong organic ligands (e.g., EDTA), a digestion step may be necessary to liberate metal ions. The UV/H₂O₂ method is effective and efficient: acidify the sample to pH ~2 and add H₂O₂ (e.g., 18 mM), then irradiate with UV-C lamps for ~2 hours [33].

- Analysis:

- Transfer an aliquot of the treated sample to an electrochemical cell containing supporting electrolyte.

- Insert the screen-printed sensor into the portable potentiostat.

- Run the pre-programmed voltammetric method (e.g., Bi-SA-ASV).

- Perform standard additions of the target metal directly into the cell; the microprocessor will automatically record the increase in peak height and calculate the original concentration in the sample.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Advanced Electrode Materials

The performance of modern instrumentation is greatly enhanced by novel electrode materials, often integrated into the sensor design.

Table 3: Key Nanomaterials for Electrode Modification in Voltammetric Sensors

| Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth (Bi) Film | Environmentally friendly electrode coating with high sensitivity for metals like Pb, Cd, Zn. Forms low-temperature fusable alloys with them [1] [31]. | Coated on screen-printed carbon electrodes for portable soil metal analysis. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs) | Increase electrode surface area and enhance electron transfer kinetics. Improve sensitivity and stability [1] [32]. | MWCNT-based paste electrodes for simultaneous detection of Cd, Pb, Cu, and Hg. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous materials with high affinity for specific metal ions, providing exceptional selectivity and pre-concentration at the electrode surface [1]. | MOF-modified glassy carbon electrodes for selective detection of Cu(II) or Pb(II) in water. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Provide a stable, high-surface-area substrate for mercury films or for direct analysis of metals like As and Hg [31]. | Au nanoparticle-modified electrodes in submersible probes for Hg(II) detection in seawater. |

Modern microprocessor-controlled instrumentation is the cornerstone of contemporary voltammetric analysis for trace metals. It provides the necessary automation, sensitivity, and ruggedness required for both sophisticated laboratory analysis and demanding in-situ environmental monitoring. The synergy of advanced electronics, innovative sensor designs, and functionalized nanomaterials has enabled researchers and environmental professionals to obtain high-quality, real-time data on metal concentrations and speciation, which is critical for understanding biogeochemical cycles and assessing ecological risks. Future advancements will likely focus on greater miniaturization, enhanced multi-parameter sensing capabilities, and the integration of artificial intelligence for autonomous data interpretation and system control [1] [31].

Voltammetric Techniques in Practice: Methods and Environmental Applications

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) for Heavy Metal Detection

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) is a powerful electrochemical technique renowned for its exceptional sensitivity in detecting trace levels of heavy metals in environmental samples. The method achieves detection limits at sub-parts-per-billion (ppb) concentrations, rivaling more expensive techniques like Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), while offering portability for on-site analysis [34] [17]. Its applicability to various matrices—including water, soil, and plant tissues—makes it invaluable for environmental monitoring, compliance enforcement, and pollution source identification [17]. This document outlines standardized protocols and applications of ASV, providing a practical framework for researchers engaged in trace metal analysis.

Principles of ASV

ASV operates through a two-stage process designed to pre-concentrate analytes for enhanced sensitivity [34].

- Electrodeposition (Pre-concentration): A cathodic (reducing) potential is applied to the working electrode, causing dissolved metal ions (Mn+) in the sample solution to be reduced and deposited onto the electrode surface as a thin film or amalgam.

- Stripping (Analysis): The potential is then swept anodically (in a positive direction). This re-oxidizes (strips) the deposited metals back into solution. The potential at which each metal is stripped serves as its identifier, while the resulting current (or integrated charge) is proportional to its concentration in the original sample [34].

The core advantage of ASV is this pre-concentration step, which accumulates the target metals over time, significantly lowering detection limits compared to other voltammetric techniques.

ASV in Environmental Analysis: Applications & Performance

ASV is adept at detecting a range of toxic heavy metals across diverse environmental samples. The tables below summarize key performance metrics and application details for various sample types.

Table 1: ASV Performance for Detecting Key Heavy Metals in Water Samples

| Analyte | Electrode & Modification | Supporting Electrolyte | Linear Range (μg/L) | Limit of Detection (LOD, μg/L) | Sample Application | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd) | GCE with in-situ Mercury Film (iMF-GCE) | Acetate Buffer | Not Specified | 0.63 | Officinal Plants | [19] |

| Lead (Pb) | GCE with in-situ Mercury Film (iMF-GCE) | Acetate Buffer | Not Specified | 0.045 | Officinal Plants | [19] |

| Arsenic (As(III)) | SPE / (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion | Acetate Buffer | 0 - 50 | 2.4 | River Water | [35] |

| Cadmium (Cd(II)) | SPE / (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion | Acetate Buffer | 0 - 50 | 0.8 | River Water | [35] |

| Lead (Pb(II)) | SPE / Fe₃O₄-Au-IL Nanocomposite | Acetate Buffer | 0 - 50 | 1.2 | River Water | [35] |

| Lead (Pb) | Bi/PTBC800/SPE | 0.1 M Acetate Buffer (pH 4.5) | Not Specified | < 2.4 | Drinking Water | [17] |

Table 2: ASV Application to Soil and Plant Matrices

| Sample Matrix | Key Consideration for ASV Analysis | Common Target Metals | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soil | Requires acid digestion for total metal analysis; complex matrix with organic/inorganic matter that can adsorb metal ions and cause interference. | Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn | [17] |

| Plant Tissues | Digestion with Aqua Regia (HCl:HNO₃) or HNO₃ alone is typical; metals may be present at very low levels in certain plant parts (e.g., seeds). | Pb, Cd, Cu, Zn | [17] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Cd and Pb in Plant Leaves using iMF-GCE

This protocol outlines a simple and cost-effective method for on-site analysis of officinal plants using a mercury-film modified glassy carbon electrode [19].

Key Equipment & Reagents:

- Potentiostat with a three-electrode system.

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) as the working electrode.

- Platinum wire or foil as the counter electrode.

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Mercury(II) nitrate solution for in-situ film formation.

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH ~4.5) as the supporting electrolyte.

- Certified reference materials for validation.

- Nitrogen gas for deaeration.

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Dry and homogenize plant leaves. Digest the material using a mixture of concentrated acids (e.g., HNO₃), potentially with microwave assistance, and dilute the digestate with acetate buffer [17].

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the GCE surface to a mirror finish with alumina slurry, then rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- In-situ Mercury Film Formation: Add a known quantity of Hg²⁺ standard to the sample/electrolyte solution. Apply a deposition potential (e.g., -1.20 V) for a set time (e.g., 195 s) with stirring. This simultaneously deposits a thin mercury film and pre-concentrates the target metals into the film [19] [34].

- Stripping Analysis: After a brief equilibration period (e.g., 15 s), perform an anodic potential sweep using the Differential Pulse (DP) mode. Record the voltammogram.

- Quantification: Identify the peak potentials for Cd and Pb. Use standard addition or an external calibration curve to quantify the metal concentrations based on peak current or area.

Optimization Notes: The parameters Edep (-1.20 V) and tdep (195 s) were optimized using experimental design (e.g., Face Centered Composite Design) to achieve recovery rates of 85.8% for Cd and 96.4% for Pb [19].

Protocol 2: Multiplexed Detection of As, Cd, and Pb in Water using a 3D-Printed Flow Cell and Modified SPEs

This advanced protocol enables simultaneous detection of multiple heavy metals in water samples with high throughput and automation potential [35].

Key Equipment & Reagents:

- Portable potentiostat.

- Custom screen-printed electrode (SPE) with dual working electrodes (WEs), an integrated Ag/AgCl quasi-reference electrode (RE), and a counter electrode (CE).

- Sensing nanocomposites:

(BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-NafionandFe₃O₄-Au-IL. - 3D-printed flow cell integrated with the SPE.

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M) as supporting electrolyte and carrier stream.

- Peristaltic or syringe pump for flow control.

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Modify the two working electrodes on the SPE by drop-casting the

(BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-NafionandFe₃O₄-Au-ILnanocomposites, respectively [35]. - System Setup: Integrate the modified SPE with the 3D-printed flow cell. Connect the flow cell to the potentiostat and pump. Use acetate buffer as the carrier solution.

- Flow-Injection Analysis: Introduce the water sample (mixed with supporting electrolyte) into the flow stream.

- Electrodeposition: Under a controlled flow rate, apply a deposition potential (e.g., -1.2 V vs. the integrated Ag/AgCl RE) for a set time (e.g., 120 s) to pre-concentrate the metals on the modified WEs.

- Stripping Analysis: Stop the flow. Perform a Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) scan. The distinct modifications on the WEs enhance the simultaneous detection of As(III), Cd(II), and Pb(II).

- Regeneration: Clean the electrode surface by applying an oxidizing potential between analyses to remove any residual material.

- Electrode Modification: Modify the two working electrodes on the SPE by drop-casting the

Optimization Notes: Key parameters to optimize include deposition time, deposition potential, and flow rate. This system demonstrated excellent recovery (95–101%) in simulated river water [35].

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

ASV Experimental Workflow

Electrode Modification for Enhanced Sensing

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for ASV Experiments

| Item | Function & Application | Example / Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common, inert working electrode substrate that can be polished to a smooth finish. Ideal for forming thin-film electrodes. | Often used with in-situ mercury or bismuth films [19] [34]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, planar electrodes enabling miniaturization and portability. Often integrated into flow cells for automated analysis. | Custom SPEs with dual WEs for multiplexed detection [35]. |

| Bismuth (Bi³⁺) Salt | A non-toxic alternative to mercury for forming thin-film electrodes. Effective for detecting Cd, Pb, Zn, especially in alkaline media. | Bi(NO₃)₃, often added directly to the sample solution for in-situ plating [34] [17]. |

| Mercury (Hg²⁺) Salt | The traditional element for forming MFEs, providing a high hydrogen overpotential and forming amalgams for sensitive detection. | Hg(NO₃)₂, used for in-situ MFE formation [19] [34]. |

| Nafion Polymer | A cation-exchange polymer used to modify electrode surfaces. It can repel anions and attract cations, improving selectivity and stability. | Used in nanocomposites like (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion [35]. |

| Acetate Buffer | A common supporting electrolyte that provides ionic strength and controls pH (~4.5) for optimal deposition and stripping of many metals. | 0.1 M concentration is widely used [35] [17]. |

| Nitrogen Gas | Used to purge dissolved oxygen from the sample solution before analysis, as oxygen can interfere with the electrochemical signal. | High-purity (≥99.99%) nitrogen is typical for deaeration. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Materials with known analyte concentrations used to validate the accuracy and recovery of the analytical method. | Certified plant or soil samples [19]. |

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) for Enhanced Sensitivity

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) is a powerful, pulsed electrochemical technique renowned for its exceptional sensitivity and rapid data acquisition capabilities. It is particularly valuable for the detection of trace metals in environmental samples, where low detection limits and high signal-to-noise ratios are paramount [36] [37]. The technique's core principle involves applying a staircase potential waveform superimposed with a symmetric square wave. The current is measured at the end of each forward and reverse potential pulse, and the net current is calculated by taking the difference between these two measurements [36]. This differential current plotting is key to SWV's performance, as it effectively cancels out the non-Faradaic (capacitive) charging current, isolating the Faradaic current resulting from electron transfer reactions at the electrode surface [38] [37]. This process significantly enhances the signal-to-noise ratio, allowing for the detection of analytes at substantially lower concentrations compared to other voltammetric techniques like linear sweep or cyclic voltammetry [36].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Square Wave Voltammetry

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Influence on Signal | Optimization Consideration for Trace Metals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Step | Estep | Governs the number of data points and scan resolution. | A smaller step increases peak resolution but also scan time. |

| Square Wave Amplitude | ESW | Directly affects peak current; larger amplitude increases signal. | Typically optimized between 25-50 mV for a balance of signal and resolution [36]. |

| Square Wave Frequency | f | Higher frequencies increase scan speed and peak current. | Increased frequency enhances sensitivity but can broaden peaks if electron transfer kinetics are slow [36]. |

SWV for Trace Metal Analysis: Advantages and Applications

The application of SWV in environmental analysis is well-established, particularly for the detection of heavy metals. Its superior sensitivity allows for direct determination of metal ions at microgram per kilogram levels, making it a strong alternative to more expensive techniques like graphite furnace atomic absorption spectrophotometry (GFAAS) [39]. The technique's versatility is demonstrated by its ability to determine multiple metal species using different stripping modes.

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) is conventionally used for metals such as Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Cu(II). In this method, metals are first electroplated onto the working electrode surface by applying a reducing potential, concentrating them into the electrode. This pre-concentration step is followed by the square-wave potential sweep that oxidizes (strips) the metals back into solution, generating the analytical signal [39]. Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (AdCSV) is another powerful approach used for metals like Co(II), Ni(II), Cr(VI), and Mo(VI). This method involves the formation of a complex between the metal ion and an added ligand, which adsorbs onto the electrode surface. A cathodic potential sweep then reduces the metal in the adsorbed complex, providing very low detection limits [39].

Table 2: SWV Performance for Heavy Metal Detection in Environmental Samples

| Analyte | SWV Mode | Detection Limit (μg/kg) | Sample Matrix | Reference Method for Validation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd(II) | Anodic Stripping | 0.03 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

| Pb(II) | Anodic Stripping | 0.4 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

| Cu(II) | Anodic Stripping | 0.04 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

| Zn(II) | Anodic Stripping | 0.1 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

| Co(II) | Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping | 0.15 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

| Ni(II) | Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping | 0.05 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

| Cr(VI) | Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping | 0.2 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

| Mo(VI) | Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping | 3.2 | Soil, Indoor-airborne Particulate Matter | GFAAS [39] |

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Heavy Metals in Soil by SWASV

Reagents and Solutions

- Supporting Electrolyte: Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.6) is commonly used for the simultaneous analysis of Cd, Pb, and Cu.

- Standard Solutions: 1000 mg/L stock solutions of each target metal ion (e.g., Cd(II), Pb(II), Cu(II)).

- Purified Water: Deionized water (18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity).

- Electrode Polishing Slurry: Alumina slurry (0.05 μm).

Equipment and Instrumentation

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with SWV capability.

- Three-Electrode System:

- Working Electrode: Mercury-film electrode (MFE) or Bismuth-film electrode (BiFE) plated on a glassy carbon (GC) substrate.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Electrochemical cell.

- pH meter.

- Analytical balance.

Sample Preparation

- Soil Digestion: Accurately weigh ~0.5 g of dried and homogenized soil sample into a digestion tube. Add 6 mL of concentrated HNO₃ and 2 mL of H₂O₂ (30%). Heat the mixture using a microwave or hotblock digester according to a standardized temperature program. After cooling, dilute the digestate to 50 mL with purified water. Filter the solution if necessary [39].

- Solution Preparation: Transfer a 10 mL aliquot of the digested sample into the electrochemical cell. Add 10 mL of the supporting electrolyte (acetate buffer) to provide a consistent pH and ionic strength. The final solution volume is 20 mL.

Electrode Preparation

- Glassy Carbon Electrode Polishing: Prior to film plating, polish the glassy carbon electrode surface on a microcloth with 0.05 μm alumina slurry for 1-2 minutes. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water after polishing.

- Mercury Film Formation (Plating): Transfer the polished electrode to a plating solution containing, for example, 50 mg/L Hg²⁺ in 0.1 M HNO₃. Apply a constant potential of -1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 300 seconds while stirring the solution. This deposits a thin mercury film on the GC surface. Remove the electrode and rinse it with deionized water.

SWASV Measurement Procedure

- Degassing: Purge the sample solution in the electrochemical cell with an inert gas (high-purity nitrogen or argon) for 600 seconds to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the analysis.

- Pre-concentration/Deposition Step: While stirring the solution, hold the working electrode at a deposition potential of -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl. This reduces the metal ions in solution, causing them to amalgamate into the mercury film. The deposition time is critical and should be optimized (typically 60-300 seconds) based on expected metal concentrations.

- Equilibration Step: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for 15 seconds while maintaining the deposition potential.

- Stripping/Detection Step: Initiate the Square-Wave Voltammetry scan. Apply a potential waveform from -1.2 V to +0.1 V vs. Ag/AgCl using the optimized SWV parameters (e.g., frequency: 25 Hz, amplitude: 50 mV, potential step: 5 mV). The oxidation (stripping) of each metal from the film produces a characteristic current peak.

- Electrode Cleaning: After each measurement, hold the electrode at a potential of +0.3 V for 60 seconds with stirring to ensure complete removal of residual metals from the film.

Calibration and Quantification

- Standard Addition Method: To account for matrix effects, use the method of standard additions. After measuring the sample, add a known volume (e.g., 50 μL) of a mixed standard solution containing all target metals to the cell.

- Repeat Measurement: Repeat the SWASV measurement (steps 1-5) for the spiked solution. Perform at least two standard additions.

- Data Analysis: Plot the peak current (in microamperes, μA) versus the concentration of the added standard (in micrograms per liter, μg/L) for each metal. Extrapolate the linear plot to the x-axis; the absolute value of the x-intercept gives the concentration of the metal in the original sample solution.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for SWV

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|