Voltammetric Techniques for Battery Material Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Electrochemical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive overview of voltammetric techniques, with a focus on Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), for characterizing advanced battery materials.

Voltammetric Techniques for Battery Material Characterization: A Comprehensive Guide for Electrochemical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of voltammetric techniques, with a focus on Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), for characterizing advanced battery materials. It covers foundational principles, key methodologies for probing reaction mechanisms and kinetics, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing experimental parameters, and best practices for data validation against established standards. Tailored for researchers and scientists, this guide serves as a critical resource for leveraging electrochemical diagnostics to accelerate the development of next-generation energy storage systems, from initial material screening to in-depth performance evaluation.

Understanding Voltammetry: Core Principles and Diagnostic Power for Battery Research

The Role of Voltammetry in Developing Next-Generation Batteries

Voltammetry encompasses a suite of electrochemical techniques critical for analyzing and optimizing battery materials. These methods apply a controlled potential to an electrochemical cell and measure the resulting current, providing rich information about the thermodynamics and kinetics of charge storage reactions. In the development of next-generation batteries, such as lithium-ion, lithium-sulfur, and post-lithium technologies, voltammetry is indispensable for screening new electrode materials, elucidating charge storage mechanisms, and evaluating degradation pathways. By revealing details on electron transfer reactions, reaction intermediates, and ion diffusion dynamics, voltammetric data directly guides the rational design of higher-performance, longer-lasting, and safer energy storage systems [1] [2].

The adaptability of voltammetry allows researchers to simulate real-world operating conditions, from fast charging to long-term cycling, within a controlled laboratory setting. This enables the prediction of battery performance and lifespan, accelerating the transition of new materials from the lab to commercialization [3].

Key Voltammetric Methods and Applications

Voltammetric techniques provide unique insights into different aspects of battery performance. The table below summarizes the core applications of key methods in next-generation battery research.

Table 1: Key Voltammetric Techniques in Battery Research

| Technique | Primary Application in Battery Research | Key Measurable Parameters |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Screening new electrode materials; studying redox reaction thermodynamics/kinetics [1]. | Peak potentials, peak currents, charge storage capacity. |

| Non-Linear Voltammetry (NLV) | Developing adaptive fast-charging protocols for entire 0-100% SOC window [4]. | Current response, optimal voltage steps, thermal data. |

| Incremental Capacity Analysis (ICA) | Identifying phase transitions in electrodes during (de)intercalation [5]. | Incremental capacity (dQ/dV) vs. voltage. |

| Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT) | Determining solid-state diffusion coefficients of ions in electrode materials [3]. | Voltage transients, diffusion coefficient (D). |

Material Screening and Mechanism Elucidation with Cyclic Voltammetry

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a foundational tool at the early research stage for screening candidate battery materials and reaction conditions. In a typical CV experiment, the electrode potential is swept linearly with time between two set limits while the current is recorded [5]. The resulting voltammogram provides a fingerprint of the electrochemical processes occurring at the electrode-electrolyte interface.

For battery electrodes, the presence, position, and shape of oxidation and reduction peaks reveal the redox potentials and reversibility of the charge storage reactions [1]. By performing CV at different scan rates, researchers can distinguish between diffusion-controlled battery-like behavior (faradaic) and surface-controlled capacitive-like charge storage. This is crucial for classifying materials and understanding their fundamental operation, whether for high-energy-density batteries or high-power supercapacitors [2]. Furthermore, repeated CV cycling is used to assess the structural stability of new electrode materials and monitor the evolution of side reactions over time [1].

Protocol: Characterizing Electrode Materials Using Cyclic Voltammetry

Aim: To evaluate the electrochemical behavior and stability of a novel electrode material via Cyclic Voltammetry. Materials: Potentiostat/Galvanostat, three-electrode cell (Working Electrode: novel material coated on current collector, Reference Electrode: e.g., Li/Li+, Counter Electrode: inert metal), electrolyte compatible with the material (e.g., LiPF₆ in organic carbonate for LIBs).

- Electrode Preparation: Fabricate the working electrode by mixing the active material, conductive carbon (e.g., Super P), and polymer binder (e.g., PVDF or a self-healing polymer [6]) in a mass ratio of 80:10:10. Use a solvent (e.g., N-Methyl-2-pyrrolidone) to form a slurry, which is then coated onto a metal current collector (e.g., Al or Cu foil) and dried thoroughly under vacuum.

- Cell Assembly: Assemble the electrochemical cell in an argon-filled glovebox to prevent moisture and oxygen contamination. Introduce the prepared working electrode, reference electrode, and counter electrode into the electrolyte.

- Initial Conditioning: Perform an initial CV cycle at a slow scan rate (e.g., 0.1 mV/s) over a stable potential window to condition the electrode and identify the main redox activity regions.

- Scan Rate Study: Run CV measurements at a series of increasing scan rates (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0 mV/s). This helps determine the charge storage mechanism (capacitive vs. diffusion-controlled) by analyzing the relationship between peak current (iₚ) and scan rate (v) (iₚ ∝ v⁰.⁵ indicates diffusion control, while iₚ ∝ v indicates surface capacitance) [2].

- Cycling Stability Test: Cycle the electrode for hundreds or thousands of cycles at a fixed, moderate scan rate. Monitor the decay in peak current and shift in peak potential over time to quantify the material's electrochemical stability [1].

- Data Analysis: Identify the redox couples from peak positions. Calculate the total charge under the CV curve for capacity estimation. Plot log(iₚ) vs. log(v) to determine the b-value and confirm the charge storage mechanism.

Adaptive Charging with Non-Linear Voltammetry

Non-Linear Voltammetry (NLV) represents a paradigm shift from traditional constant current-constant voltage (CC-CV) charging. Instead of applying a constant current, NLV uses a series of short, constant voltage (CV) steps interspersed with brief rest periods. The current response and temperature are monitored at each step, and the algorithm self-adjusts the subsequent voltage steps based on the battery's real-time state-of-charge (SOC), state-of-health (SOH), and current draw [4].

This adaptive charging protocol has demonstrated significant performance advantages, particularly for fast-charging applications. Research has shown that NLV charging outperforms CCCV methods, especially when the total charging time is below 20 minutes. The short rest periods inherent to the NLV method allow for crucial internal electrical and thermal redistribution within the cell, preventing brutal degradation endings observed in some CCCV-fast-charged cells and making it a preferred technology for electric vehicle charging [4].

Protocol: Implementing a Non-Linear Voltammetry Fast-Charging Sequence

Aim: To apply an adaptive NLV protocol for fast-charging a lithium-ion battery while minimizing degradation. Materials: Battery tester capable of precise voltage and current control, temperature chamber, target lithium-ion battery cell.

- Initialization: Place the battery in a temperature-controlled environment (e.g., 25°C). Measure and record the open-circuit voltage (OCV) to estimate the initial SOC.

- Charging Loop: Initiate the charging sequence by applying a short (e.g., 10-30 second) constant voltage (CV) step. The magnitude of this voltage is determined by the initial OCV and can be slightly higher.

- Response Monitoring: During the CV step, monitor the current response and the surface temperature of the cell.

- Rest Period: Terminate the CV step and impose a short rest period (e.g., 5-10 seconds). Measure the voltage relaxation and temperature.

- Algorithmic Decision: The charging algorithm processes the data (current, voltage, temperature) from the previous step. Based on this, it non-linearly determines the voltage level for the next CV step [4].

- Iteration: Repeat steps 2-5, continuously adapting the applied voltage based on the battery's dynamic response. This loop continues until the cell reaches its maximum voltage limit and full charge.

- Termination: The protocol is terminated when the current drops below a very low threshold or a 100% SOC signal is achieved.

Analyzing Ionic Diffusion using GITT

While not a pure voltammetry technique, the Galvanostatic Intermittent Titration Technique (GITT) combines transient current pulses with voltage measurement, providing critical information on ion transport kinetics. GITT is considered one of the most reliable methods for determining the solid-state diffusion coefficient (D) of ions (e.g., Li⁺) within electrode materials, a parameter that often limits the rate capability of a battery [3].

The method involves applying a constant current pulse for a fixed duration (τ), followed by a long rest period to allow the cell voltage to relax to equilibrium. This "pulse-relaxation" sequence is repeated across the entire SOC window. The diffusion coefficient is calculated from the voltage transient during the pulse and the steady-state voltage change, using a solution to Fick's second law [3].

Table 2: Key Parameters for GITT Experimental Setup [3]

| Parameter | Typical Value/Range | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Current Pulse Magnitude | 0.05C - 0.2C (low rate) | Ensures system remains in quasi-linear regime for simplified calculation. |

| Current Pulse Duration (τ) | 5 - 30 minutes | Must be short enough to satisfy τ ≪ L²/D. |

| Rest Period | 1 - 4 hours (or until equilibrium) | Allows voltage to stabilize, ensuring measurement of steady-state voltage change. |

The Research Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and their functions in voltammetry-based battery research.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Battery Voltammetry

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Core instrument for applying precise voltage/current waveforms and measuring the electrochemical response [5]. |

| Polymer Binders (e.g., Self-healing binders) | Maintain electrode structural integrity; SHPBs autonomously repair microcracks caused by volume changes, extending cycle life [6]. |

| Alicyclic/Nonlinear Polyimides | Serve as high-performance polymer matrices for binders or electrochromic devices; enhance ionic conductivity and stability [7]. |

| Two-Dimensional (2D) Materials (e.g., MXenes, TMDs) | Model electrode systems for studying ion intercalation; high surface area and tunable chemistry ideal for voltammetric analysis [2]. |

| Reference Electrodes (e.g., Li/Li⁺) | Provide a stable, known potential against which the working electrode potential is measured and controlled. |

Experimental Workflow for Voltammetric Analysis

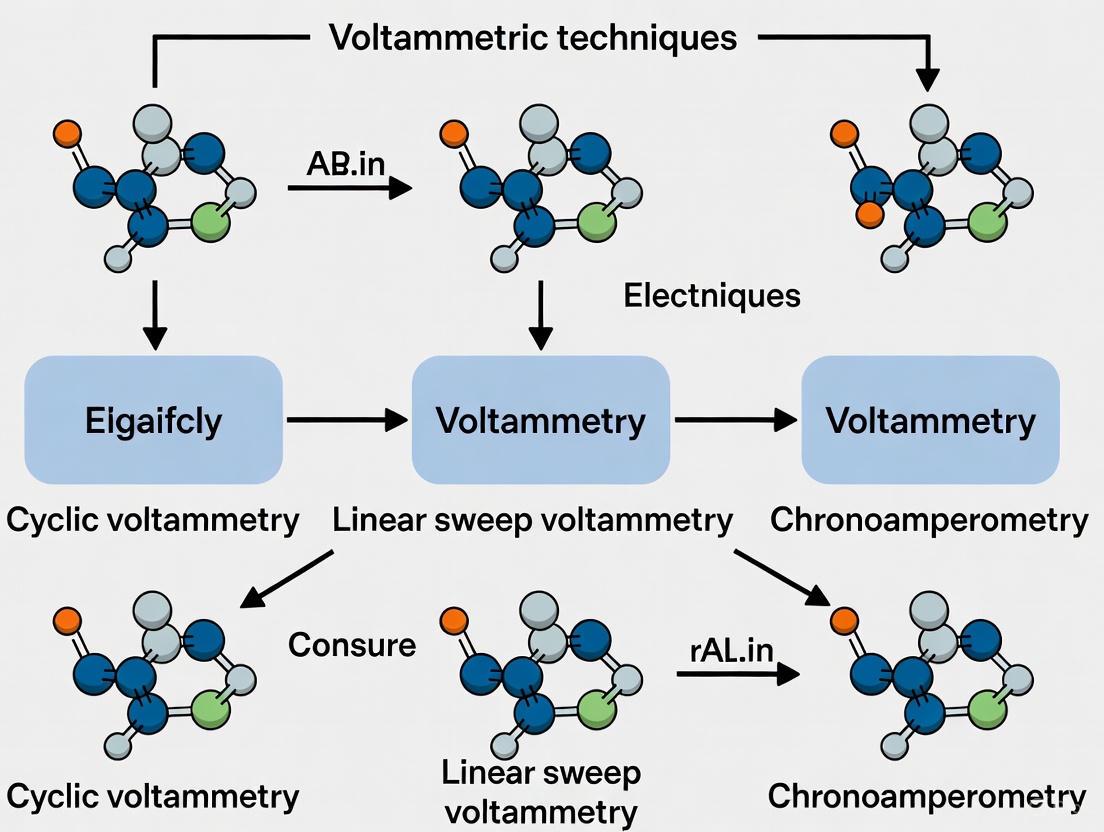

The diagram below outlines a generalized workflow for characterizing a new battery material using a combination of voltammetric techniques.

Data Interpretation and Integration with Other Techniques

Interpreting voltammetry data requires correlating electrochemical features with material properties. In CV, sharp, symmetric peaks often indicate highly reversible processes, while broad peaks may suggest slow kinetics or multiple overlapping reactions. The voltage hysteresis between charge and discharge peaks is a key indicator of polarization and energy efficiency. In ICA, the position and amplitude of dQ/dV peaks are characteristic of specific phase transitions within the electrode material, and their shift or fade upon cycling is a direct metric of degradation [5].

To build a comprehensive understanding, voltammetry must be integrated with other characterization methods. For instance, ex-situ or in-situ techniques like X-ray diffraction (XRD) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) can be used to correlate voltammetric peaks with structural changes in the crystal lattice or evolution of the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) [2]. This multi-modal approach is essential for linking electrochemical performance directly to underlying physical and chemical phenomena, enabling the rational design of next-generation batteries.

The development of advanced rechargeable batteries is inextricably linked to the sophisticated characterization of electrode materials. Among the most powerful electrochemical techniques for diagnosing material properties is cyclic voltammetry (CV), a potent tool that provides unparalleled insights into redox mechanisms, reaction kinetics, and stability characteristics crucial for battery performance and longevity. This application note details the principles, diagnostic criteria, and experimental protocols for utilizing CV as a primary diagnostic tool for electrode materials within the broader context of voltammetric techniques for battery material characterization research. When integrated with complementary methods such as chronoamperometry (CA) and structural characterization, CV forms an comprehensive analytical framework for understanding and optimizing battery materials from fundamental principles to practical application.

CV operates by scanning the potential of a working electrode linearly in both forward and backward directions while precisely measuring the current response [8]. The resulting voltammogram serves as an electrochemical fingerprint, containing rich information about the electron transfer processes occurring at the electrode-electrolyte interface. For battery researchers, this technique offers a controlled approach to investigate the redox behavior of electrode materials under conditions that simulate actual battery operation, enabling the prediction of performance characteristics without fabricating complete cells. The strategic application of CV allows researchers to decipher critical parameters including diffusion coefficients, electron transfer kinetics, and reaction mechanisms—all essential intelligence for designing next-generation energy storage materials with enhanced capacity, stability, and rate capability.

Theoretical Foundations of Cyclic Voltammetry

Fundamental Principles and Key Parameters

Cyclic voltammetry is performed by scanning the potential of a working electrode relative to a reference electrode in both forward and backward directions while monitoring the current [8]. This potential excursion perturbs the electrochemical system, inducing oxidation or reduction of electroactive species. The resulting plot of current versus potential, called a cyclic voltammogram, provides characteristic features that reveal fundamental information about the redox processes. Two parameters are particularly significant: the peak potentials (Epa for anodic peaks and Epc for cathodic peaks), which relate to the formal potential (E°') of the redox couple, and the peak currents (Ipa and Ipc), which correlate with the concentration of the electroactive species and its diffusion coefficient [8].

The formal potential of a redox couple is approximated by the midpoint between the anodic and cathodic peak potentials, often termed E1/2 or Emp [8]. This value represents a thermodynamic parameter that indicates the inherent redox activity of the material. For battery electrode materials, this potential directly correlates with the operational voltage of the battery, making it a crucial parameter for predicting and tuning battery characteristics. The separation between anodic and cathodic peak potentials (ΔEp) provides information about the reversibility of the electron transfer reaction, with values close to 59/n mV (where n is the number of electrons transferred) indicating a highly reversible system—a desirable characteristic for efficient battery materials with minimal polarization losses.

The characteristic "duck shape" of a cyclic voltammogram arises from the changing dimensions of the diffusion layer during the potential scan [8]. As redox-active species are consumed at the electrode surface, a concentration gradient forms, driving diffusion from the bulk solution. The current initially increases as the potential reaches the redox active region, then decays after reaching a peak value as species become depleted near the electrode surface. This current response is governed by the Randles-Ševčík equation (at 25°C), which describes the relationship between peak current and experimental parameters [8]:

Where Ip is the peak current (A), n is the number of electrons transferred, A is the electrode area (cm²), D is the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s), C is the concentration (mol/cm³), and υ is the scan rate (V/s).

Diagnostic Information from Voltammetric Responses

The shape and position of features in a cyclic voltammogram provide diagnostic information about the electrochemical processes occurring at the electrode interface. Well-defined, symmetric redox peaks with minimal separation suggest reversible electron transfer, while broad, asymmetric peaks with large separations often indicate slow electron transfer kinetics or complex reaction mechanisms. For battery materials, these characteristics directly translate to rate capability and efficiency—critical parameters for high-performance energy storage systems.

The scan rate dependence of CV responses offers particularly valuable insights into the underlying reaction mechanisms. When the peak current scales linearly with the square root of the scan rate, the process is diffusion-controlled, whereas a linear relationship with the scan rate itself suggests surface-confined or adsorption-controlled processes [8]. Battery researchers can exploit this relationship to distinguish between diffusion-limited intercalation reactions and surface-dominated pseudocapacitive storage mechanisms—a fundamental distinction that guides material design strategies for either high-energy or high-power applications. The appearance of additional peaks or changes in peak ratios with varying scan rates may indicate coupled chemical reactions (EC mechanisms), providing evidence for complex reaction pathways or degradation mechanisms that impact battery cycle life.

Complementary Voltammetric Techniques

Chronoamperometry for Diffusion and Kinetic Analysis

Chronoamperometry (CA) serves as a powerful complement to CV by providing quantitative information about diffusion characteristics and reaction kinetics. In a CA experiment, the potential is stepped from a value where no faradaic reaction occurs to a potential sufficient to drive a diffusion-limited electrochemical reaction, and the resulting current transient is monitored as a function of time [9] [10]. This current decay follows the Cottrell equation, which describes diffusion-controlled current at a planar electrode [9]:

Where I(t) is the time-dependent current, F is Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol), and t is time [9] [8]. For battery materials, CA enables the determination of diffusion coefficients for ions within electrode structures—a critical parameter governing rate capability. The technique is particularly valuable for studying electrocatalytic materials by measuring steady-state performance at operating potentials [10].

Double-step chronoamperometry, where the potential is stepped back to its initial value after a specified time, provides additional mechanistic information, particularly for systems where the product of the initial electrode reaction undergoes subsequent chemical transformations [10]. This approach can reveal details about the stability of reaction intermediates and coupled chemical reactions that may affect battery performance and lifetime. Integration of the current signal in chronoamperometry yields charge-time relationships (chronocoulometry), which can more accurately distinguish between faradaic and capacitive processes by separating the total charge into diffusion-controlled and surface components [10].

Stripping Voltammetry for Trace Analysis

Stripping voltammetric techniques offer exceptional sensitivity for quantifying specific ionic species and are particularly valuable for analyzing trace metal impurities in battery electrolytes or studying dissolution processes in electrode materials. These methods employ a preconcentration step followed by a stripping step, achieving detection limits in the parts-per-billion to parts-per-trillion range [11] [12].

Anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) involves the electrochemical reduction and deposition of metal ions onto the working electrode at a controlled potential, followed by an anodic potential sweep that oxidizes and strips the deposited metal back into solution [11] [12]. The resulting oxidation current provides quantitative information about the original metal ion concentration. Cathodic stripping voltammetry (CSV) operates on a similar principle but uses an anodic deposition step to form an insoluble salt film on the electrode surface, followed by cathodic stripping [11] [12]. Adsorptive stripping voltammetry, conversely, relies on non-electrolytic preconcentration through adsorption of the analyte or its complexes on the electrode surface [11].

For battery research, these techniques are invaluable for detecting trace metal contaminants that can catalyze electrolyte decomposition or studying the dissolution of electrode components during cycling—critical factors affecting battery longevity and safety.

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Material Characterization

Electrochemical Cell Assembly and Preparation

Proper experimental setup is fundamental to obtaining reliable and reproducible voltammetric data. The following protocol outlines the standard procedure for assembling a three-electrode cell for characterizing battery electrode materials:

Electrode Preparation: For working electrodes, prepare electrode material films by casting slurries containing the active material (80-90%), conductive carbon (5-10%), and binder (5-10%) on current collectors (typically copper for anodes or aluminum for cathodes) [13]. Alternatively, for fundamental studies, use glassy carbon, platinum, or gold electrodes polished to a mirror finish using successively finer alumina suspensions (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) followed by thorough rinsing with purified water and appropriate solvents [14].

Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare electrolyte solutions using high-purity solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, dimethyl carbonate, or water for aqueous systems) and appropriate supporting electrolytes (e.g., LiPF6 for non-aqueous lithium systems, KCl or H2SO4 for aqueous systems) at concentrations typically between 0.1-1.0 M. Degas electrolytes by bubbling with inert gas (argon or nitrogen) for at least 15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with electrochemical measurements [14].

Cell Assembly: Assemble the electrochemical cell with the working electrode, reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl for aqueous systems, Li/Li+ for non-aqueous lithium systems), and counter electrode (typically platinum wire or mesh) positioned to ensure uniform current distribution. Maintain consistent electrode placement and geometry between experiments to ensure comparable results.

Standard Cyclic Voltammetry Protocol

The following step-by-step protocol details the acquisition and analysis of cyclic voltammograms for battery electrode materials:

Instrument Setup: Initialize the potentiostat and verify electrical connections. Set the initial parameters including potential range, scan rate, and number of cycles. Typical initial conditions might include a potential window appropriate for the material under investigation (e.g., -0.2 to 1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl for aqueous systems, 1.5-4.5 V vs. Li/Li+ for lithium cathode materials), scan rates of 0.01-1 V/s, and 3-10 cycles [8] [14].

Background Measurement: Record a background voltammogram in the supporting electrolyte without the electroactive species to identify features arising from the electrolyte, electrodes, or impurities. This background should be featureless within the potential window of interest, with current responses primarily representing capacitive charging.

Sample Measurement: Introduce the electrode material or electroactive species and record cyclic voltammograms under identical conditions. For battery materials, this may involve using a composite electrode as the working electrode or studying active materials deposited directly on inert substrates.

Multi-Scan Rate Analysis: Perform CV measurements at multiple scan rates (e.g., 0.01, 0.02, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 V/s) to probe mass transport limitations and reaction mechanisms. The relationship between peak current and scan rate (or square root of scan rate) provides critical diagnostic information.

Data Analysis: Determine formal potentials from the average of anodic and cathodic peak potentials. Calculate peak separation (ΔEp) to assess electrochemical reversibility. Analyze the scan rate dependence of peak currents to distinguish between diffusion-controlled and surface-confined processes.

The experimental workflow for comprehensive electrode characterization is visualized below:

Electrode Characterization Workflow

Complementary Technique Protocols

Chronoamperometry Protocol:

- Set initial potential at a value where no faradaic reaction occurs (determined from CV)

- Apply potential step to a value sufficient to drive diffusion-limited reaction (typically ≥120 mV beyond E°')

- Monitor current transient for predetermined duration (typically 1-300 s)

- For double-step chronoamperometry, step potential back to initial value after specified time

- Analyze data using Cottrell equation to determine diffusion coefficients or detect coupled chemical reactions [9] [8]

Rotating Disk Electrode (RDE) Voltammetry Protocol:

- Mount working electrode in rotating disk assembly

- Perform linear sweep voltammetry at fixed rotation rates (e.g., 400, 900, 1600, 2500 rpm)

- Analyze limiting current vs. square root of rotation rate (Levich plot) to determine diffusion coefficients

- Analyze half-wave potential shifts with rotation rate (Koutecký-Levich plot) to extract kinetic parameters

Diagnostic Parameters and Their Interpretation

Key CV Parameters for Battery Material Assessment

Systematic analysis of cyclic voltammetry data provides quantitative parameters essential for evaluating battery electrode materials. The table below summarizes key diagnostic parameters and their significance for battery performance:

| Parameter | Definition | Diagnostic Significance | Ideal Values for Battery Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Potential (E°') | Midpoint between anodic and cathodic peak potentials | Determines operating voltage; indicates thermodynamic favorability of redox reactions | High values for cathodes, low values for anodes to maximize cell voltage |

| Peak Separation (ΔEp) | Difference between anodic and cathodic peak potentials | Indicates electrochemical reversibility; reflects kinetic limitations | ≤59/n mV for highly reversible systems; minimal increase with scan rate |

| Peak Current Ratio (Ipa/Ipc) | Ratio of anodic to cathodic peak currents | Reveals chemical stability of redox states; indicates side reactions | Close to 1.0 for chemically reversible systems without follow-up reactions |

| Scan Rate Exponent (b) | Exponent in relationship Ip ∝ υ^b | Distinguishes diffusion-controlled (b=0.5) from surface-confined (b=1.0) processes | b=0.5 for intercalation materials; b=1.0 for capacitive materials |

| Peak FWHM | Full width at half maximum of redox peaks | Suggests number of electrons transferred or presence of multiple processes | ~90.6/n mV for ideal Nernstian systems; consistent across multiple cycles |

| Cycle Stability | Change in peak currents/positions with cycling | Indicates structural stability and resistance to degradation | Minimal change over tens to hundreds of cycles |

These parameters collectively provide a comprehensive assessment of battery material performance. For example, a well-behaved intercalation cathode material would exhibit sharp, symmetric redox peaks with minimal separation that remain stable over multiple cycles, while a material undergoing structural degradation would show broadening peaks, increasing peak separation, and decreasing peak currents with cycling.

Advanced Diagnostic Criteria

Beyond basic parameters, advanced analysis of CV data can reveal sophisticated mechanistic information:

Coupled Chemical Reactions (EC Mechanisms): Appearance of cathodic peaks without corresponding anodic peaks (or vice versa) suggests chemical reactions following electron transfer that consume the electrogenerated species. Such mechanisms are common in battery materials where redox reactions trigger structural transformations or side reactions with electrolytes.

Nucleation Processes: Asymmetric current spikes or crossover between forward and reverse scans may indicate nucleation-controlled phase transformations, frequently observed in conversion-type electrode materials or alloying anodes where new phases form during redox reactions.

Adsorption Processes: Symmetric peak shapes with linear Ip-υ relationships (rather than Ip-υ^1/2) suggest surface-confined redox processes, characteristic of pseudocapacitive charge storage or monolayer formation on electrode surfaces.

Diffusion Anisotropy: Differences in peak sharpness or shape between anodic and cathodic sweeps may indicate different diffusion pathways or coefficients for oxidized and reduced species, often observed in materials with structural anisotropy or different ionic mobilities for insertion and extraction.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful voltammetric characterization requires carefully selected materials and reagents. The following table details essential components for reliable electrochemical analysis of battery materials:

| Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrodes | Glassy carbon, Platinum, Gold disk, Composite electrodes | Provide controlled surface for electrochemical reactions; composite electrodes mimic practical battery configuration |

| Reference Electrodes | Ag/AgCl (aqueous), Li/Li+ (non-aqueous), Hg/Hg2SO4 | Maintain fixed potential reference; selection depends on electrolyte compatibility |

| Counter Electrodes | Platinum wire, Platinum mesh, Carbon rods | Complete electrical circuit without interfering with working electrode measurements |

| Supporting Electrolytes | LiPF6, LiClO4 (non-aqueous), KCl, H2SO4 (aqueous) | Provide ionic conductivity without participating in faradaic reactions; concentration typically 0.1-1.0 M |

| Solvents | Acetonitrile, Propylene carbonate, Dimethyl carbonate, Water | Dissolve electrolytes and facilitate ion transport; must be electrochemically inert in potential window of interest |

| Binder Materials | Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) | Adhere active materials to current collectors in composite electrodes; should be electrochemically inert |

| Conductive Additives | Carbon black, Graphene, Carbon nanotubes | Enhance electronic conductivity in composite electrodes; minimize ohmic losses |

| Purity Standards | Ferrocene (for non-aqueous), Potassium ferricyanide (aqueous) | Validate experimental setup and reference potential calibration |

Proper selection and preparation of these components is critical for obtaining meaningful electrochemical data. For instance, the choice of solvent and electrolyte directly impacts the accessible potential window, while appropriate electrode pretreatment ensures reproducible surface conditions. Researchers should rigorously dry non-aqueous electrolytes and remove oxygen from both aqueous and non-aqueous systems to prevent interference from moisture or dissolved oxygen in critical potential regions.

Case Studies: CV Analysis in Battery Material Research

Organic Electrode Material Characterization

Organic compounds represent a promising class of sustainable electrode materials for next-generation batteries. CV plays a crucial role in characterizing their redox mechanisms and stability. For example, quinone-based compounds exhibit well-defined, reversible two-electron, two-proton redox couples in protic electrolytes, with formal potentials that correlate with molecular structure and substituent effects [13]. CV analysis reveals how conjugation length, electron-withdrawing/donating groups, and molecular architecture influence redox potentials—enabling rational design of organic materials with tailored operating voltages.

In one representative study, CV of a quinone-based polymer electrode material showed two distinct redox couples corresponding to sequential reduction of quinone units. The minimal peak separation (<60 mV) and proportional peak current relationship with scan rate indicated highly reversible redox behavior with rapid kinetics. However, continuous cycling revealed a gradual decrease in peak currents and emergence of new redox features, suggesting progressive structural reorganization or side reactions—highlighting a stability challenge common to organic electrodes that requires further material engineering [13].

Intercalation Compound Analysis

Intercalation materials, such as transition metal oxides for lithium-ion battery cathodes, typically exhibit characteristic CV features reflecting phase transitions during ion insertion/extraction. For instance, LiCoO2 shows a main redox couple around 3.9 V vs. Li/Li+ corresponding to the Co³⁺/Co⁴⁺ redox pair, with peak shapes and positions that evolve with cycling due to structural changes and interfacial phenomena [13].

CV analysis of LiFePO4 reveals exceptionally sharp peaks with small separation (~30 mV) when nano-structured and carbon-coated, indicating highly reversible lithium insertion/extraction with minimal polarization. The peak width at half maximum closely matches the theoretical value for a single-phase reaction, confirming the two-phase mechanism characteristic of this material. Scan rate studies show the expected square root dependence of peak current, confirming solid-state diffusion control with calculated lithium diffusion coefficients on the order of 10⁻¹⁴-10⁻¹⁶ cm²/s, consistent with literature values obtained by other techniques [13].

Conversion and Alloying Material Investigation

Conversion-type materials (e.g., transition metal oxides, sulfides) and alloying anodes (e.g., Si, Sn) typically exhibit more complex CV signatures due to multiple phase transformations. Initial cycles often differ significantly from subsequent cycles as materials undergo activation processes and structural rearrangements.

For a silicon nanoparticle-based anode, the first cathodic sweep shows a broad, irreversible peak around 0.7-0.9 V vs. Li/Li+ corresponding to solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation, followed by a sharp increase in current below 0.1 V due to lithium alloying with silicon to form LixSi phases. The anodic sweep reveals a broad peak around 0.3-0.5 V associated with dealloying. In subsequent cycles, the SEI formation peak diminishes while the alloying/dealloying peaks become more pronounced and shift slightly, indicating stabilization of the electrode structure and interface [13].

Data Visualization and Analysis Approaches

Strategic Data Presentation

Effective visualization of voltammetric data enhances interpretation and communication of research findings. The following approaches facilitate comprehensive analysis:

Overlaid Multi-Scan CVs: Plotting cyclic voltammograms obtained at different scan rates on the same axes highlights changes in peak positions, shapes, and currents with timescale, immediately revealing kinetic limitations or mechanistic complexities.

Normalized CVs: Displaying current divided by the square root of scan rate (I/υ^1/2) normalizes for expected diffusion-controlled behavior, making deviations from ideal behavior more apparent and facilitating comparison between different materials or conditions [8].

Peak Parameter Plots: Graphical representation of peak current vs. scan rate (or square root of scan rate), peak potential vs. log(scan rate), and peak separation vs. scan rate provides quantitative assessment of reaction mechanisms and kinetics.

3D CV Arrays: For complex materials with multiple redox states or potential-dependent phase transformations, three-dimensional plots of current vs. potential vs. cycle number effectively visualize electrochemical evolution during cycling.

The relationship between experimental parameters and diagnostic outcomes is summarized below:

Parameter-Diagnostic Relationships

Quantitative Analysis Methods

Beyond visual inspection, quantitative analysis transforms CV data into fundamental parameters:

Randles-Ševčík Analysis: Plotting peak current against the square root of scan rate yields a straight line whose slope contains the diffusion coefficient, enabling quantitative comparison of ion transport in different materials.

Peak Fitting: Deconvoluting overlapping peaks using Gaussian or Lorentzian functions separates contributions from multiple redox processes, particularly valuable for complex materials with several active centers or sequential phase transformations.

Kinetic Parameter Extraction: Analysis of peak potential shifts with scan rate using Laviron's method yields standard rate constants for electron transfer, distinguishing between facile and sluggish interfacial charge transfer.

Capacitive Contribution Analysis: Separating capacitive (surface-controlled) and diffusion-controlled current contributions using the relationship i = k₁υ + k₂υ^1/2 quantifies the proportion of charge storage from surface versus bulk processes, critical for designing high-power materials.

Cyclic voltammetry remains an indispensable diagnostic tool in the battery researcher's arsenal, providing rich, multifaceted information about electrode materials that directly translates to battery performance characteristics. When properly executed and interpreted, CV reveals thermodynamic parameters, kinetic limitations, reaction mechanisms, and stability issues critical for developing advanced energy storage systems. The integration of CV with complementary techniques such as chronoamperometry and stripping voltammetry creates a powerful analytical framework that spans timescales from milliseconds to hours and concentration ranges from bulk to trace levels.

As battery technologies evolve toward more complex materials including multi-electron systems, solid-state electrolytes, and unconventional charge carriers, voltammetric techniques will continue to adapt and provide critical insights. Emerging approaches such as ultra-high-speed CV, coupled with spectroscopic techniques, and implementation in multi-electrode arrays promise to expand the information accessible through these electrochemical methods. For researchers dedicated to advancing battery performance, safety, and sustainability, mastering the interpretation of the CV curve remains an essential skill—one that transforms simple current-voltage measurements into a comprehensive diagnostic report for electrode materials.

In the development of next-generation post-lithium batteries, cyclic voltammetry (CV) serves as an indispensable electroanalytical technique for screening and characterizing new electrode materials [1]. This technique provides critical insights into the thermodynamic and kinetic parameters governing electrochemical processes, enabling researchers to optimize materials for enhanced energy storage performance. The characterization of redox potentials, peak separation, and electrochemical reversibility forms the cornerstone of evaluating electrode materials, as these parameters directly correlate with battery efficiency, cycling stability, and rate capability. This application note details the key electrochemical parameters essential for battery material characterization, providing standardized protocols and diagnostic criteria for research scientists engaged in energy storage development.

Theoretical Framework

Cyclic voltammetry involves applying a triangular potential waveform to a working electrode in a three-electrode cell configuration while measuring the resulting current [15]. The resulting plot of current versus potential, called a cyclic voltammogram, provides characteristic features that reveal fundamental electrochemical properties. When the electrode potential reaches a value sufficient to drive oxidation or reduction of an analyte, current flows due to electron transfer. This current peaks as the process becomes limited by diffusion of fresh analyte to the electrode surface [16].

For battery research, CV is particularly valuable for initial material screening and subsequent in-depth characterization [1]. The technique helps researchers understand charge storage mechanisms, identify suitable potential windows for battery operation, and assess the stability of electrode materials through repeated cycling.

Table 1: Fundamental Parameters in Cyclic Voltammetry for Battery Material Characterization

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Significance in Battery Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Redox Potential | E⁰' | Thermodynamic potential of redox couple | Indicates operating voltage of electrode materials |

| Peak Separation | ΔEp | Difference between anodic and cathodic peak potentials (Epa - Epc) | Diagnoses electrochemical reversibility and kinetic limitations |

| Peak Current Ratio | ipa/ipc | Ratio of anodic to cathodic peak currents | Reveals stability of electrogenerated species |

| Scan Rate | ν | Rate of potential change (V/s) | Probes mass transport and electron transfer kinetics |

Key Electrochemical Parameters

Formal Redox Potential (E⁰')

The formal redox potential (E⁰') represents the thermodynamic midpoint potential of a redox couple and is characteristic of the electrochemical species under investigation [17]. For a reversible system, E⁰' is calculated as the average of the anodic and cathodic peak potentials:

E⁰' = (Ep,f + Ep,r)/2 [17]

In battery research, this parameter indicates the operational voltage of electrode materials and helps identify redox couples active within the electrochemical window of the electrolyte [1]. The formal potential is particularly valuable for comparing different materials and selecting compatible redox couples for full cell configurations.

Peak Separation (ΔEp)

Peak separation (ΔEp) is defined as the difference between the anodic and cathodic peak potentials (ΔEp = Epa - Epc) [18]. This parameter serves as a primary indicator of electrochemical reversibility:

- Reversible systems: ΔEp = 59.2/n mV at 25°C (independent of scan rate) [18]

- Quasi-reversible systems: ΔEp > 59.2/n mV, increasing with scan rate [18]

- Irreversible systems: Large ΔEp values (hundreds of mV), often with absence of return peak [19]

For battery materials, small ΔEp values indicate fast electron transfer kinetics, which correlates with better rate capability and reduced polarization during charge/discharge cycles.

Current Ratio (ipa/ipc)

The ratio of anodic to cathodic peak currents (ipa/ipc) provides information about the stability of the electrogenerated species [18]. For a reversible system with stable oxidized and reduced forms, this ratio equals unity (ipa/ipc = 1) [18]. Deviations from unity indicate chemical reactions following electron transfer, which degrade battery performance over multiple cycles.

When the product of electron transfer undergoes a subsequent chemical reaction (EC mechanism), the peak current ratio becomes less than 1 [20]. This behavior signals instability in the electrode material or reaction intermediates, critical information for predicting cycle life in battery systems.

Scan Rate Dependence

The dependence of CV parameters on scan rate provides deep insight into charge storage mechanisms and kinetic limitations [15]:

- Reversible systems: Peak potentials remain constant with changing scan rate; peak currents increase linearly with the square root of scan rate [19] [15]

- Irreversible systems: Peak potentials shift with increasing scan rate; plotting Ep versus log(ν) typically yields a slope of ~60 mV/decade [19]

For battery materials, the scan rate dependence helps distinguish between diffusion-controlled (battery-like) and surface-controlled (capacitive) processes, enabling optimization of material architecture for specific energy storage applications.

Table 2: Diagnostic Criteria for Electrochemical Reversibility in Battery Materials

| Parameter | Reversible System | Quasi-Reversible System | Irreversible System |

|---|---|---|---|

| ΔEp | ≈59/n mV, scan rate independent [18] [15] | >59/n mV, increases with scan rate [18] | >>59/n mV, strong scan rate dependence [19] |

| ipa/ipc | ≈1 [18] | <1 [18] | <<1 or no reverse peak [20] |

| Peak Potential | Constant with scan rate [19] | Moderate shift with scan rate | Large shift with scan rate (~60 mV/decade) [19] |

| Battery Implications | Excellent cycle life, high efficiency [15] | Moderate kinetics, may require nano-structuring | Poor cycle life, large voltage polarization |

Experimental Protocols

Electrochemical Cell Setup

Materials and Equipment:

- Potentiostat with three-electrode configuration

- Working electrode: Glassy carbon, platinum, or gold disk electrodes (1-3 mm diameter)

- Reference electrode: Ag/AgCl (aqueous) or Ag/Ag⁺ (non-aqueous)

- Counter electrode: Platinum wire or mesh

- Electrolyte solution: High-purity salt dissolved in appropriate solvent (e.g., 0.1 M TBAPF₆ in acetonitrile)

- Analyte: Purified battery material (typically 1-5 mM concentration)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish working electrode with alumina slurry (0.05 μm) on a microcloth pad, followed by sequential sonication in deionized water and solvent for 2 minutes each [16].

- Solution Preparation: Dissolve supporting electrolyte in purified solvent at concentration ≥0.1 M to minimize solution resistance. Add analyte at 1-5 mM concentration [16].

- Oxygen Removal: Purge solution with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen [21].

- Instrument Calibration: Verify potential accuracy using a reversible standard (e.g., ferrocene/ferrocenium in non-aqueous systems).

- Experiment Setup: Immerse electrodes in solution, ensuring proper alignment and connection. Apply potential window appropriate for the electrolyte stability and analyte redox activity.

Standard CV Characterization Protocol

Parameter Selection:

- Initial Potential: Select a potential where no faradaic processes occur

- Vertex Potentials: Choose to encompass all redox events of interest

- Scan Rates: Typically 10-1000 mV/s for battery materials, with multiple rates for diagnostic purposes [15]

Data Collection:

- Begin with a wide potential window (-1.0 to +1.0 V vs. reference) to identify all redox activity

- Narrow window to focus on specific redox couples

- Collect CVs at minimum of five different scan rates (e.g., 25, 50, 100, 200, 500 mV/s)

- Perform replicate measurements (n≥3) to ensure reproducibility

- Maintain constant temperature (±1°C) throughout experiments

Data Analysis:

- Identify peak potentials (Epa and Epc) using instrument software

- Calculate ΔEp = Epa - Epc

- Measure peak currents (ipa and ipc) from appropriate baselines

- Plot ip versus ν1/2 to verify diffusion control

- Plot Ep versus log(ν) for irreversible systems

Stability Assessment Protocol

Multi-Cycle CV:

- Run continuous CV cycles (typically 20-100 cycles) at fixed scan rate

- Monitor changes in peak current ratios and peak potentials

- Calculate capacity retention from integrated charge under peaks

Scan Rate Studies:

- Collect CVs at minimum of five scan rates spanning at least one order of magnitude

- Plot ip versus ν1/2 - linear relationship indicates diffusion control

- Plot ip versus ν - linear relationship suggests capacitive behavior

- Analyze ΔEp as function of scan rate to quantify kinetic limitations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for CV Experiments in Battery Research

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolytes | TBAPF₆ (tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate), LiPF₆, KCl | Provides ionic conductivity; minimizes migration effects; determines electrochemical window [16] |

| Solvents | Acetonitrile, propylene carbonate, DMF (dry, distilled) | Dissolves analyte and electrolyte; determines potential window; affects solvation structure [16] |

| Reference Electrodes | Ag/AgCl (aqueous), Ag/Ag⁺ (non-aqueous), Fc/Fc⁺ (internal) | Provides stable, known potential reference; enables accurate potential measurement [21] |

| Working Electrodes | Glassy carbon, platinum, gold (polished to mirror finish) | Site of electron transfer; material affects kinetics and window [16] |

| Redox Standards | Ferrocene, potassium ferricyanide, Ru(NH₃)₆Cl₃ | Validates experimental setup; calibrates potential scale [20] |

| Purging Gases | High-purity nitrogen or argon (O₂ < 1 ppm) | Removes interfering oxygen; prevents side reactions [21] |

Data Interpretation in Battery Material Context

Diagnostic Case Studies

Ideal Battery Material (Reversible System): A high-performance Li-ion cathode material typically exhibits ΔEp values close to 59 mV for one-electron processes, with ipa/ipc ≈ 1 across multiple cycles. Such behavior indicates minimal polarization and high coulombic efficiency, essential for long cycle life. The formal potential E⁰' should remain stable over repeated cycling, indicating structural stability of the host material.

Problematic Behavior (Irreversible System): Materials showing large ΔEp values (>100 mV) that increase with scan rate, coupled with ipa/ipc << 1, suggest slow kinetics and structural instability. Such materials typically exhibit rapid capacity fade in battery applications. Irreversibility often stems from phase transformations, slow solid-state diffusion, or parasitic reactions with the electrolyte.

Quasi-Reversible Systems: Many practical battery materials fall into this category, with ΔEp values between 70-150 mV. Through scan rate studies, researchers can determine whether the limitation arises from electron transfer kinetics or mass transport. Nano-structuring approaches can often improve performance by addressing mass transport limitations.

Advanced Analysis Techniques

Randles-Ševčík Analysis: For reversible systems, the peak current follows the Randles-Ševčík equation:

ip = 2.69×10⁵n³/²ACD¹/²ν¹/² [18]

where n = electron number, A = electrode area (cm²), C = concentration (mol/cm³), D = diffusion coefficient (cm²/s), and ν = scan rate (V/s). This relationship allows calculation of diffusion coefficients, critical for understanding rate limitations in battery materials.

Kinetic Parameter Extraction: For quasi-reversible systems, the variation of ΔEp with scan rate enables calculation of the standard heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant (ks) [18]. This parameter quantifies the kinetic barrier for electron transfer, guiding material modification strategies.

The systematic characterization of redox potentials, peak separation, and electrochemical reversibility through cyclic voltammetry provides foundational insights critical for advancing battery material research. The protocols and diagnostic frameworks presented in this application note enable researchers to quantitatively assess key performance parameters early in material development, guiding the rational design of next-generation energy storage systems. Standardized implementation of these CV methodologies across research laboratories will enhance comparability of results and accelerate the development of high-performance post-lithium batteries.

The Randles-Ševčík equation stands as a fundamental pillar in electroanalytical chemistry, providing the quantitative relationship between peak current, scan rate, and diffusion for reversible redox processes. First derived independently by John Edward Brough Randles and Antonín Ševčík in 1948, this equation has become an indispensable tool for characterizing electrode processes in diverse fields, including battery material research [22] [23]. For researchers investigating battery materials such as lithium cobalt oxide (LiCoO₂) and graphite anodes, the equation provides a mathematical foundation to extract critical parameters including diffusion coefficients, electroactive surface areas, and electron transfer kinetics from cyclic voltammetry data [24]. Its enduring relevance lies in its ability to distinguish diffusion-controlled processes from those limited by adsorption or slow electron transfer kinetics, thereby enabling accurate interpretation of complex electrode processes.

This application note details the theoretical principles, practical implementation, and analytical protocols for employing the Randles-Ševčík equation within battery characterization workflows. By providing structured methodologies for data collection, analysis, and interpretation, we aim to equip researchers with standardized procedures for quantifying mass transport and kinetic parameters essential for optimizing electrochemical energy storage systems.

Theoretical Foundation

Mathematical Formulation

The Randles-Ševčík equation quantitatively describes the peak current ((i_p)) response in cyclic voltammetry for electrochemically reversible systems where both reactant and product are soluble and electron transfer is rapid relative to mass transport [25] [22]. The general form of the equation is expressed as:

[i_p = 0.4463 \, nFAC \left( \frac{nF \nu D}{RT} \right)^{1/2}]

For practical applications at standard laboratory temperature (25°C = 298.15 K), the equation simplifies to:

[i_p = (2.69 \times 10^5) \, n^{3/2} A D^{1/2} C \nu^{1/2}]

The equation establishes that for diffusion-controlled reversible systems, the peak current exhibits a square-root dependence on scan rate, a key diagnostic criterion for identifying mass transport limitations [25] [22].

Table 1: Parameters of the Randles-Ševčík Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Current | (i_p) | A | Maximum current at peak potential |

| Number of Electrons | (n) | - | Electrons transferred in redox event |

| Electrode Area | (A) | cm² | Electroactive surface area |

| Diffusion Coefficient | (D) | cm²/s | Measure of species mobility in solution |

| Concentration | (C) | mol/cm³ | Bulk concentration of electroactive species |

| Scan Rate | (\nu) | V/s | Rate of potential sweep |

Diagnostic Significance in Battery Research

The Randles-Ševčík equation provides critical diagnostic capabilities for battery material characterization:

- Reversibility Assessment: A linear plot of peak current ((i_p)) versus the square root of scan rate ((\nu^{1/2})) indicates a diffusion-controlled, reversible process [25] [24]. Significant deviations from linearity suggest complications from adsorption, kinetic limitations, or ohmic resistance.

- Kinetic Regime Identification: For a reversible system, the peak separation ((\Delta Ep)) between anodic and cathodic peaks should be approximately (59/n) mV at 25°C and remain unchanged with increasing scan rate [26] [22]. Values exceeding this theoretical minimum or scan rate-dependent widening of (\Delta Ep) indicate quasi-reversible or irreversible electron transfer.

- Diffusion Control Verification: The logarithmic analysis of (\log(i_p)) versus (\log(\nu)) yields additional insights. A slope of 0.5 confirms diffusion control, while a slope approaching 1.0 suggests an adsorption-controlled process [27].

Experimental Protocols

Determining the Diffusion Coefficient ((D))

Principle: This protocol uses the Randles-Ševčík equation to determine the diffusion coefficient of an electroactive species in battery electrolytes, such as Li⁺ in organic carbonate solvents [25] [24].

Materials & Equipment:

- Three-electrode cell or coin cell configuration

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat (e.g., IEST ERT6008-5V100mA, CHI 760D)

- Working electrode (e.g., LiCoO₂ coated on current collector)

- Counter electrode (Lithium metal foil)

- Reference electrode (Li⁺/Li reference)

- Electrolyte (e.g., 1M LiPF₆ in EC/DMC)

- Analyte species with known concentration

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Battery Characterization

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Specification |

|---|---|---|

| LiCoO₂ Cathode Material | Active material for Li⁺ intercalation/deintercalation studies | >99.5% purity, mass loading ~10 mg/cm² |

| LiPF₆ in EC/DMC | Standard Li-ion battery electrolyte | 1M concentration, <20 ppm H₂O |

| Lithium Metal Foil | Counter and reference electrode | Thickness 0.45 mm, 99.9% purity |

| Conductive Carbon Additive | Enhancing electrode electronic conductivity | Super P, >99.5% purity |

| Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) | Electrode binder | MW ~534,000, 5 wt% in NMP |

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Assemble an electrochemical cell with precisely known electrode geometric area ((A)). For battery studies, this may be a coin cell or three-electrode pouch cell.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing a known, fixed concentration ((C)) of the redox-active species (e.g., Li⁺ in the electrode material) in appropriate supporting electrolyte.

- Voltammetric Data Collection:

- Record cyclic voltammograms at multiple scan rates (e.g., 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1.0 mV/s) over a potential window that encompasses the redox event of interest.

- Ensure minimal ohmic drop through proper cell design and iR compensation where appropriate.

- Maintain constant temperature (preferably 25°C) throughout experiments.

- Data Analysis:

- Measure the peak current ((ip)) for each voltammogram at different scan rates.

- Plot (ip) versus (\nu^{1/2}).

- Perform linear regression on the data. The plot should yield a straight line passing through the origin for a reversible system.

- Calculate the diffusion coefficient ((D)) using the simplified equation at 25°C, rearranged as: [ D = \left( \frac{\text{slope}}{2.69 \times 10^5 \cdot n^{3/2} A C} \right)^2 ]

Determining Electroactive Surface Area ((A))

Principle: This methodology calculates the effective electroactive area of a porous or modified battery electrode, which often differs significantly from its geometric area [26] [23].

Procedure:

- Reference System Selection: Employ a stable, reversible redox couple with known diffusion coefficient ((D)) and number of electrons transferred ((n)), such as 1.0 mM potassium ferricyanide in 1.0 M KNO₃ ((D = 7.6 \times 10^{-6}) cm²/s) [26].

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- Record cyclic voltammograms of the reference system at multiple scan rates using the electrode of unknown surface area.

- Verify system reversibility by confirming (\Delta E_p) is close to (59/n) mV and independent of scan rate.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot (i_p) versus (\nu^{1/2}) for the known redox probe.

- Calculate the electroactive area ((A)) from the slope of the plot using the rearranged equation: [ A = \frac{\text{slope}}{2.69 \times 10^5 \cdot n^{3/2} C D^{1/2}} ]

Validation: For a freshly polished planar glassy carbon electrode, the calculated electroactive area should closely approximate the geometric area. Significant deviations indicate surface roughness, porosity, or fouling [26].

Workflow for Data Acquisition and Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the systematic workflow for applying the Randles-Ševčík equation in battery material characterization:

Diagram 1: Randles-Ševčík Analysis Workflow

Data Analysis & Interpretation

Quantitative Data Analysis

Table 3: Experimental Data for Paracetamol as a Model System [28]

| Scan Rate (V/s) | √Scan Rate (V¹/²/s¹/²) | Anodic Peak Current, Ipa (μA) | Cathodic Peak Current, Ipc (μA) | Peak Separation, ΔEp (mV) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.025 | 0.158 | 4.15 | 2.45 | 128 |

| 0.050 | 0.224 | 5.80 | 3.45 | 135 |

| 0.100 | 0.316 | 8.10 | 4.75 | 146 |

| 0.150 | 0.387 | 10.00 | 5.90 | 158 |

| 0.200 | 0.447 | 11.55 | 6.80 | 168 |

| 0.250 | 0.500 | 12.85 | 7.60 | 177 |

| 0.300 | 0.548 | 14.05 | 8.25 | 186 |

Analysis of the data in Table 3 reveals characteristic behavior of a quasi-reversible system:

- The ratio Ipc/Ipa remains relatively constant at approximately 0.59, indicating the presence of chemically coupled reactions consuming the redox species [28].

- ΔEp increases significantly with scan rate (from 128 mV to 186 mV), confirming quasi-reversible electron transfer kinetics rather than a purely reversible process.

Advanced Considerations for Battery Materials

Quasi-Reversible Systems: Many practical battery materials exhibit quasi-reversible behavior, requiring modification of the standard Randles-Ševčík equation [26]:

[i_p = (2.69 \times 10^5 \, n^{3/2} A D C \nu^{1/2}) \cdot K(\Lambda, \alpha)]

where (K(\Lambda, \alpha)) is a dimensionless parameter accounting for the kinetics of electron transfer. The parameter (\Lambda) is calculated as (\Psi(\pi n D F \nu / RT)^{1/2}), where (\Psi) is a kinetic parameter derived from the Nicholson analysis [28].

Irreversible Systems: For totally irreversible systems (typically (n\Delta E_p > 200) mV), the peak current is described by [26]:

[i_p = (2.99 \times 10^5) \, n (\alpha n') A D^{1/2} C \nu^{1/2}]

where (\alpha) is the charge transfer coefficient and (n') is the number of electrons transferred before the rate-determining step.

Validation with Battery Materials: Application to LiCoO₂/graphite systems demonstrates the equation's utility. At low scan rates (0.1 mV/s), ΔEp ≈ 60 mV confirms highly reversible Li⁺ intercalation, while higher scan rates (0.5 mV/s) show ΔEp widening to 90 mV, indicating charge-transfer resistance and kinetic polarization [24].

The Randles-Ševčík equation provides an essential framework for quantifying and interpreting electrochemical processes in battery materials. Through systematic implementation of the protocols outlined in this application note, researchers can reliably extract diffusion coefficients, electroactive surface areas, and kinetic parameters critical for optimizing electrode formulations and electrolyte systems. The equation's diagnostic power in distinguishing diffusion-controlled processes from those limited by adsorption or slow electron transfer makes it invaluable for advancing battery technology. When applied with careful attention to system reversibility and appropriate use of modified equations for quasi-reversible systems, the Randles-Ševčík equation remains a cornerstone of electrochemical characterization in energy storage research.

Distinguishing Diffusion-Controlled and Surface-Controlled Processes

In battery material characterization research, voltammetric techniques are frontline tools for investigating reactions on electrode surfaces. A fundamental aspect of this analysis is determining whether an electrochemical process is diffusion-controlled or surface-controlled (adsorption-controlled), as this distinction dictates the reaction kinetics, the analytical methods used, and the ultimate performance and application of the energy storage material [1] [28]. In diffusion-controlled processes, the rate of the electrochemical reaction is limited by the mass transport of electroactive species from the bulk solution to the electrode surface. Conversely, in surface-controlled processes, the reaction rate is governed by the kinetics of electron transfer and the adsorption of species onto the electrode surface itself, with the current directly proportional to the electrode area. Accurately distinguishing between these mechanisms is therefore critical for developing next-generation post-lithium batteries, optimizing their charge-storing behavior, and understanding interfacial processes that are pivotal to battery performance and lifespan [1] [29]. This application note provides detailed protocols for distinguishing these processes using cyclic voltammetry, framed within the broader context of battery material characterization.

Theoretical Background

In cyclic voltammetry, the relationship between the peak current (Ip) and the scan rate (ν) reveals the nature of the rate-determining step. The power dependence of the peak current on the scan rate is given by Ip ∝ ν^b, where the exponent b is the key diagnostic parameter [28].

A process is diffusion-controlled when the mass transport of reactants to the electrode surface is the slowest step. For an ideal, reversible diffusion-controlled system, the peak current is directly proportional to the square root of the scan rate (Ip ∝ ν^1/2), yielding a

b-value of 0.5. This relationship is formally described by the Randles-Ševčík equation (for a reversible system): Ip = (2.69 × 10^5) * n^3/2 * A * D^1/2 * C * ν^1/2 wherenis the number of electrons,Ais the electrode area (cm²),Dis the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s),Cis the bulk concentration (mol/cm³), andνis the scan rate (V/s) [28].A process is surface-controlled (or adsorption-controlled) when the charge transfer is confined to species adsorbed onto the electrode surface. In this case, the peak current is directly proportional to the scan rate itself (Ip ∝ ν^1), yielding a

b-value of 1.0. The corresponding current equation is: Ip = (n²F² / 4RT) * ν * A * Γ whereΓis the surface coverage of the adsorbed species (mol/cm²), and F, R, and T have their usual meanings.

Many real-world systems, especially in battery research, exhibit mixed control, where the b-value falls between 0.5 and 1.0, indicating that both diffusion and adsorption phenomena influence the current response. The following table summarizes the key characteristics of these processes.

Table 1: Key Characteristics for Distinguishing Reaction Control Mechanisms in Cyclic Voltammetry

| Feature | Diffusion-Controlled Process | Surface-Controlled Process |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Current (Ip) Dependence | Ip ∝ ν^1/2 | Ip ∝ ν^1 |

| Diagnostic 'b' value (from log(Ip) vs log(ν)) | b ≈ 0.5 | b ≈ 1.0 |

| Primary Rate Limitation | Mass transport of analyte to the electrode | Kinetics of electron transfer & adsorption |

| Typical Electrochemical System | Dissolved redox couples in solution (e.g., paracetamol [28], Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻) | Monolayer adsorption on a surface (e.g., underpotential deposition, some battery interfaces [29]) |

| Peak Separation (ΔEp) | May increase with scan rate for quasi-reversible systems [28] | Can be small and invariant with scan rate |

Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the procedure for acquiring and analyzing cyclic voltammetry data to distinguish between diffusion-controlled and surface-controlled processes, using a standard three-electrode cell configuration common in battery material research.

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details the essential materials and reagents required to perform these experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Working Electrode | Provides a well-defined, inert surface for electrochemical reactions. Its known area is crucial for quantitative calculations [28]. |

| Reference Electrode (e.g., SCE, Ag/AgCl) | Provides a stable, fixed potential reference against which the working electrode potential is measured and controlled. |

| Counter Electrode (e.g., Platinum wire) | Completes the electrical circuit by carrying the current flowing from the working electrode. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., LiClO₄, KCl) | Dissociates into ions to provide sufficient conductivity in the solution while minimizing ohmic (iR) drop. It should be electroinactive in the potential window of interest [28]. |

| Electroactive Species (Analyte) | The material under investigation, such as a synthesized battery electrode material, paracetamol for model studies, or a redox standard [28]. |

| Solvent (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile) | The medium in which the experiment is performed. It must dissolve the electrolyte and analyte and be stable across the desired potential window. |

| Polishing Supplies (e.g., Alumina Powder) | Used to clean and renew the electrode surface, ensuring reproducible and uncontaminated experimental conditions [28]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

Figure 1: Experimental and Data Analysis Workflow for Distinguishing Electrochemical Processes.

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the glassy carbon working electrode (or other material of interest) with 0.2 µm alumina powder slurry on a polishing cloth to create a fresh, reproducible surface [28]. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and an appropriate solvent (e.g., acetone, ethanol), then dry.

- Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the electroactive species (e.g., 1 x 10⁻⁶ M paracetamol or a battery material slurry) and a high concentration of supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M LiClO₄ or KCl) to ensure solution conductivity and minimize uncompensated resistance [28].

- Solution Degassing: Purge the electrochemical cell solution with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for approximately 15 minutes prior to measurements to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the redox reactions of interest [28].

- Cell Assembly: Assemble the conventional three-electrode cell with the polished working electrode, a clean platinum wire counter electrode, and an appropriate reference electrode (e.g., Saturated Calomel Electrode, SCE).

- Data Acquisition: Perform cyclic voltammetry experiments across a wide range of scan rates. A recommended starting range is from 0.025 V/s to 0.300 V/s, with incremental steps (e.g., 0.025 V/s) [28]. Ensure the potential window is set to fully encompass the redox peaks of the analyte.

- Data Analysis: For each cyclic voltammogram recorded, measure the anodic peak current (Ipa) and the cathodic peak current (Ipc), as well as their corresponding peak potentials (Epa and Epc).

- Diagnostic Plotting:

- Plot the peak current (Ip, either anodic or cathodic) against the square root of the scan rate (ν^1/²).

- On a separate graph, plot the peak current (Ip) against the scan rate (ν).

- Plot the logarithm of the peak current (log Ip) against the logarithm of the scan rate (log ν).

- Mechanism Determination:

- Perform linear regression on the log(Ip) vs. log(ν) plot. The slope of this line is the

b-value. - If the

b-value is approximately 0.5, and the Ip vs. ν^1/² plot is linear, the process is predominantly diffusion-controlled. - If the

b-value is approximately 1.0, and the Ip vs. ν plot is linear, the process is predominantly surface-controlled. - A

b-value between 0.5 and 1.0 suggests a mixed control mechanism, requiring further analysis.

- Perform linear regression on the log(Ip) vs. log(ν) plot. The slope of this line is the

Data Analysis and Interpretation

The following section provides a detailed guide to analyzing the acquired data, complete with quantitative methods for calculating key electrochemical parameters relevant to battery research, such as the diffusion coefficient (D₀) and heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant (k⁰) [28].

Workflow for Data Analysis

Figure 2: Data Interpretation and Parameter Calculation Logic.

Quantitative Parameter Calculation

For processes identified as diffusion-controlled or quasi-reversible, the following calculations are essential for a deeper characterization of the battery material.

Table 3: Methods for Calculating Key Electrochemical Parameters for Diffusion-Controlled Processes

| Parameter | Recommended Method & Equation | Explanation and Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient (D₀) | Modified Randles-Ševčík Equation:Ip = (2.69 × 10⁵) * n³/² * A * D₀¹/² * C * ν¹/² | This equation is particularly effective for calculating the diffusion coefficient [28]. Rearrange to solve for D₀ using the slope of the Ip vs. ν¹/² plot. Ensure the number of electrons (n) and electrode area (A) are accurately known. |

| Transfer Coefficient (α) | Eₚ - Eₚ/₂ Equation:For a reversible system: α = (47.7 / (Eₚ - Eₚ/₂)) mV (at 25°C) | This method is effective for deriving the symmetry factor that affects activation energy at the electrode surface [28]. Eₚ/₂ is the potential where the current is half the peak current. |

| Heterogeneous Electron Transfer Rate Constant (k⁰) | Kochi and Gileadi Methods | These methods are identified as reliable alternatives for the calculation of k⁰ for quasi-reversible reactions [28]. The Nicholson and Shain method (k⁰ = Ψ(πnD₀Fν/RT)¹/²) can overestimate values, though a plot of ν⁻¹/² versus Ψ can yield accurate results. |

Case Study: Paracetamol Electrolysis

Research on paracetamol serves as an excellent case study. Cyclic voltammetry of paracetamol shows a quasi-reversible system with a peak separation (ΔEp) that increases with scan rate (from 0.128 V to 0.186 V), indicating a slow electron transfer process and not merely uncompensated resistance [28]. Furthermore, the ratio of the cathodic to anodic peak currents (Ipc/Ipa) remains constant at approximately 0.59, which is less than unity, indicating a chemically coupled reaction (EC' mechanism) following the initial electron transfer [28]. Diagnostic plots of Ip vs. ν and Ip vs. ν¹/² confirmed that the process is diffusion-controlled, providing a real-world example of the protocol's application [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit

This section lists critical software and tools that facilitate the experimental and analysis workflow described in this note.

Table 4: Essential Software Tools for Voltammetric Analysis and Diagram Creation

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function & Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| CHI Electrochemical Workstation & DigiSim | Data Acquisition & Simulation | Electrochemical workstations (e.g., CHI 760D) run cyclic voltammetry experiments. Integrated software like DigiSim allows for digital simulation of voltammograms to validate calculated parameters (k⁰, α, D₀) against experimental data [28]. |

| LabPlot | Data Visualization & Analysis | A free, open-source, cross-platform data visualization and analysis software. It is ideal for importing, plotting, and performing regression analysis (e.g., on Ip vs. ν data) and supports many data import formats [30]. |

| Edraw.AI / Chemix | Scientific Diagramming | Online editors that provide rich libraries of scientific symbols for drawing professional experimental setup diagrams and lab apparatus schematics quickly and easily [31] [32]. |

| WebAIM Contrast Checker | Accessibility & Design | A tool to verify that the color contrast ratios in created diagrams and presentations meet WCAG (Web Content Accessibility Guidelines) standards, ensuring clarity and readability for all audiences [33]. |

Applied Voltammetric Analysis: Techniques and Protocols for Material Investigation

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for Screening and Mechanistic Studies

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) is a powerful and versatile electrochemical technique extensively used for investigating reaction mechanisms involving electron transfer. Its capability to generate species during a forward potential scan and probe their fate during the reverse scan makes it indispensable for studying the thermodynamics and kinetics of redox processes. Within the field of battery material characterization research, CV is a fundamental tool for the initial screening and subsequent in-depth mechanistic analysis of new electrode materials, playing a critical role in the development of next-generation post-lithium batteries [1] [34]. By applying a linearly varying potential to an electrochemical cell and monitoring the resulting current, researchers can extract valuable qualitative and quantitative information about the charge-storage behavior of materials, which is essential for advancing energy storage technologies [1] [34].

Fundamental Principles of Cyclic Voltammetry

In a CV experiment, the potential applied to a working electrode is swept linearly with time between two set limits, known as the switching potentials. This sweep creates a triangular waveform. When the potential reaches a value sufficient to drive a redox reaction, a current peak is observed. The key measurable parameters from a cyclic voltammogram are the peak potentials (Epc and Epa) and the peak currents (ipc and ipa) for the cathodic and anodic processes, respectively [34].

The experiment is performed using a three-electrode configuration:

- Working Electrode: The electrode at which the reaction of interest occurs, typically made from inert conductive materials like platinum, graphite, or a stationary mercury drop [34].