Unstable Baseline in Cyclic Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Troubleshooting

This article provides a systematic resource for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with unstable baselines in cyclic voltammetry (CV).

Unstable Baseline in Cyclic Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Guide from Fundamentals to Advanced Troubleshooting

Abstract

This article provides a systematic resource for researchers and drug development professionals grappling with unstable baselines in cyclic voltammetry (CV). It covers the fundamental causes of baseline instability, explores methodological approaches for stable measurements in applications like drug analysis and antioxidant assessment, offers a step-by-step troubleshooting protocol, and discusses validation techniques against other analytical methods. By integrating foundational knowledge with practical solutions, this guide aims to enhance data reliability and experimental efficiency in electrochemical research for biomedical and clinical applications.

Understanding the Unstable CV Baseline: Root Causes and Fundamental Principles

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving Baseline Instability

Encountering an unstable baseline is a common challenge in cyclic voltammetry (CV) that can compromise data quality. The table below provides a systematic guide to diagnosing and resolving the root causes of this issue.

Table: Troubleshooting Guide for Baseline Instability in Cyclic Voltammetry

| Observed Symptom | Potential Causes | Recommended Resolution Steps | Underlying Principle |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline drift (steady rise or fall over time) | - Unstable reference electrode (blocked frit, depleted fill solution) [1].- Contaminated electrode surfaces [2] [3].- Temperature fluctuations or insufficient system warm-up [2]. | - Check and refill/replace the reference electrode [1].- Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 μm) and rinse thoroughly [1].- Allow the potentiostat and cell to warm up for ~30 minutes for thermal equilibrium [3]. | A stable potential reference and a clean, reproducible electrode surface are prerequisites for a steady capacitive background current. |

| Hysteresis in baseline (large, reproducible "duck-shaped" background) | - High charging (capacitive) currents inherent to the experimental setup [1] [4].- Faulty working electrode with poor internal contacts [1]. | - Decrease the scan rate to reduce the rate of capacitor charging/discharging [1].- Use a smaller working electrode to minimize the effective electrode-solution interface area [1].- Subtract a background scan obtained in pure electrolyte [4]. | The electrode-solution interface acts as a capacitor. Charging current is directly proportional to scan rate and electrode area. |

| Noisy or non-flat baseline | - Poor electrical connections or grounding [1].- Contaminated electrodes or electrolyte [2].- Electrical pickup from the environment [1]. | - Ensure all cables and connectors are secure and intact [1].- Re-polish and clean all electrodes; prepare fresh electrolyte solution [2] [1].- Use proper shielding on cables and ensure the cell is grounded [1]. | Contamination and poor connections introduce unpredictable resistance and unwanted redox reactions, increasing noise. |

| Flatlining (very small, noisy, unchanging current) | - Working electrode is not properly connected to the potentiostat or solution [1].- Severely passivated (fouled) electrode surface [3]. | - Check the connection of the working electrode cable [1].- Clean the working electrode surface rigorously (polishing or electrochemical cleaning) [1] [3]. | A disconnected or fully blocked electrode prevents faradaic and significant capacitive current flow, leaving only system noise. |

The following workflow provides a logical sequence for diagnosing and correcting baseline instability.

Advanced Technique: Baseline Drift Detrending for Long-Term Experiments

For long-duration experiments like Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV), traditional background subtraction can fail due to inherently unstable background currents. A proven advanced solution is the application of a zero-phase high-pass filter (HPF) [5] [6].

Experimental Protocol: Applying a High-Pass Filter for Drift Removal

This methodology allows for the analysis of FSCV data over several hours by removing low-frequency drift while preserving the kinetic information of the phasic analyte response (e.g., dopamine) [5].

Table: Protocol for High-Pass Filter Baseline Correction

| Step | Action | Parameters & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Data Preparation | Structure the dataset as a matrix where current is recorded over time (temporal data) at each applied voltage point [5]. | Ensure data is continuous and time-stamped. |

| 2. Filter Selection | Apply a zero-phase high-pass filter to the temporal data at each individual voltage point [5]. | A zero-phase filter prevents distortion of the signal's phase. |

| 3. Parameter Setting | Set the filter's cutoff frequency to a very low value [5]. | Effective cutoff frequencies are typically between 0.001 Hz and 0.01 Hz [5]. |

| 4. Validation | Compare the filtered data against a known, stable signal (e.g., electrically evoked analyte release) to ensure kinetic features are preserved [5]. | This step confirms the drift was removed without distorting the signal of interest. |

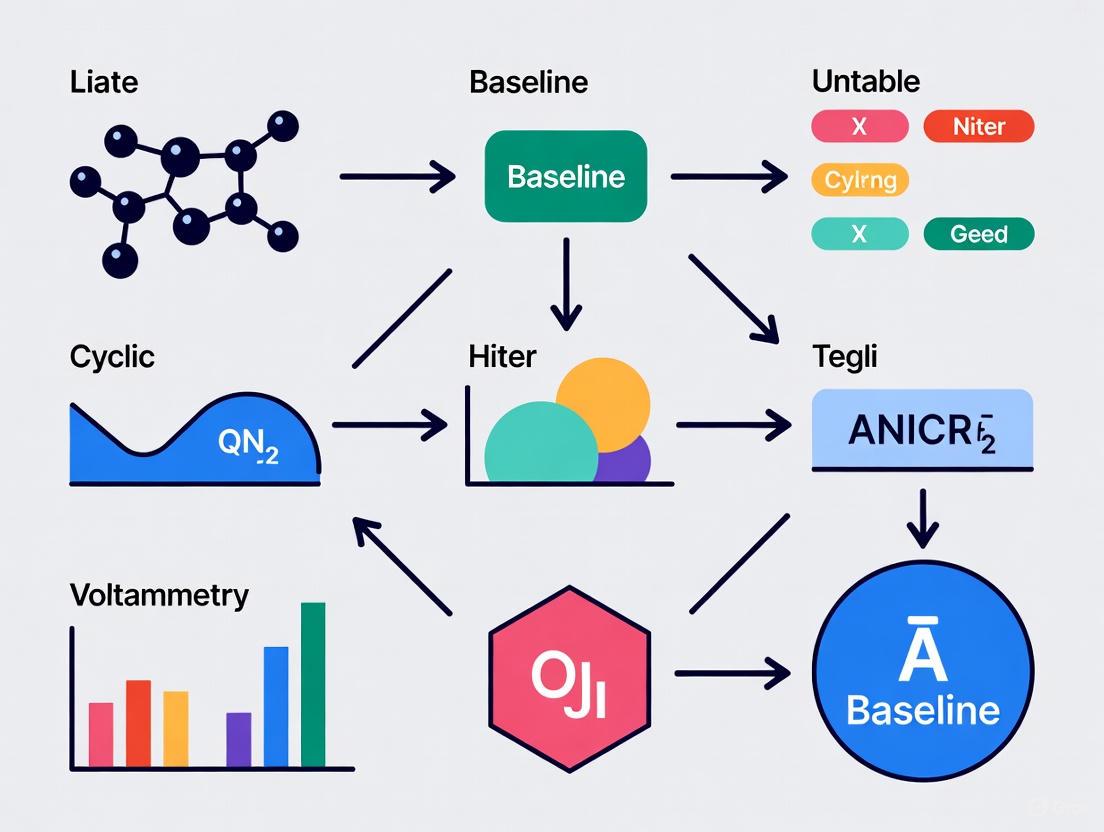

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for implementing this digital filtering technique.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My baseline has a large, reproducible "hump" or "duck shape." Is this instability, and how can I fix it? A: A reproducible, hysteresis-shaped background is often due to charging currents, not instability. This is a predictable capacitive effect of the electrode-solution interface [1] [4]. To reduce it, lower your scan rate, use a smaller working electrode, or digitally subtract a background scan recorded in pure electrolyte solution [1] [4].

Q2: I've polished my electrode, but the baseline is still noisy. What should I check next? A: After confirming electrode cleanliness, investigate your connections and environment. Ensure all cables are securely connected and that the reference electrode frit is not blocked [1]. Implement proper shielding for your cables and electrochemical cell to guard against external electromagnetic interference [1].

Q3: Are there algorithmic methods to correct for baseline drift in existing data? A: Yes, computational methods are highly effective. Besides the high-pass filter technique described above, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) can also be used for background drift reduction, though it may be less effective than a high-pass filter for some long-term data [5]. Many modern potentiostat software packages include built-in baseline correction tools.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Materials for Cyclic Voltammetry Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale | Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Alumina Polishing Slurry (e.g., 0.05 μm) | For mechanical polishing of solid working electrodes (e.g., glassy carbon, Pt) to create a fresh, reproducible surface [1]. | A sequential polishing routine with decreasing particle sizes (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, then 0.05 μm) yields the best results. |

| High-Purity Electrolyte Salt (e.g., TBAPF₆, LiClO₄) | Provides ionic conductivity in the solution without introducing electroactive impurities that can cause extraneous peaks or baseline shifts [1]. | Must be highly purified and dried. The choice of ion can influence electrochemical windows and analyte behavior. |

| Aprotic Solvents (e.g., Acetonitrile, DMF) | Used for non-aqueous electrochemistry, offering wide potential windows and stability for organic molecules and energy materials research [7]. | Must be rigorously dried and purified to remove water and oxygen, which can react with electrogenerated species. |

| Quasi-Reference Electrode (e.g., bare Ag wire) | A simple, inexpensive reference for initial diagnostic tests when a traditional reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) is suspected of failure [1]. | Its potential is not fixed and can drift; it is best for troubleshooting, not for reporting formal potentials. |

| Zero-Phase High-Pass Filter Algorithm | A computational tool for post-processing data to remove low-frequency baseline drift from long-term experiments [5] [6]. | Available in signal processing toolkits (e.g., in MATLAB or Python's SciPy). Critical for fast-scan voltammetry over hours. |

In cyclic voltammetry, the electrode-solution interface behaves fundamentally as a capacitor, leading to the phenomenon of capacitive hysteresis in your baseline measurements. When your potentiostat applies a linearly changing potential, it must constantly charge and discharge this interfacial capacitor, resulting in a current that is out of phase with the voltage scan. This non-faradaic charging current appears as a reproducible hysteresis loop in your baseline on forward and backward scans, distinct from faradaic currents generated by electron transfer to electroactive species [1] [8].

The extent of this hysteresis is directly influenced by your experimental parameters. Higher scan rates produce more pronounced hysteresis because the capacitor must be charged more rapidly, requiring greater current. Similarly, using working electrodes with larger surface areas increases the effective capacitance, amplifying the hysteresis effect [1]. Understanding and controlling these factors is essential for researchers distinguishing between capacitive artifacts and genuine faradaic processes in drug development research.

FAQs on Capacitive Hysteresis and Baseline Instability

Q1: What is the fundamental cause of capacitive hysteresis in cyclic voltammetry?

The electrode-solution interface acts as an electrical capacitor, known as the electrochemical double-layer. When a potential is applied, the electrode surface accumulates charge and electrostatically retains an excess of aqueous cations or anions. During a voltammetric scan, a current flows solely to charge and discharge this interfacial structure as the potential changes. This capacitative current (also described as nonfaradaic current) is the direct cause of the hysteresis observed in your baseline [8].

Q2: How can I distinguish between capacitive hysteresis and faradaic peaks?

Capacitive hysteresis typically appears as a smooth, reproducible background shape that mirrors the voltage scan direction, while faradaic processes produce distinct peaks at characteristic potentials. To isolate the faradaic signal, run a background scan without your analyte present to record the capacitive baseline, then subtract this from your experimental data. The hysteresis will be present in both scans, while faradaic peaks will only appear when your electroactive compound is in solution [1].

Q3: What experimental factors amplify capacitive hysteresis in my measurements?

Several key factors increase capacitive hysteresis:

- Faster scan rates: Increase the current required to charge the double-layer capacitor

- Larger electrode surface area: Increases the capacitance of the interface

- Higher electrolyte concentrations: Can affect the double-layer structure

- Electrode material: Different materials have different intrinsic capacitance properties [1]

Q4: How does capacitive hysteresis relate to broader baseline instability issues?

While capacitive hysteresis is a predictable, reproducible effect, general baseline instability is often non-reproducible across runs and indicates experimental problems. True instability can stem from contamination, electrode fouling, gas bubbles, equipment issues, or changing experimental conditions. Unlike the consistent hysteresis pattern, genuine instability causes integration problems and leads to inaccurate quantitative results [2] [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Hysteresis and Instability

Problem: Excessive Capacitive Hysteresis Obscuring Faradaic Signals

Possible Causes and Solutions:

Scan rate too high

- Solution: Reduce your scan rate to decrease charging current demands

- Protocol: Perform successive scans at 50, 20, and 10 mV/s to observe the reduction in hysteresis

Electrode surface area too large

- Solution: Use a working electrode with smaller dimensions

- Protocol: Switch to a microelectrode if available, noting that the smaller area reduces capacitive effects

Insufficient electrolyte concentration

- Solution: Ensure adequate supporting electrolyte (typically 0.1-1.0 M) to properly form the double-layer

- Protocol: Verify your electrolyte-to-analyte concentration ratio is at least 100:1

Problem: Non-Reproducible Baseline Instability

Diagnostic Procedure:

- Perform condensation test to isolate contamination in sample introduction systems [2]

- Check all electrical connections using a 10 kΩ resistor in place of your electrochemical cell [1]

- Verify electrode cleanliness by polishing working electrode with 0.05 μm alumina slurry [1]

- Test reference electrode by temporarily using a quasi-reference electrode (silver wire) [1]

Common Fixes:

- Clean or replace inlet liner and replace septum if using flow systems [2]

- Bake out analytical column (without exceeding temperature limits) to remove contaminants [2]

- Leak test all fittings and check gas supply quality [2]

- Polish working electrode to remove adsorbed species affecting capacitance [1]

Experimental Parameters and Specifications

Table 1: Technical Specifications Affecting Capacitive Measurements

| Parameter | Typical Range | Effect on Capacitive Hysteresis | Optimization Guidelines |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scan Rate | 1-2000 mV/s [9] | Higher rates increase hysteresis | Use slower scans (10-100 mV/s) for better signal distinction |

| Potential Window | -1200 to +1200 mV (practical) [9] | Wider windows increase total charge | Use minimal span needed for your redox events |

| Current Ranges | ±1 μA to ±1000 μA [9] | Lower ranges highlight hysteresis | Select appropriate range for your faradaic signal magnitude |

| Electrode Area | Varies by electrode type | Larger areas increase capacitance | Use smallest feasible electrode for your application |

| Electrolyte Concentration | 0.1-1.0 M | Lower concentrations can distort double-layer | Maintain high electrolyte:analyte ratio (>100:1) |

Table 2: Comparison of Current Types in Voltammetry

| Current Type | Origin | Dependence | Effect on Voltammogram | Elimination/Reduction Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Capacitive (Charging) Current | Double-layer charging | Scan rate, electrode area | Hysteresis in baseline | Background subtraction, slower scan rates |

| Faradaic Current | Electron transfer reactions | Analyte concentration | Characteristic peaks | Essential for analysis - preserve |

| Residual Current | Potentiostat circuitry, impurities | Fixed system noise | Small, noisy baseline | System cleaning, proper grounding |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Background Subtraction for Hysteresis Correction

Purpose: Isolate faradaic signals from capacitive hysteresis using background subtraction [1] [8]

Materials:

- Identical electrochemical cell setup

- Purified solvent and supporting electrolyte (no analyte)

- Identical electrode set and positioning

Procedure:

- Prepare your experimental solution with analyte and record cyclic voltammogram

- Thoroughly clean cell and electrodes

- Prepare identical solution without analyte (background solution)

- Using identical instrument parameters, record background voltammogram

- Subtract background current values from experimental current values at each potential

- The resulting voltammogram displays primarily faradaic processes

Validation: The subtracted voltammogram should show reduced baseline hysteresis while maintaining faradaic peak integrity.

Protocol 2: System Verification with Resistor Test

Purpose: Verify potentiostat and connections are functioning properly, eliminating them as instability sources [1]

Materials:

- 10 kΩ resistor

- Standard electrode cables

Procedure:

- Disconnect your electrochemical cell

- Connect reference and counter electrode cables to one side of resistor

- Connect working electrode cable to other side of resistor

- Run potential scan from +0.5 V to -0.5 V

- Verify result is straight line obeying Ohm's law (V = IR)

- Any deviations indicate potentiostat or cable issues

Troubleshooting: Nonlinear responses or noise indicate potentiostat problems requiring service or cable replacement.

Signaling Pathways and System Relationships

Capacitive Hysteresis Mechanism

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Reliable Voltammetry

| Material/Reagent | Function | Usage Notes | Quality Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., TBAP, LiClO₄) | Provides ionic conductivity; determines double-layer structure | Use 100:1 ratio with analyte; ensure high purity | Low water content; electrochemically inert in potential window |

| Electrode Polishing Kit (0.05 μm alumina) | Renews electrode surface; ensures reproducible capacitance | Polish between experiments; ultrasonic cleaning | Consistent particle size; contamination-free |

| High-Purity Solvents (acetonitrile, DCM) | Dissolves analyte and electrolyte; determines potential window | Dry and degas before use; store properly | Low water content; minimal electroactive impurities |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Provide consistent surface area; disposable use | Follow cleaning protocols; check connector integrity [9] | Lot-to-lot consistency; stable reference electrode |

| Quasi-Reference Electrodes (silver wire) | Troubleshooting reference electrode issues | Temporary replacement for diagnosis [1] | Clean surface; stable potential |

| Background Electrolyte Solution | For background subtraction protocol | Identical to experimental minus analyte | Match purity and concentration exactly |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the most common symptoms of cable faults or poor connections in a cyclic voltammetry setup? Common symptoms include a noisy, small, and unchanging current, voltage or current compliance errors from the potentiostat, an unusual or distorted voltammogram that may change shape on repeated cycles, and a baseline that is not flat [1]. If the working electrode is not properly connected, the potential may change but little to no faradaic current will be measured [1].

2. How can I systematically test if my potentiostat and cables are functioning correctly? A general troubleshooting procedure suggests bypassing the electrochemical cell [1]:

- Disconnect the cell and connect the electrode cable to a 10 kΩ resistor.

- Connect the reference and counter cables to one side of the resistor and the working electrode cable to the other.

- Run a scan (e.g., from +0.5 V to -0.5 V). If the equipment is working, the result will be a straight line where all currents follow Ohm's law (V=IR) [1]. Some manufacturers supply a test chip that can be used for a similar purpose, providing a known, predictable response [1].

3. My reference electrode is suspected to be faulty. How can I check it? You can perform a test by modifying your setup [1]:

- Set up your cell as usual, but connect the reference electrode cable to the counter electrode (in addition to the counter electrode cable).

- Run a linear sweep experiment with your analyte. If a standard, though potentially shifted and slightly distorted, voltammogram is obtained, it indicates a problem with the reference electrode.

- Check for a blocked frit or air bubbles at the bottom of the reference electrode. As a further test, replacing the reference with a clean silver wire (a quasi-reference electrode) can confirm the issue [1].

4. Why is the baseline in my voltammogram not flat, and what can I do about it? A non-flat baseline can be caused by problems with the working electrode, such as poor internal contacts or seals [1]. Additionally, charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts like a capacitor, can cause hysteresis [1]. To mitigate this, you can:

- Reduce the scan rate.

- Increase the concentration of your analyte.

- Use a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1].

5. What should I check if the potentiostat shows a "Voltage Compliance" error? This error means the potentiostat cannot maintain the desired potential between the working and reference electrodes [1]. Check:

- Counter Electrode Connection: Ensure it is properly submerged in the solution and connected to the potentiostat [1].

- Quasi-Reference Electrode: If using one, ensure it is not touching the working electrode [1].

6. What should I check if the potentiostat shows a "Current Compliance" error? This error is often due to a short circuit, causing a large current [1]. Check that the working and counter electrodes are not touching inside the solution [1].

Troubleshooting Data and Protocols

Table 1: Common Issues and Diagnostic Steps

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Diagnostic Action |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage compliance error | Counter electrode disconnected or out of solution; QRE touching WE [1] | Check all electrode connections and placements in solution [1]. |

| Current compliance error | Working and counter electrodes touching (short circuit) [1] | Visually inspect electrode spacing in the cell [1]. |

| Small, noisy current | Poor connection to the working electrode [1] | Check cable and connector integrity; ensure WE is properly seated [1]. |

| Unusual voltammogram, different each cycle | Faulty reference electrode connection; blocked frit; air bubbles [1] | Perform the reference electrode test; check for blockages [1]. |

| Large hysteresis in baseline | Charging currents at the electrode-solution interface [1] | Reduce scan rate, increase analyte concentration, or use a smaller WE [1]. |

| Unexpected peaks | Impurities in system or solvent/electrolyte [1] | Run a background scan without the analyte [1]. |

Table 2: Electrode-Specific Connection Issues

| Electrode | Common Connection Issues | Troubleshooting and Maintenance |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Poor electrical contact; surface fouling; poor seal causing high resistivity or capacitance [1]. | Polish with alumina slurry; clean via electrochemical cycling in H₂SO₄ (for Pt); ensure good contact with holder [1]. |

| Reference Electrode | Blocked frit (salt-bridge); air bubbles; contaminated fill solution; drifting potential [10]. | Check for and remove bubbles; ensure frit is not blocked; replace fill solution; use a fresh quasi-reference electrode for testing [1] [10]. |

| Counter Electrode | Disconnected; not submerged; isolated by a blocked frit in an isolation tube [1] [10]. | Ensure electrode is submerged and connected; if using an isolation tube, pre-fill it with electrolyte to ensure solution contact on both sides of the frit [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: General Potentiostat and Cable Check

This protocol helps isolate the problem to the potentiostat, cables, or the electrochemical cell [1].

- Equipment: Potentiostat, connecting cables, a 10 kΩ resistor.

- Procedure:

- Disconnect all cables from the electrochemical cell.

- Connect the Reference (REF) and Counter (CE) electrode cables to one lead of the resistor.

- Connect the Working (WE) electrode cable to the other lead of the resistor.

- On the potentiostat, set up a linear sweep voltammetry experiment, scanning from +0.5 V to -0.5 V.

- Expected Outcome: A successful test will result in a straight-line current-voltage plot that obeys Ohm's Law (V = IR). Any other result indicates a fault with the potentiostat or cables [1].

Experimental Protocol: Reference Electrode Functionality Check

This test helps verify if the reference electrode is the source of an issue [1].

- Equipment: Standard electrochemical cell setup.

- Procedure:

- Set up the cell with working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode as normal.

- Modify the connections: Connect the reference electrode cable to the counter electrode (along with the counter electrode cable). This effectively removes the reference electrode from the controlling circuit.

- Run a standard linear sweep or cyclic voltammetry experiment with your analyte.

- Expected Outcome: If a recognisable voltammogram (though shifted in potential and somewhat distorted) appears, it confirms a problem with the original reference electrode. You should then inspect its frit for blockages or replace it [1].

Workflow and Material Guides

Troubleshooting Workflow Diagram

The diagram below outlines a logical sequence for diagnosing common equipment and connection issues.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key items used in the experiments and troubleshooting protocols cited in this field.

| Item | Function / Relevance |

|---|---|

| Alumina Polish (0.05 μm) | Used for polishing working electrodes to refresh and activate the surface, removing adsorbed contaminants [1]. |

| Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) | A common electrolyte used in alkaline electrochemical studies, such as investigations into the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) [11]. |

| Sulfolane (SL) | A solvent studied for use in high-temperature electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries due to its high thermal and oxidative stability [12]. |

| Vinylene Carbonate (VC) | A functional electrolyte additive that helps form a stable Solid Electrolyte Interphase (SEI) on electrodes, improving battery cycle life [12]. |

| Acetaminophen in Contact Lens Solution | Used as a standard test solution to verify the proper function of a cyclic voltammetry system, producing a characteristic "duck-shaped" voltammogram [13]. |

| Ruthenium Hexamine (RuHex) | A reversible redox probe commonly used for sensitive electrochemical characterization of newly fabricated electrodes [14]. |

Troubleshooting FAQs: Direct Solutions for Experimental Challenges

FAQ 1: My potentiostat reports a "voltage compliance" error. What is the most likely cause and how can I resolve it?

A voltage compliance error occurs when the potentiostat is unable to maintain the desired potential between the working and reference electrodes [1]. The most common causes are a disconnected counter electrode or a quasi-reference electrode that is physically touching the working electrode [1].

Resolution Protocol:

- Inspect Electrode Connections: Ensure the counter electrode cable is securely connected to the potentiostat and that the counter electrode itself is fully submerged in the electrolyte solution.

- Check Electrode Placement: Verify that no electrodes are touching each other within the cell. Use the cell lid or electrode holders to ensure proper spacing.

- Test with a Simple System: If the error persists, perform a diagnostic scan using a 10 kΩ resistor in place of the electrochemical cell. Connect the reference and counter cables to one side of the resistor and the working electrode cable to the other. A scan from +0.5 V to -0.5 V should yield a straight line obeying Ohm's law (V=IR), confirming the potentiostat and cables are functional [1].

FAQ 2: My cyclic voltammogram shows an unusual shape or looks different on repeated cycles. What should I investigate first?

This problem frequently stems from an issue with the reference electrode, specifically its electrical connection to the solution [1]. A blocked frit or an air bubble trapped at the tip of the reference electrode can disrupt the potential measurement, causing unstable and distorted voltammograms [1].

Resolution Protocol:

- Inspect the Reference Frit: Check for visible blockages or crystallization at the porous frit of the reference electrode.

- Dislodge Air Bubbles: Gently tap the electrode or the cell to dislodge any air bubbles. Ensure the electrode tip is fully immersed.

- Test with a Quasi-Reference Electrode: Replace the reference electrode with a clean silver wire (a quasi-reference electrode) and run the measurement again. If a correct response is obtained, it confirms an issue with the original reference electrode, likely a blocked frit [1].

FAQ 3: The baseline of my voltammogram is not flat and shows significant hysteresis. Is this a sign of a faulty electrode?

Not necessarily. A hysteretic baseline, which looks different on the forward and backward scans, is primarily due to the charging current at the electrode-solution interface, which behaves like a capacitor [1]. While faults in the working electrode can exacerbate this, it is often a fundamental characteristic of the setup.

Resolution Protocol:

- Adjust Experimental Parameters: You can reduce the charging current by:

- Polish the Working Electrode: To rule out surface contamination, polish the working electrode with a fine alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 μm) and rinse it thoroughly [1].

- Perform a Background Scan: Always run a CV scan of just the electrolyte solution (without analyte) and subtract it from your sample scan. This removes the capacitive background current inherent to your specific cell setup [15].

Diagnostic Guide: Linking Symptoms to Physical-Chemical Causes

The table below summarizes the core issues, their observable symptoms, and underlying physical-chemical origins.

Table 1: Diagnostic Guide for Common CV Baseline Issues

| Physical-Chemical Origin | Primary Observable Symptom | Underlying Cause & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Uncompensated Resistance (Ru) | Peak potential separation (ΔEp) increases with scan rate, distorted reversible response [15]. | Solution resistance between working and reference electrodes causes an iR drop. This unmeasured voltage drop distorts the applied potential, slowing electron transfer kinetics and widening peaks [15]. |

| Blocked Reference Electrode Frit | Unusual, drifting, or non-reproducible voltammograms; unstable baseline between cycles [1]. | A blocked frit (e.g., by salt crystals or debris) increases electrical resistance, preventing the reference electrode from maintaining a stable potential. The system behaves like a capacitor, leading to drifting measurements [1]. |

| Air Bubbles in the Reference Electrode | Noisy, drifting baseline; "unusual looking" or shifting voltammograms [1]. | An air bubble trapped between the frit and the internal wire of the reference electrode breaks the electrical circuit. This prevents a stable reference potential from being established [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Problem Resolution

Protocol 1: General Potentiostat and Electrode Functionality Test

This procedure helps isolate whether a problem originates from the potentiostat/cables or the electrodes themselves [1].

- Disconnect the Electrochemical Cell.

- Connect a 10 kΩ Resistor: Connect the reference (RE) and counter (CE) electrode cables to one terminal of the resistor. Connect the working electrode (WE) cable to the other terminal.

- Run a Diagnostic Scan: Set a cyclic voltammetry method to scan from +0.5 V to -0.5 V and back.

- Analyze the Result: A correct, functional system will produce a straight, linear current response that follows Ohm's law (V = IR). Any other result indicates a problem with the potentiostat or cables [1].

Protocol 2: Diagnosis and Cleaning of a Blocked Reference Electrode Frit

If a quasi-reference electrode works but your standard reference electrode does not, the frit is likely blocked [1].

- Inspection: Visually inspect the frit at the tip of the reference electrode for any discoloration or solid material.

- Flushing (for Refillable Electrodes): If possible, carefully expel a small amount of filling solution from the electrode to clear the frit.

- Solvent Cleaning: For persistent blockages, place the electrode tip in a warm solvent (e.g., deionized water, ethanol) for several hours to dissolve the blockage. Note: Ensure the solvent is compatible with the reference electrode's construction materials and filling solution. The principle is similar to cleaning HPLC column frits, where reversed-flow with an appropriate solvent is used to dislodge particles [16].

- Replacement: If cleaning fails, the reference electrode should be replaced.

Research Reagent and Material Solutions

The following table lists key materials essential for reliable cyclic voltammetry experiments.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Stable CV Measurements

| Item | Function & Importance in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Alumina Polishing Slurry (0.05 μm) | Used for resurfacing the working electrode to a mirror finish. Removes adsorbed contaminants that can cause sloping baselines or unwanted peaks, ensuring reproducible surface chemistry [1]. |

| High-Purity Electrolyte Salt | Provides ionic conductivity in the solution. Must be electrochemically inert over the potential window of interest. Impurities can introduce extraneous faradaic currents and unexpected peaks [1]. |

| Quasi-Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag wire) | A simple, bare silver wire serves as a diagnostic tool. It can be used to quickly determine if a problem is caused by a faulty commercial reference electrode [1]. |

| Test Cell Chip / 10 kΩ Resistor | Used for potentiostat verification. The test chip provides known electrical pathways, while the resistor simulates a simple cell, allowing you to confirm the instrument's functionality before troubleshooting complex cell issues [1]. |

Diagnostic Workflow for Unstable Baselines

The following diagram outlines a logical pathway for diagnosing and resolving the core issues discussed in this guide.

This technical support document addresses a critical challenge in electrochemical research: unstable baselines in cyclic voltammetry (CV). A primary source of this instability is electrode fouling, the accumulation of unwanted material on the electrode surface, which alters its electrochemical properties [17]. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting and FAQs to help researchers identify, address, and prevent fouling-related issues, ensuring the accuracy and reliability of experimental data.

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosis of Fouling-Related Baseline Issues

The following table outlines common symptoms of electrode fouling and their underlying causes.

Table 1: Symptoms and Causes of Electrode Fouling

| Observed Symptom | Possible Fouling Cause | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable or drifting baseline [1] [18] | Buildup of insulating organic layers or proteins [19] | The fouling layer acts as a capacitor, leading to charging currents and hysteresis [1]. |

| Gradual decrease in peak current (loss of sensitivity) [17] | Biofouling or chemical fouling on the working electrode [19] [17] | The fouling layer physically blocks diffusion of the analyte to the electrode surface and hinders electron transfer [19]. |

| Shift in peak potential [17] | Fouling of the working electrode or reference electrode [17] | On the working electrode, fouling can slow electron transfer kinetics. On a Ag/AgCl reference electrode, contamination from species like sulfide ions alters its stable potential [17]. |

| Unexpected peaks [1] | Adsorption of impurity molecules or degradation products | Impurities from solvents, electrolytes, or the atmosphere can adsorb onto the surface and become electroactive [1]. |

Systematic Troubleshooting Procedure

Follow this logical workflow to systematically identify the source of persistent problems. This procedure, adapted from general CV troubleshooting [1], helps isolate issues related to the instrument, cables, or electrodes.

Electrode Cleaning Protocols

The table below summarizes established cleaning methods for different electrode types. Always rinse electrodes thoroughly with purified water (e.g., Millipore Milli-Q) after cleaning [20].

Table 2: Electrode Cleaning Methods and Applications

| Electrode Type | Cleaning Method | Protocol Details | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Gold Electrodes (SPGEs) | Electrochemical Cleaning [20] | 150 µL of 3% H₂O₂ and 0.1 M HClO₄; 10 CV cycles from -700 mV to 2000 mV (vs. Ag/AgCl) at 100 mV/s [20]. | Mutation detection, genosensors [20]. |

| Platinum Electrodes | Electrochemical Cycling [1] | Cycle potential in 1 M H₂SO₄ between the potentials for H₂ and O₂ evolution. | General-purpose cleaning of Pt surfaces. |

| General Working Electrodes | Mechanical Polishing [1] | Polish with 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth, followed by sonication in water and methanol [1]. | Removal of adsorbed species and physical debris. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My baseline shows a large, reproducible hysteresis on forward and backward scans. Is this fouling? This is often caused by charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts as a capacitor [1]. While this can be exacerbated by a fouling layer, it is primarily an intrinsic property of the system. You can reduce this effect by decreasing the scan rate, increasing analyte concentration, or using a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1].

Q2: Why do I see a peak shift in my voltammograms after implanting an electrode in a biological sample? Peak shifts, particularly in vivo, can be due to fouling of both the working and reference electrodes [17]. While working electrode fouling is common, the reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) is also vulnerable. For example, sulfide ions in the brain can react with the Ag/AgCl, decreasing its open circuit potential and causing a measurable peak shift in your voltammograms [17].

Q3: I've cleaned my electrode, but sensitivity is still low. What else could be wrong? Confirm that your cleaning procedure was effective and appropriate for your electrode material. A poorly connected working electrode can also result in very small, noisy currents [1]. Check all physical connections. Furthermore, ensure your reference electrode is not blocked. A blocked frit or air bubble can break electrical contact, leading to unusual and unstable voltammograms [1].

Q4: Are there advanced techniques to detect fouling in industrial processing equipment? Yes, electrochemical techniques like Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) using microelectrodes show great promise [19]. The principle is that the attachment of a fouling layer to the microelectrode surface leads to a lower current response compared to a clean electrode, allowing for detection [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents used in electrode cleaning, characterization, and fouling research as discussed in the cited literature.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Fouling Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Alumina Polish (0.05 µm) | Mechanical abrasion to remove surface contaminants from solid electrodes [1]. | Polishing glassy carbon or platinum working electrodes before experiments [1]. |

| Potassium Ferricyanide/Ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Redox probe for characterizing electrode surface quality and electron transfer kinetics [20]. | Using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) to test electrode performance before and after cleaning [20]. |

| Perchloric Acid (HClO₄) | Component of electrochemical cleaning solutions for oxidizing organic contaminants [20]. | Used with H₂O₂ in a specific electrochemical protocol to clean screen-printed gold electrodes [20]. |

| Hydrogen Peroxide (H₂O₂) | Oxidizing agent in chemical and electrochemical cleaning procedures [20]. | Part of the "piranha" solution variant for removing organic residues from electrode surfaces [20]. |

| Sulfide Ions (S²⁻) | Model foulant for studying chemical fouling of reference electrodes (Ag/AgCl) [17]. | Investigating the mechanism of peak potential shifts in voltammetry during in vivo experiments [17]. |

| 11-mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA) | Self-assembled monolayer (SAM) for functionalizing gold surfaces in biosensor development [20]. | Immobilizing DNA probes on screen-printed gold electrodes for genosensing applications [20]. |

Achieving Stable Baselines in Real-World Applications: From Drug Discovery to Biomarker Detection

Within the context of thesis research on unstable baselines in cyclic voltammetry (CV), the pre-treatment and modification of working electrodes emerge as a critical first line of defense. An unstable baseline, characterized by drift, excessive noise, or non-reproducible background current, can obscure faradaic signals, compromise detection limits, and lead to inaccurate quantitative results [2] [8]. This instability often originates from the state of the electrode surface, including contaminants, variable surface oxides, or inconsistent electrochemical activity [21] [22]. This technical support center guide outlines proven protocols for electrode pre-treatment and modification, providing researchers and scientists in drug development with detailed methodologies to enhance signal stability, improve reproducibility, and achieve reliable electrochemical measurements.

Core Concepts: Pre-Treatment vs. Modification

Electrode Pre-treatment refers to the in-situ or ex-situ preparation of a bare electrode to achieve a clean, electrochemically active, and reproducible surface. The goal is to remove contaminants and create a consistent baseline for measurements [21] [23].

Electrode Modification involves applying a coating or film to the electrode surface to impart new properties, such as increased selectivity towards a specific analyte or enhanced electrocatalytic activity [24].

The logical relationship between these processes, their objectives, and their outcomes is summarized in the following workflow:

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Electrochemical Pre-treatment of a Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE)

This protocol is adapted from a published method for activating a GCE to resolve the overlapping signals of dopamine and ascorbic acid, a common interference issue in neurochemical research [21].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Alumina Slurry (0.5 µm) | Abrasive polishing agent for physically removing old surface layers and contaminants. |

| Phosphate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 6.0) | Supporting electrolyte for the electrochemical activation step; provides ionic conductivity. |

| Deionized Water | For rinsing electrodes to remove all polishing residues and soluble impurities. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Mechanical Polishing:

- Prior to the first use, polish the GCE surface thoroughly with a 0.5 µm alumina slurry on a micro-cloth pad.

- Use a figure-eight polishing motion for 30-60 seconds with moderate pressure [23].

- Rinse the electrode copiously with deionized water to remove all alumina particles.

Electrochemical Activation:

- Place the cleaned GCE in an electrochemical cell containing 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) as the supporting electrolyte.

- Using a potentiostat, perform cyclic voltammetry with the following parameters [21]:

- Potential Range: 1.5 V to 2.0 V (vs. SCE)

- Number of Cycles: 10 scans

- Scan Rate: Not specified in the source, but a standard rate of 100 mV/s is typically suitable.

- Remove the electrode from the cell and rinse it with deionized water. The GCE is now activated and ready for use.

Troubleshooting Tip: If the baseline remains unstable after this procedure, the electrode may require more extensive cleaning. A second polishing step with a finer alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 µm) can be performed, followed by repeating the electrochemical activation [23].

Protocol 2: Tryptophan Modification for Enhanced Dopamine Detection

This protocol describes the electrodeposition of L-Tryptophan (TRP) onto a carbon-fiber microelectrode to boost sensitivity and selectivity for dopamine, which is highly relevant for neurodegenerative disease research [24].

Research Reagent Solutions:

| Reagent/Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| L-Tryptophan (TRP) in PBS | The modifying agent that forms a film on the electrode to facilitate electron transfer. |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | The electrolyte medium for the electrodeposition process. |

| Lithium Perchlorate (LiClO₄) | A conducting salt added to the deposition solution to enhance current flow. |

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | A physiologically relevant medium for subsequent analyte detection and calibration. |

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Electrode Pre-Cycling:

- Fabricate or obtain a carbon-fiber microelectrode.

- Prior to modification, cycle the electrode in aCSF in a potential window of -0.4 V to 1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at 60 Hz for 15 minutes, then at 10 Hz for 5 minutes to stabilize the background current [24].

Tryptophan Electrodeposition:

- Prepare a deposition solution of 1-10 mM L-Tryptophan in PBS, with the addition of 0.1 M LiClO₄.

- Transfer the electrode to the TRP deposition solution.

- Using a slow scan rate of 0.02 V/s, cycle the potential between -1.7 V and 1.8 V for 3 complete cycles to form the TRP film on the carbon surface [24].

- Remove the electrode, rinse gently, and store in PBS or aCSF until use.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: Why is the baseline in my CV experiment unstable and drifting? A: Baseline drift is a common symptom of an impure or changing electrode surface. The primary causes are:

- Contaminated Electrode: Adsorption of solution impurities or sample components onto the electrode surface over time [2].

- Unstable Reference Electrode: A clogged junction or depleted fill solution in the reference electrode can cause potential drift [25].

- Incomplete Electrode Conditioning: The electrode may not have been cycled sufficiently to reach a stable, oxidized state before data collection [21].

Q2: I have polished my electrode, but the redox peaks are still broad and the peak separation is large. What should I do? A: Broad peaks and large peak separation (ΔEp) indicate slow electron transfer kinetics. This suggests that mechanical polishing alone is insufficient.

- Action: Implement an electrochemical pre-treatment protocol (see Protocol 1) immediately after polishing. This process creates functional groups on the carbon surface that facilitate faster electron transfer, sharpening the peaks and reducing ΔEp [21] [22].

Q3: How can I make my electrode selective for my analyte of interest when interferents are present? A: Electrode modification is the standard approach to this problem.

- Action: Apply a selective membrane or film, such as the Tryptophan modification detailed in Protocol 2. This film can repel interfering anions (like ascorbate) at physiological pH while attracting cationic analytes (like dopamine), or it can catalyze the reaction of your target molecule, thereby resolving overlapping signals [21] [24].

Troubleshooting Quick-Reference Table

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unstable, drifting baseline | Contaminated electrode surface | Repolish electrode and perform electrochemical pre-treatment [2] [21] |

| Low sensitivity / signal | Passivated or fouled electrode | Electrode pre-treatment or application of a catalytic modifier (e.g., TRP) [24] [22] |

| Poor reproducibility between scans | Inconsistent electrode surface state | Strict adherence to a standardized pre-treatment protocol before each measurement [21] [23] |

| Overlapping peaks from interferents | Lack of selectivity | Modify electrode with a selective agent (e.g., Nafion, TRP) to repel or discriminate against interferents [21] [24] |

Performance Data of Different Electrode Surfaces

The following table summarizes quantitative performance improvements achievable through the electrode engineering techniques discussed in this guide.

| Electrode Type / Treatment | Target Analyte | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activated GCE (Electrochemically pre-treated) | Dopamine (DA) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | 6.2 × 10⁻⁷ M | [21] |

| Activated GCE (Electrochemically pre-treated) | Dopamine (DA) | Linear Range | 6.5 × 10⁻⁷ – 1.8 × 10⁻⁵ M | [21] |

| TRP-modified Carbon Fiber | Dopamine (DA) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | 2.48 ± 0.34 nM | [24] |

| TRP-modified Carbon Fiber | Dopamine vs. Ascorbic Acid | Selectivity (DA/AA) | 15.57 ± 4.18 | [24] |

| Uncoated Carbon Fiber (for comparison) | Dopamine (DA) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | 8.35 ± 0.41 nM | [24] |

| Pre-treated GCE (in H₂SO₄) | Catechol (CC) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.94 µM | [22] |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting an Unstable or Noisy Baseline

An unstable, drifting, or noisy baseline is a common issue that can obscure Faradaic peaks and compromise data integrity. Follow this systematic procedure to identify and resolve the problem [1].

Check Electrode Connections and Setup: Ensure all cables (working, counter, and reference electrodes) are properly connected to the potentiostat and are intact. Poor contacts can generate unwanted signals and noise [1]. Confirm that the counter electrode is submerged and correctly connected; improper connection can prevent the potentiostat from controlling the potential, leading to instability [1].

Inspect and Polish the Working Electrode: Problems with the working electrode are a primary cause of a non-ideal baseline [1]. Polish the working electrode (e.g., with 0.05 μm alumina) and wash it thoroughly to remove any absorbed species [1]. For a Pt electrode, you can clean it by cycling in 1 M H₂SO₄ solution between potentials where H₂ and O₂ are produced [1].

Verify the Reference Electrode: An incorrectly set-up reference electrode can cause an unusual-looking voltammogram that changes on repeated cycles [1]. Check that the salt-bridge or frit is not blocked and that no air bubbles are trapped at the bottom [1]. You can test this by temporarily using a bare silver wire as a quasi-reference electrode; if the response improves, the original reference electrode may be faulty [1].

Check for System Impurities: Unusual peaks or a drifting baseline can be caused by impurities in the electrolyte, solvent, or from atmospheric contamination [1]. Run a background scan of only the electrolyte and solvent to identify if the issue originates from an impurity. Ensure all glassware is meticulously cleaned.

Adjust Experimental Parameters: A large, reproducible hysteresis in the baseline is often due to the capacitive charging current of the electrode-solution interface [1]. This can be mitigated by reducing the scan rate, using a higher concentration of supporting electrolyte, or employing a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1].

Guide 2: Troubleshooting a Flat or Clipped Voltammogram

The absence of expected peaks or a signal that appears "clipped" often points to issues with instrument settings or solution composition.

Verify Current Range Setting: A flat signal can occur if the actual current exceeds the potentiostat's set range, causing the signal to clip [26]. Solution: Open your potentiostat settings and adjust the current range to a higher value (e.g., from 100 µA to 1000 µA) [26].

Confirm Analyte and Electrolyte Presence: A very small, noisy, but unchanging current may indicate that the working electrode is not properly connected, or that the analyte is absent from the solution [1]. Solution: Double-check the working electrode connection and confirm the solution contains your target analyte at a sufficient concentration alongside the necessary supporting electrolyte [1].

Check Electrolyte Conductivity: The molar conductivity of your electrolyte solution is critical. If the electrolyte concentration is too low or the ion pairing is too strong, solution resistance will be high, distorting the voltammogram. Solution: Ensure a sufficient concentration of supporting electrolyte (typically 0.1 M or higher). Note that the solvent's viscosity also affects conductivity; for example, the bio-solvent Cyrene has high viscosity, leading to lower molar conductivity [27].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: How do I select an appropriate scan rate for my experiment? The choice of scan rate depends on your goal. Use slow scan rates (e.g., 1-50 mV/s) to study steady-state behavior or reactions with slow kinetics. Use faster scan rates (0.1-5 V/s) to study rapid reaction kinetics or to minimize diffusion layer thickening [28]. If you observe large hysteresis in the baseline, the scan rate may be too high, increasing capacitive charging currents; reduce the scan rate to mitigate this [1].

Q2: What factors should I consider when choosing a supporting electrolyte? Key factors include:

- Solubility: The salt must dissolve sufficiently in your solvent.

- Voltage Window: The electrolyte must be electrochemically inert within your chosen potential range to avoid decomposition.

- Conductivity: Prefer electrolytes with high molar conductivity to minimize solution resistance. Salts with smaller cations (e.g., MeEt₃N⁺) often show higher conductivity than larger ones (e.g., Bu₄N⁺) in high-viscosity solvents [27].

- Ion-Pairing: Be aware that large anions like PF₆⁻ have larger association constants, which can reduce conductivity [27].

Q3: My voltammogram has an unexpected peak. What could be the cause? Unexpected peaks are often due to:

- Impurities: Contaminants in the solvent, electrolyte, or from the atmosphere [1].

- Edge of Potential Window: A peak appears as the scanning potential approaches the solvent/electrolyte decomposition limit. Run a background scan without your analyte to identify these peaks [1].

- Electrode Surface Redox Processes: The electrode material itself may undergo surface reactions.

Q4: How can I define a suitable potential window for a new solvent/electrolyte system? The practical potential window is determined by the oxidation and reduction limits of your specific combination of solvent and supporting electrolyte. It is not a fixed property of the solvent alone. Determine it experimentally by running a cyclic voltammetry scan in your electrolyte solution without the analyte present. The anodic and cathodic currents will rise sharply at the decomposition limits, defining your usable window [27].

Experimental Parameter Tables

| Parameter | Configurable Range | Typical Settings for Different Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Scan Rate | 1×10⁻⁴ to 10,000 V/s | Steady-state: 1-50 mV/sStandard electrode studies: 0.01 - 5 V/sUltrafast kinetics (microelectrodes): Up to kV/s |

| Initial/Final Potential | -10 V to +10 V | Aqueous systems: Typically within ±2.0 VOrganic systems: Can extend to ±5.0 V |

| Cycle Number | 1 to 500,000 | Most experiments: 3-50 cycles |

| Solvent | Boiling Point (°C) | Dielectric Constant (ε) | Viscosity (cP at 20°C) | Green Credentials |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyrene (DLG) | 203 | 37.3 | 14.5 | Biodegradable, bio-renewable, non-toxic |

| DMF | 153 | 36.7 | 0.92 | Toxic, environmental concern |

| NMP | 202 | 33 | 1.65 | Toxic, environmental concern |

| DMSO | 189 | 46.7 | 1.99 | -- |

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function & Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Tetraalkylammonium Salts(e.g., Bu₄NBF₄, Et₄NPF₆) | Common supporting electrolyte for organic electrochemistry. Provides conductivity without participating in reactions [27]. | Smaller cations (MeEt₃N⁺) provide higher conductivity than larger ones (Bu₄N⁺). Anions with large radii (PF₆⁻) favor ion-pairing [27]. |

| Sulfolane (SL) | A polar aprotic solvent for high-temperature Li-ion batteries. Offers high oxidative stability (>5 V) and thermal robustness [12]. | Has strong coordination ability with Li⁺, which can hinder formation of a stable inorganic SEI. Requires additives like VC for stable interphases [12]. |

| Vinylene Carbonate (VC) | A functional electrolyte additive. Polymerizes to form a stable solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) on anode surfaces, improving cycle life [12]. | Its moderate coordination ability and passivation capability enable controllable formation of thermally stable SEIs, especially in SL-based electrolytes [12]. |

| NaOH | Used for pH adjustment in electrochemical lithium recovery processes [29]. | NaOH-adjusted electrolytes can provide the highest lithium-ion recovery efficiency from spent batteries, though competing cations (Na⁺) can impact long-term selectivity [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

- Prepare Solution: Create a solution containing your analyte of interest, a supporting electrolyte (at a concentration typically 50-100 times that of the analyte), and a solvent that dissolves both.

- Assemble Cell: Add the electrolyte solution to the electrochemical cell.

- Insert Electrodes: Place the lid on the cell and insert the working, counter, and reference electrodes into the solution.

- Connect Hardware: Connect the cell to the potentiostat.

- Configure Software: Start the electrochemistry software and enter the desired experimental parameters (initial/final potential, scan rate, number of cycles, etc.).

- Run Experiment: Initiate the measurement.

This protocol uses multi-scan-rate CV to characterize a reversible redox couple.

- Run Multi-Scan CV: Perform cyclic voltammetry experiments at several scan rates (e.g., 25, 50, 100 mV/s).

- Measure Peak Potentials: For a reversible system, the formal redox potential (E°') is calculated as the average of the anodic (Epa) and cathodic (Epc) peak potentials: E°' = (Epa + Epc)/2.

- Determine Reversibility: For a reversible, diffusion-controlled reaction, the peak separation is ΔEp = Epa - Epc ≈ 59/n mV (at 298 K). Use this to estimate the electron transfer number (n).

- Validate with Randles-Sevcik: For a reversible system, the peak current (ip) is proportional to the square root of the scan rate (v^1/2). Plot ip vs. v^1/2; a linear relationship confirms a diffusion-controlled process.

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What are the most common causes of an unstable or drifting baseline in cyclic voltammetry?

Several factors can cause baseline instability. Charging currents at the electrode-solution interface act like a capacitor, leading to hysteresis in the baseline on forward and backward scans [1] [30]. This effect is intensified at higher scan rates. Problems with the working electrode, such as poor contacts in the internal structure, poor seals, or surface fouling, can lead to high resistivity, high capacitances, noise, or sloping baselines [1]. A non-ideal reference electrode can also be a source of instability. If the reference electrode is not in proper electrical contact with the solution (e.g., due to a blocked frit or air bubbles), it can act like a capacitor, causing leakage currents that unexpectedly change the potential and result in an unusual-looking or unstable voltammogram [1]. Finally, slow changes in the electrochemical cell over prolonged recording times, such as electrode surface erosion, fouling, or complex changes in the sample matrix itself, can contribute to nonlinear background drift [31].

Q2: My baseline is not flat and has a significant slope. Is this a problem for quantitative analysis?

Yes, a non-flat baseline can be a significant problem for quantitative analysis, as it can distort the true faradaic current from your analyte, leading to inaccurate peak identification and concentration measurements [1] [30]. To achieve sensitive determination of analytes, the faradaic signal must be isolated from the nonfaradaic (capacitative) background current [30]. While a sloping baseline can sometimes be caused by unknown processes at the electrodes [1], several methods can be used to correct for it, which are detailed in the troubleshooting guide below.

Q3: How can I test if my potentiostat and electrodes are functioning correctly?

A general troubleshooting procedure can help isolate problems with your equipment [1]. You can disconnect the electrochemical cell and connect the electrode cables to a 10 kΩ resistor. Connect the reference and counter cables to one side, and the working electrode cable to the other. Scanning the potentiostat over a range (e.g., ±0.5 V) should produce a straight line where all currents follow Ohm's law (V=IR). Alternatively, if your potentiostat comes with a test chip, you can use it to verify the system's response. Another method is to bypass the reference electrode by connecting the reference electrode cable directly to the counter electrode in a standard cell setup. Running a linear sweep should produce a standard, though potentially shifted and slightly distorted, voltammogram. If this works, the issue likely lies with the reference electrode [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Unstable Baseline

Observed Symptom: The cyclic voltammogram has a drifting baseline, large hysteresis, or is generally unstable over time or between cycles.

| Troubleshooting Step | Detailed Protocol & Rationale | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Verify Electrode Connections & Setup | Check that all three electrodes are properly connected to the potentiostat and are fully submerged in the solution. Ensure the reference electrode is not in physical contact with the counter electrode. Inspect cables for damage [1]. | Eliminates simple connection errors and short circuits that cause noise, compliance errors, and instability [1]. |

| 2. Inspect and Clean the Working Electrode | Polish the working electrode with a fine slurry like 0.05 μm alumina and wash it thoroughly to remove adsorbed species. For a Pt electrode, a more rigorous cleaning can be performed by cycling it between potentials where H₂ and O₂ are evolved in a 1 M H₂SO₄ solution [1]. | Removes surface contaminants that can cause fouling, high resistance, and capacitive effects, leading to a non-straight baseline [1]. |

| 3. Check Reference Electrode Integrity | Ensure the salt-bridge or frit is not blocked and that no air bubbles are trapped at the bottom. A quick test is to replace the reference electrode with a clean silver wire (a quasi-reference electrode) and run a measurement. If the baseline stabilizes, the original reference electrode is likely faulty or blocked [1]. | Confirms that the reference electrode is in proper electrical contact with the solution, providing a stable potential for measurement [1]. |

| 4. Optimize Experimental Parameters | Reduce the scan rate. Charging current is proportional to scan rate; a lower scan rate minimizes its contribution [1]. Use a smaller working electrode. The charging current is also dependent on the electrode surface area [1]. Increase analyte concentration if possible, to improve the faradaic-to-charging current ratio [1]. | A reduction in the dominant capacitive and hysteresis effects, leading to a more stable and flatter baseline. |

| 5. Apply Post-Experiment Data Processing | Apply a background subtraction by taking a voltammogram of just the electrolyte and subtracting it from the sample voltammogram [1] [4]. For long-term drift, use a digital high-pass filter. A zero-phase high-pass filter with a very low cutoff frequency (e.g., 0.001-0.01 Hz) applied to the time-series data at each voltage point can effectively remove drifting patterns while preserving the analyte's faradaic signal [31]. | A corrected voltammogram with a stable, flat baseline, allowing for accurate measurement of faradaic peak currents and potentials. |

Experimental Protocol: Baseline Correction via High-Pass Filtering

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating effective baseline drift removal for sensitive electrochemical measurements over many hours [31].

Objective: To remove slow, nonlinear background drift from cyclic voltammetry data to enable accurate quantitative analysis.

Materials and Software:

- A computer with MATLAB and Statistics Toolbox (Release 2016b or later) or equivalent software capable of implementing digital filters.

- A data set of continuously recorded cyclic voltammograms (e.g., over 5-24 hours) showing baseline drift.

Methodology:

- Data Import: Import the full set of cyclic voltammetry data into the software. The data should be structured as a matrix where each row represents a single voltammogram (current vs. voltage points), and each column represents a time series of current measured at a specific voltage point.

- Filter Design: Implement a zero-phase second-order Butterworth high-pass infinite impulse response (IIR) filter. The "zero-phase" aspect is critical as it filters the data without shifting the temporal alignment of the signals.

- Filter Application Direction: Apply the high-pass filter across the time series at each individual voltage point. This is different from the typical low-pass filtering applied across a single voltammogram to reduce noise. This method targets the slow drift over time.

- Cutoff Frequency Selection: Set the filter's cutoff frequency to a very low value. The study found effective drift removal in the range of 0.001 Hz to 0.01 Hz for data collected at a 10 Hz repetition rate. This preserves the phasic faradaic signals (like a drug oxidation peak) while removing the slow trend.

- Validation: Validate the filtered data by ensuring that the characteristic redox features (peak shape, potential, and temporal kinetics) of your analyte are preserved. The baseline after filtering should be stable and flat.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Essential Material | Function in Ensuring Baseline Stability |

|---|---|

| Alumina Polishing Slurry | Used for mechanical polishing of the working electrode surface (e.g., glassy carbon) to remove adsorbed contaminants and restore a fresh, reproducible surface, minimizing non-faradaic currents [1]. |

| High-Purity Electrolyte | Provides the conductive medium for the experiment. Impurities in the electrolyte are a common source of extraneous peaks and can contribute to a shifting baseline as they oxidize/reduce [1]. |

| Inert Gas (N₂ or Ar) | Used to purge the electrochemical cell solution of dissolved oxygen before measurement. Oxygen is an electroactive species that can produce large, irreversible reduction waves, severely distorting the baseline and obscuring analyte signals [4]. |

| Quasi-Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag wire) | A simple, bare silver wire can serve as a temporary reference electrode for diagnostic purposes. It helps determine if baseline instability originates from a faulty commercial reference electrode with a clogged frit [1]. |

| Potentiostat Test Chip/Resistor | A built-in or supplied test circuit (e.g., a 10 kΩ resistor) used to verify the proper function of the potentiostat and its cables independently of the electrochemical cell, a key first step in troubleshooting [1]. |

Baseline Stability Data Analysis Table

The following table summarizes quantitative findings and parameters related to baseline stability from key studies.

| Parameter / Method | Quantitative Value / Effect | Application Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|

| Charging Current | Proportional to scan rate (ν) and electrode capacitance (Cdl) [15]. | A fundamental source of baseline hysteresis. Minimized by decreasing scan rate or using a smaller electrode [1] [15]. |

| Peak Current Separation (ΔEp) | >59.2/n mV indicates quasi-reversibility or uncompensated resistance [15]. | Used to diagnose slow electron transfer or solution resistance, which can distort the baseline and peaks [15]. |

| High-Pass Filter Cutoff Frequency | Effective range: 0.001 Hz to 0.01 Hz [31]. | Successfully removed drift in 5-24 hour FSCV recordings of dopamine, preserving faradaic features [31]. |

| Pilot Ion Method Accuracy | Fe(II) prediction error: ~13% (avg., for >15 μM); S(-II) prediction error: up to 58% [30]. | A method to correct for electrode sensitivity drift, improving quantitative accuracy despite baseline instability [30]. |

Workflow for Diagnosing Baseline Issues

The diagram below outlines a systematic workflow for diagnosing and resolving common baseline stability problems in cyclic voltammetry.

Logical Relationship of Baseline Correction Methods

This diagram categorizes the primary methods for addressing baseline instability, showing how they relate to the stage of the experiment at which they are applied.

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Why is my cyclic voltammogram flatlining or showing no faradaic current?

A flatlining signal or the absence of expected redox peaks is a common issue when analyzing complex extracts. The causes and solutions are summarized in the table below.

Table: Troubleshooting a Flatlining or No-Faradaic-Current CV Signal

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal is a flat, horizontal line | Incorrect current range setting [26] | Verify if the expected current exceeds the selected range. | Increase the current range setting (e.g., from 100 µA to 1000 µA) [26]. |

| No faradaic current, small noisy signal only | Working electrode is not properly connected to the cell [1] | Check all cable connections. Perform a general troubleshooting procedure with a test resistor or cell [1]. | Ensure the working electrode is fully submerged and has a secure electrical connection [1]. |

| No current flow, potential voltage compliance errors | Poor connection to the counter electrode [1] | The potentiostat may show "voltage compliance" errors. | Check that the counter electrode is properly connected and submerged in the solution [1]. |

FAQ 2: Why is my baseline unstable, sloping, or showing large hysteresis?

An unstable or sloping baseline is frequently encountered in practice and can be caused by several factors related to the electrode, the cell, or the experimental parameters.

Table: Troubleshooting an Unstable or Sloping Baseline

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large, reproducible hysteresis between forward and backward scans | High charging currents [1] | This is often scan-rate dependent. | Reduce the scan rate, increase analyte concentration, or use a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1]. |

| Non-straight baseline | Problems with the working electrode itself (e.g., poor internal contacts, poor seals) [1] | Check for physical defects. Polish and clean the electrode. | Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry and wash it thoroughly. For Pt, clean by cycling in H2SO4 [1]. |

| Baseline looks different on repeated cycles | Reference electrode not in electrical contact with the cell (blocked frit/air bubbles) [1] | Use the reference electrode as a quasi-reference (connect its cable to the counter electrode). If a standard voltammogram appears, the reference is faulty [1]. | Check for and remove air bubbles; ensure the frit is not blocked. Replace the reference electrode if necessary [1]. |

FAQ 3: Why do I see unexpected peaks in my antioxidant extract voltammogram?

Unexpected peaks can obscure the analytical signal and lead to misinterpretation of the antioxidant capacity.

Table: Troubleshooting Unexpected Peaks

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peaks not originating from the analyte | 1. System impurities (chemicals, atmosphere, degraded components) [1]2. Edge of the electrochemical window [1] | Run a rigorous background/blank scan with all components except the antioxidant extract [1]. | 1. Use high-purity solvents and electrolytes. Maintain an inert atmosphere if needed [1].2. Identify and note the window's limits from the blank. |

| Poor reproducibility of peaks and currents | 1. Uncontrolled pH [32]2. Un-optimized supporting electrolyte [32] | Test the same extract concentration with different supporting electrolytes and buffer solutions. | Always use a buffered supporting electrolyte to maintain a constant pH, which is crucial for reproducibility [32]. |

Experimental Protocols

Standard Operating Procedure: Determining Electrochemical Quantitative Index (EQI) for Antioxidant Capacity

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to analyze the antioxidant capacity of açaí pulp, a complex natural extract, using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) [32].

1. Solution and Sample Preparation

- Supporting Electrolyte: Prepare a 0.1 M phosphate buffer solution (PBS) or 0.1 M KCl. Using a buffer is critical for maintaining pH and ensuring reproducibility [32] [33].

- Antioxidant Extract:

- For a frozen pulp sample like açaí, thaw it at room temperature.

- Perform an extraction using a solvent like ethanol (e.g., 10 mL of 99% EtOH for 47.77 g of pulp) in an ultrasonic bath for 15 minutes.

- Centrifuge the crude material (e.g., at 1000 rpm for 10 min) and filter it [32].

- Add a specific aliquot of the extract (e.g., 100 µL) to the supporting electrolyte (e.g., 25 mL total volume) to achieve the desired concentration (e.g., 0.2%) [32].

2. Electrode Setup and Preparation

- Working Electrode: Glassy Carbon (GC) electrode.

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire or large surface area Pt electrode.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl).

- Electrode Cleaning: Prior to each measurement, polish the glassy carbon working electrode with alumina powder (e.g., 1 and 0.5 µm), then rinse thoroughly with ethanol and deionized water [33].

3. Instrumentation and Measurement Parameters

- Potentiostat: Use a modern potentiostat (e.g., CHI760B).

- Cell Conditions: Perform measurements in an anaerobic atmosphere by purging the cell with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for several minutes before scanning [33].

- CV Parameters:

4. Data Analysis and EQI Calculation

- The Electrochemical Quantitative Index (EQI) can be calculated from the cyclic voltammogram to provide a quantitative measure of total antioxidant capacity. For a 0.2% açaí extract, an EQI of about 2.3 µA/V was reported [32].

- The calculation typically involves the anodic peak current, with the EQI representing the current per unit scan rate, providing a normalized index for comparison.

Workflow for Reliable Antioxidant CV Analysis

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials and Reagents for Antioxidant CV

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon (GC) Working Electrode | The standard electrode surface for oxidizing antioxidant compounds like phenolics and flavonoids. Provides a reproducible and stable surface [32] [33]. | Used for determining the EQI of açaí pulp extracts and analyzing dietary supplements [32] [33]. |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Provides a stable and known reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled [32] [33]. | Standard reference electrode used in antioxidant studies of açaí and dietary supplements [32] [33]. |

| Phosphate Buffer Salts (PBS) | Provides a buffered supporting electrolyte to maintain constant pH, which is crucial for obtaining reproducible redox potentials and currents [32]. | Used to maintain pH while analyzing açaí pulp extracts [32]. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | A common supporting electrolyte to ensure sufficient ionic conductivity in the solution with minimal redox activity in the analytical window [33]. | Used as a supporting electrolyte (0.1 M) for the analysis of dietary supplements [33]. |

| Alumina Polishing Powder | Used for mechanical polishing and cleaning of the solid working electrode surface between measurements to remove adsorbed species and restore a fresh, active surface [33]. | GC electrode was polished with 1 and 0.5 µm alumina powder prior to each measurement in dietary supplement analysis [33]. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Flatlining or Clipped Cyclic Voltammetry Signal

Problem: During a Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) experiment, the recorded current signal is flat or appears clipped, failing to show the expected oxidation-reduction peaks [26].

- Cause: The most common cause is an incorrect current range setting. If the actual current produced by the electrochemical reaction exceeds the maximum value of the selected range, the instrument cannot measure it accurately, resulting in a flat or "clipped" signal [26].

- Solution:

- Open your potentiostat's settings software.

- Locate the current range or compliance setting.

- Adjust the range to a significantly higher value (e.g., from 100 µA to 1000 µA).

- Re-run your CV experiment [26].

Unstable Baseline in SEC Measurements

Problem: The spectroscopic (UV-Vis or IR) baseline drifts or is noisy during SEC experiments, making it difficult to identify accurate absorption changes.

- Cause 1: Aging or unstable light source. The lamp in the spectrometer may be near the end of its life or require a longer warm-up time [34] [35].

- Solution:

- Cause 2: Poor alignment or dirty optical components. This includes dirty cuvettes, scratched optical windows on the SEC cell, or misaligned light paths [35] [36].

- Solution:

- Clean the cuvette and the optically transparent electrode (OTE) with an appropriate, lint-free cloth and solvent.

- For parallel transmission configurations, verify the perfect alignment of the light beam relative to the working electrode [36].