Underpotential Deposition Stripping Voltammetry: Fundamentals, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Underpotential Deposition Stripping Voltammetry (UPD-SV), a highly sensitive electrochemical technique for trace metal analysis.

Underpotential Deposition Stripping Voltammetry: Fundamentals, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Underpotential Deposition Stripping Voltammetry (UPD-SV), a highly sensitive electrochemical technique for trace metal analysis. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of UPD, detailed methodological protocols for various metal ions, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing assays. The content also includes a critical validation and comparative analysis against other spectroscopic methods, highlighting UPD-SV's significant potential for biomedical and clinical research applications, including environmental monitoring and diagnostics.

What is Underpotential Deposition? Core Principles and Thermodynamic Foundations

Underpotential deposition (UPD) is an electrochemical phenomenon where a metal adlayer deposits onto a foreign substrate at potentials more positive than its thermodynamic reduction potential. This fundamental process, driven by stronger adsorbate-substrate interactions compared to bulk metal bonds, enables precise monolayer formation critical for advanced electrocatalysis and sensitive electroanalytical techniques. This whitepaper examines UPD's core principles, characterization methodologies, and applications, providing researchers with comprehensive frameworks for exploiting this phenomenon in materials science and analytical chemistry.

Underpotential deposition describes the reversible electrochemical deposition of a metal monolayer onto a chemically different substrate from a solution containing its cations, occurring at potentials significantly less negative than the thermodynamic Nernst potential for bulk deposition [1]. This fundamental deviation from equilibrium thermodynamics arises from the stronger metal-substrate bond formation compared to the metal-metal bond of the bulk deposit, resulting in a thermodynamically favorable process at underpotentials [1].

The UPD process is intrinsically limited to approximately a single monolayer due to this interfacial energy difference. Once the substrate surface is covered, subsequent deposition follows bulk deposition thermodynamics at overpotentials (negative of the Nernst potential) [1] [2]. The UPD shift (ΔE), defined as the difference between the bulk deposition potential and the UPD monolayer stripping potential, provides quantitative insight into the adsorption energy and follows work function differences between substrate and depositing metal [1].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

Thermodynamic Basis

The thermodynamic driving force for UPD originates from the free energy gain associated with adatom-substrate bond formation. When the interaction energy between depositing metal atoms (M) and substrate surface (S) exceeds the cohesive energy of the bulk metal M, deposition occurs at potentials positive of the Nernst equilibrium potential (E₀) for the Mⁿ⁺/M couple [1].

The UPD shift follows the relationship: [ ΔEUPD = E{M/M^{n+}} - E{UPD} \propto (φS - φM)/n ] where φS and φ_M represent the work functions of substrate and depositing metal, respectively, and n is the number of electrons transferred [1]. Recent research has proposed the "Standard UPD potential" as a fundamental thermodynamic parameter to characterize UPD systems more consistently [3].

Structural Considerations

UPD processes are exceptionally sensitive to substrate crystallography. For instance, Pb UPD on low-index copper crystals exhibits distinct voltammetric profiles corresponding to Cu(111), Cu(100), and Cu(110) surfaces, enabling UPD as an in-situ structural analysis tool [1]. The resulting adlayer structures often form specific superlattices dictated by lattice mismatch and interfacial energy minimization, such as the filled honeycomb structure observed for Pb on Ag(111) versus the c(2×2) structure on Ag(100) [1].

Table 1: Characteristic UPD Systems and Structural Properties

| System | UPD Shift (mV) | Adlayer Structure | Substrate Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pb on Cu(hkl) | Variable with crystal face | Structure-sensitive | Highly sensitive [1] |

| Pb on Ag(111) | ~140 (theoretical) | Filled honeycomb 3(2×2) | Face-specific [1] |

| Pb on Ag(100) | ~110 (theoretical) | c(2×2) | Face-specific [1] |

| Tl on Au | Well-defined peaks | Submonolayer coverage | Polycrystalline [2] |

| Cu on Au | 650 ± 20 | Not specified | Anion-dependent [3] |

Experimental Characterization Methods

Voltammetric Techniques

Cyclic voltammetry serves as the primary method for investigating UPD processes. The characteristic voltammogram features distinct deposition and stripping peaks at potentials positive of the reversible Nernst potential. For example, Pb UPD on stepped Cu(111) surfaces exhibits three characteristic peaks (A₁, A₂, A₃) corresponding to adsorption at steps, terraces, and completion of the monolayer, respectively [1].

Stripping voltammetry provides exceptional sensitivity for trace metal detection by coupling UPD accumulation with anodic stripping. This approach exploits the sharp, sensitive response from monolayer deposition where analyte ad-atoms cover only 0.01-0.1% of the electrode surface, enabling efficient accumulation within short timeframes [2].

Table 2: Analytical Performance of UPD-Based Stripping Voltammetry

| Analyte | Electrode | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tl(I) | Rotating Au film | 5–250 μg·L⁻¹ | 0.6 μg·L⁻¹ | Water, tea samples [2] |

| In(III) | SBiμE (ASV) | 5×10⁻⁹–5×10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ | 1.4×10⁻⁹ mol L⁻¹ | Environmental waters [4] |

| In(III) | SBiμE (AdSV) | 1×10⁻⁹–1×10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ | 3.9×10⁻¹⁰ mol L⁻¹ | Environmental waters [4] |

Complementary Characterization Techniques

Electrochemical quartz crystal microbalance (EQCM) enables simultaneous monitoring of mass changes and current during UPD, confirming monolayer deposition through correlation of charge transfer with mass uptake [1]. Scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) provides atomic-resolution visualization of UPD adlayer structures, revealing detailed spatial organization such as the bilayer structure proposed for Pb on Ag(100) [1]. X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XANES/EXAFS) elucidates the oxidation state and coordination environment of deposited single atoms, as demonstrated for Ir single atoms on Co(OH)₂ nanosheets [5].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Thallium Determination by UPD-Stripping Voltammetry

This protocol enables sensitive Tl(I) detection at trace levels using a rotating gold film electrode (AuFE) [2].

Electrode Preparation

- Substrate: Glassy carbon electrode

- Gold deposition: Potentiostatic electrodeposition from 1 mM H[AuCl₄] solution at -300 mV (vs. Ag/AgCl, 3.5 M KCl) for 300 s

- Result: Gold film with sub-nanoscale morphology and developed surface area

Measurement Conditions

- Supporting electrolyte: 10 mM HNO₃ and 10 mM NaCl OR citrate medium to overcome Pb(II) and Cd(II) interferences

- Accumulation potential: Optimized for Tl UPD peaks identified in cyclic voltammetry

- Accumulation time: 210 s for detection limit of 0.6 μg·L⁻¹

- Stripping technique: Square wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SW-ASV)

- Instrumental optimization: Full factorial design to determine optimal parameters

Analytical Performance

- Linear range: 5–250 μg·L⁻¹ (R² > 0.995)

- Applications: Successful determination in drinking water, river water, and black tea samples with satisfactory recovery values

Protocol: Fabrication of Single-Atom Catalysts via Electrochemical Deposition

This universal approach applies to wide metal and support ranges for SAC fabrication [5].

Electrochemical System

- Configuration: Standard three-electrode system

- Working electrode: Support material loaded on glassy carbon electrode

- Electrolyte: 1 M KOH with 100 μM metal precursor (e.g., IrCl₄)

- Deposition parameters:

- Cathodic deposition: Potential range 0.10 to -0.40 V (vs. relevant reference)

- Anodic deposition: Potential range 1.10 to 1.80 V (vs. relevant reference)

- Scan rate: 5 mV s⁻¹ for 1-10 scanning cycles

Key Considerations

- Mass loading control: Upper limit exists for SAC formation (e.g., 3.5-4.7% for Ir/Co(OH)₂)

- Concentration effect: SAC formation possible up to 150 μM Ir concentration

- Characterization: HAADF-STEM, XANES/EXAFS confirm atomic dispersion

Applications in Materials Science and Analytics

Single-Atom Catalyst Fabrication

Electrochemical deposition serves as a universal route for SAC fabrication applicable to wide metal and support ranges. The deposition pathway determines electronic states: cathodically deposited Ir single atoms on Co(OH)₂ exhibited oxidation states between +3 and +4, while anodically deposited Ir reached states higher than +4 [5]. These electronic differences impart distinct catalytic properties: cathodically deposited SACs show excellent hydrogen evolution reaction activity, while anodically deposited SACs excel in oxygen evolution reaction [5].

Environmental and Biological Monitoring

UPD-based stripping voltammetry enables trace metal determination in complex matrices. The technique provides low detection limits, minimal sample pretreatment, and portability for field analysis. For thallium determination, the UPD approach eliminates interferences through selective monolayer deposition, overcoming challenges from Pb(II) and Cd(II) in conventional stripping methods [2]. Similarly, In(III) determination using solid bismuth microelectrodes represents an environmentally friendly alternative to mercury electrodes while maintaining excellent sensitivity [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for UPD Research

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrodes | UPD substrate | Poly/mono-crystalline Au, Ag; Bismuth film electrodes (BiFE); Solid bismuth microelectrodes (SBiμE) [2] [4] |

| Metal Precursors | Source of depositing metal | Soluble salts (IrCl₄, Pb²⁺, Tl⁺, In³⁺) in low concentrations (100 μM range) [5] |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Conductivity and ionic strength | Acidic media (HNO₃); Alkaline media (KOH); Acetate buffer (pH 3.0); Citrate medium [2] [4] |

| Complexing Agents | Enhanced selectivity in AdSV | Cupferron (for In(III)); Morin; Ammonium pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (APDC) [4] |

| Electrochemical Cell | Three-electrode system | Working, reference (Ag/AgCl), and counter electrodes [5] |

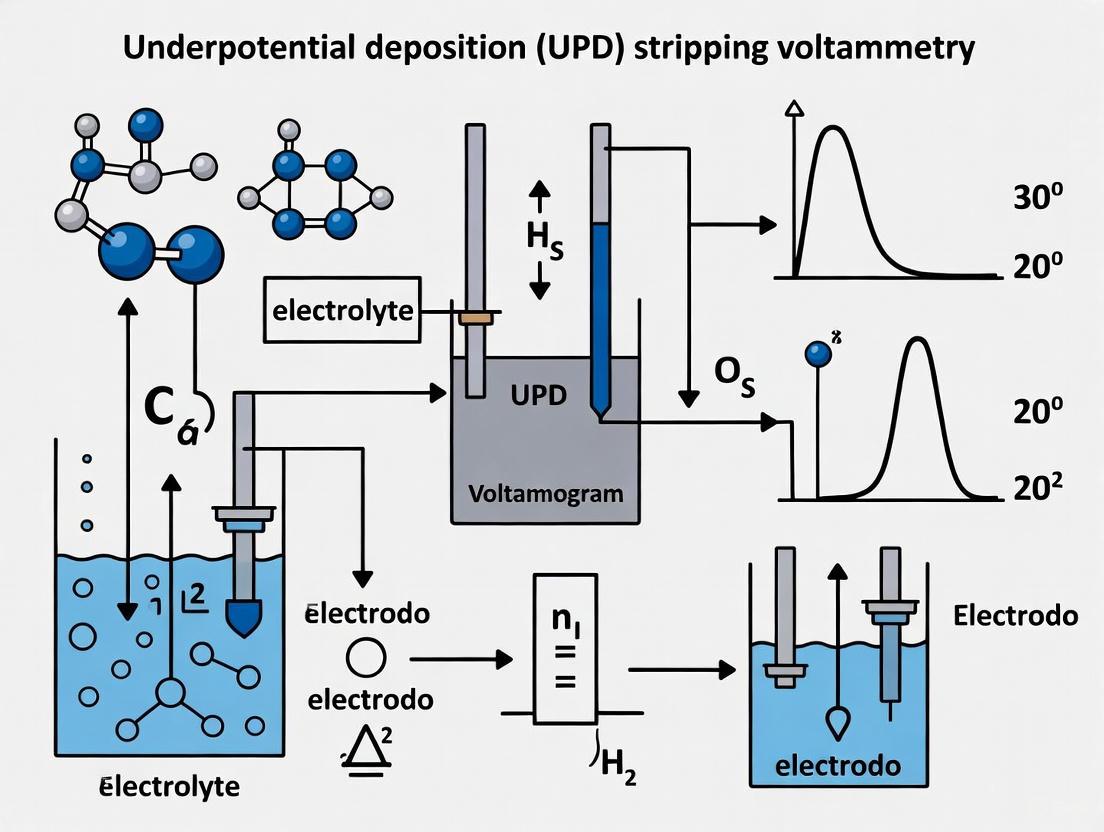

Visualizing UPD Processes and Workflows

Underpotential deposition represents a fundamental electrochemical process with far-reaching applications in modern materials science and analytical chemistry. The phenomenon's core characteristic—deposition at potentials positive of the Nernst potential—enables precise monolayer formation, atomic-scale materials engineering, and highly sensitive analytical determinations. As research advances, standardized characterization parameters like the "Standard UPD potential" promise enhanced comparability across studies [3]. Coupled with emerging applications in single-atom catalysis and environmental monitoring, UPD continues to offer versatile methodologies for surface engineering at the atomic scale.

This whitepaper examines the fundamental role of thermodynamic driving forces, specifically work function differences and adsorption energy, in controlling interfacial processes such as underpotential deposition (UPD) and molecular adsorption. The precise control of these forces enables the formation of well-defined bimetallic surfaces and organic monolayers with tailored electronic properties, which are crucial for advanced electrochemical applications including sensing and catalysis. Drawing upon recent surface science investigations, we establish the quantitative relationship between intrinsic material properties and the resulting interfacial structure, providing researchers with a framework for predicting and optimizing surface modifications for specific technological applications.

The electronic properties of devices and catalysts are profoundly influenced by metal-organic interfaces and bimetallic surfaces at conductive electrodes. Underpotential deposition (UPD), an electrochemical process where a monolayer of a foreign metal deposits onto a substrate at potentials positive of the Nernst equilibrium potential, represents a powerful method for creating such tailored interfaces [6]. The thermodynamic driving force for UPD originates primarily from the work function difference between the substrate and depositing metal, which leads to stronger adatom-substrate bonding compared to adatom-adatom bonding in the bulk deposit. This process enables the creation of well-defined bimetallic electrode surfaces with modified electronic properties.

Similarly, for molecular adsorption, the thermodynamic drive dictates whether organic molecules adsorb in their pure form or extract substrate atoms to form two-dimensional metal-organic frameworks (2D-MOFs) [7]. The interplay between adsorption energy, molecular structure, and substrate properties determines the final interface structure and composition, with significant implications for interface electronic structure and functionality. Understanding these fundamental principles provides the foundation for controlling interfacial processes in applications ranging from molecular electronics to electrocatalysis.

Theoretical Framework

Fundamental Thermodynamic Principles

The thermodynamic driving force in UPD and molecular adsorption systems can be understood through the interplay of several key energy terms:

- Work Function Difference (ΔΦ): The difference in work function between the substrate (Φsubstrate) and depositing metal (Φdepositing metal) creates an electronic driving force. Electrons flow from the metal with lower work function to the one with higher work function until Fermi level equilibrium is established, creating a dipole layer that lowers the system's free energy.

- Adsorption Energy (E_ads): The energy gain when an adatom or molecule binds to the substrate surface compared to its reference state. For UPD, this must be more negative than the energy of incorporation into the bulk lattice.

- Interface Formation Energy: The total energy change associated with creating the new interface, including chemical bonding contributions, strain energy, and electrostatic interactions.

For a molecular adsorption system, the overall energy balance can be expressed as: ΔGads = Emolecule-substrate - Esubstrate - Emolecule where a negative ΔGads indicates a spontaneous adsorption process. The magnitude of ΔGads determines the stability of the adsorbed layer and whether substrate atom extraction is thermodynamically favorable [7].

The Role of Work Function in UPD

In UPD systems, the underpotential shift (ΔUP) correlates linearly with the work function difference: ΔUP ∝ (Φsubstrate - Φdepositing metal)

This relationship emerges because the electron transfer between metals with different work functions creates stronger metal-substrate bonds compared to metal-metal bonds in the bulk depositing metal. The deposited monolayer effectively smoothes the work function difference, with the first monolayer experiencing the strongest driving force. Subsequent layers deposit at or near the Nernst potential, as the work function difference driving force is substantially diminished after the first monolayer.

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Parameters in UPD and Adsorption Systems

| Parameter | Definition | Experimental Determination | Impact on Interface Structure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Work Function Difference (ΔΦ) | Energy required to remove an electron from the Fermi level to vacuum | Kelvin Probe, Ultraviolet Photoelectron Spectroscopy (UPS) | Determines UPD deposition potential and monolayer stability |

| Adsorption Energy (E_ads) | Energy change upon adsorption of species onto substrate | Temperature-Programmed Desorption (TPD), Calorimetry | Controls molecular conformation and whether substrate atom extraction occurs |

| Underpotential Shift (ΔUP) | Difference between UPD potential and Nernst potential | Cyclic Voltammetry | Quantitative measure of UPD driving force |

| Coherent Position | Average position of adsorbate atoms relative to substrate lattice | Normal-Incidence X-Ray Standing Waves (NIXSW) | Reveals adsorption geometry and bond lengths |

Experimental Evidence and Quantitative Data

UPD-Modified Molecular Junctions

Recent investigations have demonstrated that UPD is a potent means for altering the tunneling energy barrier at molecule-electrode contacts. In studies of alkyl self-assembled monolayers (SAMs), replacement of a conventional Au electrode with a bimetallic Cu UPD on Au electrode resulted in significant enhancements in the Seebeck coefficient: up to 2-fold for alkanoic acid monolayers and 4-fold for alkanethiol monolayers [6].

Quantum transport calculations indicate these enhancements originate from UPD-induced changes in the shape or position of transmission resonances corresponding to gateway orbitals. The presence of the Cu UPD adlayer significantly alters the electronic structure at the molecule-electrode interface, which depends on the choice of the anchor group [6]. This demonstrates how work function differences and adsorption energy can be harnessed to tune electronic properties for molecular electronics.

Table 2: Thermoelectric Performance of SAMs on Mono-metallic and UPD-based Bimetallic Electrodes

| SAM Molecule | Electrode Type | Seebeck Coefficient (μV/K) | Enhancement Factor | Dominant Transport Orbital |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n-alkanethiols (HSCn) | AuTS (ME) | Baseline (Reference) | 1.0x | HOMO |

| n-alkanethiols (HSCn) | Cu-UPD/AuTS (BE) | 4x baseline | 4.0x | HOMO |

| n-alkanoic acids (HO2CCn–1) | AgTS (ME) | Baseline (Reference) | 1.0x | HOMO |

| n-alkanoic acids (HO2CCn–1) | Cu-UPD/AuTS (BE) | 2x baseline | 2.0x | HOMO |

Thermodynamic Control in Molecular Adsorption

Quantitative structural investigations of TCNQ and F4TCNQ on Ag(100) surfaces reveal how thermodynamic factors control interface structure. These systems lie at the boundary between pure organic monolayer formation and substrate atom extraction, making them ideal model systems [7].

A room-temperature commensurate phase of adsorbed TCNQ does not incorporate Ag adatoms but adopts an inverted bowl configuration long predicted by theory. In contrast, a similar phase of adsorbed F4TCNQ does lead to Ag adatom incorporation in the overlayer, with the cyano end groups twisted relative to the planar quinoid ring [7]. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations show this behavior is consistent with adsorption energetics, with the stronger electron-acceptor F4TCNQ providing greater thermodynamic drive for adatom extraction.

Annealing the commensurate TCNQ overlayer phase leads to an incommensurate phase that does incorporate Ag adatoms, demonstrating that the inclusion (or exclusion) of metal atoms into organic monolayers results from both thermodynamic and kinetic factors [7].

Experimental Protocols

UPD Adlayer Formation and Characterization

Protocol 1: Formation of Cu UPD on Au substrates

Substrate Preparation: Prepare template-stripped gold (AuTS) substrates to ensure atomically flat surfaces. Clean substrates by Ar+ ion sputtering (1 keV) and annealing cycles in UHV conditions.

Electrochemical Setup: Use a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell with Pt counter electrode and appropriate reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl). Use N₂-saturated solution containing 1 mM CuSO₄ and 0.1 M H₂SO₄ as electrolyte.

Cyclic Voltammetry: Perform CV measurements between appropriate potential ranges (e.g., +0.4 V to -0.2 V vs. reference) to identify UPD features. Distinct peaks corresponding to UPD (A1 and A2 for deposition, D1 and D2 for stripping) and overpotential deposition (B1 and C1 for deposition and stripping, respectively) should be observed [6].

UPD Layer Formation: Hold potential at identified UPD deposition peak to form complete monatomic Cu adlayer.

Characterization: Confirm UPD layer using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Cu 2p spectrum should exhibit doublet peaks at 931.9 and 951.8 eV, corresponding to Cu 2p₃/₂ and Cu 2p₁/₂, respectively. The binding energy of Cu 2p₃/₂ for the Cu adlayer on gold should be lower by ~0.7 eV than that (932.6 eV) of bulk Cu [6].

Molecular Monolayer Formation on UPD Surfaces

Protocol 2: Self-Assembled Monolayer Formation on UPD-Modified Electrodes

Surface Preparation: Transfer UPD-modified electrodes to appropriate solvent for SAM formation while minimizing air exposure.

SAM Deposition: Immerse substrates in 1-3 mM solution of molecular adsorbate (e.g., n-alkanethiols or n-alkanoic acids) in ethanol for 12-24 hours to form complete monolayers.

Rinsing and Drying: Thoroughly rinse samples with pure solvent to remove physisorbed material and dry under nitrogen stream.

SAM Characterization:

- Use XPS to verify monolayer formation. For alkanethiols on Cu-UPD/Au, S 2p signal should display doublet peak at 162.1 and 163.3 eV, attributed to S 2p₃/₂ and 2p₁/₂, respectively.

- For alkanoic acids, C 1s XP spectrum should exhibit two peaks at 284.5 and 287.3 eV assigned to alkyl carbons and bonding carboxylate group, respectively. No signal characteristic of free carboxylic acid (~288.5 eV) should be detected [6].

Quantitative Structural Analysis

Protocol 3: Normal-Incidence X-Ray Standing Waves (NIXSW)

Sample Preparation: Prepare well-ordered adsorption phases on single-crystal surfaces. Characterize using low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) to confirm surface structure and quality.

Data Collection: Collect NIXSW data by measuring C 1s, N 1s, and F 1s photoelectron spectra as incident photon energy is stepped through the (200) Bragg reflection near normal incidence to the (100) surface.

Data Analysis: Compare relative intensity of component peaks as a function of photon energy with standard formulas to determine optimum values of coherent fraction and coherent positions. These parameters allow determination of adsorbate atom positions relative to substrate lattice with ~0.01 Å precision [7].

Visualization of Core Concepts

Thermodynamic Driving Forces in UPD and Adsorption

Experimental Workflow for UPD-based Junction Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UPD and Adsorption Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example | Critical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Template-Stripped Gold (AuTS) | Provides atomically flat substrate for well-defined interfaces | UPD substrate, molecular adsorption studies | Surface roughness, crystal orientation ((100), (111)) |

| CuSO₄ in H₂SO₄ electrolyte | Enables Cu UPD process | Formation of Cu UPD adlayers on Au substrates | Concentration (1 mM CuSO₄, 0.1 M H₂SO₄), dissolved O₂ removal |

| n-alkanethiols (HSCn) | Forms self-assembled monolayers | Molecular junction studies, interface engineering | Chain length (n = 4, 6, 8, 10, 12), purity |

| n-alkanoic acids (HOOCn) | Forms self-assembled monolayers | Molecular junction studies, comparison with thiols | Chain length (n = 8, 10, 12, 14), binding mode |

| Eutectic Ga-In (EGaIn) | Forms soft top contacts for junction measurements | Molecular junction electrical characterization | Oxide formation (Ga₂O₃), tip size and shape |

| TCNQ/F4TCNQ molecules | Strong electron acceptor molecules | Model systems for molecular adsorption studies | Purification, deposition rate control |

Within the framework of underpotential deposition (UPD) stripping voltammetry research, the concepts of the monolayer limit and reversibility are foundational for developing sensitive and reproducible electrochemical sensors. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of these core characteristics, detailing how the self-limiting nature of UPD—where deposition ceases after formation of a single atomic layer—confers significant advantages for trace-level metal detection. We present structured experimental protocols, quantitative performance data, and essential reagent toolkits to guide researchers in implementing these techniques for applications ranging from environmental heavy metal monitoring to pharmaceutical analysis. The systematic integration of UPD with stripping voltammetry enables exceptional sensitivity for toxic metals like lead and arsenic at concentrations relevant to drinking water safety standards, while maintaining simplified instrumentation compatible with portable field deployment.

Underpotential deposition describes an electrochemical phenomenon where a metal ion (M²⁺) is reduced and deposited onto an electrode substrate composed of a different metal (S) at a potential positive of its thermodynamic reduction potential [8]. This occurs due to the stronger chemical interaction between the depositing metal ad-atom and the foreign substrate surface compared to the interaction in the bulk depositing metal itself. The UPD process is intrinsically self-limited to a single atomic layer, as the favorable substrate-adatom interactions that drive underpotential deposition are replaced by bulk metal interactions once the first monolayer is complete; subsequent layers then deposit at the thermodynamically expected (more negative) potential in a process termed overpotential deposition (OPD) [8]. This fundamental monolayer limit is the cornerstone of UPD's analytical utility.

The reversibility of the UPD system—referring to the electrochemical equilibrium and the kinetics of both deposition and stripping processes—is equally critical. In a highly reversible system, the deposited monolayer can be oxidatively "stripped" from the electrode surface during the anodic scan with minimal hysteresis and energy dissipation, yielding sharp, well-defined peaks ideal for quantitative analysis [8] [9]. The combination of the monolayer limit and high reversibility makes UPD exceptionally suitable for integration with anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV), creating a powerful analytical technique (UPD-ASV) for trace metal analysis. This coupling leverages the preconcentration benefits of stripping voltammetry while the UPD mechanism ensures a uniform, single-layer deposit that enhances reproducibility, simplifies the stripping signal, and reduces analysis time by eliminating the need for extended deposition periods required for bulk deposition [8].

Experimental Protocols for UPD-Stripping Voltammetry

Electrode Preparation and Conditioning

Gold Electrode Pretreatment Protocol: The working electrode's surface state is paramount for reproducible UPD. For polycrystalline gold electrodes or arrays, the following conditioning procedure is recommended [8]:

- Mechanical/Chemical Cleaning: Clean electrodes by immersion in acetone with slow stirring (50 rpm) for 5 minutes, followed by copious rinsing with ultra-pure water (18.2 MΩ·cm). For gold electrodes, subsequent UV/ozone treatment for 25 minutes is highly effective for removing organic contaminants.

- Electrochemical Activation: After drying, perform cyclic voltammetry in a deaerated 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) by scanning the potential between +1.5 V and -1.0 V vs. a Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) until a stable voltammogram is obtained, indicating a clean, electroactive surface.

- Post-analysis Regeneration: Following metal ion detection, regenerate the electrode surface by immersing in concentrated (69%) HNO₃ to dissolve any residual deposits, then rinse thoroughly with ultra-pure water. Store in ultra-pure water when not in use.

Protocol for Solid Bismuth Microelectrode (SBiµE): Bismuth electrodes are an environmentally friendly alternative to mercury [10].

- Activation: Prior to each measurement in an acetate buffer (pH 3.0) supporting electrolyte, apply an activation potential of -2.4 V for 20 seconds (for ASV) or -2.5 V for 45 seconds (for Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry, AdSV).

- This activation step ensures a fresh, reproducible electrode surface for analysis.

UPD-ASV Measurement Procedure

The following generalized protocol, adaptable for metals like Pb, As, and In, is performed in a standard three-electrode cell [8] [9] [10]:

- Solution Deaeration: Purge the analytical solution containing the target metal ion and supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M NaCl or 0.01 M KNO₃) with an inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for at least 10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the reduction and stripping signals.

- UPD Preconcentration (Deposition): Apply a constant deposition potential (Edep) that is positive of the metal's Nernst potential for the UPD region. The optimal Edep is metal- and substrate-specific. For example:

- For Lead (Pb²⁺) on gold, deposition occurs at potentials around -0.025 V to -0.275 V vs. SCE [8].

- For Arsenic speciation on gold, use Edep = -0.9 V vs. a suitable reference for As(III) and Edep = -1.3 V for total As [9].

- Stir the solution during deposition to enhance mass transport of metal ions to the electrode surface. The deposition time is typically short (10-60 seconds) due to the monolayer limit.

- Equilibration: After deposition, stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for a brief period (e.g., 10-15 seconds) to reduce convective contributions to the current.

- Stripping Scan: Initiate the anodic (positive-going) potential scan to oxidize and strip the deposited metal monolayer. The scan can be performed using linear sweep voltammetry (LSV), square-wave voltammetry (SWV), or sampled-current voltammetry (as in EASCV) [8]. The stripping peak potential (Ep) is characteristic of the metal and its interaction with the substrate.

Table 1: Optimized Deposition and Stripping Parameters for Selected Metals via UPD-ASV

| Analyte | Electrode | Supporting Electrolyte | UPD Deposition Potential (Edep) | Stripping Peak Potential (Ep) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Gold Array | 0.1 M NaCl | -0.025 V to -0.275 V vs. SCE | ~ -0.2 V to -0.1 V (vs. SCE) | [8] |

| Arsenic (As(III)) | Gold Macro | Aqueous solution | -0.9 V | Characteristic peak for As(0)/As(III) | [9] |

| Total Arsenic | Gold Macro | Aqueous solution | -1.3 V | Characteristic peak for As(0)/As(III) | [9] |

| Indium (In(III)) | SBiµE | 0.1 M Acetate Buffer (pH 3.0) | -1.2 V (Accumulation) | Scan from -1.0 V to -0.3 V | [10] |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

The charge passed during the stripping peak (Q), which is directly proportional to the area under the peak, is related to the surface concentration of the metal (Γ) by the equation: Q = nFAΓ, where n is the number of electrons transferred per atom, F is the Faraday constant, and A is the electrode area. This relationship allows for quantitative determination of the analyte concentration in the bulk solution via a calibration curve constructed from standard additions or external standards. The sharp, well-defined nature of UPD stripping peaks simplifies this integration process compared to the broader peaks often encountered in OPD-stripping.

Quantitative Performance Data

The UPD-ASV methodology delivers exceptional analytical performance for trace metal detection, as evidenced by the following compiled data from recent studies.

Table 2: Analytical Figures of Merit for UPD-based Stripping Voltammetry

| Analyte | Linear Dynamic Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Technique & Electrode | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Not explicitly stated | 1.16 mg L⁻¹ (≈ 5.6 µM) | EASCV / Gold Array | Current intensities 300x higher than LSASV | [8] |

| Arsenic (As) | 0.01 µM – 0.1 µM | 0.8 µg L⁻¹ (0.01 µM) | UPD-ASV / Gold Macro | Measures total As and speciates As(III)/As(V) | [9] |

| Indium (In(III)) | 5 nM to 500 nM | 1.4 nM | ASV / SBiµE | Green, mercury-free electrode | [10] |

| Indium (In(III)) | 1 nM to 100 nM | 0.39 nM | AdSV / SBiµE | Superior LOD with cupferron as chelator | [10] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of UPD-stripping voltammetry relies on a carefully selected set of reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for UPD-ASV Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Specification / Purity | Critical Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Gold wire (∅ = 3 mm), photolithographed gold array (∅ = 0.5 mm), or Solid Bismuth Microelectrode (SBiµE) | Provides the substrate for UPD; material choice dictates UPD potential and specificity. |

| Reference Electrode | Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) or Ag/AgCl (KCl-sat) | Provides a stable, known reference potential for all applied potentials. |

| Counter Electrode | Platinum wire or coil | Completes the electrical circuit, carrying current from the working electrode. |

| Metal Salt Standards | High-purity (>99%) Pb(NO₃)₂, As₂O₃, InCl₃, etc. | Source of analyte for calibration and method development. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | High-purity NaCl, KNO₃, Acetate Buffer (pH 3.0) | Carries current, defines ionic strength, and controls pH/potential window. |

| Complexing Agent (for AdSV) | Cupferron, etc. | Selectively complexes with target metal for adsorptive accumulation (used in AdSV). |

| Ultra-pure Water | 18.2 MΩ·cm resistivity (e.g., Millipore Simplicity) | Minimizes background contamination and interference from ionic impurities. |

| Cleaning Solutions | Acetone, HNO₃ (69%), UV/Ozone cleaner | Essential for electrode pre-treatment and post-analysis regeneration. |

Schematic Workflows and Logical Relationships

UPD-Stripping Voltammetry Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the core experimental workflow and the underlying processes at the electrode-solution interface during a UPD-ASV analysis.

Categorical Advantages of UPD

The unique characteristics of the monolayer limit and reversibility confer a set of distinct advantages over conventional overpotential deposition, as summarized in the following diagram.

The strategic exploitation of the monolayer limit and electrochemical reversibility in underpotential deposition stripping voltammetry provides a powerful pathway for the sensitive, reproducible, and efficient detection of trace metals. The self-terminating nature of UPD ensures the formation of a uniform, single-layer deposit, which, when coupled with a highly reversible stripping process, yields sharp analytical signals that facilitate straightforward quantification. As detailed in this guide, the successful application of UPD-ASV hinges on meticulous electrode preparation, optimization of deposition potentials specific to the analyte-substrate pair, and an understanding of the underlying thermodynamics and kinetics. The provided protocols, performance data, and reagent toolkit offer researchers a solid foundation for deploying this technique in demanding analytical scenarios, from ensuring water safety to advancing materials science. Future developments in electrode nanostructuring and the discovery of new UPD systems promise to further expand the capabilities and applications of this elegant electrochemical method.

Underpotential Deposition-Stripping Voltammetry (UPD-SV) represents a powerful electrochemical technique that synergistically combines the selective preconcentration capabilities of underpotential deposition (UPD) with the sensitive detection power of stripping voltammetry (SV). This integrated approach has emerged as a cornerstone methodology in trace metal analysis, particularly for environmental monitoring, biomedical research, and quality control in pharmaceutical development. The fundamental principle underpinning UPD-SV leverages the phenomenon where metal ions deposit onto a more noble electrode substrate at potentials positive of their thermodynamic Nernst potential, forming a stable submonolayer or monolayer of ad-atoms [2]. This deposition process is subsequently followed by anodic stripping, where the deposited material is oxidatively removed from the electrode surface, generating a quantifiable current signal proportional to analyte concentration [11].

The UPD effect occurs specifically when the work function of the substrate electrode material significantly differs from that of the depositing metal, creating a strong electrochemical adsorption energy that facilitates deposition at underpotentials [2]. This phenomenon plays a crucial role in processes related to electrocatalysis, semiconductor compound synthesis, and particularly in trace metal determination by stripping voltammetry on solid electrodes. Compared to bulk deposition under overpotential deposition (OPD) conditions, applying the UPD effect combined with subsequent anodic dissolution offers several significant analytical advantages, including enhanced sensitivity through efficient accumulation within short time periods, improved selectivity through separation of specific UPD/OPD peaks, and better analytical reproducibility due to minimal changes in electrode surface structure [2].

The UPD-SV Experimental Framework

Essential Instrumentation and Components

The UPD-SV workflow requires specific instrumentation and carefully controlled experimental conditions to achieve optimal analytical performance. A standard configuration employs a potentiostat capable of precise potential control and sensitive current measurement, coupled with a three-electrode electrochemical cell arrangement [12]. The working electrode serves as the cornerstone of the UPD-SV system, with noble metal electrodes—particularly gold film electrodes (AuFE)—demonstrating exceptional performance for various applications [2].

Table 1: Core Components of the UPD-SV Experimental Setup

| Component | Specification | Function in UPD-SV Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Gold film electrode (AuFE) on glassy carbon substrate | Provides noble surface for UPD process; prepared by potentiostatic electrodeposition |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl (3.5 M KCl) | Maintains stable potential reference throughout measurement |

| Counter Electrode | Platinum wire or mesh | Completes electrical circuit without interfering with measurement |

| Potentiostat | Computer-controlled with SW-ASV capability | Applies potential sequences and measures resulting currents |

| Supporting Electrolyte | 10 mM HNO₃ + 10 mM NaCl or citrate medium | Provides conducting medium; minimizes interference effects |

The gold film electrode preparation follows a meticulous protocol where gold is potentiostatically electrodeposited onto a glassy carbon substrate from a 1 mM H[AuCl₄] solution at a potential of -300 mV (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 300 seconds [2]. The resulting gold film exhibits sub-nanoscale morphology and a developed surface area, creating an ideal substrate for UPD processes. The electrode rotation capability, typically implemented through a rotating disk electrode configuration, enhances mass transport during the deposition step, significantly improving accumulation efficiency [2] [12].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for UPD-SV Applications

| Reagent | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Chloride (H[AuCl₄]) | Electrode substrate preparation | Forms gold film electrode on glassy carbon substrate |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 3.0) | Supporting electrolyte | Provides optimal acidic environment for indium determination |

| Nitric Acid (10 mM) with NaCl (10 mM) | Supporting electrolyte | Identified optimal for thallium UPD peak formation |

| Citrate Medium | Complexing electrolyte | Eliminates Pb(II) and Cd(II) interferences in thallium analysis |

| Cupferron | Chelating agent for AdSV | Forms adsorbable complexes with metal ions like In(III) |

Operational Protocol and Methodology

UPD-SV Workflow Implementation

The UPD-SV methodology follows a systematic sequence of steps designed to maximize analytical sensitivity while maintaining selectivity. The complete workflow integrates electrode preparation, experimental parameter optimization, sample preparation, and data analysis components into a cohesive analytical procedure.

Step-by-Step Experimental Procedure

Electrode Preparation and Activation: The gold film electrode requires careful preparation and activation before analysis. The activation step employs a potential of -2.4 V to -2.5 V (depending on the target analyte) to reduce any bismuth oxide layers that may form on metallic bismuth surfaces, ensuring optimal analyte access during the accumulation stage [4]. For a solid bismuth microelectrode (SBiµE), activation at -2.5 V for AdSV measurements and -2.4 V for ASV measurements has been established as optimal [4].

Optimization of Experimental Parameters: A full factorial design approach is recommended for establishing optimal instrumental parameters for square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SW-ASV) determination [2]. Critical parameters requiring optimization include:

- Supporting electrolyte composition: 10 mM HNO₃ with 10 mM NaCl has been identified as optimal for thallium UPD peak formation [2].

- Accumulation potential and time: Typically several tenths of a volt more negative than the formal potential of the target species [12].

- Electrode rotation rate: Constant rotation (typically 2000 rpm) during deposition enhances mass transport [2].

- Square-wave parameters: Amplitude and frequency require optimization for maximum signal-to-noise ratio [2].

UPD Deposition Phase: The deposition step applies an underpotential (positive of the Nernst potential) to the working electrode for a predetermined accumulation time (typically 210 seconds for trace analysis) while maintaining solution stirring or electrode rotation [2]. During this phase, target metal ions form a submonolayer on the electrode surface through the UPD process, where ad-atoms cover only 0.01-0.1% of the working electrode surface [2].

Equilibration Period: Following the deposition phase, stirring ceases while maintaining the deposition potential for a brief period (typically 15-30 seconds) to allow the deposited material to distribute evenly across the electrode surface [11].

Stripping and Detection: The working electrode potential is swept linearly or through a series of pulses toward positive potentials, oxidizing the deposited metal ad-atoms. The resulting current is measured, with oxidation peaks appearing at characteristic potentials for each species [12] [11]. Square-wave stripping voltammetry (SWSV) has demonstrated superior sensitivity for UPD-SV applications, with the stripping signal recorded as a result of a positive potential change from -1.0 to -0.3 V for ASV procedures [4].

Electrode Regeneration: Following each measurement cycle, the electrode undergoes a cleaning step at a more oxidizing potential than the analyte of interest to fully remove any residual material before subsequent analyses [11].

Analytical Performance and Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The UPD-SV workflow delivers exceptional analytical performance for trace metal detection, as demonstrated through various application studies:

Table 3: Analytical Performance of UPD-SV for Trace Metal Detection

| Analyte | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Supporting Electrolyte | Accumulation Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thallium(I) | 5–250 μg·L⁻¹ | 0.6 μg·L⁻¹ | 10 mM HNO₃ + 10 mM NaCl | 210 s |

| Indium(III) - ASV | 5 × 10⁻⁹ – 5 × 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ | 1.4 × 10⁻⁹ mol L⁻¹ | Acetate buffer (pH 3.0) | 20 s |

| Indium(III) - AdSV | 1 × 10⁻⁹ – 1 × 10⁻⁷ mol L⁻¹ | 3.9 × 10⁻¹⁰ mol L⁻¹ | Acetate buffer (pH 3.0) | 10 s |

The implementation of UPD principles significantly enhances method selectivity compared to conventional stripping voltammetry. For thallium determination, interfering effects from Pb(II) and Cd(II) ions showing mutual peak overlap in nitric acid medium were successfully overcome in citrate medium [2]. This selectivity improvement stems from the specific adsorption energies involved in the UPD process, which can be tuned through careful selection of electrode material and supporting electrolyte composition.

Applications in Real-World Matrices

The UPD-SV methodology has been successfully applied to complex sample matrices, demonstrating its practical utility in various fields:

- Environmental Monitoring: Analysis of drinking water, river water, and tea samples with nanomolar thallium additions achieved satisfactory recovery values, validating method accuracy in environmental matrices [2].

- Biomedical Research: The exceptional sensitivity of UPD-SV makes it suitable for determining trace metal concentrations in biological fluids, though this application requires careful consideration of matrix effects [2].

- Industrial Quality Control: The technique's ability to detect μg/L concentrations of analytes positions it as a valuable tool for quality assessment in pharmaceutical development and other industries requiring trace metal analysis [13].

Advanced Technical Considerations

UPD Mechanism and Theoretical Framework

The enhanced sensitivity of UPD-SV stems from the fundamental mechanism of underpotential deposition, which can be visualized through the following processes:

The UPD process occurs when the deposition potential (Ee) is more positive than the Nernst equilibrium potential (E₀), resulting in the formation of a monolayer or submonolayer of target metal ad-atoms on the substrate [2]. This surface confinement creates distinct thermodynamic and kinetic advantages compared to bulk deposition under overpotential deposition (OPD) conditions. The UPD phenomenon is electrode-specific, with gold electrodes demonstrating particular efficacy for thallium determination, while silver and gold-silver alloys show varying performance characteristics [2].

Interference Management and Optimization Strategies

Successful implementation of UPD-SV requires careful management of potential interferents and optimization of key parameters:

Interference Elimination: For thallium determination, Pb(II) and Cd(II) interferences presenting mutual peak overlap in nitric acid medium were successfully eliminated using citrate medium [2]. This approach demonstrates how strategic selection of supporting electrolyte can resolve analytical challenges.

Electrode Material Selection: Gold film electrodes provide an optimal balance between electrochemical performance, reproducibility, and environmental friendliness compared to traditional mercury electrodes [2]. The development of solid bismuth microelectrodes (SBiµE) with 25 μm diameter further advances environmentally friendly alternatives while maintaining favorable signal-to-noise ratios [4].

Parameter Optimization Strategy: A systematic approach to optimization should prioritize accumulation potential, followed by accumulation time, supporting electrolyte pH, and finally instrumental parameters such as square-wave amplitude and frequency [2] [4]. Statistical experimental design approaches, including full factorial designs, efficiently identify optimal parameter sets while revealing potential interaction effects [2].

The UPD-SV workflow represents a sophisticated integration of fundamental electrochemical principles with practical analytical methodology, delivering exceptional sensitivity and selectivity for trace metal determination. The technique's capability to achieve detection limits in the nanomolar to picomolar range, combined with its relative instrumental simplicity and cost-effectiveness, positions it as a valuable tool for researchers and analytical professionals across multiple disciplines.

Future development trajectories for UPD-SV methodology include the refinement of environmentally friendly electrode materials such as bismuth-based electrodes, implementation of miniaturized systems for field-deployable analysis, and expansion of application domains to include speciation analysis and multidimensional detection schemes. The continued integration of UPD principles with advanced stripping voltammetry modalities promises to further enhance the capabilities of this already powerful analytical technique, solidifying its role in the evolving landscape of trace analysis methodology.

In the realm of electrochemical analysis, underpotential deposition-stripping voltammetry (UPD-SV) stands out for its exceptional sensitivity and selectivity in trace metal detection. This technique hinges on a two-stage process where a target metal ion is first deposited as a sub-monolayer of ad-atoms onto a substrate electrode at a potential more positive than its Nernst equilibrium potential (underpotential deposition, or UPD), followed by anodic stripping to re-oxidize and quantify the accumulated analyte [2]. The substrate electrode is not merely a passive component but the very foundation upon which the entire analytical process is built. Its properties dictate the efficiency of UPD, the sharpness of the stripping signal, and ultimately, the sensitivity, reproducibility, and practical applicability of the method [2]. The choice of substrate material directly influences key analytical figures of merit, including the limit of detection, linear dynamic range, and ability to discriminate against interfering species, making its selection and preparation paramount for successful UPD-stripping voltammetric research [2].

The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism of UPD-Stripping Voltammetry on a substrate electrode.

The Functions and Selection Criteria of the Substrate Electrode

The substrate electrode in UPD-SV performs multiple critical functions. Primarily, it provides a defined, catalytically active surface that facilitates the UPD process, enabling the formation of a strong adatom-substrate bond that is more favorable than adatom-adatom interactions [2]. This specific interaction is the thermodynamic driver for deposition at underpotentials, allowing for the formation of a stable, often highly ordered, sub-monolayer of the analyte metal. Furthermore, the substrate must serve as an efficient conductor for electron transfer during both the deposition and stripping steps. The kinetics of these electron transfers, which are influenced by the substrate's electronic properties, directly affect the sharpness of the stripping peak and thus the resolution of the analysis [14].

The selection of an appropriate substrate material is guided by several key considerations:

- UPD Affinity: The material must exhibit a well-defined UPD process with the target analyte, characterized by a distinct, reproducible stripping peak [2].

- Potential Window: The substrate must provide a wide and electrochemically stable potential window in the chosen electrolyte, free from significant interfering reactions like solvent electrolysis [14].

- Surface Morphology and Reproducibility: A consistent and well-defined surface morphology is crucial for achieving reproducible analytical signals between measurements and across different electrode batches [2].

- Fouling Resistance: The substrate should be resistant to passivation or fouling by matrix components in complex samples to maintain analytical performance [15].

Comparative Analysis of Common Substrate Electrode Materials

Table 1: Key substrate electrode materials, their characteristics, and applicability in UPD-stripping voltammetry.

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Exemplary UPD-SV Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Excellent UPD host for Tl, Cu, Ag; wide cathodic potential range; low reactivity [2] [14]. | Anodic window limited by surface oxidation; relatively expensive [14]. | Determination of Tl(I) using a rotating gold-film electrode (AuFE) [2]. |

| Silver (Ag) | Strong UPD interactions with various metals; can be deposited via UPD on Au [16]. | Prone to oxidation in air, complicating handling and storage [16]. | Used as an UPD layer on Au to modify interfacial properties of self-assembled monolayers [16]. |

| Platinum (Pt) | Electrochemically inert; easy to fabricate into various geometries [14]. | Low hydrogen overvoltage limits cathodic range; can catalyze unwanted side reactions [14]. | Often used in fundamental UPD studies, though less common for specific metal trace analysis. |

| Glassy Carbon | Good cathodic potential range; low cost and availability [14]. | Can require frequent surface polishing; quality varies between suppliers [14]. | Often serves as a substrate for in-situ prepared film electrodes (e.g., AuFE) [2]. |

| Mercury (Hg) | Excellent cathodic window; renewable surface; forms amalgams [14]. | Toxic; limited anodic window; soft and mechanically unstable [14]. | Traditional use in anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV), but use is declining [2]. |

Case Study: A Gold-Film Substrate for Thallium Determination

A recent, advanced application of UPD-SV is the trace determination of thallium(I) using a rotating gold-film electrode (AuFE), which showcases the critical role of a meticulously prepared substrate [2]. In this methodology, the AuFE was not a bulk gold electrode but a nanostructured film potentiostatically electrodeposited onto a glassy carbon substrate. This design leverages the advantages of gold as a UPD host for thallium while utilizing glassy carbon as a robust and conductive mechanical support [2]. The resulting gold film was characterized by a sub-nanoscale morphology and a highly developed surface area, which enhanced the analytical sensitivity by providing more sites for UPD.

The experimental protocol for this method can be broken down into two main phases: electrode preparation and the voltammetric measurement.

Experimental Protocol: Electrode Preparation and Measurement

Part A: Fabrication of the Gold-Film Electrode (AuFE)

- Substrate Preparation: A glassy carbon electrode is meticulously polished with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.3 µm and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad to a mirror finish, followed by sequential sonication in ethanol and deionized water to remove any adsorbed particles.

- Gold Electrodeposition: The clean glassy carbon substrate is immersed in a plating solution of 1 mM hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (H[AuCl~4~]) [2].

- Film Growth: A constant potential (e.g., -300 mV vs. Ag/AgCl, 3.5 M KCl) is applied for a defined period (e.g., 300 s) to electrodeposit a thin, uniform gold film onto the substrate surface [2]. The rotation of the electrode during this step can promote a more uniform film formation.

Part B: UPD-Stripping Voltammetric Measurement of Tl(I)

- Accumulation / UPD Step: The prepared AuFE is rotated and immersed in the sample solution containing Tl(I) ions, typically in a supporting electrolyte like 10 mM HNO~3~ and 10 mM NaCl. A deposition potential is applied that is positive of the Tl+/Tl redox couple, selectively driving the UPD of thallium ad-atoms onto the gold surface for a fixed time (e.g., 210 s) [2].

- Equilibration: The rotation is stopped, and the solution is allowed to become quiescent for a brief moment.

- Stripping Step: The potential is scanned in a positive direction using a square-wave waveform. The instrumental parameters (amplitude, frequency, step potential) are optimized, often via factorial design, to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio [2].

- Signal Recording: The anodic stripping current is measured, resulting in a sharp peak at the characteristic potential where Tl ad-atoms are oxidized back to Tl+ ions. The peak height or area is proportional to the concentration of Tl(I) in the sample [2].

Table 2: Optimized analytical performance for Tl(I) determination using UPD-SV on a rotating gold-film electrode [2].

| Analytical Parameter | Performance Value |

|---|---|

| Linear Range | 5 – 250 µg L⁻¹ |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | 0.6 µg L⁻¹ (at 210 s accumulation) |

| Coefficient of Determination (R²) | > 0.995 |

| Key Interferents Addressed | Pb(II) and Cd(II) interferences eliminated using citrate medium |

The following workflow summarizes the detailed experimental protocol for UPD-stripping voltammetry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of UPD-SV relies on a suite of carefully selected reagents and materials. The following table details key components used in the featured Tl(I) determination method and their specific functions [2].

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for UPD-stripping voltammetry experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | Serves as a mechanically robust and conductive substrate for the electrodeposition of the gold film [2]. |

| Hydrogen Tetrachloroaurate (H[AuCl₄]) | The precursor solution from which the active gold film substrate is electrodeposited onto the glassy carbon base [2]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., HNO₃/NaCl) | Provides ionic conductivity, controls the pH, and defines the electrochemical environment, influencing the UPD process and stripping peak potential [2]. |

| Citrate Buffer / Medium | Acts as a complexing agent to mask interfering ions like Pb(II) and Cd(II), preventing their co-deposition and ensuring selectivity for Tl(I) [2]. |

| Standard Tl(I) Solution | Used for calibration to establish the relationship between stripping peak current and analyte concentration [2]. |

The substrate electrode is unequivocally the cornerstone of underpotential deposition-stripping voltammetry. Its identity, morphology, and preparation protocol are not mere experimental details but are deterministic factors for the analytical outcome. The case study of thallium determination on a nanostructured gold-film electrode demonstrates how a rationally chosen and fabricated substrate can yield a method with impressive sensitivity, a wide linear range, and robust selectivity against interferences. As UPD-SV continues to evolve, the exploration of novel substrate materials—including advanced alloys, carbon nanomaterials, and engineered nanostructures—promises to further push the boundaries of trace analysis, enabling researchers and drug development professionals to tackle increasingly complex analytical challenges in environmental monitoring, medical diagnostics, and material sciences.

UPD-SV in Practice: Method Development for Trace Metal Analysis

Within the framework of underpotential deposition (UPD) stripping voltammetry research, electrode selection forms the foundational pillar determining analytical efficacy. UPD stripping voltammetry is a highly sensitive electrochemical technique that combines a preconcentration step, where analytes are deposited onto an electrode surface at a potential less negative than their thermodynamic reduction potential, with a subsequent stripping step for quantitative analysis [9] [12]. The choice of electrode material directly governs the efficiency of both UPD and stripping processes, influencing sensitivity, selectivity, speciation capability, and practical applicability. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of advanced electrode substrates—from established gold films and mesoporous platinum to modern mercury-free alternatives—framing their unique properties within detailed experimental protocols to empower researchers in pharmaceutical development and beyond.

The operational principle of stripping voltammetry consists of three main stages [12]:

- Preconcentration/Deposition: Species of interest are accumulated onto the electrode surface.

- Equilibration: Stirring is stopped, and the system is allowed to reach a quiescent state.

- Stripping: The deposited species are oxidized (Anodic Stripping Voltammetry, ASV) or reduced (Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry, CSV) back into solution, generating a measurable current.

When UPD is employed in the deposition step, it allows for selective deposition and often improves the stability and reproducibility of the deposited layer, which is crucial for sensitive detection [9].

Electrode Substrates: Material Properties and Analytical Applications

Gold Macroelectrodes

Gold electrodes are exceptionally well-suited for UPD-based stripping analysis of specific analytes like arsenic, offering tunable selectivity through potential control.

- Key Properties: High affinity for arsenic deposition, chemical stability, and a well-defined surface chemistry that facilitates UPD processes.

- Analytical Performance: Demonstrates linear responses for arsenic species in the range of 0.01 μM–0.1 μM, achieving limits of detection as low as 0.01 μM (0.8 μg L⁻¹), sufficient for monitoring drinking water below the WHO threshold of 0.13 μM (10 μg L⁻¹) [9].

- Speciation Capability: The deposition potential can be manipulated to differentiate between arsenic species. A deposition potential of -1.3 V enables measurement of total arsenic, while a potential of -0.9 V selectively measures As(III). The As(V) concentration can then be calculated by subtraction [9].

Mesoporous Platinum

Mesoporous platinum substrates, characterized by their extremely high surface area, are prized for enhancing preconcentration and signal amplification.

- Key Properties: Ultra-high electroactive surface area, superior electrical conductivity, and catalytic activity that promotes the UPD and stripping reactions.

- Role in UPD: The porous network provides a vast number of nucleation sites for UPD, significantly increasing the amount of analyte that can be deposited. This directly translates to lower detection limits and improved sensitivity in the stripping step.

Mercury-Free Substrates: Glassy Carbon and Beyond

The drive towards environmentally benign and operationally safer analytical methods has spurred the development and adoption of mercury-free electrodes.

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE): A widely used mercury-free substrate known for its broad anodic potential window, chemical inertness, and smooth, reproducible surface. Its performance can be enhanced by modifying its surface with films or nanoparticles [17]. In the study of Aripiprazole (ARP), a GCE was used as the working electrode, achieving a linearity range from 0.221 μM to 13.6 μM with a detection limit of 0.11 μM in stripping mode [17].

- Mercury Film Electrodes (MFE): While still containing mercury, MFEs represent a step away from the Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) by using a thin mercury film plated onto a solid substrate like a Glassy Carbon or Wax-Impregnated Graphite Rotating Disk Electrode (RDE). This configuration is often employed with stirring or rotation to maintain constant deposition conditions [12].

- Bismuth and Antimony Films: These are considered the most promising "green" alternatives to mercury, forming low-temperature alloys with many metals and offering well-defined, sensitive stripping signals without the toxicity concerns.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Electrode Substrates in Stripping Voltammetry

| Electrode Material | Key Analytical Feature | Representative Analyte | Reported Detection Limit | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Macroelectrode | UPD for speciation | Arsenic (As(III) & Total As) | 0.01 μM (0.8 μg L⁻¹) [9] | Species selectivity via potential control, excellent for UPD | Limited cathodic potential window |

| Mesoporous Platinum | High surface area | N/A | Information missing from search | Signal amplification, high catalytic activity | Can be more complex to fabricate |

| Glassy Carbon (GCE) | Broad potential window | Aripiprazole (ARP) | 0.11 μM [17] | Versatile, easily modified, robust | Can suffer from adsorption-related fouling |

| Mercury Film (MFE) | Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) | Various metals | Information missing from search | Wide cathodic window, renewable surface | Toxicity of mercury, solid electrodes often preferred |

| Bismuth Film | "Green" alternative | N/A | Information missing from search | Low toxicity, comparable performance to mercury for many metals | Limited pH and potential stability window |

Experimental Protocols: From Electrode Preparation to Quantification

Protocol 1: UPD-based Speciation of Arsenic Using Gold Macroelectrodes

This protocol enables the separate quantification of As(III) and total inorganic arsenic in water samples [9].

- Apparatus: Potentiostat (e.g., CHI 760), three-electrode cell with gold macroelectrode as working electrode, Pt wire auxiliary electrode, and Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrode [17].

- Reagents: Standard solutions of As(III) and As(V) in a suitable supporting electrolyte (e.g., dilute HCl or acetate buffer). High-purity deionized water (e.g., from a system like Human Power I+) [17].

- Procedure:

- Electrode Cleaning (Induction Period): Place the sample solution into the electrochemical cell. Deoxygenate with purified argon for 15 minutes. Hold the working electrode at a cleaning potential (e.g., +0.5 V) for a specified duration to remove any previous contaminants [12].

- Analyte Deposition: Purge with argon for 30 seconds between runs. Step the potential to the deposition potential.

- Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for a brief period (e.g., 10-30 seconds) [12].

- Stripping: Initiate a positive-going potential sweep from the deposition potential to a more positive final potential (e.g., +0.5 V). The sweep can be linear, or use pulsed techniques like Differential Pulse (DPSV) or Square Wave (SWSV) for enhanced sensitivity [12].

- Relaxation Period: Conclude by holding the electrode at the final potential for ~1 second before returning to idle [12].

- Data Analysis: The arsenic concentration is proportional to the charge passed during the stripping peak. Construct a calibration curve by plotting stripping peak current (or area) against standard concentration for both deposition potentials. Calculate As(V) concentration by subtracting the As(III) concentration (from -0.9 V deposition) from the total arsenic concentration (from -1.3 V deposition) [9].

Protocol 2: Sensitive Drug Determination via Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry on Glassy Carbon

This protocol, adapted from the determination of Aripiprazole, highlights how adsorption, rather than UPD, can be leveraged for extreme sensitivity in drug analysis [17].

- Apparatus: Potentiostat, three-electrode cell with Glassy Carbon Working Electrode (GCE), Pt wire auxiliary electrode, and Ag/AgCl reference electrode. pH meter [17].

- Reagents:

- Stock Drug Solution: 5.0 mM Aripiprazole (ARP) in methanol. Protect from light [17].

- Supporting Electrolyte: Britton-Robinson (BR) buffer, pH 4.0. Prepare by mixing phosphoric acid, boric acid, and acetic acid, then adjust pH with NaOH or HCl [17].

- Pharmaceutical/Serum Samples: Tablets are powdered and dissolved in methanol. Serum or urine samples are spiked and diluted with BR buffer [17].

- Electrode Preparation: Prior to each measurement, polish the GCE surface with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 μm) on a microcloth, then rinse thoroughly with deionized water and methanol [17].

- Procedure:

- Adsorptive Accumulation: Transfer 10.0 mL of the ARP solution in BR buffer (pH 4.0) to the cell. Deoxygenate with argon for 15 minutes. While the solution is under stirring, hold the electrode at an accumulation potential (e.g., +0.8 V, chosen to promote adsorption without causing oxidation) for a fixed time (e.g., 60 seconds) [17].

- Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow a 2-second equilibration period [17].

- Stripping Scan: Record the voltammogram by applying a positive-going square-wave or differential-pulse scan towards +1.3 V. The oxidation peak for ARP appears at approximately +1.15 V [17].

- Quantification: The method shows a linear range from 0.221 μM to 13.6 μM in stripping mode, with a LOD of 0.11 μM. Assay recovery from tablets, human serum, and urine ranges from 95.0% to 104.6% [17].

Visualizing the Experimental Workflow and UPD Mechanism

The following diagrams, generated using Graphviz with a high-contrast color palette, illustrate the core concepts and procedures.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A carefully selected set of reagents and materials is fundamental to the success of any UPD stripping experiment.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for UPD Stripping Voltammetry

| Item | Technical Function | Exemplars & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Instrument for applying controlled potentials/currents and measuring the electrochemical response. | CHI 760 analyzer; WaveNow/WaveNano portable potentiosts. Key parameters include 16-bit DAC resolution for accurate waveform generation [12] [17]. |

| Working Electrode | Surface where UPD and stripping occur; defines selectivity and sensitivity. | Gold macroelectrode (for As), Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Mesoporous Pt, Bismuth Film Electrode [9] [17]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for the working electrode. | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl), stored in appropriate electrolyte [17]. |

| Auxiliary Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit in the three-electrode cell. | Platinum wire [17]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducts current and fixes the ionic strength/pH of the solution. | Britton-Robinson (BR) buffer, acetate buffer, HCl. Use analytical reagent grade chemicals [17]. |

| Purification Gas | Removes dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with reduction reactions. | Purified Argon (99.99%), with deoxygenation for 15 min before first run [17]. |

| Calibration Standards | Solutions of known concentration for constructing the analytical calibration curve. | Prepared from high-purity standard materials (e.g., 99.0% drug standard) in solvent (e.g., methanol), protected from light [17]. |

| Surface Polishing | Maintains a clean, reproducible electrode surface for reliable measurements. | Alumina slurry (0.05 μm) on microcloth polishing pad [17]. |

Proven UPD-SV Protocols for Ag, Pb, Cu, Tl, and As

Underpotential Deposition Stripping Voltammetry (UPD-SV) represents a powerful electroanalytical technique that combines the unique properties of underpotential deposition with the exceptional sensitivity of stripping voltammetry. Underpotential deposition (UPD) describes the phenomenon where a metal ion is electrochemically deposited onto a foreign substrate at a potential more positive than its thermodynamic reduction potential, typically resulting in the formation of up to a monolayer of coverage [18]. This process differs fundamentally from overpotential deposition (OPD), where bulk deposition occurs at potentials more negative than the formal potential. When coupled with stripping voltammetry—an technique known for its remarkable sensitivity due to an analyte preconcentration step [19]—UPD creates a powerful analytical method particularly suited for trace metal analysis.

The exceptional sensitivity of stripping voltammetry stems from its two-step operational principle. First, during the preconcentration step, target analytes are accumulated onto or into the working electrode surface. Second, during the stripping step, the accumulated analyte is stripped back into solution while measuring the current response, which is proportional to its concentration [19] [20]. This combination allows UPD-SV to achieve detection limits as low as 10-10–10-12 mol L-1, making it ideal for environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical quality control, and clinical analysis [19]. The technique's specificity for different metal ions can be enhanced through careful selection of electrode materials, deposition potentials, and supporting electrolytes, enabling selective determination even in complex matrices.

Theoretical Foundations and Analytical Advantages

UPD-SV leverages the fundamental principle that the deposition of a metal monolayer onto a foreign substrate often occurs at potentials positive to the Nernst potential for bulk deposition. This thermodynamic driving force arises from the favorable metal-substrate interactions, which lower the free energy of adsorption compared to the bulk metal [18]. The UPD process is typically characterized by two distinct oxidation stripping peaks during the positive-going scan: the more negative peak corresponds to bulk deposited layers, while the more positive peak represents the more strongly adsorbed monolayer deposited directly at the electrode surface [18].

The analytical advantages of UPD-SV are substantial. First, at low analyte concentrations where the metallic deposit covers only a small percentage of the electrode surface, the electrode structure remains largely unchanged, significantly improving measurement precision. This characteristic also diminishes the need for frequent electrode cleaning and reactivation between measurements [18]. Second, since UPD requires less than a monolayer coverage, deposition times can be shortened, leading to faster analysis times. Third, some UPD processes can be performed in the presence of dissolved oxygen, eliminating the time-consuming degassing step typically required in conventional stripping voltammetry [18]. Furthermore, the technique can be adapted for speciation studies and fractionation analysis, as different oxidation states of elements often deposit at different potentials [19].

Table 1: Comparison of UPD-SV with Conventional Stripping Voltammetry

| Parameter | UPD-SV | Conventional Stripping Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Coverage | Sub-monolayer (<1 monolayer) | Multilayer (bulk deposition) |

| Deposition Potential | More positive than Nernst potential | More negative than Nernst potential |

| Electrode Surface Stability | High (minimal surface alteration) | Moderate to low (surface changes possible) |

| Analysis Time | Generally shorter deposition | Longer deposition often required |

| Oxygen Sensitivity | Can often work without deaeration | Typically requires deoxygenation |

| Intermetallic Compound Formation | Reduced risk | Higher risk, especially at mercury films |

Experimental Protocols for Specific Metal Ions

UPD-SV Protocol for Lead (Pb) at Silver Electrodes

The determination of lead using UPD-SV at silver electrodes represents a well-established protocol with excellent sensitivity and reproducibility. The procedure utilizes silver electrodes fabricated from recordable compact discs (CDs), providing an economical and accessible platform for analysis [18].

Working Electrode Preparation: Silver working electrodes are manufactured from recordable compact discs by cutting the CD into appropriate-sized pieces and peeling apart the polycarbonate layers to expose the reflective silver layer. Electrical contact is established using a crocodile clip attached to coaxial cable, with the active surface area defined and insulated using epoxy resin or similar insulating material [18].

Experimental Conditions:

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 M HCl

- Deposition Potential: -0.50 V (vs. SCE) for UPD process

- Deposition Time: 100 seconds with solution stirring

- Equilibration Period: 15 seconds quiescence after deposition

- Stripping Technique: Differential Pulse ASV from -0.5 V

- Pulse Parameters: Step height of 2.4 mV, step width of 0.2 s, pulse amplitude of 50 mV, pulse duration of 50 ms [18]

Analytical Performance: This method exhibits a distinct UPD stripping peak for Pb at approximately 0.37 V (vs. SCE), with the bulk deposition stripping peak appearing at 0.49 V. The protocol has been successfully applied to the determination of Pb in environmental water samples, with demonstrated recovery of 95% for samples fortified with 100 ng/mL Pb and a coefficient variation of 2.7% [18].

UPD-SV Protocol for Copper (Cu) and Platinum (Pt) at Nitrogen-Doped Graphene

The UPD protocol for copper at nitrogen-doped graphene (np-NG) electrodes demonstrates the potential for single-atom catalysis and sensitive determination, with extension to platinum through a galvanic replacement process.

Electrode Modification: Nanoporous nitrogen-doped graphene (np-NG) is synthesized on a nanoporous Ni template using chemical vapor deposition with melamine as carbon and nitrogen sources, resulting in a material with approximately 6.3% nitrogen content [21].

Copper UPD Procedure:

- Electrolyte: 0.1 M H₂SO₄ saturated with Ar, containing 2 mM CuSO₄

- Deposition Potential: +0.10 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Deposition Time: 120 seconds

- Electrode System: Ag/AgCl reference electrode (3.0 M KCl) and Pt sheet counter electrode [21]

Spectroscopic and electrochemical analyses confirm that pyridine-like N defect sites serve as the specific sites for UPD of copper single atoms. The resulting np-NG/Cu electrode can be subsequently converted to a Pt single-atom catalyst (np-NG/Pt) through galvanic replacement by transferring to an Ar-saturated 50 mM H₂SO₄ solution containing 2 mM K₂PtCl₄ and allowing to stand for 10 minutes at open circuit potential [21].

Table 2: Summary of UPD-SV Protocols for Different Metal Ions

| Metal Ion | Electrode Material | Supporting Electrolyte | Deposition Potential | Key Analytical Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb | Silver (from CD) | 0.1 M HCl | -0.50 V (vs. SCE) | Deposition time: 100 s; Stripping peak: ~0.37 V (UPD) |

| Cu | N-doped graphene | 0.1 M H₂SO₄ + 2 mM CuSO₄ | +0.10 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) | Deposition time: 120 s; Specific sites: pyridine-like N defects |