Troubleshooting Background Current in Voltammetry: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing background current in voltammetry.

Troubleshooting Background Current in Voltammetry: A Complete Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on managing background current in voltammetry. It covers the fundamental principles of capacitive and faradaic background currents, outlines systematic methodologies for accurate measurement and analysis, presents a step-by-step diagnostic and optimization protocol for common issues, and establishes validation frameworks to ensure data reliability. The content synthesizes expert troubleshooting strategies with a focus on applications in sensitive biomedical analysis, enabling scientists to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of their electrochemical measurements.

Understanding Background Current: Origins, Components, and Impact on Data Fidelity

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is background current in voltammetry? Background current, often observed as a non-zero baseline in voltammograms, is the current measured in the absence of the target faradaic reaction. It primarily consists of two components: the non-faradaic (or capacitive) current, due to the charging and discharging of the electrical double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface, and currents from faradaic processes stemming from impurities or electrolyte breakdown [1] [2] [3].

What is the fundamental difference between faradaic and non-faradaic current? The distinction lies in electron transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface.

- Faradaic Process: Involves the transfer of electrons across the electrode interface, leading to the oxidation or reduction of electroactive species. This current is governed by Faraday's law and is the source of your analytical signal [3].

- Non-Faradaic (Capacitive) Process: Involves no net transfer of electrons. It is a charging/discharging process where ions in the solution rearrange at the electrode surface, forming a capacitor-like structure called the electrical double layer. The current associated with this charging is the non-faradaic or capacitive current [2] [3].

Why is a large background current problematic? A large or unstable background current compromises data quality and sensor performance by:

- Reducing Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): Obscuring the smaller faradaic current from your analyte.

- Limiting Electrode Surface Area: High capacitive currents can saturate instrument amplifiers, preventing the use of larger electrodes for enhanced signal [2].

- Complicating Data Analysis: Requires complex digital background subtraction during data processing [2].

- Causing Distorted Voltammograms: Leading to sloping baselines or large hysteresis [1].

My cyclic voltammetry baseline is not flat and has a large hysteresis. What is the cause? A non-flat baseline with significant hysteresis between forward and backward scans is primarily due to charging currents in the electrode [1]. The electrode-solution interface acts as a capacitor, which must be charged before the electrochemical process, creating this hysteresis. You can mitigate it by:

- Decreasing the scan rate [1].

- Increasing the concentration of your analyte [1].

- Using a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Background Current Issues

Problem 1: High Capacitive Background Current

Observed Symptom: A large, reproducible hysteresis in the baseline of a cyclic voltammogram, or a large, sloping background that obscures the faradaic peaks [1].

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Excessively High Scan Rate. The capacitive current is directly proportional to the scan rate, while the faradaic current is proportional to the square root of the scan rate. Thus, at higher scan rates, the capacitive background becomes more dominant.

- Solution: Reduce the potential scan rate. This allows the double layer to charge/discharge with less current and gives the faradaic process more prominence [1].

- Cause: Electrode Surface Area is Too Large. The magnitude of the capacitive current is directly proportional to the electrode's surface area.

- Cause: High Electrolyte Concentration. While electrolyte is necessary, very high concentrations can contribute to a larger double-layer capacitance.

- Solution: Ensure your electrolyte concentration is sufficient for supporting the faradaic reaction but is not excessively high.

Problem 2: Unusual Peaks or Drifting Baseline

Observed Symptom: Unexpected peaks appear in the voltammogram, or the baseline current drifts over successive cycles [1].

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Impurities. Contaminants from chemicals, the atmosphere, or degraded cell components can introduce unexpected faradaic processes [1].

- Solution: Run a background scan with only the electrolyte and solvent. Use high-purity reagents. Ensure proper cleaning of the electrochemical cell and electrodes.

- Cause: Poor Electrical Contacts or Blocked Reference Electrode. Unstable contacts can generate noise and drifting signals. A blocked reference electrode frit can cause the reference to act like a capacitor, leading to drifting potentials and unusual voltammograms [1].

- Solution: Check that all cables and connectors are intact. Polish the working electrode. For a blocked reference, check for air bubbles or a clogged frit [1].

Problem 3: No or Very Small Current Detected

Observed Symptom: A very small, noisy, but otherwise unchanging current is detected, with no faradaic response from the analyte [1].

Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Working Electrode Not Properly Connected. If the working electrode is not connected to the cell, the potential will change, but no faradaic current will flow [1].

- Solution: Check the connection of the working electrode cable. Ensure the electrode is properly submerged in the solution.

This protocol provides a systematic approach to isolate and identify the source of background current.

Objective: To distinguish between non-faradaic (capacitive) currents and faradaic currents from impurities in your electrochemical system.

Principle: By comparing voltammograms of a blank electrolyte solution against a solution with a well-known redox couple, you can characterize the background and its impact on your signal.

Materials:

- Potentiostat

- Standard three-electrode cell (see "Research Reagent Solutions" below)

- High-purity electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl or TBAPF6)

- High-purity solvent

- Known redox standard (e.g., 1 mM Ferrocene in acetonitrile)

- Alumina polishing slurry (0.05 µm)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon) with 0.05 µm alumina slurry, rinse thoroughly with solvent, and dry [1].

- Blank Solution Measurement:

- Prepare a solution containing only the supporting electrolyte and solvent.

- Insert the clean electrodes into the cell.

- Record a cyclic voltammogram over your potential window of interest, using a moderate scan rate (e.g., 100 mV/s).

- Observation: The resulting voltammogram represents your total background current. A featureless, "duck-shaped" curve indicates a primarily capacitive background. Any distinct peaks indicate faradaic processes from impurities [4].

- Standard Redox Couple Measurement:

- Add a known, reversible redox couple (like Ferrocene) to the blank solution.

- Record a cyclic voltammogram under identical conditions.

- Observation: The well-defined peaks of the standard allow you to assess the reversibility of your system and see how the background current contributes to the overall shape of the voltammogram [4].

- Data Analysis:

- Digitally subtract the blank voltammogram (Step 2) from the standard voltammogram (Step 3). This subtraction removes the capacitive background, leaving a cleaner faradaic signal.

- Use the Randles-Sevcik equation to analyze the peak current of your standard. The peak current for a reversible system is given by:

- ( ip = (2.69 \times 10^5) \cdot n^{3/2} \cdot A \cdot D^{1/2} \cdot C \cdot v^{1/2} )

- Where ( ip ) is the peak current (A), ( n ) is the number of electrons, ( A ) is the electrode area (cm²), ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s), ( C ) is the concentration (mol/cm³), and ( v ) is the scan rate (V/s) [4]. A significant deviation from the expected value may indicate issues like electrode fouling.

Advanced Technique: Hardware Suppression of Non-Faradaic Current

For applications requiring the highest sensitivity, such as detecting low-concentration analytes in complex matrices like serum, digital background subtraction may be insufficient.

Technology: Differential Potentiostat (DiffStat) The DiffStat uses a two-working-electrode configuration (W1 and W2) with matched transimpedance amplifiers. The current from a "blank" working electrode (W2) is analog-subtracted in real-time from the current at the experimental working electrode (W1). Since the non-faradaic background is identical at both electrodes, it is suppressed at the source, before digitization [2].

Benefits:

- Order-of-magnitude improvement in sensitivity by removing the capacitive baseline [2].

- Enables the use of larger electrode surface areas without amplifier saturation [2].

- Simplifies data processing by outputting a signal that is predominantly faradaic current [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key materials and their functions for troubleshooting and minimizing background current.

| Item | Function & Rationale | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Working Electrode | Standard electrode for many aqueous and non-aqueous applications. Provides a wide potential window and reproducible surface. | Requires meticulous polishing with alumina between experiments to remove adsorbed species and ensure a fresh, clean surface [1]. |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for accurate potential control in aqueous solutions. | Ensure the salt-bridge (frit) is not blocked and there are no air bubbles, which can cause unstable potentials and distorted voltammograms [1]. |

| Platinum Wire Counter Electrode | Conducts current from the source to the solution to balance the current at the working electrode. | A large surface area is crucial to prevent it from becoming a limiting factor in the electrochemical cell [4]. |

| High-Purity Electrolyte Salts (e.g., KCl, TBAPF6) | Provides ionic conductivity in the solution while minimizing faradaic contributions from impurities. | Use the highest purity available. Even trace impurities can introduce unexpected faradaic peaks [1]. |

| Alumina Polishing Slurry (0.05 µm) | Used for abrasive polishing of solid working electrodes to regenerate a clean, reproducible surface. | Essential for removing adsorbed species that can cause non-faradaic capacitive currents or spurious faradaic peaks [1]. |

| Faradaic Standard (e.g., Ferrocene) | A well-characterized, reversible redox couple used to calibrate the electrochemical system and assess performance. | The peak separation ((\Delta E_p)) should be close to 59/n mV for a reversible system. A larger value indicates high resistance or slow electron transfer kinetics [4]. |

| Dovitinib dilactic acid | Dovitinib dilactic acid, MF:C27H33FN6O7, MW:572.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dracorhodin perchlorate | Dracorhodin perchlorate, MF:C17H15ClO7, MW:366.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What causes the non-faradaic, "background" current in my voltammetry experiments? The background current, also known as the residual or capacitive current, is primarily caused by the charging of the electrical double-layer capacitance at the electrode-solution interface [5]. Unlike faradaic current from electron transfer reactions, this current arises from the rearrangement of ions and solvent dipoles at the electrode surface as the applied potential changes [5]. Under most experimental conditions, this background is distinctly nonlinear due to the potential dependence of the capacitance itself [6].

Q2: Why is my baseline not flat and shows large hysteresis? Hysteresis in the baseline is primarily due to these charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts like a capacitor [1]. The electrode must be charged before any faradaic process occurs. This effect can be exacerbated by a faulty working electrode or, for solid electrodes, the interface's non-ideal Constant Phase Element (CPE) behavior, which causes a dissipative, non-ideal capacitive response [7].

Q3: My voltammogram has an unexpected peak. Could this be related to the background? While unexpected peaks are often from impurities or electrolyte decomposition, a sharp increase in current at the potential window's edge can be mistaken for a peak [1]. To confirm, always run a background scan using only your electrolyte solution (without the analyte) to establish the electrochemical window and identify features originating from the electrolyte-electrode interface itself [5].

Q4: How does the choice of electrode material affect the double-layer background? The electrode material is critical. Liquid electrodes like mercury exhibit a well-defined, purely capacitive double-layer [7]. In contrast, solid electrodes (e.g., Pt, Au, carbon) often display CPE behavior, where the capacitance is "dispersed" and the interface behaves in a more complex, non-ideal fashion [7]. This can lead to more complex background shapes.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Primary Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noisy or erratic data [8] | Unstable reference electrode; Poor electrical contacts; Contaminated working electrode. | Check reference electrode stability with a pseudo-reference; inspect all connections [1]. | Ensure reference electrode frit is not blocked; rinse and repolish working electrode; check for loose cables [8] [1]. |

| Large, reproducible hysteresis in baseline [1] | Charging currents from the double-layer capacitance. | Reduce the scan rate; if the hysteresis decreases, the capacitive current is the culprit. | Decrease scan rate; increase analyte concentration; use a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1]. |

| Sloping or non-flat baseline [1] | Unknown processes at the electrode; possible faults in the working electrode. | Perform a general equipment check using a test resistor or cell [1]. | Repolish and clean the working electrode thoroughly [1]. |

| Very small, noisy current (no faradaic response) [1] | Working electrode is not properly connected or is contaminated. | Check if the measured potential changes but no faradaic current flows. | Ensure the working electrode is properly connected and submerged; clean and repolish the electrode surface [1]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol for Background Correction in Voltammetry

Accurate quantification of faradaic signals requires subtracting the non-faradaic background.

- Record the Background Voltammogram: Under the exact same experimental conditions (electrode, electrolyte, solvent, scan rate, etc.), perform your voltammetric scan in a solution containing only the supporting electrolyte [1].

- Record the Sample Voltammogram: Without changing any settings, run the scan again with your analyte present in the electrolyte.

- Subtract the Signals: Digitally subtract the background current from the sample current at each potential to obtain the pure faradaic signal. For techniques like AC Voltammetry, this correction can be performed on a per-harmonic basis [6].

Protocol for Electrode Preparation and Maintenance

Proper electrode preparation is essential for minimizing anomalous background signals [8] [1].

- Mechanical Polishing: For solid working electrodes, polish the surface with a fine alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad to a mirror finish [1].

- Rinsing: Thoroughly rinse the electrode with pure solvent (e.g., water, acetone) to remove all polishing material [8].

- Electrochemical Cleaning (for Pt electrodes): In a clean 1 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ solution, cycle the electrode potential between the regions where hydrogen and oxygen evolution occur to desorb contaminants [1].

- Storage: Store electrodes properly according to manufacturer guidelines. For reference electrodes, this often involves keeping the frit moist in the correct filling solution [8].

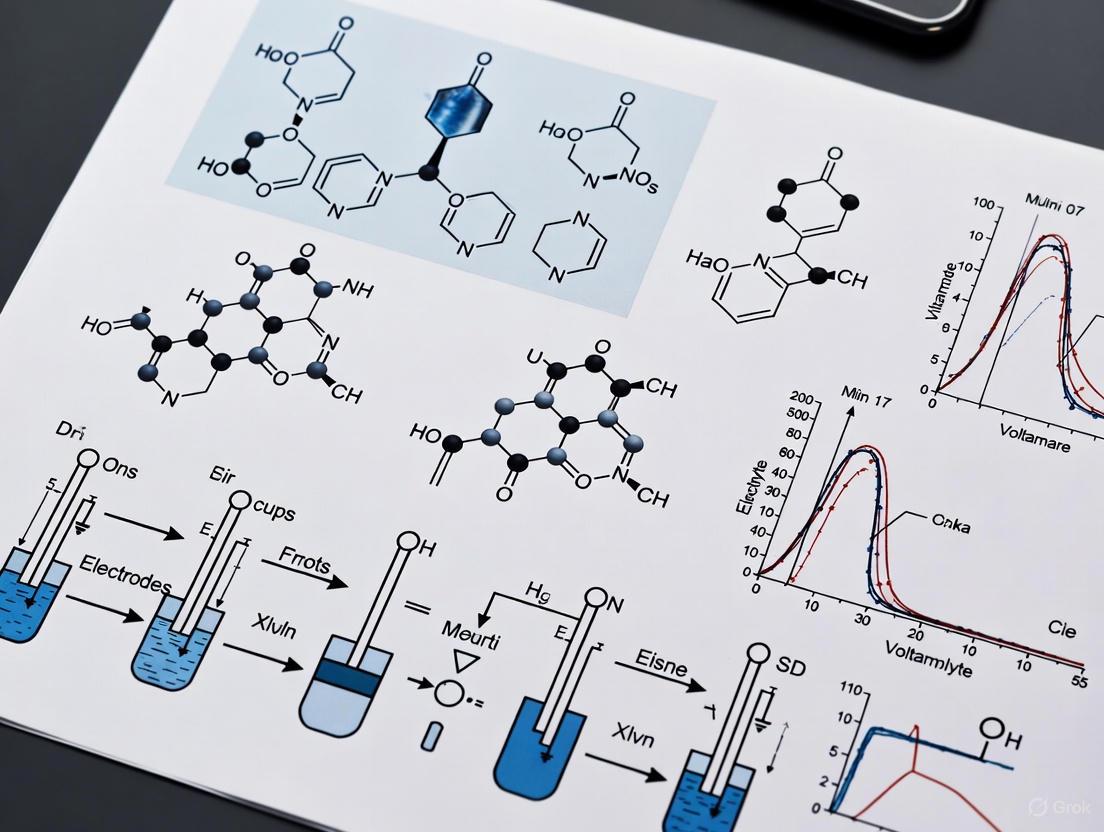

Visualizing the Signal Composition

The following diagram illustrates how the total current in a voltammogram is composed of both faradaic and capacitive components, and how experimental parameters like scan rate affect them.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, NaClOâ‚„, Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) [9] | Carries current and minimizes resistive loss (IR drop); defines the ionic environment. | Must be electrochemically inert in the potential window of interest and sufficiently soluble [9]. |

| Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, SCE) [8] [10] | Provides a stable, known potential for accurate control of the working electrode potential. | Check for blocked frits and stable fill solution [8]. Avoid using a Luggin capillary in high-temperature experiments where bubbles may form [8]. |

| Working Electrode (e.g., Pt, Glassy Carbon, Au) [10] | The surface where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs. | Surface history is critical. Always clean and repolish before use [1]. For corrosion studies (LPR), use disposable coupons to avoid surface area uncertainty from corrosion [8]. |

| Counter (Auxiliary) Electrode (e.g., Pt wire, graphite rod) [8] [10] | Completes the electrical circuit by balancing the current at the working electrode. | Ensure it is not coated by a non-conductive film (e.g., oil) and is properly submerged [8]. |

| Alumina Polishing Powder (0.05 µm) [1] | For refreshing the working electrode surface to a reproducible, clean state. | Essential for removing contaminants and adsorbed species that distort the background signal [1]. |

| DS28120313 | DS28120313, MF:C16H17N5O2, MW:311.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| dTRIM24 | dTRIM24, MF:C55H68N8O13S2, MW:1113.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

How do electrode material and condition contribute to unwanted current?

The choice and maintenance of the working electrode are primary factors influencing unwanted background current and noise.

- Electrode Material: Different materials have unique electrochemical windows—the potential range in which they are inert. Using a potential outside this window causes the electrode itself to react, creating a large background current. For example, mercury electrodes are excellent for reduction studies due to their high overpotential for hydrogen evolution but are easily oxidized at positive potentials [10] [11].

- Electrode Surface Fouling: The adsorption of solution impurities or reaction products onto the electrode surface can block electron transfer. This fouling alters the electrode's capacitive properties, often leading to a sloping baseline, increased hysteresis, or unexpected peaks in the voltammogram [1] [12].

- Poor Electrical Connection: A faulty connection to the working electrode can result in a very small, noisy, and unchanging current, as the electrochemical system is effectively disconnected [1].

Diagnostic Protocol: To isolate an electrode issue, follow this procedure:

- Inspect and Clean: Physically inspect the electrode for cracks or damage. For carbon-based electrodes, polish the surface with 0.05 μm alumina slurry and rinse thoroughly. For a platinum electrode, electrochemical cleaning can be performed by cycling the potential in a 1 M H2SO4 solution between the potentials for H2 and O2 evolution [1].

- Test in a Known System: Run a cyclic voltammetry experiment with a well-understood redox couple, such as potassium ferricyanide, in a supporting electrolyte. A distorted or absent signal confirms an issue with the electrode surface or connection [12].

- Replace Components: Substitute the working electrode with a new or known-good one. If the problem persists, replace the cables to eliminate poor connections as the source [1].

How does the electrolyte composition affect background current?

The supporting electrolyte is crucial for minimizing unwanted currents related to solution resistance.

- Insufficient Ionic Strength: The primary role of the electrolyte is to carry current between the working and counter electrodes. If the electrolyte concentration is too low, the solution resistance increases, leading to a significant iR drop. This drop distorts the voltammogram, causing peak broadening, a shift in peak potential, and overall shape distortion [13] [14].

- Electrolyte Purity: Chemical impurities in the solvent or electrolyte can be redox-active. These impurities will undergo oxidation or reduction within your potential window, creating unexpected peaks or elevating the background current [1] [13].

- Solvent Window: Every solvent has a finite electrochemical stability window. Exceeding these limits by applying too high or too low a potential will cause the solvent or electrolyte to break down, generating a large and irreversible background current [13].

Diagnostic Protocol: To confirm an electrolyte-related issue:

- Run a Background Scan: Always perform a control experiment by collecting a cyclic voltammogram of the pure solvent and supporting electrolyte without your target analyte. Any peaks or high background in this scan are due to the electrolyte system or solvent impurities [1].

- Increase Electrolyte Concentration: Ensure your supporting electrolyte is present in sufficient excess (typically 0.1 M to 1.0 M) to provide high ionic strength and minimize iR drop [13].

- Purify Components: Use high-purity solvents and electrolytes. Consider further purification methods, such as distillation or recrystallization, if impurity-related peaks are persistent [13].

What is the relationship between scan rate and unwanted charging current?

The scan rate directly controls the non-faradaic charging current, which is a major component of unwanted background current.

- Charging Current Dominance: In cyclic voltammetry, the electrode-solution interface behaves like a capacitor. When the potential is changed, a charging current flows to alter the charge on this "double-layer capacitor." This current does not involve electron transfer to analytes and is therefore a key source of background. The magnitude of this charging current is directly proportional to the scan rate and the electrode's capacitance [1] [12].

- Diffusion-Layer Effects: For a freely diffusing analyte, the faradaic (signal) peak current is proportional to the square root of the scan rate. In contrast, the charging current is directly proportional to the scan rate. Therefore, at very high scan rates, the charging current can become the dominant feature, obscuring the faradaic signal of interest and reducing the signal-to-noise ratio [15] [12].

Diagnostic Protocol: To characterize the effect of scan rate:

- Perform a Scan Rate Study: Run cyclic voltammetry experiments on your system across a range of scan rates (e.g., from 10 mV/s to 1000 mV/s).

- Analyze Peak Current Dependence: Plot the log of the peak current (ip) against the log of the scan rate.

- A slope close to 0.5 indicates the process is controlled by diffusion of a solution-based species [15].

- A slope close to 1.0 suggests the redox species is adsorbed onto the electrode surface [15] [12].

- A rising baseline with increasing scan rate confirms a significant contribution from charging current.

- Optimize Scan Rate: Choose a scan rate that provides a clear faradaic signal with an acceptable background. If the charging current is too high, reduce the scan rate [1].

The table below summarizes key parameters and their quantitative effects on the voltammetric signal.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Experimental Parameters on Voltammetric Current

| Parameter | Effect on Faradaic Peak Current (ip) | Effect on Charging Current (ic) | Diagnostic Power |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scan Rate (v) | ip ∠v1/2 (diffusion control) [15] [12] | ic ∠v [1] [12] | Distinguishes diffusion (slope ~0.5) from adsorption (slope ~1.0) [15]. |

| Analyte Concentration (c) | ip ∠c [12] | No direct effect | Confirms analyte identity and enables quantitative calibration. |

| Electrode Area (A) | ip ∠A [1] | ic ∠A [1] | Larger areas increase both signal and background. |

Diagnostic Workflows

Troubleshooting Unwanted Currents

Current Dependence on Scan Rate

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes solution resistance (iR drop) and carries current. | Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate for non-aqueous systems; alkali metal perchlorates or nitrates for aqueous systems [13]. |

| High-Purity Solvent | Dissolves analyte and electrolyte without introducing redox-active impurities. | Acetonitrile is common for non-aqueous electrochemistry; must be dry and stored over molecular sieves [13]. |

| Redox Standard | Validates electrode performance and instrument calibration. | Potassium ferricyanide in KCl buffer is a common reversible standard [12]. |

| Alumina Polish | Refreshes the working electrode surface to remove adsorbed contaminants. | 0.05 μm alumina slurry in water for polishing glassy carbon and metal electrodes [1]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for the working electrode. | Ag/AgCl (aqueous) or Ag/Ag+ (non-aqueous) are common. Check that the frit is not blocked [1] [14]. |

| Dubermatinib | Dubermatinib, CAS:1341200-45-0, MF:C24H30ClN7O2S, MW:516.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Durlobactam Sodium | Durlobactam Sodium, CAS:1467157-21-6, MF:C8H10N3NaO6S, MW:299.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

FAQs

My baseline current is not flat and has a significant slope. What should I do?

A sloping baseline is often attributable to processes at the working electrode, though the exact origins can be complex and are not always fully known. First, ensure your electrode is clean and well-polished. A sloping baseline can also be caused by a capacitive charging current, which can be mitigated by using a slower scan rate, a higher analyte concentration, or a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1].

Why does my cyclic voltammogram look different on repeated cycles?

This is typically caused by an unstable reference electrode or changes in the working electrode surface. Check that your reference electrode is in proper electrical contact with the solution (e.g., no blocked frits or air bubbles). If using a quasi-reference electrode, such as a bare silver wire, its potential can drift. Additionally, the analyte or its products may be adsorbing onto or fouling the working electrode surface, changing its properties with each cycle [1].

I see an unexpected peak in my voltammogram. How can I identify its source?

Unexpected peaks are frequently due to impurities or the system approaching the edge of the electrochemical window. The first step is to run a background scan with only the solvent and supporting electrolyte; any peaks that remain are not from your primary analyte. Common impurities include oxygen, water (in non-aqueous systems), or contaminants from the electrolyte or glassware [1].

What is background current and why is it a critical parameter in voltammetric bio-assays?

Background current, often called the charging or capacitive current, is the current measured in the absence of your target analyte. It originates from processes other than the specific redox reaction you are investigating. In voltammetric systems, it is primarily caused by the charging of the electrical double-layer at the electrode-solution interface and the oxidation or reduction of trace impurities or the electrolyte itself [1] [10].

Minimizing the background current is paramount because it constitutes the baseline noise from which you must distinguish your analytical signal. A high or unstable background current directly elevates the method's limit of detection (LOD), as the smallest detectable signal must be statistically significant against this background noise. Furthermore, it can compromise analytical accuracy by distorting the shape, peak current, and peak potential of your voltammogram, leading to incorrect interpretation of data, especially at low analyte concentrations common in bio-assays [1] [16].

Common sources can be categorized as follows [1]:

- Electrode-Related Issues:

- Surface Contamination: Adsorbed species from the atmosphere, sample matrix, or previous experiments.

- Poor Electrode Polish: A rough electrode surface increases the effective surface area and can trap impurities.

- Electrode Material: The choice of material (e.g., glassy carbon, platinum, mercury) and its inherent properties affect the background window.

- Solution-Related Issues:

- Impure Electrolyte/Solvent: Trace electroactive species in salts or solvents are a frequent culprit.

- Dissolved Oxygen: Oxygen is electroactive and produces a significant reduction current, which can obscure analytical signals.

- Sample Matrix Effects: Components in complex biological samples (e.g., proteins, cells) can foul the electrode or be electroactive themselves.

- Instrumental and Setup Issues:

- Electrical Pickup and Noise: Poor cable connections or shielding.

- High Scan Rates: The charging current is directly proportional to the scan rate.

- Uncompensated Resistance: Can lead to distorted and offset voltammograms.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

The baseline of my voltammogram is not flat and shows a significant slope or hysteresis. What should I do?

A non-flat baseline, particularly one with hysteresis between forward and backward scans, is often due to charging currents and other capacitive effects at the working electrode [1].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Polish and Clean the Working Electrode: Gently polish the electrode with 0.05 μm alumina slurry and wash it thoroughly to remove any absorbed species. For platinum electrodes, a recommended cleaning protocol is to cycle the potential between the regions where H₂ and O₂ are produced in a 1 M H₂SO₄ solution [1].

- Reduce the Scan Rate: The charging current is directly proportional to the scan rate. Decreasing the scan rate will reduce the background contribution. If you must use a high scan rate, ensure your analyte concentration is sufficiently high to produce a Faradaic signal that dominates the charging current [1].

- Check for Electrode Defects: Inspect the electrode for cracks or poor internal seals, which can lead to high resistivity and capacitance, causing sloping baselines [1].

- Use a Background Subtraction Technique: Always run a "blank" voltammogram containing only your electrolyte and solvent. Subtract this background signal from your sample voltammogram to isolate the Faradaic current of your analyte.

My voltammogram looks unusual or different on repeated cycles, and I suspect my reference electrode. How can I diagnose this?

An unstable or incorrectly set up reference electrode is a common cause of drifting or inconsistent voltammograms [1].

Diagnostic Procedure:

- Check Electrical Contact: Ensure the reference electrode's salt-bridge or frit is not blocked and that no air bubbles are trapped at its tip, preventing electrical contact with the solution [1].

- Test with a Quasi-Reference Electrode: Replace your reference electrode with a bare silver wire (a quasi-reference electrode) and run the measurement again. If a stable and expected response is obtained, the issue likely lies with your original reference electrode [1].

- Short-Circuit Test: As a diagnostic step, you can connect the reference electrode cable directly to the counter electrode (in addition to the counter electrode cable). Running a linear sweep with an analyte present should result in a standard, though shifted and slightly distorted, voltammogram. If you do not obtain this response, the problem may be with the working or counter electrodes [1].

I am getting voltage or current compliance errors from my potentiostat. What is happening?

These errors indicate that the potentiostat cannot maintain the desired potential or that the current has exceeded safe limits.

- Voltage Compliance Error: The potentiostat cannot control the potential between the working and reference electrodes. This can happen if your quasi-reference electrode is touching the working electrode, or if the counter electrode has been removed from the solution or is disconnected [1].

- Current Compliance Error: A very large current is being generated, often due to a short circuit. Check that the working and counter electrodes are not touching inside the cell [1].

How does background current directly affect the calculation of the Limit of Detection (LOD)?

The LOD is fundamentally tied to the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), where the background current is a major contributor to the noise. Several formal methods for LOD estimation explicitly incorporate the background signal [16].

Common LOD Calculation Methods:

- Signal-to-Noise (S/N): The LOD is often defined as the concentration that yields an analyte signal three times the standard deviation of the background noise: LOD = 3 × N (where N is the noise) [16].

- Measurement of Blanks: The LOD can be calculated from multiple measurements of a blank solution using the formula: LOD = X̄B + 3.3 × σB, where X̄B is the mean signal of the blank and σB is its standard deviation [16].

- Visual and Serial Dilution: The lowest concentration at which an analyte peak can be reliably distinguished from the background (visually or via a predefined SNR) is reported as the LOD. This involves analyzing serial dilutions and comparing the signal to the baseline noise near the analyte response [16].

A high or unstable background current increases N and σB, thereby directly elevating the calculated LOD and making your method less sensitive.

What strategies can I use to minimize background current and improve my LOD?

Proactive Strategies for a Low Background:

- Meticulous Electrode Preparation: Consistent polishing and cleaning are the most critical steps.

- Purge with Inert Gas: Always deoxygenate your solution by purging with high-purity nitrogen or argon for 10-15 minutes before measurements.

- Use High-Purity Reagents: Use the highest grade of electrolyte and solvents available to minimize electroactive impurities.

- Optimize Electrode Material and Geometry: Select an electrode material with a wide potential window suitable for your analyte. Smaller electrodes generally have lower charging currents.

- Employ Pulse Voltammetric Techniques: Techniques like Square-Wave Voltammetry can discriminate against charging current, offering lower LODs compared to Cyclic Voltammetry [16].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Detailed Methodology: Estimating LOD via Serial Dilution and Signal-to-Noise

This protocol is adapted from common approaches for voltammetric methods as discussed in the literature [16].

1. Solution Preparation:

- Prepare a stock solution of your analyte at a known, relatively high concentration in your selected electrolyte/solvent system.

- Prepare a blank solution containing only the electrolyte and solvent.

- Create a series of standard solutions via serial dilution from the stock solution.

2. Instrumental Parameters (Example for Square-Wave Voltammetry):

- Technique: Square-Wave Voltammetry (for its low background).

- Potential Window: Set to encompass the analyte's oxidation/reduction peak.

- Frequency: 25 Hz

- Pulse Amplitude: 50 mV

- Step Potential: 5 mV

- Equilibrium Time: 10 s

3. Procedure:

- Purge the electrochemical cell with inert gas for 15 minutes.

- Insert the polished working electrode, reference electrode, and counter electrode.

- Record voltammograms for the blank solution (n=5).

- Record voltammograms for each standard solution in the dilution series, from highest to lowest concentration.

4. Data Analysis:

- For the blank measurements, identify a quiet region of the baseline near the expected peak position. Calculate the noise as the standard deviation (σ) of the current in this region, or as the peak-to-peak difference.

- For each standard, measure the peak height (current) of the analyte.

- Calculate the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) for each concentration: SNR = (Analyte Peak Current) / (σ of Blank).

- The LOD is the concentration that yields an SNR ≥ 3.

The following table summarizes how different calculation methods can lead to varying LOD values for the same analyte, highlighting the importance of reporting the method used. Data is illustrative, based on trends discussed in the literature [16].

Table 1: Comparison of LOD Estimation Methods for a Model Analytic (e.g., Naltrexone) using Square-Wave Voltammetry

| Estimation Method | Formula / Description | Calculated LOD (μM) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Visual Evaluation | Lowest concentration with a discernible peak. | 0.10 | Simple and intuitive. |

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | LOD = 3 × σBlank | 0.08 | Directly incorporates baseline noise. |

| Measurement of Blanks | LOD = X̄B + 3.3 × σB | 0.12 | Statistical rigor using blank population. |

| Calibration Curve | LOD = 3.3 × (Std Error of Regression) / Slope | 0.09 | Utilizes full calibration data. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Their Functions in Voltammetric Bio-Assays

| Item | Function & Importance | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | The site of the electrochemical reaction. Its material defines the usable potential window and sensitivity. | Glassy Carbon (GC), Pt, Au, Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) [10]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode is controlled. | Ag/AgCl (3M KCl), Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE). |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow. | Pt wire or coil. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes solution resistance (IR drop). Suppresses migration current. | KCl, Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), TBAPF6 (for organic solvents). |

| Solvent | Dissolves the analyte and electrolyte. Its electrochemical stability defines the potential window. | Water, Acetonitrile (MeCN), Dimethylformamide (DMF). |

| Polishing Supplies | Maintains a fresh, reproducible, and clean electrode surface, which is critical for a stable background. | Alumina slurry (0.05 μm), diamond paste, polishing pads. |

| Dynasore | Dynasore, CAS:304448-55-3, MF:C18H14N2O4, MW:322.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| EAI045 | EAI045, MF:C19H14FN3O3S, MW:383.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Workflow Visualizations

Diagram: Systematic Troubleshooting of High Background Current

Diagram: Relationship Between Background Current and LOD

Systematic Measurement and Analytical Techniques for Background Current

Why is my cyclic voltammetry baseline not flat, and how can I fix it?

A non-flat baseline, often showing significant hysteresis (differences between forward and backward scans), is a common issue in voltammetry. This is primarily due to charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts like a capacitor that must be charged before the electrochemical process occurs [1]. Other contributing factors include problems with the working electrode itself, such as poor contacts, adsorption of solution species, or surface oxidation [17] [1].

Troubleshooting and Solutions:

- Adjust Experimental Parameters: You can reduce the charging current by decreasing the scan rate, increasing the concentration of your analyte, or using a working electrode with a smaller surface area [1].

- Clean or Polish the Electrode: Contamination is a major cause of poor baselines. Mechanical polishing or electrochemical cleaning can remove adsorbed species and restore a clean, active surface [17] [1].

- Ensure Proper Connections: Check that all cables and connectors to your electrodes are intact and secure, as poor contacts can generate unwanted signals and noise [1].

What is the most effective method to clean and regenerate my electrode?

The optimal cleaning method depends on your electrode material and the nature of the contamination. The goal is to achieve a clean, reproducible surface without causing physical damage.

Comparison of Electrode Cleaning Methods

| Method | Typical Application | Key Protocol Details | Key Findings / Effectiveness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Polishing [17] [18] | Solid electrodes (e.g., Glassy Carbon, Pt) | Use abrasive slurries (e.g., 0.05 µm alumina) on a polishing pad. A robotic arm can automate this. | A 2025 study found that the polishing pattern (figure-eight vs. circular) did not significantly affect the final surface quality [17]. Effectively removes corrosion and contaminants [17]. |

| Electrochemical Treatment [1] [19] [18] | Carbon-based electrodes (e.g., Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes) | Apply a potential program (e.g., cycling in Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ or applying a high anodic potential in deionized water) to oxidize surface contaminants. | A 2025 study showed that treating a carbon fiber electrode at 1.75 V in deionized water for 26 minutes successfully regenerated its surface and sensitivity to dopamine [19]. |

| Chemical Cleaning [18] | Screen-printed Gold and Platinum electrodes | Immerse electrodes in solvents (acetone, ethanol) or oxidizing solutions (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚). | A study on screen-printed electrodes found Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ and ethanol effective, reducing polarization resistance (Rp) by up to 92.78% for platinum and 47.34% for gold [18]. |

| Combined CV Cycling [18] | Screen-printed electrodes | Run multiple cyclic voltammetry cycles in a supporting electrolyte at a low scan speed (e.g., 10 mV/s). | Used as a final step after chemical cleaning to ensure a stable and clean surface. Multiple cycles with low scanning speed are most effective [18]. |

How do I troubleshoot a signal that is flatlining or has unexpected peaks?

Flatlining Signal

If your signal is flatlining, the issue is often related to your instrument settings or connections [1] [20].

- Check Current Range: A flat line can occur if the actual current exceeds the selected range, causing the signal to be clipped. Solution: Increase the current range setting on your potentiostat (e.g., from 100 µA to 1000 µA) [20].

- Verify Working Electrode Connection: If the working electrode is not properly connected to the electrochemical cell, the potential may change, but no faradaic current will flow. Solution: Check that the working electrode is securely connected and submerged [1].

Unexpected Peaks

Unexpected peaks can arise from several sources.

- Impurities: Peaks may come from impurities in the chemicals, atmosphere, or from component degradation [1].

- Edge of Potential Window: A peak may occur if the scanning potential approaches the solvent's or electrolyte's electrochemical limit [1].

- Diagnosis: Run a background scan without your analyte present. If the peak disappears, it is related to your analyte. If it remains, it is likely an impurity or a system artifact [1].

What role does electrolyte selection play in achieving a stable background current?

The supporting electrolyte is crucial for conducting current and controlling the electrical double layer at the electrode interface. Its properties directly impact the background current and overall signal stability.

- High Purity: Always use high-purity electrolytes to minimize faradaic contributions from impurities, which can cause drift and unwanted peaks [1].

- Appropriate Potential Window: Select an electrolyte that is electrochemically inert over your entire potential scan range. Using a potential that causes the electrolyte to break down will lead to large, irreversible background currents [1].

- Sufficient Concentration: The electrolyte concentration should be significantly higher (typically 50-100 times) than the analyte concentration to ensure low solution resistance and minimize ohmic drop (iR drop).

Are there advanced data processing techniques to improve baseline stability?

Yes, moving beyond traditional background subtraction can significantly improve data interpretation and stability, especially for in vivo or complex media applications.

- Background-Inclusive Voltammetry: Instead of subtracting a pre-recorded background current, newer approaches analyze the total current (faradaic and non-faradaic). This retains valuable information about the electrode surface state and the chemical microenvironment, which can aid in analyte identification [21].

- Machine Learning (ML) for Analysis: Machine learning models, such as partial least squares regression (PLSR) or artificial neural networks, can be trained on background-inclusive data. These models learn to distinguish analyte-specific signals from the complex background, potentially improving prediction accuracy and closing the gap between in vitro calibrations and in vivo measurements [22] [21] [23].

Experimental Workflow for Reliable Baseline Acquisition

The following diagram outlines a systematic workflow for electrode preparation and system setup to achieve a clean and stable voltammetric baseline.

Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetry

This table lists essential materials and their functions for preparing and troubleshooting voltammetric experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Alumina Polishing Slurry (0.05 µm) | Abrasive for mechanical polishing to create a flat, clean, and reproducible electrode surface. | Removing oxide layers and adsorbed contaminants from glassy carbon working electrodes [17]. |

| High-Purity Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., Na₂SO₄, KCl, phosphate buffer) | Carries current and minimizes migration of the analyte. Establishes a stable and known electrochemical window. | Creating a defined ionic environment for detecting 0.01 M K₄[Fe(CN)₆] in a standard solution [17]. |

| Electrochemical Redox Standard (e.g., K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) | A well-characterized probe for verifying electrode performance and system functionality. | Quality control check post-polishing to confirm a clean, active electrode surface [17] [18]. |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for preparing aqueous solutions and rinsing electrodes to avoid contamination. | Rinsing electrodes after mechanical polishing to remove all alumina residue [19]. |

| Acetone & Ethanol | Organic solvents for chemical cleaning to remove organic contaminants and grease. | Initial degreasing step for screen-printed platinum and gold electrodes [18]. |

FAQs

What is the fundamental purpose of a blank measurement in electrochemical analysis? A blank measurement, also known as a background measurement, is acquired using the exact experimental setup and matrix as the test sample but without the target analyte. Its primary purpose is to record all non-faradaic currents and system artifacts, which can then be computationally subtracted from the sample measurement to isolate the current solely from the redox activity of the analyte. This is crucial for obtaining accurate peak potentials and currents, which are essential for quantitative analysis [24] [1].

My voltammogram has an unusual shape or shows unexpected peaks after background subtraction. What could be wrong? Unexpected peaks or shapes can arise from several sources:

- Impurities: Contaminants in the solvent, electrolyte, or from the atmosphere can introduce extraneous redox peaks. A common source is oxygen dissolved in the solution.

- Electrode Contamination: The working electrode surface can become fouled by adsorbed species from previous experiments, altering its electrochemical properties.

- Systematic Subtraction Errors: If the blank and sample matrices are not perfectly matched, subtraction can introduce artifacts rather than remove them. This is a significant challenge in complex biological matrices where the sample itself can affect the background [24] [1] [25].

Why is my baseline not flat, and how does this affect background subtraction? A non-flat or sloping baseline is often due to high charging currents, which occur because the electrode-solution interface behaves like a capacitor. This capacitance must be charged before the faradaic process begins, contributing to the total current. A sloping baseline complicates background subtraction because the charging behavior in the blank may not perfectly match that in the sample, leading to poor subtraction at the edges of the scan window. This can be mitigated by decreasing the scan rate, using a smaller working electrode, or increasing the analyte concentration [1].

How can I verify if my potentiostat and electrodes are functioning correctly before performing a blank measurement? A general troubleshooting procedure can isolate issues with the equipment [1]:

- Disconnect the Electrochemical Cell: Replace it with a known resistor (e.g., 10 kΩ).

- Connect the Cables: Connect the reference (RE) and counter (CE) electrode cables to one side of the resistor and the working electrode (WE) cable to the other.

- Run a Scan: Perform a linear sweep (e.g., from +0.5 V to -0.5 V). A correct setup will produce a straight-line voltammogram that obeys Ohm's law (V = IR). Any deviation indicates a problem with the potentiostat or cables.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: No Faradaic Current is Observed, Only a Small Noisy Signal

Description When running a measurement, only a very small, noisy, and largely unchanging current is detected, with no discernible redox peaks.

Diagnosis and Solution This typically indicates that the working electrode is not properly connected to the potentiostat or the electrochemical cell. The system can still control the potential, but no faradaic current can flow. To resolve this [1]:

- Check Connections: Ensure the working electrode cable is securely connected to both the potentiostat and the electrode.

- Inspect the Electrode: Confirm the working electrode is fully submerged in the solution and that the electrical contact within the electrode holder is firm.

Problem: Large, Reproducible Hysteresis in the Baseline

Description The forward and backward scans of a cyclic voltammogram do not overlap, creating a large "hysteresis loop" in the baseline, even in the absence of analyte.

Diagnosis and Solution This is primarily caused by charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts as a capacitor. The hysteresis is a direct measurement of this charging process. To minimize this effect [1]:

- Reduce Scan Rate: Slower scan rates give the double-layer capacitor more time to charge, reducing the charging current.

- Use a Smaller Electrode: A smaller electrode surface area reduces the total capacitance.

- Increase Electrolyte Concentration: A higher concentration of supporting electrolyte decreases the solution resistance, which can improve the capacitive behavior.

Problem: Significant Background Artifacts After Subtraction in Complex Matrices

Description After subtracting the blank measurement, the resulting voltammogram shows significant artifacts, distortions, or an unstable baseline, making it difficult to identify the analyte's true signal.

Diagnosis and Solution In complex matrices like biological fluids, the sample matrix itself can alter the background current compared to a pure solvent blank. A standard subtraction fails because the backgrounds are not identical. An advanced method to overcome this is the "Add to Subtract" technique [24].

- Principle: A small volume of a concentrated standard solution of the background-interfering species (e.g., glucose in blood serum) is added to the sample itself. A second spectrum is acquired, which contains the original signals plus an amplified signal from the added standard.

- Procedure:

- Acquire the initial spectrum of the sample (

I). - Add a small, known amount of concentrated standard to the sample, mix, and equilibrate.

- Acquire the second spectrum (

I'). - Computationally subtract the spectra to eliminate the background signal. The factors for subtraction (

afor the amount added,bfor instrumental variation) are determined using regions of the spectrum with only metabolite or only background signals [24].

- Acquire the initial spectrum of the sample (

The mathematical interpretation is as follows [24]:

The initial spectrum intensity I_i at a frequency i is a sum of glucose (G_i), other metabolites (M_i), and noise (ε_i):

I_i = G_i + M_i + ε_i

After adding glucose, the second spectrum is:

I'_i = b(aG_i + M_i) + ε'_i where a>1 and b≈1.

The final estimate for the metabolite signal is derived as:

M^i = (a^ b^ I_i - I'_i) / (b^(a^ - 1))

General Voltammetry Troubleshooting Procedure

This workflow, based on the procedure proposed by Bard and Faulkner, helps systematically identify the source of a problem [1]:

Table 1: Target Charging Current Characteristics under Different Conditions [1]

| Condition | Electrode Type | Expected Current | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standard Conditions | Macro (Area = a cm²) | ~200 μA cmâ»Â² mMâ»Â¹ * a * c | For a reversible one-electron reduction at 0.1 V/s. |

| Standard Conditions | Ultramicro (Radius = r μm) | ~0.2 nA μmâ»Â¹ mMâ»Â¹ * r * c | For a reversible one-electron reduction at 0.1 V/s. |

Table 2: Common Voltammetry Issues and Observable Symptoms [1]

| Problem | Observed Symptom | Likely Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Voltage Compliance Error | Potentiostat error message; potential not maintained. | RE disconnected, CE disconnected/removed, RE touching WE. |

| Current Compliance Error | Potentiostat shuts down; very high current reading. | WE and CE are touching, causing a short circuit. |

| Unstable Reference Electrode | Voltammogram looks different on repeated cycles; distorted shapes. | Blocked frit in RE, air bubbles, RE not in electrical contact with cell. |

| High Capacitance / Hysteresis | Large, reproducible hysteresis loop in the baseline. | High charging currents from electrode geometry or high scan rate. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Background Subtraction in Voltammetry

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃, TBAPF₆) | Minimizes solution resistance and governs ionic strength. Suppresses migration current, ensuring current is primarily diffusion-controlled. | Must be inert in the potential window of interest and highly purified to avoid introducing redox-active impurities. |

| Alumina Polishing Suspension (0.05 μm) | Provides a reliable and reproducible method for cleaning and renewing the working electrode surface between experiments. | Essential for removing adsorbed contaminants that can alter background current and cause fouling. |

| Test Cell / Resistor (e.g., 10 kΩ) | A simple electronic component used to verify the basic functionality of the potentiostat and its cables independently of an electrochemical cell. | A critical first step in any troubleshooting procedure to isolate instrument problems from chemical/electrode problems [1]. |

| Quasi-Reference Electrode (e.g., bare Ag wire) | A simple reference electrode alternative useful for diagnosing issues with a traditional reference electrode. | Not as stable as a true Ag/AgCl electrode, but can confirm if a problem lies with the frit or fill solution of the main reference electrode [1]. |

| Standard Addition Spikes | Concentrated solutions of the target analyte or known interfering species (e.g., glucose). | Used in advanced background subtraction techniques, like "Add to Subtract," to correct for matrix effects in complex samples [24]. |

| 4-Epianhydrotetracycline hydrochloride | 4-Epianhydrotetracycline hydrochloride, CAS:4465-65-0, MF:C22H23ClN2O7, MW:462.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| eCF309 | eCF309 is a potent, selective, cell-permeable mTOR inhibitor (IC50 = 15 nM). For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnosis or therapy. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary causes of a sloping or non-flat baseline in voltammetry? A sloping or non-flat baseline in voltammetry is often caused by charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts as a capacitor. Additional factors include processes at the electrodes with currently unknown origins and fundamental issues with the working electrode itself, such as poor internal contacts or seals leading to high resistivity and capacitances [1].

Q2: How can I determine if my unusual cyclic voltammogram results from equipment malfunction? A general troubleshooting procedure can isolate the issue [1]:

- Test the Potentiostat and Cables: Disconnect the cell and connect the electrode cables to a ~10 kΩ resistor. Scan over a range (e.g., ±0.5 V). A correct result is a straight line obeying Ohm's law.

- Test the Reference Electrode: Set up the cell but connect the reference electrode cable to the counter electrode. Run a linear sweep. A standard, though shifted and slightly distorted, voltammogram indicates a problem with the reference electrode (e.g., a blocked frit or air bubbles).

- Inspect the Working Electrode: Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry or use electrochemical cleaning protocols to remove adsorbed species.

Q3: My signal is dominated by high-frequency noise. Which technique is more suitable? The Fourier Transform approach is highly effective for isolating and removing specific noise frequencies. By transforming the signal to the frequency domain, you can identify and filter out narrowband noise components that obscure the faradaic signal, thereby enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio [26].

Q4: I need to smooth my data while preserving the peak shapes for quantitative analysis. What do you recommend? The Savitzky-Golay (S-G) filter is excellent for this purpose. It works by fitting a low-degree polynomial to successive subsets of data points, effectively smoothing the data while preserving the height and width of sharp peaks, which is crucial for accurate quantitative measurements [27] [28].

Q5: What are the known limitations of the standard Savitzky-Golay filter, and are there modern improvements? Standard S-G filters have poor noise suppression at frequencies above the cutoff and can create artifacts, especially near data boundaries and when calculating derivatives [29]. Two modern improvements are:

- Savitzky-Golay with Weights (SGW): Using a window function (e.g., Hann-square) as weights during the polynomial fit substantially improves stopband attenuation [29].

- Modified Sinc (MS) Kernel: A convolution kernel based on the sinc function with a Gaussian-like window offers excellent stopband suppression and a flat passband [29].

Q6: Can these data processing techniques be applied to real-time monitoring systems? Yes. Recent research demonstrates the combination of Fast-scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) with Fourier Transform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (FTEIS) for real-time monitoring of both neurotransmitter release and electrode surface changes (biofouling) in vivo with subsecond temporal resolution [30].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Background Current and Baseline Issues

A stable background current is foundational for reliable voltammetric analysis. This guide addresses common baseline anomalies.

Symptoms & Causes Table

| Symptom | Possible Causes | Next Investigation Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Large reproducible hysteresis in baseline | Charging (capacitive) currents at electrode-solution interface [1] | Verify if symptom matches classic capacitive charging shape [1] |

| Baseline is not flat/sloping | Unknown electrode processes; Working electrode faults (poor contacts, seals) [1] | Perform general equipment troubleshooting procedure [1] |

| Baseline drift over long experiments | Biofouling of electrode surface; Changing properties of reference electrode [30] | Use FTEIS to monitor electrode capacitance in real-time [30] |

| Unusual peaks in background | Electrode poisoning; Impurities in solvent/electrolyte; Edge of potential window [1] | Run a background scan without analyte; Check all reagents for purity [1] |

Step-by-Step Diagnostic Workflow:

Guide 2: Choosing and Applying a Noise Reduction Filter

Selecting the right filter is critical for preserving the integrity of your electrochemical signal.

Filter Selection and Performance Table

| Filter Type | Key Feature | Best Use Case | Performance Metric (Typical) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Savitzky-Golay (Standard) | Peak shape preservation [27] | Smoothing while retaining peak heights [27] | SNR improvement: ~10% over moving average [31] |

| Savitzky-Golay (Windowed) | Reduced "boxy" artifacts [32] | Signal & image smoothing [32] | Better high-frequency suppression [32] |

| Fourier Transform | Frequency-domain isolation [26] | Removing specific noise frequencies [26] | Enhances faradaic visibility [26] |

| Moving Average | Computational simplicity [27] | Highlighting long-term trends [27] | High noise reduction can distort signal [27] |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Applying a Savitzky-Golay Filter This protocol is based on established mathematical procedures for digital smoothing and differentiation [27].

- Preprocess the Data: Ensure data points are equally spaced. Handle any missing values or outliers prior to smoothing.

- Choose Filter Parameters: The two critical parameters are:

- Window Length (m): The number of adjacent data points used for each polynomial fit. Must be an odd number. A larger window increases smoothing but may over-smooth sharp features.

- Polynomial Degree (n): The degree of the polynomial fitted to the data within the window. A higher degree can capture more curvature but may overfit noise. Degrees of 2 or 3 are common.

- Apply the Filter: For each data point in the sequence (excluding boundaries), a polynomial of degree

nis fitted to thempoints in the window centered on that point. The value of the polynomial at the central point becomes the new smoothed value [27] [33]. - Handle Boundaries: Be aware that standard convolutional S-G filters perform poorly near the start and end of the data range. Use methods like linear extrapolation or the Whittaker-Henderson smoother for these regions [29].

- Validate Results: Compare the smoothed signal to the original. Ensure critical features (peak positions, heights) have not been unduly distorted.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Essential Materials for Reliable Voltammetry and Data Processing

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Alumina Slurry (0.05 μm) | For mechanical polishing of solid working electrodes to obtain a fresh, reproducible surface free of adsorbed contaminants [1]. |

| Ultra Microelectrodes (UMEs) | Provide steady-state currents, higher sensitivity, increased mass transport, and ability to be used in high-resistance solutions. They help mitigate issues like electrode fouling and background currents from surface changes [34]. |

| Gold or Carbon Fiber UMEs | Specific UME types used in advanced detection methods (e.g., for salbutamol monitoring) and in-vivo neurotransmitter sensing (FSCV), respectively [34] [30]. |

| Electrochemical Conditioning Solution (e.g., 1 M H2SO4 for Pt) | Used to electrochemically clean and activate electrode surfaces by cycling potentials to produce Hâ‚‚ and Oâ‚‚, removing adsorbed species [1]. |

| Quasi-Reference Electrode (e.g., bare Ag wire) | A simple diagnostic tool to determine if a problem with the baseline or signal is due to a blockage or failure of a standard reference electrode [1]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) Solution | Used in controlled studies to simulate the biofouling of electrodes that occurs in complex biological environments like the brain [30]. |

| FTEIS-Compatible Potentiostat | Instrumentation capable of performing Fourier Transform Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy, allowing for real-time monitoring of electrode health during experiments [30]. |

| Edasalonexent | Edasalonexent|NF-κB Inhibitor|For Research Use |

| Elq-300 | Elq-300, CAS:1354745-52-0, MF:C24H17ClF3NO4, MW:475.8 g/mol |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is the Randles circuit and why is it critical for diagnosing background current issues?

The Randles circuit is a fundamental equivalent electrical model used to interpret data from Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). It models the key processes at an electrode-electrolyte interface [35]. For researchers troubleshooting background current in voltammetry, this circuit is indispensable because it deconvolutes the total current into its faradaic (from electron transfer) and non-faradaic (the capacitive, background current) components. The non-faradaic current is primarily attributed to the charging of the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) [36] [37]. By using EIS to fit experimental data to the Randles model, you can quantitatively isolate and quantify the Cdl and the solution resistance (Rs), which are major contributors to the background signal that can obscure faradaic currents in voltammetry [38] [35].

Q2: During EIS fitting, my data shows a depressed semicircle. Does this invalidate the Randles model?

Not at all. A depressed or flattened semicircle is a common observation in real-world electrochemical systems. It indicates that the double-layer capacitance does not behave as an ideal capacitor. In such cases, the ideal capacitor (Cdl) in the standard Randles circuit is replaced with a Constant Phase Element (CPE) [35]. The CPE is a non-intuitive circuit element whose impedance is defined as Z(CPE) = 1/[Q(jω)^n], where Q is the CPE constant and n is the CPE exponent. The value of n (ranging from 0 to 1) quantifies the deviation from ideal capacitive behavior: n=1 for an ideal capacitor, n=0.5 may suggest diffusion-like behavior, and lower values are often associated with surface heterogeneity, roughness, or porosity [38].

Q3: I've quantified a very high solution resistance (Rs). How does this impact my voltammetric measurements?

A high solution resistance (Rs) leads to a significant voltage drop (iR drop) between the working and reference electrodes. This uncompensated resistance causes several problems [1] [38]:

- Peak Distortion: Voltammetric peaks can become broader and shifted in potential.

- Decreased Resolution: It becomes harder to resolve closely spaced redox events.

- Inaccurate Kinetics: Measured electron transfer rates can appear slower than they truly are. If your EIS analysis reveals a high Rs, you should consider using a supporting electrolyte at a higher concentration, using a more conductive solvent, or employing your potentiostat's iR compensation feature (if available) during voltammetric experiments [1] [39].

Q4: My EIS data is noisy, especially at low frequencies. What are the potential causes?

Low-frequency noise in EIS spectra often stems from instability in the electrochemical system over the long measurement time required for low-frequency data points. Common causes include [38]:

- System Instability: The electrode surface or the bulk solution composition might be changing (e.g., adsorption of impurities, film degradation, reaction product buildup).

- Drift: A failure to maintain a steady-state condition throughout the experiment.

- Poor Electrode Connection: Loose cables or a poorly connected working electrode can also generate unwanted signals and noise [1]. To mitigate this, ensure your system has reached a stable open-circuit potential before starting the measurement, verify all connections are secure, and confirm that your cell is not drifting significantly over time.

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Cdl and Rs via EIS

This section provides a detailed step-by-step methodology for determining the double-layer capacitance (Cdl) and solution resistance (Rs) of your electrochemical system using EIS and Randles circuit fitting.

Step-by-Step Workflow

The logical flow of the experiment, from setup to data interpretation, is outlined below.

Detailed Methodology

Step 1: System Setup and Instrumentation

- Electrochemical Cell: Set up a standard three-electrode cell [14] [37]. Ensure the working electrode is clean and well-polished (e.g., with 0.05 μm alumina slurry) to ensure a reproducible surface [1].

- Potentiostat: Use a potentiostat with EIS capability. Key specifications to consider are a wide frequency range (e.g., 100 kHz to 10 mHz), low current noise, and accurate phase measurement [37].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing your analyte and a high concentration (typically 0.1 M to 1.0 M) of supporting electrolyte (e.g., KCl, TBAPF6). The supporting electrolyte minimizes the contribution of ionic migration to the current and reduces the overall solution resistance (Rs) [36].

Step 2: Establish Initial Conditions

- Immerse the electrodes in the solution and allow the system to stabilize. Monitor the open-circuit potential (OCP) until it reaches a steady state (minimal drift over 5-10 minutes). This ensures the system is at equilibrium before perturbation [38].

Step 3: Configure and Run EIS Measurement

- DC Bias: Often, the EIS measurement is performed at the open-circuit potential. Alternatively, you can apply a DC potential relevant to your voltammetric study, ensuring it is within the potential window where no faradaic reaction occurs to isolate the double-layer charging.

- AC Parameters: Apply a small sinusoidal AC voltage with an amplitude of 5-10 mV. This small signal ensures the system response is pseudo-linear [38] [37].

- Frequency Scan: Perform the impedance measurement over a wide frequency range, typically from 100 kHz (or 1 MHz) down to 100 mHz (or 10 mHz). The high-frequency data is critical for determining Rs, while the low-frequency data characterizes the capacitive behavior [36] [37].

Step 4: Data Collection and Preliminary Inspection

- The potentiostat's software will output a data file containing, at a minimum, the frequency (f), the real part of the impedance (Z'), and the imaginary part (-Z'') [36] [38].

- Immediately plot the data as a Nyquist plot (-Z'' vs. Z') and a Bode plot (|Z| and Phase vs. Frequency). Visually inspect the data for quality—a well-defined semicircle at high frequencies suggests a clean measurement of the interface [38] [37].

Step 5: Equivalent Circuit Modeling

- Using the EIS analysis software (e.g., provided with your potentiostat or dedicated software like ZView), begin the fitting process.

- Select the Randles circuit as your initial model. The basic structure is:

Solution Resistance (Rs)in series with a parallel combination ofDouble-Layer Capacitance (Cdl)and a series connection ofCharge Transfer Resistance (Rct)andWarburg Impedance (W)[35]. - For Background Current Analysis: In a potential region with no faradaic reaction, Rct will be very large. You can often replace the (Rct + W) branch with a simple, large resistor or, for a more rigorous fit, retain the full model and confirm that the fitted Rct is indeed large.

- If the semicircle is depressed, replace the ideal capacitor (Cdl) with a Constant Phase Element (CPE) [35].

Step 6: Parameter Extraction and Validation

- Execute the complex non-linear least squares (CNLS) fitting algorithm. The software will output the best-fit values for Rs, Cdl (or Q and n if using a CPE), and Rct.

- Assess the "goodness of fit" by examining the chi-squared (χ²) value and visually comparing the simulated curve from the fitted parameters to your raw data. A good fit should lie directly over the data points.

Key Experimental Parameters Table

The following table summarizes the critical parameters for a successful EIS experiment aimed at quantifying Cdl and Rs.

| Parameter | Typical Value or Setting | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| AC Amplitude | 5 - 10 mV | Ensures system pseudo-linearity, preventing harmonic generation and distortion [38] [37]. |

| Frequency Range | 100 kHz (or 1 MHz) to 100 mHz | Captures high-frequency solution resistance (Rs) and low-frequency capacitive (Cdl) behavior [36]. |

| DC Bias Potential | Open-Circuit Potential (OCP) or a potential with no faradaic current | Isolates the double-layer charging process from faradaic electron transfer reactions. |

| Points per Decade | 5 - 10 | Provides sufficient data resolution for accurate fitting across the frequency range. |

| Supporting Electrolyte Concentration | 0.1 M - 1.0 M | Minimizes solution resistance (Rs) and suppresses ionic migration current [36]. |

Data Interpretation and Analysis

Visualizing the Randles Circuit and EIS Response

The diagram below illustrates the standard Randles equivalent circuit and the characteristic shape of its impedance spectrum on a Nyquist plot.

The Randles circuit model (left) and its corresponding Nyquist plot (right). The high-frequency intercept on the x-axis gives the solution resistance (Rs). The diameter of the semicircle provides the charge-transfer resistance (Rct), and the shape of the low-frequency data (the Warburg tail) contains information about diffusion. The capacitance (Cdl) influences the shape and size of the semicircle [38] [35].

Troubleshooting Common EIS Fitting Problems

The table below lists common issues encountered when fitting EIS data to the Randles circuit and provides practical solutions.

| Observed Problem | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Poor fit at high frequency | Incorrect inductance from cables; poor electrode connection. | Use short, shielded cables; ensure all connections are tight; check for inductive loop in data [1] [38]. |

| No well-defined semicircle | Very fast kinetics (very low Rct); system instability. | Verify DC potential is in a region with finite electron transfer rate; check system stability over time [38]. |

| Extreme depression of semicircle (low 'n' value) | High electrode surface roughness or heterogeneity. | Repolish the working electrode to a mirror finish to create a more ideal, smooth surface [1] [35]. |

| Large scatter in low-frequency data | System not at steady-state; signal-to-noise is too low. | Ensure system is stable before measuring; increase the AC amplitude slightly (e.g., to 10 mV) if possible [38]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat with EIS Capability | The core instrument that applies the precise potential/current signals and measures the system's impedance response [37]. |

| Three-Electrode Cell | Standard setup consisting of a Working Electrode (reaction site), Reference Electrode (stable potential reference), and Counter Electrode (completes circuit) [14]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current to minimize solution resistance (Rs) and suppresses ionic migration, ensuring current is primarily from diffusion [36]. |

| Polishing Supplies | Alumina or diamond slurry used to create a clean, reproducible, and smooth electrode surface, which is critical for consistent results [1]. |

| Faradaic Probe Molecule | A well-characterized redox couple like Ferrocene or Potassium Ferricyanide, used to validate the setup and fitting procedure [38]. |

| EML 425 | EML 425, MF:C27H24N2O4, MW:440.5 g/mol |

Diagnosing and Resolving High or Unstable Background Current

What are the first steps to diagnose a cyclic voltammetry system that shows no faradaic current?

If your system detects only a very small, noisy, but otherwise unchanging current, this typically indicates that the current flow between the working and counter electrodes is blocked, leaving only the residual current from the potentiostat circuitry [1]. Follow this systematic procedure to identify the issue.

- Step 1: Potentiostat and Cable Verification. Disconnect the electrochemical cell and connect the electrode cable to a resistor of similar resistance to a cell (e.g., a 10 kΩ resistor). Connect the reference and counter cables to one side of the resistor and the working electrode cable to the other. Scan the potentiostat over an appropriate range (e.g., +0.5 V to -0.5 V). If the system is working correctly, the result will be a straight line where all currents follow Ohm's law (V=IR) [1]. Some systems provide a test chip for this purpose, which should yield a predictable response, such as a straight line from 0 to 1 μA when scanned from 0 to 1 V [1].