Sodium and Potassium ISE Measurement: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the potentiometric measurement of sodium and potassium ions using Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs).

Sodium and Potassium ISE Measurement: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals on the potentiometric measurement of sodium and potassium ions using Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs). It covers the foundational principles of ISE operation, including the latest advances in solid-contact materials like conductive polymers and nanocomposites. The scope extends to detailed methodological protocols for clinical and pharmaceutical applications, a thorough troubleshooting guide for measurement optimization, and a critical validation framework comparing ISE performance against reference techniques like ICP-OES and flame photometry. By synthesizing current research and practical insights, this guide aims to support the accurate and reliable application of ISE technology in biomedical research and therapeutic monitoring.

Principles and Innovations in Sodium and Potassium Ion-Selective Electrodes

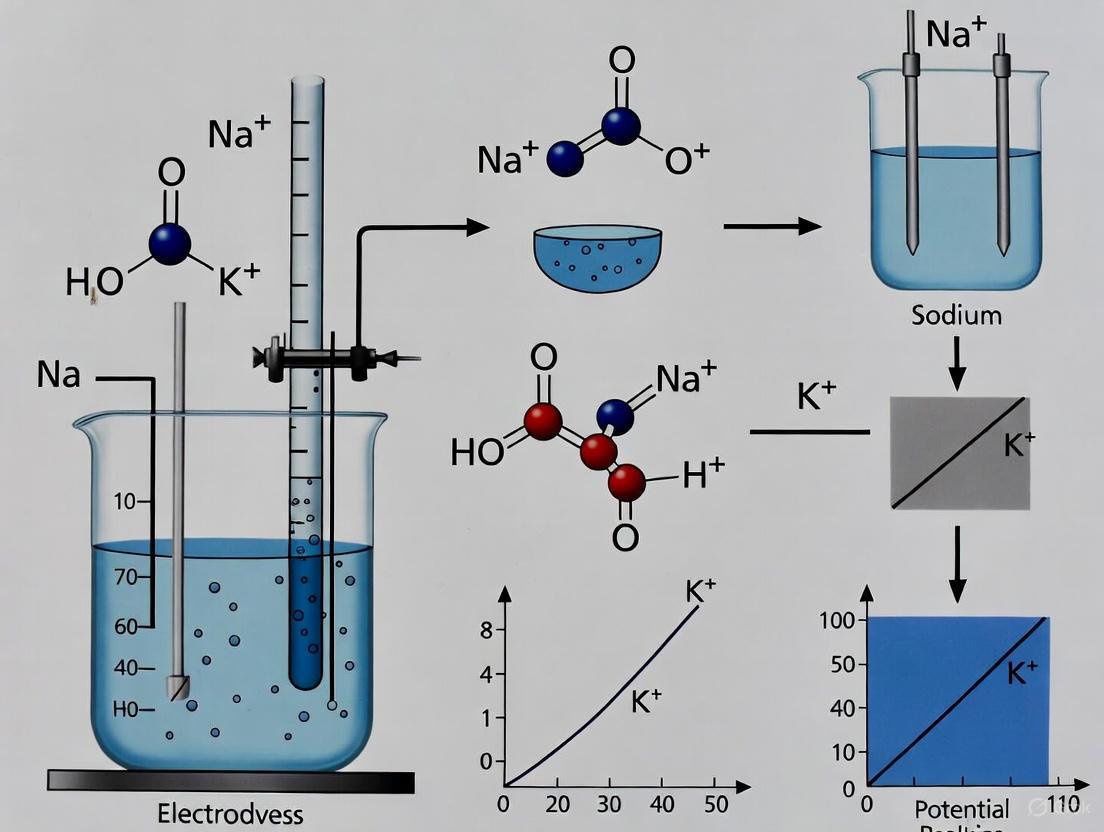

Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) represent a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, providing a direct, economical, and often rapid means for determining specific ion concentrations in complex samples. As potentiometric sensors, ISEs operate on the fundamental principle of measuring an electrochemical potential without significant current flow. This technique has revolutionized ion quantification across diverse fields, from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring and pharmaceutical research. The core theoretical framework governing ISE response is the Nernst equation, a fundamental relationship that bridges the measured electrical potential to the activity (effective concentration) of the target ion in solution.

Within the specific context of sodium and potassium research, ISEs offer unparalleled advantages. The ability to measure these physiologically critical ions directly in undiluted biological fluids like plasma, sweat, or urine without extensive sample preparation makes them indispensable for both clinical assays and drug development studies. The ongoing research in ISE technology focuses on enhancing selectivity, stability, and miniaturization for applications such as wearable sensors and point-of-care devices, underscoring their continued relevance in scientific advancement.

Theoretical Foundation: The Nernst Equation

Fundamental Principles

The Nernst equation provides the quantitative relationship between the electrochemical potential generated across an ion-selective membrane and the activity of the target ion in the sample solution. For an ion-selective electrode, the potential difference (voltage, U) between the ISE and a reference electrode is described by the following form of the Nernst equation [1]:

U = U₀ ± S log(a)

In this equation:

- U is the measured potential difference in millivolts (mV).

- U₀ is a constant potential specific to the measuring system, which includes the intrinsic potentials of both the ISE and the reference electrode [1].

- S is the slope of the electrode response, also known as the Nernstian slope.

- a is the activity of the target ion.

The ± sign depends on the charge of the measured ion; a plus (+) sign is used for positively charged cations like Na+ and K+, while a minus (-) sign is used for negatively charged anions [1].

The Nernstian Slope and Ion Activity

The theoretical slope (S) is a critical parameter defining the sensitivity of the ISE. For a simply charged ion (charge z = ±1) such as sodium (Na+) or potassium (K+), the theoretical Nernst slope at 25°C is 59.16 mV per decade change in ion activity [1]. This means that for every ten-fold change in the ion's activity, the measured potential changes by approximately 59.16 mV. For divalent ions (e.g., Ca2+, z = ±2), the theoretical slope is halved to about 29.58 mV per decade.

Ion activity (a) represents the "effective concentration" of an ion that participates in the electrochemical reaction. It accounts for the non-ideal behavior of ions in solution, particularly at higher concentrations, and is influenced by the sample's ionic strength or "matrix effect" [1]. In many practical applications, and with appropriate calibration procedures, the activity term in the Nernst equation is effectively replaced by the mass concentration (e.g., mg/L) [1].

The graphical representation of the Nernst equation, a plot of the measured potential (U) versus the logarithm of the ion activity (log a), yields a straight line. This calibration curve is the foundation for determining unknown ion concentrations from sample measurements. It is important to note that real electrode responses can deviate from this ideal linearity, particularly at very low concentrations near the detection limit, where the electrode may exhibit a diminished response [1].

ISE Measurement System and Components

A functional ISE measurement system, known as a measuring chain, requires several key components working in concert [1]. The core elements are the Ion-Selective Electrode itself, a Reference Electrode, and a high-impedance voltmeter. The entire system must be highly resistive to ensure that measurement currents are kept minimal, preventing value-changing polarization and potential damage to the electrodes [1].

Ion-Selective Electrode Structure and Membrane Types

The ISE is constructed with a shaft containing a built-in ion-selective membrane, which is the critical component responsible for the sensor's specificity [1]. The membrane generates an ion-specific potential at its surface according to the Nernst equation. The type of membrane material defines the class of ISE and its target ions:

- Glass Membranes: Primarily used for pH measurements, these membranes feature a thin expanding layer in the glass that allows for ion exchange. Specific glass types can also be formulated to measure other cations like sodium (Na+) [1].

- Solid Body Membranes: These membranes are composed of hardly soluble salts such as lanthanum fluoride (for fluoride ions), silver chloride (for chloride ions), or silver sulfide [1].

- Synthetic Material Membranes: Synthetic polymers like Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), plasticized and incorporated with specialized ionophores (ion-recognizing molecules), can be tailored for a wide range of ions, including potassium (K+), calcium (Ca2+), and sodium (Na+) [1] [2].

Reference Electrode and Measurement Circuit

The reference electrode provides a stable, constant electrochemical potential that is independent of the sample composition [1]. This stable reference point is essential for accurately measuring the potential change generated by the ISE. Common reference systems use a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) element in a solution of fixed chloride concentration, housed within a body that allows for controlled electrical contact with the sample via a porous junction.

The high-impedance voltmeter measures the potential difference (voltage) between the ISE and the reference electrode. The "high-impedance" specification is crucial because it ensures that virtually no current flows through the electrochemical cell during measurement, adhering to the principles of potentiometry and preserving the integrity of the potential reading [1].

Advanced ISE Applications in Sodium and Potassium Research

Clinical Standardization and Analysis

In clinical chemistry, accurate measurement of sodium and potassium in plasma is critical for diagnosing and managing numerous conditions. The CLSI C29-A2 standard provides a definitive protocol for standardizing direct ISE systems to ensure their results are traceable to the flame photometric reference method, which is essential for reliable clinical practice [3]. This standard involves using human serum pools with known ion concentrations to verify the accuracy of direct potentiometric instruments, ensuring consistency across different analytical platforms and laboratories [3].

Wearable Sweat Sensing

Recent advancements have led to the development of wearable potentiometric sensors for real-time, simultaneous monitoring of sodium, potassium, and pH in human sweat. These devices are exemplary of ISE technology's potential. One such platform is a flexible, wireless sensor that uses specific sensing materials for each analyte [4]:

- Na0.44MnO2 as the sensing material for sodium ions (Na+)

- K2Co[Fe(CN)6] (a Prussian blue analogue) as the sensing material for potassium ions (K+)

- Polyaniline (PANI) as the sensing material for pH

This integrated system collects signals and transmits them via Wi-Fi to a smartphone, allowing for real-time monitoring of physiological status during exercise. Reported performance shows high sensitivity, with slopes of 59.7 ± 0.8 mV/decade for Na+ and 57.8 ± 0.9 mV/decade for K+, closely matching the theoretical Nernstian slope [4].

Calibration-Free and Reusable Sensors

Innovations in sensor design aim to overcome traditional limitations such as the need for frequent calibration. Research into reusable screen-printed ion-selective electrodes (SP-ISEs) employs a carbon paste and PEDOT: PEDOT-S back contact to achieve exceptional potential stability [2]. These sensors for Na+ and Ca2+ have demonstrated a stable calibration intercept over multiple calibrations across different batches for periods of 12 hours and over 7 days, enabling reliable "calibration-free" operation that is highly desirable for routine environmental or clinical sampling [2].

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Advanced ISE Sensors for Na+ and K+

| Sensor Type / Application | Target Ion | Reported Sensitivity (mV/decade) | Linear Range | Key Material / Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wearable Sweat Sensor [4] | Sodium (Na+) | 59.7 ± 0.8 | 10 mM - 100 mM | Na0.44MnO2 |

| Wearable Sweat Sensor [4] | Potassium (K+) | 57.8 ± 0.9 | 1 mM - 100 mM | K2Co[Fe(CN)6] |

| Reusable SP-ISE [2] | Sodium (Na+) | 52.1 ± 2.0 | Not Specified | Carbon paste/PEDOT: PEDOT-S back contact |

| Theoretical Ideal | Monovalent Ion | 59.16 | N/A | N/A |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Standard Calibration of a Sodium or Potassium ISE

This protocol outlines the steps for generating a calibration curve for a sodium or potassium ISE, which is essential for quantifying ions in unknown samples.

1. Principle and Scope The potential of an ISE is measured in a series of standard solutions with known concentrations. A plot of potential vs. log(concentration) is constructed, and the resulting calibration curve is used to determine the concentration of unknown samples.

2. Research Reagent Solutions Table 2: Essential Materials for ISE Calibration

| Item | Function / Specification |

|---|---|

| Sodium or Potassium ISE | Ion-selective electrode with appropriate membrane (e.g., glass for Na+, valinomycin-based PVC for K+). |

| Reference Electrode | Double-junction Ag/AgCl electrode is often recommended to prevent contamination. |

| High-Impedance Potentiometer | Meter capable of measuring mV with high input impedance (>10¹² Ω). |

| Standard Solutions | A series of at least 5 solutions (e.g., 0.1 mM, 1 mM, 10 mM, 100 mM) prepared by serial dilution from a certified stock. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | A concentrated salt solution (e.g., 1-2 M NaCl or NH4Cl) added to all standards and samples to swamp variations in background ionic strength. |

3. Procedure

- Setup: Connect the ISE and reference electrode to the potentiometer. Ensure the electrodes are clean and conditioned according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Measurement Order: Begin with the most dilute standard and proceed to the most concentrated. Rinse the electrodes thoroughly with deionized water between measurements and gently blot dry.

- Potential Reading: Immerse the electrodes in the first standard solution, add the required volume of ISA, and stir gently and consistently. Record the stable mV reading once it stabilizes (typically after 30-60 seconds).

- Replication: Repeat Step 3 for each standard solution in the series.

- Data Analysis: Plot the recorded potential (mV, y-axis) against the logarithm of the ion concentration (log[ion], x-axis). Perform linear regression to obtain the equation of the line (y = slope * x + intercept) and the correlation coefficient (R²).

Protocol: On-Body Validation of a Wearable Na+/K+ Sweat Sensor

This protocol, adapted from recent research, describes the validation of a wearable ISE platform for sweat analysis [4].

1. Principle A flexible sensor array with integrated Na+, K+, and pH electrodes is attached to the skin. A microfluidic channel, often made from a paper strip, transports sweat from the skin to the sensors. Potentiometric signals are recorded wirelessly in real-time.

2. Key Materials

- Fabricated wearable sensor platform with three working electrodes (WE1, WE2, WE3) coated with Na0.44MnO2 (for Na+), K2Co[Fe(CN)6] (for K+), and PANI (for pH) [4].

- A shared quasi-reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl/PVB) [4].

- A paper strip to act as a microfluidic sweat channel.

- A miniature printed circuit board (PCB) for signal processing and Wi-Fi transmission to a smartphone.

3. Procedure

- Sensor Assembly: The paper strip is embedded as the fluidic channel and the sensor platform is mounted on the skin.

- On-Body Testing: The participant engages in exercise to induce sweat production.

- Real-Time Monitoring: The PCB microcontroller collects potentials from each sensor, processes the data, and transmits it via Wi-Fi to a host smartphone application.

- Data Conversion: The application converts the received potentials into ion concentrations using pre-established calibration curves for each sensor.

The potentiometric principle, anchored by the robust theoretical framework of the Nernst equation, continues to be a powerful tool for ion quantification. Ion-Selective Electrode technology has evolved from traditional laboratory benchtop analyzers to sophisticated, wearable, and calibration-free systems. In the specific field of sodium and potassium research, this evolution enables applications ranging from standardized clinical diagnostics in centralized laboratories to real-time, personalized physiological monitoring. Understanding the fundamental operation of ISEs, their practical calibration, and the latest technological advancements is therefore crucial for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to leverage this versatile and powerful analytical technique.

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are fundamental tools in modern analytical chemistry, enabling the precise quantification of specific ions in complex samples. Their application in sodium and potassium research is particularly critical in both clinical diagnostics and pharmaceutical development. The evolution from traditional liquid-contact to advanced solid-contact designs represents a significant technological leap, addressing key limitations related to miniaturization, stability, and field deployment [5]. This article delineates the architectural principles, performance characteristics, and practical methodologies for both ISE types, with a specific focus on sodium and potassium measurement within a research context.

The core principle of ISE operation is potentiometric measurement, where the electrical potential difference across an ion-selective membrane is measured against a reference electrode and related to the target ion activity via the Nernst equation [6] [7]. For monovalent ions like Na+ and K+ at 25°C, the theoretical Nernstian slope is 59.16 mV per decade of ion activity change [7]. This foundational principle underpins all ISE designs, though the physical realization of this principle has evolved substantially.

ISE Architectures: From Liquid-Contact to Solid-Contact

Liquid-Contact ISEs (LC-ISEs)

Traditional LC-ISEs feature an internal filling solution that mediates contact between the ion-selective membrane and an internal reference electrode [5]. This architecture, while reliable, introduces several inherent constraints: the inner solution is susceptible to evaporation and osmotic pressure effects, requires careful maintenance, and limits the potential for device miniaturization due to the difficulty in reducing the filling solution volume to the microliter level [5].

Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs)

Solid-contact ISEs eliminate the internal liquid phase by incorporating a solid-contact (SC) layer between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the electronic conduction substrate (ECS) [8] [5]. This SC layer functions as an ion-to-electron transducer, a crucial role that enables the potentiometric signal to be measured. The removal of the inner filling solution confers significant advantages, including ease of miniaturization, robustness, suitability for chip integration, and capability for measurements in complex environments [5]. This makes SC-ISEs ideal for portable, wearable, and in-field analytical devices.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental structural and operational differences between these two designs.

Performance Comparison and Quantitative Data

Analytical Performance in Clinical Measurement

The measurement of sodium and potassium is vital in clinical chemistry, and the choice of ISE method can impact results, especially with problematic samples. A 2025 comparative study highlighted significant discrepancies between direct and indirect ISE methods in samples with elevated triglyceride (TG) levels.

Table 1: Negative Bias in Indirect ISE Measurements in High Triglyceride Samples [9]

| Analyte | TG 20.01-30.00 mmol/L | TG >60.00 mmol/L |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na+) | -2.31% | -6.88% |

| Potassium (K+) | -3.86% | -12.05% |

| Chloride (Cl-) | -4.58% | -10.59% |

The study demonstrated that the negative bias for all three electrolytes worsened with increasing triglyceride concentration, with potassium being the most severely affected. The authors developed platform-specific linear correction formulas that successfully brought the differences within clinically acceptable thresholds (|4| mmol/L for Na+ and Cl-, |0.5| mmol/L for K+) [9]. This underscores the importance of understanding methodological differences in sodium and potassium research.

Temperature Resistance of Solid-Contact Materials

The performance of SC-ISEs is highly dependent on the properties of the solid-contact layer. A 2024 study systematically evaluated the temperature resistance of potassium SC-ISEs based on different transduction materials, measuring potential stability over time as a key metric.

Table 2: Temperature Resistance of K+-SCISEs with Different Solid Contacts [8]

| Solid-Contact Material | Potential Stability at 10°C (µV/s) | Potential Stability at 23°C (µV/s) | Potential Stability at 36°C (µV/s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perinone Polymer (PPer) | 0.11 | 0.05 | 0.06 |

| Nanocomposite (MWCNT/CuO) | 0.12 | 0.08 | 0.09 |

| Conductive Polymer (POT) | Data not specified in results | Data not specified in results | Data not specified in results |

Electrodes modified with the perinone polymer and the nanocomposite (multi-walled carbon nanotubes with copper(II) oxide nanoparticles) exhibited the best overall resistance to temperature changes, demonstrating near-Nernstian responses, stable measurement ranges, and the lowest detection limits across the tested temperature range from 10°C to 36°C [8].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Solid-Contact Potassium ISE

This protocol outlines the construction of a valinomycin-based K+-SCISE, adapted from recent research [8].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Electronic Conduction Substrate: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE).

- Solid-Contact Materials: e.g., perinone polymer (PPer) or carbon nanotube/CuO nanocomposite.

- Polymer Matrix: High molecular weight Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC).

- Plasticizer: bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) or equivalent.

- Ionophore: Valinomycin.

- Ion Exchanger: Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (KTpClPB).

- Solvent: Tetrahydrofuran (THF), analytical grade.

2. Fabrication Procedure:

- Step 1: Substrate Preparation. Polish the GCE surface with successive grades of alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry.

- Step 2: Application of Solid-Contact Layer. Deposit the selected SC material (e.g., PPer or nanocomposite) onto the clean GCE surface. This can be achieved via drop-casting or electrochemical deposition of a well-dispersed suspension of the material.

- Step 3: Preparation of Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Cocktail. Precisely weigh and combine the following components in a glass vial:

- 1.0 wt% Valinomycin (Ionophore)

- 0.5 wt% KTpClPB (Ion Exchanger)

- 65.5 wt% Plasticizer (DOS)

- 33.0 wt% PVC Polymer Matrix

- Add ~1 mL of THF and stir until all components are fully dissolved to form a homogeneous cocktail.

- Step 4: Membrane Deposition. Using a micropipette, drop-cast a defined volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the ISM cocktail onto the prepared solid-contact layer. Allow the THF to evaporate slowly under ambient conditions for at least 24 hours, forming a uniform, dry polymeric membrane.

3. Conditioning and Calibration:

- Before first use, condition the fabricated K+-SCISE by soaking in a 0.01 M KCl solution for 24 hours.

- For calibration, measure the potential in a series of standard KCl or KNO3 solutions (e.g., from 1 x 10⁻⁷ M to 1 x 10⁻¹ M) while stirring. Plot the measured potential (mV) against the logarithm of the K+ activity to obtain the calibration curve, slope, and linear range.

Protocol: Mitigating Lipid Interference in Clinical Serum Analysis

This protocol describes a procedure to identify and correct for triglyceride-induced bias in indirect ISE measurements of sodium and potassium, based on a 2025 clinical study [9].

1. Reagents and Equipment:

- Analyzers: One equipped with direct ISE (e.g., Vitros 5600) and one with indirect ISE (e.g., Roche Cobas 8000).

- Control Samples: Normal and pathological level quality control materials.

- Patient Samples: Serum samples with a range of triglyceride levels.

- Triglyceride Assay: Colorimetric method.

2. Procedure:

- Step 1: Sample Analysis. Measure sodium and potassium concentration in all patient samples using both the direct and indirect ISE platforms.

- Step 2: Triglyceride Measurement. Quantify triglyceride levels in all samples using the colorimetric method.

- Step 3: Data Analysis. Calculate the percentage bias for Na+ and K+ between the two methods ([Resultindirect - Resultdirect]/Result_direct * 100%). Correlate the bias values with the corresponding triglyceride concentrations.

- Step 4: Validation. For samples with significant TG levels (>20 mmol/L), the direct ISE method provides a more accurate result. Platform-specific correction formulas can be developed and applied to the indirect ISE results to align them with the direct ISE values, bringing them within predefined clinical acceptance limits.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Materials for Fabricating Solid-Contact Na+ and K+ ISEs

| Item Name | Function / Role in ISE | Example Components |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophore | Selectively binds the target ion, imparting selectivity to the membrane. | Valinomycin (for K+); ETH 157, 2120 (for Na+) [8] [5]. |

| Ion Exchanger | Imparts ionic conductivity; establishes Donnan exclusion for neutral carriers. | Sodium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate (NaTFPB), KTpClPB [5]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Provides the structural backbone of the ion-selective membrane. | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), Polyurethane, Acrylic esters [10] [5]. |

| Plasticizer | Provides membrane fluidity, dissolves active components, influences dielectric constant. | bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS), 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (NOPE) [10] [5]. |

| Solid-Contact Material | Transduces ion flux in the membrane to electron flow in the conductor; critical for stability. | Conductive Polymers (e.g., POT, PEDOT), Carbon Nanotubes, Metal Oxide Nanoparticles, Composites [8] [5]. |

Current Research and Future Perspectives

Recent developments in SC-ISEs focus on optimizing the three core components: the ion-selective membrane, the solid-contact layer, and the conductive substrate [5]. Research aims to enhance sensor stability, reproducibility, and biocompatibility for wearable applications. A significant challenge is the long-term potential drift, which is being addressed by developing novel solid-contact materials with higher hydrophobicity and redox capacitance, such as the nanocomposites described in [8].

Furthermore, the application of ISEs in complex, real-world environments like small and medium-sized rivers highlights ongoing challenges with temperature fluctuations and interfering ions, even as their utility for real-time, in-situ monitoring is confirmed [7]. Future research directions will likely involve the creation of multi-sensor arrays for simultaneous multi-analyte detection, further miniaturization for point-of-care testing, and the integration of machine learning for advanced data interpretation and drift correction.

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are potentiometric sensors that convert the activity of a specific ion in solution into an electrical potential, serving as fundamental tools in biological research and clinical diagnostics [11]. The core of their functionality lies in two key components: the ionophore and the ion-selective membrane (ISM). The ionophore is a selective ion receptor that binds the target ion, while the ISM is a physicochemically tailored phase that separates the sample solution from the inner electrode system, facilitating the development of a membrane potential [12] [13]. The selectivity for sodium (Na⁺) and potassium (K⁺) ions is not inherent but is engineered through the molecular design of these components, primarily governed by the selective complexation of the ion by the ionophore within the membrane phase [13]. This selective binding creates a charge separation at the solution-membrane interface, generating a potential described by the Nernst equation, which relates the measured voltage to the logarithm of the target ion's activity [11]. The precise measurement of Na⁺ and K⁺ is crucial in contexts ranging from neuronal activity and cardiac function studies to sweat electrolyte monitoring and drug screening assays [14] [15].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Na⁺ and K⁺ Ion-Selective Electrodes

| Characteristic | Sodium (Na⁺) ISE | Potassium (K⁺) ISE |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Ionophore Example | Sodium Ionophore X [13] | Valinomycin [14] [13] |

| Typical Membrane Material | PVC-based polymers, PVC-SEBS blends, Siloprene [16] [15] | PVC-based polymers, PVC-SEBS blends, Siloprene [16] [15] |

| Complex Stoichiometry | 1:1 (Ion: Ionophore) [13] | 1:1 (Ion: Ionophore) [13] |

| Typical Sensitivity (in vitro) | 48.8 - 57.1 mV/decade [15] [17] | 50.5 mV/decade [15] |

| Key Interfering Ions | K⁺, Ca²⁺, Li⁺ (dependent on ionophore) [13] | Na⁺, NH₄⁺ (dependent on ionophore) [11] |

The Molecular Basis of Selectivity: Ionophores and Binding

Selectivity in ISEs is achieved through ionophores, which are organic molecules that act as selective hosts for specific ions. These molecules form transient complexes with the target ion, facilitating its extraction from the aqueous sample into the hydrophobic membrane phase. The stability and specificity of this complex are quantified by the complex formation constant, a key parameter determining the sensor's selectivity against interfering ions [13].

Valinomycin, a classic K⁺ ionophore, is a macrocyclic antibiotic that envelops K⁺ ions in a cage-like structure, forming a stable 1:1 complex. Its high selectivity for K⁺ over Na⁺ arises from the perfect fit of the K⁺ ion into its coordination sphere, with a logarithmic complex formation constant (log β) of 9.69 ± 0.25 [13]. For Na⁺ sensing, Sodium Ionophore X (e.g., bis(crown ether)) is commonly used, also forming a 1:1 complex with a log β of 7.57 ± 0.03 [13]. The difference in these binding constants directly translates to the ability of a K⁺-selective membrane containing valinomycin to preferentially respond to K⁺ even in the presence of a high background of Na⁺ ions.

Diagram 1: Ionophore-Mediated Ion Transfer at the Membrane Interface.

Material Engineering: Ion-Selective Membranes

The ion-selective membrane is not merely a passive support for the ionophore; it is a dynamically engineered component that dictates the sensor's analytical performance, stability, and longevity. The membrane is typically composed of a polymer matrix, a plasticizer, the ionophore, and often a lipophilic additive [15] [11].

The polymer matrix, most commonly polyvinyl chloride (PVC), provides the structural backbone. The plasticizer, such as dioctyl sebacate (DOS), gives the membrane flexibility and governs its diffusional properties, ensuring the ionophore and ion complexes are mobile. Recent advances have focused on improving membrane stability. For instance, incorporating block copolymers like polystyrene-block-poly(ethylene-butylene)-block-polystyrene (SEBS) into PVC matrices has been shown to significantly mitigate the formation of an undesired water layer between the membrane and the underlying electrode, a primary cause of signal drift in solid-contact ISEs. Membranes with a PVC:SEBS ratio of 30:30 wt% have demonstrated exceptional long-term stability with potential drift below 0.04 mV/h [15]. Alternative matrix materials like Siloprene have also proven effective, showing stable responses over at least six weeks [16].

Table 2: Composition and Performance of Advanced Ion-Selective Membranes

| Membrane Component / Property | Conventional PVC Membrane | PVC-SEBS Blend Membrane [15] | Siloprene Membrane [16] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | PVC and SEBS block copolymer | Siloprene (silicone-polyurethane) |

| Primary Function | Structural integrity, host for components | Structural integrity, suppressed water layer formation | Structural integrity, adhesion to solid-state devices |

| Key Performance Metric | Moderate stability, subject to drift | Ultra-low drift (< 0.04 mV/h for Na⁺) | Stable response over >6 weeks |

| Ideal Application | General laboratory ISEs | Wearable, long-term monitoring sensors | Solid-state/FET-integrated sensors (e.g., SiNWs) |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

This protocol details the creation of a flexible, wearable sensor for real-time electrolyte monitoring.

- Key Reagents & Materials: Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase powder, HCl, HF, Poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) powder, Acetone, N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF), CO₂ laser engraver, Sodium Ionophore X, PVC, SEBS copolymer, plasticizer (e.g., DOS), lipophilic additive (e.g., NaTFPB).

- Procedure:

- Synthesis of MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ): Etch 1.0 g of Ti₃AlC₂ powder in a mixture of 12 mL HCl, 2 mL HF, and 6 mL DI water at 35°C for 24 h with stirring. Wash the resulting multilayer MXene via repeated centrifugation with DI water until supernatant pH is neutral (~6). Dry the sediment in a vacuum oven at 75°C.

- Fabrication of MXene@PVDF Nanofiber (MPNF) Mat: Disperse the multilayer MXene powder in a binary solvent (acetone:DMF, 7:5 v/v) to achieve a 2.1 wt% dispersion. Add PVDF powder (12 wt% of total mass) and stir at 55°C for 2 h. Electrospin the solution at 18 kV, with a flow rate of 2.0 mL/h and a tip-to-collector distance of 12 cm. Collect nanofibers on aluminum foil and dry.

- Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG) Electrode Patterning: Use a CO₂ laser engraver to carbonize the electrospun MPNF mat, converting the PVDF matrix into porous graphene (LIG) and simultaneously generating TiO₂ nanoparticles from the MXene, resulting in an MPNFs/LIG@TiO₂ hybrid electrode.

- Membrane Cocktail Preparation & Sensor Assembly: Prepare an ISM cocktail by dissolving 30 wt% PVC, 30 wt% SEBS, and appropriate amounts of plasticizer, Sodium Ionophore X, and lipophilic additive in tetrahydrofuran (THF). Drop-cast this cocktail onto the LIG electrode to form the Na⁺-selective membrane. A similar process with a K⁺ ionophore (e.g., valinomycin) is used to fabricate a K⁺ sensor on the same patch.

Diagram 2: Workflow for Fabricating a Solid-Contact Patch Sensor.

This protocol describes a method for simultaneous detection of both ions using organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs), ideal for microfluidic applications.

- Key Reagents & Materials: PEDOT:PSS solution, Photoresist and substrates for microfabrication, Valinomycin, Sodium Ionophore X, PVC, plasticizer (e.g., DOS), tetrahydrofuran (THF), Microfluidic flow cell system.

- Procedure:

- OECT Array Fabrication: Utilize photolithography and microfabrication techniques to pattern an array of micro-scale PEDOT:PSS OECTs on a substrate.

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Integration: Prepare two separate ISM cocktails for Na⁺ and K⁺ in THF, containing the respective ionophores. Use a spin-coating technique to deposit the Na⁺-ISM onto a defined set of OECTs and the K⁺-ISM onto another set on the same array.

- Microfluidic Integration and Measurement: Integrate the OECT microarray with a microfluidic cell to control the delivery of the sample solution. Connect the OECTs to a source measure unit. Measure the transistor's response (e.g., threshold voltage shift or drain current change) in real-time as the sample flows over the array. The response is correlated to the ion concentration in the sample.

- Optimization Note: The study found that a trade-off exists between sensitivity and selectivity based on membrane thickness and composition. Reducing membrane thickness increases sensitivity but can decrease selectivity, requiring optimization for the specific application [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Na⁺/K⁺ ISE Research and Development

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophores | Selective molecular recognition of target ion; primary determinant of sensor selectivity. | Valinomycin (for K⁺) [14] [13]; Sodium Ionophore X (for Na⁺) [13]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Forms the bulk of the membrane; provides mechanical stability and hosts other components. | PVC (conventional), SEBS block copolymer (for stability), Siloprene (for solid-state devices) [16] [15]. |

| Plasticizer | Imparts fluidity to the membrane; enables mobility of ionophore and ion complexes. | Dioctyl Sebacate (DOS), 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) [15]. |

| Lipophilic Additive | Prevents the co-extraction of sample anions into the membrane; improves selectivity and response time. | Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB) [15]. |

| Solid-Contact Transducer | Converts ionic signal from membrane into electronic signal for potentiometric reading; critical for miniaturized, stable ISEs. | Laser-Induced Graphene (LIG), PEDOT:PSS, Carbon-infused PLA (3D-printed) [18] [15] [17]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, constant potential against which the indicator ISE potential is measured. | Ag/AgCl (most common) [11]. |

The accurate potentiometric measurement of sodium and potassium ions is fundamental to biomedical research and drug development. Solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) represent a significant advancement over traditional liquid-contact electrodes, offering superior mechanical robustness, ease of miniaturization, and compatibility with integrated sensor systems [19]. The core challenge, however, lies in ensuring the long-term potential stability of these devices. The interface between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the electron-conducting substrate is a critical point where unwanted water layer formation can cause potential drift, degrading sensor performance [20] [21]. This application note details how advanced solid-contact materials—including conductive polymers, carbon nanotubes, and their nanocomposites—mitigate these issues, thereby enhancing the stability and reliability of sodium and potassium measurements within a research setting.

The Role of Solid-Contact Materials

The primary function of a solid-contact material is to act as an efficient ion-to-electron transducer, providing a stable interface between the ionic conduction domain of the ISM and the electronic conduction domain of the electrode substrate [19]. A high-performance solid contact must possess several key characteristics:

- High Capacitance: Enables the solid contact to accommodate charge from the membrane without significant potential drift, which is crucial for both short-term stability and a low detection limit [22] [19].

- Hydrophobicity: Prevents the formation of a thin water layer between the ISM and the underlying substrate, a primary cause of potential instability and long-term drift [23] [21].

- Fast Redox Activity or Double-Layer Charging: Facilitates rapid transduction of ionic currents to electronic currents (and vice versa) [23].

The transition from a traditional liquid-contact to a solid-contact electrode structure is illustrated below.

Key Material Classes and Performance Data

Conductive Polymers

Conductive polymers (CPs) are a dominant class of solid-contact materials due to their mixed ionic and electronic conductivity, which enables efficient charge transduction.

- Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Polystyrene sulfonate (PEDOT:PSS) is widely known for its high conductivity and stability. Its commercial availability in various formulations (e.g., Clevios PH1000) allows for tuning of properties such as conductivity and work function [24] [25]. The PSS polyelectrolyte acts as a dopant and stabilizer, enabling water processability [24].

- Polyaniline (PANI) is valued for its straightforward electrochemical polymerization, which allows for direct deposition of ultrathin, adherent films onto electrodes [20]. Its redox activity provides a robust mechanism for charge transduction.

- Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) is a highly hydrophobic polymer that effectively suppresses water layer formation. Its lipophilic nature integrates well with polymeric ISMs, though it typically exhibits lower redox capacitance compared to PEDOT or PANI [23] [21].

Carbon Nanomaterials

Carbon nanomaterials, such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and carbon black (CB), are valued for their high electrical conductivity and immense double-layer capacitance, which originates from their large specific surface area [22] [23].

- CNTs can be functionalized (e.g., with carboxylic acid groups) to improve dispersion and interaction with the ISM. They function primarily through capacitive double-layer charging and can be engineered for selective ion capture when coupled with an ISM [22].

- Carbon Black is an attractive, low-cost alternative to other carbon allotropes. It forms semi-graphitic chain structures with high porosity and demonstrates superhydrophobic behavior, contributing to excellent potential stability. CB dispersions are also noted for their high stability and resistance to interference from light, O₂, and CO₂ [23].

Composite and Hybrid Materials

Composite materials synergistically combine the advantages of their individual components, often leading to superior performance.

- CP-Carbon Composites: Combining CPs with carbon nanomaterials merges the high capacitance of carbon with the mixed conductivity and hydrophobicity of polymers. For example, a composite of POT and carbon black demonstrated a large electrochemically active surface area and a high static contact angle of 139.7°, indicating strong hydrophobicity [23].

- Polymer-Functionalized Nanoparticles: Incorporating nanoparticles, such as silica functionalized with PVC, into the sensing film can drastically improve mechanical hardness and selectivity. One study reported a hardness of 5.2 GPa for a nanocomposite film, two orders of magnitude higher than conventional plasticized PVC [26].

Table 1: Performance Summary of Key Solid-Contact Materials for K+-ISEs

| Material | Slope (mV/decade) | Detection Limit (M) | Linear Range (M) | Key Characteristics | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| POT-Carbon Black | 57.6 ± 0.8 | 10⁻⁶.² | 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻¹ | High hydrophobicity (CA=139.7°), resistant to O₂/CO₂/light | [23] |

| PEDOT:PSS (with Valinomycin) | 61.3 | 10⁻³ | 10⁻³ – 10⁻¹.⁵ | High conductivity, good transparency, commercial availability | [23] |

| PANI (as transducer) | ~58 | 10⁻⁵.⁸ | 10⁻⁵ – 10⁻¹ | Excellent adhesion via electropolymerization, stable potential | [20] |

| Graphene (with Valinomycin) | 58.4 | 10⁻⁶.² | 10⁻⁵.⁸ – 10⁻¹ | High double-layer capacitance, large surface area | [23] |

| CNT-based Actuator | N/A | N/A | N/A | Enables controlled K+ uptake from thin-layer samples | [22] |

Table 2: Performance of Solid-Contact ISEs for Various Ions

| Target Ion | Solid-Contact Material | Ionophore | Detection Limit (M) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag⁺ | Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | Not specified | 2.0 × 10⁻⁹ | [21] |

| K⁺ | Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | Valinomycin | 10⁻⁷ | [21] |

| I⁻ | Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | [9] Mercuracarborand-3 (MC3) | 10⁻⁸ | [21] |

| Pb²⁺ | Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | Lead Ionophore IV | ~10⁻⁹ (from graph) | [21] |

| Ca²⁺ | Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | Calcium Ionophore IV | ~10⁻⁹ (from graph) | [21] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a PANI-based Solid-Contact K⁺-ISE

This protocol details the construction of a potassium-selective electrode using an electro-polymerized PANI layer as the solid contact [20].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Aniline monomer solution: 0.1 M aniline in 0.1 M sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄).

- Polymerization solution: 0.1 M H₂SO₄ electrolyte.

- Membrane cocktail: For 1 g total mass, combine 1.0 wt% Valinomycin (potassium ionophore I), 0.5 wt% Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (KTpClPB, lipophilic salt), 32.5 wt% PVC (polymer matrix), and 66.0 wt% 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (2-NPOE, plasticizer), dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF).

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry.

- Polyaniline Electropolymerization:

- Immerse the cleaned GCE in the aniline monomer solution.

- Perform cyclic voltammetry (e.g., 20 cycles) between -0.2 V and +0.9 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 50 mV/s to deposit a PANI film.

- Rise the modified electrode (GCE/PANI) with deionized water and dry.

- Ion-Selective Membrane Deposition:

- Drop-cast 100 μL of the membrane cocktail onto the GCE/PANI surface.

- Allow the solvent (THF) to evaporate slowly at room temperature for at least 12 hours to form a uniform film.

- Conditioning: Condition the finished electrode (GCE/PANI/ISM) in a 0.01 M KCl solution for 12-24 hours before use.

The workflow for this fabrication process is summarized below.

Protocol: Fabrication of a POT/Carbon Black Nanocomposite-Based K⁺-ISE

This protocol creates a solid contact from a composite of POT and carbon black, leveraging the properties of both materials [23].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- POT solution: Dissolve poly(3-octylthiophene-2,5-diyl) in tetrahydrofuran (THF).

- Carbon Black (CB) dispersion: Disperse CB in THF.

- POT-CB composite dispersion: Mix the POT and CB dispersions. POT acts as a dispersant for CB, forming a stable suspension.

- Membrane cocktail: As described in Protocol 4.1.

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the glassy carbon electrode as in Step 1 of Protocol 4.1.

- Solid-Contact Layer Deposition:

- Drop-cast the POT-CB composite dispersion onto the GCE surface and allow it to dry, forming the GCE/POT-CB electrode.

- Ion-Selective Membrane Deposition:

- Drop-cast the K⁺-selective membrane cocktail onto the GCE/POT-CB electrode.

- Allow the THF to evaporate slowly at room temperature.

- Conditioning: Condition the finished electrode in a dilute KCl solution.

Assessment: Characterization of Solid-Contact Performance

The following electrochemical techniques are essential for validating the performance of newly fabricated SC-ISEs [19].

- Chronopotentiometry (CP): Apply a constant current (e.g., ±1 nA) for 60 s and record the potential change. The potential drift (

dE/dt) is used to calculate the capacitance (C = i / (dE/dt)). A lower drift and higher capacitance indicate better potential stability. - Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Record impedance spectra (e.g., from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz) at the open-circuit potential. The low-frequency impedance is related to the capacitance of the solid contact, with a larger value (often represented by a steeper line in the low-frequency region) being desirable.

- Water Layer Test: Measure the potential response of the electrode when switching between primary ion (e.g., 0.01 M KCl) and an interfering ion (e.g., 0.01 M NaCl) solution. A stable potential, without slow drifts indicative of re-equilibration, confirms the absence of a significant water layer.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for Fabricating Solid-Contact ISEs

| Reagent/Solution | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS Dispersions | Conductive polymer solid contact; hole injection layer | Clevios PH1000 for high-conductivity transparent electrodes [24] [25] |

| Aniline Monomer | Precursor for electropolymerization of PANI | Creating an adherent ion-to-electron transducer layer [20] |

| Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | Hydrophobic conductive polymer solid contact | Suppressing water layer formation in SC-ISEs [21] [23] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High-surface-area capacitive solid contact | Enhancing charge storage capacity and stability; creating ion-capturing actuators [22] |

| Carbon Black (CB) | Low-cost, hydrophobic carbon material | Forming composites with CPs to increase capacitance and hydrophobicity [23] |

| Valinomycin | Potassium ionophore | Imparting high K⁺ selectivity over Na⁺ and other cations in the ISM [23] [21] [26] |

| Sodium Tetrakis[3,5-Bis(Trifluoromethyl)Phenyl]Borate (NaTFPB) | Lipophilic anionic additive | Anion excluder in cation-selective membranes; controls membrane permselectivity |

| Poly(Vinyl Chloride) (PVC) | Polymer matrix for ion-selective membranes | Forming the bulk of the sensing membrane [20] [26] |

| 2-Nitrophenyl Octyl Ether (o-NPOE) | Plasticizer for polymeric membranes | Provides a low-resistance, ion-solvating environment within the PVC matrix [20] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Organic solvent | Dissolving membrane components and casting films |

The strategic selection and application of advanced solid-contact materials are paramount for developing high-performance SC-ISEs for sodium and potassium research. Conductive polymers like PEDOT:PSS, PANI, and POT offer distinct transduction mechanisms and protective hydrophobicity. Carbon nanomaterials provide exceptional double-layer capacitance. By moving towards composite and hybrid materials, researchers can engineer interfaces that combine the benefits of multiple material classes, resulting in devices with unprecedented stability, selectivity, and robustness. The protocols and data summarized herein provide a foundation for the rational design and fabrication of such next-generation potentiometric sensors.

The core function of a Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrode (SC-ISE) is to convert an ionic activity in an aqueous sample into an electronic signal that can be measured by a potentiometer. This process, known as signal transduction, occurs at the critical interface between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the underlying electron-conducting substrate. Unlike traditional liquid-contact ISEs, SC-ISEs eliminate the internal filling solution, enabling miniaturization and simpler use [27] [8]. However, this design creates a fundamental challenge: the ISM conducts ions, while the substrate conducts electrons. Without an effective mediator, this interface exhibits high electrical resistance, leading to poor potential stability, signal drift, and the formation of an undesirable water layer [27] [8]. The ion-to-electron transducer is a material layer incorporated into the SC-ISE to resolve this mismatch, facilitating a stable and reversible conversion of signal from ionic to electronic form, which is the most critical determinant of overall sensor performance [28] [27].

Transduction Mechanisms and Material Performance

The mechanism of transduction depends primarily on the electrochemical properties of the solid-contact material. The two predominant mechanisms are the redox capacitance mechanism, typical of conducting polymers, and the double-layer capacitance mechanism, exhibited by capacitive materials like carbon nanostructures.

Redox Capacitance Mechanism: Conducting polymers, such as PEDOT or poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT), act as mixed ionic and electronic conductors. Their backbone allows for electronic conduction, while the polymer matrix allows for ionic mobility. Transduction occurs through the reversible oxidation and reduction of the polymer chain. When the activity of the target ion changes at the ISM/sample interface, it induces a change in the potential that drives a redox reaction in the polymer, thereby generating or consuming electrons and producing the measurable potential signal [27]. This mechanism provides a high, stable redox capacitance.

Double-Layer Capacitance Mechanism: Carbon-based nanomaterials like graphene, reduced graphene oxide (RGO), and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) operate based on the formation of an electrochemical double layer at their high-surface-area interface with the ion-selective membrane. A physical separation of charge occurs, creating a capacitance. A change in ion activity at the membrane alters the potential, which is translated into a change in the charge distribution within this double layer, thus generating the signal [29] [28] [27]. The effectiveness of this mechanism is directly proportional to the capacitance of the material [29].

The following diagram illustrates the core architecture of an SC-ISE and these two primary transduction pathways.

Comparative Performance of Transducer Materials

Extensive research has been conducted to evaluate the performance of different transducer materials. The table below summarizes key electrochemical parameters for several prominent materials, highlighting their impact on SC-ISE performance.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Common Ion-to-Electron Transducer Materials

| Transducer Material | Transduction Mechanism | Reported Capacitance | Potential Drift (ΔE/Δt) | Slope (K+, mV/decade) | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene [28] | Double-layer Capacitance | 383.4 ± 36.0 µF | 2.6 ± 0.3 µV s⁻¹ | 61.9 ± 1.2 | Highest capacitance, low drift, high hydrophobicity minimizes water layer. |

| MWCNTs [27] | Double-layer Capacitance | Not Specified | 34.6 µV s⁻¹ | 56.1 ± 0.8 | Excellent conductivity, high surface area, provides good stability. |

| PEDOT(PSS) [29] | Redox Capacitance | Proportional to film capacitance | Not Specified | ~58 (Coulometric) | Good ionic-to-electronic transduction, stable potential. |

| Polyaniline (PANi) [27] | Redox Capacitance | Not Specified | Not Specified | Not Specified | Good redox properties, performance can vary with doping. |

| Perinone Polymer (PPer) [8] | Redox Capacitance | Not Specified | 0.05 - 0.06 µV s⁻¹ | Near-Nernstian | Excellent temperature resistance, high stability. |

| Nanocomposite (MWCNTs/CuO) [8] | Mixed | Not Specified | 0.08 - 0.09 µV s⁻¹ | Near-Nernstian | Synergistic effects, improved stability and temperature resistance. |

Advanced Coulometric Signal Transduction

While traditional potentiometry measures potential at equilibrium, coulometric signal transduction represents an advanced method that measures the total charge required to alter the potential of the solid contact in response to a change in sample ion activity [29]. This method offers significant advantages in sensitivity. For instance, a coulometric setup utilizing a two-compartment cell and a GC/RGO working electrode has been shown to detect a 0.2% change in K+ concentration, a level of sensitivity difficult to achieve with classical potentiometry [29].

A key innovation is the use of a two-compartment cell to overcome speed limitations. In this configuration, the ISE is placed in the sample compartment and connected as a reference electrode, while a separate working electrode (e.g., GC/PEDOT or GC/RGO) is placed in a detection compartment filled with a supporting electrolyte. The two compartments are connected via a salt bridge [29]. This design ensures that no current passes through the ISE itself, avoiding current-induced polarization that can cause instability and drift. Furthermore, since the current flows through the low-impedance working electrode, the response time decreases dramatically from minutes to seconds [29].

Table 2: Key Advantages of Two-Compartment Coulometric Transduction

| Feature | Traditional Single-Compartment Cell | Two-Compartment Cell |

|---|---|---|

| Current Path | Current flows through the ISE. | No current flows through the ISE. |

| Polarization Effects | Susceptible to current-induced polarization. | Polarization of the ISE is avoided. |

| Signal Stability | Potential drift more likely. | Enhanced potential stability. |

| Response Time | Slow (on the order of minutes). | Fast (on the order of seconds). |

| Sensitivity | Limited by potentiometric resolution. | High; can detect 0.2% concentration changes [29]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Graphene-Based K+-SC-ISE

This protocol details the construction of a solid-contact potassium ISE using graphene as the transducer, based on materials known for high performance [28].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- Ion-Selective Membrane Components: High molecular weight Poly(Vinyl Chloride) (PVC), valinomycin (ionophore), potassium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (KTFPB) (ion-exchanger), bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) or 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) (plasticizer) [29] [8].

- Transducer Material: Graphene dispersion or powder [28].

- Solvent: Tetrahydrofuran (THF), for dissolving the membrane components.

- Substrate: Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) or Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE).

- Standard Solutions: KCl standards for calibration, from 10⁻² M to 10⁻⁷ M. Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA), e.g., 0.1 M LiOAc or NH₄Cl [30].

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Polish the GCE with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.3 µm) and rinse thoroughly with deionized water. If using SPCEs, use as received.

- Transducer Layer Deposition: Deposit the graphene dispersion onto the electrode surface. This can be achieved by drop-casting a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the dispersion and allowing it to dry under ambient conditions or in an oven at a mild temperature (e.g., 50°C).

- Membrane Solution Preparation: In a glass vial, dissolve the membrane components in THF. A typical composition is: 1 mg ionophore (valinomycin), 0.5 mg KTFPB, 33 mg PVC, and 66 mg plasticizer [8].

- Membrane Deposition: Once the transducer layer is dry, drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the membrane cocktail onto the modified electrode. Allow the THF to evaporate slowly, covered, for at least 12 hours to form a homogeneous, dry film.

- Conditioning: Before use and between measurements, condition the prepared SC-ISE in a 0.01 M KCl solution for a minimum of 12 hours (or overnight) to hydrate the membrane and establish a stable potential.

Protocol 2: Coulometric Transduction Using a Two-Compartment Cell

This protocol describes the setup and measurement for highly sensitive coulometric detection [29].

Materials:

- Fabricated K+-SC-ISE (from Protocol 1) or a commercial K+-ISE with internal filling solution.

- Two-compartment electrochemical cell.

- Working Electrodes: Glassy Carbon (GC) electrode modified with PEDOT(PSS) or Reduced Graphene Oxide (RGO).

- Counter Electrode: Pt wire or coil.

- Salt Bridge: Ag/AgCl wire or a tube filled with agarose gel in supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl).

- Potentiostat with coulometry capability.

Procedure:

- Cell Setup: Place the K+-ISE in the sample compartment containing the sample or standard solution. Connect it as the reference electrode (RE) to the potentiostat. Place the GC/PEDOT (or GC/RGO) working electrode (WE) and the Pt counter electrode (CE) in the detection compartment filled with 0.1 M KCl. Connect the two compartments with the Ag/AgCl wire or salt bridge [29].

- System Connection: Connect the K+-ISE (in the sample compartment) as the REFERENCE lead of the potentiostat. Connect the GC/PEDOT as the WORKING electrode and the Pt wire as the COUNTER electrode [29].

- Measurement: Set the potentiostat to a coulometric (charge integration) mode. The change in potassium ion activity in the sample compartment alters the potential of the K+-ISE. This, in turn, drives a Faradaic current at the GC/PEDOT electrode in the detection compartment. The potentiostat applies a potential to maintain the system and integrates the resulting current over time to yield a cumulative charge.

- Data Analysis: Plot the cumulative charge (Q) against the logarithm of the K+ ion activity. The slope of this plot will be proportional to the capacitance of the PEDOT or RGO layer [29].

The workflow for this advanced measurement is detailed below.

Protocol 3: Electrochemical Characterization of SC-ISEs

Characterizing the fabricated SC-ISEs is crucial for validating transducer performance.

1. Chronopotentiometry (CP): * Purpose: To evaluate potential stability and calculate capacitance. * Procedure: In a constant concentration solution (e.g., 0.01 M KCl), apply a small constant current (e.g., +1 nA or +5 nA) for a set duration (e.g., 60 s), followed by a current of the same magnitude but opposite sign (-1 nA or -5 nA) for the same duration. * Data Analysis: The capacitance (C) is calculated from the potential slope (ΔE/Δt) during the current pulse: C = I / (ΔE/Δt), where I is the applied current. A lower potential drift (ΔE/Δt) indicates better potential stability [28] [8].

2. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): * Purpose: To analyze the resistive and capacitive properties of the electrode layers (charge transfer resistance, bulk resistance, double-layer capacitance). * Procedure: Measure the impedance spectrum, typically at open circuit potential, over a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz with a small amplitude AC voltage (e.g., 10 mV). * Data Analysis: Fit the resulting Nyquist plot to an equivalent circuit model to extract parameters like bulk resistance (R₆) and double-layer capacitance (C~dl~) [27].

Impact of External Factors and Best Practices

The performance of SC-ISEs is influenced by several external factors that must be controlled for reliable measurement results, particularly in the context of sodium and potassium analysis.

Temperature: Temperature directly affects the slope of the electrode response, as defined by the Nernst equation. The theoretical slope for a monovalent ion increases by approximately 2 mV/decade for every 10°C rise in temperature [31] [8]. It is critical that the temperature of calibration standards and samples is kept constant. Electrodes with transducers like perinone polymer (PPer) and MWCNT/CuO nanocomposites have demonstrated superior resistance to temperature changes, maintaining stable performance across a range from 10°C to 36°C [8].

pH and Interfering Ions: The measurable pH range is ion-specific, and a pH outside this window can lead to inaccurate readings. For cations, low pH can cause interference from H⁺ ions. The composition of the ion-selective membrane (ionophore selectivity) is designed to minimize interference from coexisting ions, but awareness of potential interferents is necessary [31]. In clinical samples, elevated triglyceride levels can cause significant negative bias in electrolyte measurements by indirect ISE methods, a discrepancy that must be mitigated through platform-specific correction formulas or the use of direct ISEs [9].

General Best Practices:

- Calibration: Always calibrate with fresh standard solutions that bracket the expected sample concentration.

- Conditioning: Condition electrodes before first use and after storage according to the specific protocol.

- Stirring: Stir samples and standards at a consistent, moderate speed to ensure equilibrium without introducing noise or heat [31].

- Storage: Store electrodes according to manufacturer or protocol specifications, typically dry or in a dilute solution of the primary ion.

The ion-to-electron transducer is the critical component that defines the performance, reliability, and analytical utility of Solid-Contact ISEs. The choice of transducer material—whether a high-capacitance carbon nanomaterial like graphene or a stable conducting polymer like PEDOT or PPer—directly governs the signal transduction mechanism, impacting key parameters such as sensitivity, stability, and response time. The adoption of advanced readout methods, such as coulometric transduction in a two-compartment cell, further pushes the boundaries of sensitivity and speed. As research continues to yield new materials and a deeper understanding of interfacial processes, the design of SC-ISEs will become even more refined, solidifying their role as indispensable tools for precise sodium and potassium measurement in research, clinical diagnostics, and drug development.

Protocols and Applications: Implementing ISE Measurement in Clinical and Pharmaceutical Settings

Within the context of ion-selective electrode (ISE) measurement of sodium and potassium, optimal calibration is a critical prerequisite for generating reliable and analytically valid data. These electrodes, widely used in pharmaceutical and clinical research for drug analysis and biological sample testing, provide distinct advantages including rapid analysis, affordability, and good precision [32]. The accuracy of these measurements is fundamentally governed by the Nernst equation, which relates the measured electrical potential to the logarithm of the ionic activity in the solution [33]. This application note details the established protocols for preparing standards, the strategic use of bracketing concentrations, and the essential evaluation of electrode slope to ensure data integrity in research on sodium and potassium.

Principles of Ion-Selective Electrode Operation

Ion-selective electrodes are potentiometric sensors that measure the activity of specific ions in solution. A typical setup includes an ion-selective membrane, which is selective for either sodium or potassium ions, and internal and external reference electrodes [33]. The core measurement is the cell potential (E~cell~), calculated as the difference between the potential of the ion-selective electrode (E~ise~) and the reference electrode (E~ref~) [33].

The relationship between the measured potential and the ion activity is described by the Nernst equation: E = K + S logC where E is the millivolt reading, K is a constant, S is the electrode slope, and C is the ion concentration [33]. The theoretical slope (S) is a critical performance parameter and is temperature-dependent.

The following diagram illustrates the core components and the logical workflow of a potentiometric measurement cell using an ISE.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The table below catalogs the key reagents and materials required for the calibration and use of sodium and potassium ion-selective electrodes.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function & Specification |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Deionized Water | Preparation of all standards and samples to prevent contamination [34]. |

| Analytically Clean Glassware | Preparation of standards to avoid introduction of contaminants [34]. |

| Primary Standard Solutions | High-purity reference materials for preparing calibration standards [35]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer (ISAB) | Adjusts all standards and samples to the same ionic strength, masks interfering ions, and ensures activity coefficients are constant for accurate concentration measurement [34] [36]. |

| Stir Bar and Stir Plate | Ensures solutions are well-mixed during calibration and measurement; a moderate, consistent stirring speed is required [34] [36]. |

| Temperature Control System | Temperature bath or probe to maintain constant temperature, as temperature alters ion activity and impacts the electrode slope [34] [36]. |

| Lint-Free Wiping Cloths | For gently blotting the electrode dry after rinsing between solutions [36]. |

Experimental Protocols

Preparation of Calibration Standards

Accurate standard preparation is the foundation of a reliable calibration.

- Source of Standards: Prepare calibration standards from high-purity reference materials [35]. Alternatively, certified prepared standards can be purchased to reduce preparation error [36].

- Concentration Bracketing: Standards must bracket the expected concentration of the sample. Use at least two standards, with concentrations that are decades apart (e.g., 0.1 mg/L and 1 mg/L for a sample expected near 0.5 mg/L). For wider concentration ranges, include a mid-range standard (e.g., 1, 10, and 100 mg/L) [34] [36].

- Preparation Technique: Use serial dilution as the most accurate method for preparing standards from a stock solution. Use pipettes for measuring small volumes to ensure precision [36].

- Freshness and Handling: Prepare standards on the day of use. Use analytically clean glassware to prevent contamination. A typical recommended volume is 100 mL of each standard in a 150 mL glass beaker [34] [36].

- Ionic Strength Adjustment: Add a consistent volume of Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer (ISAB) to every standard and sample immediately before measurement. A common ratio is 2 mL of ISA per 100 mL of solution [36].

Electrode Conditioning and Calibration Workflow

The following protocol ensures the electrode is stabilized and calibrated correctly.

Protocol: ISE Startup and Calibration

- Electrode Preparation: Install the correct sensor module (if applicable), open the refill hole, and fill the reference chamber with clean fill solution above the level of the sample [36].

- Conditioning: Soak the electrode in a mid-range standard (e.g., 10 mg/L) for approximately 2 hours before first use to condition it [36].

- Temperature Equilibration: Ensure all standards and samples are at the same temperature, ideally 25°C, for the highest accuracy [34] [36].

- Calibration Order: Begin calibration with the lowest concentration standard and progress to higher concentrations. This minimizes carry-over effects from more concentrated solutions [34] [36].

- Rinsing: Between each standard, rinse the electrode thoroughly with deionized water and blot dry with a lint-free cloth [36].

- Stirring: Place the beaker on a stir plate and use a slow to moderate, consistent stirring speed throughout calibration and measurement [34] [36].

- Measurement: Immerse the electrode in the standard, ensuring the outer reference junction is fully submerged. Record the reading once it stabilizes [36].

The workflow for the entire process, from preparation to slope evaluation, is summarized in the following diagram.

The Bracketing Calibration Strategy

Bracketing is a quality control practice where calibration standards are run before and after a set of unknown samples. This strategy directly compensates for instrument drift or changes in electrode response that can occur during a long sequence of analyses [37].

- Purpose: Bracketing standards monitor system stability and ensure that the calibration remains valid throughout an analytical run, which is critical for long sequences in stability studies or content uniformity testing [37].

- Procedure: A calibration standard (typically at a mid-range concentration) is injected at the start of the sequence, after every set of samples (e.g., every 10-20 injections), and at the end of the sequence [37]. The sample results are then calculated based on the calibration curve from the bracketing standards that enclose them.

- Acceptance Criteria: The response factor of the bracketing standard should be within a predefined tolerance (e.g., ±2% to ±5%) of its initial calibration value. If it falls outside this range, recalibration is necessary, and the affected samples may need to be re-injected [37].

Evaluation of Calibration Slope

The calibration slope is a direct indicator of electrode health and performance.

- Theoretical Basis: The slope indicates the change in millivolts per tenfold change in concentration (mV/decade) [33].

- Acceptance Range: For monovalent ions like sodium (Na⁺) and potassium (K⁺), the measured slope should be between 52 and 62 mV per decade at 25°C [36]. A slope outside this range suggests a faulty electrode, contaminated solutions, or improper calibration technique.

- Corrective Actions: If the slope is non-Nernstian, possible actions include: re-preparing fresh standards, checking for reference electrode issues, cleaning the membrane, or replacing the electrode.

Table 2: Calibration Slope Acceptance Criteria for Key Ions

| Ion | Valency | Expected Slope Range (mV/decade) |

|---|---|---|

| Sodium (Na⁺) | Monovalent | 52 - 62 |

| Potassium (K⁺) | Monovalent | 52 - 62 |

| Calcium (Ca²⁺) | Divalent | 26 - 31 |

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Divalent | 26 - 31 |

Data Presentation: Protocols and Quality Control

Table 3: Summary of Critical Calibration Protocols

| Protocol Step | Key Specification | Rationale & Quality Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Standard Bracketing | ≥2 standards, decades apart, bracketing sample [34]. | Ensures accurate interpolation; failing to bracket can cause significant error. |

| Calibration Order | From lowest to highest concentration [34] [36]. | Minimizes carry-over contamination from concentrated standards. |

| Ionic Strength Adjustment | Add ISAB to all standards & samples equally [34] [36]. | Mashes interfering ions, controls activity, fundamental for accurate concentration readout. |

| Temperature Control | All solutions at constant temp (±1°C), ideally 25°C [34] [36]. | Temperature alters ion activity and electrode slope; non-constant temp introduces drift. |

| Slope Evaluation | 52-62 mV/decade for Na⁺/K⁺ [36]. | Primary quality control for electrode function; non-Nernstian slope invalidates data. |

| Recalibration Frequency | At start of day; verify every 2 hours with a low standard (±2% mV criteria) [36]. | Ensures continued calibration validity over time and corrects for electrode drift. |

Adherence to the detailed protocols for standard preparation, bracketing, and slope evaluation outlined in this document is fundamental for achieving accurate and reliable results in sodium and potassium research using ion-selective electrodes. By systematically implementing these procedures—including the use of bracketing standards to monitor drift, rigorously controlling ionic strength and temperature, and validating electrode performance through slope checks—researchers can ensure the generation of robust, high-quality data suitable for pharmaceutical development and critical biomedical analysis.

Accurate measurement of sodium and potassium ions is foundational to clinical diagnostics and pharmacological research. Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are widely used for this purpose due to their speed and specificity [38] [39]. However, the precision of these measurements is profoundly influenced by the pre-analytical phase—specifically, how biological samples are collected, processed, and stored prior to analysis [40] [41]. Variations in sample handling can introduce significant errors, affecting diagnostic conclusions and research outcomes. This article details standardized protocols for preparing serum, plasma, urine, and sweat to ensure the integrity of sodium and potassium measurements using ISE technology, framed within the context of rigorous bioanalytical science.

Understanding Biological Matrices and Their Challenges

Every biological matrix has a unique composition that presents specific challenges for ionic analysis. Recognizing these inherent characteristics is the first step in developing a robust sample preparation protocol.

- Blood, Plasma, and Serum: Blood is composed of cells suspended in plasma, while serum is the fluid remnant after blood has clotted. Plasma constitutes about 55% of blood fluid and contains proteins, glucose, and minerals [40]. A critical consideration for potassium measurement is the fact that results for K+ were higher for serum than for whole blood, and higher for whole blood than for plasma [38]. This is often attributable to potassium release from platelets and other cells during clotting and processing.

- Urine: This matrix is approximately 95% water, with the remainder consisting of inorganic salts (sodium, phosphate, sulfate, ammonia), urea, and creatinine [40]. Its high salt content can contribute to matrix effects, and analyte concentrations often require normalization against creatinine levels [42].

- Sweat: Comprised of about 99% water with sodium chloride as the primary solute, sweat is the gold-standard matrix for diagnosing conditions like cystic fibrosis [40]. Lipophilic drugs and ions can passively diffuse into sweat glands, making sample collection without contamination a key challenge [40].

The "matrix effect," where other components in a sample interfere with the measurement of the target analyte, is a central hurdle. Phospholipids in plasma [40] or hemolysis in blood samples can alter the true concentration of electrolytes measured by an ISE. Potassium-selective electrodes, which use valinomycin as an ionophore, are notably subject to interference from cations like rubidium, cesium, and ammonium [39].

Essential Sample Handling Protocols

The following protocols are designed to minimize pre-analytical variability and ensure sample integrity for accurate sodium and potassium analysis.

Serum Preparation Protocol

- Collection: Draw blood using Serum Separator Tubes (SST), which are recommended for higher-quality separation [42].

- Clotting: Allow the blood to clot in an upright position for at least 30 minutes at room temperature [42].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge for 10 minutes at 1,000 × g to separate the clot from the serum [42].

- Aliquoting and Storage: Carefully remove the serum aliquot immediately after centrifugation. Run the assay immediately or aliquot into polypropylene tubes and store at -20°C to -80°C [42]. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles.

- Special Considerations:

- Hemolysis: Hemolysis results in the release of intracellular potassium, drastically elevating measured levels. Grossly hemolyzed samples are not suitable for accurate potassium analysis [42].

- Consistency: Be consistent with the sample type (e.g., serum or plasma) used throughout a single study, as analyte concentrations can differ between them [42].

Plasma Preparation Protocol

- Collection: Draw blood using tubes containing EDTA as an anticoagulant, which is recommended over other types [42].

- Precautions: If heparin must be used, employ no more than 10 IU per mL of blood collected, as an excess can provide falsely high values [42].

- Centrifugation: Centrifuge for 10 minutes at 1,000 × g within 30 minutes of blood collection to separate cells from plasma [42].

- Aliquoting and Storage: Remove the plasma layer and assay immediately or aliquot into polypropylene tubes for storage at -20°C to -80°C [42].

- Note: Values for potassium are more stable for whole blood stored at 20°C than at 4°C or 37°C [38].

Urine Preparation Protocol

- Collection: Perform either a 24-hour urine collection or a second morning void collection [42].

- Clearing: Centrifuge the sample briefly to pellet debris [42].

- Thawing (if frozen): Thaw frozen samples completely, mix well by vortexing, and centrifuge prior to assay to remove particulates [42].

- Normalization: For spot urine samples like the second morning void, normalize the analyte value against creatinine (e.g., units/mg of creatinine) to account for urine concentration [42].

- Dilution: Determine an optimal dilution factor for the assay. Use the provided Assay Buffer as the diluent [42].

Sweat Preparation Protocol

While the search results confirm sweat's diagnostic importance and general composition [40], they do not provide a specific, detailed collection and preparation protocol for ISE analysis. Standard practice in this field typically involves:

- Stimulation: Using pilocarpine iontophoresis to stimulate sweat glands.

- Collection: Absorbing sweat onto a pre-weighed gauze or filter pad within a sealed collection device to prevent evaporation.

- Processing: Eluting the sweat from the collection material using a standardized volume of a diluent suitable for the ISE system.

- Analysis: Promptly measuring ion concentrations to avoid time-dependent changes.