Selectivity Coefficients in Ion-Selective Electrode Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), with a focused examination of selectivity coefficients—a critical performance parameter for researchers and drug development professionals.

Selectivity Coefficients in Ion-Selective Electrode Validation: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for the validation of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), with a focused examination of selectivity coefficients—a critical performance parameter for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational theory of the Nikolskii-Eisenman equation, practical methodologies for coefficient determination using Gran plots and standard addition techniques, and strategies for troubleshooting and optimization to ensure accuracy. Furthermore, it details validation protocols against reference methods like ICP-OES for biomedical and pharmaceutical applications, aligning with ICH guidelines to support the development of reliable, stability-indicating analytical methods.

Understanding Selectivity Coefficients: The Core of ISE Specificity

Selectivity Coefficient (K^pot_A,B) and its Significance in the Nikolskii-Eisenman Equation

The selectivity coefficient, denoted as K^pot_A,B, is a fundamental parameter in ion-selective electrode (ISE) potentiometry, defining an electrode's ability to distinguish a particular ion (the primary ion, A) from others (interfering ions, B) present in the same solution [1]. This parameter is critically important for validating ion-selective electrodes, especially in complex matrices like those encountered in drug development where excipients and other active compounds may cause interference. The significance of the selectivity coefficient is formally encapsulated within the Nikolskii-Eisenman equation, which extends the classic Nernst equation to account for the electrode's response in mixed-ion solutions [2] [3]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the selectivity coefficient's role, the experimental protocols for its determination, and its practical implications for researchers and scientists engaged in analytical method development and validation.

Theoretical Framework: The Nikolskii-Eisenman Equation

The Nikolskii-Eisenman equation is the cornerstone for understanding and quantifying the potentiometric response of an ISE in the presence of interfering ions.

Mathematical Formalism

The empirical Nikolskii-Eisenman equation is expressed as follows:

E = E0 + (RT / zAF) ln[aA + K^pot_A,B (aB)^(zA/zB)] [2] [3]

Where:

- E: The measured electromotive force (EMF).

- E0: A constant term encompassing the standard potentials of the ISE and the reference electrode.

- R: The universal gas constant.

- T: The absolute temperature.

- F: The Faraday constant.

- zA and zB: The charges of the primary ion (A) and interfering ion (B), respectively.

- aA and aB: The activities of the primary and interfering ions in the solution.

- K^pot_A,B: The potentiometric selectivity coefficient.

Interpretation of the Selectivity Coefficient

The selectivity coefficient, K^pot_A,B, is a dimensionless constant that reflects the relative response of the ISE to the interfering ion (B) compared to the primary ion (A) [1].

- K^pot_A,B = 1: The sensor exhibits a similar response to both ion A and ion B, indicating no selectivity.

- K^potA,B < 1: The ISE is more selective for the primary ion (A). The smaller the value, the greater the electrode's preference for ion A over ion B [1] [2]. For example, if K^potA,B = 10⁻³, the electrode is 1000 times more responsive to ion A than to ion B [3].

- K^pot_A,B > 1: The ISE is more selective for the interfering ion (B).

A critical advancement in the field is the recognition that modern ISEs can achieve extraordinarily low selectivity coefficients, sometimes smaller than 10⁻¹⁰ or even 10⁻¹⁵, representing an improvement in interference discrimination by up to a billion-fold compared to historical ISEs [4]. The theoretical relationship between the Nikolskii-Eisenman equation, the selectivity coefficient, and the resulting sensor potential is illustrated in the following signaling pathway.

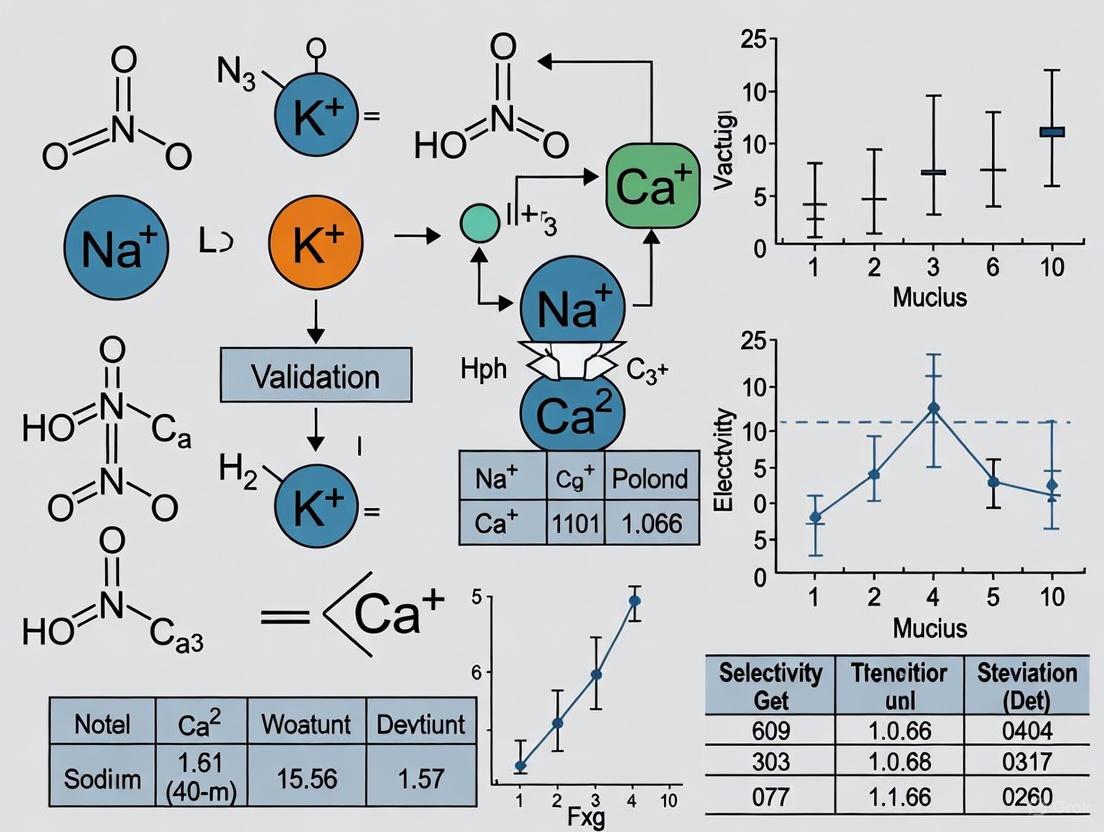

Diagram 1: The signaling pathway of an ISE, showing how the primary (aA) and interfering (aB) ion activities, combined with the selectivity coefficient (K^pot_A,B), determine the measured potential (E) via the Nikolskii-Eisenman equation.

Experimental Protocols for Determining K^pot_A,B

The IUPAC recommends specific methods for determining the selectivity coefficient, primarily the fixed interference method and, less desirably, the separate solution method [1]. The value of K^pot_A,B is not an absolute thermodynamic constant but depends on the experimental conditions and the method used for its evaluation [1].

Fixed Interference Method (FIM)

This method is generally preferred by IUPAC [1].

- Principle: The potential of the ISE is measured in a series of solutions where the activity of the primary ion (A) varies, but the activity of a single interfering ion (B) is held constant at a high, fixed level.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a set of standard solutions with a fixed, high background concentration of the interfering ion (B). The activity of the primary ion (A) should range from very low to sufficiently high to dominate the response.

- Measure the EMF of the ISE in each of these solutions.

- Construct a calibration curve of EMF vs. log(aA).

- Data Analysis: The resulting curve will typically show a non-linear region at low aA (where the interference is significant) and a linear, Nernstian region at high aA. The intersection point of the extrapolated linear portions of the curve is used to determine the value of aA from which K^pot_A,B can be calculated [3].

Separate Solution Method (SSM)

This method is considered less desirable than FIM but is still used, particularly for initial screening [1].

- Principle: The EMF of the ISE is measured in two separate solutions: one containing only the primary ion (A) and another containing only the interfering ion (B), both at the same activity.

- Procedure:

- Measure the EMF (EA) in a solution with activity aA of the primary ion.

- Measure the EMF (EB) in a solution with the same activity aB = aA of the interfering ion.

- Data Analysis: The selectivity coefficient is calculated using a formula derived from the Nikolskii-Eisenman equation. A significant limitation of the classical SSM is that low selectivity coefficients determined this way can be time-dependent. An Improved Separate Solution Method (ISSM) has been developed, which uses a linear extrapolation of time-dependent data to obtain more reliable values of low selectivity coefficients (down to n × 10⁻⁷) [5].

Other Advanced and Historical Methods

Researchers have developed other techniques, such as:

- Linearized Multiple Standard Addition Techniques: Using Gran-type linear functions under bi-ionic conditions for evaluation [6].

- Flow Injection with Simplex Optimization: Employing an ion-selective array and fractional factorial design to characterize electrode parameters, including selectivity [7].

The workflow for the two primary methods is summarized in the following diagram.

Diagram 2: A workflow comparing the Fixed Interference Method (FIM) and the Separate Solution Method (SSM) for determining selectivity coefficients.

Comparative Analysis of Selectivity Coefficient Data

The performance of an ISE is highly dependent on the membrane composition, particularly the ionophore. The following table compares the selectivity of a potassium ion-selective electrode (based on valinomycin) against various interfering ions, demonstrating its excellent discrimination capabilities, especially against Na⁺ and Ca²⁺.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Selectivity Coefficients (K^pot_K,B) for a Valinomycin-Based Potassium ISE [2]

| Interfering Ion (B) | Selectivity Coefficient (K^pot_K,B) | Inference on Selectivity |

|---|---|---|

| Rubidium (Rb⁺) | 1 × 10⁻¹ | Moderate interference due to similar ionic properties. |

| Cesium (Cs⁺) | 4 × 10⁻³ | Low interference. |

| Ammonium (NH₄⁺) | 7 × 10⁻³ | Low interference. |

| Sodium (Na⁺) | 3 × 10⁻⁴ | High selectivity for K⁺ over Na⁺. |

| Magnesium (Mg²⁺) | 1 × 10⁻⁵ | Very high selectivity for K⁺. |

| Calcium (Ca²⁺) | 7 × 10⁻⁷ | Extremely high selectivity for K⁺. |

The impact of an interfering ion on the analytical performance of an ISE is not solely determined by the selectivity coefficient but also by its concentration in the sample. As shown in the diagram below, a stronger interferent (higher K^pot_A,B) or a higher interferent concentration leads to a higher practical detection limit and a shorter useful analytical range [3].

Diagram 3: The effect of interfering ions on the detection limit (LD) of an ISE. A stronger interferent (higher K^pot_A,B) elevates the LD, shortening the usable analytical range.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The construction and performance of an ISE are dictated by the composition of its ion-selective membrane (ISM). The following table details the key components required to formulate a typical solvent polymeric membrane for a research-grade ISE.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Fabricating Ion-Selective Membranes [3] [8]

| Component | Function | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophore | The key component that selectively binds to the target ion, imparting selectivity to the membrane. | Valinomycin (for K⁺), crown ethers, calixarenes, synthetic host molecules [4] [3]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Provides the structural backbone and mechanical stability for the membrane. | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane, silicone rubber [3] [8]. |

| Plasticizer | Imparts plasticity and fluidity to the membrane, governs the dielectric constant, and influences ionophore selectivity. | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS), 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE), dibutyl phthalate (DBP) [3] [8]. |

| Ion Exchanger | Introduces mobile ionic sites into the membrane, crucial for achieving permselectivity and lowering electrical resistance. | Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB), potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (KTPCIPB) [8]. |

| Solvent | Used to dissolve the membrane "cocktail" before casting or coating. | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), cyclohexanone (CH) [3]. |

The selectivity coefficient K^pot_A,B is more than a mere correction factor in the Nikolskii-Eisenman equation; it is a critical figure of merit for validating any ion-selective electrode. Its accurate determination via IUPAC-recommended protocols, such as the Fixed Interference Method, is non-negotiable for developing robust analytical methods, particularly in drug development where precision and reliability are paramount. The revolutionary improvements in the lower limits of detection and selectivity of modern ISEs, with coefficients now reaching as low as 10⁻¹⁵, have fundamentally expanded the utility of potentiometry into the realms of trace environmental and bioanalysis [4]. For researchers, a deep understanding of this parameter is essential for selecting the appropriate sensor, designing validation experiments, and correctly interpreting analytical data in complex, multi-ionic samples.

How Interfering Ions Impact ISE Response and Measurement Accuracy

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) represent a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, enabling the quantification of specific ions in complex matrices ranging from biological fluids to environmental samples. The accuracy of these measurements, however, is fundamentally governed by the electrode's ability to distinguish target ions from interfering ions with similar characteristics. Selectivity—the preferential response of an ISE to its primary ion over other ions present in solution—is arguably the most critical parameter determining ISE viability for real-world applications [9]. When interfering ions influence the electrode response, measurement accuracy can be significantly compromised, leading to erroneous data interpretation and potential consequences in clinical, environmental, and pharmaceutical settings.

The fundamental mechanism of potentiometric ISE operation relies on the development of a phase boundary potential at the interface between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the sample solution. This potential, described by the Nikolsky-Eisenman equation, varies logarithmically with the activity of the primary ion but is also influenced by the presence of interfering ions [10]. The ISM typically consists of a polymer matrix (commonly PVC) plasticized with specific agents to confer optimal membrane fluidity and incorporating several key components: an ionophore responsible for selective ion recognition, ion exchangers to facilitate ion transport, and additives to optimize performance [8]. When interfering ions compete with target ions for binding sites within the ISM or at the interface, the established potential deviates from the ideal Nernstian response, introducing systematic errors that can be challenging to identify without rigorous validation protocols.

Theoretical Foundations of Interference Mechanisms

The Nikolsky-Eisenman Equation and Selectivity Coefficients

The theoretical framework for understanding ion interference is predominantly based on the Nikolsky-Eisenman equation, which extends the Nernst equation to account for the presence of multiple ion species:

Diagram 1: Fundamental mechanisms through which interfering ions impact ISE response, including competitive binding, steric factors, and electric double layer (EDL) effects.

The potentiometric response of an ISE in the presence of interfering ions is quantitatively described by the Nikolsky-Eisenman equation:

[ E = E^0 + \frac{RT}{zF} \ln(ai + K{ij}^{pot}aj^{zi/z_j}) ]

Where (E) is the measured potential, (E^0) is the standard potential, (R) is the gas constant, (T) is temperature, (F) is Faraday's constant, (zi) and (zj) are the charges of the primary and interfering ions, respectively, (ai) and (aj) are their activities, and (K{ij}^{pot}) is the potentiometric selectivity coefficient [9]. The selectivity coefficient (K{ij}^{pot}) represents the primary quantitative measure of an ISE's ability to discriminate against interfering ions. A (K_{ij}^{pot}) value of 1.0 indicates equal response to both primary and interfering ions, while values << 1.0 indicate preference for the primary ion, and values >> 1.0 indicate preference for the interfering ion.

Complex Stoichiometry and Non-Classical Response Patterns

Recent research has revealed that interference mechanisms can be more complex than traditionally conceptualized. Rather than simple competitive binding at equivalent sites, interfering ions may form complexes of different stoichiometries with ionophores within the membrane phase. When a primary ion and interfering ion form complexes with different stoichiometries that coexist in the ISE membrane over a wide activity range, apparently non-Nernstian responses can occur, including super-Nernstian slopes (exceeding theoretical limits), sub-Nernstian slopes, or even potential dips [10]. For instance, studies with fluorophilic crown ether ionophores have demonstrated simultaneous formation of 1:1 and 1:2 complexes with both primary and interfering ions, significantly affecting not only potentiometric selectivities but also resulting in super-Nernstian responses in the lower activity range of calibration curves [10]. These phenomena highlight that the traditional model of interference as simple competition at equivalent binding sites represents an oversimplification of the actual complexation equilibria occurring within ISMs.

Experimental Evidence of Interference Effects

Quantitative Data on Ion Interference

Table 1: Experimentally determined selectivity coefficients (log K(^{pot}_{ij})) for various ISE configurations, illustrating the range of interference effects encountered with different membrane compositions.

| Primary Ion | Interfering Ion | Membrane Composition | log K(^{pot}_{ij}) | Reference/Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cs+ | Na+ | Fluorophilic crown ether in fluorous membrane | -2.5 to -4.2 | Fixed Interference Method [10] |

| K+ | NH4+ | Fluorophilic 18-crown-6 ether with 71 mol% ionic sites | -1.8 | Separate Solution Method [10] |

| Cl- | HCO3- | Clinical analyzers (Cobas Integra, Hitachi) | Variable, potentially positive | Clinical Observation [9] |

| Na+ | K+ | PEDOT:PSS-based solid-contact ISE | -2.1 | Separate Solution Method [11] |

| K+ | Na+ | Valinomycin-based solid-contact ISE | -3.4 | Separate Solution Method [11] |

| Mg2+ | Ca2+ | Commercial NOVA ISE | -2.8 | Flow-through evaluation [9] |

The data in Table 1 illustrates several important patterns in ion interference. First, the fluorophilic crown ether membrane demonstrates exceptional discrimination against sodium ions when measuring cesium, with selectivity coefficients as low as -4.2 log units [10]. Second, the well-established valinomycin-based potassium ISE shows the expected high selectivity against sodium interference (-3.4 log units) [11]. Third, and perhaps most notably, clinical observations have revealed significant variability in chloride ISE selectivity against bicarbonate, with some clinical analyzers demonstrating potentially positive selectivity coefficients (preference for the interfering bicarbonate ion over chloride), leading to clinically significant errors in patient samples [9].

Method-Dependent Variability in Interference Effects

Table 2: Comparison of interference effects between direct (dISE) and indirect (iISE) measurement technologies for sodium and potassium determination in clinical samples with abnormal protein or lipid content.

| Sample Characteristic | Affected Ion | dISE Result (mmol/L) | iISE Result (mmol/L) | Absolute Difference | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperproteinemia (≥8 g/dL) | Na+ | Higher | Lower | ≥5 mmol/L | Pseudohyponatremia [12] |

| Hyperproteinemia (≥8 g/dL) | K+ | Higher | Lower | ≥0.5 mmol/L | Potential misclassification [12] |

| Hypercholesterolemia (≥300 mg/dL) | Na+ | Higher | Lower | ≥5 mmol/L | Pseudohyponatremia [12] |

| Normal protein & lipid | Na+ | Comparable | Comparable | <2 mmol/L | Minimal clinical significance |

| Normal protein & lipid | K+ | Comparable | Comparable | <0.2 mmol/L | Minimal clinical significance |

The data in Table 2 highlights a crucial methodological consideration in interference studies. The electrolyte exclusion effect in indirect ISEs (which incorporate a predilution step) causes significant underestimation of sodium and potassium concentrations in samples with elevated proteins or lipids, while direct ISEs (which measure samples without predilution) provide accurate results unaffected by nonaqueous phase variations [12]. This methodological discrepancy can lead to clinically significant misinterpretation, particularly in critical care settings where serial monitoring may employ different technologies interchangeably. For sodium, clinically relevant disagreements (≥5 mmol/L) occurred in a high percentage of samples with hyperproteinemia or hypercholesterolemia, while for potassium, approximately 3.6% of total samples showed clinically significant disagreement (≥0.5 mmol/L) [12].

Methodologies for Investigating Interference Effects

Standard Protocols for Selectivity Assessment

The experimental determination of selectivity coefficients follows standardized methodologies established by IUPAC and other regulatory bodies. The most commonly employed approaches include:

Separate Solution Method (SSM): This method involves measuring the electrode response in separate solutions, each containing only the primary ion or only the interfering ion at the same activity. The potential values obtained are used to calculate the selectivity coefficient using the following relationship:

[ \log K{ij}^{pot} = \frac{(Ej - Ei)ziF}{RT\ln(10)} + \left(1 - \frac{zi}{zj}\right)\log a_i ]

Where (Ei) and (Ej) are the measured potentials for primary ion (i) and interfering ion (j) at activity (a_i) [10]. The SSM provides a straightforward approach particularly useful for initial screening of potential interferences.

Fixed Interference Method (FIM): In this approach, the electrode response is measured for a series of primary ion activities while maintaining a constant, high background level of the interfering ion. The resulting calibration curve is analyzed, and the intersection point between the Nernstian region and the interference plateau is used to calculate the selectivity coefficient according to:

[ K{ij}^{pot} = \frac{ai}{aj^{zi/z_j}} ]

Where (ai) is the primary ion activity at the intersection point, and (aj) is the fixed activity of the interfering ion [10]. The FIM more closely approximates real-world conditions where target ions must be measured in the presence of potentially interfering species.

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Beyond standard potentiometric protocols, comprehensive interference investigation incorporates several additional methodological considerations:

Complex Stoichiometry Determination: As revealed in recent research, thorough investigation of interference mechanisms requires determination of complex formation constants and stoichiometries for both primary and interfering ions. This involves fitting experimental response curves using phase boundary models that account for the simultaneous presence of multiple complex species in the membrane phase [10]. Techniques such as the sandwich membrane method and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy provide supplementary data on complexation equilibria.

Real-World Validation: For ISEs intended for specific applications, validation against reference methods in realistic matrices is essential. As demonstrated in sweat analysis studies, comparison with inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) provides critical verification of ISE performance despite potential complications from differing measurement ranges (requiring sample dilution for ICP-OES but not for ISEs) [11]. Similarly, clinical applications require correlation studies with established diagnostic platforms and assessment of diagnostic concordance.

Environmental Monitoring Protocols: When deploying ISEs for environmental monitoring, as in river water analysis, interference assessment must account for temperature fluctuations, long-term drift, and the complex ionic background of natural waters. In such applications, the challenges of interference are compounded by the need for continuous monitoring without frequent recalibration [13].

Diagram 2: Comprehensive experimental workflow for evaluating interfering ion effects on ISE response, incorporating standard methods, complex stoichiometry studies, and real-world validation.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methods

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for investigating ion interference in ISEs, with specifications and functional roles.

| Reagent/Material | Functional Role | Specification Guidelines | Interference Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionophores | Selective ion recognition | Purity >99%, stoichiometry characterization | Determines fundamental selectivity patterns |

| Ionic site additives | Charge balance in membrane | Lipophilicity optimization, purity verification | Affects interference via concentration optimization |

| Polymer matrix | Structural support | PVC (K-value: 68-65), alternative polymers | Influences diffusion coefficients of interfering ions |

| Plasticizers | Membrane fluidity control | Appropriate polarity, low water solubility | Modulates partitioning of interfering species |

| Ionic strength adjusters | Sample matrix control | High purity, selective complexation | Suppresses interference from specific ions |

| Reference electrodes | Stable potential reference | Stable junction potential, appropriate filling solution | Critical for accurate potential measurements |

| Standard solutions | Calibration and validation | NIST-traceable, appropriate matrix matching | Essential for meaningful selectivity coefficients |

The materials and reagents detailed in Table 3 form the foundation of rigorous interference studies. Proper selection and characterization of each component is essential for generating reliable, reproducible selectivity data. Particularly critical are the ionophores, which determine the fundamental recognition capabilities of the ISM, and the ionic site additives, which must be carefully optimized to exclude interfering ions of the same charge sign as the primary ion [8] [14]. The polymer matrix and plasticizers collectively determine the membrane transport properties that influence how quickly interfering ions can partition into and diffuse through the ISM, potentially affecting response times and conditioning requirements.

Implications for Analytical Applications

The impact of interfering ions extends beyond theoretical considerations to practical implications across diverse application domains:

In clinical diagnostics, electrolyte measurements are particularly vulnerable to interference effects, with documented cases of bicarbonate interference leading to falsely elevated chloride readings in specific analyzer models [9]. The discrepancy between direct and indirect ISE methods further complicates clinical interpretation, particularly for sodium measurements in patients with abnormal protein or lipid profiles [12]. These effects can lead to misdiagnosis or inappropriate treatment if not properly recognized by laboratory staff and clinicians.

In environmental monitoring, studies of river water quality have demonstrated that while ISEs show promise for event detection of ammonium, potassium, chloride, and nitrate, interference from the complex ionic background of natural waters presents significant challenges for accurate quantification [13]. Temperature fluctuations compound these interference effects, necessitating sophisticated compensation algorithms or frequent recalibration for reliable operation in dynamic environmental systems.

In pharmaceutical analysis, ISEs used for drug quantification must be thoroughly evaluated for interference from excipients, metabolites, and degradation products. For instance, in the determination of benzydamine hydrochloride, method validation specifically included testing in the presence of oxidative degradants to ensure selective measurement of the intact drug substance [15]. Such validation is particularly critical for stability-indicating methods where selective quantification of the active ingredient amidst degradation products is essential for accurate shelf-life determination.

Interfering ions impact ISE response and measurement accuracy through multifaceted mechanisms that extend beyond simple competitive binding to include complex stoichiometry effects, method-dependent artifacts, and matrix-specific interactions. Comprehensive characterization of these effects requires application of standardized protocols like the Separate Solution and Fixed Interference Methods, supplemented by advanced techniques for determining complex formation constants and stoichiometries. The growing recognition of phenomena such as super-Nernstian responses resulting from multiple complex formation highlights the sophistication of modern interference analysis. For researchers and practitioners employing ISE technology, rigorous assessment and ongoing monitoring of interference effects remains essential for generating reliable analytical data across diverse application domains from clinical diagnostics to environmental surveillance. Future advances in selective membrane materials and computational modeling of interference mechanisms will further enhance the accuracy and applicability of ion-selective electrode technology in increasingly complex analytical scenarios.

The Relationship Between Ion Activity, Charge, and Electrode Potential

In electrochemical sensing, the relationship between ion activity, ionic charge, and the resulting electrode potential forms the cornerstone of potentiometric measurement techniques, particularly for ion-selective electrodes (ISEs). This relationship is quantitatively described by the Nernst equation, which establishes that the measured potential between an ISE and a reference electrode is proportional to the logarithm of the activity of the target ion [16] [17]. The fundamental equation for a monovalent ion takes the form:

U = U₀ + (2.303 × R × T / F) × log(a)

Where U is the measured potential, U₀ is the standard electrode potential, R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature in Kelvin, F is the Faraday constant, and a is the ion activity [17].

For ions of different charges, the equation modifies to account for the electron transfer number n (which corresponds to the ionic charge):

U = U₀ ± (2.303 × R × T / (n × F)) × log(a)

The sign in the equation is positive for cations and negative for anions [17]. This direct dependence on ionic charge means that for the same activity level, a divalent ion (n=2) will generate half the potential slope of a monovalent ion (n=1), significantly impacting sensor design and interpretation.

Theoretical Foundation: From Concentration to Activity

The Critical Distinction: Activity vs. Concentration

A fundamental concept in potentiometry is that electrodes respond to ion activity, not ion concentration. Activity represents the effective concentration of an ion, accounting for its interactions with other ions and molecules in solution [18]. The relationship between activity (a), concentration (C), and the activity coefficient (γ) is given by:

The activity coefficient (γ) is a dimensionless parameter that approaches 1 in infinitely dilute solutions but decreases as ionic strength increases, making the activity less than the concentration in most practical measurements [16]. The following table illustrates how the activity coefficient for a monovalent ion changes with concentration:

Table 1: Activity Coefficient Variation with Ion Concentration

| Ion Concentration (mol/L) | Activity Coefficient (γ) |

|---|---|

| 1 × 10⁻⁵ | 0.998 |

| 1 × 10⁻⁴ | 0.988 |

| 1 × 10⁻³ | 0.961 |

| 1 × 10⁻² | 0.901 |

| 1 × 10⁻¹ | 0.751 |

Source: [16]

This distinction explains why analytical procedures require the use of Ionic Strength Adjusters (ISA) or Total Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffers (TISAB). These solutions maintain a constant ionic background across standards and samples, ensuring that activity coefficients remain consistent and that measured potential differences reflect actual changes in the target ion's concentration rather than variations in ionic strength [17].

The Challenge of Single-Ion Activities

The thermodynamic definition and measurement of single-ion activities have been historically challenging, with some authorities considering them either unmeasurable or physically meaningless [19]. This creates a fundamental paradox for potentiometry, as the interpretation of ISE measurements conceptually depends on single-ion activities. This challenge is particularly evident with the pH electrode, where IUPAC has noted that "pH cannot be measured independently because calculation of the activity involves the activity coefficient of single ion" [19].

Recent research has proposed novel thermodynamic approaches to address this challenge. These methods involve measuring contact potentials between a solution and an external electrode, using extrapolation to zero concentration and ionic strength to determine single-ion activity coefficients, potentially providing a gold standard for validating other methods [19].

Experimental Framework for Electrode Validation

Core Methodologies and Protocols

Validating the relationship between ion activity, charge, and electrode potential requires standardized experimental protocols. The following workflow outlines the key steps in sensor preparation, calibration, and validation:

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for ISE validation.

Ion-Selective Membrane Preparation

For polymer-based ISEs, the membrane is typically fabricated by dissolving an ion-pair complex, polyvinyl chloride (PVC), and a plasticizer in tetrahydrofuran (THF) [20]. The ion-pair complex is formed by combining the target ion with a lipophilic counterion; for example, benzydamine hydrochloride (BNZ·HCl) can be paired with tetraphenylborate (TPB⁻) to create a BNZ-tetraphenylborate associated complex [20]. This solution is cast into a Petri dish and allowed to evaporate slowly, producing a master membrane approximately 0.1 mm thick from which sensing discs are cut.

Electrode Assembly and Conditioning

The membrane disc is affixed to an electrode body using THF as an adhesive. The assembled sensor requires conditioning by immersion in a standard solution of the target ion (e.g., 10⁻² M) for several hours to establish a stable equilibrium of the measuring ion in the membrane [20] [17]. Proper conditioning is essential for achieving reproducible and accurate measurements.

Calibration and Measurement

Calibration involves measuring the potential across a series of standard solutions with known activities, typically covering a concentration range of 10⁻² to 10⁻⁶ M [20]. The potential is plotted against the logarithm of the ion activity to generate a calibration curve. The resulting plot should display a linear region (typically 4-6 decades of concentration) where the response follows the Nernst equation, with slopes of approximately 59.16 mV/decade for monovalent ions and 29.58 mV/decade for divalent ions at 25°C [20] [17].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for ISE Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membrane Components | ||

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Polymer matrix for sensing membrane | Primary structural component for polymer-based ISEs [20] |

| Plasticizers (e.g., Dioctyl phthalate/DOP) | Provides fluidity and ion mobility in membrane | Improves response time and sensitivity [20] |

| Ion-Pair Complex | Provides selectivity for target ion | BNZ-TPB for benzydamine sensing [20] |

| Electrochemical Measurement | ||

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | Maintains constant ionic strength | Minimizes activity coefficient variations [17] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent for membrane preparation | Dissolves PVC and membrane components [20] |

| Reference Electrode | Provides stable reference potential | Ag/AgCl reference electrode [20] |

| Validation Techniques | ||

| ICP-OES/ICP-MS | Reference method for validation | Quantifies ion concentration in sweat samples [21] |

Performance Comparison: Electrode Types and Characteristics

Comparative Analysis of ISE Performance Metrics

Different electrode configurations offer distinct advantages and limitations for various applications. The following table compares key performance characteristics across electrode types:

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Ion-Selective Electrode Types

| Parameter | Conventional PVC ISE | Coated Graphite Solid-State ISE | Historical Context: Glass Electrode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Slope (mV/decade) | 58.09 (for BNZ⁺) [20] | 57.88 (for BNZ⁺) [20] | ~59.16 (theoretical for monovalent) [17] |

| Linear Range | 10⁻⁵–10⁻² M [20] | 10⁻⁵–10⁻² M [20] | 14 decades (pH electrode) [17] |

| Detection Limit | 5.81 × 10⁻⁸ M [20] | 7.41 × 10⁻⁸ M [20] | - |

| Response Time | Minutes (equilibration) [20] | Fast response [20] | Rapid (seconds to minutes) |

| Selectivity Issues | Moderate (Nikolsky equation) [17] | Moderate (Nikolsky equation) | Excellent for H⁺, poor for Na⁺ [17] |

| Key Advantages | Well-established protocol | Eliminates internal solution, miniaturization potential | Exceptional selectivity for H⁺ [17] |

| Limitations | Requires internal solution | More complex fabrication | Limited to specific ions [17] |

Method Comparison: Potentiometry vs. Reference Techniques

When evaluating ISE performance against reference analytical techniques, researchers have employed statistical methods including paired t-tests and mean absolute relative difference (MARD) analysis [21]. One study comparing solid-contact ISEs with ICP-OES for sweat sodium and potassium analysis demonstrated that while ISEs provided a promising alternative, "better accuracy is required" despite statistical validation of feasibility [21]. This highlights the importance of proper validation against established reference methods, particularly for complex biological matrices where activity coefficients may differ significantly from aqueous standards [18].

Advanced Considerations: Selectivity and Real-World Applications

The Selectivity Challenge

A fundamental limitation of ISEs is their susceptibility to interference from ions with similar characteristics to the target ion. The Nikolsky-Eisenman equation extends the Nernst equation to account for these interfering ions:

U = U₀ ± (2.303 × R × T / (n × F)) × log(aᵢ + Σkᵢⱼ × aⱼ^(n/m))

Where aᵢ is the activity of the primary ion, aⱼ is the activity of interfering ion j, and kᵢⱼ is the selectivity coefficient [17]. The selectivity coefficient represents the electrode's preference for the interfering ion relative to the primary ion; a smaller value (closer to zero) indicates better selectivity. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between key parameters in electrode response:

Diagram 2: Key parameters affecting electrode potential.

Selectivity coefficients can be determined using various methods, including the separate solution method and mixed solution method, with recent approaches utilizing multiple standard addition techniques and Gran-type linear functions for more accurate determination [22].

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biological Analysis

ISEs have found significant application in pharmaceutical analysis, with recent research demonstrating their effectiveness for determining drugs such as benzydamine hydrochloride in pure form, pharmaceutical creams, and biological fluids [20]. The method has proven particularly valuable as a stability-indicating technique, successfully detecting the active pharmaceutical ingredient in the presence of its oxidative degradant without matrix interference [20].

In biological monitoring, solid-contact ISEs have emerged as promising platforms for wearable sweat sensors, enabling real-time, non-invasive monitoring of electrolytes like sodium and potassium [21]. However, challenges remain in establishing correlation between sweat ion levels and physiological conditions, highlighting the need for continued validation against gold standard techniques like ICP-OES and ICP-MS [21].

The relationship between ion activity, charge, and electrode potential provides the fundamental theoretical foundation for potentiometric sensing with ion-selective electrodes. While the Nernst equation establishes the basic relationship, real-world applications must account for numerous factors including activity coefficients, interfering ions, and electrode design. Contemporary research continues to refine our understanding of these relationships, particularly through the development of solid-contact electrodes and improved validation methodologies. As the field advances, the integration of rigorous theoretical principles with practical experimental validation will remain essential for developing reliable electrochemical sensors for pharmaceutical, environmental, and clinical applications.

Exploring Different ISE Membrane Types and Their Inherent Selectivity

Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) are potentiometric sensors that convert the activity of a specific ion dissolved in a solution into an electrical potential. The core component of any ISE is the ion-selective membrane, which is responsible for the device's selectivity and overall performance. This membrane selectively allows the target ion to cross, generating a measurable potential difference that follows the Nernst equation, thereby enabling the quantification of the ion's activity. The development of ISEs has expanded across numerous fields, including biomedical research, environmental monitoring, and industrial process control, driven by their portability, real-time measurement capabilities, and cost-effectiveness [23] [24].

The fundamental principle of ISE operation hinges on the creation of a membrane potential. This potential develops when the ion-selective membrane separates two solutions with different activities of the target ion—typically an internal reference solution and the sample solution under test. Ions migrate across the membrane along their concentration gradient, and if the membrane is perfectly selective for that ion, the generated potential difference is directly related to its concentration in the sample. The selectivity of the membrane is therefore paramount, as it ensures that the signal is generated predominantly by the ion of interest and not by interfering species [25].

Classification and Comparison of ISE Membrane Types

Ion-selective membranes can be broadly categorized into four main types based on their material composition and mechanism of action: glass membranes, crystalline membranes, ion-exchange resin membranes, and enzyme electrodes. Each type possesses distinct structural properties, selectivity profiles, and operational advantages and limitations. The following table provides a structured comparison of these membrane types, summarizing their key characteristics, common analytes, and performance attributes.

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Ion-Selective Electrode Membrane Types

| Membrane Type | Material Composition | Common Analytes | Selectivity Mechanism | Key Advantages | Inherent Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membranes [23] [24] | Silicate or chalcogenide glass | H⁺, Na⁺, Ag⁺ [23] [24] | Ion-exchange at glass surface [24] | Excellent chemical durability, works in aggressive media [23] | Limited to single-charged cations; susceptible to alkali and acidic errors [23] |

| Crystalline Membranes [26] [24] | Mono- or polycrystallites (e.g., LaF₃, Ag₂S) [26] [27] | F⁻, Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, S²⁻ [26] [23] | Lattice ion incorporation & transport [24] | High selectivity; only ions fitting crystal structure interfere [23] [24] | Membrane surface can be fouled by oxidation over time [26] |

| Ion-Exchange Resin / Liquid/PVC Membranes [26] [24] [25] | PVC polymer matrix with plasticizer and ionophore (e.g., Valinomycin) [26] [25] | K⁺, NH₄⁺, Ca²⁺, NO₃⁻ [26] [28] | Ionophore-facilitated transport [29] [25] | Highly customizable for many ions; wide applicability [24] | Lower physical/chemical durability; finite "survival time" [24] |

| Enzyme Electrodes [23] [24] | Enzyme-loaded membrane covering a standard ISE (e.g., pH) | Glucose, Urea, other substrates [24] | Enzyme reaction produces a detectable ion (e.g., H⁺) [23] | Extends ISE principle to non-ionic analytes [24] | Complex "double-reaction" mechanism; not a true direct ISE [24] |

In-Depth Analysis of Selectivity Mechanisms

The inherent selectivity of each membrane type stems from a distinct physical or chemical mechanism that preferentially interacts with the target ion.

Crystalline Membranes: The selectivity of crystalline membranes, such as the LaF₃ membrane used in fluoride ISEs, is determined by the crystal lattice structure. The membrane only responds to ions that can enter and migrate through this lattice. For the fluoride electrode, the membrane is a single crystal of lanthanum fluoride doped with europium fluoride to lower its electrical resistance. It exhibits 100% selectivity for fluoride ions, with the only significant interference being OH⁻ ions at high pH, which can be mitigated by buffering samples to a pH between 4 and 8 [26]. The interference occurs because OH⁻ ions react with lanthanum to form lanthanum hydroxide, releasing fluoride ions and artificially elevating the reading [26].

Ion-Exchange Resin (Polymer) Membranes: The selectivity of PVC-based membranes is conferred by ionophores—specialized organic molecules trapped within the plasticized polymer matrix that act as ion carriers [25]. These ionophores have molecular structures designed to bind specific ions. A classic example is the potassium-selective electrode, which uses the macrocyclic antibiotic valinomycin as its ionophore. Valinomycin has a cavity that is almost exactly the size of a potassium ion (K⁺), allowing it to form stable complexes and transport K⁺ across the membrane. This precise fit makes the electrode up to 5000 times more selective for potassium than for sodium. However, it is not entirely specific and can also respond to ammonium ions (NH₄⁺) if they are present in high concentrations [26] [25]. The performance of these membranes is highly dependent on the diffusion of the ion-ionophore complex, which is facilitated by the plasticizer. Increasing the plasticizer content from 20% to 70% can increase the ion permeability of the PVC membrane by up to ten thousand-fold [25].

Glass Membranes: Glass membranes, most commonly used in pH electrodes, operate via an ion-exchange process at the hydrated gel layer on the glass surface. The composition of the glass is tailored to be selective for specific single-charged cations like H⁺, Na⁺, and Ag⁺. Their selectivity is influenced by the "alkali error" at high pH (low H⁺ concentration), where the electrode becomes responsive to interfering alkali ions like Na⁺, and the "acidic error" at very low pH, where the electrode response becomes non-linear [23].

Figure 1: Fundamental signaling pathways and selectivity mechanisms in ISE membranes. The diagram illustrates how different membrane types utilize distinct physical-chemical processes to selectively filter target ions and generate a measurable electrical potential.

Experimental Protocols for ISE Validation and Performance Assessment

Validating the performance of an ISE, particularly its selectivity, is a critical step in research and development. Standard experimental protocols assess key performance metrics such as the lower detection limit, response time, slope, and most importantly, the selectivity coefficient.

Fabrication of Solid-Contact Pb²⁺-ISEs with Carbon Nanomaterial Interlayers

A modern approach to constructing stable all-solid-state ISEs involves using carbon-based nanomaterials as an electron-ion exchanger to improve the stability of the potential reading. The following protocol, adapted from recent research, details the fabrication of a lead (Pb²⁺) ion-selective electrode [30].

Electrode Pretreatment: Begin with a glassy carbon (GC) electrode polished sequentially with aqueous dispersions of alumina powder (0.5, 0.3, and 0.05 μm). Clean the polished electrode ultrasonically in deionized (DI) water and then anhydrous ethanol, each for 3 minutes. Dry under a stream of nitrogen gas. Validate the successful pretreatment using cyclic voltammetry in a 1 mM potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) solution; a potential difference of less than 80 mV between the oxidation and reduction peaks indicates a well-prepared electrode surface [30].

Intermediate Layer Application: Prepare a 1 mg/mL uniform suspension of the carbon nanomaterial (e.g., graphene, multi-walled carbon nanotube, or fullerene) in DI water via ultrasonic vibration for 12 hours. Drop-cast 50 μL of this suspension onto the pretreated GC electrode and allow it to dry at room temperature. This forms the electron-ion exchanger layer (e.g., GC/GR). Characterize the hydrophobicity of this layer using contact angle measurements, as a high contact angle (e.g., 132.5° for graphene) indicates superior resistance to the formation of a water layer, which enhances potential stability [30].

Ion-Selective Membrane Coating: Prepare the membrane cocktail by dissolving the required components in tetrahydrofuran (THF). A typical formulation for a Pb²⁺-ISE includes lead ionophore IV (1.4 wt%), sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB, 0.6 wt%), a plasticizer like o-nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE, 63 wt%), and poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC, 35 wt%), for a total mass of 250 mg. Drop-cast 20 μL of this cocktail evenly onto the intermediate layer and allow the THF solvent to evaporate completely at room temperature, forming the final solid-contact ISE (e.g., GC/GR/Pb²⁺-ISE) [30].

Conditioning and Calibration: Condition the fabricated electrodes in a 10⁻³ M Pb(NO₃)₂ solution for at least 12 hours, followed by conditioning in a 10⁻⁹ M Pb(NO₃)₂ solution for over 24 hours. To obtain the calibration curve, measure the electromotive force (EMF) in a series of Pb(NO₃)₂ solutions with concentrations ranging from 10⁻¹¹ M to 10⁻³ M. The Nernstian slope, linear range, and lower detection limit can be determined from this curve [30].

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for fabricating and validating a solid-contact Pb²⁺ ion-selective electrode. Key characterization steps ensure the quality of the electrode surface, intermediate layer, and final sensor performance.

Determination of the Selectivity Coefficient

The selectivity coefficient (( K_{A,B}^{pot} )) is a quantitative measure of an ISE's ability to distinguish the primary ion (A) from an interfering ion (B). Its determination is fundamental to electrode validation.

- Separate Solution Method (SSM): This common method involves measuring the EMF of the ISE in two separate solutions, one containing only the primary ion (A) at a fixed activity (( aA )) and another containing only the interfering ion (B) at the same activity (( aB )). The selectivity coefficient is then calculated using a modified form of the Nernst equation. A ( K_{A,B}^{pot} ) value much less than 1 indicates high selectivity for ion A over ion B, while a value greater than 1 indicates the electrode is more responsive to the interfering ion [24].

The experimental data from the Pb²⁺-ISE study demonstrates how this validation is applied in practice. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of Pb²⁺-ISEs with different carbon nanomaterial interlayers, highlighting the impact of material choice on sensor performance [30].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Solid-Contact Pb²⁺-ISEs with Different Carbon Nanomaterial Interlayers

| Electrode Type | Nernstian Slope (mV/decade) | Detection Limit (M) | Average Response Time (s) | Reported Lifetime | Key Characteristic (Contact Angle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GC/GR/Pb²⁺-ISE [30] | 26.8 | 3.4 × 10⁻⁸ | 42.6 | 1 month | 132.5° (High Hydrophobicity) |

| GC/MWCNT/Pb²⁺-ISE [30] | Data not fully specified in source | Data not fully specified in source | Data not fully specified in source | Data not fully specified in source | Lower than GR |

| GC/C60/Pb²⁺-ISE [30] | Data not fully specified in source | Data not fully specified in source | Data not fully specified in source | Data not fully specified in source | Poor dispersibility |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The fabrication and validation of ISEs require a specific set of chemical reagents and materials. The following table details essential items for constructing polymer-based ISEs, such as the Pb²⁺-ISE described in the experimental protocol.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ISE Fabrication

| Item Name | Function / Role in ISE Fabrication | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(Vinyl Chloride) (PVC) [30] | The polymer matrix that forms the structural backbone of the sensing membrane. | Serves as the solid, inert support (35 wt%) for the ion-selective cocktail in Pb²⁺-ISEs and other polymer-membrane electrodes [30]. |

| Ionophore [25] [30] | The active sensing component that selectively complexes with the target ion. | Lead ionophore IV (1.4 wt%) is used to impart selectivity for Pb²⁺ ions [30]. Valinomycin is the classic ionophore for K⁺-selective electrodes [26] [25]. |

| Plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE) [30] | Imparts fluidity to the PVC membrane, allowing ion and ionophore mobility. | o-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE, 63 wt%) is used to plasticize the membrane, facilitating ion transport and determining the membrane's dielectric constant [30]. |

| Ionic Additive (e.g., NaTFPB) [30] | Lipophilic salt added to reduce membrane resistance and tune selectivity, often by minimizing the interference from lipophilic sample anions. | Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB, 0.6 wt%) is incorporated into the Pb²⁺-selective membrane [30]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) [30] | A volatile organic solvent used to dissolve all membrane components into a homogenous cocktail. | Used to dissolve PVC, ionophore, plasticizer, and additive before drop-casting on the electrode substrate [30]. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (e.g., Graphene) [30] | Act as an electron-ion exchanger in solid-contact ISEs, translating ion flux in the membrane into electron flow in the electrode. | A graphene suspension is drop-cast to form a hydrophobic, conductive intermediate layer that prevents the formation of a thin water film and stabilizes the electrode potential [30]. |

Current Research and Applications in ISE Technology

Recent advancements in ISE technology focus on improving stability, ease of use, and application in complex real-world matrices. Research is actively developing calibration-free and reusable sensor platforms. For instance, one study developed reusable screen-printed ion-selective electrodes (SP-ISEs) for sodium and calcium that maintained a stable calibration intercept for multiple calibrations over 7 days, demonstrating their potential for reliable, long-term environmental monitoring without frequent recalibration [14].

In applied environmental science, ISEs are key components in integrated systems for pollution control. A 2025 study successfully used a suite of ISEs (for NO₃⁻, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Na⁺) in a closed-loop soilless greenhouse cropping system. The real-time measurements from the ISEs were fed into a decision support system (DSS) to automatically control fertilizer injection, which maintained optimal root-zone nutrients, increased tomato yield by 7.6%, and enhanced nitrogen use efficiency by 23%, thereby minimizing environmental pollution [28].

In the clinical and point-of-care diagnostics field, the validity and practicality of ISEs continue to be demonstrated. A 2025 study validated the use of portable Na⁺ and K⁺ ion selective electrode probes for measuring human milk sodium-to-potassium ratios at the point-of-care in mothers with inflammatory breast conditions. The ISEP measurements for the Na⁺:K⁺ ratio showed a substantial correlation with the reference method (ICP-OES), and the testing was rated as highly acceptable by the participating mothers, underscoring its clinical utility [31].

The exploration of different ISE membrane types reveals a direct relationship between membrane composition and inherent selectivity. From the crystal lattice of LaF₃ to the molecular recognition of valinomycin, each membrane employs a distinct mechanism to filter target ions, defining the electrode's analytical capabilities. The ongoing validation research, exemplified by studies on solid-contact electrodes with advanced nanomaterials like graphene, continues to push the boundaries of ISE performance, enhancing their stability, sensitivity, and suitability for real-world applications. As evidenced by their successful use in environmental monitoring, precision agriculture, and clinical diagnostics, a fundamental understanding of membrane selectivity remains the cornerstone of developing robust and reliable potentiometric sensors.

Determining Selectivity Coefficients: Best Practices and Protocols

Separate Solution Method (SSM) and Fixed Interference Method (FIM)

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are potentiometric sensors that include a selective membrane to minimize matrix interferences, with the most common example being the pH electrode [32]. The ability of an ISE to distinguish between the target ion and interfering ions is quantitatively expressed by the potentiometric selectivity coefficient (Kₚₒₖⁱʲ) [33] [2]. This coefficient is a critical performance parameter, as it defines the electrode's specificity in the presence of other ions with similar properties [2]. The selectivity coefficient is fundamentally rooted in the Nikolsky-Eisenman equation, which describes the electrode potential in mixed solutions [33] [34]:

E = const. + (RT/zᵢF)ln[aᵢ + ∑(Kₚₒₖⁱʲ × aⱼ^(zᵢ/zⱼ))]

Where E is the measured potential, R is the gas constant, T is absolute temperature, F is the Faraday constant, zᵢ and zⱼ are the charges of the primary and interfering ions, aᵢ is the activity of the primary ion, and aⱼ is the activity of the interfering ion [33]. A smaller selectivity coefficient value indicates better discrimination against the interfering ion [2]. The accurate determination of this parameter is essential for validating ISE performance, particularly in complex matrices encountered in clinical, environmental, and pharmaceutical applications [32] [21].

Separate Solution Method (SSM)

Principle and Experimental Protocol

The Separate Solution Method (SSM) assesses electrode selectivity by measuring the response to separate solutions containing only the primary ion or only the interfering ion, each at the same activity [33] [35]. According to IUPAC's original recommendations, 0.1 mol L⁻¹ aqueous electrolyte solutions should be used for both the primary ion and interfering ion in SSM evaluations [33].

The experimental protocol for SSM involves the following key steps:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions containing only the primary ion (I) across a relevant concentration range

- Prepare separate solutions containing only each potential interfering ion (J) at identical concentrations

- Measure the electrode potential response for each solution separately

- Construct the potential versus activity curves for each ion

- Calculate selectivity coefficients using the difference in potential responses at equal activities

For ions with the same charge, the selectivity coefficient can be determined from the potential difference between the two separate solution response curves at the same activity [35]. The method is based on the assumption that the electrode exhibits a Nernstian response to both the primary and interfering ions [33].

Applications and Advantages

SSM has proven particularly valuable for initial screening of new electrode materials and ionophores during development stages [33]. The method provides a convenient approach to compare selectivity patterns across different electrode designs and membrane compositions under identical conditions [33]. A notable application example includes the characterization of a renewable carbon paste electrode for lead ion detection, where SSM helped verify the electrode's high selectivity for Pb²⁺ against potential interferents [36].

The primary advantage of SSM lies in its experimental simplicity and requirement for minimal chemical preparation [33]. By testing ions in separate solutions, SSM avoids complex interactions that can occur in mixed ion environments, providing clear, interpretable data on intrinsic electrode selectivity toward individual ion species.

Fixed Interference Method (FIM)

Principle and Experimental Protocol

The Fixed Interference Method (FIM) evaluates selectivity by measuring the electrode response to the primary ion in the presence of a constant, fixed background of interfering ions [33] [34]. This approach better represents realistic measurement conditions where multiple ions typically coexist [34].

The standard FIM experimental protocol consists of these steps:

- Prepare a series of solutions with varying concentrations of the primary ion (typically across several orders of magnitude)

- Maintain a constant, fixed activity of the interfering ion in all solutions

- Measure the electrode potential for each solution

- Plot the potential versus the logarithm of the primary ion activity

- Determine the selectivity coefficient from the intersection point of the linear portions of the resulting curve

The selectivity coefficient Kₚₒₖⁱʲ is calculated using the following relationship derived from the Nikolsky-Eisenman equation:

Kₚₒₖⁱʲ = aᵢ / (aⱼ^(zᵢ/zⱼ))

Where aᵢ is the activity of the primary ion at the intersection point, and aⱼ is the fixed activity of the interfering ion [34].

Applications and Advantages

FIM has been extensively applied in situations where practical electrode behavior in complex matrices must be evaluated [34]. For instance, commercial ammonium ISEs have been characterized using FIM to determine selectivity against biologically relevant interfering ions (Li⁺, Na⁺, K⁺) present simultaneously, mimicking conditions found in human serum [34].

The principal advantage of FIM is its ability to simulate real-world measurement conditions where multiple interfering ions coexist with the target analyte [34]. This provides more practically relevant selectivity data compared to methods using single-ion solutions. Additionally, FIM can better account for non-ideal electrode behavior and complex ion interactions that may occur in mixed solutions.

Critical Comparison of SSM and FIM

Methodological Comparison

Table 1: Direct comparison between SSM and FIM characteristics

| Parameter | Separate Solution Method (SSM) | Fixed Interference Method (FIM) |

|---|---|---|

| Solution Composition | Separate solutions containing only primary OR interfering ion | Mixed solutions with varying primary ion and fixed interfering ion background |

| IUPAC Recommendation | Originally recommended (1976) but considered less desirable for practical applications [34] | Preferred method as it better represents actual use conditions [34] |

| Information Provided | Intrinsic selectivity for comparison of different electrodes/membranes [33] | Practical selectivity under simulated real-use conditions [34] |

| Complexity | Simpler experimental setup | More complex, requires careful control of interfering ion background |

| Assumptions | Assumes Nernstian response to all ions [33] | Less dependent on Nernstian behavior for interfering ions |

| Ion Interactions | Does not account for ion interactions in mixed solutions | Captures some ion interaction effects |

Limitations and Challenges

Both methods face limitations when dealing with ions of different charge states [33] [34]. The theoretical foundation becomes more complex, and additional assumptions are required for meaningful interpretation of results. SSM specifically suffers from providing an unrealistic representation of practical electrode behavior since it tests ions in isolation rather than in mixtures [34].

A significant limitation of traditional SSM and FIM approaches is their inability to fully predict electrode performance in real samples containing multiple interfering ions simultaneously [34]. This has led to the development of modified methods, such as the "mixed ion response" approach that extends FIM to include multiple interfering ions at concentrations resembling real samples [34].

Experimental Protocols and Data Interpretation

Detailed SSM Protocol

- Solution Preparation: Prepare primary ion solutions at concentrations spanning the expected working range (typically 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹ M). Prepare separate interfering ion solutions at identical concentration ranges.

- Measurement Conditions: Use constant temperature control. Measure potentials after stabilization (typically 1-2 minutes per solution).

- Data Collection: Record potential values for each standard solution. Plot E vs. log(aᵢ) for both primary and interfering ions.

- Calculation: For ions with equal charge: logKₚₒₖⁱʲ = (Eⱼ - Eᵢ)/(RT/zᵢF) where Eᵢ and Eⱼ are potentials measured for primary and interfering ions at the same activity.

Detailed FIM Protocol

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions with primary ion activity varying from 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹ M. Add a fixed background of interfering ion at a constant activity (typically 10⁻² or 10⁻³ M).

- Measurement: Measure electrode potential for each solution. Plot potential vs. logarithm of primary ion activity.

- Data Analysis: Identify the intersection point between the linear Nernstian region and the interference plateau. Calculate selectivity coefficient using: Kₚₒₖⁱʲ = aᵢ/(aⱼ^(zᵢ/zⱼ)), where aᵢ is the primary ion activity at the intersection point.

Research Reagent Solutions for Selectivity Testing

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for selectivity coefficient determination

| Reagent/Chemical | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophores | Selective molecular recognition elements in membrane | Valinomycin (K⁺) [21], ETHT 5506 (Mg²⁺) [33], Sodium ionophore X (Na⁺) [21], BMAPP (Pb²⁺) [36] |

| Polymer Matrices | Membrane scaffold material | Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) [36] [21], Poly(decyl methacrylate) [37] |

| Plasticizers | Provide membrane flexibility and influence dielectric constant | o-Nitrophenyloctyl ether (o-NPOE) [36], Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) [21] |

| Ionic Additives | Control membrane permselectivity and reduce resistance | Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (Na-TFPB) [21], Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (KTpClPB) [33] |

| Solid Contacts | Transduce ion-to-electron signal in all-solid-state ISEs | PEDOT:PSS [14] [21], Carbon nanotubes [37] |

Method Selection Guidelines

Choosing between SSM and FIM depends on the specific research objectives:

- Use SSM when: Screening new ionophores or membrane compositions, comparing fundamental selectivity patterns across different electrode designs, or when seeking IUPAC-recommended standardized data for publication [33].

- Use FIM when: Evaluating electrode performance for specific applications with known interferents, testing under conditions mimicking real samples, or when practical relevance outweighs standardization needs [34].

For comprehensive electrode characterization, employing both methods provides complementary information: SSM offers fundamental insights into intrinsic selectivity, while FIM reveals practical performance limitations [33] [34].

Workflow Diagrams

SSM and FIM Experimental Workflows: This diagram illustrates the procedural pathways for both selectivity assessment methods, highlighting their distinct approaches from solution preparation to final calculation.

ISE Application Domains Relying on Selectivity Data: This diagram showcases the various fields that depend on accurate selectivity coefficients for reliable ion-selective electrode applications, from environmental monitoring to clinical diagnostics.

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are potentiometric sensors that measure the activity of specific ions in solution through selective membrane interactions [38] [39]. These analytical devices generate an electrical potential proportional to the logarithm of target ion activity according to the Nernst equation, making them valuable tools across clinical, environmental, and industrial applications [38] [40].

The standard addition method significantly enhances measurement accuracy when analyzing complex sample matrices where interfering substances may alter instrument response [41]. Unlike traditional calibration using separate standard solutions, standard addition introduces known amounts of the analyte directly into the sample, effectively compensating for matrix effects by maintaining consistent background interference across all measurements [41] [42].

Table 1: Comparison of Calibration Methods for Ion-Selective Electrodes

| Method Type | Key Principle | Best Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Point Standardization | Uses one standard to determine kA | Limited concentration ranges; clinical automated analyzers | Assumes linear response; error in kA carries over to sample results [42] |

| Multiple-Point Standardization | Calibration curve with ≥3 standards | Wide concentration ranges; research applications | More time-consuming; requires additional standards [42] |

| Standard Addition | Known analyte amounts added directly to sample | Complex matrices (biological fluids, environmental samples) | Multiple measurements required; careful pipetting essential [41] |

Theoretical Foundation: The Nernst Equation and Gran Plots

The Nernst Equation Principle

The fundamental relationship governing ISE response is the Nernst equation:

Where E is the measured potential, E° is the standard electrode potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature in Kelvin, z is the ion charge, F is Faraday's constant, and a is the ion activity [39]. For dilute solutions, activity approximates concentration, simplifying the equation to:

Temperature significantly impacts ISE response, as the theoretical slope (S = RT/zF) increases by approximately 2 mV/decade for each 10°C temperature increase [43]. This temperature dependence necessitates careful control during measurements or appropriate correction factors.

Gran Plot Methodology

Gran plots utilize an antilog transformation of potentiometric data to convert the logarithmic Nernstian response into a linear relationship. This transformation enables more accurate determination of original analyte concentration by extrapolating the linear plot to the horizontal axis. The Gran approach offers several advantages:

- Minimizes electrode non-idealities by focusing on linear response regions

- Reduces impact of experimental error through multiple data points

- Provides visual confirmation of measurement validity through linearity assessment

Experimental Protocol: Multiple Standard Addition with ISEs

Step 1: Sample Preparation

Collect and prepare sample aliquots of equal volume (Vx) with unknown analyte concentration (Cx). For solid samples, appropriate digestion or extraction may be necessary, as demonstrated in fluoride analysis of packaging materials where combustion prepares samples for ISE measurement [44].

Step 2: Standard Additions

Prepare a series of test solutions, each containing equal volumes of the sample, then add increasing volumes (Vs) of a standard solution with known concentration (Cs) to successive aliquots [41]. Include one control solution containing only sample and solvent.

Step 3: Potential Measurements

Immerse the ISE and reference electrode in each solution, allowing potential stabilization between measurements. Record the potential (E) for each solution, ensuring constant temperature throughout the procedure [43].

Step 4: Gran Plot Transformation

Convert potential readings to concentration-dependent values using an antilog transformation, typically plotting 10^(E/s) versus added standard volume, where s represents the electrode slope [4].

Step 5: Linear Regression and Concentration Calculation

Perform linear regression on the transformed data. The x-intercept (volume axis) corresponds to -Vx, enabling calculation of the original unknown concentration using the relationship between sample volume, standard concentration, and intercept value [41].

Research Reagent Solutions for ISE Applications

Table 2: Essential Materials for Ion-Selective Electrode Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membrane Components | Determines electrode selectivity and sensitivity | All ISE applications [38] [39] |

| Ionophores | Selective ion recognition and binding | Target-specific ISEs (e.g., valinomycin for potassium) [38] [43] |

| Polymeric Matrix (PVC) | Provides mechanical stability for membrane | Membrane-based ISEs [39] |

| Plasticizers | Enhances membrane fluidity and ion transport | Improved response times [39] |

| Ion Exchangers | Facilitates ion exchange within membrane | Lower detection limits [39] |

| TISAB Solutions | Controls ionic strength and pH | Fluoride ISE measurements [44] |

| Standard Solutions | Calibration and standard addition | All quantitative applications [41] [42] |

Comparative Performance Data

Table 3: ISE Performance Comparison with Alternative Techniques

| Analytical Technique | Detection Limits | Matrix Tolerance | Cost & Accessibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| ISE with Standard Addition | Nanomolar to micromolar range [39] | Moderate (improved with standard addition) [41] | Low cost; widely accessible [40] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Parts per trillion (ultra-trace) [39] | Low (requires sample digestion) | High cost; specialized labs [39] |

| Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) | Parts per billion (trace) [39] | Low (matrix interference issues) | Moderate cost; common but specialized [39] |

Advanced Considerations for Method Validation

Temperature Compensation Strategies

Temperature variations significantly impact ISE response, with theoretical slope increasing from approximately 56.18 mV/decade at 10°C to 61.37 mV/decade at 36°C for monovalent ions [43]. Electrodes modified with nanocomposite materials or conductive polymers like poly(3-octylthiophene-2,5-diyl) demonstrate improved temperature resistance [43].

Selectivity Coefficient Determination

The selectivity coefficient (Kpot) quantifies an ISE's ability to distinguish the target ion from interferents. Modern ISEs achieve remarkable selectivity, with some coefficients below 10^-10 [4]. These values are typically determined using the separate solution method or fixed interference method and should be documented during validation.

Minimizing Aqueous Layer Effects

Solid-contact ISEs (SCISEs) eliminate internal solutions but risk forming an aqueous layer between the membrane and conductor, causing potential drift [43]. Using hydrophobic intermediate layers like conductive polymers or carbon nanotube-ionic liquid nanocomposites enhances potential stability [43] [45].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

ISE with standard addition provides particular value in pharmaceutical applications including:

- Drug concentration measurements in blood plasma or urine [41]

- Quality control of active pharmaceutical ingredients and excipients

- Dissolution testing and drug release monitoring

The method's ability to compensate for complex biological matrices makes it indispensable for accurate determinations where traditional calibration would suffer from matrix effects [41].

Gran-type linear functions coupled with multiple standard addition techniques provide a robust methodology for accurate ion concentration determination using ISEs, particularly in complex sample matrices encountered in pharmaceutical research. This approach effectively compensates for matrix effects while leveraging the simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and real-time measurement capabilities of potentiometric sensors. Proper implementation requires careful attention to temperature control, electrode selection, and methodological consistency to ensure reliable results suitable for drug development applications.

Experimental Design for Working Under Bi-ionic Conditions

A bi-ionic potential (BIP) arises when an ion-exchange membrane (IEM) separates two solutions of different electrolytes with a common co-ion but different counter-ions [46]. This electrochemical potential is a critical parameter for characterizing membrane selectivity and understanding ion transport phenomena. The theoretical foundation for BIP is built upon the extended Nernst-Planck equation, which describes the interdiffusion process controlled by both the membrane itself and the adjacent diffusion boundary layers (DBLs) [46]. Accurate measurement of BIP provides invaluable insights into membrane properties and behavior, which is essential for applications ranging from environmental monitoring to pharmaceutical development.

The complexity of bi-ionic systems necessitates sophisticated modeling approaches that account for multiple simultaneous factors. Comprehensive theoretical studies have demonstrated that accurate BIP prediction requires consideration of non-zero co-ion flux, variable water flow, a variable selectivity coefficient, and an affinity coefficient different from unity [46]. Research indicates that among these parameters, the affinity coefficient exerts the most significant influence on BIP across concentration ranges, while the selectivity coefficient and water flow primarily affect BIP at higher common concentrations [46]. This understanding forms the critical theoretical foundation for designing effective experiments under bi-ionic conditions.

Experimental Design Framework for Bi-ionic Potentials

Core System Configuration and Parameters

Establishing a robust experimental framework for bi-ionic potential measurements requires careful control of system components and environmental conditions. The fundamental setup consists of an ion-exchange membrane separating two electrolyte solutions with different counter-ions but a common co-ion, with electrodes positioned on either side to measure the resulting potential difference [46]. The diffusion boundary layers adjacent to the membrane surfaces play a critical role in the overall transport process, with their thickness varying significantly based on stirring conditions—from approximately 59 μm at high stirring rates to 196 μm without stirring [46].

The experimental determination of BIP involves monitoring the potential development over time until a stable value is reached. This requires precise control and measurement of at least twelve distinct parameters, including three obtained from literature and others determined through independent experiments [46]. Key parameters that must be carefully controlled include: