Screen-Printed Electrodes for Heavy Metal Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in screen-printed electrode (SPE) technology for the electrochemical detection of heavy metal ions.

Screen-Printed Electrodes for Heavy Metal Detection: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest advancements in screen-printed electrode (SPE) technology for the electrochemical detection of heavy metal ions. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and professionals in drug development and environmental monitoring, it covers foundational principles, cutting-edge methodologies, and optimization strategies. The scope ranges from the exploration of novel nanomaterials and electrode modifications to the practical application of various voltammetric techniques. It further addresses critical troubleshooting for enhancing sensitivity and selectivity, and validates performance through comparative analysis with traditional spectroscopic methods and real-sample applications. The integration of IoT and machine learning for real-time, on-site monitoring is also highlighted, presenting SPEs as a robust, portable, and cost-effective solution for modern analytical challenges.

The Foundation of Screen-Printed Electrodes: Principles, Materials, and Advantages

Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) represent a transformative technology in electrochemistry, providing reliable, portable, affordable, and versatile platforms for analytical monitoring across environmental, clinical, and agricultural fields [1]. These disposable electrochemical cells are manufactured via mass-production printing techniques, enabling cost-effective fabrication while maintaining consistent performance characteristics. Their architecture typically integrates a three-electrode system—working electrode (WE), counter electrode (CE), and reference electrode (RE)—on a single planar substrate, creating a complete sensing platform ideal for on-site analysis and point-of-care testing [1] [2]. The global market for metal-based SPEs is experiencing robust growth, projected to reach $207 million in 2025 with a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 9.5% from 2025 to 2033, reflecting their expanding adoption [3] [2].

Within the specific context of heavy metal detection, SPEs offer distinct advantages over traditional laboratory techniques. They enable rapid, sensitive detection of toxic metals like lead, mercury, cadmium, and copper at concentrations below regulatory limits, making them invaluable for environmental monitoring and food safety applications [1] [4]. Their disposable nature eliminates cross-contamination risks between samples, while their portability facilitates real-time, in-situ measurements in resource-limited settings where traditional instruments are impractical [5].

Design and Architecture of SPEs

Fundamental Components

The architecture of a standard SPE consists of several key components layered on an inert substrate:

- Substrate: Typically made from ceramic, plastic, or flexible polyester materials, providing mechanical support for the entire electrode system [6].

- Electrode System: A three-electrode configuration is standard:

- Working Electrode (WE): The core sensing element where the electrochemical reaction occurs. Metal-based WEs often utilize gold (Au), platinum (Pt), or silver (Ag), chosen for their excellent conductivity and electrochemical properties [3] [1].

- Counter Electrode (CE): Usually made from carbon or noble metals, completing the electrical circuit with the working electrode.

- Reference Electrode (RE): Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode is measured. Silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) is commonly used [5] [7].

- Conductive Tracks: Metallic traces that connect the electrode elements to the external measuring instrument.

- Insulating Layer: A dielectric material that covers unnecessary exposed areas, defining the active electrode area and preventing short circuits.

Material Considerations for Heavy Metal Detection

The selection of electrode materials significantly influences sensitivity, selectivity, and overall performance in heavy metal detection:

Table 1: Common Metal-Based Electrode Materials and Their Properties

| Material | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications in Heavy Metal Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Easy functionalization, high conductivity, suitable for thiol chemistry | Higher cost, can form intermetallic compounds with some metals | Preferred for ASV of Hg, Pb; often modified with self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) [1] |

| Platinum (Pt) | Excellent chemical stability, wide potential window | Expensive, can catalyze hydrogen evolution | Useful in corrosive environments or for detection requiring extreme potentials [3] |

| Silver (Ag) | Lower cost, good conductivity | Prone to oxidation, can dissolve at anodic potentials | Often used as reference electrode component; sometimes in bimetallic nanoparticles [8] |

Manufacturing Processes

Screen-Printing Technique

The manufacturing of SPEs primarily utilizes screen-printing technology, a thick-film deposition process that enables high-volume production with excellent reproducibility [6]. The fundamental manufacturing workflow involves:

- Stencil Preparation: A mesh screen is patterned with a design that defines the electrode geometry.

- Ink Deposition: Conductive ink is spread across the screen using a squeegee, forcing the ink through the patterned areas onto the substrate.

- Curing: The printed electrodes are heat-treated at specific temperatures to evaporate solvents and solidify the ink, ensuring mechanical stability and optimal electrical conductivity.

- Insulation Layer Application: A dielectric layer is printed to expose only the active electrode areas and connection pads.

This process allows for precise control over electrode geometry and thickness, which are critical parameters affecting electrochemical performance. The manufacturing is characterized by moderate market concentration, with key players like DuPont, Heraeus, and Johnson Matthey collectively holding over 35% market share, while smaller companies focus on niche segments [3].

Advanced Manufacturing and Modification Techniques

Recent advancements have introduced sophisticated modification techniques to enhance SPE performance:

- Drop-Casting: A simple method where modifier solutions (e.g., nanoparticle dispersions, polymer solutions) are precisely applied to the electrode surface [7] [6].

- Electrodeposition: Electrochemical deposition of metals or polymers onto the working electrode surface, enabling controlled formation of nanostructures [5].

- Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs): Molecular layers that spontaneously organize on electrode surfaces (particularly gold), providing specific binding sites for heavy metals [1].

- Advanced Printing Technologies: Emerging approaches like 3D printing offer unprecedented flexibility in electrode design and potential for customization, though this technology is still developing for electrochemical sensors [9].

Table 2: Comparison of SPE Manufacturing and Modification Approaches

| Manufacturing/Modification Approach | Key Characteristics | Impact on Sensor Performance | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Screen-Printing | High-throughput, cost-effective, good reproducibility | Establishes baseline performance; limited to available inks | Low; established industrial process |

| Drop-Casting Modification | Simple, equipment-free, versatile | Can enhance sensitivity but may affect reproducibility | Low; accessible to most laboratories |

| Electrochemical Deposition | Controlled thickness, can create nanostructures | Significantly improves sensitivity and LOD | Moderate; requires potentiostat |

| SAM Functionalization | Molecular-level control, specific binding sites | Enhances selectivity toward target metals | Moderate to high; requires specific chemistry |

Experimental Protocols for Heavy Metal Detection

Electrode Modification with Nafion-PSS Composite

Purpose: To enhance electrode surface hydrophilicity and selectivity for trace heavy metal sensing [6].

Materials:

- Carbon-based SPE (e.g., Metrohm DropSens)

- Nafion solution (e.g., 5 wt% in lower aliphatic alcohols)

- Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PSS) solution

- Deionized water

- Micropipettes and tips

- Drying oven or ambient drying setup

Procedure:

- Prepare a composite solution by mixing Nafion and PSS at a 3:1 volume ratio.

- Homogenize the mixture via vortex mixing or sonication for 5 minutes.

- Using a micropipette, deposit 5 µL of the Nafion-PSS composite solution onto the working electrode surface.

- Allow the modified electrode to dry at room temperature for 60 minutes or at 40°C for 15 minutes.

- Condition the modified electrode in acetate buffer (pH 4.5) for 10 minutes before initial use.

- Store modified electrodes in dry conditions when not in use.

Validation: The successful modification can be verified through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and water contact angle (WCA) measurements, which should show reduced charge transfer resistance and improved hydrophilicity, respectively [6].

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry for Lead and Cadmium Detection

Purpose: Simultaneous determination of Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ ions in aqueous samples [8] [6].

Materials:

- Modified SPE (e.g., Nafion-PSS/SPE or AgBiS₂ nanoparticle-modified SPE)

- Electrochemical analyzer (potentiostat)

- Acetate buffer solution (0.1 M, pH 4.5)

- Standard solutions of Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ (1000 ppm)

- Nitrogen gas for deaeration

- Stirrer or magnetic stir plate

Procedure:

- Prepare calibration standards by diluting Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ stock solutions in acetate buffer to concentrations ranging from 5-100 ppb.

- Transfer 10 mL of sample or standard to the electrochemical cell.

- Deaerate the solution with nitrogen gas for 5 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Optimize the deposition potential and time based on the specific modification: typically -1.2 V for 90-120 seconds with stirring.

- After the deposition step, cease stirring and allow 15 seconds for solution equilibration.

- Perform anodic scanning from -1.0 V to -0.2 V using square-wave parameters (frequency: 25 Hz, amplitude: 50 mV, step potential: 5 mV).

- Record the stripping peaks at approximately -0.5 V for Pb²⁺ and -0.7 V for Cd²⁺.

- Quantify metal concentrations using the standard addition method or calibration curves.

Performance Metrics: For a properly modified electrode, limits of detection (LOD) should reach 0.41 nM (85 ppt) for Pb²⁺ and 13.83 ppb for Cd²⁺, sufficient for monitoring below WHO-recommended levels [8] [1].

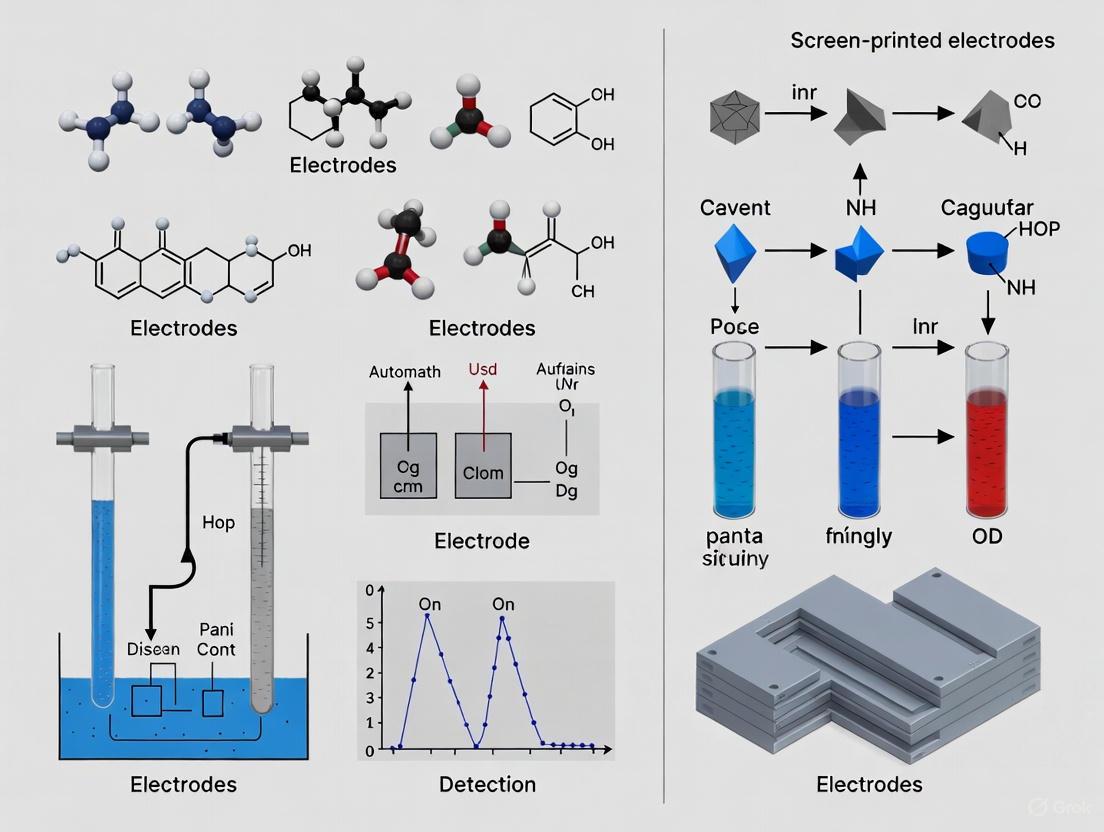

Diagram 1: Heavy Metal Detection Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SPE-Based Heavy Metal Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Applications | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nafion Polymer | Cation-exchange polymer; selectively pre-concentrates cationic heavy metals | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ detection; often combined with PSS | Chemical inertness, sulfonate ligands for cation exchange [6] |

| Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) - PSS | Enhances hydrophilicity and cation capture; improves mass transport | Composite with Nafion for enhanced sensitivity | Hydrophilic, -SO₄²⁻ ligands, improves electrode wettability [6] |

| Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Bi, Ag) | Enhance electron transfer, provide catalytic sites, lower detection limits | AuNPs for Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺; Bi for Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ | High surface area, excellent conductivity, functionalizable [5] [8] |

| Carbon Dots (CDs) | Zero-dimensional carbon nanoparticles; improve electron-transfer kinetics | Zn(II), Cu(II) detection; sustainable/biomass-derived | Eco-friendly, highly biocompatible, durable, quenchable emissions [7] |

| Ionophores | Selective ion recognition elements in membrane coatings | Ion-selective electrodes for specific heavy metals | Macrocyclic compounds that encapsulate specific ions [4] |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 4.5) | Optimal supporting electrolyte for ASV of heavy metals | Most Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ detection protocols | Ideal pH for metal deposition without hydrogen evolution [8] [6] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The application of SPEs in heavy metal detection continues to evolve with several emerging trends:

- Integration with Microfluidics: Combining SPEs with microfluidic systems creates lab-on-a-chip devices that offer improved sample handling, automation, and portability [3].

- Nanomaterial Enhancements: Incorporation of advanced nanomaterials including graphene, carbon nanotubes, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) significantly boosts sensitivity and selectivity [2] [10].

- IoT and Automation: Integration with Internet of Things (IoT) platforms enables remote monitoring and real-time data transmission, as demonstrated in recent systems for multiplexed heavy metal sensing in water samples [5].

- Artificial Intelligence Integration: Machine learning algorithms, particularly convolutional neural networks (CNNs), are being employed to process complex electrochemical signals and improve classification accuracy for multiple heavy metals in mixtures [5] [10].

Diagram 2: SPE Technology Ecosystem for Heavy Metal Detection

The future of SPE development will likely focus on improving manufacturing processes to enhance scalability and cost-effectiveness while addressing current challenges related to long-term stability and reproducibility. With ongoing advancements in materials science, manufacturing technologies, and data analytics, SPEs are poised to become increasingly sophisticated tools for heavy metal detection across diverse application domains.

Why SPEs? Advantages over Traditional Laboratory Techniques like AAS and ICP-MS

The accurate detection of heavy metal ions is a cornerstone of environmental monitoring, public health protection, and various industrial processes. For decades, the gold standard for this analysis has relied on traditional laboratory-based techniques such as Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [11] [12]. While these methods offer high accuracy and sensitivity, they present significant limitations for rapid, on-site analysis. This document, framed within a broader thesis on screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) for heavy metal detection, delineates the compelling advantages of SPEs and provides detailed protocols for their application, empowering researchers and scientists to transition from centralized laboratories to decentralized, field-based analysis.

Comparative Analysis: SPEs vs. Traditional Laboratory Techniques

Electrochemical sensors based on screen-printed electrodes are displacing standard methods by offering a viable alternative that combines analytical performance with operational practicality [13]. The table below summarizes the critical differences.

Table 1: Comparison of Heavy Metal Detection Techniques

| Parameter | Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | AAS / ICP-MS |

|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation & Cost | Portable, affordable instrumentation; low-cost disposable electrodes [14] [13] | High-cost, complex equipment [11] [7] |

| Operation & Workflow | Simple operation; minimal sample pre-treatment; rapid analysis [11] [14] | Complex operation; meticulous sample pre-treatment required [11] |

| Portability & Use Case | Excellent portability for on-site and in-situ monitoring [14] [13] | Laboratory-bound; requires sample transportation [12] |

| Analysis Speed | Fast response (minutes) [11] | Time-consuming procedures [7] |

| Performance | High sensitivity, low detection limits (e.g., sub-ppb for Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺) [11] [8] | High sensitivity and accuracy |

The Core Advantages of Screen-Printed Electrodes

Disposability and Miniaturization

SPEs integrate working, reference, and counter electrodes onto a single, compact substrate, such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or polyester [15]. This design enables their mass production as disposable, single-use devices, eliminating cross-contamination risks and the need for tedious cleaning and polishing procedures required for traditional electrodes [16]. Their small size is ideal for portable sensors and wearable electronics [15].

Tunable Sensitivity and Selectivity through Surface Modification

A key strength of SPEs is the ability to engineer their performance by modifying the working electrode's surface. This allows researchers to tailor sensors for specific analytes. Common modifiers include:

- Bismuth-based Films: A non-toxic and environmentally friendly alternative to mercury, known for its excellent ability to form alloys with heavy metals, thereby enhancing stripping voltammetry signals [11] [17].

- Nanomaterials: Graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, and metal nanoparticles (e.g., silver, cobalt) are incorporated to increase the electroactive surface area, improve electrical conductivity, and provide electrocatalytic properties [11] [12] [16].

- Carbon Dots: Biomass-derived carbon dots can enhance electron-transfer kinetics and current intensity, improving detection limits [7].

- Polymers: Coatings like poly(sodium-4-styrene sulfonate) can improve mechanical stability and mitigate interferences [17].

Experimental Protocols: Representative Studies

The following protocols illustrate how modified SPEs are applied in heavy metal detection research.

Protocol 1: Simultaneous Detection of Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ Using a Bismuth/GO-Modified SPE

This protocol is adapted from a study demonstrating simultaneous detection with low limits [11].

1. Sensor Fabrication:

- Working Electrode Modification: Mix a bismuth/graphene oxide (Bi/GO) hybrid powder directly into a commercial conductive carbon ink. Print this composite ink onto a polyethylene terephthalate (PET) substrate using a screen-printing mold. Cure the electrode as per ink specifications.

- Activation: Electrochemically activate the prepared SPE in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M acetate buffer, pH 4.5) by applying a conditioning potential.

2. Detection via Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV):

- Supporting Electrolyte: Use 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) as the analysis medium.

- Pre-concentration / Deposition: Immerse the electrode in the sample solution and deposit the target metals onto the Bi/GO surface by applying a potential of -1.2 V for 90 seconds under stirring.

- Stripping & Measurement: After a quiet time of 10 seconds, scan the potential in a positive direction using a square-wave voltammetry (SWV) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) mode. The oxidation (stripping) of the accumulated metals produces distinct current peaks.

- Calibration: The peak current is proportional to the metal ion concentration. The reported linear detection range is 5–50 μg/L, with limits of detection (LOD) of 1.55 μg/L for Cd²⁺ and 1.31 μg/L for Pb²⁺ [11].

Protocol 2: Direct Detection of As(V) Using Ag-NP Modified Carbon Nanofiber SPE

This protocol enables the direct detection of the highly toxic arsenate ion without pre-reduction [16].

1. Sensor Modification:

- Nanoparticle Synthesis: Synthesize silver nanoseeds (Ag-NS) by chemical reduction of silver nitrate with sodium borohydride in the presence of trisodium citrate and sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPSS) as stabilizers.

- Electrode Preparation: Drop-cast 5 μL of the synthesized Ag-NS solution onto the working electrode of a commercial carbon-nanofiber-based SPE (Metrohm DropSens, ref. 110CNF). Allow it to dry at room temperature.

2. Detection via Differential Pulse ASV (DPASV):

- Supporting Electrolyte: Use 0.01 M hydrochloric acid (HCl, pH 2.0). Note: No deoxygenation is required for As(V) detection with this method.

- Pre-concentration / Deposition: Apply a deposition potential of -0.6 V for 60 seconds with stirring.

- Stripping & Measurement: Record the DPASV signal from -0.4 V to -0.1 V. The peak for As(0) to As(V) oxidation appears at around -0.3 V (vs. Ag/AgCl).

- Calibration: The method achieved a LOD of 0.6 μg/L for As(V) in spiked tap water, validating its suitability for real samples [16].

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow for heavy metal detection using modified SPEs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for SPE-Based Heavy Metal Sensing

| Item | Function / Description | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrode (Base) | Disposable platform with integrated 3-electrode system. Carbon is the most common working electrode material [15]. | Commercial SPCE (e.g., Metrohm DropSens) [16] or homemade PVC-based SPCE [15]. |

| Conductive Inks | Form the conductive tracks and electrodes. Can be carbon, silver, or gold-based [15]. | Carbon ink mixed with Bi/GO hybrid [11]; Graphite ink for homemade electrodes [15]. |

| Electrode Modifiers | Enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and catalytic properties. | Bismuth salts [11] [17], Silver Nanoparticles (Ag-NPs) [16], Starch-derived Carbon Dots (CDs) [7], Cobalt-doped Carbon Nanofibers (CoCNFs) [12]. |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Provide ionic conductivity and set the pH for optimal analyte deposition and stripping. | Acetate buffer (for Cd/Pb) [11], Hydrochloric acid (for As(V)) [16], Acetic acid (for Zn/Cu) [7]. |

| Standard Solutions | Used for calibration and method validation. | 1000 mg/L ICP standards of target heavy metals (e.g., Cd, Pb, As) [16]. |

Diagram 2: The role of electrode modifiers in enhancing SPE performance.

The transition from traditional techniques like AAS and ICP-MS to screen-printed electrodes is justified by a compelling combination of analytical performance and practical utility. SPEs deliver the sensitivity and selectivity required for trace-level heavy metal detection while offering unmatched advantages in portability, cost, speed, and ease of use [13]. The capacity to finely tune their properties through surface modification makes them a versatile and powerful tool for researchers. As demonstrated in the provided protocols, SPE-based sensors are capable of achieving detection limits that meet or exceed regulatory guidelines, solidifying their potential as reliable tools for on-site environmental monitoring, point-of-care diagnostics, and rapid food safety analysis.

The accurate detection of heavy metal ions (HMIs) represents a critical challenge in environmental monitoring, food safety, and public health. Electrochemical techniques, particularly voltammetry, have emerged as powerful tools that offer rapid, sensitive, and cost-effective analysis compared to traditional spectroscopic methods like atomic absorption spectrometry (AAS) or inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) [18] [19]. These electrochemical methods are especially well-suited for integration with modern sensing platforms, including disposable screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), which facilitate portability for on-site field measurements [13] [7]. When properly designed, these systems can achieve detection limits at parts-per-billion (ppb) concentrations, meeting or exceeding the stringent guidelines set by regulatory agencies such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA) [18] [8].

The performance of electrochemical sensors heavily depends on both the selected voltammetric technique and the careful modification of electrode surfaces. Techniques including Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) each provide unique mechanisms for enhancing signal-to-noise ratios, minimizing background contributions, and improving overall detection sensitivity [20] [21]. Concurrently, the strategic modification of electrodes with nanomaterials such as gold nanorods (AuNRs), carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene derivatives, or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) creates synergistic effects that significantly boost electrocatalytic activity, increase electroactive surface area, and facilitate faster electron transfer kinetics [22] [18] [10]. This application note details the core principles, experimental protocols, and practical applications of DPV, SWASV, and CV specifically within the context of heavy metal detection using screen-printed electrode platforms.

Core Technique Principles and Comparative Analysis

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Cyclic Voltammetry serves as a fundamental technique for initial electrode characterization and qualitative analysis of electrochemical processes. In CV, the potential applied to the working electrode is scanned linearly between two set limits (initial and final potentials) before reversing direction back to the starting point. This triangular waveform perturbation generates a current response that provides rich information about the redox behavior, kinetics, and mechanistic pathways of electroactive species [20]. The resulting voltammogram presents characteristic oxidation and reduction peaks whose positions (peak potentials, Ep) offer insights into the thermodynamics of the electron transfer process, while the peak currents (ip) can be quantitatively related to analyte concentration through established equations like the Randles-Ševčík equation [7]. For heavy metal analysis, CV is particularly valuable for diagnosing the reversibility of redox couples, evaluating the electrochemical stability window of the electrolyte system, and confirming the successful modification and enhanced performance of electrode surfaces prior to employing more sensitive quantitative techniques like DPV or SWASV [19].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

Differential Pulse Voltammetry is a highly sensitive pulse technique specifically engineered to minimize the non-Faradaic charging current that often obscures the Faradaic current of interest in conventional voltammetry. The DPV waveform consists of a series of small, fixed-amplitude potential pulses (typically 10-100 mV) superimposed on a gradually increasing linear baseline potential [23] [20]. The critical innovation of DPV lies in its current sampling protocol: current is measured twice for each pulse—once immediately before the pulse application (I1) and again at the end of the pulse duration (I2). The differential current (ΔI = I2 - I1) is then plotted against the applied baseline potential. Because the charging current decays exponentially while the Faradaic current decays more slowly (approximately as t⁻¹/², according to the Cottrell equation), this sampling strategy effectively cancels out a significant portion of the non-Faradaic background [20]. The resulting voltammogram displays peak-shaped responses where the peak height is directly proportional to analyte concentration. DPV is exceptionally well-suited for the trace-level quantification of heavy metals and organic compounds, offering superior resolution for distinguishing between species with similar redox potentials [21].

Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV)

Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry combines an efficient preconcentration (electrodeposition) step with the sensitive Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) readout, making it arguably the most powerful voltammetric technique for ultra-trace heavy metal analysis. The SWASV process is a two-stage operation [18] [20]. First, during the deposition step, target metal ions (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺) in the sample solution are electrochemically reduced to their metallic state (M⁰) and concentrated onto the working electrode surface by applying a constant, sufficiently negative potential. This pre-concentration step dramatically enhances the concentration of the analyte at the electrode surface relative to the bulk solution. Second, during the stripping step, the potential is scanned toward positive values using a SWV waveform. This oxidation (stripping) process converts the deposited metals back into ions, generating sharp, highly sensitive current peaks. The square-wave waveform itself applies a symmetrical square pulse forward and reverse at each potential step, and the net current (difference between forward and reverse currents) is plotted, effectively rejecting capacitive contributions [20]. This dual enhancement—through electrodeposition and capacitive current rejection—enables SWASV to achieve detection limits in the sub-ppb range, which is essential for compliance with regulatory standards for drinking water and food products [8] [19].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Voltammetric Techniques for Metal Sensing

| Feature | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Qualitative analysis, mechanism study, electrode characterization [20] | Quantitative trace analysis, especially for irreversible systems [20] [21] | Ultra-trace quantitative analysis of metals [18] [19] |

| Key Principle | Linear potential sweep with reversal | Small amplitude pulses with differential current sampling [23] | Preconcentration (deposition) followed by stripping with SWV [18] |

| Detection Limit | Moderate (µM range) | Low (nM range) [22] [21] | Very Low (sub-nM or ppb range) [8] [19] |

| Advantages | Rapid diagnostics, provides rich kinetic data | Minimizes capacitive current, high sensitivity [23] [20] | Extremely high sensitivity, multi-metal detection capability [13] |

| Limitations | Higher background current, less sensitive for quantification | Slower than SWV | Longer analysis time due to deposition step, risk of intermetallic compound formation |

Experimental Protocols for Heavy Metal Detection

Electrode Modification and Preparation

The modification of screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) is a critical step in enhancing sensor performance. A common and effective approach involves drop-casting nanomaterial dispersions onto the working electrode surface.

- Protocol: Drop-casting Modification of SPEs with Carbon Nanomaterials

- Materials: Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE), carbon nanomaterial (e.g., MWCNTs, graphene oxide, carbon dots), stabilizing agent (e.g., chitosan, Nafion), ultrasonic bath, micropipette [22] [7].

- Procedure:

- Dispersion Preparation: Disperse 1 mg of the carbon nanomaterial (e.g., MWCNTs) in 1 mL of a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF or water with 0.25% Nafion) via sonication for 30-60 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension [22].

- Surface Cleaning: Pre-clean the bare SPE by cycling it in a suitable buffer solution (e.g., 0.1 M PBS, pH 7.4) using CV until a stable background voltammogram is obtained.

- Modification: Using a micropipette, deposit a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the nanomaterial dispersion directly onto the working electrode surface [7].

- Drying: Allow the modified electrode to dry thoroughly under ambient conditions or under an infrared lamp. This forms a stable, modified sensing layer.

- Conditioning: Condition the modified SPE by performing CV scans in a clean supporting electrolyte to stabilize the surface before analytical measurement.

Protocol for SWASV Detection of Pb(II) and Cd(II)

This protocol outlines the simultaneous determination of lead and cadmium using an AgBiS₂ nanoparticle-modified SPE, a relevant example from recent literature [8].

- Materials: AgBiS₂-modified SPE or Bismuth-film modified SPE (BiF-SPE), 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) or 3 mM HCl as supporting electrolyte, standard solutions of Pb(II) and Cd(II), potentiostat [8] [19].

- Procedure:

- Setup: Place the modified SPE into the electrochemical cell containing the sample solution (e.g., water sample) and an appropriate supporting electrolyte (e.g., 3 mM HCl). Ensure a deoxygenation step is performed by purging with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for 300-600 seconds if dissolved oxygen is a concern [8].

- Optimization of Parameters: Set the SWASV parameters based on the specific electrode and target analytes. Typical optimized conditions may include:

- Deposition Potential: -1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference)

- Deposition Time: 90-120 seconds (with stirring)

- Equilibrium Time: 10-15 seconds (without stirring)

- Square Wave Parameters: Frequency: 15-25 Hz; Amplitude: 25-50 mV; Potential Step: 4-6 mV [8].

- Preconcentration/Deposition: Apply the deposition potential (-1.2 V) to the working electrode for the specified time (e.g., 90 s) while stirring the solution. This reduces the metal ions (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) to their metallic forms (Pb⁰, Cd⁰) and concentrates them onto the electrode surface.

- Stripping Scan: After a brief equilibrium period without stirring, initiate the voltammetric scan from a negative potential (e.g., -1.0 V) to a more positive potential (e.g., -0.2 V) using the square-wave waveform. The deposited metals are oxidized (stripped) back into solution, generating characteristic current peaks.

- Data Analysis: Identify each metal by its unique peak potential (e.g., Cd at ~ -0.8 V, Pb at ~ -0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl). Quantify the concentration by measuring the peak current and comparing it to a calibration curve constructed from standard additions or external standards. Under optimal conditions, detection limits as low as 4.41 ppb for Pb and 13.83 ppb for Cd can be achieved with suitable modifiers [8].

Protocol for Quantitative Analysis Using DPV

DPV is highly effective for direct oxidation-based detection of metal ions or for sensing in conjunction with complexation reactions.

- Materials: Modified SPE (e.g., AuNRs/MWCNT/PEDOT:PSS/GCE), supporting electrolyte (e.g., acetate buffer, pH 4.5), standard nitrite or metal ion solutions, potentiostat [22] [21].

- Procedure:

- Setup: Immerse the modified SPE in an electrochemical cell containing the analyte of interest (e.g., nitrite in processed meat samples) dissolved in a suitable supporting electrolyte.

- Parameter Setting: Configure the DPV parameters. Typical settings include:

- Measurement: Record the DPV voltammogram. The technique's differential nature will yield a peak-shaped response.

- Quantification: Measure the height of the oxidation peak. Construct a calibration plot of peak current versus analyte concentration, which is typically linear over a defined range (e.g., 0.2–100 µM for nitrite with a LOD of 0.08 µM using advanced nanocomposites) [22]. Use this plot to determine the unknown concentration in samples.

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for heavy metal detection, from electrode modification to the final analytical signal generation, highlighting the pathways enhanced by material modifications and algorithmic processing.

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for heavy metal detection using modified SPEs, featuring sample pretreatment and algorithmic data processing to enhance sensitivity and accuracy [18] [10].

The signaling pathway at the electrode-solution interface, particularly for a stripping-based mechanism, is crucial for understanding sensor function. The following diagram details the sequence of electrochemical signaling events that occur during a typical SWASV measurement.

Diagram 2: Electrochemical signaling pathway for anodic stripping voltammetry, showing the key steps from ion arrival to current signal generation [18] [20].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Electrochemical Metal Sensing

| Category/Item | Specific Examples | Function and Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Platforms | Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) [7] | Disposable, portable, cost-effective substrate; serves as the foundational platform for modifications. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) [22], Graphene Oxide (GO) [18], Carbon Dots (CDs) [7] | Enhance electroactive surface area and electron transfer kinetics; improve sensitivity and stability of the sensor. |

| Metal Nanoparticles | Gold Nanorods (AuNRs) [22], Silver-based NPs (AgBiS₂) [8], Bismuth (Bi) Film | Provide high electrocatalytic activity; Bi and AgBiS₂ are eco-friendly alternatives to mercury for stripping analysis [8]. |

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS [22], Polypyrrole, Polyaniline | Act as conductive binders and enhance charge collection/transport; can improve film stability and selectivity. |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Acetate Buffer (pH ~4.5) [19], HCl (e.g., 3 mM) [8], Potassium Nitrate (KNO₃) | Provide ionic conductivity, control pH, and define the electrochemical window; choice affects metal complexation and deposition efficiency. |

| Pretreatment Reagents | Hydrogen Peroxide (for Fenton Oxidation) [10], Nitric Acid (for Digestion) [19] | Digest organic matter and break down complexes in complex matrices (e.g., soil, food) to liberate target metal ions for detection. |

The integration of advanced electrochemical techniques—DPV, SWASV, and CV—with strategically modified screen-printed electrodes creates a powerful and versatile analytical toolkit for heavy metal detection. The exceptional sensitivity of SWASV, coupled with the excellent resolution of DPV and the diagnostic power of CV, addresses a wide spectrum of analytical challenges, from ultra-trace monitoring in water to speciation in complex environmental samples. The ongoing development of novel nanomaterial modifiers and the incorporation of machine learning algorithms for data processing are poised to further push the boundaries of sensitivity, selectivity, and reliability [21] [10]. This robust, cost-effective, and portable methodology holds immense promise for transitioning heavy metal analysis from centralized laboratories to the field, thereby enabling more widespread monitoring and ultimately contributing to improved environmental and public health protection.

Heavy metal pollution poses a significant threat to global public health and environmental safety. Among the various toxic metals, lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), and mercury (Hg) represent some of the most concerning contaminants due to their widespread occurrence and severe toxicological impacts [24] [25]. These metals persist indefinitely in the environment, bioaccumulate through the food chain, and exert deleterious effects on human health even at low exposure levels [26]. The toxicity of these metals is fundamentally linked to their chemical speciation, with the ionic forms Pb(II), Cd(II), As(III), and Hg(II) being particularly toxic due to their bioavailability and reactivity with critical cellular components [25] [27]. Understanding their specific mechanisms of toxicity, health impacts, and detection methodologies is crucial for environmental monitoring, risk assessment, and therapeutic intervention. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of these critical heavy metal targets, with particular emphasis on their relevance to detection research using screen-printed electrode (SPE) technology.

Toxicological Profiles and Health Impacts

Heavy metals induce toxicity through multiple interconnected mechanisms, primarily involving oxidative stress, enzyme inhibition, and biomolecular damage [24] [25]. The following sections detail the specific toxicological profiles of each metal, with Table 1 providing a comparative summary of their health impacts.

Table 1: Comparative Toxicological Profiles of Critical Heavy Metal Ions

| Heavy Metal Ion | Major Exposure Sources | Primary Organ Toxicity | Molecular Mechanisms of Toxicity | Carcinogenicity Classification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb(II) - Lead | Contaminated water (lead pipes), batteries, paint, gasoline, construction materials [28] | Central nervous system, kidneys, hematopoietic system [25] [28] | Inhibition of δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) and ferrochelatase (disrupting heme biosynthesis); induction of oxidative stress; increased inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6) in CNS [24] [25] | IARC: Probable human carcinogen (Group 2A) |

| Cd(II) - Cadmium | Cigarette smoke, metal plating, batteries, industrial emissions [25] [28] | Kidneys, bones, respiratory system [25] | Induction of oxidative stress; disruption of Zn, Ca, and Fe homeostasis; apoptosis; endoplasmic reticulum stress; miRNA expression dysregulation [24] [25] | IARC: Known human carcinogen (Group 1) |

| As(III) - Arsenic | Herbicides, insecticides, contaminated water, seafood, algae [28] | Skin, cardiovascular system, nervous system, liver [25] [26] | Binding to thiol groups in proteins; uncoupling of oxidative phosphorylation; generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS); inhibition of DNA repair [24] [25] | IARC: Known human carcinogen (Group 1) |

| Hg(II) - Mercury | Liquid in thermometers, dental amalgam fillings, seafood, batteries, topical antiseptics [25] [28] | Kidneys, central nervous system, gastrointestinal tract [25] | Binding to sulfhydryl groups in proteins and enzymes; glutathione peroxidase inhibition; reduction of aquaporins mRNA expression; ROS production [24] [25] | IARC: Possibly carcinogenic to humans (Group 2B) |

Pb(II) - Lead Toxicity

Lead exposure represents a significant global health concern, particularly in developing nations with inadequate regulatory controls. A recent study among adolescents in Tanzania found a alarming prevalence of elevated blood lead levels, with a median blood lead concentration of 4.74 μg/dL, significantly associated with sustained high blood pressure in this young population [29]. The neurotoxic effects of lead are particularly severe in children, where exposure can lead to behavioral and cognitive problems, reduced IQ, and learning disabilities [26] [28]. The molecular mechanism of lead toxicity involves the disruption of heme biosynthesis through inhibition of key enzymes including δ-aminolevulinic acid dehydratase (ALAD) and ferrochelatase [25]. Lead can also replace zinc in certain enzyme systems, including the Zn(II)–Cys3 site in ALAD, leading to altered protein structure and function [24].

Cd(II) - Cadmium Toxicity

Cadmium exposure occurs primarily through cigarette smoke, contaminated food, and industrial processes. The metal has an exceptionally long biological half-life (10-30 years) in humans due to its slow excretion rate, leading to progressive accumulation in tissues, particularly the kidneys [25]. Cadmium exerts toxic effects through multiple pathways, including dysregulation of essential element homeostasis (calcium, zinc, and iron), induction of oxidative stress, and initiation of apoptotic pathways [25]. Chronic cadmium exposure is associated with renal dysfunction, degenerative bone disease (Itai-Itai disease), and increased cancer risk, with a recent review indicating a 31% increased risk of lung cancer following exposure [26]. The mechanism of renal toxicity involves the formation of cadmium-metallothionein complexes (Cd-MT) that are absorbed by the kidneys, where cadmium is released and causes damage to proximal tubule cells [25].

As(III) - Arsenic Toxicity

Arsenic exists in both organic and inorganic forms, with inorganic arsenic (iAs) being the most toxicologically significant. Arsenite (As(III)) exhibits higher toxicity than arsenate (As(V)) due to its greater reactivity with biological molecules [24]. The primary mechanism of arsenic toxicity involves binding to thiol groups in proteins and enzymes, leading to their functional impairment [25]. Arsenic also acts as an uncoupler of oxidative phosphorylation, inhibiting ATP formation and cellular energy production [25]. Chronic arsenic exposure is associated with characteristic skin lesions, peripheral neuropathy, cardiovascular dysfunction, and various forms of cancer, including skin, lung, and bladder cancers [25] [26]. The carcinogenicity of arsenic is linked to its ability to cause DNA damage and genomic instability through oxidative stress generation and inhibition of DNA repair mechanisms [25].

Hg(II) - Mercury Toxicity

Mercury toxicity varies depending on its chemical form, with organic mercury compounds (particularly methylmercury) exhibiting greater toxicity than inorganic forms [25]. The toxicity order is defined as Hg⁰ < Hg²⁺, Hg⁺ < CH₃-Hg [25]. Mercury's primary molecular mechanism involves high-affinity binding to sulfhydryl groups in proteins and enzymes, leading to structural and functional alterations [24] [25]. This interaction disrupts multiple cellular processes, including antioxidant defense (through glutathione peroxidase inhibition), membrane transport (via reduction of aquaporins mRNA expression), and oxidative metabolism [25]. Mercury exposure primarily affects the nervous system and kidneys, with symptoms ranging from sensory disturbances and motor dysfunction to renal failure in severe cases [25] [28].

Analytical Detection Framework

Electrochemical detection methods, particularly those utilizing screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), have emerged as powerful tools for heavy metal monitoring due to their portability, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for field deployment [13] [7] [27]. These attributes address significant limitations of traditional laboratory-based techniques like atomic absorption spectroscopy and inductively coupled plasma methods, which despite their sensitivity, are expensive, require complex sample preparation, and lack portability for on-site analysis [27] [30].

Detection Principles

Anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) is the predominant electrochemical technique for heavy metal detection due to its exceptional sensitivity for trace metal analysis [27] [30]. The ASV process involves two fundamental steps:

- Pre-concentration: Target metal ions in solution are electrochemically reduced and deposited onto the working electrode surface at a specific cathodic potential, forming an amalgam or thin film.

- Stripping: The deposited metals are re-oxidized (stripped) from the electrode by applying a positive potential sweep, generating a current peak for each metal at its characteristic oxidation potential [30].

The quantitative analysis is based on the linear relationship between peak current and metal ion concentration, while the peak potential provides qualitative identification [7].

Diagram 1: ASV detection workflow for heavy metals using SPEs.

Screen-Printed Electrode Platforms

Screen-printed electrodes constitute complete electrochemical cells fabricated on planar substrates, integrating working, counter, and reference electrodes [31]. Their disposable nature eliminates cross-contamination and tedious cleaning procedures required with conventional electrodes [13]. Significant research efforts focus on enhancing SPE performance through:

- Surface modifications with nanomaterials (carbon dots, graphene oxide, bismuth nanoparticles, metal oxides) to increase active surface area, enhance electron transfer kinetics, and improve selectivity [7] [27] [30].

- Electrochemical pretreatment (polarization, cleaning) to remove adventitious contaminants and activate the carbon surface [30].

- Chemical functionalization with specific ligands (amino groups, α-aminophosphonates) that selectively complex target metal ions [27].

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Selected Modified SPEs for Heavy Metal Detection

| Electrode Modification | Target Metal Ions | Detection Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amino-functionalized Gold SPE (SPGE-N) | Pb²⁺ | Square Wave ASV | 1-10 nM | 0.41 nM (0.085 μg/L) | [27] |

| Phosphonate-functionalized Gold SPE (SPGE-P) | Hg²⁺ | Square Wave ASV | 1-10 nM | 35 pM (0.007 μg/L) | [27] |

| Starch Carbon Dots Modified Carbon SPE | Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺ | Cyclic Voltammetry | Zn: 0.5-10 ppm; Cu: 0.25-5 ppm | Zn: 0.122 ppm; Cu: 0.089 ppm | [7] |

| Bismuth-Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposite on ECP-treated Carbon SPE | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ | Square Wave ASV | N/A | Sub-ppb range | [30] |

Experimental Protocols

Functionalization of Gold Screen-Printed Electrodes for Selective Pb(II) and Hg(II) Detection

This protocol describes the modification of gold screen-printed electrodes (SPGEs) with amino (Tr-N) or α-aminophosphonate (Tr-P) functional groups for selective detection of Pb²⁺ and Hg²⁺ ions, based on the research by [27].

Materials and Reagents

- Gold screen-printed electrodes (SPGEs, Metrohm-DropSens)

- Dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP) cross-linker

- Anhydrous dimethylformamide (DMF)

- Tr-N and Tr-P ligands (synthesized as described in [27])

- Lead nitrate (≥99.95% purity)

- Mercury nitrate monohydrate (≥99.99% purity)

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5)

- Ethanol (HPLC grade)

- Double-distilled water

Equipment and Instrumentation

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with square wave voltammetry capability

- Three-electrode electrochemical cell

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

- Micropipettes (1-10 μL, 10-100 μL, 100-1000 μL)

- Ultrasonic bath

- Nitrogen gas supply for deaeration

Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrode Functionalization:

- SPGE Cleaning: Electrochemically clean bare SPGEs by cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ between 0 V and +1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference) at 100 mV/s for 20 cycles.

- DSP Self-Assembled Monolayer Formation: Prepare 2 mM DSP solution in anhydrous DMF. Deposit 5 μL of this solution onto the gold working electrode surface and incubate for 2 hours at room temperature in a humidity-controlled environment.

- Ligand Immobilization: Prepare 1 mM solutions of Tr-N or Tr-P ligands in anhydrous DMF. Rinse the DSP-modified electrodes with DMF to remove physically adsorbed DSP, then apply 5 μL of the ligand solution and incubate for 4 hours.

- Electrode Washing: Thoroughly rinse the functionalized electrodes (now SPGE-N or SPGE-P) with DMF and ethanol to remove unbound ligands, then dry under a gentle nitrogen stream.

Electrochemical Measurements:

- Supporting Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) as supporting electrolyte.

- Standard Solution Preparation: Prepare stock solutions of Pb²⁺ and Hg²⁺ (1000 ppm) in double-distilled water, then dilute with acetate buffer to desired concentrations (1-10 nM range).

- Instrument Parameters Setup: Configure the square wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SWASV) method with the following optimized parameters:

- Conditioning potential: -0.1 V for 30 s

- Deposition potential: -1.0 V for 120 s (with stirring)

- Equilibrium time: 10 s

- Square wave parameters: Frequency 25 Hz, amplitude 25 mV, step potential 5 mV

- Measurement Procedure: Transfer 10 mL of sample solution to the electrochemical cell. Immerse the functionalized SPGE and perform the SWASV measurement. Record the stripping voltammograms.

- Data Analysis: Measure peak currents at characteristic potentials (-0.5 V for Pb²⁺ and +0.25 V for Hg²⁺). Construct calibration curves by plotting peak current versus metal ion concentration.

Electrochemical Polishing and Modification of Carbon SPEs for Cd(II) and Pb(II) Detection

This protocol describes the electrochemical polishing (ECP) treatment and subsequent modification with bismuth-reduced graphene oxide (Bi-rGO) nanocomposite to enhance carbon SPE sensitivity for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ detection, based on the research by [30].

Materials and Reagents

- Multi-array carbon screen-printed electrodes (cSPEs, 8 working electrodes)

- Sulfuric acid (0.1 M)

- Bismuth (III) nitrate pentahydrate

- Graphene oxide powder

- Sodium borohydride

- Ethylene glycol

- Sodium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5)

- Potassium hexacyanoferrate (II) trihydrate

- Potassium hexacyanoferrate (III)

- Cadmium and lead standard solutions for AAS

Equipment and Instrumentation

- Multichannel potentiostat (e.g., STAT-i-MULTI8, Metrohm DropSens)

- Field-emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM)

- Raman spectrometer

- Ultrasonic probe

- Centrifuge

Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrochemical Polishing Treatment:

- ECP Setup: Fill electrochemical cell with 0.1 M H₂SO₄ as polishing electrolyte.

- Potential Cycling: Subject cSPE working electrodes to continuous potential cycling between ±1.5 V at a scan rate of 20 mV/s for 10 cycles using a multichannel potentiostat.

- Electrode Rinsing: After ECP treatment, thoroughly rinse electrodes with double-distilled water and dry at room temperature.

Bi-rGO Nanocomposite Preparation:

- GO Dispersion: Prepare a 1 mg/mL dispersion of graphene oxide in double-distilled water using probe ultrasonication for 30 minutes.

- Bi-rGO Synthesis: Add bismuth nitrate (5 mM final concentration) to the GO dispersion. Stir for 30 minutes, then add sodium borohydride (10 mM final concentration) as reducing agent.

- Incubation and Washing: Incubate the mixture at 60°C for 2 hours with continuous stirring. Centrifuge the resulting Bi-rGO nanocomposite at 10,000 rpm for 10 minutes, then wash twice with double-distilled water and resuspend in ethylene glycol.

Electrode Modification and Measurement:

- Nanocomposite Deposition: Deposit 5 μL of Bi-rGO nanocomposite suspension onto the ECP-treated working electrode surface and dry at 40°C for 1 hour.

- Electrochemical Characterization: Characterize the modified electrode using cyclic voltammetry (5 mM ferro/ferricyanide redox couple in 0.1 M KCl, scan rate 100 mV/s) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy.

- Heavy Metal Detection: Perform SWASV measurements in sodium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) using the following parameters:

- Deposition potential: -1.2 V for 120 s (with stirring)

- Rest period: 10 s

- Stripping scan: -1.0 V to -0.2 V

- Square wave parameters: Frequency 25 Hz, amplitude 25 mV, step potential 5 mV

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Heavy Metal Detection Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable electrochemical platforms for heavy metal detection | ItalSens IS-HM (carbon working electrode) [31]; Gold SPEs (Metrohm-DropSens) [27]; Multi-array carbon SPEs [30] |

| Electrode Modifiers | Enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and electron transfer kinetics | Carbon dots (from starch) [7]; Bismuth-reduced graphene oxide (Bi-rGO) nanocomposite [30]; Amino (Tr-N) and α-aminophosphonate (Tr-P) functional groups [27] |

| Cross-linking Agents | Facilitate covalent immobilization of recognition elements on electrode surfaces | Dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP) for gold surface functionalization [27] |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Provide ionic conductivity and control pH during electrochemical measurements | Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) [27]; Sodium acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) [30] |

| Standard Reference Materials | Preparation of calibration standards and method validation | Lead nitrate (≥99.95%); Mercury nitrate monohydrate (≥99.99%); Cadmium and lead standards for AAS [27] [30] |

| Electrochemical Cell Components | Enable controlled electrochemical measurements | Three-electrode cell systems; Stirring equipment for preconcentration step; Nitrogen purging setup for deoxygenation [27] [30] |

Diagram 2: Interrelationship between toxicity mechanisms, detection principles, and mitigation strategies for heavy metals.

The critical heavy metal ions Pb(II), Cd(II), As(III), and Hg(II) represent significant environmental health threats due to their persistence, bioaccumulation potential, and multifaceted toxicity mechanisms. Understanding their specific molecular interactions and health impacts provides the necessary foundation for developing effective detection and mitigation strategies. Screen-printed electrode technology, particularly when enhanced through surface modifications and functionalization, offers a promising platform for sensitive, selective, and field-deployable heavy metal monitoring. The experimental protocols outlined in this application note provide researchers with robust methodologies for electrode development and application, supporting ongoing efforts to address the global challenge of heavy metal pollution through advanced analytical solutions. Future research directions should focus on developing multi-array sensors for simultaneous detection of multiple metals, improving selectivity in complex matrices, and integrating SPE systems with portable readout devices for real-time environmental monitoring and point-of-care testing.

Advanced Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Metal Sensing

The accurate detection of heavy metals in environmental, food, and clinical samples represents a critical analytical challenge with significant implications for public health and ecosystem protection. Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) have emerged as premier platforms for electrochemical sensing due to their portability, low cost, and suitability for field-deployable analysis [1]. However, bare SPEs often suffer from insufficient sensitivity, selectivity, and fouling resistance when deployed in complex sample matrices [7]. The strategic modification of electrode surfaces with advanced nanomaterials addresses these limitations by enhancing electron transfer kinetics, providing specific binding sites for target analytes, and protecting the electrode from nonspecific interactions [32].

Among the diverse range of nanomaterials available, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), bismuth-based materials, and carbon dots (CDs) have demonstrated exceptional promise as electrode modifiers. These materials offer complementary advantages: AuNPs provide high conductivity and catalytic activity [33], bismuth forms low-temperature alloys with heavy metals and offers a environmentally friendly alternative to mercury [34], and CDs contribute abundant functional groups for metal chelation with excellent biocompatibility [7]. This application note provides a structured comparison of these three modifier classes, detailed experimental protocols for their implementation, and practical guidance for researchers developing electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection.

Performance Comparison of Electrode Modifiers

Table 1: Comparative analytical performance of gold nanoparticle, bismuth, and carbon dot-based modifiers for heavy metal detection.

| Modifier Type | Specific Material | Target Analytes | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Electrode Platform | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | Nanoporous Gold (NPG) | Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺ | 1-100 μg/L (Pb²⁺)10-100 μg/L (Cu²⁺) | 0.4 μg/L (Pb²⁺)5.4 μg/L (Cu²⁺) | Screen-printed carbon electrode | High surface area, excellent conductivity, wide linear range [33] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Gold Nanoclusters (GNPs-Au) | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ | 1-250 μg/L | 1 ng/L | Bare gold electrode | Ultra-low detection limits, 7.2× increased surface area [35] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Functionalized SPGEs | Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺ | 1-10 nM | 0.41 nM (Pb²⁺)35 pM (Hg²⁺) | Gold screen-printed electrode | Excellent selectivity via specific functionalization [1] |

| Bismuth Composites | BSA/g-C₃N₄/Bi₂WO₆/GA | Multiple heavy metals | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | Superior antifouling (maintains 90% signal after 1 month in biofluids) [34] |

| Bismuth Composites | AgBiS₂ nanoparticles | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ | 50-200 ppb | 4.41 ppb (Pb²⁺)13.83 ppb (Cd²⁺) | Screen-printed electrode (nanocarbon black paste) | Cost-effective, disposable, suitable for environmental monitoring [8] |

| Carbon Dots | Starch-derived CDs | Zn(II), Cu(II) | 0.5-10 ppm (Zn)0.25-5 ppm (Cu) | 0.122 ppm (Zn)0.089 ppm (Cu) | Screen-printed electrode | Eco-friendly, excellent repeatability, >90% recovery in spiked samples [7] |

Table 2: Characteristics and recommended applications for different modifier types.

| Modifier Type | Sensitivity | Selectivity Tuning | Fouling Resistance | Ease of Fabrication | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles | Very High | High (via surface functionalization) | Moderate | Moderate | Ultra-trace detection in environmental waters |

| Bismuth Composites | High | Moderate | Very High | Moderate to Difficult | Complex matrices (wastewater, biofluids) |

| Carbon Dots | Moderate to High | Moderate (via functional groups) | High | Easy | Green chemistry applications, routine monitoring |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Nanoporous Gold Modification for Lead and Copper Detection

This protocol details the fabrication of a nanoporous gold-modified screen-printed carbon electrode (NPG/SPCE) for simultaneous detection of Pb²⁺ and Cu²⁺ using the dynamic hydrogen bubble template (DHBT) method [33].

Reagents and Materials

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) with carbon working, carbon counter, and Ag/AgCl reference electrodes

- Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄)

- Sulfuric acid (H₂SO₄), 0.5 M

- Hydrochloric acid (HCl), 0.1 M

- Stock solutions of Pb²⁺ and Cu²⁺ (1000 μg/mL)

- Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

Equipment

- Potentiostat with square wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SWASV) capability

- Field emission scanning electron microscope (for characterization)

- Energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (for characterization)

- Time- and speed-regulated stirring device

Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrode Modification:

- Pre-clean the SPCE by alternatively washing with ultrapure water and ethanol three times, then dry at room temperature.

- Prepare deposition solution containing 4 mM HAuCl₄ in 0.5 M H₂SO₄.

- Drop 50 μL of the deposition solution onto the SPCE surface.

- Apply a constant potential of -3.0 V for 40 seconds to electrodeposit NPG.

- Rinse the modified electrode thoroughly with ultrapure water to remove residual HAuCl₄ and H₂SO₄.

- Characterize the successful fabrication using SEM and EDX analysis (optional for routine application).

Heavy Metal Detection:

- Prepare supporting electrolyte of 0.1 M HCl.

- Transfer 1 mL of electrolyte to an electrochemical cell.

- Add appropriate volumes of Pb²⁺ and Cu²⁺ standard solutions to achieve desired concentrations.

- Mount the NPG/SPCE in the cell and connect to the potentiostat.

- Optimize deposition potential at -1.2 V with deposition time of 300 seconds while stirring at 200 rpm.

- Perform square wave anodic stripping voltammetry with the following parameters:

- Potential increment: 4 mV

- Frequency: 25 Hz

- Potential range: -0.8 V to 0.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl reference)

- Record the stripping peaks at approximately -0.5 V for Pb²⁺ and -0.05 V for Cu²⁺.

- Quantify metal concentrations using calibration curves of peak current versus concentration.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- The hydrogen evolution at -3.0 V is essential for forming the porous structure; ensure consistent potential application.

- If reproducibility issues occur, verify the freshness of the deposition solution.

- Poorly defined peaks may indicate insufficient deposition time or contaminated electrolytes.

Protocol 2: Bismuth Composite Electrode for Complex Matrices

This protocol describes the preparation of an antifouling bismuth composite electrode using BSA/g-C₃N₄/Bi₂WO₆/GA for robust heavy metal detection in complex samples like biofluids and wastewater [34].

Reagents and Materials

- Bovine serum albumin (BSA)

- g-C₃N₄ (two-dimensional graphite carbon nitride)

- Flower-like bismuth tungstate (Bi₂WO₆)

- Glutaraldehyde (GA, crosslinker)

- Supporting electrolytes appropriate for target matrices

Equipment

- Ultrasonic bath for mixing

- Potentiostat with cyclic voltammetry capability

- X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (for characterization, optional)

Step-by-Step Procedure

Composite Preparation:

- Prepare pre-polymerization solution containing BSA and g-C₃N₄ as main functional monomers.

- Add glutaraldehyde as crosslinker and flower-like Bi₂WO₆ as heavy metal co-deposition anchor.

- Mix and treat the solution ultrasonically until uniformly dispersed.

Electrode Modification:

- Drop-cast the pre-polymerized solution immediately onto the electrode surface.

- Allow the coating to form a complete film.

- Crosslink the composite matrix to enhance functionality and stability.

Performance Evaluation:

- Test electrochemical performance using cyclic voltammetry in standard potassium ferrocyanide/ferricyanide redox system.

- Cycle the electrode between oxidation and reduction potentials.

- Analyze the potential difference (ΔEp) and corresponding current density to evaluate electron transfer kinetics.

- For antifouling assessment, incubate electrodes in 10 mg/mL human serum albumin solution for 1 day and measure performance retention.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- Ensure complete crosslinking for optimal antifouling properties.

- The BSA/g-C₃N₄/Bi₂WO₆/GA coating should retain >90% current density after HSA exposure.

- If sensitivity decreases, verify the ratio of conductive materials in the composite.

Protocol 3: Starch-Derived Carbon Dot Modification for Zinc and Copper Detection

This protocol outlines the synthesis of carbon dots from starch and their application for modifying screen-printed electrodes to detect Zn(II) and Cu(II) [7].

Reagents and Materials

- Cassava starch flour

- Sodium hydroxide

- Acetone

- Copper sulfate (CuSO₄) and zinc sulfate (ZnSO₄)

- Acetic acid

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes

Equipment

- Convevective oven for hydrothermal treatment

- Centrifuge

- FTIR spectrometer for functional group analysis

- Zetasizer for particle size and zeta potential analysis

Step-by-Step Procedure

Carbon Dots Synthesis:

- Mix cassava starch flour in 16 mL solution containing distilled water, sodium hydroxide, and acetone.

- Perform hydrothermal treatment using convective oven at 175°C for 1 hour 45 minutes.

- Centrifuge the resulting mixture at 3000 rpm for 20 minutes.

- Collect the supernatant containing carbon dots.

Electrode Modification:

- Drop-cast 5 μL of CDs solution onto the working electrode of SPE.

- Allow the electrode to dry at room temperature.

Heavy Metal Detection:

- Perform cyclic voltammetry measurements between -1.0 to +1.0 V at scan rate of 200 mV/s.

- Use 0.5 M acetic acid as supporting electrolyte.

- Detect Zn(II) and Cu(II) in concentration ranges of 0.5-10 ppm and 0.25-5 ppm, respectively.

- Calculate enhancement factor using the formula: [ \text{Enhancement factor} = \frac{I{pa\text{ (modified)}}}{I{pa\text{ (unmodified)}}} ] where (I_{pa}) refers to the oxidation peak current.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- Ensure proper degradation of starch to glucose during hydrothermal treatment.

- Verify CD formation through FTIR functional group analysis.

- If detection limits are unsatisfactory, optimize the CD concentration in the modification solution.

Signaling Mechanisms and Workflow

Diagram 1: Heavy metal detection involves three key processes enhanced by specific modifiers. Bismuth facilitates alloy formation, gold nanoparticles enhance electron transfer, and carbon dots improve analyte preconcentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential materials and reagents for electrode modification studies.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) | Gold precursor for nanoparticle synthesis | NPG/SPCE fabrication [33] |

| Bismuth tungstate (Bi₂WO₆) | Bismuth source with stable crystal structure | Antifouling composites [34] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Protein matrix for antifouling coatings | Bio-compatible electrode surfaces [34] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Crosslinking agent for polymer matrices | Stabilizing 3D composite structures [34] |

| Starch biomass | Carbon source for sustainable CD synthesis | Green electrode modifiers [7] |

| Screen-printed carbon electrodes | Disposable electrode platforms | Field-deployable sensor platforms [7] [33] |

| dithiobis(succinimidylpropionate) (DSP) | Crosslinker for gold surface functionalization | SAM formation on SPGEs [1] |

The selection of an appropriate electrode modifier depends critically on the specific analytical requirements and sample matrix. Gold nanoparticle-based modifiers offer superior sensitivity with detection limits extending to ng/L levels, making them ideal for ultra-trace environmental monitoring [35] [33]. Bismuth composites demonstrate exceptional resilience in complex matrices such as wastewater and biofluids, maintaining 90% signal integrity after prolonged exposure [34]. Carbon dots provide an eco-friendly alternative with good sensitivity and excellent reproducibility for routine monitoring applications [7].

For researchers implementing these protocols, careful attention to modification reproducibility is essential. Characterization of modified surfaces through electrochemical impedance spectroscopy and scanning electron microscopy is recommended during method development. Additionally, validation in real sample matrices with comparison to standard reference methods ensures analytical reliability. The continued advancement of these modification strategies promises to expand the capabilities of electrochemical sensors for addressing pressing challenges in environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics.

The rapid and accurate detection of heavy metal ions (HMIs) in environmental and biological matrices is a critical challenge in analytical chemistry. Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) have emerged as powerful platforms for this purpose due to their disposability, portability, and suitability for mass production [36] [37]. However, bare SPEs often lack the sensitivity and selectivity required for trace-level detection, necessitating strategic surface modifications [7] [36].

This application note details the development and performance of two advanced synergistic nanocomposites—Electrochemically Reduced Graphene Oxide/Bismuth (ERGO/Bi) and Gold-Decorated Magnetite Nanoparticles in Ionic Liquid (Fe₃O₄-Au-IL)—for enhancing the electrochemical detection of heavy metals. These composites leverage the unique properties of their components to achieve remarkable sensitivity, selectivity, and stability, making them ideal for deployment in SPE-based sensors for environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics [38] [39].

Nanocomposite Properties and Synergistic Mechanisms

ERGO/Bi Nanocomposite

The ERGO/Bi composite is designed to maximize the electroactive surface area and enhance the preconcentration of target metal ions. The individual components contribute the following key properties:

- ERGO: Provides a highly conductive, two-dimensional network with a vast surface area, facilitating rapid electron transfer and increasing the number of binding sites for metal ions [40].

- Bismuth (Bi): Acts as an excellent "green" alternative to mercury, forming multicomponent alloys with heavy metals during the electrochemical deposition step. This significantly enhances the stripping signal and improves the reproducibility of the sensor [38].

The synergy in this system arises from the combination of ERGO's superior conductivity and large surface area with Bi's exceptional alloying ability, resulting in a sensor with low background noise, well-defined stripping peaks, and high sensitivity for metals like Cd(II) and Pb(II) [38].

Fe₃O₄-Au-IL Nanocomposite

The Fe₃O₄-Au-IL composite is engineered to combine superior adsorption properties with high electrocatalytic activity.

- Fe₃O₄ Magnetic Nanoparticles (MNPs): Possess excellent adsorption capacity towards HMIs like As(III) due to their high surface-to-volume ratio and affinity for metal species. Their superparamagnetism also offers potential for magnetic confinement and sensor regeneration [39] [41] [42].

- Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): Exhibit high electrocatalytic activity, excellent conductivity, and favor the reduction and deposition of certain heavy metals, particularly As(III) [39].

- Ionic Liquid (IL): Serves as a robust binder and conductivity enhancer. It forms a high-performance composite paste, improves the electron transfer rate, and stabilizes the nanoparticle dispersion on the electrode surface [38] [39].

The synergistic effect here is multi-faceted. The linker-free decoration of AuNPs with tiny Fe₃O₄ NPs minimizes the distance between the adsorbed analyte on magnetite and the catalytic gold surface, ensuring efficient electron transfer [39]. The IL matrix further amplifies this by providing a highly conductive and stable medium. This architecture is particularly effective for the sensitive detection of arsenite [39].

Performance Data and Comparative Analysis

The analytical performance of the two nanocomposites for the detection of key heavy metals is summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of ERGO/Bi and Fe₃O₄-Au-IL Nanocomposites

| Nanocomposite | Target Analyte | Detection Technique | Linear Range (μg/L) | Detection Limit (μg/L) | Real Sample Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi/Fe₃O₄/IL-SPE [38] | Cd(II) | DPASV | 0.5 – 40 | 0.05 | Soil samples |

| Fe₃O₄-Au-IL/GCE [39] | As(III) | SWASV | 1 – 100 | 0.22 | Synthetic river & wastewater |

| Au Nanostar/SPE [36] | Cd(II), As(III), Se(IV) | SWASV | Not Specified | 1.62, 0.83, 1.57 | Ground & surface water |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Bi/Fe₃O₄/IL-SPE for Cd(II) Detection

This protocol outlines the procedure for modifying a screen-printed electrode with ionic liquid, Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles, and an in-situ bismuth film for the detection of cadmium [38].

4.1.1 Materials and Reagents

- Screen-printed electrode (SPE)

- Ionic liquid: n-octylpyridinium hexafluorophosphate (OPFP)

- Graphite powder (< 30 μm)

- Cellulose acetate, cyclohexanone, acetone

- Chitosan flakes, acetic acid

- Nano-Fe₃O₄ powder

- Standard solutions of Bi(III) and Cd(II) (1000 mg/L)

- Phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 5.0)

4.1.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Fabrication of IL-SPE: Prepare a homogeneous ink by dissolving 0.05 g cellulose acetate in 2.5 mL cyclohexanone and 2.5 mL acetone. Add 0.5 g OPPF and 2.0 g graphite powder and mix thoroughly. Pipette the composite ink onto the surface of a bare SPE and anneal at 80 °C for 30 minutes [38].

- Preparation of Fe₃O₄/Chitosan Dispersion: Dissolve 0.2 g chitosan flakes in 100 mL of 1.0% acetic acid solution. Disperse 0.1 mg of Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles into 10 mL of 0.2 wt% chitosan solution using ultrasonic treatment for 2 hours [38].

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 2.0 μL of the Fe₃O₄/CHT dispersion onto the surface of the IL-SPE and dry at 50 °C for 30 minutes to obtain the Fe₃O₄/ILSPE [38].

- Electrochemical Measurement: Prepare the sample solution containing Cd(II) and 400 μg/L Bi(III) in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (pH 5.0). Under stirring, deposit Cd(II) and Bi(III) onto the electrode at -1.2 V for 240 s. After a 20 s equilibration period, perform Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) from -1.2 V to 0 V using the following parameters: increment E: 0.01 V; amplitude: 25 mV; pulse width: 0.2 s; sample width: 0.02 s; pulse period: 0.5 s [38].

Diagram 1: Workflow for Bi/Fe₃O₄/IL-SPE Fabrication and Cd(II) Detection.

Protocol 2: Fabrication of Fe₃O₄-Au-IL/GCE for As(III) Detection

This protocol describes a linker-free method to synthesize a Fe₃O₄-Au nanocomposite, embed it in an ionic liquid, and modify a glassy carbon electrode for the sensitive detection of arsenite [39].

4.2.1 Materials and Reagents

- Glassy carbon electrode (GCE)

- Hydrogen tetrachloroaurate (HAuCl₄·3H₂O)

- Ferrous chloride (FeCl₂·4H₂O), Ferric chloride (FeCl₃·6H₂O)

- Ammonium hydroxide (NH₄OH, 25%)

- Ionic liquid ([C₄dmim][NTf₂])

- Sodium acetate trihydrate, acetic acid (for 0.2 M acetate buffer)

- Arsenic trioxide (As₂O₃) for As(III) stock solution

4.2.2 Step-by-Step Procedure

- Synthesis of Fe₃O₄-Au Nanocomposite:

- Fe₃O₄ NPs: Prepare magnetite nanoparticles via a co-precipitation method using FeCl₂ and FeCl₃ in a basic medium (NH₄OH) at low temperature (80 °C) and atmospheric pressure [39].

- Linker-free Decoration: Grow Au nanoparticles (approx. 70 nm) and decorate them with tiny Fe₃O₄ NPs (approx. 10 nm) without using any chemical linkers. This ensures minimal distance between the metal and metal oxide phases [39].

- Electrode Modification: Mix the synthesized Fe₃O₄-Au nanocomposite with the ionic liquid to form a homogeneous paste. Apply this Fe₃O₄-Au-IL composite onto the pre-cleaned surface of a GCE and allow it to dry [39].

- Electrochemical Measurement: Use Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV). Prepare the sample in 0.2 M acetate buffer. The deposition potential and time should be optimized. Typically, As(III) is deposited onto the electrode surface by applying a negative potential, followed by an anodic stripping scan. The excellent adsorption of As(III) onto the Fe₃O₄ NPs, combined with the electrocatalytic activity of the AuNPs, yields a strong and quantifiable current response [39].

Diagram 2: Workflow for Fe₃O₄-Au-IL/GCE Fabrication and As(III) Detection.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table lists key materials and their functions for developing these advanced electrochemical sensors.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials