Redox Reaction Principles in Electroanalysis: Foundations, Methods, and Advanced Applications for Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of redox principles underpinning modern electroanalytical techniques, tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development.

Redox Reaction Principles in Electroanalysis: Foundations, Methods, and Advanced Applications for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of redox principles underpinning modern electroanalytical techniques, tailored for researchers and scientists in drug development. It bridges fundamental theory—covering electron transfer mechanisms, the Nernst equation, and oxidation number rules—with practical methodological applications in organic, enzymatic, and microbial electrosynthesis. The content further addresses critical troubleshooting aspects of electrode selection, cell design, and reaction optimization, and validates these concepts through comparative analysis of techniques and the emerging role of machine learning in predicting redox potentials. The synthesis offers a actionable framework for applying electroanalysis to enhance innovation in biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles of Redox Chemistry and Electron Transfer Mechanisms

This technical guide provides a foundational framework for understanding redox reaction principles within modern electroanalysis research. We delineate the core concepts of oxidation and reduction through the lens of electron transfer (the OIL RIG principle) and the formal assignment of oxidation states, establishing their critical role in predicting reaction spontaneity, quantifying analyte concentration, and designing novel electrochemical sensors. The document integrates standard reduction potential data, detailed experimental methodologies for cyclic voltammetry, and specialized visualization tools to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the necessary theoretical and practical knowledge for advancing redox-based analytical techniques.

In electroanalytical chemistry, redox reactions—a portmanteau of reduction-oxidation—are fundamental processes where the oxidation states of the reactants change [1]. These reactions involve the transfer of electrons between chemical species [2]. The precise monitoring and control of these electron-transfer events form the basis of a wide array of analytical techniques, including potentiometry, amperometry, and voltammetry, which are indispensable for drug quantification, biomarker detection, and elucidating metabolic pathways [3]. Understanding the principles governing oxidation and reduction is therefore not merely an academic exercise but a prerequisite for innovation in sensor design and development. This guide details the two primary conceptual frameworks used to describe these processes: the OIL RIG principle, which tracks the actual movement of electrons, and oxidation states, a bookkeeping tool for predicting reactivity and understanding reaction pathways.

Core Principles: Defining Oxidation and Reduction

The terms oxidation and reduction are always defined in relation to one another, as they occur simultaneously in a reaction [4] [1].

The OIL RIG Principle

OIL RIG is a mnemonic for Oxidation Is Loss, Reduction Is Gain, of electrons [4] [2].

- Oxidation is defined as the loss of electrons by a molecule, atom, or ion [2].

- Reduction is defined as the gain of electrons by a molecule, atom, or ion [2].

For example, in the reaction between zinc and copper ions: [ \ce{Zn(s) + Cu^{2+}(aq) -> Zn^{2+}(aq) + Cu(s)} ] The ionic equation is ( \ce{Zn + Cu^{2+} -> Zn^{2+} + Cu} ). This can be split into two half-reactions:

- Oxidation half-reaction (Zinc is oxidized): ( \ce{Zn -> Zn^{2+} + 2e^{-}} ) [1]

- Reduction half-reaction (Copper is reduced): ( \ce{Cu^{2+} + 2e^{-} -> Cu} ) [1]

Oxidizing and Reducing Agents

- A reducing agent (or reductant) is the substance that donates electrons and is itself oxidized in the process [4] [1].

- An oxidizing agent (or oxidant) is the substance that accepts electrons and is itself reduced in the process [4] [1].

In the zinc-copper example, zinc metal is the reducing agent, and the copper(II) ion is the oxidizing agent.

Oxidation States as a Bookkeeping Tool

Oxidation states (or oxidation numbers) are theoretical charges assigned to atoms in molecules or ions, providing a powerful method for tracking electron shifts in redox reactions, even when the bonding is covalent and no actual ions are present [5] [6].

Rules for Assigning Oxidation States

The following rules are applied in a hierarchical manner to determine the oxidation state of an element in a substance [5] [6] [7].

- Elemental Form: The oxidation state of an uncombined element is zero (e.g., ( \ce{Na} ), ( \ce{O2} ), ( \ce{P4} )) [6] [7].

- Monatomic Ions: The oxidation state is equal to the charge on the ion (e.g., ( \ce{Na+} ) is +1, ( \ce{Cl-} ) is -1) [6] [7].

- Hydrogen: Usually +1 when combined with nonmetals (e.g., ( \ce{H2O} ), ( \ce{HCl} )). It is -1 in metal hydrides (e.g., ( \ce{NaH} ), ( \ce{LiAlH4} )) [5] [6].

- Oxygen: Usually -2 (e.g., ( \ce{H2O} ), ( \ce{CO2} )). Exceptions include peroxides (( \ce{O2^{2-}} )), where it is -1 (e.g., ( \ce{H2O2} )), and in compounds with fluorine, like ( \ce{OF2} ), where it is +2 [5] [6] [8].

- Fluorine: Always -1 in its compounds [5] [6].

- Halogens (Cl, Br, I): Usually -1, except in compounds with oxygen or fluorine where they can have positive states [5] [6].

- Neutral Compounds: The sum of the oxidation states of all atoms in a neutral molecule is zero [5] [6].

- Polyatomic Ions: The sum of the oxidation states of all atoms equals the charge on the ion [5] [6].

Relating Oxidation State Change to Redox

- Oxidation involves an increase in oxidation state [5] [6].

- Reduction involves a decrease in oxidation state [5] [6].

For instance, in the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide, oxygen undergoes a disproportionation (simultaneous oxidation and reduction): [ \ce{2H2O2(aq) -> 2H2O(l) + O2(g)} ] In ( \ce{H2O2} ), the oxidation state of O is -1. In ( \ce{H2O} ), it is -2 (reduction), and in ( \ce{O2} ), it is 0 (oxidation) [7].

Quantitative Framework: Standard Reduction Potentials

The tendency of a species to gain electrons and be reduced is quantified by its standard reduction potential (( E^\circ )), measured in volts under standard conditions relative to the Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) [9] [1].

Key Standard Reduction Potentials

Table 1: Selected Standard Reduction Potentials for Common Half-Reactions. A more positive ( E^\circ ) indicates a greater tendency for reduction [9].

| Standard Cathode (Reduction) Half-Reaction | ( E^\circ ) (volts) |

|---|---|

| ( \ce{F2(g) + 2e^{-} <=> 2F^{-}(aq)} ) | +2.866 |

| ( \ce{MnO4^{-}(aq) + 8H+(aq) + 5e^{-} <=> Mn^{2+}(aq) + 4H2O(l)} ) | +1.507 |

| ( \ce{Cu^{2+}(aq) + 2e^{-} <=> Cu(s)} ) | +0.342 |

| ( \ce{2H+(aq) + 2e^{-} <=> H2(g)} ) | 0.000 (defined) |

| ( \ce{Zn^{2+}(aq) + 2e^{-} <=> Zn(s)} ) | -0.763 |

| ( \ce{Li+(aq) + e^{-} <=> Li(s)} ) | -3.040 |

Predicting Redox Spontaneity

The standard cell potential, ( E^\circ{\text{cell}} ), is calculated as: [ E^\circ{\text{cell}} = E^\circ{\text{cathode}} - E^\circ{\text{anode}} ] where the cathode is the half-cell where reduction occurs and the anode is the half-cell where oxidation occurs [1]. A positive ( E^\circ{\text{cell}} ) indicates a spontaneous reaction under standard conditions. For example, a ( \ce{Zn}/\ce{Zn^{2+}} ) half-cell (( E^\circ = -0.763 \text{V} )) coupled with a ( \ce{Cu^{2+}}/\ce{Cu} ) half-cell (( E^\circ = +0.342 \text{V} )) yields: [ E^\circ{\text{cell}} = 0.342\ \text{V} - (-0.763\ \text{V}) = +1.105\ \text{V} ] This positive value confirms the spontaneous nature of the reaction ( \ce{Zn + Cu^{2+} -> Zn^{2+} + Cu} ) [1].

Experimental Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry of a Ferrocene Derivative

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a central technique in electroanalysis for studying redox properties. Below is a generalized protocol for characterizing a redox-active molecule like ferrocene, a common internal standard.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential materials and reagents for a typical cyclic voltammetry experiment.

| Item | Specification | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Ferrocene carboxylic acid | ≥95% purity | Model redox-active analyte for method validation. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | 0.1 M Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF6) | Dissolved in anhydrous acetonitrile. Provides ionic conductivity without participating in the redox reaction. |

| Solvent | Anhydrous Acetonitrile | Inert solvent to dissolve analyte and electrolyte. |

| Working Electrode | Glassy Carbon (3 mm diameter) | The surface at which the redox reaction of the analyte is monitored. |

| Counter Electrode | Platinum wire | Completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow. |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode is measured. |

| Potentiostat | --- | The instrument that applies the controlled potential and measures the resulting current. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the glassy carbon working electrode sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water followed by the solvent (acetonitrile) and dry.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution of 1.0 mM ferrocene carboxylic acid in acetonitrile with 0.1 M TBAPF6 as the supporting electrolyte. Transfer 15 mL of this solution to the electrochemical cell.

- Instrument Setup: Assemble the three-electrode system in the cell. Connect the working, reference, and counter electrodes to the potentiostat. Deoxygenate the solution by purging with an inert gas (e.g., N2 or Ar) for at least 10 minutes.

- Data Acquisition: Set the initial potential to 0.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl. Scan the potential first in the positive direction to a high vertex potential of +0.8 V, then reverse the scan back to the initial potential (0.0 V). Use a scan rate of 100 mV/s. Record the current response as a function of the applied potential.

- Data Analysis: Identify the anodic peak potential (( E{pa} )) and cathodic peak potential (( E{pc} )) from the resulting voltammogram. The formal reduction potential (( E^{\circ'} )) is approximated as (( E{pa} + E{pc})/2 ). The peak separation (( \Delta Ep = E{pa} - E_{pc} )) should be close to 59 mV for a reversible, one-electron transfer process.

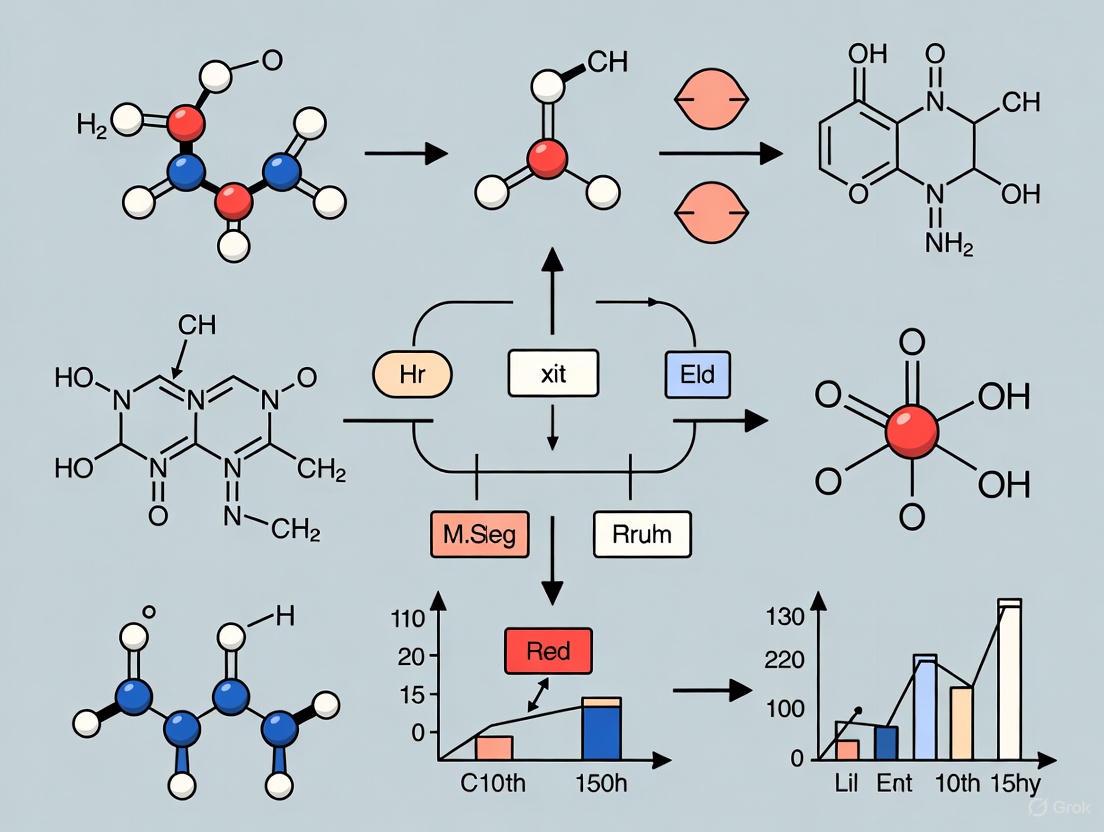

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and decision points in a redox experiment, from setup to data interpretation.

Diagram 1: Redox experiment workflow.

Advanced Applications in Electroanalysis Research

The principles of redox chemistry are pivotal in cutting-edge research areas.

Multi-Redox Reactions in Supercapacitors

Transition metal compounds are exploited in energy storage due to their multiple, accessible oxidation states. For instance, ternary transition metal oxides like cobalt-nickel-zinc oxide (CoNiZn-O) exhibit superior performance because different metal ions (e.g., Co²⁺/Co³⁺, Ni²⁺/Ni³⁺) undergo redox reactions at distinct but overlapping potentials. This "multi-redox" behavior effectively widens the operational potential window of the electrode and increases the total charge stored, thereby enhancing the energy density of supercapacitors [3]. Ions without variable states, like Zn²⁺, can act as structural "spectator ions," enhancing stability and electronic conductivity [3].

Mechanochemically Mediated Electrosynthesis

A nascent and innovative field combines mechanochemistry (solid-state grinding) with electrochemistry. This involves a uniquely designed mechano-electrochemical cell (MEC) connected to an external power source [10]. This synergistic technique allows for precise electrochemical control during milling, enabling redox transformations for substrates with low solubility in traditional solvents. This method aligns with green chemistry principles by significantly reducing solvent use, improving yields, and accelerating reaction times for organic transformations relevant to pharmaceutical development, such as the reduction of aromatic bromides or oxidative coupling for sulfonamide synthesis [10].

A rigorous comprehension of oxidation-reduction, framed by the OIL RIG principle and the systematic assignment of oxidation states, is a cornerstone of electroanalytical science. The quantitative framework provided by standard reduction potentials allows researchers to predict reaction spontaneity and design experiments a priori. As demonstrated by advanced applications in multi-redox energy materials and solvent-free electrosynthesis, these foundational principles continue to enable innovative research and technological development. For the drug development scientist, mastering these concepts is essential for leveraging electrochemical methods in analysis, synthesis, and understanding the redox biology that underpains drug action and metabolism.

Marcus theory, originally developed by Rudolph A. Marcus starting in 1956, provides a theoretical framework to explain the rates of electron transfer reactions—the process by which an electron moves from a donor species to an acceptor species [11]. This theory successfully addresses a fundamental question in physical chemistry: how to explain the observed activation energy in electron transfer reactions where no chemical bonds are formed or broken, and where the reaction partners remain weakly coupled and retain their individuality [11]. For this groundbreaking work, R. A. Marcus received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1992, and his theory has become indispensable for understanding electron transfer processes across chemistry, biology, and materials science, including applications in photosynthesis, corrosion, chemiluminescence, and charge separation in solar cells [11].

Within electroanalysis research, particularly in pharmaceutical development, understanding electron transfer kinetics is crucial for designing sensitive detection systems and understanding redox behavior of biological molecules. The theory's ability to quantify how fast electron transfer occurs at electrode interfaces makes it particularly valuable for analytical applications in drug discovery and development [12] [13].

Theoretical Foundations

The Fundamental Problem in Electron Transfer

In outer sphere redox reactions, no chemical bonds are formed or broken—only an electron is transferred between species. A classic example is the self-exchange reaction between Fe²⁺ and Fe³⁺ in aqueous solution [11]. Unlike conventional chemical reactions where structural changes define a reaction coordinate path, outer sphere electron transfer lacks obvious nuclear coordinate changes. Nevertheless, these reactions exhibit measurable activation energies, requiring a theoretical explanation that differs from transition state theory [11].

The key insight of Marcus theory addresses this paradox by recognizing that although the reactants themselves undergo minimal structural change, solvent reorganization plays the crucial role in determining the activation barrier. The solvent molecules must rearrange their orientations to stabilize the new charge distribution that results after electron transfer, and this reorganization energy provides the dominant contribution to the activation barrier [11].

The Marcus Model: Key Concepts

Marcus theory introduces several fundamental concepts to explain electron transfer kinetics:

- Weak Coupling: Donor and acceptor remain distinct entities throughout the process, unlike in transition state theory where reactants become strongly coupled [11].

- Franck-Condon Principle: Electron transfer occurs much faster than nuclear motion, meaning nuclear positions remain unchanged during the actual electron "jump" [11].

- Solvent Reorganization: The surrounding solvent molecules must reorganize to create a configuration where the energies of reactant and product states are equal, enabling the electron transfer to occur [11].

- Thermal Fluctuations: Thermal energy enables the solvent to transiently access this special configuration, making the reaction temperature-dependent [11].

The theory separates the polarization of the medium into two components: fast electronic polarization (Pₑ) and slow orientational polarization (Pᵤ), which have dramatically different time constants and respond differently to the electron transfer event [11].

Mathematical Formulation

The core Marcus theory expression for the electron transfer rate constant is:

[ k_{ET} = A \cdot e^{-\Delta G^{\ddagger}/RT} ]

Where (\Delta G^{\ddagger}) represents the activation free energy given by:

[ \Delta G^{\ddagger} = \frac{(\lambda + \Delta G^\circ)^2}{4\lambda} ]

In this fundamental relationship:

- λ is the reorganization energy, representing the energy required to reorganize the nuclear coordinates (both inner sphere and outer sphere) from the reactant to the product configuration without transferring the electron [14] [15].

- ΔG° is the standard Gibbs free energy change for the reaction [14].

- A is the pre-exponential factor that includes electronic coupling elements [11].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Marcus Theory

| Parameter | Symbol | Physical Meaning | Role in Electron Transfer |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reorganization Energy | λ | Nuclear + environmental energy needed to distort from reactant to product geometry | Determines the barrier height; larger λ generally slows transfer |

| Driving Force | -ΔG° | Gibbs free-energy difference between initial and final states | Provides the thermodynamic incentive for electron transfer |

| Electronic Coupling | Hₐb | Quantum-mechanical overlap between donor and acceptor states | Dictates the probability of electron tunneling between states |

| Activation Energy | ΔG‡ | Free energy barrier that must be overcome for reaction to occur | Determines the exponential factor in the rate expression |

The reorganization energy λ can be further decomposed into inner-sphere (λᵢ) and outer-sphere (λₒ) contributions [15]. Inner-sphere reorganization energy comes from changes in bond lengths and angles within the reactant complexes themselves, while outer-sphere reorganization energy originates from reorientation of the solvent molecules in the surrounding environment [11] [15].

Experimental Methodologies and Analysis

Electrochemical Techniques for Studying Electron Transfer

Electrochemical methods provide powerful experimental approaches for investigating electron transfer kinetics and quantifying Marcus parameters:

Cyclic Voltammetry: This frontline technique analyzes reactions at electrode surfaces by measuring current response to linearly scanned potential [13]. Key parameters obtained include peak potentials (Eₚₐ, Eₚ꜀), peak currents (Iₚₐ, Iₚ꜀), and peak separation (ΔEₚ), which inform about the electron transfer kinetics and mechanism [13].

Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM): An advanced tip-based technique that creates a redox cycle between tip and substrate, allowing localized measurement of electron transfer rates at specific surface sites with high spatial resolution [16].

Heterogeneous Electron Transfer Rate Constant (k₀): This parameter categorizes electrochemical reactions as reversible (k₀ > 2×10⁻² cm/s), quasi-reversible (k₀ = 2×10⁻² to 3×10⁻⁵ cm/s), or irreversible (k₀ < 3×10⁻⁵ cm/s) based on the rate of electron transfer relative to the experimental timescale [13].

Determining Marcus Parameters

Experimental determination of Marcus parameters requires careful methodology selection:

- Transfer Coefficient (α): Best calculated using the Eₚ - Eₚ/₂ equation for quasi-reversible systems [13].

- Diffusion Coefficient (D₀): Effectively determined using the modified Randles-Ševčík equation [13].

- Rate Constant (k₀): Reliably calculated using Kochi and Gileadi methods, while the Nicholson and Shain method may overestimate values in certain cases [13].

For complex systems like paracetamol electro-oxidation, digital simulation of cyclic voltammograms using software such as DigiSim validates these parameters and accounts for coupled chemical reactions that complicate electron transfer processes [13].

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Parameter Determination in Electron Transfer Studies

| Method | Primary Use | Key Parameters Obtained | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry | Initial characterization of redox behavior | Eₚₐ, Eₚ꜀, ΔEₚ, Iₚₐ, Iₚ꜀ | Distinguish diffusion-controlled (Iₚ ∝ √ν) from adsorption-controlled (Iₚ ∝ ν) processes |

| SECM in Feedback Mode | Localized ET kinetics at heterogeneous surfaces | k₀ with spatial resolution | Reveals site-specific activity from defects, edges, dopants |

| Digital Simulation (DigiSim) | Validation of mechanism and parameters | k₀, α, D₀ for complex mechanisms | Essential for reactions with coupled chemical steps |

| First-Principles Calculations with ML | Predicting redox potentials | Absolute Uᵣₑdₒₓ for half-cells | Combines thermodynamic integration with machine learning force fields |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Electron Transfer Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene-Family Nanomaterials (GFNs) | Tunable electrode platforms with modifiable electronic structure | Studying effects of defects, doping on ET kinetics [16] |

| Redox Mediators (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻, Fc/Fc⁺) | Outer-sphere redox probes for quantifying ET kinetics | Benchmarking electrode performance [16] |

| Supporting Electrolytes (e.g., LiClO₄) | Maintain ionic strength; minimize migration effects | Isolate diffusion-controlled processes [13] |

| Quantum Dots (e.g., CdSe, PbS) | Photo-donors with tunable band structure | Investigating interfacial charge transfer to metal oxides [15] |

| Metal Oxides (e.g., TiO₂, ZnO) | Electron acceptors with continuum states | Modeling heterojunction charge separation [15] |

Advanced Concepts and Current Research

The Marcus Inverted Region

One of the most significant predictions of Marcus theory is the inverted region, where electron transfer rates decrease with increasing exothermicity beyond a certain point [15]. This counterintuitive behavior arises because when the driving force (-ΔG°) exceeds the reorganization energy (λ), the system must overcome an increasingly larger barrier as the parabolic free energy surfaces intersect higher on the product curve [15].

In classical Marcus theory, the rate constant exhibits a parabolic dependence on the driving force:

- Normal region: kₑₜ increases as -ΔG° increases (0 < -ΔG° < λ)

- Activationless region: kₑₜ reaches maximum when -ΔG° = λ

- Inverted region: kₑₜ decreases as -ΔG° further increases (-ΔG° > λ) [15]

Despite its theoretical importance, direct observation of the inverted region in quantum dot-metal oxide systems has proven challenging due to competing processes like Auger-assisted electron transfer, continuum acceptor states, and interfacial defect complexity [15].

Computational Approaches

Modern computational methods have significantly advanced our ability to predict and understand electron transfer parameters:

First-Principles Calculations with Machine Learning: Combining thermodynamic integration with machine learning force fields enables accurate prediction of redox potentials for half-cell reactions. This approach has successfully predicted potentials for Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ (0.92 V vs. experimental 0.77 V), Cu²⁺/Cu⁺ (0.26 V vs. 0.15 V), and Ag²⁺/Ag⁺ (1.99 V vs. 1.98 V) couples [17].

Reference Potential Strategy: Using the O 1s level of water as a fixed reference point instead of the vacuum level provides more accurate alignment of redox levels in periodic boundary condition calculations, reducing finite-size errors [17].

Hybrid Functionals: Density functionals with exact exchange (e.g., PBE0 with 25% exact exchange) significantly improve accuracy over semi-local functionals, which typically exhibit errors around 0.5 V due to incorrect hybridization with redox levels [17].

Interfacial Electron Transfer in Nanomaterials

Nanoscale materials exhibit unique electron transfer characteristics that expand traditional Marcus theory:

Graphene-Family Nanomaterials (GFNs): Electron transfer kinetics at graphene surfaces are strongly influenced by topological defects (~10¹²/cm² density), oxygen functional groups (C/O ratio: 4:1-12:1), nitrogen doping, and edge plane hydrogen-bonding sites (density: 0.1-1.0 μm⁻¹) [16].

Quantum Dot-Metal Oxide Systems: Semiconductor quantum dots offer tunable conduction band levels through size control, enabling precise manipulation of driving force. Their large absorption cross-sections and multiple exciton generation capabilities make them ideal for studying photo-induced electron transfer [15].

Electronic Structure Effects: The available density of states near the Fermi level (-0.2 to +0.2 eV) and quantum capacitance significantly influence electron transfer kinetics in low-dimensional materials [16].

Applications in Electroanalysis and Drug Discovery

Marcus theory provides the fundamental framework for understanding and optimizing electron transfer processes in analytical and pharmaceutical applications:

Quantum Electroanalysis in Drug Discovery

Recent advances in quantum electroanalysis leverage the common quantum electrodynamics principles governing both electron transport in molecular electronics and electron transfer in electrochemical reactions [12]. This enables:

Real-time Monitoring: In situ access to electronic structures of interfaces incorporating organic semiconductors, quantum dots, graphene, and redox dynamics within peptide structures under physiological conditions [12].

Binding Affinity Determination: Modification of these interfaces with molecular receptors allows quantification of binding affinity constants through shifts in electronic structure signals upon ligand binding [12].

Enhanced Sensitivity: Attomolar-level sensitivities permit accurate measurement of binding affinities for low-molecular-weight ligand-receptor pairs, providing advantages over traditional optical technologies like surface plasmon resonance [12].

Electrochemical Analysis of Pharmaceutical Compounds

The principles of Marcus theory guide the electrochemical analysis of drug compounds:

Paracetamol Case Study: Electrochemical analysis of paracetamol demonstrates complex electron transfer with coupled chemical reactions, exhibiting quasi-reversible behavior with peak separation (ΔEₚ) increasing from 0.128 V to 0.186 V as scan rate increases from 0.025 V/s to 0.300 V/s [13].

Method Selection: Accurate parameter extraction requires careful method selection based on reaction mechanism, as different calculation methods yield varying results for transfer coefficients and rate constants [13].

Interface Engineering: Strategic design of electrode interfaces with controlled defects and dopants enhances electron transfer kinetics for sensitive detection of pharmaceutical compounds [16].

Visualizing Electron Transfer: Conceptual Diagrams

Marcus Theory Free Energy Relationships

Experimental Workflow for Electron Transfer Kinetics

Marcus theory continues to provide the fundamental framework for understanding electron transfer kinetics more than six decades after its initial development. Its parabolic energy relationship successfully explains diverse phenomena across chemistry, biology, and materials science. For electroanalysis research in drug discovery, the theory offers critical insights for designing sensitive detection systems, optimizing electrode interfaces, and understanding redox behavior of pharmaceutical compounds.

Current research continues to expand Marcus theory's applications through nanomaterial engineering, computational advances, and sophisticated experimental techniques. The integration of machine learning with first-principles calculations, the development of quantum electroanalysis methods, and the precise manipulation of interfacial properties in graphene-family nanomaterials represent exciting frontiers where Marcus theory principles continue to guide innovation in electroanalytical science.

Electrodes serve as the fundamental interface for electron transfer in electrochemical cells, governing the efficiency and specificity of redox reactions central to electroanalysis. This whitepaper examines the role of electrodes through the lens of redox reaction principles, detailing the kinetic regimes and material properties that dictate electron transfer dynamics. We present structured experimental protocols for interrogating electrode-electrolyte interfaces, supported by quantitative data and visualization of electron transfer pathways. Within the context of bio-electroanalysis and drug development, we explore how engineered electrodes facilitate direct measurement of redox-active species and cellular communication molecules. The methodologies and analyses herein provide a framework for advancing electrochemical research tools, with particular relevance for biosensing and pharmaceutical applications.

In electrochemical systems, electrodes are not merely conductive surfaces but dynamic interfaces where critical redox processes are initiated, mediated, and controlled. The fundamental function of an electrode is to facilitate the transfer of electrons to and from chemical species in solution, thereby driving oxidation and reduction reactions essential to electroanalysis [18]. The principles of redox chemistry dictate that the efficacy of this electron transfer is governed by the electrochemical potential, the intrinsic properties of the electrode material, and the structure of the electrode-electrolyte interface [19].

Within bio-electroanalysis and drug development research, mastering electron transfer at electrodes enables the direct interrogation of biological redox systems. This includes measuring stable redox molecules like NADH and ascorbate, reactive signaling molecules like hydrogen peroxide, and probing cellular communication networks through secreted redox mediators [20]. The ability to electronically intercept and modulate these molecular messages provides a unique vantage point for understanding and controlling biological function, creating a crucial bridge between biology and electronics [20]. This whitepaper dissects the core mechanisms, materials, and methodologies that define the role of electrodes in facilitating electron transfer, providing researchers with a technical guide grounded in redox principles.

Theoretical Framework: Electron Transfer Kinetics and Regimes

Electron transfer reactions at an electrode are governed by the electronic interaction between the reactant and the electrode material, coupled with reorganization of the solvent and molecular moieties. The strength of this electronic interaction, quantified by the coupling parameter ( V{eff} ) or the chemisorption function ( \Delta(ε) ), is central to determining the reaction mechanism and rate [19]. The parameter ( \Delta(ε) ) is proportional to the density of states (DOS) of the electrode material: ( \Delta(ε) ≈ π|V{eff}|²ρ_{elec}(ε) ) [19].

Depending on the strength of the electronic coupling, electron transfer reactions can be categorized into three distinct kinetic regimes, as illustrated in Figure 1 [19]:

- Nonadiabatic Regime (Weak Coupling): Electronic interactions are weak. The system can pass the transition state without electron transfer occurring. The reaction rate is first-order with respect to the coupling strength, and the pre-exponential factor in the rate constant is proportional to ( \Delta ).

- Adiabatic Regime (Intermediate Coupling): Interactions are sufficiently strong that electron transfer occurs every time the system reaches the transition state. The system maintains electronic equilibrium, and solvent dynamics (friction) influences the rate. For outer-sphere reactions, the rate constant becomes almost independent of ( \Delta ), and the activation barrier is described by Marcus-Hush theory.

- Catalytic Regime (Strong Coupling): Very strong interactions lead to a significant lowering of the activation energy, producing a catalytic effect. The rate constant increases with coupling strength. This regime is typical for inner-sphere reactions where the reactant chemisorbs to the electrode surface.

Table 1: Kinetic Regimes of Electron Transfer at Electrodes

| Kinetic Regime | Coupling Strength | Electron Transfer Probability | Dependence on ( \Delta ) | Typical Reaction Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonadiabatic | Weak | Less than unity | Linear | Outer-sphere |

| Adiabatic | Intermediate | Unity | Independent | Outer-sphere |

| Catalytic | Strong | Unity | Increases | Inner-sphere |

The nature of the electron transfer is also classified by the proximity of the reactant to the electrode surface:

- Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer: The reactant retains its entire solvation shell and is not in direct contact with the electrode surface. At least one layer of solvent separates the reactant and electrode. The reaction rate is primarily determined by the reorganization energy (λ) of the solvent [19].

- Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer: The reactant experiences strong electronic interactions (chemisorption), potentially losing its solvation shell and forming a chemical bond with the electrode. Bond-breaking and formation can occur, leading to a strong dependence on the electrode material's chemical identity [19].

Electrode Materials and Characterization

The electronic structure of the electrode material fundamentally shapes the electron transfer process. Different materials—metals, semiconductors, and carbonaceous forms like graphene—possess distinct density of states (DOS) profiles that influence electrochemical response, especially in nonadiabatic regimes [19].

Material Classes and Electronic Structure

- Metals: Typically exhibit a high, constant density of states around the Fermi level, leading to adiabatic electron transfer for most reactions. Their high conductivity makes them ideal for many electroanalytical applications.

- Semiconductors: Characterized by a bandgap, their DOS shows a sharp onset from zero at the band edge. This structure makes electron transfer highly sensitive to the applied potential, as the population of charge carriers is much lower than in metals [19].

- Graphene and Carbon Materials: These materials offer a unique DOS that is linear around the Fermi level. This dimensionality influences electron transfer kinetics, which can be tuned by the number of layers and defect engineering [19].

The current-overpotential relationship for a nonadiabatic reduction reaction highlights the role of the electronic structure [19]: ( j{red} = \frac{P|V{eff}|²}{ℏ} (4πλkBT)^{-1/2} \int{-\infty}^{+\infty} ρ{elec}(ε) f{FD}(ε, T{elec}) W{ox}(ε, λ, η) dε ) where ( ρ{elec}(ε) ) is the material's DOS and ( f{FD} ) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution. Model calculations using idealized DOS for different materials produce distinct voltammetric shapes, providing a fingerprint for the underlying electron transfer mechanism [19].

Quantitative Electrochemical Response by Material

Table 2: Electrochemical Response of Different Electrode Materials

| Electrode Material | Density of States (DOS) Profile | Typical Electron Transfer Regime | Pre-exponential Factor (k°, cm s⁻¹) | Key Feature / Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metals (e.g., Pt, Au) | High and constant near Fermi level | Adiabatic | ~10⁴ | High conductivity; ideal for inner-sphere catalysis (e.g., HER) |

| Semiconductors (e.g., Si, TiO₂) | Sharp onset from zero at band edge | Nonadiabatic / Adiabatic (controversial) | Varies with potential | Potential-dependent kinetics; useful for photoelectrochemistry |

| Graphene | Linear around Fermi level | Controversial (can be either) | Dimensionality-dependent | Tunable properties; favorable π-π stacking for aromatic molecules |

| Glassy Carbon | Complex, disordered | Often treated as metallic | Lower than metals | Wide potential window; good for bio-sensing |

Experimental Protocols for Interfacial Analysis

A deep understanding of electrode-electrolyte interfaces requires modeling and experimental protocols that span from the local microscale to system-level macroscopic sizes [21]. The following methodologies are critical for probing electron transfer.

Protocol: Voltammetric Interrogation of Electron Transfer Kinetics

Objective: To determine the electron transfer regime and measure kinetic parameters for a redox species at a chosen electrode material.

Materials:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: For applying potential and measuring current.

- Working Electrode: The material under study (e.g., Pt disk, graphene-modified electrode).

- Counter Electrode: Pt wire.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl or SCE.

- Electrolyte Solution: High-purity supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl, 0.1 M H₂SO₄).

- Redox Probe: A well-characterized outer-sphere couple (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) or a specific inner-sphere reactant of interest (e.g., H₂O₂).

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the working electrode sequentially with alumina slurries of decreasing particle size (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each polish and sonicate in water or ethanol for 2 minutes to remove adsorbed particles.

- Cell Assembly: Introduce the clean working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode into the electrochemical cell containing the electrolyte and redox probe. Decorate the solution with an inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) for at least 15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) Measurement:

- Record CVs at a range of scan rates (e.g., from 0.01 to 10 V s⁻¹).

- For a reversible (fast) outer-sphere system, the peak separation (ΔEp) should be close to 59/n mV and independent of scan rate. An increasing ΔEp with scan rate indicates quasi-reversible kinetics.

- Data Analysis:

- Use the Nicholson method for quasi-reversible systems to estimate the standard rate constant (k°) from the scan rate dependence of ΔEp.

- Analyze the peak current (ip) vs. the square root of scan rate (v¹/²) to confirm diffusion-controlled transport.

- A lower measured k° value, particularly for an outer-sphere probe, suggests a weaker electronic coupling, potentially indicating a more nonadiabatic character.

Protocol: Electrochemical Interception of Redox Mediators in Cell Communication

Objective: To electrochemically measure the concentration and activity of redox-active molecules involved in cellular signaling.

Materials:

- Electrochemical Workstation: Capable of low-potential amperometry or voltammetry.

- Modified or Unmodified Working Electrode: Selection depends on the target analyte. For hydrogen peroxide, a Pt electrode is standard. For phenazines, a graphene-modified electrode exploits π-π stacking to enhance signal [20].

- Cell Culture Chamber: Integrated with the electrochemical cell for real-time monitoring.

Procedure:

- Electrode Selection and Modification:

- For stable redox molecules (e.g., NADH, ascorbate, phenazines), use a bare or graphene-modified electrode [20].

- For specific reactive species (e.g., H₂O₂), apply a constant oxidizing or reducing potential and measure the faradaic current.

- For enhanced specificity, immobilize an enzyme (e.g., oxidase) on the electrode surface to act as a recognition element and redox mediator [20].

- Calibration: Record the electrochemical response (e.g., current in amperometry) in standard solutions of the target mediator to establish a calibration curve.

- Sample Measurement: Introduce the cell culture supernatant or place the electrode directly into the culture medium. The presence of the redox mediator will produce a concentration-dependent current.

- Signal Deconvolution: For complex mixtures, use techniques like dynamic multi-potential voltammetry to deciphere signals from multiple redox-active species simultaneously [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electrode-Centric Research

| Item / Reagent | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Core instrument for applying controlled potentials/currents and measuring electrochemical response. |

| Pt, Au, Glassy Carbon Working Electrodes | Standard electrode materials for general electroanalysis, each with different DOS and catalytic properties. |

| Graphene-modified Electrodes | Electrode platform with favorable π-π stacking for enhanced measurement of aromatic redox mediators like phenazines [20]. |

| Redox Mediators (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻, [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺) | Well-behaved outer-sphere redox probes for characterizing electrode kinetics and surface area. |

| Enzymes (e.g., Glucose Oxidase, Laccase) | Biological recognition elements for biosensors; catalyze substrate conversion and exchange electrons with mediators/electrodes [20]. |

| Supporting Electrolytes (e.g., KCl, H₂SO₄) | Provide ionic conductivity and control the electric double layer structure at the electrode-electrolyte interface. |

| Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM) | Advanced technique using a micro- or nano-electrode probe to map local electrochemical activity and topography [22]. |

Applications in Bio-Electroanalysis and Drug Development

The principles of electrode-enabled electron transfer find critical application in bio-electroanalysis, particularly in probing and controlling biological systems.

Intercepting Cellular Communication: Cells secrete redox-active molecules (e.g., hydrogen peroxide, phenazines, catecholamines) as part of their communication network. Electrodes can directly measure these molecules, acting as external receivers. This allows researchers to eavesdrop on biological processes like bacterial quorum sensing or immune responses in real-time [20]. For instance, hydrogen peroxide, elicited during infection, can be measured by a locally placed electrode to monitor an immune response [20].

Redox Electrogenetics for Controlled Intervention: Beyond measurement, electrodes can be used to control biological communication. By applying potentials, electrodes can generate or consume specific redox species that influence cellular behavior. This creates a "redox channel" for bidirectional information transfer between biology and electronics, enabling closed-loop feedback control of biological function [20]. This approach is transformative for precisely modulating cellular processes in drug development and synthetic biology.

Nanoscale Electroanalysis: The advent of nanoelectrodes and scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) has pushed the limits of spatial resolution. This allows for electrochemical imaging of single cells and even single entities, providing unprecedented insight into localized redox events and heterogeneity at the cellular level [22].

Visualizing Electron Transfer Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Electron Transfer Pathway at an Electrode. This workflow illustrates the decision tree for electron transfer, leading to inner-sphere (strong coupling) or outer-sphere (weak/intermediate coupling) reaction pathways, culminating in product formation.

Diagram 2: Core Experimental Workflow for Electrode Kinetics. The diagram outlines the key steps for a standard electrochemical experiment, from electrode preparation to data analysis, linked to common measurement techniques.

The Nernst equation represents a cornerstone of electrochemical theory, providing a fundamental relationship between electrode potential, standard potential, temperature, and reactant concentrations. This technical guide examines the theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and experimental validations of the Nernst equation within the context of redox reaction principles for electroanalysis research. We present comprehensive mathematical formulations, detailed experimental protocols for empirical verification, and advanced considerations for research applications in pharmaceutical and analytical sciences. The content specifically addresses the needs of researchers and drug development professionals requiring precise electrochemical measurements for sensor development, bioavailability studies, and metabolic reaction monitoring.

Theoretical Foundations

Thermodynamic Derivation

The Nernst equation finds its roots in thermodynamic principles, specifically connecting electrochemical cell potential to Gibbs free energy. The fundamental relationship begins with the expression for Gibbs free energy change under non-standard conditions:

ΔG = ΔG° + RT ln Q [23]

where ΔG represents the Gibbs free energy change, ΔG° denotes the standard free energy change, R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹), T is absolute temperature in Kelvin, and Q is the reaction quotient.

For electrochemical systems, the Gibbs free energy relates directly to electrical work through the expression:

where n represents the number of electrons transferred in the redox reaction, F is Faraday's constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹), and E is the cell potential. Under standard conditions, this relationship becomes:

Combining these equations yields the most general form of the Nernst equation:

E = E° - (RT/nF) ln Q [23] [25] [26]

For half-cell reduction reactions, the equation specifically describes the reduction potential:

E = E° - (RT/nF) ln (aRed/aOx) [25] [27]

where aRed and aOx represent the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively.

Mathematical Formulations

The Nernst equation admits several mathematical forms depending on experimental context and convenience:

Table 1: Mathematical Forms of the Nernst Equation

| Form | Equation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| General Form | E = E° - (RT/nF) ln Q | Fundamental thermodynamic form |

| Half-Cell Reduction | E = E° - (RT/nF) ln (aRed/aOx) | Single electrode potential |

| Concentration-Based | E = E° - (RT/nF) ln ([Red]/[Ox]) | Dilute solutions |

| 298K Simplified | E = E° - (0.05916/n) log Q | Room temperature experiments |

| Formal Potential | E = E°' - (RT/nF) ln ([Red]/[Ox]) | Non-ideal conditions |

The conversion from natural logarithm to base-10 logarithm incorporates the factor 2.303, since ln(x) = 2.303 log(x). At standard temperature (298.15 K), the pre-logarithmic term simplifies considerably:

E = E° - (0.05916/n) log Q [23] [24] [26]

This simplification arises from calculating (2.303 × R × T)/F where R = 8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹, T = 298.15 K, and F = 96,485 C·mol⁻¹:

(2.303 × 8.314 × 298.15)/96485 ≈ 0.05916 V [23] [28]

For a general redox reaction expressed as:

aA + bB ⇌ cC + dD

the reaction quotient Q takes the form:

Q = [C]c[D]d / [A]a[B]b [26]

where concentrations are used for solutes and partial pressures for gases.

Quantitative Data Presentation

Temperature Dependence

The Nernst equation exhibits significant temperature sensitivity through the RT/nF term. The following table presents the temperature coefficient at varying conditions:

Table 2: Temperature Dependence of the Pre-logarithmic Factor (2.303RT/F)

| Temperature (°C) | Temperature (K) | Pre-logarithmic Factor (V) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 | 288.15 | 0.056 | Biological systems |

| 25 | 298.15 | 0.0592 | Standard conditions |

| 37 | 310.15 | 0.0615 | Physiological studies |

| 40 | 313.15 | 0.0630 | Accelerated stability testing |

| 60 | 333.15 | 0.0671 | High-temperature processes |

The temperature dependence follows the relationship:

Pre-logarithmic Factor = (2.303 × R × T)/F [29] [26]

where the factor increases linearly with absolute temperature.

Equilibrium Relationships

At equilibrium, the cell potential E becomes zero, and the reaction quotient Q equals the equilibrium constant K. This provides a powerful connection between electrochemical measurements and thermodynamic parameters:

0 = E° - (RT/nF) ln K

Rearranging yields:

or in base-10 logarithmic form at 298K:

E° = (0.05916/n) log K [23] [24] [28]

This relationship enables determination of equilibrium constants from electrochemical measurements, with implications for drug-receptor binding studies and metabolic reaction equilibria.

Experimental Protocols

Verification of Nernst Equation Using Daniell Cell

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Materials for Daniell Cell Experimentation

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Function in Experiment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zinc sulfate heptahydrate | ACS grade, ≥99.0% | Provides Zn²⁺ ions for anode compartment | |

| Copper sulfate pentahydrate | ACS grade, ≥98.0% | Provides Cu²⁺ ions for cathode compartment | |

| Zinc electrode | Puratronic, 99.999% metal basis | Anode material (Zn | Zn²⁺ half-cell) |

| Copper electrode | Puratronic, 99.999% metal basis | Cathode material (Cu | Cu²⁺ half-cell) |

| Potassium chloride | ACS grade, ≥99.0% | Salt bridge electrolyte | |

| Agarose | Molecular biology grade | Salt bridge matrix stabilization | |

| Deionized water | HPLC grade, 18.2 MΩ·cm | Solvent preparation |

Methodology

Electrode Preparation: Polish zinc and copper electrodes with successive grits of silicon carbide paper (ending with P1200), followed by sonication in deionized water for 5 minutes to remove surface impurities [30].

Electrolyte Preparation: Prepare zinc sulfate solutions across concentration range 0.001 M to 1.0 M using serial dilution with HPLC grade water. Similarly, prepare copper sulfate solutions from 0.001 M to 1.0 M. Record exact concentrations using calibrated analytical balance (±0.0001 g) [30].

Salt Bridge Fabrication: Dissolve 3g agarose in 100mL of 1M KCl solution with gentle heating until clear. Transfer to U-tube apparatus and allow to solidify at 4°C for 30 minutes [28].

Cell Assembly: Assemble the Daniell cell in a dual-chamber electrochemical apparatus with the salt bridge connecting the two compartments. Maintain temperature control at 25.0°C ± 0.1°C using a circulating water bath [30].

Potential Measurement: Connect electrodes to high-impedance digital multimeter (resolution 0.1 mV) through appropriate shielding to minimize electromagnetic interference. Allow system to stabilize for 300 seconds before recording equilibrium potential. Perform triplicate measurements for each concentration combination [30].

Data Analysis: Plot measured EMF against log(Q) where Q = [Zn²⁺]/[Cu²⁺]. Perform linear regression to determine slope and compare with theoretical Nernst value (-0.02958 V for n=2) [28] [30].

Determination of Formal Potential

Background

The formal potential (E°') represents the practical counterpart to the standard potential, accounting for non-ideal behavior in real solutions:

E°' = E° - (RT/nF) ln(γRed/γOx) [25]

where γRed and γOx are the activity coefficients of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively.

Methodology

Prepare a series of solutions with fixed total concentration of redox couple but varying ratio of oxidized to reduced species (e.g., Fe³⁺/Fe²⁺ with constant ionic strength) [25] [27].

Measure half-cell potential against appropriate reference electrode (e.g., Ag|AgCl|KClsat).

Plot measured potential against log([Ox]/[Red]).

Perform linear regression: the intercept at log([Ox]/[Red]) = 0 provides the formal potential E°'.

The slope should approximate 0.05916/n V at 25°C for ideal Nernstian behavior.

Advanced Research Applications

Electroanalysis in Pharmaceutical Research

The Nernst equation provides fundamental principles for numerous electroanalytical techniques employed in drug development:

Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs): Potentiometric sensors exhibit Nernstian response to specific ions, with slope values indicating the charge of the target species. Pharmaceutical applications include monitoring drug ion release, metabolic byproducts, and electrolyte imbalances [26].

Bioavailability Studies: Redox potential measurements correlate with drug molecule activity, providing insights into metabolic transformations and oxidative stability. The Nernst equation facilitates quantification of reaction tendencies under physiological conditions [31].

Metabolic Pathway Analysis: Monitoring NAD⁺/NADH and other cofactor ratios through their redox potentials enables real-time assessment of metabolic flux in cellular systems, with applications in toxicity screening and mechanism of action studies [26].

Recent Methodological Advances

Contemporary research has expanded Nernstian principles to complex systems:

Volumetric Capacitance in Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs): Advanced modeling incorporates Nernst-Planck-Poisson equations with explicit volumetric capacitance terms for predicting OECT behavior in biological sensing applications [31].

Two-Dimensional Nernst-Planck-Poisson Simulations: Recent implementations extend traditional 1D models to 2D geometries, enabling more accurate prediction of electrochemical device performance, particularly for miniaturized sensor platforms [31].

Limitations and Practical Considerations

Activity Versus Concentration

The fundamental Nernst equation utilizes activities rather than concentrations, creating divergence in high ionic strength solutions:

ai = γiCi

where ai is the activity, γi is the activity coefficient, and Ci is the concentration [25] [28]. For dilute solutions (typically <0.001 M), activity coefficients approach unity, enabling concentration approximations. In pharmaceutical matrices with high ionic strength, activity corrections become essential for accurate interpretation.

Non-Ideal Behavior

Several factors can cause deviation from ideal Nernstian response:

Kinetic Limitations: Slow electron transfer kinetics create overpotential, particularly in biological redox couples with complex coordination environments [28].

Chemical Side Reactions: Subsequent chemical steps (EC mechanisms) alter effective concentration ratios at the electrode surface [27].

Adsorption Phenomena: Surface adsorption of reactant or product species modifies effective activities, particularly in drug compounds with hydrophobic moieties [28].

Temperature Considerations

While standard potentials are typically referenced to 25°C, pharmaceutical applications often require physiological temperature (37°C). The temperature dependence of E° must be considered for precise work:

where α represents the temperature coefficient of the specific redox couple, typically determined empirically.

The Nernst equation remains an indispensable tool in electroanalytical research, providing a fundamental bridge between thermodynamic principles and measurable electrochemical potentials. For drug development professionals, understanding its proper application—including limitations related to activity coefficients, temperature effects, and non-ideal behavior—is essential for accurate interpretation of potentiometric data. Recent advances in multidimensional modeling continue to expand its utility in complex biological systems, ensuring its continued relevance in pharmaceutical research and development.

Redox reactions, involving the transfer of electrons between chemical species, form the foundational principles of electroanalysis research. These reactions are characterized by simultaneous oxidation (loss of electrons) and reduction (gain of electrons) processes [32]. In drug development and analytical chemistry, understanding and controlling redox processes enables researchers to quantify biomolecular interactions, develop diagnostic sensors, and study metabolic pathways [12]. The accuracy of these advanced applications depends fundamentally on the precise balancing of redox equations, which ensures mass and charge conservation in electrochemical systems [33].

This technical guide provides researchers with comprehensive methodologies for balancing redox reactions using two systematic approaches: the half-reaction method and the oxidation number change method. Mastery of these techniques is essential for designing reproducible experiments in electroanalytical chemistry, particularly in quantitative drug discovery assays where redox-tagged peptides and graphene monolayers provide attomolar-level sensitivity for binding affinity measurements [12].

Fundamental Concepts of Redox Reactions

Oxidation Number Fundamentals

The oxidation number represents the imaginary charge left on an atom when all other atoms in a compound are removed in their usual oxidation states [32]. These values follow specific assignment rules:

- Atoms in elemental form have an oxidation number of zero

- For monatomic ions, the oxidation number equals the charge

- Oxygen typically exhibits an oxidation number of -2 (except in peroxides)

- Hydrogen is typically +1 when bonded to nonmetals, -1 when bonded to metals

- The sum of oxidation numbers in a neutral compound equals zero; for polyatomic ions, it equals the ion's charge

In redox reactions, an increase in oxidation number indicates oxidation, while a decrease indicates reduction [32].

Types of Redox Reactions

Redox reactions in electroanalytical chemistry manifest in several distinct forms:

- Combination Reactions: Two substances combine to form a single compound [32]

- Decomposition Reactions: A compound splits into two or more components [32]

- Displacement Reactions: An ion or atom in a compound is replaced by another element [32]

- Disproportionation Reactions: The same element undergoes both oxidation and reduction [33] [32]

The Half-Reaction Method: A Systematic Approach

The half-reaction method provides a systematic approach to balancing complex redox equations, particularly in aqueous solutions where water molecules and their fragments (H⁺, OH⁻) participate in the reaction [33] [34]. This method is indispensable for balancing reactions where trial-and-error approaches prove insufficient [33].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Write the Skeleton Equation Construct the unbalanced ionic equation containing the primary redox participants [33].

Step 2: Assign Oxidation Numbers Identify elements undergoing oxidation number changes [33] [32].

Step 3: Identify Oxidation and Reduction Half-Reactions Divide the reaction into oxidation and reduction components [33] [34].

Step 4: Balance Each Half-Reaction Separately Balance atoms, then charges by adding electrons [33] [34] [32].

Step 5: Equalize Electron Transfer Find the least common multiple of electrons and multiply half-reactions accordingly [34].

Step 6: Combine Half-Reactions Sum the adjusted half-reactions, canceling electrons and common species [33] [34].

Step 7: Verify Balance Confirm balanced atoms and charges on both sides [33].

The following workflow illustrates the systematic procedure for the half-reaction method:

Handling Aqueous Solutions: Acidic and Basic Conditions

In electroanalytical research, most redox reactions occur in aqueous solutions where water, H⁺, or OH⁻ participate directly [34]. The approach differs for acidic versus basic conditions:

Acidic Conditions Protocol:

- Balance oxygen atoms by adding H₂O to the deficient side

- Balance hydrogen atoms by adding H⁺ to the deficient side

- Balance charge by adding electrons [33] [34]

Example: MnO₄⁻ to Mn²⁺ in acid:

Basic Conditions Protocol:

- First, balance as in acidic conditions

- Add equal OH⁻ to both sides to neutralize H⁺

- Combine H⁺ and OH⁻ to form H₂O

- Simplify by canceling duplicate H₂O molecules [34]

Example: MnO₄⁻ to MnO₂ in base:

The Oxidation Number Change Method

The oxidation number change method provides an alternative approach that tracks electron transfer through changes in oxidation states [32].

Step-by-Step Protocol

Step 1: Assign Oxidation Numbers Identify all oxidation numbers for atoms in the reaction [32].

Step 2: Identify Changes Determine which atoms increase or decrease oxidation numbers [32].

Step 3: Calculate Electron Transfer Multiply the oxidation number change by the number of atoms undergoing change [32].

Step 4: Equalize Electron Transfer Use coefficients to balance total electrons lost and gained [32].

Step 5: Balance Remaining Atoms Balance other elements by inspection after redox components are balanced [32].

Practical Application Example

Balance: KMnO₄ + FeSO₄ + H₂SO₄ → MnSO₄ + Fe₂(SO₄)₃ + K₂SO₄ + H₂O

Step 1: Identify redox participants:

- Mn: +7 (KMnO₄) to +2 (MnSO₄) → Reduction

- Fe: +2 (FeSO₄) to +3 (Fe₂(SO₄)₃) → Oxidation

Step 2: Calculate electron changes:

- Each Mn gains 5 electrons (+7 to +2)

- Each Fe loses 1 electron (+2 to +3)

Step 3: Balance electron transfer:

- 5 Fe atoms needed for each Mn atom (5 electrons total)

Step 4: Apply coefficients:

- 2KMnO₄ requires 10FeSO₄

- Final balanced equation:

The following workflow illustrates the oxidation number method:

Comparative Analysis of Balancing Methods

Table 1: Method Selection Guidelines for Electroanalytical Applications

| Parameter | Half-Reaction Method | Oxidation Number Method |

|---|---|---|

| Best For | Aqueous solutions, electrode processes, complex ions | Organic molecules, gas-phase reactions, non-aqueous systems |

| Electron Tracking | Explicit as e⁻ in half-reactions | Implicit through oxidation number changes |

| Acid/Base Handling | Systematic H₂O, H⁺, OH⁻ addition | Requires additional steps for media |

| Charge Balance | Directly addressed in each step | Verified at completion |

| Research Applications | Electrolysis, battery systems, biosensors | Stoichiometric calculations, synthesis planning |

Table 2: Redox Reaction Examples in Analytical Chemistry

| Reaction System | Analytical Application | Balancing Method |

|---|---|---|

| MnO₄⁻/Fe²⁺ in H₂SO₄ | Classical iron determination | Half-reaction |

| I₃⁻/S₂O₃²⁻ | Iodometric titrations | Half-reaction |

| Cr₂O₇²⁻/SO₂ in acid | Environmental SO₂ monitoring | Both methods |

| H₂O₂/MnO₄⁻ in acid | Peroxide quantification | Half-reaction |

| Br₂/OH⁻ disproportionation | Bromine speciation studies | Oxidation number |

Advanced Electroanalytical Applications

Quantum Electroanalysis in Drug Discovery

Contemporary drug discovery leverages redox principles through quantum electroanalysis (QEA), where redox-tagged peptides and graphene monolayers quantify binding affinity constants under physiological conditions [12]. This approach provides attomolar-level sensitivities, enabling accurate measurement of low-molecular-weight ligand-receptor binding affinities - a significant advancement over traditional optical technologies like surface plasmon resonance [12].

In QEA systems, balanced redox equations precisely describe the electron transfer events that occur during ligand-receptor interactions. The half-reaction method proves particularly valuable for modeling these complex interfacial electron transfers where quantum electrodynamics principles govern both electron transport and electron transfer processes [12].

Experimental Protocol: Standardization of Permanganate

Objective: Standardize KMnO₄ solution using reagent grade sodium oxalate [33].

Principle: Redox reaction between oxalic acid and permangan ion in acidic solution [33].

Balanced Equation (via half-reaction method):

Procedure:

- Weigh pure sodium oxalate and dissolve in distilled water

- Acidify with sulfuric acid

- Titrate with KMnO₄ solution at 60-70°C

- Endpoint: persistent faint pink color (excess MnO₄⁻) [33]

Calculations:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Electroanalytical Reagents for Redox Studies

| Reagent | Specifications | Primary Function | Storage & Handling |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Permanganate (KMnO₄) | ACS grade, 99.0% min, low MnO₂ content | Strong oxidizing agent for titrimetric analysis | Brown glass, ambient temperature, protect from light |

| Sodium Oxalate (Na₂C₂O₄) | Primary standard grade, 99.95% purity | Reducing agent for standardizing oxidants | Desiccator, 25°C, low humidity |

| Potassium Iodide (KI) | ACS grade, 99.0% min, heavy metals <5ppm | Weak reducing agent, source of I₃⁻ | Amber container, protect from air and light |

| Sodium Thiosulfate (Na₂S₂O₃·5H₂O) | ACS grade, 99.5% purity | Iodometric titrations, reducing agent | Stable solution with Na₂CO₃ preservative |

| Cerium(IV) Sulfate | 0.1N ± 0.0005N standard solution | Strong acid-stable oxidant | Stable in H₂SO₄, resists chloride interference |

The half-reaction and oxidation number methods provide robust frameworks for balancing redox equations in electroanalytical research. While the half-reaction method offers systematic handling of aqueous phase reactions and explicit electron accounting, the oxidation number method provides efficient stoichiometric determinations for complex molecular systems.

In advanced applications such as quantum electroanalysis, these fundamental balancing techniques enable precise quantification of biomolecular interactions through redox-active interfaces. The continued refinement of these methodological approaches supports innovation in pharmaceutical research, environmental monitoring, and energy conversion technologies where accurate redox stoichiometry forms the basis of quantitative analysis.

As electroanalytical methods evolve toward increasingly sensitive measurements, the precise balancing of redox reactions remains an essential skill for researchers developing next-generation analytical platforms in drug discovery and diagnostic applications.

Electroanalytical Techniques and Their Applications in Synthesis and Bioanalysis

Electroanalytical chemistry provides powerful tools for investigating redox reaction principles, with transient techniques like chronoamperometry (CA) and chronopotentiometry (CP) offering unique insights into reaction mechanisms and kinetics. These controlled potential and controlled current methods enable researchers to probe diffusion processes, determine concentrations of redox-active species, and analyze coupled electrochemical-chemical reactions with high precision. Within the framework of electroanalysis research, these techniques find extensive application across diverse fields including electrocatalyst development, battery research, sensor design, and materials synthesis. The fundamental distinction between these methods lies in their controlled parameters: chronoamperometry applies a potential step and measures the resulting current transient, while chronopotentiometry applies a current step and monitors the potential response over time. Both techniques are performed in unstirred solutions where diffusion is the primary mass transport mechanism, allowing for quantitative analysis of electrochemical processes under well-defined conditions. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these core techniques, their theoretical foundations, experimental protocols, and research applications relevant to scientists and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

Chronoamperometry (CA)

Chronoamperometry is a potential step technique where the potential of the working electrode is stepped from a value at which no faradaic reaction occurs to a value sufficient to drive a diffusion-limited electrode reaction. The resulting current is monitored as a function of time, providing information about the rate of mass transport and reaction kinetics [35] [36].

In CA, when the potential is stepped to a value sufficiently beyond the formal potential (E°) of the redox couple (typically >118 mV for a reversible system), the concentration of the electroactive species at the electrode surface is rapidly depleted to near zero. This establishes a concentration gradient that extends further into the solution with time, in a region known as the diffusion layer [37]. The current decay observed in chronoamperometry follows the Cottrell equation, which describes the diffusion-limited current at a planar electrode under mass-transport control [36] [37]:

i(t) = (nFAC√D)/(√π√t)

Where:

- i(t) = current at time t (A)

- n = number of electrons transferred

- F = Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol)

- A = electrode area (cm²)

- C = bulk concentration (mol/cm³)

- D = diffusion coefficient (cm²/s)

- t = time (s)

The Cottrell equation predicts that the current decreases proportionally with the square root of time, yielding a characteristic hyperbolic decay curve. In practice, the initial current contains a significant contribution from capacitive current associated with charging the electrical double layer at the electrode-solution interface. This non-faradaic component decays exponentially and is typically negligible after the first few milliseconds [36] [37].

Chronopotentiometry (CP)

Chronopotentiometry is a galvanostatic technique in which a constant current is applied between the working and counter electrodes, and the resulting potential of the working electrode is measured relative to a reference electrode as a function of time [38] [39].

In CP, application of a constant current forces oxidation or reduction of electroactive species at the working electrode surface. As the reaction proceeds, the concentration of the reactant at the electrode surface decreases until it is depleted to zero, at which point the potential rapidly shifts to values where a new electrode process can occur [38]. The time required to deplete the surface concentration to zero is known as the transition time (τ), which is related to the analyte concentration through the Sand equation [38]:

τ^(1/2) = (nFA√πC√D)/(2i)

Where:

- τ = transition time (s)

- i = applied current (A)

For a reversible system under diffusion control, the potential-time curve follows a characteristic shape described by:

E = E_(τ/4) + (RT/nF)ln(τ^(1/2) - t^(1/2))/(t^(1/2))

Where E_(τ/4) represents the potential at one-quarter of the transition time, which corresponds to the formal potential E°' for a reversible system [38].

Technical Comparison of Techniques

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Chronoamperometry and Chronopotentiometry

| Parameter | Chronoamperometry (CA) | Chronopotentiometry (CP) |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Parameter | Potential | Current |

| Measured Response | Current vs. time | Potential vs. time |

| Key Equation | Cottrell equation | Sand equation |

| Primary Applications | Diffusion studies, mechanistic analysis, sensor development | Reaction mechanism studies, battery charge/discharge, electrodeposition |

| Mass Transport | Diffusion-controlled | Diffusion-controlled |

| Transition Point | Not applicable | Transition time (τ) |

| Capacitive Current Handling | Poor at short times | Very poor |

| Typical Output | Decaying current transient | S-shaped potential curve |

Table 2: Electrochemical Cell Conditions and Setup

| Component | Chronoamperometry | Chronopotentiometry |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Configuration | 3-electrode system | 3-electrode system |

| Working Electrode | Static (Pt, Au, GC, Hg) | Static (Pt, Au, GC, Hg) |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl, SCE, Hg/Hg₂Cl₂ | Ag/AgCl, SCE, Hg/Hg₂Cl₂ |

| Counter Electrode | Pt wire or mesh | Pt wire or mesh |

| Solution Conditions | Unstirred, excess supporting electrolyte | Unstirred, excess supporting electrolyte |

| Key Parameters | Step potential, duration | Applied current, duration |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Chronoamperometry Experimental Setup

The basic protocol for chronoamperometry involves the following steps [35]:

Initial Conditions: The working electrode is held at an initial potential (Ei) where no faradaic reaction occurs for a specified induction period (typically 2-10 seconds) to establish initial equilibrium conditions.

Potential Step: The potential is instantaneously stepped to a final value (Es) sufficiently beyond the formal potential of the redox couple to drive the reaction at diffusion-limited rates.

Current Monitoring: The resulting current is monitored at regular intervals throughout the electrolysis period (forward step period), which typically ranges from milliseconds to several hundred seconds.

Relaxation Period: The potential may be returned to the initial value or another value during a relaxation period, allowing the system to re-equilibrate.

For a 1 mM acetaminophen solution in saline, a typical CA experiment might apply a potential step from 0 V to 0.7 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) with a duration of 60 seconds, sampling at 100 ms intervals [35]. Data analysis typically involves plotting current versus time and applying the Cottrell equation to determine diffusion coefficients or concentrations. For more advanced analysis, Cottrell plots (i vs. t^(-1/2)) or Anson plots (Q vs. t^(1/2)) can be generated to verify diffusion control and extract quantitative parameters [35].

Chronopotentiometry Experimental Setup

The standard chronopotentiometry protocol consists of [38]:

Induction Period: A set of initial conditions are applied to the electrochemical cell, typically with zero current applied, allowing the system to equilibrate.

Current Step: A constant current is applied between the working and counter electrodes, with the magnitude selected based on the analyte concentration and electrode area.

Potential Monitoring: The working electrode potential relative to the reference electrode is recorded at regular intervals as it changes with time.

Transition Time Measurement: The experiment continues until well past the transition time (τ), where the potential rapidly shifts due to depletion of the electroactive species.

Relaxation Period: The current is returned to zero or another specified value during a relaxation period.

For a 1 mM acetaminophen solution, a typical CP experiment might apply a constant current of 1 μA for 30 seconds, monitoring the potential at 100 ms intervals [38]. The transition time is identified as the point of maximum slope (inflection point) in the potential-time curve, which can be precisely determined using tangent methods [38].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Typical Composition/Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes migration current, provides ionic conductivity | 0.1-1.0 M KCl, NaClO₄, TBAPF₆ in organic solvents |

| Redox Probes | System characterization, diffusion studies | 1-5 mM K₃Fe(CN)₆, Ru(NH₃)₆Cl₃, ferrocene |

| Electrode Polishing | Surface reproducibility | Alumina suspensions (0.05-1.0 μm), diamond polish |

| Surface Modifiers | Electrode functionalization | Thiols for Au, silanes for oxide surfaces, Nafion |

| Aqueous Buffers | pH control in biological studies | Phosphate buffer (0.05-0.1 M, pH 7.4) |

| Non-aqueous Solvents | Extended potential window | Acetonitrile, DMF, DMSO with 0.1 M TBAPF₆ |

Applications in Electroanalysis Research

Materials Synthesis and Electrodeposition

Both chronoamperometry and chronopotentiometry find significant application in the electrochemical synthesis of advanced materials. A comparative study on the electrochemical synthesis of zinc oxide nanorods demonstrated that the choice of electrochemical method significantly influences the morphology and properties of the resulting nanostructures [40]. When CA (constant potential of -1.0 V) and CP (constant current density of 1.5 mA/cm²) were employed, distinct morphological differences were observed: CA produced vertically aligned ZnO nanorods, while CP resulted in flower-like ZnO nanostructures [40]. These morphological variations led to different charge transfer resistances, recombination resistances, and charge mobilities when applied as electron transport layers in inverted polymer solar cells, with the flower-like nanostructures exhibiting superior photovoltaic performance [40].

Similarly, in the electrochemical synthesis of nickel-cobalt layered double hydroxides (Ni-Co LDHs) on nickel-coated graphite for water splitting applications, CA, CP, and cyclic voltammetry (CV) produced materials with distinct morphologies, compositions, and electrochemical behaviors [41]. Atomic force microscopy revealed that the Ni-Co LDH synthesized via CA exhibited a more uniform surface morphology compared to the CV-synthesized material, which showed higher surface heterogeneity with a roughness average (Ra) of 221 nm, indicating a more extensive active surface area [41]. These differences directly influenced the electrochemical performance for both the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and oxygen evolution reaction (OER).

Mechanistic Studies and Kinetic Analysis