Potentiometry vs Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Sensitivity Comparison for Biomedical Analysis

This article provides a systematic comparison of sensitivity between potentiometry and voltammetry, two cornerstone electrochemical techniques in biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Potentiometry vs Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Sensitivity Comparison for Biomedical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a systematic comparison of sensitivity between potentiometry and voltammetry, two cornerstone electrochemical techniques in biomedical and pharmaceutical research. We explore their fundamental principles, operational mechanisms, and key sensitivity determinants through foundational theory and current methodological applications. The analysis covers practical implementation strategies, troubleshooting approaches for sensitivity enhancement, and validation protocols for reliable analytical results. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes recent advances including novel materials, miniaturized systems, and emerging trends to guide optimal technique selection for specific sensitivity requirements in clinical diagnostics and therapeutic monitoring.

Core Principles: Understanding the Fundamental Sensitivity Mechanisms

Sensitivity is a paramount figure of merit in analytical chemistry, critically determining the applicability and reliability of any technique. In electrochemical methods, sensitivity is rigorously defined as the slope of the calibration curve, representing the change in output signal per unit change in analyte concentration [1]. This fundamental parameter, however, manifests differently across electrochemical techniques due to their distinct operational principles and signal generation mechanisms.

This guide provides a objective comparison between two cornerstone electrochemical methods—potentiometry and voltammetry—focusing on their sensitivity characteristics within the context of trace analysis. The discussion is framed around experimental data and fundamental principles to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the information necessary to select the optimal technique for their specific analytical challenges.

Fundamental Principles and Operational Modes

At their core, electrochemical techniques measure electrical properties arising from redox reactions. Potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes (a working indicator electrode and a reference electrode) under conditions of equilibrium, where the measured potential relates to analyte activity via the Nernst equation [2] [3]. In contrast, voltammetry is a dynamic technique that applies a controlled potential profile to a working electrode and measures the resulting current generated by the oxidation or reduction of analytes [4] [3]. This fundamental difference in the measured signal (potential vs. current) directly influences how sensitivity is defined, quantified, and achieved in each method.

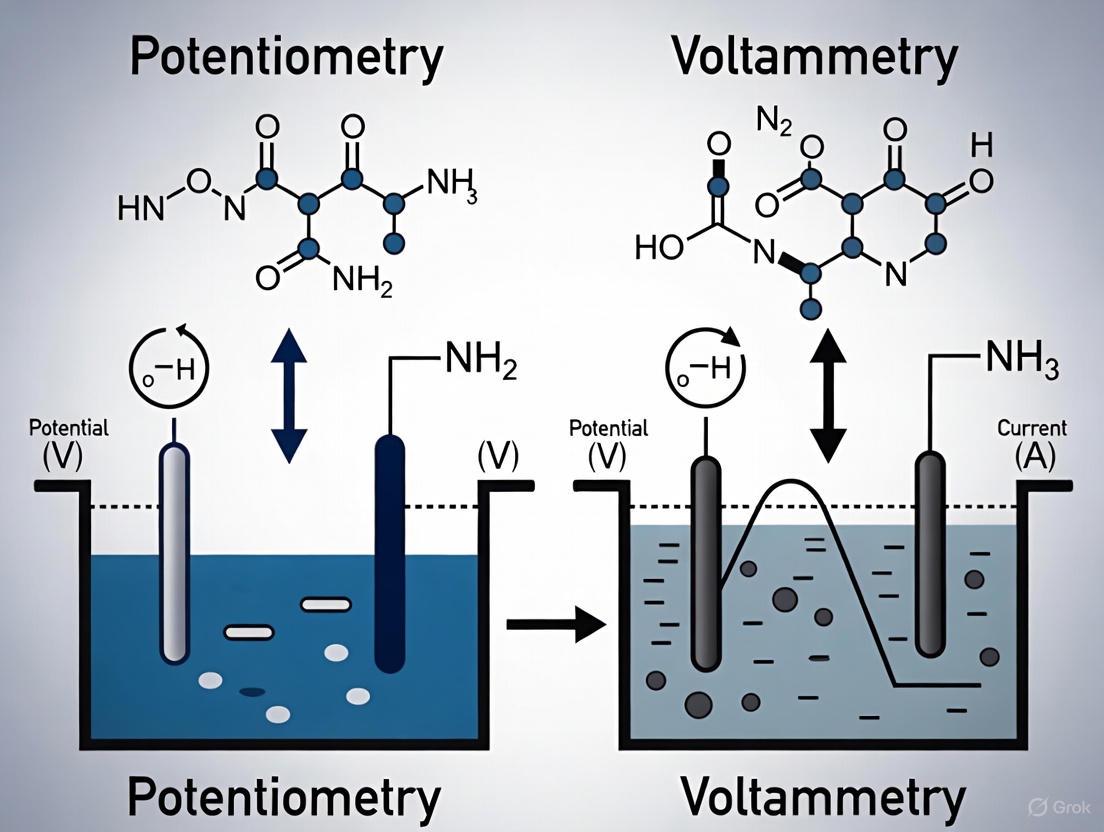

The following diagram illustrates the core operational workflows and logical relationships for each technique, highlighting their contrasting approaches to signal measurement.

Comparative Sensitivity Performance Data

The theoretical basis for sensitivity translates into practical performance, which can be quantitatively compared using key analytical figures of merit. The following table summarizes experimental data from direct comparisons and recent sensor studies, highlighting the typical working ranges and detection capabilities of advanced potentiometric and voltammetric sensors.

Table 1: Comparative Analytical Performance of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Analyte | Method | Specific Technique / Sensor | Linear Range (M) | Reported Detection Limit (M) | Sensitivity | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium (Cd²⁺) | Potentiometry | Solid-contact Cd²⁺-ISE | Not Specified | ( 2.0 \times 10^{-10} ) | Not Specified | [5] |

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Potentiometry | Solid-contact Pb²⁺-ISE | Not Specified | ( 2.0 \times 10^{-9} ) | Not Specified | [5] |

| Nitrite (NO²⁻) | Voltammetry | AuNRs/MWCNT/PEDOT:PSS/GCE | ( 2.0 \times 10^{-7} ) to ( 1.0 \times 10^{-4} ) | ( 8.0 \times 10^{-8} ) | 0.0634 μA μM⁻¹ cm⁻² | [1] |

| Nitrite (NO²⁻) | Voltammetry | AuNRs/ErGO/PEDOT:PSS/GCE | ( 8.0 \times 10^{-7} ) to ( 1.0 \times 10^{-4} ) | ( 2.0 \times 10^{-7} ) | 0.0451 μA μM⁻¹ cm⁻² | [1] |

Interpretation of Performance Data

The data in Table 1 reveals that both modern potentiometry and voltammetry are capable of achieving detection limits in the nanomolar range or lower, making them suitable for trace analysis [5] [1]. The sensitivity in voltammetry is often reported as a direct quantitative value (e.g., μA μM⁻¹ cm⁻²), reflecting the slope of the current-versus-concentration plot [1]. In potentiometry, while a "sensitivity" value is less commonly stated in the same way, the lower detection limit serves as a key performance metric, demonstrating its ability to respond to minute changes in analyte activity at trace levels [5].

Experimental Protocols for Direct Comparison

A direct, side-by-side comparison of potentiometry and anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) for measuring cadmium and lead offers the most insightful data for sensitivity assessment [5]. The following protocols detail the key methodologies from such a study.

Potentiometric Measurements for Cadmium and Lead

- Electrode Preparation: The solid-contact ion-selective microelectrodes (ISEs) are prepared using specialized ionophores. The Cd²⁺-ISE membrane incorporates ETH 5435 ionophore, while the Pb²⁺-ISE uses Lead Ionophore IV. The membrane components are dissolved in dichloromethane and degassed with N₂ before coating the microelectrodes [5].

- Conditioning Protocol: The fabricated Cd²⁺-ISE is conditioned sequentially in ( 10^{-3} ) M Cd(NO₃)₂ and then in ( 10^{-9} ) M Cd(NO₃)₂ containing ( 10^{-3} ) M Ca(NO₃)₂ (one day each). The Pb²⁺-ISE is conditioned in ( 10^{-3} ) M Pb(NO₃)₂ and subsequently in ( 10^{-9} ) M Pb(NO₃)₂ containing ( 10^{-4} ) M HNO₃ (one day each). This conditioning is critical for achieving low detection limits [5].

- Measurement: Potentiometric measurements are performed at room temperature (22°C) in a 100 mL sample using a high-impedance interface and a data acquisition board, with a commercial double-junction reference electrode completing the circuit [5].

Anodic Stripping Voltammetric (ASV) Measurements

- Electrode System: A three-electrode system is used, comprising a bismuth-coated glassy carbon (GC) working electrode, a platinum wire counter electrode, and a Ag/AgCl reference electrode [5].

- Electrode Preparation (Bismuth Film Deposition): The GC electrode is meticulously polished with alumina slurry, rinsed, and ultrasonically cleaned. The bismuth film is pre-plated by immersing the electrode in a solution containing 100 ppm Bismuth in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.6) and applying a deposition potential of -0.6 V for 10 minutes with slow stirring [5].

- Measurement Protocol: Analysis is performed in an acetate buffer medium. The method involves a preconcentration step where a deposition potential is applied for 5 minutes with stirring (-0.9 V for Pb, -1.2 V for Cd). This is followed by a square-wave voltammetric scan in a quiescent solution, which strips the deposited metals back into solution, generating the analytical current signal [5].

Critical Comparison: Selectivity and Practical Considerations

While sensitivity is crucial, the practical utility of an analytical method is equally dependent on its selectivity. A key finding from direct comparative studies is that potentiometric ISEs can offer higher selectivity in the presence of excess interfering metal ions like thallium, indium, and tin, which are common interferents in ASV operations [5].

The selectivity of an ISE is quantified by its potentiometric selectivity coefficient (( K_{A,B}^{pot} )). For instance, the Cd²⁺-ISE demonstrated logarithmic selectivity coefficients of -4.8 for In³⁺ and -5.2 for Tl⁺, while the Pb²⁺-ISE showed a value of -5.8 for Sn²⁺, indicating a strong preference for the primary ion over the interferent [5]. In voltammetry, overlapping stripping peaks from different metals can pose significant analytical challenges, requiring careful optimization of the waveform and potential control to resolve signals.

The following diagram outlines the logical decision-making process for selecting the appropriate technique based on analytical goals and sample matrix.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of both potentiometric and voltammetric sensors is heavily dependent on the materials used in their construction. The table below lists key reagents and their functions based on the protocols discussed.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Sensors

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophores (e.g., ETH 5435, Lead Ionophore IV) | Selective binding of target ions in the membrane phase. | Potentiometric ISEs for Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ [5]. |

| Lipophilic Ionic Additives (e.g., NaTFPB) | Balances charge in the sensing membrane, improves selectivity, and lowers detection limit. | Potentiometric ISEs [5]. |

| Copolymer Matrices (e.g., MMA-DMA) | Forms the polymeric membrane backbone; reduces ion fluxes to achieve lower detection limits. | Solid-contact ISEs [5]. |

| Bismuth (Bi) | Non-toxic "green" alternative to mercury for forming films on electrodes for metal preconcentration. | Bismuth-film working electrode for ASV [5]. |

| Gold Nanorods (AuNRs) | Nanostructured material providing high surface area, good biocompatibility, and fast electron transfer. | Voltammetric nitrite sensor [1]. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (MWCNTs, ErGO) | Enhance electrode conductivity and surface area; improve electrocatalytic activity and sensitivity. | Composites in voltammetric sensors [1]. |

| Conductive Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Increases electrode conductivity and can contribute to selectivity; used to composite with nanomaterials. | Electrode modifier in voltammetric sensors [1]. |

The choice between potentiometry and voltammetry for achieving optimal sensitivity is not a matter of one technique being universally superior. Instead, it requires a careful consideration of the analytical problem. Modern potentiometry excels in applications demanding high selectivity and low detection limits for specific ions in complex matrices without the need for a preconcentration step. Conversely, voltammetry offers powerful multi-analyte capability and exceptionally low detection limits, particularly when coupled with stripping techniques, and provides valuable insights into reaction mechanisms. The most robust analytical strategy may involve leveraging these techniques in parallel or developing hybrid systems to exploit their complementary strengths, thereby providing a more comprehensive analytical solution for demanding fields like drug development and environmental monitoring [5].

Potentiometric sensing is a cornerstone electrochemical technique that measures the potential difference (voltage) between two electrodes under conditions of zero or negligible current flow. This fundamental principle distinguishes it from other electrochemical methods, such as voltammetry and amperometry, which involve applying potentials and measuring resulting currents. As a potentiometric sensor operates without drawing significant current, the measurement is non-destructive and does not alter the chemical composition of the sample solution, making it exceptionally valuable for continuous monitoring and analysis of delicate biological systems [6] [7]. The core of this technique relies on the Nernst equation, which provides a quantitative relationship between the measured potential and the activity (concentration) of the target ion. Modern potentiometric sensors have evolved into sophisticated devices, including solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) and wearable formats, finding expansive applications in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical analysis [8].

This guide objectively compares the performance of potentiometric sensing with its primary alternative, voltammetric sensing, focusing on their fundamental operational principles, sensitivity, and suitability for different analytical scenarios, particularly in the context of drug development and biomedical research.

Theoretical Foundation: The Nernst Equation

The Nernst equation is the fundamental theoretical framework that governs potentiometric sensing. It describes the relationship between the electromotive force (EMF) of an electrochemical cell and the activities of the ions involved in the cell reaction [6]. For a general electrode reaction for a cation, ( M^{n+} + ne^- \rightleftharpoons M ), the Nernst equation is expressed as:

[ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln\left(\frac{1}{a{M^{n+}}}\right) = E^0 + \frac{2.303 RT}{nF} \log(a{M^{n+}}) ]

Variables of the Nernst Equation:

- ( E ): The measured electrode potential (in Volts, V)

- ( E^0 ): The standard electrode potential for the ion-selective system (V)

- ( R ): The universal gas constant (8.31439 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹)

- ( T ): The absolute temperature in Kelvin (K)

- ( n ): The charge number of the ion

- ( F ): The Faraday constant (96495.7 C·mol⁻¹)

- ( a_{M^{n+}} ): The activity of the target ion ( M^{n+} ) [6]

At a standard temperature of 25°C (298.15 K), the term ( \frac{2.303 RT}{F} ) simplifies to approximately 0.05916 V. Thus, for a monovalent ion (n=1), the potential changes by about 59.16 mV for every tenfold change in ion activity. For a divalent ion (n=2), the change is approximately 29.58 mV per decade [6]. This logarithmic relationship is the reason why potentiometric sensors can exhibit a very wide dynamic range, often spanning several orders of magnitude of concentration.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental components and the working logic of a potentiometric sensor based on the Nernst equation.

Potentiometric vs. Voltammetric Sensing: A Performance Comparison

The choice between potentiometric and voltammetric sensing depends heavily on the specific analytical requirements. The table below summarizes a direct comparison of their core characteristics, drawing on experimental data from dopamine sensing studies as a representative model [9].

Table 1: Performance comparison between potentiometric and voltammetric sensing for analyte detection.

| Feature | Potentiometric Sensing | Voltammetric Sensing |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Signal | Potential (Voltage) | Current |

| Current Flow | Zero or negligible (non-faradaic) | Significant (faradaic) |

| Analyte Consumption | Virtually zero | Yes (oxidation/reduction) |

| Theoretical Basis | Nernst Equation | Cottrell, Randles-Sevcik Equations |

| Selectivity Mechanism | Ionophore-mediated recognition | Applied potential & surface catalysis |

| Detection Limit (Dopamine) | Requires highly selective ionophore [9] | Down to 10⁻⁹ M or lower [9] |

| Small Sample Volume Suitability | Excellent (no analyte depletion) [9] | Challenged by analyte consumption & diffusion [9] |

| Key Advantage | No analyte consumption; intrinsic selectivity for cations over anions [9] | Very low detection limits; catalytic signal amplification [9] |

| Key Limitation | Requires highly selective ionophores for many analytes [9] | Diffusion-limited; requires stirring for optimal performance [9] |

As evidenced by the data, potentiometric sensing holds an intrinsic advantage in applications where sample preservation is critical or where the analyte is a cation and common interferences are anions [9]. For instance, in dopamine sensing, the primary interferents, ascorbic acid, and uric acid, are anionic and do not significantly interfere with cationic potentiometric sensors. In contrast, voltammetry excels when ultra-low detection limits are required, achieved by measuring the current from the electrochemical oxidation or reduction of the analyte itself [9].

Experimental Protocols for Potentiometric Sensing

The development and application of a potentiometric sensor involve a series of methodical experimental steps. The following workflow and detailed protocol are synthesized from multiple sensor development studies [10] [11].

Detailed Protocol: Fabrication and Calibration of a Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrode (SC-ISE)

The following protocol is typical for creating a coated graphite or carbon paste electrode, as used for the detection of ions like Pb²⁺ and Cu²⁺ [10] [11].

Sensor Fabrication:

- Membrane Preparation: Combine the key components in a mortar or via dissolution: Ionophore (e.g., 1-6% by weight), Polymeric matrix (e.g., PVC, 32%), Plasticizer (e.g., Nitrobenzene or o-NPOE, 40-65%), and a Lipophilic additive (e.g., NaTPB, 2%). The exact composition is optimized for each sensor [10] [11].

- Electrode Assembly: For a coated graphite electrode, the membrane cocktail is directly applied onto a graphite rod or screen-printed electrode. For a carbon paste electrode, the membrane components are thoroughly mixed with graphite powder and a plasticizer to form a homogeneous paste, which is then packed into an electrode body [11].

- Conditioning: The newly fabricated sensor is soaked in a solution containing the target ion (e.g., 10⁻³ M Pb²⁺ or Cu²⁺ solution) for several hours (often 24 hours) to establish a stable equilibrium at the membrane surface [11].

Calibration and Performance Characterization:

- Calibration Curve: The conditioned sensor is connected to a high-impedance potentiometer alongside a standard reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl). The potential is measured in a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target ion, typically ranging from 10⁻⁷ M to 10⁻¹ M [10] [11].

- Data Analysis: The measured potential (E) is plotted against the logarithm of the ion activity (log a). A linear regression fit is applied to the linear portion of the plot. The slope of the line should be close to the theoretical Nernstian slope (∼59.2 mV/decade for n=1, ∼29.6 mV/decade for n=2), and the detection limit is determined from the intersection of the two linear segments of the calibration curve [11] [6].

- Selectivity Determination: The potentiometric selectivity coefficient (( K_{A,B}^{pot} )) is a critical parameter, quantifying the sensor's ability to distinguish the primary ion from interferents. It is determined using methods like the Separate Solution Method (SSM), Fixed Interference Method (FIM), or Matched Potential Method (MPM) [11].

Validation with Real Samples:

- The sensor's performance is validated by analyzing real samples (e.g., water, serum, pharmaceutical formulations) and comparing the results with those obtained from a standard reference method like Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) or Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS). Statistical tests (e.g., t-test) are used to confirm there is no significant difference between the results [10] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of a potentiometric sensor is highly dependent on the quality and composition of its materials. The table below lists key components used in modern sensor fabrication [10] [11] [8].

Table 2: Key materials and reagents for fabricating potentiometric sensors.

| Material/Reagent | Function | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophore | The molecular recognition element that selectively binds the target ion. | Crown ethers (e.g., Dicyclohexyl-18-crown-6), synthetic molecules, Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Schiff bases [9] [10] [11]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Provides the structural backbone for the ion-selective membrane. | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), Silicone rubber [10] [11]. |

| Plasticizer | Imparts plasticity and mobility to membrane components; can influence dielectric constant. | o-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE), Nitrobenzene, Dioctyl phthalate (DOP) [10] [11]. |

| Ion-Exchanger | Introduces initial ionic sites in the membrane and governs the intrinsic membrane permselectivity. | Potassium tetrakis(p-Cl-phenyl)borate (KClTPB) [9]. |

| Solid Contact Material | Replaces the inner filling solution; mediates ion-to-electron transduction. | Conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT), Carbon nanomaterials (e.g., MWCNTs), Nanocomposites [8]. |

| Solvent | Dissolves membrane components for homogeneous film casting. | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Cyclohexanone [9]. |

Advanced Applications and Future Trends

Potentiometric sensing continues to evolve, with several advanced formats enhancing its applicability in biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

- Wearable Sensors: A major trend is the development of wearable potentiometric sensors for the continuous monitoring of electrolytes (e.g., K⁺, Na⁺), metabolites, and even pharmaceuticals in biofluids like sweat and interstitial fluid. This is particularly valuable for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of pharmaceuticals with a narrow therapeutic index [8].

- 3D-Printed and Paper-Based Sensors: 3D printing offers rapid prototyping and customization of electrode designs, while paper-based sensors provide a cost-effective, disposable platform for point-of-care (POC) testing, ideal for in-field analysis [8].

- Light-Addressable Potentiometric Sensors (LAPS): LAPS is a semiconductor-based sensor that allows for spatially resolved chemical imaging. It can be integrated into multi-electrode systems to simultaneously monitor electrochemical reactions and ion distributions in solution [7].

- Drug Analysis in Biological Samples: Potentiometric sensors have been successfully applied to determine concentrations of various drug molecules in complex biological matrices like blood serum and urine, offering a simple and rapid alternative to more complex techniques [12].

Electrochemical analysis is a versatile discipline in analytical chemistry that measures electrical properties like current, voltage, or resistance to determine the chemical properties of a solution [3]. These methods have become indispensable tools across clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and materials science due to their excellent sensitivity for trace-level analysis, wide linear dynamic range, and relatively low cost of instrumentation [3]. At the heart of every electrochemical measurement is a chemical reaction involving the transfer of electrons, known as a redox reaction, which can be driven by an external electrical potential or can itself generate a potential [3].

Electrochemical techniques are broadly categorized based on the electrical property being measured and how it is controlled. Voltammetry encompasses techniques that measure current as a function of an applied potential, providing both qualitative and quantitative information about electroactive species [3] [8]. In contrast, potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes when no net current is flowing through the cell, providing a direct function of the concentration or activity of a specific ion in the solution [3] [8]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these fundamental electrochemical approaches, with a focused examination of their relative sensitivities and applications in modern research and development contexts, particularly in pharmaceutical and environmental sciences.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison

Voltammetry: Current as a Function of Applied Potential

Voltammetry is a dynamic electrochemical technique that measures the current passing through an electrochemical cell as the applied potential is systematically varied [3]. The resulting plot of current versus potential, called a voltammogram, provides a wealth of qualitative and quantitative information about the analyte, including its identity, concentration, and details about the kinetics and mechanisms of redox reactions [3]. The fundamental setup for most voltammetric analysis involves a three-electrode system: a working electrode where the redox reaction of interest occurs, a reference electrode that provides a stable and known potential, and a counter electrode that completes the circuit [3].

Various voltammetric techniques have been developed, each with specific advantages. Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) involves scanning the potential in a forward and reverse direction, creating a characteristic butterfly-shaped current-potential curve that reveals information about reaction reversibility, electron transfer rates, and the presence of intermediate species [3]. Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) applies small, successive potential pulses to the working electrode and measures the current difference between forward and reverse pulses, significantly minimizing background current and resulting in a much better signal-to-noise ratio [13]. Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is another pulsed technique known for high sensitivity in trace analysis of organic compounds, pharmaceuticals, and heavy metals [3].

Potentiometry: Potential Measurement at Zero Current

Potentiometry measures the potential difference between two electrodes (an indicator electrode and a reference electrode) when no significant current is flowing through the cell [3] [8]. This potential difference is related to the concentration of a specific ion in the solution by the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the potential of an electrode and the concentration of the species undergoing a redox reaction [3]. The most familiar application of potentiometry is pH measurement using a glass electrode, but the technique has been extended to numerous other ions through the development of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) [3].

Potentiometric sensors are classified based on the nature of the interface on the backside of the ion-selective membrane: liquid-contact (LC-ISE) and solid-contact (SC-ISE) electrodes [8]. Solid-contact ion-selective electrodes have gained prominence due to advantages such as ease of miniaturization, portability, stability, and enhanced detection in complex matrices [8]. Recent trends in potentiometric sensors include 3D printing for improved flexibility and precision in manufacturing, paper-based sensors for cost-effective point-of-care analysis, and wearable sensors for continuous monitoring of biomarkers, electrolytes, and pharmaceuticals [8].

Comparative Analysis: Voltammetry vs. Potentiometry

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Voltammetry and Potentiometry

| Parameter | Voltammetry | Potentiometry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Current | Potential difference |

| Current Flow | Significant | Negligible (zero-current) |

| Primary Applications | Trace metal analysis, drug quantification, reaction mechanism studies [3] | pH measurement, ion-selective electrodes for Na+, K+, F−, clinical electrolyte analysis [3] |

| Sensitivity | Excellent for trace-level analysis (nM to pM range) [14] | Good for ion activity measurements (μM to mM range) [8] [11] |

| Selectivity | Achieved through potential control and electrode modification [14] | Achieved through ion-selective membranes [8] [11] |

| Information Obtained | Both qualitative and quantitative [3] | Primarily quantitative [3] |

| Technique Variants | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) [3] [13] | Direct potentiometry, potentiometric titrations [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Voltammetric Experimental Design

Voltammetric experiments require careful optimization of parameters to achieve high sensitivity and reproducibility. A recent study demonstrating the determination of hazardous 2-nitrophenol (2-NP) in environmental samples provides an excellent example of systematic voltammetric method development [14]. The researchers prepared a modified glassy carbon electrode through the electropolymerization of 2-amino nicotinamide (2-AN) and used Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) for quantification [14].

The experimental workflow comprised several critical steps. Electrode modification began with polishing the glassy carbon electrode, followed by electropolymerization of 2-AN using cyclic voltammetry with the optimum number of deposition cycles determined to be 5 [14]. The modified electrode surface was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm successful attachment of 2-AN to the GC surface [14]. For the SWV measurements, parameters including pulse amplitude, frequency, and potential step were optimized using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) experimental design to achieve the highest current response for 2-NP [14]. The reduction peak of 2-NP in Britton-Robinson buffer solution at pH 1.01 was used for quantitative determination [14]. The method was validated through the analysis of real samples including tap water and river water, with percentage relative standard deviation values between 1.0 and 3.9 and recovery values between 97.1 and 103.6% [14].

Diagram 1: Voltammetric Experimental Workflow. The diagram illustrates the systematic steps involved in developing a voltammetric method, from electrode preparation to method validation.

Potentiometric Sensor Fabrication and Measurement

The development of a potentiometric sensor for Cu(II) detection in environmental and pharmaceutical samples illustrates a comprehensive approach to potentiometric method design [11]. The researchers developed a graphite-based sensor modified with a Schiff base ligand (2-(((3-aminophenyl) imino) methyl) phenol) for selective determination of Cu(II) ions [11].

The sensor fabrication process involved several key stages. The Schiff base ligand was synthesized via a condensation reaction between m-phenylenediamine and 2-hydroxybenzaldehyde in ethanol, with the product characterized by FT-IR and 1H-NMR spectroscopy [11]. The carbon paste electrode was prepared by thoroughly mixing 250 mg of graphite powder with 5-20 mg of the synthesized ionophore and 0.1 mL of plasticizer, then filling the paste into a Teflon holder serving as the electrode body [11]. The sensor surface was characterized using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) combined with energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) for morphological analysis and elemental composition [11]. Potentiometric measurements were performed using a double-junction silver-silver chloride reference electrode, with the potential response measured across varying Cu(II) concentrations [11]. The sensor's performance was validated through the analysis of real samples including spiked water, multivitamin supplements, and vegetable foliar, with results compared to atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) as a reference method [11].

Sensitivity Comparison: Experimental Data Analysis

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Direct comparison of recent research applications demonstrates the distinct sensitivity profiles of voltammetric and potentiometric techniques across different analyte classes. The following table summarizes experimental detection capabilities reported in recent studies for both techniques.

Table 2: Sensitivity Comparison of Voltammetric and Potentiometric Techniques from Recent Studies

| Technique | Analyte | Matrix | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Square Wave Voltammetry | 2-Nitrophenol | Environmental water | 9.9 nM - 603 µM | 2.92 nM | [14] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry | Thymoquinone | Nigella sativa products | Not specified | 8.9 nM | [15] |

| Potentiometry | Cu(II) ions | Water, pharmaceuticals | 1×10⁻⁷ - 1×10⁻¹ M | 5.0×10⁻⁸ M (50 nM) | [11] |

| Potentiometry | Pb(II) ions | Aquatic environments | Not specified | 1.5×10⁻⁸ M (15 nM) | [16] |

| Potentiometry | Ca(II) ions | Extracellular fluid | 0.1 mM - 1 mM | Not specified | [17] |

| Potentiometry | Hg(II) ions | Aqueous solutions | 10⁻⁶ - 10⁻¹ M | Not specified | [18] |

Analysis of Sensitivity Profiles

The data presented in Table 2 reveals important insights about the sensitivity characteristics of voltammetric versus potentiometric techniques. Voltammetry demonstrates exceptional sensitivity for specific organic compounds, with detection limits reaching the nanomolar range, as evidenced by the 2.92 nM detection limit for 2-nitrophenol and 8.9 nM for thymoquinone [14] [15]. Modern potentiometric sensors also achieve impressive detection capabilities for metal ions, with demonstrated detection limits of 50 nM for Cu(II) and 15 nM for Pb(II) [11] [16]. The sensitivity of potentiometric sensors is highly dependent on the ionophore used in the selective membrane, with recent advancements in materials science contributing to improved performance [8] [11] [16].

Potentiometric sensors typically exhibit Nernstian response behavior, with theoretical slopes of approximately 29.6 mV per decade for monovalent ions and 19.7 mV per decade for divalent ions at 25°C [3]. Experimental studies have confirmed this behavior, with reported slopes of 29.571 mV per decade for Cu(II) [11], 33.0 mV per decade for Hg(II) [18], and approximately 20 mV per decade for Ca(II) [17]. This logarithmic relationship between potential and concentration provides potentiometry with a wide dynamic range, typically covering 4-6 orders of magnitude of concentration [11].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of electrochemical techniques requires specific materials and reagents optimized for each methodology. The following table details key components used in contemporary voltammetric and potentiometric research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Techniques

| Category | Specific Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Technique |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Glassy Carbon Electrode | Working electrode substrate for modifications | Voltammetry [14] |

| Electrode Materials | Carbon Paste Electrode | Customizable working electrode matrix | Both [11] [15] |

| Electrode Materials | Silver/Silver Chloride Electrode | Stable reference electrode | Both [3] [15] |

| Modifiers/ Ionophores | 2-Amino Nicotinamide (2-AN) | Electrode modifier for enhanced 2-NP detection | Voltammetry [14] |

| Modifiers/ Ionophores | Schiff Base Ligands | Selective ionophores for metal ion recognition | Potentiometry [11] |

| Modifiers/ Ionophores | Thiophanate-Methyl (TPM) | Selective binding agent for Pb²⁺ detection | Potentiometry [16] |

| Modifiers/ Ionophores | BAPTA-based Copolymer | Calcium-selective polymer matrix | Potentiometry [17] |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Britton-Robinson Buffer | Versatile pH buffer for electrochemical studies | Voltammetry [14] |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Various Plasticizers (o-NPOE, DOP, TCP) | Membrane components for ion-selective electrodes | Potentiometry [11] |

Voltammetric and potentiometric techniques offer complementary capabilities for chemical analysis, each with distinct advantages for specific applications. Voltammetry provides exceptional sensitivity for trace-level analysis of electroactive organic compounds and offers the unique capability for mechanistic studies of redox processes. Potentiometry excels in direct ion activity measurements with relatively simple instrumentation, wide dynamic range, and recent advancements enabling miniaturization for point-of-care testing and continuous monitoring applications.

The choice between these techniques ultimately depends on the specific analytical requirements, including the nature of the target analyte, required detection limits, sample matrix, and available instrumentation. For researchers investigating redox-active pharmaceuticals or requiring mechanistic insights into electron transfer processes, voltammetric techniques offer unparalleled capabilities. For applications focused on monitoring specific ions in complex matrices like biological fluids or environmental samples, modern potentiometric sensors with advanced materials provide robust, selective, and sensitive detection.

Recent trends in both fields point toward increased miniaturization, materials innovation, and integration with portable instrumentation, expanding the applications of electrochemical analysis in field testing, point-of-care diagnostics, and continuous monitoring systems. The convergence of these techniques with advanced manufacturing methods like 3D printing and nanotechnology promises to further enhance their sensitivity, selectivity, and accessibility for research and applied analytical applications.

Electrochemical sensors are powerful tools in analytical chemistry, with potentiometry and voltammetry representing two foundational techniques. Potentiometry measures the potential difference between an indicator electrode and a reference electrode under conditions of zero current, with the signal being proportional to the logarithm of the target analyte concentration. In contrast, voltammetry applies a potential waveform to an electrode and measures the resulting current, which is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species. The fundamental difference in their signal generation mechanisms—potential versus current measurement—leads to distinct performance characteristics in terms of sensitivity, detection limits, and dynamic range. These differences make each technique uniquely suited to particular applications, from environmental monitoring to pharmaceutical analysis and clinical diagnostics.

This guide provides a systematic comparison of key sensitivity parameters between potentiometric and voltammetric sensors, supported by experimental data from recent research. Understanding these parameters is essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select the optimal analytical technique for their specific application needs.

Comparative Analysis of Sensitivity Parameters

Table 1: Comparison of Sensitivity Parameters for Potentiometric Sensors

| Analyte | Sensor Type | Linear Range | Response Slope (mV/decade) | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium ions | Solid-contact ISE | 240 μM–250 mM | 57.1 | 2.4 μM | [19] |

| Copper ions | Graphite-based CPE | 0.1 μM–0.1 M | 29.57 | 0.05 μM | [20] |

| Calcium ions | BAPTA-based polymer | 0.1–1 mM | 20.0 | - | [17] |

| Bisoprolol | PVC membrane ISE | 1 μM–10 mM | 52.0 | 2.6 μM | [21] |

| Alverine | PVC membrane ISE | 1 μM–10 mM | 56.0 | 1.75 μM | [21] |

| Bromazepam | ISE (BRZ-PTA) | 1 μM–1 mM | 54.0 | - | [22] |

| Bromazepam | ISE (BRZ-TPB) | 1 μM–1 mM | 57.0 | - | [22] |

Table 2: Comparison of Sensitivity Parameters for Voltammetric Sensors

| Analyte | Sensor Type | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobramycin | MIP/Au-SPE | 0.001–60 pg/mL | 1.9 pg/mL | [23] |

| Melatonin | BDDE/CCPSA | - | 14.6 μg/L | [24] |

| Melatonin | BDDE/SWV | - | 110 μg/L | [24] |

| Luteolin | NC@ZIF-8/GCE | 0.05–30 μM | 0.011 μM | [25] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Characterization

Sensor Fabrication and Optimization

The construction of high-performance electrochemical sensors requires meticulous attention to material selection and fabrication protocols. For potentiometric sensors, a common approach involves preparing ion-selective membranes composed of poly(vinyl chloride) plasticized with various mediators such as o-nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE), dioctyl phthalate (DOP), or dibutyl sebacate (DBS). The electroactive components typically include ion-pair complexes formed between the target ion and appropriate counter ions such as phosphotungstic acid (PTA) or sodium tetraphenylborate (TPB). These components are dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and evaporated to form membranes of consistent thickness (typically 0.1 mm), which are then mounted on electrode bodies and conditioned in standard solutions of the target analyte for 24 hours prior to use [21] [22].

For voltammetric sensors, surface modification is crucial for enhancing sensitivity and selectivity. A representative protocol involves polishing glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) with alumina slurry to a mirror finish, followed by modification with advanced nanocomposites. For instance, nitrogen-doped hollow carbon sphere @ZIF-8 (NC@ZIF-8) composites can be prepared by synthesizing hollow carbon spheres using SiO₂ as a template, followed by in-situ growth of ZIF-8 crystals. The resulting composite is dispersed in a Nafion-containing solution, and a precise volume (typically 5 μL) is drop-cast onto the GCE surface and dried to create a uniform sensing layer [25].

Measurement Procedures and Data Acquisition

Potentiometric measurements are performed by immersing the conditioned indicator electrode along with an appropriate reference electrode (typically Ag/AgCl) in standard solutions with concentrations spanning the expected dynamic range. The potential is recorded under zero-current conditions after stabilization, and the values are plotted against the logarithm of analyte concentration. The ideal Nernstian slope is 59.16 mV/decade for monovalent ions and 29.58 mV/decade for divalent ions at 25°C, with deviations indicating non-ideal behavior [20] [21].

Voltammetric techniques encompass various potential waveforms and measurement strategies. For cyclic voltammetry (CV), the potential is scanned linearly between designated initial and switching potentials while recording the current response. Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) applies potential pulses superimposed on a linear ramp, measuring the current difference just before and at the end of each pulse to minimize capacitive currents. Square wave voltammetry (SWV) uses a symmetrical square wave superimposed on a staircase ramp, offering excellent sensitivity and rejection of background currents. Constant current potentiometric stripping analysis (CCPSA), used for melatonin detection, involves an accumulation step where the analyte is concentrated onto the electrode surface, followed by a stripping step where the accumulated species is oxidized or reduced while monitoring the potential as a function of time [24] [25].

Limit of Detection Determination

The limit of detection (LOD) represents the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the analytical background. Multiple approaches exist for LOD determination in electrochemical sensors. The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) method defines LOD as the concentration yielding a signal three times the standard deviation of the blank measurement (LOD = 3 × σ) [26]. The linear calibration method calculates LOD using the formula LOD = 3.3 × σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank response and S is the slope of the calibration curve. For voltammetric sensors, visual evaluation through serial dilution until the voltammetric peak becomes indistinguishable from background noise provides a practical estimation, though this approach is more subjective [26]. Recent studies emphasize the importance of determining realistic LOD values under intermediate precision conditions that account for sample preparation, matrix effects, and measurement variability encountered in actual applications [26].

Visual Guide to Electrochemical Sensing

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Sensor Development

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Screen-printed gold electrodes (Au-SPE) | Transducer platform | Tobramycin detection [23] |

| Boron-doped diamond electrodes (BDDE) | Working electrode with wide potential window | Melatonin determination [24] | |

| Glassy carbon electrodes (GCE) | Versatile working electrode base | Luteolin sensor [25] | |

| Graphite powder | Conductive matrix for carbon paste electrodes | Copper ion sensor [20] | |

| Polymer Matrices | Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | Membrane matrix for ion-selective electrodes | Bisoprolol, alverine, bromazepam sensors [21] [22] |

| Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrene-sulfonate) (PEDOT-PSS) | Conductive polymer for solid-contact electrodes | Calcium ion sensor [17] | |

| Plasticizers | o-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) | Solvent mediator for membrane electrodes | Various ISEs [20] [21] [22] |

| Dioctyl phthalate (DOP) | Alternative plasticizer | Membrane optimization [22] | |

| Ion Exchangers | Potassium tetrakis(p-chlorophenyl) borate (KTpClPB) | Anionic additive for cation-selective membranes | Pharmaceutical ISEs [21] |

| Sodium tetraphenylborate (TPB) | Ion-pairing agent for drug sensors | Bromazepam sensor [22] | |

| Nanomaterials | Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Signal amplification | Tobramycin MIP sensor [23] |

| Nitrogen-doped hollow carbon spheres | Enhanced conductivity and surface area | Luteolin sensor [25] | |

| ZIF-8 metal-organic framework | High surface area for analyte preconcentration | Luteolin sensor [25] | |

| Solvents | Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Membrane solvent for PVC-based ISEs | Sensor fabrication [22] |

| Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) | Supporting electrolyte | Electrochemical measurements [23] [25] |

The comparative analysis of sensitivity parameters reveals distinct advantages for both potentiometric and voltammetric techniques. Potentiometry generally offers wider linear ranges (typically spanning 3-6 orders of magnitude) and well-defined Nernstian response slopes, making it ideal for applications requiring the quantification of ionic species across broad concentration ranges, particularly in pharmaceutical quality control and environmental monitoring [19] [21]. The technique benefits from simple instrumentation, operational stability, and the ability to measure colored or turbid samples without interference.

In contrast, voltammetry demonstrates superior detection limits, often reaching picomolar or even sub-nanomolar levels, making it the technique of choice for trace analysis of electroactive organic compounds, pharmaceutical residues, and biomarkers in complex matrices [23] [25]. The trade-off typically involves narrower linear ranges and more complex measurement protocols that may require careful optimization of multiple waveform parameters.

Technique selection should be guided by the specific analytical requirements: potentiometry for broad-range ionic measurements with operational simplicity, and voltammetry for ultra-trace determination of electroactive compounds where higher sensitivity justifies more complex operational protocols. Recent advancements in materials science, particularly the development of novel nanomaterials and selective recognition elements, continue to push the sensitivity boundaries of both techniques, expanding their applications in pharmaceutical analysis, clinical diagnostics, and environmental monitoring.

The performance of electrochemical sensors is fundamentally governed by the properties of the electrode-solution interface. For researchers and drug development professionals, the choice between potentiometric and voltammetric techniques hinges on a deep understanding of how electrode materials and their surface characteristics control sensitivity, selectivity, and detection limits. While potentiometry measures potential at zero current, and voltammetry measures current under applied potential, both techniques rely on optimized electrode interfaces for effective analyte detection [9] [27]. Recent advances in nanostructured materials and surface modification strategies have significantly enhanced our ability to tailor these interfaces for specific sensing applications, pushing detection limits to trace levels for biologically and clinically relevant analytes [28] [27].

This guide provides a systematic comparison of how surface properties govern sensitivity in these two prominent electrochemical approaches, supported by experimental data and protocols relevant to pharmaceutical and clinical research.

Fundamental Principles and Sensitivity Mechanisms

Core Sensing Mechanisms

The fundamental difference in how potentiometric and voltammetric sensors generate signals leads to distinct considerations for electrode design and surface modification.

Potentiometric Sensors measure the equilibrium potential difference across an electrode interface relative to a reference electrode, which changes in response to analyte activity. This technique benefits from minimal analyte consumption, making it particularly suitable for small sample volumes or continuous monitoring where preserving sample integrity is crucial [9]. The potential is governed by the Nernst equation, and sensitivity is expressed as the Nernstian slope (mV/decade).

Voltammetric Sensors measure the current resulting from the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive analyte at a controlled potential. Sensitivity in this technique relates to the magnitude of the faradaic current, which is proportional to analyte concentration. A significant consideration is analyte consumption during the measurement process, which can be a limiting factor in small sample volumes or at low concentrations [9].

Key Electronic and Geometric Surface Properties

The following table summarizes the critical surface properties that influence sensitivity in both techniques.

Table 1: Key Surface Properties Governing Electrode Sensitivity

| Property | Impact on Potentiometric Sensitivity | Impact on Voltammetric Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|

| Electrocatalytic Activity | Indirect; affects equilibrium potential and response time. | Direct; lowers overpotential, increases electron transfer rate, and boosts current response. |

| Surface Area | Minimal impact on Nernstian slope, but can improve signal-to-noise ratio. | Major impact; directly increases faradaic current (i~Area). |

| Interfacial Architecture | Critical for ionophore-analyte interaction and membrane stability. | Critical for mass transport and accessibility of active sites. |

| Electrical Conductivity | Ensures efficient potential measurement; high conductivity is essential. | Directly influences electron transfer kinetics and measured current. |

| Binding Affinity/Selectivity | Governed by ionophore in the membrane; dictates selectivity and sensitivity. | Governed by surface modifiers; can be engineered for specific analyte recognition. |

Comparative Analysis: Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry

Direct Comparison of Advantages and Limitations

The choice between potentiometry and voltammetry involves trade-offs between sensitivity, selectivity, and practical implementation. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental operational difference between the two techniques.

The core operational differences lead to distinct practical advantages and limitations, which are compared in the table below.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Feature | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Signal | Potential (V) at zero current [9] | Current (i) from redox reactions [9] |

| Analyte Consumption | Virtually zero [9] | Significant (can be a limitation in small volumes) [9] |

| Typical Detection Limit | ~10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁸ M (highly dependent on ionophore) [9] [18] | Can reach ~10⁻⁹ M or lower with modified surfaces [9] |

| Selectivity Mechanism | Ionophore-analyte binding affinity in a membrane [9] | Applied potential and surface catalyst selectivity [9] |

| Impact of Mass Transport | Minimal | Critical; diffusion can be the rate-limiting step [9] |

| Key Advantage | Ideal for small volumes and continuous monitoring | Very high sensitivity and tunable via potential control |

| Primary Challenge | Requires highly selective ionophores for accurate measurement [9] | Susceptible to electrode fouling and interference from surface-active species [28] |

Quantitative Performance Data

Experimental data from recent studies highlights how material choices and surface modification directly impact sensor metrics. The following table compiles performance data for different electrode materials and modifications.

Table 3: Experimental Sensor Performance of Selected Electrode Materials and Modifications

| Analyte | Electrode Material / Modification | Technique | Reported Sensitivity / Performance | Detection Limit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hg²⁺ Ions | WS₂-WO₃/Poly-2-aminobenzene-1-thiol Nanocomposite [18] | Potentiometry | Nernstian slope: 33.0 mV/decade [18] | Not Specified (Linear from 10⁻⁶ M) |

| Hg²⁺ Ions | WS₂-WO₃/Poly-2-aminobenzene-1-thiol Nanocomposite [18] | Cyclic Voltammetry | Sensitivity: 2.4 μA/M [18] | Not Specified (Linear from 10⁻⁶ M) |

| Dopamine | Bare Gold and Platinum Microelectrodes [9] | Voltammetry | -- | ~10⁻⁷ M (in 200 μl samples) [9] |

| Prostate Cancer Gene (PCA3) | DNA-coated Gold Electrode with PVA Protection [29] | Amperometry (CRISPR-based) | -- | Demonstrated after 2-month storage [29] |

Advanced Materials and Surface Modification Strategies

Material Classes and Their Functions

The integration of advanced functional materials has been a key driver in improving sensor sensitivity.

- Nanostructured Materials: Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and metal nanoparticles provide a large surface area, excellent conductivity, and the ability to adsorb various analytes, significantly boosting the current response in voltammetry and improving the signal-to-noise ratio in potentiometry [28] [27].

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Materials like ZIF-8 and HKUST-1 offer high porosity and tunable structures that enhance interaction with target analytes. Their large surface areas provide numerous active sites, improving sensitivity for heavy metal ions, gas sensing, and biosensing [30] [27].

- Conducting Polymers: Polymers such as polyaniline (PANI) and polypyrrole (PPy) improve both electrochemical properties and mechanical stability when used to modify electrode surfaces. They offer biocompatibility and signal amplification properties, making them suitable for bio-detection [27].

- 2D Xenes: Silicene, a silicon analogue of graphene, shows promise for energy storage but is also relevant for sensing due to its high theoretical capacity, large surface area, and low diffusion energy barrier for ions [31].

Surface Modification Techniques

Modifying the electrode surface is crucial for optimizing its interface with the sample. Common techniques include:

- Drop Casting: A simple method where a droplet of modifier suspension is applied to the electrode surface and dried. A key challenge is the "coffee-ring" effect, which can lead to inhomogeneous coating [28].

- Electrochemical Deposition: A versatile method for fabricating layers of metal nanostructures or polymers on the electrode surface with precise control over thickness and morphology using either potentiostatic or potentiodynamic modes [28].

- Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs): Used to create highly ordered, single-molecule-thick layers on electrode surfaces, providing a platform for immobilizing biorecognition elements like enzymes or antibodies [27].

- Layer-by-Layer (LbL) Assembly: Allows for precise construction of multi-layered sensor surfaces with controlled composition and thickness, improving electrochemical response and selectivity [27].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Characterization

Protocol: Fabrication of a Nanocomposite-Modified Electrode for Heavy Metal Sensing

This protocol outlines the synthesis and modification steps for creating a potentiometric Hg²⁺ sensor, as exemplified by the WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT nanocomposite [18].

Nanocomposite Synthesis (Oxidative Polymerization):

- Dissolve 0.06 M of the monomer 2-aminobenzene-1-thiol (2ABT) in 1.0 M hydrochloric acid (HCl).

- Add 0.14 M of an oxidizing agent (e.g., K₂S₂O₈) to initiate free radical formation and polymerize the monomer to P2ABT.

- Allow the reaction to proceed for 24 hours at ambient temperature.

- To form the WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT nanocomposite, use a mixture of Na₂WO₄ and K₂S₂O₈ as oxidizing agents in the presence of the monomer, facilitating the integration of WO₃ and WS₂ into the polymer matrix over 24 hours [18].

Electrode Modification (Drop Casting):

- Prepare a stable suspension or solution of the synthesized WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT nanocomposite.

- Apply a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the suspension onto the surface of a clean, polished electrode (e.g., glassy carbon or gold).

- Allow the solvent to evaporate under controlled conditions (e.g., room temperature or under an infrared lamp) to form a thin, uniform film [28] [18].

Potentiometric Measurement (Two-Electrode Cell):

- Use the modified electrode as the working electrode and a calomel electrode (Hg/Hg₂Cl₂) or another suitable reference electrode.

- Immerse the electrode pair in standard solutions of Hg²⁺ with concentrations ranging from 10⁻⁶ M to 10⁻¹ M.

- Measure the equilibrium potential (in mV) for each solution without applying any current.

- Plot the potential vs. the logarithm of the Hg²⁺ concentration to obtain the calibration curve and calculate the Nernstian slope [18].

Protocol: Investigating Dopamine via Cyclic Voltammetry with Bare Electrodes

This protocol describes a voltammetric approach for detecting neurotransmitters like dopamine in small volumes, highlighting the critical role of mass transport [9].

Cell and Electrode Preparation:

- Use a miniature electrochemical cell (e.g., a "barrel" type cell with a 200 µL volume) to accommodate small sample volumes.

- Employ a standard three-electrode system: a bare gold or platinum microelectrode as the working electrode, a platinum wire as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Clean the working electrode surface meticulously according to established procedures (e.g., polishing, electrochemical cleaning) to ensure reproducibility [9].

Cyclic Voltammetry Measurement:

- Prepare dopamine solutions in a suitable buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer saline) across the desired concentration range (e.g., 10⁻⁷ M to 10⁻⁴ M).

- Set the potentiostat parameters: a scan rate typically between 50-100 mV/s, and a potential window that encompasses the oxidation and reduction peaks of dopamine (e.g., -0.2 V to +0.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl).

- Run the cyclic voltammetry scans for each dopamine solution. Note that without stirring, the diffusion of dopamine to the electrode surface can be the limiting factor [9].

Data Analysis:

- Record the peak oxidation current (iₚ) for each voltammogram.

- Plot the peak current (iₚ) against the dopamine concentration to establish the calibration curve and determine the sensor's sensitivity.

- To overcome diffusion limitations, consider using microelectrode arrays, which enhance mass transport and provide a steadier signal [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrode Development and Sensing

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrodes | A common, stable baseline working electrode material with a wide potential window, often used as a substrate for modifications [28]. |

| Gold and Platinum Electrodes | Preferable for biomolecule immobilization (e.g., thiolated DNA) and applications requiring a well-defined, clean metal surface [29] [9]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Used in potentiometry; typically consist of PVC, a plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE), an ionophore, and an ion exchanger to provide selectivity for specific ions [9]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes & Graphene | Nanostructured carbon materials used to modify electrodes, providing high surface area and enhanced electron transfer kinetics [28] [27]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (ZIF-8) | Porous crystalline materials used as modifying agents to create high-surface-area electrodes with selective adsorption properties [27]. |

| Conducting Polymers (PANI, PPy) | Polymers used to coat electrodes, improving conductivity, stability, and providing a matrix for embedding recognition elements [27]. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Kits | Pre-formulated reagents for creating ordered monolayers on gold surfaces, used for functionalizing electrodes with specific molecular groups [27]. |

| CRISPR Cas12 Enzyme | A biological recognition element used in novel biosensors; upon detecting target DNA/RNA, it cleaves reporter DNA on the electrode, generating an electrical signal [29]. |

| Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA) | A polymer used as a protective coating to stabilize DNA on electrode surfaces, extending sensor shelf-life [29]. |

The sensitivity of both potentiometric and voltammetric sensors is profoundly dictated by the physicochemical properties of the electrode-solution interface. Potentiometry offers distinct advantages for small-volume analysis due to its non-consumptive nature, but its success is contingent on the development of highly selective recognition layers. Voltammetry provides superior sensitivity and is highly tunable through material design and potential control, though it must overcome challenges related to mass transport and fouling. The ongoing integration of advanced nanomaterials like MOFs, conducting polymers, and 2D materials, coupled with sophisticated surface modification strategies, continues to push the boundaries of detection. For researchers in drug development, this evolving toolkit enables the design of increasingly sensitive, selective, and robust electrochemical sensors for a wide range of applications, from therapeutic monitoring to diagnostic assays.

Practical Implementation: Achieving Optimal Sensitivity in Real-World Applications

The pursuit of maximum analytical sensitivity is a central goal in electrochemical sensor development, driving innovations in fields from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring. Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) represent a cornerstone of potentiometric sensing, valued for their simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and real-time measurement capabilities [32]. The fundamental operation of ISEs relies on measuring the potential difference across an ion-selective membrane at zero current, with the signal following a logarithmic relationship to ion activity as described by the Nernst equation [3] [32].

This guide objectively compares the sensitivity performance of potentiometric ISEs against voltammetric techniques, with a specific focus on design principles that enhance detection limits. While voltammetry often achieves lower detection limits through pre-concentration steps like in anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) [33] [34], modern ISE designs incorporating advanced materials and nanostructures are progressively closing this sensitivity gap while maintaining superior selectivity and operational simplicity.

Fundamental Principles and Sensitivity Comparison

Core Principles of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

Potentiometric and voltammetric techniques operate on fundamentally different principles, which directly impact their sensitivity characteristics and applications. The table below compares their core operational mechanisms:

Table 1: Fundamental comparison of potentiometric and voltammetric techniques

| Feature | Potentiometry (ISE) | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Potential (voltage) at zero current [3] | Current as function of applied potential [3] |

| Governing Equation | Nernst equation [3] [32] | Butler-Volmer kinetics [35] |

| Detection Limit | Typically 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁸ M [32] | Can reach 10⁻¹¹ to 10⁻¹⁴ M with pre-concentration [33] [34] |

| Selectivity Mechanism | Ion-selective membrane [32] | Potential control and electrode modification [18] [34] |

| Technique Variants | Direct potentiometry, potentiometric titration [3] | Cyclic voltammetry, square wave voltammetry, anodic stripping voltammetry [33] [3] |

Quantitative Sensitivity Comparison

Direct comparison of reported detection limits for various metal ions reveals the distinct sensitivity profiles of these techniques:

Table 2: Experimental detection limits reported for potentiometric and voltammetric sensors

| Analyte | Technique | Sensor Design | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd²⁺ | Potentiometry | IIP/PVC membrane | 6.3 × 10⁻¹⁰ M | [34] |

| Cd²⁺ | Voltammetry (ASV) | IIP/Graphene Oxide | 7.0 × 10⁻¹⁴ M | [34] |

| Cu²⁺ | Voltammetry (ASV) | Carbon-based ISE | Nanomolar range | [33] |

| Hg²⁺ | Potentiometry | WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT nanocomposite | ~10⁻⁶ M (Nernstian response from 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻¹ M) | [18] |

| Ag⁺ | Potentiometry | Calix[4]arene/MWCNT | 4.1 × 10⁻⁶ M | [36] |

| Ca²⁺ | Potentiometry | Carbon-based μISE | 1 × 10⁻⁶ M | [33] |

The data demonstrates that voltammetric techniques, particularly those incorporating pre-concentration steps, generally achieve significantly lower detection limits—sometimes by several orders of magnitude. However, advanced ISE designs utilizing ion-imprinted polymers (IIPs) and nanomaterials are progressively bridging this sensitivity gap while maintaining the operational simplicity inherent to potentiometry.

Key Design Principles for Enhanced ISE Sensitivity

Membrane Composition and Ionophore Design

The ion-selective membrane represents the core recognition element of an ISE, and its composition directly determines sensor sensitivity and selectivity:

Ion-Selective Membranes: These membranes function based on selective ion recognition, typically employing ionophores that create coordination sites specific to target ions [32]. The selectivity pattern follows the Eisenman sequence, which describes the relative free energy differences during ion exchange [37].

Ion-Imprinted Polymers (IIPs): These advanced materials create molecular cavities complementary to the target ion in shape, size, and coordination chemistry. A Cd²⁺-IIP sensor demonstrated remarkable selectivity by using a benzo[f]chromene-based monomer that formed specific coordination sites for cadmium ions [34].

Macrocyclic Ligands: Molecules like calix[4]arene provide pre-organized cavity structures that selectively complex specific ions. In silver ion sensing, calix[4]arene demonstrated superior affinity over other potential ionophores, enabling selective Ag⁺ detection in pharmaceutical formulations [36].

Nanomaterial Integration and Solid-Contact Designs

Modern ISE designs increasingly incorporate nanomaterials and solid-contact configurations to enhance sensitivity:

Carbon Nanotubes as Transducers: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) serve as efficient ion-to-electron transducers in solid-contact ISEs. Their hydrophobic nature prevents formation of water layers at the electrode-membrane interface, significantly improving potential stability and signal reproducibility [36].

Graphene Oxide Enhancements: The large surface area and excellent electrical conductivity of graphene oxide significantly enhance electron transfer kinetics when incorporated into voltammetric sensors, contributing to the extremely low detection limits observed in IIP/GO composite sensors [34].

Nanochannel-Based Membranes: Precisely engineered nanochannels with dimensions approaching the Debye length can create ion-selective environments through overlapping electrical double layers. Surface charge, channel dimensions, and morphology critically influence ion transport selectivity, particularly for challenging separations like lithium extraction from complex matrices [38] [37].

Interface Engineering and Signal Transduction

The interface between the membrane and electrode conductor plays a crucial role in determining ISE sensitivity:

Solid-Contact Designs: Traditional liquid-contact ISEs have been largely superseded by solid-contact designs that eliminate internal solution requirements, enhance miniaturization potential, and improve mechanical stability [36]. The carbon-based Ca²⁺-selective microelectrode exemplifies this approach, achieving a Nernstian slope of 29 mV/decade with a 1 μM detection limit [33].

Minimizing Water Layer Formation: Unintended water layers at the electrode-membrane interface cause potential drift and instability. Hydrophobic intermediate layers like MWCNTs effectively block water penetration, maintaining interface integrity and signal stability over extended operation [36].

Diagram 1: ISE signal transduction pathway

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Optimization

Fabrication of Solid-Contact ISE with MWCNT Interlayer

The following protocol details the fabrication of a high-sensitivity solid-contact ISE, optimized for silver ion detection [36]:

Electrode Pretreatment: Clean screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) sequentially with ethanol and deionized water, then dry under nitrogen stream.

MWCNT Dispersion Preparation: Disperse 2.0 mg of multi-walled carbon nanotubes in 1.0 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF) using 30 minutes of ultrasonic agitation.

Transducer Layer Application: Deposit 10 μL of MWCNT dispersion onto the SPE working electrode surface. Allow solvent evaporation at room temperature for 12 hours.

Membrane Cocktail Preparation: Combine the following components in a glass vial:

- 150 mg plasticizer (NPOE)

- 75 mg PVC polymer

- 1.5 mg ionophore (calix[4]arene)

- 0.8 mg ionic additive (NaTetrakis)

- 1.5 mL THF solvent

Membrane Deposition: Apply 20 μL of membrane cocktail over the MWCNT-modified electrode. Allow THF evaporation for 24 hours at room temperature to form a uniform sensing membrane.

Conditioning: Condition the completed ISE in 1.0 × 10⁻³ M AgNO₃ solution for 24 hours before calibration.

Sensor Calibration and Performance Validation

Proper calibration and validation are essential for accurate sensitivity determination:

Calibration Protocol: Prepare standard solutions across the concentration range from 1.0 × 10⁻⁷ to 1.0 × 10⁻² M. Measure the potential response of the ISE for each standard, allowing stabilization until potential drift falls below 0.1 mV/min.

Data Analysis: Plot measured potential (mV) against logarithm of ion activity. Perform linear regression on the linear portion to determine slope (mV/decade), linear range, and detection limit.

Detection Limit Calculation: Calculate the method detection limit (MDL) from the calibration curve using the IUPAC recommended approach: intersection of the two linear segments of the calibration curve, or as concentration corresponding to three times the standard deviation of the blank signal.

Selectivity Assessment: Determine potentiometric selectivity coefficients (Kᵖᵒₜₐ,ᴮ) using the separate solution method (SSM) or matched potential method (MPM) with relevant interfering ions.

Research Reagent Solutions for ISE Development

The table below summarizes essential materials and their functions in advanced ISE fabrication:

Table 3: Key research reagents for ISE development and their functions

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in ISE | Considerations for Sensitivity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ionophores | Calix[4]arene, crown ethers, ion-imprinted polymers [34] [36] | Molecular recognition element for target ions | Determines selectivity coefficient and detection limit |

| Polymer Matrices | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), silicone rubber [33] [36] | Structural support for membrane components | Affects ion diffusion and membrane stability |

| Plasticizers | 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE), dioctyl sebacate (DOS) [33] [36] | Provides membrane flexibility and modulates dielectric constant | Influences ionophore solubility and mobility |

| Ionic Additives | Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB) [36] | Controls membrane permselectivity and reduces ohmic resistance | Critical for optimizing response slope |

| Transducer Materials | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene oxide, conductive polymers [34] [36] | Converts ionic signal to electronic signal in solid-contact ISEs | Reduces impedance and improves signal stability |

| Membrane Solvents | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), cyclohexanone [33] [36] | Dissolves membrane components for deposition | Affects membrane morphology and performance |

Advanced Nanochannel-Based Membrane Design

Emerging membrane designs utilizing nanochannels and nanopores represent a frontier in ion-selective membrane technology, particularly for challenging separations such as lithium extraction [38] [37]. The design principles for these advanced membranes include:

Diagram 2: Nanochannel membrane design principles

Surface Charge Engineering: Creating fixed negative charges within nanochannels generates cation selectivity through electrostatic interactions. When channel dimensions approach the Debye length (typically 1-100 nm), overlapping electrical double layers create ion-selective environments [37].

Dimensional Control: Nanochannel size must be precisely tuned to match the target application's ionic strength. For lithium extraction from brines, channel dimensions must facilitate discrimination between similarly sized monovalent cations (Li⁺, Na⁺, K⁺) [38] [37].

Multi-parameter Optimization: Maximum sensitivity requires coordinated optimization of surface charge, wettability, external driving force, and nanochannel morphology. These parameters interact complexly to determine ultimate membrane performance [38].

The pursuit of maximum potentiometric sensitivity in Ion-Selective Electrodes requires a multifaceted approach spanning membrane composition, interface engineering, and structural design. While voltammetric techniques currently demonstrate superior detection limits for trace metal analysis, advanced ISE designs incorporating ion-imprinted polymers, nanomaterial transducers, and solid-contact configurations are progressively narrowing this sensitivity gap.

The optimal technique selection depends critically on application requirements. Potentiometric ISEs offer operational simplicity, excellent selectivity, and cost-effectiveness for direct measurements, while voltammetric methods provide unparalleled sensitivity when trace-level detection is paramount. Future developments in nanochannel-based membranes and hybrid techniques that combine potentiometric and voltammetric operation hold particular promise for achieving both exceptional sensitivity and selectivity in electrochemical sensing.

The quest for ultra-sensitive detection of chemical species, particularly in complex matrices like biological fluids or environmental samples, places a premium on analytical technique selection. Within electrochemical analysis, two primary philosophies emerge: voltammetry, which measures current resulting from a controlled potential change, and potentiometry, which measures potential at zero current [3]. This guide frames the comparison of advanced voltammetric methods within this broader context, highlighting that while potentiometry offers the advantage of being non-consumptive of the analyte—a critical factor for small sample volumes—voltammetry often provides superior sensitivity and the ability to detect multiple analytes simultaneously [9] [3]. The following sections provide a detailed objective comparison of key voltammetric techniques, supported by experimental data and protocols, to guide researchers in selecting the optimal method for their trace analysis challenges.

Voltammetry encompasses a family of techniques that quantify an analyte based on the current-flow resulting from an applied potential waveform. The choice of waveform and measurement strategy directly impacts sensitivity, detection limit, and resolution. Table 1 summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the primary voltammetric methods discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Voltammetric Techniques for Trace Analysis

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Key Advantages | Typical Detection Limits | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Scans potential linearly in a forward and reverse direction [3]. | Rapid assessment of reaction kinetics and reversibility [3]. | ~10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁷ M [9] | Studying redox mechanisms, electrode kinetics [3]. |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Applies small potential pulses and measures the current difference just before and during the pulse [3]. | Minimizes capacitive background current, leading to high sensitivity [3]. | ~10⁻⁸ to 10⁻⁹ M [9] [39] | Trace analysis of organic compounds, pharmaceuticals, and metals [3]. |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Applies a symmetrical square wave on a staircase ramp, measuring current at the end of each forward and reverse pulse [40]. | Very fast scan times and extremely low detection limits; can effectively reject capacitive currents [40]. | Can be superior to DPV [40] | Ultra-trace metal analysis and sensitive detection of organic molecules [40]. |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Pre-concentrates metal ions onto the electrode by reduction, then oxidizes (strips) them back into solution while measuring current [39]. | Exceptional sensitivity due to the pre-concentration step [39]. | 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹⁰ M (ppt-ppb range) [39] | Determination of trace heavy metals (e.g., Pb, Cd, Cu) in water [40] [39]. |

| Cyclic Voltammetric Stripping (CVS) | Cycles potential to repeatedly plate and strip a metal, measuring the charge required, which is affected by organic additives [41] [42]. | Measures the effective activity of organic additives in a plating bath, emulating the full process [41]. | Varies by additive | Quantitative analysis of organic additives in electroplating baths [41] [42]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Voltammetric Methods

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) for Trace Metal Detection

ASV is a premier method for detecting trace metal ions at parts-per-billion levels, outperforming many spectroscopic techniques in cost and portability [40] [39].