Potentiometry vs Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Guide to Electroanalytical Fundamentals and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of two foundational electrochemical techniques—potentiometry and voltammetry—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Potentiometry vs Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Guide to Electroanalytical Fundamentals and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a thorough comparative analysis of two foundational electrochemical techniques—potentiometry and voltammetry—tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the core principles, theoretical underpinnings, and essential instrumentation, including the roles of working, reference, and counter electrodes. The scope extends to detailed methodological protocols for various techniques like ion-selective electrode (ISE) potentiometry and cyclic voltammetry, highlighting their specific applications in clinical chemistry, trace metal analysis, and drug quantification. The content also addresses common troubleshooting scenarios, optimization strategies for sensitivity and selectivity, and a direct, evidence-based comparison of the techniques' performance in validation studies. This guide synthesizes foundational knowledge with practical application to empower informed technique selection in biomedical and pharmaceutical development.

Core Principles and Instrumentation: Understanding the Building Blocks of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

Electroanalytical techniques are fundamentally built upon the interaction of electricity and chemistry, primarily measuring electrical outputs such as potential, charge, or current and their relationship to chemical parameters [1]. The choice of technique is determined by the specific electrical signal generated during an electrochemical reaction or process. This technical guide delineates two foundational approaches: potentiometry, which measures potential (electromotive force, emf) at negligible current flow, and voltammetry, which measures current response while systematically varying the applied potential [1]. These methodologies form the bedrock for countless applications in pharmaceutical analysis, clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and biomedical research.

The distinction is more than procedural; it reflects a fundamental divergence in the underlying electrochemical information being probed. Potentiometry is a thermodynamically focused technique, providing information about equilibrium states and activities of ionic species. In contrast, voltammetry is a kinetically focused technique, revealing information about rates of electron transfer, mass transport, and reaction mechanisms [1]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of both techniques, offering a structured comparison and detailed experimental protocols for researchers and drug development professionals.

Zero-Current Potential Measurement: Fundamentals of Potentiometry

Theoretical Foundation

Potentiometry involves measuring the potential difference between two electrodes—an indicator electrode and a sample-independent reference electrode—when the net current flowing through the cell is negligible or zero [1]. This measured potential, often called the open circuit potential (OCP), zero-current potential (ZCP), or corrosion potential, represents the electrochemical equilibrium where the rates of anodic and cathodic reactions are equal [2].

The cornerstone of quantitative potentiometry is the Nernst equation, which relates the measured potential to the activity of the target ion. For a general cell reaction, the Nernst equation is expressed as:

[ \phi{\text{emf}} = \phi° - \frac{RT}{vF} \ln \prodi ai^{vi} ]

where:

- (\phi_{\text{emf}}) is the measured electromotive force (zero-current potential)

- (\phi°) is the standard cell potential

- (R) is the universal gas constant

- (T) is the absolute temperature

- (v) is the stoichiometric number of electrons transferred

- (F) is the Faraday constant

- (a_i) is the activity of component (i)

- (v_i) is the stoichiometric coefficient of component (i) [2]

Measurement System Components

A typical potentiometric cell comprises several key components:

- Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE): The working electrode whose potential depends on the activity of a specific ion in solution. The ISE features an ion-selective membrane containing an ionophore that selectively recognizes the target ion [1].

- Reference Electrode: Maintains a constant, known potential regardless of the sample composition. Common types include Ag/AgCl and calomel electrodes, though all-solid-state versions are emerging for miniaturized systems [3].

- High-Impedance Voltmeter: Measures the potential difference without drawing significant current (typically less than 1 pA), ensuring operation under essentially zero-current conditions [1].

Two primary architectures exist for ISEs: Liquid-Contact (LC-ISE) with an internal filling solution, and Solid-Contact (SC-ISE) where a solid transducer layer replaces the internal solution, offering advantages in miniaturization and robustness [1].

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Zero-Current Potential

Objective: To determine the activity/concentration of a target ion (e.g., K⁺) in an aqueous solution using a solid-contact ion-selective electrode.

Materials and Equipment:

- Solid-contact ion-selective electrode for target ion

- Stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl)

- High-impedance potentiometer or potentiostat

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

- Thermostatted sample chamber (25°C)

- Standard solutions of known activity for calibration

- Sample solutions of unknown concentration

Procedure:

- Electrode Conditioning: Soak the ion-selective electrode in a solution containing the target ion (0.01 M) for at least 1 hour before initial use. For subsequent uses, condition for 15-30 minutes.

- Calibration Curve:

- Rinse both electrodes with deionized water and gently blot dry.

- Immerse the electrodes in the lowest concentration standard solution under gentle stirring.

- Allow the system to stabilize until the potential drift is less than 0.1 mV/min (typically 3-5 minutes).

- Record the stable potential reading.

- Repeat this process with standard solutions of increasing concentration, covering the expected sample concentration range.

- Sample Measurement:

- Rinse electrodes thoroughly with deionized water between measurements.

- Immerse electrodes in the unknown sample under identical conditions (stirring, temperature).

- Record the stable potential after stabilization.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the calibration curve (potential vs. log activity).

- Determine the slope and intercept of the linear region (should be close to Nernstian slope, e.g., ~59.2 mV/decade for monovalent ions at 25°C).

- Calculate the sample concentration from the measured potential using the calibration curve equation.

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain constant temperature throughout measurements as potential is temperature-dependent.

- Ensure ionic strength is relatively constant across standards and samples using an ionic strength adjustment buffer.

- Verify electrode stability and Nernstian slope as quality control measures.

- For OCP measurements in corrosion studies, monitor potential until stability indicates equilibrium between anodic and cathodic reactions [2].

Current Response to Varied Potential: Fundamentals of Voltammetry

Theoretical Foundation

Voltammetry encompasses a group of techniques that measure current as a function of applied potential. Unlike potentiometry, voltammetry explicitly applies a controlled potential to the working electrode and monitors the resulting faradaic current from the oxidation or reduction of analytes [1].

The applied potential provides the driving force for electron transfer reactions, while the measured current reflects the rate of these reactions. The current response is influenced by several factors:

- Electrode kinetics: The inherent rate of electron transfer at the electrode surface.

- Mass transport: The movement of analyte to the electrode surface, primarily through diffusion, convection, and migration.

- Double-layer effects: The structure of the electrode-solution interface influences the distribution of ions and potential.

The fundamental relationship in voltammetry is described by the Butler-Volmer equation, which relates current density to overpotential:

[ i = i0 \left[ \exp\left(\frac{\alphaa F\eta}{RT}\right) - \exp\left(-\frac{\alpha_c F\eta}{RT}\right) \right] ]

where:

- (i) is the current density

- (i_0) is the exchange current density

- (\alphaa) and (\alphac) are the anodic and cathodic charge transfer coefficients

- (\eta) is the overpotential ((E - E_{eq}))

Overvoltage ((\eta)) is defined as the difference between the applied potential ((E)) and the equilibrium potential ((E_{eq})) [2].

Measurement System Components

A voltammetric system requires three essential electrodes:

- Working Electrode: Where the reaction of interest occurs (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, platinum).

- Counter Electrode (Auxiliary Electrode): Completes the electrical circuit, often made of platinum.

- Reference Electrode: Maintains a stable potential reference against which the working electrode potential is controlled (e.g., Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel) [1].

Modern potentiostats provide sophisticated control of applied potential waveforms (linear sweep, staircase, pulses) while precisely measuring the resulting current, enabling various voltammetric techniques with different sensitivity and application profiles.

Experimental Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry

Objective: To characterize the electrochemical behavior of a redox-active pharmaceutical compound (e.g., acetaminophen) in aqueous solution.

Materials and Equipment:

- Potentiostat with three-electrode capability

- Working electrode (e.g., 3 mm diameter glassy carbon)

- Counter electrode (platinum wire)

- Reference electrode (Ag/AgCl)

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4)

- Nitrogen gas for deaeration

- Standard solution of analyte

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation:

- Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry (0.05 μm) on a microcloth pad.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and then with the electrolyte solution.

- Cell Assembly:

- Place 10-20 mL of electrolyte solution into the electrochemical cell.

- Add an appropriate volume of analyte stock solution to achieve the desired concentration.

- Assemble the three-electrode system with careful positioning.

- Solution Deaeration:

- Bubble nitrogen gas through the solution for at least 10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Maintain a nitrogen blanket above the solution during measurements.

- Instrument Parameters:

- Initial potential: +0.1 V (where no faradaic reaction occurs)

- Switching potential 1: +0.7 V

- Switching potential 2: 0.0 V

- Scan rate: 50-100 mV/s (initial measurement)

- Sensitivity: Auto-ranging or appropriate fixed range

- Measurement:

- Initiate the potential scan according to the parameters.

- Record the current response throughout the potential cycle.

- Repeat for different scan rates to study mass transport effects.

- Data Analysis:

- Identify peak potentials (Epa and Epc) for oxidation and reduction processes.

- Calculate peak separation (ΔEp = Epa - Epc).

- Determine the formal potential (E°' = (Epa + Epc)/2).

- Analyze peak current versus scan rate (ip ∝ v¹/² for diffusion-controlled processes).

Critical Considerations:

- Ensure proper electrode cleaning between measurements to prevent contamination.

- Control temperature for reproducible results.

- Use sufficiently supported electrolyte to minimize resistance effects.

- Verify reference electrode stability throughout experiments.

Comparative Analysis: Key Technical Distinctions

Fundamental Differences

The table below systematically compares the core characteristics of potentiometry and voltammetry:

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Signal | Potential (V) | Current (A) |

| Controlled Parameter | Current (~0) | Potential |

| Primary Information | Thermodynamic (activity) | Kinetic (rate) |

| Detection Limit | Typically 10⁻⁵ - 10⁻⁷ M | Typically 10⁻⁷ - 10⁻¹¹ M |

| Selectivity | High (ion-selective membranes) | Moderate (potential window) |

| Technique Variants | Direct potentiometry, potentiometric titration | Cyclic, linear sweep, square wave, pulse voltammetrics |

| Sample Consumption | Minimal | Minimal to moderate |

| Measurement Time | Seconds to minutes (equilibrium) | Minutes (scanning) |

| Miniaturization Potential | Excellent (solid-contact ISEs) | Good (microelectrodes) |

Operational Characteristics and Application Profiles

Table 2: Operational Characteristics and Applications

| Aspect | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode System | Two-electrode (WE, RE) | Three-electrode (WE, RE, CE) |

| Current Level | Negligible (< 1 pA) | Measurable (nA to mA) |

| Concentration Dependence | Logarithmic (Nernstian) | Linear (under diffusion control) |

| Primary Applications | Ion sensing, pH measurement, titration end-point detection | Redox behavior studies, electron transfer kinetics, trace analysis, sensor development |

| Pharmaceutical Relevance | Drug dissolution testing, electrolyte monitoring in formulations | Active ingredient quantification, metabolic studies, impurity detection |

| Advantages | Simple instrumentation, wide concentration range, high selectivity for specific ions | High sensitivity, rich mechanistic information, multi-analyte capability in some cases |

| Limitations | Requires stable reference, limited to ionic species, slower response for some membranes | Susceptible to fouling, requires dissolved oxygen removal in many cases, more complex data interpretation |

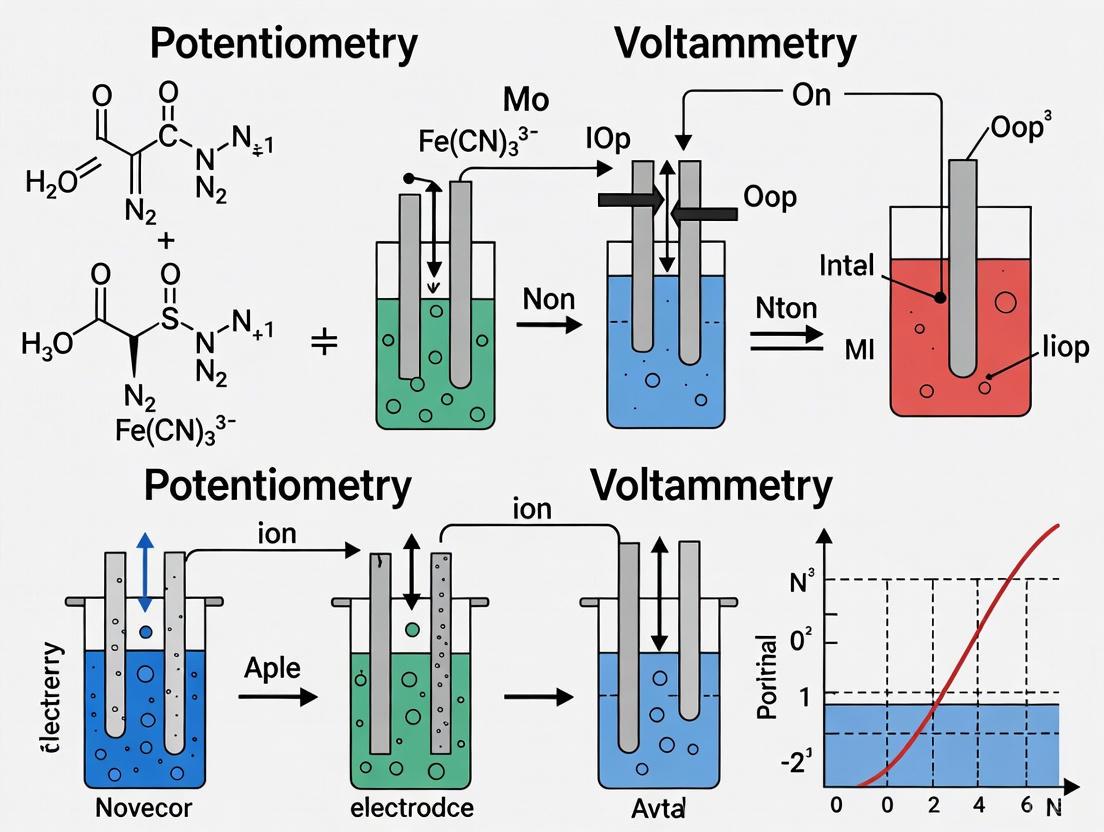

Visualization of Core Concepts

Potentiometric Measurement Setup

Diagram 1: Potentiometric cell schematic showing zero-current operation.

Voltammetric Measurement Setup

Diagram 2: Voltammetric three-electrode system with potential control and current measurement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Electroanalytical Experiments

| Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Selective recognition of target ions | PVC matrix with ionophore (e.g., valinomycin for K⁺), plasticizer, additive |

| Reference Electrodes | Provide stable potential reference | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl), double-junction designs for harsh samples |

| Solid-Contact Materials | Ion-to-electron transduction in SC-ISEs | Conducting polymers (PEDOT), carbon nanomaterials (graphene, MWCNTs), nanocomposites |

| Electrode Materials | Working electrode substrates | Glassy carbon, gold, platinum, boron-doped diamond, screen-printed electrodes |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Control ionic strength, minimize resistance | KCl, NaClO₄, phosphate buffers, TEAB in organic solvents |

| Redox Probes | System characterization and validation | Potassium ferricyanide, ruthenium hexamine, quinones |

| Ionic Liquids | Alternative media, low volatility | BMIM-PF₆, EMIM-TFSI for extended potential windows |

| Polymer Membranes | Electrode modification, selectivity | Nafion for cation exchange, chitosan for biocompatibility |

Potentiometry and voltammetry offer complementary approaches to electrochemical analysis, each with distinct strengths and applications. Potentiometry provides thermodynamic information about ionic activities under equilibrium conditions with high selectivity, making it ideal for continuous monitoring and direct concentration measurements. Voltammetry delivers rich kinetic and mechanistic information through controlled perturbation of equilibrium states, offering superior sensitivity for trace analysis and detailed studies of electron transfer processes.

The choice between these techniques depends fundamentally on the analytical question: potentiometry excels at answering "how much" of a specific ion is present, while voltammetry reveals "how" redox processes occur and at what rates. Advances in materials science, particularly in solid-contact reference electrodes [3] and nanocomposite transducers [1], continue to push the boundaries of both techniques, enabling new applications in miniaturized systems, wearable sensors, and point-of-care diagnostics. For researchers in pharmaceutical development and biomedical sciences, mastery of both approaches provides a comprehensive toolkit for addressing diverse analytical challenges from formulation optimization to metabolic studies.

This technical guide explores the Nernst equation as the fundamental principle underlying potentiometric measurements, framing this relationship within a broader comparative analysis of potentiometric and voltammetric methodologies. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this distinction is crucial for selecting appropriate analytical techniques for pharmaceutical and biological analysis. The Nernst equation provides the theoretical foundation for zero-current potentiometric measurements, where potential is measured as a function of ion activity, whereas voltammetric techniques operate under current-measuring principles with controlled potential variations [4]. This whitepaper examines the mathematical formalism, experimental validation, and practical implementation of the Nernst equation in modern analytical contexts, with particular emphasis on pharmaceutical applications including anti-epileptic drug monitoring [5] [6].

Electrochemical analysis methods measure electrical properties such as voltage, current, or resistance to gain insights into the chemical properties of a solution [4]. These methods have become indispensable tools in clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and materials science due to their excellent sensitivity for trace-level analysis, wide linear dynamic range, and relatively low cost of instrumentation [4].

At the heart of every electrochemical measurement is a chemical reaction involving the transfer of electrons, known as a redox reaction [4]. The Nernst equation describes the relationship between the electrochemical potential of an electrode and the composition of the solution in which it is immersed, serving as the cornerstone of potentiometric measurements [4]. This fundamental relationship enables the quantitative determination of ion activities or concentrations without causing significant electrolysis or current flow through the solution.

The comparative framework between potentiometry and voltammetry represents a fundamental dichotomy in electrochemical analysis. Potentiometry measures potential difference at zero current to determine analyte concentration, while voltammetry measures the current generated as a function of a controlled, changing potential to obtain both qualitative and quantitative data [4]. This distinction in operational principles dictates their respective applications in research and development settings.

Theoretical Foundation of the Nernst Equation

Mathematical Formalism

The Nernst equation is derived from the principles of thermodynamics and relates the measured electrode potential to the standard electrode potential and the activities (or concentrations) of the species involved in the electrochemical reaction [7] [8]. For a general half-cell reduction reaction expressed as:

[ \text{Ox} + z\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{Red} ]

The Nernst equation is written in its most fundamental form as:

[ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}} \tag{1} ]

Where:

- (E_{\text{red}}) is the half-cell reduction potential at the temperature of interest

- (E_{\text{red}}^{\ominus}) is the standard half-cell reduction potential

- (R) is the universal gas constant (8.31446261815324 J K⁻¹ mol⁻¹)

- (T) is the absolute temperature in kelvins

- (z) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction

- (F) is the Faraday constant (96485.3321233100184 C mol⁻¹)

- (a{\text{Red}}) and (a{\text{Ox}}) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [8]

For practical applications, it is often more convenient to use the base-10 logarithmic form of the equation:

[ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{2.303 RT}{zF} \log{10} \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a_{\text{Ox}}} \tag{2} ]

At standard temperature (25 °C or 298.15 K), the constants can be combined to yield a simplified form:

[ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{0.0591}{z} \log{10} \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a_{\text{Ox}}} \tag{3} ]

This temperature-dependent simplification is particularly useful for laboratory applications under standard conditions [9].

Activity Versus Concentration

In the fundamental Nernst equation, chemical activities ((a)) are used rather than concentrations to account for non-ideal behavior in electrochemical systems. The chemical activity of a species i is related to its measured concentration (Ci) through the relationship (ai = γi Ci), where (γ_i) is the activity coefficient [8]. For dilute solutions, activity coefficients approach unity, and concentrations can be used directly as approximations. However, in solutions with higher ionic strength, this approximation becomes less valid.

To address this limitation, the concept of formal potential ((E_{\text{red}}^{\ominus'})) is introduced, which incorporates the activity coefficients into an adjusted standard potential:

[ E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{γ{\text{Red}}}{γ{\text{Ox}}} \tag{4} ]

This allows the Nernst equation to be expressed using concentrations rather than activities:

[ E{\text{red}} = E{\text{red}}^{\ominus'} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{C{\text{Red}}}{C{\text{Ox}}} \tag{5} ]

The formal potential represents the reversible potential of an electrode at equilibrium immersed in a solution where reactants and products are at unit concentration [8]. This practical adjustment makes the Nernst equation more accessible for routine analytical applications where concentrations are measured directly.

Extension to Full Cell Potentials

For a complete electrochemical cell consisting of two half-cells, the Nernst equation can be applied to calculate the overall cell potential:

[ E{\text{cell}} = E{\text{cell}}^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln Q_r \tag{6} ]

Where (E{\text{cell}}^{\ominus}) is the standard cell potential and (Qr) is the reaction quotient for the overall cell reaction [8]. This application is particularly valuable for predicting battery voltages and understanding corrosion processes.

Table 1: Various Forms of the Nernst Equation and Their Applications

| Form | Equation | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| General Form | (E = E^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}}) | Fundamental thermodynamic applications |

| Base-10 Logarithmic | (E = E^{\ominus} - \frac{2.303 RT}{zF} \log{10} \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a_{\text{Ox}}}) | Practical laboratory calculations |

| Simplified (25°C) | (E = E^{\ominus} - \frac{0.0591}{z} \log{10} \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a_{\text{Ox}}}) | Standard condition measurements |

| Concentration-Based | (E = E^{\ominus'} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{C{\text{Red}}}{C{\text{Ox}}}) | Analytical applications with known concentrations |

| Full Cell Potential | (E{\text{cell}} = E{\text{cell}}^{\ominus} - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln Q_r) | Battery and corrosion studies |

The Nernst Equation in Potentiometric Measurements

Fundamental Principle of Potentiometry

Potentiometry is a zero-current electrochemical technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes when no net current is flowing through the cell [4]. This potential is a direct function of the concentration or activity of a specific ion in the solution, as described by the Nernst equation [4]. The technique is considered a cornerstone of pH and ion measurement due to its simplicity, accuracy, and wide applicability.

In potentiometric measurements, the potential developed across an ion-selective membrane or interface is measured under conditions of essentially zero current flow. This equilibrium potential provides quantitative information about the activity of the target ion in solution. The measured potential (E) is related to the ion activity (a) through the Nernstian relationship:

[ E = E^0 + \frac{2.303 RT}{zF} \log_{10} a \tag{7} ]

Where (E^0) is a constant that includes the standard potential of the electrode system and the potential of the reference electrode [4]. For monovalent ions (z = ±1) at 25°C, the slope of the response is 59.16 mV per decade change in activity, while for divalent ions (z = ±2), the slope is 29.58 mV per decade.

Electrochemical Cell Configuration

The fundamental setup for most quantitative potentiometric analysis involves an electrochemical cell typically containing three key components [4]:

Working Electrode (WE): This is where the redox reaction of interest occurs. The potential of this electrode is precisely controlled relative to a reference electrode. In potentiometry, this is often an ion-selective electrode (ISE).

Reference Electrode (RE): This electrode provides a stable and known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured or controlled. It is crucial for maintaining a constant baseline. Common examples include the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and the silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode.

Counter Electrode (CE): This electrode completes the circuit. It carries the current needed to balance the current flowing at the working electrode, ensuring that the potential of the working electrode is not influenced by the current passing through the reference electrode.

The three-electrode system provides precise control over the potential of the working electrode, ensuring that the current flowing at the working electrode does not affect the stable potential of the reference electrode, leading to more accurate and reliable measurements [4].

Figure 1: Technique Comparison: Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry

Comparative Framework: Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry

Fundamental Operational Differences

Understanding the distinction between potentiometry and voltammetry is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical method for drug development applications. While both are electrochemical techniques, their operational principles and applications differ significantly [4]:

Potentiometry is a passive technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes at zero current. This potential develops spontaneously due to the difference in ion activities across a selective membrane and is governed by the Nernst equation. The method is non-destructive and provides direct measurement of ion activities without altering the sample composition significantly.

Voltammetry is an active technique that applies a controlled, varying potential to the working electrode and measures the resulting current. This current results from redox reactions occurring at the electrode surface and is proportional to the concentration of electroactive species. Voltammetric techniques are dynamic and can provide information about reaction kinetics, mechanisms, and diffusion coefficients.

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Potentiometric and Voltammetric Techniques

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Potential difference at zero current | Current as function of applied potential |

| Governing Equation | Nernst equation | Current-voltage relationships |

| Excitation Signal | None (zero current) | Varied potential (sweep, pulse, step) |

| Primary Application | Ion activity/concentration measurement | Redox behavior, trace analysis, kinetics |

| Sensitivity | ~10⁻⁶ to 10⁻¹ M | ~10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻⁶ M |

| Selectivity | High with ion-selective membranes | Moderate to high with modified electrodes |

| Sample Consumption | Minimal | Moderate to high |

| Technique Variants | Direct potentiometry, potentiometric titration | Cyclic voltammetry, differential pulse, square wave |

Information Content and Applications

The different operational principles of potentiometry and voltammetry yield complementary information about analytical samples:

Potentiometric applications include:

- pH measurement using glass electrodes

- Ion-selective electrodes for sodium (Na⁺), potassium (K⁺), calcium (Ca²⁺), fluoride (F⁻), and chloride (Cl⁻) in clinical labs for electrolyte analysis

- Environmental monitoring for water quality assessment

- Potentiometric titrations where the endpoint is determined by a sharp change in potential [4]

Voltammetric applications include:

- Trace metal analysis in environmental samples

- Drug quantification in pharmaceutical formulations

- Reaction mechanism studies through cyclic voltammetry

- Detection of organic compounds and heavy metals using pulsed techniques [4]

For pharmaceutical researchers, this distinction is critical when designing analytical methods. Potentiometry offers simple, direct measurement of specific ions, while voltammetry provides richer information about redox properties and reaction mechanisms of drug compounds.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Potentiometric Sensor Development Protocol

The development of potentiometric sensors for pharmaceutical analysis follows a systematic approach:

Step 1: Electrode Design and Preparation

- Select appropriate ion-selective membrane composition based on the target analyte

- Incorporate ionophores, plasticizers, and polymer matrices for membrane formation

- Prepare the electrode body with internal filling solution or solid contact

Step 2: Electrode Conditioning

- Soak the newly prepared electrode in a standard solution of the target analyte

- Allow the electrode potential to stabilize typically for 24-48 hours

- Establish stable baseline potential before calibration

Step 3: Calibration Procedure

- Prepare standard solutions of the analyte across the concentration range of interest

- Measure the electrode potential in each standard solution under zero-current conditions

- Plot potential (E) versus logarithm of analyte activity (log a)

- Determine slope, linear range, and detection limit from the calibration curve

Step 4: Sample Measurement

- Measure electrode potential in unknown samples using the same conditions

- Determine analyte concentration from the calibration curve

- Use standard addition method for samples with complex matrices

Step 5: Validation and Optimization

- Evaluate selectivity coefficients against potential interfering ions

- Assess response time, reproducibility, and long-term stability

- Optimize membrane composition based on performance characteristics

This protocol has been successfully applied to the determination of anti-epileptic drugs in pharmaceutical and biological samples, demonstrating the practical utility of potentiometric methods in drug development [5].

Experimental Verification of the Nernst Equation

To experimentally verify the Nernst equation and determine key electrode parameters:

Objective: Confirm the Nernstian response of an ion-selective electrode and determine its slope, linear range, and detection limit.

Materials:

- Ion-selective electrode and appropriate reference electrode

- Standard solutions of analyte across concentration range

- High-impedance potentiometer or pH/mV meter

- Magnetic stirrer with temperature control

- Volumetric flasks and laboratory glassware

Procedure:

- Prepare standard solutions of the analyte covering at least three orders of magnitude in concentration.

- Temperature-equilibrate all solutions to 25°C ± 0.1°C.

- Immerse the electrode system in the most dilute standard and measure the potential under stirring.

- Rinse electrodes thoroughly with distilled water and proceed to the next standard in increasing concentration order.

- Record the stable potential reading for each standard solution.

- Plot E (mV) versus log(concentration) and perform linear regression.

- Calculate the experimental slope and compare with theoretical Nernstian slope (59.16/z mV/decade at 25°C).

Data Analysis:

- Experimental slope = (RT/zF) × 2.303 × 1000 mV/decade

- Correlation coefficient (r) should exceed 0.999 for ideal Nernstian response

- Linear range determined from concentrations where response remains linear

- Detection limit typically calculated as concentration where E deviates by 18/z mV from extrapolated linear region

Figure 2: Potentiometric Experimental Workflow

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful implementation of potentiometric methods based on the Nernst equation requires specific materials and instrumentation. The following table details essential components for potentiometric research in pharmaceutical applications.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Potentiometric Analysis

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrodes | pH electrode, cation-selective electrodes (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺), anion-selective electrodes (Cl⁻, F⁻) | Sensing element that generates potential response proportional to target ion activity |

| Reference Electrodes | Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel electrode (SCE) | Provides stable, known reference potential against which working electrode potential is measured |

| Potentiometer | High-impedance (>10¹² Ω) pH/mV meter | Measures potential difference under zero-current conditions without drawing significant current |

| Ionophores | Neutral carriers, charged carriers specific to target ions | Selective molecular recognition elements incorporated into sensor membranes |

| Polymer Matrices | PVC, polyurethane, silicone rubber | Provides structural support for ion-selective membranes |

| Plasticizers | o-NPOE, DOS, DBP | Implements membrane fluidity and governs dielectric properties |

| Ionic Additives | Lipophilic salts (e.g., KTpClPB) | Controls membrane resistivity and reduces interference |

| Standard Solutions | Certified reference materials, analytical grade salts | Used for electrode calibration and method validation |

| Buffer Solutions | pH buffers, ionic strength adjusters | Controls sample pH and maintains constant ionic background |

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Drug Analysis and Quality Control

Potentiometric methods based on the Nernst equation have found extensive applications in pharmaceutical analysis due to their simplicity, selectivity, and capability for direct measurement in colored or turbid samples without requiring pretreatment [6]. The successful use of developed sensors in real sample analysis has made potentiometric sensors the center of attention in pharmaceutical quality control [6].

Specific applications include:

- Active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) quantification in dosage forms

- Dissolution testing and drug release profiling

- Stability testing of pharmaceutical formulations

- Content uniformity assessment of solid dosage forms

- Ion-level monitoring in parenteral solutions

For example, potentiometric sensors have been developed for the determination of anti-epileptic drugs in pharmaceutical and biological samples, providing rapid and cost-effective alternatives to chromatographic methods [5]. These sensors offer adequate sensitivity for therapeutic drug monitoring and quality control applications.

Real Sample Analysis and Validation

The application of potentiometric sensors to real sample analysis requires careful consideration of matrix effects and potential interferents. Key validation parameters include:

- Accuracy: Typically assessed through recovery studies in real samples, with acceptable recovery rates of 95-105%

- Selectivity: Evaluated using the separate solution method or fixed interference method to determine selectivity coefficients

- Precision: Expressed as relative standard deviation (RSD) of repeated measurements

- Working concentration range: Determined from the linear portion of the calibration curve

- Detection limit: Lowest measurable concentration distinguishable from zero

Recent reviews highlight that hundreds of different potentiometric sensors have been developed and successfully applied to real sample analysis with high recovery rates [6]. This demonstrates the maturity and reliability of potentiometric methods based on the Nernst equation for pharmaceutical applications.

The Nernst equation remains the fundamental theoretical principle governing potentiometric response, providing the mathematical foundation that relates electrode potential to analyte activity or concentration. Within the comparative framework of electrochemical techniques, potentiometry's distinctive feature is its operation under zero-current conditions, directly harnessing the Nernstian relationship for quantitative analysis.

For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this fundamental relationship is essential for leveraging potentiometric methods in pharmaceutical analysis. The technique offers distinct advantages for drug quality control, therapeutic drug monitoring, and formulation analysis, particularly when rapid, cost-effective分析方法 are required without compromising accuracy.

As electrochemical sensor technology continues to evolve, with advancements in miniaturization, materials science, and signal processing, the Nernst equation will maintain its central role in the development and application of potentiometric sensors across pharmaceutical research and development.

The universal three-electrode system is a fundamental cornerstone of modern electrochemical research, providing the precise control and measurement capabilities required to advance fields from material science to drug development. This configuration, comprising a Working Electrode, Reference Electrode, and Counter Electrode, enables researchers to isolate and study complex electrochemical phenomena with unprecedented accuracy [10]. Its development in the 1920s addressed critical limitations of the simpler two-electrode setup, primarily by separating the current-carrying and potential-sensing functions into distinct circuits [10]. Within the broader thesis of electrochemical analytical techniques, the three-electrode system serves as the physical implementation platform that bridges the theoretical principles of potentiometry and the dynamic measurements of voltammetry [4]. By providing a stable potential reference point while allowing significant current flow, this system empowers researchers to extract both quantitative concentration data and qualitative mechanistic insights across diverse experimental conditions [11] [12].

System Architecture and Theoretical Framework

The "Three-Electrode, Two-Circuit" Principle

The operational principle of the three-electrode system can be conceptualized as two separate circuits working in tandem [11]:

- Potential Control Circuit: This high-impedance pathway connects the Working Electrode and Reference Electrode, featuring a voltmeter that accurately measures the potential difference between them without drawing significant current [10] [12].

- Current Flow Circuit: This lower-impedance pathway connects the Working Electrode and Counter Electrode, featuring an ammeter that measures the current resulting from the electrochemical reaction of interest [11] [10].

This separation is crucial because it prevents the current flow from polarizing the Reference Electrode, thereby maintaining a stable potential reference throughout the experiment [10]. The electrochemical workstation (potentiostat) uses the feedback from the potential control circuit to adjust current flow through the current flow circuit, maintaining the desired potential at the Working Electrode regardless of current magnitude [12].

Diagram 1: The dual-circuit architecture of a three-electrode system.

Comparative Analysis: Two-Electrode vs. Three-Electrode Systems

The evolution from two-electrode to three-electrode systems represented a quantum leap in electrochemical measurement capabilities, particularly for research requiring precise potential control.

Table 1: Fundamental differences between two-electrode and three-electrode systems

| Parameter | Two-Electrode System | Three-Electrode System |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Configuration | Working + Counter/Reference combined | Working, Reference, and Counter as separate electrodes |

| Potential Measurement | Measures total cell voltage between WE and CE | Measures potential difference between WE and RE only |

| Current Path | Flows between WE and CE | Flows primarily between WE and CE |

| Reference Stability | Compromised by current flow | Maintained stable (minimal current through RE) |

| IR Drop Compensation | Difficult or impossible | Possible through measurement and compensation |

| Measurement Accuracy | Lower, especially for kinetic studies | High, suitable for precise kinetic measurements |

| Typical Applications | Simple conductivity, basic battery testing | Advanced research: mechanism studies, sensor development, kinetic analysis |

The critical limitation of the two-electrode system lies in its inability to distinguish the working electrode potential from the counter electrode potential and solution resistance effects [11]. As current flows, the counter electrode polarizes, and voltage drops occur across the solution, making the true working electrode potential uncertain [10]. The three-electrode system resolves this by introducing a dedicated Reference Electrode that maintains a stable potential, enabling accurate measurement and control of the working electrode potential regardless of current magnitude or solution resistance [12].

Electrode Roles, Specifications, and Selection Criteria

Working Electrode: The Reaction Site of Interest

The Working Electrode serves as the stage where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs, and its properties must be carefully matched to the experimental objectives [10].

- Material Selection: Common materials include glassy carbon, platinum, gold, and various forms of carbon (carbon paper, graphite) depending on the required potential window, surface properties, and chemical inertness [11].

- Surface Preparation: Reproducible surface pretreatment is essential for experimental reproducibility. Protocols may include mechanical polishing, electrochemical cleaning, or specific chemical treatments [10].

- Geometric Considerations: The electrode surface area must be well-defined and typically standardized to enable comparison between experiments [10].

Reference Electrode: The Potential Anchor

The Reference Electrode provides the stable potential benchmark against which the Working Electrode potential is controlled and measured [12].

- Fundamental Requirement: Must maintain a constant electrochemical potential with negligible current flow [12].

- Common Reference Systems:

Counter Electrode: Current Completion Element

The Counter Electrode completes the electrical circuit by providing a surface for the balancing electrochemical reaction to occur [12].

- Material Requirements: Should be chemically inert with high conductivity and sufficient surface area to avoid becoming rate-limiting [11] [10].

- Selection Considerations: Platinum and graphite are common choices, though careful selection is needed to prevent contamination in prolonged experiments [11].

Table 2: Electrode selection guide for different experimental conditions

| Electrode Type | Common Materials | Key Characteristics | Optimal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Glassy carbon, Pt, Au, carbon paper, metal foams | Defined surface area, reproducible surface, chemically inert | Reaction-dependent: GCE for general electrochemistry, specialized materials for specific reactions |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl, SCE, Hg/HgO | Stable, known potential, minimal current draw | Electrolyte pH-dependent: SCE (acidic), Ag/AgCl (neutral), Hg/HgO (alkaline) |

| Counter Electrode | Pt wire/mesh, graphite rod | High conductivity, large surface area, chemical stability | Reaction-dependent: graphite preferred when Pt dissolution may contaminate system |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

System Setup and Electrode Preparation

Proper experimental setup begins with meticulous electrode preparation and cell configuration [11]:

Working Electrode Preparation Protocol:

- Surface Polishing: For solid electrodes like glassy carbon, sequentially polish with alumina slurry of decreasing particle size (1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad

- Sonication: Remove adsorbed particles by sonicating in purified water for 1-2 minutes

- Electrochemical Activation: Perform cyclic voltammetry in a clean electrolyte until stable response is achieved

- Catalyst Deposition (if applicable): Prepare catalyst ink by dispersing catalyst material in appropriate solvent with binder

- Drop-casting: Apply controlled volume of ink to electrode surface and allow to dry

Electrochemical Cell Assembly:

- Electrode Placement: Position Reference Electrode close to Working Electrode surface to minimize uncompensated solution resistance

- Counter Electrode Positioning: Place Counter Electrode symmetrically to ensure uniform current distribution

- Gas Purging: For reactions involving gases, saturate electrolyte with appropriate gas before measurements

Core Electrochemical Techniques: Operational Protocols

Cyclic Voltammetry Methodology

Cyclic Voltammetry is a powerful technique for studying electrode reaction mechanisms and kinetics [4].

Standard Protocol:

- Initial Parameters: Set starting potential where no faradaic reaction occurs

- Vertex Potentials: Define reversal potentials based on redox processes of interest

- Scan Rate Selection: Typically 1-1000 mV/s, depending on system kinetics

- Cycle Definition: Specify number of cycles to assess stability

Data Interpretation:

- Reversible systems show symmetrical reduction and oxidation peaks

- Peak separation (ΔEp) provides information about electron transfer kinetics

- Peak current proportionality to square root of scan rate indicates diffusion control

Linear Sweep Voltammetry for Reaction Analysis

LSV is particularly valuable for quantifying electrocatalytic activity, such as in hydrogen evolution or oxygen evolution reactions [11].

HER/OER Testing Protocol:

- Potential Range Selection: Set based on thermodynamic considerations and reference electrode

- Scan Rate: Use slow scan rates (typically 1-5 mV/s) for quasi-steady-state measurements

- IR Compensation: Apply appropriate compensation based on electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data

- Gas Saturation: Purge electrolyte with appropriate gas before measurements

Diagram 2: Standard workflow for three-electrode system experimentation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of three-electrode systems requires careful selection of consumables and materials tailored to specific experimental needs.

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for three-electrode experiments

| Category | Specific Items | Function/Purpose | Selection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Glassy carbon electrodes, platinum wire, graphite rods, carbon paper, metal foams | Provide platforms for electrochemical reactions | Choose based on potential window, chemical stability, and catalytic properties |

| Reference Systems | Ag/AgCl pellets, SCE components, Hg/HgO elements | Establish stable potential reference | Select based on electrolyte compatibility and required potential range |

| Electrolytes | Sulfuric acid, potassium hydroxide, phosphate buffers, lithium perchlorate | Provide ionic conductivity and define electrochemical environment | Consider pH requirements, potential window, and compatibility with analytes |

| Cell Components | Glass electrolytic cells, O-rings, electrode holders, gas dispersion tubes | Contain experiment and maintain proper electrode positioning | Choose materials compatible with electrolytes (glass, PTFE preferred) |

| Preparation Supplies | Alumina polishing powders, Nafion solution, isopropanol, ultrasonication baths | Enable electrode preparation and catalyst deposition | Use high-purity materials to prevent contamination |

| Specialty Chemicals | Conductive carbon blacks, specific catalyst materials, redox mediators | Enhance conductivity or facilitate specific reactions | Select based on mechanism under investigation |

Advanced Applications and Research Context

Contextualizing Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry Research

Within electrochemical research methodologies, the three-electrode system enables the distinct capabilities of both potentiometry and voltammetry:

Potentiometric Applications:

- Zero-current potential measurements for concentration determination [4]

- Ion-selective electrode measurements following Nernst equation principles [4]

- Stable reference potential enables precise measurement of equilibrium potentials [12]

Voltammetric Applications:

- Dynamic current measurement during controlled potential sweeps [4]

- Investigation of electron transfer kinetics and reaction mechanisms [13]

- Trace analysis through pulsed techniques (DPV, SWV) [4]

The three-electrode system is particularly crucial for voltammetric studies where accurate potential control is essential for meaningful results, especially in systems with significant current flow [11].

Case Study: Heavy Metal Detection in Environmental Samples

Research demonstrates the application of three-electrode systems in detecting Hg²⁺ ions using a WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT nanocomposite sensor [14]. The system employed:

- Working Electrode: Nanocomposite-modified electrode

- Reference Electrode: Calomel electrode

- Counter Electrode: Graphite electrode

This configuration enabled both cyclic voltammetry measurements showing increasing current response with Hg²⁺ concentration, and potentiometric detection with a Nernstian slope of 33.0 mV/decade [14]. The study highlights how proper three-electrode configuration facilitates multiple measurement techniques on the same system, providing complementary data for robust analysis.

Troubleshooting and Optimization Strategies

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

- Unstable Potentials: Often caused by clogged reference electrode frits or insufficient chloride concentration in reference systems

- Noisy Current Signals: Frequently results from poor shielding, ground loops, or insufficient filtering

- Non-reproducible Results: Commonly stems from inconsistent working electrode pretreatment or contamination

- Uncompensated Resistance Effects: Mitigated by proper reference electrode placement and appropriate IR compensation techniques [11]

Optimization Guidelines for Specific Applications

High-Precision Kinetic Studies:

- Minimize uncompensated resistance through careful cell design

- Use fast-response reference electrodes

- Apply appropriate IR compensation strategies [11]

Trace Analysis Applications:

- Implement electromagnetic shielding

- Utilize differential pulse or square wave voltammetry

- Employ background subtraction techniques [4]

Extended Duration Experiments:

- Select counter electrode materials that won't contaminate system

- Monitor reference electrode stability throughout experiment

- Consider use of pseudo-reference electrodes with periodic calibration [10]

The universal three-electrode system remains an indispensable platform for advanced electrochemical research, providing the necessary architecture to discriminate between potentiometric and voltammetric approaches while delivering the precision required for modern analytical applications. Its continued evolution supports increasingly sophisticated investigations into reaction mechanisms, materials properties, and analytical detection schemes across scientific disciplines. By mastering the principles, configurations, and methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers can leverage the full potential of this fundamental electrochemical tool to advance their scientific objectives.

In the realm of electrochemical analysis, potentiometry stands as a fundamental technique distinguished by its measurement of electrical potential under conditions of zero or negligible current flow. This method contrasts sharply with voltammetry, which measures current as a function of an applied potential, requiring a three-electrode system for precise control. The distinct advantage of potentiometry lies in its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to provide direct information about ion activities in solution [4] [1]. At the heart of every potentiometric measurement lies the indicator electrode, a device whose potential responds selectively to the activity of a specific ion in solution. This technical guide focuses on two cornerstone components of modern potentiometry: the classic glass membrane electrode and the broader family of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs). These sensors have become indispensable across chemical, biological, pharmaceutical, and environmental disciplines due to their exceptional selectivity, sensitivity, and adaptability [4] [15]. Understanding their operating principles, construction, and applications is crucial for researchers leveraging potentiometric methods, particularly when compared to the dynamic measurements of voltammetry.

Theoretical Foundations: The Potentiometric Principle

The fundamental principle of potentiometry is governed by the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the measured electrochemical potential of an electrode and the activity (effective concentration) of an ion in solution. For an ion, ( A ), with charge ( z ), the potential of an ideal indicator electrode, ( E ), is given by:

[ E = \text{constant} + \frac{RT}{zF} \ln a_A ]

Where ( R ) is the universal gas constant, ( T ) is the temperature in Kelvin, ( F ) is the Faraday constant, and ( a_A ) is the activity of ion ( A ) [16] [17]. The "constant" term includes the standard potential of the electrode and the potential of the reference electrode. At a temperature of 25°C, and converting from natural logarithm to base-10 logarithm, the equation simplifies to a more practical form:

[ E = \text{constant} + \frac{0.05916}{z} \log a_A ]

This Nernstian response produces a linear plot of ( E ) versus ( \log a_A ), with a slope of ( 59.16/z ) mV per decade, which serves as a benchmark for evaluating electrode performance [16] [18]. Potentiometric measurements are performed using an electrochemical cell comprising an indicator electrode and a reference electrode with a stable, fixed potential. The overall cell potential is measured with a high-impedance voltmeter to ensure current flow remains virtually zero, preserving solution composition [18].

The Glass Membrane Electrode

Composition and Structure

The glass membrane electrode represents the oldest and most well-known type of ion-selective electrode. While most famously used for pH measurement, specialized glass formulations can confer selectivity for other single-charged cations like sodium (Na⁺) and silver (Ag⁺) [16] [19]. The core component is a thin, ion-exchange glass membrane, typically composed of silicate or chalcogenide glass, which is fused to the end of an inert glass or plastic body. The membrane is an amorphous, rigid, and hygroscopic material [16] [19]. The internal structure of a typical pH glass electrode consists of several layers:

- Internal Solution: A solution of constant pH and activity, typically a buffered chloride solution.

- Internal Reference Electrode: Most commonly a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) wire immersed in the internal solution.

- Glass Membrane: A hydrated glass layer that develops on both the inner and outer surfaces of the membrane after immersion in an aqueous solution. This hydrated gel layer is critical for the electrode's function [16].

Response Mechanism and Selectivity

The potential across the glass membrane develops due to an ion-exchange process within the hydrated gel layers. For a pH electrode, hydrogen ions (H⁺) from the solution interact with binding sites on the surface of the hydrated glass. The key to the membrane's function is that the glass composition is tailored so that H⁺ binds more strongly to these sites than any other cation. This differential binding affinity establishes a boundary potential at the interface between the sample solution and the membrane, as well as at the interface between the internal solution and the membrane [16]. The overall membrane potential, ( E{\text{mem}} ), depends on the difference in H⁺ activity between the sample (( a{\text{H⁺, samp}} )) and the internal solution (( a_{\text{H⁺, int}} )):

[ E{\text{mem}} = E{\text{asym}} - \frac{RT}{F} \ln \frac{a{\text{H⁺, int}}}{a{\text{H⁺, samp}}} ]

Where ( E_{\text{asym}} ) is an asymmetry potential that accounts for minor differences between the two membrane surfaces [16]. Since the activity of H⁺ in the internal solution is fixed, the measured potential is directly proportional to the pH of the sample. The selectivity of the glass membrane is intrinsically tied to its chemical composition. For instance, a common pH-sensitive glass contains SiO₂, Na₂O, and CaO. The selectivity for H⁺ over Na⁺ is high but not infinite; in highly alkaline solutions (high Na⁺, low H⁺), the electrode may exhibit a slight response to sodium ions, known as the "alkaline error" [19].

Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs)

General Principles and Classification

Ion-selective electrodes are potentiometric sensors that incorporate a specialized membrane capable of selectively binding a target ion. The core component is the ion-selective membrane (ISM), which separates the sample solution from the internal electrode assembly. As with the glass electrode, the membrane potential develops due to the selective partitioning of the target ion between the sample and the membrane phase, following a Nernstian relationship [16] [19]. ISEs are broadly classified based on the nature and composition of their membrane, each offering distinct advantages and suited for different analytical challenges. The table below summarizes the primary types of ISE membranes.

Table 1: Classification of Ion-Selective Electrode Membranes

| Membrane Type | Composition | Target Ions | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membrane [19] | Silicate or chalcogenide glass | H⁺, Na⁺, Ag⁺ | Excellent chemical durability, good selectivity, well-established for pH |

| Crystalline Membrane [16] [19] | Mono- or polycrystalline solids | F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻, CN⁻, S²⁻, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ | High selectivity (only ions introducing into crystal lattice interfere), robust |

| Ion-Exchange Resin (Polymeric) Membrane [20] [19] | PVC or other polymers plasticized with ion exchanger/ionophore | Wide variety (K⁺, Ca²⁺, NH₄⁺, NO₃⁻, drug cations/anions) | Highly versatile, wide array of ionophores available, most widespread type |

| Enzyme Electrode [19] | Enzyme layer over a standard ISE | Substrates like glucose, urea, etc. | "Double reaction" mechanism; enzyme produces a detectable ion (e.g., H⁺) |

Response Mechanism of Polymeric Membrane ISEs

The functioning of a modern polymeric ISE, common in pharmaceutical and research applications, involves a sophisticated interplay of components. The membrane is typically composed of polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plasticized to create a viscous organic liquid phase, in which several key components are dissolved [20]:

- Ionophore: A neutral or charged carrier molecule that selectively binds to the target ion. Its selectivity dictates the electrode's performance.

- Ionic Additive: A lipophilic salt (e.g., potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl) borate, KTpClPB) to control the membrane's ionic properties and improve selectivity and detection limit [20] [15].

- Plasticizer: Provides the liquid matrix and can also influence the membrane's dielectric constant and ionophore solubility.

The potential is generated as the target ion, for instance, a drug cation (( C^+ )), partitions from the aqueous sample into the organic membrane phase, facilitated by selective complexation with the ionophore. This creates a phase boundary potential at the sample-membrane interface. The ionic additive ensures the membrane remains conductive and helps establish a stable potential [20] [15].

Electrode Design: From Liquid-Contact to Solid-Contact

The physical design of ISEs has evolved significantly, leading to improved stability and miniaturization.

- Liquid-Contact ISEs: This traditional design features an internal filling solution containing the target ion at a fixed activity. An internal reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) is immersed in this solution. While reliable, these electrodes can suffer from evaporation or leakage of the internal solution, limiting their shelf-life and making miniaturization difficult [1] [15].

- Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs): This advanced design eliminates the internal solution, replacing it with a solid conductive layer that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer. This layer is coated with the ion-selective membrane. SC-ISEs are mechanically robust, easier to miniaturize, and ideal for disposable sensors or point-of-care devices [1] [15]. The ion-to-electron transduction in the solid contact layer can occur via two primary mechanisms:

- Redox Capacitance: Using conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT, polyaniline) that undergo reversible oxidation/reduction, translating ionic signal to an electronic signal [1].

- Electric-Double-Layer Capacitance: Using carbon-based nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes) or composite materials that form a capacitive interface at the ISM/transducer boundary [1].

The following diagram illustrates the architecture and charge-transfer mechanism of a solid-contact ISE.

Experimental Protocols in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Fabrication of a Solid-Contact ISE for Drug Analysis

The development of ISEs for monitoring drug release, as demonstrated for propranolol and lidocaine, involves a multi-step fabrication and testing protocol [20].

1. Membrane Cocktail Preparation:

- Composition: Combine 33% PVC (polymer matrix), 66% 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE, plasticizer), and 1% potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl) borate (KTpClPB, ionic additive) by weight [20].

- Dissolution: Dissolve this "dry" mixture in an organic solvent, typically tetrahydrofuran (THF), to create a "membrane cocktail" (e.g., 20% w/w dry part in THF) [20].

2. Solid-Contact Electrode Assembly:

- A conductive substrate (e.g., a rolled carbon cloth) is mounted inside an electrode body.

- The membrane cocktail is drop-cast onto the substrate surface in multiple aliquots (e.g., 450 µL total, in 100 µL portions every 30 minutes) to allow slow, even evaporation of the solvent and form a homogeneous membrane [20].

- The assembled electrode is conditioned by soaking in a solution of the target drug (e.g., 1.0 × 10⁻³ M propranolol HCl in 10⁻² M HCl, pH 2.0) for 24-48 hours to establish a stable potential [20].

3. Potentiometric Measurement and Drug Release Study:

- The conditioned ISE and a separate reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) are immersed in a stirred dissolution vessel containing the release medium.

- A drug-loaded dosage form (e.g., a polymer film or a drug-coated porous cellulose substrate) is introduced.

- The potential is recorded continuously (e.g., every 10 seconds) using a high-impedance data acquisition system.

- The potential values are converted to concentration values using a pre-established calibration curve, allowing the construction of a real-time drug release profile [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The following table details key materials and reagents required for fabricating and applying ISEs in a research context, based on the cited experimental work.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for ISE Fabrication and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) [20] | Serves as the polymeric matrix for the ion-selective membrane, providing structural integrity. | High molecular weight PVC (Fluka Selectophore) [20]. |

| Plasticizer [20] | Imparts plasticity to the PVC membrane, creating a liquid-like phase for ion diffusion; can influence dielectric constant. | 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE) [20]. |

| Ionophore (Ion Carrier) [15] | The key selective element; specifically complexes with the target ion, dictating sensor selectivity. | Valinomycin for potassium; custom ionophores for drugs [19] [15]. |

| Ionic Additive (Lipophilic Salt) [20] | Improves membrane conductivity, reduces membrane resistance, and lowers the detection limit by minimizing co-ion interference. | Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl) borate (KTpClPB) [20]. |

| Solid-Contact Transducer Material [1] [15] | Facilitates ion-to-electron transduction in solid-contact ISEs; provides high capacitance and stable potential. | Conducting polymers (PEDOT), carbon cloth, carbon nanotubes, graphene [20] [1]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) [20] | Volatile organic solvent used to dissolve membrane components for drop-casting. | Tetrahydrofuran (Fluka Selectophore) [20]. |

| Reference Electrode [4] [20] | Provides a stable, known reference potential against which the ISE potential is measured. | Ag/AgCl/3 M KCl reference electrode (e.g., Metrohm) [20]. |

Comparative Analysis with Voltammetry and Future Outlook

Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry: A Technical Comparison

While both are electrochemical techniques, potentiometry and voltammetry differ fundamentally in their operational principles and the information they provide, making them complementary tools.

Table 3: Core Differences Between Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Potential (Voltage) at zero current [4] [1] | Current as a function of applied potential [4] |

| Electrode System | Two-electrode system (Indicator + Reference) [18] | Three-electrode system (Working, Reference, Counter) [4] [1] |

| Fundamental Equation | Nernst Equation [16] [18] | Butler-Volmer Equation (and others) [4] |

| Output | Ion activity (concentration) [16] | Redox behavior, kinetics, concentration [4] |

| Selectivity Source | Selective membrane/ionophore [16] [19] | Applied potential and electrode surface [4] |

| Power Consumption | Very low (measures at equilibrium) [1] | Higher (applies potential to drive current) [1] |

Emerging Trends and Future Directions

The field of potentiometric sensors is rapidly advancing, driven by new materials and technologies. Key trends include:

- Miniaturization and Wearable Sensors: SC-ISEs are ideal for integration into wearable devices for non-invasive health monitoring (e.g., epidermal patches, smart watches) that can track electrolytes or drug levels in real-time using wireless protocols like Bluetooth [1] [15].

- Advanced Transducer Materials: Research is focused on nanocomposite materials (e.g., MoS₂ nanoflowers with Fe₃O₄, tubular gold nanoparticles) that offer ultra-high capacitance and signal stability, pushing the limits of detection and reproducibility [1].

- Novel Manufacturing Techniques: Additive manufacturing (3D printing) and paper-based microfluidic devices are being explored to create low-cost, disposable, and complex sensor geometries for point-of-care testing [1].

- Expanded Pharmaceutical Applications: ISEs are increasingly used for content uniformity testing, dissolution profiling of immediate-release dosage forms, and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) due to their ability to provide continuous, real-time data without sample pretreatment [20] [15].

In conclusion, glass membranes and ion-selective electrodes represent a powerful and versatile class of indicator electrodes that are central to the potentiometric technique. Their continued evolution, particularly toward solid-contact designs and miniaturized formats, ensures they will remain at the forefront of analytical science, offering researchers and drug development professionals robust tools for precise ionic measurement.

Within the broader research context comparing potentiometry and voltammetry, understanding the core components of voltammetric systems is paramount. While potentiometry measures the potential at zero current to determine ion activity, voltammetry is a dynamic technique that applies a controlled potential to a working electrode and measures the resulting current, providing rich information about the identity and concentration of electroactive species [21]. The working electrode (WE) is the central component in any voltammetric system, serving as the stage where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs [22]. Its material composition critically influences the sensitivity, selectivity, and scope of an analysis by defining the potential window, electron transfer kinetics, and susceptibility to fouling.

This guide provides an in-depth examination of the four most historically and practically significant working electrode materials: mercury, gold, platinum, and glassy carbon. Each material offers a unique set of electrochemical properties that make it suitable for specific applications, from the detection of heavy metals to the analysis of pharmaceutical compounds. By presenting a detailed comparison of their characteristics, experimental protocols for their use, and their modern applications, this document aims to serve as an essential resource for researchers and scientists in selecting the optimal working electrode for their analytical challenges.

Core Principles of the Working Electrode

In a standard three-electrode voltammetric cell, the working electrode's potential is precisely controlled relative to a stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or SCE), while the current is measured between the WE and an auxiliary (or counter) electrode [21]. The primary function of the WE is to facilitate the transfer of electrons to or from analyte molecules in solution. The choice of WE material directly determines several key experimental parameters:

- Potential Window: The range of potentials over which the electrode is stable and the background current from electrolyte decomposition is minimal. This window dictates which redox couples can be studied [23] [24].

- Electron Transfer Kinetics: The rate at which electrons are exchanged between the electrode and the analyte, which affects the sharpness and reversibility of the voltammetric response.

- Surface Renewability and Reproducibility: The ease with which a fresh, reproducible electrode surface can be generated, which is crucial for quantitative analysis.

- Fouling Resistance: The electrode's susceptibility to deactivation by adsorption of reactants or products.

An ideal polarizable electrode behaves like a capacitor, allowing its potential to be varied without significant Faradaic current flow; the potential range where this occurs is known as the "potential window" [24]. The presence of electroactive species adds a potential-dependent Faradaic resistance and a Warburg impedance related to diffusion into the equivalent circuit [24].

Material-Specific Analysis

Mercury Electrodes

Merits and Limitations: Mercury electrodes, including the Dropping Mercury Electrode (DME) and Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE), are characterized by their exceptionally high overpotential for hydrogen evolution [21]. This property provides an extensive cathodic (reductive) potential window, allowing access to the reduction of metal ions like Zn²⁺ that would be obscured by solvent breakdown at other electrodes [23] [25]. A freshly renewable, atomically smooth surface is easily produced, ensuring excellent reproducibility [21] [24]. A unique advantage is mercury's ability to form amalgams with many metals, which is exploited in preconcentration techniques like Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) [23]. However, mercury's limited anodic window due to its own oxidation and its significant toxicity have reduced its prevalence in modern laboratories [23] [24].

Applications: Mercury electrodes are the traditional choice for the determination of heavy metal ions (e.g., Pb, Cd, Tl, In, Zn) via ASV [24]. Their renewable surface is also beneficial for studying electrochemical reduction mechanisms in organic chemistry.

Modern Trends: To mitigate toxicity concerns while retaining analytical benefits, mercury is often used as a thin film plated onto a solid electrode substrate like glassy carbon [23] [21].

Gold Electrodes

Merits and Limitations: Gold electrodes offer a wider cathodic potential range than platinum and lack the distinct hydrogen adsorption/desorption waves seen on platinum, resulting in a cleaner background in certain regions [25] [24]. A principal merit of gold is its well-established surface chemistry, particularly its ability to form robust self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) with thiol-containing molecules, enabling the creation of highly specific chemical sensors [23]. A key limitation is its tendency to oxidize at relatively modest anodic potentials, especially in the presence of chloride ions, which restricts its anodic window [23] [24].

Applications: Gold is widely used for the detection of thiols and in the construction of biosensors through SAM-based modifications [25]. Recent research focuses on nanostructured gold and its alloys for enhanced sensing. For instance, a 2025 study detailed a gold-mercury-platinum (AuHgPt) nanoalloy for the light-enhanced electrochemical detection of hydrogen peroxide, leveraging the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect of gold nanoparticles [26]. Another study developed a gold particle-modified glassy carbon electrode for monitoring the drug dipyrone [27].

Platinum Electrodes

Merits and Limitations: Platinum is a favored electrode material due to its excellent electrochemical inertness and ease of fabrication into various forms (wire, disk, plate) [23]. It exhibits high overpotential for oxygen evolution, making it suitable for anodic studies in organic and inorganic chemistry [25]. Its most significant drawback is its low hydrogen overpotential, which limits its useful cathodic range in aqueous solutions as hydrogen evolution occurs at fairly modest negative potentials (E = -0.059 × pH) [23]. Platinum surfaces are also prone to contamination and can require activation cycles.

Applications: Platinum is a conventional electrode for detecting hydrogen peroxide and various oxides [25]. It is also extensively used in electrocatalysis research (e.g., for fuel cells) and for the study of oxidative reactions where a wide anodic window is required.

Glassy Carbon Electrodes

Merits and Limitations: Glassy carbon (GC) is a sp²-bonded carbon material with a dense, impermeable, and hard "vitreous" structure [28] [24]. It boasts a wide potential window in both anodic and cathodic directions, good chemical inertness, and a relatively low cost [23] [28]. It is considered chemically stable despite relatively large overpotentials for oxygen and hydrogen evolution [25]. A limitation is that the quality and performance of glassy carbon can vary significantly between sources and batches. It is also difficult to machine and requires proper polishing to maintain performance [23].

Applications: Glassy carbon is arguably the most versatile working electrode. It serves as the foundational substrate for a vast array of chemically modified electrodes. Its applications span the detection of neurotransmitters, pharmaceutical compounds (e.g., antidepressants), environmental pollutants, and heavy metals [28]. A 2025 review highlighted its prominent role in the voltammetric sensing of numerous antidepressant drugs due to its excellent properties [28].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Common Working Electrode Materials

| Material | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | High H⁺ overpotential (wide cathodic window); Renewable, smooth surface; Forms amalgams [23] [21] | Narrow anodic window; High toxicity [23] | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry of heavy metals (Pb, Cd, Zn) [24] |

| Gold | Wide cathodic window; No H-adsorption waves; Ideal for thiol SAMs [23] [25] [24] | Limited anodic window due to oxidation [23] | Thiol detection; Biosensors; AuHgPt nanoalloy for H₂O₂ sensing [26] [25] |

| Platinum | Electrochemically inert; High O₂ overpotential (good anodic window); Various geometries [23] [25] | Low H₂ overpotential (limited cathodic window); Expensive; Surface contamination [23] | H₂O₂ detection; Electrocatalysis (fuel cells); Organic oxidations [25] |