Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry: A Comparative Guide to Advantages, Disadvantages, and Applications in Environmental Monitoring

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two foundational electrochemical techniques—potentiometry and voltammetry—for environmental monitoring.

Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry: A Comparative Guide to Advantages, Disadvantages, and Applications in Environmental Monitoring

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparative analysis of two foundational electrochemical techniques—potentiometry and voltammetry—for environmental monitoring. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the core principles, operational mechanisms, and key performance characteristics of each method. The scope ranges from foundational concepts and methodological applications for detecting analytes like heavy metal ions and pharmaceuticals to troubleshooting common challenges and optimizing sensor performance with advanced materials. A critical validation and comparative analysis equips readers to select the appropriate technique based on sensitivity, selectivity, cost, and field-deployment requirements, with insights into future directions shaped by AI, IoT, and smart sensor technologies.

Core Principles: Understanding Potentiometry and Voltammetry in Environmental Sensing

In the field of environmental monitoring, the demand for precise, rapid, and cost-effective analytical methods is constant. Electrochemical analysis has emerged as a powerful discipline, providing researchers with versatile tools for detecting and quantifying pollutants in complex environmental samples. At its core, this field involves measuring electrical properties—such as voltage or current—to gain insights into the chemical composition of a solution [1]. Among the various electroanalytical methods available, potentiometry and voltammetry represent two foundational approaches with distinct principles and applications. These techniques have become indispensable in modern environmental research, from tracking heavy metals in water bodies to monitoring nutrient levels in soil [2] [3].

Potentiometry and voltammetry differ fundamentally in what they measure. Potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes when no significant current is flowing through the electrochemical cell [4] [5]. In contrast, voltammetry is a dynamic technique that measures the current response generated when a controlled, changing potential is applied to the working electrode [6] [7]. This critical distinction dictates their respective advantages, limitations, and ideal applications in environmental research.

This comparison guide provides an objective analysis of both techniques, focusing on their performance characteristics, experimental requirements, and suitability for various environmental monitoring scenarios. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each method, researchers can select the most appropriate technique for their specific analytical challenges in drug development and environmental science.

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Foundations

Potentiometry: Theory of Zero-Current Measurement

Potentiometry is based on the measurement of an electrochemical cell's potential under static conditions where no current—or only negligible current—flows through the system [4] [5]. This technique relies on the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the electrode potential and the concentration (more accurately, the activity) of the target ion in solution [4] [1]. The Nernst equation is expressed as:

[E = E^0 + \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q]

Where (E) is the measured potential, (E^0) is the standard potential of the system, (R) is the universal gas constant, (T) is the temperature, (n) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction, (F) is the Faraday constant, and (Q) is the reaction quotient [4].

In practical terms, a potentiometric cell consists of a reference electrode with a stable, known potential and an indicator electrode that responds to the activity of the target ion [4]. The most common example is the pH glass electrode, where the potential difference across a thin glass membrane varies as a function of the hydrogen ion activity on opposite sides of the membrane [4] [5]. Modern potentiometry primarily utilizes ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), which incorporate specialized membranes designed to respond selectively to specific ions such as Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, F⁻, Cl⁻, and various heavy metals [2] [1]. The potential stability of the reference electrode significantly impacts the long-term stability of potentiometric measurements, with Ag/AgCl electrodes being among the most commonly used reference systems [2].

Voltammetry: Theory of Current Response to Applied Potential

Voltammetry encompasses a category of electroanalytical methods where information about an analyte is obtained by measuring the current as the potential is systematically varied over time [6] [7]. Unlike potentiometry, voltammetry is considered a dynamic electrochemical method where electron transfer reactions occur at the electrode-solution interface, generating a faradaic current that follows Faraday's law [7] [8]. This current is measured as the dependent variable while controlling the potential as the independent variable [7].

The theoretical foundation of voltammetry involves several key equations beyond the Nernst equation. The Butler-Volmer equation describes the relationship between current, potential, and time by accounting for the kinetics of electrochemical reactions:

[j = j0 \cdot \left{\exp\left[\frac{\alphaa zF\eta}{RT}\right] - \exp\left[-\frac{\alpha_c zF\eta}{RT}\right]\right}]

Where (j) is the current density, (j0) is the exchange current density, (\alphaa) and (\alpha_c) are the anodic and cathodic charge transfer coefficients, (z) is the number of electrons transferred, (\eta) is the overpotential, and other terms maintain their standard meanings [7].

At high overpotentials, this simplifies to the Tafel equation:

[\eta = \pm A \cdot \log{10}\left(\frac{i}{i0}\right)]

Which relates overpotential to the current and is useful for determining reaction rates [7]. Additionally, Fick's laws of diffusion are essential for understanding how analytes move toward the electrode surface, particularly in stationary solution techniques where diffusion is the primary mass transport mechanism [7].

Voltammetric experiments typically employ a three-electrode system consisting of a working electrode where the reaction of interest occurs, a reference electrode that maintains a stable potential, and a counter electrode that completes the electrical circuit [7] [1]. This configuration provides precise control over the working electrode potential and enables accurate current measurements [1].

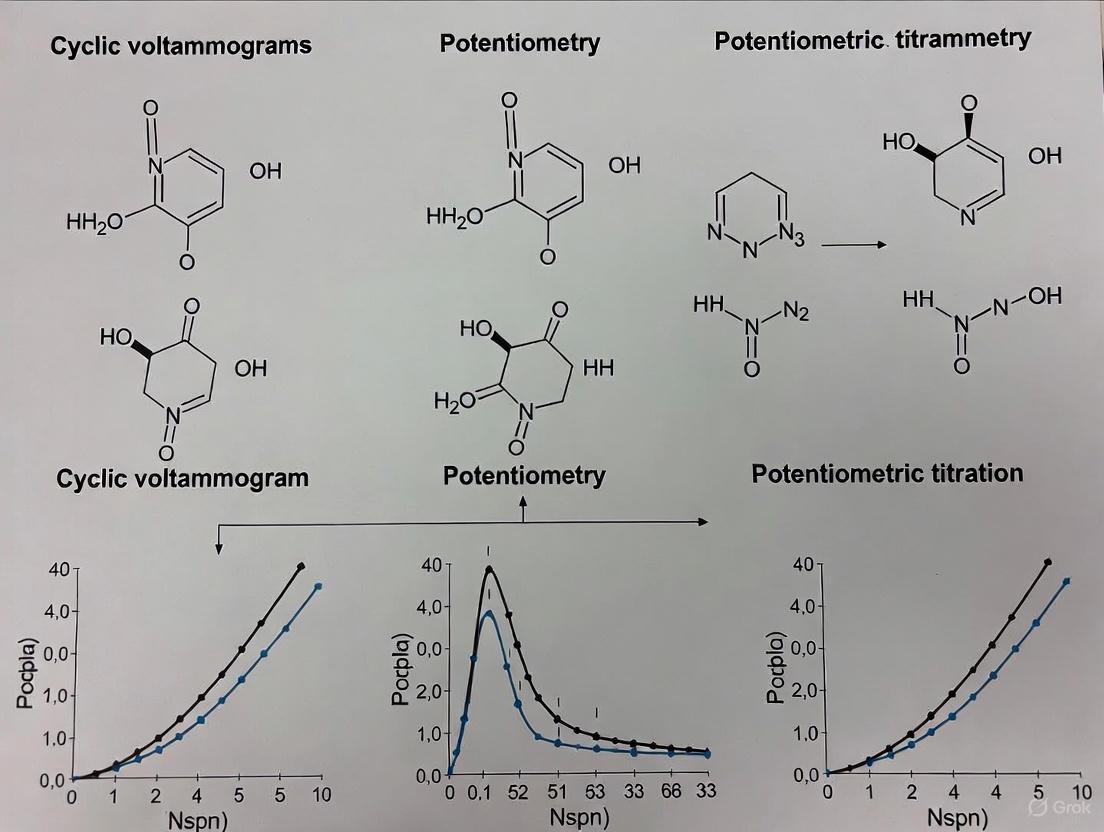

Figure 1: Fundamental principles of potentiometry and voltammetry, highlighting their distinct measurement approaches.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Potentiometric Experimental Protocol for Environmental Monitoring

Potentiometric measurements follow a relatively straightforward protocol that leverages the direct relationship between potential and ion activity. A typical experimental procedure for determining ion concentrations in environmental samples involves the following steps:

Electrode Preparation: Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are conditioned according to manufacturer specifications, which typically involves soaking in a standard solution of the target ion. Reference electrodes are checked for proper filling solution and intact junctions [2] [5].

Calibration: The ISE system is calibrated using a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target ion. The potential is measured for each standard, and a calibration curve is constructed by plotting potential versus logarithm of concentration. According to the Nernst equation, this relationship should be linear with a slope of approximately 59.16/z mV per decade at 25°C (where z is the ion charge) [4] [5].

Sample Measurement: Environmental samples (water, soil extracts, etc.) are measured under identical conditions to the standards. The ionic strength is often adjusted using an ionic strength adjustment buffer (ISAB) to maintain constant activity coefficients and minimize junction potentials [5]. For soil pore water analysis, samples may require filtration to remove particulate matter [9].

Data Analysis: The measured potential values for unknown samples are converted to concentration values using the established calibration curve. Most modern potentiometric systems include software that automatically performs this conversion [1].

Recent advances in potentiometric protocols include the development of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) that eliminate the internal filling solution, thereby enhancing mechanical stability and facilitating miniaturization [2]. These electrodes incorporate conducting polymers or carbon-based materials as ion-to-electron transducers, improving their suitability for field deployment in environmental monitoring [2].

Voltammetric Experimental Protocol for Trace Metal Analysis

Voltammetric methods offer more varied protocols depending on the specific technique employed. The following describes a general protocol for anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV), a highly sensitive method for trace metal analysis in environmental samples:

Solution Preparation: The supporting electrolyte is added to the sample to ensure sufficient conductivity and minimize migration effects. Common supporting electrolytes for environmental analysis include acetate buffers for lead and cadmium determination, and ammonia buffers for zinc and copper analysis [6] [7].

Deaeration: The solution is purged with an inert gas (nitrogen or argon) for 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which would otherwise interfere with the measurement through its reduction current [6] [8]. A blanketing layer of inert gas is maintained above the solution during measurement.

Preconcentration Step: A potential is applied to the working electrode that is sufficient to reduce the target metal ions, causing them to deposit onto the electrode surface as amalgams (for mercury electrodes) or as thin films. This step typically lasts for 1-5 minutes with solution stirring to enhance mass transport [6].

Equilibration: The stirring is stopped, and the solution is allowed to become quiescent for 15-30 seconds before the potential scan [8].

Stripping Step: The potential is scanned in the positive direction (for anodic stripping), causing the deposited metals to be oxidized back into solution. The resulting current is measured as a function of the applied potential, producing peaks at characteristic potentials for each metal [6].

Quantification: Peak currents are proportional to concentration, with quantification achieved through standard addition or calibration curves [7].

More advanced voltammetric protocols include differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV), which apply potential pulses to minimize charging currents and enhance signal-to-noise ratios, thereby lowering detection limits [1]. Recent innovations include the use of 3D-printed electrodes modified with specific catalysts or recognition elements for enhanced selectivity [9].

Performance Comparison in Environmental Monitoring

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The performance of potentiometry and voltammetry can be objectively compared across several key metrics relevant to environmental monitoring. The table below summarizes experimental data and characteristics for both techniques:

Table 1: Performance comparison of potentiometry and voltammetry for environmental monitoring applications

| Performance Metric | Potentiometry | Voltammetry | Experimental Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limits | ~1-10 µM for most ions [2] | ~0.1-1 nM for stripping techniques [6] | Nitrate detection: 66.99 µM (potentiometry) [9] vs. heavy metals at nM levels (voltammetry) [6] |

| Selectivity | High for primary ion, but susceptible to interference from similar ions [2] | Good, with overlapping peaks resolvable by modern electronics [7] | Ion-selective membranes vs. peak separation in voltammograms [2] [7] |

| Analysis Time | Rapid (seconds to minutes) [3] | Moderate to slow (minutes to tens of minutes) [6] | Direct measurement vs. requiring deposition/stripping steps [2] [6] |

| Multi-analyte Capability | Typically single analyte per sensor [2] | Multiple analytes in single scan [7] | Array of sensors needed vs. multiple peaks in voltammogram [2] [1] |

| Sample Volume Requirements | Low to moderate (mL range) [5] | Very low (µL possible with microelectrodes) [6] | Standard electrodes vs. ultramicroelectrodes [6] [5] |

| Field Deployment | Excellent (portable ISE meters common) [9] | Good (portable potentiostats available) [9] | Commercial portable meters for both techniques [9] |

Based on the comparative performance data and experimental observations, each technique exhibits distinct advantages and limitations for environmental monitoring applications:

Potentiometry Advantages:

- Simplicity and cost-effectiveness: Potentiometric systems are generally simpler and more affordable than voltammetric instruments, making them accessible for widespread use [3] [1].

- Rapid analysis: Direct measurement without need for preconcentration steps enables fast analysis, suitable for real-time monitoring [2] [3].

- Miniaturization potential: Solid-contact ISEs can be easily miniaturized for embedded systems and point-of-care devices [2].

- Suitability for colored/turbid samples: Unlike optical methods, potentiometry works effectively with colored or turbid environmental samples [2].

Potentiometry Limitations:

- Limited sensitivity: Detection limits are typically in the micromolar range, restricting applications for trace analysis [2].

- Selectivity challenges: While modern ionophores have improved selectivity, interference from chemically similar ions remains a concern [2].

- Single-analyte capability: Each sensor typically responds to only one ion, requiring multiple sensors for comprehensive analysis [2].

Voltammetry Advantages:

- Exceptional sensitivity: Stripping techniques can achieve detection limits in the nanomolar to picomolar range, ideal for trace metal analysis [6].

- Multi-analyte capability: Multiple analytes can be determined simultaneously in a single scan if their redox potentials are sufficiently separated [7] [1].

- Chemical speciation information: The ability to distinguish between different oxidation states of elements provides valuable speciation data [6].

- * Wide linear dynamic range*: Voltammetric methods typically exhibit linear responses across several orders of magnitude of concentration [1].

Voltammetry Limitations:

- Complexity and cost: Instrumentation is more sophisticated and expensive than basic potentiometric systems [1].

- Longer analysis times: Preconcentration steps in stripping methods significantly increase total analysis time [6].

- Susceptibility to fouling: Electrode surfaces can be poisoned by adsorption of organic matter in environmental samples [6].

- Requirement for deaeration: Oxygen removal adds complexity to the measurement procedure [6] [8].

Table 2: Suitability assessment of potentiometry and voltammetry for different environmental monitoring scenarios

| Environmental Application | Recommended Technique | Rationale | Key Experimental Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nutrient Monitoring (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺) | Potentiometry | Sufficient sensitivity for typical concentrations (>1 µM); cost-effective for widespread deployment [2] [9] | Use ion-selective electrodes with appropriate membranes; adjust ionic strength [9] |

| Trace Metal Analysis in Water | Voltammetry | Ultra-trace detection required (nM-pM); multi-analyte capability advantageous [6] | Employ stripping techniques with efficient deposition times; mercury films or bismuth electrodes [6] |

| Soil Pore Water Analysis | Potentiometry | Suitable for major ions; minimal sample preparation; compatible with field deployment [9] | Filter samples to prevent clogging; use solid-contact electrodes for better stability [9] |

| Continuous Monitoring Systems | Potentiometry | Rapid response enables real-time data; lower power requirements [2] | Implement sensor arrays for multiple parameters; regular calibration checks [2] |

| Speciation Studies | Voltammetry | Ability to distinguish oxidation states (e.g., Cr(III)/Cr(VI), As(III)/As(V)) [6] | Optimize pH and electrolyte composition to preserve species during analysis [6] |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of potentiometric and voltammetric methods requires specific reagents and materials tailored to each technique. The following table details essential research solutions and their functions:

Table 3: Essential research reagent solutions and materials for potentiometry and voltammetry

| Reagent/Material | Function | Technique | Specific Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Recognition element for target ions | Potentiometry | Contains ionophores selective for specific ions (e.g., valinomycin for K⁺) [2] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides conductivity; minimizes migration | Voltammetry | Inert salts like KCl, KNO₃; concentration typically 0.1-1.0 M [7] |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster | Fixes activity coefficients; reduces junction potentials | Potentiometry | Solutions like TISAB (Total Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer) for fluoride analysis [5] |

| Electrode Polishing Materials | Renews electrode surface | Voltammetry | Alumina slurries (0.3-0.05 µm) or diamond paste for solid electrodes [6] |

| Reference Electrode Fill Solution | Maintains stable reference potential | Both | 3M KCl for Ag/AgCl electrodes; saturated KCl for calomel electrodes [2] [1] |

| Deoxygenation Agents | Removes dissolved oxygen | Voltammetry | High-purity nitrogen or argon gas; oxygen scavengers for special applications [6] [8] |

| Conducting Polymers | Ion-to-electron transduction | Potentiometry | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene), polyaniline in solid-contact ISEs [2] |

| Modifier Materials | Enhensitivity and selectivity | Voltammetry | Mercury films, bismuth coatings, nanomaterials on electrode surfaces [6] |

Figure 2: Decision workflow for selecting between potentiometry and voltammetry in environmental monitoring applications.

Potentiometry and voltammetry represent complementary analytical techniques with distinct strengths that make them suitable for different environmental monitoring scenarios. Potentiometry excels in applications requiring rapid, cost-effective measurement of major ions at micromolar concentrations or higher, with particular advantages in field-deployable systems and continuous monitoring applications. Voltammetry offers superior sensitivity for trace analysis, multi-analyte capability, and chemical speciation information, making it indispensable for monitoring heavy metals and other contaminants at environmentally relevant concentrations.

The choice between these techniques should be guided by specific analytical requirements including target analytes, required detection limits, sample matrix, available resources, and desired throughput. Recent advancements in both fields—including the development of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes, novel ionophores, 3D-printed electrode designs, and portable potentiostats—continue to expand the capabilities and applications of both techniques in environmental research [2] [9].

As environmental monitoring faces increasingly complex challenges, from emerging contaminants to the need for higher spatial and temporal resolution data, both potentiometry and voltammetry will play crucial roles in providing the analytical data necessary for informed decision-making in environmental protection and public health.

Electrochemical analysis represents a versatile discipline in analytical chemistry, measuring electrical properties like voltage and current to gain insights into the chemical properties of a solution [1]. For researchers and scientists engaged in environmental monitoring and drug development, potentiometry and voltammetry stand as two cornerstone techniques. These methods provide distinct approaches to quantification, with potentiometry focusing on potential measurement under zero-current conditions, and voltammetry exploring current response under an applied potential [1] [2]. The operational principles of these techniques are governed by different fundamental relationships: the Nernst equation for potentiometry and current-voltage relationships for voltammetry. The selection between these methods hinges on the specific analytical requirements, including desired sensitivity, selectivity, need for speciation data, and the operational context, whether in a controlled laboratory or for field-based analysis. This guide provides a objective comparison of these techniques, detailing their principles, applications, and performance to inform method selection for environmental and pharmaceutical research.

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundations

The Nernst Equation in Potentiometry

Potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the potential (electromotive force, EMF) of an electrochemical cell to determine the activity (and thus concentration) of ionic species in solution [1] [2]. The core principle governing this relationship is the Nernst Equation:

E = E⁰ - (RT/zF) ln(a)

Where E is the measured potential, E⁰ is the standard electrode potential, R is the ideal gas constant, T is temperature, z is the charge number of the ion, F is Faraday’s constant, and a is the activity of the target ion [10]. This equation establishes a logarithmic relationship between the measured potential and the ionic activity. In practice, Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) are the primary tools for potentiometric measurement. Their response to interfering ions is more accurately described by the Nikolsky-Eisenman equation [10]:

E = E⁰ ± (2.303RT/zF) log( aI + Σ KIJ * aJ^(zI/zJ) )

Where a_I is the activity of the primary ion, a_J is the activity of the interfering ion J, and K_I_J is the potentiometric selectivity coefficient, a critical parameter for evaluating sensor performance in complex matrices [10].

Current-Voltage Relationships in Voltammetry

In contrast to potentiometry, voltammetry is a dynamic technique that applies a controlled, varying potential to a working electrode and measures the resulting current [1]. The resulting plot of current versus applied potential is called a voltammogram, which provides both qualitative and quantitative information about the analyte [1]. The current response is governed by the Randles-Ševčík equation (for reversible systems at planar electrodes), which describes how the peak current (i_p) in a voltammogram is related to the analyte concentration:

i_p = (2.69 × 10^5) * n^(3/2) * A * D^(1/2) * C * v^(1/2)

Where n is the number of electrons transferred, A is the electrode area, D is the diffusion coefficient, C is the analyte concentration, and v is the scan rate [1]. This relationship highlights that the current is directly proportional to concentration, forming the basis for quantitative analysis. Different voltammetric techniques, such as Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) for studying reaction mechanisms and Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) for ultra-trace metal detection, manipulate the applied potential waveform to enhance sensitivity and selectivity [11].

Experimental Comparison: Performance and Protocols

The table below summarizes key performance metrics for potentiometry and voltammetry, illustrating their distinct capabilities.

Table 1: Comparative Analytical Performance of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Performance Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Signal | Potential (Volts) [1] | Current (Amperes) [1] |

| Detection Limit | As low as 10⁻¹⁰ M for Pb²⁺ [10] | ~10⁻¹¹ M for heavy metals [12] |

| Linear Range | Typically 10⁻¹⁰ to 10⁻² M [10] | Varies, can be very wide [1] |

| Sensitivity | Near-Nernstian (~28-31 mV/decade for Pb²⁺) [10] | Very high (nA/μM or lower) [11] |

| Primary Output | Ion activity (concentration) [1] | Concentration, reaction kinetics & mechanism [1] |

| Sample Consumption | Low, can be miniaturized [2] | Very low (μL scale) [11] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To illustrate the practical application of these techniques, here are detailed protocols for representative environmental monitoring tasks.

Protocol 1: Potentiometric Determination of Lead Ions using a Solid-Contact ISE

This protocol is adapted from recent innovations in lead sensing [10].

- Sensor Preparation: Employ a solid-contact ion-selective electrode (SC-ISE) architecture. The transducer layer may consist of a nanocomposite material (e.g., MoS₂ nanoflowers filled with Fe₃O₄ or tubular gold nanoparticles) to enhance capacitance and signal stability. The ion-selective membrane (ISM) is cast on top, containing a lead-ionophore for selectivity [10].

- Calibration: Prepare a series of standard Pb²⁺ solutions across a concentration range (e.g., 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻³ M) in a constant ionic strength background. Immerse the Pb²⁺-ISE and a stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) in each standard solution under stirring.

- Measurement: Measure the equilibrium potential (EMF) at zero current for each standard. Plot the measured potential (E) vs. the logarithm of Pb²⁺ activity (log a_Pb²⁺) to obtain a calibration curve. The slope should be near-Nernstian (≈29 mV/decade at 25°C) [10].

- Sample Analysis: Measure the potential of the unknown environmental sample (e.g., water extract from soil). Determine the concentration from the calibration curve. The selectivity coefficient (K_Pb_J) against common interferents like Cu²⁺ or Zn²⁺ should be predetermined to assess accuracy in complex matrices [10].

Protocol 2: Voltammetric Detection of Cadmium using a Bismuth Film Sensor

This protocol is based on the development of a "green" polymer lab chip sensor for cadmium [11].

- Electrode Preparation: Use a planar carbon or gold working electrode integrated into a microfluidic chip. A bismuth (Bi) film is deposited in situ by adding a Bi(III) solution to the sample or by pre-plating [11].

- Sample Pre-treatment: Mix the water sample with an acetate buffer (pH ~4.65) and 0.1 M KCl as the supporting electrolyte to ensure consistent pH and ionic strength [11].

- SWASV Measurement: Perform Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) with the following steps:

- Pre-concentration/Deposition: Apply a constant negative deposition potential (e.g., -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for a fixed time (e.g., 60-300 seconds) while stirring. This reduces and deposits Cd²⁺ (and Bi³⁺) as an amalgam onto the working electrode.

- Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for a short period (e.g., 10-30 seconds).

- Stripping: Apply a positive-going square-wave potential scan (e.g., from -1.2 V to -0.2 V). This oxidizes (strips) the metals back into solution, generating characteristic current peaks [11].

- Data Analysis: Identify Cd²⁺ by its characteristic peak potential. The peak current height is proportional to the concentration in the original sample, which is quantified using a standard addition or calibration curve method. Parameters like deposition potential and time are optimized for sensitivity and precision [11].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The table below lists key reagents, materials, and their functions essential for experiments in these fields.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specification & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membrane Cocktail | Forms sensing component of ISEs [11]. | Contains ionophore (for selectivity), polymer matrix (e.g., PVC), plasticizer, and ionic additives. Critical for determining sensor selectivity and lifetime. |

| Solid-Contact Transducer Materials | Replaces internal solution in modern SC-ISEs [2]. | Conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT) or nanomaterials (e.g., carbon nanotubes, MXenes). Provides ion-to-electron transduction, high capacitance, and signal stability [2] [10]. |

| Bismuth Precursor | Forms environmentally friendly electrode for heavy metal detection [11]. | Bismuth rods (99.99%) or Bi(III) salts. Provides a non-toxic alternative to mercury electrodes for anodic stripping voltammetry with excellent sensitivity [11]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster / Buffer | Conditions sample for reproducible analysis [11]. | Acetate buffer (pH 4.65) with 0.1 M KCl for Cd(II) detection. Maintains constant pH and ionic strength, minimizing junction potentials and ensuring stable diffusion coefficients. |

| Nanomaterial Modifiers | Enhances electrode sensitivity and selectivity [13]. | Graphene, carbon nanotubes, metal nanoparticles. Increases electroactive surface area, improves electron transfer kinetics, and can be functionalized for specific analyte recognition. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides stable, known reference potential [1]. | Ag/AgCl (with KCl electrolyte) is most common. Essential for maintaining a constant baseline potential in both potentiometric and voltammetric cells. |

Operational Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental operational workflows for potentiometry and voltammetry, highlighting the distinct signaling pathways that lead to their respective analytical outputs.

Potentiometric Sensing Workflow

Diagram 1: Potentiometric Sensing Workflow. This flowchart shows the zero-current measurement pathway. The process begins with ion recognition, leading to a stable potential difference that is measured and related to concentration via the Nernst equation.

Voltammetric Sensing Workflow

Diagram 2: Voltammetric Sensing Workflow. This chart illustrates the pathway where an applied potential drives a redox reaction, generating a current that is measured and plotted to create a voltammogram for analysis.

Potentiometry and voltammetry offer complementary strengths for the modern researcher. The choice between them is not a matter of superiority, but of strategic alignment with analytical goals. Potentiometry, with its simplicity, portability, and direct readout of ion activity, is ideal for decentralized, continuous monitoring of specific ions like pH, electrolytes, or targeted heavy metals [1] [2] [10]. Voltammetry excels in situations demanding ultra-trace detection, speciation capabilities, and detailed insights into reaction kinetics, making it a powerful tool for quantifying multiple heavy metals simultaneously or studying fundamental electrochemical processes [1] [11].

The future of both techniques is being shaped by material science and manufacturing innovations. The integration of novel nanomaterials and conducting polymers as transducers is pushing detection limits and enhancing stability for both ISEs and voltammetric electrodes [2] [10] [13]. Additive manufacturing, particularly 3D printing, is emerging as a disruptive force, enabling rapid prototyping of customized electrodes and fluidic cells, which decreases costs and accelerates sensor development [2] [9]. Furthermore, the convergence of these electrochemical platforms with Internet of Things (IoT) technology and the development of low-cost, portable potentiostats are paving the way for widespread, real-time environmental sensor networks [9]. For researchers, this evolving landscape means that these classic techniques are becoming more accessible, powerful, and integrated than ever before.

The accurate and timely monitoring of ions and molecules in environmental samples is a cornerstone of understanding and protecting ecosystems. Within the realm of electrochemical sensors, two principal architectures have emerged as vital tools: potentiometric sensors, namely Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) and their advanced counterpart, Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs); and voltammetric sensors, which typically employ a three-electrode system. Potentiometry measures the potential (voltage) across an electrochemical cell under conditions of zero or negligible current flow, relating this potential to the activity (effective concentration) of a target ion [4]. In contrast, voltammetry applies a controlled potential and measures the resulting current, which is proportional to the concentration of an electroactive species that is oxidized or reduced at the working electrode [14]. The choice between these techniques involves significant trade-offs in sensitivity, selectivity, cost, and operational complexity. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these essential sensor architectures, focusing on their application in environmental monitoring and research, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Fundamental Principles and Architectures

Potentiometric Sensors: Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs)

Traditional Liquid-Contact ISEs consist of an ion-selective membrane (ISM), an internal filling solution, and an internal reference electrode [15]. The ISM is the heart of the sensor, typically composed of a polymer matrix (like PVC), a plasticizer, an ionophore (a selective ion-recognition molecule), and an ion exchanger [15]. When the ISE is immersed in a sample solution, a phase boundary potential develops across the membrane based on the differential concentration of the target ion between the sample and the internal solution. This potential, measured against an external reference electrode, is described by the Nernst equation: E = E⁰ + (RT/zF) ln(a), where E is the measured potential, E⁰ is the standard potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is the ion's charge, F is Faraday's constant, and a is the ion's activity in the sample [16] [4]. A Nernstian response, typically ~59 mV per decade of activity change for a monovalent ion at 25°C, confirms proper sensor function.

Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) represent a significant evolution, eliminating the internal filling solution. In an SC-ISE, a solid-contact (SC) layer is placed between the ion-selective membrane and the electron-conducting substrate (electrode) [15]. This layer acts as an ion-to-electron transducer, resolving the inherent instability of earlier coated-wire electrodes and enabling miniaturization, portability, and resistance to pressure and orientation changes [17] [15] [18]. The SC layer functions through one of two primary mechanisms:

- Redox Capacitance: Using conducting polymers (e.g., polyaniline, poly(3-octylthiophene)) that undergo reversible oxidation/reduction, coupled with ion exchange [15] [16].

- Electric Double-Layer (EDL) Capacitance: Using high-surface-area materials like carbon nanotubes, graphene, or nanocomposites to create a large capacitive interface [15] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core architectural and operational differences between these potentiometric sensors.

Architectural comparison of Liquid-Contact and Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes.

Voltammetric Sensors: The Three-Electrode System

Voltammetry is a controlled-potential technique where the current resulting from the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species is measured. The three-electrode system is the standard configuration, comprising [14]:

- Working Electrode (WE): The electrode where the reaction of interest occurs (e.g., oxidation of a metal ion). Materials include glassy carbon, platinum, gold, or mercury.

- Counter Electrode (CE): Also called the auxiliary electrode, it completes the electrical circuit and balances the current flowing at the WE.

- Reference Electrode (RE): Provides a stable, known potential against which the WE's potential is precisely controlled and measured. Common examples are Ag/AgCl and saturated calomel electrodes (SCE).

This configuration, typically operated with a potentiostat, separates the current-carrying (CE) and potential-measuring (RE) functions. This prevents polarization of the RE and allows for precise control of the WE potential, enabling the study of reaction kinetics and the sensitive detection of multiple analytes [14]. The system's operation is based on applying a potential waveform (e.g., a linear sweep or pulses) to the WE and measuring the faradaic current that flows as a consequence.

Schematic of a three-electrode system, showing the distinct roles of each component.

Experimental Protocols & Key Research Reagents

To illustrate the practical implementation of these sensors, here are detailed protocols for fabricating and characterizing a state-of-the-art SC-ISE and for setting up a standard three-electrode voltammetric cell.

Detailed Protocol: Fabrication of a Graphene/Polyaniline Nanocomposite SC-ISE

The following protocol, adapted from a recent study on Letrozole detection, highlights the use of nanomaterials to enhance SC-ISE performance [20].

1. Preparation of Polyaniline (PANI) Nanoparticles:

- Method: Micellar emulsion chemical polymerization.

- Procedure: In a round-bottomed flask, add 50 mL of water along with equimolar amounts (1.30 M) of aniline (5.95 mL) and sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS, 18.75 g) as a surfactant. Mechanically stir the mixture for one hour until a milky white solution forms.

- Slowly add 50 mL of ammonium persulfate (APS, 1.30 M) dropwise to initiate polymerization. Maintain the temperature at 20°C using a thermostated bath.

- After 2.5 hours, a dark green dispersion indicating PANI formation is obtained.

- Purification: Dialyze the PANI dispersion against deionized water for 48 hours using a dialysis membrane (12,000 Da MWCO) to remove unreacted monomers and surfactant. Subsequently, centrifuge the purified dispersion.

2. Preparation of Graphene Nanocomposite (GNC) Dispersion:

- Method: Solution dispersion.

- Procedure: Weigh 10.00 mg of graphene powder and disperse it in 1.00 mL of xylene by sonication for 5 minutes.

- In a separate tube, dissolve 95.00 mg of high molecular weight PVC in 3.00 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF), followed by the addition of 0.20 mL of the plasticizer dioctyl phthalate (DOP).

- Mix the contents of both tubes and sonicate for 10 minutes to form a homogeneous GNC dispersion.

3. Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Cocktail and Electrode Assembly:

- The ISM is formulated by combining the ionophore (e.g., 4-tert-butylcalix[8]arene for cationic drugs), ionic sites, plasticizer, and polymer matrix.

- For the solid-contact electrode, the GNC/PANI nanocomposite is first drop-cast onto the conductive substrate (e.g., a glassy carbon electrode) and allowed to dry, forming the SC layer.

- The ISM cocktail is then drop-cast onto the solid-contact layer and left to evaporate, forming a stable, hydrophobic plastic membrane.

4. Conditioning and Calibration:

- Condition the newly fabricated SC-ISE in a solution containing the target ion (e.g., 1 × 10⁻² M Letrozole in 1:4 HCl) for 24 hours to establish a stable equilibrium.

- Calibrate by measuring the potential in a series of standard solutions (e.g., from 1 × 10⁻⁸ to 1 × 10⁻² M). Plot the potential (mV) versus the logarithm of ion activity to obtain the calibration curve, slope, and linear range [20].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Key reagents for fabricating and operating Ion-Selective Electrodes.

| Reagent Category | Example Compounds | Function in the Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC), Polyurethane, Acrylic Esters | Provides the physical backbone and mechanical stability for the ion-selective membrane [20] [15]. |

| Plasticizers | Dioctyl phthalate (DOP), 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (2-NPOE), Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) | Solubilizes membrane components, lowers electrical resistance, and influences ionophore selectivity and lifespan [21] [15]. |

| Ionophores | Valinomycin (for K⁺), 4-tert-butylcalix[8]arene (for cations), synthetic ion carriers | The key recognition element; selectively binds to the target ion, imparting selectivity to the sensor [20] [17] [15]. |

| Ion Exchangers | Sodium tetraphenylborate (NaTPB), Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB) | Introduces permselectivity and facilitates ion exchange at the membrane-sample interface [20] [21] [15]. |

| Solid-Contact Materials | Polyaniline (PANI), Poly(3-octylthiophene), Graphene, Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Acts as an ion-to-electron transducer, improving potential stability and preventing water layer formation [20] [17] [15]. |

Comparative Performance Analysis

Analytical Performance in Environmental Context

The choice between SC-ISEs and three-electrode voltammetry involves balancing key performance metrics, as summarized below.

Table 2: Comparative performance of SC-ISEs and Three-Electrode Voltammetry for environmental monitoring.

| Performance Parameter | Solid-Contact ISEs (Potentiometry) | Three-Electrode Systems (Voltammetry) |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | ~1×10⁻⁸ to 1×10⁻⁶ M (favorable for trace analysis) [20] [18] | Can be extremely low (e.g., nanomolar with stripping techniques) [18] |

| Sensitivity (Slope) | Nernstian (e.g., ~59 mV/decade for K⁺); logarithmic response provides wide dynamic range [20] [16] | Linear current vs. concentration; high sensitivity for faradaic processes [14] |

| Selectivity | High for primary ion over others, dictated by ionophore; can be tuned chemically [20] [15] | Good; can be controlled via applied potential and surface modification |

| Measurement Speed & Temporal Resolution | Fast (seconds), suitable for real-time tracking (e.g., drug dissolution) [21] | Scan time dependent (seconds to minutes); high temporal resolution possible |

| Lifetime & Stability | Good (weeks to months); potential drift can be an issue without proper solid-contact design [17] [16] | Dependent on electrode fouling; can require frequent surface renewal |

| Multi-analyte Capability | Typically single ion per sensor; requires sensor arrays ("electronic tongue") [18] | Inherently multi-analyte; different species oxidize/reduce at different potentials in a single scan [22] |

Operational and Practical Considerations

Table 3: Practical comparison of operational factors and applications.

| Operational Factor | Solid-Contact ISEs | Three-Electrode Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Miniaturization & Portability | Excellent; ideal for wearable, in-situ, and portable devices [15] [18] | Good; systems are becoming increasingly portable |

| Robustness & Maintenance | Robust once fabricated; no internal solution to refill. Requires conditioning and periodic calibration [15] [16] | Requires careful electrode maintenance (polishing, cleaning). RE requires proper upkeep. |

| Ease of Fabrication | Moderate; dependent on membrane and SC layer fabrication. Screen-printing allows mass production [21] [16] | Well-established; commercial electrodes are widely available |

| Power Consumption | Very low; measures potential at zero current [15] [18] | Higher; requires current flow for measurement |

| Cost | Low per sensor, especially disposable screen-printed versions [21] [18] | Higher initial instrument (potentiostat) cost; recurring costs for electrodes |

| Ideal Application Scenarios | Long-term, continuous monitoring of specific ions (e.g., K⁺ in water, H⁺ for pH) [18] [19]; wearable sweat sensors [18] | Trace metal analysis in water [18]; detection of organic pollutants; studying reaction mechanisms |

Within the context of environmental monitoring research, the choice between SC-ISEs and three-electrode voltammetric systems is not a matter of superiority, but of suitability for the specific analytical challenge.

Solid-Contact ISEs (Potentiometry) are the preferred tool for dedicated, continuous, or in-field monitoring of a specific ion where simplicity, low cost, low power, and portability are critical. Their strength lies in providing a direct, rapid reading of ionic activity, making them ideal for networked sensors tracking parameters like pH, potassium, or calcium over time in rivers, soils, or effluents [18] [19].

Three-Electrode Systems (Voltammetry) excel in applications requiring ultra-low detection limits, speciation analysis, or the simultaneous detection of multiple electroactive species. Their power is in leveraging applied potential to probe different analytes in a single measurement, making them indispensable for quantifying trace heavy metals (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) in water samples or for characterizing complex environmental mixtures [14] [18].

Advances in materials science, particularly the development of novel solid-contact layers like laser-induced graphene and nanocomposites, are continuously improving the stability and reproducibility of SC-ISEs, pushing them toward calibration-free operation [15] [19]. Concurrently, the development of portable, user-friendly potentiostats is expanding the field applications of voltammetry. The informed researcher, by understanding the fundamental principles, performance trade-offs, and experimental requirements outlined in this guide, can strategically deploy these powerful electrochemical tools to advance environmental science and protection.

Electrochemical detection has emerged as a cornerstone technique for environmental analysis due to its exceptional sensitivity, precision, and capability for real-time monitoring [23]. This field encompasses several powerful methodologies, with potentiometry and voltammetry representing two fundamentally different approaches with complementary strengths. The selection between these techniques is a critical decision for researchers and analysts working in environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and clinical diagnostics. Potentiometry, which measures the potential difference between two electrodes under conditions of zero current flow, offers remarkable simplicity and operational efficiency [24] [1]. In contrast, voltammetry, which measures current as a function of systematically applied potential, provides superior sensitivity and the unique capability to detect multiple analytes simultaneously [25] [1]. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these two analytical workhorses, focusing on their inherent advantages, limitations, and practical implementation in research and environmental monitoring contexts. By understanding their fundamental principles and operational characteristics, scientists can make informed decisions about which technique best addresses their specific analytical challenges, particularly when dealing with complex environmental samples where both trace-level detection and operational practicality are paramount considerations.

Fundamental Principles and Instrumentation

Potentiometry: Measuring Potential at Zero Current

Potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the potential difference (voltage) between two electrodes when no significant current is flowing through the electrochemical cell [1]. This measured potential serves as a direct indicator of the concentration (more precisely, the activity) of a specific ion in solution, as described by the Nernst equation [24] [26] [27]. The fundamental setup for a potentiometric measurement requires two primary components: a reference electrode, which maintains a stable, known potential, and an indicator electrode, which develops a potential that varies with the activity of the target ion [24] [27]. The most common example of potentiometry is the ubiquitous pH meter, which uses a glass electrode sensitive to hydrogen ions [1].

The relationship between the measured potential and ion concentration is quantitatively described by the Nernst equation: [ E = E^0 + \frac{RT}{nF} \ln(a) ] where (E) is the measured electrode potential, (E^0) is the standard electrode potential, (R) is the universal gas constant, (T) is the temperature in Kelvin, (n) is the number of electrons transferred in the electrode reaction, (F) is the Faraday constant, and (a) is the activity of the ion [26] [27]. This equation forms the theoretical foundation for all potentiometric measurements, enabling the conversion of a voltage reading into a concentration value.

Voltammetry: Measuring Current as a Function of Applied Potential

Voltammetry is a dynamic technique that involves measuring the current that flows in an electrochemical cell as the applied potential is systematically varied [1]. Unlike potentiometry, voltammetry intentionally drives redox reactions at the working electrode, and the resulting current provides both qualitative and quantitative information about the electroactive species present in solution. The current is proportional to the concentration of the analyte, and the potential at which the redox event occurs serves as a characteristic fingerprint for its identity [25]. Voltammetry typically employs a three-electrode system—consisting of a working electrode, a reference electrode, and a counter electrode—to provide precise control over the applied potential and accurate measurement of the faradaic current [1].

The three-electrode configuration is crucial for sensitive voltammetric measurements. The working electrode is where the redox reaction of interest occurs; its material (e.g., mercury, carbon, gold, platinum) is chosen based on the target analyte and required potential window. The reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel electrode) provides a stable potential reference point, while the counter electrode (often made of platinum) completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow without affecting the potential measurement at the working electrode [1]. This setup enables voltammetry to achieve exceptional sensitivity, with some variants capable of detecting analytes at concentrations as low as 10⁻¹² M [25].

Figure 1: Fundamental operational principles of potentiometry and voltammetry, highlighting their core measurement approaches and outputs.

Comparative Analysis: Core Strengths and Technical Specifications

The choice between potentiometry and voltammetry involves careful consideration of their inherent strengths and limitations, which stem from their fundamental operational principles. The table below provides a systematic comparison of their key technical characteristics, highlighting how each technique addresses different analytical needs in environmental and pharmaceutical research.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of technical specifications between potentiometry and voltammetry

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Potential (Voltage) [1] | Current [1] |

| Current Flow | Zero or negligible current [2] [1] | Significant, measured current [1] |

| Primary Output | Millivolts (mV) [27] | Current (µA) vs. Potential (V) plot (Voltammogram) [1] |

| Detection Limit | Generally ≥ 10⁻⁷ M [26] | Can reach 10⁻¹² M with stripping techniques [25] |

| Selectivity Source | Ion-selective membrane [24] [2] | Applied potential and electrode material [25] |

| Multianalyte Capability | Typically single analyte per sensor [1] | Yes, via distinct peak potentials [25] |

| Power Consumption | Very low [2] | Moderate to high (requires applied potential) |

| Instrument Simplicity | High; simple circuitry [26] | Moderate to complex; requires potentiostat [1] |

| Sample Consumption | Non-destructive; sample can be reused [27] | Often destructive; analyte may be consumed [25] |

Inherent Advantages and Limitations

Potentiometry's Strengths and Weaknesses Potentiometry offers several compelling advantages for specific applications. Its simplicity and robustness make it ideal for routine analysis and field use, while its low power consumption is advantageous for portable and wearable sensors [2] [26]. The technique is largely unaffected by sample color or turbidity, a significant benefit for complex environmental matrices, and its non-destructive nature allows for repeated measurements on the same sample [24] [27]. However, potentiometry faces limitations in sensitivity, often making it unsuitable for trace-level analysis, and its selectivity can be compromised by interfering ions with similar properties [26]. Furthermore, most potentiometric sensors are designed for a single analyte, requiring multiple sensors for a complete ionic profile [1].

Voltammetry's Strengths and Weaknesses Voltammetry excels in areas where potentiometry falls short. Its most notable strength is its exceptional sensitivity, particularly with techniques like anodic stripping voltammetry that pre-concentrate the analyte on the electrode surface [25]. The ability to perform multianalyte detection in a single measurement by resolving distinct peak potentials provides a significant efficiency advantage [25]. Voltammetry also provides rich mechanistic information about redox processes, including electron transfer kinetics and reaction reversibility, which is invaluable for fundamental research [1]. The primary limitations of voltammetry include its higher complexity and cost of instrumentation, its susceptibility to electrode fouling in complex matrices, and potential interferences from dissolved oxygen or the formation of intermetallic compounds in stripping analysis [28] [25].

Experimental Protocols for Environmental Monitoring

Potentiometric Protocol for Nitrate Detection in Water

The following protocol details the determination of nitrate ions in water samples using a potentiometric ion-selective electrode (ISE), suitable for environmental screening applications [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Nitrate ion-selective electrode and appropriate reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) [11]

- Potentiometer or pH/mV meter with high input impedance

- Nitrate standard solutions for calibration (e.g., 10⁻² M to 10⁻⁵ M KNO₃)

- Ionic strength adjustment buffer (ISAB), typically 0.1 M Al₂(SO₄)₃ or 0.1 M K₂SO₄

- Magnetic stirrer and Teflon-coated stir bars

- Laboratory glassware (beakers, volumetric flasks)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Condition the nitrate ISE by soaking in a 10⁻³ M KNO₃ solution for at least 30 minutes prior to use. Ensure the reference electrode is filled with the appropriate filling solution.

- Calibration:

- Prepare a series of standard nitrate solutions covering the concentration range of 10⁻² M to 10⁻⁵ M.

- Add equal volumes of ISAB to each standard to maintain a constant ionic strength.

- Immerse the electrodes in the most dilute standard under gentle stirring. Record the stable potential reading in mV.

- Rinse the electrodes with deionized water and blot dry. Repeat for each standard in order of increasing concentration.

- Plot the potential (mV) versus the logarithm of the nitrate concentration. The slope should be close to -59.1 mV/decade at 25°C as per the Nernst equation.

- Sample Measurement:

- Mix the water sample with an equal volume of the same ISAB used for calibration.

- Immerse the cleaned electrodes and record the stable potential under the same stirring conditions used during calibration.

- Determine the nitrate concentration from the calibration curve.

- Quality Control: Analyze a certified reference material or a mid-level standard as an unknown to verify accuracy.

Voltammetric Protocol for Trace Cadmium Detection via SWASV

This protocol describes the determination of trace cadmium (Cd(II)) in water using Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) with a bismuth-film electrode, a highly sensitive and environmentally friendly alternative to mercury-based electrodes [11].

Materials and Reagents:

- Voltammetric analyzer (potentiostat) compatible with SWASV

- Glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon working electrode

- Platinum wire counter electrode and Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Bismuth standard solution (e.g., 1000 mg/L Bi(III) in 1% HNO₃)

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.6) containing 0.1 M KCl as supporting electrolyte [11]

- Cadmium standard solutions for calibration

- High-purity nitrogen gas for deaeration

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: If using a solid electrode, polish the working electrode surface with 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth, rinse thoroughly with deionized water, and sonicate for 1 minute to remove adsorbed particles.

- Bismuth Film Plating (In-situ):

- Transfer 10 mL of the sample or standard into the electrochemical cell.

- Add acetate buffer and KCl to achieve final concentrations of 0.1 M, and add Bi(III) standard to a final concentration of 400 μg/L.

- Purge the solution with nitrogen for 8-10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Analysis via SWASV:

- Deposition Step: Apply a deposition potential of -1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl while stirring the solution. Maintain this for a defined time (e.g., 60-300 seconds, depending on the expected Cd concentration) to simultaneously deposit and pre-concentrate both bismuth and cadmium onto the working electrode.

- Equilibration Step: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for 10-15 seconds.

- Stripping Step: Initiate the square-wave potential scan from -1.4 V to -0.2 V. Use the following typical SWV parameters: frequency 25 Hz, pulse amplitude 25 mV, step potential 5 mV.

- The cadmium stripping peak typically appears at approximately -0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

- Calibration and Quantification:

- Record the stripping voltammograms for a series of cadmium standard additions.

- Measure the peak height (or area) for each standard addition.

- Construct a standard addition curve by plotting peak current versus cadmium concentration.

- Determine the unknown concentration in the sample from the standard addition plot.

Figure 2: Comparative workflow for environmental analysis of nitrate (via potentiometry) and cadmium (via voltammetry), highlighting key methodological differences.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The successful implementation of potentiometric and voltammetric methods relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table catalogs the key components required for experiments featured in this guide and related analytical workflows.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for potentiometric and voltammetric analysis

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Specification Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) | Potentiometric sensing of specific ions (e.g., NO₃⁻, K⁺, Na⁺, Ca²⁺) [24] [1] | Selectivity determined by membrane composition (ionophore). Require regular calibration [2]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides stable, known potential reference point [24] [1] | Ag/AgCl or double-junction types preferred to prevent clogging/contamination [2]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer (ISAB) | Maintains constant ionic strength in sample; masks interfering ions [11] | Composition is ion-specific (e.g., 0.1 M Al₂(SO₄)₃ for nitrate ISE) [11]. |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | Versatile working electrode for voltammetry; broad potential window [11] | Requires periodic polishing with alumina slurry to refresh surface [11]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, integrated three-electrode cells for portable voltammetry [29] | Substrates: ceramic, glass, or paper. Carbon-based inks reduce environmental footprint [29]. |

| Bismuth (Bi(III)) Standard | "Green" alternative to mercury for forming electrodes in stripping voltammetry [11] | Used for in-situ plating of bismuth film electrodes for heavy metal detection [11]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes migration current in voltammetric cell [11] | e.g., Acetate buffer (pH ~4.6) or KCl (0.1 M). Must be electroinactive in potential window [11]. |

The comparative analysis of potentiometry and voltammetry reveals a clear paradigm of complementary strengths. Potentiometry stands out for its operational simplicity, low power demands, and non-destructive nature, making it an ideal choice for routine ion concentration measurements, field-based environmental monitoring, and applications where cost and ease-of-use are primary concerns [26] [27]. Its limitations in sensitivity and single-analyte focus are counterbalanced by its robustness. Conversely, voltammetry excels in situations demanding ultra-trace detection limits, multi-analyte capability, and detailed mechanistic information [25] [1]. The trade-off for this enhanced performance is greater instrumental complexity, higher power consumption, and more involved experimental procedures.

The choice between these techniques is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with analytical goals. For high-throughput screening of major ions in environmental or clinical samples, potentiometry offers an efficient and practical solution. For investigating trace-level contaminants like heavy metals in water or elucidating redox mechanisms in pharmaceutical compounds, voltammetry is the unequivocal technique of choice. Future developments in miniaturization, the integration of novel nanomaterials, and the creation of robust wearable platforms will further solidify the role of both techniques in the analytical scientist's toolkit, enabling more sophisticated, sensitive, and sustainable environmental and biomedical analysis [2] [29].

Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Environmental Analysis

Within environmental monitoring and research, the selection of an appropriate electrochemical sensing technique is critical. Potentiometry and voltammetry represent two foundational pillars, each with distinct advantages and limitations dictated by their underlying principles. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, focusing on their performance for specific target analytes, supported by experimental data and protocols.

Technique Comparison: Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry

The core difference lies in the measurement of potential at zero current (potentiometry) versus the measurement of current as a function of applied potential (voltammetry).

Diagram Title: Core Principles of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics and Applicability

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Potential (V) | Current (A) |

| Principle | Nernstian equilibrium at ion-selective membrane | Non-equilibrium, faradaic current from redox reactions |

| Primary Output | Ion Activity (logarithmic relation) | Concentration (linear relation via calibration) |

| Typical Detection Limit | 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻⁸ M | 10⁻⁸ – 10⁻¹¹ M |

| Multi-Analyte Detection | No (requires sensor array) | Yes (with distinct redox potentials) |

| Suitability for Ions | Excellent (e.g., Pb²⁺, Li⁺, NH₄⁺) | Good for metals, poor for many simple ions |

| Suitability for Organics | Poor (requires selective membrane) | Excellent (e.g., pesticides, drugs, phenols) |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Common Environmental Analytes

| Analytic (Example) | Technique | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Key Interferences | Reference Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead (Pb²⁺) | Potentiometry (Pb-ISE) | 10⁻¹ – 10⁻⁶ M | 5.0 × 10⁻⁷ M | Hg²⁺, Ag⁺, Cu²⁺ | EPA 200.8 (ICP-MS) |

| Voltammetry (SWASV) | 10⁻⁸ – 10⁻¹⁰ M | 2.1 × 10⁻¹⁰ M | Cu²⁺, Tl⁺, Surfactants | ||

| Lithium (Li⁺) | Potentiometry (Li-ISE) | 10⁻¹ – 10⁻⁵ M | 8.0 × 10⁻⁶ M | Na⁺, H⁺ | EPA 200.7 (ICP-OES) |

| Voltammetry | Not applicable (non-redox active) | - | - | ||

| Ammonium (NH₄⁺) | Potentiometry (NH₄-ISE) | 10⁻¹ – 10⁻⁵ M | 1.5 × 10⁻⁵ M | K⁺, Cs⁺ | EPA 350.1 (Colorimetry) |

| Atrazine (Pesticide) | Potentiometry | Not commonly used | - | - | EPA 507 (GC) |

| Voltammetry (DPV) | 0.1 – 10 µM | 0.03 µM | Other s-triazines |

SWASV: Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry; DPV: Differential Pulse Voltammetry; ISE: Ion-Selective Electrode

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Potentiometric Determination of Pb²⁺ in Water

- Principle: The potential of a Pb²⁺-selective electrode (ISE) relative to a reference electrode is measured and correlated to Pb²⁺ activity via the Nernst equation.

- Procedure:

- Calibration: Immerse the Pb-ISE and reference electrode in a series of standard Pb(NO₃)₂ solutions (e.g., 10⁻³ M to 10⁻⁶ M) with constant ionic strength adjusted with KNO₃ (0.1 M).

- Measurement: Record the stable potential (mV) for each standard. Plot potential vs. log[Pb²⁺] to obtain a calibration curve.

- Sample Analysis: Rinse electrodes, immerse in the filtered water sample, record the potential, and determine concentration from the calibration curve.

- Data Analysis: The slope of the calibration curve should be close to the theoretical Nernstian slope (~29.5 mV/log decade for Pb²⁺ at 25°C).

Protocol B: Voltammetric Determination of Pb²⁺ and Atrazine

- Principle: Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) is used for stripping analysis of Pb²⁺, while Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is used for the direct oxidation of Atrazine.

- Procedure for Pb²⁺ (SWASV):

- Electrode Setup: Use a Glassy Carbon Working Electrode, Ag/AgCl Reference, and Pt Counter Electrode.

- Pre-concentration/Deposition: Apply a negative potential (-1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) to the working electrode in the stirred sample for 120 seconds, reducing Pb²⁺ to Pb⁰ and depositing it on the electrode.

- Stripping: Turn off stirring. Scan the potential from -1.0 V to -0.2 V using a Square Wave waveform. The deposited Pb⁰ is oxidized back to Pb²⁺, producing a current peak.

- Procedure for Atrazine (DPV):

- Electrode Setup: Same as above, but often with a modified electrode (e.g., carbon nanotube paste).

- Measurement: Scan the potential from +0.8 V to +1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) in a quiescent, buffered solution (e.g., pH 7 phosphate buffer) using a DPV waveform. Atrazine oxidizes, producing a characteristic current peak.

- Data Analysis: The peak current is proportional to the concentration of the analyte. Calibration with standard solutions is required.

Diagram Title: Key Voltammetric Measurement Modes

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for Electrochemical Environmental Sensing

| Item | Function | Example (Potentiometry) | Example (Voltammetry) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Site of the electrochemical reaction | Ion-Selective Membrane Electrode (e.g., Pb-ISE) | Glassy Carbon, Mercury Film, Boron-Doped Diamond |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, fixed potential | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) Sat. Calomel Electrode |

| Counter/Auxiliary Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit | Pt wire | Pt wire or coil |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster | Minimizes matrix effects on activity | KNO₃, NaCl | Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KNO₃, Acetate Buffer) |

| Electrode Modifier | Enhances selectivity and sensitivity | Ionophores (e.g., Valinomycin for K⁺) | Nafion, Carbon Nanotubes, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers |

| Standard Solutions | For calibration and quality control | Certified Pb²⁺, Li⁺, NH₄⁺ standards | Certified Metal/Organic Analyte standards |

In the realm of environmental monitoring and resource recovery, electrochemical analysis provides powerful tools for detecting pollutants and managing critical materials. While techniques like voltammetry are renowned for their high sensitivity and ability to provide both qualitative and quantitative data, potentiometry offers distinct advantages through its simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for continuous monitoring [1] [2]. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern potentiometric sensors against other analytical techniques through two detailed case studies: detecting toxic lead ions in environmental samples and recovering valuable lithium from spent lithium-ion batteries.

The core principle of potentiometry involves measuring the potential difference between an indicator electrode and a reference electrode under zero-current conditions, with the signal relating to analyte concentration via the Nernst equation [1] [30]. Recent innovations have significantly enhanced these sensors' capabilities, pushing detection limits to trace levels and enabling applications in complex matrices [2] [10].

Case Study 1: Lead Detection in Environmental Samples

Lead contamination remains a critical global health concern due to its persistent toxicity, bioaccumulative nature, and widespread occurrence in water, food, and industrial environments [10]. Even at trace levels, lead exposure causes severe neurological, cardiovascular, and developmental disorders, particularly in children [31] [10].

Experimental Protocols for Lead Sensing

Recent research has developed sophisticated potentiometric sensors for lead detection:

TPM-Based Sensor Preparation: A potentiometric sensor was fabricated using thiophanate-methyl (TPM) compound as the ionophore. The performance was tested in various Pb²⁺ solutions, with reliability confirmed through response time, pH range, titration, and lifetime studies. Interaction mechanisms between Pb²⁺ and TPM were investigated using LC-MS/MS, FTIR analyses, and DFT studies, confirming binding through sulfur atoms [32].

MOF-Based Sensor Preparation: A metal-organic framework based on Zn²⁺, ethylenediamine and 4-methyl-1,2,4-triazole-3-thiol was synthesized and characterized. Density functional theory computations investigated the interaction of this ZMTE-MOF with various cations, showing the strongest interaction with Pb²⁺. A coated graphite PVC-membrane electrode was developed using ZMTE-MOF as the neutral ion carrier with optimized composition [31].

Measurement Protocol: For both sensor types, potential measurements were performed against a reference electrode in standard Pb²⁺ solutions. The electrodes were conditioned in appropriate solutions before measurements, and potentials were recorded across varying concentrations to establish calibration curves [32] [31].

Performance Data Comparison

Table 1: Performance comparison of potentiometric lead sensors and reference methods.

| Analytical Method | Detection Limit (mol/L) | Linear Range (mol/L) | Response Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPM Potentiometric Sensor [32] | 1.5 × 10⁻⁸ | Not specified | Not specified | High selectivity, 4-week lifetime, suitable for aquatic environments | Limited pH range (4-12) |

| ZMTE-MOF Potentiometric Sensor [31] | 7.5 × 10⁻⁸ | 1.0 × 10⁻⁷ to 1.0 × 10⁻¹ | 5 seconds | 4-month lifetime, wide dynamic range, rapid response | Requires pH control (2.0-8.0) |

| ICP-MS (Reference Method) [31] | ~10⁻¹⁰ or lower | Wide | Sample preparation dependent | Extremely low detection limits, multi-element capability | High instrumentation cost, requires skilled operators, complex sample preparation |

| Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy [10] | ~10⁻⁸-10⁻⁹ | Varies | Sample preparation dependent | Well-established technique, good sensitivity | Limited single-element capability, requires sample digestion |

Table 2: Comparison of electrochemical techniques for lead monitoring.

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry | Coulometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Signal | Potential (zero current) [1] | Current (function of applied potential) [1] [30] | Charge passed [1] |

| Sensitivity | High (down to 10⁻¹⁰ M for Pb²⁺) [10] | Very high (trace level detection) [1] | Absolute method (no calibration needed) [1] |

| Selectivity | High (ionophore-dependent) [32] [31] | Moderate to high (potential-controlled) [1] | Low (interferences from other reducible species) |

| Cost & Complexity | Low to moderate [10] | Moderate [1] | Moderate |

| Suitability for Field Use | Excellent (portable, low power) [2] [10] | Good (portable systems available) | Limited |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal (tolerates turbid/colored samples) [2] | Often requires degassing, supporting electrolyte [1] | Varies |

Sensor Workflow and Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow and mechanism of action for potentiometric lead sensors:

Case Study 2: Lithium Recovery from Battery Recycling

The growing demand for lithium-ion batteries necessitates efficient recycling processes to recover valuable materials like lithium and cobalt. Potentiometric sensors enable real-time monitoring of lithium concentrations during hydrometallurgical recovery processes [33] [34].

Experimental Protocols for Lithium Monitoring

Microsensor Preparation: A potentiometric microsensor was designed by modifying LiFePO₄ onto a Pt microelectrode as a solid contact for lithium-ion recognition without an ion-selective membrane. This design provided high stability and fast response time [33].

Battery Material Leaching: In the recovery process, spent lithium cobalt oxide cathodes were dissolved using a choline chloride:ethylene glycol-based deep eutectic solvent with added HCl. Complete dissolution was achieved within 2 hours at 80°C with precise proton addition [34].

Real-time Monitoring: The potentiometric microsensor was deployed to dynamically monitor Li⁺ concentrations throughout the leaching and recovery process, providing real-time data for process optimization [33].

Performance Data Comparison

Table 3: Performance comparison of lithium monitoring techniques in battery recycling.

| Analytical Method | Detection Limit | Measurement Range | Analysis Time | Suitability for Process Monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LiFePO₄ Potentiometric Microsensor [33] | Not specified | Applicable to process concentrations | Real-time (continuous) | Excellent (fast response, in-situ capability) |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry | ~ppb level | Wide | Minutes to hours (after sample collection) | Poor (requires sample removal, offline analysis) |

| Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy | ~ppb level | Wide | Minutes to hours (after sample collection) | Poor (requires sample removal, offline analysis) |

| Traditional Potentiometric ISEs | ~10⁻⁶ M | 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻¹ M | Minutes (continuous) | Good (but may have stability issues in complex matrices) |

Table 4: Lithium-ion battery recycling hydrometallurgical process parameters.

| Process Parameter | DES Leaching with HCl [34] | Conventional Acid Leaching [34] | Organic Acid Leaching [34] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Temperature | 80°C | 60-90°C | 40-80°C |

| Time | 2 hours | 30 min to 6 hours | Varies |

| Efficiency | Complete dissolution | High efficiency | Moderate to high efficiency |

| Environmental Impact | Lower (green solvents) | High (acidic effluents) | Moderate |

| Monitoring Requirements | Real-time Li⁺ concentration | Periodic sampling | Periodic sampling |

Battery Recycling and Monitoring Process

The following diagram illustrates the lithium-ion battery recycling process with integrated potentiometric monitoring:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Essential research reagents and materials for potentiometric sensor development.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophores (TPM, MOFs, specific organic compounds) | Selective target ion recognition and binding [32] [31] | Lead sensors (TPM, ZMTE-MOF), various ion-selective electrodes |

| Polymer Matrices (PVC, others) | Membrane formation for ion-selective electrodes [31] | Sensor construction, ion-selective membrane support |

| Plasticizers (Nitrobenzene, others) | Modify membrane flexibility and improve ionophore mobility [31] | Optimize sensor response characteristics |

| Solid Contact Materials (Conducting polymers, carbon-based materials, nanomaterials) | Ion-to-electron transduction in solid-contact ISEs [33] [2] | Lithium microsensor (LiFePO₄), modern solid-contact electrodes |

| Deep Eutectic Solvents (Choline chloride:ethylene glycol) | Green alternative for metal dissolution in recycling [34] | Lithium cobalt oxide cathode leaching in battery recycling |

| Reference Electrodes (Ag/AgCl, others) | Provide stable, known reference potential [1] [30] | Essential component of all potentiometric measurements |

The case studies presented demonstrate how modern potentiometry provides robust analytical solutions across different environmental and industrial applications. For lead detection, potentiometric sensors offer detection limits approaching more complex techniques like AAS, while maintaining advantages of portability, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for field deployment [32] [10]. In lithium-ion battery recycling, potentiometric microsensors enable real-time process monitoring that traditional laboratory methods cannot provide [33].

The comparison between potentiometry and voltammetry reveals complementary strengths: while voltammetry generally offers superior sensitivity for trace analysis, potentiometry excels in operational simplicity, continuous monitoring capability, and minimal sample preparation requirements [1] [2]. Recent innovations in materials science, including novel ionophores, solid-contact architectures, and nanomaterial integration, continue to expand the capabilities of potentiometric sensors, addressing previous limitations and opening new application frontiers in environmental monitoring and resource recovery [2] [10].

For researchers and drug development professionals, these advances in potentiometric sensing provide valuable tools for therapeutic drug monitoring, quality control in pharmaceutical manufacturing, and environmental safety assessment, particularly where continuous monitoring or point-of-care testing is required [2].