Potentiometry for Water Quality Monitoring: Principles, Sensor Innovations, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of potentiometric techniques for water quality monitoring, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Potentiometry for Water Quality Monitoring: Principles, Sensor Innovations, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of potentiometric techniques for water quality monitoring, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of potentiometry, examines cutting-edge sensor technologies like microbial potentiometric sensors (MPS) and solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), and details their application in detecting critical parameters and contaminants, including lead ions and nutrients. The content offers practical guidance on troubleshooting common issues, validating sensor performance, and compares potentiometry with traditional methods like titration. By synthesizing recent advancements, this review highlights the transformative potential of potentiometric sensors in ensuring water quality for pharmaceutical processes and public health protection.

The Principles and Evolution of Potentiometric Water Analysis

Potentiometry is a fundamental electrochemical method critical for quantitative analysis in fields ranging from environmental monitoring to clinical diagnostics. This technique measures the potential (voltage) of an electrochemical cell under static conditions, where no current—or only negligible current—flows, thereby leaving the cell's composition unchanged [1]. The measured potential provides a direct relationship to the activity (concentration) of target ions in solution. The theoretical backbone governing this relationship is the Nernst equation, formulated by Walther Hermann Nernst in 1889 [1]. This principle enables the precise determination of ion concentrations, forming the basis for modern potentiometric sensors, including ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) widely used for water quality assessment [2].

This article details the core principles of the Nernst equation, its integration into potentiometric measurement systems, and provides structured application notes and experimental protocols for researchers developing potentiometric methods for water quality monitoring.

Theoretical Foundations

The Nernst Equation: Derivation and Significance

The Nernst equation establishes a quantitative relationship between the electrochemical cell potential under non-standard conditions and the standard electrode potential, temperature, and the reaction quotient. It is derived from the thermodynamic relationship of Gibbs free energy [3] [4].

For a general reduction reaction: [ \text{M}^{n+} + n\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{M} ]

The Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q ] where:

- (E) is the measured electrode potential

- (E^0) is the standard electrode potential

- (R) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹)

- (T) is the absolute temperature in Kelvin

- (n) is the number of electrons transferred in the redox reaction

- (F) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C mol⁻¹)

- (Q) is the reaction quotient [2] [3]

At 25°C (298 K), the equation simplifies to: [ E = E^0 - \frac{0.0592}{n} \log Q ]

This simplified form is extensively used in laboratory settings for its convenience [3] [4]. The equation accurately describes how electrode potential varies with the activity of ions involved in the electrochemical reaction. For potentiometric sensors, (Q) relates to the activity of the target ion, enabling direct concentration measurement from potential readings [2].

Activity versus Concentration

A critical distinction in potentiometric measurements is that the Nernst equation relates potential to ion activity, not concentration. Activity ((a)) incorporates the effective concentration of an ion in solution, accounting for electrostatic interactions with other ions. It is defined as (a = \gamma C), where (\gamma) is the activity coefficient and (C) is the molar concentration [1] [5].

In dilute solutions (<10⁻³ M), the activity coefficient approaches unity, and activity can be approximated by concentration. However, in solutions with high ionic strength, this approximation fails, and activity must be considered for accurate measurements. Standard procedures involve using ionic strength adjusters to maintain a consistent and high ionic background, thereby making the activity coefficient constant and allowing concentration to be directly proportional to activity [1].

Potentiometric Measurement Systems

System Components and Configuration

A potentiometric cell comprises two primary electrodes immersed in an electrolyte solution, completing an electrical circuit.

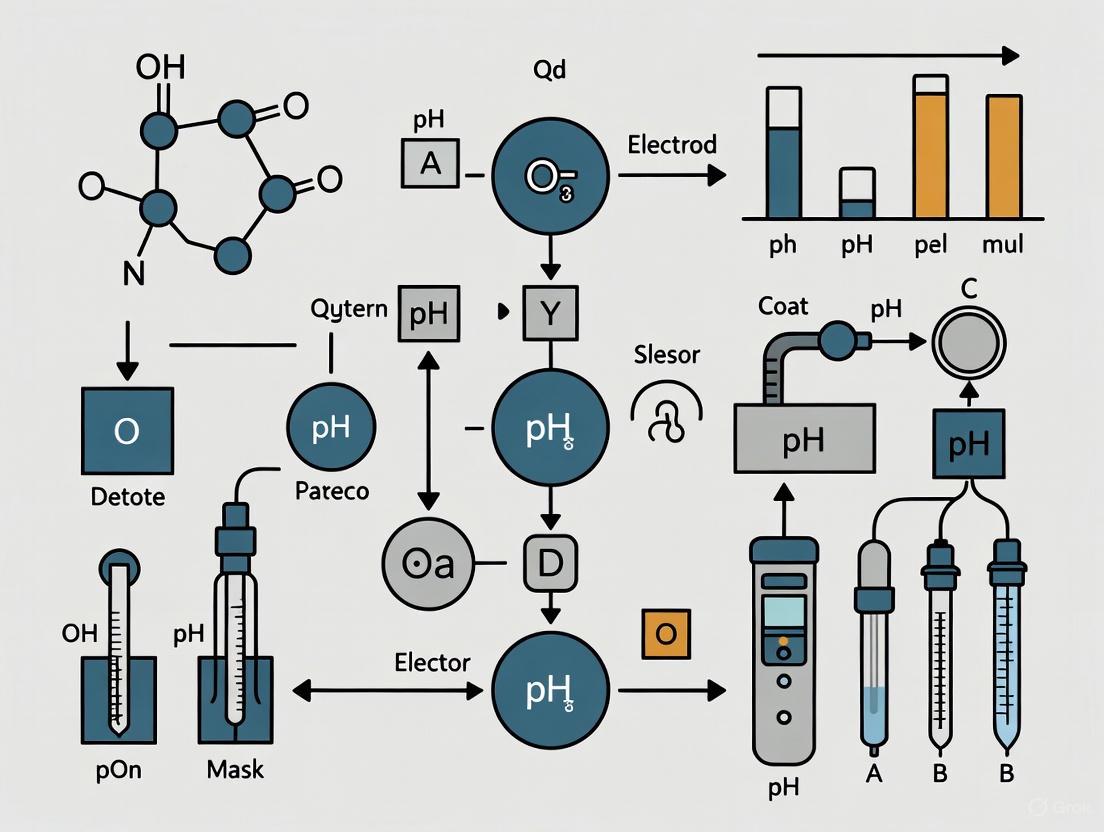

Diagram 1: Configuration of a basic potentiometric cell.

- Indicator Electrode (Working Electrode): Responds selectively to the activity of the target ion. Its potential follows the Nernst equation relative to the target ion concentration [2] [1].

- Reference Electrode: Maintains a constant, known potential independent of the sample composition. Common types include Ag/AgCl, calomel (Hg/Hg₂Cl₂), and standard hydrogen electrodes (SHE). It provides a stable reference point for the measurement [2] [6].

- Potentiometer: A high-impedance voltmeter that measures the potential difference between the electrodes without drawing significant current, ensuring the cell composition remains unchanged [1].

- Salt Bridge: Contains an inert electrolyte (e.g., KCl) and connects the two half-cells, completing the electrical circuit by allowing ion migration while preventing solution mixing [1].

The overall cell potential is calculated as: [ E{\text{cell}} = E{\text{ind}} - E{\text{ref}} + E{\text{sol}} ] where (E{\text{ind}}) is the indicator electrode potential, (E{\text{ref}}) is the reference electrode potential, and (E_{\text{sol}}) is a small potential drop across the test solution [6].

Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs)

Ion-selective electrodes are a class of potentiometric sensors designed for specific ion detection. Their core component is an ion-selective membrane that facilitates selective interaction with the target ion [2].

Primary ISE Types:

- Glass Membrane Electrodes: Used primarily for pH measurement. The glass membrane selectively responds to H⁺ ions [2].

- Crystalline Membrane Electrodes: Employ solid-state crystalline materials (e.g., LaF₃ for fluoride ISE) that selectively bind target ions [2].

- Polymer Membrane Electrodes: Incorporate an ion-selective ionophore embedded in a polymer matrix (e.g., PVC) to selectively complex with target ions (e.g., K⁺) [2].

- Gas-Sensing Electrodes: Measure dissolved gases (e.g., CO₂, NH₃) by detecting pH changes in an internal solution separated from the sample by a gas-permeable membrane [2].

The potential developed across the ISE membrane is described by the Nernst equation, providing a linear relationship between the measured potential and the logarithm of the target ion's activity.

Application Notes for Water Quality Monitoring

Performance Characteristics of Potentiometric Sensors

The effectiveness of ISEs in analytical applications is governed by several key performance parameters, summarized in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Key performance characteristics of ion-selective electrodes

| Parameter | Description | Impact on Measurement | Ideal Value/Characteristic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Selectivity | Ability to respond to target ion over interfering ions | Determines measurement accuracy in complex matrices | High selectivity (low selectivity coefficient, KPoti,j << 1) [2] |

| Sensitivity | Change in potential per concentration decade (Nernstian slope) | Affects detection limit and resolution | ~59.2/z mV per decade at 25°C [2] |

| Response Time | Time to reach stable potential after concentration change | Impacts analysis speed and suitability for real-time monitoring | < 1 minute (depends on membrane thickness, stirring) [2] |

| Detection Limit | Lowest measurable ion activity | Defines application range for trace analysis | Typically 10⁻⁵ to 10⁻⁸ M [2] |

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of potentiometric methods requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the target analyte.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for potentiometric sensing

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophore | Membrane-active component that selectively binds target ion | Valinomycin for K⁺ sensing; pyrrole-based derivatives for phosphate [7] |

| Polymer Matrix | Inert membrane scaffold | Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) for polymer membrane ISEs [2] |

| Plasticizer | Provides fluidity and solubility for ionophore | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) [2] |

| Ionic Additive | Optimizes membrane conductivity and reduces interference | Lipophilic salts (e.g., KTpClPB) [2] |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | Masks sample variability and fixes ionic strength | High concentration inert salt (e.g., NH₄NO₃) for direct measurement [2] |

Recent research highlights novel ionophores for environmentally relevant anions. For instance, pyrrole-based "bipedal/tripodal" ligands and molecular cages function as effective hydrogen-bond donors for potentiometric sensing of phosphate and fluoride in environmental samples like自来水, soil, and river water [7]. Similarly, N-alkyl/aryl ammonium resorcinarenes have demonstrated high selectivity for pyrophosphate in complex samples [7].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Calibration of an Ion-Selective Electrode

This protocol details the standard procedure for constructing a calibration curve for an ISE, essential for quantifying ion concentrations in unknown samples.

Materials:

- Ion-selective electrode and compatible reference electrode

- Potentiometer (high-impedance mV meter)

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars

- Thermostatted beaker (25°C recommended)

- Volumetric flasks and pipettes

- Standard stock solutions of the target ion (e.g., 0.1 M, 0.01 M, 0.001 M)

- Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) solution

Procedure:

- Preparation of Standard Solutions: Prepare a series of at least 5 standard solutions by serial dilution, spanning the expected concentration range of the sample (e.g., 10⁻² M to 10⁻⁵ M). Add a consistent, small volume of ISA to each standard to maintain constant ionic strength.

- Instrument Setup: Connect the ISE and reference electrode to the potentiometer. Place the electrodes in a beaker containing a rinsing solution (e.g., distilled water) under gentle stirring.

- Potential Measurement:

- a. Immerse the electrodes in the most dilute standard solution.

- b. Record the stable mV reading once the potential drift is less than 0.1 mV per minute (typically 1-3 minutes).

- c. Rinse the electrodes thoroughly with distilled water between measurements.

- d. Repeat steps a-c for all standard solutions in order of increasing concentration.

- Data Analysis:

- a. Plot the measured potential (mV, y-axis) against the logarithm of the ion activity (log a, x-axis).

- b. Perform linear regression analysis on the data points. The calibration curve should yield a straight line.

- c. The slope of the line should be close to the theoretical Nernstian slope (±59.2/z mV per decade at 25°C). The intercept relates to the standard potential E⁰ [2] [4].

For accurate results, the temperature should be kept constant, and the calibration should be performed on the same day as sample analysis.

Protocol: Potentiometric Titration for Water Hardness

Potentiometric titration is used to determine the concentration of an analyte by monitoring the potential change upon adding a titrant. This protocol outlines the determination of water hardness (Ca²⁺ and Mg²⁺ ions) via complexometric titration with EDTA.

Materials:

- Ion-selective electrode (e.g., Ca²⁺ ISE) or general metallic indicator electrode

- Reference electrode (double-junction type recommended)

- Automatic burette for titrant delivery

- Magnetic stirrer

- pH 10 buffer solution (ammonia/ammonium chloride)

- Standard 0.01 M EDTA titrant solution

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Pipette a known volume (e.g., 50 mL) of the water sample into a titration beaker. Add 1-2 mL of pH 10 buffer solution to maintain the pH for complex formation.

- Electrode Setup: Place the indicator and reference electrodes into the sample solution. Start gentle magnetic stirring.

- Titration:

- a. Begin adding the EDTA titrant in small, controlled increments (e.g., 0.5 mL).

- b. After each addition, allow the potential to stabilize and record both the volume of titrant added and the corresponding potential (mV).

- c. Reduce the increment size near the expected equivalence point where large potential jumps occur.

- Endpoint Determination:

- a. Plot the recorded potential (E) versus the volume of titrant (V).

- b. Alternatively, calculate the derivative (ΔE/ΔV) and plot it against volume.

- c. Identify the equivalence point as the volume at the maximum of the derivative peak (the steepest point of the titration curve) [6].

- Calculation: Calculate the total water hardness as CaCO₃ using the volume of EDTA consumed at the equivalence point, its concentration, and the sample volume.

The workflow for this analytical process is summarized in the diagram below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for a potentiometric titration experiment.

Data Analysis and Validation

Interpreting Calibration Data and Calculating Concentration

The calibration curve is the primary tool for converting the potential reading of an unknown sample into a concentration value. After obtaining the linear regression equation ( E = \text{slope} \times \log a + \text{intercept} ), the concentration of an unknown sample is calculated by:

- Measuring the potential ((E_{\text{sample}})) of the unknown sample under the same conditions as the standards.

- Subtracting the intercept from (E{\text{sample}}) and dividing by the slope to find (\log a): [ \log a = \frac{E{\text{sample}} - \text{intercept}}{\text{slope}} ]

- Calculating the activity (and thus concentration, considering the activity coefficient) by taking the antilog.

Method Validation Parameters

To ensure reliability for water quality monitoring, potentiometric methods should be validated using the following parameters:

- Accuracy: Assessed by measuring certified reference materials (CRMs) or spiked recovery studies in relevant water matrices. Recovery should typically be between 90-110%.

- Precision: Determined by calculating the relative standard deviation (RSD) of repeated measurements (e.g., n=5) of the same sample.

- Detection Limit (LOD): Estimated as the concentration corresponding to the signal of the blank plus three times the standard deviation of the blank. For ISEs, it is often taken from the calibration curve's lower limit of linearity.

Adherence to these validation protocols ensures that the potentiometric data generated is robust, reliable, and suitable for environmental reporting and decision-making.

Potentiometry is an electrochemical method that measures the potential (voltage) of an electrochemical cell under conditions of zero or negligible current flow. This technique is fundamental for determining the activity (effective concentration) of ions in solution and is widely used in water quality monitoring due to its simplicity, portability, and cost-effectiveness [8] [1]. A typical potentiometric cell consists of two electrodes immersed in a solution: an indicator electrode (or working electrode) and a reference electrode [1]. The core principle is that the potential difference between these two electrodes is proportional to the logarithm of the target ion's activity, as described by the Nernst equation [9] [10]. For water quality analysis, this allows for direct, in-situ measurements of critical ions like lead, nitrate, and ammonium, providing real-time data essential for environmental protection [8] [11] [10].

Reference vs. Indicator Electrodes

In a potentiometric measurement system, the indicator and reference electrodes perform distinct but complementary functions. Their core attributes are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Attributes of Indicator and Reference Electrodes

| Attribute | Indicator Electrode | Reference Electrode |

|---|---|---|

| Definition & Function | Provides analytical information; its potential changes in response to the activity of the specific analyte ion in the solution [12] [1]. | Provides a stable, known, and constant reference potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured [12] [1]. |

| Role in Measurement | Senses the analyte; generates the variable signal of the measuring chain [9]. | Completes the electrical circuit; anchors the measurement with a fixed potential [9]. |

| Material Composition | Made from materials that interact reversibly with the target ion (e.g., specialty glasses, crystalline solids, polymer membranes doped with ionophores) [9] [12]. | Typically made of inert materials like platinum and includes a stable electrolyte solution with a fixed concentration of ions (e.g., Ag/AgCl in saturated KCl) [12]. |

| Potential Response | Potential follows the Nernst equation, changing with the logarithm of the analyte ion's activity [10]. | Potential remains constant and is unaffected by the composition of the sample solution [12]. |

| Common Examples | Glass pH electrode, ion-selective electrodes (e.g., for Pb²⁺, NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺) [12]. | Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode, Calomel electrode [12]. |

The following diagram illustrates the functional relationship and signal pathway within a potentiometric cell.

Ion-Selective Membranes

The heart of a modern ion-selective electrode (ISE) is its ion-selective membrane. This component is responsible for the sensor's selectivity, determining its ability to respond to one specific ion in the presence of others [9] [13]. The membrane creates a potential by establishing an electrochemical equilibrium between the sample solution and the membrane phase, which is measured relative to the reference electrode [8].

Table 2: Types and Characteristics of Ion-Selective Membranes

| Membrane Type | Composition | Target Ions | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membranes | Thin glass film with a specific ion-sensitive composition [9]. | H⁺ (pH), Na⁺ [9]. | The classic membrane for pH electrodes; excellent for H⁺, requires special glass formulations for other ions [9]. |

| Solid-Body Membranes | Crystalline materials made from hardly soluble salts (e.g., LaF₃, AgCl, Ag₂S) [9]. | F⁻, Cl⁻, S²⁻, Ag⁺ [9]. | Durable and selective; the crystalline structure allows only specific ions to penetrate and be detected [9]. |

| Synthetic Material (Polymer) Membranes | Plasticized poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) matrix containing an ionophore (ion receptor), ion exchanger, and plasticizer [8] [9]. | Pb²⁺, NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, and many others [8] [10]. | Highly versatile; the ionophore dictates selectivity. This is the most common type for custom ISEs and can be tailored for a wide range of ions [8] [13]. |

Application Notes for Water Quality Monitoring

The Researcher's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Potentiometric Water Analysis

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrode | The core sensor. Choose based on the target ion (e.g., Pb²⁺-ISE, NO₃⁻-ISE). Modern solid-contact ISEs are preferred for field deployment [8] [10]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides the stable potential required for all measurements. Ag/AgCl with a salt bridge (e.g., filled with KCl) is common [12]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | A solution added to standards and samples to maintain a constant ionic background, ensuring activity coefficients are stable and measurements reflect concentration [1]. |

| Standard Solutions | A series of solutions with known, precise concentrations of the target ion, used for electrode calibration [9]. |

| Potentiometer / High-Impedance Voltmeter | The measuring instrument. Must have a high input impedance to prevent current draw, which would distort the measurement [9]. |

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Lead Ions (Pb²⁺) in Water

This protocol outlines the steps for quantifying lead ions in an environmental water sample using a solid-contact Pb²⁺ ion-selective electrode.

1. Scope and Application This method is suitable for determining free Pb²⁺ activity in freshwater samples, such as groundwater, rivers, and lakes. The typical working range for modern Pb²⁺-ISEs is from 10⁻¹⁰ M to 10⁻² M, which covers relevant environmental and regulatory concentrations [10].

2. Principle The potential of the Pb²⁺-selective electrode, which contains a membrane with a lead-specific ionophore, is measured relative to a reference electrode. The measured potential (E) is related to the logarithm of the Pb²⁺ activity by the Nernst equation [10]: E = E₀ + (RT / 2F) ln(a_Pb²⁺) Where E₀ is the standard potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, and F is Faraday's constant. Under constant ionic strength, activity can be correlated to concentration.

3. Equipment and Reagents

- Lead Ion-Selective Electrode (solid-contact)

- Double-junction reference electrode

- High-impedance potentiometer or pH/mV meter

- Magnetic stirrer with Teflon-coated stir bar

- Volumetric flasks (50 mL, 100 mL)

- Micropipettes

- Lead nitrate stock solution (1000 mg/L Pb²⁺)

- Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer (ISA), e.g., 0.1 M KNO₃

4. Step-by-Step Procedure

- Step 4.1: System Setup. Connect the Pb²⁺-ISE and reference electrode to the potentiometer. Ensure the reference electrode's outer chamber is filled with the appropriate electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KNO₃).

- Step 4.2: Calibration.

- Prepare a series of Pb²⁺ standard solutions (e.g., 10⁻² M, 10⁻³ M, 10⁻⁴ M, 10⁻⁵ M) by serial dilution of the stock solution. Add a constant volume of ISA to each standard.

- Immerse the electrodes in the most dilute standard (e.g., 10⁻⁵ M). Stir gently and constantly.

- Record the stable mV reading.

- Rinse the electrodes with deionized water and blot dry. Repeat the measurement for each standard in order of increasing concentration.

- Plot a calibration curve of mV reading vs. log₁₀[Pb²⁺].

- Step 4.3: Sample Measurement.

- Mix a known volume of the filtered water sample with an equal volume of ISA.

- Immerse the cleaned electrodes into the prepared sample.

- Stir gently and record the stable mV reading.

- Determine the concentration of Pb²⁺ in the sample from the calibration curve.

5. Data Analysis The calibration curve should yield a linear range with a slope close to the theoretical Nernstian value (~29 mV per decade for Pb²⁺ at 25°C) [10]. The sample concentration is determined by interpolating the measured mV value on this curve. For complex samples, the method of standard additions may be used to verify results and account for matrix effects.

The workflow for this protocol, from preparation to data analysis, is outlined below.

Electrochemical sensors, particularly those based on the potentiometric principle, have become fundamental tools for ion sensing in water quality monitoring. For decades, the glass pH electrode has been the standard for pH measurement. However, the field is undergoing a significant transformation driven by advances in materials science and manufacturing technologies. The emergence of solid-state sensors and screen-printed electrodes is addressing long-standing limitations of traditional sensors, offering enhanced durability, miniaturization, and cost-effectiveness for environmental monitoring applications. [14] [15] [16]

This evolution is particularly pivotal for water quality research, where continuous, reliable, and widespread monitoring is essential. Modern solid-state potentiometric sensors, especially those fabricated via printing technologies, are opening new possibilities for real-time water quality assessment in diverse environments, from municipal supplies to complex aquatic systems like the Baltic Sea. [14] [15] This application note details the key advancements, provides a quantitative comparison of sensor technologies, and outlines standardized protocols for the evaluation of modern screen-printed sensors in water quality research.

The Technological Shift in Sensing

The Traditional Glass Electrode and Its Limitations

The conventional glass pH electrode operates on the potentiometric principle, measuring the electrical potential difference that develops across a special glass membrane responsive to hydrogen ion activity. Despite its long history of reliable service, this technology presents several challenges for modern water quality monitoring applications:

- Fragility: The glass body is prone to breakage, creating safety hazards and risking sample contamination. This fragility makes them unsuitable for turbulent waters or harsh field environments. [17] [15]

- Complex Fabrication and Miniaturization: The intricate structure and internal liquid filling solution complicate manufacturing and severely restrict potential for miniaturization and integration into modern electronic systems. [15]

- Maintenance Requirements: Glass electrodes require regular calibration and careful storage, increasing the long-term operational burden. [18]

The Advent of Solid-State and Screen-Printed Sensors

Solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) represent the most significant advancement in potentiometric sensor configuration. These sensors eliminate the internal liquid solution, replacing it with a solid-contact layer that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer between the ion-selective membrane and the conductive substrate. This fundamental redesign overcomes the limitations of traditional electrodes, enabling greater miniaturization, flexibility, and mechanical robustness. [14] [16]

Screen-printing technology has emerged as a powerful manufacturing method for these solid-state sensors. This technique involves forcing a viscous paste (ink) through a patterned screen mesh onto a substrate. After printing, the layers are dried and sintered at high temperatures to form durable, functional films. [14] [17] The key advantages of this approach include:

- Low-Cost and Mass Production: The process is simple, inexpensive, and highly scalable, allowing for the production of disposable or single-use sensors. [14] [15]

- Design Flexibility and Miniaturization: Sensors can be easily customized in shape and size, facilitating the development of miniaturized, portable, and multi-parameter sensing systems. [14] [19]

- Robustness: Sensors printed on ceramic substrates like alumina exhibit high physical and chemical durability, suitable for various environmental conditions. [17]

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Potentiometric Sensor Technologies for Water Quality Monitoring

| Feature | Traditional Glass Electrode | Modern Solid-State/Screen-Printed Electrode |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | Nernstian (-59.16 mV/pH at 25°C) | Near-Nernstian (e.g., -57.5 to -59.4 mV/pH for RuO₂) [17] [19] |

| Response Time | Seconds to minutes | Fast (seconds) [17] |

| Physical Form | Rigid, fragile glass | Robust, flexible substrates possible |

| Miniaturization Potential | Low | High [14] |

| Manufacturing Cost | High | Low [14] [15] |

| Maintenance | Requires regular calibration and wet storage | Low maintenance; disposable use possible |

Metal Oxides: The Foundation of Modern Solid-State pH Sensors

Metal oxides, particularly those of platinum group metals, have proven to be excellent sensing materials for solid-state pH electrodes. Their pH sensitivity arises from the electrochemical phenomena at the electrode-electrolyte interface, where proton exchange leads to a measurable potential shift governed by the Nernst equation. [17] [15]

Among these, ruthenium(IV) oxide (RuO₂) has been identified as a premier material due to its mixed electronic-ionic conductivity, near-Nernstian sensitivity, fast response, low drift, chemical stability, and biocompatibility. [17] Recent research focuses on making these sensors more sustainable by reducing the content of rare and expensive RuO₂. Promising results have been achieved by creating mixed metal oxide compositions, such as cobalt oxide (Co₃O₄) mixed with RuO₂. Studies show that a 50 mol% Co₃O₄ - 50 mol% RuO₂ composition can achieve performance on par with pure RuO₂, offering a path toward cheaper and more environmentally friendly sensors without compromising functionality. [15]

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for fabricating and applying screen-printed sensors in water quality research.

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Fabrication and Characterization

This protocol details the procedure for creating robust, screen-printed pH electrodes based on RuO₂ for water quality assessment.

1. Materials and Reagents:

- Substrate: Alumina (Al₂O₃, 96%) plates.

- Conductive Paste: Ag/Pd thick-film paste (e.g., ESL 9695).

- Sensing Paste: Anhydrous RuO₂ powder, Ethyl cellulose binder, Terpineol solvent.

- Insulation: Non-corrosive polydimethylsiloxane coating (e.g., DOWSIL 3140).

- Equipment: Screen-printer, drying oven, high-temperature furnace, agate mortar.

2. Fabrication Procedure:

- Step 1: Prepare RuO₂ Paste. Grind RuO₂ powder with ethyl cellulose and terpineol in an agate mortar for 20 minutes to achieve a homogeneous paste with optimal rheology for printing.

- Step 2: Print Conductive Layer. Screen-print the Ag/Pd paste onto the alumina substrate. Dry at 120°C for 15 minutes and then fire at 860°C for 30 minutes in a furnace.

- Step 3: Print Sensing Layer. Screen-print the prepared RuO₂ paste over part of the conductive layer to ensure good electrical contact. Dry the printed layer at 120°C for 15 minutes.

- Step 4: Sinter Sensing Layer. Fire the electrodes at the final sintering temperature (e.g., 800–900°C) for 1 hour. This step is critical for burnout of organics and formation of the stable sensing surface.

- Step 5: Assemble Electrode. Solder a copper wire to the exposed end of the conductive track. Insulate the connection and the conductive track with the silicone resin, leaving only the RuO₂ sensing area exposed. Cure the resin as per manufacturer instructions (e.g., 48 hours at room temperature).

This protocol standardizes the evaluation of key performance metrics for any solid-state pH sensor.

1. Materials and Equipment:

- Test Instrumentation: High-impedance multimeter/data acquisition system (e.g., Keithley Series 2002) connected to a computer.

- Software: Data logging software (e.g., LabVIEW).

- Reference Electrode: Commercial single-junction Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Buffer Solutions: Standard pH buffer solutions covering a range of at least pH 2 to pH 12.

2. Characterization Procedure:

- Step 1: Sensor Conditioning. Before the first measurement, condition the fabricated sensor in a pH 7.0 buffer or deionized water for approximately 30 minutes.

- Step 2: Sensitivity and Linearity Measurement.

- Immerse the sensor and the reference electrode in a series of standard buffer solutions, typically from low to high pH.

- Record the potential (EMF) reading for each solution once a stable value is reached (e.g., drift < 0.1 mV per minute).

- Plot the measured EMF (mV) versus the pH value. The slope of the linear regression line (mV/pH) indicates the sensitivity. A slope close to -59.16 mV/pH at 25°C is considered Nernstian.

- Step 3: Response Time Assessment.

- Transfer the sensor from one buffer solution to another with a different pH (e.g., a change of 2 pH units).

- Record the potential continuously with time. The response time is typically reported as the time taken to reach 95% of the final stable potential value.

- Step 4: Selectivity Evaluation.

- Using the Separate Solution Method, measure the potential of the sensor in solutions containing the primary ion (H⁺) and potential interfering ions (e.g., Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺) at the same activity (e.g., 0.01 M).

- Calculate the potentiometric selectivity coefficient (log Kₚₒₜ) using the Nicolsky-Eisenman equation. A value << 1 indicates good selectivity for H⁺ over the interferent.

Table 2: Key Performance Metrics from Recent Studies on Screen-Printed Metal Oxide pH Sensors

| Sensor Material | Sensitivity (mV/pH) | Linearity (pH range) | Response Time | Stability / Drift | Application in Real Water Samples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pure RuO₂ [17] | ~ -59.4 (Near-Nernstian) | 2 - 12 | Fast (seconds) | Low hysteresis, small drift | Max. deviation of 0.11 pH units vs. glass electrode |

| 50% Co₃O₄ - 50% RuO₂ [15] | Near-Nernstian | Broad range | Not specified | Good stability and selectivity | Accurate in tap, river, lake, and Baltic Sea water |

| Pd-based Sensor [19] | -57.5 | Not specified | Integrated in a multi-parameter system | Part of an integrated monitoring platform | Used for drinking water monitoring |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Solid-State Sensor Development

| Item Name | Function / Application | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Oxide Powders | Active sensing material for potentiometric pH electrodes. | RuO₂, IrO₂, Co₃O₄, TiO₂ [17] [15] |

| Conductive Pastes | Forming the conductive base layer (substrate) for the sensor. | Ag/Pd paste (ESL 9695), Carbon/graphite ink [17] [20] |

| Polymer Matrix | Forms the bulk of the ion-selective membrane (for ISEs). | Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) [20] [16] |

| Plasticizers | Imparts flexibility and modulates the properties of the polymer membrane. | ortho-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE), Dibutyl phthalate (DBP) [20] [16] |

| Ionophores / Ion-Exchangers | Provides selectivity for specific ions in Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs). | Valinomycin (for K⁺), Phosphotungstic acid (PTA) for cations [20] [16] |

| Binders & Solvents | Used in paste formulation for screen printing; provides consistency and adhesion. | Ethyl cellulose (binder), Terpineol (solvent) [17] [15] |

Application in Water Quality Monitoring: A Case Study

The true value of these advanced sensors is demonstrated in real-world environmental monitoring. A compelling case study involves the deployment of screen-printed pH sensors based on the 50% Co₃O₄ - 50% RuO₂ composition for measuring pH at various depths in the Baltic Sea. [15]

This application highlights several critical advantages:

- Durability in Harsh Environments: The robust, solid-state construction withstands the challenging conditions of marine monitoring, where glass electrodes would be at high risk of breakage.

- Accuracy and Reliability: The sensors provided accurate measurements comparable to those from a conventional glass electrode, confirming their validity for serious scientific research and environmental data collection. [15]

- Potential for Multi-Parameter Systems: As demonstrated in other systems, pH sensors can be integrated with other sensors (e.g., for free chlorine, temperature, specific ions) on a single platform, enabling comprehensive water quality assessment. [19]

The integration of machine learning and artificial intelligence (AI) tools with sensor data further enhances their capability. Research shows that signals from sensor arrays can be used to predict multiple water quality parameters (e.g., turbidity, chlorophyll, dissolved oxygen) with high accuracy, offering a cost-effective approach for comprehensive water body monitoring. [18]

Potentiometry is a well-established electrochemical technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes to determine the activity of a target ion, providing a direct and rapid readout of analyte concentrations [21]. This technique has become a cornerstone in analytical chemistry, particularly for water quality monitoring, due to its powerful combination of operational simplicity, low cost, and immediate results. These inherent advantages make it an indispensable tool for researchers and environmental scientists who require reliable, on-site analysis of water contaminants. This document outlines the fundamental principles and practical protocols that leverage these benefits for effective water quality assessment.

The following table summarizes the key advantages of potentiometric sensors that make them particularly suitable for water quality monitoring applications.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Potentiometric Sensors for Water Quality Monitoring

| Advantage | Technical Description | Impact in Water Quality Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Simplicity of Design & Operation | Measures potential at near-zero current; simple instrumentation and straightforward data interpretation [21]. | Enables use by field technicians with minimal training; reduces operational complexity and error. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Low-cost materials and fabrication; no need for expensive or complex instrumentation [21]. | Facilitates widespread sensor deployment and high-frequency sampling within limited budgets. |

| Real-Time Monitoring | Direct, rapid response to ion activity changes; provides a continuous data stream [21]. | Allows for immediate detection of pollutant spills or sudden shifts in water chemistry. |

| High Selectivity | Utilizes ion-selective membranes with tailored ionophores for specific analytes [21]. | Enables accurate measurement of specific ions (e.g., heavy metals, nutrients) in complex water matrices. |

| Portability & Miniaturization | Ease of design and modification allows for the fabrication of small, portable devices [21]. | Supports in-field and point-of-care (POC) testing, eliminating the need for sample transport to a central lab. |

Experimental Protocols for Water Quality Analysis

Protocol: Determination of Heavy Metals in Water Samples using Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes (SC-ISEs)

This protocol details the measurement of heavy metal ions, such as lead (Pb²⁺) or copper (Cu²⁺), in freshwater samples using a solid-contact ISE, which offers superior stability and portability for field analysis compared to traditional liquid-contact electrodes [21].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Heavy Metal Ion Detection

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membrane | A polymer matrix (e.g., PVC) containing an ionophore specific to the target metal ion, a plasticizer, and ionic additives [21]. |

| Solid-Contact Transducer Layer | A material such as a conducting polymer (e.g., PEDOT) or carbon nanomaterial that converts ionic signal to electronic potential, replacing the inner filling solution [21] [22]. |

| Reference Electrode | A low-maintenance, solid-state reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) to complete the potentiometric circuit [21]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | A solution added to all standards and samples to fix the ionic background, ensuring accurate potentiometric measurement. |

| Standard Solutions | A series of solutions with known concentrations of the target ion for sensor calibration and quantification. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Sensor Preparation and Calibration:

- Connect the solid-contact ISE and reference electrode to a high-input impedance potentiometer or data acquisition system.

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of the target ion (e.g., Pb²⁺) across the expected concentration range (e.g., 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻² M).

- Add a constant volume of ISA to each standard solution.

- Immerse the electrodes in the standard solutions from the lowest to the highest concentration under gentle stirring.

- Record the stable potential (EMF) reading for each standard.

- Plot the measured EMF (mV) versus the logarithm of the ion activity (log a) to obtain the calibration curve, which should be linear (Nernstian response).

Sample Measurement:

- Collect the water sample and filter if necessary to remove particulate matter.

- Add the same volume of ISA to the water sample as used during calibration.

- Immerse the cleaned electrodes in the prepared sample and record the stable EMF value.

- Use the calibration curve to determine the concentration of the target ion in the sample.

Quality Control:

- Perform a standard addition periodically to verify accuracy and check for matrix effects.

- Re-calibrate the sensor periodically according to the observed signal drift to ensure data reliability.

Protocol: In-Field Screening of Nutrients using Paper-Based Potentiometric Sensors

This protocol describes the use of low-cost, disposable paper-based sensors for the semi-quantitative, point-of-care detection of nutrients like ammonium (NH₄⁺) in water bodies, which is crucial for assessing eutrophication [21].

Workflow Diagram

Procedure Notes

- Step 1 (Patterning): The paper substrate is typically patterned with wax printing or photolithography to create defined hydrophobic channels and sensing zones.

- Step 2 (Depot): The solid-contact material (e.g., a carbon ink) and the ion-selective membrane cocktail are deposited dropwise into the sensing zone and allowed to dry.

- Step 3 (Application): A small, measured volume of the water sample is applied to the sample zone, which wicks to the sensing area.

- Step 4 & 5 (Measurement): Alligator clips or a custom holder connect the paper sensor to the potentiometer. The measured potential is compared to a pre-established calibration curve stored on the device to determine the concentration range.

Signaling Pathways and Sensor Mechanisms

Understanding the underlying mechanism of signal generation is critical for the proper design and application of potentiometric sensors.

Potentiometric Sensor Signal Transduction Pathway

The following diagram illustrates the sequence of events from the sample introduction to the final electronic readout, highlighting the ion-to-electron transduction that is central to the sensor's function.

Solid-Contact Ion-to-Electron Transduction Mechanisms

The solid-contact layer is crucial for the stability of modern, miniaturized sensors. The diagram below details the two primary mechanisms by which this layer operates, explaining the chemistry behind the signal.

The Redox Capacitance Mechanism relies on the reversible oxidation and reduction of a conducting polymer (CP) solid contact. When a cation (M⁺) from the sample interacts with the ion-selective membrane (ISM), an electron (e⁻) is transferred from the underlying conductor to the oxidized polymer (CP⁺), reducing it (CP⁰) and maintaining charge neutrality, which generates the potential signal [22]. The Electric-Double-Layer Capacitance Mechanism operates in carbon-based nanomaterials, which possess a high surface area. The potential change at the ISM/sample interface causes ions to accumulate at the solid-contact/ISM interface, forming an electric double layer. This ionic charging is compensated by electrons in the underlying conductor, creating a capacitance that transduces the signal [21].

Advanced Sensor Technologies and Their Real-World Applications

Microbial Potentiometric Sensor (MPS) technology represents a paradigm shift in environmental monitoring, leveraging the metabolic activity of endemic biofilms to detect and predict multiple water quality parameters in real-time. Unlike traditional sensors that require frequent maintenance, calibration, and are susceptible to biofouling, MPS technology utilizes biofilms as natural sensing elements, enabling long-term, maintenance-free operation [23]. This approach capitalizes on the ability of electroactive microbial communities to respond to subtle changes in their aquatic environment by altering their electrochemical potential [23] [18].

The fundamental operating principle involves measuring the open-circuit potential (OCP) between a biofilm-populated sensing electrode and a reference electrode [23]. When microorganisms metabolize organic matter or respond to environmental stressors, they generate electrons that are temporarily stored by internal electron acceptors such as cytochromes [24]. This electron accumulation alters the potential of the sensing electrode relative to the reference electrode, creating a measurable signal that correlates with specific water quality parameters [23] [24]. The technology has demonstrated exceptional durability, with some sensors functioning without interruption for periods exceeding two years [23].

Operational Principles and Signaling Pathways

The MPS signaling mechanism is governed by complex biogeochemical processes within the biofilm matrix. As microorganisms catalyze substrate metabolism, they generate electrons that cannot be transferred to final electron acceptors due to the open-circuit operation [24]. Consequently, these electrons are temporarily stored by internal electron acceptors, primarily cytochromes, which alters the open circuit potential between the indicator and reference electrodes [24]. This potential shift serves as the primary signal output that correlates with environmental changes.

MPS Signaling Pathway and Operational Principle

The signaling pathway begins when environmental changes trigger metabolic responses in the biofilm microorganisms. These microbes produce electrons through substrate metabolism, which accumulate in internal electron acceptors due to the open-circuit configuration. This electron storage creates a measurable potential shift that is captured by the data acquisition system and processed through machine learning algorithms to predict multiple water quality parameters simultaneously [23] [24] [18].

Performance Metrics and Detection Capabilities

MPS technology has demonstrated exceptional performance across diverse application scenarios, from wastewater treatment monitoring to toxic metal detection. The tables below summarize the quantitative detection capabilities and performance characteristics of various MPS configurations.

Table 1: MPS Detection Capabilities for Organic and Toxic Substances

| Target Analyte | MPS Configuration | Detection Limit | Response Time | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Oxygen Demand (BOD) | Pt/C-free cathode | 1 mg L⁻¹ | 1 hour | 1-99 mg L⁻¹ | [24] |

| Acetic Acid | Pt/C-free cathode | 1 mM | 1 hour | 1-100 mM | [24] |

| Formaldehyde | Pt/C-modified cathode | 0.004% | Not specified | Not specified | [24] |

| Escherichia coli | MnO₂-modified electrode | 11 CFU/mL | 5 minutes | 11-10⁸ CFU/mL | [25] |

| Citrobacter youngae | MnO₂-modified electrode | 12 CFU/mL | 5 minutes | 12-10⁸ CFU/mL | [25] |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MnO₂-modified electrode | 23 CFU/mL | 5 minutes | 23-10⁸ CFU/mL | [25] |

Table 2: Toxic Metal Detection Sensitivity Using MPS Technology

| Toxic Metal | Sensitivity Order | Coefficient of Determination (R²) | Responsiveness | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selenium (Se) | Highest | >0.995 | <1 μmol/L | [26] [27] |

| Cadmium (Cd) | ↑ | >0.995 | <1 μmol/L | [26] [27] |

| Lead (Pb) | ↑ | >0.995 | <1 μmol/L | [26] [27] |

| Silver (Ag) | ↑ | >0.995 | <1 μmol/L | [26] [27] |

| Nickel (Ni) | ↑ | >0.995 | <1 μmol/L | [26] [27] |

| Zinc (Zn) | Lowest | >0.995 | <1 μmol/L | [26] [27] |

The exceptional sensitivity of MPS technology enables detection of toxic metal cations at concentrations below 1 μmol/L, with performance comparable to expensive analytical instruments [26] [27]. The sensor response is metal-specific, following the sensitivity order: Se > Cd > Pb > Ag > Ni > Zn when normalized for molar concentration [26].

Integrated Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: MPS Fabrication and Biofilm Establishment

Objective: To fabricate a microbial potentiometric sensor system and establish an electroactive biofilm on the sensing electrode surface.

Materials Required:

- Graphite rods (6 mm diameter × 50 mm length) or graphite plates (80 mm × 10 mm × 2 mm)

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Waterproofing epoxy resin

- Data acquisition system (high-impedance measurement circuitry capable of measuring potentials with 0.004% DC accuracy)

- Water sample from target monitoring environment

- Optional: Pt/C catalyst for cathode modification [24]

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Cut graphite materials to specified dimensions. If using modified electrodes, prepare coating solution containing MnO₂ (0.5 M), PTFE (5% v/v), and n-butanol dispersed in deionized water. Suspend graphite electrodes in coating solution and ultrasonicate at 60°C for 30 minutes. Dry overnight at 80°C followed by heat annealing at 360°C for 60 minutes [25].

- Sensor Assembly: Waterproof all connections except the active sensing surface using epoxy resin. Position reference electrode adjacent to sensing electrode with separation distance of 2-5 cm.

- Biofilm Establishment: Immerse the sensor array in the target water environment or laboratory bioreactor. Allow endemic microorganisms to naturally colonize the electrode surface for 2-4 weeks until a stable biofilm is established.

- Signal Verification: Monitor open-circuit potential daily. A stable, reproducible signal indicates mature biofilm formation. The sensor is ready for deployment when potential variations are less than ±5 mV over 24 hours [23].

Protocol 2: Organic Carbon and BOD Monitoring in Wastewater

Objective: To monitor organic carbon loading and biochemical oxygen demand in wastewater treatment systems using MPS technology.

Materials Required:

- Established MPS system with mature biofilm

- Continuous stirred tank reactor (CSTR) or direct wastewater immersion setup

- Data acquisition system recording at 30-minute intervals

- Comparative sensors (DO, ORP, pH) for validation [23]

Procedure:

- System Calibration: Correlate MPS signals with standard BOD measurements for the specific wastewater stream. Record baseline potential during low organic loading periods.

- Continuous Monitoring: Deploy MPS sensors at various locations in the treatment train. Record potentials at 30-minute intervals continuously.

- Data Interpretation: Monitor potential increases indicating rising organic carbon concentrations. The signal pattern reflects the treatment phase in batch processes [23].

- Validation: Compare MPS data with conventional DO and ORP sensor readings. MPS signals should correlate with organic carbon trends while operating reliably under anoxic and anaerobic conditions where conventional sensors fail [23].

Protocol 3: Toxic Metal Detection and Quantification

Objective: To detect and quantify toxic metal concentrations in aquatic matrices using MPS technology.

Materials Required:

- Established MPS system with three graphite-based electrodes

- Metal ion solutions (single-ion and multiple-ion mixtures)

- Batch reactor system

- Data acquisition system [26]

Procedure:

- Baseline Establishment: Record stable OCP in metal-free water matrix for 24 hours to establish baseline potential.

- Sample Exposure: Introduce metal ion solutions to the batch reactor. Test both single-ion solutions and realistic mixtures resembling electroplating wastewater compositions.

- Signal Monitoring: Record potential changes every minute for the first hour, then every 15 minutes until signal stabilization.

- Quantification: Use the inhibition portion of the signal area, normalized by molar concentration, to quantify metal concentrations. Generate calibration curves for each metal of interest [26].

MPS Experimental Workflow for Multi-Parameter Monitoring

The experimental workflow begins with sensor fabrication and biofilm establishment, followed by continuous monitoring and signal acquisition. The captured signals are processed through machine learning algorithms to predict multiple water quality parameters, with final validation against conventional analytical methods [23] [18].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for MPS Technology

| Item | Specifications | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graphite Electrodes | Rods (6 mm diameter) or plates (80×10×2 mm) | Biofilm support matrix | High surface area, biocompatible, non-corrosive [23] [24] |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | RE-1B, potential 195 mV vs RHE at 25°C | Stable reference potential | Essential for potentiometric measurements [25] |

| MnO₂ Modification | 0.5 M in PTFE/n-butanol solution | Enhances electrode reactivity | Increases surface area and redox reactions [25] |

| Pt/C Catalyst | 20-40% platinum on carbon | Cathodic modification | Improves detection of toxic substances [24] |

| Data Acquisition System | High-impedance (>10 MΩ), 0.004% DC accuracy | Signal measurement | Critical for accurate OCP measurement [23] [25] |

| PTFE Binder | 5% v/v in dispersion | Electrode modification | Provides structural integrity to modified electrodes [25] |

Advanced Applications and Machine Learning Integration

The integration of machine learning tools with MPS technology has expanded its capabilities beyond single-parameter detection to comprehensive water quality assessment. Studies have demonstrated that temporal MPS signal patterns can predict various parameters with remarkable accuracy when processed with ML/AI algorithms [18].

In a nine-month field deployment, MPS signals were used to predict turbidity, conductivity, chlorophyll, blue-green algae, dissolved oxygen, and pH in irrigation canals with Normalized Root Mean Square Error (NRMSE) values below 6.5% for most parameters, except dissolved oxygen at 10.45% [18]. The prediction of algal and chlorophyll concentrations was particularly precise, with NRMSE values below 3% [18].

This approach enables water quality monitoring of multiple parameters using a single composite MPS signal, significantly reducing the number of sensors required and associated maintenance costs. The system effectively creates a "digital fingerprint" of water quality by decoding the complex signal patterns generated by biofilm communities in response to environmental changes [18].

Microbial Potentiometric Sensor technology represents a significant advancement in environmental monitoring, leveraging the natural sensing capabilities of biofilm communities to provide maintenance-free, long-term detection of multiple water quality parameters. With demonstrated capabilities in monitoring organic carbon, toxic metals, algal concentrations, and various conventional water quality parameters, MPS technology offers a versatile and cost-effective alternative to traditional sensor technologies.

The integration of machine learning algorithms further enhances the utility of MPS by enabling prediction of multiple parameters from composite signal patterns. As research continues to refine electrode materials, biofilm composition, and data processing algorithms, MPS technology is poised to become an increasingly valuable tool for researchers and water management professionals seeking comprehensive, real-time understanding of aquatic systems.

Within the framework of developing advanced potentiometric methods for water quality monitoring, lead (Pb²⁺) ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) have emerged as a critical technology. The exceptional toxicity and bioaccumulative nature of lead, particularly in aquatic environments, necessitates detection methods that are not only highly sensitive and selective but also suitable for on-site, real-time analysis [28]. Modern Pb²⁺-ISEs meet this need by achieving remarkable detection limits as low as 10⁻¹⁰ M, coupled with broad linear ranges and the ruggedness required for environmental surveillance [28] [29]. This application note details the protocols and material requirements for implementing these high-performance sensors, providing researchers with a clear pathway to accurate lead quantification in complex water matrices.

Performance Metrics and Material Innovations

The pursuit of lower detection limits and enhanced stability has driven innovation in both the materials and architecture of Pb²⁺-ISEs. The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of modern Pb²⁺-ISEs, highlighting the capabilities that make them viable for trace-level water analysis.

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Modern Lead (Pb²⁺) Ion-Selective Electrodes

| Performance Parameter | Reported Range/Value | Key Enabling Materials & Designs |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | As low as 10⁻¹⁰ M [28] | Solid-contact designs with nanomaterials, ionic liquids, conducting polymers [28] [30] |

| Linear Range | 10⁻¹⁰ M to 10⁻² M [28] | Optimized ionophores (e.g., D2EHPA) in polymer matrices (e.g., PVC, polyurethane) [28] [31] |

| Sensitivity (Slope) | ~28–31 mV per decade (near-Nernstian for divalent ion) [28] [32] | High-selectivity ionophores and effective ion-to-electron transduction layers |

| Response Time | ~10 seconds (for some designs) [31] | Thin, homogeneous membranes with high ionophore mobility |

| Lifetime/Stability | Varies; e.g., 6 days demonstrated for specific PU-based ISE [31] | Hydrophobic membrane components to prevent leaching; stable solid-contact layers [30] |

A key architectural advancement is the shift from traditional liquid-contact ISEs to solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs). SC-ISEs eliminate the internal filling solution, which reduces maintenance, improves mechanical stability, and facilitates miniaturization and portability for field use [21] [30]. The solid-contact layer, often composed of conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT, polyaniline) or carbon nanomaterials, serves as an ion-to-electron transducer, critically influencing the sensor's potential stability and reproducibility [21] [30].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The construction and operation of high-performance Pb²⁺-ISEs rely on a specific set of materials and reagents. The following table catalogs these essential components and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Pb²⁺-ISE Fabrication and Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophore | Selectively binds Pb²⁺ ions in the membrane phase | D2EHPA [31]; synthetic ionophores; critical for sensor selectivity. |

| Polymer Matrix | Provides structural backbone for the ion-selective membrane (ISM) | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane (PU) [31] [30]. |

| Plasticizer | Imparts plasticity to the ISM, influences dielectric constant | DOS, DBP, NOPE; ensures proper function of ionophore [30]. |

| Ion Exchanger | Introduces immobile sites for ion exchange, improves conductivity | NaTFPB, KTPCIPB; helps exclude interfering ions [30]. |

| Solid-Contact Material | Facilitates ion-to-electron transduction in SC-ISEs | Conducting polymers (PEDOT), carbon nanotubes, graphene [21] [30]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | Masks varying ionic strength in samples, fixes pH | Added to all standards and samples; improves accuracy [32] [33]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for measurement | Ag/AgCl double-junction electrodes are commonly used. |

Experimental Protocol: Calibration and Measurement of Aqueous Pb²⁺

This protocol outlines the steps for calibrating a Pb²⁺-ISE and measuring unknown water samples, incorporating best practices for achieving optimal accuracy and repeatability.

Materials and Pre-Measurement Preparation

- Equipment: Pb²⁺ Ion-Selective Electrode, Reference Electrode, pH/mV Meter with ISE mode, magnetic stirrer and stir bars, analytical balance, 100 mL and 150 mL glass beakers, volumetric flasks, pipettes.

- Reagents: High-purity deionized (DI) water, lead nitrate (Pb(NO₃)₂) for stock solutions, recommended Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA).

- Electrode Preparation:

- Refill Reference Electrode: Ensure the reference electrode's fill solution is at the proper level and the refill hole is open during calibration and measurement [32].

- Condition the ISE: Soak the Pb²⁺-ISE in a mid-range standard (e.g., 10⁻⁴ M or 10⁻⁵ M) for approximately 2 hours prior to initial use [32].

- Short-Term Storage: Between measurements, store the electrode in a mid-range standard with the refill hole closed [32].

Calibration Procedure

- Prepare Standards: Prepare at least two, but preferably three, standard solutions that bracket the expected sample concentration. For trace analysis, a decade separation (e.g., 10⁻⁶ M, 10⁻⁵ M, 10⁻⁴ M) is effective. Use serial dilution for accuracy and prepare standards fresh on the day of use [32] [33].

- Add ISA: Transfer 100 mL of each standard to a 150 mL beaker. Add the specified volume of ISA (e.g., 2 mL per 100 mL) to each beaker [32].

- Set Up Measurement: Place the electrodes in the solution. Ensure the reference junction and ISE membrane are fully immersed. Use a stir plate to mix all standards and samples at a slow, consistent speed [32].

- Calibrate in Order: Begin with the lowest concentration standard.

- Rinse the electrodes thoroughly with DI water and gently blot dry with a lint-free cloth between each solution.

- Immerse the electrodes in the standard, allow the reading to stabilize, and record the mV value or enter the concentration as directed by the meter's calibration routine.

- Proceed to the next highest standard [32] [33].

- Evaluate Calibration: The meter will generate a calibration curve. Verify the electrode slope. For divalent Pb²⁺, the ideal Nernstian slope is approximately 29.58 mV/decade at 25°C. A slope between 26-31 mV/decade is typically acceptable [32].

Sample Measurement

- Prepare Sample: For each unknown water sample, measure 100 mL into a beaker and add the same volume of ISA as used for the standards [32] [33].

- Measure: Place the beaker on the stirrer, immerse the electrodes, and allow the mV reading to stabilize.

- Analyze: The meter will use the calibration curve to display the Pb²⁺ concentration directly.

- Recalibration: Recalibrate the electrode at the beginning of each day. For high-accuracy work, verify the calibration every 2 hours by measuring a fresh low standard; recalibrate if the reading drifts by more than ±2% [32].

Diagram 1: ISE Measurement Workflow

Signaling Pathway and Transduction Mechanism

The operation of a solid-contact Pb²⁺-ISE relies on a well-defined signaling pathway that converts the chemical activity of Pb²⁺ ions in solution into a stable, measurable electrical potential.

Diagram 2: Pb²⁺-ISE Signaling Pathway

- Selective Complexation: At the sample/ISM interface, the ionophore (L) selectively complexes with Pb²⁺ ions from the water sample, establishing a phase boundary potential described by the Nernst equation [28] [34].

- Ion Transport: The complexation event perturbs the equilibrium within the ISM, causing the movement of ionic species (e.g., Pb²⁺-ionophore complexes, counter-ions) through the membrane [30].

- Ion-to-Electron Transduction: At the ISM/Solid-Contact layer interface, ionic charge is converted into electronic charge. In a conducting polymer-based SC layer, this occurs via a reversible redox reaction that stabilizes the potential at this critical interface [21] [30].

- Potential Measurement: The cumulative potential difference across the entire ISE, which is proportional to the logarithm of the Pb²⁺ activity, is measured against a reference electrode under zero-current conditions [28] [21]. This measured potential (EMF) is the final electrical signal.

Potentiometric sensors are vital tools for ensuring water safety, with their performance being fundamentally governed by the electrode materials. The development of novel electrode materials, such as screen-printed ruthenium oxide (RuO₂) pH electrodes and ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) enhanced with nanomaterials, addresses the growing need for robust, sensitive, and deployable water quality monitoring solutions. These materials overcome significant limitations of conventional sensors, such as the fragility of glass pH electrodes and the poor stability of traditional liquid-contact ISEs, particularly in complex environmental matrices [17] [21]. This document details the application and experimental protocols for these advanced materials within a research framework focused on potentiometry for water quality monitoring.

Screen-Printed RuO₂ pH Electrodes

RuO₂-based electrodes have emerged as a superior alternative to glass electrodes due to their mechanical robustness, chemical durability, and excellent potentiometric performance in a wide range of aqueous environments, from industrial wastewater to natural water bodies [17].

Performance Characteristics and Applications

Extensive characterization of screen-printed RuO₂ electrodes sintered at different temperatures (800°C, 850°C, 900°C) demonstrates their suitability for environmental water quality testing. The table below summarizes key performance metrics established through controlled laboratory studies.

Table 1: Potentiometric performance characteristics of screen-printed RuO₂ pH electrodes.

| Performance Parameter | Experimental Findings | Measurement Context |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (Slope) | Close to Nernstian behavior (approximately 51-59 mV/pH) | pH buffer solutions [17] [35] |

| Linearity | Good linearity across tested pH range | pH buffer solutions [17] |

| Response Time | Fast response | Dynamic pH change [17] |

| Drift | Small potential drift over time | Continuous measurement in buffer [17] |

| Hysteresis | Low hysteresis | Cyclic pH measurements [17] |

| Cross-Sensitivity | Low response to interfering cations (e.g., Na⁺, K⁺, Li⁺, Ca²⁺) and anions (e.g., Cl⁻, NO₃⁻, SO₄²⁻, ClO₄⁻) | Solutions with added interfering ions [17] |

| Real-sample Accuracy | Maximum deviation of 0.11 pH units from conventional glass electrode | Various real water sources [17] [36] [37] |

| Adhesion & Microstructure | Better adhesion of the RuO₂ layer at lower sintering temperatures (e.g., 800°C) | Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) analysis [17] |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Characterization of Screen-Printed RuO₂ Electrodes

Objective: To fabricate a screen-printed RuO₂ pH electrode on an alumina substrate and characterize its potentiometric response.

I. Materials Fabrication

- RuO₂ Paste Preparation: Mix anhydrous RuO₂ powder with ethyl cellulose (binder) and terpineol (solvent) in an agate mortar for 20 minutes to achieve a homogeneous, printable paste [17].

- Substrate Preparation:

- Use a standard 96% alumina substrate.

- Screen-print a Ag/Pd conductive paste (e.g., ESL 9695) onto the substrate to form the inner conducting layer.

- Dry at 120°C for 15 minutes.

- Fire the substrate with the conductive layer at 860°C for 30 minutes in a belt furnace [17].

- RuO₂ Layer Deposition:

- Screen-print the prepared RuO₂ paste onto the substrate, ensuring it slightly overlaps the Ag/Pd conductive layer.

- Dry the printed electrode at 120°C for 15 minutes.

- Sinter the electrode in a box furnace at a target temperature (e.g., 800°C, 850°C, or 900°C) for 1 hour to burn out organics and sinter the RuO₂ layer [17].

- Final Assembly:

- Solder a copper wire to the exposed end of the Ag/Pd conducting layer for electrical contact.

- Encapsulate the electrical contact and conducting layer with a non-corrosive coating (e.g., DOWSIL 3140 RTV silicone resin), leaving only the RuO₂ sensing area exposed.

- Cure the silicone resin at room temperature for 48 hours [17].

II. Potentiometric Characterization

- Apparatus: Standard potentiometric setup with the fabricated RuO₂ electrode as the working electrode and a commercial reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl). Connect the electrodes to a high-impedance data acquisition system (e.g., National Instruments voltage input module) via a unity gain buffer amplifier [17].

- Procedure:

- Calibration and Sensitivity: Immerse the RuO₂ and reference electrodes in a series of standard pH buffer solutions (e.g., pH 4, 7, 10). Measure the equilibrium potential in each solution. Plot the potential (E) vs. pH and perform linear regression. The slope should be close to the theoretical Nernstian value (-59.16 mV/pH at 25°C) [17].

- Response Time: Rapidly transfer the electrode pair from one pH buffer to another with a significant pH difference (e.g., from pH 7 to pH 4). Record the potential until a stable value is reached (e.g., change < 0.1 mV per minute). The time taken to reach 95% of the final potential is the response time [17].

- Cross-Sensitivity: Prepare solutions containing a fixed pH but varying concentrations of potential interfering ions (e.g., 0.1 M NaCl, NaNO₃, Na₂SO₄). Measure the potential in these solutions and compare it to the potential in a pure pH buffer. A negligible change in potential indicates low cross-sensitivity [17].

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages of this experimental protocol.

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs)

The integration of nanomaterials into ISEs as solid-contact (SC) ion-to-electron transducers has revolutionized potentiometric sensing, enabling the development of miniaturized, stable, and highly sensitive sensors for water contaminants [21].

Nanomaterial Platforms and Their Functions

Nanomaterials enhance SC-ISEs by providing a high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and superior capacitance, which minimizes potential drift and improves signal stability [21]. The table below lists key nanomaterial classes and their roles in ISEs.

Table 2: Key nanomaterial classes and their functions in solid-contact ISEs.

| Nanomaterial Class | Specific Examples | Function in ISE |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-based | Graphene, Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs), Colloid-imprinted Mesoporous Carbon | Ion-to-electron transduction; High capacitance and water repellency [21] |

| Conducting Polymers | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polyaniline (PANI), Poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT) | Ion-to-electron transduction; Redox capacitance [21] |

| Metallic & Metal Oxide | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Tubular Au-TTF nanocomposites, Fe₃O₄, MoS₂ nanoflowers | Signal amplification; Stabilization of composite structure; Enhanced capacitance [21] |

| MXenes | Ti₃C₂Tₓ | Ion-to-electron transduction; High conductivity and tunable surface chemistry [21] |

| Nanocomposites | MoS₂/Fe₃O₄, POM/GO (Polyoxometalate/Graphene Oxide) | Synergistic effects; Enhanced stability, capacitance, and electron transfer kinetics [21] |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a Nanomaterial-Based Solid-Contact ISE

Objective: To fabricate a solid-contact ISE for heavy metal ions (e.g., Pb²⁺) using a nanomaterial-based transducer layer.

I. Solid-Contact ISE Fabrication

- Electrode Substrate Preparation: Use a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or screen-printed carbon electrode as the substrate. Polish the GCE sequentially with alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0 µm and 0.3 µm) and sonicate in deionized water and ethanol to create a clean, smooth surface [21].

- Deposition of Nanomaterial Transducer Layer:

- Prepare a dispersion of the selected nanomaterial (e.g., MWCNTs or PEDOT:PSS) in a suitable solvent (e.g., water/ethanol).

- Deposit the transducer layer onto the prepared substrate via drop-casting or electrodeposition. For drop-casting, apply a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the nanomaterial dispersion and allow it to dry under ambient conditions or with mild heating [21].

- Preparation of Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM):

- The ISM cocktail is typically composed of:

- Polymer Matrix: Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC).

- Plasticizer: e.g., 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE).

- Ionophore: A selective chelator for the target ion (e.g., ionophore IV for Pb²⁺).

- Ionic Additive: e.g., Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (KTpClPB).

- Dissolve these components in a volatile solvent such as tetrahydrofuran (THF) [21].

- The ISM cocktail is typically composed of:

- Membrane Deposition: Drop-cast the prepared ISM cocktail directly onto the dried nanomaterial transducer layer. Allow the THF to evaporate slowly, forming a uniform polymeric membrane. Condition the finished ISE by soaking in a solution containing the primary ion (e.g., 1.0 × 10⁻³ M Pb(NO₃)₂) for several hours before use [21].

II. Electrochemical Characterization of the SC-ISE

- Apparatus: Potentiostat, the fabricated SC-ISE, a reference electrode, and a counter electrode.

- Procedure:

- Potentiometric Performance: Follow a similar calibration procedure as for the RuO₂ electrode, using standard solutions of the target ion (e.g., Pb²⁺). Determine the slope, linear range, and limit of detection from the E vs. log a(Pb²⁺) plot.

- Water Layer Test: Perform a potentiometric water layer test by sequentially measuring the potential in a solution of the primary ion (e.g., Pb²⁺), then in a solution of an interfering ion (e.g., Na⁺ or Ca²⁺), and finally again in the primary ion solution. A stable potential with no significant drifts or dips upon returning to the primary solution indicates the absence of a detrimental water layer between the membrane and the transducer, a key sign of a high-quality SC-ISE [21].

- Chronopotentiometry: Apply a small constant current (e.g., ±1 nA) to the SC-ISE and record the potential transient. The potential drift (ΔE/Δt) is inversely proportional to the capacitance of the solid contact. A high capacitance, provided by the nanomaterials, results in a very small drift, indicating excellent potential stability [21].

The logical relationships between the nanomaterial properties and the resulting sensor performance are illustrated below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for developing novel potentiometric electrodes.

| Item Name | Function/Application | Exemplary Specifications / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Anhydrous RuO₂ Powder | Active pH-sensitive material for screen-printed electrodes | Purity: ≥99.9%; Particle size control is crucial for paste rheology [17] |

| Ag/Pd Thick-Film Paste | Conductive layer for screen-printed electrodes | e.g., Electro-Science Laboratories #9695; Fired at 860°C [17] |

| Alumina Substrate (96%) | Mechanically robust and chemically inert substrate | Provides high tolerance to various environmental conditions [17] |

| Ion-Selective Ionophores | Provides selectivity in ISE membranes | e.g., Lead ionophore IV; Select based on target analyte (Pb²⁺, Ca²⁺, K⁺, etc.) [21] |

| Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) | Polymer matrix for ion-selective membranes | High molecular weight; Provides mechanical stability to the membrane [21] |

| Plasticizers (e.g., o-NPOE) | Solvates ionophore and confers mobility to ions within the ISM | Determines membrane dielectric constant and influences selectivity [21] |

| Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Nanomaterial for solid-contact transduction in ISEs | Functionalized (e.g., carboxylated) for better dispersion and adhesion [21] |

| Potentiostat / High-impedance Data Logger | Instrumentation for potential measurement | Critical for accurate EMF measurement without current draw [17] [38] |

Potentiometry, a well-established electrochemical technique, provides a powerful and versatile method for the sensitive and selective measurement of a variety of analytes by measuring the potential difference between two electrodes. This allows for a direct and rapid readout of ion concentrations, making it a valuable tool in diverse applications including environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical analysis, and clinical diagnostics [21]. The core principle involves measuring the potential of an electrochemical cell under static conditions where no current—or only negligible current—flows, thereby leaving the cell's composition unchanged [39]. The advent of Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs), which generate useful membrane potentials, has significantly extended the application of potentiometry to a diverse array of analytes beyond simple redox equilibria [39].

The integration of Machine Learning (ML) with potentiometric sensing represents a paradigm shift, transforming these sensors from simple data collection tools into intelligent, predictive systems. Pattern recognition, a critical branch of machine learning, focuses on the development of algorithms and technologies that recognize patterns and regularities in data [40]. In the context of potentiometry, ML algorithms can process complex, multi-dimensional data from sensor arrays to perform tasks such as detecting a regularity or pattern within large sets of data, classifying sensor responses, predicting temporal trends in analyte concentrations, and identifying subtle patterns indicative of sensor drift or interference [41] [40]. This synergy is particularly powerful in water quality monitoring, where it enables the extraction of meaningful information from the complex, noisy, and multivariate data often generated by potentiometric sensor arrays deployed in real-world environments.

Machine Learning Approaches for Potentiometric Signal Processing

Core Pattern Recognition Paradigms