Potentiometry and Voltammetry: Principles, Applications, and Advanced Methodologies for Biomedical Research

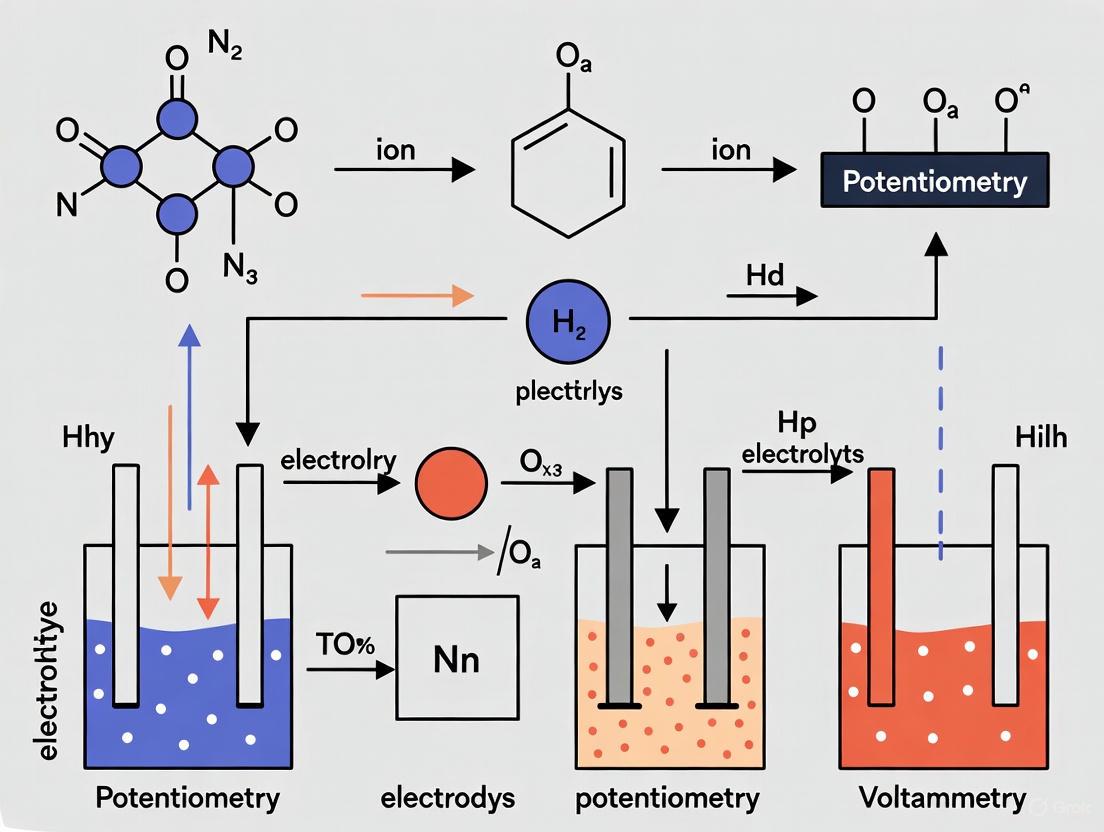

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of potentiometry and voltammetry, two foundational electrochemical techniques with profound implications for drug development and biomedical analysis.

Potentiometry and Voltammetry: Principles, Applications, and Advanced Methodologies for Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of potentiometry and voltammetry, two foundational electrochemical techniques with profound implications for drug development and biomedical analysis. Tailored for researchers and scientists, the content progresses from core principles and instrumentation to cutting-edge applications in therapeutic drug monitoring and wearable sensors. It offers practical guidance on method optimization, troubleshooting common errors, and validating analytical procedures. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with contemporary methodological advances and comparative analysis, this resource serves as a vital guide for implementing these techniques reliably and effectively in research and clinical settings.

Core Principles and Instrumentation of Electroanalytical Techniques

Electroanalytical chemistry provides a powerful suite of techniques for quantifying analytes and understanding electrochemical processes. Among these, potentiometry and voltammetry represent two fundamental approaches with distinct principles and applications. Potentiometry measures the potential (voltage) of an electrochemical cell under conditions of zero current flow, providing information about ion activities or concentrations [1] [2]. In contrast, voltammetry measures the current resulting from applying a controlled potential profile to an electrochemical cell, enabling both qualitative and quantitative analysis of electroactive species [1] [3]. These techniques form the cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, with applications spanning clinical diagnostics, pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and materials science [1]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, methodologies, and key differentiators between these essential analytical techniques within the context of basic electrochemical research.

Fundamental Principles of Potentiometry

Theoretical Foundation

Potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes—an indicator electrode and a reference electrode—when negligible current flows through the electrochemical cell [2] [4]. The measured potential is related to the activity (effective concentration) of specific ions in solution through the Nernst equation, which for a generic cation Mⁿ⁺ is expressed as:

E = E⁰ - (RT/nF)ln(1/a_Mⁿ⁺) [3] [4]

Where:

- E is the measured potential

- E⁰ is the standard electrode potential

- R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K)

- T is the absolute temperature in Kelvin

- n is the number of electrons transferred

- F is Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol)

- a_Mⁿ⁺ is the activity of the ion Mⁿ⁺

At 25°C, the Nernst equation simplifies to approximately 59.16 mV per decade of activity change for monovalent ions (n=1) and 29.58 mV per decade for divalent ions (n=2) [4]. This logarithmic relationship enables potentiometry to measure ion concentrations across a wide dynamic range.

Instrumentation and Electrode Systems

A typical potentiometric cell consists of several key components that work together to enable accurate measurement:

Reference Electrode: Provides a stable, well-defined potential that remains constant throughout the measurement. Common examples include the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode [1] [4]. These electrodes maintain a constant potential via a redox couple with fixed composition.

Indicator Electrode: Responds selectively to the activity of the target ion in solution. Several types exist:

- Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs): Incorporate membranes designed to respond preferentially to specific ions such as fluoride (F⁻), calcium (Ca²⁺), or nitrate (NO₃⁻) [5] [1].

- Glass Membrane Electrodes: Most commonly used for pH measurement, featuring a glass membrane responsive to hydrogen ions [5] [6].

- Redox Electrodes: Inert metals like platinum or gold that respond to redox couples in solution [4].

Ion-Selective Membranes: The heart of modern potentiometric sensors, these membranes contain ionophores that selectively bind target ions. Recent advances include solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) that replace traditional inner filling solutions with conducting polymers or carbon-based nanomaterials, enhancing stability and enabling miniaturization [7].

The potential difference between the indicator and reference electrodes is measured using a high-impedance voltmeter that draws negligible current, ensuring the measurement does not perturb the system equilibrium [8].

Experimental Methodologies

Direct Potentiometry

Direct potentiometry involves measuring the potential of a sample solution and determining analyte concentration directly from a calibration curve. The methodology includes:

- Calibration: Measuring potentials of standard solutions with known concentrations to establish the relationship between potential and log(concentration) [6].

- Sample Measurement: Measuring the potential of the unknown sample under identical conditions.

- Data Analysis: Calculating sample concentration from the calibration curve using the Nernst equation.

This approach is widely used in pH measurement and ion-selective electrode applications for rapid concentration determination [1] [4].

Potentiometric Titrations

Potentiometric titrations monitor the potential change as a titrant is added to determine the titration endpoint:

- Titrant Addition: Incrementally adding titrant to the sample solution while continuously monitoring potential.

- Endpoint Detection: Identifying the equivalence point from the inflection point in the potential versus volume curve.

- Application: Particularly valuable for colored or turbid solutions where visual indicators fail, and for automated titration systems [1] [4].

This method is extensively used in acid-base, complexometric, redox, and precipitation titrations [8].

Fundamental Principles of Voltammetry

Theoretical Foundation

Voltammetry encompasses electrochemical techniques that measure current as a function of applied potential [2] [3]. Unlike potentiometry, voltammetry actively drives redox reactions by applying sufficient potential to cause electron transfer at the working electrode interface. The resulting current is proportional to the concentration of electroactive species and provides information about redox potentials, reaction kinetics, and diffusion characteristics.

The theoretical basis can be understood through the Fermi level concept: when electrode potential is adjusted, the Fermi level (highest energy level of electrons in the electrode) shifts. Oxidation occurs when the Fermi level drops below the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) of an analyte, while reduction occurs when it rises above the lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) [3]. The applied potential at which current flows identifies the redox species, while the magnitude of current quantifies its concentration.

Two types of current are observed in voltammetry:

- Faradaic current: Results from redox reactions of analytes at the electrode surface.

- Charging current: arises from the electrostatic charging of the electrode-solution interface (electric double layer) and represents the background signal [3].

Instrumentation and Electrode Systems

Voltammetry typically employs a three-electrode system that provides superior potential control compared to two-electrode configurations:

Working Electrode: Where the redox reaction of interest occurs. Common materials include glassy carbon, platinum, gold, and mercury (for polarography) [1] [8]. The working electrode material is selected based on the potential window and analytes of interest.

Reference Electrode: Maintains a stable potential reference, identical to those used in potentiometry (Ag/AgCl, SCE) [1].

Counter Electrode (Auxiliary Electrode): Completes the electrical circuit, typically made from inert materials like platinum wire [1].

Modern voltammetry utilizes sophisticated potentiostats to control the applied potential and precisely measure the resulting current. The system is often housed in an electrochemical cell that controls solution conditions and excludes oxygen when necessary.

Experimental Methodologies

Cyclic Voltammetry

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is the most widely used voltammetric technique, applying a linear potential sweep that reverses direction at a set vertex potential [9]. The methodology includes:

- Potential Scanning: Linearly sweeping potential from an initial value to a vertex potential, then reversing back to the initial value.

- Current Measurement: Recording current throughout the potential cycle.

- Data Presentation: Plotting current versus potential to produce a voltammogram.

For a reversible system, key parameters include:

- Peak current (ip): Related to concentration by the Randles-Ševčík equation: ip = (2.69×10⁵)n³/²AD¹/²Cv¹/² (at 25°C) [9]

- Peak separation (ΔE_p): 59/n mV for a reversible one-electron transfer [9]

- Formal potential (E°): Average of anodic and cathodic peak potentials

CV provides information about redox potentials, electron transfer kinetics, and reaction mechanisms [9] [10].

Other Voltammetric Techniques

Various voltammetric techniques offer specialized capabilities:

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Applies small potential pulses to enhance sensitivity and minimize charging current effects [1].

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): Uses a square waveform for rapid scanning and excellent sensitivity [1].

- Staircase Voltammetry: Applies potential in stair-step increments, measuring current at the end of each step [8].

- Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV): Preconcentrates analytes onto the electrode surface before stripping, achieving exceptional sensitivity for trace metal analysis [5].

Table 1: Comparison of Major Voltammetric Techniques

| Technique | Potential Waveform | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Linear sweep with reversal | Qualitative mechanism studies, redox potentials | Reaction mechanism analysis, kinetic studies [9] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Small pulses on linear ramp | High sensitivity, minimized charging current | Trace analysis, organic compounds, pharmaceuticals [1] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Square waveform | Fast scanning, excellent sensitivity | Trace analysis, kinetic studies [1] |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Deposition followed by linear sweep | Ultra-trace detection (ppb-ppt) | Heavy metal analysis, environmental monitoring [5] |

| Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) | Single linear sweep | Simple redox profiling | Basic electrochemical characterization [8] |

Key Differences Between Potentiometry and Voltammetry

Understanding the distinctions between potentiometry and voltammetry is essential for selecting the appropriate analytical approach for a given application. The fundamental differences span theoretical basis, experimental setup, measurement outputs, and practical applications.

Table 2: Comprehensive Comparison of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Quantity | Potential (voltage) | Current |

| Current Flow | Negligible (zero-current) | Significant (current measured) |

| Theoretical Basis | Nernst equation | Nernst equation combined with mass transport |

| Electrode System | Two-electrode typical (indicator & reference) | Three-electrode typical (working, reference, & counter) |

| Information Obtained | Ion activity/concentration | Redox properties, concentrations, kinetics, mechanisms |

| Dynamic Range | Typically 10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁵ M | Typically 10⁻³ to 10⁻¹² M |

| Sensitivity | Moderate | Very high (especially stripping methods) |

| Selectivity | High (with ion-selective membranes) | Moderate (based on redox potentials) |

| Sample Consumption | Non-destructive | Minimal consumption at electrode surface |

| Primary Applications | pH, ion-selective measurements, titrations | Trace analysis, kinetic studies, mechanistic studies |

The most fundamental distinction lies in what each technique measures: potentiometry measures potential at zero current, while voltammetry measures current while applying controlled potential [1] [3]. This difference dictates their respective applications—potentiometry excels at direct ion activity measurements, while voltammetry provides comprehensive information about redox processes.

Advanced Applications and Recent Developments

Potentiometric Advancements

Recent innovations in potentiometry have significantly expanded its capabilities and applications:

Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes (SC-ISEs): Replace traditional inner filling solutions with solid transduction layers, enabling miniaturization, improved stability, and resistance to fouling. Materials include conducting polymers (PEDOT, polyaniline) and carbon-based nanomaterials (graphene, carbon nanotubes) [7].

Wearable Potentiometric Sensors: Enable continuous monitoring of electrolytes (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺) and metabolites in biological fluids for healthcare applications [7].

3D-Printed Electrodes: Utilize additive manufacturing for rapid prototyping of customized electrode geometries with improved performance characteristics [7].

Paper-Based Potentiometric Sensors: Offer low-cost, disposable platforms for point-of-care testing and environmental monitoring in resource-limited settings [7].

These advances have enabled potentiometric applications in therapeutic drug monitoring, detection of biomarkers in biological fluids, and continuous health monitoring through wearable devices [7].

Voltammetric Advancements

Voltammetry has similarly evolved with cutting-edge developments:

Multiscan-Rate CV Analysis: Provides comprehensive insights into reaction mechanisms, diffusion control, and electron transfer kinetics by examining scan-rate dependencies [10].

Modified Electrodes: Incorporate chemically designed interfaces to enhance selectivity and sensitivity for specific analytes, including electrocatalysts for fuel cells and battery materials [10].

Ultrafast Voltammetry: Employ microelectrodes and high-speed potentiostats to study rapid electron transfer processes with scan rates up to kV/s [10].

High-Throughput Screening: Enable rapid evaluation of electrocatalyst libraries and battery materials for energy research applications [10].

These developments have proven particularly valuable in battery research, where multi-scan-rate CV provides critical insights into electrode reversibility, reaction mechanisms, and failure diagnostics [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Analysis

| Item | Function | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Electrodes | Provide stable potential reference | Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel (SCE) | Choose based on compatibility with solution chemistry [1] |

| Working Electrodes | Site of electrochemical reaction | Glassy Carbon, Pt, Au, Hg (for polarography) | Select based on potential window and analyte [1] [8] |

| Electrolyte Salts | Provide ionic conductivity, control ionic strength | KCl, LiClO₄, TBAPF₆ (for non-aqueous) | Must be electroinactive in potential range of interest [9] |

| Ionophores | Selective ion recognition in ISEs | Valinomycin (K⁺), ETH 129 (Ca²⁺) | Critical for potentiometric selectivity [5] [7] |

| Polymer Membranes | Matrix for ion-selective membranes | PVC, Silicone rubber | Provide mechanical stability for ISEs [7] |

| Redox Probes | System characterization | Ferrocene, K₃Fe(CN)₆, Ru(NH₃)₆Cl₃ | Used for electrode performance validation [9] |

| Supporting Materials | Electrode modification | Carbon nanotubes, conducting polymers, nanoparticles | Enhance sensitivity and stability [7] |

Potentiometry and voltammetry represent complementary pillars of electroanalytical chemistry, each with distinct principles, methodologies, and application domains. Potentiometry excels in direct ion activity measurements with relative simplicity and excellent selectivity, while voltammetry offers unparalleled capabilities for studying redox processes with high sensitivity and rich mechanistic information. Recent advances in both techniques continue to expand their applications in biomedical research, environmental monitoring, and energy materials development. Understanding their fundamental differences enables researchers to select the optimal approach for specific analytical challenges and contributes to the continued advancement of electrochemical science. As these techniques evolve through nanomaterials integration, miniaturization, and advanced manufacturing, their importance in analytical chemistry and related fields will undoubtedly continue to grow.

The Nernst equation stands as a cornerstone of electrochemistry, providing the critical link between the thermodynamic potential of an electrochemical cell and the concentrations of the chemical species within it. This fundamental relationship is the theoretical bedrock upon which potentiometric measurement is built, a technique ubiquitously applied from clinical blood gas analyzers to environmental heavy metal sensors. For researchers in drug development, understanding the Nernst equation is paramount for designing biosensors, characterizing redox-active pharmaceutical compounds, and interpreting data from techniques like cyclic voltammetry [11] [12]. This guide delineates the theoretical derivation of the equation, its practical application in potentiometry, and detailed experimental protocols for its validation, framed within a broader research context on electrochemical analytical techniques.

Theoretical Foundation

Derivation from Thermodynamic Principles

The Nernst equation is a thermodynamic relationship derived from the principles of Gibbs free energy in electrochemical systems. For a general redox reaction:

$$\ce{Ox + n e^- -> Red}$$

The Gibbs free energy change, ΔG, under non-standard conditions is given by:

Equation 1: ΔG = ΔG⁰ + RT ln Q [13]

where ΔG⁰ is the standard Gibbs free energy change, R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹), T is the temperature in Kelvin, and Q is the reaction quotient. In electrochemistry, the electrical work done by a galvanic cell is equal to the decrease in Gibbs free energy, leading to:

Equation 2: ΔG = -nFE [13] [14]

Here, n is the number of moles of electrons transferred in the reaction, F is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹), and E is the cell potential. Under standard conditions, this becomes:

Equation 3: ΔG⁰ = -nFE⁰ [13]

Substituting Equations 2 and 3 into Equation 1 yields:

Equation 4: -nFE = -nFE⁰ + RT ln Q

Dividing both sides by -nF provides the most general form of the Nernst equation:

Equation 5: E = E⁰ - (RT/nF) ln Q [13] [15]

For the general reaction aOx + n e⁻ ⇌ bRed, the reaction quotient Q is (a_Red)^b / (a_Ox)^a, where a denotes the chemical activity. At 25 °C (298 K), and converting from natural logarithm to base-10 logarithm (ln Q = 2.303 log Q), the equation simplifies to the widely used form:

Equation 6: E = E⁰ - (0.0592 V / n) log Q [13] [16]

This simplified form is instrumental for rapid calculation of potentials under standard laboratory conditions. The following diagram illustrates the logical derivation pathway from fundamental thermodynamic principles to the final Nernst equation.

The Concept of Formal Potential

A critical consideration for practical research is the distinction between standard potential (E⁰) and formal potential (E⁰'). The standard potential is defined when all reactants and products are at unit activity. However, in real experimental settings, ionic strength, pH, and side reactions influence the effective potential. The formal potential is a corrected value defined as the measured potential when the concentration ratio of oxidant to reductant is unity, and the concentrations of all other species are specified [15] [17]. It is related to the standard potential by:

Equation 7: E⁰' ≈ E⁰ - (RT/zF) ln (γRed / γOx)

where γ represents the activity coefficient. For accurate work, especially in quantitative analysis, using tabulated formal potentials for specific media is essential, as they incorporate effects of activity coefficients and solution conditions [16] [15].

The Nernst Equation in Potentiometric Measurement

Potentiometry involves measuring the potential of an electrochemical cell under conditions of zero current, where the potential is directly related to analyte concentration via the Nernst equation [16] [11]. This forms the basis for ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) and pH meters.

Core Components of a Potentiometric Cell

A typical two-electrode potentiometric cell for sensing, as used in studies like the detection of Hg²⁺ ions, consists of [12]:

- Working Electrode (Indicator Electrode): The electrode whose potential is sensitive to the analyte concentration. Its surface is often modified with a selective membrane or nanocomposite (e.g., WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT for Hg²⁺) [12].

- Reference Electrode: An electrode with a stable, well-known, and constant potential (e.g., calomel or Ag/AgCl), which serves as the baseline for measuring the working electrode's potential [8] [12].

The measured cell potential (Ecell) is the difference between the potentials of the working (*E*ind) and reference (Eref) electrodes: *E*cell = Eind - *E*ref. The indicator electrode's potential is governed by the Nernst equation for the target ion [16].

Quantitative Relationship for Analysis

For a cationic analyte Mⁿ⁺, the half-cell reduction reaction is:

$$\ce{M^{n+} + n e^- -> M}$$

Applying the Nernst equation (Equation 6) and assuming the activity of the solid metal M is 1, the potential of the indicator electrode becomes:

Equation 8: E_ind = E⁰' - (0.0592 V / n) log (1 / [Mⁿ⁺]) = E⁰' + (0.0592 V / n) log [Mⁿ⁺]

The overall cell potential is then:

Equation 9: E_cell = K + (0.0592 V / n) log [Mⁿ⁺]

where K is a constant grouping E⁰' and the reference electrode potential. This linear relationship between E_cell and log [Mⁿ⁺] is the foundation of quantitative potentiometric analysis. The ideal Nernstian slope at 25°C is 59.2/n mV per decade of concentration, and a deviation from this slope can indicate non-ideal behavior or issues with the electrode [12]. The workflow below details the steps involved in a standard potentiometric sensing experiment.

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Protocol: Potentiometric Sensor Calibration and Measurement

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used in developing nanocomposite-based ion sensors and standard potentiometric practice [12].

Objective: To determine the concentration of an analyte (e.g., Hg²⁺) in a test solution using a custom potentiometric sensor.

Materials:

- Potentiostat or high-impedance voltmeter.

- Custom working electrode (e.g., WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT nanocomposite film on a conductive substrate).

- Reference electrode (e.g., Calomel electrode, Hg/Hg₂Cl₂).

- Standard solutions of the analyte (e.g., Hg²⁺ solutions from 10⁻⁶ M to 10⁻¹ M).

- Test solutions (unknown concentration and natural samples).

- Magnetic stirrer and stir bars.

Procedure:

Electrode Preparation: Synthesize and immobilize the sensing material (e.g., the WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT nanocomposite) on the working electrode surface. The nanocomposite is synthesized via oxidative polymerization of 2-aminobenzene-1-thiol in the presence of Na₂WO₄ and K₂S₂O₈ as oxidants, resulting in a flower-shaped structure that provides a high surface area and affinity for the target ion [12].

Calibration:

- a. Arrange the equipment in a two-electrode cell configuration.

- b. Immerse the working and reference electrodes in the first standard solution (e.g., 10⁻⁶ M Hg²⁺).

- c. Under constant stirring, measure the stable cell potential (in V) once the reading has stabilized (no current flow).

- d. Rinse the electrodes thoroughly with deionized water between measurements.

- e. Repeat steps b-d for all standard solutions (e.g., up to 10⁻¹ M Hg²⁺).

Sample Measurement:

- a. Immerse the electrodes in the test solution (unknown concentration).

- b. Measure the stable cell potential as before.

- c. (Optional) Perform a standard addition for validation.

Data Analysis:

- a. Plot the measured potential (E, mV) vs. the logarithm of the standard concentrations (log [Hg²⁺]).

- b. Perform a linear regression analysis on the data points. The slope should be close to the theoretical Nernstian slope (~59.2/n mV/decade for a divalent ion like Hg²⁺; a reported value is ~33.0 mV/decade, indicating possible non-ideal behavior or a different reaction stoichiometry [12]).

- c. Use the linear equation (E = slope × log [C] + intercept) to calculate the concentration of the unknown test solution from its measured potential.

Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 1: Essential materials for potentiometric sensor research based on the featured protocol.

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Membrane/Composite | The active sensing element; selectively binds the target ion, generating a potential change. | WS₂-WO₃/Poly-2-aminobenzene-1-thiol nanocomposite for Hg²⁺ sensing [12]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable and constant reference potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured. | Calomel (Hg/Hg₂Cl₂) or Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrodes [8] [12]. |

| Oxidizing Agent | Used in the synthesis of conductive polymer-based nanocomposites. | Potassium persulfate (K₂S₂O₈) [12]. |

| Potentiostat | An electronic instrument that controls the potential and measures the current in a multi-electrode cell. Used for characterization (e.g., CV) and in three-electrode setups [8]. | CHI608E instrument used for cyclic voltammetry characterization [12]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and maintains constant ionic strength, minimizing activity coefficient variations. | HCl was used as the acid medium during polymer synthesis [12]. |

Quantitative Data from Experimental Studies

Table 2: Experimentally determined Nernstian parameters for ion sensing.

| Analyte | Sensing Material | Theoretical Slope (mV/decade) | Experimental Slope (mV/decade) | Linear Range (M) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hg²⁺ | WS₂-WO₃/P2ABT Nanocomposite | ~29.6 (for n=2) | 33.0 | 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻¹ | [12] |

| H⁺ (pH) | Standard Glass Electrode | 59.2 (for n=1) | ~59.2 | 0 to 14 | [16] |

Advanced Research Context: Integration with Voltammetry

While potentiometry is a zero-current technique, the Nernst equation is equally vital for interpreting results from controlled-current techniques like cyclic voltammetry (CV), a cornerstone of electrochemical research in drug development [11].

In CV, the potential of a working electrode (in a three-electrode cell with working, reference, and counter electrodes) is swept linearly and then reversed. The resulting current-potential plot provides information on redox potentials, kinetics, and reaction mechanisms [8] [11]. For a reversible redox couple (Ox + n e⁻ ⇌ Red), the Nernst equation dictates the concentration ratio at the electrode surface. The characteristic peak separation (ΔE_p) is about 59/n mV at 25°C, a direct consequence of Nernstian behavior [18]. Furthermore, for systems involving coupled proton-electron transfers (common in organic molecules and biomolecules), the Nernst equation is extended to account for pH:

Equation 10: E = E⁰' - (0.0592 V / n) log ([Red] / [Ox]) - (0.0592 V * m / n) pH

where m is the number of protons transferred [18]. This relationship allows researchers to map complex reaction mechanisms using the "scheme of squares" framework and to predict how redox potentials of drug candidates will shift under physiological pH conditions [18].

The Nernst equation is far more than a theoretical formula; it is the indispensable link between chemical energy and electrical potential that underpins modern potentiometric measurement. Its application, from the simple calibration of a pH electrode to the intricate design of novel nanocomposite sensors for environmental toxins, demonstrates its enduring power. For the research scientist, a deep understanding of this equation, including its assumptions and the nuances of formal potential, is crucial for designing robust experiments, interpreting electrochemical data, and developing new analytical methods. As electrochemical techniques continue to evolve, particularly in the realms of miniaturized sensors and computational prediction of redox properties (e.g., via Density Functional Theory [18]), the Nernst equation will remain a fundamental pillar, guiding innovation in drug development, environmental monitoring, and materials science.

This guide details the core instrumentation foundational to research in potentiometry and voltammetry. These electrochemical techniques are pivotal in diverse fields, from drug development and environmental monitoring to energy storage research.

Potentiometry and voltammetry are foundational electrochemical techniques used for quantitative analysis and studying electron-transfer processes. Potentiometry involves measuring the potential of an electrochemical cell under static, zero-current conditions to determine analyte activity or concentration [19] [20]. In contrast, voltammetry applies a controlled potential to a working electrode and measures the resulting current, providing information about analyte concentration, reaction kinetics, and thermodynamics [21] [22]. The core instrumentation for both techniques centers on a three-electrode system—comprising working, reference, and counter electrodes—and a potentiostat, which precisely controls or measures the electrical parameters within the cell [23] [24] [20]. The selection of appropriate electrodes, cell design, and potentiostat capabilities directly impacts the sensitivity, accuracy, and applicability of experimental results.

Essential Electrode Types and Their Functions

The three-electrode system is the standard configuration for modern electrochemical experiments, as it enables precise control of the potential at the working electrode interface [20].

Working Electrodes

The working electrode (WE) is the site where the reaction of interest occurs. Its material and surface state are critical and must be carefully prepared and reproduced [24].

Table 1: Common Working Electrode Materials and Applications

| Material | Key Properties | Common Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon | Conductive, reusable, relatively inert [24] | General purpose voltammetry, HPLC detection [22] | Requires polishing for surface reproducibility [24] |

| Platinum & Gold | Conductive, inert, easily cleaned [24] | Electrocatalysis, oxidation studies [8] | Can be prone to surface oxidation or poisoning [21] |

| Mercury (Drop/Film) | Renewable surface, high hydrogen overpotential, forms amalgams [21] [22] | Stripping analysis, reduction of metal ions [22] | Toxic; limited anodic potential range due to its own oxidation [21] [22] |

Reference Electrodes

The reference electrode (RE) provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled or measured. Ideally, no current flows through it [24] [20].

Table 2: Common Reference Electrodes

| Type | Composition | Standard Potential (approx. vs. SHE) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/AgCl | Ag wire coated with AgCl in KCl solution [24] | +0.197 V (in 3M KCl) | Very common; relatively stable [24] |

| Saturated Calomel (SCE) | Hg in contact with Hg₂Cl₂ in sat. KCl [24] | +0.241 V | Common; contains mercury [24] |

| Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) | Pt in H₂ gas and H⁺ activity of 1 [24] | 0.000 V by definition | Theoretical standard; rarely used in routine lab work [24] |

Counter Electrodes

The counter electrode (CE), also known as the auxiliary electrode, completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow through the cell. It is typically an inert material with a large surface area, such as a platinum wire or mesh, to ensure it does not limit the current flow [24] [20].

Diagram 1: Three-Electrode System Function

Potentiostats: Operational Principles and Market Landscape

A potentiostat is an electronic instrument that controls the potential between a working electrode and a reference electrode while measuring the current flowing between the working and counter electrodes [23].

Core Operational Principles

The fundamental component of a potentiostat is an operational amplifier (op-amp) configured in a feedback loop [23]. The user applies a voltage signal, Vi. The op-amp outputs a voltage, Vo, to the counter electrode. An electrometer continuously measures the potential difference between the reference and working sense leads (Vfeedback). This measured potential is fed back to the op-amp's non-inverting input. If Vfeedback differs from the setpoint Vi, the op-amp adjusts its output Vo until the two values are equal, thereby maintaining the desired potential at the working electrode [23]. The current is not measured directly but is calculated using Ohm's Law by measuring the voltage drop across a known internal resistor (R_wrk) [23].

Diagram 2: Potentiostat Signal Path

Instrument Types and Market Analysis

The potentiostat market is evolving with technological advancements and growing application areas.

Table 3: Potentiostat Market Overview

| Segment | Analysis & Forecast | Key Drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Bipotentiostats dominate; Polypotentiostats fastest-growing [25] [26] | Demand for sophisticated multi-electrode studies and high-throughput analysis [25] [26] |

| Product | Portable/handheld segment growing [26] | Miniaturization enables field applications (environmental, on-site testing) [26] |

| Application | Environmental testing leads; Pharmaceutical applications growing rapidly [25] [26] | Stringent regulations (EPA, FDA); drug discovery and biosensing needs [25] [26] |

| Region | North America leads (≈40% share); Asia-Pacific fastest-growing [25] [26] | Robust research infrastructure, regulations; APAC growth driven by industrialization and energy R&D [25] [26] |

| Market Size | Global market to grow at a CAGR of 7.5% (2025-2032), from USD 215.0 billion in 2024 to USD 383.45 billion by 2032 [26] | Demand in energy storage, environmental monitoring, and life sciences [26] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

General Cell Assembly and Electrode Preparation

- Cell Selection: Use an inert material (glass, Teflon) for the electrochemical cell to minimize unwanted reactions [8].

- Electrolyte Preparation: Dissolve a high concentration of inert electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl) in a purified solvent to minimize resistive losses (Ohmic drop) and eliminate electrostatic migration of the analyte [21].

- Electrode Setup:

- Working Electrode: Polish solid electrodes (e.g., glassy carbon) with alumina slurry on a polishing cloth to a mirror finish. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water [24]. For mercury-based electrodes, follow manufacturer instructions for drop formation.

- Reference Electrode: Ensure it is filled with the correct electrolyte solution and that the porous frit is not clogged.

- Counter Electrode: A platinum wire or coil, cleaned if necessary by flaming with a hand torch, is typically used [24].

- Deaeration: Purge the solution with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for 5-10 minutes before analysis to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere electrochemically [21].

- Positioning: Place the reference electrode's Luggin capillary close to the working electrode to reduce Ohmic drop, but not so close as to disturb diffusion [24].

Key Voltammetric and Potentiometric Techniques

Table 4: Common Electrochemical Techniques for Analysis

| Technique | Principle | Typical Protocol | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Potential is swept linearly between two limits and back [8] [22]. | Scan rate: 10-1000 mV/s. Start at 0 V, scan negative to -1.0 V, then reverse to +1.0 V, and return to 0 V. | Studying redox reversibility, electron transfer kinetics, and reaction mechanisms [22]. |

| Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) | Potential is swept linearly in one direction [8]. | Scan rate: 1-100 mV/s. Hold initial potential for 5 s, then scan to the final potential. | Quantitative determination, studying electrochemical reactions [8]. |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Analyte is preconcentrated by electrodeposition at a negative potential, then oxidized (stripped) during an anodic potential sweep [21]. | Deposition: Hold at -1.2 V for 60-300 s with stirring. Equilibration: 15 s without stirring. Stripping: LSV to +0.1 V. | Ultra-trace analysis of metals (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) [21]. |

| Potentiometry | Measures the open-circuit potential (at zero current) of a cell using an ion-selective electrode (ISE) vs. a reference [19] [20]. | Calibrate ISE with standard solutions. Immerse in sample, wait for potential to stabilize (30-60 s), record value. | Direct measurement of ion activity (e.g., pH, Ca²⁺, Na⁺) [19]. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 5: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃, Phosphate Buffer) | Carries current, minimizes Ohmic drop, and fixes ionic strength and pH [21]. |

| Redox Probes (e.g., K₃Fe(CN)₆/K₄Fe(CN)₆, Ru(NH₃)₆Cl₃) | Used for electrode characterization and benchmarking sensor performance. |

| Electrode Polishing Supplies (Alumina, Silica slurry, Polishing cloths) | Essential for reproducible renewal of solid electrode surfaces [24]. |

| Solvents (Deionized Water, Acetonitrile, Dichloromethane) | Dissolve analyte and electrolyte; choice depends on analyte solubility and potential window needed. |

| Nanomaterials (CNTs, Graphene, Metal Nanoparticles) | Modify electrode surfaces to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and electron transfer kinetics [27]. |

Mastering the core instrumentation of electrodes, cells, and potentiostats is a prerequisite for rigorous research in electrochemistry. The choice of working electrode material dictates the accessible potential window and reactions that can be studied. The reference electrode ensures potential control and measurement accuracy, while the counter electrode facilitates current flow. The potentiostat acts as the central command unit, executing experimental techniques and collecting data. As the field advances, trends toward miniaturization, multi-channel systems for high-throughput analysis, and the integration of AI for data interpretation are shaping the next generation of electrochemical instrumentation, further solidifying its role in scientific and industrial advancement.

In the realm of electrochemical analysis, particularly within voltammetry, the observed current signal is a composite response arising from distinct physical processes occurring at the electrode-electrolyte interface. For researchers and drug development professionals utilizing techniques like cyclic voltammetry to study redox-active drug compounds or to develop biosensing platforms, deconvoluting this total current is paramount for accurate data interpretation. The total current ((i{total})) measured in any voltammetric experiment can be fundamentally described as the sum of two primary components: the faradaic current ((if)) and the capacitive current ((i_c)), as expressed in Equation 1.

Equation 1: Total Voltammetric Current (i{total} = if + i_c)

This technical guide delves into the origin, characteristics, and controlling factors of these two current types, providing a foundational understanding within the broader context of potentiometric and voltammetric research principles. Mastery of these concepts enables scientists to design better experiments, optimize sensor parameters, and extract kinetically meaningful data from complex electrochemical systems, such as those encountered in pharmaceutical analysis and diagnostic device development.

Fundamental Definitions and Origins

Faradaic Current

The faradaic current, also known as the faradaic current, is the electrical current generated directly by the reduction or oxidation of a chemical substance at the electrode surface [28] [29]. This process involves the actual transfer of electrons across the electrode-electrolyte interface via a redox reaction, making it a faradaic process governed by Faraday's law [29]. The amount of chemical change at the electrode is directly proportional to the quantity of electricity passed, linking the current directly to analyte concentration. In voltammetry, the faradaic current is the signal of interest as it provides information about the identity, concentration, and reaction kinetics of the electroactive species [30]. For instance, in drug development, the faradaic current generated by the oxidation of a pharmaceutical compound can be used to determine its concentration and study its metabolic stability.

Capacitive Current

The capacitive current, sometimes termed non-faradaic current, has a purely physical origin and does not involve electron transfer or a chemical reaction [31] [29]. It arises from the rearrangement of ions in the solution in response to a change in the electrode's potential. The charged electrode surface and the layer of oppositely charged ions form an electrical double layer (EDL), which behaves as an electrical capacitor [31] [32] [30]. When the potential is changed, this capacitor must be charged or discharged, resulting in a transient current flow. This current is often considered a background signal or noise in voltammetric experiments because it does not originate from the analyte of interest [31] [30]. However, its management is critical for achieving low detection limits in analytical applications.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Faradaic and Capacitive Currents

| Feature | Faradaic Current | Capacitive Current |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Electron transfer via redox reactions [28] [29] | Charging/discharging of the electrical double layer [31] [32] |

| Governed by | Faraday's Law [29] | Physics of capacitor charging [31] |

| Dependence on Potential | Determined by redox potential and kinetics [30] | Directly proportional to the rate of potential change [31] |

| Chemical Change | Yes, new chemical species are formed [28] | No, only rearrangement of ions [31] |

| Primary Role in Analysis | Signal of interest for quantification | Background current to be minimized |

Physical Principles and Governing Equations

The Faradaic Process and Electron Transfer

Faradaic processes entail the transfer of electrons between the electrode and electroactive species in the solution. The ease of this electron transfer dictates whether a system is electrochemically reversible (fast kinetics, Nernstian) or irreversible (slow kinetics) [30]. The current is governed by both the mass transport of the analyte to the electrode surface (via diffusion, migration, or convection) and the kinetics of the electron transfer reaction itself. A key concept is the limiting current, which is the maximum faradaic current achievable when the rate of the reaction is constrained by mass transfer [28]. In analytical applications, this limiting current is often proportional to the bulk concentration of the analyte. A specialized component of the faradaic current is the migration current, which results from the movement of ionic electroactive species due to the electric field between the electrodes [28]. This effect can be suppressed by adding a high concentration of supporting electrolyte, which increases the solution's conductivity and ensures that mass transport occurs primarily by diffusion.

The Electrical Double Layer and Capacitive Charging

The interface between a charged electrode and an ionic solution does not consist of a single plane of charge but a structured region known as the electrical double layer (EDL). The EDL's structure, comprising an inner layer (Helmholtz layer) and a diffuse layer (Gouy-Chapman layer), results in a capacitance, known as the double-layer capacitance ((C_{dl})) [32] [30]. When the electrode potential ((E)) is changed, the charge ((Q)) stored in this capacitor must change accordingly, as described by Equation 2.

Equation 2: Charge on the Electrical Double Layer (Q = C_{dl} \times E)

The capacitive current ((i_c)) is the time derivative of this charge. For a linear potential sweep, as used in cyclic voltammetry (CV) with a scan rate ((\nu = dE/dt)), the theoretical capacitive current is constant and given by Equation 3 [31].

Equation 3: Capacitive Current in a Linear Potential Sweep (ic = \frac{dQ}{dt} = C{dl} \times \frac{dE}{dt} = C_{dl} \times \nu)

However, in practice, digital potentiostats apply potential in small discrete steps. In this scenario, after each step, the capacitive current decays exponentially with time ((t)), following Equation 4, where (R_s) is the solution resistance [31].

Equation 4: Exponential Decay of Capacitive Current After a Potential Step (ic = I0 \times e^{(-t/(Rs C{dl}))})

This property is exploited in pulsed voltammetric techniques to measure the faradaic current after the capacitive current has largely decayed, thereby improving the signal-to-noise ratio.

Comparative Analysis: Key Parameters and Behavior

The temporal evolution and parameter dependence of faradaic and capacitive currents differ significantly, which is the key to their identification and separation.

Table 2: Comparative Behavior of Current Components

| Parameter | Faradaic Current | Capacitive Current |

|---|---|---|

| Time Dependence | Decays as (t^{-1/2}) (for diffusion control) [31] | Decays exponentially with time ((e^{-t/RC})) [31] |

| Scan Rate ((\nu)) Dependence (CV) | Proportional to (\nu^{1/2}) [33] | Proportional to (\nu) [31] [33] |

| Electrode Area ((A)) Dependence | Proportional to (A) | Proportional to (A) |

| Solution Resistance ((R_s)) Dependence | Complex dependence on cell geometry | Decay constant is (Rs C{dl}) [31] |

| Impact of Surface Roughness | Increases with effective area | Increases significantly with area ((i_c \propto A)) [31] |

A critical difference lies in their decay profiles following a potential step. The faradaic current for a diffusing species decays more slowly ((t^{-1/2})) compared to the rapid exponential decay of the capacitive current. Furthermore, in cyclic voltammetry, the peak faradaic current scales with the square root of the scan rate, while the capacitive background current scales linearly with the scan rate. This means that at higher scan rates, the capacitive current becomes a more dominant contributor to the total signal, which can obscure the faradaic peaks of interest.

Diagram 1: Current Decay Profiles

Experimental Protocols for Current Analysis

Methodology for Capacitive Current Measurement

The capacitive current can be quantified by performing voltammetric experiments in the absence of any electroactive analyte.

Protocol:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing only the supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl or PBS) in a purified solvent. The supporting electrolyte should be of high purity to minimize faradaic currents from impurities.

- Electrode Setup: Utilize a standard three-electrode system: a polished working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon), a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and a counter electrode (e.g., Pt wire).

- Data Acquisition: Record a cyclic voltammogram over the potential window of interest. Since no redox species is present, the observed current is predominantly the capacitive current, comprising the double-layer charging and any residual currents from minor impurities [30].

- Analysis: The resulting voltammogram represents the capacitive background. In a true linear potential sweep, this current is constant (as per Eq. 3), but with digital potentiostats, it appears as a low, featureless background [31]. The magnitude of this current is directly related to the double-layer capacitance ((C_{dl})) of the working electrode.

Methodology for Characterizing Faradaic Processes

The faradaic process of a specific analyte is characterized by its voltammetric response in the presence of a redox probe.

Protocol:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing a known concentration of a reversible redox couple, such as 1 mM Potassium Ferricyanide ((K3[Fe(CN)6])) in 1 M KCl supporting electrolyte.

- Electrode Setup: Use a polished and clean three-electrode system as described in 5.1.

- Data Acquisition: Run cyclic voltammetry at various scan rates (e.g., from 10 mV/s to 1000 mV/s).

- Analysis:

- The voltammograms will show distinct oxidation and reduction peaks.

- The peak separation ((\Delta Ep)) is used to assess the reversibility of the reaction (接近 59 mV for a reversible one-electron transfer).

- Plotting the peak current ((ip)) against the square root of the scan rate ((\nu^{1/2})) should yield a straight line, confirming a diffusion-controlled faradaic process [33]. The magnitude of the faradaic current is indicative of the electron transfer rate at the interface [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The selection of appropriate materials is critical for controlling the relative contributions of faradaic and capacitive currents in an experiment.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Role | Example in Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes migration current (a faradaic component) and provides conductivity, which reduces solution resistance ((R_s)) and can affect capacitive current decay [28] [30]. | Potassium Chloride (KCl), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) |

| Redox Probe | A well-characterized electroactive species used to study and calibrate faradaic response and electrode kinetics [34]. | Potassium Ferricyanide ((K3[Fe(CN)6])), Ferrocene |

| Working Electrode | The surface where the redox reaction (faradaic) and double-layer formation (capacitive) occur. Its material and area directly influence both currents [31] [1]. | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Gold Electrode, Platinum Electrode |

| Polishing Supplies | To create a smooth, reproducible electrode surface. A smoother surface reduces the electrochemical area, thereby lowering the capacitive current [31]. | Alumina slurry, Diamond paste |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode potential is controlled, ensuring accurate measurement of redox potentials [1] [35]. | Ag/AgCl electrode, Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) |

| Solvent | The medium for the electrolyte and analyte. Its permittivity ((\epsilonr)) influences the double-layer capacitance ((C{dl})) and thus the capacitive current [31]. | Water, Acetonitrile (ACN), Dimethylformamide (DMF) |

Diagram 2: Signal Deconvolution Workflow

Implications in Potentiometry and Voltammetry Research

Understanding these currents is vital across electrochemical techniques. In potentiometry, the goal is to measure potential at zero current, theoretically eliminating both faradaic and capacitive components [1] [35]. However, in dynamic techniques like voltammetry, both are present. The capacitive current is a primary source of noise that limits the detection limit and obscures the faradaic signal of trace analytes, a critical concern in detecting low-abundance biomarkers or drugs [30].

Advanced voltammetric methods like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) are designed to minimize the capacitive current's contribution by sampling the current after the capacitive surge has decayed, thus significantly improving the signal-to-noise ratio for faradaic processes [1] [30]. This principle is also exploited in electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Furthermore, in the field of supercapacitors, the distinction is fundamental: Electrical Double-Layer Capacitors (EDLCs) store energy non-faradaically (via capacitive charging), while pseudocapacitors utilize fast, reversible faradaic reactions [29]. For drug development professionals, this knowledge is essential when designing biosensors or studying the electrochemical behavior of drug molecules, as it allows for the optimization of assay sensitivity and reliability.

Potentiometry is a fundamental electrochemical analysis technique that measures the electrical potential between two electrodes when the cell current is zero [35]. This method relies on the principle that the potential difference between a reference electrode and an indicator electrode is related to the activity of specific ions in a solution, as described by the Nernst equation [6] [35]. Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) represent a crucial category of potentiometric sensors designed to respond selectively to a single ionic species in a solution [36] [35]. The core component of an ISE is a selective membrane that generates a potential signal dependent on the activity of the target ion, while remaining relatively insensitive to other ions present in the sample [35].

The historical development of ISEs dates back to the mid-1960s, when modern potentiometry began with the introduction of the first membrane electrode based on a liquid ion exchanger and the first ionophore-based solvent polymeric membrane using polyvinyl chloride (PVC) [37]. These innovations paved the way for ISEs to become standard tools in clinical analysis, with over a billion potentiometric measurements performed worldwide annually for ions including Na+, K+, Ca2+, and Cl− [37]. The past two decades have witnessed remarkable improvements in ISE technology, with the lower limit of detection improving by a factor of up to one million and discrimination factors for interfering ions improving by up to one billion [37].

This technical guide examines the evolution of ISE architectures from traditional liquid-contact designs to modern solid-contact systems, with particular emphasis on their working principles, performance characteristics, and applications in pharmaceutical and biomedical research.

Fundamental Principles of Potentiometric Analysis

The Nernst Equation and Potentiometric Response

The theoretical foundation of ISE operation is governed by the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the measured potential and the activity of the target ion [36] [35]. For a monovalent ion, the Nernst equation is expressed as:

E = E° + (0.0592/n) × log(a₁)

Where E represents the measured potential, E° is the standard electrode potential, n is the charge number of the ion, and a₁ is the activity of the ion in the sample solution [35]. The term 0.0592 V/concentration decade represents the theoretical Nernstian slope at 25°C for monovalent ions, while for divalent ions, the theoretical slope is 0.0296 V/concentration decade [35].

The potential generated across the ISE membrane consists of two components: one at the outer surface (EM1) and one at the inner surface (EM2) [35]. The membrane potential (Emem) is expressed as the difference between these two potentials:

Emem = EM1 – EM2

When all other potentials in the electrochemical cell are held constant, the membrane potential becomes proportional to the ion activity in the external sample solution [35]. It is crucial to note that this potential is not generated directly by a redox reaction but is a phase boundary potential derived from the transfer of the ion of interest across a concentration gradient—no oxidation or reduction reaction occurs [35].

Basic Components of Potentiometric Cells

A typical potentiometric cell consists of three essential components [1]:

Working Electrode (WE): This is where the redox reaction of interest occurs. The potential of this electrode is precisely controlled relative to a reference electrode.

Reference Electrode (RE): This electrode provides a stable and known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured or controlled. Common examples include the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) and the silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode.

Counter Electrode (CE): This electrode completes the circuit and carries the current needed to balance the current flowing at the working electrode.

The Ag/AgCl electrode is particularly important as it serves both as an internal electrode in potentiometric ISEs and as a reference electrode half-cell of constant potential [35]. This electrode consists of a silver wire or rod coated with AgCl(s) in contact with a solution of constant chloride activity, which sets the half-cell potential according to the reaction:

AgCl(s) + e− Ag°(s) + Cl−

Classification of Ion-Selective Electrodes

Traditional Liquid-Contact ISEs (LC-ISEs)

Traditional liquid-contact ion-selective electrodes (LC-ISEs) employ an internal filling solution that contacts the inner surface of the ion-selective membrane, with the membrane positioned between the inner filling solution and the sample solution [38] [39]. The internal solution typically contains a fixed concentration of the target ion and a chloride salt to maintain a stable potential at the internal Ag/AgCl reference element [35].

Despite their widespread historical use and reliable performance, LC-ISEs suffer from several inherent limitations [38]:

- Evaporation, permeation, and pressure effects: The internal filling solution is susceptible to evaporation or changes due to variations in sample temperature and pressure, affecting electrode response.

- Osmotic pressure effects: Differences in ion strength between the sample and internal solution can cause water to move in or out of the internal filling solution, leading to volume changes or stratification of the ion-selective membrane.

- Ionic flux: A steady-state ionic flux exists between the inner filling solution and the test solution, which can affect the lower limit of detection.

- Miniaturization challenges: It is difficult to reduce the volume of the internal filling solution to the milliliter level, making miniaturization problematic.

These limitations have motivated the development of alternative ISE architectures that eliminate the internal filling solution while maintaining or improving performance characteristics.

Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs)

Solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) represent a significant advancement in potentiometric sensor technology by replacing the internal liquid contact with a solid-contact (SC) layer that serves as an ion-to-electron transducer [38]. In SC-ISEs, a solid-contact layer is formed between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and the electronic conduction substrate (ECS), completely eliminating the need for an internal filling solution [38].

The advantages of SC-ISEs over their liquid-contact counterparts include [38]:

- Easy miniaturization and chip integration: The solid-state architecture facilitates fabrication of miniature sensors and integration with electronic chips.

- Enhanced stability: SC-ISEs demonstrate improved mechanical and potential stability.

- Reduced maintenance: Elimination of liquid components removes issues related to solution evaporation or leakage.

- Portability: Solid-contact designs are more robust and suitable for field applications.

- Complex environment detection: SC-ISEs perform more reliably in challenging measurement conditions.

SC-ISEs have been widely used in conjunction with portable, wearable, and intelligent detection devices, making them ideal for on-site analysis and timely monitoring in environmental, industrial, and medical fields [38].

Membrane-Based Classifications

Ion-selective electrodes can be further classified according to the type of membrane employed, each with distinct characteristics and applications:

Table 1: Classification of Ion-Selective Electrodes by Membrane Type

| Membrane Type | Composition | Selectivity Profile | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membranes | Silicate or chalcogenide glass with added metal oxides [36] [35] | Single-charged cations (H+, Na+, Ag+) [36]; double-charged metal ions (Cd2+, Pb2+) with chalcogenide glass [36] | High durability in aggressive media [36]; robust with minimal maintenance [35] | Alkali error at high pH; acidic error at low pH [36]; high electrical resistance [35] |

| Crystalline Membranes | Poly- or monocrystalline substances (e.g., LaF3 for fluoride ISE) [36] | Anion and cation of the membrane-forming substance [36] | Good selectivity; no internal solution required [36] | Limited to ions that match crystal structure [36] |

| Ion-Exchange Resin Membranes | Organic polymer membranes with ion-exchange substances [36] | Wide range of single-atom and multi-atom ions; anionic selectivity [36] | Most common ISE type; versatile for various ions [36] | Lower physical and chemical durability for anionic electrodes [36] |

| Polymer Membrane Electrodes | PVC matrix with ionophore, plasticizer, and additives [35] | Wide variety of cations (K+, Na+, Ca2+, Li+, Mg2+) and anions (Cl−) [35] | Tunable selectivity; suitable for clinical applications [35] | Requires careful optimization of membrane composition [35] |

Advanced Solid-Contact ISE Architectures

Transduction Mechanisms in SC-ISEs

The solid-contact layer in SC-ISEs serves as a crucial ion-to-electron transducer, converting the ionic signal from the membrane into an electronic signal measurable by the external circuit. Depending on the conversion mechanism, solid-contact materials can be classified into two main categories:

Redox Capacitance-Type SC-ISEs

Redox capacitance-type SC-ISEs incorporate conductive materials with large oxidation-reduction capacitance between the ECS and ISM [38]. Conducting polymers (CPs) are particularly effective for this application, as they exhibit both electronic conductivity and ionic conductivity through doping processes [38]. The redox reactions occurring during the conversion of charge carriers from ions to electrons in CP-based SC-ISEs can be represented by:

CP+A−(SC) + M+(SIM) + e− ⇌ CP°A−M+(SC) (for cationic response)

CP+R−(SC) + e− ⇌ CP°(SC) + R−(SIM) (for anionic response)

Where CP represents the conducting polymer, A− refers to doping ions, M+ represents target cations, and R− represents hydrophobic counterions [38]. The deposition of conducting polymers on the ECS is typically achieved through methods such as drop casting from polymer solutions or electrochemical polymerization, both conducive to mass production and commercialization [38].

Electric Double-Layer (EDL) Capacitance-Type

Electric double-layer (EDL) capacitance-type SC-ISEs rely on the formation of an electrical double layer at the ISM/SC interface [38]. In this mechanism, one side of the interface carries ionic charges due to the accumulation of cations and anions from the ion-selective membrane, while the other side carries charges formed by electrons or holes from the electronic conductor [38]. The capacitance of the EDL determines the potential stability of the electrode, with higher capacitance values leading to better performance.

Composition and Optimization of SC-ISEs

The performance of SC-ISEs depends critically on the optimization of three key components: the ion-selective membrane (ISM), the solid-contact (SC) layer, and the electronic conduction substrate (ECS) [38].

Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Optimization

The ISM is the most important component of SC-ISEs and typically consists of four essential elements [38]:

- Ion carrier: Responsible for selectively extracting target ions from the sample interface into the ISM. Ion carriers generally have functional group structures that can accommodate target ions or provide coordination spaces and sites for ion-specific binding. Highly hydrophobic ion carriers prevent leakage of membrane components into the sample.

- Ion exchanger: Introduces ions with opposite charges into the membrane to reduce interference, facilitates the exchange process between the ISM and target ions, and increases ISM conductivity. Common ion exchangers include sodium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl) borate (NaTFPB) and potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl) borate (KTPCIPB).

- Polymer matrix: Provides necessary physical and mechanical properties while serving as the ISM backbone. Widely used matrices include polyvinyl chloride (PVC) and its derivatives, acrylic esters, polyurethane, polystyrene, and silicone rubber.

- Plasticizer: Improves plasticity or fluidity of active components in the ISM. Appropriate plasticizer selection ensures both physical properties and high fluidity. Common plasticizers include bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), and 2-nitrophenyloctyl ether (NPOE).

Solid-Contact Layer Materials

Recent research has focused on developing advanced materials for the solid-contact layer to enhance transducer properties. Carbon-based nanomaterials, particularly multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), have demonstrated excellent performance as ion-to-electron transducers [39]. MWCNT layers improve potential stability by preventing the formation of a water layer at the interface between the electrode surface and the polymeric sensing membrane due to their hydrophobic nature [39].

Other promising materials for solid-contact layers include:

- Conducting polymers: Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), polypyrrole, and polyaniline derivatives.

- 3D-printed materials: Carbon-infused polylactic acid for fabricating transducers via fused-deposition modeling [40].

- Nanocomposites: Hybrid materials combining carbon nanomaterials with conducting polymers to leverage synergistic effects.

Performance Characterization of SC-ISEs

The development of SC-ISEs requires comprehensive characterization to evaluate their performance for practical applications. Key performance parameters include:

- Response slope: The measured potential change per decade change in ion activity, ideally approaching the theoretical Nernstian value (59.2 mV/decade for monovalent ions at 25°C) [40].

- Limit of detection (LOD): The lowest ion activity that can be reliably detected, typically defined by IUPAC recommendations [39].

- Selectivity coefficients: Quantitative measures of the electrode's ability to discriminate against interfering ions [37].

- Response time: The time required to reach a stable potential reading after exposure to a sample solution.

- Potential stability: Measured as potential drift over time, with high-performance SC-ISEs demonstrating drifts as low as ~20 μV per hour [40].

- Lifetime: The operational period during which the sensor maintains acceptable performance characteristics.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Representative SC-ISEs

| Target Ion | Solid-Contact Material | Linear Range (M) | Slope (mV/decade) | LOD (M) | Stability (μV/h) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | Carbon-infused PLA (3D-printed) [40] | 2.4×10⁻⁴ to 2.5×10⁻¹ | 57.1 | 2.4×10⁻⁶ | ~20 | Human saliva analysis [40] |

| Ag+ | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes [39] | 1.0×10⁻⁵ to 1.0×10⁻² | 61.0 | 4.1×10⁻⁶ | N/R | Pharmaceutical analysis (silver sulfadiazine) [39] |

Experimental Protocols for SC-ISE Fabrication and Characterization

Fabrication of Solid-Contact ISEs with MWCNT Transducer Layer

The following protocol outlines the fabrication of solid-contact ISEs with multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) transducer layers, as demonstrated for silver ion detection in pharmaceutical applications [39]:

Materials and Reagents

- Ion-selective membrane components: Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) of high molecular weight, plasticizer (e.g., 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether - NPOE), ionophore (e.g., Calix[4]arene for Ag+ selectivity), ion exchanger (e.g., sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate), and tetrahydrofuran (THF) as solvent [39].

- Solid-contact material: Multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) powder.

- Electrode substrates: Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) with conductive tracks.

- Reference electrode: Ag/AgCl double-junction reference electrode with appropriate filling solutions.

Fabrication Procedure

MWCNT layer preparation: Disperse MWCNT powder in an appropriate solvent (e.g., ethanol) to form a homogeneous suspension. Deposit the MWCNT suspension onto the working electrode area of the SPE and allow to dry, forming a uniform transducer layer.

Ion-selective membrane preparation: Prepare the membrane cocktail by dissolving the following components in THF:

- PVC polymer matrix (typically 30-33% by weight)

- Plasticizer (60-65% by weight)

- Ionophore (1-5% by weight)

- Ion exchanger (0.5-2% by weight)

Membrane deposition: Deposit the membrane cocktail directly onto the MWCNT-modified SPE surface using drop-casting or spin-coating techniques. Allow the THF solvent to evaporate slowly, forming a homogeneous ion-selective membrane with typical thickness of 100-300 μm.

Conditioning: Condition the fabricated SC-ISE in a solution containing the target ion (e.g., 1.0 × 10⁻³ M AgNO₃ for Ag+-ISE) for 12-24 hours before use to establish stable equilibrium conditions.

Conditioning and Calibration Protocol

Proper conditioning and calibration are essential for obtaining reliable measurements with SC-ISEs:

Conditioning: Immerse the newly fabricated SC-ISE in a solution containing the primary ion at approximately 1.0 × 10⁻³ M concentration for 12-24 hours [39].

Calibration curve preparation: Prepare standard solutions of the primary ion across the concentration range of interest (typically 1.0 × 10⁻⁷ to 1.0 × 10⁻¹ M). Measure the potential response of the SC-ISE in each standard solution, starting from the most dilute to the most concentrated.

Data analysis: Plot the measured potential (mV) against the logarithm of the primary ion activity. Determine the slope, linear range, and limit of detection from the calibration curve according to IUPAC recommendations.

Selectivity Coefficient Determination

The potentiometric selectivity coefficient (Kₚₒₜᴬ,ᴮ) quantifies the ability of an ISE to distinguish between the primary ion (A) and interfering ions (B). The matched potential method (MPM) or separate solution method (SSM) can be employed:

Separate Solution Method (SSM): Measure the potential of the SC-ISE in separate solutions containing only the primary ion (A) or only the interfering ion (B) at the same activity (aₐ = aʙ). Calculate the selectivity coefficient using:

log Kₚₒₜᴬ,ᴮ = (Eʙ - Eₐ) / S

Where Eₐ and Eʙ are the measured potentials in solutions of A and B, respectively, and S is the experimental slope of the calibration curve.

Matched Potential Method (MPM): First measure the potential in a reference solution containing the primary ion at a specified activity. Then add a solution of the interfering ion until the same potential change is obtained. The selectivity coefficient is calculated from the ratio of activities.

SC-ISE Fabrication Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for SC-ISE Development

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Solid-Contact ISE Development

| Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane, acrylic esters, polystyrene [38] | Provides structural backbone for ion-selective membrane; determines mechanical properties | PVC most common; alternative polymers offer different hydrophobicity and compatibility |

| Plasticizers | bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE) [38] [39] | Imparts mobility to membrane components; affects dielectric constant | Choice influences selectivity and lifetime; typically 60-65% of membrane mass |

| Ionophores | Calix[4]arene (for Ag+) [39], valinomycin (for K+), natural/synthetic ion carriers [38] | Molecular recognition element providing selectivity for target ions | Hydrophobic structure prevents leaching; concentration typically 1-5% of membrane |

| Ion Exchangers | Sodium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB), potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (KTPCIPB) [38] | Introduces permselectivity; facilitates ion exchange process | Critical for controlling membrane permselectivity; typically 0.5-2% of membrane |

| Transducer Materials | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) [39], conducting polymers (PEDOT, polypyrrole) [38], 3D-printed carbon-infused PLA [40] | Converts ionic signal to electronic signal; prevents water layer formation | Hydrophobic materials enhance potential stability; high capacitance desirable |

| Solvents | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), cyclohexanone [39] | Dissolves membrane components for deposition | High purity essential to prevent interference; evaporated after membrane formation |

Recent Advances and Future Perspectives

Emerging Trends in SC-ISE Technology

The field of solid-contact ISEs continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends shaping future developments:

3D-printed sensors: Fully 3D-printed solid-contact potentiometric sensors represent a cutting-edge advancement in fabrication technology [40]. These sensors utilize stereolithographically printed ion-selective membranes and carbon-infused polylactic acid transducers fabricated via fused-deposition modeling. Research has demonstrated the ability to manipulate transducer hydrophobicity based on print angle and thickness, leading to highly stable sensors with minimal potential drift (~20 μV per hour) [40].

Miniaturization and wearable sensors: The solid-contact architecture enables fabrication of miniature sensors for wearable applications and point-of-care testing. Recent developments focus on integration with portable and intelligent detection devices for real-time health monitoring [38].

Multisensor arrays and data analysis: Ion-selective electrode arrays combined with advanced classification algorithms, including machine learning, artificial neural networks, and deep learning, enable complex sample analysis in agricultural, environmental, and clinical applications [41].

Green sensor technology: Growing emphasis on developing environmentally friendly sensors with reduced toxicity ion carriers and sustainable materials [39]. Assessment tools such as the Analytical Eco-scale, Green Analytical Procedure Index (GAPI), and Analytical Greenness Metric (AGREE) are being employed to evaluate the environmental impact of SC-ISE methodologies [39].

Current Challenges and Research Directions

Despite significant advances, several challenges remain in the widespread adoption and improvement of SC-ISE technology:

Potential drift and long-term stability: While modern SC-ISEs demonstrate improved stability compared to liquid-contact systems, further work is needed to enhance long-term potential stability, particularly for continuous monitoring applications [38].

Reproducibility and mass production: Achieving high reproducibility in sensor fabrication remains challenging, especially for mass production. Standardization of manufacturing processes is essential for commercial applications [38].

Biocompatibility and in vivo applications: For biomedical applications, improving the biocompatibility of SC-ISEs and ensuring stable performance in complex biological matrices requires continued research [38].

Multianalyte detection: Developing reliable platforms for simultaneous detection of multiple analytes using sensor arrays with minimal cross-talk represents an active research frontier [41].

Evolution from Liquid-Contact to Solid-Contact ISEs

The classification of ion-selective electrodes has evolved significantly from traditional liquid-contact designs to advanced solid-contact architectures. This transition has addressed fundamental limitations of LC-ISEs related to miniaturization, stability, and practical deployment while opening new possibilities in sensor technology. SC-ISEs leverage innovative materials and fabrication techniques, including carbon nanomaterials, conducting polymers, and 3D-printing technologies, to achieve performance characteristics that enable their use in portable, wearable, and field-deployable sensors.

The continued advancement of SC-ISE technology relies on interdisciplinary approaches combining materials science, electrochemistry, and engineering to optimize the composition and structure of ion-selective membranes, solid-contact transducer layers, and electrode substrates. As research addresses current challenges related to long-term stability, reproducibility, and biocompatibility, solid-contact ISEs are poised to play an increasingly important role in pharmaceutical research, clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and personalized medicine.