Potentiometric Sensors for Pharmaceutical Drug Monitoring: Advances in Solid-Contact Designs, Wearable Integration, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in potentiometric sensors for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM).

Potentiometric Sensors for Pharmaceutical Drug Monitoring: Advances in Solid-Contact Designs, Wearable Integration, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive review of the latest advancements in potentiometric sensors for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the fundamental principles of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), the critical shift from liquid-contact to solid-contact designs using novel materials like conducting polymers and carbon nanomaterials, and their application in monitoring drugs with narrow therapeutic indices in biological fluids. The scope extends to emerging trends including 3D-printed, paper-based, and wearable potentiometric sensors for decentralized clinical analysis and point-of-care testing. The discussion includes methodologies for optimizing sensor performance, addressing key challenges in selectivity and stability, and protocols for analytical and clinical validation, positioning potentiometry as a powerful, versatile tool for the future of personalized medicine.

Principles and Evolution of Potentiometric Drug Sensors

Potentiometric sensors have evolved from fundamental principles based on the Nernst equation to sophisticated modern readout systems capable of precise pharmaceutical drug monitoring. This transformation has been propelled by advances in solid-contact electrodes, miniaturization through printing technologies, and enhanced signal processing techniques. These developments have enabled the transition of potentiometric sensing from traditional laboratory settings to point-of-care diagnostic applications, offering rapid, cost-effective analysis of pharmaceutical compounds. This application note details the core principles, fabrication methodologies, and experimental protocols underlying modern potentiometric sensors, with particular emphasis on their application within pharmaceutical research and therapeutic drug monitoring.

Potentiometry represents a cornerstone of electrochemical analysis, enabling the determination of ion activities and concentrations through potential measurement under zero-current conditions [1]. In pharmaceutical sciences, the ability to monitor drug concentrations in complex biological matrices is paramount for therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies, and quality control processes. Modern potentiometric sensors have undergone significant transformation through the development of solid-contact electrodes and advanced manufacturing techniques, including both 2D and 3D printing technologies [2]. These innovations have addressed critical challenges in sensor miniaturization, reproducibility, and integration, paving the way for their application in wearable devices and electronic skin for continuous physiological monitoring [2]. This document outlines the fundamental principles and practical implementation of potentiometric sensors tailored specifically for pharmaceutical research applications.

Fundamental Principles

The Nernst Equation

The theoretical foundation of potentiometry rests upon the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the measured electrochemical potential and the activity of target ions in solution [1]. The equation is expressed as:

E = E° + (RT/nF) ln(a_i)

Where:

- E is the measured electrode potential

- E° is the standard electrode potential

- R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/(mol·K))

- T is the temperature in Kelvin

- n is the charge number of the ion

- F is Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol)

- a_i is the activity of the ion of interest [1]

For practical analytical applications where concentration rather than activity is measured, the equation can be adapted to relate potential to the logarithm of the concentration of the target analyte, establishing the fundamental working principle for quantitative analysis using ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) [1].

Potentiometric Cell Architecture

A conventional potentiometric measurement requires a complete electrochemical cell comprising several essential components. The system employs two electrodes: an indicator electrode (or working electrode) whose potential responds to the activity of the target ion, and a reference electrode that maintains a constant, known potential regardless of the solution composition [1]. These electrodes are immersed in the sample solution, which is connected via a salt bridge containing an inert electrolyte to complete the electrical circuit while preventing mixing of solutions [1]. The potential difference between these electrodes is measured under conditions of zero current flow, ensuring the system remains at equilibrium and the composition of the solution remains unchanged during measurement [1].

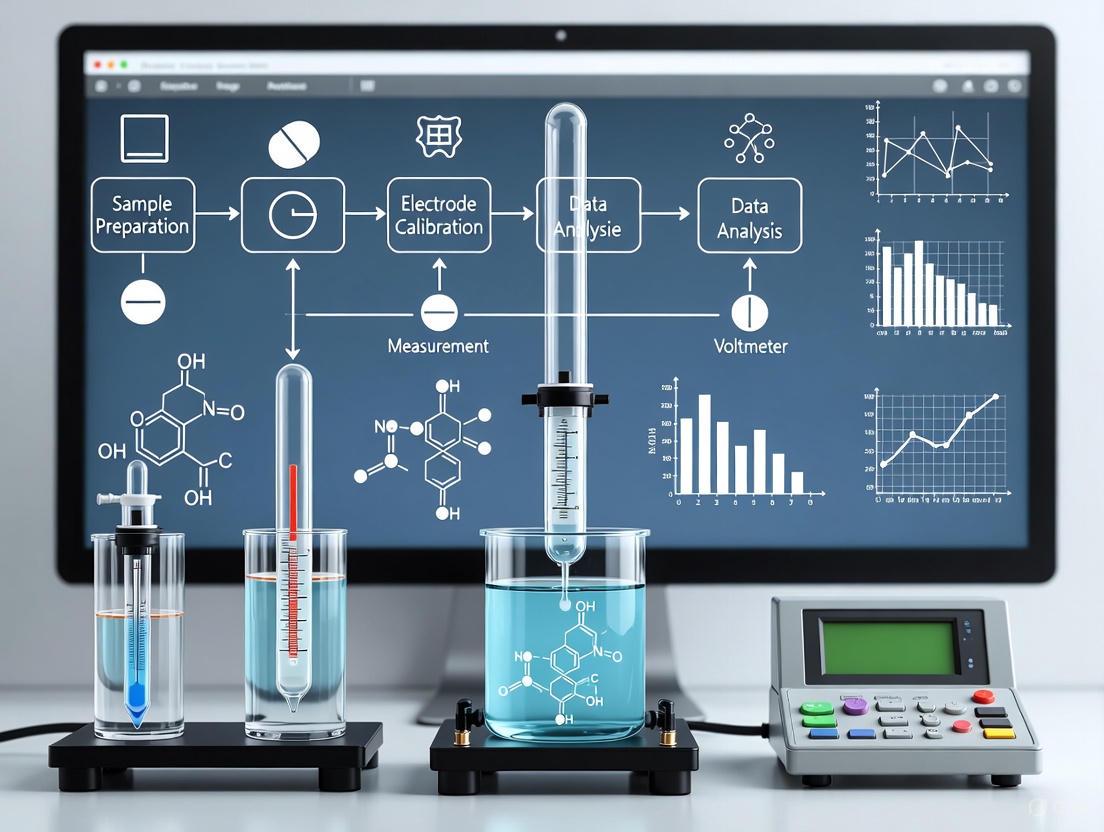

Diagram 1: Fundamental architecture of a potentiometric cell showing key components and signal flow.

Modern Potentiometric Readouts

Evolution from Conventional to Solid-Contact Sensors

The transition from traditional liquid-contact to solid-contact electrodes represents the most significant advancement in potentiometric sensor design [2]. Conventional sensors utilized internal filling solutions, which imposed limitations on miniaturization, orientation requirements, and maintenance needs. Solid-contact sensors eliminate this liquid component by incorporating an ion-to-electron transducer layer between the ion-selective membrane and the conductive electrode substrate [2]. This architectural innovation has enabled the development of miniaturized, robust, and flexible sensors compatible with point-of-care testing and wearable monitoring devices [2]. The solid-contact configuration has now become the mainstream design for modern potentiometric applications, particularly in pharmaceutical and clinical settings where miniaturization and operational simplicity are paramount.

Advanced Fabrication Methods

Printing technologies have revolutionized potentiometric sensor fabrication, enabling precise, reproducible, and scalable manufacturing. The table below summarizes the primary printing methods employed in modern sensor production:

Table 1: Printing Technologies for Potentiometric Sensor Fabrication

| Method | Type | Key Characteristics | Typical Applications | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screen Printing | 2D (Stencil) | Simplicity, low cost, high efficiency, wide applicability [2] | Disposable sensors, stretchable electrodes on flexible substrates [2] | Pattern resolution limitations, contact-based process |

| Inkjet Printing | 2D (Non-stencil) | Digital manufacturing, high resolution, non-contact process [2] | Precise deposition of sensing membranes, customized electrode patterns [2] | Ink formulation challenges, potential nozzle clogging |

| Spray/Electrospray Printing | 2D (Stencil) | Uniform thin films, adaptable to various substrates [2] | Fabrication of sensitive membranes using ion-selective cocktails [2] | Material waste concerns, requires masking |

| 3D Printing | Additive | Complex geometries, integrated functional structures [2] | Reproducible sensitive membranes, customized sensor housings [2] | Limited resolution, material compatibility considerations |

Miniaturization and Point-of-Care Adaptation

The development of miniaturized potentiometric devices for point-of-care applications has focused on addressing the ASSURED criteria (Affordable, Sensitive, Specific, User-friendly, Rapid and robust, Equipment-free, and Deliverable to end-users) established by the World Health Organization [3]. Recent innovations in this domain include various sensor configurations:

- Strip-type sensors: Planar devices with co-planar indicator and reference electrodes patterned on a single substrate

- Sandwich-type sensors: Multi-layer architectures that incorporate microfluidic channels for sample handling

- Fully integrated sensors: Systems that incorporate sampling, detection, and readout components in a single device

- Fiber and yarn-based sensors: Textile-integrated sensors for wearable health monitoring applications [3]

Each configuration presents distinct advantages and challenges regarding fabrication complexity, analytical performance, and user operability, with the optimal selection dependent on the specific pharmaceutical monitoring application.

Application in Pharmaceutical Drug Monitoring

Sensor Design for Drug Analysis

The application of potentiometric sensors to pharmaceutical drug monitoring requires careful design considerations to address the complex matrices and specific analytical challenges presented by biological samples. Effective drug monitoring sensors typically incorporate:

- Drug-selective membranes: Polymeric membranes containing ionophores with selective recognition capabilities for target pharmaceutical compounds [2]

- Solid-contact transducers: Intermediate layers that facilitate stable ion-to-electron transduction, often utilizing conductive polymers or nanostructured carbon materials

- Miniaturized reference electrodes: Integrated reference systems that maintain stable potential in small sample volumes

- Sample handling interfaces: Components that enable direct analysis of complex biological samples such as blood, serum, or urine with minimal pretreatment

The development of novel high-performance ionophores remains a key research focus, continually expanding the range of detectable pharmaceutical analytes [2].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Screen-Printed Potentiometric Sensors

Principle: Create disposable, cost-effective sensors through stencil-based deposition of conductive and sensing inks [2].

Materials:

- Screen printer with appropriate mesh size

- Conductive ink (e.g., carbon, silver/silver chloride)

- Polymer matrix (e.g., PVC, polyurethane)

- Plastic or ceramic substrate

- Ion-selective cocktail (ionophore, ion exchanger, plasticizer)

- Reference membrane components

Procedure:

- Substrate Preparation: Clean and dry the substrate material (typically plastic or ceramic) to ensure proper adhesion of printed layers.

- Electrode Printing: Align the stencil pattern and sequentially print conductive tracks, working electrode, and reference electrode using appropriate inks.

- Curing: Thermally cure the printed electrodes according to ink manufacturer specifications (typically 60-80°C for 30-60 minutes).

- Ion-Selective Membrane Application: Prepare the ion-selective cocktail by dissolving membrane components (1-2% ionophore, 0.5-1% ion exchanger, 30-33% polymer matrix, and balance plasticizer) in tetrahydrofuran.

- Membrane Deposition: Apply the ion-selective cocktail solution via drop-casting or spraying onto the working electrode area.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the solvent to evaporate slowly under ambient conditions for 24 hours to form a homogeneous membrane.

- Conditioning: Condition the completed sensors in a solution containing the target ion (typically 10⁻³ M) for 12-24 hours before use.

Quality Control:

- Verify electrode conductivity using impedance measurements

- Confirm membrane adhesion through visual inspection and stability testing

- Test batch-to-batch reproducibility using standard solutions

Diagram 2: Workflow for fabricating screen-printed potentiometric sensors for drug monitoring.

Protocol 2: Calibration and Measurement Procedure for Drug Analysis

Principle: Establish quantitative relationship between sensor potential and drug concentration using standard solutions [1].

Materials:

- Potentiometric sensor (fabricated as in Protocol 1)

- High-impedance potentiometer or pH/mV meter

- Standard solutions of target drug (e.g., 10⁻² to 10⁻⁶ M)

- Stirring platform

- Temperature control system

- Data recording system

Procedure:

- Sensor Preparation: Remove sensors from conditioning solution and rinse gently with deionized water.

- Standard Preparation: Prepare at least five standard solutions spanning the expected concentration range (typically 10⁻² to 10⁻⁶ M) in appropriate background electrolyte.

- Measurement Sequence: Immerse sensors in standard solutions from lowest to highest concentration under constant stirring.

- Potential Recording: Record the stable potential reading for each standard solution (typically achieved within 30-180 seconds depending on sensor design).

- Calibration Curve: Plot potential (mV) versus logarithm of drug concentration and perform linear regression analysis.

- Sample Measurement: Immerse sensors in unknown samples and record stable potential values.

- Concentration Determination: Calculate sample concentrations from the calibration curve using the measured potential values.

Quality Assurance:

- Perform daily calibration with fresh standard solutions

- Monitor slope and intercept consistency for sensor performance tracking

- Include quality control samples with known concentrations to verify accuracy

- Maintain constant temperature during measurements (±1°C)

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Potentiometric Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Typical Composition/Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Cocktail | Recognition element for target analyte | Ionophore (1-2%), Polymer matrix (30-33%), Plasticizer (balance), Additives (0.5-1%) [2] | Composition must be optimized for each specific drug target |

| Solid-Contact Material | Ion-to-electron transduction | Conducting polymers (PEDOT, polypyrrole), nanostructured carbons (graphene, CNTs) [2] | Critical for potential stability; prevents water layer formation |

| Conductive Inks | Electrode fabrication | Carbon, silver, silver/silver chloride pastes [2] | Compatibility with substrate and membrane materials is essential |

| Reference Membrane | Stable reference potential | PVC matrix with salt additives (KCl, NaCl) [3] | Must demonstrate low drift in biological samples |

| Conditioning Solution | Sensor activation and storage | Solution containing target ion (10⁻³ M) in appropriate background | Conditioning time affects response stability and reproducibility |

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Analytical Performance Metrics

The quantitative performance of potentiometric sensors for pharmaceutical applications is evaluated using several key metrics:

- Response Slope: Determined from the calibration curve, with theoretical Nernstian slope being 59.16 mV/decade at 25°C for monovalent ions [1]. Significant deviations may indicate non-ideal behavior or membrane formulation issues.

- Limit of Detection (LOD): Calculated by extrapolation from the linear response region, typically defined as the concentration where the response curve intersects the baseline potential plus three standard deviations [3].

- Selectivity Coefficients: Quantified using the Separate Solution Method or Fixed Interference Method to evaluate sensor performance in the presence of potentially interfering ions endemic to pharmaceutical or biological samples.

- Response Time: Typically measured as the time required to reach 95% of the final steady-state potential after sample introduction, critical for high-throughput applications and point-of-care testing.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Diagram 3: Diagnostic and troubleshooting pathway for common potentiometric sensor performance issues.

The evolution from the fundamental Nernst equation to modern potentiometric readouts has transformed pharmaceutical drug monitoring capabilities, enabling precise, rapid, and cost-effective analysis of therapeutic compounds. Advances in solid-contact electrodes, printing technologies, and miniaturized designs have addressed previous limitations while opening new applications in point-of-care testing and continuous monitoring. The experimental protocols and analytical frameworks presented in this application note provide researchers with practical methodologies for implementing potentiometric sensing in pharmaceutical research. Future developments will likely focus on further miniaturization, multi-analyte detection capabilities, and enhanced integration with digital health platforms, continuing to expand the role of potentiometry in pharmaceutical sciences and personalized medicine.

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) is a critical component of precision medicine, enabling the optimization of drug dosage to maximize efficacy while minimizing toxicity. This practice is especially vital for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI), where the difference between the minimum effective concentration and the minimum toxic concentration is small [4] [5]. Traditional TDM methods, including chromatography and immunoassays, often require skilled operators, involve complex sample preparation, and typically capture drug concentrations only at a single time point, failing to monitor dynamic changes [6].

Potentiometry, an electrochemical technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes under conditions of negligible current flow, presents a powerful alternative [4] [7]. The emergence of advanced potentiometric sensors, particularly solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs), offers a compelling solution for TDM. These sensors are characterized by their ease of design, rapid response, high selectivity, and suitability for miniaturization and continuous monitoring [4] [7] [8]. This application note details the intrinsic advantages of potentiometric sensors for NTI drug monitoring and provides a validated experimental protocol for their application.

Advantages of Potentiometry for NTI Drug TDM

The following table summarizes the key challenges in NTI drug monitoring and how potentiometric sensors address them.

Table 1: Addressing NTI Drug Monitoring Challenges with Potentiometry

| Monitoring Challenge for NTI Drugs | Potentiometric Solution | Impact on TDM |

|---|---|---|

| Need for rapid, frequent measurement | Rapid response time (e.g., ~15 seconds [9]) and direct readout | Enables near-real-time dose adjustment and high-throughput analysis. |

| Risk of toxic side effects from small concentration fluctuations | High selectivity via ionophores [7] [8] and low detection limits (e.g., 10-8 mol L-1 [9]) | Accurately measures clinically relevant concentration ranges, minimizing false results. |

| Requirement for simple, cost-effective analysis | Ease of design, fabrication, and modification [4] [5]; minimal sample pre-treatment | Reduces operational complexity and cost, suitable for point-of-care testing. |

| Desire for continuous monitoring | Compatibility with wearable platforms [4] [6] and solid-contact designs [7] [8] | Allows for tracking dynamic pharmacokinetic profiles, moving beyond single time-point data. |

The Solid-Contact Advantage

A significant advancement in potentiometry is the transition from traditional liquid-contact ISEs to solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs). SC-ISEs replace the inner filling solution with a solid-contact layer that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer, overcoming issues of evaporation, mechanical instability, and difficult miniaturization associated with their liquid-contact counterparts [7] [8]. Key materials used as solid contacts include:

- Conducting Polymers (CPs): Such as poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) and polyaniline (PANI), which operate via a redox capacitance mechanism [8].

- Carbon-based nanomaterials: Including graphene, carbon nanotubes, and colloid-imprinted mesoporous carbon, which function based on a high electric-double-layer capacitance [7] [8].

- Nanocomposites: Materials like MoS2 nanoflowers filled with Fe3O4 or tubular gold nanoparticles, which provide synergistic effects, enhancing capacitance and signal stability [7].

These materials are pivotal for developing the next generation of robust, miniaturized, and wearable potentiometric sensors for continuous TDM [8].

Experimental Protocol: Potentiometric Determination of an NTI Drug

This protocol provides a generalized methodology for determining drug concentration in a pharmaceutical formulation using a solid-contact potentiometric sensor. The example can be adapted for various NTI drugs by selecting an appropriate ionophore.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function/Brief Description |

|---|---|

| Ionophore | A selective molecular recognition element (e.g., Schiff base, macrocyclic compound) that binds the target drug ion. |

| Polymer Matrix | (e.g., PVC) Forms the bulk of the ion-selective membrane. |

| Plasticizer | (e.g., o-NPOE, DBP) Provides mobility for membrane components and influences dielectric constant. |

| Ionic Additive | (e.g., Lipophilic salt) Ensures ionic conductivity and reduces membrane resistance. |

| Solid-Contact Material | (e.g., PEDOT, Carbon nanotubes) Ion-to-electron transducer layer on the electrode substrate. |

| Graphite Powder | Conductive substrate for carbon paste electrodes [9]. |

| Standard Drug Solution | High-purity reference standard for sensor calibration and validation. |

Sensor Fabrication Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the multi-step process for fabricating a solid-contact potentiometric sensor.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Preparation of the Solid-Contact Layer

- Select an electrode substrate (e.g., glassy carbon, screen-printed carbon). Deposit the solid-contact material. For conducting polymers like PEDOT, this can be achieved via electrochemical polymerization or drop-casting a ready-made dispersion. For carbon nanomaterials, prepare a homogeneous ink and drop-cast it onto the substrate, allowing it to dry [8].

Preparation of the Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM)

- Combine the following components in a glass vial:

- Polymer matrix (e.g., PVC): 30-33 mg (wt. 33%)

- Plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE): 60-66 mg (wt. 66%)

- Ionophore (specific to the target drug): 0.5-2 mg (wt. 1-2%)

- Lipophilic ionic additive (e.g., NaTPB or KTFPB): ~0.5 mg (wt. 1%)

- Add ~1 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF) to the vial and cap it. Vortex the mixture until all components are completely dissolved, forming a homogeneous ISM cocktail [9].

- Combine the following components in a glass vial:

Sensor Assembly and Conditioning

- Using a micropipette, deposit a precise volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the ISM cocktail directly onto the solid-contact layer.

- Allow the THF to evaporate slowly at room temperature for at least 12 hours, forming a uniform polymeric membrane.

- Condition the assembled sensor by soaking it in a standard solution of the target drug (e.g., 1.0 × 10-3 mol L-1) for 24 hours to establish a stable potential [9].

Calibration, Measurement, and Data Analysis

Calibration

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of the drug across a concentration range (e.g., 1 × 10-7 to 1 × 10-2 mol L-1) using a constant ionic strength background.

- Immerse the conditioned sensor and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) in the standard solutions from the lowest to the highest concentration.

- Measure the equilibrium potential (in mV) for each solution under stirring. Rinse the sensor gently with deionized water between measurements.

- Plot the measured potential (E) vs. the logarithm of the drug concentration (log C). The plot should yield a linear Nernstian response (slope of ~59.2/z mV/decade for cations at 25°C) [7] [9].

Sample Analysis

- For pharmaceutical formulations (e.g., tablets), weigh and powder a representative number of tablets. Dissolve an accurately weighed portion of the powder in the appropriate solvent and dilute to volume.

- Measure the potential of the sample solution using the calibrated sensor.

- Determine the drug concentration in the sample from the calibration curve.

Method Validation

- Assess the sensor's performance according to the following criteria, ideally over multiple days to establish intermediate precision [10]:

- Linearity: Coefficient of determination (R²) of the calibration curve.

- Accuracy: Recovery studies (e.g., 95-105%) by standard addition or comparison with a reference method.

- Precision: Repeatability (intra-day) and intermediate precision (inter-day), expressed as Relative Standard Deviation (RSD %).

- Selectivity: Determine potentiometric selectivity coefficients (KpotA,B) against common interfering ions using the Separate Solution Method (SSM) or Fixed Interference Method (FIM) [9].

- Assess the sensor's performance according to the following criteria, ideally over multiple days to establish intermediate precision [10]:

Table 3: Exemplary Performance Characteristics of a Potentiometric Sensor

| Performance Parameter | Exemplary Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Linear Range (mol L-1) | 1 × 10-7 – 1 × 10-1 | [9] |

| Nernstian Slope (mV/decade) | 29.571 ± 0.8 (for a divalent ion) | [9] |

| Detection Limit (mol L-1) | 5.0 × 10-8 | [9] |

| Response Time | ~15 seconds | [9] |

| Working pH Range | 3.5 – 6.5 | [9] |

| Lifespan | > 2 months | [9] |

Future Perspectives: Wearable Potentiometric Sensors

The future of TDM lies in continuous, real-time monitoring, and potentiometry is perfectly positioned to enable this through wearable sensors [4] [6]. These devices can be integrated into patches or textiles to measure drug concentrations non-invasively in biofluids like sweat, thereby providing a comprehensive pharmacokinetic profile [8] [6].

The logical pathway from a laboratory sensor to a personalized dosing recommendation is outlined below.

Potentiometric sensors offer a critical advantage for the TDM of NTI drugs. Their simplicity, speed, low cost, and high selectivity directly address the limitations of conventional analytical techniques. The advent of solid-contact and wearable sensors further extends their applicability towards continuous, real-time monitoring, paving the way for a new era of truly personalized pharmacotherapy. The protocol provided herein serves as a robust foundation for researchers and scientists to harness this powerful technology in drug development and clinical monitoring.

Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) are potentiometric sensors that quantitatively measure the activity of specific ions in solution, forming a critical technology platform for pharmaceutical research and therapeutic drug monitoring [11] [7]. The core function of an ISE relies on an ion-selective membrane (ISM) that generates a membrane potential by selectively interacting with target ions [12]. The configuration of the interface behind this membrane fundamentally differentiates ISE designs, primarily into liquid-contact (LC-ISE) and solid-contact (SC-ISE) configurations [12] [7]. This application note details the anatomical structure, working principles, and performance characteristics of both configurations within the specific context of pharmaceutical drug analysis, providing validated experimental protocols for their implementation.

Structural Configurations and Operational Principles

Liquid-Contact ISE (LC-ISE) Anatomy

The traditional LC-ISE employs an internal filling solution as a stable ionic bridge between the ion-selective membrane and the internal reference electrode [7]. Its structure consists of:

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM): A polymer membrane (typically PVC or acrylic) containing an ionophore (selective ion carrier), ion exchanger, plasticizer, and polymer matrix [12].

- Internal Filling Solution: An aqueous solution containing a fixed concentration of the target ion [7].

- Internal Reference Electrode: Typically an Ag/AgCl wire immersed in the internal solution, providing a stable potential reference [12] [7].

The potential difference (EMF) measured between the ISE and an external reference electrode follows the Nernst equation: E = E⁰ + (RT/zF)ln(a), where S = RT/zF represents the theoretical Nernstian slope (approximately 59.16 mV/decade for a monovalent ion at 23°C) [13]. The primary function of the internal solution is to establish a stable potential at the interface between the inner reference electrode and the back side of the ISM [12].

Solid-Contact ISE (SC-ISE) Anatomy

SC-ISEs eliminate the internal filling solution, replacing it with a solid-contact (SC) layer that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer [12] [7]. This design revolutionizes the electrode by enabling miniaturization, portability, and simplified manufacturing [13]. The three core components are:

- Conductive Substrate: An electron-conducting material such as glassy carbon, platinum, or screen-printed electrodes [12].

- Solid-Contact (SC) Layer: A material with both ionic and electronic conductivity that facilitates the transduction of ionic currents from the membrane to electronic currents in the substrate [14].

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM): Similar in composition to that used in LC-ISEs [12].

Two primary mechanisms govern the transduction at the SC layer [12] [14]:

- Redox Capacitance Mechanism: Utilizes conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT, PANI, POT) that undergo reversible oxidation/reduction reactions, providing a stable potential through their high redox capacitance [12] [14].

- Electric Double-Layer (EDL) Capacitance Mechanism: Employs capacitive materials like carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene, or nanocomposites, where charge separation at the ISM/SC interface creates a stable double-layer capacitance [12] [14].

Figure 1: Anatomical comparison of Liquid-Contact and Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes.

Comparative Analysis: LC-ISE vs. SC-ISE

The structural differences between the two configurations lead to distinct performance characteristics, particularly relevant to pharmaceutical applications such as drug dissolution testing and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) [11] [15].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of LC-ISE and SC-ISE Configurations

| Parameter | Liquid-Contact ISE (LC-ISE) | Solid-Contact ISE (SC-ISE) |

|---|---|---|

| Key Structural Feature | Internal filling solution [7] | Solid-contact transduction layer [12] |

| Miniaturization Potential | Limited by internal solution volume [12] | Excellent, ideal for wearable sensors [11] [7] |

| Potential Stability | Generally stable, but sensitive to filling solution changes [12] | Can achieve high stability with optimal SC layer [13] [14] |

| Maintenance Requirements | High (refill solution, membrane maintenance) [12] | Low (no liquid components) [13] |

| Response Time | Seconds to minutes | Often < 10-30 seconds [15] [16] |

| Lifetime | Months with maintenance | Weeks to months (single-use possible) [11] |

| Primary Limitations | Solution evaporation/leakage, pressure/temperature sensitivity, difficult miniaturization [12] | Potential water layer formation, signal drift with poor SC layer [13] [17] |

| Ideal Pharmaceutical Use Case | Benchtop dissolution testing, quality control labs [15] | Portable analysis, wearable monitors, in-field testing [11] [7] |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of a Solid-Contact ISE for Drug Analysis

This protocol details the construction of a SC-ISE with a conductive polymer solid-contact layer, suitable for the determination of cationic drugs (e.g., Venlafaxine, Lidocaine, Propranolol) [15] [14].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for SC-ISE Fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Polymer matrix for the ISM, provides structural integrity [12] [14] | High molecular weight, Selectophore grade [14] |

| Plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE, DOS) | Imparts plasticity and mobility to membrane components, influences dielectric constant [12] | 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE), Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS) [12] [14] |

| Ionophore | Selectively binds target ion (drug molecule) [12] | Drug-specific (e.g., ion-pair complex, macrocyclic host) [16] [17] |

| Ion Exchanger (e.g., NaTFPB, KTpClPB) | Introduces ionic sites into membrane, crucial for proper operation with neutral ionophores [12] [15] | Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl) borate (KTpClPB) [15] |

| Solid-Contact Material | Ion-to-electron transducer (e.g., Conducting polymer, MWCNTs) [14] | Poly(3-octylthiophene-2,5-diyl) (POT), Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) [13] [14] |

| Conductive Substrate | Electron-conducting support [12] | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) [13] [17] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent for membrane casting [15] [14] | Analytical grade, anhydrous |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Substrate Preparation: Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) successively with fine alumina slurries (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) to a mirror finish. Ricate thoroughly with distilled water and dry [13].

- Solid-Contact Layer Deposition:

- Option A (Conducting Polymer): Prepare a 1-5 mg/mL solution of the conducting polymer (e.g., POT) in a suitable solvent (e.g., tetrahydrofuran or acetonitrile). Deposit 10-50 µL of this solution onto the polished GCE surface and allow it to dry under ambient conditions to form a thin film [13] [14].

- Option B (Nanomaterial): Disperse 1-2 mg of MWCNTs in 1 mL of organic solvent (e.g., xylene/THF mixture) via sonication. Drop-cast 10-50 µL of the dispersion onto the GCE and dry [13] [17].

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Cocktail Preparation: In a glass vial, accurately weigh and combine the following components to make approximately 200 mg of total membrane mass [15] [14]:

- 1.0 wt% Ionophore (e.g., drug-TPB⁻ ion-pair)

- 0.5-1.0 wt% Ion Exchanger (e.g., NaTFPB)

- 32-65 wt% Plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE)

- 33-66 wt% Polymer Matrix (e.g., PVC) Add 1-2 mL of THF and stir until the components are completely dissolved, forming a homogeneous, viscous cocktail.

- Membrane Deposition: Drop-cast 50-100 µL of the ISM cocktail directly onto the prepared solid-contact layer. Carefully cover the vial and allow the THF to evaporate slowly over 24-48 hours at room temperature to form a uniform, dry membrane with a thickness of 100-300 µm [15] [14].

- Electrode Conditioning: Soak the newly fabricated SC-ISE in a stirring solution of the target drug (e.g., 1.0 × 10⁻³ M Venlafaxine HCl or Lidocaine HCl) for 12-24 hours (or overnight) to establish a stable equilibrium at the membrane-sample interface [15] [14].

- Calibration and Use: Calibrate the conditioned electrode in a series of standard solutions of the target drug (e.g., from 1 × 10⁻⁷ M to 1 × 10⁻² M). Measure the potential versus a commercial Ag/AgCl reference electrode under stirring. A stable, Nernstian response (slope of ~59 mV/decade for monovalent cation) confirms successful fabrication [14] [16].

Figure 2: Solid-contact ISE fabrication workflow.

Application in Pharmaceutical Analysis: Drug Release Monitoring

SC-ISEs are ideally suited for monitoring drug release from solid dosage forms due to their rapid response, minimal sample preparation, and ability to analyze colored/turbid solutions [11] [15].

Experimental Workflow for Drug Release Profiling:

- Setup: Use the fabricated drug-selective SC-ISE and a reference electrode in a standard dissolution vessel (e.g., 100 mL volume, 300 rpm, 37°C) containing the dissolution medium [15].

- Measurement: Introduce the drug-loaded dosage form (e.g., a polymer film or a coated porous substrate) into the medium.

- Data Acquisition: Continuously record the potential output of the SC-ISE at short intervals (e.g., every 10 seconds) using a high-impedance data acquisition system [15].

- Data Conversion: Convert the measured potential (mV) to drug concentration (mol/L) in real-time using the pre-established calibration curve [15].

- Validation: Compare the resulting release profile with data obtained from a standard technique like UV spectrophotometry to validate the method [15].

This potentiometric method offers significant advantages over UV spectroscopy, as it is unaffected by sample turbidity, air bubbles, or the presence of other UV-absorbing excipients, providing a more robust and direct measurement of drug activity [15].

The evolution from liquid-contact to solid-contact configurations represents a significant advancement in ISE technology, directly addressing the needs of modern pharmaceutical research. While LC-ISEs remain robust for controlled laboratory environments, SC-ISEs offer superior advantages in miniaturization, portability, and operational simplicity, enabling their application in wearable sensors and point-of-care diagnostic devices [11] [7]. The critical design choice lies in selecting and optimizing the solid-contact material—whether based on redox capacitance (conducting polymers) or double-layer capacitance (nanocarbons)—to ensure potential stability and prevent the formation of a detrimental water layer [13] [14] [17]. By providing a detailed anatomical understanding and a validated fabrication protocol, this application note equips researchers to effectively utilize ISEs for advanced pharmaceutical analysis, including therapeutic drug monitoring and real-time dissolution testing.

Potentiometric sensors, specifically ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), are established tools in electrochemical analysis for determining ion concentrations in diverse samples. Traditional liquid-contact ISEs (LC-ISEs) contain an internal solution that facilitates ion-to-electron transduction. While effective, this design suffers from fundamental limitations including mechanical instability, evaporation or leakage of the internal solution, challenges in miniaturization, and a short shelf-life, restricting their use in miniaturized, portable, or wearable applications [7] [18].

The "solid-contact revolution" addresses these limitations by replacing the internal solution with a solid-contact (SC) layer, also known as an ion-to-electron transducer. This innovation has given rise to solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs), which offer superior mechanical robustness, ease of miniaturization and integration, enhanced potential stability, and the prevention of a detrimental water layer between the membrane and the substrate [7] [18]. This transition is particularly impactful for pharmaceutical drug monitoring, enabling the development of point-of-care devices, wearable sensors for real-time therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM), and highly reproducible, automated production [19] [20]. This document details the critical materials, experimental protocols, and applications underpinning this technological shift.

Key Transducer Materials and Performance

The solid-contact layer is the core of an SC-ISE, responsible for efficient ion-to-electron transduction and potential stability. Various classes of materials have been explored, each with distinct properties and transduction mechanisms.

Table 1: Critical Assessment of Common Ion-to-Electron Transducer Materials

| Material Class | Example Materials | Reported Performance Metrics | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polypyrrole (PPy) | Capacitance: N/AShort-term drift: N/AMechanism: Redox Capacitance [18] | High redox capacitance, good electrical conductivity, well-established deposition methods. | Susceptible to interferences from O₂, CO₂, and light; Swelling in aqueous solutions can affect stability. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Capacitance: N/AShort-term drift: N/AMechanism: EDL Capacitance [21] [18] | Very high surface area, hydrophobicity, excellent electrical conductivity. | Potential for agglomeration; Batch-to-batch variability. |

| Graphene-based Materials | Graphene, Graphene Oxide, Reduced Graphene Oxide | Capacitance: 383.4 ± 36.0 µFShort-term drift: 2.6 ± 0.3 µV s⁻¹Total Resistance: 216.1 ± 27.4 kΩ [21] | Highest reported capacitance, very hydrophobic, high electroactive surface area, low potential drift. | Cost and complexity of production for some forms. |

| Nanocomposites | Fe₃O₄/MoS₂, Tubular Gold Nanoparticles (Au-TFF) | Capacitance: HighShort-term drift: N/AMechanism: Synergistic [7] | Tailored properties, enhanced stability and capacitance, improved electron transfer kinetics. | More complex synthesis and fabrication process. |

| 3D-Printed Carbon-Composites | Polylactic acid-Carbon Black (PLA-CB) | Cost: ~€0.32/sensor [20]Reproducibility (E⁰ RSD): ± 3 mV [20] | Extreme low cost, automated fabrication, high reproducibility, custom designs. | Lower conductivity compared to pure carbon materials; Requires optimization of print parameters. |

*N/A: Specific values not provided in the cited search results, but the mechanism is confirmed.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Graphene-Based SC-ISEs for Lithium Sensing

This protocol outlines the procedure for creating high-performance SC-ISEs using graphene as a transducer, adapted from a critical assessment study [21].

Principle: A commercially available screen-printed electrode (SPE) modified with graphene provides the solid-contact transducer substrate. A lithium-ion selective membrane (ISM) is then drop-cast onto this substrate to create the final sensor.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 2: Essential Materials for Graphene-Based Lithium SC-ISE

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Graphene-modified SPE | Serves as the ion-to-electron transducer and conductive substrate. |

| Lithium Ionophore | The selective recognition element within the ISM that complexes with Li⁺ ions. |

| Ion Exchanger | (e.g., NaTFPB) Provides ionic sites in the membrane for proper potentiometric response. |

| Plasticizer | (e.g., DOS) Creates a fluid matrix for the ISM, enabling ion mobility. |

| Polymer Matrix | (e.g., PVC or PU) Provides structural integrity to the ISM. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Volatile solvent used to dissolve the ISM components for drop-casting. |

Procedure:

- ISM Cocktail Preparation: In a glass vial, prepare the ISM cocktail by dissolving the following components in THF (e.g., 1 mL total volume):

- Lithium Ionophore (e.g., 1% by weight)

- Ion Exchanger (e.g., Sodium Tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (NaTFPB), 0.5% by weight)

- Plasticizer (e.g., Dioctyl Sebacate (DOS), 65% by weight)

- Polymer Matrix (e.g., Poly(Vinyl Chloride) (PVC), 32.5% by weight)

- Membrane Deposition: Using a micropipette, apply 5 aliquots of 10 µL of the ISM cocktail onto the working electrode surface of the graphene-modified SPE. Allow each aliquot to dry completely for 20 minutes at room temperature before applying the next.

- Final Conditioning: After the final layer is deposited, allow the sensor to dry for an additional 1 hour. Condition the completed SC-ISE overnight in a solution of 10 mM LiCl to equilibrate the membrane.

- Potentiometric Measurement: Connect the SC-ISE and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) to a high-input impedance potentiometer. Measure the potential while immersing the electrodes in a series of standard Li⁺ solutions with stirring. Construct a calibration curve by plotting the measured potential (mV) vs. the logarithm of Li⁺ activity.

Protocol 2: Automated Fabrication of 3D-Printed Solid-Contact ISEs

This protocol describes a highly reproducible and automated method for producing SC-ISEs using multimaterial fused filament fabrication (FFF) 3D-printing [20].

Principle: A 3D printer is used to fabricate an electrode body with an integrated well, using an insulating filament (PETg) and a conductive carbon-composite filament (PLA-CB) that functions as both the electrode and the ion-to-electron transducer.

Procedure:

- Electrode Design: Design a 3D model of the electrode (e.g., dimensions 30 × 10 × 1.2 mm) featuring a recessed well (e.g., 5 mm diameter) to contain the ISM. The design should include a base insulator layer, a conductive CB-PLA electrode layer, and a top insulator layer.

- Slicing and Setup: Export the design as an STL file and import it into a slicer program (e.g., PrusaSlicer). Use the following key print settings:

- Infill: 100%

- Extrusion Multiplier: 1.1 (to prevent void formation)

- Nozzle Temperature: 240 °C (for CB-PLA)

- Bed Temperature: 90 °C

- Print Speed: 25 mm/s

- Multimaterial Printing: Execute the print using a single-nozzle printer with a modified gcode to perform filament swaps. This will produce a complete, insulated electrode with a CB-PLA working electrode at the bottom of the well.

- ISM Application and Conditioning: Prepare a potassium-ISM cocktail (e.g., 1% valinomycin, 0.5% NaTFPB, 65% DOS, 33.5% PVC in THF). Apply 5 × 10 µL aliquots of the cocktail into the well of the 3D-printed electrode, allowing each to dry for 20 minutes. Condition the finished 3DP-SC-ISE overnight in 10 mM KCl.

Response Mechanisms of Solid-Contact Transducers

The potential stability in SC-ISEs is governed by the interfacial capacitance at the substrate/ISM junction. Two primary mechanisms have been experimentally verified, depending on the transducer material [18].

Redox Capacitance Mechanism: This mechanism is characteristic of conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT) that exhibit reversible redox behavior. The ion-to-electron transduction is achieved via a reversible Faradaic process. The potential is thermodynamically defined and highly stable because the redox couple's concentrations are fixed within the polymer layer [18]. For a PEDOT-based K⁺-ISE, the overall reaction can be summarized as:

PEDOT⁺Y⁻ (SC) + K⁺ (aq) + e⁻ (GC) ⇌ PEDOT (SC) + Y⁻ (ISM) + K⁺ (ISM)Electric-Double-Layer (EDL) Capacitance Mechanism: This non-Faradaic mechanism is typical for carbon-based materials like graphene, CNTs, and CB. The transduction occurs through the electrostatic separation of charges at the interface between the electronic conductor and the ionic conductor (ISM), forming an EDL. The high stability of these transducers stems from their exceptionally high surface area and hydrophobicity, which lead to a large capacitance and effectively prevent the formation of a water layer [21] [18].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Drug Monitoring

The solid-contact revolution has directly enabled advanced applications in pharmaceutical research and clinical monitoring.

Wearable Sensors for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM): SC-ISEs are ideal for wearable, non-invasive monitoring of pharmaceutical drugs in biofluids like sweat. For example, an enzyme-based wearable sensor was developed for real-time detection of the anti-Parkinson's drug L-Dopa in sweat, demonstrating a strong correlation with blood pharmacokinetic profiles [19]. This allows for personalized dosing and minimizes side effects.

Rapid Purity and Potency Analysis: SC-ISEs can be designed for specific drugs to rapidly assess purity during industrial production. A quality-by-design (QbD) approach was used to develop a potentiometric sensor for Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) that is highly selective against its toxic starting materials (DCQ and HND). This enables at-line monitoring of reaction kinetics and final product purity without complex instrumentation [22].

High-Reproducibility Production for Clinical Use: Automated fabrication methods like 3D printing are critical for producing highly reproducible SC-ISEs suitable for clinical TDM. The consistency in standard potential (E⁰) offered by these methods moves the field closer to "calibration-free" sensors, simplifying their use by end-users in decentralized healthcare settings [20] [23].

Biomarker Comparison Across Biological Fluids

The selection of an appropriate biological matrix is fundamental to the success of any drug monitoring protocol. Blood, urine, and saliva each offer distinct advantages and limitations for quantifying pharmaceutical compounds and their metabolites.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Biological Matrices for Drug Monitoring

| Feature | Blood/Plasma/Serum | Urine | Saliva |

|---|---|---|---|

| Invasiveness | Invasive (venipuncture) [24] | Non-invasive | Non-invasive [25] [24] [26] |

| Collection Ease | Requires trained personnel [27] | Simple, but requires restroom facilities | Simple, no special training needed [25] [26] |

| Matrix Complexity | High (proteins, cells, lipids) | Moderate to High | Moderate (proteins, enzymes, microbes) [26] |

| Biomarker Concentration | Represents systemic circulation | Often concentrated; suitable for metabolite profiling | Generally lower, correlates with free, unbound drug fraction [27] |

| Primary Applications | Gold standard for pharmacokinetics (TDM) [27] | Compliance testing, metabolite identification, occupational exposure | Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM), especially for drugs with narrow therapeutic index [28] [27] |

| Correlation to Blood Levels | Reference standard | Variable, often qualitative or semi-quantitative | Strong correlation for specific drugs (e.g., paracetamol) [27] |

| Key Analytical Challenges | Sample preprocessing (centrifugation), hemolysis | Variable dilution (requires creatinine correction), analyte stability | Contamination (food debris, oral hygiene), lower analyte concentration, requires sensitive sensors [26] [27] |

Saliva is particularly advantageous for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) as it often contains the free, pharmacologically active fraction of a drug [27]. Its non-invasive nature facilitates frequent sampling, improving patient compliance and enabling real-time pharmacokinetic profiling [25]. For instance, paracetamol concentrations in saliva show a strong correlation with plasma levels, making it a viable alternative for monitoring [27].

Advanced Analytical Methodologies

Potentiometric Sensor Platforms

Potentiometric sensors are a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry for ion concentration determination. The core principle involves measuring the potential difference between an Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) and a reference electrode under conditions of negligible current flow [7].

Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes (SC-ISEs) represent a significant advancement over traditional liquid-contact ISEs. They eliminate the inner filling solution, which enhances mechanical stability, prevents solution evaporation, and allows for easier miniaturization and integration into wearable formats [7] [8]. A key component of SC-ISEs is the solid-contact layer, which acts as an ion-to-electron transducer.

Table 2: Common Solid-Contact Materials Used in Potentiometric Sensors

| Material Category | Examples | Key Properties & Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymers | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polypyrrole (PPy), Polyaniline (PANI) | Function primarily via a redox capacitance mechanism, providing stable potential and efficient transduction [8]. |

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials | Carbon nanotubes, Graphene, Mesoporous carbon | Offer a high double-layer capacitance due to their large surface area, contributing to signal stability [8]. |

| Nanocomposites | MoS2 nanoflowers with Fe3O4; Tubular gold nanoparticles with Tetrathiafulvalene | Combine materials for a synergistic effect, enhancing capacitance, stability, and electron transfer kinetics [8]. |

The mechanism of solid-contact ISEs can follow one of two primary pathways, depending on the transducer material. The redox capacitance mechanism is typical for conducting polymers, where the polymer's oxidation/reduction provides the charge transfer. In contrast, carbon-based materials often operate via an electric-double-layer (EDL) capacitance mechanism, storing charge at the electrode-electrolyte interface [8].

Protocol: Fabrication of a Solid-Contact Potentiometric Sensor

This protocol outlines the steps for creating a generalized solid-contact ion-selective electrode for drug monitoring [8].

- Reagents & Materials: Conducting substrate (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, screen-printed electrode); Solid-contact material (e.g., PEDOT:PSS dispersion, carbon nanotube solution); Ion-selective membrane components: Ionic receptor (ionophore), Ion-exchanger, Polymer matrix (e.g., PVC), Plasticizer; Solvent (e.g., Tetrahydrofuran - THF); Standard solutions of the target drug for calibration.

- Equipment: Potentiostat/Galvanostat; Electrochemical cell; Micropipettes; Ultrasonic bath; Spin coater (optional); Fume hood.

Procedure:

- Substrate Pretreatment: Clean the conducting substrate mechanically (e.g., with alumina slurry) and/or electrochemically (e.g., by cycling in sulfuric acid) to ensure a pristine surface.

- Solid-Contact Layer Deposition: Deposit the transducer material onto the substrate.

- For conducting polymers: This can be done via drop-casting of a polymer solution or by electrochemical polymerization (e.g., chronocoulometry) for more controlled film growth [8].

- For nanomaterials: Drop-cast a homogenous dispersion of the nanomaterial (e.g., carbon nanotubes) and allow the solvent to evaporate.

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Cocktail Preparation: In a glass vial, dissolve the polymer matrix (e.g., ~30 mg PVC), plasticizer (e.g., ~60-65 mg), ionophore (e.g., ~1-5 mg), and ion-exchanger (e.g., ~0.5-2 mg) in a suitable volatile solvent (e.g., 1-2 mL THF).

- Membrane Deposition: Using a micropipette, drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the ISM cocktail directly onto the solid-contact layer. Allow the solvent to evaporate slowly under a glass beaker to form a homogeneous, tacky film.

- Conditioning & Calibration: Condition the newly fabricated sensor in a solution containing the target ion (e.g., 1 mM drug solution) for several hours or overnight to establish a stable equilibrium potential. Calibrate the sensor by measuring its potential in a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target drug.

Protocol: Quantification of Paracetamol in Saliva Using a Smartphone-Based Electrochemical Biosensor

This protocol details a specific application for monitoring paracetamol (acetaminophen) in artificial saliva, leveraging smartphone technology for point-of-care testing [27].

- Reagents & Materials: Artificial saliva; Paracetamol standards; Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4); Electrochemical cell; Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) or a custom low-cost potentiostat (e.g., KickStat); Smartphone with dedicated app (e.g., "MediMeter").

- Equipment: Low-cost potentiostat (e.g., KickStat) compatible with a smartphone [27]; Micropipettes; Vortex mixer.

Procedure:

- Sample Collection & Preparation: Collect saliva sample via passive drool or using a standardized collection device. Centrifuge the sample (e.g., at 10,000 × g for 5 min) to remove particulates and obtain a clear supernatant. For initial method development, use artificial saliva spiked with paracetamol [27].

- Sensor System Setup: Connect the electrochemical sensor (e.g., SPCE) to the potentiostat, which is interfaced with a smartphone running the analytical application.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Transfer a fixed volume (e.g., 50 µL) of the prepared sample or standard onto the sensor. Initiate the measurement through the smartphone app. An optimized electrochemical technique (e.g., chronoamperometry or differential pulse voltammetry) is applied to quantify paracetamol.

- Data Analysis: The smartphone application automatically records the electrochemical signal (e.g., current) and correlates it to a pre-established calibration curve (R² = 0.988 reported for paracetamol [27]). The result, displaying the paracetamol concentration, is presented on the smartphone screen within approximately one minute [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagent Solutions for Sensor Fabrication and Drug Analysis

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Ionophores | Molecular recognition elements within the Ion-Selective Membrane that selectively bind to the target drug ion [8]. |

| Polymer Matrices (e.g., PVC) | Form the bulk of the sensing membrane, providing a supportive matrix for the ionophore and other components [8]. |

| Plasticizers (e.g., DOS, o-NPOE) | Impart flexibility and mobility to the polymer membrane, influencing ionophore dynamics and sensor lifespan [8]. |

| Ion-Exchangers | Introduce ionic sites into the membrane to ensure permselectivity and a stable Nernstian response [8]. |

| Conducting Polymers (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Serve as the solid-contact layer, transducing the ionic signal from the membrane into an electronic signal for measurement [8]. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (e.g., MWCNTs) | Used as high-surface-area solid-contact materials or electrode modifiers to enhance signal stability and sensitivity [8]. |

| Artificial Saliva | A simulated biological fluid used for method development, optimization, and calibration to mimic the matrix of human saliva [27]. |

| Enzymes (for enzymatic assays) | Biological recognition elements used in biosensors to impart high specificity for the target analyte (e.g., enzyme-based paracetamol sensors) [27]. |

Sensor Fabrication, Material Innovations, and Real-World Deployment

The evolution of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) represents a significant advancement in potentiometric sensing for pharmaceutical drug monitoring. Unlike traditional liquid-contact ISEs, SC-ISEs eliminate the internal filling solution, enabling miniaturization, better portability, and more robust detection limits [14]. The critical component in these sensors is the transducer layer, which facilitates the conversion of an ionic signal from the recognition event into an electronic signal that can be measured by the underlying electrode [8]. This ion-to-electron transduction is vital for creating stable, reliable, and sensitive sensors suitable for pharmaceutical applications such as therapeutic drug monitoring and quality control [5].

The selection of transducer material directly governs key sensor performance parameters, including potential stability, sensitivity, detection limit, and operational lifespan. Ideal transducer materials must exhibit high capacitance, excellent hydrophobicity to prevent the formation of water layers, and both electronic and ionic conductivity [8] [14]. Within this context, conducting polymers like poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) and polyaniline (PANI), alongside carbon-based nanomaterials such as multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and graphene, have emerged as the most promising and extensively researched materials. This application note provides a comparative analysis of these materials and details standardized protocols for their implementation in potentiometric sensors for pharmaceutical analysis.

Transduction Mechanisms and Material Properties

The mechanism of ion-to-electron transduction varies fundamentally between conducting polymers and carbon-based nanomaterials, directly influencing sensor design and performance.

Mechanism of Conducting Polymers (PEDOT, PANI)

Conducting polymers function primarily through a redox capacitance mechanism [8] [14]. These polymers possess a conjugated backbone that can be switched between oxidized and reduced states. When used as a transducer in a cation-selective sensor, the overall reaction can be summarized as follows [8]: CP⁺ + B⁻(SC) + L(ISM) + M⁺(aq) + e⁻(C) ⇌ CP⁰(SC) + B⁻(ISM) + LM⁺(ISM) Here, CP⁺/CP⁰ represents the oxidized/reduced state of the conducting polymer (e.g., PEDOT, PANI), B⁻ is the doping anion, L is the ionophore in the ion-selective membrane (ISM), M⁺ is the target cation, and C is the underlying conductor. This reversible redox reaction provides a high thermodynamic capacitance, stabilizing the potential at the interface between the electron-conducting substrate and the ion-conducting membrane [14].

Mechanism of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials (MWCNTs, Graphene)

In contrast, carbon-based nanomaterials like MWCNTs and graphene rely on a double-layer capacitance mechanism [14]. These materials feature exceptionally high specific surface areas. When employed as a transducer, they form an electrical double layer at the interface with the ion-selective membrane. The capacitance of this double layer ((C{dl})) is a crucial parameter, as it dictates the potential stability; a higher (C{dl}) results in lower potential drift [14]. The extensive surface area of MWCNTs and graphene maximizes this double-layer capacitance, leading to highly stable sensor outputs.

The diagram below illustrates and contrasts these two primary transduction mechanisms.

Comparative Performance of Transducer Materials

The choice of transducer material has a direct and measurable impact on the electrochemical characteristics of the resulting sensor. A rational study comparing MWCNTs, PANi, and ferrocene demonstrated distinct performance outcomes [14].

Table 1: Comparative Electrochemical Performance of Different Transducer Materials for VEN-TPB Ion-Pair Based SC-ISEs [14]

| Transducer Material | Slope (mV/decade) | Detection Limit (mol/L) | Linear Range (mol/L) | Potential Drift (ΔE/Δt, µV/s) | Double-Layer Capacitance (C~dl~, µF) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNTs | 56.1 ± 0.8 | 3.8 × 10⁻⁶ | 1.0 × 10⁻² – 6.3 × 10⁻⁶ | 34.6 | 850 |

| PANi | 55.6 ± 0.7 | 5.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 1.0 × 10⁻² – 8.0 × 10⁻⁶ | 39.8 | 620 |

| Ferrocene | 54.8 ± 0.5 | 7.9 × 10⁻⁶ | 1.0 × 10⁻² – 1.3 × 10⁻⁵ | 47.2 | 390 |

Table 2: Key Characteristics and Applications of Primary Transducer Materials

| Material | Primary Mechanism | Key Advantages | Reported Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| PEDOT | Redox Capacitance | High conductivity, good stability, commercial availability | Widely used as a stable solid contact in various SC-ISEs [8]. |

| PANi | Redox Capacitance | Easy synthesis, good environmental stability, acid-doping capability | Used as a transducer for Venlafaxine HCl sensors [14]. |

| MWCNTs | Double-Layer Capacitance | Very high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, mechanical strength | Demonstrated the best overall performance (capacitance, drift) for Venlafaxine HCl detection [14]. |

| Graphene/Graphene Nanoplatelets | Double-Layer Capacitance | Ultra-high surface area, superior hydrophobicity prevents water layer formation | Used as a transducer layer to stabilize potential response and prevent water layer formation in Donepezil and Memantine sensors [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Sensor Fabrication and Modification

This protocol describes the functionalization of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with graphene nanoplatelets and a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP)-based membrane for the selective detection of pharmaceutical drugs like Donepezil (DON) and Memantine (MEM) [29].

Workflow Overview:

Materials:

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) (e.g., OD: 10 mm, ID: 5 mm)

- Graphene Nanoplatelets (6–8 nm thick, 5 microns wide) [29]

- Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) for the target drug (see Protocol 2 for synthesis)

- Poly(Vinyl Chloride) (PVC), high molecular weight

- Plasticizer (e.g., 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether - o-NPOE)

- Ionic exchanger (e.g., Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate - K-TCPB)

- Tetrahydrofuran (THF), analytical grade

- Ultrasonication bath

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the GCE surface with successive grades of alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and then with ethanol. Dry at room temperature [29].

- Graphene Transducer Layer Deposition: Disperse 1.0 mg of graphene nanoplatelets in 1.0 mL of a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF) via ultrasonication for 30-60 minutes to form a homogeneous suspension. Deposit a known volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of this suspension onto the polished GCE surface and allow it to dry under ambient conditions, forming a uniform solid-contact layer [29].

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Preparation: Weigh the following components into a glass vial:

- 100 mg of PVC

- 200 mg of plasticizer (o-NPOE)

- 1-5 mg of the synthesized MIP (as ionophore)

- 0.5-2 mg of ionic exchanger (K-TCPB)

- Dissolve the mixture in 2 mL of THF and stir until a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained [29].

- Membrane Casting: Drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the membrane cocktail directly onto the graphene-modified GCE. Allow the THF to evaporate slowly, preferably by covering the vial loosely, to form a uniform, tacky film over the transducer layer.

- Sensor Conditioning: Before the first measurement, condition the fabricated sensor by soaking in a stirring solution of the target drug (e.g., 1.0 × 10⁻³ M Donepezil HCl) for 12-24 hours. For daily use, store the sensor dry and re-condition in a standard drug solution for 30-60 minutes [29].

Protocol 2: Synthesis of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

This protocol details the synthesis of MIPs via precipitation polymerization, which can be incorporated into the ISM to provide superior selectivity against interfering ions and the co-formulated drug [29].

Materials:

- Template Molecule: Target drug (e.g., Donepezil or Memantine)

- Functional Monomer: Methacrylic acid (MAA)

- Cross-linker: Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA)

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN)

- Porogenic Solvent: Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Pre-polymerization Mixture: In a glass-capped bottle, dissolve 0.5 mmol of the target drug (template) in 40.0 mL of DMSO. Add 2.0 mmol of MAA and sonicate the mixture for 15 minutes to allow pre-complex formation.

- Polymerization Initiation: To the mixture, add 8.0 mmol of EGDMA (cross-linker) and 0.6 mmol of AIBN (initiator). Sonicate briefly for 1 minute to ensure complete dissolution and mixing.

- Oxygen Removal: Purge the solution with nitrogen gas for 15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can inhibit the free-radical polymerization.

- Polymerization Reaction: Place the sealed bottle in a thermostatic oil bath at 60 °C for 24 hours to complete the polymerization process.

- Template Removal: After polymerization, wash the resulting polymer particles repeatedly with a solvent (e.g., methanol:acetic acid, 9:1 v/v) to remove the template molecule completely. This leaves behind specific recognition cavities. Finally, dry the MIP under vacuum at 60 °C until a constant weight is achieved [29].

Protocol 3: Electrochemical Characterization of Transducer Layers

Characterizing the transducer layer is crucial for predicting sensor performance. Key parameters include double-layer capacitance ((C_{dl})) and potential drift.

Materials:

- Fabricated SC-ISEs

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Electrochemical cell with reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) and counter electrode (e.g., Pt wire)

- Aqueous solution of 0.1 M KCl (or other suitable electrolyte)

Part A: Capacitance Measurement via Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

- Setup: Immerse the fabricated SC-ISE, a reference electrode, and a counter electrode in a 0.1 M KCl solution.

- Measurement: Run an EIS spectrum at the open-circuit potential over a frequency range of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz with a small amplitude AC voltage (e.g., 10 mV).

- Analysis: Fit the obtained impedance spectrum to a suitable equivalent circuit. The double-layer capacitance ((C{dl})) can be extracted from the constant phase element (CPE) values in the low-frequency region of the spectrum. A higher (C{dl}) indicates better potential stability [14].

Part B: Potential Drift Assessment via Chronopotentiometry (CP)

- Setup: Use the same three-electrode setup as in Part A.

- Measurement: Apply a constant current (e.g., ±1 nA) for a set duration (e.g., 60 seconds) and record the potential change over time.

- Analysis: Calculate the potential drift (ΔE/Δt) from the slope of the potential-time curve. A lower drift value signifies a more stable sensor [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for SC-ISE Fabrication and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Electron-conducting substrate | Provides a stable, polished surface for transducer layer deposition. |

| Graphene Nanoplatelets | Double-layer capacitance transducer | Hydrophobic material that prevents water layer formation; enhances signal stability [29]. |

| Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) | Redox capacitance transducer | Conducting polymer known for high stability and conductivity; often used doped with poly(styrene sulfonate) (PSS) [8]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Double-layer capacitance transducer | Provides very high surface area, leading to high capacitance and low potential drift [14]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Selective recognition element in ISM | Synthetic receptor that creates shape-specific cavities for the target drug, drastically improving selectivity [29]. |

| Poly(Vinyl Chloride) (PVC) | Matrix polymer for ISM | Forms the bulk of the ion-selective membrane, providing mechanical stability [29] [14]. |

| Plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE) | ISM component | Dissolves ionophores, provides mobility for ions within the membrane, and influences selectivity [29]. |

| Ionic Exchanger (e.g., K-TCPB) | ISM component | Introduces permselectivity and facilitates ion exchange at the membrane-sample interface [29]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent | Used to dissolve PVC, plasticizer, and ionophores to create a homogeneous membrane cocktail for casting. |

Potentiometric sensors have emerged as powerful electroanalytical tools in pharmaceutical research, particularly for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). These sensors combine the simplicity, portability, and cost-effectiveness of potentiometry with the molecular-level design of sensing membranes capable of selective drug recognition. The core component of such sensors is the ion-selective membrane (ISM), a meticulously formulated layer whose composition directly dictates analytical performance. This application note details the strategic design of ISMs, focusing on the critical triad of components: ionophores (molecular recognition elements), plasticizers (membrane media and solvents), and polymer matrices (structural scaffolds). Framed within a broader thesis on potentiometric sensors for pharmaceutical drug monitoring, this guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with detailed protocols and foundational knowledge to develop robust, selective, and biocompatible sensors for precise drug quantification.

Core Components of the Sensing Membrane

The performance, selectivity, and stability of a potentiometric sensor are governed by the careful selection and proportioning of its membrane components. The table below summarizes the function and key considerations for each critical component.

Table 1: Critical Components of a Potentiometric Sensing Membrane

| Component | Primary Function | Key Considerations & Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophore | Selective recognition and binding of the target ion/drug. | Selectivity, binding constant, lipophilicity. E.g., valinomycin (K⁺), calix[8]arene (Palonosetron) [30], Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) (Safinamide) [31]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Provides structural integrity to the membrane. | Biocompatibility, mechanical stability, film-forming ability. E.g., Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC), polyurethane (PU), poly(methyl methacrylate-co-decyl methacrylate) [32]. |

| Plasticizer | Imparts flexibility and governs the membrane's dielectric constant. | Biocompatibility & leaching potential, lipophilicity, viscosity. E.g., Dioctyl phthalate (DOP), 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE), bis(2-ethylhexyl sebacate) (DOS) [33]. |

| Ion Exchanger | Ensures ionic conductivity and electroneutrality within the membrane. | Compatibility with the ionophore-target complex. E.g., Sodium tetraphenylborate (Na-TPB) for cations [34] [30]. |

| Additives | Enhance performance characteristics like conductivity or hydrophobicity. | Function-specific. E.g., Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) to prevent water layer formation [31]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials required for the formulation of potentiometric sensing membranes as described in the cited research.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Membrane Fabrication

| Reagent / Material | Typical Function | Brief Explanation of Role |

|---|---|---|

| High MW Poly(Vinyl Chloride) (PVC) | Polymer Matrix | Serves as an inert, structural backbone for the membrane [34] [35]. |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent | Dissolves membrane components for homogeneous film casting [34]. |

| Dioctyl Phthalate (DOP) / o-NPOE | Plasticizer | Solvates ionophore and ion exchanger, imparts membrane flexibility, and modulates permittivity [34] [30]. |

| Sodium Tetraphenylborate (Na-TPB) | Ion Exchanger | Provides lipophilic counter-ions to maintain membrane electroneutrality [34] [30]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | Ionophore | Synthetic, biomimetic receptor with tailored cavities for highly selective target binding [31]. |

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Solid-Contact Transducer | Hydrophobic layer that prevents water formation and enhances signal transduction in all-solid-state sensors [31]. |

Experimental Protocols for Membrane Fabrication and Drug Analysis

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for fabricating a coated graphite all-solid-state ion-selective electrode (ASS-ISE) and applying it to pharmaceutical analysis, based on validated research [34].

Protocol: Fabrication of a Coated Graphite All-Solid-State Ion-Selective Electrode (ASS-ISE)

Aim: To construct a robust, disposable sensor for the determination of benzydamine hydrochloride (BNZ·HCl) in pharmaceutical cream and biological fluids [34].

Workflow Overview:

Step 1: Preparation of the Ion-Pair Complex

- Procedure: Mix 50 mL of a 10⁻² M solution of the target drug (cationic, e.g., BNZ·HCl) with 50 mL of a 10⁻² M solution of sodium tetraphenylborate (Na-TPB) as the lipophilic anion.

- Precipitation: Allow the resulting solid precipitate (drug-TPB ion-pair) to equilibrate with the supernatant for 6 hours.

- Isolation: Collect the solid by filtration, wash thoroughly with bi-distilled water, and air-dry the powdered ion-pair complex at ambient temperature for 24 hours [34].

Step 2: Formulation of the Sensing Membrane Cocktail

- Weighing: Accurately weigh the following components into a glass petri dish:

- 10 mg of the synthesized ion-pair complex.

- 45 mg of plasticizer (e.g., Dioctyl phthalate, DOP).

- 45 mg of high molecular weight PVC.

- Dissolution: Add 7 mL of tetrahydrofuran (THF) and mix thoroughly until a homogeneous solution is obtained [34].

Step 3: Membrane Casting on Graphite Substrate

- Substrate Preparation: Use a graphite rod electrode (e.g., 4 mm diameter) housed in a Teflon holder. Polish the exposed surface to a shiny finish and clean.

- Coating: Dip the polished surface of the graphite electrode into the membrane cocktail solution.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the THF to evaporate completely at room temperature, leaving a thin, uniform PVC film adhered to the graphite surface [34] [35].

Step 4: Sensor Conditioning and Calibration

- Conditioning: Condition the assembled sensor by immersing it in a 10⁻² M solution of the target drug for 4 hours to establish a stable equilibrium at the membrane-sample interface.

- Calibration: Measure the electromotive force (EMF) of the sensor in a series of standard drug solutions across a concentration range (e.g., 10⁻⁶ M to 10⁻² M). Use a pH/mV meter with a double-junction Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Data Plotting: Construct a calibration curve by plotting the measured potential (mV) against the logarithm of the drug activity (concentration). A Nernstian slope of approximately 59.2 mV/decade at 25°C for a monovalent ion confirms proper sensor function [34].

Protocol: Enhancing Selectivity with Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs)

Aim: To incorporate a MIP as a highly selective ionophore for the determination of Safinamide (SAF) in dosage forms and biological fluids [31].

Procedure:

- MIP Synthesis: Prepare the MIP via precipitation polymerization using the target drug (SAF) as a template, methacrylic acid (MAA) as a functional monomer, and ethyleneglycoldimethacrylate (EGDMA) as a cross-linker.

- Template Removal: After polymerization, leach the template molecules from the polymer matrix using a suitable solvent to create specific recognition cavities.

- Membrane Incorporation: Disperse the obtained MIP particles into the standard PVC membrane cocktail (replacing the ion-pair complex) and proceed with the sensor fabrication as described in Protocol 3.1 [31].

Performance Gain: The MIP-based sensor for Safinamide demonstrated a Nernstian slope of 59.30 mV/decade, a low detection limit of 8.0 × 10⁻⁷ M, and excellent selectivity over interfering ions and the drug's degradation products [31].

Advanced Material Strategies for Enhanced Performance

Biocompatibility and Safety

For sensors intended for wearable or implantable use (e.g., continuous monitoring), the biocompatibility of every membrane component is critical. Traditional components like PVC, oNPOE, and DOS plasticizers, along with some ionophores, can exhibit cytotoxicity and may leach into biological fluids [33].