Potentiometric Cell Setup and Components: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive overview of potentiometric cell technology, from foundational principles to cutting-edge applications in biomedical research and drug development.

Potentiometric Cell Setup and Components: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of potentiometric cell technology, from foundational principles to cutting-edge applications in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the core components and setup of electrochemical cells, detailing the function of indicator and reference electrodes, and explains the governing Nernst equation. The review covers significant methodological advancements, including the design of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs), the use of novel transducer materials like conducting polymers and nanomaterials, and innovative fabrication techniques such as 3D printing for rapid prototyping. It also addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for enhancing sensor stability, selectivity, and longevity, and discusses rigorous validation protocols and comparative analyses with other analytical techniques. Aimed at researchers and drug development professionals, this guide serves as a vital resource for leveraging potentiometric sensors in clinical diagnostics, therapeutic drug monitoring, and continuous health monitoring.

Core Principles and Components of a Potentiometric Cell

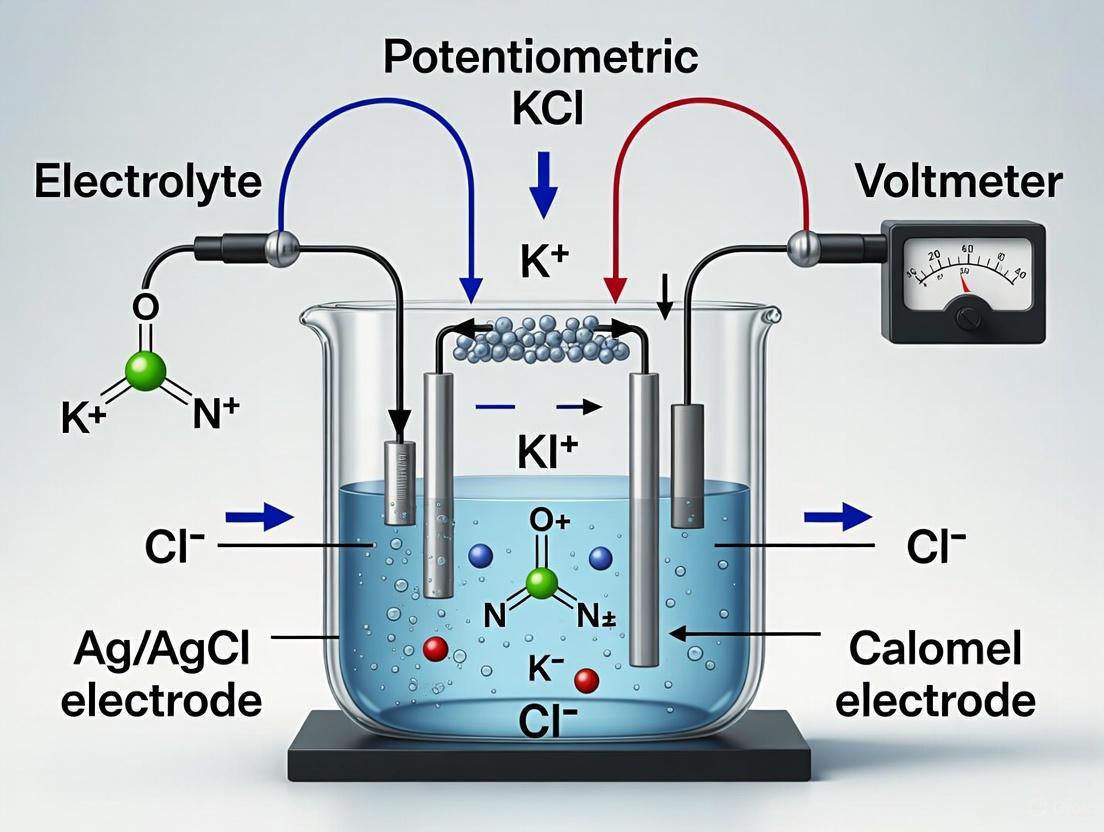

Potentiometry is a fundamental technique in instrumental analysis that involves measuring the potential (or voltage) of an electrochemical cell under static conditions, where no significant current flows through the system [1] [2]. This quantitative method relies on the measurement of the electrical potential difference between two electrodes—an indicator electrode and a reference electrode—when they are immersed in an analyte solution [3]. The measured potential is then related to the concentration of the analyte of interest through the Nernst equation, making potentiometry a powerful tool for quantitative analysis across chemistry, biology, and environmental science [2] [3].

The historical development of potentiometry dates back to the early 20th century when it was first used to measure pH levels in solutions [3]. A significant breakthrough occurred in 1906 when Cremer discovered that the potential difference across a thin glass membrane is a function of pH when opposite sides of the membrane contact solutions with different H₃O⁺ concentrations [2]. This discovery led to the development of the glass pH electrode in 1909, paving the way for modern ion-selective electrodes that have expanded potentiometric applications to a diverse array of analytes [2].

In the context of a broader thesis on potentiometric cell setup and components, understanding the fundamental principles of the two-electrode system is crucial. The conventional cell notation represents this system as reference electrode || indicator electrode, where the measured cell potential is Ecell = Eind - Eref [4]. This configuration forms the basis for all potentiometric measurements, with the reference electrode providing a stable, known potential against which changes in the indicator electrode's potential can be measured and correlated to analyte activity [4].

Theoretical Foundations

The Nernst Equation

The theoretical basis of potentiometry is rooted in the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the electrochemical cell potential and the concentration of ions in a solution [1] [3]. For a metal electrode immersed in a solution of its own ions at 25°C, the potential (E) is given by:

E = E⁰ + (0.0592/n) × logC [1]

Where:

- E⁰ represents the standard electrode potential

- n is the valency of the ions

- c is the concentration of ions

In a more general form applicable to various electrochemical systems, the Nernst equation is expressed as:

E = E⁰ - (RT/nF) lnQ [3]

Where:

- R is the gas constant

- T is the temperature in Kelvin

- F is the Faraday constant

- Q is the reaction quotient

It is crucial to note that the Nernst equation relates electrode potential to the activity of electroactive species, not directly to their concentration [2]. This distinction is particularly important in potentiometry, where the difference between activity and concentration cannot be ignored, unlike in some other electrochemical techniques where this difference introduces negligible error [2].

Potential Measurement Principles

In potentiometric measurements, the potential difference between the indicator and reference electrodes is measured under conditions of zero or negligible current flow [1] [2]. This static measurement ensures that the composition of the electrochemical cell remains unchanged during analysis, making potentiometry a non-destructive technique ideal for quantitative analysis [2] [3]. The indicator electrode generates a potential (Eind) that depends on analyte concentration, while the reference electrode maintains a constant potential (Eref) throughout the measurement [1] [4]. The salt bridge connecting the two half-cells completes the electrical circuit while preventing mixing of analyte components [1].

Table 1: Key Components of a Potentiometric Cell and Their Functions

| Component | Symbol | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Electrode | Eref | Provides a stable, known reference potential independent of analyte composition |

| Indicator Electrode | Eind | Generates potential that varies with analyte activity/concentration |

| Salt Bridge | Ej | Completes electrical circuit while minimizing mixing of solutions; generates negligible potential |

| Analyte | A | Solution of interest containing the ions to be measured |

Components of the Potentiometric Cell

Reference Electrodes

Reference electrodes are designed to maintain a constant, stable potential regardless of the composition of the analyte solution [1] [4]. An ideal reference electrode should be easily assembled, rugged, insensitive to analyte concentration, and exhibit reversible behavior obeying the Nernst equation [1]. While the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) is the primary reference standard against which all other electrode potentials are measured, its practical use is limited due to complexity and sensitivity to interfering substances [1]. Instead, two main reference electrodes find widespread application in modern potentiometry.

The saturated calomel electrode (SCE) is based on the redox couple between Hg₂Cl₂ (calomel) and Hg [1] [4]. The electrode reaction is:

Hg₂Cl₂(s) + 2e⁻ ⇌ 2Hg(l) + 2Cl⁻(aq) [1]

The potential of the SCE depends on the activity of Cl⁻ ions and is typically +0.2444 V at 25°C when using saturated KCl [1] [4]. The SCE consists of an inner tube packed with a paste of Hg, Hg₂Cl₂, and KCl, situated within a second tube containing a saturated KCl solution, with a porous wick serving as a salt bridge to the test solution [4]. A significant disadvantage of the SCE is that the solubility of KCl is temperature-sensitive, causing the electrode's potential to decrease at higher temperatures (+0.2444 V at 25°C vs. +0.2376 V at 35°C) [4].

The silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode is another widely used reference system based on the reduction of AgCl to Ag [1] [4]. The electrode reaction is:

AgCl(s) + e⁻ ⇌ Ag(s) + Cl⁻(aq) [1]

The potential of the Ag/AgCl electrode is +0.199 V when used with saturated KCl [1]. This electrode is simple, inexpensive, very stable, non-toxic, and can be used with saturated KCl or lower concentrations, or even directly in seawater [1]. The potential of this electrode, like the SCE, depends on both the concentration of KCl and the temperature [1].

Table 2: Comparison of Common Reference Electrodes

| Parameter | Standard Hydrogen Electrode | Saturated Calomel Electrode | Silver/Silver Chloride Electrode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode System | Pt (H₂ (1 atm), H⁺ (1M) | Hg, Hg₂Cl₂, KCl (sat'd) | Ag, AgCl, KCl (sat'd) |

| Electrode Reaction | 2H⁺ + 2e⁻ ⇌ H₂ | Hg₂Cl₂(s) + 2e⁻ ⇌ 2Hg(l) + 2Cl⁻(aq) | AgCl(s) + e⁻ ⇌ Ag(s) + Cl⁻(aq) |

| Potential (at 25°C) | 0.000 V (by definition) | +0.2444 V | +0.199 V |

| Advantages | Primary standard; usable over entire pH range | Easy construction; stable potential | Simple; inexpensive; stable; non-toxic |

| Disadvantages | Easily poisoned; difficult H₂ pressure regulation | Temperature-dependent; toxic mercury | Can be difficult to prepare |

Indicator Electrodes

Indicator electrodes respond selectively to the activity of the target analyte in solution, generating a measurable potential (Eind) that varies with analyte concentration [1]. These electrodes are classified into several types based on their construction and operating principles.

Metallic indicator electrodes include several categories. Electrodes of the first kind are pure metal electrodes in direct equilibrium with their cations (e.g., Cu in Cu²⁺ solution) [1]. While simple, they lack selectivity and may be pH-dependent or easily oxidized [1]. Electrodes of the second kind respond to anions by forming precipitates or stable complexes (e.g., Ag electrode for Cl⁻ determination) [1]. Inert metallic electrodes (e.g., Pt, Au, Pd, C) serve as electron sources or sinks for redox systems without participating in the reaction [1].

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) utilize selective membranes that convert the activity of a specific ion dissolved in a solution into an electrode potential [1]. Also known as membrane electrodes, ISEs include several types. Glass membrane electrodes are commonly used for pH measurements and other cations [1]. Liquid membrane electrodes use a water-immiscible liquid ion exchanger suspended in a polymeric membrane [1]. Crystalline-membrane electrodes employ solid-state membranes made from insoluble inorganic salts [1]. Gas-sensing electrodes are complete galvanic cells with gas-permeable membranes that allow determination of dissolved gases like CO₂, NH₃, and O₂ [1].

Salt Bridge and Liquid Junction Potential

The salt bridge is a crucial component that connects the reference and indicator electrode compartments while preventing mixing of their solutions [1]. Typically containing an inert electrolyte such as KCl, the salt bridge allows ionic current to flow between the half-cells, thus completing the electrical circuit [2]. The porous frits at the ends of the salt bridge enable the electrolyte's ions to move freely while minimizing solution mixing [2].

A phenomenon known as liquid junction potential occurs at the interface between two solutions containing different electrolytes or different concentrations of the same electrolyte [1]. This potential arises from the unequal mobilities of positive and negative ions diffusing across the boundary [1]. While the salt bridge is designed to minimize this junction potential (designated Ej), it cannot be completely eliminated and must be considered in precise potentiometric measurements [1].

Measurement Techniques and Applications

Potentiometric Measurement Methods

Two primary approaches are employed in potentiometric measurements: direct potentiometry and potentiometric titration [1]. Direct potentiometry provides a rapid and convenient method for directly determining the activity of cations or anions in solution by measuring the potential difference between the indicator and reference electrodes and relating it to concentration via the Nernst equation [1]. This method requires careful calibration and is particularly useful for continuous monitoring applications [3].

Potentiometric titration involves measuring the potential of a suitable indicator electrode as a function of titrant volume [1]. This technique provides more reliable data than conventional titration methods, especially when dealing with colored or turbid solutions where visual endpoint detection is problematic [1]. Potentiometric titrations can be automated and offer high accuracy and precision for quantitative analysis of ions and molecules [3]. The endpoint is determined from the inflection point in the sigmoidal-shaped titration curve, where the potential change per unit volume of titrant is maximal [1].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Calibration of Potentiometric Systems: Regular calibration is essential for accurate potentiometric measurements [1]. The calibration method involves measuring the potential of standard solutions with known concentrations and constructing a calibration curve of potential versus log(concentration) [1]. The standard addition method, where known increments of standard solution are added to the unknown sample, is particularly useful for analyzing complex matrices [1].

Validation of Reference Electrodes: To ensure measurement accuracy, reference electrodes should be periodically validated [5]. This involves performing an Open Circuit Voltage (OCV) measurement in a two-electrode setup using a "golden" reference electrode (a dedicated validation electrode) [5]. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) in Galvanostatic Mode (GEIS) can also be used to check reference electrode impedance, which should be below 1 kΩ for proper operation [5].

Potential Measurement Protocol: The precise measurement of cell potential requires allowing the system to reach equilibrium, typically by stirring the solution and waiting for a stable reading [2]. Measurements should be conducted at constant temperature due to the temperature dependence of the Nernst equation [1] [3]. The high-input impedance potentiometer must draw negligible current (typically < 10⁻¹² A) to prevent polarization effects and maintain the system at equilibrium [2].

Applications in Research and Industry

Potentiometry finds diverse applications across multiple scientific disciplines. In environmental monitoring, ion-selective electrodes are used to measure ions like nitrate, chloride, and fluoride in water samples, providing crucial data for water quality assessment [3]. In biological and pharmaceutical research, potentiometric methods enable the determination of ions like potassium and sodium in biological samples, with enzyme-based electrodes extending applications to molecules like glucose and urea [3]. Industrial process control utilizes potentiometric sensors for real-time monitoring of chemical parameters in manufacturing processes, with their non-destructive nature allowing continuous operation without disrupting production [3].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Potentiometric Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Technical Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity KCl Solution | Electrolyte for reference electrodes and salt bridges | Saturated (≈4.2 M) or specific molarities (0.1 M, 1.0 M); provides stable potential and minimizes liquid junction potential |

| Standard Buffer Solutions | pH calibration and electrode characterization | Certified pH values at specific temperatures (e.g., pH 4.01, 7.00, 10.01); traceable to national standards |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster (ISA) | Sample pretreatment for ion-selective electrodes | Adjusts ionic background to constant level; masks interfering ions; composition specific to target analyte |

| Electrode Storage Solutions | Maintenance of electrode function and longevity | Prevents dehydration of sensing membranes; composition matches electrode type (e.g., diluted standard for pH electrodes) |

| Standard Ion Solutions | Calibration of ion-selective electrodes | Certified reference materials with known ion activities; cover expected concentration range of samples |

Advanced Considerations and Methodological Challenges

Electrode Selection and Optimization

Choosing the appropriate electrode system requires careful consideration of the analytical requirements and sample matrix. For pH measurements, glass electrodes offer exceptional selectivity for H⁺ ions and are unaffected by the presence of oxidizing or reducing agents [1]. However, glass electrodes exhibit alkaline error at pH > 9, where they become responsive to alkali cations, and acid error at pH < 0.5, where pH readings become higher than actual values [1]. For anion measurements, crystalline-membrane electrodes using materials like LaF₃ (for F⁻ determination) provide excellent selectivity and sensitivity [1]. These solid-state electrodes are typically made from crushed powder that is melted and formed, sometimes doped with elements like EuF₂ in LaF₃ membranes to increase conductivity by creating anion vacancies [1].

Liquid membrane electrodes represent another important category, employing hydrophobic ion-exchange agents dissolved in organic solvents immobilized in porous polymer membranes [1]. The calcium dialkyl phosphate electrode, for instance, uses a water-insoluble compound that binds Ca²⁺ strongly, making it ideal for measuring calcium ions in physiological processes [1]. Similarly, the K⁺-selective electrode utilizes valinomycin, an antibiotic that forms stable complexes with potassium ions, providing exceptional selectivity over other cations [1].

Method Validation and Quality Control

Ensuring the reliability of potentiometric measurements requires rigorous method validation and quality control protocols. Key validation parameters include accuracy (evaluated through recovery studies with spiked samples), precision (assessed by repeated measurements), detection limit (typically determined as the concentration corresponding to the signal-to-noise ratio of 3:1), and selectivity (quantified using the Nicolsky-Eisenman equation to account for interfering ions) [1] [5].

The impedance of reference electrodes should be periodically checked using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) with a two-electrode connection [5]. High impedance values (typically > 1 kΩ) indicate junction blockage or aging, which can manifest as high-frequency artifacts in EIS measurements or inductive loops in Nyquist plots [5]. A simple solution to address high impedance in reference electrodes is adding a capacitor in parallel, which provides a low-impedance path at high frequencies [5].

Troubleshooting and Maintenance

Effective maintenance of potentiometric systems is essential for long-term reliability. Common issues include slow response times (often caused by membrane fouling or aging), drifting potentials (typically due to reference electrode degradation or temperature fluctuations), and erratic readings (frequently resulting from air bubbles, poor connections, or insufficient grounding) [1] [5].

Regular maintenance protocols should include proper storage in recommended solutions, periodic cleaning of membrane surfaces, rejuvenation of clogged junctions by soaking in appropriate solutions, and validation against certified reference materials [1] [5]. For glass electrodes, dehydration can cause irreversible damage, while for reference electrodes, ensuring a steady flow of electrolyte (1-2 mL/hr) through the junction maintains stable performance [1].

In potentiometric analysis, the accurate measurement of an electrochemical cell's potential under static (zero-current) conditions provides a powerful tool for determining ionic activity in solution [6]. The fundamental setup consists of two essential half-cells: the ion-selective electrode (ISE), which responds to the activity of a specific target ion, and the reference electrode, which maintains a stable, known potential independent of the solution's composition [6] [7]. Together, these components form a complete circuit for determining analyte concentration based on the Nernst equation, which relates the measured potential to the logarithm of the ionic activity [8] [9] [10]. This guide deconstructs the roles, operating principles, and interactions of these critical components within the context of a potentiometric cell, providing a technical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals.

The ISE and reference electrode perform distinct but complementary functions. Their core characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Core Functions and Characteristics of ISEs and Reference Electrodes

| Component | Primary Role | Key Characteristic | Measured Signal |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | Senses the activity of a specific ion in the sample solution [8] [10] | Selective Permeability: Its membrane allows only the target ion to influence the potential [8] [11]. | Potential change relative to the reference electrode [11]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, reproducible reference potential against which the ISE's potential is measured [6] [7] | Potential Stability: Its potential remains constant regardless of the sample composition [7]. | Constant, known potential completes the circuit [6]. |

The overall cell potential, E~cell~, is the difference between the potentials of these two electrodes [10]: E~cell~ = E~ISE~ - E~ref~.

In-Depth Analysis of the Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE)

Operating Principle and the Nernst Equation

The heart of an ISE is its ion-selective membrane [8]. When this membrane separates two solutions with different activities of the target ion, a membrane potential develops due to an ion-exchange or ion-transport process at each solution-membrane interface [8]. This charge separation creates a measurable electrical potential. In a typical setup, the internal solution of the ISE has a fixed concentration of the analyte, while the external solution is the sample [8]. The potential developed at the ISE is governed by the famous Nernst equation, which for a cation I^z+^ is [9] [6]:

E = E⁰ + (RT/zF) ln(a)

where E is the measured potential, E⁰ is a constant standard potential, R is the universal gas constant, T is the temperature in Kelvin, F is Faraday's constant, z is the charge on the ion, and a is the activity of the ion I^z+^ in the sample solution [9]. This equation confirms that the ISE's response is logarithmic and proportional to the ionic activity, not the concentration directly.

Key Types of Ion-Selective Membranes

The selectivity of the ISE is determined almost entirely by the composition of its membrane [8]. The four primary types of membranes are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2: Types of Ion-Selective Membranes in ISEs

| Membrane Type | Composition | Selectivity Examples | Key Features & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membranes [11] [10] | Silicate or chalcogenide glass [11]. | H⁺, Na⁺, Ag⁺ [10]. Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ (chalcogenide) [11]. | High chemical durability; subject to alkali/acidic error in extreme pH [11]. |

| Crystalline Membranes [9] [10] | Mono- or polycrystalline solids [10]. | F⁻ (LaF₃ membrane), Ag⁺, S²⁻ (Ag₂S membrane) [9]. | Excellent selectivity; only ions entering crystal structure interfere [10]. |

| Liquid/Polymer Membranes [8] [9] | Plasticized PVC polymer with ionophore [9]. | K⁺ (valinomycin), Ca²⁺, NO₃⁻, various others [8] [9]. | Most widespread type; highly versatile but can have limited durability [10]. |

| Enzyme Electrodes [11] [10] | Enzyme-loaded membrane over a true ISE [10]. | Glucose, Urea, etc. [11]. | "Double-reaction" mechanism; not a true ISE but used similarly [10]. |

The development of new ionophores and polymer matrices, such as plasticizer-free poly(methyl methacrylate-co-decyl methacrylate), continues to enhance the performance and biocompatibility of liquid-membrane ISEs [12].

In-Depth Analysis of the Reference Electrode

The Role of a Stable Reference Potential

While the ISE produces a variable signal, the reference electrode must provide an invariant potential to complete the circuit and serve as a benchmark [7]. An ideal reference electrode exhibits high chemical stability, minimal potential drift, and low junction potential [7]. Its potential should be unaffected by the composition of the test solution.

Common Reference Electrode Systems

Several reference electrode systems are commonly used, each with a well-defined half-cell reaction and standard potential.

Table 3: Common Reference Electrode Systems and Their Properties

| Electrode Type | Half-Cell Reaction | Potential vs. SHE (at 25°C) | Best Applications & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) [10] [7] | AgCl(s) + e⁻ ⇌ Ag(s) + Cl⁻ [7] | +0.197 V (in saturated KCl) [7] | Mercury-free; widely used in biological and environmental research [7]. |

| Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [10] [7] | Hg₂Cl₂(s) + 2e⁻ ⇌ 2Hg(l) + 2Cl⁻ [10] | +0.244 V [7] | Stable and robust; contains toxic mercury [10] [7]. |

| Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE) [10] | 2H⁺(aq) + 2e⁻ ⇌ H₂(g) [10] | 0.000 V (by definition) [10] | Primary standard; inconvenient for routine lab use [10] [7]. |

Modern research is also advancing all-solid-state and plastic reference electrodes. These designs often use a conducting polymer (e.g., poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) or PEDOT) as an ion-to-electron transducer, coated with a non-selective polymer membrane containing lipophilic salts to eliminate dependence on sample composition [13]. This innovation is crucial for developing disposable, miniaturized, and robust potentiometric cells.

The Complete Potentiometric Cell and Measurement

In a practical measurement, the ISE and reference electrode are immersed in the same sample solution [6]. The potential difference between them is measured by a high-impedance potentiometer or pH meter, which ensures near-zero current flow and preserves the composition of the solution at the electrode interfaces [9] [6]. The relationship between the components and the measured signal is illustrated in the following diagram.

Diagram 1: Potentiometric cell signal pathway.

Experimental Protocol: Calibration of an Ion-Selective Electrode

To quantify analyte levels, an ISE must be calibrated with solutions of known concentration [11].

- Step 1: Preparation of Standard Solutions. Prepare a series of standard solutions encompassing the expected concentration range of the analyte. For example, for a calcium ISE, standards might range from 0.1 mM to 10 mM [12].

- Step 2: Measurement of Potential. Immerse the ISE and reference electrode in each standard solution, from the most dilute to the most concentrated. Measure the stable potential (in mV) for each standard after the reading stabilizes [11].

- Step 3: Construction of Calibration Curve. Plot the measured potential (E) versus the logarithm of the ion activity (log a). The plot should be linear and follow the Nernst equation [11].

- Step 4: Analysis of Unknowns. Measure the potential of the unknown sample and use the calibration curve to determine its ionic activity.

Advanced Research and Material Innovations

The field of potentiometric sensors is being revolutionized by new materials that improve performance, especially for biomedical applications. A key innovation is the use of conducting polymers like PEDOT and polythiophenes, which act as excellent ion-to-electron transducers in solid-contact ISEs, eliminating the need for an internal liquid filling solution [13] [12]. This simplifies miniaturization and fabrication of disposable sensors [13].

Furthermore, researchers are now covalently integrating ion-recognition sites directly into the conducting polymer backbone. For instance, a recent study developed a calcium-sensitive potentiometric sensor by electrochemically copolymerizing 2,2'-bithiophene (BT) with the calcium-chelating agent BAPTA [12]. This design integrates the ion-recognition element and the transducer within a single macromolecule, mitigating issues like ionophore leaching and enhancing sensor longevity [12]. Such sensors show Nernstian responses (≈20 mV/decade for Ca²⁺) and high selectivity, making them promising for early detection of inflammation or infection around orthopedic implants where local calcium concentration is elevated [12].

Reagent Toolkit for a Modern Potentiometric Sensor

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Fabricating a Solid-Contact Polymer-Based ISE

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Conducting Polymer | Serves as an ion-to-electron transducer; provides electrical contact [12]. | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) [13], Polythiophene derivatives [12]. |

| Ionophore (Ion Receptor) | Selectively binds the target ion, imparting selectivity to the sensor [8] [9]. | Valinomycin (for K⁺) [8], BAPTA (for Ca²⁺) [12]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Forms the bulk of the sensing membrane, hosting the ionophore and other components [9] [12]. | Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) [9], plasticizer-free poly(methyl methacrylate-co-decyl methacrylate) [12]. |

| Lipophilic Salt | Reduces membrane resistance and minimizes interference from ambient light and O₂/CO₂ [13]. | Used in non-selective membranes for reference electrodes [13]. |

| Solid Support | Provides a mechanical base for depositing the sensor layers. | Plastic transparent foil (e.g., for laser printers) [13]. |

The potentiometric cell is an elegant system whose accuracy hinges on the precise and complementary functions of its two components: the ion-selective electrode and the reference electrode. The ISE provides a variable signal that is analytically rich with information about the target ion, while the reference electrode provides the stable foundation against which that signal is measured. A deep understanding of their respective roles, from the fundamental Nernstian response and membrane selectivity to the necessity of a stable reference potential, is critical for researchers designing experiments or developing new analytical methods. Ongoing materials science innovations, particularly in conducting polymers and covalently integrated recognition sites, are pushing the boundaries of what these sensors can achieve, opening new doors for applications in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and real-time biomedical sensing.

Potentiometric sensors represent one of the most widely used sensing devices in (bio)chemical analysis, performing billions of measurements globally each year [14]. These sensors operate under static conditions where no current—or only negligible current—flows through the electrochemical cell, allowing measurement of potential without changing the system's composition [15]. The theoretical foundation governing this potentiometric response is the Nernst equation, formulated in 1889, which relates an electrochemical cell's potential to the concentration of electroactive species in the cell [15]. This fundamental principle enables the quantitative analysis of ionic species across diverse fields including pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics.

Within drug development specifically, potentiometric methods offer significant advantages for the direct determination of pharmaceuticals in line with green analytical chemistry principles [16]. These approaches provide rapid, cost-efficient, and environmentally friendly analysis without requiring complex sample preparation or purification, making them particularly valuable for routine analysis and quality control in pharmaceutical manufacturing [16] [17].

Theoretical Foundation of the Nernst Equation

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formulation

The Nernst equation provides a quantitative relationship between the standard electrode potential, temperature, and the activities (or concentrations) of reactants and products involved in a redox reaction [18]. It serves as a crucial bridge between thermodynamics and electrochemical cell potential, enabling calculation of cell potential under non-standard conditions [18].

The general form of the Nernst equation is expressed as:

$$ E = E^\circ - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln Q $$

Where:

- E = cell potential under non-standard conditions

- E° = standard cell potential

- R = universal gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K)

- T = temperature in Kelvin

- n = number of moles of electrons transferred in the redox reaction

- F = Faraday constant (96485 C/mol)

- Q = reaction quotient [18]

At room temperature (298 K), this equation simplifies to a more practical form using base-10 logarithms:

$$ E = E^\circ - \frac{0.05916}{n} \log Q $$

This simplified version is particularly valuable for rapid calculations in laboratory settings [18].

The Reaction Quotient (Q) and Activity

For a general reaction:

$$ aA + bB \leftrightarrow cC + dD $$

The reaction quotient Q is calculated as:

$$ Q = \frac{[C]^c [D]^d}{[A]^a [B]^b} $$

It is essential to recognize that the Nernst equation properly relates to the activities of the reactants and products rather than their concentrations [15]. Activity accounts for non-ideal behavior in solutions and differs from concentration, particularly in non-dilute systems. This distinction is crucial in potentiometry, where the accurate determination of analyte activity directly impacts measurement precision [15].

Table 1: Key Components of the Nernst Equation

| Component | Symbol | Description | Typical Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Potential | E | Measured potential under non-standard conditions | Volts (V) |

| Standard Cell Potential | E° | Potential under standard conditions (1 M, 1 atm, 298 K) | Volts (V) |

| Gas Constant | R | Universal physical constant relating energy and temperature | 8.314 J/mol·K |

| Temperature | T | Absolute temperature of the system | Kelvin (K) |

| Electrons Transferred | n | Number of moles of electrons in redox reaction | Dimensionless |

| Faraday Constant | F | Electric charge of one mole of electrons | 96485 C/mol |

| Reaction Quotient | Q | Ratio of product and reactant activities | Dimensionless |

Potentiometric Sensor Configuration and Components

Basic Potentiometric Cell Setup

A typical potentiometric electrochemical cell consists of two half-cells, each containing an electrode immersed in a solution of ions whose activities determine the electrode's potential [15]. These half-cells are connected by a salt bridge containing an inert electrolyte such as KCl, which completes the electrical circuit while preventing mixing of the half-cell solutions [15].

The two primary electrodes in a potentiometric cell are:

- Indicator/Working Electrode: This electrode responds to the analyte's activity and is typically designed to be selective toward a specific ion of interest [15].

- Reference Electrode: This electrode maintains a known, fixed potential throughout the measurement, providing a stable reference point against which the indicator electrode's potential can be measured [15].

By convention, the indicator electrode serves as the cathode (where reduction occurs) and the reference electrode as the anode (where oxidation occurs) in the potentiometric cell [15].

Evolution from Liquid-Contact to Solid-Contact Electrodes

The earliest potentiometric sensors were liquid-contact ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), which used an internal filling solution with a sensing membrane positioned between this solution and the sample [16]. While effective, these electrodes presented limitations including potential liquid leakage and challenges in miniaturization [16].

Modern potentiometry has largely transitioned to solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs), which offer superior simplicity, stable and reproducible responses, ease of handling, and long-term storage capabilities [16]. These solid-contact configurations have overcome the limitation of liquid filling, enabling greater miniaturization, integration, and flexibility in sensor design [14].

A prominent type of SC-ISE is the screen-printed electrode (SPE), which has gained increasing attention due to its disposable nature, low production cost, and suitability for mass fabrication [16]. The advancement of printing technologies has opened a new paradigm for low-cost, large-scale fabrication of a new generation of potentiometric ion sensors suitable for wearable devices and electronic skin applications [14].

Diagram 1: Solid-contact potentiometric sensor configuration showing signal pathway from sample to measurement.

Advanced Sensor Fabrication: Printing Technologies

The development of compatible fabrication techniques has become a critical focus in potentiometric sensor advancement, with printing technology emerging as a particularly promising solution [14]. Printing offers reduced fabrication costs, simplified patterning techniques, and accelerated prototyping implementation, making it ideal for producing next-generation sensors [14].

Screen Printing Technology

Screen printing has been the most extensively used technique for fabricating printed potentiometric sensors, valued for its simplicity, low cost, high efficiency, and wide applicability [14]. This stencil printing technique uses a squeegee to force paste through a screen mesh onto a target substrate, creating well-defined conductive patterns [14].

In sensor fabrication, screen printing typically produces a three-layered structure:

- Conductive layer: Provides the electrical connection, often using carbon or silver-based inks

- Insulating layer: Defines the active electrode area and prevents short circuits

- Sensing layer: Contains the ion-selective components that determine sensor specificity [14]

Emerging Printing Methodologies

Beyond screen printing, several other printing technologies have shown promise for potentiometric sensor fabrication:

- Inkjet Printing: A digital manufacturing technique that deposits precise droplets of functional inks without physical contact with the substrate, enabling high-resolution patterns and complex geometries [14].

- Wax Printing: Creates hydrophobic barriers on paper-based substrates to define fluidic pathways and electrode structures, particularly useful for low-cost diagnostic devices [14].

- 3D Printing: Includes fused deposition modeling (FDM) and stereolithography (SLA) techniques that can build reproducible sensitive membranes and integrated functional structures layer by layer [14].

Despite these advancements, a fully printed potentiometric sensor has not yet been truly realized, representing a significant opportunity for future research and development [14].

Experimental Implementation in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Sensor Development for Silver Sulfadiazine Detection

A recent study demonstrates the practical application of potentiometric sensors in pharmaceutical analysis through the development of a solid-contact ion-selective electrode for detecting silver ions released from silver sulfadiazine (SSD) in wound care formulations [16]. This research employed a two-step optimization procedure to create sensors with enhanced selectivity and stability.

Initial Optimization - Ionophore Selection: Six different ionophores were evaluated to enhance sensor selectivity, with Calix[4]arene demonstrating the highest affinity for silver ions [16]. The inclusion of a cation-exchanger in the polymeric membrane ensured selective response toward Ag⁺ ions from SSD, exhibiting excellent permselectivity [16].

Secondary Optimization - Transducer Integration: A layer of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) was incorporated between the Calix[4]-containing polymeric membrane and the solid-contact screen-printed electrode [16]. This MWCNT layer functioned as an efficient ion-to-electron transducer, improving potential stability by preventing the formation of a water layer at the interface between the electrode surface and the polymeric sensing membrane [16].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for potentiometric determination of silver sulfadiazine in pharmaceutical formulations.

Sensor Performance and Validation

The optimized MWCNT-modified sensor demonstrated exceptional analytical performance, achieving:

- High accuracy: 99.94% ± 0.413

- Wide linear response range: 1.0 × 10⁻⁵ to 1.0 × 10⁻² M

- Low detection limit: 4.1 × 10⁻⁶ M

- Near-Nernstian behavior: Slope of 61.029 mV/decade [16]

The sensor exhibited high selectivity for Ag⁺ ions from SSD in the presence of sodium hyaluronate in the pharmaceutical dosage form, enabling direct determination without extraction from the formulation [16]. This represents a significant advantage over traditional chromatographic methods that often require complex sample preparation and use of hazardous organic solvents [16].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Potentiometric Sensors in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Analyte | Sensor Type | Linear Range (M) | Detection Limit (M) | Slope (mV/decade) | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Silver ions from SSD | MWCNT/SPE | 1.0×10⁻⁵ to 1.0×10⁻² | 4.1×10⁻⁶ | 61.029 | Pharmaceutical formulation [16] |

| Atenolol | Coated Graphite Electrode | 6.2×10⁻⁶ to 1.0×10⁻² | 1.8×10⁻⁶ | 52.95 | Pure and commercial products [17] |

| Atenolol | Coated Wire Electrode | 4.5×10⁻⁸ to 1.0×10⁻² | 1.3×10⁻⁸ | 56.23 | Pure and commercial products [17] |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and implementation of potentiometric sensors requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the target analyte and sensor configuration. The following table summarizes key components used in advanced potentiometric sensor research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Potentiometric Sensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Calix[4]arene | Ionophore with specific binding affinity for target ions | Selective recognition of Ag⁺ ions in silver sulfadiazine sensors [16] |

| Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Solid-contact transducer for ion-to-electron signal conversion | Enhancing potential stability in screen-printed electrodes [16] |

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Polymer matrix for ion-selective membranes | Structural component of sensing membranes [16] |

| 2-Nitrophenyl Octyl Ether (NPOE) | Plasticizer for polymeric membranes | Improving membrane flexibility and ion mobility [16] |

| Sodium Tetrakis [3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate | Ion-exchanger for cation-selective membranes | Establishing permselectivity in Ag⁺-selective sensors [16] |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Solvent for membrane component dissolution | Preparing ion-selective membrane cocktails [16] |

| Screen-printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Conductive substrates for solid-contact sensors | Disposable, cost-effective sensor platforms [16] |

The Nernst equation continues to serve as the fundamental principle governing potentiometric response more than a century after its formulation. Its enduring relevance is evidenced by the sophisticated sensor technologies developed for pharmaceutical analysis, where precise potential measurements enable accurate quantification of target analytes in complex matrices. The ongoing evolution from traditional liquid-contact electrodes to advanced solid-contact configurations fabricated using modern printing technologies demonstrates the dynamic nature of this field.

For drug development professionals, potentiometric sensors offer compelling advantages including rapid analysis, minimal sample preparation, compatibility with green chemistry principles, and cost-effectiveness. The continued refinement of these sensors—particularly through the development of novel ionophores, enhanced transducer materials, and advanced fabrication techniques—promises to further expand their applications in pharmaceutical quality control, therapeutic drug monitoring, and clinical diagnostics. As printing technologies mature and our understanding of interfacial processes deepens, the realization of fully integrated, disposable potentiometric sensors for point-of-care testing appears increasingly attainable, potentially transforming how pharmaceutical analysis is performed in both developed and resource-limited settings.

In potentiometry, the potential of an indicator electrode is proportional to the analyte's activity, measured under static conditions where no current—or only negligible current—flows through the electrochemical cell, thus leaving its composition unchanged [19] [20]. Metallic electrodes constitute a primary class of indicator electrodes used for such potentiometric measurements, where the electrode potential responds to the activity of specific ions in the solution [19]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the classification, operating principles, and experimental protocols for metallic electrodes of the first, second, and third kind, contextualized within potentiometric cell setup and components research.

The foundational principle governing the response of these electrodes is the Nernst equation, which relates the electrochemical cell's potential to the concentration of electroactive species. For a generic reduction reaction ( \text{M}^{n+} + n\text{e}^- \rightleftharpoons \text{M(s)}), the Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^0{\text{M}^{n+} / \text{M}} - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{1}{a{\text{M}^{n+}}} ] where (E) is the measured potential, (E^0) is the standard electrode potential, (R) is the universal gas constant, (T) is temperature, (n) is the number of electrons transferred, (F) is the Faraday constant, and (a_{\text{M}^{n+}}) is the activity of the metal ion [19] [20]. The subsequent sections delineate the characteristics of each electrode kind, supported by quantitative data and experimental methodologies.

Electrodes of the First Kind

Principle and Theory

Electrodes of the first kind consist of a pure metal element in direct contact with a solution containing its own ion [19]. The potential developed at the electrode-solution interface is a direct function of the activity of the corresponding metal cation in the solution. A classic example is a copper electrode immersed in a solution of ( \text{Cu}^{2+} ) ions, governed by the following redox reaction: [ \text{Cu}^{2+}(aq) + 2e^{-} \rightleftharpoons \text{Cu}(s) ] The Nernst equation for this system at 25°C is: [ E = E{\mathrm{Cu}^{2+} / \mathrm{Cu}}^{\mathrm{o}} - \frac{0.05916}{2} \log \frac{1}{a{\mathrm{Cu}^{2+}}} = +0.3419 \mathrm{V} - \frac{0.05916}{2} \log \frac{1}{a{\mathrm{Cu}^{2+}}} ] When incorporated into a potentiometric electrochemical cell with a saturated calomel reference electrode (SCE), the overall cell potential is: [ E{\text{cell}} = E{\text{ind}} - E{\text{SCE}} = +0.3419 \mathrm{V} - \frac{0.05916}{2} \log \frac{1}{a{\mathrm{Cu}^{2+}}} - 0.2224 \mathrm{V} ] This simplifies to a general form for electrodes of the first kind: [ E{\mathrm{cell}} = K - \frac{0.05916}{n} \log \frac{1}{a{M^{n+}}} = K + \frac{0.05916}{n} \log a{M^{n+}} ] where (K) is a constant incorporating the standard-state potential of the ( \text{M}^{n+}/\text{M} ) redox couple and the potential of the reference electrode [19].

Experimental Protocol and Setup

The following workflow details the setup and measurement procedure for characterizing an electrode of the first kind.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Mechanically polish the metallic electrode (e.g., Cu, Ag) with successively finer abrasives (e.g., alumina slurry) to a mirror finish, followed by rinsing with deionized water and an appropriate solvent to remove any surface contaminants [19].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions with known activities of the target metal ion (e.g., ( \text{Cu}^{2+} )). Use an inert electrolyte (e.g., KNO₃) to maintain a constant ionic strength [20].

- Cell Assembly: Immerse the prepared metallic electrode and a stable reference electrode (e.g., Saturated Calomel Electrode, SCE, or Ag/AgCl) into the analyte solution. Connect the two electrodes to a high-impedance potentiometer, ensuring minimal current draw [19] [20].

- Potential Measurement: Record the cell potential ((E_{\text{cell}})) once a stable reading is obtained, indicating equilibrium at the electrode-solution interface.

- Data Analysis: Plot (E{\text{cell}}) against ( \log a{M^{n+}} ). A linear relationship with a slope close to ( \frac{0.05916}{n} ) V at 25°C confirms Nernstian behavior [19].

Limitations and Applicable Metals

Electrodes of the first kind are subject to several limitations. Their performance can be compromised by slow kinetics of electron transfer at the metal-solution interface, the formation of metal oxides on the electrode surface, and interfering side reactions [19]. Furthermore, some metals are susceptible to oxidation by acids, as exemplified by the reaction of zinc with H⁺: [ \text{Zn}(s) + 2\text{H}^{+}(aq) \rightleftharpoons \text{H}_{2}(g) + \text{Zn}^{2+}(aq) ] Consequently, their use is restricted to a specific set of metals, primarily limited to Ag, Bi, Cd, Cu, Hg, Pb, Sn, Tl, and Zn [19].

Electrodes of the Second Kind

Principle and Theory

Electrodes of the second kind are metallic electrodes whose potential is governed by the activity of an anion that forms a sparingly soluble salt with the electrode's metal cation [19]. These are typically used to determine anion concentrations. A common example is the silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode, which can function as a reference electrode when the Cl⁻ activity is fixed or as an indicator electrode for Cl⁻ activity.

The system involves two simultaneous equilibria. The primary electrode reaction is: [ \text{Ag}^{+}(aq) + e^{-} \rightleftharpoons \text{Ag}(s) ] The potential is given by the Nernst equation: [ E = 0.7996\ \text{V} + 0.05916 \log a{\text{Ag}^{+}} ] This potential is coupled with the solubility equilibrium of the precipitated salt: [ \text{AgCl}(s) \rightleftharpoons \text{Ag}^{+}(aq) + \text{Cl}^{-}(aq) ] The solubility product constant is ( K{sp, \text{AgCl}} = a{\text{Ag}^{+}} \cdot a{\text{Cl}^{-}} ), which can be rearranged to ( a{\text{Ag}^{+}} = \frac{K{sp, \text{AgCl}}}{a{\text{Cl}^{-}}} ). Substituting into the Nernst equation yields: [ E = 0.7996\ \text{V} + 0.05916 \log \frac{K{sp, \text{AgCl}}}{a{\text{Cl}^{-}}} = 0.7996\ \text{V} + 0.05916 \log K{sp, \text{AgCl}} - 0.05916 \log a{\text{Cl}^{-}} ] This simplifies to: [ E = K' - 0.05916 \log a{\text{Cl}^{-}} ] where ( K' ) is a new constant amalgamating the standard potential and the solubility product [19]. Thus, the electrode potential responds to the logarithm of the chloride ion activity.

Experimental Protocol for Anion Determination

The following workflow outlines the process for using an electrode of the second kind to determine anion concentration.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Fabrication: For a Ag/AgCl electrode, anodize a clean silver wire in a KCl solution (e.g., at +0.6 V vs. SCE for several minutes) to form a uniform, low-solubility AgCl layer on its surface [19] [21].

- Cell Assembly and Measurement: For determining an anion like I⁻, saturate the analyte solution with AgI. Assemble the potentiometric cell as described in Section 2.2, using the prepared electrode (e.g., Ag) and a reference electrode [19].

- Calibration: Measure (E{\text{cell}}) for a series of standard solutions with known anion activities. Construct a calibration curve of (E{\text{cell}}) versus ( \log a_{\text{anion}} ).

- Analysis: Measure the potential for the unknown sample and determine the anion activity from the calibration curve. The slope of the calibration curve should be close to ( \frac{-0.05916}{n} ) V, where (n) is the charge of the anion.

Electrodes of the Third Kind

Principle and Theory

Electrodes of the third kind are employed to determine the activity of a metal ion (( \text{M}^{1} )) that forms a complex or a sparingly soluble salt with a second metal (( \text{M}^{2} )), which itself comprises the electrode. The system involves a cascade of equilibria linking the activity of ( \text{M}^{1} ) to the potential.

For instance, a zinc electrode can be used to determine the activity of ( \text{Mg}^{2+} ) if the solution is saturated with both ( \text{ZnC}2\text{O}4 ) and ( \text{MgC}2\text{O}4 ). The equilibria involved are:

- Electrode Equilibrium: ( \text{Zn}^{2+} + 2e^- \rightleftharpoons \text{Zn}(s) )

- Solubility Equilibrium for Zn: ( \text{ZnC}2\text{O}4(s) \rightleftharpoons \text{Zn}^{2+} + \text{C}2\text{O}4^{2-} )

- Solubility Equilibrium for Mg: ( \text{MgC}2\text{O}4(s) \rightleftharpoons \text{Mg}^{2+} + \text{C}2\text{O}4^{2-} )

The concentration of the common oxalate ion (( \text{C}2\text{O}4^{2-} )) is controlled by these simultaneous equilibria. From the solubility products, ( K{sp, \text{Zn}} = a{\text{Zn}^{2+}} \cdot a{\text{C}2\text{O}4^{2-}} ) and ( K{sp, \text{Mg}} = a{\text{Mg}^{2+}} \cdot a{\text{C}2\text{O}4^{2-}} ). Combining these relationships and substituting into the Nernst equation for the zinc electrode shows that the electrode potential becomes a function of ( \log a_{\text{Mg}^{2+}} ).

Experimental Considerations

Electrodes of the third kind are less common in practice due to significant experimental challenges. Achieving and maintaining simultaneous saturation with two solid phases within the electrochemical cell is difficult and can lead to slow response times and unstable potentials. Ensuring that the system reaches a stable equilibrium where all three equilibria are properly established requires careful control and is often not practical for routine analytical applications.

Comparative Analysis of Electrode Types

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three classes of metallic electrodes for direct comparison.

Table 1: Comparison of Metallic Electrodes of the First, Second, and Third Kind

| Feature | Electrodes of the First Kind | Electrodes of the Second Kind | Electrodes of the Third Kind |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Species | Own cation (( \text{M}^{n+} )) [19] | Anion forming insoluble salt with ( \text{M}^{n+} ) (e.g., Cl⁻, I⁻) [19] | Cation (( \text{M}^{1} )) forming insoluble salt/ complex with a ligand that also binds ( \text{M}^{2} ) of the electrode [19] |

| Governing Principle | Direct Redox Equilibrium: ( \text{M}^{n+} + n e^- \rightleftharpoons \text{M} ) | Solubility + Redox Equilibrium | Coupled Solubility + Redox Equilibrium |

| Nernstian Slope | ( +\frac{0.05916}{n} \text{V} ) (for cation) | ( -\frac{0.05916}{n} \text{V} ) (for anion) | ( +\frac{0.05916}{n} \text{V} ) (for cation ( \text{M}^{1} )) |

| Key Advantage | Simple principle and direct measurement. | Enables potentiometric measurement of anions. | Theoretically allows measurement of metals that cannot form direct electrode systems. |

| Key Limitation | Limited to few metals; prone to interferences [19]. | Requires solution saturation with the insoluble salt for accurate response [19]. | Experimentally complex; requires multiple equilibria; slow and unstable response. |

| Common Examples | Cu in ( \text{Cu}^{2+} ); Ag in ( \text{Ag}^{+} ) [19] | Ag electrode in AgCl-saturated solution for Cl⁻ detection [19] | Zn electrode in solution saturated with ( \text{ZnC}2\text{O}4 ) and ( \text{MgC}2\text{O}4 ) for ( \text{Mg}^{2+} ) |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful experimentation with metallic electrodes requires specific materials and reagents. The following table details the essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Potentiometric Experiments with Metallic Electrodes

| Item | Function and Specification |

|---|---|

| High-Impedance Potentiometer | Measures the potential difference between the indicator and reference electrode without drawing significant current, which is crucial for maintaining equilibrium conditions at the electrode surface [20]. |

| Reference Electrodes | Provides a stable, known reference potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured. Examples: Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE), Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) [19] [20]. |

| Pure Metal Wires/Disks | Serve as the basis for fabricating indicator electrodes. Common types: Ag, Cu, Zn, Pb, and Cd wires of high purity (≥ 99.9%) [19]. |

| Ionic Strength Adjuster | A high-concentration, inert electrolyte (e.g., KNO₃, KCl) added to both standard and sample solutions to maintain a constant ionic strength, ensuring that the activity coefficient of the analyte remains constant [20]. |

| Polishing Supplies | Alumina powder or slurry (various grades from 1.0 µm to 0.05 µm) and polishing pads/cloths for creating a clean, reproducible electrode surface before each experiment [19]. |

| Sparingly Soluble Salts | High-purity salts (e.g., AgCl, AgI) for saturating solutions when working with electrodes of the second kind or for coating electrode surfaces [19]. |

Metallic electrodes of the first, second, and third kind represent foundational components in the potentiometric analysis of ionic species. Electrodes of the first kind provide a direct measurement of their cation's activity, while electrodes of the second kind elegantly extend this principle to anion sensing through coupled solubility equilibria. Although electrodes of the third kind offer a theoretical pathway for analyzing cations that lack their own reversible electrode, their practical application is limited by experimental complexity. A thorough understanding of the Nernst equation, the equilibria governing each system, and meticulous experimental technique are paramount for obtaining reliable and accurate potentiometric measurements. This knowledge forms a critical foundation for researchers and drug development professionals working with electrochemical sensors and analytical methods.

Potentiometric ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are a cornerstone of modern electrochemical analysis, providing a powerful and versatile method for the sensitive and selective measurement of a wide variety of analytes [22]. These sensors measure the potential difference between a working electrode and a reference electrode under zero-current conditions, allowing for direct and rapid readout of ion concentrations in diverse fields including clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and pharmaceutical analysis [22]. The evolution of this technology from traditional liquid-contact designs to advanced solid-contact configurations represents a pivotal transformation in sensor capabilities, enabling new applications in miniaturized, portable, and wearable devices [22] [23]. This review chronicles the key historical developments, technical innovations, and material advancements that have defined the journey from liquid-contact to solid-contact ISEs, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical foundation for understanding modern potentiometric sensor design.

Fundamental Principles of Potentiometric Sensing

Potentiometric sensors are electrochemical devices that respond to the activity of specific ions in a solution by generating a measurable potential between a reference electrode and a working electrode under zero current conditions [24]. The potential developed at the working electrode arises from the selective interaction between an ion-selective membrane and the target ions, fundamentally described by the Nernst equation:

[E = E^0 + \frac{RT}{zF}\ln a]

where E is the measured potential, E⁰ is the standard potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is the ion charge, F is Faraday's constant, and a is the ion activity [25] [24]. For monovalent ions at 25°C, this equation yields a theoretical slope of approximately 59.16 mV per decade change in concentration [24].

The core component of any ISE is the ion-selective membrane (ISM), which can be glass (e.g., for pH sensors), crystalline, or polymeric liquid membranes based on polyvinyl chloride (PVC) doped with selective ionophores, plasticizers, and additives [24] [23]. These membranes are designed to achieve a Nernstian response while discriminating against interfering ions through selective binding interactions [23].

Table 1: Critical Analytical Parameters for Evaluating ISE Performance

| Parameter | Definition | Evaluation Method |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Slope of calibration curve (mV/decade) | Comparison to theoretical Nernstian value [24] |

| Detection Limit | Lowest detectable ion activity above background | Calculated from intersection of linear response segments [25] |

| Linear Range | Concentration interval with proportional response | Determined from calibration curves [25] |

| Selectivity | Ability to discriminate against interfering ions | Selectivity coefficients via SSM or fixed interference method [12] |

| Response Time | Time to reach stable potential after concentration change | Measured experimentally after solution transition [12] |

| Stability | Signal drift over time (µV/s) | Potential monitoring under constant conditions [25] |

The Era of Liquid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes

Design and Operational Principles

Traditional liquid-contact ISEs (LC-ISEs) consist of three main components: an ion-selective membrane, an internal electrolyte solution (inner-filling solution), and an internal reference electrode (typically Ag/AgCl) [22] [23]. The ISM is selective for the target ion, while the internal electrolyte contains a fixed concentration of the target ion [22]. The internal reference electrode, immersed in the internal electrolyte, provides ion-to-electron transduction [22]. The potentiometric measurement depends on the potential difference between the external reference electrode and the ISE, driven by the difference in target ion activity between the external sample and internal solutions [22].

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their widespread historical use and reliability under controlled conditions, LC-ISEs present significant limitations that hinder their application in modern sensing contexts [23]. These limitations include:

- Mechanical Instability: The presence of liquid components makes LC-ISEs susceptible to orientation and movement effects [22].

- Evaporation and Leakage: The internal filling solution can evaporate or leak, reducing shelf-life and requiring careful maintenance [22] [23].

- Miniaturization Difficulties: Reducing the volume of the internal filling solution below milliliter levels presents significant engineering challenges [23].

- Osmotic Pressure Effects: Differences in ion strength between samples and internal solutions cause water transport, leading to volume changes or membrane stratification [23].

- Steady-State Ionic Flux: Continuous ion exchange occurs between the internal filling solution and test solution, affecting long-term stability [23].

These factors collectively limited the development of LC-ISEs for emerging applications requiring miniaturization, portability, and field deployment [23].

The Solid-Contact Revolution: Key Historical Milestones

The transition from liquid-contact to solid-contact ISEs represents one of the most significant advancements in potentiometric sensing, enabled by materials science innovations and conceptual breakthroughs in ion-to-electron transduction.

First-Generation Solid-Contact Electrodes

The first solid-contact electrodes, known as Coated Wire Electrodes (CWEs), were developed by R. W. Cattrall and H. Freiser in 1971 [24]. Their design consisted of metal wires directly coated with an ion-selective polymer membrane, initially for calcium ion detection [24]. While this eliminated the internal solution, these early CWEs suffered from poor potential stability and reversibility due to the different conductivity types at the membrane-electrode interface (ionic versus electronic) and the lack of an efficient ion-to-electron transduction mechanism [25] [24].

The Conductive Polymer Breakthrough

A pivotal moment in SC-ISE development came with the discovery of electrically conductive polymers by Hideki Shirakawa and colleagues, which earned the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2000 [24]. These materials possess mixed electronic and ionic conductivity, making them ideal mediators between the ionic conduction of the membrane and electronic conduction of the substrate [12].

In the early 1990s, Lewenstam's team pioneered the application of conductive polymers as solid contacts, using polypyrrole (PPy) as an intermediate layer between the ion-selective membrane and electrical output [24]. This innovation significantly improved potential stability compared to simple coated wire electrodes and established conductive polymers as the cornerstone of modern SC-ISE design [24].

Nanomaterial and Nanocomposite Integration

The 2000s and 2010s witnessed the emergence of various nanomaterials as superior solid-contact materials, including carbon nanomaterials (carbon nanotubes, graphene), metal and metal oxide nanoparticles, and composite materials [22] [25]. These nanomaterials offer ultra-high surface areas, superior conductivity, and enhanced hydrophobicity compared to bulk materials [22].

Recent research has focused on developing nanocomposites with synergistic effects to further enhance sensing performance. For instance, embedding Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles within MoS₂ nanoflowers prevents structural collapse while increasing capacitance of the solid-contact layer [22]. Similarly, tubular gold nanoparticles with tetrathiafulvalene (Au-TFF) solid contacts have demonstrated high capacitance and stability for potassium detection [22].

Technical Mechanisms: Ion-to-Electron Transduction

The fundamental operation of SC-ISEs relies on efficient ion-to-electron transduction at the interface between the ion-selective membrane and the solid-contact layer. Two primary mechanisms have been experimentally verified for this transduction process [22] [23].

Redox Capacitance Mechanism

Conductive polymers (e.g., poly(3-octylthiophene), polypyrrole, PEDOT) function through reversible redox reactions that facilitate charge transfer [23]. When the ISM contacts the sample solution, target ion extraction occurs, generating an ionic signal. This signal is transduced to an electronic signal through the reversible oxidation or reduction of the conductive polymer backbone, as described by:

[ \text{CP}^+ \text{A}^- (\text{SC}) + \text{M}^+ (\text{SIM}) + e^- \rightleftharpoons \text{CP}^\circ \text{A}^- \text{M}^+ (\text{SC}) ]

[ \text{CP}^+ \text{R}^- (\text{SC}) + e^- \rightleftharpoons \text{CP}^\circ (\text{SC}) + \text{R}^- (\text{SIM}) ]

where CP represents the conductive polymer, A⁻ is the anion, M⁺ is the target cation, and R⁻ is the anionic site in the membrane [23]. This mechanism provides high capacitance and stable potential through Faradaic processes [23].

Electric Double-Layer Capacitance Mechanism

Carbon-based materials (carbon nanotubes, graphene) and certain metal nanoparticles operate through non-Faradaic processes, forming an electric double-layer at the interface [23]. When ions accumulate at the ISM/SC interface, electrons redistribute in the solid contact to maintain charge neutrality, creating a capacitor-like structure described by:

[ C = \frac{\varepsilonr \varepsilon0 A}{d} ]

where C is capacitance, εᵣ is the dielectric constant, ε₀ is vacuum permittivity, A is the surface area, and d is the double-layer thickness [23]. The high surface area of nanomaterials significantly increases this capacitance, leading to improved potential stability [22] [23].

Performance Comparison: Liquid vs. Solid Contact ISEs

The evolution from liquid-contact to solid-contact designs has yielded significant improvements across multiple performance parameters, particularly for applications requiring miniaturization, portability, and continuous monitoring.

Table 2: Comprehensive Performance Comparison: Liquid-Contact vs. Solid-Contact ISEs

| Parameter | Liquid-Contact ISEs | Solid-Contact ISEs | Technological Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanical Stability | Poor (internal solution effects) [22] | Excellent (all-solid-state) [23] | Enables wearable, portable sensors [22] |

| Miniaturization Potential | Limited (ml-scale internal solution) [23] | Excellent (no volume constraints) [25] [23] | Chip integration, in vivo monitoring [23] |

| Response Time | Seconds to minutes [22] | Rapid (seconds) [22] [12] | Real-time monitoring capability [22] |

| Potential Stability | Good (with careful maintenance) [23] | Good to Excellent (with optimized SC) [25] | Reduced calibration frequency [25] |

| Manufacturing Complexity | Moderate (assembly required) [22] | Simple (layer-by-layer fabrication) [24] | Mass production, disposable sensors [24] |

| Sensitivity (Slope) | Nernstian (theoretical limit) [24] | Near-Nernstian to Nernstian [25] | Comparable analytical performance [25] |

| Lifespan | Limited (evaporation, flux) [23] | Extended (properly formulated) [25] | Reduced maintenance and replacement |

Advanced Materials for Next-Generation Solid-Contact ISEs

Conducting Polymers and Their Derivatives

Conducting polymers remain the most widely used solid-contact materials due to their excellent transduction properties. Common systems include poly(3-octylthiophene) (POT), poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), polypyrrole (PPy), and more specialized polymers like perinone-based materials (PPer) [25] [12]. Recent innovations focus on covalently incorporating ion-recognition sites directly into the polymer backbone, creating multifunctional materials that combine ion-to-electron transduction with selective recognition [12]. For example, a BAPTA-based potentiometric copolymer sensor for calcium detection integrates the selective calcium chelating properties of BAPTA directly into a polythiophene matrix via electrochemical polymerization [12].

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Carbon nanomaterials offer exceptional hydrophobicity, high electrical conductivity, and large surface areas. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), graphene, colloid-imprinted mesoporous carbon, and their functionalized derivatives have been successfully employed as solid contacts [22] [25]. These materials typically operate through the electric double-layer capacitance mechanism and demonstrate excellent potential stability, particularly when formulated as nanocomposites with polymers or metal nanoparticles [25].

Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles

Metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver) and metal oxide nanoparticles (e.g., CuO, Fe₃O₄) provide alternative transduction mechanisms and high capacitance [25]. Gold nanoparticles functionalized with tetrathiafulvalene have shown exceptional potential stability for potassium detection [22], while copper(II) oxide nanoparticles demonstrate favorable temperature resistance when combined with carbon nanotubes in nanocomposite structures [25].

Nanocomposite Materials

Recent research emphasizes nanocomposites that combine multiple material classes to achieve synergistic effects. For instance, combining carbon nanotubes with copper oxide nanoparticles creates a composite with enhanced conductivity, capacitance, and mechanical stability compared to either component alone [25]. Similarly, embedding Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles within MoS₂ nanoflowers prevents structural collapse while increasing electrochemical capacitance [22].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Solid-Contact ISE Development

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function in SC-ISE | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conductive Polymers | PEDOT:PSS, POT, PPer, Polypyrrole [25] [12] | Ion-to-electron transducer (redox mechanism) [23] | Mixed ionic/electronic conductivity, reversible electrochemistry [12] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | MWCNTs, Graphene, Mesoporous Carbon [22] [25] | Ion-to-electron transducer (EDL mechanism) [23] | High surface area, hydrophobicity, electrical conductivity [25] |

| Metal/Metal Oxide NPs | Gold NPs, CuO NPs, Fe₃O₄ NPs [22] [25] | Capacitive intermediate layer | High capacitance, tunable surface chemistry [25] |

| Ionophores | Valinomycin (K⁺), BAPTA derivatives (Ca²⁺) [25] [12] | Selective ion recognition in ISM | High selectivity, sufficient lipophilicity [12] |

| Polymer Matrices | PVC, Acrylic esters, Polyurethane [24] [23] | ISM structural backbone | Mechanical stability, component compatibility [23] |

| Plasticizers | DOS, DBP, NOPE [23] | Adjust ISM mobility and dielectric | High lipophilicity, low volatility [23] |

| Ion Exchangers | NaTFPB, KTPCIPB, KTFPB [23] | Establish permselectivity | Lipophilic salts, Donnan exclusion [23] |

Experimental Protocols for SC-ISE Development and Characterization

Electrode Fabrication Methodology

Protocol 1: Solid-Contact Layer Deposition

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with polished glassy carbon electrodes (GCEs) or screen-printed electrodes. Sequentially polish with alumina suspensions (1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm), followed by thorough rinsing with deionized water and ethanol [25].

- Nanomaterial Dispersion: Prepare dispersions of solid-contact materials (e.g., MWCNTs at 1 mg/mL in DMF with 1-hour ultrasonication) [25].

- Layer Deposition: Apply the dispersion via drop-casting (e.g., 5 µL of MWCNT dispersion) and allow solvent evaporation under ambient conditions or controlled temperature [25].

- Conductive Polymer Electropolymerization: For polymer-based contacts, use electrochemical polymerization from monomer solutions (e.g., 0.01 M 3-octylthiophene in acetonitrile with 0.1 M LiClO₄ as supporting electrolyte) using cyclic voltammetry between appropriate potential limits for multiple cycles [12].

Protocol 2: Ion-Selective Membrane Application

- Membrane Cocktail Preparation: Dissolve membrane components in tetrahydrofuran (THF): PVC (32-33 wt%), plasticizer (65-66 wt%), ionophore (0.5-1.5 wt%), and lipophilic additive (0.5-1 wt%) [25] [23].

- Membrane Deposition: Apply the cocktail via drop-casting (e.g., 50-100 µL per electrode) onto the solid-contact layer and allow THF evaporation for 24+ hours [25].

- Conditioning: Condition the prepared electrodes in a solution of the primary ion (e.g., 0.01 M KCl for potassium ISEs) for 24 hours before use [25].

Potentiometric Characterization Methods

Protocol 3: Calibration and Sensitivity Measurement

- Solution Preparation: Prepare standard solutions of the primary ion across a concentration range (typically 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹ M) with constant ionic strength adjusted using appropriate electrolyte (e.g., 0.01 M MgCl₂ or NaNO₃) [25].

- Measurement Procedure: Measure potential values in order of decreasing concentration, starting with the most diluted solution, under continuous stirring. Record potential once stable (change < 0.1 mV/min) [25].

- Data Analysis: Plot potential versus logarithm of ion activity. Calculate slope from linear regression of the linear region and determine detection limit from intersection of extrapolated linear segments [25].

Protocol 4: Selectivity Coefficient Determination

- Separate Solution Method (SSM): Measure potential in separate solutions each containing only the primary ion (I) or interfering ion (J) at the same activity (e.g., 0.01 M). Calculate selectivity coefficient using: [ \log K{I,J}^{pot} = \frac{(EJ - EI)zF}{RT\ln 10} + \left(1 - \frac{zI}{zJ}\right)\log aI ] where E₁ and E₂ are measured potentials, z is charge, and a is activity [12].

- Fixed Interference Method (FIM): Measure potential in solutions with constant background of interfering ion (e.g., 0.01 M) while varying primary ion concentration. Determine detection limit for primary ion and calculate selectivity coefficient from this value [12].

Protocol 5: Stability and Reproducibility Assessment

- Short-Term Stability: Measure potential in fixed concentration solution over 1-2 hours. Calculate drift as µV/s or µV/h from linear regression of potential versus time [25].

- Long-Term Stability: Perform daily calibrations over 2-4 weeks. Monitor changes in slope, detection limit, and standard potential to assess lifespan [25].

- Temperature Resistance Testing: Perform complete calibrations at different temperatures (e.g., 10°C, 23°C, 36°C) using thermostated measurement cells. Compare slope, detection limit, and potential stability across temperatures [25].

Emerging Applications and Future Perspectives

The evolution to solid-contact ISEs has enabled transformative applications across multiple fields. In clinical medicine, SC-ISEs now facilitate continuous monitoring of electrolytes (K⁺, Na⁺, Ca²⁺) and pharmaceuticals through wearable sensors and point-of-care devices [22] [12]. For biomedical applications, implantable SC-ISEs enable real-time detection of inflammatory markers, such as elevated calcium concentrations around orthopedic implants, allowing early identification of infection [12].

Environmental monitoring benefits from robust, miniaturized SC-ISEs for field deployment, detecting heavy metals (Cu²⁺, Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺), nutrients (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺), and chloride in soil and water samples [22]. Industrial process control employs SC-ISEs for quality assurance and therapeutic drug monitoring, particularly for pharmaceuticals with narrow therapeutic indices [22].

Future development trajectories include advanced manufacturing through 3D printing techniques (FDM, SLA) for customizable, low-cost sensor production [22] [24]. Multifunctional nanocomposites will continue to enhance stability, selectivity, and compatibility with complex sample matrices [25]. The convergence of SC-ISEs with wearable platforms and Internet of Things (IoT) systems will further expand their role in personalized medicine and environmental sensing [22] [23].