Portable Electrochemical Sensing for Pharmaceutical Monitoring: Advances in Point-of-Care Diagnostics and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

This comprehensive review explores the transformative potential of portable electrochemical sensing technologies in pharmaceutical monitoring.

Portable Electrochemical Sensing for Pharmaceutical Monitoring: Advances in Point-of-Care Diagnostics and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the transformative potential of portable electrochemical sensing technologies in pharmaceutical monitoring. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it examines the fundamental principles driving innovation in point-of-care diagnostics, wearable sensors, and decentralized healthcare systems. The article critically analyzes current methodologies including screen-printed electrodes, aptamer-based platforms, and antifouling nanocomposites for detection of pharmaceuticals from paracetamol to controlled substances. It addresses key optimization challenges in specificity, sensitivity, and real-world implementation while providing comparative validation against gold-standard techniques like HPLC and GC-MS. By synthesizing foundational research with practical applications and future perspectives, this work serves as an essential resource for advancing portable pharmaceutical analysis in clinical, forensic, and personalized medicine contexts.

Fundamentals and Emerging Trends in Portable Electrochemical Pharmaceutical Analysis

The Expanding Role of Electrochemical Sensing in Decentralized Healthcare

Electrochemical sensing is revolutionizing decentralized healthcare by enabling rapid, accurate, and on-site analysis of pharmaceutical compounds outside traditional laboratory settings [1]. The rising demand for portable, accessible monitoring technologies has driven significant progress in electrochemical device development, making them ideal tools for ensuring therapeutic effectiveness, drug safety, and patient compliance [1]. These advanced analytical tools are capable of real-time measurement of key parameters, including active pharmaceutical ingredient levels, metabolites, and potential contaminants in various biological and environmental matrices [1]. This expansion aligns with the broader thesis that portable electrochemical sensing represents a transformative approach to pharmaceutical monitoring, particularly for personalized medicine, environmental surveillance, and point-of-care diagnostics in low-resource settings [1] [2].

The transition from conventional laboratory techniques to decentralized electrochemical platforms addresses critical limitations in traditional pharmaceutical monitoring, including lengthy analysis times, complex equipment requirements, and the need for specialized personnel [2]. Modern electrochemical sensors offer high precision, ease of use, affordability, quick analysis, minimal sample requirements, and robust operation across diverse environments from clinical laboratories to remote field settings [1]. This technological shift is particularly significant for therapeutic drug monitoring, where real-time concentration data can inform dosage adjustments and improve treatment outcomes while reducing risks of toxicity or underdosing [1].

Key Technological Advances in Portable Electrochemical Sensing

Device Miniaturization and Materials Innovation

Recent advances in microfabrication techniques have enabled the development of compact, highly sensitive electrochemical platforms suitable for decentralized healthcare applications. Screen printing, inkjet printing, laser ablation, lithography, and three-dimensional (3D) printing have improved the ability to produce precise, reproducible, and scalable sensors tailored for specific pharmaceutical monitoring tasks [1]. These manufacturing approaches have facilitated the miniaturization of electrochemical cells and electrodes, resulting in reduced device size, power consumption, reagent consumption, and sample volume requirements while simultaneously boosting sensitivity and selectivity [1]. Modern portable sensors can achieve detection at very low concentrations, often reaching nanomolar or picomolar levels, making them suitable for monitoring drugs with narrow therapeutic windows [1].

Material science innovations have been equally crucial to advancing portable electrochemical sensing. The exploration of new substrates, coatings, and hybrid materials has significantly improved sensor performance characteristics. Graphene derivatives, conducting polymers (CPs), metallic nanoparticles, and magnetic nanoparticles have demonstrated particular utility in enhancing sensitivity, longevity, and resistance to interfacial degradation phenomena like biofouling [1]. These nanomaterials facilitate improved analyte extraction, enhanced signal amplification, and greater stability in complex biological matrices such as blood, saliva, and urine [1].

Power and Connectivity Integration

The practical deployment of electrochemical sensors in decentralized settings has been accelerated through innovations in autonomous operation and data transmission. The integration of self-powered circuits, including galvanic cells, biofuel cells, and nanogenerators, has expanded applications to remote or decentralized locations, disaster zones, and field conditions without standard power sources [1]. These power solutions enable longer operation times, enhanced portability, and lower logistical demands, which are vital for field use, emergency health response, and humanitarian efforts [1].

Complementing these hardware advances, the evolution of user-friendly mobile applications and cloud systems for data management has further increased accessibility. Wireless communication protocols such as Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, near-field communication (NFC), radio-frequency identification (RFID), and long-range (LoRa) enable real-time data transmission and analytics [1]. This connectivity infrastructure allows non-experts to interpret results accurately and respond quickly, while also facilitating the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) for advanced data analysis and decision support [1].

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Recent Portable Electrochemical Sensors for Pharmaceutical Monitoring

| Analyte Class | Sensor Platform | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Real-World Application | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dihydroxy Benzene Isomers | Polysorbate 80-modified CPE | Not Specified | Not Specified | Environmental tap water monitoring | [3] |

| Pharmaceutical Compounds | Portable Nanomaterial-based Sensors | Nanomolar to Picomolar | Varies by analyte | Therapeutic drug monitoring | [1] |

| Cortisol | Aptamer-based Microfluidic Sensor | Not Specified | Not Specified | Stress biomarker monitoring | [4] |

| Protein Kinase A | Aptamer-functionalized AuNP EIS Chip | Not Specified | Not Specified | Cancer biomarker detection | [4] |

Table 2: Electrochemical Detection Methods and Their Pharmaceutical Applications

| Detection Method | Measurement Principle | Common Electrode Materials | Pharmaceutical Applications | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometric | Current measurement at fixed potential | Glassy carbon, screen-printed carbon | Enzyme-substrate reactions, drug metabolism studies | [5] [4] |

| Voltammetric | Current measurement during potential sweep | Carbon paste, graphene composites | Simultaneous detection of drug isomers, contaminant screening | [3] [5] |

| Potentiometric | Potential measurement at zero current | Ion-selective membranes, FETs | Ion concentration monitoring, pH sensing | [5] |

| Impedimetric | Impedance change measurement | Gold, carbon nanomaterials | Label-free biomolecular interaction studies | [5] [4] |

Experimental Protocols for Pharmaceutical Electrochemical Sensing

Protocol 1: Simultaneous Detection of Dihydroxy Benzene Isomers in Aqueous Samples

Background and Principle: Hydroquinone (HQ) and catechol (CC) are toxic phenolic compounds used as basic feedstocks in pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and plastic industries [3]. These positional isomers coexist in various samples, making their simultaneous detection challenging. This protocol describes the use of a polysorbate 80-modified carbon paste electrode (polysorbate/CPE) to resolve their overlapped oxidation signals through surfactant-mediated enhancement of electron transfer kinetics [3]. The method demonstrates the application of surfactant-modified electrodes to improve electrocatalytic properties, stability, and reproducibility while eliminating surface fouling issues common in complex matrices [3].

Materials and Reagents:

- Graphite powder (≥99.99%, average particle size <45 μM)

- Silicone oil (binder)

- Polysorbate 80 (non-ionic surfactant)

- Hydroquinone (HQ, ≥99%)

- Catechol (CC, ≥99%)

- NaH₂PO₄·2H₂O and Na₂HPO₄ for phosphate buffer (0.2 M, various pH)

- Double distilled water

- Saturated calomel reference electrode (SCE)

- Platinum wire counter electrode

Equipment:

- Electrochemical workstation (e.g., CHI660D)

- Teflon tubes with copper wire contacts

- Smooth paper for electrode polishing

- Standard laboratory glassware

Procedure:

- Bare Carbon Paste Electrode (bare/CPE) Preparation:

- Homogeneously mix graphite powder and silicone oil binder in a 70:30 ratio [3].

- Fill the uniform paste into the end of a Teflon hole and polish on smooth paper.

- Insert copper wire into the Teflon tube for electrical contact.

Polysorbate/CPE Modification:

- Prepare 25.0 mM polysorbate-80 solution in double distilled water.

- Drop cast an optimized volume of polysorbate-80 solution onto the bare/CPE surface.

- Allow to stand for five minutes at room temperature for monolayer formation.

- Rinse gently with distilled water to remove excess polysorbate-80 solution [3].

Electrochemical Measurement:

- Assemble three-electrode system with polysorbate/CPE as working electrode, SCE as reference, and platinum wire as counter electrode.

- Prepare standard solutions of HQ and CC in 0.2 M phosphate buffer (optimal pH 7.0).

- Perform differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) with parameters: potential range 0-0.6 V, pulse amplitude 50 mV, pulse width 50 ms.

- Record well-resolved oxidation peaks for HQ and CC at approximately 0.15 V and 0.25 V, respectively [3].

Sample Analysis:

- Collect tap water samples and filter through 0.45 μm membrane.

- Spike with known concentrations of HQ and CC standards.

- Measure using the established DPV procedure and calculate recovery rates.

Data Analysis:

- Plot calibration curves of peak current versus concentration for both HQ and CC.

- Calculate detection limits using 3σ/slope criteria, where σ is standard deviation of blank measurements.

- Determine recovery percentages for real sample analysis to validate method accuracy.

Protocol 2: Aptamer-Based Microfluidic Sensing for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

Background and Principle: This protocol describes a microfluidic aptasensor platform for label-free therapeutic drug monitoring, exemplifying the integration of miniaturized fluid handling with electrochemical detection for decentralized healthcare applications [4]. The approach utilizes aptamer-functionalized gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) to enhance the net area available for target capture and enable unhindered diffusion of analytes toward the binding surface without requiring labeling, immobilization, or washing processes [4].

Materials and Reagents:

- Glassy carbon electrodes

- Microfluidic chip with nanoslit microwells on glass substrate

- Aptamer-functionalized AuNPs (thiol-modified)

- Target pharmaceutical compound (e.g., cortisol)

- sulfo-NHS and EDC for covalent immobilization

- Supporting electrolyte solution (e.g., phosphate buffer with ascorbic acid)

Equipment:

- Electrochemical workstation with square wave voltammetry capability

- Microfluidic flow control system

- Indium tin oxide (ITO) electrodes for some configurations

Procedure:

- Sensor Fabrication:

- For PEC biosensors: deposit ZnO/graphene (ZnO/G) composite on ITO electrode [4].

- Electrodeposit AuNPs on ZnO/G composite.

- Immobilize thiolated aptamer on AuNP surface via self-assembled monolayer formation.

Microfluidic Integration:

- Integrate working electrode into microfluidic channel.

- Functionalize with amine-terminated aptamer using EDC/sulfo-NHS chemistry to attach to carboxylic groups on electrode surface.

Measurement Protocol:

- Introduce sample containing target pharmaceutical into microfluidic channel.

- Allow binding reaction to proceed for optimized incubation time.

- Apply square wave voltammetry (SWV) by scanning working electrode potential in positive direction (-0.5 to -1.2 V range) with frequency of 100 Hz [4].

- Monitor current changes resulting from aptamer-target binding.

Data Interpretation:

- For impedimetric sensors: measure impedance changes before and after target binding.

- For conductometric sensors: calculate resistance change (ΔR/R₀) where ΔR is difference in resistance after incubation and R₀ is original resistance.

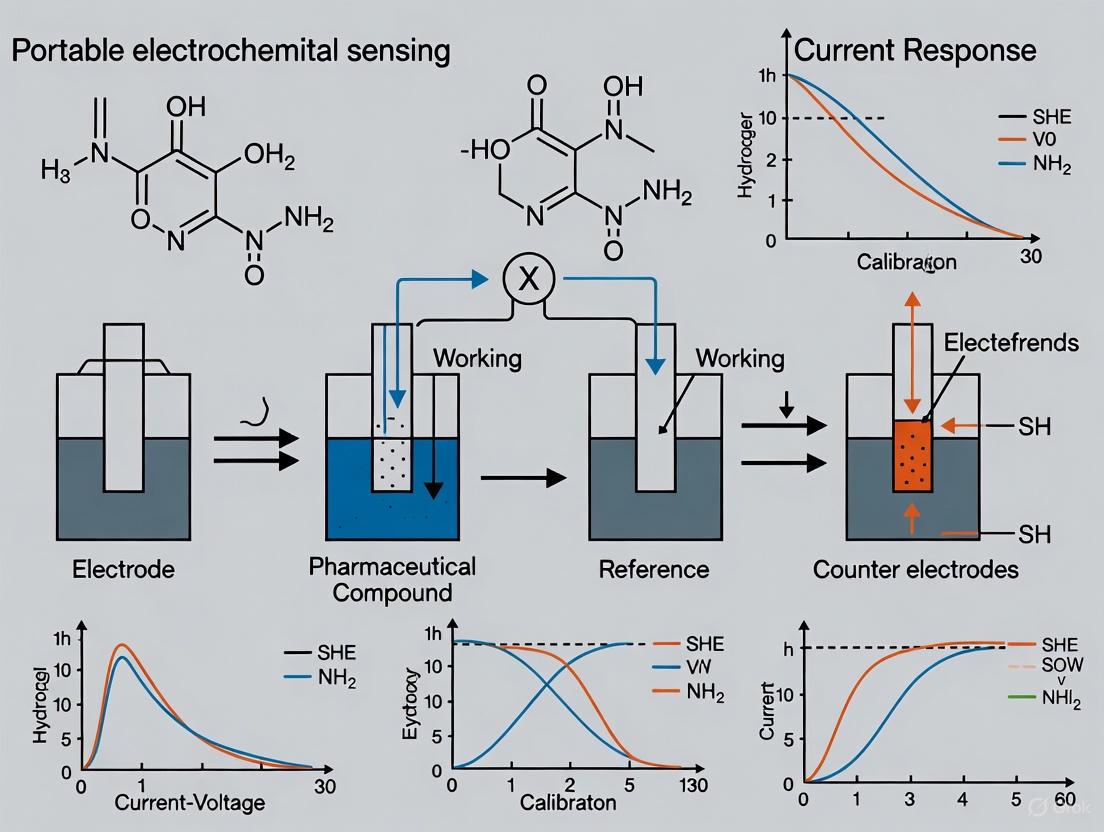

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The operational principles of electrochemical pharmaceutical sensing involve well-defined signaling pathways and experimental workflows that can be visualized to enhance understanding of the underlying mechanisms. The following diagrams illustrate key processes in portable electrochemical sensing systems.

Diagram 1: Electrochemical Sensing Signaling Pathway

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Sensor Preparation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of electrochemical sensing protocols for pharmaceutical monitoring requires specific reagents and materials optimized for decentralized healthcare applications. The following table details essential components of the research toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmaceutical Electrochemical Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications | Key References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Paste | Working electrode substrate for facile modification | Graphite powder:silicone oil (70:30 ratio) | [3] |

| Surfactant Modifiers | Enhance electron transfer, prevent fouling | Polysorbate 80, CTAB (ionic and non-ionic surfactants) | [3] |

| Nanomaterial Enhancers | Signal amplification, increased surface area | Graphene derivatives, metallic nanoparticles, magnetic nanoparticles | [1] |

| Biological Recognition Elements | Target-specific binding | Aptamers, enzymes, antibodies, molecularly imprinted polymers | [1] [2] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain optimal pH, ionic strength | Phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 7.0), supporting electrolytes | [3] |

| Microfluidic Components | Miniaturized fluid handling, sample processing | Glass chips with nanoslit microwells, PDMS channels | [4] |

| Reference Electrodes | Stable potential reference | Saturated calomel electrode (SCE), Ag/AgCl | [3] |

| Abt-072 | Abt-072, CAS:1132936-00-5, MF:C24H27N3O5S, MW:469.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| AS1708727 | AS1708727, MF:C24H24Cl2N2O2, MW:443.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Electrochemical sensing has fundamentally expanded capabilities for decentralized healthcare by providing robust, sensitive, and portable platforms for pharmaceutical monitoring. The integration of advanced materials, miniaturization strategies, self-powered systems, and intelligent data analytics has transformed these technologies from laboratory curiosities to practical tools for real-world applications [1]. The experimental protocols and technical approaches detailed in these application notes provide researchers with validated methodologies for implementing electrochemical sensing in diverse contexts, from environmental monitoring of pharmaceutical contaminants to point-of-care therapeutic drug monitoring [3] [4].

Despite remarkable advances, the full potential of electrochemical sensing in decentralized healthcare requires continued addressing of practical challenges, including long-term stability in complex biological matrices, scalability of manufacturing processes, regulatory alignment, and demonstration of cost-effectiveness in real-world settings [1]. Future developments will likely focus on enhancing multi-analyte detection capabilities, improving connectivity with healthcare information systems, developing more robust antifouling materials, and creating increasingly autonomous operation through advanced power solutions [1]. As these technological innovations mature, electrochemical sensing is poised to become an indispensable component of decentralized healthcare infrastructure, ultimately improving pharmaceutical safety, therapeutic outcomes, and accessibility across diverse healthcare settings.

Electrochemical sensors have emerged as powerful analytical tools for the detection of pharmaceutical compounds, including anti-inflammatory drugs, antibiotics, and key disease biomarkers [6]. Their operational principle involves converting a specific biological or chemical interaction into a quantifiable electrical signal, such as current, potential, or impedance [7]. This detection paradigm is particularly suited for point-of-care (POC) diagnostics due to its inherent compatibility with miniaturization, portability, and rapid analysis [8] [6]. The growing demand for decentralized healthcare solutions is fueling the expansion of the POC diagnostics market, which is projected to reach $25 billion by 2031 [9]. This application note details the key advantages of these sensing platforms—rapid diagnostics, cost-effectiveness, and point-of-care deployment—and provides standardized protocols for their implementation in pharmaceutical monitoring and drug development research.

Key Advantages and Quantitative Performance Metrics

Rapid Diagnostic Capabilities

The primary advantage of electrochemical sensors is their significantly reduced time-to-result compared to traditional laboratory methods. Conventional techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry, while highly accurate, are constrained by labor-intensive workflows, extended processing times, and the need for specialized laboratory infrastructure [10] [6]. In contrast, electrochemical platforms can provide results in minutes, enabling swift clinical decision-making [11]. For instance, POC blood gas analyzers can deliver critical results for electrolytes and lactate in approximately 4.5 minutes, a pace that nearly equals or even surpasses central laboratory turnaround times in real-world settings [11]. This speed is crucial in critical care and emergency departments, where rapid diagnostic turnaround has been shown to reduce patient length of stay and improve outcomes [11]. The integration of advanced nanomaterials like graphene and carbon nanotubes further amplifies electron transfer kinetics, enabling sub-nanomolar detection limits for biomarkers such as tryptophan, which is relevant in cancer and neurodegenerative disease diagnostics [10].

Cost-Effectiveness and Operational Efficiency

Electrochemical sensing platforms offer substantial economic benefits across the healthcare spectrum. A key driver of cost reduction is the decreased reliance on centralized laboratories, which lowers overhead associated with specialized equipment and personnel [11]. Studies have demonstrated that the implementation of POC diagnostic platforms in ambulatory settings can lead to a 21% reduction in the number of tests ordered per patient and a remarkable 89% decline in follow-up phone calls, optimizing clinical operations [11]. From a direct cost perspective, one study found that a standard panel of diagnostic tests cost $9.93 more per patient when performed using traditional methods compared to POC systems [11]. The analytical components themselves are also cost-effective; screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), which are often mass-producible and single-use, minimize reagent consumption and eliminate the need for costly cleaning procedures [8] [6].

Point-of-Care Deployment and Accessibility

The form factor and operational simplicity of modern electrochemical sensors make them ideal for deployment at the point of care, which includes bedside monitoring in hospitals, clinics, and even patient homes [8] [11]. This decentralization of testing enhances patient access to quality diagnostics, particularly in remote or underserved regions [11]. Technological advancements have led to the development of ready-to-use portable devices, wearable patches, and smartphone-integrated sensing platforms that empower non-specialists to conduct sophisticated analyses [8]. The use of small sample volumes (e.g., a single drop of blood) is a significant advantage, especially in pediatric care where repeated phlebotomy can lead to significant blood loss [11]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) algorithms is augmenting the capabilities of these decentralized systems by improving signal-to-noise ratios, deconvoluting complex data, and enabling real-time, data-driven clinical decisions [10] [7].

Table 1: Quantitative Market and Performance Metrics for Rapid Diagnostic Platforms

| Metric Category | Specific Parameter | Value or Projection | Source/Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Market Analysis | Global POC Diagnostics Market (2031) | $25 Billion | [9] |

| Global Rapid Diagnostics Market (2032) | $24.28 Billion | [12] | |

| Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) | 6.6% - 9.7% | [9] [12] | |

| Performance Speed | POC Blood Gas Analysis Turnaround | ~4.5 minutes | [11] |

| Abbott ID NOW COVID-19 Assay (Positive) | 6 minutes | [11] | |

| Reduction in Hospital Length of Stay with POC CRP | 30 minutes (19%) | [11] | |

| Economic Impact | Cost Savings per Test Panel (POC vs. Standard) | $9.93 | [11] |

| Reduction in Tests Ordered per Patient | 21% | [11] | |

| Reduction in Follow-up Phone Calls | 89% | [11] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Fabrication and Pharmaceutical Detection

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Nanomaterial-Modified Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE)

This protocol describes the modification of a carbon-based Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) with a nanocomposite to enhance sensitivity and selectivity for pharmaceutical analysis [10] [6].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Carbon-based Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs)

- Graphene oxide (GO) or multi-walled carbon nanotube (MWCNT) dispersion (1 mg/mL in DMF)

- Metal nanoparticle solution (e.g., 1 mM HAuClâ‚„ for gold nanoparticles)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 0.1 M, pH 7.4

- Target-specific recognition element (e.g., aptamer, antibody, or molecularly imprinted polymer)

- EDC/NHS crosslinking reagents (for bioreceptor immobilization)

2. Equipment:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Analytical balance

- Ultrasonic bath

- Micro-pipettes

- Vortex mixer

- Oven or drying rack at 40 °C

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: Step 1: Electrode Pre-treatment

- Condition the bare SPE by performing 10 cycles of Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) from -0.2 V to +0.6 V at a scan rate of 50 mV/s.

- Rinse the electrode gently with deionized water and dry under a stream of nitrogen gas.

Step 2: Nanomaterial Modification

- Dilute the GO/MWCNT dispersion to 0.5 mg/mL in a 1:1 water/ethanol solution and sonicate for 30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension.

- Using a micro-pipette, drop-cast 5 µL of the nanomaterial suspension onto the working electrode surface.

- Allow the electrode to dry in a controlled environment at 40 °C for 1 hour.

Step 3: Functionalization with Recognition Element

- Prepare a 1 µM solution of the aptamer or antibody in 0.1 M PBS.

- If using covalent immobilization, activate the nanomaterial surface by applying a mixture of 10 µL EDC (400 mM) and NHS (100 mM) for 30 minutes.

- Rinse the electrode with PBS to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Drop-cast 5 µL of the bioreceptor solution onto the modified working electrode and incubate in a humid chamber for 2 hours at room temperature.

- Rinse thoroughly with PBS to remove any physisorbed molecules.

Step 4: Storage

- Store the fabricated sensor at 4 °C in a dry environment until use.

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Detection of an Anti-inflammatory Drug using Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

This protocol outlines the quantitative detection of a model nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), such as diclofenac or ibuprofen, using the modified SPE from Protocol 1 [6].

1. Reagents and Materials:

- Fabricated nanomaterial-modified SPE (from Protocol 1)

- Standard stock solution of the target NSAID (e.g., 1 mM in methanol)

- Acetate or phosphate buffer (0.1 M, optimal pH for the target drug)

- Synthetic urine or spiked serum samples for validation

2. Equipment:

- Potentiostat connected to a computer

- SPE connector

- Micro-pipettes

- Volumetric flasks and beakers

3. Step-by-Step Procedure: Step 1: Preparation of Standard Solutions

- Prepare a series of standard solutions of the target NSAID by serial dilution of the stock solution in the selected 0.1 M buffer. The concentration range should typically cover from 0.1 µM to 100 µM.

Step 2: Instrument Parameter Setup

- Configure the DPV method on the potentiostat with the following typical parameters:

- Potential window: Optimized for the drug's oxidation potential (e.g., 0.0 to +1.0 V).

- Modulation amplitude: 50 mV.

- Pulse width: 50 ms.

- Scan rate: 10 mV/s.

Step 3: Calibration and Sample Measurement

- Place a 50 µL drop of the blank buffer solution onto the sensor's electrochemical cell.

- Run the DPV method to record a background scan.

- For each standard and sample, place a 50 µL drop on the sensor and run the DPV method.

- Rinse the electrode thoroughly with deionized water between each measurement.

- Record the peak current value for each concentration.

Step 4: Data Analysis

- Plot a calibration curve of peak current (µA) versus analyte concentration (µM).

- Perform a linear regression analysis. The limit of detection (LOD) can be calculated as 3σ/slope, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank signal.

- Use the resulting calibration equation to determine the concentration of the target drug in unknown samples.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Electrochemical Sensor Operational Workflow

Technology Synergy Driving Key Advantages

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Sensor Development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized electrochemical cell. | Mass-producible, portable, integrable with portable potentiostats. [8] [6] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (Graphene, CNTs) | Electrode nanomodifiers. | High surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, enhance electron transfer. [10] [6] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic biorecognition elements. | High stability, target-specific cavities, robust in various conditions. [10] |

| Aptamers | Biorecognition elements. | Single-stranded DNA/RNA oligonucleotides, high affinity and specificity for targets. [10] |

| Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Pt, Co) | Electrode nanomodifiers and catalysts. | Catalyze redox reactions, lower overpotential, amplify signal. [10] |

| Portable Potentiostat | Instrument for applying potential and measuring current. | Compact, battery-operated, often with Bluetooth/Wi-Fi for data transfer. [8] |

| AS2863619 | AS2863619, MF:C16H14Cl2N8O, MW:405.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Asciminib | Asciminib|CAS 1492952-76-7|ABL Myristoyl Pocket Inhibitor | Asciminib is a potent, allosteric BCR-ABL1 inhibitor for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and not for human consumption. |

The paradigm for drug monitoring is shifting from centralized laboratories to decentralized, point-of-need testing, driven by significant advances in portable electrochemical sensing. These technologies enable rapid, sensitive, and quantitative analysis of both therapeutic and illicit substances across diverse matrices, including blood, saliva, urine, and environmental samples. This application note details the current technological landscape, provides validated experimental protocols for the development and use of these sensors, and discusses their application in clinical and forensic settings. The integration of advanced materials, self-powered systems, and data analytics is framed within the broader context of enhancing therapeutic efficacy, ensuring patient safety, and supporting public health initiatives.

The rising demand for portable, accurate, and accessible drug monitoring technologies is being met by remarkable advances in electrochemical device development [1]. These tools are capable of real-time measurement of active pharmaceutical ingredients, metabolites, and contaminants in various matrices, which is critical for ensuring therapeutic effectiveness, drug safety, patient compliance, and regulatory standards [1]. The convergence of device miniaturization, the use of novel nanomaterials, and the integration of intelligent data analytics is paving the way for powerful diagnostic systems that can be deployed from the clinic to the field [1] [8].

This document provides a structured overview of the current landscape, covering key technologies, detailed experimental protocols, and essential research reagents. It is designed to equip researchers and scientists with the practical knowledge to develop and implement portable electrochemical sensing solutions for comprehensive drug monitoring.

Current Technologies in Portable Electrochemical Sensing

Portable electrochemical sensors are ideal for decentralized analysis due to their high precision, ease of use, affordability, quick analysis, and minimal sample requirements [1]. Recent progress has been concentrated in several key areas.

Device Architectures and Materials

The core of this revolution lies in the design of the sensing interfaces. Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) have become a cornerstone technology, enabling low-cost, mass-producible, and disposable sensors [13] [8]. The sensitivity and selectivity of these platforms are dramatically enhanced through modification with conductive nanomaterials.

Table 1: Key Nanomaterials and Their Functions in Electrochemical Sensors

| Material Class | Example | Primary Function | Demonstrated Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Derivatives | Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Flake Graphite [13] | Increase electroactive surface area; enhance electron transfer kinetics [13] | Ofloxacin detection in urine [13] |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [13] | Catalyze reactions; improve conductivity and signal amplification [13] | Metronidazole in milk/water [13] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Ce-BTC MOF, ZIF-67 [13] | Provide high surface area and tunable porosity for selective analyte capture [13] [14] | Ketoconazole in pharmaceuticals/urine [13] |

| Conducting Polymers | Poly(eriochrome black T), PEDOT:PSS [13] [15] | Act as both conductive matrix and selective recognition element [13] [15] | Methdilazine hydrochloride detection [13] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Duplex MIP [13] | Create synthetic, antibody-like cavities for highly specific target binding [13] | Azithromycin in serum/urine [13] |

System Integration and Readout

Modern systems integrate the electrochemical cell with miniaturized potentiostats and user-friendly interfaces for real-time data visualization [1]. A prominent trend is coupling sensors with smartphones, which serve as powerful processors for controlling experiments, capturing data, and visualizing results [1] [8]. Furthermore, the development of self-powered systems—utilizing galvanic cells, biofuel cells, or nanogenerators—is expanding applications to remote, resource-limited, and field settings without access to standard power sources [1].

Experimental Protocols

The following protocols provide a foundational methodology for developing and utilizing modified carbon-based electrodes for pharmaceutical analysis.

Protocol: Fabrication of a Modified Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE)

This protocol outlines the procedure for creating a carbon paste electrode modified with conductive materials, such as flake graphite and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), for the detection of drugs like ofloxacin [13].

Principle: The conductive modifiers significantly increase the electroactive surface area and enhance electron transfer kinetics, leading to lower detection limits and higher sensitivity.

Materials & Reagents:

- Graphite powder

- Paraffin oil

- Flake graphite (FG)

- Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs)

- Mortar and pestle

- Electrode body (e.g., Teflon tube with a copper wire contact)

- Ofloxacin standard

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

Procedure:

- Preparation of Modified Carbon Paste:

- In a mortar, thoroughly mix 70% (w/w) graphite powder with 10% flake graphite and 5% MWCNTs.

- Add 15% (w/w) paraffin oil as a binding agent and mix until a homogeneous, waxy paste is formed.

- Electrode Packing:

- Pack the resulting modified paste firmly into the cavity of a Teflon tube electrode body.

- Insert a copper wire into the back of the paste to establish an electrical connection.

- Smooth the electrode surface by polishing on a clean sheet of paper until a shiny surface is achieved.

- Electrochemical Measurement (Square-Wave Adsorptive Anodic Stripping Voltammetry, SW-AdASV):

- Prepare a standard or sample solution containing ofloxacin in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4).

- Immerse the modified CPE, along with a platinum wire counter electrode and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, in the solution.

- Apply an accumulation potential (e.g., -0.4 V) for 60 seconds while stirring to pre-concentrate the analyte on the electrode surface.

- After a 10-second equilibration period, record the square-wave voltammogram by scanning from +0.8 V to +1.3 V.

- The oxidation peak current for ofloxacin will be observed at approximately +1.1 V. The peak current is proportional to the concentration of ofloxacin in the solution.

Protocol: Drug Detection Using a Smartphone-Based Potentiostat

This protocol describes the use of a commercial or custom-built smartphone-controlled potentiostat for quantitative drug analysis, enabling true point-of-care testing.

Principle: A screen-printed electrode, often modified with specific recognition elements, is connected to a miniaturized potentiostat that communicates with a smartphone app. The app controls the electrochemical parameters and visualizes the results in real-time [1] [8].

Materials & Reagents:

- Smartphone with dedicated electrochemical sensing application

- Miniaturized potentiostat (e.g., connected via Bluetooth)

- Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE), modified or unmodified

- Analyte standard (e.g., glucose, paracetamol)

- Buffer solution

Procedure:

- System Setup:

- Launch the sensing application on the smartphone and establish a connection with the portable potentiostat via Bluetooth.

- Insert the SPCE into the port on the potentiostat.

- Sample Preparation and Loading:

- Prepare a standard or sample solution (e.g., diluted serum, urine, or dissolved pharmaceutical tablet) in an appropriate buffer.

- Pipette a small volume (e.g., 50-100 µL) of the solution onto the active surface of the SPCE, covering both the working and reference electrodes.

- Method Selection and Data Acquisition:

- Select the desired electrochemical technique from the app's interface (e.g., Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) or Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)).

- Initiate the measurement. The app will send instructions to the potentiostat to apply the predefined potential sequence.

- The resulting current will be measured by the potentiostat and transmitted back to the smartphone.

- Data Analysis and Visualization:

- The smartphone application will display the voltammogram in real-time (e.g., current vs. potential plot).

- The app may automatically calculate and display the analyte concentration based on a pre-loaded calibration curve.

The workflow for this protocol is logically structured in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful development of portable electrochemical sensors relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Sensor Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Example | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Substrates | Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCEs), Glassy Carbon Electrodes (GCEs), Carbon Paste Electrodes (CPEs) [13] | Provide a versatile, low-cost, and solid conductive foundation for constructing the sensor. |

| Conductive Modifiers | Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs), Graphene Oxide, Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) [13] | Enhance sensitivity and electron transfer rate. Increase the effective surface area of the electrode. |

| Recognition Elements | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), Enzymes (e.g., Horseradish Peroxidase), Antibodies [13] [16] | Impart high specificity and selectivity for the target analyte, reducing interference. |

| Binding Matrices | Ionic Liquids (ILs), Nafion, Chitosan [13] | Stabilize and improve the adhesion of modifiers to the electrode surface. Can also aid in selectivity. |

| Signal Probes | Ferricyanide, Methylene Blue [1] | Used as redox mediators to facilitate electron transfer in certain sensing schemes, improving signal strength. |

| Ascorbyl Palmitate | Ascorbyl Palmitate, CAS:137-66-6, MF:C22H38O7, MW:414.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| TC Ask 10 | TC Ask 10, MF:C21H23Cl2N5O, MW:432.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Applications and Quantitative Performance

The utility of these sensors is demonstrated by their performance in detecting a wide range of analytes in complex samples.

Table 3: Performance Metrics of Selected Portable Electrochemical Sensors

| Analytic (Matrix) | Sensor Architecture | Detection Method | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ofloxacin (Pharmaceuticals, Urine) | [10%FG/5%MW] CPE | SW-AdAS | 0.60 to 15.0 nM | 0.18 nM | [13] |

| Ketoconazole (Pharmaceuticals, Urine) | Ce-BTC MOF/IL/CPE | DPV, Chronoamperometry | 0.1-110.0 µM | 0.04 µM | [13] |

| Azithromycin (Urine, Serum) | MIP/CP ECL Sensor | ECL | 0.10-400 nM | 0.023 nM | [13] |

| Methdilazine HCl (Syrup, Urine) | poly(EBT)/CPE | SWV | 0.1-50 µM | 0.0257 µM | [13] |

| Metronidazole (Milk, Tap Water) | AgNPs@CPE | Not Specified | 1-1000 µM | 0.206 µM | [13] |

| Sulfamethoxazole (Urine, Water) | Fe₃O₄/ZIF-67 /ILCPE | DPV | 0.01-520.0 µM | 5.0 nM | [13] |

Portable electrochemical sensors have profoundly advanced the field of drug monitoring by enabling rapid, sensitive, and decentralized analysis [1]. The transition from laboratory prototypes to real-world applications, however, faces challenges related to long-term stability in complex biological matrices, scalability of manufacturing, and navigating regulatory pathways [1]. Future development will be shaped by the deeper integration of autonomous, self-powered systems [1] and sophisticated data-driven analytics, including artificial intelligence and machine learning, to process complex electrochemical data and improve accuracy [1]. As these technologies mature, they hold the undeniable potential to transform personalized medicine, environmental surveillance, and forensic science, making precise chemical analysis accessible anywhere.

Portable electrochemical sensing is revolutionizing pharmaceutical monitoring by enabling rapid, sensitive, and decentralized analysis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), metabolites, and potential contaminants in various biological and environmental matrices [1]. The core functionality of these sensors hinges on the sophisticated interplay between three fundamental components: the electrode material, the signal transduction mechanism, and the subsequent signal processing. Advances in microfabrication, nanomaterials, and data analytics have propelled the development of compact, autonomous, and intelligent sensing platforms suitable for point-of-care diagnostics, environmental surveillance, and therapeutic drug monitoring [1] [8]. These Application Notes provide a detailed overview of the core principles, supported by structured data and experimental protocols, to guide researchers and scientists in the design and implementation of these sensors within pharmaceutical research.

Core Principles and Component Analysis

Electrode Materials and Their Properties

The working electrode serves as the cornerstone of any electrochemical sensor, and its material composition directly dictates the sensor's analytical performance, including sensitivity, selectivity, and stability. Recent research focuses on novel materials and nanocomposites to enhance these properties.

Table 1: Key Electrode Materials for Pharmaceutical Electrochemical Sensing

| Material Class | Specific Examples | Key Properties | Impact on Sensor Performance | Typical Applications in Pharma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Graphene, Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) [17] [18] | High electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, good biocompatibility | Enhances electron transfer kinetics and sensitivity; MWCNTs showed superior capacitance and low potential drift in SC-ISEs [18] | Detection of venlafaxine [18], various biomarkers [17] |

| Conducting Polymers | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene):Poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS), Polyaniline (PANi) [19] [18] | Mixed ionic-electronic conduction, volumetric charging, biocompatibility | Serves as both transducer and catalyst; enables ion-to-electron transduction in solid-contact ISEs and OECTs [18] [19] | OECT-based aptasensors [19], ion-selective electrodes [18] |

| Novel 2D Materials | MXene, Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (TMDs), Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [17] [20] | Ultra-high surface-to-volume ratio, tunable electronic properties, high porosity | Increases electroactive surface area; allows for pre-concentration of analytes, boosting signal amplification [17] | Glucose sensing (Ni-MOF) [17], chloramphenicol detection (Cr-MOF) [17] |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Magnetic Nanoparticles [1] | Excellent electrocatalytic properties, facilitate easy functionalization | Used to modify electrode surfaces, improving catalytic activity and immobilization of biorecognition elements [1] | Nanobiosensor development [1] |

Signal Transduction Mechanisms

Transduction mechanisms convert the biological or chemical recognition event into a quantifiable electrical signal. The choice of mechanism depends on the nature of the recognition element and the target analyte.

Table 2: Common Electrochemical Transduction Mechanisms

| Transduction Mechanism | Measured Quantity | Principle | Advantages | Common Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amperometry / Voltammetry | Current | Measurement of current resulting from the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive species at a constant or varying potential. | High sensitivity, wide linear range, suitability for miniaturization | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) [1] [21] [19] |

| Potentiometry | Potential | Measurement of the potential difference between working and reference electrodes under conditions of zero current. | High selectivity for specific ions, simple instrumentation | Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs), Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) [18] |

| Impedimetry | Impedance (Resistance & Reactance) | Measurement of the opposition to current flow when a small amplitude AC potential is applied across the electrode interface. | Label-free detection, capable of monitoring binding events in real-time | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [22] [18] |

| Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) | Light Intensity | Measurement of light emitted from electrochemically generated excited-state species during a redox reaction. | Very low background signal, high sensitivity, and good temporal/spatial control [23] | ECL with luminol or Ru(bpy)₃²⺠systems [23] |

| Transistor-Based | Current Modulation | Use of a transistor (e.g., OECT) where the current flowing in the channel is modulated by a gate potential tied to the sensing event. | Inherent signal amplification, high transconductance, suitable for complex fluids [19] | Organic Electrochemical Transistors (OECTs) [19] |

Advanced Signal Processing and Data Analytics

The raw signal from the transducer is processed to extract meaningful analytical information. For portable sensors, this often involves integration with digital systems.

- Chemometrics: Multivariate data analysis tools such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) and Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression are indispensable for processing complex, high-dimensional electrochemical data, enabling robust calibration and interpretation in the presence of interfering species in biological matrices [1].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) and other machine learning algorithms are increasingly used for pattern recognition, enhancing the accuracy and selectivity of the sensors. They facilitate real-time decision-making in point-of-care settings [1].

- Mobile and Cloud Integration: User-friendly mobile applications and cloud systems allow for real-time data visualization, management, and analytics. Wireless communication protocols like Bluetooth and Wi-Fi enable the transmission of data from the sensor to a smartphone or central server, increasing accessibility for non-experts [1].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication and Testing of a Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrode (SC-ISE)

This protocol outlines the development of a SC-ISE for the determination of an antidepressant drug, venlafaxine, based on a comparison of transduction materials [18].

1. Apparatus and Reagents:

- Apparatus: Potentiometer (e.g., Jenway 3510 pH/mV meter), double-junction Ag/AgCl reference electrode, screen-printed carbon electrodes as the substrate.

- Reagents: High molecular weight PVC, plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE), ionophore or ion-pair (VEN-TPB−), tetrahydrofuran (THF), transduction materials (MWCNTs, PANi, ferrocene), venlafaxine hydrochloride standard, phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 6.0).

2. Ion-Pair (VEN-TPB−) Preparation: - Mix 10 mL of 10â»Â² mol/L VEN solution with 10 mL of 10â»Â¹ mol/L sodium tetraphenylborate (NaTPB) solution. - A white precipitate of VEN-TPB− ion-pair will form. Wash the precipitate multiple times with deionized water using centrifugation. Dry the product under ambient conditions [18].

3. Sensor Fabrication: - Transducer Layer Deposition: Disperse 2 mg of transduction material (e.g., MWCNTs) in 1 mL of solvent (e.g., DMF). Deposit 5-10 µL of this dispersion onto the screen-printed working electrode and allow it to dry. - Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Cocktail Preparation: In a glass vial, mix thoroughly the following components: - 150 mg o-NPOE (plasticizer, ~66% w/w) - 75 mg PVC (polymer matrix, ~33% w/w) - 2.5 mg VEN-TPB− ion-pair (active recognition element, ~1.1% w/w) - Dissolve the mixture in 1.5 mL of THF. - Membrane Deposition: Cast 5-10 µL of the ISM cocktail onto the previously modified transducer layer. Allow the THF to evaporate overnight, forming a uniform polymeric membrane [18].

4. Potentiometric Measurement and Characterization: - Conditioning: Soak the newly fabricated SC-ISE in a 10â»Â³ mol/L VEN solution for 24 hours. - Calibration: Measure the electromotive force (EMF) of the SC-ISE in a series of VEN standard solutions (e.g., from 10â»â· to 10â»Â² mol/L) prepared in phosphate buffer (pH 6.0). Plot EMF vs. log[VEN] to obtain the calibration slope, linear range, and detection limit. - Electrochemical Characterization: - Chronopotentiometry (CP): Apply a constant current of ±1 nA for 60 s to evaluate the potential drift and calculate the capacitance of the sensor. - Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Perform EIS in a frequency range from 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz at open-circuit potential to assess the bulk resistance (R₆) and double-layer capacitance (C_dl) [18].

Protocol: OECT-Amplified Aptamer-Based Sensor for Protein Detection

This protocol describes the integration of an OECT with an electrochemical aptamer-based (E-AB) sensor to achieve significant signal amplification for detecting proteins like Transforming Growth Factor Beta 1 (TGF-β1) [19].

1. Device Fabrication (Monolithic Integration): - Use multi-step photolithography, vapor deposition, and etching to pattern the following on a single substrate: - Au working electrodes: Functionalize with thiol-modified aptamers. - On-chip Ag/AgCl reference electrode. - PEDOT:PSS counter electrode: This also serves as the channel of the OECT. Define interdigitated drain and source electrodes (with high W/L ratio) beneath the PEDOT:PSS layer [19].

2. Aptamer Functionalization: - Incubate the Au working electrode with a solution of aptamers specific to TGF-β1, which are modified with a thiol group on one end for anchoring to gold and a redox reporter (e.g., methylene blue) on the other end. - Backfill with a passivating alkanethiol (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol) to minimize non-specific adsorption [19].

3. Sensor Operation and Measurement: - Traditional E-AB Mode: Perform Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) using the Au electrode (working), on-chip Ag/AgCl (reference), and PEDOT:PSS (counter). Monitor the change in redox peak current as a function of TGF-β1 concentration. - ref-OECT Amplification Mode: Simultaneously with the SWV measurement, apply a constant drain voltage (Vₚₛ) to the OECT. Monitor the change in drain current (ID) as the ionic current from the working electrode (gate current, IG) modulates the doping level and conductivity of the PEDOT:PSS channel. The I_D response will be amplified by 3-4 orders of magnitude compared to the bare E-AB sensor current [19].

Protocol: 3D-Printed Multiplexed Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Sensor

This protocol covers the fabrication and use of a low-cost, 3D-printed ECL sensor for simultaneous detection of glucose and lactate [23].

1. Sensor Fabrication via 3D Printing: - Printer: Use a dual-extrusion fused deposition modeling (FDM) 3D printer. - Materials: Conductive carbon-loaded polylactic acid (PLA) filament and standard white PLA filament. - Design and Printing: Print the sensor body with the white PLA. Simultaneously, print the interdigitated electrodes (IDEs) using the conductive carbon-PLA directly into the sensor body. The IDE design should feature multiple pairs of fingers (e.g., 6 pairs with 0.5 mm width and 0.5 mm spacing) to enhance signal via redox cycling. - Post-processing: Polish the electrode surfaces lightly with fine-grit sandpaper to improve conductivity [23].

2. Enzyme Immobilization: - Prepare separate solutions of Glucose Oxidase (GOx) and Lactate Oxidase (LOx) in a suitable buffer. - Deposit the GOx solution into one designated reaction well and the LOx solution into an adjacent well on the IDE platform. Allow the enzymes to adsorb and dry.

3. ECL Measurement and Smartphone Readout: - Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing luminol (e.g., 1-7 mM) in a basic buffer (e.g., with 0.1 M NaOH). - Measurement: Add the sample (or standard) containing glucose and lactate to the sensor wells. Apply an optimized DC voltage (e.g., using a portable DC-DC converter) to the IDEs. - Detection: The enzymatic reaction produces Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚, which reacts with luminol under electrochemical stimulation to emit light. Capture the emitted light using a smartphone camera placed in a dark box. The intensity of the ECL signal is proportional to the analyte concentration [23].

Visualization of Core Concepts

Signaling Pathway of an Electrochemical Aptasensor with OECT Amplification

Workflow for Solid-Contact ISE Development and Characterization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Portable Pharmaceutical Electrochemical Sensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function / Role | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Loaded PLA Filament | Conductive filament for 3D printing customized electrode architectures [23]. | Enables rapid, low-cost fabrication of sensors with complex geometries like interdigitated electrodes (IDEs). |

| PEDOT:PSS | Conducting polymer used as a transduction layer or as the active channel in OECTs [19]. | Provides high capacitance and mixed ionic-electronic conduction for signal amplification. |

| Nucleic Acid Aptamers | Biorecognition elements with high specificity and stability; can be functionalized with redox reporters and thiol groups [19] [1]. | Used in E-AB sensors for targets from small molecules to proteins; offer tunable binding properties. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous 2D nanomaterials with ultra-high surface area for electrode modification [17] [20]. | Pre-concentrate analytes at the electrode surface, significantly enhancing sensitivity (e.g., in glucose sensing). |

| Luminol | An ECL luminophore that emits light upon electrochemical oxidation in the presence of a coreactant (e.g., Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) [23]. | Core reagent in ECL sensors; enables highly sensitive detection with low background noise. |

| Ion-Selective Membrane Components (PVC, o-NPOE, Ionophores) | Form the selective sensing layer in potentiometric sensors like SC-ISEs [18]. | The composition determines selectivity, sensitivity, and lifespan of the ion-selective electrode. |

| Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) Chips | Disposable, miniaturized platforms integrating working, reference, and counter electrodes [18] [8]. | Provide a reproducible and mass-producible base for building various types of electrochemical sensors. |

| Gusacitinib | Gusacitinib, CAS:1425381-60-7, MF:C24H28N8O2, MW:460.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Clofutriben | Clofutriben, CAS:1204178-50-6, MF:C19H16ClF3N4O2, MW:424.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Emerging Trends in Wearable and Smartphone-Integrated Sensing Platforms

The field of pharmaceutical monitoring and clinical research is undergoing a significant transformation, driven by advancements in portable sensing technologies. The convergence of wearable sensors and smartphone-integrated platforms is creating new paradigms for decentralized, real-time data collection. These technologies enable continuous physiological monitoring outside traditional laboratory settings, providing richer data sets for drug development professionals and clinical researchers [24] [25]. This shift is particularly relevant for portable electrochemical sensing, which is emerging as a powerful tool for therapeutic drug monitoring, adherence tracking, and personalized medicine applications [1].

Framed within the broader context of a thesis on portable electrochemical sensing for pharmaceutical research, these application notes detail the practical implementation, experimental protocols, and key considerations for leveraging these integrated platforms. The global digital health market, projected to surpass $900 billion by 2030, underscores the immense potential and growing adoption of these connected technologies in clinical trials and healthcare delivery [26].

Emerging Technology Platforms and Applications

The landscape of sensing platforms is diverse, ranging from commercial wearables to sophisticated, research-grade electrochemical systems. The table below summarizes the key categories and their primary applications in pharmaceutical and clinical research.

Table 1: Overview of Sensing Platform Categories and Applications

| Platform Category | Example Technologies | Primary Data Collected | Pharmaceutical/Clinical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wrist-Worn Wearables | Verisense IMU, ActiGraph, Fitbit, E4 by Empatica [27] [24] | Actigraphy, Heart Rate (HR), Sleep Patterns, Electrodermal Activity [24] | Activity/Sleep monitoring in oncology, neurodegenerative diseases; safety and efficacy endpoint in clinical trials [27] [24] |

| Skin-Interfaced Patches | BioStampRC, HealthPatch [24] | Electrocardiography (ECG), Skin Temperature, Actigraphy [24] | Continuous vital sign monitoring in early-phase clinical trials for safety pharmacology [24] |

| Smartphone-Integrated Electrochemical Sensors | Portable potentiostats (PalmSens), Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) [28] [29] | Concentration of specific analytes (e.g., drugs, creatinine, controlled substances) [1] [28] [29] | Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM), detection of controlled substances, point-of-care creatinine testing for renal function [1] [28] [29] |

| Textile-Embedded Sensors | Hexoskin Smart Shirts [24] | HR, Heart Rate Variability (HRV), ECG, Breathing Rate [24] | Cardiorespiratory monitoring in naturalistic settings for treatment effect assessment [24] |

Key Trends and Capabilities

- AI and Data Analytics: Modern platforms increasingly incorporate AI-driven analytics and machine learning to transform raw sensor data into actionable insights. This is crucial for identifying digital biomarkers and predicting clinical outcomes [26] [1].

- Autonomous Operation: The development of self-powered circuits, including galvanic cells and biofuel cells, expands the application of electrochemical sensors to remote or decentralized locations without standard power sources [1].

- Multi-Device Interoperability: Enterprise-grade solutions are emerging that offer multi-device connectivity through unified APIs, allowing for harmonized data collection from various sensor types in a single study [26].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Smartphone-Based Electrochemical Detection of Creatinine

Creatinine is a crucial biomarker for kidney function, and its monitoring is essential in assessing drug toxicity and patient health. The following protocol details a method for quantifying creatinine in human blood serum using a smartphone-based electrochemical sensor [29].

Principle: As creatinine is electrochemically inactive, a standard copper solution is added as an electro-activator to form an electrochemically active creatinine-copper complex. This complex is oxidized on a screen-printed electrode (SPE) modified with a Ti3C2Tx@poly(l-Arg) nanocomposite, which enhances electrocatalytic activity. The current from this oxidation is measured and correlated to creatinine concentration [29].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Creatinine Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Ti3C2Tx MXene | A two-dimensional conductive material that provides a high surface area and metallic conductivity, serving as the foundational sensing substrate. |

| Poly(L-Arginine) [poly(l-Arg)] | A conducting polymer that forms a nanocomposite with Ti3C2Tx, improving the electrode's stability and electrocatalytic properties. |

| Standard Copper Solution | Acts as an electro-activator, forming an electrochemically active complex with otherwise inactive creatinine molecules. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 | Serves as the electrolyte solution, maintaining a physiologically relevant pH for the redox reaction. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, miniaturized three-electrode systems (working, counter, reference) that form the core of the portable sensor. |

Step-by-Step Workflow:

Sensor Fabrication:

- Synthesize Ti3C2Tx MXene by etching Ti3AlC2 powder in a solution of 9M HCl and Lithium Fluoride for 24 hours.

- Prepare the Ti3C2Tx@poly(l-Arg) nanocomposite by mixing the synthesized MXene with the poly(l-Arg) polymer.

- Drop-cast the prepared nanocomposite onto the working electrode area of a commercial carbon-based Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) and allow it to dry.

Sample Preparation:

- Mix the blood serum sample with a standard copper solution to form the creatinine-copper complex.

- Dilute the mixture with a pH 7.4 Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) solution.

Measurement and Data Acquisition:

- Connect the modified SPE to a handheld potentiostat (e.g., Sensit Smart from PalmSens) interfaced with a smartphone via Bluetooth.

- Apply a drop of the prepared sample onto the SPE surface.

- Through a dedicated smartphone application, initiate Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), an electrochemical technique that applies potential pulses and measures the resulting faradaic current.

- The smartphone application controls the parameters, collects the data, and displays the results in real-time.

Data Analysis:

- The oxidation peak current of the creatinine-copper complex, measured via DPV, is proportional to the creatinine concentration.

- The concentration in the unknown sample is determined by interpolating the peak current against a pre-established calibration curve (linear range: 1–200 μM, detection limit: 0.05 μM).

The following workflow diagram illustrates the integrated process from sample preparation to result visualization.

Protocol 2: On-Site Electrochemical Detection of Controlled Substances

This protocol describes a portable method for the rapid identification of controlled substances like cocaine, MDMA, amphetamine, and ketamine at points of need, such as border crossings or music festivals, which is also relevant for forensic pharmaceutical analysis [28].

Principle: Many illegal drugs and pharmaceutical compounds contain electroactive functional groups (e.g., amino groups). Their oxidation or reduction at a carbon-based Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) produces a characteristic current profile in techniques like Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV). This "electrochemical profile" serves as a fingerprint for identification [28].

Step-by-Step Workflow (Dual-Sensor Method for Multi-Analyte Detection):

Equipment Setup:

- Prepare a kit containing a portable potentiostat with Bluetooth (e.g., MultiPalmSens4), disposable carbon SPEs, and vials of two different buffers: pH 12 PBS and pH 7 PBS with formaldehyde (pH7F).

- Connect the potentiostat to a smartphone or tablet running the corresponding data acquisition software.

Sample Preparation:

- Transfer a small amount of the powdery or liquid evidence into two separate vials, one containing the pH 12 buffer and the other containing the pH7F buffer. The formaldehyde in the pH7F buffer derivatizes amphetamine, making it electroactive.

Simultaneous Measurement:

- Insert two separate SPEs into the potentiostat's dual-sensor connector.

- Apply a drop of the pH 12 sample solution to the first SPE and a drop of the pH7F sample solution to the second SPE.

- From the smartphone interface, launch a pre-programmed SWV method to acquire electrochemical profiles from both sensors simultaneously.

Data Analysis and Identification:

- The software combines the two electrochemical profiles into a "superprofile."

- This superprofile is compared against a pre-built library of electrochemical profiles for known substances using a tailor-made script.

- The software outputs the identification of the controlled substance based on the best match. This method has demonstrated 87.5% accuracy in identifying substances in seized samples [28].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful implementation of portable sensing platforms relies on a core set of materials and reagents. The following table details these essential components.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Portable Electrochemical Sensing

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Low-cost, disposable, three-electrode cells (working, counter, reference) that form the backbone of portable electrochemical measurements, eliminating the need for bulky traditional electrodes [1] [28]. |

| Portable Potentiostat | A miniaturized instrument that applies controlled potential waveforms to the electrochemical cell and measures the resulting current. Modern versions offer Bluetooth connectivity for smartphone control [28] [29]. |

| Nanomaterial-based Inks/Composites | (e.g., Graphene, MXenes, Metallic Nanoparticles). Used to modify SPEs to enhance sensitivity, stability, and selectivity towards specific analytes [1] [29]. |

| Specific Recognition Elements | (e.g., Aptamers, Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), Enzymes). Provide high specificity by binding to the target pharmaceutical analyte, reducing interference from complex sample matrices like blood or saliva [1] [28]. |

| Buffer Solutions at Varied pH | Crucial for controlling the electrochemical environment. The redox behavior of many pharmaceutical compounds is pH-dependent, which can be exploited for identification and quantification [28]. |

| Chemometric/AI Software | Software tools incorporating Principal Component Analysis (PCA), Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs), etc., are essential for processing complex electrochemical data and converting it into reliable, interpretable results [1]. |

| ASS234 | ASS234, MF:C29H37N3O, MW:443.6 g/mol |

| Tolinapant | Tolinapant, CAS:1799328-86-1, MF:C30H42FN5O3, MW:539.7 g/mol |

Implementation in Clinical Trial Protocols

Integrating wearable sensors into clinical trials requires careful protocol design to minimize participant burden and ensure data quality. The following table summarizes operational requirements based on different study objectives, derived from real-world examples [27].

Table 4: Protocol Examples for Wearable Sensor Integration in Clinical Trials

| Protocol Requirement | Example 1: Periodic Monitoring | Example 2: Long-Term Continuous Monitoring | Example 3: Minimal-Contact Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| Objective | Collect 5 days of continuous data between monthly site visits [27] | Collect 6 months of continuous 24/7 activity and sleep data [27] | Collect 2 months of continuous data with no interim data upload [27] |

| Equipment Provided | Sensor + Base Station (for automated data upload) [27] | Sensor + Base Station [27] | Sensor only (no Base Station) [27] |

| Participant Burden | Wear sensor for 5 days; keep Base Station plugged in [27] | Continuous wear; keep Base Station plugged in [27] | Continuous wear for 60 days; no other actions [27] |

| Site Staff Burden | Monthly battery change; compliance review and reminder (approx. 5 min/visit) [27] | Less frequent visits for battery replacement; remote compliance monitoring [27] | Initial setup and final retrieval only; data uploaded after device return [27] |

| Data Flow | Daily automated upload via Base Station for compliance monitoring [27] | Weekly automated upload for compliance monitoring [27] | Bulk manual upload at the end of the 60-day period [27] |

Key Considerations for Clinical Integration

- Sensor Selection: Prioritize sensors that collect data relevant to testing the study hypothesis while considering patient comfort and adherence, especially for specific populations like pediatrics or the elderly [30].

- Regulatory and Validation Strategy: A device lacking regulatory approval for a specific use can still be employed in clinical research. The focus should be on rigorous protocol design, data collection, and clinical validation within the specific Context of Use (COU) to generate defensible evidence for regulatory submissions [24] [30].

- Interoperability and Data Management: Choose platforms that support interoperability between diverse devices and electronic health record (EHR) systems. Leveraging cloud-based infrastructure with built-in compliance (e.g., HIPAA-ready) is critical for managing large, continuous data streams [26].

The following diagram outlines the logical decision process for selecting and integrating a sensing platform into a clinical trial protocol.

Advanced Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Pharmaceutical Sensing

Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) represent a transformative technology in electrochemical sensing, offering a disposable, low-cost, and portable platform that integrates working, reference, and counter electrodes onto a single substrate [31]. For researchers and drug development professionals, SPEs provide an exceptional tool for pharmaceutical monitoring, enabling applications ranging from drug compound accuracy confirmation to contaminant detection in medication powders [32]. The global SPE market, valued at USD 652.46 million in 2025 and projected to reach USD 1.5 billion by 2035, reflects the growing adoption of this technology across healthcare sectors [32].

The significance of SPEs in pharmaceutical research stems from their compatibility with point-of-care testing (PoCT) and decentralized diagnostic solutions [32]. Their disposability eliminates cross-contamination between samples, while their mass-produced consistency ensures analytical reproducibility—critical factors in drug development workflows. Furthermore, the adaptability of SPEs to various sensing platforms, including wearable and implantable medical devices, positions them as foundational components in the future of therapeutic monitoring and personalized medicine [32].

Fabrication of Screen-Printed Electrodes

Fundamental Manufacturing Process

Screen printing electrodes involves an additive manufacturing technique where conductive inks are deposited through a patterned mesh screen onto various substrates [33]. The process begins with designing electrode patterns using specialized software, followed by creating a stencil that defines the electrode layout [33]. A squeegee then forces the viscous conductive ink through the mesh openings onto the substrate, forming the precise electrode pattern. The printed electrodes undergo thermal curing to solidify the ink and ensure adhesion to the substrate [34].

Key to successful SPE fabrication is the formulation of conductive inks, which typically consist of functional materials (carbon, metals), binders for adhesion, and solvents for viscosity control [33]. The composition of these inks significantly influences the electrochemical performance, stability, and reproducibility of the final electrodes. Common substrate materials include polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyester, polycarbonate, and ceramics, selected based on flexibility, temperature resistance, and biocompatibility requirements [33].

Materials and Configurations

SPEs are categorized primarily by their conductive materials, with carbon-based and metal-based electrodes representing the two main classifications. Carbon-based SPEs utilize materials such as graphite, carbon nanotubes, graphene, or carbon black as the conductive element [33]. These electrodes dominate the market, holding over 58.2% share, largely due to their affordability, disposability, and integration capabilities with miniaturized devices [32]. Carbon SPEs offer wide potential windows, low background currents, and chemical inertness, making them suitable for various pharmaceutical applications.

Metal-based SPEs employ conductive materials including gold, platinum, silver, and palladium [33]. The global market for metal-based SPEs is projected to reach $207 million in 2025, with a compound annual growth rate of 9.5% from 2025 to 2033 [35] [36]. These electrodes often provide enhanced conductivity and can facilitate specific surface modifications, such as self-assembled monolayers through thiol chemistry on gold surfaces [33]. Silver or silver/silver chloride inks are commonly used for reference electrodes, functioning as "quasi-reference" or "pseudo-reference" electrodes due to their relatively stable potential [33].

Table 1: Screen-Printed Electrode Material Comparison

| Material Type | Composition | Key Advantages | Common Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based | Graphite, graphene, carbon nanotubes, carbon black | Cost-effective, wide potential window, low background current | Drug compound analysis, contaminant detection, metabolic monitoring |

| Metal-Based | Gold, platinum, silver, palladium | High conductivity, facile surface modification, enhanced sensitivity | Biomarker detection, enzymatic sensors, therapeutic drug monitoring |

| Silver/Silver Chloride | Silver, silver chloride particles | Stable reference potential, compatibility with biological systems | Reference electrode for biosensors, ion-selective electrodes |

Protocol: Fabrication of Chitosan-Based SPEs for Biomedical Applications

Background: Chitosan substrates provide excellent biocompatibility and mechanical stability for SPEs used in pharmaceutical and biomedical applications [34]. This protocol details the fabrication of SPEs on chitosan film substrates, adapted from cardiac patch research for potential pharmaceutical monitoring applications.

Materials:

- Chitosan (70 kDa and 300 kDa molecular weights, ≥75% deacetylated)

- Acetic acid (0.1 N solution)

- Sodium hydroxide (1 N solution)

- Carbon ink (e.g., SC-1010, ITK)

- Silver ink (e.g., NT-6307-2, PERM TOP)

- Distilled water

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- Petri dishes

- Screen-printing apparatus (e.g., Model NSP-1A, YULISHIH INDUSTRIAL Co., Ltd.)

- Oven for thermal curing

- UV sterilization equipment

Procedure:

- Prepare Chitosan Film Substrate:

- Dissolve chitosan powder in 0.1 N acetic acid solution to prepare 2% (w/v) chitosan solutions.

- Cast the solutions into Petri dishes and dry overnight in an oven at 40°C to obtain uniform thin films.

- Induce gelation by immersing the films in 1 N NaOH at room temperature.

- Thoroughly wash the gelled films with distilled water to remove residual reagents.

- Air-dry the films under ambient conditions and store in a desiccator (20-30% relative humidity) until use [34].

Fabricate Electrodes via Screen Printing:

- Mount the chitosan film securely in the screen-printing apparatus.

- Apply carbon ink through the patterned screen to form the working and counter electrodes.

- Cure the carbon electrodes at 60°C for 30 minutes.

- Apply silver ink through the corresponding pattern to form reference electrodes.

- Cure the silver electrodes at 120°C for 60 minutes [34].

Post-processing and Sterilization:

- Condition the fabricated SPEs in PBS (pH 7.4) for 24 hours to simulate physiological conditions.

- Sterilize the chitosan-SPE patches using continuous ultraviolet (UV) irradiation for 24 hours under aseptic conditions in a laminar flow cabinet [34].

Quality Control:

- Perform adhesion testing using the cross-cut method (ASTM D3359-95 standard) to ensure ink adhesion to the chitosan substrate [34].

- Characterize electrochemical performance using cyclic voltammetry with standard redox probes.

- Evaluate mechanical properties through tensile testing if flexibility is required for the application.

Surface Modification of SPEs for Enhanced Pharmaceutical Sensing

Modification Strategies and Their Applications

Surface modification of SPEs is crucial for enhancing their sensitivity, selectivity, and stability for pharmaceutical monitoring applications. These modifications tailore the electrode surface to specific analytical needs, overcoming limitations of bare electrodes and enabling detection of specific pharmaceutical compounds.

Physical Modifications include plasma treatment using oxygen or argon to introduce functional groups and increase surface energy, improving wettability and adhesion for subsequent modifications [33]. Nanomaterial addition, such as incorporating gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), graphene oxide (GO), or carbon nanotubes (CNTs), increases the electroactive surface area and enhances electron transfer kinetics [33] [29].

Chemical Modifications involve creating specific recognition interfaces through polymer coatings, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), or self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) [33]. These layers provide selective binding sites for target analytes, significantly improving sensor specificity in complex biological matrices like blood serum or pharmaceutical formulations.

Table 2: Surface Modification Techniques for SPEs in Pharmaceutical Applications

| Modification Type | Materials Used | Key Benefits | Pharmaceutical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterial Enhancement | AuNPs, GO, CNTs, MXenes (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | Increased surface area, enhanced electron transfer, catalytic properties | Biomarker detection, drug metabolism studies, sensitive analyte detection |

| Polymer Coatings | Poly(l-Arg), Nafion, chitosan | Improved selectivity, reduced fouling, entrapment of recognition elements | Selective drug monitoring, exclusion of interferents, biosensor fabrication |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Polymer matrices with template cavities | High specificity, artificial antibody-like recognition | Therapeutic drug monitoring, contaminant detection in pharmaceuticals |

| Electrochemical Activation | Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚ treatment, potential cycling | Increased surface defects, functional groups, enhanced reversibility | Sensor preconditioning, improved sensitivity for redox reactions |

Protocol: Electrochemical Activation of Carbon-Based SPEs