Overcoming SCF Convergence Challenges in Electrochemical Calculations: A Guide for Computational Researchers

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence presents a significant hurdle in computational electrochemistry, where systems often feature small HOMO-LUMO gaps, open-shell configurations, and complex solute-electrode interactions.

Overcoming SCF Convergence Challenges in Electrochemical Calculations: A Guide for Computational Researchers

Abstract

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence presents a significant hurdle in computational electrochemistry, where systems often feature small HOMO-LUMO gaps, open-shell configurations, and complex solute-electrode interactions. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and scientists, exploring the foundational causes of convergence failure in electrochemical systems, detailing specialized methodological approaches like Grand Canonical DFT and advanced SCF algorithms, offering practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies from multiple quantum chemistry packages, and discussing validation techniques to ensure physically meaningful results. By synthesizing current methodologies and best practices, this work aims to enhance the reliability and efficiency of quantum chemical simulations in electrocatalysis and biomedical applications.

Why Electrochemical Systems Challenge SCF Solvers: Root Causes and Electronic Structure Complexities

The Unique Convergence Landscape of Electrochemical Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What does "SCF convergence" mean in the context of electrochemical calculations? Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence is the process of iteratively solving the electronic structure equations until the energy and electron density of the system no longer change significantly between cycles. In electrochemical systems, this process is complicated by the presence of conductive electrodes, liquid electrolytes, and the application of an electrical potential, making convergence more difficult to achieve than in standard chemical systems. [1] [2]

Q2: My calculation stops with an "SCF convergence failure" error. What are the first steps I should take? Initial troubleshooting steps should follow a logical isolation process [3] [4]:

- Simplify the System: Test your setup on a smaller, known system to verify your methodology.

- Check Initial Guess: Ensure you are starting from a sensible initial electron density and wavefunction. A poor initial guess is a common culprit.

- Increase SCF Iterations: Temporarily increase the maximum number of SCF steps to rule out an overly strict limit.

- Verify Electrode Model: Confirm that your model of the electrochemical interface (e.g., slab thickness, vacuum/water layer size) is physically sound and properly constructed to avoid spurious interactions. [2]

Q3: How does the application of an electrode potential affect SCF convergence? The grand canonical (constant potential) approach, essential for modeling working electrochemical conditions, directly controls the electron chemical potential of the system. This explicit potential control alters the electronic structure landscape and can introduce states that are challenging for standard SCF algorithms to resolve, often requiring specialized techniques like Fermi smearing or density mixing to ensure stable convergence. [1]

Q4: Why are electrochemical interfaces particularly challenging for SCF algorithms? Electrochemical interfaces represent a complex convergence landscape due to several factors [2]:

- Physical Complexity: They involve a junction between a solid conductor (electrode) and a liquid ionic solution (electrolyte), each with vastly different dielectric properties.

- Multiple Components: The system contains a diverse mix of atoms (metals, oxygen, hydrogen, various ions) with different electronegativities and bonding characteristics. [5]

- Dynamic Nature: The interface is not static; atoms, particularly protons in water, are in constant motion, leading to a fluctuating electronic environment. [2]

Troubleshooting Guide: A Step-by-Step Walkthrough

Follow this structured guide to diagnose and resolve SCF convergence problems in your electrochemical simulations.

Step 1: Dummy Cell Test (Methodology Verification) Before introducing the full complexity of an electrochemical cell, verify your computational setup and methodology.

- Action: Perform a calculation on a simple, well-understood redox couple or a bulk piece of your electrode material using the same computational settings (functional, basis set, pseudopotentials).

- Expected Outcome: The calculation should converge smoothly.

- Interpretation: If this fails, the problem lies with your core computational parameters, not the interface model. If it passes, proceed to Step 2. [3]

Step 2: Isolate the Problem Component Reintroduce complexity gradually to identify the problematic component.

- Action 1: Test the Electrode in Vacuum. Run an SCF calculation on your electrode slab without the electrolyte. If it converges, the issue is likely related to the electrolyte or the interface.

- Action 2: Test the Electrolyte Separately. Run a molecular dynamics simulation of your electrolyte solution using a classical force field to ensure its structure is equilibrated before introducing it to the DFT calculation. [2]

- Interpretation: This process helps you determine whether to focus troubleshooting efforts on the electrode, the electrolyte, or their interaction.

Step 3: System-Specific Checks Based on the outcome of Step 2, perform targeted checks.

If the problem is with the electrode or initial setup:

- Check for Metallic Systems: For metallic electrodes like Pt(111) or Au(111), standard SCF methods can fail. Use techniques like Fermi smearing with an electronic temperature (e.g., 300 K) and Broyden density mixing to help convergence. [2]

- Verify Slab Stoichiometry: Ensure your electrode slab is stoichiometric to avoid introducing excess charge or holes that can prevent convergence. [2]

- Improve Initial Guess: Use the electron density from a related, converged calculation as a starting point for your target system.

If the problem is with the interface or electrolyte:

- Ensure Proper Solvation: Confirm that the water density in the bulk-like region of your model is correct (~1 g/cm³). [2]

- Check for Ionic Conductivity: In a real electrochemical cell, the electrolyte must conduct ions to complete the circuit. While this is explicitly modeled in simulations, a poorly constructed interface model can mimic a blocked circuit, leading to instability. Ensure no artificial barriers (like an excessively large vacuum gap) are preventing ion stabilization in the model. [3] [6]

Step 4: Advanced SCF Tuning If the above steps do not resolve the issue, advanced tuning of the SCF procedure is required. The table below summarizes key parameters and their typical values for challenging electrochemical systems.

Table 1: SCF Algorithm Parameters for Electrochemical Systems

| Parameter | Standard Value | Recommended for Challenging Systems | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCF Convergence Threshold | ( 1 \times 10^{-6} ) a.u. | ( 1 \times 10^{-5} ) a.u. (loosen initially) | Target accuracy for the wavefunction optimization. |

| Fermi Smearing | N/A | 300 K (for metals) | Smears electronic occupancy around Fermi level, aiding metallic convergence. |

| Mixing Method | Simple/DIIS | Broyden / Pulay | Improves the update of the electron density between cycles. |

| Mixing Fraction | 0.05-0.2 | 0.05-0.1 | The fraction of new density mixed into the old. Too high can cause oscillation. |

| Algorithm (Non-Metallic) | DIIS | Orbital Transformation (OT) | OT can be more robust and faster for insulating systems. |

| Algorithm (Metallic) | DIIS | Second-Generation Car-Parrinello (SGCP) | SGCP is efficient for metals and large systems. [2] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Evaluating the Effect of Potential on Electrochemical Reactions Using a Grand Canonical Method

This protocol outlines the steps for performing fixed-potential calculations, which are central to modeling electrochemical systems and are prone to SCF convergence issues. [1]

1. Software and Prerequisites

- Software: Install a DFT package capable of grand canonical calculations, such as CP2K/QUICKSTEP. [2]

- Knowledge: Familiarity with basic DFT concepts and the software's input file structure is assumed.

2. Preparing the Electrochemical Interface Model

- Slab Creation: Cleave the bulk crystal of your electrode material along the desired facet (e.g., Pt(111), SnO2(110)). Create a symmetric slab to avoid a net dipole moment perpendicular to the surface. [2]

- Solvation: Use a tool like PACKMOL to fill a simulation box with water molecules at a density of 1 g/cm³. Equilibrate this water box using classical molecular dynamics with a force field like SPC/E. [2]

- Interface Construction: Merge the equilibrated slab and water box to create the initial interface structure. Saturate under-coordinated surface atoms with water molecules where possible.

- Equilibration: Perform a short (e.g., 20-30 ps) ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulation of the full interface to equilibrate the structure at the target temperature (e.g., 330 K). Use the final snapshot of this simulation as the starting point for your fixed-potential calculations. [2]

3. Configuring the Fixed-Potential Calculation

- Input File Setup: In your DFT input file, activate the settings for grand canonical DFT calculations. This typically involves specifying the electron chemical potential (the potential) and the charge of the system.

- SCF Parameters: Set the SCF parameters as detailed in Table 1. For metallic electrodes, ensure Fermi smearing and a robust mixing algorithm like Broyden are enabled.

- Convergence Aids: It is often beneficial to first run a calculation with a looser SCF convergence criterion and use the resulting electron density as the initial guess for the production run with tighter criteria.

4. Execution and Analysis

- Run the Calculation: Submit the job and monitor the SCF convergence in the output file.

- Analyze Output: Upon successful convergence, analyze the resulting charge distribution, density of states, and free energy of the system at the applied potential to gain insight into the electrochemical reaction. [1]

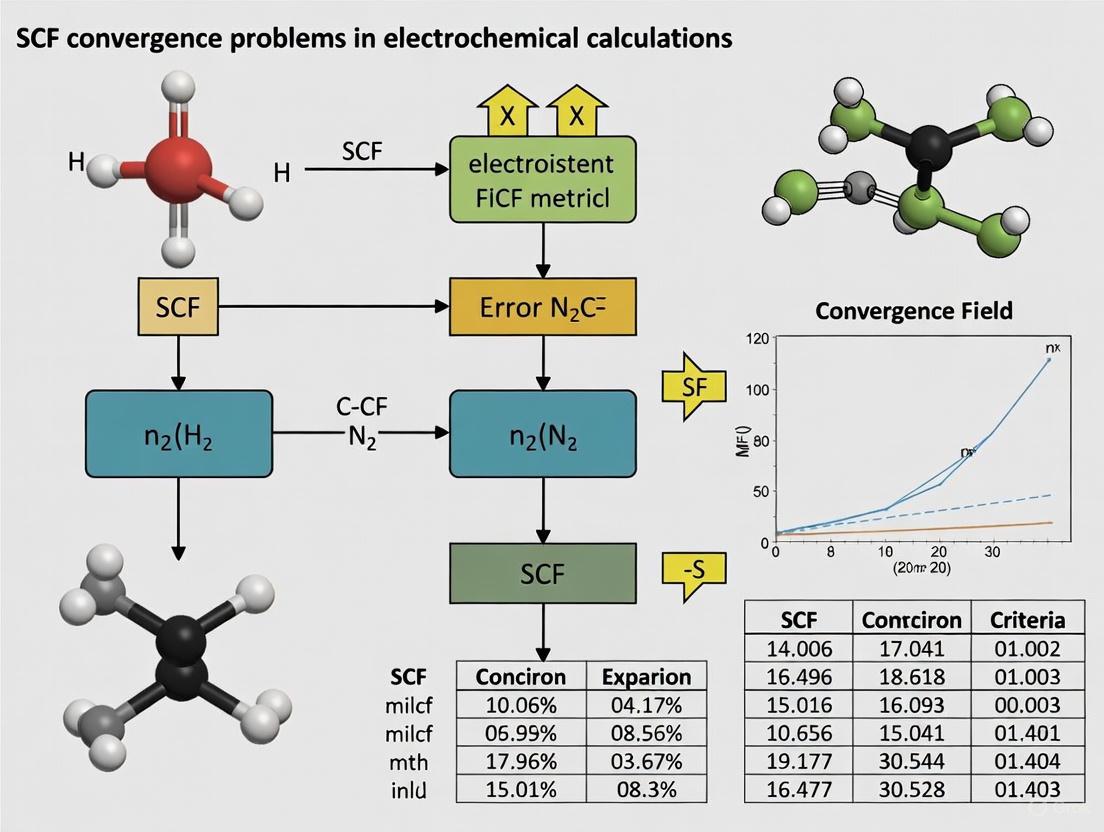

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists key computational "reagents" and their functions in setting up and troubleshooting electrochemical calculations.

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Electrochemical Interface Modeling

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose | Example in Use |

|---|---|---|

| CP2K | A DFT package specializing in atomistic simulations of condensed matter systems, particularly efficient for molecular dynamics and systems with large unit cells. | Used for running AIMD simulations of Pt(111)-water interfaces with Gaussian and plane-wave basis sets. [2] |

| LAMMPS | A classical and (with plugins) quantum molecular dynamics simulator. | Used for running MLMD (Machine Learning Molecular Dynamics) simulations with potentials from DeePMD-kit. [2] |

| DeePMD-kit | A package for building and running machine learning potentials (MLPs) trained on DFT data. | Used to create MLPs that extend simulation timescales to nanoseconds while maintaining AIMD accuracy. [2] |

| DP-GEN / ai2-kit | Concurrent learning packages for automatically generating training datasets for MLPs. | Used in an active learning workflow to explore the configuration space of an interface and build robust MLPs. [2] |

| PACKMOL | A tool for setting up initial configurations of molecular dynamics simulations by packing molecules in defined regions. | Used to fill a simulation box with water molecules to create an electrolyte solution for the interface model. [2] |

| SPC/E Water Model | A classical, rigid water model used for force-field-based equilibration of the electrolyte. | Used to pre-equilibrate the water box before merging it with the DFT-level electrode slab. [2] |

| Goedecker-Teter-Hutter (GTH) Pseudopotentials | Pseudopotentials that describe the core electrons, freeing up computational resources for valence electrons. | Standard in CP2K simulations to describe core-electron interactions for elements like O, H, Zn, Mn, etc. [2] |

| Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) Functional | A popular generalized gradient approximation (GGA) exchange-correlation functional in DFT. | Commonly used to describe electron interactions in electrochemical interface studies, though it has known limitations for van der Waals forces and band gaps. [2] |

Impact of Small HOMO-LUMO Gaps and Metallic Character on SCF Stability

FAQs on SCF Convergence in Electrochemical Systems

1. Why do my electrochemical interface calculations, particularly for metals or small-gap semiconductors, frequently fail to converge?

Systems with small or zero HOMO-LUMO gaps, such as metals or certain semiconductor electrodes, present a fundamental challenge for the Self-Consistent Field (SCF) procedure. The core issue is that the energetic ordering of molecular orbitals can switch during the iterative SCF optimization. This leads to discontinuities in the optimization process, resulting in very slow convergence or outright failure [7]. In metallic systems, the presence of many near-degenerate electronic levels around the Fermi level exacerbates this problem [8].

2. What are the primary computational strategies to stabilize SCF convergence for such challenging systems?

Two main strategies, often used in conjunction, are employed:

- Fractional Orbital Occupations: This technique smears the electron occupation over several orbitals near the Fermi level, mimicking a finite electronic temperature. This prevents sharp, discontinuous changes in the density matrix when orbital energies cross, thereby stabilizing the SCF cycle [7] [2].

- Advanced SCF Accelerators and Parameters: Using more robust SCF convergence algorithms and carefully tuning their parameters can significantly improve stability. This includes methods like DIIS with a larger number of expansion vectors and lower mixing parameters, or alternative algorithms like MESA, LISTi, EDIIS, and the Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) method [8].

3. How does the choice of basis set and planewave cutoff in CP2K/QUICKSTEP calculations affect SCF stability for metallic interfaces?

In the CP2K code, which uses a mixed Gaussian and plane-wave (GPW) basis set, convergence must be approached for both the Gaussian basis set and the auxiliary plane-wave basis concurrently. An insufficiently high plane-wave cutoff (CUTOFF in the &MGRID section) for the electron density can lead to numerical inaccuracies that destabilize the SCF process, especially for metals with delocalized electrons. It is crucial to increase the cutoff toward the complete basis set limit to ensure a stable and accurate calculation [9].

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving SCF Instabilities

Step 1: Initial System Checks

Before adjusting advanced parameters, rule out simple issues.

- Verify Geometry: Ensure your electrochemical interface model has realistic bond lengths and angles. A high-energy, non-physical geometry is a common root cause of convergence problems [8].

- Confirm Spin Multiplicity: For systems containing transition metals (e.g., Pt, CoO), ensure you are using the correct spin multiplicity and an unrestricted spin formalism if needed [8].

- Reuse Converged Potentials: In a geometry optimization, use a moderately converged electronic structure from a previous step as the initial guess for the next step [8].

Step 2: Algorithm Selection and Parameter Tuning

If basic checks pass, proceed to adjust SCF controls. The following table summarizes key parameters for the DIIS algorithm, which can be adjusted for a "slow but steady" convergence approach [8].

| Parameter | Standard Default | Recommended Value for Problematic Systems | Explanation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mixing | 0.2 | 0.015 | Fraction of new Fock matrix used. Lower values increase stability. |

| Mixing1 | 0.2 | 0.09 | Mixing parameter for the very first SCF cycle. |

| N (DIIS Vectors) | 10 | 25 | Number of previous steps used for extrapolation. More vectors increase stability. |

| Cyc (Start Cycle) | 5 | 30 | Number of initial SCF cycles before DIIS acceleration starts. |

Example input for a difficult system in a typical DFT code:

Step 3: Employing Electron Smearing and Fractional Occupations

For systems with a vanishing HOMO-LUMO gap (metals, narrow-gap semiconductors), enforcing fractional orbital occupations is often the most effective solution. The table below outlines the key parameters for the pseudo-Fractional Occupation Number (pFON) method [7].

| Parameter | Description | Recommended Setting |

|---|---|---|

| OCCUPATIONS | Activates fractional occupations. | 2 (for pFON) |

| FONTSTART | Initial electronic temperature (K). | 300 K (room temperature) or higher for difficult cases. |

| FONTEND | Final electronic temperature (K). | 300 K or as low as possible. |

| FON_NORB | Number of orbitals above/below Fermi level for smearing. | Number of valence orbitals (e.g., 10). |

| FONETHRESH | DIIS error threshold to freeze occupations. | 5 (freeze at 10⁻⁵) or one step above your SCF convergence criterion. |

Example input for a Pt system using pFON in Q-Chem [7]:

Note: Electron smearing alters the total energy. The smearing parameter (electronic temperature) should be kept as low as possible, and multiple restarts with successively smaller values can be used to approach the zero-temperature limit [8].

Step 4: Utilizing Advanced SCF Accelerators

If DIIS and smearing are insufficient, consider switching the SCF convergence accelerator. The Augmented Roothaan-Hall (ARH) method, for instance, directly minimizes the total energy and can be a viable, though computationally more expensive, alternative for the most difficult cases [8].

Experimental Protocols for Electrochemical Interface Modeling

The following workflow, based on the methodology used to create the ElectroFace dataset, details the steps for generating a stable and physically meaningful model of an electrochemical interface for AIMD or MLMD simulations [2].

Key steps in the workflow:

- Slab Preparation: Generate a symmetric, stoichiometric slab from the bulk crystal to avoid spurious dipole interactions and excess charge [2].

- Water Phase Equilibration: Create and classically equilibrate a box of water molecules to ensure a realistic liquid structure before introducing the interface [2].

- Density Adjustment: Iteratively run short AIMD simulations and adjust the number of water molecules until the density in the bulk-like region of the liquid phase is correct (1.0 g/cm³ within a 5% error margin). This ensures the interface model is physically realistic [2].

- Production Run: Use the final, validated structure from step 3 to launch extended AIMD or machine-learning accelerated MD (MLMD) simulations [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential computational "reagents" and their functions for managing SCF convergence in electrochemical simulations.

| Item / Method | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| pFON (pseudo-Fractional Occupation Numbers) | Smears electron occupation over near-degenerate orbitals to stabilize SCF in metallic/small-gap systems [7]. |

| Fermi Smearing | Alternative to pFON; uses a Fermi-Dirac distribution for orbital occupation at a finite electronic temperature (e.g., 300 K) [2]. |

| DIIS (Direct Inversion in Iterative Subspace) | Standard SCF convergence accelerator; parameters (N, Mixing) can be tuned for stability [8]. |

| ARH (Augmented Roothaan-Hall) | Alternative, robust SCF minimizer used when DIIS fails [8]. |

| Machine Learning Potentials (DeePMD-kit) | Enables nanosecond-scale MD simulations at near-DFT accuracy after training on AIMD data, bypassing direct SCF convergence in long runs [2]. |

| Grimme D3 Dispersion Correction | Accounts for van der Waals interactions, critical for accurate description of adsorption and interface structure [2]. |

| GTH Pseudopotentials | Represents core electrons, reducing computational cost while maintaining accuracy for valence electrons [2]. |

| SPC/E Water Force Field | A classical model used for the efficient pre-equilibration of the water phase before QM/MM or pure AIMD simulations [2]. |

SCF Convergence Decision Workflow

When faced with an SCF convergence problem, follow this logical pathway to identify and apply the appropriate solution.

Challenges of Open-Shell Configurations in Transition Metal Complexes and Radicals

Troubleshooting Guide: Resolving SCF Convergence Failures

Q: My SCF calculation for an open-shell transition metal complex fails to converge. What are the primary causes and immediate steps I should take?

A: Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence failures are common when calculating open-shell transition metal systems due to their complex electronic structures. The main physical reasons include small HOMO-LUMO gaps leading to oscillating orbital occupations, open-shell electronic configurations with localized d-orbitals, and issues with the initial orbital guess [8] [10] [11]. Systems with magnetic anisotropy or near-degenerate states are particularly problematic [12] [11].

Immediate troubleshooting steps:

- Verify Molecular Geometry: Ensure bond lengths and angles are chemically reasonable. Check coordinate units and for unrealistic close contacts [8] [11].

- Confirm Spin Multiplicity: Use the correct spin-unrestricted formalism and manually set the total spin if necessary [8].

- Use a Better Initial Guess: Converge a simpler method (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP) and read orbitals for a restart, or try

PAtom,Hueckel, orHCoreguesses [10]. - Increase SCF Iterations: For calculations nearly converged, increase the maximum iteration count (e.g.,

%scf MaxIter 500 end) [10].

Q: Which SCF convergence algorithms and parameters are most effective for difficult open-shell cases?

A: Standard DIIS algorithms often struggle. For difficult cases in ORCA, employ dedicated convergence keywords and parameter adjustments.

Table: SCF Convergence Algorithms and Settings for Open-Shell Systems

| Method/Setting | Description | Typical Use Case | ORCA Input Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| SlowConv/VerySlowConv | Increases damping to stabilize large initial density fluctuations [10]. | General purpose for oscillating SCF. | ! SlowConv |

| KDIIS with SOSCF | Alternative algorithm, often faster than DIIS [10]. | When standard DIIS is slow or fails. | ! KDIIS SOSCF |

| TRAH (Trust Radius Augmented Hessian) | Robust second-order converger, automatically activates in ORCA 5+ if DIIS struggles [10] [13]. | Pathological cases; guarantees a local minimum [13]. | (Active by default) |

| Level Shifting | Artificially raises virtual orbital energies to prevent oscillation [8] [10]. | Small HOMO-LUMO gaps. | %scf Shift Shift 0.1 end |

| DIIS Parameter Adjustment | Using more expansion vectors (DIISMaxEq) increases stability [10]. |

Severe convergence problems (e.g., metal clusters). | %scf DIISMaxEq 25 end |

| Electron Smearing | Uses fractional occupations to help converge metallic systems or those with near-degenerate states [8]. | Very small or zero HOMO-LUMO gap. | %scf Smear 0.01 end |

For pathological cases (e.g., metal clusters), a combination of settings is often required [10]:

Q: How do I select appropriate convergence tolerances for production calculations on transition metal complexes?

A: Tighter-than-default tolerances are often necessary. ORCA provides predefined convergence keywords. The TightSCF criterion is recommended for transition metal complexes [13].

Table: SCF Convergence Tolerances in ORCA (Selected) [13]

| Criterion | LooseSCF | MediumSCF | StrongSCF | TightSCF | Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TolE | 1e-5 | 1e-6 | 3e-7 | 1e-8 | Energy change between cycles. |

| TolMaxP | 1e-3 | 1e-5 | 3e-6 | 1e-7 | Maximum density change. |

| TolRMSP | 1e-4 | 1e-6 | 1e-7 | 5e-9 | RMS density change. |

| TolErr | 5e-4 | 1e-5 | 3e-6 | 5e-7 | DIIS error convergence. |

FAQ: Addressing Common Computational Challenges

Q: How significant are relativistic and dispersion effects on the conformational energies of open-shell 3d metal complexes?

A: The influence depends on the metal and ligand environment. For first-row (3d) transition metals, scalar relativistic effects on conformational energies are generally negligible [12]. In contrast, intramolecular dispersion interactions (e.g., from Grimme's D3 correction with BJ damping) can be crucial, especially for complexes with bulky substituents in close proximity [12]. Always account for dispersion in such systems.

Q: What fast computational methods provide reliable conformational energies for open-shell transition metal complexes?

A: Performance varies significantly across methods. A study on the 16OSTM10 database shows that while cheap methods are available, they should be used cautiously [12].

Table: Performance of Computational Methods for OSTM Conformational Energies [12]

| Method Class | Examples | Average Pearson Correlation (ρ) with Reference DFT | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional DFT | PBE-D3(BJ), PBE0-D3(BJ), ωB97X-V | 0.91 | Reliable reference methods. |

| Composite DFT | PBEh-3c, B97-3c | 0.93 | Good balance of speed and accuracy. |

| Semiempirical (GFNn) | GFN1-xTB, GFN2-xTB | 0.75 | Moderate performance; use with caution. |

| Force Field | GFN-FF | 0.62 | Poor performance; not recommended. |

| Semiempirical (Traditional) | PM6, PM7 | 0.53 | Poor performance; avoid. |

Q: My system has a very small or zero HOMO-LUMO gap. What specific techniques can help achieve convergence?

A: Small gaps cause "charge sloshing" and orbital occupation flipping [11]. Solutions include:

- Electron Smearing: Apply a small finite electron temperature (

%scf Smear 0.001 end), gradually reducing it in subsequent restarts [8]. - Level Shifting: This stabilizes the SCF procedure [8] [10].

- Converge a Closed-Shell State: If possible, converge a 1- or 2-electron oxidized/reduced (closed-shell) state and use its orbitals as a guess for the target open-shell system [10].

- Use a Sufficiently Accurate Grid: Numerical noise from an insufficient integration grid can prevent convergence [10] [11].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Systematic Conformational Search for Flexible Open-Shell Complexes This methodology is adapted from the creation of the 16OSTM10 database [12].

- Initial Structure Selection: Retrieve structures from crystallographic databases (e.g., CSD). Select complexes with a first-row transition metal, an open-shell ground state, and at least 5 rotatable bonds.

- Ground State Optimization: Optimize the initial structure at the

PBE-D3(BJ)/def2-SVPlevel, testing relevant spin multiplicities. Re-evaluate energy at a higher level (e.g.,PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP) to confirm the ground state. - Multireference Diagnostics: Perform

DLPNO-CCSD(T)/cc-pVDZcalculations to obtain T1/T2 diagnostics. Exclude compounds with significant multireference character (T1 > 0.025 or T2 > 0.15) if using single-reference methods [12]. - Conformer Generation: Use an automated algorithm to generate 30-35 spatially diverse conformers.

- Pre-optimization: Pre-optimize all conformers using a fast, low-cost method (e.g.,

PBE/λ1in Priroda) [12]. - Final Optimization and Energy Benchmarking: Optimize unique conformers at the

PBE-D3(BJ)/def2-SVPlevel. Calculate final single-point energies for all conformers using a robust reference method (e.g.,PBE0-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVPorωB97X-V/def2-TZVP) to build the conformational energy profile.

Workflow for Conformational Energy Benchmarking

Protocol 2: Robust SCF Convergence Protocol for Problematic Systems This protocol combines recommendations from ORCA and ADF documentation [8] [10].

- Initial Checks: Verify geometry and spin state.

- Standard SCF Procedure: Run with default settings. If it converges, proceed.

- Enable Robust Converger: If slow or oscillating, use

! SlowConvor allowTRAHto activate automatically [10] [13]. - Advanced DIIS Tuning: For persistent failure, increase DIIS memory (

DIISMaxEq) and reduce Fock matrix rebuild frequency (directresetfreq) [10]. - Improved Initial Guess: Converge a simpler method or different charge/spin state and restart with

! MORead[10]. - Last Resort - Smearing/Shifting: For systems with tiny HOMO-LUMO gaps, apply minimal electron smearing or level shifting [8].

Troubleshooting Protocol for SCF Convergence

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Computational Tools for Open-Shell Transition Metal Research

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| 16OSTM10 Database | A benchmark database of 10 conformations for each of 16 open-shell TM complexes [12]. | Used for validation and training of fast methods (SE, FF, ML). |

| Composite DFT Methods (B97-3c, PBEh-3c) | Low-cost DFT methods with minimized basis sets and built-in corrections [12]. | Good speed/accuracy for conformational energies (ρ ≈ 0.93) [12]. |

| GFNn-xTB Methods | Semiempirical methods with generally good performance for geometries and energies [12]. | Use with caution for OSTM conformational energies (average ρ = 0.75) [12]. |

| D3(BJ) Dispersion Correction | Adds empirical dispersion interactions to DFT [12]. | Crucial for complexes with bulky ligands [12]. |

| DLPNO-CCSD(T) | High-level wavefunction method for accurate energies and diagnostics [12]. | Used for T1/T2 diagnostics to exclude multireference systems [12]. |

| ROCIS Method | Restricted Open-Shell CI Singles method for spectroscopy [14]. | Calculates transition metal L-edge X-ray absorption spectra including spin-orbit coupling [14]. |

| TRAH SCF Algorithm | Trust Radius Augmented Hessian SCF converger [10] [13]. | Robust second-order method for difficult cases; default in ORCA 5+ [10]. |

The Role of Diffuse Basis Sets and Fractional Electrons in Constant-Potential Calculations

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why are my electrochemical calculations failing to converge, and how are diffuse basis sets involved?

SCF convergence problems are frequently encountered in systems with very small HOMO-LUMO gaps, which are common in electrochemical environments and systems with dissociating bonds [8]. Diffuse basis sets, while essential for accuracy in describing non-covalent interactions and anions, significantly reduce the sparsity of the one-particle density matrix [15]. This "curse of sparsity" leads to a late onset of the low-scaling regime and larger cutoff errors, making convergence more difficult and computationally expensive [15].

FAQ 2: What is the relationship between fractional electrons and constant-potential calculations?

In the context of simulating electrochemical reactions, a Grand Canonical approach within density functional theory can be used where fractional numbers of electrons represent an open system in contact with an electrode at a given electrochemical potential [16]. This approach explicitly includes the electrochemical potential, allowing for the modeling of systems where electron exchange with a reservoir is possible.

FAQ 3: When should I use diffuse functions in my basis set for electrochemical calculations?

Diffuse functions are essential for obtaining accurate interaction energies, particularly for non-covalent interactions and charged species common in electrochemical environments [15]. However, they come with a significant computational cost and can hinder SCF convergence. They should be used when studying processes where electron density is more dispersed, such as in anions, excited states, or weak interactions, but may be avoided in initial calculations on challenging systems to establish convergence first [15].

FAQ 4: What practical SCF convergence techniques can I implement for difficult systems?

For problematic SCF convergence, several techniques can be employed:

- Change to different SCF convergence acceleration methods like MESA, LISTi, or EDIIS [8]

- Adjust DIIS parameters: increase the number of expansion vectors (N=25), increase initial cycles before DIIS starts (Cyc=30), and reduce mixing parameters (Mixing=0.015) for more stable convergence [8]

- Utilize electron smearing to simulate a finite electron temperature using fractional occupation numbers, which helps overcome convergence issues in systems with many near-degenerate levels [8]

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing SCF Convergence Failures in Electrochemical Calculations

Symptoms: SCF cycles oscillate without converging, calculations terminate due to maximum cycle limits, or energies fluctuate wildly.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Verify System Physicality

Validate Electronic Structure Description

Implement Advanced SCF Accelerators

- Switch from default DIIS to alternative methods like ARH (Augmented Roothaan-Hall) for difficult systems [8]

- Use the following parameter set as a starting point for problematic cases:

Apply Electron Smearing or Level Shifting

- Implement electron smearing with fractional occupation numbers to distribute electrons over near-degenerate levels [8]

- Use level shifting to artificially raise virtual orbital energies (note: this affects properties involving virtual levels) [8]

- Keep smearing values as low as possible and use successive restarts with reduced values [8]

Guide 2: Managing Basis Set Selection Trade-offs

Symptoms: Accurate results require diffuse functions but make calculations computationally prohibitive or unstable.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Understand the Accuracy-Sparsity Trade-off

Table 1: Basis Set Performance for Non-Covalent Interactions (NCI) with ωB97X-V Functional

Basis Set NCI RMSD (M+B) (kJ/mol) Time (s) for DNA Fragment def2-SVP 31.51 151 def2-TZVP 8.20 481 def2-TZVPPD 2.45 1440 aug-cc-pVDZ 4.83 975 aug-cc-pVTZ 2.50 2706 aug-cc-pV6Z 2.41 57954 Data adapted from [15]. RMSD values reference aug-cc-pV6Z. M+B indicates combined method and basis set error.

Implement Strategic Basis Set Selection

- Use def2-TZVPPD or aug-cc-pVTZ as minimum for accurate NCI results [15]

- For initial scans, use smaller basis sets without diffuse functions, then refine with diffuse-augmented basis sets

- Consider the CABS (complementary auxiliary basis set) singles correction with compact, low l-quantum-number basis sets as an alternative [15]

Employ Mixed Basis Set Approaches

- Use different basis sets for different atoms via the

genkeyword [17] - Apply more complete basis sets to reactive centers and smaller basis sets to spectator atoms

- Example implementation for a platinum complex:

- Use different basis sets for different atoms via the

Guide 3: Implementing Constant-Potential Methods with Fractional Electrons

Symptoms: Difficulty maintaining constant potential in electrochemical simulations or representing open systems.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Establish Grand Canonical DFT Framework

- Implement fractional electron counts to represent open systems in contact with electrodes [16]

- Develop SCF procedures that accommodate fractional electron numbers with minimal additional computational effort [16]

- Combine with implicit solvent models to represent electrochemical environments [16] [18]

Address Computational Challenges

- Utilize moderately converged electronic structures from previous calculations as initial guesses [8]

- Implement robust convergence criteria that account for fractional occupation effects

- Employ restart capabilities to build upon partially converged wavefunctions

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol 1: Systematic Approach for Difficult SCF Convergence

Initial Setup and Validation

Gradual Refinement Procedure

Final Calculation with Diffuse Functions

- Employ previously converged density as initial guess

- Use aggressive SCF convergence criteria (8-10 cycles) [18]

- Monitor SCF behavior for oscillations and adjust mixing parameters if needed

Protocol 2: Basis Set Selection Strategy for Electrochemical Systems

Accuracy Requirement Assessment

- Determine whether non-covalent interactions, anion characterization, or charge transfer processes are central to the study

- Reference Table 1 to select appropriate basis set based on target accuracy and computational resources [15]

Progressive Basis Set Approach

- Conduct geometry optimizations with moderate basis sets (def2-SVP, def2-TZVP)

- Perform single-point energy calculations with diffuse-augmented basis sets (def2-TZVPPD, aug-cc-pVTZ)

- For highest accuracy, utilize progressively larger basis sets (cc-pVQZ, cc-pV5Z) with diffuse functions [15]

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Computational Resources for Electrochemical Calculations

| Resource/Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Diffuse-Augmented Basis Sets | Accurately describe non-covalent interactions, anions, and dispersed electron densities | Essential for interaction energies, charged species, excited states [15] |

| Electron Smearing | Enable convergence via fractional occupation of near-degenerate orbitals | Metallic systems, small-gap systems, transition states [8] |

| Effective Core Potentials (ECPs) | Reduce computational cost by replacing core electrons with pseudopotentials | Systems with heavy elements (transition metals, lanthanides) [17] |

| Implicit Solvent Models | Represent solvent effects without explicit solvent molecules | Electrochemical environments, solution-phase systems [18] |

| SCF Acceleration Algorithms (DIIS, DIIS-GDM, ARH) | Improve and stabilize SCF convergence | Problematic systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps or open-shell configurations [8] [18] |

| Mixed Basis Set Approaches | Apply different basis sets to different atoms for efficiency balance | Large systems where accuracy is only needed at reactive centers [17] |

Workflow Visualization

Frequently Asked Questions

1. Why does my geometry optimization fail to converge or my molecule "explode"?

Geometry optimization failures can often be traced back to the initial structure. An implausible starting geometry—such as atoms placed too close together, or a mix-up between coordinate units (Angstroms vs. Bohr)—can cause the optimization to fail catastrophically [19]. Furthermore, for heavy elements, ensure you are using an appropriate basis set that includes necessary functions or an effective core potential (ECP) to properly describe the core electrons [19]. In rare cases, the optimizer's internal coordinate system may be unsuitable for your molecule; switching to a Cartesian coordinate system (using the !COpt keyword in ORCA) can resolve this [19].

2. What does an "imaginary vibrational mode" mean after a frequency calculation on my optimized structure?

Imaginary frequencies (reported as negative wavenumbers, e.g., -70 cm⁻¹) indicate that the optimized geometry is not a true minimum on the potential energy surface but a saddle point [19].

- Small imaginary modes (below ~100 cm⁻¹) are often caused by numerical noise. This can be addressed by increasing the integration grid size (e.g., moving from

!DefGrid2to!DefGrid3) or using the!TightOptkeyword for a more precise geometry optimization [19]. - Larger imaginary modes typically mean the optimization converged to a transition state instead of a minimum. This often happens when the starting geometry possesses high symmetry. The solution is to distort the starting geometry away from this symmetric structure [19].

3. My SCF calculation won't converge. What are the first things I should check?

Before adjusting advanced SCF settings, always verify the basics [19] [10]:

- Coordinates: Are the atom positions reasonable? Visualize them.

- Charge and Multiplicity: Are they correct for your system?

- Basis Set: Are you using a diffuse basis set (e.g.,

aug-cc-pVTZ)? These can cause linear dependency issues, making convergence difficult. Consider a less diffuse alternative [19]. - System Stability: Are you calculating an anion in the gas phase? It may be unstable without a solvation model (like CPCM) to stabilize it [19].

4. I see a "Not enough memory" error. How do I control memory in ORCA?

Memory in ORCA is controlled per core using the %maxcore keyword. The value is specified in MB. The total memory used is maxcore * number of cores [19].

- Example:

%maxcore 3000withnprocs 6uses 6 * 3000 = 18,000 MB (18 GB) total [19]. - Best Practice: Do not request more than 75% of the physical memory available on a node, as ORCA can occasionally use more than the

maxcoresetting [19].

5. What should I do if my geometry optimization stops because the SCF did not converge?

In ORCA, by default, a geometry optimization will stop if the SCF fails to converge in a given cycle [10]. You can modify this behavior, but a better strategy is to address the root cause of the SCF failure. Use the guidelines in the SCF convergence section below to stabilize the calculation. For a single-point energy calculation, ORCA will not proceed to post-HF steps if the SCF is not fully converged [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing and Fixing SCF Convergence Problems

Self-Consistent Field (SCF) convergence is fundamental to most quantum chemistry calculations. Follow this logical workflow to diagnose and resolve issues.

Detailed Methodologies for Key SCF Protocols:

- Addressing Numerical Noise: If you suspect the integration grid (DFT) or COSX grid (RIJCOSX approximation) is causing noise, increase the grid size. In ORCA, use

!DefGrid3for a tighter grid than the defaultDefGrid2[19]. - Using Damping Algorithms: For systems with large initial energy fluctuations (common in open-shell transition metal complexes), use the

!SlowConvor!VerySlowConvkeywords. These automatically increase damping to help guide the SCF to convergence [10]. - Specialist SCF Algorithms:

- KDIIS with SOSCF: The

!KDIIS SOSCFcombination can offer faster convergence for some difficult cases. If the SOSCF algorithm itself fails, you can delay its start with a%scf SOSCFStart 0.00033 endblock [10]. - Tweaking DIIS: For pathological cases (e.g., metal clusters), increase the number of Fock matrices used in the DIIS extrapolation inside the SCF block:

%scf DIISMaxEq 15 end(default is 5). You can also force a full rebuild of the Fock matrix every iteration withdirectresetfreq 1to eliminate numerical noise, though this is computationally expensive [10].

- KDIIS with SOSCF: The

Resolving Geometry and Import Errors

Incorrect molecular geometry is a primary cause of calculation failures. This includes both user-created structures and those imported from databases or other software.

Common Geometry Pitfalls and Solutions:

| Pitfall | Description | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Invalid Starting Geometry | Atoms placed impossibly close or with unrealistic bond lengths/angles [19]. | Always visualize your structure before calculation. Use chemical knowledge to create a plausible initial geometry. |

| Unit Confusion | Accidentally using Bohr coordinates when the software expects Angstroms, or vice-versa [19]. | Double-check the input requirements of your computational chemistry software and ensure your coordinate file is saved in the correct unit. |

| Linear Dependency (Basis Set) | Using very large, diffuse basis sets (e.g., aug-cc-pVQZ) on systems with many atoms, leading to numerical instability [19] [10]. |

Use a smaller or less diffuse basis set. The ma-def2 series can be a good alternative to aug-cc-pV sets for some applications [19]. |

| Heavy Element Misconfiguration | Missing effective core potentials (ECPs) or key basis functions for heavy atoms [19]. | Consult basis set repositories (e.g., EMSL) to ensure you have a consistent basis set and ECP for all elements. Use the ! PrintBasis keyword in ORCA to verify. |

Experimental Protocol: Generating a Robust Initial Guess

For systems that are notoriously difficult to converge (e.g., open-shell transition metal complexes or conjugated radical anions), a multi-step protocol is recommended [10]:

- Simplify the System: Perform a single-point energy calculation using a simpler, more robust method and basis set (e.g., BP86/def2-SVP).

- Converge the Simple Calculation: Ensure the SCF converges for this simpler case. You may need to use

!SlowConvor other keywords from the troubleshooting guide above. - Read the Orbitals: Use the converged orbitals from the simple calculation as the starting guess for your more advanced target calculation (e.g., DLPNO-CCSD(T)/def2-TZVPP). This is done in ORCA with the

! MOReadkeyword and a%moinp "simple_calc.gbw"block [10]. - Proceed with Target Calculation: The advanced calculation will now begin from a much better initial guess, significantly improving the chances of SCF convergence.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Electrochemistry

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Continuum Solvation Model (e.g., CPCM) | Mimics the electrochemical environment (e.g., a solvent) by embedding the molecule in a polarizable continuum, crucial for calculating realistic redox potentials and stabilizing anions [19]. |

| Diffuse Basis Sets (e.g., aug-cc-pVXZ) | Provides a more accurate description of electron-rich regions, such as those in anions or excited states, which are critical in electron transfer processes [19]. |

| Effective Core Potential (ECP) | Replaces the core electrons of heavy atoms with a potential, reducing computational cost and allowing the study of transition metal catalysts prevalent in electrochemical systems [19]. |

| Integration Grid (e.g., DefGrid1-3) | The numerical grid used to integrate the Exchange-Correlation functional in DFT. A finer grid (higher number) reduces numerical noise, which is essential for stable geometry optimizations and frequency calculations [19]. |

| SCF Convergence Accelerators (e.g., DIIS, SOSCF) | Algorithms that help the SCF procedure find a stable solution for the electron density, which is often challenging for the open-shell species common in electrochemistry [10]. |

Advanced SCF Algorithms and Constant-Potential Methods for Electrochemical Simulations

Theoretical Foundation and Key Concepts

What is Grand Canonical DFT (GCDFT) and how does it differ from standard DFT?

Answer: Grand Canonical Density Functional Theory (GCDFT) is an extension of traditional DFT that enables calculations at a constant electrochemical potential (μ), rather than with a fixed number of electrons. This approach is particularly crucial for modeling electrochemical systems where electron transfer occurs at electrode-electrolyte interfaces. In standard canonical ensemble DFT, the electron number (N) is fixed, and the total electronic energy (E) is minimized. In contrast, GCDFT minimizes the grand canonical free energy (Ω) defined as:

Ω = EDFT - μN - (1/β)Sel

where EDFT is the DFT electronic energy, μ is the chemical potential, N is the electron number, β is the inverse temperature, and Sel is the electronic entropy. This formulation allows the electron number to vary adaptively between self-consistent field (SCF) iterations, making it particularly suitable for simulating electrochemical processes under constant potential conditions [20] [21].

What are the primary applications of GCDFT in electrochemical research?

Answer: GCDFT has become an indispensable tool in computational electrochemistry with several key applications:

- Electrocatalyst Screening: High-throughput discovery of efficient catalysts for reactions such as hydrogen evolution, oxygen reduction, and CO₂ reduction

- Battery Material Design: Investigation of electrode-electrolyte interfaces in lithium-ion and beyond-lithium batteries

- Corrosion Studies: Modeling dissolution and passivation processes at metal surfaces under electrochemical potential control

- Interface Phenomena: Understanding potential-dependent solvent reorganization and ion adsorption at solid-liquid interfaces The unique capability to explicitly control electrode potential in first-principles calculations enables researchers to directly simulate experimental conditions and predict thermodynamic and kinetic parameters for electrochemical reactions [20] [21].

Implementation and Methodology

What is the computational workflow for implementing GCDFT?

Answer: Implementing GCDFT requires a self-consistent procedure that simultaneously optimizes the electron density and chemical potential. The following diagram illustrates the key computational workflow:

The implementation differs significantly from conventional DFT in its direct minimization of the grand canonical potential over density matrices with adaptive updating of electron number between SCF iterations. This approach stores the one-electron reduced density matrix (1RDM) as the central variational parameter, which is more practical in Gaussian-type orbital (GTO) bases than in plane-wave frameworks due to storage considerations [20].

What basis sets and solvation models are recommended for GCDFT calculations?

Answer: The choice of basis sets and solvation models critically impacts the accuracy and efficiency of GCDFT simulations:

Table: Essential Computational Components for GCDFT Implementation

| Component | Type/Options | Purpose in GCDFT | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis Sets | Gaussian-type orbitals (GTOs) | Discretize Hamiltonian and density matrices | Recently developed GTOs that extrapolate to basis set limit are recommended [20] |

| Solvation Models | Implicit linear dielectric + ionic response | Model solvent/electrolyte environment | Introduces <50% overhead vs. gas-phase; essential for interfacial electrochemistry [20] |

| XC Functionals | PBE, PBEsol, vdW-DF-C09 | Approximate exchange-correlation | PBEsol and vdW-DF-C09 show lower errors in oxide materials [22] |

| Grand Canonical Integrator | Variational minimization | Directly minimize Ω with adaptive electron number | More robust than Pulay mixing schemes; avoids multiple fixed-N calculations [20] |

For electrochemical applications, the integration of GCDFT with implicit solvation models that account for both linear dielectric response and ionic screening is particularly important. These solvation schemes introduce minimal computational overhead (less than 50% compared to gas-phase calculations) while enabling realistic modeling of solid-liquid interfaces [20].

Troubleshooting SCF Convergence Problems

Why does GCDFT present unique SCF convergence challenges?

Answer: GCDFT introduces additional complexity to SCF convergence due to the coupled optimization of electron density and chemical potential. Common issues include:

- Strong Density Oscillations: Large fluctuations in early iterations due to simultaneous updates of density matrix and electron number

- Charge Sling-shotting: Unphysical hopping between electron numbers when chemical potential is near degenerate energy levels

- Implicit Solvation Coupling: Additional self-consistency between electron density and solvent reaction field

- Small HOMO-LUMO Gaps: Metallic systems or those with near-degenerate states exacerbate convergence difficulties

These problems are particularly prevalent in transition metal complexes, open-shell systems, and materials with localized d- and f-electron configurations where multiple redox states compete energetically [8] [10] [20].

What specific strategies improve GCDFT SCF convergence?

Answer: Based on implementation experience across multiple codes, the following strategies have proven effective:

Table: SCF Convergence Accelerators for GCDFT Calculations

| Method | Mechanism | Best For | GCDFT Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS with Extended Subspace | Extrapolates Fock matrix using history | Most systems | Increase DIISMaxEq to 15-40 for difficult cases [10] |

| Damping | Mixes old and new Fock matrices | Initial oscillations | Apply 20-50% damping in first 5-10 cycles [8] [23] |

| Level Shifting | Artificially increases HOMO-LUMO gap | Small-gap systems | 0.1-0.3 Hartree shift; delays convergence but improves stability [8] [23] |

| Electron Smearing | Fractional occupancies via finite temperature | Metallic systems | Use multiple restarts with successively smaller smearing values [8] |

| Direct Minimization | Variational optimization of grand potential | Pathological cases | Native to GCDFT implementation; avoids DIIS issues [20] |

| TRAH/SOSCF | Second-order convergence | Near solution | Enable after initial convergence; adjust startup threshold [10] [13] |

For particularly challenging systems, this combination of settings provides a robust starting point:

Additionally, ensuring appropriate integral tolerances (tightened to 10⁻¹⁴) and using larger integration grids (minimum 99,590 points) prevents numerical noise from hindering convergence [24] [20].

How does initial guess selection impact GCDFT convergence?

Answer: The initial guess is particularly critical in GCDFT because it establishes the starting point for both electron density and chemical potential optimization:

- Superposition of Atomic Potentials (VSAP): Generally provides the most balanced starting point for GCDFT

- Fragment/Projection Methods: Using converged densities from similar systems or smaller basis sets significantly improves initial guess quality

- Closed-shell Precursors: For open-shell systems, first converging a closed-shell configuration (possibly with fractional oxidation states) provides orbitals that can be read into the target GCDFT calculation

- Checkpoint Restarts: In optimization sequences, reading orbitals from previous geometry steps dramatically improves convergence

For transition metal systems with multiple accessible oxidation states, initializing from a moderately converged electronic structure of a known redox state often provides better starting points than atomic superposition methods [8] [23].

Integration with Implicit Solvation

How does implicit solvation affect GCDFT convergence and implementation?

Answer: Implicit solvation models introduce additional self-consistency between the electron density and the solvent reaction field, which can both stabilize and complicate GCDFT convergence:

The solvent interaction creates an additional potential that depends on the electron density, requiring a nested self-consistency loop. While this coupling can sometimes stabilize convergence by damping oscillations, it more frequently introduces additional challenges due to the non-linear response of the solvation model. Implementation-wise, the solvation terms must be included in the Fock matrix construction and updated alongside the density matrix during the SCF procedure [20].

Successful implementations employ a unified variational framework where the solvation terms are fully incorporated into the grand canonical free energy minimization, rather than treated as an external perturbation. This approach ensures consistent convergence behavior and avoids artifacts that can arise from sequential optimization of electronic and solvation degrees of freedom [20].

Validation and Error Analysis

How can researchers validate their GCDFT implementation and identify errors?

Answer: Comprehensive validation is essential for reliable GCDFT calculations:

- Electron Number Consistency: Verify that the computed electron number stabilizes at physically reasonable values and doesn't exhibit unphysical drifting during simulations

- Potential Calibration: Check alignment between computed and expected electrochemical potentials using reference systems with known redox properties

- Grid Sensitivity: Test dependence of results on integration grid quality, particularly for meta-GGA and hybrid functionals

- Basis Set Convergence: Ensure properties of interest are stable with respect to basis set size, noting that GTOs require careful treatment of basis set superposition error

- Solvation Model Limits: Validate implicit solvation predictions against explicit solvent calculations or experimental data where available

Recent studies emphasize that error quantification should include both functional-specific deviations (e.g., LDA's overbinding vs. PBE's overestimation of lattice constants) and implementation-specific numerical errors. Statistical analysis of errors across relevant material classes provides essential "error bars" for predictive GCDFT simulations [22].

Frequently Asked Questions

My GCDFT calculation oscillates between different electron numbers. How can I stabilize it?

Answer: Electron number oscillations typically occur when the chemical potential aligns with a dense manifold of electronic states. Implement the following remedies:

- Increase damping factors (0.3-0.5) specifically during initial cycles

- Apply moderate level shifting (0.1-0.3 Hartree) to artificially increase HOMO-LUMO separation

- Use electron smearing with finite electronic temperature (100-300K) to smooth state occupations

- Reduce the aggressiveness of DIIS extrapolation by decreasing the number of DIIS vectors or delaying DIIS startup

- For persistent cases, employ direct minimization methods that are more robust than DIIS for these scenarios [8] [20] [23].

How do I determine the appropriate chemical potential for my GCDFT simulation?

Answer: The chemical potential in electrochemical applications is typically referenced to standard electrodes:

- Computational Standard Hydrogen Electrode (SHE): Reference against the H⁺/H₂ redox couple at pH 0, U = 0 V vs. SHE

- Work Function Alignment: For surface calculations, align the internal chemical potential with the work function of a reference electrode

- Potential Scaling: Use linear response theory to connect computational chemical potentials to experimental potentials

- Systematic Sampling: For unknown systems, perform calculations across a range of chemical potentials to map the potential-dependent behavior

Recent implementations facilitate this by directly specifying the electrode potential relative to standard references, with automatic conversion to the corresponding chemical potential in the calculation [20] [21].

What are the most common mistakes when implementing GCDFT for electrochemical interfaces?

Answer: Frequent pitfalls include:

- Insufficient Solvation: Using gas-phase calculations or inadequate solvation models for interfacial electrochemistry

- Incorrect Potential Referencing: Failing to properly align the computational chemical potential with experimental reference electrodes

- Poor Convergence Criteria: Stopping calculations prematurely before electron number and grand potential are fully converged

- Inadequate Basis Sets: Using basis sets with insufficient flexibility to describe potential-dependent electron transfer

- Ignoring Ensemble Effects: Neglecting that GCDFT inherently describes ensembles of states with fluctuating electron number

- Grid Inconsistencies: Using different integration grids for different chemical potentials, introducing numerical noise [24] [22] [20].

By addressing these areas systematically, researchers can avoid common pitfalls and implement robust GCDFT simulations for electrochemical applications.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the primary cause of SCF convergence failures? SCF convergence failures typically occur due to a poor initial guess for the molecular orbitals or the system having a small HOMO-LUMO gap, which can cause oscillations in the iterative process. This is particularly common in complex systems like open-shell transition metal complexes or those with delocalized electronic structures.

Which SCF algorithm is the most robust when the default DIIS fails? When the default DIIS algorithm fails, the Geometric Direct Minimization (GDM) algorithm is highly recommended as a robust fallback [25]. GDM is an improved version of the Direct Minimization approach and is less prone to the oscillatory behavior that can plague DIIS in difficult cases.

How can I improve the initial guess to aid convergence? Using a better initial guess than the default core Hamiltonian can significantly improve SCF convergence. Recommended methods include [23]:

- Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD): Projects atomic densities onto the molecular basis set.

- Parameter-free Hückel guess: Uses atomic HF calculations to build an initial Hückel matrix.

- Reading from a checkpoint file: Using orbitals from a previous, similar calculation.

What advanced techniques can stabilize convergence for metallic or small-gap systems? For systems with a small HOMO-LUMO gap, such as metallic systems or some electrochemical interfaces, these techniques can help [23] [2]:

- Level Shifting: Increases the energy gap between occupied and virtual orbitals, stabilizing the update.

- Damping: Mixes a portion of the old Fock matrix with the new one to prevent large, unstable changes.

- Fractional Occupations/Smearing: Uses electronic temperature (e.g., Fermi smearing) to assign fractional occupations, which is often essential for metallic systems.

How do I know if my converged wavefunction is physically meaningful? A converged SCF wavefunction may sometimes be a saddle point rather than a minimum. Performing a stability analysis is crucial to check if the solution is stable to internal or external perturbations (e.g., transforming from RHF to UHF) [23]. An unstable wavefunction indicates that a different electronic state, often with a different spin symmetry, might be the true ground state.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Common SCF Convergence Failures

| Symptoms | Recommended Actions | Algorithm / Remedy | Key Parameters to Adjust |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large initial error/oscillations | Improve initial guess, use damping | SAD or Hückel guess [26] [23], Damping [23] | damp = 0.5 (PySCF) [23], SCF_GUESS = SAD (PSI4) [26] |

| Slow convergence/oscillation in late stages | Use DIIS acceleration, switch to GDM | DIIS [25] [26], GDM [25] | SCF_ALGORITHM = GDM (Q-Chem) [25] |

| Convergence failure due to small HOMO-LUMO gap | Apply level shift, use smearing | Level Shifting [23], Fermi Smearing [2] | level_shift = 0.3 (PySCF) [23], ELECTRONIC_TEMPERATURE (CP2K) [2] |

| Convergence to unphysical saddle point | Perform stability analysis, change spin/initial guess | Stability Analysis [23], Maximum Overlap Method (MOM) [25] | newton().kernel() for 2nd-order SCF (PySCF) [23] |

Guide 2: SCF Algorithm Decision Flow

This workflow helps you select the best algorithm and strategies for your calculation.

Guide 3: Advanced Protocol for Electrochemical System Convergence

Electrochemical interfaces pose unique challenges. This protocol, based on a recent study of a gold nanocluster electrocatalyst, outlines a robust approach [27].

Objective: Achieve SCF convergence for an electrochemical interface simulation where the electronic structure may change significantly during the reaction (e.g., ligand dissociation).

Computational Methods (as implemented in CP2K):

- Software: CP2K/QUICKSTEP [27] [2].

- Functional: PBE-D3 [2].

- Basis Set: Gaussian-type DZVP [2].

- Pseudopotentials: GTH [2].

SCF Protocol:

- Initialization: Use the

MULTI_SECANTorMULTI_STEPPERmethod as the default SCF solver [28]. - Mixing: Start with an initial damping parameter (

MIXING) of 0.075, allowing the program to auto-adapt it [28]. - Convergence Criterion: Set a strict SCF convergence criterion (e.g.,

1e-7a.u.) to ensure high accuracy for forces in AIMD [2]. - Metallic Systems: For metallic interfaces, employ Fermi smearing with an electronic temperature of 300-500 K and use the Broyden mixing scheme to ensure charge density convergence [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in SCF Calculations |

|---|---|

| DIIS (Direct Inversion in the Iterative Subspace) | The default algorithm in many codes. It extrapolates the Fock matrix by minimizing the error vector from previous iterations, leading to fast convergence for well-behaved systems [25] [26]. |

| GDM (Geometric Direct Minimization) | A robust fallback when DIIS fails. GDM minimizes the energy directly using geometric principles and is less prone to convergence oscillations [25]. |

| Second-Order SCF (SOSCF) | A Newton-type method that uses orbital Hessian information to achieve quadratic convergence. It is powerful but computationally more expensive per iteration [25] [23]. |

| Level Shifter | A numerical stabilizer that increases the energy gap between occupied and virtual orbitals, preventing divergence in systems with small HOMO-LUMO gaps [23]. |

| Fermi Smearing | A technique that assigns fractional orbital occupations based on electronic temperature, essential for converging metallic systems and small-gap semiconductors [2]. |

| Stability Analysis | A post-convergence check to determine if the obtained wavefunction is a true minimum or an unstable saddle point, guiding the search for the correct ground state [23]. |

| Checkpoint File | A file containing the wavefunction from a previous calculation, serving as an excellent initial guess for a new, similar calculation and dramatically improving convergence [23]. |

Quantitative Comparison of SCF Algorithms

| Algorithm | Typical Convergence Speed | Stability | Memory/Cost | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIIS | Fast [26] | Moderate | Low | Standard closed-shell and open-shell systems with a reasonable HOMO-LUMO gap [25]. |

| GDM / GDM_LS | Slower but steady | High | Moderate | Fallback for DIIS failures; systems prone to oscillation [25]. |

| ADIIS | Fast | Moderate | Low | Similar to DIIS; performance may be comparable to RCA [25]. |

| Second-Order (e.g., Newton) | Quadratic (Very Fast) [23] | High | High (requires Hessian) | Difficult convergence problems where other methods fail [25] [23]. |

| MOM (Maximum Overlap Method) | Varies | High for target state | Low | Calculating excited states or preventing root flipping during optimization [25]. |

In the context of electrochemical calculations research, achieving self-consistent field (SCF) convergence is a fundamental challenge. The choice of initial guess profoundly impacts the stability, speed, and ultimate success of these computations. While the Superposition of Atomic Densities (SAD) provides a robust starting point for many systems, modern electrochemical research increasingly involves complex interfaces, non-equilibrium structures, and emerging materials that demand more specialized approaches. This technical support guide addresses the limitations of standard guesses and provides advanced methodologies for overcoming persistent SCF convergence failures in electrochemical systems, enabling researchers to obtain reliable results for challenging computational scenarios.

Understanding Initial Guess Types: A Technical FAQ

What are the primary limitations of the core Hamiltonian guess?

The core Hamiltonian guess (also known as the one-electron guess) generates molecular orbital coefficients by diagonalizing the core Hamiltonian matrix while completely ignoring interelectronic interactions [29]. While exact for one-electron systems, this approach produces significant inaccuracies in molecular environments: it creates incorrect atomic shell structure and causes all electrons to crowd onto the heaviest atom in the system [29]. These deficiencies make the core guess typically extremely inaccurate, and it should only be used as a last resort when more sophisticated methods fail.

When should researchers prefer SAP over SAD guesses?

The Superposition of Atomic Potentials (SAP) guess represents a major improvement over the core guess as it correctly describes atomic shell structure while retaining a simple form [29]. SAP introduces the interelectronic interactions missing from the core guess through a superposition of pretabulated atomic potentials derived from fully numerical exchange-only LDA calculations employing spherically averaged densities [29]. Researchers should select SAP when: (1) Using general (read-in) basis sets where SAD is unavailable; (2) Working with systems containing atoms lacking pretabulated density matrices; (3) Facing convergence failures with SAD in large or complex electrochemical systems. SAP is particularly valuable for electrochemical interface studies where accurate potential description is critical.

How does AUTOSAD differ from standard SAD, and when is it necessary?

AUTOSAD provides a method-specific SAD guess generated on-the-fly by running separate atomic calculations on all non-equivalent atoms in the system, in contrast to the standard SAD approach that relies on pretabulated density matrices [29]. This approach is necessary when: (1) Using user-customized general basis sets; (2) Requiring method-specific initial guesses beyond standard approximations; (3) Working with mixed basis sets where standard SAD is unavailable. However, AUTOSAD shares the limitations of producing a non-idempotent density matrix and not generating molecular orbitals, making it incompatible with direct minimization methods [29].

What are the advantages of the purified SAD (SADMO) approach?

The SADMO guess addresses two significant limitations of the standard SAD approach: it provides guess orbitals and ensures idempotency of the initial density matrix [29]. This purification process involves diagonalizing the non-idempotent SAD density matrix to obtain natural orbitals, then recreating an idempotent density matrix through aufbau occupation of these orbitals [29]. The advantages include: (1) Compatibility with SCF algorithms requiring orbitals (direct minimization methods); (2) Reduced SCF iterations due to initial idempotency; (3) Improved convergence stability. However, SADMO remains unavailable for general (read-in) basis sets [29].

Quantitative Comparison of Initial Guess Methods

Table 1: Comprehensive Comparison of Initial Guess Methods for Electrochemical Calculations

| Method | Basis Set Compatibility | Orbital Output | Idempotent | Computational Cost | Recommended Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAD | Internal basis sets only | No | No | Low | Standard systems with internal basis sets [29] |

| SAP | All basis sets (internal & read-in) | Yes | Yes | Moderate | General basis sets, poor SAD convergence [29] |

| AUTOSAD | Internal & general basis sets | No | No | High (atomic calculations) | User-customized basis sets, method-specific needs [29] |

| SADMO | Internal basis sets only | Yes | Yes | Low | Direct minimization methods, faster convergence [29] |

| Core Hamiltonian | All basis sets | Yes | Yes | Very Low | Last resort only [29] |

| GWH | All basis sets | Yes | Yes | Very Low | ROHF jobs with old SCF code [29] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Guide for SCF Convergence Failures in Electrochemical Systems

| Problem Symptom | Recommended Initial Guess | Key Parameters | Expected Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Failure with large basis sets | SAD or AUTOSAD | GUESS_GRID for precision | Robust convergence in expanded basis [29] |

| Poor convergence with user-defined basis | SAP or AUTOSAD | Basis set quality checks | Improved description of molecular environment [29] |

| Oscillating convergence in direct minimization | SADMO | Convergence thresholds | Stable, monotonic convergence [29] |

| Metallic system convergence issues | SAP with elevated GUISS_GRID | Electronic temperature, mixing parameters | Improved metallic state description [29] |

| Transition metal system failures | SAP with dense integration grid | GUESS_GRID = 2 or 3 | Accurate d-electron description [29] |

Advanced Methodologies for Challenging Electrochemical Systems

AI-Accelerated Workflows for Interface Systems

For complex electrochemical interface systems, traditional initial guess methods may prove insufficient. The ElectroFace dataset demonstrates how artificial intelligence-accelerated ab initio molecular dynamics (AI²MD) can generate specialized starting points for interface calculations [2]. This approach combines active learning workflows with molecular dynamics to produce robust initial structures for charged interfaces:

Initial Structure Generation: Create slab-vacuum models through surface cleavage with symmetric, stoichiometric slabs to avoid spurious dipole interactions [2]

Water Interface Equilibration: Merge slab with pre-equilibrated water boxes using PACKMOL, followed by 5-ps AIMD simulations to achieve proper water density (1.0 g/cm³ ±5%) [2]

Active Learning Training: Extract 50-100 evenly distributed structures from AIMD trajectories as initial training set for machine learning potentials [2]

Concurrent Learning Expansion: Implement iterative training-exploration-screening-labeling cycles using DP-GEN or ai2-kit to expand reference data [2]

Production MLMD Simulations: Generate 20-30 ps ML trajectories using LAMMPS with DeePMD-kit potentials for nanosecond-scale sampling [2]

Specialized Protocols for Electrode-Electrolyte Interfaces

Electrochemical interface modeling requires careful preparation of initial structures to ensure physical realism and SCF convergence:

Initial Structure Preparation for Electrochemical Interfaces

Research Reagent Solutions: Computational Tools for Advanced Initial Guesses

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Specialized Initial Guesses in Electrochemical Research

| Tool/Package | Primary Function | Application in Initial Guess | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP2K/QUICKSTEP | AIMD Simulations | Generate reference data for ML potentials | Gaussian/plane-wave mixed basis, GTH pseudopotentials [2] |

| DeePMD-kit | Machine Learning Potentials | Create ML potentials for active learning | Deep neural network potentials, LAMMPS integration [2] |

| DP-GEN | Concurrent Learning | Automated training set expansion | Exploration-screening-labeling workflow [2] |

| LAMMPS | MD Simulations | Production MLMD trajectories | Compatibility with DeePMD-kit, extensible [2] |

| ai2-kit | Workflow Automation | Proton transfer analysis, ML workflows | Integration with common DFT/MD packages [2] |

| ECToolkits | Analysis | Water density profile analysis | Python-based, interface characterization [2] |

Implementation Workflow for Optimal Initial Guess Selection

Initial Guess Selection Algorithm

Expert Recommendations for Specific Electrochemical Applications

Battery Electrode Materials

For Li-ion battery electrode materials like LiFePO₄ and LiMnO₂, which exhibit complex electronic structure and potential thermal runaway issues, multi-scale frameworks combining density functional theory with empirical electrochemical modeling provide superior initial guesses [30]. Implement DFT-refined electrode properties (dielectric constants, bond strengths, energy states, structural stability) as temperature-dependent parameters in continuum models [30].

Complex Interface Systems

For solid-liquid electrochemical interfaces, leverage the ElectroFace dataset of AI²MD trajectories for charge-neutral interfaces of 2D materials, zinc-blend-type semiconductors, oxides, and metals [2]. Use these pretrained trajectories as initial guesses for: (1) Electric double layer model construction; (2) Counter ion placement; (3) Active learning initialization; (4) Interface property benchmarking [2].

Molecular Dynamics Integration

In AIMD simulations of electrochemical interfaces, employ specialized protocols: Use PBE functional with D3 dispersion correction, DZVP basis sets with 400-600 Ry plane-wave cutoffs, GTH pseudopotentials, and elevated temperature (330K) to avoid PBE water glassy behavior [2]. For metallic systems, implement Fermi smearing (300K electronic temperature) with Broyden mixing or SGCPMD for SCF convergence [2].

Fractional Electron Occupations and Fermi Smearing for Metallic Systems

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are fractional electron occupations and why are they necessary in DFT calculations for metals?

Fractional electron occupations, often introduced via Fermi smearing techniques, are a computational method where electronic states are not strictly occupied (1) or empty (0). Instead, a fractional occupancy is assigned within a certain energy width around the Fermi level. This is crucial for metallic systems because it replaces the discontinuous, binary filled/empty occupation with a smoother function, which dramatically improves the numeric stability and convergence of the self-consistent field (SCF) procedure. In metals, the electronic bands cross the Fermi level, meaning that even with a dense k-point mesh, small changes during the SCF cycle can cause large, oscillatory shifts in orbital occupations. Smearing techniques mitigate this problem [31].

Q2: My SCF calculation for a metal cluster oscillates and will not converge. Could smearing help?