Optimizing Differential Pulse Voltammetry: A Strategic Guide for Sensitive Bioanalysis in Drug Development

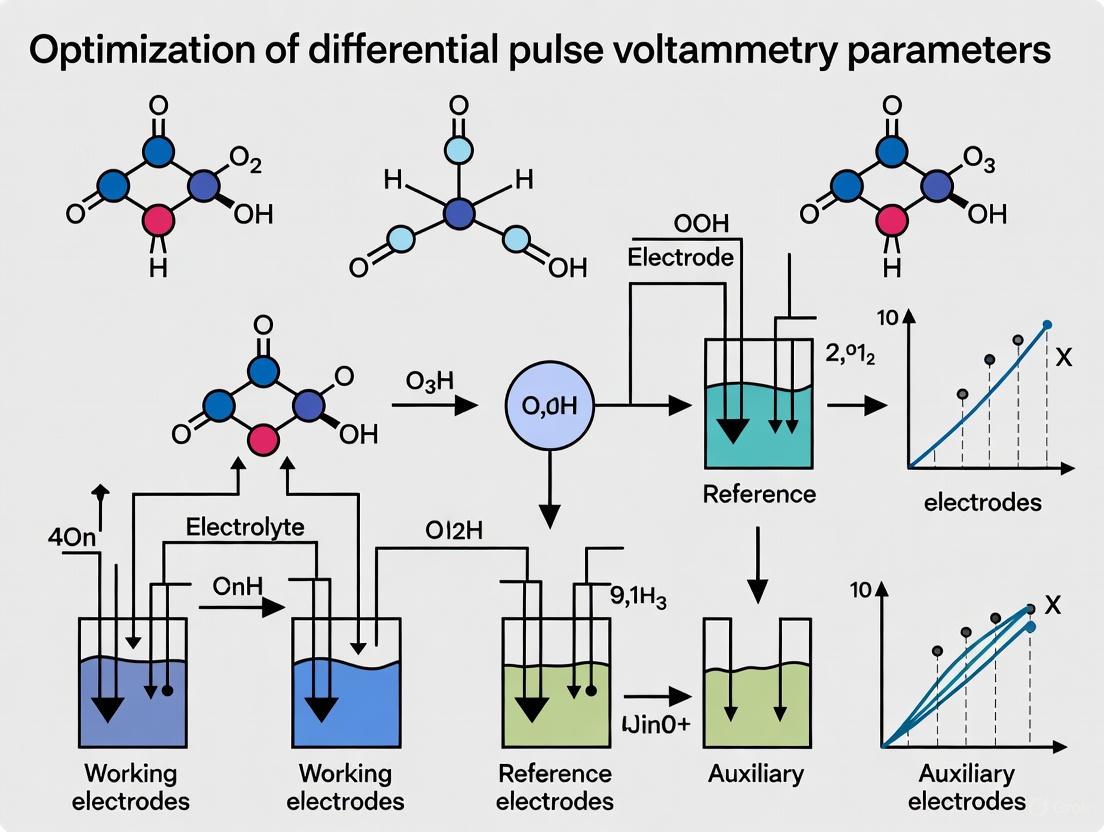

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) parameters to achieve superior analytical performance.

Optimizing Differential Pulse Voltammetry: A Strategic Guide for Sensitive Bioanalysis in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) parameters to achieve superior analytical performance. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, it details how strategic parameter selection enhances sensitivity, minimizes background current, and enables the detection of biomolecules and pharmaceuticals at trace levels. The content explores modern optimization methodologies like Design of Experiments (DoE), tackles common troubleshooting scenarios, and outlines validation protocols to ensure reliable, reproducible results for complex matrices such as biological fluids, supporting critical analytical tasks in biomedical research.

Understanding Differential Pulse Voltammetry: Principles and Advantages for Bioanalysis

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is capacitive current, and why is it a problem in electroanalysis? Capacitive current (or charging current) is the current required to charge the electrical double layer at the electrode-solution interface, much like charging a capacitor. It does not involve electron transfer to electroactive species (faradaic reactions). Since it decays exponentially with time, its presence can overwhelm the faradaic current from the analyte, especially at low concentrations, leading to poor signal-to-noise ratios and higher limits of detection [1] [2].

2. How does the DPV pulse sequence specifically cancel out the capacitive current? In DPV, the potential waveform consists of small-amplitude pulses superimposed on a staircase ramp. The current is sampled twice for each step: just before the pulse is applied (Ir) and at the end of the pulse (If). The capacitive current decays rapidly and is approximately equal at these two sampling points. Therefore, when the difference, δI = If – Ir, is calculated, the capacitive current contributions effectively cancel out, leaving a predominantly faradaic signal [1] [3] [4].

3. How do I choose the optimal pulse parameters for my DPV experiment? Optimal parameters depend on your specific system, but typical starting values are listed in the table below. For highly sensitive determination, a systematic optimization of parameters like pulse amplitude, width, and increment using a method like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is recommended to achieve the highest signal-to-noise ratio [5].

4. My DPV baseline is not flat. What could be the cause? A non-flat baseline can be caused by issues with the working electrode, such as a contaminated surface or poor electrical contacts. It can also result from fundamental electrochemical processes at the electrode whose origins are not fully understood. Polishing the working electrode and ensuring all connections are secure can often mitigate this issue [6].

5. What is the key difference between DPV and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) in minimizing capacitive current? Both techniques use pulsed waveforms and differential current sampling to minimize capacitive current. A key operational difference is that SWV applies symmetrical forward and reverse pulses at a high frequency, allowing for faster scan rates. The current difference (forward - reverse) is plotted, which also effectively suppresses the background [1] [7] [8].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Unusual or distorted voltammogram | Blocked reference electrode frit or air bubbles; poor electrical contacts [6]. | Check that the reference electrode is not blocked. Ensure all electrodes are properly connected and submerged. Use the general troubleshooting procedure to isolate the fault [6]. |

| Very small, noisy current | Working electrode not properly connected to the cell or potentiostat [6]. | Check the connection to the working electrode. Ensure the electrode surface is clean and properly positioned in the solution. |

| Voltage compliance error | Counter electrode removed from solution or disconnected; quasi-reference electrode touching the working electrode [6]. | Verify all electrodes are connected correctly and fully immersed in the electrolyte. Ensure no electrodes are short-circuited by physical contact. |

| Large, reproducible hysteresis in baseline | Charging currents from the electrode-solution interface [6]. | Reduce the scan rate, increase analyte concentration, or use a working electrode with a smaller surface area [6]. |

| Unexpected peaks | Impurities in the solvent, electrolyte, or from atmospheric contamination; scanning near the edge of the potential window [6]. | Run a background scan without the analyte. Use high-purity chemicals and ensure a clean experimental setup. |

Experimental Parameter Optimization

The table below provides standard and optimized parameter ranges for DPV based on literature, which can serve as a starting point for method development.

Table 1: DPV Parameter Guide for Experimental Design

| Parameter | Typical Range (General) | Example from Optimized 2-NP Research [5] | Function & Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Amplitude | 10 – 100 mV [3] [2] | 50 mV (for SWV) | Increases faradaic response; larger values give higher but broader peaks. |

| Pulse Width | ~50 ms [1] | 50 ms (for SWV) | Time for capacitive current to decay; longer times enhance faradaic-to-capacitive current ratio [1]. |

| Pulse Increment (Step Height) | 2 – 10 mV [1] [4] | 10 mV (for SWV) | Determines potential scan resolution; smaller steps improve peak definition. |

| Sample Period | End of pulse (e.g., last 50%) [3] [7] | Optimized via RSM | Critical timing for measuring faradaic current after capacitive decay. |

Core Principle Visualization

DPV Pulse and Current Sampling Diagram

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for DPV Electroanalysis

| Item | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃) | Carries current and minimizes solution resistance; ensures the electric field is applied effectively [1] [5]. |

| Electroactive Probe (e.g., K₄Fe(CN)₆) | Used for system calibration and characterization; provides a well-understood, reversible redox couple [1]. |

| Solvent (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile) | Dissolves analyte and electrolyte; must be electrochemically inert in the potential window of interest [5]. |

| Modified Electrode Surfaces | Enhances sensitivity and selectivity; used for specific analyte detection (e.g., 2-AN/GC for 2-nitrophenol) [5]. |

| pH Buffer Solutions | Controls proton activity; essential for studying proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) reactions [5] [7]. |

Core Principles of Differential Pulse Voltammetry

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is a powerful electroanalytical technique prized for its exceptional sensitivity and low limits of detection, often in the 10-8 to 10-9 M range, making it a preferred method for quantifying trace-level analytes [4] [9]. Its core advantage lies in its unique waveform and current sampling method, which effectively suppresses non-Faradaic (charging) current to isolate the Faradaic current generated by redox reactions [4] [2].

The fundamental operating principle involves applying a series of small, constant-amplitude voltage pulses (typically 10–100 mV) superimposed on a linearly increasing staircase potential ramp [4]. The current is sampled twice for each pulse:

- Just before the potential pulse is applied (

i1). - At the end of the pulse (

i2).

The final signal plotted on the voltammogram is the difference between these two currents (Δi = i2 - i1) versus the applied potential [4] [3]. Because the non-Faradaic charging current decays rapidly and contributes almost equally to both i1 and i2, subtracting them effectively cancels out this background component. The Faradaic current, which is concentration-dependent, changes significantly during the pulse, resulting in a strong, well-defined peak signal [4]. This produces a peak-shaped voltammogram where the peak height is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species, and the peak potential is characteristic of the specific analyte [4] [2].

Diagram: DPV Current Sampling Mechanism

Technical Support & Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common DPV Experimental Issues

| Problem Phenomena | Potential Causes | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Peak Current / Poor Sensitivity | Non-optimal pulse parameters; Fouled working electrode; Low analyte concentration. | 1. Verify parameter settings (Amplitude, Pulse Width).2. Check electrode surface under microscope.3. Test with a standard solution. | 1. Optimize pulse parameters (see Table 3) [10].2. Re-polish and clean the working electrode.3. Increase deposition time for stripping analysis. |

| Wide or Asymmetric Peaks | Excessive pulse amplitude; Irreversible redox reaction; Slow electron transfer kinetics. | 1. Reduce pulse amplitude incrementally.2. Compare with a known reversible probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻). | 1. Lower pulse amplitude to improve resolution [4].2. Consider electrode modification to enhance kinetics [11]. |

| High Background Noise | Electrical interference; Unstable reference electrode; Contaminated electrolyte. | 1. Use a Faraday cage.2. Check reference electrode potential.3. Prepare fresh supporting electrolyte. | 1. Ensure proper grounding and shielding.2. Replace or refurbish the reference electrode.3. Re-purify electrolytes and use high-purity solvents. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Inconsistent electrode surface; Drifting potential; Uncontrolled temperature. | 1. Record multiple scans on fresh surface.2. Monitor reference electrode stability.3. Note laboratory temperature fluctuations. | 1. Implement strict electrode pre-treatment protocol [12].2. Use a fresh reference electrode or internal standard.3. Perform experiments in a temperature-controlled environment. |

| No Peak Observable | Incorrect potential window; Deactivated electrode; No electroactive species present. | 1. Confirm the redox potential of the analyte.2. Test electrode with a standard redox couple.3. Verify analyte stability and composition. | 1. Widen the potential scan range based on CV scouting.2. Re-prepare or re-modify the working electrode [11] [12].3. Confirm the analyte is electroactive within the chosen window. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is DPV more sensitive than Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)? DPV's superior sensitivity stems from its differential current sampling, which minimizes the contribution of the capacitive (charging) current to the overall signal. In CV, the charging current can obscure the Faradaic current, especially at low analyte concentrations. DPV effectively subtracts this background, yielding a higher signal-to-noise ratio [4] [2].

Q2: How do I choose the optimal pulse parameters for a new experiment? Start with manufacturer-recommended default values (e.g., pulse amplitude 50 mV, pulse width 50 ms) [4]. For maximum performance, use a systematic optimization approach like Response Surface Methodology (RSM). Key parameters to optimize are pulse amplitude, pulse width, and step potential (or scan rate), as these significantly impact peak current and shape [11] [10]. The optimal value for one parameter often depends on the others, highlighting the need for multivariate optimization.

Q3: My target analytes have overlapping peaks. How can I resolve them? DPV naturally produces narrower peaks than other voltammetric techniques, which aids in resolution [2]. If peaks still overlap, you can:

- Adjust the electrolyte pH to differentially shift the formal potentials of the analytes [11] [10].

- Modify the working electrode surface with materials (e.g., polymers, nanoparticles) that selectively interact with one analyte, altering its electron transfer kinetics and peak potential [11] [12].

- Reduce the pulse amplitude to decrease peak width, though this also reduces peak height [4].

Q4: Can DPV be used for simultaneous detection of multiple analytes? Yes, this is one of its key strengths. If the redox potentials of the analytes are sufficiently separated (e.g., by >100 mV), DPV can resolve them into distinct peaks, allowing for simultaneous quantification in a single run. This has been successfully demonstrated for isomers like hydroquinone and catechol, as well as neurotransmitters like dopamine and serotonin [11] [2].

Optimizing DPV Parameters: A Practical Guide

Critical Parameters and Optimization Strategies

| Parameter | Function & Impact on Signal | Recommended Starting Range | Optimization Guidance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Amplitude | Height of the potential pulse. Increases peak current but can cause peak broadening and decrease resolution for closely spaced analytes [4]. | 10 - 100 mV | Use RSM to find the optimum. A study found a quadratic effect, where both too low and too high amplitudes reduce the optimal signal [10]. |

| Pulse Width | Duration of the potential pulse. Allows the non-Faradaic current to decay, improving the signal-to-noise ratio. A longer pulse width can increase sensitivity [4]. | 50 - 100 ms | Optimize via RSM. Interacts with pulse amplitude; the optimal value is often found within the experimental range, not necessarily at the endpoints [10]. |

| Step Increment (Potential Step) | The change in baseline potential between pulses. Affects the effective scan rate and peak definition. A smaller step provides more data points per peak [4] [3]. | 2 - 10 mV | A smaller step increment (e.g., 0.001V) was found to significantly improve peak current and clarity in some optimized systems [10]. |

| Scan Rate | Determined by Step Increment and Pulse Period. Influences analysis time and signal intensity. | Varies | Faster scans save time but may reduce signal quality. Optimize by adjusting step increment and pulse period [3]. |

| Electrode Modification | Not a software parameter, but crucial. Modifying the electrode surface can enhance electron transfer, increase surface area, and impart selectivity [11] [12]. | N/A | Use materials like graphene, carbon nanotubes, molecularly imprinted polymers, or metal nanoparticles to lower detection limits and improve selectivity [11] [12] [13]. |

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing DPV via Response Surface Methodology

This protocol is adapted from research on simultaneous determination of hydroquinone and catechol [11] and lead(II) [10].

1. Define Objective and Response

- Objective: Maximize the peak current (Ip) for your target analyte(s).

- Response Variable: Measured peak height from the DPV voltammogram.

2. Select Critical Parameters and Ranges

- Based on literature and screening experiments, select key parameters. Typically, these are Pulse Amplitude, Pulse Width, and Step Potential (or Scan Rate) [11] [10].

- Define a realistic experimental range for each (e.g., Pulse Amplitude: 25-75 mV).

3. Design and Execute Experiments

- Use a statistical design like a Box-Behnken Design (BBD). A BBD for three parameters requires only 15 experiments, making it highly efficient [10].

- Perform the DPV experiments in a randomized order to minimize the effect of external noise.

- Instrument Setup: Use a standard three-electrode system (Glassy Carbon Working Electrode, Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode, Pt Counter Electrode) and a potentiostat with DPV capability [4] [12].

4. Analyze Data and Build Model

- Input the experimental data into statistical software.

- Fit the data to a quadratic model and perform Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) to identify significant parameters and interaction effects.

- The model will show if the effect of a parameter is linear or quadratic [10].

5. Validate the Model and Determine Optimum

- The software will predict the parameter values that yield the maximum peak current.

- Perform a confirmation experiment using these predicted optimal conditions. The measured response should closely match the predicted value.

Diagram: DPV Optimization Workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function & Role in DPV Analysis |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common working electrode substrate known for its electrochemical inertness, conductivity, and suitability for modification with various films and polymers [12]. |

| Reference Electrode (Ag/AgCl) | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled and measured. Essential for reproducible results [4]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, Phosphate Buffer) | Carries current and minimizes ohmic resistance (iR drop) in the solution. Its composition and pH can profoundly affect redox potentials and reaction rates [11] [10]. |

| Electrode Modifiers (e.g., Graphene, CNTs, Polymers) | Used to functionalize the electrode surface to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and stability. They can catalyze reactions, pre-concentrate analyte, or prevent fouling [11] [12] [13]. |

| Redox Probes (e.g., K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) | Used to characterize the electroactive surface area and electron transfer kinetics of an electrode before and after modification [12] [13]. |

| Cross-linking Agents (e.g., Glutaraldehyde) | Used to immobilize biological recognition elements (like enzymes) onto modified electrode surfaces for biosensor development [12]. |

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is a powerful electrochemical technique prized for its high sensitivity and low detection limits, often enabling quantification of analytes in the parts-per-billion (ppb) range [4]. Its effectiveness hinges on a specific applied waveform that minimizes non-Faradaic (charging) current, thereby enhancing the measurement of the Faradaic current from the redox reaction of interest [4] [14]. This article provides a detailed examination of the key parameters that define the DPV waveform—pulse amplitude, pulse width, and interval time—and offers practical guidance for researchers aiming to optimize these parameters for their specific applications.

The core principle of DPV involves applying a series of small, constant-amplitude potential pulses superimposed upon a linearly increasing staircase potential ramp [4] [2]. The current is sampled twice for each step: once immediately before the pulse is applied (I1) and once at the end of the pulse (I2). The differential current (ΔI = I2 - I1) is then plotted against the baseline potential, resulting in a peak-shaped voltammogram [4] [3] [2]. This differential measurement is key to the technique's sensitivity, as the charging current, which decays rapidly, contributes almost equally to both I1 and I2 and is thus effectively canceled out [4].

Deconstructing the DPV Waveform Parameters

The DPV waveform is characterized by several critical parameters that directly control the experiment's sensitivity, resolution, and speed. Understanding and optimizing these parameters is essential for obtaining high-quality data. The table below summarizes the core parameters and their typical values.

Table 1: Key Parameters of the DPV Waveform

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Amplitude | ΔE or E~pulse~ | 10 – 100 mV [4] [2] | The height of the potential pulse superimposed on the staircase ramp. |

| Pulse Width | τ~pulse~ | ~50 ms [4] | The duration for which the potential pulse is applied. |

| Sample Period | τ~sample~ | Specified within pulse width [3] | The time window at the end of the pulse where the second current (I2) is sampled. |

| Pulse Increment (Step E) | ΔE~step~ | 2 – 10 mV [4] | The step size of the staircase potential between pulses. |

| Pulse Period | τ~period~ | ~100 ms [4] | The total duration of one complete pulse cycle. |

Pulse Amplitude

The pulse amplitude is the height of the potential pulse, typically between 10 and 100 mV [4] [2]. It is a primary factor controlling the sensitivity of the technique. A larger pulse amplitude generally increases the Faradaic current response, leading to a higher peak current [4]. However, this comes at the cost of decreased peak resolution; larger pulses can cause adjacent peaks to merge, making it difficult to discriminate between species with similar redox potentials [4]. Therefore, selecting the pulse amplitude involves a trade-off between sensitivity and resolution.

Pulse Width and Sample Period

The pulse width is the duration of the potential pulse, often around 50 milliseconds [4]. This parameter, along with the sampling time, is crucial for discriminating against the charging current. The charging current decays exponentially with time, while the Faradaic current decays more slowly (as a function of 1/√t) [14]. By setting a sufficiently long pulse width and sampling the current at the end of the pulse, the contribution of the charging current to the measurement is minimized [3] [14]. The "Sample Period" or "Post-pulse width" is the specific time window at the end of the pulse where the current I2 is measured [3].

Pulse Increment and Interval Time

The pulse increment (or step potential) is the change in the baseline staircase potential from one pulse to the next, typically between 2 and 10 mV [4]. This parameter, combined with the pulse period, determines the effective scan rate. A smaller increment results in a higher-resolution voltammogram, revealing more detail in the peak shape, but it also increases the total duration of the experiment.

Troubleshooting Common DPV Issues

Even with a sound theoretical understanding, researchers often encounter practical challenges. This section addresses common issues and provides targeted troubleshooting advice.

Table 2: DPV Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Suggested Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Pulse width too short; sampling time not optimized. | Increase the pulse width to allow more time for the capacitive current to decay [14]. Ensure the current is sampled at the very end of the pulse [3]. |

| Poor Peak Resolution | Pulse amplitude too large; pulse increment too large. | Decrease the pulse amplitude to sharpen the peaks [4]. Use a smaller pulse increment to increase the data density across the peak [4]. |

| Peak Current Too Low | Pulse amplitude too small. | Increase the pulse amplitude within the typical range (10-100 mV) to enhance the Faradaic response [4]. |

| Experiment Duration Too Long | Pulse increment too small; pulse period too long. | Increase the pulse increment to cover the potential range faster, balancing the need for speed with required resolution [4]. |

| Non-Linear Calibration Curve | Analyte adsorption or surface fouling; incorrect baseline. | Clean and/or re-polish the working electrode between runs. Verify that the chosen initial potential is where no Faradaic reaction occurs [2]. |

FAQs on DPV Waveform Optimization

Q: How do I systematically find the optimal DPV parameters for a new analyte? A: A one-variable-at-a-time approach can be used, but for greater efficiency, statistical optimization methods like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) are highly effective. RSM allows you to change multiple variables (e.g., pulse amplitude, pulse width, increment) simultaneously and model their interactions with a reduced number of experiments, pinpointing the ideal parameter set [5].

Q: My DPV peak is broad and asymmetric. What does this indicate? A: A broad peak can indicate electrochemical irreversibility in the redox reaction [2]. As the irreversibility of the reaction increases, the peak base widens and its height decreases. This is a characteristic of the system under study. You can try adjusting the solution conditions (e.g., pH) or confirm the irreversibility using a technique like Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

Q: Is the peak potential (E~p~) in DPV equal to the formal potential (E⁰)? A: Not exactly. For a reversible system, the peak potential in DPV is approximately equal to the half-wave potential (E~1/2~), which is close to E⁰. More precisely, the relationship is given by E~peak~ = E~1/2~ - (ΔE / 2), where ΔE is the pulse amplitude [15]. For irreversible systems, E~p~ will deviate further from E~1/2~ [2].

Q: When should I use DPV over Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)? A: Both are sensitive pulse techniques. DPV is excellent for quantitative analysis of a single analyte or a few well-separated analytes due to its high sensitivity. SWV is significantly faster and can be better for studying surface-bound species or reaction mechanisms, but its waveform can be more complex to optimize. DPV is often preferred for its simplicity in quantitative applications [3].

An Experimental Protocol for Parameter Optimization

The following workflow provides a step-by-step methodology for optimizing DPV parameters, incorporating statistical design for efficiency.

Title: DPV Parameter Optimization Workflow

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Preliminary Scouting with CV: Begin by running a Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) experiment to identify the redox potential of your target analyte. This helps define the relevant potential window for your DPV scan [2].

- Set Initial DPV Parameters: Input the estimated potential range into your potentiostat software. Use moderate initial parameters as a starting point (e.g., Pulse Amplitude: 50 mV, Pulse Width: 50 ms, Pulse Increment: 5 mV) [4].

- Design of Experiments (DoE): Instead of a one-variable-at-a-time approach, employ a statistical method like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with a Box-Behnken Design (BBD). This allows you to efficiently study the interactive effects of pulse amplitude, pulse width, and pulse increment on your response variables (peak current and peak width) with a minimal number of experimental runs [5].

- Execution and Modeling: Run the DPV experiments as specified by your experimental design. Record the peak current (which should be maximized for sensitivity) and the peak width at half-height (which should be minimized for resolution). Use statistical software to build a model that predicts these responses based on the input parameters.

- Optimization and Validation: The model will help you identify the optimal parameter set. Finally, validate these optimized parameters by analyzing independent standard solutions to confirm the method's performance, including its linearity and detection limit [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful DPV experiment relies on more than just waveform parameters. The choice of electrodes and supporting electrolyte is equally critical.

Table 3: Essential Materials for DPV Experiments

| Item | Function | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat | The main instrument that applies the potential waveform and measures the resulting current. | Gamry Interface, Pine Research WaveNow, BASi Epsilon series [4] [14]. |

| Three-Electrode System | A setup that ensures accurate potential control and current measurement. | Working Electrode: Glassy Carbon (GC), Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE), modified screen-printed electrodes [4] [5]. Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel (SCE) [4]. Counter Electrode: Platinum wire [4]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes the solution's resistance (iR drop). Its pH and composition can affect redox potentials. | Phosphate buffer, acetate buffer, KCl, TBATFB in non-aqueous systems [5]. |

| Modifier for Electrodes | Enhances sensitivity, selectivity, and stability by pre-concentrating the analyte or facilitating electron transfer. | 2-amino nicotinamide (2-AN) [5], gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) [5], multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) [2]. |

| Deaeration System | Removes dissolved oxygen, which can cause interfering reduction currents. | Nitrogen (N₂) or Argon (Ar) gas sparging. |

Title: Three-Electrode Cell Setup

FAQs: Fundamental Concepts for Troubleshooting

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between Faradaic and capacitive currents?

Faradaic and capacitive currents are two distinct processes that occur at the electrode-electrolyte interface:

- Faradaic Current: This is caused by electron transfer across the electrode interface, leading to the reduction or oxidation (redox reaction) of electroactive species [16]. It provides the analytical signal for most electrochemical sensing applications.

- Capacitive Current (Non-Faradaic): This originates from the charging and discharging of the electrical double-layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface. It involves the rearrangement of ions and solvent dipoles with no electron transfer or chemical reaction [16].

Q2: Why is understanding this distinction critical for optimizing my DPV parameters?

The ratio of Faradaic to capacitive current directly determines the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPR). Faradaic current is your "signal," while the capacitive current is a key component of the "noise" or background. Enhancing SNR is a primary goal of DPV parameter optimization, as a higher SNR leads to lower detection limits and more reliable quantification [17].

Q3: My DPV baseline is sloping and non-uniform. Is this related to capacitive effects?

Yes, a sloping baseline is often a manifestation of a significant and potential-dependent capacitive current. The total capacitance at the interface is not a perfect constant and can vary with the applied electrode potential, leading to a non-linear background. Proper background subtraction and the selection of a suitable potential window can mitigate this.

Q4: How does the electrode material influence these currents?

Electrode material properties, especially surface area and morphology, profoundly impact both currents. A high-surface-area material (e.g., porous carbon) will have a larger double-layer capacitance, increasing the capacitive background. However, if the material is also pseudocapacitive (e.g., functionalized graphene, certain metal oxides), it can undergo fast, reversible surface redox reactions that contribute additively to the total charge storage, enhancing the Faradaic signal [17].

Q5: What are "pseudocapacitive" processes, and how do they differ from battery-like reactions?

Pseudocapacitance is a special type of capacitive Faradaic charge storage [17]. It involves electron transfer but exhibits a current response that is capacitive in nature (e.g., a rectangular cyclic voltammogram). This is distinct from non-capacitive, battery-like Faradaic processes, which show sharp current peaks in CV. Pseudocapacitive materials are highly desirable as they combine high energy density with high power.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common DPV Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High capacitive background relative to Faradaic signal. | 1. Run a CV in your electrolyte without the analyte to measure capacitive current.2. Check if the issue persists at different scan rates (capacitive current is scan-rate dependent). | 1. Optimize DPV parameters: Increase pulse amplitude or extend pulse time.2. Electrode Treatment: Clean/polish the electrode to restore surface properties.3. Use a background subtraction algorithm. |

| Broad or Asymmetric Peaks | Slow electron transfer kinetics (kinetic limitations of the Faradaic process). | Perform a CV at different scan rates. If the peak separation increases with scan rate, kinetics are slow. | 1. Modify the electrode surface with a catalyst or mediator.2. Adjust the electrolyte: Change pH or use a different supporting electrolyte.3. Increase measurement temperature to enhance reaction kinetics. |

| Poor Reproducibility | Electrode Fouling by adsorption of reaction products or impurities, changing the double-layer structure. | Compare consecutive DPV scans; a decaying signal indicates fouling. | 1. Implement a regular electrode cleaning protocol between measurements.2. Use a protective membrane (e.g., Nafion) on the electrode.3. Ensure electrolyte is pure and free of contaminants. |

| Non-Linear Calibration Curve | At high concentrations, the electrode surface becomes saturated, or the diffusion layers of adjacent molecules overlap. | Check if the problem is more pronounced at higher concentrations. | 1. Dilute the sample into the linear range.2. Shorten the deposition or accumulation time for stripping techniques.3. Use a standard addition method for quantification. |

| Unexpected Shifts in Peak Potential | Changes in the local pH or ionic strength at the electrode interface. | Measure the formal potential of a standard redox couple in your solution. | 1. Use a high-concentration, pH-buffered supporting electrolyte.2. Ensure the reference electrode is stable and properly calibrated. |

Experimental Protocols for Investigating Interfacial Processes

Protocol 1: Deconvoluting Capacitive and Faradaic Contributions using Cyclic Voltammetry

Objective: To quantitatively determine the charge storage contributions from capacitive and Faradaic processes in your system.

Materials:

- Potentiostat (e.g., validated portable platform like μBIOPOT) [18]

- Working, counter, and reference electrodes

- Electrolyte solution (with and without analyte)

Methodology:

- Record Background CV: In the supporting electrolyte alone (no electroactive analyte), record cyclic voltammograms at multiple scan rates (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100 mV/s). This current is predominantly capacitive.

- Record Total CV: Repeat the CV measurements in the same scan rates with your analyte present. The current now contains both capacitive and Faradaic components.

- Data Analysis: At a fixed potential, plot the total current (i) from step 2 against the scan rate (v) and the square root of the scan rate (v¹/²). Use the power-law relationship: ( i = av^b ). A

b-value of 1.0 indicates ideal capacitive behavior, while 0.5 indicates diffusion-controlled Faradaic behavior. The capacitive contribution (k₁v) and diffusion-controlled contribution (k₂v¹/²) can be quantified by fitting the data to: ( i(V) = k1v + k2v^{1/2} ) [17].

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) for Interface Characterization

Objective: To model the electrode-electrolyte interface and identify resistances and capacitances associated with Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes.

Materials:

- Potentiostat with EIS capability

- Three-electrode setup

Methodology:

- Setup: Perform EIS at the DC potential of interest (e.g., the formal potential of your analyte) with a small AC amplitude (e.g., 10 mV) over a wide frequency range (e.g., 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz) [19].

- Equivalent Circuit Fitting: Model the obtained Nyquist plot using an appropriate equivalent circuit. A common model for a Faradaic interface is a solution resistance (Rₛ) in series with a parallel combination of a charge transfer resistance (R₍cₜ₎) and a constant phase element (CPE), sometimes in series with a Warburg element (W) for diffusion [19] [20].

- Interpretation:

- R₍cₜ₎: The diameter of the semicircle in the Nyquist plot represents the charge transfer resistance for the Faradaic reaction. A smaller R₍cₜ₎ indicates faster kinetics.

- CPE: Often used instead of a pure capacitor to model the non-ideal double-layer capacitance.

- The low-frequency region is dominated by the Faradaic processes, while the high-frequency region relates to solution resistance and double-layer charging.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Pt Working Electrode | Inert, polycrystalline surface ideal for fundamental studies of reactions like oxygen reduction; easily cleanable and reproducible [19]. |

| Protic Ionic Liquid (PIL) Electrolyte | Wide electrochemical window, high thermal stability, low vapor pressure. Useful for studying electrochemistry at elevated temperatures and understanding ion-specific effects on the double-layer [19]. |

| Redox Probe (e.g., Ferri/Ferrocyanide) | A well-understood, reversible redox couple used for diagnostic purposes. Used to validate instrument performance (e.g., μBIOPOT [18]) and characterize electrode kinetics/active area. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, Phosphate Buffer) | Provides high ionic conductivity while minimizing migration current. Buffers pH to ensure stable reaction conditions, which is critical for proton-coupled electron transfers. |

| Nafion Membrane | A proton-exchange membrane used to coat electrodes. It can minimize fouling by rejecting negatively charged interferents and is essential for creating stable biosensor interfaces. |

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Electrode Interface Processes

DPV Optimization Workflow

Equivalent Circuit Model

Voltammetry encompasses a family of electroanalytical techniques used to study electroactive species by measuring current as a function of applied potential. This technical guide provides a comparative overview of three prominent voltammetric methods—Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)—with particular emphasis on their operational principles, experimental parameters, and applications in pharmaceutical and bioanalytical research. Understanding the distinctions between these techniques is fundamental to selecting the appropriate method for specific analytical challenges, especially in trace analysis for drug development where sensitivity, selectivity, and speed are critical factors. This document supports researchers in optimizing DPV parameters within a broader methodological framework, providing troubleshooting guidance and technical protocols for enhanced experimental outcomes.

Fundamental Principles and Waveforms

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) employs a linear potential sweep that reverses direction at a specified vertex potential, creating a cyclic waveform. The potential is swept between two limits at a constant scan rate, and the resulting current is measured to provide information about the thermodynamics and kinetics of redox reactions [21]. The characteristic "duck-shaped" voltammogram for reversible systems reveals redox potentials, reaction reversibility, and the presence of intermediates [22].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) applies small-amplitude potential pulses (typically 10-100 mV) superimposed on a slowly increasing linear baseline potential [3] [2]. The current is sampled twice per pulse cycle: immediately before the pulse application and again at the end of the pulse. The plotted signal represents the difference between these two current measurements (ΔI = I₂ - I₁), which effectively cancels out most non-Faradaic (charging) current [4] [15]. This differential measurement approach yields peak-shaped voltammograms where peak height is proportional to analyte concentration [2].

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) utilizes a symmetrical square wave superimposed on a staircase potential ramp. The waveform consists of forward and reverse pulses of equal amplitude and duration within each cycle [23]. Current is sampled at the end of both the forward and reverse pulses, and the difference between these currents is plotted against the applied potential [23] [22]. This dual sampling strategy effectively minimizes capacitive background currents while providing enhanced sensitivity and faster scan rates compared to other pulsed techniques [23].

Visual Comparison of Waveforms and Signals

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental differences in potential waveforms and resulting current responses for CV, DPV, and SWV.

Technical Comparison of Key Parameters

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Voltammetric Technique Characteristics

| Parameter | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Mechanistic & kinetic studies [21] [22] | Quantitative trace analysis [2] [4] | Quantitative analysis & diagnostic studies [23] |

| Waveform Type | Linear potential sweep with reversal [21] | Staircase ramp with superimposed pulses [3] [4] | Staircase with symmetrical square wave [23] |

| Current Measurement | Continuous during sweep [21] | Difference before/after pulse (ΔI = I₂ - I₁) [3] [2] | Difference between forward/reverse pulses (ΔI = Iƒ - Iᵣ) [23] |

| Background Suppression | Poor (high charging current) [22] | Excellent (minimizes capacitive current) [2] [4] | Excellent (minimizes capacitive current) [23] |

| Sensitivity | Moderate (10⁻⁵–10⁻⁶ M) [22] | High (10⁻⁷–10⁻⁸ M) [22] [4] | Very High (up to 10⁻⁸ M) [23] |

| Speed | Moderate to Fast (scan rate dependent) | Slow (due to pulse sequence) [2] | Very Fast (rapid pulse sequences) [23] |

| Signal Output | Wave-shaped (current vs. potential) [22] | Peak-shaped (ΔI vs. potential) [2] [15] | Peak-shaped (ΔI vs. potential) [23] |

| Information Obtained | Redox potentials, reaction reversibility, kinetics [21] | Quantitative concentration data, half-wave potential [2] | Quantitative concentration data, diagnostic information [23] |

Table 2: Optimal Experimental Parameters for Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Parameter | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Scan Rate | 10–1000 mV/s [21] | 1–20 mV/s (effective) [4] | 100–1000 mV/s (effective) [23] |

| Pulse Amplitude | Not Applicable | 10–100 mV [3] [4] | 10–100 mV [23] |

| Pulse Width | Not Applicable | 10–100 ms [3] [4] | 1–100 ms [23] |

| Step Potential | Not Applicable | 1–10 mV [4] | 1–10 mV [23] |

| Typical Electrodes | Glassy Carbon, Pt, Au [21] | Glassy Carbon, Modified Electrodes, Mercury [2] [4] | Screen-printed, Modified Electrodes [23] [24] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standard DPV Protocol for Trace Analysis

This protocol outlines the general procedure for conducting DPV analysis for trace-level quantification, adaptable for pharmaceutical compounds and biological molecules.

Instrument Preparation: Utilize a potentiostat capable of pulse measurements (e.g., Gamry Instruments, Pine Research potentiostats) with PV220 Pulse Voltammetry Software or equivalent [4]. Connect the three-electrode system: Working Electrode (glassy carbon, screen-printed carbon, or modified electrode), Reference Electrode (Ag/AgCl or Saturated Calomel Electrode), and Counter Electrode (platinum wire or auxiliary electrode) [3] [4].

Solution Preparation: Prepare supporting electrolyte appropriate for the analyte (e.g., phosphate buffer for biological molecules, acetate buffer for heavy metals). Degas solution with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with measurements [22].

Parameter Configuration: Set initial and final potentials based on the redox characteristics of the analyte (determined from preliminary CV scans). Configure pulse parameters: Pulse Amplitude = 50 mV, Pulse Width = 50 ms, Pulse Increment = 2–10 mV, and Sample Period to occur near the end of the pulse [3] [4]. Use the "AutoFill" or "I Feel Lucky" features in software like AfterMath for reasonable starting parameters if unknown [3].

Measurement Procedure: Equilibrate the electrode at the initial potential during the induction period (if used). Execute the DPV scan, during which the instrument automatically applies the pulse sequence, measures currents I₁ and I₂, calculates ΔI, and plots the differential voltammogram [3] [2].

Data Analysis: Identify the peak potential (Eₚ) for qualitative identification. Measure peak height (ΔIₚ) for quantitative analysis using a calibration curve of peak current versus analyte concentration [2] [4].

Representative Research Application: SWV for Food Safety

A recent study demonstrates the application of SWV for detecting 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) in honey [24]. Researchers developed a cost-effective method using screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) modified with a nanocomposite of nickel oxide and carbon black (NiO-CB). The modified electrode enhanced sensitivity and selectivity for HMF detection. The SWV method provided a wide linear concentration range (10.0–200.0 mg kg⁻¹) with limits of detection and quantification suitable for regulatory compliance monitoring. This application highlights SWV's advantages for field-deployable analysis without needing complex sample preparation, offering a rapid alternative to HPLC methods [24].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What causes a flatlining signal in voltammetry experiments? A flat or clipped signal often results from an incorrect current range setting. If the actual current exceeds the selected range, the signal appears flat. Adjust the current range to a higher value (e.g., 1000 µA instead of 100 µA) to resolve this issue [25].

How do I choose between DPV and SWV for quantitative analysis? Select DPV for maximum sensitivity in detecting trace analytes (e.g., heavy metals, neurotransmitters) where detection limit is the primary concern [2] [4]. Choose SWV for faster analysis times and when additional diagnostic information about the electrode process is beneficial [23]. SWV is particularly advantageous for rapid screening applications [24].

Why is my DPV peak broad or poorly defined? Broad peaks may result from excessive pulse amplitude, too rapid scan rate, or electrode fouling. Optimize by reducing pulse amplitude to 10-50 mV, decreasing the pulse increment to 2-5 mV, and ensuring proper electrode cleaning between measurements [4] [15].

Can I use the same electrode for both CV and DPV experiments? Yes, the same working electrode materials (glassy carbon, gold, platinum) are suitable for both techniques [21] [4]. However, ensure the electrode is thoroughly cleaned between techniques, especially when switching from CV (which may generate reaction products) to DPV for quantitative measurements.

What is the purpose of the induction period in pulse voltammetry methods? The induction period allows the electrochemical cell to equilibrate at initial conditions before intentional perturbation. This "calms" the cell by allowing potentials and currents to stabilize, resulting in more reproducible data [3] [23].

Troubleshooting Guide

Table 3: Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| No peak observed | Incorrect potential range; Low analyte concentration; Electrode poisoning | Run CV to determine redox potential; Increase concentration or use pre-concentration; Clean/repolish electrode |

| High background noise | Electrical interference; Uncompensated resistance; Contaminated electrolyte | Use Faraday cage; Enable iR compensation; Purify electrolyte and degas solution |

| Poor reproducibility | Unstable reference electrode; Electrode fouling; Temperature fluctuations | Check reference electrode integrity; Clean electrode between runs; Use temperature-controlled cell |

| Peak current too low | Incorrect current range; Electrode passivation; Slow electron transfer kinetics | Increase current range setting; Activate electrode surface; Modify electrode to enhance kinetics |

| Multiple unexpected peaks | Solution impurities; Electrode contamination; Secondary reactions | Purify solutions and electrolytes; Thoroughly clean electrode; Change electrolyte or adjust pH |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Equipment for Voltammetric Analysis

| Item | Function/Purpose | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat | Instrument for applying potential and measuring current | Gamry Interface Series, Pine Research WaveDriver, PalmSens EmStat3 [3] [4] |

| Working Electrodes | Surface where redox reaction occurs | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Platinum Electrode, Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) [21] [24] |

| Reference Electrodes | Provide stable potential reference | Ag/AgCl (3M KCl), Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [21] [22] |

| Counter Electrodes | Complete electrical circuit | Platinum wire, Graphite rod [21] [22] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provide ionic conductivity without reacting | Phosphate buffer, Acetate buffer, Lithium perchlorate [22] [24] |

| Electrode Modifiers | Enhance sensitivity and selectivity | Nickel Oxide-Carbon Black (NiO-CB) composite, Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) [2] [24] |

| Degassing Agents | Remove interfering oxygen | Nitrogen gas (N₂), Argon gas (Ar) [22] |

DPV, CV, and SWV each offer distinct advantages for different analytical scenarios in pharmaceutical and bioanalytical research. CV remains the premier technique for initial mechanistic studies and characterizing redox behavior, while DPV provides exceptional sensitivity for quantifying trace analytes where detection limit is paramount. SWV combines high sensitivity with rapid analysis times, making it suitable for high-throughput screening and diagnostic applications. The optimal technique selection depends on the specific analytical requirements—whether the priority is mechanistic understanding (CV), ultratrace quantification (DPV), or rapid analysis with good sensitivity (SWV). By understanding their fundamental differences and appropriate applications, researchers can effectively leverage these powerful electroanalytical tools to advance their drug development and bioanalysis projects.

Methodology and Real-World Applications: From Electrode Selection to Pharmaceutical Quantification

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: How do I optimize DPV parameters for the best sensitivity and resolution?

The optimization of Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) parameters involves balancing trade-offs between sensitivity, peak resolution, and analysis time. The three most critical parameters are pulse amplitude, pulse duration (or width), and scan rate (often controlled by pulse increment and period) [26]. There is no single universal setting; parameters must be tailored to your specific electrochemical system and analytical goals, such as detecting a single analyte at low concentrations or resolving multiple species with similar redox potentials [3] [26].

FAQ: My DPV peaks are too small. Which parameter should I adjust first?

To increase peak current, you should first consider adjusting the Pulse Amplitude [26]. The peak current is directly proportional to the pulse amplitude [3]. However, be aware that using a pulse amplitude that is too large will cause peak broadening and a shift in peak potential, which can be detrimental when trying to resolve multiple analytes [26]. Alternatively, you can also increase the Pulse Width, as longer pulses can lead to higher peak currents, though this will also increase the total experiment time [26].

FAQ: My peaks for two different analytes are overlapping. How can I improve resolution?

To improve the resolution between adjacent peaks, you can:

- Reduce the Pulse Amplitude. While this may decrease the peak height, it results in narrower peaks, making it easier to distinguish between species with similar redox potentials [26].

- Decrease the Scan Rate. A slower scan rate (achieved by adjusting the pulse period and increment) also leads to narrower peaks and better separation [26].

- Increase the Pulse Width. Longer pulse times can lead to narrower peaks, improving the ability to detect multiple analytes simultaneously, though at the cost of longer experiment durations [26].

FAQ: The baseline in my voltammogram is noisy or unstable. What could be the cause?

A noisy or unstable baseline can often be traced to the working electrode's condition. Before performing DPV, proper electrode pretreatment and conditioning are crucial [26]. This process stabilizes the electrode surface by applying pre-set potentials, which minimizes surface state variations and improves reproducibility. For reusable disk electrodes, this may involve polishing and cycling in a specific medium, like sulfuric acid [26].

Quantitative Parameter Selection Guide

The following tables summarize the core parameters to optimize in a DPV experiment and their specific effects on the voltammogram. Use them as a guide for troubleshooting and method development.

Table 1: Core DPV Parameters and Their Effects on Analytical Performance

| Parameter | Typical Range | Primary Effect | Trade-offs and Secondary Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pulse Amplitude [4] [15] [26] | 10 - 100 mV | Increases peak current [3] [26]. | High amplitude broadens peaks and can shift peak potential, reducing resolution for multiple analytes [26]. |

| Pulse Width/Duration [4] [26] | ~50 ms [4] | Affects peak shape and current [26]. | Longer pulses can yield narrower peaks and higher signal but increase total experiment time [26]. |

| Scan Rate [26] | N/A (see below) | Faster scans reduce measurement time. | Higher scan rates cause peak broadening, making it harder to resolve multiple analytes [26]. |

| Pulse Increment (Step Potential) [3] [4] | 2 - 10 mV [4] | Defines the potential resolution of the voltammogram [26]. | Smaller increments provide higher resolution data but result in longer experiments [26]. |

Table 2: Advanced and System Parameters to Consider

| Parameter | Description | Guideline |

|---|---|---|

| Initial/Final Potential [3] [4] | Defines the start and end of the potential window. | Set to encompass the redox potentials of your target analyte(s) [3]. |

| Current Sampling | Timing of current measurement before (pre-pulse) and at the end (post-pulse) of the potential pulse [3] [4] [2]. | Key to canceling capacitive background current. Standard settings in instrument software are typically a good starting point [3]. |

| Electrode Conditioning [26] | Applying specific potentials to stabilize the electrode before the scan. | Critical for achieving a stable baseline and reproducible results. Protocol depends on electrode material and analyte [26]. |

Experimental Protocol: Systematic Optimization of DPV Parameters

This protocol outlines a methodology for optimizing DPV parameters, drawing from practices used in research to develop sensitive detection methods for compounds like 2-nitrophenol and viloxazine [5] [27].

Preliminary Setup and Electrode Preparation

- Objective: Establish a stable baseline and a known redox system.

- Materials:

- Potentiostat with DPV capability.

- Standard three-electrode system: Working Electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon, BDD), Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and Counter Electrode (e.g., Pt wire) [4].

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M Acetate buffer, pH 5.0) [27].

- Target analyte or a standard redox probe (e.g., 1 mM Potassium Ferricyanide).

- Procedure:

- Clean and Condition the working electrode according to the manufacturer's specifications or published methods for your analyte [26]. For a glassy carbon electrode, this often involves polishing and potential cycling in a clean supporting electrolyte.

- Immerse the electrodes in the electrolyte solution containing your analyte.

- Start with default parameters from your instrument's "AutoFill" or "I Feel Lucky" function, if available, as a reasonable starting point [3]. Typical initial values are: Pulse Amplitude = 50 mV, Pulse Width = 50 ms, Step Potential = 5 mV.

- Run an initial DPV scan to establish a baseline response.

One-Variable-at-a-Time (OVAT) Optimization

- Objective: Determine the approximate effect of each primary parameter on your specific system.

- Procedure:

- Pulse Amplitude: Keeping other parameters constant, run a series of DPV scans while increasing the pulse amplitude from 10 mV to 100 mV in increments of 10-20 mV [26]. Plot the peak current and peak width against the amplitude to find the value that offers the best compromise between signal strength and resolution.

- Pulse Width/Duration: With the optimized amplitude, vary the pulse width (e.g., from 25 ms to 200 ms). Observe the effect on peak current and shape, noting that longer pulses generally narrow the peak but lengthen the experiment [26].

- Scan Rate/Step Potential: Finally, adjust the step potential (e.g., from 1 mV to 10 mV) to modify the effective scan rate. A smaller step potential gives a higher-resolution voltammogram but takes longer to complete [26].

Refined Optimization Using Statistical Design

- Objective: For advanced method development, efficiently find the global optimum by accounting for parameter interactions.

- Procedure:

- Based on the results from OVAT, define a feasible range for each parameter (Pulse Amplitude, Pulse Width, Step Potential).

- Utilize a statistical method like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) with a Box-Behnken Design (BBD) [5]. This approach allows you to study the impact of multiple parameters and their interactions with a minimal number of experimental runs.

- The model will generate a multivariate equation that predicts the optimal parameter set for maximizing your desired outcome (e.g., peak current, signal-to-noise ratio).

Parameter Interdependence Workflow

The diagram below visualizes the decision-making process for optimizing key DPV parameters.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials for DPV Experiments in Drug Development

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrode | Working electrode known for wide potential window, low background current, and high resistance to fouling, ideal for organic molecules like pharmaceuticals [27]. | Used for sensitive determination of the antidepressant viloxazine in tap and river water [27]. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 5) | A common supporting electrolyte for optimizing the electrochemical response of organic analytes, particularly those involving proton-coupled electron transfers [27]. | Selected as the optimal supporting electrolyte for viloxazine oxidation, providing the highest peak current [27]. |

| 2-Amino Nicotinamide (2-AN) | A modifier compound used to create an electropolymerized film on a glassy carbon electrode, enhancing its sensitivity and selectivity for a specific target analyte [5]. | Used to modify a GC electrode for the highly sensitive determination of the environmental pollutant 2-nitrophenol [5]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, integrated electrodes offering portability and convenience for rapid, field-deployable analysis [28]. | Commercial SPEs were used with an AD5940 AFE for method development in ferricyanide solution [28]. |

Troubleshooting Common Sensor Issues

Q1: My sensor is producing erratic or noisy readings. What could be the cause? Several factors related to your electrode system could be responsible for noisy data:

- Poor Electrical Connections: Check the connection between the working electrode (e.g., a cylinder insert) and its holder. A spring-loaded contact in the holder can become recessed or corroded over time, leading to poor contact and noisy data. The shaft may need repair or replacement [29].

- Contaminated or Poorly Prepared Electrode Surface: For glassy carbon electrodes, ensure the surface is meticulously polished and cleaned before modification. For metal electrodes like steel coupons, a protective hydrocarbon coating from the factory must be removed by rinsing with a solvent like acetone to prevent interference at the electrode-electrolyte interface [29].

- Unstable Reference Electrode: A drifting or unsteady reference potential is a common source of error. This can be caused by a blocked frit (in standard reference electrodes like Ag/AgCl), a contaminated inner fill solution, or high impedances. If using a pseudo-reference electrode, ensure it is made from a non-polarizable metal and is chemically stable in your electrolyte [29].

- Improper Cell Setup and Environmental Factors: Using plastic beakers with a magnetic stirrer can generate static charge, which offsets the reference potential and causes erratic readings. Switch to a glass vessel. Furthermore, ensure all wiring is clean, dry, and physically isolated from AC power lines to prevent electromagnetic noise [30].

Q2: My modified electrode has a slow response time and low sensitivity. How can I improve it? A slow response often indicates an issue with the electrode surface or the modification layer.

- Aged or Fouled Electrode: As electrodes age, especially gel-filled types, their response naturally slows down. Electrodes can also become clogged by sample components. Clean the electrode according to manufacturer guidelines; warm, soapy water can remove organics, while dilute acid can address inorganic deposits. After cleaning, rehydrate the electrode by soaking it in a buffer solution [30].

- Suboptimal Nanomaterial Modification: The performance of a nanomaterial-enhanced sensor is highly dependent on the modifier's properties. Ensure your nanomaterial (e.g., carbon nanotubes, graphene, or metal nanoparticles) is well-dispersed and uniformly coated on the electrode surface. The high surface area and electrocatalytic properties of these materials are crucial for enhancing electron transfer and improving sensitivity [5] [31].

- Insufficient Electrolyte Purity: Trace impurities in the electrolyte can poison the catalyst sites on your modified electrode. Use high-purity electrolytes and solvents. Remember that irreversibly adsorbing impurities present at part-per-billion levels can substantially alter the electrode surface and degrade performance [32].

Q3: I am getting inconsistent results between experiments. How can I improve reproducibility? Reproducibility is critical for reliable data and is often compromised by subtle experimental variations.

- Reusing Modified Electrodes: Avoid reusing electrodes, especially after experiments involving corrosion or fouling. The surface area, morphology, and catalytic sites will be altered, making it impossible to return the electrode to its original state. Use a fresh or freshly modified electrode for each experiment [29].

- Inconsistent Electrode Modification: The process of modifying the electrode (e.g., electropolymerization, drop-casting) must be highly controlled. Follow a strict, documented protocol for the number of deposition cycles, concentration of modifier, and drying conditions to ensure a consistent modified layer from one experiment to the next [5].

- Uncontrolled Environmental Conditions: Temperature fluctuations can cause apparent drift in readings. Allow your electrode and sample to reach the same temperature before taking measurements [30]. Also, account for the "method-defined" nature of many electrochemical measurands; the results are intrinsically linked to the exact method of measurement, including operating conditions [32].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is a three-electrode system preferred over a two-electrode system for sensitive voltammetric measurements? A stable reference electrode potential is crucial for accurate measurement. In a two-electrode setup where the same rod serves as both reference and counter electrode, even a very small current passing through it can change its potential. This instability reduces the reliability of your measurements. A three-electrode system isolates the reference electrode, ensuring its potential remains stable throughout the experiment [29].

Q2: What are the key advantages of using nanomaterials to modify electrode surfaces? Nanomaterials provide significant enhancements over bare electrodes due to their unique properties [31]:

- High Surface Area: Provides more active sites for reactions, increasing sensitivity.

- Enhanced Electron Transfer: Materials like carbon nanotubes and graphene exhibit excellent electrical conductivity, catalyzing redox reactions.

- Tunable Properties: Their chemical and physical properties can be tailored for specific analytes, improving selectivity.

- Signal Amplification: Noble metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold, silver) have high catalytic activity and can amplify the electrochemical signal [33].

Q3: How do I choose the right nanomaterial for my specific analyte? The choice depends on the analyte's properties and the desired sensor function. The table below summarizes nanomaterials and their common applications in pharmaceutical drug detection, which can serve as a guide [31].

Table 1: Nanomaterial-Based Sensor Systems for Drug Detection

| Drug Family | Drug/Compound Name | Nanomaterial-Based Sensor System |

|---|---|---|

| Analgesics | Paracetamol | Carbon nanotubes, Graphene, Metallic nanoparticles [31] |

| Morphine | Gold nanoparticle/Nafion modified carbon paste electrode, MWCNT/Chitosan modified GCE [31] | |

| Anti-epileptics | Carbamazepine | MWCNT on a glassy carbon electrode, Fullerene-C60-modified GCE [31] |

| Gabapentin | Ag nanoparticles modified MWCNT, Nickel oxide nanotube modified electrode [31] | |

| Anesthetics | Procaine | MWCNT coated glassy carbon electrode [31] |

Q4: What is the importance of optimizing voltammetric parameters, and how can it be done efficiently? Parameters like pulse amplitude, frequency, and potential step in techniques like Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) directly influence the current response and thus the sensitivity of your detection. Manually optimizing each parameter is time-consuming. Using a statistical approach like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) allows you to change multiple variables simultaneously and model their interactions with a minimal number of experimental runs, leading to a robust and optimized method [5].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Modification of a Glassy Carbon Electrode with 2-Amino Nicotinamide (2-AN)

This protocol, adapted from a study on detecting 2-nitrophenol, outlines a general approach for creating a modified sensor [5].

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Polish the bare Glassy Carbon (GC) electrode with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water after polishing.

- Electropolymerization: Prepare a solution containing the 2-AN monomer and a supporting electrolyte (e.g., Tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate in a suitable solvent). Place the polished GC electrode into the solution.

- Cyclic Voltammetry Deposition: Using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), cycle the potential within a predetermined window for a specific number of cycles (e.g., 5 cycles) to electropolymerize the 2-AN onto the GC surface, forming the 2-AN/GC sensor.

- Sensor Characterization: Characterize the modified surface using techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) to confirm the successful attachment of the polymer. Electrochemical characterization using a standard redox probe like ferricyanide is also recommended [5].

Workflow Diagram: Sensor Development and Troubleshooting

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing a nanomaterial-modified sensor and the primary troubleshooting steps for common issues.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and reagents used in the fabrication and operation of carbon-based and nanomaterial-enhanced sensors.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sensor Fabrication and Experimentation

| Item | Function / Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | A common working electrode substrate; provides a wide potential window and chemical inertness [5]. | Surface must be polished to a mirror finish before modification for reproducibility [32]. |

| 2-Amino Nicotinamide | An example modifier; forms an electropolymerized film on the GC surface for selective analyte detection [5]. | The number of deposition cycles must be optimized for a highly sensitive layer [5]. |

| Noble Metal Nanoparticles | Signal amplifiers; materials like gold and silver nanoparticles enhance conductivity and provide electrocatalytic activity [31]. | Must be well-dispersed on the electrode surface to prevent aggregation and ensure uniform performance. |

| Carbon Nanotubes | Electrode modifiers; improve electron transfer kinetics and increase effective surface area [5] [31]. | Can be multi-walled (MWCNT) or single-walled (SWCNT); may require functionalization for optimal dispersion. |

| Tetrabutylammonium Tetrafluoroborate | A common supporting electrolyte; provides ionic conductivity in non-aqueous or mixed electrochemical systems [5]. | Must be of high purity to avoid introducing electroactive impurities that interfere with measurements [32]. |

| Britton-Robinson Buffer | A versatile buffer solution; used to maintain a specific pH during electrochemical experiments [5]. | The pH can significantly impact the electrochemical behavior of analytes and must be carefully controlled. |

The selection of an appropriate supporting electrolyte and buffer system is a critical step in optimizing electrochemical experiments, particularly in analytical techniques like differential pulse voltammetry (DPV). The electrolyte environment dictates fundamental parameters including conductivity, potential window, double-layer structure, and the local pH at the electrode-solution interface. These factors, in turn, profoundly influence electron transfer kinetics, reaction mechanisms, analytical sensitivity, and selectivity. This guide provides troubleshooting and best practices for selecting and optimizing these components to ensure reproducible and high-fidelity electrochemical data within the context of advanced research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is my baseline not flat, and why do I see large hysteresis between forward and backward scans? This is often due to charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts as a capacitor. The issue can be exacerbated by faults in the working electrode or high electrochemical cell resistance. To resolve this:

- Reduce the scan rate.

- Increase the concentration of your supporting electrolyte.

- Use a working electrode with a smaller surface area.

- Ensure your working electrode is properly polished and cleaned [6].

Q2: My potentiostat gives a "voltage compliance" error. What does this mean? This error indicates that the potentiostat is unable to maintain the desired potential between the working and reference electrodes. This can happen if:

- The counter electrode has been removed from the solution or is not connected properly.

- You are using a quasi-reference electrode and it is touching the working electrode, creating a short circuit [6].

Q3: Why is the shape or position of my voltammogram different on repeated cycles? An unstable voltammogram often points to an issue with the reference electrode. If the reference electrode is not in proper electrical contact with the solution (e.g., due to a blocked frit or an air bubble), it can act like a capacitor, causing the potential to drift. Check that the frit is not blocked and no bubbles are trapped. You can test this by temporarily using a bare silver wire as a quasi-reference electrode [6].

Q4: How do buffering agents specifically affect my electrochemical measurements? Buffering agents do more than just set the initial pH. They play a dynamic role in the electrochemical cell by mitigating large shifts in local pH caused by electrode reactions. Even species not directly part of the buffer system, like dissolved CO₂ from air or pH indicator dyes, can exert a significant buffering effect and slow down the propagation of pH gradients, thereby altering the observed electrochemical response [34]. Selecting a buffer with sufficient capacity for your current density is essential.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Electrolyte and Buffer Issues

The following table outlines common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem | Symptom | Likely Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| High Background Current | Noisy, sloping, or non-flat baseline; large hysteresis [6]. | Insufficient electrolyte concentration leading to high solution resistance; contaminated electrode. | Increase concentration of supporting electrolyte; polish and clean working electrode thoroughly [6]. |

| Unstable Voltammogram | Peaks shift between cycles; non-reproducible results [6]. | Unstable reference electrode potential; blocked frit; pH drift at electrode surface. | Check reference electrode for blockages; use a fresh reference electrolyte; employ a stronger buffer system. |

| Unexpected Peaks | Extra peaks not attributed to the analyte [6]. | Impurities in electrolyte, solvent, or from system components; electrode contamination. | Run a background scan with only supporting electrolyte; use high-purity reagents; clean cell and electrodes. |

| Distorted Peak Shape | Broad, asymmetric, or split peaks. | The electrolyte or buffer interacts chemically with the analyte; inappropriate solvent or pH. | Change the supporting electrolyte or buffer composition; verify the solvent compatibility. |

| Poor Signal-to-Noise | Very small, noisy current detected [6]. | Working electrode not properly connected; extremely low analyte concentration. | Check connection to working electrode; confirm electrode is submerged; increase analyte concentration if possible. |

Experimental Protocols for Optimization

Protocol 1: Optimization of Voltammetric Parameters using Response Surface Methodology (RSM)

This methodology is highly effective for systematically optimizing multiple interdependent voltammetric parameters with a minimal number of experimental runs [5].

- Identify Key Parameters: Select the critical parameters to optimize. For Differential Pulse Voltammetry, these typically include pulse amplitude, frequency, and potential step [5].

- Design the Experiment: Use a statistical design like the Box-Behnken Design (BBD), which efficiently explores the parameter space and allows for the study of interaction effects between variables [5].

- Run Experimental Trials: Perform the voltammetric measurements according to the experimental matrix generated by the BBD.

- Model and Analyze: Fit the experimental data (e.g., peak current) to a multivariate regression model. The generated equation describes the relationship between the parameters and the response.

- Locate the Optimum: Use the model to identify the parameter values (e.g., specific pulse amplitude, frequency, and step) that predict the maximum peak current or other desired analytical output [5].

The logical workflow for this optimization process is outlined below.

Protocol 2: Selection and Characterization of Support Electrolyte and pH

The correct choice of support electrolyte and pH is foundational to a successful experiment.

- Choose Electrolyte Type: Select a chemically inert supporting electrolyte (e.g., KCl, Na₂SO₄, TBATFB, phosphate buffers) that provides high ionic strength without reacting with the analyte or electrodes [5] [34]. The electrolyte must be soluble in the chosen solvent.

- Determine Support Electrolyte pH:

- Prepare a series of solutions with the same concentration of your analyte and supporting electrolyte, but varying pH levels using appropriate buffers (e.g., phosphate, acetate, borate) [5].

- Perform voltammetric scans across this pH series.

- Plot the peak current and peak potential against pH. The pH that yields the highest peak current and most well-defined peak is typically optimal for analytical sensitivity [5].

- Evaluate Buffer Capacity: The buffer's ability to maintain a stable pH at the electrode surface is dependent on its concentration and intrinsic buffering capacity. Higher current densities require buffers with greater concentration to prevent large local pH shifts that can distort results [34].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists essential materials and their functions for setting up optimized voltammetric experiments.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Inert Salts (e.g., KCl, Na₂SO₄, TBATFB) | Serves as the supporting electrolyte; carries current, minimizes solution resistance, and defines the ionic strength without participating in reactions [5]. | General voltammetry in aqueous (KCl) and non-aqueous (TBATFB in acetonitrile) systems [5]. |

| Buffer Compounds (e.g., Phosphate, Borate, Acetate) | Maintains a stable and known pH in the bulk solution and, crucially, helps mitigate pH changes at the electrode surface during reaction [34] [35]. | Studying pH-dependent electrochemical reactions; analysis in biological matrices where pH is critical [5]. |

| Electrode Modifiers (e.g., 2-Amino Nicotinamide, Au Nanoparticles) | Modified on the working electrode surface to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and stability via specific interactions (e.g., π-π, hydrogen bonding) with the target analyte [5]. | Sensitive detection of specific hazardous compounds like 2-nitrophenol in environmental samples [5]. |

| pH-Sensitive Dyes (e.g., Thymol Blue) | Used for non-invasive, optical measurement of local pH gradients within the electrochemical cell to validate and inform transport models [34]. | Visualizing and quantifying pH front propagation from electrodes in fundamental studies [34]. |