Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Sensors: Advanced Tools for Pharmaceutical and Clinical Detection

This article comprehensively reviews the latest advancements in nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors, with a specific focus on their application in pharmaceutical analysis and clinical diagnostics.

Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Sensors: Advanced Tools for Pharmaceutical and Clinical Detection

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the latest advancements in nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors, with a specific focus on their application in pharmaceutical analysis and clinical diagnostics. It explores the foundational principles of how nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, and graphene enhance sensor performance. The scope extends to cover specific methodological applications for detecting drugs, biomarkers, and toxins, alongside a critical discussion on overcoming key challenges such as reproducibility and real-sample matrix effects. Finally, the review provides a comparative analysis of sensor performance and future perspectives, highlighting the transformative potential of these sensors for point-of-care diagnostics and personalized medicine, offering researchers and drug development professionals a holistic view of the field's current state and future trajectory.

The Building Blocks: How Nanomaterials Revolutionize Electrochemical Sensing

In the rapidly advancing field of electrochemical sensing, functional nanomaterials have emerged as indispensable components for developing next-generation biosensors. Their integration addresses critical challenges in the detection of low-abundance analytes, from disease biomarkers to environmental contaminants [1]. The unique physicochemical properties of nanomaterials—including their high surface-to-volume ratio, exceptional electrical conductivity, and tunable surface chemistry—enable significant enhancements in sensor performance [2] [3]. This technical guide examines the three core functions of nanomaterials in electrochemical biosensors: serving as platforms for biomolecule immobilization, acting as mediators for signal generation, and engineering signal amplification architectures. Within the context of a broader thesis on nanomaterial-based sensors for electrochemical detection, this review provides researchers and drug development professionals with a detailed analysis of material properties, experimental methodologies, and performance metrics essential for advancing biosensing capabilities toward attomolar detection limits and point-of-care applications [4] [3].

Nanomaterial Synthesis and Fundamental Properties

The synthesis of nanomaterials tailors their structural and electrochemical properties for specific biosensing applications. Synthesis strategies are broadly classified into bottom-up and top-down approaches [3]. For instance, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and covalent organic frameworks (COFs) are typically synthesized via solvothermal or microwave-assisted methods, enabling controlled crystallization and yielding materials with ultrahigh surface areas and uniform pore distributions [3]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are produced through chemical vapor deposition (CVD), while metallic nanoparticles like gold are commonly prepared by chemical reduction, permitting meticulous size control [3].

Table 1: Key Properties of Nanomaterial Classes Used in Electrochemical Sensors

| Nanomaterial Class | Specific Examples | Key Properties | Primary Roles in Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based | Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene (GR), Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | High electrical conductivity, large surface area (~2630 m²/g for graphene), excellent mechanical strength, tunable surface functional groups [4] [1] [5]. | Signal amplification, electrode modification, immobilization support [2] [5]. |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | High surface-to-volume ratio, excellent biocompatibility, strong adsorption capabilities, surface plasmon resonance, facile modification [2] [3] [5]. | Signal generation, immobilization matrix, signal labels, electron transfer facilitation [2] [5]. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles | Magnetite (Fe₃O₄) | Superparamagnetism, low toxicity, biocompatibility, easy separation via external magnetic field [2] [6]. | Immobilization support, separation and concentration of analytes [2] [6]. |

| Porous Frameworks | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Covalent Organic Frameworks (COFs) | Ultrahigh surface area, tunable porosity, modular functionalization, high thermal and chemical stability [2] [3]. | High-capacity immobilization, signal amplification, selective molecular transport [3]. |

| Quantum Dots | Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) | Size-dependent electrochemiluminescence, efficient charge transfer, high biocompatibility [2] [3]. | Signal generation, signal labels, electron transfer promotion [2] [3]. |

The fundamental properties of these nanomaterials directly enable their core roles. The high surface-area-to-volume ratio increases biomolecule loading capacity, while quantum confinement effects and macroscopic quantum tunneling endow them with exceptional electrocatalytic activity and electronic properties distinct from bulk materials [3]. These characteristics are foundational to their functions in immobilization, signal generation, and amplification.

Core Function 1: Immobilization of Biomolecules

The Role of Nanomaterials in Immobilization

Nanomaterials provide an ideal platform for immobilizing biorecognition elements such as enzymes, antibodies, and aptamers. Their large surface area increases the loading capacity of these biological molecules, thereby enhancing the sensor's analytical performance and electrical conductivity [3] [6]. A crucial advantage is the ability of nanomaterials to create a favorable microenvironment that helps stabilize the immobilized biomolecules, often leading to increased activity and stability against denaturation caused by temperature, pH, or solvents [6]. This stability allows for repeated use of the biosensor, significantly improving cost-effectiveness [6].

Common Immobilization Methodologies

Several techniques are employed to attach biomolecules to nanomaterials, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Table 2: Comparison of Common Enzyme Immobilization Methods on Nanomaterials

| Method | Mechanism | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adsorption | Relies on weak forces (van der Waals, ionic, hydrogen bonds). | Simple, cost-effective, rapid, minimal chemical modification of enzyme. | Low stability; enzyme prone to leaching under changing pH, ionic strength, or temperature. | [6] |

| Covalent Binding | Forms strong, stable linkages between enzyme and functionalized support. | Prevents enzyme leakage, high thermal and operational stability, reusable for multiple cycles. | Risk of enzyme denaturation, complex process requiring expensive reagents, potential loss of activity. | [6] |

| Entrapment | Enzymes are confined within a porous matrix or framework. | Protects enzymes from environmental changes (e.g., pH, temperature). | Diffusion limitations restrict substrate access, reducing reaction rates; enzyme recovery is challenging. | [6] |

Experimental Protocol: Covalent Immobilization of an Aptamer on a COF-Modified Electrode

Objective: To immobilize a DNA aptamer onto a COF-modified glassy carbon electrode (GCE) for specific target capture [3].

Materials:

- Covalent Organic Framework (COF) suspension: (e.g., 1 mg/mL in DMF)

- Amino-terminated DNA aptamer: (e.g., 10 µM in TE buffer)

- Glutaraldehyde (GA) solution: (2.5% v/v in phosphate buffer)

- Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS): (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Ethanolamine solution: (1 M, pH 8.0)

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE)

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Polish the GCE sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry under nitrogen. Deposit 5 µL of the COF suspension onto the pre-cleaned GCE surface and allow it to dry at room temperature.

- Surface Activation: Wash the COF/GCE with PBS. Incubate the electrode with 10 µL of glutaraldehyde solution for 30 minutes at room temperature. Rinse gently with PBS to remove unbound glutaraldehyde.

- Aptamer Immobilization: Spot 10 µL of the amino-terminated aptamer solution onto the activated COF/GCE surface. Incubate in a humid chamber for 2 hours at 37°C to facilitate the formation of Schiff base bonds between the aldehyde groups and the aptamer's amino groups.

- Surface Blocking: To reduce non-specific binding, treat the electrode with 10 µL of ethanolamine solution for 15 minutes to quench any remaining active aldehyde groups.

- Rinsing and Storage: Rinse the prepared aptasensor (aptamer/COF/GCE) thoroughly with PBS to remove physically adsorbed aptamers. The sensor can be stored in PBS at 4°C until use.

The successful immobilization can be confirmed by techniques like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), where an increase in charge-transfer resistance after each modification step indicates successful layer-by-layer assembly [3].

Core Function 2: Signal Generation

Nanomaterials as Signal Probes and Transducers

In electrochemical biosensors, nanomaterials act as efficient signal probes and transducers by converting biological recognition events into measurable electrical signals. This function is critical for achieving high-sensitivity detection. Certain nanomaterials, such as quantum dots and electroactive metal-organic frameworks, are intrinsically electroactive and can serve as excellent signal labels [3]. For example, graphene oxide/Prussian blue (GO/PB) nanocomposites can function as an electrochemical probe, providing a strong and stable signal in sandwich-type biosensing platforms [5]. The exceptional electrical conductivity of materials like graphene and carbon nanotubes facilitates rapid electron transfer between the redox center of biomolecules and the electrode surface, thereby enhancing the signal strength for metrics such as current or conductivity changes [2] [4].

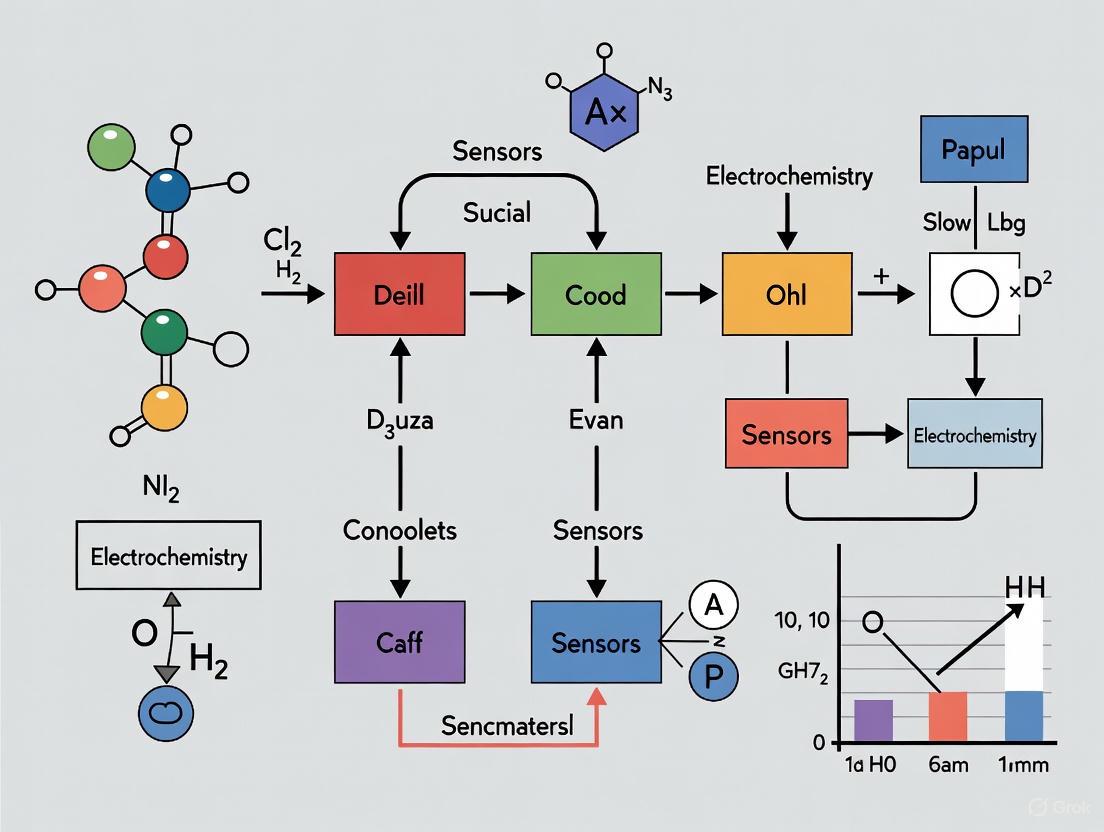

Visualizing Signal Generation Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms by which nanomaterials contribute to signal generation in electrochemical biosensors.

Core Function 3: Signal Amplification

Architectures and Strategies for Amplification

Signal amplification is paramount for detecting ultralow concentrations of target analytes, such as disease biomarkers or environmental contaminants, often required to reach attomolar levels [3]. Nanomaterials enable multidimensional signal amplification architectures that synergistically combine porous nanomaterials, biocatalysis, and nucleic acid circuits [3]. Key strategies include:

- Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrocatalysis: Nanomaterials like gold–graphene hybrids or thorn-like Au@Fe3O4 nanoparticles exhibit ultrahigh catalytic activity, which can significantly amplify electrochemical signals [3] [5].

- Enzyme-Based Catalytic Systems: Enzymes such as horseradish peroxidase (HRP) are used in combination with substrates like tyramide to create catalytic cycles that generate a large number of electroactive products on the sensor surface [3].

- Nucleic Acid Amplification: Techniques such as nuclease-assisted target recycling allow for the repeated use of a single target molecule to trigger multiple signaling events, dramatically enhancing sensitivity [5].

Quantitative Performance of Amplification Strategies

The integration of these strategies with various nanomaterials has led to remarkable improvements in sensor performance, as evidenced by the following comparative data.

Table 3: Performance of Nanomaterial-Based Signal Amplification Strategies

| Amplification Strategy | Nanomaterial Used | Target Analyte | Achieved Detection Limit | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanocomposite & Aptasensor | MWCNTs-AuNPs/CS-AuNPs/rGO-AuNPs | Oxytetracycline (OTC) | 30.0 pM | [5] |

| Nanocomposite & Aptasensor | Reduced Graphene Oxide–Polyvinyl Alcohol & AuNPs | E. coli O157:H7 | 9.34 CFU mL⁻¹ | [5] |

| Immunosensor & Nanocomposite | Reduced Graphene Oxide-Multiwalled Carbon Nanotube & PAMAM/AuNPs | Cancer Antigen 125 (CA 125) | 6 μU mL⁻¹ | [4] |

| Immunosensor & Nanocomposite | Graphene–Graphitic Carbon Nitride | Neuron-Specific Enolase (NSE) | 3 pg mL⁻¹ | [4] |

| Multidimensional Architectures | COFs, MOFs, Enzyme Cascades, DNA Circuits | Various Biomarkers | Attomolar (aM) to Femtomolar (fM) range | [3] |

Experimental Protocol: Building a Sandwich-Type Immunosensor with Signal Amplification

Objective: To detect a protein biomarker (e.g., Neuron-Specific Enolase, NSE) using a sandwich immunosensor with a nanocomposite for signal amplification [4].

Materials:

- Primary antibody (Ab₁): Specific to the target biomarker.

- Secondary antibody (Ab₂): Specific to a different epitope of the target biomarker.

- Nanocomposite material: e.g., Graphene–graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite.

- Screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE)

- Blocking buffer: e.g., 1% BSA in PBS.

- Washing buffer: e.g., PBS with 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST).

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Deposit the graphene–graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite onto the working area of the SPCE and allow it to dry. This layer enhances the electrode's conductivity and surface area.

- Capture Antibody Immobilization: Incubate the modified electrode with a solution of the primary antibody (Ab₁) for 1 hour at 37°C. The antibodies adsorb onto the nanocomposite surface.

- Blocking: Treat the electrode with blocking buffer for 30 minutes to cover any remaining active sites on the nanocomposite, thus preventing non-specific binding in subsequent steps.

- Target Antigen Capture: Incubate the sensor with the sample containing the target biomarker for 40 minutes at 37°C. Wash thoroughly with washing buffer to remove unbound antigens.

- Signal Amplification and Detection: Incubate the sensor with the secondary antibody (Ab₂), which is conjugated to the graphene–graphitic carbon nitride nanocomposite, for 1 hour at 37°C. This forms the "sandwich" (Ab₁ / Antigen / Ab₂-Nanocomposite). After a final wash, perform an electrochemical measurement such as differential pulse voltammetry (DPV). The nanocomposite label amplifies the electrochemical signal, which is proportional to the concentration of the captured antigen [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Nanomaterial-Based Electrochemical Sensors

| Item | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal label, immobilization matrix, catalyst. [2] [5] | High biocompatibility, easy functionalization via thiol chemistry, strong adsorption. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Electrode modifier to enhance conductivity and surface area. [2] [4] | High aspect ratio, excellent electrical conductivity, can be functionalized with carboxyl groups. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Base substrate for immobilization; enhances electron transfer. [4] [5] | High conductivity, residual oxygen-containing groups for biomolecule attachment. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous carrier for high-density immobilization of recognition elements. [2] [3] | Ultrahigh surface area, tunable porosity, modular functionalization. |

| Magnetic Nanoparticles (Fe₃O₄) | Solid support for immobilization; enables easy separation via magnet. [2] [6] | Superparamagnetic, biocompatible, cost-effective. |

| Glutaraldehyde (GA) | Crosslinker for covalent immobilization of biomolecules. [6] | Bifunctional reagent, reacts with amine groups on proteins and supports. |

| Specific Aptamers | Biorecognition element for aptasensors. [2] [5] | High affinity and specificity, synthetic, stable, modifiable with functional groups. |

| Nuclease Enzymes (e.g., DNase I) | For enzyme-assisted target recycling amplification strategies. [5] | Cleaves specific nucleic acids, enabling cyclic amplification. |

The strategic application of nanomaterials through their three core roles—immobilization, signal generation, and amplification—has fundamentally advanced the capabilities of electrochemical biosensors. By providing robust platforms for biomolecule attachment, directly transducing biological events into measurable signals, and enabling sophisticated amplification architectures, nanomaterials are pushing detection limits toward the attomolar range [3]. This progress is critical for applications in early disease diagnosis, environmental monitoring, and food safety [2] [4] [1]. Future developments will likely focus on the convergence of these nanomaterials with microfluidics for miniaturization, artificial intelligence for data analysis, and the design of green, sustainable materials, ultimately paving the way for scalable, high-performance, and accessible sensing platforms that can meet the demands of global health and industry [3] [1].

Nanomaterials have revolutionized the field of electrochemical sensing, providing unprecedented sensitivity, selectivity, and miniaturization capabilities. This whitepaper provides a comprehensive technical overview of four fundamental classes of nanomaterials—metal nanoparticles (NPs), carbon-based nanomaterials (NMs), quantum dots (QDs), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs)—within the context of advanced electrochemical detection research. These materials serve as critical components in sensor design, functioning as electrode modifiers, signal amplifiers, and recognition element scaffolds. The unique properties emerging at the nanoscale, including high surface-to-volume ratios, quantum confinement effects, and tunable surface chemistry, have enabled researchers to overcome traditional limitations in analytical sensing. For drug development professionals and research scientists, understanding these material systems is essential for developing next-generation diagnostic tools and monitoring devices that offer rapid, accurate, and cost-effective analysis across healthcare, environmental monitoring, and food safety applications.

Core Nanomaterial Classes in Electrochemical Sensing

Metal Nanoparticles (MNPs)

Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) are among the most extensively utilized metal nanoparticles in electrochemical sensing due to their exceptional conductivity, chemical stability, and biocompatibility. Their large surface-to-volume ratio provides ample space for immobilizing recognition elements such as antibodies, aptamers, or DNA strands. AuNPs enhance electron transfer between the electrode surface and analytes, significantly improving signal response. Researchers have successfully integrated AuNPs with various scaffolding materials to create advanced sensing platforms. For instance, when decorated on graphene aerogels, AuNPs form composites that demonstrate femtomolar detection limits for Hg²⁺ ions, leveraging triple-amplification strategies involving DNA loading enhancement and electron transfer facilitation [7]. Similarly, AuNPs combined with metal-metal porphyrin frameworks (MMPF-6(Fe)) have shown exceptional performance in hydroxylamine detection, achieving detection limits as low as 0.004 μmol/L by reducing anode overpotential and amplifying electrochemical signals [8].

Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) offer high conductivity and strong catalytic activity, serving as effective electron reservoirs that suppress electron-hole recombination processes. This property makes them particularly valuable in electrochemical reactions where maintaining charge separation is crucial. When deposited on two-dimensional zinc-based MOFs, AgNPs have demonstrated superior electrocatalytic activity for H₂O₂ detection compared to other noble metal nanoparticles, achieving a detection limit of 1.67 μmol/L [8]. The combination of AgNPs with graphene quantum dots has further expanded their application scope, enabling ultrasensitive detection of pesticides such as acetamiprid [9].

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Carbon-based nanomaterials represent a diverse family of nanostructures with exceptional electrical, mechanical, and chemical properties that make them ideal for electrochemical sensing applications.

Graphene and its derivatives, including graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO), possess remarkable electrical conductivity, extensive specific surface area, and an extended conjugated structure that promotes rapid electron transfer [7]. The abundant oxygen-containing functional groups in GO facilitate straightforward chemical modifications and enhance interactions with target analytes [7]. These properties translate to sensors with higher sensitivity, lower detection thresholds, and faster response times compared to traditional carbon electrodes. Graphene derivatives have been successfully employed in detecting heavy metals like Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Hg²⁺, often achieving detection limits in the parts per billion range, which is crucial for environmental monitoring and food safety applications [7].

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), including both single-walled (SWCNTs) and multi-walled (MWCNTs) varieties, exhibit outstanding electrical conductivity and mechanical strength. Their unique tubular structure and high aspect ratio create efficient electron transfer pathways in composite materials [10]. However, CNTs face challenges with agglomeration due to strong van der Waals interactions, which can lead to heterogeneous film formation and reproducibility issues without proper functionalization and dispersion techniques [11]. When effectively integrated into sensor designs, CNT-based modifiers significantly enhance sensitivity for detecting environmental contaminants, including phenolic compounds, drugs, pesticides, and heavy metal ions [12].

Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) represent a zero-dimensional carbon nanomaterial that integrates the π-conjugated structure of graphene with size-dependent quantum confinement effects [9]. GQDs feature tunable electronic band gaps, excellent electrical conductivity, chemical versatility, and good biocompatibility. Their small size (typically 2-10 nm) and abundant edge sites make them ideal for signal amplification in electrochemical detection systems [9]. GQDs have been successfully employed in sensors for heavy metals like Cr(VI) and Hg²⁺, often demonstrating superior performance when functionalized or combined with metal nanoparticles like silver or copper [9].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Carbon-Based Nanomaterials in Heavy Metal Detection

| Nanomaterial | Target Analyte | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Graphene oxide-based composite | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ | Sub-ppb level | 1-100 μg/L | [7] |

| AuNP-graphene-cysteine composite | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ | Not specified | Simultaneous detection | [7] |

| Graphene aerogel-AuNP composite | Hg²⁺ | 0.16 fM | Not specified | [7] |

| Polyaniline/GQD-modified electrode | Cr(VI) | Not specified | Rapid detection | [9] |

| Dimercaprol-functionalized GQDs | Hg²⁺ | Ultrasensitive | Not specified | [9] |

Quantum Dots (QDs)

Quantum dots are semiconducting nanocrystals (2-10 nm) that exhibit unique size-tunable optical and electronic properties due to quantum confinement effects [13]. While traditionally valued for their fluorescence properties in optical sensing, QDs have gained significant traction in electrochemical applications due to their high surface area, catalytic activity, and ability to facilitate electron transfer processes.

Graphene Quantum Dots (GQDs) bridge the gap between carbon nanomaterials and traditional semiconductor QDs, offering the electrical conductivity of graphene with the quantum confinement effects of zero-dimensional structures [9]. GQDs can be synthesized through both top-down methods (breaking down larger carbon structures) and bottom-up approaches (building from molecular precursors), providing flexibility in structural design and functionalization [9]. The presence of various oxygen-containing functional groups on GQD surfaces enables easy modification with recognition elements and enhances their dispersion in aqueous solutions, a critical factor for reproducible sensor fabrication.

Semiconductor Quantum Dots, such as CdSe and CdTe, provide high electrocatalytic activity but often require careful surface engineering to improve stability and reduce potential toxicity. These materials have been successfully incorporated in electrochemical sensors for biomarkers, environmental contaminants, and pharmaceuticals, where they serve as signal amplifiers and electron transfer facilitators [13].

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

MOFs are crystalline porous materials formed through the self-assembly of metal ions or clusters with organic linkers, creating structures with exceptionally high specific surface areas, tunable pore sizes, and abundant active sites [8]. While their inherent low conductivity has historically limited electrochemical applications, this challenge has been addressed through the formation of composites with conductive materials.

MOF-Metal Nanoparticle Composites represent a powerful synergy where MOFs provide a structured porous matrix that prevents nanoparticle aggregation while metal nanoparticles enhance electrical conductivity and catalytic activity [8]. For instance, AuNPs supported on zeolitic imidazolate framework-67 (ZIF-67) demonstrated excellent performance for detecting methylmercury (CH₃Hg⁺) with a detection limit of 0.05 μg/L, leveraging the MOF's ability to inhibit nanoparticle agglomeration and maintain active surface sites [8].

MOF-Carbon Composite materials integrate the high porosity and selective adsorption capabilities of MOFs with the exceptional electrical conductivity of carbon nanomaterials. These hybrids have been employed in sensors for simultaneous detection of multiple heavy metals, including Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Cu²⁺, often showing wider linear ranges and lower detection limits compared to single-component modifiers [14].

Table 2: MOF Composites in Electrochemical Sensing Applications

| MOF Composite | Metal Center | Application | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AuNP/MMPF-6(Fe) | Iron | Hydroxylamine detection | 0.004 μmol/L | 0.01–20.0 μmol/L | [8] |

| AuNPs/ZIF67 | Cobalt | CH₃Hg⁺ detection | 0.05 μg/L | 1–25 μg/L | [8] |

| AuNP/ZIF-L | Zinc | Acetaminophen detection | 1.02 μmol/L | 3.50 μmol/L-0.56 mmol/L | [8] |

| AgNP/2D Zn-MOF | Zinc | H₂O₂ detection | 1.67 μmol/L | 5.0-70 mmol/L | [8] |

| Fc-NH₂-UiO-66/trGNO | Zirconium | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺ detection | Not specified | Simultaneous detection | [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Nanomaterial Synthesis and Functionalization

Synthesis of Graphene Quantum Dots can be achieved through both top-down and bottom-up approaches. Top-down methods typically involve electrochemical exfoliation of graphene oxide under ambient conditions, producing GQDs with tunable multicolor emissions [9]. Bottom-up synthesis approaches utilize carbonization of molecular precursors or eco-friendly green synthesis methods that employ natural carbon sources [9]. Functionalization of GQDs with specific recognition elements, such as dimercaprol for mercury detection, is typically performed through covalent bonding strategies that exploit the oxygen-containing functional groups on GQD surfaces [9].

Preparation of MOF-Metal Nanoparticle Composites commonly employs one-pot synthesis, post-synthetic modification, or electrodeposition methods [8]. The selection of appropriate synthesis techniques depends on the desired morphology, particle size distribution, and specific application requirements. For instance, AuNPs can be immobilized on MOF surfaces through electrostatic adsorption, while AgNPs may be deposited via electrochemical methods to ensure controlled nucleation and growth [8]. Critical parameters requiring optimization include metal precursor concentration, reduction time and temperature, and stabilizing agents to prevent aggregation while maintaining accessibility to active sites.

Electrode Modification and Sensor Fabrication

The process of transferring nanomaterials from solution to functional electrode interfaces represents a critical step in sensor development. Layer-by-Layer (LbL) assembly, Langmuir-Blodgett (LB), and Langmuir-Schaefer (LS) deposition techniques enable precise control over film thickness, molecular alignment, and interfacial architecture [10]. These methods facilitate the creation of supramolecular assemblies with well-defined layered structures that promote ion-conductive channels and porous architectures beneficial for electrochemical sensing [10].

For graphene-based electrodes, common modification approaches include drop-casting of dispersed materials, electrochemical deposition, and the formation of hybrid inks for screen-printing [7]. A key consideration is achieving homogeneous, reproducible surface coverage while maintaining the nanomaterial's intrinsic properties. Recent advances have demonstrated that laser-reduced graphene oxide (LRGO) sensors exhibit enhanced electroanalytical response due to improved surface conductivity and controlled reduction patterns [7].

Electrochemical Detection Protocols

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry techniques, particularly Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV), have emerged as the gold standard for heavy metal detection due to their exceptional sensitivity and capability for multi-analyte measurement [7]. The standard protocol involves a two-step process: (1) electrochemical deposition of metal ions onto the modified working electrode at a controlled negative potential, and (2) stripping step where the deposited metals are oxidized back into solution while measuring the resulting current [7]. Key parameters requiring optimization include deposition potential and time, supporting electrolyte composition, and stripping waveform parameters.

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) offers enhanced sensitivity for organic molecule detection by minimizing capacitive background currents [14]. Standard experimental conditions typically involve pulse amplitudes of 50-100 mV, pulse times of 25-50 ms, and scan rates of 10-20 mV/s [14]. For integrated sensor systems, DPV parameters may be optimized for compatibility with subsequent data processing algorithms, including convolutional neural networks for signal interpretation [14].

Advanced Integration and Data Processing

The convergence of nanotechnology with artificial intelligence and IoT systems represents the cutting edge of electrochemical sensor development. Recent demonstrations have shown that convolutional neural networks (CNN) can effectively process complex voltammetric signals to classify heavy metal ions with high accuracy, overcoming traditional challenges with signal interpretation in mixed analyte environments [14]. The integration of these data processing capabilities with IoT platforms enables remote monitoring and real-time data accessibility, significantly expanding the practical implementation potential of nanomaterial-based sensors [14].

The workflow for such integrated systems typically involves signal acquisition via DPV or SWASV, feature extraction using machine learning algorithms, classification and quantification of analytes, and data visualization through cloud-connected interfaces [14]. This approach has demonstrated remarkable success in simultaneous detection of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Hg²⁺ in real water samples, with classification accuracy exceeding 99% in controlled conditions [14].

Signaling Pathways and Sensing Mechanisms

The exceptional performance of nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors arises from well-defined signaling pathways and sensing mechanisms that operate at the nanoscale. The following diagram illustrates the fundamental electron transfer processes and recognition events that underpin these advanced sensing platforms.

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrochemical Sensing

The diagram above illustrates the collaborative roles of different nanomaterials in enhancing electrochemical sensing performance. Metal nanoparticles provide catalytic sites that lower activation energies for redox reactions, while carbon nanomaterials facilitate rapid electron transfer through their conjugated structures. MOFs contribute through selective recognition capabilities based on their tunable pore architectures, and quantum dots act as efficient redox mediators due to their quantum confinement effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development of nanomaterial-based electrochemical sensors requires careful selection of materials and reagents. The following table provides a comprehensive overview of essential components and their functions in sensor fabrication and operation.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Nanomaterial-Based Sensor Development

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterials | Gold nanoparticles, Graphene oxide, Carbon nanotubes, Graphene quantum dots, ZIF-67, UiO-66 | Electrode modification to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and stability | Purity, dispersion stability, functional group density, batch-to-batch reproducibility |

| Electrode Materials | Glassy carbon electrodes, Screen-printed carbon electrodes, Indium tin oxide (ITO) substrates | Signal transduction platform | Surface polishability, conductivity, chemical stability, reusability |

| Recognition Elements | Aptamers, Antibodies, Molecularly imprinted polymers, Cysteine, DNA strands | Selective target binding and recognition | Binding affinity, stability, immobilization efficiency, non-specific adsorption |

| Electrochemical Reagents | Potassium ferricyanide, Phosphate buffer solutions, KCl electrolyte, Ag/AgCl ink | Electrolyte support and reference systems | Ionic strength, pH buffering capacity, oxygen content, contaminant levels |

| Signal Amplifiers | Methylene blue, Ferrocene derivatives, Metal nanoclusters | Redox markers for signal enhancement | Electrochemical reversibility, stability, binding specificity, background signal |

| Fabrication Aids | Nafion, Chitosan, Poly(diallyldimethylammonium chloride) | Binders and stabilizing agents for film formation | Biocompatibility, conductivity, film-forming ability, permeability |

The strategic integration of metal nanoparticles, carbon-based nanomaterials, quantum dots, and metal-organic frameworks has fundamentally transformed electrochemical sensing capabilities. Each material class contributes unique properties that address specific challenges in sensor design, from signal amplification and electron transfer enhancement to selective recognition and structural stability. The continued advancement of synthesis methods, functionalization strategies, and integration protocols will further expand the application scope of these materials in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and industrial process control. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these nanomaterial systems provides a foundation for developing next-generation analytical platforms that offer the sensitivity, specificity, and practicality required for modern analytical challenges.

Synthesis and Functionalization Strategies for Tailored Sensor Interfaces

The advancement of sensor technology is increasingly dependent on the precision engineering of interfaces at the nanoscale. Functional nanomaterials have emerged as pivotal components in sensor design, fundamentally enhancing detection capabilities across clinical, environmental, and industrial monitoring applications [15]. When materials are engineered at the nanoscale (dimensions smaller than 100 nm), their intrinsic physicochemical properties—including optical, electrical, and chemical characteristics—undergo significant changes compared to their bulk counterparts [15]. This phenomenon, driven primarily by the high surface-area-to-volume ratio and quantum confinement effects, enables unprecedented control over sensor interface behavior [15]. This technical guide examines contemporary synthesis and functionalization strategies for creating tailored sensor interfaces, framed within the broader context of advancing nanomaterial-based electrochemical detection research.

Nanomaterial Synthesis for Sensor Interfaces

The synthesis of nanomaterials establishes the fundamental foundation for sensor performance. Selection of appropriate synthesis methods directly influences critical sensor parameters including sensitivity, selectivity, and stability.

Hydrothermal Synthesis for Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Hydrothermal synthesis provides a versatile approach for generating carbon-based nanomaterials, particularly carbon quantum dots (CQs). This method involves reactions in aqueous solutions at elevated temperatures and pressures, enabling precise control over nanomaterial properties [15].

- Application in Biomedical Sensing: Recent investigations have focused on optimizing hydrothermal protocols for synthesizing red-emitting carbon dots (r-CDs) for advanced medical applications. However, challenges remain in achieving reproducible and controlled synthesis of long-wavelength CDs, highlighting the need for continued protocol refinement [15].

- Process Considerations: Successful implementation requires careful parameter control including precursor concentration, temperature profiles, reaction duration, and pH conditions. These factors collectively influence the surface functional groups, emission properties, and quantum yield of the resulting nanomaterials [15].

Vapor-Phase Deposition Techniques

Vapor-phase deposition methods enable the creation of highly uniform thin films and nanostructures with exceptional purity and controlled morphology.

- Metal-Organic Chemical Vapor Deposition (MOCVD): This technique has been successfully employed for growing TiO₂ thin films on modified stainless-steel mesh substrates for sensing applications. The resulting films demonstrate excellent performance in photocatalytic degradation tests, forming the basis for effective chemical oxygen demand (COD) sensors [15].

- Thermal Evaporation: For plasmonic applications, thermal evaporation has been utilized to fabricate monometallic Au nano-islands on glass substrates. These nanostructures can be subsequently covered with a thin layer of silicon dioxide to create enhanced platforms for confocal fluorescence and Raman microscopies [15].

Czochralski Crystal Growth

For specialized sensing applications requiring high-temperature stability and precise piezoelectric properties, single-crystal growth techniques are indispensable.

- Process Overview: The Czochralski method involves pulling a seed crystal from a melt of precisely formulated raw materials. This technique has been applied to grow specialized crystals like yttrium calcium oxyborate (YCOB) and Ba₂TiSi₂O₈ (BTS) for high-temperature vibration sensing [16].

- Implementation Parameters: Typical processes utilize iridium crucibles with controlled atmosphere conditions (e.g., nitrogen with 4% oxygen), pulling rates of 0.3–1 mm/h, and rotation speeds of 10–30 rpm. Post-growth annealing is often required to prevent crystal cracking and ensure optimal performance [16].

- Limitations: While yielding exceptional materials, these methods face challenges in commercial scalability and require specialized manufacturing facilities, potentially limiting widespread adoption [16].

Table 1: Comparison of Nanomaterial Synthesis Methods for Sensor Interfaces

| Method | Key Applications | Technical Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrothermal Synthesis | Carbon quantum dots, fluorescent nanomaterials | Facile parameter control, sustainable preparation, good crystallinity | Reproducibility challenges in wavelength control [15] |

| Czochralski Growth | Piezoelectric single crystals (YCOB, BTS) | High-quality crystals, excellent thermal stability | High cost, specialized equipment, scalability challenges [16] |

| MOCVD | Metal oxide thin films (TiO₂) | Uniform film thickness, high purity, controlled stoichiometry | High equipment cost, complex precursor handling [15] |

| Thermal Evaporation | Plasmonic nano-islands (Au, Ag) | Simple apparatus, good morphological control | Limited to volatile materials, potential contamination [15] |

Functionalization Strategies for Enhanced Specificity

Surface functionalization represents a critical step in transitioning nanomaterials from generic substrates to tailored sensing interfaces with molecular recognition capabilities.

Quantitative Functionalization of Biopolymers

Achieving precise control over functionalization density is essential for reproducible sensor performance. Recent advances in azetidinium-amine reactions have enabled quantitative functionalization of chitosan biopolymers with unprecedented control [17].

- Process Details: This approach utilizes azetidinium functionalized coupler molecules reacted with chitosan in aqueous environments using 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) as a base. The method achieves exceptional conversion rates (>90%) with remarkably low E-factor (<0.1), representing a green chemistry approach [17].

- Performance Advantages: This strategy demonstrates excellent correlation (80-100%) between experimentally defined degree of functionalization (determined by reagent ratios) and the actual degree of functionalization measured by ¹H NMR spectroscopy. This precision enables researchers to systematically design sensor interfaces with predetermined binding densities [17].

Graphene Functionalization for Electrochemical Sensing

Graphene and its derivatives provide exceptional platforms for electrochemical sensor development due to their high surface area and excellent electron transfer capabilities.

- Composite Structures: Functionalization of graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) with various nanomaterials including ZnO nanorods, carbon nanotubes, Au nanoparticles, and conducting polymers like polyaniline has yielded significant improvements in electrochemical performance [18].

- Sensor Applications: These functionalized materials have been successfully incorporated into screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) for detecting diverse analytes ranging from clinical biomarkers to environmental contaminants. The synergistic effects between graphene derivatives and functionalization materials enable decreased overpotential and increased peak current in voltammetric detection [18].

Table 2: Functionalization Strategies for Specific Sensor Applications

| Functionalization Approach | Target Nanomaterial | Sensor Application | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Azetidinium-Amine Reaction | Chitosan biopolymer | Customizable biosensing platforms | Quantitative functionalization (>90%), predefined modification density [17] |

| Nanocomposite Formation | Graphene oxide/reduced GO | Electrochemical detection | Enhanced electron transfer, improved sensitivity and selectivity [18] |

| Polymer Modification | Glassy carbon electrodes | Pharmaceutical detection (e.g., metronidazole) | High efficiency electrochemical detection supported by theoretical calculations [15] |

| DNA-based Functionalization | Graphene derivatives | Genetic mutation detection | Specificity for single-nucleotide polymorphisms [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Development

Protocol: Hydrothermal Synthesis of Carbon Quantum Dots

Objective: Synthesis of red-emitting carbon quantum dots (r-CDs) for advanced medical applications [15].

Materials:

- Carbon precursor (citric acid or analogous compound)

- Solvent (deionized water)

- Nitrogen or argon gas for inert atmosphere

- Hydrothermal reactor with Teflon liner

- Purification equipment (dialysis membrane or filtration system)

Procedure:

- Dissolve the carbon precursor in deionized water at predetermined concentration.

- Transfer the solution to a Teflon-lined hydrothermal reactor, seal securely.

- Heat the reactor to temperatures between 150-200°C for 2-10 hours, optimizing for desired emission properties.

- Allow reactor to cool naturally to room temperature.

- Recover the crude product and purify through dialysis or filtration to remove unreacted precursors and byproducts.

- Characterize using fluorescence spectroscopy, TEM, and XRD analysis.

Technical Notes: Reproducibility challenges in achieving specific emission wavelengths require careful control of precursor composition, reaction time, and temperature profiles [15].

Protocol: Azetidinium-Mediated Chitosan Functionalization

Objective: Quantitative functionalization of chitosan with predetermined modification density [17].

Materials:

- Chitosan (low or high molecular weight)

- Azetidinium functionalized coupler molecules

- 1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane (DABCO) base

- Deionized water (pH adjusted to 7-9)

- Standard synthetic laboratory equipment

Procedure:

- Dissolve chitosan in pH-controlled deionized water.

- Add azetidinium functionalized coupler molecules at stoichiometric ratio corresponding to desired degree of functionalization.

- Introduce DABCO base to catalyze the reaction.

- Heat reaction mixture to 80-100°C with continuous stirring for 4-12 hours.

- Purify the functionalized chitosan product through precipitation and washing.

- Characterize using ¹H NMR spectroscopy to determine actual degree of functionalization.

Technical Notes: This method achieves exceptional atom economy and quantitative conversion, with actual functionalization closely matching theoretically predicted values based on reagent ratios [17].

Visualization of Sensor Fabrication Workflows

Workflow for Nanomaterial-Based Sensor Development

Diagram 1: Sensor Development Workflow. This flowchart outlines the systematic process for developing nanomaterial-based sensors, from initial synthesis to final performance validation.

Functionalization Strategy Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Functionalization Mechanism. This diagram illustrates the quantitative functionalization process using azetidinium-amine chemistry to create tailored sensor interfaces with specific recognition properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Sensor Interface Development

| Material/Reagent | Function in Sensor Development | Specific Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Chitosan | Biopolymer substrate providing biocompatibility and amine functional groups | Base material for quantitative functionalization using azetidinium chemistry [17] |

| Graphene Oxide/Reduced GO | Enhances electron transfer, provides large surface area for biomolecule immobilization | Modifier for screen-printed electrodes in electrochemical detection [18] |

| Azetidinium Couplers | Enables quantitative functionalization with predetermined modification density | Attaching diverse hydrophobic moieties to chitosan backbone with controlled density [17] |

| Metal Precursors | Forms nanoparticles and nanostructures for catalytic and plasmonic applications | Creating Au nano-islands for plasmonic-enhanced spectroscopy [15] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes | Disposable platforms for rapid electrochemical analysis | Base substrates for graphene-modified electrochemical sensors [18] |

| MXene V₂C | Provides enhanced temperature sensitivity in composite sensors | Improving efficiency in all-fiber temperature sensors (0.32 dB/°C) [15] |

The strategic synthesis and functionalization of nanomaterial interfaces represents a cornerstone of modern sensor technology. Through controlled synthesis methods like hydrothermal growth and vapor deposition, coupled with precise functionalization approaches such as azetidinium-amine chemistry, researchers can now engineer sensor interfaces with tailored properties for specific detection challenges. These advancements are particularly impactful in electrochemical detection systems, where nanomaterial-enhanced interfaces significantly improve sensitivity, selectivity, and operational stability. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly unlock new possibilities in sensor design, enabling more sophisticated detection platforms for biomedical, environmental, and industrial applications.

The Synergy Between Nanomaterial Properties and Enhanced Electrochemical Performance

The integration of nanomaterials into electrochemical systems has revolutionized the capabilities of sensing and energy storage technologies. This synergy stems from the fundamental principle that unique physicochemical properties emerging at the nanoscale—such as high surface area, exceptional electrical conductivity, and tunable surface chemistry—directly translate to enhanced electrochemical performance [19]. These properties collectively address key limitations of conventional bulk materials, enabling the development of devices with superior sensitivity, selectivity, stability, and efficiency [20] [19]. This technical guide explores the mechanistic relationship between nanomaterial properties and electrochemical performance, providing a foundational resource for research into advanced electrochemical detection systems.

Fundamental Properties of Nanomaterials and Their Electrochemical Roles

The exceptional electrochemical performance of nanomaterial-based systems can be attributed to a core set of enhanced physical and chemical properties. The table below summarizes these key properties and their specific roles in electrochemical applications.

Table 1: Core Nanomaterial Properties and Their Electrochemical Functions

| Nanomaterial Property | Electrochemical Function | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| High Surface-to-Volume Ratio [19] [2] | Provides abundant active sites for analyte adsorption, catalytic reactions, and ion intercalation [2]. | Increases sensitivity, enhances signal-to-noise ratio, and improves catalytic efficiency. |

| Exceptional Electrical Conductivity [21] | Facilitates rapid electron transfer between the analyte and the electrode surface [19]. | Enables fast response times, high current density, and improved rate capability. |

| Tunable Surface Chemistry [20] [21] | Allows for functionalization with specific biorecognition elements (aptamers, antibodies) and catalysts [2]. | Confers high selectivity for target analytes and reduces fouling/interference. |

| Mechanical Flexibility [21] | Enables integration with flexible substrates for wearable and implantable sensors. | Allows for conformable electronics and durable device operation under strain. |

| Tailorable Morphology & Porosity [2] | Creates hierarchical structures that control mass transport and diffusion pathways. | Enhances accessibility to active sites and can provide molecular sieving capabilities. |

The interplay of these properties is not merely additive; it often creates synergistic effects. For instance, the high conductivity of MXenes, combined with their mechanically flexible layered structure and easily functionalizable surfaces, makes them ideal for creating highly sensitive and durable strain and pressure sensors for wearable health monitoring [21].

Key Nanomaterial Classes and Their Performance Characteristics

Different classes of nanomaterials leverage the fundamental properties from Table 1 in distinct ways, making them suited for specific electrochemical applications. Their performance can be quantified through key metrics as summarized below.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Key Nanomaterial Classes in Electrochemical Applications

| Nanomaterial Class | Example Materials | Key Performance Metrics | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials [20] [19] | CNTs, Graphene, SWCNHs | High conductivity (e.g., >20,000 S cm⁻¹ for MXenes [21]), large specific surface area (e.g., 2630 m²/g for graphene), excellent stability. | Dopamine detection with LOD of 11 nM [19]; Ultrasensitive gas and biosensors. |

| Metal & Metal Oxide Nanoparticles [2] [22] [23] | AuNPs, MgONPs, Ag-doped Co₃O₄ | High catalytic activity, strong plasmonic effects, specific capacitance (e.g., 99 F g⁻¹ for MgONPs [22]). | Li-ion battery anodes [24]; Lithium ion detection with sensitivity of 78.66 μAmM⁻¹cm⁻² [23]. |

| MXenes [21] | Ti₃C₂Tₓ | Ultrahigh conductivity, hydrophilicity, tunable surface terminals, excellent charge storage capability (>2800 F cm⁻³) [21]. | Strain sensors (Gauge Factor ~228 [21]); NH₃, CH₄ gas sensors; Heavy metal detection. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [2] [25] | Cu-BDC, ZIF-8 | Ultrahigh porosity, tunable pore size, immense internal surface area. | Aflatoxin B1 detection [2]; Imidacloprid detection with LOD of 1.5 nM [25]. |

| Quantum Dots (QDs) [2] | Graphene QDs, CdSe QDs | Size-tunable band gap, strong photoluminescence, high quantum yield. | Signal labels in biosensing; Fluorescence-based electrochemical detection. |

Experimental Protocols: Fabrication and Evaluation of Nanomaterial-Based Sensors

To translate the theoretical advantages of nanomaterials into functional devices, reproducible and well-controlled experimental protocols are essential. The following section details common methodologies for sensor fabrication and evaluation, drawing from specific examples in the literature.

Sensor Fabrication via Co-precipitation and Electrode Modification

The synthesis of Ag-doped Co₃O₄ nanochips (Ag@CNCs) for lithium detection provides a robust protocol for creating metal oxide-based sensors [23].

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: A 0.1 M solution of cobalt chloride hexahydrate (CoCl₂·6H₂O) is prepared in 100 mL of distilled water.

- Doping: 2 mL of a 0.1 M silver nitrate (AgNO₃) solution is added to the cobalt solution under magnetic stirring (400 rpm) at ambient temperature for 15 minutes.

- Precipitation: A 1 M sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution is added dropwise to the mixture until the pH reaches 12, inducing the co-precipitation of Ag and Co species.

- Ageing and Washing: The mixture is heated at 333 K (60 °C) for 6 hours with continuous stirring. The resulting precipitate is filtered and washed repeatedly with distilled water and ethanol until a neutral pH is achieved.

- Calcination: The washed precipitate is dried at 363 K (90 °C) for 4 hours, manually crushed into a fine powder, and finally annealed in a muffle furnace at 873 K (600 °C) for 4 hours to form crystalline Ag@CNCs.

- Electrode Modification: A bare gold electrode is polished with 0.05 μm alumina powder and sonicated in ethanol and water. 1 mg of the synthesized Ag@CNCs is dispersed in 5 mL of ethanol via ultrasonication for 15 minutes. A drop of this dispersion is cast onto the clean gold electrode and dried at 40°C for 2 hours. A final drop of Nafion binder is applied to secure the nanomaterial layer [23].

Synthesis of Composite Nanomaterials via Galvanic Replacement

For more complex nanostructures, such as the Pt-Ag@Cu-BDC MOF composite used for insecticide detection, advanced synthesis methods are employed [25].

Procedure:

- MOF Synthesis and Metal Incorporation: The copper-based MOF (Cu-BDC) is first synthesized. Silver nanoparticles (Ag NPs) are then incorporated into the porous framework of the MOF.

- Galvanic Replacement: The Ag@Cu-BDC composite is exposed to a solution containing platinum ions (Pt ions). A galvanic replacement reaction occurs spontaneously, where the surface of the Ag NPs is partially replaced by Pt NPs due to the difference in their reduction potentials.

- Sensor Fabrication: The resulting Pt-Ag@Cu-BDC MOF nanocomposite is dispersed in a suitable solvent and used to modify a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). The hierarchical and micro-mesoporous structure of the MOF supports the bimetallic nanoparticles, facilitating fast electron transfer for the reduction of imidacloprid [25].

Electrochemical Evaluation Using a Three-Electrode System

The performance of fabricated sensors is typically evaluated using a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell [19] [23].

Setup and Measurements:

- Cell Configuration: The system consists of a nanomaterial-modified working electrode, a platinum wire or foil counter electrode, and a stable reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or saturated calomel electrode). The electrodes are immersed in an electrolyte solution containing the target analyte.

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): This technique assesses the redox behavior and electrocatalytic activity of the modified electrode. The potential is scanned linearly between two set limits while the current is measured. An increase in peak current or a shift in redox potential indicates enhanced performance [19] [22].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): EIS is used to evaluate electron-transfer properties at the electrode interface. The data, often presented as a Nyquist plot, can show a lower charge-transfer resistance (Rₜ) for nanomaterial-modified electrodes, signifying faster electron transfer kinetics [19].

- Chronoamperometry/DPV: For quantitative detection, techniques like chronoamperometry (current measured at a fixed potential over time) or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) are used to construct calibration curves, determine the linear detection range, and calculate the limit of detection (LOD) [19] [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental protocols rely on a foundational set of high-purity reagents and materials. The following table details these key components and their functions in nanomaterial-based electrochemical research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Salt Precursors (e.g., CoCl₂·6H₂O, AgNO₃, TTIP) [23] [26] | Source of metal ions for nanoparticle and metal oxide synthesis. | Co-precipitation of Ag-doped Co₃O₄ nanochips [23]. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (e.g., CNTs, Graphene) [19] [24] | Conductive electrode modifier; high surface area support. | CNT-coated microelectrodes for in vivo dopamine detection [19]. |

| Stabilizing Agents (e.g., PVA, Nafion) [26] [23] | Control nanoparticle growth and prevent aggregation; binder for electrode modification. | Optimizing stability and size of TiO₂–SiO₂ NPs [26]; Immobilizing Ag@CNCs on electrode [23]. |

| MOF Linkers (e.g., Benzene-1,4-dicarboxylic acid) [25] | Organic ligands that coordinate with metal ions to form porous MOF structures. | Synthesis of the Cu-BDC MOF support [25]. |

| Electrochemical Reagents (KOH, Na₂SO₄, LiCl) [22] [23] | Electrolyte for electrochemical testing; source of target analyte. | 2 M KOH electrolyte for MgONPs supercapacitor testing [22]; Lithium detection studies [23]. |

| Functionalization Agents (Aptamers, Antibodies) [2] | Biorecognition elements that confer selectivity to the sensor. | Immobilization on electrode surfaces for specific detection of AFB1 [2]. |

The enhanced electrochemical performance observed in nanomaterial-based systems is a direct and synergistic consequence of their intrinsic properties. The high surface area provides a greater number of active sites, the exceptional conductivity facilitates rapid electron transfer, and the tunable surface chemistry enables precise interaction with target analytes. As research continues to address challenges related to stability, reproducibility, and scalable manufacturing [20] [21], the rational design of next-generation nanomaterials promises to further push the boundaries of sensitivity, selectivity, and application scope for electrochemical sensors and energy storage devices. Future progress will likely hinge on the integrated use of computational design, advanced synthesis, and robust fabrication protocols to fully harness this powerful synergy.

From Theory to Practice: Sensor Designs and Their Drug Detection Applications

Electrochemical sensors have been transformed into powerful analytical tools through integration with advanced nanomaterials and highly specific biorecognition elements. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three predominant sensor platforms—aptasensors, immunosensors, and molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) sensors—within the context of nanomaterial-based electrochemical detection research. The strategic incorporation of nanomaterials such as gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) has substantially enhanced sensor performance by improving electron transfer kinetics, signal amplification, and bioreceptor immobilization efficiency [2] [27]. These advancements have enabled detection limits reaching femtogram per milliliter (fg/mL) to attomolar (aM) concentrations, which is critical for applications in clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety [28] [27]. This review comprehensively addresses the fundamental principles, design considerations, experimental protocols, and recent technological developments for each sensor class, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a practical framework for sensor selection, optimization, and implementation.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Analysis

Core Sensing Mechanisms and Biorecognition Elements

Immunosensors rely on the specific antigen-antibody (Ag-Ab) interaction as their primary recognition mechanism. Antibodies are proteins naturally evolved to bind targets with high affinity and specificity. Traditional immunosensors employ whole monoclonal antibodies (∼150 kDa), though derivatives like antigen-binding fragments (Fab', ∼50 kDa), single-chain variable fragments (scFv, ∼30 kDa), and single-chain antibodies (scAb, ∼40 kDa) offer advantages due to their smaller size, enabling higher immobilization density and potentially improved sensitivity [29]. The binding event is typically transduced electrochemically via direct, sandwich, or competitive assay formats, with signal generation resulting from the formation of Ab-Ag complexes on the electrode surface [28].

Aptasensors utilize aptamers—single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides—as recognition elements. These molecules are identified through Systematic Evolution of Ligands by Exponential Enrichment (SELEX) and bind to specific targets (proteins, small molecules, cells) by folding into unique three-dimensional structures [29] [27]. Compared to antibodies, aptamers offer advantages including superior stability, ease of chemical synthesis and modification, minimal batch-to-batch variability, and the ability to target molecules with low immunogenicity [27] [30]. Their functionalization often includes modifications with thiol, amino, or biotin groups to facilitate oriented immobilization on nanomaterial-modified electrodes [27].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Sensors employ synthetic polymeric materials containing tailor-made recognition sites complementary to the target analyte in size, shape, and functional group orientation [31] [32]. MIPs are fabricated by copolymerizing functional monomers and cross-linkers in the presence of a template molecule (the target analyte). Subsequent template removal creates cavities that exhibit specific rebinding affinity [2]. MIP sensors overcome limitations of biological receptors by offering exceptional physical and chemical stability, reusability, and compatibility with harsh environments, making them suitable for detecting small molecules, toxins, and environmental pollutants [31] [32].

Performance Comparison and Selection Criteria

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Immunosensors, Aptasensors, and MIP Sensors

| Parameter | Immunosensors | Aptasensors | MIP Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biorecognition Element | Antibodies (whole or fragments) | DNA/RNA aptamers | Synthetic polymers |

| Production Method | Biological production (hybridoma/recombinant) | Chemical synthesis (SELEX) | Chemical synthesis (electropolymerization) |

| Development Time/Cost | High cost, several months | Moderate cost, weeks | Low cost, days |

| Stability | Moderate (sensitive to temperature/pH) | High (thermostable, reusable) | Excellent (robust in harsh conditions) |

| Target Range | Proteins, cells, pathogens (limited for small molecules) | Proteins, cells, ions, small molecules | Primarily small molecules, some macromolecules |

| Modification Flexibility | Moderate (genetic engineering required) | High (easy chemical modification) | High (tunable monomer composition) |

| Typical Detection Limit | fg/mL – pg/mL [28] | fM – aM [27] | pg/mL – ng/mL [31] |

| Real Sample Matrix Effect | Susceptible to interference | Susceptible to nuclease degradation | Minimal susceptibility |

| Key Limitation | Batch variability, limited shelf life | Susceptibility to nuclease degradation | Occasional template leakage, heterogeneity of binding sites |

The selection of an appropriate sensor platform depends on the specific application requirements. Immunosensors remain the gold standard for complex protein targets where ultra-high specificity is paramount [29]. Aptasensors offer versatility for diverse targets and are ideal for point-of-care applications requiring robust, stable receptors [27]. MIP sensors provide the most practical solution for small molecule detection in challenging environments where biological receptors would denature [32]. Recent research has also explored hybrid approaches combining different biorecognition elements to leverage the advantages of each platform [29].

Nanomaterial Integration and Signal Enhancement

Nanomaterials play a pivotal role in enhancing the analytical performance of electrochemical sensors through various mechanisms, including increased electrode surface area, improved electron transfer kinetics, and efficient bioreceptor immobilization.

Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) are extensively utilized due to their excellent conductivity, high surface-to-volume ratio, and facile functionalization with thiolated biomolecules. In immunosensors, AuNPs provide a stable platform for antibody immobilization while enhancing electrochemical signal response [28]. Similarly, in aptasensors, AuNPs facilitate electron transfer and can serve as anchoring points for aptamer attachment [27].

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials including graphene oxide (GO), carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and their derivatives offer exceptional electrical conductivity and large specific surface area. GO's abundant functional groups facilitate strong π-π stacking interactions with nucleic acids, making it particularly valuable in aptasensors for both immobilization and fluorescence quenching in optical detection platforms [27] [30].

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and other porous nanomaterials provide ultrahigh surface areas and tunable pore structures that enable efficient preconcentration of target analytes, thereby significantly lowering detection limits [2] [27]. MOFs can be integrated into both aptasensors and MIP sensors to enhance loading capacity and create optimized molecular recognition environments.

Magnetic Nanoparticles enable simple sample preparation and preconcentration through external magnetic field separation, effectively reducing matrix effects in complex samples [2]. This is particularly beneficial for food and environmental samples where interfering substances are prevalent.

Table 2: Functional Roles of Nanomaterials in Electrochemical Sensors

| Nanomaterial Class | Key Functions | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Ag) | Signal amplification, bioreceptor immobilization, enhanced electron transfer | AuNPs in CEA immunosensor [28]; AgNPs in MIP sensor for tobramycin [31] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (CNTs, GO, graphene) | High surface area, excellent conductivity, π-π stacking with biomolecules | GO in fluorescent aptasensor for FB1 [30]; CNTs in heavy metal sensors [33] |

| Metal Oxides (MnO₂, Fe₃O₄) | Catalytic activity, porous structure, magnetic separation | γ-MnO₂ in CEA immunosensor [28]; δ-FeOOH in fluorescent aptasensor [30] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks | Ultrahigh porosity, preconcentration, tunable functionality | MOF-based aptasensors for disease biomarkers [27] |

| Quantum Dots | Signal labels, photoelectrochemical activity | CdTe QDs in dual-target FRET sensor for mycotoxins [30] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fabrication of a Nanocomposite-Modified Immunosensor

Protocol for Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) Immunosensor [28]

Reagents and Materials: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE, 2 mm diameter), sodium alginate (SA), gold nanoparticles (AuNPs, 250 µM), chitosan (CS), potassium permanganate (KMnO₄), CEA antibody, CEA antigen, phosphate buffer (PB, 50 mM, pH 7.5), bovine serum albumin (BSA), potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻).

Step 1: Synthesis of γ-MnO₂-Chitosan Nanocomposite

- Prepare a 60 g/L solution of KMnO₄.

- Slowly add KMnO₄ solution to a mixture containing 0.3 g chitosan, 4 mL ethanol, and 2 mL water.

- Vigorously stir the mixture for 8 hours at room temperature.

- Filter the resulting precipitate (γ-MnO₂-CS), wash thoroughly with distilled water, and dry at 60°C for 12 hours.

- Prepare a dispersion by sonicating 2.5 mg of the dried nanocomposite in 5 mL distilled water.

Step 2: Synthesis of Citrate-Modified AuNPs

- Boil 50 mL of 0.5 mM HAuCl₄ solution under reflux.

- Rapidly add 5 mL of 38.8 mM sodium citrate solution to the boiling gold solution.

- Continue stirring until the solution color changes from yellow to wine red, indicating nanoparticle formation.

- Filter the solution to remove any aggregates.

- Determine AuNP concentration using the Beer-Lambert equation.

Step 3: Electrode Modification and Immunosensor Assembly

- Polish the GCE sequentially with 0.3 and 0.05 µm alumina slurry, followed by rinsing with distilled water and ethanol.

- Deposit 6 µL of SA solution (2.5 mM in PB) onto the GCE surface and dry at room temperature.

- Apply 8 µL of the synthesized AuNP solution to the SA-modified electrode and dry.

- Add 8 µL of the γ-MnO₂-CS nanocomposite dispersion to the electrode and allow to dry.

- Immobilize anti-CEA antibody by dropping 8 µL of antibody solution onto the modified electrode and incubating overnight at 4°C.

- Block non-specific binding sites with 5 µL of 1% BSA solution for 45 minutes at room temperature.

- The fabricated immunosensor is now ready for CEA detection in serum samples.

Step 4: Electrochemical Detection and Quantification

- Incubate the immunosensor with CEA standard solutions or sample for 30 minutes.

- Perform electrochemical measurements using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) in 2.5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ solution.

- Apply the following parameters: potential range from -0.1 to +0.6 V, modulation amplitude of 0.05 V, step potential of 0.004 V.

- Monitor the current decrease at the oxidation peak due to the formation of Ab-Ag complexes.

- Construct a calibration curve by plotting current response against CEA concentration (linear range: 10 fg/mL to 0.1 µg/mL).

Development of a Constant Potential-Prepared MIP Sensor

Protocol for In Vivo Analysis of Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) [32]

Reagents and Materials: Stainless steel working electrode, o-phenylenediamine (OPD), indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), tryptophan (Trp), phosphate buffer (PB, 0.1 M, pH 5.2-8.2).

Step 1: Constant Potential Electropolymerization

- Prepare a polymerization solution containing 5.0 mM OPD and 2.5 mM IAA (template) in PB (pH 6.0).

- Immerse the working electrode in the polymerization solution along with reference (Ag/AgCl) and counter (Pt) electrodes.

- Apply a constant potential of 0.45 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 400 seconds to form the MIP film.

- For comparison, prepare control sensors using cyclic voltammetry (CV: 0-0.8 V, 100 mV/s, 20 cycles).

Step 2: Template Removal

- After electropolymerization, thoroughly rinse the MIP sensor with ethanol and distilled water to remove the physically adsorbed template.

- Place the sensor in an electrochemical cell containing clean PB (pH 6.0).

- Apply CV scanning between 0 and 0.8 V until a stable voltammogram is obtained, indicating complete template removal.

Step 3: Rebinding and Detection Procedure

- Incubate the MIP sensor in standard solutions or real samples containing IAA for 20 minutes.

- Remove the sensor from the sample solution and rinse gently with distilled water.

- Transfer the sensor to a detection cell containing PB (pH 6.0).

- Perform electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements with a frequency range from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz at a formal potential of 0.25 V.

- Monitor the increase in charge transfer resistance (Rct) which is proportional to the amount of IAA bound to the MIP film.

- For interference studies, prepare solutions containing both IAA and tryptophan in varying ratios.

Step 4: In Vivo Analysis in Tomato Fruits

- Fabricate needle-shaped MIP sensors using stainless steel substrates.

- Carefully insert the MIP sensor directly into tomato fruits.

- Allow in vivo incubation for 20 minutes to facilitate IAA extraction.

- Remove the sensor and perform EIS measurement as described above.

- Use binary regression analysis with both IAA and Trp MIP sensors to address selectivity challenges from structurally similar compounds.

Fabrication of an Electrochemical Aptasensor

General Protocol for Aptasensor Development [27] [30]

Reagents and Materials: Gold electrode or screen-printed electrode, thiol- or amino-modified DNA aptamer, appropriate cross-linkers (e.g., EDC/NHS), nanomaterials (e.g., AuNPs, GO, CNTs), tris-EDTA buffer, target analyte, redox probes ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ or methylene blue).

Step 1: Electrode Pretreatment and Nanomaterial Modification

- Clean the electrode surface according to manufacturer's specifications (typically mechanical polishing for GCE or electrochemical cleaning for gold electrodes).

- For gold electrodes, perform electrochemical activation in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ by CV scanning.

- Deposit selected nanomaterials: For AuNPs, use electrodeposition or drop-casting; for GO or CNTs, disperse in suitable solvent and drop-cast onto electrode surface.

Step 2: Aptamer Immobilization

- For thiol-modified aptamers: Incubate the nanomaterial-modified electrode with 1-10 µM aptamer solution in immobilization buffer (e.g., Tris-EDTA with Mg²⁺) for 12-16 hours at 4°C to form self-assembled monolayers.

- For amino-modified aptamers: First activate the electrode surface with appropriate linkers (e.g., glutaraldehyde for amine surfaces or EDC/NHS for carboxyl-functionalized nanomaterials), then incubate with aptamer solution.

- Rinse thoroughly with buffer to remove physically adsorbed aptamers.

- Block remaining active sites with 1-2 mM 6-mercapto-1-hexanol (for thiol systems) or BSA/ethanolamine (for amino systems).

Step 3: Target Binding and Electrochemical Detection

- Incubate the aptasensor with sample solutions containing the target analyte for optimal time (typically 30-60 minutes).

- Rinse gently with buffer to remove unbound molecules.

- Perform electrochemical measurement using preferred technique:

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Monitor increase in charge transfer resistance in [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ solution.

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Measure current decrease of redox probes.

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): Detect conformational change-induced signal variations.

- For label-free detection, directly monitor changes in electrochemical parameters upon target binding.

- For labeled detection, use enzyme- or nanoparticle-conjugated secondary probes for signal amplification.

Diagram 1: Electrochemical sensor fabrication workflow illustrating the generalized preparation procedure for immunosensors, aptasensors, and MIP sensors, highlighting both common steps and platform-specific processes.

Advanced Sensing Strategies and Applications

Signal Amplification Techniques

Modern electrochemical sensors employ sophisticated signal amplification strategies to achieve exceptional sensitivity:

Enzyme-Based Amplification: Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) and glucose oxidase (GOx) are commonly conjugated to secondary antibodies or aptamers to catalyze reactions that generate electroactive products, significantly amplifying the detection signal [27]. Recent approaches utilize enzyme-assisted recycling amplification where nucleases digest aptamer-target complexes, releasing the target for multiple binding events [30].

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Amplification: Nanomaterials contribute to signal amplification through various mechanisms. Catalytic nanomaterials such as MnO₂ nanoflakes exhibit peroxidase-like activity, while AuNPs and CNTs facilitate electron transfer and can be used as carriers for multiple enzyme or aptamer units [2]. Graphene oxide efficiently quenches fluorescence in optical aptasensors, enabling sensitive "signal-on" detection when targets displace probes from the GO surface [30].

CRISPR-Cas Integration: The CRISPR-Cas system has been recently integrated with aptasensors for amplified detection. In one approach for fumonisin B1 (FB1) detection, target binding triggers collateral cleavage activity of Cas12a, resulting in dramatic signal amplification through nucleic acid degradation [30]. This synergistic combination of aptamer recognition and CRISPR amplification enables attomolar detection limits.

Application-Specific Sensor Designs