Molecular Imprinting Technology in Pharmaceutical Electroanalysis: Advanced Sensors for Selective Detection and Biomedical Applications

This article comprehensively reviews the application of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) in the electrochemical analysis of pharmaceuticals, catering to researchers and drug development professionals.

Molecular Imprinting Technology in Pharmaceutical Electroanalysis: Advanced Sensors for Selective Detection and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively reviews the application of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) in the electrochemical analysis of pharmaceuticals, catering to researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles of MIPs as robust, biomimetic recognition elements that serve as synthetic alternatives to antibodies. The scope extends to methodological advances, including the design of conducting polymer-based sensors and nanocomposite materials for enhanced sensitivity. It addresses critical troubleshooting aspects such as optimizing selectivity and managing template leakage. Finally, the article provides a validation framework, comparing MIP-sensor performance with traditional analytical techniques and evaluating their application in complex biological and environmental matrices for therapeutic drug monitoring and pharmaceutical residue detection.

Molecular Imprinting Fundamentals: Designing Synthetic Receptors for Pharmaceutical Targets

Molecular imprinting technology (MIT) is a technique for creating template-shaped cavities in polymer matrices with predetermined selectivity and high affinity, mimicking the natural "lock and key" model used by enzymes for substrate recognition [1]. A Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) is the synthetic receptor resulting from this process, featuring cavities complementary in size, shape, and chemical functionality to a chosen template molecule [2]. Within the field of pharmaceutical electroanalysis, MIPs serve as robust, synthetic recognition elements in sensors, overcoming the limitations of biological receptors such as antibodies and enzymes, particularly in terms of stability, cost, and shelf-life [3] [4]. This application note details the core principles and provides a practical protocol for developing MIPs for electroanalytical applications.

Core Principles and Imprinting Approaches

The fundamental process of molecular imprinting involves three critical stages: 1) the formation of a complex between a template molecule and functional monomer(s) in solution, 2) polymerization of this complex in the presence of a cross-linking agent, and 3) removal of the template to reveal a complementary cavity [1] [5]. The binding site's specificity is governed by the geometry and the spatial arrangement of functional groups within the cavity.

The choice of imprinting strategy is crucial and depends on the nature of the template and the intended application. The three primary approaches are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key Approaches in Molecular Imprinting

| Approach | Template-Monomer Interaction | Advantages | Disadvantages | Common Use in Electroanalysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Covalent [1] | Reversible covalent bonds (e.g., boronic esters, ketals). | Homogeneous, well-defined binding sites. | Slow binding kinetics, limited template variety. | Less common due to slower rebinding. |

| Non-covalent [1] [2] | Self-assembly via hydrogen bonds, ionic, van der Waals forces. | Wide applicability, easy preparation, fast kinetics. | Binding site heterogeneity, risk of non-specific binding. | Most widely used, ideal for sensors. |

| Ionic/Metallic [1] | Coordination with metal ions (e.g., Cu²⁺, Zn²⁺). | Enhanced strength and selectivity in aqueous media. | Requires templates with metal-coordinating groups. | Growing use for water-based sensing (e.g., biological fluids). |

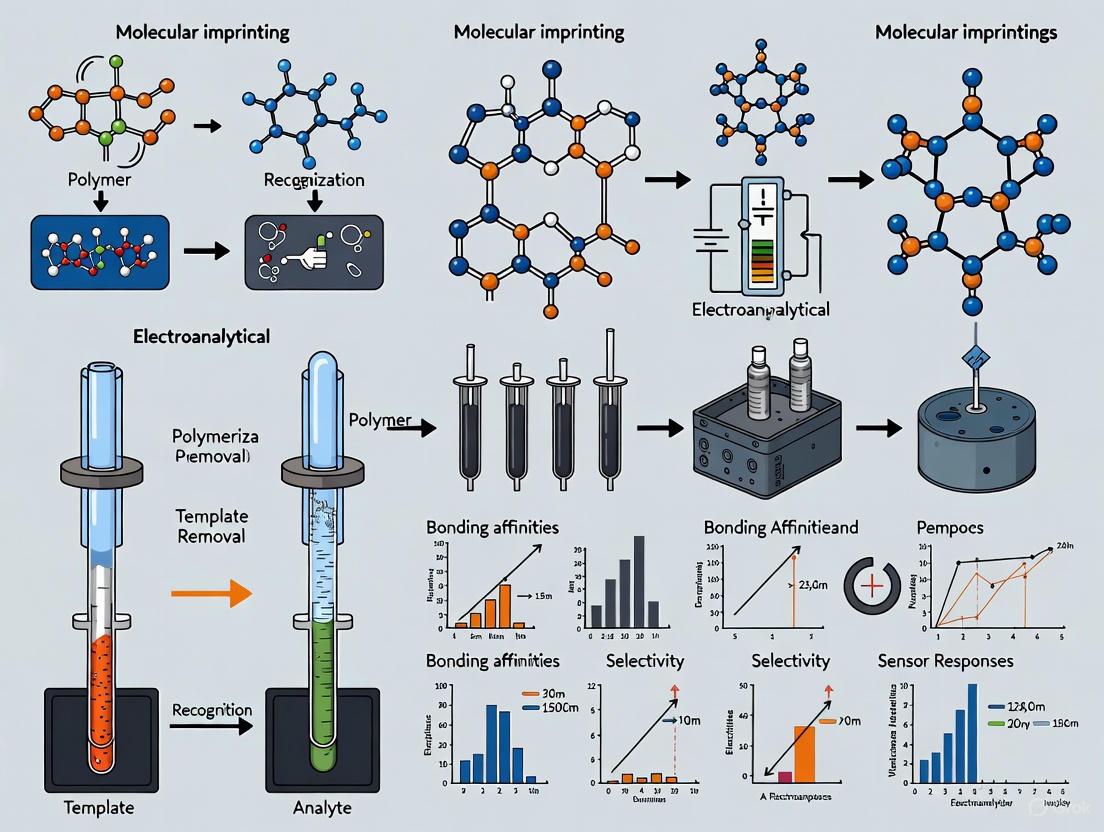

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for the creation of a molecularly imprinted polymer, with emphasis on the non-covalent approach.

Diagram 1: General MIP synthesis and application workflow.

Advanced Considerations: Electric Field-Assisted Imprinting

Recent advancements aim to overcome traditional MIT challenges, such as heterogeneous binding sites and incomplete template removal. Electric field-assisted imprinting has emerged as a powerful strategy, particularly for fabricating electrochemical sensors [6].

During synthesis, an external electric field can orient polar template and monomer molecules, leading to a more uniform distribution and optimal alignment of binding sites. During the analytical application, the electric field can enhance mass transfer of the target analyte to the MIP-modified electrode surface, significantly improving the sensor's response speed and sensitivity [6]. The diagram below outlines the mechanisms of electric field assistance.

Diagram 2: Benefits of electric field assistance in MIP lifecycle.

Experimental Protocol: MIP-Modified Electrochemical Sensor for Pregabalin

This protocol details the synthesis of a highly selective MIP-based electrochemical sensor for the detection of Pregabalin (PGB), adapted from a recent study [4]. The sensor integrates a Copper Metal-Organic Framework (Cu-MOF) to enhance surface area and electrocatalytic activity.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Supplier Example |

|---|---|---|

| Pregabalin (PGB) | Template molecule | Sigma-Aldrich or Merck |

| Ortho-Phenylenediamine (o-PD) | Functional monomer for electropolymerization | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Copper(II) Acetate Monohydrate | Metal precursor for Cu-MOF synthesis | Sigma-Aldrich |

| 4-Aminobenzoic Acid | Organic ligand for Cu-MOF synthesis | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Graphite Powder & Paraffin Oil | Components for Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE) | Sigma-Aldrich |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) 0.1 M, pH 7.0 | Supporting electrolyte for electrochemical measurements | Prepared in-lab |

| Solvents (Ethanol, Water) | Porogen and cleaning | N/A |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Part A: Synthesis of Cu-MOF

- Dissolve 249.5 mg of Copper(II) acetate monohydrate and 42.0 mg of 4-aminobenzoic acid in a suitable solvent (e.g., ethanol/water mixture) [4].

- Allow the reaction to proceed under coprecipitation conditions, then collect the resulting Cu-MOF crystals via centrifugation.

- Wash the crystals thoroughly with the solvent and dry under vacuum.

Part B: Fabrication of MIP-Modified Sensor

- Prepare Cu-MOF/CPE: Mix graphite powder uniformly with the synthesized Cu-MOF (e.g., 95:5 w/w%). Incorporate paraffin oil to form a homogeneous paste. Pack the paste into an electrode body (e.g., 3.5 mm diameter) and smooth the surface.

- Electropolymerization (Critical Step for MIP formation):

- Prepare a polymerization solution containing 2.0 mM PGB (template) and 4.0 mM o-PD (monomer) in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0).

- Place the Cu-MOF/CPE in the solution along with Pt counter and Ag/AgCl reference electrodes.

- Using Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), scan the potential between -0.5 V and +0.8 V for 15 cycles at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. This deposits a thin, PGB-imprinted poly(o-PD) film on the electrode.

- Template Removal: Gently rinse the electrode and transfer it to a clean electrochemical cell containing only 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.0). Perform CV scans over a suitable potential range (e.g., 0.0 to +0.8 V) until a stable voltammogram is obtained, indicating complete extraction of the PGB template. The sensor (Cu-MOF/MIP-POPD/CPE) is now ready for use.

Part C: Electrochemical Measurement and Analysis

- Rebinding: Incubate the MIP-sensor in a sample solution containing an unknown concentration of PGB for a fixed time (e.g., 10-15 minutes) to allow selective rebinding.

- Detection: Using Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), record the electrochemical signal in a clean 0.1 M PBS solution. The change in current (typically a decrease due to the insulating properties of the bound PGB) is proportional to the concentration.

- Quantification: Construct a calibration curve by plotting the DPV response versus the logarithm of known PGB concentrations. The sensor from the source study exhibited linear ranges of 0.003–0.09 µM, 0.1–1 µM, and 1–90 µM with a detection limit of 1.2 nM [4].

Application in Pharmaceutical Electroanalysis

The primary application of MIPs in the context of this thesis is as the recognition element in electrochemical sensors for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). A notable example is an electrochemical microfluidic chip integrated with an MIP for the trace measurement of drugs like warfarin sodium, cyclophosphamide, and carbamazepine [7]. This system demonstrated a remarkably low detection limit of 8 × 10⁻¹² M for warfarin, sufficient for monitoring drug levels in plasma [7]. The "gate effect" mechanism, where binding of the target analyte modulates the permeability of the polymer film, is often responsible for the high sensitivity of such MIP-based sensors.

Molecular imprinting creates robust, synthetic receptors with exceptional selectivity for target analytes. When combined with electrochemical transducers and advanced materials like MOFs, MIPs form the basis for highly sensitive, specific, and cost-effective sensors. The protocol outlined herein for pregabalin provides a template that can be adapted for the analysis of a wide range of pharmaceutical compounds, supporting advanced research in drug development and clinical monitoring.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are synthetic materials designed to mimic the molecular recognition capabilities of natural biological receptors, such as antibodies and enzymes [8]. These artificially generated receptors are created through the template-induced formation of specific recognition sites within a polymer matrix [9]. The resulting materials possess a unique combination of properties including robustness, high affinity, specificity, and low-cost production, making them attractive alternatives to natural receptors in electroanalytical applications [9] [10]. Over the past few decades, MIPs have evolved from scientific curiosities to viable sensing elements that can circumvent the limitations of their biological counterparts, particularly in the demanding environment of pharmaceutical analysis [10] [8].

The fundamental principle behind molecular imprinting involves the formation of complementary cavities in a polymer network that match the template molecule in size, shape, and chemical functionality [10]. This process, often compared to the Fischer's lock and key analogy for enzyme-substrate interactions, creates artificial recognition sites capable of selectively rebinding target analytes even in complex matrices [8]. Subsequent advancements in polymer science and nanotechnology have further enhanced MIP performance, driving their application in medical and forensic diagnostics [9].

Within pharmaceutical research, electrochemical biosensors represent powerful tools for detecting clinically relevant biomolecules, offering sensitive and specific detection accompanied by rapid response, user-friendly operation, portability, and real-time analysis [10]. The integration of MIPs as recognition elements in these sensing platforms has significantly expanded their capabilities for monitoring drugs, antibiotics, and biomarkers in various sample types [11] [12].

Comparative Advantages of MIPs Over Biological Receptors

The replacement of natural receptors with MIPs in electroanalytical systems addresses several critical limitations associated with biological recognition elements. While natural antibodies exhibit exceptional specificity, their practical implementation in sensors is constrained by instability under harsh environmental conditions, expensive synthesis procedures, and limited durability [10]. MIPs offer a compelling alternative with distinct advantages for pharmaceutical electroanalysis.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of MIPs versus Biological Antibodies in Electroanalytical Applications

| Characteristic | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Biological Antibodies |

|---|---|---|

| Stability | High physicochemical stability; stable under harsh conditions (extreme pH, temperature, organic solvents) [10] | Limited stability; require strict physiological conditions [10] [13] |

| Production Cost & Shelf Life | Low-cost production; simple synthesis; long shelf life [9] [10] | Expensive and time-consuming production; limited shelf life [10] |

| Production Time | Relatively rapid preparation [10] | Lengthy in vivo or in vitro production [10] |

| Versatility | Compatible with various solvents and extreme conditions; wide range of possible templates [10] [8] | Primarily restricted to aqueous media and mild conditions [13] |

| Reusability | Reusable and durable in most cases [10] | Often limited to single-use [10] |

The superior stability of MIPs is particularly valuable for pharmaceutical analysis where sensors may encounter diverse sample matrices or require extended deployment. Their robustness under non-physiological conditions enables applications across wider pH and temperature ranges than possible with biological receptors [8]. Furthermore, the simplicity of their production makes specific recognition units more readily available compared to relying on antibody production, which often involves animal hosts or complex cell cultures [10].

The versatility of possible templates allows MIPs to be developed for recognition and rebinding of challenging analytes, including small molecules, proteins, and even viruses or microorganisms [10] [8]. This flexibility, combined with their ease of adaptation to various biomedical applications, positions MIPs as transformative elements in separation technologies, diagnostics, (bio)sensing, and drug delivery [10].

MIP Synthesis and Integration Methods

The creation of effective molecularly imprinted polymers involves multiple synthesis approaches, each with distinct advantages for particular applications. The fundamental process encompasses three key steps: (1) pre-assembly of functional monomers around a template molecule, (2) polymerization to form a cross-linked network, and (3) template removal to create specific recognition cavities [10].

Synthesis Approaches

Table 2: Common Molecular Imprinting Methods for Electrochemical Sensors

| Imprinting Method | Key Features | Best For |

|---|---|---|

| Bulk Imprinting | Pre-polymer mixture coats transducer surface; template entrapped during curing; removed via elution [10] | Small molecule templates; general purpose applications |

| Surface Imprinting | Requires support material; binding sites positioned near polymer surface; creates thin polymer films [10] | Protein imprinting; improved accessibility to binding sites |

| Electropolymerization | Electrochemical energy initiates polymerization; precise film thickness control; direct transducer modification [13] | Integrated sensor development; controlled thin-film formation |

The selection of appropriate functional monomers and cross-linkers is crucial for creating high-affinity binding sites. In covalent imprinting, developed by Wulff and Sarhan, template molecules are connected to functional monomers through reversible covalent bonds, providing excellent control over binding site uniformity [8]. Alternatively, non-covalent imprinting, pioneered by Mosbach et al., relies on self-assembly through hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, or hydrophobic effects between template and monomers, offering greater flexibility and simpler preparation [10] [8].

For electrochemical sensors specifically, electropolymerization has emerged as a particularly valuable synthesis method. This approach enables direct formation of MIP films on electrode surfaces through application of controlled potential or current, allowing precise control over film thickness and morphology [13]. The resulting electropolymerized MIPs (e-MIPs) are especially suitable for miniaturized sensors and point-of-care devices [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for MIP Development

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MIP-Based Electroanalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Purpose | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Provide complementary chemical groups for template binding | Acrylic acid, methacrylic acid, vinylpyridine [8] |

| Cross-linkers | Create rigid 3D polymer network around template | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA), divinylbenzene [8] |

| Initiators | Begin polymerization reaction under specific conditions | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, thermal), riboflavin (photochemical) [8] |

| Nanomaterials | Enhance sensor sensitivity and surface area | MWCNTs, graphene, gold nanoparticles, quantum dots [13] |

| Electrode Materials | Serve as transduction platform for signal measurement | Glassy carbon, carbon paste, screen-printed electrodes [12] [14] |

The integration of nanomaterials has been particularly transformative for MIP-based sensors, with nanoparticles, multiwalled carbon nanotubes, quantum dots, and graphene structures significantly enhancing sensitivity and electrical properties [13]. These nanocomposites address the inherently poor electrical conductivity of traditional MIPs, improving electron transfer kinetics and overall sensor performance [13] [14].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Development of Electropolymerized MIP (e-MIP) Sensor for Pharmaceutical Compounds

Objective: To create an electropolymerized molecularly imprinted polymer sensor for selective detection of target pharmaceuticals in complex samples.

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical workstation with potentiostat

- Three-electrode system: Working electrode (glassy carbon, gold, or screen-printed), reference electrode (Ag/AgCl), counter electrode (platinum wire)

- Template molecule (target pharmaceutical)

- Functional monomers (e.g., o-phenylenediamine, pyrrole, aniline)

- Supporting electrolyte (e.g., phosphate buffer, acetate buffer)

- Nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, multiwalled carbon nanotubes) for electrode modification

- Solvents for template removal (e.g., methanol:acetic acid mixtures)

Procedure:

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish working electrode with alumina slurry (0.3 µm and 0.05 µm) on microcloth

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between polishing steps

- Clean via electrochemical cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ until stable cyclic voltammogram obtained

Nanomaterial Modification (Optional Enhancement):

- Prepare dispersion of nanomaterial (e.g., 1 mg/mL graphene oxide in DMF)

- Deposit predetermined volume onto electrode surface

- Allow to dry under infrared lamp or at controlled temperature

Electropolymerization Solution Preparation:

- Prepare solution containing template molecule (2-10 mM) and functional monomer (20-100 mM) in selected supporting electrolyte

- Degas with nitrogen or argon for 5-10 minutes to remove oxygen

Polymerization via Cyclic Voltammetry:

- Immerse electrode system in polymerization solution

- Apply cyclic voltammetry between predetermined potential limits (e.g., -0.5 to +0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Complete 10-30 cycles at scan rate of 50 mV/s

- Monitor current decrease with successive cycles, indicating polymer film growth

Template Removal:

- Transfer modified electrode to clean supporting electrolyte without template

- Apply electrochemical overpotential or cyclic voltammetry in different potential window

- Alternatively, use solvent extraction with methanol:acetic acid (9:1 v/v) with gentle stirring

- Confirm template removal by stabilization of electrochemical signal

Rebinding Studies and Sensor Characterization:

- Expose MIP-modified electrode to standard solutions of template at varying concentrations

- Incubate for predetermined time (5-15 minutes) with gentle stirring

- Measure electrochemical response using differential pulse voltammetry, square wave voltammetry, or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

- Compare with non-imprinted polymer (NIP) control to determine imprinting factor

Validation:

- Determine linear range, detection limit, and quantification limit using standard additions

- Evaluate selectivity against structurally similar compounds

- Assess reproducibility through multiple sensor preparations

- Test stability over time with proper storage conditions

Protocol: MIP-Modified Carbon Paste Electrode (MIP-CPE) for Drug Analysis

Objective: To prepare a carbon paste electrode modified with molecularly imprinted polymers for sensitive determination of pharmaceutical compounds.

Materials and Equipment:

- Graphite powder

- Mineral oil or paraffin as binding agent

- Pre-synthesized MIP particles (prepared via bulk polymerization)

- Mortar and pestle for mixing

- Electrode body for paste packing

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode and platinum counter electrode

Procedure:

MIP Synthesis via Bulk Polymerization:

- Dissolve template (target drug, 0.5-1 mmol), functional monomer (2-4 mmol), and cross-linker (10-20 mmol) in porogenic solvent

- Add radical initiator (e.g., AIBN, 1% w/w)

- Purge with nitrogen or argon for 5 minutes to remove oxygen

- Seal and polymerize at 60°C for 12-24 hours

- Grind resulting polymer and sieve to desired particle size (25-50 µm)

- Extract template thoroughly using Soxhlet extraction or repeated washing

- Dry under vacuum at 40-60°C

Carbon Paste Preparation:

- Mix graphite powder and MIP particles in predetermined ratio (typical MIP content: 10-20% w/w)

- Add mineral oil (typically 30-40% w/w of total paste)

- Blend thoroughly in mortar until homogeneous paste obtained

- For control electrode, prepare NIP-modified carbon paste following same procedure

Electrode Assembly:

- Pack paste firmly into electrode cavity

- Smooth surface against weighing paper or similar smooth surface

- Electrical contact established through plunger mechanism

Measurement Procedure:

- Pre-condition electrode by cycling in clean supporting electrolyte

- Incubate in sample solution with stirring for predetermined accumulation time

- Transfer to electrochemical cell with clean supporting electrolyte

- Apply appropriate voltammetric technique for quantification

- Renew electrode surface by gently pushing out small amount of paste and polishing on smooth paper

Applications: This approach has been successfully applied for determination of analgesic drugs, antibiotics, antivirals, cardiovascular drugs, and therapeutic agents affecting the central nervous system [12].

Applications in Pharmaceutical Electroanalysis

The implementation of MIP-based sensors has demonstrated significant utility across diverse pharmaceutical analysis scenarios, particularly for compounds where traditional analytical methods face limitations.

Antibiotic Monitoring

MIP sensors have been extensively developed for antibiotic determination in environmental, food, and biological matrices [11]. The electrochemical detection of antibiotics is crucial for preventing antibiotic resistance development and ensuring food safety. Published works have covered the electroanalysis of a wide range of different antibiotic classes, including β-lactams, tetracyclines, quinolones, macrolides, and aminoglycosides [11]. Both electropolymerized MIPs and those developed by other polymerization techniques have been successfully applied, with approximately 60 publications and patents focusing on e-MIPs for antibiotic detection [11].

Biomarker Detection and Clinical Diagnostics

The detection of protein-based biomarkers represents a particularly challenging application area where MIPs offer distinct advantages. Unlike small molecular targets, proteins present special challenges due to their size, irreversible conformational changes, and complex structure [10]. Recent approaches in surface imprinting have enabled the development of MIP sensors capable of recognizing specific protein biomarkers, driving applications in medical diagnostics [10]. These sensors facilitate early disease detection and subsequent monitoring of disease progression through rapid, selective, and cost-effective detection of clinically relevant biomolecule analytes [10].

Comprehensive Pharmaceutical Analysis

MIP-modified electrodes have been created for various pharmaceutical compounds including analgesic drugs, antibiotics, antivirals, cardiovascular drugs, and therapeutic agents affecting the central nervous system [12]. The carbon paste electrode platform, modified with MIPs, has emerged as particularly promising due to beneficial properties including ease of electrode modification, facile surface renewability, low background currents, and versatile modification capabilities [12]. This approach addresses the lack of sufficient selectivity of traditional carbon paste electrodes while maintaining their practical advantages.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers represent a transformative technology in pharmaceutical electroanalysis, offering robust artificial antibodies that overcome the limitations of biological receptors. Their superior stability, cost-effectiveness, and versatility position them as ideal recognition elements for electrochemical sensors targeting pharmaceutical compounds, biomarkers, and environmental contaminants [9] [10]. The continued advancement of MIP technology, particularly through integration with nanomaterials and improved synthesis methodologies, promises further enhancements in sensitivity and selectivity [13] [14].

Future perspectives for MIP-based sensors include increased adoption of lab-on-a-chip systems, integration with artificial intelligence for data interpretation, and development of commercial platforms for point-of-care testing [15]. These advancements will solidify the role of MIPs as indispensable tools in modern pharmaceutical research, quality control, and clinical diagnostics, ultimately contributing to more efficient drug development and improved patient outcomes.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are synthetic polymeric materials engineered to possess specific recognition sites for a target molecule, known as the template. Their function as "artificial receptors" or "plastic antibodies" makes them particularly valuable in electroanalysis, where they provide the critical selectivity needed for detecting pharmaceuticals in complex matrices [16] [17]. The fundamental principle of molecular imprinting involves the polymerization of functional monomers and cross-linkers around a template molecule. Subsequent removal of the template leaves behind cavities that are complementary in size, shape, and chemical functionality, enabling the MIP to selectively rebind the target analyte [18] [2]. The advantages of MIPs—including high physical and chemical robustness, cost-effectiveness, resistance to harsh conditions, and long shelf life—make them superior to natural biological receptors for many analytical applications, particularly in the development of stable and reusable electrochemical sensors [18] [17] [11].

Core Components of MIPs

The successful development of a MIP relies on the careful selection and combination of four key components. The interactions between these components determine the affinity, selectivity, and overall performance of the final polymer.

Template Molecules

The template is the target molecule around which the complementary binding site is created. In pharmaceutical electroanalysis, the template is typically the drug molecule or a structural analogue that needs to be detected [19].

- Selection Criteria: The ideal template should be chemically stable under polymerization conditions, possess functional groups capable of interacting with monomers, and be available in sufficient purity [19].

- Single vs. Multiple Templates: While single-template MIPs (ST-MIPs) are highly selective for one analyte, multi-template MIPs (MT-MIPs) can be synthesized for the simultaneous recognition of several analytes. The MT-MIP strategy offers significant advantages for multi-analyte sensing, including reduced solvent consumption, cost-effectiveness, and shorter analysis time [19].

Functional Monomers

Functional monomers are the cornerstone of molecular recognition. They contain functional groups that interact with the template molecule via non-covalent (e.g., hydrogen bonding, ionic interactions, van der Waals forces) or covalent bonds to form a complex prior to polymerization [18] [16]. The choice of monomer is paramount for creating high-affinity binding sites.

Table 1: Common Functional Monomers and Their Applications

| Monomer | Chemical Nature | Primary Interaction with Template | Exemplary Template in Pharmaceuticals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methacrylic Acid (MAA) | Acidic | Hydrogen bonding, Ionic | Ametryn (Herbicide) [20], Antibiotics [11] |

| Acrylamide (AAm) | Neutral | Hydrogen bonding | Histamine [21] |

| 2-Vinylpyridine (2-VP) / 4-Vinylpyridine (4-VP) | Basic | Hydrogen bonding, Ionic | Drugs [19] |

Advances in monomer selection now heavily utilize computational simulation to screen large databases of monomers and predict the strength and nature of monomer-template interactions before embarking on resource-intensive laboratory synthesis [16] [22].

Cross-linkers

Cross-linkers are multifunctional molecules that create a rigid, three-dimensional polymer network around the template-monomer complex. This network stabilizes the binding sites and maintains their structural integrity after the template is removed [2] [21].

- Functions: The cross-linker controls the polymer morphology, stabilizes the imprinted binding site, and imparts mechanical stability to the polymer matrix [2].

- Common Cross-linkers: Ethylene Glycol Dimethacrylate (EGDMA) is one of the most widely used cross-linkers in non-covalent imprinting [19] [20]. Others include divinylbenzene (DVB) and N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide (BIS) [19] [21].

- Cross-linker Optimization: The type and amount of cross-linker are critical. While a high degree of cross-linking provides rigidity, some flexibility can be beneficial for rebinding. A systematic study on polyacrylamide-based MIPs found that a cross-linker with a four-methylene spacer (BA4) offered an optimal balance, leading to high binding capacity and selectivity for histamine [21].

Polymerization Methods and Initiators

Polymerization is the process of forming the highly cross-linked polymer. The method chosen determines the physical format and properties of the MIP, which are crucial for its integration into electrochemical sensors.

Table 2: Common Polymerization Methods for MIP Synthesis

| Method | Procedure | Advantages | Disadvantages | Suitability for Electroanalytical Sensors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bulk Polymerization | Polymerization in a monolithic block, followed by grinding and sieving [19]. | Simple, universal method [19]. | Irregular particle shapes, heterogeneous binding sites, potential damage to cavities during grinding [19]. | Moderate; irregular particles can be mixed into carbon paste electrodes (CPEs) [12]. |

| Precipitation Polymerization | Polymerization in a dilute solution where the polymer becomes insoluble and precipitates [19] [20]. | Produces spherical, monodisperse particles in a one-step process [19] [20]. | Requires large amounts of solvent and template [19]. | High; spherical particles are ideal for creating uniform modified electrodes [20]. |

| Electropolymerization | Monomers are directly polymerized onto an electrode surface by applying a potential [11]. | Direct formation of thin, homogeneous MIP films on the transducer surface; excellent control over film thickness [11]. | Limited to electroactive monomers. | Very High; the preferred method for fabricating sensitive and reproducible electrochemical sensors [11]. |

Polymerization is typically initiated by thermal decomposition or photoactivation of an initiator, such as azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN), which generates free radicals to start the chain reaction [19] [20].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of MIP Microspheres via Precipitation Polymerization for Sensor Application

This protocol outlines the synthesis of MIP microspheres using ametryn as a template, which can subsequently be incorporated into a carbon paste electrode for electrochemical detection [20].

Materials:

- Template: Ametryn (AME)

- Functional Monomers: Methacrylic acid (MAA), Acrylamide (AAm), or 2-Vinylpyridine (2-VP)

- Cross-linker: Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA)

- Initiator: Azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN)

- Porogenic solvent: Toluene

- Washing solvent: Methanol/Acetic acid (6:4, v/v)

Procedure:

- In a 250 mL conical flask, combine 1.0 mmol of AME, 5.0 mmol of a functional monomer (e.g., MAA), 20.0 mmol of EGDMA, and 30 mg of AIBN in 100 mL of toluene.

- Sonicate the mixture for 10 minutes to ensure complete dissolution and degas with nitrogen gas for 15 minutes in an ice-water bath to remove oxygen.

- Seal the flask tightly and place it in a water bath at 80 °C for 6 hours to complete the polymerization reaction.

- After polymerization, collect the polymer particles by centrifugation (e.g., 4000 rpm for 15 min) and dry at room temperature.

- Extract the template by continuously washing the polymer with the methanol/acetic acid solution until the template can no longer be detected in the washings by UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Finally, rinse the polymers with pure methanol to remove residual acetic acid and dry at room temperature.

- For electrochemical application, the synthesized MIP microspheres are mixed with graphite powder and a binder (e.g., paraffin oil) to fabricate a modified carbon paste electrode (MIP-CPE) [12].

Protocol 2: Investigating Cross-linker Effects on MIP Performance

This protocol describes a method to systematically study the impact of cross-linker flexibility on MIP adsorption properties, as demonstrated for histamine imprinting [21].

Materials:

- Functional Monomer: Acrylamide (AAm)

- Cross-linkers: N,N'-Polymethylenebis(acrylamide) with spacer lengths of 1, 2, 4, and 6 methylenes (BA1, BA2, BA4, BA6).

- Template: Histamine (HA)

- Other reagents: Initiator (e.g., AIBN), porogen, silica support for surface imprinting.

Procedure:

- Synthesize a series of MIPs using the same template (HA), functional monomer (AAm), and polymerization method, but vary the cross-linker (BA1, BA2, BA4, BA6). Synthesize corresponding Non-Imprinted Polymers (NIPs) without the template for each cross-linker.

- Characterize the polymers using techniques like BET surface area analysis and FT-IR.

- Perform batch rebinding experiments: incubate a fixed amount of each MIP (e.g., 10 mg) with a solution of HA (e.g., 20 mL of a 50 mg L⁻¹ solution) at room temperature.

- Measure the concentration of HA in the solution at various time intervals using a suitable analytical method (e.g., HPLC-UV) to establish adsorption kinetics.

- Determine the binding capacity (Q, mg g⁻¹) for each MIP and its corresponding NIP.

- Calculate the Imprinting Factor (IF) for each cross-linker: IF = QMIP / QNIP.

- Conduct competitive adsorption assays with structurally similar interfering substances (e.g., tyramine, melamine) to evaluate selectivity.

Expected Outcome: The study by Boukadida et al. found that the cross-linker BA4 (with a 4-methylene spacer) provided the optimum binding capacity and selectivity, demonstrating that a degree of flexibility can be more beneficial than extreme rigidity [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Reagents for MIP Development and Fabrication

| Reagent Category & Examples | Function in MIP Development |

|---|---|

| Functional Monomers (Methacrylic Acid, Acrylamide, 4-Vinylpyridine) | To provide functional groups for interaction with the template, forming a pre-polymerization complex [18] [20]. |

| Cross-linkers (EGDMA, N,N'-methylenebisacrylamide) | To create a rigid, porous polymer network that stabilizes the shape and position of the imprinted cavities [19] [21]. |

| Initiators (AIBN, Potassium Persulfate) | To generate free radicals and initiate the polymerization reaction, either thermally or photochemically [19] [20]. |

| Porogenic Solvents (Toluene, Acetonitrile, Chloroform) | To dissolve all components and create the pore structure within the polymer during synthesis [19] [20]. |

| Graphite Powder & Paste Binder (Paraffin Oil) | To form the conductive carbon paste matrix for embedding synthesized MIP particles to create an electrochemical sensor [12]. |

Workflow and Signaling Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for the development and application of a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer for electrochemical pharmaceutical analysis, integrating the key components and protocols discussed.

The development of Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) has been transformed by the integration of theoretical and computational approaches. These tools provide atomistic insights into the molecular recognition processes fundamental to MIP function, moving development from empirically-guided to rationally-designed synthesis [23]. Within pharmaceutical electroanalysis, this paradigm shift enables the creation of highly selective biomimetic sensors for monitoring drugs, metabolites, and emerging contaminants with unprecedented efficiency [11] [15]. Computational methods are now employed to study all stages of the molecular imprinting process—from the pre-polymerization mixture and polymerization process to ligand-MIP rebinding—thereby accelerating the design of robust analytical platforms [23].

Theoretical and Computational Foundations

Thermodynamic Principles of Molecular Imprinting

The recognition properties of MIPs are fundamentally governed by the thermodynamics of the pre-polymerization mixture. The formation of template-functional monomer complexes is an equilibrium process dictated by the Gibbs free energy of binding (ΔGbind). A more favorable (negative) ΔGbind drives the equilibrium towards complex formation, leading to a larger number of high-fidelity binding sites in the final polymer [23].

The comprehensive thermodynamic treatment of this interaction, as detailed by Williams, factorizes ΔGbind into its constituent contributions [23]: ΔGbind = ΔGt+r + ΔGr + ΔGh + ΔGvib + ∑ΔGp + ΔGconf + ΔGvdW

Table: Components of Gibbs Free Energy in Molecular Imprinting

| Term | Description | Impact on MIP Design |

|---|---|---|

| ΔGt+r | Penalty from loss of translational/rotational freedom | Favors use of multi-dentate monomers over high concentrations of single-point monomers [23]. |

| ΔGr | Penalty from restriction of internal bond rotation | Favors rigid templates, which yield MIPs with higher selectivity and narrower site distribution [23]. |

| ∑ΔGp | Sum of interacting polar group contributions | In organic solvents, selectivity is driven by strong polar interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonds) [23]. |

| ΔGh | Contribution from hydrophobic interactions | In aqueous environments, hydrophobic effects can drive complexation [23]. |

Key Computational Strategies

The adoption of computational strategies has been crucial for navigating the complex, interdependent equilibria involved in MIP synthesis [23]. These methods have seen a significant increase in application over the past decade, driven by more accessible computational power and software [23].

Table: Computational Methods for MIP Development

| Method | Primary Application in MIP Development | Key Outputs |

|---|---|---|

| Electronic Structure Calculations (e.g., DFT) | Studying monomer-template interactions in the pre-polymerization phase [23]. | Binding energies, optimal binding geometries, interaction sites [24]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Simulating the pre-polymerization mixture and polymer-ligand interactions, including the effects of solvent, cross-linkers, and initiators [23] [24]. | Stability of template-monomer complexes, simulation of polymer morphology and binding site heterogeneity [23]. |

| Molecular Mechanics | High-throughput virtual screening of large monomer databases against a template molecule [2]. | Ranking of functional monomers based on their computed affinity for the template [2]. |

| Multivariate Analysis | Optimizing polymer composition by simultaneously evaluating multiple synthesis variables [23]. | Identification of key factors influencing MIP performance and optimal synthesis conditions [23]. |

Application Notes: Computational Protocol for MIP-Based Sensor Design

This protocol outlines the computational design of a MIP for the detection of an antibiotic, followed by its integration into an electrochemical sensor, relevant for pharmaceutical quality control and environmental monitoring [11].

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for developing a MIP-based electrochemical sensor.

Detailed Computational Methodology

Protocol 1: Virtual Screening and Pre-polymerization Analysis

Objective: To identify the most suitable functional monomer and solvent for creating a high-affinity MIP against a target pharmaceutical compound.

Materials & Software:

- Target Molecule: A 3D structure file of the pharmaceutical (e.g., an antibiotic like a quinolone or β-lactam).

- Software: Molecular modeling suite (e.g., GROMACS [24]), quantum chemistry software (for DFT), and visualization tool (e.g., UCSF Chimera [24]).

- Monomer Library: Digital libraries of common functional monomers (e.g., methacrylic acid, itaconic acid, vinylpyridine).

Procedure:

- Geometry Optimization: Optimize the 3D structure of the target molecule and all candidate monomers using density functional theory (DFT) methods to obtain their most stable conformations [23].

- Molecular Docking/Monomer Screening: Employ molecular mechanics or semi-empirical methods to screen the monomer library. Calculate the binding energy (ΔE) for each template-monomer complex. ΔE = E(template–monomer complex) – [E(template) + E(monomer)] A more negative ΔE indicates a stronger interaction [24] [2].

- MD Simulation of Pre-polymerization Mixture:

- Construct a simulation box containing the template, the top-ranked functional monomer(s) in a predetermined ratio (e.g., 1:4), cross-linker (e.g., EGDMA), and solvent molecules.

- Run an all-atom MD simulation for several nanoseconds to observe the stability of the template-monomer complexes under conditions mimicking the actual synthesis [23].

- Analyze the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of the complexes and the number of persistent hydrogen bonds or other key interactions over the simulation time. Stable complexes with multiple persistent interactions suggest a promising formulation [23].

- Solvent Selection: The solvent (porogen) should solubilize all components. Its polarity should complement the primary template-monomer interactions—low-polarity solvents enhance polar interactions, while water can leverage hydrophobic effects [23]. The choice can be guided by calculating the solvation free energy of the template and complexes in different solvents.

Experimental Validation and Sensor Fabrication

Protocol 2: MIP Synthesis and Electrochemical Sensor Fabrication

Objective: To synthesize the computationally designed MIP and integrate it into an electrochemical sensor for the detection of the target analyte.

Research Reagent Solutions:

Table: Essential Materials for MIP-based Sensor Development

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomer | Provides complementary chemical groups to interact with the template. | Methacrylic acid (hydrogen bonding), Vinylpyridine (ionic interactions) [2]. |

| Cross-linker | Stabilizes the imprinted cavities and provides mechanical rigidity to the polymer matrix. | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA), Divinylbenzene (DVB) [25] [2]. |

| Polymerization Initiator | Generates free radicals to initiate the polymerization reaction. | Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) [24] [2]. |

| Porogenic Solvent | Dissolves all components and creates pore structure during polymerization. | Acetonitrile, Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), Chloroform [24]. |

| Electroactive Polymer | Used for electrosynthesis of MIPs; acts as both the matrix for imprinting and the conductive layer on the electrode. | Polypyrrole (Ppy), Polyaniline (PANI), Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) [25]. |

Procedure:

- MIP Synthesis (Bulk Polymerization):

- Dissolve the target analyte (template), selected functional monomer, cross-linker, and initiator (e.g., AIBN) in the porogenic solvent based on the computationally optimized ratios [24].

- Purge the solution with nitrogen or argon to remove oxygen, which inhibits free-radical polymerization.

- Initiate polymerization by heating or UV irradiation. For the melamine MIP case study, polymerization at 60°C with AIBN was optimal [24].

- After polymerization, grind the resulting polymer block and sieve it to obtain particles of desired size.

- Extract the template molecules using a suitable solvent (e.g., methanol:acetic acid mixture) until no template can be detected in the washings [2].

- Sensor Fabrication (Electropolymerization):

- Prepare a solution containing the template, electroactive monomer (e.g., pyrrole), and supporting electrolyte.

- Immerse the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, gold) in the solution.

- Deposit the MIP film by performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) or chronoamperometry by applying a suitable potential window or constant potential [25]. The film's properties can be tuned by varying the number of CV cycles, applied potential, or charge passed [25].

- Remove the template from the electropolymerized film by washing with an appropriate solvent, leaving behind specific recognition cavities [26].

- Electrochemical Detection:

- Incubate the MIP-modified electrode in a sample solution containing the target analyte to allow rebinding.

- After incubation and rinsing, transfer the electrode to a clean electrochemical cell containing only a supporting electrolyte.

- Perform a sensitive electrochemical technique such as Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV). These techniques minimize capacitive background current, enhancing the sensitivity for detecting the bound electroactive analyte [11] [15]. The oxidation/reduction peak current is proportional to the concentration of the bound analyte.

Case Study: Computational Design of a Melamine-Imprinted Polymer

A representative study demonstrates the power of this integrated approach. Researchers developed a MIP for melamine detection using computational tools to accelerate the design process [24].

Computational Design: The team used the GROMACS molecular simulation suite to determine the ideal stoichiometric ratio between the melamine template and the functional monomer, itaconic acid. The simulations confirmed the formation of strong hydrogen bonds, which was the basis for the high specificity [24].

Experimental Validation: The polymer was synthesized using DVB as a cross-linker and itaconic acid as the monomer in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). The resulting MIP exhibited an imprinting factor (IF) of 2.25, indicating successful creation of specific binding sites. This MIP was successfully deployed in an HPLC system for the rapid detection of melamine in spiked milk samples, with each run taking only 7-8 minutes [24]. This case highlights how computational modeling can reduce experimental trial time and optimize the final polymer's performance.

Computational design and quantum mechanical modeling have fundamentally changed the landscape of MIP development. By providing deep insights into the thermodynamic and molecular forces at play, these tools enable the rational design of synthetic receptors with predetermined recognition properties [23]. When this rational design is coupled with the simplicity, sensitivity, and portability of electrochemical transducers, it creates a powerful platform for pharmaceutical analysis [11] [15]. The continued integration of advanced simulations, multivariate analysis, and nanotechnology promises to further enhance the sensitivity and specificity of MIP-based sensors, solidifying their role as indispensable tools in drug development, therapeutic monitoring, and environmental safety [15].

Fabrication and Applications: Building Next-Generation Electrochemical MIP-Sensors for Pharmaceuticals

Electropolymerization Techniques for MIP Film Synthesis on Electrode Surfaces

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are synthetic biomimetic receptors that possess specific recognition sites for target molecules, complementing them in size, shape, and functional groups [27]. The integration of MIPs with electrochemical transducers creates robust sensors highly suitable for pharmaceutical analysis, offering advantages over biological receptors including superior stability, lower cost, and longer shelf life [28] [29]. Electropolymerization has emerged as a highly effective method for synthesizing MIP films directly on electrode surfaces, enabling precise control over film properties and ensuring excellent reproducibility [28] [30]. This protocol details the application of electropolymerization for MIP-based sensor development within pharmaceutical electroanalysis.

Fundamental Principles of MIP Electropolymerization

Electropolymerization involves the voltage- or current-induced oxidation of polymerizable monomers, leading to the formation of a polymeric film on the working electrode surface [28]. This method allows for in-situ synthesis of the MIP recognition layer directly on the transducer. During the process, functional monomers are organized around the template molecule (the pharmaceutical target). Subsequent polymerization, in the presence of a cross-linker, "freezes" this structure, and template removal creates specific recognition cavities within the polymer matrix [27].

A key advantage of electropolymerization is the fine control it offers over film thickness by adjusting the total charge passed during deposition [28] [31]. This is particularly crucial for macromolecular imprinting to prevent irreversible template entrapment and to facilitate mass transfer [32]. The method is compatible with aqueous solutions and room temperature operation, preserving the structural integrity of biomacromolecule templates [33]. Commonly used electropolymerizable monomers include pyrrole, aniline, o-phenylenediamine (o-PD), 3-aminophenylboronic acid (APBA), and scopoletin [28].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Bulk Imprinting via Electropolymerization

This standard one-pot procedure is suitable for imprinting small molecule pharmaceuticals.

- Step 1: Pre-polymerization Solution Preparation. Dissolve the template molecule (e.g., 0.5-5 mM), functional monomer (e.g., 10-50 mM), and cross-linker (if applicable) in a suitable solvent or electrolyte (e.g., phosphate buffer, acetonitrile). The monomer-to-template ratio should be optimized computationally or empirically [28].

- Step 2: Electrode Pretreatment. Clean the working electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon Electrode, GCE; or Gold Electrode) according to standard procedures (e.g., polishing with alumina slurry, sonicating in water and ethanol, and electrochemical cycling in a clean solution) [34].

- Step 3: Film Deposition. Immerse the pretreated working electrode in the pre-polymerization solution. Perform electropolymerization using a potentiodynamic (e.g., Cyclic Voltammetry, CV, for 5-20 cycles) or galvanostatic method. Control the film thickness by regulating the number of cycles or the total charge passed [31].

- Step 4: Template Removal. Remove the MIP-modified electrode from the polymerization solution and rinse it gently. Extract the template molecules by immersing the electrode in a suitable elution solvent (e.g., methanol-acetic acid mixture) under stirring for 10-30 minutes. Repeat the washing until no template is detected in the washings [35].

- Step 5: Sensor Validation. Characterize the MIP film electrochemically using a redox probe like [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ via CV or Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to confirm successful template removal and cavity formation [33].

Protocol 2: Surface Imprinting with Covalent Template Immobilization

This advanced protocol is designed for proteins and macromolecules, confining binding sites to the surface for improved accessibility [32] [28].

- Step 1: Electrode Functionalization. For a gold electrode, incubate it in a solution of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) forming molecule (e.g., 4-aminothiophenol) for several hours. Rinse thoroughly. Then, activate the terminal amino groups by reacting with a bifunctional linker like glutaraldehyde [33] [32].

- Step 2: Template Immobilization. Incubate the functionalized electrode in a solution of the protein template (e.g., lysozyme) to allow for covalent immobilization via the linker. Rinse rigorously to remove physically adsorbed molecules [33] [28].

- Step 3: Electropolymerization. Perform electropolymerization from a solution containing the monomer(s) but no free template. Carefully control the polymerization charge to form an ultrathin film that partially embeds the surface-bound protein [32].

- Step 4: Linker Cleavage and Template Extraction. Cleave the covalent linker (e.g., by chemical or electrochemical means) to release the template protein, leaving behind surface-exposed, highly specific cavities [28].

- Step 5: Binding Assay. Evaluate the binding performance and selectivity of the sensor using impedimetric or voltammetric techniques [33].

Performance Comparison of Electropolymerized MIP Sensors

Table 1: Analytical performance of selected electropolymerized MIP sensors for different analytes.

| Target Analyte | Monomer Used | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lysozyme (Protein) | Scopoletin | 2.2 - 292 mg/L | 0.9 mg/L (62 nM) | [33] |

| Peramivir (Drug) | 4-AP / o-PD | 1 - 10 pM | 0.158 pM | [34] |

| 17β-Estradiol | 0.5 - 100 nM | 0.12 nM | [36] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for MIP electropolymerization.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Explanation | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Polymerizable units that interact with the template, forming the basis of the recognition cavity. | Pyrrole, aniline, o-phenylenediamine (o-PD), scopoletin, 3-aminophenylboronic acid (APBA) [28] [30]. |

| Cross-linkers | Agents that create a rigid 3D polymer network, stabilizing the imprinted cavities. | Often inherent in electropolymerization, but can be added (e.g., ethylene glycol dimethacrylate - EGDMA in some schemes) [35]. |

| Electrochemical Cell | Setup for performing electropolymerization and subsequent electrochemical measurements. | Three-electrode system: Working Electrode (GCE, Au), Reference Electrode (Ag/AgCl), Counter Electrode (Pt wire) [34]. |

| Template Molecules | The target molecules around which the polymer is formed, creating specific binding sites. | The pharmaceutical compound of interest (e.g., Peramivir, Lysozyme) or a structural analog [33] [34]. |

| Elution Solvent | A solution used to remove the template molecule from the polymerized film, revealing the cavities. | Methanol:acetic acid mixtures, or other solvents that disrupt template-monomer interactions without damaging the polymer [35]. |

| Redox Probe | An electroactive marker used to characterize the MIP film and transduce the binding event. | Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) is commonly used in CV and EIS [33] [31]. |

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing an electropolymerized MIP-based electrochemical sensor, from design to application.

Signaling and Detection Mechanisms

The binding of an analyte to the MIP film can be translated into an electrochemical signal through several mechanisms:

- Direct Electron Transfer (DET): Applicable for electroactive analytes (e.g., certain drugs, metalloproteins). The binding event brings the redox-active target close to the electrode surface, enabling its direct electrochemical oxidation or reduction, which is measured as a faradaic current [31].

- Redox Marker Modulation: For electroinactive analytes, a redox probe (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) is used. Analyte binding to the MIP cavities blocks the access of the probe to the electrode surface, changing the electron transfer kinetics. This "gate effect" is measured via CV or EIS as an increase in charge transfer resistance (Rₑₜ) [33] [31].

- Catalytic Activity: If the target is an enzyme or the MIP itself is catalytically active, the sensor can detect the electroactive product of an enzymatic reaction, providing an amplified signal [31].

Electropolymerization provides a powerful and versatile methodology for the synthesis of MIP films directly on electrode surfaces. The precise control over film thickness, the ability to operate under mild conditions, and the straightforward integration with the transducer make this technique particularly attractive for fabricating robust and sensitive sensors for pharmaceutical analysis. The provided protocols for both bulk and surface imprinting offer researchers a foundation for developing MIP-based electrochemical sensors tailored to specific analytical challenges in drug development and monitoring.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) are synthetic biomimetic receptors that possess specific recognition sites for target molecules, functioning similarly to natural antibody-antigen interactions [37] [38]. The integration of MIPs with electrochemical transducers has revolutionized the development of robust, selective, and cost-effective chemical sensors for pharmaceutical analysis [37] [11]. The incorporation of conducting polymers such as polypyrrole (PPy), polyaniline (PANI), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) as transducing elements in MIP-based sensors significantly enhances electron transfer kinetics, improves conductivity, and increases active surface area, leading to substantially improved analytical performance [39] [40]. This protocol outlines the fundamental principles and practical methodologies for developing high-performance MIP sensors utilizing these advanced conducting polymer matrices within the context of pharmaceutical electroanalysis.

Fundamental Principles and Signaling Mechanisms

Conducting polymers enhance MIP sensor performance through multiple synergistic mechanisms. They provide a high-surface-area matrix that facilitates the creation of well-defined recognition cavities while enabling efficient signal transduction from binding events to measurable electrical outputs [37] [38]. The electrical conductivity arises from conjugated π-electron backbones that allow charge mobility along the polymer chains [40]. When combined with molecular imprinting techniques, these polymers create a robust sensing interface where molecular recognition is directly converted to quantifiable electrochemical signals through mechanisms such as capacitance changes, potential shifts, or current variations [37] [38].

The signaling pathway in conducting polymer-based MIP sensors can be summarized as follows:

Performance Comparison of Conducting Polymer-Based MIP Sensors

The selection of appropriate conducting polymers significantly impacts sensor performance characteristics including sensitivity, detection limit, linear range, and selectivity. The table below summarizes recent advances and performance metrics for MIP sensors incorporating PPy, PEDOT, and their composites.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Conducting Polymer-Based MIP Sensors

| Target Analyte | Polymer System | Detection Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection | Sensitivity | Application Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| L-Tyrosine | Fc/PEDOT:PSS-PPy | DPV | 100 pM - 5 mM | 2.31 × 10⁻¹¹ M | N/A | Amino acid detection [39] |

| Dopamine | PEDOT-PPy | DPV | 5 nM - 200 µM | 5 nM | 7.27 µA/µM cm² | Neurotransmitter sensing [40] |

| Dopamine | PEDOT:Nafion | Amperometry | N/A | 4-5 nM | N/A | Neurotransmitter sensing [40] |

| Ciprofloxacin | Fe₃O₄@Pt/COF-MIP | ECL | N/A | Picomolar level | N/A | Environmental pollutant [37] |

| Acrylamide | MIP-PPy/MoS₂/rGO/Au | PEC | N/A | Micromolar level | N/A | Environmental pollutant [37] |

| Cardiac Troponin T | Alumina-MIP | Voltammetry | N/A | ng/mL level | N/A | Cardiac biomarker [37] |

| Ovalbumin | AuNPs-MIP | Voltammetry | N/A | fg/mL level | N/A | Protein detection [37] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of PEDOT-PPy Hybrid MIP Sensor for Dopamine Detection

Principle: This protocol describes the development of a highly selective and sensitive dopamine sensor utilizing a PEDOT-PPy hybrid matrix polymerized on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). The composite enhances conductivity and provides a high-surface-area substrate for creating specific dopamine recognition sites [40].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for PEDOT-PPy MIP Sensor Fabrication

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | 3 mm diameter | Primary transducer substrate |

| Pyrrole monomer | ≥98% purity | Functional monomer for PPy matrix |

| EDOT monomer | 97% purity | Functional monomer for PEDOT matrix |

| Dopamine HCl | Pharmaceutical standard | Template molecule |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate | Electrophoresis grade | Dopamine stabilizer |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline | 0.1 M, pH 7.4 | Polymerization and measurement medium |

| Acetonitrile | HPLC grade | Solvent for monomer preparation |

| Lithium perchlorate | ≥95% purity | Supporting electrolyte |

| Ferro/ferricyanide solution | 1 mM in 0.1 M KCl | Electroactive probe for characterization |

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish the GCE surface sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth pad.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each polishing step.

- Sonicate in ethanol:water (1:1 v/v) for 5 minutes to remove residual alumina particles.

- Perform electrochemical activation in 0.1 M H₂SO₄ by cyclic voltammetry (CV) from -0.2 to +1.0 V at 100 mV/s for 20 cycles until stable voltammograms are obtained.

Preparation of Monomer Solution:

- Prepare a monomer solution containing 0.02 M pyrrole and 0.01 M EDOT in acetonitrile:water (3:1 v/v).

- Add 0.1 M lithium perchlorate as supporting electrolyte.

- Dissolve dopamine hydrochloride (5 mM) as the template molecule in the monomer solution.

- Add 1 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate to stabilize dopamine against oxidation during polymerization.

Electropolymerization:

- Transfer the monomer-template solution to an electrochemical cell.

- Employ potentiostatic deposition at +0.9 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 120 seconds under gentle stirring.

- Alternatively, use cyclic voltammetry between -0.2 V and +0.8 V at 50 mV/s for 15 cycles.

- Monitor the current decrease indicating polymer film growth on the electrode surface.

Template Removal:

- Immerse the modified electrode in a mixture of methanol:acetic acid (9:1 v/v).

- Apply gentle stirring for 30 minutes to extract dopamine molecules.

- Repeat the extraction process three times with fresh solution.

- Verify complete template removal by the absence of dopamine oxidation peak in CV scans.

Sensor Characterization:

- Characterize the modified electrode using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in 1 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ in 0.1 M KCl.

- Calculate the electroactive surface area using the Randles-Sevcik equation from CV at different scan rates.

- Validate imprinting efficiency by comparing current response with non-imprinted polymer (NIP) control.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting:

- Maintain oxygen-free environment during polymerization to prevent premature dopamine oxidation.

- Optimize polymerization cycles to achieve optimal film thickness (typically 100-200 nm).

- Ensure complete template removal by monitoring until stable baseline is achieved in buffer solution.

Protocol 2: Development of Ferrocene/PEDOT:PSS-PPy Nanocomposite for Label-Free Amino Acid Sensing

Principle: This protocol details the fabrication of a label-free MIP sensor utilizing ferrocene-doped PEDOT:PSS-PPy composite for ultrasensitive detection of poorly electroactive amino acids. The ferrocene moiety acts as an intrinsic redox probe, while the PEDOT:PSS-PPy matrix enhances electron transfer and provides immobilization platform for MIP receptors [39].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Nanocomposite Preparation:

- Prepare PEDOT:PSS aqueous dispersion (1.5% w/w) and mix with chemically synthesized PPy nanoparticles (prepared via oxidative polymerization) in 3:1 mass ratio.

- Add 5 mM ferrocene carboxylic acid to the polymer mixture and sonicate for 30 minutes until homogeneous.

- Centrifuge at 5000 rpm for 10 minutes to remove any aggregates.

Electrode Modification:

- Drop-cast 10 µL of the Fc/PEDOT:PSS-PPy nanocomposite onto pre-polished GCE.

- Allow to dry under infrared lamp for 15 minutes to form uniform film.

- Characterize the modified surface using scanning electron microscopy to verify porous morphology.

MIP Immobilization:

- Prepare MIP microspheres specific to target amino acid (e.g., L-tyrosine) using bulk polymerization with methacrylic acid functional monomer and ethylene glycol dimethacrylate crosslinker.

- Disperse MIP particles (1 mg/mL) in Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.4) and drop-cast 5 µL onto Fc/PEDOT:PSS-PPy modified electrode.

- Immobilize via electrostatic adsorption by applying +0.5 V for 60 seconds in three-electrode system.

Sensor Operation and Measurement:

- Incubate the sensor in standard or sample solutions containing target analyte for 5 minutes with gentle stirring.

- Perform differential pulse voltammetry from +0.2 V to +0.6 V with pulse amplitude 50 mV and pulse width 50 ms.

- Measure the ferrocene oxidation current decrease proportional to target concentration due to hindered electron transfer upon binding.

Validation Parameters:

- Determine limit of detection (LOD) and quantification (LOQ) from calibration curve.

- Evaluate imprinting factor by comparing with non-imprinted control.

- Assess selectivity against structurally similar interferents.

- Test reproducibility through relative standard deviation of 5 replicate measurements.

Advanced Applications in Pharmaceutical Analysis

The unique properties of conducting polymer-based MIP sensors have enabled significant advances in pharmaceutical electroanalysis:

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: MIP sensors incorporating PPy and PEDOT have been successfully applied for monitoring various pharmaceuticals including antibiotics [11], anticancer drugs [37], and antipsychotic medications [37]. For instance, an electrochemical sensor for gemcitabine employed CuCo₂O₄/NCNTs and ferrocene incorporated within MIP matrix for ratiometric on-off response, demonstrating excellent performance in biological samples [37].

Biomarker Detection: Cardiac troponin T detection was achieved using anodic molecular-imprinted nanocomposite electrodes with high-conductivity alumina additives, reaching sensitivity at nanogram per milliliter levels for cardiovascular disease diagnosis [37]. Similarly, ovalbumin detection at femtogram per milliliter levels was demonstrated using anti-ovalbumin antibody modified gold nanoparticles as amplifiers in sandwich-structured electrochemical sensors [37].

Neurotransmitter Sensing: PEDOT-PPy hybrid electrodes have shown exceptional performance for dopamine sensing with linear response from 5 nM to 200 µM and low limit of detection of 5 nM, enabling precise monitoring of neurological conditions [40]. The composite structure provides the necessary selectivity to distinguish dopamine from interfering species such as ascorbic acid which has similar oxidation potential.

The integration of conducting polymers including PPy, PANI, and PEDOT with molecular imprinting technology has substantially advanced the field of pharmaceutical electroanalysis. These hybrid materials combine the exceptional molecular recognition capabilities of MIPs with enhanced signal transduction properties of conducting polymers, resulting in sensors with superior sensitivity, selectivity, and stability. The protocols outlined herein provide robust methodologies for developing such sensors, with particular emphasis on practical implementation considerations. Future developments in this field will likely focus on multi-analyte detection platforms, advanced nanomaterial composites, miniaturized portable devices for point-of-care testing, and integration with artificial intelligence for data interpretation [37] [15]. As these technologies mature, conducting polymer-based MIP sensors are poised to become indispensable tools in pharmaceutical research, quality control, and clinical diagnostics.

{toc}

Nanocomposite-Enhanced MIP Sensors: Integrating Carbon Nanotubes, Metal Oxides, and Magnetic Nanoparticles

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) represent a transformative approach in the field of chemical sensing, offering artificial receptors with specific recognition sites for target molecules. The integration of MIPs with electrochemical transducers has created powerful sensors for pharmaceutical analysis, combining high selectivity with the advantages of electrochemical methods: low cost, portability, and sensitivity [41]. The emergence of nanocomposite-enhanced MIP sensors marks a significant technological leap, addressing key limitations of traditional MIPs by incorporating functional nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes, metal oxides, and magnetic nanoparticles. These advanced materials work synergistically to dramatically improve sensor performance by increasing surface area, enhancing electron transfer kinetics, facilitating easy separation, and boosting overall stability and sensitivity [42] [43]. Within the broader thesis on molecular imprinting technologies for electroanalysis of pharmaceuticals, this application note provides detailed protocols and performance data for developing these next-generation sensors, enabling researchers to reliably quantify pharmaceutical compounds in complex matrices including biological and environmental samples.

Technical Background and Signaling Mechanisms

Fundamental Principles of MIP-based Sensors

Molecular imprinting technology creates synthetic polymers with tailor-made recognition cavities complementary to the target analyte in shape, size, and functional groups. The fabrication process involves the co-polymerization of functional and cross-linking monomers in the presence of the target molecule, which acts as a template. Subsequent removal of the template leaves behind cavities capable of selectively rebinding the target analyte [41] [42]. When these MIPs are employed as recognition elements in electrochemical sensors, the binding event is transduced into a measurable electrical signal (e.g., current, potential, or impedance change). The specificity of the molecular imprinting process makes these sensors exceptionally suitable for monitoring drugs in complex environments like biological fluids and environmental water samples, where interfering compounds are commonplace [44].

The Enhancing Role of Nanocomposites

The incorporation of nanomaterials into MIP sensors addresses several intrinsic challenges:

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): Both multi-walled (MWCNTs) and single-walled CNTs are extensively used. Their high electrical conductivity facilitates electron transfer between the electrode surface and the MIP layer, significantly boosting the electrochemical response. Furthermore, their large specific surface area provides an excellent scaffold for MIP formation, increasing the density of recognition sites [44] [42]. Carboxylated CNTs (e.g., MWCNT-COOH) offer improved functionalization and dispersion, leading to more uniform MIP films [44].

- Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Nanoparticles of magnetite (Fe₃O₄), titanium dioxide (TiO₂), and others contribute to sensor performance. Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles are particularly valuable for their magnetic properties, enabling the precise positioning of the recognition layer on the electrode surface under an external magnetic field, which simplifies sensor assembly and enhances reproducibility [43]. Additionally, metal oxides can improve catalytic activity and stability.

- Magnetic Nanocomposites: The combination of magnetic nanoparticles with conductive materials like CNTs creates magnetic carbon nanocomposites (MCNCs). These hybrid materials synergistically combine the easy separation and manipulation offered by magnetism with the superior electrical and structural properties of carbon nanomaterials [43].

The following diagram illustrates the signaling mechanism and the synergistic roles of different nanocomponents in an MIP-based electrochemical sensor.

Application Notes: Sensor Performance and Analysis

The integration of nanocomposites has enabled the development of high-performance MIP sensors for a diverse range of pharmaceuticals. The following table summarizes the analytical performance of selected nanocomposite-enhanced MIP sensors as reported in recent literature.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Nanocomposite-Enhanced MIP Sensors for Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Target Analytic | Sensor Type / Nanocomponents | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Application Matrix | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estrone (E1) | MIP-ECL / Ru(bpy)₃²⁺, MWCNTs, Nafion | 0.1 – 200 μg/L | 0.0047 μg/L | Environmental Water, Clinical Samples | [44] |

| Azithromycin | Piezoelectric / MIP@SiO₂, MWCNTs, Fe₃O₄ | 5 – 160 μg/mL | Not Specified | Standard Solutions | [43] |

| Erythromycin | Piezoelectric / MIP@SiO₂, MWCNTs, Fe₃O₄ | 10 – 160 μg/mL | Not Specified | Standard Solutions | [43] |

| Erythromycin | Piezoelectric / SiO₂@SiO₂, MWCNTs, Fe₃O₄ | 20 – 400 μg/mL | Not Specified | Standard Solutions | [43] |

| Macrolides (e.g., Erythromycin) | Electrochemical / MIP, CNTs, Nanoparticles | Varies by configuration | Improved vs. non-nano MIP | Pharmaceutical Forms, Biological Specimens | [41] [42] |

These performance data demonstrate key advantages of nanocomposite enhancement. The MIP-ECL sensor for Estrone achieves an remarkably low LOD, suitable for trace-level environmental and clinical analysis [44]. The use of magnetic nanocomposites in macrolide antibiotic sensors provides robust and reproducible platforms, with the linear range varying based on the specific core-shell polymer architecture employed [43]. Across various studies, the consistent finding is that nanomaterials contribute to increased sensitivity and selectivity compared to traditional MIP sensors [41] [42].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Synthesis of Core-Shell MIP on Magnetic Carbon Nanocomposite for Macrolide Antibiotics

This protocol details the synthesis of a recognition layer for piezoelectric sensors for antibiotics like erythromycin and azithromycin, based on the work of Bizina et al. (2023) [43].

Reagents and Materials

- Template: Target macrolide antibiotic (e.g., Erythromycin or Azithromycin).

- Functional Monomer: Selection depends on template functionality (e.g., methacrylic acid).

- Cross-linker: Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA).

- Initiator: Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN).

- Core Material: Silicon dioxide (SiO₂) nanoparticles, synthesized via the Stöber method.

- Nanocomposites: Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) and magnetic Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles.

- Solvents: Acetonitrile, toluene (HPLC grade).

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Core Particle Synthesis: Synthesize monodisperse SiO₂ nanoparticles (cores) using the Stöber method by hydrolyzing tetraethyl orthosilicate (TEOS) in an ethanol/ammonia/water mixture. Vary the reagent ratio to control final particle size.

- Pre-polymerization Complex Formation: Dissolve the template (antibiotic), functional monomer, and cross-linker in a porogenic solvent (e.g., acetonitrile) in a sealed vial. Allow the mixture to pre-associate for 1 hour with gentle stirring.

- Core-Shell Polymerization:

- Add the synthesized SiO₂ core particles to the pre-polymerization mixture.

- Purge the mixture with nitrogen gas for 10 minutes to remove oxygen.

- Add the initiator (AIBN) and place the vial in a water bath at 60°C for 24 hours to complete the polymerization.

- Template Removal: After polymerization, extensively wash the resulting core-shell particles (MIP@SiO₂) with a methanol-acetic acid solution (9:1, v/v) to leach out the template molecules. Continue until the template cannot be detected in the washings (e.g., by UV-Vis spectroscopy).

- Magnetic Nanocomposite Integration: Disperse the template-free MIP@SiO₂ particles and MWCNTs in a suitable solvent. Add pre-synthesized Fe₃O₄ nanoparticles to form the final Magnetic Carbon Nanocomposite (MCNC) suspension.

Critical Steps and Troubleshooting

- Core Size Control: The size and uniformity of the SiO₂ cores are critical for reproducibility. Precisely control the temperature and reagent ratios during the Stöber synthesis.