Microelectrodes in Voltammetry: Principles and Advances for Enhanced Sensitivity in Biomedical Research

This article explores the pivotal role of microelectrodes in advancing voltammetric sensitivity for biomedical applications.

Microelectrodes in Voltammetry: Principles and Advances for Enhanced Sensitivity in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article explores the pivotal role of microelectrodes in advancing voltammetric sensitivity for biomedical applications. It covers the foundational principles that give microelectrodes their superior performance, including enhanced mass transport and reduced iR drop. The article details methodological innovations such as fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) and specific applications in neurotransmitter monitoring and disease diagnosis. It also addresses key challenges like biofouling and outlines optimization strategies through electrode design and material modifications like carbon coatings and surface roughening. Finally, it provides a comparative analysis of different electrode materials and geometries, validating their performance for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to implement these high-sensitivity tools.

Why Size Matters: The Fundamental Principles of Microelectrodes for High-Sensitivity Detection

Microelectrodes are a foundational tool in modern electroanalysis, characterized by their small physical dimensions, which confer significant advantages over conventional macroelectrodes. Within the context of voltammetry, their defining feature is the ability to enhance measurement sensitivity dramatically, enabling the detection of analytes at trace and ultratrace concentrations. This document delineates the key characteristics and standardized dimensional scales of microelectrodes, providing a framework for their application in sensitive voltammetric research, particularly in pharmaceutical and environmental analysis.

Defining Characteristics and Dimensional Scales

The performance of a microelectrode is governed by its physical and electrochemical properties. The table below summarizes the core defining characteristics and typical dimensional scales encountered in research and commercial applications.

Table 1: Key Characteristics and Dimensional Scales of Microelectrodes

| Characteristic | Definition & Significance | Typical Scale / Range | Impact on Voltammetric Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Dimension | The smallest dimension (e.g., diameter of a disk, width of a band) that defines the electrode's active area. [1] | Ultramicroelectrodes (UMEs): < 25 µm [1]Microelectrodes: ~1 µm to ~100 µm [2] | Enables radial (hemispherical) diffusion, leading to enhanced mass transport, steady-state currents, and high signal-to-noise ratios. [1] |

| Geometric Surface Area (GSA) | The two-dimensional area of the electrode's electroactive surface. | 20 µm² to ~2000 µm² (for planar circular electrodes) [1] | Smaller GSA reduces capacitive currents, improving sensitivity in low-concentration detection. [3] [4] |

| Electrode Impedance | The total opposition to current flow, comprising charge-transfer and solution resistance. | 0.1 MΩ to 5 MΩ (highly dependent on material and GSA) [2] | Lower impedance minimizes signal distortion and thermal noise, crucial for high-fidelity neural recording and low-concentration voltammetry. [5] [6] |

| Diffusion Profile | The pattern of analyte mass transport to the electrode surface. | Macroelectrodes: Linear diffusion.Microelectrodes: Radial/hemispherical diffusion. [1] | Hemispherical diffusion provides a steady flux of analyte, yielding sigmoidal, steady-state voltammograms ideal for quantitative analysis. [1] |

Table 2: Common Microelectrode Materials and Their Applications in Voltammetry

| Material | Key Properties | Common Voltammetric Applications | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fiber | Biocompatible, low-cost, excellent spatiotemporal resolution, diameters ~7-10 µm. [7] | Neurotransmitter detection (e.g., dopamine, serotonin) using Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV). [7] [8] | Measuring tryptophan dynamics with improved sensitivity and selectivity. [8] |

| Bismuth (Solid) | Environmentally friendly alternative to mercury, low toxicity. [3] | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) for heavy metal ions (e.g., Pb(II)) in environmental waters. [3] | Determination of Pb(II) with a detection limit of 3.4 × 10⁻¹¹ mol L⁻¹ using a 25 µm solid bismuth microelectrode. [3] |

| Lead (Solid) | Facile fabrication, renewable surface. [4] | Adsorption Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) for organic pharmaceuticals. [4] | Determination of sildenafil citrate in pharmaceuticals using a 25 µm solid lead microelectrode. [4] |

| Sputtered Iridium Oxide (SIROF) | High charge storage capacity, excellent for stimulation and recording. [1] | Neural stimulation and recording; less common in classic voltammetry but used in electrochemical biosensing. | Used on microelectrodes as small as 20 µm² for effective charge injection. [1] |

| Gold & Platinum | High conductivity, biocompatible, easily functionalized. [9] | Biosensing, DNA detection, and fundamental electrochemical studies. [10] [9] | Microfabricated gold microelectrodes for sensitive detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA. [10] |

Experimental Protocol: Determination of Pb(II) using a Solid Bismuth Microelectrode

The following protocol details a specific application of a solid bismuth microelectrode (SBiµE) for the ultrasensitive detection of lead ions, demonstrating the practical implementation of the principles outlined above. [3]

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function / Description |

|---|---|

| Solid Bismuth Microelectrode (SBiµE) | Working electrode (Ø = 25 µm). Environmentally friendly alternative to mercury electrodes. [3] |

| Acetate Buffer (1 mol L⁻¹, pH 3.4) | Supporting electrolyte. Provides a consistent ionic strength and pH for the electrochemical reaction. [3] |

| Pb(II) Standard Solution | Primary analyte. A 1 g L⁻¹ stock solution is diluted daily to prepare working standards. [3] |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Provides a stable and known reference potential for the electrochemical cell. [3] |

| Platinum Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit in the three-electrode setup, carrying the current. [3] |

| Autolab PGSTAT 10 Analyzer | Potentiostat/Galvanostat used to control the potential and measure the resulting current. [3] |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Preparation: On each day of measurement, polish the SBiµE on 2500-grit silicon carbide paper. Rise thoroughly with triply distilled water and place it in an ultrasonic bath for 30 seconds to remove any residual polishing material. [3]

- Solution Preparation: Prepare the sample or standard solutions in a 0.1 mol L⁻¹ acetate buffer (pH 3.4). For a calibration curve, use Pb(II) standards in the concentration range of 1 × 10⁻¹⁰ to 3 × 10⁻⁸ mol L⁻¹. [3]

- Instrumental Setup: Configure the potentiostat for Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (DPASV). Set up the conventional three-electrode cell with the SBiµE as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl as the reference, and a platinum wire as the counter electrode. [3]

- Activation & Accumulation (Pre-concentration):

- Stripping & Measurement:

- After the accumulation time, stop the stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for 10 seconds.

- Initiate the differential pulse stripping scan from -1.4 V towards more positive potentials. The deposited lead is oxidized back to Pb(II), generating a characteristic current peak. The peak current is proportional to the concentration of Pb(II) in the solution. [3]

- Data Analysis: Measure the height of the stripping peak for each standard and sample. Construct a calibration curve by plotting peak current versus Pb(II) concentration. Use this curve to determine the unknown concentration of Pb(II) in environmental water samples. [3]

Logical Workflow and Signaling Pathway

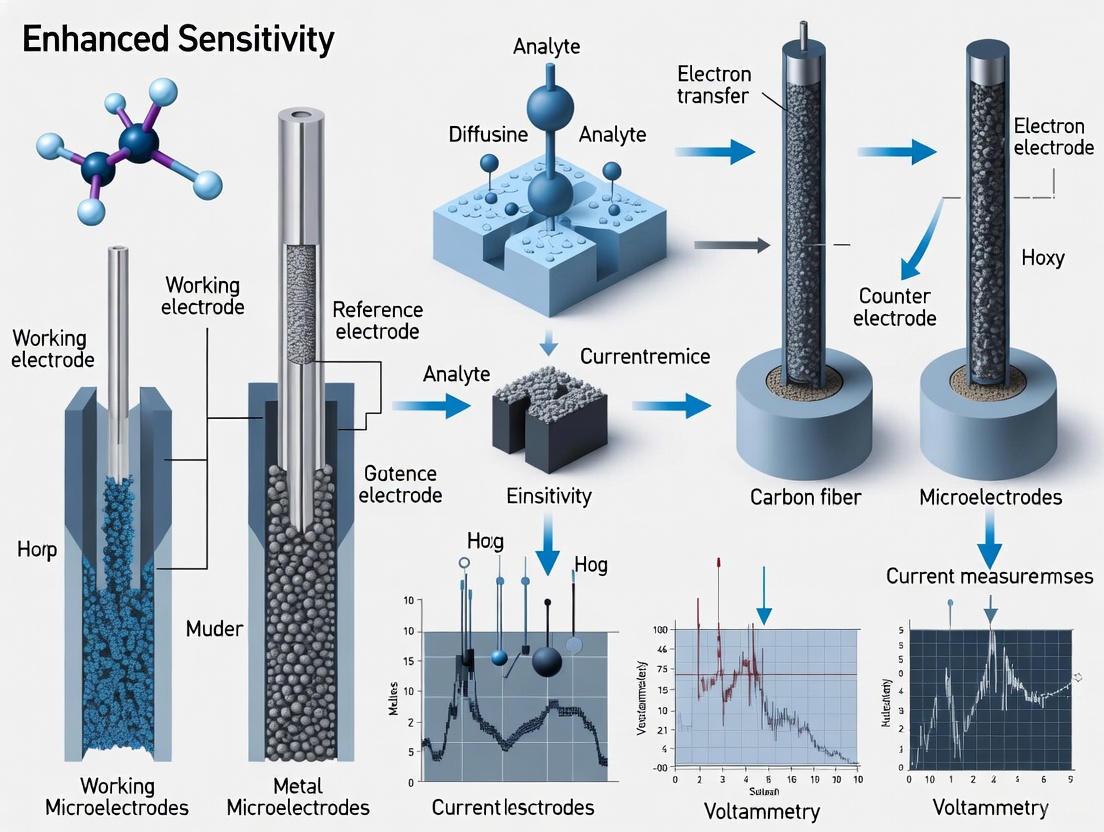

The diagram below illustrates the experimental and conceptual pathway for enhancing sensitivity using a microelectrode in this voltammetric protocol.

In electrochemical sensing and voltammetry, mass transport—the process by which analyte molecules move from the bulk solution to the electrode surface—fundamentally dictates the sensitivity, response time, and overall performance of the measurement. Unlike conventional macroelectrodes, where mass transport is dominated by linear, planar diffusion, microelectrodes (with at least one critical dimension in the micrometer range) enable a unique hemispherical diffusion profile [11]. This diffusion geometry arises because the size of the electrode becomes comparable to the diffusion layer thickness, allowing molecules to converge on the active surface from all directions in a hemispherical space [11] [12].

This shift from planar to hemispherical diffusion is not merely geometrical; it confers significant analytical advantages. It leads to enhanced mass transport rates, rapidly established steady-state signals, reduced interference from uncompensated resistance (iR drop), and dramatically lower capacitive currents [11] [12]. These properties are crucial for applications demanding high spatial and temporal resolution, such as in vivo neurochemical monitoring [13] and the study of rapid reaction kinetics [12]. This application note details the underlying principles, experimental protocols, and key applications of hemispherical diffusion, providing researchers with the tools to leverage this mechanism for enhanced sensitivity in voltammetric research.

Theoretical Foundations and Advantages

Comparative Diffusion Profiles

The core difference between macroelectrodes and microelectrodes lies in their respective diffusion fields, which directly shape their voltammetric output.

- Planar Diffusion at Macroelectrodes: At traditional macroelectrodes (e.g., with a diameter of 3 mm), the diffusion field is semi-infinite and linear perpendicular to the planar electrode surface [11]. During a voltammetric scan, the current rises as electroactive species near the surface are oxidized or reduced but subsequently peaks and falls as the reaction becomes limited by the rate at which fresh species can diffuse through the depleted layer. This results in the characteristic peak current seen in cyclic voltammograms [11].

- Hemispherical Diffusion at Microelectrodes: When the electrode radius is sufficiently small (typically ≤ 25 μm) [12], the diffusion layer can expand radially outward in three dimensions, forming a hemisphere. This geometry provides a much larger flux of analyte to the electrode surface because diffusion can occur from a larger volume of solution. In a voltammetric experiment, this manifests as a rise to a steady-state limiting current instead of a transient peak, creating a sigmoidal-shaped voltammogram [11] [12].

Quantitative Advantages

The hemispherical diffusion field at microelectrodes leads to several quantifiable benefits critical for advanced sensing, especially in resistive media and for fast kinetics.

Table 1: Quantitative Advantages of Microelectrodes vs. Macroelectrodes

| Parameter | Macroelectrode (Planar Diffusion) | Microelectrode (Hemispherical Diffusion) | Impact on Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Magnitude | Peak currents on the order of mA (e.g., ±1.5 mA) [11] | Steady-state currents on the order of nA (e.g., ±50 nA) [11] | Enables operation in highly resistive environments; minimizes overall power requirements. |

| Ohmic Drop (iR Drop) | Significant, can distort voltammograms [11] | Greatly reduced or eliminated [11] | Allows for experiments in low-ionic-strength solvents (e.g., nonpolar solvents, supercritical fluids) without supporting electrolyte. |

| Signal-to-Noise (S/N) | Lower due to higher capacitive currents | Higher due to lower capacitive currents and steady-state signal [11] [13] | Improves detection limits, crucial for tracing low-concentration analytes in complex matrices. |

| Mass Transport Rate | Lower, planar diffusion leads to depletion | Enhanced, convergent diffusion sustains flux [12] | Enables the study of fast electron transfer kinetics and short-lived intermediate species. |

| Steady-State Achievement | Not achieved under typical scan rates | Achieved almost instantly, leading to sigmoidal CVs [12] | Simplifies quantitative analysis as current is directly proportional to concentration. |

The steady-state limiting current ((i{lim})) at a disk microelectrode is described by the equation: [ i{lim} = 4nFDCr ] where (n) is the number of electrons, (F) is the Faraday constant, (D) is the diffusion coefficient, (C) is the bulk concentration, and (r) is the radius of the microelectrode [12]. This relationship highlights the direct proportionality between the current and the electrode radius, contrasting with the area-dependent (radius squared) peak current at macroelectrodes.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Gold Disk Microelectrode (Au DME)

This protocol outlines the fabrication of a gold disk microelectrode suitable for voltammetric studies leveraging hemispherical diffusion [13].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Key Materials for Microelectrode Fabrication and Characterization

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Microwire | Serves as the electroactive sensing material. | Diameter ~10-25 μm, defines the electrode radius. |

| Borosilicate Glass Capillary | Provides the insulating sheath. | - |

| Laser Puller | Creates a sealed glass capillary containing the microwire. | - |

| Polishing Setup | Creates a smooth, flush disk electrode surface. | Alumina suspension (e.g., 0.05 μm) [12]. |

| Electrochemical Workstation | For electrode characterization and experiments. | Potentiostat with pA/nA current resolution. |

| Ferrocene Methanol Solution | Redox mediator for electrochemical characterization. | 0.5 mM in supporting electrolyte [14]. |

| α-Methyl Ferrocene Methanol | Alternative redox mediator for steady-state validation. | - |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Sealing the Wire: Insert a segment of gold microwire into a borosilicate glass capillary. Use a laser-assisted pipette puller to heat and pull the capillary, creating a vacuum-tight seal around the wire.

- Polishing to Disk Geometry: Secure the pulled capillary in a holder and carefully polish the tip on a microcloth with successively finer alumina slurries (e.g., starting with 1.0 μm and finishing with 0.05 μm) until a smooth, flat, and flush disk surface is obtained under microscopic inspection. The final polish with 0.05 μm alumina is critical for a clean, reproducible electroactive surface [12].

- Electrochemical Characterization: Characterize the fabricated Au DME electrochemically to confirm its size and proper function.

- Submerge the electrode in a solution containing a well-defined redox couple (e.g., 0.5 mM ferrocene methanol or 1 mM potassium ferrocyanide in 0.1 M KCl).

- Perform cyclic voltammetry at a slow scan rate (e.g., 10-50 mV/s).

- A well-fabricated microelectrode will exhibit a sigmoidal voltammogram. The steady-state limiting current ((i{lim})) can be used to calculate the electrode's electroactive radius ((r)) using the equation: (r = i{lim} / (4nFDC)).

Protocol 2: Investigating Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) Intermediates using a Gold Ultramicroelectrode (UME)

This protocol utilizes the enhanced mass transport of a UME combined with Rapid Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (RSCV) to capture and quantify transient reaction intermediates [12].

Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- Gold UME: Commercially available or fabricated, with a diameter of 25 μm [12].

- Potassium Hydroxide (KOH): Provides the alkaline electrolyte (0.5 M).

- Gases: High-purity O₂ and N₂ for saturating and deaerating the solution.

- Potentiostat: Capable of high-speed voltammetry (RSCV).

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the Au UME sequentially with emery papers (e.g., mesh 1200, 1600) and finally with a 0.05 μm alumina suspension. Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water [12].

- Cell Setup: Use a standard three-electrode cell with the Au UME as the working electrode, a graphite rod as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl) reference electrode. Ensure the cell is airtight, fitted with ports for gas bubbling (N₂ and O₂).

- Steady-State Validation: Fill the cell with N₂-saturated 0.5 M KOH. Record a cyclic voltammogram of a known redox species (e.g., α-methyl ferrocene methanol) at a slow scan rate to confirm a sigmoidal response and determine the experimental radius of the UME.

- RSCV Measurement of ORR: Replace the solution with O₂-saturated 0.5 M KOH. Perform RSCV over a potential window from open circuit potential to a sufficiently negative potential (e.g., -0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl) and back, across a range of scan rates (e.g., 0.1 to 10 V/s).

- Data Analysis: At high scan rates, the voltammograms will show distinct peaks (C1, C2 for reduction, A1 for oxidation) corresponding to the sequential reduction of O₂ to peroxide (HO₂⁻) and further to hydroxide (OH⁻), and the re-oxidation of the peroxide intermediate [12]. Integrate the peak areas to quantify the charge associated with each process, enabling the determination of formation rates for these transient species.

Diagram 1: RSCV-UME Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Microelectrode Studies

| Category/Item | Specific Example | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Redox Mediators | Potassium ferri/ferrocyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) [11] | A classic, reversible redox couple for characterizing electrode performance and surface area. |

| Redox Mediators | Ferrocene methanol / α-Methyl ferrocene methanol [14] [12] | A stable, one-electron transfer mediator with pH-independent formal potential, ideal for UME characterization. |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Potassium Chloride (KCl), Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) [11] | Provides ionic conductivity, minimizes ohmic drop, and defines the electrochemical window and pH. |

| Target Analytes | Dopamine (DA) [13] | A key neurochemical; its oxidation current is used as an analytical signal in aptasensors. |

| Target Analytes | Oxygen (O₂) [12] | A fundamental reactant in ORR studies; used to probe reaction mechanisms and intermediates. |

| Recognition Elements | Anti-DA specific aptamer [13] | A molecular recognition element that confers selectivity when immobilized on a microelectrode surface. |

| Electrode Materials | Gold (Au) disk microelectrode [13] | A common, versatile electrode material that can be easily modified with thiol-based chemistries. |

| Cleaning & Polishing | Alumina suspension (0.05 μm) [12] | Used for fine polishing to achieve a mirror-finish, electrochemically clean electrode surface. |

Applications in Advanced Research

The unique properties of microelectrodes under hemispherical diffusion have enabled breakthroughs across multiple fields.

- In Vivo Neurochemical Monitoring: The small size and enhanced mass transport of microelectrodes make them ideal for implantable sensors. For example, a gold disk microelectrode with a radius of 2 μm, functionalized with a dopamine-specific aptamer, has been used for the label-free detection of dopamine in brain slices with high spatial resolution and a low detection limit of 0.11 μM [13]. The small currents and minimal iR drop are essential for functioning in the resistive brain environment.

- Interrogation of Reaction Mechanisms: The RSCV-UME combination is a powerful methodology for studying complex electrocatalytic reactions like the Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR). On a gold UME, this approach has identified and allowed for the quantification of the peroxide anion (HO₂⁻) intermediate, providing key insights into the reaction pathway and kinetics that are difficult to obtain with larger electrodes [12].

- Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Imaging: Microelectrode arrays (MEAs) are used in ECL microscopy to visualize electrochemical reactions. The diffusion of reactive intermediates (e.g., TPrA• radicals in the Ru(bpy)₃²⁺/TPrA system) away from each microelectrode creates a well-defined ECL-emitting layer. The thickness of this layer is directly influenced by the hemispherical diffusion field and can be tuned by the electrode material and reactant concentration [14].

Visualization of Core Concepts

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental differences in diffusion profiles and their resultant voltammetric signatures, which are central to understanding microelectrode superiority.

Diagram 2: Diffusion Profiles and Resulting Voltammetric Output

In the field of electrochemical sensing, particularly for neurochemical monitoring and biomedical applications, the transition from macroelectrodes to microelectrodes represents a significant technological advancement. Microelectrodes, defined as electrodes with at least one critical dimension on the scale of microns (typically ≤ 25 μm), offer fundamental electrochemical benefits that enable enhanced sensing capabilities [15]. These advantages are particularly evident in two key performance parameters: the reduction of iR drop (ohmic drop) and the improvement of signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). The iR drop refers to the voltage loss that occurs due to the inherent resistance of the electrolyte, electrode material, and electrical connections within an electrochemical system [7]. This phenomenon can lead to distorted electrochemical signals, particularly at high scan rates where fast electron transfer kinetics are required. Simultaneously, the improved SNR of microelectrodes allows for the detection of lower analyte concentrations—a critical requirement for measuring physiologically relevant neurotransmitter levels. This application note explores the theoretical foundation, experimental evidence, and practical protocols underlying these advantages, providing researchers with a comprehensive resource for implementing microelectrode-based sensing in voltammetry applications.

Fundamental Principles

The iR Drop Phenomenon and its Minimization in Microelectrodes

In electrochemical systems, the iR drop is an undesirable voltage loss that occurs between the working and reference electrodes due to the electrical resistance (R) of the electrolyte solution and the current flow (i) [7]. This effect can significantly distort voltammetric measurements by causing peak broadening, shifting peak potentials, and reducing measurement accuracy, especially in poorly conducting media or at high current densities [15]. The magnitude of iR drop is directly proportional to both the current flowing through the system and the solution resistance.

Microelectrodes fundamentally minimize iR drop through their reduced dimensions and the resulting hemispherical diffusion profile. As electrode size decreases, the current passing through the electrode decreases proportionally to r² (where r is the electrode radius), while the resistance increases only proportionally to 1/r. This relationship leads to a net reduction in iR drop, which scales with the electrode radius [15]. This advantage becomes particularly crucial in biomedical sensing applications where measurements are often performed in low-ionic-strength solutions or when using fast scan rates, such as in Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) where scan rates of 400 V/s are common [16].

Signal-to-Noise Ratio Enhancement Mechanisms

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) represents the ratio of the desired analytical signal to the background noise, determining the detection limit and measurement precision of an electrochemical sensor. Microelectrodes enhance SNR through several interconnected mechanisms. Their small dimensions result in a reduced RC constant (the product of resistance and capacitance), which enables faster response times and measurement of rapid chemical processes [15]. This is particularly valuable for monitoring neurotransmitter dynamics, which occur on sub-second timescales.

Additionally, the enhanced mass transport to microelectrode surfaces—governed by hemispherical (3D) diffusion rather than linear (1D) planar diffusion—results in higher steady-state currents relative to background charging currents [12]. The smaller surface area of microelectrodes also generates significantly lower capacitive charging currents, which constitute a major source of background noise in voltammetric measurements [15]. These combined effects enable microelectrodes to achieve lower detection limits, with carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFMEs) successfully detecting neurotransmitters at nanomolar concentrations relevant to physiological monitoring [17].

Table 1: Comparative Electrode Properties and Their Impact on iR Drop and SNR

| Property | Macroelectrode | Microelectrode | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Critical Dimension | Millimeters (mm) | Micrometers (μm) | Fundamental size difference enabling microelectrode advantages |

| Diffusion Profile | Linear (planar) diffusion | Hemispherical (3D) diffusion | Enhanced mass transport, steady-state currents [12] |

| Current Level | High (proportional to r²) | Low (proportional to r²) | Reduced iR drop [15] |

| Capacitive Current | High | Low | Improved signal-to-noise ratio [15] |

| RC Time Constant | Large | Small | Faster response times, measurement of faster processes [15] |

| iR Drop | Significant | Minimal | Accurate potential control, especially in low ionic strength media [15] |

| Spatial Resolution | Low (bulk measurements) | High (localized measurements) | Targeted sensing in complex environments (e.g., brain tissue) |

Experimental Evidence and Performance Data

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Recent studies directly comparing microelectrode and macroelectrode performance demonstrate clear advantages of miniaturized sensing platforms. Carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFMEs), typically 7-30 μm in diameter, have shown exceptional performance in neurotransmitter detection, with their small diameter minimizing tissue damage while providing high conductivity and excellent biocompatibility [18] [16]. When comparing 30 μm bare CFMEs to conventional 7 μm CFMEs, the larger microelectrodes exhibited a 2.7-fold higher sensitivity in vitro (33.3 ± 5.9 pA/μm² versus 12.2 ± 4.9 pA/μm²) [16]. This enhanced sensitivity directly results from the improved mass transport and reduced iR drop at microelectrode surfaces.

The geometric configuration of microelectrodes further influences their performance. Cone-shaped 30 μm CFMEs, created through electrochemical etching, demonstrated a 3.7-fold improvement in in vivo dopamine signals compared to conventional cylindrical CFMEs [16]. This design mitigates insertion-induced tissue damage while maintaining the electrochemical advantages of microelectrodes, resulting in both enhanced signal quality and improved biocompatibility. The reduced iR drop in these miniaturized platforms enables clear discrimination of Faradaic currents from background charging, which is particularly valuable for detecting low neurotransmitter concentrations amidst complex biological matrices.

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Different Carbon Fiber Microelectrode (CFME) Designs

| Electrode Type | Diameter | Sensitivity (in vitro) | In Vivo Dopamine Signal | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard CFME | 7 μm | 12.2 ± 4.9 pA/μm² [16] | 24.6 ± 8.5 nA [16] | Minimal tissue damage, comparable to neuron size [16] |

| Bare CFME | 30 μm | 33.3 ± 5.9 pA/μm² [16] | 12.9 ± 8.1 nA [16] | Enhanced mechanical robustness, higher sensitivity |

| Cone-Shaped CFME | 30 μm (base) | Not specified | 47.5 ± 19.8 nA [16] | Superior in vivo performance, reduced tissue damage, enhanced longevity |

Advanced Microelectrode Platforms

Recent innovations in microelectrode design have further leveraged the advantages of reduced iR drop and improved SNR. Carbon-coated microelectrodes (CCMs) created through electroplating and mild annealing of graphene-based coatings demonstrate exceptional performance characteristics, with dopamine sensitivity (125.5 nA/μM) significantly outperforming commercial carbon fiber electrodes (15.5 nA/μM) while maintaining a low detection limit of 5 nM [17]. This enhanced sensitivity stems from the large specific surface area of the carbon coating combined with the inherent electrochemical advantages of microelectrodes.

The scalability of microelectrode arrays represents another significant advancement, with researchers successfully fabricating monolithic 100-channel CCM arrays that maintain uniform electrochemical performance across all channels [17]. This scalability enables high spatial resolution mapping of neurochemical activity while preserving the beneficial iR drop and SNR characteristics of individual microelectrodes. The compatibility of these arrays with standard microfabrication processes further enhances their utility for both research and potential clinical applications.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes (CFMEs)

This protocol details the standard procedure for fabricating carbon fiber microelectrodes for neurotransmitter detection [16].

Materials and Equipment

- Carbon fiber (e.g., AS4 for 7 μm CFMEs; available from World Precision Instruments for 30 μm CFMEs)

- Glass capillaries for insulation

- Capillary puller

- Epoxy resin

- Scalpel or precision cutting tool

- FSCV system (e.g., National Instruments USB-6363 with custom LabVIEW software)

- Tris buffer (15 mM Trizma phosphate, 3.25 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM CaCl₂, 1.25 mM NaH₂PO₄, 1.2 mM MgCl₂, and 2.0 mM Na₂SO₄, pH adjusted to 7.4)

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Fiber Preparation: Aspirate a single carbon fiber into a glass capillary.

- Pulling: Use a capillary puller to heat and pull the glass capillary, creating a sealed insulation around the carbon fiber with a tapered tip.

- Trimming: Using a scalpel, carefully trim the exposed carbon fiber to a final length of approximately 100 μm.

- Connection: Secure the pulled capillary to a suitable electrical connector using conductive epoxy or metal alloy, ensuring stable electrical contact with the carbon fiber.

- Insulation Check: Verify the integrity of the glass insulation under microscope to prevent current leakage.

- Electrochemical Preconditioning: Before first use, precondition the CFME using FSCV with a 1.5 V sweep (−0.4 V to 1.5 V at 400 V/s, 30 Hz) followed by application of the standard FSCV waveform (−0.4 V to 1.3 V sweep; 10 Hz) until a stable background current is achieved.

Quality Control

- Examine electrode tip under microscope for proper sealing and fiber exposure.

- Perform cyclic voltammetry in a standard dopamine solution (e.g., 1 μM) to verify sensitivity and response characteristics.

- Electrodes should demonstrate stable background currents with minimal noise before experimental use.

Protocol 2: Electrochemical Etching for Cone-Shaped CFMEs

This protocol describes the electrochemical etching method to create cone-shaped CFME tips, which improve penetration and reduce tissue damage during in vivo implantation [16].

Materials and Equipment

- Fabricated 30 μm CFME (from Protocol 1)

- Direct current power supply

- Linear actuator system

- Tris buffer (as prepared in Protocol 1)

- Electrochemical cell

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Setup Configuration: Mount the CFME vertically on a linear actuator positioned above an electrochemical cell containing Tris buffer.

- Initial Immersion: Lower the CFME until approximately 1 mm of the carbon fiber is submerged in the Tris buffer.

- Voltage Application: Apply a direct current voltage of 10 V to the submerged carbon fiber segment.

- Actuator Movement: After 20 seconds of electrolysis, activate the linear actuator to move the electrode upward at a constant speed (approximately 5-10 μm/s).

- Etching Process: Continue the voltage application during upward movement, which gradually exposes the carbon fiber to air while the submerged portion continues etching, forming the cone shape.

- Process Termination: Stop the voltage and retract the electrode once the desired cone height (100-120 μm) is achieved.

- Rinsing: Rinse the etched CFME thoroughly with deionized water to remove buffer residues.

Quality Control

- Verify cone geometry and dimensions under microscope.

- Test mechanical integrity through gentle manipulation.

- Validate electrochemical performance following Preconditioning steps in Protocol 1.

Protocol 3: Electrochemical Activation and Regeneration in Deionized Water

This protocol describes a simple method to activate and regenerate carbon fiber microelectrodes using only deionized water, restoring electrochemical performance for contaminated or fouled electrodes [19].

Materials and Equipment

- Deionized water

- Potentiostat

- Standard three-electrode cell

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) for testing

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Setup: Place the CFME as working electrode in an electrochemical cell containing only deionized water.

- Potential Application: Apply a constant potential of 1.75 V for 26.13 minutes.

- Rinsing: After treatment, rinse the electrode thoroughly with deionized water.

- Testing: Validate regeneration by measuring the differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) response in a standard dopamine solution (1.0 × 10⁻⁷ to 1.0 × 10⁻⁴ mol/L).

Quality Control

- Regenerated electrodes should show a linear DPV response to dopamine (R² = 0.9961) with a detection limit of 3.1 × 10⁻⁸ mol/L [19].

- Electrodes should demonstrate stable responses across multiple measurements.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Electrode Dimension Effects on Diffusion and Current

CFME Fabrication and Etching Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Microelectrode Fabrication and Testing

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Specifications/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fiber | Electrode sensing material | AS4 for 7 μm CFMEs (Hexcel); 30 μm available from World Precision Instruments [16] |

| Tris Buffer | Electrochemical testing medium | 15 mM Trizma phosphate, 3.25 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM CaCl₂, 1.25 mM NaH₂PO₄, 1.2 mM MgCl₂, 2.0 mM Na₂SO₄, pH 7.4 [16] |

| Dopamine HCl | Primary analyte for validation | Prepare 1 mM stock in Tris buffer with 50 μM perchloric acid; dilute to experimental concentrations [16] |

| Graphene Oxide Dispersion | Carbon coating precursor | For CCM fabrication; enables room temperature electroplating [17] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Stability testing medium | For evaluating electrochemical stability of coated electrodes [17] |

| Deionized Water | Electrode regeneration | Electrochemical activation at 1.75 V for 26.13 minutes restores performance [19] |

| Glutaraldehyde | Enzyme immobilization | Cross-linking agent for biosensor fabrication with BSA matrix [20] |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Enzyme stabilization matrix | Protein matrix for immobilizing glutamate oxidase and GABASE enzymes [20] |

Microelectrodes are indispensable tools in modern electroanalytical chemistry, particularly in voltammetry for enhanced sensitivity research. The selection of electrode material—platinum, gold, or carbon-based systems—profoundly influences key performance parameters including sensitivity, selectivity, stability, and fouling resistance. Each material offers distinct electrochemical properties that make it suitable for specific applications, from neurochemical monitoring to environmental analysis. This application note provides a comprehensive comparison of these essential electrode materials, summarizing quantitative performance data and detailing standardized experimental protocols to guide researchers and drug development professionals in selecting and implementing the most appropriate microelectrode systems for their specific analytical challenges.

Comparative Material Properties and Applications

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Microelectrode Materials

| Material | Key Advantages | Optimal Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum (Pt) | Excellent electrocatalytic activity, high conductivity, corrosion resistance [20] | H₂O₂ detection for enzymatic biosensors (GABA, Glutamate) [20] | Surface fouling, expensive, requires activation/cleaning protocols [20] |

| Gold (Au) | Ease of functionalization, well-defined self-assembled monolayers, good conductivity [13] | Label-free aptasensors, dopamine detection with molecular recognition elements [13] | Softer metal, potential for oxide formation |

| Carbon-Based Systems | Wide potential window, biocompatibility, rich surface chemistry, resistance to fouling [7] [21] | Neurotransmitter sensing (dopamine, serotonin), FSCV, long-term implantation [7] [21] [22] | Batch-to-batch variability (CFMEs), complex fabrication for advanced forms [7] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Comparison for Neurotransmitter Detection

| Material & Type | Analyte | Sensitivity | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt (Roughened) | GABA | 45 ± 4.4 nA μM⁻¹ cm⁻² | 1.60 ± 0.13 nM | Not specified | [20] |

| Pt (Roughened) | Glutamate | 1,510 ± 47.0 nA μM⁻¹ cm⁻² | 12.70 ± 1.73 nM | Not specified | [20] |

| Carbon-Coated (CCM) | Dopamine | 125.5 nA/μM | 5 nM | 50 nM to 1 μM | [22] |

| Glassy Carbon (GC-MEA) | Dopamine & Serotonin | Reliable FSCV performance confirmed | Not specified | Not specified | [21] |

| Gold Disk (Aptasensor) | Dopamine | Not specified | 0.11 μM | 0.5 to 27 μM | [13] |

Material-Specific Application Notes

Platinum Microelectrodes

Platinum microelectrodes are valued for their exceptional electrocatalytic properties, particularly in the detection of hydrogen peroxide, which is a critical byproduct in enzymatic biosensors for non-electroactive neurotransmitters like GABA and glutamate [20]. Their high conductivity and corrosion resistance make them ideal for demanding biological environments. Performance is highly dependent on surface condition, necessitating activation procedures. Electrochemical roughening (ECR) using square wave pulses has been shown to significantly enhance sensitivity by creating unique surface morphologies and pore geometries that facilitate H₂O₂ adsorption and electron transfer [20].

Gold Microelectrodes

Gold microelectrodes excel in applications requiring precise surface functionalization, such as label-free electrochemical aptasensors [13]. Their well-established chemistry for forming self-assembled monolayers allows for the immobilization of specific molecular recognition elements like DNA aptamers. This enables highly selective detection of target analytes, as the recognition event brings the analyte close to the electrode surface, facilitating its oxidation or reduction. Fabrication of gold disk microelectrodes with radii as small as 1.25-4 μm provides high spatial resolution for studying neurochemical dynamics in complex biological tissues like brain slices [13].

Carbon-Based Microelectrodes

Carbon-based systems represent the most diverse family of electrode materials, encompassing carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFMEs), glassy carbon (GC), and innovative carbon-coated microelectrodes (CCMs). They are characterized by a wide electrochemical working window, excellent biocompatibility, and resistance to fouling [7] [21]. Recent advances include "all"-glassy carbon microelectrode arrays (MEAs), where both electrodes and interconnects are made from a homogeneous GC layer, eliminating adhesion issues between dissimilar materials and enhancing long-term electrochemical durability [21]. Carbon-coated microelectrodes, created via a low-temperature process involving electroplating and mild annealing, offer high sensitivity, scalability (up to 100 channels), and easy integration with standard microfabrication processes [22].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Electrochemical Roughening of Platinum Microelectrodes

Purpose: To significantly enhance the sensitivity of Pt microelectrodes for H₂O₂ and neurotransmitter detection by creating a structured, porous surface [20].

Materials:

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), 0.1 M, pH 7.4

- Commercially available Pt MEAs (e.g., R1-Pt MEA from CenMET)

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat with function generator capability

Procedure:

- Initial Cleaning: Clean the Pt microelectrode surface by cycling the potential in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ between -0.2 V and +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 100 mV/s for 20-30 cycles.

- Roughening Setup: Place the electrode in 0.1 M PBS. Connect the Pt working electrode, a Pt wire counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode to the potentiostat.

- Apply Roughening Pulses: Apply a symmetric square wave potential with the following parameters:

- Upper Vertex Potential: +1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Lower Vertex Potential: -0.25 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Frequency: Systematically vary between 150 Hz and 6,000 Hz. Optimal H₂O₂ sensitivity is typically observed at frequencies of 250 Hz and 2,500 Hz [20].

- Duration: 30 seconds.

- Post-Treatment Validation: Characterize the roughened surface using Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) to confirm the formation of porous structures and use Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in a standard redox probe like 1 mM Potassium Ferricyanide to verify increased electroactive surface area.

Protocol: Activation and Regeneration of Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes (CFMEs) in Deionized Water

Purpose: To restore the electrochemical performance of passivated or fouled CFMEs without the use of additional electrolytes [19].

Materials:

- High purity deionized water (resistivity ≥18 MΩ·cm)

- CFMEs

- Potentiostat

Procedure:

- Setup: Immerse the fouled/inactivated CFME and the necessary reference and counter electrodes in a cell containing pure deionized water.

- Apply Activation Potential: Hold the CFME at a constant potential of +1.75 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for a duration of 26.13 minutes [19].

- Characterize Regenerated Surface: After activation, characterize the electrode using Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or CV. The regenerated CFME should show a linear response (R² > 0.996) to dopamine in the concentration range of 0.1 μM to 100 μM, with a limit of detection as low as 31 nM [19]. The mechanism is attributed to the introduction of oxygen-containing functional groups that regenerate the electrochemically active surface.

Protocol: Fabrication of Carbon-Coated Microelectrodes (CCMs)

Purpose: To transform conventional gold microelectrodes into highly sensitive and stable carbon-based sensors for neurotransmitter detection via a scalable, low-temperature process [22].

Materials:

- Fabricated gold microelectrodes (on Si or Kapton substrates)

- Aqueous Graphene Oxide (GO) dispersion

- Nitrogen (N₂) environment oven or tube furnace

- Potentiostat for electrodeposition

- Photoresist and developer for confinement patterning

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Clean the gold microelectrode surface with standard solvents (acetone, isopropanol) and dry with N₂.

- Electroplating (Optional with Confinement): Use potentiostatic deposition to reduce the GO dispersion onto the gold surface, forming a ~100 nm thick carbon coating. To maintain high spatial resolution, a photoresist (PR) confinement method can be used prior to deposition, with lift-off performed afterward [22].

- Stabilization Annealing: Anneal the coated electrode at 250 °C for 1 hour in an N₂ environment. Note: This mild annealing step is critical, as it drastically improves electrochemical stability by reducing the interlayer spacing of the carbon coating (from 4.0 Å to 3.7 Å) and decreasing oxygen content, which prevents water/ion infiltration [22].

- Quality Control: Validate the CCMs using CV to confirm a wide electrochemical window (-0.6 V to +1.5 V) and the absence of the gold oxidation peak at +1.2 V. Test sensitivity to dopamine, which for a 60×60 μm² CCM should be approximately 125.5 nA/μM [22].

Experimental Workflows and Material Relationships

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Microelectrode Applications

| Item | Function/Application | Example Usage |

|---|---|---|

| SU-8 Photoresist | A negative epoxy-based photoresist used as a precursor for fabricating glassy carbon (GC) structures via pyrolysis [21]. | Spin-coated, patterned, and then pyrolyzed at high temperatures (e.g., 900°C) under inert gas to create GC microelectrodes and interconnects [21]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) Dispersion | Used for electroplating carbon coatings onto metal microelectrodes at room temperature [22]. | Electrodeposited on gold microelectrodes and annealed at 250°C to form stable, high-sensitivity carbon-coated microelectrodes (CCMs) for dopamine sensing [22]. |

| Anti-Dopamine Aptamer | A single-stranded DNA molecule that acts as a molecular recognition element, binding to dopamine with high specificity [13]. | Self-assembled on the surface of gold disk microelectrodes to create label-free electrochemical aptasensors for selective dopamine detection [13]. |

| Enzyme Cocktail (GOx, GABASE) | Biological recognition elements for detecting non-electroactive neurotransmitters like glutamate and GABA [20]. | Co-immobilized with a BSA/glutaraldehyde matrix on Pt microelectrodes. Enzymes convert the target neurotransmitter to H₂O₂, which is electrochemically detected [20]. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) & Glutaraldehyde | Used to create a cross-linked protein matrix for immobilizing enzymes on electrode surfaces [20]. | Mixed with enzymes (e.g., Glutamate Oxidase) and applied to the electrode surface, where glutaraldehyde cross-links the proteins, forming a stable hydrogel film [20]. |

Voltammetric techniques are indispensable in modern analytical science, providing powerful means to probe electrochemical reactions. This article details the core principles, applications, and protocols for three pivotal techniques: Amperometry, Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV), and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV). Framed within microelectrode research for enhanced sensitivity, these methods enable real-time, high-resolution measurement of dynamic processes in complex environments from pharmaceutical formulations to the living brain [23] [24]. The development of carbon-based microelectrodes has been instrumental in pushing the detection limits of these techniques, allowing for the quantification of neurochemicals at nanomolar concentrations with sub-second temporal resolution [17] [25].

Amperometry (A-SECM) involves holding the working electrode at a constant potential and measuring the resulting current from the oxidation or reduction of an analyte. It provides excellent temporal resolution but offers limited chemical information, making it ideal for monitoring concentration changes of a single, known species [26] [24]. In Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy (SECM), the amperometric mode is used to map surface topography and reactivity by recording a single current value at each point in a raster scan [26].

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) employs a linear potential sweep that reverses direction at a set switching potential. The resulting cyclic voltammogram provides rich qualitative information on the thermodynamics and kinetics of redox processes, making it a cornerstone for fundamental electrochemical characterization [27].

Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) is a variant of CV that uses exceptionally high scan rates (typically 100–1000 V/s). This speed enables the acquisition of a full voltammogram within tens of milliseconds, allowing for the real-time tracking of rapid chemical events, such as neurotransmitter release [24] [28] [29]. A key aspect of FSCV is background subtraction, which isolates the small Faradaic current of the analyte from the much larger background charging current, yielding a characteristic "signature" for the detected molecule [28] [29].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics and applications of these techniques.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Core Voltammetric Techniques

| Feature | Amperometry | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Principle | Constant potential; measures current from redox reaction [24]. | Linear potential sweep reversed at a vertex; measures current [27]. | High-rate triangular potential waveform; measures current with background subtraction [28] [29]. |

| Primary Application | Single-analyte sensing, SECM feedback imaging, monitoring exocytosis [26] [24]. | Qualitative analysis of redox mechanisms, reaction kinetics, and thermodynamics [27]. | Real-time monitoring of rapid neurotransmitter dynamics in vivo [24] [28]. |

| Temporal Resolution | Highest (electronic sampling rate, <1 ms) [24] [28]. | Low (scan typically over seconds) [27]. | High (typically 100 ms per voltammogram) [28]. |

| Sensitivity (LOD for Dopamine) | Low (25-100 nM) [28]. | Varies with system. | High (~10 nM) [28]. |

| Selectivity | Low; responds to all species oxidized/reduced at the applied potential [24] [28]. | Moderate; based on formal potential of the redox couple [27]. | Highest; based on the unique shape of the background-subtracted cyclic voltammogram [28] [29]. |

| Data Output | Current vs. time trace [26]. | Current vs. potential plot (voltammogram) [27]. | 3D data (current vs. potential vs. time), represented as 2D false color plots [28]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: FSCV for In Vivo Dopamine Sensing

This protocol describes the setup and execution of FSCV using a carbon-fiber microelectrode (CFME) for monitoring dopamine dynamics in the brain of an anesthetized rodent [24] [28] [29].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Fabricate a cylindrical CFME by sealing a single carbon fiber (Ø 7–10 µm) in a pulled glass capillary. The fiber should be trimmed to extend 50–100 µm beyond the glass insulation [25] [28].

- Electrochemical Pre-treatment (Optional): Condition the CFME by applying the FSCV waveform (e.g., -0.4 V to +1.3 V vs. Ag/AgCl, 400 V/s) in a blank pH 7.4 buffer solution for 20-30 minutes until the background current stabilizes. This process creates oxygen-containing functional groups that enhance dopamine adsorption and sensitivity [28].

- System Setup: Connect the CFME as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl wire as a reference electrode, and a stainless-steel wire placed in contact with tissue as the auxiliary electrode. Configure the potentiostat with the "dopamine waveform" parameters:

- In Vivo Implantation: Anesthetize the animal and secure it in a stereotaxic frame. Perform a craniotomy and implant the CFME into the target brain region (e.g., striatum) using stereotaxic coordinates.

- Data Acquisition: Begin FSCV recording. The software will continuously apply the triangular waveform, record the total current, and perform background subtraction. Data is typically visualized as a false color plot, where the color intensity represents the current at a given potential and time [28].

- Electrical Stimulation (Optional): To evoke dopamine release, insert a stimulating electrode into the dopamine pathway (e.g., medial forebrain bundle) and deliver a brief, biphasic electrical pulse train (e.g., 60 pulses, 60 Hz, 2 ms pulse width) [24].

- Post-experiment Calibration: Upon completion of the in vivo experiment, remove the CFME and calibrate its sensitivity by recording FSCV responses in a standard solution of known dopamine concentrations (e.g., 0.5 µM, 1.0 µM) in PBS at pH 7.4.

Protocol: Voltammetric SECM (V-SECM) for Multi-Analyte Imaging

This protocol uses FSCV at each point of an SECM scan to create spatially resolved maps of multiple chemical species simultaneously, as demonstrated for the ECE reaction of acetaminophen [26].

Workflow Overview:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Tip and Substrate Preparation: Fabricate a Pt or Au disk ultramicroelectrode (10–100 µm diameter) as the SECM tip by sealing a metal wire in soft glass and polishing to a mirror finish [26]. Prepare the substrate of interest (e.g., another microelectrode for generating reactant and product species).

- Cell Setup and Positioning: Fill the electrochemical cell with an electrolyte solution containing a mediator (e.g., 1 mM DMPPD or acetaminophen). Mount the tip and substrate on the SECM stage. Approach the tip to within a few tip diameters of the substrate surface using a precision positioning system.

- Define Scan Parameters: Using the SECM control software, define a two-dimensional raster grid over the area to be scanned. Set the step size (e.g., 5-20 µm) and dwell time at each point.

- V-SECM Scan Execution: Initiate the scan. At each grid point, the system pauses and executes a single, rapid FSCV scan (e.g., 300 V/s from -0.2 V to +0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl). The entire cyclic voltammogram is saved, rather than a single current value [26].

- Data Analysis and Imaging: After the scan, process the four-dimensional data set (current, potential, x-position, y-position). To create a concentration map for a specific analyte, extract the current at its characteristic oxidation or reduction potential from the voltammogram at every pixel. For example, in the acetaminophen (APAP) ECE reaction, distinct maps can be generated for APAP, its hydroquinone (HQ) intermediate, and the benzoquinone (BQ) product [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

The performance of voltammetric techniques is highly dependent on the materials and reagents used. The table below lists essential components for experiments in enhanced sensitivity research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fiber Microelectrode (CFME) [25] [28] | Primary sensor for FSCV; its small size and carbon surface enable high spatiotemporal resolution and analyte adsorption. | Typically 7-10 µm diameter; made from polyacrylonitrile (PAN)-based fibers for faster electron transfer kinetics [25]. |

| Carbon-Coated Microelectrode (CCM) [17] | A novel, scalable alternative to CFMEs; graphene-based coating on a gold electrode provides high stability and sensitivity. | Offers high yield and uniformity for array fabrication; demonstrated dopamine LOD of 5 nM [17]. |

| MWCNT-Modified Diamond Electrode [30] | A hybrid microsensor combining the wide potential window of diamond with the high surface area and electrocatalytic properties of carbon nanotubes. | Enhances sensitivity and selectivity; enables distinct detection of dopamine and serotonin in mixtures [30]. |

| N,N-dimethyl-1,4-phenylenediamine (DMPPD) [26] | A redox mediator used in SECM feedback mode experiments to characterize surface reactivity and topography. | Undergoes a 2e-, 1H+ oxidation at the electrode; serves as a stable mediator species [26]. |

| Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry Waveform [28] [29] | The applied potential profile that defines the selectivity and sensitivity of FSCV for a given analyte. | The classic "dopamine waveform" is -0.4 V to +1.3 V at 400 V/s. Parameters are optimized for other analytes like serotonin [28]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4 [30] | A standard physiological buffer used for electrode calibration, in vitro testing, and as a base for artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). | Provides a stable ionic strength and pH, mimicking the biological environment. |

Advanced Material and Method Development

The pursuit of enhanced sensitivity has driven innovation in electrode materials and fabrication techniques. Carbon-coated microelectrodes (CCMs) represent a significant advancement, where a graphene-based coating is electroplated onto a gold microelectrode and stabilized with mild annealing. This process creates a dense, stable carbon surface with interlayer spacing of 3.7 Å, which resists water/ion infiltration and enables high-performance FSCV sensing of monoamines with a limit of detection of 5 nM for dopamine [17]. A major advantage of CCMs is their scalability, allowing for the fabrication of high-density, uniform arrays with up to 100 channels, which is challenging with traditional carbon fibers [17].

Other advanced materials include hybrid multiwall carbon nanotube (MWCNT) films on boron-doped diamond. The nanotubes dramatically increase the electroactive surface area and provide abundant adsorption sites, leading to a greater than 125-fold improvement in sensitivity for dopamine compared to the unmodified diamond surface [30]. Polymer coatings, such as Nafion, are also routinely applied to confer selectivity by repelling anionic interferents like ascorbic acid, which is present in the brain at much higher concentrations than target neurotransmitters [30] [28].

Method development has also focused on waveform optimization. Simply extending the holding potential to more negative values or the switching potential to more positive values can significantly enhance sensitivity for cationic and neutral molecules, respectively, by modulating analyte adsorption [28]. Furthermore, developing novel waveform shapes is crucial for expanding FSCV to new neurochemicals like serotonin, adenosine, and histamine, while also mitigating electrode fouling, a common challenge with certain analytes [28].

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Neurochemistry and Diagnostics

Real-time monitoring of neurotransmitters is crucial for advancing our understanding of brain function, neurological disorders, and the development of novel therapeutics. The ability to track dynamic changes in dopamine (DA), serotonin (5-HT), and glutamate (Glu) concentrations with high temporal and spatial resolution provides invaluable insights into neurochemical processes underlying behavior, cognition, and disease states. Traditional methods like microdialysis, while valuable, offer poor temporal resolution (typically 5-15 minutes) due to the time required for sample collection and analysis [31]. This limitation has driven the development of advanced electrochemical sensing platforms, particularly those employing microelectrodes, which enable monitoring on a sub-second timescale commensurate with neuronal signaling events [32] [33].

The integration of microelectrodes with voltammetric techniques represents a significant breakthrough in neurochemical sensing. These platforms leverage the unique properties of carbon-based materials, including high biocompatibility, excellent electrochemical performance, and minimal tissue disruption [7]. Recent innovations in material science, electrode design, and surface functionalization have substantially enhanced the sensitivity, selectivity, and multiplexing capabilities of these devices, allowing researchers to simultaneously monitor multiple neurotransmitters in complex biological environments [34] [35]. This application note details standardized protocols and methodologies for real-time monitoring of DA, 5-HT, and Glu using microelectrode-based platforms, with particular emphasis on their application within microelectrode voltammetry research.

Detection Technologies and Performance Metrics

Electrochemical Sensing Platforms

Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes (CFMEs) are constructed from carbon fibers (∼7–10 microns in diameter) insulated in pulled glass capillaries [7]. Their microscale dimensions cause minimal tissue damage, making them ideal for in vivo applications. CFMEs fabricated from polyacrylonitrile (PAN)-based precursors offer faster electron transfer kinetics and lower background currents, while pitch-based fibers exhibit higher conductivity suitable for detecting analytes with larger oxidation currents [7].

Glassy Carbon (GC) Microelectrodes are lithographically patterned on flexible polymer substrates, forming robust arrays for simultaneous multi-site detection [35]. GC surfaces are rich in electrochemically active functional groups, exhibit good adsorption characteristics, and possess antifouling properties, enabling stable and repeatable detection of electroactive neurotransmitters at concentrations as low as 10 nM [35].

Enzyme-Linked Biosensors are essential for detecting non-electroactive neurotransmitters like glutamate. These sensors employ oxidase enzymes (e.g., glutamate oxidase) immobilized on electrode surfaces. The enzyme catalyzes the conversion of the target neurotransmitter to an electroactive byproduct (typically hydrogen peroxide, H₂O₂), which is then detected amperometrically or voltammetrically [33] [35].

Electrochemical Techniques

Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) applies a rapid triangular waveform (typically 400 V/s) to the working electrode, generating background-subtracted cyclic voltammograms that serve as electrochemical fingerprints for identifying electroactive analytes like DA and 5-HT [33]. FSCV offers sub-second temporal resolution, making it ideal for tracking transient neurotransmitter release events [35].

Fixed Potential Amperometry (FPA) maintains a constant potential sufficient to oxidize the target analyte. FPA provides superior temporal resolution compared to FSCV and is particularly advantageous when coupled with enzyme-linked biosensors for monitoring non-electroactive species [33]. The simplified data output (current versus time) facilitates real-time analysis.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Neurotransmitter Detection Methods

| Method | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Key Neurotransmitters | Detection Limit | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microdialysis with HPLC | 5-15 minutes | Limited by probe size (~mm) | DA, 5-HT, Glu, others | ~1.0 µM for Glu [31] | Broad analyte panel, established methodology |

| CFME with FSCV | Sub-second (ms) | Micrometer scale | DA, 5-HT (electroactive) | ~10 nM for DA [7] | Excellent temporal resolution, identification via voltammogram |

| Enzyme-Linked FPA | ~1 second | Micrometer scale | Glu, Adenosine (non-electroactive) | Nanomolar range [33] [35] | Detects non-electroactive analytes, good temporal resolution |

| SWCNT Sensor | Sub-second to seconds | Micrometer scale | DA, 5-HT | Nanomolar in cell culture [34] | Selective in complex media, biocompatible |

Table 2: Quantitative Detection Limits for Key Neurotransmitters

| Neurotransmitter | Detection Method | Sensor Type | Reported Detection Limit | Linear Range | Test Environment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine (DA) | FSCV | Carbon Fiber Microelectrode | Not explicitly quantified in results | Not specified | In vivo (rat striatum) [33] |

| Dopamine (DA) | Electrochemical | Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube (SWCNT) | Nanomolar | Not specified | In vitro (cell culture medium) [34] |

| Serotonin (5-HT) | Electrochemical | Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube (SWCNT) | Nanomolar | Not specified | In vitro (cell culture medium) [34] |

| Glutamate (Glu) | FPA / Amperometry | Glutamate Oxidase Biosensor | Not explicitly quantified in results | Not specified | In vivo (pig cortex) [33] |

| Glutamate (Glu) | FSCV | GluOx-functionalized GC Microelectrode | 10 nM | Not specified | In vitro [35] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes (CFMEs)

Principle: CFMEs are constructed by sealing a single carbon fiber within a glass capillary, providing an exposed carbon surface for electrochemical detection with minimal tissue damage [7].

Materials:

- Polyacrylonitrile (PAN)-based carbon fibers (e.g., T-650, ~7 μm diameter) [7]

- Glass capillaries (e.g., borosilicate)

- Capillary puller

- Epoxy resin (high-insulation resistance)

- Syringe and needle for fiber aspiration

- Microscope

Procedure:

- Capillary Pulling: Pull glass capillaries using a capillary puller to create two tapered shanks.

- Fiber Aspiration: Aspirate a single carbon fiber into the pulled capillary using a syringe and needle under microscopic guidance [7].

- Sealing: Apply a small amount of epoxy resin to the back end of the capillary to secure the carbon fiber in place and ensure electrical insulation. Allow to cure completely.

- Cutting: Carefully trim the protruding carbon fiber to expose a clean, disc-shaped electrode surface at the tip.

- Electrical Connection: Back-fill the capillary with a conductive material (e.g., graphite paste or silver paint) and insert a wire to establish an electrical connection to the carbon fiber.

- Quality Control: Inspect the final CFME under a microscope to ensure proper sealing and a clean, unobstructed electrode surface. Perform electrochemical characterization in a standard solution (e.g., dopamine in PBS) to verify performance.

Protocol 2: Functionalization of Microelectrodes for Glutamate Detection

Principle: Non-electroactive glutamate is detected indirectly by immobilizing glutamate oxidase (GluOx) on the electrode surface. GluOx catalyzes the conversion of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate, producing H₂O₂, which is electrochemically oxidized and detected [35].

Materials:

- Fabricated GC or Pt microelectrodes [35]

- L-Glutamate Oxidase (GluOx) enzyme

- Cross-linker solution (e.g., containing glutaraldehyde or other cross-linking agents)

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Selectively permeable membrane (e.g., Nafion or m-phenylenediamine) to block interferents [33]

Procedure:

- Surface Preparation: Clean and activate the microelectrode surface according to standard protocols (e.g., plasma etching for GC electrodes) [35].

- Enzyme Matrix Preparation: Prepare an enzyme immobilization matrix by mixing GluOx with BSA (as a stabilizer) in a cross-linker solution such as glutaraldehyde [35].

- Drop Casting: Apply a small, controlled volume of the enzyme matrix onto the microelectrode surface using a micro-pipette under a microscope.

- Curing: Allow the enzyme layer to cure and cross-link, typically at room temperature or 4°C for a specified period.

- Membrane Coating (Optional): Apply a selective permeable membrane (e.g., Nafion) via dip-coating or drop-casting to enhance selectivity by excluding anionic interferents like ascorbic acid [33].

- Calibration: Calibrate the functionalized biosensor in standard glutamate solutions of known concentrations in PBS (e.g., 0-100 μM) to establish sensitivity and linear range.

Protocol 3: In Vivo Real-Time Monitoring in Rodent Brain

Principle: This protocol describes the simultaneous measurement of electrically evoked neurotransmitter release in an anesthetized rodent model using a wireless electrochemical system like the Wireless Instantaneous Neurotransmitter Concentration System (WINCS) [33].

Materials:

- WINCS or similar FSCV/FPA-capable potentiostat [33]

- Fabricated CFME (for DA) or enzyme-linked biosensor (for Glu)

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Stereotaxic apparatus

- Anesthetized rat (e.g., with urethane)

- Stimulating electrode (for Deep Brain Stimulation - DBS)

- Data acquisition software (e.g., custom LABVIEW or MATLAB scripts)

Procedure:

- Animal Preparation: Anesthetize the rodent and secure it in a stereotaxic frame. Maintain body temperature throughout the procedure.

- Stereotaxic Surgery: Perform a craniotomy at the coordinates for the target brain region (e.g., striatum for DA, thalamus for adenosine, cortex for Glu).

- Electrode Implantation: Implant the CFME or biosensor into the target region. Place the stimulating electrode in the afferent pathway (e.g., Medial Forebrain Bundle for DA release in striatum). Implant the Ag/AgCl reference electrode in the contralateral brain hemisphere or subcutaneous tissue [33].

- System Setup: Connect the working and reference electrodes to the WINCS potentiostat. For FSCV of DA, apply a triangular waveform (-0.4 V to +1.3 V and back, 400 V/s, 10 Hz). For FPA of Glu, apply a fixed potential of +0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl [33].

- Stimulation & Recording: Initiate electrical stimulation (e.g., DBS parameters: 60-150 Hz, 100-200 μA, 100-200 μs pulse width) while simultaneously recording the electrochemical signal.

- Data Analysis: For FSCV, use background subtraction to visualize the cyclic voltammogram and confirm DA identity by its characteristic oxidation/reduction peaks. For FPA, analyze the current-time trace to quantify Glu concentration changes.

- Histology: Upon experiment completion, perfuse the animal and verify electrode placement histologically.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Neurotransmitter Monitoring

| Item Name | Function / Application | Key Characteristics | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Fiber Microelectrode (CFME) | Working electrode for in vivo detection of electroactive neurotransmitters (DA, 5-HT). | ~7 µm diameter, minimal tissue damage, fast electron transfer kinetics [7]. | Real-time monitoring of electrically evoked dopamine release in rat striatum using FSCV [33]. |

| Glassy Carbon (GC) Microelectrode | Lithographically patterned working electrode for array-based sensing. | Mechanically robust, patternable, rich in surface functional groups, anti-fouling properties [35]. | Fabrication of multi-electrode probes for simultaneous detection of multiple neurotransmitters in vitro [35]. |

| Glutamate Oxidase (GluOx) Enzyme | Biological recognition element for glutamate biosensors. | Catalyzes conversion of glutamate to α-ketoglutarate and H₂O₂ [35]. | Functionalization of GC or Pt microelectrodes to enable indirect electrochemical detection of glutamate [35]. |

| Selective Permeable Membrane (e.g., Nafion) | Coating to enhance biosensor selectivity. | Cation exchanger; excludes anionic interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid) [33]. | Coating on glutamate biosensors to improve signal accuracy in complex biological fluids [33]. |

| WINCS (Wireless Instantaneous Neurotransmitter Concentration System) | Wireless potentiostat for FSCV and FPA. | Battery-powered, Bluetooth telemetry, compliant with medical device standards [33]. | Intraoperative neurochemical monitoring during deep brain stimulation in animal models [33]. |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotube (SWCNT) Sensor | Working electrode for enhanced sensitivity and selectivity. | High surface area, biocompatible, capable of operating in complex media [34]. | Real-time detection of nanomolar dopamine and serotonin directly from cell culture medium [34]. |

Detection Pathways and Data Interpretation

Understanding the distinct electrochemical pathways for different neurotransmitters is crucial for sensor design and data interpretation.

Pathway Explanation:

- Direct Detection (Dopamine/Serotonin): Electroactive neurotransmitters like dopamine are detected directly at the electrode surface. Upon applying a sufficient potential, dopamine is oxidized to dopamine-o-quinone, releasing electrons that generate a measurable oxidation current. The characteristic redox potentials revealed in a cyclic voltammogram serve as a fingerprint for analyte identification [7] [33].

- Enzyme-Mediated Indirect Detection (Glutamate): Glutamate is not electroactive. Biosensors use immobilized glutamate oxidase (GluOx) to catalyze its reaction with oxygen and water, producing α-ketoglutarate and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). The H₂O₂ is then oxidized at the electrode surface (at a fixed potential of ~+0.6 V vs. Ag/AgCl), generating a current proportional to the original glutamate concentration [33] [35]. This two-step process enables real-time monitoring of this critical excitatory neurotransmitter.

The protocols and methodologies outlined herein provide a robust framework for implementing real-time neurotransmitter monitoring in both basic research and drug development contexts. The integration of advanced microelectrode platforms with sophisticated electrochemical techniques like FSCV and FPA has fundamentally transformed our capacity to observe neurochemical dynamics at unprecedented resolution. These tools are indispensable for elucidating the mechanisms of neurological diseases, screening novel therapeutic compounds, and advancing the development of closed-loop neuromodulation systems. As material science and sensor engineering continue to progress, future developments will likely focus on enhancing the multiplexing capabilities, long-term stability, and clinical applicability of these powerful monitoring platforms.

In Vivo Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV) in Behaving Animals

Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) has emerged as a premier electrochemical technique for the real-time detection of neurochemical dynamics in the brains of awake, behaving subjects. This method enables the measurement of sub-second, phasic changes in electroactive neurotransmitters with unparalleled temporal and spatial resolution, providing critical insights into the neurochemical underpinnings of behavior, learning, and motivation [36]. The technique's exceptional sensitivity (in the nanomolar range) and millisecond temporal resolution make it uniquely suited for capturing the rapid dopamine transients that are implicated in reward processing, goal-directed behavior, and motor control [36] [37].

The core of this methodology relies on carbon-fiber microelectrodes (CFMEs), which are biologically compatible, cause minimal tissue damage, and possess excellent electrochemical properties for neurotransmitter detection [38]. Recent innovations in microelectrode design and material science have been central to enhancing the sensitivity and functionality of FSCV. Developments such as cone-shaped electrode geometries [18], carbon nanotube coatings [7] [38], and novel surface treatments [38] are pushing the boundaries of what is measurable, allowing researchers to probe neurochemical signaling with increasing precision and for extended durations. These advancements frame FSCV within the broader context of microelectrode research aimed at achieving enhanced sensitivity and chronic stability for both basic neuroscience and clinical applications [7] [39] [18].

Principles and Advancements in FSCV Microelectrodes

Fundamental Mechanism of FSCV

FSCV operates by applying a rapid, triangular waveform (e.g., from –0.4 V to +1.3 V and back at 400 V/s) to a carbon-fiber working electrode implanted in the brain [36] [18]. This potential sweep oxidizes and reduces electroactive neurotransmitters, such as dopamine, that are present in the extracellular space. The resulting current is measured, producing a cyclic voltammogram that serves as an electrochemical fingerprint, allowing for both the identification and quantification of the specific neurochemical [39] [37]. A key feature of FSCV is background subtraction, which removes the relatively stable charging current to reveal the faradaic current of the analyte, enabling the detection of nanomolar concentration changes against a complex biological background [38].

Microelectrode Design for Enhanced Sensitivity

The performance of FSCV is intrinsically linked to the physical and chemical properties of the microelectrode. Continuous research focuses on optimizing these properties to improve sensitivity, selectivity, and longevity.

Table 1: Carbon-Fiber Microelectrode Designs and Performance Characteristics

| Electrode Type | Diameter | Key Features | Sensitivity (In Vitro) | In Vivo Dopamine Signal | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard CFME [18] | 7 µm | Standard construction; PAN-based fiber | 12.2 ± 4.9 pA/µm² | 24.6 ± 8.1 nA | Minimal tissue damage; good biocompatibility | Limited mechanical durability; prone to breakage |

| Bare CFME [18] | 30 µm | Larger diameter; increased surface area | 33.3 ± 5.9 pA/µm² | 12.9 ± 8.1 nA | High mechanical strength; enhanced in vitro sensitivity | Significant tissue damage; reduced in vivo signal |

| Cone-Shaped CFME [18] | 30 µm (base) | Electrochemically etched tip | Information Not Specified | 47.5 ± 19.8 nA | Superior in vivo signal; reduced glial activation; 4.7x longer lifespan | Complex fabrication process |

| Flame-Etched CFME [38] | ~7 µm | Increased surface roughness | Increased current per unit area | Effective for single-pulse detection | Increased sensitivity; decreased pH sensitivity | - |

| CNT-Coated CFME [38] | ~7 µm | Coated with carbon nanotubes | Enhanced for serotonin and dopamine | Enabled simultaneous dopamine/serotonin detection | Reduced fouling; improved sensitivity and selectivity | Coating stability over time |

Beyond geometric innovations, surface treatments and modifications are crucial for enhancing electrode performance. Coatings like Nafion (an anionic polymer) or covalent modification with 4-sulfobenzene improve selectivity for catecholamines like dopamine by repelling common anionic interferents such as ascorbic acid [38]. Incorporating carbon nanotubes (CNTs) onto the electrode surface increases the effective surface area and electron transfer rates, which enhances sensitivity and reduces biofouling, a common challenge where proteins and other biomolecules adsorb to the electrode and diminish its function [7] [38]. These advancements in microelectrode technology directly contribute to the core thesis of developing more sensitive and robust tools for neurochemical sensing.

Experimental Protocol: In Vivo FSCV in Behaving Rats