Method Validation in Titration: A Comprehensive Guide to Potentiometric vs. Volumetric Analysis for Pharmaceutical Scientists

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating potentiometric and volumetric titration methods.

Method Validation in Titration: A Comprehensive Guide to Potentiometric vs. Volumetric Analysis for Pharmaceutical Scientists

Abstract

This article provides a definitive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating potentiometric and volumetric titration methods. It covers foundational principles, practical applications, and troubleshooting strategies, with a focused comparison on validation parameters like accuracy, precision, and specificity as defined by ICH Q2(R1) and USP <1225>. The content synthesizes current methodologies and market trends to empower scientists in selecting and validating the optimal titration technique for ensuring product quality and regulatory compliance in biomedical and clinical research.

Core Principles: Understanding Titration Fundamentals and Industry Shifts

Titration is a fundamental quantitative analytical technique used to determine the concentration of an unknown substance in a solution. The core principle involves the gradual addition of a reagent, known as the titrant, from a burette to the sample solution, known as the analyte, until the chemical reaction between the two is complete [1]. The critical moment in any titration is identifying this completion point, termed the endpoint or equivalence point. The endpoint is the point at which the amount of titrant added is chemically equivalent to the amount of substance present in the sample [2]. The accuracy and precision of the entire analytical process hinge on the correct detection of this endpoint.

This article explores the defining characteristics of volumetric titration, with a specific focus on manual analysis and the principles of endpoint detection. It objectively compares this traditional method against the modern alternative of potentiometric titration, framing the discussion within the rigorous context of method validation required for research and drug development. By examining the underlying principles, experimental protocols, and validation data, scientists can make an informed choice regarding the most appropriate titration method for their specific application.

Core Principles of Volumetric Titration

Volumetric titration is characterized by its reliance on measuring the volume of a titrant of known concentration required to reach the endpoint. The foundation of this method is a stoichiometric reaction—one where the relationship between the reactants is known and definitive—such as acid-base, redox, precipitation, or complexation [2].

The central component of the volumetric method is the detection of the endpoint. In manual volumetric titration, this is most commonly achieved through the use of visual indicators. These indicators are substances added to the analyte that produce an observable physical change, typically a color change, at or very near the equivalence point [2]. The choice of indicator is paramount and depends entirely on the specific chemistry of the titration reaction.

- Acid-Base Titrations: Indicators for these titrations are weak acids or bases that change color within a specific pH range. For example, phenolphthalein changes from colorless to pink around pH 8.3, making it suitable for strong acid-strong base titrations. Methyl orange, which changes from yellow to red between pH 3.1 and 4.4, is used when a strong acid is titrated with a strong base [2].

- Redox Titrations: The indicators used are more specific to the reactants. Some change color after reacting with excess titrant (e.g., starch turning blue in the presence of iodine), while others change in response to the solution's electrode potential [2].

- Precipitation Titrations: In the Mohr method for chloride determination, potassium chromate is added to form a reddish-brown silver chromate precipitate once all chloride ions have reacted, signaling the endpoint [2].

- Complexometric Titrations: Ionochromic dyes, such as those used with EDTA titrations, form colored complexes with metal ions. The endpoint is marked by a sharp color change when the metal ion is fully complexed by the titrant and the dye is released [2].

The simplicity of this visual detection is both the greatest strength and the most significant weakness of manual volumetric titration, a point that will be elaborated on in the comparison with instrumental methods.

Potentiometric Titration: An Instrumental Alternative

In contrast to volumetric titration's visual cues, potentiometric titration employs an instrumental approach to endpoint detection. This technique measures the potential difference (voltage) between two electrodes—an indicator electrode and a reference electrode—immersed in the sample solution as the titrant is added [1] [2].

The potential of the indicator electrode changes in response to the concentration of a specific ion in the solution (e.g., H+ for acid-base reactions), while the reference electrode maintains a constant potential. The measured voltage does not change linearly but exhibits a sharp jump at the equivalence point. Instead of watching for a color change, the analyst plots the potential against the volume of titrant added, generating a characteristic S-shaped titration curve. The endpoint is precisely determined by locating the steepest point (the inflection point) of this curve [3].

This method offers an objective, numerical determination of the endpoint, eliminating the subjectivity of human color perception. It is versatile and can be applied to all types of titration reactions, provided a suitable electrode is selected [2].

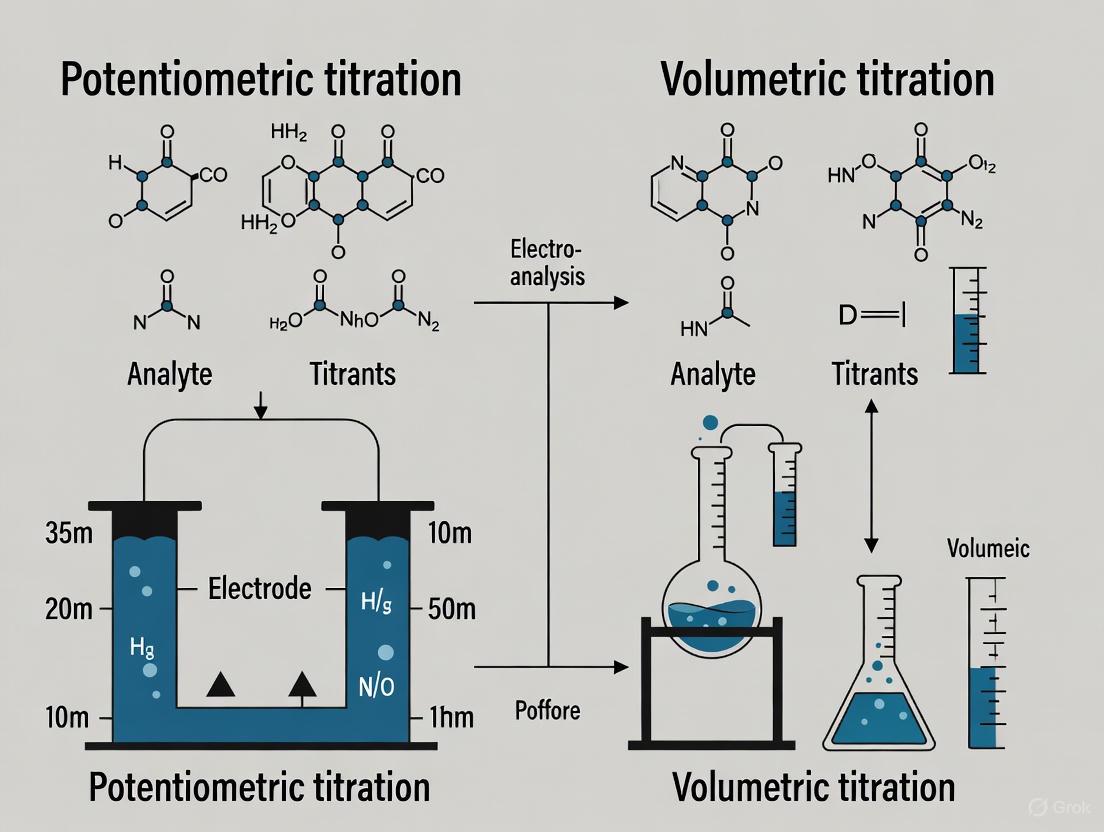

Visualizing Potentiometric Endpoint Detection

The following diagram illustrates the key difference in endpoint detection between manual and potentiometric titration, culminating in the generation of the titration curve.

Comparative Analysis: Volumetric vs. Potentiometric Titration

The choice between manual volumetric and potentiometric titration involves a careful trade-off between simplicity, cost, accuracy, and applicability. The following table provides a structured comparison based on key analytical figures of merit, synthesizing information from the search results.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of manual volumetric and potentiometric titration methods.

| Factor | Manual Volumetric Titration | Potentiometric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy | High in well-controlled systems with a skilled analyst [1]. | Generally high accuracy and precision for clear aqueous samples; less subjective [1] [2]. |

| Precision | Lower precision; susceptible to human error in reading burettes and perceiving endpoints [2]. | Higher precision; automated systems reduce human variability [2] [4]. |

| Endpoint Detection | Visual observation of color change using chemical indicators [2]. | Instrumental measurement of potential change; endpoint is the inflection point on a titration curve [2] [3]. |

| Subjectivity | High; perception of color change varies between individuals [2] [3]. | Low; objective, numerical output [1]. |

| Sample Versatility | Limited to clear, colorless, or lightly colored samples; turbid or dark samples can obscure the endpoint [1] [5]. | High; effective for colored, turbid, and complex matrices where visual indicators fail [1] [2]. |

| Cost & Equipment | Low initial cost (burette, flasks, indicators) [1]. | Higher initial cost (pH meter, electrodes, potential for automation) [2]. |

| Automation Potential | Low; inherently manual and labor-intensive [1]. | High; easily integrated into automated titrators and continuous monitoring systems [1] [3]. |

| Skill Required | Requires trained analyst for precise technique and endpoint interpretation [1]. | Easier to perform; requires training on instrument operation and maintenance [1]. |

| Data Provided | Primarily the endpoint volume; no information on reaction progression [1]. | Full titration curve; provides data on buffering capacity and can identify multiple endpoints [1]. |

Supporting Experimental Data and Validation

The differences highlighted in Table 1 are substantiated by experimental data and validation protocols. For instance, a study on automating organic matter content detection reported that manual titration is prone to difficulties in determining the endpoint, especially with complex samples where local reactions can cause color reversion after stirring [6]. In contrast, the automated machine vision system achieved a titration error of less than 0.2 mL and showed no statistically significant difference from manual results at a 95% confidence level, demonstrating the potential for automation to match or exceed manual precision while improving consistency [6].

From a method validation perspective, key parameters such as accuracy, precision, and specificity are more readily demonstrated and documented with potentiometric systems. As per regulatory guidelines like USP <1225> and ICH Q2(R1), validation requires demonstrating that a method is unaffected by small variations in procedure or sample composition [4]. Potentiometry excels in specificity, as it can often distinguish between different components in a mixture. For example, in the titration of potassium bicarbonate with an impurity of potassium carbonate, potentiometry clearly showed two distinct endpoints, whereas a visual method might have seen a single, blurred color transition [4]. Furthermore, the precision of automated potentiometric titration is superior, as it eliminates the variability introduced by different analysts manually adding titrant and judging color changes [4].

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

Key Experimental Protocol: Manual Acid-Base Titration

A typical protocol for a manual acid-base titration, using a strong base to titrate a strong acid, is outlined below.

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a standardized solution of sodium hydroxide (NaOH) as the titrant. Precisely measure a known volume of the unknown hydrochloric acid (HCl) solution into a clean Erlenmeyer flask.

- Indicator Addition: Add 2-3 drops of phenolphthalein indicator to the acid solution in the flask. The solution will remain colorless.

- Titration: Fill a clean burette with the standardized NaOH solution. Record the initial burette reading. While continuously swirling the flask, slowly add the NaOH solution from the burette to the acid.

- Endpoint Detection: As titration proceeds, a faint pink color may appear where the titrant enters the solution but will disappear upon swirling. Continue adding titrant drop by drop until a faint pink color persists throughout the solution for at least 30 seconds. This is the visual endpoint.

- Calculation: Record the final burette reading. The difference between the initial and final readings is the volume of titrant used. Using the known concentration of the NaOH and the reaction stoichiometry (1:1 for HCl:NaOH), calculate the concentration of the HCl analyte.

The Scientist's Titration Toolkit

The following table details essential reagents, materials, and equipment used in titration laboratories.

Table 2: Key research reagents and essential materials for titration experiments.

| Item | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| Burette | A precision glassware with a stopcock for accurately dispensing variable volumes of titrant [2]. |

| Primary Standards | High-purity, stable compounds (e.g., potassium hydrogen phthalate) used to determine the exact concentration of the titrant solution [4]. |

| Visual Indicators | Chemical substances (e.g., phenolphthalein, methyl orange) that signal the endpoint via a color change [2]. |

| pH Electrode | A combined sensor used in potentiometric titrations to measure the potential related to the H+ ion concentration; essential for acid-base titrations [2] [3]. |

| Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) | Used in potentiometric titrations to measure the potential of specific ions (e.g., chloride, calcium), enabling specific complexometric or precipitation titrations [2]. |

| Autotitrator | An automated instrument that controls titrant addition, records data (volume and potential), and calculates the endpoint, ensuring high precision and data integrity [4] [3]. |

Volumetric titration, defined by its reliance on volume measurement and visual endpoint detection, remains a cornerstone of analytical chemistry due to its simplicity and low cost. Its principles are foundational for understanding stoichiometry and analytical technique. However, within the rigorous framework of modern research and drug development, where method validation, data integrity, and precision are paramount, manual volumetric titration shows significant limitations.

The comparative analysis demonstrates that potentiometric titration offers superior precision, objectivity, and specificity, making it the more reliable and robust choice for validated methods. Its ability to handle complex samples, provide full titration curves, and integrate seamlessly into automated workflows aligns with the demands of high-throughput laboratories and stringent regulatory environments. While manual volumetric titration retains its value in educational settings and for simple, clear samples, the advancement toward instrumental endpoint detection represents the standard for critical scientific and industrial applications.

In the realm of analytical chemistry, titration methods represent a cornerstone for quantitative analysis, enabling researchers to determine the concentration of unknown substances with precision. Among these techniques, potentiometric titration has emerged as a sophisticated alternative to traditional volumetric titration, particularly in pharmaceutical and research applications where accuracy, reliability, and method validation are paramount. This analytical approach replaces visual indicator detection with electrochemical potential measurements, offering distinct advantages for complex sample matrices and method validation protocols.

While volumetric titration relies on visual color changes of chemical indicators to signal the titration endpoint, potentiometric titration measures the potential difference between two electrodes as a function of the added titrant volume. This fundamental difference in detection methodology creates significant implications for accuracy, applicability, and validation parameters in pharmaceutical analysis and research settings. As regulatory requirements for analytical method validation become increasingly stringent, understanding the comparative performance characteristics of these techniques is essential for scientists and drug development professionals.

Principles and Theoretical Framework

Fundamental Mechanism of Potentiometric Titration

Potentiometric titration operates on the principle of measuring the electrochemical potential of a solution during a titration process, rather than relying on visual indicators. This technique employs an electrochemical cell consisting of two electrodes—an indicator electrode and a reference electrode—immersed in the analyte solution [7] [8]. The reference electrode maintains a constant, known potential, while the indicator electrode responds to changes in the concentration (activity) of the ionic species involved in the titration reaction [9].

As titrant is added to the analyte solution, the concentration of the target species changes, altering the potential of the indicator electrode relative to the reference electrode. The relationship between potential and concentration is governed by the Nernst equation, which for a general reduction reaction (Ox + ne⁻ → Red) is expressed as:

[E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln\frac{[Red]}{[Ox]}]

Where E is the electrode potential, E⁰ is the standard electrode potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is Faraday's constant, and [Red] and [Ox] are the concentrations of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [7]. This fundamental relationship enables precise monitoring of the titration progress and accurate endpoint determination.

Electrode Systems and Technology

The performance of potentiometric titration heavily depends on the electrode technology employed. The reference electrode, typically a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode or calomel electrode, provides a stable reference potential against which changes are measured [9] [8]. The indicator electrode varies based on the application and may include glass membrane electrodes for pH measurements, metallic electrodes for redox titrations, or ion-selective electrodes for specific ions [7] [8].

In modern potentiometric systems, specialized electrodes have been developed for specific analytical applications. For pharmaceutical analysis, composite electrodes and solid-state membranes offer improved selectivity and reduced interference from sample matrix components. The continuous development of electrode technology has significantly expanded the applications of potentiometric titration in complex sample matrices encountered in pharmaceutical and biological research.

Comparative Analysis: Potentiometric vs. Volumetric Titration

Endpoint Detection Mechanisms

The fundamental distinction between potentiometric and volumetric titration lies in their endpoint detection methodologies. This difference significantly impacts their application scope, accuracy, and reliability in pharmaceutical analysis and research settings.

(Titration Endpoint Detection Mechanisms)

Performance Comparison in Pharmaceutical Analysis

Quantitative comparisons between potentiometric and volumetric titration methods reveal significant differences in analytical performance characteristics, particularly in pharmaceutical quality control applications.

Table 1: Method Performance Comparison for Zinc Pyrithione Quantification in Shampoo Samples

| Performance Parameter | Potentiometric Titration | Complexometric Volumetric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity (LOD) | 0.0038% | 0.0534% |

| Precision (RSD%) | <1% | <1% |

| Accuracy (% Recovery) | >99% | >99% |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal | Moderate |

| Analysis Time | Shorter | Longer |

| Automation Potential | High | Low |

Data adapted from validation study of zinc pyrithione quantification methods [10]

The enhanced sensitivity of potentiometric titration (approximately 14-fold lower detection limit) demonstrates its superior capability for quantifying low analyte concentrations, a critical requirement in pharmaceutical analysis where active ingredients may be present at low concentrations or where impurity profiling requires sensitive detection methods.

Applications Spectrum in Pharmaceutical Research

Both titration methods find applications across pharmaceutical research and quality control, but their relative advantages make them suitable for different analytical scenarios.

Table 2: Method Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Analysis

| Application Area | Potentiometric Titration | Volumetric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Acid-Base Titration | Excellent (especially for colored solutions) [8] | Good (clear solutions only) [11] |

| Redox Titration | Excellent (e.g., Fe²⁺ with KMnO₄) [9] [8] | Moderate (subjective endpoint) |

| Complexometric Titration | Excellent (metal ion quantification) [8] | Good (indicator dependent) [10] |

| Precipitation Titration | Excellent (e.g., chloride with AgNO₃) [8] | Moderate (indicator limitations) |

| Pharmaceutical Formulations | Excellent (direct analysis) [10] | Moderate (interference issues) |

| Biochemical Systems | Excellent (redox potential studies) [12] | Not applicable |

Experimental Protocols and Method Validation

Potentiometric Titration Protocol for Pharmaceutical Analysis

A validated potentiometric titration method for zinc pyrithione quantification in shampoo formulations exemplifies a robust pharmaceutical analysis protocol [10]:

Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 6.3 g of shampoo sample and transfer to the titration cell. Add 50 mL of deionized water and 10 mL of fuming hydrochloric acid (37%).

Instrumentation Setup: Assemble the automatic titrator (Mettler Toledo T70) with a platinum indicator electrode (DMI 140-SC) and Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Ensure constant stirring throughout the titration process.

Titration Procedure: Titrate the sample with 0.05 M iodine solution using incremental additions. Monitor the potential change after each addition until equilibrium is established (typically 30 seconds between additions).

Endpoint Determination: Record the titration curve (potential vs. titrant volume). Determine the endpoint mathematically from the inflection point of the sigmoidal curve using the first or second derivative method.

Calculation: Calculate the zinc pyrithione concentration based on the titrant consumption at the endpoint and the known stoichiometry of the reaction.

Volumetric Titration Protocol for Comparative Analysis

The comparative volumetric method for the same analytical application follows a traditional approach [10]:

Sample Preparation: Weigh 6.0 g of shampoo sample and dilute with 50 mL of deionized water. Add 2.5 mL of hydrochloric acid with heating and gentle stirring for 10 minutes. Add 0.5 mL of hydrogen peroxide and cool the mixture.

pH Adjustment: Adjust the pH using ammonia solution and add 2.5 mL of ammonium chloride/ammonia buffer (pH = 10).

Indicator Addition: Add eriochrome black T indicator solution until a distinct violet color is observed.

Titration Procedure: Titrate with 0.01 M EDTA solution while continuously swirling the titration flask.

Endpoint Determination: Observe the color change from violet to blue, indicating the equivalence point. Record the volume of titrant consumed.

Calculation: Determine the zinc pyrithione concentration based on EDTA consumption and reaction stoichiometry.

Method Validation Parameters

For pharmaceutical applications, both methods must undergo comprehensive validation as per ICH and USP guidelines [10]. Key validation parameters include:

- Selectivity: Assessment of interference from placebo components and degradation products under stress conditions (photolysis, thermolysis, oxidation).

- Linearity: Evaluation across concentration ranges (typically 0.2-1.4% w/w for zinc pyrithione) with determination coefficients (R²) >0.99.

- Precision: Determination of repeatability (RSD% <1%) and intermediate precision through inter-day and inter-analyst studies.

- Accuracy: Recovery studies at multiple concentration levels with acceptable recovery rates (98-102%).

- Robustness: Evaluation of method resilience to deliberate variations in operational parameters (pH, temperature, sample weight, stirring time).

Advanced Applications and Specialized Techniques

Biochemical and Pharmaceutical Research Applications

Potentiometric titration finds specialized applications in biochemical and pharmaceutical research beyond routine quality control. The method is particularly valuable for determining reduction potentials of redox-active cofactors in proteins and enzymes, providing critical insights into electron transfer processes relevant to drug metabolism and therapeutic mechanisms [12].

In biopharmaceutical characterization, potentiometric titrations enable the study of metalloproteins and enzyme systems under various physiological conditions. These applications often combine potentiometric measurements with spectroscopic techniques such as electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) to correlate electrochemical properties with structural features [12]. The ability to monitor redox states and protonation events in biological macromolecules makes this technique invaluable for understanding drug-receptor interactions and metabolic pathways.

Material Characterization and Polymer Analysis

In pharmaceutical material science, potentiometric titration provides critical data for biomaterial characterization. A prominent application involves determining the degree of deacetylation (DDA) in chitosan-based biomaterials, a key parameter influencing drug delivery system performance [12]. The protocol involves dissolving a known quantity of chitosan in a standard HCl solution and titrating against NaOH while monitoring pH changes. The inflection points in the titration curve correspond to specific protonation events, enabling calculation of amine content and DDA percentage using established equations [12].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Successful implementation of potentiometric titration methods requires specific reagents and instrumentation tailored to the analytical application.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Potentiometric Titration

| Item | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Electrode | Provides stable reference potential for measurements | Ag/AgCl electrode, calomel electrode [9] [8] |

| Indicator Electrode | Responds to changes in analyte concentration during titration | Platinum electrode, glass pH electrode, ion-selective electrodes [8] |

| Redox Mediators | Facilitate electron transfer in biochemical systems | 1,2-naphthoquinone, methyl viologen, ruthenium complexes [12] |

| Titrant Solutions | Standardized solutions for analyte reaction | Iodine (0.05 M), EDTA (0.01 M), NaOH, HCl [10] |

| Buffer Systems | Maintain constant pH for specific applications | Phosphate buffer, ammonium chloride/ammonia buffer (pH 10) [10] |

| Automatic Titrator | Precise titrant delivery and potential measurement | Mettler Toledo T70 with endpoint detection algorithms [10] |

The comparative analysis of potentiometric and volumetric titration methods reveals a complex landscape where each technique occupies distinct niches in pharmaceutical research and quality control. Potentiometric titration offers superior sensitivity, objectivity, and automation capability, making it particularly valuable for complex sample matrices, low analyte concentrations, and method validation protocols requiring robust data integrity. The technique's independence from visual endpoint detection eliminates subjective interpretation, while continuous potential monitoring provides comprehensive reaction progress data beyond simple endpoint determination.

Volumetric titration maintains relevance in resource-limited settings and for applications where rapid analysis outweighs precision requirements. Its simplicity, lower equipment costs, and established history in pharmaceutical analysis ensure its continued utilization for routine quality control of formulations with favorable analytical characteristics. However, the limitations in analyzing colored or turbid solutions and the subjective nature of visual endpoint detection restrict its application in modern pharmaceutical research and regulatory submissions.

The selection between these analytical approaches ultimately depends on specific application requirements, regulatory expectations, available resources, and required data quality. For drug development professionals and researchers, understanding the comparative advantages, limitations, and validation parameters of both techniques enables informed method selection based on analytical science principles rather than tradition or convenience alone. As pharmaceutical analysis continues to advance toward increasingly automated and data-rich methodologies, potentiometric titration will likely assume greater prominence in the researcher's analytical toolkit, particularly for challenging applications requiring validated, robust analytical methods.

Titration remains a cornerstone analytical technique across pharmaceutical, chemical, and materials science industries. The methodology, however, is undergoing a significant transformation, shifting from traditional manual volumetric titration toward automated potentiometric systems. This evolution is driven by increasing demands for data integrity, reproducibility, and operational efficiency in research and quality control environments, particularly in highly regulated sectors like drug development [13] [1].

This guide objectively compares the performance of automated potentiometric titration with manual alternatives, framing the discussion within the broader context of method validation research. For scientists and drug development professionals, the choice between these systems impacts not only daily workflows but also the fundamental reliability of the data supporting critical decisions.

Performance Comparison: Automated Potentiometric vs. Manual Volumetric Titration

A direct comparison of key performance parameters reveals the operational and scientific advantages of automation.

Table 1: Systematic Performance Comparison of Titration Methods

| Performance Parameter | Automated Potentiometric Titration | Manual Volumetric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy & Precision | High accuracy and precision; based on objective electrode data; precision dosing to 0.001 mL [13] [14] | Dependent on analyst skill; subjective visual endpoint detection; lower dosing precision [13] [1] |

| Repeatability (\% RSD) | Excellent (e.g., <1% RSD demonstrated in pharmaceutical validation) [15] | Variable; susceptible to inter-operator differences [13] |

| Data Traceability | Full automated data logging; customizable GLP reports; easy audit trails [13] [14] | Manual transcription prone to error; limited inherent traceability [13] |

| Sample & Reagent Consumption | Lower consumption due to smaller sample sizes and high dosing accuracy [13] | Larger sample sizes and titrant volumes often needed for reliable visual detection [13] |

| Analyst Time & Labor | Significantly reduced active bench time; walk-away operation [13] [16] | Labor-intensive; requires constant attention throughout the titration [1] [14] |

| Throughput | High, especially when integrated with autosamplers (e.g., 18+ samples per batch) [13] | Low to moderate, limited by analyst availability and speed [13] |

| Hazard Management | Reduced exposure to hazardous chemicals; enclosed reagent systems [16] [14] | Higher risk of exposure during manual handling and disposal [16] |

The quantitative data in Table 1 underscores a clear trend: automated potentiometric systems provide superior analytical robustness while creating a more efficient and safer laboratory environment.

Experimental Protocols and Validation Data

A Validated Method for Pharmaceutical Analysis

A 2022 study developed and validated a non-aqueous potentiometric titration method for quantifying Favipiravir in pharmaceutical dosage forms, showcasing the rigor achievable with automation [15].

- Methodology: The titration was performed using a standardized 0.1 N perchloric acid titrant in a non-aqueous medium. The potentiometric endpoint was detected automatically, eliminating the need for a visual indicator [15].

- Validation Data:

- Precision: The method was found to be precise with a percent relative standard deviation (\%RSD) of less than 1% (n=6).

- Linearity: It showed strict linearity (r² > 0.9999) across a range of 10% to 50% w/v of the target analyte weight.

- Accuracy: Percentage recovery was reported between 99.65% to 100.08%, confirming high accuracy.

- Ruggedness: The method was found rugged when checked by different analysts and using different lots of reagents [15].

This protocol exemplifies how automated potentiometric titration meets the stringent validation requirements of pharmaceutical development, providing a reliable foundation for quality control.

Core Workflow of a Potentiometric Titration

The fundamental principle of potentiometric titration involves measuring the potential between a reference electrode and an indicator electrode as a function of the added titrant volume [12] [9]. The endpoint is determined by identifying the inflection point in the potential-versus-volume curve, which corresponds to the equivalence point of the chemical reaction [13] [9].

Diagram 1: Potentiometric titration workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation and validation of titration methods rely on a set of essential reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Potentiometric Titration

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| Indicator Electrode | Sensor (e.g., pH, ion-selective) that responds to the activity of the analyte/participating ion; the core of objective endpoint detection [13] [12]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, fixed potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured [9]. |

| Standardized Titrant | A reagent of precisely known concentration; its purity and stability are critical for method accuracy [15] [14]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Maintains a constant ionic strength, minimizing activity coefficient changes and ensuring a stable potential response [9]. |

| Redox Mediators | Used in some redox titrations to facilitate electrical communication between the electrode and analyte, ensuring a well-defined endpoint [12]. |

| pH Buffers | Essential for electrode calibration and for titrations where the reaction is pH-dependent [1]. |

Visualizing the Automated Potentiometric System Workflow

Modern automated systems integrate several components to create a seamless, walk-away operation. The system's software controls the entire process, from dosing and data acquisition to endpoint calculation and report generation, ensuring unattended operation and full traceability [13] [17] [16].

Diagram 2: Automated titration system interaction.

The driving forces behind the shift to automated potentiometric systems are clear and compelling. The move is propelled by the intertwined needs for data integrity mandated by modern regulations, the demand for operational efficiency in competitive R&D environments, and the universal scientific pursuit of accurate and reproducible results. While manual volumetric titration retains a place in educational settings or applications where cost is the primary constraint, the evidence from performance comparisons and validation studies firmly positions automated potentiometric titration as the superior choice for research and drug development professionals. The initial capital investment is rapidly offset by savings in time, reagents, and the invaluable currency of reliable data [13] [16].

Market Landscape and Adoption Trends in Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Sectors

In the highly regulated pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries, the precision and reliability of analytical methods are paramount for ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy. Titration, a fundamental analytical technique for concentration determination, is primarily executed through volumetric and potentiometric methods. The choice between these methods significantly impacts data integrity, operational efficiency, and regulatory compliance. This guide provides an objective comparison of potentiometric and volumetric titration, framing the analysis within the broader context of method validation to support informed decision-making by researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The global market for automated analytical instrumentation, including potentiometric titration systems, is poised for steady growth, projected to be valued at $261 million in 2025 with a Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 2.5% [18]. The pharmaceutical and biotechnology sector constitutes the largest end-market segment, accounting for an estimated 35% of the total market [18]. This adoption is driven by stringent regulatory requirements and the critical need for precise, traceable results in quality control (QC) and research and development (R&D) [18].

Technical Comparison: Potentiometric vs. Volumetric Titration

The core distinction between these techniques lies in their endpoint detection mechanisms. Volumetric titration typically relies on a visual color change from an indicator, whereas potentiometric titration measures the change in electrical potential between two electrodes [2] [19].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Titration Methods

| Characteristic | Volumetric Titration | Potentiometric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Measurement of reagent volume added to cause a visual color change at the endpoint [2]. | Measurement of electrical potential change between an indicator and a reference electrode to determine the endpoint [2] [12]. |

| Endpoint Detection | Visual observation of indicator color change [1] [2]. | Electrochemical sensor (e.g., platinum electrode) detecting a voltage shift [20] [2]. |

| Primary Output | Volume of titrant consumed [20]. | Titration curve (Potential vs. Titrant Volume) [2] [12]. |

| Automation Potential | Lower; available with specialized equipment [1]. | High; easily automated and integrated into continuous systems [1] [18] [19]. |

| Level of Subjectivity | High; prone to human error in color perception [1] [2]. | Low; objective, instrument-based measurement [1] [19]. |

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Pharmaceutical and Biotechnology Applications

| Performance Metric | Volumetric Titration | Potentiometric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Accuracy & Precision | High in well-controlled systems, but variable due to subjectivity [1]. | Higher precision and accuracy; minimizes human error [1] [2] [19]. |

| Sample Versatility | Excellent for complex matrices (e.g., suspensions, high-color samples) where electrodes may foul [1]. | Ideal for clear aqueous solutions; performance can be affected by high-salt, oily, or viscous samples [1]. |

| Throughput & Labor | Labor-intensive and time-consuming, especially in manual mode [1] [21]. | High throughput with automation; minimal analyst involvement required [1] [18] [19]. |

| Data & Compliance | Manual data recording; less suitable for electronic data integrity requirements. | Compliance-ready data logging; sophisticated software for analysis and reporting aids in regulatory compliance [18]. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Lower initial equipment cost; higher long-term labor and reagent costs [1] [2]. | Higher initial investment; lower per-sample cost and better ROI in high-volume or regulated environments [1] [18]. |

The Karl Fischer Method: A Specialized Case Study

Karl Fischer (KF) titration is the gold standard for specific water content determination, a critical parameter in pharmaceutical stability [20] [21]. This method exemplifies the volumetric vs. coulometric (an advanced potentiometric) dichotomy:

- Volumetric KF Titration: Uses a reagent with a known concentration of iodine. It is suitable for samples with water content ranging from 0.01% to 100% [20] [21].

- Coulometric KF Titration: Iodine is generated electrochemically within the cell. It offers unparalleled sensitivity for trace moisture, ideal for samples with water content from 1 ppm to 5% [20] [21].

The specificity of the KF reaction for water makes it superior to non-specific methods like loss-on-drying (LOD) [20] [21]. However, it can be susceptible to interference from certain functional groups, necessitating method optimization [21].

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

A robust method validation is essential for establishing that a titration procedure is suitable for its intended use. The following protocols outline key experiments for comparing potentiometric and volumetric methods.

Protocol for Accuracy and Precision Determination

This experiment assesses the trueness (closeness to true value) and precision (repeatability) of each method.

- Objective: To determine the accuracy and precision of potentiometric and volumetric titration methods for the assay of a standard active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) solution.

- Materials:

- Standard solution of a known API (e.g., 0.1 M HCl)

- Titrant of known concentration (e.g., 0.1 M NaOH)

- Appropriate visual indicator (e.g., phenolphthalein for volumetric acid-base titration)

- Potentiometric titrator with pH electrode

- Burette, volumetric flasks, and pipettes

- Procedure:

- Prepare a standardized titrant solution and document its exact concentration.

- For the volumetric method, pipette a precise volume of the standard API solution into an Erlenmeyer flask. Add 2-3 drops of indicator. Titrate until the endpoint color change is observed and record the volume of titrant used. Repeat at least six times (n=6).

- For the potentiometric method, pipette the same volume of standard API into a beaker. Immerse the pH electrode. Start the automated titrator to add titrant while recording the pH and volume. The endpoint is determined from the inflection point of the resulting sigmoidal curve. Repeat at least six times (n=6).

- For both methods, calculate the measured concentration of the API for each replication.

- Data Analysis:

- Accuracy: Calculate the percent recovery for each replication:

(Measured Concentration / Known Concentration) * 100. Report the mean recovery. - Precision: Calculate the relative standard deviation (RSD) of the measured concentrations from the six replicates for each method.

- Accuracy: Calculate the percent recovery for each replication:

The potentiometric method is expected to yield a higher accuracy (mean recovery closer to 100%) and a significantly lower RSD, demonstrating superior precision and reduced operator subjectivity [2] [19].

Protocol for Robustness Testing with Complex Matrices

This experiment evaluates the method's performance when analyzing real-world, complex samples.

- Objective: To compare the ability of potentiometric and volumetric titration to accurately determine the analyte concentration in a complex, buffered pharmaceutical formulation.

- Materials:

- A formulated product (e.g., a buffered solution, a suspension, or a colored liquid).

- Appropriate titrant and indicators.

- Potentiometric titrator with a relevant electrode (pH, redox, etc.).

- Procedure:

- For the volumetric method, prepare and titrate the sample as described in Protocol 3.1. Note any challenges, such as difficulty observing the color change due to the sample's inherent color or turbidity.

- For the potentiometric method, perform the titration automatically. The system will generate a full titration curve.

- Data Analysis:

- Compare the clarity of the endpoint determination. For volumetric titration, note the subjectivity of the visual change.

- For potentiometric titration, inspect the titration curve. A well-defined, steep inflection point indicates a robust and precise endpoint, even in complex matrices [1] [12]. A distorted curve may indicate electrode fouling or slow reaction kinetics.

Volumetric titration may be preferred for specific challenging samples like highly colored solutions or suspensions where electrodes fail, while potentiometry excels at mapping complex buffering systems found in many formulations [1].

Workflow and System Configuration

The fundamental workflows for manual volumetric and automated potentiometric titration differ significantly, impacting labor, speed, and data handling. The diagrams below illustrate these logical processes.

Volumetric Titration Workflow

Automated Potentiometric Titration Workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key materials and reagents required for establishing and executing titration methods in a pharmaceutical R&D or QC setting.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Titration Methods

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Volumetric Titrant | A solution of known concentration (e.g., NaOH, HCl) that reacts with the analyte. | Requires regular standardization (titer determination) to ensure accuracy [20]. |

| Visual Indicators | Substances that change color at/near the endpoint (e.g., phenolphthalein, methyl orange). | Selection is critical and depends on the reaction type and expected endpoint pH [2]. |

| Potentiometric Electrode | Sensor pair (indicator + reference) that measures potential change in the solution. | Selection (pH, redox, ion-selective) depends on the titration reaction [2]. Requires regular calibration and maintenance [1]. |

| Karl Fischer Reagents | Specialized reagents (alcohol, SO₂, base, I₂) for water-specific determination [20]. | Volumetric: reagent with known water equivalence. Coulometric: reagent for iodine generation. May require methanol-free versions for ketones/aldehydes [21]. |

| Certified Reference Materials | Substances with certified purity/water content (e.g., disodium tartrate dihydrate). | Used for system suitability testing, method validation, and titrant standardization to ensure overall accuracy [21]. |

The choice between potentiometric and volumetric titration is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific application. The experimental data and market trends consistently demonstrate that automated potentiometric titration offers significant advantages in precision, automation, cost-efficiency for high-volume labs, and data integrity, making it the growing standard for regulated pharmaceutical and biotechnology environments [1] [18] [19].

However, volumetric methods retain their value for specific scenarios, including labs with low initial budgets, the analysis of samples that interfere with electrodes, or when a simple, rapid test is sufficient. Furthermore, specialized volumetric methods like Karl Fischer titration remain indispensable for specific analyses like high-water content determination.

The ongoing innovation in automated titration systems, focused on enhanced software, miniaturization, and advanced sensors, will continue to solidify the role of objective, automated potentiometric systems in ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of future pharmaceuticals [18].

Practical Implementation: Selecting the Right Method for Your Application

In the rigorous framework of method validation for analytical techniques, selecting the appropriate titration method is a critical decision that directly impacts the accuracy, reproducibility, and efficiency of quantitative analysis. This guide provides an objective comparison between potentiometric titration and volumetric titration, focusing on their performance across diverse sample matrices—aqueous, complex, and viscous. The fundamental distinction lies in endpoint detection: potentiometric titration measures a change in electrical potential between an indicator electrode and a reference electrode, while volumetric titration relies on observing a visual change, such as a color shift, using a chemical indicator [22] [23]. Within pharmaceutical development and other precision-driven industries, this choice is not merely procedural but foundational to ensuring data integrity and regulatory compliance.

The selection of a titration method must be guided by the specific characteristics of the sample matrix. The following table summarizes the core performance attributes of each method against the key sample types, providing a high-level guide for method selection.

| Sample Matrix | Potentiometric Titration | Volumetric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solutions | Excellent. Offers high accuracy and real-time monitoring for clear aqueous samples [1]. | Good. Suitable for routine analysis of simple aqueous solutions where a clear visual endpoint is attainable [1]. |

| Complex Matrices | Excellent. Ideal for colored, turbid, or opaque solutions where visual indicators fail. Effective for samples with multiple buffering agents [22] [1]. | Poor. Visual endpoint detection is compromised by sample color or turbidity, leading to subjective and inaccurate readings [22]. |

| Viscous Samples | Good. Effective, though may require sample preparation or electrode resistant to fouling. Successfully used for ointments and creams [24]. | Poor. Challenging due to hindered color uniformity and mixing efficiency, which can obscure the visual endpoint [1]. |

Detailed Performance Analysis and Experimental Data

Quantitative Performance Metrics

Beyond the qualitative matrix fit, the choice between methods is supported by quantifiable performance data. The following table consolidates key metrics from validation studies and comparative analyses.

| Performance Metric | Potentiometric Titration | Volumetric Titration | Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Precision (RSD%) | Typically < 1% [10] | Subject to higher variability | A study on ZnPT assay found RSD% below 1% for potentiometric method [10]. |

| Detection Sensitivity | Higher | Lower | In ZnPT assay, LOQ for potentiometric was 0.0038% vs. 0.0534% for volumetric [10]. |

| Analysis Time | Faster for automated systems; can be slower if potential stabilization is needed [23] | Generally fast, especially for manual routine analysis [23] | Automated potentiometric titration of APIs like sulfanilamide takes 3-5 minutes [24]. |

| Total Acidity in Wine (Aberrance) | Benchmark | 0.1 - 0.4 g L⁻¹ aberrance from potentiometric | A study on wine found aberrances in this range for volumetric vs. potentiometric results [25]. |

Case Studies and Experimental Protocols

Case Study 1: Assay of Zinc Pyrithione (ZnPT) in Shampoo

- Objective: To validate and compare complexometric (volumetric) and potentiometric titration methods for quantifying ZnPT in shampoo [10].

- Sample Matrix: Complex and viscous (shampoo).

- Potentiometric Protocol: 6.3 g of shampoo was weighed and transferred to the titration cell with 50 mL of water and 10 mL of fuming hydrochloric acid. The mixture was titrated with 0.05 M iodine solution using an automatic titrator. The endpoint was determined by a platinum electrode [10].

- Volumetric Protocol: 6.0 g of shampoo was diluted in 50 mL of water. Then, 2.5 mL of hydrochloric acid was added with heating and stirring for ten minutes. After pH adjustment with an ammonia solution and a buffer (pH=10), the sample was titrated with 0.01 M EDTA using eriochrome black T as an indicator. The endpoint was a color change from violet to blue [10].

- Results: The potentiometric method demonstrated superior sensitivity (Limit of Quantification of 0.0038% vs. 0.0534%) and precision (RSD < 1%) compared to the volumetric method, making it more reliable for quality control [10].

Case Study 2: Total Acidity in Wine

- Objective: To compare the determination of total acidity in wines using potentiometric and volumetric titration [25].

- Sample Matrix: Complex and colored (red, white, and rosé wines).

- Protocol: Thirty-seven wine samples were analyzed. Potentiometric titration was performed automatically with different titrant addition rates. The results were compared to those obtained by conventional volumetric titration with a color indicator [25].

- Results: The total acidity values depended on the method used. While a good correlation was found, significant aberrances of 0.1 to 0.4 g L⁻¹ were observed for some wines, highlighting the potential for error in the volumetric method when dealing with colored samples [25].

Method Selection Workflow

The decision-making process for selecting the appropriate titration method can be visualized as a logical pathway based on sample properties and analytical requirements. The following diagram outlines this workflow:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful execution of titration methods, whether for development or validation, relies on a set of key reagents and instruments. The following table details these essential materials and their functions.

| Tool Category | Specific Examples | Function in Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Electrodes | Glass pH Electrode, Platinum Electrode, Ion-Selective Electrodes, Reference Electrodes (e.g., Ag/AgCl) [22] [9] | Serves as the indicator electrode to measure potential change specific to the analyte (pH, redox species, ions) [22]. |

| Titrants | Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH), Hydrochloric Acid (HCl), Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid (EDTA), Sodium Thiosulfate, Iodine Solution [24] [10] | The standard solution of known concentration that reacts with the analyte. Choice depends on reaction type (acid-base, complexometric, redox) [24] [10]. |

| Chemical Indicators | Phenolphthalein, Eriochrome Black T, Starch [10] | Provides a visual color change at the endpoint in volumetric titration. Not used in potentiometric titration [23] [10]. |

| Buffers & Reagents | Ammonia Buffer (pH=10), Potassium Bromide (KBr), Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) [24] [10] | Adjusts pH for optimal reaction, acts as a catalyst, or aids in sample digestion and preparation [24] [10]. |

| Instrumentation | Automatic Titrator (e.g., Titrando), Potentiometer, Burette [22] [24] | Automates titrant addition and endpoint detection (potentiometric) or enables precise volume measurement (volumetric) [22] [24] [23]. |

In the highly regulated field of pharmaceutical analysis, the determination of active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) potency and purity is not merely a procedural step but a critical component of quality by design (QbD) initiatives and risk reduction in drug manufacturing [24]. Titration, one of the most economical, fastest, and most reliable analytical techniques, plays a fundamental role in this process, with current United States Pharmacopeia-National Formulary (USP-NF) monographs recommending titration for approximately 630 APIs and 110 excipients [24]. Within this landscape, a significant methodological shift is occurring: the transition from traditional volumetric titration using visual indicators to modern potentiometric titration with electrochemical endpoint detection. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these techniques within the specific context of drug potency and API analysis, framed by the rigorous demands of method validation in pharmaceutical settings.

The United States Pharmacopeia Chapter <541> now officially accepts automated titration as a modern titration method, defining an automated titrator as a "multifunctional processing unit that is able to perform the steps of a titration" [26]. This regulatory recognition underscores the scientific and practical evolution in titration methodologies, positioning potentiometric approaches as pharmaceutically relevant and compliant for quality control applications.

Fundamental Principles: A Technical Comparison

Core Mechanism and Endpoint Detection

The fundamental distinction between potentiometric and volumetric titration lies in their endpoint detection mechanisms, which directly impacts their application in pharmaceutical analysis.

Potentiometric Titration relies on measuring the electrical potential difference between two electrodes—an indicator electrode and a reference electrode—as the titrant is added to the analyte solution [22] [23]. The endpoint is determined by identifying the inflection point on a titration curve where the potential change is most rapid [22]. This method does not depend on visible color changes, making it particularly suitable for colored, turbid, or opaque solutions common in pharmaceutical formulations [22].

Volumetric Titration (also known as titrimetry) is based on measuring the volume of titrant required to react completely with the analyte, with the endpoint determined by observing a color change or the formation of a precipitate using chemical indicators [23]. This visual determination introduces a subjective element that can affect accuracy and reproducibility.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Titration Techniques

| Attribute | Potentiometric Titration | Volumetric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Basis | Potential difference (voltage) between electrodes [23] | Volume of reagent required [23] |

| Endpoint Detection | Monitoring potential change via indicator electrode [22] [23] | Visual observation of color change/precipitate [23] |

| Subjectivity | Objective, instrument-based | Subjective, operator-dependent |

| Solution Requirements | Suitable for colored/turbid solutions [22] | Requires clear solutions for visual detection |

Method Validation and Regulatory Compliance

From a method validation perspective, potentiometric titration offers traceable and documentable results, which aligns with the current Good Manufacturing Practice (cGMP) requirements and the FDA's QbD initiative [24]. Automated potentiometric systems can be 21 CFR Part 11 compliant, meeting all ALCOA+ (Attributable, Legible, Contemporaneous, Original, and Accurate) requirements for data integrity [26]. The validation of titration methods is crucial in pharmaceutical quality assurance, with suitability for an intended analytical purpose proven through validation in accordance with regulatory guidelines such as USP General Chapter <1225> [26].

Experimental Performance Data: Quantitative Comparison in Pharmaceutical Applications

Accuracy and Precision in API Assay

Comparative studies demonstrate the technical performance of both methods in quantifying pharmaceutical substances.

Microtitration Development for Early-Stage APIs: In drug discovery and early development, limited API material is available for analysis. Conventional potentiometric titration typically requires 1 mmol (~400-500 mg) of material for accurate quantitation [27]. A developed microtitration method using potentiometric detection requires only 5-10 mg of sample while maintaining accuracy comparable to conventional titration [27]. In validation studies, the %RSD values for calculated weight percent results from triplicate microtitrations were 0.6% and 0.5% for different analysts, with deviations from conventional titration within 1.0% [27]. This demonstrates that potentiometric methods can be successfully miniaturized for pharmaceutical applications with minimal material.

Comparative Study on Total Acidity Determination: Although not specific to pharmaceuticals, a comparative study on wine acidity determination provides insight into methodological performance. The research found that total acidity results depended on the methods used, with aberrances ranging from 0.1 to 0.4 g L⁻¹ between methods for some samples [25]. However, a good correlation between potentiometric and volumetric methods was observed, with potentiometric titration providing accurate results at a recommended titrant addition rate of 2 mL min⁻¹ [25].

Table 2: Accuracy Comparison of Conventional vs. Micro Potentiometric Titration for APIs

| API Compound | Sample Amount (Conventional) | Sample Amount (Micro) | Deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compound A (Basic) | 444.2 mg | 5.2 mg | 0.9% [27] |

| Basic API 1 | ~500 mg | 3-7 mg | <1.1% [27] |

| Basic API 2 | ~500 mg | 3-7 mg | <1.1% [27] |

| Acidic API 1 | ~500 mg | 3-7 mg | <1.1% [27] |

| Acidic API 2 | ~500 mg | 3-7 mg | <1.1% [27] |

| Acidic API 3 | ~500 mg | 3-7 mg | <1.1% [27] |

Application-Specific Performance Data

Analysis of Sulfanilamide: The purity of sulfanilamide, used for treating vaginal yeast infections, can be determined in aqueous solution by automatic potentiometric titration using sodium nitrite as titrant [24]. With potassium bromide added as a catalyst and a Pt Titrode electrode, purity determination takes only 3-5 minutes with high accuracy [24].

Analysis of Ketoconazole: Due to its low solubility (<1 mg/mL), ketoconazole concentration is determined by non-aqueous acid-base potentiometric titration using perchloric acid as titrant and a Solvotrode easyClean electrode [24]. This method provides results in 3-5 minutes, demonstrating the adaptability of potentiometric titration to non-aqueous systems common in pharmaceutical analysis [24].

Excipient Analysis: Potentiometric titration is used for the characterization of excipients such as surfactants, edible oils, and lubricants [24]. For surfactants, specific electrodes are available for anionic, cationic, and nonionic types, replacing the classic manual Epton method with improved accuracy and repeatability [24].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Potentiometric Titration Protocol for API Analysis

The following workflow represents a standardized approach for potentiometric titration of APIs:

Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh 5-500 mg of API (depending on whether micro or conventional titration is performed) and dissolve in appropriate solvent (aqueous or non-aqueous based on solubility) [24] [27].

Electrode Selection: Choose appropriate electrodes based on reaction type:

- Combined pH electrode with reference electrolyte (3 mol/L KCl) for water-soluble acidic/basic APIs [26]

- Combined pH electrodes with alcoholic reference electrolyte (e.g., Solvotrode) for water-insoluble weak acids/bases or organic solvents [26]

- Pt metal electrodes (e.g., Pt Titrode) for redox titrations [26] [24]

- Ag metal electrodes for precipitation titrations [26]

- Ion-selective electrodes for complexometric titrations [26]

Titration Parameters: For microtitration of early-development compounds: use 1 mL burette, microelectrode (3 mm diameter), and 0.01 N titrant [27]. For conventional titration: use 20 mL burette, standard electrode (12 mm diameter), and 0.1 N titrant [27].

Endpoint Detection: Employ dynamic equivalence point titration where the first derivative of the rate of change of the potential measured against the volume added determines the endpoints [27].

Volumetric Titration Protocol for Comparison

Sample Preparation: Similar dissolution process as potentiometric method but requires clear, colorless solutions for accurate visual detection.

Indicator Selection: Choose appropriate chemical indicator based on reaction type (e.g., phenolphthalein for acid-base titrations, starch for redox titrations) [26] [23].

Titration Procedure: Add titrant gradually while swirling the solution, observing color changes. The endpoint is determined when a persistent color change is observed [23].

Calculation: Determine titrant volume at endpoint and calculate concentration based on stoichiometry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Pharmaceutical Titration

Electrode Selection Guide

Table 3: Electrode Selection for Different Pharmaceutical Titration Applications

| Application Type | Recommended Electrode | Pharmaceutical Examples | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Acid-Base Titration | Combined pH electrode with reference electrolyte c(KCl) = 3 mol/L [26] | Water-soluble acidic and basic APIs and excipients [26] | Standard aqueous applications |

| Non-Aqueous Acid-Base Titration | Combined pH electrodes with alcoholic reference electrolyte (e.g., LiCl in EtOH) [26] | Ketoconazole, caffeine; water-insoluble weak acids/bases [26] [24] | Solvent-resistant, specialized electrolytes |

| Redox Titration | Pt metal electrodes (e.g., combined Pt ring electrode, Pt Titrode) [26] | Captopril, paracetamol; antibiotic assays, peroxide value [26] | Inert electrode for electron transfer reactions |

| Precipitation Titration | Ag metal electrodes (e.g., combined Ag ring electrode) [26] | Dimenhydrinate; iodide in oral solutions [26] | Silver-based for halide determinations |

| Complexometric Titration | Ion-selective electrodes (e.g., combined calcium-selective electrode) [26] | Calcium succinate; metal salts in APIs [26] | Ion-specific membrane selectivity |

Instrumentation and Reagents

Automated Titrator: Multifunctional processing unit that performs titration steps automatically [26]. Modern systems offer 21 CFR Part 11 compliance for pharmaceutical applications [26].

Burettes: Precision dispensing systems—1 mL for microtitration [27], 20 mL for conventional titration [27].

Reference Standards: USP-grade reference materials for titrant standardization and system qualification [24].

Titrants: Standardized solutions (typically 0.1 N for conventional, 0.01 N for microtitration) including HCl, NaOH, perchloric acid, sodium nitrite, silver nitrate, and EDTA depending on application [24] [27].

Advantages and Limitations in Pharmaceutical Context

Advantages of Potentiometric Titration

Objective Detection: Removes subjectivity of visual color changes, providing reproducible results between analysts and laboratories [26] [23].

Application Range: Suitable for colored, turbid, or opaque solutions where visual indicators are ineffective [22].

Automation Capability: Fully automatable process from titrant addition to result calculation, reducing human error and increasing throughput [26] [24].

Multi-Parameter Data: Provides additional information such as pKa values and ionization states important for drug candidate selection [27].

Miniaturization Potential: Can be scaled down to microtitration for early development when API is scarce [27].

Limitations and Considerations

Equipment Cost: Requires specialized instruments including potentiometer and electrodes, which are more expensive than simple burettes [23].

Technical Expertise: Requires understanding of electrode selection, maintenance, and potential interpretation [22].

Interference Sensitivity: Presence of interfering substances can affect potential measurements [23].

Process Speed: Can be slower than volumetric titration as the potential difference needs to stabilize before endpoint determination [23].

Within the rigorous framework of pharmaceutical analysis and method validation, potentiometric titration emerges as a superior technique for API potency determination and quality control applications. The objective, automated nature of potentiometric methods, combined with their adaptability to various sample types (including colored solutions and non-aqueous systems) and miniaturization potential for early-stage development, positions them as the modern standard for pharmaceutical titration [22] [26] [24].

While volumetric titration retains value for simple, routine analyses with clear solutions and when equipment cost is a primary concern [23], the regulatory acceptance of automated titration [26], combined with the demands of current Good Manufacturing Practices and quality by design initiatives [24], makes potentiometric titration the recommended approach for drug potency and API analysis in modern pharmaceutical development and manufacturing environments. The method's ability to provide digitized, traceable results with minimal subjectivity aligns with the data integrity requirements of contemporary pharmaceutical quality systems, justifying its implementation despite higher initial equipment investment.

In pharmaceutical, chemical, and food manufacturing, the quality of raw materials is paramount for ensuring final product safety, efficacy, and consistency. Titration, a cornerstone analytical technique of quantitative analysis, is indispensable in raw material testing for determining the concentration of a specific analyte in a sample. It provides the high accuracy and reproducibility demanded by stringent quality control protocols and regulatory bodies. The choice between volumetric titration (using a visual indicator to detect the endpoint) and potentiometric titration (using electrodes to measure the endpoint) significantly impacts the reliability, efficiency, and cost-effectiveness of the analysis [1] [2]. This guide objectively compares these two methods within the critical context of method validation, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the data needed to select the appropriate technique for their raw material testing.

Volumetric vs. Potentiometric Titration: A Comparative Analysis

Volumetric titration is a traditional wet chemistry method where a titrant of known concentration is added to the analyte until a chemical reaction is complete, signaled by a color change from a visual indicator [1] [2]. In contrast, potentiometric titration employs an electrode system to measure the potential difference (voltage) in the solution throughout the titration. The resulting titration curve is plotted, and the equivalence point is precisely identified at its steepest section, eliminating subjective visual interpretation [2].

The following table summarizes the core differences between these two techniques, highlighting their performance in a quality control setting.

Table 1: Comprehensive comparison of volumetric and potentiometric titration for quality control

| Feature | Volumetric Titration | Potentiometric Titration |

|---|---|---|

| Basic Principle | Visual endpoint detection via color-changing indicator [2]. | Instrumental endpoint detection via potential measurement using electrodes [2]. |

| Accuracy & Precision | High accuracy in well-controlled systems; precision susceptible to human error in visual judgment [1] [2]. | High precision and accuracy; objective measurement pinpoints equivalence point more reliably [2]. |

| Sample Versatility | Excellent for complex matrices (buffered systems, colored/turbid samples) where electrodes may foul [1]. | Ideal for clear aqueous solutions; performance can be hampered by high-salt, oily, or viscous samples [1]. |

| Automation Potential | Low for manual methods; automated titrators exist but require specialized setup [1]. | Highly automatable; easily integrated into continuous monitoring systems and automated workflows [1] [4]. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Lower initial equipment cost; higher long-term labor and reagent costs [1]. | Higher initial investment in equipment and electrodes; lower per-sample cost and labor in high-volume use [1]. |

| Ease of Use & Expertise | Requires significant analyst expertise for precise technique and endpoint interpretation [1]. | Easier to perform; requires training on electrode maintenance and calibration [1]. |

| Regulatory & Data Integrity | Manual data recording is prone to error; meets compendial requirements but with higher audit risk [28]. | Superior data integrity; automated systems provide electronic records, audit trails, and meet FDA 21 CFR Part 11 guidelines [4]. |

| Key Applications in Raw Material Testing | Quality control of raw materials with inherent color or turbidity; alkalinity/acidity testing where buffering capacity is informative [1]. | High-throughput QC of clear raw materials (acids, bases, salts); analysis where precise equivalence point detection is critical [1] [29]. |

Experimental Protocols for Method Validation

To ensure a titration method is suitable for its intended use in raw material testing, it must be rigorously validated. The following protocols outline key experiments to compare and validate volumetric and potentiometric methods, based on standards such as USP General Chapter <1225> and ICH Q2(R1) [4].

Protocol for Determining Accuracy and Precision

Objective: To assess the closeness of agreement between the measured value and the true value (accuracy) and the degree of scatter among the measured values (precision) [4].

Materials:

- Certified reference standard or raw material of known high purity (e.g., potassium hydrogen phthalate for acid-base titration) [30].

- Appropriately calibrated titrant (e.g., NaOH 0.1 mol/L).

- For Volumetric: Required visual indicator (e.g., phenolphthalein).

- For Potentiometric: Calibrated pH electrode and autotitrator.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh six to nine portions of the reference standard across the concentration range of interest (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target test concentration) [4].

- Titration:

- Volumetric: Dissolve each sample in the appropriate solvent. Add the indicator and titrate manually until the first persistent color change. Record the titrant volume.

- Potentiometric: Dissolve each sample and titrate using an autotitrator. The instrument will record the titration curve and calculate the endpoint.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the recovered amount or concentration for each determination.

- Accuracy: Report as percent recovery, calculated as (Mean Measured Concentration / True Concentration) × 100%. The result should be close to 100% [4].

- Precision: Calculate the Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) of the multiple determinations. For repeatability, an RSD of less than 1% is typically expected [4].

Protocol for Assessing Linearity

Objective: To demonstrate that the analytical procedure produces results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte in the sample [4].

Materials: As described in Section 3.1.

Method:

- Sample Preparation: Accurately weigh at least five different portions of the reference standard, covering a defined range (e.g., 50% to 150% of the expected sample weight) [4].

- Titration: Titrate each sample using the established method (volumetric or potentiometric).

- Data Analysis:

- Plot a graph of the titrant volume consumed (y-axis) against the sample mass (x-axis).

- Perform a linear regression analysis on the data.

- Report the coefficient of determination (R²). A value of R² > 0.999 is indicative of excellent linearity for titration, an absolute method [4].

Protocol for Establishing Specificity

Objective: To prove that the method can unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of potential interferences like impurities, excipients, or degradation products [4].

Materials:

- Pure analyte raw material.

- Potential interferents expected in the raw material (e.g., potassium carbonate in potassium bicarbonate).

- Appropriate solvent.

Method:

- Sample Preparation:

- Prepare a sample of the pure analyte.

- Prepare a sample of the analyte with a known, significant amount of the interferent added.

- Titration: Titrate both samples using the potentiometric method.

- Data Analysis:

- Overlay the titration curves of the pure and the spiked sample.

- Specificity is demonstrated if the curve of the pure analyte shows a single, sharp endpoint, and the curve of the spiked sample either shows no shift in the primary endpoint or shows a distinct, separate endpoint for the interferent [4]. Volumetric methods often lack this diagnostic capability.

Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

The following table details the key reagents and materials required for reliable titration in a quality control laboratory.

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for titration in quality control

| Item | Function & Importance | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Standards (e.g., KHP, TRIS) [30] | High-purity reference materials used for exact titrant standardization. Essential for accuracy. | Must be of high purity, stable, and non-hygroscopic. |

| Certified Titrants | Solutions of known concentration used as the reaction agent. | Concentration must be verified regularly via standardization; base titrants are susceptible to CO₂ absorption [30]. |

| Visual Indicators (e.g., phenolphthalein) [2] | Substances that change color at/near the endpoint in volumetric titration. | Selection is critical and depends on the reaction type and expected endpoint pH [2]. |

| Potentiometric Sensor (pH/ISE & Reference Electrode) [1] | Measures potential change to detect the equivalence point objectively. | Requires regular calibration, cleaning, and proper storage. Performance degrades over time [1] [31]. |

| Analytical Balance [30] | Precisely weighs samples and standards. | Readability of 0.1 mg or better is critical for minimizing weighing errors, especially with small sample masses [30]. |

| CO₂ Absorbent (e.g., Soda Lime) [30] | Protects alkaline titrants (e.g., NaOH) from atmospheric CO₂, which alters concentration. | Placed in a drying tube on the titrant reservoir; must be changed regularly. |

Workflow and Logical Diagrams

The diagrams below illustrate the logical workflow for method selection and the scientific principle of potentiometric detection.

Diagram 1: Titration Method Selection Workflow. This flowchart aids in selecting the appropriate titration technique based on sample characteristics and laboratory requirements.

Diagram 2: Principle of Potentiometric Endpoint Detection. This diagram visualizes the causal chain from titrant addition to the instrumental detection of the equivalence point, which eliminates subjective judgment.

In today's high-volume laboratory environments, the integration of automated titration systems represents a critical advancement in analytical efficiency and data quality. Despite the proven benefits of automation, approximately 60% of laboratories still rely on manual titration methods, primarily due to perceived lower initial costs and established protocols [32]. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of automated titration systems against manual alternatives, focusing specifically on their application in high-throughput workflows and framing the analysis within broader research on method validation for potentiometric versus volumetric titration.

Automated titration systems have evolved significantly from their first introduction in the mid-1960s, offering increasingly sophisticated capabilities for precision dispensing, endpoint detection, and data integrity that substantially outperform manual methods [33]. For research and drug development professionals, the selection between automated and manual titration involves careful consideration of throughput requirements, regulatory compliance needs, and method validation imperatives that form the foundation of reliable analytical data.

Comparative Analysis: Automated vs. Manual Titration Performance

Throughput and Efficiency Metrics