Mercury-Free Future: A Comprehensive Guide to Alternative Electrodes for Stripping Analysis in Biomedical Research

This article provides a critical evaluation of mercury electrode alternatives for stripping analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical analysis.

Mercury-Free Future: A Comprehensive Guide to Alternative Electrodes for Stripping Analysis in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a critical evaluation of mercury electrode alternatives for stripping analysis, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development and clinical analysis. With increasing regulatory pressure and a global shift towards green chemistry, the move away from traditional mercury electrodes is imperative. We explore the foundational principles, operational methodologies, and practical applications of leading mercury-free electrodes, including bismuth, gold, and carbon-based materials. The content offers a direct performance comparison, troubleshooting guidance for complex matrices like biological fluids, and validation protocols to ensure data reliability. This guide serves as an essential resource for laboratories transitioning to safer, sustainable, and highly sensitive electroanalytical techniques.

Why Move Away from Mercury? The Drive for Safer, Sustainable Electroanalysis

The Toxicity and Environmental Impact of Mercury Electrodes

Mercury electrodes have long been a cornerstone of electrochemical analysis, particularly in stripping voltammetry techniques prized for their exceptional sensitivity in detecting trace metals. Their widespread use, however, belies significant concerns regarding toxicity and environmental impact. This guide objectively examines the performance of traditional mercury-based electrodes against emerging mercury-free alternatives, providing researchers with the data necessary to make informed, responsible choices. The evaluation is framed within a critical thesis: while mercury electrodes remain a performance benchmark, technological advances have rendered mercury-free alternatives not only viable but often preferable when balancing analytical performance with environmental and safety considerations. The discussion encompasses the full lifecycle of these electrodes, from their role in the laboratory to their contribution to the global mercury pollution cycle, offering a comprehensive comparison grounded in experimental data.

Toxicity and Environmental Persistence of Mercury

The utility of mercury electrodes is inextricably linked to the element's intrinsic toxicity and its dangerous pathway through the environment. Mercury is ranked as the third most toxic substance by the US Government Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, behind only arsenic and lead [1]. Its release into the environment, whether from laboratory waste or industrial processes, initiates a persistent and damaging cycle.

Molecular Mechanisms of Toxicity

The toxicity of mercury manifests at the cellular level through several distinct mechanisms, each contributing to its profound health impacts:

- Binding to Sulfhydryl Groups: Mercury exhibits a high affinity for sulfhydryl (-SH) and thiol groups in proteins and enzymes, leading to macromolecular structural changes and functional disruption [1] [2]. This binding can alter membrane permeability and inactivate critical enzymes.

- Oxidative Stress and Mitochondrial Dysfunction: Mercury exposure induces oxidative stress by promoting the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), partly due to its ability to act as a catalyst for Fenton-type reactions [1]. This oxidative damage is coupled with mitochondrial dysfunction, which disrupts cellular energy production and calcium homeostasis [1].

- DNA Damage: Mercury compounds can cause direct damage to DNA, posing a genotoxic risk and potentially contributing to carcinogenesis [1] [2].

Health Impacts and Pharmacokinetics

The health effects of mercury are systemic, affecting nearly every organ system. The nervous system is the primary repository for mercury, where it can accumulate with a half-life as long as 20 years in the brain, leading to neurotoxicity, tremors, sleep disturbances, and impaired cognitive skills [1] [2]. Other documented effects include:

- Cardiovascular and Hematological Effects: Mercury accumulation in the heart is linked to cardiomyopathy, and it can compete with iron for binding sites on hemoglobin, leading to anemia [1].

- Renal and Pulmonary Toxicity: The kidneys are particularly vulnerable, with exposure linked to acute tubular necrosis and glomerulonephritis. Inhalation of mercury vapors can cause pulmonary fibrosis and bronchitis [1] [2].

- Immunological and Reproductive Damage: Mercury impairs immune system function, particularly polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs), increasing susceptibility to infections. It also poses significant risks to the reproductive system and embryonic development [1] [2].

The toxicokinetic profile varies by form. Inhaled elemental mercury vapor is readily absorbed and has a whole-body half-life of approximately 60 days [1]. The most significant human exposure route to organic methylmercury (MeHg) is through consumption of contaminated fish and seafood [1] [2]. Once ingested, MeHg is efficiently absorbed and can bioaccumulate in the food chain, with a biological half-life of 39 to 70 days [2].

The Mercury Lifecycle and Global Impact

The environmental impact of mercury is a global challenge. Human activities have increased global atmospheric mercury levels by three to five times since industrialization [3]. A critical development is the shifting geographical pattern of emissions. While the Global North and China have seen declining emissions in recent decades due to environmental regulations, these reductions have been completely offset by rapid growth in Global South countries [3]. Consequently, global emissions continue to rise slightly since the 2013 Minamata Convention, a global treaty designed to protect human health and the environment from mercury emissions [3].

Table: Global Anthropogenic Mercury Emission Trends (1960-2021)

| Region/Parameter | 1960 Status | 2021 Status | Key Drivers of Change |

|---|---|---|---|

| Global North | Accounted for nearly half of global emissions | Share decreased to only 10% | Strict air pollution controls, shift to renewable energy [3] |

| China | Not a major emitter | Reached 566 Mg in 2021, but shows recent downward trend | Rapid industrial expansion, followed by recent emission controls [3] |

| Global South (excl. China) | Minor emitter | Produced two-thirds of global emissions in 2021 | ASGM, fossil fuel combustion, cement production [3] |

| Largest Emission Sector | Non-ferrous metal production | Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining (ASGM) | ASGM emissions hit 975 Mg in 2021, a ten-fold increase from 1960 [3] |

This persistent release ensures mercury continues to circulate in the atmosphere-soil-water distribution cycles, where it can remain for years [1]. The element's volatility allows it to travel long distances, contaminating regions far from the original source. In aquatic systems, mercury is converted by microorganisms into methylmercury, its most toxic form, which then bioaccumulates and biomagnifies in the food web, ultimately reaching humans [2]. This global biogeochemical cycle, exacerbated by ongoing emissions, means that every gram of mercury used in a laboratory setting contributes to a significant and persistent environmental health problem.

Performance Comparison: Mercury vs. Alternative Electrodes

While the toxicity of mercury is clear, its historical use in electroanalysis is rooted in superior electrochemical properties. This section provides a performance-based comparison, evaluating mercury against leading alternatives across key analytical parameters to determine if modern substitutes can meet the demanding requirements of trace metal analysis.

The Legacy Performance of Mercury Electrodes

Mercury electrodes, particularly the Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) and Mercury Film Electrodes (MFE), are considered the gold standard for a reason [4] [5]. Their performance benefits are multifaceted:

- Excellent Conductivity: Mercury provides a highly conductive surface for efficient electron transfer during deposition and stripping steps [5].

- Formation of Amalgams: Mercury's ability to form amalgams with many analytes of interest (e.g., Zn, Cd, Pb, Cu) allows for efficient pre-concentration and well-defined, easily stripped signals [4] [5].

- Renewable Surface: The HMDE offers a perfectly renewable, smooth surface, which is crucial for achieving high reproducibility between measurements [4].

- High Hydrogen Overpotential: This property suppresses hydrogen gas evolution, allowing for the application of very negative deposition potentials necessary to reduce a wider range of metal ions without interference from the solvent breakdown [5].

These properties collectively enable mercury electrodes to achieve remarkable sensitivities, with detection limits capable of reaching 10â»Â¹â° to 10â»Â¹Â¹ M for many metal ions, making them competitive with sophisticated techniques like ICP-MS [4] [5]. MFEs, where a thin mercury film is plated onto a glassy carbon electrode, offer enhanced sensitivity over HMDEs due to their higher surface-to-volume ratio [5].

Promising Mercury-Free Electrode Materials

Significant research efforts have been dedicated to finding less toxic alternatives that match or, in some contexts, surpass mercury's capabilities. The most successful alternatives include:

- Bismuth (Bi): Bismuth is widely regarded as the most promising mercury substitute. It can be used in a similar fashion to form in-situ or ex-situ films and shares key properties with mercury, such as the ability to form alloys with other metals and a relatively high hydrogen overpotential [6] [5]. A key advantage is its compatibility with alkaline media, where mercury forms insoluble oxides, thus expanding the analytical window [5].

- Gold (Au): Gold electrodes are particularly valuable for analyzing metals like mercury itself, as well as arsenic and selenium. They form well-defined intermetallic compounds and exhibit excellent conductivity [4] [5]. A notable application is the

scTRACE Goldelectrode, which has been successfully used to monitor bismuth and antimony(III) stabilizers in electroless nickel plating baths with excellent recovery rates [6]. - Other Materials: Metals like tin (Sn) have also been investigated as film electrodes, though they are less commonly used than bismuth or gold [5]. Composite electrodes, such as graphite electrodes modified with a mercury salt-containing polymer (e.g.,

ItalSens IS-HM), represent a compromise, minimizing the amount of mercury used while attempting to retain its beneficial properties [4].

Table: Comparative Analytical Performance of Electrode Materials in Stripping Voltammetry

| Electrode Material | Key Analytical Strength | Reported Limit of Detection (Example) | Notable Advantages / Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury Film Electrode (MFE) | Wide range of amalgam-forming metals | Pb, Cu in biodiesel: Low nM range [5] | Gold standard sensitivity; High toxicity [5] |

| Bismuth Film Electrode (BiFE) | Pb, Cd, Zn, Tl | Pb²âº: 1.4 nM [5] | Low toxicity, works in alkaline media [5] |

| Gold Electrode | Hg, As, Se, Bi, Sb(III) | Effective for process control in plating baths [6] | Highly selective for specific metals; Low toxicity [6] [5] |

| Mercury/Bismuth Composite | Attempts to balance performance and safety | -- | Minimizes mercury use; still contains mercury [4] |

Critical Performance Trade-offs

The transition to mercury-free electrodes involves navigating specific trade-offs. Bismuth electrodes, while excellent for many applications, may not match the extreme negative potential window of mercury in all media, potentially limiting the range of analyzable metals in some cases [5]. Gold electrodes can be susceptible to surface fouling and may require more careful maintenance [5]. Furthermore, the well-established understanding of intermetallic compound formation and its effects in mercury systems is still being developed for these newer materials. However, the experimental data clearly demonstrates that for a core set of environmentally and clinically relevant heavy metals—including Pb, Cd, and Zn—bismuth-based electrodes provide sensitivity and limits of detection that are comparable to their mercury counterparts [5]. This, combined with their lower toxicity and the ability to operate in alkaline conditions, makes them a compelling alternative for most routine analyses.

Experimental Protocols and Research Toolkit

The practical implementation of stripping analysis, whether with mercury or alternative electrodes, requires standardized protocols and a specific set of research reagents. This section details a core methodology and outlines the essential toolkit for conducting these sensitive measurements.

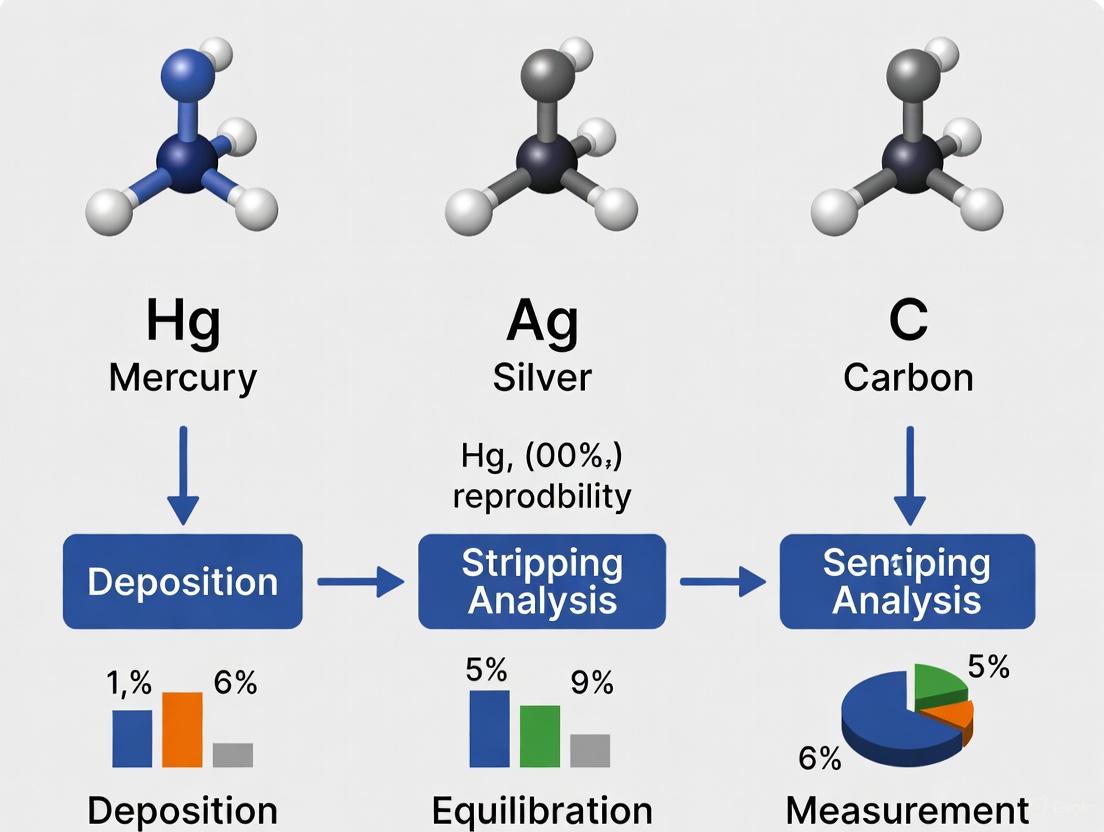

Generalized Stripping Voltammetry Workflow

The fundamental steps of a stripping analysis are consistent across electrode types, involving a pre-concentration (deposition) step followed by a measurement (stripping) step. The following diagram and protocol outline a standard anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) procedure, adaptable for various electrode materials.

Diagram Title: Stripping Voltammetry Workflow

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Electrode Preparation (Cleaning/Activation): The working electrode must be in a clean, reproducible state. For a glassy carbon electrode, this involves polishing with alumina slurry. For certain mercury-free electrodes like the Bi Drop or

scTRACE Gold, a specific electrochemical activation might be required [6] [5]. - Film Deposition (For in-situ electrodes): For in-situ MFEs or BiFEs, a potential is applied to co-deposit the electrode material (e.g., Hg²⺠or Bi³âº) and the analyte metals onto the inert substrate (e.g., glassy carbon) from the sample solution. This is typically done for 30-300 seconds with stirring [4] [5].

- Analyte Pre-concentration: A cathodic potential (

E_deposition) sufficient to reduce the target metal ions is applied for a fixed time (t_deposition), typically 30-300 seconds, while the solution is stirred. This deposits the metals onto/into the film electrode [4]. - Equilibration: The stirring is stopped, and the solution is allowed to become quiescent for a short period (e.g., 30 seconds). This reduces the capacitive current before the stripping step [4].

- Stripping: A voltammetric technique (e.g., Linear Sweep, Differential Pulse, or Square Wave Voltammetry) is applied to sweep the potential to more anodic values. This oxidizes (strips) the deposited metals back into solution, generating a current peak for each metal [4] [5]. Square Wave Voltammetry is often favored for its sensitivity and speed.

- Data Processing: The resulting voltammogram is analyzed. The potential of each peak identifies the metal, while the peak current or charge is proportional to its concentration in the sample, often determined using a standard addition method [4].

The Researcher's Toolkit

Conducting robust stripping analysis requires a set of specific reagents and instrumentation.

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment for Stripping Analysis

| Item | Function / Description | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat | Instrument that applies potential and measures current. | Core of the electrochemical setup. |

| Working Electrode | Surface where deposition and stripping occur. | HMDE, MFE, or Hg-free (e.g., Bi Drop, scTRACE Gold) [6] [4]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl). | Essential for accurate potential control. |

| Counter/Auxiliary Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit (e.g., Pt wire). | -- |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducting salt solution that minimizes ohmic drop. | e.g., Acetate buffer, HCl, Nitric acid [6] [5]. |

| Standard Solutions | Known concentrations of target metals for calibration. | Used for standard addition method. |

| Complexing Agents | Used in AdSV to form adsorbable complexes with the analyte. | e.g., cupferron, catechol [7]. |

| Purified Gases | Nitrogen or Argon for deaeration to remove dissolved oxygen. | Oxygen can interfere by being reduced. |

| Fosifidancitinib | Fosifidancitinib, CAS:1237168-58-9, MF:C21H21FN5O7P, MW:505.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Candicidin A3 | Candicidin A3, CAS:58591-23-4, MF:C59H86N2O18, MW:1111.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The evidence demonstrates a clear trajectory in electrochemical analysis: the scientific community is moving decisively toward mercury-free alternatives. The severe toxicity and persistent environmental impact of mercury, compounded by its complex global lifecycle and rising emissions in developing nations, render its continued use unsustainable and ethically questionable [1] [3] [2].

While mercury electrodes historically set the standard for sensitivity in stripping voltammetry, the performance gap has narrowed remarkably. Materials like bismuth now offer comparable analytical performance for a wide range of metals, with the added benefits of lower toxicity, compliance with stringent international regulations (e.g., RoHS), and operational flexibility in media like alkaline solutions where mercury fails [6] [5]. Gold and other specialized electrodes further expand the toolbox for specific applications.

For the modern researcher, the choice is no longer between performance and safety. Mercury-free sensors such as the Bi Drop and scTRACE Gold provide a viable, high-performance pathway that aligns with the principles of green chemistry and occupational health. The experimental protocols and data presented herein offer a foundation for laboratories to confidently transition away from mercury, contributing to a reduction in its environmental burden while maintaining the highest standards of analytical rigor. The future of trace metal analysis is unequivocally mercury-free.

The Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive, a pioneering piece of European Union legislation, has fundamentally reshaped the manufacturing of electrical and electronic equipment (EEE) by restricting the use of specific hazardous substances [8]. While often associated with consumer goods, its influence extends powerfully into research laboratories, driving a significant shift away from traditional materials, particularly those containing lead and mercury [9]. The directive's core objective is to reduce environmental and health risks associated with the manufacture, use, and disposal of electronic equipment, promoting the production of safer, more environmentally friendly products [8].

For researchers and scientists, understanding RoHS is no longer merely a matter of regulatory compliance but a crucial component of sustainable and responsible science. The directive restricts ten substances, including lead (0.1% by weight) and mercury (0.1% by weight), with stringent maximum concentration limits in homogeneous materials [8]. Although some research and development equipment may qualify for exemptions, these are often limited in time and scope [8]. The regulatory push is clear, compelling the scientific community to seek out and validate high-performance alternatives to legacy tools, such as mercury-based electrodes in electrochemical stripping analysis, without compromising data quality or analytical performance.

RoHS and Its Direct Impact on Laboratory Instrumentation

The RoHS directive's scope is broad, encompassing most electrical and electronic equipment, which includes a vast array of standard laboratory instruments [8]. For the scientific community, the transition is particularly impactful for analytical techniques that have historically relied on mercury and lead. The directive's substance restrictions are not static; they are subject to ongoing review and tightening, with exemptions for specific applications having finite lifetimes [10] [11].

A key area of focus is the phase-out of mercury. RoHS 3 has introduced time-limited exemptions for mercury in various lamps, including UV lamps used in scientific instrumentation, with many set to expire on February 24, 2027 [11]. Beyond lighting, the pressure is on to replace mercury in other components, such as sensor fill materials, with manufacturers now offering mercury-free and alternative fill sensors specifically for sensitive applications in food and medical sectors [12]. Similarly, the use of lead, particularly in specialized solders for high-reliability equipment like servers and network infrastructure, is under constant review, with exemptions potentially expiring as soon as 2026 [10]. This regulatory environment creates a tangible and urgent need for laboratories to future-proof their analytical methodologies by adopting robust, RoHS-compliant technologies.

Mercury Electrodes in Stripping Analysis: The Traditional Gold Standard

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) is a powerful trace electroanalytical technique known for its exceptional sensitivity, with detection limits capable of reaching (sub)nanomolar concentrations [13]. For decades, the Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) has been the quintessential working electrode for this method, and it remains the benchmark against which alternatives are measured [13] [14].

The HMDE's superior performance is attributed to several unique properties [13]:

- Excellent Reproducibility: The electrode surface is easily renewed with each new, identical mercury drop, avoiding hysteresis effects.

- Wide Cathodic Potential Window: Mercury favors a high overpotential for hydrogen evolution, allowing the detection of metals that would otherwise be masked by solvent electrolysis.

- Efficient Amalgam Formation: Many metal ions are efficiently reduced and preconcentrated into the mercury drop, forming amalgams that lead to sharp, well-defined stripping peaks.

These properties have made HMDE the recommended approach in reference laboratories for the simultaneous determination of trace metal ions like Zn²âº, Cd²âº, Pb²âº, and Cu²âº, even in complex matrices like digested soil samples [13]. However, the high toxicity of mercury and its impending regulatory restrictions under directives like RoHS have motivated an intensive search for definitive replacements [13].

Objective Comparison of Mercury Electrode Alternatives

The search for alternatives has yielded several promising electrode materials. The following table provides a structured, quantitative comparison of the HMDE against the most prominent RoHS-compliant candidates, based on reported experimental data.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Working Electrodes for Stripping Analysis of Metal Ions

| Electrode Type | Key Features | Detection Limit (Hg²âº) | Linear Range (Hg²âº) | Reproducibility (RSD) | Multi-Ion Analysis Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) | Renewable surface, forms amalgams, wide potential window [13]. | Not specified for Hg²âº; (sub)nanomolar for other metals [13]. | Not specified for Hg²âº. | Excellent (<5%) [15]. | Excellent for Zn²âº, Cd²âº, Pb²âº, Cu²⺠[13]. |

| Bismuth Film Electrode (BiFE) | RoHS-compliant, "mercury-like" behavior, low toxicity [15]. | Not specified. | Not specified. | Similar to mercury films [15]. | Good for several heavy metals. |

| Nitrogen-Doped Graphene (NRGO) | High affinity for Hg²âº, high surface area, excellent conductivity [16]. | 0.35 nM (0.07 ppb) [16]. | 1 nM - 10 μM [16]. | ~3.8% (for 6 successive measurements) [16]. | Possible, but demonstrated for Hg²âº. |

| Gold Nanoparticle/ Graphene | High sensitivity, catalytic properties [16]. | 6 ppt (0.03 nM) [16]. | Not specified. | Not specified. | Not specified. |

| Sulfur-Doped Porous rGO | Soft-soft interaction with Hg²⺠for high selectivity [16]. | 0.5 nM [16]. | Not specified. | Not specified. | Not specified. |

The data reveals that while HMDE offers unparalleled versatility for multi-ion analysis, advanced nanomaterials like nitrogen-doped graphene can match or even surpass its sensitivity for specific analytes like mercury, achieving detection limits far below the WHO guideline of 30 nM (6 ppb) for drinking water [16]. Bismuth film electrodes present a more direct, lower-tech replacement with performance characteristics closest to traditional mercury films [15].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Alternatives

To facilitate the adoption of these alternatives, detailed and reproducible experimental protocols are essential. Below are methodologies for two prominent RoHS-compliant approaches.

Method 1: Mercury Detection using a Nitrogen-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide (NRGO) Electrode

This protocol outlines the modification of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with NRGO for the highly sensitive detection of mercury ions (Hg²âº), as detailed in the research of Li et al. (2020) [16].

1. Electrode Modification:

- Synthesis of NRGO: Graphene oxide (GO) is thermally treated under an NH₃ atmosphere at 800°C to incorporate nitrogen atoms into the graphene lattice [16].

- Preparation of NRGO Ink: Disperse 2 mg of the synthesized NRGO in 1 mL of a water-ethanol mixture (1:1 v/v) and sonicate for 30 minutes to form a homogeneous suspension [16].

- Modification of GCE: Polish a bare glassy carbon electrode (3 mm diameter) with alumina slurry, rinse thoroughly with deionized water, and dry. Pipette 6 μL of the NRGO ink onto the GCE surface and allow it to dry under an infrared lamp to obtain the NRGO/GCE [16].

2. Experimental Procedure and Parameters:

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 M acetate buffer solution (pH 5.0) [16].

- Pre-concentration/Deposition Step: Immerse the NRGO/GCE in the sample solution containing Hg²âº. Stir the solution at 400 rpm and apply a deposition potential of -0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 180 seconds. This step reduces Hg²⺠to Hgâ° and accumulates it on the electrode surface via chelation with the nitrogen sites [16].

- Equilibration: After deposition, stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for 10 seconds [16].

- Stripping Step: Initiate a square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SWASV) scan from -0.6 V to +0.4 V. Use the following parameters: frequency of 50 Hz, pulse amplitude of 25 mV, and a step potential of 4 mV [16].

- Regeneration: Between measurements, regenerate the electrode surface by applying a potential of +0.6 V for 60 seconds in a clean supporting electrolyte to oxidize and remove any residual mercury [16].

Method 2: Multi-Metal Analysis using a Bismuth Film Electrode (BiFE)

This protocol is adapted from standard practices for bismuth film electrodes, which are widely recognized as the most practical mercury-free alternative for multi-metal analysis [15].

1. Electrode Preparation:

- Substrate Preparation: Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or a screen-printed carbon electrode sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina slurry. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each polishing step [15].

- In-situ Bismuth Film Plating: Introduce the supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M acetate buffer, pH 4.5) containing a known concentration of Bi(III) ions (typically 200-400 μg/L) and the target analytes. The bismuth film is electroplated onto the substrate in-situ simultaneously with the target metals during the deposition step [15].

2. Experimental Procedure and Parameters:

- Pre-concentration/Deposition Step: Deposit the target metals and bismuth at a potential of -1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 60-300 seconds with solution stirring [15].

- Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow a rest period of 10-15 seconds [15].

- Stripping Step: Record the stripping signal using a square-wave voltammetry scan from -1.4 V to +0.2 V. The bismuth and target metals are oxidized (stripped) from the electrode surface at their characteristic potentials, producing distinct peaks for simultaneous multi-metal analysis [15].

The following workflow diagram visualizes the key steps common to stripping analysis, highlighting the points of differentiation between traditional and modern approaches.

Diagram 1: Generalized Workflow for Anodic Stripping Voltammetry. The "Electrode Modification" and "Regeneration" steps are where RoHS-compliant alternatives most significantly diverge from traditional mercury-based methods.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Transitioning to RoHS-compliant stripping analysis requires specific materials. The following table lists key reagents and their functions for the protocols described above.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for RoHS-Compliant Stripping Analysis

| Material/Reagent | Function in the Experiment | Exemplary Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Provides a pristine, inert, and conductive substrate for electrode modification [16]. | Base electrode for coating with NRGO or for in-situ BiFE plating. |

| Nitrogen-Doped Reduced Graphene Oxide (NRGO) | Electrode modifier; nitrogen atoms act as chelation sites for enhanced pre-concentration of metal ions like Hg²⺠[16]. | Sensitive and selective detection of mercury ions. |

| Bismuth(III) Nitrate | Source of Bi³⺠ions for the in-situ formation of a bismuth film electrode (BiFE) on the carbon substrate [15]. | Multi-metal analysis of Zn²âº, Cd²âº, Pb²âº, etc. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 4.5-5.0) | Serves as the supporting electrolyte; maintains optimal pH for the deposition and stripping of many heavy metal ions [16]. | Standard electrolyte for ASV of most heavy metals. |

| Standard Metal Ion Solutions | Used for calibration curves to quantify the concentration of unknown analytes in samples. | Essential for all quantitative analysis. |

| Fructose-arginine | Fructose-arginine, CAS:25020-14-8, MF:C12H24N4O7, MW:336.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fulacimstat | Fulacimstat, CAS:1488354-15-9, MF:C23H16F3N3O6, MW:487.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The regulatory drive embodied by RoHS is unequivocally accelerating innovation in electrochemical research. While the hanging mercury drop electrode has set a high bar for analytical performance, the scientific community has responded with sophisticated alternatives that are not only compliant but also highly competitive. Materials like nitrogen-doped graphene demonstrate that it is possible to achieve exceptional, single-analyte sensitivity surpassing even traditional methods [16]. Meanwhile, more established options like bismuth film electrodes offer a robust and practical path for routine multi-analyte trace metal detection [15].

The transition to a lead- and mercury-free lab is no longer a hypothetical future but a present-day reality. By understanding the regulatory landscape, objectively evaluating the performance of new technologies against traditional benchmarks, and adopting standardized experimental protocols, researchers can confidently navigate this shift. The move toward RoHS-compliant methodologies represents a convergence of regulatory necessity and scientific progress, fostering the development of analytical chemistry that is not only more sustainable and safe but also more advanced.

Stripping analysis is a powerful electrochemical technique renowned for its exceptional sensitivity in trace metal detection. Its core principle hinges on a two-step process that separates the signal generation in time from the analyte collection, enabling the detection of metal ions at concentrations as low as the nanomolar and sub-nanomolar level [17] [13]. For decades, the hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE) was the cornerstone of this technique due to its excellent reproducibility, wide cathodic potential window, and ability to form amalgams with many metals [13]. However, owing to the high toxicity of mercury, the field has vigorously pursued "green" alternative electrode materials, primarily bismuth (Bi), but also antimony (Sb), tin (Sn), and gold (Au) [18] [19].

The following diagram illustrates the foundational two-step workflow of anodic stripping voltammetry, which is common to both traditional and modern electrodes.

The Two-Step Mechanism for Ultra-Sensitive Detection

The remarkable sensitivity of stripping analysis is achieved by de-coupling the detection event from a preliminary analyte preconcentration phase [18] [13].

- Preconcentration and Equilibration: In this first step, the target metal ions (e.g., Cd²âº, Pb²âº, Zn²âº) in solution are electrochemically reduced and deposited onto the working electrode surface. A constant potential is applied, and the solution is stirred, leading to the accumulation of the metal as a thin film or, in the case of mercury, an amalgam [13]. This step concentrates the analytes from a large sample volume onto a small electrode surface, effectively amplifying the future signal. A quiet, unstirred equilibration period often follows to ensure a uniform concentration profile at the electrode surface [13].

- Stripping and Quantification: The second step is the actual measurement. The potential is scanned in an anodic (positive) direction, causing the accumulated metals to oxidize back into ions and re-dissolve into the solution [13]. This "stripping" process generates a measurable current. Each metal oxidizes at a characteristic potential, producing distinct peaks in the voltammogram. The height or area of these peaks is directly proportional to the concentration of the metal in the original sample, allowing for precise quantification [17] [19].

Quantitative Comparison of Electrode Performance

The search for viable mercury alternatives has yielded several promising materials. The table below summarizes the key analytical performance metrics of these electrodes for the detection of common heavy metals, based on experimental data from the literature.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Electrodes for Stripping Analysis of Heavy Metals

| Electrode Type | Target Metals | Linear Range (mol/L or µg/mL) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) [13] | Zn²âº, Cd²âº, Pb²âº, Cu²⺠| Not specified | (Sub)nanomolar | Excellent reproducibility; Wide potential window; Ideal for multi-ion analysis [13]. | High toxicity of mercury [13]. | Analysis of digested soil samples [13]. |

| Bismuth-Film Electrode (BiFE) on Copper [17] | Cd²âº, Pb²âº, Zn²⺠| 2x10â»â¸ to 1x10â»â¶ mol/L (for Cd²âº) | Not specified | "Environmentally friendly"; Low toxicity; Well-defined peaks with low background [17]. | Requires acidic media (pH < 4.3); Bismuth hydroxide forms at higher pH [17]. | Analysis in acidified tap water and plant extracts [17]. |

| Bismuth-Film on Paper-Based Carbon [19] | Cd(II), Pb(II), In(III) | 0.1 to 10 µg/mL | 0.4 µg/mL (Cd), 0.1 µg/mL (Pb) | Sustainable, low-cost, and easily disposable platform [19]. | Less sensitive than mercury films; Could not determine Cu(II) [19]. | Determination of metals in tap water [19]. |

| Mercury-Film on Paper-Based Carbon [19] | Cd(II), Pb(II), In(III), Cu(II) | 0.1 to 10 µg/mL | 0.04 µg/mL (In), 0.1 µg/mL (Pb), 0.2 µg/mL (Cu) | High sensitivity; capable of detecting a wider range of metals [19]. | Higher toxicity and associated handling/disposal concerns [19]. | Direct comparison with bismuth films on the same platform [19]. |

| Gold-Plated/ Nanoparticle SPE [18] | Hg, Pb, As, Cu | Varies by application | Excellent for Hg and As | Excellent for Hg and As determination; uses underpotential deposition (UPD) for enhanced sensitivity [18]. | Not a general replacement for all metals; best for specific applications [18]. | Used in automated systems and for Hg determination in urine [18]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility, the methodology for electrode preparation and measurement must be precisely defined.

Protocol 1: Ex Situ Preparation of a Bismuth-Film Electrode (BiFE)

This protocol is adapted from studies using carbon-based substrates [19].

- Electrode Preparation: Begin with a clean carbon working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, screen-printed carbon, or a paper-based carbon electrode).

- Film Deposition: Place the electrode in a separate plating solution containing a bismuth salt (e.g., 10â»Â³ M Bi(III) in a 0.1 M acetate buffer with 0.5 M Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„ as a supporting electrolyte, pH 4.0) [19].

- Electrodeposition: Apply a constant, negative deposition potential (e.g., -1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for a set time (e.g., 60-120 seconds) with solution stirring. This reduces Bi³⺠ions to Biâ°, forming a thin bismuth film on the electrode surface.

- Rinsing: Remove the electrode from the plating solution, rinse it gently with deionized water, and then transfer it to the sample solution for analysis [19].

Protocol 2: Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) Measurement

This general protocol is used following electrode preparation, whether for HMDE, BiFE, or other film electrodes [13].

- Sample Deaeration: Place the sample solution (e.g., in 0.1 M acetate buffer, pH 4.0) in the electrochemical cell. Purge with an inert gas like nitrogen or argon for approximately 10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the analysis [13].

- Preconcentration (Deposition): Immerse the working electrode. While stirring the solution, apply a constant deposition potential (e.g., -1.1 V for Zn, Cd, and Pb) for a fixed time (e.g., 120 seconds). This causes the reduction and deposition of target metal ions onto the electrode.

- Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for a short period (e.g., 30 seconds) while maintaining or slightly adjusting the potential [13].

- Stripping Scan: Initiate the voltammetric scan. Using a technique like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV), scan the potential in the anodic direction. In DPV, for example, a pulse amplitude of 25 mV and a pulse step of 4 mV might be used [17] [13]. The oxidation of each metal produces a characteristic current peak.

- Data Analysis: Measure the peak currents. The concentration of the analytes is determined by constructing a calibration curve of peak current versus standard concentration or by using the standard addition method [13].

The interplay between the preconcentration and stripping steps, and how it leads to high sensitivity, is visualized below.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stripping Analysis

| Item | Function in Stripping Analysis |

|---|---|

| Bismuth(III) Salt (e.g., from a standard ICP solution) [19] | The precursor for forming the bismuth-film working electrode, either ex situ or in situ. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH ~4.0) [19] | A common supporting electrolyte that provides a controlled ionic strength and acidic pH, essential for the deposition and stability of bismuth films. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., Na₂SO₄, KNO₃) [19] | Carries the current in the solution, minimizes ohmic drop, and defines the ionic medium. |

| Metal Ion Standard Solutions (e.g., Cd²âº, Pb²âº) [17] [19] | Used for calibration curves and the standard addition method to quantify analyte concentrations in unknown samples. |

| Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) Cards [18] [19] | Disposable, mass-produced electrochemical cells (working, reference, and counter electrodes) that offer convenience and reproducibility. |

| Paper-Based Carbon Electrodes [19] | Ultra-low-cost, hydrophilic, and easily disposable substrates that are particularly suited for decentralized analysis. |

| (R)-Funapide | (R)-Funapide, CAS:1259933-16-8, MF:C22H14F3NO5, MW:429.3 g/mol |

| G007-LK | G007-LK, MF:C25H16ClN7O3S, MW:530.0 g/mol |

In conclusion, while the HMDE remains a benchmark for performance in stripping analysis due to its unparalleled sensitivity and reproducibility [13], bismuth-film electrodes have emerged as a truly viable, environmentally friendly alternative for many applications, especially for the detection of Cd, Pb, and Zn [17] [19]. The choice of electrode involves a trade-off between the superior analytical performance of mercury and the significantly reduced toxicity and practical advantages of bismuth and other "green" metals. The ongoing research in material science, particularly in nanostructuring and new substrate engineering, continues to narrow this performance gap, further solidifying the role of stripping analysis as a critical tool for trace metal detection.

Electrochemical stripping analysis is a powerful trace-level analytical technique renowned for its exceptional sensitivity, with detection limits often reaching the parts-per-trillion (ppt) level [15] [20]. For decades, mercury electrodes were the cornerstone of this method due to their excellent electrochemical properties, including a wide cathodic potential window and renewable surface [21]. However, the high toxicity of mercury and associated legal restrictions on its use and disposal have driven the scientific community to develop effective, environmentally friendly alternatives [22] [23].

This guide objectively compares the performance of the four most prominent "green" electrode materials—Bismuth, Antimony, Gold, and Carbon—that have emerged as viable replacements for mercury in stripping analysis. Framed within the broader thesis of advancing mercury-free electrochemical research, this article provides researchers and scientists with a detailed comparison of these alternatives, supported by experimental data and protocols to inform their selection and application in analytical methods and drug development.

Material Properties and Performance Comparison

The following sections detail the properties of each mercury-free electrode material, and their performance is summarized quantitatively in Table 1.

Bismuth (Bi)

- Overview and Properties: The bismuth-film electrode (BiFE), introduced in 2000, is widely regarded as the most successful mercury alternative [22] [24]. Bismuth is relatively non-toxic and forms "fusing" alloys with heavy metals like lead and cadmium, analogous to mercury amalgams [23]. Its performance is comparable to that of mercury-film electrodes (MFEs), with a wide accessible potential window (typically from -1.2 V to -0.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) [24].

- Typical Fabrication: BiFEs are commonly prepared by in-situ or ex-situ electroplating of a bismuth salt onto a carbon substrate like glassy carbon or a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) [22] [24]. A key advantage is the ability to perform analysis in non-deaerated solutions, simplifying the experimental procedure [24].

- Electroanalytical Performance: Bismuth electrodes exhibit well-defined, sharp stripping peaks for several trace metals. For example, a bismuth-coated carbon electrode achieved a detection limit of 0.3 µg/L (ppb) for lead following a 10-minute deposition period [24]. The electrodes also show high reproducibility, with relative standard deviations (RSD) of 2.4% and 4.4% for repetitive measurements of Cd and Pb, respectively [24].

Antimony (Sb)

- Overview and Properties: The antimony-film electrode (SbFE), introduced more recently, offers an interesting performance profile with unique electroanalytical characteristics [22] [25]. Like bismuth, antimony has significantly lower toxicity than mercury.

- Typical Fabrication: SbFEs are also prepared by electroplating onto a substrate [25]. Recent research focuses on optimizing the plating conditions and degree of substrate coverage to enhance electrochemical performance, which is critically evaluated using redox probes like Neutral Red [25].

- Electroanalytical Performance: Antimony electrodes are particularly useful for determining metals like nickel(II) and have been successfully applied in complex matrices such as wastewater [25]. They demonstrate a low charge transfer resistance (as low as 6 Ω was reported for a well-covered SbFE), which contributes to their sensitive response [25].

Gold (Au)

- Overview and Properties: Gold electrodes are not a new material but are exceptionally well-suited for specific applications. Their high affinity for mercury and arsenic makes them the best choice for determining these elements [22]. The phenomenon of underpotential deposition (UPD) of metals like Hg and Pb on gold enhances deposition efficiency and sensitivity [22].

- Typical Fabrication: Gold-modified SPCEs can be fabricated by electroplating a thin coat of gold (often forming nanoparticles) or by using commercially available gold-loaded carbon inks [22].

- Electroanalytical Performance: Gold electrodes are predominantly used for detecting Hg and As. A notable application involved a "wearable" sensor on neoprene textile with a gold-plated SPE for determining copper in marine environments, showcasing its potential for field analysis [22].

Carbon-Based Electrodes

- Overview and Properties: Carbon materials, including glassy carbon, carbon paste, and graphite-epoxy composites, serve as the most common substrates for modified electrodes [23]. Their appeal lies in their chemical inertness, wide potential window, and low cost.

- Typical Fabrication: The versatility of carbon is evident in various designs. Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) allow for mass production of disposable sensors [22]. Graphite-epoxy composite electrodes (GECE) offer robustness and the advantage of being easily polished to renew their surface [23].

- Electroanalytical Performance: While unmodified carbon electrodes can be used for some analytes, their primary role is as a substrate for other modifier materials like Bi, Sb, or Au. The composite structure can lead to a higher signal-to-noise ratio and improved detection limits [23].

Table 1: Comparative Electroanalytical Performance of Mercury-Free Electrodes for Key Metal Ions

| Electrode Material | Target Analytes | Detection Limit (ppb) | Linear Range | Reproducibility (RSD%) | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bismuth (BiFE) | Cd, Pb, Tl, Zn | 0.3 (for Pb) [24] | Low ppb range [24] | 2.4–4.4% [24] | Performance closest to mercury |

| Antimony (SbFE) | Ni, Cd, Pb, Cu | Varies by analyte [25] | -- | -- | Low charge transfer resistance [25] |

| Gold (Au) | Hg, As, Cu, Pb | -- | -- | -- | Best for Hg and As analysis [22] |

| Carbon (GECE) | Cd, Pb, Zn | -- | -- | -- | Robust, inexpensive substrate [23] |

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Preparation and Use

To ensure reproducible and reliable results, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below is a generalized workflow for anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV), followed by material-specific preparation methods.

Generalized Anodic Stripping Voltammetry Workflow

The core sequence of steps in a typical stripping analysis is consistent across different electrode materials [15] [26]:

- Preconcentration/Deposition Step: A negative potential is applied to the working electrode in a stirred solution, reducing metal ions (Mâ¿âº) and depositing them onto the electrode surface (e.g., as an amalgam in Bi or as a film on Au). The deposition time (30 s to 10 min) and potential are optimized for the target analytes [26].

- Rest Period: Stirring is stopped, and the potential is maintained for a short period (e.g., 5-30 s) to allow the deposited metals to distribute evenly and for the solution to become quiescent [15] [26].

- Stripping Step: The potential is swept anodically (from negative to positive) using a voltammetric technique (e.g., square-wave or differential pulse). The deposited metals are re-oxidized (stripped), generating a characteristic current peak for each metal. The peak current is proportional to the analyte concentration in the original solution [15] [26].

Material-Specific Electrode Preparation Protocols

Protocol for In-Situ Bismuth-Film Electrode (BiFE) [24]:

- Use a glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon electrode as the substrate.

- Prepare a sample or standard solution containing the target metal ions and add Bi(III) to a final concentration of 400 µg/L.

- Simultaneously deposit the bismuth and target metals by applying a deposition potential of -1.3 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 2-5 minutes in the stirred solution.

- Proceed with the rest and stripping steps. The bismuth film is formed and stripped simultaneously with the analytes in each cycle.

Protocol for Ex-Situ Antimony-Film Electrode (SbFE) [25]:

- Prepare a separate plating solution containing a salt of Sb(III), such as potassium antimony tartrate.

- Immerse a clean screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) into the plating solution.

- Apply a constant potential or current to electrodeposit the antimony film onto the SPCE surface. The specific potentiostatic conditions (potential and time) determine the morphology and coverage of the film, which directly impact performance.

- Remove the modified SbFE, rinse it, and then place it into the sample solution for the stripping analysis.

Protocol for Gold-Modified Electrodes [22]:

- For electroplating, immerse a carbon SPE in a solution containing Au(III) (e.g., from HAuClâ‚„).

- Apply a reducing potential to deposit Au nanoparticles onto the carbon surface.

- Alternatively, use commercially available gold nanoparticle dispersions and drop-cast a small volume onto the electrode surface, allowing it to dry.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of stripping analysis with these electrodes requires a set of essential reagents and materials.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example Application / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth(III) Salt | Precursor for forming the bismuth film on the electrode. | E.g., Bismuth citrate; used for in-situ plating of BiFEs [24]. |

| Antimony(III) Salt | Precursor for forming the antimony film on the electrode. | E.g., Potassium antimony tartrate; used for ex-situ plating of SbFEs [25]. |

| Gold Plating Solution | Source of Au(III) ions for electrode modification. | E.g., Tetrachloroauric acid solution; used to electroplate gold nanoparticles onto SPCEs [22]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducting medium that minimizes resistive losses and controls pH. | E.g., Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH ~4.5) or HCl (10 mM) [26] [23]. |

| Standard Metal Solutions | Calibrants for quantitative analysis. | Aqueous standards of Cd(II), Pb(II), etc., at mg/L or µg/L concentrations [26]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, mass-produced electrochemical cells. | Carbon SPEs serve as a versatile and inexpensive substrate for modification with Bi, Sb, or Au [22]. |

| Complexing Ligand | Enables adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV) for non-electroactive metals. | E.g., Dimethylglyoxime for Ni(II) and Co(II) determination [22]. |

| Galloflavin Potassium | Galloflavin Potassium, MF:C12H5KO8, MW:316.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Garvagliptin | Garvagliptin, CAS:1601479-87-1, MF:C18H23F2N3O3S, MW:399.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Selection Guide and Concluding Outlook

The choice of electrode material is dictated by the specific analytical problem. The following diagram provides a logical pathway for material selection, and the concluding remarks look toward future developments.

The field of mercury-free electroanalysis is dynamic, with current research focused on several promising fronts. The synthesis and application of bimetallic nanomaterials, such as bismuth-antimonate nanosheets, aim to harness synergistic effects to further improve sensitivity and stability [27] [28]. Furthermore, the drive towards decentralized analysis continues to fuel the development of disposable, miniaturized screen-printed sensors modified with these "green" metals for on-site environmental and clinical monitoring [22]. As these materials and fabrication techniques evolve, the performance gap with mercury will continue to narrow, solidifying the role of bismuth, antimony, gold, and carbon as the foundational materials for the future of sustainable stripping analysis.

Implementing Mercury-Free Electrodes: Protocols for Biomedical and Clinical Samples

The accurate detection of trace heavy metals in biological fluids like blood and urine is a critical challenge in clinical, occupational, and environmental health. For decades, anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) using mercury-based electrodes has been the cornerstone of electrochemical trace metal analysis due to its exceptional sensitivity and reproducibility [19]. However, the high toxicity of mercury has driven the scientific community to seek safer, environmentally friendly alternatives [17] [19]. This pursuit has positioned bismuth-film electrodes (BiFEs) as a leading candidate, combining low toxicity with exemplary electrochemical performance [17] [29]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of bismuth-film electrodes against other mercury-free alternatives, focusing on their preparation, optimization, and application for detecting heavy metals in complex biological matrices such as blood and urine, thereby framing their role within the broader thesis of mercury replacement in stripping analysis research.

Competing Electrode Platforms for Stripping Analysis

The transition away from mercury electrodes has led to the development and refinement of several alternative platforms. The following table offers a structured comparison of their key characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Electrode Platforms for Anodic Stripping Voltammetry of Heavy Metals

| Electrode Type | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Representative Performance (LOD for Pb²âº) | Suitability for Blood/Urine |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury Film Electrodes (MFEs) | High sensitivity; Excellent reproducibility; Wide negative potential window [19] | High toxicity; Specialized waste disposal [19] | ~0.1 µg/mL [19] | Limited due to toxicity and matrix effects |

| Bismuth Film Electrodes (BiFEs) | Low toxicity; "Environmentally friendly"; High sensitivity comparable to Hg; Well-defined stripping signals [17] [19] [29] | Performance can degrade above pH ~4.3 due to hydroxide formation [17] [30] | Sub-µg/mL to ng/mL range (varies with substrate) [31] [17] | Excellent (demonstrated in urine and blood sera) [31] [30] |

| Graphite-Epoxy Composite Electrodes (GECE) | Mercury-free; Simple design; Robust; Behave as microelectrode array [32] | Generally lower sensitivity compared to BiFEs and MFEs [32] | ~1 ppb (µg/L) [32] | Moderate (requires acidic media) |

| Bismuth Bulk Electrodes (BiBE) | No film deposition required; Effective in neutral pH samples (e.g., urine, rainwater) [30] | Not a thin film; Requires more bismuth material | 8.09 mg/L for Zn(II) (in urine) [30] | Excellent for direct analysis of undisturbed samples [30] |

Experimental Protocols for Bismuth Film Electrodes

Substrate Selection and Preparation

The substrate electrode forms the conductive foundation for the bismuth film. Common choices include:

- Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCEs): Ideal for disposable, low-cost sensors. The surface is typically used as-received after verification of conductivity [19].

- Glassy Carbon Electrodes (GCEs): For reusable platforms, the surface must be meticulously polished with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad, followed by sonication and rinsing with deionized water to create a mirror-finish, reproducible surface [17].

- Paper-Based Carbon Electrodes: A sustainable, low-cost option. These are fabricated by wax-printing hydrophobic barriers on chromatography paper, followed by drop-casting a carbon ink suspension to create the working electrode zone [19] [29].

Bismuth Film Deposition:Ex SituandIn SituMethods

The bismuth film can be formed on the substrate via two primary methods, with ex situ offering greater control for complex matrices.

- Ex Situ Deposition: This involves electroplating the bismuth film onto the substrate in a separate solution prior to sample analysis. A common protocol involves placing the electrode in a deaerated solution of 5-10 mg/L Bi(III) in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH ~4.0) or 0.1 M HNO₃. A deposition potential of -0.8 V to -1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) is applied for 60-240 seconds with stirring. This pre-plates a uniform, adherent bismuth film [19] [30].

- In Situ Deposition: Here, a Bi(III) salt (e.g., 100-400 µg/L Bi(III)) is added directly to the acidified sample solution. During the preconcentration step, both the target metals and bismuth are simultaneously deposited onto the electrode surface, forming the film in situ. This method is simpler but offers less control over film morphology [17] [19].

Analysis of Heavy Metals in Blood and Urine

The following workflow details the optimized protocol for biological samples, based on studies analyzing Pb²⺠in blood sera and Zn²⺠in urine [31] [30].

- Sample Pre-treatment: Blood sera or urine samples typically require dilution (e.g., 1:1) and acidification with a supporting electrolyte like 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0) or 0.1 M HNO₃. This step decomplexes metals from proteins and other organic ligands and ensures an optimal pH for deposition [31] [30].

- Preconcentration/Deposition: Transfer the prepared sample to the electrochemical cell. For ex situ BiFEs, apply a deposition potential (e.g., -1.2 V to -1.4 V for Zn, -1.0 V for Pb and Cd) for a controlled time (30-300 s) with stirring. This reduces and accumulates the target metal ions into the bismuth film, forming an amalgam [31] [30].

- Stripping and Measurement: After a brief equilibration period (5-15 s), initiate the stripping step. A square-wave or differential pulse anodic potential scan is applied from the deposition potential to a more positive potential (e.g., -1.0 V to -0.2 V). The metals are re-oxidized ("stripped") from the amalgam, producing characteristic current peaks at specific potentials (e.g., Pb ~ -0.5 V, Cd ~ -0.7 V vs. Ag/AgCl) [31] [17].

- Quantification: The peak current is proportional to the concentration of the metal in the solution. Quantification is typically performed using the standard addition method to compensate for matrix effects in complex samples like blood and urine [19] [30].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for heavy metal analysis using ex situ bismuth film electrodes.

Performance Data and Comparison

The effectiveness of BiFEs is demonstrated by direct comparisons with mercury films and other alternatives, supported by quantitative experimental data.

Table 2: Experimental Detection Limits and Linear Ranges for Heavy Metals on Different Electrodes

| Electrode | Metal Ion | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Matrix | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BiFEs on HAp-Carbon | Pb²⺠| Not Specified | Clear peaks at -0.55V | Blood Sera | [31] |

| BiFEs on Paper Carbon | Pb²⺠| Up to 10 µg/mL | ~0.1 µg/mL | Tap Water | [19] [29] |

| Mercury Films on Paper Carbon | Pb²⺠| 0.1 - 10 µg/mL | 0.1 µg/mL | Tap Water | [19] [29] |

| Bismuth Bulk Electrode | Zn²⺠| 20 - 160 µg/L | 8.09 µg/L | Urine | [30] |

| Graphite-Epoxy Composite | Pb²⺠| Not Specified | 1 µg/L (ppb) | Standard Solution | [32] |

The data shows that while mercury films may still hold a slight edge in absolute sensitivity for some metals, bismuth-based electrodes provide analytically relevant detection limits that are suitable for monitoring toxic metals like lead and cadmium at clinically and environmentally significant levels.

Optimization and Troubleshooting

- pH Management: The formation of insoluble bismuth hydroxide above pH 4.3 is a major constraint [17]. This makes sample acidification mandatory. The bismuth bulk rotating disk electrode (BiB-RDE) has been successfully used in neutral pH samples like urine, offering a path to analyze undisturbed samples [30].

- Intermetallic Compounds: The formation of intermetallic compounds between co-deposited metals (e.g., Cu-Zn) can distort signals. This can be mitigated by optimizing the deposition potential, adding a chemical masking agent (e.g., gallium), or using a shorter deposition time [30].

- Fouling in Biological Matrices: Proteins and other macromolecules in blood and urine can foul the electrode surface. Sample dilution and acidification are the primary countermeasures. The use of paper-based substrates, which can act as a filter, also helps mitigate this issue [19].

Figure 2: A decision pathway for selecting the appropriate bismuth electrode and deposition method based on sample properties.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents required for developing and working with bismuth film electrodes.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bismuth Film Electrode Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Standard Solution | Source of Bi(III) for film formation | 1000 mg/L Bi(III) in 2-5% HNO₃ (e.g., from Fluka Analytical) [19] |

| Acetate Buffer | Supporting electrolyte; controls pH | 0.1 M, pH ~4.0, with 0.5 M Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„ as background electrolyte [31] [19] |

| Metal Standard Solutions | For calibration and quantification | 1000 mg/L certified standards of Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu in dilute acid [19] |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPCEs) | Disposable electrode substrate | DRP-110 (Carbon working/auxiliary, Ag reference) from Metrohm-Dropsens [19] |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Reusable electrode substrate | 3 mm diameter, polished with 0.05 µm alumina slurry [17] |

| Wax Printer & Chromatography Paper | For fabricating paper-based electrodes | Xerox ColorQube, Whatman Grade 1 paper [19] |

| Potentiostat with Software | Instrumentation for voltammetric measurements | Autolab PGSTAT with GPES software; equipment capable of SWV and DPV [19] |

| GB1107 | GB1107, MF:C20H16Cl2F3N3O4S, MW:522.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Gcn2-IN-1 | Gcn2-IN-1, MF:C19H18N10O, MW:402.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Bismuth-film electrodes have unequivocally emerged as a viable, environmentally friendly successor to mercury-based electrodes for the stripping voltammetry of heavy metals. Their performance in terms of sensitivity, detection limit, and ability to handle complex biomatrices like blood and urine is comparable, and in some cases superior, to other mercury-free alternatives like graphite-epoxy composites. While challenges such as optimal performance in acidic media persist, ongoing research into electrode substrates and bismuth nanostructures continues to broaden their application scope. For researchers and drug development professionals requiring reliable, sensitive, and sustainable tools for metal detection in biological systems, bismuth-film electrodes represent a mature and compelling technology within the landscape of modern analytical chemistry.

The search for robust alternatives to mercury electrodes represents a significant trend in modern electroanalytical chemistry. For decades, stripping voltammetry has been recognized for its exceptional sensitivity in trace element analysis, yet the toxicity of mercury electrodes has driven the development of solid-state alternatives. Among these, solid gold electrodes have emerged as powerful, environmentally friendly platforms capable of determining numerous toxic elements at regulatory levels. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of the scTRACE Gold electrode—a prominent commercial solid-state sensor—against other gold-based electrodes reported in recent research. The assessment focuses on analytical figures of merit, practical implementation requirements, and applicability for speciation analysis, providing scientists with critical data for selecting appropriate methodologies for their specific trace element determination needs.

Gold electrodes exhibit particular affinity for elements like arsenic and mercury, forming amalgams or intermetallic compounds that enable highly sensitive stripping analysis. The scTRACE Gold electrode specifically addresses several practical limitations of traditional gold electrodes through its unique design featuring an integrated three-electrode system on a single printed platform [33] [34]. This guide examines how such design innovations translate to performance advantages in real-world applications, particularly for researchers monitoring trace metals in environmental, food, and clinical matrices.

Technical Comparison of Gold Electrode Platforms

Design and Operational Characteristics

The scTRACE Gold electrode incorporates a gold micro-wire working electrode thinner than a human hair, with reference and auxiliary electrodes screen-printed on the reverse side [33] [34]. This integrated design eliminates the need for separate electrodes and makes reference electrode maintenance obsolete. A significant practical advantage is its short preparation time—the electrode is ready for use within minutes without extensive preconditioning [33] [35].

In contrast, traditional solid gold electrodes and gold nanoparticle-modified glassy carbon electrodes (AuNPs-GCE) typically require three-electrode cells with separate components. These often involve more complex preparation procedures, including mechanical polishing, electrochemical activation, or nanoparticle deposition steps [36] [37]. Gold electrodes fabricated from recordable CDs (CD-R) represent a low-cost alternative, manufactured by extracting the gold reflective layer from commercial CDs and encapsulating it with epoxy resin [38]. While extremely economical, these homemade electrodes require laborious fabrication and lack standardization.

Modification Strategies for Enhanced Functionality

A key advancement in gold electrode technology is the application of surface modifications to expand analytical capabilities. The scTRACE Gold electrode can be enhanced with thin metallic films to determine elements that show poor response on bare gold:

- Silver film modification enables highly sensitive determination of lead, with detection limits of 0.4 µg/L using the 884 Professional VA system [39] [40].

- Bismuth film modification facilitates the determination of nickel and cobalt as their dimethylglyoxime (DMG) complexes, transferring established methods from mercury electrodes to a mercury-free platform [39].

- Mercury film modification allows determination of chromium(VI) as a complex with diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA), providing detection limits of 2 µg/L despite the intention to avoid mercury [39] [40].

These modification approaches demonstrate how the scTRACE Gold platform can be adapted to specific analytical challenges while maintaining the practical advantages of a solid-state electrode system.

Performance Data Comparison

Table 1: Analytical performance of scTRACE Gold electrode for trace element determination in water

| Analyte | Matrix | Detection Limit (µg/L) | Recovery (%) | RSD (%) | Method Details |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arsenic | Drinking water | 1.0 | 92 (at 10 µg/L) | 6.5 | Direct determination [33] |

| Copper | Surface water | 0.5 | 107 (at 5 µg/L) | 2.0 | Direct determination [33] |

| Iron | Drinking water | 10 | 91 (at 20 µg/L) | 1.0 | Direct determination [33] |

| Lead | Drinking water | 0.4 (lab), 0.6 (portable) | 96 (at 10 µg/L) | 5.0 | With Ag film modification [39] |

| Nickel | Drinking water | 0.2 (lab), 1.0 (portable) | 99 (at 1 µg/L) | 5.0 | With Bi film modification, as DMG complex [39] |

| Chromium(VI) | Drinking water | 2 | 115 (at 30 µg/L) | 2.0 | With Hg film modification, as DTPA complex [39] |

Table 2: Comparison of gold electrode platforms for mercury determination in biological samples

| Electrode Type | Matrix | Detection Limit | Quantification Limit | Comparison Method | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| scTRACE Gold (unmodified) | Water | ~1 µg/L (inferred) | Not specified | ICP | [33] |

| Solid Gold Electrode (SGE) | Fish | Not specified | <1 mg/kg (wet weight) | DMA, CV-AAS | [36] |

| Au Nanoparticle-Modified GCE | Fish | Not specified | 0.06 mg/kg (wet weight) | DMA | [36] [37] |

| CD-R Gold Electrode | Fish | 0.30 µg/L | 1.0 µg/L | CVAAS | [38] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Determination of Arsenic in Drinking Water with scTRACE Gold

Methodology Summary: The protocol employs direct anodic stripping voltammetry without electrode modification. After simply connecting the scTRACE Gold electrode to the voltammetric analyzer, the sample is acidified with hydrochloric acid to approximately 0.1 M concentration [33] [34]. The measurement sequence includes a deposition step at a negative potential where arsenic is reduced and deposited onto the gold surface, followed by a stripping scan from negative to positive potentials where the deposited arsenic is oxidized back into solution, producing the analytical signal.

Key Parameters: Deposition potential: -0.4 V; Deposition time: 60-120 s; Stripping technique: Square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry; Analysis time: ~10 minutes per sample [33] [35].

Performance Notes: The method achieves a detection limit of 1 µg/L, one-tenth of the WHO guideline value of 10 µg/L, with a recovery of 92% at the regulatory limit and relative standard deviation of 6.5% [33]. This demonstrates sufficient precision and accuracy for compliance monitoring of arsenic in drinking water.

Mercury Determination in Fish with Gold Nanoparticle-Modified Electrodes

Sample Preparation: Two digestion approaches were compared: conventional microwave digestion using concentrated nitric acid and a simplified field digestion procedure using a commercial food warmer with nitric acid [37]. The field method provides adequate sample preparation for voltammetric analysis while being more accessible for on-site applications.

Electrode Preparation: Gold nanoparticle-modified glassy carbon electrodes (AuNPs-GCE) were prepared by electrodeposition from a solution of tetrachloroauric acid, creating a high-surface-area platform that enhances mercury preconcentration [36] [37].

Analysis Parameters: Square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SW-ASV) was performed with a deposition potential of -0.4 V for 300 seconds, followed by a square-wave scan from -0.4 V to +0.4 V. The method was validated against Direct Mercury Analysis (DMA) and Cold Vapor Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (CV-AAS) [36] [37].

Performance Notes: The AuNPs-GCE achieved a quantification limit of 0.06 mg/kg in fish tissue, performance comparable to DMA, with excellent agreement between laboratory and field preparation methods [37].

Analytical Workflows Diagram

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for trace element analysis using different gold electrode platforms, highlighting key decision points and procedural variations.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for trace element speciation with gold electrodes

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| scTRACE Gold electrode | Working electrode with integrated reference/counter | All applications | Ready-to-use, no maintenance required [33] |

| Tetrachloroauric acid | Source for gold nanoparticle electrodeposition | AuNP-modified electrode preparation | Enables creation of high-surface-area electrodes [36] |

| Dimethylglyoxime (DMG) | Complexing agent for nickel and cobalt | Ni/Co determination in water | Forms electroactive complexes for adsorptive stripping [39] |

| Diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (DTPA) | Complexing agent for chromium(VI) | Cr(VI) determination in water | Enables speciation of toxic Cr(VI) form [39] |

| Silver nitrate | Source for silver film modification | Lead determination | Renewable surface extends electrode lifetime [39] |

| Bismuth nitrate | Source for bismuth film modification | Nickel/cobalt determination | Mercury-free alternative for these elements [39] |

| Hydrochloric acid (0.05-0.1 M) | Supporting electrolyte and sample acidification | Arsenic, copper determination | Optimal concentration varies by application [33] [38] |

Comparative Advantages and Limitations

scTRACE Gold Electrode System

Advantages:

- Integrated three-electrode design eliminates additional electrode costs and maintenance [33] [34]

- Rapid preparation time enables immediate use after connection [33] [35]

- Modification capability expands determinable elements [39] [40]

- Compatibility with both laboratory (884 Professional VA) and portable (946 Portable VA) instruments facilitates field analysis [33] [39]

Limitations:

- Higher initial cost compared to homemade electrodes

- Limited to predetermined surface area and geometry

- May still require mercury films for certain applications (e.g., Cr(VI)), counteracting mercury-reduction goals [39]

Alternative Gold Electrode Platforms

Solid Gold Electrodes (SGE):

- Provide well-established electrochemistry with extensive literature support [36]

- Require regular polishing and electrochemical pretreatment

- Need separate reference and counter electrodes

Gold Nanoparticle-Modified Electrodes (AuNPs-GCE):

- Enhanced sensitivity due to increased surface area [36] [37]

- Require careful optimization of nanoparticle deposition parameters

- May exhibit better antifouling properties in complex matrices

CD-R-Based Gold Electrodes:

- Extremely low cost (fabricated from commercial CDs) [38]

- Suitable for resource-limited settings

- Lack reproducibility between batches

- Time-consuming fabrication process

The scTRACE Gold electrode represents a significant advancement in solid-state electrode technology, offering practical advantages for routine analysis through its integrated design and simplified operation. While traditional solid gold electrodes and nanoparticle-modified variants continue to provide viable alternatives—particularly for specialized applications or budget-constrained environments—the scTRACE Gold system delivers a balanced combination of performance, practicality, and flexibility for most trace element monitoring scenarios.

For researchers transitioning from mercury-based electrodes, the modification strategies available for the scTRACE Gold platform enable determination of a wide range of elements previously accessible only with mercury electrodes. The analytical performance summarized in this guide demonstrates that modern gold electrodes generally meet or exceed regulatory requirements for trace metal determination in environmental and food matrices, solidifying their position as fundamental tools in contemporary stripping analysis research.

Antimony-Based Electrodes for Monitoring Stabilizers in Compliance with RoHS

The Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) directive significantly influences material selection in electronic equipment and analytical chemistry by restricting specific dangerous substances [41]. For researchers monitoring trace heavy metals and stabilizers, this has accelerated the search for alternatives to traditional mercury electrodes, which are limited due to mercury's toxicity [17]. Among the most promising "environmentally friendly" alternatives are electrodes based on bismuth and antimony (Sb) [17] [25].

Antimony-based electrodes offer a compelling combination of analytical performance and regulatory alignment. While not currently restricted under RoHS, antimony's use is subject to specific limitations, particularly in children's products and food contact materials, making its compliant application a key research focus [42]. This guide objectively compares the performance of antimony-film electrodes with other prominent alternatives, providing researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed for their application in compliant analysis.

Performance Comparison of Mercury-Alternative Electrodes

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of antimony-based electrodes alongside other common mercury-free alternatives, based on recent experimental findings.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Electrodes for Anodic Stripping Voltammetry

| Electrode Type | Typical Substrate | Sensitivity / Performance | Linear Range (for Cd²âº) | Detection Limit | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimony Film (SbFE) | Screen-Printed Carbon (SPCE) | Low charge transfer resistance (6 Ω); High sensitivity to Ni(II) [25] | Not specified | Not specified | "Green" metal; Low cost; Suitable for novel sensor development [25] | Performance dependent on film coverage [25] |

| Bismuth Film (BiFE) | Glassy Carbon, Copper | Well-defined peaks, low background [17] | 2x10â»â¸ to 1x10â»â¶ mol Lâ»Â¹ [17] | Not specified | "Environmentally friendly"; Low toxicity; High reproducibility [17] | Requires acidic media (pH < 4.3) [17] |

| Tin Film (SnFE) | Not specified | Effective for simultaneous determination of Cr(III) & Cd(II) [25] | Not specified | Not specified | Effective alternative [25] | Not extensively covered in results |

| Mercury Film (HgFE) | Platinum | Historical reference standard | - | - | High reproducibility, sensitivity [17] | High toxicity; Environmental and safety concerns [17] |

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Preparation and Testing

Fabrication of Antimony Film Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (Sb/SPCEs)

The performance of SbFEs is highly dependent on the fabrication process, particularly the pre-plating conditions and the resulting coverage of the substrate [25].

- Modification Principle: Antimony is deposited onto a screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) surface via a potentiostatic electrodeposition process. The properties of the resulting film can be tuned by varying the deposition potential and time [25].

- Electrode Characterization: The modified electrodes should be characterized using a combination of techniques to correlate structure with function.