Mercury-Free Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry: Principles, Electrodes, and Applications in Biomedical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the principles and applications of adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV) utilizing mercury-free electrodes, a critical advancement for modern analytical chemistry and drug development.

Mercury-Free Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry: Principles, Electrodes, and Applications in Biomedical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the principles and applications of adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV) utilizing mercury-free electrodes, a critical advancement for modern analytical chemistry and drug development. Tailored for researchers and scientists, we explore the foundational mechanisms of adsorptive accumulation and stripping, detail the operation and selection of environmentally friendly electrodes like bismuth-based and carbon-based sensors. The scope extends to method development for pharmaceuticals and biomarkers, optimization strategies to overcome analytical challenges, and rigorous validation against established techniques. This resource aims to equip professionals with the knowledge to implement sensitive, reliable, and sustainable voltammetric methods in their workflows.

Core Principles and the Rise of Mercury-Free Electrodes in Modern Voltammetry

Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) is a powerful electroanalytical technique renowned for its exceptional sensitivity in trace-level measurements. Unlike conventional stripping methods that rely on electrolytic deposition, AdSV achieves preconcentration via a non-faradaic process, where the analyte accumulates on the working electrode surface through adsorption [1] [2]. This fundamental difference significantly expands the scope of stripping analysis to include a wide range of organic compounds and metal ions that do not readily form amalgams or electrolytically deposit, establishing AdSV as a versatile tool for researchers and drug development professionals [1].

The core of the AdSV mechanism lies in its two-stage process: a preconcentration step involving the controlled interfacial accumulation of the analyte, followed by a stripping step where the surface-confined species is measured voltammetrically [1]. The voltammetric response is directly proportional to the surface concentration, with the relationship between surface and bulk concentrations often described by adsorption isotherms such as the Langmuir isotherm [1]. This technique's versatility allows for the determination of trace levels of various reducible and oxidizable compounds, including pharmaceuticals like digoxin, as well as biological macromolecules such as DNA and proteins [1].

Fundamental Principles and Mechanism

The Adsorptive Preconcentration Step

The preconcentration step in AdSV is a controlled adsorption process where the analyte accumulates at the electrode-solution interface without electron transfer. This step is typically performed at a constant potential, often with solution stirring to enhance transport, for a predetermined time that controls the analytical sensitivity [1] [3]. The extent of accumulation is governed by the adsorption isotherm, with the Langmuir model frequently providing the relationship between surface concentration (Γ) and bulk concentration (C_b) [1]. For many analytes at trace levels (10⁻⁷–10⁻¹⁰ M), a linear adsorption isotherm is obeyed, resulting in a linear response between the stripping current and analyte concentration [1].

Several factors critically influence adsorption efficiency. The chemical nature of the analyte dictates its affinity for the electrode surface, with surface-active compounds accumulating most effectively [1]. The electrode material (mercury, carbon, or modified electrodes) significantly impacts both adsorption capacity and the subsequent electron transfer kinetics [1] [4]. The accumulation potential must be optimized to enhance adsorption while avoiding undesirable faradaic processes, and the solution conditions (pH, ionic strength, composition) can profoundly affect the analyte's adsorption behavior and stability [3].

The Voltammetric Stripping Step

Following the adsorption period and a brief equilibration, the stripping step involves applying a potential scan to initiate the redox reaction of the adsorbed species. The resulting current is directly proportional to the surface concentration of the analyte [1]. Various voltammetric techniques can be employed for this measurement, including linear sweep, differential pulse, and square-wave voltammetry, with pulse techniques generally offering superior sensitivity and resolution by minimizing capacitive currents [3].

The shape and position of the stripping peak provide crucial analytical and mechanistic information. The peak current (ip) serves as the quantitative analytical signal, while the peak potential (Ep) aids in qualitative identification [5]. For a surface-confined species, the peak current is expected to scale linearly with the scan rate (v) for an ideal adsorbed layer, following the equation: i_p = (n²F²/4RT)ΓAv, where n is the number of electrons, F is Faraday's constant, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, Γ is surface concentration, and A is electrode area [5].

Mercury-Free Electrode Systems

The development of robust mercury-free electrode systems represents a significant advancement in AdSV, addressing toxicity concerns while maintaining analytical performance.

Modified Carbon Electrodes

Glassy carbon electrodes (GCEs) serve as foundational substrates for various modifications. Their performance can be enhanced through electrochemical pretreatment, which roughens the surface and introduces oxygen-containing functional groups that facilitate analyte adsorption via hydrogen bonding or electrostatic interactions [4]. For instance, pretreatment in sulfuric acid at 1.8 V significantly increases surface roughness and oxygen content, as confirmed by SEM/EDX and FT-IR, enhancing electron transfer kinetics and adsorption capacity for compounds like alprazolam [4].

Film-modified electrodes represent another strategic approach. Bismuth film-modified GCEs (BiF/GCE) and lead film-modified GCEs (PbF/GCE) offer environmentally friendly alternatives with favorable electrochemical properties [6]. These films are typically deposited in situ from solutions containing Bi(NO₃)₃ or Pb(NO₃)₂, providing well-defined signals for the determination of various organic molecules, including novel anticancer agents [6].

Performance Comparison of Mercury-Free Electrodes

Table 1: Comparison of Mercury-Free Electrodes Used in AdSV

| Electrode Type | Modification Method | Typical Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemically Pretreated GCE | Anodic polarization in acidic medium | Determination of alprazolam, aripiprazole [4] [7] | Simple preparation, enhanced adsorption via oxygen functional groups, low cost | Limited reproducibility between pretreatments, potential fouling |

| Bismuth Film GCE (BiF/GCE) | In situ electrodeposition from Bi³⁺ solutions | Quantitative determination of anticancer agents [6] | Environmentally friendly, well-defined signals, wide potential window | Limited anodic range, pH-dependent performance |

| Lead Film GCE (PbF/GCE) | In situ electrodeposition from Pb²⁺ solutions | Ultrasensitive detection of anticancer agents [6] | High sensitivity, well-defined signals, good reproducibility | Toxicity concerns, interference from surface oxides |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Electrode Preparation and Modification

Electrochemical Pretreatment of GCE: Polish the GCE successively with finer alumina slurries (e.g., down to 0.3 μm) on a polishing cloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water. Immerse the electrode in 0.5-1.0 M H₂SO₄ and apply a constant potential of 1.8 V for 60-300 seconds [4]. Alternatively, use potential cycling in the same electrolyte. Rinse the pretreated electrode and characterize using cyclic voltammetry in a standard redox probe like Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻ to verify enhanced electron transfer [4].

In Situ Bismuth Film Formation on GCE: Transfer 10 mL of supporting electrolyte (e.g., acetate buffer, pH 4.6) to the electrochemical cell. Add Bi(NO₃)₃ to a final concentration of 10 μmol/L [6]. Deoxygenate with nitrogen or argon for 5-8 minutes. Apply a deposition potential of -1.0 V to -1.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 30-120 seconds with stirring to deposit the bismuth film. The electrode is now ready for the adsorptive accumulation step [6].

Optimized Analytical Procedure for Drug Determination

The following protocol exemplifies the determination of an antipsychotic drug, aripiprazole, using adsorptive stripping voltammetry:

Solution Preparation: Prepare a Britton-Robinson (B-R) buffer support electrolyte (pH 4.0 for aripiprazole) by mixing phosphoric acid, boric acid, and acetic acid, then adjusting pH with NaOH or HCl [7] [8].

Accumulation Step: Transfer 10.0 mL of the buffer to the electrochemical cell. Add the standard or sample solution. Purge with inert gas (argon or nitrogen) for 15 minutes initially and 30 seconds between runs. Apply an accumulation potential (0.0 V for aripiprazole) while stirring the solution for a predetermined time (30-120 seconds) to allow adsorptive accumulation [7] [8].

Equilibration Period: Stop stirring and wait for 10-20 seconds to allow solution quiescence [3].

Stripping Step: Initiate the voltammetric scan (differential pulse or square-wave) toward positive potentials for oxidation or negative potentials for reduction. For aripiprazole, use a square-wave anodic adsorptive stripping voltammetry (SWAAdSV) scan from 0.0 V to 1.3 V with parameters: frequency 50 Hz, pulse amplitude 50 mV, step potential 4 mV [7] [8].

Measurement: Record the oxidation peak at approximately 1.15 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for aripiprazole. Use standard addition or calibration curve for quantification [7] [8].

Table 2: Optimized Operational Parameters for Selected Pharmaceutical Compounds

| Analyte | Electrode | Supporting Electrolyte | Accumulation Potential | Accumulation Time | Stripping Technique | Peak Potential | LOD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole [7] [8] | GCE | BR buffer, pH 4.0 | 0.0 V | 30 s | SWAdSV | +1.15 V | 0.11 μM |

| Alprazolam [4] | EPGCE | BR buffer, pH 9.0 | -0.80 V | 120 s | AdCSV | -1.06 V | 0.03 mg/L |

| Rosiglitazone [3] | HMDE | BR buffer, pH 5.0 | -0.20 V | 120 s | SWAdSV | -1520 mV | 3.2×10⁻¹¹ M |

| Anticancer Agent DIB [6] | PbF/GCE | Acetate buffer, pH 4.6 | -0.4 V | 10 s | SWAdSV | -0.68 V | 1.5 μg/L |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for AdSV Experiments

| Reagent Solution | Composition/Preparation | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Britton-Robinson (BR) Buffer | Mixture of 0.04 M each: boric acid, phosphoric acid, acetic acid; adjust pH with NaOH or HCl [7] [3] | Versatile supporting electrolyte for wide pH range (2-12) | Suitable for various pharmaceuticals; minimal interference with adsorption |

| Electrochemical Pretreatment Solution | 0.5-1.0 M sulfuric acid [4] | Introduces oxygen functional groups and increases surface roughness on GCE | Enhances adsorption via hydrogen bonding; critical for sensitive detection |

| Bismuth Plating Solution | 10 μmol/L Bi(NO₃)₃ in supporting electrolyte [6] | Forms bismuth film on GCE for enhanced sensing | Environmentally friendly alternative to mercury; in situ deposition preferred |

| Protein Precipitation Reagent | Methanol with 0.1 M NaOH and 5% w/v ZnSO₄·7H₂O [3] | Removes proteins from biological samples prior to analysis | Essential for serum/plasma analysis; prevents electrode fouling |

Analytical Performance and Applications

Quantitative Determination in Pharmaceutical and Biological Matrices

AdSV demonstrates exceptional performance for pharmaceutical analysis, with detection limits frequently reaching nanomolar to picomolar levels. The technique successfully determines compounds like aripiprazole in tablet formulations, human serum, and urine with good recoveries (95.0%-104.6%) and relative standard deviations typically below 10% [7] [8]. For alprazolam determination using an electrochemically pretreated GCE, the method displays two linear ranges (0.1-4 mg/L and 4-20 mg/L) with excellent repeatability (%RSD < 4.24%) and recovery (82.0%-109.0%) in beverage samples [4].

The exceptional sensitivity of AdSV enables ultratrace measurements, with detection limits as low as 3.2×10⁻¹¹ M for rosiglitazone using a 120-second accumulation [3]. This sensitivity is further enhanced when AdSV is coupled with catalytic reactions, enabling detection of platinum at 10⁻¹² M levels [1]. Such remarkable sensitivity makes AdSV particularly valuable for monitoring drug levels in biological fluids and studying pharmacokinetics.

Selectivity Enhancement Strategies

Several approaches effectively enhance method selectivity in complex matrices. The medium-exchange technique allows the accumulation to be performed in the sample matrix, followed by transfer of the electrode to a clean solution for the stripping measurement, effectively separating the analyte from non-adsorbing interferents [1]. Permselective coatings, such as cellulose acetate films, can be applied to the electrode surface to minimize interferences from co-adsorbing surfactants or other surface-active compounds [1]. For biological samples, solid-phase extraction (SPE) using C18 cartridges effectively isolates the analyte from the complex matrix before analysis, as demonstrated for anticancer drug determination in serum [6].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

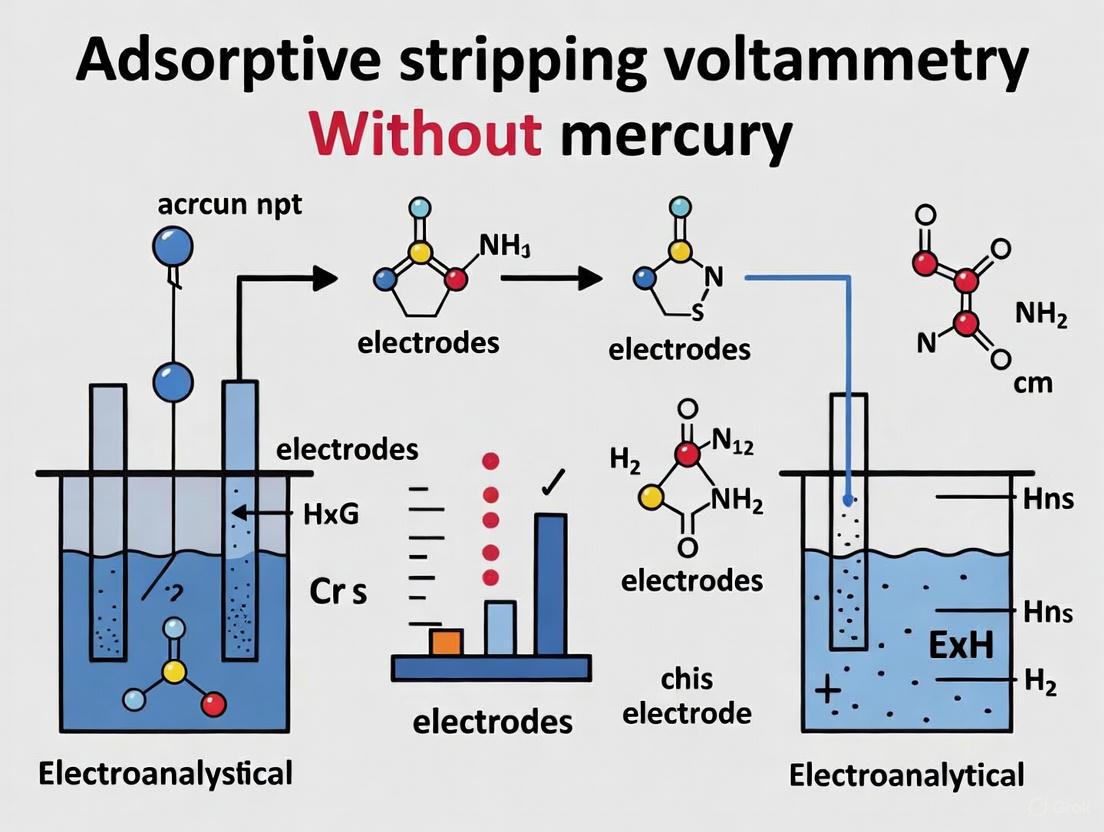

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry. This diagram illustrates the sequential steps involved in a typical AdSV analysis, highlighting the critical accumulation and stripping phases.

Diagram 2: Fundamental Mechanism of Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry. This diagram illustrates the molecular-level processes from analyte transport to signal generation, emphasizing the adsorption and redox steps.

Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry represents a sophisticated yet accessible analytical technique that combines effective interfacial accumulation with advanced voltammetric measurement. The methodology provides exceptional sensitivity for trace analysis of pharmaceuticals, biological macromolecules, and metal complexes, with the growing implementation of mercury-free electrode systems enhancing its environmental compatibility and practical applicability. Through careful optimization of accumulation conditions, electrode modification, and stripping parameters, researchers can develop highly sensitive and selective methods suitable for complex matrices including pharmaceutical formulations and biological fluids. The continued development of modified electrode materials and strategic selectivity enhancement approaches promises to further expand the utility of AdSV in drug development and biomedical research.

Why Move Beyond Mercury? Drivers for Eco-Friendly and User-Safe Electrodes

For decades, mercury-based electrodes were considered the gold standard in electroanalytical chemistry, particularly for stripping voltammetry techniques such as adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV). Their high sensitivity, renewable surface, wide cathodic potential range, and reproducibility made them ubiquitous in research and analytical laboratories for detecting heavy metal ions [9]. However, growing awareness of mercury's severe toxicity and environmental persistence has driven a fundamental reassessment of its role in modern analytical science. The movement toward eco-friendly and user-safe electrodes represents a significant shift, motivated by converging drivers including regulatory pressures, workplace safety requirements, technological advancements in nanomaterials, and evolving environmental standards [10] [11] [12].

This transition is particularly relevant within the context of adsorptive stripping voltammetry without mercury, where researchers are developing sophisticated alternative materials that not only match mercury's analytical performance but in many cases surpass it. The principles of AdSV—depending on the initial accumulation of an analyte onto the electrode surface followed by voltammetric measurement—require electrode materials with excellent adsorption characteristics, high sensitivity, and stability [13]. Modern mercury-free electrodes are increasingly meeting these requirements through innovative material designs and functionalization strategies. This whitepaper examines the technical drivers behind this transition, evaluates current alternative electrode technologies, and provides detailed methodologies for researchers implementing mercury-free electrochemical systems.

The Compelling Case for Transitioning from Mercury

Toxicity, Environmental, and Regulatory Drivers

Mercury poses significant environmental and health risks that directly impact laboratory safety and waste management. Elemental mercury vaporizes at room temperature, producing colorless, odorless vapor that is difficult to detect and poses long-term exposure risks, especially when spills occur in cracks of lab benches or floor tiles [12]. The environmental persistence of mercury means that once released, it can circulate in ecosystems for extended periods, accumulating in organisms and entering the food chain [14].

Regulatory frameworks worldwide have responded to these risks. The Minamata Convention on Mercury, a global treaty, specifically addresses mercury reduction and elimination across multiple sectors, driving policy changes in signatory countries [15]. Institutional environmental health and safety departments now strongly recommend replacing mercury-containing devices with safer alternatives and impose strict requirements for mercury storage, spill management, and disposal [11] [12] [16]. Disposal of mercury-containing equipment requires specialized hazardous waste handling, as it cannot be placed in regular trash or drained [11] [14]. These regulatory and safety concerns have become primary drivers for the scientific community to develop high-performance alternatives.

Technical Limitations of Mercury Electrodes

Beyond safety concerns, mercury electrodes present several technical limitations that hinder their application in modern analytical contexts:

- Oxygen interference requiring deaeration through nitrogen purging

- Limited anodic potential range preventing analysis of easily oxidizable species

- Poor mechanical stability and sensitivity to vibration

- Low portability and suitability for miniaturization

- Unsuitability for online and in-situ monitoring applications [9] [13]

These limitations have become more significant with the growing demand for field-deployable sensors, point-of-care diagnostics, and continuous monitoring systems. The development of solid-state electrodes addresses these limitations while eliminating mercury's toxicity.

Performance Comparison: Mercury vs. Mercury-Free Electrodes

The advancement of nanomaterials and surface modification techniques has enabled mercury-free electrodes to achieve analytical performance comparable to, and in some cases superior to, traditional mercury-based systems.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Mercury and Mercury-Free Electrodes for Metal Ion Detection

| Electrode Type | Detection Limit for Metal Ions | Linear Range | Key Advantages | Main Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury (HMDE) | ~10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹² M (varies by metal) | Wide | Excellent renewal, high reproducibility, wide cathodic potential | High toxicity, poor portability, oxygen sensitivity |

| Bismuth Film | 1.4×10⁻⁹ M for In(III) (ASV) [13] | 5×10⁻⁹ to 5×10⁻⁷ M [13] | Low toxicity, well-defined signals, multi-element detection | Potential window limitations in alkaline media |

| Bismuth Bulk | 3.9×10⁻¹⁰ M for In(III) (AdSV) [13] | 1×10⁻⁹ to 1×10⁻⁷ M [13] | No bismuth addition to sample, favorable signal-to-noise ratio | Mechanical stability over long-term use |

| Functionalized Nanocomposites | Sub-nanomolar for various heavy metals [17] | Varies with composite design | Enhanced selectivity, antifouling properties, customizable | Complex synthesis, characterization requirements |

Table 2: Electrode Modification Materials and Their Functions in Mercury-Free Sensing

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Key Functions | Impact on Sensor Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Graphene, CNTs, reduced graphene oxide [17] | High conductivity, large surface area, functional groups for metal binding | Enhanced electron transfer, preconcentration of analytes, improved LOD |

| Metal Nanoparticles | Au, Ag, Bi, Sb nanoparticles [17] [10] | Catalytic activity, mediation of electron transfer, formation of alloys with target metals | Signal amplification, increased sensitivity and selectivity |

| Conducting Polymers | Polyaniline, polypyrrole, polydopamine [17] [10] | Ion-exchange properties, molecular recognition, preconcentration | Selective extraction, interference rejection, stability enhancement |

| Selective Ligands | Cupferron, morin, dithiocarbamates [13] | Complexation with specific metal ions, facilitated adsorption | Enhanced selectivity, enables adsorptive stripping approaches |

Implementation Guidelines: Mercury-Free Electrode Systems

Solid Bismuth Microelectrode for Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry

The solid bismuth microelectrode (SBiµE) represents a significant advancement in mercury-free electroanalysis, combining environmental safety with excellent analytical performance [13]. The following protocol details its application for indium(III) detection using AdSV with cupferron as a chelating agent, demonstrating principles applicable to other metal ions.

Experimental Protocol: Indium(III) Detection Using SBiµE AdSV

Materials and Reagents:

- Solid bismuth microelectrode (SBiµE) with 25 µm diameter [13]

- Acetate buffer (0.1 mol/L, pH 3.0±0.05) as supporting electrolyte [13]

- Cupferron solution (0.01 mol/L) as complexing agent [13]

- Indium(III) standard solutions prepared by serial dilution from stock

- Electrochemical workstation with three-electrode configuration

- Purified nitrogen gas for deaeration (optional)

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Electrode Activation:

- Apply activation potential of -2.5 V vs. reference electrode for 45 seconds

- This step reduces any bismuth oxide on the electrode surface, ensuring access to metallic bismuth during accumulation [13]

- Optimize activation time to maximize analytical signal while avoiding excessive reduction

Sample Preparation:

- Mix 10 mL of sample/standard solution with 1 mL of acetate buffer

- Add 50 µL of cupferron solution (0.01 mol/L) as complexing agent

- For AdSV, the complex formation between indium(III) and cupferron enables analyte accumulation

Analyte Accumulation:

- Apply accumulation potential of -0.65 V vs. reference electrode for 10 seconds with solution stirring

- During this step, the indium(III)-cupferron complex adsorbs onto the electrode surface

- Optimize accumulation time based on target analyte concentration

Voltammetric Measurement:

- After equilibrium period (5-10 seconds), initiate negative potential sweep from -0.4 V to -1.0 V

- Record the voltammogram, noting the peak current at approximately -0.7 V corresponding to indium(III) reduction

- Use standard addition method for quantification in complex matrices

Electrode Regeneration:

- Clean electrode between measurements by applying mild oxidizing potential

- Verify electrode performance regularly with standard solutions

Method Validation:

- Linear range: 1×10⁻⁹ to 1×10⁻⁷ mol/L [13]

- Detection limit: 3.9×10⁻¹⁰ mol/L (0.39 nM) [13]

- Precision: Typically <5% RSD for multiple measurements

- Recovery: Validate with spiked environmental water samples (e.g., Baltic Sea water) [13]

Nanocomposite-Modified Electrodes for Heavy Metal Ion Detection

Functionalized nanocomposites represent another promising approach for mercury-free electrodes, leveraging synergistic effects between different nanomaterials to enhance sensor performance [17].

Experimental Protocol: Carbon-Metal Nanocomposite Electrode for Heavy Metal Detection

Materials and Reagents:

- Carbon nanostructures: Graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes [17]

- Metal nanoparticles: Bismuth, antimony, gold, or tin oxide nanoparticles [17]

- Binding agents: Nafion, chitosan, or conducting polymers

- Substrate electrodes: Glassy carbon, screen-printed carbon, or carbon paste electrodes

- Heavy metal standard solutions: Pb(II), Cd(II), Hg(II), Zn(II), etc.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Nanocomposite Synthesis:

- Prepare carbon support material (e.g., reduce graphene oxide using chemical or electrochemical methods)

- Deposit metal nanoparticles onto carbon support using electrochemical deposition or chemical reduction

- Functionalize with selective ligands (e.g., dithiocarbamates, porphyrins) for target metal ions [17]

Electrode Modification:

- Polish substrate electrode with alumina slurry (if using solid electrodes)

- Prepare nanocomposite ink by dispersing 2 mg nanocomposite in 1 mL solvent with 10 µL binder

- Deposit 5-10 µL ink onto electrode surface and dry under infrared lamp

- Condition modified electrode in buffer solution by cyclic voltammetry

Electrochemical Measurement:

- Employ anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) for heavy metal detection:

- Accumulation step: Apply negative potential (-1.2 to -1.4 V) with stirring for 60-300 seconds

- Equilibrium period: 10-15 seconds without stirring

- Stripping step: Record positive potential sweep from -1.0 to -0.3 V

- For speciated analysis, use adsorptive stripping voltammetry with selective complexing agents

- Employ anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) for heavy metal detection:

Data Analysis:

- Identify metals based on characteristic peak potentials

- Quantify using standard addition method to account for matrix effects

- For multi-element analysis, deconvolute overlapping peaks using standard mixtures

Method Performance:

- Detection limits: Sub-ppb for Pb(II), Cd(II), Hg(II) in optimized systems [17]

- Linear range: Typically 2-3 orders of magnitude [17]

- Selectivity: Excellent rejection of common interferents (Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Na⁺) [17]

- Stability: >50 measurements with <10% signal degradation for properly designed composites [17]

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for Mercury-Free Electroanalysis

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Mercury-Free Electrode Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Electrode System | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Substrates | Glassy carbon, screen-printed carbon, gold disk, carbon paste | Provides conductive foundation for modifications | Surface polishing critical for solid electrodes; screen-printed electrodes offer disposable option |

| Bismuth Precursors | Bismuth nitrate, bismuth oxide, bismuth nanoparticles | Forms bismuth film or bulk bismuth electrode active surface | In-situ plating requires bismuth ion addition; ex-situ plating enables controlled film formation |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Graphene oxide, multi-walled carbon nanotubes, carbon black | Enhances conductivity, surface area, and active sites | Functionalization (oxygen groups, nitrogen doping) improves metal adsorption properties |

| Selective Ligands | Cupferron, dithiocarbamates, porphyrins, crown ethers | Enables selective complexation with target metal ions | Critical for AdSV approaches; choice depends on target metal and matrix |

| Conducting Polymers | Polyaniline, polypyrrole, polydopamine | Provides ion-exchange properties, stability, functional groups | Can be synthesized electrochemically or chemically; composite formation enhances durability |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Acetate buffer, phosphate buffer, nitric acid, KCl | Provides ionic conductivity and controls pH | Choice affects sensitivity, selectivity, and potential window; acetate buffer (pH 3-5) common |

Current Research Frontiers and Future Perspectives

The field of mercury-free electrodes continues to evolve rapidly, with several promising research directions emerging. Multi-sensor platforms and electronic tongues represent one significant advancement, where arrays of differently modified electrodes coupled with pattern recognition enable simultaneous detection of multiple analytes in complex matrices [9]. These systems are particularly valuable for environmental monitoring where multiple heavy metal contaminants may coexist.

Advanced functionalization strategies are enhancing selectivity toward specific metal ions. Molecularly imprinted polymers, biomimetic ligands, and genetically engineered peptides offer unprecedented specificity for target analytes [17] [10]. These approaches are increasingly important for speciation analysis, where distinguishing between different oxidation states of metals (e.g., Cr(III) vs. Cr(VI), Fe(II) vs. Fe(III)) is critical for accurate risk assessment [10].

The integration of mercury-free electrodes with microfluidics and field-deployable platforms represents another frontier. Miniaturized systems combining sample preparation, separation, and detection enable rapid on-site analysis without the need for centralized laboratories [17] [9]. These developments are particularly relevant for environmental monitoring, point-of-care diagnostics, and resource-limited settings.

Future research needs include improving long-term stability in complex matrices, enhancing reproducibility for commercial applications, and developing standardized validation protocols for mercury-free electrodes across different application domains [17] [10]. As these technologies mature, they are expected to completely replace mercury-based electrodes in most analytical applications, fulfilling the dual goals of analytical excellence and environmental responsibility.

The transition to eco-friendly and user-safe electrodes represents both an ethical imperative and a technological opportunity for the electrochemical community. Drivers including toxicity concerns, regulatory pressures, and technical requirements for modern analytical applications have accelerated the development of high-performance alternatives to mercury electrodes. Materials such as bismuth, antimony, and functionalized nanocomposites now offer sensitivity and selectivity comparable to traditional mercury-based systems while providing additional benefits including portability, compatibility with flow systems, and suitability for miniaturization.

The protocols and methodologies presented in this whitepaper provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing mercury-free electrodes in adsorptive stripping voltammetry applications. As research continues to address current challenges related to stability, reproducibility, and validation, mercury-free electrodes are poised to become the new standard in electrochemical analysis, enabling safer laboratory environments while maintaining the high-quality analytical data required for advanced research and regulatory compliance.

The pursuit of mercury-free electrode materials represents a critical evolution in electroanalytical chemistry, driven by stringent environmental and safety concerns associated with traditional mercury electrodes. This transition is particularly vital for adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV), a technique prized for its exceptional sensitivity in trace metal analysis. The core challenge has been to identify alternative materials that match mercury's performance—specifically its wide cathodic potential window, reproducible surface, and high hydrogen overvoltage—without its inherent toxicity. Among the most promising alternatives are bismuth-based sensors, carbonaceous platforms, and modified graphite felts, each offering unique properties suitable for sophisticated electrochemical analysis [18] [10].

This technical guide examines the principles, performance, and practical applications of these key mercury-free electrode materials within the framework of modern stripping voltammetry. The development of these materials not only addresses environmental and safety requirements but also expands the capabilities of electrochemical detection for environmental monitoring, biomedical diagnostics, and industrial analysis [19].

Fundamental Principles of Bismuth-Based Electrodes

Bismuth-based electrodes have emerged as the leading mercury alternative for stripping voltammetry, combining an attractive environmental profile with exemplary electrochemical performance. The fundamental appeal of bismuth lies in its ability to form multi-metal alloys with target analytes during the preconcentration step, analogous to mercury's behavior but with significantly lower toxicity [20].

Operational Mechanisms

Bismuth functions through electrolytic co-deposition with target metals onto a substrate electrode, typically carbon-based. This process creates a bismuth-film electrode (BiFE) where the deposited bismuth facilitates the formation of fused alloys with analytes such as lead, cadmium, zinc, and indium. The stripping process then generates sharp, well-defined peaks suitable for quantitative analysis. Two primary configurations exist: ex situ deposition, where the bismuth film is pre-plated before analysis, and in situ deposition, where bismuth ions are added directly to the sample solution and simultaneously deposited with target analytes [18] [20].

The electron transfer kinetics at bismuth interfaces are particularly favorable for metal reduction and oxidation, contributing to the technique's high sensitivity. Furthermore, bismuth electrodes exhibit a wide operational potential window (extending to approximately -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl in many configurations) and low background currents, enabling the detection of metals at trace concentrations [18].

Comparative Performance: Bismuth vs. Mercury

Extensive research has demonstrated that properly configured bismuth electrodes can achieve analytical performance comparable to mercury electrodes for many key heavy metals. A study comparing paper-based electrodes modified with mercury or bismuth films found both capable of simultaneously quantifying Cd(II), Pb(II), and In(III), with bismuth presenting a more sustainable alternative. While mercury films demonstrated marginally better sensitivity (LOD for Pb(II): 0.1 µg/mL for Hg vs. 0.4 µg/mL for Bi), the bismuth-based approach provided sufficient sensitivity for many practical applications like water quality monitoring [18].

Table 1: Analytical Performance Comparison of Electrode Materials for Metal Detection

| Electrode Material | Target Analytes | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury-film (paper-based) | Cd(II), Pb(II), In(III), Cu(II) | 0.1-10 µg/mL | 0.04-0.4 µg/mL | [18] |

| Bismuth-film (paper-based) | Cd(II), Pb(II), In(III) | 0.1-10 µg/mL | 0.1-0.4 µg/mL | [18] |

| Solid Bismuth Microelectrode (ASV) | In(III) | 5×10⁻⁹ - 5×10⁻⁷ mol/L | 1.4×10⁻⁹ mol/L | [13] |

| Solid Bismuth Microelectrode (AdSV) | In(III) | 1×10⁻⁹ - 1×10⁻⁷ mol/L | 3.9×10⁻¹⁰ mol/L | [13] |

| Bismuth-coated Carbon | Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II) | 10-100 µg/L | <5 µg/L | [20] |

Carbon-Based Electrode Platforms

Carbon electrodes provide a versatile foundation for mercury-free electroanalysis, available in numerous forms including glassy carbon, carbon paste, screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs), and emerging paper-based carbon platforms. Their appeal lies in excellent conductivity, broad potential windows, robust physical properties, and ease of modification with catalytic films or functional layers [18].

Material Variations and Properties

Glassy carbon electrodes offer an impermeable surface with excellent electrochemical inertia, making them suitable for precise analytical measurements. Carbon paste electrodes, composed of carbon particles suspended in a binder, provide easily renewable surfaces that minimize passivation effects. Screen-printed carbon electrodes represent a significant advancement for decentralized analysis, offering disposable, low-cost platforms ideal for field measurements [18].

Recent innovations include paper-based carbon electrodes, which leverage cellulose substrates to create three-dimensional, hydrophilic platforms that facilitate rapid analyte transport to the electrode surface. The inherent porosity of paper allows for efficient wicking of solutions, enabling analysis with small sample volumes while maintaining the conductive pathways necessary for electrochemical measurements [18].

Surface Modification Strategies

The performance of carbon electrodes is frequently enhanced through strategic surface modifications:

- Nanomaterial Integration: Incorporating graphene, carbon nanotubes, or metal nanoparticles increases effective surface area and electron transfer kinetics [19].

- Polymer Films: Applying ion-exchange or permselective membranes improves selectivity by excluding interfering species [10].

- Bismuth Composites: Creating carbon-bismuth composite materials combines the conductive properties of carbon with bismuth's exceptional stripping voltammetry performance [21].

Table 2: Carbon Electrode Types and Their Applications in Stripping Voltammetry

| Carbon Electrode Type | Key Advantages | Common Modifications | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon | Smooth surface, excellent reproducibility | Bismuth films, nanoparticle decoration | Laboratory-based trace metal analysis |

| Carbon Paste | Renewable surface, low cost | Bismuth powder composites, ionophores | Field measurements, educational use |

| Screen-Printed Carbon | Disposable, mass-producible | In situ bismuth films, nanostructures | Portable sensors, single-use devices |

| Paper-Based Carbon | Low cost, biodegradable, 3D structure | Bismuth films, wax patterning | Point-of-care testing, environmental monitoring |

Graphite Felt as a Three-Dimensional Electrode Platform

Graphite felt represents a highly porous, three-dimensional electrode material with an extensive specific surface area that promotes exceptional mass transport characteristics. While traditionally employed in energy storage systems like vanadium redox flow batteries, its properties show significant promise for electroanalytical applications, particularly where high sensitivity is required [22].

Structural and Electrochemical Properties

The fibrous network of graphite felt creates an interconnected conductive matrix with abundant active sites for electrochemical reactions. This architecture facilitates rapid analyte diffusion throughout the electrode volume rather than just surface interactions, potentially increasing preconcentration efficiency in stripping techniques. The material exhibits strong corrosion resistance and high electrical conductivity, maintaining stability across wide potential ranges [22].

Functionalization and Catalytic Enhancement

A key advancement in graphite felt technology involves surface modification with bismuth to enhance electrochemical performance. Research demonstrates that electrodepositing bismuth particles onto graphite felt fibers significantly improves electron transfer kinetics for various redox reactions. In one study, Bi-modified graphite felts exhibited 9.47% higher voltage efficiency in electrochemical systems compared to unmodified felts, highlighting the catalytic effect of bismuth integration [22].

The modification process typically involves electrochemical deposition from Bi³⁺ solutions (e.g., BiCl₃ in dilute HCl) at controlled potentials. Optimization of deposition parameters—including voltage (0.8-1.6 V), duration, and solution concentration—allows precise control over bismuth particle size and distribution, enabling tailored electrode performance for specific analytical applications [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Preparation of Bismuth-Film Carbon Electrodes

Protocol 1: Ex Situ Bismuth Film Deposition on Carbon Electrodes

This method creates a stable bismuth film prior to sample analysis, eliminating bismuth introduction into the sample solution [18].

- Surface Preparation: Polish glassy carbon electrodes sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between polishing steps and sonicate in ethanol/water (1:1) for 2 minutes to remove residual alumina.

- Deposition Solution: Prepare a 10⁻³ M bismuth solution in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0) containing 0.5 M sodium sulfate as supporting electrolyte. Alternatively, use BiCl₃ in 0.1 M HCl for the bismuth source.

- Electrodeposition: Immerse the cleaned carbon electrode in the bismuth solution and apply a potential of -1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 2-5 minutes with continuous stirring. This reduces Bi³⁺ to Bi⁰, forming a uniform film on the electrode surface.

- Film Characterization: Verify film quality through cyclic voltammetry in acetate buffer or microscopic examination. The electrode is now ready for analysis without further bismuth addition to samples.

Protocol 2: In Situ Bismuth Film Formation

This approach simplifies analysis by co-depositing bismuth and analytes directly from the sample mixture [20].

- Sample Preparation: To the sample solution, add bismuth ions at a final concentration of 100-400 µg/L along with the supporting electrolyte (typically 0.1 M acetate buffer, pH 4.0-4.5).

- Simultaneous Deposition: Apply a deposition potential of -1.2 V to -1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 60-300 seconds with stirring, concurrently accumulating both bismuth and target metals.

- Stripping Analysis: Execute the stripping scan (e.g., square-wave voltammetry from -1.2 V to 0 V) to quantify analytes. The bismuth film forms and strips during each analysis cycle.

Fabrication of Paper-Based Carbon Electrodes with Bismuth Modification

This protocol details creation of low-cost, disposable electrodes ideal for field analysis [18].

- Substrate Patterning: Print hydrophobic wax barriers on chromatography paper (Whatman Grade 1) using a wax printer, creating defined hydrophilic zones for the electrode and fluid transport.

- Wax Melting: Heat the patterned paper to 80°C for 5-10 minutes to melt the wax, allowing it to penetrate through the paper thickness and create effective fluidic barriers.

- Carbon Ink Application: Apply 2 µL of carbon ink suspension (e.g., Gwent Group C10903P14) via drop-casting onto the designated working electrode area on the reverse side of the paper.

- Drying and Curing: Air-dry the electrodes for 60 minutes followed by oven curing at 60°C for 30 minutes to stabilize the conductive layer.

- Bismuth Functionalization: Modify the paper carbon electrode using either ex situ (as in Protocol 1) or in situ bismuth deposition methods described above.

Bismuth Modification of Graphite Felt for Enhanced Performance

This procedure enhances the electrochemical activity of graphite felt through bismuth particle deposition [22].

- Pretreatment: Thermally treat polyacrylonitrile-based graphite felt at 500°C for 5 hours in air to increase surface functionality and wettability.

- Plating Solution: Prepare 0.1 M Bi³⁺ solution by dissolving Bi₂O₃ in 3 M hydrochloric acid with stirring until completely dissolved.

- Electrochemical Deposition: Immerse pretreated graphite felt (3×3×0.5 cm) as both anode and cathode in the plating solution with 3 cm electrode separation. Apply constant voltage of 1.2 V for 10 minutes using a DC power supply, depositing granular bismuth particles on the cathode felt.

- Post-treatment: Rinse the modified felt thoroughly with distilled water to remove residual plating solution and dry at 80°C for 24 hours before use.

Diagram 1: Generalized workflow for bismuth-modified electrode preparation and analysis in stripping voltammetry.

Analytical Procedure for Indium Detection Using Solid Bismuth Microelectrode

This optimized protocol demonstrates the application of bismuth electrodes for trace metal analysis using both anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) and adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV) [13].

- Electrode Activation: Apply an activation potential of -2.4 V (ASV) or -2.5 V (AdSV) for 20-45 seconds in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 3.0) to reduce surface bismuth oxide and refresh the electrode surface.

- Analyte Accumulation: For ASV, apply -1.2 V for 20 seconds to electrodeposit indium onto the bismuth surface. For AdSV, apply -0.65 V for 10 seconds in the presence of 3.0 µmol/L cupferron as a complexing agent to accumulate In(III)-cupferron complexes via adsorption.

- Stripping Scan: Record the analytical signal by scanning potential from -1.0 V to -0.3 V (ASV) or from -0.4 V to -1.0 V (AdSV) using square-wave voltammetry parameters (frequency: 25 Hz, amplitude: 50 mV, step potential: 5 mV).

- Calibration: Construct calibration curves using standard additions, achieving linear ranges from 5×10⁻⁹ to 5×10⁻⁷ mol/L (ASV) and 1×10⁻⁹ to 1×10⁻⁷ mol/L (AdSV).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Mercury-Free Voltammetry

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Purity | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bismuth(III) chloride (BiCl₃) | ≥99% | Source of Bi³⁺ for film formation | Dissolve in dilute HCl to prevent hydrolysis |

| Bismuth oxide (Bi₂O₃) | ≥99% | Alternative Bi³⁺ source | Requires dissolution in acid |

| Sodium acetate buffer | 0.1 M, pH 4.0-4.5 | Supporting electrolyte | Maintains optimal pH for metal deposition |

| Acetic acid | Analytical grade | pH adjustment | Used with sodium acetate for buffer preparation |

| Sodium sulfate | ≥99% | Supporting electrolyte | Increases conductivity without complexing metals |

| Cupferron | ≥98% | Chelating agent for AdSV | Enables adsorptive accumulation of In(III), Fe(III) |

| Pyrogallol Red | ≥95% | Complexing agent | Used in speciation analysis of Sb(III)/Sb(V) |

| Carbon ink | C10903P14 (Gwent Group) | Conductive electrode material | For screen-printed and paper-based electrodes |

| Graphite felt | PAN-based, 5 mm thickness | 3D electrode substrate | Requires thermal or chemical activation before use |

| Whatman Chromatography Paper | Grade 1 | Cellulose substrate | Hydrophilic properties aid fluid transport |

Analytical Performance and Applications

Interference Management and Selectivity

A critical consideration in implementing mercury-free electrodes is understanding and managing potential interferents that can impact analytical accuracy. Studies comparing ASV and AdSV techniques with bismuth electrodes have revealed that interference effects vary significantly based on the analytical approach and the nature of interfering substances.

Surfactants and humic substances typically cause more significant signal suppression in ASV compared to AdSV, due to competitive adsorption at the electrode surface during the accumulation step. In contrast, complexing agents like EDTA exhibit more pronounced interference in AdSV methods, as they compete directly with the added chelator (e.g., cupferron) for the target metal ion [13].

The charge characteristics of interferents also influence their effect based on the technique employed. Positively charged surfactants generally cause greater signal depression in ASV, while negatively charged humic substances interfere more significantly with AdSV measurements. This understanding enables analysts to select the most appropriate method based on sample composition or implement pretreatment steps to minimize interference effects [13].

Real-World Application Case Studies

- Water Quality Monitoring: Paper-based bismuth film electrodes have been successfully deployed for determination of Cd(II), Pb(II), and In(III) in tap water samples using standard addition methodology, demonstrating accuracy comparable to conventional methods with the advantages of low cost and easy disposability [18].

- Indium Speciation in Seawater: Solid bismuth microelectrodes have enabled determination of In(III) in Baltic Sea water and synthetic seawater samples at ultra-trace levels (sub-nanomolar), highlighting the method's sensitivity and resistance to salt matrix interference [13].

- Energy Storage Enhancement: Bismuth-modified graphite felts in vanadium redox flow batteries demonstrated 9.47% higher voltage efficiency at 80 mA/cm² current density, illustrating the catalytic properties of bismuth beyond analytical applications [22].

Diagram 2: Interference mechanisms in stripping voltammetry techniques, showing how different interferents affect ASV and AdSV methods.

The development of mercury-free electrode materials represents a significant advancement in electroanalytical chemistry, successfully addressing environmental concerns while maintaining the high sensitivity required for trace metal analysis. Bismuth-based electrodes have established themselves as the primary mercury alternative, offering comparable analytical performance with dramatically reduced toxicity. Carbon-based platforms provide versatile substrates for various configurations from disposable sensors to sophisticated laboratory electrodes, while graphite felts offer three-dimensional architectures with exceptional mass transport properties.

Future research directions will likely focus on nanomaterial integration to further enhance sensitivity and selectivity, development of multi-element arrays for simultaneous analysis, and creation of increasingly robust field-deployable sensors. The integration of bismuth with emerging carbon materials such as graphene and carbon nanotubes shows particular promise for next-generation sensors. Additionally, the application of these mercury-free platforms to broader analytical challenges—including speciation analysis, biological monitoring, and real-time environmental sensing—will continue to expand their utility across scientific disciplines.

As these technologies mature, standardization of preparation protocols and comprehensive validation across diverse sample matrices will be essential for widespread adoption. The ongoing refinement of bismuth, carbon, and graphite felt electrodes ensures that stripping voltammetry will remain a powerful analytical technique while aligning with modern principles of green chemistry and environmental responsibility.

In the development of mercury-free adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV), the adsorption isotherm serves as a fundamental theoretical cornerstone. It provides the critical mathematical relationship between the concentration of an analyte at the electrode surface and the resulting analytical signal. For researchers designing novel electrode materials and methods, understanding this relationship is paramount for optimizing sensitivity and detection limits. This guide explores the core principles of adsorption isotherms, their mathematical formulations, and their practical application in modern electroanalytical research.

Theoretical Foundations of Adsorption Isotherms

An adsorption isotherm is a graph or mathematical expression that represents the variation in the amount of adsorbate (the substance being adsorbed) on the surface of an adsorbent with changes in its pressure or concentration in the bulk phase, at a constant temperature [23] [24] [25]. In the context of electroanalysis, the "adsorbent" is the electrode surface, and the "adsorbate" is the target analyte. The isotherm describes the dynamic equilibrium established between the concentration of material deposited on the adsorbent surface and the concentration of material remaining in the solution [23].

The temperature is held constant because the equilibrium is highly temperature-dependent. The name "isotherm" itself underscores this condition, derived from "iso-" (same) and "therm" (temperature) [24]. The primary information gleaned from an isotherm includes the surface coverage (θ), which is the fraction of active sites occupied, and the maximum adsorption capacity, which indicates the point at which all active sites are saturated [23] [24].

Classification and Types of Adsorption Isotherms

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) has classified experimental adsorption isotherms into six primary types (I through VI), each indicative of the underlying texture and pore structure of the adsorbent material [26]. The most relevant for adsorptive stripping voltammetry on functionalized surfaces are summarized below.

Table: IUPAC Classification of Adsorption Isotherms Relevant to AdSV

| Type | Shape | Common Adsorbent Materials | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | Monotonic plateau | Microporous materials (e.g., Zeolites, Activated Carbon) [26] | Monolayer adsorption on a surface with predominant micropores [23]. |

| II | Sigmoidal (S-shaped) | Non-porous or macroporous materials (e.g., Nonporous Silica) [26] | Multilayer adsorption on an open, non-porous surface [23]. |

| IV | Sigmoidal with hysteresis loop | Mesoporous materials (e.g., Mesoporous Silica, Alumina) [26] | Monolayer-multilayer adsorption followed by capillary condensation in mesopores, indicated by hysteresis [23]. |

The shape of the isotherm, particularly the presence of a hysteresis loop between the adsorption and desorption branches, provides critical information about the surface morphology. Hysteresis occurs when the pores that fill from their narrow mouths are discharged from their wide mouths, a phenomenon common in mesoporous solids [23]. For voltammetric applications, Type I and IV isotherms are often targeted, as they suggest a high affinity and capacity for the analyte.

Quantitative Analysis: Key Isotherm Models

To translate the experimental isotherm into quantitative parameters, several mathematical models are used. The choice of model helps distinguish between physisorption and chemisorption and reveals the nature of the electrode-analyte interaction.

Table: Key Mathematical Models for Analyzing Adsorption Isotherms

| Model | Equation | Parameters | Physical Interpretation & Assumptions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Langmuir | ( \theta = \frac{KL Ce}{1 + KL Ce} ) | ( KL ): Langmuir constant (affinity)( qm ): Max. monolayer capacity (mg/g) | - Homogeneous surface- Monolayer coverage- No interaction between adsorbed species- Ideal for chemisorption [23] [24] |

| Freundlich | ( qe = KF Ce^{1/nF} ) | ( KF ): Freundlich constant (capacity)( 1/nF ): Heterogeneity factor | - Heterogeneous surface- Multilayer adsorption- Empirical model for physisorption [23] [24] |

| Temkin | ( qe = BT \ln(AT Ce) ) | ( AT ): Temkin equilibrium constant( BT ): Constant related to heat of sorption | - Accounts for adsorbate-adsorbate interactions- Assumes a linear decrease in adsorption heat with coverage [27] |

| Dubinin-Radushkevic (D-R) | ( qe = q{DR} \exp(-K{DR} \varepsilon^2) )( E = 1 / \sqrt{2K{DR}} ) | ( q_{DR} ): D-R monolayer capacity( E ): Mean free energy of adsorption (kJ/mol) | - Distinguishes physisorption (E < 8 kJ/mol) from chemisorption (E = 8-16 kJ/mol) [23] |

The fitness of a model is typically evaluated using the coefficient of determination (R²), where a value closest to 1 indicates the best fit [23] [27]. The Langmuir model is particularly significant in AdSV, as it often describes the formation of a stable, monolayer film of analyte on the electrode surface prior to the stripping step, a process that is directly linked to the resulting voltammetric peak current [28] [29].

Experimental Protocols for Isotherm Determination

Obtaining a reliable adsorption isotherm is a foundational step in characterizing a new adsorptive stripping voltammetry method. The following protocol outlines a standard batch equilibrium process, adaptable for characterizing electrode materials.

Materials and Reagents

The "Research Reagent Solutions" and essential materials required for these experiments are listed below.

Table: Essential Reagents and Materials for Adsorption Isotherm Studies

| Item | Specification / Function |

|---|---|

| Stock Solution | High-purity standard solution of the target analyte (e.g., 1000 mg/L Hg(II) or other metal ions) [28] [29]. |

| Background Electrolyte | A buffer solution (e.g., phosphate, acetate) to maintain a constant pH and ionic strength during experiments [29] [30]. |

| pH Adjusters | Dilute solutions of HCl and NaOH for precise pH control, which critically affects analyte speciation and adsorption [28] [30]. |

| Adsorbent / Electrode | The material under investigation (e.g., functionalized nanofiber membrane, composite activated carbon) [28] [29]. |

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of solutions with identical electrolyte composition and a fixed mass of the adsorbent (e.g., 0.02 g), but with varying initial concentrations of the analyte (C₀), for example, from 10 to 100 mg/L [28] [29].

- Equilibration: Agitate the solutions in sealed containers using a mechanical shaker at a constant temperature (e.g., room temperature) and mixing speed (e.g., 180 RPM) until adsorption equilibrium is reached. The required contact time must be determined beforehand via kinetic studies [28] [30].

- Separation and Analysis: Once equilibrium is reached, separate the adsorbent from the solution, typically by filtration or centrifugation. Analyze the remaining equilibrium concentration (Cₑ) of the analyte in the supernatant using a suitable analytical technique (e.g., Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometry, Inductively Coupled Plasma, etc.) [27] [28].

- Data Calculation: For each initial concentration, calculate the amount of analyte adsorbed per unit mass of adsorbent at equilibrium (qₑ, in mg/g) using the mass balance equation: ( qe = \frac{(C0 - C_e) V}{m} ) where V is the volume of the solution (L), and m is the mass of the adsorbent (g) [28] [30].

- Isotherm Construction: Plot the calculated equilibrium adsorption capacity (qₑ) against the equilibrium concentration (Cₑ) to obtain the experimental adsorption isotherm.

The following workflow diagram illustrates the logical sequence from experiment to data interpretation.

Relating Surface Coverage to Voltammetric Signal

In adsorptive stripping voltammetry, the final and most critical step is linking the surface coverage (θ) described by the isotherm to the intensity of the analytical signal—the voltammetric peak current (iₚ). The adsorption isotherm provides the pre-concentration relationship: ( \theta = f(Ce) ). Under Langmuirian conditions, this is ( \theta = \frac{KL Ce}{1 + KL C_e} ) [24].

The peak current in stripping voltammetry is generally proportional to the surface concentration of the adsorbed analyte (Γ), which is itself proportional to θ (i.e., Γ = θ · Γₘₐₓ, where Γₘₐₓ is the maximum surface concentration). Therefore, the peak current can be expressed as:

( i_p \propto \Gamma \propto \theta )

This direct proportionality means that the voltammetric signal is a direct reporter of the surface coverage. The validity of this relationship allows researchers to use cyclic voltammetry to analyze adsorption processes directly. Advanced procedures can transform a set of voltammograms taken at different scan rates into a scan-rate independent, hysteresis-free adsorption isotherm, enabling highly accurate determination of adsorption kinetics and equilibrium [31]. By modeling this relationship, researchers can optimize accumulation times and potentials to maximize the signal for a given bulk concentration, thereby pushing the detection limits of their mercury-free AdSV methods.

The adsorption isotherm is far more than a simple equilibrium diagram; it is a powerful conceptual and quantitative framework that connects the surface chemistry at an electrode to the analytical signal in adsorptive stripping voltammetry. A rigorous understanding of different isotherm types and models allows scientists to characterize new adsorbent materials, elucidate mechanisms, and optimize experimental parameters. As research into sustainable, mercury-free electroanalysis progresses, the principles of the adsorption isotherm will continue to be indispensable for developing sensitive, reliable, and robust analytical methods.

Developing and Applying AdSV Methods with Specific Mercury-Free Electrodes

The pursuit of environmentally friendly and sensitive analytical techniques has propelled the development of bismuth-based electrodes as a premier alternative to traditional mercury-based sensors in stripping voltammetry. Adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV) is a powerful electroanalytical technique known for its exceptional sensitivity for trace metal and organic species determination, achieved through a preconcentration step where analytes are adsorbed onto the working electrode surface prior to electrochemical measurement [32]. For decades, mercury electrodes were the standard for such analyses; however, their high toxicity has driven the search for safer, "green" alternatives [33] [34]. Bismuth has emerged as the most promising successor, offering low toxicity, a well-defined stripping response, and insensitivity to dissolved oxygen [34] [35].

This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the three primary configurations of bismuth-based electrodes: bismuth film electrodes (BiFEs), solid bismuth microelectrodes, and solid bismuth microelectrode arrays. It details their design principles, fabrication methodologies, experimental protocols, and performance characteristics within the context of modern, mercury-free electroanalytical research.

Bismuth-Based Electrode Architectures and Properties

Bismuth Film Electrodes (BiFEs)

Bismuth film electrodes are typically formed by the electrochemical reduction of Bi(III) ions onto a conductive substrate, such as a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) [34] [35]. This can be done ex-situ (plating the film before exposure to the analyte) or in-situ (co-depositing bismuth and the target analytes simultaneously from the same solution) [36]. The in-situ method is particularly popular for its simplicity.

A key advantage of BiFEs is their ability to form alloys/fusible alloys with numerous metals, such as Pb, Cd, Zn, Tl, and In, which facilitates the accumulation of these metals during the deposition step and leads to sharp, well-defined stripping peaks [35] [13]. Their performance is highly dependent on the ratio of bismuth to target metal ion concentration (cBi/cM). Recent studies recommend a cBi/cM ratio between 5 and 40 to balance sensitivity and precision, contrasting with the historical use of a large excess of bismuth [36]. Excessively thick films (high cBi/cM ratios) can increase mass transfer resistance and diminish the analytical signal [36].

Solid Bismuth Microelectrodes

Solid bismuth microelectrodes (SBiµEs) represent a significant evolution, moving away from a thin film to an electrode made entirely of solid bismuth. A common design is a bismuth wire or disk sealed within an insulating sheath, with a typical diameter of 25 µm [13]. This design eliminates the need to add Bi(III) ions to the measurement solution, thereby simplifying the procedure and further reducing toxic waste [33] [13].

The microelectrode geometry confers distinct advantages, including enhanced mass transport via spherical diffusion, reduced ohmic drop (iR drop), and the ability to operate in unstirred solutions and low-ionic-strength media [33] [37]. Furthermore, the high ratio of spherical diffusion to linear diffusion at microelectrodes leads to a favorable signal-to-noise ratio, which can yield lower detection limits [33].

Solid Bismuth Microelectrode Arrays

Solid bismuth microelectrode arrays integrate multiple individual bismuth microelectrodes within a single casing, functioning in parallel [33] [37]. A notable example consists of 43 single capillaries, each about 10 µm in diameter, filled with metallic bismuth [33].

This architecture amplifies the total measurable current while retaining the beneficial microelectrode characteristics of each individual element [33] [38]. Compared to a single microelectrode, the array produces amplified currents that are more resistant to noise, enabling more robust and sensitive measurements [33]. Fabrication methods range from packing bismuth-filled capillaries to advanced microlithographic approaches, where bismuth is sputtered onto a patterned silicon wafer to create defined microdisk arrays [37].

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The tables below summarize the analytical performance of different bismuth-based electrode configurations for the determination of various inorganic and organic analytes.

Table 1: Performance of Bismuth Electrodes for Trace Metal Detection

| Electrode Type | Analyte | Technique | Linear Range (mol L⁻¹) | Detection Limit (mol L⁻¹) | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Bi Microelectrode Array [33] | Cd(II) | ASV | 5 × 10⁻⁹ to 2 × 10⁻⁷ | 2.3 × 10⁻⁹ | Acetate Buffer (pH 4.6), 60 s deposition |

| ^ | Pb(II) | ASV | 2 × 10⁻⁹ to 2 × 10⁻⁷ | 8.9 × 10⁻¹⁰ | ^ |

| Solid Bi Microelectrode [13] | In(III) | ASV | 5 × 10⁻⁹ to 5 × 10⁻⁷ | 1.4 × 10⁻⁹ | Acetate Buffer (pH 3.0), 20 s accumulation |

| ^ | In(III) | AdSV | 1 × 10⁻⁹ to 1 × 10⁻⁷ | 3.9 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Acetate Buffer (pH 3.0), Cupferron, 10 s accumulation |

| Lithographed Bi Microelectrode Array [37] | Cd(II) & Pb(II) | ASV | — | ~ µg L⁻¹ level | Measurements in static solution |

| Bismuth Film Electrode [34] | Ni(II) | AdSV | Up to 80 µg L⁻¹ | 0.8 µg L⁻¹ (180 s adsorption) | Dimethylglyoxime (DMG) as complexing agent |

Table 2: Performance for Organic Compound Detection

| Electrode Type | Analyte | Technique | Linear Range (mol L⁻¹) | Detection Limit (mol L⁻¹) | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid Bi Microelectrode Array [38] | Sunset Yellow | AdSV | 5 × 10⁻⁹ to 1 × 10⁻⁷ | 1.7 × 10⁻⁹ | Supporting electrolyte (pH 9.7), 60 s accumulation |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Determination of Cd(II) and Pb(II) using a Solid Bismuth Microelectrode Array

This protocol is adapted from the procedure for a reusable solid bismuth microelectrode array [33].

- Working Electrode: Solid bismuth microelectrode array (e.g., 43 microelectrodes, individual diameter ~10 µm).

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.05 mol L⁻¹ acetate buffer, pH 4.6.

- Activation Step: Apply a brief, high-negative-potential pulse to reduce any bismuth oxide on the electrode surface before the measurement cycle.

- Deposition/Accumulation Step: Deposit the target metals at a potential of -1.2 V for 60 s under stirred conditions.

- Equilibration Step: Stop stirring and allow the solution to remain quiescent for a defined period (e.g., 10-30 s).

- Stripping Step: Record the anodic stripping voltammogram using a square-wave or differential pulse waveform by scanning the potential from a more negative value to a less negative value (e.g., -1.2 V to -0.3 V). The peaks for Cd and Pb appear at characteristic potentials.

- Cleaning Step: Apply a positive potential (e.g., +0.3 V) with stirring to remove residual metals from the bismuth surface, preparing the electrode for the next measurement.

Protocol 2: Determination of Ni(II) using a Bismuth Film Electrode via AdSV

This protocol is based on the adsorptive stripping voltammetry of nickel using a pre-plated bismuth film [34].

- Working Electrode: Bismuth film plated on a glassy carbon electrode (BiFE/GCE).

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Supporting Electrolyte: Ammonia buffer (pH ~9).

- Complexing Agent: Dimethylglyoxime (DMG).

- Film Plating (ex-situ): Plate the bismuth film onto the clean GCE from a separate solution containing Bi(III) ions.

- Accumulation/Adsorption Step: Accumulate the Ni(II)-DMG complex on the BiFE surface by adsorbing at a suitable potential (e.g., -0.7 V) for 90-180 s under stirred conditions. The complex adsorbs onto the electrode without electrolysis.

- Equilibration Step: Stop stirring and wait briefly (~10 s).

- Stripping Step: Scan the potential in the negative direction using a square-wave or differential pulse waveform (e.g., from -0.7 V to -1.2 V). The reduction current of the adsorbed Ni(II)-DMG complex is measured, producing a peak at approximately -1.03 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

Protocol 3: Determination of In(III) using a Solid Bismuth Microelectrode via ASV and AdSV

This protocol highlights the use of a single solid bismuth microelectrode for a critical metal [13].

- Working Electrode: Solid bismuth microelectrode (diameter 25 µm).

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl.

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 mol L⁻¹ acetate buffer, pH 3.0.

- Activation Step: Apply -2.4 V for 20 s (for ASV) or -2.5 V for 45 s (for AdSV).

- For ASV:

- Accumulation Step: -1.2 V for 20 s.

- Stripping Step: Positive potential scan from -1.0 V to -0.3 V.

- For AdSV (using cupferron as chelating agent):

- Accumulation Step: -0.65 V for 10 s.

- Stripping Step: Negative potential scan from -0.4 V to -1.0 V.

Figure 1: Generalized Experimental Workflow for Bismuth-Based Electrodes in Stripping Voltammetry. The workflow encompasses both Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) and Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) paths, highlighting the critical activation step essential for solid bismuth electrodes [33] [13] [38].

Advanced Material & Antifouling Strategies

A significant challenge in analyzing complex matrices (e.g., biofluids, wastewater) is electrode fouling by organic surfactants or biomolecules, which reduces sensitivity and reliability. Recent research focuses on developing advanced bismuth composites with inherent antifouling properties.

One innovative approach involves creating a 3D porous cross-linked polymer matrix. A composite of bovine serum albumin (BSA), 2D graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄), and conductive bismuth tungstate (Bi₂WO₆) has shown remarkable antifouling performance [39]. This coating prevents nonspecific interactions, enhances electron transfer, and maintained 90% of its signal after one month in untreated human plasma, serum, and wastewater [39]. The synergistic effect of the porous structure and bismuth-based materials allows for sensitive and multiplexed detection of heavy metals in these challenging environments.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Bismuth-Based Electroanalysis

| Item | Function / Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth (III) Standard Solution | Source for in-situ or ex-situ plating of bismuth film electrodes (BiFEs). | Determining Cd, Pb, Zn, Ni [34] [36]. |

| Solid Bismuth Microelectrode (/Array) | Ready-to-use, eco-friendly working electrode; requires no Bi(III) addition. | Determining Tl, In, Cd, Pb, Sunset Yellow [33] [13] [38]. |

| Acetate Buffer | Common supporting electrolyte for acidic pH conditions (e.g., pH 3.0 - 4.6). | Optimal for determination of many metals (Cd, Pb, In) [33] [13]. |

| Ammonia Buffer | Common supporting electrolyte for basic pH conditions (e.g., pH ~9). | Required for Ni(II) and Co(II) determination with DMG [34] [32]. |

| Complexing Agents (e.g., DMG, Cupferron) | Form adsorbable complexes with target metals in AdSV, enabling trace-level detection. | DMG for Ni/Co [34] [32]; Cupferron for In(III) [13]. |

| Antifouling Composites (e.g., BSA/g-C₃N₄/Bi₂WO₆) | Polymer coatings to prevent surface fouling in complex samples like plasma or wastewater. | Analysis of heavy metals in biofluids and environmental water [39]. |

Bismuth-based electrodes have firmly established themselves as the leading mercury-free platform for sensitive and reliable stripping voltammetry. The evolution from bismuth film electrodes to solid bismuth microelectrodes and their arrays represents a significant advancement, combining environmental friendliness with enhanced analytical performance. The provided protocols, performance data, and toolkit offer researchers a foundation for implementing these sensors. Future developments will continue to focus on robustness, miniaturization for point-of-care testing, and sophisticated antifouling coatings to tackle increasingly complex real-world samples, further solidifying the role of bismuth in modern electroanalysis.

The pursuit of sensitive, selective, and environmentally friendly electroanalytical methods has driven significant innovation in electrode design. Within the context of principles of adsorptive stripping voltammetry without mercury, carbon-based electrodes have emerged as premier substrates. Among these, graphite felt and glassy carbon represent two distinct and highly valuable classes of materials. Graphite felt offers a three-dimensional, porous architecture conducive to high analyte accumulation, while glassy carbon provides a robust, well-defined surface that is exceptionally amenable to chemical modification. This technical guide details the properties, modification strategies, and analytical applications of these electrodes, providing a foundation for their use in sensitive stripping voltammetric detection of metals and biomolecules, thereby eliminating the need for toxic mercury electrodes.

The Landscape of Carbon-Based Electrodes in Stripping Voltammetry

Carbon materials are favored in electroanalysis due to their broad potential window, chemical inertness, rich surface chemistry, and low cost. The shift from mercury-based electrodes has focused research on solid carbon electrodes, which can be broadly categorized as follows.

- Composite Electrodes: These are made from graphite or carbon powders mixed with binders like epoxy resins or paraffin. They are attractive because they can be modified in the bulk during fabrication, leading to highly reproducible surfaces. A specific feature is their strength, chemical inertness, and stability in organic solvents [40].

- Impregnated Graphite Electrodes (IGE): These are porous graphite electrodes impregnated with materials like paraffin-polyethylene or epoxy resins. The surface has good adsorbability and is readily modified with specific reagents. They are particularly useful in abrasive stripping voltammetry for the analysis of solid microparticles [40].

- Thick-Film (Screen-Printed) Electrodes: These reproducible and inexpensive electrodes are fabricated from carbon- or graphite-containing inks. Their design allows for easy surface modification or the addition of modifiers directly to the ink, making them ideal for disposable sensors in environmental and clinical monitoring [40].

- Carbon Microelectrodes: Fabricated from carbon fibers, these electrodes offer unique advantages, including reduced capacitive currents, increased mass transfer rates, and negligible ohmic potential drops. These properties allow for analysis in high-resistance solutions and are the basis for miniature sensors for in vivo measurements [40].

Within this diverse field, graphite felt and glassy carbon serve as critical platforms, each offering unique advantages for trace analysis.

Graphite Felt Electrodes

Properties and Advantages

Graphite felt is a mass-produced, porous carbon material commonly used in redox flow batteries. Its application in electroanalysis is gaining traction due to its low cost and disposable nature. GF's defining characteristic is its three-dimensional porous network, which provides a high surface area for analyte accumulation. An elegant wetting technique allows GF electrodes to be used in quiescent solution, making them suitable for standard electrochemical cells without requiring flow systems [41].

Experimental Protocol: Anodic Stripping Voltammetry of Silver

The following protocol details the use of a GF electrode for the trace analysis of silver ions, achieving a limit of detection (LOD) of 25 nM [41].

- Electrode Preparation: A piece of graphite felt is cut to a suitable size. No further physical processing is required.

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: A standard three-electrode system is used.

- Working Electrode: Graphite felt.

- Reference Electrode: Ag/AgCl (for analysis in 0.1 M HNO₃).

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 M HNO₃.

- Analytical Procedure:

- Pre-concentration/Deposition: The electrode is immersed in the quiescent sample solution containing Ag⁺. A deposition potential of -0.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) is applied for a set time (e.g., 120 seconds) to reduce Ag⁺ to Ag⁰ and deposit it onto the GF surface.

- Equilibration: The stirring is stopped, and the solution is allowed to become quiescent for a few seconds.

- Stripping: A linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) scan is performed in the positive direction from -0.4 V to +0.4 V. This oxidizes the deposited silver metal back to Ag⁺, generating a measurable anodic stripping peak.

- Calibration: The peak current is measured and plotted against the concentration of Ag⁺ to create a calibration curve with a linear range spanning two orders of magnitude.

Performance Data

Table 1: Analytical performance of a graphite felt electrode for silver detection.

| Analyte | Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Supporting Electrolyte |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag⁺ | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry | Two orders of magnitude | 25 nM | 0.1 M HNO₃ |

Glassy Carbon Electrodes

Properties and Advantages