Ion-Selective Electrodes: Principles, Advances, and Applications in Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs), potent tools for determining ionic activity in solution.

Ion-Selective Electrodes: Principles, Advances, and Applications in Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs), potent tools for determining ionic activity in solution. It covers the foundational principles rooted in the Nernst equation and traces the evolution from classical glass electrodes to modern solid-contact (SC-ISEs) and ion-selective field-effect transistors (ISFETs). Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, the scope extends to methodological applications in pharmaceutical analysis, drug release monitoring, and wearable biosensing. The content also addresses critical practical aspects, including calibration protocols, troubleshooting for accuracy, and the imperative validation of ISE results against gold-standard techniques to ensure data reliability in research and development.

From Nernst to Novel Materials: The Core Principles and Evolution of ISEs

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) represent a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, operating on the fundamental potentiometric principle of measuring potential differences to determine ion activity in solution. As a type of potentiometric sensor, ISEs measure the potential difference that develops across a selective membrane when it separates two solutions containing different concentrations of the target ion [1]. This electrochemical potential, which is governed by the renowned Nernst equation, provides the theoretical foundation that enables researchers to quantify specific ions with remarkable precision and selectivity.

The inherent advantages of ISEs—including their simplicity, affordability, rapid analysis, precision, and capability for real-time monitoring—make them particularly valuable across diverse fields, with significant applications in pharmaceutical research and drug development [2]. Their ability to provide direct measurements without extensive sample pretreatment, coupled with their portability for in-situ monitoring, positions ISEs as powerful tools for researchers investigating drug release profiles, content uniformity, and dissolution testing [3] [4]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, operational mechanisms, and practical implementation of ISEs, with particular emphasis on their growing importance in pharmaceutical applications.

Theoretical Foundations: The Nernst Equation and Potentiometric Response

The Nernst Equation as the Governing Principle

The electrochemical behavior of ion-selective electrodes is quantitatively described by the Nernst equation, which relates the measured electrode potential to the activity of the target ion in solution [1]. The standard form of the Nernst equation is:

[ E = E^0 + \frac{RT}{zF} \ln a_i ]

Where:

- E: Measured electrode potential (V)

- E⁰: Standard electrode potential (V)

- R: Universal gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹)

- T: Absolute temperature (K)

- z: Charge of the target ion

- F: Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹)

- aᵢ: Activity of the target ion (dimensionless) [1]

At a standard temperature of 25°C (298 K), the equation simplifies to a more practical form:

[ E = E^0 + \frac{0.0592}{z} \log a_i ]

This simplified expression reveals that for a monovalent ion (z=1), the electrode potential changes by approximately 59.2 mV for every tenfold change in ion activity, while for a divalent ion (z=2), the change is approximately 29.6 mV per decade [1] [5]. This predictable logarithmic relationship enables precise quantification of ion concentrations across a wide dynamic range, typically spanning several orders of magnitude.

The Potentiometric Measurement System

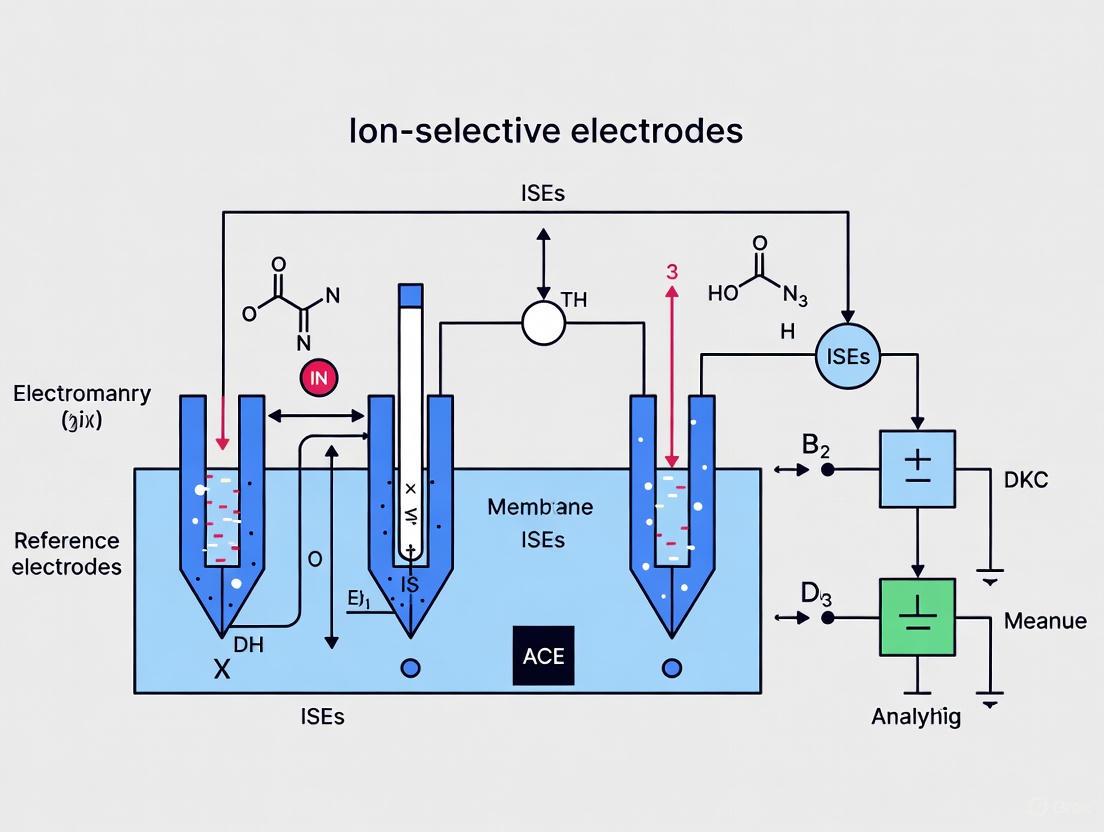

A complete potentiometric measurement system requires two essential components: the ion-selective electrode (indicator electrode) and a reference electrode that maintains a constant potential regardless of the sample composition [1]. The potential difference between these electrodes, measured under conditions of zero current flow, forms the basis of the analytical signal [1] [2].

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental working principle of an ISE and its relationship with the reference electrode within a potentiometric cell:

Figure 1: ISE Potentiometric Measurement Principle

The cell potential (E_cell) is calculated as the difference between the indicator and reference electrode potentials [6]:

[ E{\text{cell}} = E{\text{ise}} - E_{\text{ref}} ]

Where Eise incorporates the potential across the ion-selective membrane (Em) and the internal reference electrode potential [6]. The membrane potential develops due to the selective partitioning of ions between the sample solution and the membrane phase, creating a charge separation at the interface [2].

ISE Architecture and Membrane Types

Fundamental ISE Design Configurations

Ion-selective electrodes are categorized based on their structural design and membrane composition. The primary architectures include:

- Liquid-Contact ISEs: Traditional design with an internal filling solution contacting the ion-selective membrane [4]

- Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs): Advanced design where the membrane is in direct contact with a solid conductive material, eliminating the internal solution [2] [3]

- Coated Wire Electrodes: Simplified solid-contact design where a wire is directly coated with the ion-selective membrane [4]

Solid-contact ISEs have gained prominence in recent research due to their enhanced mechanical stability, miniaturization potential, and reduced maintenance requirements compared to traditional liquid-contact designs [2] [3]. The solid-contact transducer material (conductive polymers, carbon-based materials, or nanomaterials) serves as an ion-to-electron transducer between the ion-selective membrane and the underlying electrode substrate [2].

Ion-Selective Membrane Typologies

The selectivity of ISEs is primarily determined by the composition of the ion-selective membrane. The four principal membrane types are characterized in the table below:

Table 1: Ion-Selective Membrane Types and Characteristics

| Membrane Type | Composition | Target Ions | Selectivity Mechanism | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membranes | Silicate or chalcogenide glass | H⁺, Na⁺, other monovalent cations | Ion-exchange at glass surface | pH electrodes, sodium ISEs [6] |

| Crystalline Membranes | Poly- or monocrystalline materials | F⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻, CN⁻, S²⁻, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ | Crystal lattice permeability | Fluoride ISE (LaF₃ crystal) [1] [6] |

| Polymer (Ion-Exchange Resin) Membranes | PVC or similar polymer with plasticizer and ionophore | Various cations and anions, including drugs | Selective ion complexation | Pharmaceutical compounds, environmental monitoring [1] [3] |

| Gas-Sensing Membranes | Gas-permeable membrane with internal electrolyte | CO₂, NH₃, NOₓ | Gas diffusion and internal pH change | Bacterial cultures, biological samples [1] [7] |

The following diagram illustrates the architectural differences between liquid-contact and solid-contact ISE designs, highlighting their key components:

Figure 2: ISE Architectural Designs Comparison

Performance Parameters and Analytical Characteristics

Key Analytical Performance Metrics

The effectiveness of ion-selective electrodes in research and analytical applications is evaluated through several critical performance parameters:

Selectivity: The ability of an ISE to respond preferentially to the target ion in the presence of interfering ions, quantified by the selectivity coefficient (Kᵢⱼ) [1]. Lower values indicate higher selectivity.

Sensitivity: The change in electrode potential per unit change in analyte concentration, reflected by the slope of the calibration curve [1]. Ideal Nernstian sensitivity is 59.2/z mV per decade at 25°C.

Detection Limit: The lowest concentration that can be reliably detected, typically defined by the IUPAC method as the intersection of the two linear segments of the calibration curve [2]. Modern SC-ISEs can achieve detection limits down to the pM level for certain applications [2].

Response Time: The time required for the electrode to reach a stable potential (typically 95% of final value) after a change in analyte concentration [1]. This parameter depends on membrane thickness, sample stirring, and measurement conditions.

Lifespan: The operational lifetime of the electrode before significant performance degradation. Well-maintained ISEs can remain functional for several months [2] [3].

Quantitative Performance of Representative ISEs

Table 2: Performance Characteristics of Representative Ion-Selective Electrodes

| Target Analyte | Linear Response Range | Slope (mV/decade) | Detection Limit | Response Time | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Letrozole (PANI sensor) | 1.00 × 10⁻⁸ – 1.00 × 10⁻² M | 20.30 | 1.00 × 10⁻⁸ M | <30 s | [4] |

| Propranolol HCl | 1.0 × 10⁻³ – 3.1 × 10⁻⁶ M | ~59 (theoretical) | 3.1 × 10⁻⁶ M | <10 s | [3] |

| Lidocaine HCl | 1 × 10⁻³ – 2 × 10⁻⁶ M | ~59 (theoretical) | 2 × 10⁻⁶ M | <10 s | [3] |

| Letrozole (GNC sensor) | 1.00 × 10⁻⁶ – 1.00 × 10⁻² M | 20.10 | 1.00 × 10⁻⁶ M | <30 s | [4] |

| Diclofenac | Not specified | Not specified | Not specified | 2-3 s | [2] |

The data demonstrates that modified solid-contact electrodes can achieve exceptionally low detection limits while maintaining rapid response times, making them particularly suitable for pharmaceutical applications requiring high sensitivity.

Experimental Protocols for ISE Implementation

ISE Calibration and Measurement Protocol

Proper calibration is essential for obtaining accurate results with ion-selective electrodes. The following protocol outlines the standard calibration procedure:

Electrode Conditioning: Immerse the ISE in a solution containing the target ion (typically 10⁻³ M) for 15-60 minutes before initial use [3] [5].

Standard Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of standard solutions spanning the expected concentration range (typically 10⁻² to 10⁻⁶ M) using appropriate buffer solutions to maintain constant ionic strength [5].

Measurement Sequence: Immerse the ISE and reference electrode in each standard solution from lowest to highest concentration while stirring consistently at 300 rpm [3].

Potential Recording: Record the stable potential reading for each standard after the response stabilizes (typically 1-3 minutes per solution) [3].

Calibration Curve Construction: Plot potential (mV) versus logarithm of ion activity and perform linear regression to determine the slope, intercept, and correlation coefficient [5].

Sample Measurement: Measure the potential of unknown samples under identical conditions and determine concentration from the calibration curve using the Nernst equation [5].

Protocol for Solid-Contact ISE Preparation (PVC-Based)

The following detailed protocol describes the preparation of a solid-contact ion-selective electrode for pharmaceutical compounds, based on established methodologies [3] [4]:

Membrane Cocktail Preparation:

- Weigh and combine membrane components: 33% PVC, 66% plasticizer (e.g., O-NPOE), and 1% ion exchanger (e.g., KTpClPB) [3]

- Dissolve the "dry" mixture in tetrahydrofuran (THF) to create a 20% (w/w) solution

- Mix thoroughly until a clear, homogeneous solution is obtained

Electrode Body Assembly:

- Cut conductive substrate (carbon cloth) to appropriate dimensions (e.g., 7 × 2 cm²)

- Roll the carbon cloth and mount inside a PVC cylinder with central cylindrical hole

- Ensure secure electrical contact with the connecting wire

Membrane Deposition:

- Apply the membrane cocktail in multiple aliquots (e.g., 100 µL portions every 30 minutes)

- Allow THF to evaporate between applications

- Total membrane cocktail application: approximately 450 µL per electrode

- Air-dry the completed membrane for 48 hours at room temperature [3]

Electrode Conditioning:

- Condition the prepared ISE in a solution containing the target drug (e.g., 1.0 × 10⁻³ M) with appropriate pH adjustment (e.g., 10⁻² M HCl, pH 2.0) for 24 hours [3]

- Store conditioned electrodes in the same solution when not in use

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages in the development and application of solid-contact ISEs for pharmaceutical analysis:

Figure 3: Solid-Contact ISE Fabrication Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for ISE Development

The following table details essential materials and their functions in ISE fabrication, particularly for pharmaceutical applications:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for ISE Fabrication

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), Ethylcellulose (EC) | Structural backbone of the membrane | Provides mechanical stability; PVC most common [3] [4] |

| Plasticizers | 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE), Di-octyl phthalate (DOP) | Imparts flexibility and governs dielectric constant | Affects ion exchanger solubility and mobility [3] [4] |

| Ion Exchangers | Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl) borate (KTpClPB), Sodium tetraphenylborate (NaTPB) | Provides initial ionic sites in membrane | Essential for proper electrode response [3] [4] |

| Ionophores | 4-tert-butylcalix-8-arene (TBCAX-8), various crown ethers | Selective complexation of target ions | Determines electrode selectivity [4] |

| Transducer Materials | Polyaniline (PANI), graphene nanocomposite (GNC), multiwall carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) | Ion-to-electron transduction in SC-ISEs | Enhances signal stability and lowers detection limit [2] [4] |

| Solvents | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), cyclohexanone | Dissolves membrane components for casting | THF most commonly used [3] [4] |

Pharmaceutical Applications and Research Implications

The application of ion-selective electrodes in pharmaceutical research has expanded significantly, driven by their unique advantages for drug analysis. Key applications include:

- Drug Release Studies: Continuous monitoring of drug release from dosage forms without sample pretreatment [3]

- Content Uniformity Testing: Rapid determination of active pharmaceutical ingredient distribution in solid dosage forms [2]

- Dissolution Testing: Real-time monitoring of dissolution profiles with high temporal resolution [3]

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Measurement of drug concentrations in biological fluids like plasma and serum [4]

- Quality Control Analysis: Routine assessment of raw materials and finished products [2] [7]

The inherent advantages of ISEs for these applications include their ability to measure ions directly in colored or turbid solutions, minimal sample volume requirements, rapid analysis times (seconds to minutes), and capability for continuous monitoring [3] [4]. Furthermore, the development of miniaturized and wearable ISE-based sensors opens new possibilities for non-invasive therapeutic drug monitoring and point-of-care diagnostics [2].

Recent advancements in solid-contact ISEs incorporating novel materials such as MXene, conductive polymers, and carbon-based nanomaterials have significantly improved detection limits, selectivity, and operational stability [2]. These developments continue to expand the applicability of potentiometric sensors in pharmaceutical research and drug development workflows.

The potentiometric principle, governed by the Nernst equation, provides the fundamental theoretical foundation for ion-selective electrode operation. Through continuous refinement of electrode designs, particularly in solid-contact configurations, and optimization of membrane compositions, ISEs have evolved into sophisticated analytical tools with expanding applications in pharmaceutical research. The ongoing development of novel materials and fabrication techniques promises to further enhance the sensitivity, selectivity, and practicality of these sensors, ensuring their continued importance in both basic research and applied analytical science.

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) represent a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, enabling the precise quantification of ionic species in complex environments ranging from clinical diagnostics to environmental monitoring [8]. These potentiometric sensors function as electrochemical cells that generate a membrane potential in response to the activity of a specific ion in solution, operating on the fundamental principle of potentiometry where the cell potential is measured at near-zero current [8]. The historical progression of ISE technology spans over a century of innovation, beginning with the pioneering development of glass membrane electrodes and culminating in today's advanced solid-contact designs that offer unprecedented miniaturization, stability, and application versatility [8] [9]. This evolutionary journey reflects continuous interdisciplinary efforts in materials science, electrochemistry, and engineering to overcome fundamental limitations while expanding analytical capabilities. Within the broader context of fundamental research on ISE principles, understanding this historical trajectory provides critical insights into how theoretical advances and material innovations have collectively shaped contemporary sensor design, performance characteristics, and application scope, particularly in demanding fields such as pharmaceutical development and clinical analysis [2].

The Early Foundations: Glass Membrane Electrodes

The genesis of ion-selective electrode technology can be traced to 1906 when Cremer invented the first glass pH electrode, marking the birth of membrane-based potentiometric sensing [8]. This pioneering discovery was rapidly adopted as a routine analytical tool by the 1930s, establishing the glass electrode as the fundamental platform for hydrogen ion activity measurement [8]. These early glass membranes operated on an ion-exchange principle facilitated by specialized silicate or chalcogenide glass formulations that demonstrated selective permeability to specific cations [8] [10].

The core mechanism of glass membrane electrodes involves the development of a phase boundary potential at the glass-solution interface, governed by the selective partitioning of ions between these phases according to the Nernst equation [8] [11]. The glass composition determines ion selectivity; traditional silicate-based glasses exhibit preferential response to single-charged cations such as H⁺, Na⁺, and Ag⁺, while chalcogenide glass formulations extend sensitivity to certain double-charged metal ions including Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ [10]. Despite their revolutionary impact, early glass electrodes presented significant limitations including high electrical resistance, susceptibility to alkaline and acidic errors at pH extremes, and limited selectivity for analytes beyond hydrogen ions [10]. Throughout the 1940s and 1950s, numerous attempts were made to develop glass compositions responsive to alternative cations, but these efforts achieved only limited success, highlighting the need for fundamentally different membrane materials and sensing mechanisms [8].

Paradigm Shifts: The Emergence of Alternative Membrane Materials

The 1960s marked a transformative period in ISE development with two groundbreaking innovations that expanded sensing capabilities beyond protons. In 1966, Frant and Ross pioneered the first commercial crystalline membrane ISE utilizing a LaF₃ single-crystal for fluoride ion detection, while Stefanac and Simon simultaneously introduced the revolutionary concept of neutral ionophores with their valinomycin-based potassium-selective electrode [8]. These developments established new paradigms in ion-selective membrane design that quickly superseded earlier attempts to modify glass compositions for non-hydrogen ions.

Crystalline Membrane Electrodes

Crystalline membranes employ polycrystalline or single-crystal materials, typically consisting of insoluble inorganic salts such as LaF₃ for fluoride detection or Ag₂S for silver or sulfide ions [8] [10]. The ion-selectivity mechanism in these systems arises from the crystal lattice structure, which contains vacancies or sites that preferentially interact with specific ions of appropriate size and charge [10] [11]. The fluoride-selective electrode based on LaF₃ crystals remains one of the most successful implementations, offering excellent selectivity with interference primarily limited to hydroxide ions at high pH [8] [10]. These crystalline systems demonstrated superior mechanical robustness and eliminated the internal solution required in glass electrodes, thereby reducing potential junction complications [10].

Polymer-Based Liquid Membrane Electrodes

The introduction of neutral ionophores represented a fundamental advancement in molecular recognition for ISEs. These hydrophobic organic compounds, such as valinomycin for potassium selectivity, are incorporated into plasticized polymer membranes where they selectively complex with target ions and facilitate their transport across the organic phase [8]. The typical membrane composition includes a polymer matrix (commonly polyvinyl chloride or PVC), a plasticizer to impart fluidity, the ionophore for recognition, and lipophilic ionic additives to establish permselectivity and reduce membrane resistance [9]. This design creates a highly tailored molecular environment where the ionophore's specific coordination chemistry dictates selectivity, enabling the development of sensors for numerous cations and anions that were previously undetectable with glass or crystalline membranes [8] [9].

Table 1: Evolution of Ion-Selective Membrane Types and Their Characteristics

| Membrane Type | Key Developments | Representative Analytes | Selectivity Mechanism | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass Membranes | Invented by Cremer (1906); routine use by 1930s [8] | H⁺, Na⁺, Ag⁺ [10] | Ion-exchange at glass surface [10] | Alkaline/acidic errors; limited cation range [10] |

| Crystalline Membranes | LaF₃ F⁻ electrode (Frant & Ross, 1966) [8] | F⁻, S²⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻ [8] [10] | Crystal lattice permeability [10] | Limited to ions compatible with crystal structure [10] |

| Liquid/Polymer Membranes | Neutral ionophores (Stefanac & Simon, 1966) [8] | K⁺, Ca²⁺, NH₄⁺, various drugs [8] [12] | Selective complexation by ionophores [8] | Membrane component leaching; limited lifetime [9] |

Theoretical Underpinnings: The Principles of Potentiometric Sensing

The operational foundation of all ISEs rests on the establishment of a stable electrochemical potential at the interface between the ion-selective membrane and the sample solution. This boundary potential (Δφₘₑₘ) follows the Nernst equation, which relates the measured potential to the logarithm of the target ion activity [8] [11]:

Δφₘₑₘ = Δφₘₑₘ⁰ + (RT/zF)ln(aᵢ)

where R is the universal gas constant, T is absolute temperature, z is the ionic charge, F is Faraday's constant, and aᵢ is the activity of the primary ion [8] [11]. Under ideal conditions, this relationship produces a linear response with a Nernstian slope of approximately 59.16/z mV per decade of activity change at 25°C [8].

The complete potentiometric cell includes both the ion-selective electrode and a reference electrode that maintains a constant potential regardless of sample composition [8] [11]. The measured cell potential (Ecell) represents the cumulative potential differences across all interfaces in the system [11]:

Ecell = Eise - Eref + Ej

where Eise is the potential of the ISE, Eref is the reference electrode potential, and Ej represents the liquid junction potential that arises at the reference electrode bridge [11]. To ensure accurate measurements, modern potentiometers feature high input impedance (>10¹³ Ω) and appropriate operational amplifiers to handle the associated minute currents while maintaining near-zero current flow through the cell [8].

The selectivity coefficient (Kᵢⱼᴾᴼᵀ) quantifies an ISE's ability to discriminate between the primary ion and interfering species, representing a critical performance parameter [8]. This coefficient is typically determined using the separate solution method or fixed interference method, with ideal sensors exhibiting very small values (≪1) for all potential interferents [8].

The Solid-Contact Revolution: Overcoming Liquid-Contact Limitations

Traditional liquid-contact ISEs (LC-ISEs) utilizing internal filling solutions presented several operational challenges including evaporation, sensitivity to temperature and pressure variations, osmotic pressure effects causing water flux, and difficulties in miniaturization [9]. The pioneering work by Cattrall and Freiser in 1971 introduced the first "coated wire electrode," eliminating the internal solution and establishing the foundation for solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) [2] [13]. However, these early designs suffered from poor potential stability and reproducibility due to high charge transfer resistance at the conductor-membrane interface [13].

The seminal 1997 publication by the Pretsch Group demonstrated that conventional LC-ISEs were biased by undesirable transmembrane ion fluxes from concentrated internal solutions, degrading analytical selectivity and sensitivity [8]. This critical insight reinvigorated the field, spurring development of SC-ISEs with controlled internal composition or complete elimination of filling solutions, yielding orders of magnitude improvement in both selectivity and detection limits [8].

Contemporary SC-ISEs incorporate a solid-contact (SC) layer between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and electron-conducting substrate (ECS), serving as an ion-to-electron transducer [9]. This architecture eliminates the internal solution, creating a two-phase system that enhances detection limits and operational robustness [13]. The solid-contact layer typically consists of conductive polymers (e.g., polyaniline, PEDOT), carbon nanomaterials (e.g., MWCNTs, graphene), or other redox-active materials (e.g., ferrocene) that provide either redox capacitance or electric double-layer capacitance to stabilize the potential [9] [13].

Contemporary Applications and Experimental Implementations

The evolution from glass electrodes to advanced SC-ISEs has profoundly expanded practical applications across pharmaceutical analysis, clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and industrial process control [8] [2]. Recent research demonstrates the versatility of modern SC-ISEs in addressing complex analytical challenges, with particular significance in pharmaceutical compound detection where simplicity, cost-effectiveness, rapid analysis, and suitability for on-site monitoring are paramount [2].

Pharmaceutical Analysis Case Studies

Benzydamine Hydrochloride Determination: A 2025 study developed both conventional PVC membrane and coated graphite all solid-state ISEs for detecting benzydamine hydrochloride (BNZ·HCl), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug [12]. The sensors employed an ion-pair complex formed between BNZ⁺ and tetraphenylborate (TPB⁻) incorporated into plasticized PVC membranes. The conventional PVC electrode demonstrated a Nernstian response of 58.09 mV/decade across a linear range of 10⁻⁵–10⁻² M with a detection limit of 5.81×10⁻⁸ M, while the all solid-state version exhibited comparable performance (57.88 mV/decade, detection limit 7.41×10⁻⁸ M) while eliminating internal solution complications [12]. Both sensors successfully determined BNZ·HCl in pharmaceutical cream and biological fluids without matrix interference and exhibited stability-indicating capability by detecting the drug in the presence of its oxidative degradant [12].

Letrozole Quantification: A 2023 investigation developed green SC-ISEs for the potentiometric determination of the anticancer drug letrozole [4]. The research compared a conventional sensor based on 4-tert-butylcalix-8-arene (TBCAX-8) as ionophore with membranes modified with graphene nanocomposite (GNC) and polyaniline (PANI) nanoparticles. The PANI-modified sensor demonstrated superior performance with the widest linear range (1.00×10⁻⁸–1.00×10⁻³ M), sub-Nernstian slope of 20.30 mV/decade, and successful application for letrozole determination in human plasma with recoveries of 88.00–96.30% [4]. This study highlighted how nanomaterial integration enhances sensor performance while aligning with green analytical chemistry principles.

Venlafaxine Hydrochloride Sensing: A 2024 systematic study compared transduction mechanisms for venlafaxine HCl detection using multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), polyaniline (PANi), and ferrocene as solid-contact materials [13]. The MWCNT-based sensor exhibited optimal electrochemical behavior with a near-Nernstian slope of 56.1 ± 0.8 mV/decade, detection limits of 3.8×10⁻⁶ mol/L, and minimal potential drift (34.6 µV/s) [13]. Comprehensive characterization using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), chronopotentiometry (CP), and cyclic voltammetry (CV) revealed that each transducer's unique chemical and physical properties directly influenced sensor performance, with MWCNTs providing superior double-layer capacitance and interfacial stability [13].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Modern Solid-Contact ISE Applications

| Analyte | Solid-Contact Material | Linear Range (M) | Slope (mV/decade) | Detection Limit (M) | Application Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benzydamine HCl [12] | Coated Graphite | 10⁻⁵–10⁻² | 57.88 | 7.41×10⁻⁸ | Pharmaceutical cream, biological fluids |

| Letrozole [4] | Polyaniline (PANI) nanoparticles | 10⁻⁸–10⁻³ | 20.30 | - | Bulk powder, dosage form, human plasma |

| Venlafaxine HCl [13] | Multiwalled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | 10⁻²–10⁻⁷ | 56.1 ± 0.8 | 3.8×10⁻⁶ | Pharmaceutical dosage forms, synthetic urine |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication of Coated Graphite Solid-Contact ISE

The following detailed methodology for constructing a coated graphite all solid-state ISE adapts procedures from recent pharmaceutical applications [12] [13]:

Ion-Pair Complex Preparation: Combine 50 mL of 10⁻² M drug solution (e.g., BNZ·HCl) with 50 mL of 10⁻² M sodium tetraphenylborate solution. Allow the precipitate to equilibrate with supernatant for 6 hours, then collect by filtration, wash thoroughly with bi-distilled water, and air-dry for 24 hours to obtain powdered ion-pair complex [12].

Sensing Membrane Formulation: Precisely weigh 10 mg of ion-pair complex, 45 mg of high-molecular-weight PVC, and 45 mg of plasticizer (e.g., dioctyl phthalate or 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether). Dissolve the mixture in 7 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF) and homogenize thoroughly [12] [13].

Electrode Assembly: Apply the membrane cocktail directly to a graphite electrode substrate using a micropipette, depositing multiple uniform layers with THF evaporation between applications. Alternatively, prepare a master membrane by casting the cocktail in a glass petri dish, allowing THF evaporation overnight, then cutting discs (typically 8-mm diameter) for attachment to electrode bodies using THF as adhesive [12].

Conditioning and Storage: Condition assembled electrodes by immersion in 10⁻² M primary ion solution for 4 hours to establish stable membrane potentials. For storage, keep electrodes dry under refrigeration when not in use to prolong lifetime [12].

Potential Measurements: Perform potentiometric measurements using a high-impedance pH/mV meter with Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Maintain minimal current flow (<1 pA) during measurements. Construct calibration curves by plotting measured potential (mV) versus logarithm of analyte activity [12] [13].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for SC-ISE Research

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Solid-Contact ISE Development

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices [12] [9] | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), Polyurethane, Acrylic esters, Silicone rubber | Provides mechanical stability and serves as membrane backbone | PVC most common; alternative polymers offer different hydrophobicity and compatibility |

| Plasticizers [12] [9] [13] | Dioctyl phthalate (DOP), Dibutyl phthalate (DBP), Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS), 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) | Imparts membrane fluidity and affects dielectric constant | Choice influences ionophore selectivity and membrane longevity |

| Ionophores/Receptors [9] [4] | Valinomycin (K⁺), 4-tert-butylcalix-8-arene (cations), Natural/synthetic ion carriers | Molecular recognition element for selective ion binding | Critical for selectivity; neutral or charged carriers available for various ions |

| Ion-Exchangers [9] | Sodium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate (NaTFPB), Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (KTPCIPB), Sodium tetraphenylborate (NaTPB) | Provides permselectivity and reduces membrane resistance | Essential for establishing Donnan exclusion in neutral carrier membranes |

| Solid-Contact Materials [9] [4] [13] | Polyaniline (PANI), PEDOT, Multiwalled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), Graphene nanocomposite, Ferrocene | Ion-to-electron transduction between membrane and conductor | Determines potential stability and capacitance; redox vs. double-layer mechanisms |

| Solvents [12] [4] | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), Cyclohexanone | Dissolves membrane components for homogeneous casting | High purity essential to prevent membrane defects; THF most common |

Future Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

The historical evolution from glass pH electrodes to contemporary solid-contact ISEs represents a remarkable century of innovation in electrochemical sensing technology. Current research frontiers focus on further enhancing SC-ISE performance through advanced nanomaterials, improved transduction mechanisms, and expanded application domains [9]. Key development areas include novel solid-contact materials with higher capacitance and better hydrophobicity to prevent water layer formation, miniaturized designs for wearable and point-of-care applications, and integration with wireless technologies for remote monitoring [2] [9]. The emergence of wearable ISE sensors utilizing Bluetooth or NFC communication protocols for non-invasive health monitoring represents a particularly promising direction [2].

Despite significant advances, challenges remain in achieving long-term stability, ensuring reproducibility across manufacturing scales, and developing environmentally benign membrane components [9]. Ongoing research aims to address these limitations through standardized characterization protocols, improved understanding of interfacial processes, and development of sustainable sensor materials [9] [13]. The integration of SC-ISEs with emerging technologies such as Internet of Things (IoT) platforms and artificial intelligence for data analysis will likely expand their impact across clinical diagnostics, environmental surveillance, and industrial process control [2] [9].

The journey from Cremer's initial glass membrane to today's sophisticated solid-contact designs exemplifies how fundamental research principles coupled with materials innovation can transform analytical capabilities. As ISE technology continues to evolve, its convergence with nanotechnology, materials science, and digital health platforms promises to further advance this century-old technology, ensuring its continued relevance in addressing emerging analytical challenges across scientific disciplines.

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are membrane-based potentiometric sensors that convert the activity of specific ions in a solution into an electrical potential [14] [15]. This transduction forms the cornerstone of a versatile analytical technique widely employed in chemical, biological, environmental, and industrial analyses. The core principle hinges on the use of a selective membrane that creates a potential difference dependent on the logarithm of the ionic activity of the target ion, as described by the Nernst equation [15] [16]. The general setup of an ISE includes the ion-selective membrane, an internal reference electrode, and an external reference electrode that completes the electrochemical cell [14].

The significance of ISE technology lies in its unique advantages. These sensors provide real-time measurements, can detect a wide range of ion concentrations, and require minimal sample preparation [14] [17]. Unlike many analytical methods, ISEs measure ion activity rather than mere concentration, which is often more relevant for understanding chemical behavior and biological activity [14]. The fundamental process can be summarized by the cell potential equation, Ecell = Eise – Eref, where Eise includes the potential of the internal reference electrode and the ion-selective membrane potential, and Eref is the potential of the external reference electrode [15]. The following diagram illustrates the core working principle of a potentiometric ISE.

Ion-Selective Membrane Typology and Function

The ion-selective membrane serves as the heart of the ISE, granting the sensor its specificity. Its primary function is to selectively permit the target ion to interact, generating a boundary potential. This potential arises from an unequal charge distribution across the membrane when the activity of the target ion differs between the sample and internal solutions [16]. Membranes are broadly classified based on their composition and physical properties, each with distinct advantages and selective affinities. The four principal types are glass, crystalline, ion-exchange resin (polymer), and enzyme-based membranes [14] [15].

Glass Membranes are primarily composed of silicate or chalcogenide glass and exhibit excellent selectivity for single-charged cations like H+ (pH electrode), Na+, and Ag+ [14] [15] [17]. Chalcogenide glass variants extend this selectivity to certain double-charged metal ions, such as Pb2+ and Cd2+ [14]. These membranes are noted for their high chemical durability, allowing operation in aggressive media [14]. However, they are susceptible to alkali and acidic errors at pH extremes and can be physically fragile [14] [18].

Crystalline Membranes can be formed from either a single crystal (e.g., LaF3 for fluoride electrodes) or a polycrystalline precipitate (e.g., Ag2S for sulfide or silver electrodes) [15] [17]. Their selectivity is inherently high because only ions capable of entering the crystal lattice can interfere with the electrode response [15]. A key advantage of some crystalline membranes is the absence of an internal solution, which simplifies design and reduces potential junctions [15].

Ion-Exchange Resin (Polymer) Membranes represent the most widespread type of ISE [15]. They consist of a polymer matrix, typically polyvinyl chloride (PVC), plasticizers, and a lipophilic ion-exchange substance or neutral carrier (ionophore) that confers selectivity [15] [19]. This design allows for the creation of selective electrodes for dozens of different ions, both cationic and anionic [15]. While highly versatile, these membranes generally have lower chemical and physical durability compared to glass or crystalline types and a finite lifetime [15].

Enzyme Electrodes are compound sensors that are often categorized under ISEs [14] [15]. They operate via a double-reaction mechanism where an enzyme immobilized in a membrane reacts specifically with a substrate. The product of this reaction (often H+ or OH−) is then detected by a true ISE, such as a pH electrode, housed within the same assembly [15]. A common example is the glucose-selective electrode [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Primary Ion-Selective Membrane Types

| Membrane Type | Composition | Target Ions (Examples) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glass | Silicate or Chalcogenide glass | H+, Na+, Ag+, Pb2+, Cd2+ | High chemical durability; Excellent for single-charged cations. | Alkaline/Acidic error; Fragile; Limited ion range. |

| Crystalline | Mono-/Polycrystalline solids (e.g., LaF3, Ag2S) | F-, S2-, CN-, Cl-, Br-, I- | Excellent selectivity; No internal solution needed for some. | Membrane dissolution over time; Limited to compatible ions. |

| Polymer (Ion-Exchange Resin) | Polymer (e.g., PVC), Plasticizer, Ionophore | K+, Ca2+, NH4+, NO3-, Cl- | Highly versatile; Can be made for many ions. | Lower durability; Finite shelf life; Anionic electrodes less stable. |

| Enzyme-Based | Enzyme layer over a standard ISE | Glucose, Urea, etc. | High specificity for neutral molecules. | Complex construction; Response depends on enzyme kinetics. |

Ionophores: The Key to Molecular Recognition

In polymer membrane-based ISEs, the ionophore is the molecular component responsible for imparting high selectivity. Ionophores are lipophilic organic compounds that can selectively and reversibly bind to a target ion, facilitating its extraction from the aqueous sample into the organic membrane phase [19] [18]. The stability constant of the complex formed between the ionophore and the target ion relative to its complexes with potential interfering ions is the primary determinant of the sensor's selectivity [20].

The purity and quality of the ionophore are critical for optimal sensor performance. Impurities such as metal ions or surfactants can leach from the membrane, causing signal drift and anomalous baseline readings [19]. Therefore, application-tested, high-purity ionophores are essential for developing reliable ISEs. The following table details key ionophores used in research and commercial sensors.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions: Selectophore-Grade Ionophores

| Ionophore Name / Reagent | Target Ion | Function-Tested Performance | Critical Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Valinomycin (Ammonium Ionophore I) [15] [19] | K+ | Linear Range: 1x10⁻⁶ to 1x10⁻¹ M; Slope: ~60.8 mV/dec [19] | Neutral carrier that forms a selective complex with K+ over Na+. |

| Calcium Ionophore I (ETH 1001) [19] | Ca2+ | Linear Range: 2x10⁻⁷ to 1x10⁻¹ M; Slope: ~28 mV/dec [19] | Neutral carrier with extremely high selectivity for Ca2+ ions. |

| Nonactin (Ammonium Ionophore I) [19] | NH4+ | Linear Range: 1x10⁻⁶ to 1x10⁻¹ M; Slope: ~60.8 mV/dec [19] | Antibiotic ionophore selective for NH4+; also used for urea detection. |

| Tetradodecylammonium Nitrate (TDDAN) [21] | NO3- | Sensitivity: up to -55 mV/pNO₃ [21] | Positively charged ion-exchanger selective for nitrate ions (NO3-). |

| Sodium Ionophore | Na+ | N/A (Typically used in glass membranes) | Components in glass membrane (e.g., Aluminosilicate) confer Na+ selectivity [14]. |

| KTFBP (Ionic Additive) [21] | N/A (Additive) | N/A | Lipophilic anionic additive (e.g., KTFBP) reduces membrane resistance and improves response time. |

Ion-to-Electron Transduction in Solid-Contact ISEs

A critical challenge in ISE design is establishing a stable potential at the interface between the ion-conductive membrane and the electron-conductive measuring instrument. In traditional ISEs, this is achieved with an internal aqueous solution. Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) eliminate this internal solution, enabling miniaturization and simpler fabrication [20] [21]. In these designs, an ion-to-electron transducer layer is interposed between the electron-conductive substrate (e.g., a metal electrode) and the ion-selective membrane. This transducer must convert ionic current in the membrane into an electronic current in the substrate, and it must exhibit a stable standard potential and high capacitance to prevent signal drift caused by the formation of thin water layers at the interface [21].

Conducting Polymers are a leading class of transducing materials. Polymers like poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT) doped with poly(styrenesulfonate) (PSS) or embedded with carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are highly effective [20] [21]. They conduct both ions and electrons and possess high redox capacitance, which stabilizes the potential at the inner interface [20]. When the sample ion activity changes, the resulting shift in the phase-boundary potential at the sample-membrane interface is compensated by a redox reaction within the conducting polymer layer, generating a transient current.

Carbon-Based Materials, such as ordered mesoporous carbon and double-walled carbon nanotubes (DWCNTs), are also used as transducers. Their high surface area provides a large double-layer capacitance, which contributes to potential stability [20] [21]. Recent research focuses on composites, such as PEDOT doped with DWCNTs, which combine the benefits of both materials to achieve improved transduction, lower detection limits, and enhanced long-term stability for sensors, such as those detecting nitrate ions [21].

The experimental workflow for fabricating and testing a solid-contact ISE with a conducting polymer transducer is illustrated below.

Advanced Signal Transduction and Amplification

While traditional ISEs rely on potentiometric (voltage) measurement, recent innovations have focused on transducing the ion-recognition event into other signals to overcome sensitivity limitations imposed by the Nernst equation (theoretical limit of 59.16/z mV per decade of activity change at 25°C) [20].

Constant Potential Coulometry is a prominent example. In this method, the potential between the SC-ISE and a reference electrode is held constant at 0 V [20]. A change in sample ion activity disturbs this equilibrium, causing a transient current to flow as the conducting polymer transducer is oxidized or reduced to compensate for the potential change. The integrated charge over time is proportional to the change in ion activity. This method offers significantly higher sensitivity, enabling the detection of minute activity changes as low as 0.1% for K+ [20]. The signal transduction and amplification principle is detailed below.

Coulometric ISE with Electronic Capacitor: To address baseline drift in constant potential coulometry, a new method introduces an external electronic capacitor in series with the ISE [20]. When the sample is changed, the potential shift is compensated by charging this external capacitor, and the current required to do so is measured. This approach eliminates the baseline drift associated with the slow redox degradation of conducting polymers and shortens the measurement time [20].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Nitrate SC-ISE with DWCNT/PEDOT Transducer

This protocol details the fabrication of a solid-contact nitrate ion-selective electrode based on a DWCNT/PEDOT transducing layer and a fluoropolysiloxane (FPSX) membrane, as explored in current research [21].

Materials and Equipment

- Working Electrode: Fabricated silicon chip with platinum ultramicroelectrode array (UMEA) [21].

- Chemical Reagents:

- Ion-to-Electron Transducer: Double-walled carbon nanotubes (DWCNTs), 3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene (EDOT) monomer.

- Ion-Selective Membrane: Fluoropolysiloxane (FPSX) polymer, Tetrahydrofuran (THF) solvent.

- Ion-Exchanger: Tetradodecylammonium nitrate (TDDAN).

- Ionic Additive: Potassium tetrakis [3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl] borate (KTFPB).

- Standard Solutions: Sodium nitrate (NaNO₃) solutions for calibration (e.g., 10⁻⁵ M to 10⁻¹ M).

- Instrumentation: Potentiostat/Galvanostat, pH/mV meter with high input impedance, Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

Step-by-Step Methodology

- Transducer Layer Deposition: The Pt working electrode is cleaned. A dispersion of DWCNTs is drop-cast onto the electrode surface and allowed to dry. Subsequently, the PEDOT polymer is electrodeposited onto the DWCNT layer from a solution containing EDOT monomer and DWCNTs using cyclic voltammetry or constant potential amperometry [21].

- Ion-Selective Membrane Preparation: The membrane cocktail is prepared by dissolving 200 mg of FPSX polymer in 1.5 mL of THF. To this, 4.2 mg of TDDAN (ion exchanger) and 2.5 mg of KTFPB (ionic additive) are added, resulting in a TDDAN:KTFPB molar ratio of 2:1 [21]. The mixture is thoroughly homogenized.

- Membrane Deposition: A small volume of the prepared membrane cocktail is drop-cast directly onto the DWCNT/PEDOT transducing layer. The device is left undisturbed to allow the THF solvent to evaporate slowly, forming a stable, solid polymeric membrane (approx. 6 µm thick) [21].

- Conditioning: The newly fabricated SC-ISE is conditioned by immersing it in a 0.01 M NaNO₃ solution for several hours (or overnight) to hydrate the membrane and stabilize the electrochemical potential.

- Calibration and Measurement: The conditioned SC-ISE is paired with an external Ag/AgCl reference electrode. The potential (EMF) is measured while the electrodes are immersed in a series of standard NaNO₃ solutions of known concentration (e.g., from 10⁻⁵ M to 10⁻¹ M), with gentle stirring. The potential is recorded once stable.

- Data Processing: The measured EMF (mV) is plotted against the logarithm of the NO₃⁻ activity (log a_NO₃⁻). The data is fitted using a linear regression to establish the calibration curve, from which the slope (sensitivity, in mV/decade) and detection limit can be determined.

Performance Metrics and Troubleshooting

- Expected Performance: A well-optimized sensor may exhibit a sensitivity of up to -55 mV per decade of NO₃⁻ activity, with a linear range from approximately 10⁻⁵ M to 10⁻¹ M [21].

- Common Issues:

- High Temporal Drift: Can be caused by the formation of a thin water layer between the membrane and the transducer. Using hydrophobic transducers (like DWCNT/PEDOT) and membranes (like FPSX) mitigates this [21].

- Slow Response Time: Can result from a membrane that is too thick or poor adhesion between layers. Optimizing the membrane thickness and deposition process is key.

- Reduced Sensitivity: Often linked to the leaching of membrane components or degradation of the ionophore/exchanger. Ensuring high-purity reagents and a well-formulated membrane is critical [19].

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are transducer devices that convert the activity of specific ions in solution into an electrical potential, functioning as membrane-based potentiometric sensors [15]. While glass membrane electrodes, particularly pH electrodes, are widely recognized, recent decades have witnessed substantial advancement in solid-state, polymer, and crystalline membrane electrodes that offer remarkable improvements in detection limits, selectivity, and application versatility [22]. These developments have fundamentally transformed potentiometric analysis, pushing detection limits from the micromolar range down to the picomolar level—an improvement factor of up to one million—while enhancing interference discrimination by factors of up to one billion [22]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, material innovations, and experimental methodologies underlying these advanced membrane electrodes, providing researchers and drug development professionals with comprehensive insights into their capabilities and implementation.

Fundamental Principles of Membrane Electrodes

The Potentiometric Sensing Mechanism

The operational principle of all ion-selective electrodes centers on the development of a membrane potential that correlates with the activity of target ions in solution. When an ion-selective membrane separates two solutions containing different activities of the analyte ion, a boundary potential develops across the membrane according to a Nernst-like relationship [16]. The overall electrochemical cell potential is measured between reference electrodes immersed in the sample and internal solutions, described by:

Ecell = Eref(int) - Eref(samp) + Emem

Where Emem represents the membrane potential, which for a target ion A with charge z follows the relationship:

Emem = Easym - (RT/zF)ln[(aA)int/(aA)samp]

This simplifies to the practical working equation:

Ecell = K + (0.05916/z)log(aA)samp at 25°C

where K is a constant incorporating all other potentials [16]. The membrane thus generates a measurable electrical potential that depends logarithmically on the activity of the target ion in the sample solution.

Membrane Ion Selectivity and Permeability

The fundamental requirement for any ion-selective membrane is its ability to preferentially permit the passage of target ions while excluding interferents. This selective permeability arises from specific molecular interactions between the membrane components and the target ion, whether through ion-exchange processes, carrier complexation, or structural compatibility with crystalline lattices [15]. The membrane's selective nature ensures that the boundary potential responds primarily to changes in the activity of the target ion, with minimal interference from other ions present in the sample matrix.

Figure 1: Working principle of an ion-selective electrode showing the key components and ion transport mechanism that generates the measurable potential difference.

Classification and Properties of Advanced Membrane Electrodes

Crystalline Membrane Electrodes

Crystalline membranes represent a sophisticated class of ISEs fabricated from mono- or polycrystalline materials that provide exceptional ionic selectivity through their defined crystal structures [23] [15]. These membranes are typically formed from low-solubility inorganic salts, with heavy metal sulfides and silver salts being particularly common [24]. The crystalline lattice structure permits only ions that can integrate into the crystal matrix to interfere with electrode response, making these membranes inherently highly selective [15].

A paradigmatic example is the fluoride selective electrode based on LaF₃ crystals, which exhibits remarkable selectivity for fluoride ions due to the perfect matching of fluoride ions with the lanthanum fluoride crystal lattice [23] [15]. The membrane operates by allowing fluoride ions to migrate through the crystal lattice defects and vacancies, generating a potential dependent on the fluoride ion activity in solution. The primary advantage of crystalline membranes is their lack of internal solution, which reduces potential junctions and enhances measurement stability [15]. Additionally, these membranes demonstrate excellent chemical durability and can function in aggressive media where other membrane types might degrade.

Solid-State and Polymer Membrane Electrodes

Solid-state and polymer membranes encompass diverse materials systems that enable ion selectivity through various mechanisms, from glass analogues to advanced polymer composites.

Glass Membranes for Monovalent Cations While traditional glass membranes are well-established for pH measurements, advanced formulations using chalcogenide glass extend selectivity to double-charged metal ions like Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ [23] [15]. These membranes operate through an ion-exchange mechanism at the glass surface, where specific cations in the solution interact with binding sites in the glass matrix. The membrane potential develops due to the differential mobility of cations within the glass structure. However, users must account for alkali error (at high pH with low H⁺ concentration) and acidic error (at low pH with high H⁺ concentration), which can introduce non-linear responses outside optimal pH ranges [23].

Solvent Polymeric Membranes Polymer membranes represent the most widespread type of ion-selective electrodes, typically utilizing polyvinyl chloride (PVC) matrices plasticized with specific compounds to create flexible, ion-sensitive films [22] [15]. These membranes incorporate ionophores—molecular recognition agents that selectively complex with target ions—and ion exchangers to establish permselectivity. The ionophores can be electrically charged or neutral compounds designed with specific binding pockets for target ions. The extensive versatility of polymer membranes allows preparation of selective electrodes for dozens of different ions through appropriate selection of ionophores and membrane compositions [15].

Composite Solid-State Electrolytes Recent advances have integrated inorganic fillers into polymer matrices to create composite electrolytes with enhanced properties. For example, PEO–LiTFSI–LATP (PELT) composite electrolytes incorporate nanosized Li₁.₃Al₀.₃Ti₁.₇(PO₄)₃ fillers into a polyethylene oxide matrix, effectively reducing crystallinity while providing additional Li⁺ transport channels [25]. These composites demonstrate improved mechanical robustness, wider electrochemical stability windows (up to 4.9 V), and enhanced Li⁺ transference numbers compared to pure polymer electrolytes [25].

Table 1: Comparison of Advanced Ion-Selective Membrane Types and Their Characteristics

| Membrane Type | Composition | Primary Ions Detected | Selectivity Mechanism | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crystalline | Mono-/polycrystallites (e.g., LaF₃, Ag₂S) | F⁻, CN⁻, S²⁻, Cl⁻, Br⁻, I⁻ | Crystal lattice compatibility | Excellent selectivity, no internal solution, chemical durability | Limited to ions matching crystal structure, mechanical brittleness |

| Glass | Silicate or chalcogenide glass | H⁺, Na⁺, Ag⁺, Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ | Surface ion-exchange | High chemical durability, works in aggressive media | Limited to single-charged and some double-charged cations, pH errors |

| Polymer | PVC with plasticizers and ionophores | K⁺, Na⁺, Ca²⁺, NO₃⁻, Cl⁻ | Ionophore complexation | Versatile for many ions, flexible, customizable | Lower physical durability, limited lifespan |

| Composite Solid-State | Polymer matrices with inorganic fillers (e.g., PEO-LATP) | Li⁺ | Hybrid transport pathways | Enhanced conductivity, mechanical strength, wide voltage window | Complex fabrication, interfacial resistance challenges |

Recent Advancements in Membrane Performance

The last decade has witnessed revolutionary improvements in ISE technology, particularly regarding lower limits of detection (LOD) and selectivity. Traditional ISEs were limited to concentrations around 10⁻⁶ M, but contemporary designs now achieve detection limits in the range of 10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹¹ M for numerous ions [22]. This million-fold improvement stems from understanding and controlling ion fluxes through the membrane. By optimizing the composition of the inner solution and reducing ion diffusion in the membrane, researchers have successfully minimized the ion fluxes that previously established a limiting concentration near the membrane surface, thereby enabling trace-level measurements [22].

Furthermore, selectivity coefficients have improved dramatically, now often reaching values smaller than 10⁻¹⁰, with some systems demonstrating selectivity better than 10⁻¹⁵ [22]. These extraordinary improvements have opened new application domains for ISEs, particularly in environmental monitoring of trace metals and bioanalysis using metal nanoparticle labels, where they can now compete with sophisticated analytical techniques like ICP-MS for specific applications [22].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fabrication of Polymer Membrane ISEs

Materials and Reagents:

- High-molecular-weight Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) - matrix material

- Plasticizers (e.g., phthalates) - impart flexibility and influence dielectric constant

- Ionophore (specific to target ion) - provides ion selectivity

- Salt solutions for internal filling - establish stable reference potential

- Tetrahydrofuran or cyclohexanone - solvent for membrane components

- Silver/silver chloride wire - internal reference electrode

Procedure:

- Dissolve 100-200 mg PVC in 2-3 mL tetrahydrofuran with continuous stirring

- Add plasticizer (typically 2:1 plasticizer to PVC ratio) and appropriate ionophore (0.5-5 mg depending on selectivity requirements)

- Stir the mixture thoroughly until a homogeneous solution is obtained

- Pour the solution into a glass ring placed on a glass plate and cover loosely to allow slow solvent evaporation over 24-48 hours

- Once solidified, punch membrane disks of appropriate diameter (typically 6-8 mm)

- Mount the membrane in an electrode body and fill with internal solution containing fixed activity of target ion

- Condition the electrode in a solution containing the target ion for 24-48 hours before use [15]

Preparation of Composite Solid-State Electrolytes

Materials and Reagents:

- Polyethylene oxide (PEO) - polymer matrix

- Lithium bis(trifluoromethane)sulfonimide (LiTFSI) - lithium salt

- Li₁.₃Al₀.₃Ti₁.₇(PO₄)₃ (LATP) - ceramic filler

- Anhydrous acetonitrile - solvent

- Aluminum oxide-coated polyethylene separator - mechanical scaffold

Procedure:

- Dissolve 1.0 g high-molecular-weight PEO (Mw = 600,000) in anhydrous acetonitrile

- Add LiTFSI at EO:Li ratio of 3:1 (mass ratio of 1:3 against polymer)

- Stir continuously at 25°C for 4 hours, then at 60°C for 2 hours

- Incorporate 0.15 g nanosized LATP ceramic filler into the PEO-LiTFSI solution

- Continue stirring for 6 hours to achieve homogeneous dispersion

- Cast the slurry into a polytetrafluoroethylene mold

- Allow solvent evaporation at ambient temperature for 6 hours

- Transfer to vacuum oven and dry at 50°C for 24 hours to remove residual solvent

- Punch electrolyte disks (19 mm diameter) in an argon-filled glovebox [25]

Integrated Electrode-Electrolyte Architecture Fabrication

To address interfacial resistance challenges in solid-state batteries, an integrated electrode-electrolyte architecture can be fabricated:

- Prepare conventional LiFePO₄ cathode by mixing active material, conductive carbon, and PVDF binder (8:1:1 ratio) in appropriate solvent

- Cast slurry onto aluminum foil and dry at 80°C for 24 hours in vacuum oven

- Uniformly coat PELT precursor solution onto the surface of dried LFP cathode

- Allow precursor infiltration at room temperature for 6 hours

- Dry in vacuum oven at 50°C for 12 hours to form compact composite interface

- Punch integrated electrode disks (16 mm diameter) in argon-filled glovebox [25]

Figure 2: Experimental workflow for fabricating polymer membrane ion-selective electrodes, highlighting key steps from component preparation to final conditioning.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Advanced Membrane Electrode Development

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Examples | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyvinyl Chloride (PVC) | Polymer matrix for membrane | Cation and anion selective electrodes | High molecular weight grades provide better mechanical stability |

| Ionophores (e.g., Valinomycin) | Molecular recognition element | K⁺-selective electrodes | Selectivity depends on molecular structure and complexation constants |

| Plasticizers (e.g., Phthalates) | Impart flexibility and adjust dielectric constant | Polymer membrane electrodes | Influence dielectric constant and ionophore solubility |

| LiTFSI | Lithium salt for ion conduction | Solid polymer electrolytes | High solubility and dissociation constant in polymer matrices |

| LATP Filler | Ceramic ion conductor | Composite solid electrolytes | Nanosized particles provide greater surface area for enhanced conduction |

| Polyethylene Oxide (PEO) | Polymer matrix for solid electrolytes | Lithium metal batteries | High molecular weight PEO provides better mechanical properties |

| Tetrahydrofuran | Solvent for membrane casting | Polymer membrane preparation | Anhydrous conditions prevent phase separation |

| Silver/Silver Chloride | Reference electrode material | Internal reference systems | Requires electrochemical conditioning for stable potential |

Analytical Performance and Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The analytical performance of advanced membrane electrodes is characterized by several key parameters. Sensitivity is reflected in the electrode slope, which ideally approaches the Nernstian value (59.16/z mV per decade of activity at 25°C). The lower limit of detection (LOD), traditionally defined by the IUPAC method as the activity where the calibration curve deviates from linearity, has been dramatically improved in modern ISEs, now reaching the 10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹² M range for many ions [22]. Selectivity coefficients (Kₚₒₜ) quantify the electrode's preference for the primary ion over interfering ions, with contemporary membranes achieving values below 10⁻¹⁰ in optimal cases [22]. Response time ranges from seconds to minutes depending on membrane thickness, composition, and the magnitude of activity change.

Applications in Research and Industry

The improved performance characteristics of modern membrane electrodes have enabled their application across diverse fields:

Environmental Monitoring ISEs with enhanced lower detection limits have been successfully applied to trace metal monitoring in environmental samples. For example, lead-selective electrodes can now measure Pb²⁺ activities down to 10⁻¹¹ M, enabling direct speciation analysis in water samples [22]. The ability to distinguish free ion activities from total concentrations makes ISEs particularly valuable for environmental speciation studies, as demonstrated by the pH-dependent response of Pb²⁺-ISEs in the presence of carbonate, which aligns perfectly with ICP-MS measurements of total lead content [22].

Bioanalysis and Medical Applications Miniaturized ISEs serve as powerful tools for bioanalysis, with sub-femtomole detection limits reported for various cations when sample volumes are reduced [22]. Enzyme electrodes coupling enzymatic reactions with potentiometric detection enable measurement of substrates like glucose, urea, and neurotransmitters [15]. In clinical settings, ISEs routinely perform billions of measurements annually for ions like Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, and Cl⁻ in blood, serum, and plasma samples [22]. Recent advances in solid-contact electrodes have further improved stability for in vivo measurements.

Energy Storage Systems Solid-state and composite electrolytes play critical roles in advanced battery technologies. The puzzle-like molecular assembly strategy using triallyl phosphate and 2,2,3,3,4,4,4-heptafluorobutyl methacrylate segments spliced into a vinyl ethylene carbonate matrix produces solid-state polymer electrolytes with high ionic conductivity (0.432 mS cm⁻¹) and Li⁺ transference numbers (0.70) at 25°C [26]. These materials enable high-voltage operation (up to 5.15 V) and support stable cycling in Li||LiNi₀.₆Co₀.₂Mn₀.₂O₂ cells for over 300 cycles, demonstrating the electrochemical robustness of modern membrane materials [26].

Future Perspectives and Research Directions

The ongoing evolution of membrane electrode technology continues to expand analytical capabilities. Several promising research directions are emerging, including the development of pulsed amperometric methods that extend beyond traditional potentiometry, novel calibration procedures that reduce demands on signal stability and reproducibility, and multifunctional membranes that combine sensing with other properties like self-powering or self-healing [22]. The integration of computational materials design with high-throughput experimentation promises to accelerate the discovery of novel ionophores and membrane compositions tailored for specific analytical challenges. As fundamental understanding of interfacial processes and mass transport in membrane systems deepens, further improvements in detection limits, selectivity, and operational stability are anticipated, solidifying the role of advanced membrane electrodes as indispensable tools in analytical chemistry, biomedical research, and energy storage technologies.

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) have undergone a revolutionary transformation with the development of solid-contact architectures, fundamentally addressing the limitations inherent in traditional liquid-contact designs. Solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) represent a significant technological advancement by eliminating the internal filling solution, thereby enabling unprecedented miniaturization, enhanced stability, and expanded application potential in fields ranging from pharmaceutical development to wearable environmental monitors [9] [27]. This transition from liquid-contact ISEs (LC-ISEs) to solid-contact systems has not only resolved fundamental operational challenges but has also opened new frontiers in sensor technology, particularly for applications requiring portability, continuous monitoring, and integration with miniaturized analytical devices.

The evolution began in 1971 with Cattrall and Freiser's pioneering "coated wire electrodes," which first demonstrated the possibility of eliminating the internal solution [27]. However, these early designs suffered from potential drift due to insufficiently defined transduction mechanisms at the membrane-conductor interface. The breakthrough came in 1992 when Lewenstam and Ivaska introduced an intermediate polypyrrole layer functioning as an "ion-to-electron transducer," establishing the modern SC-ISE architecture that has since become the state-of-the-art standard [27]. Subsequent research has focused on refining this core concept through novel materials and improved interfacial designs, leading to the current generation of high-performance SC-ISEs with exceptional potential stability, reproducibility, and detection capabilities [9] [28].

Fundamental Limitations of Liquid-Contact ISEs

Traditional liquid-contact ISEs feature an internal filling solution that serves as a bridge between the ion-selective membrane (ISM) and an internal reference electrode. While this design has proven effective for laboratory applications, it presents several inherent limitations that restrict its practical implementation beyond controlled environments [9].

Table 1: Key Limitations of Liquid-Contact ISEs

| Limitation Category | Specific Technical Challenges | Impact on Performance and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Physical Instability | Evaporation, permeation, and pressure/temperature-induced volume changes of internal solution [9] | Signal drift, requirement for careful maintenance, limited operational environments |

| Miniaturization Barriers | Difficulty reducing internal solution volume below milliliter level [9] | Bulky designs, incompatible with wearable/microfabricated devices |

| Ionic Flux Issues | Steady-state ionic flux between inner filling and test solutions [9] | Limited detection range, shortened electrode lifetime |

| Mechanical Complexity | Osmotic pressure differences causing water transfer and membrane stratification [9] | Compromised membrane integrity, potential delamination |

These limitations collectively restricted LC-ISEs from achieving their full potential in field-deployable, miniaturized, and continuous monitoring applications. The internal solution component fundamentally constrained the physical design, necessitating a paradigm shift toward all-solid-state architectures [9] [27].

SC-ISE Architecture and Working Principles

Core Structural Components

The modern SC-ISE features a sophisticated three-layer architecture that enables its superior performance characteristics:

Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM): The recognition element typically composed of a polymer matrix (usually PVC), plasticizer, ionophore (selective molecular recognition agent), and ion exchanger [9]. This membrane selectively interacts with target ions in the sample solution, generating an ion-specific potential.

Solid-Contact (SC) Layer: The ion-to-electron transducer positioned between the ISM and conductive substrate. This critical component replaces the internal solution of traditional ISEs and exists in two primary varieties based on transduction mechanism: redox-capacitive materials (conducting polymers, ferrocene derivatives) and electric double-layer (EDL) capacitive materials (carbon nanomaterials, nanostructured metals) [9] [13].

Electron-Conducting Substrate (ECS): The underlying electrode material (typically glassy carbon, gold, or screen-printed electrodes) that provides electrical connection to the measurement instrumentation [9] [29].

Ion-to-Electron Transduction Mechanisms

The fundamental operation of SC-ISEs relies on two distinct transduction mechanisms for converting ionic currents in the ISM to electronic currents in the ECS:

Redox Capacitance Mechanism: Utilizes materials with reversible redox properties, such as conducting polymers (PEDOT, PANi, polypyrrole) or molecular redox couples (ferrocene) [13] [27]. When target ions enter the SC layer, they trigger compensatory redox reactions that generate electron flow while maintaining charge neutrality. For example, in PEDOT-based transducers, the overall reaction can be represented as:

This mechanism establishes a thermodynamically defined potential that follows Nernstian behavior [27].

Electric Double-Layer (EDL) Capacitance Mechanism: Employed by high-surface-area materials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and porous carbon structures [13] [29]. These materials function as electrochemical capacitors where ions accumulate at the SC/ISM interface, creating separated ionic and electronic charge layers that behave as a capacitor. The resulting potential stability is proportional to the capacitance of the SC layer, with higher capacitance yielding improved stability against current-induced polarization [9] [29].

Critical Materials and Experimental Methodologies

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials for SC-ISE Development

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for SC-ISE Fabrication

| Material Category | Specific Examples | Function and Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC), polyurethane, polystyrene, acrylic esters [9] | Provides structural backbone for ISM, determines mechanical properties and compatibility |

| Plasticizers | Bis(2-ethylhexyl) sebacate (DOS), 2-nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE), dibutyl phthalate (DBP) [9] [3] | Enhances membrane fluidity, controls dielectric constant, influences ionophore selectivity |

| Ionophores | Calix[n]arenes, crown ethers, cyclodextrins, natural/synthetic ion carriers [9] [29] | Provides selective molecular recognition of target ions through specific binding |

| Ion Exchangers | Sodium tetrakis(pentafluorophenyl)borate (NaTFPB), potassium tetrakis[3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]borate (KTFPB) [9] [3] | Introduces counter-ions for charge balance, facilitates ion exchange, establishes Donnan exclusion |

| Redox Transducers | PEDOT, PANi, polypyrrole, ferrocene derivatives [13] [27] | Enables redox capacitance mechanism with reversible ion-to-electron transduction |

| EDL Capacitive Materials | Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), single-walled CNTs, graphene, 3D-ordered porous carbon [13] [29] | Provides high surface area for double-layer capacitance, enhances potential stability |

| Conductive Substrates | Glassy carbon electrodes, screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), gold films [9] [29] | Serves as electron-conducting foundation, enables electrical connection to instrumentation |

Standard Fabrication Protocol for SC-ISEs

Based on methodologies successfully implemented in recent studies [13] [3] [29], the following protocol represents current best practices for SC-ISE fabrication:

Step 1: Substrate Preparation

- Polish glassy carbon electrodes (GCE, 3mm diameter) successively with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina slurries

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol between polishing steps

- Alternatively, use commercially available screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) for disposable configurations

Step 2: Solid-Contact Layer Deposition

- For CNT-based contacts: Prepare 1 mg/mL dispersion of MWCNTs in ethanol and deposit 10-20 μL onto substrate

- For conducting polymers: Electropolymerize monomer solution (e.g., 0.1 M EDOT in acetonitrile) via cyclic voltammetry (typically 10 cycles between -0.5 and +1.2 V)

- Allow deposited layers to dry thoroughly under ambient conditions or controlled temperature

Step 3: Ion-Selective Membrane Formulation

- Prepare membrane cocktail containing:

- 1.0 wt% ionophore (e.g., calix[4]arene for Ag⁺ sensing)

- 0.5 wt% ion exchanger (e.g., NaTFPB)

- 32.5 wt% PVC polymer matrix

- 66.0 wt% plasticizer (e.g., NPOE)

- Dissolve components in 2-3 mL tetrahydrofuran (THF) and mix thoroughly

Step 4: Membrane Deposition and Conditioning

- Deposit 50-100 μL of membrane cocktail onto solid-contact layer

- Allow THF solvent to evaporate slowly for 24-48 hours at room temperature

- Condition completed electrode in 0.01 M solution of target ion for 12-24 hours before use

Performance Validation Methodologies

Comprehensive characterization of SC-ISEs requires multiple electrochemical techniques to evaluate different performance aspects [13]:

Potentiometric Measurements:

- Calibrate in primary ion solutions across concentration range (typically 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹ M)

- Determine slope, linear range, and detection limit from EMF vs. log concentration plot

- Calculate selectivity coefficients using Separate Solution Method or Fixed Interference Method

Chronopotentiometry:

- Apply constant current (±1 nA) for 60 seconds

- Measure potential drift (ΔE/Δt) as stability indicator

- Calculate capacitance from C = i/(dE/dt), where higher capacitance indicates better stability

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS):

- Scan frequency range from 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz at open-circuit potential

- Fit data to equivalent circuit to determine bulk resistance (Rᵦ), double-layer capacitance (C𝒹𝓁), and geometric capacitance (Cℊ)

Water Layer Test:

- Immerse electrode in primary ion solution (e.g., 0.01 M)

- Transfer to interfering ion solution (e.g., 0.1 M) of different primary ion concentration