Innovative Electrode Materials for Advanced Trace Metal Analysis: A Comprehensive Review for Biomedical Research

This comprehensive review explores groundbreaking advancements in novel electrode materials for trace metal analysis, addressing critical needs in biomedical research and drug development.

Innovative Electrode Materials for Advanced Trace Metal Analysis: A Comprehensive Review for Biomedical Research

Abstract

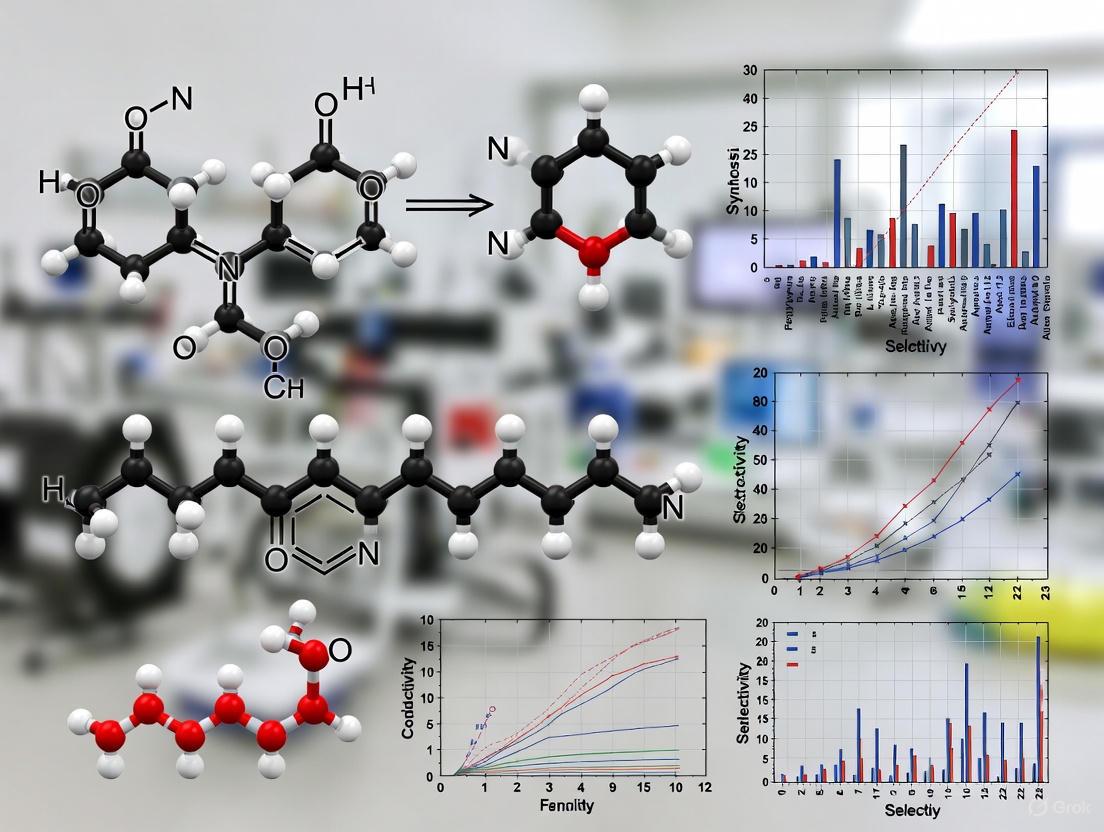

This comprehensive review explores groundbreaking advancements in novel electrode materials for trace metal analysis, addressing critical needs in biomedical research and drug development. We examine the foundational principles driving the shift from traditional mercury electrodes to innovative bismuth, nanostructured, and metal-organic framework (MOF) composites. The article details methodological applications of stripping voltammetry techniques enhanced by nanomaterials, provides troubleshooting strategies for sensor optimization, and presents rigorous validation protocols comparing electrochemical sensors against established techniques like ICP-MS and AAS. This resource equips researchers with practical knowledge to implement these sensitive, cost-effective detection systems for monitoring essential and toxic metals in pharmaceutical products, clinical diagnostics, and environmental samples.

Beyond Mercury: The New Generation of Electrode Materials for Trace Metal Detection

The Critical Need for Novel Electrode Materials in Modern Trace Metal Analysis

The increasing global contamination of water and soil systems by heavy trace elements (HTEs) presents a significant environmental and public health crisis. Toxic metals such as lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and arsenic (As) persist in the environment, bioaccumulating in ecosystems and entering the human food chain with documented consequences including kidney damage, neurological disorders, respiratory failure, and various cancers [1]. This concerning reality has drawn attention from major international institutions including the World Health Organization (WHO), Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), all emphasizing the necessity of rigorous HTE monitoring in environmental media [1].

Traditional analytical methods like atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS), inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), and X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRFS) have long served as the gold standard for heavy metal detection due to their high sensitivity and precision [1]. However, these techniques present significant limitations: they require expensive equipment, high maintenance costs, skilled personnel, and are generally confined to laboratory settings, making them unsuitable for continuous, real-time, in-situ monitoring [2] [3]. In response to these constraints, the scientific community has turned to electrochemical sensing technologies as a promising alternative, with the development of novel electrode materials emerging as the most critical frontier for advancing the field of trace metal analysis [1] [4].

Limitations of Traditional Methods and Established Electrodes

The Problem with Conventional Analytical Techniques

Traditional methods for metal analysis, while sensitive, suffer from inherent drawbacks that limit their application in modern environmental monitoring. The requirement for sophisticated instrumentation and controlled laboratory environments prevents their deployment for field-scale analysis and real-time monitoring [1]. Furthermore, the processes involved are often labor-intensive and lack the portability needed for on-site detection, creating significant delays between sample collection and result acquisition [2] [3]. These limitations are particularly problematic for managing environmental contamination events where rapid response is crucial.

The Mercury Electrode Dilemma and the Search for Alternatives

Mercury-based electrodes have historically been the preferred choice for electrochemical trace metal detection, particularly in stripping voltammetry, because many metals form amalgams with mercury, providing excellent preconcentration capabilities and well-defined electrochemical signals [5]. However, the high toxicity of mercury has driven stringent regulations and a pressing need for safer alternatives [2] [5]. While solid electrodes made from materials like carbon, gold, or platinum offer non-toxic alternatives, they introduce new complexities. At such solid electrodes, metal deposition occurs via underpotential deposition (UPD), where a monolayer of metal deposits at potentials positive of the thermodynamic Nernst potential, followed by bulk deposition [5]. This phenomenon creates multiple reduction and stripping signals, complicating data interpretation compared to mercury electrodes [5].

Emerging Electrode Materials and Their Performance Metrics

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrodes

The integration of nanostructured materials into electrode design has dramatically improved the sensitivity, selectivity, and portability of electrochemical sensors [1]. These nanomaterials provide exceptionally high surface areas, enhanced electron transfer kinetics, and the ability for specific functionalization to target particular metal ions.

Table 1: Key Nanomaterial Classes for Electrode Modification

| Nanomaterial Class | Representative Materials | Key Properties | Target Metals |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Single/Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs), graphene | High conductivity, large surface area, functionalizable surface | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺, Cu²⁺ |

| Metal/Metal Oxide Nanoparticles | Bismuth, antimony, metal oxides | Low toxicity, alloying capability, high hydrogen overpotential | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Zn²⁺, Ni²⁺ |

| Polymer & Hybrid Nanocomposites | Conductive polymers, biopolymers | Selective binding, matrix stability, fouling resistance | Multiple simultaneous detection |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Various crystalline porous structures | Ultra-high porosity, tunable pore chemistry, selective recognition | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺ |

| 2D Materials | MoS₂, graphene | Layered structure, tunable bandgap, abundant edge active sites | Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺ |

Bismuth-Based Electrodes

Bismuth-based electrodes have emerged as one of the most successful mercury-free alternatives, first reported by Joseph Wang in 2000 [2]. Bismuth offers a broad electrochemical window, low toxicity, and the ability to form alloys with numerous heavy metals [2] [3]. Crucially, bismuth exhibits high hydrogen overpotential similar to mercury, enabling noise-free measurements at negative potentials [2]. The innovative Bi drop electrode represents a recent advancement—a solid-state electrode using a 2mm diameter bismuth drop as the working electrode that requires only electrochemical activation rather than film deposition or polishing [2] [3]. This electrode enables simultaneous determination of cadmium and lead, as well as nickel and cobalt, with detection limits in the low μg/L and even ng/L range, sufficient to monitor WHO guideline values for drinking water [2].

Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrodes

Boron-doped diamond (BDD) electrodes represent another promising material class, offering an extremely wide potential window, low background current, and high physical and chemical stability [6]. Optimized BDD electrodes with a doping concentration of 8000 ppm have demonstrated impressive detection limits of 0.43-0.74 μg/L for Cd(II), Pb(II), and Cu(II) ions, with accuracy and precision within 5% in real samples spiked with 100 μg/L of these metals [6]. Their exceptional selectivity and long-term stability make BDD electrodes particularly suitable for online water environment monitoring systems [6].

Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS₂) and Other 2D Materials

Molybdenum disulfide (MoS₂), a transition metal dichalcogenide, has gained significant research attention for electrochemical sensing applications [7]. Its layered structure, tunable bandgap, and abundant edge active sites make it particularly suitable for heavy metal detection [7]. MoS₂ exists in multiple crystalline phases, with the metastable 1T phase exhibiting metallic character and superior conductivity compared to the semiconducting 2H phase [7]. Research interest in MoS₂-based electrochemical sensors has grown remarkably since 2016, with both annual publications and citation counts showing rapid expansion [7].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Emerging Electrode Materials

| Electrode Material | Detection Technique | Target Metals | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi Drop Electrode [2] | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ | 0.1 μg/L (Cd), 0.5 μg/L (Pb) | Up to guideline limits | Mercury-free, no polishing required, suitable for automation |

| Bi Drop Electrode [2] | Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry | Ni²⁺, Co²⁺ | 0.2 μg/L (Ni), 0.1 μg/L (Co) | Up to guideline limits | Simultaneous detection, excellent reproducibility |

| Boron-Doped Diamond [6] | Differential-Pulse ASV | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺ | 0.43-0.74 μg/L | Wide linear range | Excellent long-term stability, corrosion resistance |

| MoS₂-Based Composites [7] | Various voltammetric techniques | Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺ | Varies by composite | Varies by composite | Tunable properties, high surface area, synergistic effects in composites |

| Underpotential Deposition-based [5] | UPD-Stripping Voltammetry | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Cu²⁺ | Nanomolar to sub-nanomolar | Short preconcentration times | High sensitivity, minimal oxygen interference |

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Development and Testing

Electrode Modification and Fabrication Protocols

The development of advanced electrodes follows meticulous fabrication protocols that vary by material type:

Nanocomposite Electrode Fabrication: For carbon nanomaterial-modified electrodes, standard protocols involve dispersing nanomaterials (e.g., SWCNTs, MWCNTs, graphene) in suitable solvents followed by deposition on substrate electrodes (typically glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon electrodes) [1]. Functionalization with specific chemical groups enhances selectivity toward target metals [1] [4].

Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation: Two primary approaches exist: ex-situ deposition where bismuth is electroplated onto the substrate electrode before measurement, and in-situ deposition where bismuth ions are added directly to the sample solution and co-deposited with the target metals [2]. The newer Bi drop electrode eliminates this step, using a solid bismuth drop that requires only electrochemical activation [2] [3].

MoS₂ Synthesis Methods: Preparation strategies include top-down approaches such as mechanical and chemical exfoliation of bulk MoS₂, and bottom-up approaches including chemical vapor deposition and hydrothermal/solvothermal synthesis [7]. The crystal phase (1T, 2H, or 3R) significantly influences electrochemical performance and can be controlled through synthesis parameters [7].

Electrochemical Detection Methodologies

Trace metal analysis predominantly utilizes stripping voltammetry techniques, which involve two fundamental steps: preconcentration and stripping [2].

Stripping Voltammetry Workflow

The primary stripping techniques include:

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV): Used for metals that can be deposited as amalgams or alloys and subsequently oxidized back to ions [2]. Applied for simultaneous determination of cadmium and lead at Bi drop electrodes with deposition times of 30-60 seconds [2].

Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV): Employed for metals that cannot be easily electrodeposited, utilizing complexation with added ligands and subsequent adsorptive accumulation [2]. Used for nickel and cobalt determination at Bi drop electrodes [2].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Often combined with stripping techniques to enhance sensitivity through background current suppression [1]. Used with BDD electrodes for simultaneous detection of Cd(II), Pb(II), and Cu(II) [6].

Underpotential Deposition-Stripping Voltammetry (UPD-SV): Utilizes the phenomenon where a metal monolayer deposits at potentials positive of the Nernst potential, offering exceptional sensitivity with short deposition times and the ability to work without removing dissolved oxygen [5].

Validation and Interference Studies

Robust electrode characterization requires comprehensive validation against certified reference materials and comparison with standard methods like ICP-MS [1]. Interference studies evaluate responses in the presence of common coexisting ions (e.g., Ca²⁺, Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺) and organic surfactants that may foul electrode surfaces [1] [5]. For complex matrices, methodologies incorporating pretreatment steps, permeable membranes, or microextraction techniques are often necessary [8]. The repeatability and reproducibility of measurements are quantified through relative standard deviations of multiple determinations, with high-performance electrodes demonstrating RSD values below 5% [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrode Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials (SWCNTs, MWCNTs, graphene) | Electrode modification to enhance surface area and electron transfer | Glassy carbon electrode modification for heavy metal detection [1] |

| Bismuth Precursors (Bi³⁺ salts, bismuth metal) | Formation of bismuth film electrodes or bismuth composite electrodes | In-situ and ex-situ bismuth film electrodes for Cd, Pb detection [2] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous modification materials with tunable affinity for specific metals | Ca²⁺ MOF for voltammetric determination of heavy metals [1] |

| Molybdenum Disulfide (MoS₂) | 2D layered material providing active sites for metal interaction | MoS₂ composites for enhanced sensitivity in HMI detection [7] |

| Complexing Agents (triethanolamine, dimethylglyoxime) | Form electroactive complexes with target metals | Ni and Co determination via adsorptive stripping voltammetry [2] |

| Supporting Electrolytes (acetate buffer, nitric acid, KCl) | Provide ionic conductivity and control pH | Standard media for anodic stripping voltammetry [2] [5] |

| Polymer Membranes (Nafion, chitosan) | Selective permeability and antifouling properties | Electrode modification to improve selectivity in complex matrices [1] [4] |

Current Challenges and Future Research Directions

Despite significant advances, several challenges persist in the development of novel electrode materials for trace metal analysis. Electrochemical sensors still face issues with electrode fouling in complex matrices, variability in environmental conditions (pH, ionic strength), and the absence of standardized calibration protocols [1]. Additionally, the long-term stability of nanomaterial-modified electrodes under continuous operation requires improvement for field-deployed sensors [1] [7].

Future research directions focus on several promising areas:

Advanced Composite Materials: Combining multiple nanomaterials to create synergistic effects, such as MoS₂-graphene hybrids that leverage both the high conductivity of graphene and the abundant active sites of MoS₂ [7].

Green and Sustainable Materials: Increasing use of biopolymers and environmentally friendly substances in electrode modification [4].

Digital Integration and Flexible Manufacturing: Incorporation of digitalization strategies and flexible manufacturing technologies to produce cost-effective, disposable electrodes [9].

Microfluidic Integration: Combining miniaturized electrodes with microfluidic systems for automated sample handling and analysis, particularly for complex matrices [7].

Machine Learning Applications: Utilizing computational approaches to optimize electrode composition, predict performance, and interpret complex electrochemical signals [7].

Electrode Material Development Trajectory

The critical need for novel electrode materials in modern trace metal analysis stems from the convergence of multiple factors: growing environmental and public health concerns about heavy metal pollution, limitations of traditional analytical methods, and the necessity to replace toxic mercury electrodes. The development of advanced materials including bismuth-based electrodes, nanomaterial composites, boron-doped diamond, and two-dimensional materials like MoS₂ has significantly advanced the field, enabling sensitive, selective, and portable detection of trace metals. These innovations align with the global trend toward real-time environmental monitoring and field-deployable analysis systems.

Future progress will depend on interdisciplinary approaches that combine materials science, electrochemistry, and engineering to overcome current challenges related to sensor stability, reproducibility, and performance in complex matrices. The continued development of novel electrode materials remains not merely an academic pursuit but an essential component of environmental protection and public health safeguarding worldwide. As research advances, these new materials will increasingly enable decentralized testing capabilities, empowering communities to monitor their own water and soil resources with laboratory-quality precision.

Electrochemical sensors play a critical role in the detection of trace metal ions in environmental, clinical, and industrial applications. Their performance is fundamentally governed by the electrode material, which serves as the transducer for electrochemical reactions. Traditional electrodes, particularly mercury-based and conventional solid-state electrodes, have long been the standard for trace metal analysis. However, these materials face significant limitations related to toxicity, environmental compatibility, and analytical performance, especially in complex matrices. These constraints have driven extensive research into novel electrode materials, including bismuth-based alternatives and nanomaterial composites, to develop next-generation sensing platforms that balance analytical excellence with environmental and operational safety. This review examines the core limitations of traditional electrodes and explores the emerging material solutions that are reshaping the landscape of electroanalytical chemistry.

Toxicity and Environmental Concerns of Mercury Electrodes

Mercury-based electrodes, particularly the hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE) and mercury film electrodes (MFE), have historically been the gold standard for anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) due to their exceptional electrochemical properties. However, their severe toxicity and environmental incompatibility present fundamental constraints for modern analytical applications.

The primary limitation of mercury electrodes stems from the inherent toxicity of mercury itself. Mercury is a potent neurotoxin that poses significant health risks through exposure during electrode preparation, operation, and disposal [2]. Its environmental persistence and bioaccumulation potential make it increasingly unsuitable for widespread field deployment or disposable sensor applications. Regulatory agencies worldwide have implemented strict controls on mercury use, driving the scientific community to seek alternatives that eliminate this hazardous material without compromising analytical performance [10].

Despite these toxicity concerns, mercury's analytical advantages are substantial. It offers a wide cathodic potential window, excellent hydrogen overpotential, renewable surface properties, and the ability to form amalgams with numerous metals, resulting in highly reproducible and well-defined stripping peaks [2]. These characteristics have made mercury electrodes particularly valuable for detecting trace metals such as lead, cadmium, zinc, and copper at parts-per-trillion levels. The challenge for alternative materials has been to match this comprehensive performance profile while eliminating toxicity concerns.

Performance Limitations of Conventional Solid Electrodes

In attempts to replace mercury electrodes, various conventional solid electrodes have been investigated, including gold, platinum, and carbon-based materials (glassy carbon, carbon paste). While these materials eliminate mercury toxicity concerns, they introduce significant performance constraints that limit their analytical utility for trace metal detection.

Fundamental Performance Constraints

The table below summarizes the key performance limitations of conventional solid electrodes compared to mercury-based systems:

| Electrode Material | Primary Limitations | Impact on Analytical Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Surface oxide formation, limited potential window, interference from metal deposition/stripping processes | Poor reproducibility, fouling in complex matrices, restricted analyte range |

| Platinum (Pt) | High catalytic activity for hydrogen evolution, strong adsorption of organic species | Limited cathodic range, surface contamination, unstable baseline |

| Glassy Carbon (GC) | Microstructural heterogeneity, surface contamination, slow electron transfer kinetics | Poor peak resolution, irreproducible responses, requirement for frequent pretreatment |

| Carbon Paste | Mechanical instability, component leaching, susceptibility to fouling | Limited lifetime, signal drift, poor performance in organic-rich samples |

A fundamental limitation of these conventional solid electrodes is their susceptibility to surface fouling and passivation in complex sample matrices. Unlike mercury's renewable surface, solid electrodes accumulate oxidation products, adsorbed organic species, and irreversible reaction products that degrade performance over time [1]. This necessitates frequent and often aggressive surface regeneration procedures including mechanical polishing, electrochemical conditioning, or chemical treatments that increase analysis time and introduce variability.

Additionally, these materials often exhibit poor reproducibility between electrodes and even between measurements on the same electrode. Microstructural variations, surface heterogeneity, and inconsistent pretreatment protocols contribute to this variability, complicating calibration and quantification [11]. Gold electrodes, for instance, develop complex oxide layers that influence metal deposition kinetics, while carbon surfaces display significant batch-to-batch variations in edge plane defects and surface functional groups.

The limited cathodic potential range of many solid electrodes, particularly noble metals, restricts their application for metals with highly negative reduction potentials. The hydrogen evolution reaction occurring at relatively positive potentials on platinum and gold surfaces interferes with the detection of zinc, manganese, and similar elements that are readily determined at mercury electrodes [2].

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Electrode Limitations

Research into electrode limitations employs standardized experimental protocols to quantitatively assess performance constraints:

Cyclic Voltammetry in Redox Probes: Electrodes are characterized in solutions containing 1.0-5.0 mM potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide ([Fe(CN)6]³⁻/⁴⁻) in 1.0 M KCl supporting electrolyte. Scan rates typically range from 10-500 mV/s. The peak separation (ΔEp) values greater than 59 mV indicate slow electron transfer kinetics, while decreases in peak current over successive cycles reveal surface fouling tendencies [11].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Conducted in the same redox probe system over frequency ranges of 0.1 Hz to 100 kHz with 10 mV amplitude. The charge transfer resistance (Rct) values derived from Nyquist plot modeling quantify electron transfer efficiency, with higher values indicating more significant performance limitations [11].

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry Standardization: Electrodes are tested in standard solutions containing 10-50 μg/L of target metals (Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn) in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) or 0.1 M HNO3. After optimizing deposition potential and time, stripping peaks are analyzed for shape, symmetry, and resolution. Peak broadening, overlap, or potential shifts indicate performance deficiencies [1] [2].

Surface Characterization: Complementary techniques including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), atomic force microscopy (AFM), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), and Raman spectroscopy correlate electrochemical performance with surface morphology, composition, and structure [11].

The Rise of Bismuth-Based Electrodes as Alternatives

Bismuth-based electrodes represent the most significant advancement in addressing both toxicity and performance limitations of traditional electrodes. First introduced by Joseph Wang in 2000, bismuth electrodes combine low toxicity with exceptional electroanalytical performance that rivals mercury in many applications [2].

Advantages of Bismuth-Based Electrodes

Bismuth offers a unique combination of properties that make it ideal for trace metal analysis:

Low Toxicity: Bismuth and its salts are considerably less toxic than mercury, with regulatory approval for pharmaceutical and cosmetic applications, significantly reducing handling and disposal concerns [2].

Favorable Electrochemical Properties: Similar to mercury, bismuth exhibits high hydrogen overpotential, which minimizes interference from hydrogen evolution and enables detection of metals with highly negative reduction potentials. It also forms well-defined "fused" alloys with heavy metals rather than conventional amalgams, resulting in sharp, well-resolved stripping peaks [2].

Multi-Element Detection Capability: Bismuth electrodes support simultaneous detection of multiple trace metals, including cadmium and lead, as well as nickel and cobalt through adsorptive stripping voltammetry, making them versatile for environmental monitoring [2].

Bismuth Electrode Configurations and Performance

The table below compares the analytical performance of different bismuth electrode configurations for trace metal detection:

| Electrode Configuration | Detection Limits (μg/L) | Target Metals | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bi Film Electrode (ex-situ) | Cd: 0.1, Pb: 0.5 [2] | Cd, Pb, Zn, Cu, Ni, Co | Wide potential window, excellent sensitivity | Film stability, preparation complexity |

| Bi Film Electrode (in-situ) | Cd: 0.15, Pb: 0.2 [2] | Cd, Pb, Zn, Mn | Simplified operation, good reproducibility | Dependence on solution conditions |

| Bi Drop Electrode | Cd: 0.1, Pb: 0.5 [2] | Cd, Pb, Ni, Co, Fe | No polishing required, excellent for online monitoring | Mechanical stability, limited surface renewal |

| Bi-Carbon Nanocomposite | Cd: <0.1, Pb: <0.1 [11] | Cd, Pb, As, Cu, Zn | Enhanced sensitivity, mechanical stability | Complex fabrication, higher cost |

The bismuth drop electrode represents a particularly innovative design that eliminates the need for film plating while maintaining excellent analytical performance. With detection limits of 0.1 μg/L for cadmium and 0.5 μg/L for lead, it meets WHO guideline values for drinking water monitoring and demonstrates remarkable reproducibility (RSD <5% for 10 measurements) [2].

Experimental Protocols for Bismuth Electrode Preparation

Ex-situ Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation: A bismuth film is electrodeposited onto a substrate electrode (typically glassy carbon or carbon paste) from a solution containing 200-400 mg/L Bi³⁺ in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.5) or 0.1 M HNO3. Deposition is performed at -1.0 V to -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 60-300 seconds with stirring. The film thickness is controlled by deposition charge [2].

In-situ Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation: Bi³⁺ ions (200-500 μg/L) are added directly to the sample solution containing target analytes. During the deposition step, both bismuth and target metals are simultaneously deposited onto the substrate electrode at -1.0 V to -1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl [2].

Bi Drop Electrode Activation: The bismuth drop electrode requires only electrochemical activation in supporting electrolyte (typically 0.1 M acetate buffer or 0.1 M KCl) by applying cyclic scans from -1.0 V to +0.5 V until a stable baseline is achieved, significantly simplifying preparation compared to film electrodes [2].

Nanomaterial-Modified Electrodes: Overcoming Performance Barriers

The integration of nanomaterials into electrode design has created unprecedented opportunities to overcome the performance limitations of traditional electrodes while maintaining environmental compatibility.

Nanomaterial Enhancement Strategies

Carbon Nanomaterials: Carbon nanotubes (single-walled and multi-walled), graphene, reduced graphene oxide, and carbon nanofibers provide high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and abundant active sites for metal deposition. These materials enhance electron transfer kinetics and preconcentration efficiency, significantly improving detection sensitivity [1] [11].

Metallic and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Bismuth, antimony, tin, and their oxide nanoparticles exhibit unique electrocatalytic properties when combined with carbon substrates. Bi-rGO (bismuth-reduced graphene oxide) nanocomposites have demonstrated exceptional sensitivity for cadmium (5.0 ± 0.1 μA/ppb/cm²) and lead (2.7 ± 0.1 μA/ppb/cm²) detection, enabling sub-ppb detection limits [11].

Two-Dimensional Materials: MXenes and transition metal dichalcogenides (e.g., MoS₂) offer tunable surface chemistry and exceptional charge transfer capabilities. MoS₂'s layered structure with abundant edge active sites provides specific binding affinities for heavy metal ions, enhancing both sensitivity and selectivity [7].

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): MOFs provide ultrahigh surface areas and precisely tunable pore structures that can be functionalized for specific metal capture. Their exceptional preconcentration capabilities make them ideal for ultra-trace detection, though conductivity limitations often require combination with other nanomaterials [1].

Electrode Modification Protocols

Electrochemical Pretreatment of Carbon Substrates: Screen-printed carbon electrodes are electrochemically pretreated in 0.1 M H₂SO₄ by cycling between ±0.5 V to ±2.0 V at 20-40 mV/s for 10-30 cycles. This treatment increases electroactive surface area by 41±1.2% and decreases charge transfer resistance by 88±2%, creating an optimal foundation for nanomaterial modification [11].

Nanocomposite Ink Preparation: Bi-rGO nanocomposite ink is prepared by dissolving 1.0 mg/mL graphene oxide in ethylene glycol with 2.0 mM Bi³⁺, followed by chemical reduction with sodium borohydride. The mixture is sonicated for 60 minutes and centrifuged to obtain a stable dispersion for electrode modification [11].

Electrode Modification Procedure: 2-5 μL of nanocomposite ink is drop-cast onto pretreated electrode surfaces and dried under infrared light or at room temperature. The modified electrode is then stabilized in supporting electrolyte by applying 5-10 cyclic voltammetry scans from -1.4 V to +0.5 V until a stable response is achieved [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below outlines key research reagents and materials essential for investigating novel electrode materials for trace metal detection:

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Nitrate Pentahydrate | Precursor for bismuth film electrodes and nanocomposites | High purity (>99.99%) required for reproducible film formation |

| Single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes | Conductivity enhancement in composite electrodes | Functionalization (COOH, OH) improves dispersion and binding |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide | High surface area substrate for metal nanoparticles | Control of oxygen content balances conductivity and functionality |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Resin | Ion-exchange polymer binder for electrode modification | Provides selectivity and anti-fouling properties but can hinder mass transfer |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 4.5) | Standard supporting electrolyte for ASV of heavy metals | Optimal for simultaneous detection of Cd, Pb, Cu without gas evolution |

| Potassium Ferricyanide | Redox probe for electrode characterization and EIS | Sensitive to surface chemistry and electron transfer kinetics |

| Metal Standard Solutions | Calibration and method validation for trace metal detection | Certified reference materials essential for accurate quantification |

| Screen-Printed Electrode Arrays | Disposable sensor platforms for field deployment | Enable high-throughput analysis with minimal sample volume |

The limitations of traditional electrodes—encompassing toxicity concerns with mercury and performance constraints with conventional solid materials—have driven remarkable innovation in electroanalytical chemistry. Bismuth-based electrodes have emerged as the leading alternative, successfully balancing environmental compatibility with analytical performance that rivals mercury in many applications. The integration of nanomaterials has further addressed fundamental limitations through enhanced surface areas, improved electron transfer kinetics, and tailored recognition properties. Future research directions will likely focus on intelligent sensor systems combining advanced materials with machine learning for signal processing, multifunctional composites that address matrix interference challenges, and sustainable fabrication methods for disposable field-deployable sensors. These advancements will continue to transform trace metal analysis, providing increasingly sophisticated solutions to the persistent challenges of toxicity, selectivity, and reliability in complex real-world samples.

The pursuit of novel electrode materials for trace metal analysis represents a critical frontier in analytical chemistry. For decades, mercury electrodes were considered the gold standard for stripping voltammetry due to their exceptional electroanalytical performance, including a wide cathodic potential window, high reproducibility, and renewable surface [12] [13]. However, mercury's significant toxicity and associated environmental and health hazards have driven the scientific community to seek safer, environmentally friendly alternatives [12]. This research context catalyzed the groundbreaking introduction of bismuth-based electrodes in 2000, which have since emerged as a revolutionary replacement that preserves the advantageous properties of mercury while eliminating its most significant drawbacks [13]. Bismuth is now recognized as a "green metal" with low toxicity and favorable electrochemical characteristics, enabling sensitive detection of heavy metals and organic compounds across environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics, and pharmaceutical applications [14] [13]. This technical guide examines the properties, advantages, and implementation of bismuth-based electrodes within the broader framework of developing novel electrode materials for trace analysis.

Fundamental Properties and Electrochemical Performance

Key Properties of Bismuth Electrode Materials

Bismuth electrodes exhibit several intrinsic properties that make them exceptionally suitable for electrochemical analysis, particularly in stripping voltammetry for trace metal detection.

Table 1: Comparative Properties of Bismuth and Mercury Electrodes

| Property | Bismuth Electrodes | Mercury Electrodes |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | Very low; considered a "green metal" [14] | High toxicity; bioaccumulative [12] |

| Hydrogen Overpotential | High; enables wide cathodic potential window [13] | Very high; excellent cathodic window [12] |

| Oxygen Interference | Insensitive to dissolved oxygen [13] | Sensitive to dissolved oxygen |

| Alloy Formation | Forms fused alloys with heavy metals [12] [13] | Forms amalgams with heavy metals [12] |

| Surface Renewability | Good with proper activation protocols [15] | Excellent with droplet dislodging |

| Background Current | Low, leading to favorable signal-to-noise ratios [12] [16] | Very low |

| Environmental Impact | Minimal; environmentally friendly alternative [14] | Significant; hazardous waste concerns |

The electrochemical behavior of bismuth electrodes centers on their ability to form alloys with numerous metal analytes during the preconcentration step of stripping analysis, analogous to mercury's amalgam formation [13]. This process involves the reduction of both bismuth ions and target metal ions onto a conductive substrate, followed by anodic stripping where the re-oxidation of each metal produces characteristic current peaks whose intensity correlates with concentration [12]. The bismuth film facilitates efficient accumulation of target metals while providing a favorable electrochemical environment for their subsequent stripping, with well-defined, sharp peaks suitable for quantitative analysis [16].

Analytical Performance Metrics

The analytical performance of bismuth-based electrodes has been extensively validated for numerous heavy metals across various sample matrices, demonstrating capabilities comparable to and sometimes surpassing mercury electrodes.

Table 2: Analytical Performance of Bismuth Film Electrodes for Heavy Metal Detection

| Target Analyte | Linear Range (µg/L) | Limit of Detection (µg/L) | Optimal Conditions | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd(II) | 0.1-10 µg/mL* | 0.4 µg/mL* | Ex-situ BiF on paper electrode, acetate buffer pH 4 | [12] |

| Pb(II) | 0.1-10 µg/mL* | 0.1 µg/mL* | Ex-situ BiF on paper electrode, acetate buffer pH 4 | [12] |

| Ni(II) | Up to 80 µg/L | 0.8 µg/L (with 180 s adsorption) | Adsorptive stripping with dimethylglyoxime | [16] |

| Zn(II) | Not specified | 0.05 µg/L | Magnetic field amplification, dual Bi precursor | [13] |

| Tl(I) | Not specified | 1 ng/L | Bismuth bulk annular band electrode | [13] |

Note: Units converted from µg/mL to µg/L for consistency: 0.1-10 µg/mL = 100-10,000 µg/L; LOD 0.4 µg/mL = 400 µg/L.

The performance of bismuth electrodes is highly dependent on optimization of key parameters, particularly the bismuth-to-metal ion concentration ratio (cBi/cM). Recent research indicates that cBi/cM ratios between 5-40 provide optimal sensitivity and precision for cadmium and lead detection, contrasting with earlier recommendations of higher ratios [17]. This optimization balances film formation characteristics with analytical performance, where insufficient bismuth leads to incomplete coverage while excess bismuth increases electrode resistance and reduces signals [17].

Comparative Advantages in Analytical Applications

Environmental and Safety Benefits

The most significant advantage of bismuth electrodes lies in their non-toxic character, addressing the primary limitation of mercury electrodes. Bismuth has very low toxicity, widespread pharmaceutical applications, and is considered an "environmentally friendly" metal [14] [13]. This eliminates occupational health hazards associated with mercury handling and minimizes environmental concerns related to waste disposal [12]. The transition to bismuth-based electrodes aligns with green chemistry principles and regulatory initiatives such as the Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive, which restricts mercury use in electrical and electronic equipment [14].

Analytical Performance Advantages

Bismuth electrodes demonstrate several performance advantages beyond their safety profile. Their insensitivity to dissolved oxygen eliminates the need for lengthy deaeration procedures, significantly reducing analysis time [13]. The electrodes exhibit well-defined, sharp stripping peaks comparable to mercury electrodes, with excellent signal-to-noise characteristics enabling trace-level detection [16]. Bismuth-based sensors also demonstrate remarkable versatility in configuration formats, including bulk electrodes, film electrodes on various substrates, screen-printed platforms, and novel composites with antifouling properties [13] [18].

Recent innovations in bismuth composite materials have addressed previous limitations in complex matrices. For instance, antifouling coatings incorporating bismuth tungstate within a 3D porous cross-linked bovine serum albumin matrix with g-C3N4 maintain 90% of signal after one month in challenging samples like human plasma, serum, and wastewater [18]. This exceptional stability enables reliable heavy metal detection in biological and environmental samples where electrode fouling previously limited practical application.

Application Versatility

The scope of bismuth-based electrodes extends beyond conventional anodic stripping voltammetry of heavy metals. Their applications now include:

- Adsorptive stripping voltammetry for metals that cannot be electrolytically plated, such as nickel and cobalt using dimethylglyoxime complexation [16] [13]

- Organic compound detection including vitamins, pharmaceuticals, and environmental contaminants [15] [13]

- Speciation analysis for differentiating oxidation states, such as Cr(III)/Cr(VI) [13]

- Wearable sensors for real-time monitoring of trace metals in biological fluids like sweat [13]

- Electrocatalytic applications including CO2 reduction to formate [19]

This remarkable versatility demonstrates how bismuth electrodes not only replace mercury but enable novel applications previously impractical with conventional electrode materials.

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Electrode Fabrication Protocols

In Situ Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation

The in situ preparation method represents the most straightforward approach for creating bismuth film electrodes (BiFEs), where bismuth ions are added directly to the sample solution and co-deposited with target analytes:

Substrate Electrode Preparation: Begin with thorough polishing of the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) using alumina suspensions (1.0 µm and 0.3 µm sequentially) on a microcloth pad. Sonicate the polished electrode in absolute ethanol and ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm) for 1 minute each to remove residual polishing materials [17].

Solution Preparation: Prepare an acetate buffer solution (0.1 M, pH 4.5) containing 0.5 M sodium sulfate as supporting electrolyte. Add Bi(III) standard solution to achieve a concentration between 100-500 µg/L, and spike with appropriate dilutions of target metal standard solutions [12] [17].

Film Deposition: Transfer the solution to an electrochemical cell employing a three-electrode configuration (pre-treated GCE as working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and platinum counter electrode). Apply a deposition potential of -1.0 V under stirred conditions for 60-300 seconds, depending on target analyte concentrations [17].

Stripping Analysis: After deposition, cease stirring and allow a 15-60 second equilibration period. Record the anodic stripping voltammogram using differential pulse or square wave modality, scanning from -1.0 V to +0.4 V [12] [17].

Diagram 1: In Situ Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation Workflow

Ex Situ Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation

Ex situ preparation involves pre-plating the bismuth film before exposure to the sample solution, offering advantages for certain applications:

Substrate Preparation: Follow the same polishing and cleaning procedure as for in situ preparation.

Bismuth Plating Solution: Prepare a separate plating solution containing 100-1000 µg/L Bi(III) in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.0-4.5) [12].

Film Formation: Immerse the pre-treated electrode in the plating solution and apply a deposition potential of -1.0 V for 60-120 seconds with stirring. The film thickness can be controlled by adjusting deposition time and Bi(III) concentration [12].

Transfer and Measurement: Rinse the bismuth-modified electrode gently with ultrapure water and transfer to the sample solution containing target analytes but no bismuth ions. Proceed with deposition and stripping steps as described in the in situ protocol [12].

Paper-Based Bismuth Electrode Fabrication

Paper substrates offer disposable, low-cost platforms for decentralized analysis:

Paper Patterning: Print hydrophobic wax barriers on chromatography paper (Whatman Grade 1) using a wax printer to define electrode areas and fluidic paths. Heat at 80°C to melt wax through the paper thickness, creating well-defined hydrophilic zones [12].

Conductive Layer Application: Prepare carbon ink by mixing carbon paste with N,N-dimethylformamide anhydrous (DMF) and homogenize using ultrasonic bath. Apply 2 µL suspension by drop-casting onto the designated working electrode area [12].

Assembly: Attach the paper-based working electrode to a screen-printed electrode card using spray adhesive, creating a hybrid disposable sensor platform [12].

Bismuth Modification: Apply either in situ or ex situ bismuth film formation as described in previous sections.

Optimal Measurement Conditions

The analytical performance of bismuth electrodes depends critically on optimization of several key parameters:

Table 3: Optimal Conditions for Bismuth-Based Electrodes

| Parameter | Optimal Range | Effect on Performance |

|---|---|---|

| pH | 4.0-4.5 (acetate buffer) | Maximizes sensitivity while minimizing hydrogen evolution [12] [17] |

| Bismuth Concentration | cBi/cM ratio 5-40 | Balances film formation and signal intensity [17] |

| Deposition Potential | -0.8 to -1.2 V | Optimizes reduction efficiency without excessive hydrogen evolution [17] |

| Deposition Time | 60-300 s | Longer times enhance sensitivity but increase analysis time [16] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | 0.1-0.5 M acetate or phosphate | Provides ionic strength without complexing target metals [12] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Bismuth Electrode Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Specific Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Standard Solutions | Source of Bi(III) for film formation | 1000 µg/mL Bi(III) in 0.1 M HNO₃ [17] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic strength and pH control | Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) [12] |

| Target Metal Standards | Analytes for method development and calibration | Cd(II), Pb(II), Zn(II) standard solutions [12] [17] |

| Complexing Agents (for AdSV) | Enable determination of non-amalgamating metals | Dimethylglyoxime for Ni and Co [16] |

| Electrode Substrates | Support for bismuth films | Glassy carbon, screen-printed carbon, carbon paste [13] |

| Surface Modifiers | Enhance selectivity and antifouling properties | g-C3N4, Bi₂WO₆, bovine serum albumin [18] |

| Polishing Materials | Electrode surface renewal | Alumina suspensions (1.0 µm, 0.3 µm) [17] |

Critical Considerations for Method Implementation

Optimization Strategies

Successful implementation of bismuth-based electrodes requires careful attention to several critical factors. The bismuth-to-metal concentration ratio (cBi/cM) profoundly impacts sensitivity and precision, with ratios of 5-40 recommended for most applications [17]. The substrate electrode material influences film adhesion and stability, with glassy carbon, carbon paste, and screen-printed electrodes demonstrating the most consistent results [13]. The deposition potential must be sufficiently negative to reduce both bismuth and target metals while avoiding excessive hydrogen evolution, particularly in less acidic media [17]. For complex matrices, incorporation of antifouling agents like cross-linked bovine serum albumin with conductive nanomaterials preserves electrode performance in biological and environmental samples [18].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

Several challenges may arise during bismuth electrode implementation. Poor film adhesion can often be addressed through substrate surface roughening via polishing or chemical pretreatment. Film inhomogeneity may result from uneven current distribution, which can be mitigated by optimizing stirring conditions during deposition. Signal degradation in complex matrices typically requires implementation of antifouling strategies or standard addition quantification rather than direct calibration. Intermetallic compound formation between certain metal pairs (e.g., copper-zinc) may cause interference, necessitating modified deposition conditions or separation protocols [13].

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting Common Bismuth Electrode Issues

Bismuth-based electrodes represent a paradigm shift in electrochemical analysis, successfully addressing the fundamental limitation of mercury toxicity while preserving and in some cases enhancing analytical performance. Their well-documented advantages including low toxicity, insensitivity to oxygen, excellent stripping characteristics, and application versatility have established bismuth as the premier alternative to mercury for trace metal analysis [13]. Ongoing research continues to expand their capabilities through novel substrate materials, advanced composites with enhanced antifouling properties, and miniaturized formats for point-of-care testing and environmental field monitoring [18]. As the scientific community increasingly prioritizes green analytical chemistry, bismuth-based electrodes stand as a testament to the possibility of developing environmentally benign alternatives without compromising analytical performance, offering a robust platform for trace metal determination across diverse application domains.

The accurate detection of trace heavy metals has emerged as a critical analytical challenge in environmental monitoring, food safety, and clinical diagnostics. Conventional analytical techniques often struggle to meet the requirements for portability, rapid analysis, and cost-effectiveness for routine monitoring. Within this context, the discovery and development of novel electrode materials has become a pivotal research focus, with nanomaterial-enhanced platforms representing the frontier of electrochemical sensor technology [4]. Carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene, and metal nanoparticles have demonstrated exceptional properties that address fundamental limitations in trace metal analysis, including enhancing sensitivity, lowering detection limits, and improving anti-fouling characteristics [20] [21] [22]. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of these advanced nanomaterial platforms, focusing on their fundamental properties, operational mechanisms, experimental implementation, and performance metrics for researchers and scientists engaged in electrode material development and sensor applications.

Fundamental Properties and Sensing Mechanisms

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

Carbon nanotubes exhibit extraordinary properties that make them ideal transducers in electrochemical sensing platforms. Their unique characteristics stem from a structure consisting of graphene sheets rolled into seamless cylindrical nanostructures, creating high aspect ratio materials with exceptional electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and chemical stability [23]. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) have proven particularly effective for electrochemical sensing applications due to their high electrical conductivity, substantial surface area, excellent electron transfer kinetics, and high transduction capacity [20]. The edge-plane-like nanotube ends are responsible for fast heterogeneous electron transfer rates for redox couples, providing enhanced electrochemical response compared to conventional carbon electrodes [23]. CNT-based sensors demonstrate capability for detecting various ionic species with high sensitivity, excellent linearity, and fast recovery and response times, making them particularly suitable for detecting metallic ions like lead, cadmium, and mercury in complex matrices [20].

Graphene and Its Derivatives

Graphene-based materials offer a distinct set of advantages for electrochemical sensing platforms. Graphene's two-dimensional honeycomb structure of sp² hybridized carbon atoms creates a network of delocalized π-electrons that yield remarkable electrical properties [24]. Derivatives including graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) have demonstrated improved electrochemical properties compared to traditional carbon materials, primarily due to their remarkably high specific surface area which increases active sites available for reactions, and an extended conjugated structure that promotes rapid electron transfer [21]. The abundant oxygen-containing functional groups in GO facilitate straightforward chemical modifications and enhance interactions with analytes [21]. These properties collectively enable higher sensitivity, lower detection thresholds, and faster response times in electrochemical sensing applications. Graphene-based nanocomposites present exceptional characteristics including great charge carrier mobility, low cost, rapid responsiveness, and high sensitivity, making them ideally suited for heavy metal sensing applications [24].

Metal Nanoparticles

Metal nanoparticles contribute unique functionalities to sensing platforms through their distinctive physical and chemical properties. Noble metal nanoparticles such as gold (Au), silver (Ag), and copper (Cu) exhibit localized surface plasmon resonance (LPSR) properties which provide outstanding contribution to colorimetric sensing fields [25]. These nanoparticles show LSPR bands at specific wavelengths (approximately 520 nm for Au, 400 nm for Ag, and 570 nm for Cu) with distinctive colloidal colors [25]. Beyond optical properties, metal nanoparticles enhance electrochemical sensors through their high catalytic activity, large surface area, and ability to facilitate electron transfer processes [22]. More recently, transition metal nanoparticles such as manganese-based nanoparticles (Mn-NPs) have emerged as cost-effective alternatives with unique advantages including multiple oxidation states, magnetic susceptibility, catalytic capabilities, and semiconductor conductivity [26]. The redox versatility of manganese nanoparticles, with oxidation states ranging from -3 to +7, enables selective interactions with various heavy metal ions and produces distinctive electrochemical signatures exploitable for selective detection [26].

Comparative Sensing Mechanisms

The sensing mechanisms employed by these nanomaterials vary significantly, offering complementary approaches for trace metal detection. Electrochemical methods, particularly anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV), leverage the exceptional electron transfer properties of CNTs and graphene for highly sensitive detection of heavy metals [23]. Voltammetric techniques offer remarkable advantages over conventional methods like HPLC and spectrophotometry, providing increased sensitivity in trace ranges (parts per billion) and enabling analysis in intricate matrices without complex pre-concentration processes [21]. Colorimetric approaches exploit the LSPR properties of metal nanoparticles, where analyte-induced aggregation or surface modification causes visible color changes detectable by naked eye or spectrophotometry [25]. Recent advances have also integrated these materials into self-healing electrode architectures that autonomously detect and repair damage, thereby extending operational lifespan and reliability under mechanical stress [27].

Diagram 1: Fundamental relationships between nanomaterial platforms, their properties, detection mechanisms, and application outcomes in trace metal analysis.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Carbon Nanotube Thread Electrode Fabrication

The development of CNT thread-based electrochemical cells represents a significant advancement in electrode miniaturization and integration. The fabrication process involves several critical stages:

Working Electrode Preparation: CNT thread is connected to a copper wire using silver conductive epoxy. The CNT thread is then completely coated with polystyrene solution (15 wt% in toluene) and air-dried at 50°C. Following this, the polystyrene-coated CNT thread is aspirated into a glass capillary, and the end of the capillary is sealed with a hot glue gun. Finally, the electrode tip is cut with a sharp blade to expose only the cross-section of the CNT thread to the solution, creating a defined microelectrode surface [23].

Reference Electrode Fabrication: A bare CNT thread electrode is electroplated with silver from a 0.3 M AgNO₃ in 1 M NH₃ solution using a standard three-electrode system. The plating process is preceded by an oxidative pretreatment at 600 mV for 30 seconds, followed by silver deposition at -100 mV for 15 minutes. The Ag-plated CNT thread is then treated with 50 mM FeCl₃ for 60 seconds to form a AgCl layer, creating a stable quasi-reference electrode comparable to conventional liquid-junction Ag/AgCl references [23].

Auxiliary Electrode Implementation: A bare CNT thread connected to a metal wire with silver conductive epoxy serves as the auxiliary electrode, completing the three-electrode cell architecture with all components based on CNT thread [23].

Graphene-Based Sensor Modification

Graphene-modified electrodes are typically prepared through various deposition techniques that optimize their electrochemical properties:

Graphene Oxide Synthesis and Reduction: Graphene oxide is commonly synthesized through modified Hummers' method or similar oxidative approaches, then reduced either chemically or electrochemically to produce rGO with restored conductivity. Laser-reduced graphene oxide (LRGO) has demonstrated enhanced electroanalytical response due to high surface conductivity [21].

Composite Formation: Graphene is often functionalized with metals, polymers, and biomaterials to increase sensing ability. Metal or metal oxide nanoparticle-modified graphene sensors leverage synergistic interactions for enhanced detection. For instance, graphene decorated with gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) has been utilized for Hg²⁺ detection with a remarkable detection limit of 6 ppt, significantly below WHO guidelines [21]. Similarly, gold nanoparticle–graphene–cysteine composites (AuNPs/GR/L-cys) with modified bismuth film electrodes have enabled simultaneous determination of Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ by square wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SWASV) [21].

Graphene Aerogel Integration: Three-dimensional graphene aerogel (GA) structures are increasingly employed for electrochemical heavy-metal sensors due to their porous network, which offers large surface area and rapid electron transport. Composites of graphene aerogel with amplified Au nanoparticles (GAs-AuNps) have been successfully implemented in aptasensors for detecting Hg²⁺ ions in complex matrices like milk [21].

Metal Nanoparticle Functionalization

The implementation of metal nanoparticles in sensing platforms requires precise synthesis and stabilization protocols:

Noble Metal Nanoparticle Synthesis: Gold, silver, and copper nanoparticles are typically synthesized through chemical reduction methods using precursors such as HAuCl₄, AgNO₃, and CuSO₄. Capping and stabilizing agents including amino acids, vitamins, and polymers are essential to prevent agglomeration and maintain long-term stability [25]. The functionalization of these nanoparticles with specific ligands enables selective interaction with target heavy metal ions.

Manganese Nanoparticle Development: Manganese-based nanoparticles are synthesized through various approaches including hydrothermal methods, chemical reduction, and sol-gel processes. To address inherent conductivity limitations, strategies such as transition metal doping (with Cu, Ni, Co, or Fe) and composite formation with conductive materials are employed [26]. These enhancements facilitate the integration of Mn-NPs into electrochemical sensing platforms while maintaining their advantageous redox properties and cost-effectiveness.

Electrode Modification Techniques: Metal nanoparticles are deposited onto electrode surfaces through methods including drop-casting, electrodeposition, chemical vapor deposition, and in-situ reduction. The modification process parameters (concentration, deposition time, potential) must be carefully optimized to control nanoparticle density, distribution, and interface properties [22].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for CNT thread electrode fabrication and subsequent analysis procedure for heavy metal detection.

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

Analytical Performance of Nanomaterial-Based Sensors

The exceptional properties of nanomaterials translate directly to enhanced analytical performance in trace metal detection. The following tables summarize key performance metrics for various nanomaterial-enhanced platforms reported in recent research.

Table 1: Performance comparison of carbon nanomaterial-based sensors for heavy metal detection

| Nanomaterial Platform | Target Analyte | Detection Technique | Linear Range | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNTs | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺ | SWASV | Not specified | Low nM range | [20] |

| CNT Thread Microelectrode | Hg²⁺ | OSWSV | Not specified | 1.05 nM | [23] |

| CNT Thread Microelectrode | Cu²⁺ | OSWSV | Not specified | 0.53 nM | [23] |

| CNT Thread Microelectrode | Pb²⁺ | OSWSV | Not specified | 0.57 nM | [23] |

| Graphene-based Sensors | Multiple HMs | Voltammetry | Varies by study | Sub-ppb range | [21] |

| AuNP-Decorated Graphene | Hg²⁺ | Electrochemical | Not specified | 6 ppt (0.03 nM) | [21] |

| Graphene Aerogel-AuNP Composite | Hg²⁺ | Aptasensing | Not specified | Low concentration | [21] |

Table 2: Performance metrics for metal nanoparticle-based sensors

| Nanomaterial Platform | Target Analyte | Detection Method | Key Advantages | Detection Limit | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Multiple HMs | Colorimetric | High extinction coefficient, tunable LSPR | Varies by functionalization | [25] |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | Multiple HMs | Colorimetric | Strong LSPR, cost-effective | Varies by functionalization | [25] |

| Copper Nanoparticles (CuNPs) | Multiple HMs | Colorimetric | Low cost, good conductivity | Varies by functionalization | [25] |

| Manganese Nanoparticles | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ | Electrochemical | Multiple oxidation states, cost-effective | Sub-ppb range | [26] |

| MnO₂@RGO Nanocomposite | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺ | Electrochemical | Enhanced sensitivity, stability | Not specified | [26] |

Critical Performance Parameters

The analytical performance of nanomaterial-enhanced platforms is evaluated through several critical parameters:

Sensitivity and Detection Limits: Nanomaterial-based sensors consistently achieve detection limits in the low nanomolar or even picomolar range for heavy metal ions, significantly surpassing conventional analytical methods for field deployment. The exceptional sensitivity stems from the combination of high surface area, efficient electron transfer, and in some cases, pre-concentration capabilities [20] [23].

Selectivity and Anti-Interference Capability: The functionalization of nanomaterials with specific ligands, polymers, or biomolecules enables remarkable selectivity in complex matrices. Molecularly imprinted polymers, biomimetic interfaces, and chelating agent modifications contribute to distinguishing target heavy metals even in the presence of competing species [22].

Stability and Reproducibility: The structural robustness of CNTs and graphene provides extended operational stability under repeated electrochemical cycling. Self-healing electrode architectures further enhance durability by autonomously repairing mechanical damage, thereby maintaining performance over extended operational periods [27].

Multiplexing Capability: The well-defined and separable electrochemical signatures enabled by nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes facilitate simultaneous detection of multiple heavy metal ions. This multiplexing capability is particularly valuable for environmental monitoring where complex contamination profiles are common [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential research reagents and materials for nanomaterial-enhanced sensor development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Examples | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Electrode modification for enhanced sensitivity and electron transfer | Pristine MWCNTs, functionalized MWCNTs | Purity, functional groups, dispersion stability |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Precursor for graphene-based composites, high surface area platform | Synthesized via Hummers' method | Degree of oxidation, exfoliation quality |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Signal amplification, catalytic activity, LSPR-based detection | Citrate-stabilized AuNPs, functionalized AuNPs | Size control, surface functionalization, stability |

| Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) | LSPR-based colorimetric sensing, electrochemical catalysis | Synthesized by chemical reduction | Oxidation prevention, aggregation control |

| Manganese Precursors | Synthesis of Mn-based nanoparticles for cost-effective sensing | MnO₂, Mn₂O₃, Mn₃O₄ nanoparticles | Oxidation state control, conductivity enhancement |

| Nafion & Conducting Polymers | Binders and conductivity enhancers for electrode modification | Nafion, polyaniline, polypyrrole | Film formation uniformity, conductivity enhancement |

| Heavy Metal Standards | Calibration and validation of sensor performance | Certified reference materials | Traceability, concentration verification |

| Buffer Systems | Electrolyte medium for electrochemical measurements | Acetate buffer (pH 4.5), phosphate buffer | pH control, ionic strength, complexation effects |

| Functionalization Ligands | Surface modification for enhanced selectivity | Cysteine, thioglycolic acid, DNA aptamers | Binding affinity, specificity, stability |

Nanomaterial-enhanced platforms comprising carbon nanotubes, graphene, and metal nanoparticles represent a transformative advancement in electrode materials for trace metal analysis. The exceptional properties of these materials—including high surface area, superior electrical conductivity, tunable surface chemistry, and unique optical characteristics—have enabled unprecedented sensitivity, selectivity, and practicality in heavy metal detection. The integration of these nanomaterials into sophisticated sensor architectures continues to push the boundaries of analytical capabilities, with detection limits routinely reaching sub-nanomolar concentrations and multiplexed analysis becoming increasingly feasible.

Future developments in this field will likely focus on several key areas: enhanced integration of multiple nanomaterials in hybrid architectures that leverage complementary advantages; improved antifouling capabilities for operation in complex real-world matrices; advanced self-healing functionalities for extended operational lifetimes; and implementation in increasingly miniaturized, portable devices for field-deployable analysis. Additionally, the exploration of emerging nanomaterials such as MXenes, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and their composites with CNTs, graphene, and metal nanoparticles presents promising avenues for further enhancing sensor performance [28]. As these technologies mature from laboratory demonstrations to commercially viable analytical tools, they hold significant potential to revolutionize environmental monitoring, food safety assurance, and clinical diagnostics through rapid, sensitive, and accessible trace metal analysis.

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Hybrid Composites for Selective Detection

Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) represent a class of crystalline porous materials constructed from metal ions or clusters coordinated with organic ligands, forming unique inorganic-organic hybrid structures with exceptional properties for sensing applications [29]. Their structural attributes, including high surface areas, tunable porosity, and abundant active sites, make MOF-based systems highly effective for detecting a wide range of analytes, from environmental pollutants to biologically significant ions [30]. The modular nature of MOFs allows for precise engineering of their chemical and electronic structures through careful selection of metal nodes and organic linkers, enabling the design of materials with specific binding affinities and enhanced electrocatalytic activity [31] [32].

In the context of trace metal analysis research, MOFs offer distinct advantages over traditional sensing materials. Their high porosity provides numerous accessible binding sites, while their tunable pore functionality enables selective recognition of target metal ions through size exclusion and chemical interactions [29]. Furthermore, the integration of MOFs with conductive substrates or their transformation into derived composites addresses inherent limitations in electrical conductivity, unlocking their potential for electrochemical sensing platforms with superior sensitivity and selectivity [31] [33]. This technical guide comprehensively explores the synthesis methodologies, detection mechanisms, and experimental protocols for leveraging MOFs and their hybrid composites in advanced sensing applications, with particular emphasis on trace metal detection.

Synthesis Strategies for MOFs and Hybrid Composites

Pristine MOF Synthesis

The solvothermal method represents a widely employed approach for synthesizing high-quality MOF crystals. For titanium-based MOFs such as MIL-125(Ti), a typical synthesis involves combining terephthalic acid (332 mg) with titanium isopropoxide (0.6 mL) in a solution of dimethylformamide (DMF) and dry methanol (1:1 v/v) [29] [34]. The mixture undergoes gentle stirring for 5 minutes at room temperature before transfer to a Teflon-lined autoclave for reaction at 150°C for 15 hours. The resulting white solid is recovered via centrifugation, washed twice with acetone, and dried sequentially in an oven at 80°C for 24 hours followed by vacuum drying at 150°C for an additional 24 hours to activate the material [34].

Alternative synthetic approaches include microwave-assisted methods that significantly reduce reaction times and enable rapid screening of synthesis conditions. The selection of metal precursors, organic linkers, solvent systems, and reaction parameters (temperature, duration, concentration) enables precise control over MOF crystallinity, morphology, and pore architecture—critical parameters governing sensing performance [31].

MOF Composite Fabrication

The integration of MOFs with functional materials enhances their electrical conductivity, stability, and functionality, creating synergistic effects that improve sensing capabilities. Primary strategies for composite formation include:

Table 1: MOF Composite Fabrication Strategies

| Strategy | Methodology | Key Advantages | Representative Composites |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical Mixing | Combining pre-synthesized MOFs and functional materials via stirring, grinding, or ultrasonic treatment | Simple operation, compositional flexibility | GDY/ZnCo-ZIF, GDY/CoMo-MOF, Fe-MOF@GDY [33] |

| In Situ MOF Growth | MOF nucleation and crystallization directly on functional substrates | Strong interfacial bonding, uniform coating | NiCo-MOF on GDY substrates [33] |

| In Situ Component Formation | Growth of functional materials on pre-formed MOF structures | Conformal coatings, controlled thickness | HsGDY wrapped on Ni-MOFs [33] |

| Carbon Composite Preparation | Grinding MOF/composite with graphite and plasticizer | Facile electrode fabrication, tunable composition | g-C3N4@Ti-MOF with graphite and o-NPOE [29] |

For graphitic carbon nitride (g-C₃N₄) composites with Ti-MOF, a straightforward approach involves grinding pre-synthesized g-C₃N₄ (10 wt% based on Ti-MOF mass) with Ti-MOF support in a mortar for 10 minutes at room temperature [29] [34]. The resulting composite is activated under vacuum at 150°C for 24 hours before use. Graphitic carbon nitride itself is synthesized through thermal treatment of urea in air at 500°C for 2 hours using a heating rate of 10°C min⁻¹ [29] [34].

Figure 1: MOF Composite Synthesis Workflow - This diagram illustrates the primary strategies for fabricating MOF-based hybrid composites, highlighting key steps in physical mixing and in situ growth approaches.

Detection Mechanisms and Electrochemical Methods

Fundamental Sensing Mechanisms

MOF-based sensing platforms operate through several interconnected mechanisms that enable selective and sensitive detection of target analytes. The molecular sieving effect allows selective access to binding sites based on analyte size and shape, while coordination interactions between metal sites in MOFs and target ions provide chemical specificity [29]. In electrochemical sensing, Faradaic processes involving electron transfer reactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface generate measurable signals proportional to analyte concentration [35]. Additionally, host-guest chemistry within MOF pores enables selective recognition through complementary functional groups and spatial confinement effects that enhance binding affinity [29].

For electrochemical detection, MOF-modified electrodes function through several mechanisms. The preconcentration effect arises from the exceptional porosity of MOFs, which can concentrate target analytes from dilute solutions onto the electrode surface, significantly enhancing detection sensitivity [35]. Electrocatalytic enhancement occurs when MOF structures facilitate charge transfer processes or lower overpotentials for redox reactions of target species [31]. Furthermore, structural transformations in stimuli-responsive MOFs can induce measurable changes in electrical or optical properties upon analyte binding, providing additional sensing modalities [36] [32].

Electrochemical Techniques for Trace Metal Detection

Various electrochemical techniques leverage these mechanisms for quantitative analysis, each offering distinct advantages for specific applications:

Table 2: Electrochemical Techniques for MOF-Based Sensing

| Technique | Principle | Key Parameters | Advantages for Metal Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Potential linear sweep between two limits with reverse scan | Peak potential (Eₚ), peak current (iₚ), scan rate (ν) | Identifies redox potentials, reveals reaction mechanisms [35] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Series of small amplitude pulses superimposed on linear baseline | Pulse amplitude, pulse duration, step potential | Enhanced sensitivity, lower detection limits, reduced background [35] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Forward and reverse pulses at each potential step | Frequency, pulse amplitude, step height | Fast scanning, excellent signal-to-noise ratio [35] |

| Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) | Single directional potential sweep | Peak current, peak potential | Simple implementation, quantitative analysis [35] |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Measurement of system response to AC potential | Charge transfer resistance (Rₜ), double-layer capacitance | Probing interfacial changes, label-free detection [37] |

For reversible processes in voltammetric techniques, the peak current follows the Randles-Sevcik equation: iₚ = (2.69×10⁸)n³/²SD¹/²ν¹/²C, where n is electron number, S is electrode surface area, D is diffusion coefficient, ν is scan rate, and C is analyte concentration [35]. This relationship forms the basis for quantitative analysis in trace metal detection.

Figure 2: MOF-Based Sensing Mechanisms - This diagram illustrates the primary mechanisms through which MOF-based sensors detect target analytes, highlighting the pathways from analyte recognition to signal generation.

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Preparation and Analysis

Carbon-Paste Electrode Fabrication

Carbon-paste electrodes (CPEs) provide a versatile platform for incorporating MOF-based sensing materials. The fabrication protocol involves the following steps:

Material Preparation: Weigh appropriate amounts of MOF or MOF composite (typically 0.20-2.0 mg), graphite powder (250 mg), and plasticizer (commonly o-nitrophenyloctyl ether/o-NPOE, 0.10 mL) [29].

Homogenization: Combine the components in an agate mortar and pestle, thoroughly grinding until achieving a homogeneous, fine paste with consistent texture and appearance.

Electrode Packing: Transfer the resulting paste into the electrode body cavity (typically a Teflon holder with 7 mm diameter, 3.5 mm depth). Apply firm pressure to ensure complete packing without air gaps.

Surface Polishing: After packing, smooth the electrode surface against wet filter paper until obtaining a shiny, uniform appearance. A stainless-steel rod inserted into the holder provides electrical contact.

Optimization of the MOF-to-graphite ratio and plasticizer selection significantly influences electrode performance. Different plasticizers including tricresyl phosphate (TCP), dibutyl phthalate (DBP), and dioctyl phthalate (DOP) can be evaluated to maximize sensor response [29].

Analytical Measurement Procedures

For calcium ion detection using g-C₃N₄@Ti-MOF modified electrodes, the following experimental procedure yields optimal results:

Electrode Conditioning: Immerse the prepared electrode in a 0.1 mM Ca²⁺ solution for 10-15 minutes before measurements to stabilize the electrochemical response.

Standard Solution Preparation: Prepare a series of Ca²⁺ standard solutions covering the concentration range from 0.1 μM to 1 mM using appropriate matrix-matching to minimize ionic strength variations.

Electrochemical Measurement: Utilize differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) with the following optimized parameters: modulation amplitude of 50 mV, modulation time of 50 ms, and step potential of 2 mV. Alternatively, open-circuit potentiometry can be employed by measuring the potential difference between the MOF-modified working electrode and a reference electrode.