Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer: Mechanisms, Applications, and Advances in Redox Chemistry

This article provides a comprehensive examination of inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms, fundamental processes in redox chemistry with critical implications across biological systems, energy storage, and synthetic methodology.

Inner-Sphere vs. Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer: Mechanisms, Applications, and Advances in Redox Chemistry

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive examination of inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms, fundamental processes in redox chemistry with critical implications across biological systems, energy storage, and synthetic methodology. We explore the foundational principles distinguishing these pathways, where outer-sphere transfers occur without shared ligands while inner-sphere mechanisms utilize bridging ligands for direct electron shuttling. The content details methodological approaches for characterizing these mechanisms and their diverse applications in electrocatalysis, photoredox chemistry, and battery technology. Practical guidance addresses common challenges in mechanism assignment and system optimization, supplemented by comparative analyses across chemical systems. By synthesizing key distinctions, emerging research trends, and their biomedical relevance, this resource equips researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to leverage these electron transfer paradigms in redox biology and therapeutic innovation.

Fundamental Principles: Distinguishing Inner-Sphere and Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Pathways

Redox reactions, the fundamental chemical processes involving electron transfer, are pivotal in fields ranging from industrial catalysis to biological energy conversion. The conceptual framework used to understand these reactions—categorizing them as inner-sphere or outer-sphere mechanisms—originated from pioneering work in the mid-20th century and continues to evolve with modern research. Henry Taube's revolutionary research in the 1950s and 1960s provided the experimental foundation for differentiating how electrons move between metal complexes, establishing that electron transfer occurs through distinct pathways with characteristic kinetics and structural requirements [1] [2]. His work demonstrated that some reactions proceed through a bridging ligand that connects two metal centers temporarily, while others occur without direct orbital interaction between reactants [3].

This classification system has proven extraordinarily durable, yet contemporary research reveals its limitations and nuances, particularly when applied to heterogeneous systems and biological catalysis. The terminology, originally developed for homogeneous transition metal complexes in solution, has since been extended to electrode surfaces, enzymatic processes, and materials science [4]. This technical guide examines the core mechanisms of electron transfer reactions from their historical origins to current applications, providing researchers with both theoretical foundations and practical methodologies for investigating these essential processes. By tracing the evolution from Taube's foundational discoveries to modern terminology and applications, this review equips scientists across disciplines with the conceptual tools to understand, design, and optimize redox-active systems for advanced technological applications.

Henry Taube's Pioneering Contributions

Historical Context and Key Discoveries

Henry Taube's groundbreaking work on electron transfer mechanisms emerged from his academic position at the University of Chicago, where he developed a graduate course on inorganic chemistry in the late 1940s. Confronted with limited textbook explanations of transition metal reactivity, Taube began a deep investigation into the reaction patterns of metal complexes [2]. During a sabbatical at Berkeley, he synthesized his findings into a seminal 1952 paper published in Chemical Reviews that would lay the foundation for modern electron transfer theory [1] [2]. This comprehensive review first established the correlation between the electronic structure of transition metal complexes and their ligand substitution rates, providing a predictive framework for understanding their redox behavior [1].

Taube's critical insight was recognizing that electron transfer between metal complexes could not be explained by a single mechanism. Through meticulous experiments using isotopically labeled compounds (particularly oxygen-18) and kinetic analysis, he demonstrated that some reactions required direct contact between metal centers via a bridging ligand, while others occurred through more distant interactions [1]. His research group specifically investigated ruthenium and osmium complexes, noting their pronounced capacity for back bonding, which proved crucial for understanding how electrons are transferred between molecules in chemical reactions [1]. This systematic work established that the geometry of coordination compounds significantly influences their reactivity in redox processes and highlighted the importance of solvent effects on electron transfer rates [3].

The Nobel Prize and Lasting Impact

The profound significance of Taube's contributions was recognized with the 1983 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, awarded specifically "for his work on the mechanisms of electron-transfer reactions, especially in metal complexes" [1]. The Nobel committee acknowledged that his correlation between electron configuration and ligand substitution, developed three decades earlier, remained the predominant theoretical framework for understanding transition metal coordination chemistry [1]. Taube's legacy extends far beyond his immediate discoveries; his conceptual framework has influenced diverse fields including photosynthesis research, solar energy conversion, and the study of electron transfer in proteins and polymers [2].

Throughout his career, Taube maintained dedication to fundamental research, driven by intellectual curiosity rather than immediate application. In his Nobel banquet speech, he reflected that "Science as an intellectual exercise enriches our culture and is in itself ennobling" [2]. This focus on foundational principles ultimately generated greater practical impact than narrowly applied research, as his mechanistic insights now underpin technologies ranging from catalysis to energy storage. Colleagues remembered Taube as "a scientist's scientist and a dominant figure in the field of inorganic chemistry" whose work "made chemistry not only challenging and stimulating, but a lot of fun as well" [1].

Core Electron Transfer Mechanisms

Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer

The inner-sphere electron transfer mechanism involves direct orbital interaction between reactant molecules through a bridging ligand that simultaneously coordinates to both metal centers [5] [4]. This mechanism dominates when at least one complex undergoes relatively rapid ligand substitution, allowing the formation of this temporary chemical bridge [5]. The bridging ligand—which may be originally bound to either the oxidant or reductant—forms a transition state complex that enables direct electron delocalization between metal centers [3]. This intimate contact typically results in significantly faster electron transfer compared to outer-sphere pathways under similar driving forces.

A classic example of inner-sphere electron transfer is the reduction of [CoCl(NH₃)₅]²⁺ by [Cr(H₂O)₆]²⁺, where chloride ion serves as the bridging ligand. In this reaction, the chloride ligand coordinated to cobalt subsequently binds to chromium, creating a bimolecular complex [(NH₃)₅Co-Cl-Cr(H₂O)₅]⁴⁺ that facilitates electron transfer from Cr(II) to Co(III) [1]. Following electron transfer, the bridged complex dissociates into [CrCl(H₂O)₅]²⁺ and [Co(H₂O)₆]²⁺ products. The hallmark of inner-sphere mechanisms is this ligand exchange accompanying electron transfer, which often leaves a "chemical signature" in the products that provides conclusive evidence for the mechanism [4].

Table 1: Characteristics of Inner-Sphere and Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Mechanisms

| Feature | Inner-Sphere Mechanism | Outer-Sphere Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Bridge Formation | Requires shared ligand between centers | No shared ligand required |

| Ligand Exchange | Involves breaking/forming chemical bonds | No chemical bonds altered |

| Rate Dependence | Sensitive to ligand identity and bridging ability | Depends on reorganization energy and driving force |

| Sensitivity | Highly sensitive to specific ligand properties | Relatively insensitive to ligand properties |

| Solvent Role | Secondary importance | Primary influence on reorganization energy |

| Example Systems | Creutz-Taube complex, chloro-bridged cobalt-chromium systems | Ruthenium hexaammine, ferrocene/ferrocenium |

Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer

In contrast to inner-sphere processes, outer-sphere electron transfer occurs without direct orbital overlap between reactants and without breaking or forming chemical bonds [5]. The reacting species retain their complete coordination spheres throughout the electron transfer event, with the electron "tunneling" through the intervening space and solvent molecules [4]. This mechanism dominates when both complexes undergo ligand substitution slowly compared to the electron transfer process itself, or when no suitable bridging ligands are available [5].

The theoretical framework for understanding outer-sphere electron transfer was largely developed by Rudolph A. Marcus, who received the 1992 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his theory relating the reaction rate to the reorganization energy and driving force [5]. Marcus theory identifies three primary contributions to the activation barrier: (1) reorganization of the solvent shell surrounding each complex, (2) changes in internal bond lengths and angles within the complexes, and (3) the electronic coupling between donor and acceptor [6]. A surprising prediction of Marcus theory, later confirmed experimentally, was the "inverted region" where electron transfer rates decrease with increasing exergonicity for very large driving forces [5].

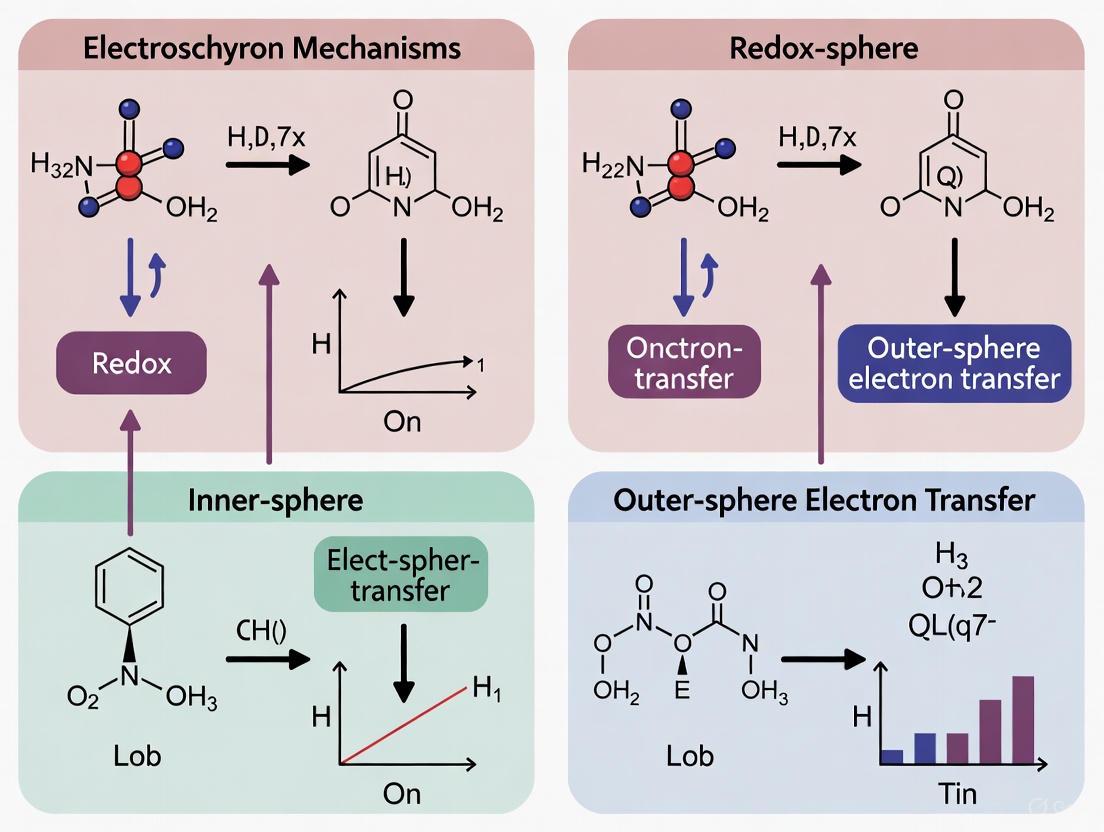

Diagram 1: Outer-sphere electron transfer process

Well-characterized examples of outer-sphere electron transfer systems include the [Ru(NH₃)₆]²⁺/³⁺ couple and the ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc+) pair [4]. These systems typically exhibit reversible electrochemistry with fast heterogeneous electron transfer rates that are relatively insensitive to electrode surface modifications, making them valuable as reference probes in electrochemical studies [4].

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization

Kinetic Analysis and Mechanism Determination

Differentiating between inner-sphere and outer-sphere mechanisms requires careful experimental design and multiple complementary approaches. Kinetic measurements provide the most direct evidence, particularly analysis of substitution rates versus electron transfer rates. For inner-sphere mechanisms, the rate of bridge formation often determines the overall reaction kinetics, while outer-sphere reactions typically correlate with parameters predicted by Marcus theory [5].

Stoichiometric analysis of products can provide definitive evidence for inner-sphere mechanisms when a ligand is quantitatively transferred from oxidant to reductant. For example, in the classic [CoCl(NH₃)₅]²⁺/[Cr(H₂O)₆]²⁺ system, the appearance of [CrCl(H₂O)₅]²⁺ as a product confirms chloride transfer accompanying electron transfer [1]. Isotopic labeling, a technique Taube employed masterfully using oxygen-18, can trace atom movement during redox processes and provide unambiguous mechanistic evidence [1].

Electrochemical methods, particularly cyclic voltammetry, enable determination of heterogeneous electron transfer rates at electrode surfaces. Small peak separations (approaching 59 mV for one-electron transfers at 25°C) indicate fast, reversible electron transfer often associated with outer-sphere characteristics, while larger separations suggest slower kinetics potentially indicating inner-sphere behavior or other complications [4]. However, researchers must exercise caution when interpreting these measurements, as many factors influence electrochemical kinetics beyond the fundamental electron transfer mechanism.

Table 2: Experimental Techniques for Mechanistic Determination

| Technique | Information Obtained | Inner-Sphere Indicators | Outer-Sphere Indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinetics | Reaction rates and activation parameters | Rate law shows ligand concentration dependence | Marcus theory correlation |

| Stoichiometry | Product distribution and ligand transfer | Bridging ligand appears in products | No ligand transfer |

| Electrochemistry | Electron transfer rates and reversibility | Sensitive to electrode surface modification | Insensitive to surface chemistry |

| Spectroscopy | Intermediate detection and structural changes | Evidence for bridged intermediates | No evidence for direct bonding |

| Isotopic Labeling | Atom movement during reaction | Label transfer between complexes | No atom transfer |

The Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Electron transfer research requires carefully selected chemical systems and characterization tools. The following research reagents represent essential materials for investigating electron transfer mechanisms:

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Electron Transfer Studies

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Outer-Sphere Mediators | [Ru(NH₃)₆]²⁺/³⁺, Ferrocene derivatives |

Reference systems for "ideal" outer-sphere behavior; potential standards |

| Inner-Sphere Systems | [CoCl(NH₃)₅]²⁺, [Cr(H₂O)₆]²⁺ |

Classic inner-sphere demonstrators; bridge-forming capabilities |

| Redox Mediators | Triarylamines, Viologens, Metallocenes | Facilitate electron transfer in electrosynthesis; shuttle electrons |

| Isotopic Tracers | ¹⁸O-labeled water, ³⁵S-labeled ligands | Mechanistic probes for atom transfer during electron exchange |

| Electrode Materials | Glassy carbon, Platinum, Gold | Working electrodes with defined surfaces for electrochemical studies |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Tetraalkylammonium salts, Alkali metal salts | Provide ionic conductivity without specific interactions |

Recent research in electrocatalysis has expanded the toolkit of redox mediators, with compounds like triarylamines (oxidation potentials 0.8-1.4 V vs. Fc/Fc+) used for oxidative transformations and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (reduction potentials -3.0 to -0.8 V) employed for reductive processes [7]. These mediators operate through outer-sphere mechanisms in electrosynthesis, enabling selective transformations of organic substrates that might otherwise require extreme potentials at bare electrodes [7].

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for mechanism determination

Modern Terminology and Current Research Frontiers

Evolving Classification in Electrochemistry

The extension of inner-sphere and outer-sphere terminology from homogeneous solution reactions to heterogeneous electron transfer at electrode surfaces has generated ongoing debate in the electrochemical community [4]. While some textbooks prominently feature this classification system, others avoid it entirely, noting that few well-characterized examples of true outer-sphere reactions exist at electrodes [4]. The [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻ (hexacyanoferrate) couple exemplifies this classification challenge, as its electron transfer characteristics range from outer-sphere to inner-sphere behavior depending on electrode surface chemistry, oxygen content, organic films, and specific adsorption [4].

This variability has led some researchers to propose that hexacyanoferrate should be considered a "multi-sphere" or "surface-sensitive" electron transfer species rather than strictly conforming to either category [4]. The traditional view that outer-sphere processes are always faster has also been questioned, as some inner-sphere systems exhibit remarkably rapid electron transfer when optimal bridging ligands and orbital alignment facilitate superexchange pathways [4]. These nuances highlight the limitations of binary classification and emphasize the need for mechanistic descriptions that acknowledge the continuum of electron transfer behavior.

Contemporary Applications and Case Studies

Current research continues to reveal new dimensions of electron transfer control, particularly in biological and biomimetic systems. A 2025 study published in Nature Communications demonstrates how outer-sphere solvent reorganization energy can be manipulated to control function in artificial copper proteins (ArCuPs) [6]. Researchers designed tetrameric assemblies featuring square pyramidal Cu(His)₄(OH₂) coordination that unexpectedly showed no catalytic activity for C-H oxidation, despite structural similarity to active trimeric Cu(His)₃ systems [6].

Through detailed analysis of electron transfer kinetics and reorganization energies, the team discovered that a specific His---Glu hydrogen bond in the tetrameric system facilitated an extended water-mediated hydrogen bonding network that significantly increased solvent reorganization energy, creating a substantial barrier to electron transfer [6]. When this hydrogen bond was disrupted through mutagenesis, the solvent reorganization energy decreased, and C-H peroxidation activity was restored [6]. This elegant study illustrates how secondary coordination sphere interactions can exert decisive control over electron transfer and catalytic function, providing insights for designing artificial enzymes with tailored redox properties.

In electrocatalysis, outer-sphere electron transfer mediators continue to enable new synthetic methodologies. Recent advances have expanded the repertoire of mediators to include carbazole-based photocatalysts (redox potentials -2.4 to -1.4 V vs. Fc/Fc+) and super electron donors (-1.8 to -0.2 V), bridging technologies between photoredox catalysis and electrosynthesis [7]. These developments highlight how fundamental electron transfer principles continue to enable innovation across chemical disciplines.

The classification of electron transfer reactions as inner-sphere or outer-sphere, established through Henry Taube's pioneering work, remains a valuable conceptual framework seven decades after its introduction. However, contemporary research reveals that these categories represent endpoints on a continuum rather than discrete boxes. The mechanistic reality often involves nuanced combinations of direct orbital interaction, solvent reorganization, and secondary coordination sphere effects that collectively determine electron transfer rates and specificity.

Future research will likely focus on quantifying and controlling these subtler aspects of electron transfer, particularly in complex environments like enzymes, interfaces, and functional materials. The integration of advanced spectroscopic techniques with computational modeling provides unprecedented ability to probe electron transfer mechanisms at atomic resolution, potentially enabling rational design of redox systems with tailored properties. As these tools reveal new details about how electrons traverse molecular landscapes, our terminology and conceptual models will continue to evolve, building upon the foundation established by Taube and his successors to create increasingly sophisticated understanding of chemical reactivity.

This technical guide examines the fundamental role of bridging ligands in inner-sphere electron transfer (ET) mechanisms. Unlike outer-sphere processes where redox centers interact without chemical bridge formation, inner-sphere ET requires a connecting ligand that enables direct orbital overlap between metal centers, dramatically influencing reaction rates, specificity, and catalytic efficiency. This whitepaper synthesizes current understanding of bridging ligand characteristics, provides experimental methodologies for their investigation, and discusses implications for drug development targeting metalloenzymes. We present quantitative data on various bridging motifs and their thermodynamic parameters, detailed protocols for mechanistic studies, and visualization of key concepts to facilitate research in redox chemistry and pharmaceutical development.

Fundamental Distinctions in Electron Transfer Pathways

Electron transfer reactions represent a cornerstone of biological energy conversion, catalytic transformations, and materials science. These processes are fundamentally categorized into two distinct mechanisms with critical implications for reaction kinetics and specificity:

Outer-sphere electron transfer: This pathway occurs without formation of a shared chemical bridge between redox centers. The reactants retain their coordination spheres intact throughout the electron transfer event, with the electron "tunneling" through space between metal centers [7]. This mechanism is characterized by relatively predictable kinetics that can be described by Marcus theory, with rates dependent on distance, reorganization energy, and thermodynamic driving force.

Inner-sphere electron transfer: This pathway proceeds through a chemical bridge that simultaneously coordinates to both metal centers during the electron transfer event [8]. The bridging ligand creates a pathway for direct orbital overlap, enabling electronic coupling that can dramatically enhance transfer rates and provide specificity through geometric constraints. The bridging ligand may be a dedicated molecular entity or a transiently shared substrate, and its chemical nature fundamentally governs the reaction thermodynamics, kinetics, and selectivity.

The distinction between these mechanisms has profound implications across chemical and biological systems. In metalloenzyme catalysis, inner-sphere mechanisms enable precise control over reactive oxygen species and substrate transformation, while in materials science, they inform the design of molecular wires and electronic devices. For pharmaceutical researchers, understanding these pathways is essential for targeting metalloenzymes in diseases ranging from cancer to neurodegenerative disorders [9] [8].

The Bridging Ligand Concept

Bridging ligands in inner-sphere ET function as molecular conduits that mediate electron flow between metal centers. Their effectiveness depends on multiple factors including orbital symmetry, energy matching, bond lengths, and coordination geometry. The bridging motif may be permanent within a molecular architecture or transiently formed during catalysis, with lifetime ranging from femtoseconds in highly exergonic processes to milliseconds in enzymatic transformations.

The critical importance of bridging ligands extends beyond simple electron shuttling—they enable reaction pathways that would be thermodynamically forbidden or kinetically inaccessible through outer-sphere mechanisms. In biological systems, nature has evolved sophisticated bridging architectures in enzymes such as cytochrome c oxidase, photosystem II, and copper amine oxidases that achieve remarkable catalytic efficiency and specificity through precisely tuned inner-sphere pathways [8].

Structural and Electronic Properties of Bridging Ligands

Key Determinants of Bridging Efficacy

The efficiency of a bridging ligand in mediating inner-sphere electron transfer depends on several interconnected structural and electronic factors:

Orbital symmetry and overlap: Effective bridging ligands possess orbitals with appropriate symmetry to interact with both metal centers simultaneously. Conjugated π-systems often excel as bridges because their delocalized orbitals provide continuous pathways for electron delocalization. The degree of orbital overlap directly correlates with electronic coupling matrix elements, which exponentially influence electron transfer rates according to Marcus theory.

Bridge length and conformational flexibility: Electron transfer rates typically decrease exponentially with increasing donor-acceptor distance, with most systems exhibiting a distance decay constant (β) of approximately 0.8-1.2 Å⁻¹ for saturated bridges and 0.2-0.6 Å⁻¹ for conjugated systems. While rigid bridges provide more predictable electronic coupling, flexible bridges may enable optimal geometry sampling that enhances average transfer rates.

Electronic energy levels: The frontier molecular orbitals of the bridge must be energetically accessible relative to the donor and acceptor states. Bridges with energetically aligned orbitals can function as true intermediaries in "hopping" mechanisms, while those with high-energy barriers act as tunneling mediators.

Coordinating atom identity and geometry: The chemical identity of atoms directly coordinated to metals (e.g., O, N, S, P) significantly influences electron density distribution at the metal centers and through the bridge. Hard-soft acid-base considerations dictate bond strengths and covalency, which directly impact electronic coupling.

Classification of Bridging Ligand Architectures

Bridging ligands can be categorized by their structural features and mediating capabilities, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Structural and Electronic Properties of Bridging Ligand Classes

| Ligand Class | Representative Motifs | Electronic Coupling Strength | Distance Decay Constant (β, Å⁻¹) | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-atom bridges | OH⁻, O²⁻, S²⁻, Cl⁻, CN⁻ | Moderate to strong | 1.8-2.5 | Binuclear metalloenzymes, molecular catalysts |

| Extended conjugated systems | Pyrazine, 4,4'-bipyridine, poly(phenylene ethynylene) | Strong | 0.2-0.4 | Molecular electronics, mixed-valence compounds |

| Biological redox mediators | Topaquinone, porphyrins, flavins | Variable | 0.4-0.8 | Enzymatic catalysis, mitochondrial respiration |

| Hybrid organic-inorganic | Cyanobenzene, ferrocenyl derivatives | Moderate | 0.5-1.0 | Molecular wires, sensing platforms |

Quantitative Thermodynamic and Kinetic Parameters

The efficacy of bridging ligands can be quantified through thermodynamic and kinetic parameters obtained from experimental and computational studies, as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Experimental Parameters for Common Bridging Ligands in Model Complexes

| Bridge Type | Metal Pair | Distance (Å) | Rate Constant (s⁻¹) | Activation Energy (kJ/mol) | Electronic Coupling (cm⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydroxo (μ-OH) | Cu(II)-Cu(II) | 3.5-4.0 | 10⁶-10⁸ | 15-35 | 120-250 |

| Oxo (μ-O) | Fe(III)-Fe(III) | 3.2-3.8 | 10⁷-10⁹ | 10-25 | 200-400 |

| Pyrazine | Ru(II)-Ru(III) | 6.8-7.2 | 10⁸-10¹⁰ | 5-15 | 400-800 |

| Cyanide | Fe(II)-Fe(III) | 7.0-7.5 | 10⁵-10⁷ | 20-40 | 80-150 |

| Chloride | Pt(II)-Pt(IV) | 4.8-5.2 | 10⁴-10⁶ | 30-50 | 50-120 |

These parameters demonstrate the dramatic variation in bridging efficacy across different chemical architectures. Conjugated organic bridges like pyrazine exhibit exceptionally strong electronic coupling and fast transfer rates, making them ideal for molecular electronic applications. In contrast, single-atom bridges, while providing weaker coupling, enable compact coordination geometries essential for many enzymatic active sites [8].

Experimental Methodologies for Investigating Bridging Ligands

Spectroscopic Techniques for Mechanism Elucidation

Determining the involvement and nature of bridging ligands in inner-sphere ET requires multidisciplinary approaches. The following protocols outline key methodologies for mechanistic investigation:

Protocol 1: Transient Absorption Spectroscopy for Bridge Identification

Objective: To detect transient bridging ligand formation and characterize its lifetime in photoinduced electron transfer reactions.

Materials:

- Purified metal complexes (donor and acceptor, ≥95% purity)

- Deoxygenated solvent appropriate to system (acetonitrile, water, or toluene)

- Femtosecond or nanosecond laser system with adequate excitation wavelength

- High-sensitivity CCD detector with time resolution matching process kinetics

- Temperature-controlled sample chamber (±0.1°C stability)

Procedure:

- Prepare donor and acceptor solutions in degassed solvent at concentrations typically between 50-500 μM, ensuring minimal oxidative degradation.

- Mix solutions in a 1:1 ratio in a sealed quartz cuvette with path length appropriate for extinction coefficients.

- Initiate electron transfer using laser pulses at wavelength optimized for selective donor excitation.

- Monitor spectral changes across UV-Vis-NIR range (250-1500 nm) with time resolution at least 10-fold faster than anticipated ET rate.

- Identify bridge-specific spectroscopic signatures through global analysis and target modeling.

- Variation of donor-acceptor distance through molecular design provides critical validation of bridging mechanism.

Data Interpretation: The appearance of intermediate spectra distinct from both donor and acceptor species indicates bridge formation. Kinetic analysis of intermediate growth and decay provides direct measurement of bridge formation rate (kformation) and electron transfer rate through the bridge (kET).

Protocol 2: Kinetic Isotope Effect Measurements for Mechanism Discrimination

Objective: To distinguish inner-sphere from outer-sphere mechanisms through analysis of substrate kinetic isotope effects.

Materials:

- Enzyme or catalyst system of interest

- Isotopically labeled substrates (e.g., deuterated, ¹⁵N, ¹⁸O)

- Anaerobic chamber for oxygen-sensitive reactions

- Stopped-flow spectrophotometer or quench-flow apparatus

- High-resolution mass spectrometer for precise isotope ratio determination

Procedure:

- Prepare multiple identical samples of catalyst system under rigorously controlled conditions.

- Initiate reaction simultaneously with natural abundance and isotopically labeled substrates.

- Quench reactions at precisely timed intervals covering the complete kinetic profile.

- Analyze product formation and remaining substrate isotope ratios using appropriate analytical methods.

- Determine kinetic parameters (kcat, KM) for each isotopic variant through Michaelis-Menten analysis.

- Calculate kinetic isotope effects as ratios of rate constants: KIE = klight/kheavy.

Data Interpretation: Significant KIEs (typically >1.5 for ²H, >1.02 for ¹⁸O) suggest inner-sphere mechanisms where bonds to the isotopic atom are broken or formed in the rate-determining step. The magnitude and temperature dependence of KIEs provide insight into the degree of nuclear reorganization involved in the ET process [8].

Computational Approaches for Bridge Characterization

Protocol 3: Density Functional Theory Calculations of Bridge Energetics

Objective: To compute electronic coupling matrix elements and reorganization energies for bridging ligand systems.

Materials:

- High-performance computing cluster with parallel processing capabilities

- Quantum chemistry software (Gaussian, ORCA, or CP2K)

- Crystal structures or optimized geometries of donor-bridge-acceptor systems

Procedure:

- Obtain initial geometries from crystallographic data or through ab initio optimization.

- Select appropriate density functional (e.g., B3LYP, M06, ωB97X-D) and basis sets for metal and ligand atoms.

- Calculate electronic coupling using fragment orbital approach or energy splitting in symmetric systems.

- Determine inner-sphere reorganization energy through potential energy surface scans along relevant normal modes.

- Validate computational methodology through comparison with experimental data for model systems.

- Perform analysis of molecular orbitals and electron density differences to visualize electron transfer pathways.

Data Interpretation: Electronic coupling values (H_AB) > 80 cm⁻¹ typically indicate strong coupling consistent with inner-sphere mechanisms. Reorganization energies (λ) for inner-sphere processes typically range 0.8-2.0 eV, with higher values indicating greater structural rearrangement during ET [10].

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer Research

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Supplier Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classical bridging ligands | Pyrazine, 4,4'-bipyridine, cyanide, azide, hydroxo bridges | Fundamental ET rate studies, structure-function relationships | Sigma-Aldrich, TCI America (>99% purity, verify by elemental analysis) |

| Redox-active metal precursors | [Ru(NH₃)₆]Cl₂, Fe(bpy)₃₂, [Co(C₂O₄)₃]³⁻ | Synthesis of donor-acceptor complexes with controlled reduction potentials | Strem Chemicals, Alfa Aesar (analyze for trace metals that may interfere) |

| Isotopically labeled compounds | H₂¹⁸O, ¹⁵NH₄Cl, D₂O, ¹³C-labeled bridging ligands | Kinetic isotope effect studies, mechanistic tracing | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Sigma-Aldrich Isotopes (verify isotopic enrichment by NMR/MS) |

| Spectroscopic probes | Nitroxide spin labels, luminescent lanthanide complexes, resonance Raman reporters | Distance measurements, structural mapping during ET | Toronto Research Chemicals, Luminescence Technology Corp. (check quantum yield/extinction coefficient) |

| Computational chemistry resources | Effective core potentials, basis set libraries, solvation models | Theoretical modeling of electronic coupling and reaction pathways | EMSL Basis Set Exchange, commercial software vendors (validate against benchmark systems) |

Biological and Pharmaceutical Implications

Bridging Ligands in Metalloenzyme Catalysis

The principles of bridging ligand-mediated electron transfer find critical application in biological systems, where metalloenzymes employ sophisticated inner-sphere mechanisms to achieve challenging biochemical transformations. Copper amine oxidases represent a particularly illuminating example, as they utilize a protein-derived topaquinone (TPQ) cofactor that mediates electron transfer between substrate and molecular oxygen via a copper center [8].

In these systems, the internal equilibrium between Cu(II)-TPQred and Cu(I)-TPQsq states creates a kinetically competent species for O₂ reduction. The mechanism proceeds through inner-sphere electron transfer where O₂ binds directly to Cu(I) to form a superoxide intermediate, followed by electron transfer from the TPQ semiquinone to yield a peroxide intermediate [8]. This precise orchestration of electron and proton transfer, mediated through carefully positioned bridging ligands and hydrogen-bonding networks, enables the enzyme to achieve rate enhancements exceeding 10⁵ compared to analogous small-molecule reactions.

The design principles observed in natural systems—including optimal bridge length, orbital alignment, and proton-coupled electron transfer—provide powerful inspiration for biomimetic catalyst development. Synthetic systems that implement these features show remarkable promise for applications ranging from renewable energy conversion to green chemical synthesis [9].

Pharmaceutical Targeting of Inner-Sphere Processes

The critical role of inner-sphere electron transfer in pathogenic microorganisms and disease-relevant human enzymes presents attractive opportunities for therapeutic intervention. Several successful pharmaceutical approaches have exploited this strategy:

Metalloenzyme inhibitors: Drugs such as neocuproine (copper chelator) and disulfiram (aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibitor) function by coordinating to catalytic metal centers through bridging ligands, disrupting native inner-sphere electron transfer processes essential for enzyme activity.

Reactive oxygen species modulation: Compounds that intercept inner-sphere electron transfer in oxidative stress pathways can mitigate tissue damage in inflammatory conditions. Superoxide dismutase mimetics often employ bridging ligands that facilitate inner-sphere dismutation of superoxide.

Anticancer agents: Rhenium and other metal-based therapeutic agents exhibit cytotoxicity through inner-sphere electron transfer processes that disrupt cellular redox homeostasis [9]. Their design incorporates ligands that bridge between the metal center and biological targets, enabling redox activation under specific physiological conditions such as hypoxia.

The development of these therapeutic approaches benefits profoundly from detailed understanding of inner-sphere mechanisms, as rational modification of bridging ligand properties enables fine-tuning of drug specificity, activation profiles, and pharmacokinetic properties.

Visualizations of Core Concepts

Diagram 1: Inner vs Outer Sphere ET Mechanisms

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Mechanism Elucidation

The critical role of bridging ligands in inner-sphere electron transfer represents a fundamental principle with far-reaching implications across chemical, biological, and pharmaceutical sciences. Through their ability to mediate direct electronic communication between metal centers, bridging ligands enable reaction pathways with enhanced rates, specificities, and catalytic efficiencies unattainable through outer-sphere mechanisms. The structural and electronic determinants of bridging efficacy—including orbital symmetry, bridge length, coordinating atom identity, and energetic alignment—provide a robust framework for designing novel electron transfer systems.

Future advancements in this field will likely emerge from several promising directions. The integration of machine learning approaches with high-throughput computational screening may enable rapid identification of optimal bridging motifs for specific applications. In synthetic biology, redesign of native electron transfer pathways through bridge engineering offers potential for creating artificial photosynthesis and bioenergy systems. For pharmaceutical development, increasingly sophisticated targeting of disease-relevant inner-sphere processes may yield therapeutics with enhanced specificity and reduced off-target effects.

As characterization techniques continue to advance, particularly in time-resolved spectroscopy and single-molecule approaches, our understanding of bridging ligand dynamics and their role in directing electron flow will undoubtedly deepen. This progress will further establish inner-sphere electron transfer as a cornerstone principle for addressing global challenges in energy, health, and sustainable technology development.

Outer-sphere electron transfer (OSET) represents a fundamental process in electrochemical systems where electrons transfer between an electrode and a reactant species without direct chemical bonding or intimate contact. In this mechanism, electron transfer occurs through an intervening layer of solvent molecules, with the reactant or product species typically located outside the inner solvent layer adjacent to an electrode surface [4]. This stands in contrast to inner-sphere electron transfer (ISET), where a central metal atom, bridging molecule, or ion is in direct contact with the electrode surface, often involving ligand exchange alongside electron transfer [4]. The conceptual foundation for understanding these processes originated in homogeneous electron transfer reactions of transition metal complexes, with seminal contributions from Nobel laureates R.A. Marcus and H. Taube providing the theoretical framework that was later extended to heterogeneous electrochemical systems [4].

The critical distinction between these mechanisms lies in their interaction with the electrode surface. OSET systems generally exhibit fast electron transfer rates that are largely unaffected by surface modifications, while ISET processes are highly sensitive to surface chemistry, oxygen functional groups, and adsorption phenomena [4]. This review comprehensively examines the molecular-level mechanisms, quantitative parameters, experimental methodologies, and practical applications of solvent-mediated outer-sphere electron transfer processes, with particular emphasis on their significance in electrochemical energy conversion and synthetic chemistry.

Fundamental Principles and Terminology

Conceptual Framework and Historical Development

The terminology of inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms was originally developed for the mechanistic interpretation of inorganic transition metal compounds in solution [4]. OSET occurs when participating species undergo ligand exchange reactions much more slowly than they participate in electron transfer processes, maintaining their solvent coordination spheres throughout the electron donor/acceptor process [4]. This OSET mechanism became the initial focus of early Marcus electron transfer theory [4].

In electrochemical systems, OSET occurs when electron transfer takes place between a reactant molecule and an electrode surface through an intervening solvent layer (the Inner Helmholtz Plane, IHP) [4]. The reactant species resides outside this immediate solvent layer, typically in the Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP) of the Electrical Double Layer (EDL), with electron transfer occurring via tunneling or electron hopping processes [4]. This mechanism is exemplified by well-characterized OSET redox systems such as ruthenium II/III hexaammine cations ([Ru(NH₃)₆]²⁺/³⁺) in aqueous solutions and ferrocene (Fc⁰/⁺) in non-aqueous solvents [4].

The Electrical Double Layer and Solvent Mediation

Under applied electrochemical potentials, the structure of the electrical double layer becomes crucial in facilitating OSET processes. At potentials below the potential of zero charge, negative charge density on the cathode surface increases, attracting more cations and forming a dense EDL [11] [12]. This EDL influences the local electrochemical environment, including interfacial pH and water structure at the interface [12]. Under high cathodic bias, the EDL can become so compact that it strongly hampers mass transport of substrates toward the electrocatalyst surface [11] [12]. Under these conditions, OSET becomes a favorable mechanism, enabling electron transfer directly over the EDL without requiring substrate adsorption to the catalyst surface [11] [12].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Outer-Sphere vs. Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer

| Parameter | Outer-Sphere ET | Inner-Sphere ET |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Contact | No direct contact | Intimate contact with electrode |

| Ligand Exchange | Not required | Often involved |

| Solvent Role | Electron transfer medium | Can be displaced |

| Surface Sensitivity | Low | High |

| Adsorption | Generally not required | Often involved |

| Rate Determination | Electron tunneling | Mixed steps possible |

| Probe Examples | [Ru(NH₃)₆]²⁺/³⁺, Fc⁰/⁺ | Hexacyanoferrate (under certain conditions) |

Quantitative Parameters and Energetics

Reorganization Energy and Marcus Theory

The solvent reorganization energy (λ) represents a critical parameter in OSET processes, quantifying the energy required to rearrange the solvent structure during electron transfer events. Recent studies with artificial copper proteins have demonstrated how variations in primary, secondary, and outer coordination-sphere interactions influence electron transfer properties and catalytic function [6]. For instance, in de novo designed tetrameric artificial copper proteins (4SCC), a significant solvent reorganization energy barrier mediated by a specific His---Glu hydrogen bond was found to render the catalyst inactive for C-H oxidation [6]. When this hydrogen bond was disrupted, the solvent reorganization energy reduced, and catalytic activity was restored, highlighting the critical role of solvent reorganization in controlling redox function [6].

Marcus-Hush-Chidsey theory provides the fundamental framework for computing OSET rates in condensed-phase systems, with thermodynamic parameters including solvent reorganization energy, reaction free energy, and activation energy calculable from equilibrium molecular dynamics simulations of reactant and product states [13]. The statistics of the vertical energy gap (ΔE), representing the difference in potential energy between reactant and product states at fixed nuclear positions, are used to construct the characteristic Marcus parabolas describing the free energy surfaces of electron transfer processes [13].

Electrochemical Parameters of Common Redox Mediators

The effectiveness of OSET processes can be enhanced through redox mediators that facilitate electron transfer between electrodes and substrates. These mediators operate exclusively via outer-sphere mechanisms without participating in inner-sphere processes such as hydrogen-atom transfer, hydride transfer, or organometallic pathways [7].

Table 2: Redox Potentials of Common Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Mediators

| Mediator Class | Representative Examples | Redox Potential Range (V vs Fc/Fc⁺) | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aromatic Hydrocarbons | Naphthalene, Pyrene | –3.0 to −0.8 V | Reductive epoxide opening |

| Triarylamines | TA-1 to TA-35 | 0.8 to 1.4 V | Oxidative transformations |

| Ferrocenes | Fc-1 to Fc-46 | –1.2 to 1.3 V | Reference standard, oxidation catalysis |

| Viologens | V-1 to V-15 | –1.1 to −0.8 V | Reduction catalysis |

| Cobaltocenes | Cc-1 to Cc-6 | –1.9 to −1.4 V | Strong reduction |

| Cerium Salts | Ce-1 | ~1.0 V | Oxidation catalysis |

These redox mediators play valuable roles in organic redox reactions by increasing selectivity through operation at lower overpotentials, enabling reactions that might be impeded by slow electron transfer kinetics, and preventing electrode fouling by preventing substrate adsorption [7]. The comprehensive tabulation of redox potentials provides researchers with accessible guidance for selecting appropriate mediators for specific electrochemical applications.

Computational and Experimental Methodologies

Path Integral Molecular Dynamics for Electron Transfer

Advanced computational methods have provided unprecedented insights into OSET mechanisms. Path integral molecular dynamics (PIMD) represents a cutting-edge approach that explicitly models the transferring electron as a classical ring-polymer, co-evolved with the molecular system using standard PIMD techniques [13]. This methodology accounts for the effects of electronic fluctuations in the reorganization energy, reaction free energy, and electron transfer activation energy—aspects neglected in the standard identity exchange scheme where the transferring electron is described implicitly via atomic partial charges [13].

Applications of this PIMD approach to study electron transfer from a ferrocyanide complex to a gold electrode have demonstrated that when the electron is represented explicitly, the calculated rates and thermodynamics show improved consistency with experimental findings compared to implicit representations [13]. Furthermore, investigations into spectator cation effects revealed that observed rate enhancements with increasing cation size originate from the ion's effect on the relative stability of reduced and oxidized states, rather than from influence on solvent reorganization energy as often speculated [13].

Experimental Characterization Techniques

Cyclic voltammetry serves as the primary experimental technique for characterizing OSET processes, with peak-to-peak separation in voltammograms used to ascertain heterogeneous electron transfer rate constants [4]. However, this approach has inherent limitations, as demonstrated by the hexacyanoferrate II/III system which can exhibit either inner-sphere or outer-sphere characteristics depending on experimental conditions [4]. Factors influencing this classification include surface oxygen species, organic surface films, cation counter-ions, adsorption phenomena, and surface hydrophilicity/hydrophobicity [4].

For well-characterized OSET systems like ruthenium II/III hexaammine cations, the lack of surface influence on electron transfer rate serves as a criterion for OSET assignment [4]. These systems maintain consistent electrochemical behavior regardless of electrode surface modification, enabling their use as reliable redox probes for determining electrochemically active surface areas—a critical parameter in electrocatalyst assessment [4].

Case Studies in CO₂ Electroreduction

Solvent-Mediated CO₂ Reduction on Silver Surfaces

Multiscale modeling approaches combining density functional theory calculations and ab initio molecular dynamics simulations have revealed fascinating OSET pathways in electrocatalytic CO₂ reduction reactions (CO₂RR) over Ag111 surfaces [11] [12]. Under high cathodic bias, a dense electrical double layer forms that hinders CO₂ diffusion toward the catalyst surface, promoting homogeneous phase reduction of CO₂ via electron transfer from the surface to the electrolyte [11] [12].

This outer-sphere mechanism favors formate formation as the CO₂RR product, with subsequent dehydration to CO via a transition state stabilized by solvated alkali cations within the EDL [11] [12]. The critical finding is that CO₂ reduction can occur directly over the EDL without requiring adsorption to the catalyst surface, representing a paradigm shift from conventional inner-sphere mechanisms that dominate the electrocatalysis literature [12].

Experimental Protocol: Investigating OSET in CO₂RR

System Setup:

- Electrode: Ag(111) single crystal surface

- Electrolyte: 0.86 M KCl with 0.06 M CO₂ saturated aqueous solution

- Cell Configuration: Two-electrode system with Ag111 slabs in super cell (33.1 × 37.2 × 265.5 ų) periodic in x and y directions [12]

Methodology:

- Classical Molecular Dynamics (CMD): Probe EDL formation at electrodes under different polarization conditions mimicked by uniform distributions of point charges behind Ag111 slabs [12]

- Density Functional Theory (DFT): Investigate outer-sphere reduction using periodic DFT with simplified models (4 × 4 × 5 slab model) [12]

- Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD): Conduct constrained simulations on 11 intermediate states using O-C-O angle as reaction coordinate (varied from 172° to 125°) for 19 ps duration [12]

Key Measurements:

- Water density oscillations within 1 nm of cathode surface

- Cation/anion accumulation in EDL region

- CO₂ configuration changes (bent anionic formation with ~172° O-C-O angle)

- Free energy profiles along reaction coordinate [12]

Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| OSET Redox Probes | [Ru(NH₃)₆]Cl₂/Cl₃, Ferrocene | Reference outer-sphere systems |

| ISET Redox Probes | K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] | Surface-sensitive comparison |

| Electrode Materials | Au, Ag(111), Glassy Carbon | Well-defined surface studies |

| Supporting Electrolytes | KCl, NaClO₄, [BMIM][NTf₂] | Electrical double layer control |

| Solvents | Acetonitrile, Water, THF | Solvation environment tuning |

| Redox Mediators | Aromatic hydrocarbons, Triarylamines, Viologens | Facilitating electron transfer |

Solvent-mediated outer-sphere electron transfer represents a fundamental process with broad implications across electrocatalysis, synthetic chemistry, and energy conversion technologies. The recognition that dense electrical double layers under high cathodic bias can promote homogeneous phase reduction via OSET mechanisms provides new design principles for electrocatalysts operable at low overpotentials with high current densities [11] [12]. Future research directions will likely focus on precisely controlling solvent reorganization energies to modulate electron transfer rates, designing tailored redox mediators for specific synthetic applications, and developing advanced computational methods that explicitly account for electronic fluctuations in electron transfer thermodynamics [7] [13] [6].

The continued refinement of our understanding of OSET processes will enable more efficient electrochemical technologies for chemical synthesis, energy conversion, and environmental remediation, highlighting the critical role of solvent mediation in controlling electron transfer phenomena at electrochemical interfaces.

Within electrochemical and catalytic research, electron transfer (ET) reactions are fundamentally categorized by their mechanism: inner-sphere (ISET) or outer-sphere (OSET). This distinction is critical for researchers designing synthetic routes, developing sensors, or creating new catalytic systems, as it dictates reaction kinetics, selectivity, and sensitivity to the environment. An ISET mechanism involves direct chemical contact between the reactant and the electrode surface, often through a bridging ligand, leading to strong surface sensitivity and frequently slower, more complex kinetics [4]. In contrast, an OSET mechanism occurs with the reactant remaining separated from the electrode by at least a solvent layer, resulting in fast, reversible electron transfer that is largely insensitive to the surface state of the electrode [4]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to the key characteristics of these two pathways—reversibility, surface sensitivity, and kinetic profiles—equipping scientists with the knowledge to characterize and leverage these mechanisms in their work.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

The terms "inner-sphere" and "outer-sphere" originated in molecular chemistry to describe electron transfer between two metal complexes in solution [4]. In an inner-sphere reaction, the two metal centers share a common ligand in a bridged intermediate, facilitating electron transfer alongside atom transfer. An outer-sphere reaction occurs without such a bridge and without breaking any chemical bonds, with the electron tunneling through the solvent shell [4].

This terminology was later extended to heterogeneous electron transfer at electrode surfaces. In this context:

- An Inner-Sphere Electron Transfer (ISET) requires specific, direct chemical interaction between an electroactive species and the electrode surface. The reactant or a bridging ligand is in intimate contact with the electrode, and the electron transfer is often coupled with chemical steps like adsorption, desorption, or bond breaking/formation [4].

- An Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer (OSET) proceeds without direct chemical interaction. The electroactive species remains in the outer Helmholtz plane (OHP) of the electrical double layer, separated from the electrode by a solvent layer. Electron transfer occurs via tunneling, and the process is not sensitive to the chemical composition of the electrode surface [4].

The primary distinction lies in the necessity of a chemical bond or specific adsorption for the reaction to proceed, which fundamentally alters the characteristics of the electron transfer process.

Key Characteristics: A Comparative Analysis

The mechanistic pathway imparts distinct and measurable properties to an electron transfer reaction. The table below summarizes the core differentiating characteristics.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Inner-Sphere and Outer-Sphere Electron Transfer Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Inner-Sphere (ISET) | Outer-Sphere (OSET) |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Sensitivity | High sensitivity to electrode material, surface oxides, and functional groups [4]. | Low sensitivity; behavior is consistent across different electrode materials [4]. |

| Reversibility | Often quasi-reversible or irreversible due to coupled chemical steps [4]. | Typically highly reversible with fast electron transfer kinetics [4]. |

| Kinetic Profile | Complex kinetics; rate constant (k⁰) is highly variable and depends on surface interactions [4]. | Simple, fast kinetics; high heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant (k⁰) [4]. |

| Adsorption | Frequently involves adsorption of the reactant, product, or an intermediate species [4]. | No specific adsorption required; species remains in solution [4]. |

| Dependence on Electrode Pretreatment | Strongly influenced by surface pre-treatment (e.g., polishing, laser scribing) [4]. | Largely unaffected by surface pre-treatment [4]. |

| Interaction with Oxygen Species | Strongly affected by the presence of surface oxygen species (e.g., oxides, carbonyls) [4]. | Unaffected by the presence of surface oxygen species [4]. |

| Example Redox Couples | Hexacyanoferrate II/III (under many conditions), Hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [4]. | Ru(NH₃)₆²⁺/³⁺, Ferrocene/Ferrocenium (Fc/Fc⁺) [4]. |

Reversibility

The reversibility of a redox couple is a key indicator of its mechanism. OSET reactions, such as those involving the Ru(NH₃)₆²⁺/³⁺ couple or ferrocene (Fc/Fc⁺), typically exhibit highly reversible electrochemistry. This is observed in cyclic voltammetry as a small peak-to-peak separation (ΔEp ≈ 59/n mV for a reversible system at 25°C), indicating fast, diffusion-controlled electron transfer that is not hampered by a slow chemical step [4].

In contrast, ISET reactions often display quasi-reversible or irreversible behavior. The electron transfer is slower because it is gated by the kinetics of the associated chemical step, such as adsorption or ligand exchange. This results in a larger ΔEp in cyclic voltammetry. A classic example is the hexacyanoferrate II/III couple, which can show a wide range of peak separations and apparent rate constants depending on the electrode surface and environment, reflecting its ISET nature under those conditions [4].

Surface Sensitivity

Surface sensitivity is perhaps the most defining characteristic. OSET reactions are notable for their lack of surface sensitivity. The rate of electron transfer is impervious to the chemical state of the electrode surface, be it the presence of oxides, specific functional groups, or the crystallographic orientation of the material. This is why OSET probes like ferrocene are ideal for referencing potentials and determining electroactive surface area [4].

Conversely, ISET reactions are highly sensitive to the electrode surface. The electron transfer rate is directly influenced by surface chemistry, including:

- Surface Oxides and Oxygen Species: The presence of carbonyl, carboxyl, or other oxide groups can significantly enhance or retard ISET [4].

- Hydrophilicity/Hydrophobicity: The affinity of the reactant for the electrode-solution interface can affect adsorption and thus the ET rate [4].

- Surface Pretreatment: Procedures like laser scribing or exposure to solvents can dramatically alter the observed kinetics for an ISET probe like hexacyanoferrate [4].

Kinetic Profiles

The kinetic profiles of the two mechanisms are fundamentally different. OSET kinetics are typically fast and can be described by standard Butler-Volmer or Marcus-Hush formalisms, where the rate is a function of the applied overpotential [14].

ISET kinetics are more complex and often involve multiple rate-determining steps. The overall rate may be governed by the electron transfer step itself, the preceding adsorption step, or a chemical step like ligand exchange. This leads to a kinetic profile that cannot be described by simple ET theory alone and results in a heterogeneous rate constant (k⁰) that is highly variable and dependent on the exact surface condition [4].

Experimental Protocols for Mechanism Identification

Cyclic Voltammetry with Surface Modification

Objective: To determine the sensitivity of a redox probe to the chemical state of the electrode surface. Methodology:

- Record a cyclic voltammogram (CV) of the redox couple of interest (e.g., 1 mM Hexacyanoferrate III in 1 M KCl) using a standard glassy carbon electrode at a set scan rate (e.g., 100 mV/s).

- Modify the electrode surface. This can be achieved through:

- Oxidative Pretreatment: Apply a strong anodic potential (+1.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 60 s) to generate surface oxides [4].

- Polishing: Gently polish the electrode with an alumina slurry to create a fresh, less-oxidized surface [4].

- Laser Treatment: Use laser scribing to create defined surface structures and edges [4].

- Record a new CV of the same redox couple under identical conditions with the modified electrode. Interpretation: A significant change (e.g., >30 mV) in the peak separation (ΔEp) or peak current after surface modification is a strong indicator of an ISET mechanism. An OSET probe will show minimal to no change in its voltammetric response [4].

Electrolyte and Counter-Ion Variation

Objective: To probe the influence of the electrical double layer and specific ion interactions on electron transfer. Methodology:

- Prepare multiple solutions of the redox species (e.g., 1 mM) with different supporting electrolytes (e.g., KCl, NaCl, LiCl, tetraalkylammonium salts) at the same concentration (e.g., 0.1 M).

- Record CVs for each electrolyte solution using the same electrode and scan rate. Interpretation: For an OSET mechanism, the ET rate should be largely unaffected by the nature of the cation. For an ISET mechanism like hexacyanoferrate, the size and charge of the cation can significantly influence the ET kinetics by affecting adsorption and the structure of the double layer [4].

Adsorption Studies via Chronoamperometry

Objective: To detect the adsorption of redox-active species onto the electrode surface. Methodology:

- Immerse a clean electrode in a solution of the redox species for a set duration (e.g., 5-30 minutes).

- Transfer the electrode to a clean cell containing only the supporting electrolyte.

- Perform a linear sweep voltammetry or cyclic voltammetry experiment. Interpretation: The observation of a redox wave in the blank electrolyte solution indicates that the species has adsorbed onto the electrode surface, which is a hallmark of an ISET process. OSET species do not typically adsorb [4].

Case Studies and Research Applications

The Ambiguous Nature of Hexacyanoferrate II/III

The hexacyanoferrate II/III couple is a quintessential case study in the complexity of mechanism assignment. While historically taught as an OSET probe, extensive research shows it frequently behaves as an ISET system [4]. Its electron transfer rate is highly sensitive to surface oxides on carbon electrodes, adsorbes on surfaces like Pt and Au, and is influenced by the cation in the electrolyte (e.g., Li⁺ vs. K⁺). This surface-sensitive behavior has led to its recommendation as a "multi-sphere" or "surface-sensitive" electron transfer species, rather than a pure OSET or ISET probe [4].

Mediated Electrosynthesis with OSET Mediators

In organic electrosynthesis, OSET mediators are valuable tools for selective redox transformations. These molecules, such as triarylamines (for oxidation) and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (for reduction), shuttle electrons between the electrode and the substrate via a fast, reversible OSET process [7]. This allows the reaction to occur at a controlled potential in the solution phase, preventing substrate decomposition on the electrode surface and improving selectivity and yield [7]. The table below lists common classes of such mediators.

Table 2: Selected Redox Mediators for Organic Electrosynthesis [7]

| Mediator Class | Redox Potential Range (V vs. Fc/Fc⁺) | Primary Application | Key Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) | -3.0 to -0.8 V | Highly reductive transformations | Naphthalene, Pyrene |

| Triarylamines | 0.8 to 1.4 V | Oxidative transformations | N,N-Dimethylaniline derivatives |

| N-Alkyl Triarylimidazoles | 0.5 to 1.0 V | Oxidative transformations | - |

| Phthalimides | -1.9 to -0.9 V | Reductive transformations | N-Hydroxyphthalimide |

| Ferrocenes | -1.2 to 1.3 V | Oxidative transformations | Ferrocene, Decamethylferrocene |

Hot-Carrier Injection in Plasmonic Photocatalysis

Recent studies on plasmonic photocathodes for reducing ferricyanide (Fe(CN)₆³⁻) have revealed coexisting ISET and OSET pathways for hot electrons. The research demonstrated an efficient inner-sphere transfer of low-energy electrons where the molecule likely adsorbs on the Au surface, allowing direct injection into its LUMO. This was accompanied by a concurrent outer-sphere transfer of high-energy electrons that tunneled through a solvent layer [15]. This duality significantly enhanced device performance and underscores the complex interplay of mechanisms in advanced catalytic systems [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Investigating Electron Transfer Mechanisms

| Item | Function/Application | Relevance to ISET/OSET |

|---|---|---|

| Ferrocene (Fc/Fc⁺) | Redox standard and OSET probe [4]. | The quintessential OSET reference; used to calibrate potentials and confirm surface inertness. |

| Ruthenium Hexaammine (Ru(NH₃)₆²⁺/³⁺) | OSET probe in aqueous solutions [4]. | A common OSET probe for aqueous systems, insensitive to surface state. |

| Potassium Hexacyanoferrate (III) | ISET/Multi-sphere redox probe [4]. | Used to characterize surface activity and interactions. Its behavior indicates surface cleanliness and functionality. |

| Various Supporting Electrolytes (KCl, NaCl, LiCl, Tetraalkylammonium Salts) | Control ionic strength and double-layer structure. | Varying the cation size/type helps probe adsorption and double-layer effects, key for identifying ISET behavior. |

| Alumina Polishing Slurries (e.g., 0.05 µm) | For reproducible electrode surface preparation. | Essential for creating a consistent starting surface before intentional modification for ISET tests. |

| Glassy Carbon Working Electrode | Standard working electrode material. | Its surface is easily modified with oxides, making it ideal for testing surface sensitivity. |

The distinction between inner-sphere and outer-sphere electron transfer mechanisms is more than a theoretical classification; it is a practical framework that governs the kinetic profile, reversibility, and surface sensitivity of redox processes. ISET mechanisms, with their complex, adsorption-dependent kinetics, are paramount in catalysis and sensor development, where surface interactions are key. OSET mechanisms, characterized by their fast, reversible, and robust nature, are indispensable as potential standards and mediators in electrosynthesis. As research advances, particularly in areas like plasmonic catalysis and materials science, the lines between these categories may blur, revealing "multi-sphere" behaviors. However, the fundamental principles of reversibility, surface sensitivity, and kinetics outlined in this guide will continue to provide researchers with the diagnostic tools needed to decode and design sophisticated electrochemical systems.

Diagrams and Workflows

ISET vs OSET Reaction Pathways

Experimental Workflow for Mechanism Identification

Kinetic Profiles Comparison

The classification of electron transfer (ET) reactions as either inner-sphere (ISET) or outer-sphere (OSET) has provided a fundamental framework for understanding redox mechanisms in electrochemistry since its development for homogeneous solution reactions. Originally applied to transition metal complexes in solution, this terminology was subsequently extended to heterogeneous electron transfer (HET) processes at electrode surfaces [4]. In classical definitions, outer sphere electron transfer occurs when reactant molecules participate in ET without exchanging ligands and without direct contact with the electrode surface, instead tunneling electrons through an intervening solvent layer, often depicted as occurring at the Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP) [4]. Conversely, inner sphere electron transfer involves an ion or molecule in a bridged ligand donor/acceptor intermediate state, with the central metal atom, bridging molecule, or ligand in intimate contact with the electrode surface [4].

However, this binary classification system proves inadequate for describing the behavior of many important redox systems, particularly the widely used hexacyanoferrate II/III (Fe(CN)₆³⁻/⁴⁻) couple. This review examines how hexacyanoferrate demonstrates characteristics of both mechanisms under different conditions, arguing for its reclassification as a multi-sphere or surface-sensitive electron transfer species that exists on a spectrum of behavior rather than fitting neatly into either traditional category [4]. This conceptual shift has significant implications for researchers and drug development professionals who utilize electrochemical probes to characterize biological and synthetic systems.

Historical Context and Theoretical Framework

The inner/outer sphere terminology originated from seminal work on homogeneous electron transfer reactions of octahedral transition metal complexes, with foundational contributions from Nobel laureates R. A. Marcus and H. Taube, among others [4]. The OSET mechanism was initially applied to systems where participating complexes undergo ligand exchange much more slowly than electron transfer, maintaining their solvent coordination spheres throughout the redox process. This OSET framework became the initial focus of early Marcus ET theory [4].

The extension of this terminology to heterogeneous electrochemical systems created operational definitions where OSET probes like ruthenium II/III hexaammine cations (Ru(NH₃)₆²⁺/³⁺) in aqueous solutions or ferrocene (Fc⁰/⁺) in non-aqueous solvents exhibit fast electron transfer largely unaffected by electrode surface composition or modification [4]. In contrast, ISET processes typically involve additional rate-determining steps beyond electron transfer itself, such as ligand exchange kinetics or surface adsorption phenomena [4].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Traditional Electron Transfer Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Inner Sphere (ISET) | Outer Sphere (OSET) |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Interaction | Intimate contact with electrode surface | Electron transfer through solvent layer |

| Rate Determination | Often limited by ligand exchange or adsorption | Primarily determined by electron transfer rate |

| Surface Sensitivity | Highly sensitive to surface composition | Largely insensitive to surface modifications |

| Typical Probes | Many technologically important reactions (H⁺ reduction, O₂ reduction) | Ru(NH₃)₆²⁺/³⁺, Ferrocene in non-aqueous solvents |

| Location | Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP) | Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP) |

The Hexacyanoferrate II/III Case Study: Challenging Traditional Classification

The hexacyanoferrate system exemplifies the limitations of binary ISET/OSET classification, displaying characteristics of both mechanisms depending on experimental conditions. This redox couple has been widely employed as a probe for characterizing electrode surfaces, assessing electrocatalysts for energy applications, detecting biological or chemical species, and determining electrochemically active surface areas [4].

Evidence for Inner Sphere Behavior

Multiple experimental observations support classification of hexacyanoferrate as an ISET system under specific conditions:

Oxygen and Surface Oxide Effects: The electron transfer rate is significantly affected by the presence of oxygen and/or surface oxides or other carbon-oxygen species such as carbonyl groups or carboxylates/carboxylic acids [4]. Studies involving highly oriented pyrolytic graphite (HOPG) indicate that increased edge plane exposure generally enhances the apparent HET rate constant (k₀) [4].

Surface Pretreatment Sensitivity: Electron transfer rates respond markedly to electrode pretreatment. For example, HOPG exposure to organic solvents decreases k₀, while laser scribing of graphene enhances HET rates [4].

Adsorption Tendencies: The hexacyanoferrate II/III redox couple adsorbs on many electrode surfaces, with continuous voltammetry showing decreased ferrocyanide oxidation current due to adsorption preceding Prussian Blue formation [4].

Evidence for Outer Sphere Behavior

Conversely, certain characteristics align with OSET behavior:

Lack of Universal Surface Sensitivity: In some configurations, particularly with carefully prepared electrodes, hexacyanoferrate displays relatively consistent ET rates across different surfaces [4].

Well-Defined Electrochemistry: The system often exhibits quasi-reversible behavior with measurable heterogeneous rate constants, allowing its use as a quantitative probe [4].

This duality has created significant confusion in the literature, with some educational resources promoting hexacyanoferrate as exclusively an OSET probe while numerous research articles demonstrate clear ISET characteristics [4].

Factors Influencing Electron Transfer Mechanism

The electron transfer behavior of hexacyanoferrate is influenced by multiple interdependent factors that collectively determine its position on the ISET-OSET spectrum.

Electrode Surface Characteristics

Surface Oxygen Species: The presence and concentration of surface oxygen functional groups significantly impact ET rates. Studies with nanohorns demonstrated that higher surface oxygen concentrations produced increased k₀ values [4].

Hydrophilicity/Hydrophobicity: Surface wettability affects hexacyanoferrate interaction with electrodes, influencing both adsorption and electron transfer efficiency [4].

Crystallographic Orientation: The density of edge plane sites on carbon electrodes correlates with enhanced ET rates, demonstrating structural sensitivity [4].

Solution Composition and Experimental Conditions

Cation Effects: The nature of the cation counter-ion influences hexacyanoferrate behavior through specific ion-pairing interactions that modulate the electrical double layer structure [4].

pH Effects: Solution pH can alter both electrode surface properties and hexacyanoferrate speciation, particularly through protonation equilibria that affect adsorption behavior [4].

Organic Contaminants: The presence of organic molecules, whether intentionally added or adventitious, can form surface films that dramatically alter ET kinetics [4].

Table 2: Experimental Factors Influencing Hexacyanoferrate Electron Transfer Behavior

| Factor | Influence on ET Mechanism | Experimental Manifestation |

|---|---|---|

| Surface Oxygen Content | Modulates adsorption and electronic coupling | Higher oxygen content generally increases k₀ |

| Electrode Material | Affects specific adsorption and electronic structure | Varying peak separations in cyclic voltammetry |

| Cation Type | Influences double layer structure and ion pairing | Changes in formal potential and ET kinetics |

| Surface Pretreatment | Alters functional groups and defect density | Laser treatment increases k₀; solvent exposure decreases k₀ |

| pH | Affects surface charge and protonation state | pH-dependent shifts in voltammetric response |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Cyclic Voltammetry for Heterogeneous ET Rate Determination

Cyclic voltammetry represents the most widely employed technique for characterizing hexacyanoferrate electron transfer behavior. The following protocol provides a standardized approach for reproducible measurements:

Electrode Preparation Protocol:

- Mechanical Polishing: Polish working electrode sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina slurry on microcloth pads

- Sonication: Sonicate in ethanol and deionized water (1:1 v/v) for 2 minutes each to remove adsorbed particles

- Electrochemical Activation: Perform potential cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ from -0.2 to 1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at 100 mV/s until stable voltammogram achieved

- Rinsing: Rinse thoroughly with high-purity deionized water (resistivity ≥ 18 MΩ·cm)

Solution Preparation:

- Prepare 1.0 mM potassium hexacyanoferrate(II) and/or 1.0 mM potassium hexacyanoferrate(III) in supporting electrolyte (typically 0.1-1.0 M KCl)

- Decoxygenate solutions with high-purity nitrogen or argon for at least 15 minutes prior to measurements

- Maintain inert atmosphere blanket during measurements

Voltammetric Parameters:

- Potential window: -0.2 to +0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Scan rates: 10 mV/s to 1000 mV/s (multiple rates required for kinetic analysis)

- Temperature control: 25.0 ± 0.1°C

- Instrument calibration: Verify using known ferrocene/ferrocenium couple

Data Analysis:

- Calculate peak separation (ΔEp) between anodic and cathodic peaks

- Determine heterogeneous rate constant (k₀) using Nicholson's method for quasi-reversible systems

- Assess diffusion coefficients using Randles-Ševčík equation

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Supplementary techniques provide additional insights into hexacyanoferrate electron transfer mechanisms:

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: Quantifies charge transfer resistance and double layer capacitance

- Scanning Electrochemical Microscopy: Maps localized electrochemical activity with spatial resolution

- Spectroelectrochemistry: Correlates electrochemical response with structural changes via UV-Vis, IR, or Raman detection

- X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy: Characterizes electrode surface composition and oxidation states

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hexacyanoferrate Studies

| Reagent | Function | Typical Concentration | Critical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium Ferrocyanide (K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) | Redox probe (reduced form) | 1.0-5.0 mM | Light-sensitive; prepare fresh solutions |

| Potassium Ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) | Redox probe (oxidized form) | 1.0-5.0 mM | Light-sensitive; check purity spectrophotometrically |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Supporting electrolyte | 0.1-1.0 M | High purity essential; minimizes specific adsorption |

| Sulfuric Acid (H₂SO₄) | Electrode activation | 0.5 M | Ultra-high purity for electrochemical applications |

| Alumina Polishing Suspension | Surface preparation | 0.05-1.0 μm | Sequential polishing for mirror finish |