Electrode-Solution Interfacial Phenomena: Fundamentals, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electrode-solution interfacial phenomena, a critical area governing processes in electrochemistry, biosensing, and drug development.

Electrode-Solution Interfacial Phenomena: Fundamentals, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of electrode-solution interfacial phenomena, a critical area governing processes in electrochemistry, biosensing, and drug development. It begins by establishing the foundational principles of the electrical double layer and interfacial charging mechanisms. The scope then progresses to cover advanced methodological approaches, including both computational modeling and cutting-edge experimental techniques for in operando visualization. A dedicated section addresses common challenges and optimization strategies for interfacial performance and stability. Finally, the article synthesizes validation frameworks and comparative analyses of different interfacial systems. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review connects fundamental interfacial science to practical applications in biomedical research and diagnostics.

Unraveling the Fundamentals: Core Principles of the Electrode-Solution Interface

The electrical double layer (EDL) is a fundamental concept in electrochemistry and surface science, describing the region of structured charges that forms at the interface between a solid surface and an adjacent liquid electrolyte. This interfacial structure is pivotal to numerous technological processes and biological systems, including energy storage devices like batteries and capacitors, electrocatalysis, biological cell membrane function, and lubrication systems [1] [2]. When a charged surface is immersed in an electrolyte, it attracts oppositely charged ions from the solution, creating two distinct charged regions: the charged surface itself and a counter-charged region in the liquid. The structure and dynamics of this EDL govern interfacial phenomena, controlling processes such as charge storage capacity, electron transfer rates, and colloidal stability [1]. Understanding the precise structure and potential distribution across this interface is therefore essential for advancing research in electrode-solution interfacial phenomena and for designing next-generation electrochemical devices.

Historical Development and Theoretical Models

The conceptual understanding of the EDL has evolved significantly over the past century, moving from simple capacitor models to increasingly sophisticated theories that account for atomic-scale structure and ion-ion interactions.

Classical EDL Models

The earliest EDL model was proposed by Helmholtz in 1879, who described the interface as a simple molecular capacitor consisting of a single layer of ions from the solution aligned rigidly at the electrode surface [2] [3]. This model presented a linear potential drop across a fixed distance but failed to account for the effects of ion concentration and thermal motion.

In the early 1900s, Gouy and Chapman independently developed a more realistic model by introducing the concept of a diffuse layer [3]. They recognized that ions in the electrolyte are not fixed but remain mobile, with their distribution governed by a balance between electrostatic attraction/repulsion and thermal motion. The Gouy-Chapman (GC) model successfully predicted that the potential decays exponentially from the electrode surface with a characteristic length scale known as the Debye length, which decreases with increasing electrolyte concentration [3]. However, this model treated ions as point charges without physical size, leading to unrealistic predictions at high potentials and concentrations.

Stern synthesized these approaches in 1920, combining the Helmholtz and Gouy-Chapman models to create the Gouy-Chapman-Stern (GCS) model [3]. This hybrid model divides the EDL into two regions: (1) an inner Stern layer (or Helmholtz layer) where ions are adsorbed directly onto the surface, and (2) an outer diffuse layer (or Gouy-Chapman layer) where ions are distributed statistically by electrostatic and thermal forces. The Stern layer accounts for the finite size of ions, while the diffuse layer captures the concentration dependence of the potential distribution.

Modern Theoretical Advances

Recent theoretical work has focused on developing more comprehensive models that accurately describe EDL behavior across diverse systems, from concentrated electrolytes to solid-state interfaces:

Density-Potential Functional Theory (DPFT): This approach hybridizes computational and conceptual methods, combining a parameterized quantum-mechanical treatment of electrons with a classical statistical treatment of charged particles in the solution phase. Unlike Kohn-Sham DFT, which requires calculating electronic orbitals, DPFT expresses the kinetic energy of electrons as an explicit functional of electron density, significantly reducing computational cost while maintaining physical accuracy [2].

Unified Core and Space Charge Model: For solid electrolytes, a recent framework simultaneously treats both the core layer and the space charge layer, incorporating variations in defect formation energy (DFE) and defect-defect interactions consistent with first-principles simulations. This model reveals that the core layer significantly impacts potential distribution and defect concentrations, substantially contributing to conductivity when the interfacial DFE is lower than the bulk DFE [4] [5].

Modified GCS Model for Water-in-Salt Electrolytes: For highly concentrated aqueous electrolytes, the classical GCS model has been adapted by incorporating ionicity (the ratio of experimental molar ionic conductivity to theoretical molar ionic conductivity) to calculate the Debye length. This modification accounts for ion pairing effects that become significant at high concentrations, accurately reproducing experimental trends in differential and EDL capacitance [3].

Table 1: Key Electrical Double Layer Models and Their Characteristics

| Model | Year | Key Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Helmholtz | 1879 | Rigid capacitor model; single ion layer; linear potential drop | Neglects ion mobility and concentration effects |

| Gouy-Chapman | 1910-1913 | Diffuse layer; ion distribution by electrostatics and thermal motion; Debye length | Treats ions as point charges; unrealistic at high potentials |

| Gouy-Chapman-Stern | 1920 | Combined Stern + diffuse layers; accounts for finite ion size | Does not fully capture atomic-scale structure or specific ion effects |

| Modern Approaches | 2000s | Atomistic simulations; density-functional theories; ion correlation effects | High computational cost; complex parameterization |

EDL Structure and Potential Distribution

The EDL structure encompasses several distinct regions, each with characteristic dimensions and physical properties that collectively determine the potential distribution across the interface.

Structural Components of the EDL

Inner Helmholtz Plane (IHP): This plane passes through the centers of specifically adsorbed ions that have lost their hydration shells and are in direct contact with the electrode surface. These ions are chemically bound to the surface.

Outer Helmholtz Plane (OHP): This plane passes through the centers of non-specifically adsorbed ions that remain fully solvated and are physically separated from the electrode by their hydration shells. The OHP conceptualizes the closest approach distance for solvated ions, typically located 0.3-0.8 nm from the surface [2].

Stern Layer: The region between the electrode surface and the OHP, containing both specifically and non-specifically adsorbed ions. The potential drops linearly across this layer.

Diffuse Layer: The region extending from the OHP into the bulk solution where ions are distributed according to a balance between electrostatic forces and thermal motion. The potential in this region decays approximately exponentially with distance from the electrode.

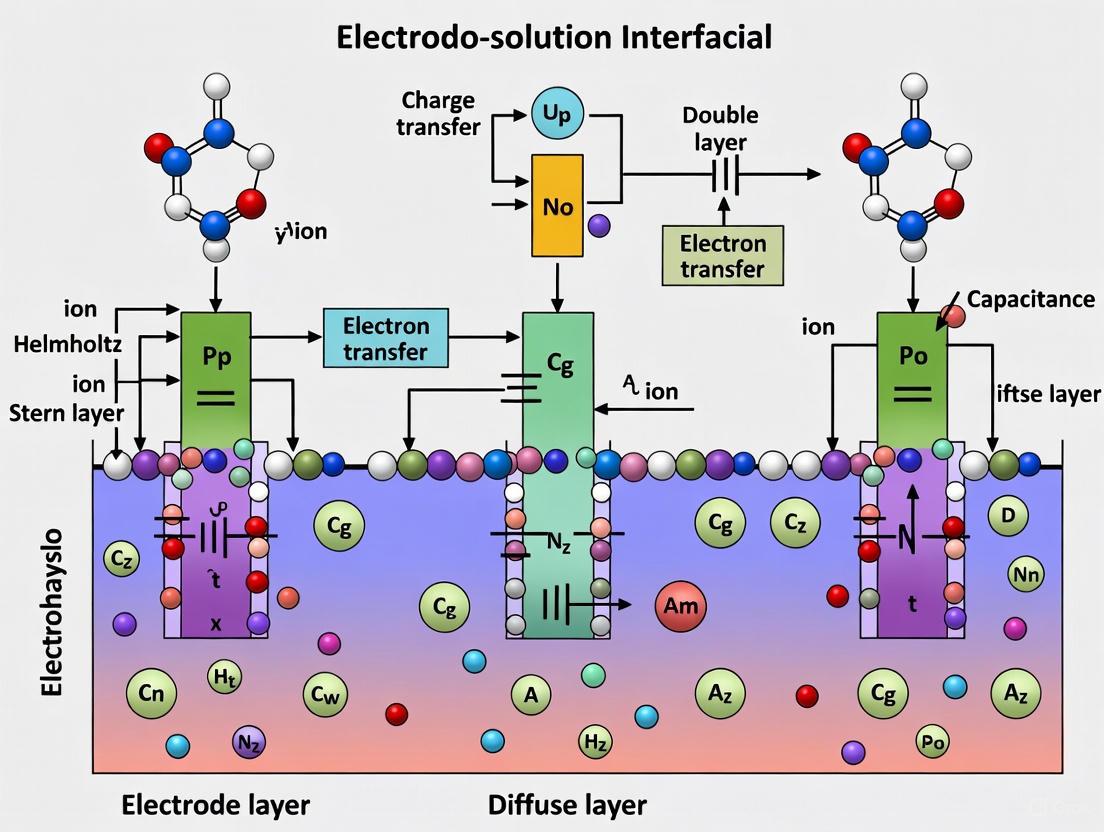

The following diagram illustrates the structure of the EDL and the corresponding potential distribution:

Potential Distribution Models

The potential distribution across the EDL varies significantly depending on the model applied:

- Helmholtz Model: Potential decreases linearly from the electrode surface to the Helmholtz plane.

- Gouy-Chapman Model: Potential decays exponentially from the electrode surface into the solution.

- Gouy-Chapman-Stern Model: Potential drops linearly across the Stern layer and exponentially through the diffuse layer.

The thickness of the diffuse layer is characterized by the Debye length (λ₉), which for a symmetric electrolyte is given by:

[ \lambdaD = \sqrt{\frac{\varepsilonr \varepsilon0 kB T}{2e^2 I}} ]

where εᵣ is the relative permittivity, ε₀ is the vacuum permittivity, k({}_{\text{B}}) is Boltzmann's constant, T is temperature, e is elementary charge, and I is ionic strength. In concentrated electrolytes, ion pairing reduces the effective concentration of charge carriers, requiring modification of the Debye length calculation using ionicity parameters [3].

Table 2: Key Parameters Governing EDL Structure and Potential Distribution

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Impact on EDL |

|---|---|---|---|

| Debye Length | λ₉ | ~1-100 nm | Determines diffuse layer thickness; decreases with concentration |

| Stern Layer Thickness | d | 0.3-0.8 nm | Distance of closest approach for solvated ions |

| Electrode Potential | E | System-dependent | Controls surface charge density and EDL structure |

| Ionic Strength | I | 1 mM - 10 M | Affects Debye length and EDL compression |

| Ionicity | α | 0-1 | Fraction of free ions; affects Debye length in concentrated electrolytes |

| Dielectric Constant | εᵣ | ~78 (water) | Medium polarity; affects electrostatic interactions |

Experimental Methodologies for EDL Investigation

Ultrafast Optical Spectroscopy

Recent advances have enabled direct observation of EDL formation dynamics using light-based techniques that circumvent the temporal limitations of electronic circuits [1].

Protocol: Ultrafast Laser Probing of EDL Dynamics at Aqueous Interfaces

- Sample Preparation: Prepare an aqueous electrolyte solution (e.g., acidified water generating H₃O⺠ions) and contain it in a temperature-controlled vessel with a flat air-liquid interface.

- Perturbation Pulse: Apply an intense infrared laser pulse to the interface, which thermally perturbs the system by removing H₃O⺠ions from the surface, disrupting the established EDL.

- Probe and Detection: After a precisely controlled time delay (femtoseconds to picoseconds), direct a second laser pulse (probe) at the interface and measure the reflected light intensity.

- Kinetic Monitoring: Repeat the measurement at varying time delays to monitor the relaxation of the perturbed system as ions move away from the interface to re-establish equilibrium.

- Data Analysis: Combine time-resolved reflectance data with computer simulations to quantify ion movement and validate theoretical models of EDL formation [1].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS)

EIS is a powerful method for characterizing the capacitive properties of the EDL across a range of frequencies.

Protocol: EDL Capacitance Measurement via EIS

- Cell Assembly: Configure a three-electrode system with the material of interest as working electrode, appropriate counter electrode, and stable reference electrode.

- Impedance Measurement: At open circuit potential, apply a small AC voltage amplitude (e.g., 10 mV) across a wide frequency range (typically 0.01 Hz to 100 kHz).

- Data Collection: Record the impedance (magnitude and phase) at each frequency.

- Analysis: Fit the resulting Nyquist or Bode plots to an equivalent circuit model containing a constant phase element (CPE) or capacitor representing the EDL. Extract the EDL capacitance values from the fit parameters [3].

Raman Spectroscopy for Ion Association Studies

Vibrational spectroscopy provides insights into ion pairing and solvation structures in bulk electrolytes and at interfaces.

Protocol: Raman Characterization of Ion Pairing in Water-in-Salt Electrolytes

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a series of electrolyte solutions across a concentration range (e.g., 0.5 to 20 mol kgâ»Â¹ for LiTFSI).

- Spectra Acquisition: Using a Raman spectrometer (e.g., Horiba LabRAM HR 800), acquire spectra of bulk solutions with appropriate laser wavelength and power settings.

- Spectral Analysis: Identify characteristic vibrational bands for free ions (e.g., TFSIâ» S-N-S bending at ~740 cmâ»Â¹) and ion pairs (shifted bands). Deconvolute spectra to quantify relative proportions of free ions and ion pairs.

- Ionicity Calculation: Determine the ionicity parameter from conductivity measurements and use it to modify the Debye length calculation in EDL models [3].

Recent Research Advances and Applications

EDL in Solid Electrolytes

Recent unified EDL models for solid electrolytes simultaneously treat both the core layer and space charge layer, incorporating defect formation energy (DFE) variations and defect-defect interactions consistent with first-principles simulations. These models demonstrate that the core layer significantly impacts potential distribution and defect concentrations, substantially contributing to conductivity when the interfacial DFE is lower than the bulk DFE. This framework enables accurate predictions of capacitance and ionic conductivity essential for solid-state electrochemical devices [4] [5].

Water-in-Salt Electrolytes

For highly concentrated aqueous electrolytes (water-in-salt electrolytes), classical EDL models break down due to extensive ion pairing. Modified GCS models that incorporate ionicity to calculate the Debye length show a sharp decrease in Debye length as concentration increases from 1 to 10 mol kgâ»Â¹, followed by an increase due to ion pairing above 10 mol kgâ»Â¹. When applied to porous carbon electrodes, dividing the Debye length by the MacMullin number (ratio of tortuosity to porosity) allows estimation of ionic radii within pores and the extent of ion desolvation, revealing optimal concentrations for fast charging (5 mol kgâ»Â¹ LiTFSI) and highest energy density (10 mol kgâ»Â¹) [3].

Tribological Applications

The EDL plays a crucial role in tribology, where the repulsive forces between similarly charged surfaces in electrolyte solutions can support normal load and reduce friction. This effect is particularly important in achieving superlubricity (coefficient of friction < 0.01) in systems such as Si₃N₄ sliding in water, where a negatively charged silica layer forms on the friction pair. The EDL repulsive interaction mechanism has also been applied to explain superlubricity in phosphoric acid-lubricated ceramic contacts [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for EDL Research

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium Salts (LiTFSI) | High purity (>99.9%), anhydrous | Model electrolyte for water-in-salt studies; forms concentrated solutions |

| Aprotic Solvents | Acetonitrile, propylene carbonate | Low dielectric constant solvents for studying ion association |

| Aqueous Electrolytes | HCl, NaCl, CsCl solutions | Fundamental studies of EDL structure in biological systems |

| Porous Carbon Electrodes | Specific surface area >1500 m²/g, controlled pore size distribution | Investigating EDL formation in confinement |

| Solid Electrolytes | Ceramic oxides (LLZO), sulfides (LGPS) | Studying EDL at solid-solid interfaces |

| Reference Electrodes | Ag/AgCl, Hg/HgO, Li/Li⺠| Potential control and measurement in three-electrode cells |

| Single Crystal Electrodes | Au(111), Pt(111), HOPG | Well-defined surfaces for fundamental EDL studies |

| AR420626 | AR420626, MF:C21H18Cl2N2O3, MW:417.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ARN14974 | ARN14974, CAS:1644158-57-5, MF:C24H21FN2O3, MW:404.4414 | Chemical Reagent |

The electrical double layer represents a complex interfacial region whose structure and potential distribution govern critical processes in electrochemical energy storage, biological systems, and tribology. While classical models (Helmholtz, Gouy-Chapman, Stern) provide foundational concepts, recent advances in both theoretical modeling and experimental characterization have revealed the intricate details of EDL formation and dynamics across diverse systems. Modern approaches including density-potential functional theory, unified core-space charge models for solid electrolytes, and modified GCS models for concentrated electrolytes have significantly enhanced our ability to predict and optimize interfacial behavior for specific applications. The continued development of ultrafast spectroscopic techniques and computational methods promises to further unravel the complexities of the electrical double layer, enabling breakthroughs in electrode-solution interfacial phenomena research and the design of next-generation electrochemical devices.

Potential of Zero Charge (PZC) and Work Function

The Potential of Zero Charge (PZC) and the Work Function are two cornerstone concepts in the fundamental understanding of electrode-solution interfacial phenomena. The PZC is defined as the specific electrode potential at which there is no net electrical charge accumulated at the electrode-electrolyte interface [6] [7]. At this potential, the charge on the metal side of the electrical double layer is precisely zero. The work function (Φ), conversely, is a vacuum-based property defined as the minimum energy required to extract an electron from the bulk of a metal to a point in vacuum just outside the metal surface [7]. In electrochemical systems, these two properties are intrinsically linked, as the work function of the electrode material provides the fundamental reference point that determines the PZC in the absence of other interfacial interactions [7].

Understanding the relationship between PZC and work function is critical for rational design of electrocatalytic materials, particularly for energy conversion applications such as fuel cells and electrolyzers where platinum-group metals are extensively utilized [8] [7]. The interface structure at the atomic scale, including surface morphology and step densities, directly influences both the work function and the PZC through phenomena such as the Smoluchowski effect, where electron spillover at step sites creates surface dipoles that modify the interfacial electrostatics [8] [6]. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these interconnected concepts, detailing both theoretical foundations and practical experimental methodologies relevant to researchers investigating electrode-solution interfaces.

Theoretical Foundations and Physical Relationships

The Electronic Structure Perspective: Work Function and Surface Potential

The work function (Φ) of a metal surface represents a fundamental electronic property that is highly sensitive to atomic-level structure and composition. As illustrated in Figure 1, the work function is defined as the energy difference between the Fermi level (EF) of the metal and the vacuum energy level just outside the material surface [7]. This can be expressed as Φ = -EF - eχ, where χ represents the surface potential arising from the electron spillover at the metal-vacuum interface that creates a surface dipole [7]. Different crystallographic orientations exhibit distinct work functions due to variations in surface dipole; for platinum, Pt(111) exhibits a work function of 5.9 eV while Pt(100) measures 5.75 eV [7].

Table 1: Work Function Values for Different Platinum Surface Orientations

| Surface Orientation | Work Function (eV) | Key Structural Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Pt(111) | 5.9 | Close-packed, smooth |

| Pt(100) | 5.75 | More open structure |

| Stepped Surfaces | Intermediate values | Step-edge dipoles present |

The surface dipole (χ) emerges from the asymmetric electron distribution at the interface, where electrons spill over from the metal into the vacuum region, creating a charge separation layer typically on the order of a few angstroms thick [7]. This dipole layer is particularly pronounced at step edges and defect sites, where the electron density redistribution follows the Smoluchowski smoothing effect, resulting in localized surface dipoles that lower the overall work function compared to flat terraces [6].

The Electrochemical Perspective: Potential of Zero Charge

In the electrochemical environment, the Potential of Zero Charge (PZC) represents the equivalent concept to the work function, but transferred to the electrode-electrolyte interface [7]. At the PZC, the potential drop across the entire interface (Δφ) is governed solely by the dipole contributions, as there is no net electronic charge on the electrode surface [7]. The relationship between the work function and PZC can be conceptually expressed as E_PZC = Φ/e + δχ, where δχ represents the modification of the surface dipole due to the presence of the solvent and specifically the orientation of solvent dipoles at the interface [7].

For ideally polarizable electrodes without specific adsorption, the PZC can be directly determined from the minimum in the differential capacitance versus potential curve in dilute electrolyte solutions [6] [7]. However, for catalytically relevant metals like platinum that exhibit significant hydrogen and hydroxyl adsorption, the situation is considerably more complex. In these systems, it becomes essential to distinguish between the potential of zero free charge (pzfc), which relates to the true electronic excess charge on the metal, and the potential of zero total charge (pztc), which includes all charge that flows through the external circuit, including both capacitive and faradaic contributions [6]. Only the pzfc correlates directly with the electronic structure properties like work function, while the pztc is the parameter most readily accessible through conventional electrochemical measurements [6].

Interfacial Structure and Solvent Effects

The structure and composition of the electrode-electrolyte interface profoundly influence the relationship between work function and PZC. Water molecules at the interface adopt specific orientations and coordination patterns that contribute to the interfacial dipole. On platinum surfaces, water molecules can exist in several distinct motifs: (1) "Chemisorbed" water that lies nearly flat on the Pt surface with oxygen coordinated to the metal; (2) "H-down" water where one O-H bond points toward the surface, forming a weak covalent interaction with Pt; and (3) "Bridging" water that hydrogen-bonds to both the first and second hydration layers [8].

Advanced computational studies using ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) have revealed that water molecules directly contacting the Pt surface become partially charged and chemisorbed, thereby behaving more like ionic species than neutral dipoles [8]. This chemisorbed water layer contributes substantially to interfacial screening and differential capacitance, particularly around the PZC where the coverage of chemisorbed water correlates linearly with both metal capacitance and potential [8]. At higher potentials, this relationship breaks down due to water coverage saturation, while at lower potentials hydrogen adsorption becomes the dominant factor [8].

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Determining Work Function under Ultra-High Vacuum Conditions

The experimental determination of work function is typically conducted under ultra-high vacuum (UHV) conditions to eliminate surface contamination. The most direct method involves Kelvin Probe Force Microscopy (KPFM), which measures the contact potential difference between a reference tip and the sample surface. The experimental workflow involves:

- Sample Preparation: Single crystal surfaces are prepared through repeated cycles of argon ion sputtering and annealing to achieve well-defined surface structures.

- Surface Characterization: Low-energy electron diffraction (LEED) and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) verify surface crystallography and absence of defects.

- Work Function Measurement: The Kelvin probe measures the contact potential difference between the sample and a reference tip of known work function, allowing absolute work function determination.

- Data Collection: Multiple measurements across different surface regions ensure statistical reliability and detect any spatial variations in work function.

This approach provides direct, quantitative work function values for different surface orientations and step densities, enabling correlation with electrochemical PZC measurements [6] [7].

Electrochemical Protocols for PZC Determination

CO Charge Displacement Method

For catalytically active metals like platinum that exhibit significant faradaic processes, the CO charge displacement method has emerged as the most reliable technique for determining the potential of zero total charge (pztc) [6]. The detailed experimental protocol is as follows:

- Electrode Preparation: A well-defined single crystal platinum electrode (e.g., Pt(111)) is prepared using the flame annealing technique developed by Clavilier [6], followed by cooling in ultrapure water saturated with an inert gas (Ar or Nâ‚‚).

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: The electrode is transferred to an electrochemical cell containing deaerated electrolyte solution (typically 0.1M HClOâ‚„ or HF) under controlled atmosphere to prevent oxygen contamination.

- Reference Electrode: A reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) or saturated calomel electrode (SCE) is used as reference, with all potentials subsequently converted to the standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) scale.

- Potential Control: The working electrode is polarized to a specific potential (E*) within the electric double layer region (typically 0.3-0.5V vs. RHE for Pt(111)).

- CO Introduction: High-purity CO gas is introduced into the cell atmosphere while maintaining constant electrode potential.

- Charge Measurement: The charge flowing through the external circuit during CO adsorption is precisely measured via integration of the current transient.

- Data Analysis: The displaced charge (qdisp) is related to the initial interfacial charge (q(E*)) through the equation: qdisp = qCO - q(E*), where qCO represents the residual charge on the CO-covered surface [6].

- PZTC Determination: The experiment is repeated at different potentials, and the pztc is identified as the potential where q(E) = 0 after accounting for the small but non-zero q_CO value.

This method has been successfully applied to determine pztc values for Pt(111) in both acidic and alkaline environments [6].

Differential Capacitance Minimum Method

For electrodes without significant faradaic processes, the classic approach involves identifying the potential at which the differential capacitance reaches a minimum in dilute electrolyte solutions [6] [9]. The experimental workflow includes:

- Electrode Preparation: A renewable pencil lead electrode can be utilized, where a fresh surface is exposed using a cutting device immediately before measurement [9].

- Impedance Spectroscopy: Electrochemical impedance spectra are recorded across a wide potential range (typically -0.5V to +0.5V vs. reference) using a small AC perturbation (5-10 mV amplitude) across frequencies from 10 kHz to 0.1 Hz.

- Differential Capacitance Calculation: The double-layer capacitance (C_dl) is extracted from the impedance data at each potential, typically by fitting the data to an appropriate equivalent circuit model.

- PZC Identification: The PZC corresponds to the potential value at which the differential capacitance curve exhibits a minimum in dilute electrolytes where specific adsorption is absent [9].

This method is particularly suitable for carbon-based materials and noble metals like gold and silver that do not exhibit significant hydrogen adsorption [6] [9].

Advanced Computational Approaches

Modern computational methods provide atomistic insights into the relationship between work function and PZC. Ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) with explicit solvent molecules allows for realistic modeling of the electrode-electrolyte interface under controlled electrode potentials [8]. Key computational protocols include:

- System Setup: Construction of stepped Pt slab models incorporating (111) terraces with (111)×(111) and (111)×(100) step edges, solvated with explicit water molecules and ions [8].

- Potential Control: Implementation of the ion imbalance method to control electrode potential by introducing an imbalance in the number of ions in solution, allowing the electrode to charge in response [8].

- Potential Drop Calculation: Evaluation of the potential drop with respect to the electrostatic potential in the bulk electrolyte region [8].

- Electronic Structure Analysis: Calculation of local density of states, d-band centers, and charge distribution profiles across the interface.

- Water Structure Analysis: Identification of water orientation motifs and their potential-dependent coverage.

These computational approaches have revealed that step edges on platinum surfaces accumulate excess positive charge and exhibit locally elevated electrostatic potential, creating a greater barrier for electron accumulation compared to terraces [8]. This fundamental insight explains the experimentally observed shift in PZC with increasing step density and provides a mechanistic understanding of why step edges often demonstrate enhanced catalytic activity [8].

Research Tools and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for PZC/Work Function Studies

| Item | Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Single Crystal Electrodes | Pt(111), Pt(100), Au(111) with various step densities | Well-defined surface structure for fundamental studies |

| Electrolyte Solutions | 0.1M HClOâ‚„, 0.1M HF, ultrapure grade | Minimize specific adsorption; HF useful for AIMD simulations |

| Reference Electrodes | Reversible Hydrogen Electrode (RHE), Saturated Calomel | Potential referencing with known relationship to SHE |

| High-Purity Gases | Argon (99.999%), CO (99.99%), Nâ‚‚ (99.999%) | Solution deaeration; CO charge displacement experiments |

| Renewable Electrodes | Pencil lead electrodes with cutting device | Fresh surfaces for each measurement; minimizes contamination |

| Computational Models | Stepped Pt slabs with (111)×(111) and (111)×(100) edges | Atomistic modeling of realistic nanostructured surfaces |

Interfacial Phenomena and Practical Implications

Surface Morphology Effects on Interfacial Properties

Surface nanostructuring profoundly influences both work function and PZC through the creation of localized electronic states and interfacial dipoles. Stepped platinum surfaces exhibit significantly different electrochemical behavior compared to atomically flat terraces [8]. Advanced AIMD simulations have revealed that:

- Step edges accumulate excess positive charge and exhibit locally elevated electrostatic potential, creating a greater barrier for electron accumulation compared to terraces [8].

- Water chemisorption saturates step edges even below the PZC, while terrace sites exhibit potential-dependent water coverage that primarily determines the differential capacitance near PZC [8].

- The d-band center shifts to higher energies at step edges, with sharper projected density of states that supports their role as active, positively charged catalytic centers [8].

These nanoscale variations in electronic structure and interfacial charging directly impact electrocatalytic activity. The electrostatic asymmetry between terraces and steps creates heterogeneous reaction environments that can selectively enhance certain electrochemical pathways while suppressing others [8].

Table 3: Effect of Surface Morphology on Interfacial Properties of Platinum

| Surface Feature | Effect on Work Function | Effect on PZC | Impact on Interfacial Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flat Terraces | Higher work function (5.9 eV for Pt(111)) | Higher PZC | Potential-dependent chemisorption |

| Step Edges | Lower work function due to Smoluchowski effect | Lower PZC | Permanent chemisorption saturation |

| (111)×(111) Steps | Intermediate reduction | Moderate PZC shift | Strong water anchoring sites |

| (111)×(100) Steps | Maximum reduction | Maximum PZC shift | Complex water ring structures |

Implications for Electrocatalysis and Sensor Design

The relationship between work function and PZC provides fundamental insights for rational design of electrocatalytic materials and electrochemical sensors. Key implications include:

Catalytic Activity Optimization: The lower PZC of step edges compared to terraces creates locally distinct electrostatic environments that influence adsorption energies of reactive intermediates. This explains why stepped surfaces often exhibit enhanced activity for reactions like hydrogen evolution/oxidation [8].

Interfacial pH Considerations: The potential difference across the interface relative to PZC governs the local proton activity, creating interfacial pH conditions that may differ significantly from the bulk solution [6]. This effect must be considered when designing sensors or catalytic systems operating near the PZC.

Nanostructuring Strategies: deliberate introduction of step edges and defects can optimize interfacial charging behavior to enhance selectivity for specific electrochemical reactions. The spatial distribution of charged sites creates heterogeneous reaction fields that can be engineered for improved performance [8].

Sensor Development: Understanding the PZC enables optimization of sensor operating potentials to minimize non-specific adsorption and background charging currents, thereby improving signal-to-noise ratios in analytical applications [9] [10].

The fundamental relationship between Potential of Zero Charge and Work Function provides a critical bridge between vacuum-based surface science and electrochemical interface phenomena. For platinum and other catalytically important metals, this relationship is modulated by surface morphology, solvent interactions, and specific adsorption processes. The experimental methodologies detailed in this guide, particularly the CO charge displacement technique for active metals and the differential capacitance approach for ideally polarizable interfaces, enable precise determination of the PZC under electrochemical conditions. Complementary computational approaches using AIMD provide atomistic insights into the potential-dependent structure of the electrical double layer and the nanoscale variations in interfacial electrostatics at terraces versus step edges.

This integrated understanding of how electronic structure (work function) manifests in electrochemical environments (PZC) establishes a predictive framework for rational design of advanced electrochemical interfaces. By controlling surface morphology to manipulate the relationship between work function and PZC, researchers can optimize interfacial charging behavior to enhance performance in diverse applications ranging from electrocatalytic energy conversion to electrochemical sensing and beyond.

Electrode-solution interfacial phenomena represent a critical frontier in modern electrochemical science, governing processes essential for energy conversion, storage, and material synthesis. The interface between a solid electrode and a liquid electrolyte serves as a dynamic region where complex charging mechanisms—including dissolution, hydration, and ion absorption—dictate system performance and efficiency. These processes occur within the electrical double layer, a nanoscale region where the organized arrangement of solvent molecules, ions, and electrode surfaces creates a unique environment with properties distinct from the bulk phases [11]. Understanding these mechanisms is paramount for advancing numerous technologies, including lithium-ion batteries, electrocatalytic systems, and carbon capture solutions.

The structure and behavior of interfacial water molecules form the foundation of these charging mechanisms. As highlighted in recent research, interfacial water serves not merely as a solvent but as an active participant in electrochemical processes, acting as a co-catalyst, regulator of reaction intermediates, and sometimes as an inducer of catalyst reconfiguration [11]. Its unique configurations—including dangling O–H water, dihedral coordinated water, and tetrahedral coordinated water—directly influence proton transfer, intermediate stabilization, and reaction kinetics. These molecular-level interactions ultimately determine macroscopic performance metrics in electrochemical devices [11].

This whitepaper examines the fundamental mechanisms of interfacial charging, with particular emphasis on dissolution, hydration, and ion absorption processes. By synthesizing recent experimental and computational advances, we aim to provide a comprehensive technical guide for researchers investigating electrode-solution interfaces across diverse applications.

Fundamental Mechanisms

Dissolution Mechanisms

Dissolution represents a critical interfacial charging mechanism wherein constituent ions transition from the solid electrode lattice into the adjacent solution phase. Recent single-ion level studies have revealed that dissolution is not a homogeneous process but exhibits strong ion-specific characteristics. For NaCl dissolution, experimental evidence demonstrates that anions (Clâ») dissolve preferentially over cations (Naâº) due to their higher polarizability, which enables stronger interactions with water dipoles [12].

The dissolution process initiates when water molecules adsorb at under-coordinated sites on the crystal surface, particularly at atomic steps and defects. Through scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) experiments, researchers have observed that a single water molecule can selectively dissolve a single Clâ» ion from a NaCl surface when manipulated to step edges [12]. The mechanism proceeds through several distinct stages:

- Water Adsorption: A water molecule adsorbs preferentially near cationic sites (Naâº) at interfacial steps, with an adsorption energy of approximately -750 meV—significantly stronger than adsorption on terraces (-385 meV) [12].

- Dipole-Induced Polarization: The water dipole moment polarizes the adjacent anion (Clâ»), concentrating its electron cloud toward the water molecule.

- Bond Weakening: This polarization weakens the ionic bond between Na⺠and Cl⻠ions in the crystal lattice.

- Ion Release: The weakened ionic bond breaks, releasing the Clâ» ion into the solution phase.

This ion-specific dissolution mechanism underscores the critical role of polarizability differences between anions and cations in determining dissolution kinetics. The findings challenge classical dissolution models that treat anions and cations equivalently, providing instead a molecular-level picture of selective ion release driven by water-ion interactions [12].

Hydration Processes

Hydration encompasses the molecular-level interactions between water molecules and dissolved ions, forming solvation shells that significantly influence interfacial charge transfer. The structure and dynamics of these hydration shells dictate ion mobility, reactivity, and stability in electrochemical environments.

The COâ‚‚ hydration reaction at air-water interfaces exemplifies the complex nature of interfacial hydration processes. Contrary to previous assumptions that interfacial reactions differ substantially from bulk processes, recent machine learning simulations reveal that COâ‚‚ hydration follows a surface-mediated "in-and-out" mechanism [13]:

- Ingress: COâ‚‚ molecules diffuse into the aqueous surface layer.

- Reaction: The dissolved CO₂ reacts with water to form carbonic acid (H₂CO₃) through a nucleophilic addition mechanism.

- Expulsion: The carbonic acid product is subsequently expelled from the solution phase.

This mechanism occurs within a surface layer that provides a bulk-like solvation environment, with similar coordination numbers and hydrogen-bonding patterns to fully solvated conditions [13]. The free energy profiles and barriers for interfacial COâ‚‚ hydration are nearly identical to those in bulk water, suggesting that hydration reactions can proceed with comparable feasibility at interfaces and in bulk solution.

Similar principles govern ion hydration in battery electrolytes, where solvation structure directly impacts electrochemical performance. In aqueous zinc-ion batteries, for instance, the hydration shell of Zn²⺠ions contains water molecules that actively participate in electrode processes. Modifying this solvation structure through electrolyte additives like tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol (THFA) can displace coordinated water molecules, thereby suppressing detrimental side reactions and improving cycling stability [14].

Ion Absorption and Interfacial Charge Transfer

Ion absorption describes the process wherein ions from the solution phase are incorporated into the electrode surface or near-surface region, facilitating charge transfer across the interface. This process is fundamental to the operation of batteries, electrocatalytic systems, and numerous other electrochemical technologies.

In lithium-ion batteries, interfacial charge-transfer kinetics govern key performance metrics such as rate capability, cycling stability, and low-temperature operation. The Butler-Volmer equation traditionally describes these kinetics, relating current (I) to overpotential (η) through the exchange current (I₀) and charge transfer coefficient (α) [15]:

[I = I_0 \left( \exp\left(\frac{\alpha F}{RT}\eta\right) - \exp\left(-\frac{(1-\alpha)F}{RT}\eta\right) \right)]

Recent investigations have revealed that complex multi-step interfacial reactions in real battery systems can yield apparent transfer coefficients that deviate significantly from the theoretically expected value of α ≈ 0.5 for simple one-electron transfer reactions. For instance, LiFePO₄ electrodes exhibit an apparent α value of ~1.5, with the true charge-transfer coefficient approaching ~3 when accounting for non-uniform current distribution effects [15].

The ion absorption process is further influenced by the structure and composition of the electrode-electrolyte interface. In graphite anodes for lithium-ion batteries, the limited interlayer spacing (0.335 nm) constrains lithium-ion insertion, particularly under fast-charging conditions [16]. Strategic interface engineering through hard carbon coatings can enhance lithium-ion absorption kinetics by providing additional storage sites and reducing diffusion barriers, ultimately improving fast-charging performance [16].

Table 1: Key Parameters in Interfacial Charging Mechanisms

| Mechanism | Governing Factors | Characteristic Energy/Time Scales | Experimental Techniques |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissolution | Ion polarizability, surface defects, water orientation, temperature | Adsorption energy: -385 to -750 meV [12] | Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM), Density Functional Theory (DFT) |

| Hydration | Ion size/charge, hydrogen bonding, solvent dipole moment, interface structure | Free energy barrier: ~22 kcal/mol for COâ‚‚ hydration [13] | Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs), Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD) |

| Ion Absorption | Applied potential, ion size, solvation energy, surface chemistry | Exchange current density: varies with material (e.g., LCO, LFP) [15] | Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), Tafel analysis, Chronopotentiometry |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Single-Ion Dissolution Experiments

The investigation of dissolution mechanisms at the single-ion level requires sophisticated experimental approaches that combine atomic-scale imaging with precise manipulation capabilities. The following protocol, adapted from pioneering work on NaCl dissolution, provides a methodology for directly observing dissolution events [12]:

Materials and Equipment:

- Ultra-high vacuum (UHV) chamber with base pressure < 1×10â»Â¹â° mbar

- Low-temperature scanning tunneling microscope (STM) capable of operating at 5-20 K

- Ag(100) single crystal substrate

- 1100 aluminum alloy foils (0.051-0.127 mm thickness)

- High-purity NaCl source for thermal evaporation

- Deuterium or tritium water sources to minimize vibrational interference

Sample Preparation:

- Clean the Ag(100) substrate through repeated cycles of Ar⺠sputtering (1 keV, 15 μA, 30 min) and annealing (770 K, 30 min) until a sharp (1×1) low-energy electron diffraction pattern is observed.

- Deposit 2-3 monolayers of NaCl onto the clean Ag(100) surface by thermal evaporation from a Knudsen cell at 770 K.

- Introduce deuterated water (Dâ‚‚O) onto the sample surface held at temperatures below 20 K to ensure individual water molecules remain isolated on the surface.

STM Manipulation and Imaging:

- Acquire high-resolution images of individual water molecules on NaCl terraces and steps using typical tunneling parameters (sample bias: 20-100 mV, tunneling current: 5-50 pA).

- Position the STM tip above a target water molecule at the step edge of a NaCl island.

- Approach the tip to a close distance (approximately 300 pm from the molecule) while reducing the sample bias below 450 mV to avoid excitation of vibrational modes.

- Drag the water molecule along desired crystallographic directions (<100> or <110>) while continuously recording tip height variations.

- Monitor for dissolution events characterized by the appearance of vacancy defects at step edges and corresponding changes in water molecule behavior.

Data Analysis:

- Analyze tip height traces during manipulation to extract frictional thresholds and interaction potentials.

- Correlate manipulation directions with dissolution probabilities.

- Calculate adsorption energies and interaction strengths from manipulation data and complementary DFT calculations.

This approach enables the direct observation of dissolution initiation at the single-ion level, providing unprecedented insight into the role of water-ion interactions in driving dissolution processes.

Machine Learning Potentials for Hydration Studies

The investigation of hydration mechanisms at interfaces benefits from advanced computational approaches that bridge accuracy and computational efficiency. Machine learning potentials (MLPs) trained on first-principles data have emerged as powerful tools for simulating complex interfacial reactions with ab initio-level accuracy. The following protocol outlines the development and application of MLPs for studying COâ‚‚ hydration at air-water interfaces [13]:

Software and Computational Resources:

- Density functional theory (DFT) packages (VASP, Quantum ESPRESSO, or CP2K)

- MLP training frameworks (MACE, NequIP, or SchNet)

- Enhanced sampling libraries (PLUMED, SSAGES)

- High-performance computing cluster with GPU acceleration

Model Development Protocol:

- Dataset Generation:

- Perform ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD) simulations of COâ‚‚-water systems at various configurations (gas phase, bulk solution, interface).

- Extract diverse molecular structures representing reactant, transition, and product states.

- Include configurations with varying COâ‚‚-water coordination environments and protonation states.

- Ensure comprehensive coverage of the relevant configurational space.

Model Training:

- Employ the MACE (Multi-Atomic Cluster Expansion) architecture, which combines atomic cluster expansion with message-passing neural networks.

- Train on energies and forces from DFT calculations using revPBE-D3, BLYP-D3, or random phase approximation (RPA) functionals.

- Implement a 80:10:10 training:validation:test split with temporal stratification to prevent data leakage.

- Utilize iterative active learning to refine the model in poorly sampled regions.

Validation and Testing:

- Calculate root-mean-square errors (RMSE) for energies (< 1 meV/atom) and forces (< 50 meV/Ã…) on test sets.

- Compare potential energy surfaces along key reaction coordinates with direct DFT calculations.

- Validate against experimental observables where available (reaction rates, spectroscopic data).

Simulation of Interfacial Hydration:

- Construct air-water interface systems with sufficient dimensions (typically > 1000 water molecules) to minimize finite-size effects.

- Perform well-tempered metadynamics simulations using collective variables that describe:

- C–O coordination number (sCO) to monitor nucleophilic attack

- Proton transfer coordinate to track acid-base chemistry

- Spatial position relative to the Gibbs dividing surface

- Extract free energy profiles and kinetic parameters from biased simulations using reweighting techniques.

- Analyze solute-solvent coordination, hydrogen bonding patterns, and solvent dynamics as functions of position relative to the interface.

This computational framework enables the investigation of hydration reactions with quantum-mechanical accuracy across extended time- and length-scales, providing molecular-level insights into interfacial reaction mechanisms.

Diagram 1: Machine Learning Potential Workflow for Hydration Studies

Electrochemical Kinetics Measurements

Quantifying interfacial charge-transfer kinetics is essential for understanding ion absorption processes in electrochemical systems. The following protocol outlines advanced electrochemical techniques for measuring charge-transfer kinetics at high current densities, as applied to lithium-ion battery materials [15]:

Materials and Equipment:

- Symmetric cell configuration with identical working and counter electrodes

- Precision potentiostat/galvanostat with high-current capability (>10 mA cmâ»Â²)

- Environmental chamber for temperature control (±0.1°C)

- Reference electrode (optional, for three-electrode measurements)

- Electrolyte with controlled moisture content (<10 ppm Hâ‚‚O)

Cell Fabrication:

- Synthesize or procure high-quality active materials with well-defined morphology (e.g., single-crystal LiCoO₂ with ∼3 μm particle size).

- Prepare electrode slurry with active material, conductive carbon, and binder in appropriate ratios (e.g., 94:3:3 by weight).

- Coat electrodes onto current collectors with controlled mass loading (~10 mg cmâ»Â²).

- Assemble symmetric cells in an argon-filled glovebox with appropriate separators and electrolyte.

Electrochemical Techniques:

- Pseudo-Steady-State Extrapolation Chronopotentiometry (S3E-CP):

- Apply a series of constant current pulses with increasing magnitude (0.1 to 10 mA cmâ»Â²).

- Use pulse durations sufficient to reach voltage pseudo-plateaus (typically 10-60 seconds).

- Include sufficient relaxation time between pulses to restore equilibrium.

- Record the overpotential (η) at the end of each pulse.

- Plot η vs. log(I) and fit the linear Tafel region to extract I₀ and α.

Large-Amplitude Galvano Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (LA-GEIS):

- Superimpose a small AC perturbation (≤ 10 mV) on a large DC current bias.

- Sweep frequency from high to low (e.g., 100 kHz to 10 mHz) at each DC current.

- Measure impedance spectra at multiple DC current densities spanning the linear and non-linear regimes.

- Extract differential charge-transfer resistance (R'ₜ) from the diameter of high-frequency semicircles.

Operando Galvano Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (O-GEIS):

- Conduct LA-GEIS measurements during slow galvanostatic cycling.

- Acquire impedance spectra at regular state-of-charge intervals throughout charge/discharge cycles.

- Monitor changes in charge-transfer kinetics as a function of lithiation degree.

Data Analysis:

- Precisely compensate for ohmic resistance (RΩ) using current-interruption or high-frequency intercept methods.

- Fit charge-transfer resistance versus current density data to the modified Butler-Volmer equation: R'â‚œ = (RT/(αFIâ‚€)) × (exp(-αFη/RT) + ((1-α)/α)exp((1-α)Fη/RT))â»Â¹

- Extract apparent α and I₀ values through non-linear regression.

- Account for non-uniform current distribution effects in porous electrodes.

This methodology enables accurate measurement of interfacial charge-transfer kinetics under operationally relevant conditions, providing crucial parameters for optimizing ion absorption processes in electrochemical devices.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Interfacial Studies

| Category | Specific Materials | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Substrate Materials | Ag(100) single crystal, Highly Oriented Pyrolytic Graphite (HOPG) | Provides atomically flat surfaces for model interface studies | Defined crystallographic orientation, low surface roughness |

| Electrode Materials | Single-crystal LiCoOâ‚‚ (LCO), LiFePOâ‚„ (LFP), Artificial graphite | Active materials for battery interface studies | Controlled morphology, well-defined electrochemistry |

| Salts & Electrolytes | Sodium chloride (NaCl), Zinc trifluoromethanesulfonate (Zn(OTf)₂), Lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF₆) | Ionic conductors for fundamental studies and applications | High purity, controlled water content, electrochemical stability |

| Additives & Modifiers | Tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol (THFA), Phenol-formaldehyde resin, Glucose | Interface modification, solvation structure control | Selective adsorption, compatibility with electrochemistry |

| Characterization Tools | 1100 Aluminum alloy foils, Polyimide tape (Kapton), Chloroplatinic acid | Experimental components for specific techniques | Thermal/electrical properties, defined thickness |

Interfacial Structure-Property Relationships

The performance of electrochemical interfaces is governed by fundamental relationships between molecular-level structure and macroscopic properties. Understanding these relationships enables the rational design of interfaces with enhanced functionality.

Water Structure and Electrocatalytic Activity

The structure and orientation of interfacial water molecules profoundly influence electrocatalytic processes. Recent studies have identified specific water configurations that correlate with enhanced activity for reactions such as the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) [11]. Dangling O–H water molecules—characterized by weak interactions between their O–H bonds and the catalyst surface—exhibit superior dissociation activity compared to other water configurations. This enhanced activity stems from reduced energy barriers for water dissociation and improved binding affinity for reactive intermediates [11].

The hydrogen bonding network of interfacial water further modulates electrocatalytic performance by influencing proton transfer kinetics. Well-connected hydrogen-bonded networks facilitate rapid proton transport through the Grotthuss mechanism, while disrupted networks can impede proton diffusion and increase overpotentials. These structure-activity relationships highlight the importance of characterizing and controlling interfacial water structure for optimizing electrocatalytic systems.

Solvation Structure and Interfacial Stability

In energy storage systems, the solvation structure of ions determines their interfacial behavior and the stability of electrode-electrolyte interfaces. In aqueous zinc-ion batteries, the hydration shell of Zn²⺠ions contains water molecules that participate in parasitic reactions at the electrode surface, leading to capacity fade and poor cycling stability [14].

Strategic modification of the solvation structure through electrolyte additives can mitigate these issues. Tetrahydrofurfuryl alcohol (THFA), for example, preferentially adsorbs onto electrode surfaces, displacing interfacial water molecules and forming a protective layer that suppresses water-induced degradation [14]. Simultaneously, THFA interacts with Zn²⺠ions, reducing the coordination number of active water molecules in the primary solvation shell. These dual effects significantly enhance interfacial stability and improve cycling performance, demonstrating how molecular-level control of solvation structure enables practical advances in electrochemical technology.

Surface Chemistry and Ion Absorption Kinetics

The chemical composition and morphology of electrode surfaces directly influence ion absorption kinetics and interfacial charge transfer. In graphite anodes for lithium-ion batteries, the limited interlayer spacing (0.335 nm) constrains lithium-ion insertion, particularly under fast-charging conditions [16]. This limitation becomes especially pronounced at high currents, where localized potential variations can drive lithium plating and dendrite formation.

Surface engineering through hard carbon coatings provides an effective strategy for enhancing ion absorption kinetics. Hybrid graphite anodes with hard carbon coatings exhibit approximately 8% higher reversible lithium content under fast-charging conditions, triple the exchange current density, and reduced Tafel slopes compared to unmodified graphite [16]. These improvements stem from the synergistic interaction between the coating and the underlying graphite, which provides additional lithium storage sites, reduces diffusion barriers, and mitigates electrode polarization. This example illustrates how tailored interface design can overcome intrinsic material limitations to achieve enhanced electrochemical performance.

Diagram 2: Interfacial Structure-Property Relationships

The investigation of interfacial charging mechanisms—dissolution, hydration, and ion absorption—reveals the profound complexity of electrode-solution interfaces. Through advanced experimental and computational techniques, researchers have uncovered fundamental principles governing these processes, from the single-ion dissolution events driven by water-ion interactions to the collective dynamics of solvation shells influencing interfacial charge transfer.

The structure and behavior of interfacial water emerge as a central theme across these mechanisms, serving not merely as a passive medium but as an active participant in electrochemical processes. Understanding and controlling water molecular configurations enables enhanced electrocatalytic activity and improved interface stability. Similarly, tailoring solvation structures and electrode surface properties allows for optimized ion absorption kinetics, directly impacting the performance of energy storage and conversion systems.

As research in this field advances, the integration of multi-scale techniques—from single-molecule manipulation to machine learning-assisted simulations—will continue to unravel the complexities of interfacial phenomena. These insights will guide the rational design of next-generation electrochemical technologies with enhanced efficiency, stability, and functionality, ultimately contributing to solutions for pressing global challenges in energy and sustainability.

The Critical Role of Interfacial Water Networks and Solvent Dynamics

The electrode–electrolyte interface constitutes the critical boundary where key electrochemical processes occur, governing the efficiency of energy conversion systems and catalytic reactions. A deep understanding of these interfaces requires the development of modelling protocols spanning from the local microscale to system-level macroscopic sizes, validated through comparison with high-quality experimental results [17]. Within this interface, water molecules form complex, dynamic networks that mediate proton transfer, influence reaction intermediate adsorption, and determine overall catalytic kinetics. Recent research has revealed that the unique properties of interfacial water molecules—including their distribution, orientation, hydrogen-bonding configuration, and interaction with solvated ions—exert profound effects on electrochemical processes ranging from hydrogen oxidation/evolution reactions to electrocatalytic hydrogenation [18]. The rigidity or flexibility of these water networks significantly impacts mass transport limitations, particularly in alkaline environments where additional energy is required for hydroxyl species to migrate from the electrolyte to the catalyst surface [19]. This technical guide examines the fundamental principles, experimental methodologies, and regulatory strategies for interfacial water networks within the broader context of electrode-solution interfacial phenomena research.

Quantitative Data on Interfacial Water Effects

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings from recent studies investigating interfacial water structure and its impact on electrochemical performance.

Table 1: Performance Enhancement Through Interfacial Water Regulation in Hydrogen Oxidation/Evolution Reactions

| Catalyst System | Modification Strategy | Performance Metric | Enhanced Value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt–Se-2 nanocatalyst | In situ Se leaching & surface Se decoration | Alkaline HOR intrinsic activity (jâ‚€,s) | 0.552 mA cmâ»Â² | [19] |

| Pt–Se-2 nanocatalyst | In situ Se leaching & surface Se decoration | Alkaline HOR mass activity (jâ‚–,m @ 50 mV) | 1.084 mA μgâ»Â¹ | [19] |

| Cos-SO-Ru nanoclusters | Sulfo-oxygen bridging between Co and Ru sites | HOR/HER activity | Significantly higher than Cos-Ru | [20] |

Table 2: Hydration Free Energy Correlation with Surface Chemistry and Pattern

| Surface Chemistry | Pattern Type | Polar Group Fraction | Hydration Free Energy (kBT) | Hydrophobicity Trend |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methyl (nonpolar) | Homogeneous | 0.0 | Lowest | Most hydrophobic |

| Amine-functionalized | Separated | 0.4 | Intermediate | Moderate hydrophobicity |

| Amide-functionalized | Separated | 0.4 | Highest | Least hydrophobic |

| Amine-functionalized | Checkered | 0.4 | Differs from separated | Pattern-dependent |

| Hydroxyl-functionalized | Both | Varying | Non-additive with fraction | Cooperative effects |

Experimental Protocols for Interfacial Water Characterization

In Situ Surface-Enhanced Infrared Absorption Spectroscopy (SEIRAS)

Application: This technique was employed to investigate the structure of interfacial water molecules during the hydrogen oxidation reaction (HOR) on reconstructed Pt–Se catalysts [19].

Detailed Methodology:

- Prepare a thin catalyst film on a reflective substrate (typically gold or platinum)

- Mount the electrode in an electrochemical cell with a calcium fluoride (CaFâ‚‚) window that is IR-transparent

- Acquire background spectra at the controlled potential in an inert atmosphere

- Introduce Hâ‚‚-saturated 0.1 M KOH electrolyte while maintaining potential control

- Collect spectra during linear sweep voltammetry cycles from 0.05 to 1.0 V vs. RHE

- Focus on the O-H stretching region (3000-3600 cmâ»Â¹) and H-O-H bending mode (~1640 cmâ»Â¹)

- Analyze spectral changes to determine water orientation and hydrogen-bonding strength

Key Findings: The accumulated electrons on surface-decorated Se atoms in Pt–Se catalysts induced regulation of the interfacial water structure, disrupting the rigid water network in the electric double-layer region and facilitating OH⻠migration to the catalyst surface [19].

Hydration Free Energy Calculation via Molecular Dynamics

Application: This computational approach quantifies interfacial hydrophobicity by measuring the thermodynamic driving forces underlying hydrophobic assembly [21].

Detailed Methodology:

- Construct atomistic models of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) with defined chemical compositions and patterns

- Perform Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations using packages like GROMACS or NAMD with water models (e.g., TIP3P, SPC/E)

- Apply Enhanced Sampling techniques, specifically Indirect Umbrella Sampling (INDUS)

- Define a cuboidal cavity (2.0 × 2.0 × 0.3 nm³) near the SAM-water interface

- Calculate the hydration free energy (μν), or excess chemical potential, which reports on water density fluctuations

- Analyze a large dataset of SAMs (58 systems) with varying polar groups, compositions, and patterns

- Identify correlations between interfacial water structure features and hydration free energies

Key Findings: Only five specific features of interfacial water structure were required to accurately predict hydration free energies, with the probability of highly coordinated water structures identified as a unique signature of hydrophobicity [21].

In Situ Reconstruction and Phase Transition Monitoring

Application: Studying the dynamic evolution of PtSeâ‚‚ catalysts during activation for alkaline hydrogen oxidation reaction [19].

Detailed Methodology:

- Synthesize hexagonal close-packed PtSeâ‚‚ alloys via colloidal method with varying Pt:Se ratios

- Prepare rotating disk electrode with catalyst ink (catalyst + carbon support + Nafion binder)

- Perform linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) cycles in Hâ‚‚-saturated 0.1 M KOH electrolyte

- Monitor current density evolution over multiple LSV sweeps until performance stabilizes

- Characterize intermediate phases using cyclic voltammetry to identify hydrogen underpotential desorption features

- Conduct ex situ X-ray diffraction at different activation stages to track phase transition from hcp to fcc

- Analyze composition changes via inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectroscopy (ICP-AES)

- Perform post-mortem characterization using HAADF-STEM, EDX mapping, and XPS

Key Findings: The activation process involved dynamic Se leaching and phase transition, resulting in surface Se atom-modified face-centered-cubic Pt-based nanocatalysts with optimized interfacial water structure [19].

Signaling Pathways and Mechanisms of Interfacial Water Regulation

The following diagrams visualize the key mechanisms and experimental workflows for studying interfacial water networks in electrochemical systems.

Interfacial Water Regulation Mechanisms in Hydrogen Electrocatalysis

Experimental Workflow for Interfacial Water Studies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for Interfacial Water Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| PtSeâ‚‚ Alloys | Model catalyst system for studying reconstruction effects | Colloidally synthesized PtSex (x = 1.5, 2, 3) with hcp structure [19] |

| CoSOâ‚„ | Source of cobalt and sulfo-oxygen bridges for bioinspired catalysts | Formation of Cos-SO-Ru atomic pairs via self-sulfidation process [20] |

| 4,4'-bipyridine | Organic ligand for constructing metal-organic precursors | Solvothermal preparation of cobalt-based nanoplates [20] |

| Oxygen-functionalized Carbon Black | Support material for anchoring metal nanoclusters | Provides surface functional groups to anchor metal ions via electrostatic interaction [20] |

| KOH Electrolyte | Alkaline medium for HOR/HER studies | 0.1 M KOH for evaluating catalyst performance in Hâ‚‚-saturated conditions [19] |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Model interfaces with controlled chemistry and patterning | Alkanethiol SAMs with methyl, amine, amide, or hydroxyl end groups [21] |

| Ru Nanoclusters | Active component for hydrogen electrocatalysis | ~2 nm Ru nanoclusters on porous carbon support [20] |

| ARN14988 | ARN14988, MF:C16H24ClN3O5, MW:373.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ARN19874 | ARN19874, MF:C19H14N4O4S, MW:394.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The critical role of interfacial water networks in electrochemical systems represents a paradigm shift in how researchers approach catalyst design and optimization. Rather than focusing exclusively on the electronic structure of catalytic materials, the findings summarized in this technical guide demonstrate that deliberate regulation of interfacial water structure—through surface modification, electric field control, or bioinspired design—offers a powerful pathway to enhance reaction kinetics, particularly in challenging alkaline environments. The experimental protocols and characterization methods outlined herein provide researchers with a comprehensive toolkit for investigating these complex interfacial phenomena. As the field advances, the integration of multi-scale modeling with advanced in situ characterization techniques will further unravel the dynamic behavior of interfacial water, enabling the rational design of next-generation electrochemical systems for energy conversion and beyond.

Probing the Interface: Advanced Computational and Experimental Techniques

The electrode-solution interface is the critical region where key electrochemical processes—such as charge transfer, ion adsorption, and the formation of the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI)—dictate the performance, efficiency, and longevity of energy storage devices [22] [23]. Understanding these complex, dynamic phenomena at the atomic scale is a formidable challenge for experimental techniques alone. Computational modeling, particularly through force-field (Classical) and ab initio molecular dynamics (AIMD), has become an indispensable tool for providing this atomistic insight [24] [25].

This technical guide delineates the core principles, methodologies, and applications of these simulation paradigms within the context of electrode-solution interfacial research. It further explores how emerging approaches, such as machine learning potentials (MLPs), are bridging the gap between the computational efficiency of classical methods and the quantum mechanical accuracy of ab initio approaches [22] [26].

Theoretical Foundations and Methodologies

Force-Field Molecular Dynamics (FF-MD)

Force-Field MD relies on pre-defined analytical potential functions to describe the interactions between atoms. The total energy of the system is typically calculated as a sum of bonded and non-bonded terms [25]:

[ E{\text{total}} = E{\text{bond}} + E{\text{angle}} + E{\text{torsion}} + E{\text{electrostatic}} + E{\text{van der Waals}} ]

The primary limitation of traditional FF-MD is its inability to model chemical reactions, as the bonding topology remains fixed. Reactive force fields (ReaxFF) overcome this by calculating bond order from interatomic distances, allowing for dynamic bond breaking and formation [24]. This is crucial for simulating processes like electrolyte decomposition and SEI formation [24].

Table 1: Key Force Fields for Interfacial Electrochemistry

| Force Field | Type | Key Features | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-reactive (e.g., SPC/E) | Classical | Fixed point charges, fast computation, cannot model reactions [26] | Ion transport, solvation structure, electric double layer (EDL) formation [25] [27] |

| ReaxFF | Reactive | Dynamic bond orders, simulates chemical reactions, higher computational cost [24] | SEI evolution, electrolyte decomposition pathways, gas generation [24] |

Ab Initio Molecular Dynamics (AIMD)

AIMD eliminates the need for pre-defined force fields by calculating the interatomic forces on-the-fly using quantum mechanics, typically within the framework of Density Functional Theory (DFT) [25]. This allows for an explicit description of electronic structure, making it uniquely suited for studying catalytic reactions, electron transfer, and the formation and breaking of chemical bonds at interfaces [22] [25]. However, this quantum accuracy comes at a high computational cost, restricting the accessible time and length scales to typically a few hundred atoms and tens of picoseconds [22] [26].

The Machine Learning Bridge: Hybrid and Accelerated Workflows

To overcome the limitations of both pure FF-MD and AIMD, machine learning potentials (MLPs) have emerged as a powerful alternative. MLPs are trained on high-fidelity data from AIMD simulations and can then model atomic interactions with near-ab initio accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [22] [26].

The HAML (Hybrid AIMD-MLP) scheme is a notable advancement, which iteratively couples AIMD and MLP-driven MD (MLP-MD) to achieve stable, long-timescale simulations of complex interface reactions [22]. In this scheme, AIMD provides accurate training data and guides the reaction pathway, while MLP-MD accelerates the simulation. The process uses an active learning strategy to ensure reliability, interrupting the MLP-MD if it ventures into poorly sampled regions of the configuration space [22]. This method has been shown to achieve speedups of over 10-20 times compared to standard AIMD while maintaining high accuracy [22].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MD Methods for Interface Modeling

| Method | Accuracy | Typical Time Scale | Typical System Size | Ability to Model Reactions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classical MD | Low to Medium | Nanoseconds to Microseconds | >100,000 atoms | No (except with ReaxFF) |

| AIMD | High (Quantum) | Picoseconds to <100ps | 100 - 1,000 atoms | Yes |

| MLP-MD / HAML | High (Near ab initio) | Nanoseconds [26] | 1,000 - 10,000 atoms | Yes |

Experimental Protocols for Key Simulations

Protocol 1: Simulating SEI Formation with ReaxFF MD

Objective: To model the electrochemical decomposition of electrolyte and the dynamic evolution of the solid-electrolyte interphase (SEI) on a lithium-metal anode [24].

System Setup:

- Construct a simulation box containing the Li-metal anode slab and electrolyte molecules (e.g., a mixture of fluorinated solvents like FEMC/FEC and LiPF₆ salt) [24].

- Apply periodic boundary conditions in all three dimensions.

Electrochemical Driving Force:

- Integrate the EChemDID (Electrochemical Dynamics with Implicit Degrees of freedom) method [24]. This applies an electrochemical potential bias between the anode and a hypothetical cathode, simulating the conditions of a operating battery.

Simulation Execution:

- Run the ReaxFF-MD simulation in an NVT ensemble (constant Number of atoms, Volume, and Temperature) using a package like LAMMPS.

- Maintain temperature at the target (e.g., 330 K) using a thermostat like Nosé-Hoover [24].

- Use a time step of 0.5 fs.

Data Analysis:

- Use tools like ReacNetGenerator to identify reaction pathways and products from the trajectory data [24].

- Track the formation of key SEI components (e.g., LiF) and gaseous byproducts (e.g., PF₃).

Protocol 2: Building a Machine Learning Potential with Active Learning

Objective: To develop a robust MLP for simulating a Pt(111)-water interface with ab initio accuracy over nanosecond timescales [26].

Initial Data Generation:

- Perform a short (20-30 ps) AIMD simulation of the interface using CP2K to generate an initial training set of ~50-100 atomic configurations, energies, and forces [26].

Active Learning Workflow:

- Training: Train an ensemble of MLPs (e.g., using DeePMD-kit) on the current dataset.

- Exploration: Run an MLP-MD simulation to sample new configurations.

- Screening: Calculate the maximum disagreement of forces predicted by the MLP ensemble for each new configuration. This identifies regions of the potential energy surface that are poorly sampled.

- Labeling: Select structures with high uncertainty and recompute their energies and forces with AIMD. Add them to the training dataset [26].

- Iterate the "Training-Exploration-Screening-Labeling" cycle until the majority (>99%) of sampled structures have low uncertainty [26].

Production Simulation:

- Use the finalized MLP to run a nanosecond-scale MLP-MD simulation of the interface with LAMMPS to investigate properties like the water structure and dynamics [26].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational workflows for AIMD, MLP, and HAML simulations:

Table 3: Key Software and Datasets for Interfacial Modeling

| Name | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| CP2K | Software | Performs AIMD simulations using a mixed Gaussian and plane-wave basis set approach [26]. | Open Source |

| LAMMPS | Software | A highly versatile MD simulator that can run Classical, ReaxFF, and MLP-MD simulations [24] [26]. | Open Source |

| DeePMD-kit | Software | Trains and runs MLPs within the Deep Potential framework [26]. | Open Source |

| DP-GEN | Software | An automated active learning platform for generating general-purpose MLPs [26]. | Open Source |

| ReacNetGenerator | Software | Analyzes reaction pathways and species from ReaxFF or AIMD trajectories [24]. | Open Source |

| ElectroFace | Dataset | A curated collection of AI-accelerated AIMD trajectories for various electrochemical interfaces (e.g., Pt, SnOâ‚‚, CoO with water) [26]. | Public Dataverse |

Force-field and ab initio molecular dynamics provide complementary and powerful capabilities for probing the complex phenomena at electrode-solution interfaces. While FF-MD is essential for sampling large systems and long timescales, AIMD delivers quantum-accurate insights into reactivity. The emergence of machine learning potentials and hybrid schemes like HAML is revolutionizing the field, enabling the simulation of previously intractable problems with both high efficiency and high fidelity. These advanced computational toolkits are paving the way for the rational design of next-generation electrochemical materials and devices, from more stable battery anodes to highly selective electrocatalysts.