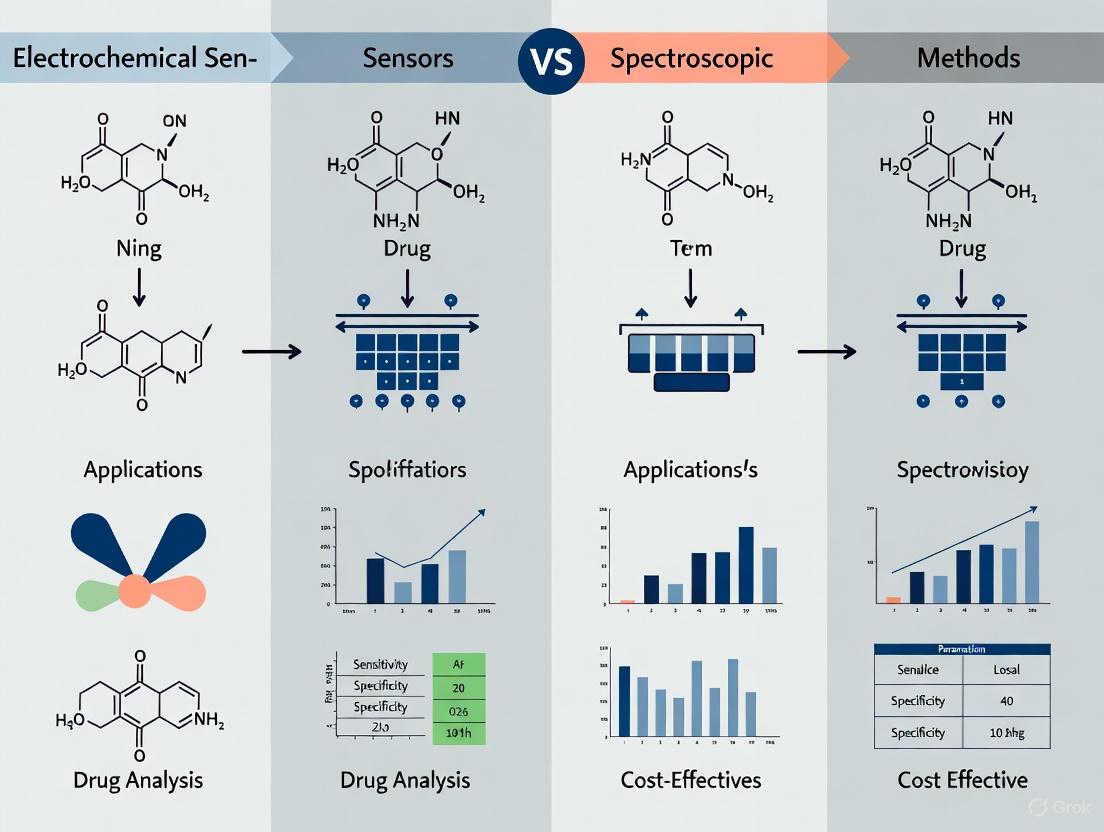

Electrochemical vs. Spectroscopic Methods for Drug Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

This article provides a comparative analysis of electrochemical and spectroscopic techniques for pharmaceutical and bioanalytical applications.

Electrochemical vs. Spectroscopic Methods for Drug Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of electrochemical and spectroscopic techniques for pharmaceutical and bioanalytical applications. It explores the fundamental principles of both methods, details their specific applications in drug and metabolite detection, and addresses common troubleshooting and optimization strategies. A direct performance comparison is presented, evaluating sensitivity, selectivity, cost, and portability to guide researchers in selecting the appropriate methodology for drug development, therapeutic monitoring, and forensic analysis.

Core Principles: Understanding Electrochemical and Spectroscopic Sensing

The accurate and sensitive detection of pharmaceutical compounds is a cornerstone of modern drug analysis, vital for therapeutic drug monitoring, quality control, and combating antibiotic resistance. While spectroscopic methods have traditionally been used, electrochemical sensors are increasingly recognized for their superior performance in many scenarios. Spectroscopic techniques, such as Raman and mass spectrometry, provide excellent molecular fingerprinting but often require sophisticated, costly equipment and extensive sample preparation, limiting their use for rapid, on-site testing [1].

In contrast, electrochemical sensors offer a powerful alternative due to their high sensitivity, rapid response, cost-effectiveness, and exceptional portability [2] [3]. These devices operate by transducing a chemical interaction into a quantifiable electrical signal, such as current, potential, or charge. For drug analysis research, this translates to the ability to detect trace levels of drugs in complex matrices like blood, sweat, or food samples with minimal pre-treatment. The core principles underpinning these sensors are categorized mainly into amperometric, potentiometric, and voltammetric techniques. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these three foundational electrochemical techniques, equipping researchers with the knowledge to select the optimal method for their specific analytical challenges in drug development.

Core Principles and Techniques

Electrochemical sensors function as transducers, converting chemical information about an analyte into an analytically useful electrical signal. Their performance is defined by the specific technique employed, each with distinct operational mechanisms and output signals.

Potentiometric Sensors

Potentiometry involves the measurement of an electrical potential (or voltage) under conditions of zero or negligible current flow [4] [3]. The measured potential is proportional to the logarithm of the target ion's activity, as described by the Nernst equation. The core component is often an Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE), which incorporates a membrane designed to be selectively interactive with a particular ion [4].

A key advancement is the move from traditional liquid-contact ISEs to solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs), which eliminate the inner filling solution. This innovation enhances mechanical stability, facilitates miniaturization, and is ideal for wearable sensors [4] [5]. The mechanism of signal transduction in SC-ISEs relies on materials like conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT, polyaniline) or carbon-based nanomaterials, which act as ion-to-electron transducers. Two primary mechanisms have been identified:

- Redox Capacitance Mechanism: The solid-contact material undergoes a highly reversible redox reaction, translating ionic signals from the membrane into electronic signals for the electrode [4].

- Electric-Double-Layer Capacitance Mechanism: An asymmetric capacitor forms at the interface between the ion-selective membrane and the solid contact, generating the transduction signal [4] [5].

Voltammetric Sensors

Voltammetry is the process of measuring the current that results from applying a controlled, varying potential to a working electrode [2]. The resulting current-potential plot (a voltammogram) provides rich information about the analyte, including its concentration, redox potential, and the kinetics of the electron transfer reaction.

Several voltammetric techniques are distinguished by their potential waveform:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): The potential is swept linearly in a triangular waveform between two set values. CV is primarily used for qualitative analysis, such as studying redox mechanisms and characterizing electrode surfaces [2].

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Small potential pulses are superimposed on a linear base potential ramp. The current is measured just before the pulse and at the end of the pulse, and the difference is plotted. This technique minimizes capacitive background current, resulting in much lower detection limits compared to CV, making it ideal for trace-level quantitative analysis [2] [6].

- Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV): A square-wave modulation is applied to a staircase ramp, offering very fast scans and high sensitivity similar to DPV.

Amperometric Sensors

Amperometry is a subset of voltammetry where a constant potential is applied, and the resulting steady-state current is measured over time [2] [3]. The current is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive analyte. This technique is highly suited for continuous monitoring and real-time analysis, as the simplified signal output is easily integrated into flow systems or portable devices. The fundamental relationship for the current in a controlled-potential experiment is described by the Cottrell equation [3].

Table 1: Comparative Overview of Key Electrochemical Techniques

| Feature | Potentiometry | Voltammetry | Amperometry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measured Signal | Potential (Voltage) | Current | Current |

| Applied Signal | Zero current | Variable potential | Constant potential |

| Primary Output | Logarithmic concentration | Current vs. Potential plot | Current vs. Time |

| Key Strength | High selectivity for ions, power efficiency, miniaturization | Rich mechanistic information, very low detection limits (e.g., DPV) | Simplicity, suitability for continuous monitoring |

| Common Drug Analysis Use | Monitoring ionic drugs (e.g., antibiotics), electrolytes in biofluids | Detection and quantification of redox-active drugs (e.g., NSAIDs, antibiotics) | Continuous biosensing, flow-injection analysis |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

The performance of electrochemical sensors is critically dependent on the choice of technique and electrode modification. The following data, synthesized from recent research, highlights their capabilities in detecting pharmaceutical compounds.

Table 2: Analytical Performance in Drug Detection

| Analyte | Technique | Electrode Modification | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Sample Matrix | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tobramycin | DPV | Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) / AgNPs on Au-SPE | 0.001 - 60 pg mLâ»Â¹ | 1.9 pg mLâ»Â¹ | Food (chicken, beef, milk) | [6] |

| Anti-inflammatory & Antibiotic Drugs | DPV, SWV | Nanostructured carbon, Metal Nanoparticles, Polymer Composites | Sub-micromolar range | Sub-micromolar to picomolar | Biological & Environmental | [2] |

| Sodium (Naâº) | Potentiometry | PEDOT:PSS/Graphene + Nafion ISM | 10â»â´ to 10â»Â² M | N/A | Human Sweat | [7] |

| Potassium (Kâº) | Potentiometry | PEDOT:PSS/Graphene + Nafion ISM | 10â»â´ to 5x10â»Â³ M | N/A | Human Sweat | [7] |

Experimental Protocols for Drug Detection

To achieve the high sensitivity and selectivity demonstrated in Table 2, rigorous experimental protocols are followed. Below is a generalized workflow for developing a modified electrochemical sensor for drug analysis, incorporating elements from the cited studies.

1. Electrode Pretreatment and Modification:

- Baseline Preparation: The working electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE)) is polished with alumina slurry and thoroughly rinsed to ensure a clean, reproducible surface [2].

- Nanomaterial Modification: To enhance the electroactive surface area and electron transfer kinetics, a dispersion of a nanomaterial (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes, MXenes) is drop-cast onto the electrode surface and allowed to dry [2].

- Recognition Layer Fabrication: A selective layer is immobilized on the nanomaterial-modified electrode. Common approaches include:

- Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP): The electrode is immersed in a solution containing the target drug (template), a functional monomer, and a cross-linker. Electropolymerization (e.g., using cyclic voltammetry) is performed to form a polymer network with specific cavities for the drug. The template is then extracted [6].

- Biosensing Elements: Enzymes, antibodies, or aptamers can be cross-linked to the surface to provide biological specificity [2] [8].

2. Electrochemical Measurement and Detection:

- The modified electrode is immersed in a buffer solution containing the target drug.

- The appropriate technique is applied:

- For quantitative detection of antibiotics like Tobramycin, DPV is often used due to its high sensitivity. The oxidation current peak of the drug (or a redox probe like ferricyanide whose signal changes upon binding) is measured [6].

- For continuous monitoring of ions, Potentiometry is used by measuring the potential difference between the ISE and a reference electrode over time [7].

- A calibration curve is constructed by plotting the signal (current for DPV, potential for potentiometry) against the logarithm of the analyte concentration.

Diagram 1: Electrochemical Sensor Experimental Workflow. This flowchart outlines the key steps for preparing a modified electrode and performing an electrochemical detection assay.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of electrochemical sensors is heavily reliant on the materials used in their construction. The table below lists key components and their functions in sensor development.

Table 3: Essential Materials for Electrochemical Sensor Research

| Material Category | Example | Function in the Sensor |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Substrates | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPE), Gold Electrode | Provides a conductive base platform for electron transfer and modification. SPEs offer disposability and portability [2] [6]. |

| Nanomaterials | Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), MXenes, Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Ag, Au) | Enhances electrical conductivity, increases surface area, and can catalyze reactions, leading to lower detection limits and higher sensitivity [2] [5]. |

| Conducting Polymers | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polyaniline (PANI) | Acts as an ion-to-electron transducer in solid-contact potentiometric sensors, stabilizing the potential and facilitating signal conversion [4] [5] [7]. |

| Recognition Elements | Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs), Aptamers, Enzymes, Antibodies | Provides high selectivity by creating specific binding sites complementary to the shape, size, and functional groups of the target molecule [2] [6] [8]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Poly(vinyl chloride) (PVC) with plasticizer, Ionophore, Ion-exchanger | Key component of potentiometric sensors; the membrane selectively interacts with the target ion, generating a potential response [4] [7]. |

| HaloPROTAC-E | HaloPROTAC-E|Potent HaloTag Degrader | HaloPROTAC-E is a potent, selective degrader of HaloTag-fused proteins (DC50 3-10 nM). For Research Use Only. Not for human or therapeutic use. |

| Henagliflozin | Henagliflozin, CAS:1623804-44-3, MF:C22H24ClFO7, MW:454.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Amperometric, potentiometric, and voltammetric techniques each offer a unique set of advantages for drug analysis research. The choice of technique is dictated by the analytical goal: voltammetry (particularly DPV) for ultra-sensitive quantification, potentiometry for stable, selective ion monitoring, and amperometry for continuous, real-time sensing.

The ongoing convergence of electrochemistry with materials science is pushing the boundaries of sensor capabilities. Future research is focused on the development of multiplexed sensors capable of simultaneously detecting several analytes, the integration of wearable platforms for point-of-care testing, and the use of artificial intelligence to interpret complex data from electronic tongue systems [2] [5] [6]. These advancements solidify the role of electrochemical sensors as indispensable, robust, and accessible tools that complement and, in many applications, surpass traditional spectroscopic methods for modern drug analysis.

The analysis of pharmaceutical compounds, both in development and in environmental and biological matrices, is a critical challenge for modern science. Within this field, a methodological debate exists between the use of electrochemical sensors and various spectroscopic techniques. This guide provides an objective comparison of four foundational spectroscopic methods—UV-Vis, IR, Raman, and Mass Spectrometry—framed within the context of drug analysis research. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the capabilities, limitations, and appropriate application domains of each technique is essential for selecting the optimal analytical tool [9].

The drive towards more sensitive, selective, and rapid analysis is fueled by the need to monitor drug concentrations for therapeutic drug monitoring, detect emerging pharmaceutical pollutants in the environment, and ensure quality control in manufacturing. While electrochemical sensors offer advantages in portability, cost, and real-time analysis, spectroscopic methods provide a powerful suite of techniques for identification, characterization, and quantification [9]. This article will dissect the fundamental principles of each spectroscopic method, compare their performance metrics with empirical data, and detail standard experimental protocols to inform method selection in pharmaceutical research.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison

Spectroscopic techniques probe the interaction of matter with electromagnetic radiation or, in the case of mass spectrometry, the mass-to-charge ratio of ionized molecules. Each method provides a unique window into molecular structure and composition.

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy measures the absorption of light in the ultraviolet and visible regions (∼200–800 nm), which promotes electrons from the ground state to an excited state [10]. The fundamental relationship governing this absorption is the Beer-Lambert Law (A = εbc), which states that absorbance (A) is proportional to the concentration (c) of the analyte, its molar absorptivity (ε), and the path length (b) of the sample [10]. This makes UV-Vis primarily quantitative in nature, ideal for determining concentrations and monitoring reaction kinetics, though it offers limited structural information.

Infrared (IR) Spectroscopy analyzes the absorption of infrared light, which excites molecular vibrations [11]. The technique is exceptionally useful for identifying organic functional groups, as these groups absorb at characteristic frequencies. For example, carbonyl groups (C=O) produce strong, sharp peaks around 1700 cmâ»Â¹, while hydroxyl groups (O-H) show broad peaks in the 3200-3600 cmâ»Â¹ region [12]. The region from 1500 to 500 cmâ»Â¹, known as the "fingerprint region," is complex and unique to each molecule, allowing for definitive identification [11] [12]. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectrometers are now the standard, offering high speed and sensitivity [11].

Raman Spectroscopy is another vibrational technique but is based on a different principle: the inelastic scattering of monochromatic light, usually from a laser [13] [14]. When light interacts with a molecule, a tiny fraction of the scattered light (Raman scattering) shifts in energy corresponding to the vibrational energies of the molecule. This shift, known as the Raman shift, is plotted to create a spectrum that serves as a "chemical fingerprint" [13]. A key distinction from IR is that Raman spectroscopy relies on a change in a molecule's polarizability during vibration, making it particularly strong for detecting symmetric vibrations and bonds like C-C, C=C, and S-S [14]. Its complementarity to IR means that some vibrations weak in an IR spectrum may be strong in a Raman spectrum, and vice-versa.

Mass Spectrometry (MS) operates on a fundamentally different principle. It does not involve light absorption but rather measures the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of gas-phase ions [15]. The process involves three core steps: (1) Ionization, where the sample is converted into ions (e.g., by Electron Ionization (EI) or Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI)); (2) Mass Analysis, where the ions are separated based on their m/z (e.g., in a Time-of-Flight (TOF) analyzer); and (3) Detection, where the abundance of each ion is recorded [15]. The resulting mass spectrum provides information on the molecular weight, elemental composition, and—through fragmentation patterns—the molecular structure.

The table below summarizes the core principles and primary applications of each technique.

Table 1: Fundamental Principles of Spectroscopic and Mass Spectrometry Techniques

| Technique | Fundamental Principle | Measured Quantity | Primary Information Obtained | Key Applications in Drug Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Electronic transitions (e.g., π→π, n→π) | Absorbance of UV/Vis light | Concentration, reaction monitoring | Quantitative analysis in dissolution testing, assay of dosage forms [10] |

| IR Spectroscopy | Absorption of IR light exciting molecular vibrations | Wavenumber (cmâ»Â¹) | Functional groups, molecular identity | Raw material identification, polymorph screening [11] [12] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Inelastic scattering of monochromatic light | Raman Shift (cmâ»Â¹) | Molecular vibrations, crystal structure | Non-destructive analysis of APIs, mapping solid dosage forms [13] [14] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Ionization and separation by mass-to-charge ratio | Mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) | Molecular weight, structure, composition | Metabolite identification, impurity profiling, bioequivalence studies [15] |

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

When selecting an analytical method for drug analysis, performance metrics such as sensitivity, selectivity, and analytical speed are paramount. The following table provides a comparative overview of these characteristics, contextualized with experimental data from pharmaceutical applications.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Spectroscopic and Mass Spectrometry Techniques in Drug Analysis

| Technique | Typical Sensitivity | Key Strengths | Key Limitations | Representative Experimental Data (from search results) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UV-Vis Spectroscopy | Moderate (μM range) | Simple operation, cost-effective, excellent for quantification | Poor for complex mixtures, low structural info, requires chromophore | Calibration curves for Rose Bengal show high linearity (R² > 0.9) for quantification [10] |

| IR Spectroscopy | High | Excellent for functional group ID, fast analysis (FTIR) | Affected by water, weak for symmetric bonds, sample prep can be complex | SF6 decomposition products (CO, SOâ‚‚) detected at low concentrations using FTIR [16] |

| Raman Spectroscopy | Variable (can be very high with SERS) | Minimal sample prep, works through packaging, good for aqueous samples | Susceptible to fluorescence, can damage samples, weak signal | Acetaminophen studied with EC-SERS; signal strongly enhanced at -600 mV potential [17] |

| Mass Spectrometry | Very High (pM-nM range) | Ultra-high sensitivity, unambiguous MW, structural info from fragmentation | Complex instrumentation, requires vacuum, can be destructive | High-resolution MS distinguishes Nâ‚‚ (28.0061) from CO (27.9949), critical for unambiguous ID [15] |

The data reveals a clear trade-off between the universality and information content of a technique and its operational complexity. For instance, the high sensitivity and structural elucidation power of Mass Spectrometry and Raman Spectroscopy (especially SERS) make them powerful for research and method development. In contrast, the robustness and simplicity of UV-Vis and IR spectroscopy sustain their utility in quality control and routine analysis [9].

A significant trend in modern analysis is the hybridization of techniques to overcome individual limitations. A prime example is the combination of electrochemistry with Raman spectroscopy, known as Electrochemical Surface-Enhanced Raman Spectroscopy (EC-SERS). This method was used to study the adsorption of acetaminophen on a copper surface, where applying an electrode potential of -600 mV significantly enhanced the Raman signal by modulating the charge transfer between the molecule and the metal substrate [17]. Similarly, one study combined electrochemical sensors with FTIR for detecting SF₆ decomposition products, leveraging the strengths of both methods to create a more reliable and accurate detection system [16]. These hybrid approaches illustrate the potential for synergistic performance that exceeds the capabilities of any single technique.

Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and reliable data, standardized experimental protocols are essential. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in this guide.

Protocol: Quantitative Analysis of a Drug Compound using UV-Vis Spectroscopy

This protocol outlines the steps to create a calibration curve and determine the concentration of an unknown sample of acetaminophen, a common analgesic, using UV-Vis spectroscopy [10].

- Instrument Calibration: Turn on the UV-Vis spectrometer and allow the lamp to warm up for at least 15 minutes. Select the appropriate wavelength (e.g., 243 nm for acetaminophen).

- Preparation of Stock Solution: Accurately weigh 50 mg of acetaminophen reference standard. Dissolve and dilute to 100 mL with a suitable solvent (e.g., water or methanol) in a volumetric flask to create a 500 μg/mL stock solution.

- Preparation of Calibration Standards: Using volumetric pipettes, dilute the stock solution to prepare at least five standard solutions covering a concentration range (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 μg/mL) in volumetric flasks.

- Blank Measurement: Fill a quartz cuvette with the pure solvent and place it in the spectrometer. Record a baseline spectrum or set the absorbance to zero.

- Standard Measurement: Replace the blank with each standard solution, one at a time. Record the absorbance at the analytical wavelength for each standard.

- Calibration Curve: Plot the absorbance (y-axis) versus the concentration (x-axis) of the standards. Perform linear regression to obtain the equation of the line (y = mx + c) and the correlation coefficient (R²). A value of 0.999 or greater is desirable.

- Analysis of Unknown: Measure the absorbance of the unknown acetaminophen sample under the same conditions. Use the calibration equation to calculate its concentration.

Protocol: Functional Group Identification using IR Spectroscopy

This protocol describes how to obtain and interpret the IR spectrum of 1-hexanol to identify its alcohol functional group [12].

- Sample Preparation (Liquid Film Method): For a neat liquid like 1-hexanol, place a single drop of the sample between two polished potassium bromide (KBr) plates to create a thin film. Clamp the plates together and mount them in the FTIR sample holder.

- Background Collection: Collect a background spectrum with no sample in the beam (or with the empty KBr plates) to correct for atmospheric absorption.

- Sample Spectral Acquisition: Place the prepared sample in the beam path and collect the IR spectrum over the range of 4000 to 500 cmâ»Â¹.

- Interpretation:

- Identify the broad, rounded "tongue-like" peak in the region of 3200-3600 cmâ»Â¹. This is the characteristic O-H stretch of an alcohol.

- Confirm the absence of a strong, sharp "sword-like" peak in the 1650-1800 cmâ»Â¹ region, which would indicate a carbonyl (C=O) group. Its absence confirms the molecule is an alcohol and not a carboxylic acid or carbonyl-containing compound.

- Note other peaks for completeness: C-H stretches just below 3000 cmâ»Â¹, and the C-O stretch around 1050-1150 cmâ»Â¹.

Protocol: Structural Confirmation using Mass Spectrometry

This protocol outlines the steps for obtaining an Electron Ionization (EI) mass spectrum of an organic molecule to confirm its molecular weight and observe its fragmentation pattern [15].

- Sample Introduction: For a volatile sample, introduce a small amount (e.g., 1 µL) via a direct insertion probe or a gas chromatography (GC) inlet. The sample is vaporized in the ion source.

- Ionization: In the high-vacuum ion source, the vaporized sample is bombarded with a high-energy electron beam (typically 70 eV). This knocks an electron out of the molecule, generating a molecular ion (Mâºâ€¢).

- Mass Analysis (Time-of-Flight): The positively charged ions are accelerated by an electric field into a flight tube. Lighter ions travel faster and reach the detector before heavier ions. The time-of-flight is converted to mass-to-charge ratio (m/z).

- Detection and Data Analysis: The detector records the abundance of ions at each m/z value. The spectrum is plotted as relative intensity vs. m/z.

- Identify the molecular ion peak, which corresponds to the molecular weight of the intact molecule.

- Analyze key fragment ions. For example, in the drug spectrum with Mâºâ€¢ at m/z 303, fragments at m/z 242 and 182 represent successive loss of functional groups, providing clues about the molecular structure.

- Check for isotope patterns. The presence of chlorine or bromine atoms gives distinctive isotope patterns (e.g., a 3:1 ratio for chlorine-35/37).

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The analytical process for drug characterization often follows a logical workflow, and the underlying mechanisms of techniques like SERS involve specific energy pathways. The following diagrams visualize these relationships.

Analytical Workflow for Drug Characterization

This diagram illustrates a decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate spectroscopic technique based on the analytical question in drug development.

Signaling Pathway in Raman Spectroscopy

This diagram depicts the energy transfer pathways involved in Rayleigh, Stokes, and Anti-Stokes scattering, which are fundamental to Raman spectroscopy.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and reagents commonly used in experiments with the discussed spectroscopic techniques, particularly in a pharmaceutical analysis context.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Function/Application | Exemplary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Bromide (KBr) Plates | IR-transparent window material for liquid sample analysis | Creating a thin film of a liquid sample (e.g., 1-hexanol) for FTIR analysis [12] |

| Electrochemical Sensor (3-electrode) | Amperometric detection of specific gases or electroactive species | Detecting CO, SO₂, and H₂S from SF₆ decomposition in combination with IR [16] |

| Cuvette (Quartz or Glass) | Sample holder for UV-Vis and fluorescence spectroscopy | Holding acetaminophen solutions for quantitative absorbance measurement [10] |

| Mass Spectrometry Calibrant | Provides known m/z peaks for accurate mass calibration | Establishing calibration curves in Time-of-Flight (TOF) mass analyzers [15] |

| SERS-Active Substrate (e.g., Cu, Au, Ag nanoparticles) | Enhances Raman signal via electromagnetic and chemical mechanisms | Studying adsorption dynamics of acetaminophen in EC-SERS experiments [17] |

| HPLC-grade Solvents (e.g., Water, Methanol) | High-purity solvents for sample preparation and mobile phases | Preparing standard solutions and blanks to minimize background interference [10] |

The Role of Transducers and Receptors in Sensor Design and Specificity

In the analytical sciences, the accurate detection of substances, particularly in complex matrices like pharmaceutical compounds and biological samples, relies on the sophisticated integration of two fundamental components: receptors and transducers. These elements work in concert to determine the specificity, sensitivity, and overall performance of a sensing device. Receptors are molecular recognition elements responsible for the selective binding of the target analyte. They define the sensor's specificity, ensuring that the signal generated originates from the intended molecule and not from interfering substances in the sample. In drug analysis, this is paramount due to the complex nature of biological fluids such as blood, urine, and saliva, which contain myriad other compounds [18] [19].

The transducer, on the other hand, serves as the signal conversion unit. It transforms the specific chemical recognition event that occurs between the receptor and the target analyte into a measurable and quantifiable electrical or optical signal. The efficiency of this transduction process directly governs the sensor's sensitivity, detection limit, and speed of analysis [20] [21]. The design and material composition of the transducer are therefore critical for achieving low limits of detection and a wide linear response range.

This guide objectively compares two dominant sensing paradigms—electrochemical sensors and spectroscopic methods—within the context of drug analysis research. The comparison is framed by examining how each technology utilizes receptors and transducers to solve analytical challenges, supported by experimental data and performance metrics. The ongoing pursuit in analytical chemistry is to develop methods that are not only accurate but also rapid, cost-effective, and suitable for use in resource-limited settings, driving innovation in both these fields [18] [2].

Fundamental Principles: How Receptors and Transducers Work

The Role of Receptors in Molecular Recognition

Receptors are the cornerstone of sensor specificity. They are engineered to have a high affinity for a particular drug molecule, effectively filtering it out from a complex sample matrix. In both electrochemical and spectroscopic systems, several types of receptors are commonly employed:

- Natural Antibodies: These proteins offer high specificity through immunochemical antigen-antibody binding. For instance, electrochemical immunosensors use antibodies immobilized on an electrode surface to capture target protein biomarkers or drug molecules, forming an immunocomplex that alters the electrical properties of the interface [19].

- Aptamers: These are single-stranded DNA or RNA oligonucleotides that fold into specific three-dimensional shapes to bind with high affinity to targets, from small molecules to proteins. They are often called "synthetic antibodies" and are valued for their stability and ease of synthesis [19].

- Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): MIPs are artificial receptors created by polymerizing functional monomers in the presence of a target molecule (the template). After template removal, cavities complementary in size, shape, and functional groups to the target remain. These "plastic antibodies" provide excellent chemical stability and are widely used in sensors for antibiotics like azithromycin and ofloxacin [18] [22].

- Ionophores and Ion-Exchange Materials: Used primarily in potentiometric sensors, these are host molecules that selectively bind to specific ions related to drugs or their metabolites. They are incorporated into a membrane and facilitate the development of a potential difference dependent on the ion's activity [18] [21].

The Role of Transducers in Signal Conversion

The transducer determines the nature of the output signal. The main categories of transducers and their operating principles are detailed below.

Table 1: Fundamental Types of Transducers and Their Principles.

| Transducer Type | Primary Measurement | Governing Principle | Common Sensor Types |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical | Electrical Signal (Current, Potential, Impedance) | Redox reactions or charge accumulation at the electrode-solution interface [20] [21]. | Amperometric, Potentiometric, Impedimetric, Voltammetric Sensors |

| Spectroscopic | Light-Matter Interaction (Absorption, Emission) | Quantized energy transitions in molecular bonds or electrons [23]. | Fluorescence, Infrared (IR), Raman, UV-Vis Spectrometers |

| Mass-Sensitive | Frequency Change | Piezoelectric effect; mass change on surface alters resonant frequency [24]. | Quartz Crystal Microbalance (QCM) |

Electrochemical Transduction Techniques

Electrochemical transducers dominate portable drug sensing due to their ease of miniaturization and high sensitivity [21]. The specific technique chosen impacts the sensor's performance:

- Amperometry & Voltammetry: Measure the current resulting from the oxidation or reduction of an electroactive drug molecule at a specific applied potential. Techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) enhance sensitivity by minimizing charging currents [18] [2].

- Potentiometry: Measures the potential difference between a working and reference electrode at near-zero current. The potential follows a logarithmic relationship with the target ion's activity, as described by the Nernst equation [20] [21].

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Measures the impedance of the electrode interface, often used for label-free detection of binding events that block electron transfer, such as an antibody capturing an antigen [19].

Spectroscopic Transduction Techniques

Spectroscopic transducers provide rich chemical structure information and are often used in laboratory-based drug analysis [23].

- Vibrational Spectroscopy (IR, Raman): Probes the absorption or scattering of light associated with molecular bond vibrations. The frequency ( ν ) is determined by the bond's force constant ( k ) and the reduced mass ( μ ) of the atoms: ν = (1/2π)√( k / μ ) [23]. This creates a unique "molecular fingerprint."

- Fluorescence Spectroscopy: Measures the emission of light from a molecule after it has been excited by a higher-energy photon. It is highly sensitive but requires the analyte to be intrinsically fluorescent or labeled with a fluorescent tag [23].

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and functional separation between receptors and transducers in a generalized sensor design.

Diagram 1: The core signaling pathway in sensor operation, showing the distinct roles of the receptor and transducer.

Comparative Analysis: Electrochemical vs. Spectroscopic Methods

This section provides a direct, data-driven comparison of the two technologies for drug analysis, focusing on their performance and practical implementation.

Analytical Performance and Experimental Data

The following table summarizes the typical performance characteristics of electrochemical and spectroscopic methods as reported in recent research for drug detection in biological and pharmaceutical samples [18] [22] [2].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Drug Analysis.

| Parameter | Electrochemical Sensors | Spectroscopic Methods (e.g., UV-Vis, Fluorescence) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Limit of Detection (LOD) | Femtomolar (fM) to micromolar (μM) [18] [22]. Common examples: 0.18 nM for Ofloxacin [22], 0.023 nM for Azithromycin [22]. | Micromolar (μM) to millimolar (mM) for UV-Vis; can be lower for fluorescence [18] [2]. |

| Sensitivity | Very High (e.g., 0.1342 μA/μM for Ketoconazole [22]) | Moderate to High (depends on molar absorptivity/quantum yield) [2] |

| Analysis Speed | Seconds to minutes [18] [21] | Minutes to hours (can involve lengthy sample prep) [22] [23] |

| Selectivity Mechanism | Primarily from receptor (MIP, antibody, aptamer); can be affected by electroactive interferents [18]. | Primarily from spectral fingerprint (IR/Raman) or specific wavelength; can suffer from overlapping peaks [23]. |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal often required; compatible with complex matrices [21]. | Often extensive; may require derivation, extraction, or purification [22] [23]. |

| Cost & Portability | Low-cost, portable devices possible (e.g., screen-printed electrodes) [22] [21]. | Generally high-cost, benchtop instrumentation; limited portability [2]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

To illustrate how these sensors are built and operated, here are detailed protocols for two representative experiments: a modified electrochemical sensor and a spectroscopic monitoring setup.

Protocol 1: Fabrication and Use of a Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE) Modified with Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) for Antibiotic Detection

This protocol is adapted from studies detecting drugs like Azithromycin and Oflexacin [18] [22].

1. Electrode Fabrication:

- Prepare Carbon Paste: Mix graphite powder and a suitable binder (e.g., paraffin oil/Nujol) in a typical 70:30 ratio (w/w) to form a homogeneous paste.

- Modify with MIP: Synthesize the MIP separately by polymerizing functional monomers (e.g., methacrylic acid) in the presence of the target antibiotic molecule (template). After polymerization, remove the template by washing to create specific recognition cavities. Incorporate the ground MIP particles into the carbon paste mixture.

- Pack the Electrode: Pack the modified carbon paste firmly into a Teflon or glass tube electrode body, ensuring electrical contact with a copper wire or rod.

2. Drug Detection Experiment (Differential Pulse Voltammetry - DPV):

- Instrument Setup: Configure a potentiostat with a three-electrode system: the modified CPE as the working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a platinum wire counter electrode.

- Calibration: Immerse the electrode system in a series of standard solutions of the target antibiotic in a supporting electrolyte (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0). Record DPV curves over a suitable potential window.

- Sample Measurement: Introduce the unknown sample (e.g., diluted urine or pharmaceutical formulation) into the cell and record the DPV signal.

- Quantification: Measure the peak current and correlate it to the antibiotic concentration using the calibration curve.

Protocol 2: Real-Time Monitoring of a Pharmaceutical Bioprocess Using In-Line Fluorescence Spectroscopy

This protocol is based on applications for monitoring fermentation and other bioprocesses [23].

1. Sensor Setup and Calibration:

- Probe Installation: Insert a sterile, non-invasive fluorescence probe directly into the bioreactor (in-line monitoring).

- Configure Spectrofluorometer: Connect the probe to a fluorescence spectrometer. Set the excitation and emission wavelengths based on the intrinsic fluorescence of the target molecule (e.g., tryptophan in proteins, NAD(P)H for metabolic monitoring).

- Develop Calibration Model: Collect fluorescence spectra from samples with known analyte concentrations (determined by off-line reference methods). Use chemometric algorithms (e.g., Partial Least Squares - PLS) to build a model correlating spectral features to concentration.

2. Process Monitoring:

- Data Acquisition: Throughout the bioprocess, continuously or intermittently collect fluorescence spectra.

- Real-Time Prediction: Feed the acquired spectra in real-time into the pre-calibrated PLS model to predict the analyte concentration.

- Process Control: Use the predicted concentration values to inform decisions or automate control actions (e.g., nutrient feeding).

The workflow for this spectroscopic monitoring is depicted below.

Diagram 2: Workflow for real-time bioprocess monitoring using in-line fluorescence spectroscopy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance and reproducibility of sensor research depend critically on the quality and suitability of the materials used. The following table lists key reagents and their functions in developing and using sensors for drug analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Sensor Development.

| Category & Item | Primary Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | ||

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Provides a polished, renewable, and versatile solid electrode surface for modification and fundamental electroanalysis [22] [2]. | Baseline electrode for studying drug redox behavior; substrate for nanomaterial coatings. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPE) | Disposable, mass-producible, portable platforms for decentralized testing. Often come as a complete three-electrode system on a chip [22] [21]. | Point-of-care therapeutic drug monitoring; forensic on-site screening. |

| Carbon Paste (CP) | A mixture of graphite powder and binder; allows easy bulk modification with receptors and nanomaterials. Surface can be renewed by simple polishing [22]. | Fabrication of MIP- or nanocomposite-modified electrodes for antibiotic detection. |

| Nanomaterials | ||

| Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Enhance electron transfer kinetics and increase electroactive surface area, leading to higher sensitivity [18] [22]. | Signal amplification in voltammetric detection of NSAIDs and antibiotics. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Exhibit high conductivity and catalytic activity; facilitate biomolecule immobilization via Au-S bonds [22] [19]. | Immobilization of antibodies in immunosensors; catalytic labeling in sandwich assays. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) / Reduced GO | Offers a large surface area with abundant oxygen-containing groups for anchoring receptors and biomolecules [22]. | Platform for constructing high-loading biosensors for protein biomarkers. |

| Receptors | ||

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic, stable receptors that provide high selectivity for small molecule drugs [18] [22]. | Selective extraction and detection of drugs like Azithromycin in urine and serum. |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based receptors with high affinity; offer design flexibility and stability compared to antibodies [19]. | Targeting specific drug molecules or protein biomarkers in compact biosensors. |

| Ionophores (e.g., Valinomycin) | Selective ion-binding molecules used in potentiometric sensor membranes [18] [21]. | Creating ion-selective electrodes for drug ions or metabolites. |

| HG6-64-1 | HG6-64-1, MF:C32H34F3N5O2, MW:577.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HG-9-91-01 | HG-9-91-01, CAS:1456858-58-4, MF:C32H37N7O3, MW:567.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between electrochemical and spectroscopic methods for drug analysis is not a matter of one being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific research question and application context. This comparison guide has delineated their respective strengths through the lens of their core components—receptors and transducers.

Electrochemical sensors excel where requirements include high sensitivity, rapid analysis, portability, and low cost. Their transduction mechanism, which converts a chemical event directly into an electrical signal, is inherently suited for miniaturization and integration into point-of-care devices. The primary challenge remains in ensuring absolute selectivity in exceptionally complex biological matrices, a problem that is being addressed through the sophisticated design of molecularly imprinted polymers, aptamers, and advanced nanocomposites [18] [21].

Spectroscopic methods offer unparalleled ability to provide detailed chemical and structural information about the analyte. Techniques like Raman and IR spectroscopy are powerful for identifying unknown compounds and validating chemical structures. However, they often require more extensive sample preparation, are generally less sensitive than advanced electrochemical techniques without pre-concentration, and involve higher instrumentation costs and lower portability [2] [23].

The future of drug analysis lies in the continued refinement of receptors for ultimate specificity and the engineering of novel transducers for extreme sensitivity. Emerging trends include the development of hybrid systems that combine the advantages of both fields, such as electrochemiluminescence, and the integration of artificial intelligence for data analysis and sensor system control, paving the way for smarter, more autonomous analytical tools in pharmaceutical research and clinical diagnostics [23].

The accurate detection and quantification of pharmaceutical compounds are fundamental to drug development, clinical diagnostics, and therapeutic monitoring. Researchers and analysts primarily rely on two families of analytical techniques: electrochemical sensors and spectroscopic methods. Electrochemical sensors transduce chemical interactions of target analytes at an electrode-sensing interface into measurable electrical signals such as current, voltage, or impedance [18] [25]. In contrast, spectroscopic methods measure the interaction of electromagnetic radiation with matter, quantifying phenomena like light absorption, emission, or scattering to identify molecular structures and concentrations [26]. The performance of any analytical method is critically evaluated based on three core metrics: sensitivity (the ability to produce a significant signal change for a small concentration change), the limit of detection (LOD) (the lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from background noise), and selectivity (the ability to measure the target analyte accurately in the presence of potential interferents) [18] [26]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of electrochemical and spectroscopic techniques based on these key performance metrics, supported by recent experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Performance Comparison: Electrochemical vs. Spectroscopic Methods

The following table summarizes the typical performance characteristics of electrochemical and spectroscopic methods for drug analysis, as evidenced by recent research.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Analytical Techniques for Drug Analysis

| Metric | Electrochemical Sensors | Spectroscopic Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Sensitivity | High (μA μMâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â² range); often enhanced via nanomaterial modification [22] [27]. | Variable; UV-Vis: μM-mM range; Fluorometry: can be highly sensitive for native-fluorescent compounds [18] [28]. |

| Typical LOD Range | Femtomolar to micromolar; commonly nanomolar range achieved with modified electrodes [18] [25] [22]. | UV-Vis: μM to mM; Fluorometry: ng/mL levels; MS-based techniques: pg/mL to fg/mL [18] [28]. |

| Inherent Selectivity | Moderate; relies on redox potential of analyte, but biological matrices cause interference. Enhanced significantly by surface modifications (e.g., MIPs, enzymes) [18] [25]. | High; techniques like MS provide structural information for definitive identification. Fluorometry is selective for native-fluorescent molecules or with derivatization [18] [28] [26]. |

| Key Strengths | Portability, rapid analysis (seconds-minutes), low cost, suitability for miniaturization and point-of-care testing, high sensitivity in complex matrices [18] [25] [22]. | High specificity (especially MS), well-established and validated protocols, non-destructive analysis (most cases), ability to identify unknown compounds [18] [26]. |

| Common Challenges | Signal drift, fouling in complex matrices, limited shelf life for some biosensors, requires calibration [18]. | Expensive instrumentation (HPLC, MS, GC-MS), requires skilled operators, complex sample preparation, often not portable [18] [25]. |

Experimental Protocols for Performance Validation

Electrochemical Sensor Protocol for Drug Detection

The following workflow outlines a standard protocol for developing and validating a nanomaterial-modified electrochemical sensor, exemplified by the detection of the anti-cancer drug Flutamide (FLT) using a diamond nanoparticle-modified screen-printed carbon electrode (DNPs/SPCE) [27].

1. Electrode Modification:

- Pretreatment: Clean the bare screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE) with deionized water and dry in an oven at 50°C [27].

- Nanomaterial Dispersion: Disperse 2 mg of diamond nanoparticles (DNPs) in 1 mL of deionized water. Sonicate the mixture for 30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension [27].

- Drop-casting: Deposit a precise volume (e.g., 4 µL) of the DNP suspension onto the active surface of the pre-treated SPCE. Allow the electrode to dry at 50°C, resulting in a stable DNPs/SPCE modified electrode [27].

2. Electrochemical Measurement and Data Analysis:

- Instrument Setup: Use a standard three-electrode system with the modified SPCE as the working electrode, Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, and a platinum wire as the counter electrode. Phosphate buffer saline (PBS) at physiological pH (7.4) is a typical supporting electrolyte [18] [27].

- Detection Technique: Apply electrochemical techniques such as Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or Cyclic Voltammetry (CV). DPV is often preferred for quantitative analysis due to its higher sensitivity and lower background current compared to CV [25] [22].

- Calibration and LOD Calculation: Measure the electrochemical response (e.g., peak current in DPV) across a range of known standard concentrations of the target drug (e.g., Flutamide). Plot the peak current versus concentration to establish a calibration curve. The LOD is typically calculated using the formula LOD = 3.3 × (Standard Deviation of the Blank Response) / (Slope of the Calibration Curve) [27]. For the DNPs/SPCE sensor, this yielded a wide linear range of 0.025–606.65 µM and an LOD of 0.023 µM for FLT [27].

- Selectivity Assessment: Test the sensor's response in the presence of common interfering species found in the sample matrix (e.g., salts, metabolites, structurally similar compounds). A selective sensor will show a significant response only to the target analyte, with minimal signal change from interferents [18].

Spectroscopic Method Protocol for Drug Detection

This protocol details a Flow Injection-Fluorometric technique for quantifying the antipsychotic drug Lurasidone (LUR), which exhibits native fluorescence due to its benzothiazole ring [28].

1. Sample and Carrier Preparation:

- Prepare a carrier stream composed of a mixture of phosphate buffer (10 mM, pH 4.5) and acetonitrile in a 30:70 (v/v) ratio. This solvent system ensures optimal fluorescence emission of LUR [28].

- Dissolve or dilute standard and sample solutions in a solvent compatible with the carrier stream.

2. Instrumental Setup and Analysis:

- Instrument Configuration: Utilize a flow injection analysis (FIA) system coupled with a fluorometric detector. Set the flow rate of the carrier stream to 0.5 mL minâ»Â¹ [28].

- Spectroscopic Parameters: Set the excitation wavelength to 316 nm and the emission wavelength to 398 nm, specific to LUR's fluorescence profile [28].

- Injection and Measurement: Inject the standard or sample solution into the flowing carrier stream. The sample plug is transported to the detector, where the fluorescence intensity at 398 nm is measured as it passes through the flow cell.

3. Data Analysis:

- Calibration Curve: Construct a calibration curve by plotting the peak area of the fluorescence signal against the known concentrations of LUR standards. The method demonstrated linearity in the range of 30–800 ng mLâ»Â¹ [28].

- LOD/LOQ Calculation: The Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ) are calculated as 7.16 ng mLâ»Â¹ and 21.7 ng mLâ»Â¹, respectively, based on the standard deviation of the response and the slope of the calibration curve [28].

- Selectivity: The method's selectivity is demonstrated by analyzing pharmaceutical formulations and spiked human plasma without excipient-related interferences, confirming its ability to accurately quantify LUR in complex matrices [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of both electrochemical and spectroscopic methods is highly dependent on the reagents and materials used. The following table lists key solutions and their functions in the featured experiments.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) | Low-cost, disposable, miniaturized platform serving as the base transducer in electrochemical sensors. | Used as the substrate for DNPs modification for FLT detection [27]. |

| Diamond Nanoparticles (DNPs) | Electrode nanomodifier; enhances electrocatalytic activity, electron transfer rate, and sensor sensitivity. | DNPs/SPCE sensor showed high sensitivity (0.403 μA μMâ»Â¹ cmâ»Â²) and low LOD for FLT [27]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic recognition elements on sensor surfaces; provide high selectivity by mimicking antibody binding sites. | Used in sensors for Azithromycin and Lurasidone to achieve selective detection in complex fluids [18] [22]. |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Electrode modifier; improve conductivity and stability, and enhance the electrochemical response. | Component of Ce-BTC MOF/IL/CPE sensor for Ketoconazole analysis [22]. |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | A common electrolyte solution in electrochemistry; maintains stable pH and ionic strength. | Used as a supporting electrolyte in most electrochemical sensing experiments [18]. |

| Acetonitrile (ACN) & Methanol | Organic solvents for mobile phases (HPLC), sample dissolution, and extraction. | Acetonitrile was a key component (70%) of the carrier solution in the LUR fluorometric assay [28]. Methanol was used for extracting drugs from seized samples in GC-MS [29]. |

The choice between electrochemical and spectroscopic methods for drug analysis involves a strategic trade-off between sensitivity, selectivity, cost, and operational requirements. As the data demonstrates, electrochemical sensors excel in providing high sensitivity and low LOD with minimal infrastructure, making them ideal for rapid, on-site screening, and point-of-care testing [18] [25] [22]. Conversely, spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques offer superior selectivity and are the gold standard for definitive identification, structural elucidation, and regulatory compliance testing, despite their higher cost and complexity [18] [28] [26]. The ongoing integration of advanced nanomaterials like MXenes and DNPs in electrochemical sensors is continuously narrowing the performance gap, particularly in selectivity [25] [27]. Ultimately, the selection of an analytical technique must align with the specific application demands, weighing the need for portability and speed against the requirement for unequivocal identification and maximum specificity.

Techniques in Action: Applications in Drug and Metabolite Detection

The rapid and sensitive detection of pharmaceuticals is crucial for therapeutic drug monitoring, environmental surveillance, and combating antibiotic resistance. While traditional spectroscopic and chromatographic methods offer precision, electrochemical sensors are emerging as powerful alternatives due to their cost-effectiveness, portability, and capacity for real-time analysis. This comparison guide objectively evaluates the performance of modern electrochemical sensors against conventional methods, with a specific focus on antibiotics, antifungals, and psychotropic drugs. Supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, this analysis provides researchers and drug development professionals with a critical overview of the capabilities and limitations of electrochemical sensing platforms in pharmaceutical analysis.

The widespread use and misuse of pharmaceutical compounds have led to their persistent presence in clinical settings and ecosystems, contributing to public health crises such as antibiotic resistance. Accurate detection of these compounds is essential, yet conventional analytical techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry (MS) are often hampered by high costs, complex sample preparation, and the need for specialized laboratory infrastructure [30] [25].

Electrochemical sensors have emerged as a promising solution, converting the interaction between a target analyte and a modified electrode surface into a quantifiable electrical signal [25]. Their advantages include simple instrumentation, low cost, high sensitivity, and portability for field-deployable analysis [30]. This guide provides a systematic, data-driven comparison of electrochemical detection strategies for major drug classes, contextualizing their performance against traditional spectroscopic methods and detailing the experimental workflows that underpin their operation.

Performance Comparison: Electrochemical vs. Spectroscopic Methods

The following table summarizes the key analytical parameters of electrochemical sensors for detecting various pharmaceuticals, compared with those of traditional spectroscopic and chromatographic techniques.

Table 1: Performance comparison of electrochemical sensors and traditional methods for pharmaceutical detection.

| Drug Category | Detection Method | Sensor Modifications / Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macrolide Antibiotics | Electrochemical | Various modified electrodes (Nanomaterials, MIPs) | Varies by specific sensor | Sub-micromolar to nanomolar | [30] |

| Chromatographic | LC-MS/MS | - | Good sensitivity & selectivity | [30] | |

| Tetracycline | Electrochemical | Cu-MOF/SPE | 0.0001 – 100 µmol Lâ»Â¹ | 1.007 nmol Lâ»Â¹ | [31] |

| Fluorescence Spectroscopy | Eu³⺠doped MOFs, Carbon quantum dots | - | Low detection limits reported | [31] | |

| Psychotropic Drugs | Electrochemical | BDD electrode (Metabolism simulation) | - | - | [32] [33] |

| Chromatographic | LC-MS/MS (TDM reference method) | - | µg/L - mg/L in biological samples | [32] | |

| Chlorpromazine | Electrochemical | MoSe₂/VC/SPCE | 0.001 – 130 µM | 0.00018 µM | [34] |

| Various Antibiotics & NSAIDs | Electrochemical | Nanomaterial-modified electrodes (CV, DPV) | - | Often sub-micromolar | [25] |

Key Performance Insights: Electrochemical sensors consistently achieve low detection limits, often rivaling traditional techniques. Their performance is significantly enhanced by electrode surface modification. For instance, a sensor for Chlorpromazine using a molybdenum diselenide/vanadium carbide (MoSeâ‚‚/VC) nanocomposite demonstrated a wide linear range and an exceptionally low LOD [34]. Similarly, a Cu-MOF-based sensor for Tetracycline showed a broad linear dynamic range over six orders of magnitude [31]. While LC-MS/MS remains the reference method for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) due to its high selectivity and sensitivity, electrochemical methods offer a complementary, rapid, and cost-effective alternative, especially for initial screening [30] [32].

Experimental Protocols for Key Electrochemical Assays

Sensor Fabrication and Modification

The core of advanced electrochemical sensing lies in the modification of the working electrode to enhance its properties.

- Material Synthesis: For a tetracycline sensor, a Copper Metal-Organic Framework (Cu-MOF) is synthesized via a solvothermal method. Terephthalic acid and copper nitrate trihydrate are dissolved in DMF and heated in a Teflon-lined autoclave at 383 K for 36 hours. The resulting blue solid is centrifuged, washed, and dried in a vacuum oven [31].

- Electrode Modification: The surface of a Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode (SPCE) is modified by drop-casting a dispersion of the synthesized Cu-MOF. A typical procedure involves dispersing the MOF powder in a solvent like ethanol or a Nafion solution, then applying a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) to the electrode surface and allowing it to dry [31]. This creates a porous, high-surface-area layer that preferentially adsorbs the target analyte.

Electrochemical Measurement and Analysis

Detection is typically performed using a standard three-electrode system (working, reference, and counter electrodes) with voltammetric techniques.

- Detection of Tetracycline via Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): The Cu-MOF-modified SPCE is immersed in a solution containing tetracycline. DPV measurements are performed by applying a series of potential pulses superimposed on a linear baseline potential. The current response is measured just before and at the end of each pulse, which minimizes background capacitive current and maximizes the Faradaic current from tetracycline oxidation/reduction. The peak current is proportional to the tetracycline concentration, allowing for quantification [31].

- Simulation of Drug Metabolism: This innovative approach uses a thin-layer electrochemical cell equipped with a Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) working electrode. A solution of the psychotropic drug is pumped through the cell while a controlled potential is applied to simulate oxidative metabolism. The resulting transformation products can be directly analyzed online via an coupled LC-MS/MS system, or the effluent can be collected for offline analysis. This setup effectively mimics Phase I metabolism and, with the addition of conjugation agents like glutathione, can also simulate some Phase II metabolic pathways [32] [33].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for developing and applying an electrochemical sensor for pharmaceutical detection, from material synthesis to data analysis.

Electrochemical Sensor Development Workflow

The workflow for simulating drug metabolism using electrochemistry, which provides an ethical and efficient alternative to in-vivo studies, is detailed below.

Electrochemical Simulation of Drug Metabolism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful development of electrochemical sensors relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents.

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for electrochemical pharmaceutical detection.

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPCEs) | Disposable, portable, and mass-producible transducer; ideal for point-of-care testing. | Base platform for Cu-MOF modification in tetracycline detection [31]. |

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrode | A robust working electrode with a wide potential window and low background current, ideal for studying redox reactions. | Working electrode in electrochemical cells for simulating oxidative drug metabolism [32] [33]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Porous materials with high surface area and tunable functionality; enhance analyte adsorption and electrocatalysis. | Cu-MOF used to modify SPCE for sensitive tetracycline detection [31]. |

| 2D Nanomaterials (e.g., MoSeâ‚‚, MXenes) | High electrical conductivity and large surface area; improve electron transfer and sensor sensitivity. | MoSeâ‚‚/VC nanocomposite used to enhance detection of chlorpromazine [34] [25]. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities for a specific analyte; provide high selectivity as a recognition element. | Used in sensors for macrolide antibiotics and other anti-infective agents to ensure specificity [30] [35]. |

| Nafion Binder | A perfluorinated ion-exchange polymer; used to immobilize modifier materials firmly onto the electrode surface. | Used in the preparation of modified electrode inks (e.g., with Cu-MOF) [31]. |

| Hispidin | Hispidin, CAS:555-55-5, MF:C13H10O5, MW:246.21 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HJC0149 | HJC0149, CAS:1430330-65-6, MF:C15H10ClNO4S, MW:335.75 | Chemical Reagent |

Electrochemical sensors present a compelling alternative to spectroscopic methods for the detection of pharmaceuticals, offering comparable sensitivity with significant advantages in cost, analysis speed, and portability. The performance of these sensors is critically dependent on the design of the electrode interface, where materials like MOFs, 2D nanocomposites, and MIPs play a transformative role. While challenges regarding sensor stability in complex matrices and reproducibility remain active areas of research, the experimental data and protocols outlined in this guide underscore the maturity and potential of electrochemical platforms. For researchers in drug development and environmental monitoring, these tools offer a viable path toward decentralized, rapid, and sustainable analytical solutions.

The accurate detection of pharmaceutical compounds is crucial in medical diagnostics, forensic toxicology, and environmental monitoring. Conventional methods for drug analysis, such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry, offer high precision but are often time-consuming, require elaborate instrumentation, and lack portability for field applications [36] [37]. In contrast, electrochemical sensors provide a compelling alternative with advantages including short analysis time, cost-effectiveness, ease of use, and low limits of detection [36] [3]. The core of these sensors is an electrode that serves as the transduction element, whose performance can be dramatically enhanced through nanomaterial modification [36].

This guide objectively compares three prominent nanomaterials—Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), Graphene, and Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)—for electrode modification, specifically focusing on their application in sensing pharmaceutical drugs. Performance is evaluated based on experimental data including detection limits, sensitivity, and selectivity reported in recent research.

Nanomaterials for Electrode Modification: A Comparative Analysis

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs)

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are crystalline compounds consisting of metal ions or clusters coordinated with organic linkers to form porous structures [36] [38]. Their exceptional properties include an extremely high surface area, tunable pore size, and structural diversity, which provide abundant active sites for analyte interaction and facilitate the diffusion of reactants [36]. However, pure MOFs often suffer from limitations such as low electrical conductivity and poor stability in aqueous environments, which can hinder their electrochemical performance [36] [38].

- Sensing Mechanism: In electrochemical sensing, MOFs function primarily by preconcentrating the target analyte within their pores due to their high porosity, thereby increasing the effective concentration at the electrode surface and amplifying the detection signal [36].

- Performance Enhancement: To overcome inherent limitations, MOFs are often composited with conductive materials. For instance, one study composited a Cu-Hemin MOF with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) to create a sensor for simultaneous detection of morphine and codeine. The MWCNTs enhanced the composite's conductivity and electron transfer rate, leading to improved sensor performance [38].

Graphene

Graphene is a two-dimensional layer of sp²-hybridized carbon atoms arranged in a honeycomb lattice. Its relevance to sensing stems from its exceptional electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, mechanical strength, and very large surface area [37]. These properties promote fast electron transfer between the analyte and the electrode, which is fundamental for sensitive electrochemical detection [37].

- Sensing Mechanism: Graphene-based electrodes enhance signals by providing a large, conductive surface for electrochemical reactions. The oxidation or reduction of drug molecules at this surface generates a current that is measured for quantification [37].

- Functionalization: Graphene oxide (GO) and reduced graphene oxide (rGO) are often used because their oxygen-containing functional groups (e.g., -OH, -COOH) enable further chemical modification and improve dispersibility. These groups can be used to anchor metal nanoparticles or other functional elements to boost selectivity and sensitivity [37].

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs)

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) are cylindrical nanostructures composed of rolled graphene sheets, classified as either single-walled (SWCNTs) or multi-walled (MWCNTs). They are favored in sensing for their unparalleled electrical conductivity, high aspect ratio, and large surface-to-volume ratio [39]. Their nanoscale dimensions and charge transport properties make them highly sensitive to surface adsorption events.

- Sensing Mechanism: The primary sensing mechanism involves changes in electrical conductance when target molecules adsorb onto the CNT surface. This adsorption can cause charge transfer or electrostatic gating effects, which shift the Fermi level and modulate conductivity [39]. In electrochemical sensors, CNTs modify the electrode to provide a large active surface area and efficient electron transport channels, accelerating electrode reaction kinetics [39].

- Overcoming Limitations: Pristine CNTs tend to aggregate and may lack selectivity. Therefore, functionalization via covalent or non-covalent methods is a mainstream approach to improve dispersibility, stability, and target-specificity. Hybridizing CNTs with polymers, metal nanoparticles, or MOFs creates synergistic effects that enhance overall sensor performance [39].

Table 1: Comparison of Key Properties of MOFs, Graphene, and CNTs

| Property | MOFs | Graphene | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Material Composition | Metal ions & organic linkers [36] | sp²-hybridized carbon atoms [37] | Rolled graphene sheets (SWCNTs/MWCNTs) [39] |

| Key Structural Feature | Highly porous crystalline framework [36] | Two-dimensional honeycomb lattice [37] | One-dimensional cylindrical nanostructure [39] |

| Electrical Conductivity | Typically low, requires compositing [36] | Exceptionally high [37] | Exceptionally high, ballistic transport [39] |

| Surface Area | Very high [36] | Very high [37] | Very high [39] |

| Ease of Functionalization | High (tunable pores & linkers) [36] | High (via oxygen-containing groups) [37] | High (covalent and non-covalent methods) [39] |

| Major Sensing Role | Analyte preconcentration & hosting active sites [36] | Providing conductive platform & enhancing electron transfer [37] | Enhancing electron transfer & acting as sensitive transducer [39] |

Performance Comparison in Pharmaceutical Drug Detection

The efficacy of nanomaterial-modified electrodes is quantitatively assessed by their limit of detection (LOD), linear detection range, and selectivity when applied to specific pharmaceutical drugs. Experimental data from recent studies highlight the performance of sensors based on MOFs, graphene, and CNTs.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data for Nanomaterial-Based Drug Sensors

| Nanomaterial / Composite | Target Drug(s) | Electrochemical Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Sample Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CHM@MWCNTs [38] | Morphine & Codeine | Not Specified | 0.09 - 30 μM | 9.2 nM (Morphine), 11.2 nM (Codeine) | Urine, Drug Injection |

| 3D Spongy Functionalized Graphene [37] | Codeine | Square Wave Voltammetry | Not Specified | 5.8 nM | Blood Plasma, Tablets |

| Graphene-Nafion Film [37] | Codeine | Cyclic Voltammetry | Not Specified | Signal improvement vs. Nafion alone | Not Specified |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide-Palladium [37] | Morphine | Not Specified | Not Specified | 40 nM | Human Urine |

| Graphene Nanosheets on GCE [37] | Morphine, Heroin, Noscapine | Not Specified | Not Specified | 0.4 μM (Morphine), 0.5 μM (Heroin) | Not Specified |

| rGO-MWCNT composite [37] | Morphine | Not Specified | Not Specified | Data for Dopamine/Uric acid interference | Not Specified |

The data demonstrates that composite materials often yield superior performance. The MOF-based composite (CHM@MWCNTs) achieved detection limits in the low nanomolar range for opioid drugs, which is comparable to, and in some cases better than, many graphene-only sensors [38] [37]. This underscores the synergy achieved by combining the high porosity of MOFs with the superior conductivity of CNTs. Furthermore, functionalized graphene sensors also show excellent, low-nanomolar LODs, confirming graphene's strong capability in drug sensing [37].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Fabrication and Measurement

Synthesis of a MOF-CNT Composite Sensor

A representative protocol for creating a Cu-Hemin MOF (CHM) composite with MWCNTs is as follows [38]:

- Synthesis of Cu-Hemin MOF: 2.0 mmol of Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O is dissolved in 100 mL distilled water (Solution A). Separately, 0.024 mmol of Hemin is dissolved in 100 mL phosphate buffer solution (pH 7.0, 10X concentration) (Solution B). Solution A is gradually added to Solution B under stirring at ambient temperature for 24 hours. The resulting silver-blue precipitate is collected via centrifugation (10 min at 6000 rpm), washed repeatedly with distilled water, and dried at room temperature.

- Composite Formation: The synthesized CHM is combined with functionalized MWCNTs. The integration is facilitated by hydrophobic interactions and van der Waals forces between the materials.

- Electrode Modification: The CHM@MWCNTs nanocomposite is dispersed in a suitable solvent (often water or ethanol) to form an ink. This ink is then drop-cast onto the surface of a clean glassy carbon electrode (GCE) and allowed to dry, forming the modified working electrode.

Key Electrochemical Measurement Techniques

The analytical performance of modified electrodes is typically evaluated using several voltammetric techniques [36]:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Scans the potential of the working electrode linearly between a lower and upper limit and then reverses the scan. It provides information on the redox potential and reversibility of the electrochemical reaction of the drug analyte. The peak current is often proportional to the analyte concentration.

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Applies a series of small voltage pulses on a linear baseline potential. It measures the current difference just before and after the pulse, which helps minimize background (capacitive) current. This technique offers higher sensitivity and is better for resolving analytes in mixtures compared to CV.

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): Similar to DPV but uses a forward-reverse pulse sequence, allowing for very fast scans and excellent signal-to-noise ratios.

Diagram 1: Electrochemical Sensor Workflow. The process from electrode modification to quantitative readout, highlighting the key measurement techniques.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Successful development of nanomaterial-modified electrochemical sensors requires specific chemical reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Sensor Fabrication

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common, polished baseline electrode platform for modification. | Used as the substrate for applying graphene nanosheets and graphene-Nafion films [37]. |

| Metal Salts | Source of metal ions (nodes) for the construction of MOFs. | Copper nitrate (Cu(NO₃)₂·3H₂O) used to synthesize Cu-Hemin MOF [38]. |

| Organic Linkers | Bridging molecules that coordinate with metal ions to form MOF structures. | Hemin, an iron-containing porphyrin, acted as the organic linker in a Cu-based MOF [38]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs/SWCNTs) | Enhance conductivity and provide a high-surface-area scaffold in composites. | MWCNTs were composited with Cu-Hemin MOF to boost electron transfer and create more active sites [38]. |

| Graphene Oxide (GO) / Reduced GO | Provides a highly conductive 2D platform with functional groups for further modification. | Used in composites with palladium nanoparticles or MWCNTs for morphine and codeine sensing [37]. |

| Nafion | A perfluorosulfonated ionomer used as a binder; can also provide some selectivity. | Combined with graphene to form a film on GCE, improving the electrical response to codeine [37]. |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | A common electrolyte solution that maintains a stable pH during electrochemical measurement. | Used as a solvent for Hemin during MOF synthesis and as the medium for electrochemical detection [38]. |

| HJC0197 | HJC0197, MF:C19H21N3OS, MW:339.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| HTL14242 | HTL14242, MF:C16H8ClFN4, MW:310.71 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Synergistic Effects and Composite Strategies

A powerful trend in the field is the creation of nanocomposites that combine the strengths of individual materials to overcome their respective weaknesses. The synergy in these composites leads to sensors with performance superior to those based on a single nanomaterial.

- MOF-CNT Composites: This strategy merges the high porosity and analyte preconcentration capability of MOFs with the exceptional electrical conductivity and fibrous network of CNTs. This addresses the poor conductivity of MOFs and prevents the aggregation of CNTs, resulting in a sensor with more active sites and faster electron transfer [38] [39].

- Graphene-MOF Composites: Combining graphene with MOFs yields materials with outstanding conductivity, structural tunability, and excellent surface chemistry. The graphene sheet acts as a conductive backbone, while the MOF provides a porous structure for enhanced analyte capture [40].