Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy in Redox Systems: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) as a powerful analytical tool for investigating redox systems, with particular relevance for biomedical and pharmaceutical research.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy in Redox Systems: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) as a powerful analytical tool for investigating redox systems, with particular relevance for biomedical and pharmaceutical research. It begins by establishing the fundamental theory of EIS, linking Ohm's Law to the complex impedance response of electrochemical interfaces and redox processes. The review then details modern methodological approaches, including equivalent circuit modeling, the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) analysis, and emerging techniques like Mechano-Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (MEIS). A significant focus is placed on troubleshooting data quality and optimizing experimental parameters to ensure reliable, physically meaningful results. Finally, the article covers advanced validation protocols, such as Kramers-Kronig relations, and compares EIS performance with complementary techniques like spectroelectrochemistry. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this work synthesizes classic principles with cutting-edge advancements to guide the effective application of EIS in characterizing complex redox biology and developing next-generation biosensors and diagnostic platforms.

Core Principles: Understanding EIS Theory and Redox System Fundamentals

The evolution from the simple, direct current (DC) principles of Ohm's Law to the sophisticated concept of complex impedance represents a foundational advancement that enabled the development of modern electrochemical analysis techniques. This transition forms the essential theoretical bridge allowing researchers to probe intricate electrochemical interfaces and processes with remarkable precision. Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) has emerged as a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique that leverages this bridge to characterize complex systems across diverse fields, from energy storage to biomedical diagnostics [1] [2]. By applying a small-amplitude alternating current (AC) signal across a frequency spectrum and analyzing the system's response, EIS provides unparalleled insights into interfacial properties, reaction kinetics, and mass transport phenomena that are inaccessible to DC techniques alone [3] [2].

The significance of EIS continues to grow in contemporary electrochemical research, particularly in the development of redox flow batteries and biosensing platforms. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding this fundamental bridge is crucial for designing more sensitive diagnostic tools, optimizing energy storage systems, and interpreting complex electrochemical data. This article outlines the core principles, key applications, and detailed experimental protocols that demonstrate the utility of EIS in advanced redox system research, providing both theoretical foundation and practical guidance for implementation across various research domains.

Theoretical Foundations: From Simple Resistance to Complex Impedance

The Starting Point: Ohm's Law

The journey from simple electrical concepts to complex impedance begins with Ohm's Law, a cornerstone of electrical theory that describes the relationship between voltage (V), current (I), and resistance (R) in DC circuits:

[I = \frac{V}{R}]

In this DC context, resistance represents a circuit element's opposition to the flow of direct current, with energy dissipation occurring as heat [1]. However, this simple model proves insufficient for analyzing circuits involving alternating current (AC) or complex electrochemical systems where energy storage and phase shifts become significant factors.

The AC Challenge and the Impedance Solution

When dealing with AC signals, the concept of resistance must be expanded to impedance (Z), which accounts not only for energy dissipation (resistance) but also for energy storage phenomena in capacitive and inductive elements [1]. The generalized form of Ohm's Law for AC systems becomes:

[I = \frac{V}{Z}]

where Z represents the complex impedance. In EIS, an AC potential of small amplitude is applied to an electrochemical system, typically varying as a function of time:

[v(t) = V_0 \sin(\omega t)]

The system responds with a current signal at the same frequency but potentially shifted in phase:

[i(t) = I_0 \sin(\omega t - \varphi)]

The impedance is thus a complex quantity consisting of both real and imaginary components:

[Z(\omega) = Z' + jZ'']

where (Z' = |Z|\cos\varphi) represents the real component (related to resistive behavior), and (Z'' = |Z|\sin\varphi) represents the imaginary component (related to capacitive or inductive behavior) [1]. This mathematical formulation enables the characterization of not only how much a system resists current flow but also how it stores and releases energy throughout the AC cycle.

Data Representation and Validation

The data obtained from EIS measurements are commonly visualized through two primary formats:

- Nyquist Plots: Display the imaginary component (-Z") against the real component (Z') of impedance across all measured frequencies [4] [5]

- Bode Plots: Display the magnitude of impedance (|Z|) and phase shift (φ) as functions of frequency [4] [5]

To ensure data quality and validity, EIS measurements must satisfy three fundamental criteria:

- Linearity: The system's response must be linearly proportional to the applied perturbation

- Causality: The response must be solely due to the applied stimulus

- Stability: The system must remain stable throughout the measurement period [3] [6]

The Kramers-Kronig relations provide a mathematical test to validate whether these conditions have been met, ensuring the impedance data are physically meaningful [1] [4].

Table 1: Fundamental Components of Complex Impedance

| Component | Symbol | Phase Angle (φ) | Energy Relationship | Common Electrochemical Correspondence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistance | R | 0° | Dissipation | Solution resistance, charge transfer |

| Capacitance | C | -90° | Storage | Double layer, surface coatings |

| Inductance | L | +90° | Storage | Cables, certain adsorption phenomena |

| Constant Phase Element | Q | -90°×(1-n) | Distributed storage | Heterogeneous surfaces, porous electrodes |

Key Application Areas in Redox System Research

Energy Storage Systems

EIS has become an indispensable tool for characterizing and optimizing electrochemical energy storage systems, particularly redox flow batteries (RFBs) and lithium-ion batteries.

In vanadium redox flow batteries (VRFBs), EIS enables researchers to:

- Monitor state of charge (SOC) and state of health (SOH) during operation [3]

- Quantify individual overvoltage contributions from electrodes, membrane, and electrolyte [3] [5]

- Perform quality control and functionality tests on full-scale stacks using non-toxic alternative fluids instead of aggressive vanadium electrolyte [5]

- Identify specific failure mechanisms such as increased contact resistance, membrane damage, or improper felt compression [5]

For lithium-metal batteries, advanced operando EIS techniques provide unprecedented insights into dynamic processes during battery operation, including:

- Lithium diffusion through various cell components

- Solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation and evolution

- Morphological changes at electrode surfaces during plating and stripping

- Dendritic growth and internal short circuit mechanisms [6]

Table 2: EIS Applications in Battery and Redox Flow Battery Research

| Application | Measurement Type | Key Parameters Extracted | Research Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| VRFB Functionality Testing | Galvanostatic EIS with alternative fluids | Ohmic resistance, charge transfer resistance, diffusion elements | Quality control without toxic electrolytes [5] |

| Lithium-Metal Interface Analysis | Operando EIS in 3-electrode cells | SEI resistance, charge transfer resistance, diffusion coefficients | Understanding dendritic growth and capacity fade [6] |

| SOC/SOH Determination | Multi-frequency EIS | Resistance increase, capacitance changes | State estimation for battery management systems [3] |

| Electrode Optimization | Potentiostatic EIS at equilibrium | Charge transfer kinetics, double layer capacitance | Developing high-performance electrode materials [3] |

Biomedical and Diagnostic Applications

EIS has emerged as a powerful technique in biomedical research and diagnostic development, particularly through its implementation in impedimetric biosensors. These applications leverage the exquisite sensitivity of EIS to biorecognition events occurring at electrode surfaces.

In diagnostic applications, EIS offers significant advantages:

- Label-free detection of biomolecules without requiring fluorescent or radioactive tags [7]

- Capability to detect non-electroactive compounds such as hormones and specific proteins that cannot be measured by direct electron transfer methods [7]

- High sensitivity for monitoring antibody-antigen interactions in real-time [8]

- Miniaturization potential for point-of-care devices and wearable sensors [7]

Notable biomedical implementations include:

- Tear fluid analysis for biomarkers of ocular and systemic diseases including glaucoma, diabetic retinopathy, Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, and cancer [7]

- Tuberculosis detection through antigen-antibody recognition on functionalized electrodes [8]

- Glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) detection for diabetes monitoring using competitive inhibition assays [8]

- Tissue characterization to differentiate between normal and cancerous tissues based on their electrical properties [8]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Basic EIS Characterization of Redox Flow Battery Cells

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for electrochemical impedance spectroscopy analysis of redox flow battery cells, adapted from established methodologies in the literature [3] [5].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for RFB EIS Characterization

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte Solution | 1.6 M Vanadium in 2 M H2SO4 (technical) or 0.01 M H2SO4 (alternative) | Provides ionic conductivity and redox-active species |

| Graphite Felt Electrodes | SGL GFD 2.5 or equivalent | High-surface-area electrode material |

| Membrane | Fumatech FAP anion exchange membrane or equivalent | Separates anolyte and catholyte while allowing ion transport |

| Bipolar Plates | Graphite with optional nickel plating | Current collection and distribution |

| Electrochemical Cell | Single-cell or multi-cell stack with flow fields | Housing for battery components |

| Pumps and Tubing | Chemically resistant (e.g., peristaltic or rotary) | Electrolyte circulation |

Procedure

Cell Assembly: Assemble the RFB cell according to manufacturer specifications, ensuring proper compression of graphite felts (typically 20-25% compression) and correct orientation of membrane and gaskets to prevent leaks.

Fluid Introduction: Fill the electrolyte reservoirs with selected fluid (technical vanadium electrolyte or alternative such as 0.01 M H2SO4). Circulate electrolyte through both half-cells at a controlled flow rate (e.g., 20-50 mL/min) to remove air bubbles and ensure complete wetting of electrodes.

Instrument Connection: Connect the potentiostat/galvanostat to the cell, ensuring proper connection to working, counter, and reference electrodes (if available). For symmetric cells, two-electrode configuration may be used.

Initial Conditioning: If using technical electrolyte, precondition the cell by performing several charge-discharge cycles at low current density to establish stable electrochemical performance.

Parameter Setting: Configure the EIS measurement parameters:

- Frequency range: 10 kHz to 0.1 Hz (or 2 kHz to 0.2 Hz for initial tests)

- AC perturbation amplitude: 0.08 V to 0.5 V (adjust to maintain linear response)

- DC bias: 0 V (equilibrium) or at specific state of charge

- Points per decade: 10-15

- Number of measurements per frequency: 5-20 for averaging

Measurement Execution: Initiate EIS measurement sequence. Monitor initial data quality through real-time Nyquist plot display.

Data Validation: Perform Kramers-Kronig test on acquired data to verify stability, linearity, and causality of the measurement.

Repeatability Assessment: Conduct at least three consecutive measurements to establish repeatability. Standard deviation should be less than 5% for key parameters.

Data Analysis: Fit validated impedance data to appropriate equivalent circuit model to extract quantitative parameters (ohmic resistance, charge transfer resistance, double layer capacitance, etc.).

Troubleshooting Notes

- If impedance spectra show excessive noise, reduce AC amplitude while ensuring sufficient signal-to-noise ratio

- If measurement fails Kramers-Kronig validation, verify system stability by extending equilibrium time or checking for electrolyte flow irregularities

- For multi-cell stacks, ensure uniform compression across all cells to prevent contact resistance variations

Protocol 2: Operando EIS for Dynamic Battery Analysis

This protocol describes the implementation of operando EIS for analyzing dynamic processes in battery systems under actual operating conditions, based on recent methodological advances [6].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Operando EIS in Battery Research

| Material/Reagent | Specifications | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Three-Electrode Cell | Custom design with reference electrode port | Enables separate monitoring of working and counter electrodes |

| Reference Electrode | Stable reference (e.g., lithiated gold micro-reference) | Provides stable potential reference during cycling |

| Working Electrode | Material of interest (e.g., lithium metal, composite electrode) | Primary electrode under investigation |

| Counter Electrode | Matching lithium metal or inert material | Completes the circuit without limiting reactions |

| Electrolyte | Battery-grade (e.g., 1 M LiPF6 in EC/DEC or similar) | Ion transport medium |

Procedure

Cell Configuration: Assemble three-electrode cell in an argon-filled glovebox (<0.1 ppm H2O and O2). Ensure precise positioning of reference electrode to minimize uncompensated resistance.

Initial Characterization: Before operando measurements, perform conventional EIS at open circuit voltage (OCV) to establish baseline impedance characteristics.

Operando Parameters: Set up combined galvanostatic cycling with EIS measurement:

- DC current density: Set according to research objectives (e.g., 0.1-1.0 mA/cm² for lithium metal studies)

- EIS frequency range: 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz (prioritize higher frequencies if system changes rapidly)

- AC amplitude: 5-10 mV superposed on DC current

- Measurement intervals: Determine based on process kinetics (e.g., every 10% SOC change or at fixed time intervals)

Simultaneous Data Acquisition: Initiate galvanostatic cycling while performing EIS measurements at predetermined intervals. Synchronize EIS data with overvoltage measurements from the galvanostatic curve.

Reference Electrode Monitoring: Continuously monitor potential of reference electrode versus a separate check electrode to verify stability throughout experiment.

Data Processing: Process operando EIS data using distribution of relaxation times (DRT) analysis to deconvolute overlapping processes without a priori equivalent circuit models [9].

Cross-Validation: Correlate impedance evolution with features in the galvanostatic voltage profile and post-mortem morphological analysis.

Control Experiments: Perform identical measurements under equilibrium conditions at selected states to distinguish kinetic effects from state-dependent changes.

Troubleshooting Notes

- If reference electrode potential drifts significantly (>10 mV), discard data and replace reference electrode

- If DC current causes significant distortion in low-frequency impedance, increase AC amplitude slightly or reduce frequency range

- For very fast processes, consider multi-sine excitation techniques to reduce measurement time [3]

Advanced Data Analysis Methods

Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) Analysis

The Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) method has emerged as a powerful alternative to traditional equivalent circuit modeling for analyzing EIS data [9]. This approach offers several advantages:

- Model-independent analysis that doesn't require a priori assumption of specific equivalent circuits

- Ability to deconvolve overlapping processes with similar time constants

- Provides a physically intuitive representation of processes distributed across different timescales

- Particularly valuable for analyzing complex systems with distributed elements, such as porous electrodes or heterogeneous interfaces

The DRT method transforms the impedance data from the frequency domain to the time domain, generating a distribution function γ(τ) that represents the probability density of relaxation processes with time constant τ [9]. Recent advances in DRT computation have improved accessibility for researchers without specialized expertise in programming or advanced mathematics, though challenges remain in standardization and automated analysis [9].

Equivalent Circuit Modeling

Despite the advantages of DRT analysis, equivalent circuit modeling remains a widely used approach for quantifying specific electrochemical processes from EIS data. The most fundamental model for electrode-electrolyte interfaces is the Randles circuit, which includes:

- Solution resistance (R_s)

- Double layer capacitance (C_dl)

- Charge transfer resistance (R_ct)

- Warburg element (W) for diffusion limitations

For more complex systems, researchers develop customized equivalent circuits that incorporate constant phase elements (CPE) to account for surface heterogeneity, transmission line models for porous electrodes, and various combinations of resistive and capacitive elements representing different physical processes in the electrochemical system [4].

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

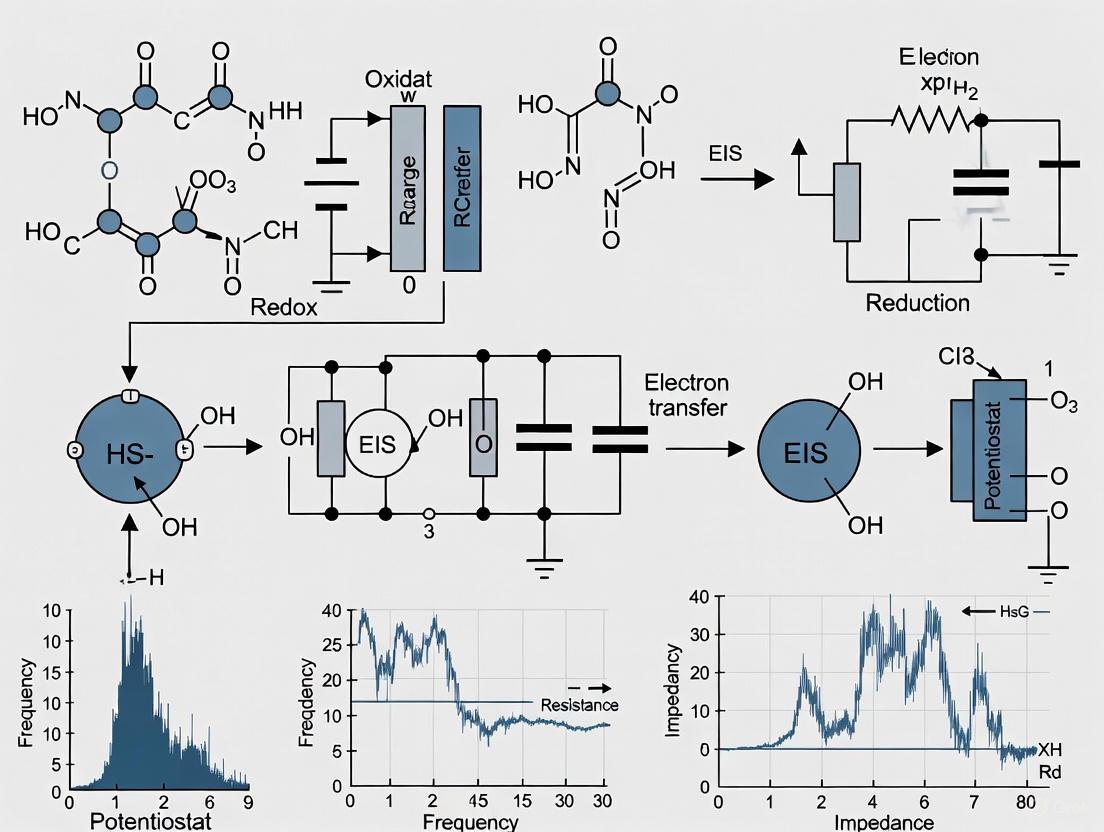

Diagram 1: Theoretical to Applied EIS Workflow. This diagram illustrates the progression from fundamental electrical principles to advanced EIS applications in research.

Diagram 2: EIS Application Ecosystem. This diagram overviews the diverse research applications of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy across multiple domains.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful frequency-domain analytical technique used to characterize complex electrochemical systems. Unlike direct current (DC) techniques that study system response as a function of time, EIS perturbs an electrochemical system with a small-magnitude alternating current (AC) signal across a range of frequencies and analyzes the resulting response. This methodology provides a powerful, non-destructive means to probe various physical and chemical processes within electrochemical cells, revealing information about electrode kinetics, double-layer phenomena, and mass transport properties that are crucial for research in battery development, sensor design, and fundamental electrochemistry [10].

The fundamental principle of EIS relies on analyzing a system's impedance (Z), a generalized form of resistance that applies to AC circuits. While electrical resistance (R), defined by Ohm's Law (R = E/I), describes the opposition to current flow in a DC circuit, impedance extends this concept to AC systems where the current and voltage relationship is frequency-dependent and may involve phase shifts [11] [12]. In an EIS experiment, a potentiostat applies a sinusoidal potential (or current) to an electrochemical cell, and the resulting current (or potential) response is measured. The impedance is then calculated from the ratio of the voltage to the current, taking into account both the magnitude and phase relationship of these signals [12].

Theoretical Foundation of Sinusoidal Perturbations

The Sinusoidal Input and Output

The EIS experiment begins with the application of a controlled, small-amplitude sinusoidal perturbation to the electrochemical system. In potentiostatic EIS, the input is a sinusoidal potential, described by the equation:

[ Et = E0 \sin(\omega t) ]

where ( Et ) is the potential at time ( t ), ( E0 ) is the amplitude of the signal, and ( \omega ) is the radial frequency (with ( \omega = 2\pi f ), and ( f ) being the frequency in hertz) [11].

In a linear system, the current response to this sinusoidal potential will be a sinusoid at the same frequency but shifted in phase, described by:

[ It = I0 \sin(\omega t + \phi) ]

where ( It ) is the current at time ( t ), ( I0 ) is the amplitude of the current signal, and ( \phi ) is the phase shift between the potential and current signals [11] [10]. The phase shift arises because different physical processes within the electrochemical cell (e.g., electron transfer, mass transport) respond to the perturbation at different rates.

The Concept of Complex Impedance

The impedance is calculated using an expression analogous to Ohm's Law but incorporating the phase relationship:

[ Z = \frac{Et}{It} = \frac{E0 \sin(\omega t)}{I0 \sin(\omega t + \phi)} = |Z| \exp(-j\phi) ]

where ( |Z| ) is the magnitude of the impedance (( E0/I0 )), and ( \phi ) is the phase angle [11] [13]. Using Euler's relationship, the impedance can be represented as a complex number:

[ Z = Z{\text{real}} + jZ{\text{imag}} ]

where the real part of the impedance, ( Z{\text{real}} = |Z|\cos\phi ), represents energy dissipation (resistive behavior), and the imaginary part, ( Z{\text{imag}} = |Z|\sin\phi ), represents energy storage (capacitive or inductive behavior) [11] [10] [13]. The complex notation conveniently captures both the magnitude and phase relationship in a single quantity, making it ideal for analyzing systems with mixed resistive and reactive components.

Table 1: Fundamental Impedance Equations and Components

| Parameter | Mathematical Expression | Physical Significance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Impedance Magnitude | ( | Z | = E0 / I0 ) | Ratio of potential amplitude to current amplitude |

| Phase Angle | ( \phi = - \omega \Delta t ) | Time shift between voltage and current signals | ||

| Real Impedance | ( Z_{\text{real}} = | Z | \cos \phi ) | In-phase component; represents resistive effects |

| Imaginary Impedance | ( Z_{\text{imag}} = | Z | \sin \phi ) | Out-of-phase component; represents capacitive/inductive effects |

| Complex Impedance | ( Z = Z{\text{real}} + j Z{\text{imag}} ) | Complete description of system's opposition to AC flow |

Experimental Protocols for EIS Measurement

Prerequisite: Establishing Linearity and Stationarity

Before conducting EIS measurements, two critical requirements must be verified to ensure meaningful data interpretation: linearity and stationarity.

Electrochemical systems are inherently non-linear, as evidenced by their curved current-voltage relationships. However, EIS analysis requires linear system behavior. This is achieved by using a sufficiently small perturbation amplitude (typically 1-10 mV) such that the system's response approximates linear behavior around the operating point [11] [10] [13]. The small signal ensures that the current response remains pseudo-linear, which is crucial for valid impedance measurements.

Stationarity requires that the system remains in a steady state throughout the measurement period, which can last from minutes to hours. The system parameters must not drift with time during the experiment. Factors such as adsorption of solution impurities, growth of oxide layers, buildup of reaction products, or temperature changes can violate the stationarity condition and lead to inaccurate results [11] [10]. Techniques such as Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) analysis can be used to check for stationarity violations during measurements [10].

Step-by-Step Measurement Protocol

System Setup: Configure a three-electrode system (working, reference, and counter electrodes) in an electrochemical cell containing the electrolyte and analyte of interest. Ensure temperature control and a stable, quiet electrochemical environment [12].

DC Polarization: Apply the desired DC potential or current to polarize the system to the specific operating point of interest (e.g., a particular state of charge in battery studies) [13].

Stabilization: Allow the system to reach a steady state at the chosen DC polarization. Monitor the current (in potentiostatic mode) or potential (in galvanostatic mode) until it stabilizes to ensure stationarity [11].

AC Perturbation Application: Apply a small sinusoidal AC perturbation (typically 1-10 mV in potentiostatic mode) superimposed on the DC polarization. The perturbation should be significantly smaller than the thermal voltage (RT/F ≈ 25 mV at room temperature) to maintain linearity [13].

Frequency Sweep: Measure the impedance across a broad frequency range, typically from high frequencies (MHz or hundreds of kHz) to low frequencies (mHz). Frequencies are usually spaced logarithmically, with 5-10 points per decade, to adequately characterize processes with different time constants [10] [12].

Signal Processing: At each frequency, measure the potential and current time-domain signals. Use a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to convert these signals to the frequency domain, extracting the amplitude and phase information needed to calculate the complex impedance [11] [12].

Data Validation: Employ quality indicators such as Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) to verify linearity and Kramers-Kronig relations or NSD to check stationarity and data consistency [10].

Diagram 1: A flowchart titled "Experimental EIS Workflow" outlining the step-by-step protocol for conducting electrochemical impedance spectroscopy measurements.

Data Representation and Interpretation

Nyquist and Bode Plots

EIS data are most commonly represented in two primary formats: Nyquist plots and Bode plots, each offering distinct advantages for data interpretation.

The Nyquist plot displays the negative imaginary component of impedance (-Z″) against the real component (Z′) on orthogonal axes, with each point on the plot representing the impedance at a specific frequency [11] [10]. In a Nyquist plot, high-frequency data typically appear on the left side of the plot, while low-frequency data appear on the right. A key limitation of the Nyquist representation is that frequency information is not explicitly shown—only implied by the position along the curve [11]. Different electrochemical processes often manifest as distinctive features in the Nyquist plot, such as semicircles (characteristic of charge-transfer processes) and diagonal lines (characteristic of diffusion-controlled processes) [13].

The Bode plot presents the same impedance data but explicitly shows frequency information. It consists of two separate graphs: the logarithm of impedance magnitude (|Z|) versus the logarithm of frequency, and phase angle (φ) versus the logarithm of frequency [11] [10] [12]. This representation facilitates direct identification of frequency-dependent behavior and is particularly useful for identifying time constants associated with different electrochemical processes.

Diagram 2: A flowchart titled "EIS Data Representation Pathways" showing how raw time-domain data is processed into different plot types used for data interpretation.

Equivalent Circuit Modeling

A common approach to interpreting EIS data involves fitting the results to an equivalent circuit model (ECM) composed of electrical elements such as resistors, capacitors, and inductors, each representing specific physical processes in the electrochemical system [11] [12]. The selection of an appropriate equivalent circuit should be guided by physical understanding of the system rather than mathematical convenience alone.

Table 2: Common Equivalent Circuit Elements and Their Physical Significance

| Circuit Element | Impedance Expression | Physical Electrochemical Correlate |

|---|---|---|

| Resistor (R) | ( Z = R ) | Solution resistance, charge transfer resistance |

| Capacitor (C) | ( Z = 1/j\omega C ) | Double-layer capacitance, surface film capacitance |

| Inductor (L) | ( Z = j\omega L ) | Inductive behavior from adsorption processes or cables |

| Constant Phase Element (Q) | ( Z = 1/[Q(j\omega)^n] ) | Non-ideal capacitance from surface heterogeneity |

| Warburg Element (W) | ( Z = \sigma(1-j)/\sqrt{\omega} ) | Semi-infinite linear diffusion |

| Voigt Circuit (R-C in parallel) | ( Z = R/(1+j\omega RC) ) | Single time-constant process (e.g., charge transfer) |

Recent advances in EIS analysis include data-driven approaches such as the Loewner framework (LF) for extracting the distribution of relaxation times (DRTs), which helps identify the most suitable equivalent circuit model for a given EIS dataset without a priori assumptions [14]. This is particularly valuable as different circuit models can sometimes produce deceptively similar spectra, complicating accurate physical interpretation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of EIS experiments requires careful selection of materials and reagents tailored to the specific electrochemical system under investigation. The following table outlines key components of a researcher's toolkit for EIS studies in redox systems.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for EIS Experiments

| Component | Specifications & Recommendations | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | With FRA capability; >10 MHz frequency range; 4-terminal sensing | Applies precise potential/current perturbations and measures response |

| Faraday Cage | Electrically shielded enclosure | Minimizes external electromagnetic interference on low-level signals |

| Electrochemical Cell | Glass or chemically inert polymer; temperature control jacket | Contains electrolyte and provides stable environment for measurements |

| Working Electrode | Pt, Au, GC, or material of interest; precisely defined area | Site of electrochemical reaction under investigation |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl, Hg/Hg₂Cl₂, or other stable reference | Provides stable, known potential reference point |

| Counter Electrode | Pt wire or mesh; sufficient surface area | Completes electrical circuit without limiting current |

| Supporting Electrolyte | High-purity salts (e.g., KCl, LiPF₆); inert in potential window | Provides ionic conductivity without participating in reactions |

| Redox Probe | Potassium ferricyanide, ruthenium hexamine, or system-specific | Provides well-characterized redox couple for system validation |

| Solvent | HPLC-grade water, acetonitrile, or other appropriate solvent | Dissolves electrolyte and redox species; determines potential window |

| Purging Gas | High-purity nitrogen or argon | Removes dissolved oxygen to prevent interference with redox reactions |

Advanced Considerations and Emerging Techniques

Quality Control and Data Validation

Ensuring data quality is paramount in EIS experiments. Several validation techniques should be employed:

- Total Harmonic Distortion (THD): Quantifies system non-linearity by measuring harmonic content in the response. A THD threshold of <5% is generally accepted to indicate acceptable linearity [10].

- Kramers-Kronig Relations: Mathematical transforms that test data causality, linearity, and stationarity. Significant deviations suggest invalid data [10].

- Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD): Assesses system stability during measurement by detecting frequency components produced by time-variance [10].

Mechano-Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (MEIS)

An emerging extension of EIS is Mechano-Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (MEIS), which probes coupled mechanical-electrochemical dynamics by measuring pressure responses to current perturbations [15]. MEIS is particularly relevant for systems where electrochemical reactions induce mechanical changes, such as electrode expansion and contraction during ion intercalation in battery materials. This technique provides complementary information to traditional EIS and is highly sensitive to states of charge and health across different electrochemical chemistries [15].

Physical Modeling Beyond Equivalent Circuits

While equivalent circuit modeling remains widespread, there is growing use of physics-based models that directly simulate impedance from fundamental equations describing electrode kinetics, double-layer capacitance, and mass transport [13]. These models, when implemented in simulation software, can provide more physically meaningful interpretations of EIS data and help avoid the pitfalls of arbitrary circuit element selection. For complex systems such as porous battery electrodes, 4D-resolved physical models (3D in space + time) can simulate EIS responses while explicitly considering different material phases and their interactions [16].

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful technique for characterizing electrochemical systems, including redox systems central to drug development research. The interpretation of EIS data heavily relies on two primary plotting methods: Nyquist and Bode plots. These visual representations transform complex impedance data into interpretable formats, enabling researchers to extract meaningful information about interfacial properties, charge transfer processes, and diffusion phenomena in redox systems. As a steady-state technique that utilizes small signal analysis, EIS is particularly valuable for probing sensitive biological systems without causing significant perturbation, making it ideal for studying redox processes in pharmaceutical applications [17] [18].

The fundamental principle of EIS involves applying a small amplitude sinusoidal potential excitation to an electrochemical cell and measuring the current response. The impedance (Z) is calculated as the ratio between the voltage and current, which are out of phase in complex systems [11] [18]. This complex impedance contains both real (Z') and imaginary (Z") components that vary with frequency, providing a wealth of information about the electrochemical system under investigation. Proper interpretation of these components through Nyquist and Bode plots forms the cornerstone of effective EIS analysis in redox research.

Theoretical Foundations of Impedance Representation

Complex Impedance and Its Components

In EIS, the impedance of an electrochemical system is represented as a complex number:

Z(ω) = Z' + jZ"

Where Z' is the real part (related to resistive properties), Z" is the imaginary part (related to capacitive/inductive properties), and j is the imaginary unit (√-1) [11]. The relationship between the excitation signal and response is characterized by both magnitude and phase shift, providing two key parameters for system characterization:

|Z| = Z₀ (magnitude) Φ (phase angle between voltage and current)

The impedance magnitude represents the overall opposition to current flow, while the phase angle provides information about the timing relationship between the applied potential and resulting current. In redox systems, these parameters are particularly sensitive to charge transfer kinetics and mass transport phenomena, making them valuable indicators for studying electron transfer processes in pharmaceutical compounds [19] [18].

Mathematical Basis for Data Representation

The mathematical foundation for EIS data representation stems from the system's response to a sinusoidal excitation. For an applied potential E(t) = E₀·sin(ωt), the current response in a linear system is I(t) = I₀·sin(ωt + Φ), where Φ is the phase shift [11] [18]. The radial frequency ω (radians/second) relates to frequency f (Hz) as ω = 2·π·f. This relationship allows the impedance to be expressed in complex notation as:

Z = E/I = Z₀(cosΦ + jsinΦ) = Z₀exp(jΦ)

This complex representation forms the basis for both Nyquist and Bode plots, with each offering unique advantages for visualizing different aspects of the impedance data, particularly in complex redox systems where multiple processes may overlap [20] [21].

Nyquist Plot Interpretation

Fundamental Principles and Axes

The Nyquist plot represents one of the most common methods for visualizing EIS data in electrochemical research. In this representation, the negative imaginary impedance (-Z") is plotted against the real part of the impedance (Z') across all measured frequencies [20] [22]. A key convention in these plots is the inversion of the imaginary axis, which places most of the data in the first quadrant of the Cartesian graph for easier visualization of patterns and shapes [22].

Each point on the Nyquist plot corresponds to the impedance at a specific frequency, though the frequency values are not explicitly shown along the curve [20] [11]. The higher frequency data typically appear on the left side of the plot, while lower frequency data progressively move toward the right [11]. This representation is particularly valuable for identifying characteristic shapes corresponding to specific electrochemical processes and circuit elements in redox systems.

Table 1: Characteristic Nyquist Plot Signatures for Common Circuit Elements

| Circuit Element | Nyquist Plot Signature | Information Extracted |

|---|---|---|

| Resistor (R) | Single point on Z' axis at Z = R | Resistance value |

| Capacitor (C) | Straight line along the -Z" axis | Ideal capacitive behavior |

| Resistor + Capacitor (Parallel) | Semicircle with diameter R | Charge transfer resistance, time constant |

| Warburg Element (Diffusion) | Diagonal line with 45° slope | Mass transport control |

| Constant Phase Element (CPE) | Depressed semicircle | Surface heterogeneity, non-ideal behavior |

Interpreting Common Patterns in Redox Systems

For redox systems commonly encountered in pharmaceutical research, the Nyquist plot often displays distinctive patterns that reveal critical information about the electrochemical processes. A typical Randles circuit (Figure 1), which models a simple electrode-electrolyte interface, produces a semicircle in the Nyquist plot at higher frequencies followed by a 45° Warburg line at lower frequencies [20] [19].

The high-frequency intercept with the real axis provides the solution resistance (Rₛ), while the diameter of the semicircle corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (Rct) [20]. The low-frequency region reveals information about mass transport limitations, with an ideal Warburg impedance appearing as a straight line at 45° [18]. The frequency at the maximum of the semicircle (Z"ₘₐₓ) relates to the double layer capacitance through fₘₐₓ = 1/(2πRctC_dl) [20].

In real redox systems, non-ideal behavior often manifests as depressed semicircles due to surface heterogeneity, which is commonly modeled using Constant Phase Elements (CPE) rather than ideal capacitors [23] [21]. The depression angle of the semicircle provides qualitative information about surface homogeneity, with greater depression indicating increased surface disorder or non-uniform current distribution.

Diagram 1: Nyquist Plot Interpretation Workflow. This diagram illustrates the systematic approach to extracting information from a Nyquist plot, from initial data examination to final parameter interpretation.

Bode Plot Interpretation

Fundamental Principles and Axes

The Bode plot provides an alternative representation of EIS data that preserves explicit frequency information. This plot consists of two separate graphs sharing a common logarithmic frequency axis (x-axis) [20] [22]. The first graph plots the logarithm of impedance magnitude (|Z|) against frequency, while the second plots phase angle (Φ) against the same frequency range [20] [18].

Unlike the Nyquist plot, the Bode plot clearly displays how impedance parameters change with frequency, making it particularly valuable for identifying processes with specific time constants [11]. The impedance magnitude plot reveals the frequency-dependent opposition to current flow, while the phase angle plot provides clear signatures of dominant electrochemical processes at different frequency ranges [22].

Interpreting Characteristic Frequency Dependencies

In Bode plot interpretation, specific frequency regions correspond to different electrochemical processes in redox systems. The phase angle plot is especially valuable for process identification, as different circuit elements produce characteristic phase signatures:

- Phase angle of 0°: Indicates purely resistive behavior (ideal resistor)

- Phase angle of -90°: Indicates purely capacitive behavior (ideal capacitor)

- Phase angle of +90°: Indicates purely inductive behavior (ideal inductor)

- Phase angles between 0° and -90°: Represent mixed resistive-capacitive behavior common in electrochemical interfaces [22]

The impedance magnitude plot typically shows plateaus and slopes that correspond to different circuit elements. A horizontal line indicates frequency-independent impedance (resistive behavior), while a slope of -1 in the impedance magnitude plot suggests capacitive behavior [20]. A phase angle peak in the Bode plot typically corresponds to a time constant in the system, with the frequency at the peak maximum related to the reciprocal of the time constant (f = 1/2πRC) [21].

Table 2: Bode Plot Interpretation Guide for Redox Systems

| Frequency Region | Z | Behavior | Phase Angle (Φ) | Dominant Process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High Frequency | Plateau | Approaches 0° | Solution resistance | ||

| Mid Frequency | Decreasing slope | Negative peak | Charge transfer kinetics | ||

| Low Frequency | Increasing slope | Approaches 0° | Mass transport/diffusion | ||

| Low Frequency | Slope = -0.5 | 45° | Warburg diffusion | ||

| Broad Frequency | Linear decrease | Constant -60° to -80° | CPE behavior |

Comparative Analysis of Plot Representations

Advantages and Limitations in Redox Applications

Both Nyquist and Bode plots offer unique advantages for analyzing EIS data in redox systems, with the choice of representation often depending on the specific information required:

Nyquist Plot Advantages:

- Enhanced sensitivity to small changes in system parameters [20]

- Direct visualization of characteristic shapes (semicircles, lines) [22]

- Easy estimation of key parameters (Rₛ, R_ct) through visual inspection [20]

- Better representation of complex circuit interactions [21]

Nyquist Plot Limitations:

- Frequency information is implicit rather than explicit [20] [11]

- Can be difficult to interpret for systems with multiple similar time constants [21]

- May require orthonormal scaling for proper shape recognition [22]

Bode Plot Advantages:

- Explicit display of frequency information [20] [11]

- Clear identification of processes with specific time constants [21]

- Better visualization of widely separated time constants [11]

- Easier identification of inductive contributions at high frequencies [21]

Bode Plot Limitations:

- Less intuitive for understanding complex circuit interactions [20]

- Characteristic shapes (semicircles) are not directly visible [22]

- Can be difficult to estimate specific parameter values visually [21]

Practical Guidelines for Plot Selection

For comprehensive analysis of redox systems, researchers should employ both representation methods to leverage their complementary strengths. The following guidelines recommend plot selection based on specific analytical needs:

- Use Nyquist plots for initial system assessment, equivalent circuit modeling, and parameter estimation from distinct features

- Use Bode plots for identifying the number of time constants, analyzing frequency-dependent behavior, and presenting data to non-specialists

- Use both plots for comprehensive analysis, validation of interpretations, and publication-quality data presentation

Modern EIS analysis software typically generates both plot types simultaneously, allowing researchers to switch between representations to gain different insights into their redox systems [20] [21].

Practical Protocols for EIS Data Analysis

Systematic Workflow for Data Interpretation

Implementing a structured approach to EIS data interpretation enhances accuracy and reproducibility in redox system characterization. The following protocol provides a step-by-step methodology for comprehensive plot analysis:

Step 1: Data Validation

- Verify data quality using Kramers-Kronig relations to ensure compliance with linearity, causality, and stability requirements [17]

- Identify and exclude non-compliant data points, particularly in low-frequency regions where system instability may occur [17]

Step 2: Initial Plot Assessment

- Examine Nyquist plot for characteristic shapes and number of apparent features

- Check Bode plot for number of phase angle peaks and impedance magnitude slopes

- Note frequency ranges corresponding to different behavioral regions

Step 3: Process Identification

- Use the frequency derivative of phase angle (dΦ/dlogf) to identify time constants with higher resolution than simple phase angle inspection [21]

- Correlate features between Nyquist and Bode representations to confirm process identification

- Distinguish between charge transfer, diffusion, and other processes based on characteristic signatures

Step 4: Equivalent Circuit Modeling

- Develop appropriate equivalent circuit based on identified processes

- Use graphical parameter estimation from plots as initial values for nonlinear fitting [21]

- Validate circuit model by comparing fitted parameters with visual estimates from plots

Step 5: Quantitative Analysis

- Extract parameters of interest (Rₛ, Rct, Cdl, W) from fitted model

- Calculate derived parameters (rate constants, diffusion coefficients) for redox systems

- Perform error analysis and uncertainty quantification

Diagram 2: EIS Data Analysis Protocol. This workflow outlines a systematic approach for interpreting EIS data from initial validation to final parameter extraction, emphasizing the complementary roles of Nyquist and Bode plots.

Advanced Graphical Analysis Techniques

Advanced graphical methods enhance the interpretation of complex EIS data from redox systems, particularly when multiple processes with similar time constants overlap:

Frequency Derivative Method:

- Calculate dΦ/dlogf to enhance resolution of overlapping time constants [21]

- Peaks in the derivative plot correspond to characteristic frequencies of individual processes

- This method provides improved frequency resolution compared to simple phase angle inspection [21]

Imaginary Impedance Slope Analysis:

- Plot log(-Z") versus log(f) to estimate CPE exponent n from the slope [21]

- The relationship follows: log(-Z") ∝ -n·log(f) + constant

- This approach avoids complications from series resistance that affect phase angle measurements [21]

Composite Graphical Analysis:

- Combine multiple graphical techniques for robust parameter estimation

- Use Nyquist plot for resistance estimation and Bode plot for capacitance and CPE exponent determination

- Cross-validate parameters obtained from different graphical methods [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials for EIS in Redox Systems

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for EIS in Redox Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function in EIS Experiments | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Supporting electrolyte for ionic conductivity | Provides controlled ionic strength; minimizes migration effects |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Physiological buffer for bio-relevant conditions | Maintains pH stability for biological redox systems |

| Ferro/Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻) | Standard redox probe for system characterization | Reversible one-electron transfer; well-established model system |

| Tris(bipyridine)ruthenium(II) ([Ru(bpy)₃]²⁺) | Alternative redox probe with different kinetics | Slower electron transfer rates; different molecular size |

| Nano-porous Carbon Electrodes | High surface area electrode material | Enhanced sensitivity; tunable porosity for size exclusion |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Kits | Surface functionalization | Controlled interface modification; biorecognition element attachment |

Emerging Trends and Advanced Applications

Data-Driven Analysis and Model Discrimination

Recent advances in EIS data interpretation have introduced data-driven approaches that complement traditional graphical analysis. The Loewner Framework (LF) represents a promising development that facilitates the identification of appropriate equivalent circuit models by extracting Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) from EIS datasets [23]. This method is particularly valuable for distinguishing between different Randles circuit variants that can produce deceptively similar impedance spectra despite representing different physical processes in redox systems [23].

For pharmaceutical researchers, these advanced methods enable more accurate model selection when studying complex redox processes in drug compounds. The LF approach provides unique DRTs that help discriminate between different equivalent circuit models, addressing a fundamental challenge in EIS data interpretation where different physical models can produce nearly identical spectra [23]. This capability is particularly valuable when extending EIS analysis to novel redox systems with unknown mechanisms.

High-Frequency and Nano-scale Applications

Advancements in EIS instrumentation have expanded the accessible frequency range, enabling investigation of faster electrochemical processes relevant to redox kinetics in drug development. High-frequency EIS (up to MHz range) provides information about double layer structure and fast charge transfer processes that were previously inaccessible [24]. Simultaneously, the development of nanoelectrode systems has opened new possibilities for localized measurements and reduced sample volumes, though these systems present significant technical challenges related to stray capacitance and increased dynamic ranges [24].

For drug development applications, these technological advances enable EIS investigation of faster electron transfer processes and measurements in smaller volumes, supporting the trend toward miniaturization and high-throughput screening in pharmaceutical research. The optimization of electrolyte and redox probe systems has concurrently improved signal-to-noise ratios, allowing researchers to transition from expensive benchtop analyzers to more affordable portable systems without sacrificing data quality [25].

Nyquist and Bode plots represent complementary approaches to visualizing and interpreting EIS data in redox systems research. While Nyquist plots offer intuitive shape-based analysis and parameter estimation, Bode plots provide explicit frequency information that enhances process identification. A systematic approach combining both representations, along with advanced graphical analysis techniques, enables comprehensive characterization of electrochemical systems relevant to drug development.

As EIS technology continues to evolve with data-driven analysis methods and expanded frequency ranges, these fundamental plotting techniques remain essential tools for extracting meaningful information from complex impedance data. The continued development of standardized protocols and interpretation guidelines will further enhance the utility of EIS as a powerful characterization technique in pharmaceutical redox research.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique used to investigate the complex interplay of mass transport and electrokinetics at the electrode-electrolyte interface. By measuring a system's response to a small amplitude alternating current (AC) signal across a wide frequency range, EIS can deconvolute individual processes with different time constants, such as charge transfer reactions, double-layer charging, and mass diffusion. This application note details the theoretical principles and practical protocols for employing EIS to model the redox-active double layer and quantify charge transfer kinetics, providing a critical toolkit for researchers in electrochemistry and drug development.

The fundamental principle of EIS extends Ohm's Law into the AC domain. Where resistance (R) describes opposition to direct current (DC) flow, impedance (Z) describes the total opposition a circuit presents to AC flow. In an electrochemical system, when a sinusoidal potential of the form ( Et = E0 \sin(\omega t) ) is applied (where ( E0 ) is the amplitude and ( \omega ) is the radial frequency), the current response in a linear, stable system is a sinusoid of the same frequency but shifted in phase: ( It = I0 \sin(\omega t + \phi) ) [11] [12]. The impedance is then a complex function defined as the ratio of the voltage to the current: ( Z(\omega) = \frac{E(t)}{I(t)} = Z0 \frac{\sin(\omega t)}{\sin(\omega t + \phi)} = Z_0 e^{-j\phi} ) [11]. This can be separated into real ((Z')) and imaginary ((Z'')) components: ( Z(\omega) = Z' + jZ'' ), where ( j ) is the imaginary unit [12].

Theoretical Background

The Redox-Active Double Layer and Charge Transfer

At the heart of every Faradaic reaction is the electrochemical double layer, a critical interface formed between a solid electrode and an ionic electrolyte. When a potential is applied, charged species from the solution arrange themselves near the electrode surface, forming a capacitor-like structure. This double layer consists of ions and solvent molecules that act as a dielectric separating the charge on the electrode from the compensating ions in the solution [12]. For a redox-active molecule in solution, electron transfer can occur through this double layer if the applied potential is sufficient to drive an oxidation or reduction reaction. This charge transfer process can be modeled as a resistor, representing the energy barrier for electron transfer [12]. The interplay between the capacitive double layer and the resistive charge transfer pathway defines the overall impedance of the interface.

Essential Circuit Elements for Modeling

Electrochemical systems are commonly modeled using Equivalent Circuit Models (ECMs), where physical processes are represented by common electrical elements. The impedance of standard components is summarized in Table 1 [11].

Table 1: Common Electrical Elements and Their Impedance

| Component | Current vs. Voltage | Impedance |

|---|---|---|

| Resistor | (E = I R) | (Z = R) |

| Inductor | (E = L \frac{di}{dt}) | (Z = j \omega L) |

| Capacitor | (I = C \frac{dE}{dt}) | (Z = \frac{1}{j \omega C}) |

The impedance of a resistor is independent of frequency and has no imaginary component. The current through a resistor remains in phase with the voltage. The impedance of an inductor increases with frequency and has a positive imaginary component, causing the current to lag the voltage by 90 degrees. The impedance of a capacitor decreases with frequency and has a negative imaginary component, causing the current to lead the voltage by 90 degrees [11]. These elements are combined in series and parallel to create models that represent the behavior of real electrochemical interfaces.

The Randles Circuit: A Fundamental Model

The most ubiquitous equivalent circuit for a simple electrode-electrolyte interface with a redox couple is the Randles Circuit. This model includes key physical processes shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Signaling Pathways in the Randles Equivalent Circuit. This diagram illustrates the pathways for current flow in a Faradaic system, showing the parallel processes of double-layer charging and the Faradaic reaction, which is followed by mass transport.

The Randles circuit, as shown in the workflow Figure 2, combines several key elements [12] [26]:

- Solution Resistance (RS): The resistance of the ionic electrolyte between the working and reference electrodes.

- Double Layer Capacitance (CDL): The capacitance arising from the charge separation at the electrode-electrolyte interface.

- Charge Transfer Resistance (RCT): The resistance associated with the kinetics of the electron transfer reaction. It is inversely proportional to the rate of the redox reaction.

- Warburg Impedance (W): A circuit element that models semi-infinite linear diffusion of redox species from the bulk solution to the electrode surface.

Figure 2. Equivalent Circuit Modeling Workflow. Logical sequence for extracting physical parameters from impedance data by fitting to the Randles model, culminating in the calculation of the standard rate constant.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Basic EIS Measurement for a Redox-Active Species

This protocol describes the steps for characterizing the charge transfer kinetics of an organic electroactive compound in solution using EIS, reinforcing data obtained from Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) [26].

Materials and Reagent Preparation

- Working Electrode: 1 mm diameter platinum disc electrode.

- Counter Electrode: Platinum wire.

- Reference Electrode: Silver wire.

- Electrolyte Solution: Prepare 4 mL of a working solution in dichloromethane containing:

- 0.1 mol·L⁻¹ Tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate (Bu₄NBF₄) as supporting electrolyte.

- 0.001 mol·L⁻¹ of the investigated organic redox-active compound.

- Polishing Supplies: Alumina slurry and a polishing cloth.

- Inert Gas: Argon gas for deaeration.

Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrode Preparation:

- Polish the platinum working electrode for 30 seconds using a polishing cloth moistened with alumina slurry. Rinse thoroughly with distilled water to remove all alumina particles [26].

- Anneal both the platinum counter electrode and silver reference electrode briefly in a butane burner flame (less than 1 second, until just red) to clean their surfaces [26].

Cell Assembly and Deaeration:

- Pipette 2 mL of the prepared working solution into a 3 mL electrochemical cell.

- Place the working, counter, and reference electrodes into the cell, ensuring they do not touch each other. Connect them to the corresponding potentiostat cables [26].

- Bubble argon gas through the solution for 20 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen. Close the gas valve before starting measurements [26].

Tentative Characterization by Cyclic Voltammetry (CV):

- Record a cyclic voltammogram from -2.0 V to +2.0 V vs. Ag/Ag⁺ at a scan rate of 100 mV·s⁻¹ [26].

- Identify the formal potential (E⁰) of the redox couple by noting the potentials of the anodic and cathodic peak maxima and calculating their average value [26].

- For potential calibration, add a small amount (~10 mg) of ferrocene into the solution as an internal standard, deaerate for 5 minutes, and record another CV around the ferrocene peak to determine its formal potential [26].

Registration of Impedance Spectra:

- In the potentiostat software, set up a potentiostatic EIS experiment in "staircase" mode with the following parameters [26]:

- Potential Range: Cover a 0.2 V window centered on the redox couple's formal potential (e.g., from E⁰ - 0.1 V to E⁰ + 0.1 V).

- Potential Increment: 0.01 V.

- Frequency Range: From 100,000 Hz (100 kHz) down to 100 Hz.

- Number of Frequencies per Decade: 10 (logarithmic spacing).

- AC Voltage Amplitude: 10 mV.

- Wait Time Between Spectra: 5 seconds.

- Initiate the measurement sequence. The instrument will automatically record an impedance spectrum at each potential step within the defined window [26].

- In the potentiostat software, set up a potentiostatic EIS experiment in "staircase" mode with the following parameters [26]:

Data Analysis and Fitting

Equivalent Circuit Fitting:

- Launch the EIS spectrum analyzer software.

- Import an impedance spectrum collected at or near the formal potential of the redox couple.

- Construct the Randles equivalent circuit (R(CR(W))): a solution resistance (Rₛ) in series with a parallel combination of a double-layer capacitance (Cₑ) and a series connection of charge-transfer resistance (Rₜ) and Warburg impedance (W) [26].

- Input initial parameter estimates to guide the fitting algorithm [26]:

- Cₑ: from 1×10⁻⁸ to 1×10⁻⁷ F

- Rₛ: from 100 to 2000 Ω

- Rₜ: from 100 to 1000 Ω

- W (Aw): from 10,000 to 50,000 Ω·s⁻⁰·⁵

- Run the fitting algorithm iteratively (typically ~5 times) until the parameter values converge and no longer change significantly [26].

Validation and Selection:

- Check the relative errors for each fitted parameter. If any parameter has an error exceeding 100%, it may be unnecessary for the model, and a simpler circuit should be tested [26].

- Assess the goodness-of-fit via the R² (parametric) and R² (amplitude) values; they should ideally be below 1×10⁻² [26].

- Repeat the fitting procedure for all recorded spectra across the potential window.

Calculation of the Redox Rate Constant (k⁰):

- For each spectrum, record the fitted charge transfer resistance (Rₜ) and its corresponding DC potential.

- Plot the inverse of the charge transfer resistance (1/Rₜ) against the applied potential.

- Fit the plotted data to the following theoretical equation to extract the standard electrochemical rate constant, k⁰ [26]: ( \frac{1}{R{ct}} = \frac{F^2 A c0 k^0}{R T} \frac{\exp \left[ \frac{\alpha F}{RT} (E - E^0) \right] }{ \left( 1 + \exp \left[ -\frac{F}{RT} (E - E^0) \right] \right ) } ) where F is the Faraday constant, A is the electrode area, c₀ is the bulk concentration of the redox species, R is the gas constant, T is the temperature, and α is the charge transfer coefficient (often assumed to be 0.5) [26].

Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for EIS of Redox Systems

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes solution resistance; carries current without participating in redox reaction. | Tetrabutylammonium tetrafluoroborate (Bu₄NBF₄) in organic solvents (e.g., dichloromethane) [26]. |

| Redox-Active Analyte | The species of interest whose charge transfer kinetics are being probed. | Organic electroactive compounds for optoelectronics, e.g., 2,8-bis(3,7-dibutyl-10H-phenoxazin-10-yl)dibenzo[b,d]thiophene-S,S-dioxide [26]. |

| Internal Potential Standard | Calibrates the potential scale against a known reference. | Ferrocene/Ferrocenium (Fc/Fc⁺) couple; added directly to the solution post-initial CV [26]. |

| Polishing Material | Creates a clean, reproducible electrode surface for reliable measurements. | Alumina (Al₂O₃) slurry of defined micron size (e.g., 0.05 µm) [26]. |

| Working Electrode | Provides the surface where the redox reaction and double-layer formation occur. | Pre-polished platinum (Pt) disc electrode (1 mm diameter) [26]. |

| Solvent | Dissolves the electrolyte and analyte to form the electrochemical medium. | Anhydrous dichloromethane (DCM) for organometallic/organic compounds [26]. |

Data Presentation and Analysis

The critical parameters extracted from EIS analysis provide a quantitative picture of the electrochemical interface. Table 3 summarizes typical outputs from fitting the Randles circuit to a reversible redox system.

Table 3: Quantitative Parameters from EIS Analysis of a Model Redox System

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Range | Physical Significance | Dependence |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solution Resistance | Rₛ | 10 - 1000 Ω | Resistance to current flow in the electrolyte. | Dependent on electrolyte conductivity and cell geometry. Independent of potential/frequency. |

| Double Layer Capacitance | Cₑ | 1×10⁻⁸ - 1×10⁻⁶ F | Capacitance of the electrode-solution interface. | Dependent on electrode material and area. Weakly dependent on potential. |

| Charge Transfer Resistance | Rₜ | 100 - 10,000 Ω | Kinetic barrier to electron transfer. | Highly dependent on potential; minimum at formal potential (E⁰). |

| Warburg Coefficient | σ | 100 - 10,000 Ω·s⁻⁰·⁵ | Resistance due to mass transport by diffusion. | Observable at low frequencies. Dependent on diffusion coefficients and concentration. |

| Standard Rate Constant | k⁰ | 0.001 - 1 cm/s | Intrinsic speed of the redox reaction. | A constant for a given redox couple and electrode material. |

Practical Implementation and Cutting-Edge Applications in Biomedicine

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique used extensively in electrochemical research, including studies of redox systems fundamental to drug development and diagnostic technologies. By applying a small amplitude sinusoidal potential across an electrochemical cell and measuring the current response, EIS non-invasively probes interface properties and reaction mechanisms [12] [11]. The resulting impedance data is most frequently interpreted through equivalent circuit modeling, where physical processes are represented by electrical circuit elements whose collective behavior matches the measured response [27]. This guide details the fundamental building blocks—the Resistor (R), Capacitor (C), Inductor (L), Warburg element (W), and Constant Phase Element (CPE)—used to construct these models, providing researchers with a framework for interpreting EIS data from redox systems.

Core Equivalent Circuit Elements

The following table summarizes the key characteristics and common physical interpretations of the fundamental equivalent circuit elements used in EIS modeling of redox systems.

Table 1: Common Equivalent Circuit Elements and Their Parameters

| Element | Symbol | Impedance (Z) Formula | Key Parameters | Physical Origin in Redox Systems |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistor | R | ( Z = R ) [28] | R: Resistance (Ω) [28] | Solution/electrolyte resistance; charge transfer resistance at the electrode interface [12] [11] |

| Capacitor | C | ( Z = (j \omega C)^{-1} ) [28] | C: Capacitance (F) [28] | Ideal polarization of the electrical double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface [12] |

| Inductor | L | ( Z = j \omega L ) [28] | L: Inductance (H) [28] | Adsorption of intermediate species on the electrode surface; wiring artifacts [11] |

| Warburg Element | W | ( \text{Re}Z = AW / \omega^{0.5} ); ( \text{Im}Z = -AW / \omega^{0.5} ) [28] | ( A_W ): Warburg coefficient (Ω s⁻⁰·⁵) [28] | Semi-infinite linear diffusion of electroactive species from the bulk solution to the electrode surface [28] |

| Constant Phase Element | CPE | ( Z = 1 / [Q (j\omega)^n] ) [28] [29] | Q: CPE constant (S·sⁿ); n: phase exponent (0 ≤ n ≤ 1) [28] [29] | Non-ideal capacitive behavior due to surface roughness, porosity, or current distribution inhomogeneities [28] [30] |

Experimental Protocols for EIS in Redox Systems

Prerequisite: System Stabilization and Linearization

Before data acquisition, ensure the electrochemical system is at a steady state. A common cause of problematic EIS data is system drift, which can invalidate the analysis [11]. The system must also be linearized, achieved by using a sufficiently small amplitude for the applied AC signal (typically 1-10 mV) [11] [31]. This small perturbation ensures the current response is pseudo-linear, a fundamental requirement for standard EIS interpretation [11].

Protocol: Potentiostatic EIS Measurement

This protocol outlines a standard potentiostatic EIS measurement, where the applied potential is perturbed and the current response is measured.

- Instrument and Cell Setup: Configure a potentiostat with a frequency response analyzer (FRA) in a standard three-electrode cell: Working Electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, gold), Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and Counter Electrode (e.g., platinum wire) [12].

- DC Bias Application: Apply the desired DC potential, which defines the operating point for the redox reaction under study.

- AC Signal Application and Sweep: Superimpose a sinusoidal AC potential wave with a fixed, small amplitude (e.g., 10 mV) onto the DC bias [12]. Sweep the frequency of this signal logarithmically from a high frequency (e.g., 100 kHz) to a low frequency (e.g., 10 mHz), measuring at 5-10 points per decade [12].

- Signal Processing at Each Frequency: For each frequency, the instrument applies a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to the measured current and potential vs. time data. This analysis extracts the fundamental frequency's amplitude and phase information [12] [11].

- Data Output and Validation: The final dataset for each frequency includes: frequency ((f), Hz), impedance magnitude ((|Z|), Ω), phase angle ((-\phi), degrees), real impedance ((Z{\text{re}}), Ω), and negative imaginary impedance ((-Z{\text{im}}), Ω) [12]. Visually inspect the data on a Nyquist plot for signs of non-stationarity, such as open or drifting semicircles.

Protocol: Data Fitting with Equivalent Circuits

- Circuit Model Selection: Based on the physical understanding of the redox system and the features of the Nyquist or Bode plot, propose an initial equivalent circuit. A simple Randles circuit (R1 + C1/(R2+W)) is a common starting point for a Faradaic reaction.

- Initial Parameter Estimation: Manually estimate initial values for the circuit elements (e.g., the high-frequency real-axis intercept gives the solution resistance, R1) [27].

- Non-Linear Least Squares Fitting: Use specialized EIS software to perform a complex non-linear least squares (CNLS) fit of the model to the data. The choice of loss function (e.g., proportional weighting, (X^2)) can significantly impact the quality of the fit and the accuracy of the extracted parameters [32].

- Model and Parameter Validation: Assess the goodness-of-fit via chi-squared values and residuals [27]. Evaluate parameter identifiability using techniques like the Cramer-Rao lower bound or sensitivity analysis to ensure the model is well-defined and the parameters are significant [27].

Visualizing Common Circuit Configurations

The following diagram illustrates the logical progression from a physical electrochemical system to its electrical analog and finally to a characteristic Nyquist plot, highlighting the contribution of individual elements.

Diagram 1: From physical system to circuit model and Nyquist plot.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials for EIS

| Item | Function/Description | Application Note |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat with FRA | Instrument that applies precise potential/current signals and measures the response. The Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) is essential for accurate phase and magnitude detection. | The instrument must be capable of measuring low currents (nA range) and low frequencies (mHz range) for many redox systems. |

| Three-Electrode Cell | Standard setup consisting of a Working Electrode, Reference Electrode, and Counter Electrode. | Enables precise control of the working electrode potential. Common in fundamental redox studies [12]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Electrochemically inert salt (e.g., KCl, NaClO₄) at high concentration (e.g., 0.1-1.0 M). | Carries ionic current and minimizes solution (ohmic) resistance. Must not react with the electroactive analyte. |

| Redox Probe / Analyte | A well-characterized redox couple (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻, [Ru(NH₃)₆]³⁺/²⁺) or the molecule/drug of interest. | Serves as the electroactive species for fundamental method validation or as the target for analysis. |

| Data Fitting Software | Software capable of complex non-linear least squares (CNLS) fitting of equivalent circuit models to EIS data. | Critical for extracting meaningful physical parameters from the raw impedance data [27] [32]. |

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful analytical technique used to probe complex electrochemical systems by applying a small amplitude alternating current (AC) potential across a frequency range and measuring the system's current response [11]. In redox biology and drug development, EIS provides unprecedented insight into electron transfer processes, cell membrane properties, and biomolecular interactions at the electrode-electrolyte interface [12].

While the Randles circuit (Figure 1) has served as the foundational model for simple electrochemical interfaces for decades, its limitations become apparent when studying complex biological systems such as living cells, protein films, and enzymatic pathways. These systems exhibit multiple overlapping time constants, distributed circuit elements, and complex diffusion phenomena that cannot be adequately captured by simplified models [14]. This application note details advanced equivalent circuit models (ECMs) and protocols specifically tailored for complex biological and redox systems, enabling researchers to extract more meaningful physiological information from impedance data.

Theoretical Background

Electrochemical Impedance Fundamentals

Impedance (Z) represents the total opposition a circuit presents to alternating current, extending the concept of resistance to AC systems. It is defined as the frequency-domain ratio of the voltage to the current, expressed as a complex function: Z(ω) = E(ω)/I(ω), where E is the potential, I is the current, and ω is the radial frequency [11]. In EIS experiments, a sinusoidal potential excitation is applied: E(t) = E₀sin(ωt), producing a current response: I(t) = I₀sin(ωt + φ), where φ is the phase shift between signals [12].

The impedance can be separated into real (Z′) and imaginary (Z″) components, calculable from the magnitude and phase angle: Z′ = |Z|cosφ and Z″ = |Z|sinφ [12]. Data is typically visualized using:

- Nyquist plots: Z′ vs. -Z″, where each point represents a different frequency

- Bode plots: log|Z| and φ vs. logω, which explicitly show frequency information [11]

Biological systems require careful attention to measurement conditions. The AC signal amplitude must be small enough (typically 1-10 mV) to ensure pseudo-linearity but large enough to overcome background noise [11]. The system must remain at steady state throughout measurement, which can be challenging for living cellular systems that may evolve over time [11].

Limitations of the Randles Circuit in Biological Systems

The conventional Randles circuit (Figure 1) models a simple electrochemical interface with solution resistance (Rₛ), charge transfer resistance (Rct), double-layer capacitance (Cdl), and Warburg diffusion element (W) [14]. While adequate for basic electrode characterization in controlled solutions, it fails to capture the complexity of biological interfaces where multiple physiological processes occur simultaneously across different timescales. Biological systems typically present distributed impedance elements, multiple time constants, and complex diffusion patterns that deviate significantly from the ideal Warburg behavior [14].

Advanced Equivalent Circuit Models for Biological Systems

Hierarchical ECM for Cellular Monolayers

For adherent cellular monolayers, a hierarchical ECM better represents the biological reality, accounting for paracellular, transcellular, and substrate electrode contributions (Figure 2).

Table 1: Circuit Elements for Cellular Monolayer ECM

| Circuit Element | Physical Meaning | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|

| Rs | Solution resistance between reference and working electrodes | 10-100 Ω |

| Rparacellular | Paracellular path resistance through tight junctions | 1-50 Ω·cm² |

| Cmembrane | Cell membrane capacitance | 1-2 μF/cm² |

| Rtranscellular | Transcellular resistance across apical/basolateral membranes | 10-200 Ω·cm² |

| CPEdl | Constant phase element for electrode double-layer | 10-100 μF/cm² |

| Wsubstrate | Finite-length Warburg for substrate-limited diffusion | Varies with cell type |

The constant phase element (CPE) is essential for modeling non-ideal capacitive behavior in biological systems, with impedance defined as ZCPE = 1/[Q(jω)n], where Q is the CPE constant and n is the dispersion exponent (0 ≤ n ≤ 1) [12].

Multi-Time Constant ECM for Protein-Modified Electrodes

Enzyme or antibody-modified electrodes exhibit multiple relaxation processes that require ECMs with several R-CPE pairs in series or nested configurations (Table 2).

Table 2: ECM Elements for Protein-Modified Electrodes

| Process | Circuit Element | Frequency Range | Biological Correlate |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electronic charge transfer | Rct + CPEdl | 10³-10⁵ Hz | Electron transfer to redox center |

| Protein reorganization | Rrec + CPErec | 1-10³ Hz | Conformational changes |

| Substrate diffusion | W or CPEdiff | 10⁻²-1 Hz | Mass transport limitation |

| Denaturation/aging | Rleak + Cleak | <10⁻² Hz | Non-specific binding/degradation |