Electrochemical Biosensors for Fusion Gene Detection: A Transformative Approach for Cancer Diagnostics

This article explores the convergence of electrochemical biosensing technology and fusion gene analysis for advanced cancer diagnostics.

Electrochemical Biosensors for Fusion Gene Detection: A Transformative Approach for Cancer Diagnostics

Abstract

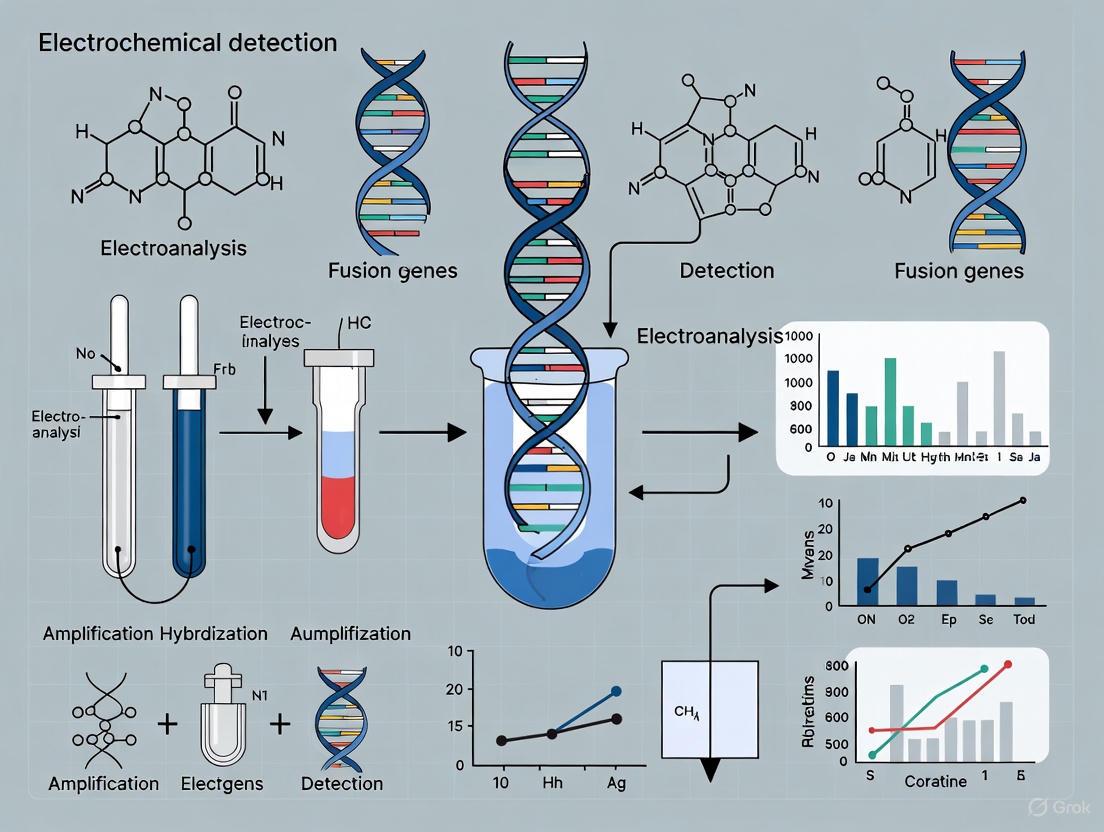

This article explores the convergence of electrochemical biosensing technology and fusion gene analysis for advanced cancer diagnostics. Fusion genes are pivotal oncogenic drivers in numerous cancers, serving as critical biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapy. While methods like FISH, PCR, and NGS are established for their detection, they often face limitations in cost, speed, and point-of-care applicability. This review details how electrochemical biosensors, enhanced by nanomaterials and microfluidics, offer a promising alternative with high sensitivity, rapid response, and potential for miniaturized, low-cost devices. We cover the foundational biology of fusion genes, the design and operational principles of electrochemical genosensors, strategies to overcome analytical and biological challenges, and a comparative analysis with traditional techniques. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this synthesis highlights the potential of electrochemical sensing to revolutionize liquid biopsy and enable routine, early cancer detection.

The Critical Role of Fusion Genes in Cancer and the Electrochemical Sensing Principle

Oncogenic gene fusions are hybrid genes resulting from chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, inversions, deletions, or tandem duplications [1]. These fusion events can create potent driver oncogenes that play a defining role in cancer pathogenesis, making them valuable clinical biomarkers for diagnosis, prognosis, and targeted therapy selection [1] [2]. The discovery of the Philadelphia chromosome in 1960, later identified as the BCR-ABL fusion in chronic myeloid leukemia (CML), marked the first recognized fusion gene in cancer [1]. Since then, numerous clinically significant fusions have been identified across diverse cancer types, including EML4-ALK in non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and NTRK fusions across multiple tumor types [1] [3].

These fusion genes typically result in constitutive activation of tyrosine kinase signaling pathways, leading to uncontrolled cell proliferation and survival [4] [3]. From a clinical perspective, fusion genes represent clonal mutations present in all cancer cells of a patient, making them ideal personal cancer targets for therapeutic intervention [5] [3]. The growing importance of detecting these biomarkers is reflected in the finding that gene fusions occur in up to 17% of all solid tumors, with certain cancer types exhibiting particularly high prevalence rates [3].

Table 1: Prevalence of Key Oncogenic Fusion Genes in Cancer

| Fusion Gene | Primary Cancer Types | Prevalence | Clinical Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| BCR-ABL | Chronic Myeloid Leukemia (CML) | ~95% of CML [4] | Defining diagnostic marker; target for TKIs |

| EML4-ALK | Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC) | 2-7% of NSCLC [3] | Targeted by multiple FDA-approved inhibitors |

| NTRK Fusions | Multiple rare tumors (e.g., secretory carcinoma, infantile fibrosarcoma) | ~100% in some rare tumors [1] [4] | Paradigm for tumor-agnostic therapy |

| TMPRSS2-ERG | Prostate Cancer | ~50% of prostate cancers [1] | Most common ETS family fusion in prostate cancer |

| RET Fusions | Thyroid Cancer, NSCLC | Varies by cancer type [1] | Target for selective RET inhibitors |

Detection Methodologies for Fusion Genes

Conventional Detection Approaches

Traditional methods for fusion gene detection include fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), immunohistochemistry (IHC), and polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based techniques [1]. While these methods remain valuable in clinical diagnostics, they possess inherent limitations for multiplexed analysis and novel fusion discovery [1]. FISH provides visual localization of chromosomal rearrangements but offers limited information about fusion partners and breakpoints. IHC detects protein overexpression resulting from fusion events but lacks specificity for specific fusion variants [1].

Next-Generation Sequencing Platforms

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have revolutionized fusion gene detection by enabling comprehensive analysis of multiple genes simultaneously [1] [5]. Both DNA-based and RNA-based NGS approaches are employed, with RNA sequencing particularly valuable for detecting functional fusion transcripts [1]. These technologies allow for the identification of novel fusion partners and rare rearrangement events that would be missed by targeted approaches. The economic and technical challenges of implementing NGS in routine clinical care globally remain a consideration, despite growing guideline recommendations [1].

Emerging Electrochemical Biosensing Platforms

Recent advancements in electrochemical biosensors present promising alternatives for fusion gene detection, particularly in resource-limited settings [6] [7]. These platforms offer cost-effective, rapid analysis with potential for point-of-care testing, addressing accessibility gaps in cancer diagnostics [6]. Nanoengineered electrochemical biosensors incorporate advanced materials to enhance sensitivity and specificity for detecting DNA, RNA, and protein biomarkers [6] [7].

The fundamental principle involves immobilization of specific capture probes (e.g., oligonucleotides complementary to fusion junction sequences) on electrode surfaces, with detection achieved through measurable electrical signals changes upon target binding [6]. Electrode geometry and surface chemistry are critically optimized parameters, with designs including disc-shaped and microneedle electrodes to improve electroanalytical performance [6]. The integration of nanomaterials such as graphene, carbon nanotubes, and metal nanoparticles significantly enhances signal amplification, enabling detection of low-abundance fusion transcripts [7].

Table 2: Comparison of Fusion Gene Detection Methodologies

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| FISH | Fluorescently labeled DNA probes bind to specific chromosomal regions | Established clinical validity; visual confirmation of rearrangement | Limited multiplexing; cannot identify novel partners |

| IHC | Antibody detection of overexpressed fusion proteins | Rapid; cost-effective; widely available | Indirect detection; limited specificity for fusion variants |

| RT-PCR | Amplification of fusion transcript sequences | High sensitivity; quantitative potential | Requires prior knowledge of fusion partners |

| NGS | Massive parallel sequencing of DNA or RNA | Comprehensive; discovers novel fusions; multiplexed | Higher cost; complex data analysis; technical expertise |

| Electrochemical Biosensors | Electrode-based detection of hybridization events | Rapid; low-cost; point-of-care potential; high sensitivity | Still in development for fusion genes; requires validation |

Experimental Protocols

RNA Extraction and Quality Control Protocol

Principle: High-quality RNA is essential for reliable fusion gene detection by sequencing or electrochemical biosensing platforms [1].

Reagents:

- TRIzol reagent or equivalent RNA stabilization solution

- DNase I enzyme for genomic DNA removal

- RNA quality assessment reagents (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer RNA kits)

- Nuclease-free water and consumables

Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Homogenize 20-30 mg of fresh frozen tissue or cell pellet in 1 mL TRIzol reagent. For formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, use specialized extraction kits designed for cross-linked RNA.

- Phase Separation: Add 0.2 mL chloroform per 1 mL TRIzol, shake vigorously for 15 seconds, and incubate at room temperature for 3 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 15 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Precipitation: Transfer aqueous phase to new tube, mix with 0.5 mL isopropyl alcohol, and incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes. Centrifuge at 12,000 × g for 10 minutes at 4°C.

- RNA Wash: Wash pellet with 75% ethanol, vortex, and centrifuge at 7,500 × g for 5 minutes at 4°C.

- DNase Treatment: Resuspend RNA pellet in nuclease-free water and treat with DNase I following manufacturer's protocol to remove genomic DNA contamination.

- Quality Control: Assess RNA integrity number (RIN) using Bioanalyzer (target RIN >7.0 for NGS) or similar system. Verify concentration by spectrophotometry (A260/A280 ratio ~2.0).

Technical Notes: For electrochemical sensing applications, additional fragmentation may be required to optimize target accessibility. Always include positive and negative control samples in each extraction batch.

Electrochemical Detection of EML4-ALK Fusion Transcript

Principle: This protocol details specific detection of the EML4-ALK fusion transcript using a nanomaterial-enhanced electrochemical biosensor [6] [7].

Reagents:

- Gold electrode array (2 mm diameter working electrodes)

- Thiolated capture probe: 5'-HS-(CH2)6-XXXXX-3' (complementary to EML4-ALK fusion junction)

- Graphene oxide-gold nanoparticle nanocomposite

- Methylene blue redox indicator

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with 0.1 M NaCl

- Target EML4-ALK fusion transcript standards

Procedure:

- Electrode Modification: Polish gold electrodes with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina slurry, rinse with deionized water, and electrochemically clean in 0.5 M H2SO4 by cyclic voltammetry scanning from 0 to 1.5 V until stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Nanocomposite Preparation: Synthesize graphene oxide-gold nanoparticle nanocomposite by chemical reduction of HAuCl4 on graphene oxide sheets. Characterize by TEM and UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Probe Immobilization: Incubate electrodes with 1 μM thiolated capture probe in PBS at 4°C for 16 hours. Backfill with 1 mM 6-mercapto-1-hexanol for 1 hour to block nonspecific binding sites.

- Hybridization: Apply 10 μL sample containing target RNA to electrode surface. Incubate at 42°C for 30 minutes in humidified chamber. Wash with PBS to remove unbound material.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform differential pulse voltammetry from -0.2 to -0.5 V in PBS containing 50 μM methylene blue. Measure reduction current at -0.35 V.

- Data Analysis: Quantify fusion transcript concentration based on calibration curve generated with known standards. Normalize signals to internal control probes.

Technical Notes: Optimal capture probe design requires precise alignment with the specific EML4-ALK variant breakpoint. Include mismatch controls to verify specificity. The assay demonstrates detection limits approaching 1 fM for synthetic targets [6].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Oncogenic fusion proteins drive tumorigenesis through constitutive activation of critical signaling pathways, particularly those involving tyrosine kinases [1] [4]. The molecular structure of kinase fusion proteins typically places the kinase domain under the control of strong promoter elements or fuses it to dimerization domains, resulting in ligand-independent activation [4] [3].

The BCR-ABL fusion protein exhibits constitutive ABL tyrosine kinase activity, leading to persistent activation of downstream pathways including RAS/MAPK, JAK/STAT, and PI3K/AKT, which collectively promote proliferation and suppress apoptosis [1]. Similarly, EML4-ALK fusions result in oligomerization through the EML4 portion, activating the ALK kinase domain and its downstream signaling cascades including RAS/ERK, STAT3, and mTOR pathways [4] [3].

NTRK fusions involve the 3' kinase domain of NTRK genes (NTRK1, NTRK2, or NTRK3) fused to various 5' partner genes, leading to ligand-independent dimerization and constitutive activation of MAPK, PI3K/AKT, and PLCγ pathways [1] [4]. These signaling events promote cell survival, proliferation, and differentiation in TRK-expressing neurons, but drive oncogenesis when activated inappropriately in other cell types.

Therapeutic Targeting and Clinical Applications

Approved Targeted Therapies

The constitutive kinase activation resulting from oncogenic fusions creates therapeutic vulnerabilities that can be exploited with targeted inhibitors [1] [3]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) have demonstrated remarkable efficacy in fusion-driven cancers, with several agents receiving FDA approval for specific fusion indications [3]. These inhibitors are classified by their mechanism of action: Type I and II inhibitors compete with ATP binding in active and inactive kinase conformations, respectively, while Type III and IV are allosteric inhibitors, and Type V are bivalent inhibitors targeting two distinct regions [3].

For ALK fusion-positive NSCLC, multiple generations of inhibitors have been developed. Crizotinib, a first-generation ALK inhibitor, showed superior response rates compared to chemotherapy (ORR 74% vs. 45% in treatment-naïve patients) but faced limitations with acquired resistance [3]. Second-generation inhibitors including ceritinib, alectinib, and brigatinib offer improved potency and central nervous system penetration, with alectinib demonstrating significantly prolonged progression-free survival compared to crizotinib (median PFS not reached vs. 10.2 months) [3]. Lorlatinib, a third-generation inhibitor, maintains efficacy against resistant mutations and showed dramatic improvement in PFS (HR: 0.28) in the CROWN trial [3].

The tissue-agnostic approval of TRK inhibitors (larotrectinib and entrectinib) for NTRK fusion-positive cancers represents a paradigm shift in precision oncology, demonstrating that molecular alterations can transcend histologic classifications in guiding therapy [1] [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Fusion Gene Investigation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Application & Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Line Models | Ba/F3 cells expressing EML4-ALK variants; KM-12 (COL1A1-PDGFB); CUTO-3.29 (EML4-ALK) [4] | Functional validation of fusion oncogenicity; drug screening | Verify fusion status regularly; use low passages |

| Antibodies | Phospho-ALK (Tyr1604); Pan-TRK (EPR17341); BCR (C-1); c-ABL (24-11) | Detection of fusion proteins and activation status; Western blot, IHC | Validate for specific applications; check species reactivity |

| qPCR Assays | Fusion-specific TaqMan assays; SYBR Green with breakpoint-specific primers | Quantitative fusion transcript detection; minimal residual disease monitoring | Design primers spanning breakpoint junctions |

| CRISPR Tools | Guide RNAs targeting fusion junctions; Cas9 expression vectors | Functional knockout of fusion genes; mechanistic studies | Verify specificity to avoid wild-type gene targeting |

| Kinase Assays | ADP-Glo Kinase Assay System; mobility shift assays | Biochemical assessment of fusion kinase activity and inhibition | Include both wild-type and fusion kinases for comparison |

| Structural Biology | KinaseFusionDB database; predicted 3D structures [4] | In silico analysis of fusion protein structure; drug binding predictions | Use for inhibitor design and resistance mechanism studies |

Experimental Workflow for Fusion Gene Analysis

A comprehensive approach to fusion gene analysis integrates multiple methodological platforms to overcome the limitations of individual techniques [1] [6]. The following workflow diagram illustrates a integrated protocol for fusion gene detection and validation:

This integrated workflow begins with appropriate sample collection and nucleic acid extraction, followed by rigorous quality control assessment [1]. Next-generation sequencing serves as a discovery platform to identify known and novel fusion events [1] [5]. Electrochemical biosensors provide rapid, cost-effective confirmation of specific fusion targets, particularly valuable for repeated monitoring or resource-limited settings [6] [7]. Orthogonal validation using established methods (FISH, RT-PCR) ensures result reliability before proceeding to functional characterization in model systems [1]. Finally, clinical correlation links molecular findings with patient outcomes and therapeutic responses.

The application of this workflow enables comprehensive fusion gene analysis while balancing diagnostic accuracy with practical considerations of cost, throughput, and technical feasibility. This approach supports both clinical diagnostics and research investigations into novel fusion events and their biological significance.

Gene fusions are hybrid genes formed when two previously independent genes combine, often as a result of chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, deletions, or inversions [8]. These events can produce chimeric proteins with novel functions or alter the regulation of gene expression, playing a significant role in cellular physiology and disease. In cancer, gene fusions are recognized as powerful driver mutations, contributing to an estimated 20% of global cancer morbidity [9]. The initial discovery of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene in chronic myeloid leukemia, resulting from a translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22 (the Philadelphia chromosome), established the foundational model for understanding the oncogenic potential of fusion genes [8]. Subsequent research has identified over 10,000 gene fusions, with their prevalence varying widely across cancer types [9]. This document details the molecular mechanisms behind gene fusion formation and provides standardized protocols for their detection, with particular emphasis on applications in developing electrochemical biosensors for cancer diagnostics.

Fundamental Mechanisms of Formation

Chromosomal Translocations

Chromosomal translocations occur when segments from two different chromosomes break and exchange places. Reciprocal translocations, involving a two-way exchange of genetic material, are a primary mechanism for gene fusion [10]. If this exchange does not result in a net gain or loss of genetic material, it is termed a balanced translocation and may not cause disease in carriers. However, it can lead to unbalanced gametes and cause disorders in offspring [10]. In a cancer context, a classic example is the formation of the BCR-ABL1 fusion gene, where the ABL1 proto-oncogene from chromosome 9 is juxtaposed with the BCR gene on chromosome 22, resulting in a constitutively active tyrosine kinase that drives leukemogenesis [8].

Table 1: Types of Chromosomal Translocations Leading to Gene Fusion

| Translocation Type | Molecular Description | Genomic Consequence | Example Fusion (Disease) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reciprocal | Exchange of segments between two different chromosomes | Can be balanced or unbalanced; may form hybrid genes | BCR-ABL1 [8] (Chronic Myeloid Leukemia) |

| Robertsonian | Fusion of two acrocentric chromosomes at the centromeres | Loss of short arms; one large metacentric chromosome is formed | Associated with increased risk of translocation Down syndrome [10] |

| Nonreciprocal | One-way transfer of genetic material to another chromosome | Unbalanced; results in gain or loss of genetic material | Implicated in Emanuel Syndrome [10] |

Interstitial Deletions

Interstitial deletions involve the loss of a segment of DNA from within a chromosome, not from the telomere. If the deleted region is between two genes, the deletion can bring the promoter or regulatory sequences of one gene into close proximity with the coding region of another, effectively fusing them into a single transcriptional unit [8]. A key example is the PAX7-FOXO1 fusion gene in rhabdomyosarcoma, which arises from a deletion on chromosome 13 that bridges the two genes [8]. This fusion creates an oncogenic transcription factor that disrupts normal muscle cell development.

Chromosomal Inversions

Chromosomal inversions occur when a segment of a chromosome breaks, rotates 180 degrees, and reinserts back into the same location. When the breakpoints of this inversion lie within two different genes, it can fuse parts of these genes while keeping the overall chromosome structure relatively intact [8]. An inversion on chromosome 8, for instance, can lead to the FGFR1::PLAG1 fusion gene, which is responsible for certain pleomorphic adenomas and myoepithelial carcinomas [8]. This inversion places the fibroblast growth factor receptor 1 gene under the control of the PLAG1 promoter, leading to its aberrant expression.

The following diagram illustrates these three primary mechanisms at the chromosomal level.

Alternative RNA-Level Mechanisms

While DNA-level rearrangements are the most common cause, gene fusions can also form at the RNA level through trans-splicing, where two separate RNA transcripts from different genes are spliced together into a single chimeric mRNA [8]. An example is the JAZF1-JJAZ1 fusion, detected in endometrial stromal sarcomas [8]. Another mechanism is transcription-induced gene fusion, where read-through transcription of adjacent genes produces a single fusion transcript without an underlying genomic rearrangement [11] [9].

Quantitative Analysis of Gene Fusion Landscapes

Large-scale genomic studies have revealed that the frequency and recurrence of gene fusions vary significantly across cancer types. Hematologic malignancies and soft tissue sarcomas show the highest prevalence, with gene fusions driving over 50% of leukemias and one-third of soft tissue tumors [9]. In contrast, their prevalence in common epithelial cancers is generally lower but remains clinically significant.

Table 2: Gene Fusion Prevalence and Functional Impact Across Cancers

| Cancer Type | Prevalence of Pathogenic Fusions | Example Oncogenic Fusion(s) | Primary Functional Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prostate Cancer | ~50% (TMPRSS2-ERG fusion alone) | TMPRSS2-ERG [9] | Overexpression of ERG transcription factor |

| Leukemias & Lymphomas | >50% | BCR-ABL1, ETV6-RUNX1, MLL fusions [9] | Constitutive kinase activity or altered transcription |

| Soft Tissue Tumors | ~33% | EWSR1-FLI1 (Ewing Sarcoma) [12] | Chimeric transcription factor driving proliferation |

| Lung Adenocarcinoma | ~6% (EML4-ALK fusion) | EML4-ALK [9] | Constitutive ALK kinase activity |

| Pilocytic Astrocytoma | High | KIAA1549-BRAF [12] | Constitutive BRAF kinase activity driving MAPK pathway |

| Lipoblastoma | Recurrent | COL3A1-PLAG1 [12] | Promoter swapping leading to PLAG1 oncogene activation |

Bioinformatic analyses of gene fusion networks have uncovered key patterns. Most fusion genes partner with a single other gene, while a few, such as MLL (KMT2A), are highly promiscuous and can fuse with over 60 different partners [9]. Furthermore, gene fusion networks often exhibit cancer-type specificity; for instance, fusions in hematopoietic and mesenchymal cancers tend to cluster in distinct regions of the overall network [9].

Experimental Protocols for Fusion Gene Detection

The accurate detection of gene fusions is critical for cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and therapeutic targeting. The following protocols outline standard and next-generation methods.

Protocol: RNA Sequencing for Genome-Wide Fusion Detection

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) is a powerful, untargeted method for discovering known and novel fusion transcripts across the entire transcriptome. A prospective study on pediatric cancers demonstrated that implementing RNA-seq increased the diagnostic yield of gene fusion detection by 38-39% compared to traditional diagnostic techniques alone [12].

Workflow Overview:

- Sample Preparation & RNA Extraction: Obtain fresh-frozen tissue or bone marrow. Isolate total RNA using a column-based or phenol-chloroform extraction method. Assess RNA integrity (RIN > 7.0 is recommended).

- Library Preparation: Deplete ribosomal RNA (ribo-depletion) to enrich for coding and non-ribosomal transcripts. Convert purified RNA into a sequencing library using a strand-specific kit (e.g., Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA).

- High-Throughput Sequencing: Sequence the libraries on a platform such as Illumina NovaSeq 6000, aiming for a minimum of 80-100 million uniquely mapped reads per sample to ensure sensitivity for low-abundance fusions [12].

- Bioinformatic Analysis:

- Alignment: Map sequencing reads to the reference genome using a splice-aware aligner (e.g., STAR).

- Fusion Calling: Process aligned reads with a dedicated fusion detection tool such as STAR-Fusion (version 1.6.0 or later) [12].

- Annotation & Filtering: Annotate candidate fusions with known databases and filter out common artifacts. Prioritize protein-protein coding fusions and those with supporting reads spanning the breakpoint.

- Validation: Confirm high-priority, novel fusions using an independent technique such as RT-PCR or FISH.

Protocol: Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH)

FISH is a targeted cytogenetic technique that uses fluorescently labeled DNA probes to visualize specific genetic regions on metaphase chromosomes or in interphase nuclei. It is a gold standard for validating fusion events detected by other methods.

Workflow Overview:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare metaphase chromosomes from dividing cells or use interphase nuclei from tissue sections (e.g., formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded - FFPE).

- Probe Selection:

- Break-Apart Probes: Two probes flanking a common breakpoint region in a gene (e.g., EWSR1). In a normal cell, the signals are co-localized (yellow). A rearrangement separates the signals (red and green).

- Fusion Probes: Two probes labeled in different colors that bind to the two genes involved in a specific fusion (e.g., BCR and ABL1). A positive result is indicated by the juxtaposition (overlap) of the two signals.

- Hybridization: Denature the probe and sample DNA simultaneously. Incubate to allow the probe to hybridize to its complementary target sequence.

- Washing and Detection: Wash away unbound probe. If using indirect detection, apply fluorescently labeled antibodies. Counterstain with DAPI to visualize the nucleus.

- Microscopy and Analysis: Visualize signals using a fluorescence microscope. Score a sufficient number of cells (e.g., 200 nuclei) for the presence of split or fused signals to determine if the fusion is present.

Protocol: Electrochemical Biosensing for Fusion Gene Detection

Electrochemical (EC) biosensors are emerging as a rapid, cost-effective, and highly sensitive alternative for detecting specific fusion gene sequences, showing great promise for point-of-care diagnostics [13].

Workflow Overview:

- Biosensor Fabrication: Functionalize a gold or screen-printed carbon electrode surface with a capture probe. This is typically a single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) sequence complementary to a specific region of the target fusion gene RNA or DNA (e.g., the unique breakpoint sequence of BCR-ABL1). Use self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) like thiolated DNA to anchor the probe on gold electrodes.

- Sample Processing and Target Amplification: Extract RNA or DNA from patient blood or tissue. For high sensitivity, amplify the target sequence using RT-PCR or isothermal amplification (e.g., LAMP, RPA). Amplicons are often labeled with an electroactive tag (e.g., methylene blue) during amplification.

- Hybridization and Assay: Incubate the prepared sample with the functionalized electrode. The target fusion gene sequence will hybridize with the immobilized capture probe, bringing the electroactive tag close to the electrode surface.

- Electrochemical Signal Transduction: Perform an electrochemical measurement, such as differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) or electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). Hybridization events cause a measurable change in current (in DPV) or impedance (in EIS).

- Signal Quantification: The magnitude of the electrochemical signal (e.g., current peak in DPV) is proportional to the amount of captured target, allowing for quantification of the fusion transcript.

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for fusion gene analysis, integrating both sequencing and biosensor approaches.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Successful detection and analysis of gene fusions rely on a suite of specialized reagents and tools.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Fusion Gene Research

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ribo-Depletion Reagents | Removes abundant ribosomal RNA during library prep, enriching for mRNA and non-coding RNA for RNA-seq. | Essential for obtaining high-quality, comprehensive transcriptome data from total RNA extracts [12]. |

| Strand-Specific Library Prep Kits | Preserves the original strand orientation of RNA transcripts during cDNA synthesis and library construction. | Critical for accurately determining the architecture and correct partner orientation of fusion transcripts in RNA-seq [12]. |

| Break-Apart FISH Probes | Fluorescently labeled DNA probes designed to flank a known common breakpoint region in a gene of interest. | Detects rearrangements of promiscuous genes like EWSR1 or ALK without prior knowledge of the fusion partner [12]. |

| Fusion-Specific FISH Probes | Two differently colored probes designed to bind the two specific genes involved in a known fusion. | Confirms the presence of a specific fusion, such as BCR-ABL1, by visualizing signal co-localization [10]. |

| Thiolated DNA Capture Probes | Single-stranded DNA probes with a thiol group that forms a self-assembled monolayer (SAM) on gold electrode surfaces. | Serves as the recognition element in an electrochemical biosensor for a specific fusion gene target [13]. |

| Electroactive Labels (e.g., Methylene Blue) | Redox-active molecules that produce a measurable current change upon a reduction-oxidation reaction at the electrode. | Used to label target amplicons; a change in signal upon hybridization indicates detection of the fusion sequence [13] [14]. |

| PRL-3 inhibitor I | PRL-3 inhibitor I, CAS:893449-38-2, MF:C17H11Br2NO2S2, MW:485.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BRD4 degrader AT1 | BRD4 degrader AT1, MF:C48H58ClN9O5S3, MW:972.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Implications for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

Understanding the precise mechanisms of gene fusion formation is paramount for designing effective electrochemical detection strategies. The knowledge that specific fusion breakpoints are consistent in certain cancers (e.g., the BCR-ABL1 breakpoint in CML) allows for the design of highly specific thiolated DNA capture probes that are complementary to these unique junctional sequences [13] [8]. This specificity is crucial for distinguishing the pathogenic fusion from wild-type transcripts in a patient sample.

Furthermore, the documented high prevalence of kinase fusions across diverse cancers (e.g., involving ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK) establishes a strong rationale for developing multiplexed electrochemical biosensors [9]. Such a device could simultaneously screen for multiple therapeutically relevant fusion targets from a single sample, aligning with the clinical need for comprehensive molecular profiling. The robust nature and potential for miniaturization of electrochemical platforms address key limitations of traditional methods, offering a path toward rapid, point-of-care fusion gene diagnostics that could greatly expand access to precision oncology [13] [14].

Electrochemical biosensing represents a revolutionary methodology that provides rapid, cost-effective, and highly sensitive detection of biological molecules. This technique measures electrical signals generated by chemical reactions at the interface of an electrode and a biological sample, where electron transfer provides quantitative information about specific biomarkers [14]. In the context of cancer diagnostics, particularly for fusion gene detection, electrochemical biosensors translate the specific recognition of nucleic acid sequences into an analytically readable electrical signal, enabling precise molecular analysis essential for precision oncology [15] [14].

The superior efficacy of electrochemical biosensors compared to conventional techniques lies in their ability to detect cancer biomarkers with enhanced specificity and sensitivity. These platforms are highly adaptable to miniaturization, allowing for the development of portable, point-of-care diagnostic devices that can bring cancer screening closer to patients. Furthermore, the integration of electrochemical systems with advanced technologies such as microfluidics and nanotechnology enhances their potential for rapid and precise detection of fusion genes, which are critical oncogenic drivers in many cancer types [14].

Fundamental Principles

Core Mechanism of Signal Transduction

The underlying principle of electrochemical detection involves monitoring electrical currents generated from redox reactions. When a chemical reaction involving electron transfer occurs, the resulting current provides quantitative information about the concentration of the target species [14]. In a typical electrochemical cell, an applied potential between working and reference electrodes drives redox reactions, with oxidation occurring at the anode (electron loss) and reduction at the cathode (electron gain).

For fusion gene detection, this principle is harnessed through biosensors functionalized with specific recognition elements (e.g., DNA probes) complementary to target fusion sequences. Hybridization events between probe and target DNA induce measurable changes in electrical properties, including current, potential, or impedance, effectively transducing molecular recognition into an analytical signal.

Key Electrochemical Techniques

Various electrochemical techniques are employed in biosensing applications, each with distinct advantages for specific detection scenarios:

Voltammetry: The applied potential to the working electrode is varied in a controlled manner while monitoring the resulting current. Different voltammetric methods provide specific benefits for biosensing applications [14].

Amperometry: Measures current at a fixed potential over time, proportional to analyte concentration.

Potentiometry: Monitors potential difference between electrodes under conditions of zero current.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Characterizes the impedance of the electrode-electrolyte interface, highly sensitive to surface binding events.

Application Notes: Fusion Gene Detection

Experimental Protocol: Electrochemical Detection of NTRK Gene Fusions

Principle: This protocol describes a sandwich hybridization assay for detecting NTRK gene fusions using screen-printed gold electrodes functionalized with specific capture and signal probes.

Materials:

- Screen-printed gold electrodes (SPGEs)

- Thiol-modified DNA capture probes complementary to NTRK fusion sequences

- RNA extracts from patient samples

- HRP-labeled signaling probes

- TMB substrate solution

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) instrument

Procedure:

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Clean SPGEs by cycling in 0.5 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ from 0 to +1.5 V until stable voltammogram obtained

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and dry under nitrogen stream

Probe Immobilization:

- Incubate electrodes with 20 μL of 1 μM thiolated capture probe in PBS for 2 hours at 25°C

- Passivate with 1 mM MCH for 30 minutes to minimize non-specific adsorption

- Wash with PBS to remove unbound probes

Target Hybridization:

- Apply 25 μL of RNA sample (diluted in hybridization buffer) to functionalized electrode

- Incubate at 37°C for 60 minutes with 80% humidity

- Wash stringently with PBS-Tween (0.05%) to remove non-specifically bound RNA

Signal Amplification:

- Incubate with HRP-conjugated detection probe (0.5 μM) for 45 minutes at 37°C

- Wash to remove unbound detection probe

- Add TMB substrate solution and incubate for 10 minutes

Electrochemical Measurement:

- Apply differential pulse voltammetry parameters:

- Potential range: -0.2 to +0.6 V

- Pulse amplitude: 50 mV

- Pulse width: 50 ms

- Scan rate: 20 mV/s

- Measure reduction current of TMB product at +0.2 V

- Compare against calibration curve for quantification

- Apply differential pulse voltammetry parameters:

Performance Data for Fusion Gene Detection

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Electrochemical Biosensors for Fusion Gene Detection

| Fusion Gene | Detection Technique | Linear Range (M) | LOD (pM) | Assay Time (min) | Clinical Sample Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EML4-ALK | DPV with AuNPs | 10â»Â¹âµ - 10â»â¹ | 0.1 | 90 | Plasma-derived RNA |

| TMPRSS2-ERG | EIS with graphene | 10â»Â¹â´ - 10â»â¸ | 1.0 | 120 | Cell lines |

| BCR-ABL1 | Amperometry with CNTs | 10â»Â¹Â³ - 10â»â· | 0.5 | 75 | Serum RNA |

| NTRK1 | Voltammetry with MB | 10â»Â¹â¶ - 10â»Â¹â° | 0.01 | 60 | Tissue biopsy |

Comparison with Conventional Methods

Table 2: Method Comparison for Fusion Gene Detection in Cancer Diagnostics

| Parameter | Electrochemical Biosensor | RNA-Seq with Arriba | RT-PCR | FISH |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 0.01-1 pM | 88/150 fusions | 1-10 pM | Moderate |

| Specificity | >95% | High | High | High |

| Turnaround Time | 60-120 min | >24 hours | 3-4 hours | 2-3 days |

| Cost per Sample | $10-20 | $500-1000 | $50-100 | $150-200 |

| RNA Input | 1-10 ng | 100-1000 ng | 10-100 ng | N/A |

| Equipment Needs | Portable potentiostat | High-performance computing | Thermal cycler | Fluorescence microscope |

| Multiplexing Capability | High | Very High | Moderate | Low |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Electrochemical Fusion Gene Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-printed electrodes | Signal transduction platform | Gold, carbon, or graphene working electrode; integrated reference/counter electrodes |

| Thiol-modified DNA probes | Capture fusion gene sequences | 25-30 nt, complementary to fusion breakpoints, 5'-thiol modification, HPLC purified |

| Redox mediators | Generate electrochemical signal | Methylene blue, ferricyanide, TMB-HRP system |

| Nanomaterial enhancers | Signal amplification | 20-40 nm gold nanoparticles, graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes |

| Blocking agents | Reduce non-specific binding | MCH, BSA, salmon sperm DNA, Tween-20 |

| Hybridization buffers | Optimize target-probe binding | SSC buffer with formamide, dextran sulfate, Denhardt's solution |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Electrochemical Fusion Gene Detection Workflow

Biosensing Principle and Interference Factors

Electrochemical biosensors represent a transformative approach in oncology, offering a powerful alternative to conventional diagnostic methods for the detection of cancer biomarkers, including fusion genes. These devices integrate a biological recognition element (such as a nucleic acid probe for a specific fusion gene) with an electrochemical transducer that converts a biological binding event into a quantifiable electrical signal [14] [16]. The global burden of cancer, with millions of new cases and deaths annually, underscores the urgent need for diagnostic tools that enable earlier detection and intervention, which significantly improves patient survival rates [17] [7]. Traditional diagnostic techniques, including tissue biopsy, computed tomography (CT), and MRI,, despite their clinical utility, often face limitations such as high cost, invasiveness, time-intensive procedures, and limited sensitivity for early-stage detection [14] [18] [19]. In contrast, electrochemical biosensors are emerging as a cornerstone of point-of-care (PoC) diagnostics, providing rapid, cost-effective, and highly sensitive detection of specific cancer biomarkers with potential for decentralized testing [14] [6] [20].

Comparative Advantage Analysis

The transition from traditional diagnostic methodologies to advanced electrochemical biosensors is driven by significant improvements in key performance parameters. The following table summarizes the comparative advantages of electrochemical biosensors across critical diagnostic criteria.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Cancer Diagnostic Methods

| Diagnostic Method | Sensitivity | Analysis Speed | Cost | Potential for Miniaturization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tissue Biopsy | High (but invasive) | Slow (days for results) | High | Low [18] |

| Mammography/CT/MRI | Moderate (limited for early stages) | Moderate to Fast | High | Low [19] |

| ELISA | Moderate (detection limit ~10â·/μL for exosomes) | Moderate (several hours) | Moderate | Moderate [16] |

| PCR/qRT-PCR | High | Slow (hours, requires thermal cycling) | High | Low to Moderate [21] |

| Electrochemical Biosensors | Very High (detects attomolar-femtomolar concentrations) [22] | Very Fast (minutes to seconds) [14] | Low [14] [7] | High (Lab-on-a-Chip platforms) [6] [21] |

Beyond the general advantages, the quantitative performance of electrochemical biosensors is exemplified in specific research applications, particularly for detecting low-abundance biomarkers like fusion gene components or exosomal cargo.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Selected Electrochemical Biosensors in Cancer Detection

| Target Biomarker | Sensor Type/Technique | Reported Sensitivity (Limit of Detection) | Linear Detection Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MicroRNA (miR-21) | Homogeneous, label-free with G-triplex/MB | [22] | ||

| Tumor-Derived Exosomes | Various electrochemical (voltammetric, impedimetric) | [16] | ||

| HER2 Protein | Nanomaterial-based immunosensor | [19] | ||

| Nucleic Acids (General) | Lab-on-a-Chip with electrochemical detection | Down to a single copy for mRNA markers [18] | [18] |

Experimental Protocols for Fusion Gene Detection

The following protocols provide a framework for developing electrochemical biosensors tailored for the detection of fusion genes, which are critical biomarkers in several cancer types.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Miniaturized Electrode Biochip

This protocol details the creation of a miniaturized, multi-electrode biochip suitable for genetic sensing applications [21].

I. Materials

- Substrate: Double-sided polished borosilicate glass wafer (150 mm diameter, 600 μm thickness).

- Metallic Layers: Chromium (Cr, 5 nm for adhesion), Gold (Au, 200 nm), Platinum (Pt, 200 nm).

- Photolithography: Positive-tone photoresist, HMDS primer, and corresponding developers/etchants.

- Passivation: Silicon Dioxide (SiOâ‚‚).

- Equipment: UV mask aligner, thermal evaporator, wet chemical etching bench.

II. Procedure

- Wafer Cleaning: Clean the glass wafer in a buffered hydrofluoric acid (HF) bath for 20 seconds, followed by rinsing with deionized water and drying.

- Deposition of Adhesion and Metal Layers:

- Use a thermal evaporator to deposit a 5 nm Cr layer followed by a 200 nm Au layer onto the clean wafer.

- Photolithography Patterning (First Mask - M1):

- Prime the wafer with HMDS at 150°C.

- Spin-coat a ~2 μm layer of positive-tone photoresist.

- Soft-bake at 100°C for 1 minute.

- Align and expose the wafer to UV light through mask M1 (defines reference and counter electrodes).

- Develop the photoresist to remove exposed areas.

- Perform wet chemical etching to transfer the pattern first to the Au and then to the Cr layers.

- Strip the remaining photoresist with acetone.

- Patterning of the Working Electrode (Second Mask - M2):

- Coat the wafer again with photoresist.

- Align and expose the wafer to UV light through dark-field mask M2 (defines the working electrode area).

- Develop the photoresist.

- Deposit a 5 nm Cr layer followed by a 200 nm Pt layer via thermal evaporation.

- Perform a lift-off process in acetone, leaving the Pt working electrode feature.

- Passivation Layer Deposition and Patterning (Third Mask - M3):

- Deposit a SiOâ‚‚ layer over the entire wafer.

- Coat with photoresist and expose through mask M3 to define the active electrode areas.

- Etch the SiOâ‚‚ to open contact windows.

- Dicing and Packaging: Dice the wafer into individual chips and package for electrical connection and fluidic interfacing.

III. Diagram: Biochip Fabrication Workflow

Protocol 2: Functional Nucleic Acid-Based Homogeneous miRNA Detection

This protocol describes a label-free, homogeneous method for detecting microRNA (e.g., a fusion gene transcript) using a functional nucleic acid probe and an integrated microelectrode (IME) [22].

I. Materials

- Integrated Microelectrode (IME): Comprising a 15 μm gold wire working electrode, carbon rod counter electrode, and homemade Ag/AgCl reference electrode assembled in a three-channel glass microtube.

- Probe: Functional nucleic acid probe (e.g., G-triplex DNA with a caged complementary sequence for the target miRNA).

- Signal Molecule: Methylene blue (MB).

- Buffer: 10 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.2) with 100 mM KCl.

- Target: Synthetic target miRNA (e.g., miR-21) or extracted RNA sample.

II. Procedure

- IME Preparation and Characterization:

- Fabricate the IME as described in the referenced literature [22].

- Characterize the IME performance using square-wave voltammetry (SWV) in a 100 μM MB solution to confirm a clear oxidation peak.

- Assay Execution:

- In a microcentrifuge tube, mix the functional nucleic acid probe with the target miRNA in phosphate buffer.

- Incubate the mixture at room temperature for a predetermined time (e.g., 30-60 minutes) to allow for hybridization and probe conformation change.

- Add MB to the mixture to a final concentration of 100 μM.

- Transfer a microliter-scale volume (e.g., 2-5 μL) of the final mixture to the IME for measurement.

- Signal Measurement:

- Perform SWV measurement using the IME.

- Record the reduction in the peak current of free MB compared to a blank (no target) control.

- Data Analysis:

- Quantify the target concentration based on the relative decrease in peak current, using a calibration curve established with known concentrations of the target miRNA.

III. Diagram: Homogeneous miRNA Detection Mechanism

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of electrochemical biosensors is critically dependent on the careful selection of materials and reagents. The following table outlines key components and their functions in sensor development.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| MXene (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) [17] | Sensor interface/electrode modifier | High electrical conductivity, chemical stability, functional versatility for enhanced signal transduction. |

| Thiol-modified Oligonucleotides [21] | Probe immobilization | Forms self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold or platinum electrodes, enabling stable surface functionalization. |

| G-triplex (G3) DNA [22] | Signal transduction probe | Forms a stable complex with methylene blue (MB) in solution, leading to a measurable change in diffusion current. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) [22] | Electroactive label | Redox indicator whose diffusion coefficient and current signal change upon binding to released G3 DNA. |

| Platinum (Pt) & Gold (Au) Electrodes [21] | Working electrode substrate | Excellent conductivity, chemical stability, and high affinity for thiol-modified biomolecules for robust sensor fabrication. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) [21] | Electrolyte/Buffer | Provides a stable ionic strength and pH environment for electrochemical measurements and biochemical reactions. |

| BRD6688 | BRD6688, MF:C16H18N4O, MW:282.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Candicidin D | Candicidin D, CAS:39372-30-0, MF:C59H84N2O18, MW:1109.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Electrochemical biosensors, with their superior sensitivity, rapid analysis, cost-effectiveness, and capacity for miniaturization, represent a paradigm shift in cancer diagnostics. The detailed protocols and material insights provided herein offer a practical roadmap for researchers aiming to develop next-generation detection platforms for fusion genes and other critical cancer biomarkers. The ongoing integration of advanced nanomaterials, innovative probe designs, and Lab-on-a-Chip technologies will further solidify the role of these sensors in enabling early cancer detection and personalized medicine.

Designing and Engineering Electrochemical Genosensors for Fusion Gene Detection

The reliable detection of fusion genes is a critical component of modern precision oncology, as these hybrid genes, formed through chromosomal rearrangements such as translocations, deletions, or inversions, act as potent drivers of malignant transformation in various cancers [23] [24]. The identification of targetable fusions in genes like ALK, ROS1, RET, and NTRK directly influences therapeutic decision-making, enabling treatment with specific tyrosine kinase inhibitors [23] [15]. However, the clinical utility of these biomarkers hinges on the accuracy of the detection methods, which is profoundly influenced by the initial probe immobilization strategies used to capture fusion gene transcripts and amplicons.

Probe immobilization forms the foundational step in numerous molecular assays, including microarrays, next-generation sequencing (NGS) library preparation, and biosensor development. The method of immobilization dictates the probe's surface density, orientation, and accessibility, thereby directly impacting the efficiency and specificity of target capture [25]. In the context of fusion gene detection, where sequence homology can be complex and expression levels variable, optimized immobilization strategies are paramount for achieving high sensitivity and minimizing false positives and negatives. This document details advanced protocols and application notes for immobilizing probes designed to capture fusion gene targets, with a specific focus on applications within electrochemical detection platforms for cancer diagnosis research.

Fusion Gene Detection Methodologies

The choice between different broad methodologies dictates the optimal probe design and immobilization strategy. The two primary approaches for targeted sequencing are hybridization capture and amplicon sequencing, each with distinct advantages [26].

Table 1: Comparison of Hybridization Capture and Amplicon Sequencing for Fusion Gene Detection

| Feature | Hybridization Capture | Amplicon Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Solution-based hybridization of biotinylated DNA/RNA probes to target, followed by immobilization on streptavidin beads | PCR amplification using target-specific primers |

| Number of Targets | Virtually unlimited by panel size | Flexible, but usually fewer than 10,000 amplicons |

| Workflow | More steps and time | Fewer steps and less time |

| Cost per Sample | Varies | Generally lower |

| On-target Rate | High uniformity across targets | Naturally high, but uniformity can vary |

| Best For | Large target regions, exome sequencing, rare variant identification | Smaller target panels, germline SNPs/indels, known fusion verification |

For electrochemical biosensors, the detection principle revolves around the translation of a specific biorecognition event (e.g., DNA hybridization) into a measurable electrical signal [27] [14] [28]. These platforms often employ a three-electrode system where the working electrode is functionalized with a capture probe. Upon hybridization with the target fusion gene sequence, a change in electrochemical properties—such as current, potential, or impedance—is measured. The immobilization of the DNA capture probe onto the electrode surface is a critical determinant of the sensor's performance, affecting its sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility [28].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Immobilization of Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) Probes on Gold Electrodes for Electrochemical Detection

This protocol describes a robust method for covalently immobilizing thiol-modified ssDNA capture probes onto gold electrodes, a common setup in electrochemical genosensors for detecting fusion transcripts like PML/RARα or BCR/ABL [28].

Materials:

- Working Electrode: Gold disk electrode (e.g., 2 mm diameter).

- Capture Probe: Thiol-modified ssDNA probe (e.g., 5'-HS-(CH₂)₆-[Gene-Specific Sequence]-3').

- Chemicals: 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH), Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP), Potassium ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]), Potassium ferrocyanide (K₄[Fe(CN)₆]), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS, pH 7.4).

- Equipment: Potentiostat, electrochemical cell.

Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the gold electrode by polishing with 0.05 µm alumina slurry, followed by sequential sonication in ethanol and deionized water for 5 minutes each. Electrochemically clean by performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ from -0.2 V to +1.5 V until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Probe Reduction: Reduce the thiolated ssDNA probe (100 µM) in 10 mM TCEP for 1 hour at room temperature to cleave any disulfide bonds.

- Probe Immobilization: Deposit 10 µL of the reduced probe solution (1 µM in PBS) onto the cleaned gold surface and incubate in a humidified chamber for 16 hours at 4°C.

- Backfilling: Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove unbound probes. Incubate with 1 mM MCH in PBS for 1 hour to passivate the remaining gold surface, which minimizes non-specific adsorption and improves probe orientation.

- Hybridization Assay: Incubate the functionalized electrode with the target DNA or RNA sample (e.g., amplified fusion gene transcripts) in a suitable hybridization buffer (e.g., 5x SSC + 0.1% Tween-20) for 30-60 minutes at a defined temperature.

- Electrochemical Measurement: Perform electrochemical measurements, such as Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), in a solution containing a redox couple like 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â». The hybridization event will cause a measurable change in the current or impedance.

Protocol 2: Functionalization of Magnetic Beads with Recombinant Fusion Proteins for Antibody-Free Capture

This innovative protocol leverages genetic engineering to create a self-immobilizing capture system, avoiding the need for complex surface chemistry [25]. It involves expressing a fusion protein between a hydrophobin (a powerful self-assembling fungal protein) and a single-chain variable fragment (ScFv) of an antibody or a specific DNA-binding domain.

Materials:

- Vmh2-ScFv Fusion Protein: Recombinantly expressed in E. coli and purified from inclusion bodies [25].

- Magnetic Beads: Plain polystyrene or carboxyl-modified magnetic beads (MBs).

- Buffers: Refolding buffer (e.g., 100 mM Tris-HCl, 0.5 M L-Arginine, 2 mM GSH/GSSG, pH 8.0), PBS.

Procedure:

- Protein Refolding: Solubilize the inclusion bodies containing the Vmh2-ScFv fusion protein in a denaturing buffer (e.g., 8 M urea). Refold the protein by rapid dilution into a refolding buffer and incubate for 24-48 hours at 4°C.

- Beads Functionalization: Incubate the refolded Vmh2-ScFv protein (e.g., 50 µg/mL) with the magnetic beads in PBS for 2 hours at room temperature with gentle agitation. The hydrophobin (Vmh2) moiety will spontaneously and irreversibly adsorb to the hydrophobic surface of the beads.

- Washing: Wash the beads three times with PBS to remove any unbound protein.

- Target Capture: The ScFv moiety is now displayed on the bead surface. Incubate the functionalized beads with the sample containing the target antigen (e.g., a fusion protein) or with amplicons that have been tagged with the corresponding epitope for 1 hour.

- Detection: After magnetic separation and washing, the captured target can be detected. In an electrochemical setup, this can be achieved by using an enzyme-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., HRP-STX) and an appropriate substrate (e.g., TMB or Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚/ABTS), which generates an electroactive product [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Probe Immobilization and Fusion Gene Capture

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Thiol-modified ssDNA | Allows for covalent attachment to gold surfaces via Au-S bonds; foundational for electrochemical DNA biosensors [28]. |

| Biotinylated DNA/RNA Probes | Used in hybridization capture; the biotin-streptavidin interaction enables immobilization on streptavidin-coated beads or surfaces for NGS [26]. |

| Hydrophobin-ScFv Fusion Protein | A self-assembling chimeric protein for direct, oriented, and antibody-free immobilization of recognition elements on various surfaces [25]. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol (MCH) | A passivating alkanethiol used to create a well-ordered self-assembled monolayer on gold, reducing non-specific binding and improving probe accessibility [28]. |

| Streptavidin-coated Magnetic Beads | Solid support for capturing biotinylated probes or targets, enabling easy concentration and washing steps in library prep or sample preparation [26]. |

| Nano-porous Gold (NPG) Electrode | A transducer with high surface area-to-volume ratio, enhancing the immobilization capacity and the sensitivity of electrochemical biosensors [28]. |

| Cathepsin inhibitor 1 | Cathepsin inhibitor 1, MF:C20H24ClN5O2, MW:401.9 g/mol |

| Caylin-1 | Caylin-1, MF:C30H28Cl4N4O4, MW:650.4 g/mol |

Workflow and Data Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the core decision-making workflow and experimental process for selecting and implementing a probe immobilization strategy for fusion gene detection.

The successful execution of these protocols yields quantitative data critical for assay validation. Key performance metrics to analyze include:

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The lowest concentration of target that can be reliably distinguished. For example, a biosensor using hydrophobin-ScFv immobilization achieved an LOD of 1.7 pg/mL for saxitoxin, demonstrating high sensitivity [25].

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio: The ratio of the specific signal from a positive hybridization to the background signal from a negative control.

- Reproducibility: The coefficient of variation of the signal across multiple replicates of the same sample.

Table 3: Example Electrochemical Performance Metrics for Different Immobilization Strategies

| Immobilization Strategy | Target Fusion/Optimization | Reported LOD | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thiolated DNA on Au | PML/RARα [28] | Sub-nanomolar range | Well-established, direct covalent linkage |

| Vmh2-ScFv on MBs | Marine toxins (Model System) [25] | 1.7 pg/mL | No surface derivatization, oriented immobilization |

| Biotin-Streptavidin | NGS panels (e.g., ALK, ROS1) [26] [29] | High on-target reads | Extreme binding affinity, versatile |

The strategic selection and optimization of probe immobilization are fundamental to the success of fusion gene detection in both biosensing and sequencing applications. As detailed in these protocols, methods range from traditional chemical conjugation (thiol-gold, biotin-streptavidin) to innovative biological approaches (hydrophobin fusions), each offering distinct advantages in terms of simplicity, orientation, and specificity. For researchers in cancer diagnostics, mastering these immobilization techniques is crucial for developing robust, sensitive, and reliable assays. The future of this field lies in the continued refinement of these strategies, particularly through the integration of novel nanomaterials and engineered proteins, to further enhance the capture efficiency and analytical performance required for the electrochemical detection of low-abundance fusion genes in complex clinical samples.

The electrochemical detection of fusion genes represents a critical frontier in the molecular diagnosis of cancer. Technologies enabling the rapid, sensitive, and specific identification of these genetic markers are essential for early diagnosis, prognostic stratification, and treatment monitoring. Conventional detection methods, including quantitative reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH), face limitations such as time-consuming protocols, requirement for sophisticated instrumentation, and high costs, restricting their utility in point-of-care settings [30] [31]. Electrochemical biosensors have emerged as a powerful alternative, offering the potential for rapid, low-cost, and highly sensitive detection. The integration of nanomaterials such as graphene, carbon nanotubes (CNTs), and metal nanoparticles into these sensing platforms has been transformative. These materials confer significant signal amplification by enhancing electrical conductivity, increasing the electroactive surface area for probe immobilization, and improving catalytic activity, thereby pushing the limits of detection for low-abundance fusion genes relevant to cancer diagnostics [32] [33] [34].

Performance of Nanomaterial-Enhanced Platforms

The table below summarizes the performance characteristics of various nanomaterial-enhanced electrochemical biosensors developed for the detection of cancer-related biomarkers, including fusion genes.

Table 1: Performance Summary of Selected Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrochemical Biosensors

| Target Analyte | Nanomaterial Platform | Detection Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PML/RARα Fusion Gene (APL) | Carbon Dots/Graphene Oxide (CDs/GO) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Not Specified | 83 pM | [30] |

| BCR/ABL Fusion Gene (CML) | Chitosan-Graphene/Polyaniline/AuNPs | Amperometry | 10 – 1000 pM | 2.11 pM | [34] |

| p16INK4a Gene | Polypyrrole-Graphene Nanofiber | Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) | 0.1 pM – 1 nM | 0.05 pM | [34] |

| miRNA-21 | AuNPs-Graphene / Cd²âº-TiPhosphate NPs | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | 10â»Â¹â¸ – 10â»Â¹Â¹ M | 0.76 aM | [34] |

| Prostate-Specific Antigen (PSA) | SWNT Forest with CNT-Abâ‚‚-HRP Bioconjugates | Amperometry | Not Specified | 4 pg mLâ»Â¹ (100 amol mLâ»Â¹) | [35] |

| α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | MWCNT-HRP Multilayers | Chemiluminescence | Not Specified | 8.0 pg mLâ»Â¹ | [36] |

| Staphylococcus Aureus (Model Pathogen) | CNFs/AuNPs/Cys/MWCNT | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | 10 – 10â· CFU mLâ»Â¹ | 2.8 CFU mLâ»Â¹ | [37] |

Experimental Protocol: Detection of PML/RARα Fusion Gene using a CDs/GO Nanocomposite Biosensor

This protocol details the fabrication and operation of an electrochemical DNA biosensor for the detection of the acute promyelocytic leukemia (APL)-associated PML/RARα fusion gene, based on a carbon dots/graphene oxide (CDs/GO) nanocomposite platform [30].

Principle

The biosensor operates on a "signal-off" mechanism. A single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) capture probe, complementary to the target PML/RARα gene sequence, is immobilized on the CDs/GO-modified electrode. Upon hybridization with the target DNA to form double-stranded DNA (dsDNA), the electrochemical indicator methylene blue (MB) exhibits reduced affinity for the dsDNA compared to the ssDNA capture probe. This hybridization event leads to a decrease in the MB Faradaic current, which is quantitatively measured using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) [30].

Materials and Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Source/Example |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene Oxide (GO) | Platform for probe immobilization; provides large surface area and oxygen functional groups for binding. | Nanjing XFNANO Technology Co., Ltd. |

| Carbon Dots (CDs) | Enhance electron transfer and conductivity of the nanocomposite; provide carboxyl groups for biomolecule attachment. | Synthesized from carbon fibers. |

| Capture Probe DNA | 22-base sequence (5'-NH₂-GGTCTCAATGGCTGCCTCCCCG-3') for specific recognition of the PML/RARα fusion gene. | Custom synthesis from Takara. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | Electrochemical indicator that differentially intercalates with ssDNA vs. dsDNA. | Sigma-Aldrich. |

| EDC & NHS | Cross-linking agents for covalent immobilization of amine-terminated DNA capture probes. | Sigma-Aldrich. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Electrolyte and washing buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4). | Prepared from Naâ‚‚HPOâ‚„ and NaHâ‚‚POâ‚„. |

| Tris-EDTA (TE) Buffer | For preparation and storage of DNA stock solutions. | Prepared from Tris-HCl and EDTA. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: Synthesis of CDs/GO Nanocomposite

- Prepare CDs from carbon fibers via acid oxidation and pyrolysis.

- Mix the prepared CDs with an aqueous dispersion of GO under vigorous stirring.

- The CDs attach to the GO sheets via π-π stacking interactions to form the CDs/GO nanocomposite, which can be produced in large quantities via this ex-situ method.

Step 2: Electrode Modification

- Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) sequentially with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina slurry, followed by rinsing with deionized water and ethanol.

- Deposit a specific volume (e.g., 5-10 μL) of the homogeneous CDs/GO nanocomposite dispersion onto the clean GCE surface.

- Allow the electrode to dry at room temperature to form the CDs/GO/GCE, which serves as the enhanced sensing platform.

Step 3: Immobilization of Capture Probe

- Activate the carboxyl groups on the CDs/GO/GCE surface by incubating with a fresh mixture of 400 mM EDC and 100 mM NHS for 10 minutes.

- Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove excess EDC/NHS.

- Apply a solution of the amine-terminated capture probe DNA (e.g., 20 μL of 1 μM solution in PBS) onto the activated electrode surface.

- Incubate for 3 hours at 37°C to allow covalent amide bond formation, immobilizing the probe.

- Wash the electrode with 0.05% Tween-20 in PBS and pure PBS to remove physically adsorbed DNA strands.

Step 4: Target Hybridization and Detection

- Incubate the DNA probe-modified electrode with a solution containing the target DNA sequence (complementary, single-base mismatch, or non-complementary) for a defined period (e.g., 1 hour) at a controlled temperature to facilitate hybridization.

- Rinse the electrode thoroughly with PBS to remove unhybridized DNA.

- Immerse the electrode in an electrochemical cell containing PBS and a defined concentration of MB.

- Record DPV signals in the potential window from -0.2 to -0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). The peak current of MB reduction is measured.

- The change in current signal before and after hybridization, or between complementary and mismatched targets, is used for quantitative and specific analysis.

Data Analysis

- Plot the DPV peak current against the concentration of the complementary target DNA to establish a calibration curve.

- The limit of detection (LOD) can be calculated using the formula LOD = 3σ/S, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank signal and S is the slope of the calibration curve.

- The biosensor's specificity is validated by comparing the signal from the fully complementary target to signals from single-base mismatch and non-complementary DNA sequences.

Signaling Pathway and Experimental Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the signaling pathway and experimental workflow for the nanomaterial-enhanced electrochemical detection of fusion genes.

Diagram 1: Workflow and Amplification Mechanism. This diagram outlines the key steps in fabricating and operating a nanomaterial-enhanced electrochemical biosensor, highlighting the core mechanisms of signal amplification provided by the nanomaterials.

Troubleshooting and Optimization Notes

- Non-specific Binding: If high background signals are observed, optimize the concentration of Tween-20 in washing buffers and ensure adequate blocking steps with agents like BSA are included [35].

- Reproducibility: To ensure consistent sensor-to-sensor performance, standardize the concentration and volume of the nanomaterial dispersion used for electrode modification, as well as the drying conditions [30] [37].

- Probe Density and Orientation: The sensitivity of the biosensor is highly dependent on the surface density and orientation of the capture probes. Systematic optimization of EDC/NHS concentration and probe immobilization time is recommended [31].

- Stability: The CDs/GO and similar nanomaterial-modified electrodes should be stored in a dry state at 4°C when not in use. The long-term stability can be monitored by periodically checking the DPV response of a standard MB solution.

Electrochemical biosensors represent a paradigm shift in the detection of cancer biomarkers, offering a powerful alternative to conventional methods like polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) that often require expensive equipment, lengthy analysis times, and specialized laboratory facilities [7] [18]. These sensors transduce biological recognition events into quantifiable electrical signals through various techniques, with voltammetry, amperometry, and impedimetry being the most prominent. The integration of these detection methods with novel materials and fabrication technologies has positioned electrochemical biosensors as next-generation tools for cancer diagnosis, particularly for detecting fusion genes—hybrid genes formed by the joining of two previously separate genes, which serve as critical diagnostic and prognostic indicators in various cancers [13] [38]. This article provides application-focused notes and detailed protocols for implementing these electrochemical transduction techniques within the specific context of fusion gene detection for cancer diagnostics.

Electrochemical Techniques: Core Principles and Comparative Analysis

Fundamental Principles

Voltammetry measures current as a function of the applied potential, providing quantitative information about the analyte based on the potential at which redox reactions occur and the magnitude of the resulting current. Common modalities include Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV). CV is particularly useful for characterizing the electrochemical behavior of a system, while SWV offers superior sensitivity for quantitative analysis due to its effective background current suppression [7] [39]. Amperometry involves measuring the current at a constant applied potential over time, with the current being directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species. This technique is known for its high sensitivity and simplicity. Impedimetry, specifically Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), measures the impedance (resistance to current flow) of an electrochemical system across a range of frequencies. It is exceptionally suited for label-free detection of binding events, such as DNA hybridization, as these events alter the interfacial properties of the electrode [7] [16].

Performance Comparison of Techniques

The table below summarizes the key characteristics, advantages, and limitations of these three primary electrochemical techniques in the context of biosensing.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Voltammetry, Amperometry, and Impedimetry

| Technique | Measured Quantity | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Typical LOD in Fusion Gene Detection |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | Current vs. Applied Potential | - High sensitivity (esp. SWV)- Can study redox mechanisms- Multi-analyte detection potential | - Can be affected by non-Faradaic processes- May require redox mediators | ~8-12 copies/mL for viral genes [40] |

| Amperometry | Current vs. Time at Constant Potential | - Very high sensitivity- Simple instrumentation and operation- Real-time monitoring capability | - Requires application of optimal potential- Primarily for electroactive analytes | Sub-micromolar range for small molecules; LOD depends heavily on signal amplification [7] |

| Impedimetry | Impedance vs. Frequency | - Label-free detection- Minimal sample preparation- Sensitive to surface modifications | - Can be influenced by non-specific binding- Data interpretation can be complex | Highly sensitive for exosome and protein detection [16] |

Application Notes: Electrochemical Detection of Fusion Genes

Fusion genes, such as BCR-ABL1 in chronic myeloid leukemia and EML4-ALK in non-small cell lung cancer, are well-established cancer drivers and therapeutic targets [13] [38]. Electrochemical biosensors offer a promising route for their detection, providing a versatile, rapid, and cost-effective platform that does not compromise on specificity or sensitivity [13]. A critical application is the discrimination between viral genome states, as demonstrated for HPV-16 in cervical cancer. The ratio of the E2 gene (often disrupted upon integration into the host genome) to the E6 gene (which is retained) serves as a surrogate marker for malignant transformation. Electrochemical duplex sensors can simultaneously quantify both genes, calculating the E2/E6 ratio to distinguish between episomal (cut-off >0.77) and integrated forms with 100% sensitivity and specificity [40].

A significant challenge in multiplexed electrochemical detection is resolving signals from multiple analytes with similar redox potentials. Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) are emerging as powerful tools to address this. AI algorithms can process complex voltammetric data to deconvolute overlapping signals, significantly improving qualitative identification and quantitative analysis in mixtures that are otherwise indistinguishable using conventional methods [39].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Duplex Sandwich Hybridization Assay for HPV E2/E6 Gene Detection

This protocol outlines the development of an electrochemical DNA biosensor for the simultaneous detection of two genes, adapted from a study validating the method with clinical samples [40].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPCEs) | Disposable, portable electrochemical cell; working and counter electrodes are carbon, reference is Ag/AgCl. |

| Streptavidin Magnetic Beads | Solid support for the immobilization of biotinylated capture probes via strong streptavidin-biotin interaction. |

| Biotinylated Capture & Reporter Probes | Single-stranded DNA probes complementary to target sequences (E2, E6); capture probe immobilizes target, reporter probe enables detection. |

| Methylene Blue (MB) | A redox-active intercalator that binds preferentially to double-stranded DNA (hybridized product), serving as the electrochemical signal reporter. |

| Poly(allylamine hydrochloride) / Poly(sodium 4-styrenesulfonate) (PAA/PSS) | Polyelectrolytes used to form a multilayer film on magnetic beads, enhancing probe loading capacity and stability. |

| Hybridization Buffer | Typically a saline-sodium citrate (SSC) buffer with controlled pH and ionic strength to promote specific DNA hybridization. |

II. Step-by-Step Procedure

Capture Probe Immobilization:

- Functionalize streptavidin-coated magnetic beads with a PAA/PSS multilayer to increase surface area and binding sites.

- Incubate the functionalized beads with biotinylated capture probes specific for the E2 and E6 genes for 30 minutes at room temperature with gentle shaking.

- Use a magnetic rack to separate and wash the beads to remove unbound probes.

Sandwich Hybridization Assay:

- Incubate the probe-immobilized beads with the extracted DNA sample for 45 minutes. Target genes (E2, E6) will hybridize with their respective capture probes.

- Add biotinylated reporter probes to the mixture and incubate for another 45 minutes, forming a "capture probe-target-reporter probe" sandwich complex.

- Perform magnetic separation and washing steps stringently to eliminate non-specifically bound material.

Electrochemical Detection & Measurement:

- Re-suspend the final bead complex in an appropriate measurement buffer.

- Place a drop of the suspension onto the SPCE.

- Add Methylene Blue to the solution as a redox indicator.

- Apply a square wave voltammetry (SWV) potential scan. The measured reduction current of Methylene Blue is proportional to the amount of double-stranded DNA present, and thus to the concentration of the target gene.

- The E2/E6 ratio is calculated from the respective SWV peak currents to determine the physical state of the HPV-16 genome.

Protocol 2: AI-Assisted Deconvolution of Multiplexed Voltammetric Signals

This protocol describes a methodology for using machine learning to resolve overlapping signals in complex voltammograms, based on research using model quinone compounds [39].

I. Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Reagents for AI-Assisted Analysis

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Bare Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Custom-made electrodes with graphite working and counter electrodes and an Ag/AgCl reference. |

| Standard Redox Probes | e.g., Ferrocyanide/Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]â´â»/³â»); provides a stable and well-understood reference signal for method validation. |

| Analyte Mixtures | Complex samples containing multiple electroactive species with similar redox potentials (e.g., hydroquinone, catechol). |