Electroanalytical vs. Traditional Techniques: A Cost-Benefit Analysis for Modern Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis for researchers and drug development professionals evaluating electroanalytical methods against traditional techniques like spectroscopy and chromatography. It explores the foundational principles of electroanalytical chemistry, including potentiometry, amperometry, and voltammetry, and examines their methodological applications in pharmaceutical analysis and biomolecule detection. The content addresses troubleshooting common limitations and optimizing performance through electrode modifications and hybrid approaches. A systematic validation framework compares key performance metrics—including sensitivity, selectivity, cost, and suitability for emerging drug modalities—enabling informed analytical strategy selection for biomedical research and quality control.

Electroanalytical vs. Traditional Techniques: A Cost-Benefit Analysis for Modern Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis for researchers and drug development professionals evaluating electroanalytical methods against traditional techniques like spectroscopy and chromatography. It explores the foundational principles of electroanalytical chemistry, including potentiometry, amperometry, and voltammetry, and examines their methodological applications in pharmaceutical analysis and biomolecule detection. The content addresses troubleshooting common limitations and optimizing performance through electrode modifications and hybrid approaches. A systematic validation framework compares key performance metrics—including sensitivity, selectivity, cost, and suitability for emerging drug modalities—enabling informed analytical strategy selection for biomedical research and quality control.

Understanding Electroanalytical Methods: Core Principles and Advantages Over Traditional Techniques

In the evolving landscape of analytical chemistry, a clear paradigm shift is occurring, moving from reliance on traditional, often cumbersome techniques toward advanced electroanalytical methods. This transition is driven by the pursuit of analytical capabilities that are not only more efficient and cost-effective but also compatible with the demands of modern, dynamic research and diagnostics. Electroanalytical techniques, particularly those leveraging modern electrochemical sensors, have emerged as powerful tools that directly address these needs. Their core advantages—high sensitivity, exceptional selectivity, and real-time monitoring capabilities—are foundational to their growing adoption across pharmaceutical, environmental, and clinical fields [1] [2].

When framed within a rigorous cost-benefit analysis, the value proposition of these methods becomes even more compelling. They offer a compelling alternative to traditional techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and mass spectrometry, which, while robust and sensitive, often involve lengthy analysis times, expensive and complex equipment, and high operational costs due to chemical usage [1] [3]. This guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of the performance of modern electroanalytical methods against traditional alternatives, focusing on their key advantages and their implications for research and drug development.

Performance Comparison: Electroanalytical Methods vs. Traditional Techniques

The following tables provide a quantitative and qualitative comparison of electrochemical methods against traditional analytical techniques, highlighting the core advantages of sensitivity, selectivity, and real-time monitoring.

| Feature | Electroanalytical Methods (e.g., Voltammetry, Amperometry) | Traditional Methods (e.g., HPLC, GC-MS) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Detection limits achievable down to sub-nanomolar (nM) levels [3]. | High sensitivity but often requires extensive sample pre-concentration. |

| Selectivity | Engineered through nanomaterials (CNTs, graphene), molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), and aptamers [3] [4]. | High intrinsic selectivity from physical separation (chromatography). |

| Real-Time Monitoring | Inherently capable of continuous, real-time measurement [5]. | Typically provides discrete, "snapshot" data points; real-time monitoring is complex and costly. |

| Analysis Speed | Rapid, from seconds to a few minutes [5]. | Lengthy run times, often 10-60 minutes per sample. |

| Sample Volume | Minimal, often in the microliter (µL) range [2] [6]. | Larger volumes typically required (milliliters). |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Lower operational costs, minimal chemical usage, potential for disposable electrodes [1] [5]. | High costs due to expensive instrumentation, solvents, and maintenance. |

| Portability | High; compatible with miniaturization for on-site and point-of-care use [1] [3]. | Very low; typically confined to centralized laboratories. |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data from Select Studies

| Analyte | Electrochemical Method / Sensor | Detection Limit | Comparison to Traditional Method | Reference Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tryptophan (Trp) | Nanomaterial-modified electrode (Gr/CNT with metal nanoparticles) | Sub-nanomolar (nM) | More sensitive than standard fluorescence spectroscopy; comparable to but faster than HPLC-MS [3]. | Analysis in biofluids (e.g., saliva) for cancer diagnostics [3]. |

| Diclofenac (NSAID) | Nanostructured carbon-based paste electrode | Not specified in excerpt, but described as "highly sensitive" | Electrochemical methods cited as affordable, environmentally friendly alternatives with minimal chemical use vs. HPLC/GC [1]. | Detection in environmental and biological samples [1]. |

| Organophosphate Pesticides | Immunosensor with nanomaterial amplification (e.g., AuNPs, CNTs) | Demonstrated detection in parts-per-billion (ppb) range | Offers rapid, on-site analysis vs. lab-bound chromatography and mass spectrometry [4]. | Environmental monitoring and food safety [4]. |

| Heavy Metals | Stripping Voltammetry (e.g., ASV) | Detection of trace metals at very low concentrations (e.g., 1 ppb for lead) [5]. | Competitive with or superior to AAS and ICP-MS for trace detection, with easier portability [7] [5]. | Multielement determination in environmental and biological samples [7] [6]. |

Experimental Protocols: Unlocking High Performance

The superior performance of modern electrochemical sensors is not accidental; it is the result of deliberate and sophisticated engineering at the molecular and material levels. The following protocols detail the core methodologies that enable high sensitivity and selectivity.

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Nanomaterial-Modified Electrode for Biomarker Detection

This protocol is typical for creating high-sensitivity sensors for compounds like tryptophan or pharmaceuticals [1] [3].

- Objective: To fabricate an electrode with enhanced electron transfer kinetics and catalytic activity for the low-level detection of an electroactive biomarker.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Base Electrode: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE) or screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE).

- Nanomaterials: Graphene oxide (GrO) dispersion, carboxylated multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs).

- Metal Nanoparticles: Tetrachloroauric acid (HAuClâ‚„) or nickel chloride (NiClâ‚‚) solution.

- Functionalization Agents: Specific aptamer or antibody for the target analyte, linking chemistry like EDC/NHS.

- Solvents: Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4), ethanol.

- Procedure:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Polish the GCE with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) and rinse thoroughly with deionized water and ethanol. For SPCEs, this step may be omitted.

- Nanocomposite Preparation: Prepare a homogeneous suspension of GrO and MWCNTs in a mixture of water and ethanol using ultrasonic agitation.

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast a precise volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the nanocomposite suspension onto the clean electrode surface and allow it to dry under an infrared lamp.

- Metal Decoration: Electrodeposit metal nanoparticles (e.g., AuNPs) onto the modified surface by performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a solution of the metal salt (e.g., HAuClâ‚„).

- Bioreceptor Immobilization: Activate the surface with EDC/NHS chemistry. Subsequently, incubate the electrode with a solution containing the specific biorecognition element (aptamer or antibody) to facilitate covalent bonding.

- Sensor Stabilization: Rinse the modified electrode and store it in a buffer at 4°C when not in use.

Protocol 2: Voltammetric Detection and Real-Time Monitoring

This protocol describes the analytical measurement process that leverages the fabricated sensor's properties [2] [6].

- Objective: To quantify the concentration of a target analyte and demonstrate real-time monitoring capability.

- Materials & Reagents:

- Fabricated Sensor: The modified electrode from Protocol 1.

- Electrochemical Workstation: Potentiostat with capabilities for CV, DPV, and amperometry.

- Analyte Solution: Standard solutions of the target molecule (e.g., tryptophan, diclofenac) at known concentrations.

- Supporting Electrolyte: A suitable buffer solution (e.g., 0.1 M PBS).

- Procedure:

- System Setup: Place the modified electrode into the electrochemical cell containing the supporting electrolyte. Connect the working, counter, and reference electrodes to the potentiostat.

- Optimization of Parameters: Using CV, identify the characteristic oxidation/reduction peak potentials of the analyte. Optimize key parameters for Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), such as pulse amplitude, pulse width, and scan rate, to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Calibration Curve:

- Record DPV signals after successive additions of the standard analyte solution.

- Measure the peak current for each concentration.

- Plot the peak current (µA) versus analyte concentration (M) to generate a calibration curve.

- Real-Time Monitoring via Amperometry:

- Set the potentiostat to amperometric mode (i-current vs. time) at a fixed potential corresponding to the analyte's oxidation.

- Under constant stirring, observe the steady-state background current.

- Introduce the sample or make continuous additions. The step-wise increase in current is directly proportional to the analyte concentration, providing a real-time trace.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Provides a clean, reproducible, and inert substrate for building the sensor interface. |

| Graphene (Gr) & Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Carbon nanomaterials that amplify the electrochemical signal by increasing the active surface area and enhancing electron transfer kinetics [3] [4]. |

| Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Co, Ni) | Further improve catalytic activity, lower the overpotential required for the redox reaction, and serve as a platform for bioreceptor immobilization [3] [4]. |

| Aptamers / Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | Act as synthetic recognition elements to confer high selectivity by specifically binding to the target analyte while excluding interferents [3] [4]. |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | Maintains a stable and physiologically relevant pH during analysis, ensuring consistent reaction conditions. |

| EDC/NHS Chemistry | A cross-linking chemistry used to covalently immobilize biorecognition elements (like antibodies or aptamers) onto the activated sensor surface. |

| HLM006474 | HLM006474, MF:C25H25N3O2, MW:399.5 g/mol |

| GSK1324726A | GSK1324726A, MF:C25H23ClN2O3, MW:434.9 g/mol |

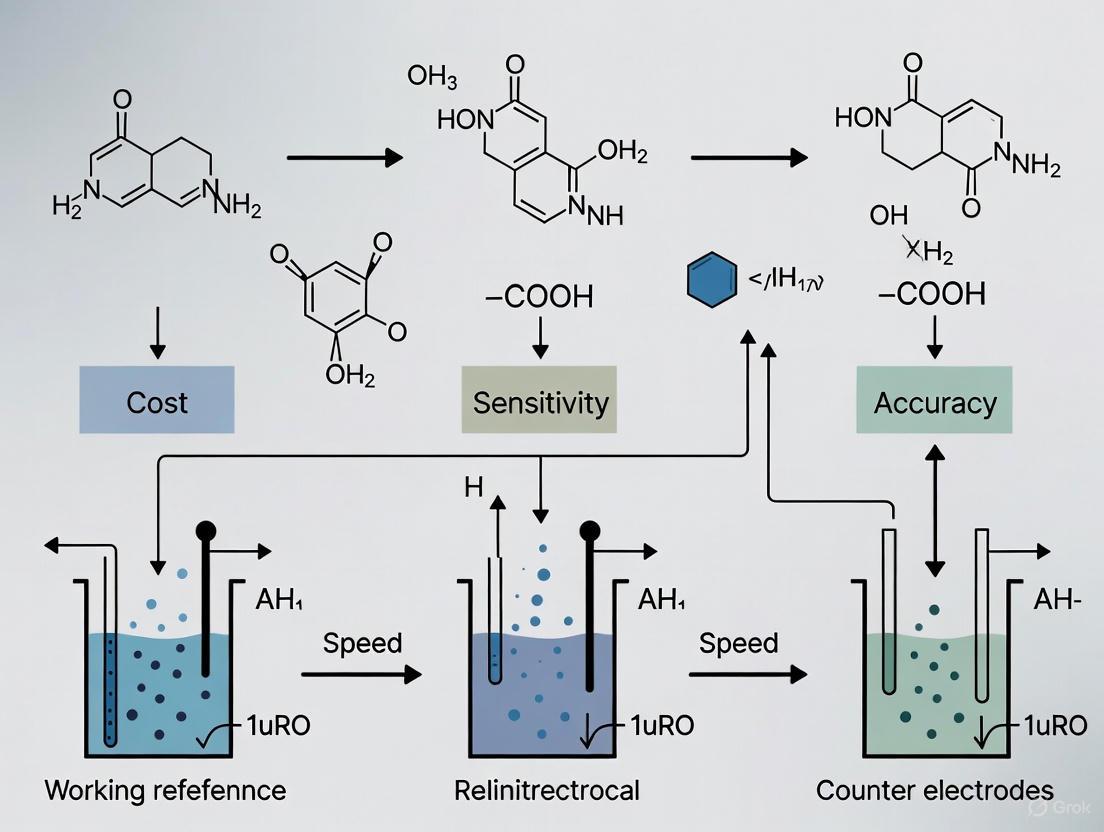

Visualizing Sensor Design and Signal Generation

The following diagrams illustrate the logical workflow of sensor fabrication and the principle of signal generation that enables real-time monitoring.

Diagram 1: Electrochemical Sensor Fabrication Workflow

Diagram 2: Real-Time Amperometric Monitoring Principle

The experimental data and comparative analysis presented in this guide objectively demonstrate that modern electroanalytical methods possess definitive advantages in sensitivity, selectivity, and real-time monitoring over traditional techniques. When integrated into a cost-benefit framework, these performance characteristics translate into significant economic and operational benefits: reduced analysis time, lower consumable costs, and the enabling of decentralized testing.

For researchers and drug development professionals, the implications are substantial. The ability to perform highly sensitive and selective therapeutic drug monitoring in real-time can accelerate pharmacokinetic studies [2]. Similarly, the rapid, on-site screening of environmental samples for pharmaceutical pollutants or toxins becomes a practical reality [1] [4]. As material science and device integration continue to advance, the performance gap is likely to widen further, solidifying the role of electrochemical diagnostics as an indispensable tool in the scientific toolkit.

In pharmaceutical research and drug development, the selection of an analytical technique is a critical decision governed by the interplay of cost, time, sensitivity, and specificity. The central challenge lies in navigating the limitations and constraints inherent to each methodology to ensure reliable, reproducible, and economically viable results. This guide provides a objective comparison between traditional techniques, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), and modern electroanalytical methods. Framed within a cost-benefit analysis, this article summarizes the core technical challenges, presents experimental data, and details standard protocols to aid researchers in making an informed choice for their specific analytical needs.

Comparative Analysis: Electroanalytical Methods vs. Traditional Techniques

The following tables provide a structured overview of the limitations and constraints of electroanalytical and traditional techniques, followed by a comparative analysis of their overall performance.

Table 1: Key Limitations of Traditional Analytical Techniques

| Technique | Key Limitations | Impact on Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) | High instrument cost, operational complexity, requires highly qualified personnel, laborious sample preparation [8]. | Increases operational costs and reliance on specialized staff; slow for urgent analysis [8]. |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Significant investment for acquisition and maintenance, high operational costs, complex sample digestion, generates hazardous waste [8]. | Limits accessibility for smaller labs; raises environmental and safety concerns [8]. |

| Chromatography (e.g., HPLC) | Often requires extensive sample preparation and expensive solvents, lower throughput compared to electrochemical methods [2]. | Increases analysis time and cost per sample; less suitable for real-time monitoring [2]. |

Table 2: Key Limitations of Electroanalytical Techniques

| Technique | Key Limitations | Impact on Research & Development |

|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | Electrode fouling, requires supporting electrolyte, selectivity issues in complex matrices, can be influenced by oxygen interference [2]. | Can lead to signal drift and unreliable data; requires method optimization for different samples [2]. |

| Potentiometry | Lower sensitivity compared to voltammetry, signal drift over time, selectivity of ion-selective membranes can be compromised [2]. | Less suitable for trace-level analysis; requires frequent calibration [2]. |

| Amperometry | Limited to electroactive species, background current can affect low-level detection, sensor stability [2]. | Restricts the range of analytes; may require frequent sensor replacement or recalibration [2]. |

Table 3: Overall Performance Comparison for Heavy Metal Determination

| Parameter | Traditional Methods (AAS, ICP-MS) | Electroanalytical Methods (e.g., Voltammetry) |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (e.g., ICP-MS: parts-per-trillion level) [8] | Very High (e.g., trace-level detection) [8] [2] |

| Multielement Analysis | Excellent (simultaneous multi-element detection) [8] | Good (Capable of simultaneous determination, e.g., Zn, Pb, Cu) [8] |

| Cost (Instrumentation & Operation) | High [8] | Relatively Low [8] |

| Analysis Speed | Slower (can be considerable) [8] | Rapid [8] |

| Sample Throughput | Moderate | High |

| Sample Volume | Moderate to High | Small (microliter range) [2] |

| Portability / In-Situ Analysis | Not suitable | Excellent (enables real-time monitoring) [8] |

| Sample Preparation | Complex, time-consuming [8] | Simpler, faster [8] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

To illustrate the practical differences, here are detailed methodologies for a common application in pharmaceutical development: the determination of heavy metal impurities or active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs).

Protocol: Heavy Metal Determination via ICP-MS

This traditional method is a benchmark for sensitivity and multi-element analysis.

- 1. Sample Digestion: Weigh approximately 0.5 g of the solid pharmaceutical sample (e.g., active pharmaceutical ingredient or finished product) into a digestion vessel. Add 5-10 mL of concentrated nitric acid (HNO₃). Perform microwave-assisted acid digestion using a standardized program (e.g., ramping to 180°C over 20 minutes and holding for 15 minutes). After cooling, dilute the digestate to 50 mL with high-purity deionized water [8].

- 2. Instrumental Analysis: Analyze the diluted sample using an ICP-MS system. Use a multi-element standard solution for calibration (e.g., ranging from 0.1 to 100 µg/L). Introduce the sample into the plasma via a peristaltic pump and nebulizer. Monitor specific ion masses for target metals (e.g., Pb: 208, Cd: 111, As: 75). Use an internal standard (e.g., Indium-115 or Rhodium-103) to correct for matrix effects and instrumental drift [8].

- 3. Data Analysis: Quantify the metal concentrations in the unknown samples by interpolating the measured signal intensities against the external calibration curve, corrected with the internal standard response.

Protocol: Drug Compound Determination via Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

This electroanalytical method offers a rapid and sensitive alternative.

- 1. Electrode Preparation: A glassy carbon electrode is polished sequentially with 1.0 µm and 0.3 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth pad, followed by rinsing thoroughly with deionized water. It is then sonicated in ethanol and water for 1 minute each to remove any adsorbed particles [2].

- 2. Solution Preparation & Deaeration: Prepare a 10 mL supporting electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer saline, pH 7.4) in an electrochemical cell. Add an aliquot of the drug standard or prepared pharmaceutical sample. Purge the solution with high-purity nitrogen gas for 600 seconds to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the measurement. Maintain a nitrogen blanket over the solution during analysis [2].

- 3. Voltammetric Measurement: Using a standard three-electrode setup (Glassy Carbon Working Electrode, Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode, Platinum Counter Electrode), perform a Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) scan. Typical parameters are: potential range from +0.8 V to -0.8 V (vs. Ag/AgCl), pulse amplitude of 50 mV, pulse width of 50 ms, and scan rate of 20 mV/s [2].

- 4. Data Analysis: Identify the drug compound by its characteristic peak potential. Quantify the concentration by measuring the peak current and comparing it to a calibration curve constructed from standard solutions.

Workflow and Logical Pathways

The diagram below illustrates the logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate analytical technique based on research goals and constraints.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Reagents and Materials for Electroanalytical Methods

| Item | Function in Research |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | A common working electrode providing a wide potential window and inert surface for electron transfer reactions in voltammetry [2]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | A high concentration of inert salt (e.g., KCl, PBS) added to the solution to minimize resistance and carry the bulk of the current, ensuring the applied potential is effectively felt by the analyte [2]. |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Polymeric membranes containing ionophores used in potentiometric sensors to provide selectivity for specific ions (e.g., Naâº, Kâº, Ca²âº) [2]. |

| Nanostructured Materials | Materials like carbon nanotubes, graphene, or metal nanoparticles used to modify electrode surfaces, enhancing sensitivity, selectivity, and stability by increasing the active surface area [8] [2]. |

| Internal Standard | A known quantity of a substance, similar to the analyte, added to samples to correct for losses during sample preparation or for instrumental variability [8]. |

| Ido-IN-1 | Ido-IN-1, MF:C9H7BrFN5O2, MW:316.09 g/mol |

| Imidafenacin hydrochloride | Imidafenacin hydrochloride, MF:C20H22ClN3O, MW:355.9 g/mol |

The choice between electroanalytical and traditional techniques is not a matter of declaring one superior to the other, but rather of aligning methodology with the specific analytical problem. Traditional methods like ICP-MS and AAS remain indispensable for their unparalleled sensitivity, specificity, and robust performance in standardized, high-throughput laboratory environments. Conversely, electroanalytical methods offer a powerful, cost-effective, and agile alternative, particularly where speed, portability, and lower operational costs are paramount. A thorough cost-benefit analysis must extend beyond the initial capital expenditure to include long-term operational costs, required operator expertise, sample throughput, and the specific data requirements of the research question. By understanding the inherent limitations and strengths of each approach, researchers can strategically select and optimize their analytical toolkit to overcome constraints and drive efficient drug development.

Analytical chemistry provides the foundation for data-driven decisions in pharmaceutical research and drug development. Selecting the appropriate analytical technique is a critical step that influences the cost, efficiency, and ultimate success of pharmaceutical projects. This guide offers an objective comparison between established traditional techniques—specifically chromatography and spectroscopy—and emerging electroanalytical methods. The comparison is framed within a cost-benefit analysis, evaluating performance metrics, operational requirements, and economic considerations to aid researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in making informed methodological choices.

This section provides a high-level overview of the core principles of each technique and a direct comparison of their key characteristics.

Core Principles

- Chromatography: Separates components of a mixture based on their differential partitioning between a mobile phase and a stationary phase. High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC), a cornerstone technique, is renowned for its high separation efficiency, broad applicability, and strong sensitivity, making it indispensable for pharmaceutical analysis [9] [10].

- Spectroscopy: Involves the interaction of light with matter to identify and quantify substances. Near-Infrared (NIR) spectroscopy, for instance, analyzes the spectral signature of a sample, which can be used for the rapid, non-destructive identification of materials [11].

- Electroanalysis: Encompasses a range of techniques that measure electrical properties (current, voltage, charge) resulting from electrochemical reactions to detect and quantify chemical species. Techniques like voltammetry and amperometry are known for their high sensitivity, rapid analysis, and cost-effectiveness [2] [5].

Comparative Characteristics

Table 1: Overall Comparison of Analytical Techniques

| Characteristic | HPLC | NIR Spectroscopy | Electroanalytical Methods |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | High (trace-level) [9] | Lower (compared to HPLC) [11] | Very High (e.g., sub-picogram levels) [2] |

| Specificity/Selectivity | High | Variable (11-37% sensitivity vs HPLC in one study) [11] | High selectivity [5] |

| Analysis Speed | Minutes per sample | Very Fast (~20 seconds) [11] | Rapid (real-time monitoring) [5] |

| Cost | High (instrumentation & solvents) [9] | Lower (portable devices) | Cost-effective [2] [5] |

| Sample Preparation | Stringent (often requires filtration) [9] | Minimal (non-destructive) [11] | Minimal (small volumes) [2] |

| Environmental Impact | High solvent consumption [9] | Low | Low |

| Primary Applications | Drug assay, impurity profiling, metabolite analysis [9] [10] | Raw material identification, counterfeit drug screening [11] | Drug/ metabolite detection, environmental monitoring, point-of-care sensors [2] [5] |

Table 2: Quantitative Performance Data from a Comparative Study (NIR vs. HPLC)

This table summarizes key findings from a study comparing a handheld NIR spectrometer with HPLC for detecting substandard and falsified drugs in Nigeria [11].

| Metric | All Medicines (N=246) | Analgesics Subset |

|---|---|---|

| HPLC Failure Rate | 25% | Not Specified |

| NIR Sensitivity | 11% | 37% |

| NIR Specificity | 74% | 47% |

| Key Limitation | NIR failed to detect many poor-quality medicines identified by HPLC. | Performance was best for analgesics but still suboptimal. |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of practical implementation, this section details standard experimental protocols for the discussed techniques.

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) Protocol

Application: Assay of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) in a solid dosage form [9] [10].

Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: A representative number of tablets are weighed and crushed into a fine powder. An exact weight of the powder is transferred to a volumetric flask, dissolved in an appropriate mobile phase or solvent, and sonicated to ensure complete dissolution. The solution is then filtered through a 0.45 µm (or smaller) membrane filter to remove particulate matter that could damage the HPLC system [9].

- System Preparation: The HPLC system is configured with the correct column (e.g., C18 reverse-phase). The mobile phase is degassed to remove dissolved gases. The column is equilibrated by pumping the mobile phase through it until a stable baseline is achieved on the detector [9].

- Injection and Separation: Using an autosampler, a precise volume (e.g., 5-20 µL) of the filtered sample solution is injected into the mobile phase stream. The high-pressure pump delivers the mobile phase, carrying the sample through the column where components separate based on their chemical affinity for the stationary phase [10].

- Detection and Analysis: Separated components elute from the column and pass through a detector (e.g., UV-Vis, Mass Spectrometry). The detector generates a signal proportional to concentration, producing a chromatogram. The retention times and peak areas are compared against standard solutions for identification and quantification [10].

Near-Infrared (NIR) Spectroscopy Protocol

Application: Rapid screening of pharmaceutical tablets for authenticity [11].

Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

- Reference Library Setup: A critical prerequisite is the development of a chemometric model and a reference library. Spectral signatures of authentic, verified drug products (including both API and excipients) must be sourced and added to the cloud-based library [11].

- Spectral Acquisition: The handheld NIR spectrometer is positioned directly on the tablet to be screened. The device emits NIR light (750-1500 nm) and captures the spectrum reflected by the tablet. This process is non-destructive and typically takes about 20 seconds [11].

- Data Analysis and Reporting: The captured spectral signature is compared in real-time to the reference library in the cloud using a proprietary machine-learning algorithm. The device reports a "match" if the signature and intensity align with the authentic product, or a "non-match" if they differ. A quality report is then sent to a connected smartphone app [11].

Electroanalytical Method (Cyclic Voltammetry) Protocol

Application: Studying the redox behavior of an active pharmaceutical ingredient [2] [5].

Workflow:

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell and Electrode Preparation: A three-electrode system is set up, consisting of a Working Electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, often polished to a mirror finish before use), a Reference Electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and a Counter Electrode (e.g., platinum wire) [2].

- Solution Preparation: The analyte (drug compound) is dissolved in a suitable solvent containing a high concentration of a supporting electrolyte (e.g., potassium phosphate buffer). The supporting electrolyte ensures the solution is conductive and minimizes the effects of migratory current [5].

- Deoxygenation: The solution is purged with an inert gas like nitrogen or argon for several minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the redox reactions of the analyte.

- Potential Sweep and Measurement: The potential of the working electrode is swept linearly between two set values (e.g., from -0.5 V to +0.5 V vs. the reference electrode) and then swept back to the initial value. The current flowing through the working electrode is measured continuously throughout this cycle [5].

- Data Interpretation: The resulting plot of current versus applied potential is called a cyclic voltammogram. The positions of the oxidation and reduction peaks provide information on redox potentials, while the peak currents can be related to the concentration of the analyte, offering insights into reaction mechanisms and kinetics [2] [5].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful execution of analytical methods relies on specific reagents and materials. The following table catalogs key items used in the protocols above.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name | Function / Description | Application Technique |

|---|---|---|

| Chromatographic Column | The core separation unit; often a reverse-phase C18 column packed with high-efficiency particles. | HPLC [9] |

| Mobile Phase Solvents | High-purity solvents (e.g., acetonitrile, methanol) and aqueous buffers that carry the sample through the column. | HPLC [9] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | An inert salt (e.g., KCl, phosphate buffer) added in high concentration to provide conductivity and control ionic strength. | Electroanalysis [5] |

| Working Electrode | The electrode where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs; common types include glassy carbon, gold, and platinum. | Electroanalysis (Voltammetry) [2] |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled (e.g., Ag/AgCl). | Electroanalysis (Voltammetry) [2] |

| NIR Spectral Library | A cloud-based database containing the spectral signatures of authentic products for comparison. | NIR Spectroscopy [11] |

The choice between techniques involves a direct trade-off between analytical performance and operational practicality.

Chromatography (e.g., HPLC): This technique remains the gold standard for definitive quantitative analysis, offering high sensitivity, specificity, and the ability to separate complex mixtures [9] [10]. However, this comes at the cost of high capital and operational expenditure, significant solvent consumption, lengthy analysis times, and the need for skilled operators and extensive sample preparation [9]. Its use is best justified for regulatory testing, rigorous impurity profiling, and pharmacokinetic studies where uncompromising data quality is paramount.

Spectroscopy (e.g., NIR): NIR's primary benefits are speed, portability, and non-destructive analysis [11]. It is ideally suited for rapid, high-throughput screening in the field or at the point of use, such as supply chain monitoring for counterfeit drugs. The major drawback is its lower sensitivity and specificity compared to HPLC, as it may fail to detect a significant proportion of substandard products, potentially leading to false negatives [11]. Its benefit is highest in preliminary screening where speed and portability outweigh the need for definitive quantification.

Electroanalysis: Electroanalytical techniques strike a compelling balance, offering very high sensitivity, rapid analysis, low cost, and minimal sample preparation [2] [5]. They are ideal for targeted analyses of electroactive species, real-time monitoring, and developing portable sensors for decentralized testing. Limitations can include selectivity issues in complex matrices and the need for the analyte to be electroactive. From a cost-benefit perspective, electroanalysis is highly advantageous for routine analysis, therapeutic drug monitoring, and environmental screening where its speed, sensitivity, and low operational cost provide a significant return on investment.

In the competitive and resource-conscious environment of pharmaceutical research, the strategic selection of an analytical technique directly impacts project efficiency, cost, and reliability. HPLC provides definitive results but at a high total cost of ownership. NIR spectroscopy offers unparalleled speed for screening but with a risk of lower accuracy. Electroanalytical methods present a powerful, cost-effective alternative for a wide range of quantitative analyses, particularly where the analyte is electroactive. A holistic cost-benefit analysis that weighs performance requirements against operational constraints enables scientists to deploy the most efficient and economically viable tool for their specific application.

In the landscape of analytical chemistry, the selection of a methodology is a critical decision that balances analytical performance with economic practicality. Electroanalytical techniques, which utilize electrical signals for the detection and quantification of chemical species, have emerged as powerful contenders against traditional methods like chromatography and spectroscopy. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide provides an objective, data-driven comparison of these technological paths. It frames the comparison within a rigorous cost-benefit analysis, evaluating not just the initial price tag but the total operational efficiency, including factors such as analysis speed, sample preparation, and potential for miniaturization and automation, which collectively define the true cost of analysis in a modern laboratory or production environment.

Fundamental Principles and Comparative Advantages

Electroanalytical techniques encompass a range of methods, including voltammetry, potentiometry, and amperometry, which measure electrical properties like current and potential to obtain information about an analyte [5] [2]. The fundamental principle involves the interaction between the analyte and an electrode surface under a controlled electrical potential, leading to redox reactions that generate a measurable signal [2]. These techniques are characterized by their direct measurement of electrical parameters, which often translates to simpler instrumental setup compared to the complex optical or separation systems of traditional methods.

The core advantages of electroanalytical methods that drive their economic proposition include:

- High Sensitivity and Selectivity: They enable the detection of analytes at trace concentrations, often at sub-picogram levels, which is crucial for applications like impurity profiling and metabolomics [5] [2].

- Rapid Analysis and Real-Time Monitoring: These techniques can provide data in seconds or minutes, facilitating quick decision-making and allowing for dynamic monitoring of chemical processes, a feature not easily afforded by traditional methods [5].

- Cost-Effectiveness: The operational costs are generally lower due to minimal reagent consumption and the potential for simplified sample preparation [5] [2]. The instrumentation itself is often less expensive and costly to maintain than traditional counterparts.

- Versatility and Portability: They can be applied to various sample matrices—liquids, gases, and solids—and are highly amenable to miniaturization, paving the way for portable, on-site sensors for field-deployable analysis [5] [12].

Comparative Performance Data: Electroanalytical vs. Traditional Techniques

The following tables summarize experimental data from published studies, objectively comparing the performance of electroanalytical techniques against traditional methods across key application areas.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection in Water

This table compares the performance of advanced anodic stripping voltammetry with established standard methods for detecting heavy metals, highlighting key operational metrics.

| Parameter | Electroanalytical Method (DP-ASV with iMF-GCE) [13] | Traditional Method (Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy) [12] | Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) [12] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit for Cadmium (Cd) | 0.63 μg Lâ»Â¹ | ~1-5 μg Lâ»Â¹ (typical) | < 0.1 μg Lâ»Â¹ |

| Detection Limit for Lead (Pb) | 0.045 μg Lâ»Â¹ | ~1-5 μg Lâ»Â¹ (typical) | < 0.1 μg Lâ»Â¹ |

| Analysis Time | Minutes (including deposition) | Several minutes per sample | Several minutes per sample |

| Sample Volume | Microliters to milliliters | Milliliters | Milliliters |

| Portability | High (suitable for on-site use) [12] | Low (lab-bound) | Low (lab-bound) |

| Approximate Cost per Sample | Low (minimal chemicals, no expensive gases) | Medium | High (high-purity gases, skilled operator) |

Table 2: General Cost and Operational Efficiency Comparison

This table provides a broader comparison of general characteristics that influence the total cost of analysis and laboratory workflow efficiency.

| Characteristic | Electroanalytical Techniques | Traditional Chromatography/Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument Capital Cost | Relatively low [5] | High |

| Operational Expense (OPEX) | Low (minimal solvent use) [2] | High (costly solvents and gases) |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal often required [2] | Can be extensive and time-consuming |

| Analysis Speed | Rapid (seconds to minutes) [5] | Slower (minutes to hours per run) |

| Sensitivity | High (detection at trace levels) [5] [2] | High |

| Multi-analyte Detection | Possible with sensor arrays | Excellent (chromatography) |

| Skill Requirement | Moderate | High (for operation and maintenance) |

| Real-time Monitoring | Yes [5] | Limited |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

To understand the practical implementation and efficiency of these methods, detailed protocols for key experiments are outlined below.

Protocol 1: On-Site Detection of Heavy Metals in Plant Material using DP-ASV

This protocol details a cost-effective and portable method for determining lead and cadmium in officinal plants [13].

- Sample Preparation: Dry and homogenize the plant leaves. Digest a weighed portion using a optimized acid mixture (e.g., nitric acid and hydrogen peroxide) on a hot block.

- Electrode Modification: Prepare an in-situ mercury film (iMF) on a glassy carbon electrode (GCE). This involves adding a mercury salt to the measurement solution and electroplating it onto the GCE surface during the analysis.

- Instrumental Parameters (Optimized): Transfer the digested sample to an electrochemical cell. Use Differential Pulse Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (DP-ASV) with the following optimized parameters:

- Deposition Potential (Edep): -1.20 V

- Deposition Time (tdep): 195 seconds

- The deposition step preconcentrates the metal ions onto the electrode surface.

- Stripping and Measurement: Apply a positive-going potential scan using a differential pulse waveform. The metals are oxidized (stripped) from the electrode back into solution, generating a current peak for each metal.

- Quantification: Measure the peak current, which is proportional to the concentration. Quantify the metal content by comparing against a calibration curve prepared with standard solutions.

Protocol 2: Enhancing Stability in Electrochemical COâ‚‚ Conversion

This protocol describes a key innovation that dramatically improves the operational stability of electrochemical reactors, a critical factor for long-term cost-effectiveness [14].

- Reactor Setup: Assemble a COâ‚‚ reduction electrolyzer containing a cathode with a silver catalyst (for CO production) and an anion exchange membrane.

- Traditional Method (Control): Humidify the input CO₂ gas by bubbling it through a water vessel. Operate the reactor and observe performance failure due to salt (KHCO₃) precipitation in the gas flow channels within approximately 80 hours.

- Innovative Acid-Humidification Method: Replace the water humidifier with an acid solution (e.g., hydrochloric, formic, or acetic acid). Bubble the COâ‚‚ gas through this acid solution before it enters the reactor.

- Operation and Monitoring: Operate the reactor under identical conditions to the control. The trace acid vapor carried into the cathode chamber shifts the local chemistry, converting low-solubility potassium bicarbonate into highly soluble salts (e.g., KCl), preventing clogging.

- Result: The system demonstrates stable operation for over 4,500 hours, a more than 50-fold improvement in operational lifetime, without significant corrosion or performance decay [14].

Workflow Visualization: Electroanalytical vs. Traditional Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the streamlined workflow of a typical electroanalytical method compared to a traditional technique, highlighting the differences in steps, time, and operational complexity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The functionality and performance of electroanalytical methods are heavily dependent on the materials and reagents used. The following table details key components and their roles in experimental setups.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials in Electroanalytical Chemistry

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A versatile working electrode with a wide potential window and good chemical inertness. | Baseline electrode for voltammetric detection of pharmaceuticals and metals [13]. |

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | Measures the activity of specific ions (e.g., Naâº, Kâº, Ca²âº) potentiometrically without current flow. | Determining ion concentrations in pharmaceutical formulations or biological fluids [5] [2]. |

| Mercury Salts (e.g., Hg(NO₃)₂) | Used to form a mercury film on electrodes for Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV). | Preconcentration and sensitive detection of trace heavy metals like lead and cadmium [13]. |

| Heavy Water (Dâ‚‚O) | Solvent used in electrochemical cells for isotope-sensitive studies or specialized reactions. | Bathing palladium targets in cold fusion/LENR experiments to electrochemically load deuterium [15]. |

| Nanostructured Materials (CNTs, Graphene) | Electrode modifiers that enhance surface area, conductivity, and catalytic activity. | Boosting sensitivity and selectivity in sensors for heavy metals or biomolecules [12]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl) | Provides ionic conductivity in solution and controls the electrical double layer at the electrode interface. | Essential background medium in all voltammetric experiments to support current flow [2]. |

| Anion Exchange Membrane | Separates compartments in an electrochemical cell while allowing anion transport. | Used in COâ‚‚ electrolyzers to prevent product mixing and manage ion migration [14]. |

| Indapamide hemihydrate | Indapamide Hemihydrate | |

| Integracin B | Integracin B, CAS:224186-05-4, MF:C35H54O7, MW:586.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The objective data and experimental protocols presented in this guide demonstrate that electroanalytical methods present a compelling economic proposition. They offer a powerful combination of high analytical performance, significantly reduced operational costs, and unparalleled efficiency through rapid analysis and portability. While traditional techniques like ICP-MS and chromatography remain indispensable for certain applications requiring ultra-trace detection or complex separations, the cost-benefit analysis strongly favors electroanalytical techniques for a wide range of routine analyses, field monitoring, and point-of-care diagnostics. The ongoing integration of nanotechnology and miniaturization continues to enhance their sensitivity and expand their application scope, solidifying their role as a cost-effective and operationally efficient toolkit for modern scientific research and industrial development.

Electroanalytical Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis

Drug Compound Quantification in Pharmaceutical Preparations

The accurate quantification of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) and adulterants is a cornerstone of pharmaceutical research, quality control, and forensic analysis. This process ensures drug safety, efficacy, and consistency, while also providing critical intelligence in combating drug counterfeiting and abuse. The selection of an appropriate analytical technique involves a careful cost-benefit analysis, weighing factors such as sensitivity, selectivity, speed, and operational expense [16] [17]. Electroanalytical methods have emerged as powerful alternatives to traditional techniques like chromatography and spectrophotometry, offering distinct advantages in specific application scenarios. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance characteristics of electroanalytical methods against traditional techniques, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in their methodological selections.

Comparative Analysis of Quantification Techniques

Performance Metric Comparison

The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of major analytical techniques used for drug compound quantification, synthesizing data from recent research applications.

Table 1: Performance comparison of analytical techniques for drug quantification

| Technique | Detection Limit | Analysis Time | Cost | Selectivity | Sample Volume | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | ~0.26 μg/mL (Favipiravir) [18] | Minutes | Low | Moderate to High | Microliters | API quantification, seized sample analysis [16] [18] |

| HPLC-UV | ~μg/mL range [17] | 10-30 minutes | High | High | Milliliters | API quantification, impurity profiling [17] |

| Spectrophotometry | ~μg/mL range [17] | Minutes | Very Low | Low | Milliliters | Raw materials, formulated products [17] |

| TLC-Densitometry | Nanogram scale [17] | 20-40 minutes | Low to Moderate | Moderate | Microliters | API quantification in combinations [17] |

Cost-Benefit Analysis Framework

When evaluating analytical techniques for drug quantification, researchers must consider multiple factors beyond mere detection limits:

Capital and Operational Costs: Electroanalytical methods and spectrophotometry offer significant advantages in equipment cost and maintenance compared to HPLC systems [16] [17]. The minimal solvent consumption of electroanalytical methods further reduces operational costs and environmental impact [2].

Analysis Time and Throughput: Voltammetric techniques can provide results within minutes, enabling rapid decision-making in quality control and forensic settings [16] [18]. The simplified sample preparation of electroanalytical methods further enhances throughput.

Selectivity and Flexibility: While HPLC offers superior separation capabilities, advanced voltammetric techniques like differential pulse and square wave voltammetry can achieve sufficient selectivity for many applications, especially when combined with optimized experimental parameters [16] [2].

Portability and Field Deployment: Miniaturized electrochemical sensors present unique opportunities for on-site testing in forensic and point-of-care applications, a capability rarely feasible with traditional chromatographic systems [16] [2].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Electroanalytical Protocol for Aminopyrine Quantification

Objective: To quantify aminopyrine in seized cocaine samples using a bare platinum electrode [16].

Materials and Equipment:

- Platinum working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, platinum counter electrode

- Voltammetric analyzer (e.g., μAutolob Type III)

- Britton-Robinson buffer (0.04 M, pH 2.0-12.0)

- Standard aminopyrine solutions (0.1-1.0 mmol Lâ»Â¹)

- seized cocaine samples

Methodology:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the platinum electrode with alumina slurry (0.01 μm) and rinse thoroughly with deionized water [16].

- Supporting Electrolyte Optimization: Prepare Britton-Robinson buffer across pH range 2.0-12.0. The highest analytical signal for aminopyrine oxidation is typically observed at alkaline pH [16].

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- Transfer 10 mL of supporting electrolyte (pH 10.0) to voltammetric cell

- Add appropriate aliquot of standard or sample solution

- Record cyclic voltammograms from 0.0 to +1.3 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- For quantitative analysis, employ square-wave voltammetry with optimized parameters: frequency 75 Hz, pulse amplitude 40 mV, step potential 10 mV [16]

- Calibration: Construct calibration curve by plotting peak current versus aminopyrine concentration in the range 0.1-1.0 mmol Lâ»Â¹ [16].

Critical Parameters: Electrode surface cleanliness, supporting electrolyte pH, accumulation time, and pulse parameters significantly influence method sensitivity and reproducibility [16].

Electroanalytical Protocol for Favipiravir Quantification

Objective: To determine favipiravir in pharmaceutical formulations and biological samples using a glassy carbon electrode with anionic surfactant [18].

Materials and Equipment:

- Glassy carbon working electrode (3 mm diameter), Ag/AgCl reference electrode, platinum counter electrode

- Voltammetric analyzer with GPES software

- Britton-Robinson buffer (0.04 M, pH 10.0)

- Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) solution (3 × 10â»â´ M)

- Standard favipiravir solutions (1.0-100.0 μg mLâ»Â¹)

Methodology:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish glassy carbon electrode with alumina suspension and rinse with water [18].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare BR buffer (pH 10.0) containing 3 × 10â»â´ M SDS [18].

- Sample Accumulation: Immerse electrode system in solution containing favipiravir and apply open-circuit potential for 60 seconds with solution stirring at 500 rpm [18].

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- After 10-second equilibration period, initiate square-wave scan from 0.0 to +1.3 V

- Use optimized parameters: frequency 75 Hz, pulse amplitude 40 mV, step potential 10 mV

- Measure oxidation peak at approximately +1.17 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) [18]

- Calibration: Construct calibration curve in concentration range 1.0-100.0 μg mLâ»Â¹ with detection limit of 0.26 μg mLâ»Â¹ [18].

Critical Parameters: Surfactant concentration, accumulation time and potential, solution pH, and pulse parameters must be rigorously controlled [18].

Traditional Spectrophotometric Protocol for Aspirin and Omeprazole

Objective: To simultaneously quantify aspirin and omeprazole in combined pharmaceutical preparations using first derivative of ratio spectra (¹DD) method [17].

Materials and Equipment:

- UV-Vis spectrophotometer with data processing capability

- Methanol (HPLC grade)

- Standard solutions of aspirin and omeprazole (100 μg/mL)

- TLC equipment (optional comparative method)

Methodology:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare standard stock solutions (100 μg/mL) of aspirin and omeprazole in methanol [17].

- Spectral Acquisition: Record zero-order absorption spectra of samples and standards in wavelength range 200-400 nm [17].

- Mathematical Processing:

- For aspirin quantification: Divide spectra of mixtures by spectrum of omeprazole standard (16 μg/mL) and obtain first derivative of ratio spectra (Δλ = 2, scaling factor = 10). Measure amplitude at 237 nm [17].

- For omeprazole quantification: Divide spectra of mixtures by spectrum of aspirin standard (40 μg/mL) and obtain first derivative of ratio spectra. Measure amplitude at 295 nm [17].

- Calibration: Construct separate calibration curves for each drug using peak amplitudes at their respective wavelengths [17].

Critical Parameters: Selection of appropriate divisor concentration, derivation parameters, and wavelength selection are crucial for method accuracy [17].

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Electroanalytical Quantification Workflow

This workflow illustrates the key steps in electroanalytical quantification of pharmaceutical compounds, highlighting critical parameters that require optimization for each specific application. The process emphasizes the importance of electrode preparation, solution conditions, and instrumental parameters in achieving reproducible and sensitive results [16] [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for pharmaceutical quantification

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples | Critical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum Electrode | Working electrode for oxidation reactions | Aminopyrine quantification in seized samples [16] | Surface cleanliness crucial; requires alumina polishing between measurements |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | Versatile working electrode for various analytes | Favipiravir determination [18] | Compatible with wide potential range; surface renewal essential |

| Britton-Robinson Buffer | Supporting electrolyte with wide pH range (2.0-12.0) | pH optimization for electrochemical reactions [16] [18] | Maintains consistent ionic strength; enables pH-dependent method optimization |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate | Anionic surfactant for sensitivity enhancement | Favipiravir analysis via adsorption improvement [18] | Concentration critical (3 × 10â»â´ M optimal); affects mass transport and adsorption |

| Alumina Polishing Slurry | Electrode surface renewal | Maintaining electrode reproducibility [16] [18] | Particle size (0.01 μm) critical for consistent surface roughness |

| Methanol (HPLC Grade) | Solvent for standard and sample preparation | Dissolving pharmaceutical compounds [17] | Purity essential to avoid interference; compatible with multiple techniques |

Electroanalytical techniques present a compelling alternative to traditional chromatographic and spectrophotometric methods for drug compound quantification, particularly when cost, speed, and portability are significant considerations. While HPLC remains the gold standard for complex separations and ultra-trace analysis, voltammetric methods offer sufficient sensitivity, selectivity, and reproducibility for many pharmaceutical applications at a fraction of the cost and analysis time [16] [18] [17].

The experimental protocols detailed herein provide researchers with validated methodologies that can be adapted for various pharmaceutical compounds through appropriate parameter optimization. As electrochemical sensors continue to evolve through nanotechnology integration and artificial intelligence implementation [2], the applicability and performance of electroanalytical methods are expected to expand further, potentially bridging the current gap with traditional techniques while maintaining their inherent advantages of simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for miniaturization.

The landscape of therapeutic and diagnostic agents is being reshaped by the development of sophisticated biomolecular modalities. Among the most prominent are antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), oligonucleotide-based therapies, and recombinant proteins, each representing a unique approach to precision medicine. ADCs combine the targeting specificity of monoclonal antibodies with the potent cell-killing ability of cytotoxic payloads, creating "magic bullets" for conditions like cancer [19]. Oligonucleotide conjugates, including emerging antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates (AOCs), leverage the gene-regulatory function of nucleic acids for targeted therapeutic intervention [20]. Simultaneously, advances in protein analysis are revolutionizing how researchers discover and validate protein biomarkers for diagnostic applications [21].

The analysis and quality control of these complex modalities present significant technical challenges, driving parallel innovation in analytical methodologies. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these emerging modalities, with a specific focus on the cost-benefit analysis of electroanalytical methods versus traditional techniques for their characterization.

Comparative Analysis of Emerging Modalities

Table 1: Comparison of Key Therapeutic Modalities

| Feature | Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | Oligonucleotide Conjugates | Therapeutic Proteins |

|---|---|---|---|

| Core Components | Antibody, Linker, Cytotoxic Payload [19] | Oligonucleotide, Linker, Targeting Ligand (e.g., Antibody, GalNAc, Lipid) [22] [20] | Engineered protein (e.g., monoclonal antibody, enzyme) |

| Primary Mechanism | Target-specific delivery of cytotoxic payload [19] | Targeted regulation of gene expression (e.g., gene silencing) [22] | Receptor binding, enzyme replacement, signaling modulation |

| Key Applications | Oncology (15 approved ADCs by 2024) [19] | Gene therapy, drug delivery, vaccine development [22] | Oncology, autoimmune diseases, metabolic disorders |

| Major Challenge | Linker instability, off-target toxicity, tumor antigen heterogeneity [23] [19] | Cellular delivery, endosomal escape, stability in biological fluids [22] [24] | Immunogenicity, production complexity, stability |

| Analytical Priority | Drug-to-Antibody Ratio (DAR), payload release kinetics, aggregation | Impurity profiling, sequence verification, quantification in plasma [24] [25] | Purity, post-translational modifications, activity |

Table 2: Market and Growth Projections (as of 2025)

| Modality | Estimated Market Size (2025) | Projected CAGR | Dominant Segment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oligonucleotide Conjugates | ~$15,000 million [22] | 12% [22] | Gene Therapy, Oligonucleotide-GalNAc for liver targeting [22] |

| Antibody-Drug Conjugates (ADCs) | 15 approved drugs, >200 in clinical development [19] | N/A | Oncology, with expansion into autoimmune diseases and infections [19] |

| Therapeutic Proteins | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Analytical Techniques: Electroanalytical vs. Traditional Methods

The complexity of novel biotherapeutics necessitates robust analytical techniques for development and quality control. Electroanalytical methods are increasingly competing with traditional techniques.

Table 3: Cost-Benefit Analysis of Analytical Methods for Oligonucleotides

| Aspect | Electroanalytical Methods | Traditional Methods (e.g., MS, HPLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Principle | Measurement of electrical signals (current, voltage) from electrochemical reactions [5] | Mass-to-charge separation, chromatographic retention |

| Speed | Rapid analysis, capable of real-time monitoring [5] | Typically slower, requires longer run times |

| Sensitivity | High sensitivity (e.g., picomole range for LNA detection) [24] | High sensitivity (e.g., attomole range for MS) |

| Selectivity | High selectivity with functionalized electrodes (e.g., probe DNA) [26] | High selectivity based on mass and fragmentation patterns |

| Cost | Cost-effective instrumentation and operation [5] | High capital and maintenance costs for instruments |

| Portability | Potential for portable, point-of-care devices [24] | Generally confined to laboratory settings |

| Multi-analyte | Limited multiplexing capabilities | High multiplexing capabilities (e.g., PRM, DIA in MS) [21] |

| Key Application | Quantifying concentration in biofluids [24], detecting hybridization [26] | Impurity characterization, sequence confirmation, diastereomeric composition [25] |

Table 4: Analysis of Protein Biomarkers: New vs. Traditional Mass Spectrometry

| Aspect | Novel High-Speed MS (e.g., Stellar MS) | Traditional Triple Quadrupole MS |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Speed | Extremely rapid Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) and MS3 targeting [21] | Standard speed, limited by predefined transitions |

| Throughput | High, suitable for large-scale biomarker validation studies [21] | Lower throughput |

| Sensitivity & Reproducibility | High sensitivity and low coefficients of variation for top ~1000 plasma proteins [21] | Well-established, but may be inferior for some targets |

| Clinical Utility | Potential to bridge discovery and routine clinical testing [21] | The current standard for validated clinical assays |

| Quantification | Enabled using 15N-labeled protein standards [21] | Relies on stable isotope-labeled peptide standards |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: Electrochemical Detection of Therapeutic Oligonucleotides

This protocol details the detection of Locked Nucleic Acid (LNA) oligonucleotides using a paper-based electrochemical biosensor, as presented in recent research [24].

- Biosensor Fabrication: A paper-based electrode is functionalized with a methylene blue-labeled DNA probe sequence that is complementary to the target LNA (e.g., LNA-anti-miR-155).

- Sample Preparation: The sample, which can be a buffer solution or undiluted human plasma, is mixed with the hybridization buffer.

- Hybridization and Measurement: The sample is applied to the biosensor. If the target LNA is present, it hybridizes with the probe on the electrode surface. This hybridization event changes the electron transfer pathway, resulting in a measurable decrease ("signal-off") in the electrochemical current when a potential is applied [24].

- Data Analysis: The reduction in current is quantified, and the concentration of the target Lonucleotide is determined from a calibration curve, achieving detection limits in the picomole range.

Protocol: Targeted Proteomic Analysis with High-Speed Mass Spectrometry

This protocol describes a streamlined workflow for quantifying protein biomarkers in plasma using a novel hybrid high-speed mass spectrometer [21].

- Sample Preparation: Plasma samples are processed, which includes depletion of high-abundance proteins and enzymatic digestion (e.g., with trypsin) to generate peptides.

- Standard Addition: 15N-labeled protein standards are added to the sample to enable absolute quantification [21].

- LC-MS/MS Analysis: The peptide mixture is separated by liquid chromatography and introduced into the mass spectrometer (e.g., Stellar MS).

- Targeted Data Acquisition: The instrument operates in a sensitive and rapid Parallel Reaction Monitoring (PRM) mode, targeting thousands of peptides originally identified in discovery proteomics experiments [21].

- Quantification and Validation: The abundance of target peptides (and thus their parent proteins) is calculated based on the signal from the 15N-labeled standards. The assay is validated for reproducibility, sensitivity, and specificity.

Visualizing Mechanisms and Workflows

ADC Mechanism and Bystander Killing Effect

Functionalized Electrode-Based DNA Sensor

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Reagent Solutions for Featured Modalities and Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Fully Humanized mAbs | Core component of newer-generation ADCs; reduces immunogenicity [19] | Used in 3rd and 4th generation ADCs like Enfortumab Vedotin [19] |

| Enzymatic Payloads | Cytotoxic agent in ADCs; causes cell death. | Topoisomerase I inhibitors (e.g., Deruxtecan), microtubule disruptors (e.g., Auristatins) [27] [19] |

| Cleavable Linkers | Connects antibody to payload; designed for stable circulation and release in target cells [23] [19] | pH-sensitive or enzyme-cleavable linkers; critical for controlling toxicity [19] |

| GalNAc Ligand | Targeting ligand for oligonucleotide conjugates; directs therapeutics to hepatocytes [22] | Enables efficient liver targeting for treatments like siRNA therapies [22] |

| Methylene Blue-labeled Probe | Electrochemical reporter for biosensors; signal changes upon hybridization [24] | Used in paper-based platform for detecting LNA oligonucleotides [24] |

| Functionalized Electrodes (MXene, GONR) | Sensor platform; provides high surface area for probe immobilization [26] | 2D nanomaterials enhance sensitivity for electrochemical DNA detection [26] |

| 15N-Labeled Protein Standards | Internal standard for mass spectrometry; enables absolute protein quantification [21] | Used in novel workflows for clinical biomarker validation [21] |

| CRISPR-Cas Proteins | Enzymatic component for signal amplification in biosensors [26] | Enhances sensitivity of electrochemical DNA sensors (e.g., CRISPR-Cas12a) [26] |

| Eganelisib | Eganelisib, CAS:1693758-51-8, MF:C30H24N8O2, MW:528.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| AZ1495 | AZ1495, CAS:2196204-23-4, MF:C21H31N5O2, MW:385.51 | Chemical Reagent |

The development of ADCs, oligonucleotide conjugates, and advanced protein therapeutics represents a significant leap toward precision medicine. A critical, parallel evolution is occurring in the analytical sciences required to characterize these complex modalities. Electroanalytical techniques offer compelling advantages of speed, cost-effectiveness, and potential for point-of-care use, making them highly suitable for specific quantitative tasks like therapeutic monitoring. However, traditional techniques like mass spectrometry remain indispensable for comprehensive characterization, including structural analysis and complex impurity profiling. The most effective research and development strategy will likely involve a synergistic approach, leveraging the strengths of both methodological families to ensure the efficacy, safety, and quality of the next generation of biotherapeutics.

Biosensor Integration for Clinical Diagnostics and Biomarker Detection

The field of clinical diagnostics is undergoing a paradigm shift, moving from centralized laboratory testing reliant on traditional techniques toward decentralized, point-of-care (POC) analysis powered by advanced biosensors. This transition is fundamentally driven by a compelling cost-benefit analysis, where electroanalytical biosensors offer significant advantages in speed, cost, and usability, often with minimal compromise on analytical performance. Biosensors are defined as instruments that use biological recognition elements (e.g., antibodies, aptamers) to detect specific analytes and convert this interaction into a measurable electrical signal [28]. The integration of these devices into clinical settings is revolutionizing the management of diseases ranging from coronary artery disease to cancer by enabling the rapid and sensitive detection of critical protein biomarkers [29] [30]. This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of integrated biosensor platforms against traditional analytical methods, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Performance Comparison: Biosensors vs. Traditional Techniques

A critical evaluation of biosensor performance against established traditional methods like Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) and chromatography is essential for understanding their practical value. The following tables summarize key performance metrics for various biosensor platforms targeting different biomarker classes.

Table 1: Overall Method Comparison: Electroanalytical Biosensors vs. Traditional Techniques

| Performance Parameter | Electroanalytical Biosensors | Traditional Methods (e.g., ELISA, Chromatography) |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Time | Minutes to a few hours [29] | Several hours to days [2] |

| Sample Volume | Microliters (µL) [2] | Milliliters (mL) |

| Sensitivity | Very High (e.g., sub-picogram levels) [2] | High |

| Specificity | High (via antibody/aptamer binding) [28] | High |

| Cost per Test | Low [5] [2] | High |

| Portability | High (miniaturized, portable systems) [29] | Low (requires lab infrastructure) |

| Ease of Use | Suitable for point-of-care use [29] | Requires trained technicians |

| Multiplexing Capability | Emerging and improving [29] | Possible but complex and expensive |

Table 2: Performance of Specific Electrochemical Biosensor Platforms for Protein Biomarkers

| Target Biomarker | Disease Context | Biosensor Platform / Technique | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| α-Fetoprotein (AFP) | Cancer (e.g., liver) | SERS Immunoassay (Au-Ag Nanostars) | 16.73 ng/mL | 0 - 500 ng/mL | [31] |

| AFP | Cancer | Electrochemical (Cu-Ag NPs / Nanocellulose) | Not Specified | Not Specified | [28] |

| Cardiac Troponin I (cTnI) | Coronary Artery Disease (CAD) | Electrochemical / POCT Immunoassay | Comparable to lab standards | Not Specified | [29] |

| Interleukin-6 (IL-6) | Sepsis / Inflammation | Paper-based Biosensor | 1.3 pg/mL | Not Specified | [32] |

| Hepatitis B e Antigen | Infectious Disease | Electrochemical (p-GO@Au & MoS2@MWCNTs) | Ultrahigh Sensitivity | Not Specified | [28] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Biosensor Types

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear understanding of the underlying methodology, this section details the experimental protocols for two major classes of biosensors highlighted in the performance tables.

Protocol 1: Sandwich-type Electrochemical Immunosensor for Protein Detection

This protocol is common for detecting protein biomarkers like AFP or cardiac troponins and involves a signal amplification step for enhanced sensitivity [28].

- Working Electrode Modification: The working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon or gold) is first cleaned and modified with a nanomaterial suspension, such as porous Graphene Oxide functionalized with Gold Nanoparticles (p-GO@Au), to increase the active surface area and improve electron transfer.

- Immobilization of Capture Antibody: A solution containing the primary (capture) antibody (e.g., anti-AFP monoclonal antibody) is drop-cast onto the modified electrode. The electrode is incubated and then washed to remove unbound antibodies, leaving a layer of specific antibodies immobilized on the surface.

- Blocking: The electrode is treated with a blocking agent, typically Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), to cover any remaining non-specific binding sites on the electrode surface. This step is critical for minimizing background noise.

- Antigen Incubation: A sample containing the target antigen (e.g., AFP) is introduced to the electrode. The antigen binds specifically to the capture antibody during an incubation period, after which the electrode is washed.

- Signal Amplification and Detection: A secondary antibody (Ab2), which is conjugated to a signal-amplifying label (e.g., Molybdenum disulfide-functionalized multiwalled carbon nanotubes decorated with Au@Pd NPs), is added. This forms the "antibody-antigen-antibody" sandwich structure. The electrochemical signal (e.g., via DPV or EIS) is measured, with the current or impedance change being proportional to the antigen concentration [28].

Protocol 2: Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering (SERS) Immunoassay

This optical biosensor protocol leverages the powerful plasmonic enhancement of nanostructures for highly sensitive detection [31].

- SERS Substrate Preparation: Au-Ag nanostars are synthesized and concentrated via centrifugation. Their performance is optimized and validated using probe molecules like methylene blue.

- Substrate Functionalization: The optimized nanostars are functionalized with a linker molecule like mercaptopropionic acid (MPA). Then, using a coupling agent (e.g., EDC/NHS), monoclonal antibodies specific to the target (e.g., anti-AFP) are covalently attached to the nanostars.

- Sample Incubation and Detection: The functionalized SERS platform is incubated with the sample solution. The intrinsic vibrational modes of the captured target biomarker (e.g., AFP) are directly measured using a Raman spectrometer, eliminating the need for a separate Raman reporter molecule [31].

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core concepts and experimental workflows for the biosensor technologies discussed.

Diagram 1: Biosensor vs. Traditional Analysis Workflow. This diagram contrasts the streamlined, rapid pathway of point-of-care biosensors with the more complex and time-consuming process of traditional laboratory-based diagnostic methods.

Diagram 2: Sandwich Electrochemical Immunosensor Workflow. This diagram details the step-by-step experimental protocol for constructing a sandwich-type electrochemical immunosensor, highlighting the role of nanomaterials and the formation of the detection complex.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and operation of high-performance biosensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details key components and their functions in a typical experimental setup.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Biosensor Development

| Item / Reagent | Function in Biosensor Experiment |

|---|---|

| Nanostructured Electrode Materials (e.g., porous Graphene Oxide (p-GO), Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs)) | Increases the electroactive surface area, enhances electron transfer kinetics, and provides a platform for biomolecule immobilization [28]. |

| Capture & Detection Antibodies | Provides the molecular recognition element for specific binding to the target protein biomarker (e.g., anti-cTnI for cardiac troponin) [29] [28]. |

| Signal Amplification Labels (e.g., MoS2@MWCNTs, Au@Pd NPs, Enzymes like HRP) | Conjugated to the detection antibody to catalytically generate or enhance the electrochemical signal, leading to lower detection limits [28]. |

| Blocking Agents (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin - BSA) | Prevents non-specific adsorption of non-target proteins to the sensor surface, thereby reducing background noise and improving specificity [28]. |

| Chemical Linkers (e.g., EDC/NHS, MPA) | Facilitates the covalent immobilization of biorecognition elements (antibodies, aptamers) onto the electrode or nanomaterial surface [31] [28]. |

| Electrochemical Redox Probes (e.g., [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â») | Used in solution to monitor changes in electron transfer efficiency at the electrode surface before and after binding events, often measured via EIS or CV. |

| IRAK inhibitor 6 | IRAK inhibitor 6, CAS:1042672-97-8, MF:C20H20N4O3S, MW:396.5 g/mol |

| Isavuconazonium Sulfate | Isavuconazonium Sulfate |

The integration of biosensors into clinical diagnostics presents a compelling value proposition based on objective cost-benefit analysis. The data clearly demonstrates that electroanalytical biosensors match or even surpass the sensitivity and specificity of traditional methods while offering unparalleled advantages in speed, cost, and potential for point-of-care use [5] [2]. The future of this field is pointed toward greater miniaturization, the integration of artificial intelligence for data interpretation, and the development of sophisticated multiplexed platforms capable of detecting panels of biomarkers simultaneously for more accurate diagnosis and risk stratification [33] [32] [29]. As nanotechnology and material science continue to advance, biosensors are poised to become indispensable tools for researchers and clinicians, ultimately paving the way for more personalized and proactive healthcare.

Environmental and Food Safety Monitoring Applications

The ongoing need to monitor environmental pollutants and ensure food safety requires analytical methods that are not only accurate but also rapid, cost-effective, and deployable in the field. This guide provides an objective comparison between modern electroanalytical techniques and traditional methods (such as chromatography and spectrophotometry) for these applications. The analysis is framed within a broader cost-benefit research thesis, providing experimental data and protocols to help researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals select the most appropriate technology.

Electroanalysis measures electrical properties like current, voltage, and charge to detect and quantify chemical species. [2] Its relevance for environmental and food safety monitoring is paramount, enabling the detection of pollutants like heavy metals, pesticides, and pharmaceutical residues in water, soil, and food samples. [5] [2] A significant shift is underway, with data-driven methods and high-throughput screening accelerating the discovery and application of new electrochemical materials and sensors. [34] [35]

Performance Comparison: Electroanalytical vs. Traditional Techniques