Electroanalytical Chemistry: Principles, Methods, and Cutting-Edge Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and modern applications of electroanalytical chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Electroanalytical Chemistry: Principles, Methods, and Cutting-Edge Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the fundamental principles and modern applications of electroanalytical chemistry, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores core concepts like faradaic processes and the Nernst equation, details key techniques including voltammetry and amperometry, and discusses their pivotal role in pharmaceutical analysis, from drug quantification to biosensing. The content also offers practical guidance on troubleshooting common experimental issues and outlines validation strategies to ensure data reliability. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with current trends like nanoelectrochemistry and AI integration, this guide serves as a valuable resource for advancing analytical capabilities in biomedical research and development.

Core Principles of Electroanalytical Chemistry: From Faraday's Law to Modern Instrumentation

Defining Electroanalytical Chemistry and Its Role in Modern Analysis

Electroanalytical chemistry is a branch of analytical chemistry that utilizes the measurement of electrical properties to obtain qualitative and quantitative chemical information about an analyte. These techniques are based on the interplay between electricity and chemistry, involving the measurement of electrical quantities such as current, potential, and charge and their relationship to chemical parameters [1] [2]. The fundamental principle underpinning these methods is the occurrence of oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions at the interface between an electrode and an analyte solution. When an analyte undergoes oxidation (loses electrons) or reduction (gains electrons), it generates an electrical signal that can be measured and correlated to its concentration [3] [4].

The significance of electroanalytical chemistry in modern analysis stems from its numerous advantages over traditional analytical techniques. It offers high sensitivity and selectivity, often enabling detection at trace levels, requires minimal sample volumes (sometimes in the microliter range), and provides the capability for real-time monitoring of chemical processes [4]. Furthermore, electroanalytical instrumentation is often compact and cost-effective compared to other analytical instruments, making it suitable for decentralized analysis outside traditional laboratories [3]. In an era where information is increasingly required in non-traditional settings, these characteristics make electroanalytical chemistry particularly valuable for clinical, environmental, food, and pharmaceutical analysis [3] [4].

Key Electroanalytical Techniques and Their Mechanisms

Electroanalytical chemistry encompasses a family of techniques, each with distinct excitation signals and measured responses. The core techniques can be categorized based on the controlled electrical property and the resulting measurement.

Voltammetry

Voltammetry involves measuring the current that flows through an electrochemical cell as the potential of the working electrode is varied in a controlled manner [1]. The resulting plot of current versus potential provides a voltammogram, which serves as a qualitative and quantitative fingerprint of the analyte. Several voltammetric techniques have been developed to enhance sensitivity and resolution:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): The potential is scanned linearly from a starting potential to a switching potential and back again. CV is paramount for studying the electrochemical behavior and reaction mechanisms of analytes, providing information on redox potentials and reaction kinetics [3] [4].

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): This technique applies a square-wave waveform superimposed on a staircase potential ramp. It is a very sensitive pulse technique that allows for fast scans and effective rejection of capacitive currents, making it ideal for trace analysis [3] [4].

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Another highly sensitive pulse technique, DPV applies small amplitude potential pulses and measures the current difference just before and at the end of each pulse. This minimizes background contributions, resulting in lower detection limits compared to direct current methods [4].

Amperometry

In amperometry, the current is measured while the potential of the working electrode is held at a constant value [1]. This technique is particularly useful when simplicity is a priority, as the instrumentation is notably simplified by not requiring a potential scan [3]. A common application is in chronoamperometry, where a potential step is applied, and the resulting current is measured as a function of time. The current-time response for a planar electrode under diffusion control is described by the Cottrell equation: i = nFACD^(1/2) / (Ï€^(1/2)t^(1/2)), where i is the current, n is the number of electrons, F is Faraday's constant, A is the electrode area, C is the bulk concentration, D is the diffusion coefficient, and t is time [3]. This relationship allows for quantitative determination of the analyte.

Potentiometry

Potentiometry involves measuring the potential of an electrochemical cell under conditions of zero current flow [1]. The measured potential is related to the concentration of an ionic analyte through the Nernst equation. The most common application is the pH electrode, but the technique extends to a wide range of ions using ion-selective electrodes (ISEs). These electrodes employ a membrane that is selectively permeable to a specific ion, making them crucial for pharmaceutical formulations and environmental monitoring [4].

Conductometry

This technique measures the ability of a solution to conduct an electrical current, which is proportional to the concentration of ions present. While less selective than other methods, it is highly useful for monitoring changes in ionic strength, such as in titration experiments [1].

Table 1: Summary of Key Electroanalytical Techniques

| Technique | Controlled Parameter | Measured Response | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | Potential | Current | Qualitative & quantitative analysis, mechanistic studies, trace detection |

| Amperometry | Potential | Current | Quantitative analysis, sensor technology, process monitoring |

| Potentiometry | Current | Potential | Ion concentration measurement (e.g., pH, specific ions) |

| Conductometry | Voltage/Current | Conductance/Resistance | Monitoring ionic strength, titrations |

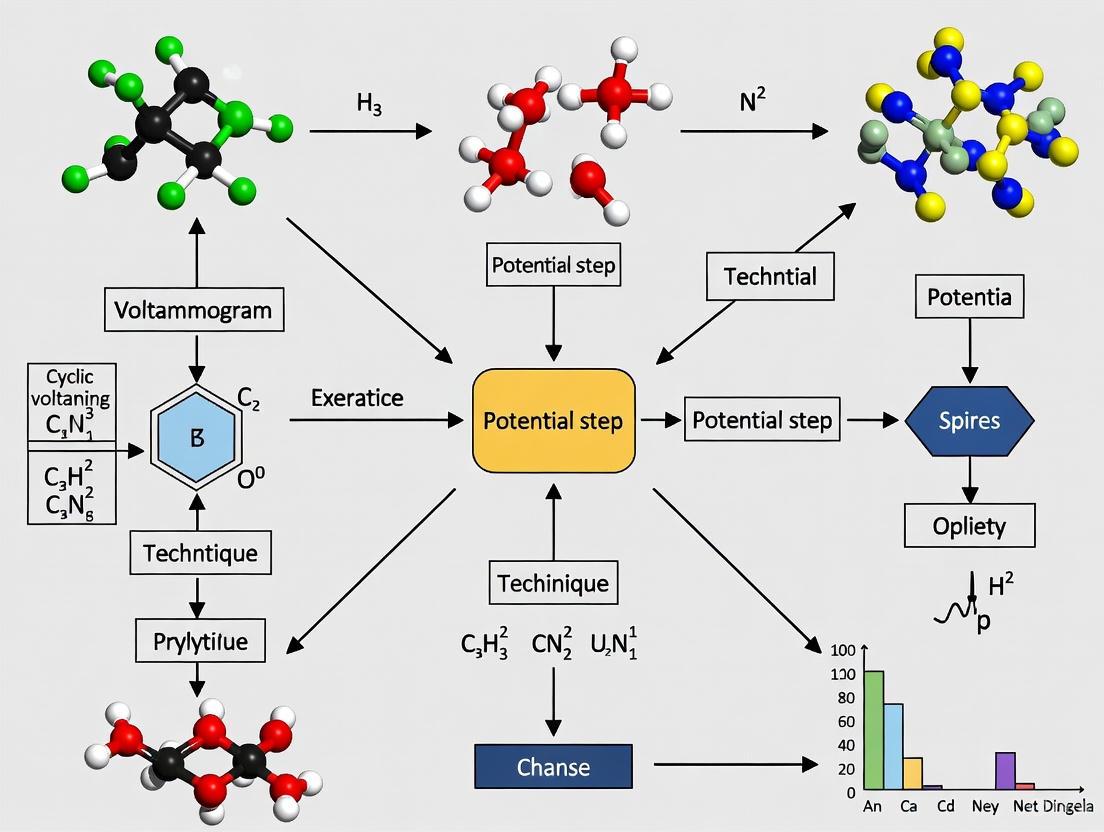

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow and logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate electroanalytical technique based on the analytical goal.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

A successful electroanalytical experiment requires careful attention to experimental design, from cell setup to data analysis. This section outlines a generalized protocol for a voltammetric determination and a specific methodology for the chronoamperometric determination of ascorbic acid using paper-based electrodes.

General Voltammetric Experiment Protocol

1. Objective: To quantify the concentration of an electroactive analyte in a solution using differential pulse voltammetry (DPV).

2. Materials and Reagents:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat: Instrument for controlling potential/current and measuring the resulting response [1].

- Three-Electrode System:

- Working Electrode: The electrode where the reaction of interest occurs (e.g., glassy carbon, platinum, gold) [1] [5].

- Reference Electrode: Provides a stable, known potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel electrode) [1].

- Counter (Auxiliary) Electrode: Completes the electrical circuit (e.g., platinum wire) [1].

- Electrochemical Cell: A container holding the analyte solution.

- Supporting Electrolyte: A high concentration of inert salt (e.g., KCl, phosphate buffer) to increase conductivity and minimize solution resistance [1].

- Analyte Standard Solutions: Prepared in the supporting electrolyte at known concentrations.

- Unknown Sample Solution: Prepared in the same supporting electrolyte.

3. Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Clean the working electrode according to the manufacturer's protocol (e.g., polish with alumina slurry on a polishing pad for solid electrodes) [1] [5].

- Cell Assembly: Place the working, reference, and counter electrodes into the electrochemical cell containing the supporting electrolyte.

- Instrument Calibration and Deaeration (optional): Purge the solution with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the analysis.

- Calibration Curve:

- Record DPV voltammograms for a series of standard solutions of known concentration. Typical DPV parameters might include a pulse amplitude of 50 mV, pulse width of 50 ms, and a step potential of 5 mV.

- Measure the peak current for each standard concentration.

- Plot a calibration curve of peak current (µA) versus analyte concentration (mol/L).

- Sample Measurement:

- Record the DPV voltammogram of the unknown sample under identical experimental conditions.

- Measure the peak current of the unknown.

- Data Analysis: Determine the concentration of the unknown sample by interpolating its peak current onto the previously constructed calibration curve.

Specific Protocol: Chronoamperometric Determination of Ascorbic Acid

This experiment demonstrates the use of a simple, low-cost paper-based electrochemical cell for decentralized analysis [3].

1. Background: Ascorbic acid (Vitamin C) is an electroactive compound that can be oxidized at a suitable electrode. Chronoamperometry is employed here for its simplicity, where a single potential step is applied, and the resulting current decay is monitored.

2. Specialized Materials:

- Paper-Based Electrodes: Conductive inks deposited on Whatman Grade 1 chromatographic paper to form the three-electrode cell [3].

- Microliter Pipettes: For handling low volumes of sample and reagents.

3. Procedure:

- Potential Step Application: The potential is stepped from an initial value (Ei), where no electrolysis occurs, to a final value (Ef), which is positive enough to cause immediate and complete oxidation of ascorbic acid at the electrode surface [3].

- Current Measurement: The current is measured as a function of time immediately after the potential step. The current decays over time as the diffusion layer thickness increases.

- Quantification: For quantitative purposes, the instantaneous current measured at a fixed time (e.g., 5 or 10 seconds) after the potential step is used. A calibration curve is constructed by plotting this instantaneous current against the concentration of ascorbic acid standards [3].

4. Data Interpretation: The current-time response can be modeled using the Cottrell equation. A linear relationship between the instantaneous current and bulk concentration allows for the determination of the unknown ascorbic acid concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, materials, and equipment essential for conducting electroanalytical experiments, particularly in a research and development context.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃, phosphate buffer) | Increases solution conductivity to reduce resistance ("iR drop"), defines the ionic strength, and may control pH, ensuring the electrochemical response is dominated by the analyte's properties [1]. |

| Solvents (e.g., Water, Acetonitrile, DMF) | The medium in which the analysis is performed. Choice depends on analyte solubility and the required electrochemical window [6]. |

| Standard Reference Electrodes (Ag/AgCl, SCE) | Provides a stable, known reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled and measured, crucial for reproducible data [1]. |

| Working Electrode Materials (Glassy Carbon, Pt, Au, Carbon Paste) | The platform where the redox reaction of the analyte occurs. Material choice affects the electrochemical window, reactivity, and susceptibility to fouling [5]. |

| Electrode Polishing Kits (Alumina, Diamond Paste) | Essential for renewing the active surface of solid electrodes, ensuring reproducible surface morphology and electrochemical activity between experiments [1] [5]. |

| Chemometric Software | Used for advanced data analysis, including experimental design (DoE), multivariate calibration, and resolution of overlapping signals from complex mixtures [7] [2]. |

| Eltrombopag olamine | Eltrombopag Olamine |

| Hydrodolasetron | Hydrodolasetron, CAS:127951-99-9, MF:C19H22N2O3, MW:326.4 g/mol |

Advanced Applications and the Role of Chemometrics

Electroanalytical chemistry has found profound applications in pharmaceutical sciences, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics due to its sensitivity and potential for miniaturization. In the pharmaceutical industry, it is indispensable for analyzing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), monitoring drug metabolites in biological fluids, and ensuring product stability and quality assurance [4] [5]. The shift towards solid electrodes has been particularly impactful, offering greater mechanical stability and a wider anodic potential range compared to traditional mercury electrodes, making them suitable for high-throughput screening of drug compounds [5].

A significant advancement in modern electroanalysis is the integration of chemometrics—the application of mathematical and statistical methods to chemical data [7] [2]. While the use of chemometrics in electroanalysis has historically lagged behind spectroscopy, it is now recognized as a powerful tool for optimizing methods and extracting maximum information from complex data.

- Experimental Optimization: Traditional "one-variable-at-a-time" optimization is inefficient and can miss interactions between factors. Chemometric tools like factorial designs (e.g., Full Factorial, Plackett-Burman) and response surface methodology (e.g., Central Composite Design, Box-Behnken Design) allow for the simultaneous study of multiple experimental factors (e.g., pH, deposition potential, pulse amplitude) [7]. This leads to identifying significant factors and finding optimal conditions with fewer experiments, saving time and resources.

- Data Analysis and Multi-Way Calibration: Electrochemical signals from complex samples like biological fluids or drug formulations often suffer from overlapping peaks. Multivariate calibration methods can mathematically resolve these signals. Techniques such as multi-way calibration (e.g., with second- or third-order data from hyphenated techniques) provide the "second-order advantage"—the ability to quantify analytes even in the presence of uncalibrated, unexpected interferences in the sample matrix [2]. This is a transformative capability for analyzing real-world samples without extensive pre-purification.

The synergy between electroanalytical techniques and chemometrics is pushing the boundaries of analytical chemistry, enabling more robust, precise, and informative analyses in complex scenarios.

The field of electroanalytical chemistry is dynamically evolving, driven by technological advancements and the demand for faster, more sensitive, and decentralized analysis. Key future trends include:

- Integration of Nanotechnology: The use of nanostructured electrodes and nanomaterials enhances sensitivity and selectivity by increasing the active surface area and facilitating electron transfer [4] [8].

- Miniaturization and Portability: The development of lab-on-a-chip systems and wearable sensors is a major focus, enabling point-of-care diagnostics, real-time patient monitoring, and on-site environmental analysis [3] [4].

- Hyphenated Techniques: Combining electrochemistry with other analytical techniques like spectroscopy or chromatography provides complementary information, offering a more comprehensive view of complex samples [8].

- Artificial Intelligence (AI): AI and machine learning are being increasingly applied to optimize experimental parameters, interpret complex datasets, and improve the predictive power of electrochemical sensors [4].

In conclusion, electroanalytical chemistry is a powerful and versatile field whose core principle is the translation of chemical information into an electrical signal. Its role in modern analysis is cemented by its inherent sensitivity, compatibility with miniaturization, and cost-effectiveness. As it continues to integrate with advancements in materials science, statistics, and micro-fabrication, its value in pharmaceutical research, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics is poised to grow even further, solidifying its status as an indispensable tool for scientists and drug development professionals.

Understanding Faradaic and Non-Faradaic Processes at the Electrode-Solution Interface

In electroanalytical chemistry, the electrode-solution interface serves as the critical boundary where electrochemical phenomena are governed by two fundamental types of processes: Faradaic and non-Faradaic. These processes underpin the operation of numerous analytical techniques, sensors, and energy storage devices central to modern chemical research and drug development. Faradaic processes involve electron transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface through redox reactions, while non-Faradaic processes involve charge accumulation at the interface without electron transfer [9]. A precise understanding of their distinct mechanisms, kinetics, and influencing factors is essential for researchers designing electrochemical experiments, interpreting analytical data, and developing novel electrochemical devices. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these fundamental processes, placing them within the context of basic principles that drive electroanalytical chemistry research.

Fundamental Principles and Definitions

Faradaic Processes

Faradaic processes are characterized by electron transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface via oxidation and reduction reactions [9]. These processes are governed by Faraday's law, which states that the amount of chemical change occurring at an electrode interface is directly proportional to the total charge passed through that interface [9]. When a substance is added to the electrolyte and undergoes oxidation or reduction at a specific potential, the resulting current flow "depolarizes" the electrode, and the substance is termed a "depolarizer" [10].

For a general redox reaction: $$O + ne^- \rightleftharpoons R$$

Five sequential events must occur: (1) transport of reactant (O) from bulk solution to the electrode surface, (2) adsorption of O onto the electrode surface, (3) charge transfer between the electrode and O, (4) desorption of product (R) from the electrode surface, and (5) transport of R away from the electrode surface back into the bulk solution [10]. Electrodes where these rapid, reversible charge-transfer reactions occur are termed charge-transfer electrodes or reversible electrodes [9] [10].

Non-Faradaic Processes

Non-Faradaic processes occur without charge transfer across the electrode-solution interface [9]. Instead, these processes involve transient changes in current or potential resulting from structural changes at the electrode-solution interface, such as adsorption, desorption, or ionic rearrangement [10]. In non-Faradaic processes, ionic charges accumulate at the working electrode surface, leading to the charging and discharging of an electrical double-layer capacitance [9].

These processes are thermodynamically or kinetically unfavorable for charge-transfer reactions [9]. Electrodes at which no charge transfer occurs regardless of applied potential—where only non-Faradaic processes take place—are termed ideally polarized electrodes [10]. An example is a mercury electrode in contact with a sodium chloride solution at potentials between 0 and -2 V [10].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Faradaic and Non-Faradaic Processes

| Characteristic | Faradaic Process | Non-Faradaic Process |

|---|---|---|

| Charge Transfer | Electron transfer across interface | No electron transfer across interface |

| Governing Law | Faraday's Law | Electrostatic principles |

| Current Type | Faradaic current | Capacitive/charging current |

| Effect on Solution Composition | Changes composition via redox reactions | No permanent compositional changes |

| Time Dependency | Can be steady-state | Transient, decays rapidly |

| Primary Applications | Batteries, sensors, electrocatalysis | Supercapacitors, double-layer studies |

Distinguishing Between Processes

Fundamental Differences

The essential distinction lies in whether charged particles transfer across the electrode from one bulk phase to another. In Faradaic processes, charged particles transfer across the electrode between bulk phases, leading to constant electrode charge, voltage, and composition under constant current application [11]. In non-Faradaic (capacitive) processes, charge is progressively stored at the interface without transfer between bulk phases [11].

This distinction clarifies that broad peaks in cyclic voltammetry (CV) diagrams do not necessarily indicate Faradaic processes, as both Faradaic and non-Faradaic materials can produce such features depending on experimental conditions [11].

Overpotential and Electrode Polarization

Overpotential represents the deviation from the equilibrium potential required to drive an electrochemical reaction at a measurable rate. When the Faradaic process is rapid with zero overpotential, the electrode is a nonpolarizable electrode [10]. When the system exhibits overpotential, the electrode is polarized, with two primary types:

- Activation polarization: Results from slow charge transfer kinetics [10]

- Concentration polarization: Results from slow movement of depolarizer or product [10]

The Butler-Volmer equation describes the current-overpotential relationship, particularly in charge-transfer-limited regimes, incorporating the exchange current and providing insights into how mass transfer affects overall reaction rates [12].

Table 2: Types of Overpotential in Electrode Processes

| Overpotential Type | Cause | Dominant in | Remedial Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activation | Slow charge transfer kinetics | Faradaic processes | Catalysts, increased temperature |

| Concentration | Limited mass transport of reactants/products | Both process types | Increased stirring, flow systems, elevated temperature |

| Reaction | Slow chemical steps preceding/following charge transfer | Faradaic processes | Catalyst design, mediator species |

| Adsorption/Desorption | Slow interfacial adsorption/desorption | Both process types | Surface modification, potential modulation |

Experimental Methodologies and Characterization

Electroanalytical Techniques

Different electrochemical techniques provide insights into Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes:

Table 3: Electroanalytical Methods for Studying Electrode Processes

| Method | Measurement Principle | Applications | Information Obtained |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | Current as function of voltage at polarized electrode | Quantitative analysis of electrochemically reducible/organic/inorganic material | Reversibility of reaction, kinetic parameters |

| Potentiometry | Potential at zero current | Quantitative ion analysis, pH measurements | Thermodynamic parameters, activity coefficients |

| Conductimetry | Resistance/conductance at inert electrodes | Ion quantification, titrations | Ionic strength, transport properties |

| Coulometry | Current and time (number of Faradays) | Exhaustive electrolysis | Total charge, reaction stoichiometry |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy | Impedance across frequency spectrum | Interface characterization, corrosion studies | Charge transfer resistance, capacitance |

Quantifying Process Efficiency

Faradaic efficiency (FE) describes the overall selectivity of an electrochemical process, defined as the amount (moles) of collected product relative to the amount that could be produced from the total charge passed, expressed as a fraction or percentage [13]. Robust FE measurements are imperative not only for describing reaction selectivity but also for supporting claims of activity and stability in electrocatalysis research [13].

For reactions with competing pathways (e.g., COâ‚‚ reduction with competing hydrogen evolution), FE measurements are essential for proper catalyst evaluation [13]. Total FE values significantly less than 100% may indicate escaped products, consumption at the counter electrode, or homogeneous reactions within the cell, while values greater than 100% may result from overestimation of sampled volume, sampling preconcentrated product, or spontaneous product generation through chemical reactions like corrosion [13].

Mass Transport Mechanisms

Three primary modes govern mass transport in electrochemical systems [10]:

Diffusion: Movement of mass due to a concentration gradient, described by the Cottrell equation for planar electrodes: ( it = \frac{nFAD^{1/2}C}{\pi^{1/2}t^{1/2}} ), where ( it ) is current at time ( t ), ( n ) is electron number, ( F ) is Faraday's constant, ( A ) is electrode area, ( D ) is diffusion coefficient, ( C ) is concentration, and ( t ) is time [10].

Migration: Movement of charged species due to a potential gradient. Adding a supporting electrolyte at high concentration (e.g., KCl or HNO₃) minimizes migration of electroactive species, ensuring they move primarily by diffusion [10].

Convection: Movement of mass due to natural (density gradients) or mechanical (stirring, rotating electrodes) forces [10].

Applications in Energy Storage and Sensing

Supercapacitors and Energy Storage

Electrochemical supercapacitors leverage both processes for energy storage:

Electric Double-Layer Capacitors (EDLCs): Rely primarily on non-Faradaic processes, storing energy via electrostatic accumulation of ionic charges at the electrode-electrolyte interface [9]. They typically use high-surface-area carbon materials and exhibit high power density and excellent cycling stability [9].

Pseudocapacitors: Utilize Faradaic processes through rapid, reversible redox reactions at the electrode surface or in bulk regions near the surface [9]. Common materials include transition metal oxides (RuOâ‚‚, MnOâ‚‚) and conducting polymers (polyaniline, polypyrrole) [9]. While offering higher energy density than EDLCs, they generally have lower power density and reduced cycling stability due to Faradaic processes being slower than non-Faradaic processes and volume changes during charge/discharge [9].

Hybrid Supercapacitors: Combine Faradaic and non-Faradaic materials in asymmetrical electrode configurations to capitalize on both advantages, improving overall cell voltage, energy, and power densities [9].

Bioelectrodes and Sensing

In biological environments, electrodes interact with body fluids through both processes [9]. Faradaic bioelectrodes establish ohmic contact, transferring electrons across the electrode-electrolyte interface via oxidation/reduction reactions [9]. Non-Faradaic bioelectrodes exhibit transient external currents due to interfacial changes like adsorption/desorption without charge transfer [9].

Binding target biomarkers to electrode surfaces changes the dielectric constant of the double-layer capacitance, enabling detection without redox reactions in some biosensing applications [9].

Advanced Concepts: Plasma Electrochemistry

Recent advances in plasma electrochemistry demonstrate complex interactions between Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes. Plasma electrochemistry replaces conventional solid electrodes with plasma (ionized gas), creating unique plasma-liquid interfaces where both processes occur simultaneously [14].

In plasma electrochemical systems, product yields can exceed theoretical charge-transfer maximums by up to 32-fold, demonstrating dominance of non-Faradaic processes through energetic species interactions rather than charge transfer alone [14]. This has significant implications for organic synthesis, where non-Faradaic processes enable reaction pathways inaccessible to conventional electrochemistry [14].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Electrode Process Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function/Purpose | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolytes | Minimize migration of electroactive species, control ionic strength | KCl, Naâ‚‚SOâ‚„, LiClOâ‚„, tetraalkylammonium salts |

| Redox Probes | Study charge transfer kinetics, calibrate systems | Potassium ferricyanide, ferrocene derivatives, Ru(NH₃)₆Cl₃ |

| Electrode Materials | Provide defined surface properties, specific catalytic activity | Glassy carbon, platinum, gold, mercury, boron-doped diamond |

| Aqueous Electrolytes | Provide protons for reactions, wide potential window in some cases | Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„, KOH, phosphate buffers |

| Organic Electrolytes | Expand potential window beyond aqueous limits | Acetonitrile, propylene carbonate with tetraalkylammonium salts |

| Ionic Liquids | Wide electrochemical window, low volatility, high thermal stability | Imidazolium, pyrrolidinium, ammonium-based cations |

| Surface Modifiers | Modify electrode interface properties, introduce specific functionality | Self-assembled monolayers, Nafion, functionalized polymers |

Faradaic and non-Faradaic processes represent fundamental interaction mechanisms at electrode-solution interfaces with distinct characteristics, applications, and implications for electroanalytical chemistry research. Faradaic processes involve electron transfer governed by Faraday's law, while non-Faradaic processes involve electrostatic charge accumulation without electron transfer. Understanding their differences enables researchers to properly design experiments, interpret electrochemical data, and develop advanced materials for sensing, energy storage, and synthesis applications. As electrochemical techniques continue evolving—with emerging fields like plasma electrochemistry revealing new complexities—the foundational principles governing these interfacial processes remain essential for scientific advancement and technological innovation.

This whitepaper delineates the foundational roles of the Nernst equation and Faraday's Law within electroanalytical chemistry, providing a critical resource for research and development scientists. These principles underpin the quantitative analysis of electrochemical systems, governing phenomena from cell potential under non-standard conditions to the mass transport in electrolytic processes. We present a consolidated theoretical framework, complete with structured quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential reagent toolkits, to facilitate advanced applications in areas including drug development and biosensor design.

Electroanalytical chemistry leverages the interplay between electrical energy and chemical change to achieve precise qualitative and quantitative analysis. Two mathematical relationships are central to this field: the Nernst Equation and Faraday's Law of Electrolysis. The Nernst equation describes the thermodynamic relationship between the electrochemical cell potential and the concentrations of reacting species [15] [16]. Conversely, Faraday's Law provides a stoichiometric bridge between the quantity of electrical charge passed through a system and the extent of electrochemical reaction occurring at the electrode interfaces [17] [18]. Together, they form the quantitative backbone for designing and interpreting experiments in fields ranging from energy storage to pharmaceutical analysis.

The Nernst Equation: Theory and Application

Fundamental Concepts and Derivation

The Nernst equation calculates the reduction potential of an electrochemical cell or half-cell under non-standard conditions. It relates the measured cell potential ((E)) to the standard electrode potential ((E^\ominus)), temperature ((T)), and the activities (often approximated by concentrations) of the chemical species involved [16]. For a general half-cell reaction: [ \text{Ox} + z\text{e}^- \longrightarrow \text{Red} ] the Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^\ominus - \frac{RT}{zF} \ln \frac{a{\text{Red}}}{a{\text{Ox}}}} ] where:

- (E) is the half-cell reduction potential at temperature (T),

- (E^\ominus) is the standard half-cell reduction potential,

- (R) is the universal gas constant (8.314 J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹),

- (T) is the absolute temperature in Kelvin,

- (z) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction,

- (F) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·molâ»Â¹),

- (a{\text{Red}}) and (a{\text{Ox}}) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [16] [19].

The equation is derived from the principles of chemical thermodynamics, connecting the change in Gibbs free energy ((\Delta G = -zFE)) under non-standard conditions to the standard free energy change and the reaction quotient (Q) [20] [19].

Table 1: Key Parameters in the Nernst Equation

| Parameter | Symbol | Standard Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Potential | (E) | Volt (V) | Electromotive force under non-standard conditions. |

| Standard Cell Potential | (E^\ominus) | Volt (V) | Electromotive force under standard conditions (all activities = 1 M). |

| Gas Constant | (R) | J·Kâ»Â¹Â·molâ»Â¹ | Fundamental constant in the ideal gas law. |

| Temperature | (T) | Kelvin (K) | Absolute temperature of the system. |

| Electrons Transferred | (z) | Dimensionless | Number of moles of electrons transferred per mole of reaction. |

| Faraday Constant | (F) | C·molâ»Â¹ | Charge of one mole of electrons. |

| Reaction Quotient | (Q) | Dimensionless | Ratio of product activities to reactant activities. |

At standard temperature (298.15 K or 25 °C), substituting the values of (R) and (F) allows the equation to be simplified for practical use [21] [19]: [ E = E^\ominus - \frac{0.0592\, \text{V}}{z} \log_{10} Q ]

Experimental Protocol: Determining a Half-Cell Potential

This protocol details the measurement of the potential of a Fe²âº/Fe³⺠redox couple under non-standard conditions using the Nernst equation.

- Objective: To experimentally determine the potential of a Fe²âº/Fe³⺠half-cell and verify the result using the Nernst equation.

- Principle: The potential of an inert electrode (e.g., Platinum or graphite) immersed in a solution containing both the oxidized (Fe³âº) and reduced (Fe²âº) forms of a redox couple can be measured against a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl or SCE). This measured potential is compared to the value calculated using the Nernst equation [22].

Materials and Equipment:

- Potentiostat or high-impedance voltmeter

- Reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl)

- Working electrode: Platinum or graphite rod

- Counter electrode (if using a potentiostat)

- Solutions of FeCl₂ and FeCl₃ (e.g., 0.5 M each)

- Supporting electrolyte (e.g., 1 M KCl)

- Volumetric flasks, pipettes, and beakers

Procedure:

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution with known concentrations of Fe²⺠and Fe³âº. For example, mix 0.5 M FeClâ‚‚ and 0.5 M FeCl₃ in a 1:1 volume ratio. Ensure a sufficient concentration of supporting electrolyte (1 M KCl) is present to minimize the liquid junction potential and maintain a constant ionic strength [22].

- Electrode Setup: Immerse the clean working electrode (Pt/graphite) and the reference electrode in the prepared solution. Connect the counter electrode if using a three-electrode potentiostat setup.

- Potential Measurement: Allow the system to stabilize and measure the open-circuit potential (or rest potential) between the working and reference electrodes. This is the reduction potential of the Fe²âº/Fe³⺠couple under the given conditions.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the theoretical potential using the Nernst equation. The standard reduction potential ((E^\ominus)) for Fe³⺠+ e⻠→ Fe²⺠is +0.77 V vs. SHE. For a 1:1 concentration ratio, (Q = [\text{Fe}^{2+}]/[\text{Fe}^{3+}] = 1), and (\log Q = 0). Therefore, the calculated potential (E = E^\ominus = 0.77) V. Convert this value to the potential versus your reference electrode and compare it with the measured value [22].

Troubleshooting:

- Unstable Readings: Ensure electrodes are clean and properly conditioned. Check for air bubbles on the electrode surface.

- Inaccurate Results: Verify the concentrations of prepared solutions and the health/calibration of the reference electrode.

Diagram 1: Nernst Equation Experimental Workflow

Faraday's Law of Electrolysis: Theory and Application

Fundamental Concepts and Formulations

Faraday's Laws of Electrolysis provide a quantitative relationship between the amount of electrical charge passed through an electrolyte and the mass of substance deposited or dissolved at an electrode.

Faraday's First Law: The mass ((m)) of a substance altered at an electrode during electrolysis is directly proportional to the quantity of electric charge ((Q)) passed through the electrolyte [17] [18]. [ m \propto Q \quad \text{or} \quad m = Z \cdot Q ] Here, (Z) is the electrochemical equivalent, the mass of substance deposited per coulomb of charge.

Faraday's Second Law: When the same quantity of electric charge is passed through different electrolytes, the masses of different substances deposited or dissolved are proportional to their equivalent weights ((E)) [18] [23]. [ \frac{m1}{E1} = \frac{m2}{E2} = \text{constant} ]

The combined mathematical expression of Faraday's laws is: [ m = \frac{Q \cdot M}{z \cdot F} ] where:

- (m) is the mass of the substance deposited or dissolved (in grams),

- (Q) is the total electric charge passed (in coulombs),

- (M) is the molar mass of the substance (in g·molâ»Â¹),

- (z) is the valency number (number of electrons transferred per ion),

- (F) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·molâ»Â¹) [18] [23].

Since charge (Q) can be expressed as current (I) multiplied by time (t) ((Q = I \cdot t)), the formula is often written as: [ m = \left( \frac{I \cdot t \cdot M}{z \cdot F} \right) ]

Table 2: Key Parameters in Faraday's Law

| Parameter | Symbol | Standard Units | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mass Deposited | (m) | Gram (g) | Mass of substance liberated at an electrode. |

| Charge | (Q) | Coulomb (C) | Total quantity of electricity passed. |

| Current | (I) | Ampere (A) | Rate of flow of electric charge. |

| Time | (t) | Second (s) | Duration for which current flows. |

| Molar Mass | (M) | g·molâ»Â¹ | Mass of one mole of the substance. |

| Equivalent Weight | (E) | g·molâ»Â¹ | Molar mass divided by valency ((M/z)). |

| Faraday Constant | (F) | C·molâ»Â¹ | Charge of one mole of electrons. |

Experimental Protocol: Electrogravimetric Analysis

This protocol describes the determination of the mass of copper deposited by electrolysis, a classic experiment demonstrating Faraday's Law.

- Objective: To deposit copper from a copper sulfate solution onto a cathode and verify that the mass change aligns with the prediction from Faraday's Law.

- Principle: A direct current is passed through a solution of CuSOâ‚„. Copper ions (Cu²âº) are reduced to metallic copper at the cathode (Cu²⺠+ 2e⻠→ Cu). The mass gain of the cathode is measured and compared to the mass calculated from the total charge passed [18].

Materials and Equipment:

- DC power supply with ammeter

- Analytical balance (0.1 mg precision)

- Copper cathode and anode (e.g., pure copper sheets)

- Electrolyte: 1 M Copper Sulfate (CuSOâ‚„) solution with sulfuric acid added to improve conductivity

- Stopwatch or timer

- Drying oven

Procedure:

- Cathode Preparation: Clean a copper cathode sheet thoroughly with a mild acid (e.g., dilute HNO₃) and distilled water. Dry it completely in an oven and allow it to cool in a desiccator. Weigh the dry cathode accurately ((m_{\text{initial}})) [18].

- Electrolysis Setup: Place the cathode and a copper anode in the CuSOâ‚„ solution. Connect the electrodes to the DC power supply, ensuring the cathode is connected to the negative terminal.

- Electrolysis Execution: Pass a constant current (e.g., 0.5 A) through the cell for a measured time (e.g., 1800 seconds or 30 minutes). Record the exact current ((I)) and time ((t)) [18].

- Post-Processing: Carefully remove the cathode, rinse it gently with distilled water to remove any electrolyte, and dry it completely in an oven. Cool the cathode in a desiccator and weigh it again ((m_{\text{final}})) [18].

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the experimental mass deposited: (m{\text{exp}} = m{\text{final}} - m{\text{initial}}).

- Calculate the total charge passed: (Q = I \cdot t).

- Calculate the theoretical mass of copper deposited using Faraday's Law. For copper, (M = 63.55 \, \text{g·mol}^{-1}) and (z = 2). [ m{\text{theoretical}} = \frac{Q \cdot M}{z \cdot F} = \frac{(I \cdot t) \cdot 63.55}{2 \cdot 96485} ]

- Compare (m{\text{exp}}) with (m{\text{theoretical}}) and calculate the percent efficiency or error.

Troubleshooting:

- Poor Adhesion of Deposit: Current density might be too high; reduce the current.

- Mass Gain Lower Than Theoretical: Check for side reactions, incomplete deposition, or loss of material during rinsing. Ensure all electrical connections are secure.

Diagram 2: Faraday's Law Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful execution of electroanalytical experiments relies on a carefully selected set of materials and reagents. The following table details key components for a general electrochemistry laboratory.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item Name | Specifications / Typical Formulation | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | 1.0 M Potassium Chloride (KCl) or 0.1 M Tetrabutylammonium Hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF₆) in non-aqueous systems. | To carry current and maintain a high, constant ionic strength, minimizing migration effects and ensuring the potential drop occurs primarily near the electrode surface. |

| Redox Probe | 1-5 mM Potassium Ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) in 1 M KCl. | A well-behaved, reversible redox couple used for characterizing electrode performance, determining active surface area, and method validation. |

| Standard Reference Electrode | Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) or Ag/AgCl (with specified KCl concentration, e.g., 3 M). | To provide a stable, known reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured, enabling accurate reporting of half-cell potentials. |

| Working Electrode | Glassy Carbon (GC), Platinum (Pt), or Gold (Au) disk electrodes (e.g., 3 mm diameter). | The site of the redox reaction of interest. The material is chosen based on its potential window, chemical inertness, and reproducibility. Requires regular polishing. |

| Counter Electrode | Platinum wire or coil. | To complete the electrical circuit in a three-electrode setup, allowing current to flow without significantly altering the composition of the solution in the working electrode compartment. |

| Electrode Polishing Kit | Alumina or diamond suspensions (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm grits) on a soft polishing cloth. | To create a fresh, clean, and reproducible electrode surface, which is critical for obtaining reliable and reproducible voltammetric results. |

| Doxepin Hydrochloride | Doxepin Hydrochloride, CAS:4698-39-9, MF:C19H22ClNO, MW:315.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| D-homoserine lactone | D-homoserine lactone, CAS:51744-82-2, MF:C4H7NO2, MW:101.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration of Principles in Electroanalytical Chemistry

The Nernst equation and Faraday's Law are not isolated concepts; they are often applied in concert to solve complex analytical problems. The Nernst equation provides the thermodynamic driving force for a reaction, while Faraday's Law quantifies the current resulting from the ensuing redox processes. This relationship is central to techniques like potentiometry (dominated by the Nernst equation) and coulometry (directly governed by Faraday's Law) [20] [19].

In amperometric biosensors, for instance, the Nernst equation can describe the equilibrium potential at the sensing interface, while the Faraday's Law governs the quantification of the faradaic current generated by the electrochemical reaction of an analyte, which is proportional to its concentration. Furthermore, the Poisson-Nernst-Planck (PNP) equations represent a more advanced, unified model that describes the migration and diffusion of ions in an electric field, combining concepts from both fundamental laws and is critical for modeling processes in confined geometries like ion-exchange membranes or biological ion channels [15] [24].

Diagram 3: Integration of Theoretical Foundations

The Nernst Equation and Faraday's Law are indispensable tools in the electroanalytical chemist's arsenal. The Nernst equation provides the fundamental thermodynamic link between concentration and electrical potential, while Faraday's Law offers a precise stoichiometric relationship for quantifying electrochemical reactions. Mastery of these relationships, including their specific applications, assumptions, and limitations, is crucial for the design and interpretation of experiments in modern research and development, particularly in the precision-demanding field of drug development. Their integrated application continues to enable innovations in sensor technology, energy storage, and bioanalytical methods.

Electroanalytical chemistry is a branch of analytical chemistry that measures electrical properties to analyze chemical solutions, relying fundamentally on the relationship between electricity and chemical reactions involving electron transfer at electrode-solution interfaces [25]. These methods are classified into major categories including potentiometric (measuring potential), voltammetric (measuring current as a function of applied potential), coulometric (measuring charge), and conductometric (measuring conductivity) techniques [25]. The signals generated—current, potential, charge, impedance—arise from chemical processes at the electrode-solution interface, with their magnitude dependent on analyte concentration and the nature of the electrode reaction, governed by fundamental relationships such as the Nernst equation and Faraday's laws [25].

At the heart of these sophisticated measurements lies the electrochemical cell, a setup critically dependent on a three-electrode system for precise control and measurement [26]. This system, comprising the working, reference, and counter electrodes, provides the essential interface between the electrical circuit and the chemical system under study [25] [27]. Understanding the distinct roles, optimal materials, and proper configuration of these three electrodes constitutes a foundational principle for researchers and scientists engaged in fields ranging from catalyst development to drug discovery [28]. The integrity of electrochemical data, essential for both fundamental research and industrial applications, is directly contingent upon the correct selection and implementation of these components.

The Three-Electrode System: A Framework for Precision

The transition from a two-electrode to a three-electrode system represents a critical advancement in electrochemical experimentation, enabling precise control and measurement unattainable in simpler setups. In a two-electrode system, a single electrode serves as both a reference and a counter, a configuration sufficient only for basic measurements with minimal current. However, this setup fails when significant current flows, as the current passage alters the composition and potential of the reference point, leading to unstable and inaccurate readings [27].

The three-electrode system elegantly resolves this limitation by functionally separating the roles of potential measurement and current carriage [26]. This system comprises:

- The Working Electrode (WE): The site of the reaction of interest.

- The Reference Electrode (RE): Provides a stable, known potential benchmark.

- The Counter Electrode (CE): Completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow.

This separation is crucial because it ensures that the reference electrode remains unpolarized—no significant current passes through it—thus maintaining its stable and well-defined potential [26] [27]. The potentiostat, the instrument at the heart of modern electrochemistry, leverages this configuration by using a feedback loop to control the potential between the working and reference electrodes while measuring the current flowing between the working and counter electrodes [27]. This arrangement allows researchers to study the kinetics and thermodynamics of electron transfer reactions at the working electrode with high accuracy and reproducibility, forming the basis for most advanced electroanalytical techniques.

Figure 1: Schematic of a three-electrode system controlled by a potentiostat.

The Working Electrode: The Site of Investigation

Role and Function

The working electrode (WE) is the cornerstone of any electrochemical experiment, serving as the stage upon which the specific reaction of interest occurs [26] [27]. It is at the surface of the WE that the analyte interacts, facilitating the transfer of electrons and generating the signal that is measured and analyzed [25]. The working electrode can be either solid or liquid, and its material composition is paramount, as it directly influences the kinetics, overpotential, and specificity of the electrochemical reaction [26]. In corrosion research, the working electrode is typically the material being studied, whereas in physical-electrochemistry experiments, it is often an inert material chosen for its conductivity and stability [26].

Common Materials and Selection

The selection of a working electrode material is dictated by the experimental requirements, including the potential window of interest, chemical inertness, and the need for a reproducible surface. Common materials and their characteristics are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Common Working Electrode Materials and Their Properties

| Material | Common Uses | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon [26] [27] | General electrochemical studies, stability tests [26] | Wide potential window, relatively inert, good for many applications [26] [27] |

| Platinum [26] [27] | Physical-electrochemistry, fuel cell research [26] | Highly conductive, resistant to corrosion, excellent for hydrogen adsorption/desorption [26] [27] |

| Gold [26] | Sensitive measurements, biosensing [26] | Excellent conductivity, low reactivity, easy to functionalize with thiols [26] |

| Silver [26] | Specialized applications, chloride detection [26] | Used in specific scenarios where its unique electrochemical properties are advantageous [26] |

| Lead [26] | Corrosion studies [26] | Employed in studies where its corrosion behavior is the focus [26] |

| Conductive Glass (e.g., ITO) [26] | Electrochromic devices, spectroelectrochemistry [26] | Used in applications requiring optical transparency [26] |

Surface Preparation and Integrity

The integrity of the working electrode's surface is non-negotiable for obtaining accurate and reproducible data. A well-prepared surface ensures that the geometric area used in calculations closely matches the true electroactive surface area, which is critical for quantitative analysis [26]. Standard preparation involves sequential polishing with increasingly fine abrasive slurries (e.g., alumina or diamond) to a mirror finish, followed by thorough rinsing to remove any residual particles [27]. For some materials, electrochemical cleaning via cycling in an appropriate supporting electrolyte is also employed. It is recommended to wear disposable gloves during handling to prevent contamination from skin oils [27]. The reproducibility of cyclic voltammograms (CVs) for a standard redox couple (e.g., Ferrocene or Potassium Ferricyanide) is a common method to verify surface integrity. A significant change in the shape or position of these CVs indicates the need for re-polishing or more rigorous cleaning [26].

The Reference Electrode: The Potential Benchmark

Role and Function

The reference electrode (RE) provides the stable and well-known potential against which the potential of the working electrode is measured and controlled [26] [27]. Its primary function is to act as a fixed benchmark in the electrochemical circuit. Unlike the working electrode, the reference electrode is designed to have minimal current passing through it, preserving its constant composition and, consequently, its stable potential [26]. This stability is essential because the overall cell potential is the sum of the potentials from the two half-reactions; by using a standardized reference electrode, any changes in the measured potential can be attributed solely to processes occurring at the working electrode [26].

Common Types and Characteristics

Reference electrodes are typically "electrodes of the second kind," where the potential depends indirectly on the concentration of a single anion, ensuring stability [27]. Common systems include:

Table 2: Common Reference Electrode Systems and Their Properties

| Type | Composition | Potential (approx. vs SHE) | Advantages & Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ag/AgCl [26] [27] | Silver wire coated with AgCl in a KCl solution (e.g., 3 M or saturated) [27] | +0.197 V vs. SHE (for saturated) | Very common, stable, reliable. Avoid in solutions where chloride contamination is an issue or where Ag⺠can precipitate [27]. |

| Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [26] [27] | Mercury in contact with calomel (Hgâ‚‚Clâ‚‚) in a saturated KCl solution [27] | +0.241 V vs. SHE | Historically popular and stable. Contains mercury, leading to environmental and safety concerns [26] [27]. |

| Mercuric Oxide Electrode [26] | Mercury oxide in a potassium hydroxide solution [26] | Varies with KOH concentration | Known for high stability in alkaline environments [26]. |

When publishing results, it is critical to clearly indicate the reference electrode used (e.g., "E / mV vs. Ag/AgCl") to allow for comparison with other studies [27].

Positioning and Ohmic Drop

The physical positioning of the reference electrode is a critical, yet often overlooked, aspect of experimental design. The solution between the RE and the WE has a finite resistance, leading to a voltage loss known as Ohmic drop (iR drop) [27]. This is the potential lost "on the way" from the reference to the working electrode, meaning the potential felt by the working electrode is less than that applied by the potentiostat. This effect is negligible in well-conducting solutions (e.g., 100 mM KCl) but becomes significant in low-conductivity media common in corrosion studies or non-aqueous electrolytes [27].

To minimize iR drop, a Luggin capillary—a glass tube with a narrow tip—is often used. It allows the reference electrode to be positioned very close to the working electrode without significantly disturbing the diffusion layer [27]. It is important to avoid placing the reference electrode too close without a Luggin capillary, as this can create an artificial crevice and alter local concentrations due to leakage from the reference electrode's filling solution [27].

The Counter Electrode: Completing the Circuit

Role and Function

The counter electrode (CE), also known as the auxiliary electrode, completes the electrical circuit in the electrochemical cell [26] [27]. Its primary function is to balance the charge transfer occurring at the working electrode. For every electron transferred from the working electrode to a molecule in solution (reduction), an electron must be simultaneously removed from the solution by the counter electrode (oxidation), and vice versa [26]. The current measured by the potentiostat is the flow of electrons from the working electrode to the counter electrode [26]. This role is fundamental; without a properly functioning counter electrode, the desired reaction at the working electrode cannot proceed in a controlled manner.

Characteristics and Materials

To perform its role effectively without introducing artifacts, the counter electrode must be designed to facilitate rapid electron transfer with minimal polarization [26]. This is typically achieved by using an inert material with a surface area significantly larger than that of the working electrode [26] [27]. A large surface area ensures that the current density at the counter electrode is low, preventing it from becoming a limiting factor and minimizing the generation of unwanted reaction products that could diffuse to the working electrode and interfere with the measurement [27].

Table 3: Common Counter Electrode Materials and Considerations

| Material | Form | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Platinum [26] [27] | Wire, mesh, or gauze [27] | Excellent conductivity, high chemical stability, inert towards most solutions, easy to clean (e.g., with a hand torch) [27]. | Expensive [26]. |

| Graphite [26] | Rod or foil | Cost-effective, good electrical conductivity, chemically inert in many environments [26]. | Can be porous, potentially releasing particles; slower response time compared to Pt [26]. |

For most routine cyclic voltammetry experiments, a simple platinum wire is sufficient. However, for high-current applications (> 1 mA) or long-term stability tests, a larger surface area form such as platinum mesh or gauze is highly recommended to ensure stable performance and avoid side reactions like water splitting [26] [27].

Experimental Protocol: Establishing a Standardized Setup

Adhering to a standardized protocol is essential for generating reliable, comparable electrochemical data, particularly in fields like catalyst evaluation for the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) [28]. The following methodology outlines a general procedure for configuring a three-electrode system.

Electrode and Cell Preparation

Working Electrode Preparation:

- Polishing: Polish the working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon) sequentially with finer abrasive slurries (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm alumina) on a micro-cloth pad. Use a figure-8 pattern to ensure an even surface.

- Rinsing: Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water (e.g., 18.2 MΩ·cm) after each polishing step to remove all abrasive particles.

- Sonication: Sonicate the electrode in both an ethanol and water bath for 1-2 minutes each to remove any adhered particles.

- Drying: Dry under a gentle stream of inert gas (e.g., Nâ‚‚ or Ar) [27].

Electrolyte Preparation:

- Use high-purity reagents and ultrapure water.

- Add a supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KNO₃, KCl, or H₂SO₄, depending on compatibility) at a concentration至少 100 times that of the analyte to ensure high conductivity and minimize migratory mass transport [25].

- Degassing: Sparge the electrolyte with an inert gas (Nâ‚‚ or Ar) for at least 15-20 minutes prior to experiments to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with many redox reactions.

Electrode Assembly:

- Immerse the clean working electrode, reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and counter electrode (e.g., Pt gauze) into the electrolyte.

- Ensure the Luggin capillary of the reference electrode is positioned approximately 1-2 times its diameter away from the working electrode surface to minimize iR drop without disrupting the diffusion layer [27].

- Verify that all electrical connections are secure and the cell is properly sealed to prevent oxygen re-entry during measurement.

System Verification and Measurement

- Potentiostat Calibration: Follow the manufacturer's instructions for instrument initialization and calibration.

- Electrode Integrity Check: Before introducing the analyte, record a cyclic voltammogram of the supporting electrolyte within the expected potential window. The CV should feature a flat, low-background current, confirming a clean electrode and pure electrolyte.

- Standard Redox Couple Test: To validate the entire system's performance, run a CV of a known standard redox couple (e.g., 1 mM potassium ferricyanide in 1 M KCl). The observed peak separation (ΔEp) should be close to the theoretical value of 59 mV for a reversible, one-electron transfer process, confirming minimal iR drop and proper setup.

Figure 2: Workflow for establishing a validated three-electrode electrochemical system.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

A properly equipped electrochemistry laboratory requires a suite of reliable reagents and materials. The following table details key components essential for configuring and executing experiments with a three-electrode system.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electroanalytical Research

| Item | Function / Purpose | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., KCl, KNO₃, H₂SO₄, TBAPF₆) [25] | Provides ionic conductivity in solution, minimizes ohmic (iR) drop, and suppresses migratory mass transport of the analyte. | Concentration should be high (e.g., 0.1 - 1.0 M) relative to the analyte. Must be electrochemically inert in the potential window of interest and not react with the analyte [25]. |

| Electrode Polishing Kits (Alumina or Diamond Slurries) [27] | For resurfacing and cleaning working electrodes to ensure a reproducible and contaminant-free electroactive surface. | Use sequential grades (e.g., 1.0 μm → 0.3 μm → 0.05 μm). Dedicated polishing pads for each slurry grade prevent cross-contamination [27]. |

| Standard Redox Probes (e.g., Potassium Ferricyanide, Ferrocene) | Used to verify the performance and cleanliness of the working electrode and the overall cell setup. | A reversible redox couple provides a known reference for peak separation (ΔEp) and confirms minimal iR drop. Ferrocene is often used in non-aqueous solvents. |

| Inert Gases (Nâ‚‚ or Ar, high purity) [28] | For degassing the electrolyte to remove dissolved oxygen, a common interferent in redox chemistry. | Sparging for 15-20 minutes is typical. Maintain a slight positive pressure over the solution during experiments to prevent Oâ‚‚ re-entry. |

| Reference Electrode Filling Solution (e.g., 3 M KCl for Ag/AgCl) [27] | Maintains the stable ionic environment and fixed chloride concentration required for a stable reference potential. | Check for crystallization around the frit and refill as needed. Ensure the solution is saturated if using a saturated electrode type. |

| Clomipramine-D3 | Clomipramine-D3, CAS:136765-29-2, MF:C19H23ClN2, MW:317.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Fingolimod-d4 | Fingolimod-d4|Internal Standard | High-purity Fingolimod-d4 stable isotope for LC-MS research. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Troubleshooting and Optimization

Even with a carefully established setup, researchers may encounter challenges. Common issues include unstable current or potential readings, which can stem from a contaminated working electrode, a clogged reference electrode frit, or an undersized counter electrode [26] [27]. High background currents often indicate an impure electrolyte or a dirty cell. Non-reproducible cyclic voltammograms warrant re-polishing and re-cleaning of the working electrode [26]. For experiments in low-conductivity solutions, iR compensation techniques (available on most modern potentiostats) should be applied cautiously, as over-compensation can lead to system instability [27].

The triumvirate of the working, reference, and counter electrodes forms the indispensable foundation of electroanalytical chemistry. Each component fulfills a distinct and vital role: the working electrode as the investigative stage, the reference electrode as the stable potential benchmark, and the counter electrode as the circuit-completing partner. A deep understanding of their respective functions, optimal materials, and proper integration within the electrochemical cell is a fundamental prerequisite for any researcher aiming to generate high-quality, reliable data. As electroanalytical methods continue to evolve and find new applications in drug development, energy storage, and sensor technology [28], the principles governing these essential components remain a cornerstone of rigorous scientific inquiry.

Electroanalytical chemistry encompasses a suite of techniques that measure electrical properties such as potential, current, charge, or conductivity to obtain qualitative and quantitative information about chemical species in solution [25]. These methods are grounded in the relationship between electricity and chemical reactions, primarily involving electron transfer at the interface between an electrode and an electrolyte solution [25]. The analytical signal's magnitude depends on the concentration of the analyte and the kinetics of the electrode reaction [25]. For researchers and drug development professionals, these techniques offer powerful tools for quantifying ions, detecting biomarkers, monitoring reaction kinetics, and analyzing compounds in complex biological matrices.

The fundamental principles governing these methods can be divided into two categories. Faradaic processes involve the actual transfer of electrons across the electrode-solution interface, forming the basis for potentiometric, voltammetric, and coulometric methods [25]. In contrast, non-faradaic processes involve changes in the structure of the electrode-solution interface without electron transfer, which is particularly relevant in conductometric methods and double-layer charging effects [25]. A critical theoretical foundation for many electroanalytical techniques is the Nernst equation, which relates the electrode potential to the activity (or concentration) of the electroactive species [29]. For the redox pair Ox/Red, the equation is expressed as:

[E = E^0 + \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{a{Ox}}{a{Red}}]

where E is the electrode potential, Eâ° is the standard electrode potential, R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, n is the number of electrons transferred, F is the Faraday constant, and a represents the activity of the oxidized and reduced species [29]. Under dilute conditions, activity can be approximated by concentration.

Comparative Analysis of Electroanalytical Techniques

The four primary categories of electroanalytical methods differ in their measured parameters, underlying principles, and key applications. The table below provides a structured comparison for these techniques.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Electroanalytical Methods

| Method | Measured Quantity | Fundamental Principle | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometry [25] | Potential (Volts) at zero current [30] | Measurement of potential difference between indicator and reference electrode under static conditions; governed by Nernst equation [31] | Ion concentration measurements (e.g., pH), clinical analysis of electrolytes, potentiometric biosensors [25] [29] |

| Voltammetry [25] | Current (Amperes) as a function of applied potential [32] | Measurement of current resulting from oxidation/reduction of analyte at a working electrode under controlled potential | Trace metal detection, neurotransmitter monitoring, detection of organic molecules, mechanistic studies [32] [33] |

| Coulometry [25] | Total Charge (Coulombs) [34] | Measurement of total charge passed during exhaustive electrolysis of an analyte; governed by Faraday's Law [34] | Karl Fischer titration for water content, determination of chloride in clinical samples, film thickness measurement [34] [35] |

| Conductometry [25] | Electrical Conductivity of a solution [36] | Measurement of a solution's ability to conduct electricity, which depends on the concentration and mobility of ionic species [37] | Acid-base and precipitation titrations, water quality monitoring, analysis of ionic strength [36] [37] |

Table 2: Operational Conditions and Signal Characteristics

| Method | Cell Type | Control Parameter | Key Mathematical Relationship |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometry | Galvanic (spontaneous) [30] | Zero current (system at equilibrium) [31] | Nernst Equation [29] |

| Voltammetry | Electrolytic (non-spontaneous) [30] | Applied potential (varied over time) [32] | Butler-Volmer Equation, Cottrell Equation [32] [33] |

| Coulometry | Electrolytic (non-spontaneous) [35] | Applied current or potential [34] | Faraday's Law ((Q = nFN)) [34] |

| Conductometry | N/A | Applied AC voltage [36] | Kohlrausch's Law (( \Lambdam = \Lambdam^0 - \Theta \sqrt{C} )) [36] |

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Potentiometric Methods

Potentiometry measures the potential difference between an indicator electrode and a reference electrode under conditions of zero or negligible current flow, thereby not altering the solution composition [31]. The reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) provides a stable, known potential, while the indicator electrode's potential varies with the analyte's activity [30]. The most common indicator electrodes are Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs), which incorporate a membrane (glass, crystalline, or polymer) that selectively binds the target ion, generating a membrane potential [30]. The measured cell potential is related to the analyte activity by the Nernst equation, providing a direct quantitative relationship.

Protocol for Potentiometric Measurement using an Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE):

- Electrode Assembly: Set up a potentiometric cell comprising the ISE (e.g., a glass pH electrode) and a stable reference electrode containing a concentrated KCl solution [30] [31].

- Calibration: Prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target ion. Immerse the electrodes in each standard solution, allow the potential to stabilize, and record the millivolt (mV) reading. Plot the potential (E) vs. the logarithm of the ion activity (log a) to obtain a calibration curve, which should be linear with a slope close to the theoretical Nernst value (59.16 mV/decade for a monovalent ion at 25°C) [30].

- Sample Measurement: Rinse the electrodes and immerse them in the sample solution. Record the stable potential reading.

- Quantification: Determine the unknown concentration of the sample from the calibration curve.

For solutions with potential interferents, the Nicolsky-Eisenman equation is used to account for the electrode's selectivity: [E = E^0 + \frac{2.303RT}{zi F} \log (ai + \sum K{i/j}^{Pot} aj^{zi/zj})] where (ai) is the activity of the primary ion, (aj) is the activity of the interfering ion, and (K{i/j}) is the selectivity coefficient [30]. Low (K{i/j}) values indicate high selectivity for the analyte.

Voltammetric Methods

Voltammetry encompasses techniques where the current at a working electrode is measured while the applied potential between the working and reference electrodes is varied in a controlled manner over time [32]. The resulting plot of current versus potential is called a voltammogram [32]. A three-electrode system is standard: a working electrode (where the reaction of interest occurs, e.g., glassy carbon, platinum), a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl, to provide a stable potential reference), and a counter (auxiliary) electrode (e.g., platinum wire, to complete the circuit) [32]. The supporting electrolyte is added to the solution to minimize resistive losses and eliminate transport by migration.

Protocol for Cyclic Voltammetry (CV):

- Cell Preparation: Prepare a solution containing the analyte and a high concentration of supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl or TBAPF6 in organic solvents) to ensure conductive media and diffusion-controlled mass transport [32].

- Electrode Setup: Insert the three electrodes (working, reference, counter) into the solution. Ensure the working electrode is clean and well-polished.

- Potential Scan: Apply a linear potential scan from an initial potential (Ei) to a upper vertex potential (Eλ) and then back to E_i. The scan rate (ν, in V/s) is a key parameter.

- Data Collection: Record the current response as a function of the applied potential to obtain the cyclic voltammogram.

- Data Analysis: Key information from the CV includes the peak potentials (Epa for oxidation, Epc for reduction), peak currents (ipa, ipc), and the separation between peak potentials (ΔEp). For a reversible system, ΔEp is approximately 59 mV/n at 25°C, and the peak current is proportional to the square root of the scan rate (i_p ∠ν^{1/2}) and the analyte concentration, as described by the Randles-Å evÄÃk equation [32].

Pulse techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) offer higher sensitivity by minimizing charging (capacitive) currents. In DPV, small potential pulses are superimposed on a linear base potential, and the current difference just before and after the pulse is plotted against the base potential, resulting in a peak-shaped voltammogram [33]. SWV uses a symmetrical square wave superimposed on a staircase waveform, measuring the forward and reverse currents to effectively reject charging current [33]. Stripping voltammetry (e.g., Anodic Stripping Voltammetry, ASV) is an extremely sensitive method for trace metal analysis. It involves a preconcentration step where metal ions are electroplated onto the working electrode at a negative potential, followed by a stripping step where the deposited metals are re-oxidized, producing a sharp peak current proportional to concentration [33].

Coulometric Methods

Coulometry is based on the measurement of the total charge (Q, in coulombs) required to completely convert an analyte from one oxidation state to another via an electrochemical reaction [34]. This is an absolute method that relies on Faraday's Law: (Q = nFN), where n is the number of electrons per mole of analyte, F is the Faraday constant (96,487 C/mol), and N is the number of moles of analyte [34]. Thus, if the charge is measured and the reaction stoichiometry is known, the amount of substance can be determined directly without calibration.

There are two main operational modes:

- Potentiostatic Coulometry: The potential of the working electrode is held constant, and the current, which decays as the analyte is consumed, is integrated over time to obtain the total charge [35]. The reaction is considered complete when the current approaches zero.

- Coulometric Titration (Amperostatic Coulometry): A constant current is applied, and the titrant is generated electrochemically from a precursor in the solution. The titrant then reacts stoichiometrically with the analyte. The reaction time (t) is measured until the endpoint is detected. The charge is calculated as Q = I * t, and the moles of analyte are determined via Faraday's Law and the reaction stoichiometry [34] [35].

Protocol for Coulometric Titration of Chloride:

- Cell Assembly: Use a cell with platinum generator electrodes (anode and cathode) and a pair of indicator electrodes for endpoint detection. The analyte solution contains the chloride sample and a gel electrolyte (e.g., potassium nitrate) [34].

- Titrant Generation: Apply a constant current. At the anode, silver ions (Agâº) are generated from a silver electrode.

- Reaction: The electrogenerated Ag⺠ions immediately react with Cl⻠in the sample to form insoluble AgCl(s).

- Endpoint Detection: When all Cl⻠has been precipitated, the first excess of Ag⺠ions causes a sharp change in potential measured by the indicator electrodes, signaling the endpoint.

- Calculation: The amount of chloride is calculated as: (N_{Cl^-} = \frac{I \cdot t}{F}), where I is the constant current (A), t is the time to reach the endpoint (s), and F is the Faraday constant.

A prominent application is the Karl Fischer coulometric titration for determining trace water content, where iodine is electrogenerated and consumed stoichiometrically by water [35].

Conductometric Methods

Conductometry measures the ability of a solution to conduct an electric current, which depends on the concentration, charge, and mobility of all ionic species present [36]. In conductometric titration, the change in conductivity is monitored as a function of titrant addition. The equivalence point is identified by a distinct change in the slope of the conductivity-versus-volume plot [37]. This method is particularly useful for colored or turbid solutions where visual indicators fail.

Protocol for Conductometric Acid-Base Titration (e.g., HCl vs. NaOH):

- Setup: Place the acid solution (HCl) in a beaker and immerse the conductivity cell (typically made of platinum electrodes).

- Initial Measurement: Measure the initial conductivity, which is high due to the high mobility of H₃O⺠ions.

- Titration: Add the base (NaOH) in small increments. After each addition, stir the solution and record the conductivity.