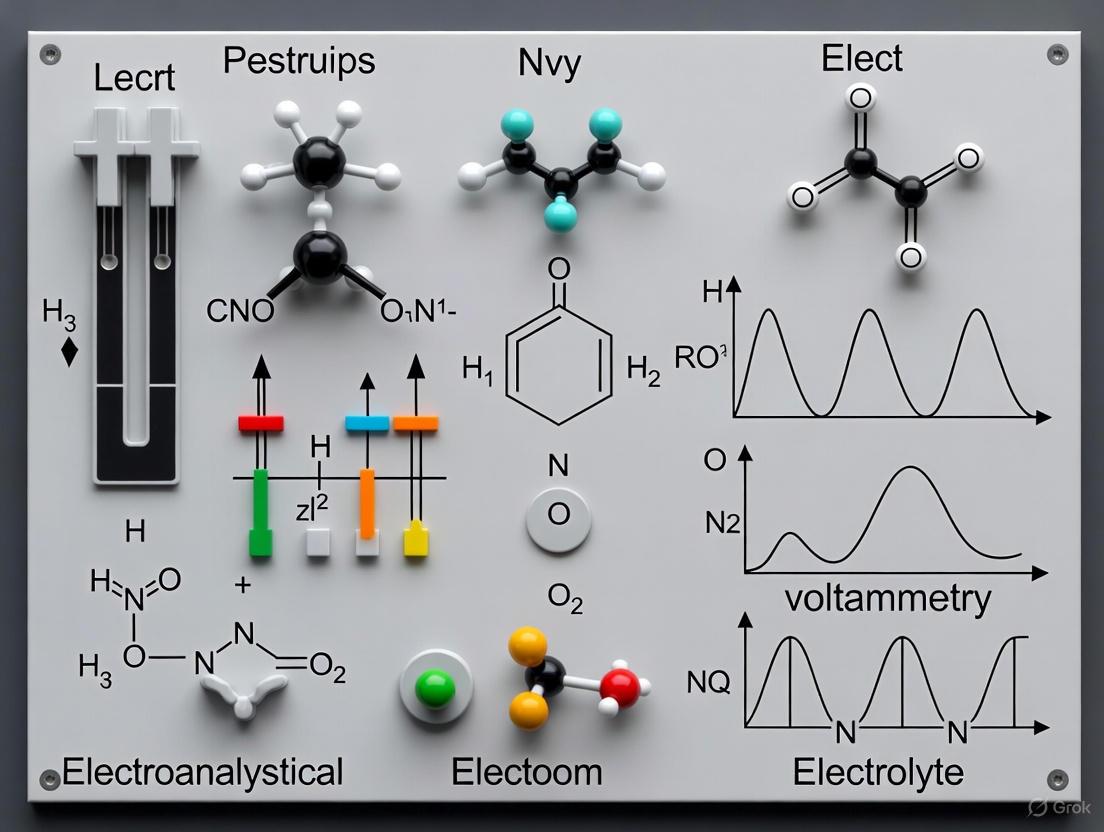

Electroanalytical Chemistry: A Beginner's Guide to Principles, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive introduction to electroanalytical chemistry.

Electroanalytical Chemistry: A Beginner's Guide to Principles, Methods, and Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive introduction to electroanalytical chemistry. It covers foundational principles, key analytical techniques like potentiometry and voltammetry, and their practical applications in pharmaceutical and clinical analysis. Readers will gain a clear understanding of how to select, optimize, and validate electrochemical methods to solve real-world challenges in drug delivery, biomolecule detection, and quality control, enhancing their research and analytical capabilities.

What is Electroanalytical Chemistry? Core Concepts and Setup

Electroanalytical chemistry comprises a suite of techniques that utilize electrical measurements to probe chemical processes, quantify analytes, and elucidate reaction mechanisms [1]. At its core, this field involves studying an analyte by measuring the potential (volts), current (amperes), or charge in an electrochemical cell containing the analyte [2]. The significance of electroanalytical chemistry has grown substantially in modern science and industry, as it offers powerful tools for decentralized determinations in clinical, food, and environmental samples where information must be obtained outside traditional laboratory settings [3]. The global expansion of this field is evidenced by increasing publication trends and dedicated international symposia, such as the "Electroanalytical Chemistry: Bridging New Horizons" session scheduled for Pacifichem 2025 [4] [1].

The fundamental principle governing electroanalytical techniques resides in the interplay between electricity and chemical reactions, primarily through oxidation-reduction (redox) processes where electrons move between atoms and electrodes [3]. When a chemical reaction occurs, electrons transfer between electrodes immersed in an electrochemical cell solution containing the analyte, generating measurable electrical signals that provide information about the identity and composition of the analyte [3]. This relationship between chemical reactions and electricity forms the foundational framework for all electroanalytical methods, enabling their application across diverse fields including pharmaceutical sciences, environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics, and biological research [5] [1].

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Framework

Core Concepts in Electrochemistry

Electroanalytical methods function on several fundamental principles that govern the relationship between electrical signals and chemical activity. The electrochemical cell represents the core platform, consisting of two half-cells, each containing an electrode immersed in a solution of ions whose activities determine the electrode's potential [6]. A salt bridge containing an inert electrolyte connects the two half-cells, completing the electrical circuit by allowing ion movement [6]. Within this cell, several key concepts dictate the behavior of analytes:

Electrode Potentials: The potential of an electrochemical cell represents the difference between the potential at the cathode (where reduction occurs) and the potential at the anode (where oxidation occurs) [6]. This relationship is quantitatively described by the Nernst equation, which relates the electrode potential to the concentrations of the redox species involved.

Current-Potential Relationship: Most electrochemical techniques rely on either controlling the current and measuring the resulting potential, or controlling the potential and measuring the resulting current [6]. Understanding this relationship is crucial, as experimentally measured potentials may differ from thermodynamic values due to factors such as ohmic potential (caused by solution resistance), concentration polarization (resulting from limited mass transport), and overpotential (the extra energy needed to drive electron transfer at a finite rate) [6].

Mass Transport Regimes: The movement of electroactive species to the electrode surface occurs through three primary mechanisms: diffusion (movement due to concentration gradients), migration (movement due to an electric field), and convection (movement due to mechanical forces) [3]. The specific transport regime significantly impacts the resulting current response.

Classification of Electroanalytical Techniques

Electroanalytical methods are broadly categorized based on which electrical parameters are controlled and measured, and whether the system is at equilibrium or in a dynamic state. Table 1 provides a comprehensive overview of the main electroanalytical techniques, their measured signals, and their primary applications.

Table 1: Classification of Major Electroanalytical Techniques

| Technique | Controlled Parameter | Measured Signal | Key Principles | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potentiometry [2] | Zero current | Potential (volts) | Measurement of potential across indicator and reference electrodes under zero-current conditions | Ion-selective measurements (e.g., pH), environmental monitoring, process control |

| Chronoamperometry [3] [2] | Potential | Current vs. time | Application of potential step; current decay follows Cottrell equation (i = nFACD¹/²/π¹/²t¹/²) | Determination of diffusion coefficients, electron transfer numbers, electroanalytical determinations |

| Voltammetry [2] [5] | Potential | Current vs. potential | Application of varying potential waveform; current response reveals redox behavior | Mechanism studies, trace analysis, pharmaceutical quantification |

| Coulometry [2] | Current or Potential | Charge (coulombs) | Complete conversion of analyte; measurement of total charge passed | Determination of number of electrons in redox processes, absolute quantification |

| Impedance Spectroscopy [3] [1] | AC Potential | Impedance vs. frequency | Application of small-amplitude AC potential; measurement of complex impedance | Surface characterization, label-free bioassays, kinetic studies |

These techniques are further divided into static techniques (where no current passes through the cell and concentrations remain constant) and dynamic techniques (where current flows and changes species concentrations) [6]. Potentiometry represents the primary static technique, while amperometry, voltammetry, and coulometry fall under dynamic techniques that provide information about reaction kinetics and mass transport phenomena.

Essential Electroanalytical Techniques and Methodologies

Potentiometry

Potentiometry involves passively measuring the potential of a solution between two electrodes—a reference electrode with a constant potential and an indicator electrode whose potential changes with the sample's composition [2]. This technique affects the solution very little in the process, as it operates under conditions of zero current [2] [6]. The measured potential difference provides information about the sample's composition, particularly when using ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) designed to respond specifically to the ion of interest [2] [5]. The most common application of potentiometry is the glass-membrane electrode used in pH meters, but modern applications have expanded to include polymeric membrane ISEs and advanced arrays that enhance sensitivity and precision in ion detection [2] [1]. A variant known as chronopotentiometry employs a constant current while measuring potential as a function of time [2].

Amperometric Techniques

Amperometry encompasses techniques where current is measured as a function of an independent variable, typically time or electrode potential [2]. Chronoamperometry, a fundamental amperometric technique, involves applying a sudden potential step to the working electrode and measuring the resulting current as a function of time [3] [2]. In a typical experiment, the potential is stepped from a value where no electrolysis occurs to a value in the mass transfer-controlled region, causing the concentration of the electroactive species at the electrode surface to drop to nearly zero and establishing a concentration gradient that drives diffusion to the electrode surface [3]. The current-time response follows the Cottrell equation (i = nFACD¹/²/π¹/²t¹/²) for a planar electrode with linear diffusion, showing current decaying inversely with the square root of time [3]. This technique is particularly valuable for determining diffusion coefficients, electrode surface areas, rate constants of coupled chemical reactions, and concentration of adsorbed material [3].

Voltammetric Techniques

Voltammetry represents a subclass of amperometry in which current is measured while varying the potential applied to the electrode [2]. This category includes several important techniques:

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): This powerful technique involves sweeping the potential linearly with time between two set values, then reversing the sweep direction, generating current responses that provide information about redox potentials, electrochemical reactivity, and reaction mechanisms [3] [5]. Although highly informative for qualitative analysis, CV is generally less suited for precise quantification compared to pulse techniques [5].

Pulse Voltammetry: Techniques such as Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) apply a series of potential pulses rather than a continuous sweep, significantly reducing background capacitive current and enhancing sensitivity for trace-level detection [3] [5]. These methods are particularly valuable for analytical applications requiring low detection limits and resolution of closely spaced redox events [5].

Stripping Voltammetry: This highly sensitive technique involves preconcentrating an analyte onto the electrode surface during a deposition step, followed by a potential sweep that strips the accumulated material back into solution, generating an enhanced current response that enables detection at ultratrace concentrations.

The following diagram illustrates the general workflow and decision process for selecting appropriate electroanalytical techniques based on analytical objectives:

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies and Procedures

Chronoamperometric Determination of Ascorbic Acid

Background and Principle: This protocol details the determination of ascorbic acid (vitamin C) concentration using chronoamperometry with paper-based electrochemical cells, suitable for advanced undergraduate or graduate students in analytical chemistry [3]. The experiment demonstrates how chronoamperometry, where current-time (i-t) curves are recorded, is particularly appropriate when analytical simplicity is a priority, as it requires no potential scanning and features simplified instrumentation [3].

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical Cell: Paper-based electrochemical cell fabricated using Whatman Grade 1 chromatographic paper with deposited conductive inks [3]

- Electrochemical Workstation: Potentiostat capable of applying potential steps and recording current-time responses

- Electrodes: Three-electrode system (working, reference, and counter electrodes) integrated into the paper device

- Reagents: Standard ascorbic acid solutions, appropriate buffer (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0)

- Samples: Fruit juices, vitamin formulations, or biological fluids (urine and serum) after appropriate dilution [3]

Experimental Procedure:

Electrode Preparation: Fabricate paper-based electrodes by depositing conductive inks on chromatographic paper, following established procedures [3]. The paper's porosity allows for storage of bioreagents and use of minimal sample volumes.

Instrument Setup: Configure the potentiostat for chronoamperometric measurements. Set the following parameters:

- Initial potential (Ei): +0.1 V (vs. reference)

- Final potential (Ef): +0.6 V (vs. reference)

- Step duration: 30-60 seconds

- Sampling rate: 10 points per second

Standard Curve Generation:

- Apply 20-50 μL aliquots of standard ascorbic acid solutions (0.1-2.0 mM) to the paper-based cell

- Apply the potential step from Ei to Ef and record the current-time response

- Measure the current at a fixed time (e.g., 5 seconds) after potential application

- Plot current versus concentration to generate a calibration curve

Sample Analysis:

- Apply diluted sample solutions to fresh paper-based cells

- Perform chronoamperometric measurements under identical conditions

- Determine ascorbic acid concentration from the standard curve

Data Analysis: The current response follows the Cottrell equation for diffusion-controlled conditions: i = nFACD¹/²/π¹/²t¹/², where i is current, n is number of electrons, F is Faraday's constant, A is electrode area, C is concentration, D is diffusion coefficient, and t is time [3]. For quantitative analysis, measure the current at a fixed time point and relate it to concentration through the standard curve. Account for the capacitive current contribution, which decays exponentially with time (i = E/Rs × e^(-t/RuCd)) and becomes negligible after the initial milliseconds [3].

Electrochemical Biosensor Development for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Background and Principle: This protocol outlines the development of electrochemical biosensors for pharmaceutical analysis, particularly for detecting drugs and their metabolites in biological fluids [5]. Electroanalytical techniques offer high sensitivity, requiring small sample volumes (often microliters) with low detection limits, enabling investigation of subpicogram levels of drug compounds and metabolites [5].

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrode Systems: Conventional (glassy carbon, gold, platinum) or nanostructured electrodes

- Biological Recognition Elements: Enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, or molecularly imprinted polymers

- Nanomaterials: Graphene oxide, metal nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes for signal enhancement

- Electrochemical Instrumentation: Potentiostat with capabilities for voltammetric and impedimetric measurements

Sensor Fabrication Procedure:

Electrode Modification:

- Polish conventional electrodes to mirror finish using alumina slurry

- Clean electrodes through potential cycling in supporting electrolyte

- Deposit nanomaterials (e.g., through electrodeposition of Au/NiO/Rh trimetallic composites or chitosan-stabilized gold nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide) to enhance electrode surface area and electron transfer kinetics [1]

Immobilization of Recognition Elements:

- Employ covalent bonding, physical adsorption, or entrapment in polymeric matrices

- For enzyme-based sensors, use cross-linking with glutaraldehyde in presence of bovine serum albumin

- For affinity sensors, immobilize antibodies or aptamers through self-assembled monolayers or avidin-biotin interactions

Optimization and Characterization:

- Characterize modified electrodes using cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

- Optimize experimental parameters (pH, incubation time, temperature) for maximum sensor response

- Validate sensor performance against standard reference methods

Pharmaceutical Application:

- Drug Quality Control: Quantify active pharmaceutical ingredients in formulations using differential pulse or square wave voltammetry [5]

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Measure drug concentrations in biological fluids with minimal sample pretreatment

- Metabolite Studies: Identify and quantify drug metabolites through their distinctive redox signatures

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful electroanalytical chemistry research requires specific materials and reagents tailored to the experimental objectives. Table 2 details essential components for developing electroanalytical methods and sensors, particularly in pharmaceutical and biological applications.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electroanalytical Chemistry

| Category/Item | Specification Examples | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials [3] [1] | Glassy carbon, platinum, gold, screen-printed electrodes, paper-based electrodes | Provide conductive surface for electron transfer reactions; influence reaction kinetics and selectivity | General voltammetry, electrode processes study |

| Nanomaterials [7] [5] [1] | Metal nanoparticles (Au, Pt), graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes, MIL-101(Cr), reduced graphene oxide | Enhance electrode surface area, improve electron transfer kinetics, catalyze reactions | Sensor signal amplification, nitrite detection [1] |

| Biological Recognition Elements [5] | Enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, binding proteins, molecularly imprinted polymers | Provide molecular recognition specificity for target analytes | Biosensors for therapeutic drug monitoring, continuous sensing systems |

| Electrode Modifiers [1] | Chitosan-stabilized gold nanoparticles, Au/NiO/Rh trimetallic composites, polyaniline composites | Enhance selectivity, minimize fouling, improve biocompatibility | Ion-selective electrodes, heavy metal detection (e.g., Pb²⁺) [1] |

| Supporting Electrolytes [3] [5] | Phosphate buffer, KCl, NaClO₄, tetraalkylammonium salts | Provide ionic conductivity; control ionic strength and electrochemical double-layer structure | All electrochemical experiments; typically 0.1-1.0 M concentration |

| Redox Probes [3] | Potassium ferricyanide, ruthenium hexamine, methylene blue | Validate electrode performance; study electron transfer kinetics | Electrode characterization, sensor development |

Applications in Pharmaceutical and Biological Sciences

Electroanalytical chemistry has emerged as a critical tool in the pharmaceutical industry, offering versatile and sensitive methods for drug analysis at various stages of development and quality control [5]. The applications span from drug discovery to environmental monitoring of pharmaceutical residues, demonstrating the field's breadth and significance.

Pharmaceutical Quality Control and Drug Development

Electroanalytical techniques play crucial roles in analyzing bulk active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), intermediate products, formulated products, impurities, and degradation products [5]. These methods offer significant advantages over traditional techniques like spectrophotometry and chromatography, including minimal sample preparation, small sample volumes, rapid analysis, and cost-effectiveness [5]. Specific applications include:

Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient Quantification: Voltammetric techniques, particularly differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) and square wave voltammetry (SWV), enable precise determination of API concentrations in formulations with high sensitivity and selectivity [5].

Stability and Degradation Studies: Monitoring degradation products through their characteristic electrochemical signatures provides insights into drug stability under various conditions [5].

Dissolution Testing: Real-time monitoring of drug release from formulations using electrochemical sensors offers advantages over traditional sampling methods [5].

Bioanalysis and Therapeutic Drug Monitoring

The detection of drugs and metabolites in biological fluids represents one of the most significant applications of electroanalytical chemistry in pharmaceutical and biomedical research [5]. Recent advancements in electrochemical instruments have made these approaches viable for monitoring therapeutic agents in complex biological matrices:

Therapeutic Drug Monitoring: Electrochemical biosensors enable precise measurement of drug concentrations in blood, serum, or urine, facilitating personalized dosing regimens and improved patient outcomes [5].

Metabolite Profiling: The distinctive redox behavior of drug metabolites allows their identification and quantification in biological samples, providing insights into metabolic pathways [5].

Continuous Monitoring Systems: Development of technologies using engineered affinity-based biosensing molecules with sufficient specificity and sensitivity enables functional sensing of arbitrary molecules for in vivo, real-time monitoring systems [4].

Environmental and Food Safety Applications

Growing concerns about pharmaceutical contamination in the environment have expanded the application of electroanalytical techniques to detect drug residues in water systems and food products [7] [5]. Electrochemical paper-based analytical devices (ePADs) have gained particular attention as sustainable and smart analytical tools for assessing drug residues in wastewater and foodstuffs [7]. These devices leverage the porosity of paper to enable very low volumes of sample and reagent usage, making them ideal for decentralized analysis [3].

Current Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of electroanalytical chemistry continues to evolve rapidly, driven by technological advancements and emerging applications across scientific disciplines. Several key trends are shaping the future of this field:

Technological Innovations

Nanomaterials and Engineered Surfaces: The integration of nanomaterials and innovative deposition techniques has significantly refined sensor performance [1]. Recent investigations demonstrate approaches such as one-step electrodeposition to modify laser-induced graphene with trimetallic composites, yielding sensors capable of rapid detection with broad linear ranges and low detection limits [1].

Miniaturization and Portable Systems: The development of portable, disposable, and autonomous sensing platforms represents a major trend, with paper-based electrochemical devices leading the way toward decentralized analysis [3] [7]. These systems are particularly valuable for applications in resource-limited settings and point-of-care testing.

Multimodal Sensing Platforms: Recent studies have demonstrated the merits of integrating optical and electrochemical transduction modalities, providing dual readouts that are both visually interpretable and quantitatively corroborated by electrochemical signals [1].

Advanced Modeling and Data Analysis: Theoretical developments in electrochemical modeling continue to inform practical sensor design [1]. The incorporation of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning algorithms for data interpretation represents a growing trend, optimizing experimental processes and enabling more sophisticated analysis of complex samples [5] [1].

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Personalized Medicine: The development of wearable and implantable electrochemical sensors opens new possibilities for real-time patient monitoring, enabling personalized medicine and more precise dosing strategies [5].

Sustainable Analytical Chemistry: Electrochemical paper-based analytical devices represent progress toward more sustainable analytical tools, aligning with green chemistry principles while maintaining analytical performance [7].

Advanced Drug Discovery Tools: Innovations such as lab-on-a-chip systems and bioelectrochemical sensors are expected to enhance the efficiency of drug development and regulatory compliance [5].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected relationship between electricity, chemistry, and biology in electroanalytical chemistry, highlighting key techniques and applications:

Electroanalytical chemistry represents a dynamic and rapidly evolving field that bridges fundamental principles of electricity with chemical and biological systems to address analytical challenges across diverse domains. The interplay between electrical signals and redox processes at electrode interfaces provides a powerful framework for quantifying analytes, elucidating reaction mechanisms, and developing innovative sensing strategies. As the field continues to advance through integration of nanomaterials, miniaturization platforms, artificial intelligence, and novel recognition elements, electroanalytical methods are poised to expand their impact in pharmaceutical research, clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and personalized medicine. The ongoing development of portable, cost-effective, and user-friendly electrochemical sensors promises to democratize analytical capabilities, making sophisticated chemical analysis accessible in resource-limited settings and paving the way for transformative applications in global health, precision medicine, and sustainable development.

In electroanalytical chemistry, the interaction between electrical energy and chemical species generates measurable signals that provide quantitative and qualitative information about an analyte. These signals are fundamentally rooted in three key electrical quantities: potential, current, and charge [8]. These three fundamental electrochemical signals form the basis of all electrochemical techniques, which are powerful tools used in diverse areas ranging from electro-organic synthesis and fuel cell studies to radical ion formation and biosensing [9]. The measurement of these signals enables researchers to determine analyte concentration, study chemical reactivity, and understand underlying reaction mechanisms.

Electrochemical techniques are broadly divided into two categories: bulk techniques, which measure a property of the solution in the electrochemical cell, and interfacial techniques, where the signal depends on species present at the interface between an electrode and the solution [8]. This guide focuses on interfacial methods, where potential, current, and charge serve as the primary analytical signals. These techniques are built upon the foundation of the electrochemical cell, typically consisting of a working electrode, a counter electrode, and a reference electrode with a stable and fixed potential [10]. The precise control and measurement of these electrical quantities allow for the development of highly sensitive, selective, and portable analytical devices that find applications in medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and fundamental research [10] [11].

Theoretical Foundations

The Electrochemical Potential

The electrochemical potential is a central thermodynamic concept that combines chemical potential with electrostatic energy contributions. In electrochemistry, it represents the total energy required to add one mole of a species to a system at constant temperature, pressure, and composition of other species [12]. Formally, the electrochemical potential ( \bar{\mu}_i ) of species i is defined as the partial molar Gibbs energy:

[ \bar{\mu}i = \left(\frac{\partial G}{\partial Ni}\right){T,P,N{j \neq i}} ]

where ( G ) is the Gibbs free energy, and ( N_i ) is the number of moles of species i [12]. For practical applications, this is commonly expressed as:

[ \bar{\mu}i = \mui + z_i F\Phi ]

where:

- ( \mu_i ) is the chemical potential of species i (J/mol)

- ( z_i ) is the valency (charge) of the ion i (dimensionless integer)

- ( F ) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C/mol)

- ( \Phi ) is the local electrostatic potential (V) [12]

This relationship highlights how both chemical concentration gradients (( \mu_i )) and electric fields (( \Phi )) drive the movement of charged species. Differences in electrochemical potential between regions are physically meaningful and measurable: species spontaneously move from areas of higher to lower electrochemical potential, and at equilibrium, the electrochemical potential for each species equalizes throughout the domain it can access [12].

Fundamental Relationships Between Signals

The three fundamental signals—potential, current, and charge—are interconnected through well-established physical relationships. Potential differences provide the driving force for electrochemical reactions, current reflects the rate of electron transfer, and charge represents the total quantity of electrons transferred over time. The relationship between current and charge is particularly direct, as charge (Q) is the integral of current (I) over time:

[ Q = \int I\, dt ]

This relationship is formally expressed in Faraday's Law of Electrolysis, which states that the amount of substance consumed or produced at an electrode is directly proportional to the total charge transferred. For a reaction involving n electrons per molecule, the moles of substance N is given by:

[ N = \frac{Q}{nF} ]

where F is Faraday's constant [8]. This fundamental principle forms the basis for coulometric methods, where charge serves as the direct analytical signal.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental relationships and dependencies between the three core electrical quantities in electroanalytical chemistry:

Figure 1: Relationship between core electrical quantities and their analytical significance. Potential provides the driving force for reactions, current measures electron transfer rate, and charge quantifies total electrons transferred.

Potential as an Analytical Signal

Theoretical Basis

Potential as an analytical signal primarily relates to the thermodynamic tendency of electrochemical reactions to occur. The most fundamental relationship governing potential-based measurements is the Nernst equation, which describes the dependence of electrode potential on analyte concentration (more precisely, activity) [8]. For a general reduction-oxidation reaction:

[ Ox + ne^- \rightleftharpoons Red ]

The Nernst equation is expressed as:

[ E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln \frac{a{Red}}{a{Ox}} ]

where:

- ( E ) is the measured potential

- ( E^0 ) is the standard electrode potential

- ( R ) is the universal gas constant

- ( T ) is the absolute temperature

- ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred

- ( F ) is Faraday's constant

- ( a{Red} ) and ( a{Ox} ) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [8]

In potentiometric methods, the potential is measured under static (zero-current or equilibrium) conditions, where the relationship between potential and concentration becomes direct and predictable through the Nernst equation [8].

Measurement Techniques and Applications

Potentiometry is the primary technique that uses potential as the analytical signal. This method involves measuring the potential of an electrochemical cell under conditions of zero current flow, which allows the system to remain at or near equilibrium [8]. The measured potential is then related to the concentration of the analyte of interest through the Nernst equation.

Key components of potentiometric measurements include:

- Reference Electrode: Maintains a fixed and stable potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured [8]

- Indicator/Working Electrode: Develops a potential that depends on the concentration of the analyte

- High-Impedance Voltmeter: Essential for ensuring minimal current flow during measurement [8]

Modern potentiometry often utilizes ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), which are designed to respond selectively to specific ions based on specialized membrane materials [8]. The most common example is the pH electrode, which selectively responds to hydrogen ions. Other ISEs are available for ions such as Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, F⁻, and Cl⁻.

The experimental protocol for a typical potentiometric measurement involves:

- Calibrating the electrode system with standard solutions of known concentration

- Measuring the potential of unknown samples under identical conditions

- Determining unknown concentrations from the calibration curve

- Maintaining constant temperature and ionic strength across all measurements

A key consideration in potentiometric measurements is the junction potential that develops at the interface between solutions of different composition, particularly at the reference electrode junction. While modern electrode designs minimize this effect, it remains a potential source of error in precise measurements [8].

Current as an Analytical Signal

Theoretical Basis

Current as an analytical signal represents the rate of electron transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface. Unlike potential measurements which occur at equilibrium, current-based techniques explicitly involve non-equilibrium conditions where net electrochemical reactions occur. The current magnitude is governed by both kinetic and mass transport factors.

The fundamental relationship describing electrode kinetics is the Butler-Volmer equation, which relates current density to overpotential:

[ j = j0 \left[ \exp\left(\frac{\alphaa F\eta}{RT}\right) - \exp\left(-\frac{\alpha_c F\eta}{RT}\right) \right] ]

where:

- ( j ) is the current density

- ( j_0 ) is the exchange current density

- ( \alphaa ) and ( \alphac ) are the anodic and cathodic charge transfer coefficients

- ( \eta ) is the overpotential (( E - E_{eq} ))

- Other terms have their usual meanings [13]

Mass transport occurs through three primary mechanisms: diffusion (movement due to concentration gradients), migration (movement due to electric fields), and convection (movement due to fluid motion) [8]. In controlled experiments, supporting electrolyte is often added to minimize migration effects, and convection may be either controlled (e.g., using a rotating disk electrode) or minimized.

Measurement Techniques and Applications

Current-based electrochemical techniques are broadly classified as voltammetric/amperometric methods, where a time-dependent potential is applied and the resulting current is measured [8]. The resulting plot of current versus applied potential is called a voltammogram, which serves as the electrochemical equivalent of a spectrum in spectroscopy, providing both quantitative and qualitative information about the species involved in oxidation or reduction reactions [8].

Table 1: Major Current-Based Electroanalytical Techniques

| Technique | Excitation Signal | Measured Response | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Linear potential ramp with reversal | Current vs. potential | Reaction mechanisms, redox potentials [10] |

| Linear Sweep Voltammetry (LSV) | Linear potential ramp | Current vs. potential | Kinetic studies, concentration analysis [14] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Staircase potential with small pulses | Current difference vs. potential | Trace analysis, resolution of overlapping signals [10] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Square wave superimposed on staircase | Current difference vs. potential | Fast scanning, sensitive detection [10] |

| Amperometry | Constant potential | Current vs. time | Biosensors, process monitoring [8] |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Small AC potential over frequency range | Current magnitude/phase vs. frequency | Surface processes, coating quality, corrosion [15] |

A typical experimental protocol for Linear Sweep Voltammetry with a Rotating Disk Electrode (LSV/RDE) involves [14]:

- Preparing the electrolyte solution with supporting electrolyte and analyte

- Polishing and cleaning the working electrode to ensure a reproducible surface

- Setting the rotation speed of the RDE to control convective mass transport

- Applying a linear potential sweep from initial to final potential

- Measuring the resulting current to generate a voltammogram

- Repeating at different rotation speeds to elucidate mass transport effects

For the ferri/ferrocyanide couple (( Fe(CN)_6^{3-/4-} )), a reversible one-electron transfer system, the LSV/RDE experiment produces sigmoidal voltammograms with well-defined limiting currents that are proportional to the square root of rotation speed according to the Levich equation [14]. This system serves as an excellent model for validating new experimental methodologies and modeling approaches [14].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a modern approach to parameter estimation from current-based measurements, combining experimental techniques with advanced modeling:

Figure 2: Workflow for electrochemical parameter estimation from current signals, highlighting the iterative nature of modern analysis approaches.

Charge as an Analytical Signal

Theoretical Basis

Charge as an analytical signal represents the total quantity of electricity that has passed through the electrochemical cell, directly corresponding to the total number of electrons transferred in electrochemical reactions. This relationship is quantitatively described by Faraday's Law of Electrolysis, which states that the charge required to electrolyze one mole of a substance is proportional to the number of electrons transferred per molecule [8].

The fundamental equation is:

[ Q = nFN ]

where:

- ( Q ) is the total charge (coulombs)

- ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred per molecule

- ( F ) is Faraday's constant (96,485 C/mol)

- ( N ) is the number of moles of substance electrolyzed

This direct proportionality between charge and the number of moles of reactant makes charge-based methods fundamentally absolute techniques that can provide highly accurate quantitative analysis without requiring calibration curves, when performed under appropriate conditions.

Measurement Techniques and Applications

Coulometry is the primary electrochemical technique that uses charge as the direct analytical signal [8]. In coulometric methods, the total charge passed during exhaustive electrolysis of the analyte is measured and related to the quantity of analyte through Faraday's law. There are two main types of coulometry:

Controlled-Potential Coulometry: The working electrode potential is maintained at a constant value throughout the experiment, ensuring 100% current efficiency for the reaction of interest [8]

Controlled-Current Coulometry: A constant current is passed through the cell, and the total electrolysis time is measured to determine charge [8]

Controlled-potential coulometry is generally preferred for analytical applications because it offers better selectivity—by maintaining the potential at a value where only the analyte of interest undergoes electrolysis, interference from other species can be minimized [8].

A typical experimental protocol for controlled-potential coulometry involves:

- Selecting an appropriate potential that ensures complete electrolysis of the analyte without causing secondary reactions

- Using a large working electrode surface area to complete the electrolysis in a reasonable time

- Implementing efficient stirring to ensure rapid mass transport of analyte to the electrode

- Measuring the current throughout the experiment and integrating it to obtain total charge

- Continuing the electrolysis until current decays to a negligible background level

The charge measurement is obtained by integrating the current over time:

[ Q = \int_{0}^{t} I\, dt ]

In modern potentiostats, this integration is performed electronically or digitally throughout the experiment.

Advanced Applications and Signal Enhancement Strategies

Electrochemical Biosensing

Electrochemical biosensors represent one of the most significant application areas where potential, current, and charge serve as analytical signals. These devices combine biological recognition elements with electrochemical transducers to create highly specific and sensitive analytical tools [10]. The basic principle involves immobilizing a biological recognition element (enzyme, antibody, nucleic acid, cell, or tissue) on the electrode surface, which then specifically interacts with the target analyte, producing an electrochemical signal proportional to the analyte concentration [10].

Signal amplification strategies have been developed to enhance the sensitivity of electrochemical biosensors, particularly for detecting low-abundance biomarkers and other analytes present at trace levels [10]. Major signal amplification approaches include:

- Nanomaterial-based amplification: Using nanoparticles, carbon nanotubes, graphene, and other nanomaterials to increase electrode surface area and enhance electron transfer kinetics [10] [11]

- Enzymatic amplification: Employing enzyme labels that generate electroactive products in catalytic amounts [10]

- Nucleic acid amplification: Incorporating techniques like PCR or isothermal amplification to increase the number of detectable molecules [10]

- Redox cycling: Creating systems where molecules undergo repeated oxidation and reduction, generating higher currents [10]

These signal enhancement strategies have enabled the development of ultrasensitive biosensors for medical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, and food safety testing [10].

Advanced Experimental Design and Parameter Estimation

Recent advances in electrochemical analysis have incorporated sophisticated computational methods for optimal experimental design (OED) to enhance parameter estimation accuracy. Deep reinforcement learning (DRL) approaches have been applied to optimize input excitation signals, thereby increasing the sensitivity of the system's response to target electrochemical parameters [13].

The Fisher Information (FI) metric serves as a key criterion for evaluating data quality in these approaches:

[ \text{FI} = \frac{1}{\sigmay^2} \sum{k=1}^{N} \left( \frac{\partial y_k}{\partial \theta} \right)^2 ]

where:

- ( \sigma_y^2 ) is the variance of measurement error

- ( \frac{\partial yk}{\partial \theta} ) is the sensitivity of the output ( yk ) to parameter ( \theta ) at data point k [13]

This approach has shown particular utility in identifying key electrochemical parameters in lithium-ion battery systems, such as anode and cathode rate constants (kₙ, kₚ), which critically influence dynamic response [13]. The inverse of FI establishes the Cramér-Rao bound, which represents the lower bound for the variance of estimation error [13].

Table 2: Key Electrochemical Parameters Accessible Through Signal Analysis

| Parameter | Symbol | Techniques | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient | D | LSV/RDE, CV, EIS | Mass transport characteristics [14] |

| Rate Constant | k⁰ | CV, LSV, EIS | Electron transfer kinetics [14] |

| Charge Transfer Coefficient | α | LSV, Tafel | Reaction mechanism symmetry [14] |

| Exchange Current Density | j₀ | EIS, Tafel | Reaction intrinsic rate [13] |

| Solution Resistance | Rₛ | EIS, Current interrupt | Uncompensated resistance [15] |

| Charge Transfer Resistance | Rₜc | EIS, CV | Kinetic barrier [15] |

| Double Layer Capacitance | Cₛd | EIS, CV | Electrode surface area [15] |

Interface Engineering for Enhanced Signal Acquisition

Recent innovations in signal interface design have significantly improved the acquisition of potential, current, and charge signals in electrochemical systems [11]. Key developments include:

- 3D-printed sensing platforms: Providing precise control over electrode architectures with enhanced surface areas and hierarchical structures that improve electron transfer kinetics [11]

- Laser-induced graphene (LIG) electrodes: Offering high conductivity, large electroactive surface area, and porous interconnected 3D structures that can be fabricated on flexible substrates [11]

- Soft and stretchable electrodes: Enabling conformal contact with biological surfaces for wearable biosensors that maintain signal integrity during movement [11]

- Microfluidic-integrated interfaces: Allowing automated sample handling, reduced sample volumes, and multiplexed detection capabilities [11]

These interface engineering advances have addressed traditional challenges such as biofouling, electrode deterioration, signal instability, and poor reproducibility, thereby enhancing the reliability of electrochemical measurements across various applications [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electroanalytical Experiments

| Item | Function | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes migration current; provides ionic conductivity | KCl, K₂SO₄, phosphate buffers, NaClO₄ [14] |

| Redox Probes | System characterization; method validation | Ferri/ferrocyanide, Hexaamminecobalt(III) [14] |

| Reference Electrodes | Provides stable, fixed potential reference | Ag/AgCl, SCE, Hg/HgO [8] [15] |

| Working Electrodes | Site of electrochemical reaction; signal generation | Glassy carbon, gold, platinum, carbon paste [14] |

| Counter Electrodes | Completes electrical circuit; facilitates current flow | Platinum wire, graphite rod [15] |

| Surface Modification Agents | Enhances selectivity and sensitivity | Nafion, chitosan, self-assembled monolayers [11] |

| Nanomaterials | Signal amplification; increased surface area | Carbon nanotubes, graphene, metal nanoparticles [10] [11] |

| Biological Recognition Elements | Provides molecular specificity | Enzymes, antibodies, aptamers, nucleic acids [10] |

These materials form the foundation for reliable electrochemical experiments across research and development applications. Proper selection and preparation of these components are critical for obtaining reproducible and meaningful data. The integration of advanced materials, particularly nanomaterials and specialized interfaces, continues to expand the capabilities of electrochemical analysis across diverse fields from fundamental research to applied diagnostics and energy storage development [10] [11].

Electrochemical cells are fundamental building blocks in modern technology, enabling the conversion between chemical and electrical energy. These devices are indispensable across a broad spectrum of applications, from powering portable electronics and electric vehicles to facilitating advanced electroanalytical techniques in drug development and diagnostic sensing [16] [17]. At their core, all electrochemical cells share three essential components: electrodes where electron transfer occurs, electrolytes that enable ion transport, and a power source that drives the electrochemical reactions. This guide provides an in-depth examination of these core components, offering researchers and scientists a detailed technical foundation for designing and interpreting electrochemical experiments within the context of electroanalytical chemistry.

Core Components and Basic Principles

Fundamental Architecture of an Electrochemical Cell

An electrochemical cell fundamentally consists of two half-cells, each containing an electrode immersed in an electrolyte solution. These half-cells are connected by an external circuit for electron flow and a salt bridge or porous membrane for ion flow, completing the electrical circuit [18]. The electrochemical reactions occurring at the interfaces between the electrodes and the electrolyte facilitate the conversion between chemical and electrical energy.

Figure 1: Core Architecture of an Electrochemical Cell. The diagram illustrates the three essential components and their subcategories that constitute a functional electrochemical system.

Electrode Functions: Anodes and Cathodes

In electrochemical cells, electrodes serve as the surfaces where oxidation and reduction reactions occur. By convention:

- Anode: The electrode where oxidation occurs, resulting in the loss of electrons. In a galvanic cell, this is the negative terminal, while in an electrolytic cell, it becomes the positive terminal [18] [19].

- Cathode: The electrode where reduction occurs, involving the gain of electrons. In a galvanic cell, this is the positive terminal, while in an electrolytic cell, it becomes the negative terminal [18] [19].

The material selection for electrodes depends on the specific application, with common choices including platinum, gold, carbon, silver, and mercury, each offering distinct electrochemical properties [17].

In-Depth Analysis of Electrolyte Systems

Classification and Properties of Electrolytes

The electrolyte is a crucial component that serves as the medium for ionic charge transfer between the electrodes, significantly influencing the performance, safety, and longevity of the electrochemical system [20] [21]. Electrolytes can be broadly classified into several categories based on their physical state and chemical composition.

Figure 2: Classification of Electrolyte Systems. The diagram categorizes electrolytes based on their physical state and chemical composition, highlighting the diversity of materials used in electrochemical applications.

Comparative Analysis of Electrolyte Systems

Table 1: Comparison of Key Electrolyte Types and Their Properties

| Electrolyte Type | Examples | Ionic Conductivity (S cm⁻¹) | Advantages | Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liquid Organic | LiPF₆ in carbonates [20] [22] | 10⁻³ – 10⁻² | High ionic conductivity, good electrode wetting [20] | Flammability, volatility, thermal instability [20] [22] | Li-ion batteries, electroanalysis [20] |

| Aqueous | H₂SO₄, KOH solutions [16] | ~10⁻¹ | Low cost, non-flammable, environmentally friendly [16] | Narrow voltage window (~1.23 V) [16] | Lead-acid batteries, Zn-CO₂ batteries [16] [21] |

| Solid Ceramic | LLZO, β-alumina [20] [23] | 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻³ | Non-flammable, high thermal stability [20] [23] | Brittleness, high interfacial resistance [20] | Solid-state batteries, sensors [20] |

| Solid Polymer | PEO, P(VDF-TrFE) [20] [24] [23] | ~10⁻⁸ (PEO) to 10⁻⁴ | Flexibility, processability, safer than liquids [20] [23] | Low room-temp conductivity, semi-crystalline [20] [23] | Solid-state batteries, flexible electronics [24] [23] |

| Gel Polymer (GPE) | PEO with liquid electrolyte [23] | 10⁻⁴ – 10⁻³ | Combines liquid conductivity with solid stability [20] [23] | Mechanical strength lower than solids [20] [23] | Flexible batteries, supercapacitors [23] |

| Ionic Liquids | EMIm-Cl, various cations/anions [20] [21] | 10⁻³ – 10⁻² | Non-flammable, low vapor pressure, wide ESW [20] | High cost, high viscosity at low temps [20] | Metal-CO₂ batteries, high-temp applications [21] |

Advanced Electrolyte Formulations: Components and Functions

Modern electrolyte systems, particularly for lithium-ion batteries, consist of sophisticated formulations containing lithium salts, organic solvents, and specialized additives, each serving specific functions [22].

Table 2: Key Components of Modern Liquid Electrolyte Formulations

| Component Type | Examples | Concentration | Primary Function | Impact on Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium Salts | LiPF₆, LiFSI, LiTFSI [22] | 0.8-1.2 M | Source of lithium ions, determines ionic conductivity [22] | LiPF₆: Good conductivity but moisture-sensitive; LiFSI: Better thermal stability [22] |

| Organic Solvents | EC, DEC, EMC, DMC [22] | Solvent mixture | Dissolve lithium salts, enable ion transport [22] | High dielectric constant (EC) aids salt dissociation; low viscosity (DMC) enhances mobility [22] |

| Film-Forming Additives | VC, FEC, VEC [22] | 0.5-5% | Form stable SEI on anode surface [22] | Protect anode, reduce capacity fade, extend cycle life [22] |

| Safety Additives | AN, SN [22] | 1-5% | Improve thermal stability, reduce flammability [22] | Enhance safety at high temperatures, prevent thermal runaway [22] |

| Specialty Additives | LiBOB, LiDFOP [22] | 0.5-3% | Address specific failure modes | LiBOB: Enhances high-temp performance; LiDFOP: Improves Si anode stability [22] |

Power Generation and Consumption in Electrochemical Cells

Galvanic vs. Electrolytic Cells

Electrochemical cells are fundamentally categorized based on their energy conversion functionality:

Galvanic Cells (also known as voltaic cells) spontaneously convert chemical energy into electrical energy through spontaneous redox reactions. These cells serve as power sources, with electrons flowing from the anode to the cathode through the external circuit [18] [19]. Common batteries represent practical applications of galvanic cells.

Electrolytic Cells consume electrical energy to drive non-spontaneous chemical reactions. An external power source applies a voltage greater than the cell's potential, forcing redox reactions to occur [18]. These cells are used for applications such as electroplating, electrolysis, and recharging batteries.

The direction of electron flow distinguishes these cell types: from anode to cathode in galvanic cells, and from the external source to the cathode (now negative) in electrolytic cells [18].

Current Types in Electrochemical Systems

The current in electrochemical cells comprises different components:

Faradaic Current: Results from the reduction or oxidation of analytes at the electrode surfaces. This current is directly related to electrochemical reactions following Faraday's law [18]. Cathodic current (positive sign) arises from reduction, while anodic current (negative sign) stems from oxidation [18].

Non-Faradaic Current: Occurs due to capacitive effects, such as the charging of the electrical double layer at the electrode-electrolyte interface, without involving redox reactions [18].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Electrode Modification Techniques for Enhanced Sensing

Surface modification of working electrodes is crucial for improving the sensitivity, selectivity, and stability of electroanalytical measurements [17]. These techniques are particularly valuable in biosensing and pharmaceutical analysis.

Physical Modification Methods

Physical methods rely on non-covalent interactions to immobilize modifiers on electrode surfaces:

- Dip Coating: Electrodes are immersed in a modifier solution/suspension for a predetermined time, then withdrawn and dried. The film thickness depends on immersion time, concentration, and withdrawal speed [17].

- Spin Coating: A small volume of modifier solution is applied to a stationary electrode, which is then rotated at high speed (e.g., 2000 rpm) to spread the material uniformly by centrifugal force [17].

- Drop Casting: A precise volume of modifier suspension is deposited onto the electrode surface and allowed to dry under controlled conditions (UV, N₂, or ambient) [17].

- Spray Coating: Modifier suspensions are aerosolized and sprayed onto electrode surfaces using carrier gas, enabling uniform large-area coatings [17].

Electrochemical Modification Methods

Electrochemical techniques offer controlled deposition of modifier layers:

- Potentiostatic Deposition: A constant potential is applied to the working electrode, maintaining it at least 0.15 V beyond the reduction potential of the target species for a specific duration (seconds to minutes) [17].

- Potentiodynamic Deposition: The electrode potential is scanned between initial and final values at a specific scan rate, allowing controlled nucleation and growth of modifier layers [17].

Electrochemical Characterization Methods

Standard electrochemical techniques provide critical information about electrode processes and interface properties:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Measures current response while cycling the potential, providing information about redox potentials, reaction kinetics, and diffusion coefficients.

- Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS): Applies small AC potential perturbations across a frequency range to characterize interface resistance, capacitance, and charge transfer processes.

- Chronoamperometry: Measures current changes over time at fixed potential, useful for studying diffusion-controlled processes and reaction mechanisms.

- Galvanostatic Charge-Discharge: Applies constant current to evaluate capacity, cycling stability, and efficiency in energy storage systems.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electrochemical Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Primary Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lithium Salts | LiPF₆, LiFSI, LiTFSI, LiClO₄ [20] [22] | Provide lithium ions for conduction | Li-ion battery research, solid-state electrolytes [20] [22] |

| Organic Solvents | Carbonates (EC, DEC, DMC), ethers [20] [22] | Dissolve salts, provide ion transport medium | Non-aqueous electrolyte formulations [22] |

| Ionic Liquids | EMIm-Cl, Pyrrolidinium-based [20] [21] | Low-volatility, wide-ESW electrolytes | High-temperature studies, metal-CO₂ batteries [21] |

| Polymer Hosts | PEO, P(VDF-TrFE), PAN [20] [23] | Solid matrix for ion conduction | Solid-state batteries, flexible electronics [24] [23] |

| Ceramic Electrolytes | LLZO, β-alumina, LATP [20] | High-stability inorganic ion conductors | All-solid-state batteries [20] |

| Electrode Materials | Glassy carbon, platinum, gold [17] | Electron transfer surfaces | Working electrodes, catalyst supports [17] |

| Redox Mediators | Ferrocene, K₃[Fe(CN)₆], Ru(NH₃)₆³⁺ | Benchmark redox couples | Electrode characterization, reference systems |

| SEI Formers | VC, FEC, LiBOB [22] | Create protective interface layers | Anode stabilization, cycle life extension [22] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of electrochemical cells continues to evolve with several promising research directions:

- Solid-State Batteries: Replacing liquid electrolytes with solid counterparts to enhance safety and energy density represents a major frontier. Current research focuses on improving interfacial stability and room-temperature conductivity [20] [24].

- Multivalent Systems: Batteries based on Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Al³⁺ offer potential for higher energy densities than single-valent systems, though challenges remain in electrolyte development and reversible deposition [20].

- Advanced Characterization: In situ and operando techniques are providing unprecedented insights into interfacial phenomena and degradation mechanisms in electrochemical systems [21].

- Sustainable Materials: Research continues into environmentally friendly electrolytes and abundant electrode materials to address resource limitations and environmental concerns [16].

- Interface Engineering: Strategic design of electrode-electrolyte interfaces is crucial for next-generation systems, particularly for stabilizing reactive metal anodes and enabling high-voltage operation [20] [21].

The fundamental components of electrochemical cells—electrodes, electrolytes, and power sources—work in concert to enable a diverse range of technologies from energy storage to analytical sensing. Understanding the properties, functions, and interactions of these components provides researchers with the foundation needed to design optimized electrochemical systems for specific applications. As research advances, the development of novel materials and interface engineering strategies continues to push the boundaries of what is possible in electroanalytical chemistry and energy storage technology. The continued refinement of these essential components will undoubtedly yield new breakthroughs in drug development, diagnostic sensing, and sustainable energy storage.

Electroanalytical chemistry encompasses a range of techniques for analyzing chemical substances by measuring electrical properties such as potential, current, and charge. These methods are fundamentally categorized based on whether the electrochemical cell operates under static conditions (no net current flow, constant analyte concentrations) or dynamic conditions (nonzero current flow, changing analyte concentrations). This classification provides a crucial framework for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals to select appropriate analytical techniques for specific applications, from pharmaceutical stress testing to environmental monitoring [25] [26].

The distinction between these operational modes significantly impacts experimental design, data interpretation, and practical applications in analytical chemistry. Static methods, including potentiometry, measure the potential of an electrochemical cell without passing significant current, leaving the solution composition unchanged. In contrast, dynamic methods, such as voltammetry and amperometry, involve chemical reactions that alter analyte concentrations through the application of a nonzero current [25] [26]. Understanding these fundamental differences enables practitioners to leverage the unique advantages of each approach for specific analytical challenges.

Core Conceptual Framework: Static vs. Dynamic Modes

Fundamental Operational Differences

The division between static and dynamic electrochemical techniques represents a fundamental dichotomy in operational principle, each with distinct characteristics and measurement approaches:

Static Methods: Characterized by the absence of significant current flow through the electrochemical cell, static techniques maintain constant analyte concentrations throughout measurement. The primary measured parameter is potential, which relates to concentration through the Nernst equation. Because no net current flows, the system remains at or near equilibrium, and the solution composition is preserved during analysis [25] [26].

Dynamic Methods: These techniques employ a nonzero current that passes through the electrochemical cell, deliberately inducing chemical reactions that alter analyte concentrations at the electrode-solution interface. The key measured parameters include current, charge, or their relationship with applied potential. Dynamic methods operate under non-equilibrium conditions, actively changing the system being measured to obtain analytical information [25] [26].

Theoretical Basis and Signaling Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting and implementing static versus dynamic electrochemical methods:

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Static Method Experimental Protocol: Potentiometry

Principle: Potentiometry involves measuring the potential of an electrochemical cell under zero-current conditions (static) to determine ion concentrations. The measured potential relates to analyte concentration through the Nernst equation [27].

Procedure:

- Electrode System Setup: Utilize a two-electrode system consisting of an indicator electrode (e.g., ion-selective electrode) and a reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) [27].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare standard solutions with known analyte concentrations and the sample solution with unknown concentration. Ensure consistent ionic strength using an ionic strength adjustment buffer [27].

- Measurement: Immerse the electrode system in each standard solution and measure the potential difference between electrodes under zero-current conditions.

- Calibration Curve: Plot potential (E) versus log(concentration) for standard solutions. The slope should approximate the theoretical Nernstian slope.

- Sample Analysis: Measure the potential of the unknown sample and determine its concentration from the calibration curve.

Key Considerations:

- Maintain constant temperature during measurements

- Ensure adequate stabilization time for each reading

- Use appropriate reference electrode with stable potential

- Account for potential interference from other ions

Dynamic Method Experimental Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry

Principle: Cyclic voltammetry applies a linearly changing potential to a working electrode while measuring the resulting current. The potential is cycled between two limits, inducing oxidation and reduction of analytes and generating characteristic current-potential profiles [27].

Procedure:

- Electrochemical Cell Setup: Implement a three-electrode system consisting of a working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon), reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl), and counter electrode (e.g., platinum wire) [28].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare the analyte solution in appropriate solvent with supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M KCl) to ensure sufficient conductivity. Deoxygenate with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes before measurements.

- Instrument Parameters: Set initial potential, scan direction, vertex potentials, and scan rate (typically 10-1000 mV/s). Multiple scan rates may be employed to study diffusion control and reaction mechanisms.

- Measurement: Initiate potential sweep and record current response. Multiple cycles may be collected to study electrode fouling or reaction intermediates.

- Data Analysis: Identify peak potentials (Epa, Epc) and peak currents (ipa, ipc). Calculate peak separation (ΔEp = Epa - Epc) and current ratios to determine electrochemical reversibility.

Key Considerations:

- Electrode surface preparation is critical for reproducibility

- IR drop compensation may be necessary for resistive solutions

- Control temperature for quantitative studies

- Use appropriate potential windows to avoid solvent/electrolyte decomposition

Comparative Experimental Study: Static vs. Dynamic Electrolysis

A comprehensive study comparing static and dynamic modes in the electrochemical oxidation of fesoterodine (FES) provides valuable insights into practical implementation differences [29]:

Experimental Design:

- System: Wall-jet flow cell with three-electrode configuration

- Analyte: Fesoterodine fumarate (pharmaceutical compound)

- Methodology: Chronoamperometry in both static and dynamic modes

- Analysis: UHPLC-PDA-QDA for product quantification

Static Mode Protocol:

- The sample solution is introduced into the electrochemical cell and remains stationary during electrolysis

- Applied potential/current is maintained for a defined duration

- Solution is removed for analysis after predetermined time

Dynamic Mode Protocol:

- Sample solution continuously flows through the electrochemical cell at controlled rate

- Applied potential/current is maintained during continuous flow

- Effluent is collected for analysis or directed to online detection systems

Key Findings:

- Both modes identified glassy carbon electrode and pH ~7 as optimal conditions

- Static mode required longer experiment durations for significant product formation

- Dynamic mode showed greater dependence on applied voltage parameters

- Product distribution (OP-2) differed between operational modes under identical electrochemical parameters

Quantitative Comparison and Data Analysis

Performance Metrics: Static vs. Dynamic Methods

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Static and Dynamic Electroanalytical Techniques

| Parameter | Static Methods | Dynamic Methods | Measurement Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Conditions | Zero net current [25] [26] | Nonzero current [25] [26] | Determines if system is at equilibrium |

| Concentration Profile | Constant analyte concentrations [25] [26] | Changing analyte concentrations [25] [26] | Impacts mass transport considerations |

| Primary Measured Signal | Potential (voltage) [25] [26] | Current or charge [25] [26] | Different analytical information obtained |

| System State | Equilibrium or near-equilibrium [26] | Non-equilibrium [26] | Affects thermodynamic interpretation |

| Typical Dynamic Range | ~10⁻¹ to 10⁻⁶ M | 10⁻³ to 10⁻⁸ M [26] | Sensitivity and application range |

| Key Applications | Ion concentration measurements, pH sensing [27] | Trace analysis, reaction mechanism studies [27] | Different analytical problem-solving capabilities |

| Information Obtained | Thermodynamic parameters, activity coefficients [27] | Kinetic parameters, diffusion coefficients, reaction mechanisms [27] | Complementary chemical information |

Fesoterodine Oxidation Study: Statistical Results

Table 2: Experimental Results from Static vs. Dynamic Mode Comparison in FES Oxidation [29]

| Experimental Factor | Static Mode Performance | Dynamic Mode Performance | Analytical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Material | Glassy carbon most effective [29] | Glassy carbon most effective [29] | Material compatibility consistent across modes |

| Optimal pH | ~7 [29] | ~7 [29] | pH optimization transferable between modes |

| Applied Voltage | Lower voltages preferred [29] | Higher voltages effective [29] | Major operational difference between modes |

| Experiment Duration | Longer times preferred [29] | Shorter times possible [29] | Throughput advantages for dynamic mode |

| Mass Transport | Diffusion-dominated [29] | Convection-enhanced [29] | Fundamental mechanistic difference |

| Product Yield (OP-2) | Time-dependent optimization [29] | Flow rate and voltage dependent [29] | Different optimization strategies required |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Electroanalytical Experiments

| Component | Function | Specific Examples | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Electrodes | Site of redox reaction with analyte | Glassy carbon, platinum, gold, boron-doped diamond [29] [28] | Material choice affects reactivity, potential window, and surface properties |

| Reference Electrodes | Provide stable, known potential reference | Ag/AgCl, calomel (SCE), hydrogen electrode [28] | Essential for accurate potential control in dynamic methods |

| Counter Electrodes | Complete electrical circuit | Platinum wire, graphite rod [28] | Should have sufficient surface area to not limit current |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Provide conductivity, minimize IR drop | Alkali metal salts, ammonium salts [28] | Must be electroinactive in potential window of interest |

| Solvents | Dissolve analyte and electrolyte | Water, acetonitrile, DMF, dichloromethane [28] | Polarity and electrochemical stability are key considerations |

| Electrocatalysts | Facilitate electron transfer | Metal complexes, organic mediators [28] | Used to lower overpotentials for challenging redox reactions |

| Cell Designs | Contain electrochemical reaction | Undivided cells, divided cells with membranes [28] | Membrane separation prevents cross-reaction of products |

Technical Implementation and Optimization Strategies

Critical Parameter Optimization

Successful implementation of electroanalytical methods requires systematic optimization of key parameters:

Electrode Selection and Preparation: The working electrode material significantly influences electron transfer kinetics, reaction overpotentials, and analytical selectivity. Glassy carbon electrodes provide a wide potential window and are suitable for many organic and inorganic analytes, as demonstrated in the fesoterodine oxidation study where glassy carbon outperformed other materials in both static and dynamic modes [29]. Proper electrode pretreatment (polishing, cleaning, activation) is essential for reproducible results.

Electrolyte and Solvent Systems: The supporting electrolyte concentration typically ranges from 0.1 to 1.0 M to ensure sufficient conductivity while minimizing migration effects. Electrolyte selection should consider potential window, solubility, and possible specific interactions with analytes. Solvents must dissolve both analyte and electrolyte while exhibiting suitable electrochemical stability in the potential range of interest [28].

Mass Transport Considerations: In dynamic methods, mass transport to the electrode surface fundamentally influences current response. Static (unstirred) conditions produce diffusion-dominated responses, while hydrodynamic conditions (stirred or flow systems) enhance mass transport and increase signals. The fesoterodine study demonstrated that dynamic (flow) mode achieved effective electrolysis at shorter times compared to static mode due to enhanced convection [29].

Advanced Methodologies: Hybrid Approaches

Modern electroanalytical applications increasingly employ hybrid techniques that combine elements of both static and dynamic operation:

Pulsed Techniques: Methods such as differential pulse voltammetry and square wave voltammetry apply potential pulses to stationary solutions, combining aspects of potential measurement (static concept) with current monitoring during applied potential steps (dynamic concept) to enhance sensitivity and rejection of capacitive currents.

Scanning Electrode Techniques: These methods maintain dynamic control while spatially mapping local variations in electrochemical activity, particularly useful for studying heterogeneous samples and corrosion processes.

Multi-technique Integration: Coupling electrochemical flow cells with chromatographic separation or mass spectrometric detection, as demonstrated in the pharmaceutical degradation study where electrolysis products were analyzed by UHPLC-PDA-QDA [29].

The distinction between static and dynamic electrochemical techniques represents a fundamental paradigm in electroanalytical chemistry with significant implications for analytical applications. Static methods, characterized by zero current and constant concentrations, provide thermodynamic information and are ideal for direct concentration measurements. Dynamic methods, employing nonzero current and changing concentrations, offer insights into reaction kinetics and mechanisms while typically providing higher sensitivity.

The comparative study of fesoterodine oxidation demonstrates that while both operational modes can achieve similar analytical goals, they require different optimization approaches and exhibit distinct operational characteristics [29]. Static mode offers simplicity and is less equipment-intensive, while dynamic mode provides enhanced mass transport and often faster analysis times.

Selection between static and dynamic techniques should be guided by analytical requirements: static methods for direct concentration measurements and thermodynamic studies; dynamic methods for trace analysis, kinetic studies, and mechanistic investigations. Understanding the fundamental principles and practical considerations of both approaches enables researchers to effectively leverage the capabilities of electroanalytical chemistry across diverse applications from pharmaceutical development to environmental monitoring.

Why Use Electrochemistry? Advantages of Sensitivity, Selectivity, and Miniaturization

Electroanalytical chemistry encompasses a suite of techniques that measure electrical properties such as current, potential, or impedance to obtain qualitative and quantitative information about chemical analytes. These methods have garnered significant attention from researchers due to their experimental simplicity, relatively low cost, and exceptionally low detection limits, typically ranging from nanomolar (nM) to micromolar (µM) [17]. A primary goal in this field is to improve the quality of life through the development of rapid diagnostic methods for common diseases, food quality control, and environmental monitoring [17]. The core advantages that make electrochemical techniques particularly powerful for these applications are their exceptional sensitivity, high selectivity, and excellent potential for miniaturization, which will be explored in detail in this guide.

The fundamental principle underlying all electrochemical sensing is the measurement of electrical signals generated from redox reactions occurring at the electrode-solution interface. When target analytes interact with a specifically designed sensor surface, they induce measurable changes in electrical properties including current, potential, and impedance [30]. The three primary electrochemical detection techniques are:

- Amperometry: Measures current at a constant potential

- Voltammetry: Measures current while scanning through a range of potentials

- Impedance Spectroscopy: Measures impedance across a spectrum of frequencies

This technical guide will explore how these fundamental measurements are leveraged to create powerful analytical tools, with a specific focus on the triumvirate of advantages that make electrochemistry indispensable for modern researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

The Sensitivity Advantage in Electrochemical Detection

Sensitivity in electrochemical sensors refers to their ability to produce a significant signal change in response to a minimal change in analyte concentration. This characteristic is crucial for detecting biologically relevant molecules and disease biomarkers that typically exist at trace levels in complex matrices.

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Signal Amplification

The integration of nanomaterials has revolutionized electrochemical sensing by dramatically enhancing sensitivity. Nanomaterials provide high surface-to-volume ratios, significantly increasing the electrochemically active surface area available for reactions [17]. This increased area allows for greater immobilization of recognition elements and more interaction sites for target analytes, thereby amplifying the detected signal.

Specific nanomaterial applications include:

- Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs): Crystalline porous materials that offer large specific surface areas, high porosity, and ease of surface modification. For instance, UiO-66-NH₂-type MOFs serve as excellent substrates for signal probe preparation due to their abundance of amine functional groups, which enable efficient chelation with metal ions and facile aptamer functionalization [31].

- Carbon Nanomaterials: Carbon nanotubes and graphene enhance conductivity and provide functional groups for biomolecule immobilization. Carboxylic acid-functionalized multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) are commonly used to modify electrode surfaces, improving electron transfer kinetics and lowering detection limits [31].