Electroanalysis for Environmental Monitoring of Pharmaceutical Residues: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of electroanalytical techniques for the monitoring and detection of pharmaceutical residues in environmental samples.

Electroanalysis for Environmental Monitoring of Pharmaceutical Residues: Techniques, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the application of electroanalytical techniques for the monitoring and detection of pharmaceutical residues in environmental samples. It covers the foundational principles of electroanalysis, including electrode materials and cell design, and explores specific methodological applications such as stripping voltammetry and biosensors for trace-level detection. The content also addresses critical challenges, including matrix interference and sensor optimization, and offers comparative analyses of electroanalytical methods against traditional techniques like HPLC and ELISA. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to highlight electroanalysis as a sensitive, cost-effective, and portable solution for environmental surveillance, supporting both regulatory compliance and proactive environmental protection.

The Rising Concern and Electroanalytical Foundation: Why Monitor Pharmaceutical Residues?

Pharmaceutical residues have emerged as a significant class of environmental contaminants due to their inherent bioactivity, persistence, and continuous introduction into ecosystems through multiple pathways. These residues, originating from human and veterinary medicine, enter the environment through a complex lifecycle that spans from production and consumption to excretion and disposal [1] [2]. A substantial portion of orally administered pharmaceutical doses (30-90%) is excreted as active substances or metabolites through urine and feces, subsequently entering wastewater treatment systems [1] [2]. Conventional wastewater treatment plants are not specifically designed to remove these synthetic compounds, resulting in their discharge into surface waters, soils, and eventually groundwater systems [3] [4].

The environmental presence of pharmaceuticals represents an "emerging concern" not only because of their detection at trace levels (ng/L to μg/L) but due to their biological potency and pseudo-persistent nature arising from continuous input [5]. These compounds are designed to interact with specific biochemical pathways in target organisms, raising significant questions about their potential effects on non-target species in the environment [1] [3]. The growing pharmaceutical market, coupled with aging populations and intensified livestock practices, suggests this environmental challenge will likely intensify without targeted intervention strategies [2].

Environmental Pathways and Fate

The journey of pharmaceutical residues through the environment follows complex and interconnected pathways, influenced by the compound's chemical properties, local infrastructure, and agricultural practices. Understanding these pathways is crucial for developing effective mitigation strategies.

Figure 1: Environmental Pathways of Pharmaceutical Residues

The primary sources of pharmaceutical pollution include hospital and municipal wastewater, livestock farming operations, aquaculture, and manufacturing facilities [1] [6]. Particularly concerning are livestock complexes, where veterinary pharmaceuticals and their metabolites are detected at high concentrations in manure and runoff, subsequently applied to agricultural lands as organic fertilizers [6]. This practice introduces pharmaceuticals directly into terrestrial systems, where they can migrate to aquatic environments through surface runoff or leaching into groundwater.

The degree of pharmaceutical transport between different environmental compartments depends primarily on a substance's absorption characteristics in soils, sedimentation systems, water bodies, and treatment plants, which varies considerably among different pharmaceutical products [1]. Key factors influencing environmental fate include the compound's hydrophobicity, chemical stability, and susceptibility to biodegradation. Continuous introduction results in "pseudo-persistence," where pharmaceuticals remain in the environment despite potentially short individual half-lives [5].

Ecological Risks and Impacts

Pharmaceutical residues in the environment pose multifaceted risks to ecosystems, with particular vulnerability observed in aquatic organisms that live in continual exposure to contaminated waters. The table below summarizes documented effects of selected pharmaceutical classes on aquatic organisms.

Table 1: Ecological Impacts of Select Pharmaceutical Classes

| Pharmaceutical Class | Example Compounds | Documented Ecological Effects | Affected Organisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Sulfathiazole, Tetracycline, Ciprofloxacin | Growth inhibition in cyanobacteria and aquatic plants; antibacterial resistance | Cyanobacteria, aquatic plants, soil bacteria |

| Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatories (NSAIDs) | Ibuprofen, Diclofenac, Naproxen | Cellular damage, adverse effects on respiration, growth, and reproductive capacity; genotoxic damage | Fish, aquatic organisms |

| Synthetic Steroids | 17α-ethinyl estradiol, Methyltestosterone | Endocrine disruption, feminization of male fish, intersex conditions, reduced fertility | Fish, reptiles, invertebrates, snails |

| Antipsychotics/Antidepressants | Carbamazepine | Behavioral alterations, inhibition of emergence in Chironomus riparius | Fish, insects |

| Lipid Regulators | Fenofibrate, Bezafibrate | Inhibition of basal EROD activity in rainbow trout hepatocyte cultures | Fish |

The mode of action for many pharmaceuticals involves interference with biochemical pathways conserved across species, making non-target organisms particularly vulnerable. For instance, ethinylestradiol (EE2), a synthetic estrogen used in oral contraceptives, acts as a potent endocrine disruptor, causing feminization of male fish and altered production of female-typical proteins such as vitellogenin [1]. These physiological changes can ultimately lead to reduced fertility and population declines, disrupting aquatic ecosystem dynamics.

Antibiotics pose a dual threat: direct toxicity to photosynthetic organisms and the promotion of antibacterial resistance. Studies of hospital and municipal purification system effluents have revealed ideal platforms for coexistence and interaction among antibiotics, bacteria, and resistance genes, which can be transmitted horizontally between bacteria through conjugation, transduction, or transformation mechanisms [1]. This creates a "cascade diffusion" problem, where resistant genes are transported throughout the environment.

Of particular concern are behavioral alterations in fish caused by psychoactive pharmaceuticals such as antipsychotics, which share neurotransmitter targets across vertebrate species [1]. As organisms are exposed continuously throughout their lifecycle—unlike the controlled exposure in laboratory settings—the long-term ecological consequences remain inadequately understood and require further investigation.

Analytical Framework: Electroanalytical Approaches

Electroanalysis has emerged as a powerful tool for detecting pharmaceutical residues in environmental samples, offering advantages in sensitivity, portability, and cost-effectiveness compared to traditional chromatographic methods. These techniques leverage the electrochemical properties of target analytes to achieve detection at environmentally relevant concentrations.

Core Electroanalytical Techniques

Voltammetric methods, particularly square wave voltammetry (SWV) and differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), are favored for pharmaceutical detection due to their high sensitivity, rapid analysis times, and minimal sample requirements [7] [8]. These pulsed techniques significantly reduce background noise, enabling detection limits in the nanomolar range. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) provides valuable information about redox mechanisms and reaction kinetics but is primarily used for qualitative characterization rather than quantification [7].

Potentiometric methods involving ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) offer complementary approaches for detecting ionic pharmaceutical species, particularly in formulations and biological samples [7]. Recent advancements have integrated these fundamental techniques with novel sensing platforms to enhance performance for environmental monitoring applications.

Protocol: Electrochemical Detection of Cefoperazone Sodium Sulbactam Sodium (CSSS)

The following protocol details the modification of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiO NPs) and multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) for sensitive detection of the antibiotic combination CSSS in environmental samples [8].

Reagent Preparation

- Phytosynthesis of NiO NPs: Prepare hibiscus flower extract by boiling 5g of dried, powdered flowers in 300mL distilled water at 90-95°C for 3 hours. Filter and centrifuge the extract to remove insoluble impurities. Mix 0.1M nickel nitrate hexahydrate solution with the flower extract in a 1:4 ratio and stir for 3 hours. Add concentrated ammonium hydroxide and stir for an additional hour. Heat the mixture at 300°C for 2 hours, then wash the resulting NiO NPs repeatedly with ethanol and distilled water. Calcinate the nanoparticles at 550°C for 3 hours before use [8].

- Nanocomposite Dispersion: Prepare separate dispersions of MWCNTs and synthesized NiO NPs in dimethylformamide (DMF) using ultrasonication for 30 minutes to achieve homogeneous suspensions.

Electrode Modification

- GCE Pretreatment: Polish the glassy carbon electrode (3mm diameter) successively with 1.0μm and 0.05μm alumina slurry on a nylon rubbing pad, followed by sonication in ethanol:water:acetone (1:1:1) mixture for 10 minutes.

- Electrochemical Cleaning: Perform cyclic voltammetry scans in 0.5M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ between -0.1V and +1.0V (vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable, reproducible voltammogram is obtained.

- Nanocomposite Deposition: Apply 8μL of NiO NP dispersion to the GCE surface and allow to dry at room temperature. Subsequently, apply 8μL of MWCNT dispersion over the NiO layer and dry completely.

- Sensor Stabilization: Condition the modified electrode (NiO/MWCNTs/GCE) by performing 10-15 cyclic voltammetry cycles in the supporting electrolyte (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) within the potential window of interest until a stable baseline is achieved.

Analytical Measurement

- Supporting Electrolyte: Prepare appropriate buffer solution (e.g., 0.1M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) as supporting electrolyte.

- Standard Addition: Introduce aliquots of CSSS standard solution to the electrochemical cell containing 10mL of supporting electrolyte.

- Square Wave Voltammetry Parameters: Apply the following optimized parameters: frequency = 15Hz, pulse amplitude = 25mV, step potential = 4mV, potential window = +0.2V to +1.2V (vs. Ag/AgCl).

- Calibration: Record square wave voltammograms after each standard addition. Plot peak current versus CSSS concentration to establish the calibration curve.

- Sample Analysis: Process environmental water samples (wastewater, surface water) through appropriate pretreatment (filtration, pH adjustment) before analysis using the standard addition method.

Performance Characteristics

This method achieves a detection limit of 3.31nM for CSSS with high selectivity and sensitivity. The NiO/MWCNT nanocomposite enhances the electrode surface area and electron transfer kinetics, resulting in an eightfold increase in peak current compared to an unmodified GCE [8]. The method demonstrates applicability across a range of environmental matrices, including wastewater and surface waters.

Advanced Sensor Platforms

Recent innovations in electroanalytical sensing include nanostructured electrodes functionalized with molecularly imprinted polymers for enhanced selectivity, lab-on-a-chip systems for field-deployable analysis, and wearable sensors for continuous environmental monitoring [7]. The integration of artificial intelligence for data interpretation and experimental optimization represents a cutting-edge development in the field, facilitating rapid screening of multiple contaminants in complex environmental samples [7].

Risk Assessment Framework

Environmental risk assessment (ERA) of pharmaceuticals follows a structured approach to characterize potential ecological impacts, typically employing a tiered system that progresses from preliminary screening to detailed investigations when risks are identified.

Risk Quantification Methodology

The core of pharmaceutical ERA involves calculating a Risk Quotient (RQ), which compares measured or predicted environmental concentrations with concentrations expected to cause adverse effects:

RQ = MEC / PNEC

Where:

- MEC = Measured Environmental Concentration

- PNEC = Predicted No Effect Concentration, derived from ecotoxicological data divided by an appropriate assessment factor (AF)

The PNEC represents the concentration below which unacceptable effects on the environment are not expected to occur. It is typically derived from the most sensitive endpoint (e.g., ECâ‚…â‚€, NOEC) for the most susceptible species, divided by an assessment factor (ranging from 10 to 1000) that accounts for uncertainties in extrapolation [6] [5].

Table 2: Environmental Risk Assessment of Select Pharmaceuticals in Water Bodies

| Pharmaceutical | Therapeutic Class | Maximum MEC (μg/L) | PNEC (μg/L) | Risk Quotient (RQ) | Risk Category |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acetaminophen | Analgesic | 8.48 | 0.1 | 84.8 | High |

| Sulfathiazole | Antibiotic | 9.21 | - | - | - |

| Florfenicol | Antibiotic | 5.89 | - | - | - |

| Carbamazepine | Antiepileptic | - | - | 0.11-0.83 | Moderate |

| Erythromycin | Antibiotic | - | - | >1 | High |

| Ibuprofen | NSAID | - | - | >1 | High |

| Diclofenac | NSAID | - | - | >1 | High |

| Naproxen | NSAID | - | - | >1 | High |

Risk categories are typically classified as: RQ < 0.1 (low risk), 0.1 ≤ RQ ≤ 1 (moderate risk), and RQ > 1 (high risk) [6] [5]. High RQ values trigger requirements for further testing and potential risk management measures.

Protocol: Environmental Risk Assessment for Pharmaceutical Residues

This protocol outlines a standardized approach for conducting preliminary risk assessment of pharmaceuticals in aquatic environments, adaptable to various geographical contexts and monitoring objectives.

Problem Formulation

- Compile Pharmaceutical Inventory: Identify pharmaceuticals of concern based on consumption data, pharmacological properties, and environmental persistence. Priority should be given to compounds with high usage volumes, low metabolic degradation, and known ecotoxicity.

- Define Assessment Boundaries: Determine spatial boundaries (e.g., watershed, aquifer) and temporal considerations (seasonal variations, continuous vs. intermittent discharge).

Exposure Assessment

- Environmental Sampling: Collect representative water samples from strategic locations (e.g., wastewater treatment plant effluents, upstream and downstream of discharge points, groundwater wells). Use grab or composite sampling approaches as appropriate.

- Sample Preservation and Preparation: Filter samples through 0.45μm glass fiber filters, adjust pH to neutral if necessary, and store at 4°C until extraction. Perform solid-phase extraction (SPE) using hydrophilic-lipophilic balance (HLB) cartridges within 14 days of collection [6].

- Analytical Quantification: Utilize LC-MS/MS with optimized multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) transitions for target pharmaceuticals. Validate method performance with recovery experiments (target: 70-130%) and establish limits of quantification [6].

- Data Quality Assurance: Include procedural blanks, duplicate samples, and surrogate standards (e.g., ¹³C-labeled analogs) to assess method accuracy and precision.

Effects Assessment

- Ecotoxicity Data Collection: Gather acute and chronic toxicity endpoints (ECâ‚…â‚€, NOEC, LOEC) from reliable sources such as the U.S. EPA ECOTOX Knowledgebase for algae, invertebrates, and fish [6].

- PNEC Derivation: Select the lowest reliable toxicity endpoint for the most sensitive species. Apply appropriate assessment factors based on data quality and completeness:

- AF = 1000 when at least one acute L(E)Câ‚…â‚€ is available

- AF = 100 when one chronic NOEC is available

- AF = 50 when two chronic NOECs are available

- AF = 10 when chronic NOECs for at least three trophic levels are available

Risk Characterization

- Risk Quotient Calculation: Compute RQ values using maximum, minimum, and mean MEC values to understand worst-case and typical scenarios.

- Uncertainty Analysis: Identify and document sources of uncertainty in exposure and effects assessments, including analytical limitations, sampling frequency, and interspecies extrapolation.

- Risk Prioritization: Rank pharmaceuticals based on their RQ values to inform monitoring priorities and potential risk management actions.

This protocol provides a standardized framework for preliminary risk assessment, with provisions for more sophisticated approaches (e.g., probabilistic assessment, mixture toxicity evaluation) when preliminary screening indicates potential concerns.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Specification | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic-Lipophilic Balance (HLB) Cartridges | 60mg, 3mL or 200mg, 6mL | Solid-phase extraction of diverse pharmaceuticals from water samples | Effective for broad polarity range; requires conditioning with methanol and reagent water before use [6] |

| LC-MS/MS Grade Solvents | Methanol, acetonitrile, acetone | Sample preparation, mobile phase components | High purity essential to minimize background interference and enhance detection sensitivity [6] |

| Deuterated Internal Standards | ¹³C- or ²H-labeled pharmaceutical analogs | Quantification calibration and recovery correction | Compensates for matrix effects and sample preparation losses; should be added before extraction [6] |

| Electrode Modification Materials | NiO nanoparticles, MWCNTs | Enhanced sensitivity in electrochemical sensors | Nanocomposite formation increases active surface area and electron transfer kinetics [8] |

| Electrochemical Cell Components | Glassy carbon working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode | Fundamental components for three-electrode measurement system | Proper electrode maintenance and polishing critical for reproducible results [8] |

| Buffer Components | Phosphate salts, acetic acid, ammonium acetate | Mobile phase modifiers, supporting electrolyte | Control pH and ionic strength to optimize separation and electrochemical response [8] |

| CCT244747 | CCT244747, MF:C20H24N8O2, MW:408.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| CCT251455 | CCT251455, MF:C26H26ClN7O2, MW:504.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Pharmaceutical residues represent a significant challenge as emerging environmental contaminants, with demonstrated potential to affect ecosystem health through multiple mechanisms including endocrine disruption, antibacterial resistance development, and direct toxicity to aquatic organisms. The continuous introduction of these biologically active compounds into environments through human and veterinary use creates a "pseudo-persistent" contamination scenario that demands sophisticated monitoring and management approaches.

Electroanalytical methods have emerged as powerful tools in the environmental chemist's arsenal, offering sensitive, cost-effective approaches for detecting pharmaceutical residues across various matrices. When coupled with robust risk assessment frameworks, these analytical techniques provide critical data for prioritizing management actions and evaluating intervention effectiveness. Future directions in the field point toward increased integration of advanced materials, miniaturized sensing platforms, and artificial intelligence to enhance monitoring capabilities and support evidence-based decision making for mitigating pharmaceutical pollution impacts on ecosystem and human health.

Core Principles of Electroanalysis for Environmental Monitoring

Electroanalysis encompasses a suite of analytical techniques that measure electrical properties—such as current, potential, and charge—to detect and quantify chemical species. In the realm of environmental monitoring, these techniques provide powerful tools for detecting pharmaceutical residues in complex matrices like water, wastewater, and biological tissues at trace concentrations [7]. The core principle involves measuring the electrical signal generated or consumed during redox reactions of target analytes at an electrode-solution interface. When applied to environmental monitoring of pharmaceuticals, electroanalysis offers significant advantages over traditional methods like chromatography, including high sensitivity, portability for on-site analysis, minimal sample preparation, and the ability to perform real-time, continuous monitoring [7] [9].

Growing scientific evidence confirms that pharmaceutical active compounds (PhACs) persist in aquatic ecosystems at concentrations capable of causing adverse effects on organisms, including reproductive disorders, growth rate impacts, and bacterial resistance development [10]. The pseudopersistent nature of these contaminants—resulting from continuous release into water bodies despite degradation—necessitates advanced monitoring approaches that electroanalysis is uniquely positioned to provide [10]. Recent advancements have further enhanced the capabilities of electroanalytical methods through the integration of nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and miniaturized sensor technology, solidifying their role as indispensable tools for modern environmental pharmaceutical analysis [7].

Core Principles and Theoretical Foundation

Fundamental Electrochemical Concepts

Electroanalytical techniques for pharmaceutical monitoring are grounded in several key principles that govern the relationship between electrical signals and chemical analytes:

Redox Reactions: Pharmaceutical compounds containing electroactive functional groups undergo oxidation or reduction at characteristic potentials when an electrical potential is applied at the electrode-solution interface. The current generated from these electron transfer processes serves as the quantitative basis for detection and measurement [7]. The specific redox behavior provides both qualitative identification through characteristic peak potentials and quantitative data through current magnitude proportional to concentration.

Mass Transport: The movement of analyte molecules to the electrode surface occurs through three primary mechanisms: diffusion (movement from high to low concentration), migration (movement due to electric field), and convection (movement due to fluid motion). In controlled electrochemical experiments, diffusion often dominates, described by Fick's laws, enabling precise quantification through limiting currents [7].

Electrode Double Layer: At the electrode-electrolyte interface, a structured layer of ions forms, creating a capacitance that influences electron transfer kinetics. Understanding and controlling this interface through electrode modification and electrolyte selection is crucial for optimizing sensor performance, especially in complex environmental samples [7].

Key Electroanalytical Techniques

Different electroanalytical techniques exploit these fundamental principles through varied potential waveforms and measurement approaches, each offering distinct advantages for pharmaceutical residue analysis:

Table 1: Key Electroanalytical Techniques for Pharmaceutical Monitoring

| Technique | Principle | Environmental Application Advantages | Typical Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Potential scanned linearly in cyclic manner between set limits | Rapid screening of redox behavior; mechanistic studies of pharmaceutical degradation | Moderate (µM-nM range) |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Series of small amplitude pulses superimposed on linear potential ramp | Minimized capacitive current; enhanced sensitivity for trace pharmaceutical detection | High (nM-pM range) |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Square waveform superimposed on staircase potential ramp | Fast scanning; effective rejection of background currents; ideal for multi-analyte screening | High (nM-pM range) |

| Amperometry | Constant applied potential with current measured over time | Continuous monitoring; flow-through systems for wastewater analysis | Moderate (µM-nM range) |

| Potentiometry | Potential measurement under zero-current conditions | Ion-selective electrodes for specific pharmaceutical ions; simple, cost-effective field measurements | Variable (depends on ion-selective electrode) |

| Stripping Voltammetry | Pre-concentration step followed by potential sweep | Ultra-trace analysis; exceptional sensitivity for heavy metals and organic pharmaceuticals | Very High (pM-fM range) |

Pulse voltammetric techniques like DPV and SWV are particularly valuable for environmental pharmaceutical analysis as their pulsed potential application significantly reduces background noise, enabling lower detection limits in complex sample matrices like wastewater and surface water [7]. The enhanced sensitivity of these pulsed techniques makes them ideal for detecting trace levels of pharmaceutical residues where accurate quantification is essential [7].

Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Voltammetric Detection of Pharmaceutical Residues

Objective: To quantitatively determine trace levels of pharmaceutical residues (e.g., ciprofloxacin, acetaminophen, sulfamethoxazole) in environmental water samples using differential pulse voltammetry.

Principle: Pharmaceutical compounds with electroactive functional groups undergo oxidation or reduction at characteristic potentials when an electrical potential is applied. The resulting current is proportional to the concentration of the analyte, enabling both identification and quantification.

Table 2: Required Reagents and Materials

| Item | Specification | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Glassy carbon electrode (3 mm diameter), often modified with nanomaterials (e.g., graphene oxide, MoS2/Au nanohybrid) | Primary sensing surface where redox reactions occur |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) | Provides stable, known potential reference point |

| Counter Electrode | Platinum wire | Completes electrical circuit without interfering with measurement |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.0) or acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5) | Provides conductive medium; controls pH and ionic strength |

| Standard Solutions | Pharmaceutical standards (1 mg/mL in methanol or acetonitrile) | Calibration and quantification |

| Solid Phase Extraction Cartridges | Oasis HLB or Mix-mode Cation Exchange (MCX) | Sample pre-concentration and clean-up |

| Electrochemical Cell | 10-20 mL volume with nitrogen gas purging capability | Houses electrodes and solution; removes dissolved oxygen |

Sample Preparation Protocol:

- Collection and Preservation: Collect water samples (surface water, wastewater effluent) in amber glass bottles pre-rinsed with ultrapure water and sample. Maintain samples at 4°C during transport and storage. Analyze within 48 hours or preserve at -20°C for longer storage [11] [10].

Filtration: Filter samples through 0.45 μm or 0.2 μm glass fiber filters (pre-baked at 450°C for 4 hours to eliminate organic contaminants) to remove suspended particulates [12] [11].

Solid Phase Extraction (SPE) for Pre-concentration:

- Condition SPE cartridge (Oasis MCX, 3 cc, 60 mg) with 3 mL methanol followed by 2 × 3 mL acidified water (pH 3.0 with formic acid).

- Acidify 200 mL filtered sample to pH 3 with 2 M formic acid.

- Load sample onto cartridge at controlled flow rate (12-15 mL/min).

- Wash cartridge with 3 mL acidified water (pH 3.0) to remove interferences.

- Elute analytes with 5 × 1 mL of methanol/2M NH₄OH (90:10, v/v).

- Evaporate eluent to dryness under gentle nitrogen stream.

- Reconstitute in 1 mL Hâ‚‚O/MeCN (95:5, v/v) for analysis [11].

Electrode Preparation:

- Polish glassy carbon working electrode with 0.05 μm alumina slurry on microcloth.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between polishing steps.

- Sonicate in 1:1 ethanol/water solution for 5 minutes to remove residual alumina.

- For modified electrodes, apply appropriate nanomaterial suspension (e.g., GO-MoS2/Au nanohybrid) and dry under infrared lamp [13].

Instrumental Parameters (DPV):

- Potential window: +0.2 to +1.2 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Pulse amplitude: 50 mV

- Pulse width: 50 ms

- Scan rate: 20 mV/s

- Equilibrium time: 10 s

- Sample volume: 10 mL in electrochemical cell

- Solution conditions: Deoxygenate with nitrogen purging for 600 s before analysis

Calibration and Quantification:

- Prepare standard additions of target pharmaceutical in the range of 0.1-100 μg/L.

- Record DPV responses after each standard addition.

- Plot peak current versus concentration to establish calibration curve.

- For unknown samples, measure peak current and determine concentration from calibration curve.

- Apply standard addition method for matrices with significant interference.

Quality Control:

- Analyze method blanks (ultrapure water) with each batch to monitor contamination.

- Include replicate samples (n=3) to assess precision.

- Use surrogate standards (e.g., deuterated analogs) to monitor extraction efficiency.

- Acceptable recovery ranges: 70-120% for most pharmaceuticals [11].

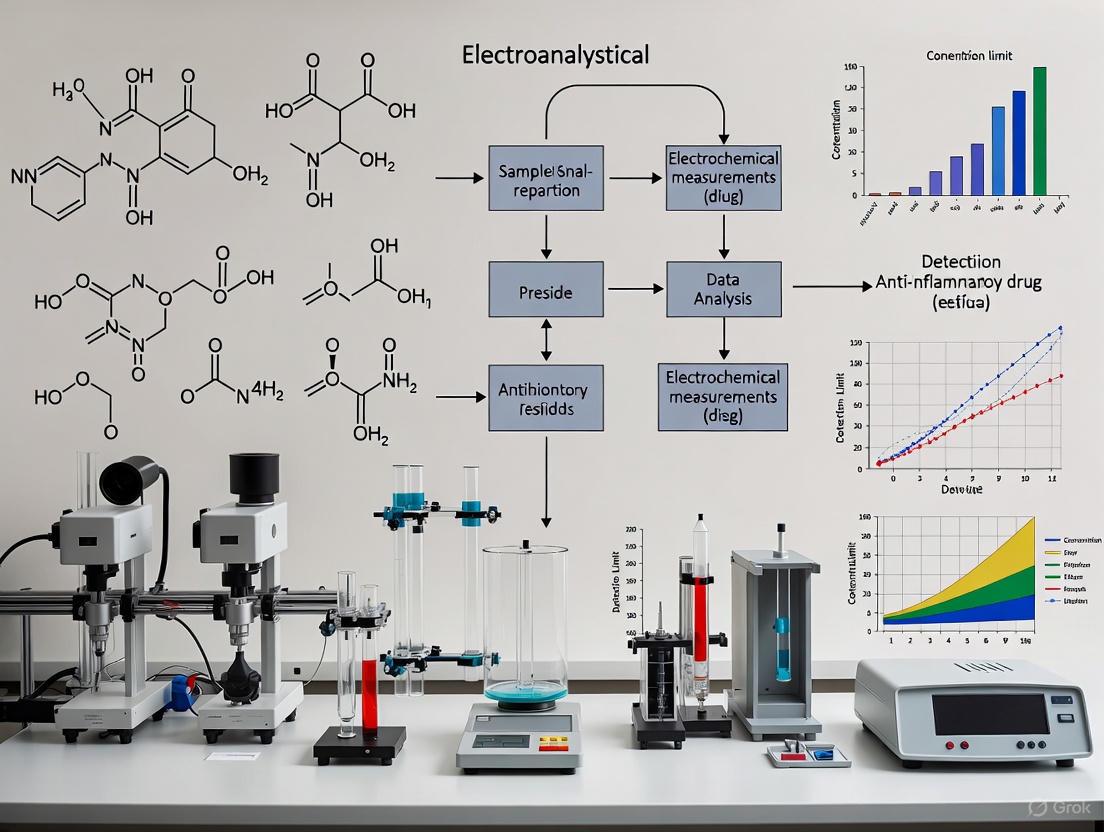

Workflow Visualization

Electrochemical Analysis Workflow

Advanced Protocol: Aptasensor for Antibiotic Detection

Objective: To develop a highly selective graphene oxide-MoS2/Au nanohybrid aptasensor for trace-level monitoring of ciprofloxacin in environmental samples.

Specialized Materials:

- Graphene oxide-MoS2/Au nanohybrid composite

- Ciprofloxacin-specific aptamer sequence

- Self-assembled monolayer (SAM) formation reagents (e.g., cysteamine)

- Cross-linking agents (e.g., EDC/NHS chemistry)

Fabrication Procedure:

- Electrodeposit Au nanoparticles on cleaned glassy carbon electrode at -0.2 V for 300 s in HAuClâ‚„ solution.

- Form self-assembled monolayer by immersing in 2 mM cysteamine solution for 2 hours.

- Activate carboxyl groups using EDC/NHS chemistry (400 mM/100 mM) for 1 hour.

- Immobilize amino-modified aptamer (1 μM concentration) for 12 hours at 4°C.

- Block non-specific sites with 1% BSA for 1 hour.

- Characterize each step using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) in [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» solution.

Detection Procedure:

- Incubate modified electrode with sample/standard for 15 minutes.

- Perform DPV measurement in 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) from +0.1 to +0.6 V.

- Monitor current decrease due to aptamer-target binding.

- Quantify ciprofloxacin concentration from 0.1 to 100 ng/L.

Performance Characteristics:

- Detection limit: 0.05 ng/L

- Recovery in real samples: 95-105%

- Selectivity: High against other fluoroquinolones

- Stability: > 95% initial response after 4 weeks storage [13]

Applications in Environmental Monitoring

Pharmaceutical Residue Detection in Aquatic Systems

Electroanalysis has demonstrated exceptional capability in detecting diverse pharmaceutical classes across various environmental compartments:

Table 3: Electroanalytical Applications for Pharmaceutical Monitoring

| Pharmaceutical Class | Specific Analytes | Electrode System | Detection Limit | Sample Matrix |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antibiotics | Ciprofloxacin, Sulfamethoxazole | GO-MoS2/Au nanohybrid aptasensor [13] | 0.005-0.015 μg/L [11] | Surface water, Wastewater |

| Analgesics/Anti-inflammatories | Ketoprofen, Paracetamol | Molecularly imprinted polymers [13] | 0.014-0.123 μg/L [11] | Hospital wastewater |

| Antiepileptics | Carbamazepine | Boron-doped diamond electrode | ~0.1 μg/L | Surface water, Biota |

| β-blockers | Atenolol, Sotalol | CNT-modified electrodes | ~0.5 μg/L | Wastewater effluent |

| Antidepressants | Venlafaxine | Graphene-based sensors | ~0.05 μg/L | Surface water |

The application of these methods has revealed significant environmental contamination patterns. For instance, sulfamethoxazole has been detected at high frequencies in both surface water (33% of analyzed samples) and hospital wastewater (81% of analyzed samples) [11]. Electroanalytical approaches have proven particularly valuable for antibiotic monitoring due to the concerning emergence of antibiotic-resistant bacteria in aquatic environments continually exposed to sub-lethal antibiotic levels [12].

Advantages Over Conventional Techniques

Electroanalytical methods offer distinct benefits compared to traditional chromatographic approaches (e.g., LC-MS/MS, GC-MS) for environmental pharmaceutical monitoring:

Cost-Effectiveness: Electroanalysis requires minimal organic solvents and less expensive instrumentation compared to LC-MS/MS systems, significantly reducing operational costs [7].

Rapid Analysis: The elimination of lengthy separation steps enables faster analysis, with some electrochemical sensors providing results within minutes compared to hours for chromatographic methods [7].

Portability and Field Deployment: Miniaturized electrochemical systems enable real-time, on-site monitoring at contamination sites, unlike laboratory-bound chromatographic instruments [7] [9].

Minimal Sample Preparation: Electrochemical sensors can often analyze minimally processed samples, reducing the need for extensive pre-concentration and clean-up steps required for chromatographic methods [7].

While LC-MS/MS remains the reference method for multi-residue analysis at ultra-trace levels, electroanalysis provides complementary capabilities particularly suited for routine monitoring, screening applications, and field-based measurements where rapid results and cost considerations are paramount [12] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electroanalysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Nanomaterial Modifiers | Enhance electrode sensitivity and selectivity through increased surface area and catalytic properties | Graphene oxide, MoS2, Au nanoparticles, CNTs [13] [7] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Provide artificial recognition elements for selective binding of target pharmaceuticals | Methacrylic acid-based polymers for specific drug templates [13] |

| Aptamer Recognition Elements | Offer high-affinity biological recognition for specific pharmaceutical compounds | Single-stranded DNA/RNA sequences for antibiotics like ciprofloxacin [13] |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Enable potentiometric detection of ionized pharmaceutical compounds | Polymeric membranes with ionophores for drug ions [7] |

| Solid Phase Extraction Sorbents | Pre-concentrate target analytes and remove matrix interferents from environmental samples | Oasis HLB, Mix-mode Cation Exchange (MCX), Strata-X [12] [11] |

| Electrode Polishing Systems | Maintain reproducible electrode surfaces for reliable measurements | Alumina and diamond polishing suspensions (0.05-1.0 μm) [7] |

| CDE-096 | CDE-096, MF:C25H20F3NO12, MW:583.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Mcl1-IN-3 | Mcl1-IN-3, MF:C27H22ClN3O4, MW:487.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Technological Advancements and Future Perspectives

Emerging Trends in Electroanalysis

The field of electroanalysis for environmental monitoring is rapidly evolving, with several cutting-edge developments enhancing pharmaceutical residue detection:

Wearable and Portable Sensors: The development of wearable and portable electrochemical sensors represents a significant trend, driven by the demand for real-time, on-site analysis of pharmaceutical contaminants in water systems [14]. These devices enable continuous monitoring at discharge points and vulnerable water bodies, providing immediate contamination alerts.

Integration of Artificial Intelligence: Machine learning and AI are increasingly incorporated to enhance data analysis, sensor design optimization, and predictive modeling in electrochemical applications [7] [14]. AI algorithms can process complex electrochemical data patterns to identify multiple pharmaceuticals simultaneously and predict degradation pathways.

Advanced Nanomaterials: Research involving sophisticated nanomaterials such as 2D materials, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and multicomponent nanocomposites is becoming increasingly prevalent, showcasing their potential to dramatically enhance sensor sensitivity, selectivity, and stability [7] [14].

Sustainable and Green Materials: A growing focus on using biocompatible and environmentally friendly materials in sensor fabrication aligns with global sustainability goals while reducing the environmental footprint of monitoring technologies themselves [14].

Relationship Between Technological Components

Technology Integration Framework

Current Challenges and Limitations

Despite significant advancements, electroanalytical approaches for environmental pharmaceutical monitoring face several challenges requiring further research:

Matrix Effects: Complex environmental samples like wastewater contain numerous interferents that can affect electrode response, necessitating improved anti-fouling strategies and selectivity enhancement [12] [7].

Multi-analyte Detection: Most current electrochemical sensors target single pharmaceuticals, whereas environmental monitoring requires simultaneous detection of multiple residues, driving development of sensor arrays and multi-plexed platforms [14].

Long-term Stability: Ensuring consistent sensor performance over extended deployment periods in variable environmental conditions remains challenging, particularly for biorecognition-based sensors [7].

Validation and Standardization: Establishing standardized protocols and comprehensive validation against reference methods is essential for regulatory acceptance of electroanalytical approaches [7].

Future developments will likely focus on autonomous sensing systems capable of long-term, unattended monitoring; multi-analyte platforms for comprehensive pharmaceutical profiling; and enhanced data integration systems combining electrochemical data with complementary parameters for comprehensive environmental assessment. As these technologies mature, electroanalysis is poised to become an increasingly central tool in environmental monitoring networks, contributing significantly to protecting aquatic ecosystems from pharmaceutical contamination.

The increasing presence of pharmaceutical residues in the environment has emerged as a significant concern for ecosystem health and water safety. Electroanalysis provides powerful, cost-effective tools for detecting these pseudo-persistent contaminants at trace levels in complex matrices. This article details the application-oriented protocols for three principal electroanalytical techniques—voltammetry, potentiometry, and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy—within the context of environmental monitoring of pharmaceutical residues. The content is structured to provide researchers and drug development professionals with practical methodologies for quantifying common pharmaceuticals like acetaminophen and ibuprofen in water samples, leveraging the latest advancements in sensor technology and nanomaterials to achieve the sensitivity and selectivity required for environmental analysis [7] [15].

Electroanalytical techniques measure electrical properties such as current, potential, or impedance to quantify chemical species. Their suitability for environmental pharmaceutical analysis stems from high sensitivity, portability for on-site monitoring, and minimal sample preparation requirements compared to traditional chromatographic methods [7] [15].

Table 1: Core Electroanalytical Techniques for Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

| Technique | Measured Signal | Key Strengths | Common Environmental Pharmaceutical Targets |

|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | Current vs. Applied Potential | Very low detection limits, broad dynamic range, detailed redox behavior information [7] [16] | Acetaminophen, Ibuprofen, Antibiotics, Neurological drugs [15] [16] |

| Potentiometry | Potential at zero current | High selectivity for specific ions, simplicity, portability, power efficiency [7] [17] | Lead (Pb²âº) and other heavy metals, Ionic species, Ammonium [18] [17] |

| Impedance Spectroscopy | Impedance vs. Frequency | Label-free detection, real-time binding monitoring, sensitivity to surface changes [19] | Pathogens, Macromolecules, Whole cells [19] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics for Advanced Electrochemical Sensors in Water Analysis

| Sensor Modifier Type | Detection Technique | Target Analytic | Reported Detection Limit | Key Material Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon-Based Nanomaterials | Voltammetry (DPV, SWV) | Acetaminophen, Ibuprofen [15] | Sub-nanomolar levels [15] | Carbon nanotubes (SWCNT, MWCNT), Graphene oxide (GO) [15] |

| Metallic Nanoparticles | Voltammetry | Acetaminophen [15] | Nanomolar range [15] | Gold (Au), Silver (Ag), Iron oxide (Fe₃O₄) nanoparticles [15] |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Voltammetry | Acetaminophen, Ibuprofen [15] | Very low (trace-level) [15] | Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks (ZIFs) [15] |

| Solid-Contact ISEs | Potentiometry | Lead (Pb²âº) ions [18] | 10â»Â¹â° M [18] | Conducting polymers, MXenes, Carbon nanotubes [17] |

Application Notes & Experimental Protocols

Voltammetry for Analgesic Detection in Water

Principle: Voltammetric techniques apply a varying potential to a working electrode and measure the resulting current from the oxidation or reduction (redox) of electroactive species. The magnitude of the current peak is proportional to the analyte concentration [7] [16]. Pulse techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) enhance sensitivity and resolution for trace analysis by minimizing capacitive background current [7] [16].

Application Note: The widespread use of analgesics like acetaminophen (APAP) and ibuprofen (IBU) makes them prevalent aquatic contaminants. Their electroactive nature allows for direct detection at chemically modified voltammetric sensors. Carbon-based electrodes modified with nanomaterials are highly effective, as the nanomaterials provide high surface area, excellent electrocatalytic activity, and improved electron transfer kinetics, enabling detection in complex water matrices such as wastewater and groundwater [15].

Protocol: Determination of Acetaminophen using a Graphene Oxide-Modified Glassy Carbon Electrode

- Objective: To quantify trace levels of acetaminophen in a purified water sample using DPV.

- Safety: Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) including lab coat, gloves, and safety glasses.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Acetaminophen analytical standard

- Graphene oxide (GO) dispersion

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4) as supporting electrolyte

- Ultrapure water (18.2 MΩ·cm)

- Glassy carbon electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter)

- Alumina polishing slurry (0.05 µm)

- Equipment:

- Potentiostat/Galvanostat

- Standard three-electrode cell: Modified GCE (working), Ag/AgCl (reference), Platinum wire (counter)

- Ultrasonic bath

- Magnetic stirrer

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the bare GCE on a microcloth with 0.05 µm alumina slurry to create a mirror-finish surface. Routine polishing is performed to ensure a clean and reproducible electrode surface. Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water and then ethanol, followed by another rinse with water.

- Electrode Modification: Deposit 5 µL of the graphene oxide dispersion onto the polished GCE surface. Allow it to dry under an infrared lamp or at room temperature to form a stable modified electrode (GO/GCE).

- Standard Solution Preparation: Prepare a 1.0 mM stock solution of acetaminophen in ultrapure water. Serially dilute this stock with the PBS electrolyte to prepare standard solutions in the concentration range of 0.1 to 50 µM.

- Instrumental Setup: Transfer 10 mL of the PBS electrolyte into the electrochemical cell. Assemble the three-electrode system. Initialize the potentiostat and configure the DPV parameters.

- DPV Parameters: Potential window: +0.2 to +0.6 V (vs. Ag/AgCl); Pulse amplitude: 50 mV; Pulse width: 50 ms; Scan rate: 20 mV/s; Sample period: 0.5 s.

- Calibration and Measurement:

- Record a background DPV scan in the pure PBS electrolyte.

- Spike the cell with a known volume of the acetaminophen standard solution to achieve the desired concentration. Stir the solution for 30 seconds, then allow it to become quiescent for 10 seconds before measurement.

- Run the DPV measurement and record the voltammogram. The oxidation peak for acetaminophen is typically observed around +0.35 - 0.45 V.

- Repeat with increasing concentrations of the standard to build a calibration curve.

- Sample Analysis: Process the environmental water sample (e.g., filtered wastewater effluent) by adding 1 mL of sample to 9 mL of PBS in the cell. Measure the DPV response and determine the acetaminophen concentration from the calibration curve (peak current vs. concentration).

Diagram 1: Voltammetric sensor preparation and analysis workflow.

Potentiometry for Heavy Metal Monitoring

Principle: Potentiometry measures the potential (electromotive force) of an electrochemical cell at zero current using an ion-selective electrode (ISE) and a reference electrode. The measured potential is logarithmically related to the activity (and thus concentration) of the target ion according to the Nernst equation [7] [17]. Modern solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) replace the traditional liquid inner filling solution with a solid-contact layer that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer, enabling miniaturization and portability for field-deployable environmental sensors [17].

Application Note: Heavy metals like lead (Pb²âº) are toxic environmental contaminants. Potentiometric sensors are ideal for routine, on-site monitoring due to their selectivity, simplicity, and low power requirements. Recent innovations using nanomaterials and conducting polymers in the solid-contact layer have significantly improved sensor performance, achieving detection limits as low as 10â»Â¹â° M and excellent selectivity in complex water samples [18] [17].

Protocol: Potentiometric Detection of Lead Ions with a Solid-Contact ISE

- Objective: To determine the concentration of lead ions in a simulated water sample using a commercially available or lab-fabricated Pb²âº-selective solid-contact ISE.

- Safety: Lead salts are toxic. Handle with care, using gloves and working in a fume hood if preparing standards. Dispose of waste according to institutional regulations.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Lead ionophore, Ion-selective membrane components (PVC, plasticizer)

- Solid-contact material (e.g., conducting polymer like PEDOT:PSS)

- Lead nitrate for standard solutions

- Potassium nitrate (0.1 M) as ionic background

- Nitric acid (0.1 M) for cleaning

- Equipment:

- Potentiometer (high-impedance mV meter)

- Pb²âº-selective Solid-Contact ISE

- Double-junction Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Magnetic stirrer

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode and Standard Preparation:

- If fabricating, the SC-ISE is prepared by depositing a solid-contact layer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) on a substrate, followed by a cocktail containing the Pb²⺠ionophore and PVC membrane [17].

- Prepare a 0.1 M lead nitrate stock solution. Perform serial dilutions with 0.1 M KNO₃ to create standard solutions from 10â»âµ M down to 10â»â¸ M.

- Sensor Conditioning: Before first use and for storage, condition the Pb²âº-ISE by soaking in a 10â»Â³ M Pb(NO₃)â‚‚ solution for at least 1 hour (or as recommended by the manufacturer) to activate the ion-selective membrane.

- Calibration Curve Measurement:

- Place the Pb²âº-ISE and reference electrode in the lowest concentration standard (e.g., 10â»â¸ M). Stir the solution gently and consistently.

- Record the stable potential reading in mV once the signal drift is less than 0.1 mV per minute.

- Rinse the electrodes thoroughly with ultrapure water and gently blot dry with a laboratory tissue.

- Repeat the measurement for each standard in order of increasing concentration.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the measured potential (mV) versus the logarithm of the Pb²⺠concentration (log[Pb²âº]).

- Perform linear regression on the linear portion of the plot. The slope should be close to the theoretical Nernstian value (~29.5 mV/decade for Pb²⺠at 25°C).

- Sample Analysis: Measure the potential of the prepared environmental water sample (diluted with 0.1 M KNO₃ if necessary) following the same procedure. Calculate the Pb²⺠concentration from the calibration equation.

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy for Pathogen Detection

Principle: EIS characterizes an electrochemical system by applying a small amplitude sinusoidal AC potential over a range of frequencies and measuring the resulting impedance (Z) [19]. In label-free biosensing, the binding of a target (e.g., a pathogen) to a bioreceptor immobilized on the electrode surface alters the interfacial properties, typically increasing the charge-transfer resistance (Rₑₜ), which can be sensitively monitored [19].

Application Note: While less common for small-molecule pharmaceuticals, EIS is a powerful technique for detecting larger biological contaminants, such as pathogens or specific proteins, in water. Its label-free, non-destructive nature allows for real-time monitoring of binding events, making it suitable for developing biosensors for environmental microbiology [19].

Protocol: EIS-based Label-free Detection of E. coli

- Objective: To monitor the binding of E. coli cells to an antibody-functionalized gold electrode using EIS.

- Safety: Follow BSL-1 protocols for handling non-pathogenic E. coli strains.

- Materials and Reagents:

- Polyclonal anti-E. coli antibody

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, pH 7.4)

- 11-Mercaptoundecanoic acid (11-MUA)

- N-(3-Dimethylaminopropyl)-N′-ethylcarbodiimide (EDC) and N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS)

- Ethanolamine hydrochloride (1 M, pH 8.5)

- E. coli K12 suspension in PBS

- Equipment:

- Potentiostat with EIS capability

- Gold disk working electrode, Pt counter electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Ultrasonic cleaner

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Functionalization:

- Clean the gold electrode with piranha solution (Caution: highly corrosive) or via electrochemical cycling.

- Immerse the electrode in a 1 mM ethanolic solution of 11-MUA for 12 hours to form a self-assembled monolayer (SAM).

- Rinse with ethanol and PBS to remove physically adsorbed thiols.

- Activate the terminal carboxylic acid groups of the SAM by immersing the electrode in a fresh mixture of 0.4 M EDC and 0.1 M NHS in PBS for 30 minutes.

- Incubate the electrode with the anti-E. coli antibody (50 µg/mL in PBS) for 1 hour, allowing amide bond formation between the antibody and the SAM.

- Deactivate any remaining active esters by treating with 1 M ethanolamine (pH 8.5) for 15 minutes to minimize non-specific binding.

- The biosensor is now ready for use.

- EIS Measurement Setup:

- Use a solution of 5 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆]/K₄[Fe(CN)₆] (1:1) in PBS as the redox probe.

- Configure the EIS parameters on the potentiostat:

- DC Potential: Open circuit potential (OCP)

- AC Amplitude: 5-10 mV

- Frequency Range: 0.1 Hz to 100,000 Hz

- Baseline and Sample Measurement:

- Place the functionalized electrode in the electrochemical cell containing the redox probe solution.

- Run the EIS measurement to obtain a baseline spectrum (Rₑₜ baseline).

- Incubate the electrode in a suspension of E. coli cells for a predetermined time (e.g., 30 minutes).

- Rinse the electrode gently with PBS to remove unbound cells.

- Transfer the electrode back to the redox probe solution and record a new EIS spectrum (Rₑₜ sample).

- Data Analysis:

- Fit the obtained EIS spectra to a modified Randles equivalent circuit to extract the charge-transfer resistance (Rₑₜ) values.

- The percentage increase in Rₑₜ (%ΔRct = [(Rctsample - Rctbaseline) / Rct_baseline] × 100) is correlated with the concentration of bound E. coli cells.

Diagram 2: EIS biosensor fabrication and measurement workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Electroanalytical Sensor Development

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Characteristic |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Electrode modifier for voltammetric sensors [15] [16] | High electrical conductivity, large surface area, electrocatalytic activity. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Electrode modifier for voltammetric and EIS biosensors [15] | Excellent electrocatalysis, biocompatibility, facilitates biomolecule immobilization. |

| Ion-Selective Ionophore | Key component of potentiometric ISE membranes [18] [17] | Provides selectivity by reversibly binding to a specific target ion (e.g., Pb²âº). |

| Conducting Polymer (e.g., PEDOT:PSS) | Solid-contact layer in SC-ISEs [17] | Transduces ionic signal to electronic signal; high redox capacitance. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Electrode modifier for voltammetric sensors [15] | Ultra-high porosity and surface area for pre-concentrating analytes. |

| Specific Bioreceptor (Antibody, Aptamer) | Recognition element for EIS biosensors [19] | Provides high specificity for the target pathogen or biomarker. |

| Cdk9-IN-2 | Cdk9-IN-2|CDK9 Inhibitor|For Research Use | |

| PROTAC CDK9 Degrader-1 | PROTAC CDK9 Degrader-1, MF:C33H35N5O7, MW:613.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Electroanalysis, a branch of analytical chemistry that measures electrical properties like current and potential to identify and quantify chemical species, has become an indispensable tool in modern pharmaceutical and environmental research [7]. These techniques offer a powerful alternative to traditional methods like spectroscopy and chromatography, particularly for applications such as monitoring pharmaceutical residues in water systems [7] [20]. The core advantages driving its adoption are exceptional sensitivity, remarkable portability for on-site analysis, and significant cost-effectiveness [7] [21] [22]. This article details these advantages within the context of environmental monitoring, providing supporting quantitative data, detailed experimental protocols, and essential resource guides for researchers.

Advantages of Electroanalysis: Quantitative Comparison

The following table summarizes the key advantages of electroanalytical techniques, particularly when compared to conventional methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) used in pharmaceutical residue analysis.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Electroanalysis for Environmental Pharmaceutical Monitoring

| Advantage | Performance Metric | Comparison to Conventional Methods (e.g., HPLC) | Example Technique/Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Detection limits as low as 1 attomolar (aM) [23]; Sub-picogram levels [7] | Can exceed sensitivity of standard UV detectors in HPLC; avoids complex pre-concentration steps. | Dissolving microdroplet electroanalysis for redox-active analytes [23]. |

| Portability | Device size: handheld or briefcase-sized; operates with microliter sample volumes [22] [7] [20]. | Replaces bulky benchtop systems; enables real-time, on-site decision-making instead of lab-only analysis [22]. | Sustainable sensor using sludge biochar/graphite ink for Imipenem detection [20]. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Up to ~40% reduction in project costs by cutting transport and lab overhead; use of low-cost, sustainable materials (e.g., biochar) [22] [20]. | Eliminates or reduces costs for expensive solvents, high-purity gases, and complex infrastructure required by HPLC. | Screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) with conductive inks [20]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Sustainable, Portable Sensor for Imipenem Detection

This protocol outlines the development of a cost-effective and portable electrochemical sensor for detecting the antibiotic imipenem in environmental water samples, using a conductive ink derived from sewage sludge biochar [20].

1. Objective: To fabricate a disposable screen-printed electrode (SPE) modified with sludge biochar for the voltammetric determination of imipenem to support environmental monitoring.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sustainable Electrochemical Sensor Fabrication

| Item Name | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Graphite Powder (Gr) | Serves as the primary conductive component of the ink due to its high electrical conductivity and layered structure [20]. |

| Sewage Sludge Biochar (BC) | A sustainable, low-cost carbon material. Enhances electrochemical performance by providing high surface area, porosity, and surface functional groups [20]. |

| Nail Polish (NP) | Acts as a polymeric binder matrix. Provides stability, viscosity control, and uniformity to the conductive composite ink [20]. |

| Acetone | Used as a solvent to dilute the nail polish binder, ensuring optimal ink viscosity for deposition [20]. |

| Screen-Printing Platform | A substrate (e.g., parchment paper) and stencil for defining the electrode geometry (working, counter, and reference electrodes) [20]. |

| Imipenem Standard | The target pharmaceutical analyte (emerging contaminant) for method development and validation [20]. |

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Biochar Preparation. Dry sewage sludge and subject it to pyrolysis in a tubular furnace (e.g., at 500°C for 2 hours under N₂ atmosphere). After cooling, grind the resulting biochar into a fine powder [20].

- Step 2: Conductive Ink Formulation. Manually mix the conductive composite using a mortar and pestle. A typical optimized mass ratio is 30% Biochar (BC), 30% Graphite (Gr), and 40% Nail Polish (NP). Add acetone dropwise to achieve a homogeneous, paste-like consistency [20].

- Step 3: Electrode Fabrication. Deposit the BC/Gr/NP ink onto a paper substrate through a stencil using the screen-printing method. Air-dry the printed electrodes at room temperature to form the final three-electrode system [20].

- Step 4: Electrochemical Measurement.

- Instrument Setup: Connect the fabricated SPE to a portable potentiostat.

- Analysis Technique: Use Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) due to its low background current and high sensitivity.

- Parameters: Set DPV parameters (e.g., modulation amplitude: 50 mV; step potential: 5 mV; scan rate: 20 mV/s).

- Procedure: Immerse the sensor in the environmental sample (e.g., water from a river or effluent). Record the DPV signal. The oxidation current of imipenem at a specific potential (e.g., ~+0.9 V vs. the pseudo-reference electrode) is proportional to its concentration [20].

4. Data Analysis: Generate a calibration curve by plotting the peak current against standard concentrations of imipenem. Use this curve to quantify the unknown concentration in the environmental sample.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Protocol: Achieving Ultra-High Sensitivity via Dissolving Microdroplet Electroanalysis

This protocol describes a novel approach for detecting redox-active analytes at attomolar concentrations by leveraging partitioning kinetics and an EC' catalytic mechanism, which is crucial for tracing ultra-dilute pharmaceutical residues [23].

1. Objective: To detect a model redox-active analyte, decamethylferrocene ((Cp*)â‚‚FeII), at attomolar levels in an aqueous solution.

2. Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

- Gold Microelectrode: A working electrode with a small radius (~6.25 µm).

- Decamethylferrocene ((Cp*)â‚‚FeII): The model redox-active analyte.

- 1,2-Dichloroethane (DCE): Organic solvent for creating microdroplets.

- Aqueous Electrolyte Solution: The bulk solution matrix.

- Oxygen Gas: Used for oxygen saturation of the solution.

3. Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Step 1: Cell Setup. Place the gold microelectrode in an electrochemical cell containing the aqueous electrolyte solution. The cell must be equipped for oxygen control [23].

- Step 2: Oxygen Saturation. Saturate the aqueous solution with oxygen. This is critical, as oxygen acts as a coreactant in the catalytic cycle, and its removal significantly hinders detection at these ultra-low concentrations [23].

- Step 3: Microdroplet Deposition. Position a microdroplet of 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE), containing a higher concentration of (Cp*)â‚‚FeII, directly atop the gold microelectrode. The analyte preferentially partitions into the DCE droplet due to its greater solubility there [23].

- Step 4: Enrichment and Detection. As the DCE microdroplet slowly dissolves into the aqueous phase, it releases the (Cp)â‚‚FeII, enriching the local concentration of the analyte near the electrode surface. Perform voltammetric measurements (e.g., linear sweep voltammetry) to record the signal. An EC' catalytic mechanism, where the electrogenerated species (Cp)â‚‚FeIII is reduced back to (Cp*)â‚‚FeII by oxygen, leads to significant signal amplification, enabling attomolar detection [23].

The detection mechanism is illustrated below:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagent Solutions

For researchers developing electroanalytical methods for environmental monitoring, the selection of electrode materials and modifiers is paramount. The table below details key materials based on the cited research.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Electroanalysis

| Material/Reagent | Core Function in Electroanalysis | Application Context from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes | Provide a large effective surface area and varied adsorption properties, enhancing electron transfer and sensitivity [21]. | Used in inkjet-printed graphene electrodes for modulating sensitivity in biomolecule detection [24]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Enable miniaturization, portability, and disposability. Operate with low sample volumes and mitigate electrode fouling [20]. | Base platform for the sustainable biochar/graphite sensor for antibiotic detection [20]. |

| Biochar (from Sewage Sludge) | A sustainable, low-cost carbon material that enhances conductivity and electroanalytical performance due to its surface functional groups [20]. | Sustainable modifier in conductive ink for imipenem detection, promoting a circular economy [20]. |

| Enzymes, Antibodies, Aptamers | Biomaterials that confer high specificity and selectivity to the sensor for a target analyte [21]. | Improve the specificity of responses to analytes in biosensors [21]. |

| Electrochemical Activation | A simple potential application process that cleans and functionalizes electrode surfaces, improving reproducibility and sensitivity [21]. | A pretreatment/treatment method for carbon-based and metal electrodes to enhance electroanalytical capabilities [21]. |

| Ceftobiprole | Ceftobiprole|C20H22N8O6S2|CAS 209467-52-7 | |

| CeMMEC13 | CeMMEC13 |

The demonstrated advantages of electroanalysis—exceptional sensitivity down to attomolar levels, the capacity for portable and on-site analysis, and significant cost savings through sustainable material use—solidify its role as a cornerstone technique for monitoring pharmaceutical residues in the environment [23] [22] [20]. The provided protocols and toolkit offer researchers practical pathways to implement these powerful methods. Future advancements, driven by the integration of nanotechnology, artificial intelligence, and sustainable design, promise to further enhance the capabilities and application scope of electroanalysis in safeguarding environmental health [7].

Electroanalytical Methods in Action: Detecting Specific Pharmaceutical Compounds

Stripping voltammetry represents a powerful electroanalytical technique renowned for its remarkable sensitivity in quantifying trace levels of heavy metals and organic compounds, making it indispensable for environmental monitoring of pharmaceutical residues. This technique excels at detecting concentrations as low as 10^-9 to 10^-10 M, fulfilling the critical need for assessing pollutants in complex aquatic matrices [25] [26]. The operational principle hinges on a two-stage process: a preliminary preconcentration of the analyte onto the working electrode surface, followed by a stripping step where the analyte is removed, generating a quantifiable current signal proportional to its concentration [27] [26]. In the context of increasing pharmaceutical contamination of water bodies—from sources like wastewater treatment plants, hospitals, and households—stripping voltammetry offers a cost-effective, portable, and highly sensitive alternative to traditional methods like chromatography or mass spectrometry [28] [7]. Its applicability spans from detecting toxic metal ions such as lead (Pb(II)) and antimony (Sb(III)) to emerging organic pharmaceutical contaminants like painkillers, providing a versatile tool for researchers and environmental scientists [29] [28] [30].

Core Principles and Techniques of Stripping Voltammetry

Stripping voltammetry encompasses several modalities, each tailored for specific analyte classes. The foundational steps of preconcentration and stripping are universal, but the mechanisms differ, allowing for the detection of a wide range of substances at trace levels.

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) is primarily used for metal ion detection. It involves the electrochemical reduction of metal ions (e.g., Pb²âº, Cd²âº) to their metallic state, depositing them onto the working electrode during the preconcentration step. Subsequently, the potential is swept in an anodic (positive) direction, oxidizing the metals back into solution. The resulting current peak is used for quantification [25] [30]. ASV is renowned for its excellent detection limits, often in the µg/L (ppb) range [25].

Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV) extends the capability to metal ions and organic compounds that are not easily plated electrochemically. In AdSV, the preconcentration step is achieved by the adsorption of the analyte or its complex with a ligand onto the electrode surface. For instance, gallium (Ga(III)) can be complexed with catechol or cupferron and accumulated via adsorption [27]. Similarly, antimony (Sb(III)) can be determined in the presence of quercetin-5′-sulfonic acid [29]. The stripping step then measures the current from the reduction or oxidation of this adsorbed layer.

Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (CSV) is the mirror image of ASV. Here, the preconcentration occurs at an oxidizing potential, where the analyte forms an insoluble salt that deposits on the electrode. During the stripping step, the potential is swept negatively, reducing the deposited film [25].

The following workflow diagram generalizes the procedural steps common to these stripping voltammetry methods:

Application Notes: Quantification of Environmental Contaminants

Trace Metal Analysis

Stripping voltammetry is exceptionally suited for monitoring heavy metals in environmental samples. Its low detection limits meet the stringent requirements for assessing water quality and soil contamination.

Table 1: Stripping Voltammetry Protocols for Trace Metal Detection

| Analyte | Method | Working Electrode | Supporting Electrolyte & Key Reagents | Linear Range (mol Lâ»Â¹) | Detection Limit (mol Lâ»Â¹) | Key Interferences Studied | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ga(III) [27] | AdSV | Hg(Ag)FE | 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ acetate buffer (pH 4.8), Catechol | 1.25×10â»â¹ – 9.0×10â»â¸ | 3.6×10â»Â¹â° | Mn(II), Pb(II), Cu(II), Fe(III), Triton X-100, Humic Acids | Tap water, River water, Soil |

| Ga(III) [27] | AdSV | PbFE/MWCNT/SGCE | 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ acetate buffer (pH 5.6), Cupferron | 3.0×10â»â¹ – 4.0×10â»â· | 9.5×10â»Â¹â° | Al(III), Cu(II), Fe(III), Ti(IV), V(V) | Tap water, River water, CRM |

| Pb(II) [30] | SWASV | NF-DA18C6-GC | 10 mmol Lâ»Â¹ HCl, Diaza-18-Crown-6, Nafion | ~5×10â»â¸ – 2.4×10â»â· | ~4×10â»Â¹â° | Cd(II), Cu(II), Fe(II) | Certified water, Natural water |

| Sb(III) [29] | AdSV | Not Specified | Quercetin-5′-sulfonic acid | Information missing from sources | Information missing from sources | Information missing from sources | Information missing from sources |

Pharmaceutical Residue Analysis

The detection of pharmaceutical residues in aquatic environments is a growing concern due to their persistence and potential ecological toxicity. Stripping voltammetry, particularly with screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), offers a viable solution for on-site screening.

Table 2: Voltammetric Analysis of Selected Pharmaceutical Painkillers in Water

| Pharmaceutical (Painkiller) | Excretion as Active Substance | Typical WWTP Removal Rate (%) | Max. Reported in Wastewater Influent (ng/L) | Max. Reported in Surface Water (ng/L) | Voltammetric Sensor Suitability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diclofenac [28] | 5–10% unchanged | 9–60 | 191,000 | 1,410 | High (Priority pollutant) |

| Ibuprofen [28] | ~1% unchanged | 78–100 | 344,000 | 400 | High |

| Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) [28] | Mostly as conjugates | 91–99 | 292,000 | 10,000 | High (Priority pollutant) |

| Naproxen [28] | <1% unchanged | 50–98 | 611,000 | 400 | High |

| Ketoprofen [28] | Metabolites (Glucuronide) | 15–100 | 10,000 | 329 | High |

The presence of these substances, even at low concentrations (ng/L to µg/L), poses risks such as oxidative stress in aquatic organisms, feminization of fish, and increased antibiotic resistance [28]. Voltammetric techniques are particularly advantageous here because they can accumulate the analyte on the electrode surface, pre-concentrating it and eliminating the need for costly and time-consuming sample pre-treatment like solid-phase extraction [28].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

This protocol details the determination of trace lead in water samples using a glassy carbon electrode modified with diaza-18-crown-6 (DA18C6) and Nafion.

4.1. The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Base working electrode; provides a clean, renewable surface for modification. |

| Diaza-18-Crown-6 (DA18C6) | Aza-crown ether modifier; selectively complexes with Pb(II) ions via host-guest interactions, enhancing preconcentration. |

| Nafion (NF) | Perfluorinated ion-exchange polymer; acts as a binder and further concentrates cationic analytes like Pb(II) via its sulfonate groups. |

| Hydrochloric Acid (HCl) | Serves as the supporting electrolyte; provides high conductivity and optimal acidic pH for analysis. |

| Ethanol | Solvent for preparing the modifier mixture (DA18C6 and Nafion). |

| Pb(II) Standard Solution | Primary standard for calibration and quantitative analysis. |

4.2. Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrode Pretreatment: Polish the bare glassy carbon electrode (3 mm diameter) with 0.3 μm alumina slurry on a porous surface. Rise thoroughly with double-distilled water and sonicate for 15 minutes in double-distilled water to remove any adsorbed particles.

Electrode Modification (Drop-Coating): Prepare a modifying solution containing 3 mmol Lâ»Â¹ DA18C6 and 3 wt% Nafion in ethanol. Apply 10 μL of this solution onto the clean, polished surface of the GCE. Allow the electrode to dry at 0°C, resulting in a stable NF-DA18C6-GC modified electrode.

Sample Preparation and Measurement:

- Transfer 10 mL of the sample solution (or standard) into the electrochemical cell. The supporting electrolyte is 10 mmol Lâ»Â¹ HCl.

- Deoxygenate the solution by purging with an inert gas (e.g., nitrogen or argon) for 5-10 minutes.

- Set the SWASV parameters as follows:

- Accumulation Potential (Eacc): -0.80 V

- Accumulation Time (tacc): 300 s

- Frequency: 15 Hz

- Initiate the analysis. During the accumulation step, Pb(II) ions are reduced to Pb(0) and concentrated in the modified layer on the electrode.

- Subsequently, run the stripping step using a square-wave potential scan towards positive potentials. The oxidation peak for Pb(0) to Pb(II) will appear at approximately -0.65 V vs. Ag/AgCl.

Calibration and Quantification: Construct a calibration curve by measuring the peak current of Pb(II) standards of known concentration under the same optimized conditions. Use this curve to determine the concentration of Pb(II) in unknown samples.

This protocol describes a highly sensitive method for quantifying trace gallium in environmental waters.

4.3. Step-by-Step Procedure

Electrode and System Setup: Use a Mercury-Silver Film Electrode (Hg(Ag)FE) as the working electrode. A standard three-electrode system (working, reference Ag/AgCl, auxiliary Pt) is used.

Sample Preparation and Complex Formation:

- Place the sample (e.g., tap or river water) in the electrochemical cell.

- Add 0.1 mol Lâ»Â¹ acetate buffer to adjust the pH to 4.8.

- Add catechol solution to the cell to act as a complexing agent for Ga(III). The Ga(III)-catechol complex adsorbs onto the electrode surface.

Measurement:

- Deoxygenate the solution with an inert gas.

- Set the AdSV parameters. Apply an accumulation potential for 60 seconds while stirring the solution. This step preconcentrates the Ga(III)-catechol complex via adsorption.

- After a quiet period (e.g., 10 s), initiate the cathodic (negative-going) potential scan for the stripping step. The reduction current of the adsorbed complex is measured.

Analysis: The height of the reduction peak is proportional to the concentration of Ga(III) in the sample. Quantification is achieved using the standard addition method to account for matrix effects in complex environmental samples.

The following diagram illustrates the specific chemical interactions and electron transfers at the modified electrode surface for the protocols described above:

Critical Advantages in Environmental Monitoring

The integration of stripping voltammetry, particularly with screen-printed electrodes (SPEs), has revolutionized environmental sampling by enabling in-situ analysis [28] [26]. SPEs, which incorporate working, reference, and counter electrodes on a single, disposable chip, are a key innovation. Their low cost, portability, and ease of use make them ideal for field-deployable devices, allowing researchers to screen water quality directly at the sampling site, thereby minimizing errors associated with sample transport and storage [28]. The sensitivity and selectivity of these systems can be further enhanced by modifying the electrode surface with materials such as carbon nanotubes, polymer films (like Nafion), bismuth, or ionic liquids, which improve preconcentration and catalytic activity [29] [28] [30]. This approach provides a robust, cost-effective, and highly sensitive tool for the ongoing monitoring of pharmaceutical residues and trace metals, essential for protecting aquatic ecosystems and human health [26].

Application Notes: On-Site Electroanalysis of Pharmaceutical Residues

The environmental monitoring of pharmaceutical residues demands analytical techniques that are not only sensitive and selective but also capable of providing rapid, on-site analysis to facilitate immediate decision-making. Advanced sensor platforms, particularly those based on screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) and portable electrochemical systems, have emerged as powerful tools to meet this need. Their low cost, disposability, and compatibility with portable potentiostats make them ideal for decentralized analysis, moving testing from centralized laboratories directly to the field [31] [32].

The core advantage of these platforms lies in their customizability. Electrode surfaces can be modified with a vast range of nanomaterials and recognition elements to enhance sensitivity and selectivity for specific pharmaceutical compounds. For instance, the integration of nanostructured materials like metal oxide nanoparticles and carbon nanotubes has been shown to significantly lower detection limits and improve electrochemical signals [7] [8]. Furthermore, the ongoing integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning with these sensors is paving the way for intelligent systems capable of deconvoluting complex signals from environmental matrices, optimizing sensor performance, and providing more reliable quantification [33].