DPV vs SWV vs CV: A Sensitivity Comparison Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the sensitivity of three key voltammetric techniques—Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)—for researchers and professionals in drug...

DPV vs SWV vs CV: A Sensitivity Comparison Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of the sensitivity of three key voltammetric techniques—Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)—for researchers and professionals in drug development and biomedical analysis. It covers the foundational principles of each method, explores their specific applications in pharmaceutical and clinical settings, offers troubleshooting and optimization strategies to maximize sensitivity and accuracy, and presents a direct comparative analysis to guide method selection for various analytical challenges, from trace-level drug detection to quality control.

Understanding Voltammetry: Core Principles of DPV, SWV, and CV

In electrochemical sensing, every measurement involves a critical battle between two types of current: faradaic current and capacitive current. The faradaic current (also known as faradaic) is the current of interest—it results from the reduction or oxidation (redox) of analyte molecules at the electrode surface. This electron transfer process provides the quantitative signal directly proportional to analyte concentration. In contrast, capacitive current (sometimes called non-faradaic or charging current) arises from the rearrangement of ions in the electrolyte solution at the electrode-electrolyte interface, effectively charging the electrical double layer like a capacitor. This background current does not involve electron transfer and contributes only to noise, obscuring the desired faradaic signal.

The fundamental goal of any sensitive electrochemical technique is therefore to maximize the faradaic current while simultaneously minimizing the capacitive current, thereby optimizing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). This principle is paramount in pharmaceutical and biomedical research, where detecting trace concentrations of neurotransmitters, drugs, or biomarkers in complex biological matrices demands exceptional sensitivity and low detection limits. The choice of voltammetric technique—Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), or Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV)—profoundly impacts the ability to achieve this goal.

Comparative Analysis of Voltammetric Techniques

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): The Qualitative Benchmark

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a widely used sweep technique where the potential is linearly scanned back and forth between two set limits while the current is measured.

- Primary Strength: Its primary strength is qualitative analysis. CV is excellent for quickly obtaining information about redox potentials, reaction reversibility, and reaction mechanisms.

- Limitation in Sensitivity: From a sensitivity standpoint, CV has a significant drawback: it measures the total current, which includes both the faradaic and capacitive components. The capacitive current in a linear potential scan can be substantial, leading to a lower signal-to-noise ratio for quantitative analysis compared to pulse techniques [1].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Enhancing Sensitivity with Pulse Sequences

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) was developed to improve upon the sensitivity limitations of CV.

- Core Mechanism: DPV applies a series of small amplitude potential pulses superimposed on a linear potential staircase. The critical feature is that the current is sampled twice for each pulse—just before the pulse is applied and again near the end of the pulse.

- Capacitive Current Minimization: The difference between these two current measurements is recorded as the analytical signal. Because the capacitive current decays rapidly after a potential change (following an exponential decay), while the faradaic current decays more slowly (following a decay according to the Cottrell equation), sampling late in the pulse and taking the difference significantly reduces the contribution of the capacitive current to the overall signal [1].

- Outcome: This process effectively maximizes the faradaic-to-capacitive current ratio, resulting in a lower background current, improved signal-to-noise, and lower detection limits compared to CV.

Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV): The Pinnacle of Speed and Sensitivity

Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) is a sophisticated pulse technique that combines and enhances the principles of other pulse methods to achieve exceptional performance [1].

- Core Mechanism: SWV uses a symmetrical square wave superimposed on a staircase potential ramp. Each square wave cycle consists of a forward pulse and a reverse pulse. The current is sampled at the end of both the forward and the reverse pulse.

- Differential Current Measurement: The key to SWV's sensitivity is that the recorded signal is the difference between the forward and reverse currents (Δi = iforward - ireverse) [1]. For a reversible redox reaction, this differential current measurement leads to a significant amplification of the faradaic peak signal.

- Simultaneous Minimization of Capacitive Current: The rapid pulsing and late current sampling strategy mean that the capacitive current, which decays exponentially to a negligible level by the end of each short pulse, is effectively nullified in the differential output [1].

- Outcome: SWV therefore offers a "double advantage": it amplifies the faradaic current through the differential measurement and minimizes the capacitive current through its pulse timing. This results in very high sensitivity, excellent signal-to-noise ratios, and extremely low detection limits. Furthermore, because the entire voltammogram is generated from a series of rapid pulses, SWV is remarkably fast.

Table 1: Comparative Summary of Key Voltammetric Techniques

| Feature | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Application | Qualitative analysis, mechanism studies | Quantitative trace analysis | High-sensitivity quantitative analysis |

| Key Strength | Rapid diagnostic capability | Good sensitivity, well-established | Excellent sensitivity & speed |

| Current Measurement | Total current during potential sweep | Difference current from pulse sequence | Net difference between forward/reverse pulse currents [1] |

| Capacitive Current Suppression | Poor | Good | Excellent [1] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Low | High | Very High |

| Experimental Speed | Slow to Moderate | Moderate | Very Fast [2] |

| Theoretical LOD (M) | ~10â»â· to 10â»â¸ | ~10â»â¸ to 10â»Â¹â° | Can reach ~10â»Â¹â° to 10â»Â¹Â¹ [2] |

Experimental Data and Protocol Comparison

Case Study 1: Determination of Vanillin

A 2022 study directly highlights the advantage of advanced signal processing in voltammetry. Researchers determined vanillin at a platinum electrode using Square-Wave Voltammetry. The raw SWV data was then processed using a second-order derivative (SD-SWV) mathematical treatment.

- Protocol: The analysis used a simple bare platinum working electrode, an Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and a platinum wire counter electrode in a phosphate buffer saline (PBS) solution (pH 7.0) [3].

- Result: This second-order derivative processing of the SWV signal effectively enhanced the resolution of the voltammetric peaks and, crucially, further minimized the contribution of the background current, which includes residual capacitive current. This led to a significant increase in analytical sensitivity for vanillin detection in food products, avoiding the need for complex electrode modifiers [3].

Case Study 2: Determination of Dopamine in Serum

A 2025 study provides a direct, quantitative comparison of several techniques for detecting the neurotransmitter dopamine (DA) using a cytosine-modified pencil graphite electrode (CT/PGE) [2].

- Protocol: The electrode was modified electrochemically in a cytosine solution. The analysis was performed in PBS at an optimized pH of 7.2. Four different voltammetric techniques were compared under the same conditions: SWV, Square-Wave Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (SWAdSV), DPV, and Differential Pulse Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (DPAdSV) [2].

- Result: The data, summarized in Table 2, demonstrates that the SWAdSV technique achieved the lowest limit of detection (LOD) at 2.28 nM, outperforming both DPV and DPAdSV. This showcases the superior ability of SWV-based methods to minimize capacitive current and maximize faradaic signal, even in a complex matrix like human plasma serum [2].

Table 2: Experimental Analytical Performance for Dopamine Detection [2]

| Voltammetric Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) |

|---|---|---|

| Square-Wave Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (SWAdSV) | 0.1 mM to 0.5 μM & 0.1 μM to 7.5 nM | 2.28 nM |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Data not fully specified in search results | Higher than SWAdSV |

| Differential Pulse Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (DPAdSV) | Data not fully specified in search results | Higher than SWAdSV |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and reagents used in the featured experiments, which are also standard in the field of advanced voltammetry.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sensitive Voltammetry

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Surface where the redox reaction occurs; can be bare or modified. | Platinum electrode [3], Pencil Graphite Electrode (PGE) [2] |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for the cell. | Ag/AgCl (with KCl or NaCl electrolyte) [3] [2] |

| Counter Electrode (Auxiliary) | Completes the electrical circuit, often an inert wire. | Platinum wire [3] [2] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducts current and controls ionic strength/pH. | Phosphate Buffer Solution (PBS) [3] [2] |

| Electrode Modifier | Enhances selectivity, sensitivity, and reduces fouling. | Cytosine film [2] |

| Analyte Standard | Pure compound used for calibration and validation. | Vanillin [3], Dopamine [2] |

| GNE-131 | GNE-131 | hNaV1.7 Inhibitor for Pain Research | |

| GNE-272 | GNE-272, MF:C22H25FN6O2, MW:424.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Current Sampling and Signal Generation in SWV

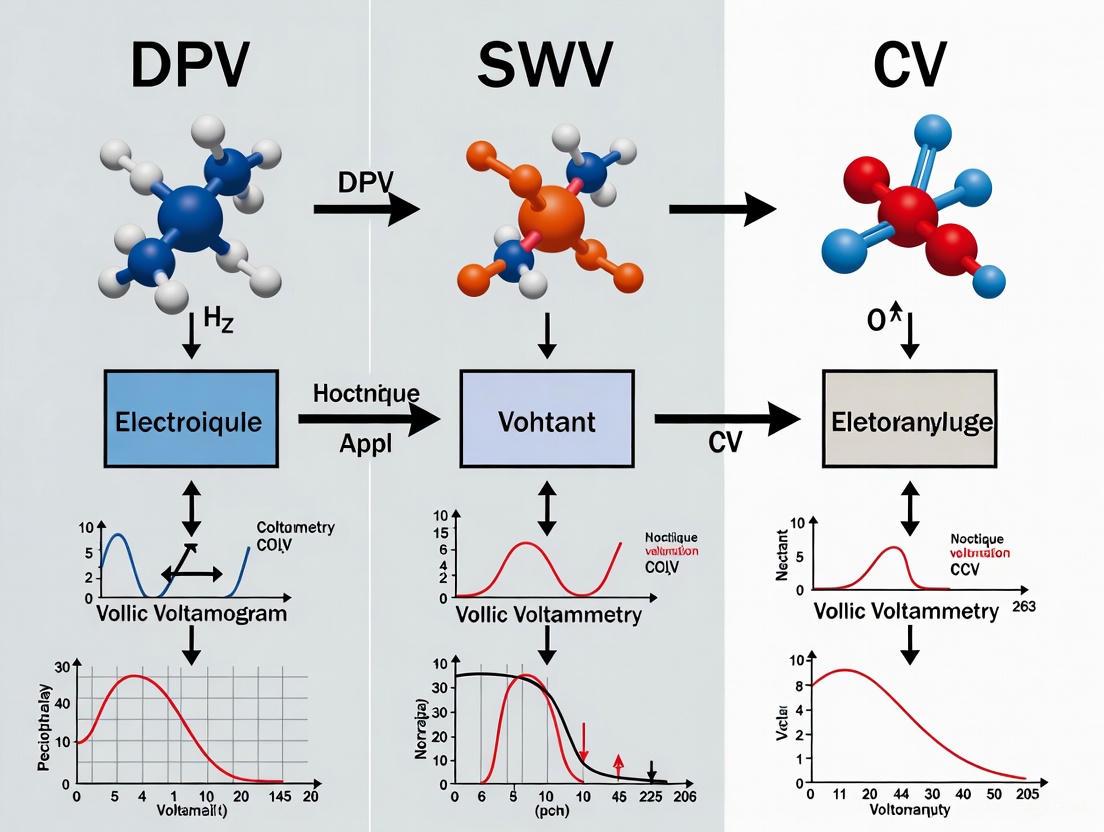

The exceptional sensitivity of SWV stems from its sophisticated current sampling protocol. The diagram below illustrates the potential waveform and the critical points of current measurement that enable the suppression of capacitive current.

This strategy is key to SWV's performance. The current is sampled at the end of each short potential pulse, a point in time where the capacitive current has decayed to a negligible value, leaving a measurement dominated by the faradaic current [1]. The final output is the difference between the forward and reverse faradaic currents, which, for a reversible system, provides a amplified, peak-shaped signal with an exceptionally low background.

The journey to maximize faradaic current and minimize capacitive current reveals a clear hierarchy among voltammetric techniques. While CV remains an indispensable tool for initial qualitative studies, its quantitative sensitivity is limited by significant capacitive current. DPV makes a substantial leap forward by using a differential pulse technique to suppress the background. However, Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) emerges as the superior technique for achieving the ultimate goal of sensitivity. Its combination of rapid square-wave pulses, differential current measurement, and advanced signal processing capabilities allows it to effectively reject capacitive current while amplifying the faradaic signal. As demonstrated by its application in detecting challenging analytes like vanillin and dopamine at nanomolar concentrations, SWV provides researchers and drug development professionals with a powerful, rapid, and highly sensitive tool for trace analysis in complex matrices.

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a foundational electrochemical technique renowned for its ability to probe redox mechanisms and characterize electron transfer processes. As a versatile potentiometric and voltammetric method, it involves applying a linearly cycled potential sweep to an electrochemical cell while monitoring the resulting current. This generates a characteristic "duck-shaped" plot known as a cyclic voltammogram, which provides critical insights into the thermodynamics of redox processes, energy levels of analytes, and kinetics of electronic-transfer reactions [4]. The technique's significance extends across numerous fields, including battery material characterization, conductive polymer analysis, supercapacitor development, fuel cell research, and the detection of bioactive compounds for health and safety monitoring [5] [4].

Within the broader context of electrochemical sensing, CV serves as a crucial tool for researchers requiring rapid qualitative assessment of electrochemical properties. When compared to other voltammetric techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), each method offers distinct advantages and limitations, particularly regarding sensitivity, selectivity, and temporal resolution. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques, focusing specifically on their sensitivity ranges and applications, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to assist researchers in selecting the optimal methodology for their specific analytical challenges.

Fundamental Principles of CV

The Basic Mechanism

Cyclic Voltammetry operates on the principle of measuring current response to a cyclically swept potential. During analysis, the working electrode potential is ramped linearly versus time between two set values, known as the switching potentials. Unlike linear sweep voltammetry, after reaching the set potential limit, the working electrode's potential is ramped in the opposite direction to return to the initial potential [6]. These potential cycles are repeated until the system reaches a steady state, with the current at the working electrode plotted versus the applied voltage to produce the cyclic voltammogram [6].

The voltage scan profile (Figure 1) follows a triangular waveform, starting from an initial potential (Ei), increasing linearly to a maximum value (Eλ), then reversing direction and returning to the starting potential [7]. The rate of voltage change over time is known as the scan rate (measured in V/s), a critical parameter that significantly influences the voltammetric response [6]. During the initial forward scan, an increasingly oxidative potential is applied, leading to oxidation of the analyte and generating an anodic current. When the direction is reversed, the reduced species can be re-oxidized, producing a cathodic current in the opposite direction [6]. The resulting voltammogram displays characteristic peaks corresponding to these oxidation and reduction events, with the position and shape of these peaks revealing crucial information about the redox properties of the system under investigation.

The Three-Electrode System

CV experiments employ a standard three-electrode configuration, which separates the role of referencing the applied potential from balancing the current produced [4]. This system consists of:

Working Electrode: The active site where redox reactions of interest occur, typically made from materials like glassy carbon, platinum, gold, or carbon paste [6] [8]. The working electrode's material composition, surface area, and morphology significantly influence the electrochemical response [9].

Reference Electrode: Maintains a stable, known potential throughout the experiment, providing a reference point against which the working electrode potential is controlled. Common examples include Ag/AgCl or calomel electrodes [6] [7]. Minimal current passes between the reference and working electrodes to prevent polarization [4].

Counter Electrode (Auxiliary Electrode): Completes the electrical circuit and enables current flow, typically constructed from materials with high conductivity such as platinum or graphite [6]. The counter electrode often has a much larger surface area than the working electrode to ensure that reactions occurring at its surface do not limit the overall process [4].

This configuration is essential for accurate measurements, as it allows the potentiostat to control the potential between the working and reference electrodes while measuring the current between the working and counter electrodes [7]. The solution consists of the solvent containing dissolved electrolyte and the species to be studied, with electrolyte added to ensure sufficient conductivity [6].

Interpreting the Cyclic Voltammogram

The characteristic cyclic voltammogram displays several key features that provide quantitative and qualitative information about the redox system:

Peak Current (ip): The maximum current observed during oxidation (ipa) or reduction (ipc). For reversible systems with diffusing species, the peak current is proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species, as described by the Randles-Sevcik equation [10]. This relationship forms the basis for quantitative analysis using CV.

Peak Potential (Ep): The potential at which the peak current occurs during oxidation (Epa) or reduction (Epc). The difference between anodic and cathodic peak potentials (ΔEp = Epa - Epc) provides information about the reversibility of the redox system [6].

Formal Potential (Eâ°'): For reversible systems, the formal potential is approximately midway between the anodic and cathodic peak potentials (Eâ°' ≈ (Epa + Epc)/2) and represents the thermodynamic redox potential of the couple under the experimental conditions [10].

The shape of the voltammogram reveals crucial information about the system. A reversible system, where both oxidized and reduced forms are stable, displays a pair of peaks of approximately equal magnitude [10]. An irreversible system, where the converted species undergoes a subsequent chemical reaction, may show only one peak or peaks with unequal magnitudes [10]. Quasi-reversible systems exhibit peak separations larger than the theoretical minimum, with this separation increasing with scan rate [10].

Sensitivity Comparison of Voltammetric Techniques

Direct Technique Comparison

The sensitivity of voltammetric techniques varies significantly based on their operational principles and how they measure faradaic current relative to non-faradaic background currents. The table below provides a quantitative comparison of CV, DPV, and SWV for neurotransmitter detection, a common application in biomedical research:

Table 1: Sensitivity and Performance Comparison of Voltammetric Techniques for Neurotransmitter Detection

| Technique | Sensitivity | Limit of Detection (Dopamine) | Selectivity | Temporal Resolution | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Moderate | ~10 nM [11] | Highest (CV shape identifies molecules) [11] | High (100 ms with 10 Hz waveform) [11] | Provides rich qualitative information on reaction mechanisms [5] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | High | Lower than CV [5] | High (resolves molecules with oxidation potentials differing >100 mV) [11] | Low (up to 1 minute) [11] | Lower detection limits, reduced background contribution [5] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | High | Lower than CV [5] | High | Low | Excellent signal intensity, rapid measurement [5] |

| Amperometry | Low (but sufficient to count molecules) [11] | 25-100 nM dopamine [11] | Low (all compounds oxidized at applied potential contribute) [11] | Highest (electronic sampling rate, <1 ms) [11] | Excellent temporal resolution [11] |

The differences in sensitivity primarily stem from how each technique handles charging currents. In CV, the measured current includes contributions from both faradaic processes (electron transfer from redox reactions) and non-faradaic processes (primarily capacitive charging of the electrical double layer) [12]. Since both currents are measured simultaneously, the faradaic signal can be obscured at low analyte concentrations. In contrast, DPV and SWV employ potential pulses that enable discrimination between faradaic and charging currents, resulting in improved signal-to-noise ratios and lower detection limits [5].

Factors Influencing CV Sensitivity

Several experimental parameters significantly impact the sensitivity of CV measurements:

Scan Rate: The capacitive charging current increases linearly with scan rate, while the faradaic peak current for diffusion-controlled systems increases with the square root of scan rate [10]. Consequently, at very high scan rates, the charging current can dominate the signal, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio. However, for adsorbed species, the faradaic current increases linearly with scan rate, potentially improving sensitivity at higher scan rates [10].

Electrode Material and Surface Area: The working electrode material significantly affects electron transfer kinetics and sensitivity. Nanomaterial-modified electrodes, incorporating carbon-based nanostructures, metal nanoparticles, or composites, enhance electrocatalytic activity, increase surface area, and improve electron transfer rates, thereby lowering detection limits [5]. Electrodes with larger surface areas generally produce higher currents, though normalization by area (current density) enables meaningful comparisons.

Voltage Window and Waveform Optimization: Extending the holding potential to more negative values enhances electrostatic adsorption of cationic molecules, increasing faradaic current and sensitivity [11]. Similarly, using more positive switching potentials can increase oxygen-containing functional groups on carbon electrodes, improving adsorption and sensitivity toward certain analytes like dopamine [11].

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Assessment

Standard CV Protocol for Sensitivity Determination

Objective: Determine the sensitivity and detection limit of CV for a target analyte (e.g., dopamine).

Materials and Reagents:

- Potentiostat with three-electrode configuration

- Carbon-fiber microelectrode (working electrode, ~7 μm diameter) [11]

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode [13]

- Platinum wire counter electrode [6]

- PBS buffer (10 mM NaHâ‚‚POâ‚„, 140 mM NaCl, 3 mM KCl, pH 7.4) [13]

- Dopamine stock solution (prepared in 0.1 N perchloric acid) [13]

- Nitrogen gas for deoxygenation [13]

Procedure:

- Prepare carbon-fiber microelectrodes by sealing carbon fibers in glass capillaries with epoxy [11].

- Soak electrodes in purified isopropanol for at least 20 minutes before use [13].

- Set up the electrochemical cell with 50 mL PBS buffer as the supporting electrolyte [13].

- Apply a triangular waveform from -0.4 V to +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) and back at a scan rate of 400 V/s, repeated at 10 Hz [13] [11].

- Cycle the electrode with the waveform for 15 minutes at 60 Hz, then 10 Hz for 15 minutes for conditioning [13].

- Perform flow injection analysis to expose the electrode to dopamine standards of known concentrations (e.g., 0.1-10 μM) [13].

- Record background current in blank solution, then measure peak currents for each dopamine standard.

- Plot peak oxidation current versus dopamine concentration to generate a calibration curve.

- Calculate sensitivity as the slope of the calibration curve (nA/μM).

- Determine the limit of detection (LOD) as three times the standard deviation of the blank divided by the sensitivity [8].

Data Analysis:

- Use background subtraction to isolate faradaic current from charging current [11].

- For reversible systems, verify that the ratio of anodic to cathodic peak currents (ipa/ipc) is approximately 1 [6].

- Confirm the linear relationship between peak current and the square root of scan rate for diffusion-controlled processes [6].

Comparative Protocol for DPV/SWV Sensitivity Assessment

Objective: Compare the sensitivity of CV with DPV and SWV for the same analyte.

Materials: Same as Protocol 4.1, with additional potentiostat capabilities for DPV and SWV.

DPV Procedure:

- Using the same electrode and solution conditions, apply a staircase potential with superimposed pulses.

- Set pulse amplitude of 20-50 mV, pulse width of 50-100 ms, and step height of 2-10 mV.

- Measure the current difference just before and at the end of each pulse.

- Plot the differential current versus base potential.

SWV Procedure:

- Apply a square wave waveform superimposed on a staircase ramp.

- Set square wave amplitude of 20-50 mV, frequency of 10-25 Hz, and step height of 2-10 mV.

- Measure currents at both forward and reverse pulses.

- Plot the net current (difference between forward and reverse currents) versus base potential.

Comparison Methodology:

- Use the same electrode surface area and analyte concentrations for all techniques.

- Calculate sensitivities for each technique from their respective calibration curves.

- Compare signal-to-noise ratios at low analyte concentrations.

- Evaluate analysis time and temporal resolution for each method.

Advanced Approaches to Enhance CV Sensitivity

Fast-Scan Cyclic Voltammetry (FSCV)

Fast-scan Cyclic Voltammetry represents a specialized implementation of CV that employs exceptionally high scan rates (typically 100 V/s to 2400 V/s) to enhance temporal resolution and sensitivity for specific applications, particularly in neuroscience [13] [11]. In FSCV, the rapid scanning reduces the diffusion layer thickness, creating steeper concentration gradients and higher faradaic currents [13]. However, these high scan rates also produce substantially larger charging currents that can overwhelm the faradaic signal [13].

Advanced strategies to mitigate charging current issues in FSCV include:

- Analog Background Subtraction (ABS): Removes charging current in real-time before digitization by recording and playing back charging current at the summing point of the current-to-voltage converter [13].

- Waveform Optimization: Modifying holding potentials, switching potentials, and incorporating holding periods (e.g., "sawhorse" waveforms) to enhance sensitivity while maintaining signal stability [13].

- Carbon Nanotube Modifications: Incorporating nanomaterials onto carbon-fiber microelectrodes to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and antifouling properties [11].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetric Sensing

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes | Enhance electron transfer, increase surface area | Dopamine detection in neural tissue [5] |

| Gold Nanoparticles | Improve electrocatalytic activity, biocompatibility | Biosensor development [5] |

| Graphene Oxide | Superior charge transfer properties | Neurotransmitter detection [5] |

| Tetrabutylammonium Hexafluorophosphate | Supporting electrolyte for nonaqueous systems | Organic solvent-based electrochemical studies [6] |

| Alkanethiol SAMs | Controlled protein immobilization | Cytochrome c electron transfer studies [12] |

| Glassy Carbon | Versatile electrode material with wide potential window | General-purpose working electrode [6] [8] |

Nanomaterial-Modified Electrodes

The integration of nanomaterials into electrode design has dramatically enhanced CV sensitivity by improving electron transfer kinetics, increasing electroactive surface area, and reducing overpotentials [5]. Key nanomaterial classes include:

- Carbon-Based Nanomaterials: Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene derivatives offer excellent electrical conductivity, high surface area-to-volume ratios, and functionalizable surfaces that promote analyte adsorption and electron transfer [5].

- Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Gold (AuNPs) and silver (AgNPs) nanoparticles provide high electrocatalytic activity and biocompatibility, while metal oxides like titanium dioxide (TiOâ‚‚) and zinc oxide (ZnO) reduce overpotentials and increase electron transfer rates [5].

- Composite Materials: Combining carbon materials with metals or polymers creates synergistic effects, offering improved sensitivity, stability, and selectivity while reducing signal interference [5].

These nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes have enabled picogram-level detection of biomarkers like TNF-α for oral cancer detection and improved monitoring of neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin, and adenosine in complex biological environments [5] [11].

Cyclic Voltammetry offers a versatile platform for electrochemical analysis with distinct advantages in mechanistic studies and qualitative characterization of redox processes. While its typical sensitivity range of approximately 10 nM for neurotransmitters like dopamine may be inferior to pulse techniques such as DPV and SWV, CV provides richer information about reaction mechanisms, reversibility, and electron transfer kinetics [11]. The technique's moderate sensitivity stems from its simultaneous measurement of faradaic and charging currents, which limits signal-to-noise ratios at low analyte concentrations.

The selection between CV, DPV, and SWV should be guided by specific analytical requirements. CV remains the preferred method for initial characterization of unknown systems, mechanistic studies, and investigations requiring rapid temporal resolution. In contrast, DPV and SWV offer superior sensitivity for trace analysis and quantitative determination of low-concentration analytes, particularly in complex matrices where background contributions are significant.

Future directions in CV sensitivity enhancement focus on nanomaterial integration, waveform optimization, and advanced signal processing techniques. The combination of FSCV with analog background subtraction, novel electrode architectures incorporating carbon nanotubes and graphene derivatives, and the application of machine learning for data analysis represent promising approaches to overcome current sensitivity limitations [13] [5] [11]. These advancements continue to expand CV's applicability in challenging analytical scenarios, including real-time monitoring of rapid neurochemical events and detection of low-abundance biomarkers in clinical diagnostics.

In the fields of pharmaceutical development, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics, the demand for analytical techniques capable of detecting compounds at increasingly lower concentrations has never been greater. Electrochemical methods, particularly voltammetric techniques, have emerged as powerful tools for trace analysis due to their exceptional sensitivity, relatively low cost, and operational simplicity. Among these techniques, Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) stands out for its exceptional ability to minimize non-Faradaic background currents, thereby enabling the detection of analytes at trace levels [14] [15].

This guide provides an objective comparison of the performance of three primary voltammetric techniques—DPV, Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)—within the context of sensitivity and trace analysis. The comparison is grounded in their fundamental operational principles, experimental parameters, and real-world analytical performance data from current research. The objective is to offer researchers and drug development professionals a clear framework for selecting the most appropriate technique for their specific sensitivity requirements.

Fundamental Principles and Technique Comparison

Operational Mechanisms

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a foundational technique where the potential is linearly swept back and forth between two set limits while the current is measured [5]. It is primarily used for qualitative analysis, providing information about reaction reversibility, electron transfer kinetics, and reaction mechanisms [5]. Its quantitative use is limited by its higher capacitive background current.

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) enhances sensitivity by applying a series of small, constant-amplitude potential pulses (typically 5–100 mV) superimposed on a slowly increasing staircase ramp [14] [15] [16]. The current is sampled twice for each pulse: just before the pulse is applied (i1) and at the end of the pulse (i2). The plotted value is the difference current (Δi = i2 - i1). This differential measurement effectively cancels out the capacitive charging current, leaving primarily the Faradaic current of interest, which results in a peak-shaped voltammogram [14] [15].

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) is another pulsed technique that combines the sensitivity of DPV with faster scan rates. It uses a staircase ramp combined with a symmetrical square wave. The current is sampled at the end of both the forward and reverse pulses of the square wave, and the net current (difference between forward and reverse currents) is plotted against the potential [1] [17]. This process also effectively suppresses the background capacitive current.

Visualizing the Current Measurement Mechanisms

The following diagrams illustrate the distinct potential waveforms and current sampling protocols that define each technique's approach to background suppression.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Core Experimental Setup

A standard experimental setup for voltammetric analysis requires several key components [14]:

- Potentiostat: An instrument capable of applying precise potential waveforms and measuring resultant currents, such as those from Gamry Instruments or Pine Research [14] [1].

- Three-Electrode System:

- Working Electrode (WE): The electrode where the redox reaction of interest occurs. Common materials include glassy carbon (GC), gold, and screen-printed electrodes, often modified with nanomaterials to enhance performance [18] [14].

- Reference Electrode (RE): Maintains a stable, known potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl or saturated calomel electrode).

- Counter/Auxiliary Electrode (CE): Completes the circuit, typically a platinum wire.

- Electrolyte Solution: A support electrolyte (e.g., phosphate buffer or Britton-Robinson buffer) to ensure sufficient conductivity [18] [19].

Representative Protocols for Sensitivity Comparison

Protocol 1: Determination of 2-Nitrophenol using DPV and SWV This protocol is adapted from a study optimizing the detection of a hazardous environmental pollutant [18].

- Electrode Modification: A glassy carbon (GC) electrode is modified via electropolymerization of 2-amino nicotinamide (2-AN) from a solution of 1 × 10â»Â³ M 2-AN in 0.1 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„ using cyclic voltammetry.

- Optimization: Critical parameters for SWV (pulse amplitude, frequency, potential step) were optimized using Response Surface Methodology (RSM) to achieve the highest current response for 2-NP.

- Analysis: Measurements are performed in a suitable supporting electrolyte (e.g., phosphate buffer, pH 7.0). The 2-AN/GC sensor demonstrated high sensitivity for 2-NP, with the optimized SWV method yielding a very low detection limit.

Protocol 2: Determination of Eszopiclone using SWV, DPV, and CV This protocol compares techniques for pharmaceutical analysis [19].

- Electrode System: A rotating glassy carbon indicator electrode, Pt auxiliary electrode, and Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Optimal SWV Conditions: Britton-Robinson buffer (pH 6.5), accumulation time of 60 s, accumulation potential of -0.1 V, amplitude of 150 mV, frequency of 15 Hz, and scan rate of 150 mV/s.

- Comparison: The study initially used CV and DPV to investigate voltammetric behavior, but the quantitative determination was performed using the more sensitive SWV method, which provided a sharp cathodic peak at -750 mV.

Analytical Performance: Quantitative Data Comparison

The sensitivity of a voltammetric technique is quantitatively expressed through its Limit of Detection (LOD), which is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be reliably distinguished from the background noise. The following table summarizes the performance of DPV, SWV, and CV as reported in recent scientific literature.

Table 1: Sensitivity Comparison of Voltammetric Techniques from Experimental Studies

| Technique | Analyte | Linear Range | Reported LOD | Application Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Various Bioactive Compounds (e.g., ascorbic acid, serotonin) | Not Specified | Low nM to µM range | Trace detection in biological & environmental samples [5]. | |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Eszopiclone (ESP) | 3 × 10â»â¶ to 5 × 10â»âµ mol/L | 1.9 × 10â»â¸ mol/L (7.5 ppb) | Pharmaceutical and biological sample analysis [19]. | |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | 2-Nitrophenol (2-NP) | Optimized via RSM | Very low (specific value optimized via RSM) | Environmental monitoring in river and tap water [18]. | |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | N/A | N/A | ~10â»âµ M (approx.) | Primarily for qualitative mechanistic studies, not trace analysis [5]. |

Table 2: Characteristic Technical and Operational Parameters

| Feature | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Use | Qualitative analysis, mechanism study [5] | Quantitative trace analysis [14] [15] | Quantitative trace analysis, fast kinetics [1] [19] |

| Background Suppression | Poor | Excellent (via differential current) [15] [16] | Excellent (via net current) [1] [17] |

| Scan Speed | Slow to Moderate | Slow | Very Fast [17] |

| Waveform | Linear sweep | Staircase with small pulses [15] | Staircase with square wave [1] |

| Output Shape | Sigmoidal (for reversible systems) | Peak [14] [16] | Peak [1] |

| Key Optimizing Parameters | Scan Rate | Pulse Amplitude, Pulse Width, Increment [15] | Amplitude, Frequency, Potential Step [1] [17] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions for researchers setting up voltammetric trace analysis experiments.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Voltammetric Trace Analysis

| Item | Function/Description | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon (GC) Electrode | A common working electrode known for its wide potential window, chemical inertness, and suitability for modification [18]. | Base electrode for sensors; can be polished and reused. |

| Nanomaterial Modifiers | Materials like Au nanoparticles, ZnO, graphene, CNTs, and composites that enhance electrocatalytic activity, surface area, and electron transfer [18] [5]. | Modifying GC electrodes to lower LOD and improve selectivity for specific analytes. |

| Reference Electrode (Ag/AgCl) | Provides a stable and reproducible reference potential for accurate measurements. | Essential component of the three-electrode system in most aqueous electrochemistry. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | A high-purity salt or buffer (e.g., KCl, phosphate buffer) to provide ionic strength and control pH, minimizing ohmic resistance. | Phosphate buffer for physiological pH studies; Britton-Robinson buffer for wide pH range work [19]. |

| Potentiostat with Pulse Software | Instrumentation capable of generating precise pulse waveforms (DPV, SWV) and measuring small currents. | Gamry Instruments with PV220 software; Pine Research AfterMath software [14] [15]. |

| GNE-495 | GNE-495, MF:C22H20FN5O2, MW:405.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GNE-4997 | GNE-4997, MF:C25H27F2N5O3S, MW:515.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The choice between DPV and SWV for ultra-sensitive trace analysis is nuanced. Both techniques far surpass CV in quantitative sensitivity due to their sophisticated background current suppression.

- DPV is an excellent choice for applications demanding the highest possible sensitivity and resolution where measurement speed is not the primary constraint. Its well-established nature and straightforward interpretation make it a robust choice for many standard trace analysis protocols [14] [15].

- SWV offers a powerful alternative, combining high sensitivity with rapid data acquisition. Its speed makes it ideal for high-throughput screening, studying fast reaction kinetics, or when rapid results are critical [1] [19] [17]. As evidenced by the studies on Eszopiclone and 2-nitrophenol, SWV is capable of achieving detection limits in the nanomolar to picomolar range, making it a premier technique for modern analytical challenges.

The ultimate selection should be guided by the specific analytical problem, including the required detection limit, the nature of the sample matrix, and available instrumentation. For the most demanding applications in drug development and clinical research, mastery of both DPV and SWV provides researchers with a comprehensive and powerful arsenal for trace-level quantification.

Voltammetry encompasses a suite of electroanalytical techniques based on applying a potential to an working electrode and measuring the resulting current. Among these, pulse voltammetric techniques offer distinct advantages over traditional methods like cyclic voltammetry (CV) or linear sweep voltammetry (LSV). Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and CV are three prominent methods used for both quantitative analysis and fundamental studies of electrode mechanisms. This guide provides an objective comparison of their performance, with a particular focus on the sensitivity of SWV relative to DPV and CV, a subject of ongoing research.

SWV is a potentiodynamic technique that combines the diagnostic value of normal pulse voltammetry (NPV), the background suppression of DPV, and the ability to directly interrogate reaction products. Its waveform consists of a series of symmetrical square-wave pulses superimposed on a staircase ramp. Current is sampled twice during each pulse cycle—once at the end of the forward pulse and once at the end of the reverse pulse. The key signal in SWV is the net current, which is the difference between these forward and reverse currents. This differential sampling strategy is crucial for minimizing the contribution of charging (capacitive) current, thereby enhancing the Faradaic (analytical) signal [1] [20].

DPV also employs a pulse waveform to minimize charging current, but its approach differs. Small amplitude pulses are superimposed on a linear potential sweep. The current is measured twice—just before the pulse application and at the end of the pulse. The voltammogram is then constructed by plotting the difference between these two current measurements against the applied potential, which effectively subtracts the background current [20].

In contrast, CV is a sweep method that applies a linear potential ramp that reverses direction at a specified vertex potential. It records the full current response throughout the scan, making it highly valuable for obtaining qualitative information about electrochemical reactions, such as determining formal potentials and diagnosing reaction mechanisms (e.g., reversible, irreversible, coupled chemical reactions). However, because it measures the total current, its signal-to-noise ratio can be lower than that of pulse techniques [21].

The following workflow outlines the general process of conducting a voltammetric analysis for a comparative study:

Performance Comparison: SWV vs. DPV vs. CV

Quantitative Comparison of Analytical Performance

The choice between SWV, DPV, and CV is often dictated by the specific analytical needs of an experiment. The table below summarizes a comparative analysis of their key characteristics, drawing from recent experimental studies.

Table 1: Comparative performance of Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV).

| Feature | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Measures net current from forward/reverse pulses [1] | Measures difference current before/after a pulse [20] | Measures total current during a linear potential sweep [21] |

| Key Parameter Optimized | Est. LOD: 1.9×10â»â¸ mol/L (7.5 ppb) for Eszopiclone [19] | Not explicitly quantified in search results, but known for high sensitivity | Not primarily designed for ultra-low LOD determination |

| Analysis Speed | Very Fast (full voltammogram in seconds) [20] | Moderate | Slow to Moderate [20] |

| Background Suppression | Excellent (via current subtraction) [1] [20] | Excellent (via differential measurement) [20] | Poor (high capacitive background) |

| Primary Application Strengths | High-sensitivity quantitative analysis, kinetics studies [22] [23] | High-sensitivity assays, immunoassays, heavy metal detection [20] | Mechanistic studies, diagnostic characterization of redox couples [21] |

| Representative Experimental Outcome | Lower error and variation in estimating electrochemical rate constants vs. CV and EIS [22] | Effective for classification of complex mixtures like honey [21] | Highest cumulative variance contribution rate (91.3%) for classifying abalone-flavoring liquids [21] |

Experimental Protocols for Comparative Studies

To ensure valid and reproducible comparisons, standardized experimental protocols are essential. The following methodologies are adapted from recent research articles that directly compared these techniques.

Protocol 1: Evaluating Electrode Kinetics for Surface-Confined Reactions This protocol is adapted from a study comparing techniques for evaluating electrochemical rate constants of hexacyanoferrates [22].

- Electrode System: Utilize a three-electrode system with screen-printed electrodes or a rotating disk glassy carbon working electrode, a platinum auxiliary electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Supporting Electrolyte: Prepare a buffer solution (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 6-7) with 0.1 M KCl as the supporting electrolyte.

- SWV Procedure: Record square-wave voltammograms across a range of frequencies (e.g., 10-100 Hz). Key parameters include an amplitude of 25 mV and a potential increment of 4 mV [22] [21].

- CV Procedure: Perform cyclic voltammetry at various scan rates (e.g., 0.05 to 1 V/s) over the same potential window.

- Data Analysis: For SWV, analyze the relationship between peak current and square-wave frequency to determine the kinetic parameter κ (kappa) and the standard heterogeneous rate constant (k₀). For CV, use the scan rate dependence of the peak potential separation to calculate k₀. Compare the estimated constants and their relative errors across techniques [22].

Protocol 2: High-Sensitivity Determination in Pharmaceutical and Biological Matrices This protocol is based on the validation and application of SWV for determining Eszopiclone [19] and Dopamine [2].

- Electrode Preparation and Modification: For analysis in complex matrices like biological fluids, a modified electrode is often required. A cytosine-modified pencil graphite electrode (CT/PGE) can be fabricated by performing cyclic voltammetry of a 1 mM cytosine solution in phosphate buffer (PBS, pH 7.2) between +0.7 and +1.9 V for 10 cycles at 100 mV/s [2].

- Optimization of Accumulation (for Stripping Techniques): In Square Wave Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (SWAdSV), an accumulation potential (e.g., -0.1 V) is applied to the working electrode for a defined time (e.g., 60 seconds) while stirring the solution. This pre-concentrates the analyte on the electrode surface, dramatically enhancing sensitivity [19] [2].

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- Calibration and Validation: Construct calibration curves for each technique by plotting peak current versus analyte concentration. Calculate and compare the Limit of Detection (LOD), Limit of Quantification (LOQ), linear range, repeatability (RSD%), and recovery for SWV and DPV [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key materials and their functions, as employed in the cited experimental studies.

Table 2: Key research reagents and materials for voltammetric analysis.

| Item Name | Function / Description | Example from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon (GC) Electrode | A widely used working electrode known for its inertness and wide potential window. | Used as a rotating indicator electrode for the determination of Eszopiclone [19]. |

| Pencil Graphite Electrode (PGE) | A disposable, cost-effective, and practical working electrode. Easy to modify for enhanced selectivity. | Employed as a substrate for cytosine modification to create a sensor for Dopamine [2]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A common supporting electrolyte that maintains a constant pH and ionic strength. | Used at pH 7.2 for the determination of Dopamine in human plasma serum [2]. |

| Britton-Robinson (B-R) Buffer | A universal buffer used over a wide pH range (e.g., pH 2 to 12) for electrochemical studies. | Utilized at pH 6.5 for the validation of the SWV method for Eszopiclone [19]. |

| Cytosine (CT) Modifier | An aromatic amine that, when electrochemically oxidized on an electrode surface, forms a film that enhances sensitivity and selectivity. | Used to modify a PGE to create a highly sensitive sensor for Dopamine, mitigating interference [2]. |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | A common reference electrode providing a stable and reproducible reference potential. | Used as the reference electrode in virtually all studies cited [19] [2]. |

| Platinum (Pt) Auxiliary Electrode | A counter electrode that completes the circuit in the three-electrode cell. | Used as the auxiliary electrode in multiple studies [19] [2]. |

| GNE-6640 | GNE-6640, MF:C20H18N4O, MW:330.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GNE-886 | GNE-886, MF:C28H30N6O3, MW:498.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative data and protocols presented in this guide underscore that the choice between SWV, DPV, and CV is not a matter of one technique being universally superior, but rather of selecting the right tool for the specific analytical task. SWV emerges as a powerful and versatile technique, particularly prized for its exceptional speed and high sensitivity, making it ideal for rapid quantitative analysis and kinetic studies [22] [23] [20]. DPV remains a robust choice for high-sensitivity assays where excellent background suppression is required [20]. CV, while less sensitive for direct quantification, is unparalleled as a diagnostic tool for elucidating reaction mechanisms and characterizing new materials or redox systems [21].

The broader thesis on sensitivity is supported by experimental evidence: for direct, rapid, and highly sensitive quantification of analytes—especially in complex matrices like pharmaceuticals and biological samples—SWV and its stripping variants offer remarkable performance. However, for fundamental electrochemical characterization and qualitative discrimination of complex mixtures, CV provides invaluable information. Ultimately, a synergistic approach, leveraging the strengths of each technique, often yields the most comprehensive understanding in electrochemical research and drug development.

Electrochemical techniques are indispensable in modern analytical science, particularly in pharmaceutical and biomedical research where the sensitive detection of bioactive compounds is paramount. Among these techniques, cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), and square wave voltammetry (SWV) are widely employed for quantitative analysis. The sensitivity of each method is fundamentally governed by its unique current response expression, which determines the signal-to-noise ratio and the lowest detectable concentration of an analyte. This guide provides a theoretical and experimental comparison of these three techniques, focusing on their current expressions and relative sensitivities to inform method selection in drug development research.

The selection of an appropriate voltammetric technique is crucial for achieving desired detection limits in analytical applications. While CV is often used for initial electrochemical characterization due to its diagnostic capabilities, pulse techniques like DPV and SWV are generally preferred for trace-level quantitative analysis because of their superior background current suppression [5]. Understanding the theoretical underpinnings of the current responses for each method allows researchers to strategically choose and optimize protocols for specific sensitivity requirements in pharmaceutical analysis.

Theoretical Foundations of Current Responses

The sensitivity of a voltammetric technique is intrinsically linked to how it measures faradaic current while minimizing non-faradaic (capacitive) background contributions. Each method employs a distinct potential waveform and current sampling protocol, resulting in fundamentally different current expressions that dictate their analytical performance.

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) Current Expression

CV applies a linear potential ramp that reverses direction at a set vertex potential. The current is measured continuously throughout the potential sweep. For a reversible system, the peak current (ip) at 25°C is described by the Randles-Å evÄÃk equation:

ip = (2.69 × 10^5) * n^(3/2) * A * D^(1/2) * C * v^(1/2)

where:

- n is the number of electrons transferred

- A is the electrode area (cm²)

- D is the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s)

- C is the concentration (mol/cm³)

- v is the scan rate (V/s) [5]

The current in CV is directly proportional to concentration but also depends on the square root of scan rate. A key limitation is that both faradaic and capacitive currents are measured without discrimination, which can compromise sensitivity at low analyte concentrations. CV is primarily used for qualitative studies of redox mechanisms, including determining reaction reversibility and formal potentials, rather than for trace-level quantification [5].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) Current Expression

DPV enhances sensitivity by applying small amplitude potential pulses superimposed on a linear staircase ramp. Current is sampled twice per pulse—just before the pulse application (i1) and at the end of the pulse (i2). The recorded signal is the difference between these two measurements (Δi = i2 - i1) [24].

For DPV, the peak current expression is complex but can be approximated as:

Δip = (nFAΔE * C * D^(1/2)) / (4 * (π * tp)^(1/2))

where:

- ΔE is the pulse amplitude

- tp is the pulse period [24]

This differential current measurement effectively suppresses capacitive background because charging currents decay rapidly while faradaic currents decay more slowly. The background rejection capability of DPV makes it substantially more sensitive than CV, with typical detection limits in the nanomolar to micromolar range [24].

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) Current Expression

SWV combines a staircase waveform with a symmetrical square wave, generating both forward and reverse current components. The net current (Δi) is calculated by subtracting the reverse pulse current (ir) from the forward pulse current (if):

Δi = if - ir [1]

The peak current for a reversible system in SWV can be expressed as:

Δip = (nFAD^(1/2) * C) / (π^(1/2) * tp^(1/2)) * Ψ

where:

- Ψ is a dimensionless peak current parameter that depends on SWV parameters including amplitude, frequency, and step potential [1]

SWV provides exceptional sensitivity because the differential measurement cancels capacitive current while amplifying the faradaic component. The technique also offers rapid data acquisition as the entire voltammogram can be recorded in a single scan with frequencies typically ranging from 1 to 100 Hz [17]. This combination of features makes SWV particularly valuable for high-throughput analysis with detection limits often extending to the nanomolar range or lower [19].

Comparative Sensitivity Analysis

The theoretical current expressions translate into distinct practical performance characteristics for each technique. The following table summarizes key sensitivity parameters based on experimental data from recent studies:

Table 1: Comparative Sensitivity Metrics for CV, DPV, and SWV

| Technique | Theoretical Current Dependency | Typical Experimental LOD Range | Key Advantages | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CV | ip ∠C * v^(1/2) | 10â»âµ - 10â»â¶ M | Provides mechanistic information; simple implementation | Poor sensitivity; high background current |

| DPV | Δip ∠C * ΔE * tp^(-1/2) | 10â»â· - 10â»â¹ M [24] | Excellent peak separation; effective background suppression | Slower scan rates; potential oxygen interference [24] |

| SWV | Δip ∠C * f^(1/2) * A [1] | 10â»â¸ - 10â»Â¹â° M [19] [2] | Fastest acquisition; highest sensitivity; robust background rejection | Complex parameter optimization; less diagnostic for mechanisms [17] |

The enhanced sensitivity of pulse techniques is clearly demonstrated in experimental studies. For example, in the determination of Eszopiclone, SWV achieved a detection limit of 1.9 × 10â»â¸ mol/L (7.5 ppb), which was significantly lower than what conventional CV could attain [19]. Similarly, for dopamine detection, SWV with adsorptive stripping demonstrated a detection limit of 2.28 nM, enabling precise measurement in biological samples like human plasma serum [2].

Table 2: Experimental Detection Limits for Bioactive Compounds

| Analyte | Technique | Electrode | LOD | Application | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eszopiclone | SWV | Glassy Carbon | 1.9 × 10â»â¸ M | Pharmaceuticals, biological samples | [19] |

| Dopamine | SWAdSV | Cytosine-modified PGE | 2.28 nM | Human plasma serum | [2] |

| Dopamine | DPV | GO/SiO₂@PANI/GCE | 1.7 μM | Urine samples | [25] |

| Thymoquinone | SWV | Carbon Paste | 8.9 nM | Nigella Sativa products | [26] |

The following diagram illustrates the operational principles and current sampling mechanisms that underlie the sensitivity differences between these three techniques:

Experimental Protocols for Sensitivity Comparison

To objectively compare the sensitivity of CV, DPV, and SWV, researchers can implement standardized experimental protocols using common electrochemical probes. The following section details methodologies for instrument configuration, electrode preparation, and data analysis to ensure reproducible sensitivity assessment.

General Instrumentation and Electrode Preparation

Most modern voltammetric studies employ a standard three-electrode system consisting of:

- Working electrode: Glassy carbon electrode (GCE), pencil graphite electrode (PGE), or carbon paste electrode (CPE) depending on application requirements [19] [2] [26]

- Reference electrode: Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) for aqueous systems [19] [2]

- Counter electrode: Platinum wire [19] [2]

Electrode pretreatment is critical for reproducible results. For GCEs, this typically involves sequential polishing with alumina slurries of decreasing particle size (1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 μm) on a microcloth pad, followed by rinsing with distilled water and sonication in ethanol and water [25]. For modified electrodes, characterization techniques such as cyclic voltammetry, electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) are recommended to verify successful surface modification [2].

Technique-Specific Parameter Optimization

CV Protocol Development:

- Initial characterization should be performed at scan rates ranging from 10-500 mV/s

- Verify reversibility by examining peak separation (ΔEp = 59/n mV for reversible systems)

- Higher scan rates increase peak current but also enlarge capacitive background [5]

DPV Parameter Optimization:

- Pulse amplitude: Typically 25-100 mV (higher amplitudes increase signal but decrease resolution)

- Pulse width: 50-100 ms

- Step potential: 2-10 mV

- Scan rate: Determined by step height and duration [24]

- Example: For heavy metal detection, a pulse amplitude of 50 mV with pulse duration of 50 ms and step duration of 500 ms effectively separated Cd and Pb peaks [24]

SWV Parameter Optimization:

- Frequency: 5-25 Hz (higher frequencies increase sensitivity but may distort peaks for kinetically slow systems)

- Amplitude: 25-50 mV

- Step potential: 1-10 mV

- Example: For Eszopiclone determination, optimal parameters were frequency = 15 Hz, amplitude = 150 mV, and step potential = 150 mV/s [19]

- Accumulation parameters: For stripping applications, accumulation potential and time must be optimized (e.g., 60 seconds at -0.1 V for Eszopiclone) [19]

Calibration and Validation Procedures

For all techniques, calibration curves should be constructed using standard addition or external calibration methods with at least five concentration points across the linear range. Method validation should include:

- Linearity: Correlation coefficient (R²) > 0.995

- Limit of Detection (LOD): Typically calculated as 3.3 × σ/S, where σ is standard deviation of blank and S is slope of calibration curve

- Limit of Quantification (LOQ): Typically calculated as 10 × σ/S

- Precision: Relative standard deviation (RSD%) for repeat measurements < 5%

- Accuracy: Recovery studies in real samples (85-115%) [19] [26]

Research Reagent Solutions

The following essential materials and reagents are critical for implementing sensitive voltammetric methods in pharmaceutical and biomedical research:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Voltammetric Analysis

| Reagent/Equipment | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Britton-Robinson (B-R) Buffer | Versatile supporting electrolyte with wide pH range (2.0-12.0) | Determination of Eszopiclone at pH 6.5 [19]; studies of pH-dependent redox behavior |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS) | Physiological pH maintenance for biomolecule analysis | Dopamine detection in biological samples [2] [25] |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Standard working electrode with wide potential window | Base electrode for modifications; GO/SiOâ‚‚@PANI composite for dopamine sensing [25] |

| Pencil Graphite Electrode (PGE) | Disposable, cost-effective alternative to GCE | Cytosine-modified electrode for dopamine detection in plasma [2] |

| Nanomaterial Modifiers (graphene oxide, metal nanoparticles, polymers) | Enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and electron transfer | GO/SiOâ‚‚@PANI composite [25]; cytosine film [2] for improved dopamine detection |

| Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) | Traditional electrode for metal ion analysis; renewable surface | Determination of heavy metals via DPV [24] |

The theoretical comparison of current expressions for CV, DPV, and SWV reveals a clear sensitivity hierarchy that aligns with experimental observations. CV's continuous current measurement provides the lowest sensitivity but valuable mechanistic information. DPV's differential current measurement offers intermediate sensitivity with excellent peak resolution. SWV's net current measurement provides the highest sensitivity due to its effective background rejection and rapid scanning capability.

For drug development professionals seeking optimal detection strategies, SWV emerges as the superior choice for trace-level quantification of bioactive compounds, particularly when modified electrodes are employed to further enhance sensitivity. DPV remains valuable when analyzing complex mixtures requiring high peak resolution, while CV maintains its essential role in initial electrochemical characterization studies. The continued advancement of nanomaterial-modified electrodes, coupled with optimized pulse voltammetric protocols, promises even greater sensitivity for pharmaceutical analysis in the future.

Applying DPV, SWV, and CV in Pharmaceutical and Clinical Analysis

Voltammetric techniques are powerful tools for trace-level analysis in both environmental monitoring and biomedical diagnostics. Among these, Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is renowned for its high sensitivity and low detection limits. This guide provides an objective comparison of DPV's performance against two common alternatives: Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) and Cyclic Voltammetry (CV). Focusing on two critical application areas—heavy metal ion (HMI) detection in water and bioactive compound sensing in clinical samples—we summarize experimental data and protocols to help researchers select the most appropriate technique for their trace-level detection needs.

Performance Comparison of Voltammetric Techniques

Fundamental Principles and Relative Advantages

The core principle of voltammetry involves applying a potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current, which provides quantitative and qualitative data on redox-active species [27]. The key distinction between techniques lies in the waveform of the applied potential.

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Applies a series of small potential pulses superimposed on a linear staircase ramp. The current is sampled twice per pulse—just before the pulse and at the end of the pulse—and the difference is plotted against the potential. This sampling method effectively suppresses non-faradaic (capacitive) background current, leading to a significantly enhanced signal-to-noise ratio and lower detection limits compared to direct current techniques [24].

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): Utilizes a symmetrical square wave superimposed on a staircase ramp. The net current is derived from the difference between forward and reverse pulses, offering high speed, sensitivity, and effective background rejection [21] [5].

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Scans the potential linearly in a triangular waveform, switching direction at a set vertex potential. It is highly valuable for studying electrode reaction mechanisms and reversibility but is generally less sensitive for quantitative trace analysis compared to pulse techniques [21] [5].

Table 1: Core Characteristics of DPV, SWV, and CV.

| Feature | DPV | SWV | CV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potential Waveform | Linear staircase with small pulses | Staircase with superimposed square wave | Linear triangular scan |

| Current Measurement | Difference between pre-pulse and pulse currents | Difference between forward and reverse pulse currents | Direct current during potential sweep |

| Key Strength | Very low detection limits, excellent peak separation | Fast, highly sensitive, efficient background rejection | Mechanistic studies, reaction reversibility |

| Typical Analysis Time | Medium | Fast | Slow to Medium |

| Best Suited For | Ultra-trace quantification | Rapid, sensitive quantification & kinetics | Qualitative mechanism analysis |

Quantitative Performance Data

The following tables consolidate experimental data from recent studies, highlighting the performance of each technique in real-world applications.

Table 2: Technique Comparison in Bioactive Compound Detection. Data adapted from a study on dopamine (DA) detection using a cytosine-modified pencil graphite electrode [2].

| Technique | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Experimental Condition |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWV | Not specified in study | Higher than stripping methods | Direct measurement |

| DPV | Not specified in study | Higher than stripping methods | Direct measurement |

| SWAdSV | 0.1 mM – 0.5 μM & 0.1 μM – 7.5 nM | 2.28 nM | 120 s accumulation time |

| DPAdSV | 0.1 μM – 7.5 nM | 3.15 nM | 120 s accumulation time |

Abbreviations: SWAdSV: Square Wave Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry; DPAdSV: Differential Pulse Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry.

Table 3: Technique Comparison in Classification and Heavy Metal Detection.

| Application | Technique | Performance Outcome | Reference & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Classification of Abalone-Flavoring Liquids [21] | CV | Highest accuracy (91.307% cumulative variance in PCA); samples highly clustered | Four-electrode sensor array (Au, Pt, Pd, W) |

| LSV | Lower classification accuracy | Same sensor array as above | |

| SWV | Lower classification accuracy | Same sensor array as above | |

| Detection of Pb and Cd in Tap Water [24] | DPV | Successfully quantified Pb: 12.41 µg/L, Cd: 12.04 µg/L | Hanging Dropping Mercury Electrode (HDME) with standard addition |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol 1: DPV for Detecting Heavy Metals in Water

This standard method for detecting trace levels of lead (Pb) and cadmium (Cd) using DPV is a well-established application of the technique [24].

- 1. Equipment & Reagents: Potentiostat (e.g., Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT), Hanging Dropping Mercury Electrode (HDME) as working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and platinum auxiliary electrode. Acetate buffer electrolyte (1 M ammonium acetate + 1 M acetic acid). Standard solutions of Pb²⺠and Cd²⺠(e.g., 1 mg/L).

- 2. Sample Preparation: Place 10 mL of water sample into the electrochemical cell. Add 0.5 mL of acetate buffer solution to provide a consistent ionic strength and pH.

- 3. Preconcentration & Measurement: Purge the solution with nitrogen to remove oxygen. A new mercury drop is formed. Under stirring, apply a deposition potential of -0.9 V for a set time (e.g., 60-120 seconds). This step reduces and accumulates Pb and Cd cations onto the Hg drop. The stirrer is then switched off, and after a brief equilibration period, the DPV measurement is initiated.

- 4. DPV Scan Parameters: A typical potential scan from -0.9 V to -0.2 V is run with pulse parameters such as pulse amplitude of 25 mV and step potential of 5 mV.

- 5. Quantification via Standard Addition: The measurement is repeated after adding known, small volumes of standard Pb and Cd solutions to the cell. The increase in peak height is used to construct a calibration curve and precisely calculate the original concentration in the sample using the standard addition method, which compensates for matrix effects.

Protocol 2: SWV for Detecting Dopamine in Serum

This protocol for sensitive detection of the neurotransmitter dopamine (DA) exemplifies the use of SWV with a modified electrode [2].

- 1. Electrode Modification: A bare Pencil Graphite Electrode (PGE) is modified by performing 10 cycles of Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in a phosphate buffer solution (PBS, pH 7.2) containing 1 mM cytosine, between +0.7 V and +1.9 V. This electro-polymerizes cytosine onto the surface, creating a cytosine-modified PGE (CT/PGE).

- 2. Optimization & Measurement: The optimal pH for DA detection is determined to be 7.2 using PBS. An accumulation time is optimized (e.g., 120 seconds) at a fixed potential to adsorb DA onto the CT/PGE surface, enhancing sensitivity. The Square Wave Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (SWAdSV) measurement is then performed from -0.4 V to +0.4 V.

- 3. Analysis: The peak current is proportional to the DA concentration. The method is validated by testing in human plasma serum, showing high recovery and selectivity against interferents like ascorbic acid and uric acid.

The workflow for this analytical process is summarized in the diagram below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table lists key materials and their functions for developing and executing voltammetric sensors for trace analysis.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Voltammetric Sensing.

| Item | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Applies potential and measures current; core instrument. | Gamry, Metrohm Autolab [2]; portable systems for field use [28]. |

| Working Electrodes | Site of redox reaction; can be modified for enhanced performance. | Glassy Carbon (GCE), Pencil Graphite (PGE) [2], Hanging Dropping Mercury (HDME) [24], Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) [29]. |

| Nanomaterial Modifiers | Enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and surface area. | Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [5] [29], graphene [5] [29], metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Ag) [27] [5]. |

| Buffer Solutions | Provide consistent pH and ionic strength (supporting electrolyte). | Acetate buffer (for heavy metals) [24], Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS for biomolecules) [2]. |

| Reference Electrodes | Maintain a stable, known potential for accurate measurement. | Ag/AgCl (in aqueous media) [2], Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE). |

| Standard Solutions | Used for calibration and quantification. | Certified standard solutions of target analytes (e.g., Pb²âº, Cd²âº, Dopamine) [24] [2]. |

| GNF179 | GNF179|Imidazolopiperazine Antimalarial Research Compound | GNF179 is a potent imidazolopiperazine for antimalarial mechanism research. It targets parasite secretory pathways. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| GNF4877 | GNF4877, MF:C25H27FN6O4, MW:494.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The relationships between these core components in a typical voltammetric sensor are illustrated below.

The choice between DPV, SWV, and CV is dictated by the specific analytical goals. CV is unparalleled for qualitative, mechanistic studies of electrode processes [21]. For rapid, sensitive quantitative analysis, SWV is a powerful tool, especially when combined with stripping methods to achieve nanomolar detection limits for biomarkers like dopamine [2]. However, for applications demanding the lowest possible detection limits and superior resolution of overlapping peaks, DPV remains the technique of choice, as evidenced by its reliable performance in the trace-level determination of toxic heavy metals in water [24]. Understanding these performance distinctions allows researchers to effectively leverage the unique capabilities of each voltammetric technique.

SWV for High-Throughput and Sensitive Analysis in Drug Formulations

The accurate and sensitive detection of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), metabolites, and impurities is a cornerstone of modern drug development and quality control. Electroanalytical techniques, particularly voltammetry, have emerged as powerful tools in pharmaceutical sciences due to their high sensitivity, cost-effectiveness, and ability to analyze complex matrices [30]. Among these techniques, Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) is increasingly recognized for its superior performance in high-throughput and sensitive analysis of drug formulations. When positioned within a broader thesis on sensitivity comparison, SWV demonstrates distinct advantages over Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), primarily due to its unique waveform that efficiently minimizes capacitive background current and maximizes the faradaic response [1] [31] [32]. This capability is crucial for detecting trace-level analytes in complex pharmaceutical samples, enabling faster analysis times necessary for screening large compound libraries during drug development. The integration of advanced nanomaterials and miniaturized sensors further amplifies these advantages, positioning SWV as an indispensable technique for modern pharmaceutical analysis aimed at improving therapeutic outcomes and ensuring drug safety [5].

Fundamental Principles: How SWV Achieves Superior Sensitivity

The exceptional sensitivity of Square Wave Voltammetry stems from its sophisticated potential waveform and current sampling protocol. SWV combines a large-amplitude square wave modulation superimposed on a staircase waveform [32]. During each cycle, the current is sampled twice: once at the end of the forward pulse (If) and once at the end of the reverse pulse (Ir) [1] [33]. The fundamental breakthrough is that the charging current decays exponentially, while the faradaic current decays more slowly according to the Cottrell equation (1/√t) [31] [32]. By sampling the current at the end of each pulse, after the capacitive current has substantially decayed, SWV effectively discriminates against this non-faradaic background component. The recorded signal is the difference current (ΔI = If - Ir), which amplifies the faradaic response while canceling out a significant portion of the background [1]. This differential current measurement, combined with the technique's fast pulse sequences, allows for excellent signal-to-noise ratios and extremely low detection limits, often reaching nanomolar (10â»â¹ M) to picomolar concentrations [5] [32]. Furthermore, the entire voltammogram can be recorded on a single mercury drop or solid electrode, contributing to its rapid analysis times [32].

Visualizing the SWV Waveform and Current Sampling

The following diagram illustrates the square wave potential waveform and the critical points of current measurement that enable its high sensitivity.

Comparative Analytical Performance: SWV vs. DPV vs. CV

A direct comparison of the three voltammetric techniques reveals significant differences in their sensitivity, speed, and suitability for quantitative analysis. CV is primarily a qualitative technique used for studying redox mechanisms and reaction kinetics, whereas DPV and SWV are pulse techniques designed for high-sensitivity quantitative analysis [30]. The following table summarizes the key performance characteristics of each technique, with quantitative data derived from experimental comparisons using ferrocyanide as a model analyte [32].

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Voltammetric Techniques for Quantitative Drug Analysis

| Parameter | Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) |

|---|---|---|---|