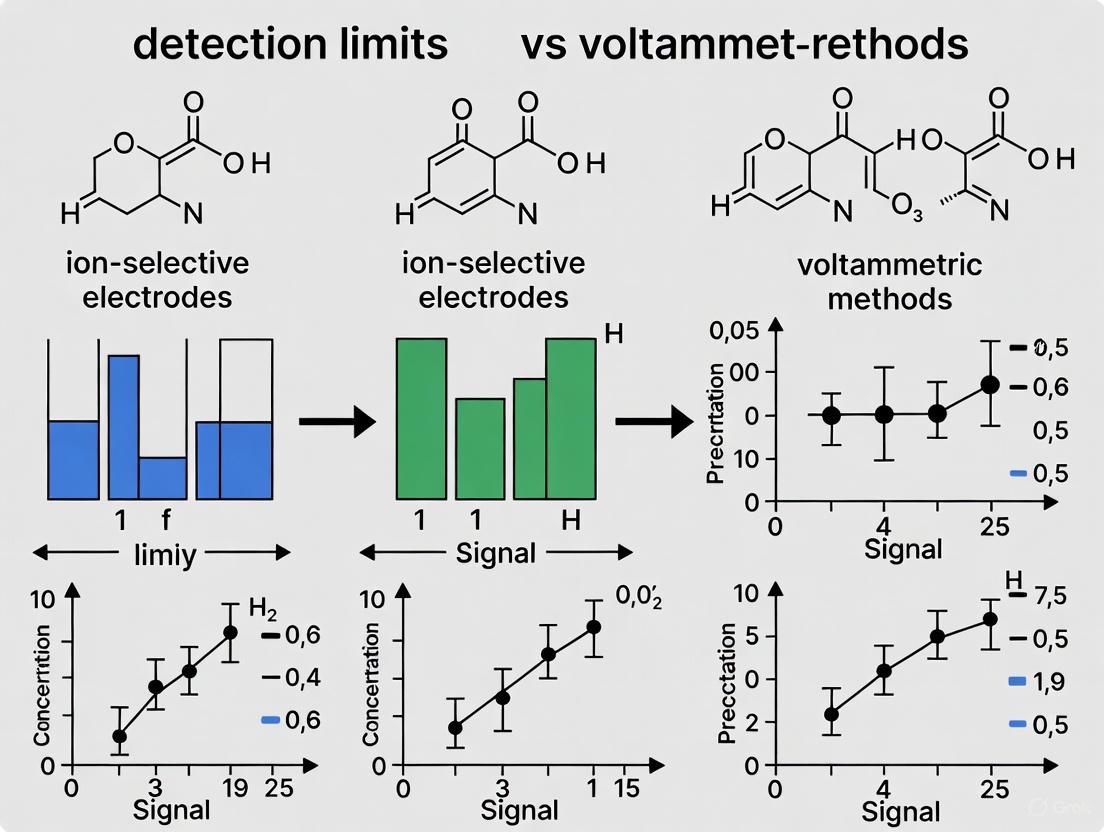

Detection Limits Showdown: Ion-Selective Electrodes vs. Voltammetric Methods in Biomedical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of detection limits between potentiometric ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) and voltammetric methods, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Detection Limits Showdown: Ion-Selective Electrodes vs. Voltammetric Methods in Biomedical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of detection limits between potentiometric ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) and voltammetric methods, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles governing sensitivity in each technique, examines methodological advances and real-world applications in pharmaceutical and clinical analysis, details strategies for optimizing and troubleshooting performance, and establishes a rigorous framework for validation and comparative assessment. By synthesizing current research, this review serves as a practical guide for selecting the appropriate analytical method based on required sensitivity, matrix complexity, and application context, ultimately supporting advancements in drug development and biomedical diagnostics.

Fundamental Principles: Understanding the Core Mechanisms Governing Detection Limits

Potentiometric ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) are electrochemical sensors that convert the activity of a specific ion in solution into an electrical potential. These tools are crucial for environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics, and industrial process control, offering precise measurements of ion concentrations in various solutions. The foundation of their operation lies in the Nernst equation, which provides the theoretical basis for their function by relating electrode potential to ion activity. This logarithmic response enables ISEs to measure ion concentrations across several orders of magnitude with a constant relative precision.

ISEs operate by measuring the potential difference between two electrodes under zero-current conditions: a working electrode (ion-selective membrane) that responds to the target ion's activity, and a reference electrode that maintains a constant potential, providing a stable reference point. The core of their sensing capability resides in ion-selective membranes that preferentially interact with the target ion based on size, charge, or specific chemical interactions. These membranes can be glass-based (e.g., for H+ ions), crystalline (e.g., LaF3 for F- ions), or polymer-based (e.g., PVC with incorporated ionophores), each designed for specific analytical applications where selective ion detection is required.

The Nernst Equation: Fundamental Principles

Mathematical Foundation

The Nernst equation provides the fundamental relationship between the measured electrode potential and the activity of the target ion in solution. The standard form of the equation is:

E = E⁰ + (RT/zF) ln(aᵢ)

Where:

- E: Measured electrode potential (V)

- E⁰: Standard electrode potential (V)

- R: Gas constant (8.314 J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹)

- T: Absolute temperature (K)

- z: Charge of the ion

- F: Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹)

- aᵢ: Activity of the target ion (dimensionless)

At 25°C (298K), the equation simplifies for monovalent ions (z=1) to approximately E = E⁰ + (0.0592V) log(aᵢ), and for divalent ions (z=2) to approximately E = E⁰ + (0.0296V) log(aᵢ). This means the electrode potential changes by 59.2 mV per tenfold change in concentration for monovalent ions and 29.6 mV for divalent ions, establishing the characteristic logarithmic response that allows ISEs to measure across broad concentration ranges.

Operational Mechanism

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental components and operational workflow of a potentiometric ion-selective electrode system:

The diagram above illustrates how the potential develops across the ion-selective membrane in response to the target ion activity in the sample solution. The membrane allows selective passage of the target ion based on size, charge, or specific interactions, creating a potential difference proportional to the logarithm of the ion activity as described by the Nernst equation. This potential is measured against the stable potential of the reference electrode under zero-current conditions, ensuring minimal disturbance to the sample.

Performance Comparison: Potentiometric ISEs vs. Voltammetric Methods

Analytical Performance Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of key performance characteristics between potentiometric ISEs and voltammetric methods for ion sensing

| Parameter | Potentiometric ISEs | Voltammetric Methods | Implications for Analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Detection Principle | Zero-current potential measurement | Current measurement during voltage sweep | ISEs are less vulnerable to interferent effects and ohmic drop problems [1] |

| Detection Limits | Typically 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹¹ M [2] [3] [4] | Generally lower (nanomolar range) [5] | Voltammetry offers higher sensitivity for trace analysis |

| Working Range | Broad (typically 4-8 decades) [2] [3] | More limited dynamic range | ISEs suitable for samples with varying concentrations |

| Selectivity | High with optimized ionophores | Moderate to high | ISE selectivity depends on membrane composition [6] |

| Measurement Speed | Fast response (seconds to minutes) [2] | Slower due to voltage scanning | ISEs better for real-time monitoring |

| Power Consumption | Low (measures equilibrium potential) | Higher (applies potential) | ISEs advantageous for field applications [1] |

| Multi-analyte Capability | Limited (single ion per sensor) | Possible with single sensor [5] | Voltammetry can distinguish multiple analytes |

| Lifetime | Months to years for classical designs [5] | Shorter for ultra-thin membranes [5] | ISEs offer better long-term stability |

Methodological Comparison in Experimental Practice

Table 2: Comparison of experimental methodologies and requirements for potentiometric ISEs versus voltammetric methods

| Experimental Aspect | Potentiometric ISEs | Voltammetric Methods | Practical Consequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instrumentation | Simple potentiometer | Potentiostat with voltage sweep capability | ISEs require less complex equipment |

| Sample Preparation | Minimal, often direct measurement | May require deaeration or addition of supporting electrolyte | ISEs more suitable for complex matrices [2] [4] |

| Skill Requirement | Lower technical expertise | Higher technical expertise | ISEs more accessible for routine analysis |

| Miniaturization Potential | Excellent, insensitive to size reduction [1] | Limited by decreased currents | ISEs better for wearable sensors [1] |

| Sensitivity to Fouling | Moderate | High | Voltammetry may require more maintenance |

| Suitability for Turbid/Colored Samples | Excellent [1] | May be problematic | ISEs applicable to wider sample types |

| Theoretical Foundation | Nernst equation | Nernst equation plus diffusion kinetics | ISEs have more straightforward interpretation |

Advanced Experimental Protocols

Sensor Fabrication and Optimization

Graphite-Based Copper Ion-Selective Electrode [2]

This protocol details the construction of a high-performance Cu(II)-selective electrode using a modified graphite sensor with a Schiff base ionophore, which demonstrated a Nernstian slope of 29.571 ± 0.8 mV per decade across a broad concentration range (1×10⁻⁷ to 1×10⁻¹ M) with a detection limit of 5.0×10⁻⁸ M.

Table 3: Research reagent solutions and materials for Cu(II)-selective electrode fabrication

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Graphite powder | Synthetic, 1-2 μm | Conductive electrode base material |

| Schiff base ligand | 2-(((3-aminophenyl)imino)methyl)phenol | Ionophore for selective Cu(II) complexation |

| o-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) | Plasticizer grade | Membrane plasticizer for optimal ion mobility |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Anhydrous | Solvent for membrane components |

| Copper sulfate pentahydrate | Analytical grade | Primary ion source for calibration |

| Interfering metal salts | Chloride salts of Mn, Cd, Zn, Ni, etc. | Selectivity assessment |

Procedure:

- Ionophore Synthesis: Prepare Schiff base ligand by condensing m-phenylenediamine (129.4 mmol, 14 g) with 2-hydroxybenzaldehyde (129.4 mmol, 15.8 g) in ethanol under reflux for 3 hours. Purify the yellowish-green product by recrystallization from diethyl ether.

- Membrane Preparation: Thoroughly mix 250 mg graphite powder, 5-20 mg ionophore, and 0.1 mL plasticizer (o-NPOE) in a mortar until homogeneous.

- Electrode Assembly: Pack the modified paste into a Teflon holder electrode body. Insert a stainless-steel rod for electrical contact.

- Conditioning: Store the prepared electrode in distilled water for 24 hours before use. Condition in 1×10⁻² M Cu(II) solution for 2 hours at 25°C prior to initial measurements.

- Potential Measurements: Measure potentials using a double-junction Ag/AgCl reference electrode against Cu(II) solutions ranging from 1×10⁻⁷ to 1×10⁻¹ M. Plot EMF versus -log[Cu²⁺] to obtain calibration curve.

Performance Validation:

- Selectivity Testing: Evaluate using Separate Solution Method (SSM), Fixed Interference Method (FIM), and Matched Potential Method (MPM) against interfering ions.

- pH Effect: Study potential stability across pH 3.5-6.5 for 1×10⁻⁴ and 1×10⁻⁵ M Cu(II) solutions.

- Lifetime Assessment: Monitor Nernstian slope and detection limit over 2-month period with regular use.

Voltammetric Ion Sensing Protocol

Voltammetric ISEs with Internal Aqueous Solution [5]

This protocol describes the adaptation of classical ISEs for voltammetric measurements, extending their functionality beyond traditional potentiometry while maintaining a longer lifetime (approximately one month) compared to solid-contact ISEs with ultra-thin membranes.

Table 4: Key reagents and materials for voltammetric ISE implementation

| Reagent/Material | Specifications | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-selective membrane | Ca, Li, or K-selective composition | Primary sensing element |

| Redox couple | Ferrocenemethanol or ferrocyanide/ferricyanide | Internal redox system for electron transfer |

| Chloride salt | Of target cation (CaCl₂, LiCl, KCl) | Internal filling solution component |

| Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) | High molecular weight | Membrane matrix material |

| Tetrahydrofuran (THF) | Anhydrous | Membrane solvent |

| Platinum wire | 1 mm diameter | Internal reference electrode |

| Ionophore | Target ion-specific | Selective ion complexation |

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Construct classical ISE with internal aqueous solution containing chloride salt of target cation and redox couple (ferrocenemethanol or ferrocyanide/ferricyanide).

- Internal Electrode Assembly: Use platinum wire as internal reference electrode in contact with the internal solution containing the redox couple.

- Voltammetric Measurements: Perform cyclic voltammetry using a potentiostat with the ISE as working electrode and appropriate external reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl).

- Data Analysis: Record oxidation and reduction peak potentials. Plot peak potentials versus log(ion activity) to verify Nernstian response.

- Lifetime Monitoring: Regularly test voltammetric response over 30-day period to assess sensor stability.

Key Observations:

- Peak potentials shift according to Nernst equation with sample composition

- Peak currents remain largely independent of analyte activity

- Detection limits can be improved using suitable background electrolytes

- Classical design with thick membranes (100-300 μm) provides longer lifetime compared to ultra-thin membranes (200-300 nm)

Recent Technological Advances

Novel Materials and Design Innovations

Recent advancements in ISE technology have focused on improving sensor stability, selectivity, and applicability to real-world samples. Solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) have gained prominence by eliminating the internal filling solution, which enhances miniaturization potential and mechanical stability [1]. These designs incorporate advanced materials including conducting polymers (polyaniline, PEDOT), carbon-based nanomaterials (MWCNTs, graphene), and nanocomposites that act as efficient ion-to-electron transducers [1] [4].

A significant innovation demonstrated in recent research is the use of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) as transducer layers, which significantly enhance sensitivity and reproducibility. For example, in BPA sensing applications, MWCNT-modified electrodes achieved exceptional detection limits of 0.000104 μmol·L⁻¹ across a broad linear range of 10,000-0.01 μmol·L⁻¹ [4]. Similar advancements in lead-selective electrodes have resulted in detection limits as low as 10⁻¹⁰ M with near-Nernstian sensitivities of 28-31 mV per decade [3].

Emerging Applications and Methodologies

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for developing and validating advanced ion-selective electrodes, from material synthesis to real-sample application:

The field has witnessed growing incorporation of machine learning approaches to optimize ISE development. Recent studies have successfully applied machine learning models, Morgan fingerprinting, and Bayesian optimization to predict ISE performance based on membrane components, significantly reducing development time and costs [7]. This data-driven approach has enabled rapid screening of ionophores and identification of optimal membrane compositions, demonstrating excellent correlation with experimental results for Na⁺, Mg²⁺, and Al³⁺ sensors.

Wearable potentiometric sensors represent another emerging application, allowing continuous monitoring of biomarkers, electrolytes, and pharmaceuticals in biological fluids [1]. These advancements, coupled with 3D printing fabrication techniques and paper-based platforms, are expanding ISE applications into point-of-care testing, personalized medicine, and environmental field monitoring.

Potentiometric ion-selective electrodes establish their distinctive analytical value through their Nernstian foundation, which provides logarithmic response across exceptionally broad concentration ranges. While voltammetric methods may offer superior detection limits for trace analysis, ISEs maintain advantages in operational simplicity, power efficiency, and suitability for complex sample matrices. Recent innovations in materials science, particularly incorporating nanomaterial transducers and optimized membrane compositions, have further enhanced ISE performance characteristics. The continued development of solid-contact designs, wearable formats, and machine-learning-optimized sensors positions potentiometric ISEs as increasingly powerful tools for pharmaceutical research, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics, complementing rather than competing with voltammetric approaches in the analytical scientist's toolkit.

Electroanalytical techniques are indispensable tools for quantifying chemical species across diverse fields, from neurochemistry to environmental monitoring. At the core of these methods lies a fundamental relationship: the faradaic current arising from redox reactions provides the quantitative signal directly proportional to analyte concentration, forming the basis for linear response and ultimately determining method sensitivity. This guide objectively compares the performance of two predominant electrochemical sensing paradigms—voltammetric methods and ion-selective electrodes (ISEs)—within the context of detection limits and practical application. Voltammetry measures current resulting from electron transfer events at an electrode surface, while potentiometric ISEs measure potential differences across a selective membrane at near-zero current. Understanding the principles governing faradaic current in voltammetry and the Nernstian response in ISEs is crucial for selecting the appropriate analytical tool for specific research needs, particularly in pharmaceutical and environmental applications where detection of low analyte concentrations is critical.

Theoretical Foundations: Faradaic Current and Nernstian Response

The Origin of Voltammetric Signals

In voltammetry, the applied potential drives electron transfer reactions, generating a faradaic current that serves as the primary analytical signal. This current is distinct from the charging current (or capacitive current) that arises from the reorganization of ions at the electrode-solution interface without electron transfer. The faradaic current ((i_f)) is governed by the Cottrell equation for diffusion-controlled processes:

[i_f = \frac{nFAC\sqrt{D}}{\sqrt{\pi t}}]

where (n) is the number of electrons transferred, (F) is Faraday's constant, (A) is the electrode area, (C) is the bulk concentration of the electroactive species, (D) is the diffusion coefficient, and (t) is time [8]. This fundamental relationship establishes the direct proportionality between faradaic current and analyte concentration, forming the basis for quantitative analysis in voltammetric methods. The strategic minimization of charging current through pulse techniques that exploit its rapid exponential decay compared to the slower decay of faradaic current represents a critical advancement for enhancing voltammetric sensitivity [8].

Principles of Ion-Selective Electrodes

Ion-selective electrodes operate on a fundamentally different principle, measuring the potential difference across an ion-selective membrane that develops in response to the activity of specific ions in solution. This potential follows the Nernst equation:

[E = E^0 + \frac{RT}{zF}\ln a]

where (E) is the measured potential, (E^0) is the standard potential, (R) is the gas constant, (T) is temperature, (z) is the ion charge, (F) is Faraday's constant, and (a) is the ion activity [9]. The theoretical Nernstian slope ((RT/zF)) defines the ideal sensitivity, approximately 59.16 mV/decade for monovalent ions at 23°C [9]. The selectivity of ISEs stems from specialized ionophores within the membrane that form selective complexes with target ions, as demonstrated in sensors for copper(II), chromium(III), and iron(III) [10] [11]. Unlike voltammetry, ISEs measure this potential at essentially zero current, avoiding faradaic processes altogether.

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Sensitivity Comparison

Voltammetric Protocol for Trace Metal Analysis

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) provides exceptional sensitivity for trace metal detection, with a well-established protocol for analyzing lead and cadmium in environmental samples [8]:

Electrode System: Employ a three-electrode potentiostat with mercury film or dropping mercury working electrode, platinum auxiliary electrode, and Ag/AgCl or SCE reference electrode [12] [13].

Preconcentration Step: Apply a negative deposition potential (-1.0 V to -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for 60-300 seconds while stirring the solution. This reduces metal ions (Mn+) to their metallic state (M⁰) and preconcentrates them into the mercury electrode, forming an amalgam.

Equilibration: Stop stirring and allow 15-30 seconds for solution equilibration.

Stripping Step: Apply a positive-going potential sweep (typically -1.0 V to +0.2 V) using differential pulse voltammetry or linear sweep voltammetry. As the potential reaches each metal's oxidation potential, it is stripped from the electrode as ions, generating characteristic current peaks.

Quantification: Measure peak currents, which are directly proportional to metal concentration in the original sample. The distinctive stripping potentials provide qualitative identification of specific metals.

This protocol leverages the dual enhancement of preconcentration and electrochemical stripping to achieve detection limits in the part-per-trillion range for many metals [8].

Potentiometric Protocol for Ion-Selective Electrodes

Fabrication and operation of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes follows this standardized protocol, as demonstrated for potassium and heavy metal sensors [10] [9]:

Electrode Fabrication:

- For solid-contact ISEs: Modify glassy carbon electrode with an ion-to-electron transducer layer (conductive polymer, MWCNTs, or nanocomposite).

- Prepare ion-selective membrane containing PVC, plasticizer (e.g., DOS), ionophore, and lipophilic additive.

- Drop-cast the membrane solution onto the modified electrode and allow solvent evaporation.

Conditioning: Soak the prepared ISE in a solution of the primary ion (e.g., 0.01 M KCl for potassium ISE) for 24 hours to establish stable membrane potentials.

Calibration: Measure potential response in standard solutions across a concentration range (typically 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻¹ M) while stirring. Record stable potential values at each concentration.

Sample Measurement: Immerse conditioned ISE in sample solution with a double-junction reference electrode. Measure potential after stabilization (< 5-10 seconds for many modern ISEs).

Data Analysis: Plot measured potential versus logarithm of ion activity. The slope should approach Nernstian value (59.16 mV/decade for K⁺), with detection limit determined from the intersection of linear response segments.

The following diagram illustrates the operational workflow for both techniques, highlighting their key distinguishing features:

Diagram Title: Operational Workflow Comparison

Performance Comparison: Detection Limits and Sensitivity

Quantitative Comparison of Analytical Figures of Merit

The following table summarizes key performance parameters for voltammetric and ion-selective electrode methods based on recent experimental studies:

| Method | Typical Detection Limit | Linear Range | Sensitivity | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry | Part-per-trillion (10⁻¹² M) [8] | 4-6 orders of magnitude [8] | Current proportional to concentration [8] | Trace metal analysis (Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu) in environmental samples [8] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry | Nanomolar (10⁻⁹ M) [8] | 1 pM - 100 mM [8] | High for reversible systems [8] | Pharmaceutical compounds, biomolecules [8] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry | Nanomolar (10⁻⁹ M) [8] | 1 pM - 100 mM [8] | Excellent for reversible systems [8] | Neurotransmitters, mechanistic studies [8] |

| Copper(II) ISE | 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ M [10] | 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ – 1.0 × 10⁻¹ M [10] | 32.15 mV/decade [10] | Water quality, clinical samples [10] |

| Chromium(III) ISE | 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ M [10] | 1.0 × 10⁻¹⁰ – 7.0 × 10⁻³ M [10] | 19.28 mV/decade [10] | Speciation of Cr(III)/Cr(VI) [10] |

| Potassium ISE | ~10⁻⁶ M [9] | 10⁻⁶ – 10⁻¹ M [9] | 56.18-61.37 mV/decade (10-36°C) [9] | Clinical analysis, physiological monitoring [9] |

| Ferric ISE | 3 × 10⁻⁹ M (solid-state) [11] | Not specified | Nernstian behavior [11] | Fe(III) determination, potentiometric titration [11] |

Temperature Dependence and Environmental Factors

Temperature significantly impacts the sensitivity of both voltammetric and potentiometric methods, though through different mechanisms. For ISEs, temperature directly affects the Nernstian slope according to the relationship (S = RT/zF), with theoretical values increasing from 56.18 mV/decade at 10°C to 61.37 mV/decade at 36°C for monovalent ions [9]. Recent studies demonstrate that electrodes modified with nanocomposite materials or perinone polymer show superior resistance to temperature changes, maintaining stable measurement ranges and detection limits across temperature variations [9]. In voltammetry, temperature influences diffusion coefficients, electron transfer kinetics, and charging current characteristics, though modern pulse techniques effectively minimize these effects through precise current sampling protocols [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Critical Materials for Electrode Fabrication and Operation

| Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Multi-walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Enhance electrical conductivity, increase surface area, improve potential stability | Solid-contact layer in ISEs [10] [9], modifier for carbon paste electrodes [10] |

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT:PSS, POT, PPer) | Ion-to-electron transduction, hydrophobicity prevents water layer formation | Solid-contact in ISEs [9] [14], active material in OECTs [14] |

| Ionophores | Molecular recognition elements providing selectivity for target ions | 4-Methylcoumarin derivatives for Cu²⁺ and Cr³⁺ [10], valinomycin for K⁺ [9], NBMCB for Fe³⁺ [11] |

| Mercury Electrodes | High hydrogen overpotential enables wide negative potential window | Dropping mercury electrode (DME), hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE) for stripping voltammetry [12] [13] |

| Glass Carbon Electrodes | Renewable surface, wide potential range, low background current | substrate for modified electrodes, working electrode in voltammetry [9] |

| Plasticizers (DOS, Paraffin Oil) | Create ion-conductive membrane phase, influence dielectric constant | Component of polymeric membranes in ISEs [10] [9] |

| Ion-Selective Membranes | Provide selective interface between solution and electrode | PVC-based membranes containing ionophore, plasticizer, additives [9] |

Comparative Analysis: Advantages and Limitations in Research Applications

Situational Advantages and Technical Constraints

The selection between voltammetric and potentiometric methods depends heavily on the specific analytical requirements and constraints of the research application:

Voltammetric methods excel in scenarios requiring:

- Ultra-trace detection of electroactive species, particularly metals at part-per-trillion levels [8]

- Speciation analysis of different oxidation states based on their distinctive redox potentials [8]

- Real-time monitoring of dynamic concentration changes with sub-second temporal resolution [8]

- Multi-analyte detection in complex mixtures through distinctive voltammetric peaks [8]

Ion-selective electrodes provide superior performance for:

- Continuous monitoring in field-deployable or wearable devices with simple instrumentation [15] [9]

- Measurement in turbid or colored samples where optical methods fail [10]

- High-throughput screening with rapid response times (<10 seconds for many ISEs) [10] [11]

- In vivo physiological monitoring with miniaturized, biocompatible platforms [15]

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental signal generation mechanisms in both techniques, highlighting their distinctive operational principles:

Diagram Title: Signal Generation Mechanisms

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

Technological Innovations Enhancing Sensitivity

Recent advancements in both voltammetric and potentiometric methods focus on overcoming traditional sensitivity limitations through novel materials and measurement configurations:

Voltammetry innovations include:

- Advanced waveform design utilizing continuous square-wave voltammetry (cSWV) to extract multiple voltammograms from single scans, enhancing signal-to-noise ratios [8]

- Nanomaterial-modified electrodes employing graphene and carbon nanotubes to increase electroactive surface area and electron transfer kinetics [8]

- Chemometric approaches applying multivariate curve resolution alternating least squares (MCR-ALS) to mathematically separate faradaic from charging currents [16]

ISE advancements feature:

- Current-driven OECT configurations that exceed the Nernst limit by one order of magnitude at low operating voltages (<0.4 V) [14]

- Solid-contact materials engineering using nanocomposites of MWCNTs and copper oxide nanoparticles to enhance potential stability and temperature resistance [9]

- Miniaturization technologies enabling microfabricated ion-selective microelectrode arrays for spatially resolved ion analyses with scanning electrochemical microscopy [15]

Convergence for Enhanced Analytical Performance

The historical distinction between voltammetric and potentiometric methods is increasingly blurring with the development of hybrid approaches that leverage advantages of both techniques. Current-driven organic electrochemical transistors (OECTs) represent one such convergence, offering voltage-normalized sensitivity exceeding 1200 mV V⁻¹ dec⁻¹—more than an order of magnitude improvement over conventional ISFETs or OECTs [14]. Similarly, the integration of voltammetric detection with separation techniques like high-performance liquid chromatography provides powerful hyphenated systems for complex sample analysis [17]. These technological synergisms, coupled with advanced materials and data processing algorithms, continue to push detection limits lower while expanding the practical application space for electrochemical sensors in pharmaceutical research, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics.

The evolution of electrochemical sensors has been significantly driven by the relentless pursuit of lower detection limits and enhanced sensitivity. In the context of ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) versus voltammetric methods, this pursuit revolves around a critical understanding of the key components that govern sensor performance: ionophores, membrane matrices, and electrode materials. While traditional potentiometric ISEs with ionophore-based membranes are well-established for their ability to quantify ion activities over several orders of magnitude, their sensitivity is fundamentally limited by the Nernstian slope, resulting in a relatively high relative error in concentration [18]. Recent research has focused on overcoming these limitations through innovative materials and alternative readout methods, including voltammetric and coulometric approaches that transcend classical potentiometric operation [18] [19] [20]. This guide provides a systematic comparison of how these core components dictate the analytical performance of ion-selective sensors, framing the discussion within the critical challenge of achieving lower detection limits.

Core Component Analysis: Structure-Function Relationships

The sensitivity and detection limits of ion-selective sensors are dictated by the synergistic interaction of three core components. The following section breaks down the structure-function relationships of each.

Ionophores: The Molecular Recognition Elements

Ionophores are the cornerstone of selectivity in ISEs. These lipophilic compounds, embedded within the sensor membrane, selectively bind to target ions, facilitating their partitioning into the organic membrane phase. The nature of this interaction directly controls the sensor's basic performance parameters.

- Function and Mechanism: In operation, the ionophore ("carrier") traps the analyte ion at the interface between the aqueous sample and the organic membrane. Without the ionophore, the analyte ion would be unable to partition effectively into the membrane. This selective complexation establishes a charge separation at the interface, generating the phase-boundary potential that is measured [21].

- Chemical Diversity: Ionophores encompass a range of structures. Common examples include macrocyclic compounds like valinomycin (for potassium) and crown ethers, as well as various synthetic chelating agents for heavy metal ions like Co²⁺, Zn²⁺, and Cd²⁺ [21] [22]. The affinity and selectivity of the ionophore for the target ion over potential interferents are paramount.

- Impact on Detection Limits: The properties of the ionophore, particularly its lipophilicity and complexation strength, significantly influence the detection limit. A low lipophilicity can cause the ionophore to leach from the membrane, leading to a gradual degradation of sensor performance and a shorter lifetime [23].

Table 1: Comparison of Select Ionophores and Their Performance Characteristics

| Ionophore Target | Example Ionophore | Key Analytical Performance | Influence on Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Potassium (K⁺) | Valinomycin | Near-Nernstian slope, excellent selectivity over Na⁺ [18] | High lipophilicity ensures long-term stability and low detection limits. |

| Iron (Fe³⁺) | N-(4-(dimethylamino)benzylidene)thiazol-2-amine [24] | Slope of 19.5 ± 0.4 mV/decade, LOD of 2.3×10⁻⁸ mol L⁻¹ [24] | Strong complexation allows for very low detection limits. |

| Divalent Cations (Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺) | Acidic chelating compounds [22] | Useful for Co, Zn, and Cd sensing; response depends on acidic properties [22] | The acidity of the ionophore is a critical factor determining the electrode's analytical parameters. |

Membrane Matrices: The Host Environment

The polymer membrane serves as the host matrix for the ionophore and other components, forming the ion-selective barrier between the sample and the inner electrode. Its composition is critical for maintaining stability and dictating the transport properties of ions.

- Standard Materials: Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) plasticized with various esters (e.g., o-nitrophenyl octyl ether, o-NPOE) has been the traditional and predominant material for fabricating ion-selective membranes [24] [23]. The plasticizer serves a dual purpose: it fluidizes the PVC polymer and also acts as a solvent for the membrane components, influencing the dielectric constant of the medium and the mobility of ions.

- Limitations and Advanced Alternatives: A primary limitation of conventional PVC membranes is the leaching of components (ionophore and plasticizer) into the sample, which limits sensor lifetime. This has spurred research into alternative materials.

- Self-Plasticized Polymers and polymers like polyurethane aim to reduce leaching by eliminating or immobilizing the low-molecular-weight plasticizer [18] [23].

- Perfluorinated Compounds offer enhanced biocompatibility and reduced fouling for medical and biological applications [23].

- Ionic Liquids have been explored as multifunctional membrane components, acting as both plasticizers and ion-exchangers [23].

- Influence on Ion Transport: The membrane matrix controls the flux of ions. By carefully controlling the magnitude and direction of the analyte ion's flux through the polymeric membrane, researchers have demonstrated a dramatic lowering of detection limits, pushing them into the nanomolar range and beyond [19].

Table 2: Comparison of Membrane Matrix Materials

| Matrix Material | Typical Composition | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasticized PVC | PVC, plasticizer (e.g., o-NPOE), ionophore, additive [24] | Well-understood, versatile, low cost | Leaching of plasticizer and ionophore limits lifetime |

| Polyurethane | Polyurethane polymer, ionophore [18] | Reduced leaching, better adhesion | Can be more challenging to formulate |

| Solvent-Free Polymeric Membranes | Polymers with covalently attached ionophores [23] | Eliminates leaching, very long lifetime | Complex synthesis, limited ionophore choices |

| Ionic Liquid Membranes | PVC or other polymer with ionic liquid [23] | Multifunctional, high stability | Behavior and interpretation can be complex |

Electrode Materials and Transduction Mechanisms

The final critical component is the electrode architecture itself, which is responsible for transducing the chemical signal (ion activity) into a measurable electrical signal. The choice here fundamentally differentiates classical ISEs from modern solid-contact and voltammetric sensors.

- Classical ISEs with Liquid Contact: These traditional electrodes use an internal aqueous solution between the ion-selective membrane and an internal reference electrode [18] [25]. While known for excellent long-term stability and reproducibility, their design complicates miniaturization and requires vertical operation.

- Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs): To overcome the limitations of liquid-contact ISEs, solid-contact electrodes were developed. These eliminate the internal solution and introduce an intermediate ion-to-electron transducer layer between the membrane and the inner electrode conductor [25]. This design simplifies construction, enables miniaturization, and allows for a wider range of applications, including wearable sensors [25].

- Voltammetric and Coulometric Operation: Moving beyond zero-current potentiometry, researchers have demonstrated that ISEs can be operated in voltammetric or coulometric modes. In one approach, a classical ISE with an internal solution containing a redox couple (e.g., ferrocenemethanol or ferri/ferrocyanide) can be used for voltammetric measurements, where the peak potential shifts Nernstianly with the sample's ion activity [18]. Alternatively, in SC-ISEs with conducting polymers, a coulometric readout can be employed. Here, a change in sample ion activity triggers a transient current that, when integrated, provides a highly sensitive charge-based signal, capable of detecting changes as small as 0.1% in ion activity [20].

The diagram below illustrates the fundamental signaling pathways and how the core components influence the sensor's output and ultimate detection limits.

Comparative Experimental Data: Potentiometric ISEs vs. Voltammetric/Coulometric Methods

The theoretical advantages of alternative sensing modes are borne out in experimental data. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies, highlighting how the choice of electrode design and readout method directly impacts achievable detection limits and sensitivity.

Table 3: Comparison of Sensor Performance Based on Design and Readout Method

| Analyte Ion | Sensor Design / Readout Method | Key Experimental Protocol | Reported Performance (Detection Limit, Sensitivity) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium, Lithium, Potassium | Classical ISE with internal solution / Voltammetry [18] | ISE internal solution contained redox couple (FcMeOH or FeCN). Cyclic voltammetry performed; peak potential shift measured. | Lifetime: ~1 month. Peak potential shift obeys Nernst law. Detection limits improved with suitable background electrolyte. |

| Potassium (K⁺) | SC-ISE with PEDOT(PSS) / Constant Potential Coulometry [20] | Potential held at 0 V vs. RE; current monitored. Charge quantified via current integration upon activity change. | Able to differentiate 0.1% change in K⁺ activity (5 µM at 5 mM). High sensitivity but longer measurement time (minutes). |

| Iron (Fe³⁺) | Coated Graphite Electrode (CGE) / Potentiometry [24] | Membrane with ionophore L2 spotted on graphite. OCP measured vs. Ag/AgCl reference. | LOD: 2.3×10⁻⁸ mol L⁻¹. Slope: 19.5 ± 0.4 mV/decade. Response time: 10 s. |

| pH | SC-ISE with Capacitor / Chronocoulometry [20] | Electronic capacitor connected in series with ISE. Current/charge measured under OCP condition. | Eliminates baseline drift of pure CP-based sensors. Shorter measurement time. Enhanced sensitivity for small activity changes. |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

To translate the theoretical concepts into practical experimentation, the following toolkit of essential materials and reagents is required for developing and fabricating high-sensitivity ion-selective sensors.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Ion-Selective Sensor Development

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophores | Molecular recognition; confers selectivity and sensitivity. | Valinomycin (for K⁺); synthetic chelators for heavy metals (e.g., for Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺) [18] [22]. |

| Polymer Matrix | Host for membrane components; forms the selective barrier. | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is standard; polyurethane for reduced leaching [18] [23]. |

| Plasticizers | Imparts fluidity to membrane; influences dielectric constant. | o-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (o-NPOE) for high dielectric constant [24]. |

| Lipophilic Additives | Prevents anion interference; governs optimal membrane polarity. | Potassium tetrakis(4-chlorophenyl)borate (NaTPB) [24]. |

| Ion-to-Electron Transducers | Converts ionic signal to electronic signal in SC-ISEs. | Conducting polymers (PEDOT:PSS), ordered mesoporous carbon, prussian blue [25] [20]. |

| Membrane Solvents | Dissolves membrane components for deposition. | Tetrahydrofuran (THF), cyclohexanone; mixtures optimize spotting uniformity [26]. |

| Internal Redox Couples | Enables voltammetric operation of classical ISEs. | Ferrocenemethanol (FcMeOH), Ferri/Ferrocyanide [18]. |

The journey toward lower detection limits and higher sensitivity in ion sensing is a materials and design challenge. As this guide illustrates, there is no single "best" component, but rather an interplay between ionophores, membranes, and electrode materials that must be optimized for a specific application. The key takeaways are:

- The ionophore remains the primary determinant of selectivity, but its lipophilicity is critical for long-term stability and low detection limits.

- The membrane matrix must be engineered to minimize component leaching and control ion fluxes, with advanced polymers gradually overcoming the limitations of plasticized PVC.

- The electrode design and readout method offer the most dramatic leaps in sensitivity. The shift from classical potentiometry to voltammetric and coulometric readouts with solid-contact designs decouples sensitivity from the Nernstian limit, enabling the detection of minuscule concentration changes.

The future of the field lies in the continued development of highly stable and selective ionophores, the integration of novel nanostructured materials as transducers, and the refinement of dynamic electrochemical techniques that amplify the fundamental signal generated by these sophisticated chemical sensors.

The pursuit of lower detection limits is a fundamental driver in analytical chemistry, directly enabling advancements in areas ranging from environmental monitoring to clinical diagnostics. Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) and voltammetric methods represent two powerful electrochemical techniques, each with distinct mechanisms and theoretical ceilings for detectability. ISEs operate under conditions of zero current, measuring a potential difference at an electrode interface that follows a logarithmic relationship with ion activity. In contrast, voltammetric techniques apply a controlled potential to drive faradaic reactions, measuring the resulting current which is directly proportional to analyte concentration. This guide provides a systematic comparison of the ultimate detectability achievable with these methods, examining the theoretical frameworks, experimental parameters, and recent advancements that push the boundaries of trace-level analysis. Understanding these factors is crucial for researchers and drug development professionals selecting the optimal analytical approach for their specific application needs, particularly when dealing with limited sample volumes or ultra-trace analytes.

Fundamental Principles and Theoretical Detection Limits

The theoretical foundation governing detection limits differs substantially between ion-selective electrodes and voltammetric methods, establishing the ultimate boundaries of their performance.

Ion-Selective Electrodes (Potentiometry): ISEs measure the equilibrium potential across a selective membrane, following a Nernstian response where the potential (E) is related to ion activity (a) by the equation E = E⁰ + (RT/zF)ln(a), where R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is ion charge, and F is Faraday's constant [5]. The detection limit is theoretically governed by the point at which the measured potential deviates from this Nernstian response due to ion fluxes across the membrane or interference from the sample matrix [27] [28]. Crucially, the signal in potentiometry is a function of ion activity, not concentration, and is independent of sample volume. This means that, in principle, there is no theoretical lower bound on the total quantity of ion that can be detected if the sample volume can be made sufficiently small, as the potential reading depends only on the ionic activity at the membrane surface [27]. Fundamental limits may eventually be encountered when sample dimensions approach the Debye length, where electroneutrality violations occur [27].

Voltammetric Methods: Voltammetric detection limits are governed by the relationship between faradaic current (from analyte redox reactions) and non-faradaic charging current. The Cottrell equation, iₜ = nFAC√(D/πt), describes the diffusion-controlled faradaic current (iₜ) where n is electrons transferred, A is electrode area, C is concentration, D is diffusion coefficient, and t is time [8]. The detection limit is reached when the faradaic current becomes indistinguishable from the charging current, which decays exponentially and much faster than the faradaic current following a potential pulse [8]. Pulse techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) exploit this differential decay by measuring current after the charging current has substantially decayed, thus improving the signal-to-noise ratio [8]. For stripping voltammetry, where analyte is preconcentrated at the electrode surface prior to measurement, detection limits can be extended by 2-3 orders of magnitude compared to direct voltammetry, reaching sub-nanomolar levels for many metals [29] [30].

Table 1: Theoretical Basis for Detection Limits in ISEs and Voltammetry

| Parameter | Ion-Selective Electrodes (Potentiometry) | Voltammetric Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Signal | Potential (logarithmic with activity) | Current (linear with concentration) |

| Governing Equation | Nernst Equation | Cottrell Equation / Butler-Volmer Kinetics |

| Theoretical Limit Factor | Ion fluxes, membrane selectivity, Debye length | Charging current, diffusion layer, electron transfer kinetics |

| Sample Volume Dependence | Independent (activity-based) | Dependent (mass-dependent current) |

| Primary Signal Influence | Ion activity at membrane interface | Analyte concentration in bulk solution |

Quantitative Comparison of Achieved Detection Limits

Experimental data from recent studies demonstrates the practical detection limits achievable across various analytes and matrixes, highlighting the strengths of each technique in different application scenarios.

Extreme Sensitivity in ISEs: With optimized membranes and carefully controlled ion fluxes, ISEs have demonstrated remarkable detection capabilities. Research has shown direct potentiometric detection of calcium, lead, and silver ions at 100 picomolar concentrations, corresponding to absolute amounts on the order of 300 attomoles (10⁻¹⁸ moles) in microliter sample volumes without any preconcentration [27]. When applying the universal detection limit definition (three times the standard deviation of background noise), extrapolated limits can reach astonishing levels: 8.4 × 10⁻¹³ M for calcium (2.5 attomoles), 7.6 × 10⁻¹² M for lead (23 attomoles), and even 3.3 × 10⁻¹⁶ M for silver (0.98 zeptomoles) [27].

Voltammetric Performance Across Techniques: The detection limits in voltammetry vary significantly with the specific technique employed. Normal pulse polarography typically achieves limits of 10⁻⁶ M to 10⁻⁷ M, while differential pulse polarography, staircase, and square-wave polarography reach between 10⁻⁷ M and 10⁻⁹ M [30]. Stripping voltammetry, with its preconcentration step, provides the lowest voltammetric detection limits, often reaching 10⁻¹⁰ M to 10⁻¹² M for many analytes [30]. For example, anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV) of tin with various working electrodes and supporting electrolytes has demonstrated detection limits in the 10⁻⁸ M to 10⁻¹⁰ M range [29], while adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV) of tin with complexing agents like tropolone or catechol has achieved detection limits as low as 5.0 × 10⁻¹² M [29].

Table 2: Experimental Detection Limits for Selected Analytes

| Analyte | Technique | Detection Limit (Molar) | Detection Limit (Moles) | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Calcium | Potentiometric ISE | 1.0 × 10⁻⁸ (traditional); 8.4 × 10⁻¹³ (extrapolated) | 300 attomoles; 2.5 attomoles (extrapolated) | Micropipette tip electrode, low ion flux membrane [27] |

| Lead | Potentiometric ISE | 1.5 × 10⁻⁹ (traditional); 7.6 × 10⁻¹² (extrapolated) | 300 attomoles; 23 attomoles (extrapolated) | Micropipette tip electrode, pH 4.0 [27] |

| Silver | Potentiometric ISE | 1.0 × 10⁻⁸ (traditional); 3.3 × 10⁻¹⁶ (extrapolated) | 300 attomoles; 0.98 zeptomoles (extrapolated) | Micropipette tip electrode [27] |

| Tin | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry | ~10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹⁰ | Varies with sample volume | Various working electrodes and supporting electrolytes [29] |

| Tin | Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry | 5.0 × 10⁻¹² | Varies with sample volume | HMDE, tropolone complex, 600s accumulation [29] |

| Dopamine | Voltammetry (bare Au/Pt) | 10⁻⁷ | ~20 femtomoles in 200μL | Miniature cylinder cell, 200μL volume [31] |

Key Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Ultralow Detection Limit ISEs

1. Electrode Fabrication: Prepare ISEs in conventional polypropylene micropipette tips with membranes containing selective ionophores (e.g., ionophores I-III for Ca²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Ag⁺ respectively). Back-side contact the membranes with an appropriate inner solution [27].

2. Membrane Optimization: Drastically reduce zero-current ion fluxes from the membrane toward the sample by using conducting polymers as ion-to-electron transducers (solid-contact) or optimized aqueous inner solutions. This minimizes the primary factor that historically biased detection limits [27].

3. Measurement in Confined Samples: For microvolume analysis, mechanically insert the pipette tip electrodes into a 1-mm i.d. silicone tubing containing a single plug of sample (approximately 3 μL) separated on either side from aqueous solutions by a plug of air. This arrangement eliminates evaporation loss and confines the sample [27].

4. Reference System: Use a sodium-selective electrode as a pseudo-reference electrode since the background sodium concentration is known and constant. This avoids contamination from conventional reference electrodes [27].

5. Data Acquisition: Measure potential-time traces, washing the cell three times with the sample (ca. 5 μL each) at low flow rate between measurements to eliminate contamination. Calculate detection limits both by the traditional method (intersection of Nernstian response with background potential) and by the universal definition (three times the standard deviation of background noise) [27].

Protocol for High-Sensitivity Voltammetric Detection

1. Electrode Selection and Modification: Select working electrode based on analyte. For tin analysis, use hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE) or mercury film electrode (MFE). For dopamine, use bare gold or platinum electrodes, or carbon-based electrodes modified with nanomaterials like graphene or carbon nanotubes to enhance electron transfer [29] [31] [32].

2. Preconcentration (for Stripping Methods): For Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) of metals, deposit the analyte onto the electrode surface at a negative potential for a set duration (e.g., 60-600 seconds). For Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (AdSV), accumulate the analyte as a complex with a ligand (e.g., tropolone, catechol) on the electrode surface [29].

3. Potential Scanning: Apply a linear potential scan in the positive direction for ASV to oxidize the concentrated metal, or the appropriate potential waveform for other techniques. Use pulse techniques (DPV, SWV) to minimize charging current and enhance sensitivity [29] [8].

4. Signal Processing: Measure peak currents and relate them to concentration through calibration curves. Employ signal averaging and background subtraction to improve signal-to-noise ratio [8].

5. Interference Management: Add Ga³⁺ to minimize interference of Cu when analyzing for Zn by forming an intermetallic compound of Cu and Ga. Use complexing agents that selectively bind the target analyte in AdSV [29] [30].

Critical Factors Controlling Ultimate Detectability

Ion-Selective Electrodes

Ion Fluxes and Membrane Composition: The dominant factor limiting ISE detection limits is zero-current ion flux from the membrane into the sample, which can deplete ions at the membrane-sample interface in dilute solutions. This can be mitigated by using membranes with reduced ionophore mobility, appropriate inner solutions, or conducting polymer intermediate layers [27] [28].

Selectivity Coefficients: The ultimate span and detection limit of an ISE are directly influenced by the selectivity coefficients (Kₚₒₜ^A,B) over interfering ions. Even minor interference becomes significant at trace levels, limiting the practical detection limit [28].

Sample Volume and Contamination: While potentiometric signals are theoretically independent of sample volume, practical measurements in ultra-small volumes require careful attention to contamination from reference electrodes and leaching from cell components [27].

Voltammetric Methods

Charging Current vs. Faradaic Current: The fundamental limitation in voltammetry is the discrimination between faradaic current (from analyte redox) and charging current (from double-layer capacitance). Pulse techniques that exploit the different decay rates of these currents are essential for low detection limits [8].

Electrode Fouling and Surface Renewal: Particularly in biological samples, electrode fouling from adsorbed proteins or oxidation products can significantly degrade detection limits over time. Using pulsed waveforms that include cleaning potentials or modified electrodes with anti-fouling properties can mitigate this [31] [32].

Mass Transport Limitations: In quiescent solutions and small volumes, diffusion-limited transport of analyte to the electrode surface can restrict current, particularly for irreversible systems. Using microelectrodes or stirred solutions during accumulation phases can enhance mass transport [31].

Intermetallic Compound Formation: In anodic stripping voltammetry of multiple metals, intermetallic compound formation (e.g., between Cu and Zn) can distort stripping peaks and degrade detection limits and accuracy [30].

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Detection

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Ionophores (Neutral Carriers) | Selective binding of target ions in ISE membranes | Ca²⁺, Pb²⁺, Ag⁺, K⁺ selective electrodes [27] [28] |

| Ion-Exchangers (e.g., KTpClPB) | Charge counterion in ISE membranes | Cation-selective polymer membranes [31] |

| Redox Couples (e.g., FcMeOH) | Provide internal redox couple in voltammetric ISEs | Internal solution for voltammetric ion sensing [5] |

| Complexing Agents (e.g., tropolone) | Form electroactive complexes with target metals | Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry of tin [29] |

| Nanomaterials (e.g., CNTs, graphene) | Enhance electron transfer, increase surface area | Voltammetric sensors for dopamine, heavy metals [32] |

| Anti-fouling Agents | Prevent surface adsorption in complex matrices | Polymer coatings for biological samples [32] |

The ultimate detectability in both ion-selective electrodes and voltammetric methods is governed by distinct theoretical frameworks and practical limitations. ISEs offer unparalleled capability for direct measurement of ultralow quantities of ions, with demonstrated attomole to zeptomole detection in confined samples, as their potentiometric signal is activity-based and independent of sample volume. Voltammetric techniques, particularly stripping methods with preconcentration, excel at achieving low concentration detection limits through sophisticated waveform design that discriminates faradaic from charging currents. The choice between these techniques ultimately depends on the specific analytical requirements: ISEs provide the advantage for direct measurement of total ion quantities in volume-limited samples without consumption of analyte, while voltammetry offers greater versatility for both organic and inorganic analytes with exceptional concentration-based detection limits. Future advancements in materials science, particularly through nanomaterial integration and optimized membrane architectures, promise to further push these detection limits while addressing challenges such as electrode fouling and selectivity in complex matrices.

Methodological Advances and Applications in Pharmaceutical and Clinical Analysis

Ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) represent a cornerstone of modern electrochemical sensing, enabling the precise quantification of ionic species across biomedical, environmental, and industrial applications. Traditional liquid-contact ISEs (LC-ISEs), while effective, suffer from inherent limitations including evaporation of internal filling solution, osmotic pressure effects, and challenges in miniaturization [33]. The evolution toward solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs) has revolutionized the field by eliminating the internal solution, thereby enhancing portability, stability, and compatibility with miniaturized systems [15] [33]. Contemporary innovations focus on integrating advanced nanomaterial transducers and refining electrode architectures to push the boundaries of sensitivity, detection limits, and operational stability.

This paradigm shift is particularly significant within the broader context of detection limits research, where SC-ISEs increasingly compete with highly sensitive voltammetric methods. While voltammetric techniques traditionally offer superior detection limits for certain applications, recent advancements in SC-ISE design have dramatically closed this performance gap, enabling detection capabilities approaching those of voltammetry while maintaining the inherent advantages of potentiometric sensing [5] [18].

Core Components and Working Principles of SC-ISEs

Architectural Foundation

Solid-contact ion-selective electrodes feature a layered architecture consisting of three essential components: a conductive substrate, a solid-contact (SC) layer functioning as an ion-to-electron transducer, and an ion-selective membrane (ISM) [33]. This configuration replaces the internal filling solution of traditional ISEs with a solid-state interface, thereby circumventing issues related to solution maintenance and enabling robust miniaturization [33].

The operational principle hinges on potentiometric measurement, where the potential difference between the SC-ISE and a reference electrode is measured under zero-current conditions [33]. When target ions interact with the ion-selective membrane, an interfacial potential develops that follows the Nernst equation, providing a logarithmic relationship between potential and ion activity [33]. The critical function of the solid-contact layer is to facilitate efficient transduction between ionic currents in the membrane and electronic currents in the conductive substrate, a process achieved through either redox capacitance or electric double-layer capacitance mechanisms [33].

Ion-Selective Membrane Composition

The ion-selective membrane represents the recognition element of the sensor and its composition critically determines analytical performance:

- Ionophores: Molecular recognition elements responsible for selectively complexing with target ions. Highly hydrophobic ionophores prevent leaching and enhance sensor longevity [33].

- Polymer Matrix: Typically polyvinyl chloride (PVC) or its derivatives, providing mechanical stability and serving as the membrane backbone [33].

- Plasticizer: Imparts plasticity and mobility to membrane components, with selection influencing dielectric constant and ionophore compatibility [33].

- Ion Exchanger: Introduces fixed ionic sites to establish Donnan exclusion and facilitate ion exchange processes [33].

Table 1: Key Components of Ion-Selective Membranes and Their Functions

| Component | Representative Examples | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrix | PVC, polyurethane, acrylic esters | Provides structural integrity and mechanical stability |

| Ionophore | Valinomycin (K⁺), Calix[4]arene (Ag⁺) | Selectively binds target ions for recognition |

| Plasticizer | DOS, NPOE, DBP | Enhances membrane fluidity and modulates permselectivity |

| Ion Exchanger | NaTFPB, KTPCIPB | Facilitates ion exchange and establishes Donnan potential |

Recent research has revealed that even seemingly inert components like electrode body materials (PVC, PTFE, PEEK) can significantly influence sensor performance, particularly for anionic measurements where selectivity variations exceeding 100-fold have been observed depending on material selection [34].

Nanomaterial Transducers: Enhancing SC-ISE Performance

Carbon-Based Nanomaterials

Carbon nanomaterials have emerged as particularly effective transducers due to their high electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, and tunable surface chemistry. Multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) have demonstrated exceptional performance in SC-ISEs, serving as efficient ion-to-electron transducers that significantly enhance potential stability [35].

The hydrophobic nature of MWCNTs plays a crucial role in preventing the formation of an undesirable water layer at the electrode/membrane interface—a common failure mechanism in SC-ISEs that causes potential drift [35]. In a specific application for silver ion detection, MWCNT-modified sensors achieved a detection limit of 4.1 × 10⁻⁶ M with a near-Nernstian slope of 61.029 mV/decade, highlighting the efficacy of this nanomaterial in practical sensing applications [35].

Other carbon nanostructures showing promise include hollow carbon nanospheres (HCN) and N-doped porous carbon coated by reduced graphene oxide (NPCs@rGO), which provide abundant sites for ion-electron transduction and further improve sensor stability and performance [15].

Conducting Polymers and Novel Composites

Conducting polymers (CPs) represent another major class of transducer materials, functioning through reversible redox reactions that provide high capacitance at the electrode/membrane interface. These materials exhibit both electronic and ionic conductivity, making them ideally suited for ion-to-electron transduction [33].

The transduction mechanism in conducting polymer-based SC-ISEs involves the reversible oxidation and reduction of the polymer backbone, coupled with the transfer of ions between the membrane and transducer layer to maintain charge neutrality [33]. This mechanism can be represented as:

CP⁺A⁻(SC) + M⁺(SIM) + e⁻ ⇌ CP°A⁻M⁺(SC) for cationic response, and

CP⁺R⁻(SC) + e⁻ ⇌ CP°(SC) + R⁻(SIM) for anionic response [33].

Advanced composite materials that combine nanomaterials with conducting polymers have demonstrated synergistic effects, further enhancing capacitance, stability, and overall transducer performance [33].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Metrics and Methodologies

Sensor Fabrication Protocols

MWCNT-Modified Silver Ion-Selective Electrode [35] The development of a solid-contact ISE for silver ion detection follows a systematic fabrication process:

- Electrode Preparation: Begin with screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) as the conductive substrate.

- Transducer Application: Deposit a layer of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) onto the electrode surface to form the ion-to-electron transduction layer.

- Membrane Formulation: Prepare the ion-selective membrane containing:

- Polymer matrix: High molecular weight polyvinyl chloride (PVC)

- Plasticizer: 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE)

- Ionophore: Calix[4]arene for selective silver ion recognition

- Ion exchanger: Sodium tetrakis [3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)phenyl] borate

- Membrane Deposition: Apply the membrane cocktail over the MWCNT layer and allow solvent evaporation to form a uniform sensing film.

Voltammetric ISE with Internal Aqueous Solution [5] [18] For voltammetric ion sensing using traditional ISE architecture:

- Electrode Assembly: Use classical ISE body with internal filling solution.

- Redox-Active Internal Solution: Prepare internal solution containing:

- Chloride salt of target cation (Ca²⁺, Li⁺, or K⁺)

- Redox couple (ferrocenemethanol or ferrocyanide/ferricyanide)

- Internal Electrode: Implement platinum wire as internal reference electrode.

- Membrane Application: Apply conventional ion-selective membrane (100-300 μm thickness) to separate internal solution from sample.

Performance Comparison

Table 2: Comparative Performance of Recent Innovative ISE Designs

| Electrode Design | Target Ion | Linear Range (M) | Detection Limit (M) | Slope (mV/decade) | Lifetime | Key Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MWCNT-SC-ISE [35] | Ag⁺ | 1.0×10⁻⁵ to 1.0×10⁻² | 4.1×10⁻⁶ | 61.03 | Not specified | MWCNT transducer layer prevents water layer formation |

| Voltammetric ISE [5] | Ca²⁺, Li⁺, K⁺ | Not specified | Improved with background electrolyte | Nernstian peak shift | ~1 month | Internal redox couple enables voltammetric sensing |

| Redox Capacitance SC-ISE [33] | Various | Varies by design | Nanomolar range achievable | Nernstian | Enhanced stability | Conducting polymers with high redox capacitance |

| Electric Double-Layer SC-ISE [33] | Various | Varies by design | Nanomolar range achievable | Nernstian | Enhanced stability | Carbon materials with high double-layer capacitance |

The Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Advanced ISE Development

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function in ISE Development |

|---|---|---|

| Polymer Matrices | PVC, polyurethane, acrylic esters, polystyrene | Forms structural backbone of ion-selective membrane |

| Ionophores | Valinomycin (K⁺), Calix[4]arene (Ag⁺), Calix[6]arene, Cucurbit[6]uril | Provides selective recognition for target ions |

| Plasticizers | DOS, NPOE, DBP, DOP | Enhances membrane fluidity and modulates dielectric properties |

| Ion Exchangers | NaTFPB, KTPCIPB, KTFPB | Establishes ion exchange sites and Donnan exclusion |

| Transducer Materials | MWCNTs, conducting polymers (PEDOT), graphene derivatives | Facilitates ion-to-electron transduction in solid-contact layers |

| Electrode Materials | Screen-printed electrodes, glassy carbon, platinum wire | Provides conductive substrate for sensor construction |

Detection Limits Perspective: SC-ISEs vs. Voltammetric Methods

The ongoing innovation in SC-ISE design occurs within the broader context of detection limits research, where the performance gap between potentiometric and voltammetric methods continues to narrow. Voltammetric techniques have traditionally offered superior detection limits, with recent methodologies achieving impressive sensitivity across various analytes [36] [37]. However, the fundamental limitation of voltammetry lies in its susceptibility to Ohm's drop and interference effects, particularly in complex sample matrices [33].

SC-ISEs present distinct advantages in this regard, as potentiometric measurements are less affected by these confounding factors [33]. Furthermore, the logarithmic response of ISEs enables quantification over extensive concentration ranges—a significant advantage for applications requiring wide dynamic range [5]. Recent breakthroughs in SC-ISE design have pushed detection limits to nanomolar concentrations, approaching the sensitivity traditionally associated with voltammetric methods while maintaining the practical advantages of potentiometric sensing [33] [5].

The emergence of voltammetric operation with ISEs represents a convergence of these methodologies, leveraging the recognition chemistry of ISEs with the sensitive measurement capabilities of voltammetry [5] [18]. This hybrid approach demonstrates Nernstian shifts in peak potentials with varying ion activities while maintaining stable peak currents—delivering the specificity of ion-selective membranes with the quantitative robustness of voltammetric analysis [18].

The innovation landscape in ion-selective electrode design demonstrates a clear trajectory toward solid-contact architectures with nanomaterial-enhanced transducers. The integration of materials such as MWCNTs, conducting polymers, and advanced carbon composites has substantially addressed historical limitations of SC-ISEs, particularly regarding potential drift and lifetime stability [33] [35]. These advancements have narrowed the performance gap with voltammetric methods while preserving the practical advantages of potentiometric sensing.

Future development in this field will likely focus on several key areas: enhanced multimodal sensing capabilities through voltammetric and potentiometric operation with a single sensor [5] [18], further miniaturization and integration with wearable platforms [15], improved green chemistry profiles through sustainable materials [35], and expanded application in complex matrices including biological and environmental samples. As these innovations continue to mature, the distinction between potentiometric and voltammetric approaches may further blur, ultimately yielding a new generation of electrochemical sensors offering the complementary advantages of both methodologies.

The accurate determination of trace-level analytes is a fundamental challenge in analytical chemistry, particularly in fields such as environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and clinical diagnostics. Electrochemical methods offer a powerful suite of tools for this purpose, combining sensitivity, selectivity, and relative operational simplicity. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three prominent voltammetric techniques—Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV). Framed within the broader context of sensor research, this guide objectively compares their performance against ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), focusing on detection limits, applicable concentration ranges, and practical implementation. The content is designed to assist researchers and scientists in selecting the most appropriate technique for their specific trace analysis requirements.

The choice between voltammetric methods and ion-selective electrodes is primarily dictated by the required sensitivity, the nature of the sample, and the analytical question being addressed. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of ISEs and the three voltammetric techniques covered in this guide.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Voltammetric Techniques and Ion-Selective Electrodes

| Technique | Typical Detection Limit | Key Advantages | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) | Nanomolar to micromolar range [38] | Portability, cost-effectiveness, fast response times, suitable for in-situ and real-time analysis [38]. | Food safety analysis, environmental monitoring of heavy metals (Al, Cu, Pb, Hg, Ni, Co, Cd, Se, Sn, Zn, As) [38]. |

| Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | 10–7 M to 10–9 M [39] | Very fast scan times, effective background suppression, suitable for studying electron transfer kinetics (kHET of 5–120 s–1) [40] [39]. | Study of immobilized redox proteins, forensic analysis of organic and inorganic analytes [40] [41]. |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | 10–7 M to 10–9 M [39] | Excellent sensitivity, very effective minimization of charging (non-Faradaic) current, well-defined peak-shaped signal [42]. | Trace analysis of drugs in pharmaceuticals and serum, detection of heavy metals in water, biomolecule sensing (dopamine, serotonin) [43] [42]. |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | 10–10 M to 10–12 M [39] | Extremely low detection limits due to pre-concentration of analyte, suitability for metal ion analysis [44] [39]. | Speciation analysis of trace metals (e.g., Cu, Zn, Cd, Pb) in natural waters, determination of In(III) in sea water [44] [45]. |

While ISEs are invaluable for portable, rapid analysis, their detection limits are generally higher than those achievable with advanced voltammetric techniques [38]. Stripping techniques like ASV are unrivaled for ultra-trace metal analysis, while pulse techniques like SWV and DPV offer high sensitivity for a broader range of electroactive species, including organic molecules.

In-Depth Analysis of Voltammetric Techniques

Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV)

SWV is a sophisticated pulsed technique known for its speed and sensitivity. The potential waveform in SWV consists of a square wave superimposed on a staircase baseline. The current is sampled at the end of each forward and reverse pulse, and the difference between these two currents is plotted against the applied potential, resulting in a peak-shaped voltammogram. This differential current effectively cancels out the capacitive background, leading to a significant enhancement of the Faradaic signal [39].

SWV is particularly powerful for kinetic studies, as it can be used to interrogate electron transfer rates of immobilized systems. For instance, it has been successfully applied to determine the heterogeneous electron transfer (HET) rate constant of cytochrome c on functionalized electrodes, with a reported applicable range of kHET from 5 to 120 s–1 [40]. This makes it suitable for a broader range of electron transfer rates compared to Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) or Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) [40]. Its fast scan rate also makes it ideal for high-throughput screening and for studying rapid reaction mechanisms.

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

DPV is a cornerstone technique for high-sensitivity quantitative analysis. In DPV, small amplitude potential pulses are applied to a staircase ramp. The current is measured immediately before the pulse application and again at the end of the pulse. The key to DPV's sensitivity is that the recorded signal is the difference between these two measurements (Δi = i₂ - i₁) [42]. Because the non-Faradaic charging current decays rapidly and contributes almost equally to both sampling points, it is effectively subtracted out, leaving a well-defined peak that is predominantly Faradaic in origin [42].

This efficient background suppression allows DPV to achieve low detection limits, often in the nanomolar range, making it a preferred method for quantifying trace levels of analytes. For example, DPV has been validated for the analysis of the anti-epileptic drug carbamazepine in serum, demonstrating performance comparable to established immunoassay methods and meeting FDA guidelines for bioanalytical methods [43]. Its application extends to environmental monitoring, where it is used for heavy metal detection, often in conjunction with stripping techniques for enhanced sensitivity [42].

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV)

ASV is a two-step technique renowned for its exceptionally low detection limits for metal ions. The analysis begins with a deposition step, where the target metal cations (e.g., Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, In³⁺) are reduced and pre-concentrated onto or into the working electrode (commonly a mercury film or bismuth electrode) at a constant negative potential. This pre-concentration step, which can last from seconds to minutes, effectively amplifies the amount of analyte at the electrode surface. Following deposition, the potential is scanned in an anodic (positive) direction, causing the accumulated metal to be oxidized back into solution. The resulting oxidation current is measured, and its magnitude is proportional to the concentration of the metal in the original solution [44] [39].

The power of ASV lies in this pre-concentration effect, which can lower detection limits to the picomolar (10–12 M) level [39]. It is extensively used for the speciation analysis of trace metals in natural waters, allowing discrimination between labile (bioavailable) and inert (organically complexed) metal fractions [44]. A recent study on indium(III) determination demonstrated a detection limit of 1.4 × 10–9 mol L–1 using ASV with a solid bismuth microelectrode, highlighting its applicability for ultra-trace analysis in complex matrices like seawater [45].

Table 2: Direct Comparison of Key Performance Metrics for SWV, DPV, and ASV

| Performance Metric | Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limit | 10–7 M – 10–9 M [39] | 10–7 M – 10–9 M [39] | 10–10 M – 10–12 M [39] |

| Analytical Signal | Peak-shaped (Difference Current) | Peak-shaped (Differential Current) | Peak-shaped (Stripping Current) |

| Key Advantage | Speed and kinetic information [40] | Excellent signal-to-noise for quantification [42] | Ultra-trace sensitivity via pre-concentration [44] |

| Primary Application Scope | Electron transfer kinetics, fast scans [40] | Quantification of trace organics/inorganics [43] [42] | Ultra-trace metal ion analysis and speciation [44] |

Experimental Protocols and Best Practices

Example Protocols from Recent Research

Protocol 1: Determination of In(III) using ASV and AdSV This protocol outlines a direct comparison of two stripping techniques for indium analysis [45].

- Working Electrode: Environmentally friendly solid bismuth microelectrode (SBiµE), diameter 25 µm.

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 mol L–1 acetate buffer (pH 3.0 ± 0.05).

- ASV Procedure:

- Activation: -2.4 V for 20 s.

- Accumulation/Deposition: -1.2 V for 20 s.

- Stripping Scan: Positive potential scan from -1.0 V to -0.3 V.

- Results: Linear range from 5×10–9 to 5×10–7 mol L–1 with a detection limit of 1.4×10–9 mol L–1 [45].

Protocol 2: Interrogating Electron Transfer Rates using SWV This study employed SWV to investigate the heterogeneous electron transfer rate of immobilized cytochrome c [40].