Cyclic Voltammetry in Modern Research: From Fundamental Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Development and Energy Science

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cyclic voltammetry (CV), a powerful electrochemical technique essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Cyclic Voltammetry in Modern Research: From Fundamental Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications in Drug Development and Energy Science

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of cyclic voltammetry (CV), a powerful electrochemical technique essential for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, including redox behavior and the Nernst equation, and explores diverse methodological applications from characterizing fuel cell catalysts and screening pharmaceutical antioxidants to assessing seed viability. The content also addresses advanced troubleshooting for data interpretation, the impact of finite diffusion, and innovative optimization strategies, including machine learning for high-throughput analysis. Finally, it examines CV's role in validation through comparative studies with other analytical techniques, offering a holistic view of its critical function in both fundamental research and applied sciences.

Understanding Cyclic Voltammetry: Core Principles and What a Voltammogram Reveals

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) stands as a cornerstone electrochemical technique, indispensable for probing the redox properties of chemical species, studying reaction mechanisms, and characterizing materials critical to advancements in conductive polymers, battery technology, and pharmaceutical development [1] [2]. The power and precision of this technique are fundamentally enabled by its underlying hardware: the three-electrode system. This configuration is not merely a convenience but a necessity for obtaining accurate, reproducible, and meaningful data. It separates the crucial function of potential measurement from the current-carrying circuit, thereby overcoming the significant limitations of simpler two-electrode setups [3] [4]. Within the broader context of research applications—from determining drug-DNA interactions to optimizing battery materials—understanding the three-electrode system is paramount [5]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of this essential setup, detailing its core principles, constituent parts, and operational protocols to empower researchers in harnessing its full potential.

The Core Principle: Why Three Electrodes Are Essential

In the early days of electrochemistry, experiments were primarily conducted using a two-electrode system. While simple, this approach had significant drawbacks, particularly in measuring and controlling electrode potentials, which led to considerable errors [3]. The introduction of the reference electrode in the 1920s created the modern three-electrode system, a innovation that dramatically improved the precision and reproducibility of electrochemical experiments [3].

The fundamental breakthrough of the three-electrode cell is its "two-circuit" conceptual design [3]. It establishes two distinct electrical pathways:

- The Potential Circuit: A high-impedance voltmeter measures and controls the potential difference between the working electrode and the reference electrode. This circuit draws negligible current, ensuring the reference electrode's potential remains stable and providing an accurate baseline for measurement.

- The Current Circuit: An ammeter measures the current flowing between the working electrode and the counter electrode. This circuit handles the sometimes substantial current required for the electrochemical reaction at the working interface.

This separation is critical because it allows the potentiostat (the instrument controlling the experiment) to precisely control the energy at which redox reactions occur at the working electrode, independent of the current flowing through the solution [1] [3]. In a two-electrode system, the voltage drop across the solution resistance (known as the iR drop) and polarization of the counter electrode obscure the true potential at the working electrode, leading to distorted data and inaccurate interpretations [3] [4]. The three-electrode system effectively eliminates this ambiguity.

System Components: Anatomy of a Three-Electrode Cell

A three-electrode system consists of three distinct components, each with a specific, non-interchangeable role. The careful selection and preparation of each electrode are vital for experimental success.

The Working Electrode (WE)

The Working Electrode is the star of the experiment; it is the site where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs [3]. Its properties must be carefully controlled to ensure reproducible results.

- Role: The stage for the redox reaction. The applied potential drives the target analyte to be oxidized or reduced at its surface [6].

- Material Requirements: It must be chemically inert relative to the electrolyte, possess a reproducible surface state, and have a defined geometric area [3].

- Common Materials: Glassy carbon, platinum, and gold are frequently used [3]. In specialized applications, composite battery electrode materials or chemically modified electrodes are employed as the WE [7] [8].

The Reference Electrode (RE)

The Reference Electrode is the cornerstone of accurate potential measurement. It provides a stable, well-known, and constant reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled and measured [1] [3].

- Role: To maintain a fixed potential, providing a baseline for all potential measurements in the system [3].

- Key Principle: It is designed to be non-polarizable, meaning its potential remains stable even if minor currents flow. In a properly configured system, minimal current passes between the RE and the WE, which is key to its stability [1].

- Common Types: The Ag/AgCl (silver/silver chloride) electrode and the saturated calomel electrode (SCE) are widespread choices. Recent research also explores simpler quasi-reference electrodes (e.g., a bare silver or platinum wire) for specific applications, though their potential may be less stable than conventional reference electrodes [9] [8].

The Counter Electrode (CE)

The Counter Electrode, also known as the auxiliary electrode, completes the electrical circuit.

- Role: To balance the current generated by the electron transfer at the working electrode [1] [3]. It supplies the current required to facilitate the reaction at the WE.

- Material and Design: It is typically made from an inert, highly conductive material like platinum or graphite [3]. A critical design rule is that the counter electrode should have a surface area significantly larger than that of the working electrode. This ensures that the reaction at the CE is not rate-limiting and that it can supply the necessary current without becoming polarized [3] [4].

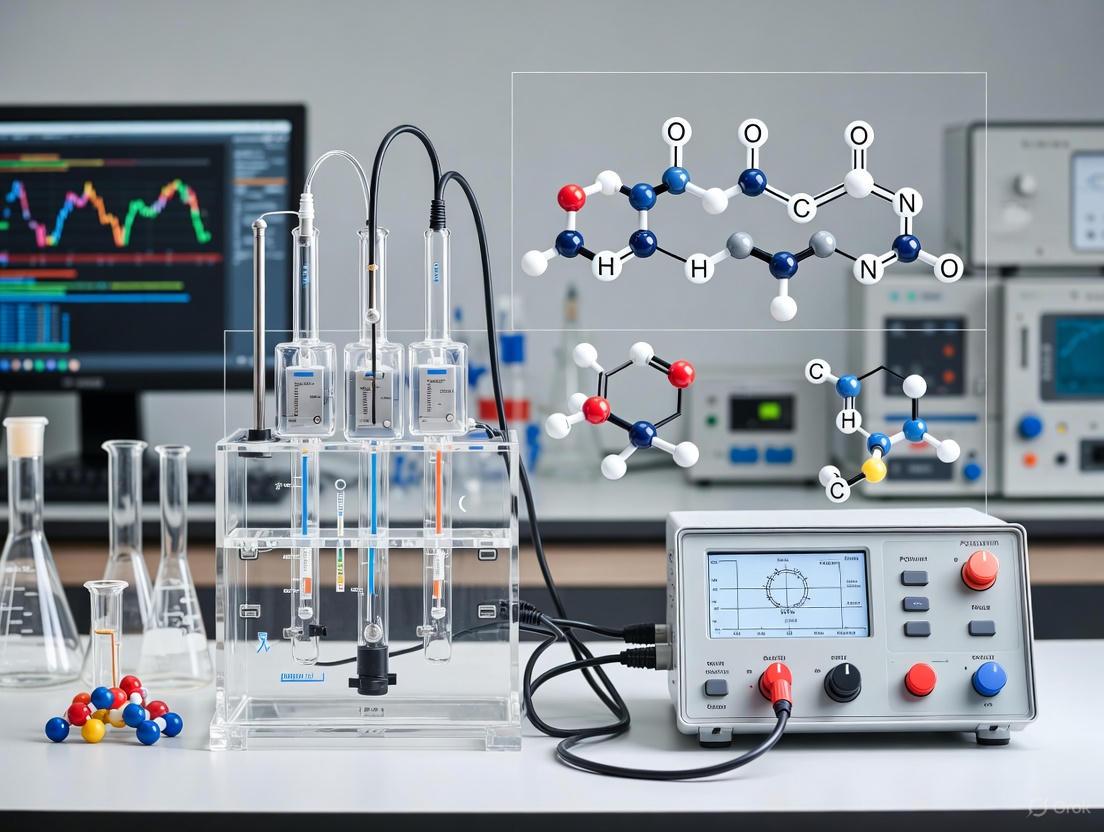

The following diagram illustrates the electrical relationships and current flow within this three-electrode setup.

Experimental Protocol: Setting Up a CV Experiment

Executing a reliable CV experiment requires meticulous attention to setup and procedure. The following workflow outlines the key stages.

Step-by-Step Methodology

Cell and Electrode Preparation: The electrochemical cell is filled with an electrolyte solution containing the analyte of interest [1]. The three electrodes are immersed in the solution. A key best practice is to position the tip of the reference electrode close to the working electrode to minimize uncompensated solution resistance (iR drop) [3]. The working electrode surface often requires polishing and cleaning to ensure a reproducible state before each experiment [3].

Electrical Connection: The potentiostat leads are connected to the corresponding electrodes. Critically, both the RED (working drive) and ORANGE (working sense) leads are connected to the working electrode. The WHITE (reference sense) lead is connected to the reference electrode, and the GREEN (counter drive) lead is connected to the counter electrode [10].

Parameter Configuration: The experimental parameters are set in the potentiostat's software. These include:

- Initial Potential (Eᵢ): The starting voltage for the sweep [2].

- Upper and Lower Potential Limits (Eλ): The vertex potentials where the scan direction reverses [6].

- Scan Rate (ν): The speed at which the potential is changed, typically expressed in mV/s or V/s. This is a critical parameter that affects the current response [1] [2].

Experiment Execution: The potentiostat begins the potential sweep. It linearly ramps the potential of the working electrode from the initial value to the first vertex potential, then reverses the sweep back through the initial potential to the second vertex, often repeating this cycle multiple times [1] [2]. Throughout this process, it meticulously records the current response at the working electrode.

Data Acquisition and Analysis: The result is a cyclic voltammogram—a plot of current (I) versus the applied potential (E) [2]. This characteristic "duck-shaped" curve is then analyzed for key features such as peak potentials (Epa and Epc) and peak currents (ipa and ipc), which contain information about the thermodynamics and kinetics of the redox process [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A successful CV experiment relies on a suite of carefully selected reagents and materials. The table below details the core components of a researcher's toolkit for a standard CV analysis.

| Item | Function & Importance | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat | The control center; applies the potential sweep and measures the resulting current with high precision and low noise [3]. | IEST Electrochemical Analyzer, Gamry Potentiostats, Ossila Potentiostat [1] [3] [2]. |

| Working Electrode | The site of the reaction of interest; material choice depends on required potential window and chemical inertness [3]. | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Platinum Disc Electrode, Gold Electrode [3] [8]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable potential reference; critical for accurate and reproducible measurements [3]. | Ag/AgCl (3M KCl), Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [3] [2]. |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the circuit; must be inert and have large surface area to avoid becoming rate-limiting [3]. | Platinum Mesh, Graphite Rod, Platinum Wire [3] [9]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes resistive loss (iR drop); must be inert in the scanned potential window [1]. | Salts in buffer solutions (e.g., Phosphate Buffer Saline, KCl, NaClO₄) [5]. |

| Redox Probe | A standard used for system validation and calibration [1] [9]. | Potassium Ferricyanide, Ferrocene [1] [9]. |

Quantitative Foundations: Key Equations in CV

The data extracted from a cyclic voltammogram can be quantified using several fundamental equations, transforming qualitative observations into hard data.

Table 2: Fundamental Equations of Cyclic Voltammetry

| Equation Name | Mathematical Formula | Parameters and Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Nernst Equation | E = E° + (RT/nF) * ln(Cₒₓ/Cᵣₑ𝒹) |

Describes the thermodynamic potential of a redox couple at equilibrium. E is the electrode potential, E° is the standard potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, n is the number of electrons, F is Faraday's constant, and Cₒₓ/Cᵣₑ𝒹 is the ratio of oxidized to reduced species [1] [2]. |

| Randles-Ševčík Equation | ip = (2.69×10⁵) * n³/² * A * D¹/² * C * ν¹/² |

Relates the peak current (ip) to the concentration (C) and diffusion coefficient (D) of the analyte. A is the electrode area, and ν is the scan rate. This equation is used for quantitative analysis and determining diffusion coefficients [1] [2]. |

| Butler-Volmer Equation | i = i₀ * [exp(αnFη/RT) - exp(-(1-α)nFη/RT)] |

Describes the kinetics of an electrochemical reaction. i is the current density, i₀ is the exchange current density, α is the charge transfer coefficient, and η is the overpotential [2]. |

Innovations and Future Directions

While the conventional three-electrode system is well-established, research continues to develop more robust, miniaturized, and user-friendly configurations. A significant innovation is the development of same-metal three-electrode systems. For example, one study demonstrated a miniaturized printed circuit board (PCB) where the counter, working, and reference electrodes were all fabricated from gold. This design simplified the setup, required only trace amounts of analyte, and showed impressive repeatability and sensitivity compared to traditional systems [9]. Another advancement is the creation of an integrated, polishable, and reusable triple electrode, which eliminates the need for a separate cell and reduces chemical consumption, making it a suitable alternative to screen-printed electrodes for certain applications [8]. These developments highlight a clear trend towards portability, integration, and operational simplicity without sacrificing analytical performance.

The three-electrode system is the unsung hero of cyclic voltammetry, providing the precise control and accurate measurement required to unlock detailed insights into redox processes. Its elegant separation of potential measurement and current flow overcomes the fundamental limitations of two-electrode setups, making it indispensable for serious electrochemical research. From elucidating drug-DNA interactions to characterizing next-generation battery materials, the principles and protocols outlined in this guide form the foundation for reliable and impactful scientific discovery. As electrochemical applications continue to expand into fields like point-of-care diagnostics and portable sensors, the ongoing innovation in electrode design ensures that the three-electrode system will remain a vital tool for researchers and drug development professionals for the foreseeable future.

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) stands as one of the most ubiquitous electrochemical techniques employed in research today due to its powerful capability for rapidly elucidating redox properties of molecules and materials. This potent characterization tool operates by cycling the potential of a working electrode in a controlled manner while measuring the resulting current, generating a plot of current versus potential known as a voltammogram [11] [12]. The widespread adoption of CV spans diverse fields including inorganic and organic synthesis, materials science, sensor development, biological system evaluation, and fundamental studies of electron transfer mechanics [12]. Within the context of a broader research thesis, understanding what CV is used for reveals its fundamental role in determining formal redox potentials, assessing electron transfer kinetics, quantifying diffusion coefficients, investigating coupled chemical reactions, and characterizing electrocatalytic materials [12] [13]. The technique provides both qualitative and quantitative insights into electrochemical systems, serving as a cornerstone method for initial redox characterization of novel compounds and functional materials [13].

The interpretation of a voltammogram centers on decoding its key features—specifically peak currents and peak potentials—which serve as fingerprints of the underlying electrochemical processes. This guide provides an in-depth technical examination of these critical parameters, detailing their theoretical foundation, practical measurement, and significance in analyzing reversible, quasi-reversible, and irreversible systems. By mastering the interpretation of these features, researchers can extract rich information about their systems of interest, from the energy levels of semiconducting polymers to the catalytic efficiency of novel electrode materials for fuel cell applications [14] [15].

Fundamental Principles of Cyclic Voltammetry

In a typical CV experiment, the potential of a working electrode is swept linearly between designated initial and vertex potentials in a triangular waveform while the current response is measured [12]. The potential sweep rate (v) is a controlled parameter that defines the experimental timescale. When the potential reaches a value sufficient to drive the reduction or oxidation of an analyte, a Faradaic current develops, creating characteristic peaks in the voltammogram [11]. The forward scan generates a cathodic peak current (ipc) for reduction processes, while the reverse scan produces an anodic peak current (ipa) for oxidation processes [11] [13].

The physical origin of these peaks lies in the interplay between electron transfer kinetics and mass transport. As the potential is swept toward the reduction potential of an analyte, current increases rapidly as the analyte is reduced at the electrode surface. This current reaches a peak when the concentration of analyte at the electrode surface approaches zero, creating a maximum concentration gradient and thus maximal flux to the electrode. The current then decays as the diffusion layer extends further into solution, requiring analyte to diffuse over greater distances to reach the electrode surface [11]. This sequence creates the characteristic peak shape observed in voltammograms.

Table 1: Fundamental Equations in Cyclic Voltammetry

| Parameter | Equation | Variables and Constants | Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Randles-Ševčík Equation (at 25°C) | ( i_p = (2.69 \times 10^5) n^{3/2} A C D^{1/2} v^{1/2} ) | n = electron number, A = electrode area (cm²), C = concentration (mol/cm³), D = diffusion coefficient (cm²/s), v = scan rate (V/s) | Relates peak current to concentration and scan rate for diffusion-controlled processes [12] [13] |

| Peak Potential Separation | ( \Delta Ep = E{pa} - E_{pc} = \frac{59}{n} mV ) (for reversible systems) | Epa = anodic peak potential, Epc = cathodic peak potential, n = number of electrons | Diagnoses electrochemical reversibility [13] |

| Formal Potential | ( E^{0'} = \frac{E{pa} + E{pc}}{2} ) | Epa = anodic peak potential, Epc = cathodic peak potential | Estimates formal reduction potential for reversible systems [11] [15] |

| Surface Adsorption Peak Current | ( i_p(ads) = \frac{n^2 F^2}{4RT} v A \Gamma ) | Γ = surface coverage of electroactive species, A = electrode area, v = scan rate | Describes current for surface-bound species [14] [16] |

The key parameters extracted from a voltammogram include the peak potentials (Epc and Epa), peak currents (ipc and ipa), and the half-wave potential (E1/2), which is often approximated as the average of the peak potentials for reversible systems [15]. These parameters provide the foundation for quantitative analysis of electrochemical systems, enabling researchers to determine concentration, identify species through their redox potentials, and assess the reversibility of electron transfer processes.

Identifying and Interpreting Key Voltammogram Features

Peak Currents and Potentials

The most prominent features of a cyclic voltammogram are the anodic and cathodic peaks, each defined by both current and potential coordinates. The anodic peak current (Ipa) and anodic peak potential (Epa) correspond to the oxidation half-cycle, where electrons flow from the analyte to the electrode, while the cathodic peak current (Ipc) and cathodic peak potential (Epc) correspond to the reduction half-cycle, where electrons flow from the electrode to the analyte [15]. According to IUPAC convention, anodic currents are plotted as positive values and cathodic currents as negative values, with potential becoming increasingly positive from left to right on the x-axis [15].

Accurate measurement of these parameters requires careful baseline establishment. The anodic peak current is measured relative to an extension of the baseline in the zero-current region preceding the redox event. The cathodic peak current measurement is more complex, as it must be measured relative to a reverse sweep baseline that resembles "a reflection of the voltammogram had the direction of the scan not been reversed" [15]. For quantitative work, charging currents should be subtracted by obtaining a background voltammogram without the analyte present and subtracting it from the sample voltammogram [15].

Diagnostic Parameters for System Characterization

The relationship between peak currents and potentials provides critical diagnostic information about the electrochemical system under investigation. Several key parameters derived from these basic measurements enable researchers to classify systems as reversible, quasi-reversible, or irreversible:

Peak Potential Separation (ΔEp): The difference between anodic and cathodic peak potentials (ΔEp = Epa - Epc) is a primary indicator of electrochemical reversibility. For a reversible one-electron transfer process at 25°C, ΔEp is approximately 59 mV, increasing to 59/n mV for an n-electron process [13]. Values larger than this theoretical minimum indicate slowed electron transfer kinetics or the influence of uncompensated solution resistance [13].

Peak Current Ratio (ipa/ipc): The ratio of the anodic to cathodic peak currents provides information about the stability of the electrogenerated species. For a fully reversible system with no following chemical reactions, this ratio should be unity (ipa/ipc = 1) at all scan rates [13]. Deviation from unity indicates chemical complications such as decomposition or dimerization of the electrogenerated species [13].

Scan Rate Dependence: The relationship between peak current and scan rate distinguishes between diffusion-controlled and adsorption-controlled processes. For species freely diffusing in solution, ip is proportional to v1/2, while for surface-confined species, ip is proportional to v [16]. This diagnostic can be applied by measuring peak currents at different scan rates and plotting ip versus v1/2 (linear for diffusion control) and ip versus v (linear for adsorption control) [16].

Table 2: Diagnostic Criteria for Electrochemical Systems

| System Type | Peak Separation ΔEp | Peak Current Ratio ipa/ipc | Scan Rate Dependence | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversible | ~59/n mV at all scan rates [13] | ≈1 at all scan rates [13] | ip ∝ v1/2 [16] | Fast electron transfer kinetics; Nernstian equilibrium maintained [13] |

| Quasi-Reversible | >59/n mV; increases with scan rate [13] | Approaches 1 at slower scan rates [16] | ip ∝ v1/2 (with deviation) [13] | Electron transfer kinetics moderately slow relative to scan rate [13] |

| Irreversible | Only one peak observed; no reverse peak [16] | N/A (only one peak) | ip ∝ v1/2 for diffusion control [16] | Very slow electron transfer or follow-up chemical reaction consuming product [16] [13] |

| Adsorption-Controlled | Variable | Variable | ip ∝ v [16] | Electroactive species adsorbed on electrode surface [16] |

Experimental Protocol: Case Study of Methanol Oxidation Catalysis

To illustrate the practical application of cyclic voltammetry in research, we examine a detailed case study investigating Ni/Al-carbonate hydrotalcite (Ni-LDH) as a catalyst for methanol oxidation reaction (MOR), a process relevant to direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs) [14].

Electrode Preparation and Modification Protocol

Synthesis of Ni/Al-Carbonate Hydrotalcite (Ni-LDH): Prepare Ni-LDH using co-precipitation method by slowly adding 0.1 L aqueous solution containing Ni(NO3)2·6H2O (0.75 mol) and Al(NO3)3·9H2O (0.25 mol) to a solution of Na2CO3 (0.05 mol in 100 mL) while maintaining constant pH of 10 using 3.33 M NaOH. Age the resulting gelatinous precipitate at 65°C for 24 hours, then filter and wash until neutral pH is achieved. Air-dry the resulting powder at room temperature [14].

Preparation of Catalyst Ink: Create a colloidal suspension by grinding the precipitated Ni-LDH into a fine powder and dissolving 50 mg in 10 mL of catalyst ink prepared with deionized water, isopropanol, and polytetrafluoroethylene resin in a 4:1:0.05 volume ratio. Agitate the suspension to ensure proper mixing, then sonicate for 2 hours to maximize dispersion of the nanomaterial [14].

Electrode Modification: Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) with 0.3 μm alumina slurry, wash with doubly distilled water, and ultrasonicate before allowing to air dry. Drop-cast the Ni-LDH suspension onto the clean GCE surface (3 mm diameter) using a micropipette and allow to dry at ambient temperature, achieving a loading amount of approximately 0.074 mg [14].

Electrochemical Measurement Conditions

Electrochemical Cell Configuration: Utilize a standard three-electrode system with the modified glassy carbon electrode (NLGC) as working electrode, platinum wire as counter electrode, and saturated calomel electrode (SCE) as reference electrode [14].

Experimental Parameters: Conduct experiments in alkaline conditions (pH 13) using degassed solutions maintained at room temperature under nitrogen atmosphere. Employ scan rates typically ranging from 0.1 to 1.0 V/s for characterization of the redox system [14].

Data Collection: Perform cyclic voltammetry measurements by scanning potential through the region of interest where Ni(II)/Ni(III) redox transitions occur (typically 0.1-0.9 V vs. SCE based on the specific system). Record current response with high sampling density (α = 0.5) for optimal signal definition [14] [12].

Data Analysis and Interpretation

Analysis of the resulting voltammograms for the Ni-LDH modified electrode revealed:

The presence of anodic and cathodic peak current densities at 0.62 V and 0.42 V, respectively, corresponding to the quasi-reversible redox behavior of Ni(II)/Ni(III) centers [14].

A linear correlation between peak current and scan rate in the non-faradaic region (0.1-0.3 V) suggested an adsorption mechanism involving the NiII-(OH)2/NiIII-OOH redox couple, while a square-root relationship indicated diffusion-controlled methanol oxidation at higher potentials [14].

The electrochemically active surface area was calculated to be 0.042 cm², and the onset potential for methanol oxidation was determined to be 5.2 V through linear sweep voltammetry [14].

Double potential chronoamperometry confirmed a one-electron redox process with a Tafel slope of 24.2 mV/dec, supporting the proposed mechanism [14].

This case study demonstrates how careful analysis of voltammetric features enables researchers to extract detailed mechanistic information about electrocatalytic systems, informing the development of more efficient fuel cell technologies.

Advanced Considerations in Voltammogram Interpretation

The Impact of Experimental Parameters

Several experimental factors can significantly influence voltammetric responses and must be considered when interpreting results:

Scan Rate Effects: The scan rate (v) controls the experimental timescale, affecting both current response and apparent reversibility. For a reversible system, peak currents increase with v1/2 while peak potentials remain constant. For quasi-reversible systems, the peak separation (ΔEp) increases with scan rate as the electron transfer kinetics become increasingly slow relative to the potential sweep rate [16] [13]. Very fast scan rates may reveal reaction intermediates that are consumed in chemical steps at slower scan rates [16].

Uncompensated Resistance (Ru): Solution resistance between working and reference electrodes can distort voltammograms, increasing peak separation and altering peak shapes. This effect can be minimized through careful electrode placement, electronic positive feedback compensation, or post-run data manipulation [13]. Uncompensated resistance can be distinguished from slow electron transfer kinetics by its dependence on analyte concentration—Ru effects increase with current (and thus concentration), while kinetic parameters remain concentration-independent [13].

Charging Currents: The non-faradaic current associated with charging the electrical double-layer (ic = vCdl, where Cdl is the double-layer capacitance) contributes to the total measured current, potentially obscuring Faradaic signals, particularly at high scan rates [13] [15]. Charging currents can be subtracted by measuring background voltammograms in supporting electrolyte alone and subtracting from sample voltammograms [15].

Troubleshooting Common Voltammetric Challenges

Researchers often encounter several common challenges when interpreting voltammograms:

Irreversible Systems: When a reverse peak is absent, the system may be irreversible due to slow electron transfer kinetics or a following chemical reaction that consumes the electrogenerated species. To distinguish these possibilities, vary the scan rate—if the reverse peak appears at faster scan rates, the irreversibility is likely due to a chemical reaction; if the peak remains absent, the electron transfer itself is likely slow [16].

Non-Ideal Peak Shapes: Asymmetric or broad peaks may indicate heterogeneous surface conditions, non-uniform adsorption, or mixed diffusion-adsorption control. Using highly polished electrodes with reproducible surfaces helps minimize these effects [16].

Background Currents: High background currents can obscure Faradaic signals, particularly at low analyte concentrations. Using electrodes with smaller surface areas or slower scan rates can improve the signal-to-noise ratio [16] [13].

The Research Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful cyclic voltammetry experiments require careful selection of reagents and materials. The following table outlines key components used in the featured methanol oxidation study and their functions in electrochemical research.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Studies

| Reagent/Material | Specification/Example | Function in Research | Case Study Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transition Metal Salts | Ni(NO3)2·6H2O, Al(NO3)3·9H2O | Precursors for electrocatalyst synthesis | Ni/Al-hydrotalcite preparation for methanol oxidation catalysis [14] |

| Alkaline Electrolyte | NaOH solutions (pH 13) | Provides conductive medium; influences reaction thermodynamics | Optimal catalytic activity for MOR under alkaline conditions [14] |

| Electrode Materials | Glassy carbon (polished with 0.3 μm alumina) | Provides conductive, inert surface for electron transfer | Working electrode substrate for Ni-LDH modification [14] |

| Reference Electrodes | Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) | Maintains fixed potential reference against which working electrode is controlled | Potential reference in three-electrode system [14] |

| Counter Electrodes | Platinum wire | Completes electrical circuit without reaction interference | Counter electrode in three-electrode cell [14] |

| Binding Agents | Polytetrafluoroethylene resin | Enhances catalyst adhesion to electrode surface | Component of catalyst ink for electrode modification [14] |

| Solvents | Deionized water, isopropanol | Disperses catalyst materials; provides medium for ion transport | Components of catalyst ink suspension [14] |

| Purge Gases | Nitrogen gas | Removes dissolved oxygen to prevent interference with redox reactions | Solution degassing prior to electrochemical measurements [14] |

The ability to decode a voltammogram by accurately identifying and interpreting key features such as peak currents and potentials remains an essential skill for researchers across numerous scientific disciplines. These parameters serve as fundamental indicators of electron transfer mechanisms, catalytic efficiency, and reaction kinetics in systems ranging from energy storage materials to biological redox mediators. The diagnostic power of cyclic voltammetry extends beyond simple identification of redox potentials to encompass sophisticated analysis of coupled chemical reactions, adsorption processes, and electron transfer kinetics through systematic variation of experimental conditions.

As electrochemical techniques continue to evolve, with recent advances including high-speed regression using machine learning algorithms to rapidly extract kinetic parameters, the fundamental principles of voltammogram interpretation remain critically important [17]. By mastering these core concepts and maintaining awareness of potential experimental artifacts, researchers can fully leverage cyclic voltammetry as a powerful tool for materials characterization, mechanistic studies, and the development of next-generation electrochemical technologies. The continued refinement of both experimental methodologies and theoretical frameworks ensures that cyclic voltammetry will maintain its position as a cornerstone technique in the researcher's analytical arsenal for the foreseeable future.

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a powerful and versatile electrochemical technique extensively employed in research to study the redox properties of chemical species. It provides critical information about electron transfer processes that occur during oxidation and reduction reactions, offering insights into the thermodynamics and kinetics of electrochemical systems [2]. In the context of pharmaceutical research and drug development, CV serves as an indispensable tool for characterizing active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), understanding reaction mechanisms, and developing sensitive analytical methods [18]. The technique's value lies in its ability to rapidly generate a species during a forward potential scan and probe its fate with the reverse scan or subsequent cycles, enabling researchers to investigate the stability and reactivity of electroactive compounds on short timescales [6].

The fundamental principle of CV involves applying a linearly cycled potential sweep to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current response. This process generates a characteristic "duck-shaped" plot known as a cyclic voltammogram, which serves as a fingerprint of the redox behavior of the analyte [1]. The interpretation of this voltammogram relies heavily on foundational mathematical models, primarily the Nernst equation which describes thermodynamic equilibrium, and the Butler-Volmer equation which governs electron transfer kinetics. Together, these equations form the theoretical backbone for extracting quantitative information from CV experiments, enabling researchers to determine formal potentials, diffusion coefficients, electron transfer rate constants, and concentration values for various analytes [2] [19].

Theoretical Foundations

The Nernst Equation: Thermodynamic Equilibrium

The Nernst equation provides the fundamental relationship between the electrode potential and the concentration of species undergoing a redox reaction at equilibrium conditions. This equation serves as the cornerstone for understanding the thermodynamic aspects of electrochemical processes in cyclic voltammetry [2].

For a general redox reaction: [ \text{O} + ne^- \rightleftharpoons \text{R} ]

The Nernst equation is expressed as: [ E = E^\circ + \frac{RT}{nF} \ln\frac{[\text{O}]}{[\text{R}]} ]

Where:

- (E) is the electrode potential

- (E^\circ) is the standard electrode potential

- (R) is the gas constant (8.314 J·K⁻¹·mol⁻¹)

- (T) is the temperature in Kelvin

- (n) is the number of electrons transferred in the redox event

- (F) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C·mol⁻¹)

- ([\text{O}]) and ([\text{R}]) are the concentrations of the oxidized and reduced species, respectively [2]

Under standard conditions of temperature (298 K), the equation simplifies to: [ E = E^\circ + \frac{0.0592}{n} \log\frac{[\text{O}]}{[\text{R}]} ]

In cyclic voltammetry, the formal potential ((E^{\circ'})) is often used in place of the standard potential to account for non-ideal behavior in real systems. For a reversible system, the formal reduction potential is calculated as the mean of the anodic and cathodic peak potentials: [ E^{\circ'} = \frac{E{pa} + E{pc}}{2} ] where (E{pa}) is the anodic peak potential and (E{pc}) is the cathodic peak potential [11] [13].

Table 1: Key Parameters from the Nernst Equation for Reversible Systems

| Parameter | Symbol | Equation/Value | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formal Potential | (E^{\circ'}) | (\frac{E{pa} + E{pc}}{2}) | Characteristic redox potential of the system |

| Peak Separation | (\Delta E_p) | (\frac{59.2}{n}) mV at 25°C | Diagnostic criterion for reversibility |

| Electron Stoichiometry | (n) | (Ep - E{p/2} > \frac{0.0565}{n}) | Determines number of electrons transferred |

Butler-Volmer Kinetics: Electron Transfer Dynamics

The Butler-Volmer equation is a fundamental relation in electrochemistry that quantifies the kinetics of electrode reactions by linking the net current density to the electrode overpotential. This equation accounts for both anodic oxidation and cathodic reduction contributions in faradaic processes, making it essential for understanding the rate of electron transfer in cyclic voltammetry experiments [19].

The standard form of the Butler-Volmer equation for a single electron transfer step is: [ i = i0 \left[ \exp\left( \frac{\alphaa F \eta}{RT} \right) - \exp\left( -\frac{\alpha_c F \eta}{RT} \right) \right] ]

Where:

- (i) is the net current density (A/cm²)

- (i_0) is the exchange current density, representing the magnitude of anodic and cathodic current densities at equilibrium

- (\alphaa) and (\alphac) are the anodic and cathodic transfer coefficients (dimensionless, typically between 0 and 1)

- (F) is the Faraday constant (96,485 C/mol)

- (\eta) is the overpotential, defined as (\eta = E - E_{eq})

- (R) is the gas constant (8.314 J/mol·K)

- (T) is the absolute temperature (K) [19]

The transfer coefficients (\alphaa) and (\alphac) quantify the symmetry of the energy barrier for electron transfer, with their sum often equaling 1 for elementary steps. The overpotential (\eta) represents the additional driving force required to drive the reaction away from equilibrium [19].

Table 2: Butler-Volmer Equation Parameters and Their Significance

| Parameter | Symbol | Typical Values | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exchange Current Density | (i_0) | 10⁻⁶ to 10⁻³ A/cm² | Intrinsic reaction rate at equilibrium |

| Anodic Transfer Coefficient | (\alpha_a) | 0.3-0.7 | Fraction of overpotential lowering oxidation barrier |

| Cathodic Transfer Coefficient | (\alpha_c) | 0.3-0.7 | Fraction of overpotential lowering reduction barrier |

| Overpotential | (\eta) | Varies with application | Deviation from equilibrium potential |

The Butler-Volmer equation simplifies under extreme overpotential conditions. At high positive overpotentials ((\eta > 50) mV), the cathodic term becomes negligible, yielding the Tafel equation for anodic processes: [ \eta = \frac{RT}{\alpha F} \ln\left( \frac{i}{i_0} \right) ]

Similarly, at high negative overpotentials, the anodic term becomes negligible, giving the cathodic Tafel equation. The Tafel slope ((b = 2.303RT/\alpha F)) provides crucial insight into the reaction mechanism, with a typical value of 120 mV per decade for a single-electron transfer with (\alpha = 0.5) at room temperature [19].

Experimental System and Setup

The Three-Electrode Configuration

Cyclic voltammetry employs a three-electrode system to precisely control the potential applied to the working electrode while accurately measuring the resulting current. This configuration is essential for maintaining a stable reference potential and ensuring that the measured current reflects only the processes occurring at the working electrode surface [20] [1].

The core components of this system are:

Working Electrode: This is the electrode where the redox reaction of interest occurs. Common materials include platinum, gold, glassy carbon, and mercury, chosen based on the potential window and reactivity requirements. The working electrode typically has a small, well-defined surface area to ensure uniform current distribution [20].

Reference Electrode: This electrode maintains a constant, stable potential against which the working electrode potential is measured. Common reference electrodes include Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel (SCE), and silver wire with ferrocene as an internal standard. The reference electrode must experience minimal current flow to prevent polarization [20] [6].

Counter Electrode (Auxiliary Electrode): Typically made from an inert material like platinum gauze with a large surface area, this electrode completes the electrical circuit and allows current to flow without significantly affecting the measurement. It ensures that the current observed at the working electrode is balanced without passing significant current through the reference electrode [20].

The potentiostat is the instrument that controls the potential between the working and reference electrodes while measuring the current between the working and counter electrodes. This separation of functions allows for precise potential control and accurate current measurement [1].

Diagram 1: Three-Electrode System

Potential Waveform and Scan Rate

In cyclic voltammetry, the potentiostat applies a triangular potential waveform to the working electrode. The potential is swept linearly from an initial potential (Eᵢ) to a final potential (E_f) – known as the switching potential – and then back to the initial potential. The slope of this excitation signal defines the scan rate (ν, in V/s), which is a critical experimental parameter that influences the voltammetric response [2] [11].

The potential during the forward scan is described by: [ E = Ei + \nu t ] After reaching the switching potential, the reverse scan follows: [ E = Es - \nu t ] where (E_s) is the potential at the switching point and (t) is time [11].

The scan rate significantly impacts the current response. Higher scan rates provide less time for diffusion, resulting in higher peak currents but also increasing the charging current background. The selection of an appropriate scan rate depends on the system under investigation and whether the goal is to study diffusion-controlled or adsorption-controlled processes [13].

Diagram 2: Potential Waveform

Quantitative Relationships in Cyclic Voltammetry

The Randles-Sevcik Equation: Diffusion-Controlled Processes

The Randles-Sevcik equation describes the relationship between the peak current and the concentration of the electroactive species for diffusion-controlled reversible systems. This equation is fundamental for quantitative analysis in cyclic voltammetry, allowing researchers to determine concentrations or diffusion coefficients from voltammetric data [2].

The Randles-Sevcik equation is expressed as: [ i_p = (2.69 \times 10^5) n^{3/2} A C D^{1/2} \nu^{1/2} ]

Where:

- (i_p) is the peak current (amperes)

- (n) is the number of electrons transferred in the redox event

- (A) is the electrode area (cm²)

- (C) is the concentration (mol/cm³)

- (D) is the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s)

- (\nu) is the scan rate (V/s) [2] [1]

At 298 K, the equation becomes: [ i_p = (2.69 \times 10^5) n^{3/2} A C D^{1/2} \nu^{1/2} ]

The key insight from this equation is that for a reversible, diffusion-controlled process, the peak current is proportional to the square root of the scan rate. This relationship provides a diagnostic criterion for distinguishing diffusion-controlled processes from adsorption-controlled processes, where the peak current is directly proportional to the scan rate [2] [13].

Table 3: Diagnostic Criteria for Reversible, Quasi-Reversible, and Irreversible Systems

| Parameter | Reversible System | Quasi-Reversible System | Irreversible System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peak Separation | (\Delta E_p = \frac{59.2}{n}) mV | (\Delta E_p > \frac{59.2}{n}) mV, increases with scan rate | (\Delta E_p > \frac{59.2}{n}) mV, large separation |

| Peak Current Ratio | (i{pa}/i{pc} = 1) | (i{pa}/i{pc} \approx 1) (deviation increases with scan rate) | (i{pa}/i{pc} \neq 1), significant imbalance |

| Scan Rate Dependence | Peak current function ((i_p/n^{1/2})) independent of scan rate | Peak current function decreases with increasing scan rate | Peak current function decreases with increasing scan rate |

| Peak Potential | Independent of scan rate | Cathodic peak shifts negative, anodic peak shifts positive with increasing scan rate | Peak potentials shift with scan rate |

Diagnostic Criteria for Electron Transfer Mechanisms

The interplay between the Nernst equation and Butler-Volmer kinetics manifests in characteristic voltammetric responses that allow researchers to classify electrode processes as reversible, quasi-reversible, or irreversible:

Reversible Systems exhibit behavior consistent with the Nernst equation, where electron transfer is fast compared to mass transport. Key characteristics include:

- Peak potential separation (\Delta Ep = E{pa} - E_{pc} = 59.2/n) mV at 25°C

- Peak current ratio (i{pa}/i{pc} = 1) at all scan rates

- Peak potentials independent of scan rate

- Formal potential (E^{\circ'} = (E{pa} + E{pc})/2) [13]

Quasi-Reversible Systems show intermediate behavior where electron transfer kinetics influence the response:

- Peak separation greater than 59.2/n mV, increasing with scan rate

- Peak current ratio approximately 1 but decreases at higher scan rates

- Peak potentials shift with scan rate

- Response depends on the ratio (ks/\nu), where (ks) is the standard heterogeneous electron transfer rate constant [13]

Irreversible Systems display complete kinetic control where reverse electron transfer is negligible:

- Large peak separation with no reverse peak observed in some cases

- Significant shift in peak potentials with scan rate

- Current governed by the Butler-Volmer equation with negligible reverse reaction term [13]

Experimental Protocols for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Method Development for Drug Compound Characterization

The application of cyclic voltammetry in pharmaceutical research requires careful method development to ensure reliable and reproducible results. The following protocol outlines a systematic approach for characterizing redox properties of drug compounds:

Solution Preparation:

- Prepare electrolyte solution with appropriate supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.4 for physiological relevance)

- Dissolve drug compound in electrolyte at typical concentration range of 0.1-1.0 mM

- Degas solution with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 10-15 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen

- Maintain constant temperature using water jacket or temperature-controlled cell

Electrode Preparation:

- Polish working electrode (typically glassy carbon) with alumina slurry (1.0, 0.3, then 0.05 μm) on microcloth

- Rinse thoroughly with purified water between polishing steps

- Sonicate in water and/or ethanol for 2 minutes to remove adsorbed particles

- Perform electrochemical activation in supporting electrolyte via potential cycling until stable background is obtained

Initial Scan Parameters:

- Set initial potential: 0.2 V more negative than expected reduction potential or 0 V vs. Ag/AgCl if unknown

- Set switching potential: 0.2 V more positive than expected oxidation potential or +1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl if unknown

- Use moderate scan rate (50-100 mV/s) for initial characterization

- Employ 2-3 cycles to assess stability of redox processes

Scan Rate Studies:

- Perform CV at multiple scan rates (e.g., 10, 25, 50, 100, 200, 500 mV/s)

- Plot peak current vs. square root of scan rate for diffusion-controlled processes

- Plot peak potential vs. log(scan rate) for kinetic analysis

- Calculate electron transfer rate constant ((k_s)) from scan rate dependence of peak separation

Data Analysis:

- Measure peak currents ((i{pa}), (i{pc})) and peak potentials ((E{pa}), (E{pc}))

- Calculate formal potential (E^{\circ'} = (E{pa} + E{pc})/2)

- Determine electron stoichiometry ((n)) from peak separation

- Calculate diffusion coefficient ((D)) using Randles-Sevcik equation

- Assess reversibility using diagnostic criteria [6] [13]

Advanced Integration Analysis for Immobilized Systems

For drug compounds that adsorb strongly or are immobilized on electrode surfaces (e.g., in modified electrodes or thin-layer cells), integration analysis of cyclic voltammograms provides enhanced information about reaction kinetics. This method is particularly valuable for studying diffusionless systems where the electrode reaction is not affected by mass transport limitations [21].

The integration analysis protocol:

System Requirements:

- Strong adsorption of reactant and product on electrode surface, OR

- Thin-layer cell configuration with scan rate not exceeding diffusion limits

- Known total charge ((Q^*)) for the immobilized species when available

Integration Procedure:

- Record cyclic voltammogram at appropriate scan rate (typically 1-50 mV/s for immobilized systems)

- Integrate current from starting potential to each potential (E) during forward scan to obtain (Q_f(E))

- Integrate current from switching potential to each potential (E) during backward scan to obtain (Q_b(E))

- Calculate concentrations of oxidized and reduced forms at each potential: [ CO(E) = \frac{Qf(E) - Qb(E)}{2nFA} \quad \text{and} \quad CR(E) = \frac{Q^* - [Qf(E) - Qb(E)]}{2nFA} ]

- Determine forward and backward reaction rates from concentration profiles

Parameter Estimation:

- Plot (\ln[kf(E)]) and (\ln[kb(E)]) vs. (E)

- Obtain standard formal potential (E^{\circ'}) from the intersection point

- Calculate standard electron transfer rate constant (k_s^{\circ}) from the slopes

- Determine transfer coefficient (\alpha) from the symmetry of the plot [21]

This integration method can be applied to cases where the cyclic voltammetric oxidation-reduction peak potential separation is greater than only 20 mV, making it suitable for a wide range of pharmaceutical compounds with quasi-reversible electron transfer behavior.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Cyclic Voltammetry in Pharmaceutical Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Typical Specifications | Pharmaceutical Application Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic conductivity; controls potential window and pH | 0.1 M concentration; high purity (>99%); appropriate pH buffer | Phosphate buffer (pH 7.4) for physiological simulation; acetate buffer for acidic conditions |

| Internal Standard | Potential calibration; reference redox couple | Ferrocene/Ferrocenium (Fc/Fc⁺) couple; E⁰ = 0.64 V vs. NHE | Adding ferrocene for potential scale normalization in non-aqueous drug studies |

| Working Electrodes | Surface for redox reactions; determines potential window | Glassy carbon (polarizable window); Pt (catalytically active); Au (thiol modification) | Glassy carbon for most drug compounds; modified electrodes for selective detection |

| Reference Electrodes | Stable potential reference | Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl); SCE; pseudo-reference with internal standard | Ag/AgCl for aqueous systems; Ag wire with Fc/Fc⁺ for non-aqueous drug studies |

| Electrode Polishing | Surface renewal and reproducibility | Alumina suspensions (1.0, 0.3, 0.05 μm); diamond polish for carbon electrodes | Sequential polishing for reproducible surface area and minimized adsorption effects |

| Oxygen Scavenging | Removal of interfering oxygen | Nitrogen (high purity, >99.998%); argon; vacuum degassing | Dissolved oxygen removal to prevent interference with drug reduction waves |

| Redox Mediators | Electron transfer facilitation | Ferricyanide; ruthenium hexamine; methylene blue | Enhancing electron transfer for drugs with slow heterogeneous kinetics |

| Surface Modifiers | Electrode functionalization | Thiols for Au; nanomaterials; polymers; enzymes | Selective detection of specific drug compounds in complex matrices |

Applications in Pharmaceutical Research and Drug Development

Cyclic voltammetry serves as a critical analytical tool throughout the drug development pipeline, from early discovery to quality control. The technique's ability to provide information about redox properties, reaction mechanisms, and concentration values makes it invaluable for pharmaceutical applications [18].

Drug Stability and Degradation Studies: CV enables rapid assessment of drug compound stability by monitoring changes in voltammetric response over multiple cycles or under different environmental conditions. The appearance of new redox peaks or changes in existing peak currents can indicate degradation products or oxidative transformation. This application is particularly valuable for understanding the stability of drugs containing easily oxidizable functional groups like phenols, amines, or heterocyclic aromatic systems [2] [18].

Metabolic Pathway Elucidation: The redox behavior of drug molecules and their metabolites can provide insights into metabolic pathways, particularly those involving oxidative transformations. By comparing the voltammetric responses of parent compounds and their suspected metabolites, researchers can hypothesize about metabolic transformation pathways and identify potential electroactive metabolites [18].

Quantitative Analysis in Formulations: Using the Randles-Sevcik equation, CV can be employed for quantitative determination of active pharmaceutical ingredients in formulations. The linear relationship between peak current and concentration allows for the development of calibration curves for drug quantification, often with detection limits in the micromolar range. While not as sensitive as pulse techniques like differential pulse voltammetry, CV provides a rapid screening method for quality control applications [2] [18].

Reaction Mechanism Studies: CV is exceptionally valuable for studying the mechanisms of electrochemical reactions involving drug compounds. Through diagnostic analysis of peak separations, scan rate dependencies, and cycle-to-cycle changes, researchers can distinguish between simple electron transfer processes and more complex mechanisms involving chemical steps following electron transfer (EC mechanisms). This information is crucial for understanding the redox behavior of drugs in biological systems and for developing electroanalytical methods [13].

The integration of CV with spectroscopic methods in spectroelectrochemistry (SEC) has further enhanced its utility in pharmaceutical analysis. This hybrid approach provides simultaneous information about redox properties and molecular structures, offering unique advantages for characterizing complex drug molecules and their transformation products [22].

The governing equations of cyclic voltammetry – the Nernst equation for thermodynamic equilibrium and the Butler-Volmer equation for electron transfer kinetics – provide the theoretical foundation for interpreting voltammetric data in pharmaceutical research. These mathematical models enable researchers to extract quantitative information about redox potentials, electron transfer rates, diffusion coefficients, and concentration values from cyclic voltammograms.

The continued advancement of electrochemical instrumentation, coupled with the development of novel electrode materials and data analysis methods, promises to further expand the applications of cyclic voltammetry in drug development. The integration of CV with other analytical techniques, particularly spectroscopic methods, creates powerful hybrid approaches that provide comprehensive characterization of pharmaceutical compounds. As the field moves toward more personalized medicine and rapid quality control methods, the principles outlined in this technical guide will remain essential for researchers exploiting cyclic voltammetry in pharmaceutical applications.

Distinguishing Reversible and Irreversible Processes from CV Shape and Peak Separation

Cyclic voltammetry (CV) is a foundational electrochemical technique where the voltage applied to a working electrode is swept linearly with time and then swept back in the reverse direction, while the resulting current is measured [2]. The resulting plot of current versus potential, called a cyclic voltammogram, provides a wealth of information about the redox properties and electron transfer kinetics of chemical species. A core application of CV in research is diagnosing the reversibility of electrochemical reactions, a characteristic paramount for assessing the stability of electrocatalysts, the efficiency of energy storage materials, and the mechanistic pathways in synthetic and biological systems [23] [15].

This technical guide delves into how the shape of the cyclic voltammogram and the separation between its characteristic peaks serve as primary diagnostics for distinguishing between reversible, quasi-reversible, and irreversible electron transfer processes. This analysis forms an essential part of a broader thesis on the applications of cyclic voltammetry, establishing it as an indispensable tool for researchers and drug development professionals who require deep insight into electrochemical reactivity.

Theoretical Foundation of Reversibility in Electrochemistry

In the context of cyclic voltammetry, the term "reversibility" has specific meanings distinct from its use in thermodynamics. In thermodynamics, a reversible process is an idealized, infinitely slow process where the system remains in equilibrium with its surroundings at every stage [24] [25]. All real-world processes are thermodynamically irreversible as they increase the entropy of the universe and cannot be perfectly reversed by an infinitesimal change in external conditions [26] [25].

In contrast, electrochemical reversibility is a practical classification of a reaction based on the time scale of the experiment and the kinetics of electron transfer. It is categorized as follows [15]:

- Chemically Reversible: The electron transfer can be reversed without any side reactions consuming the initial product.

- Thermodynamically Reversible (Nernstian): The electron transfer is sufficiently fast that equilibrium at the electrode surface is maintained throughout the potential sweep. The surface concentrations of the redox species follow the Nernst equation.

- Practically Reversible: This term is often used when both chemical and thermodynamic reversibility are observed on the experimental time scale.

An electrochemically irreversible system is one where the electron transfer kinetics are slow, or a fast chemical reaction consumes the product of the electron transfer, making the back reaction impossible within the experiment's timeframe [16].

Diagnostic Features in a Cyclic Voltammogram

The key to diagnosing reversibility lies in analyzing specific features of the cyclic voltammogram. A classic, "duck-shaped" voltammogram for a reversible, diffusion-controlled system with a single electron transfer displays several characteristic peaks and parameters [15].

Key Voltammogram Parameters

- Anodic Peak Potential (Epa) and Current (Ipa): The potential and current at the peak of the oxidation wave.

- Cathodic Peak Potential (Epc) and Current (Ipc): The potential and current at the peak of the reduction wave.

- Peak Potential Separation (ΔEp): The difference between the anodic and cathodic peak potentials (ΔEp = Epa - Epc). This is a critical parameter for assessing reversibility.

- Formal Potential (E°): For a reversible system, the formal potential is approximately the midpoint between the two peak potentials (E°' ≈ (Epa + Epc)/2) [16].

- Peak Current Ratio (Ipa/Ipc): The ratio of the absolute magnitudes of the anodic and cathodic peak currents.

Table 1: Diagnostic CV Parameters for Different Systems

| System Type | Peak Separation ΔEp | Peak Current Ratio Ipa/Ipc | Scan Rate Dependence of ΔEp | Scan Rate Dependence of Ip |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reversible | ~59/n mV at 25°C | ≈1 | Independent | Ip ∝ v^(1/2) |

| Quasi-Reversible | >59/n mV | ≈1 | Increases with scan rate | Ip ∝ v^(1/2) (deviation at high v) |

| Irreversible | No reverse peak, or very large ΔEp | N/A | Increases with scan rate | Ip ∝ v^(1/2) |

A Workflow for Diagnosing Reversibility

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for classifying an electrochemical system based on its cyclic voltammogram.

Characterizing Reversible, Quasi-Reversible, and Irreversible Systems

The Reversible (Nernstian) System

A reversible system exhibits fast electron transfer kinetics, allowing equilibrium to be maintained at the electrode surface according to the Nernst equation throughout the potential sweep [16] [15].

- CV Shape: A pair of symmetric, well-defined oxidation and reduction peaks.

- Peak Separation: The peak potential separation (ΔEp) is small and constant, ideally about (59/n) mV at 25°C, where

nis the number of electrons transferred [16]. - Peak Current Ratio: The ratio of the anodic to cathodic peak currents (|Ipa/Ipc|) is equal to 1 [15].

- Scan Rate Dependence: The peak currents (Ip) are proportional to the square root of the scan rate (v^(1/2)), as described by the Randles-Ševčík equation. The peak potentials and their separation do not shift with changing scan rate [16] [27].

A classic example is the ferro/ferricyanide couple ([Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻/³⁻), often used as a benchmark for reversible behavior [28].

The Quasi-Reversible System

As the scan rate increases, the electron transfer kinetics may become too slow to maintain Nernstian equilibrium. This leads to a quasi-reversible system, which displays characteristics between reversible and irreversible.

- CV Shape: A pair of broader oxidation and reduction peaks.

- Peak Separation: ΔEp is greater than (59/n) mV and increases with increasing scan rate [16].

- Peak Current Ratio: The ratio |Ipa/Ipc| may still be close to 1.

- Scan Rate Dependence: The peak current may still roughly follow Ip ∝ v^(1/2), but the widening ΔEp is the key indicator of kinetic limitation.

The Irreversible System

In an irreversible system, the electron transfer kinetics are very slow, or the product of the electron transfer is consumed by a subsequent chemical reaction [16].

- CV Shape: Only one peak (either anodic or cathodic) is present. The reverse peak is absent because the species needed for the back reaction is no longer available [16] [15].

- Peak Separation: Not applicable in the same way, as only one peak is observed. If a very small reverse peak is forced, the ΔEp would be very large.

- Scan Rate Dependence: For a purely irreversible system with no follow-up chemistry, the peak current is still proportional to v^(1/2), but the peak potential shifts significantly with scan rate.

A key diagnostic is to perform CV at different scan rates. If a missing reverse peak appears at a very fast scan rate, it indicates that the system is irreversible due to a follow-up chemical reaction (EC mechanism). The fast scan "outruns" the chemical step, allowing the back electron transfer to occur [16].

Experimental Protocol for Determining Reversibility

The following section provides a detailed methodology for a standard CV experiment designed to diagnose reversibility, using the well-established ferro/ferricyanide redox couple.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Their Functions

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat | Instrument that controls the potential and measures current (e.g., MedPstat, Ossila Potentiostat, IEST ERT6008) [28] [15] [27]. |

| Three-Electrode Cell | Standard electrochemical cell configuration. |

| Working Electrode | Surface where redox reaction occurs (e.g., Pt, Au, glassy carbon). Must be clean and polished. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel Electrode). |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit (e.g., Pt wire or coil). |

| Potassium Ferricyanide (K₃Fe(CN)₆) | Oxidized species of the redox probe. |

| Potassium Ferrocyanide (K₄Fe(CN)₆) | Reduced species of the redox probe. |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Supporting electrolyte (1 M) to minimize solution resistance. |

| Deionized Water | Solvent for preparing aqueous solutions. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a solution containing 5 mM K₃Fe(CN)₆ and 5 mM K₄Fe(CN)₆ in 1 M KCl using deionized water [28].

- Electrode Preparation: Clean the working electrode (e.g., Platinum Wire Electrode) according to standard protocols, often involving polishing and rinsing with deionized water [28] [15].

- Cell Setup: Introduce 30 mL of the prepared solution into an electrochemical cell. Immerse the working, reference, and counter electrodes into the solution.

- Oxygen Removal: Gently bubble an inert gas (e.g., N₂ or Ar) through the solution for ~10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with the measurement [15].

- Instrument Connection: Connect the electrodes to the potentiostat—Red for Working Electrode (WE), Blue/Black for Reference Electrode (RE), and Black for Counter Electrode (CE) [28].

- Parameter Configuration: In the potentiostat software, set the parameters for the cyclic voltammetry experiment:

- Initial Potential: e.g., -0.2 V (vs. Ref.)

- Switching Potential 1: e.g., +0.6 V (vs. Ref.)

- Final Potential: Set to the initial potential to complete the cycle.

- Scan Rate: Begin with a slow scan rate, e.g., 0.1 V/s.

- Number of Cycles: 3-5 cycles to ensure stability.

- Data Acquisition: Start the measurement. The voltammogram will be displayed in real-time.

- Multi-Scan Rate Experiment: Repeat the measurement at several different scan rates (e.g., 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5 V/s) using a fresh solution or after ensuring the electrode surface is unchanged.

Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Peak Identification: For each scan rate, identify the anodic peak potential (Epa), cathodic peak potential (Epc), anodic peak current (Ipa), and cathodic peak current (Ipc).

- Calculate Key Parameters:

- Calculate ΔEp = Epa - Epc for each scan rate.

- Calculate the ratio |Ipa/Ipc| for each scan rate.

- Plot Dependencies:

- Create a plot of Peak Current (Ip) vs. Square Root of Scan Rate (v^(1/2)). A linear relationship suggests a diffusion-controlled process [27].

- Create a plot of ΔEp vs. Scan Rate (v). A constant ΔEp indicates reversibility, while an increasing ΔEp indicates quasi-reversibility.

- Classification: Use the criteria outlined in Table 1 and the decision workflow to classify the system.

Advanced Considerations and Broader Research Context

The Nicholson Parameter for Quantifying Reversibility

For quasi-reversible systems, the Nicholson parameter provides a quantitative method to determine the dimensionless kinetic parameter (Ψ), which is related to the electron transfer rate constant (k⁰). This allows researchers to move beyond qualitative classification to obtaining quantitative kinetic data from CV experiments [15].

Distinguishing Adsorbed and Diffusing Species

The diagnosis of reversibility can be complicated if the redox species is adsorbed onto the electrode surface rather than freely diffusing. For adsorbed species, the CV peaks are sharp and symmetrical, and the peak current (Ip) is directly proportional to the scan rate (v), not its square root [16]. This distinction is crucial in fields like sensor design and surface science [23].

Applications in Research and Drug Development

Understanding electrochemical reversibility is critical across numerous domains:

- Battery Research: CV is a "diagnostic report" for electrode materials. A small ΔEp indicates highly reversible Li⁺ intercalation, which is crucial for high-performance batteries with low polarization and long cycle life [27].

- Drug Development: Studying the redox behavior of antibiotic molecules like amoxicillin can reveal quasi-reversible behavior and interactions with metal ions, guiding prescription advice to avoid co-administration [23].

- Biosensors and Bioelectrochemistry: CV is used to measure the electron transfer rates of immobilized redox proteins, which is fundamental to developing biosensors and understanding biological redox processes [29].

- Electrocatalyst Characterization: In fuel cell research, CV is used to characterize synthesized catalysts (e.g., Pt-Ru) and their catalytic activities, where reversibility informs on the efficiency of the catalytic cycles [23].

The shape of the cyclic voltammogram, specifically the presence and separation of redox peaks and their dependence on experimental parameters like scan rate, provides a powerful, in-situ diagnostic toolkit for classifying electrochemical systems. Mastering the interpretation of these features allows researchers to distinguish reversible, quasi-reversible, and irreversible processes reliably. This knowledge is not merely academic; it is the cornerstone of rational material design in energy storage, the development of sensitive analytical biosensors, and the understanding of complex redox mechanisms in pharmaceutical and biological systems. As a core technique within the electrochemical repertoire, cyclic voltammetry's role in deciphering electron transfer reversibility ensures its continued indispensability in scientific research and industrial development.

Cyclic Voltammetry in Action: Key Research Applications Across Scientific Fields

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a powerful and ubiquitous electrochemical technique used to study the kinetics of electrochemical reactions by measuring current while cycling the potential of a working electrode [30]. In the context of renewable energy research, CV is indispensable for probing and developing efficient electrocatalysts for reactions critical to fuel cell technology, such as the methanol oxidation reaction (MOR) [31] [14]. This technique provides a direct window into the electrode-solution interface, allowing researchers to decipher complex reaction mechanisms, evaluate catalytic activity, and determine crucial kinetic parameters [32] [33]. The output, a cyclic voltammogram (I-E curve), serves as a fingerprint of the electrochemical processes occurring at the electrode surface, offering insights into the energetics of redox reactions, the dynamics of electron transfer, and the rates of coupled chemical reactions [32] [30]. This guide details the application of CV in characterizing MOR catalysts, framed within the broader thesis that CV is a fundamental tool for advancing electrochemical energy conversion research.

Fundamentals of Cyclic Voltammetry

Core Principles and Technique

Cyclic Voltammetry operates by applying a linear potential sweep between two set limits (the vertex potentials) and measuring the resulting current [30]. The potential (E) is defined as a function of time (t) and scan rate (v), typically starting at an initial potential (Ei) where no significant current flows [33]. For a simple, reversible one-electron transfer process (O + e⁻ ⇌ R), the current response is governed by the interplay between electron transfer kinetics and mass transport of reactants and products via diffusion [33]. The shape of the voltammogram reveals the reversibility of the reaction, which is classified as reversible, quasi-reversible, or irreversible based on the relative rates of electron transfer and mass transport [33] [30].

- Reversible Process: Electron transfer is much faster than mass transport. The system obeys the Nernst equation, and the voltammogram exhibits symmetric oxidation and reduction peaks with a peak separation (ΔEp) of approximately 59 mV for a one-electron process at 25°C [33].

- Quasi-Reversible Process: Intermediate case where electron transfer and mass transport rates are comparable. The peak separation is larger than 59 mV and increases with scan rate [30].

- Irreversible Process: Electron transfer is much slower than mass transport. The reverse scan peak is absent, and the peak potential shifts significantly with scan rate [33] [30].

The following diagram illustrates the core principle of potential scanning and electron transfer in CV.

Information Derived from Cyclic Voltammetry

CV provides a wealth of qualitative and quantitative information, making it a cornerstone technique in electrocatalysis research. The table below summarizes the key parameters that can be extracted from a cyclic voltammogram.

Table 1: Key Information Obtainable from Cyclic Voltammetry Analysis

| Parameter | Description | Application in Electrocatalysis |

|---|---|---|

| Peak Current (Ip) | The maximum current observed during a redox event. | Proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species and the square root of the scan rate in diffusion-controlled processes; indicates catalytic activity [33] [30]. |

| Peak Potential (Ep) | The potential at which the peak current occurs. | Identifies the redox potential of a reaction; shifts in Ep can indicate changes in reaction kinetics or catalyst binding energy [33]. |

| Peak Separation (ΔEp) | The difference between anodic and cathodic peak potentials. | Diagnoses electrochemical reversibility; smaller ΔEp values indicate faster electron transfer kinetics [33] [30]. |

| Electrochemically Active Surface Area (ECSA) | The area of the catalyst actively participating in the electrochemical reaction. | Evaluates the density of active sites, often calculated from the charge under a non-Faradaic (capacitive) current region or a known surface redox couple [14]. |

| Onset Potential | The potential at which the Faradaic current for a catalytic reaction begins to significantly increase. | A key metric for catalyst efficiency; a lower onset potential signifies a more efficient catalyst that operates closer to the thermodynamic potential [14]. |

Application to Methanol Oxidation Reaction (MOR)

The Importance of MOR and Catalyst Challenges

The methanol oxidation reaction (MOR) is the critical anodic process in direct methanol fuel cells (DMFCs), which are promising energy conversion devices due to their high efficiency and low pollutant emissions [14]. The most common and effective catalysts for MOR are based on platinum (Pt). However, a major challenge is catalyst poisoning by carbon monoxide (CO) and other intermediates (e.g., HCHOad, COHad) generated during methanol oxidation [31]. These species strongly adsorb onto the Pt active sites, blocking them from further reaction with fresh methanol molecules, which leads to a rapid decline in fuel cell performance [31]. This has driven extensive research into more CO-tolerant catalysts, such as PtRu alloys, and lower-cost, non-precious metal alternatives [31] [14].

Interpreting the MOR Cyclic Voltammogram

A typical cyclic voltammogram for MOR on a Pt-based catalyst features two distinct oxidation peaks [31]:

- Forward Scan Peak (Pf): Arises from the oxidation of freshly chemisorbed methanol molecules.

- Backward Scan Peak (Pb): Observed during the reverse potential sweep.

For years, the ratio of the forward to backward peak currents (jf/jb) was intensively used as a criterion to evaluate a catalyst's tolerance to CO poisoning, with a higher ratio implying better CO oxidation capability [31]. However, recent studies using advanced techniques like Differential Electrochemical Mass Spectrometry (DEMS) have demonstrated that both peaks primarily originate from the direct oxidation of freshly adsorbed methanol, not from accumulated carbonaceous residues [31]. The hysteresis between the peaks is now understood to be related to the changing state of the catalyst surface: at high potentials in the forward scan, the Pt surface becomes oxidized, and the backward peak is linked to methanol oxidation on this oxidized surface as it is reduced during the reverse scan [31]. Therefore, the peak area ratio (Sf/Sb) is a more appropriate descriptor for the reducibility of the oxidized catalyst surface formed at high potential [31].

Case Study: Ni/Al-Carbonate Hydrotalcite as a Non-Precious MOR Catalyst

Ni/Al-carbonate-based layered double hydroxide (Ni-LDH) has emerged as a promising, cost-effective catalyst for MOR in highly alkaline conditions [14]. The CV of a glassy carbon electrode modified with Ni-LDH (NLGC) shows a quasi-reversible redox couple with anodic and cathodic peaks corresponding to the Ni(II)/Ni(III) transition [14]. The proposed mechanism for MOR on NLGC involves:

- Electrochemical generation of the active Ni(III) species: NiII-(OH)₂ → NiIII-OOH + e⁻

- Catalytic oxidation of methanol by NiIII-OOH to CO₂ or other products like formate.

The catalytic current is proportional to the surface coverage of the electroactive Ni species, and the brucite-like layers of the hydrotalcite structure enhance charge transport, contributing to the catalyst's efficiency [14]. The experimental workflow and reaction pathway for this system are illustrated below.

Experimental Protocols & Data Analysis

Detailed Methodology for MOR Catalyst Evaluation

The following protocol outlines a standard procedure for evaluating a MOR catalyst using CV, based on studies of Ni-LDH and similar systems [31] [14].

Electrode Preparation:

- Working Electrode: A glassy carbon electrode (GCE, e.g., 3 mm diameter) is meticulously polished with a 0.3 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth. It is then rinsed thoroughly with doubly distilled water and ultrasonicated in water for 1-2 minutes to remove any adsorbed alumina particles, followed by air drying.

- Catalyst Ink Preparation: 5 mg of the catalyst powder (e.g., Ni-LDH) is dispersed in a mixture of 975 μL of solvent (typically 4:1 v/v water:isopropanol) and 25 μL of a binder (e.g., 5% Nafion solution) via vortex mixing and then sonication for 30-60 minutes to form a homogeneous ink.