Current vs. Potential: A Guide to Voltammetry and Potentiometry for Pharmaceutical Analysis

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of voltammetry and potentiometry, two cornerstone electrochemical techniques in pharmaceutical research and drug development.

Current vs. Potential: A Guide to Voltammetry and Potentiometry for Pharmaceutical Analysis

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of voltammetry and potentiometry, two cornerstone electrochemical techniques in pharmaceutical research and drug development. It explores their foundational principles, focusing on the measurement of current under an applied potential versus the measurement of potential at zero current. The scope extends to methodological applications in drug quantification, metabolite monitoring, and ion analysis, alongside practical troubleshooting for sensor optimization. A direct comparative analysis equips scientists with the knowledge to select the appropriate technique, highlighting how their complementary strengths are advancing therapeutic drug monitoring, point-of-care diagnostics, and personalized medicine.

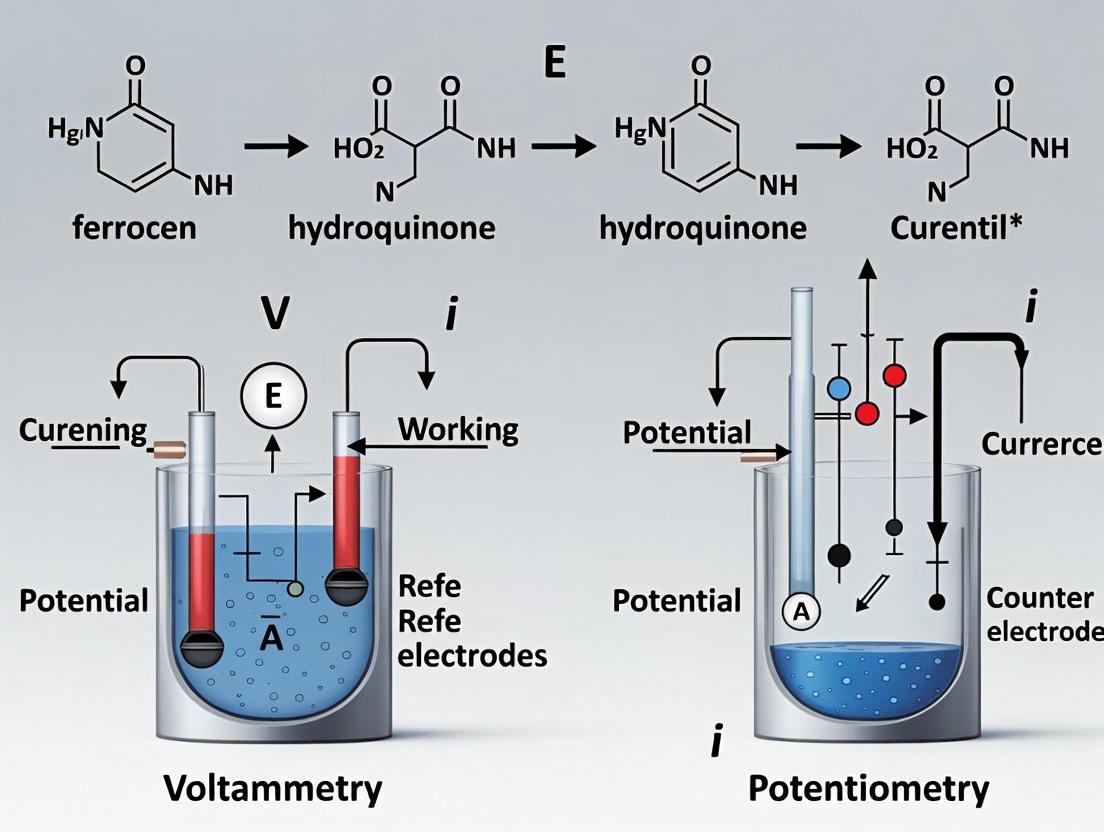

Core Principles: Understanding Voltammetry's Current and Potentiometry's Potential

Electrochemical analysis encompasses a powerful suite of techniques for quantifying analytes, studying reaction mechanisms, and monitoring processes in fields ranging from drug development to environmental science. Among these techniques, potentiometry and voltammetry represent two fundamental, yet philosophically distinct, approaches. The core distinction lies in what is controlled and what is measured. Potentiometry is a static, equilibrium technique that measures a potential difference (voltage) at zero current flow to determine analyte activity. In contrast, voltammetry is a dynamic, non-equilibrium technique that applies a controlled potential profile and measures the resulting current response due to faradaic reactions [1] [2]. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical guide to these methods, framing them within the broader context of research into signal generation and measurement. We will dissect their theoretical foundations, experimental protocols, and applications, with a particular emphasis on the critical relationship between the controlled signal and the measured response for each technique.

Theoretical Foundations and Core Principles

Potentiometry: Measuring Potential at Equilibrium

Potentiometry is defined as the measurement of an electrical potential (electromotive force) between two electrodes in an electrochemical cell when the net current flowing through the cell is zero or negligible [3] [4]. This zero-current condition is crucial as it ensures the measurement does not alter the solution's composition through electrolysis, making it an equilibrium technique [2].

The fundamental setup involves two electrodes: a reference electrode, which maintains a stable, known potential, and an indicator electrode (or ion-selective electrode, ISE), which develops a potential that depends on the activity (concentration) of a specific ion in the solution [5] [3]. The potential difference between these two electrodes is related to the analyte's activity by the Nernst equation [1] [5] [3]. For a monovalent ion, the relationship is:

E = E° + (0.0592/n) * log(a)

Where E is the measured potential, E° is the standard electrode potential, n is the number of electrons transferred, and a is the ion activity. This equation predicts a linear relationship between the measured potential and the logarithm of the ion activity, with a slope of approximately 59.2 mV per decade for a monovalent ion at 25°C [3]. The potential generated in ISEs is a phase boundary potential resulting from the selective transfer of ions across a membrane, not directly from a redox reaction [3].

Voltammetry: Measuring Current from Applied Potential

Voltammetry encompasses a group of techniques where the current flowing through an electrochemical cell is measured as a function of the applied potential to the working electrode [1] [2]. Unlike potentiometry, voltammetry is a dynamic technique that intentionally drives faradaic reactions (electron transfer) at the working electrode surface.

The applied potential provides the driving force for the oxidation or reduction of an analyte. The resulting faradaic current is proportional to the rate of this electron transfer reaction and, under controlled conditions, to the concentration of the analyte in the bulk solution [1] [2]. The current is limited by mass transport—the process by which analyte molecules diffuse from the bulk solution to the electrode surface to replenish those that have reacted. A key challenge in voltammetry is distinguishing the faradaic current from the capacitive current (or charging current), which arises from the charging and discharging of the electrical double layer at the electrode-solution interface and does not involve a chemical reaction [2]. Advanced voltammetric techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) are specifically designed to minimize the contribution of this capacitive current, thereby enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio for trace-level analysis [1] [6].

Table 1: Core Principles of Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Feature | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Parameter | Current (held at zero) | Potential (systematically varied) |

| Measured Signal | Potential (Voltage, E) | Current (I) |

| Cell State | Equilibrium (Static) | Non-Equilibrium (Dynamic) |

| Fundamental Equation | Nernst Equation | Fick's Laws of Diffusion & Faraday's Law |

| Primary Signal Source | Selective ion partitioning across a membrane | Electron transfer (redox) reaction rate |

| Typical Electrode Setup | Two-electrode (Reference & Indicator) | Three-electrode (Working, Reference, & Counter) |

Experimental Setups and Methodologies

The Potentiometric Cell and Electrode Types

A basic potentiometric cell requires two electrodes immersed in the sample solution [3]. The reference electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) provides a constant, stable potential against which changes are measured [1]. The indicator electrode responds selectively to the ion of interest. Key types of indicator electrodes include:

- Glass Membrane Electrodes: Used primarily for pH measurement and, with specific glass compositions, for sodium ions [3].

- Polymer Membrane Electrodes (ISEs): These use a poly(vinyl chloride) membrane impregnated with an ionophore (a selective ion-binding molecule) and a plasticizer. They are widely used for ions like K⁺, Ca²⁺, Li⁺, and Cl⁻ in clinical and environmental analysis [7] [3].

- Solid-State Electrodes: Employ a crystalline membrane, such as LaF₃ for fluoride ion detection [8].

A critical modern trend is the move toward solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs), which eliminate the internal filling solution of traditional ISEs. This is achieved using a solid-contact layer (e.g., conducting polymers or carbon-based nanomaterials like MXenes or carbon nanotubes) that acts as an ion-to-electron transducer. This design enables easier miniaturization, better portability, and enhanced stability, which is vital for point-of-care devices and wearable sensors [7].

The Voltammetric Cell and Key Techniques

The standard voltammetric setup is a three-electrode system [1] [2]. The working electrode (e.g., glassy carbon, gold, mercury) is where the redox reaction of interest occurs. Its potential is precisely controlled relative to the reference electrode. The counter (or auxiliary) electrode (e.g., platinum wire) completes the electrical circuit, carrying the current so that no net current flows through the reference electrode, thus preserving its stable potential [1]. This arrangement, managed by a potentiostat, allows for precise control of the working electrode potential.

Common voltammetric techniques include:

- Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): The potential is scanned linearly in a forward and reverse direction. It is a primary tool for studying electrode reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and reversibility [1].

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Small potential pulses are superimposed on a linear baseline. Current is sampled just before and at the end of each pulse, and the difference is plotted. This minimizes capacitive current, making DPV highly sensitive for trace quantitative analysis [1] [6].

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): Another pulsed technique with a square-wave modulation, offering very fast scans and high sensitivity [1].

- Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV): An extremely sensitive technique for metal ions. The analyte is first electroplated (pre-concentrated) onto the working electrode at a constant potential. Subsequently, it is stripped off (re-dissolved) by scanning the potential, producing a sharp, measurable current peak [9].

Diagram 1: DPV Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Successful implementation of these electrochemical methods relies on a suite of specialized materials and reagents.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

| Item | Function/Description | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Instrument that controls potential (potentiostat) or current (galvanostat) and measures the resulting electrochemical signal [10]. | Commercial benchtop systems, portable/pocket potentiostats. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for both potentiometric and voltammetric measurements [1]. | Ag/AgCl (Silver/Silver Chloride), SCE (Saturated Calomel Electrode). |

| Ion-Selective Membrane | The heart of an ISE; selectively binds the target ion, generating a membrane potential [3]. | PVC membranes with ionophores (e.g., valinomycin for K⁺), LaF₃ crystals (for F⁻). |

| Working Electrodes | The electrode where the reaction of interest occurs; material choice depends on the application and potential window [1]. | Glassy Carbon (GC), Gold, Platinum, Mercury (e.g., HMDE). |

| Solid-Contact Materials | Transduce ionic signal to electronic current in solid-contact ISEs; crucial for miniaturization [7]. | Conducting Polymers (e.g., PEDOT), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current in solution and minimizes migration of the analyte; ensures the reaction is diffusion-controlled [2]. | Inert salts (e.g., KCl, KNO₃, phosphate buffers). |

| Nanomaterial Modifiers | Enhance electrode sensitivity, selectivity, and stability by increasing surface area and providing binding sites [9]. | Carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs), metal nanoparticles (Au, Pt), Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs). |

Advanced Applications and Current Research Trends

Potentiometry in Clinical and Biomedical Sensing

Potentiometry has evolved far beyond the traditional pH meter. A significant trend is its integration into wearable sensors for the continuous monitoring of biomarkers, electrolytes, and even pharmaceuticals in biological fluids like sweat and interstitial fluid [7]. For instance, solid-contact ISEs are being developed for monitoring sodium and potassium levels in athletes or patients. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) is another critical application, where potentiometric sensors measure drug concentrations in biofluids, which is especially vital for pharmaceuticals with a narrow therapeutic index [7]. Furthermore, the use of 3D printing and the development of low-cost, disposable paper-based potentiometric sensors are opening new avenues for rapid, in-field (point-of-care) diagnostic testing [7].

Voltammetry in Trace Analysis and Environmental Monitoring

Voltammetry excels in the sensitive and selective detection of electroactive species. Its pulse techniques (DPV, SWV) and stripping methods (ASV) are workhorses for trace metal analysis in environmental samples [1] [9]. Recent research focuses on enhancing these methods with nanomaterials to create advanced sensors. For example, electrodes modified with carbon nanotubes, graphene, or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) exhibit improved sensitivity and selectivity for heavy metals like Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, and Hg²⁺ in water and soil [9]. These nanomaterial-based voltammetric sensors offer a portable, cost-effective alternative to traditional lab-based methods like ICP-MS for real-time, on-site environmental monitoring [9]. In pharmaceutical research, voltammetry is routinely used for drug quantification and studying drug metabolism pathways.

Table 3: Comparison of Analytical Performance and Applications

| Aspect | Potentiometry | Voltammetry (e.g., DPV/ASV) |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limit | ~10⁻⁶ to 10⁻⁸ M [7] | ~10⁻⁸ to 10⁻¹¹ M (especially with stripping) [9] |

| Selectivity | High (from ionophore in membrane) | Moderate to High (from potential & electrode modification) |

| Primary Applications | Clinical electrolytes (Na⁺, K⁺, Cl⁻), pH, environmental monitoring (NO₃⁻, NH₄⁺) [5] [7] [3] | Trace metal analysis, drug compound quantification, redox mechanism studies [1] [9] |

| Sample Throughput | High (suitable for continuous monitoring) | Moderate (scanning takes time) |

| Miniaturization & Portability | Excellent (solid-contact ISEs, wearables) [7] | Good (hand-held potentiostats available) |

Potentiometry and voltammetry are two pillars of modern electroanalytical chemistry, each defined by a distinct paradigm of signal measurement. Potentiometry, as a zero-current technique, provides a direct measure of ion activity through potential readings, governed by the Nernst equation. Its strength lies in its simplicity, selectivity, and suitability for continuous monitoring, as evidenced by its dominant role in clinical electrolyte analysis and its emerging applications in wearable sensors. Voltammetry, a controlled-potential technique, derives its analytical power from measuring the faradaic current resulting from forced redox reactions. Its dynamic nature makes it exceptionally powerful for trace-level quantitative analysis, mechanistic studies, and environmental sensing, particularly when coupled with advanced pulse techniques and nanomaterial-enhanced electrodes. The choice between these techniques is not a matter of superiority but of strategic alignment with the analytical problem at hand—whether the research question is best answered by an equilibrium measurement of ion activity or by a dynamic probe of electron transfer kinetics and concentration. For drug development professionals and researchers, a deep understanding of these defining signals is essential for selecting the optimal tool to unlock critical chemical information.

Voltammetry represents a cornerstone of electroanalytical chemistry, dedicated to studying the current response generated by an electrochemical cell as a function of an applied potential. This technique provides a powerful platform for quantifying electroactive species, offering high sensitivity, rapid response, and detailed insights into electron transfer kinetics and reaction mechanisms. The fundamental principle involves applying a controlled, time-varying potential to a working electrode within an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current, which is proportional to the concentration of the analyte undergoing oxidation or reduction [11] [12]. The resulting plot of current versus applied potential, known as a voltammogram, serves as a unique fingerprint for analyte identification and quantification [12].

This guide is framed within a broader research context contrasting voltammetry with potentiometry, another primary electroanalytical technique. While voltammetry measures current at a controlled potential, potentiometry measures the potential (voltage) of an electrochemical cell at near-zero current to determine ion activity [7] [5]. Potentiometry is renowned for its simplicity and direct readout of ion concentrations via the Nernst equation, making it ideal for continuous monitoring and portable ion-selective electrodes [7]. In contrast, voltammetry excels in sensitivity for trace-level analysis, the ability to detect multiple analytes simultaneously, and the provision of rich information about reaction kinetics and thermodynamics, making it indispensable for complex analytical challenges in drug development, neuroscience, and environmental monitoring [9] [12].

Fundamental Principles of the Voltammetric Cell

Core Components and the Signal Generation Process

At the heart of voltammetry is the voltammetric cell, a system designed to facilitate and measure electrochemical reactions. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathway and the relationship between the applied potential and the measured faradaic current.

The process begins when a potential waveform is applied to the working electrode. This potential provides the energy necessary to drive the transfer of electrons between the electrode surface and the target analyte in solution [12]. This electron transfer induces a redox reaction in the analyte, either oxidizing it (loss of electrons) or reducing it (gain of electrons). The rate of this electron transfer is directly controlled by the applied potential. The movement of electrons to or from the electrode constitutes a faradaic current, which is the primary analytical signal in voltammetry [11]. This current is measured and plotted against the applied potential to produce a voltammogram, which the instrument's system can use for further control and analysis.

Essential Components of a Voltammetric Cell

A typical voltammetric cell operates with a three-electrode configuration, which offers superior potential control compared to a two-electrode system. The key components are detailed below.

- Working Electrode (WE): This is the electrode where the reaction of interest occurs. Its material is chosen based on the analyte and the required potential window. Common materials include glassy carbon, gold, platinum, and carbon-based materials like carbon nanotubes or graphene [9] [11]. The surface of the working electrode is often modified with nanomaterials or polymers to enhance sensitivity and selectivity [11].

- Counter Electrode (CE) (or Auxiliary Electrode): This electrode, often made of an inert wire like platinum, completes the electrical circuit. It allows current to flow through the cell, ensuring that the current measured at the working electrode is solely due to the redox reactions occurring at its surface.

- Reference Electrode (RE): This electrode (e.g., Ag/AgCl) maintains a stable, known, and constant potential throughout the experiment [7]. It serves as a reference point against which the potential of the working electrode is precisely controlled and measured, ensuring the accuracy and reproducibility of the applied potential waveform.

- Electrolyte Solution: The cell contains a solution of an electrolyte (e.g., KCl, phosphate buffer) in which the analyte is dissolved. This electrolyte is chemically inert over the potential range of interest and has a much higher concentration than the analyte. Its primary function is to carry the current between the electrodes by ionic conduction, minimizing the solution's electrical resistance.

Key Voltammetric Techniques and Methodologies

Voltammetry encompasses a family of techniques, each defined by its specific applied potential waveform, which is tailored to optimize sensitivity, selectivity, or speed for different analytical scenarios.

Common Voltammetric Techniques

Table 1: Overview of Common Voltammetric Techniques

| Technique | Waveform Description | Key Features and Output | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) [11] [13] [12] | Potential is swept linearly in a forward and reverse direction. | Provides information on reaction reversibility, redox potentials, and electron transfer kinetics. Produces peaks for oxidation and reduction. | Studying reaction mechanisms, characterizing modified electrodes, determining formal potentials. |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) [9] [11] [12] | Small amplitude pulses superimposed on a linear base potential. | High sensitivity and low detection limits by minimizing charging (capacitive) current. Produces a peak-shaped voltammogram. | Trace-level detection of analytes in complex matrices (e.g., biomarkers, heavy metals). |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) [14] [11] [12] | A square wave is superimposed on a staircase waveform. | Very fast and highly sensitive. Effectively rejects capacitive current by measuring the difference between forward and reverse currents. | Rapid, sensitive detection for biosensing and trace analysis. |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) [9] [12] | Two-step: Preconcentration at a negative potential, followed by an anodic (positive) potential sweep. | Extremely low detection limits (parts-per-trillion) for metals. | Ultra-trace heavy metal analysis (e.g., Pb, Cd, Hg) in environmental and biological samples. |

| Normal Pulse Voltammetry (NPV) [15] [12] | Series of increasing potential pulses of short duration applied to a constant initial potential. | Minimizes capacitive current by measuring current at the end of each pulse. | Analytical measurements where minimizing capacitive contributions is critical. |

Experimental Protocol: Representative Voltammetric Workflow

The following diagram and protocol outline a general workflow for a voltammetric experiment, which can be adapted for specific techniques like CV or DPV.

- Cell Assembly and Electrode Preparation: Clean the working electrode according to standard protocols (e.g., polishing on a microcloth with alumina slurry for glassy carbon). Rinse thoroughly with deionized water. Assemble the three-electrode system in the electrochemical cell, ensuring proper placement of the working, counter, and reference electrodes [11].

- Introduction of Electrolyte and Deaeration: Fill the cell with the appropriate electrolyte solution. For experiments involving reducible analytes (e.g., oxygen), purge the solution with an inert gas like nitrogen or argon for at least 15-20 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere by undergoing reduction. Maintain a blanket of gas over the solution during measurement.

- System Calibration and Validation (Optional but recommended): Perform a calibration using a standard solution of a known redox couple, such as potassium ferricyanide, to verify the system's performance and the cleanliness of the electrode. In Cyclic Voltammetry, this confirms the redox potential and reversibility of the standard.

- Introduction of Analyte: Introduce the analyte of interest into the cell, typically via micropipette. Stir the solution gently (if using magnetic stirring) to ensure homogeneous distribution. Allow the solution to become quiescent before measurement if stirring is not part of the technique.

- Application of Potential Waveform and Data Acquisition: Using the potentiostat, select and configure the desired voltammetric technique (e.g., CV, DPV, SWV) and its parameters (e.g., initial/final potential, scan rate, pulse amplitude, frequency). Initiate the experiment. The potentiostat will apply the waveform and record the current response, generating the voltammogram in real-time.

- Data Analysis and Interpretation: Analyze the resulting voltammogram. Identify peak currents and potentials. For quantitative analysis, construct a calibration curve by measuring the peak current at different analyte concentrations. For kinetic studies, analyze how peak currents and potentials shift with scan rate.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of a voltammetric sensor is highly dependent on the materials used in its construction, particularly the working electrode and its modifications.

Table 2: Key Materials for Voltammetric Sensor Development

| Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Voltammetric Cell |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Glassy Carbon (GC), Gold (Au), Platinum (Pt) [11] | Provide a conductive, electroactive surface for electron transfer. Choice depends on potential window and analyte reactivity. |

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), Graphene, Graphene Oxide (GO) [9] [11] | Enhance electron transfer kinetics, increase electrode surface area, and improve sensitivity due to their high conductivity and unique structures. |

| Metal & Metal Oxide Nanoparticles | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs), Fe3O4, ZnO [9] [11] | Provide electrocatalytic activity, reduce overpotentials for redox reactions, and can be used for biomolecule immobilization. |

| Polymers & Composites | Poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT), Polyaniline, Chitosan-based composites [7] [11] | Used as permselective membranes to block interferents, for immobilization of recognition elements (enzymes, aptamers), or as ion-to-electron transducers. |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Potassium Chloride (KCl), Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), Sodium Perchlorate (NaClO4) [13] | Carry ionic current, control ionic strength, and fix the pH of the solution to ensure the electrochemical reaction is not limited by solution resistance. |

| Redox Mediators / Standards | Potassium Ferricyanide ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻/⁴⁻), Ferrocenedimethanol (Fc(MeOH)₂ [13] | Used for system validation, electrode characterization, and to study electron transfer kinetics. Also used as labels or mediators in biosensors. |

Advanced Applications and Future Perspectives

Voltammetric cells have moved beyond basic research and are now pivotal in cutting-edge applications. In neurochemical monitoring, carbon-fiber microelectrodes used with fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) enable real-time, in vivo detection of neurotransmitters like dopamine with high spatiotemporal resolution [12]. In pharmaceutical analysis, voltammetry is used for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of pharmaceuticals with narrow therapeutic indices, offering a rapid alternative to traditional chromatographic methods [7] [12]. In environmental monitoring, techniques like ASV are indispensable for detecting trace heavy metals such as lead, cadmium, and mercury in water samples at parts-per-trillion levels [9] [12].

The future of voltammetry is being shaped by several key trends. The integration of nanomaterials like MXenes, metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), and hybrid nanocomposites continues to push the boundaries of sensor sensitivity and selectivity [9] [11]. There is a growing emphasis on miniaturization and portability, with the development of wearable sensors and 3D-printed electrode platforms for point-of-care testing and field analysis [7]. Finally, the fusion of voltammetry with digital technologies, such as artificial intelligence and machine learning, is beginning to automate signal processing, enable adaptive recalibration, and extract complex patterns from multivariate voltammetric data, opening new frontiers in intelligent sensing [11].

Potentiometry is a cornerstone electrochemical technique characterized by its operation at zero-current conditions. Unlike dynamic methods like voltammetry that measure current from electron transfer, potentiometry passively measures the potential difference, or electromotive force (EMF), between two electrodes to determine the activity of target ions in solution [7] [16]. This fundamental distinction makes it a powerful tool for direct, non-destructive chemical analysis.

The technique's significance is underscored by its diverse applicability across clinical diagnostics, environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical analysis, and industrial process control [7] [1]. Its principle is governed by the Nernst equation, which describes the relationship between the measured potential and the ionic activity of the analyte [17]. A core advantage of this zero-current approach is its minimal consumption of the analyte and relative insensitivity to solution turbidity or color, making it suitable for complex real-world samples [7].

This guide details the core components, functioning, and experimental implementation of potentiometric cells, framing this discussion within a broader research context that contrasts potential measurement in potentiometry with current measurement in voltammetry.

Core Components of a Potentiometric Cell

A typical potentiometric cell consists of two primary electrodes immersed in the sample solution, completing an electrochemical cell where the potential is measured without significant current flow [17].

The Indicator Electrode

The indicator (or working) electrode's potential varies in response to the activity of the specific ion of interest. The most common types are Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs), which incorporate a membrane designed to be selective for a particular ion [7] [1].

- Membrane Types: ISEs use various membrane materials to achieve selectivity, including glass (for H⁺, Na⁺), crystalline solids, or polymeric membranes impregnated with ionophores (ion-binding molecules) [18].

- Response Mechanism: The potential develops across the ion-selective membrane due to the unequal distribution of ions between the sample and the membrane phase, a process governed by the Nernst equation [17].

The Reference Electrode

The reference electrode provides a stable, known, and constant potential against which the indicator electrode's potential is measured [1] [17]. Its stability is critical for the accuracy of the entire measurement.

- Common Types: The Ag/AgCl (silver/silver chloride) and saturated calomel (SCE) electrodes are most frequently used [1] [19].

- Key Feature: A reference electrode maintains a constant potential by employing a reversible half-cell containing an electrolyte of fixed composition [17]. A salt bridge (often filled with concentrated KCl) facilitates ionic contact with the sample solution while minimizing the mixing of electrolytes [17].

Table 1: Key Electrodes in a Potentiometric Cell

| Electrode Type | Function | Key Characteristics | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Electrode | Responds to the activity of a specific ion in the sample solution. | Potential changes log-linearly with ion activity (Nernstian response). High selectivity for target ion. | pH glass electrode; Ca²⁺, K⁺, Pb²⁺ ion-selective electrodes [1] [20]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for measurement. | Constant electrochemical potential; unaffected by sample composition. | Ag/AgCl electrode; Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [1] [19]. |

Cell Diagram and Potential Development

The overall cell potential (E~cell~) is the difference between the potentials of the indicator and reference electrodes: E~cell~ = E~ind~ − E~ref~ [19]. This measured potential, E~cell~, is related to the analyte's activity (a~I~) by the Nernst equation: E = E⁰ + (2.303RT/zF) log(a~I~) where E⁰ is the standard electrode potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is the ion's charge, and F is the Faraday constant [17] [20].

Potentiometry vs. Voltammetry: A Core Methodological Contrast

The fundamental difference between potentiometry and voltammetry lies in what is controlled and what is measured, leading to distinct applications and information outputs [1] [10].

Potentiometry: This is a zero-current technique. The potential difference between the indicator and reference electrode is measured under conditions of thermodynamic equilibrium, with no significant current flowing through the cell [7] [16]. The output is a potential related to ionic activity by the Nernst equation. It is primarily used for direct determination of ion concentrations/activities [1].

Voltammetry: This is a controlled-potential technique. The current flowing through the cell is measured as the applied potential at the working electrode is systematically varied [1] [16]. This is a dynamic, non-equilibrium method where electron transfer (current flow) is central. It provides both quantitative and qualitative information about electroactive species, including their concentration, redox potentials, and reaction kinetics [1].

Table 2: Contrasting Potentiometry and Voltammetry

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Controlled Variable | None (zero current) / Open Circuit Potential | Electrode Potential |

| Measured Signal | Potential (Volts) | Current (Amperes) |

| Current Flow | Negligible (Theoretical Zero) | Significant (Measured Directly) |

| Governing Equation | Nernst Equation | Nernst Equation & Fick's Laws of Diffusion |

| Primary Information | Ionic Activity / Concentration | Redox Behavior, Concentration, Kinetics |

| System State | Equilibrium / Near-Equilibrium | Non-Equilibrium / Dynamic |

| Common Electrode Setup | Two-Electrode (Indicator & Reference) | Three-Electrode (Working, Reference, & Counter) |

| Example Application | pH measurement, clinical electrolyte analysis [7] [1] | Trace metal detection, studying reaction mechanisms [1] |

Experimental Protocol: Potentiometric Titration for Iron Determination

Potentiometric titration showcases the application of a potentiometric cell to monitor the progress of a redox reaction, determining the endpoint without a visual indicator [19]. The following protocol details the determination of Fe²⁺ concentration using a potassium permanganate (KMnO₄) titrant.

Principle

A sample containing Fe²⁺ is titrated with a standardized KMnO₄ solution. The redox reaction between MnO₄⁻ and Fe²⁺ causes a change in the solution's potential. An indicator electrode (e.g., platinum) senses this change relative to a reference electrode. The endpoint is identified as the point of maximum potential change on a plot of measured potential (E~cell~) versus titrant volume [19].

Key Reaction: [ \ce{MnO4^{-} + 8H+ + 5Fe^{2+} -> Mn^{2+} + 5Fe^{3+} + 4H2O} ] The Nernst equation for the permanganate half-reaction is: [ E{PM} = E^{∘}{PM} - \frac{RT}{5F} \ln{\frac{[Mn^{2+}]}{[MnO_4^{-}][H^{+}]^8}} ] The cell potential is measured as E~cell~ = E~ind~ − E~ref~, where E~ind~ is the potential of the platinum indicator electrode and E~ref~ is the potential of a reference electrode like Ag/AgCl [19].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Potentiometric Titration

| Reagent/Solution | Function / Role in the Experiment |

|---|---|

| Fe²⁺ Solution (Analyte) | The solution of unknown concentration to be determined. Acts as the reducing agent in the redox titration [19]. |

| KMnO₄ Solution (Titrant) | Standardized oxidizing agent of known concentration. Reacts stoichiometrically with the Fe²⁺ analyte [19]. |

| Platinum (Pt) Electrode | Serves as the indicator electrode. Its potential changes as the ratio of [Fe³⁺]/[Fe²⁺] (and [MnO₄⁻]/[Mn²⁺]) shifts during the titration [19]. |

| Ag/AgCl Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential against which the Pt indicator electrode's potential is measured [19]. |

| Acid (e.g., H₂SO₄) | Provides the H⁺ ions required for the permanganate half-reaction, ensuring the reaction proceeds correctly and at a practical rate [19]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Cell Assembly: Place a known volume of the Fe²⁺ sample solution into a clean beaker. Acidify it with sulfuric acid to provide the necessary H⁺ ions. Immerse the cleaned platinum indicator electrode and the Ag/AgCl reference electrode into the solution [19].

- Instrument Setup: Connect the electrodes to a high-impedance voltmeter (potentiometer). Ensure the solution is being stirred constantly using a magnetic stirrer to maintain homogeneity.

- Initial Measurement: Record the initial cell potential (EMF) and the initial burette reading of the KMnO₄ titrant.

- Titration and Data Collection: Begin adding the KMnO₄ titrant in small increments (e.g., 0.5-1.0 mL). After each addition, allow the potential to stabilize and then record the volume added and the corresponding cell potential. As the endpoint is approached (indicated by larger potential jumps), reduce the titrant increments to 0.1 or 0.2 mL.

- Post-Endpoint Data: Continue adding titrant and recording potential and volume for several mL after the endpoint to fully define the titration curve.

- Endpoint Determination: Plot the measured cell potential (E~cell~) against the volume of KMnO₄ titrant added. The equivalence point is identified as the volume at the steepest inflection point of the sigmoidal-shaped curve. This can be found precisely by calculating the first derivative (ΔE/ΔV) of the titration data.

- Calculation: Use the volume at the equivalence point (V~eq~), the known concentration of the KMnO₄ titrant (C~KMnO4~), and the stoichiometry of the reaction to calculate the moles and concentration of Fe²⁺ in the sample.

Advanced Sensor Architectures and Applications

The field of potentiometry has evolved significantly beyond traditional glass electrodes, with innovations enhancing performance in complex matrices.

Solid-Contact Ion-Selective Electrodes (SC-ISEs)

Modern research focuses on Solid-Contact ISEs (SC-ISEs), which eliminate the internal filling solution of traditional ISEs. This design offers superior mechanical stability, ease of miniaturization, and portability [7]. The solid-contact layer, situated between the ion-selective membrane and the electronic conductor, functions as an ion-to-electron transducer [7]. Common transducer materials include:

- Conducting Polymers: e.g., polyaniline, PEDOT [7].

- Nanomaterials: Carbon nanotubes, graphene, and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) that provide high capacitance and stability [7].

- Nanocomposites: Materials like MoS₂ nanoflowers filled with Fe₃O₄ are engineered to create synergistic effects, preventing structural collapse and enhancing electrochemical characteristics [7].

Applications in Research and Industry

The versatility of potentiometric sensors is demonstrated by their wide-ranging applications:

- Clinical Diagnostics and Biomedical Applications: Continuous monitoring of electrolytes (Na⁺, K⁺, Ca²⁺, Cl⁻) and blood gases is vital in critical care [7] [1]. Wearable potentiometric sensors are emerging for non-invasive monitoring of biomarkers and electrolytes in sweat or interstitial fluid [7]. Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) is another crucial application, especially for pharmaceuticals with a narrow therapeutic index, where potentiometric sensors can track drug concentrations in biological fluids [7].

- Environmental and Industrial Monitoring: Potentiometric sensors are deployed for detecting heavy metals like lead (Pb²⁺), copper (Cu²⁺), and mercury (Hg²⁺) in water and soil [7] [20]. They are also used for determining anions such as nitrate (NO₃⁻) and chloride (Cl⁻), which are critical for assessing water quality and agricultural runoff [7]. In industry, they play a role in quality control for pharmaceuticals and detergent manufacturing [7] [21].

- Agro-Food and Forensic Sciences: Analysis of ions in soils, plant materials, and food products is a common application [21]. Potentiometry is also used in forensic analysis for detecting drugs or toxic substances at crime scenes with minimal sample preparation [7].

The potentiometric cell, operating on the fundamental principle of zero-current potential measurement, remains an indispensable tool in the analytical scientist's arsenal. Its simplicity, selectivity, and direct readout of ionic activity, as described by the Nernst equation, provide distinct advantages for quantitative analysis across diverse fields. The ongoing innovation in sensor design—particularly through solid-contact architectures, novel nanomaterials, and the development of wearable platforms—ensures that potentiometry will continue to be a vital technique for precise chemical sensing in both laboratory and real-world settings. By understanding its core principles and contrasting them with dynamic techniques like voltammetry, researchers can better select and optimize the appropriate electrochemical method for their specific analytical challenges.

In the realm of modern electroanalytical chemistry, particularly within pharmaceutical and bioanalytical research, two fundamental measurement paradigms exist: the measurement of current in voltammetry and the measurement of potential in potentiometry. These approaches form the cornerstone of quantitative analysis for diverse applications ranging from drug detection in biological matrices to environmental monitoring of pharmaceutical residues [22]. The distinction between these techniques is not merely operational but stems from fundamental differences in what is controlled and what is measured in the electrochemical cell [10].

Voltammetric techniques involve applying a time-dependent potential to an electrochemical cell and measuring the resulting current as a function of that potential [23]. This current signal is intrinsically linked to the rate of electron transfer and mass transport of analyte to the electrode surface. In contrast, potentiometry passively measures the potential of a solution between two electrodes at zero current, a measurement that relates to the thermodynamic activity of ions in solution [16]. This in-depth technical guide explores the core governing equations of these methods—the Randles-Ševčík equation for voltammetry and the Nernst equation for potentiometry—framed within the context of current versus potential measurement research for drug development applications.

The Nernst Equation: The Thermodynamic Foundation of Potentiometry

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formalism

Potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the potential difference between two electrodes (a reference electrode and an indicator electrode) when no net current is flowing through the cell [1] [16]. This measured potential is a direct function of the concentration or activity of a specific ion in the solution, as described by the Nernst equation. For a general redox reaction: $$Ox + ne^- \rightleftharpoons Red$$ the Nernst equation is expressed as: $$E = E^0 - \frac{RT}{nF} \ln\frac{a{Red}}{a{Ox}}$$ where (E) is the measured potential, (E^0) is the standard electrode potential, (R) is the universal gas constant, (T) is the absolute temperature, (n) is the number of electrons transferred in the half-reaction, (F) is the Faraday constant, and (a{Red}) and (a{Ox}) are the activities of the reduced and oxidized species, respectively [1].

In practice, for ion-selective electrodes (ISEs), the equation is often simplified to: $$E = E^0 - \frac{0.05916}{n} \log[a]$$ at 25°C, where ([a]) is the activity of the ion of interest [1]. A key advantage of potentiometric sensing is its non-destructive nature, as it virtually does not consume the analyte during measurement, making it particularly valuable for small sample volumes with low analyte concentrations [24].

Experimental Protocols and Applications in Drug Development

Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) Methodology for Drug Ion Analysis The fundamental setup for potentiometric analysis involves an electrochemical cell with two electrodes: a reference electrode that provides a stable, known potential, and an indicator electrode whose potential changes with the sample's composition [16]. Ion-selective electrodes are designed to respond selectively to a single type of ion through incorporation of specific ionophores in the membrane [1].

- Electrode Preparation: For a custom ISE, a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) membrane is typically prepared containing a plasticizer (e.g., 2-nitrophenyloctyl ether), an ion exchanger (e.g., potassium tetrakis(p-Cl-phenyl)borate), and for enhanced selectivity, a neutral ionophore (e.g., dicyclohexyl-18-crown-6 for dopamine sensing) [24]. This membrane cocktail is dissolved in tetrahydrofuran (THF) and cast into a mold or directly applied to an electrode body.

- Measurement Protocol: The ISE and reference electrode are immersed in the sample solution. The potential difference between them is measured after stabilization, ensuring zero current conditions. The potential is recorded and related to the analyte concentration via a calibration curve constructed from standard solutions [1] [24].

- Data Analysis: A plot of (E) vs. (\log[a]) yields a straight line with a slope of approximately (59.16/n) mV/decade at 25°C. Deviations from this slope may indicate non-ideal behavior or issues with the electrode.

Potentiometry is invaluable in pharmaceutical research for electrolyte analysis in clinical labs, monitoring ionic drugs, and potentiometric titrations where the endpoint is determined by a sharp change in potential, providing greater accuracy than visual indicators [1]. Recent research explores novel ionophores for neurotransmitters like dopamine, aiming to overcome selectivity challenges against common interferences such as ascorbic and uric acids [24].

The Randles-Ševčík Equation: The Quantitative Bridge in Voltammetry

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Formalism

Voltammetry is a dynamic technique that measures the current passing through an electrochemical cell as a function of the applied potential [1]. The resulting current-potential plot is called a voltammogram. For a reversible system at a planar macroelectrode, the peak current in linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) or cyclic voltammetry (CV) is described by the Randles-Ševčík equation: $$ip = (2.69 \times 10^5) \cdot n^{3/2} \cdot A \cdot D^{1/2} \cdot C \cdot \nu^{1/2}$$ where (ip) is the peak current (A), (n) is the number of electrons transferred, (A) is the electrode area (cm²), (D) is the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s), (C) is the bulk concentration (mol/cm³), and (\nu) is the scan rate (V/s) [23].

This equation highlights that the measured current is directly proportional to the analyte concentration and the square root of the scan rate, indicating a diffusion-controlled process. Unlike the thermodynamic relationship in potentiometry, the Randles-Ševčík equation deals with kinetics and mass transport. The current is a measure of the rate of the electrochemical reaction, which is why voltammetry is often described as an "active" technique that consumes a small amount of analyte [24] [23].

Experimental Protocols and Applications in Drug Development

Cyclic Voltammetry Protocol for Trace Drug Detection Voltammetry requires a three-electrode system: a Working Electrode (WE) where the reaction of interest occurs, a Reference Electrode (RE) to maintain a known potential, and a Counter Electrode (CE) to complete the circuit [1]. This configuration provides precise control over the working electrode potential.

- Electrode Preparation and Modification: Common working electrodes include glassy carbon (GCE), carbon paste (CPE), and screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) [22]. To enhance sensitivity and selectivity for specific drug targets, the electrode surface is often modified. This can involve drop-casting a suspension of nanomaterials (e.g., graphene, carbon nanotubes, MXenes, or metal nanoparticles) to increase surface area and electron transfer kinetics [22]. The modified electrode is then thoroughly rinsed and dried.

- Measurement Protocol: The three-electrode system is immersed in an electrolyte solution containing the analyte. For cyclic voltammetry, the potential is swept linearly between two set limits at a defined scan rate (e.g., 0.01 to 1 V/s) while the current is recorded. Multiple cycles may be run to assess electrode stability and reaction reversibility [1] [22].

- Data Analysis: The voltammogram is analyzed for peak potentials (for qualitative identification) and peak currents (for quantitative analysis). A plot of (i_p) vs. (\nu^{1/2}) should yield a straight line for a diffusion-controlled process, validating the application of the Randles-Ševčík equation. Quantitative analysis is performed using a calibration curve of peak current versus analyte concentration.

Voltammetry's ability to provide both qualitative and quantitative data makes it a preferred method for a wide range of pharmaceutical applications, from quantifying heavy metals in drug precursors to analyzing the concentration of a new drug compound like antibiotics or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [1] [22]. Advanced pulsed techniques such as Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) offer even higher sensitivity for trace analysis by minimizing background (charging) current [1] [22].

Comparative Analysis: Measurement Paradigms and Analytical Figures of Merit

The core distinction between these techniques lies in their fundamental measurement approach: potentiometry measures potential at zero current (a thermodynamic equilibrium measurement), while voltammetry measures current as a function of applied potential (a kinetic measurement involving analyte consumption) [24]. This fundamental difference dictates their respective applications, advantages, and limitations in drug research.

Table 1: Comparative analysis of potentiometry and voltammetry core characteristics.

| Feature | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Governing Equation | Nernst Equation | Randles-Ševčík Equation |

| Measured Signal | Potential (V) | Current (A) |

| Current Flow | Virtually zero [24] | Measured and controlled |

| Analyte Consumption | Negligible [24] | Measurable, though small [24] |

| Primary Application | Ion activity (pH, Na⁺, K⁺) [1] | Redox-active species (drugs, metals) [1] |

| Key Advantage | Non-destructive; ideal for small volumes [24] | High sensitivity; qualitative & quantitative data [1] |

| Key Challenge | Achieving high selectivity with ionophores [24] | Mass transport limitations in small volumes [24] |

Table 2: Analytical performance and typical applications in pharmaceutical sciences.

| Parameter | Potentiometry | Voltammetry |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit | ~10⁻⁸ M (varies with ISE) [24] | Can reach 10⁻⁹ M or lower with modified electrodes [22] [24] |

| Selectivity | Achieved via ionophore in membrane [1] | Achieved via potential control & surface modification [22] |

| Sample Volume | Suitable for very small volumes (e.g., 200 µL) [24] | Microelectrodes enable work in small volumes [24] |

| Pharma Application Example | Electrolyte analysis in clinical formulations [1] | Detection of antibiotics, NSAIDs in bio-fluids [22] |

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental implementation of these electrochemical techniques relies on a standardized set of reagents and materials.

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions and materials for electrochemical analysis.

| Reagent/Material | Function/Description | Typical Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for measurements. | Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE), Ag/AgCl electrode [1] [23]. |

| Working Electrode | The electrode where the controlled reaction occurs. | Glassy Carbon (GCE), Gold, Platinum, Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) [22] [23]. |

| Counter/Auxiliary Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit, carrying the current. | Platinum wire [1] [23]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current and minimizes migration; sets ionic strength. | Phosphate buffer, KCl, NaClO₄ [22]. |

| Ionophore | A host molecule that selectively binds a target ion in ISE membranes. | Dicyclohexyl-18-crown-6 (for cations), valinomycin (for K⁺) [24]. |

| Membrane Components (ISE) | Form the ion-selective membrane. | PVC (polymer matrix), oNPOE (plasticizer), KTpClPB (ion exchanger) [24]. |

| Nanomaterials | Modify electrode surfaces to enhance sensitivity and selectivity. | Graphene, Carbon Nanotubes, Metal Nanoparticles, MXenes [22]. |

Experimental Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the fundamental operational and signaling pathways for potentiometric and voltammetric measurements.

The Nernst and Randles-Ševčík equations govern two distinct yet complementary electrochemical universes: the thermodynamic world of equilibrium potential and the kinetic world of faradaic current. For researchers in drug development, the choice between potentiometric and voltammetric methods hinges on the specific analytical problem. Potentiometry, with its minimal analyte consumption, is ideal for direct ion activity measurement where suitable selective membranes exist. Voltammetry, with its superior sensitivity and rich mechanistic information, is unparalleled for detecting redox-active pharmaceutical compounds at trace levels in complex matrices.

Future trends point toward the miniaturization of these platforms into portable, paper-based analytical devices [25] and the integration of advanced materials like MXenes [22] and quantum principles [26] to push the boundaries of sensitivity and selectivity. The ongoing convergence of these techniques with automation and machine learning [27] promises to further solidify electrochemical analysis as an indispensable tool in the drug development pipeline.

Electrochemical analysis techniques are fundamental tools in modern research, enabling the characterization of redox processes, material properties, and chemical concentrations. These techniques are broadly categorized based on whether they measure current or potential, which dictates their experimental setup and application. Voltammetry is a class of techniques that involves measuring the current response of an electrochemical system while varying an applied potential. In contrast, potentiometry is a technique that involves measuring the potential difference between two electrodes under conditions of zero or negligible current flow [28] [29]. This fundamental distinction—measuring current under applied potential versus measuring equilibrium potential—is the cornerstone upon which their respective electrode systems are built. The selection between a three-electrode voltammetric cell and a two-electrode potentiometric cell is therefore determined by the very nature of the electrochemical information sought.

This guide details the two primary electrode systems: the three-electrode setup essential for voltammetric techniques like Cyclic Voltammetry (CV), and the two-electrode cell utilizing Ion-Selective Electrodes (ISEs) for potentiometric measurements. The content is framed within a broader thesis on analytical measurement, contrasting the dynamic current monitoring of voltammetry with the equilibrium potential measurement of potentiometry.

Three-Electrode Systems for Voltammetry

Principles and Configuration

Voltammetry encompasses techniques where the current at a working electrode is measured as the applied potential is systematically varied [30] [29]. This process drives redox reactions, and the resulting current provides information on reaction kinetics, thermodynamics, and analyte concentration. The three-electrode system is critical for these measurements because it separates the functions of potential control and current carrying [31].

A typical three-electrode system consists of:

- Working Electrode (WE): This is the electrode where the reaction of interest occurs. Its potential is controlled and measured relative to the reference electrode. Common materials include glassy carbon, platinum, and gold [31].

- Counter Electrode (CE) / Auxiliary Electrode: This electrode completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow through the cell. It is typically made from an inert material like platinum or graphite and has a large surface area to ensure it does not become a limiting factor in the measurement [30] [31].

- Reference Electrode (RE): This electrode provides a stable, known, and constant reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is both controlled and measured. It is designed so that minimal current passes through it, preserving its stable potential. Common examples include the Ag/AgCl electrode and the Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) [31] [32].

The system operates via a potentiostat, an electronic instrument that creates two distinct circuits: a potential circuit between the WE and RE for accurate potential control, and a current circuit between the WE and CE for current measurement [31]. This separation is vital because if significant current were to pass through the reference electrode, its potential would drift due to polarization, leading to inaccurate measurements [33].

Experimental Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a powerful and widely used voltammetric technique for studying the redox properties of electroactive species [30] [29].

Methodology:

- Cell Assembly: Prepare an electrochemical cell containing the electrolyte and analyte solution. Insert the three electrodes: Working Electrode, Counter Electrode, and Reference Electrode. Ensure the RE is positioned close to the WE to minimize uncompensated solution resistance [31].

- Instrument Setup: Connect the electrodes to a potentiostat. Set the initial potential, upper potential limit, lower potential limit, and the scan rate (e.g., 0.1 V/s). The potential is swept linearly from the initial potential to the upper limit.

- Scan Reversal: Upon reaching the upper potential limit, the scan direction is reversed, and the potential is swept back to the lower limit. This cycle may be repeated multiple times [30].

- Data Collection: The potentiostat measures the current flowing at the working electrode as a function of the applied potential. The result is a cyclic voltammogram—a plot of current (I) vs. potential (E) [30].

Data Interpretation: A typical CV for a reversible redox couple displays a "duck-shaped" plot. Key features include [30]:

- Anodic Peak Current (ipa) and Potential (Epa): Correspond to the oxidation half-reaction.

- Cathodic Peak Current (ipc) and Potential (Epc): Correspond to the reduction half-reaction.

- For a reversible, diffusion-controlled system, the peak currents are equal in magnitude but opposite in sign (|ipa| = |ipc|), and the peak separation (ΔEp = Epa - Epc) is approximately 59 mV for a one-electron transfer process.

The peak current is quantitatively described by the Randles-Ševčík equation (at 298 K): [ ip = (2.69 \times 10^5) \cdot n^{3/2} \cdot A \cdot D^{1/2} \cdot C \cdot v^{1/2} ] where ( ip ) is the peak current (A), ( n ) is the number of electrons transferred, ( A ) is the electrode area (cm²), ( D ) is the diffusion coefficient (cm²/s), ( C ) is the concentration (mol/cm³), and ( v ) is the scan rate (V/s) [30].

The diagram below illustrates the experimental workflow and current response in a cyclic voltammetry experiment.

Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetry

Table 1: Key reagents and materials for voltammetry experiments.

| Item | Function/Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat | Electronic instrument that controls the potential between WE and RE and measures current between WE and CE [31]. | Essential for all voltammetric experiments. |

| Working Electrode | Surface where the redox reaction of interest occurs [31]. | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Platinum (Pt) Electrode, Gold (Au) Electrode. Surface pre-treatment is critical for reproducibility [31]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for the working electrode [31] [32]. | Ag/AgCl, Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE). Must maintain stable composition. |

| Counter Electrode | Conducts current to balance the reaction at the working electrode [30] [31]. | Platinum wire, graphite rod. Should have a large surface area. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Conducts current and minimizes migration of the analyte via ionic strength adjustment [30]. | Inert salts (e.g., KCl, KNO₃, TBAPF₆) at concentrations typically >0.1 M. |

| Redox Active Analyte | The chemical species under investigation. | e.g., Ferrocene, often used as an internal standard [30]. |

| Solvent | Dissolves the electrolyte and analyte. | Water, Acetonitrile (MeCN), Dichloromethane (DCM). Must be pure and electrochemically inert in the potential window of interest. |

Ion-Selective Electrodes for Potentiometry

Principles and Configuration

Potentiometry is an electrochemical technique where the potential (electromotive force, EMF) between two electrodes is measured under conditions of zero or negligible current flow [7] [29]. This measured potential is related to the activity (concentration) of a specific ion in solution via the Nernst equation. The core sensor in this technique is the Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) [34] [32].

A typical potentiometric cell requires only two electrodes [28]:

- Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE): This is the sensing electrode. It incorporates a specialized membrane that selectively interacts with the target ion, generating a membrane potential that depends on the ionic activity. The key component is the ion-selective membrane, which can be glass, crystalline, or a polymer-based ion-exchange resin [32] [35].

- Reference Electrode: This electrode maintains a constant and known potential, independent of the sample solution's composition. It completes the electrochemical cell and provides a stable reference point for the measurement [32] [35].

The fundamental principle is described by the Nernst equation, which relates the measured cell potential (E) to the activity of the target ion (aion): [ E = E^0 \pm \frac{2.303RT}{zF} \log(a{ion}) ] where E⁰ is the standard cell potential, R is the gas constant, T is temperature, z is the ion's charge, and F is the Faraday constant [28] [35]. The sign is positive for cations and negative for anions. The term (2.303RT/zF) is the Nernstian slope; for a monovalent ion (z=1) at 25°C, it is 59.16 mV per decade change in activity [35].

Experimental Protocol: Direct Potentiometry with an ISE

Direct potentiometry is a straightforward method for determining the concentration of an ion in a sample solution.

Methodology:

- Calibration:

- Prepare a series of standard solutions with known concentrations of the target ion, incorporating an Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer (ISAB) to maintain a constant background ionic strength. This ensures that activity coefficients are constant, allowing concentration to be used in place of activity [35].

- Immerse the ISE and reference electrode in each standard solution, starting with the most dilute.

- Measure the stable potential (EMF) for each standard.

- Plot the measured EMF (mV) versus the logarithm of the ion concentration (log C). The plot should be linear, conforming to the Nernst equation [35].

- Sample Measurement:

- Immerse the cleaned ISE and reference electrode into the unknown sample solution, which should also contain the same ISAB.

- Measure the stable potential (EMF).

- Determine the unknown concentration from the calibration curve using the measured EMF value.

Data Interpretation: The calibration curve's linear range defines the usable concentration range for the ISE. The detection limit is typically the concentration at which the calibration curve significantly deviates from linearity [35]. The slope of the calibration curve should be close to the theoretical Nernstian value for ideal behavior. A real calibration curve may show sub-Nernstian response at very low concentrations [35].

The diagram below illustrates the structure and operating principle of a solid-contact ion-selective electrode (SC-ISE), a common modern configuration.

Research Reagent Solutions for Potentiometry

Table 2: Key reagents and materials for potentiometry with Ion-Selective Electrodes.

| Item | Function/Description | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | The sensing electrode with a membrane selective for a specific ion [32]. | pH glass electrode, Fluoride ISE (LaF₃ crystal), Potassium ISE (Valinomycin/PVC membrane). |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable reference potential against which the ISE potential is measured [32] [35]. | Ag/AgCl with fixed KCl filling solution. Junction potential must be stable. |

| Ionic Strength Adjustment Buffer (ISAB) | Added to standards and samples to maintain constant ionic strength, fix pH, and mask interfering ions [35]. | Critical for accurate measurement; composition depends on analyte and sample matrix. |

| Standard Solutions | Solutions of known concentration for calibrating the ISE [35]. | Should bracket the expected unknown concentration; prepared with high-purity reagents. |

| High-Impedance Potentiometer / pH Meter | Measures the potential difference between the ISE and reference electrode [34] [35]. | Requires high input impedance (>10¹² Ω) to prevent current draw and electrode polarization [34]. |

Core Functional Distinctions

Table 3: A direct comparison of the three-electrode voltammetry system and the two-electrode potentiometry system.

| Feature | Three-Electrode System (Voltammetry) | Ion-Selective Electrode (Potentiometry) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Measurement | Current (i) as a function of applied potential [29]. | Potential (EMF) at zero current [7] [29]. |

| Key Relationship | Current ∝ Rate of redox reaction & analyte concentration [30]. | Potential ∝ log(Ion Activity) via Nernst equation [28] [35]. |

| Electrode Configuration | Working, Counter, and Reference Electrodes [31]. | Ion-Selective Electrode and Reference Electrode [32] [35]. |

| System State | Dynamic (non-equilibrium); potential is actively scanned [30]. | Static (equilibrium); potential is measured at steady-state [7]. |

| Information Obtained | Redox potentials, reaction kinetics, diffusion coefficients, electron transfer mechanisms [30] [29]. | Ionic activity (concentration) of a specific ion [34] [32]. |

| Key Instrument | Potentiostat [30] [31]. | High-impedance Voltmeter / pH Meter [34] [35]. |

| Data Output | Cyclic Voltammogram (I vs. E plot) [30]. | Calibration curve (EMF vs. log C) and single EMF reading [35]. |

Advanced Trends and Research Impact

The fields of voltammetry and potentiometry continue to evolve, driven by advancements in materials science and manufacturing:

Voltammetry: Recent progress focuses on using microelectrodes and nanoelectrodes for enhanced spatial resolution and sensitivity, and the development of novel electrode materials like carbon nanomaterials to improve electrocatalytic properties and detection limits [29]. Integration with other techniques, such as spectroscopy, is also a growing trend for studying complex systems [29].

Potentiometry: The most significant recent trends involve the move toward solid-contact ISEs (SC-ISEs), which eliminate the internal filling solution of traditional ISEs. This improves mechanical stability, enables miniaturization, and allows for longer sensor lifetime [7]. Key developments in this area include:

- Novel Transducer Materials: Use of conducting polymers (e.g., PEDOT), carbon nanotubes, graphene, and MXenes as the solid-contact layer to enhance capacitance and signal stability [7].

- 3D Printing: Allows for rapid prototyping and fabrication of ISEs with complex geometries, accelerating sensor optimization and development [7].

- Wearable Sensors: The miniaturization and solid-contact design enable the integration of ISEs into wearable devices for continuous monitoring of electrolytes (e.g., K⁺, Na⁺) and drugs in biological fluids like sweat [7].

These advancements are particularly impactful for the target audience of researchers and drug development professionals. Voltammetry is indispensable for characterizing redox-active drug molecules, studying electron transfer mechanisms in biological systems, and developing biosensors. Potentiometry, especially with the advent of miniaturized and wearable SC-ISEs, offers powerful tools for therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) of pharmaceuticals with narrow therapeutic indices and for real-time tracking of critical electrolytes in clinical settings [7].

Techniques in Action: Applying Voltammetry and Potentiometry in Drug Development

Electroanalytical techniques have emerged as powerful tools in the pharmaceutical industry, offering distinct advantages for drug development, quality assurance, and therapeutic monitoring. Unlike traditional methods such as chromatography and spectrophotometry, electroanalysis provides high sensitivity, rapid analysis, cost-effectiveness, and minimal sample preparation requirements [36]. Among these techniques, voltammetry represents a particularly versatile family of methods that measure current as a function of applied potential to obtain both qualitative and quantitative information about electroactive species [1]. This stands in direct contrast to potentiometry, which measures potential at zero current and is primarily used for ion activity measurements [7] [1].

The fundamental principle of voltammetry involves applying a controlled potential to an electrochemical cell containing a working electrode, reference electrode, and counter electrode, then measuring the resulting current generated by redox reactions at the working electrode interface [1]. This current response provides a wealth of information about the analyte, including its concentration, redox properties, and reaction kinetics. For pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals, voltammetric techniques offer unparalleled capabilities for detecting active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), monitoring drug metabolites in biological fluids, ensuring product stability, and screening for impurities [36].

This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of three cornerstone voltammetric techniques—cyclic voltammetry (CV), differential pulse voltammetry (DPV), and square wave voltammetry (SWV)—with a specific focus on their application to pharmaceutical analysis. The content is structured to serve as both a foundational reference and a practical resource for implementing these methods in research and quality control environments.

Fundamental Principles: Current Measurement in Voltammetry Versus Potential Measurement in Potentiometry

Comparative Theoretical Foundations

Understanding the distinction between voltammetry and potentiometry begins with recognizing their fundamental measurement approaches. Voltammetry is a dynamic technique that applies a controlled, changing potential to drive redox reactions while measuring the resulting faradaic current.- This current is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species and provides information about reaction kinetics and mechanisms [1]. In contrast, potentiometry is a zero-current technique that measures the equilibrium potential across an interface, relating this potential to analyte concentration through the Nernst equation without net electrochemical reaction occurring [7] [1].

The practical implications of this distinction are significant for pharmaceutical analysis. Voltammetry's current measurement enables exceptional sensitivity, with detection limits often reaching nanomolar or even picomolar concentrations, making it ideal for trace analysis of drugs and metabolites [36]. Potentiometry, while excellent for continuous monitoring of ions like sodium, potassium, and calcium in clinical settings, typically offers higher detection limits and is primarily limited to ionic species [7] [1].

Instrumentation and Cell Configuration

Both voltammetry and potentiometry employ electrochemical cells with working, reference, and counter electrodes. However, voltammetry requires precise potential control and current measurement capabilities provided by modern potentiostats [37]. The working electrode material (glassy carbon, platinum, mercury, or modified electrodes) significantly influences sensitivity and selectivity in voltammetric analysis, while potentiometric systems rely primarily on ion-selective membranes with specific recognition elements [7] [1].

Table 1: Core Differences Between Voltammetry and Potentiometry

| Parameter | Voltammetry | Potentiometry |

|---|---|---|

| Measured Signal | Current | Potential |

| Applied Signal | Variable potential | Zero current |

| Detection Limits | Nanomolar to picomolar | Millimolar to micromolar |

| Primary Applications | Trace drug analysis, metabolite monitoring, reaction mechanism studies | Ion activity measurement (Na+, K+, Ca2+), continuous monitoring |

| Information Obtained | Concentration, kinetics, reaction mechanisms | Ion activity/centration |

| Technique Variants | CV, DPV, SWV, NPV | Direct potentiometry, potentiometric titration |

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV): Fundamentals and Experimental Protocol

Theoretical Principles and Pharmaceutical Applications

Cyclic voltammetry is the most widely used voltammetric technique for initial electrochemical characterization of pharmaceutical compounds. In CV, the potential is scanned linearly from an initial value to a switching potential, then reversed back to the starting potential at a controlled scan rate [1]. The resulting current-potential plot (voltammogram) provides characteristic "peaks" corresponding to oxidation and reduction processes, yielding crucial information about redox potentials, reaction reversibility, electron transfer kinetics, and coupled chemical reactions [36].

For pharmaceutical analysis, CV serves as an indispensable tool for investigating the electrochemical behavior of new drug entities, studying metabolic pathways, and understanding degradation mechanisms [36]. The technique provides qualitative "fingerprints" of redox processes that help researchers predict stability, understand metabolic transformations, and design electroanalytical methods for quantification.

Experimental Protocol for Drug Compound Characterization

Equipment and Reagents:

- Potentiostat with cyclic voltammetry capability

- Three-electrode system: Working electrode (glassy carbon, platinum, or modified electrode), reference electrode (Ag/AgCl or SCE), counter electrode (platinum wire)

- Electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.04 M Britton-Robinson buffer, pH 2.0-12.0) [38]

- Nitrogen gas for deaeration

- Drug compound standard solution

Procedure:

- Prepare supporting electrolyte solution appropriate for the drug's solubility and electrochemical properties. Common choices include Britton-Robinson buffer for wide pH range studies or phosphate buffer for physiological pH simulations [38].

- Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry (0.05 μm) on a microcloth pad, rinse thoroughly with deionized water, and dry.

- Transfer 10-15 mL of supporting electrolyte to the electrochemical cell and deaerate with nitrogen for 8-10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen.

- Immerse the three-electrode system in the solution and initiate a blank CV scan to establish baseline electrode behavior.

- Add known aliquots of drug standard solution to the cell using a micropipette, mixing between additions.

- Record cyclic voltammograms across the relevant potential window at scan rates typically ranging from 20-500 mV/s.

- Analyze peak current versus scan rate relationships to determine whether processes are diffusion-controlled or adsorption-controlled.

- Calculate redox potentials (Epa, Epc), peak separation (ΔEp), and peak current ratios (Ipa/Ipc) to assess reaction reversibility.

Data Interpretation: Reversible systems display peak separation (ΔEp) of approximately 59/n mV, with peak current ratio near unity. Quasireversible and irreversible processes show larger peak separations and unequal peak currents. The relationship between peak current and square root of scan rate indicates diffusion control, while direct proportionality to scan rate suggests adsorption control [36].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Fundamentals and Experimental Protocol

Theoretical Principles and Pharmaceutical Applications

Differential pulse voltammetry is a highly sensitive pulse technique that effectively minimizes non-faradaic (charging) current, enabling significantly lower detection limits compared to CV [37]. In DPV, a series of small amplitude potential pulses (typically 10-100 mV) is superimposed on a linear staircase potential ramp. Current is sampled twice per pulse—just before pulse application and at the end of the pulse—with the difference between these measurements plotted against the base potential [37]. This differential current measurement cancels most capacitive background current, dramatically improving signal-to-noise ratio for trace analysis [1] [37].

DPV has proven exceptionally valuable in pharmaceutical analysis for quantifying drugs in complex matrices like serum, urine, and pharmaceutical formulations [39] [40]. Its high sensitivity and minimal interference make it ideal for therapeutic drug monitoring, pharmacokinetic studies, and quality control of low-dose formulations.

Experimental Protocol for Trace Drug Quantification

Equipment and Reagents:

- Potentiostat with DPV capability (e.g., Gamry Instruments with PV220 Pulse Voltammetry Software) [37]

- Three-electrode system appropriate for analysis (HMDE for reducible compounds, solid electrodes for oxidizable compounds)

- Supporting electrolyte optimized for target drug (e.g., Clark-Lubs buffer for zalcitabine) [40]

- Standard drug solutions and quality control samples

Procedure:

- Select optimal supporting electrolyte and pH based on preliminary CV studies or literature data. For zalcitabine analysis, Clark-Lubs buffer (pH 2.0) provided maximal response [40].

- Prepare electrode system. For hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE), dispense a fresh drop for each measurement.

- Transfer 10 mL of supporting electrolyte to the electrochemical cell and deaerate with nitrogen for 5-8 minutes.

- Set DPV parameters based on compound characteristics:

- Record background voltammogram in pure supporting electrolyte.

- Add known aliquots of standard drug solution, recording DPV after each addition.

- Construct calibration curve by plotting peak current versus concentration.

- For formulation analysis, prepare samples by dissolving tablets/serum in appropriate solvent, filtering if necessary, and diluting to working range [39].

Validation Parameters: