Comparative Analysis of Electrochemical Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of electrochemical techniques for detecting toxic heavy metals, a critical capability for researchers and professionals in environmental monitoring and public health.

Comparative Analysis of Electrochemical Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection: Advances, Applications, and Future Directions

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of electrochemical techniques for detecting toxic heavy metals, a critical capability for researchers and professionals in environmental monitoring and public health. It explores the foundational principles of voltammetric and non-voltammetric methods, details the integration of nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes and metal-organic frameworks to enhance sensor performance, and addresses key challenges such as electrode fouling and matrix effects. A comparative analysis validates these techniques against traditional spectroscopic methods, highlighting their superior portability, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for real-time, on-site monitoring to support advanced biomedical and clinical research.

The Critical Need for Heavy Metal Detection and Electrochemical Fundamentals

The Growing Environmental and Public Health Crisis from Heavy Metals

Heavy metal pollution, intensified by rapid industrialization and urbanization, presents a profound global challenge to environmental stability and public health [1]. Metals such as lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and arsenic (As) are detrimental even at trace concentrations, posing threats due to their high toxicity, carcinogenic potential, and bioaccumulative nature in the food chain [2] [3] [4]. The detection of these contaminants is not merely an analytical procedure but a critical line of defense. As socio-economic activities intensify, the influx of heavy metals into soil and water bodies increasingly endangers ecosystems and human health, threatening the very foundation of human development [5]. In response, the field of analytical chemistry has advanced significantly, moving from conventional, lab-bound instrumentation to the development of innovative, rapid, and field-deployable sensing technologies. This review focuses on objectively comparing modern electrochemical detection techniques within this broader thesis, evaluating their performance against traditional and alternative analytical methods to guide researchers and scientists in selecting optimal tools for their work.

Comparative Analysis of Heavy Metal Detection Techniques

The selection of an appropriate analytical technique is paramount and depends on the specific requirements of sensitivity, selectivity, cost, and portability. Traditional instrumental methods like Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) and Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) are reference standards known for their high sensitivity and accuracy [4]. However, their utility in rapid, on-site screening is limited by their complex sample preparation, expensive instrumentation, and need for specialized technical expertise [3] [4]. In contrast, emerging technologies have been designed to bridge this gap.

Lateral Flow Assays (LFA), for instance, have gained prominence due to their minimal operational requirement, low cost (each test strip < $1), and rapid results (10–30 minutes) [4]. By integrating nanomaterials like gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) and specific recognition elements like DNA aptamers, LFA can achieve detection limits in the nM to pM range for ions like Hg²⁺, Cd²⁺, and Pb²⁺, making them ideal for initial field screening [4].

Optical sensors, particularly those utilizing Quantum Dots (QDs), offer another powerful alternative. Their remarkable optical properties—including high photoluminescence, broad absorption spectra, and size-tunable emission—make them excellent for multiplexed detection, allowing for the simultaneous assessment of multiple heavy metal analytes in a single experiment [1]. They provide high sensitivity and the capacity for in-situ, real-time analysis [1].

At the forefront of technological innovation are electrochemical sensing platforms. These systems distinguish themselves through their ease of use, swiftness, and excellent suitability for expeditious, on-site detection [3]. Their performance is greatly enhanced by the integration of nanomaterials and novel sensing strategies, which improve both sensitivity and selectivity. The following sections will provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of these electrochemical techniques, which are the primary focus of this guide.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Heavy Metal Detection Technologies

| Technique | Detection Principle | Typical Sensitivity (LOD) | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrochemical Sensors [3] | Measurement of current/voltage from redox reactions | Sub-nM to nM | Portability, rapid analysis, low cost, high sensitivity | Susceptible to matrix interference, requires electrode maintenance |

| Lateral Flow Assays (LFA) [4] | Visual readout on nitrocellulose membrane | nM to pM | Extreme simplicity, low cost, no instrument needed, strong portability | Semi-quantitative at best without a reader, limited multiplexing |

| Quantum Dots (Optical) [1] | Modulation of fluorescence emission | nM range | High sensitivity, capacity for multiplexing, real-time analysis | Potential photobleaching, complex probe synthesis |

| ICP-MS [4] | Ionization and mass-to-charge ratio detection | ppt (ng/L) range | Exceptional sensitivity and multi-element detection | Very expensive, complex operation, lab-bound |

| AAS [4] | Absorption of light by free atoms | ppb (µg/L) range | High accuracy, well-established technique | Single-element analysis, requires skilled operator |

Performance and Experimental Data of Electrochemical Techniques

Electrochemical sensing technology encompasses a variety of techniques, each with distinct operational principles and performance metrics. The core of these sensors often involves a working electrode (WE), whose surface is modified with nanomaterials or recognition elements to enhance its interaction with specific heavy metal ions [3]. The choice of electrochemical technique directly influences the sensitivity, selectivity, and detection limit of the analysis.

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) is one of the most sensitive electrochemical methods. It involves a two-step process: first, heavy metal ions in the solution are electrochemically reduced and pre-concentrated onto the working electrode surface. This is followed by an anodic (oxidation) scan where the deposited metals are stripped back into the solution, generating a current peak. The peak potential is characteristic of the metal, while the peak current is proportional to its concentration [3]. The integration of nanomaterials like Bismuth Nanoparticles (BiNPs) or Graphene Oxide (GO) on the electrode surface has been shown to significantly increase the active surface area and improve the pre-concentration efficiency, leading to dramatically lower detection limits [3].

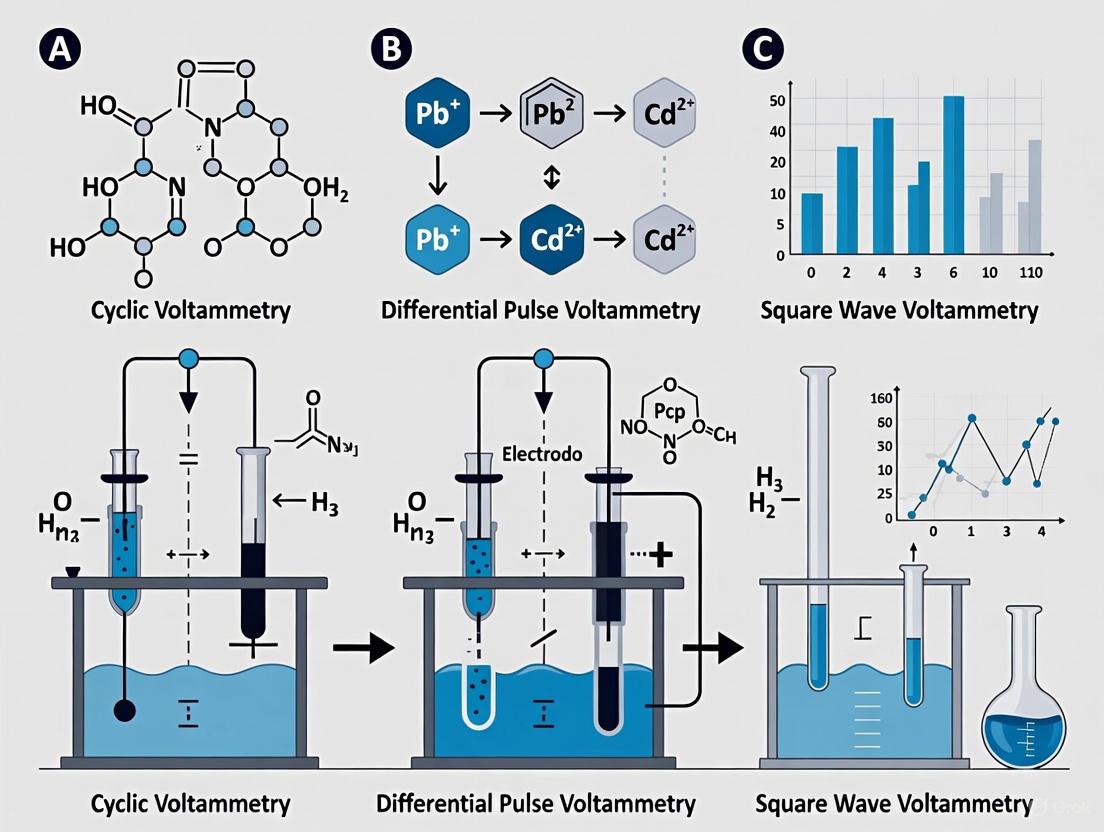

Other prominent techniques include Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), which minimizes background charging current to enhance measurement sensitivity, and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS), which probes the resistance to charge transfer at the electrode interface, often used in label-free biosensing applications [3].

The experimental data from recent studies underscores the effectiveness of these advanced electrochemical strategies. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent research, highlighting the role of innovative materials and methods.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Data of Advanced Electrochemical Sensors for Heavy Metal Ions

| Target Ion | Electrode/Sensing Platform | Technique | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Key Nanomaterial Used |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺ | Bi-based Sensor | ASV | ~0.1 nM | 0.5 - 50 nM | Bismuth Nanoparticles (BiNPs) [3] |

| Hg²⁺ | Aptamer-based Sensor | DPV | ~1 pM | 0.01 - 100 nM | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [4] |

| Cu²⁺ | DNA-based Sensor | Voltammetry | 0.1 nM | Not Specified | Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [4] |

| Multiple Ions | Paper-based SPE (pSPCE) | SWV | Sub-ppb | Wide range | Graphene (GR) / Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [3] |

| Cd²⁺ | Ion-Selective Electrode | Potentiometry | nM range | Not Specified | Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) [1] |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) with a Bismuth-Modified Electrode

This protocol details a standard procedure for the simultaneous detection of Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺ using a Bismuth-modified screen-printed carbon electrode (SPCE), a common configuration in modern research [3].

1. Reagent Preparation:

- Acetate Buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.5): Used as the supporting electrolyte to maintain a consistent pH and ionic strength.

- Bismuth Stock Solution: A 1000 ppm Bi³⁺ solution is used for the in-situ or ex-situ plating of bismuth on the electrode.

- Standard Solutions: 1000 ppm stock solutions of Pb²⁺ and Cd²⁺, diluted to required concentrations with deionized water.

2. Electrode Modification and Measurement:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: The bare SPCE is cleaned by cycling the potential in a blank electrolyte solution to achieve a stable background current.

- Bismuth Film Deposition (in-situ method): The measurement solution is prepared by mixing the acetate buffer, a known concentration of Bi³⁺ (e.g., 400 ppb), and the sample containing target metals. The bismuth film is co-deposited with the target metals by applying a constant negative potential (e.g., -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for a fixed time (e.g., 120 seconds) with stirring.

- Pre-concentration/Deposition: During the deposition step, both the target metal ions (Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) and Bi³⁺ are reduced and deposited onto the electrode surface, forming a "bi-electrode."

- Stripping Analysis: The stirring is stopped, and after a 15-second equilibration period, the voltammetric scan is initiated. Using Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), the potential is scanned from a negative to a more positive value (e.g., -1.2 V to -0.2 V). The deposited metals are oxidized (stripped) back into the solution, generating distinct current peaks at characteristic potentials (e.g., Cd at ~ -0.8 V, Pb at ~ -0.5 V).

- Quantification: The peak current is measured and plotted against the metal ion concentration to create a calibration curve for unknown samples.

Signaling Pathways and Workflows

The detection of heavy metals, particularly in biological contexts, is crucial because these ions trigger specific and damaging signaling pathways that lead to cellular toxicity. Furthermore, the operational workflow of a sensor defines its efficiency and application.

Molecular Toxicity Pathway of Heavy Metals

Heavy metals like lead and arsenic induce toxicity primarily through oxidative stress and by mimicking essential elements. The following diagram illustrates the core mechanism.

Generalized Workflow for Electrochemical Sensor Operation

A standard operational procedure for an electrochemical heavy metal sensor, from preparation to data analysis, can be visualized in the following workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The development and operation of high-performance heavy metal sensors rely on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The selection listed in the table below is critical for researchers designing experiments in electrochemical sensing.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Sensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function and Role in Detection | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) [3] | Disposable, portable platform integrating working, reference, and counter electrodes; ideal for field deployment. | Carbon, Gold (SPAuE), Bismuth-coated |

| Nanomaterials [1] [3] | Enhance electrode surface area, electron transfer kinetics, and pre-concentration of metal ions. | CNTs, Graphene (GO, rGO), AuNPs, BiNPs |

| Recognition Elements [4] | Provide high specificity and selectivity for target metal ions through chemical or biological binding. | DNA aptamers, Ion-Selective Membranes (ISM), Functional Nucleic Acids (FNA) |

| Ion-Selective Membranes (ISMs) [1] | Key component in potentiometric sensors; selectively allow the target ion to interact with the electrode. | Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) based membranes with ionophores |

| Supporting Electrolyte [3] | Conducts current and controls ionic strength and pH during measurement, crucial for signal stability. | Acetate buffer, Nitric acid, Potassium chloride |

| Polymer Substrates [3] | Provide flexible and robust support for printed electrodes and microfluidic channels. | PET, PC, PEN, PI |

The growing crisis of heavy metal contamination demands a robust and multifaceted analytical response. While traditional methods like ICP-MS remain the gold standard for laboratory-based, ultra-sensitive multi-element analysis, the field is decisively moving toward rapid, on-site, and intelligent detection systems [3] [4]. Among the alternatives, electrochemical sensing technology stands out for its excellent balance of high sensitivity, portability, low cost, and rapid analysis, making it perfectly suited for environmental monitoring, food safety, and public health protection [3]. The integration of novel nanomaterials and specific biorecognition elements has further elevated its performance, enabling the detection of heavy metals at clinically and environmentally relevant levels.

Future development will focus on creating multiplexed platforms for simultaneous detection of several contaminants, integrating sensors with portable readers and smartphone technology, and leveraging artificial intelligence (AI) for data analysis and prediction, as seen in emerging tensor completion models for soil pollution mapping [3] [5]. The ultimate goal is a network of smart, connected, and highly accessible tools that can provide real-time data to scientists and regulators, enabling timely interventions and safeguarding the environment and public health from the pervasive threat of heavy metals.

Limitations of Traditional Spectroscopic Methods (AAS, ICP-MS, XRFS)

The accurate detection of heavy metals is a critical requirement across numerous scientific and industrial fields, including environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical development, and food safety. For decades, traditional spectroscopic techniques such as Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), and X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRFS) have served as the analytical backbone for elemental analysis. While these methods have proven invaluable, they possess inherent limitations that can impact their efficiency, applicability, and cost-effectiveness. Within the context of a broader thesis exploring advanced electrochemical techniques for heavy metal detection, this guide provides an objective comparison of these established spectroscopic methods. By synthesizing their performance data, experimental protocols, and specific constraints, this analysis aims to furnish researchers and drug development professionals with a clear framework for selecting appropriate analytical strategies, particularly as the field increasingly embraces innovative electrochemical solutions.

Comparative Performance Data

The following tables summarize the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of AAS, ICP-MS, and XRFS, based on experimental data and industry applications.

Table 1: Fundamental Analytical Characteristics of Traditional Spectroscopic Methods

| Feature | AAS | ICP-MS | XRFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Detection Limit | Parts per billion (ppb) | Parts per trillion (ppt) [6] [7] | Parts per million (ppm) [8] [6] [7] |

| Destructive Analysis | Yes | Yes [6] | No [8] [6] [7] |

| Sample Throughput | Low (sequential element analysis) | High (simultaneous multi-element) [9] | Very High (simultaneous multi-element) [7] |

| Sample Preparation | Extensive (digestion required) | Extensive (digestion & dilution required) [6] [7] | Minimal (often direct solid analysis) [8] [6] [7] |

| Analysis Speed | Minutes per element | Minutes per multi-element suite | Seconds to minutes per multi-element suite [7] |

Table 2: Operational and Economic Considerations

| Consideration | AAS | ICP-MS | XRFS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Initial Instrument Cost | Moderate | Very High [9] [6] | Low to Moderate (benchtop), High (portable) [8] [6] |

| Operational Cost | Moderate (gases, lamps) | High (specialized gases, maintenance, reagents) [8] [6] | Low (minimal consumables) [8] [6] |

| Technical Expertise Required | Moderate | High [9] [6] | Low to Moderate [6] |

| Portability | None | None [6] | Yes (portable systems available) [6] [7] |

Detailed Methodologies and Limitations

Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS)

AAS operates on the principle of measuring the absorption of optical radiation by free atoms in the gaseous state. The sample is typically atomized in a flame or graphite furnace, and light from a hollow-cathode lamp specific to the target element is passed through the vapor.

- Key Limitations: The technique is fundamentally single-elemental, making multi-element analysis slow and inefficient. Its sensitivity, while sufficient for many applications, is outperformed by ICP-MS. The requirement for sample digestion introduces significant preparation time and the risk of contamination or incomplete dissolution of the sample matrix [7]. Furthermore, the need for different lamps for different elements and the consumption of high-purity gases increase operational complexity and cost.

Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS)

ICP-MS is a highly sensitive technique where a liquid sample is nebulized and introduced into a high-temperature argon plasma (~6000-10000 K), which efficiently atomizes and ionizes the elements. The resulting ions are then separated and quantified based on their mass-to-charge ratio by a mass spectrometer [9] [6].

Experimental Protocol for Soil Analysis (as cited in [9]):

- Sample Collection & Preparation: Soil samples are collected and air-dried, followed by homogenization using an agate mortar and pestle or a stainless-steel grinder.

- Acid Digestion: A representative sub-sample (e.g., 0.5 g) is subjected to digestion with a mixture of strong acids (e.g., HNO₃, HCl, HF) in a closed-vessel microwave digestion system to completely dissolve the solid matrix and liberate the target elements.

- Dilution: The digested solution is diluted to a specific volume with high-purity deionized water.

- Analysis & Quantification: The diluted solution is introduced into the ICP-MS. The instrument is calibrated with matrix-matched multi-element standard solutions, and an internal standard (e.g., Indium or Rhodium) is often used to correct for instrumental drift and matrix effects.

Key Limitations: The sample digestion process is a major bottleneck, being time-consuming and requiring the use of hazardous, high-purity acids, which generates chemical waste [9] [6] [7]. The technique is also susceptible to spectral interferences (e.g., from polyatomic ions) and matrix effects that can skew results if not properly corrected [9] [7]. The most significant barriers are the very high capital cost of the instrument, substantial operational expenses for gases and maintenance, and the need for a controlled laboratory environment and highly skilled operators [9] [6].

X-Ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRFS)

XRFS is a technique where a sample is irradiated with high-energy X-rays, causing the ejection of inner-shell electrons. When outer-shell electrons fill these vacancies, they emit characteristic secondary (fluorescent) X-rays unique to each element, which are detected and quantified [6].

Experimental Protocol for Direct Solid Analysis (as cited in [7]):

- Sample Collection: Solid samples (e.g., soil, sediment) are collected.

- Homogenization & Presentation: Samples are air-dried and ground to a fine, homogeneous powder to minimize particle size and heterogeneity effects.

- Presentation: The powdered sample is often presented to the instrument in a dedicated sample cup, potentially with a polypropylene film window.

- Direct Analysis: The sample cup is placed in the spectrometer, and analysis is performed directly without any chemical treatment. The software provides a quantitative readout of elemental concentrations based on a pre-loaded calibration.

Key Limitations: The primary limitation is its higher detection limit compared to ICP-MS and AAS, making it unsuitable for quantifying elements at ultra-trace (ppb or ppt) levels [6] [7]. The analysis can be significantly affected by matrix effects, including variations in particle size, mineralogy, and moisture content, which can influence the X-ray signal and require matrix-matched standards for accurate quantification [9] [6]. For bulk analysis, a homogeneous sample is critical, and the penetration depth of the X-rays is relatively shallow, potentially making the analysis sensitive to surface condition [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential materials and reagents commonly used with these spectroscopic techniques, highlighting their specific functions in the analytical process.

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Spectroscopic Analysis

| Item | Primary Function | Associated Technique(s) |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Acids (HNO₃, HCl, HF) | Digest and dissolve solid samples for liquid introduction analysis. | ICP-MS, AAS [9] [7] |

| Multi-Element Standard Solutions | Calibrate the instrument for quantitative analysis across a range of elements. | ICP-MS, AAS, XRFS |

| Certified Reference Materials (CRMs) | Validate analytical methods and ensure accuracy and precision. | All |

| Argon Gas | Serve as the plasma gas (ICP-MS) or purge gas (XRFS). | ICP-MS, XRFS [8] [6] |

| Helium Gas | Boost sensitivity for light elements by creating a purge atmosphere. | XRFS [8] |

| Internal Standards (e.g., Indium, Rhodium) | Correct for instrumental drift and matrix effects during analysis. | ICP-MS [9] |

Workflow and Decision-Making Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the typical analytical workflow for ICP-MS and XRFS, highlighting the key steps where their distinct limitations and advantages manifest. It also maps the logical decision-making process for selecting an appropriate technique based on analytical goals.

The limitations of traditional spectroscopic methods are well-defined and consequential. AAS struggles with speed and single-element analysis. ICP-MS, while exceptionally sensitive, is burdened by high costs, complex operation, and a reliance on destructive sample preparation. XRFS offers superb speed and minimal preparation but lacks the sensitivity required for trace-level analysis. This objective comparison underscores that there is no universally superior technique; the choice depends entirely on the specific analytical requirements regarding detection limits, sample type, throughput, budget, and data quality objectives. Understanding these constraints is paramount for researchers and is the very impetus driving the investigation and adoption of complementary analytical techniques, such as advanced electrochemical sensors, which promise portability, rapid analysis, and low cost for specific application niches.

The accurate and timely detection of heavy metals in environmental and biological samples is a critical challenge in analytical chemistry, with direct implications for public health, environmental protection, and industrial safety. While traditional laboratory techniques like atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS) have long been the gold standard, a significant paradigm shift is occurring toward electrochemical sensing techniques [10] [11]. This shift is driven by three core advantages that make electrochemical methods particularly suited for modern analytical needs: exceptional portability, low cost, and capabilities for real-time analysis. This review provides a comprehensive comparison of electrochemical sensing against traditional spectroscopic methods, with a specific focus on heavy metal detection, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies.

Performance Comparison: Electrochemical vs. Traditional Techniques

Electrochemical sensors offer a compelling alternative to traditional spectroscopic methods, particularly for field deployment and resource-limited settings. The table below summarizes a direct performance comparison based on key analytical metrics.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Heavy Metal Detection Techniques

| Feature | Traditional Spectroscopic Methods (AAS, ICP-MS) | Electrochemical Sensors | Experimental Evidence & Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Portability | Large, benchtop instruments requiring laboratory settings [10]. | Miniaturized, portable systems; wearable formats and smartphone integration demonstrated [12] [13] [14]. | Portable wireless potentiostat developed (<$6.4, 41.5 mm × 76.5 mm) for on-site detection [14]. |

| Cost | High initial capital, maintenance, and operational costs [15]. | Very low-cost; cost-effective equipment and fabrication [16] [14]. | A study reports a portable potentiostat for under $6.4, highlighting extreme cost-efficiency [14]. |

| Analysis Speed & Real-Time Capability | Time-consuming, requires sample pre-treatment and skilled operation; not suitable for real-time monitoring [10] [15]. | Rapid response (seconds to minutes); enables continuous, real-time, and in-situ monitoring [16] [13]. | Real-time, in-situ monitoring of heavy metals in water and soil highlighted as a key advantage [10]. |

| Sensitivity & Limit of Detection (LOD) | Exceptional sensitivity (e.g., ICP-MS can detect at sub-ppb to ppt levels) [11]. | Good to excellent sensitivity; suitable for regulatory compliance testing. | Graphene-based sensors show low LODs for heavy metals in meta-analysis [17]. IoT sensor reported LODs of 0.62 μM for Pb²⁺ and 0.72 μM for Hg²⁺ [15]. |

| Ease of Use & Skill Requirement | Requires highly trained technicians for operation and data interpretation [15]. | Simplified operation; user-friendly interfaces and automated data analysis via machine learning [15]. | IoT and deep learning integration automates interpretation of complex data for non-experts [15]. |

| Multi-analyte Detection | Can detect multiple elements but often requires complex parameter adjustments. | High potential for simultaneous detection of multiple heavy metals in a single run [15]. | A single sensor simultaneously quantified Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Hg²⁺ in water samples [15]. |

Experimental Protocols for Heavy Metal Detection

The performance of electrochemical sensors is highly dependent on the experimental protocol, from electrode modification to the final measurement. The following workflow and corresponding details outline a standard approach for fabricating and operating a nanomaterial-modified sensor for heavy metals.

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for electrochemical heavy metal detection.

Sensor Fabrication and Modification

The first critical step involves preparing and modifying the working electrode to enhance its analytical performance.

- Electrode Substrate Preparation: Common substrates include screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs) or innovative low-cost supports like carbon threads mounted on recycled plastic bottles [15]. SPCEs are commercially available and integrate all three electrodes (working, reference, counter) into a single, disposable chip [13].

- Surface Modification with Nanomaterials: To boost sensitivity and selectivity, the working electrode surface is modified with nanomaterials. For instance, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) can be electrodeposited onto a carbon thread surface. This is achieved by immersing the electrode in a solution of chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄) and applying a constant potential or using cyclic voltammetry to reduce Au³⁺ to Au⁰, forming a nanoparticle layer [15]. Other effective materials include graphene derivatives [17], MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) [12] [11], and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) [10] [11].

- Sensor Characterization: Post-modification, the electrode is characterized using techniques like Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) and Energy-Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy (EDS) to confirm the morphology and elemental composition of the nanostructured layer [15].

Sample Pre-treatment and Measurement

- Sample Pre-treatment: For water samples, common pre-treatment includes acidification to a low pH (e.g., pH 2 using HCl-KCl buffer) to stabilize metal ions and prevent adsorption to container walls [15]. For complex matrices like soil, more intensive pre-treatment such as Fenton oxidation or microwave digestion may be required to break down organic matter that can cause interference [11].

- Electrochemical Measurement - Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV): This is the most common and sensitive electrochemical technique for trace metal analysis. A standard ASV protocol involves two main steps [10] [15]:

- Pre-concentration/Deposition: The sensor is immersed in the sample solution, and a negative potential is applied to the working electrode. This reduces the target metal ions (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) to their metallic state (Pb⁰, Cd⁰), which are deposited onto the electrode surface. The deposition time and potential are optimized for each metal.

- Stripping: After deposition, the potential is swept toward positive values (e.g., from -1.0 V to +0.5 V using Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)). This re-oxidizes the deposited metals back into ions, generating a characteristic current peak for each metal. The peak current is proportional to the concentration of the metal in the sample, while the peak potential identifies the metal species.

- Data Processing: Advanced studies now integrate machine learning (ML) and deep learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), to process the complex voltammetric data from mixtures of heavy metals. This improves the accuracy of identifying and quantifying individual metals in the presence of signal overlaps [15] [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The performance of electrochemical sensors is enabled by specific materials and reagents. The following table details essential components used in advanced sensing research.

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Sensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | Two-dimensional conductive nanomaterials that provide a high surface area and active sites, enhancing electrocatalytic activity and signal sensitivity [12] [11]. | Used in a nanocomposite with poly(l-Arg) for ultrasensitive, non-enzymatic creatinine detection in blood serum [12]. |

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Excellent conductors that facilitate electron transfer and can be functionalized to enhance the deposition of heavy metals during the stripping analysis [15]. | Electrodeposited on carbon threads for simultaneous multiplexed detection of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Hg²⁺ [15]. |

| Graphene & Derivatives | Provides high electrical conductivity and a large specific surface area, lowering the detection limit for heavy metal ions [17]. | Graphene-based electrodes are a major research focus for detecting heavy metals like Pb, Hg, and Cd in food and water [17]. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Highly porous crystalline materials that can be designed to selectively pre-concentrate target analytes near the electrode surface, boosting sensitivity and selectivity [10] [11]. | Fc-NH₂-UiO-66 MOF composite was used with graphene oxide for simultaneous detection of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Cu²⁺ [10]. |

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable, mass-producible planar electrodes that form the foundational substrate for portable, single-use sensors [13]. | Widely used as the platform for developing low-cost, on-site sensors for food safety and environmental monitoring [13]. |

Electrochemical sensing has firmly established itself as a powerful analytical paradigm, distinguished by its superior portability, low cost, and real-time analysis capabilities. As demonstrated by the experimental data and protocols, the strategic integration of nanomaterials and advanced data processing algorithms continues to push the boundaries of sensitivity and selectivity, rivaling traditional methods in many application scenarios. For researchers in environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics, and food safety, electrochemical platforms offer a versatile, cost-effective, and field-deployable toolkit that is poised to play an increasingly critical role in global health and safety protection.

Electrochemical sensors are analytical devices that convert a chemical response into a quantifiable and processable electrical signal [18]. Their core function relies on the interaction between electrical energy and chemical changes, primarily through oxidation (loss of electrons) and reduction (gain of electrons) reactions that occur at the sensor interface [19]. A typical electrochemical biosensor consists of several key components: a) bioreceptors that specifically bind to the analyte; b) an interface architecture where the specific biological event occurs; c) a transducer element that picks up the signal; d) detector circuitry that converts and amplifies the signal; and e) a data presentation interface [18]. The popularity of electrochemical sensing stems from several inherent advantages: low theoretical detection limits (often down to picomole levels), high accuracy, rapid analysis, cost-effectiveness, and easy miniaturization for field-portable applications [18] [16]. These characteristics make electrochemical detection particularly valuable for environmental monitoring, clinical diagnostics, food safety, and industrial process control [19] [16].

In the specific context of heavy metal detection, electrochemical sensors offer distinct advantages over traditional analytical methods such as Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS), Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS), and X-ray Fluorescence Spectroscopy (XRFS) [10] [20]. While these conventional techniques provide high sensitivity and precision, they are typically confined to laboratory settings due to their high cost, large instrumentation, complex operation, and requirement for skilled personnel [10] [20]. Electrochemical alternatives, particularly when enhanced with nanomaterials, provide a reliable, portable, and cost-effective solution for real-time, on-site monitoring of toxic heavy metals in environmental samples [3] [10].

Fundamental Detection Principles and Signal Transduction

Electrochemical detection is governed by several fundamental principles where electrical parameters are measured to deduce information about the analyte's identity and concentration. The most established transduction principles include amperometry, potentiometry, and impedimetry [18] [19] [16].

Amperometric Transduction operates by applying a constant potential to the working electrode and measuring the resulting current generated from the electrochemical oxidation or reduction of an analyte [19] [16]. This current is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species, as described by the Cottrell equation [16]. The technique is characterized by its high sensitivity and low detection limits but requires the analyte to be electroactive [16].

Potentiometric Transduction involves measuring the potential difference between a working electrode and a reference electrode under conditions of zero current flow [18] [16]. The measured potential relates to the analyte concentration via the Nernst equation. A common example is the ion-selective electrode (ISE), widely used for measuring pH and specific ions [16]. Potentiometric sensors are simple and low-cost but may suffer from slower response times compared to amperometric sensors [16].

Impedimetric Transduction utilizes Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to measure the impedance (both resistance and reactance) of a system over a range of frequencies [18] [19]. Binding events at the electrode surface alter the interfacial properties, changing the impedance. EIS is particularly valuable for studying biomolecular interactions and sensor development due to its label-free nature and ability to provide information about the electrode interface [19].

The following diagram illustrates the core signal transduction process in a typical electrochemical sensor.

Comparative Analysis of Electrochemical Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection

Voltammetric Methods: Principles and Performance

Voltammetric techniques are the most prominent electrochemical methods for heavy metal detection due to their exceptional sensitivity and capability for simultaneous multi-metal analysis [10] [20]. These methods involve applying a potential waveform to the working electrode and measuring the resulting current, which provides both qualitative (based on redox potential) and quantitative (based on current magnitude) information about the analytes [10].

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) is widely regarded as one of the most sensitive electrochemical techniques for metal ion detection [3] [10] [20]. The method operates in two key stages: first, an electrodeposition step where metal ions in solution are reduced and pre-concentrated onto the working electrode surface at a constant negative potential; second, a stripping step where the applied potential is swept in a positive direction, oxidizing the deposited metals back into solution and generating characteristic current peaks [10]. The intensity of these peaks is directly proportional to the concentration of the corresponding metal ions in the sample. Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) is a particularly effective variant that enhances sensitivity and speed by combining a square wave with a staircase potential sweep [20] [21].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) is another highly sensitive technique that applies potential pulses with increasing amplitude and measures the current difference just before and after each pulse [10] [15]. This differential measurement minimizes contributions from capacitive currents, resulting in lower detection limits compared to conventional cyclic voltammetry. DPV has been successfully employed for multiplexed detection of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, and Hg²⁺ with detection limits in the micromolar range [15].

The table below provides a comparative summary of the key voltammetric techniques used in heavy metal detection.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Voltammetric Techniques for Heavy Metal Detection

| Technique | Detection Principle | Key Metals Detected | Typical Detection Limits | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Pre-concentration followed by anodic stripping | Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺, Zn²⁺, Cu²⁺ | ppt to ppb range [10] | Extremely high sensitivity, multi-metal detection [20] | Longer analysis time, electrode fouling [10] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Combination of square wave and staircase potential | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺ [15] | ~0.62-1.38 µM [15] | Fast scan rate, effective background suppression [10] | Complex waveform optimization |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Current measurement before/after potential pulses | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺ [15] | ~0.62-1.38 µM [15] | Low detection limits, minimized capacitive current [10] | Slower than SWV |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Linear potential sweep between two limits | Various redox-active metals | µM to mM range [18] | Rich mechanistic information, simple implementation [18] | Lower sensitivity compared to stripping methods |

The Role of Nanomaterials and Sensor Modifications

The integration of nanomaterials has dramatically enhanced the performance of electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection [3] [10] [21]. These materials improve sensor sensitivity, selectivity, and stability through various mechanisms including increased surface area, enhanced electron transfer kinetics, and specific interactions with target metal ions [10] [21].

Carbon Nanomaterials: Graphene and its derivatives (graphene oxide, reduced graphene oxide), carbon nanotubes (single-walled and multi-walled), and graphene aerogels provide exceptionally high surface areas and excellent electrical conductivity [10] [21]. For instance, reduced graphene oxide (rGO) serves as an ideal substrate preventing aggregation of metal oxides while facilitating electron transfer [20] [21].

Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), bismuth nanoparticles (BiNPs), iron oxide (Fe₃O₄), and other metal oxides offer high catalytic activity and specific affinity toward heavy metal ions [3] [10] [21]. Gold nanoparticle-modified electrodes have been successfully employed for detecting Hg²⁺ with detection limits as low as 6 ppt [21].

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) and Ion-Imprinted Polymers (IIPs) provide highly selective recognition sites for specific heavy metal ions through their tunable porous structures and functional groups [3] [10]. MOFs like Ca²⁺ MOFs have demonstrated efficient sorption and voltammetric determination of heavy metal ions in aqueous media [10].

Table 2: Nanomaterial-Enhanced Sensor Performance for Heavy Metal Detection

| Nanomaterial Category | Specific Materials | Target Metals | Enhancement Mechanism | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanomaterials | Graphene (GR), Graphene Oxide (GO), Reduced GO (rGO) | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺ [21] | High surface area, excellent conductivity, abundant functional groups [21] | AuNPs/GR/L-cys for Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ detection [21] |

| Metal/Metal Oxide Nanoparticles | Gold NPs (AuNPs), Bismuth NPs (BiNPs), Fe₃O₄, Co₃O₄ | Hg²⁺, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺ [10] [21] | Catalytic activity, specific binding affinity, synergistic effects [10] | Hg²⁺ detection at 6 ppt using AuNPs/GR [21] |

| Composite Materials | rGO/MOx, Polymer nanocomposites, MOFs | Multiple simultaneous detection [10] [20] | Combined advantages, prevented aggregation, tailored facets [20] | Co₃O₄ nanoplates with (111) plane showed better sensing than (001) plane [20] |

| Ion-Imprinted Polymers | Methacrylic acid (MAA)-based polymers | Specific target ions [3] | Molecular recognition, cavity specificity [3] | High selectivity for pre-determined ions [3] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Experimental Setup and Electrode Modification

A typical electrochemical sensing experiment employs a three-electrode system consisting of a working electrode (sensing electrode), a reference electrode (typically Ag/AgCl), and a counter/auxiliary electrode (often platinum or graphite) [18]. The working electrode serves as the transduction element where the biochemical reaction occurs, while the reference electrode maintains a known and stable potential, and the counter electrode completes the electrical circuit [18].

A common electrode modification protocol involves these key steps. First, the electrode surface is cleaned mechanically (polishing with alumina slurry) and/or electrochemically (cycling in suitable electrolyte) [20]. Next, nanomaterial dispersion is prepared by sonicating the nanomaterial (e.g., graphene oxide, carbon nanotubes) in a suitable solvent [21]. The working electrode is then modified by drop-casting a precise volume of the nanomaterial dispersion onto its surface and allowing it to dry [21]. For composite materials, additional steps may include electrochemical deposition of metal nanoparticles (e.g., AuNPs) onto the pre-modified electrode surface [21] [15].

The following workflow diagram illustrates a typical experimental process for heavy metal detection using modified electrodes.

Key Research Reagent Solutions and Materials

Successful implementation of electrochemical heavy metal detection relies on specific reagents and materials that facilitate sensor fabrication, modification, and operation. The table below details essential research reagents and their functions in experimental protocols.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrochemical Heavy Metal Detection

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) | Disposable electrode platforms for portable sensing | Carbon, gold (SPAuE), or customized surfaces [3] [10] |

| Ionic Liquids (ILs) | Electrode modifiers to enhance conductivity and sensitivity | n-octylpyridinum hexafluorophosphate (OPFP) [20] |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Provide ionic strength, minimize solution resistance | HCl-KCl buffer (pH 2), acetate buffer [10] [15] |

| Metal Salts | Preparation of standard solutions for calibration | Cd(NO₃)₂, Pb(NO₃)₂, CuSO₄, HgCl₂ [15] |

| Functionalization Agents | Provide specific binding sites for metal ions | L-cysteine, polyethyleneimine (PEI), DNA aptamers [3] [21] |

| Nanomaterial Dispersions | Electrode modification to enhance sensitivity | Graphene oxide, MWCNTs, AuNPs, BiNPs [3] [10] |

Emerging Trends and Future Perspectives

The field of electrochemical heavy metal detection continues to evolve with several emerging trends enhancing sensor capabilities and application scope. Integration with IoT and AI represents a significant advancement, enabling remote monitoring and intelligent data interpretation [15]. Recent research demonstrates the successful combination of electrochemical sensors with convolutional neural networks (CNN) for accurate classification and quantification of heavy metal ions in mixed samples, achieving high precision, recall, and F1 scores [15].

Novel sensing materials with tailored properties continue to push detection limits. Laser-reduced graphene oxide (LRGO) sensors show enhanced electroanalytical response due to high surface conductivity [21]. Similarly, facet-dependent electrochemical behavior of materials like Co₃O₄ nanoplates with specific crystal planes (111) demonstrates superior sensing performance compared to other configurations [20].

Point-of-care and portable diagnostics are expanding the deployment of electrochemical sensors beyond traditional laboratory settings. Recent developments in low-cost, disposable electrodes fabricated using carbon threads on recycled plastic substrates highlight efforts to create accessible monitoring solutions for resource-limited regions [15]. Stabilization of biorecognition elements (e.g., DNA coatings protected with polyvinyl alcohol) further enhances field-deployability by extending sensor shelf-life to several months, even under challenging storage conditions [22].

Future research directions will likely focus on increasing multiplexing capabilities for simultaneous detection of broader metal panels, improving antifouling properties for complex sample matrices, standardizing calibration protocols for better reproducibility, and developing fully integrated systems combining sample preparation, detection, and data transmission in compact, user-friendly platforms [10] [21] [15]. These advancements will strengthen the role of electrochemical sensing in addressing global challenges related to environmental monitoring, food safety, and public health protection.

Advanced Voltammetric Techniques and Nanomaterial-Enhanced Sensing

This guide provides an objective comparison of three prominent electrochemical techniques—Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV)—for the detection of heavy metals. Aimed at researchers and scientists, it evaluates their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols, to inform method selection in environmental monitoring and analytical research.

The detection of heavy metal ions (HMIs) is a critical global challenge due to their high toxicity, environmental persistence, and potential for bioaccumulation. Techniques capable of sensitive, selective, and rapid analysis are essential for safeguarding public health and ecosystems [23] [24]. While traditional methods like Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) and Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) offer high sensitivity, they are often laboratory-bound, expensive, and time-consuming, limiting their use for widespread, on-site monitoring [25] [20] [24].

Electrochemical techniques, particularly voltammetry, have emerged as powerful alternatives, offering a compelling combination of high sensitivity, portability, affordability, and rapid analysis [23] [24]. Among them, Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV), and Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) are highly regarded for trace-level determination. ASV, in particular, is recognized for its exceptional sensitivity, often achieving detection limits in the parts per billion (ppb) range by combining a pre-concentration step with a stripping measurement [25] [26]. The effectiveness of these techniques is further enhanced by modern electrode materials, including screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) and nanocomposites, paving the way for sophisticated, portable, and automated sensing platforms [25] [23].

Technical Principles and Mechanisms

Understanding the distinct operating principles of each technique is fundamental to selecting the appropriate method for a given analytical challenge.

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)

SWV is a pulsed technique that applies a symmetrical square wave superimposed on a staircase potential ramp. The current is sampled twice during each square wave cycle: once at the end of the forward pulse (Iforward) and once at the end of the backward pulse (Ireverse) [27]. The key signal in SWV is the difference between these two currents (ΔI = Iforward - Ireverse), which is plotted against the applied potential. This differential current measurement effectively suppresses the capacitive background current, significantly enhancing the signal-to-noise ratio. The waveform is characterized by its frequency (the inverse of the square wave period) and amplitude (the height of the square wave pulse) [27]. A higher frequency can decrease analysis time but may need optimization to avoid capacitive interference [27]. SWV is considered a virtually non-diffusion-limited system because the reverse pulse regenerates the consumed species, preventing depletion near the electrode surface and leading to sharp, well-defined peaks [27].

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

In DPV, a fixed-amplitude pulse is superimposed on a slowly changing linear baseline potential. The current is measured twice for each pulse: just before the pulse is applied (i1) and just before the pulse ends (i2) [28]. The differential current (i1 - i2) is plotted versus the applied potential. This process minimizes the contribution of capacitive current, as the charging current decays more rapidly than the faradaic current. DPV is characterized by parameters such as pulse amplitude, pulse duration, and step potential [28]. While highly sensitive, DPV can be slower than SWV and is sometimes considered less applicable to a wide range of systems due to potential interference from oxygen and the need for slower scan rates [28].

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV)

ASV is a two-step technique designed for ultra-trace analysis. The first step is a pre-concentration or deposition step, where the target metal ions (e.g., Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺) in the solution are reduced and deposited onto the working electrode at a constant, sufficiently negative potential. This step accumulates the analytes onto or into the electrode, significantly enhancing concentration [29] [26]. For a mercury film electrode (MFE), the deposition involves the formation of an amalgam: M²⁺ + 2e⁻ + Hg → M(Hg) [29]. The second step is the stripping step, where the potential is scanned in an anodic (positive) direction. This re-oxidizes the deposited metals back into the solution: M(Hg) → M²⁺ + 2e⁻ + Hg [29]. The resulting current peak is measured, and its magnitude is proportional to the concentration of the metal in the solution. The stripping step can be performed using various waveforms, including a linear sweep, SWV, or DPV, with SWV being a common choice for its speed and sensitivity [29] [25]. The combination of pre-concentration and sensitive stripping makes ASV one of the most sensitive voltammetric techniques.

Figure 1: The core two-step workflow of Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV), highlighting the pre-concentration (deposition) and measurement (stripping) phases.

Comparative Performance Analysis

The following tables summarize key performance metrics and optimized experimental parameters for SWV, DPV, and ASV, based on published studies for heavy metal detection.

Table 1: Comparison of Detection Limits and Linear Ranges for Heavy Metal Ions

| Heavy Metal Ion | Technique | Electrode Type | Detection Limit (μg/L) | Linear Range (μg/L) | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd(II) | SWV (Anodic Stripping) | Mercury Film Electrode (MFE) | 0.03 | Not Specified | [29] |

| Pb(II) | SWV (Anodic Stripping) | Mercury Film Electrode (MFE) | 0.4 | Not Specified | [29] |

| Cd(II) | DPV (Anodic Stripping) | Hanging Dropping Mercury Electrode (HDME) | ~12.04 (Calculated in tap water) | Not Specified | [28] |

| Pb(II) | DPV (Anodic Stripping) | Hanging Dropping Mercury Electrode (HDME) | ~12.41 (Calculated in tap water) | Not Specified | [28] |

| As(III) | SWASV | (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion / Fe₃O₄-Au-IL modified SPE | 2.4 | 0–50 | [25] |

| Cd(II) | SWASV | (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion / Fe₃O₄-Au-IL modified SPE | 0.8 | 0–50 | [25] |

| Pb(II) | SWASV | (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion / Fe₃O₄-Au-IL modified SPE | 1.2 | 0–50 | [25] |

Table 2: Optimized Experimental Parameters from Literature

| Parameter | SWV [29] | DPV [28] | ASV with Flow Cell [25] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Acidified samples (5 mM HNO₃) | Acetate Buffer (1 mol/L ammonium acetate + 1 mol/L acetic acid) | Not Specified |

| Deposition Potential | Optimized for each metal (e.g., -1.2 V for Cd, Pb) | -0.9 V (for Cd and Pb) | Optimized for multiplex detection |

| Deposition Time | Optimized for each metal | 60-180 seconds | Optimized (varies with flow rate) |

| Stripping Mode | Square Wave | Differential Pulse | Square Wave |

| Key Advantage | Very fast, sensitive, shortening analysis time | Good peak separation for closely positioned peaks | Automated, high-throughput, real-time potential |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: SWV for Soil and Airborne Particulate Matter

This protocol is adapted from a study determining eight heavy metals (Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn, Co, Ni, Cr, Mo) in soil and indoor-airborne particulate matter without digestion [29].

- 1. Electrode System: A glassy carbon-working electrode with a deposited mercury film (MFE) is used as the working electrode, with a Ag/AgCl (sat'd KCl) reference electrode and a platinum wire counter electrode [29].

- 2. Sample Preparation: Acidified samples using 5 mM HNO₃ as supporting electrolyte [29].

- 3. Deposition Step: For metals like Zn(II), Cd(II), Pb(II), and Cu(II), a deposition potential is applied to reduce and accumulate the metals into the mercury film. The deposition potential and time are optimized for each metal ion [29].

- 4. Stripping Step: Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) is performed. The potential is scanned in the positive direction using a square wave waveform, oxidizing the metals back into solution. For other metals like Co(II) and Ni(II), a Square Wave Adsorptive Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWAdSV) method is used, where the metals are accumulated by adsorption of their complexes on the electrode surface [29].

- 5. Data Analysis: The peak current in the resulting voltammogram is proportional to the concentration. The method achieved detection limits as low as 0.03 μg/kg for Cd(II) with a standard deviation below 2% [29].

Protocol: DPV for Lead and Cadmium in Tap Water

This protocol outlines the use of DPV with a standard addition method for quantifying Pb and Cd in tap water [28].

- 1. Electrode System: A Hanging Dropping Mercury Electrode (HDME) is used as the working electrode, with a double junction Ag/AgCl reference electrode [28].

- 2. Electrolyte Preparation: 10 mL of the water sample is mixed with 0.5 mL of acetate buffer (1 mol/L ammonium acetate + 1 mol/L acetic acid) [28].

- 3. Pre-conditioning: Nitrogen purging is performed in the stirring solution, and a new Hg drop is formed [28].

- 4. Deposition and Stripping: A reduction potential of -0.9 V is applied to accumulate Pb and Cd onto the Hg drop with stirring. The stirrer is then switched off, and the DPV measurement is performed by scanning the potential from -0.9 V to -0.2 V, oxidizing the accumulated metals [28].

- 5. Standard Addition: The measurement is repeated after two sequential additions of standard Pb and Cd solutions. The peak heights (at ~-0.58 V for Cd and ~-0.40 V for Pb) are plotted against the added concentration. The unknown concentration in the sample is calculated from the x-intercept of the regression line [28].

Protocol: Multiplexed ASV in a 3D-Printed Flow Cell

This advanced protocol demonstrates simultaneous detection of As(III), Cd(II), and Pb(II) using a flow system integrated with modified screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) [25].

- 1. Sensor Fabrication: SPEs are fabricated on a polyimide substrate. The working electrodes are modified with specific nanocomposites: (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion and Fe₃O₄-Au-IL to enhance sensing of the target HMIs [25].

- 2. Flow Cell Design: A 3D-printed flow cell is designed and optimized using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to ensure efficient electrodeposition and minimize dead volume. The SPEs are integrated into this cell [25].

- 3. Flow Analysis: The water sample is introduced into the flow system. Parameters such as deposition time, deposition potential, and flow rate are optimized [25].

- 4. In-situ Deposition and Stripping: The heavy metals are electrodeposited onto the modified working electrodes and then stripped using the Square Wave ASV technique, all within the flow cell [25].

- 5. Data Collection: The system provides simultaneous voltammograms for the target metals. The platform was successfully applied to simulated river water with recoveries of 95–101%, demonstrating high accuracy in complex matrices [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Materials and Reagents for Voltammetric Heavy Metal Detection

| Item Category | Specific Examples | Function in the Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrodes | Mercury Film Electrode (MFE), Hanging Dropping Mercury Electrode (HDME), Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs), Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | The primary site for the electrochemical reaction and sensing of the analyte. The material critically influences sensitivity and selectivity [29] [28] [25]. |

| Electrode Modifiers | Bismuth oxycarbonate ((BiO)₂CO₃), Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO), Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Fe₃O₄ Magnetic Nanoparticles, Ionic Liquids (IL), Nafion | Enhance electrode performance by increasing active surface area, improving electron transfer, and providing selectivity towards specific heavy metal ions [25] [20]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Acetate Buffer, Nitric Acid (HNO₃), Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Carries the current in solution, controls pH, and defines the ionic strength, which can influence the voltammetric response and peak shape [29] [28]. |

| Standard Solutions | Certified reference materials of Cd(II), Pb(II), As(III), etc. | Used for calibration and the standard addition method to quantify the concentration of unknown samples accurately [28]. |

SWV, DPV, and ASV are powerful voltammetric techniques for heavy metal detection, each with distinct strengths. ASV, particularly when coupled with a sensitive stripping technique like SWV, offers superior sensitivity for ultra-trace analysis due to its pre-concentration step. SWV is characterized by its high speed, sensitivity, and effectiveness in preventing surface depletion. DPV provides excellent resolution for distinguishing between analytes with closely spaced peak potentials.

The future of this field lies in the continued development of robust, non-toxic electrode materials to replace mercury, the design of advanced nanostructured materials for enhanced selectivity, and the integration of these sensors into automated, portable, and multiplexed platforms for real-time environmental monitoring [25] [23] [26]. The combination of sophisticated electrochemical techniques with novel materials science holds the key to addressing the growing challenges of heavy metal pollution.

The Role of Stripping Voltammetry for Ultra-Sensitive Trace Analysis

Stripping voltammetry stands as a powerful electroanalytical technique renowned for its exceptional sensitivity in detecting trace and ultra-trace levels of various analytes, particularly heavy metal ions. Its unparalleled detection limits, often reaching parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels, position it as a critical tool for environmental monitoring, clinical analysis, and food safety. This guide provides a detailed comparison of stripping voltammetry against other electrochemical and spectroscopic techniques, supported by experimental data and protocols from current research.

Fundamental Principles and Comparison with Broader Electrochemical Techniques

Electrochemical techniques for heavy metal detection can be broadly categorized based on the measured signal: current, potential, conductivity, impedance, or electrochemiluminescence [30]. Stripping voltammetry is a subset of voltammetric techniques, which measure current as a function of applied potential.

How Stripping Voltammetry Achieves Ultra-Sensitivity: The exceptional sensitivity of stripping voltammetry stems from its two-step operational process:

- Preconcentration/Deposition Step: A potential is applied to the working electrode, cathodic enough to reduce target metal ions in the solution to their elemental state, thereby depositing them onto the electrode surface [31]. This step concentrates the analytes from the bulk solution onto a small surface area.

- Stripping/Measurement Step: The potential is then swept in an anodic direction, oxidizing the deposited metals back into solution. The resulting current peak is measured, with its intensity being proportional to the concentration of the metal in the original sample [31]. This combination of preconcentration and sensitive measurement is key to its ultra-trace capabilities.

The table below compares stripping voltammetry with other common analytical techniques used for heavy metal ion detection.

Table 1: Comparison of Stripping Voltammetry with Other Analytical Techniques

| Technique | Principle | Typical Detection Limit | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stripping Voltammetry (e.g., SWASV, DPASV) | Electrochemical preconcentration followed by dissolution and current measurement [31] | ppt to ppb range [32] [25] | Ultra-trace sensitivity, portability for on-site use, low cost, simultaneous multi-metal detection [33] | Requires skilled optimization, electrode fouling can occur |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS) | Ionization of sample and mass-to-charge separation | ppt range | Excellent sensitivity, wide dynamic range, multi-element capability | High instrument cost, complex operation, laboratory-bound, requires skilled personnel [33] [25] |

| Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy (AAS) | Absorption of light by free atoms in the gaseous state | ppb range | High specificity, well-established technique | Typically single-element analysis, requires a light source, laboratory-bound [33] |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Optical Emission Spectrometry (ICP-OES) | Measurement of light emitted by excited ions in a plasma | ppb range | Good for major and minor elements, multi-element capability | Higher detection limits than ICP-MS, high instrument cost, laboratory-bound [33] |

| Standard Voltammetry (e.g., DPV, SWV) | Measurement of faradaic current from redox reactions without a preconcentration step | µM to nM range | Simplicity, good for mechanistic studies, diagnostic value [34] | Less sensitive than stripping methods, not suitable for ultra-trace analysis |

Experimental Protocols in Modern Research

The following experimental workflows and parameters are derived from recent studies to illustrate the practical application of stripping voltammetry.

Workflow for a Typical Stripping Voltammetry Experiment

The diagram below outlines the generalized workflow for an Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) experiment, as commonly applied in heavy metal detection.

Detailed Experimental Parameters from Recent Studies

Table 2: Comparison of Experimental Protocols from Recent Stripping Voltammetry Studies

| Parameter | Al₂NiCoO₅ Nanoflakes (ANC/GCE) [32] | BiVO₄ Nanospheres (BiVO₄/GCE) [35] | AuNP-Modified Carbon Thread [36] | Nanocomposite-Modified Screen-Printed Electrodes [25] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target Analytes | Cu²⁺, Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺, Cd²⁺ | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺ | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺ | As(III), Cd(II), Pb(II) |

| Electrode Modifier | Al₂NiCoO₅ nanoflakes | Sol-gel synthesized BiVO₄ nanospheres | Electrodeposited Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | (BiO)₂CO₃-rGO-Nafion; Fe₃O₄-Au-IL nanocomposites |

| Detection Technique | Anodic Stripping Differential Pulse Voltammetry (ASDPV) | Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) |

| Reported LOD | Pb²⁺: 0.00154 ppbHg²⁺: 0.00232 ppbCu²⁺: 0.00261 ppbCd²⁺: 0.00114 ppb | Cd²⁺: 2.75 µMPb²⁺: 2.32 µMCu²⁺: 2.72 µMHg²⁺: 1.20 µM | Cd²⁺: 0.99 µMPb²⁺: 0.62 µMCu²⁺: 1.38 µMHg²⁺: 0.72 µM | As(III): 2.4 µg/LPb(II): 1.2 µg/LCd(II): 0.8 µg/L |

| Linear Range | Not specified | 0 to 110 µM | 1 to 100 µM | 0 to 50 µg/L |

| Sample Matrix | Simulated blood serum, drinking water, tap water | Environmental and industrial samples | Lake water (real samples) | Simulated river water |

| Key Advantages Cited | Ultra-low LOD, successful application in complex bio-matrices like serum | Wide linear range, dual functionality (sensing & antimicrobial activity) | Use of discarded plastic substrate, IoT integration, deep learning for signal processing | Integration with 3D-printed flow cell for automated, high-throughput analysis |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The performance of stripping voltammetry is highly dependent on the careful selection of electrodes and modifiers.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stripping Voltammetry

| Item | Function/Description | Examples from Research |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | The surface where the electrochemical reaction occurs; its material and modification dictate sensitivity and selectivity. | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) [32] [35], Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) [25], Carbon Thread Electrode [36], Inkjet-Printed Electrodes [37] |

| Electrode Modifiers / Nanomaterials | Enhance electrode surface area, provide catalytic active sites, and improve selectivity towards specific metal ions. | Al₂NiCoO₅ nanoflakes [32], BiVO₄ nanospheres [35], Bismuth film [33], Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) [36], Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) [25] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries the current in the solution, maintains a constant ionic strength, and can influence the stripping peak potential and shape. | Acetate Buffer [37], HCl-KCl Buffer [36] |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable and known potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled. | Ag/AgCl (3M KCl) [35], Ag/AgCl quasi-reference electrode (on SPEs) [25] |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow through the cell. | Platinum wire [35], Graphite-based (on SPEs) [25] |

Advanced Trends and Future Outlook

The field of stripping voltammetry is rapidly evolving with several cutting-edge trends:

- Miniaturization and Point-of-Source Testing: The development of screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) and other disposable platforms allows for the creation of portable, low-cost sensors ideal for on-site environmental monitoring [25].

- Integration with Flow Systems: Coupling stripping voltammetry with 3D-printed flow cells enables automated, high-throughput analysis of multiple samples with minimal dead volume and reduced risk of contamination [25].

- Advanced Data Processing with AI: Deep learning algorithms, such as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), are being employed to interpret complex voltammetric signals from mixtures of heavy metals, significantly improving classification accuracy and quantification in the presence of overlapping peaks [36].

- IoT and Remote Monitoring: Sensors are being integrated with Internet of Things (IoT) platforms, enabling remote data acquisition, real-time monitoring of water quality, and user-friendly data interfaces accessible to non-experts [36].

- Sustainable Material Development: Research is focused on using biodegradable substrates, such as cellulose-based papers, for electrode fabrication to reduce electronic waste and create more environmentally friendly sensors [37].

The contamination of water and soil by heavy metals such as lead (Pb), mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), and arsenic (As) represents a significant global threat to ecosystem integrity and public health [10] [38]. These toxic elements are non-biodegradable, bioaccumulative, and often carcinogenic, posing dangerous risks even at trace concentration levels [10] [21]. Traditional analytical methods for heavy metal detection—including atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS)—while highly sensitive, are constrained by their laboratory-bound nature, high operational costs, complex sample preparation, and inability to provide real-time monitoring data [10] [3] [38].

Electrochemical sensing technologies have emerged as a powerful alternative, characterized by their simplicity, portability, cost-effectiveness, and suitability for on-site environmental monitoring [10] [3]. The integration of nanomaterials has been pivotal in advancing these technologies, substantially improving sensor sensitivity, selectivity, and stability [10] [21] [38]. Among the most promising nanomaterials are carbon nanotubes (CNTs), graphene and its derivatives, and metal/metal oxide nanoparticles, which enhance electrochemical performance through their unique structural and electronic properties [10] [21] [39]. These materials increase the electroactive surface area, facilitate rapid electron transfer, and can be functionalized to improve affinity for specific heavy metal ions [21] [39].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three nanomaterial classes—carbon nanotubes, graphene, and metal nanoparticles—focusing on their performance in electrochemical heavy metal detection. By presenting structured experimental data, detailed methodologies, and analytical performance metrics, this review serves as a resource for researchers and scientists developing next-generation environmental sensors.

Performance Comparison of Nanomaterials

The integration of nanomaterials significantly enhances the analytical performance of electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection. The table below provides a comparative overview of the three primary nanomaterial classes based on critical performance parameters.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Nanomaterials in Heavy Metal Detection

| Nanomaterial | Key Advantages | Limitations | Typical Detection Limits | Heavy Metals Detected |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | High electrical conductivity, large specific surface area, excellent mechanical flexibility [10] [40] [41]. | Potential aggregation, moderate selectivity without functionalization [10]. | Sub-nM to μM range [10] [41]. | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Hg²⁺, Cu²⁺ [10] [41]. |

| Graphene & Derivatives | Extremely high surface area, exceptional electron mobility, facile functionalization [42] [21] [39]. | Sheet restacking can reduce active area, synthesis method affects consistency [21] [39]. | ppt to ppb range (e.g., Hg²⁺: 6 ppt) [21]. | Hg²⁺, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, As³⁺, Cr³⁺ [21]. |

| Metal & Metal Oxide Nanoparticles | High catalytic activity, strong adsorption sites, synergistic effects in composites [10] [21] [35]. | Cost and long-term stability concerns for noble metals (e.g., Au, Pt) [21]. | Low μM range (e.g., Cd²⁺: 2.75 μM, Pb²⁺: 2.32 μM) [35]. | Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, Cu²⁺, Hg²⁺ [21] [35]. |

Synergistic Effects in Nanocomposites

Superior sensor performance is often achieved by combining nanomaterials to create synergistic effects in hybrid architectures [10] [21]. These composites integrate the advantages of individual components, leading to enhanced sensitivity and selectivity.

- CNT-Metal Composites: Decorating CNTs with metal nanoparticles (e.g., gold nanoparticles, AuNPs) increases electrode conductivity and provides more active sites for metal ion deposition. For instance, an AuNP/graphene/cysteine composite demonstrated excellent simultaneous detection of Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ [21].

- Graphene-Metal Oxide Systems: Combining graphene with metal oxides (e.g., BiVO₄ nanospheres) results in a high surface area conductive platform that improves the preconcentration of heavy metal ions and enhances the stripping voltammetry signal [35].

- Three-Dimensional Architectures: Materials like graphene aerogel (GA) with dispersed AuNPs create a porous 3D network that facilitates high DNA loading for aptasensors and enables ultra-sensitive, femtomolar detection of Hg²⁺ ions [21].

Experimental Protocols for Heavy Metal Detection

This section outlines standard experimental methodologies for fabricating and evaluating nanomaterial-modified electrochemical sensors for heavy metal detection. The following workflow visualizes the general experimental process.

Sensor Fabrication and Modification Protocols

CNT Film-based Electrode Fabrication

- Objective: To create a flexible, high-surface-area working electrode using carbon nanotube films for efficient electron transfer [40] [41].

- Materials: Pristine multi-walled or single-walled CNTs, dispersing agent (e.g., N,N-Dimethylformamide), flexible substrate (e.g., polymer), binder.

- Procedure:

- CNT Dispersion: Disperse CNTs in a suitable solvent (e.g., DMF) using ultrasonication to create a homogeneous suspension.

- Film Formation: Deposit the CNT suspension onto a substrate (e.g., glassy carbon electrode or flexible polymer) via drop-casting, spray-coating, or dry-printing [40].

- Drying: Allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature or in a vacuum oven to form a stable, conductive CNT film.

- Post-treatment: Optionally, perform thermal or plasma treatment to enhance conductivity and stability.

Graphene Oxide Modification and Reduction

- Objective: To synthesize reduced graphene oxide (rGO) with high conductivity and abundant active sites for heavy metal adsorption [21] [39].

- Materials: Graphite powder, oxidizing agents (e.g., KMnO₄, NaNO₂), reducing agents (e.g., hydrazine hydrate, ascorbic acid).

- Procedure:

- GO Synthesis: Oxidize graphite using Hummers' method or improved versions to create graphene oxide [39].

- Exfoliation: Ultrasonicate GO in water to exfoliate it into single or few-layer sheets.

- Electrode Modification: Deposit GO suspension onto the electrode surface (e.g., glassy carbon electrode).

- Reduction: Chemically reduce GO to rGO using a reducing agent (e.g., hydrazine vapor) or electrochemically reduce it by applying a negative potential scan [21].

Metal Nanoparticle Decoration

- Objective: To deposit catalytic metal nanoparticles (e.g., Au, Bi) onto carbon nanostructures to enhance sensitivity and selectivity [21] [35].

- Materials: Metal salt precursor (e.g., HAuCl₄, Bi(NO₃)₃), reducing agent (e.g., sodium citrate, NaBH₄), supporting electrolyte.

- Procedure:

- Chemical Deposition: Mix the nanomaterial substrate (e.g., CNT or graphene dispersion) with a metal salt solution. Add a reducing agent under stirring to nucleate and grow metal nanoparticles on the substrate surface [21].

- Electrodeposition: Immerse the nanomaterial-modified electrode in a solution containing the metal salt. Apply a constant potential or cyclic potential scans to electrodeposit metal nanoparticles directly onto the electrode surface [35].

Electrochemical Detection of Heavy Metals

Square Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV)

- Objective: To simultaneously detect and quantify multiple heavy metal ions at trace levels with high sensitivity [10] [35].

- Materials: Nanomaterial-modified working electrode, reference electrode (Ag/AgCl), counter electrode (Pt wire), supporting electrolyte (e.g., acetate buffer, HCl), standard solutions of target heavy metal ions.

- Procedure:

- Preconcentration/Deposition: Immerse the electrode system in a stirred sample solution containing target ions. Apply a negative deposition potential (e.g., -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl) for a specific time (60-180 s) to reduce and deposit metal ions onto the electrode surface as amalgams or elemental forms [35].

- Equilibrium: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for about 10-15 seconds.

- Stripping Scan: Apply a square wave potential scan in the positive direction (e.g., from -1.2 V to +0.5 V). As the potential reaches the oxidation potential of each metal, it strips (oxidizes) back into the solution, generating a characteristic current peak [35].