Bismuth Film Electrodes vs. Mercury Electrodes: A Comprehensive Performance Analysis for Modern Electroanalysis

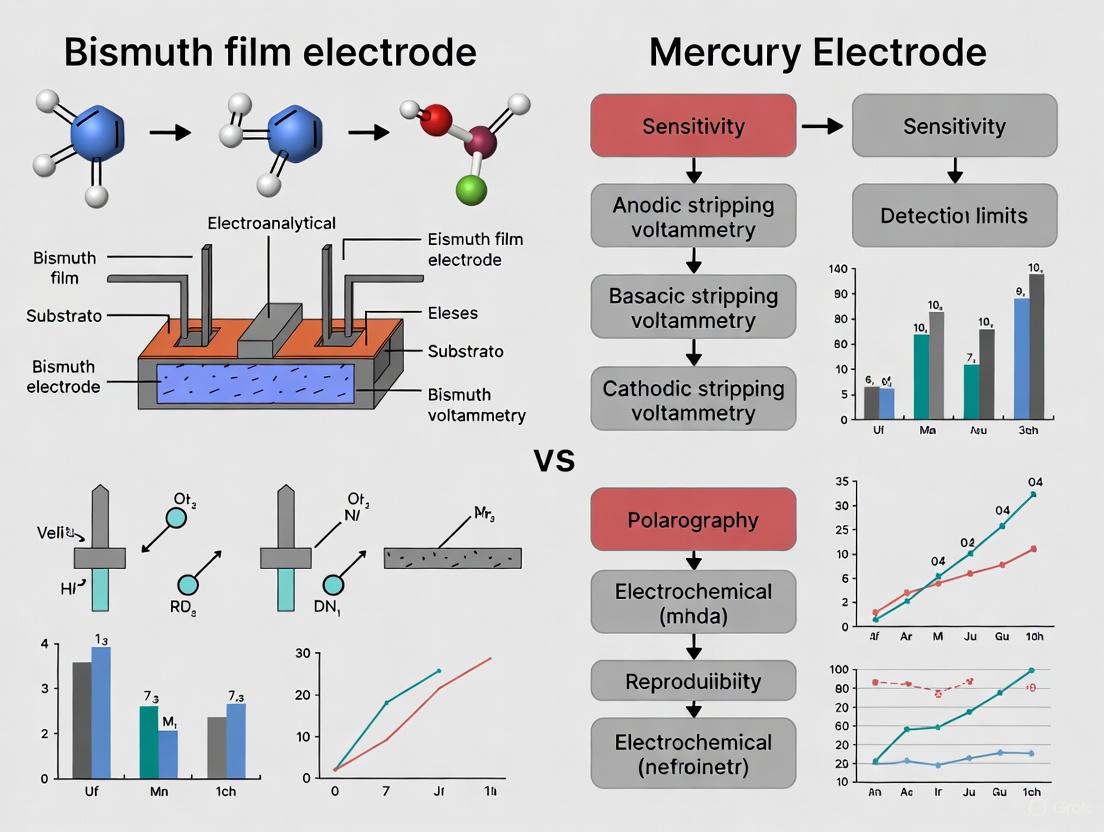

This article provides a critical comparison of bismuth film electrodes (BiFEs) and traditional mercury electrodes, focusing on their performance, applications, and suitability for researchers and drug development professionals.

Bismuth Film Electrodes vs. Mercury Electrodes: A Comprehensive Performance Analysis for Modern Electroanalysis

Abstract

This article provides a critical comparison of bismuth film electrodes (BiFEs) and traditional mercury electrodes, focusing on their performance, applications, and suitability for researchers and drug development professionals. It covers the foundational principles driving the shift towards environmentally friendly 'green electrochemistry,' detailed methodologies for fabricating and characterizing BiFEs, strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing their performance, and a rigorous validation against mercury-based standards. The analysis synthesizes current research to guide the selection and implementation of these sensors in sensitive analytical tasks, including heavy metal detection and pharmaceutical analysis, highlighting BiFE's potential as a low-toxicity, high-performance alternative.

The Rise of Green Electrochemistry: Why Replace Mercury Electrodes?

The Established Legacy and Inherent Toxicity of Mercury Electrodes

For decades, mercury electrodes represented the gold standard in electroanalytical chemistry, particularly for the determination of trace metals using stripping voltammetry techniques. Their widespread adoption was driven by exceptional electrochemical properties: a high hydrogen overvoltage that extended the useful cathodic potential window, an atomically smooth and renewable surface, and excellent reproducibility for trace metal analysis [1]. The hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE) and mercury film electrodes (MFE) became fundamental tools for detecting heavy metals at parts-per-billion levels in environmental, clinical, and industrial samples [2].

However, the well-documented toxicity of mercury has necessitated a paradigm shift toward safer alternatives. Mercury is recognized as one of the top ten chemicals of major public health concern by the World Health Organization, with toxic effects including neurological damage, kidney impairment, and cardiovascular problems [3]. This review examines the established legacy of mercury electrodes alongside the compelling safety and performance data driving the adoption of bismuth-based alternatives in modern analytical laboratories.

Performance Comparison: Mercury vs. Bismuth Film Electrodes

Analytical Performance Metrics

Table 1: Comparison of analytical performance for heavy metal detection using mercury and bismuth film electrodes.

| Parameter | Mercury Film Electrodes | Bismuth Film Electrodes |

|---|---|---|

| Detection Limit (Cd(II)) | <0.1 μg/L [2] | 1.7-11.0 μg/L [4] [5] |

| Detection Limit (Pb(II)) | <0.1 μg/L [2] | 0.7-11.5 μg/L [4] [5] |

| Linear Range | 0.1-10 μg/mL [2] | 2-100 μg/L [5] |

| Reproducibility | Excellent (renewable surface) [1] | Good to excellent (RSD <5%) [6] |

| Sensitivity | Excellent for Cd, Pb, Cu, Zn [2] | Comparable for Cd, Pb; poor for Cu [2] |

Operational and Safety Considerations

Table 2: Practical and safety considerations for electrode selection.

| Consideration | Mercury Electrodes | Bismuth Film Electrodes |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | High toxicity; affects nervous, respiratory, cardiovascular systems [3] | Very low toxicity; environmentally friendly [7] [5] |

| Waste Disposal | Requires special hazardous waste procedures [8] | Standard laboratory disposal [7] |

| Electrode Preparation | Relatively complex; careful handling required [1] | Simple ex situ or in situ plating [4] [6] |

| Regulatory Concerns | Increasing regulatory restrictions [8] | Minimal regulatory concerns |

| Applicability | Broad spectrum of metals [2] | Limited for some metals (e.g., copper) [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Representative Experimental Design: Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation

The following experimental workflow visualizes the typical preparation and analysis procedure for bismuth film electrodes in heavy metal detection:

Detailed Methodological Protocols

Mercury Film Electrode Protocol for Trace Metal Analysis

Traditional mercury film electrodes are prepared by electrodepositing a thin mercury layer on a substrate such as glassy carbon or carbon paste. The standard methodology involves:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish the substrate electrode to a mirror finish using alumina slurry (0.05 μm), followed by thorough rinsing with deionized water [2].

- Mercury Film Deposition: Deposit the mercury film from a solution containing 100-500 mg/L Hg(II) in 0.1 M HCl or HNO₃ by applying a potential of -0.9 to -1.0 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 5-15 minutes with stirring [2].

- Sample Preconcentration: Transfer the sample to an electrochemical cell, deoxygenate with inert gas (N₂ or Ar) for 5-8 minutes, and apply a deposition potential (-1.2 to -1.4 V) for 60-600 seconds with stirring [2].

- Stripping Analysis: Record the anodic stripping voltammogram using differential pulse or square-wave mode with the following parameters: pulse amplitude 25-50 mV, step potential 2-5 mV, frequency 10-50 Hz [2].

- Electrode Cleaning: Apply a cleaning potential (+0.2 to +0.5 V) for 30-60 seconds between measurements to remove residual metals [2].

Bismuth Film Electrode Protocol for Trace Metal Analysis

The bismuth film electrode protocol shares similarities with the mercury approach but utilizes significantly less toxic materials:

- Electrode Substrate Preparation: Various substrates can be employed including screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs), pencil-lead graphite, or glassy carbon. For SPCEs, pretreatment may include plasma cleaning or electrochemical activation in acetate buffer (pH 4.5) at +1.6 V to +1.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 1-2 minutes [5] [9].

- Bismuth Film Formation (In-situ Method): Add Bi(III) directly to the sample solution (final concentration 100-400 μg/L) and simultaneously deposit bismuth and target metals during the preconcentration step at -1.0 to -1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl [4] [5].

- Bismuth Film Formation (Ex-situ Method): Pre-deposit the bismuth film from a separate solution containing 500-1000 μg/L Bi(III) in acetate buffer (pH 4.5) by applying -1.0 to -1.2 V vs. Ag/AgCl for 60-120 seconds with stirring [6].

- Analysis Parameters: For simultaneous Cd(II) and Pb(II) determination, use square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry with deposition potential -1.1 to -1.4 V, deposition time 120-300 seconds, amplitude 25-50 mV, frequency 15-35 Hz, and step potential 4-6 mV [4] [5].

- Electrode Protection: For enhanced stability, protect the bismuth film with a Nafion coating (1.5 μL of 2% solution in ethanol) to prevent oxidation and improve reproducibility in complex matrices [9].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key reagents and materials for electrode preparation and analysis.

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Standard Solution (Bi(III)) | Formation of bismuth film | Typically used at 100-400 μg/L for in-situ plating [4] [5] |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 4.5) | Supporting electrolyte | Optimal for Cd and Pb analysis; provides consistent ionic strength [4] [2] |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Solution | Electrode protector | Forms cation-exchange membrane; improves stability [9] |

| Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes | Disposable substrate | Low-cost; suitable for decentralized analysis [5] [9] |

| Pencil-Lead Graphite | Electrode substrate | Inexpensive alternative with good conductivity [4] |

| Mercury(II) Acetate | Mercury film formation | High purity required; significant toxicity concerns [2] |

| Standard Metal Solutions (Cd, Pb) | Calibration and quantification | Use certified reference materials for accurate quantification [4] [2] |

Toxicity and Safety Considerations: A Compelling Case for Transition

The occupational hazards associated with mercury present a compelling argument for transitioning to bismuth-based alternatives. A recent investigation of an electronics waste recycling facility in Ohio revealed that workers exposed to mercury vapor showed significantly elevated urine mercury levels (median 41.3 μg/g creatinine versus ACGIH BEI of 20.0 μg/g creatinine), with symptoms including metallic taste, difficulty thinking, and personality changes [8]. The median job tenure of affected workers was only 8 months, highlighting the rapid accumulation and potent toxicity of mercury even in controlled environments [8].

Mercury toxicity extends beyond occupational settings, with potential health impacts including neurological damage, kidney dysfunction, cardiovascular effects, and reproductive disorders [3]. The environmental persistence and bioaccumulation of mercury compounds further compound these risks, creating significant disposal challenges for analytical laboratories using mercury-based electrodes [3].

In contrast, bismuth exhibits exceptionally low toxicity, with bismuth salts widely used in pharmaceutical applications (e.g., gastrointestinal medicines) at gram quantities without significant adverse effects [7]. This favorable toxicological profile eliminates special handling requirements and significantly reduces waste disposal costs and complexities.

While mercury electrodes established a formidable legacy in electrochemical analysis through their exceptional sensitivity and reproducible performance, the well-documented toxicity and associated regulatory burdens have rendered them increasingly impractical for modern laboratories. Bismuth film electrodes emerge as a viable, environmentally-friendly alternative that delivers comparable analytical performance for most common heavy metals, particularly cadmium and lead.

The transition to bismuth-based electrodes aligns with the principles of green chemistry and sustainable laboratory practices, eliminating significant hazardous waste streams while maintaining the sensitivity, reproducibility, and cost-effectiveness required for routine trace metal analysis. Future developments in bismuth-based electrode materials and modification strategies will likely further close the performance gap for specific applications where mercury electrodes currently maintain an advantage, solidifying bismuth's role as the preferred material for electrochemical stripping analysis in 21st-century laboratories.

Growing regulatory pressures concerning workplace safety and environmental pollution are actively reshaping the materials used in electrochemical research and analysis. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) enforces strict standards to protect workers from hazardous substances, while the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) regulates the lifecycle of toxic materials through acts like the Mercury Export Ban Act (MEBA) of 2008 [10]. MEBA effectively prohibited the export of elemental mercury from the United States as of January 1, 2013, to reduce its availability in domestic and international markets [10]. This regulatory landscape, combined with mercury's well-documented toxicity, has accelerated the search for safer, high-performance alternatives, positioning bismuth as a leading candidate to replace mercury in electrochemical electrodes [11].

Performance Comparison: Bismuth vs. Mercury Electrodes

Extensive research has demonstrated that bismuth-film electrodes (BiFEs) offer a compelling combination of performance, safety, and environmental compatibility. The following table summarizes key performance metrics from recent studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Bismuth-Film and Mercury Electrodes for Heavy Metal Detection

| Feature | Bismuth-Film Electrode (BiFE) | Mercury Electrode |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity & Environmental Impact | Low toxicity, environmentally friendly [11] | Highly toxic, subject to strict regulations (e.g., EPA Mercury Export Ban) [10] [12] |

| OSHA & Regulatory Status | Favored; reduces workplace hazard exposure | Strictly regulated; requires extensive controls and disposal protocols |

| Analytical Performance (Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺) | Well-defined peaks, low background current; comparable sensitivity and detection limits to mercury [13] [11] | Traditionally the benchmark for high sensitivity and reproducibility [11] |

| Linear Range (for Cd²⁺) | From 2×10⁻⁸ to 1×10⁻⁶ mol L⁻¹ [11] | Not specified in available sources |

| Detection Limit (for Cd²⁺) | Achievable at nanomolar concentrations (e.g., 0.044 μmol L⁻¹ or ~4 ng/mL) [13] | Not specified in available sources |

| pH Operating Range | Limited in neutral/alkaline media (above pH ~4.3) due to hydroxide formation [11] | Operates over a wider pH range |

| Electrode Fabrication | Electrodeposition onto various substrates (e.g., Cu, Au, C) [14] | Not specified in available sources |

| Key Application | Simultaneous determination of Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ in water and food samples [13] | Removal of mercury from contaminated water [12] |

A 2025 study directly compared bismuth film electrodes made from recycled bismuth (BiATPS-FE) against those made from standard bismuth precursors (Bi-STD) for detecting cadmium and lead. Using square-wave anodic stripping voltammetry (SWASV), the study found that BiATPS-FE displayed a similar voltammetric response toward both analytes compared to the standard electrode [13]. The sensor exhibited excellent detection limits, confirming that bismuth electrodes can perform on par with mercury-based systems for critical environmental monitoring tasks [13].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Fabrication of Bismuth-Film Electrodes

The performance of bismuth-film electrodes is highly dependent on the fabrication protocol. Below are two established methods for electrode preparation.

Table 2: Key Protocols for Bismuth-Film Electrode Fabrication

| Protocol Step | Bismuth-Film via DC Electrodeposition [14] | Bismuth-Film via Pulse/Reverse Electrodeposition [14] |

|---|---|---|

| Substrate Preparation | Gold-plated brass or steel panels used as cathode/working electrode. | Same as DC method. |

| Plating Solution | 0.15 M Bi(NO₃)₃, 1.4 M glycerol, 1.2 M KOH, 0.33 M tartaric acid, pH adjusted to ~0.08 with HNO₃. | Same as DC method. |

| Electrodeposition Parameters | Direct current at 1.5 mA/cm² for 24-96 hours at room temperature with stirring. | Pulse/Reverse current with a density of 1.5 mA/cm². Pulse sequence: forward current (30 ms), zero current (10 ms), reverse current (1 ms), zero current (10 ms). |

| Resulting Film | Thick films (>100 µm), elongated surface features, good adhesion. | Thick films (>100 µm), mixed morphology (elongated and "blocky" features), larger grain size. |

Analytical Measurement via Anodic Stripping Voltammetry

The core analytical procedure for detecting trace metals using bismuth-film electrodes is anodic stripping voltammetry. The following workflow outlines the general process, which can be adapted for specific techniques like Square-Wave ASV (SWASV) or Differential Pulse ASV (DPASV).

The specific operational parameters from recent studies are detailed below:

- Preconcentration: The bismuth-film working electrode is immersed in the sample solution and a negative deposition potential (e.g., -1.4 V vs. Ag/AgCl) is applied for a set time (e.g., 120 s) with stirring. During this step, both Bi³⁺ ions (to refresh the film) and target metal ions like Cd²⁺ and Pb²⁺ are electro-reduced and pre-concentrated into the bismuth film, forming an alloy [13] [11].

- Equilibration: The stirring is stopped for a short quiet period (e.g., 10 s) to allow the solution to become quiescent before the stripping step [11].

- Stripping: The potential is scanned in a positive direction using a pulsed voltammetric technique such as Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) or Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV). For example, a SWV scan from -1.4 V to -0.2 V at a frequency of 25 Hz may be used [13]. As the potential sweeps, each amalgamated metal is re-oxidized (stripped) back into the solution, generating a characteristic current peak.

- Data Analysis: The resulting voltammogram is analyzed. The peak current is proportional to the concentration of the metal ion in the original sample, allowing for quantification via a calibration curve [13] [11].

- Electrode Renewal: The electrode can be regenerated by holding it at a positive potential in a clean, acidic supporting electrolyte to remove any residual metals, making it ready for the next analysis [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful fabrication and application of bismuth-film electrodes require specific chemical reagents and materials. The following table lists key components and their functions based on the protocols cited in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Bismuth-Film Electrode Work

| Item | Function/Description | Example from Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth (III) Nitrate | High-purity source of Bi³⁺ ions for electroplating the film. | Bismuth(III) nitrate pentahydrate (99.999%) [14] |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Provides ionic conductivity and controls pH during electrodeposition and analysis. | Nitric acid (HNO₃) for pH adjustment; Acetate buffer for analysis [13] [14] |

| Complexing/Plating Agents | Stabilize Bi³⁺ ions in solution and moderate film growth for uniform, adherent deposits. | Glycerol and Tartaric Acid in KOH base [14] |

| Electrode Substrates | Base material on which the bismuth film is deposited; choice affects adhesion and conductivity. | Gold-plated brass, Glassy Carbon, Copper substrates [11] [14] |

| Standard Solutions | Used for calibration and validation of the analytical method. | Certified standard solutions of Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, etc. [13] |

The convergence of stringent regulatory frameworks from OSHA and the EPA with robust scientific research has firmly established bismuth-film electrodes as a viable and superior alternative to mercury electrodes for many applications. While challenges such as operational pH limitations remain, the exceptional analytical performance, low toxicity, and regulatory compliance of bismuth make it the material of choice for the future of electroanalysis, particularly in the environmental monitoring of toxic heavy metals like cadmium and lead.

Electrochemical analysis has long relied on mercury-based electrodes for the determination of heavy metals and organic compounds. Mercury electrodes offer exceptional electrochemical properties, including a renewable, atomically smooth surface, a wide negative potential window, and high hydrogen overvoltage, which enables sensitive detection of various analytes [1]. However, mercury's significant toxicity and associated environmental and safety concerns have triggered an extensive search for alternative electrode materials [2] [15]. Among the proposed substitutes, bismuth-based electrodes have emerged as the most promising replacement, combining remarkable electrochemical performance with low toxicity and widespread pharmaceutical acceptance [11] [15]. This review comprehensively compares bismuth and mercury electrode performance within the context of modern electroanalytical research, providing experimental data and methodologies to guide researchers and development professionals in adopting this environmentally friendly alternative.

Toxicity and Environmental Profile: Bismuth vs. Mercury

Toxicity Comparison

The fundamental driver for transitioning from mercury to bismuth electrodes lies in their drastically different toxicity profiles.

- Mercury is classified by the World Health Organization as one of the most harmful substances to human health, affecting the nervous system, brain development, and is particularly dangerous for children and unborn babies [12]. It is bioaccumulative in the food chain, with freshwater fish often containing high levels [12].

- Bismuth, in contrast, has unusually low toxicity for a heavy metal [16]. Its compounds account for about half of global bismuth production and are used in cosmetics, pigments, and pharmaceuticals, notably bismuth subsalicylate, used to treat diarrhea [16]. While very high doses over extended periods can cause reversible nephropathy or encephalopathy, its safety profile is substantially superior to mercury [17].

Environmental and Regulatory Considerations

Stringent global regulations govern mercury management due to its environmental persistence and health impacts [12]. Bismuth's low environmental impact and use in pharmaceutical applications make it a compliant and sustainable choice for industrial and research applications, aligning with green chemistry principles [11] [15].

Electrochemical Performance Comparison

Analytical Performance in Trace Metal Detection

The table below summarizes the performance of bismuth and mercury film electrodes in detecting heavy metals via anodic stripping voltammetry (ASV), a key technique for trace metal analysis.

Table 1: Performance comparison of bismuth and mercury film electrodes for heavy metal detection

| Metal Ion | Electrode Type | Linear Range (µg/mL) | Limit of Detection (µg/mL) | Supporting Electrolyte | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd(II) | Mercury film (paper-based) | 0.1 - 10 | 0.04 | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] |

| Bismuth film (paper-based) | 0.1 - 10 | 0.4 | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] | |

| Bismuth film on Cu | 2.24x10⁻³ - 11.2x10⁻³ (mol/L) | - | Acidified tap water | [11] | |

| Pb(II) | Mercury film (paper-based) | 0.1 - 10 | 0.1 | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] |

| Bismuth film (paper-based) | 0.1 - 10 | 0.1 | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] | |

| In(III) | Mercury film (paper-based) | 0.1 - 10 | 0.04 | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] |

| Bismuth film (paper-based) | 0.1 - 10 | 0.04 | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] | |

| Cu(II) | Mercury film (paper-based) | 0.1 - 10 | 0.2 | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] |

| Bismuth film (paper-based) | Not determinable | - | Acetate buffer pH 4.0 | [2] | |

| Zn(II) | Bismuth film on Cu | Well-defined peaks obtained | - | Non-deaerated solutions | [11] |

Key Performance Insights

- Sensitivity and Linearity: Mercury films generally provide slightly lower detection limits for some metals like Cd(II) [2]. However, bismuth films demonstrate comparable sensitivity for Pb(II) and In(III), with linear ranges identical to mercury, making them suitable for many practical applications [2].

- Metal Specificity: A notable limitation of bismuth films is their inability to determine Cu(II), which is readily quantifiable with mercury films [2]. This must be considered in multi-analyte setups.

- Operational Advantages: Bismuth film electrodes (BiFEs) produce well-defined peaks with low background current and can be used in non-deaerated solutions, simplifying the analytical procedure [11].

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Preparation and Analysis

Detailed Methodologies for Bismuth Film Electrodes

Protocol 1: In Situ Bismuth Film Formation on Glassy Carbon Electrode for Germanium Detection [18]

This protocol is ideal for rapid analysis of Ge(IV) using adsorptive stripping voltammetry (AdSV), with all steps performed in a single cell.

- Electrode System: Glassy carbon working electrode (1 mm diameter), Ag/AgCl reference electrode, Pt wire auxiliary electrode.

- Supporting Electrolyte: 0.1 mol L⁻¹ acetic acid solution.

- Chemical Modifiers: 2.5 × 10⁻⁵ mol L⁻¹ Bi(III) and 5 × 10⁻⁴ mol L⁻¹ chloranilic acid (complexing agent).

- Procedure:

- Bismuth Film Plating: Apply -1.0 V for 20 seconds with stirring. This reduces Bi(III) to metallic bismuth, forming the film on the glassy carbon surface.

- Analyte Accumulation: Apply -0.35 V for 30 seconds with stirring. This non-electrochemical step accumulates Ge(IV)-chloranilic acid complexes on the bismuth film.

- Stripping Measurement: Scan the potential from -0.35 V to -0.8 V using differential pulse voltammetry. The cathodic stripping peak for the reduction of the accumulated complex appears at approximately -0.54 V.

- Electrode Cleaning: Between measurements, clean the electrode at -1.4 V for 15 s and then at +0.3 V for 15 s under stirring to remove the bismuth film and any residual analytes.

Protocol 2: Ex Situ Bismuth Film on Screen-Printed Electrodes (SPEs) with Nafion Coating [15]

This method produces more stable and robust electrodes suitable for complex matrices, though it requires a separate plating step.

- Electrode System: Screen-printed carbon working and counter electrodes, with an external Ag/AgCl (3 M KCl) reference electrode.

- Electrode Pretreatment (Optional but Recommended):

- Treatment A (Acidic): Pre-oxidize the SPE at +1.50 V in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 4.4) for 120 s.

- Treatment B (Basic): Pre-oxidize the SPE at +1.20 V in a saturated sodium carbonate solution for 240 s.

- Ex Situ Bismuth Plating:

- Dip the pretreated SPE into a 0.1 mM bismuth solution in acetate buffer (pH 4.4).

- Apply a reduction potential of -1.20 V for 30 s to deposit the bismuth film.

- Nafion Coating: Immediately drop-cast 1 µL of a 5 wt% Nafion solution onto the bismuth-modified working electrode surface. Air-dry and use immediately. The Nafion layer improves mechanical stability and alleviates interferences.

- Analysis (e.g., for Cd and Pb): Perform the analysis in acetate buffer. The deposition is done at -1.20 V for 60 s with stirring, followed by a differential pulse stripping scan.

The workflow for the ex situ preparation of Nafion-coated bismuth film electrodes is summarized below:

- Electrode System: Paper-based carbon working electrode integrated with a screen-printed carbon card.

- Mercury Film Formation: The mercury film is electrodeposited ex situ from a 10⁻³ M mercury(II) acetate solution in 0.1 M HCl by applying a negative potential.

- Analysis via Anodic Stripping Voltammetry:

- Preconcentration: Metal ions are reduced and preconcentrated into the mercury film by applying a negative potential.

- Stripping: The potential is swept anodically, oxidizing each metal out of the amalgam at a characteristic potential. The peak current is proportional to the metal's concentration.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials required for preparing and working with bismuth film electrodes, based on the cited experimental protocols.

Table 2: Essential research reagents and materials for bismuth film electrode research

| Item | Typical Specification / Example | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Salt | Bismuth nitrate pentahydrate (Bi(NO₃)₃·5H₂O), 98%+ | Source of Bi(III) ions for electrochemical deposition of the bismuth film [18] [15]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.0-4.4); Nitric acid (TraceSelect) | Provides consistent ionic strength and pH, crucial for controlling deposition efficiency and stripping peak shape [2] [15]. |

| Complexing Agent (for AdSV) | Chloranilic acid, Catechol, Pyrogallol | Forms an adsorbable complex with the target metal ion (e.g., Ge(IV)), enabling highly sensitive adsorptive stripping voltammetry [18]. |

| Ion-Exchange Polymer | Nafion perfluorinated resin (5 wt% solution) | Coated onto the BiFE to improve mechanical stability, reduce fouling, and minimize interferences from surface-active compounds [15]. |

| Electrode Substrates | Glassy Carbon (polished); Screen-Printed Carbon Electrodes (SPEs) | Provides the conductive base for the bismuth film. SPEs offer disposability and suitability for field analysis [18] [15]. |

| Standard Solutions | Cd(II), Pb(II), etc. (1000 mg/L certified standards) | Used for calibration and validation of the analytical method [15]. |

| pH Adjuster | Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH), Nitric Acid (HNO₃, sub-boiling distilled) | For precise adjustment of electrolyte pH, which is critical for bismuth film quality and analytical signal [19] [15]. |

Application Scope and Limitations

Ideal Applications for Bismuth Film Electrodes

- Environmental Water Monitoring: Bismuth electrodes successfully determine trace levels of Cd(II), Pb(II), and Zn(II) in tap water and plant extracts, validating their use for environmental monitoring [2] [11].

- Analysis in Oxygenated Solutions: BiFEs can be used in non-deaerated solutions, unlike many other electrodes, which simplifies and speeds up the analytical process [11].

- Portable and Disposable Sensors: The compatibility of bismuth with low-cost, disposable substrates like paper and screen-printed electrodes makes it ideal for developing decentralized, on-site testing kits [2].

Current Limitations and Research Directions

- pH Limitation: A significant challenge is the formation of bismuth hydroxide on the film surface at pH above ~4.3, which leads to non-reproducible measurements. This restricts analysis to slightly acidic media and hinders on-site monitoring of neutral water samples [11].

- Metal Specificity: The inability to determine copper with bismuth films is a notable limitation for applications requiring full heavy metal panels [2].

- Film Stability: Bismuth films can oxidize over time, requiring careful standardization of experimental conditions. Electrodes are often best used immediately after preparation [15].

The relationship between electrode selection, key properties, and analytical outcomes can be visualized as follows:

Bismuth stands as an ideal candidate to replace mercury in electrochemical sensors, primarily due to its low toxicity and established safety profile in pharmaceutical applications. While mercury electrodes may still hold a slight edge in ultimate sensitivity and ability to detect a wider range of metals like copper, bismuth film electrodes demonstrate comparable performance for critical analytes such as lead, cadmium, and zinc. The operational advantages of BiFEs—including their use in non-deaerated solutions and excellent compatibility with disposable, low-cost platforms—make them a superior choice for next-generation environmental monitoring, pharmaceutical analysis, and point-of-care testing. Ongoing research addressing pH limitations and film stability will further consolidate bismuth's role as the leading environmentally friendly alternative in electroanalysis.

In the field of electroanalysis, electrode material selection governs fundamental performance characteristics including sensitivity, detection window, and environmental impact. For decades, mercury electrodes were considered the gold standard for trace metal and organic compound analysis due to their exceptional electrochemical properties. However, growing environmental and safety concerns regarding mercury's toxicity have accelerated the search for viable alternatives. Bismuth-based electrodes have emerged as the most promising substitute, offering a "green" profile with comparable analytical performance. This guide provides an objective comparison of these two electrode systems, examining their core principles, experimental performance data, and methodological protocols to inform researcher selection for specific analytical applications.

Fundamental Properties Comparison

The distinct physical and chemical properties of mercury and bismuth fundamentally shape their electrochemical behavior and application suitability.

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Mercury and Bismuth Electrodes

| Property | Mercury Electrodes | Bismuth Film Electrodes (BiFEs) |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity & Environmental Impact | High toxicity; bioaccumulative; hazardous waste disposal challenges [2] | Very low toxicity; environmentally "friendly"; widespread pharmaceutical use [11] |

| Cathodic Potential Window | Very wide, extending down to ~-2.5 V vs. Ag/AgCl in some configurations [2] | Wide negative potential range; suitable for reduction of many species [2] [20] |

| Surface Characteristics | Atomically smooth, renewable surface (e.g., DME, HMDE) [21] | Film homogeneity depends on deposition conditions (e.g., citrate improves it) [22] |

| Key Analytical Mechanism | Formation of amalgams with metals [2] | Formation of multicomponent alloys or intermetallic compounds with metals [2] |

| Typical Substrates | Stand-alone drops/films; carbon fiber [23] | Coated onto glassy carbon, carbon paste, screen-printed carbon, or copper substrates [2] [11] [22] |

Experimental Performance and Analytical Figures of Merit

Quantitative assessment reveals distinct performance profiles for each electrode material across different analytes.

Heavy Metal Ion Analysis

Stripping voltammetry for trace heavy metal detection remains a primary application. The following data summarizes performance under optimized conditions.

Table 2: Analytical Performance in Anodic Stripping Voltammetry for Heavy Metals

| Analyte | Electrode Type | Linear Range (µg/mL) | Limit of Detection (LOD, µg/mL) | Key Experimental Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cd(II) | Mercury Film on Paper [2] | 0.1 - 10 | 0.04 | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte |

| Bismuth Film on Paper [2] | Information missing | Information missing | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte | |

| Pb(II) | Mercury Film on Paper [2] | 0.1 - 10 | 0.1 | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte |

| Bismuth Film on Paper [2] | Information missing | Information missing | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte | |

| Cu(II) | Mercury Film on Paper [2] | 0.1 - 10 | 0.2 | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte |

| Bismuth Film on Paper [2] | Not determinable | Not determinable | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte | |

| In(III) | Mercury Film on Paper [2] | 0.1 - 10 | 0.04 | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte |

| Bismuth Film on Paper [2] | Information missing | Information missing | Acetate buffer (pH 4.0), Na₂SO₄ background electrolyte | |

| Cd(II) | Bismuth Film on Copper [11] | ~2x10⁻⁸ to 1x10⁻⁶ mol/L | Information missing | Non-deaerated solutions, Differential Pulse Voltammetry |

Organic Compound and Pharmaceutical Analysis

The application of these electrodes extends to organic molecules, exemplified by the determination of pharmaceuticals like desloratadine (DESL).

Table 3: Performance in Pharmaceutical Analysis (Desloratadine)

| Electrode Type | Technique | Linear Range (µM) | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Supporting Electrolyte |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bismuth Film Electrode (BiFE) [20] | LS-CSV* | 0.1 - 4.0 | 11.70 nM (3.64 μg/L) | BR buffer (pH 8.0) with CTAB |

| Hanging Mercury Drop (HMDE) [20] | SWV | 1.5 - 10.0 | 229 nM | BR buffer (pH 10.0) |

| Glassy Carbon (GCE) [20] | SWV | 25.5 - 1500 | 2.75 nM | PBS (pH 9.0) |

*LS-CSV: Linear Sweep-Cathodic Stripping Voltammetry SWV: Square Wave Voltammetry

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Standardized methodologies are critical for achieving reproducible and reliable results with both electrode types.

Protocol: Mercury Film Formation on Paper-Based Carbon Electrodes

This protocol is adapted from the work on paper-based sensors for heavy metal determination [2].

- Step 1: Substrate Preparation. Fabricate paper-based working electrodes by wax-printing hydrophobic patterns on chromatography paper (e.g., Whatman Grade 1). Melt the wax at 80°C and cool to room temperature. Modify the paper by drop-casting 2 µL of a carbon ink suspension on one side ("bottom side") to create the conductive surface [2].

- Step 2: Film Deposition. Prepare a 10⁻³ M mercury solution by dissolving mercury(II) acetate in 0.1 M HCl. Place the paper-based working electrode in this solution and apply a negative potential for a controlled duration to electrodeposit a thin mercury film onto the carbon surface. This ex situ deposition significantly reduces mercury usage compared to conventional mercury electrodes [2].

- Step 3: Analysis via Anodic Stripping Voltammetry.

- Preconcentration: Immerse the modified electrode in the sample solution (e.g., in 0.1 M acetate buffer pH 4.0, 0.5 M in sodium sulphate). Apply a negative potential to reduce and preconcentrate metal ions (like Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺) into the mercury film, forming amalgams.

- Stripping: Apply a positive-going potential sweep. Each metal is selectively oxidized, generating a characteristic current peak. The peak current is proportional to the metal's concentration in the solution [2].

Protocol: Bismuth Film Formation on Various Substrates

Bismuth films can be applied to different substrates, with deposition conditions critically affecting performance [2] [22].

- Step 1: Substrate Selection & Preparation. Common substrates include glassy carbon (GCE), screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs), or copper. The substrate must be thoroughly cleaned (if solid) prior to modification [2] [11].

- Step 2: Film Deposition (Ex Situ or In Situ).

- Ex Situ Deposition (Recommended for controlled morphology): Prepare a 10⁻³ M bismuth solution in acetate buffer. Immerse the substrate electrode in this solution and apply a negative potential to electrodeposit the bismuth film. The use of additives like sodium citrate in HCl solution produces a more homogeneous film with higher bismuth content and better adherence (BiFE-Cit), leading to superior analytical performance compared to films from HCl alone (BiFE-HCl) [2] [22].

- In Situ Deposition (Simpler): The bismuth salt (e.g., from a standard Bi(III) solution for ICP) is added directly to the sample solution containing the analytes. The bismuth film and target metals are co-deposited during the preconcentration step [2].

- Step 3: Analysis via Anodic Stripping Voltammetry. The procedure is analogous to that used with mercury films. Metals are preconcentrated by forming alloys with the bismuth film and subsequently stripped. A key advantage is that BiFEs often do not require the removal of dissolved oxygen, simplifying and speeding up the analysis [20] [11].

The workflow for preparing and using these modified electrodes is summarized below.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful experimentation requires specific chemical reagents and materials, each serving a distinct function in electrode preparation and analysis.

Table 4: Essential Reagents and Materials for Electrode Fabrication and Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury(II) Acetate | Precursor for electrolytic deposition of mercury films [2]. | High toxicity requires careful handling and dedicated waste streams. |

| Bismuth Standard (for ICP) | Precursor for in-situ or ex-situ electrodeposition of bismuth films [2] [20]. | Low toxicity; forms homogeneous films, especially with additives like citrate [22]. |

| Sodium Citrate | Additive in bismuth plating solutions to improve film homogeneity, bismuth content, and adherence to substrates [22]. | Critical for producing high-performance, reproducible BiFEs on copper and other substrates. |

| Acetate Buffer (pH 4.0) | Supporting electrolyte and pH control for heavy metal determination [2]. | Provides optimal pH for deposition/stripping of many metal ions. |

| Cetyltrimethylammonium Bromide (CTAB) | Cationic surfactant used to enhance electrochemical signals of organic compounds (e.g., desloratadine) on BiFEs [20]. | Accumulates at electrode/solution interface, can increase analyte signal via preconcentration or catalytic effects. |

| Screen-Printed Electrode (SPE) Cards | Low-cost, disposable, and portable electrochemical platforms [2]. | Ideal for decentralized analysis; paper-based carbon versions offer ultimate disposability. |

| Carbon Ink | Conductive material for fabricating working electrodes on paper or ceramic substrates [2]. | Enables low-cost, customizable sensor design. |

The choice between mercury and bismuth electrodes is not a simple substitution but a strategic decision based on analytical requirements and practical constraints.

Select Mercury Electrodes For:

- Applications demanding the highest possible sensitivity, especially for trace metal analysis where its superior performance in certain systems is critical [2] [23].

- Analysis requiring an extremely wide cathodic potential window or the unique formation of amalgams [2].

- Fundamental studies benefiting from a perfectly renewable, atomically smooth surface [21].

Select Bismuth Film Electrodes For:

- Routine environmental, pharmaceutical, and food monitoring where a favorable trade-off between performance, safety, and cost is essential [20] [11].

- On-site or decentralized analysis where the low toxicity and easy disposal of bismuth are major advantages [2].

- Applications where dissolved oxygen removal is impractical, as BiFEs can often function in non-deaerated solutions [11].

- Laboratories aiming to minimize hazardous waste and eliminate the risks associated with mercury handling [2].

The enduring scientific value of mercury electrodes is undeniable, particularly for foundational electrochemistry. However, for the vast majority of modern analytical applications—especially those requiring sustainability, portability, and safety—bismuth film electrodes represent a mature, robust, and environmentally responsible alternative. Future research will continue to optimize bismuth-based platforms, further closing the performance gap while leveraging their inherent "green" credentials.

From Lab to Application: Fabricating and Using Bismuth Film Electrodes

The performance of electrodeposited films is profoundly influenced by the deposition technique employed, with pulse/reverse current (PRC) and direct current (DC) methods offering distinct advantages for producing thick, stable films. This comparison is particularly relevant within the broader context of bismuth film electrodes emerging as a environmentally friendly alternative to traditional mercury electrodes in electrochemical research. Mercury electrodes have been widely used for decades due to their excellent electrochemical properties, including a wide cathodic potential window and high reproducibility [2]. However, concerns over mercury's toxicity and environmental impact have driven the search for safer alternatives [2]. Bismuth-based electrodes have gained significant attention as a "green" alternative, offering low toxicity while maintaining favorable electrochemical characteristics such as high sensitivity for heavy metal detection and insensitivity to dissolved oxygen [24]. The electrodeposition process itself plays a critical role in determining the morphological, mechanical, and electrochemical properties of these bismuth films, making the choice between PRC and DC electrodeposition crucial for optimizing electrode performance in analytical applications and drug development research.

Fundamental Principles of Electrodeposition Techniques

Direct Current (DC) Electrodeposition

DC electrodeposition employs a constant current or potential throughout the deposition process, resulting in continuous metal ion reduction at the cathode surface. This method's simplicity and straightforward implementation make it widely accessible, though it presents challenges for producing thick, homogeneous films. In DC plating, the diffusion layer at the electrode surface continuously grows, leading to depletion of metal ions and potentially resulting in porous, dendritic, or rough deposits, particularly at higher current densities [25]. The morphology of DC-plated films is highly dependent on operating parameters, with current density significantly affecting film quality. Studies on bismuth electrodeposition have demonstrated that current densities that are too high (e.g., 180 mA/cm² or 50 mA/cm²) produce films with inconsistent topographies and poor adhesion, often delaminating from the substrate [26]. Optimal bismuth films with good surface smoothness have been achieved at lower current densities of 1.5-2.5 mA/cm² [26].

Pulse and Pulse Reverse Current (PRC) Electrodeposition

Pulse electrodeposition utilizes controlled alternating cycles of current or potential, while pulse reverse current incorporates periodic current reversal. Table 1 summarizes the key parameters and their functions in these advanced techniques.

Table 1: Key Parameters in Pulse and Pulse Reverse Electrodeposition

| Parameter | Function in Pulse Deposition | Effect on Film Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Forward Pulse Current/Voltage (iₚ) | Determines metal reduction rate during on-time | Controls nucleation density, deposition rate |

| Forward Pulse On-Time (Tₒₙ(p)) | Duration of deposition cycle | Affects grain size, surface morphology |

| Forward Pulse Off-Time (Tₒff(p)) | Allows ion concentration recovery | Reduces diffusion layer thickness, improves uniformity |

| Reverse Pulse Current/Voltage (iₙ) | Introduces periodic anodic dissolution | Removes dendritic growth, refines microstructure |

| Reverse Pulse On-Time (Tₒₙ(ₙ)) | Duration of dissolution cycle | Controls leveling effect, smooths surface |

The PRC method provides enhanced control over film morphology through several mechanisms. During the off-time, the diffusion layer collapses, allowing fresh electrolyte to reach the electrode interface and maintain a steeper concentration gradient [26]. The reverse (anodic) pulse selectively dissolves preferentially higher current density areas such as dendrite tips and protrusions, resulting in a smoother, more uniform surface [25]. This periodic dissolution also promotes recrystallization and can reduce internal stresses within the deposited film [26].

Experimental Protocols for Bismuth Film Electrodeposition

Electrolyte Composition and Substrate Preparation

The electrolyte formulation and substrate preparation are fundamental to obtaining high-quality bismuth films regardless of the deposition technique. A typical plating solution for bismuth electrodeposition contains: bismuth nitrate (0.15 M) as the metal ion source, glycerol (1.4 M) and tartaric acid (0.33 M) as complexing agents to stabilize Bi³⁺ ions and moderate film growth, potassium hydroxide (1.2 M) for pH adjustment, and nitric acid to adjust the pH to approximately 0.08 [26]. Solution pH is critical for film adhesion, with optimal bismuth coatings obtained in highly acidic conditions (pH 0.01-0.1), while higher pH values produce poorly adherent films [26].

The substrate preparation protocol involves: using platinized titanium as an anode/counter electrode, employing gold-plated brass or steel panels (with approximately 5 µm thick gold coating) as the cathode/working electrode, cleaning the substrate surface to ensure good adhesion, and suspending the electrodes in the plating solution with mechanical stirring using a magnetic stir bar to ensure uniform ion transport [26]. All depositions are typically performed at room temperature [26].

DC Electrodeposition Methodology

The standard DC electrodeposition protocol for bismuth films involves: setting up a two-electrode configuration with optimized electrode placement, applying a constant current density of 1.5 mA/cm² for the desired deposition time (e.g., 24-96 hours for thick films), maintaining constant stirring at approximately 200-300 rpm to ensure electrolyte homogeneity, and monitoring deposition progress visually and through charge calculations [26]. The deposition efficiency for DC-plated bismuth films typically exceeds 70%, with growth rates varying based on hydrodynamics and cathode placement [26].

Pulse/Reverse Current Electrodeposition Methodology

The PRC electrodeposition protocol for bismuth films utilizes a millisecond-scale pulse waveform with the following parameters: forward (cathodic) current density of 1.5 mA/cm², reverse (anodic) current density typically 20-50% of the forward current, forward pulse duration ranging from milliseconds to seconds, reverse pulse duration typically shorter than forward pulse duration (e.g., 10-20% of total cycle time), and duty cycle (ratio of on-time to total cycle time) optimized for specific morphology requirements [26]. The total deposition time must be adjusted to account for the duty cycle, with typical bismuth film depositions requiring 24-96 hours to achieve thicknesses >100 µm [26].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for bismuth film electrodeposition comparing DC and PRC methodologies

Performance Comparison: Structural and Mechanical Properties

Film Morphology and Surface Characteristics

The deposition technique significantly influences the surface morphology and structural characteristics of bismuth films. DC-plated bismuth films typically exhibit elongated surface features with Sa (arithmetical mean height) values of approximately 2.6-5.2 µm at optimal current densities (1.5-2.5 mA/cm²) [26]. When plated for extended durations (96 hours), DC-plated films develop very thin, elongated morphological features [26]. In contrast, PRC-plated bismuth films display a mixed morphology with regions of both elongated features and "blockier" morphological structures with feature sizes of approximately 2-5 µm in diameter [26]. This distinct morphology difference demonstrates how the electrodeposition waveform directly affects surface architecture.

Cross-sectional analysis reveals significant differences in grain structure between deposition techniques. Electron backscatter diffraction (EBSD) analysis of 96-hour plated bismuth films shows that DC-plated coatings have an estimated grain size of 19 µm, while PRC-plated coatings exhibit substantially larger grains of approximately 41 µm [26]. This grain size difference is attributed to the suspected high presence of twinning in DC-plated grains and the recrystallization effects facilitated by the reverse current cycles in PRC plating [26].

Thickness, Deposition Rate, and Mechanical Stability

Table 2 compares the key performance metrics of bismuth films prepared by DC and PRC electrodeposition based on experimental studies.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DC vs. PRC Bismuth Films

| Performance Parameter | DC Electrodeposition | Pulse/Reverse Electrodeposition |

|---|---|---|

| Typical Film Thickness | ≥100 µm (24-96 hours) | ≥100 µm (24-96 hours) |

| Deposition Efficiency | >70% | >70% |

| Surface Roughness (Sa) | 2.6-5.2 µm (at 1.5-2.5 mA/cm²) | Generally smoother with blockier features |

| Grain Size | ~19 µm (with suspected twinning) | ~41 µm |

| Wear Resistance | Similar to PRC films | Similar to DC films |

| Morphology | Elongated features | Mixed: elongated and blocky features |

| Process Control | Simple | Enhanced (grain size, morphology) |

Progressive load scratch testing (0.1 to 40 N) performed on polished bismuth films plated for 96 hours revealed similar wear resistance properties between PRC and DC electroplated films despite their microstructural differences [26]. This indicates that both methods can produce mechanically robust coatings suitable for applications requiring durability. The deposition efficiency for both techniques typically exceeds 70%, though film thickness varies considerably for shorter deposition times (80-290 µm for 24-hour plating) due to hydrodynamic factors and cathode placement [26]. For extended depositions (96 hours), DC plating generally yields thicker films than pulsed plating, attributed to the lower effective current resulting from the duty cycle in pulse sequences [26].

Electrochemical Performance and Analytical Applications

Stripping Voltammetry for Heavy Metal Detection

The electrochemical performance of bismuth films compares favorably with traditional mercury films in stripping voltammetry applications. Table 3 presents detection capabilities for heavy metals using bismuth and mercury film electrodes.

Table 3: Analytical Performance of Bismuth vs. Mercury Film Electrodes

| Performance Metric | Bismuth Film Electrodes | Mercury Film Electrodes |

|---|---|---|

| Cd(II) LOD | 0.4 µg/mL | ~0.1 µg/mL |

| Pb(II) LOD | 0.1 µg/mL | ~0.04 µg/mL |

| In(III) LOD | 0.04 µg/mL | Similar sensitivity |

| Cu(II) Detection | Limited performance | 0.2 µg/mL |

| Environmental Impact | Low toxicity | Highly toxic |

| Oxygen Sensitivity | Insensitive | Sensitive |

| Linear Range | 0.1-10 µg/mL for Cd, Pb, In | Similar range |

Bismuth films demonstrate particular effectiveness for detecting cadmium (Cd(II)), lead (Pb(II)), and indium (In(III)), with detection limits suitable for environmental monitoring applications [2]. However, bismuth films show limited performance for copper (Cu(II)) detection compared to mercury films [2]. The ex situ deposition of bismuth films on paper-based electrodes has been successfully demonstrated, offering a sustainable, low-cost analytical platform for heavy metal determination in aqueous solutions [2].

Hydrogen Evolution Reaction and Catalytic Applications

The hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) activity of electrodeposited bismuth films has been evaluated using a three-electrode configuration with a standard calomel reference electrode, carbon rod counter electrode, and bismuth working electrode in 10% HNO₃ solution [26]. Bismuth's high hydrogen evolution overpotential enables higher current efficiency for reductive processes in electrochemical devices, making it suitable for applications such as electrocatalytic CO₂ reduction and organic waste degradation [26]. The morphology control afforded by PRC electrodeposition may enhance these catalytic applications, as surface morphology has been shown to significantly influence electrocatalytic properties [26].

Research Reagent Solutions for Electrodeposition Studies

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Bismuth Film Electrodeposition

| Reagent/Chemical | Function in Electrodeposition | Typical Concentration |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth (III) nitrate pentahydrate | Source of Bi³⁺ ions for film formation | 0.15 M |

| Glycerol | Complexing agent to stabilize Bi³⁺ ions | 1.4 M |

| Tartaric acid | Chelating agent to moderate film growth | 0.33 M |

| Potassium hydroxide | pH adjustment | 1.2 M |

| Nitric acid | Final pH adjustment to optimal range | pH ~0.08 |

| Sodium citrate | Additive for homogeneous film structure | Variable |

| Sodium ligninsulfonate | Surfactant for improved microstructure | Variable |

The selection between pulse/reverse current and direct current electrodeposition techniques depends on the specific application requirements for bismuth film electrodes. PRC electrodeposition offers superior control over film morphology, grain structure, and surface characteristics, producing more homogeneous films with tailored microstructures. This method is particularly advantageous for applications requiring precise morphology control, such as electrocatalytic devices and specialized sensors. DC electrodeposition provides a simpler, more straightforward approach for producing thick bismuth films (>100 µm) with good mechanical stability and deposition efficiency, making it suitable for applications such as radiation shielding where simpler morphology may be acceptable.

For researchers and drug development professionals implementing these techniques, PRC is recommended when maximal control over film architecture is required, or when manufacturing reproducible, high-performance analytical sensors. DC deposition represents a cost-effective solution for applications requiring thick, stable bismuth films where sophisticated power supplies are unavailable. Both techniques can produce bismuth films with excellent mechanical properties and adhesion when optimized parameters are employed, offering a environmentally friendly alternative to mercury-based electrodes while maintaining competitive analytical performance for most heavy metal detection applications.

The performance of an electrode is fundamentally dictated by the physical and chemical properties of its active surface. For bismuth film electrodes (BiFEs), a leading environmentally friendly alternative to traditional mercury-based electrodes, these properties are controlled during the electrodeposition process. This guide provides a detailed, data-driven comparison of the key parameters—current density, pH, and chelating agents—that define the plating process, framing the discussion within the broader research context of bismuth versus mercury electrode performance. The optimization of these parameters is critical for developing BiFEs with superior sensitivity, stability, and reproducibility for applications in drug development and environmental monitoring [14] [2].

Core Plating Parameter Comparison

The electrodeposition of a homogeneous and mechanically stable bismuth film is highly sensitive to plating conditions. The table below summarizes the optimal and sub-optimal ranges for key parameters as established by contemporary research.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Plating Parameters for Bismuth Film Electrodes

| Parameter | Optimal Range/Value | Sub-Optimal/Detrimental Range/Value | Observed Effect on Bismuth Film |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current Density | 1.5 - 2.5 mA/cm² [14] | 50 - 180 mA/cm² [14] | Optimal: Smooth, bright films (Sa: 2.6-5.2 µm). Good adhesion.Sub-Optimal: Inconsistent topography, rough films (Sa >50 µm). Poor adhesion, often delaminates. |

| Solution pH | 0.01 - 0.1 (Highly Acidic) [14] | > 0.1 [14]; > pH 4.3 [11] | Optimal: Robust, adherent films.Sub-Optimal: Poor adhesion (wipeable); formation of bismuth hydroxide leads to non-reproducible measurements. |

| Deposition Mode | Pulse/Reverse & Direct Current (DC) [14] | — | Pulse/Reverse: Mixed morphology, "blockier" features (~2-5 µm). Larger grain size (~41 µm). [14]DC: Elongated surface features. Smaller grain size (~19 µm, likely skewed by twinning). [14] |

| Deposition Efficiency | > 70% [14] | — | Consistent for both pulsed and DC plating at 1.5 mA/cm², enabling films >100 µm thick. [14] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear basis for comparison, the following subsections detail specific methodologies from the literature for plating bismuth films and applying them in analytical procedures.

Electrodeposition of Thick, Stable Bismuth Films

This protocol is adapted from work focused on depositing micron-scale thick bismuth films for applications like radiation shielding, which require exceptional mechanical stability [14].

- Plating Solution Composition: The electrolyte consists of 0.15 M bismuth (III) nitrate pentahydrate, 1.4 M glycerol, 1.2 M potassium hydroxide (KOH), and 0.33 M tartaric acid. The pH is critically adjusted to approximately 0.08 using nitric acid (HNO₃) [14].

- Electrode Configuration & Conditions: A two-electrode system is used with a platinized titanium anode and a gold-plated brass or steel cathode. Deposition is performed at room temperature with stirring. A low current density of 1.5 mA/cm² is applied, either via Direct Current (DC) or a pulse/reverse waveform, for a duration of 24 to 96 hours to achieve thicknesses ≥100 µm [14].

- Key Analysis Methods: Film characterization includes Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) for morphology and thickness, Electron Backscatter Diffraction (EBSD) for grain size, and scratch testing with a tribometer for wear resistance and adhesion assessment [14].

In Situ Preparation of Analytical Bismuth Film Electrodes

This protocol is common in stripping voltammetry for heavy metal detection and involves depositing the bismuth film directly onto the working electrode in the presence of the analytes [27].

- Solution Preparation: A solution of 0.1 M HEPES buffer is prepared, containing Bi(III) ions (e.g., 200-1000 ppb), the target metal ions (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Zn²⁺), and a chelating agent like 8-hydroxyquinoline (oxine) at ~581 ppb at a pH of ~6 [27].

- Film Deposition & Analysis: The glassy carbon working electrode is placed in the solution alongside Ag/AgCl reference and platinum counter electrodes. An accumulation potential of -1.6 V is applied for 240 seconds while the electrode rotates. During this step, Bi(III) and other metal ions are co-deposited onto the electrode surface. The stripping and adsorption step is then performed at -0.7 V for 10 seconds, followed by a negative-going square-wave voltammetric scan to quantify the metals [27].

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

The table below lists key reagents and materials used in the featured experiments, along with their critical functions in the plating and analysis processes.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bismuth Film Electrode Preparation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Protocol | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Bismuth (III) Nitrate | Source of Bi³⁺ ions for electrodeposition. | Primary bismuth salt used in plating solution [14] [27]. |

| Tartaric Acid & Glycerol | Acts as chelating agents to stabilize Bi³⁺ ions in solution and moderate film growth [14]. | Used in the thick-film electrodeposition protocol [14]. |

| 8-Hydroxyquinoline (Oxine) | Chelating agent that forms complexes with target metal ions, enhancing their preconcentration on the electrode surface for improved sensitivity and selectivity in stripping voltammetry [27]. | Used for the simultaneous determination of Pb(II), Cd(II), and Zn(II) [27]. |

| Nitric Acid (HNO₃) | Used to adjust the plating solution to the required highly acidic pH (~0.08) [14]. | Critical for achieving adherent films in the thick-film protocol [14]. |

| Acetate Buffer | Provides a consistent pH environment (e.g., pH 4.0) for the ex situ formation of bismuth films and subsequent analytical measurements [2]. | Used as the background electrolyte for heavy metal determination [2]. |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | A common, well-defined substrate for the in situ or ex situ formation of bismuth films for analytical applications [27] [28]. | Used as the base working electrode [27]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the two primary pathways for preparing and utilizing bismuth film electrodes, as detailed in the experimental protocols.

Figure 1: Bismuth film electrode preparation and application workflows for structural and sensing applications.

Performance in Context: Bismuth vs. Mercury Electrodes

The drive to optimize bismuth film plating parameters is largely motivated by the need for a non-toxic replacement for mercury electrodes. The table below compares their performance based on key metrics.

Table 3: Performance Comparison of Bismuth vs. Mercury Film Electrodes

| Performance Metric | Bismuth Film Electrode (BiFE) | Mercury Film Electrode |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity & Environmental Impact | Low toxicity; "environmentally friendly" [11] [2]. | Highly toxic; use is restricted due to environmental and safety concerns [27] [11] [2]. |

| Heavy Metal Detection | Effective for Cd(II), Pb(II), Zn(II) [27] [2]. Cannot determine Cu(II) in some configurations [2]. | Highly sensitive for a wide range of metals including Cd(II), Pb(II), In(III), Cu(II) [2]. |

| Sensitivity (Detection Limit) | LOD for Cd(II): ~0.17 ppb (with oxine) [27]. | LOD for Cd(II): ~0.1 µg/mL (0.1 ppb) reported for film on paper electrode [2]. |

| Linear Range | e.g., Cd(II): 2-110 ppb (with oxine) [27]. | e.g., Cd(II): 0.1-10 µg/mL (100-10,000 ppb) on paper electrode [2]. |

| pH Limitations | Performance degrades above pH ~4.3 due to hydroxide formation [11] [2]. | Operates effectively over a wider pH range [2]. |

The systematic optimization of plating parameters is the cornerstone of producing high-performance bismuth film electrodes. As the data demonstrates, a low current density (~1.5 mA/cm²) and a highly acidic pH (~0.08) are non-negotiable for producing adherent, homogeneous films [14]. The choice of chelating agents, such as tartaric acid for film stability or 8-hydroxyquinoline for analytical sensitivity, provides researchers with powerful tools to tailor electrodes for specific applications [14] [27]. While mercury electrodes historically set the benchmark for sensitivity and a wide analytical window, the optimized BiFE presents a compelling, low-toxicity alternative that meets the demands of modern, responsible research and drug development, particularly for the detection of key heavy metal contaminants like Cd(II) and Pb(II) [27] [2].

The development of advanced nanocomposites for electrochemical sensing represents a frontier in analytical chemistry, driven by the need for high sensitivity, selectivity, and environmentally sustainable materials. Within this domain, the comparison between bismuth-based electrodes and traditional mercury electrodes has emerged as a particularly significant research area. Mercury electrodes have long been valued in electroanalysis for their excellent electrochemical properties, including a wide cathodic window, high reproducibility, and well-defined stripping signals for heavy metals [2]. However, the well-documented toxicity of mercury and associated environmental and safety concerns have prompted an extensive search for viable alternatives [15]. Bismuth-based electrodes have emerged as the most promising replacement, offering a compelling combination of low toxicity, environmental friendliness, and excellent electrochemical performance [29] [24].

The integration of nanoscale components—specifically bismuth sulfide (Bi₂S₃) nanorods, polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers, and reduced graphene oxide (rGO)—represents a sophisticated approach to enhancing electrode performance. This nanocomposite architecture leverages the unique properties of each component: the semiconductor properties of Bi₂S₃, the highly ordered branching structure and molecular uniformity of PAMAM dendrimers, and the exceptional electrical conductivity and large surface area of rGO [30]. When strategically combined, these materials create a synergistic system that addresses limitations of traditional electrodes while opening new possibilities in sensor design. This review comprehensively examines the performance of this advanced nanocomposite against traditional and alternative materials, providing experimental data and methodological details to guide researchers in the field of electrochemical sensor development.

Material Components and Properties

PAMAM Dendrimers: Structural Scaffolds

Polyamidoamine (PAMAM) dendrimers are hyper-branched, monodisperse polymers with unparalleled molecular uniformity and narrow molecular weight distribution [31]. Their well-defined architecture consists of three core components: an ethylenediamine core, a repetitive branching amidoamine internal structure, and a primary amine terminal surface that enables customizable surface chemistry [31]. These nanomaterials are synthesized in an iterative process where each subsequent step produces a new "generation" with larger molecular diameters, twice the number of reactive surface sites, and approximately double the molecular weight of the preceding generation [31]. The functional terminal groups act as "molecular Velcro," providing numerous sites for chemical modification and interaction with other nanocomponents [31]. In electrochemical applications, PAMAM dendrimers contribute several advantages, including stable molecular weight, molecular uniformity, specific size, definite shape, and abundant surface branches that can act as affinity ligands for pharmaceutical compounds [30].

Reduced Graphene Oxide: Conductive Networks

Reduced graphene oxide (rGO) is a two-dimensional, one-atom-thick sp²-bonded carbon network derived from graphene oxide (GO) through chemical reduction processes [30]. This transformation removes oxygen-containing functional groups, enhancing its electrical conductivity and electrocatalytic activity compared to its precursor [30]. The reduction process decreases the interlayer d-spacing from 8.05 Å in GO to 3.72 Å in rGO, indicating the successful removal of oxygen-containing functional groups and restoration of the conductive graphitic network [30]. rGO offers exceptional properties for electrochemical applications, including fine electron transport capabilities, high surface area, mechanical flexibility, and desirable electrochemical stability [30]. Its two-dimensional structure provides an ideal substrate for anchoring other nanomaterials, preventing their agglomeration and thereby maintaining a high effective surface area for electrochemical reactions [30].

Bismuth Sulfide Nanorods: Semiconductor Components

Bismuth sulfide (Bi₂S₃) is an n-type semiconductor with a direct energy band gap ranging from 1.2 to 1.7 eV [30]. The n-type semiconductor material contains numerous free electrons that play a significant role in electrical conductivity [30]. Bi₂S₃ is recognized as a powerful sensor modifier due to its excellent photovoltaic properties, natural abundance, and desirable environmental compatibility [30]. When combined with carbon substrates like rGO, Bi₂S₃ forms composite structures that mitigate agglomeration issues, thereby preserving the effective surface area necessary for sensitive detection [30]. The nanorod morphology, as demonstrated in field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) images, provides a high surface-to-volume ratio that enhances sensor performance [30].

Mercury Electrodes: Traditional Benchmark

Mercury electrodes have served as the traditional benchmark in electrochemical stripping analysis for decades, offering a large cathodic window, exceptional reproducibility, and low background signals [2] [15]. Their affinity for heavy metals made them particularly valuable for trace metal analysis via anodic stripping voltammetry [2]. However, mercury is a dangerous heavy metal with recognized toxicity and bioaccumulation potential in many species, creating significant environmental and safety concerns [2] [32]. These concerns, coupled with regulatory pressures, have motivated the scientific community to seek less toxic alternatives that maintain comparable analytical performance.

Table 1: Core Component Properties and Functions in the Nanocomposite

| Component | Key Properties | Primary Function in Composite | Structural Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| PAMAM Dendrimers | Hyper-branched polymers with molecular uniformity; multiple terminal functional groups [31] | Molecular scaffold; increases active surface area; provides binding sites [30] | Generations 0-10 with increasing molecular weight (517-934,720 g/mol) and surface groups (4-4096) [31] |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | Two-dimensional carbon network; high electrical conductivity; large surface area [30] | Conductive network; electron transport; substrate for component assembly [30] | Interlayer d-spacing of 3.72 Å; sheet-like morphology with high surface area [30] |

| Bismuth Sulfide (Bi₂S₃) | n-type semiconductor; band gap 1.2-1.7 eV; environmentally compatible [30] | Semiconductor component; enhances electron transfer; provides catalytic sites [30] | Nanorod structure; elemental composition of Bi and S [30] |

| Mercury (Comparative) | Wide cathodic window; low background current; high reproducibility [2] | Traditional benchmark for performance comparison [2] | Liquid metal; forms amalgams with heavy metals [2] |

Nanocomposite Fabrication and Characterization

Synthesis Strategies and Experimental Design

The fabrication of the rGO/PAMAM/Bi₂S₃ nanocomposite employs a strategic sonochemical method that ensures optimal integration of the component materials. This approach represents a novel preparation strategy where PAMAM is utilized to enhance the surface interaction between Bi₂S₃ nanorods and rGO sheets [30]. The sonochemical method offers distinct advantages over conventional approaches, being simpler, faster, and more efficient for composite preparation [30]. A particularly innovative aspect of the synthesis is the application of experimental design methodology, specifically central composite design (CCD) and response surface methodology, to determine the optimal composition of components [30]. This systematic approach enables researchers to understand curvature and interaction terms while optimizing the experimental variables affecting nanocomposite performance, resulting in a purposefully designed material architecture with enhanced electrochemical properties.

Structural and Morphological Characterization

Comprehensive characterization of the synthesized nanocomposite reveals its structural and morphological attributes. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM) images demonstrate the three-dimensional structure of the individual components and their integration in the final composite [30]. The micrographs show rGO sheets with accumulated Bi₂S₃ nanorods, with evident thickness increase in rGO sheets resulting from PAMAM application [30]. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometry (EDX) analysis confirms the purity of the synthesized nanoparticles, showing that the prepared Bi₂S₃ sample consists exclusively of S and Bi elements [30]. Elemental mapping further reveals uniform distribution of contributing elements throughout the synthesized nanoparticles [30]. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns provide additional structural evidence, with a characteristic sharp diffraction peak for GO at 2θ = 10.98° (corresponding to an interlayer d-spacing of 8.05 Å) disappearing after hydrothermal reduction and being replaced by a new weak peak at 2θ = 23.89° for rGO (d-spacing of 3.72 Å) [30]. This decreased d-spacing confirms the successful removal of oxygen-containing functional groups during the reduction process.

Electrode Modification and Sensor Fabrication

The application of the rGO/PAMAM/Bi₂S₃ nanocomposite as an electrode modifier follows a carefully optimized procedure. The composite material is deposited on the electrode surface, creating a modified electrode platform for electrochemical sensing [30]. This modification significantly increases the active surface area of the sensor—approximately 5 times compared to the bare electrode [30]. The enhanced surface area, combined with the synergistic effects of the component materials, creates multiple pathways for electron transfer and analyte interaction, resulting in substantially improved sensor performance characteristics including sensitivity, detection limit, and linear response range.

Performance Comparison: Nanocomposite vs. Alternative Electrodes

Analytical Performance Metrics

The rGO/PAMAM/Bi₂S₃ nanocomposite demonstrates exceptional performance when evaluated for electrochemical sensing applications, particularly in the detection of salbutamol (SAL), a β₂-adrenergic agonist abused in animal feed [30]. The sensor exhibits dramatically improved sensitivity, with a 35-fold increase compared to the bare electrode [30]. It achieves an exceptionally low detection limit of 1.62 nmol/L for salbutamol, along with a broad linear range from 5.00 to 6.00 × 10² nmol/L [30]. The sensor also displays acceptable selectivity, good repeatability (1.52–3.50%), excellent reproducibility (1.88%), and satisfactory accuracy with recovery rates of 84.6–97.8% in real samples [30]. These performance metrics indicate a robust sensing platform suitable for practical applications in food safety control.

When compared to bismuth film electrodes (BiFE) on alternative substrates, the nanocomposite shows superior performance characteristics. Conventional bismuth film electrodes on paper-based carbon substrates demonstrate detection limits for heavy metals in the range of 0.04-0.4 µg/mL for Cd(II), Pb(II), and In(III) [2]. The modification of bismuth films with Nafion coatings or carbon nanotubes can further enhance their performance, though not to the level achieved by the rGO/PAMAM/Bi₂S₃ nanocomposite [15]. The exceptional performance of the nanocomposite stems from the synergistic integration of its components: PAMAM dendrimers provide numerous functional groups and prevent agglomeration, rGO offers superior electrical conductivity and large surface area, and Bi₂S₃ nanorods contribute semiconductor properties and catalytic sites.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Electrode Materials for Analytic Detection

| Electrode Material | Target Analyte | Detection Limit | Linear Range | Sensitivity Enhancement | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rGO/PAMAM/Bi₂S₃ Nanocomposite | Salbutamol | 1.62 nmol/L | 5.00–600 nmol/L | 35× vs. bare electrode | [30] |

| Bismuth Film Electrode (Paper-based) | Cd(II), Pb(II), In(III) | 0.1–0.4 µg/mL | 0.1–10 µg/mL | Not specified | [2] |

| Mercury Film Electrode (Paper-based) | Cd(II), Pb(II), In(III), Cu(II) | 0.04–0.4 µg/mL | 0.1–10 µg/mL | Most sensitive method | [2] |

| SPE with Bismuth Film & Nafion | Cd(II), Pb(II) | Low µg/L range | Not specified | Improved stability | [15] |

Environmental and Practical Considerations

Beyond analytical performance, the rGO/PAMAM/Bi₂S₃ nanocomposite offers significant advantages in terms of environmental compatibility and practical application. The composite utilizes bismuth, which has very low toxicity compared to mercury, addressing the primary concern associated with traditional electrodes [2] [29]. The materials selection also considered commercialization potential, prioritizing biodegradable and inexpensive materials that are easy to prepare without expensive equipment [30]. This strategic approach contrasts with alternative sensors utilizing multi-walled carbon nanotubes (considered hazardous with expensive preparation technology) or silver-palladium nanoparticles (cost-prohibitive due to precious metal content) [30].