Beyond Mercury: Why Solid Electrodes Are Revolutionizing Biomedical Analysis and Drug Development

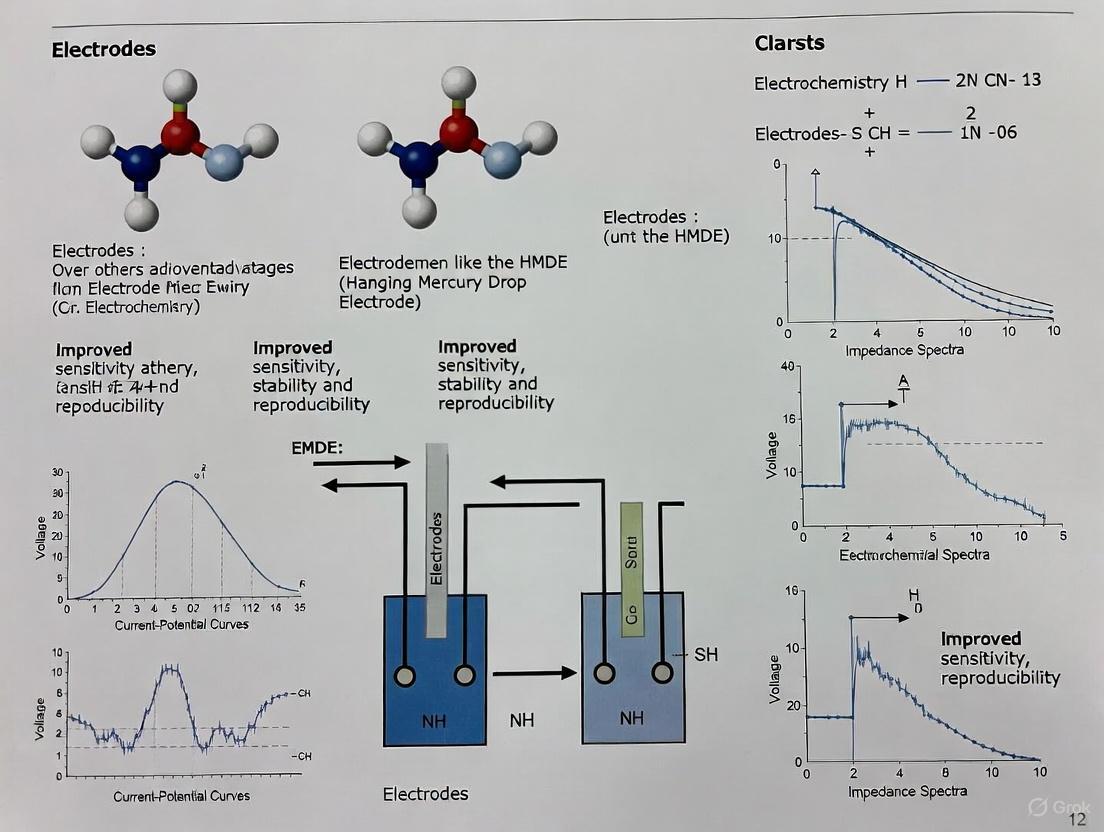

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the pivotal shift from traditional hanging mercury drop electrodes (HMDE) to modern solid electrodes.

Beyond Mercury: Why Solid Electrodes Are Revolutionizing Biomedical Analysis and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals on the pivotal shift from traditional hanging mercury drop electrodes (HMDE) to modern solid electrodes. It explores the foundational limitations of HMDE, including toxicity, poor anodic range, and low mechanical robustness. The content details the advanced methodologies enabled by solid electrodes, such as miniaturized biosensors, electrophoretic drug delivery platforms, and enhanced anodic detection. It further offers practical guidance for troubleshooting interfacial and stability challenges, and concludes with a rigorous validation framework for selecting electrode materials based on application-specific requirements in pharmaceutical and clinical research.

Understanding HMDE Limitations and the Solid Electrode Paradigm Shift

The Historical Legacy and Inherent Drawbacks of HMDE

The Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) represents a cornerstone of electrochemical analysis, with a historical legacy spanning decades of research and application. As a liquid metal electrode, the HMDE operates on the principle of a mercury drop suspended from a capillary, providing a renewable, homogenous surface for electrochemical measurements [1] [2]. Its development marked a significant advancement in polarography and voltammetry, enabling highly sensitive detection of numerous analytes.

Despite its historical importance, the HMDE possesses inherent drawbacks that have prompted the scientific community to increasingly favor solid electrode alternatives. This transition is driven by practical considerations including toxicity concerns, operational limitations, and advancements in solid-state materials science. Within drug development and modern analytical chemistry, understanding this shift is crucial for selecting appropriate methodologies that balance sensitivity, practicality, and safety.

This technical guide examines the HMDE's operational fundamentals, acknowledges its analytical strengths, and critically evaluates its limitations within the context of contemporary research demands. The thesis underpinning this analysis is that while the HMDE offers exceptional electrochemical properties for specific applications, solid electrodes provide a superior combination of safety, versatility, and practicality for most modern research environments, particularly in regulated industries like pharmaceutical development.

HMDE: Fundamentals and Historical Context

Operational Principles and Instrumentation

The HMDE functions as a working electrode within a three-electrode potentiostat system, which also includes a reference electrode (typically Ag/AgCl or SCE) and an auxiliary electrode (often platinum or glassy carbon) [2] [3]. The key to its operation lies in the precisely controlled formation of a fresh mercury drop at the end of a capillary. This is achieved either through a micrometer screw mechanism (in classic HMDE) or a solenoid-driven plunger (in Static Mercury Drop Electrodes, SMDE) [2].

The typical experimental setup involves an electrochemical cell where the HMDE is positioned alongside the reference and counter electrodes. The process begins with careful deaeration of the solution using an inert gas like nitrogen to remove dissolved oxygen, which can interfere with measurements [3]. During analysis, a time-dependent potential waveform is applied to the working electrode relative to the fixed potential of the reference electrode, while the current flowing between the working and auxiliary electrodes is measured [2]. The mercury drop itself, with a standard radius of approximately 0.1 cm, provides a consistent, spherical working surface for electrochemical reactions [3].

Key Advantages and Historical Significance

The historical persistence of HMDE in electrochemical analysis stems from several unique advantageous properties:

- Renewable Surface: Each new mercury drop provides a pristine, smooth surface that is identical to the previous one, eliminating carry-over contamination and the need for mechanical polishing required by solid electrodes. This ensures excellent reproducibility between measurements [2] [3].

- High Hydrogen Overpotential: Mercury possesses an exceptionally high overpotential for hydrogen evolution. This expands the accessible cathodic potential window to approximately -1 V vs. SCE in acidic solutions and as negative as -2 V vs. SCE in basic solutions, enabling the study of difficult-to-reduce species without solvent electrolysis interference [2].

- Amalgam Formation: Many metal ions can dissolve into the mercury to form amalgams during reduction, which facilitates sensitive analysis of metals like Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Cu²⁺ via techniques such as Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) [3].

- Favorable Mass Transport: The hemispherical shape of the mercury drop and its expansion (in the case of Dropping Mercury Electrode, DME) creates efficient diffusion conditions for analytes migrating to the electrode surface [2].

These properties made HMDE indispensable for pioneering electroanalytical techniques, including polarography (for which Jaroslav Heyrovský received the Nobel Prize in 1959), stripping voltammetry, and studies of adsorption phenomena.

Diagram 1: HMDE Experimental Workflow

Critical Drawbacks and Limitations of HMDE

Toxicity and Environmental Concerns

The most significant drawback of HMDE is the high toxicity of mercury and its compounds. Mercury poses severe health risks through inhalation of vapors or skin contact, affecting the nervous, digestive, and immune systems. This toxicity creates substantial challenges:

- Laboratory Safety Protocols: Requiring specialized ventilation, spill containment measures, and personal protective equipment [3].

- Waste Disposal Complications: Generating hazardous waste that requires costly and regulated disposal procedures [3].

- Regulatory Restrictions: Increasingly stringent regulations governing mercury use in industrial and research settings [3].

The toxicity issue has motivated extensive research into alternative electrodes, with one review acknowledging the difficulty in finding replacements that match HMDE's performance despite the "elegant approaches already reported" [3].

Limited Anodic Potential Window

While HMDE provides an excellent cathodic potential window, it suffers from a severely restricted anodic potential range. Mercury undergoes oxidation at potentials more positive than approximately -0.3 V to +0.4 V versus SCE, depending on the solvent and electrolyte composition [2]. This limitation prevents the study of electrochemical reactions requiring high positive potentials, including the oxidation of many biologically relevant compounds and organic molecules.

Mechanical Fragility and Operational Complexity

The physical nature of liquid mercury introduces several practical challenges:

- Capillary Clogging: The fine capillaries (20-50 μm bore size) used in HMDE are susceptible to clogging from impurities or air bubbles, requiring meticulous maintenance [2].

- Vibration Sensitivity: The hanging drop is vulnerable to dislodgement by mechanical vibrations, compromising experimental stability.

- Flow System Incompatibility: HMDE is poorly suited for flow-through analysis systems or online monitoring applications, limiting its integration with modern automated analytical platforms [3].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of HMDE and Solid Electrodes

| Parameter | HMDE | Solid Electrodes (Pt, Au, Carbon) |

|---|---|---|

| Cathodic Potential Window | -1.0 V to -2.0 V vs. SCE [2] | +0.2 V to -1.0 V vs. SCE (varies) [2] |

| Anodic Potential Window | -0.3 V to +0.4 V vs. SCE [2] | Up to +1.2 V vs. SCE (Pt in acid) [2] |

| Surface Renewal | Excellent (new drop for each measurement) [3] | Requires mechanical polishing/cleaning [2] |

| Toxicity | High (elemental mercury) [3] | None to low |

| LOD for Metal Ions | (Sub)nanomolar levels [3] | Typically higher than HMDE [3] |

| Mechanical Stability | Poor (sensitive to vibrations) | Excellent |

| Flow System Compatibility | Poor [3] | Excellent |

The Solid Electrode Advantage in Modern Research

Material Diversity and Customization

Solid electrodes offer researchers a diverse palette of materials with tunable properties for specific applications. Common materials include:

- Platinum and Gold: Excellent for oxidations, with wide potential windows in positive direction [2].

- Glassy Carbon: Versatile material with relatively wide potential window and low reactivity [3].

- Carbon Paste: Customizable composite allowing modification with various compounds [2].

- Bismuth and Antimony Films: Emerging as environmentally friendly alternatives for metal detection [3].

This material diversity enables researchers to select electrodes based on specific experimental requirements, including potential range, catalytic activity, and surface functionality.

Surface Modification and Functionalization

Unlike HMDE, solid electrodes provide a stable platform for surface modification, opening possibilities for enhanced selectivity and sensitivity:

- Electropolymerized Films: Creating selective membranes for specific analytes.

- Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs): Providing controlled surface chemistry for biosensing.

- Nanomaterial Composites: Incorporating carbon nanotubes, graphene, or metal nanoparticles to enhance electrocatalytic properties and surface area [3].

- Biomolecule Immobilization: Enabling biosensors through attachment of enzymes, antibodies, or DNA probes.

These modification strategies allow researchers to design electrode interfaces with tailored properties for specific analytical challenges, particularly valuable in pharmaceutical analysis where selectivity toward specific drug molecules is crucial.

Practical Advantages for Drug Development

For pharmaceutical researchers and drug development professionals, solid electrodes offer significant practical benefits:

- Regulatory Compliance: Avoids mercury-related regulatory hurdles in Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) environments.

- High-Throughput Screening: Compatibility with automated systems and multi-well platforms.

- Microfabrication Potential: Can be miniaturized for lab-on-a-chip devices or in vivo sensing.

- Diverse Application Range: Suitable for studying both reductive and oxidative processes of drug molecules.

Experimental Protocols: HMDE versus Solid Electrodes

HMDE Protocol for Trace Metal Analysis Using ASV

The following detailed methodology outlines the simultaneous determination of Zn²⁺, Cd²⁺, Pb²⁺, and Cu²⁺ using HMDE with Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV), adapted from recent research [3]:

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Nitric Acid (5 M): For sample digestion and acidification.

- Metal Standard Solutions: Prepared from lead nitrate, copper nitrate, zinc nitrate, and cadmium nitrate in deionized water.

- Nitrogen Gas (High Purity): For deaeration.

- Supporting Electrolyte: Typically acetate buffer (pH 4.5) or nitric acid solution.

Experimental Procedure:

- Electrode Setup: Install HMDE in voltammetric cell with Ag/AgCl reference electrode and glassy carbon auxiliary electrode [3].

- Sample Preparation: Dilute sample aliquot with supporting electrolyte to final volume of 20 mL. For soil samples, prior digestion with HNO₃ is required [3].

- Deaeration: Purge solution with N₂ for 10 minutes to remove dissolved oxygen [3].

- Deposition Step: Apply deposition potential of -1.1 V for 120 seconds with continuous stirring to preconcentrate metal ions into mercury drop as amalgams [3].

- Equilibration: Cease stirring and allow 30 seconds for solution quiescence [3].

- Stripping Step: Initiate square-wave potential scan from -1.1 V to +0.15 V using parameters: frequency = 40 Hz, pulse amplitude = 25 mV, step potential = 4 mV [3].

- Data Processing: Perform baseline subtraction and peak integration for quantification [3].

- Electrode Renewal: Dispose mercury drop and generate fresh drop for subsequent measurements [3].

Diagram 2: Anodic Stripping Voltammetry Protocol

Selenium Study on HMDE: Exemplary Application

A detailed cyclic voltammetric study of Se(IV) on HMDE in HNO₃ medium illustrates the electrode's capabilities and complexities [4]:

Experimental Conditions:

- Apparatus: BAS 100A potentiostat with PAR Model 303 SMDE system [4].

- Electrode System: HMDE working electrode, Ag/AgCl reference electrode, Pt auxiliary electrode [4].

- Selenium Solution: 0.1309 g SeO₂ in 100 mL water [4].

- Background Electrolyte: HNO₃ at varying concentrations.

- Parameters: Varying scan rates (e.g., 10-500 mV/s), multiple scans.

Key Findings:

- Irreversible Reduction: HSeO₃⁻ and H₂SeO₃ reduction is chemically irreversible [4].

- Passivation Effects: Reduction products form passivating layers on HMDE surface [4].

- Multiple Peaks: Depending on scan rate, multiple reduction peaks appear between +200 mV and -950 mV [4].

- Complex Mechanism: Involves formation of HgSe, Se(0), and H₂Se through coupled chemical reactions [4].

This study exemplifies both the analytical power of HMDE for elucidating complex electrode mechanisms and the challenges of interpreting results due to surface passivation and multiple interrelated processes.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HMDE Experiments

| Reagent/Equipment | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Mercury | Triple-distilled, high-purity | Working electrode material |

| Supporting Electrolyte | HNO₃, acetate buffer, KCl | Provides conductivity, controls pH |

| Standard Solutions | Certified reference materials | Quantification and calibration |

| Nitrogen Gas | High purity (99.99%) | Removal of dissolved oxygen |

| Capillary Tubing | 20-50 μm bore size [2] | Mercury drop formation |

| Reference Electrode | Ag/AgCl, SCE | Stable potential reference |

| Cleaning Solutions | Nitric acid, ethanol | Cell and capillary decontamination |

The Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode occupies a significant position in the historical development of electroanalytical chemistry, providing unparalleled performance for specific applications, particularly trace metal analysis through anodic stripping voltammetry. Its renewable surface properties, wide cathodic potential window, and amalgam-forming capability have established a legacy that continues to influence electrochemical practice.

However, the inherent drawbacks of HMDE—primarily its toxicity, limited anodic potential range, and operational constraints—have accelerated the adoption of solid electrode alternatives in modern research environments. For drug development professionals and researchers, solid electrodes offer superior practicality, modification versatility, and compatibility with contemporary analytical systems.

The transition from HMDE to advanced solid electrodes represents not merely a substitution of materials but an evolution in electrochemical capability. While HMDE remains the reference method for certain applications, the future of electroanalysis in pharmaceutical and chemical research undoubtedly lies with the continued development of modified solid electrodes that combine analytical performance with practical advantages, ultimately expanding the possibilities for sensing, detection, and mechanistic study across scientific disciplines.

Toxicity and Environmental Concerns of Mercury-Based Electrodes

Mercury-based electrodes, particularly the Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE), have been foundational tools in electrochemistry since the invention of polarography by Jaroslav Heyrovský. Their unique properties, including a renewable surface, high hydrogen overvoltage, and atomically smooth surface, made them the preferred choice for fundamental electrochemical studies and trace analysis for decades [5]. The liquid state of mercury provides a homogeneous, reproducible interface that is difficult to achieve with solid electrodes. However, mercury is also a potent neurotoxin with significant environmental persistence, leading to stringent regulations and a strong research push toward safer alternatives [6] [7].

This whitepaper examines the toxicity and environmental concerns associated with mercury-based electrodes within the broader context of transitioning to solid-state electrode systems. While mercury electrodes offer exceptional analytical performance, their environmental and safety liabilities have accelerated the development of advanced solid-contact electrodes that offer comparable performance without the associated hazards. The movement toward "green electrochemistry" reflects a broader scientific consensus that analytical performance must be balanced with environmental responsibility and workplace safety [6].

Toxicity Profile and Environmental Impact

Health Effects and Exposure Pathways

Mercury exposure poses severe health risks, particularly through inhalation of mercury vapor, which is rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream. Chronic exposure, even at low levels, can lead to cumulative neurological effects including tremors, memory loss, and difficulty concentrating [8]. Kidney damage and other systemic effects are also well-documented consequences of mercury toxicity. The bioaccumulation of mercury in the food chain, particularly through methylation by bacterial action in aquatic environments, creates significant secondary exposure pathways through food consumption, especially fish [9].

Occupational Hazards in Scientific Settings

Recent investigations at recycling facilities highlight the very real occupational hazards associated with handling mercury-containing materials. At an Ohio electronics waste and lamp recycling facility, six of fourteen workers showed elevated urine mercury levels, with a median job tenure of only eight months [8]. Notably, 83% of workers in lamp recycling areas had urine mercury levels exceeding the ACGIH Biological Exposure Index, with median personal air exposures of 64.8 μg/m³ – far above the recommended exposure limit of 25 μg/m³ [8]. These findings demonstrate that mercury exposure remains a significant concern in occupational settings where mercury-containing devices are processed or handled.

Table 1: Occupational Mercury Exposure Findings at an Electronics Recycling Facility

| Metric | Finding | Reference Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Workers with elevated urine mercury | 6 of 14 workers | ACGIH BEI: 20.0 μg/g creatinine |

| Median urine mercury (lamp areas) | 41.3 μg/g creatinine | ACGIH BEI: 20.0 μg/g creatinine |

| Median personal air exposure | 64.8 μg/m³ | ACGIH TLV: 25 μg/m³ |

| Area contamination (material storage) | 60.5 μg/m³ | ACGIH TLV: 25 μg/m³ |

| Maximum area contamination | 106.3 μg/m³ | OSHA PEL: 100 μg/m³ |

Regulatory Landscape

Global regulatory frameworks have increasingly restricted mercury use. The European Union has developed a comprehensive body of legislation covering all aspects of the mercury lifecycle, from primary mining to waste disposal [7]. The revised EU regulation on mercury that entered into force in July 2024 further restricts the remaining uses of mercury within the EU [7]. In the United States, the Environmental Protection Agency regulates mercury in consumer products and mandates specific disposal procedures for mercury-containing devices [10]. These regulations have directly impacted laboratory use of mercury electrodes, with many institutions implementing complete phase-outs due to liability and waste disposal concerns.

Advantages of Solid Electrodes Over HMDE

Environmental and Safety Benefits

The primary advantage of solid electrodes lies in their elimination of mercury hazards from the laboratory environment. Solid electrodes require no special handling procedures, generate no toxic waste, and present no risk of spills or vapor exposure. This aligns with the principles of green chemistry, which emphasizes the design of chemical products and processes that reduce or eliminate the use of hazardous substances [6]. The transition to mercury-free electrodes also eliminates the complex waste disposal requirements and costs associated with mercury-containing residues.

Practical Analytical Advantages

Beyond environmental benefits, solid electrodes offer several practical advantages for analytical chemistry and sensor development:

- Durability and mechanical stability for field-deployable sensors and continuous monitoring applications

- Compatibility with modern microfabrication techniques for miniaturization and integration into lab-on-a-chip devices

- Extended potential windows for certain applications, particularly in the positive potential range

- Surface functionalization capabilities through covalent modification and nanostructuring

- Elimination of the need for surface renewal procedures required with HMDE

Solid-contact ion-selective electrodes (SC-ISEs) have become particularly valuable for pharmaceutical analysis, offering simplicity, affordability, rapid analysis, and precision for direct measurements in complex matrices [11]. Their robustness and ease of use make them suitable for quality control environments and point-of-care testing applications where mercury electrodes would be impractical.

Emerging Solid Electrode Materials and Technologies

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Electrodes

Recent advances in nanotechnology have produced solid electrodes with performance characteristics rivaling or exceeding those of mercury-based systems. Gold nanoparticle-modified boron-doped diamond (AuNP-BDD) electrodes have demonstrated exceptional sensitivity for mercury detection at concentrations as low as 0.5 ppb, while completely eliminating mercury from the electrode material itself [9]. These electrodes leverage the high specific surface area of nanomaterials to achieve enhanced electron transfer rates while maintaining excellent electrochemical stability.

Carbon-Based and Composite Materials

Carbon materials, including graphene, carbon nanotubes, and conducting polymers like polyaniline (PANI), have emerged as particularly promising alternatives [12]. Graphene-polyaniline nanocomposites combine the exceptional conductivity of graphene with the redox activity and stability of PANI, creating ion-to-electron transducers that stabilize electrode potential and prevent water layer formation [12]. These composites have enabled the development of solid-contact ion-selective electrodes with detection limits extending to the nanomolar range for pharmaceutical applications [12].

Silica-Based Electrodes (SBEs)

Silica-based electrodes represent another emerging trend, offering a durable and porous inorganic framework that allows for rapid mass transport and covalent binding of functional groups [13]. These electrodes can be tailored through functionalization and hybridization with conductive materials to overcome limitations in conductivity while maintaining excellent chemical stability. SBEs are particularly valuable for environmental monitoring of heavy metal ions, where their high sensitivity and selectivity enable trace detection of hazardous pollutants [13].

Table 2: Comparison of Mercury vs. Solid Electrode Materials

| Parameter | Mercury Electrodes | Solid Electrodes |

|---|---|---|

| Surface renewal | Excellent (inherent) | Requires polishing/cleaning |

| Hydrogen overvoltage | High | Variable |

| Toxicity | High | None to low |

| Waste disposal | Complex, costly | Simple |

| Miniaturization potential | Limited | Excellent |

| Surface functionalization | Limited | Extensive |

| Field deployment | Impractical | Excellent |

| Cost of operation | High (disposal, safety) | Low |

Experimental Protocols for Solid Electrode Systems

Protocol: Preparation of Gold Nanoparticle-Modified BDD Electrode

This protocol for creating a mercury-free electrode for heavy metal detection is adapted from recent research on mercury determination [9]:

- Substrate Preparation: Begin with a boron-doped diamond (BDD) electrode synthesized via chemical vapor deposition with approximately 200 μm film thickness.

- Surface Cleaning: Clean the BDD surface electrochemically by applying 0.7 V for 15 seconds in 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 5).

- Nanoparticle Deposition: Electrochemically deposit gold nanoparticles using a high reduction voltage (-0.7 V to -1.2 V) from a highly concentrated gold ion solution (≥1 mM HAuCl₄).

- Characterization: Verify deposition by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), confirming dense nanoparticle packing on micro-sized BDD crystal irregularities.

- Stability Testing: Perform cyclic voltammetry for 50 cycles in the operational voltage range to confirm electrochemical stability, with characteristic gold peaks at 0.3-0.4 V.

Protocol: Fabrication of Graphene-Polyaniline Nanocomposite SC-ISE

This protocol for pharmaceutical analysis sensors is based on recent work with Remdesivir detection [12]:

Nanocomposite Synthesis:

- Prepare dispersible PANI-graphene composite by coating aniline monomers with graphene platelets

- Polymerize aniline in the presence of graphene using reverse-phase polymerization with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)

- Centrifuge the resulting nanocomposite and disperse in N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP)

Electrode Fabrication:

- Apply the G/PANI nanocomposite as a thin layer on the solid substrate (e.g., glassy carbon)

- Cover with ion-selective membrane containing appropriate ionophore (e.g., Calix-8-arene for drug molecules)

- Cure overnight at room temperature

Performance Validation:

- Test potential stability via water layer test and potential drift measurements

- Evaluate linear response range (typically 10⁻⁷ to 10⁻² mol/L for optimized sensors)

- Verify detection limit (approximately 100 nmol/L for pharmaceutical compounds)

The Research Toolkit: Essential Materials for Modern Electrode Development

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Solid Electrode Development

| Material/Reagent | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Graphene nanoplatelets | Ion-to-electron transducer, enhances conductivity and hydrophobicity | Solid-contact ISEs for pharmaceutical analysis [12] |

| Polyaniline (PANI) | Conducting polymer transducer, stabilizes potential | Drug sensors with improved response time and lifetime [12] |

| Gold nanoparticles | Catalytic activity, increased surface area | Mercury detection electrodes [9] |

| Boron-doped diamond | Robust substrate with wide potential window | Base electrode for nanoparticle modification [9] |

| Mesoporous silica | High surface area substrate with tunable porosity | Heavy metal ion sensors [13] |

| Ionophores (e.g., Calix-8-arene) | Selective target recognition | Ion-selective membranes for specific analytes [12] |

| N-methylpyrrolidone (NMP) | Dispersion solvent for nanocomposites | Preparation of G/PANI nanocomposites [12] |

Methodological Workflow Visualization

Workflow Comparison: Solid vs. Mercury Electrodes

The toxicity and environmental concerns associated with mercury-based electrodes have fundamentally shifted electrochemical research toward safer, more sustainable solid-state alternatives. While mercury electrodes historically offered superior performance for specific applications, modern nanomaterial-enhanced solid electrodes now provide comparable sensitivity and selectivity without the associated hazards. The continuing evolution of graphene-based composites, conducting polymers, and functionalized silica materials promises further performance enhancements while aligning with the principles of green chemistry. For researchers in pharmaceutical development and analytical sciences, the transition to mercury-free electrode systems represents both an environmental responsibility and a strategic opportunity to adopt more robust, versatile, and field-deployable analytical platforms.

Limited Anodic Potential Range and Passivation Issues

The hanging mercury drop electrode (HMDE) has long been recognized as an exceptional tool for the voltammetric determination of electrochemically reducible organic compounds, offering a broad cathodic potential window, easily renewable surface, and high sensitivity capable of reaching subnanomolar detection limits. [14] However, significant limitations including limited mechanical stability and concerns about mercury toxicity have driven the search for alternative solid electrodes. [14] While solid electrodes present promising alternatives, they introduce distinct challenges, primarily limited anodic potential range and susceptibility to passivation, which can compromise analytical performance. This technical guide examines these critical limitations within the broader context of advancing electrochemical methodologies for modern research and drug development applications, providing structured data comparisons, detailed experimental protocols, and practical mitigation strategies.

Fundamental Challenges with Solid Electrodes

The Passivation Phenomenon

Passivation refers to the gradual formation of a surface layer on the electrode that hinders electron transfer and ion migration. In electrocoagulation applications, this layer typically consists of metal oxides and hydroxides that accumulate over time. [15] For organic compound analysis, passivation often occurs through the adsorption of reaction products or the formation of polymeric films. For instance, during the electrooxidation of 4-hydroxy-TEMPO—a nitroxide radical relevant for flow battery applications—a polymeric-type passivation layer composed of 4-hydroxy-TEMPO-like subunits forms over the electrode surface. [16] This layer is not observed with the parent TEMPO molecule, highlighting how specific molecular functionalities can dramatically influence passivation behavior. [16]

The extent of passivation is influenced by multiple factors including voltage scan rate and analyte concentration. Studies demonstrate that passivation increases at higher 4-hydroxy-TEMPO concentrations and lower scan rates, underscoring the importance of studying electrochemical materials under conditions relevant to their proposed applications. [16]

Comparative Electrode Characteristics

Table 1: Comparison of Electrode Properties and Passivation Behavior

| Electrode Type | Potential Window (Cathodic) | Passivation Susceptibility | Surface Renewal Method | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMDE | Very broad | Low | Easy drop renewal | High hydrogen overvoltage, excellent renewal [14] |

| Polished AgSAE (p-AgSAE) | Broad | Moderate | Mechanical polishing, electrochemical activation [14] [17] | Robust, "green" alternative, no liquid Hg [14] |

| Mercury Meniscus Modified AgSAE (m-AgSAE) | Broad comparable to HMDE [14] | Lower than p-AgSAE | Mercury meniscus renewal (weekly) [17] | Good for routine analysis, relatively easy renewal [14] |

| Bismuth Film Electrode (BiFE) | Broad in cathodic region | Variable, depends on substrate and plating | Film replating (ex situ or in situ) [17] | Low toxicity, favorable electroanalytical properties [17] |

| Glassy Carbon Electrode | Limited anodic range | High for complex matrices | Mechanical polishing, chemical treatment | Good electrical properties, widely available |

Experimental Methodologies for Electrode Preparation and Analysis

Electrode Preparation Protocols

Procedure 1: Preparation of Polished Silver Solid Amalgam Electrode (p-AgSAE)

- Surface Abrasion: Before first use, abrade the electrode surface on soft emery paper. [17]

- Polishing: Polish on a polyurethane pad using alumina suspension (particle size 1.1 μm) followed by alumina powder (0.50 μm). [17]

- Activation: Activate the polished electrode in a stirring solution of 0.20 mol L⁻¹ KCl at a potential of -2200 mV for 5 minutes. [17]

- Maintenance: Repeat polishing once or twice weekly during long-term measurement series. Perform activation at the beginning of each day or after pauses longer than one hour. [17]

Procedure 2: Preparation of Mercury Meniscus Modified AgSAE (m-AgSAE)

- Base Preparation: Begin with a properly prepared p-AgSAE. [17]

- Meniscus Formation: Immerse the electrode tip into liquid mercury to create a mercury meniscus. [17]

- Maintenance: Renew the mercury meniscus typically once per week to maintain consistent performance. [17]

Procedure 3: Ex Situ Plating of Bismuth Film Electrode (BiFE) on GCE

- Surface Preparation: Polish the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) sequentially using 1 μm, 0.3 μm, and 0.05 μm alumina slurry. [16]

- Cleaning: Ultrasonicate the polished electrode in ethanol followed by deionized water. [16]

- Film Deposition: Deposit the bismuth film from a Bi³⁺ solution (e.g., 10 mg L⁻¹) using appropriate deposition potential and time. [17]

Voltammetric Analysis of Organic Compounds

Differential Pulse Voltammetry Parameters for Dantrolene Sodium Analysis [17]

- Supporting Electrolyte: Britton-Robinson buffer (pH 6.0 for AgSAEs; pH 5.0 for BiFE)

- Scan Rate: 40 mV s⁻¹

- Pulse Height: -60 mV (AgSAEs, HMDE); -50 mV (BiFE)

- Pulse Width: 40 ms (AgSAEs, HMDE); 60 ms (BiFE)

- Accumulation Potential: +200 mV (for all electrodes)

- Deaeration: Purge with nitrogen for 5 minutes before analysis and maintain nitrogen atmosphere during measurements.

Table 2: Analytical Performance for Dantrolene Sodium Determination [17]

| Electrode | Technique | LOD (mol L⁻¹) | Linear Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HMDE | AdS SWV | 2.1 × 10⁻¹⁰ | Not specified | Lowest LOD, mercury-related concerns |

| m-AgSAE | DPV | Comparable to HMDE | Well-defined linearity | Good alternative to HMDE |

| p-AgSAE | DPV | Slightly higher than m-AgSAE | Sufficient linearity | More prone to passivation |

| BiFE (ex situ) | DPV | ~10⁻⁷ | Linear | Environmentally friendly, higher LOD |

Mitigation Strategies for Passivation

Operational Approaches

Polarity Reversal: Applying periodic polarity reversal in electrochemical systems can effectively reduce surface layer buildup. Research in electrocoagulation demonstrates that polarity reversal in aluminum-based systems reduces passivation, converts the Al₂O₃ insulating layer into porous Al(OH)₃, and improves Faradaic efficiency. [18] The effectiveness varies by electrode material, with iron electrodes showing less consistent benefits from polarity reversal. [18]

Current Mode Modulation: Switching from direct current to pulsed current or alternating pulsed current modes can help mitigate passivation by allowing the electrode surface to recover between pulses, reducing continuous buildup of passivating layers. [15]

Optimized Hydrodynamics: Enhanced flow conditions improve hydrodynamic scouring of the electrode surface, preventing the accumulation of passivating layers. This approach is particularly effective in flow injection analysis and HPLC systems with amperometric detection. [14]

Chemical and Material Solutions

Chloride Addition: Introducing chloride ions into the solution can alleviate passivation effects by competing with adsorbing species and potentially forming soluble complexes with metal ions. Studies show NaCl reduces passivation and lowers energy consumption in electrochemical processes. [18]

Surface Engineering: Designing electrodes with porous structures or composite materials can reduce passivation by providing higher surface areas and alternative reaction pathways. Electrodes with renewable surfaces represent another approach to addressing passivation. [14]

Natural Additives: Environmentally friendly materials such as mucilage extracted from Egyptian taro have shown potential in enhancing electrochemical treatment processes, though their effectiveness varies depending on the target analyte and system conditions. [19]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Electrode Passivation Studies

| Item | Function/Application | Example Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Silver Solid Amalgam Electrodes (AgSAE) | Primary working electrode for reducible organic compounds | Available as p-AgSAE or m-AgSAE [14] [17] |

| Bismuth Film Electrodes (BiFE) | Environmentally friendly alternative to mercury electrodes | Ex situ or in situ plating on GCE [17] |

| Alumina Polishing Suspensions | Electrode surface preparation and renewal | Particle sizes: 1.1 μm, 0.3 μm, 0.05 μm [16] [17] |

| Britton-Robinson Buffer | Versatile supporting electrolyte for pH studies | pH range 2.0-12.0, composed of H₃PO₄, H₃BO₃, CH₃COOH [17] |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Supporting electrolyte and passivation mitigation agent | High purity (>99%), reduces passivation effects [18] |

| Nitrogen Gas | Solution deaeration for oxygen removal | Purity class 4.0 [17] |

| Standardized Redox Probes | Electrode performance validation | e.g., Potassium ferricyanide, ruthenium hexamine |

The limitations of solid electrodes regarding anodic potential range and passivation present significant but manageable challenges in electrochemical analysis. While silver amalgam and bismuth-based electrodes offer viable alternatives to HMDE with their broader cathodic windows and reduced toxicity, their susceptibility to passivation requires careful experimental design and mitigation strategies. The comparative data presented in this guide demonstrates that through appropriate electrode selection, optimized operational parameters, and targeted passivation mitigation approaches, researchers can effectively leverage the advantages of solid electrodes while minimizing their limitations. Future developments in electrode materials and surface engineering hold promise for further overcoming these challenges, particularly for sensitive applications in pharmaceutical analysis and drug development where reliability and reproducibility are paramount.

Mechanical Fragility and Challenges in Automation

Solid electrodes, particularly in the context of all-solid-state batteries (ASSBs), represent a significant advancement in energy storage technology, promising greater safety and higher energy density compared to systems using liquid electrolytes [20] [21]. Unlike the Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE), which utilizes a liquid metal with inherently renewable surfaces, solid electrodes are characterized by their rigid, static structure. The primary advantage of solid electrodes over HMDE lies in their elimination of toxic mercury, enhanced mechanical stability for integration into devices, and potential for miniaturization [21]. However, this shift from a liquid to a solid interface introduces significant challenges related to mechanical fragility and complexities in automated manufacturing, which this article will explore in depth.

Fundamental Mechanical Properties and Fragility

The performance and longevity of solid electrodes are critically dependent on their mechanical properties. The inherent fragility of many solid inorganic electrolytes manifests primarily through their high Young's modulus (a measure of stiffness) and susceptibility to fracture under stress.

Material Stiffness and Fabrication Pressure

The rigidity of solid electrolytes necessitates the application of high pressure during cell fabrication to ensure intimate solid-solid contact, which is crucial for efficient ion transport. The required fabrication pressure is directly correlated with the material's Young's modulus [22].

Table: Mechanical Properties of Selected Solid Inorganic Electrolytes

| Electrolyte Type | Example Composition | Young's Modulus (GPa) | Implied Fabrication Pressure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxide | Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂ (LLZO) | 145.6 - 150 [22] | Very High |

| Oxide | Li₁.₃Al₀.₃Ti₁.₇(PO₄)₃ (LATP) | 115 [22] | Very High |

| Sulfide | Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂ (LGPS) | 37.2 [22] | High |

| Sulfide | Li₂S–P₂S₅ | 18.5 - 23.3 [22] | Moderate-High |

| Halide | Li₃YCl₆ (Representative) | Information Missing | N/A |

| Polymer | PEO-based | 0.082 - 0.69 [22] | Low |

As shown in the table, oxide-based electrolytes are exceptionally stiff, while sulfide electrolytes exhibit lower, yet still significant, rigidity. This high stiffness directly translates to the need for fabrication pressures reaching hundreds of megapascals to achieve viable ionic contact in lab-scale cells [22].

Operational Stresses and Electro-Chemo-Mechanical Failure

Beyond fabrication, mechanical challenges persist during operation. The volume changes of electrode materials during charge and discharge cycles induce significant recurrent stress at the solid-solid interfaces [22]. Unlike liquid electrolytes that can flow to maintain contact, solid interfaces are prone to decoupling. This leads to:

- Loss of ionic contact, increasing internal resistance.

- Propagation of micro-cracks through brittle electrolyte materials.

- Lithium dendrite growth into grain boundaries and pores, potentially leading to short circuits [22].

These failure modes are exacerbated by the stack pressure required to maintain contact during operation. Industrially, the acceptable operation pressure for large-format cells is targeted at no more than 2 MPa, a threshold that many lab-scale systems significantly exceed, creating a major challenge for scaling [22].

Challenges in Automating Solid Electrode Integration

The mechanical properties of solid electrolytes create substantial hurdles for automating their manufacturing, a process critical for commercial viability.

Pressure-Related Automation Hurdles

The high pressures required are difficult to implement in a continuous, automated industrial process. Applying hundreds of megapascals of uniform pressure becomes increasingly challenging as cell size increases, as it requires massive forces that can exceed the strength of peripheral metallic components and lead to uneven pressure distribution [22]. This pressure uniformity is critical; non-uniform pressure causes inconsistent lithium-ion flux and localized stress concentrations, accelerating degradation [22]. The need for such precise, high-pressure environments conflicts with the high-speed, scalable processes required for mass production.

Interface Engineering and Processing

The solid-solid interface is not a single point of failure but a complex, multi-layered challenge. Key issues include:

- Chemical Instability: Reactions between electrode and electrolyte materials can form high-resistance interphases [20].

- Thermal Expansion Mismatch: Different rates of thermal expansion between materials can break interfaces during temperature fluctuations [21].

- Poor Sinterability: Many solid electrolyte materials require high-temperature sintering to achieve density, which can be incompatible with adjacent materials and difficult to control in a continuous process [21].

Automating the creation of stable, low-resistance interfaces remains a central challenge in the field. The transition from lab-scale to industrial manufacturing requires addressing these interconnected materials and processing challenges simultaneously [20].

Experimental Protocols for Assessing Mechanical Fragility

Rigorous experimental characterization is essential for developing robust solid electrode systems. The following methodologies are critical for evaluating mechanical integrity.

Residual Stress Analysis

This protocol maps the internal stresses induced in solid electrolyte pellets during fabrication. As described in a study on LLZTO pellets [22]:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare polished and unpolined LLZTO pellets.

- Stress Mapping: Use X-ray diffraction or similar techniques to analyze stress distribution on the pellet surface.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the median stress and proportion of the surface under compressive vs. tensile stress. One study found that polishing with 2000# sandpaper increased the average surface stress from 26 MPa to 143 MPa and created a more uniform stress state, which theoretically promotes more homogeneous lithium deposition [22].

Electro-Chemo-Mechanical Cycling Test

This protocol evaluates the stability of the solid-solid interface under operating conditions.

- Cell Assembly: Fabricate a symmetric Li|SSE|Li or full ASSB cell under a defined stack pressure.

- Operational Stress Application: Cycle the cell (charge/discharge) under a controlled, monitored external pressure.

- In-Situ Monitoring: Use electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) at regular intervals to track the increase in interfacial resistance, indicating contact loss.

- Post-Mortem Analysis: After cycling, disassemble the cell and use microscopy (e.g., SEM) to observe physical delamination, crack formation, or dendrite penetration at the interfaces.

Critical Pressure Determination

This experiment identifies the minimum pressure required for stable operation.

- Variable Pressure Fixture: Place the ASSB in a test fixture capable of applying a known, adjustable stack pressure.

- Performance Threshold: Cycle the cell at progressively lower pressures until the voltage noise exceeds a threshold (e.g., ±10 mV) or a short circuit occurs, indicating the failure point [22].

- Data Correlation: Correlate the failure pressure with the electrolyte's Young's modulus and the electrode's volume expansion coefficient.

Diagram 1: Solid Electrode Failure Pathways. This chart illustrates the logical sequence of events, from applied stress to ultimate failure, driven by the material's high stiffness.

Strategies for Mitigating Fragility and Enabling Automation

Addressing the fragility of solid electrodes requires a multi-faceted approach targeting materials, interfaces, and system design.

Material-Level Strategies

Developing more compliant solid electrolyte materials is a primary goal. Research focuses on:

- Viscoelastic Electrolytes: Designing electrolytes with low elastic modulus, such as a recently developed viscoelastic SSE with a modulus of 1.5 GPa, enabling operation at pressures below 0.1 MPa [22].

- Composite Electrolytes: Creating mixtures of polymers and inorganic fillers to achieve a balance of ionic conductivity and mechanical compliance [21].

Interface Engineering Strategies

Innovative interface designs can decouple the need for global high pressure.

- Self-Densifying Interlayers: Using interlayers that densify under low pressure. An example is a self-regulated carbon interlayer with 89% densification strain, enabling anode-free ASSBs to operate at 7.5 MPa [22].

- Surface Polishing: Modifying surface morphology to create more uniform stress distribution, which can promote homogeneous lithium deposition and resist dendrite penetration [22].

System-Level Strategies

At the device level, engineering solutions can manage pressure more effectively.

- Constant Pressure Springs: Integrating mechanical springs with a low spring rate (e.g., 5.5 lb mm⁻¹) into the cell stack to maintain a constant, low pressure (e.g., 5 MPa) despite volume changes in the electrodes [22].

- Elevated Temperature Operation: Running ASSBs at higher temperatures (e.g., 80°C) can soften interfaces and reduce the required operating pressure to as low as 2 MPa [22].

Diagram 2: Low-Pressure ASSB Strategy Map. This diagram categorizes the primary strategies being pursued to overcome the pressure-related challenges in solid-state batteries.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Materials

Table: Key Reagents and Materials for Solid Electrode Research

| Item | Function/Relevance |

|---|---|

| LLZO (Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂) Pellets | Model oxide solid electrolyte for studying high-modulus material behavior and interface reactions [21]. |

| Sulfide SSE (e.g., Li₁₀GeP₂S₁₂) | High-ionic-conductivity electrolyte for investigating pressure requirements in sulfide systems [22]. |

| Polishing Sandpaper (e.g., 2000#) | For surface finishing of electrolyte pellets to modify surface stress state and improve interfacial contact [22]. |

| Metallic Li Foil | Standard counter/reference electrode material; its softness and reactivity are key factors in interface design [22]. |

| Carbon Interlayer Materials | Components for creating self-densifying interlayers that reduce required stack pressure [22]. |

| Uniaxial/Isostatic Press | Equipment for applying controlled fabrication pressure (often 100s of MPa) to lab-scale cells [22]. |

| Spring-Loaded Test Fixture | Device for applying and maintaining a defined, low stack pressure during cell cycling and testing [22]. |

The transition from HMDE to solid electrodes trades the fluid adaptability of a liquid metal for the structural and environmental benefits of a solid system. However, this shift introduces a core challenge: the mechanical fragility of rigid solid electrolytes and the complex, high-pressure processes required for their integration. These challenges currently manifest as significant barriers to the automated, large-scale manufacturing of high-performance ASSBs. Overcoming these hurdles requires a concerted effort in materials science to develop more compliant electrolytes, in interface engineering to create resilient contacts, and in system design to manage pressure efficiently. The future of solid electrode technology hinges on converting mechanically fragile lab curiosities into automatable, industrially viable components.

The evolution of electrochemical analysis and energy storage technologies has been marked by a significant transition from liquid-phase to solid-phase electrode systems. While hanging mercury drop electrodes (HMDE) once dominated trace metal analysis and fundamental electrochemical studies due to their reproducible liquid surface and wide cathodic potential window, their severe limitations—particularly mercury's toxicity and limited anodic potential range—have driven the development of alternative solid electrode materials [23]. Solid electrodes, fabricated from carbon, noble metals, and conductive polymers, offer enhanced operational safety, mechanical robustness, and compatibility with modern instrumentation and miniaturized systems. This technical guide examines the fundamental characteristics, preparation methodologies, and performance advantages of major solid electrode classes within the context of their growing superiority over traditional mercury-based systems for contemporary research and industrial applications.

The paradigm shift toward solid electrodes represents more than just a safety improvement; it enables new analytical capabilities, particularly in the anodic potential region where mercury oxidizes. Furthermore, solid electrodes facilitate surface modifications and functionalization, allow integration into flow systems and portable devices, and support advanced energy storage systems where mercury electrodes are entirely unsuitable. This transition has accelerated with the commercial availability of various solid electrode formats, including screen-printed electrodes that provide disposable, reproducible platforms for decentralized analysis [24].

Fundamental Properties and Comparative Advantages of Solid Electrodes

Performance Characteristics of Solid Electrode Materials

Solid electrode systems encompass a diverse range of materials, each with distinct electrochemical properties suitable for specific applications. The selection of an appropriate solid electrode material depends on multiple factors, including the required potential window, background current, susceptibility to fouling, reproducibility, and cost. Carbon-based materials offer wide potential windows in the positive direction and moderate background currents, while noble metals provide excellent conductivity but may exhibit limited cathodic ranges due to hydrogen evolution. Conductive polymers combine the processability of plastics with tunable electronic properties, enabling the design of customized electrode surfaces [25].

The following table summarizes the key electrochemical properties of major solid electrode classes compared to HMDE:

Table 1: Comparative Electrochemical Properties of Solid Electrodes versus Hanging Mercury Drop Electrodes

| Electrode Material | Useful Potential Window (vs. SCE) | Key Advantages | Principal Limitations | Ideal Application Areas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Mercury Drop (HMDE) | -2.5 to +0.3 V [23] | Highly reproducible surface; Wide cathodic window; Excellent for metal reduction [23] | Mercury toxicity; Limited anodic window; Mechanical complexity [23] | Trace metal analysis (cathodic region); Polarography |

| Glasslike Carbon | -1.3 to +1.2 V | Low porosity; Easy polishing; Chemically inert | Surface aging effects; Requires regeneration | Electroanalysis; Biosensors |

| Boron-Doped Diamond | -1.5 to +2.3 V | Extremely wide window; Very low background; Remarkable stability | Higher cost; Limited surface functionalities | harsh environment analysis; Electrosynthesis |

| Platinum | -0.8 to +1.3 V | Excellent conductivity; Surface oxide formation | Catalytic activity interferes; Hydrogen evolution | Fuel cells; Oxidation studies |

| Gold | -0.8 to +1.2 V | Easy surface modification; SAM formation | Soft material; Limited cathodic range | Surface chemistry studies; Biosensors |

| Conductive Polymers (PEDOT) | -0.8 to +0.9 V [25] | Tunable properties; Easy fabrication; Flexible | Limited potential window; Long-term stability issues | Biosensors; Flexible electronics |

Operational Advantages Over Mercury-Based Electrodes

Solid electrodes present several decisive operational advantages that explain their displacement of HMDE in most contemporary applications. Foremost is the elimination of mercury toxicity, which addresses critical safety and environmental concerns associated with the use, disposal, and potential accidental release of mercury [23]. This advantage alone has driven regulatory restrictions on mercury electrodes in many industrial and academic settings.

The expanded anodic potential window of solid electrodes enables studies of oxidative processes that are inaccessible with HMDE, which oxidizes at approximately +0.3 V [23]. Carbon and noble metal electrodes maintain their integrity at positive potentials exceeding +1.0 V, facilitating the detection of biologically relevant compounds like neurotransmitters, pharmaceuticals, and organic molecules that undergo oxidation. This capability is particularly valuable in pharmaceutical research and biological monitoring.

Enhanced mechanical robustness and form factor flexibility represent another significant advantage. Solid electrodes can be fabricated in various geometries (disks, bands, arrays) and integrated into flow cells, portable sensors, and implantable medical devices—applications where liquid mercury electrodes are impractical [24]. Screen-printed electrode technology has further advanced this advantage by enabling mass production of disposable, reproducible electrode platforms that incorporate working, reference, and counter electrodes on a single chip [24].

Surface functionalization capabilities of solid electrodes far exceed those of mercury. Carbon surfaces can be modified with molecular layers, nanoparticles, or catalysts; gold forms stable self-assembled monolayers with various terminal functionalities; and conductive polymers can be tailored at the molecular level to enhance selectivity toward specific analytes [26] [25]. This tunability enables the design of sensors with optimized performance characteristics for targeted applications.

Carbon-Based Solid Electrodes

Material Classifications and Properties

Carbon-based electrodes represent the most diverse category of solid electrodes, with variants ranging from traditional graphite and glassy carbon to advanced materials like boron-doped diamond (BDD) and carbon nanotubes. The appeal of carbon materials stems from their relatively wide potential windows, chemical inertness across a broad pH range, low cost, and rich surface chemistry that facilitates modification. The electrical conductivity of carbon materials arises from their sp² hybridized structure, which enables electron delocalization across the carbon lattice [25].

Glassy carbon, perhaps the most widely used carbon electrode material, features a tangled ribbon structure that produces an isotropic material with low porosity, high hardness, and minimal permeability to gases and liquids. These properties make it ideal for electroanalysis where minimal background current and surface reproducibility are critical. Boron-doped diamond electrodes, on the other hand, represent a premium carbon electrode material with an exceptionally wide potential window (~3.5 V), extremely low background currents, and outstanding physical and chemical stability [25].

Experimental Protocols for Carbon Electrode Preparation and Activation

Glassy Carbon Electrode Polishing Protocol:

- Begin with successive abrasive treatments using diamond suspensions or alumina slurries of decreasing particle size (typically 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm).

- Apply gentle pressure while polishing on a wet polishing cloth using figure-8 motions to ensure even surface treatment.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each grade change to prevent cross-contamination of abrasive particles.

- After the final polish, sonicate in deionized water for 1-2 minutes to remove embedded polishing material.

- Perform electrochemical activation through potential cycling (e.g., 10 cycles from -0.5 to +1.0 V at 100 mV/s in 0.1 M H₂SO₄) until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Validate electrode activity using a standard redox probe such as 1 mM potassium ferricyanide in 1 M KCl; the peak separation (ΔEp) should be ≤70 mV for a well-activated surface.

Carbon Nanotube Modified Electrode Fabrication:

- Prepare a homogeneous CNT dispersion by adding 5 mg of multi-walled or single-walled carbon nanotubes to 10 mL of dimethylformamide (DMF) or water with 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS).

- Sonicate the mixture for 30-60 minutes using a probe sonicator until no visible aggregates remain.

- Deposit 5-20 µL of the CNT suspension onto a pre-polished glassy carbon or screen-printed carbon electrode surface.

- Allow the solvent to evaporate under ambient conditions or with mild heating (40-60°C).

- Rinse gently with deionized water to remove excess surfactant that might interfere with electrochemical measurements.

- Characterize the modified surface using cyclic voltammetry and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy to verify enhanced surface area and electron transfer properties.

Diagram 1: Carbon electrode preparation workflow highlighting key surface treatment stages.

Noble Metal Solid Electrodes

Gold, Platinum, and Silver Electrode Systems

Noble metal electrodes, particularly gold and platinum, play essential roles in electrochemical research due to their excellent conductivity, chemical stability, and well-defined surface electrochemistry. Gold electrodes excel in surface modification studies thanks to their ability to form strong Au-S bonds with thiol-containing molecules, enabling the creation of highly organized self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) for biosensor applications. Platinum electrodes offer superior catalytic activity for numerous reactions, including hydrogen evolution and oxygen reduction, making them invaluable in energy conversion studies [24].

Silver electrodes have gained renewed attention as substrates for mercury film electrodes (MF-AgSPE) in anodic stripping voltammetry, combining the advantages of solid electrodes with the beneficial electrochemical properties of mercury. As Josypcuk et al. demonstrated, "silver screen-printed electrodes covered by mercury film (MF-AgSPE) and mercury meniscus (m-AgSPE) were designed, prepared and tested" to create systems that "allow to perform measurements at high negative potentials" while utilizing commercially producible platforms [24]. This approach mitigates some mercury handling concerns while preserving analytical performance.

Surface Characterization and Activation Methods

Single-Crystal vs. Polycrystalline Surfaces:

- Single-crystal noble metal electrodes (e.g., Au(111), Pt(100)) provide atomically flat, well-defined surfaces for fundamental studies but require complex preparation and are fragile.

- Polycrystalline electrodes are practically oriented with randomly oriented crystal domains, offering robustness and ease of maintenance at the cost of surface heterogeneity.

Gold Electrode Activation Protocol:

- Mechanically polish with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) on a microcloth pad until a mirror finish is achieved.

- Rinse thoroughly with ultrapure water to remove all abrasive particles.

- Electrochemically clean by cycling between -0.3 and +1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ at 100 mV/s until a stable voltammogram characteristic of clean gold is obtained.

- For specific crystal facet exposure, use flame annealing with a butane torch followed by cooling in ultrapure water-saturated atmosphere.

Silver Solid Amalgam Electrode Preparation:

- Start with commercial silver screen-printed electrodes (AgSPE) with a typical working electrode diameter of 1.6 mm [24].

- Prepare a mercury(II) nitrate solution in 0.1 M nitric acid with concentration appropriate for the desired film thickness.

- Electrodeposit mercury onto the silver surface at a controlled potential of -0.5 V (vs. Ag pseudo-reference) for precisely defined duration (approximately 15 minutes for a 20 µm thick film) [24].

- Alternatively, transfer a precisely defined mercury drop from an HMDE to create a mercury meniscus electrode (m-AgSPE) [24].

- Allow the mercury-silver system to stabilize; the deposited mercury dissolves silver and "gradually converts into solid or paste amalgam" [24].

Table 2: Noble Metal Electrode Properties and Typical Activation Parameters

| Metal Electrode | Key Surface Characteristics | Optimal Polishing Material | Electrochemical Activation Conditions | Characteristic Redox Markers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gold (Au) | Affinity for thiol groups; Oxide formation >+1.2 V | Alumina (0.05 µm) | Cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ (-0.3 to +1.5 V) | Gold oxide reduction peak (~+0.9 V) |

| Platinum (Pt) | High catalytic activity; Hydrogen adsorption | Diamond paste (1 µm) | Cycling in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ (-0.2 to +1.2 V) | Hydrogen adsorption/desorption regions |

| Silver (Ag) | Mercury amalgamation; Sulfide sensitivity | Alumina (0.05 µm) | Cycling in 0.1 M KNO₃ (-0.5 to +0.5 V) | Silver oxide reduction (~+0.3 V) |

| Silver Amalgam (m-AgSPE) | Liquid amalgam surface; High hydrogen overpotential [24] | Not required | Mercury deposition then maturation | Comparable to pure mercury electrodes [24] |

Conductive Polymer-Based Electrodes

Synthesis and Electronic Properties

Conductive polymers (CPs) represent a unique class of solid electrode materials that combine the electronic properties of semiconductors and metals with the mechanical properties and processability of traditional polymers. The fundamental requirement for polymer conductivity is an extended π-conjugated system along the polymer backbone, featuring alternating single and double bonds that allow electron delocalization [25]. In their neutral state, most conductive polymers are semiconductors or insulators; however, upon "doping" through oxidation or reduction, charge carriers (polarons and bipolarons) are introduced, dramatically increasing conductivity by several orders of magnitude [25].

The most extensively studied conductive polymers for electrochemical applications include polyaniline (PANI), polypyrrole (PPy), and poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene) (PEDOT). Each offers distinct advantages: PANI exhibits multiple oxidation states with different colors and conductivity levels; PPy provides high conductivity and straightforward polymerization; PEDOT delivers outstanding environmental stability and moderate transparency in its conducting state [26]. The conductivity ranges of these materials span from 10-100 S/cm for PANI to 10-7500 S/cm for PPy, making them suitable for various electrochemical applications [25].

Electrochemical Synthesis and Modification Protocols

Electrochemical Polymerization of Polypyrrole Films:

- Prepare the polymerization solution containing 0.1 M pyrrole monomer and 0.1 M supporting electrolyte (e.g., KCl, NaNO₃, or p-toluenesulfonate) in deionized water or acetonitrile.

- Place the working electrode (typically Pt, Au, or glassy carbon) in the solution along with appropriate counter and reference electrodes.

- Apply a constant potential of +0.7 to +0.9 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) or use cyclic voltammetry between -0.5 and +0.9 V at a scan rate of 20-50 mV/s.

- Continue polymerization until the desired film thickness is achieved (typically 5-30 minutes, depending on application).

- Remove the electrode and rinse thoroughly with deionized water to remove monomer and oligomer species.

- Electrochemically characterize the film by cycling in a monomer-free electrolyte solution to determine the redox activity and stability.

Chemical Synthesis of Polyaniline Nanocomposites:

- Dissolve 0.2 M aniline monomer in 1 M HCl solution with stirring.

- Separately, prepare an oxidant solution of 0.25 M ammonium persulfate in 1 M HCl.

- Cool both solutions to 0-5°C in an ice bath to control the exothermic polymerization reaction.

- Slowly add the oxidant solution to the monomer solution with constant stirring.

- Continue reaction for 4-6 hours, during which the color changes from clear to dark green, indicating the formation of conducting emeraldine salt form.

- Filter the resulting precipitate and wash repeatedly with 1 M HCl followed by acetone.

- Dry the product under vacuum at 40-60°C for 24 hours.

- For nanocomposite formation, disperse carbon nanomaterials (graphene, CNTs) or metal nanoparticles in the monomer solution before polymerization.

Diagram 2: Conductive polymer synthesis pathways showing electrochemical and chemical approaches.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Methodologies

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Solid Electrode Research and Application

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Specification | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alumina Polishing Suspensions | α-Alumina, 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm grades in deionized water | Electrode surface refinement | Sequential use from coarse to fine; prevents cross-contamination |

| Potassium Ferricyanide | K₃[Fe(CN)₆] (ACS grade), 1-10 mM in 0.1-1 M KCl | Electrode activity validation | Reversible redox couple; ΔEp ≤70 mV indicates well-activated surface |

| Nafion Perfluorinated Resin | 5% solution in lower aliphatic alcohols and water | Cation-exchange polymer coating | Enhances selectivity toward cations; rejects anions and interferents |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer Precursors | Alkanethiols (e.g., 6-mercapto-1-hexanol, 1-dodecanethiol) | Surface functionalization | Forms organized monolayers on gold; controls interfacial properties |

| Pyrrole Monomer | ≥98% purity, stored under nitrogen at 4°C | Conductive polymer synthesis | Distill before use to remove oxidation products; light-sensitive |

| Lithium Perchlorate | Battery grade, dried at 100°C under vacuum | Non-aqueous electrolyte | Wide potential window in organic solvents; hygroscopic |

| Silver Ink | Metallic silver particles in organic binder | Screen-printed electrode fabrication | Commercial pastes for mass production of disposable electrodes [24] |

| Mercury(II) Nitrate | Hg(NO₃)₂ in 0.1 M HNO₃ | Mercury film electrode preparation | Used for MF-AgSPE formation; requires careful handling and disposal [24] |

Advanced Solid Electrode Systems in Energy Storage

The development of solid electrodes has been particularly transformative in energy storage technologies, where the limitations of mercury electrodes are absolute. Solid-state battery electrodes represent a rapidly growing market, projected to increase from $1100 Million in 2021 to $1923.9 Million by 2025, with an expected CAGR of 15% during 2025-2033 [27]. This growth is driven by demands for higher energy density, enhanced safety, and longer cycle life compared to traditional liquid electrolyte systems [28].

Advanced solid electrode compositions in energy storage include lithium metal anodes with protective interlayers to mitigate dendrite formation, hybrid composite electrodes combining polymer frameworks with inorganic fillers, and sophisticated manufacturing approaches such as powder metallurgy for porosity control and extrusion methods for continuous roll-to-roll production [28]. These innovations are enabling the convergence of high-volume automotive requirements with high-value consumer electronics applications, creating new opportunities for solid electrode technologies that far exceed the capabilities of any mercury-based system.

The comprehensive advantages of solid electrodes over hanging mercury drop electrodes extend beyond the obvious elimination of mercury toxicity to encompass superior operational flexibility, enhanced anodic potential range, and compatibility with modern analytical and energy storage platforms. Carbon-based electrodes provide versatile platforms for general electroanalysis, noble metals offer exceptional conductivity and surface modification capabilities, while conductive polymers enable customizable electronic properties and mechanical flexibility. The ongoing innovation in solid electrode technology—particularly in screen-printed formats, nanocomposite materials, and solid-state battery systems—ensures their continued dominance in electrochemical research and commercial applications. As material synthesis and fabrication methodologies advance, solid electrodes will further expand their performance advantages, ultimately rendering mercury-based systems obsolete for all but the most specialized analytical applications.

Leveraging Solid Electrode Capabilities for Advanced Biomedical Applications

Miniaturization and In Vivo Sensing with Solid-State Platforms

The transition from traditional sensing platforms, notably the Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE), to solid-state electrodes represents a pivotal shift in electrochemical and bio-sensing technology. While HMDEs have been valued for their reproducible surface and wide potential window, they suffer from significant drawbacks including toxicity, lack of miniaturization potential, and impracticality for in vivo or implantable applications. Solid-state platforms overcome these limitations by offering robust, non-toxic, and miniaturizable alternatives that enable direct biological integration, continuous monitoring, and point-of-care diagnostics. This paradigm shift is particularly crucial for advancing in vivo sensing, drug development, and personalized healthcare, where real-time, reliable data from within the body can transform therapeutic outcomes.

The core advantages of solid-state electrodes over HMDE stem from their material composition and structural integrity. Solid-state electrodes utilize materials such as metals, metal oxides, carbon-based materials, and conductive polymers fabricated into rigid or flexible substrates suitable for specific biological environments [29]. This fundamental difference enables their application in miniaturized systems for intracranial monitoring, salivary diagnostics, and continuous physiological tracking—applications entirely inaccessible to mercury-based systems. Furthermore, the compatibility of solid-state electrodes with microfluidic systems and wireless technology facilitates the development of compact, wearable, and implantable devices that operate autonomously within complex biological matrices [30] [31].

Core Advantages of Solid-State Electrodes over HMDE

The limitations of HMDE have driven the scientific community toward developing sophisticated solid-state alternatives. The comparative advantages extend beyond mere toxicity concerns to encompass performance, practicality, and integration potential.

Table 1: Fundamental Advantages of Solid-State Electrodes over HMDE

| Aspect | Hanging Mercury Drop Electrode (HMDE) | Solid-State Electrodes |

|---|---|---|

| Toxicity & Environmental Impact | Highly toxic mercury poses health and environmental risks [29]. | Non-toxic, biocompatible materials (e.g., Au, Pt, carbon, polymers) [32] [33]. |

| Miniaturization Potential | Very poor; limited by liquid mercury's physical properties. | Excellent; compatible with micro/nanofabrication techniques for microfluidic and implantable devices [30] [34]. |

| Mechanical Stability & Robustness | Low; electrode surface is transient and fragile. | High; stable, durable surfaces suitable for long-term and in vivo use [33] [29]. |

| Suitability for In Vivo Implantation | None; toxic and mechanically unstable. | High; biocompatible and can be engineered for flexibility to match tissue mechanics [33]. |

| Operational Practicality | Requires specialized equipment for drop formation and mercury containment. | Simple operation; can be pre-fabricated, stored, and integrated into automated systems [30] [29]. |

Beyond the fundamental advantages outlined in Table 1, solid-state platforms enable advanced functionalities. Their mechanical properties can be tailored to match biological tissues, a critical factor for chronic implants. For instance, neural tissues have a soft consistency (Young’s modulus of 1–10 kPa), and interfacing with traditional rigid materials creates a mechanical mismatch that induces inflammatory responses [33]. Modern solid-state interfaces can be fabricated from soft conductive polymers or hydrogels, significantly improving biocompatibility and long-term signal stability by mitigating foreign body reactions [32] [33].

Material Platforms and Fabrication Methodologies

The performance of solid-state sensors is intrinsically linked to their material composition and fabrication strategy. Recent research has focused on enhancing conductivity, biocompatibility, and mechanical matching with biological tissues.

Key Material Classes

- Conductive Hydrogels: These represent a cutting-edge material class that combines ionic conductivity with tissue-like mechanical properties. For example, semi-dry hydrogel electrodes for electroencephalography (EEG) are synthesized from polymers like N-acryloyl glycinamide (NAGA) and hydroxypropyltrimethyl ammonium chloride chitosan (HACC). They exhibit excellent mechanical properties (compression modulus ~65 kPa), antibacterial properties, and stable contact impedance (<400 Ω over 12 hours), making them ideal for long-term biosensing [32].

- Metal Oxides and Nitrides: Used extensively for potentiometric sensors, such as pH electrodes, these materials offer robustness, chemical inertness, and Nernstian sensitivity. Metal nitrides, in particular, demonstrate superior performance in challenging redox environments compared to metal oxides [29].

- Conductive Polymers: Polymers like poly(3,4-ethylenedioxythiophene)-poly(styrenesulfonate) (PEDOT:PSS) are crucial for all-solid-state ion-selective electrodes. They serve as an ion-to-electron transduction layer between the electron-conducting substrate and the ion-selective membrane, improving stability and potentiometric response [30].

Fabrication of a Microfluidic All-Solid-State Ion-Selective Electrode

The integration of solid-state electrodes with microfluidics exemplifies the miniaturization potential of this technology. The following protocol details the fabrication of a sensor for real-time salivary ion monitoring [30].

- Substrate Preparation: A polyethylene terephthalate (PET) film is cleaned with isopropyl alcohol to remove contaminants.

- Electrode Deposition: A thin adhesion layer of titanium (30 nm) followed by a gold layer (50 nm) is deposited onto the PET substrate using a physical vapor deposition system (e.g., SVC-700TM).

- Patterning and Sensing Site Definition: A protective PET layer is laminated onto the metalized film, leaving a defined sensing region (e.g., 3 mm diameter) exposed.

- Transduction Layer Application: PEDOT:PSS conducting polymer is drop-cast (2.5 μL) onto the exposed sensing area and thermally cured at 140 °C for 5 minutes.

- Ion-Selective Membrane (ISM) Casting: A membrane cocktail is prepared by dissolving specific ionophores, polyvinyl chloride (PVC) as a matrix, 2-Nitrophenyl octyl ether (NPOE) as a plasticizer, and ion-exchanger in tetrahydrofuran (THF). This cocktail is drop-cast onto the PEDOT:PSS layer and allowed to dry, forming the sensing membrane.

- Microfluidic Integration: A polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) layer, molded to create a flow channel (e.g., 3 mm width, 0.5 mm height), is bonded to a separate glass substrate. This assembly is then aligned and attached to the sensor substrate, creating a sealed flow path over the electrode.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Solid-State Sensor Fabrication

| Material/Reagent | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| PEDOT:PSS | Conducting polymer for ion-to-electron transduction in all-solid-state electrodes. | Serves as the intermediate layer in ion-selective electrodes to stabilize potential [30]. |

| N-acryloyl glycinamide (NAGA) | Monomer for forming tough, biocompatible hydrogel networks. | Used in semi-dry EEG electrodes for brain-computer interfaces [32]. |