Advancing Accuracy in Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Validation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on achieving high accuracy in Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS).

Advancing Accuracy in Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on achieving high accuracy in Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS). Covering the journey from fundamental principles to advanced applications, it details the essential theoretical requirements of linearity, stationarity, and causality. The article explores robust experimental methodologies, advanced signal processing techniques, and systematic troubleshooting for common measurement errors. It further establishes a rigorous framework for data validation using the Kramers-Kronig relations and statistical model selection criteria like AIC and BIC. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with modern computational and methodological advances, this resource aims to empower scientists to generate reliable, reproducible, and meaningful EIS data for critical applications in biosensing and biomedical research.

Mastering EIS Fundamentals: The Pillars of Accurate Measurement

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) and what core principle does it extend?

EIS is a powerful analytical technique that characterizes complex electrochemical systems by measuring their impedance—a more general form of resistance—across a range of frequencies [1] [2]. It directly extends Ohm's Law, which defines resistance (R) as the ratio of voltage (E) to current (I) in a direct current (DC) system: E = IR [3] [4]. EIS applies this same ratio concept but uses a small-amplitude alternating current (AC) signal, leading to the definition of impedance (Z) as the ratio of the time-varying voltage to the time-varying current: Z = E(ω) / I(ω) [4]. This allows EIS to study not just resistive behavior, but also capacitive and inductive processes that are frequency-dependent [5].

2. Why must the AC excitation signal used in EIS be kept small (typically 1-10 mV)? Electrochemical cells are inherently non-linear, meaning doubling the voltage will not necessarily double the current [3]. A large excitation signal would probe this non-linear region, distorting the response. A small AC signal (e.g., 1-10 mV rms) ensures the system operates in a pseudo-linear region of its current-voltage curve [3] [5]. This is critical for obtaining a sinusoidal current response at the same frequency as the input, which is a fundamental assumption for the subsequent impedance analysis [3].

3. What is the critical steady-state assumption in EIS, and what happens if it is violated? A core assumption of EIS is that the electrochemical system is at a steady state throughout the measurement, which can take from several minutes to hours [3]. If the system is drifting (e.g., due to adsorption of impurities, temperature changes, or degradation), the resulting impedance data can be inaccurate and lead to wildly incorrect interpretations when fitted with standard equivalent circuit models [3] [6]. Drift is a significant challenge in systems like batteries, where the state changes rapidly even during a single charge-discharge cycle [6].

4. My Nyquist plot has an unexpected shape. What could be the cause? Unexpected shapes in a Nyquist plot often point to non-ideal system behavior or measurement artifacts. The table below summarizes common issues.

Table: Troubleshooting Common EIS Data Artifacts

| Observation | Potential Cause | Troubleshooting Action |

|---|---|---|

| Incomplete or depressed semicircle[s] [3] | Surface roughness, porosity, or non-uniform current distribution [7]. | Check electrode preparation and surface homogeneity; consider using Constant Phase Elements (CPE) in equivalent circuit models. |

| Low-frequency data scattering upwards [4] | System instability or drift during the long measurement time at low frequencies [3]. | Verify system is at steady-state; use a Faraday cage to reduce noise [5]; consider faster measurement techniques like multi-sine EIS [6]. |

| Data points are noisy or erratic | Electrical noise or poor electrode connections [5]. | Use a Faraday cage; ensure all connections are secure and electrodes are properly immersed in the electrolyte [5]. |

| Inductive loop (data points in negative -Zimag quadrant) | Adsorption processes or relaxation of surface species [3]. | Review the electrochemical processes; may require a more complex equivalent circuit model. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Standard Protocol for Potentiostatic EIS Measurement

This protocol outlines the key steps for a basic 3-electrode potentiostatic EIS experiment, commonly used for analyzing coated metals or corrosion performance [5].

1. Electrode and Cell Setup:

- Working Electrode (WE): The material under investigation (e.g., a coated aluminum panel). A portion of bare metal must be exposed to make an electrical connection [5].

- Counter Electrode (CE): An inert conductor such as a graphite or platinum rod [5].

- Reference Electrode (RE): A stable reference such as a Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) or Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl) [5].

- Electrolyte: Fill the cell with an appropriate solution (e.g., 0.6 M NaCl for corrosion studies) [5] [7].

- Connections: Connect the potentiostat leads: Working and Working Sense to the WE, Reference to the RE, and Counter to the CE. For low-current measurements, place the entire cell inside a Faraday cage and connect its Floating Ground lead to the cage to reduce electrical noise [5].

2. Instrument Configuration: Configure the software with parameters appropriate for your system. The values below are an example for a coated metal sample [5].

- Initial Frequency: 10000 Hz (High frequency)

- Final Frequency: 0.1 Hz (Low frequency)

- Points per Decade: 10 (Logarithmically spaced)

- AC Voltage: 10 mV (rms amplitude)

- DC Voltage: The desired potential vs. the reference (e.g., open circuit potential)

- Optimize for: Normal (A balance of speed and data quality)

3. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- Initiate the experiment. The potentiostat will apply a sine wave at each frequency and measure the current response, often displaying it as a Lissajous curve [5].

- After the frequency sweep, fit the acquired data (commonly displayed in a Nyquist or Bode plot) to an appropriate equivalent circuit model (e.g., a model containing a solution resistor and a constant phase element) using simulation software [3] [5].

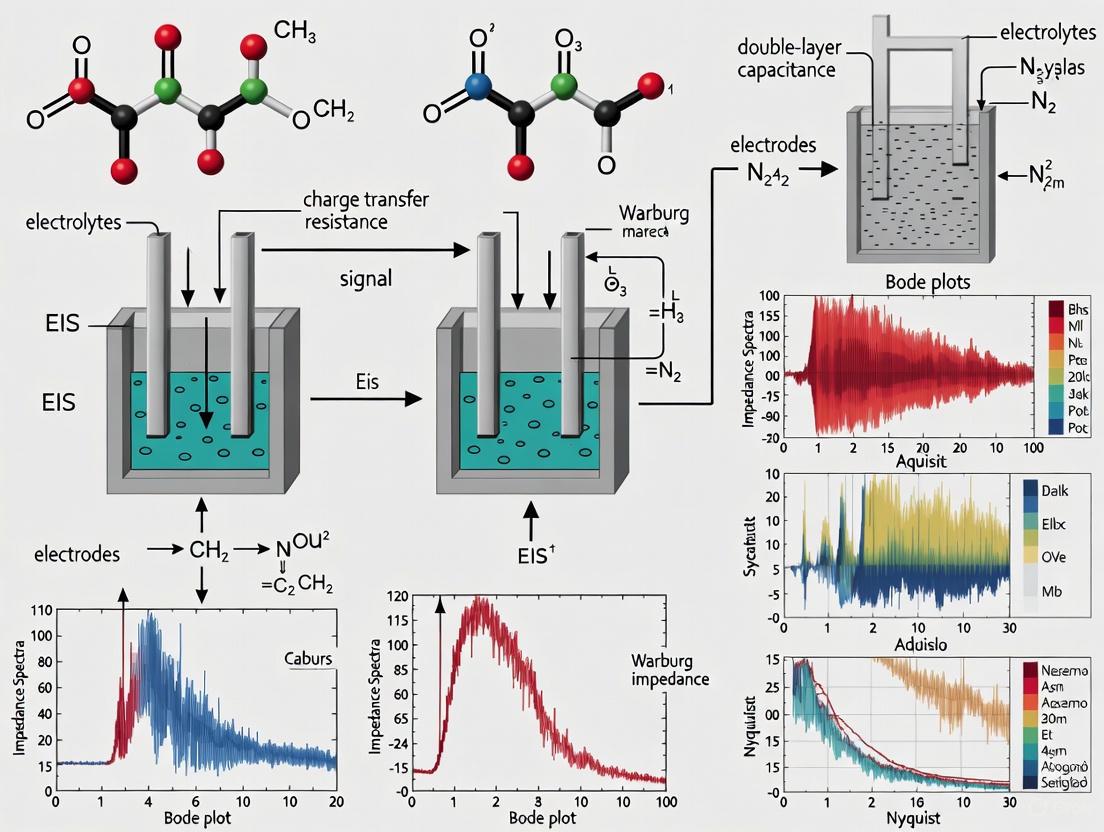

Workflow for EIS Measurement and Data Validation

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for a robust EIS experiment, incorporating key steps to ensure data accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Materials & Reagents

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for a Standard EIS Experiment

| Item | Function / Purpose | Example from Search Results |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat / Galvanostat with FRA | The core instrument that applies the AC potential/current and measures the resulting current/potential response. | Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT302N [7]; Gamry potentiostats [5]. |

| Three-Electrode Cell | Provides a controlled electrochemical environment. The setup minimizes uncompensated resistance and provides a stable reference potential. | Working Electrode (sample), Counter Electrode (graphite/Pt), Reference Electrode (SCE/AgAgCl) [5] [7]. |

| Electrolyte Solution | Provides ionic conductivity between the electrodes. Its composition is critical and depends on the application (e.g., corrosion, batteries). | 0.6 M NaCl solution for corrosion studies [7]; 37 wt.% NaOH for other alloy tests [7]. |

| Faraday Cage | A metallic enclosure that shields the electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic interference, crucial for accurate low-current measurements [5]. | Gamry Faraday Shield [5]. |

| Conductive Adhesive & Epoxy Resin | Used to create a reliable electrical connection to the back of the working electrode and to seal it, exposing only a defined surface area to the electrolyte. | Method for preparing 2205 alloy samples [7]. |

| Equivalent Circuit Modeling Software | Software used to fit experimental EIS data to physical or empirical models to extract quantitative parameters (e.g., charge transfer resistance). | ZView2 software [7]; Zahner's software with Z-HIT algorithm [6]; Gamry Echem Analyst [5]. |

Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) is a powerful technique revolutionizing research in electrochemistry, from battery material optimization to biosensor development [8]. However, its reliability hinges on fulfilling three critical hypotheses: linearity, stationarity, and causality [9] [8]. When any of these conditions is not met, EIS spectra become biased, leading to erroneous conclusions about the studied system [9]. This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support to ensure your EIS data meets these fundamental requirements, thereby enhancing the accuracy of your research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why are linearity, stationarity, and causality so critical for EIS? EIS theory is based on the analysis of Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) systems [8]. The impedance concept, defined by Ohm's generalized law in the frequency domain, is only valid if the system under investigation is causal (the response is solely due to the applied perturbation), linear (obeys the superposition principle), and stationary (its properties do not change during the measurement) [9]. Non-fulfillment distorts the measured spectrum, compromising subsequent analysis like equivalent circuit modeling [9].

2. My electrochemical system is inherently non-linear. How can I perform EIS? Most electrochemical systems are inherently non-linear due to factors like logarithmic interfacial reactions (Buttler-Volmer kinetics) [10] [9]. The solution is to use a perturbation signal with a sufficiently small amplitude. This ensures that the system's response is examined over a very small portion of its steady-state curve, which can be approximated as linear (see Figure 6) [8]. The challenge lies in finding an amplitude that is small enough for linearity but large enough for a good signal-to-noise ratio [9].

3. What are the practical signs that my EIS measurement is non-stationary? A clear sign is a drift in the DC potential or current during the measurement. Furthermore, the impedance spectrum may show poor reproducibility or a low-frequency tail that behaves unphysically. Techniques like the Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) indicator can quantify this effect by detecting frequencies in the output signal generated by the system's time-variance [8]. For example, EIS on a battery under discharge current may only be valid above a certain frequency threshold (e.g., 0.1 Hz) where the NSD is low [8].

4. How can I check for causality in my EIS data? Causality is intrinsically linked to linearity and stationarity and is most commonly validated using the Kramers-Kronig (K-K) relations [10]. These are integral relations that link the real and imaginary parts of the impedance. If the data violates these relations, one or more of the fundamental conditions (causality, linearity, stationarity) is not met [9]. An alternative and increasingly popular method is the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) analysis. It has been mathematically proven that the DRT kernel inherently satisfies the K-K relations, providing a convenient tool for data validation [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Non-Linearity Distortion

Diagnosis: Non-linearity generates non-fundamental harmonics in the output signal. When a mono-frequency sinusoidal perturbation is applied to a non-linear system, the response contains not only the fundamental frequency but also its integer multiples (harmonics) [9]. This distorts the EIS spectrum.

- Quantitative Check: Use Total Harmonic Distortion (THD). THD calculates the percentage of harmonic content in the output signal relative to the fundamental. A threshold of 5% is generally accepted to separate linear from non-linear responses [8].

- Qualitative Check: Observe Lissajous figures (I-V plots) during measurement. A perfectly elliptical shape indicates a linear response, while distortion indicates non-linearity [9].

Solutions:

- Reduce Perturbation Amplitude: Decrease the amplitude of your AC stimulus until the THD is below the 5% threshold across all frequencies [8]. Note that lower amplitudes reduce the signal-to-noise ratio, requiring a careful balance [9].

- Use Harmonic Analysis: Employ a frequency response analyzer that can measure harmonic content. This data can be used to optimize the perturbation amplitude for each frequency point [9].

Table 1: Methods for Linearity Assessment and Their Characteristics

| Method | Principle | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) [8] | Quantifies harmonic distortion in output signal | Quantitative, objective, high sensitivity [9] | Requires equipment capable of harmonic analysis |

| Lissajous Figures [9] | Visual inspection of current-voltage plot | Simple, can be done in real-time during measurement | Qualitative, subjective for low-level distortions [9] |

| Kramers-Kronig Relations [9] | Checks data consistency with integral transforms | Foundational theoretical test | Low sensitivity to non-linearity [9] |

Issue 2: Non-Stationarity (Time-Variance)

Diagnosis: Non-stationarity occurs when the system's properties change during the EIS measurement. This is common in battery EIS under load (changing State of Charge) or in corroding electrodes (changing surface state) [10] [8].

- Quantitative Check: Use the Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) indicator. Similar to THD, NSD quantifies frequency components generated by time-variance, providing a frequency-dependent measure of non-stationarity [8].

- Experimental Check: Monitor the open-circuit voltage (OCV) or steady-state current before and after the EIS measurement. A significant drift indicates a non-stationary system.

Solutions:

- Ensure Steady-State: Before measuring, wait until the system's OCV and other parameters have stabilized. For battery testing, this may require long rest periods after charging/discharging [8].

- Minimize Measurement Time: Use faster EIS techniques, such as Dynamic EIS (DEIS) or multi-sine methods, which can acquire a full spectrum in a shorter time, reducing the window for the system to drift [10].

- Use DRT for Diagnosis: The Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) can be used to qualitatively diagnose low-frequency non-stationarity and time-variance in EIS data [10].

Issue 3: Causality Violation and Data Validation

Diagnosis: Causality is violated if the system's response is not solely caused by the applied perturbation (e.g., due to external noise or instrument artifacts). This is often diagnosed indirectly via K-K relations or DRT [10] [9].

Solutions:

- Kramers-Kronig (K-K) Validation: Apply K-K transforms to your impedance data. If the transformed real part does not match the measured real part (and vice versa), the data is non-causal, non-linear, or non-stationary [9].

- DRT-based Validation: Use the DRT transform as a validation tool. Since the DRT solving kernel inherently satisfies the K-K relations, it provides a robust and often numerically convenient path for EIS data validation [10].

- Improve Shielding and Grounding: To prevent external electromagnetic interference from causing non-causal responses, ensure proper shielding of your electrochemical cell and cables.

The logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing violations of the critical triad is summarized in the following diagram:

EIS Data Validation Workflow

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Optimizing Perturbation Amplitude via Harmonic Analysis

This protocol provides a quantitative method to find the optimal perturbation amplitude that ensures linearity while maintaining a good signal-to-noise ratio [9].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Initial Setup: Select a single, mid-range frequency (e.g., 1 Hz). Set your potentiostat to apply a sinusoidal potential (or current) perturbation.

- Data Acquisition: For a series of increasing perturbation amplitudes, record the raw current and voltage signals in the time domain,

I(t)andU(t). - Frequency Domain Transformation: Apply a Fourier transform to the raw signals to obtain the spectra

Î(ϑ)andÛ(ϑ). - Harmonic Calculation: For each amplitude, calculate the ratio

Rof the sum of the magnitudes of the 2nd and 3rd harmonics to the magnitude of the fundamental harmonic in the output signal. - Determine Optimal Amplitude: Plot the calculated ratio

Ragainst the perturbation amplitude. The optimal amplitude is the largest value for whichRremains below your chosen threshold (e.g., 5% for THD) [8]. - Full Spectrum Measurement: Use the determined optimal amplitude (or a slightly smaller value) to perform the full frequency sweep of your EIS experiment.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for EIS Experiments

| Item | Function in EIS Experiment |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with FRA | Core instrument for applying controlled perturbations and measuring precise responses. |

| Faraday Cage | Metallic enclosure to shield the electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic noise, ensuring causality. |

| Thermostated Cell Holder | Maintains constant temperature, a key factor in ensuring stationarity during long measurements. |

| Electrochemical Cell (3-electrode) | Provides a controlled environment with working, counter, and reference electrodes for accurate potential measurement. |

| Validated Electrolyte | High-purity electrolyte with known conductivity and minimal contaminants to avoid spurious electrochemical processes. |

Protocol 2: Validating Data using DRT and K-K Relations

This protocol uses the Distribution of Relaxation Times (DRT) as a powerful tool for validating the quality of your EIS data against the fundamental requirements [10].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Measure EIS Data: Acquire your impedance spectrum

Z(ω)across the desired frequency range. - Perform DRT Transform: Calculate the DRT

γ(τ)from your measuredZ(ω)data. This involves solving an ill-posed inverse problem, typically using ridge regression or Tikhonov regularization. - Perform Inverse DRT Transform: Use the calculated DRT

γ(τ)to reconstruct the impedance spectrumZ'(ω)via the inverse DRT transform. - Compare and Validate: Compare the reconstructed spectrum

Z'(ω)with your original measured dataZ(ω). A good agreement indicates that the data is consistent with the behavior of an LTI system and thus likely satisfies linearity, stationarity, and causality. - (Alternative) Standard K-K Check: As a complementary step, apply classical Kramers-Kronig relations to your data. Check if the real part calculated from the imaginary part via K-K transforms matches the measured real part.

The application of the DRT method for data preprocessing and validation is illustrated below:

DRT-Based Preprocessing Workflow

Understanding Measurement Assumptions and System Stability

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the three fundamental conditions for obtaining valid EIS data? For EIS data to be considered valid, the electrochemical system under test must meet three primary conditions [11]:

- Stability: The system must not change with respect to time and must return to its initial state after the AC signal is removed.

- Causality: The measured output signal must be solely caused by the applied input signal.

- Linearity: The system's response must be linearly proportional to the applied perturbation. This is typically achieved by using a small excitation signal amplitude (e.g., 1-20 mV) [3] [11].

Q2: Why do my low-frequency EIS data often appear distorted or noisy? Distortion at low frequencies is a classic symptom of a system that is not at a steady state or is time-variant [12]. Because low-frequency measurements take a long time (minutes or even hours per point), any slow drift in the system—such as corrosion, adsorption, surface degradation, or temperature fluctuations—becomes visible in the data. High-frequency data, being measured quickly, are less affected by such drift [3] [12].

Q3: How can I quickly check if my system is behaving linearly during an EIS measurement? Most modern potentiostat software can display a Lissajous plot (a plot of the instantaneous current vs. potential) in real-time [11]. For a linear system, this plot should form a perfect, clean ellipse. If the ellipse appears distorted or "banana-shaped," it indicates nonlinear system behavior, often due to an excessively large excitation amplitude [11].

Q4: What is a simple method to correct for time-variance in my EIS measurements? One established method is to use the Z Inst (Instantaneous Impedance) tool, which implements an algorithm developed by Stoynov and Savova [12]. This involves:

- Acquiring multiple successive impedance spectra over time.

- Interpolating the data to create a 3D impedance "surface" (impedance vs. frequency vs. time).

- Taking cross-sections of this surface to reconstruct the instantaneous impedance spectrum at any specific point in time, effectively correcting for the time-based drift [12].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Distorted Low-Frequency Data Due to System Drift

Symptoms: A "tail" or strange shape in the Nyquist plot at low frequencies that doesn't correspond to expected model behavior; a rising Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) factor at low frequencies [12].

Required Materials: Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for EIS Stability

| Item | Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat with EIS Capability | Applies the AC signal and measures the cell's current/voltage response. |

| Electrochemical Cell | The system under test, including working, counter, and reference electrodes. |

| Data Analysis Software (e.g., EC-Lab) | For data acquisition, visualization, and analysis (e.g., Z Inst correction). |

| Thermostatted Bath/Chamber | Maintains a constant temperature to minimize one major source of system drift. |

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Verify Drift: Before starting the EIS measurement, monitor the open circuit potential (OCP) or current at your DC setpoint for a significant period. If a steady drift is observed, the system is not stable [11].

- Allow Settling Time: After setting your DC bias, incorporate a sufficient settling time into your experimental protocol before the EIS sine waves begin. This allows the system to reach a steady state [11].

- Check Data Quality Indicators: Use quality indicators like Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) if your instrument provides them. An increasing NSD at low frequencies confirms time-variant behavior [12].

- Apply Correction: If the measurement must be performed on a drifting system, use the Z Inst method described in FAQ A4. Acquire several quick scans and use the software to reconstruct the instantaneous impedance [12].

Problem 2: Non-Linear System Response

Symptoms: Distorted Lissajous plots; the measured impedance changes when the amplitude of the excitation signal is changed [11].

Step-by-Step Protocol:

- Reduce Excitation Amplitude: Begin by significantly reducing the amplitude of your AC signal. A common range for potentiostatic EIS is 5 to 20 mV [11].

- Perform Amplitude Test: Conduct a series of EIS measurements at a single frequency while varying the AC amplitude. Plot the resulting impedance magnitude versus the amplitude.

- Identify the Linear Range: The range of amplitudes over which the impedance magnitude remains constant is your "pseudo-linear" range. Select an amplitude from within this range for your full spectrum measurement [3] [11].

- Monitor in Real-Time: Use the real-time Lissajous plot display to ensure a clean elliptical shape forms during the measurement [11].

Problem 3: Enhancing Measurement Speed for Time-Variant Systems

Symptoms: Needing to characterize a system that changes rapidly, making traditional sweep-based EIS too slow.

Advanced Protocol: Using Optimized Multi-Sine Signals Traditional EIS applies one frequency at a time. Multi-sine EIS applies a signal containing many frequencies simultaneously, drastically reducing measurement time [13].

- Signal Synthesis: Create an excitation current signal,

I_multisine, which is a sum of multiple sine waves [13]:I_multisine = Σ A_i * sin(ω_i * t + ϕ_i)whereA_i,ω_i, andϕ_iare the amplitude, angular frequency, and phase of the i-th frequency component. - Parameter Optimization:

- Frequency Selection: Optimize the selection of frequencies to cover the desired range efficiently [13].

- Amplitude Optimization: Adjust amplitudes based on the system's impedance characteristics to improve the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) across all frequencies [13].

- Phase Optimization: Optimize the phases

ϕ_ito create a signal with a low crest factor (peak-to-RMS ratio), which reduces the instantaneous power demand on the potentiostat [13].

- Application and Analysis: Apply the optimized multi-sine signal to the cell, measure the voltage response, and use a Fourier transform to deconvolve the individual frequency responses and calculate the impedance spectrum [13].

Experimental Workflow Diagram The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing common EIS stability issues, integrating the methods described in the troubleshooting guides.

Data Presentation

Table 1: EIS Quality Indicators and Interpretation [12] [11]

| Quality Indicator | What it Measures | Ideal Value / Shape | Indication of a Problem |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lissajous Plot | Linearity: Plot of instantaneous current vs. voltage. | A clean, undistorted ellipse. | A distorted, "banana-shaped" plot. |

| Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD) | System stationarity over the measurement duration. | A low, consistent value across all frequencies. | A significant increase in value, especially at low frequencies. |

| Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) | The appearance of harmonics due to non-linearity. | A low value (minimal harmonics). | A high value, indicating a non-linear response. |

Table 2: Comparison of EIS Measurement Techniques for System Stability [13] [12]

| Technique | Principle | Advantages | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Sweep EIS | Applies single-frequency sine waves sequentially. | High accuracy per point; well-established analysis. | Long measurement time; highly susceptible to low-frequency drift. |

| Z Inst (Instantaneous Impedance) | Interpolates multiple sequential spectra to create a time-correction. | Corrects for time-variance; provides a "snapshot" of impedance. | Requires multiple measurements; more complex data analysis. |

| Optimized Multi-Sine EIS | Applies many frequencies simultaneously in one optimized signal. | Very fast (e.g., >85% time savings); suitable for dynamic systems [13]. | Requires sophisticated signal synthesis and processing; potential for higher error if not optimized [13]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a Nyquist plot and a Bode plot?

Both plots display Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) data but present the information differently [14] [15].

- Nyquist Plot: This is a single plot in the complex plane where the negative imaginary impedance (-Z") is plotted against the real impedance (Z') for each frequency [14] [4]. A key limitation is that the frequency information is not directly visible on the plot trace; the highest frequencies are typically on the left and the lowest on the right [15]. It is highly sensitive to changes and is popular in electrochemistry because parameters can often be read directly from the plot, such as the solution resistance from the left intercept of a semicircle [14].

- Bode Plot: This consists of two separate plots sharing a common logarithmic frequency axis [14]. One plot shows the logarithm of the impedance magnitude (|Z|), and the other shows the phase angle (Φ) versus log frequency [3] [15]. The advantage is that all information, including frequency, is clearly visible, making it easier to understand the behavior of single components [14].

Q2: What does a "semicircle" in a Nyquist plot tell me about my electrochemical system?

A semicircle in a Nyquist plot is characteristic of a single "time constant" and often represents a parallel combination of a resistor and a capacitor [14] [3]. In a simplified Randles circuit model for an electrode-electrolyte interface [14]:

- The leftmost intercept of the semicircle with the real (Z') axis corresponds to the solution resistance (Rsol).

- The diameter of the semicircle corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (Rct).

- The frequency at the top of the semicircle (where -Z" is maximum) can be used to calculate the double layer capacitance (Cdl) using the formula:

f_max = 1 / (2π R_ct C_dl)[14].

Real-world systems may show depressed or multiple semicircles, indicating non-ideal behavior or multiple electrochemical processes [3].

Q3: How can I tell from a Bode plot if my system is behaving capacitively or resistively?

The phase angle (Φ) on the Bode plot provides a quick way to identify the dominant behavior at any given frequency [15]:

- A phase angle near 0° indicates purely resistive behavior [14] [15].

- A phase angle near -90° indicates purely capacitive behavior [14] [15].

- A phase angle of +90° would indicate purely inductive behavior, though this is less common in basic electrochemical cells [15].

In a typical Randles circuit, the phase angle starts at 0° at very high frequencies, increases to a peak (e.g., towards -90°), and then falls back to 0° at low frequencies [14].

Troubleshooting Common Data Issues

Issue 1: Unrealistic Inductive Loops at High Frequency

- Symptoms: The Nyquist plot shows a tail looping into the negative quadrant (-Z") at high frequencies [16].

- Causes: This is often an artifact caused by stray inductance in the measurement setup, not a property of the electrochemical cell itself. This can be caused by long connecting wires, the physical arrangement of cables (especially if they form loops), or even the geometry of a test fixture like a cylindrical battery [16]. The impedance of an inductor increases with frequency (

Z_L = jωL), which manifests as a positive imaginary impedance [16]. - Solutions:

- Use short and twisted connection cables.

- Avoid creating loops with the measurement leads.

- Keep current-carrying and voltage-sensing cables close together to minimize the enclosed area and reduce magnetic coupling [16].

Issue 2: Scatter and Inaccuracies at Low Frequency

- Symptoms: Data points at the low-frequency end of the spectrum (right side of Nyquist plot) appear noisy, scattered, or drift from an expected trend.

- Causes:

- System Instability: The electrochemical system is not at a steady state. Factors like adsorption of impurities, growth of surface layers, or temperature changes can cause the system to drift during the sometimes lengthy measurement [3].

- External Noise: The system is susceptible to low-frequency environmental noise.

- Solutions:

- Ensure the system has reached a stable steady state before beginning the measurement.

- For high-impedance samples, place the cell inside a Faraday cage to shield it from external electromagnetic noise [16].

Issue 3: Distorted Semicircles and Non-Ideal Capacitive Behavior

- Symptoms: The semicircle in the Nyquist plot is depressed (looks like a semi-ellipse) or tilted, rather than a perfect half-circle centered on the x-axis.

- Causes: Real-world surfaces are often rough and chemically heterogeneous, unlike the ideal capacitor assumed in simple models. This distribution of properties leads to a distribution of time constants [14].

- Solutions:

- Use a Constant Phase Element (CPE) instead of an ideal capacitor when fitting the data with an equivalent circuit. The CPE's impedance is defined as

Z_CPE = 1 / [Q(jω)^n], wherenis an exponent (0 ≤ n ≤ 1). Annof 1 represents an ideal capacitor, while lower values represent increasing non-ideality.

- Use a Constant Phase Element (CPE) instead of an ideal capacitor when fitting the data with an equivalent circuit. The CPE's impedance is defined as

Essential Experimental Protocols for High-Quality EIS

Protocol 1: Ensuring System Linearity and Stability

EIS theory requires that the system is linear, causal, and stable over the measurement time [3] [16].

- Verify Pseudo-Linearity: Use a small-amplitude excitation signal (typically 1-10 mV) to ensure the cell's response is pseudo-linear. A large signal will provoke a non-linear response and distort the results [3].

- Confirm Steady State: Monitor the open circuit potential (OCP) of the system. The system is considered stable when the OP drift is minimal (e.g., < 1 mV/min) over a period significantly longer than the time required for one EIS measurement.

- Check for Harmonics: Some advanced potentiostats can measure harmonic responses. The significant presence of harmonics indicates non-linear behavior, suggesting the excitation amplitude should be reduced [3].

Protocol 2: Optimizing Measurement Speed with Multi-Sine Signals

Traditional EIS uses a sequence of single-frequency sine waves, which can be time-consuming, especially at low frequencies. A modern approach uses optimized multi-sine signals to accelerate data acquisition [13].

Methodology:

- Signal Synthesis: A multi-sine excitation current signal is generated by summing several sinusoidal signals of different frequencies [13]:

I_multisine = Σ A_i * sin(ω_i*t + φ_i) - Signal Optimization:

- Frequency Selection: Optimize the selection of frequencies to cover the desired decade range efficiently.

- Amplitude Optimization (Ai): Adjust amplitudes based on the battery's impedance characteristics to enhance the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), particularly at high frequencies [13].

- Phase Optimization (φi): Optimize the phases of the individual sine waves to reduce the peak value of the composite signal, lowering the instantaneous power demand on the instrument [13].

- Application and Measurement: Apply the single, optimized multi-sine signal to the cell and measure the voltage response.

- Post-Processing: Use a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) to deconvolve the response signal into its frequency components and calculate the impedance at each frequency [13].

Validated Results: One study achieved a full spectrum measurement (0.1 Hz to 1 kHz) in ~31 seconds—an 86% time saving compared to traditional methods—with a maximum magnitude error of 0.47% and phase error of 0.23° [13].

Table 1: Common Circuit Elements and Their Impedance Signatures

| Component | Impedance Formula | Nyquist Plot Representation | Bode Plot (Phase) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resistor (R) | Z = R | A single point on the real axis [14] | Constant at 0° [14] [15] |

| Capacitor (C) | Z = 1 / (jωC) | A straight line along the negative imaginary axis [14] | Constant at -90° [14] [15] |

| Inductor (L) | Z = jωL | A straight line along the positive imaginary axis | Constant at +90° [15] |

| Resistor & Capacitor (Parallel) | Z = (1/R + jωC)⁻¹ | A semicircle with diameter R [14] | Phase shifts from 0° to a peak toward -90° and back to 0° [14] |

Table 2: Multi-Sine vs. Traditional Single-Sine EIS Performance

| Parameter | Traditional Single-Sine | Optimized Multi-Sine (Example) |

|---|---|---|

| Measurement Time (0.1 Hz - 1 kHz) | ~495 s [13] | ~31 s [13] |

| Time Savings | Baseline | 86.12% [13] |

| Maximum Magnitude Error | Not specified | 0.47% [13] |

| Maximum Phase Error | Not specified | 0.23° [13] |

| Key Advantage | High accuracy per point, well-established | Extreme speed, suitable for dynamic systems [13] |

| Key Disadvantage | Slow, potential for system drift [3] [13] | Complex signal optimization required [13] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Key Components for EIS Research and Analysis

| Item | Function in EIS Research |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with FRA | The core instrument that applies the AC potential/current and measures the cell's response. A Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) is essential for accurate impedance measurements. |

| Faraday Cage | A grounded metallic enclosure that shields the electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic noise, crucial for measuring high-impedance samples [16]. |

| Low-Stray Capacitance Cables | Specially designed cables (e.g., with active shielding) that minimize stray capacitance, which can distort high-frequency measurements [14] [16]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled and measured. A stable reference is critical for valid EIS data. |

| Equivalent Circuit Fitting Software | Software used to model the impedance spectrum by fitting it to an equivalent electrical circuit, allowing the quantification of physical parameters (e.g., Rct, Cdl). |

Diagnostic Diagrams

Diagram 1: EIS Data Diagnosis Workflow

Diagram 2: Randles Circuit Model

Precision in Practice: Robust Experimental Techniques and Advanced Signal Design

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Electrode Configuration

Q1: What is the standard electrode configuration for a reliable EIS experiment?

The most common and recommended configuration for a reliable Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) experiment is the three-electrode system [5]. This setup consists of:

- Working Electrode (WE): This is the material or sample under investigation (e.g., a coated metal, a battery electrode, or a sensor surface). The Working (green) and Working Sense (blue) leads from the potentiostat are connected here [5] [17].

- Reference Electrode (RE): This electrode (e.g., Saturated Calomel - SCE, or Silver/Silver Chloride - Ag/AgCl) provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured and controlled. The Reference (white) lead is connected here [5].

- Counter Electrode (CE): Also known as the auxiliary electrode, this electrode (often made of inert materials like graphite or platinum) completes the electrical circuit by supplying the current required to balance the current at the working electrode. The Counter (red) lead is connected here [5].

This configuration ensures that the current is measured only at the working electrode, while the reference electrode maintains a stable potential, leading to more accurate and interpretable results [5].

Q2: What are the critical steps for verifying my electrode connections?

Incorrect cable connections are a primary source of experimental error. Please verify the following [5] [17]:

- Cable Connections: Ensure the correct potentiostat leads are attached to the corresponding electrodes, as detailed in the table below.

- Electrode Exposure: Confirm that all electrodes are properly submerged in and exposed to the electrolyte solution [5].

- Electrical Contact: For the working electrode, ensure a secure electrical connection is made to a bare, uncoated portion of the sample [5].

Table: Standard Potentiostat Lead Connections for a Three-Electrode Setup

| Potentiostat Lead | Lead Color (Gamry Example) | Connected To | Function |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working | Green | Working Electrode | Carries current to/from the sample under test [5]. |

| Working Sense | Blue | Working Electrode | Senses the potential at the working electrode with high accuracy [5]. |

| Reference | White | Reference Electrode | Senses the potential of the reference electrode to control the cell [5]. |

| Counter | Red | Counter Electrode | Supplies the current needed to balance the working electrode current [5]. |

| Floating Ground | Black | Faraday Cage | Connected to a Faraday cage to shield the experiment from external electrical noise [5]. |

Q3: My EIS data is noisy, especially at low currents. How can I improve the signal quality?

Excessive noise often stems from external electrical interference. To mitigate this:

- Use a Faraday Cage: Place your entire electrochemical cell inside a grounded Faraday cage. This metallic enclosure blocks external electromagnetic fields, which is critical for low-current measurements [5]. Connect the potentiostat's Floating Ground (black) lead to the cage [5].

- Avoid Ground Loops: Ensure your potentiostat is not accidentally connected to earth ground in multiple places, as this can create "ground loops" that introduce noise. The potentiostat is designed to be electrically floating (isolated) [17].

- Check Reference Electrode Impedance: A reference electrode with a very high impedance can cause instability and noise. You can test for this by temporarily configuring a two-electrode experiment (clipping the white reference lead to the counter electrode alongside the red lead). If the experiment stabilizes, the reference electrode may be faulty [17].

Troubleshooting Common Instrumentation & Data Quality Issues

This section addresses specific error messages and data anomalies, providing steps for diagnosis and resolution.

Q4: What does the error "Unable to Control AC Cell Current/Voltage" mean, and how do I fix it?

This error typically occurs at higher frequencies when the potentiostat's frequency response analyzer (FRA) cannot generate a signal large enough to achieve the requested potential or current, often because it has reached its output amplitude limit [18].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Increase Electrolyte Conductivity: A high solution resistance can cause this issue. Try using a more conductive electrolyte (e.g., higher concentration of supporting electrolyte) [18].

- Lower AC Signal Amplitude: Reduce the amplitude of the applied AC signal (e.g., from 10 mV to 5 mV). A smaller signal may be easier for the instrument to control [18].

- Adjust Frequency Range: Avoid very high frequencies if they are not essential for your experiment. The problem is most prevalent in this region [18].

- Verify Initial Impedance Estimate: Ensure the "Estimated Z" parameter in your software is within a factor of 5 of your cell's actual impedance at the starting frequency. A poor estimate can lead to incorrect initial instrument settings [5].

Q5: The measurement status shows "Timeout" or "Cycle Limit." What is the impact on my data?

These status messages indicate that the FRA struggled to make a high-quality measurement within the allotted time or number of AC cycles. While a data point was recorded, it "may or may not be a good estimate of the test cell's impedance" [18]. You should treat this data with caution.

Recommended Actions:

- Increase Measurement Precision: In your experiment setup, change the "Optimize for" parameter from "Fast" to "Normal" or "Low Noise." This forces the instrument to take more cycles per measurement, improving signal averaging and data quality at the cost of longer experiment duration [5].

- Check for System Stability: Ensure your electrochemical system is stable over time. Drifting potentials can prevent a stable reading.

- Re-measure: If possible, re-run the measurement at the problematic frequencies.

Table: Common EIS Status/Error Messages and User Actions

| Message | Description | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Timeout / Cycle Limit | The measurement did not stabilize within the set time or cycle limit. Data quality is uncertain [18]. | Increase measurement time/precision ("Optimize for: Normal/Low Noise"); verify system stability [5]. |

| Unable to Control AC Cell Current | The FRA cannot generate a sufficient signal, often at high frequencies [18]. | Increase electrolyte conductivity; lower AC amplitude; avoid non-essential high frequencies [18]. |

| Stuck in Reading Loop | The system cannot find potentiostat settings to get a valid reading, often on the first frequency [18]. | Check that the "Estimated Z" parameter is accurate [5] [18]. Ensure all electrodes are connected and submerged [5]. |

Experimental Protocol: Executing a Standard Potentiostatic EIS Experiment

The following workflow outlines the key steps for performing a potentiostatic EIS experiment, from setup to data acquisition. Adhering to this protocol is fundamental for improving the accuracy and reproducibility of your research.

Diagram: Potentiostatic EIS Experimental Workflow

Step-by-Step Methodology:

Electrode and Cell Setup:

- Prepare the working electrode as required (e.g., polish, clean, or coat) [5].

- Assemble the electrochemical cell using a standard three-electrode configuration [5].

- Connect the potentiostat leads to their respective electrodes as described in Table 1 [5] [17].

- Fill the cell with the chosen electrolyte solution.

- Place the entire cell inside a Faraday cage and connect the Floating Ground lead to it to minimize electrical noise [5].

Software Configuration:

- In the potentiostat software, select "Potentiostatic EIS" as the experiment type [5].

- DC Voltage: Set this to your desired potential offset, often the Open Circuit Potential (OCP) of the system [5] [19].

- AC Voltage: Set the amplitude of the sinusoidal perturbation. A common value is 10 mV RMS to ensure the system's linear response [5].

- Frequency Range: Define the initial (high) and final (low) frequencies. A typical range might be 100 kHz to 100 mHz [4] [20]. The sweep proceeds from high to low frequency.

- Points per Decade: Set the number of data points, commonly 10 points per decade [5].

- Estimated Z: Provide a reasonable estimate of your cell's impedance at the initial frequency. This helps the potentiostat optimize its hardware settings for the first measurement [5].

Run Experiment:

Data Analysis:

- Once complete, analyze the data by inspecting the Nyquist and Bode plots [4] [20].

- The core of EIS analysis involves fitting the data to an Equivalent Circuit Model (ECM) that represents the physical processes in your electrochemical system (e.g., solution resistance, double-layer capacitance, charge transfer resistance) [4] [19]. The Randles circuit is a common starting model for many systems [4] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table: Key Materials and Reagents for EIS Experiments

| Item | Function / Role | Example Types & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat / Galvanostat | The core instrument that applies the controlled potential or current and measures the resulting response. Must include a Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) for EIS [5]. | Various manufacturers (e.g., Gamry, Sciospec). Specifications should match impedance and frequency range of the study. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known reference potential for accurate control and measurement of the working electrode potential [5]. | Saturated Calomel (SCE), Silver/Silver Chloride (Ag/AgCl). Check for stability and low impedance [5] [17]. |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the current circuit. Must be electrochemically inert in the experimental window to avoid side reactions [5]. | Platinum mesh, graphite rod, stainless steel [5]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Increases the conductivity of the solution, minimizing the uncompensated solution resistance (Rs) which can distort measurements [4]. | Inert salts like KCl, NaNO3, TBAPF6. Choice depends on solvent and chemical compatibility. |

| Faraday Cage | A metallic enclosure that shields the sensitive electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic interference, crucial for low-current measurements [5]. | Commercially available shields or custom-built grounded metal boxes/mesh. |

| Electrochemical Cell | The container that holds the electrolyte and electrodes. Design affects volume, electrode positioning, and reproducibility. | Standard cells (e.g., Gamry PTC1, Paracell), or custom-made glass cells [5]. |

This guide provides detailed methodologies and troubleshooting support for selecting fundamental parameters in Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to enhance data accuracy and reliability in electrochemical research.

▎Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the core parameter definitions?

- AC Amplitude: The magnitude of the alternating current or voltage excitation signal, typically maintained at a low level (e.g., 1-10 mV for voltage control) to ensure the system response is pseudo-linear [3].

- Frequency Range: The span of frequencies, from initial to final, over which the impedance is measured (e.g., from mHz to MHz), determining which electrochemical processes are probed [8] [5].

- Points per Decade: The number of data points collected for every tenfold change in frequency, controlling the spectral resolution and detail of the impedance curve [5].

2. Why is a small AC amplitude typically used? A small AC amplitude (e.g., 1-10 mV RMS for potentiostatic mode) is crucial to ensure the system operates in a pseudo-linear region [3]. Excessive amplitude drives the electrochemical system into non-linearity, distorting the output signal with harmonics and making the data unreliable [8].

3. How do I determine the appropriate frequency range for my experiment? The optimal frequency range depends on the kinetics of the processes under investigation [8]. A broad range (e.g., 100 kHz to 10 mHz) is common to capture all relevant processes. The initial (highest) and final (lowest) frequencies should be selected so that the time constants of interest fall within this range [5].

4. What is a good starting value for Points per Decade, and what are the trade-offs? A common starting point is 10 points per decade [5]. Higher values provide better resolution of circuit features but increase the total measurement time, risking data distortion from system non-stationarity. Fewer points make the measurement faster but may miss critical features in the impedance spectrum.

▎Troubleshooting Common Parameter Issues

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low-frequency data scatter | System drift (non-stationarity) during long measurements [3] | Reduce Points per Decade, narrow the Frequency Range, verify system stability before measuring. |

| Distorted Nyquist plot semicircles | AC Amplitude is too large, causing non-linear response [8] | Decrease the AC Amplitude; use Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) analysis to verify linearity [8]. |

| Incomplete or missing features in the impedance spectrum | Frequency Range is too narrow, or Points per Decade is too low [5] |

Widen the Frequency Range to cover all expected time constants; increase Points per Decade. |

| Noisy data at high frequencies | Electrical noise/interference, or poorly optimized hardware settings [5] | Use a Faraday cage, ensure proper grounding and shielding [5]; use the instrument's "Low Noise" optimization mode. |

▎Quantitative Data and Best Practices

Table 1: Typical Parameter Values for Common Applications

| Application | Typical AC Amplitude (RMS) | Typical Frequency Range | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Corrosion Study (Coated Metal) | 10 mV (Voltage) | 100 kHz to 100 mHz | [5] |

| Battery Module (Power) | Optimized Multi-sine Current | 1 kHz to 0.1 Hz | [13] |

| General Battery Diagnostics | Not Specified | 0.01 Hz to 1 kHz | [13] |

Table 2: Impact of Sampling Parameters on Measurement Quality

| Parameter | Impact on Measurement Quality | Recommended Value / Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Points per Decade | Determines spectral resolution. A value of 10 is standard [5]. | 10 points/decade is a robust starting point [5]. |

| Signal Amplitude Optimization | Critical for Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR). Unoptimized amplitude leads to high errors [13]. | Optimize amplitude based on system impedance; a study achieved a 0.47% magnitude error with optimized multi-sine signals [13]. |

| Phase Optimization (for multi-sine) | Reduces peak signal value and instantaneous power demand [13]. | Use phase optimization algorithms to create a more "balanced" excitation signal [13]. |

▎Experimental Protocol for Parameter Selection and Validation

The following workflow provides a systematic methodology for selecting and validating key EIS parameters to ensure data accuracy.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Define System and Objective: Clearly identify the electrochemical system and the processes you intend to study.

- Set Initial Parameters:

- AC Amplitude: Begin with a small amplitude, such as 10 mV RMS in potentiostatic mode, to stay within a pseudo-linear regime [5] [3].

- Frequency Range: Make an initial estimate based on the characteristic time constants of the physical processes you are studying. For a broad overview, a range from 100 kHz to 10 mHz is a common starting point [8].

- Points per Decade: Set to 10 for adequate initial resolution [5].

- Perform an Initial EIS Scan.

- Validate Data Quality:

- Linearity Check: Use quality indicators like Total Harmonic Distortion (THD). A THD value below 5% is a good threshold for linearity. If exceeded, reduce the AC amplitude [8].

- Stationarity Check: Use indicators like Non-Stationary Distortion (NSD). High NSD at low frequencies suggests the system changed during measurement. Consider narrowing the frequency range or reducing points per decade to shorten acquisition time [8].

- Iterate and Finalize: Adjust parameters based on validation results and perform the final measurement.

▎Research Reagent and Equipment Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Equipment for Reliable EIS

| Item | Function in EIS Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat | Applies excitation signal and measures cell response. | Select based on required current range and frequency capability (e.g., Gamry 1010E for up to 1A, 2 MHz) [21]. |

| Faraday Cage | Shields the electrochemical cell from external electromagnetic noise. | Critical for measuring low-current signals accurately [5]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for accurate voltage control/measurement. | Use stable types like Saturated Calomel (SCE) or Ag/AgCl [5]. |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the current path in a 3-electrode setup. | Typically made of inert materials like graphite or platinum [5]. |

| Four-Wire (Kelvin) Connection | Separate force and sense lines for accurate impedance measurement. | Mitigates error from cable and contact resistance, essential for low-impedance samples like batteries [22]. |

| Calibration Standards | Used to characterize and remove systematic errors from the test fixture. | Requires known standards (e.g., precision resistors) to generate error coefficients [22]. |

| Thermal Chamber | Maintains a constant temperature during measurement. | Vital as impedance is highly temperature-sensitive [22]. |

▎Advanced Workflow: Multi-Signal Optimization

For applications requiring the highest speed and accuracy, such as in-line battery testing, advanced methods using optimized multi-sine signals can be implemented. The diagram below outlines this sophisticated parameter optimization process.

Procedure Explanation:

- Define Target Frequencies: Select the specific frequencies for which impedance data is needed, optimizing their distribution to minimize measurement time [13].

- Optimize Individual Amplitudes: Adjust the amplitude of each sinusoidal component within the multi-sine signal based on the system's impedance characteristics. This enhances the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) across all frequencies [13].

- Optimize Signal Phase: Adjust the phase of each component to reduce the Crest Factor (peak value) of the composite signal. This lowers the instantaneous power demand on the instrument [13].

- Set Engineering Parameters: Configure sampling frequency, signal power, and the number of measurement periods to finalize the measurement protocol [13].

- Generate & Apply Signal: The optimized multi-sine signal is applied to the electrochemical cell in a single excitation step.

- Compute Impedance: The system's response is measured, and the impedance at each target frequency is simultaneously calculated using Fourier Transform techniques [13]. This method has been shown to reduce measurement time by over 86% while keeping magnitude errors below 0.5% [13].

Traditional single-sine signals are used because EIS theory requires the electrochemical system to be Linear, Time-Invariant (LTI), and at a steady state [3] [23]. A small-amplitude (1-10 mV) single-sine wave helps ensure pseudo-linearity by perturbing the system so minimally that its response appears linear [3]. This simplifies data analysis, as the system's impedance is defined and constant at each frequency. Furthermore, the required mathematical transforms and equivalent circuit modeling are well-established for single-frequency responses.

What are the primary limitations of single-sine measurements?

The most significant limitation is measurement time. Characterizing a system across a wide frequency range (e.g., from mHz to kHz) by sweeping through each frequency sequentially is inherently slow [24]. This can be problematic for systems that may drift over time. Additionally, the low amplitude, while ensuring linearity, can result in a low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in noisy environments [23]. Finally, the system's linearity is assumed rather than actively verified during the measurement.

What are multi-sine signals, and how do they improve EIS?

Multi-sine signals are a composite waveform containing a mixture of multiple frequencies excited simultaneously [23]. This approach dramatically reduces measurement time, as data for all frequencies are acquired concurrently rather than in a slow sequential sweep. This enables "fast EIS," with some studies achieving impedance measurements in under 10 seconds [24]. The speed gain makes EIS feasible for real-time monitoring of dynamic systems, such as batteries under changing load conditions.

How can harmonic analysis improve the accuracy of my EIS measurements?

Harmonic analysis involves examining the output signal for frequency components that are integer multiples (harmonics) of the input excitation frequency [3] [23]. In a perfectly linear system, no harmonics are generated. The presence and amplitude of harmonics, quantified by metrics like Total Harmonic Distortion (THD), serve as a direct indicator of system non-linearity [23]. This provides a built-in check for the validity of the LTI assumption, helping researchers identify when excitation amplitudes are too large or when the system itself is inherently non-linear, thereby improving measurement accuracy and reliability.

Advanced signals introduce new complexities. Multi-sine signals require sophisticated signal processing, such as high-performance Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) analysis, to deconvolve the mixed-frequency response [4]. The data acquisition system must have a high signal-to-noise ratio and dynamic range to accurately measure the smaller response at each individual frequency within the composite signal [23]. Furthermore, ensuring that the combined power of a multi-sine signal does not push the system into a non-linear regime requires careful design of the excitation profile.

Troubleshooting Guide

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution | Verification Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Distorted Lissajous figures (non-elliptical shapes) [4] | System non-linearity due to excessive excitation amplitude [3]. | Reduce the amplitude of the excitation signal (potential or current). | Re-measure; the Lissajous figure should form a clean, tilted oval. Check that THD is minimized [23]. |

| "Noisy" or unreproducible impedance spectra | Low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), often from small excitation signals in electrically noisy environments [23]. | For single-sine: increase averaging. For multi-sine: ensure DAQ system has high SNR (>100 dB for 24-bit ADC). Use a Faraday cage. | Measure a known, stable resistor-capacitor circuit; the spectrum should be smooth and match the model. |

| Long measurement times causing system drift | Slow, sequential frequency sweep of traditional single-sine EIS [24]. | Switch to a multi-sine excitation signal to acquire all frequencies of interest simultaneously. | Monitor a key parameter (e.g., Open Circuit Voltage) before and after the EIS scan; the drift should be negligible. |

| Inconsistent results between measurements | Violation of Steady-State or LTI conditions; the system is changing during the measurement [3]. | Ensure the system is at a thermal and electrochemical steady state before starting. Validate linearity with harmonic analysis. | Plot the Lissajous figure and FFT for a mid-range frequency; the oval should be consistent and harmonics low [23]. |

| Presence of significant harmonics in the FFT | System non-linearity [3] [23]. | Reduce excitation amplitude. If harmonics persist, the system may be inherently non-linear; consider smaller DC bias or alternative techniques. | Analyze the FFT of the current response; the amplitude at harmonic frequencies should be very small compared to the fundamental. |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol: Validating Linearity Using Harmonic Analysis

This protocol provides a methodology to experimentally verify the linearity assumption critical for accurate EIS.

Methodology:

- Setup: Configure your potentiostat for a standard potentiostatic EIS experiment. Use a standard potassium ferrocyanide/ferricyanide redox couple in buffer solution as a test electrochemical system.

- Initial Measurement: Perform a standard single-sine EIS measurement with a low, commonly-used amplitude (e.g., 10 mV RMS). Center the DC potential at the half-wave potential of the redox couple.

- Harmonic Detection: At a single, mid-range frequency (e.g., 10 Hz), perform a second measurement where you collect the current response with a high sampling rate and use FFT analysis to examine the frequency spectrum of the response [23].

- Amplitude Sweep: Repeat step 3, progressively increasing the excitation amplitude (e.g., 20 mV, 50 mV).

- Analysis: Calculate the Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) or simply note the amplitude of the (2^{nd}) and (3^{rd}) harmonics relative to the fundamental frequency for each amplitude level [23].

Expected Outcome:

- At low amplitudes, harmonics will be negligible.

- As the amplitude increases past a certain point, the harmonic amplitudes will become significant, indicating the onset of non-linear behavior. This defines the maximum usable excitation amplitude for accurate EIS on this system.

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of different excitation signals, based on data from recent research and application notes [3] [24] [23].

| Excitation Signal Type | Measurement Speed | Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | Linearity Verification | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-Sine Sweep | Slow (minutes to hours) | Moderate, improves with averaging | Not inherent; requires separate test | Standard laboratory characterization of stable systems. |

| Multi-Sine/Composite | Very Fast (<10 seconds) [24] | Can be lower per frequency; requires high-quality DAQ [23] | Not inherent | Real-time monitoring, high-throughput testing, systems prone to drift. |

| Single-Sine with Harmonic Analysis | Slow | Moderate, improves with averaging | Inherent via THD/harmonic amplitude [23] | Validating measurement accuracy and probing system non-linearity. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in EIS Research |

|---|---|

| Potentiostat/Galvanostat with FRA | The core instrument that applies the precise excitation signals (potential or current) and measures the system's response. A Frequency Response Analyzer (FRA) module is essential [4]. |

| Faraday Cage | A shielded enclosure that blocks external electromagnetic fields, crucial for protecting low-amplitude signals from environmental noise, especially when using small excitation amplitudes [23]. |

| Standard Redox Couple (e.g., Ferri/Ferrocyanide) | A well-understood electrochemical system used for validating the performance and accuracy of the EIS setup and methodology. |

| High-Precision Data Acquisition (DAQ) System | A system with a high signal-to-noise ratio (e.g., 24-bit ADC) and synchronous sampling is critical for resolving the small responses from multi-sine and low-amplitude signals [23]. |

| Equivalent Circuit Modeling Software | Software used to fit a mathematical model of the electrochemical system (composed of resistors, capacitors, etc.) to the collected impedance data, enabling the extraction of physical parameters [3]. |

Visualization: Workflow for Advanced Signal Validation

The diagram below illustrates a recommended workflow for implementing and validating advanced excitation signals, incorporating checks for linearity and data quality.

Advanced EIS Signal Validation Workflow: This flowchart outlines the process of using advanced excitation signals like multi-sine, highlighting critical validation steps such as harmonic analysis to ensure data accuracy and system linearity.

Hybrid Optimization and Equivalent Circuit Modeling for Parameter Estimation

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is hybrid optimization in EIS modeling, and why is it more effective than single-method approaches? Hybrid optimization combines global and local optimization algorithms to overcome the limitations of each. The methodology typically uses Differential Evolution (DE) as a global search to explore the parameter space broadly, avoiding local minima, followed by the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm for precise local refinement [25]. This two-step process is particularly effective for EIS data, where parameter collinearity (e.g., between CPE parameters Q and n) can trap single-method optimizers in suboptimal solutions [25].

Q2: My model fails the Kramers-Kronig validation. What does this mean, and what should I check? Failure to satisfy the Kramers-Kronig (KK) relations indicates that the fundamental assumptions of linearity, causality, and stability of the system have been violated [25]. To troubleshoot:

- Experimentally: Verify that your measurement used a sufficiently small perturbation signal amplitude to ensure a linear system response.

- Data Quality: Inspect the data for instrumental artifacts or excessive noise, particularly at low frequencies.

- Model Structure: Reconsider your chosen equivalent circuit; a KK failure may mean the model itself is physically inconsistent with the system under study [25].

Q3: How do I objectively choose the best equivalent circuit model from several candidates? Beyond minimizing the residual error, use statistical model selection criteria that penalize complexity. The Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are recommended for this purpose [25]. A lower AIC or BIC score indicates a better model, balancing goodness-of-fit with parsimony. For example, a study found that while the Randles circuit is sufficient for ideal interfaces, the Randles+CPE model provides a better fit (lower AIC) when significant non-ideality or higher noise is present [25].

Q4: Why are my CPE parameters (Q and n) exhibiting high uncertainty? The parameters of the Constant-Phase Element (CPE) often show high correlation or collinearity [25]. This means different combinations of Q and n can produce a similarly good fit to the data, making their individual values hard to pin down. To improve identifiability:

- Ensure your experimental frequency window is wide enough to excite the time constants relevant to the CPE's behavior.

- Consider fixing the exponent n to a physically plausible value (e.g., 0.5 for porous electrodes, 0.8-1 for a non-ideal capacitor) if the data quality does not allow both parameters to be fitted robustly [25].

Q5: What are the most critical factors for ensuring accurate and repeatable EIS measurements on battery modules? For low-impedance systems like batteries, measurement integrity is critical. Key factors include [22]:

- Fixturing: Use a 4-wire Kelvin connection with separate force and sense cables to eliminate cable and contact resistance errors.

- Calibration: Perform a full system calibration with known impedance standards (e.g., short circuit and precision shunts) across your measurement frequency range. Uncalibrated measurements can have errors exceeding 30% at 1 kHz [22].

- Environmental Control: Strictly control temperature and State of Charge (SoC), as variations here introduce significant errors, especially at low-to-medium frequencies.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Fit at High and Low Frequencies

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High-frequency data points deviate from the model. | Uncompensated solution resistance (R_s) and fixture inductance (L) [25] [22]. |

- Add an R_s term in series with your circuit model.- For very high frequencies (>1 kHz), consider adding a series inductor (L) to account for wiring [25]. |

| Significant deviation in the low-frequency tail (e.g., not a clean 45° line). | Incorrect diffusion model or non-ideal capacitive behavior [25]. | - For semi-infinite linear diffusion, use the Warburg impedance (Z_W).- For non-ideal capacitive interfaces, replace the ideal capacitor (C) with a Constant-Phase Element (CPE) [25]. |

Problem 2: Parameter Estimates with High Uncertainty or Non-Physical Values

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fitted parameters change drastically with different initial guesses. | The optimization is converging to local minima [25]. | Implement a hybrid optimization strategy: use a global method like Differential Evolution (DE) to find a good starting point, then refine with Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) [25]. |

| Parameters have very wide confidence intervals or are non-physical (e.g., negative resistances). | Poor parameter identifiability due to collinearity or insufficient data [25]. | - Enforce strict physical bounds during fitting (e.g., R_s > 0).- Quantify uncertainty using a non-parametric bootstrap approach [25]. |

Problem 3: Model Validation Failures

This workflow diagram outlines a systematic approach for model diagnosis and validation:

Experimental Protocols

Detailed Methodology: Hybrid Optimization for EIS

This protocol is based on the analytical-computational framework that integrates equivalent circuit modeling with a hybrid optimization pipeline [25].

Circuit Selection and Analytical Definition:

Parameter Initialization and Bounding:

Hybrid Optimization Execution:

- Stage 1 - Global Search: Run the Differential Evolution (DE) algorithm. Configure DE to explore the bounded parameter space thoroughly, which helps avoid local minima [25].

- Stage 2 - Local Refinement: Use the best solution from DE as the initial guess for the Levenberg-Marquardt (LM) algorithm. LM will efficiently fine-tune the parameters to achieve a minimum root-mean-square error (RMSE) [25].

Uncertainty Quantification:

- Perform non-parametric bootstrap analysis on the optimized parameters. This involves repeatedly resampling the residuals, refitting the model, and calculating new parameter estimates to build an empirical distribution of their values [25].

- Report the mean and confidence intervals (e.g., 95%) from the bootstrap distribution for each parameter.

Model Validation and Selection:

Protocol for Ensuring EIS Measurement Accuracy on Battery Modules

This protocol ensures data quality for low-impedance systems, derived from automotive battery module testing [22].

Fixture Setup:

- Use a 4-wire Kelvin connection with high-current force cables and twisted-pair sense wires.

- Position force cables for positive and negative poles close together to minimize magnetic coupling loop areas [22].

System Calibration:

- Replace the device-under-test (DUT) with a calibration fixture.

- Measure three known standards: a short circuit (0 Ω), and at least two precision coaxial shunts (e.g., 10 mΩ and 100 mΩ) over the entire frequency range [22].

- Compute error coefficients and apply them to correct all subsequent DUT measurements (

ZcDUT) [22].

Environmental Stabilization:

- Place the test module in a temperature-controlled chamber.

- Condition the module to a precise State of Charge (SoC) and temperature.

- Allow for a sufficient rest period post-charging to ensure voltage and temperature stabilization before measurement [22].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Key Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance in EIS |

|---|---|

| Precision Calibration Shunts (e.g., 10 mΩ, 100 mΩ) | Known impedance standards essential for calibrating the EIS tester and correcting systematic errors, especially critical for low-impedance measurements [22]. |

| Electrolyte Solution | The ionic conductor in the electrochemical cell. Its composition and concentration directly affect the solution resistance (R_s) and interface kinetics [25]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured, crucial for valid three-electrode cell measurements. |

Essential Computational Tools

| Item | Function / Relevance in EIS Modeling |

|---|---|

| Global Optimizer (DE) | Stochastic, population-based algorithm used in the first stage of hybrid optimization to find a near-global solution without requiring precise initial guesses [25]. |

| Local Optimizer (LM) | Gradient-based algorithm used after DE for fast and precise convergence to the local minimum, refining the parameter estimates [25]. |

| Bootstrap Resampling Algorithm | A statistical method for non-parametric uncertainty quantification, providing confidence intervals for fitted parameters [25]. |

| Kramers-Kronig Validator | A software routine or test to check the physical consistency of the measured impedance data or the fitted model [25]. |

Troubleshooting EIS Experiments: Identifying and Correcting Common Error Sources

Diagnosing Non-Linearity with Total Harmonic Distortion (THD)

FAQs: Understanding THD and Non-Linearity in EIS

What is Total Harmonic Distortion (THD), and why is it important for EIS? Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) is a quantitative measure that calculates the extent of non-linear behavior in an electrochemical system during an EIS measurement. It quantifies the ratio of the root mean square (RMS) magnitudes of the harmonics in the response signal to the RMS magnitude of the fundamental frequency [27] [28]. It is a crucial quality indicator because EIS theory assumes the system is linear, but most real electrochemical systems are inherently non-linear. Applying a small-amplitude excitation signal makes the system pseudo-linear. THD provides a numerical value to verify that the chosen amplitude is sufficiently small to yield valid impedance data [8].

What is an acceptable THD value for a valid EIS measurement? A THD value below 5% is generally considered acceptable for assuming linear system behavior [28] [8]. A THD factor of 0% represents a perfectly linear signal, while values exceeding 5% indicate significant non-linearity, meaning the excitation amplitude is likely too large and the resulting impedance data may be erroneous [27].

Why does my THD value change with frequency? Non-linearity is often more pronounced at lower frequencies. The THD factor typically increases as the measurement frequency decreases because the system has more time to deviate from a purely sinusoidal response at lower frequencies [27] [8]. Therefore, it is essential to check the THD value across the entire measured frequency spectrum.

How does non-linearity affect my impedance data? Non-linearity can lead to significant distortions in the impedance data. In a non-linear system, the impedance diagram (e.g., Nyquist plot) can become dependent on the excitation amplitude, which should not occur in a linear system [29]. For instance, the diameter of a semicircle in a Nyquist plot might decrease as the excitation amplitude increases, leading to an incorrect interpretation of the system's properties [29] [28].

Troubleshooting Guide: High THD Values

Problem: High THD (>5%) across all frequencies.

- Potential Cause & Solution: The excitation amplitude is too large.

Problem: High THD only at low frequencies.

- Potential Cause & Solution: This is a common behavior in electrochemical systems.

- Action 1: If possible, further reduce the AC amplitude specifically for the low-frequency range.

- Action 2: Apply drift compensation techniques if available in your potentiostat software, as system drift can contribute to low-frequency distortion [28].

- Action 3: If the high THD persists, truncate the low-frequency data from your analysis and report the frequency above which the data is valid based on the THD indicator [8].

Problem: High THD accompanied by a changing impedance spectrum over time.

- Potential Cause & Solution: The system is not at a steady state (Non-Stationary).