Advanced Voltammetry in Electrochemical Sensor Development: From Foundational Principles to Biomedical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electrochemical sensor development using voltammetry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Advanced Voltammetry in Electrochemical Sensor Development: From Foundational Principles to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of electrochemical sensor development using voltammetry, tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles of voltammetric techniques and their advantages over traditional analytical methods. The content details advanced methodologies and material innovations, such as nanostructured composites and metal oxides, for detecting pharmaceuticals, heavy metals, and biomarkers. A dedicated section on troubleshooting and optimization addresses common experimental challenges to ensure data reliability and sensor reproducibility. Finally, the article covers the critical path from laboratory validation to commercial application, including performance benchmarking against established techniques and navigating the regulatory approval process for clinical and point-of-care devices.

Core Principles and Advantages of Voltammetry in Sensor Design

Core Principles and Methodologies

Voltammetry encompasses a suite of electrochemical techniques that measure the current resulting from the application of a controlled potential to a working electrode in an electrochemical cell. These methods are fundamental for qualitative and quantitative analysis of electroactive species, playing a critical role in the development of advanced electrochemical sensors. [1] The following sections detail four key voltammetric methods essential for modern sensor research.

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV)

Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) is a highly sensitive technique primarily used for trace metal analysis. The method operates in two main stages: first, an electrochemical deposition step where metal ions in solution are reduced and pre-concentrated onto the working electrode surface at a constant, negative potential. This is followed by a stripping step, where the potential is swept in an anodic (positive) direction, re-oxidizing the deposited metals back into solution. The resulting current peak provides quantitative and qualitative information about the target analytes. The exceptional sensitivity of ASV, which allows for detection at parts-per-billion or even parts-per-trillion levels, stems from this effective pre-concentration process. ASV is particularly valued in environmental monitoring for detecting toxic heavy metals such as lead (Pb), cadmium (Cd), and mercury (Hg) in water and soil. [2]

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV)

Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) enhances sensitivity for trace analysis by minimizing the contribution of non-Faradaic (charging) current. The technique applies a linear potential ramp superimposed with small, regular potential pulses. The current is sampled twice for each pulse: just before the pulse is applied and again near the end of the pulse. The difference between these two current measurements is plotted against the base potential. [1] This differential current output effectively cancels out a significant portion of the capacitive background current, yielding a peak-shaped voltammogram where the peak height is directly proportional to the analyte concentration. DPV is widely used for its low detection limits and excellent resolution, making it suitable for detecting organic molecules, pharmaceuticals, and biomolecules in complex matrices. [2]

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) is a powerful and versatile technique for studying the mechanism of redox reactions and electron transfer kinetics. In CV, the potential of the working electrode is swept linearly between two set limits (an initial and a final potential) and then swept back, forming a triangular waveform. [1] The resulting plot of current versus potential, called a cyclic voltammogram, provides characteristic information such as redox potentials (Epa and Epc), peak currents (Ipa and Ipc), and the reversibility of the electrochemical reaction. A reversible system typically shows a peak separation (ΔEp) of about 59/n mV. CV is extensively used for characterizing electrode surfaces, probing reaction mechanisms, and evaluating the performance of modified electrodes and sensor materials. [1]

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV)

Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) is a fast, sensitive pulse technique ideal for analytical applications. A symmetrical square wave, characterized by a specific frequency and amplitude, is superimposed on a staircase potential waveform. The current is sampled at the end of each forward pulse and each reverse pulse. The net current, calculated as the difference between the forward and reverse currents, is plotted against the applied potential, producing sharp, peak-shaped voltammograms. [1] The key advantage of SWV is its speed and exceptional sensitivity, which is often higher than DPV in reversible systems. [1] This makes it highly suitable for rapid detection and quantification, as demonstrated in applications ranging from the quantification of thymoquinone in herbal products to the detection of leucine for soil health assessment. [3] [4]

Comparative Analysis of Voltammetric Techniques

Table 1: Comparative characteristics of key voltammetric methods.

| Method | Excitation Waveform | Key Output | Primary Applications | Key Advantages | Typical LOD Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASV | Deposition at fixed potential, followed by linear anodic sweep. | Current peak during stripping phase. | Trace metal analysis (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺, Hg²⁺). [2] | Extremely high sensitivity due to pre-concentration. | Parts-per-billion (ppb) to parts-per-trillion (ppt) levels. [2] |

| DPV | Linear ramp with small, regular pulses. | Peak plot of differential current vs. potential. | Detection of organic molecules, drugs, biomolecules. [2] | Low detection limit by minimizing charging current. [1] | Nanomolar to picomolar range. |

| CV | Linear potential sweep between two limits and back. | Current vs. potential plot (cyclic voltammogram). | Mechanistic studies, electrode characterization, reversibility. [1] | Provides rich qualitative data on redox behavior. | Less sensitive than pulse techniques for quantification. |

| SWV | Staircase ramp with superimposed square wave. | Peak plot of net current (forward-reverse) vs. potential. | Rapid, sensitive quantification of various analytes. [3] [4] | Fast and highly sensitive; efficient rejection of background current. [1] | Sub-nanomolar levels achievable. [3] |

Table 2: Summary of experimental parameters from recent sensor applications.

| Analyte | Voltammetric Method | Working Electrode | Linear Range | Reported LOD | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Heavy Metals (e.g., Pb²⁺) | ASV | Nanomaterial-modified (e.g., Bi/Bi₂O₃-carbon). [2] | Varies with modification | Sub-ppb levels. [2] | Water and soil quality monitoring. [2] |

| Thymoquinone | SWV | Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE). [4] | -- | 8.9 nmol·L⁻¹ (based on peak height). [4] | Analysis of Nigella sativa seed oil and supplements. [4] |

| Leucine | SWV | ssDNA-modified CPE. [3] [5] | 0.213–4.761 μg/L. [3] | 0.071 μg/L. [3] | Assessing soil health. [3] |

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Development

Protocol: Determination of Leucine using ssDNA-Modified Sensor

This protocol details the development of a carbon paste electrode (CPE) modified with single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) for the sensitive detection of leucine via Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), as applied to soil health assessment. [3] [5]

- Objective: To fabricate a biosensor for quantifying leucine in soil samples by exploiting its interaction with guanine residues in ssDNA.

- Materials:

- Graphite powder and paraffin oil for CPE preparation. [3]

- Single-stranded DNA (ssDNA), thermally denatured.

- Leucine standard solutions.

- Supporting electrolyte: Acetate or phosphate buffer (pH ~7). [3]

- Electrochemical cell with three-electrode setup: ssDNA-modified CPE (working electrode), Ag/AgCl reference electrode, and platinum wire auxiliary electrode.

- Sensor Fabrication:

- Prepare carbon paste by thoroughly mixing graphite powder and paraffin oil in a ratio of 1.0 g to 0.3 mL. [4]

- Pack the paste into an electrode body to create an unmodified CPE.

- Modify the CPE surface by applying a drop of thermally denatured ssDNA solution and allowing it to dry, forming a thin, conductive ssDNA layer. [3]

- Voltammetric Measurement:

- Immerse the modified electrode in a cell containing the supporting electrolyte and the soil sample extract or standard leucine solution.

- Record a Square Wave Voltammogram (SWV) under optimized parameters (e.g., frequency, amplitude, step potential). The characteristic oxidation peak of guanine in ssDNA will be observed at approximately +0.86 V (vs. Ag/AgCl). [3]

- Monitor the decrease in the guanine oxidation peak current upon interaction with leucine over a fixed time. The percent decrease in current is proportional to the leucine concentration. [3]

- Calibration: Construct a calibration curve by plotting the decrease in guanine peak current (or its absolute value after interaction) against the concentration of leucine standards. The method demonstrated linearity in the range of 0.213–4.761 μg/L. [3]

- Validation: Apply the method to a spiked soil sample and compare recovery rates to validate accuracy. [3]

Protocol: Detection of Heavy Metals using ASV with Nanomaterial-Modified Electrodes

This protocol outlines the use of Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) with advanced nanomaterial-modified electrodes for the sensitive detection of heavy metal ions in environmental samples. [2]

- Objective: To quantify trace levels of heavy metal ions (e.g., Pb²⁺, Cd²⁺) in water samples.

- Materials:

- Working Electrode: Glassy carbon or carbon paste electrode modified with nanomaterials such as Bismuth-based films, carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs/MWCNTs), or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). [2]

- Reference and Auxiliary electrodes: Ag/AgCl and platinum wire, respectively.

- Supporting electrolyte: A low-pH buffer (e.g., acetate buffer) is commonly used.

- Standard solutions of target metal ions.

- Electrode Modification:

- Clean and polish the bare working electrode.

- Apply the nanomaterial suspension (e.g., Bi nanoparticles, functionalized CNTs) via drop-casting or electrodeposition to enhance surface area, conductivity, and selectivity. [2]

- ASV Measurement:

- Deposition Step: Apply a constant, negative deposition potential (e.g., -1.2 V) to the electrode immersed in the degassed sample solution under stirring. This reduces the metal ions (Mn⁺) to their metallic form (M⁰) and deposits them onto the electrode surface. Optimize the deposition time based on expected analyte concentration.

- Equilibration Step: Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for a short period (e.g., 10-30 seconds).

- Stripping Step: Initiate a positive potential sweep (e.g., from the deposition potential to +0.2 V) using a sensitive technique like SWV or DPV. The deposited metals are re-oxidized (stripped), generating distinct current peaks for each metal. The peak potential identifies the metal, and the peak current is proportional to its concentration. [2]

- Data Analysis: Identify metals by their characteristic stripping potentials and quantify them using a calibration curve constructed from standard additions.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key research reagents and materials for voltammetric sensor development.

| Category | Item | Typical Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Electrode Materials | Carbon Paste (Graphite & Paraffin oil) [3] [4] | Versatile, renewable working electrode surface; easily modified. |

| Glassy Carbon | Polished, stable surface for a wide potential window. | |

| Metal Nanoparticles (e.g., Bi, Au) | Enhance conductivity and catalytic activity; used in ASV. [2] | |

| Nanomaterials | Carbon Nanotubes (SWCNTs, MWCNTs) [2] | Increase effective surface area and electron transfer rate. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [2] | Provide high porosity and selective binding sites for analytes. | |

| Biorecognition Elements | Single-Stranded DNA (ssDNA) [3] | Used as a bioreceptor for specific interactions with targets like leucine. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) [6] | Synthetic polymers with tailor-made cavities for selective analyte binding. | |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Acetate Buffer | Common electrolyte for ASV and studies in mildly acidic conditions. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | Mimics physiological conditions; used for biosensing. | |

| Britton-Robinson Buffer | Universal buffer for a wide pH range (2.0–6.0). [4] |

In the field of electrochemical sensor development, the three-electrode system represents a fundamental experimental configuration that enables precise measurement and control for voltammetry research. Unlike simple two-electrode systems, this advanced configuration separates the functions of potential measurement and current flow, allowing researchers to accurately study electrochemical processes at the working electrode interface where sensing occurs [7] [8]. This separation is critical for developing sensitive and reliable electrochemical sensors, as it eliminates potential inaccuracies caused by the polarization of the counter electrode and solution resistance effects [8].

The three-electrode system has revolutionized electrochemical research since its development in the 1920s, replacing the less precise two-electrode configurations previously used [8]. For sensor development, this system provides the necessary framework for investigating electrode materials, characterizing interface properties, and optimizing detection parameters for various analytes—from pharmaceutical compounds to environmental pollutants [9]. The precision offered by this system enables researchers to correlate specific electrochemical signatures with analyte concentration, forming the basis for quantitative sensor applications in drug development and clinical diagnostics [7].

System Components and Functions

The Working Electrode (WE)

The working electrode serves as the cornerstone of any electrochemical sensor, functioning as the platform where the redox reaction of interest occurs [7]. In sensor applications, the working electrode's surface is often modified with specific recognition elements (e.g., enzymes, antibodies, molecularly imprinted polymers, or nanomaterials) that enhance selectivity toward target analytes [9]. The electrode material must exhibit high electrical conductivity, chemical stability across the potential window of interest, and suitable surface properties for modification.

Common working electrode materials include glassy carbon (GC), platinum (Pt), gold (Au), and increasingly, various forms of carbon nanomaterials [7] [9]. For instance, one patent describes a sensor for heavy metal detection using a glassy carbon electrode modified with multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) and zeolitic imidazolate framework (ZIF-8) to enhance sensitivity toward Pb(II) and Cu(II) ions [9]. The working electrode represents where the critical electron transfer events occur that generate the analytical signal in voltammetric sensing.

The Reference Electrode (RE)

The reference electrode provides a stable, known potential against which the working electrode potential is measured and controlled [7]. In sensor applications, this stability is paramount, as any drift in the reference potential would directly translate to inaccuracies in the measured analyte oxidation/reduction potentials. Reference electrodes maintain a constant potential by establishing a reversible redox couple in a solution of fixed composition, such as Ag/AgCl in saturated KCl or saturated calomel (SCE) [7].

For the reference electrode to function effectively in sensing applications, it should ideally draw negligible current to prevent polarization [8]. The proximity of the reference electrode to the working electrode surface is also critical, as it minimizes uncompensated solution resistance (iR drop) that can distort voltammetric signals [8]. In miniaturized sensor systems, maintaining a stable reference potential presents significant challenges that often require innovative reference electrode designs [10].

The Counter Electrode (CE)

Also known as the auxiliary electrode, the counter electrode completes the electrical circuit with the working electrode, allowing current to flow through the electrochemical cell [7]. While the counter electrode does not participate directly in the sensing mechanism, its proper selection is essential for maintaining measurement stability. The counter electrode typically has a larger surface area than the working electrode to ensure that its electrochemical processes do not limit the overall current flow [7].

Common counter electrode materials include platinum wire, graphite rods, or other inert conductive materials that can sustain the redox reactions (often electrolyte decomposition) necessary to balance the electron flow generated at the working electrode [7]. In sensor applications, the counter electrode should be chemically inert to prevent contamination of the solution with dissolution products that might interfere with the sensing process [8].

Table 1: Electrode Functions and Common Materials in Three-Electrode Systems for Sensor Development

| Electrode Type | Primary Function | Common Materials | Critical Parameters for Sensing |

|---|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | Site of analyte redox reaction; signal generation | Glassy carbon, platinum, gold, carbon nanotubes, modified electrodes | Surface area, modification layer, electron transfer kinetics, fouling resistance |

| Reference Electrode | Provides stable potential reference | Ag/AgCl, saturated calomel electrode (SCE), Hg/HgO | Potential stability, minimal current draw, chemical compatibility with solution |

| Counter Electrode | Completes current circuit with working electrode | Platinum wire/mesh, graphite rod, stainless steel | High surface area, electrochemical inertness, minimal polarization |

System Configuration and Operation

Electrical Connections and Instrumentation

The three-electrode system operates through a potentiostat, an electronic instrument that maintains a constant potential between the working and reference electrodes while measuring the current flowing between the working and counter electrodes [11]. This configuration creates two distinct circuits: (1) a potential control circuit between the working and reference electrodes, and (2) a current flow circuit between the working and counter electrodes [12]. The separation of these circuits is fundamental to the system's precision.

In a standard configuration, the working electrode connects to both the working sense (potential measurement) and working drive (current application) leads of the potentiostat [11]. The reference electrode connects exclusively to the reference sense lead to monitor potential without drawing significant current, while the counter electrode connects to the counter electrode drive lead to complete the current circuit [11]. Proper connection is essential, as any inconsistency can introduce measurement errors detrimental to sensor calibration.

The Role of the Electrolyte Solution

The electrolyte solution containing the analyte of interest serves as the medium for ion conduction between the electrodes [13]. In sensor applications, the electrolyte composition (pH, ionic strength, buffer capacity) significantly influences electron transfer kinetics and must be carefully controlled to ensure reproducible results [9]. Supporting electrolytes at sufficiently high concentration (typically 0.1-1.0 M) ensure that current is carried primarily by ions from the electrolyte rather than the analyte, maintaining consistent mass transport conditions [13].

Experimental Protocols for Sensor Characterization

Electrode Modification Protocol for Heavy Metal Detection

The following detailed protocol adapts methods from a patent describing the development of a voltammetric sensor for Pb(II) and Cu(II) detection [9], representing a typical electrode modification approach for sensing applications:

Working Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish a glassy carbon electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter) successively with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between polishing steps.

- Sonicate in deionized water for 1 minute to remove adsorbed alumina particles.

- Clean electrochemically in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ solution using cyclic voltammetry between -0.3 and +1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

Nanomaterial Suspension Preparation:

- Disperse 5 mg of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) in 5 mL of Nafion solution (0.5% in ethanol).

- Sonicate the mixture for 60 minutes to achieve a homogeneous black suspension.

- For composite materials, combine MWCNT with ZIF-8 (2:1 mass ratio) before adding to Nafion solution.

Electrode Modification:

- Deposit 5 μL of the prepared suspension onto the clean GCE surface.

- Allow to dry under ambient conditions for 4 hours to form a stable modified layer.

- Rinse gently with deionized water to remove loosely adsorbed material.

- Store the modified electrode in a desiccator when not in use.

Measurement Procedure:

- Immerse the modified electrode in 10 mL of acetate buffer solution (0.1 M, pH 5.0) containing the target heavy metal ions.

- Apply a deposition potential of -1.2 V for 180 seconds with stirring to pre-concentrate metals on the electrode surface.

- Record square-wave voltammetry scans from -1.0 to -0.2 V using the following parameters: frequency 25 Hz, amplitude 25 mV, step potential 4 mV.

- Measure the oxidation peak currents at approximately -0.5 V (Pb) and -0.1 V (Cu) for quantification.

Table 2: Reagent Solutions for Electrochemical Sensor Development

| Reagent | Composition/Concentration | Function in Sensor Development |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH 5.0) | Provides consistent ionic strength and pH control; influences analyte redox potentials |

| Electrode Modifier | 1 mg/mL MWCNT in 0.5% Nafion | Enhances electrode surface area and electron transfer kinetics; provides binding sites |

| Metal Standard Solutions | 1000 ppm Pb(II) and Cu(II) in 2% HNO₃ | Source of analytes for calibration curve generation and sensitivity determination |

| Electrode Polishing Suspension | 0.05 μm alumina powder in deionized water | Creates reproducible electrode surface morphology; removes adsorbed contaminants |

Protocol for Supercapacitor-Based Sensor Characterization

This protocol, adapted from JoVE methodology for supercapacitor characterization [13], provides a framework for evaluating the electrochemical properties of sensor materials:

Electrode Fabrication:

- Combine 80 wt% active material (e.g., porous carbon, metal oxide), 10 wt% conductive additive (carbon black), and 10 wt% binder (PTFE).

- Add 0.1-0.2 mL of isopropanol to form a homogeneous slurry.

- Roll the mixture into a thin film (0.1-0.2 mm thickness) using a roller.

- Compress the film onto a stainless steel current collector (1 cm² area) using an electrode press.

- Dry at 80°C for 24 hours to remove residual solvent.

Three-Electrode Cell Assembly:

- Connect the prepared working electrode to potentiostat leads.

- Position the reference electrode (Ag/AgCl) close to the working electrode surface.

- Place a platinum mesh counter electrode in the solution.

- Add sufficient electrolyte (e.g., 2 M H₂SO₄) to immerse all electrodes.

- Ensure no air bubbles are trapped on electrode surfaces.

Cyclic Voltammetry Measurements:

- Configure the potentiostat sequence for cyclic voltammetry.

- Set potential window appropriate for the material (e.g., -0.2 to 0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl).

- Program multiple scan rates (e.g., 10, 20, 30, 50, 100 mV/s) to study kinetics.

- Set quiet time to 0 seconds and segments to 21 for 10 cycles.

- Configure sampling interval based on scan rate (e.g., 0.333 s for 10 mV/s).

Data Collection and Analysis:

- Record minimum of 3 replicates for each measurement condition.

- Calculate specific capacitance from CV data using: C = (∫idV)/(2×v×m×ΔV), where v is scan rate, m is active mass, and ΔV is potential window.

- Plot peak current vs. scan rate to determine adsorption-controlled (linear) vs. diffusion-controlled (square root) processes.

Advanced Applications in Sensor Research

Battery Performance Monitoring

The three-electrode configuration finds specialized applications in battery research, where it enables monitoring of individual electrode potentials during operation. In one study, researchers implemented a three-electrode system in lithium-ion batteries to evaluate different graphite anode materials [14]. By introducing a lithium reference electrode, they could precisely monitor the anode potential during charging, identifying conditions that risk lithium plating—a critical safety parameter in battery development [14].

This approach revealed that small particle size (7 μm) and carbon coating in graphite materials improved kinetics, as evidenced by higher end-charge potentials (further from 0 V vs. Li/Li⁺) at increased charging rates [14]. Such insights directly inform the development of safer, faster-charging batteries for medical devices and other applications requiring reliable power sources.

Solid Oxide Cell Characterization

In high-temperature solid oxide cells, three-electrode configurations face unique challenges but provide essential insights for sensor development in harsh environments. Proper reference electrode placement and design are critical for obtaining reliable data on individual electrode performance in these all-solid-state systems [10]. Research in this area focuses on minimizing measurement distortion caused by the system geometry and the solid electrolyte, advancing our understanding of electrochemical processes at elevated temperatures [10].

Troubleshooting and Optimization Guidelines

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Unstable Potentials: Often caused by clogged reference electrode frits or insufficient chloride concentration in reference electrolytes. Verify reference electrode integrity by measuring against a second reference electrode [7].

Distorted Voltammetric Shapes: May result from excessive solution resistance, particularly in non-aqueous or low-ionic-strength solutions. Position the reference electrode closer to the working electrode or incorporate IR compensation [8].

Irreproducible Signals: Frequently stems from inconsistent working electrode surface preparation. Standardize polishing protocols and implement electrochemical cleaning procedures between measurements [9].

Drifting Baselines: Can indicate electrode fouling or unstable modified layers. Incorporate regeneration steps in measurement sequences or optimize modification procedures for enhanced stability [9].

Data Quality Validation

Reference Electrode Verification: Periodically check reference electrode potential using standard redox couples (e.g., ferricyanide/ferrocyanide) [7].

System Validation: Test using known concentrations of potassium ferricyanide to calculate effective electrode area and verify expected Randles-Sevcik behavior [13].

Background Subtraction: Always record background currents in pure supporting electrolyte and subtract from sample measurements [9].

Future Perspectives in Sensor Development

The ongoing evolution of three-electrode systems continues to enable advances in electrochemical sensor technology. Current research focuses on miniaturization for point-of-care diagnostic devices, development of novel electrode materials including graphene and other 2D materials, and integration with microfluidic systems for automated sample processing [15]. The emergence of flexible and wearable sensors represents another frontier where three-electrode configurations are being adapted for non-traditional form factors [15].

Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with electrochemical sensing is creating new opportunities for analyzing complex data from three-electrode systems, enabling multi-analyte detection and advanced signal processing [15]. These developments, coupled with standardized protocols as described in this application note, will continue to expand the capabilities of electrochemical sensors for pharmaceutical, environmental, and clinical applications.

Electrochemical sensors, particularly those based on voltammetric techniques, have become cornerstone analytical tools in modern chemical and biomedical research. These sensors operate by measuring the current resulting from redox reactions of an analyte under an applied potential, providing a powerful platform for quantifying a wide range of substances [16]. The integration of advanced nanomaterials and innovative fabrication methods has further enhanced their performance, making them indispensable for applications requiring high sensitivity, portability, cost-effectiveness, and rapid analysis [17] [18]. For drug development professionals and researchers, these attributes translate to practical advantages in therapeutic drug monitoring, environmental analysis, and diagnostic development, enabling precise measurements even in complex matrices like blood, saliva, and urine [19].

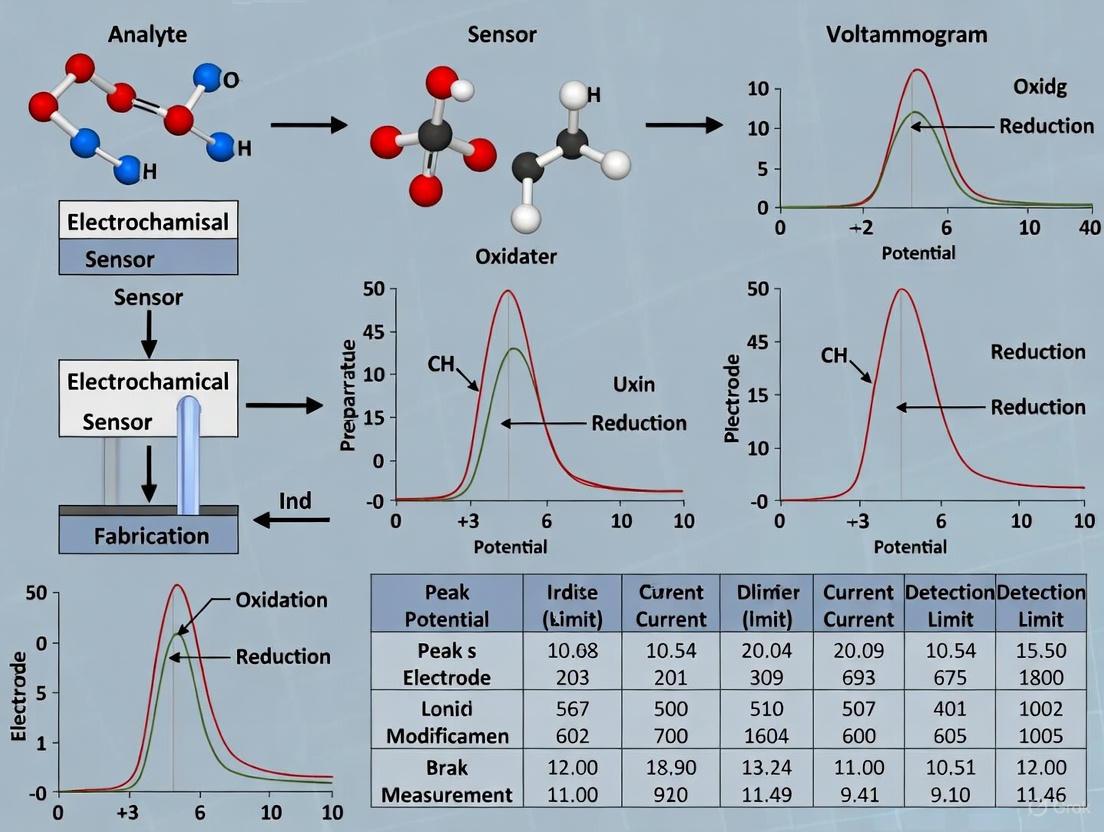

This document outlines the core advantages of voltammetric electrochemical sensors through structured data comparison, detailed experimental protocols, and visual workflows, providing a comprehensive resource for scientists engaged in sensor development and application.

Core Advantages and Performance Metrics

The performance of voltammetric sensors is quantified through key analytical figures of merit. The following table summarizes the reported performance for detecting various analytes, highlighting the direct impact of material selection and technique on sensitivity and detection speed.

Table 1: Analytical Performance of Nanomaterial-Modified Voltammetric Sensors

| Target Analyte | Sensor Modification | Technique | Detection Limit | Dynamic Range | Analysis Time | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dopamine [16] | Graphene Oxide | DPV | Low picomolar | Not Specified | Rapid | Medical Diagnostics |

| TNF-α (Cancer Biomarker) [16] | AgNP-decorated MXene | DPV | Picogram-level | Not Specified | Rapid | Medical Diagnostics |

| Heavy Metals [16] | Carbon Nanotubes | DPV | Not Specified | Not Specified | Rapid | Environmental Monitoring |

| NSAIDs & Antibiotics [20] | Hybrid Nanomaterials | DPV, SWV | Sub-micromolar | Wide | < 5 minutes | Pharmaceutical / Environmental |

| Pathogens (S. typhimurium) [21] | Gold Leaf with Magnetic Beads | EIS | Not Specified | Not Specified | Rapid | Food Safety |

The fundamental strengths of these sensors can be categorized into four key areas:

- Sensitivity: The exceptional sensitivity, often achieving sub-micromolar to picomolar detection limits, stems from enhanced electron transfer kinetics and increased surface area provided by nanomaterials [16] [20]. Techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) and Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) are particularly effective by minimizing background capacitive current, thereby resolving low-abundance analytes in complex samples [16] [20].

- Portability and Miniaturization: Voltammetric sensors are inherently suited for miniaturization and integration into portable, point-of-care, and wearable devices [17] [18]. Fabrication techniques like screen printing and 3D printing enable the production of compact, planar electrode systems, facilitating on-site analysis outside central laboratories [21].

- Cost-Effectiveness: The use of low-cost materials and scalable manufacturing methods, such as screen printing and laser ablation of gold leaves, makes these sensors highly economical [21]. This advantage is crucial for producing disposable sensors for single-use applications, preventing cross-contamination [18].

- Rapid Analysis: Voltammetric sensors provide short response times, enabling real-time or near-real-time monitoring. Techniques like SWV allow for fast scanning, and the direct transduction of chemical events into electrical signals eliminates lengthy incubation or separation steps common in other methods [16] [20].

Table 2: Comparison of Voltammetric Techniques for Sensor Applications

| Technique | Principle | Key Advantages | Ideal for Detecting |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Linear potential sweep in forward and reverse directions. | Insights into reaction reversibility and kinetics. | Redox-active drugs (e.g., NSAIDs, antibiotics) [20]. |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Small potential pulses on a linear base potential. | High sensitivity, low background, low detection limits. | Trace biomarkers (e.g., dopamine, uric acid) [16]. |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Square wave superimposed on a staircase waveform. | Fast scanning, excellent sensitivity, efficient background rejection. | Bioactive compounds for rapid screening [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Cyclic Voltammetry with a Standard Redox Probe

This protocol provides a standardized methodology for characterizing the basic performance and electroactive surface area of a newly fabricated voltammetric sensor using the ferri/ferrocyanide redox couple, a benchmark system [22].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Sensor Characterization

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Potassium Ferricyanide (K₃[Fe(CN)₆]) | Component of the redox probe; provides the oxidized species ([Fe(CN)₆]³⁻). |

| Potassium Ferrocyanide (K₄[Fe(CN)₆]) | Component of the redox probe; provides the reduced species ([Fe(CN)₆]⁴⁻). |

| Potassium Chloride (KCl) | Supporting electrolyte; ensures high ionic strength to minimize resistance. |

| Potentiostat | Instrument for applying potential and measuring current. |

| Three-Electrode Cell | Standard electrochemical setup: Working, Reference, and Counter electrodes [16]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Solution Preparation: Prepare a stock solution of 5 mM K₃[Fe(CN)₆] and 5 mM K₄[Fe(CN)₆] in 1 M KCl using deionized water [22].

- Instrument Setup: Connect the potentiostat to the three-electrode cell. The working electrode is the sensor under test, a Platinum coil serves as the counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl electrode is the reference [22].

- Electrode Preparation: Rinse the working electrode thoroughly with deionized water before immersion.

- Experiment Configuration: In the potentiostat software, select the Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) technique. Set the parameters [22]:

- Initial Potential: +0.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl)

- Upper Vertex Potential: +0.8 V

- Lower Vertex Potential: 0.0 V

- Final Potential: +0.5 V

- Scan Rate: 50 mV/s

- Number of Cycles: 3-10

- Data Acquisition: Immerse the electrode system in 30 mL of the prepared redox probe solution. Start the experiment. The software will display the voltammogram in real-time.

- Data Analysis: After completion, identify the anodic (Ipa) and cathodic (Ipc) peak currents and potentials. A well-functioning, reversible system will have a peak separation (ΔEp) close to 59 mV. The electroactive surface area can be calculated using the Randles-Ševčík equation.

Workflow Visualization

Advanced Sensor Development: Signal Enhancement with Nanomaterials

To achieve the high sensitivity required for detecting low-concentration drugs or biomarkers, signal enhancement through nanomaterial modification is critical. The following diagram illustrates the logical pathway for enhancing sensor performance.

The integration of nanomaterials such as carbon-based nanostructures, metal nanoparticles, and composites enhances sensor performance by improving electrical conductivity, providing electrocatalytic activity, and increasing the effective surface area for analyte binding [16] [20]. For instance, a sensor modified with graphene oxide achieves picomolar detection limits for dopamine, while those using gold nanoparticles benefit from their high electrocatalytic activity and biocompatibility [16]. These modifications are foundational to developing sensors capable of operating in complex biofluids like serum and saliva, where high sensitivity and resistance to fouling are paramount [19].

The accurate quantification of chemical species, ranging from essential metabolites to toxic heavy metals, is a cornerstone of pharmaceutical development and environmental monitoring. For decades, techniques such as Atomic Absorption Spectrometry (AAS), Inductively Coupled Plasma (ICP) spectroscopy, and High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) have been the established standards. While reliable, these methods often involve high operational costs, complex sample preparation, and require laboratory-bound, bulky instrumentation, limiting their use for rapid, on-site analysis [23] [24] [25].

In contrast, electrochemical methods, particularly voltammetry, have emerged as powerful, cost-effective, and sensitive alternatives. Voltammetric techniques leverage the electrochemical activity of analytes, measuring current as a function of an applied potential to provide both qualitative and quantitative information. This application note, framed within a broader thesis on electrochemical sensor development, details how modern voltammetry, especially when enhanced with novel materials and data analysis algorithms, can effectively replace traditional methods for specific analytical challenges in drug development and beyond. We provide a direct performance comparison and detailed protocols to facilitate the adoption of these streamlined techniques.

Performance Comparison: Voltammetry vs. Traditional Techniques

The choice of analytical technique depends on the specific application, required detection limits, sample complexity, and available resources. The following tables summarize the key characteristics of each method.

Table 1: Comparison of Analytical Technique Capabilities

| Technique | Multi-Element/Analyte Capability | Typical Sample Volume | Sample Preparation Complexity | Portability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Voltammetry | Limited simultaneous detection | Low (µL to mL) | Low to Moderate | High |

| AAS (Flame) | Single element | High (mL) | Low | Low |

| AAS (Graphite Furnace) | Single element | Low (µL) | Moderate | Low |

| ICP-MS/OES | Multi-element | Low (mL) | Moderate (often requires dilution) | Low |

| HPLC | Multi-analyte | Low (µL to mL) | Moderate to High (e.g., derivatization) | Low |

Table 2: Comparison of Operational and Analytical Figures of Merit

| Technique | Detection Limit (General) | Analytical Range | Equipment & Operational Cost | Analysis Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stripping Voltammetry | ppt-ppb (e.g., 0.002-0.007 µg/L for metals) [26] | Wide | Low | Fast |

| AAS (Flame) | ppb | Moderate | Low | Fast |

| AAS (Graphite Furnace) | ppt-ppb | Moderate | Moderate | Slow |

| ICP-OES | ppb | Wide | High | Fast |

| ICP-MS | ppt-ppb | Wide | Very High | Fast |

| HPLC-UV/Vis | ppb | Wide | High | Moderate |

A concrete example of voltammetry's superior sensitivity for specific applications is the determination of trace cobalt and chromium in human urine. Catalytic Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry (CAdSV) demonstrated significantly lower detection limits compared to Electrothermal AAS (ET-AAS), enabling reliable analysis at sub-ppb levels found in non-occupationally exposed populations [26].

Table 3: Direct Comparison of CAdSV vs. ET-AAS for Urine Analysis [26]

| Analyte | Technique | Detection Limit (µg/L) | Precision (R.S.D.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cobalt (Co) | CAdSV | 0.007 | < 5% |

| ET-AAS | 0.13 | < 5% | |

| Chromium (Cr) | CAdSV | 0.002 | < 5% |

| ET-AAS | 0.18 | < 5% |

Detailed Voltammetric Protocols

The following protocols are exemplary of how voltammetry can be applied to real-world analytical problems, showcasing its versatility and power.

Protocol 1: Simultaneous Detection of As³⁺ and Hg²⁺ in Water by Anodic Stripping Voltammetry

This protocol outlines the modification of a glassy carbon electrode (GCE) and the subsequent detection of two highly toxic heavy metals, achieving detection limits meeting WHO guidelines for drinking water [24].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cobalt oxide nanoparticles (Co₃O₄): Serves as a porous, high-surface-area substrate for depositing AuNPs, enhancing the catalytic surface.

- Gold nanoparticles (AuNPs): Acts as a superior catalytic surface for the oxidation and adsorption of As³⁺ and Hg²⁺, facilitating electron transfer.

- Acetate buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.6): Serves as the supporting electrolyte, optimizing the deposition and stripping efficiency for both metal ions.

- Standard stock solutions of As³⁺ and Hg²⁺ (1000 ppm): Used for preparing calibration standards and spiking real samples.

Experimental Workflow:

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish a bare GCE with alumina slurry (0.05 µm) and rinse thoroughly with deionized water. Clean electrochemically via Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) in 0.5 M H₂SO₄.

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast a suspension of Co₃O₄ nanoparticles onto the GCE surface and dry. Subsequently, drop-cast a solution of pre-synthesized AuNPs onto the Co₃O₄/GCE and allow to dry, forming the Co₃O₄/AuNP nanocomposite.

- Sample Preparation: Mix the water sample (river, drinking water) with an equal volume of 0.1 M acetate buffer (pH ~4.6). For quantification, use standard addition methods.

- Anodic Stripping Voltammetry:

- Deposition: Immerse the modified electrode in the stirred sample solution. Apply a deposition potential of -0.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 30-60 seconds to reduce and pre-concentrate As⁰ and Hg⁰ onto the electrode surface.

- Stripping: After a quiet period (10 s), initiate a square-wave voltammetric scan from -0.4 V to +0.7 V. The deposited metals are oxidized, generating characteristic current peaks at their respective potentials (~0.1 V for As³⁺ and ~0.4 V for Hg²⁺).

- Data Analysis: Measure the peak currents. Plot the peak current versus metal concentration from standard additions to generate a calibration curve and calculate the concentration in the unknown sample. The sensor demonstrates a wide linear dynamic range (10-900 ppb for As³⁺ and 10-650 ppb for Hg²⁺) with excellent recovery (96-116%) in real samples [24].

Protocol 2: Quantification of Copper Ions in Complex Cell Culture Media using SWASV and Machine Learning

This protocol addresses the significant challenge of analyzing metals in complex, organic-rich matrices like cell culture media, where interferents can obscure signals. The integration of machine learning with Square-Wave Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (SWASV) overcomes this limitation [27].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Cell culture media (MEM, DMEM, F12K): The complex sample matrix containing amino acids, vitamins, and other interferents.

- Copper sulfate (CuSO₄) stock solution (0.01 M): Prepared in 0.1 M nitric acid for calibration standards.

- Phosphate buffer and Acetate buffer: For adjusting sample pH to physiological (7.4) or acidic (4.0) conditions to improve signal definition.

- Gold working electrode: Provides a stable and reproducible surface for copper deposition and stripping.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Sensor and System Setup: Use a three-electrode system with a gold working electrode, a stainless-steel counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Electrode Cleaning: Clean the gold electrode by performing 10 CV cycles in 50 mM H₂SO₄ between -0.3 V and +1.5 V.

- Sample Preparation: Spike the commercial cell culture medium (e.g., MEM, DMEM) with known concentrations of Cu²⁺ (e.g., 1-20 µM). Dilute the sample 1:1 with acetate buffer to achieve pH 4, which enhances the stripping peak shape.

- SWASV Measurement:

- Deposition: Apply a potential of -0.4 V for 30 seconds to deposit metallic copper onto the gold electrode.

- Stripping: Record the voltammogram using a square-wave waveform (e.g., pulse amplitude 30 mV, frequency 25 Hz) over a potential range from -0.4 V to +0.7 V.

- Machine Learning-Enhanced Data Analysis:

- Feature Extraction: From each recorded voltammogram, extract multiple features beyond just peak height (e.g., peak potential, peak width, full width at half maximum, curve shape descriptors).

- Model Training and Prediction: Train a supervised machine learning model (e.g., Support Vector Machine - SVM, or Naïve Bayes - NB) using the extracted features from a training set of known concentrations. This model learns the complex relationship between the voltammetric signature and the Cu²⁺ concentration, even in the presence of interferents. The trained model can then predict the concentration in unknown samples with high accuracy (e.g., >96% for SVM in MEM media) [27].

Protocol 3: Determination of Emerging Contaminants using Differential Pulse Voltammetry

This protocol demonstrates the application of voltammetry for organic molecule detection, comparing performance directly with HPLC and UV-vis spectrophotometry [25].

Research Reagent Solutions:

- Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) Electrode: Provides a wide potential window, low background current, and high resistance to fouling.

- Emerging Contaminant Stock Solutions: Caffeine (CAF), Paracetamol (PAR), Methyl Orange (MO) in acidic or neutral medium.

- Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., Na₂SO₄ or H₂SO₄): Provides ionic conductivity for the electrochemical cell.

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- System Setup: Employ a three-electrode system featuring a BDD working electrode, a platinum counter electrode, and an Ag/AgCl reference electrode.

- Sample Preparation: Dilute the water sample (synthetic effluent, tap water, groundwater) in the supporting electrolyte (e.g., 0.5 M H₂SO₄ or Na₂SO₄). For complex matrices, filtration may be necessary.

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) Measurement: Record a DPV voltammogram over a suitable potential range (e.g., 0 V to +1.5 V for CAF, PAR, MO) using optimized parameters (pulse amplitude, step potential, modulation time). Well-resolved oxidation peaks for each analyte will appear.

- Data Analysis and Cross-Validation:

- Construct a calibration curve by plotting the peak current intensity against the concentration of standard solutions.

- For validation, analyze the same sample set using reference techniques like HPLC and UV-vis. The BDD-based DVP method shows satisfactory agreement with these methods, with detection limits of 0.69 mg L⁻¹ for CAF, 0.84 mg L⁻¹ for PAR, and 0.46 mg L⁻¹ for MO, confirming its suitability as a low-cost, rapid alternative for monitoring these contaminants in effluents [25].

Voltammetry, particularly in its advanced forms such as stripping techniques and when coupled with modern materials (nanoparticles, BDD) and data analysis approaches (machine learning), presents a compelling alternative to traditional spectroscopic and chromatographic methods. Its key advantages—high sensitivity, portability, low cost, rapid analysis, and minimal reagent consumption—make it exceptionally suitable for a wide range of applications in drug development, environmental monitoring, and clinical diagnostics.

As demonstrated in the protocols, voltammetry can match or even surpass the performance of AAS and ICP-MS for specific trace metal analyses and provide a robust, cost-effective solution for organic contaminant monitoring that challenges HPLC. For researchers developing electrochemical sensors, these protocols provide a foundation for replacing conventional, resource-intensive techniques with streamlined, information-rich voltammetric methods, thereby accelerating analytical workflows and enabling new possibilities for decentralized testing.

Voltammetry is a powerful category of electroanalytical techniques in which current is measured as a function of an applied potential. The resulting plot of current versus potential is called a voltammogram, which serves as a unique electrochemical fingerprint for identifying and quantifying analytes [28]. These techniques have revolutionized bioactive compound detection in pharmaceutical and clinical research by providing rapid, sensitive, and selective measurement capabilities for neurotransmitters, antioxidants, pharmaceuticals, and biomarkers [16] [28].

The fundamental principle underpinning voltammetry involves applying a varying potential to an electrochemical cell containing the analyte of interest. This applied potential drives oxidation or reduction (redox) reactions at the working electrode surface, generating a measurable current [16]. The magnitude of this current is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species, enabling both qualitative identification (based on characteristic peak potentials) and quantitative analysis [29]. For researchers developing electrochemical sensors, understanding how to interpret the current-potential relationships in voltammograms is essential for optimizing sensor design, improving sensitivity, and ensuring accurate quantification of target analytes in complex matrices.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Major Voltammetric Techniques

| Technique | Potential Waveform | Key Advantages | Typical Applications in Sensor Development | Detection Limits |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Linear sweep reversed at vertex potential | Assesses reaction reversibility, studies electron transfer kinetics | Characterization of electrode modification, studying redox mechanisms [16] | ~1 µM [28] |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Small pulses superimposed on linear base potential | Minimizes capacitive current, superior sensitivity | Trace analysis of pharmaceuticals, simultaneous detection of multiple biomarkers [16] [28] | ~1 pM-100 nM [28] |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Square wave superimposed on staircase waveform | Fast scanning, efficient background suppression | Rapid screening, real-time monitoring, reversible systems [16] [28] | ~1 pM-100 nM [28] |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) | Preconcentration at negative potential followed by anodic sweep | Ultra-trace metal detection | Heavy metal monitoring in environmental/clinical samples [28] | Part-per-trillion [28] |

Fundamental Concepts in Voltammogram Interpretation

The Three-Electrode System

Voltammetric measurements typically employ a three-electrode system, which is fundamental to ensuring controlled potential application and accurate current measurement [29]. The system consists of:

- Working Electrode (WE): The electrode where the redox reaction of interest occurs, often fabricated from inert materials such as glassy carbon, gold, or platinum, and frequently modified with nanomaterials or recognition elements to enhance sensitivity and selectivity [29] [16].

- Reference Electrode (RE): Maintains a stable, known potential (e.g., Ag/AgCl) against which the working electrode potential is controlled and measured without passing significant current [29].

- Counter Electrode (AE): Completes the electrical circuit, allowing current to flow through the cell while preventing contamination of the reference electrode [29].

This configuration is managed by a potentiostat, an electronic instrument that controls the potential between the working and reference electrodes while measuring the current between the working and counter electrodes [29].

Diagram 1: Three-electrode system configuration for voltammetric measurements. The potentiostat precisely controls the working electrode potential relative to the reference electrode while measuring current at the counter electrode.

Faradaic vs. Capacitive Currents

Understanding voltammograms requires distinguishing between two fundamental types of current:

- Faradaic Current: Results from the reduction or oxidation of electroactive species at the electrode surface, following Faraday's law where current is directly proportional to the number of electrons transferred in the redox reaction [29]. This is the analytically useful signal that correlates with analyte concentration.

- Capacitive Current: Also called charging current, arises from the rearrangement of ions and solvent molecules at the electrode-electrolyte interface, effectively charging the electrical double layer like a capacitor [29]. This non-faradaic current constitutes the primary background signal in voltammetry.

The ratio of faradaic to capacitive current critically determines the sensitivity and detection limits of voltammetric techniques [29]. Modern pulse voltammetric methods are specifically designed to minimize the contribution of capacitive current by exploiting its faster decay compared to faradaic current following potential perturbations [28].

Mass Transport Mechanisms

For a redox reaction to occur, analyte molecules must reach the electrode surface through three primary mass transport mechanisms:

- Diffusion: Movement due to concentration gradients established when electroactive species are consumed or generated at the electrode surface [29].

- Migration: Movement of charged species in an electric field.

- Convection: Bulk movement of solution due to stirring, flow, or electrode rotation.

In most controlled voltammetric experiments, diffusion represents the dominant mass transport mechanism, with the resulting current described by the Cottrell equation for a potential step experiment: i_c = nFACD^(1/2)/(π^(1/2)t^(1/2)) [28].

Voltammogram Plotting Conventions and Features

Plotting Conventions

When interpreting voltammograms, researchers must first identify the plotting convention used, as two predominant systems exist:

- IUPAC Convention: Anodic (oxidizing) currents are plotted upward on the vertical axis, and more positive (anodic) potentials are plotted to the right on the horizontal axis [30]. This has become the default in modern electrochemistry literature.

- Polarographic (Classic) Convention: Cathodic (reducing) currents are plotted upward, and negative (cathodic) potentials are plotted to the right [30]. This tradition originates from early polarography work.

These conventions affect the visual appearance of voltammograms but not the underlying electrochemical information. The IUPAC convention is generally recommended for new research publications for consistency and broader understandability [30].

Characteristic Voltammogram Features

A typical voltammogram displays several characteristic features that provide crucial information about the redox process:

- Peak Potential (E_p): The potential at which the current reaches its maximum value, characteristic of the specific redox couple and useful for analyte identification.

- Peak Current (i_p): The maximum current value, proportional to analyte concentration according to the Randles-Ševčík equation for cyclic voltammetry.

- Half-Wave Potential (E_1/2): In polarography, the potential at which the current reaches half its limiting value, characteristic of the redox couple.

- Limiting Current: The current plateau observed at sufficiently extreme potentials where the redox process is mass-transport limited.

The shape and positions of these features reveal information about electron transfer kinetics, reaction mechanisms, and adsorption processes.

Experimental Protocols for Voltammetric Analysis in Sensor Development

Protocol: Electrode Modification with Nanomaterials for Enhanced Biosensing

Purpose: To modify working electrode surfaces with carbon nanomaterials to enhance sensitivity, selectivity, and electron transfer kinetics for neurotransmitter detection [16].

Materials:

- Glassy carbon electrode (GCE, 3 mm diameter)

- Graphene oxide (GO) dispersion (1 mg/mL in deionized water)

- Phosphate buffer saline (PBS, 0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Nitrogen gas (high purity)

- Target analytes (dopamine, ascorbic acid, uric acid)

Procedure:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Polish the GCE sequentially with 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth pad. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between each polishing step and after the final polish.

- Electrochemical Cleaning: Perform cyclic voltammetry in 0.5 M H₂SO₄ from -0.2 to +1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at 100 mV/s for 20 cycles until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

- Nanomaterial Modification: Dispense 8 µL of the GO dispersion onto the pre-treated GCE surface and allow to dry under ambient conditions for 2 hours.

- Electrochemical Reduction: Immerse the GO-modified electrode in PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and apply a constant potential of -1.0 V for 600 seconds to produce electrochemically reduced graphene oxide (ERGO).

- Sensor Characterization: Perform CV in 5 mM K₃Fe(CN)₆/K₄Fe(CN)₆ in 0.1 M KCl from -0.2 to +0.6 V at scan rates of 25-500 mV/s to verify enhanced electroactive surface area.

- Analytical Application: Transfer modified electrode to PBS containing varying concentrations of target analytes and record DPV from 0 to +0.6 V with pulse amplitude 50 mV, pulse width 50 ms.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If modification appears non-uniform, optimize dispersion concentration and sonication time.

- If electron transfer kinetics remain sluggish, consider alternative reduction parameters or composite materials.

- If reproducibility is poor, ensure consistent polishing and modification procedures.

Protocol: Differential Pulse Voltammetry for Simultaneous Detection of Biomarkers

Purpose: To simultaneously detect multiple biomarkers (e.g., dopamine, uric acid, ascorbic acid) in physiological samples using DPV to overcome overlapping signals [16].

Materials:

- Nanomaterial-modified working electrode (from Protocol 4.1)

- Ag/AgCl reference electrode

- Platinum wire counter electrode

- PBS (0.1 M, pH 7.4)

- Standard solutions of dopamine, uric acid, and ascorbic acid

- Artificial cerebrospinal fluid or diluted serum samples

Procedure:

- Instrument Setup: Configure the potentiostat for DPV with the following parameters: initial potential -0.2 V, final potential +0.6 V, pulse amplitude 50 mV, pulse width 50 ms, step height 4 mV, step time 0.5 s.

- Background Measurement: Place the modified electrode in blank PBS and record a background voltammogram.

- Standard Addition: Spike the PBS with increasing concentrations of mixed standard solutions (e.g., 1, 5, 10, 25, 50 µM of each analyte) and record DPV after each addition.

- Sample Analysis: Replace standard solution with filtered artificial cerebrospinal fluid or diluted serum sample (1:10 with PBS) and record DPV.

- Standard Addition to Sample: Spike the sample with known standard concentrations to verify detection and account for matrix effects.

- Data Analysis: Measure peak currents for each analyte and construct calibration curves relating current to concentration.

Validation:

- Calculate limits of detection (LOD) as 3σ/slope and limits of quantification (LOQ) as 10σ/slope, where σ is the standard deviation of the blank.

- Determine reproducibility through repeated measurements (n=5) of the same sample.

- Assess recovery (95-105%) through standard addition methods.

- Verify selectivity in the presence of potential interferents (e.g., glucose, lactate, acetaminophen).

Table 2: Advanced Voltammetric Techniques for Specific Applications in Sensor Development

| Technique | Key Parameters | Optimal Use Cases | Data Interpretation Guidelines | Common Pitfalls |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic Voltammetry | Scan rate (10-1000 mV/s), potential window | Mechanism studies, electrode characterization, reversibility assessment | Peak separation (ΔEp) indicates reversibility; ip ∝ ν^(1/2) for diffusion control | Ohmic drop at high scan rates, non-ideal electrode geometry |

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry | Pulse amplitude (10-100 mV), pulse width (10-100 ms), step time | Trace analysis, simultaneous detection, irreversible systems | Peak current proportional to concentration; peak potential identifies species | Excessive pulse amplitude distorts shape; adsorption causes broadening |

| Square Wave Voltammetry | Frequency (1-100 Hz), step height (1-10 mV), amplitude (10-50 mV) | Fast screening, kinetic studies, reversible systems | Forward/reverse currents provide kinetic information; high frequency enhances sensitivity | Incorrect frequency selection masks signals; charging current at high frequencies |

| Anodic Stripping Voltammetry | Deposition potential/time, rest period, stripping scan rate | Ultra-trace metal detection, environmental monitoring | Peak area correlates with concentration; standard addition essential for complex matrices | Intermetallic compound formation, incomplete stripping, mercury electrode toxicity |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetric Sensor Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example Formulation | Storage/Stability Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrode Modifiers | Enhance sensitivity and selectivity | Graphene oxide dispersion (1 mg/mL in DI water) [16] | 4°C, stable for 2-3 months; sonicate before use |

| Metal Nanoparticles | Improve electrocatalytic properties | Gold nanoparticle colloid (10 nm diameter, 0.01% HAuCl₄) [16] | Dark, 4°C; avoid freezing and aggregation |

| Supporting Electrolytes | Provide conductivity, control ionic strength | Phosphate buffer saline (0.1 M, pH 7.4) or KCl (0.1 M) | Room temperature; check for microbial growth in buffers |

| Polymer Membranes | Enhance selectivity, reduce fouling | Nafion perfluorinated resin (0.5-5% in lower aliphatic alcohols) | Sealed container, room temperature; prone to evaporation |

| Biorecognition Elements | Provide molecular specificity | Enzyme solutions (e.g., tyrosinase for phenol detection) [28] | -20°C for long-term storage; activity assays recommended |

| Standard Solutions | Calibration and quantification | Dopamine hydrochloride (10 mM in 0.1 M HClO₄) [16] | -20°C, protected from light and oxygen; prepare fresh weekly |

| Anti-fouling Agents | Prevent surface contamination | Bovine serum albumin (BSA, 0.1-1% in buffer) | 4°C; avoid repeated freeze-thaw cycles |

| Redox Probes | Electrode characterization | Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide (5 mM each in 0.1 M KCl) [16] | Dark, room temperature; discard if discolored |

Advanced Applications in Sensor Development and Data Interpretation

Nanomaterial-Enhanced Sensors for Bioactive Compound Detection

The integration of nanomaterials has dramatically advanced voltammetric sensor capabilities for pharmaceutical and clinical applications [16]. Key developments include:

- Carbon Nanostructures: Carbon nanotubes and graphene derivatives provide exceptional electrical conductivity, high surface area, and functional groups for biomolecule immobilization, enabling picogram-level detection of cancer biomarkers like TNF-α [16].

- Metal and Metal Oxide Nanoparticles: Gold (AuNPs) and silver (AgNPs) nanoparticles exhibit high electrocatalytic activity and biocompatibility, while metal oxides like titanium dioxide (TiO₂) and zinc oxide (ZnO) reduce overpotentials and increase electron transfer rates [16].

- Composite Materials: Combining carbon materials with metals or polymers creates synergistic effects, such as AgNP-decorated MXene (Ti₃C₂-AgNPs) and hydrogel-based graphene sensors that achieve unprecedented sensitivity for neurotransmitter detection [16].

These nanomaterial-enhanced sensors enable precise detection of biomarkers including dopamine, serotonin, uric acid, and ascorbic acid at clinically relevant concentrations in complex matrices like blood serum and artificial cerebrospinal fluid [16].

Flow Analysis Systems for Environmental Monitoring

Recent innovations have integrated voltammetric sensors into flow analysis systems for on-site environmental monitoring, as demonstrated by a system developed for cobalt and nickel detection in river water [31]. This approach features:

- All-in-One Sensor Design: A compact three-electrode system with a bismuth-film modified working electrode optimized for simultaneous detection of Co and Ni using linear scan voltammetry [31].

- High-Frequency Monitoring Capability: The system captures short-lived contamination events that would be missed by conventional spot sampling, with sensitivity in the µg L⁻¹ range [31].

- Automated Data Processing: Custom Python code processes over 1000 data points within seconds, enabling real-time decision making [31].

This automated voltammetric platform demonstrates the translation of laboratory-based electrochemical techniques to robust field-deployable sensors for environmental surveillance and industrial process monitoring.

Diagram 2: Comprehensive workflow for developing nanomaterial-modified voltammetric sensors, from electrode design and modification through electrochemical characterization to real-world application validation.

Interpretation of current-potential relationships in voltammograms represents a cornerstone of electrochemical sensor development. The systematic understanding of voltammetric features, combined with strategic selection of techniques and appropriate electrode modifications, enables researchers to design sensors with exceptional sensitivity, selectivity, and reliability for pharmaceutical, clinical, and environmental applications. Future directions in this field point toward increased integration with artificial intelligence for automated signal processing, development of multifunctional wearable platforms, and creation of sustainable nanomaterial-based sensors for real-time, on-site monitoring applications that will further expand the impact of voltammetric analysis in scientific research and public health protection.

Methodologies, Materials, and Cutting-Edge Applications

The integration of nanomaterials into electrochemical sensing platforms has marked a revolutionary advance in voltammetric analysis. Voltammetric sensors, which measure current resulting from the oxidation or reduction of an analyte under an applied potential, form the backbone of modern electrochemical detection [16]. The performance of these sensors is fundamentally governed by the properties of the working electrode surface. Modification of this electrode with nanomaterials such as Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs), Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs), MXenes, and Metal Oxides dramatically enhances key sensor metrics by providing a larger active surface area, improving electron transfer kinetics, and introducing electrocatalytic activity [16] [20]. These enhancements are critical for applications ranging from the detection of low-abundance disease biomarkers and pharmaceutical compounds in biological fluids to monitoring environmental pollutants and ensuring food safety [16] [20] [32]. This document provides detailed application notes and standardized protocols for the modification of electrodes with these key nanomaterials, framed within the broader context of developing advanced electrochemical sensors for health and safety monitoring.

Table 1: Key Performance Enhancements from Nanomaterial Electrode Modifiers

| Nanomaterial | Primary Function | Key Advantages | Typical Analytes Detected |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) | Electrocatalysis, Bioconjugation | High conductivity, excellent biocompatibility, facile surface functionalization | Pharmaceutical drugs, biomarkers, antibiotics [16] [20] |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Electron transfer, Surface area increase | High aspect ratio, excellent electrical conductivity, mechanical stability | Neurotransmitters (dopamine, serotonin), uric acid [16] [33] |

| MXenes | Conductivity, Signal amplification | Metallic conductivity, hydrophilic surface, tunable chemistry | Antibiotics, NSAIDs, cancer biomarkers [20] [34] [35] |

| Metal Oxides | Electrocatalysis, Stability | Reduced overpotential, high stability, catalytic activity | Nitrite, resorcinol, ascorbic acid [16] [32] [36] |

Properties and Selection Criteria for Nanomaterials

The selection of a nanomaterial for electrode modification is a strategic decision based on its intrinsic properties and the requirements of the target analyte.

Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs): AuNPs are prized for their high electrocatalytic activity and biocompatibility. They facilitate direct electron transfer for many biomolecules and can be easily functionalized with thiolated ligands, antibodies, or aptamers to impart selectivity [16] [20]. Their ability to decrease overpotential and amplify Faradaic signals makes them ideal for constructing sensitive biosensors.

Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs): CNTs, including single-walled and multi-walled (MWCNTs), create a nanoscale network on the electrode surface. This network significantly increases the electroactive surface area and promotes the electron transfer rate between the analyte and the electrode. They are particularly effective in resolving the overlapping signals of co-existing electroactive species, such as dopamine, ascorbic acid, and uric acid [16] [34].

MXenes: As a family of two-dimensional transition metal carbides/nitrides, MXenes (e.g., Ti₃C₂Tₓ) offer a unique combination of metallic conductivity and hydrophilic surfaces [34]. Their high surface area and abundant surface functional groups (-O, -OH, -F) enable strong interactions with various analytes and other nanomaterials in composite films, preventing aggregation and enhancing stability [33] [37]. They are emerging as superior substrates for signal amplification.

Metal Oxides: Nanostructured metal oxides like zinc oxide (ZnO), titanium dioxide (TiO₂), and copper oxide (CuO) are widely used for their electrocatalytic properties and chemical stability [32] [36]. They can catalyze the redox reactions of many small molecules, thereby reducing the required energy (overpotential) and increasing the sensor's sensitivity and selectivity.

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Electrode Modification

The following protocols describe standardized methods for modifying a standard 3-mm Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE). Volumes and concentrations may be scaled for electrodes of different sizes.

Protocol 1: Modification with Gold Nanoparticles (AuNPs) via Electrodeposition

Principle: This method uses a constant potential to reduce AuCl₄⁻ ions from solution onto the electrode surface, forming a stable, nanostructured layer of AuNPs.

Materials:

- Chloroauric acid (HAuCl₄)

- Potassium chloride (KCl) or Sodium nitrate (NaNO₃)

- Nitric acid (HNO₃), 0.1 M

- Aqueous alumina slurry (0.05 µm)

Procedure:

- Electrode Polishing: Polish the GCE sequentially with 0.05 µm alumina slurry on a microcloth. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water between polishing steps.

- Electrochemical Cleaning: Place the polished GCE in a 0.1 M HNO₃ solution. Perform Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) between -0.3 V and +1.3 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 20-30 cycles or until a stable CV profile is obtained. Rinse with deionized water.

- Electrodeposition Solution: Prepare a solution of 0.5 - 1.0 mM HAuCl₄ in 0.1 M KCl or NaNO₃.

- Nanoparticle Deposition: Immerse the cleaned GCE in the electrodeposition solution. Apply a constant potential of -0.4 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 30-60 seconds under gentle stirring.

- Electrode Rinsing: Remove the electrode from the solution and rinse it gently with deionized water to remove any loosely adsorbed ions or particles. The modified AuNPs/GCE is now ready for use or further functionalization.

Protocol 2: Modification with Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) via Drop-Casting

Principle: A stable dispersion of MWCNTs is prepared and a precise volume is cast onto the electrode surface, forming a uniform, conductive film upon solvent evaporation.

Materials:

- Pristine MWCNTs

- N,N-Dimethylformamide (DMF) or Sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) aqueous solution

- Nafion perfluorinated resin solution (optional)

Procedure:

- Electrode Preparation: Polish and clean the GCE as described in Protocol 1, Steps 1-2.

- MWCNT Dispersion: Weigh 1-2 mg of pristine MWCNTs and disperse them in 1 mL of solvent (e.g., DMF or 0.1% SDS aqueous solution) using ultrasonic agitation for 30-60 minutes to achieve a homogeneous, black suspension.

- Film Casting: Using a micropipette, deposit a precise aliquot (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the MWCNT dispersion onto the mirror-like surface of the cleaned GCE.

- Solvent Evaporation: Allow the electrode to dry at room temperature or under a gentle infrared lamp until all solvent has evaporated, leaving a uniform black film.

- Membrane Application (Optional): For improved mechanical stability and anti-fouling properties in complex matrices, cast an additional 2-3 µL of a diluted Nafion solution (e.g., 0.05% in ethanol) over the MWCNT film and let it dry. The resulting MWCNTs/Nafion/GCE is ready for electrochemical characterization.

Protocol 3: Fabrication of a MWCNT/MXene Nanocomposite Film

Principle: This protocol creates a synergistic nanocomposite where MWCNTs act as conductive spacers between MXene sheets, preventing restacking and enhancing charge transfer.

Materials:

- Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene multilayer powder (commercially available or synthesized from Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase)

- MWCNTs (from Protocol 2)

- Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) or Tetramethylammonium hydroxide (TMAOH)

Procedure:

- MXene Delamination: Prepare a multilayer MXene suspension (e.g., 1 mg/mL) in deionized water. To delaminate the multilayers into few-layer flakes, add an intercalator like DMSO or TMAOH, followed by vigorous shaking and ultrasonication for ~1 hour under argon atmosphere. Centrifuge the resulting colloidal solution to collect the supernatant containing delaminated MXene nanosheets [33] [37].

- Nanocomposite Preparation: Mix the delaminated MXene colloidal solution with a pre-dispersed MWCNT solution (from Step 2 of Protocol 2) to achieve the desired weight ratio (e.g., 5 wt% MWCNT). Subject the mixture to ultrasonication for 30 minutes to form a homogeneous MWCNT/MXene nanocomposite [33].

- Electrode Modification: Drop-cast 5-10 µL of the MWCNT/MXene nanocomposite suspension onto a pre-cleaned GCE and allow it to dry at room temperature. The final MWCNT/MXene/GCE should be stored in a dry environment if not used immediately.

Protocol 4: Modification with Zinc Oxide (ZnO) Nanorods via Hydrothermal Synthesis

Principle: This in-situ growth method creates a highly structured, high-surface-area film of ZnO nanorods directly on the electrode surface.

Materials:

- Zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O)

- Hexamethylenetetramine (C₆H₁₂N₄)

- Seed layer solution: Zinc acetate dihydrate and ethanol

Procedure:

- Seed Layer Deposition: Clean the GCE and drop-cast a solution of zinc acetate in ethanol (e.g., 10 mM) onto its surface. Dry and anneal at ~350°C for 30 minutes to form a thin ZnO seed layer.

- Growth Solution Preparation: Prepare an aqueous growth solution containing 25 mM Zn(NO₃)₂·6H₂O and 25 mM hexamethylenetetramine.

- Hydrothermal Growth: Immerse the seed-layer-coated GCE upside down in the growth solution. Heat the solution to 90-95°C and maintain this temperature for 2-4 hours in a sealed container to allow for the oriented growth of ZnO nanorods.

- Post-treatment: Carefully remove the electrode, rinse it with deionized water to remove any residual reactants, and dry it in air. The ZnO_NRs/GCE is now ready for sensing applications [32].

Workflow for Sensor Development and Signal Measurement

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for developing a nanomaterial-modified voltammetric sensor, from electrode preparation to data analysis.

Diagram 1: Workflow for developing a nanomaterial-modified voltammetric sensor, covering preparation, modification, characterization, and analytical testing.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

A well-equipped laboratory for nanomaterial-based electrode modification requires the following essential reagents and materials.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Electrode Modification

| Category | Item | Primary Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrodes & Cells | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE) | Base working electrode platform | Standard substrate for modification [20] |

| Ag/AgCl & Pt Wire | Reference & Counter Electrodes | Complete the 3-electrode cell setup [16] | |

| Nanomaterials | HAuCl₄, AgNO₃ | Precursor for metal nanoparticles | Electrodeposition of AuNPs and AgNPs [16] [20] |

| MWCNTs, Graphene Oxide | Conductive carbon nanostructures | Enhancing surface area and electron transfer [16] [33] | |

| MXene (Ti₃C₂Tₓ) | 2D conductive material | High-sensitivity signal amplification [33] [34] | |

| ZnO, TiO₂ NPs | Metal oxide catalysts | Electrocatalytic oxidation/reduction of analytes [32] [36] | |

| Chemical Reagents | Alumina Slurry (0.05 µm) | Abrasive for electrode polishing | Creating a mirror-finish, clean electrode surface |