Advanced Strategies for Improving Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a systematic framework for enhancing signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in voltammetric analyses, addressing critical needs in biomedical research and pharmaceutical development.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Signal-to-Noise Ratio in Voltammetry: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a systematic framework for enhancing signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in voltammetric analyses, addressing critical needs in biomedical research and pharmaceutical development. Covering foundational principles to advanced applications, we explore electrode engineering strategies, methodological optimizations using response surface methodology, and practical troubleshooting for common instrumentation issues. The content validates electrochemical methods against established techniques like HPLC and demonstrates their efficacy in complex matrices including biological and environmental samples. This comprehensive guide equips researchers with practical knowledge to achieve superior analytical sensitivity, reliability, and detection limits in diverse research applications.

Understanding Signal-to-Noise Ratio Fundamentals in Electrochemical Systems

What is Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) in Voltammetry and Why is it Critical for Research?

Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a fundamental metric that quantifies how clearly a voltammetric sensor can detect an analyte against the background "noise" of the system. It is defined as the ratio of the faradaic current (signal produced by the redox reaction of the target analyte) to the random fluctuations in the background current (noise). An SNR ≥ 3 is generally accepted as the threshold for reliable detection [1].

High SNR is essential for reliable and precise detection, especially at low analyte concentrations where differences are subtle. It directly impacts a sensor's Limit of Detection (LOD)—the lowest analyte concentration that can be reliably distinguished from background noise. A higher SNR allows for a lower LOD, which is crucial in applications like drug development and diagnostic sensing where detecting trace amounts is paramount [1].

Key Parameters Affecting SNR in Voltammetry

The SNR in voltammetric measurements is influenced by several interdependent parameters. Understanding and optimizing these is key to improving data quality.

Table 1: Key Parameters Impacting SNR in Voltammetry

| Parameter | Effect on Signal & Noise | Impact on SNR | Typical Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electroactive Surface Area (ESA) | A larger ESA increases the faradaic signal by enabling higher loading of biorecognition elements and increasing analyte interaction [1]. | Increases | Use microstructured or porous electrode materials to maximize the true reactive area [1]. |

| Scan Rate | Faster scan rates increase capacitive (charging) current, which can dominate and increase background noise. Slower scan rates allow the capacitive current to decay more than the faradaic current [2] [3]. | Variable | Use slower scan rates to minimize capacitive background, or use pulse techniques that discriminate against charging current [2] [3] [4]. |

| Square-Wave Frequency & Amplitude | Frequency and amplitude strongly influence the measured current from the redox reporter. Optimal pairing maximizes the binding-induced change in signal (gain) [5]. | Can significantly increase | Simultaneously optimize frequency and amplitude for the specific sensor architecture and redox reporter; this can more than double signal gain [5]. |

| Electrode Kinetics & Redox Reporter | The intrinsic electron transfer rate of the redox reporter (e.g., Methylene Blue vs. Ferrocene) dictates the optimal voltammetric parameters for maximum signal [5]. | Determines optimal parameters | Match the voltammetric technique and its parameters (e.g., square-wave frequency) to the electron transfer kinetics of the reporter [5]. |

| Uncompensated Solution Resistance | High resistance can lead to distorted voltammograms, voltage compliance errors, and resistive heating, which contributes noise [6] [3]. | Decreases | Ensure proper electrode connection, use supporting electrolyte at sufficient concentration, and consider instrumental positive feedback compensation (iR compensation) [3]. |

Troubleshooting Common SNR Problems: An FAQ Guide

FAQ 1: My voltammogram has a large, hysteretic background and no visible peaks. How can I reduce the capacitive background?

- Problem: A large, reproducible hysteresis in the baseline is primarily due to charging currents at the electrode-solution interface, which acts like a capacitor [3].

- Solution:

- Switch Technique: Employ pulse voltammetric techniques like Normal Pulse Voltammetry (NPV) or Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV). These techniques apply potential pulses and sample the current after the capacitive current has decayed exponentially, leaving mostly the faradaic current [2] [4].

- Adjust Parameters: Decrease the scan rate. The charging current is proportional to the scan rate, while the faradaic current is proportional to its square root. Slower scans reduce the capacitive contribution [3].

- Use a Smaller Electrode: Reduce the surface area of the working electrode, as the capacitive current is directly proportional to it [3].

FAQ 2: The potentiostat reports a "voltage compliance error" and the signal is noisy or absent. What should I check?

- Problem: The potentiostat cannot maintain the desired potential between the working and reference electrodes, often due to high circuit resistance [3].

- Solution:

- Check Electrode Connections: Ensure all cables (Working, Counter, Reference) are securely connected to the potentiostat and the corresponding electrodes in the cell [3].

- Verify Electrode Placement: Confirm that all three electrodes are properly submerged in the electrolyte solution. A disconnected reference electrode is a common cause [3].

- Inspect the Reference Electrode: Check that the frit (porous tip) of the reference electrode is not blocked. A blocked frit creates a high resistance connection [3].

- Check for Shorts: Ensure the working and counter electrodes are not touching, as this creates a short circuit [3].

FAQ 3: My baseline is not flat and has an unexpected slope or shape. What could be the cause?

- Problem: A non-straight baseline can originate from problems with the working electrode or unknown processes at the electrodes [3].

- Solution:

- Clean the Working Electrode: Polish the working electrode with a fine alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 μm) to remove adsorbed species that can cause residual currents. For Pt electrodes, electrochemical cleaning in 1 M H2SO4 by cycling between the potentials for H2 and O2 evolution can be effective [3].

- Check for Impurities: Run a background measurement in the pure electrolyte (without analyte) to identify if the slope comes from impurities in the solvent, electrolyte, or from a degraded component [3].

- Inspect Electrode Integrity: Internal faults in the working electrode, such as poor electrical contacts or compromised seals, can lead to high resistivity and sloping baselines [3].

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol for SNR Optimization

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to optimizing Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) parameters for maximum SNR, based on research into electrochemical DNA sensors [5].

Objective: To find the optimal combination of square-wave frequency and amplitude that maximizes the signal gain (and thus SNR) for a specific sensor and redox reporter.

Materials:

- Potentiostat capable of SWV.

- Fabricated Sensor on electrode.

- Electrolyte solution (with and without target analyte).

Procedure:

- Initial Setup: Place the sensor in the electrolyte solution (without target) and connect it to the potentiostat.

- Parameter Mapping: Program the potentiostat to perform SWV scans over a wide range of frequencies (e.g., 5 Hz to 5 kHz) and amplitudes (e.g., 1 mV to 100 mV). This can often be automated using a script.

- Data Collection (Background): For each frequency/amplitude pair, record the square-wave voltammogram and note the peak current.

- Data Collection (Signal): Introduce a saturating concentration of the target analyte into the cell. Repeat Step 3 to collect voltammograms for all parameter pairs in the presence of the target.

- Data Analysis:

- For each (frequency, amplitude) pair, calculate the signal gain:

Gain = [(I_signal - I_background) / I_background] * 100%. - Create a 2D contour map or numerical table plotting the signal gain as a function of both frequency and amplitude.

- For each (frequency, amplitude) pair, calculate the signal gain:

- Identification of Optima: Identify the frequency/amplitude pairing that yields the highest positive (or most negative, for "signal-off" sensors) signal gain. This is the optimal condition for your sensor.

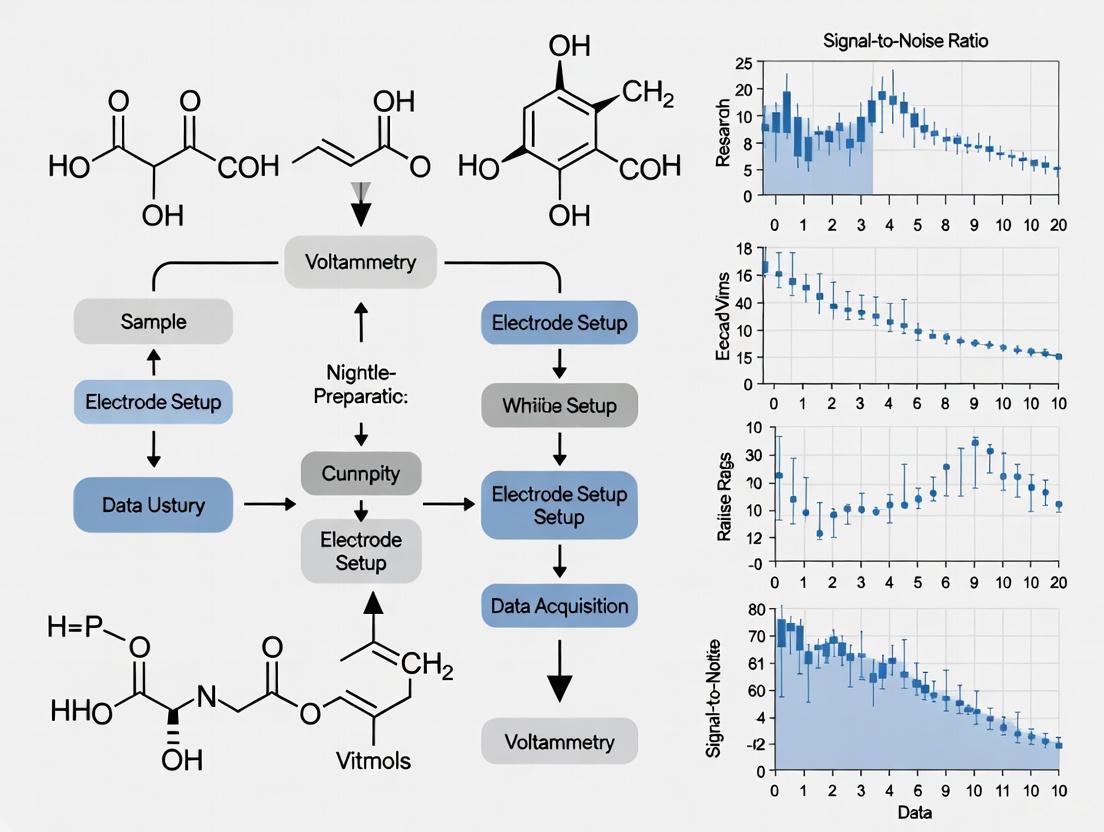

Visual Guide to the Optimization Workflow:

Figure 1: A workflow diagram for the systematic optimization of Square-Wave Voltammetry parameters to achieve maximum signal gain and SNR.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetric Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte | Minimizes uncompensated solution resistance (iR drop) by carrying the majority of the ionic current. This prevents distorted voltammograms and improves SNR [3]. | Inert salts at high concentration (e.g., 0.1-1.0 M KCl, LiTFSI, phosphate buffer) [7]. |

| Redox Reporter | A molecule that undergoes reversible electron transfer, providing the measurable faradaic signal. Its intrinsic electron transfer kinetics dictate optimal instrument parameters [5]. | Methylene Blue, Ferrocene, Anthraquinone. Choice affects optimal square-wave frequency [5]. |

| Electrode Polishing Kit | A clean, reproducible electrode surface is critical for a stable baseline and low noise. Polishing removes adsorbed contaminants [3]. | Alumina or diamond slurries (e.g., 0.05 μm alumina) on a microcloth pad [3]. |

| Validated Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, known potential for the working electrode. A blocked or faulty reference is a common source of noise and error [3]. | Ag/AgCl (3M KCl) or Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE). Always check the frit is not clogged [3]. |

| High-Surface-Area Electrode Material | Increases the electroactive surface area (ESA), leading to higher signal for the same geometric area, thereby improving SNR and lowering the LOD [1]. | Porous carbon materials (e.g., activated carbon), nanostructured gold, or screen-printed electrodes [1] [7]. |

In voltammetry research, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) is a critical determinant of data quality, impacting the sensitivity, limit of detection, and overall reliability of analytical measurements. Electrochemical signals are susceptible to a variety of noise sources that can obscure faradaic currents, which are the primary signals of interest in analytical sensing. These noises can be fundamentally categorized as thermal (Johnson-Nyquist) noise, flicker (1/f) noise, and interference (environmental) noise. Effectively troubleshooting these issues is paramount for researchers and scientists developing robust electrochemical sensors for applications in drug development and clinical diagnostics. This guide provides a structured approach to identifying and mitigating these noise sources to improve SNR in voltammetric experiments.

Fundamental Noise Types: Characteristics and Origins

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three fundamental noise types encountered in electrochemical systems.

Table 1: Fundamental Noise Types in Electrochemical Cells

| Noise Type | Origin | Spectral Density | Dependence | Primary Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal (Johnson) Noise | Thermal agitation of charge carriers in resistive components. | White noise (frequency-independent). | Proportional to √(R × T × Δf), where R=resistance, T=temperature, Δf=bandwidth. [8] | Lower cell impedance, use lower-temperature electrolytes, filter high frequencies. |

| Flicker (1/f) Noise | Surface phenomena, adsorption/desorption, and slow chemical processes at the electrode-electrolyte interface. | Inversely proportional to frequency (1/f). | Increases with decreasing frequency; dominant at low frequencies. [8] | Use higher-frequency techniques (e.g., Square-Wave Voltammetry), polish electrodes, apply coatings. |

| Interference Noise | External electromagnetic fields, ground loops, imperfect connections, and equipment. | Often appears at specific frequencies (e.g., 50/60 Hz power line). | Dependent on lab environment, cable routing, and grounding. [9] | Proper shielding and grounding, use short/shielded cables, Faraday cages. [9] |

Figure 1: A taxonomy of fundamental noise sources in electrochemical cells, showing their primary characteristics and origins.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs and Solutions

General Workflow for Noise Diagnosis

A systematic approach is essential for efficient noise troubleshooting. The following workflow, adapted from established electrochemical practices [3], helps isolate the root cause.

Figure 2: A logical workflow for diagnosing the source of noise in an electrochemical setup.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My voltammogram has a significant, non-flat baseline with large hysteresis between forward and backward scans. What is the cause, and how can I fix it? [3]

- Problem Identification: A sloping or hysteretic baseline is frequently caused by high charging currents at the working electrode. The electrode-solution interface acts as a capacitor, which must be charged before the faradaic process can occur. This effect is pronounced with high scan rates, large electrode surface areas, or high-resistance solutions.

- Solution:

- Reduce Scan Rate: Lowering the voltammetric scan rate reduces the rate of capacitor charging, thereby decreasing the charging current.

- Use a Smaller Electrode: Employ a working electrode with a smaller active surface area.

- Increase Analyte Concentration: A larger faradaic current relative to the charging current will improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Check Electrode Integrity: Ensure the working electrode is properly sealed, as faults like poor internal contacts or exposed glass can introduce additional capacitance. [3]

FAQ 2: I observe a constant, low-level, noisy signal with no faradaic peaks. What should I check first? [3] [9]

- Problem Identification: A small, noisy current with no discernible faradaic features often points to a poor connection at the working electrode. This prevents the faradaic current from flowing while the potentiostat can still apply a potential, resulting in only residual circuit noise being recorded.

- Solution:

- Inspect Connections: Verify that the cable to the working electrode is securely connected. Check for corroded or loose alligator clips. [3]

- Test the Electrode: Disconnect the working electrode and check its continuity with an ohmmeter if possible.

- Clean the Electrode: Polish the working electrode surface with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.05 μm) and rinse thoroughly to remove any adsorbed contaminants that might be blocking electron transfer. [3]

FAQ 3: My signal is very noisy, especially when using a rotating electrode system. The noise frequency seems related to the rotation speed. [9]

- Problem Identification: Noise correlated with rotation speed is typically of mechanical origin.

- Solution:

- Inspect Brush Contacts: Open the rotator housing and check the carbon brush contacts that touch the rotating shaft. The shaft surface should be smooth and free of corrosion. The brush contact surface should be a well-aligned, smooth groove. A misaligned groove can cause squeaking and vibrations, translating into electrical noise. [9]

- Polish or Replace Brushes: If the brush contact is misaligned or worn, polish its end with sandpaper on a flat surface to remove the old groove, or replace it entirely. Brush contacts should be replaced before the carbon portion is worn through. [9]

- Ensure Proper Grounding: Ground the rotator motor case by connecting the chassis ground of the rotator control unit to the chassis ground of the potentiostat. This can reduce electromagnetic interference from the motor itself. [9]

FAQ 4: I keep getting voltage or current compliance errors, and the signal is distorted. What does this mean? [3]

- Problem Identification: A "voltage compliance" error means the potentiostat cannot maintain the desired potential between the working and reference electrodes. A "current compliance" error indicates a short-circuit condition, where an excessively large current is flowing.

- Solution:

- For Voltage Compliance: Ensure your reference electrode is properly connected, submerged, and not clogged. A blocked frit creates high impedance, preventing the potentiostat from controlling the potential. [3] [9]

- For Current Compliance: Check that the working and counter electrodes are not touching inside the electrochemical cell, as this creates a short circuit. [3]

FAQ 5: How can I improve the selectivity of my sensor in complex biological fluids like plasma or blood? [10]

- Problem Identification: Biological samples are rich in macromolecules (e.g., proteins) that can adsorb to the electrode surface (fouling), altering its properties and reducing selectivity.

- Solution:

- Sensor Modification: Apply a molecularly imprinted polymer (MIP) as a thin film on your electrode. This polymer creates artificial receptors for your target analyte, imparting high selectivity and antifouling properties by blocking larger molecules from reaching the electrode surface. [10]

- Electrode Engineering: Use nanostructured materials like multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs) decorated with ligand-free gold nanoparticles. This enhances the electrocatalytic activity and can provide a more stable platform. [10]

- Pulse Techniques: Utilize techniques like adsorptive stripping voltammetry or differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) to selectively pre-accumulate the analyte and measure it with higher sensitivity. [10]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential materials and their functions as demonstrated in recent, advanced electrochemical sensor research.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sensor Development and Noise Mitigation

| Material / Reagent | Function in Experimental Protocol | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | A selective recognition layer that provides antifouling properties and enhances selectivity in complex matrices. [10] | Detection of serotonin in plasma. [10] |

| Multiwall Carbon Nanotubes (MWCNTs) | Nanostructured material to increase electroactive surface area and enhance electron transfer kinetics. [10] | Base transducer material for sensor construction. [10] |

| Gold Nanoparticles (Au NPs) | Electrocatalyst to lower the overpotential and increase the sensitivity of the redox reaction. [10] | Catalyzing the oxidation of serotonin. [10] |

| Metal Vapor Synthesis (MVS) | A method for producing ligand-free metal nanoparticles, allowing for a stable and controlled anchoring on supporting materials. [10] | Synthesis of pure Au NPs for anchoring on MWCNTs. [10] |

| Carbon Paste Electrode (CPE) | A versatile, renewable, and environmentally friendly working electrode material. [11] | Determination of thymoquinone in herbal products. [11] |

| Ag/AgCl Wire (Quasi-Reference) | A simple, frit-less reference electrode for troubleshooting high-impedance connections from clogged frits. [9] | Diagnosing and replacing a noisy commercial reference electrode. [9] |

| Alumina Polishing Slurry | (e.g., 0.05 μm) For mechanically refreshing and cleaning the working electrode surface to restore performance. [3] | Removing adsorbed contaminants to reduce flicker noise and improve reproducibility. [3] |

Experimental Protocol: A Case Study in Reliable Sensor Design

The following detailed methodology is adapted from a study on detecting serotonin in plasma, showcasing a holistic approach to achieving reliability and a high signal-to-noise ratio in a challenging biological matrix [10].

Aim: To develop a robust voltammetric sensor for serotonin in plasma with high selectivity and antifouling properties.

Methodology:

Electrode Modification:

- Synthesis of Au NPs: Produce ligand-free gold nanoparticles via Metal Vapor Synthesis (MVS). [10]

- Functionalization of MWCNTs: Anchor the Au NPs onto multiwall carbon nanotubes using a controlled radical functionalization technique to ensure a stable composite. [10]

- Electrode Coating: Deposit the MWCNT/Au NP composite onto the base electrode substrate to form the sensing platform.

- MIP Layer Formation: Apply a thin layer of molecularly imprinted polymer over the modified electrode. This layer is synthesized in the presence of serotonin molecules, which are later removed, leaving behind specific cavities for serotonin recognition. [10]

Optimization of Voltammetric Parameters:

- Employ a Design of Experiment (DoE) approach. Instead of testing one variable at a time, use a statistical model (e.g., a factorial design) to systematically vary key parameters of the Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) method—such as pulse amplitude, step potential, and modulation time—and identify the optimal combination that maximizes the signal response (sensitivity). [10]

Measurement via Adsorptive Stripping Voltammetry:

- Accumulation Step: Apply a constant potential to the sensor while stirring the plasma sample. This selectively pre-concentrates serotonin molecules into the MIP cavities. This step enhances the faradaic signal while minimizing interference from non-accumulated species.

- Stripping Step: Record the voltammogram using the optimized DPV parameters. The oxidation current of the accumulated serotonin is measured, which is proportional to its concentration in the sample. [10]

Outcome: This protocol resulted in a sensor with a sensitivity of 6.7 μA μmol L−1 cm−2 and a limit of detection of 1.0 μmol L−1 in plasma, performance comparable to that achieved in simple buffer solutions, demonstrating excellent resilience to matrix effects and fouling. [10]

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. How does the choice of electrode material directly affect my baseline signal? The electrode material fundamentally determines the electrochemical interface's physical and chemical properties. Materials like carbon (glassy carbon, graphite, carbon fiber) possess a rich surface chemistry with oxygen-containing functional groups. These groups influence the double-layer capacitance, a primary component of the non-Faradaic (charging) current that constitutes your baseline [12] [13]. Furthermore, the material's microstructure and conductivity affect the electron-transfer rate and contact resistance. A higher resistance leads to a larger voltage drop (iR drop), which can distort the voltammetric wave and elevate the apparent baseline noise [12]. For instance, carbon-fiber microelectrodes are prized in neurochemistry because their surface functional groups promote the adsorption of cationic neurotransmitters, enhancing the Faradaic signal relative to the capacitive background [14] [13].

2. Why does my baseline show a large hysteresis or slope, and how is electrode geometry involved? A sloping or hysteretic baseline is often dominated by charging currents. The electrode-solution interface behaves like a capacitor, and this capacitor must be charged and discharged as the potential is scanned [3] [15]. The magnitude of this charging current is directly proportional to the electrode surface area and the scan rate [3]. A larger electrode geometry (e.g., a macroelectrode vs. a microelectrode) has a greater surface area and thus a larger capacitance, resulting in a more pronounced sloping baseline [14] [15]. This effect can be mitigated by using a smaller electrode, decreasing the scan rate, or increasing the concentration of the analyte [3].

3. We are developing a chronic biosensor and our baseline signal drifts over time. What material-related factors could be causing this? Chronic baseline drift is frequently a symptom of electrode fouling (or biofouling). This occurs when proteins, lipids, or other biomolecules adsorb onto the electrode surface, altering its properties [13]. Fouling can change the double-layer capacitance and increase the electron-transfer resistance, leading to an unstable baseline and a loss of sensitivity [13]. Strategies to combat this include using specially modified electrodes with anti-fouling layers (e.g., blocking layers like mercaptohexanol on gold) [16] or applying waveforms that periodically "clean" the surface by driving it to extreme potentials to oxidize adsorbed contaminants [14] [13].

4. How does optimizing the distribution of conductive particles in a composite electrode improve my signal-to-noise ratio? In composite electrodes (e.g., graphite–epoxy), the goal is not simply to maximize the conductive particle loading. An optimal distribution creates an efficient percolation network for electron transport while minimizing random conductive pathways that contribute to noise [12]. Research has shown that the maximum conductive particle loading does not always correspond to the optimal loading in terms of the signal-to-noise ratio. An optimized, homogeneous distribution of graphite particles lowers the overall ohmic resistance and double-layer capacitance, which directly translates to a higher signal-to-noise ratio and a lower limit of detection [12].

Troubleshooting Common Baseline Issues

| Problem | Potential Root Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Noisy, unstable baseline [3] | Poor electrical connection; Loose cable; High solution resistance. | Check all connectors with an ohmmeter; Perform potentiostat diagnostic test with a resistor [3]. | Secure all connections; Ensure robust electrode construction; Increase electrolyte concentration. |

| Large hysteresis in baseline [3] | High charging currents from large electrode surface area; Faulty electrode with internal capacitance. | Reduce scan rate; Test with a smaller electrode; Compare baseline in analyte vs. blank solution. | Decrease scan rate; Use a microelectrode; Polish/clean the working electrode [3] [17]. |

| Baseline drift over time [16] [13] | Electrode fouling from adsorbed species; Unstable reference electrode; Gradual surface modification. | Perform a background scan in pure electrolyte; Check reference electrode integrity (e.g., clogged frit) [3]. | Implement an anti-fouling layer (e.g., MCH, Nafion); Use a waveform that cleans the surface; Replace reference electrode [16] [13]. |

| Unexpected peaks in baseline [3] | Impurities in electrolyte/solvent; Edge of solvent electrochemical window; Degradation of electrode/material. | Run a background measurement with a fresh, analyte-free electrolyte solution. | Re-purify solvents/electrolytes; Narrow the potential scan window; Re-polish or re-fabricate the electrode. |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Carbon-Fiber Microelectrode for Low-Baseline Noise

Objective: To construct a cylindrical carbon-fiber microelectrode (CFME) with a small geometric surface area to minimize capacitive charging currents, ideal for fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) in vivo [14] [13].

Materials:

- Single carbon fiber (∼7 μm diameter)

- Borosilicate glass capillary (e.g., 1.2 mm OD, 0.68 mm ID)

- Vertical or horizontal electrode puller

- Epoxy resin (e.g., Epon 828)

- Syringe with isopropyl alcohol

- Sharp scalpel or scissors

Procedure:

- Aspiration: A single carbon fiber is aspirated into the borosilicate glass capillary.

- Pulling: The capillary is placed on a commercial electrode puller and heated and pulled to form a tapered glass seal around the carbon fiber.

- Sealing (Optional but Recommended): The tapered tip may be deliberately broken under a microscope and then resealed with epoxy resin. This step increases robustness and reduces the shunt capacitance between the fiber and the solution [14].

- Trimming: Using a sharp scalpel and under a microscope, the protruding carbon fiber is trimmed to the desired length (typically 50-200 μm). A longer fiber increases sensitivity but reduces spatial resolution.

- Curing and Connection: The epoxy is allowed to cure fully. An electrical connection is then made to the carbon fiber at the back of the capillary using a conductive material such as silver paint or a metal wire.

Protocol 2: Surface Polishing of a Glassy Carbon Electrode

Objective: To restore a smooth, reproducible surface on a glassy carbon (GC) electrode, ensuring consistent electron-transfer kinetics and a stable baseline.

Materials:

- Glassy carbon working electrode

- Polishing pads (multiple grits)

- Alumina or diamond polishing slurry (e.g., 1.0 μm, 0.3 μm, and 0.05 μm)

- Deionized water

- Ultrasonic bath

Procedure:

- Coarse Polish: On a clean polishing pad, apply a slurry of 1.0 μm alumina. Polish the electrode surface using a figure-eight pattern with moderate pressure. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- Fine Polish: Move to a fresh pad and use a 0.3 μm alumina slurry. Repeat the figure-eight polishing. Rinse thoroughly.

- Mirror Finish: Finally, on a third clean pad, use a 0.05 μm alumina slurry to achieve a mirror finish. Rinse thoroughly.

- Sonication: Place the electrode in an ultrasonic bath filled with deionized water for 1-2 minutes to remove any embedded alumina particles.

- Electrochemical Activation (Optional): The polished electrode can be electrochemically activated by performing cyclic voltammetry in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.5 M H₂SO₄) between the solvent limits to clean and activate the surface [17].

Table 1: Impact of Electrode Geometry on Key Signal Parameters

| Electrode Geometry | Typical Surface Area | Charging Current | Impact on Spatial Resolution | Typical Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Macroelectrode (e.g., 2 mm GC disc) | ~0.03 cm² | High | Low (bulk measurement) | Standard quantitative analysis in stirred solutions [15]. |

| Microelectrode (e.g., 10 μm radius carbon fiber) | ~3 x 10⁻⁶ cm² | Low | High (discrete brain regions) | Fast-scan cyclic voltammetry (FSCV) in vivo; measurements in resistive media [14] [13]. |

| Ultramicroelectrode Array | Tunable (Low per element) | Medium (scales with active area) | Medium | Sensors combining low noise with higher total signal output [12]. |

Table 2: Electrode Material Properties and Their Electrochemical Consequences

| Electrode Material | Key Characteristics | Heterogeneous Electron-Transfer Rate (k⁰) | Double-Layer Capacitance | Fouling Resistance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glassy Carbon (GC) | Hard, amorphous carbon; smooth surface. | Moderate to Fast | Moderate | Moderate [18]. |

| Carbon Nanotube (CNT) Modified | High aspect ratio, large effective surface area. | Not significantly altered from bare GC for some probes [18]. | High (due to large surface area) | Varies with functionalization [18]. |

| Carbon-Fiber | Rich in edge planes & oxygen groups; promotes cation adsorption. | Fast for catecholamines | Low to Moderate | Good, but can be improved with coatings like Nafion [14] [13]. |

| Boron-Doped Diamond (BDD) | Low background current, wide potential window. | Slow to Moderate | Very Low | Excellent [19]. |

Visualizing the Interaction Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function in Electrode Preparation & Signal Optimization |

|---|---|

| Alumina Polishing Slurries (0.05, 0.3 μm) | To create a smooth, reproducible electrode surface, ensuring consistent kinetics and a stable baseline by removing contaminants and previous surface layers [17] [16]. |

| Epoxy Resin (e.g., Epon 828) | Used as an insulating matrix in composite electrodes or to seal carbon fibers in glass capillaries. Its optimization affects the distribution of conductive particles and the electrode's mechanical stability [12] [14]. |

| Functionalized Carbon Nanotubes (fCNTs) | Dispersed and drop-cast on electrodes to modify the surface. Increases effective surface area and can enhance signal (current), but requires careful dispersion to avoid agglomeration that increases noise [18]. |

| Cationic Surfactant (e.g., DDAB) | Used in dispersing nanomaterials like CNTs. In bulk solution, it can form organized layers on the electrode surface, improving the dispersion of analytes and modifying the interfacial properties, leading to better current responses [18]. |

| Mercaptohexanol (MCH) | A blocking agent used in biosensors (e.g., on gold surfaces). It forms a self-assembled monolayer that displaces non-specifically adsorbed molecules, reducing fouling and minimizing non-Faradaic background current [16]. |

Recent Advances in Nanoscale Electrochemical Imaging and Attoliter-Volume Detection

Troubleshooting Guides for Nanoscale Electrochemical Experiments

FAQ 1: My electrochemical measurements show inconsistent signals and high background noise. How can I improve the signal-to-noise ratio?

Issue: Inconsistent signals and high background noise in voltammetry often stem from suboptimal instrument settings, contamination, or inefficient data processing.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Optimize Square-Wave Voltammetry Parameters: For techniques like E-DNA sensors, signal gain is highly dependent on the parameters of the square-wave potential pulse.

- Simultaneously adjust the frequency and amplitude of the square-wave pulse. The optimal pairing depends on the redox reporter used (e.g., methylene blue vs. ferrocene) and the probe's structure [5].

- For example, a sensor with a methylene blue reporter achieved a 315% signal gain at 25 mV amplitude and 750 Hz frequency, which was a 2-fold improvement over non-optimized parameters [5].

- Use the Kinetic Differential Measurement (KDM) method. This involves subtracting signals recorded at optimized "signal-on" and "signal-off" frequencies to correct for baseline drift and further enhance the signal-to-noise ratio [5].

- Apply Advanced Data Smoothing: Use algorithmic filters to denoise stored voltammetric data.

- Select the optimal smoothing filter (e.g., Savitzky-Golay, moving median, wavelet-based routines) based on the shape of your voltammetric curve and the type of noise present. The best filter for one data set may not be optimal for another [20].

- An evaluation formula that considers the improvement in analytical parameters (calibration linearity, detection limit, accuracy) after smoothing, rather than just the signal-to-noise ratio of a single curve, is recommended for selecting the best filter [20].

- Ensure Sample and Reagent Purity:

- Check for endotoxin contamination. Endotoxins can cause immunostimulatory reactions and mask the true biocompatibility and performance of nano-formulations. Work under sterile conditions using pyrogen-free water and reagents [21].

- Test for nanoparticle aggregation by measuring size distribution under biologically relevant conditions (e.g., in plasma), as the reported size can differ significantly from manufacturer specifications and can change in different dispersing media [21].

FAQ 2: My optical imaging of electrochemical interfaces has poor spatial resolution and fails to detect single entities at high concentrations. What can I do?

Issue: The detection volume is too large, preventing the isolation of individual molecules or nanoparticles.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Implement Confocal Total-Internal-Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) Microscopy: This technique can drastically reduce the detection volume.

- A confocal TIRF microscope can generate an detection volume of less than 5 attoliters (5 x 10⁻¹⁸ L) at a water-glass interface. This is almost two orders of magnitude smaller than conventional confocal microscopy, enabling the isolation of individual molecules at high analyte concentrations [22] [23].

- This system uses a parabolic mirror objective for diffraction-limited supercritical focusing and fluorescence collection, providing excellent spatial resolution and a high signal-to-background ratio for single-molecule detection [22].

FAQ 3: I am observing unexpected artifacts and blurring in my Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) images during in-situ electrochemical experiments.

Issue: Artifacts can arise from sample preparation, the electrochemical cell setup, or environmental factors, compromising image quality.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Address Cryo-TEM Ice Contamination:

- Problem: Crystalline ice contaminants obscure nanoparticles.

- Solution: Ensure rapid freezing in liquid ethane to form vitreous ice. Use freshly dispensed liquid nitrogen, work in a dehumidified environment, and pre-cool all tools to prevent ice crystal formation [24].

- Minimize Sample Drift:

- Problem: Blurred images due to sample movement during acquisition.

- Solution: Ensure the grid is securely mounted. Check that the ice or grid substrate is not too thin and unstable. Investigate and mitigate environmental vibrations affecting the microscope [24].

- Mitigate Electron Beam Effects:

Quantitative Data on Signal Optimization

The following table summarizes the quantitative gains achievable by optimizing square-wave voltammetry parameters, as demonstrated for E-DNA sensors [5].

Table 1: Signal Gain Optimization through Square-Wave Voltammetry Parameters

| Redox Reporter | Optimal Square-Wave Amplitude | Optimal Square-Wave Frequency | Resulting Signal Gain | Type of Gain |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylene Blue | 25 mV | 750 Hz | +315% | Signal-On |

| Methylene Blue | 25 mV | 20 Hz | -82% | Signal-Off |

| Anthraquinone | 10 mV | 100 Hz | +173% | Signal-On |

| Ferrocene | 25 mV | 7.5 kHz | -43% | Signal-Off |

The table below compares key optical and electron microscopy techniques for nanoscale electrochemical imaging, highlighting their roles in improving the signal-to-noise ratio and spatial resolution.

Table 2: Comparison of Advanced Microscopy Techniques for Nanoscale Imaging

| Microscopy Technique | Key Principle | Key Advantage for SNR/Resolution | Example Application in Energy Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confocal TIRF [22] [23] | Confocal detection with total internal reflection fluorescence. | Attoliter (5x10⁻¹⁸ L) detection volume for isolating single molecules at high concentration. | Probing single-molecule electrochemistry at interfaces. |

| In-situ TEM [25] | Miniaturized electrochemical cell inside TEM column. | Atomic-scale spatial resolution for real-time visualization. | Visualizing solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) formation and dendrite growth in batteries. |

| Super-Resolution Fluorescence [26] | Localization of single fluorophores beyond diffraction limit. | Nanoscale spatial resolution for mapping heterogeneous reactions. | Imaging electrocatalytic activity at individual nanoparticles. |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPRM) [26] | Tracking changes in refractive index near a metal surface. | Excellent sensitivity for monitoring dynamic adsorption/desorption. | Real-time, label-free imaging of molecular adsorption at electrode interfaces. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Techniques

Protocol: Optimizing Square-Wave Voltammetry for Maximum Signal Gain

This protocol is adapted from research on maximizing the signal of Electrochemical DNA (E-DNA) sensors [5].

Principle: Signal gain in reagentless electrochemical sensors depends on binding-induced changes in electron transfer kinetics, which are sensitive to the parameters of the square-wave potential pulse.

Materials:

- Potentiostat capable of high-frequency square-wave voltammetry.

- Fabricated electrochemical sensor (e.g., an electrode modified with a redox-tagged probe).

- Solution of the target analyte.

Procedure:

- Initial Setup: Record a square-wave voltammogram of the sensor in a blank solution (without target) using a standard set of parameters (e.g., 25 mV amplitude, 100 Hz frequency).

- Generate 2D Parameter Map:

- Program the potentiostat to perform a series of square-wave scans over a wide range of amplitudes (e.g., 1 mV to 100 mV) and frequencies (e.g., 5 Hz to 5000 Hz). This will require 150+ individual voltammograms.

- Repeat this entire procedure after incubating the sensor with a saturated concentration of the target analyte.

- Data Analysis:

- For each amplitude/frequency pair, extract the peak current from both the blank and target voltammograms.

- Create a 2D numerical map where the signal gain (e.g.,

(I_target - I_blank) / I_blank) is plotted as a function of amplitude and frequency.

- Parameter Selection: Identify the amplitude/frequency pairing that yields the maximum positive (signal-on) or negative (signal-off) gain from the 2D map.

- Implementation: Use this optimized parameter set for all subsequent quantitative measurements with the sensor.

Protocol: Assembling a Probe-Type In-situ TEM Electrochemical Cell

This protocol describes the setup for observing battery materials using in-situ TEM [25].

Principle: A nanoscale electrochemical cell is assembled inside a TEM using a specialized holder, allowing real-time observation of processes like lithiation and dendrite growth.

Materials:

- Probe-type in-situ TEM holder.

- Metal rod probes (e.g., Tungsten).

- Active electrode material (e.g., Si nanowire, MoS₂ flake).

- Li metal (for anode).

- Ionic liquid electrolyte or solid electrolyte (Li₂O).

Procedure:

- Anode Preparation: Fix a small piece of Li metal to one probe. A native Li₂O layer will form on its surface, acting as a solid electrolyte.

- Cathode Preparation: Fix the nanoscale electrode material (e.g., a single nanowire) to a second, movable probe.

- Cell Assembly: Inside an argon-filled glovebox, introduce a small amount of ionic liquid electrolyte onto the electrode surfaces if an all-solid-state cell is not being used.

- Transfer to TEM: Secure the assembled probe into the TEM holder, ensuring it is properly sealed.

- In-situ Experiment: Insert the holder into the TEM. Use the probe controls to bring the electrode material into contact with the Li₂O/Li (for solid-state) or the electrolyte. Apply a bias voltage to initiate electrochemical reactions while simultaneously recording TEM images, spectra, or diffraction patterns.

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists essential materials used in the advanced experiments cited in this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Methylene Blue [5] | Redox reporter in E-DNA and similar biosensors. | Electron transfer kinetics dictate optimal square-wave frequency/amplitude. |

| Ionic Liquid Electrolyte [25] | Electrolyte for in-situ TEM batteries. | Enables electrochemical reactions in the high vacuum of the TEM. |

| Uranyl Formate / Acetate [24] | Negative stain for TEM sample preparation. | Provides high contrast; can form stain crystals that obscure particles if not fresh. |

| Holey Carbon TEM Grid [24] | Support film for cryo-TEM samples. | Particles suspended in holes provide best contrast; some samples prefer continuous carbon. |

| Parabolic Mirror Objective [22] [23] | Optical element in confocal TIRF. | Enables diffraction-limited focusing to achieve attoliter detection volumes. |

Signaling Pathway and Workflow Diagrams

Troubleshooting Pathway for SNR Improvement

Strategic Approach to Advanced Imaging

Critical Relationships Between SNR, Detection Limits, and Analytical Sensitivity in Biomedical Applications

In analytical chemistry, particularly in biomedical and voltammetric research, the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) is a foundational concept that directly determines the efficacy and reliability of an experiment. It serves as the master guide for assessing data quality [27]. The primary task in trace analysis is often the detection of minute quantities of substances, such as pollutants, contaminants, or degradation products. If the detected signal of a substance is not sufficiently distinguishable from the unavoidable baseline noise of the analytical method, the substance may go undetected altogether [27]. This relationship is formalized through the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantification (LOQ), which are critical method validation parameters. This technical support center outlines the fundamental relationships between SNR, LOD, and LOQ, provides troubleshooting guides for common experimental issues, and offers detailed protocols for optimizing voltammetric measurements to enhance analytical sensitivity.

Fundamental Definitions and Relationships

What are SNR, LOD, and LOQ?

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR): A measure comparing the level of a desired signal to the level of background noise. In its simplest form for a Boolean signal, it can be calculated as the difference between the mean "true" value and the mean "false" value, divided by the noise amplitude [28]. It is the key parameter for explaining most detector-related correlations [27].

- Limit of Detection (LOD): The minimum sample concentration at which a substance signal can be reliably detected. An SNR between 3:1 and 10:1 is often used as a rule of thumb for LOD in real-life analytical conditions, though a ratio of 3:1 is a common standard [27].

- Limit of Quantification (LOQ): The minimum sample concentration at which a substance signal can be reliably quantified. A typical signal-to-noise ratio for LOQ is 10:1, though in practice, values from 10:1 to 20:1 are often required for challenging conditions [27].

Quantitative Framework for SNR, LOD, and LOQ

The following table summarizes the formal definitions and quantitative relationships between these key parameters.

Table 1: Key Definitions and Quantitative Relationships for SNR, LOD, and LOQ

| Parameter | Formal Definition | Calculation & Relationship | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) | A measure of how distinguishable a signal is from background noise. | For a general Boolean signal: $SNR{dB} = 20 \log{10}\frac{ | \mu{true} - \mu{false} | }{2\sigma}$ [28].In HPLC/voltammetry: $SNR = \frac{\text{Signal Height}}{\text{Baseline Noise Height}}$ [27]. |

| Limit of Detection (LOD) | The minimum concentration that can be detected, but not necessarily quantified, under stated experimental conditions. | Typically defined as a concentration yielding an SNR of 3:1 [27]. | ||

| Limit of Quantification (LOQ) | The minimum concentration that can be quantitatively measured with stated accuracy and precision. | Typically defined as a concentration yielding an SNR of 10:1 [27]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Materials and Reagents

The selection of electrodes, electrolytes, and other components is critical for obtaining a high SNR and low detection limits.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Voltammetry

| Item | Function & Importance | Best Practice Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Working Electrode | The surface where the electrochemical reaction of interest occurs. Its material and area directly influence current response and sensitivity [29]. | Carbon-based electrodes (e.g., carbon-fiber microelectrodes) are popular for neurochemical sensing due to high biocompatibility and spatiotemporal resolution [30]. The surface area must be well-defined for accurate current density normalization (mA/cm²) [29]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable, well-defined reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is controlled [29]. | Select for chemical compatibility with the measurement environment. Avoid chloride-containing fillers if chloride poisons the catalyst. Its placement via a Luggin-Haber capillary is critical to minimize uncompensated resistance [31]. |

| Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit by carrying the current so that no current flows through the reference electrode [29]. | The material must be chosen to avoid dissolution, which can contaminate the solution and artificially enhance performance (e.g., Pt counters for "Pt-free" catalysts) [31]. |

| Supporting Electrolyte | Carries current in the solution and controls the ionic strength. Minimizes the solution resistance (Ru). | Purity is paramount. Impurities at the part-per-billion level can substantially alter the electrode surface and reaction kinetics. Use the highest purity grade available and robust cell cleaning protocols [31]. |

| Solvent | Dissolves the analyte and electrolyte. | Must be degassed to remove dissolved oxygen if it interferes with the redox reaction of interest. |

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on SNR and Detection Limits

Q1: My voltammogram has a high background current and a sloping baseline. What could be the cause? A: A non-ideal baseline is often related to problems with the working electrode or high capacitive charging currents [3]. This can be caused by:

- Capacitive Charging: The electrode-solution interface acts as a capacitor. This effect can be reduced by decreasing the scan rate, increasing analyte concentration, or using a working electrode with a smaller surface area [3].

- Electrode Fouling: Species adsorbing to the electrode surface can change its capacitive properties. Polish the working electrode with alumina slurry or use an electrochemical cleaning procedure (e.g., potential cycling in clean sulfuric acid for Pt electrodes) [3].

- Electrode Defects: Poor internal contacts or seals in the electrode can lead to high resistivity or capacitance [3].

Q2: Why is my measured current very small and noisy, even with analyte present? A: This typically indicates a problem with the electrical connection to the working electrode, meaning the electrochemical cell is effectively an open circuit. Since the counter electrode is likely properly connected (otherwise a voltage compliance error would occur), you should check the connection to the working electrode [3].

Q3: I am getting voltage or current compliance errors. What should I check? A: These errors occur when the potentiostat cannot maintain the desired cell conditions.

- Voltage Compliance Error: The potentiostat cannot achieve the potential difference between working and reference electrodes. Check that your reference electrode is properly connected and not touching the working electrode. Also, ensure the counter electrode is submerged and connected [3].

- Current Compliance Error: This is often caused by a short circuit, where the working and counter electrodes are touching, generating a large current [3].

Q4: How does data smoothing affect my SNR, LOD, and LOQ? A: Data smoothing (e.g., using a time constant, Savitzky-Golay, or Fourier transform filters) can artificially improve the SNR by reducing baseline noise [27] [20]. However, over-smoothing is a critical risk. It can flatten and broaden small analyte peaks to the point where they merge with the baseline, effectively raising your practical LOD and LOQ by causing you to miss low-concentration analytes [27]. It is always best practice to collect high-quality raw data and apply gentle, post-acquisition smoothing if necessary, so the original data is preserved [27].

Q5: My cyclic voltammogram looks unusual or changes shape with repeated cycles. What is wrong? A: This is frequently due to an issue with the reference electrode. If it is not in proper electrical contact with the solution (e.g., due to a blocked frit or an air bubble), it can act like a capacitor, causing drifting potentials and unstable voltammograms [3]. Check the reference electrode's connection and frit.

Experimental Protocols for SNR Optimization

Protocol: Utilizing Pulse Voltammetry to Enhance SNR

Pulse voltammetric techniques (e.g., Normal Pulse, Differential Pulse, Square Wave) are designed specifically to discriminate against charging current, thereby improving SNR and lowering detection limits [30] [2].

Principle: After a potential step, the charging current decays exponentially, while the faradaic current decays more slowly, as a function of 1/(time)½ [30] [2]. By applying short potential pulses and measuring the current at the end of each pulse (after the charging current has largely decayed), the measured current is primarily faradaic [2].

Procedure:

- Select the Technique:

- Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV): Applies fixed-amplitude pulses on a slowly changing base potential. The current difference before and after the pulse is plotted, effectively subtracting the background charging current. Excellent for trace detection of irreversible systems [30].

- Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV): Applies a symmetrical square wave on a staircase ramp. The net current (forward - reverse) is plotted. It is very fast and provides a high SNR, ideal for reversible and quasi-reversible systems [30].

- Parameter Optimization:

- Pulse Width/Step Width: This defines the duration of the potential pulse. It must be long enough for the charging current to decay (typically > 5RuCdl) [2].

- Sample Period: Set the instrument to measure the current at the end of the pulse width. Many potentiostats allow averaging over a short period (e.g., 1 ms) to further reduce noise [2].

- Pulse Amplitude (DPV) or Square Wave Amplitude (SWV): This parameter affects the sensitivity and peak shape. Optimize for your specific system according to the instrument manual.

The workflow for this optimization process is outlined below.

Protocol: Anodic Stripping Voltammetry (ASV) for Trace Metal Detection

ASV is a powerful two-step technique that combines an electrochemical preconcentration step with a stripping step, drastically improving SNR for trace metal analysis [30].

Principle: Metal ions are first electrochemically reduced and concentrated into a mercury or carbon electrode surface by applying a negative potential for a fixed time. This preconcentration step amplifies the signal. The potential is then scanned in a positive direction (e.g., using Linear Sweep Voltammetry), oxidizing (stripping) each metal from the surface. Each metal produces a sharp peak current at its characteristic potential, which is proportional to its concentration in the original sample [30].

Procedure:

- Preconcentration Step:

- Set the initial potential to a value sufficiently negative to reduce the target metal ion(s).

- Hold this potential for a controlled deposition time (e.g., 30-300 seconds) while stirring the solution. The longer the deposition time, the greater the signal amplification.

- Equilibration Period:

- Stop stirring and allow the solution to become quiescent for a short period (e.g., 15 seconds).

- Stripping Step:

- Scan the potential positively using a technique like LSV or DPV.

- The oxidation of each metal produces a characteristic peak. The peak current is used for quantification.

Logical Pathway from Measurement to Quantification

The relationship between experimental parameters, data quality indicators, and final analytical figures of merit is a logical sequence. Understanding this pathway is key to method optimization. The following diagram illustrates the complete workflow from experimental setup to final result interpretation.

Electrode Engineering and Advanced Voltammetric Techniques for Enhanced SNR

FAQs: Troubleshooting Electrode Performance

Q1: Why is my voltammogram noisy or showing an unstable baseline?

A noisy or unstable baseline can be caused by several factors related to your experimental setup [3] [32].

- High Impedance Connections: Check that all cables and connectors to the electrodes are intact and making good contact. Visually inspect for any corrosion, cracks, or damaged plugs [32].

- Blocked Reference Electrode: A blocked frit in your reference electrode or air bubbles trapped in the Haber-Luggin capillary can cause significant noise and instability. Gently tap the cell or use a pipette ball to remove air bubbles [3] [32].

- Potentiostat Settings: The current range setting on your potentiostat may be inappropriate for your experiment's impedance. Adjusting the current range can help stabilize the signal [32].

- Working Electrode Issues: A poorly prepared or fouled working electrode can also lead to a non-straight baseline. Repolishing the electrode can often resolve this [3].

Q2: My experiment is triggering a "voltage compliance" error. What does this mean?

A voltage compliance error indicates that the potentiostat is unable to maintain the desired potential between the working and reference electrodes [3]. Common causes include:

- The counter electrode has been removed from the solution or is not connected properly [3].

- The reference electrode is not in electrical contact with the solution, for instance, due to a blocked frit or an air bubble [3].

- The counter electrode's activity is insufficient to support the reaction at the working electrode, or the distance between the working and counter electrodes is too large, leading to a high voltage loss in the electrolyte [32].

Q3: How can I improve the selectivity of my carbon-fiber electrode for dopamine against other monoamines like serotonin?

Poor selectivity between neurotransmitters with similar oxidation potentials is a common challenge. A proven strategy is to functionalize the electrode with a multi-layer membrane [33].

- Ion-Exchange Membrane: Coating the electrode with Nafion, an ion-exchange membrane, can repel negatively charged interferents and enrich cationic analytes like dopamine.

- Enzyme Layer: Incorporating a layer of the enzyme monoamine oxidase B (MAO-B) selectively breaks down interferents like serotonin and norepinephrine, while dopamine remains relatively unaffected. This bilayer approach has been shown to successfully discriminate dopamine in vitro and in vivo [33].

Q4: After modifying my electrode, the signal is very small or non-existent. What could be wrong?

If you measure only a very small, noisy, and unchanging current, the most likely cause is a poor connection to the working electrode [3]. Although the potentiostat can control the potential, no faradaic current can flow if the working electrode is not properly connected. Check the cable and connector for the working electrode. If the counter electrode were disconnected, it would typically trigger a voltage compliance error instead [3].

Q5: What is the "coffee-ring" effect in drop coating and how can I avoid it?

The "coffee-ring" effect occurs when a droplet of modifier suspension dries on an electrode surface, causing suspended particles to concentrate at the edge and form a ring-shaped, inhomogeneous coating [34]. This leads to inconsistent catalytic performance. To address this:

- Use Electrowetting: Applying an electric field can change the wetting properties of the surface, enhancing particle mobility and leading to a more uniform distribution during drying [34].

- Employ Hydrophobic Surfaces: Using highly hydrophobic electrode surfaces minimizes adhesion and helps prevent particle agglomeration, resulting in a more even coating [34].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Electrochemical Issues

This guide summarizes frequent problems, their causes, and solutions to help you quickly diagnose your experiment.

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common Electrochemical Sensor Issues

| Observed Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Noisy or Unstable Baseline [3] [32] | High impedance connections; Blocked reference electrode frit; Air bubbles; Incorrect potentiostat settings. | Check all cables and connectors; Clear reference electrode blockage; Remove air bubbles; Adjust potentiostat current range. |

| Voltage Compliance Error [3] | Counter electrode disconnected or out of solution; Reference electrode not in contact; High solution resistance. | Ensure counter electrode is submerged and connected; Check reference electrode frit; Use a Haber-Luggin capillary to minimize IR drop [32]. |

| Unexpected Peaks in Voltammogram [3] | Impurities in solvent/electrolyte; Electrode surface contamination; Approaching the edge of the solvent's potential window. | Run a background scan without analyte; Repolish the working electrode; Use high-purity reagents. |

| Non-Flat or Hysteretic Baseline [3] | High charging currents (capacitive effects); Faults in the working electrode structure. | Decrease the scan rate; Use a smaller working electrode; Ensure the working electrode is properly sealed and polished. |

| Small or No Signal [3] | Poor connection to the working electrode; Working electrode not properly immersed. | Check the working electrode cable and connector; Ensure the electrode is submerged to the minimum immersion depth [35]. |

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Modification and Testing

Protocol 1: Creating a Dopamine-Selective Biosensor with MAO-B/Nafion Coating

This protocol details the fabrication of a biosensor for selective dopamine (DA) detection in the presence of serotonin (5-HT) and norepinephrine (NE), significantly improving the signal-to-noise ratio for DA [33].

Materials:

- Carbon-fiber microelectrode (e.g., 7-20 µm diameter fibers)

- Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B) enzyme

- Cellulose powder

- Nafion solution

- Glutaraldehyde solution (25%)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

Method:

- Electrode Preparation: Aspirate two carbon fibers into a glass capillary, then taper and seal it with epoxy resin, leaving ~100 µm of fiber exposed [33].

- Enzyme Layer Coating: Soak the exposed carbon fiber tip in a solution of 20% MAO-B and 5% cellulose. Air dry for 30-60 minutes at room temperature [33].

- Cross-Linking: Expose the MAO-B/cellulose-coated tip to glutaraldehyde vapor (from a boiling 25% solution) for 30 minutes to cross-link and stabilize the enzyme layer [33].

- Ion-Exchange Layer: Apply a final coating of Nafion over the cross-linked layer and allow it to dry. This creates a dual-layer membrane: an inner MAO-B/cellulose layer for enzymatic selectivity and an outer Nafion layer for ion-exchange [33].

- Validation: Test the biosensor in PBS by adding 1 µM each of DA, 5-HT, and NE. The modified electrode should show a significantly higher response to DA compared to 5-HT and NE [33].

Protocol 2: General Procedure for Troubleshooting Cyclic Voltammetry

This systematic procedure helps isolate the source of a problem when you obtain an unusual or distorted cyclic voltammogram [3].

Materials:

- Potentiostat

- Test resistor (e.g., 10 kΩ) or manufacturer's test cell chip

- Electrochemical cell with analyte, electrolyte, and solvent

- Alternative reference electrode (e.g., bare silver wire quasi-reference electrode)

- Alumina slurry (0.05 µm) for electrode polishing

Method:

- Test Potentiostat and Cables: Disconnect the cell. Connect the reference and counter cables to one end of a 10 kΩ resistor and the working cable to the other. Run a scan (e.g., +0.5 V to -0.5 V). The result should be a straight line obeying Ohm's law (V=IR). If not, the issue is with the potentiostat or cables [3].

- Test Reference Electrode: Set up the cell normally, but connect the reference cable to the counter electrode. Run a linear sweep. If a standard-looking voltammogram (though potential-shifted) appears, the original reference electrode is faulty. Check for blockages or replace it with a quasi-reference electrode (a bare silver wire) to confirm [3].

- Test Working Electrode: If steps 1 and 2 pass, the issue likely lies with the working electrode. Repolish it with 0.05 µm alumina slurry and rinse thoroughly. For Pt electrodes, further cleaning can be done by cycling in 1 M H₂SO₄ between the potentials for H₂ and O₂ evolution [3].

Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials used in advanced electrode modification for enhancing sensor performance.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Electrode Modification and Their Functions

| Material / Reagent | Function in Electrode Modification |

|---|---|

| Nafion [33] | Ion-exchange membrane coating; improves selectivity by repelling anions and enriching cations like dopamine. |

| Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B) [33] | Enzyme layer; selectively metabolizes interfering neurotransmitters (e.g., serotonin) to enhance target analyte specificity. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [36] [34] | Nanostructured material; provides high surface area and excellent conductivity, enhancing sensitivity and electron transfer. |

| Polyaniline (PANI) & Polypyrrole (PPy) [37] [36] [34] | Conducting polymers; used to modify electrode surfaces, improving electrochemical properties, stability, and biocompatibility. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) [36] | Porous materials; offer high surface area and tunable pores for selective analyte adsorption and sensing. |

| Gold (Au) & Thiolated Probes [38] | Electrode material/immobilization chemistry; enables covalent binding of biomolecules (e.g., DNA, antibodies) via gold-thiol bonds for stable biosensors. |

| Glutaraldehyde [33] [34] | Bifunctional cross-linker; used to stabilize enzyme layers and other modifiers on the electrode surface. |

| Alumina Slurry (0.05 µm) [3] | Polishing agent; for refreshing and cleaning electrode surfaces to ensure reproducible results. |

Experimental and Troubleshooting Workflows

Diagram 1: Sensor Fabrication and Validation

Diagram 2: Systematic Voltammetry Troubleshooting

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the main advantages of using a cone-shaped carbon fiber microelectrode over a standard cylindrical one? The cone-shaped geometry provides a superior balance of mechanical robustness, enhanced sensitivity, and improved biocompatibility. The tapered design reduces insertion force and minimizes tissue displacement during implantation into the brain. This leads to significantly less acute tissue damage and a reduced glial cell response (a marker of inflammation), which in turn results in higher quality and more stable neurotransmitter signals in vivo [39] [40] [41].

Q2: My in vivo dopamine signals are lower than expected with a new 30 µm diameter electrode, even though it performed well in vitro. What could be the cause? This is a common issue when using larger-diameter electrodes. The reduced signal is likely due to increased tissue damage upon insertion. A larger, blunt electrode tip displaces more neural tissue, triggering a more severe local inflammatory response and potentially disrupting the very neurochemical environment you are trying to measure [39] [40]. Switching from a bare 30 µm fiber to a cone-shaped 30 µm design has been shown to resolve this, improving in vivo dopamine signals by 3.7-fold while reducing glial activation [39] [40].

Q3: How can I improve the longevity and durability of my carbon fiber microelectrodes (CFMEs) for chronic experiments? Increasing the fiber diameter is one effective strategy. Studies show that 30 µm cone-shaped CFMEs can have a 4.7-fold longer lifespan than conventional 7 µm CFMEs in erosion tests simulating chronic use [39] [40]. The cone shape maintains this mechanical advantage while solving the tissue damage problem associated with larger diameters. This design is therefore highly recommended for long-term monitoring applications [39] [40] [41].

Q4: My electrode seems to be fouling, leading to a loss of sensitivity over time. What are my options? Beyond physical design, surface modification can prevent fouling. Modifying the electrode surface with carbon nanoparticles or specific nanomaterials like carbon nanospikes (CNSs) can enhance electron transfer kinetics and act as a physical barrier to prevent fouling from polymerized neurochemicals [42]. Using porous carbon structures that trap analytes can also enhance selectivity and mitigate fouling issues [42].

Troubleshooting Guide

| Problem | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Sensitivity In Vivo | Excessive tissue damage from electrode insertion Severe inflammatory response (glial activation) | Switch to a cone-shaped tip geometry [39] [40] Verify reduced glial activity via Iba1/GFAP markers [39] |

| Poor Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High electrode electrical noise Signal loss from tissue damage | Ensure proper electrode conditioning [39] Use a 30 µm cone-shaped CFME for higher inherent sensitivity and lower tissue impact [39] [43] [40] |

| Short Electrode Lifespan | Mechanical degradation/breaking Electrochemical over-oxidation of carbon fiber | Use a larger diameter (e.g., 30 µm) cone-shaped CFME for superior durability [39] [40] Avoid overly aggressive waveforms that accelerate over-oxidation [39] |

| Unstable Readings/Drift | Biofouling on electrode surface Loose electrical connections | Apply anti-fouling surface modifications (e.g., carbon nanoparticle coatings) [42] Check all physical connections and impedance [44] |

Experimental Data & Performance Comparison

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for different carbon fiber microelectrode designs, highlighting the advantages of the cone-shaped geometry.

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Comparison of Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes

| Electrode Type | Diameter (µm) | In Vitro Sensitivity (pA/µm²) | In Vivo Dopamine Signal (nA) | Relative Lifespan | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard CFME [39] [43] [40] | 7 | 12.2 ± 4.9 | 24.6 ± 8.5 | 1.0 x (Baseline) | Standard for in vivo work; minimal tissue damage. |

| Bare CFME [39] [43] [40] | 30 | 33.3 ± 5.9 | 12.9 ± 8.1 | ~4.7 x (vs. 7µm) | High sensitivity in vitro, but causes tissue damage, reducing in vivo signal. |

| Cone-Shaped CFME [39] [40] [41] | 30 (tip) | Information Missing | 47.5 ± 19.8 | ~4.7 x (vs. 7µm) | Superior design: Combines high sensitivity, excellent in vivo signal, and long lifespan. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of 30 µm Cone-Shaped Carbon Fiber Microelectrodes

This protocol is adapted from the method used in recent studies [39] [40].

- Preparation: Obtain a 30 µm diameter carbon fiber. Assemble a homemade electrochemical etching system consisting of a DC power supply and a linear actuator.

- Setup: Submerge a 1 mm segment of the carbon fiber in Tris buffer (pH 7.4).

- Etching: Apply a direct current voltage of 10 V to the submerged fiber for 20 seconds. Simultaneously, use the linear actuator to move the electrode upward at a constant speed. This gradual exposure to air during electrolysis is what forms the cone shape.

- Finalization: Control the final cone height to between 100 and 120 µm by precisely adjusting the speed of the actuator. After etching, the electrode is sealed in glass or an insulator, leaving the custom-shaped tip exposed.

Protocol 2: Assessing Biocompatibility via Immunofluorescence

To validate that the cone-shaped design reduces tissue damage, follow this post-implantation analysis [39] [40].

- Implantation: Implant the fabricated microelectrodes into the target brain region of an animal model using standard surgical procedures.

- Tissue Extraction: After a set period, perfuse the animal and extract the brain. Section the brain tissue containing the electrode implantation track.

- Staining: Immunostain the tissue sections using primary antibodies for classic glial cell markers:

- Iba1 to identify activated microglia.

- GFAP to identify activated astrocytes.

- Imaging and Analysis: Image the stained tissue sections using fluorescence microscopy. Quantify the intensity and distribution of Iba1 and GFAP staining around the implantation site. Compared to standard or bare larger electrodes, the cone-shaped design should show significantly lower signal for these markers, indicating a reduced inflammatory response and better biocompatibility [39] [40].

Diagram: Fabrication and Performance Relationship

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Fabrication and Testing

| Item | Function/Description | Source Example |

|---|---|---|

| 30 µm Carbon Fiber | The core material for the microelectrode. Larger diameter improves mechanical strength. | World Precision Instruments (WPI) [39] [40] |

| Tris Buffer | An electrochemical stable buffer used during the electrochemical etching process and for in vitro testing. | Sigma-Aldrich [39] [40] |

| DC Power Supply | Provides the precise voltage (10V DC) required for the controlled electrochemical etching. | Standard lab equipment |

| Linear Actuator | Provides the precise vertical movement during etching to form the cone shape. | Homemade or commercial system [39] [40] |

| Iba1 & GFAP Antibodies | Primary antibodies for immunofluorescence staining to identify activated microglia and astrocytes, quantifying tissue response. | Various biological suppliers |

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | A solution that mimics the ionic composition of brain fluid, used for in vitro testing that more closely mimics in vivo conditions. | Can be prepared in-lab from salts [45] |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is the primary advantage of Square-Wave Voltammetry (SWV) over techniques like Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)?

SWV offers superior sensitivity and background current suppression compared to CV. Its pulse sequence measures current in both forward and reverse pulses, and the resulting difference current effectively minimizes non-faradaic (charging) background current. This makes it particularly powerful for detecting low concentrations of analytes [46].

Q2: How do I know if my SWV parameters are optimized?

A well-optimized SWV experiment will yield a sharp, symmetrical peak with a high signal-to-noise ratio for your target analyte. If the peak is broad, asymmetric, or the baseline is noisy, parameter optimization is likely required. For quantitative work, optimization using a systematic method like Response Surface Methodology (RSM) is recommended to find the parameter combination that produces the highest peak current [47] [48].

Q3: Can SWV be used for quantitative analysis?

While SWV is often praised for its diagnostic capabilities, it can absolutely be used for quantitative analysis. The peak current is directly proportional to the concentration of the electroactive species, allowing for the construction of calibration curves. The high sensitivity of SWV makes it suitable for detecting very low concentrations, with reported limits of detection (LOD) in the nanomolar range [46] [47] [48].

Q4: My SWV peaks are very broad. Which parameter should I adjust first?

A broad peak often suggests a slow electron transfer process or suboptimal waveform parameters. You should first investigate increasing the square wave amplitude. A higher amplitude can lead to sharper peaks and increased peak current, as it provides a greater driving force for the electrochemical reaction [46] [48].

Troubleshooting Common Issues

| Issue | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low Peak Current | Suboptimal amplitude, frequency, or increment. | Systematically optimize parameters using RSM. Generally, increase amplitude and frequency within instrumental limits [47] [48]. |

| High Background Noise | Sampling width too long, improper electrode conditioning, or electrical interference. | Shorten the sampling width, ensure proper electrode cleaning/pretreatment, and use shielded cables in a grounded Faraday cage [46]. |

| Irreproducible Peaks | Electrode fouling, unstable electrical contact, or drifting chemical system. | Clean or polish the electrode surface, check all connections, and ensure chemical stability of the analyte solution [46]. |

| Non-Symmetrical Peaks | Quasi-reversible or irreversible electrode kinetics. | Confirm the reversibility of your system. Optimizing parameters like frequency can help; lower frequencies may improve shape for slower kinetics [46]. |

SWV Parameters and Optimization

Core Parameters for Optimization

The performance of SWV is highly dependent on three key parameters, which define the applied waveform and must be optimized for each specific application to maximize current response [46] [47] [48].

- Square Wave Amplitude (Esw): The height of each individual pulse (in mV). This parameter dictates the driving force for the electrochemical reaction. Increasing the amplitude typically enhances the peak current and sharpens the peak, but excessive values can lead to distortion.

- Square Wave Frequency (f): The number of complete forward-reverse cycles per second (in Hz). Frequency is inversely related to the square wave period (

f = 1/P). Higher frequencies speed up analysis but can reduce peak current for electrochemically irreversible systems. - Step Potential (Estep): Also known as the pulse increment (in mV). This is the change in the baseline potential with each subsequent pulse. It controls the potential resolution of the scan; a smaller step potential results in a finer scan.

Optimized Parameter Sets

The table below summarizes parameter values for different analytical scenarios, illustrating how they can be tuned for specific goals.