Advanced Strategies for Improving Selectivity in Electrochemical Sensors: Materials, Methods, and Clinical Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies to enhance the selectivity of electrochemical sensors, a critical parameter for their application in biomedical research and drug development.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Selectivity in Electrochemical Sensors: Materials, Methods, and Clinical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of contemporary strategies to enhance the selectivity of electrochemical sensors, a critical parameter for their application in biomedical research and drug development. It explores the foundational principles of selective recognition, details advanced material and methodological approaches, and offers practical guidance for troubleshooting and optimization. By synthesizing recent advances and providing a comparative analysis of sensor validation techniques, this resource equips researchers with the knowledge to develop highly selective sensors for accurate analyte detection in complex biological matrices, from fundamental research to point-of-care diagnostics.

The Fundamentals of Sensor Selectivity: Principles and Recognition Mechanisms

Defining Selectivity in Electrochemical Sensing

What is selectivity in electrochemical sensors?

Selectivity refers to a sensor's ability to accurately detect and measure a specific target analyte in a complex mixture without interference from other substances present in the sample matrix. For electrochemical sensors, this means generating an electrical signal primarily from the intended chemical or biological target while minimizing responses from interfering species [1].

Why is achieving selectivity particularly challenging in complex biological media?

Biological fluids like blood, urine, or saliva contain a multitude of interfering components, including proteins, metabolites, salts, and cells [1]. These complex matrices can cause several issues:

- Non-specific adsorption of proteins and other biomolecules onto the sensor surface [1]

- False signals from electroactive interferents such as ascorbic acid, dopamine, uric acid, and epinephrine [2]

- Matrix effects that alter the sensor's electrochemical response [1]

- Sensor fouling and degradation from prolonged exposure to complex samples [1]

FAQs on Selectivity Challenges

The table below summarizes major interfering substances and their effects:

| Interference Category | Specific Examples | Impact on Sensor Performance |

|---|---|---|

| Electroactive Small Molecules | Ascorbic acid (AA), dopamine (DA), uric acid (UA), epinephrine (EP) [2] | Direct oxidation/reduction at similar potentials as target analyte [2] |

| Proteins and Biomacromolecules | Serum albumin, immunoglobulins, fibrinogen [1] | Non-specific binding and surface fouling [1] |

| Cells and Particulates | Blood cells, circulating tumor cells, bacteria [1] | Physical blockage of electrode surface [1] |

| Ionic Species | Sodium, potassium, chloride, calcium ions [3] | Alteration of electrochemical double layer and charge transfer [3] |

How do researchers quantify and report selectivity?

Selectivity is typically quantified using selectivity coefficients determined from current responses to target analytes versus interfering substances [2]. For a sensor to be considered highly selective, it should generate a significantly stronger signal for the target compound compared to potential interferents at similar concentrations.

What strategies can improve sensor selectivity?

Multiple approaches can enhance selectivity:

- Advanced materials with molecular recognition capabilities [1] [4]

- Surface modification techniques to create selective barriers [1] [4]

- Electrochemical waveform optimization such as triple-pulse amperometry [2]

- Multiplexing and array-based sensing to distinguish patterns from multiple targets [1]

Troubleshooting Guide: Selectivity Issues

Problem: Poor selectivity against specific interferents

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Consistent false positives from particular interferents | Sensor surface lacks specificity for target vs. structurally similar compounds | Implement molecularly imprinted polymers or aptamer-based recognition elements [4] |

| Signal suppression in complex media | Biofouling from proteins or cells | Apply anti-fouling coatings like PEG or zwitterionic polymers [1] |

| Inconsistent selectivity across samples | Variable sample composition (pH, ionic strength) | Incorporate sample pretreatment or standardize buffer conditions [1] |

Problem: Signal drift and instability in complex media

| Observed Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Gradual signal degradation over time | Sensor fouling or passivation from sample components | Use pulsed electrochemical cleaning methods like triple-pulse amperometry [2] |

| Changing baseline in continuous monitoring | Reference electrode instability or membrane degradation | Implement regular calibration and reference electrode maintenance [3] [5] |

| Irregular noise or spikes | Poor electrical contacts or connection issues | Check electrode connections and cable integrity [6] |

Experimental Protocol: Selectivity Optimization

Protocol for Evaluating and Optimizing Selectivity

This protocol outlines a systematic approach for assessing and improving sensor selectivity, based on methodologies used in recent research [2].

Materials Required:

- Potentiostat with multi-pulse amperometry capability

- Modified working electrode (e.g., PEDOT/nano-Au composite film) [2]

- Reference electrode (Ag/AgCl recommended)

- Counter electrode (platinum wire or graphite rod)

- Target analyte of interest at relevant concentrations

- Potential interferents specific to application context

- Appropriate buffer solution

Procedure:

Sensor Preparation

- Modify working electrode with selective materials (e.g., polymer/nanoparticle composites)

- Condition electrode in buffer solution until stable baseline achieved

Selectivity Assessment

- Measure sensor response to target analyte across relevant concentration range

- Challenge sensor with individual interferents at physiologically relevant concentrations

- Test sensor with mixture of target and interferents

- Calculate selectivity coefficients from current responses [2]

Electrochemical Optimization

Validation

- Assess sensor repeatability and stability over multiple cycles

- Determine detection limit and linear range in presence of interferents

- Verify performance in real or simulated complex samples

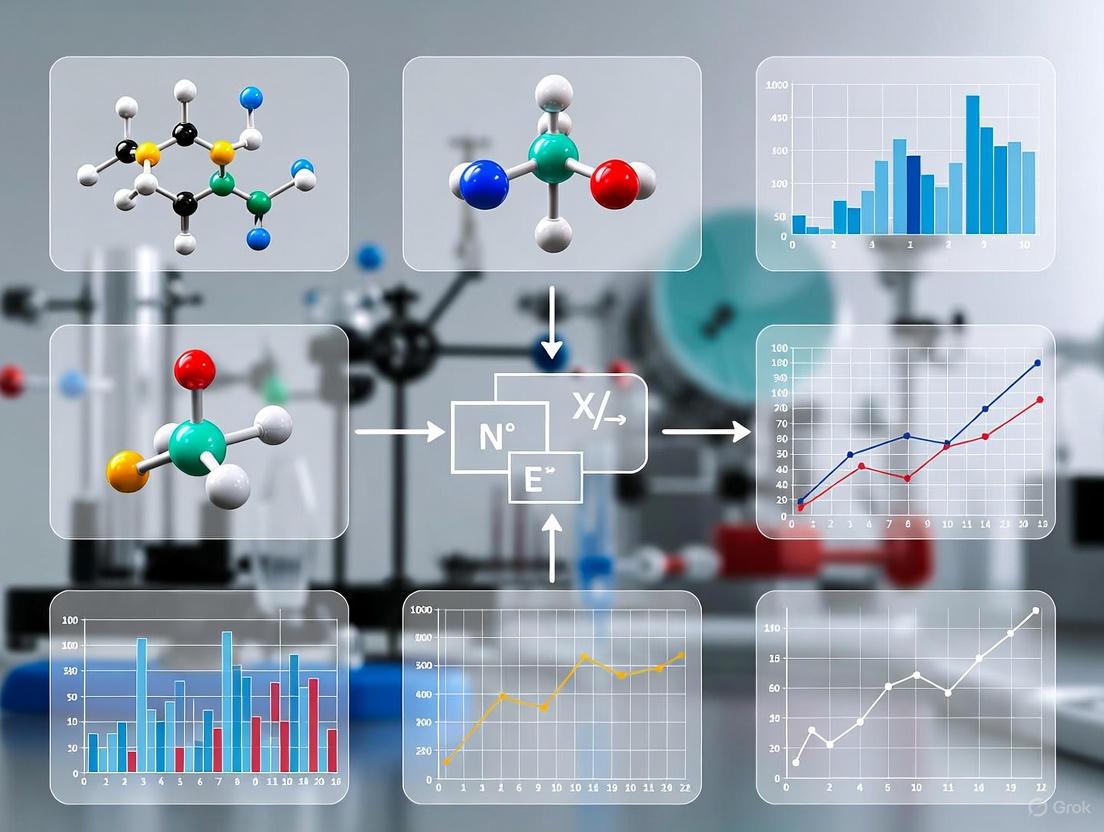

Visualization: Selectivity Optimization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for Enhanced Selectivity

The table below summarizes key materials and their functions for developing selective electrochemical sensors:

| Material/Reagent | Function in Enhancing Selectivity | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | High porosity and tunable structures for selective analyte interaction [4] | Heavy metal detection, gas sensing [4] |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers | Create specific molecular cavities for target recognition [4] | Toxin detection, biomarker sensing [4] |

| Aptamers | Nucleic acid-based recognition elements with high specificity [1] | Cancer biomarker detection, drug monitoring [1] |

| Ionophores | Selective binding sites for specific ions in ISEs [3] | Sodium, potassium, chloride detection [3] |

| Conducting Polymers (PEDOT) | Provide selective charge transport and antifouling properties [2] | Hydrogen sulfide detection [2] |

| Nanoparticles (Au, Pt) | Enhance electron transfer and enable surface functionalization [2] | Exosome detection, antibiotic sensing [1] [7] |

| Carbon Nanomaterials (CNTs, Graphene) | Large surface area for immobilization and enhanced sensitivity [1] [4] | Multiplexed detection, antibiotic residues [7] |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) | Control interfacial properties and reduce nonspecific binding [4] | Biosensor interfaces, electrode functionalization [4] |

Core Principles of Molecular Recognition in Electrochemical Systems

Molecular recognition is the cornerstone of selective electrochemical sensing, governing the specific interaction between a sensor and its target analyte amidst complex sample matrices. For researchers and drug development professionals, achieving high selectivity is often the most significant challenge in developing reliable sensors for clinical, environmental, or food safety applications [4] [8]. This technical support center addresses the fundamental principles and practical experimental issues encountered when working with molecular recognition in electrochemical systems, framed within the broader thesis of improving sensor selectivity.

Molecular recognition in electrochemical sensors is typically achieved through synthetic receptors that mimic biological systems' ability to distinguish between molecules based on size, shape, and functional groups [8]. These specific interactions are responsible for converting biological events into quantifiable electronic signals that can be processed and analyzed [9]. The precise control over the delicate interplay between surface nano-architectures, surface functionalization, and the chosen sensor transducer principle determines the ultimate sensitivity and selectivity of the sensor [9].

Fundamental FAQ: Molecular Recognition Principles

What is molecular recognition in electrochemical systems?

Molecular recognition refers to the specific, non-covalent interaction between a synthetic receptor (host) and a target analyte (guest) at the electrode-solution interface. This interaction is responsible for the selective binding that precedes the electrochemical transduction of the binding event into a measurable signal [8] [9]. These interactions include hydrogen bonds, coordinate bonds, hydrophobic forces, π-π interactions, van der Waals forces, and electrostatic effects [8]. The complementarity of these interactions provides the molecular specificity crucial for accurate sensing.

Why is improving selectivity particularly challenging in complex biological samples?

Biological samples like serum, blood, and urine contain numerous electroactive interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, dopamine, uric acid) that can generate non-specific signals, obscuring the target analyte response [2] [9]. Even minor pH and ionic strength variations in biofluids can significantly affect sensor response, particularly for immunosensors [9]. Furthermore, electrode fouling from protein adsorption or sulfur deposition (in Hâ‚‚S sensing) can passivate the electrode surface, reducing sensitivity and reproducibility over time [2].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Issues

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Possible Causes | Solution Strategies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Signal Response | Low sensitivity/sluggish response | • Electrode fouling/passivation• Incorrect electrode conditioning• Slow mass transport to electrode | • Implement triple-pulse amperometry cleaning pulses [2]• Ensure proper sensor conditioning (16-24 hrs for ISE) [10]• Use nanomaterials to increase surface area [4] |

| Poor selectivity against interferents | • Non-specific binding to sensor surface• Insufficient recognition element specificity | • Optimize surface modification with SAMs [4]• Use composite films (e.g., PEDOT/nano-Au) [2]• Employ molecular imprinting for specific cavities [11] | |

| Measurement Quality | High signal drift & poor reproducibility | • Temperature fluctuations• Unstable reference electrode• Inconsistent calibration | • Calibrate using interpolation, not extrapolation [10]• Maintain stable process sample temperature [10]• Perform one-point offset calibrations in service [10] |

| Erratic readings in real samples | • Air bubbles on sensing element• Complex matrix effects• Protein fouling in biological fluids | • Install sensor at 45° angle to prevent bubble trapping [10]• Use sample conditioning/pH adjustment [10]• Implement nanostructured antifouling coatings [4] | |

| Sensor Lifetime | Short operational lifespan & stability issues | • Chemical degradation of recognition layer• Biofouling in complex matrices• Improper storage conditions | • Store ISE sensors upright to maintain integrity [12] [10]• Use robust synthetic receptors (MIPs, aptamers) [8] [11]• Apply protective membranes (Nafion) [4] |

Core Methodologies: Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Selectivity

Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Sensor Fabrication

Molecular imprinting creates synthetic polymer receptors with high affinity for a target molecule through a "lock and key" mechanism similar to natural antibody-antigen interactions [11]. The protocol involves creating template-shaped cavities in polymer matrices with memory of the template molecules.

Detailed Protocol:

- Pre-complexation: Mix the target analyte (template) with functional monomers (e.g., methacrylic acid, vinylpyridine) in a suitable porogenic solvent. Allow self-assembly via non-covalent interactions for 15-60 minutes.

- Polymerization: Add cross-linking monomer (e.g., ethylene glycol dimethacrylate) and radical initiator (e.g., AIBN). Purge with nitrogen or argon to remove oxygen.

- Initiation: Initiate polymerization thermally (50-70°C) or photochemically (UV light, 365 nm) for 12-24 hours.

- Template Removal: Extract the template molecules using Soxhlet extraction with methanol-acetic acid (9:1 v/v) until no template is detected in the washings by HPLC or UV-Vis.

- Electrode Modification: Disperse the ground MIP particles in ethanol or water (1-5 mg/mL) and deposit on the electrode surface (e.g., 5-10 μL). Dry under ambient conditions or nitrogen flow [11].

Critical Notes: Use "dummy template" strategies for targets that are expensive, unstable, or poorly soluble to avoid template bleeding into analytical matrices [11]. For protein imprinting, minimize harsh conditions that can denature the template during polymerization.

Electrode Modification with Composite Nanomaterials for Hâ‚‚S Sensing

This protocol details the construction of a highly selective hydrogen sulfide sensor using a PEDOT/nano-Au composite film, which demonstrated excellent selectivity against common interferents in biological fluids [2].

Detailed Protocol:

- Electrode Pretreatment: Clean the glassy carbon electrode (GCE) successively with 0.3 and 0.05 μm alumina slurry on a microcloth. Rinse with distilled water and dry.

- Gold Nanoparticle Synthesis: Prepare nano-Au by reducing HAuCl₄ with sodium citrate (1% w/v) at 100°C for 15 minutes until wine-red color appears.

- Electropolymerization: Immerse the GCE in a solution containing 0.01 M EDOT and 1% nano-Au in 0.1 M LiClOâ‚„. Perform cyclic voltammetry between -0.2 and +1.5 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) for 10 cycles at 50 mV/s.

- Sensor Stabilization: Rinse the modified electrode and cycle in clean PBS (pH 7.4) until a stable CV is obtained.

- Detection Method: Employ triple-pulse amperometry with distinct cleaning and measurement pulses to mitigate electrode surface passivation from sulfur deposition [2].

Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) Conditioning and Calibration

Proper conditioning and calibration are essential for obtaining accurate and reproducible results with ion-selective electrodes, particularly in complex samples.

Detailed Protocol:

- Conditioning: Soak the new or regenerated ISE in the lower concentration calibration solution for 16-24 hours before first use. This allows the organic membrane system to reach equilibrium with the aqueous solution [10].

- Calibration Solution Preparation: Prepare calibrating solutions not more than one decade apart, bridging the anticipated sample concentration. For complex samples, add matrix constituents to the calibrating solution to mirror the actual sample background [10].

- Two-Point Calibration:

- Rinse the conditioned sensor with the first calibrating solution.

- Immerse in the first calibrating solution, wait for signal stabilization (typically 2-5 minutes), and set the first calibration point.

- Rinse with the second calibration solution (do not use distilled water for rinsing).

- Immerse in the second calibrating solution, wait for stabilization, and set the second calibration point.

- Validation: Regularly validate sensor sensitivity with standard solutions. Recalibrate when sensitivity changes exceed 5% [10].

Critical Notes: Always use interpolation rather than extrapolation for concentration determination. Avoid rinsing with distilled water between calibration points as this dilutes the solution on the sensor surface and increases response time [10].

Performance Data: Quantitative Comparison of Recognition Elements

The selection of molecular recognition elements significantly impacts sensor performance. The table below compares key characteristics of different recognition strategies for electrochemical sensors.

Table: Comparison of Molecular Recognition Strategies for Electrochemical Sensors

| Recognition Element | Detection Limit | Selectivity | Stability | Fabrication Complexity | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) | nM-pM range [11] | High (similar to antibodies) [11] | Excellent (thermal/chemical) [8] [11] | Moderate | Food contaminants, toxins, pharmaceuticals [11] |

| Aptamers | nM-fM range [13] | Very high (specific folding) [13] | Good (refolding possible) [13] | Moderate (SELEX required) | Biomarkers, clinical diagnostics [13] |

| Enzymes | µM-nM range [9] | Moderate (substrate specific) [9] | Moderate (sensitive to conditions) [9] | Low | Metabolites, neurotransmitters, glucose [9] |

| Antibodies | pM-fM range [9] | Very high (immunospecific) [9] | Moderate (biological degradation) [8] | High | Pathogens, biomarkers, hormones [9] |

| Macrocyclic Compounds | µM-nM range [14] | Moderate to high (host-guest) [14] | Excellent (chemical/thermal) [14] | Low to Moderate | Metal ions, organic molecules [14] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Reagent Solutions for Molecular Recognition Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Provide complementary interactions with template | MIP synthesis, polymer films [11] | Choose based on template functional groups (H-bonding, ionic) |

| Cross-linkers | Create rigid polymer network with defined cavities | MIP synthesis, stabilizing recognition layers [11] | Higher cross-linking increases stability but may slow mass transfer |

| Macrocyclic Compounds | Host-guest recognition via supramolecular chemistry | Ion detection, small molecule sensing [14] | Crown ethers for metals, cyclodextrins for organic compounds |

| Self-Assembled Monolayer (SAM) Reagents | Create ordered interface for bioreceptor immobilization | Surface functionalization, reducing non-specific binding [4] | Alkanethiols on gold, silanes on metal oxides |

| Nanomaterials | Enhance surface area, electron transfer, signal amplification | Electrode modification, signal enhancement [4] | Graphene, CNTs, metal nanoparticles (Au, Pt) |

| Aptamers | Synthetic nucleic acid recognition elements | Specific target binding (ions, molecules, cells) [13] | Selected via SELEX; can be denatured and regenerated |

| Rencofilstat | Rencofilstat, CAS:1383420-08-3, MF:C67H122N12O13, MW:1303.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| cwhm-12 | CWHM-12|Potent αV Integrin Antagonist|RUO | Bench Chemicals |

Visualization: Molecular Recognition Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram Title: Molecular Recognition Mechanisms and Signal Transduction

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Sensor Development

Troubleshooting Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

The following table summarizes frequent problems encountered when working with electrochemical sensors based on MOFs and conducting polymers, along with their likely causes and solutions [15].

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Inconsistent Electrode Response | Electrode fouling or contamination [15]. | - Visually inspect the electrode surface [15].- Perform electrochemical cleaning (e.g., cyclic voltammetry) [15].- Mechanically polish the electrode to restore the surface [15]. |

| Unstable electrical contacts in composite materials. | - Ensure homogeneous mixing of MOF/conducting polymer composites.- Verify all electrical connections are secure. | |

| Unstable Baseline or Signal Noise | Electrical interference from instrumentation [15]. | - Use shielding (e.g., a Faraday cage) [15].- Ensure proper grounding of the instrument [15].- Apply signal filtering or averaging techniques [15]. |

| Fluctuations in temperature or electrolyte composition [15]. | - Use a temperature-controlled cell [15].- Employ a pH buffer to maintain stable electrolyte conditions [15]. | |

| Slow Sensor Response Time | Inefficient mass transport through the MOF pores. | - Optimize MOF film thickness to balance porosity and diffusion distance.- Activate MOF pores before use (e.g., via solvent exchange and heating). |

| Drying out or dilution of the internal electrolyte (for electrochemical gas sensors) [16]. | - Ensure operating humidity is maintained between 20% and 60% RH [16].- Restore sensor by exposing it to the opposite extreme of humidity for several days [16]. | |

| Loss of Sensitivity/Selectivity | Degradation or leaching of active materials (MOFs, polymers). | - Characterize composite stability via accelerated aging tests.- Implement protective membranes (e.g., Nafion) where appropriate. |

| Poisoning of active sites by interfering species. | - Introduce a selective membrane over the active layer.- Pre-treat the sample to remove known interferents. | |

| Sensor Signal Drift | Unstable reference electrode potential. | - Check the integrity of the reference electrode and replace if necessary.- Use a stable internal reference for solid-state sensors. |

| Changes in the ionic strength or pH of the analyte solution [10]. | - Use a background electrolyte to fix the ionic strength.- Employ a buffer solution to maintain a constant pH [10]. |

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow

The logical flow for diagnosing and resolving issues follows a structured path. The diagram below outlines this systematic approach, which begins with identifying the problem and proceeds through checks of physical components, instrumentation, and experimental conditions [15].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the typical operational lifespan of electrochemical sensors, and what factors affect it? [16]

The operational lifespan varies significantly with the target gas and environment. Sensors for common gases like CO or H₂S can last 2-3 years, while sensors for exotic gases like HF may last 12-18 months. High-quality O₂ or NH₃ sensors can function for up to 5 years. The primary factors affecting lifespan are:

- Humidity: Operating outside 20-95% RH can cause electrolyte dilution (high humidity) or drought (low humidity), leading to failure [16].

- Temperature: Repeated exposure to high temperatures (e.g., >50°C) can cause electrolyte drought and baseline drift [16].

- Target Gas Concentration: Consistently high concentrations of the target gas can shorten sensor life [16].

- Cross-interfering Gases: Some gases can poison the catalyst, permanently damaging the sensor [16].

Q2: How often should I calibrate my electrochemical sensor? [16]

Calibration frequency depends on application requirements, sensor quality, and environmental conditions. A common practice is to perform an initial calibration after sensor installation, recheck accuracy after one month, and then extend the interval to 3, 6, or even 12 months once the sensor stabilizes. Always follow industry standards and government regulations relevant to your application [16].

Q3: Why is my sensor's response unstable after storage, and how do I condition it? [10]

Instability after storage is often due to the sensor not being in equilibrium with the aqueous solution. For ion-selective electrodes (ISEs) with organic membranes, conditioning by soaking in a low-concentration calibration standard for 16-24 hours before use is recommended. This allows the organic system to stabilize. Solid-state sensors also require conditioning, though often for a shorter period [10].

Q4: What is the most reliable way to determine if a sensor has failed? [16]

The only reliable method is to measure the sensor's response through a "bump test" or calibration. A failed sensor will show a zero current output even when exposed to the target gas. If the response time (T90) is significantly longer than specified or sensitivity is drastically reduced during calibration, the sensor needs replacement [16].

Q5: How critical is temperature control for accurate potentiometric measurements? [10]

Temperature is highly critical. The Nernst equation defines that for monovalent ions, a 1 mV change in potential alters the concentration reading by at least 4%. A temperature discrepancy of 5°C can cause this 1 mV change. Furthermore, the activity coefficient of the analyte ion itself changes with temperature, an effect that cannot be easily compensated for. For optimum measurement, calibrate and operate the sensor under stable temperature conditions [10].

Experimental Protocols

Synthesis of a ZIF-67/CNT/PAni Ternary Composite Electrode

This protocol details the synthesis of a high-performance composite electrode material for supercapacitors, as reported in recent literature [17].

- Objective: To create a ternary composite material (ZIF-67/CNT/PAni) that synergistically combines the high surface area of a Metal-Organic Framework (MOF), the electrical conductivity of carbon nanotubes, and the redox activity of a conducting polymer for enhanced electrochemical energy storage [17].

- Principle: The procedure involves the in-situ growth of ZIF-67 crystals in the presence of a pre-dispersed CNT network, followed by the polymerization of aniline to form a conductive polyaniline (PAni) matrix that interlinks the components.

Materials:

- ZIF-67 Precursors: Cobalt nitrate hexahydrate (Co(NO₃)₂·6H₂O) and 2-Methylimidazole.

- Conductive Additive: Multi-walled or single-walled Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs).

- Conducting Polymer: Aniline monomer and an oxidant (e.g., ammonium persulfate).

- Solvents: Methanol or deionized water.

Procedure:

- Dispersion of CNTs: Disperse a specific mass of CNTs (e.g., 50 mg) in 50 mL of solvent using probe sonication for 30-60 minutes to form a homogeneous black suspension.

- In-situ Growth of ZIF-67: Add stoichiometric amounts of cobalt nitrate and 2-methylimidazole separately to the CNT suspension under constant stirring. Allow the reaction to proceed for a specified time (e.g., 4-24 hours) at room temperature.

- Isolation of ZIF-67/CNT Intermediate: Centrifuge the resulting mixture to collect the solid ZIF-67/CNT composite. Wash the solid several times with fresh solvent to remove unreacted precursors, and then dry it in an oven at 60-80°C.

- Polymerization of Aniline: Re-disperse the dried ZIF-67/CNT powder in an acidic aqueous solution (e.g., 1M HCl). Add a specific volume of aniline monomer to the suspension and stir vigorously.

- Formation of Ternary Composite: Slowly add an aqueous solution of ammonium persulfate (the oxidant) dropwise to the stirring mixture to initiate the polymerization of aniline. Continue stirring for several hours (e.g., 4-12 hours) until the color of the solution darkens, indicating the formation of polyaniline (PAni).

- Product Recovery: Filter the final product (ZIF-67/CNT/PAni) and wash repeatedly with deionized water and ethanol. Dry the composite thoroughly under vacuum at 50-60°C overnight.

Key Notes:

- The entire synthesis can be performed via a combination of stirring and sonication, making it simple and scalable [17].

- The ratios of ZIF-67, CNT, and aniline can be optimized to achieve the desired porosity and conductivity.

Electrode Conditioning and Pretreatment for Optimal Performance

Proper conditioning is vital for achieving a stable and reproducible electrode response [15] [10].

- Objective: To activate the electrode surface, ensure electrochemical stability, and minimize background noise before experimental measurements.

- Materials: Electrolyte solution (e.g., 0.1 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„, PBS), polishing kits (alumina powder), and lint-free wipes.

- Procedure for Solid Electrodes (e.g., Glassy Carbon):

- Mechanical Polishing: Polish the electrode surface sequentially with finer grades of alumina slurry (e.g., 1.0, 0.3, and 0.05 µm) on a micro-cloth pad.

- Rinsing: Rinse thoroughly with deionized water after each polishing step to remove all alumina residues.

- Sonication: Sonicate the electrode in deionized water and then ethanol for 2-5 minutes each to remove any adsorbed particles.

- Electrochemical Activation: Perform cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„) over a potential window of -0.2 to 1.0 V (vs. Ag/AgCl) at a scan rate of 50-100 mV/s until a stable CV profile characteristic of a clean electrode is obtained (typically 20-50 cycles).

- Procedure for Modified and Composite Electrodes:

- Electrochemical Stabilization: Immerse the newly fabricated modified electrode (e.g., ZIF-67/CNT/PAni) in the electrolyte solution that will be used for measurement.

- Run multiple CV cycles (e.g., 10-30 cycles) within the operating potential window until the voltammogram becomes stable and reproducible. This process helps to wet the porous structure and stabilize the redox states of the active materials.

The workflow for preparing and conditioning a modified electrode, from synthesis to stabilization, involves several key stages. The diagram below visualizes this multi-step process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section lists essential materials and their functions for developing and working with advanced functional materials in electrochemistry.

| Item | Function / Role in Research |

|---|---|

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) | Provide ultra-high surface area and tunable porosity for analyte adsorption and size-selective recognition. The chemical environment within pores can be designed for specific interactions [17] [18]. |

| Conducting Polymers (CPs) | Act as proficient signal transducers due to their high electrical conductivity and redox activity. They can be electrochemically switched between states, enabling signal amplification [18]. |

| Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) | Serve as conductive scaffolds within composite materials. They facilitate rapid electron transfer, create more charge transfer channels, and improve the mechanical stability of the composite film [17]. |

| Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIF-67) | A specific class of MOFs known for their high thermal and chemical stability. They are ideal for creating composite electrode materials for energy storage and sensing [17]. |

| Electrochemical Gas Sensor | A device that detects specific gases by measuring the current generated from an oxidation or reduction reaction at an electrode. It consists of a working electrode, counter electrode, and reference electrode in an electrolyte [19]. |

| Ion-Selective Electrode (ISE) | A sensor that measures the activity of a specific ion in solution by producing a potential difference. It uses a selective membrane (e.g., PVC-based or solid-state) to achieve specificity [10]. |

| Reference Electrode | Provides a stable and known reference potential against which the working electrode's potential is measured, ensuring accurate potentiometric measurements. |

| Cyclobenzaprine Hydrochloride | Cyclobenzaprine Hydrochloride, CAS:6202-23-9, MF:C20H22ClN, MW:311.8 g/mol |

| Dactolisib Tosylate | Dactolisib Tosylate, CAS:1028385-32-1, MF:C37H31N5O4S, MW:641.7 g/mol |

The Role of Surface Chemistry and Electrode Modification

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This section addresses common experimental challenges in electrochemical sensor development, providing targeted solutions to enhance selectivity and reliability.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What are the most common causes of an inconsistent electrode response? Inconsistent response is often caused by electrode fouling or contamination, where substances accumulate on the electrode surface, altering its properties. Other sources include instrumentation malfunctions and suboptimal experimental conditions (e.g., fluctuating temperature or pH) [15].

How can I minimize electrical noise and interference in my experiment? Electrical noise can be minimized by using shielding techniques like Faraday cages, ensuring proper grounding of instrumentation, and applying noise reduction techniques such as signal filtering or averaging [15].

Why is electrode conditioning and pretreatment critical? Conditioning and pretreatment activate the electrode surface, enhance its electrochemical response, improve stability, and reduce the risk of subsequent fouling or contamination, leading to more reproducible and reliable results [15].

My sensor's sensitivity has dropped. What should I check first? First, visually inspect the electrode surface for signs of fouling or damage. Then, perform electrochemical cleaning via techniques like cyclic voltammetry or mechanical polishing to restore the active surface [15].

How does surface modification improve sensor selectivity? Modification layers, such as molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs), self-assembled monolayers (SAMs), or immobilized biorecognition elements (enzymes, aptamers), create specific binding sites that preferentially interact with the target analyte, minimizing interference from other species [4] [20].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Unstable Baseline or High Background Noise A stable baseline is crucial for accurate signal measurement. Noise can obscure detection, especially for analytes at trace levels.

- Solution 1: Inspect and Clean the Electrode. Fouling is a primary cause. Implement a cleaning protocol suitable for your electrode material, such as mechanical polishing or electrochemical cycling in a clean supporting electrolyte [15].

- Solution 2: Verify Experimental Conditions. Ensure temperature control and use a high-quality, adequately concentrated electrolyte solution to minimize solution resistance [15].

- Solution 3: Check Instrumentation and Connections. Ensure all cables and connections are secure. Use proper shielding and grounding to mitigate external electrical interference [15].

Problem: Poor Selectivity in Complex Samples Interference from structurally similar compounds or matrix components is a major hurdle in biological and environmental sensing.

- Solution 1: Optimize the Surface Modification Layer. The choice and density of the recognition element (e.g., aptamer, MIP) are critical. Fine-tuning the fabrication protocol can enhance specificity [4] [20].

- Solution 2: Employ a Protective Membrane. Coating the sensor with a permselective membrane (e.g., Nafion) can block access of large, negatively charged interferents like proteins or uric acid to the electrode surface [21].

- Solution 3: Optimize the Electrochemical Technique. Use pulsed techniques like Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) or Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV), which minimize background capacitive current, improving resolution between analytes with similar redox potentials [20].

Problem: Low Sensitivity and High Detection Limit Insufficient sensitivity prevents detection of low analyte concentrations, which is vital for early disease diagnosis or monitoring trace environmental contaminants.

- Solution 1: Increase Electroactive Surface Area. Modify the electrode with high-surface-area nanomaterials like graphene, carbon nanotubes, or metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) to enhance the number of reaction sites and amplify the signal [4] [21].

- Solution 2: Incorporate Electrocatalytic Materials. Use nanomaterials such as metal nanoparticles (Pt, Au) or MXenes (e.g., Nb₄C₃Tₓ) to lower the overpotential for the reaction of interest, thereby increasing the Faradaic current and improving the signal-to-noise ratio [21] [20].

- Solution 3: Use Signal Amplification Strategies. Employ strategies such as enzymatic labels or redox cycling to multiplicatively enhance the electrochemical signal generated by each binding event [20].

Experimental Protocols for Electrode Modification

Detailed methodologies for key surface modification techniques are critical for reproducibility and performance optimization.

Protocol: Drop Coating of Nanomaterial Inks

Drop coating is a simple and widely used method for modifying electrode surfaces with nanomaterial suspensions [22].

- Step 1: Surface Preparation. Clean the bare electrode (e.g., Glassy Carbon Electrode, GCE) according to standard procedures (e.g., polishing on alumina slurry, rinsing with water and solvent) to ensure a clean, reproducible surface [15].

- Step 2: Ink Dispersion. Disperse the nanomaterial (e.g., reduced Graphene Oxide, rGO) in a suitable solvent (e.g., water, ethanol) via sonication to create a homogeneous suspension or ink [23].

- Step 3: Precise Deposition. Using a micropipette, deposit a specific, small volume (e.g., 5-10 µL) of the ink directly onto the active surface of the working electrode.

- Step 4: Drying. Allow the solvent to evaporate under controlled conditions (e.g., at room temperature, under an infrared lamp, or in a desiccator) to leave a thin, uniform film of the nanomaterial on the electrode surface. Note: To avoid the "coffee-ring" effect, which causes uneven deposition, techniques such as electrowetting or the use of highly hydrophobic surfaces can be employed [22].

Protocol: Electrochemical Deposition of Polymers or Metals

Electrochemical deposition allows for precise control over the thickness and morphology of the modifying layer [22].

- Step 1: Preparation of Electrolytic Bath. Prepare a solution containing the monomer (e.g., pyrrole) for polymer deposition or the metal salt (e.g., HAuClâ‚„ for Au nanoparticles) for metal deposition in a suitable supporting electrolyte [21].

- Step 2: Selection of Deposition Mode.

- Potentiostatic (Galvanostatic) Mode: Apply a constant potential (or current) for a defined duration to drive the deposition reaction [22].

- Potentiodynamic Mode (e.g., Cyclic Voltammetry): Cycle the potential over a set range multiple times. The polymer film grows or metal deposits with each cycle, allowing fine control over the film thickness [22].

- Step 3: Rinsing and Stabilization. After deposition, rinse the modified electrode thoroughly with deionized water to remove any loosely adsorbed species. The modified electrode may be stabilized by cycling in a clean electrolyte solution.

Quantitative Performance Data

The following table summarizes the analytical performance of select electrochemical sensors from recent literature, highlighting the impact of advanced materials on sensitivity and detection limits.

Table 1: Performance of Advanced Electrochemically Modified Sensors

| Target Analyte | Electrode Modification | Detection Technique | Linear Detection Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ampicillin [23] | Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) on GCE | Not Specified | 0.02 μM – 2.56 μM | 6.75 nM | Pharmaceutical monitoring |

| Dopamine [21] | LIG-Nb₄C₃Tₓ MXene-PPy-FeNPs | Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | 1 nM – 1 mM | 70 pM | Neurotransmitter detection in urine |

| Heavy Metals (Cd²âº, Pb²âº, Cu²âº, Hg²âº) [4] | ZIF-8@PANI on GCE | Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Not Specified | Well-separated peaks for simultaneous detection | Environmental water monitoring |

| Procalcitonin [19] | Au nanoparticles / Nanocomposite | Amperometry | 1.5 pg mLâ»Â¹ to 50 ng mLâ»Â¹ | 0.8 pg mLâ»Â¹ | Sepsis biomarker |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 2: Essential Materials for Sensor Surface Modification

| Material / Reagent | Function in Electrode Modification |

|---|---|

| Graphene & Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) [4] [21] | Provide a high surface area, excellent electrical conductivity, and electrocatalytic activity, enhancing electron transfer and signal sensitivity. |

| Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) (e.g., ZIF-8) [4] | Offer ultra-high porosity and tunable structures for selective analyte preconcentration and sensing, improving selectivity and limit of detection. |

| Metal Nanoparticles (Au, Pt, Fe) [4] [21] | Act as electrocatalysts to facilitate redox reactions, serve as anchoring points for biomolecules, and increase the electroactive surface area. |

| Conducting Polymers (e.g., Polypyrrole (PPy), Polyaniline (PANI)) [4] [21] | Enhance conductivity, provide a versatile matrix for embedding recognition elements, and improve the stability of the modified layer. |

| MXenes (e.g., Nb₄C₃Tₓ) [21] [20] | Two-dimensional materials with high metallic conductivity and hydrophilic surfaces, excellent for enhancing charge transfer and signal transduction. |

| Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) [4] | Create well-ordered, dense monolayers on electrode surfaces (e.g., gold) for precise and stable immobilization of biorecognition elements. |

| Dactylfungin B | Dactylfungin B, CAS:146935-35-5, MF:C41H64O9, MW:700.9 g/mol |

| Dactylocycline B | Dactylocycline B, CAS:125622-13-1, MF:C31H38ClN3O14, MW:712.1 g/mol |

Workflow and Signaling Pathway Diagrams

Signal Transduction Pathways

Sensor Development Workflow

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Enzyme-Based Sensors

Q: My enzyme sensor shows a significant loss of signal response over time. What could be the cause?

- A: Signal decay is often due to enzyme denaturation or leaching from the electrode surface. Ensure your immobilization method (e.g., cross-linking with glutaraldehyde, entrapment in a polymer like Nafion) is robust. Check storage conditions; enzymes typically require buffered solutions at 4°C. Also, confirm that your substrate or the reaction environment (pH, temperature) is not inactivating the enzyme.

Q: I observe a high background current in my amperometric enzyme sensor. How can I reduce it?

- A: A high background can be caused by interferents (e.g., ascorbic acid, uric acid) that are oxidized at the working potential. Apply a permselective membrane (e.g., poly-phenylenediamine, Nafion) over the enzyme layer to block anionic interferents. Alternatively, use a lower working potential or a different redox mediator.

Antibody-Based Sensors (Immunosensors)

Q: My immunosensor has low sensitivity and a poor detection limit. What can I optimize?

- A: Low sensitivity often stems from poor antibody orientation or low density on the sensor surface. Use a site-directed immobilization strategy (e.g., via oxidized Fc-glycans or protein A/G) instead of random amine-coupling. Also, optimize your incubation times and washing stringency to improve the signal-to-noise ratio.

Q: The sensor regeneration for re-use is inconsistent and damages the antibody. What should I do?

- A: Harsh regeneration conditions (e.g., low pH glycine) can denature antibodies. Test a series of milder eluents (e.g., pH 2.5-3.0 glycine, high ionic strength solutions, or mild detergents). If regeneration remains problematic, consider single-use, disposable sensor strips.

Aptamer-Based Sensors

Q: My aptamer fails to bind its target after immobilization on the gold electrode.

- A: Immobilization can block the aptamer's binding pocket. Ensure you are using a thiol-modified aptamer with a spacer (e.g., a poly-T sequence) between the thiol group and the binding sequence to provide flexibility and distance from the surface. A pre-incubation "folding" step in the appropriate buffer (with Mg²⺠if needed) is also critical before immobilization.

Q: The reproducibility between sensor batches is low.

- A: This is commonly due to inconsistent aptamer surface density and folding. Standardize your immobilization protocol, including the concentration of the aptamer solution and the incubation time. Use a reliable method like electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) to quantitatively verify surface coverage for each batch.

Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP)-Based Sensors

Q: My MIP sensor shows high non-specific binding.

- A: Non-specific binding occurs if the polymer matrix is too non-polar or the template removal is incomplete. Optimize the monomer-to-template ratio and include more hydrophilic functional monomers in your recipe. Aggressively validate template removal using techniques like HPLC or mass spectrometry to ensure all leaching is complete.

Q: The MIP sensor response is slow.

- A: Slow kinetics are typical if the binding sites are deep within a dense polymer matrix. Create a MIP layer that is thinner or more porous. Consider synthesizing the MIP as nanoparticles and then depositing them on the electrode to increase surface area and reduce diffusion paths.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Fabrication of a Thiolated Aptamer-based Electrochemical Sensor

- Objective: To immobilize a specific DNA aptamer on a gold electrode for target detection.

- Materials: Gold disk electrode, thiol-modified aptamer, TCEP, 6-mercapto-1-hexanol, binding buffer.

- Steps:

- Electrode Prep: Polish the gold electrode with alumina slurry, sonicate in water and ethanol, and electrochemically clean in 0.5 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„.

- Aptamer Reduction: Reduce disulfide bonds in the thiol-aptamer stock with 10 mM TCEP for 1 hour.

- Immobilization: Incubate the clean electrode in 1 µM reduced aptamer solution in binding buffer for 16 hours at 4°C.

- Backfilling: Rinse and immerse the electrode in 1 mM 6-mercapto-1-hexanol for 1 hour to passivate uncoated gold surfaces.

- Validation: Characterize using EIS and Cyclic Voltammetry in a 5 mM [Fe(CN)₆]³â»/â´â» solution.

Protocol 2: Cross-linking of Glucose Oxidase on a Platinum Electrode

- Objective: To create a stable enzymatic layer for glucose detection.

- Materials: Pt electrode, Glucose Oxidase (GOx), Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Glutaraldehyde (25%).

- Steps:

- Electrode Prep: Clean the Pt electrode via cycling in 0.5 M Hâ‚‚SOâ‚„.

- Enzyme Mix: Prepare a mixture of 10 mg/mL GOx and 5 mg/mL BSA in 10 µL of 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.0).

- Cross-linking: Add 2 µL of 2.5% glutaraldehyde to the enzyme mix. Vortex gently.

- Deposition: Drop-cast 5 µL of the mixture onto the Pt electrode and let it dry for 1 hour at 4°C.

- Rinsing: Rinse thoroughly with phosphate buffer to remove unbound enzyme and cross-linker.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Comparison of Key Characteristics for Recognition Elements

| Feature | Enzymes | Antibodies | Aptamers | MIPs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Production | Biological extraction / Fermentation | In vivo (animals) | In vitro (SELEX) | Chemical synthesis |

| Cost | Moderate | High | Low (once sequenced) | Very Low |

| Stability | Low (Temp, pH sensitive) | Moderate (can denature) | High (Thermostable) | Very High (Robust) |

| Development Time | Months | 3-6 months | 2-3 months | Weeks |

| Key Challenge | Denaturation, Leaching | Batch variability, Regeneration | Sensitive to nucleases | Non-specific binding |

The Scientist's Toolkit

| Reagent / Material | Function |

|---|---|

| Gold Disk Electrode | Provides a clean, flat surface for thiol-based immobilization (aptamers, antibodies). |

| Nafion | A cation-exchange polymer used to coat sensors, reducing interference from anions like ascorbate. |

| Glutaraldehyde | A homobifunctional cross-linker for covalently immobilizing proteins (enzymes, antibodies) onto aminated surfaces. |

| Protein A/G | Bacterial proteins that bind the Fc region of antibodies, ensuring proper orientation during immobilization. |

| TCEP | A reducing agent used to cleave disulfide bonds in thiol-modified DNA/RNA, preparing them for surface attachment. |

| 6-Mercapto-1-hexanol | An alkanethiol used to "backfill" on gold surfaces, displacing non-specifically bound DNA and creating a well-ordered monolayer. |

| Dactylocycline E | Dactylocycline E, CAS:146064-01-9, MF:C31H39ClN2O13, MW:683.1 g/mol |

| Dalbavancin | Dalbavancin, CAS:171500-79-1, MF:C88H100Cl2N10O28, MW:1816.7 g/mol |

Visualizations

Sensor Fabrication Workflow

Sensor Signal Generation Path

Methodologies for Enhanced Selectivity: From Material Design to Sensing Techniques

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses frequently asked questions and common experimental challenges encountered when working with Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs) and Layer-by-Layer (LbL) assembly for electrochemical sensor development.

Self-Assembled Monolayers (SAMs)

Q1: Why is my SAM-modified electrode exhibiting inconsistent electron transfer rates (k0ET)?

Inconsistent electron transfer kinetics often stem from an incomplete or poorly formed monolayer.

- Cause & Solution: A loosely packed SAM with low density allows the redox protein to penetrate closer to the electrode surface, shifting the operational regime. Electron transfer rates (k0ET) show a biphasic dependence on SAM thickness: a distance-independent regime for thin SAMs (often n < 10 carbons in alkanethiols) and an exponential distance-dependence for thicker, well-formed SAMs (n > 10) [24].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify SAM Formation Time: Ensure the substrate is immersed in the thiol solution for a sufficient time (often 24-48 hours) to form a densely packed monolayer [24].

- Control Chain Length: Use alkanethiols with chain lengths greater than 10 carbons (e.g., HS-(CH2)11-X) to ensure you are operating in the predictable, exponential distance-dependent regime [24].

- Solvent Quality: Use high-purity, appropriate solvents (e.g., ethanol) to prevent contamination that disrupts self-assembly.

Q2: How can I prevent the denaturation of redox proteins on my electrode surface?

Direct adsorption of proteins onto bare metal electrodes often causes partial or total denaturation, impairing function [24].

- Cause & Solution: The bare electrode surface presents a hostile, non-physiological environment. SAMs act as a biocompatible cushion.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Tailor ω-Substituents: Match the terminal functional group (X) of your alkanethiol (HS-(CH2)n-X) to the protein. Create charged (e.g., -COOH, -NH2), hydrophobic, or hydrophilic surfaces to interact with complementary patches on the protein, promoting correct orientation and stability [24].

- Use Functionalized SAMs: Employ ω-groups that can specifically cross-link with surface residues or coordinate the protein's metal center. This chemisorption minimizes desorption and rotational diffusion, enhancing stability [24].

Q3: What are the critical parameters for achieving high selectivity with SAMs in complex matrices?

The primary challenge is interference from fouling agents in biological or environmental samples.

- Cause & Solution: Non-specific adsorption of proteins, lipids, or other molecules can block the electrode surface. A densely packed SAM is the first defense, and further functionalization is often needed.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Maximize Packing Density: As outlined in [25], use SAMs with long, linear alkyl chains to strengthen van der Waals forces and create a dense, impermeable monolayer that blocks interfering species.

- Incorporate Selectivity Layers: Modify the SAM surface with a thin layer of Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP), as demonstrated for serotonin sensing. This imparts both high selectivity and antifouling properties [26].

General Electrode Modification & Measurement

Q4: My electrochemical sensor shows erratic readings and poor reproducibility. What could be wrong?

This is a common issue often related to electrode preparation, calibration, and physical measurement conditions.

- Cause & Solution: Multiple factors, from unstable immobilization to air bubbles, can cause this.

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Check Physical Installation: Ensure the sensor is installed at a 45-degree angle above horizontal to prevent air bubbles from trapping on the sensing surface. Never install the sensor horizontally or inverted [10].

- Stabilize Temperature: Potential changes with temperature. A 5°C discrepancy can alter the concentration reading by at least 4%. Use built-in temperature sensors and allow sufficient time (up to 60 minutes) for the sensor to reach thermal equilibrium with the solution [10].

- Validate Calibration: Always use an interpolation method with two calibration standards that bracket the expected sample concentration. Extrapolation is not acceptable for accurate measurements [10]. Rinse with the next calibration standard, not DI water, between points to avoid diluting the surface and increasing response time [10].

Q5: How can I systematically optimize the many variables in sensor fabrication?

The "one factor at a time" (OFAT) approach is inefficient and can miss interacting factors.

- Cause & Solution: Sensor construction involves multiple steps (electrode preparation, nanomaterial modification, biorecognition element immobilization), each with several variables [27].

- Troubleshooting Steps:

- Adopt Multivariate Optimization: Use Design of Experiments (DoE) methodologies. This approach simultaneously tests multiple factors (e.g., immobilization pH, concentration, time) to find the global optimum and reveal interactions between variables, leading to a more robust and high-performing sensor [27].

Experimental Protocols & Data

This section provides detailed methodologies for key experiments and summarizes critical performance data.

Protocol: Fabrication of a DNPs-Modified Screen-Printed Carbon Electrode (DNPs/SPCE)

This protocol, adapted from [28], details the creation of a highly conductive and stable nanomaterial-modified electrode.

- Objective: To modify an SPCE with diamond nanoparticles (DNPs) for enhanced electrocatalytic activity and electron transfer, suitable for sensing applications like the detection of anti-cancer drugs.

Materials:

- Screen-printed carbon electrodes (SPCEs, e.g., Zensor TE-100).

- Diamond nanopowder (<10 nm).

- Deionized (DI) water.

- Ethanol.

- Oven.

- Ultrasonic bath.

Procedure:

- Electrode Pre-treatment: Thoroughly clean the SPCEs with DI water and dry in an oven at 50°C until completely dry.

- Dispersion Preparation: Disperse 2 mg of DNPs into 1 mL of DI water. Ultrasonicate the mixture for 30 minutes to achieve a homogeneous suspension.

- Drop-Casting: Using a micropipette, drop-cast 4 µL of the DNP suspension onto the pre-treated working electrode surface of the SPCE.

- Drying: Dry the modified electrode at 50°C to evaporate the solvent and form a stable DNPs film.

- Validation: The successful modification can be confirmed using techniques like SEM for morphology and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) to demonstrate reduced charge transfer resistance (Rct) in a [Fe(CN)6]3−/4− redox probe [28].

Protocol: Constructing a Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) Sensor

This protocol summarizes the creation of a highly selective MIP-based sensor for propofol, as described in [29].

- Objective: To develop an electrochemical sensor with high selectivity for a target molecule (propofol) using electropolymerized molecularly imprinted polymers.

Materials:

- Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE).

- Graphene Oxide (GO).

- Pyrrole monomer.

- LiClO4.

- Propofol (template molecule).

- Electrochemical workstation.

Procedure:

- GCE Modification: Thermally reduce GO to reduced graphene oxide (rGO) and electrodeposit it onto the GCE surface (rGO/GCE).

- Electropolymerization: Prepare a solution containing LiClO4, pyrrole, and the template molecule (propofol). Perform electropolymerization on the rGO/GCE to form a MIP film (MIPs/rGO/GCE).

- Template Removal: Extract the propofol template molecules from the polymer matrix, leaving behind specific recognition cavities.

- Sensor Use: The MIPs/rGO/GCE can now be used for detection, where the rebinding of the target molecule to the cavities produces a measurable electrochemical signal [29].

The table below summarizes the performance of various modified electrodes reported in the literature, highlighting the impact of different modification strategies.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of Selected Modified Electrodes from Literature.

| Target Analyte | Electrode Modification | Linear Range | Limit of Detection (LOD) | Key Feature / Function of Modification | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flutamide (FLT) | DNPs / SPCE | 0.025 – 606.65 µM | 0.023 µM | DNPs provide excellent conductivity and electrocatalytic activity. | [28] |

| Propofol (PPF) | MIPs / rGO / GCE | 0.5 – 250 µM | 0.08 µM | MIP layer grants high selectivity; rGO enhances sensitivity. | [29] |

| Serotonin | AuNPs/MWCNT with MIP | Not Specified | 1.0 µmol L-1 | MIP layer provides selectivity and antifouling properties in plasma. | [26] |

| Cytochrome c | Tripeptide SAMs on Au | Not Specified (ET rates studied) | Not Applicable | Mimics protein-protein interactions; enables study of spin-dependent ET. | [24] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

This table lists key materials used in the featured electrode modification strategies and their primary functions.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Electrode Modification.

| Material / Reagent | Function in Modification | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| ω-substituted Alkanethiols (e.g., HS-(CHâ‚‚)â‚â‚-X) | Forms the SAM backbone; the chain length controls electron tunneling distance, and the ω-group (X) controls surface properties (charge, hydrophobicity) for protein binding [24]. | Longer chains (n>10) provide predictable ET kinetics; choice of X dictates protein orientation and stability. |

| Diamond Nanoparticles (DNPs) | Electrode modifier that provides excellent biocompatibility, high conductivity, and enhanced electrocatalytic activity for sensing applications [28]. | An emerging nanomaterial that offers a non-cytotoxic, cost-effective alternative to other carbon nanomaterials. |

| Molecularly Imprinted Polymer (MIP) | A synthetic polymer containing cavities complementary to a target molecule, imparting high selectivity and antifouling properties to the sensor [26] [29]. | The "template removal" step is critical for creating functional recognition sites. |

| Reduced Graphene Oxide (rGO) | A nanomaterial used to modify the electrode surface, increasing the electroactive area and improving electron transfer kinetics [29]. | Serves as an excellent substrate for the subsequent formation of other layers, like MIPs. |

| Tripeptide SAMs (e.g., Cys-containing) | Provides a surface that better mimics natural protein-protein interactions, potentially offering more bio-relevant immobilization [24]. | Can influence electron transfer pathways in a chiral-dependent manner. |

| Danicopan | Danicopan|Factor D Inhibitor|For Research Use | Danicopan is a potent oral Factor D inhibitor. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO) and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic procedures. |

| Daprodustat | Daprodustat (GSK1278863) HIF-PH Inhibitor | Daprodustat is a potent, orally active HIF-PH inhibitor for anemia research. This product is for Research Use Only (RUO). Not for human consumption. |

Workflow & Conceptual Diagrams

The following diagram illustrates the core conceptual relationship between SAM structure, its properties, and the resulting electron transfer behavior on a modified electrode.

Diagram 1: The interrelationship between the molecular structure of a self-assembled monolayer (SAM), its physical and chemical properties, and the resulting electron transfer (ET) behavior with an immobilized redox protein. The path to a specific ET regime (Frictionally Controlled ET or Non-Adiabatic ET) is determined by the SAM's structure [24] [25].

Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs) for Template-Specific Recognition

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What are the primary advantages of using MIPs in electrochemical sensors over natural biological receptors? MIPs offer significant advantages including high physical and chemical robustness, excellent stability under harsh chemical conditions, cost-effective synthesis, reusability, and long shelf life. Unlike biological receptors such as antibodies, they do not require animal hosts for production and maintain their stability over time, making them ideal for applications in complex matrices [30] [31] [32].

2. How can I improve the selectivity and binding capacity of my MIP? A highly effective strategy is the use of dual-functional monomers. This approach employs two different types of monomers in the polymer synthesis, which can create a more complementary and diverse set of interactions (e.g., hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces, electrostatic) with the template molecule. This synergistic effect often results in higher selectivity and adsorption capacity compared to MIPs made with a single monomer [33].

3. My MIP-based sensor shows high non-specific binding. What could be the cause? High non-specific binding is a common challenge. Key factors to investigate include:

- Incomplete template removal: Ensure the template is thoroughly leached from the polymer matrix using an appropriate solvent [34] [32].

- Suboptimal monomer-template ratio: An excess of functional monomer can lead to non-specific binding sites. Computational screening or combinatorial methods can help optimize this ratio [30] [33].

- Polymer morphology: The choice of porogenic solvent influences the pore size and surface area, which can affect diffusion and non-specific adsorption [32] [33].

4. What are the common electrochemical techniques used for detection with MIP-based sensors? Several voltammetric techniques are commonly employed, each with its own strengths. The table below summarizes the key techniques and their applications [35] [36].

Table 1: Common Electrochemical Detection Techniques for MIP Sensors

| Technique | Principle | Key Advantages | Example Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Differential Pulse Voltammetry (DPV) | Measures current difference before and after a pulse application. | High sensitivity and resolution, low detection limits. | Detection of Zidovudine (ZDV) in serum [35]. |

| Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) | Scans potential cyclically between two set values. | Ideal for characterizing sensor properties and redox behavior. | Studying electron transfer kinetics on a sensor surface [35] [34]. |

| Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) | Applies a small AC potential and measures impedance. | Label-free detection, sensitive to surface binding events. | Characterizing the rebinding of a target to an MIP layer [35]. |

| Square Wave Voltammetry (SWV) | Uses a square-wave modulated potential. | Fast scan rates and effective noise reduction. | Trace analysis of electroactive species [36]. |

5. Which substrate materials are most suitable for fabricating high-performance MIP electrochemical sensors? The choice of substrate is critical for enhancing sensitivity. Nanostructured materials are highly favored:

- Nanoporous Gold Leaf (NPGL): Provides a large, conductive surface area in a rigid 3D framework, preventing aggregation and improving stability [34].

- Carbon Nanotubes (CNTs) and Graphene: Offer high electrical conductivity and large surface area, though their distribution on the electrode can sometimes be non-uniform [34].

- Conductive Polymers: Materials like polypyrrole and polyaniline are versatile and can be used as both the sensing matrix and the transducer [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Poor Sensor Sensitivity and High Detection Limit

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inefficient Electron Transfer.

- Solution: Incorporate conductive nanomaterials into the MIP layer. Decorating the MIP with materials like nanoporous gold (NPG), multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs), or graphene can significantly enhance electrical conductivity and increase the active surface area, leading to a stronger signal [34] [38].

- Cause: Low Binding Site Accessibility.

- Cause: Suboptimal Electrochemical Technique.

Lack of Selectivity (Cross-Reactivity)

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inadequate Monomer-Template Complex.

- Solution: Employ a computational design approach. Before synthesis, use molecular modeling to screen and select functional monomers that have the highest binding energy and most complementary interactions with the target template. This ensures the formation of a stable pre-polymerization complex [30] [32].

- Cause: Structural Similarity of Interferents.

- Solution: Utilize dual-functional monomers. As mentioned in the FAQs, using two different monomers can create a more defined binding cavity that better matches the size, shape, and functional groups of the target molecule, thereby rejecting closely related interferents [33].

- Cause: Non-Specific Binding on the Polymer Surface.

- Solution: Optimize the template-to-monomer ratio and the cross-linker density. A very high cross-linker density can create a very rigid matrix that hinders template access, while a very low density can lead to unstable binding sites. Systematic optimization is key [30].

Low Reproducibility Between Sensor Batches

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Inconsistent Polymer Film Formation.

- Cause: Inhomogeneous Composite Mixtures.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Fabrication of a Core MIP-Based Electrochemical Sensor via Photopolymerization

This protocol is adapted from a study detailing the detection of Zidovudine (ZDV) and outlines a general approach for creating a selective MIP sensor [35].

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Working Electrode: Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE)

- Template: Target analyte (e.g., Zidovudine)

- Functional Monomers: Acrylamide (ACR), Hydroxyethyl methacrylate (HEMA)

- Cross-linker: Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA)

- Photoinitiator: 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone

- Coupling Agent: 3-(trimethoxysilyl) propyl methacrylate (TMSPMA)

- Solvents: Methanol, Acetic acid

- Electrochemical Probe: Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide (K~3~[Fe(CN)~6~]/K~4~[Fe(CN)~6~])

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Electrode Pretreatment:

- Polish the GCE with alumina slurry (e.g., 0.3 µm and 0.05 µm) on a microcloth to create a mirror finish.

- Rinse thoroughly with deionized water and then with methanol.

- Dry the electrode at room temperature.

Surface Silanization (Optional for improved adhesion):

- Treat the clean GCE with a solution of TMSPMA to introduce methacrylate groups on the surface. This provides anchor points for the polymer layer.

Pre-polymerization Mixture:

- Dissolve the template (e.g., ZDV), functional monomers (ACR and HEMA), cross-linker (EGDMA), and photoinitiator in a suitable porogenic solvent (e.g., methanol). The typical molar ratio for template:monomer:cross-linker is 1:4:20, but this should be optimized.

MIP Deposition and Polymerization:

- Drop-coat a small, precise volume (e.g., 5 µL) of the pre-polymerization mixture onto the surface of the GCE.

- Place the electrode under a UV lamp (e.g., at 365 nm) for a specified duration (e.g., 15-30 minutes) to initiate the photopolymerization process and form a rigid polymer network around the template.

Template Removal:

- Place the polymer-modified electrode (MIP/GCE) in a washing solution, typically a mixture of methanol and acetic acid (e.g., 9:1 v/v).

- Agitate gently (e.g., via stirring or sonication) until the template molecules are completely extracted from the polymer matrix, leaving behind specific recognition cavities. Confirm complete removal by the absence of an electrochemical signal from the template.

Sensor Characterization:

- Use Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) and Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy (EIS) in a solution containing the ferricyanide/ferrocyanide redox probe.

- A successful imprinting is indicated by a decrease in the current (or an increase in impedance) after polymerization (due to the non-conductive polymer layer), and a recovery of the signal after template extraction (as cavities open up for the probe to reach the electrode).

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for MIP-Based Electrochemical Sensor Development

| Reagent Category | Example | Function | Technical Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Monomers | Acrylamide (ACR), Methacrylic acid (MAA), o-Phenylenediamine (o-PD) | Interact with the template to form a pre-complex; create specific binding sites after polymerization. | Selection is template-dependent. o-Phenylenediamine is popular for electro-polymerization [34] [33]. |

| Cross-linkers | Ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA), N,N'-Methylenebis(acrylamide) | Stabilize the imprinted cavities, provide mechanical stability, and control polymer porosity. | A high cross-linker ratio (70-90%) is typical for creating a rigid structure [35] [30]. |

| Initiators | 2-hydroxy-2-methylpropiophenone, Azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) | Generate free radicals to initiate the polymerization reaction. | Photo-initiators are for UV-induced polymerization; thermal initiators like AIBN require heat [35]. |

| Porogenic Solvents | Acetonitrile, Methanol, Chloroform | Dissolve all polymerization components and control the porous structure of the polymer. | Aprotic solvents like acetonitrile often yield MIPs with better performance [33]. |

| Electrode Substrates | Glassy Carbon Electrode (GCE), Nanoporous Gold Leaf (NPGL), Screen-printed Electrodes (SPE) | Serve as the conductive platform for MIP attachment and electrochemical signal transduction. | NPGL offers a high surface area and excellent conductivity for enhanced sensitivity [34]. |

Advanced Configuration: Enhancing Performance with Nanomaterials

Protocol: Decorating Nanoporous Gold with an MIP Layer for Ultra-Sensitive Detection

This advanced protocol leverages a nanostructured substrate to create a high-performance sensor, as demonstrated for Metronidazole (MNZ) detection [34].

Workflow Overview:

Procedure Highlights:

- Substrate Preparation: Use a nanoporous gold leaf (NPGL) electrode as the base platform. NPGL's 3D sponge-like structure provides a massive surface area for MIP immobilization.

- Electropolymerization: Immerse the NPGL electrode in a solution containing the target template (e.g., MNZ) and the selected functional monomer (e.g., o-phenylenediamine). Use Cyclic Voltammetry (CV) to scan the potential repeatedly over a defined range. This causes the monomer to polymerize directly onto the NPGL surface, entrapping the template molecules within the growing polymer film.

- Template Extraction and Testing: Remove the template by washing with a suitable solvent (e.g., diluted H~2~SO~4~). The sensor's performance is evaluated by monitoring the change in the electrochemical signal of a redox probe (e.g., Fe(CN)~6~^3-/4-^) before and after rebinding the target analyte. A significant signal change indicates successful and sensitive detection.

This configuration results in sensors with remarkably low detection limits, as demonstrated by the reported value of 1.8 × 10^(-11) mol L^(-1) for MNZ [34].

Leveraging Nanocomposites and Hybrid Materials for Synergistic Effects

Technical Support Center: Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

This technical support center is designed to assist researchers in overcoming common experimental challenges in the development of electrochemical sensors based on nanocomposites and hybrid materials. The guidance is framed within the broader thesis context of improving sensor selectivity.

Frequently Asked Questions & Troubleshooting

Q1: How can I improve the selectivity of my nanocomposite-based electrochemical sensor when detecting biomarkers in complex biological fluids?

- Challenge: Non-specific binding and interference from other molecules in samples like blood or serum reduce sensor accuracy.

- Solution:

- Utilize Synergistic Composites: Combine materials with complementary properties. For instance, integrate MXenes (for high conductivity and hydrophilicity) with specific biorecognition elements like aptamers or antibodies. The MXene provides an excellent transduction platform, while the biorecognition element offers the required molecular specificity [39].

- Surface Functionalization: Modify the surface of carbon-based nanomaterials (like graphene or CNTs) with functional groups or molecules that preferentially attract the target analyte. The use of functionalized graphene oxide to disperse CNTs can create a more uniform composite that enhances selective pathways [40].

- Employ Molecularly Imprinted Polymers (MIPs): Create synthetic recognition sites within your nanocomposite that are complementary in shape and size to your target molecule, thereby significantly enhancing selectivity.

Q2: My electrode modifier shows poor dispersion in the matrix, leading to inconsistent sensor performance. What can I do?

- Challenge: Nanomaterials like graphene or CNTs tend to agglomerate due to strong van der Waals forces, resulting in inhomogeneous composites and unreliable data.

- Solution:

- Chemical Functionalization: Treat nanomaterials to introduce surface charges or functional groups that improve compatibility with the polymer matrix. For instance, the functionalization of graphene and its derivatives remains a crucial technique to achieve enhanced performance and better dispersion [41].

- Optimized Synthesis Protocols: Employ synthesis methods that prevent restacking. For MXenes, intercalation and delamination steps are critical to obtaining well-dispersed, single-layer flakes [39].

- Advanced Dispersion Techniques: Use methods like ultrasonication homogenously within the matrix resin. This has been shown to be highly efficient for dispersing nanoparticles like graphite and aerosol in epoxy/polyester blends [42].

Q3: What strategies can prevent the restacking of two-dimensional (2D) nanosheets like MXene or graphene in my composite?

- Challenge: Restacking of 2D nanomaterials reduces the active surface area, diminishing sensitivity and charge transfer efficiency.

- Solution:

- Create Hybrid Structures: Use spacer materials between the 2D layers. A synergistic approach involves integrating MXenes with carbon-based nanomaterials or metal oxides. This not only prevents restacking but can also create a synergistic effect that enhances sensor performance [41] [39].

- Form 3D Architectures: Construct three-dimensional porous networks (e.g., foams) from the 2D materials. This maintains a high surface area and facilitates ion transport. The development of a CNTs-multilayered graphene edge plane core-shell hybrid foam is an example of such a structure [43].

Q4: How can I achieve a synergistic effect from hybrid nanofillers, such as combining carbon nanotubes (CNTs) and graphene?

- Challenge: Simply mixing two nanofillers does not guarantee enhanced properties; sometimes, it can lead to antagonistic effects.

- Solution:

- Optimize the Filler Ratio: Synergy is often ratio-dependent. Experimental data using a Design of Experiments (DoE) approach for MWCNTs and Graphene Nanosheets (GNs) in epoxy suggests that mechanical properties like hardness and reduced modulus are highly influenced by the specific MWCNTs:GNs ratio [40]. Systematic variation is key.

- Leverage Geometric Compatibility: Use fillers with different geometries that complement each other. For instance, 1D CNTs can bridge the gaps between 2D graphene sheets, creating a more robust and interconnected conductive network for both electrons and heat, which lowers the percolation threshold and enhances electrical and thermal conductivity [40].

Experimental Protocols for Key Nanocomposite Systems

The following tables summarize detailed methodologies for synthesizing and characterizing two prominent hybrid nanocomposite systems for sensor applications.

Table 1: Protocol for MXene-Carbon Nanomaterial Hybrid Composite Electrode

| Step | Description | Key Parameters | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. MXene Synthesis | Selective etching of Al from Ti₃AlC₂ MAX phase using concentrated HF or LiF/HCl solution. | Etching time (12-24h), temperature (35-40°C), washing pH (~6) [39]. | To obtain multilayer Ti₃C₂Tₓ MXene. |

| 2. MXene Delamination | Intercalation of organic molecules (e.g., DMSO) followed by manual shaking or sonication. | Centrifugation speed (3500 rpm for delaminated nanosheets) [39]. | To obtain single- or few-layer MXene flakes. |

| 3. Hybrid Ink Preparation | Mixing delaminated MXene colloidal solution with a dispersion of carbon nanomaterials (e.g., CNTs, graphene). | Sonication power, duration; Mass ratio of MXene to carbon nanomaterial. | To form a homogeneous, restacking-resistant hybrid ink. |