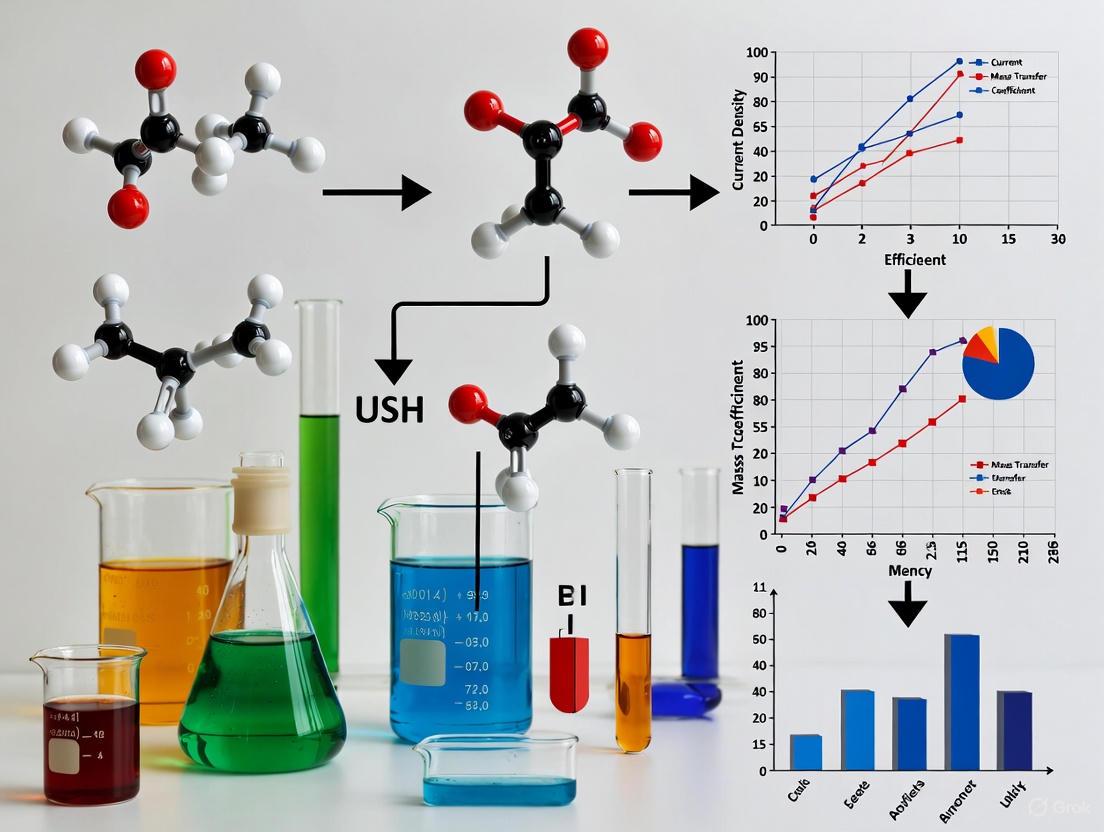

Advanced Strategies for Improving Mass Transport in Electrochemical Cells: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

This article comprehensively explores the critical challenge of mass transport limitations in electrochemical cells, a pivotal factor governing the performance of technologies from sustainable energy conversion to biomedical sensors.

Advanced Strategies for Improving Mass Transport in Electrochemical Cells: From Fundamentals to Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the critical challenge of mass transport limitations in electrochemical cells, a pivotal factor governing the performance of technologies from sustainable energy conversion to biomedical sensors. We examine foundational principles of species transport to and from electrode surfaces, review cutting-edge in situ diagnostic techniques like laser interferometry and fluorescence imaging for visualizing interfacial phenomena, and present practical optimization strategies addressing bubble management and electrode architecture. A comparative analysis of reactor designs and mass transport enhancement methods provides a framework for selecting solutions based on performance metrics and application requirements. Synthesizing insights across these domains, the discussion highlights direct implications for developing next-generation electrochemical biosensors, drug screening platforms, and clinical diagnostic devices with enhanced sensitivity and reliability.

Understanding the Fundamentals: The Critical Role of Mass Transport in Electrochemical Performance

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is electrochemical mass transfer and why is it a bottleneck? Electrochemical Mass Transfer is the process encompassing the transport of chemical species (reactants and products) in an electrochemical system, driven by concentration gradients and electric potential gradients [1]. It governs the rate at which reactants reach the electrode surface for reaction and products are removed [1]. In many processes, mass transfer becomes the rate-limiting step, meaning it is the bottleneck that controls the overall reaction speed, impacting energy conversion efficiency and device performance [1].

What are the three primary mechanisms of mass transport? The three basic mechanisms are diffusion, migration, and convection [2].

- Diffusion: The spontaneous movement of material from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration [2].

- Migration: The movement of charged particles (ions) in an electric field [2].

- Convection: The bulk movement of the electrolyte solution, often induced by stirring, pumping, or natural density differences [1] [2].

How can I experimentally identify a mass transport limitation in my system? A key experimental indicator is observing that the current changes with variations in flow rate or stirring speed [3]. If the binding or reaction rate becomes faster at higher flow rates, it suggests the process is influenced by mass transport [3]. To test this, inject one analyte concentration at several flow rates and observe the binding curve [3].

What are the consequences of mass transport limitations in solid-state batteries? Mass transport limitations, particularly the large impedance at the solid-electrolyte-electrode interface, lead to poor rate capability and cycle performance [4]. This interfacial resistance can increase dramatically after only a few charge/discharge cycles due to losses in interfacial contact and increased diffusional barriers, causing a significant drop in capacity [4].

Which techniques can visualize mass transport in situ? Several in situ techniques can visualize mass transport, each with strengths and limitations [5].

- Laser Interferometry: A label-free, non-invasive optical technique with high spatiotemporal resolution for visualizing interfacial concentration fields [5].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Imaging: Can map species distribution, but often has lower spatiotemporal resolution and involves expensive instrumentation [5].

- Fluorescence Imaging: Quantifies specific ion concentrations but requires exogenous fluorescent probes which may perturb the system [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Slow Reaction Rates and Poor Rate Capability

Potential Cause: Mass transport is the rate-limiting step, meaning the transport of reactants to the electrode surface is too slow to keep up with the electron transfer reactions [1].

Solutions:

- Increase Convection: Introduce or increase the stirring rate or electrolyte flow rate to enhance the bulk transport of material to the electrode surface [3] [1].

- Optimize Electrolyte: Choose electrolytes with higher ionic conductivity and diffusion coefficients to improve the rate of ion movement [1].

- Redesign Electrode: Use porous electrodes with high surface area and well-defined pore structures to minimize diffusion distances and facilitate electrolyte transport [1].

Problem: High Interfacial Resistance in Solid-State Batteries

Potential Cause: High internal resistance for lithium-ion transfer over the solid-solid electrode-electrolyte interfaces, often due to poor contact, space charge layers, or interface reactions [4].

Solutions:

- Improve Interfacial Contact: Establish intimate contact between electrode and electrolyte particles through nanosizing of electrode materials and intimate mixing during electrode preparation [4].

- Apply Coating Layers: Coat electrodes with an oxide barrier layer to improve interface stability and enable high-rate cycling [4].

- Monitor Interface Evolution: Use techniques like two-dimensional lithium-ion exchange NMR to non-invasively measure lithium-ion interfacial transport and guide interface design [4].

Problem: Non-uniform Current Distribution

Potential Cause: Non-uniform mass transfer across the electrode surface, leading to certain areas experiencing higher current densities than others, which can cause localized degradation [1].

Solutions:

- Optimize Flow Fields: In flow cells, use carefully designed flow channels (optimized with Computational Fluid Dynamics simulations) to ensure uniform reactant delivery across the entire electrode surface [1].

- Use Supporting Electrolyte: Add an inert electrolyte in excess (10-100 fold) to the solution to dissipate the electric field and minimize the contribution of migration to the flux, making mass transport more uniform and dominated by diffusion [2].

Key Data and Experimental Protocols

Quantitative Comparison of In Situ Visualization Techniques

| Technique | Lateral Spatial & Temporal Resolution | Key Applications | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Interferometry [5] | 0.3–10 μm; 0.01–0.1 s | Real-time monitoring of concentration fields | Requires optical windows; not species-specific |

| NMR Imaging [5] | 50–500 μm; seconds–minutes | 3D mapping of species distribution | Low spatiotemporal resolution; expensive |

| Raman Spectroscopy [5] | 0.3–10 μm; 0.5–60 s per point | Molecular fingerprinting of specific species | Weak signals; poor temporal resolution |

| Fluorescence Imaging [5] | 0.2–1 μm; 0.01–0.1 s | Quantifying specific ion concentrations | Requires fluorescent probes; photobleaching |

| Scanning Ion Conductance Microscopy (SICM) [5] | 10–20 nm; seconds–minutes per frame | Nanoscale mapping of local ion concentration | Slow scanning; probe may disturb environment |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Interfacial Lithium-Ion Transport via 2D EXSY NMR

This protocol is adapted from research on solid-state batteries to access the bottleneck of lithium-ion transport over the solid-electrolyte-electrode interface [4].

1. Objective: To quantitatively measure the spontaneous lithium-ion exchange between a solid electrolyte (e.g., argyrodite Li~6~PS~5~Br) and an electrode (e.g., Li~2~S), providing insight into interfacial conductivity [4].

2. Materials Preparation:

- Synthesis: Prepare the argyrodite solid electrolyte (e.g., Li~6~PS~5~Br) via ball milling followed by annealing at 300°C for 5 hours [4].

- Cathode Mixture Preparation: Create intimate mixtures of the solid electrolyte and the electrode material. Critical parameters include:

3. Electrochemical Cycling:

- Assemble solid-state cells (e.g., vs. an In foil anode) and subject them to galvanostatic charge/discharge cycles within a relevant voltage window (e.g., 0–3.5 V vs. In) [4].

- This step is crucial for evaluating how cycling affects the interfacial transport properties.

4. NMR Measurement and Analysis:

- Technique: Employ two-dimensional exchange NMR spectroscopy (2D-EXSY) on the prepared mixtures at different stages (pristine and after cycling) [4].

- Selectivity: The measurement is enabled by the difference in NMR chemical shift between the lithium nuclei in the solid electrolyte and the electrode material, providing unique selectivity for charge transfer over the phase boundaries [4].

- Outcome: This non-invasive method allows direct assessment of the lithium-ion transport across the interface and its evolution, showing how preparation and cycling dramatically influence the kinetics [4].

Experimental Protocol: Visualizing Concentration Fields via Laser Interferometry

This protocol outlines the use of laser interferometry for in situ visualization of concentration gradients at electrode-electrolyte interfaces [5].

1. Objective: To directly visualize and quantify the ion concentration field evolution at an electrode-electrolyte interface with high spatiotemporal resolution.

2. System Setup:

- Interferometer Configuration: Use a Mach-Zehnder interferometer or digital holography setup [5].

- Electrochemical Cell: Configure a cell with transparent optical windows to allow laser beam passage. The electrode can be oriented vertically or horizontally, with the vertical configuration being more prone to inducing natural convection [5].

- Laser Illumination: For interfacial concentration gradients, use a lateral (side) illumination geometry where the laser beam illuminates the interface at an oblique angle [5].

3. Measurement Principle:

- The core principle involves monitoring the phase difference (Δφ) between an object beam passing through the interface region and a reference beam [5].

- Changes in ion concentration alter the refractive index of the electrolyte, which in turn changes the optical path length and the phase of the object beam [5].

- This phase difference is captured as an interference pattern on a detector (e.g., a CCD/CMOS sensor) [5].

4. Data Processing and Reconstruction:

- Key Methods: Use fringe shift analysis, phase-shifting interferometry, or digital holography to reconstruct the phase distribution from the recorded interference patterns [5].

- Concentration Field: Convert the quantified phase maps into two-dimensional concentration fields, enabling dynamic analysis of processes like diffusion layer formation, ion depletion, and metal electrodeposition [5].

Diagnostic Framework and Research Toolkit

Decision Framework for Diagnosing Mass Transport Limitations

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow to diagnose mass transport issues in electrochemical experiments.

Diagnostic Workflow for Mass Transport Issues

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Relevance in Research |

|---|---|

| Supporting Electrolyte (e.g., inert salts) | Added in excess (10-100 fold) to dissipate the electric field, minimizing migration and isolating the diffusive component of mass transport for study [2]. |

| Nano-sized Electrode Materials | Increasing the surface area and reducing diffusion path lengths within the electrode composite is crucial for achieving measurable charge transfer over solid-solid interfaces [4]. |

| Solid-State Electrolytes (e.g., Argyrodites like Li~6~PS~5~X) | Model systems for studying the critical challenge of interfacial ion transport in next-generation batteries, allowing the bottleneck to be probed directly [4]. |

| Fluorescent Probes / Dyes | Used in fluorescence microscopy to tag specific ions, allowing their concentration to be visualized, though they may perturb the system [5]. |

| Flow Cell with Optimized Flow Fields | Engineered channels ensure efficient and uniform reactant delivery and product removal, which is critical for minimizing concentration polarization in devices like fuel cells and flow batteries [1]. |

In electrochemical systems, the faradaic current is a direct measure of the electrochemical reaction rate at the electrode and is governed by two key processes: the rate of charge transfer across the electrode-electrolyte interface and the rate of mass transport, which is the movement of material from the bulk solution to the electrode surface [2]. There are three fundamental mass transport mechanisms, each with a distinct driving force [2] [6].

- Diffusion: The spontaneous movement of a species due to a concentration gradient, typically from a region of high concentration to a region of low concentration [2].

- Migration: The movement of charged particles (ions) driven by an electric field within the solution [2].

- Convection: The transport of material due to the bulk movement of the fluid, which can be either forced (e.g., stirring, pumping) or natural (e.g., caused by density or temperature gradients) [2] [6].

The combined flux of a species is described by the Nernst-Planck equation, which integrates all three mechanisms [2]: [ \mathrm{J{(x,t)} = -[D (∂C{(x,t)} / ∂x)] - (zF/ RT)\: D\: C{(x,t)} + C{(x,t)}ν_{x\, (x,t)}} ] Where the terms represent the fluxes from diffusion, migration, and convection, respectively.

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

Common Experimental Issues and Solutions

Q: My voltammogram shows drawn-out or poorly defined waves, and the current is lower than expected. What could be the cause?

A: This is often a symptom of issues related to mass transport or the electrode surface.

- Check your working electrode surface: The surface may be contaminated with adsorbed polymers or other blocking materials [7]. Recondition the electrode by following the supplier's guidelines for polishing, chemical, or electrochemical treatment [7].

- Verify solution convection: For experiments intended to be diffusion-controlled, ensure the solution is quiet and free from vibrations or temperature gradients that can cause uncontrolled convection, especially for experiments longer than 20 seconds [2] [6].

- Confirm supporting electrolyte: Ensure you have added a sufficient quantity (typically 10-100 fold excess) of an inert electrolyte (e.g., KCl) to suppress migratory flux. Without it, migration can distort the current response [2].

Q: The current in my experiment is unstable and shows excessive noise. How can I fix this?

A: Noise typically stems from electrical connections or external interference.

- Inspect all contacts: Check for poor connections at the electrode leads or the instrument connector. Tarnished or rusty contacts can be polished or replaced [7].

- Use a Faraday cage: Place your electrochemical cell inside a Faraday cage to shield it from external electromagnetic interference [7].

Q: I am not getting any significant current response. What basic checks should I perform?

A: Follow a systematic troubleshooting approach to isolate the problem [7].

- Dummy Cell Test: Replace the electrochemical cell with a 10 kΩ resistor. Run a CV from +0.5 V to -0.5 V at 100 mV/s. You should obtain a straight line intersecting the origin with currents of ±50 μA. A correct response indicates the instrument and leads are functioning properly, and the problem lies with the cell [7].

- Cell in 2-Electrode Configuration: If the dummy test passes, reconnect the cell but connect both the reference and counter electrode leads to the counter electrode. If you now obtain a typical voltammogram, the issue is likely with your reference electrode (e.g., a clogged frit or air bubble) [7].

Optimizing for Controlled Mass Transport

Q: How can I design an experiment where mass transport is dominated by a single, well-defined mechanism?

A: To study a specific process, you can isolate its contribution.

- For purely diffusion-controlled conditions:

- For controlled, forced convection:

- Use specialized hydrodynamic electrodes like the Rotating Disc Electrode (RDE). The rotation imposes a defined, controllable convective flow, allowing for precise modeling of mass transport [6].

Quantitative Data and Experimental Protocols

Table 1: Core Mass Transport Mechanisms in Electrochemistry

| Mechanism | Driving Force | Governing Law (1-D Flux) | Method for Control/Suppression |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion | Concentration Gradient | ( J = -D \frac{∂C}{∂x} ) (Fick's First Law) [2] [6] | Use unstirred solutions; Short experiment duration [2]. |

| Migration | Electric Field / Potential Gradient | ( J = -\left( \frac{zF}{RT} \right) D C \frac{∂φ}{∂x} ) [2] | Add excess inert supporting electrolyte (e.g., KCl, TBAPF~6~) [2] [6]. |

| Convection | Bulk Fluid Motion | ( J = C ν_{x} ) [2] [6] | Use quiet solutions (natural convection) or well-defined flow (e.g., RDE) [6]. |

Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Mass Transport Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function / Rationale | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Inert Supporting Electrolyte | Dissipates the electric field in solution, suppressing migratory flux of the electroactive species. Allows for the study of pure diffusion [2] [6]. | Potassium chloride (KCl), Tetrabutylammonium hexafluorophosphate (TBAPF~6~) |

| Well-Defined Redox Probe | A stable, reversible couple with known kinetics used to characterize the mass transport regime and electrode performance. | Ferrocene/Ferrocenium, Potassium ferricyanide/ferrocyanide |

| High-Purity Solvent | Minimizes background current and prevents interference from impurities. Choice depends on the electrochemical window needed. | Acetonitrile, Dichloromethane, Water |

| Solid Working Electrode | A defined surface area is crucial for quantitative current measurements. Can be resurfaced for reproducibility. | Glassy Carbon, Platinum, Gold disk electrodes |

Advanced Systems: High-Concentration Electrolytes

Modern research increasingly involves high-concentration electrolytes (HCEs) like ionic liquids and water-in-salt electrolytes [8]. In these systems, classical models for diffusion and electron transfer can break down due to strong interionic interactions and the formation of ion pairs or clusters [8]. Key considerations include:

- Mass Transport: The Stokes-Einstein relationship for estimating diffusion coefficients may not hold, and diffusion becomes more complex [8].

- Heterogeneous Electron Transfer (HET): Kinetics at the interface of two-dimensional materials (like graphene) with HCEs can deviate significantly from behavior in conventional electrolytes, requiring updated theoretical models [8].

Diagrams and Workflows

Mass Transport Mechanism Decision Flow

Experimental Workflow for Isolating Diffusion

Diagnostic Guide: Troubleshooting Mass Transport Issues

Use the flowchart below to diagnose common performance issues related to mass transport in your electrochemical experiments. This systematic approach helps connect observed problems to their root causes in diffusion, convection, or migration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Electrochemical Fundamentals

What is mass transport and why is it critical for device performance? Mass transport refers to the movement of chemical species to and from the electrode surface in an electrochemical system. It directly governs reaction rates, efficiency, and stability in energy and biomedical devices [6]. Inadequate mass transport creates concentration gradients at the electrode-electrolyte interface, limiting current densities and causing performance degradation. In biomedical devices like glucose sensors or implantable power sources, this can lead to inaccurate readings or reduced operational lifespan [10] [11].

What are the three modes of mass transport?

- Diffusion: Movement of species due to concentration gradients, described by Fick's laws [6].

- Convection: Bulk movement of electrolyte due to external forces (e.g., stirring, pumping, or natural convection from density differences) [6].

- Migration: Movement of charged species due to potential gradients in the electrolyte [6].

How can I experimentally identify if my experiment is limited by mass transport? A key indicator is when the current reaches a limiting plateau despite increasing applied voltage, showing that reactant supply to the electrode surface cannot keep pace with electron transfer. Techniques like cyclic voltammetry at different scan rates can help characterize this: a shift from kinetic to mass transport control appears as scan rate increases [12].

Troubleshooting Common Problems

My electrochemical cell shows unstable current and excessive noise during long experiments. What could be wrong? This often indicates problems with uncontrolled convection [7] [6]. Natural convection from temperature variations or vibrations becomes significant in experiments lasting more than 20 seconds. Solutions include:

- Placing your cell in a Faraday cage to reduce electrical noise [7]

- Using forced convection systems like rotating disc electrodes or flow cells to dominate natural convection

- Checking for and eliminating vibration sources

- Ensuring all connections are secure and free from corrosion [7]

The measured current is much lower than theoretically predicted. How should I troubleshoot? Follow this systematic approach [7]:

- Perform a dummy cell test: Replace the cell with a 10 kΩ resistor. Run a CV from +0.5 V to -0.5 V at 100 mV/s. You should get a straight line through the origin with currents of ±50 μA. This verifies your instrument is working correctly.

- Test in 2-electrode configuration: Connect both reference and counter leads to the counter electrode. If you now get a typical voltammogram, the issue likely lies with your reference electrode (e.g., clogged frit, air bubbles) [7].

- Check electrode immersion and connections: Ensure all electrodes are properly immersed and leads are intact.

- Examine the working electrode surface: It may be contaminated, partially blocked, or require polishing/conditioning [7].

My device performance degrades rapidly. Could mass transport be involved? Yes. Poor mass transport can accelerate degradation. For example, in metal deposition, limited ion transport can lead to dendrite formation [5]. In fuel cells or batteries, local depletion causes uneven current distribution, stressing materials. Enhancing mass transport via pulsating flow or optimized flow fields can improve stability and longevity [9].

Performance Enhancement Strategies

What are practical methods to enhance mass transport in laboratory reactors?

- Forced Convection Systems: Use rotating disc electrodes or flow-through cells for well-defined, quantifiable flow.

- Pulsating Flow: A 3D-printed diaphragm pulsator can increase the mass transport coefficient significantly—from 2.3 × 10⁻³ cm/s to 4.5 × 10⁻³ cm/s as demonstrated in one study, effectively doubling mass transfer [9].

- Background Electrolyte: Use a high concentration of inert salt (e.g., KCl) to suppress migratory transport, ensuring diffusion and convection dominate [6].

- Electrode Design: Use high-surface-area electrodes or 3D structures to reduce diffusion distances.

How does improving mass transport impact overall device metrics? Enhanced mass transport directly boosts key performance indicators as shown in the table below:

Table 1: Performance Benefits of Improved Mass Transport

| Device Metric | Impact of Enhanced Mass Transport | Underlying Reason |

|---|---|---|

| Efficiency | Increases | Reduces overpotential losses; maximizes reactant utilization. |

| Reaction Rate | Accelerates | Delivers reactants to active sites faster, supporting higher current densities. |

| Stability | Improves | Prevents localized depletion, dendrite formation [5], and uneven electrode wear. |

| Signal-to-Noise | Improves (Sensors) | Increases Faradaic current relative to background capacitive current. |

| Operational Lifespan | Extends | Mitigates degradation mechanisms caused by concentration gradients. |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Mass Transport Studies

| Item | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Potassium Ferri/Ferrocyanide | Redox probe for quantifying mass transport coefficients. | Used in limiting current experiments to measure mass transfer rates [9]. |

| High Purity Inert Salts (e.g., KCl) | Background electrolyte to suppress migration. | Concentration should be much higher (e.g., 0.1-1 M) than that of the electroactive species [6]. |

| Chemically Resistant Diaphragm Material (FKM) | Key component for custom pulsators handling corrosive electrolytes. | Enables construction of devices for acidic/alkaline electrolytes [9]. |

| Polishing Supplies (Alumina, Diamond Paste) | Electrode surface preparation for reproducible hydrodynamics. | Essential for ensuring a defined, clean surface with predictable mass transport [7]. |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring Mass Transport Enhancement via Pulsating Flow

This protocol outlines how to quantify mass transport enhancement using a custom 3D-printed pulsator, based on the hardware described by [9].

Objective: To determine the mass transport coefficient (kₘ) under constant and pulsating flow conditions using the ferri/ferrocyanide redox couple.

Materials and Equipment:

- Electrochemical workstation (potentiostat)

- Custom 3D-printed diaphragm pulsator [9] or commercial equivalent

- Standard electrochemical flow cell with working, counter, and reference electrodes

- Peristaltic or membrane pump for baseline flow

- Electrolyte: Solution of 0.01 M K₃Fe(CN)₆, 0.01 M K₄Fe(CN)₆, and 0.5-1.0 M KCl as supporting electrolyte

Procedure:

- Cell Setup: Assemble the flow cell and connect the electrolyte reservoir, pump, and pulsator in a closed loop. Ensure all components are chemically compatible.

- Baseline Measurement:

- Circulate electrolyte using the pump at a constant flow rate with the pulsator off.

- Perform a linear sweep voltammogram (LSV) at a slow scan rate (e.g., 5 mV/s) around the formal potential of the redox couple.

- Identify the limiting current plateau (i_lim) where the current becomes independent of voltage.

- Pulsating Flow Measurement:

- Activate the diaphragm pulsator at a defined frequency (e.g., 2 Hz) and amplitude.

- Repeat the LSV measurement under identical conditions as the baseline.

- Record the new, higher limiting current (i_lim,pulse).

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mass transport coefficient for each condition using the relationship:

i_lim = n F A kₘ C where n is electrons transferred, F is Faraday's constant, A is electrode area, and C is bulk reactant concentration. - The enhancement factor is given by kₘ,pulse / kₘ,constant.

Expected Outcome: The study [9] demonstrated that this method can achieve an approximate doubling of the mass transport coefficient, from 2.3 × 10⁻³ cm/s to 4.5 × 10⁻³ cm/s.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: What is a concentration boundary layer and why is it important in my electrochemical experiments?

A concentration boundary layer is a thin layer of fluid adjacent to a surface where the concentration of a chemical species changes rapidly from the surface concentration to the bulk fluid concentration [13]. Understanding this layer is crucial because it determines the mass transfer rate in your electrochemical cell. The mass transfer resistance is primarily confined within this boundary layer, so its thickness and characteristics directly impact the efficiency of processes like electrodialysis, sensing, and catalytic reactions [13] [14]. If not properly accounted for, inaccurate predictions of reaction rates and system performance will occur.

Q2: My experimental results show a thinner concentration boundary layer than theoretical predictions. What factors could be causing this?

Several experimental factors can lead to a thinner concentration boundary layer than expected [13]:

- Higher fluid velocity: Increased flow rates enhance convective mixing, reducing boundary layer thickness

- Surface roughness: Rough surfaces disrupt laminar flow and promote turbulence, enhancing mixing

- Chemical reactions at the surface: Surface reactions that consume species create steeper concentration gradients

- Lower diffusion coefficients: Slower diffusive transport results in thinner boundary layers Check your flow rate calibration, surface preparation methods, and whether unexpected surface reactions might be occurring. The Schmidt number (Sc), which represents the ratio of momentum diffusivity to mass diffusivity, also influences this relationship—higher Schmidt numbers typically yield thinner concentration boundary layers relative to velocity boundary layers [13].

Q3: How can I visualize concentration boundary layers in my electrochemical flow cell setup?

A proven method involves using a dilute indicator solution that changes color upon reaction with species generated at electrode surfaces [14]. For example, in an electrodialysis cell operating above limiting current density, H+ ions formed on the membrane surface can react with a pH-sensitive indicator to create a colored trace that visually reveals the boundary layer thickness [14]. This method has been validated to agree well with theoretical predictions and limiting current density measurements. Ensure your indicator concentration is sufficiently low to avoid affecting the natural hydrodynamics, and use imaging systems capable of capturing the color development at appropriate temporal resolution.

Q4: I observe unstable concentration gradients in my microfluidic gradient generator. How can I maintain stable gradients without fluid flow disturbances?

Traditional flow-based gradient generators are susceptible to flow disturbances. Implement a two-layer microfluidic device separated by a semipermeable membrane [15]. The upper layer contains flowing sample and buffer solutions, while the lower layer contains a flow-free gradient forming microchamber. The membrane allows molecular diffusion while preventing bulk fluid flow, creating stable concentration gradients unaffected by flow variations [15]. This approach eliminates shear forces on cells and maintains gradient stability despite flow rate fluctuations in the supply channels. For initial setup, applying a slight pressure difference between sample and buffer channels can accelerate gradient establishment, after which equalized flow rates maintain a flow-free environment in the gradient chamber [15].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Inconsistent mass transfer rates in repeated electrochemical experiments

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Uncontrolled flow hydrodynamics | Measure flow rates with calibrated equipment; use flow visualization techniques | Implement precision flow control systems; ensure fully developed flow before measurement zone |

| Surface fouling or contamination | Perform surface analysis (SEM, AFM); compare initial vs. used surface properties | Establish rigorous cleaning protocols; implement surface regeneration steps between experiments |

| Variations in boundary layer thickness | Use boundary layer visualization techniques [14]; measure concentration profiles | Standardize flow cell geometry; maintain consistent flow rates and fluid properties |

Problem: Discrepancy between computational models and experimental boundary layer measurements

| Possible Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate mesh resolution in simulations | Perform mesh sensitivity analysis; compare y-plus values across simulations | Refine mesh near walls; ensure sufficient cells across boundary layer (6+ for "thick" approach) [16] |

| Incorrect boundary conditions | Verify surface concentrations match experimental conditions; check bulk concentration values | Implement appropriate wall functions; validate with known test cases |

| Unaccounted surface porosity | Characterize surface morphology; measure actual electrode geometry | Incorporate porosity effects in models; use adjusted Levich model for non-flat electrodes [17] |

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Quantitative Data on Boundary Layer Characteristics

Table 1: Key Dimensionless Numbers for Boundary Layer Analysis

| Dimensionless Number | Formula | Physical Significance | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sherwood Number (Sh) | Sh = k·L/D | Ratio of convective to diffusive mass transfer [13] | Varies with flow regime |

| Schmidt Number (Sc) | Sc = ν/D | Ratio of momentum diffusivity to mass diffusivity [13] | 10³ for gases to 10³ for liquids |

| Reynolds Number (Re) | Re = ρ·v·L/μ | Ratio of inertial to viscous forces [13] | <2000 (laminar), >4000 (turbulent) |

Table 2: Comparison of Concentration Boundary Layer Visualization Techniques

| Technique | Resolution | Applications | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator Reaction Method [14] | ~μm | Electrodialysis cells, electrode processes | Requires transparent surfaces; pH-dependent |

| Computational Fluid Dynamics [16] | ~cell size | Complex geometries, parametric studies | Computational cost; model validation needed |

| Flow-Free Gradient Generation [15] | ~chamber scale | Cell biology studies, shear-sensitive applications | Longer setup times; complex fabrication |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Visualization of Concentration Boundary Layers

This protocol adapts the method from Pérez-Herranz et al. for visualizing concentration boundary layers in electrochemical systems [14].

Materials Required:

- Electrochemical flow cell with transparent viewing window

- pH-sensitive indicator solution (e.g., phenolphthalein, bromocresol green)

- Buffer solutions at varying pH levels

- Precision syringe pumps for flow control

- Microscope with camera system for visualization

- Data acquisition system for simultaneous electrochemical measurements

Step-by-Step Procedure:

Cell Preparation: Clean the electrochemical cell thoroughly to remove any contaminants. For the indicator method, ensure all transparent surfaces are free of scratches or defects that could distort visualization.

Solution Preparation: Prepare a dilute indicator solution that will undergo a visible color change upon reaction with species generated at your electrode surface. For H+ visualization, use a pH indicator that transitions within your expected pH change range.

System Assembly: Assemble the flow cell, ensuring leak-free connections. Position the visualization apparatus (camera, microscope) to capture the region of interest near the electrode or membrane surface.

Initial Baseline Operation: Flow the indicator solution through the cell without applied potential/current to establish a baseline color profile. Capture reference images.

Electrochemical Activation: Apply conditions that generate the species of interest (e.g., operate above limiting current density to generate H+ ions). The reaction between the electrogenerated species and the indicator will produce a colored trace revealing the concentration boundary layer.

Image Acquisition: Continuously capture images throughout the experiment at defined time intervals. Ensure consistent lighting conditions throughout.

Thickness Measurement: Determine boundary layer thickness as the distance from the surface where the concentration reaches 99% of the bulk concentration, as indicated by the color transition boundary [13] [14].

Validation: Compare visualized boundary layer thickness with theoretical predictions and/or limiting current measurements to validate the technique.

Troubleshooting Notes:

- If color development is weak, increase indicator concentration slightly, but avoid concentrations that significantly alter solution properties

- For quantitative analysis, calibrate color intensity against known concentrations

- Ensure the visualization method does not interfere with the natural hydrodynamics of the system

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Boundary Layer Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| pH-Sensitive Indicators | Visualization of H+ or OH- concentration gradients via color change [14] | Choose indicator with pKa matching expected pH change; use minimal concentration |

| Conductive CNT/CB/PLA Filament | 3D-printing of customized electrochemical cells with embedded electrodes [17] | Enables rapid prototyping of complex flow geometries; requires surface activation |

| Semipermeable Membranes | Separation of flow channels from gradient chambers while allowing diffusion [15] | Select appropriate pore size to allow molecular diffusion while blocking bulk flow |

| Ag/AgCl Paste | Reference electrode integration in 3D-printed electrochemical cells [17] | Provides stable reference potential; compatible with various electrolyte solutions |

Visualization Diagrams

Concentration Boundary Layer Fundamentals

Visualization Technique Selection Guide

Cutting-Edge Methods and Applications: Techniques for Visualizing and Enhancing Transport

Essential Concepts: Your Questions Answered

FAQ 1: What is the core principle behind using laser interferometry for concentration field mapping?

Laser interferometry is a label-free, non-invasive optical technique that visualizes concentration fields by detecting changes in a solution's refractive index [5]. During an electrochemical process, ion concentration changes at the electrode-electrolyte interface alter the refractive index of the solution. An interferometer passes a laser beam through this region (the "object beam") and combines it with a separate "reference beam." The resulting interference pattern, composed of dark and light fringes, encodes the phase difference between the two beams, which is directly related to the concentration gradient. This allows for real-time, high-resolution visualization of mass transport phenomena [5] [18].

FAQ 2: How does Digital Holography differ from traditional interferometry in this context?

While both techniques rely on interferometry, Digital Holography (DH) streamlines the process by digitally recording the entire interference pattern (the hologram) using a CCD or CMOS sensor [5]. This hologram is then numerically reconstructed by a computer to calculate both the amplitude and phase-contrast images of the specimen simultaneously. This bypasses the need for complex optical alignment and photographic processing required in some traditional interferometers, and provides a direct quantitative measurement of the phase distribution caused by concentration changes [18].

FAQ 3: What are the most common issues that lead to a low-contrast or noisy interferogram?

Poor interferogram quality often stems from several factors:

- Vibrations: External mechanical vibrations disrupt the precise alignment between the object and reference beams, causing blurry or unstable fringes. Use an optical table with active or passive vibration damping.

- Unstable Laser Source: A laser with poor coherence length or power fluctuations will degrade interference. Ensure your laser is single-mode and has a coherence length greater than the maximum optical path difference in your setup.

- Poor Beam Alignment and Collimation: Misaligned beams or a diverging beam profile reduce interference efficiency. Precisely align optics and use spatial filters to clean and collimate the beam.

- Unclean Optical Components: Dust or smudges on lenses, windows, or mirrors scatter light, introducing noise. Keep all optical components meticulously clean.

FAQ 4: My reconstructed phase map shows unexpected artifacts. What could be the cause?

Artifacts in phase maps can arise from:

- Speckle Noise: Caused by light scattering from rough surfaces or particles in the solution. Using a partially coherent light source or applying digital filtering during reconstruction can mitigate this.

- Phase Unwrapping Errors: The calculated phase is "wrapped" between -π and π. Errors in the unwrapping algorithm, often due to noise or rapid phase changes, create sharp, unnatural lines in the map. Using a more robust unwrapping algorithm is key.

- Unaccounted Background Drift: Temperature gradients or slow mechanical drift can cause a background phase shift. Recording a reference interferogram (without the electrochemical process) and subtracting it from subsequent measurements can correct this.

FAQ 5: During vapor-fed electrolyzer operation, why does performance drop despite high water vapor activity?

Our research shows that even at 100% relative humidity (water activity = 1), a vapor-fed system achieves significantly lower current densities than a liquid-fed system [19]. This is not solely a mass transport limitation but is strongly linked to membrane hydration. The water content (λ, molecules of H₂O per sulfonic acid group) absorbed by a polymer electrolyte membrane is lower when exposed to water vapor compared to liquid water. Since proton conductivity is linearly correlated with λ, the lower hydration in vapor-fed operation increases ohmic resistance, leading to performance loss and potential membrane dry-out at higher currents [19].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Challenges

Problem 1: No or Poor Fringe Formation in Interferometer

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| No interference fringes | Incorrect beam path alignment; beams not coherent. | Realign the interferometer. Check laser coherence length. |

| Fringes are blurry | Mechanical vibrations; dirty optics. | Use vibration isolation table. Clean all lenses and mirrors. |

| Fringes are unstable | Unstable laser output; air turbulence in beam paths. | Let laser warm up; enclose beam paths. |

Problem 2: Weak or No Signal in Concentration Measurement

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | Inadequate laser power; low camera sensitivity. | Increase laser power (if sample allows); use a camera with higher quantum efficiency. |

| No measurable concentration field | Electrochemical reaction rate is too slow. | Increase applied current/potential to enhance reaction and concentration gradient. |

| Signal is inconsistent with model | Incorrect cell geometry inducing convection. | Verify electrode orientation; a vertical electrode can induce natural convection [5]. |

Problem 3: Artifacts in Digital Holography Reconstruction

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Salt-and-pepper noise in reconstruction | Speckle noise from coherent laser source. | Apply a median or Gaussian filter during image pre-processing. |

| "Zebra-stripe" patterns | Phase unwrapping errors. | Use a quality-guided or least-squares phase unwrapping algorithm. |

| Slow, drifting background | Thermal drift in the setup. | Control ambient temperature; use a reference hologram for background subtraction. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol: Mapping the Diffusion Layer in an Electrochemical Cell

This protocol details the use of in-line digital holography to visualize the transient concentration field during copper electrodeposition, based on the work of Fang et al. [18].

1. Objective To quantitatively measure the two-dimensional concentration distribution and thickness of the diffusion layer at a Cu electrode interface during galvanostatic electrodeposition.

2. Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function |

|---|---|

| Copper Sulfate (CuSO₄) Solution (0.24 mol dm⁻³) | Electrolyte providing Cu²⁺ ions for electrodeposition. |

| Copper Rod Working Electrode (2 mm diameter) | Surface where electrodeposition and concentration changes occur. |

| Copper Sheet Counter Electrode | Completes the electrical circuit. |

| Saturated Calomel Electrode (SCE) | Provides a stable reference potential. |

| Luggin Capillary | Minimizes ohmic potential drop between working and reference electrodes. |

3. Holographic Setup and Procedure

- Optical Configuration: An in-line holographic setup is used. A laser beam is expanded, collimated, and passed through the electrochemical cell. The beam exiting the cell (the object beam) interferes with the undisturbed part of the beam (the reference beam).

- Data Recording: The resulting holograms are recorded directly by a CCD camera at regular intervals during the electrochemical process.

- Electrochemical Process: A constant current (galvanostatic mode) is applied to the copper working electrode, initiating the reduction of Cu²⁺ ions to metallic copper (Cu²⁺ + 2e⁻ → Cu). This depletes ions at the interface, creating a concentration gradient.

4. Data Processing and Analysis

- Numerical Reconstruction: The recorded digital holograms are reconstructed using the Kirchhoff-Helmholtz transform, which allows the calculation of the complex amplitude of the object wave at any plane [18].

- Phase Extraction: The phase map of the reconstructed wavefront is extracted. The phase difference (Δφ) is directly proportional to the change in the average concentration of the CuSO₄ solution.

- Conversion to Concentration: The relationship is given by:

Δφ = (2π / λ) * L * (dn/dc) * ΔCwhereλis the laser wavelength,Lis the thickness of the electrochemical cell,dn/dcis the refractive index concentration gradient of the solution, andΔCis the concentration change. By knowingdn/dc, the phase map is converted into a quantitative 2D concentration map.

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Comparative Analysis of In-Situ Imaging Techniques

The table below summarizes key parameters for various techniques used to study electrochemical interfaces, highlighting the position of laser interferometry [5].

| Technique | Lateral Spatial & Temporal Resolution | Detection Limit (Concentration Change) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Laser Interferometry/Digital Holography | 0.3–10 μm; 0.01–0.1 s | <10⁻⁴ mol L⁻¹ | Requires optical windows; not species-specific; vibration-sensitive |

| Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) | 50–500 μm; seconds–minutes | 10⁻⁵–10⁻³ mol L⁻¹ | Low spatiotemporal resolution; very expensive instrumentation |

| Raman Spectroscopy | 0.3–10 μm; 0.5–60 s per point | ~10⁻⁶ mol L⁻¹ | Requires Raman-active groups; poor temporal resolution |

| Fluorescence Imaging | 0.2–1 μm; 0.01–0.1 s | 10⁻⁷–10⁻⁶ mol L⁻¹ | Requires fluorescent probes that can perturb the system |

Advanced Applications: Integrating Machine Learning

Machine learning (ML), particularly deep neural networks (DNNs), is emerging as a powerful tool to overcome challenges in digital holography, such as noisy reconstructions from dense particle fields or complex backgrounds. Shao et al. demonstrated a ML approach using a modified U-net architecture that significantly improved particle extraction and 3D localization from holograms [20].

Key ML adaptations for digital holography include:

- U-net with Skip Connections: Effectively uses information spread over large areas of the hologram by combining local and global features.

- Residual Connections: Increase training speed and help avoid local minima.

- Swish Activation Function: Outperforms ReLU for sparse targets (like particle centroids) by keeping more parameters active during training.

This ML-based holography can be extended to analyze complex concentration fields, offering higher speed and accuracy than conventional reconstruction methods, especially in challenging conditions with high noise [20].

Troubleshooting Guide: Operando Bubble Dynamics

This section addresses common issues encountered when using prism-embedded cells and high-frequency impedance for monitoring gas bubble evolution in electrochemical cells.

Q1: The resistance signal from my single-frequency impedance measurement is unstable and noisy. What could be wrong?

A: An unstable signal often originates from an incorrectly identified optimum frequency.

- Potential Cause 1: The selected frequency has a significant phase component, meaning it is still influenced by faradaic processes.

- Solution: Re-calibrate the optimum frequency for your specific electrode and electrolyte conditions. The proper frequency is one where the phase angle is minimized (typically <1 degree), which minimizes contributions from charge transfer and mass transport. This frequency must be determined individually for different electrodes and electrolytic conditions via AC impedance measurements [21].

- Potential Cause 2: External electrical noise or mechanical vibrations.

- Solution: Ensure all cables are properly shielded and the electrochemical cell is placed on a vibration-damping table. Verify that all connections are secure.

Q2: My optical observations of bubble evolution do not correlate well with the electrochemical resistance signal. How can I improve correlation?

A: This discrepancy usually points to a limitation in the optical setup or data interpretation.

- Potential Cause 1: The optical field of view is not representative of the entire electrode area contributing to the electrochemical signal.

- Solution: Ensure the camera is focused on the primary region of bubble activity, typically near the electrode surface. For porous 3D electrodes, the prism-embedded cell design is critical to capture bubbles within the pores. Correlate the signals by using a fast Fourier transform (FFT) of the resistance variation, which can reveal characteristic frequencies of bubble evolution that can be matched to optical sequences [21].

- Potential Cause 2: The current density is too high, creating a froth layer that obscures visual analysis.

- Solution: This is a known limitation of optical methods. The single-frequency impedance technique is particularly valuable here, as it can still provide meaningful data under conditions where optical methods fail [21].

Q3: What does a large amplitude in the dynamic resistance variation indicate?

A: A larger amplitude in the resistance fluctuations indicates more sluggish gas bubble evolution. It points to a larger number of gas bubbles that are slow to grow and detach from the electrode surface, leading to greater blocking of active sites and higher resistance [21].

Troubleshooting Guide: FLIM for Local Concentration Mapping

This section addresses challenges in applying Fluorescence Lifetime Imaging (FLIM) to map local concentrations of species like Ca²⁺ or pH in electrochemical environments.

Q1: My fluorescence lifetime image has a poor signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), making quantification difficult.

A: A poor SNR in FLIM can stem from several factors related to the sample and the instrument.

- Potential Cause 1: The fluorophore concentration is too low, or the excitation intensity is insufficient.

- Solution: Optimize the concentration of the fluorescent dye (e.g., OGB-1 for Ca²⁺). Increase the laser power within limits to avoid photobleaching. Use a high-numerical-aperture (NA) objective to collect more emitted photons [22].

- Potential Cause 2: The sample is scattering or has high background fluorescence (autofluorescence).

- Solution: Use two-photon excitation (TPE) combined with non-descanned detection (NDD) for deeper tissue imaging and to reduce out-of-focus background [22]. Choose fluorophores with longer wavelengths to minimize scattering.

- Potential Cause 3: Insufficient photon counts for statistically robust lifetime fitting.

- Solution: Increase the acquisition time per pixel or frame. For dynamic processes, this may require a balance between temporal resolution and accuracy.

Q2: How can I be sure that a change in fluorescence lifetime is due to a specific ion concentration (e.g., Ca²⁺) and not other factors?

A: This is a critical consideration for reliable quantitative mapping.

- Potential Cause: The fluorescence lifetime is sensitive to multiple environmental parameters, including pH, temperature, viscosity, and the presence of other quenchers [22] [23].

- Solution:

- Use a Robust Sensor Dye: Select a dye whose lifetime is known to be highly specific to your target analyte. For example, Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1) is well-characterized for Ca²⁺ mapping because its lifetime is highly sensitive to nanomolar [Ca²⁺] but largely independent of physiological changes in pH, Mg²⁺, Zn²⁺, temperature, and micro-viscosity [22].

- Perform a Calibration: Create an in-situ calibration curve that directly correlates the measured fluorescence lifetime to the [Ca²⁺] value under controlled conditions matching your experiment [22].

- Leverage FLIM's Advantage: Remember that unlike intensity-based measurements, the lifetime is independent of dye concentration, photobleaching, and excitation intensity fluctuations, making it a more robust parameter for quantification [22] [23].

- Solution:

Q3: The FLIM acquisition is too slow to capture rapid changes in local concentration during my experiment.

A: Traditional FLIM based on time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) can be slow.

- Solution: Investigate faster imaging procedures. Some FLIM methodologies allow for the calculation of images where a specific decay time is suppressed, enabling rapid visualization of regions with distinct lifetimes without full lifetime fitting at every time point [23]. Alternatively, optimize your acquisition parameters (e.g., pixel dwell time, image size) for a better speed-accuracy trade-off.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why is monitoring gas bubble evolution and local concentration important in electrochemical research? A: Efficient mass transport is often the rate-limiting step in electrochemical processes. Gas bubbles adhering to electrodes can block active sites, increasing overpotential and causing energy losses of up to 40% in industrial water electrolysis [21]. Similarly, mapping local concentrations of reactants or products is crucial for understanding and mitigating concentration overpotentials and optimizing reactor design [22] [23].

Q2: What is the main advantage of using single-frequency impedance over optical methods for bubble monitoring? A: Its primary advantage is the ability to function in non-transparent industrial electrolyzers and at high current densities where optical methods become impractical due to frothing or the cell's opaque construction [21].

Q3: What makes FLIM superior to intensity-based fluorescence measurements for concentration mapping? A: FLIM's contrast is based on the fluorescence lifetime, which is independent of the fluorophore concentration, excitation intensity, photobleaching, and sample thickness. This makes it a much more robust and quantitative technique for functional imaging compared to intensity-based methods, which can be affected by all these factors [22] [23].

Q4: Are there other methods to enhance mass transport in electrochemical flow cells? A: Yes, recent research focuses on innovative flow field designs. For instance, 3D-printed biomimetic channels inspired by natural patterns (e.g., river meanders) can enhance the mass transfer coefficient by inducing chaotic movement, with one study reporting a performance enhancement by a factor of 1.9 compared to a standard rectangular channel [24]. Another approach uses a cost-effective 3D-printed diaphragm pulsator to create sinusoidal pulsating flow, which doubled the mass transport coefficient in a test cell [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below details key materials and their functions for the experiments discussed.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item | Function / Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oregon Green BAPTA-1 (OGB-1) | Fluorescent Ca²⁺ indicator for FLIM. Its lifetime is sensitive to nanomolar [Ca²⁺] [22]. | Preferred for its specificity; lifetime is largely unaffected by pH, temperature, and viscosity changes [22]. |

| Hetero-hierarchical Ni(OH)₂@N-NiC/NF Catalyst | Advanced bifunctional electrode for water splitting. Used to study optimized gas bubble evolution [21]. | Exhibits superaerophobicity and anisotropic morphology, leading to minimal bubble size and ultrafast release rate [21]. |

| Biomimetic Flow Field | 3D-printed flow channel for electrochemical cells to enhance mass transfer [24]. | Design based on space-filling curves from differential growth (e.g., river meanders). Increases performance by promoting chaotic flow [24]. |

| Diaphragm Pulsator | A 3D-printed device to generate pulsating electrolyte flow [25]. | Cost-effective (~€500). Enhances mass transport via adjustable, sinusoidal pulsation, controlled by an Arduino microcontroller [25]. |

| Phase-Sensitive Image Intensifier | Core component of a FLIM setup for gain modulation at high frequencies [23]. | Acts as a 2D phase-sensitive detector to capture lifetime information from all pixels simultaneously. |

Protocol: Operando Monitoring of Gas Bubble Evolution

- System Setup: Configure a standard three-electrode electrochemical cell. For optical correlation, use a prism-embedded cell coupled with a high-speed/resolution camera.

- Determine Optimum Frequency: Before the gas evolution reaction, run an AC impedance measurement (EIS) at the relevant operating potential. From the phase-frequency spectrum, identify the frequency where the phase angle is minimized (<1 degree) [21].

- Operando Measurement: Apply the desired current/potential for water splitting. Simultaneously, record the impedance at the single optimum frequency over time and capture optical videos of the electrode surface.

- Data Analysis: Analyze the dynamic resistance (R) variation. The amplitude of fluctuation correlates with bubble coverage and evolution speed. Use FFT on the resistance data to identify characteristic frequencies. Correlate with optical data via image processing to link specific resistance events to bubble nucleation, growth, and detachment [21].

Protocol: FLIM for Mapping Local Ca²⁺ Concentrations

- Sample Preparation: Load the system (e.g., neurons, astroglia, or an electrochemical boundary layer model) with the OGB-1 dye [22].

- Calibration: Create a calibration curve by measuring the fluorescence lifetime of OGB-1 in solutions with known [Ca²⁺] under controlled conditions (pH, temperature) [22].

- FLIM Acquisition: Use a confocal microscope upgraded with a FLIM kit. Excite the sample with a pulsed laser (e.g., two-photon at 800 nm). Detect emitted photons with a single-photon-sensitive detector (e.g., SPAD). The TCSPC unit records the time between excitation pulses and photon arrival [22].

- Lifetime Calculation: For each pixel, build a histogram of photon arrival times. Fit the decay curve to extract the fluorescence lifetime.

- Concentration Mapping: Convert the lifetime image into a [Ca²⁺] map using the pre-established calibration curve [22].

Table 2: Quantitative Data Summary for Mass Transfer Enhancement

| Method / Parameter | Key Quantitative Result | Context & Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Frequency Impedance | Measures dynamic resistance (R) variation correlated to bubble coverage [21]. | A bigger amplitude indicates sluggish bubble evolution and greater active site blocking. |

| 3D-Printed Biomimetic Channels | Mass transfer enhancement factor of 1.9 vs. rectangular channel [24]. | Induces chaotic advection to overcome diffusion limitations in flow cells. |

| 3D-Printed Diaphragm Pulsator | Increased mass transport coefficient from 2.3 × 10⁻³ cm/s (constant flow) to 4.5 × 10⁻³ cm/s [25]. | Provides a low-cost method to enhance transport via programmable sinusoidal pulsation. |

| Bubble-Induced Energy Loss | Up to 40% efficiency loss in industrial water electrolysis [21]. | Highlights the critical importance of effective bubble management. |

Workflow and System Diagrams

FLIM System Configuration for Electrochemical Mapping

Operando Bubble Monitoring Workflow

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the primary advantages of using a 3D-printed milli-fluidic device with an integrated channel band electrode over a traditional setup?

A1: 3D-printed milli-fluidic electrochemical devices offer several key advantages [17] [26]:

- Controllable Mass Transport: Mass transport is well-defined and can be controlled over a wide range of flow rates under laminar flow conditions.

- Integrated Fabrication: Devices, including electrodes and channels, can be fabricated in a single platform using a "print–pause–print" methodology, eliminating complex assembly.

- Design Flexibility: Additive manufacturing allows for rapid prototyping and the creation of complex, customized three-dimensional architectures that are difficult to achieve with conventional methods like soft lithography or micromachining.

- Reduced Cost and Time: They avoid the need for cleanroom facilities and expensive processes such as photolithography and sputtering, making them more accessible.

- Minimal Sample Consumption: The layout allows for the use of small amounts of samples and reagents during operation.

Q2: My 3D-printed electrode is producing unstable and low current signals. What could be the cause and how can I fix it?

A2: Unstable and low currents are commonly linked to poor electrode activation or inherent structural properties. Here is a troubleshooting guide:

- Cause 1: Inadequate Electrode Activation. The as-printed conductive polymer (e.g., CNT/CB/PLA) surface may be covered with a thin, non-conductive polymer layer.

- Solution: Implement a post-printing activation process. This involves [17]:

- Mechanical Polishing: Gently polish the in-channel electrode surface with fine-grit sandpaper or alumina slurry to expose the conductive fillers.

- In-channel Electrochemical Treatment: Perform cyclic voltammetry in a suitable electrolyte (e.g., 0.1 M PBS) to further clean and activate the electrode surface electrochemically.

- Solution: Implement a post-printing activation process. This involves [17]:

- Cause 2: Electrode Porosity and Geometry. The Fused Deposition Modeling (FDM) printing process can create porous electrodes with non-flat (bumped, inlaid, recessed) geometries, which disrupts uniform mass transport and the expected current response [17].

- Solution: Account for this in your data analysis. Use adjusted theoretical models, like the modified Levich equation, that incorporate non-flat electrode geometries. Bumped electrodes generally provide better current yield [17].

Q3: How does device porosity, inherent to FDM 3D printing, affect my electrochemical measurements, and can it be beneficial?

A3: Porosity has a significant and dual-natured impact [17]:

- Challenge: Porosity can create inner microchannels, leading to non-uniform mass transport. This can cause different mass transport regimes (diffusion, transition, and convection) to emerge simultaneously within the same device, complicating data prediction and interpretation.

- Opportunity: Porosity can be harnessed to create localized transport channels. These micro-features can enhance mass transport in specific regions of the electrode, potentially increasing sensitivity or creating unique electrochemical environments.

- Recommendation: Use computational simulations and the newly developed transition-specific analytical models to understand and predict current responses under these complex conditions [17].

Q4: What are "localized transport channels" and how can I design them into my 3D-printed device?

A4: Localized transport channels are micro-scale pathways or structures engineered into the electrode or its immediate vicinity to direct and enhance the flow of electroactive species to specific active sites. They are a key strategy to mitigate mass transport limitations [27].

- Design Principle: The goal is to create a porous network or defined microstructures within the catalyst layer that facilitate the efficient delivery of reactants (e.g., oxygen) to the electrode surface.

- Implementation in 3D Printing: You can design these features directly into your CAD model before printing. For example, you can create:

- A micro-lattice or mesh structure within the electrode volume.

- Strategically placed micro-pillars or channels adjacent to the electrode.

- A graded porosity structure that becomes denser near the electrode surface. Experimental and numerical efforts are ongoing to optimize these structures for specific applications, such as fuel cells and sensors [27].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Poor Electrode Performance in 3D-Printed Devices

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Low and unstable current signal | Non-conductive surface layer from printing | Perform mechanical polishing and in-channel electrochemical activation [17] |

| Current response deviates from theory | Electrode porosity and non-ideal geometry | Use computational models adjusted for FDM electrode shapes; consider using a bumped electrode geometry [17] |

| High background noise | Contaminated electrode surface | Clean the device with deionized water and repeat the electrochemical activation protocol |

| Signal drift over time | Partial clogging or adsorption in porous channels | Flush the channel with a strong solvent or acid/base (compatible with the device material) |

Guide 2: Addressing Mass Transport and Flow-Related Issues

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Unpredictable current at different flow rates | Simultaneous diffusion/convection regimes due to porosity | Apply the "transition-specific" analytical model for data analysis; run simulations to understand device-specific behavior [17] |

| Low limiting current | Inefficient mass transport to electrode surface | Redesign device to include localized transport channels (e.g., porous meshes or micro-lattices); increase flow rate [27] |

| Bubbles trapped in channel | Device porosity allowing gas permeation or degassing | Pre-degas solutions; apply a brief back-pressure if possible; consider sealing the external device walls |

Experimental Protocol: Fabrication and Activation of a 3D-Printed Milli-Fluidic Electrochemical Device

This protocol details the "print–pause–print" methodology for creating a functional device with integrated band electrodes [17].

Objective: To fabricate and activate a 3D-printed milli-fluidic device with working, counter, and reference channel band electrodes.

Materials and Reagents:

- Conductive Filament: CNT/CB/PLA (e.g., LATIOHM B61-01, 1.75 mm diameter).

- Insulating Filament: Clear PLA (1.75 mm diameter).

- 3D Printer: FDM desktop printer (e.g., UP mini 2).

- 3D Pen: For electrode integration.

- Electrolyte: 100 mM Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4, containing 100 mM KCl.

- Reference Electrode Material: Ag/AgCl paste.

- Polishing Supplies: Fine-grit sandpaper (e.g., P1000-P2000) or alumina powder (0.3 µm and 0.05 µm).

Procedure:

- Device Design: Create a CAD model of your fluidic channel and the electrode layout. The model should be split into parts to allow for electrode insertion.

- Print Base Layer: Use the clear PLA filament to print the bottom part of the fluidic channel.

- Pause Printing and Insert Electrodes: When the printer reaches the layer where electrodes are to be placed, pause the print.

- Use the 3D pen loaded with the conductive CNT/CB/PLA filament to draw the working and counter electrodes directly onto the printed base layer.

- Apply the Ag/AgCl paste to form the pseudo-reference electrode.

- Resume Printing: Continue the printing process with clear PLA to encapsulate the electrodes and complete the channel structure. This results in a fully integrated device.

- Electrode Activation:

- Mechanical Polishing: Gently polish the in-channel electrode surfaces using fine-grit sandpaper or alumina slurry to remove the outer non-conductive polymer layer and expose the conductive CNT/CB network. Rinse thoroughly with deionized water.

- Electrochemical Treatment: Connect the device to a potentiostat. Fill the channel with the PBS electrolyte. Perform cyclic voltammetry (e.g., from -0.5 V to +0.8 V vs. the Ag/AgCl reference at a scan rate of 100 mV/s) for 20-50 cycles until a stable voltammogram is obtained.

Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| CNT/CB/PLA Conductive Filament | Serves as the material for fabricating working and counter electrodes directly within the 3D-printed device [17] |

| Clear PLA Filament | Forms the insulating, structural body of the milli-fluidic device, providing channels and reservoirs [17] |

| Ag/AgCl Paste | Used to create a stable and easily integrated pseudo-reference electrode within the printed device [17] |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) with KCl | A standard electrolyte solution for electrochemical experiments; the KCl provides a high concentration of Cl⁻ ions necessary for the stability of the Ag/AgCl reference electrode [17] |

Table 1: Mass Transport Regimes and Current Models in 3D-Printed Milli-Fluidic Electrodes

| Mass Transport Regime | Key Characteristics | Applicable Current Model |

|---|---|---|

| Convective Regime | High flow rate; current is limited by the rate of reactant delivery to the electrode via bulk flow. | Adjusted Levich Model (accounts for non-flat electrode geometry) [17] |

| Diffusive Regime | Low or no flow; current is limited by the diffusion of reactant through a stagnant layer to the electrode surface. | Fick's Law of Diffusion |

| Transition Regime | Intermediate flow rate; a mix of diffusion and convection controls the current. Often observed in porous FDM structures. | New Transition-Specific Analytical Model (accounts for simultaneous regimes) [17] |

Table 2: Comparison of Electrode Integration Methods in 3D-Printed Fluidics

| Fabrication Method | Key Advantage | Key Challenge |

|---|---|---|

| Print-Pause-Print [17] | Single-step, integrated fabrication of electrodes and channels; strong mechanical integration. | Requires precise printer control; risk of layer misalignment upon resumption. |

| Post-printing Insertion [26] | Allows use of conventional electrodes (e.g., wires, foils); material choice is independent of printability. | Requires sealing to prevent leaks; more complex assembly. |

| Direct Ink Writing | Can print a wider variety of conductive inks (e.g., metals, polymers). | Often requires multi-material printers or post-printing sintering/curing. |

Diagrams and Workflows

Device Fabrication Workflow

Mass Transport in Porous Electrode

FAQs: Troubleshooting Mass Transport in Advanced Reactors

Microfluidic Reactor Systems

Q1: My mixing efficiency in microfluidic droplets is poor, leading to inconsistent reaction yields. How can I improve this?

Poor mixing in microdroplets is a common challenge due to the laminar flow conditions (low Reynolds number) inherent in microfluidic systems [28]. This results in reliance on slow diffusive mixing [28].

- Problem: Laminar flow and high Peclet number limit mixing to diffusion [29] [28].

- Solution: Implement active mixing via Parametric Droplet Oscillation [29].

- Protocol: After droplet coalescence, apply an AC voltage with a driving frequency roughly twice the droplet's natural resonance frequency. This induces shape oscillations that generate internal convective vortices, significantly accelerating mixing [29].

- Key Parameters: Monitor the mixing index fluctuation; an oscillatory pattern indicates successful induction of chaotic convection [29].

Q2: The target recruitment and selectivity in my microfluidic biosensor are lower than expected.

This issue often arises from sluggish mass transport to the sensor interface, which blurs the distinction between specific and non-specific binding [30].

- Problem: Mass transport is the rate-limiting step for high-affinity binding, and low flux reduces both sensitivity and selectivity [30].

- Solution: Leverage Microfluidic Confinement to enhance flux [30].

- Protocol: Use a 3D-printed microfluidic cell with a confined channel height. Reduce the channel height according to the Levich equation (Jchannel ∝ V_f / (A * h)^(2/3)), which dramatically increases the mass transport coefficient (kLev) [30].

- Key Parameters: A reduction from a 1000 µm to a 20 µm channel height has been shown to boost target response magnitude by 600% and selectivity by 300% in a reagentless format [30].

Hollow Fiber Membrane Contactor (HFMC) Systems

Q3: The CO2 capture efficiency of my HFMC system has degraded rapidly over time.

A sharp decline in performance is typically caused by membrane wetting and fouling, which drastically increase mass transfer resistance [31] [32] [33].

- Problem: Pores become flooded with liquid absorbent, and foulants accumulate on the membrane surface [33].

- Solution: Utilize Superhydrophobic Hollow Fiber Membranes [33].

- Protocol: Employ a hollow fiber membrane with a superhydrophobic surface modification (e.g., mimicking lotus leaf structures). This creates a high contact angle and stable Cassie-Baxter state, preventing pore penetration and fouling [33].

- Key Parameters: Compare the performance of commercial polypropylene (PP) or polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) membranes with an in-house developed, highly porous PVDF membrane with silane-based surface modification. The modified PVDF membrane maintains stable CO2 flux and operates close to the theoretical non-wetted mode during long-term operation [33].

Q4: How do I select the right membrane and model transport for my HFMC application?

Choosing an inappropriate membrane or oversimplifying the transport model leads to inaccurate performance predictions and suboptimal design [32].

- Problem: Membrane materials have varying wettability, porosity, and chemical stability, which directly impact mass transfer and longevity. A 1D model may be insufficient for capturing complex flow and concentration fields [32] [34].

- Solution:

- Material Selection: For carbon capture with chemical solvents, prioritize superhydrophobic materials (e.g., surface-modified PVDF) to minimize wetting. Consider commercial PP for less demanding applications and dense PDMS for scenarios where wetting must be completely avoided, albeit with lower initial flux [33].

- Modeling Approach: Start with a 1D resistance-in-series model for initial design and scaling calculations. For detailed analysis of flow distribution, localized wetting, and concentration gradients, employ 2D/3D porous media models solved using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) [32].

Electrochemical Systems with Complex Electrolytes

Q5: My measured electron transfer kinetics in high-concentration electrolytes are inconsistent with theoretical predictions.

Accurately measuring heterogeneous electron transfer (HET) in high-concentration electrolytes (HCEs) like ionic liquids is complex due to deviations from classical theories [8].

- Problem: HCEs have strong interionic interactions, ion pair formation, and unique solvation structures that affect mass transport and the double layer. Existing models often fall short [8].

- Solution:

- Calibrate Measurements: Carefully account for ohmic drop (iR drop) and secondary current distribution effects, which can significantly distort kinetic measurements in HCEs [8].

- Use Advanced Techniques: Employ scanning electrochemical microscopy (SECM) to directly probe HET kinetics at the electrode-HCE interface, as conventional methods may be inadequate [8].

- Validate Diffusion Coefficients: Do not assume the Stokes-Einstein relationship holds. Measure diffusion coefficients experimentally in the specific HCE being used, as they are critical for calculating the HET rate constant (k⁰) [8].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Microfluidic Mixing and Biosensing

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Performance Metric to Monitor |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low mixing efficiency in droplets | Pure diffusive mixing at high Peclet number [29] [28] | Actuate parametric oscillation with AC voltage at ~2ƒ₀ [29] | Mixing index fluctuation and vorticity magnitude [29] |

| Slow target binding in biosensor | Mass transport-limited recruitment to the surface [30] | Reduce microfluidic channel height to increase flux [30] | Binding association rate (kon,obs); Target response magnitude [30] |

| High non-specific background signal | Low selectivity due to sluggish specific binding kinetics [30] | Enhance convective flux to favor specific over non-specific binding [30] | Selectivity ratio (∂SA/∂t / ∂SI/∂t) [30] |

Table 2: Troubleshooting Hollow Fiber Membrane Contactors

| Observed Problem | Potential Root Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Performance Metric to Monitor |

|---|---|---|---|